- Food & Drink

latest posts

A New Culinary Experience at Side Project Brewing: Elevated Bar Fare Meets World-Class Beer

Why Understanding Your Preferences Is Crucial in Travel Planning

Traveling is an exhilarating and enriching experience that allows people to explore new places, cultures, and cuisines. Whether you’re planning a weekend getaway or a month-long adventure, every journey begins with a choice – where to go. However, while the destination is undoubtedly important, it’s equally crucial to understand your preferences when planning your trip. Your travel preferences can significantly impact the overall experience, from the activities you engage in to the memories you create. This article explores why understanding your choices is crucial in travel planning and how it can elevate your adventures.

The Importance of Personalization

Minimizing stress.

Travel can be stressful, especially when faced with unfamiliar environments, languages, and customs. However, knowing your preferences can serve as a powerful stress-reduction tool. For instance, if you’re an introvert, choosing a more secluded destination or accommodations can provide much-needed solitude and tranquility. On the other hand, extroverts may thrive in bustling urban areas with plenty of social interactions. Theme parks like Universal Studios and tourist attractions may delight some travelers, while others might find them overwhelming. For the former, get tickets for Universal Studios early and plan your visit during off-peak hours to enjoy shorter lines and a more relaxed experience. You can minimize stress and enhance your overall well-being by aligning your preferences with your travel choices.

Maximizing Enjoyment

Imagine embarking on a hiking expedition when you despise the outdoors or planning a culinary tour when you’re a picky eater. In both scenarios, the likelihood of enjoying your trip decreases significantly. Understanding your preferences allows you to avoid pitfalls and select activities that genuinely pique your interest. This ensures a higher level of enjoyment and minimizes the risk of disappointment or frustration.

The Impact on Accommodation

Budget vs. luxury.

Budget constraints often play a significant role in travel decisions. Understanding your financial preferences is essential to strike the right balance between affordability and comfort. If you’re a budget-conscious traveler, you may opt for hostels, guesthouses, or Airbnb rentals . Conversely, if you prefer luxury and pampering, boutique hotels or upscale resorts might be more your style. Acknowledging your financial preferences allows you to find accommodations that fit your budget without compromising quality.

Location Matters

The location of your accommodation can shape your entire trip. Do you prefer staying in the heart of the action, within walking distance of popular attractions, or in a quieter, residential neighborhood? Your choice can impact your daily routine and overall experience. If you value convenience and accessibility, a central location might be ideal. However, a less touristy area could be more appealing if you seek tranquility and authenticity.

Planning for Travel Companions

Communication and compromise.

Effective communication and compromise are essential when traveling with others. Understanding their preferences and finding common ground can prevent conflicts and enhance the overall experience. Discuss your travel goals, interests, and expectations beforehand to create a well-rounded itinerary that accommodates everyone’s preferences.

Balance in Activities

Each member likely has different preferences and interests if you’re traveling with a group. Strive for balance in your activities and create an itinerary that includes a variety of experiences. This way, everyone can indulge in their favorite activities while exploring new interests.

Flexibility

Flexibility is crucial when traveling with companions. Sometimes, you may need to adjust your plans or make spontaneous decisions to accommodate the preferences of others. You can make the most of your collective travel experience by embracing flexibility and a spirit of adventure.

Enhancing Your Travel Memories

Authentic Experiences

Choosing activities and destinations that resonate with your preferences makes you more likely to have authentic and meaningful experiences. These experiences include interacting with locals, immersing yourself in the culture, and discovering hidden gems that align with your interests.

Personal Growth

Traveling in line with your preferences can also foster personal growth. It encourages you to step out of your comfort zone , try new things, and embrace different perspectives. Whether conquering fear, learning a new skill, or gaining a deeper appreciation for a specific culture, travel can transform and enrich your life.

Lasting Impressions

The memories you create during your travels are the souvenirs that stay with you long after you return home. By understanding your preferences and planning a trip that caters to them, you’re more likely to create lasting impressions you’ll cherish forever.

In travel planning, understanding your preferences is not a luxury but a necessity. It’s the compass that guides you to destinations and experiences that resonate with your individuality. By aligning your travel choices with your preferences, you maximize enjoyment, minimize stress, and create memories that are uniquely yours. So, the next time you embark on a journey, take the time to reflect on your preferences and let them lead you on a path of discovery and fulfillment. Travel is not just about the destination; it’s about the journey, and understanding your preferences ensures that every step of that journey is tailored to your desires and dreams.

you might also like

Exploring Crypto Havens: Countries Steering the Future with Tax Incentives

Strategic Ways to Cash Out Crypto with Minimal Tax Impact

How to Protect Yourself from SIM Swapping (AT&T)

Travel Preferences: What’s Your Style?

- 21498 Views

- May 4, 2012

Shaping Cultural Experiences

Share this:.

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- 14033 Views

- May 10, 2012

Update & BBC News Link

- 16996 Views

- May 11, 2012

From Nigeria to Boston

When you first meet Oluwagbeminiyi Osidipe, you encounter a very vibrant, friendly, and unique personality. Oluwagbeminiyi or Niyi – as she shortened her name for simplicity – was named by her mother, who had a “very personal experience” when she had her, Niyi explained. Niyi is a Yoruba Nigerian transplant who arrived in the U.S. in 2006. As one of the most densely populated (West) African countries, Nigeria derives its name from the river that spans its land. To the South, it borders the Gulf of Guinea to the Atlantic Ocean. Originally colonized by the British, Nigeria gained independence in 1960. Its main ethnic groups are the Hausa, Igbo and Yoruba, who speak English and their own respective languages, while major religions include Islam, Christianity and indigenous beliefs. Niyi shares her story, her views on politics, cultural differences she’s embraced with humor, and what we can learn from each other by expressing curiosity. Her message is simple: travel enriches us through its exposure to new cultures, and enables us to grow.

- May 16, 2012

Mark Twain on Travel

“Travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness, and many of our people need it sorely on these accounts. Broad, wholesome, charitable views of men and things cannot be acquired by vegetating in one little corner of the earth all one’s lifetime.” (American author Mark Twain, Innocents Abroad).

Have you had the opportunity to travel (extensively, within your country, or even once abroad)? Can you relate to Twain’s sentiments? How does travel enrich us?

- 10347 Views

- May 19, 2012

Pleasing The Taste Palate

Food has the wonderful quality of uniting us no matter where we are. There is nothing partisan or narrow-minded about food. It simply invites us to indulge, create recipes, and share with others. Two of my favorite Polish dishes (included in collage) are pierogies and barszcz czerwony – a beetroot soup – served on Christmas Eve in Poland. How does food bring us together? What are some of your favorite dishes and why? Can food trigger memories?

- May 23, 2012

Stereotypes: Truth or Fiction?

- May 29, 2012

Annual Human Rights Report

- May 31, 2012

Euro Crisis & Emerging Stereotypes

- June 4, 2012

Remembering Tiananmen

- 10206 Views

- June 7, 2012

Coffee's Uniting Power

- 14007 Views

- January 28, 2015

- Local Culture

Whether you’re a seasoned traveler, a part-time traveler (like I am), or beginning to explore, travel has something for everyone.

- Maybe you prefer guided tours where you stick with a group and explore historic sites and learn about a country’s culture together.

- Perhaps you can’t wait to travel solo , where you make your own schedule and meet new people along the way.

- Or maybe, you love the idea of an adventure where you push your physical boundaries through hiking, biking and other activities.

- And, then there’s luxury travel with all-inclusive resorts where you get pampered and you can kick back!

- What’s your preferred travel style? (for example: luxury or adventure)? Why?

- Describe your ideal trip and how your travel style fits into that. Got a pic?

- What advice would you share with someone who might be hesitant to explore different travel styles? #CultureTravChat

- Tell us about a time you really pampered yourself during travel. Got a pic? #CultureTravChat

- Have you ever strayed from your favorite travel style to explore a new one? What did you learn? #CultureTravChat

- Ever travel with limited access to electricity or clean water? What’d you enjoy about that trip? Got a pic? #CultureTravChat

- What do different travel styles teach us about ourselves? Do they influence our experiences?

JOIN THE CHAT:

1. Follow @nicolette_o on Twitter for chat announcements/questions. 2. Use #CultureTravChat in each tweet – so others can always read your tips! 3. Invite friends to join, and RT anything you personally find interesting.

- #CultureTravChat

- guided tour

- solo travel

- travel preferences

- travel style

Comments (33)

8 tips for crafting the ultimate surprise getaway for your beloved - senior cruise planning and tips.

[…] conversations where they might have mentioned a love for the beach, mountains, or historical sites. Understanding these preferences is key to planning a trip that they’ll […]

Discovering the Distance: Phnom Penh to Sihanoukville Journey – Home

[…] Enjoy well-appointed rooms, convenient locations, and a host of amenities suitable for various travel preferences. […]

Adding a Saved Traveler on JetBlue: Your Complete Guide – Atlas-blue.com

[…] removing a Saved Traveler is irreversible. Ensure this action aligns with the desired changes in travel preferences or companionship before […]

Secret Getaways: Planning the Ultimate Surprise Getaway for Your Beloved - Savor Our City

[…] aspirations is paramount. By choosing a location that resonates with their soul, you not only honor their preferences but also elevate the overall experience, making it more than just a trip – it becomes a journey […]

Unveiling the California to Phoenix Connection: Understanding Visitor Trends | Cassadaga Hotel

[…] of Californian travelers. Weather conditions, acting as both maestro and muse, wield influence over travel preferences, with the sunlit allure of Phoenix beckoning during the colder months. It’s not merely a […]

How to Change Your Departure Pal: A Comprehensive Guide – AdamsAirMed

[…] of your trip aligns seamlessly. From selecting the ideal departure time to coordinating with your travel preferences, it’s the departure pal that lays the foundation for a hassle-free […]

Discovering the Best Itinerary: How Many Days to Explore Hawaii’s Big Island – Kauai Hawaii

[…] the island’s boundless allure. With an array of recommended itinerary lengths, catering to various travel preferences and interests, you’re poised to traverse this volcanic gem in a manner that resonates with […]

Exploring Groupon: How to Find Deals by Departure City – AdamsAirMed

[…] explore various destinations, accommodations, and experiences. The options are diverse, catering to different travel preferences and […]

Traveling from California to Idaho: A Comprehensive Guide | Cassadaga Hotel

[…] beforehand helps you identify the specific regions, cities, and activities that align with your travel preferences. Whether you’re drawn to the bustling streets of Los Angeles, the serene beauty of Lake […]

Mastering the Art of Scoring Great Deals for Your Departure Flight – AdamsAirMed

[…] the realm of travel planning, a wise journey begins with a comprehensive understanding of your travel preferences. It’s not merely about booking a departure flight; it’s about crafting an experience […]

How Far is Bastrop from Houston? – CityOfLakeway.com

[…] with ease. By leveraging these resources, you can find the best flight options that align with your travel preferences and […]

Exploring Multi-City Packages on Kayak.com – Ozark

[…] emerges with the selection of payment options. Kayak.com recognizes that diversity extends beyond travel preferences, encompassing payment methods as well. The platform accepts a range of options, making it […]

Proximity of Bedford Plaza Hotel to T Line: A Convenient Stay | LexingtonDownTownHotel.com

[…] Alternative Modes of Transportation: A Comparative Glimpse: While the T Line presents an enticing proposition, other modes of transportation offer their own distinct advantages that cater to different travel preferences. […]

Enchanting Amalfi Coast Road Trip: Exploring the Sorento and Portofino Routes – Neveazzurra

[…] the Portofino. We’d like to assist you in determining which direction to take based on your travel preferences. Explore breathtaking landscapes, cultural treasures, and hidden gems that await you if you choose […]

Exploring Paradise: Lake Como vs. Amalfi Coast – Neveazzurra

[…] into the rich cultural tapestries, we unveil a treasure trove of experiences that cater to diverse travel preferences. Prepare to be captivated by the spellbinding geographical beauty and intricate cultural heritage […]

How to Get to Siem Reap from Poipet – Home

[…] this picturesque distance, an array of transportation options awaits, each tailored to suit various travel preferences and budgets. Below, we outline the available modes of transportation, ensuring you’re […]

Journey from Atlantic City to North Bergen: Exploring the Distance and Route – Twin Lights Light House

[…] landscapes, hidden gems, and intriguing possibilities. You can choose the path that best suits your travel preferences, whether you prefer scenic highways or a leisurely ride on public […]

How to Travel from Heathrow to Chipping Campden – Atlas-blue.com

[…] Bus services provide an affordable and convenient alternative for travelers heading from Heathrow to Chipping Campden. Multiple bus companies operate routes between Heathrow Airport and the town, offering a flexible schedule to accommodate different travel preferences. […]

Step-by-Step Guide To Starting A Travel Agency In Denmark: Preparation Legal Requirements And Marketing Strategies – Home

[…] online travel agencies. When it comes to startup markets, you need the right set of opportunities. Travel preferences such as Eco-travel are also popular among visitors, as they prefer to book accommodations and eat […]

Which Is More Southern Cancun Or Honolulu – Kauai Hawaii

[…] Ultimately, the best way to compare the cost of these two destinations is to consider your own travel preferences and […]

The Pros And Cons Of Flying First Class – EclipseAviation.com

[…] only flying a short distance, economy class may be just fine. Finally, consider your own travel preferences. If you prefer to have more space and privacy on a flight, first class may be worth the […]

The Benefits Of Guided Tours: Why A Local Guide Is The Best Way To Experience A New Place – Home

[…] situations. Our team can customize trips to the group’s interests based on the group’s travel preferences and expectations of an active holiday because we understand how important it is for us to enjoy our […]

Island Life Vs Vegas: Which Is More Fun? – Kauai Hawaii

[…] is no definitive answer to this question as everyone’s travel preferences are different. However, most people generally feel that 3-4 days is a sufficient amount of time to […]

Vacation Rentals Vs Hotels – Hotels & Discounts

[…] costs vary greatly around the world. Examine your destination, amenities, and travel preferences. Consider whether Airbnb or a hotel offers a better deal. Travel experts give their recommendations […]

How Many Nights Should You Spend In Hawaii? We Recommend A Minimum Of Five! – Kauai Hawaii

[…] a variety of beautiful accommodations in a variety of Hawaiian Islands cities. You can change your travel preferences, change your destination, or even change your dates. Southwest Vacations offers free nights and […]

5 Tips For Solo Travelers In Cambodia – Home

[…] is no one definitive answer to this question, as everyone’s travel preferences and interests will differ. However, some suggested Cambodia solo travel itineraries could include […]

Tickets Can Be Booked In Advance Online Or Through A Travel Agent The Different Ways To Travel From Bangkok To Cambodia – Home

[…] There are a few different ways to travel from Bangkok to Cambodia, depending on your budget and travel preferences. The most popular way to travel from Bangkok to Cambodia is by bus. The journey takes around eight […]

The Distance Between Iceland And Texas – CityOfLakeway.com

[…] airlines offering direct flights between the two locations. However, depending on your budget and travel preferences, there are also a number of other options available, including travelling by boat or by […]

How Far In Advance To Book Hawaii Flight – Kauai Hawaii

[…] If you plan to visit Hawaii, there are several ways to get there, depending on your budget and travel preferences. Most economy class flights between the United States and Honolulu cost between $500 and $800 round […]

Oooh I’m really looking forward to this one! See you there!

Thanks for sharing! Excited to have you and hear about your experiences! 🙂

I love making my own itineraries so I will never do a full guided tour of a country! Solo (or with a companion) traveler all the way!

Thanks for sharing! I’m with you on that, but curious to hear more from fellow travelers. Will you be joining tomorrow? 🙂

Let us know what you think Cancel reply

- 8 Tips for Crafting the Ultimate Surprise Getaway for Your Beloved - Senior Cruise Planning and Tips on Travel Preferences: What’s Your Style?

- Discovering the Distance: Phnom Penh to Sihanoukville Journey – Home on Travel Preferences: What’s Your Style?

- Adding a Saved Traveler on JetBlue: Your Complete Guide – Atlas-blue.com on Travel Preferences: What’s Your Style?

- Secret Getaways: Planning the Ultimate Surprise Getaway for Your Beloved - Savor Our City on Travel Preferences: What’s Your Style?

- Learning a New Language: Before or After Travel? - Culture With Travel on How to Meaningfully Immerse Yourself

- Traveling off the beaten path in Cuba

- Four Tips for Building a Cross-Cultural Family

- David Hoffmann Interview – CultureTrav

- 5 Things I Wish I’d Known About Being A Digital Nomad

- Trip to Australia: Expect the Unexpected

Join Us On Facebook!

Enter your email address to subscribe to the blog and get new posts!

Email Address

- Get IGI Global News

- Language: English

- All Products

- Book Chapters

- Journal Articles

- Video Lessons

- Teaching Cases

Shortly You Will Be Redirected to Our Partner eContent Pro's Website

eContent Pro powers all IGI Global Author Services. From this website, you will be able to receive your 25% discount (automatically applied at checkout), receive a free quote, place an order, and retrieve your final documents .

What is Travel Preferences

Related Books View All Books

Related Journals View All Journals

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Complexity and simplification in understanding travel preferences among tourists.

- 1 Norwegian School of Hotel Management, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Stavanger, Stavanger, Norway

- 2 Department of Psychosocial Science, Faculty of Psychology, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway

Travel preferences are complex phenomena, and thus cumbersome to deal with in full width in diagnostic and strategic planning processes. The aim of the present investigation was to explore to what extent individual preferences can be simplified into structures, and if tourists can be grouped into preference clusters that are viable and practically applicable for tourism planning. Building on prior studies that have validated survey instruments designed to measure different tourist role orientations, we used a factor analytical approach to develop a simplified structure of individual preferences, and a standard clustering technique for grouping tourists into preference clusters. Further analyses indicated that preference clusters based on reduced factor preference-data are to some extent related to context-specific valuations, perceptions, and revisit intentions; however, the magnitude of differences between groups was rather small. Overall findings provide reason to suggest that the identified preference clusters are insufficient when it comes to explaining variability in which aspects tourists emphasize as part of their vacation. Possible managerial implications and methodological limitations of the present investigation are noted.

Introduction

A fundamental need for any business or public planning in the tourism sector is to map heterogeneity among people ( Dolnicar, 2008 ) and to understand the psychological processes involved in the construction of the tourist experience ( Larsen, 2007 ). Products and services offered within the sector are complex and individual preferences may comprise one or more of the following elements: nature, culture, food, activities, social interaction etc. The experiences of a destination will comprise an even more complicated process involving both elements that a person has preferences for, and numerous additional expected and unexpected exposures to elements that may be important for the total experience. Planners and managers in the tourism industry who are eager to make evidence-based decisions may therefore benefit from searching, surveying, incorporating, synthesizing, and presenting such information; for a more broad discussion on opportunities for tourism marketing research, see Dolnicar and Ring (2014) .

While information about preferences can be available from public source materials, such as the number of tourists visiting a specific destination at a given moment in time, further information that is more detailed can be collected and then be evaluated by the tourism industry itself. For this purpose, there have been numerous market segmentation studies to suggest a wide range of objective and subjective measures aimed at categorizing individuals into groups ( Díaz-Martín et al., 2000 ; Frochot and Morrison, 2000 ). The groups developed in these studies more often than not were data-driven, and in spite of them producing adequate segmentation of specific groups in particular contexts and at a given point in time, the resulting segments were less comparable across studies; thus, limiting cumulative knowledge development. And even though these studies quite often were able to simplify the data-structure, the obtained structure was typically not standard and transferable across studies, and the stability of the segments was not a major concern ( Dolnicar, 2008 ).

An inspection of the existing literature suggests that efforts to simplify and structure data addressing preference heterogeneity in tourism settings have progressed along different lines. Some studies have focused on simplifying the structure of the data by reducing its complexity through collapsing the number of independent elements into broader categories (e.g., Mo et al., 1993 ; Jiang et al., 2000 ; Gnoth and Zins, 2010 ), whereas other studies have attempted to group together travelers based on homogeneity alongside individual preferences (e.g., Yiannakis and Gibson, 1992 ; Gibson and Yiannakis, 2002 ). The empirical investigation reported as part of this paper sequentially addresses both of the aforementioned approaches. We first simplify the data structure of the preference-data through a factor analytic approach, and then group the tourists into clusters based on the simplified preference-data. These procedures are followed by a validation of the clusters by evaluating if they are useful for explaining context-related valuations, perceptions, and revisit intentions; for reviews on psychological and sociological approaches to understanding travel motivations, see Heitmann (2011) and Dann (2018) .

One of the first attempts to describe and categorize tourists stems from Cohen (e.g., 1972) who distinguished four types based on their relationship with the tourism industry and the host country. 1 On one hand, there are individuals who engage in institutionalized arrangements that have a strong need for familiarity, low interest for adventures, and little contact with local culture or hosts (described as the “organized mass tourist”), whereas others in this category are less rigid insofar that they allow some greater room for personal choice (described as the “individual mass tourist”). On the other hand, there are individuals traveling independently that restrict any meeting with the industry unless unavoidable (described as the “explorer”), and those who refuse contact with the industry altogether, put as much distance between themselves and their familiar home environment as possible, and become part of the host culture (described as the “drifter”). It is the extent by which individuals seek to move away from their familiar (social and cultural) environment that shapes their relationship with the tourism industry ( Cohen, 1972 ) and their respective mode of experience ( Cohen, 1979 ). While there is empirical evidence to support the view that tourists can be clustered according to the aforementioned types ( Snepenger, 1987 ), some scholars argued that these are merely examples of an even larger number of possible roles individuals can take on when traveling for leisure purposes ( Yiannakis and Gibson, 1992 ).

The International Tourist Role Scale (ITR; Mo et al., 1993 ) operationalizes the abovementioned taxonomy by distinguishing individuals based on their preferences on a novelty-familiarity continuum. The scale comprises of 20 items that aim at measuring one of three distinct dimensions used to differentiate tourists in an international context. One so-called “destination-oriented” dimension that measures the degree to which tourists prefer novel versus familiar holiday destinations. Another so-called “travel services” dimension that attempts to measure the degree to which tourists prefer institutionalized arrangements at their holiday destination. As well as an additional so-called “social contact” dimension, that seeks to assess the degree to which tourists prefer contact with local residents at their holiday destination. Previous research has reported empirical evidence in favor of a three-dimensional structure proposed by the original 20-item version ( Mo et al., 1994 ) as well as by a revised 16-item version ( Jiang et al., 2000 ).

With the above studies having focused upon confirming the psychometric properties of the ITR scale, others have demonstrated its predictive validity in explaining aspects of the tourist experience. For example, Wolff and Larsen (2019) showed that people who prefer traveling to familiar rather than unfamiliar destinations tend to be less likely to show an interest in trying out new food. The same study found that people who like better to avoid institutionalized forms of tourism were on average more interested in trying out new food than those favoring the opposite; the same applied to those who prefer seeking out social encounters with local people and culture. Others studies indicate that individual differences on one or more of the dimensions outlined by the ITR scale can be associated with social interactions experienced by guests ( Basala and Klenosky, 2001 ), risk perceptions about international tourism ( Lepp and Gibson, 2003 ), importance ascribed to vacation activities ( Keng and Cheng, 1999 ), and preferred social contacts with hosts ( Fan et al., 2017 ). Further research suggests that the degree to which individuals emphasize either one of the proposed dimensions can vary as a function of cultural values ( Gnoth and Zins, 2010 ).

Research Aims

Previous studies attempting to validate theoretically developed tourist typologies have employed different methods including quantitative approaches (e.g., Mo et al., 1993 ) as well as qualitative approaches (e.g., Uriely et al., 2002 ). The present paper draws upon the idea that tourists differ in their preferences, and that considering these differences can yield useful information for planners and managers in the tourism industry. Consequently, the following section reports on an empirical investigation that set out to explore the relationship between travel preferences, destination valuations, destination perceptions, and revisit intentions. Research on these aspects can provide useful insights for at least two reasons: to gain some better understanding about what tourists search for in their vacation and to provide some guidance for those interested in developing products and services that address these preferences at a given destination.

Materials and Methods

Participants.

The analyzed data comprises the responses from N = 2041 individuals who were visiting Western Norway during the summer months. Norway as a holiday destination tends to attract visitors from abroad who seek to experience both nature and culture, preferably in combination ( Innovation Norway, 2018 ). Participants were between 18 and 82 years ( M age = 37.06, SD age = 14.88), were on trips that lasted between 1 day and more than 2 years ( Mdn days = 12), and the most prevalent day for filling in the questionnaire was at day five during their current trip ( Mdn days = 5). They differed in a variety of different ways including their gender (47.8% men, 52.0% female), accommodation (camping facility 15.0%, private pension 12.7%, HI hostel 10.8%, hotel 28.3%, cruise ship 8.7%, not specified 22.6%), continent (Europe 67.6%, North America 12.8%, South America 2.3%, Oceania 5.0%, Asia 7.5%, Africa 0.7%), and tourism type (international 94.9%, domestic 3.8%). 2

To recruit participants, research assistants first approached potential participants at well-known sightseeing spots, either in person or in groups, accompanied by the question of whether they are on vacation. In a second step, research assistants invited them to participate in a study on tourist experiences granted that they affirmed positive to the prior questions. A written statement on the questionnaire informed participants that there are no right (or wrong) answers, and that each of the answers would be handled confidentially. Informed consent was implied by the completion of the questionnaire.

Each participant responded to a survey distributed as part of a larger research project investigating various aspects of the tourist experience (paper questionnaire, four pages long, English language). Items included in the survey focused upon a broad range of topics relevant to illuminate experiences, perceptions, and behaviors in tourism settings; yet, this paper focuses exclusively on the aforementioned socio-demographic characteristics (see above), as well as on measures pertaining to travel preferences, destination valuations, destination perceptions, and revisit intentions (see below).

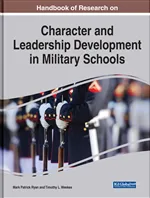

Travel preferences were measured with a revised 16-item version ( Jiang et al., 2000 ) of the ITR scale ( Mo et al., 1993 , 1994 ). The revised scale comprises three subscales that measure reported preferences with regard to the destination itself, travel arrangements, and socio-cultural aspects linked to traveling. Respondents were asked to indicate their agreement to each of the item statements presented on a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = Strongly disagree, 7 = Strongly agree; see Table 1 ).

Table 1. Measurement items for travel preferences.

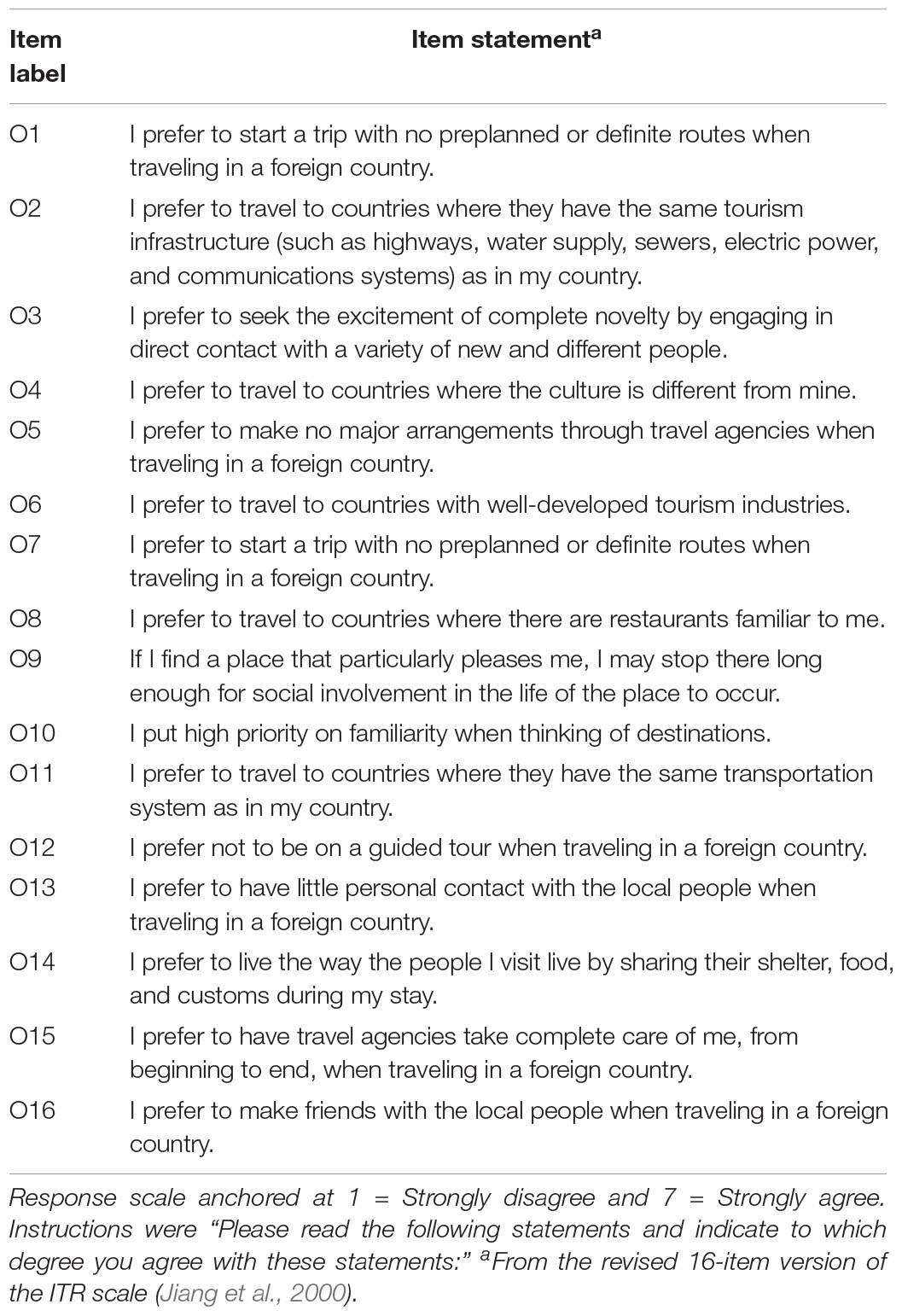

Destination valuations were measured with 13 item statements asking participants about how important various aspects relating to their current trip were when they initially bought the trip. For each statement, respondents were asked to rate the importance of the aspect when buying the current trip using a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = Not important, 7 = Very important; see Table 2 ).

Table 2. Measurement items for destination valuations a and destination perceptions b .

Destination perceptions were assessed using a similar approach as outlined above; that is, the same selection of items were rated on the extent to which the present trip to the country offered each respective aspect, which was again made based on a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = Not at all, 7 = Very much; see Table 2 ).

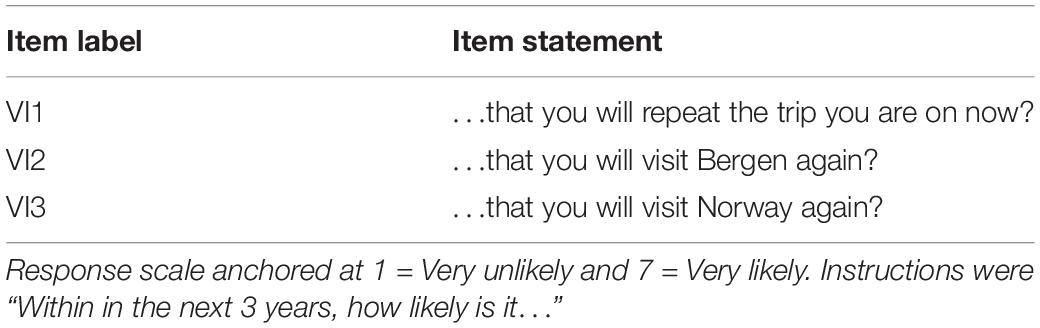

All surveys contained the measures described above, yet one share of the distributed surveys ( n = 1162) further included three items to measure revisit intentions. Respondents indicated the likelihood by which they – within the next 3 years – would repeat the current trip, revisit the same city, and/or revisit the same country. Higher scores on a 7-point Likert-type scale were taken as greater revisit intentions respectively (1 = Very unlikely, 7 = Very likely; see Table 3 ).

Table 3. Measurement items for revisit intentions.

The statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics v. 25 in the following order. First, we re-validated the factor structure of a revised version of the ITR scale. Second, we used the developed factor structure for grouping tourists into preference segments (clusters) and then we evaluated the concurrent validity of the groups by analyzing demographic differences between these segments. Third, we analyzed if (and how) the valuation of destination aspects varies between groups; the same analysis was run with destination perceptions and revisit intentions as dependent variables.

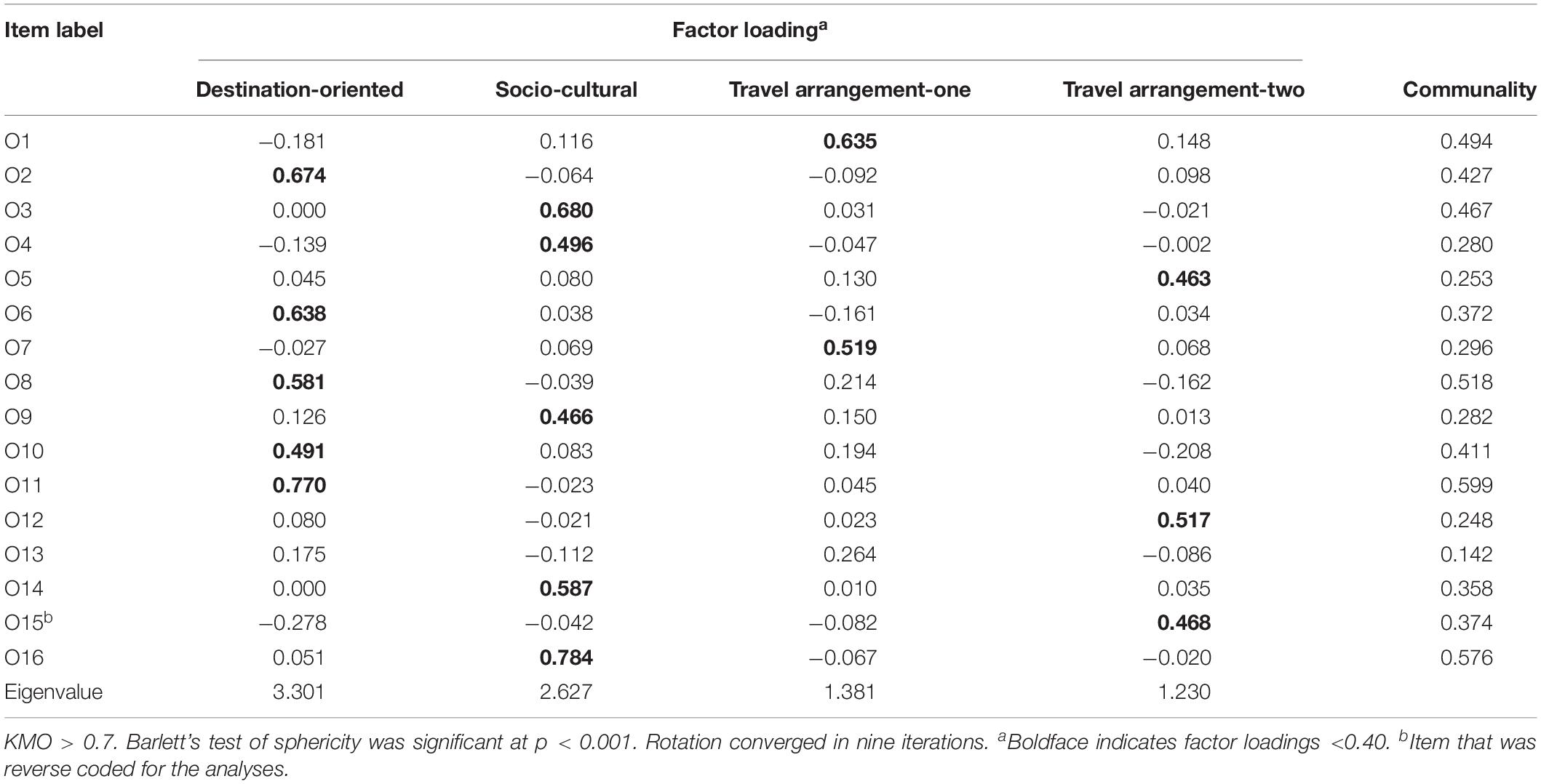

Factor Analyses

Jiang et al. (2000) suggested three substantial factors addressing destination-oriented, socio-cultural, and travel arrangement aspects when people choose to go on vacation abroad. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was well above 0.5 and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant at p < 0.001, which indicates that the current data was suitable for factor analysis (see Field, 2018 ). Table 4 contains results from an exploratory factor analysis (principal axis analysis with direct oblimin rotation). The analyses produced a slightly diverging pattern with four factors having an eigenvalue greater than one. The fourth factor (eigenvalue 1.23), containing items O5, O12, and O15, split the travel arrangement factor in two. A parallel analysis ( Horn, 1965 ) performed on 1000 random datasets with 16 variables resulted in an average eigenvalue of the fourth factor of 1.09, indicating that the eigenvalue of the fourth factor of the present set is marginally above a random value.

Table 4. Pattern matrix, exploratory factor analysis, principal axis, oblimin rotation, 16 items.

Table 4 shows that most items were well accounted for by the factor structure, with factor loadings above 0.40 on the main factor and comparatively low cross loadings. Item O13 was excluded from further analyses because only items with factor loadings greater than 0.40 were retained for more exploration. Item O15 showed a modest loading on the travel arrangement-two dimension, but also a non-negligible cross loading on the destination-oriented dimension. This item was retained for further analyses after an inspection of its corresponding Marker Index, which was above the recommended 0.40 threshold ( Gallucci and Perugini, 2007 ).

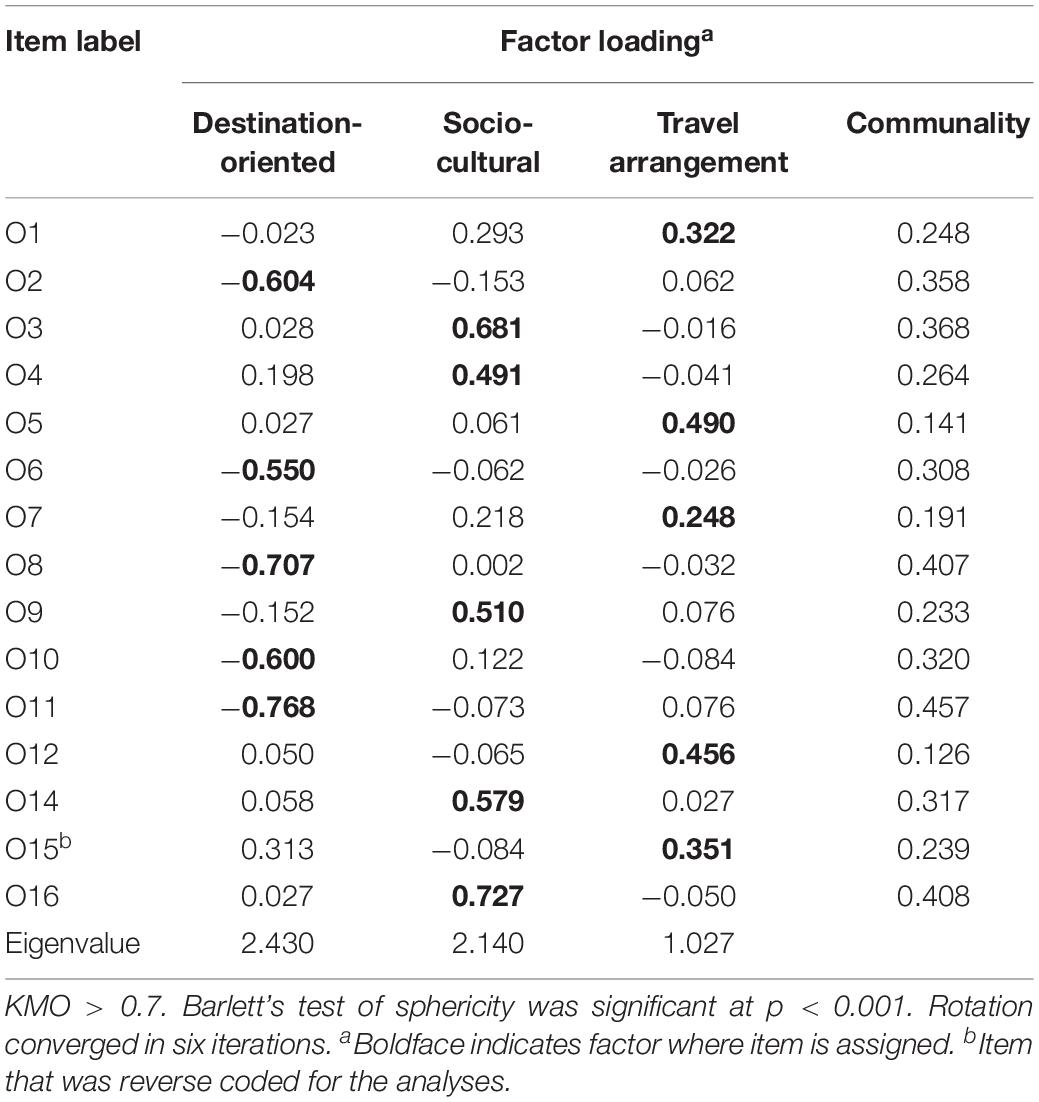

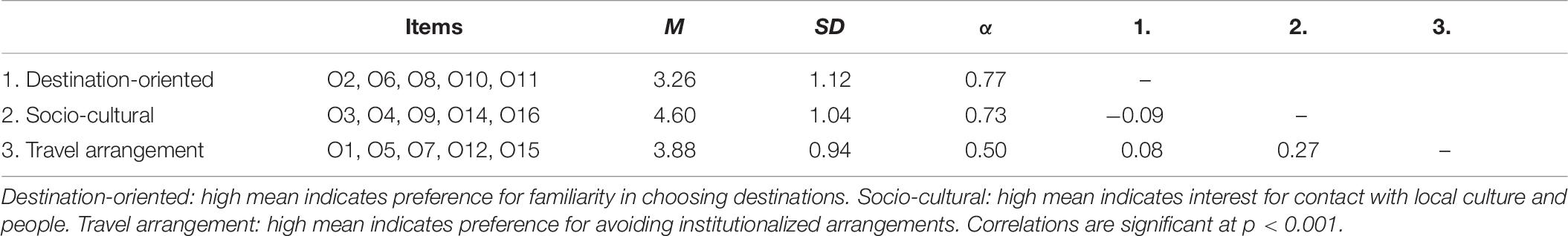

Rather than unequivocally reproducing the factor structure reported by Jiang et al. (2000) , the current data suggests that the scale could be developed further to improve fit to the data, particularly by splitting travel arrangement aspects in two factors. Including an extra factor would nevertheless only account for a marginal part of the total variance, whereas some of the common variance of this tentative factor may further be due to sample- or context-specific features. We therefore chose to keep the three-factor structure to allow direct comparisons with other studies that have utilized the scale. This means that we calculated average scores for each individual respondent on each of the three dimensions displayed in Table 5 . Each item was weight equally (unit weights) and cross loadings of items were not included ( Steenkamp and Baumgartner, 1998 ). An overview of descriptive statistics, Cronbach’s alpha, and bivariate correlations of the three dimensions is reported in Table 6 .

Table 5. Pattern matrix, exploratory factor analysis, principal axis, oblimin rotation, 15 items.

Table 6. Descriptive statistics, Cronbach’s alpha, and bivariate correlations.

Cluster Analyses

Distinct clusters were uncovered using a multistep cluster analysis with individual scores on the three dimensions as inputs. We used a simplified version of the procedure recommended by Dolnicar and Leisch (2003) . The respondents were randomly split into an analysis sample and a validation sample. We used the non-hierarchical K-means method on the analysis sample to identify an initial optimal solution that was next used as cluster seeds for a restricted analysis in the validation sample. The constrained solution was then compared to an unconstrained solution in the same sample; the fit was evaluated with the validity coefficient Kappa. This procedure was repeated for solutions with two to six clusters. Kappa values for the two-, three-, four-, five-, and six-cluster solutions were 0.57, 0.81, 0.74, 0.99, and 0.62 respectively. The high value for the five-cluster solution suggested that these clusters were homogenous and distinct from each other. A discriminant analysis with the five clusters as the dependent variable and dimensions as the independent variables correctly classified 98% of the cases. Thus, individual preferences on the three dimensions yield a high degree of convergence and cohesion along the five preference clusters (see Table 7 ).

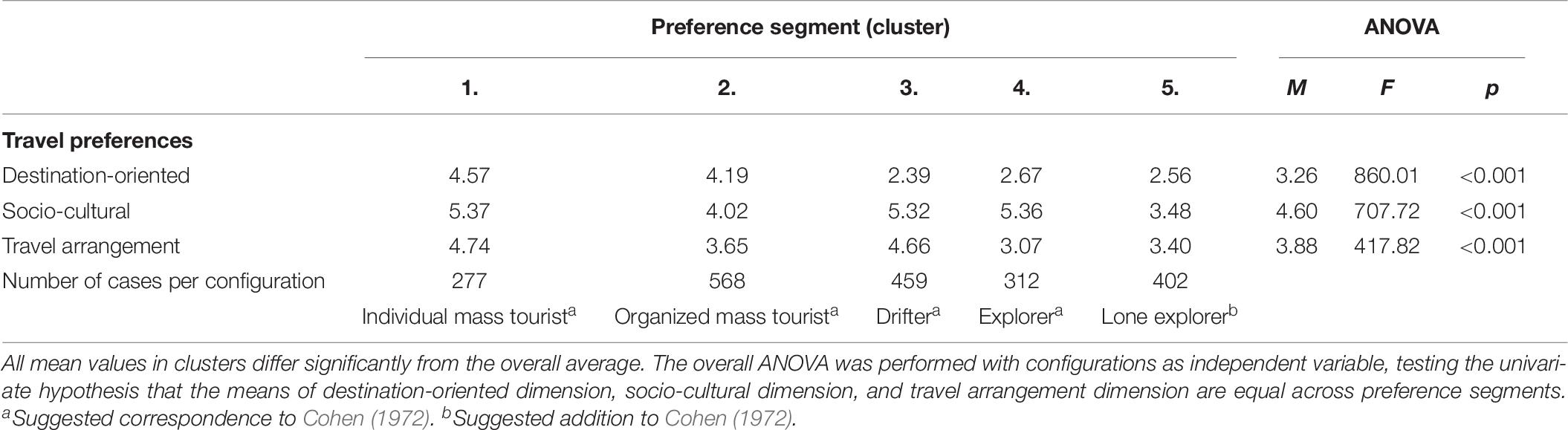

Table 7. Mean differences in travel preferences by cluster.

Table 7 also reveals that the five clusters differ significantly along each dimension. Cluster 1 is high on the destination-oriented, the socio-cultural, and the travel arrangement dimension, corresponding to the “individual mass tourist”. Cluster 2 is high on the destination-oriented dimension, and low on the socio-cultural and travel arrangement dimensions, which corresponds to the preferences of the “organized mass tourist”. Cluster 3 is low on the destination-oriented dimension but high on the socio-cultural and travel arrangement dimensions, which is similar to the “drifter”. Cluster 4 is similar to the aforementioned in the sense that it is low on the travel-oriented dimension, which makes it correspond to the “explorer”. Cluster 5 scores fairly low on all three dimensions; this type appears to be similar to the previous, albeit with no strong preferences for social contact with locals and cultural immersion. We suggest labeling this additional group as the “lone explorer”, noting that the viability and structure of the group still has to be validated. Each one of the five emerging preference clusters reflect shared perceptions of 14, 28, 23, 16, and 20 percent of the respondents respectively; and even though some clusters are slightly larger than the “organized mass tourist” configuration, each one reflects the shared perceptions of a significant number of tourist.

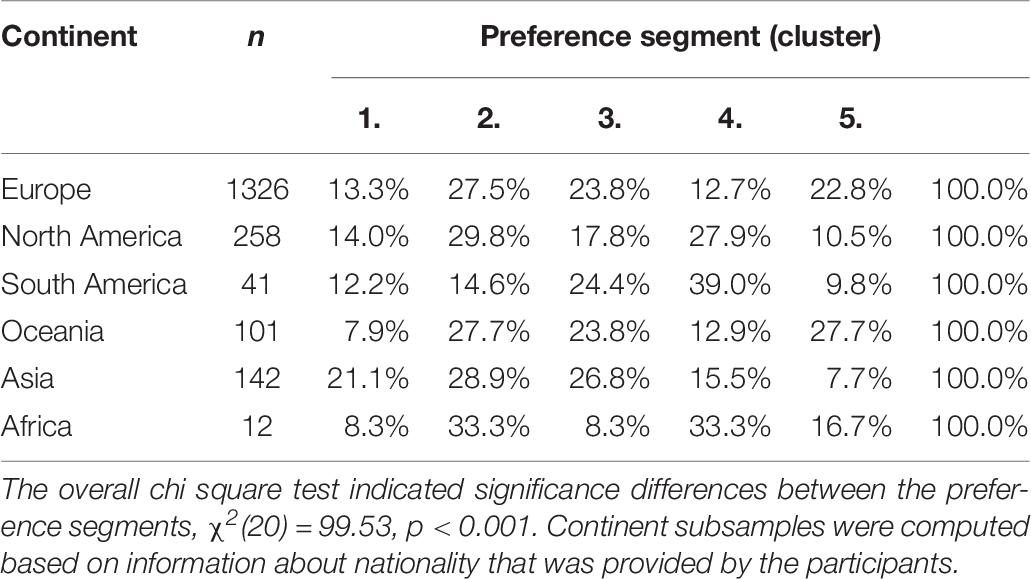

To test whether the clusters revealed in the analysis can be associated with individual factors, we ran a cross-table with gender as dependent variable and the five clusters as independent. There were no significant gender differences χ 2 (4) = 2.12, p = 0.71. We also checked for age differences between the clusters. An analysis of variance suggested that the identified clusters were not closely related to age, F (4, 1954) = 9.28, p < 0.001, except for the “organized mass tourist” segment being slightly older ( M = 39.01) and the “explorer” segment slightly younger ( M = 33.55) than the total average ( M = 37.92). Table 8 reports the results on whether the continent participants originated from related to the clusters. Though the number of respondents was quite low in some continents, and that not all differences were significant, the table indicates that “explorer” (Cluster 4) and “lone explorer” (Cluster 5) originate in somewhat different proportions from the continents.

Table 8. Cluster members by continent.

Further Cluster Validations

If we assume that the clusters based on travel preferences are meaningful, they could relate to valuations of a destination before the trip as well as to perceptions of a destination during the visit. To simplify further analyses, we performed an exploratory factor analysis (principal axis analysis with oblique rotation) on items measuring the initial buying valuations. Item TA1 (affordable price) did not load on any factors, which is why it was decided to remove TA1 from the further analyses. Item TA4 (opportunity to go fishing) formed a single factor, and since this could be a context-specific valuation, we decided to also exclude this item. The remaining items formed three substantial factors that could be labeled “sustainable” (i.e., TA11, TA12, TA13), “nature” (i.e., TA2, TA3, TA6), and “active” (i.e., TA5, TA7, TA8, TA9, TA10). For each factor, average scores were computed with unit weights and no cross loadings; the same factor structure was thereafter used to compute three corresponding average scores for items measuring destination perceptions.

Relationships between the clusters and destination valuations were evaluated with an ANOVA with the valuation of elements of the buying process as dependent variables and the five clusters as the independent variable. The expectation is that preference clusters, because they have different preferences, will value these elements quite differently. A similar set of analysis was run with destination perceptions as dependant variables and the five clusters as the independent variable.

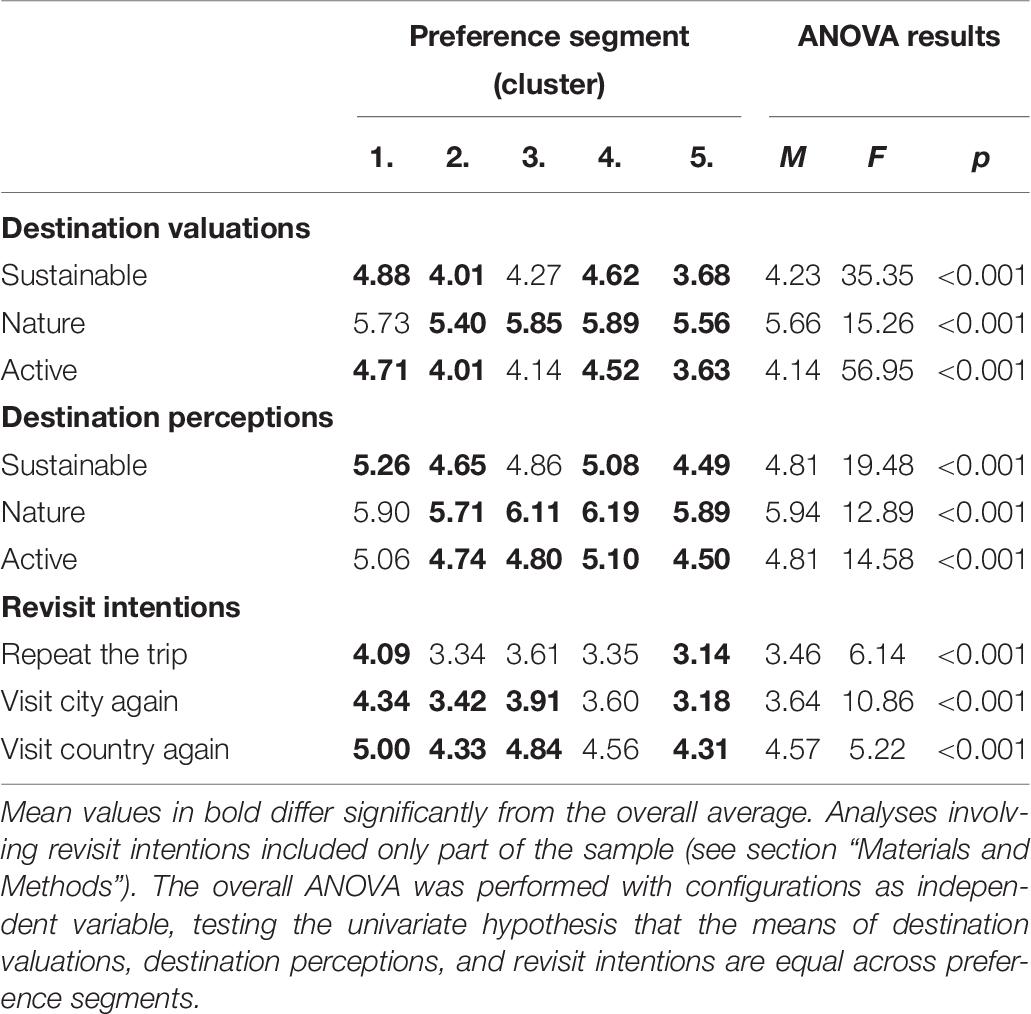

Table 9 shows that although not all differences are significant, destination valuations and destination perceptions tend to vary between preference clusters; however, these differences are comparatively small considering the available response scale options. The same table reports results on associations between the preference clusters and revisit intentions, showing that some clusters differed in their intention to repeat the trip, as well as in their intention to visit the city or the country again.

Table 9. Mean differences in destination valuations, destination perceptions, and revisit intentions by cluster.

The analyzed data failed to invariantly replicate the factor scores from earlier applications of the revised ITR scale ( Jiang et al., 2000 ), which is in line with other studies ( Gnoth and Zins, 2010 ). These small irregularities may signal that the factor structure of the scale is not yet fully developed, or they could be due to contextual or sample-specific processes in the current data. Because the aim was to further opportunities for comparative analyses, and since the analyzed data only weakly suggested a four-factor solution, we chose to stay with a three-factor structure (see Table 5 ).

Our analyses indicated that based on the three dimensions tapped into by the revised ITR scale, individuals can be meaningfully grouped into clusters that mimic the four types by Cohen (1972) . A closer look at the results from the cluster analyses suggested to furthermore distinguishing the “explorer” type into two sub-forms. Both prefer to visit new places, yet one group prefers cultural immersion and to meet and blend with local people, whereas the other group puts much less emphasis on cultural immersion and social contact. This supports previous literature suggesting that dividing the proposed four types further into sub-forms could prove useful to elicit information about more homogenous groups ( Uriely, 2009 ). A next step could be to test if the same clustering pattern emerges among individuals who visit destinations other than currently investigated. Further applications of the revised framework will open for much needed comparable studies, which have the potential to benefit the communication between cooperating stakeholders.

The clustering had a high discriminant validity in that most of the participants clearly belonged to one, and only one of the preference clusters. Nonetheless, these different clusters did not report very different valuations of destination aspects when they initially bought the trip, and only moderate differences in their intentions to return. This seems to suggest that although the tested framework has been proliferating in research, clusters derived from individual preferences for novelty and familiarity are not complete for explaining individual destination choices. An interpretation of these pattern results is that in spite of its intuitive appeal, the present study only establishes weak evidence that the suggested taxonomy has nomological validity at the individual level ( Churchill, 1979 ).

Results from the present study suggested preferential differences between tourists from different continents, in particular between the two segments in our suggested expansion of Cohen’s explorer segment. For example, the proportion of those classified as a “lone explorer” was greater for individuals from the Oceania region than for any other subsample. If it should be the case that the identified preference clusters reflect stable patterns, these might as well relate to many aspects of the tourist experience, of which we have explored only a small fraction. Research in this vein may consider including measures of cultural values to increase the robustness of its findings. There is some indication in the literature that individual scores on dimensions included in the ITR scale can be explained partly through values that are shared by individuals visiting a given destination ( Gnoth and Zins, 2010 ).

Regarding the extent to which broader travel preferences are attached to what aspects tourists emphasize in their vacation, as can be indicated through valuations and perceptions, there was only low predictive validity. This fits to an earlier investigation by Larsen et al. (2011) who found that budget travelers were more likely to agree with statements that ascribe themselves to the “drifter” than mainstream tourists. Although the former were on average more likely to see themselves as more individualistic compared with their mainstream counterpart, both groups were quite similar when it comes to other psychological characteristics. Larsen and colleagues speculated that this might be rooted in the self-perception of backpackers and their socially constructed views of themselves as a group with distinguishing characteristics. Our current findings support this interpretation in the sense that revisit intentions were only to a limited extent (if at all) associated with broader travel preferences, at least when considering the three dimensions included in the revised ITR scale. This ties in well with literature suggesting that having a sole focus on the extent to which individuals seek novelty versus familiarity provides an incomplete picture with regard to understanding the complexity of tourist behavior ( Chen et al., 2011 ).

The revised ITR scale has a potential to reproduce stable clustering for practitioners across time, travelers and contexts, and theoretically meaningful and comparable clusters, but much research remains before unequivocal management recommendations can be made. 3 In our analyses of the preference-data, we applied the simple K-means clustering technique that is sensitive to sample specific variance. By our rigorous use of estimation samples and validation samples for establishing the number of clusters, as well as the cluster structure, we lowered the risk of sample specific findings. An important fact is that the sample was rather heterogeneous despite that all parts of the data collection took place at the same destination. It contains individuals with different socio-demographic characteristics, that varied in the duration of their traveling, and that were approached at different points during their trip. All this together lowers the probability of sample specific findings, but still, the study will have to be replicated with samples from other destinations to support our present findings.

Forthcoming studies that follow up on our suggestion to replicate the current findings in other destinations could address some limitations of the present investigation. First, given that all constructs were assessed in the same questionnaire, the predictive ability of the clusters could have been inflated by common method variance. We tried to design the questionnaire to limit common method variance by keeping measures of the different constructs well separated in the questionnaire, by wording them differently, by applying different response scales, and to lower method-dependent social desirability issues by letting the participants complete the questionnaire by themselves. Still, these remedies cannot exclude the presence of common method variance in the data ( Podsakoff et al., 2012 ). Future studies are well advised to use different methods for assessing behavior associated with each cluster to get reliable and valid estimates of the associations ( Podsakoff et al., 2003 ). Second, it is because of the cross-sectional design of the current study that we cannot make any conclusion about whether the clustering based on individual scores of the revised ITR scale remains stable across time. If such stability can be demonstrated for at least certain time periods, an interesting future development would be to predict future buying behavior within these periods. Third, forthcoming studies would benefit from broadening the scope toward measures of actual buying behavior since intentions to return are an imperfect predictor for future destination choices ( McKercher and Tse, 2012 ). Fourth, Cronbach’s alpha was acceptable for the destination-oriented (α = 0.77) and socio-cultural dimension (α = 0.73) but poor for the travel arrangement dimension (α = 0.50), based on conventional guidelines (see Streiner, 2003 ). This represents a noteworthy limitation to the present investigation as clustering that relies upon aggregated measures on each of the three dimensions may lead to biased and less precise clusters, which in succession, may pose a threat to the validity of the reported findings.

This paper shows that findings from earlier applications of the revised ITR scale replicate to a certain extent in the current sample; the three main dimensions of the scale are with a few modifications reproduced. Further analyses show that the tourists can be grouped (clustered) into preference segments based on the main dimensions included in the scale, which in turn appear to be quite similar to the suggested tourist types of Cohen (1972) . When comparing data on the importance assigned to specific aspects when buying the trip, or on the extent to which these aspects were offered at the destination, the various preference segments were dissimilar. Since the magnitude of these differences was rather small, preference-based clusters of tourists have nonetheless only to a limited extent different valuations and perceptions; the same seems to be the case when comparing different groups on their revisit intentions.

It is important to note that belonging to one particular preference cluster may not be unequivocally stable, just as tourist roles might develop and change over time ( Gibson and Yiannakis, 2002 ). To get a deeper understanding of the psychological processes that take part in shaping tourist experiences, future research could extend the scope beyond theoretically developed taxonomies as employed in the present case. It seems plausible that the extent by which initial valuations correspond with perceptions during the trip constitutes another aspect that feeds into how a destination is experienced, and related decisions, potentially more so than whether individuals report to prefer more (or less) novelty (or familiarity) if traveling away from home. A more detailed discussion on how a psychological approach can be a useful starting point for social scientific enquiries on tourist experiences is provided by Larsen (2007) as well as Larsen et al. (2017) .

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

This work complied with the general guidelines for research ethics by the Norwegian National Committees for Research Ethics in the Social Sciences and the Humanities (NESH). Formal approval by an ethics committee was not required as per applicable institutional guidelines and regulations.

Author Contributions

RD, SL, and KW contributed to the conception, design, and data collection of the study. TØ performed the statistical analysis. TØ and RD wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Data collection was funded by the Department of Psychosocial Science (Småforsk).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

- ^ The assumption that novelty seeking is an important factor underlying individual travel decisions can also be found in the social psychological model of tourism motivation ( Iso-Ahola, 1982 ), the psychographic approach ( Plog, 2001 ), and the travel career pattern approach ( Pearce and Lee, 2005 ) amongst others.

- ^ The reported number only refers to respondents who were 18 years and over at the time of the data collection. Total percentages are not 100 for each of the listed categories due to some missing values.

- ^ Note that our empirical development of the preference clusters was based on the revised ITR scale, which is but one of a number of theoretically founded alternatives (e.g., Yiannakis and Gibson, 1992 ; Keng and Cheng, 1999 ).

Basala, S. L., and Klenosky, D. B. (2001). Travel-style preferences for visiting a novel destination: a conjoint investigation across the novelty-familiarity continuum. J. Travel Res. 40, 172–182. doi: 10.1177/004728750104000208

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Chen, Y., Mak, B., and McKercher, B. (2011). What drives people to travel: integrating the tourist motivation paradigms. J. China Tour. Res. 7, 120–136. doi: 10.1080/19388160.2011.576927

Churchill, G. A. (1979). A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. J. Mark. Res. 16, 64–73. doi: 10.2307/3150876

Cohen, E. (1972). Toward a sociology of international tourism. Soc. Res. 39, 164–182.

Google Scholar

Cohen, E. (1979). A phenomenology of tourist experiences. Sociology 13, 179–201. doi: 10.1177/003803857901300203

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Dann, G. M. S. (2018). “Why, oh why, oh why, do people travel abroad?,” in Creating Experience Value in Tourism , eds N. K. Prebensen, J. S. Chen, and M. Uysal, (Wallingford: CABI), 44–56. doi: 10.1079/9781786395030.0044

Díaz-Martín, A. M., Iglesias, V., Vázquez, R., and Ruiz, A. V. (2000). The use of quality expectations to segment a service market. J. Serv. Mark. 14, 132–146. doi: 10.1108/08876040010320957

Dolnicar, S. (2008). “Market segmentation in tourism,” in Tourism Management: Analysis, Behaviour and Strategy , eds G. A. Woodside, and D. Martin, (Wallingford: CABI), 129–150. doi: 10.1079/9781845933234.0129

Dolnicar, S., and Leisch, F. (2003). Winter tourist segments in austria: identifying stable vacation styles using bagged clustering techniques. J. Travel Res. 41, 281–292. doi: 10.1177/0047287502239037

Dolnicar, S., and Ring, A. (2014). Tourism marketing research: past, present and future. Ann. Tour. Res. 47, 31–47. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2014.03.008

Fan, D. X. F., Zhang, H. Q., Jenkins, C. L., and Tavitiyaman, P. (2017). Tourist typology in social contact: an addition to existing theories. Tour. Manag. 60, 357–366. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2016.12.021

Field, A. (2018). Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics , 5th Edn, London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Frochot, I., and Morrison, A. M. (2000). Benefit segmentation: a review of its applications to travel and tourism research. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 9, 21–45. doi: 10.1300/J073v09n04-02

Gallucci, M., and Perugini, M. (2007). The marker index: a new method of selection of marker variables in factor analysis. TPM Test Psychom. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 14, 3–25.

Gibson, H., and Yiannakis, A. (2002). Tourist roles: needs and the lifecourse. Ann. Tour. Res. 29, 358–383. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(01)00037-8

Gnoth, J., and Zins, A. H. (2010). Cultural dimensions and the international tourist role scale: validation in asian destinations? Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 15, 111–127. doi: 10.1080/10941661003629920

Heitmann, S. (2011). “Tourist behaviour and tourism motivation,” in Research Themes for Tourism , eds P. Robinson, S. Heitmann, and P. Dieke, (Wallingford: CABI), 31–44. doi: 10.1079/9781845936846.0031

Horn, J. L. (1965). A rationale and test for the number of factors in factor analysis. Psychometrika 30, 179–185. doi: 10.1007/BF02289447

Innovation Norway, (2018). Key Figures for Norwegian Travel and Tourism 2018. Available at: https://assets.simpleviewcms.com/simpleview/image/upload/v1/clients/norway/Key_figures_for_norwegian_tourism_2018_f9ac4f82-7b02-4fee-a67b-dcf98c4bd403.pdf doi: 10.1007/bf02289447

Iso-Ahola, S. E. (1982). Toward a social psychological theory of tourism motivation: a rejoinder. Ann. Tour. Res. 9, 256–262. doi: 10.1016/0160-7383(82)90049-4

Jiang, J., Havitz, M. E., and O’Brien, R. M. (2000). Validating the international tourist role scale. Ann. Tour. Res. 27, 964–981. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(99)00111-5

Keng, K. A., and Cheng, J. L. L. (1999). Determining tourist role typologies: an exploratory study of singapore vacationers. J. Travel Res. 37, 382–390. doi: 10.1177/004728759903700408

Larsen, S. (2007). Aspects of a psychology of the tourist experience. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 7, 7–18. doi: 10.1080/15022250701226014

Larsen, S., Doran, R., and Wolff, K. (2017). “How psychology can stimulate tourist experience studies,” in Visitor Experience Design , eds N. Scott, J. Gao, and J. Ma, (Wallingford: CABI).

Larsen, S., Øgaard, T., and Brun, W. (2011). Backpackers and mainstreamers: realities and myths. Ann. Tour. Res. 38, 690–707. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2011.01.003

Lepp, A., and Gibson, H. (2003). Tourist roles, perceived risk and international tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 30, 606–624. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(03)00024-0

McKercher, B., and Tse, T. S. M. (2012). Is intention to return a valid proxy for actual repeat visitation? J. Travel Res. 51, 671–686. doi: 10.1177/0047287512451140

Mo, C., Havitz, M. E., and Howard, D. R. (1994). Segmenting travel markets with the International Tourism Role (ITR) scale. J. Travel Res. 33, 24–31. doi: 10.1177/004728759403300103

Mo, C., Howard, D. R., and Havitz, M. E. (1993). Testing an international tourist role typology. Ann. Tour. Res. 20, 319–335. doi: 10.1016/0160-7383(93)90058-B

Pearce, P. L., and Lee, U.-I. (2005). Developing the travel career approach to tourist motivation. J. Travel Res. 43, 226–237. doi: 10.1177/0047287504272020

Plog, S. (2001). Why destination areas rise and fall in popularity: an update of a cornell quarterly classic. Cornell Hotel Restaur. Adm. Q. 42, 13–24. doi: 10.1177/0010880401423001

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., and Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., and Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 63, 539–569. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

Snepenger, D. J. (1987). Segmenting the vacation market by novelty-seeking role. J. Travel Res. 26, 8–14. doi: 10.1177/004728758702600203

Steenkamp, J. E. M., and Baumgartner, H. (1998). Assessing measurement invariance in cross-national consumer research. J. Consum. Res. 25, 78–107. doi: 10.1086/209528

Streiner, D. L. (2003). Starting at the beginning: an introduction to coefficient alpha and internal consistency. J. Pers. Assess. 80, 99–103. doi: 10.1207/S15327752JPA8001-18

Uriely, N. (2009). Deconstructing tourist typologies: the case of backpacking. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 3, 306–312. doi: 10.1108/17506180910994523

Uriely, N., Yonay, Y., and Simchai, D. (2002). Backpacking experiences: a type and form analysis. Ann. Tour. Res. 29, 520–538. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(01)00075-5

Wolff, K., and Larsen, S. (2019). Are food-neophobic tourists avoiding destinations? Ann. Tour. Res. 76, 346–349. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2018.10.010

Yiannakis, A., and Gibson, H. (1992). Roles tourists play. Ann. Tour. Res. 19, 287–303. doi: 10.1016/0160-7383(92)90082-Z

Keywords : tourist role orientation, destination valuations, destination perceptions, revisit intentions, novelty, familiarity

Citation: Øgaard T, Doran R, Larsen S and Wolff K (2019) Complexity and Simplification in Understanding Travel Preferences Among Tourists. Front. Psychol. 10:2302. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02302

Received: 01 May 2019; Accepted: 26 September 2019; Published: 17 October 2019.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2019 Øgaard, Doran, Larsen and Wolff. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Torvald Øgaard, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Change in travel accommodation preferences continues

Despite successful vaccination programs in many countries around the world, the continued challenges around COVID-19, like the new Omicron variant, have brought back travel restrictions and social distancing requirements across the globe. STR’s Tourism Consumer Insights team continues to keep a close eye on tourism trends as well as travel accommodation preferences because of the pandemic.

In November 2021, shortly before news of Omicron had surfaced, STR undertook a new online survey using its Traveler Panel –an engaged audience of travel consumers–to examine sentiment and how it might affect industry fortunes at this uncertain time. The research gathered the views of nearly 1,500 global travelers.

Leisure preferences

A new standard of preferences has been set since the beginning of COVID-19, and accommodation in the current situation continues to be less desirable than in pre-pandemic times.

Travelers continue to prefer short-term rentals and smaller size hotels (properties with less than 50 rooms) due to lingering concerns about the virus. In November 2021, traveler interest in short-term rentals was 12% above the pre-pandemic level of interest. In the context in which consumers continue to seek space and wish to minimize their contact with others, it is perhaps not surprising that self-catering and smaller sized accommodation continue to standout.

On the flipside, due to the room share factor and communal facilities, hostels are significantly less attractive compared with pre-pandemic times (-61% net interest in November 2021). At the same time, there’s a sense that economy and budget operators are less well perceived in the current situation as well.

Reflecting these accommodation preferences, travelers continue to seek out more rural experiences to escape the crowds and engage more with the outdoors. More than 30% of respondents agreed that they preferred these types of trips in the current situation compared with before the pandemic.

Many have been forced to holiday at home in the last year or so and there is a sense now that domestic tourism is more appealing (as well as being more common) than international tourism (domestic trip +11% net interest versus international trip -12% net interest). This is perhaps due to a combination of recent positive staycation experiences and concerns around the potential hassle and inconveniences of international travel, such as testing protocols, potential quarantine, and infection risk.

Another type of trip which is less appealing in the current environment is event-specific trips (-48% net interest). This is likely linked to heightened concerns of infection by attending a mass event.

Traditional determinants of choice

The importance of reviews and recommendations has increased in recent waves. More than 20% who had booked accommodation recently stated these were a key factor which had influenced their choice where to stay. Meanwhile, the importance of cancellation policies continues to diminish (18% in November 2021 vs. 23% in July 2021 vs. 29% in February 2021).

Interestingly, while consideration of hotel social distancing policies appears to be less significant now with fewer personal health concerns due to vaccination, there has been no decline in the importance of cleanliness. This finding suggests that consumers may have new perspectives and expectations regarding cleanliness post-pandemic.

The latest research shows that accommodation preferences and behaviors are continuing to shift and evolve in response to the current COVID-19 situation. Aspects which were important in the past, like the location and perceived value for money offering of accommodation, continue to be relevant and important. However, new preferences and behaviors have led to new opportunities and challenges for the industry. Efforts to capitalize on consumers’ new-kindled interest in the outdoors and a “sense of space,” and enabling flexible bookings are a few relevant strategies for remaining competitive.

NOTE: This research was undertaken in early November 2021 before the Omicron variant emerged. As a result, respondents’ views do not represent the newest situation around COVID-19.

For more industry information each day, follow us on LinkedIn , Facebook , and Twitter .

For further insights into covid-19’s impact on global hotel performance, visit our content hub ..

Welcome to STR

Please select your region below to continue.

- Deutschland

- Asia, Australia & New Zealand

- Europe, Middle East & Africa

- United States & Canada

- Latinoamérica

Aerial views: How brands can cater to a new breed of traveler as borders reopen

The travel industry is kicking into gear. Border and quarantine restrictions are easing up with increasing vaccination rates, and people are ready to travel even as the pandemic lingers. 1 Those traveling at this time, however, will no longer behave like pre-pandemic travelers.

Indeed, new research on APAC’s four biggest travel markets: Australia, India, Indonesia, and Japan, reveals that among travelers now, there is a 3X increase in intent to travel internationally. Sixty-one percent of travelers have also indicated a preference toward international travel for future leisure vacations, and the majority intend to travel for longer periods, and plan to visit only one or two countries per trip. 2

With this shift in travel trends from “when” to “how,” brands will have to adapt to the needs, preferences, and expectations of this new breed of traveler, and find ways to reach and excite them to go on trips.

Here’s what we’ve learned about this new breed of traveler that can help your brands prepare for the future of travel.

The traveler we’ve not met before

Given the complex nature of traveling during a pandemic, travelers will need to spend more time researching and planning, and they will want to get the most out of their trips. Across the four markets, we saw a 17% increase in the average booking time. In particular, travelers spent an average of 56 days planning for international travel, which is 30% longer than the time taken to plan domestic travel. 3

The effort that goes into planning international leisure trips means that for the new breed of traveler, such trips are likely to be longer and more focused milestone events than was the case pre-pandemic. Our research shows that travelers are twice as likely to make fewer trips than before, and they are also 3X more likely to cover only one or two countries per trip. 4

When they travel, they’ll make time to do, see, and spend more: 25% say they will travel for more than two weeks, and around 87% of travelers will organize international trips that last five days or longer. 5 This is an increase from 2019, when tourist stays at international accommodations averaged three to four days. 6

The preferences of this new breed of traveler mean it’s even more critical for brands to engage them throughout the path to purchase, from research and discovery to bookings and activities.

The new breed of traveler

They also have a strong preference for luxury and convenience, and they are willing to spend more to pamper themselves. For one, we’ve seen a growth in clicks for accommodations that are more than $300 per night. 7 Additionally 78% of travelers say they would be interested in luxury stays and experiences, with 77% interested in package holiday tours. 8

When these travelers have to quarantine as part of their trip, they prefer to spend their time meaningfully. Our research shows that they are twice as likely to opt for entertainment-related amenities in their quarantine accommodation, including streaming services and fitness equipment, over and above options such as upgraded meals, bigger rooms, and balcony views. The only exception was with travelers from Japan, for whom the option to have a balcony and fresh air appealed the most. 9 For hotel, lifestyle, and entertainment brands, this means an opportunity to get creative and offer services that will appeal to this new breed of traveler.

Wooing the new traveler as borders reopen

With the industry seeing a fundamental shift to a less-frequent and high-ticket-size travel model, marketers in the know have been adjusting their business models accordingly. For example, Rakuten Travel has been catering to this new breed of traveler by promoting its luxury hotel inventory.

Sustain engagement over diverse marketing channels

As a niche holiday destination, Tourism New Zealand knew it had to get a head start on engaging travelers, so it launched a multimarket campaign in key international markets, including Australia, telling travelers to “stop dreaming about New Zealand and go.”

The campaign ran across all major channels, including cinema, TV, on-demand, social, and digital to reach as wide an audience as possible. PR and trade activity also supported the campaign.

René de Monchy, chief executive of Tourism New Zealand, says: “We found we had to keep engaging with consumers to get them to dream about New Zealand. We also really accelerated our digital channels by enabling them to convert business for New Zealand.”

Use digital to reach and inspire travelers

To stay top-of-mind among travelers, travel-booking company Klook experimented with live events on its mobile app, where it could reach a wide audience with content geared toward their various interests.

Some live events were sales-driven, whereas others invited people to share travel ideas and trends. The live sessions enabled audiences to interact with the hosts and to connect with others on the livestream. One session hosted by a celebrity, for example, received over 11,000 comments from participants within the first hour of streaming, and many of the comments were from people sharing travel ideas and suggestions.

By offering entertaining and educational content around travel, Klook gave people reasons to open its travel app and start thinking about and planning for future travels.

Indeed, brands that understand and meet the needs and expectations of this new breed of traveler are well-poised to capture travel demand as it rebounds. To do this, brands should keep up-to-date with changing traveler preferences and adapt quickly to shifts in demand. Investing in a strong digital presence will also help brands reach APAC’s growing online population and be ready for the future of travel.

Others are viewing

Marketers who view this are also viewing

Why hotels need new ways to unlock APAC’s travel surge for business growth

The state of travel in apac: identifying trends to prepare for the road ahead, charting a bumpy path to travel recovery in apac: latest insights and tools, consumer insights and marketing strategies to help you navigate 2023 with confidence, 3 ways you can work smarter, not harder, and drive results with ai in marketing, travel trends for southeast asia, cumarran kaliyaperumal, hermione joye, sources (3).

1,2,3,4,5,8,9 Google-commissioned Kantar Travel Trends research, AU, ID, IN, JP, n=3999, 2021.

6 Google Internal Data, AU, ID, IN, JP, 2019 vs. 2021.

7 Google Internal Data, AU, ID, IN, JP, Growth, 2019 vs. 2021.

Others are viewing Looking for something else?

Complete login.

To explore this content and receive communications from Google, please sign in with an existing Google account.

- Destinations

Check Out the Factors Influencing Airline Preferences and Booking Behavior

When it comes to choosing an airline for their travel needs, travelers consider various factors that influence their preferences, loyalty, and booking behavior. From pricing and convenience to service quality and loyalty programs, these factors play a crucial role in shaping travelers’ decisions. Let’s delve into the key factors influencing airline preferences and booking behavior. And explore how airlines can cater to these preferences to attract and retain customers.

Pricing and Value for Money

Price is often a key consideration for travelers. They compare ticket prices across different airlines to find the best deal that offers value for money. While budget-conscious travelers may prioritize lower fares, others may be willing to pay a premium for added benefits such as flexibility in ticket changes or more inclusive fares. Airlines that offer competitive pricing and transparent fare structures are more likely to capture the attention of cost-conscious travelers.

Flight Schedule and Convenience

The convenience of flight schedules plays a crucial role in travelers’ decisions. Airlines that offer a wide range of departure and arrival times, as well as multiple route options, give travelers the flexibility to plan their trips according to their preferences. Additionally, airlines that operate from well-connected airports and provide efficient ground services contribute to a seamless travel experience.

Service Quality and Reputation

Service quality and reputation greatly impact travelers’ choices. It is one of the key factors influencing airline preferences and booking behavior . Positive experiences, such as friendly and attentive staff, comfortable seating, on-time departures, and efficient baggage handling, enhance overall customer satisfaction. Airlines that consistently deliver exceptional service and prioritize customer needs are more likely to gain loyal customers and positive word-of-mouth recommendations.

Safety and Reliability

Safety and reliability are paramount for travelers when choosing an airline. Airlines that have a strong safety record, adhere to strict maintenance and operational standards, and invest in modern aircraft instill confidence in passengers. Regularly updated safety protocols, transparent communication about safety measures, and efficient crisis management procedures create trust and positively influence travelers’ preferences.

Loyalty Programs and Rewards

Loyalty programs play a significant role in travelers’ booking behavior. Airlines with robust loyalty programs that offer attractive rewards, such as free flights, upgrades, priority boarding, and access to exclusive lounges, can significantly influence travelers’ choices. Providing personalized offers and incentives to loyal customers further strengthens their allegiance to the airline.

Ancillary Services and In-Flight Amenities