Sperm Whale

The inspiration for the white whale of Moby Dick, sperm whales have the largest heads, biggest brains, and make the loudest sound of any animal on Earth

Region: Arctic, Antarctica

Destinations: Lofoten, Cape Verde, South Orkney Islands, Antarctic Peninsula, South Shetland Islands, Greenland, Svalbard, Falkland Islands, South Georgia, Ascension Island, St. Helena, Tristan da Cunha, Iceland

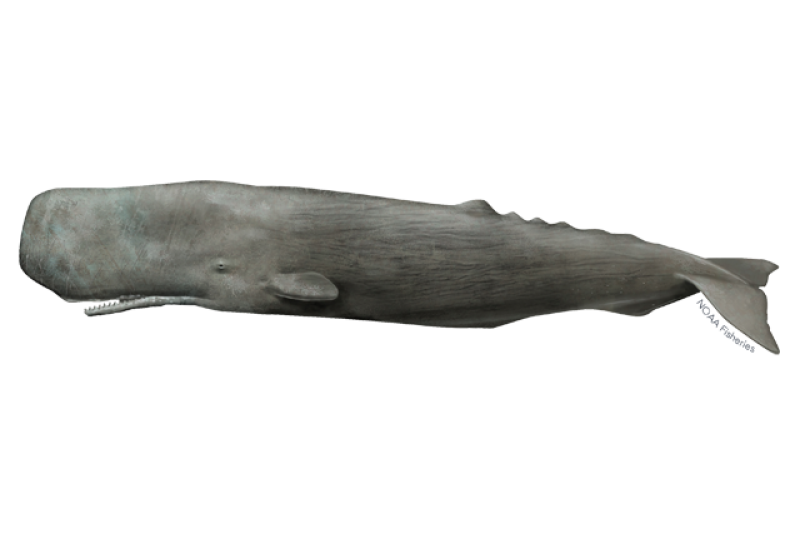

Name : Sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus)

Length : 16-20 metres (53-66 feet)

Weight : 40,000-55,000 kg (88,000- 12,000 pounds)

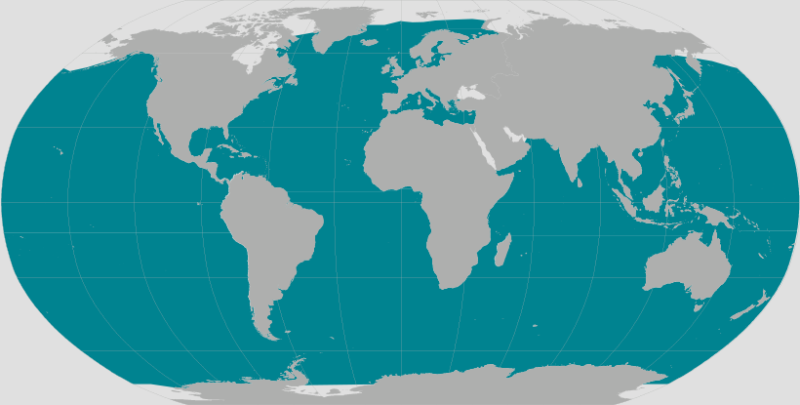

Location : Sub-Arctic, sub-Antarctic, and Atlantic waters

Conservation status : Vulnerable

Diet : Mainly squid, but also fish, octopi, rays, and megamouth sharks

Appearance : Long, block-shaped head comprising up to 1/3 of the whale’s body, with grey or black skin, which tends to be wrinkled behind the head and on the sides. Short, wide flippers, broad, triangular fluke, and a single blowhole.

Picture by Thomas Laumeyer

How do sperm whales hunt?

Sperm whales usually eat a little over 900 kg (almost 2,000 pounds) of food per day. To find their prey (preferably giant squid), they dive somewhere between 300 and 1,200 metres (990 and 4,000 feet), though they can go as deep as 2 km (1.2 miles) while on the hunt. An average dive lasts about an hour. Using echolocation to focus on their prey, sperm whales generate a series of clicks that are the loudest animal-caused noises in the world. A sperm whale’s teeth along its bottom jaw are about 18 to 20 cm long (7.1 to 7.9 inches), fitting into sockets along the underside of the palate. The upper teeth of a sperm whale never grow out of its upper jaw. Scientists believe that sperm whales and giant squid are natural enemies. While no actual battles have ever been observed, sperm whales sometimes carry round scars believed to have come from the suckers of giant squid. When hunting smaller fish, sperm whale pods can work together to force feeder fish into ball-like clumps that are more substantial to eat than individuals.

Are sperm whales social?

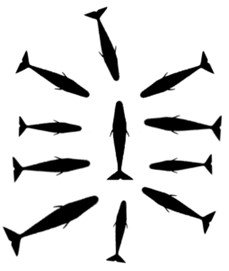

When they are not breeding, adult male sperm whales live on their own. Female sperm whales and offspring, however, gather into pods of up to 20 members. The male sperm whale generally leave around 4 years old, sometimes forming a pod of its own with other young adult males. This pod will also eventually split up as the males age. Adult male sperm whales are the only members of the species that venture into the colder waters approaching the poles, while the pods of female and young sperm whales remain in tropical and temperate zones. Sperm whales spend most of their time on the hunt, but sometimes they break off in the afternoon to engage in more social behaviour. This includes calling to each other and rubbing against each other. When attacked, sperm whales form a “marguerite formation,” surrounding a vulnerable pod member with their tails thrust outward to ward off harassers.

How fast can sperm whales swim?

A sperm whale’s normal cruising speed ranges somewhere around 5 to 15 kph (3 to 9 mph). When they speed up, sperm whales can swim approximately 35 to 45 kph (22 to 28 mph), and they can maintain these speeds for about an hour.

What are sperm whale mating rituals like?

Sperm whale males reach sexual maturity around 18 years old and females at 9 years old. Males battle for mating rights, then breed with multiple females. Male sperm whales do not create harems of females like other animals. The sperm whale pregnancy term lasts about 15 months, resulting in a single calf. The birth is a social event, with the rest of the sperm whale pod forming a protective barrier around the birthing mother and her calf. Female sperm whales mate once every 4 to 20 years until they are about 40 years old.

How long do sperm whales live?

Sperm whales have a lifespan similar to humans, living about 70 years. Males do not reach full size until they are about 50.

How many sperm whales are there today?

Global abundance is not known but is broadly estimated to be about 360,000, making sperm whales one of the most abundant of all the great whales .

Do sperm whales have any predators?

Orcas are the largest natural threat to sperm whales, though pilot whales and false killer whales are also known to hunt them. Orcas go after entire sperm whale pods and will try to take a calf or even a female, but the male sperm whales are generally too big and aggressive to be hunted. Aside from the usual commodities (food, blubber, oil), sperm whales have other materials that were valuable during the high whaling eras:

- Spermaceti – A waxy substance used in a variety of pharmaceuticals as well as candles, ointments, cosmetics, and weather proofing

- Ambergris – Waxy and flammable, this material forms in the sperm whale’s digestive track by irritation from squid beaks. Sperm whales produce it over the course of years to help with the passing of objects that do not otherwise break down in their digestive track. Ambergris was heavily used by the perfume industry, but its rarity eventually led to the search for other substances.

Do sperm whales attack people?

While sperm whales generally retreat from ships, on very rare occasions they have been known to ram small boats. Some scientists believe sperm whales remember past human aggression and have become hostile, but others think their collisions are purely accidental.

Seven suitable sperm whale facts

- Sperm whales have the biggest heads and brains on Earth. Their brains are five times heavier than a human’s.

- The white whale in Moby Dick was based on two real-life sperm whales: a whale that rammed and sank the ship Essex and an albino adult male named Mocha Dick .

- Sperm whales are named after the spermaceti pulled from their bodies.

- Sperm whales fertilize the oceans with their feces, which floats upward and is consumed by phytoplankton.

- Male adult sperm whales very occasionally have been known to attack orcas to compete for food.

- A sperm whale’s heart weighs about the same as two average adult male humans (125 kg or 275 pounds).

- The highest sound pressure level ever recorded from an animal was from a sperm whale off the coast of northern Norway. The single click reached 235 (dB re 1 μ Pa), which is equal to the sound pressure of the Saturn V rocket heard at about one meter distance (3 feet). This recording proved the “the Big Bang” hypothesis, which stated that sperm whales could stun or even kill prey with sound.

Sperm Whales

Physeter macrocephalus

Historical Significance

Though not as talked about as the California gray whale, humpback, or blue, the sperm whale is an animal of extremes. These whales are unique for having the largest brain of any animal, being the largest toothed predator, the most sexually dimorphic cetacean species, and their highly social way of life. However, it was their industrial value that initially grabbed the attention of humans. Through the 18th and 19th Centuries, sperm whale oil was responsible for keeping the streets lit at night, was the main ingredient in clean-burning spermaceti candles and lamps in homes and businesses, and was the main ingredient in soaps and cosmetics. Lastly, spermaceti oil lubricated the machines of the Industrial Revolution. Sperm whales were like oil reservoirs, while the whalers were the Shell or BP of the era. Because the sheer volume of spermaceti oil contained in one animal was so high, sperm whaling (the hunting and processing of sperm whales) became one of the most profitable endeavors of the time.

Sperm Whale Facts

Order: Cetacea

Suborder: Odontocetes (toothed)

Family: Physeteridae

Species: P. macrocephalus

Status: Vulnerable

Weight: 15-45 Tonnes

Sperm whales were not only coveted and hunted for their monetary value, but they were also feared and pondered by scientists and literary scholars since the first whale was hunted in 1712, off the coast of Nantucket. Herman Melville, who was also a whaler, used the sperm whale as his muse in one of the world’s most recognized novels, Moby Dick. Melville describes “…touching the great inherent dignity of the sublimity of the sperm whale…”. Or there is the lesser-known Natural History of the Sperm Whale written in 1839 by an English surgeon and on-deck whaling observer, Thomas Beale. Beale’s novel is known to be a work selected by scholars for holding cultural importance while contributing to our base knowledge of sperm whales today. While there are many more books, Beal’s novel is just another example of the impact these magnificent animals have had on our history and culture. Sperm whales have been and continue to be the muse and subject of study for many writers of folklore, scientific journaling, research, and literature.

Size and Identification

The most notable physical feature of the Sperm whale is its robust, square-shaped head, which takes up about 1/3 of its body length. The sides of the body have a bumpy or wrinkled appearance starting behind the head. The signature of sperm whales is a relatively small, narrow bottom jaw lined with the largest teeth of any predator in the world. Though the upper jaw is devoid of teeth, it is lined with sockets perfectly formed to fit the lower teeth. The upper jaw is merely a structure encompassed by the spermaceti organ. The box-shaped head is likely scarred from feisty past prey, natural ocean hazards, or other sperm whales. A single blowhole is set to the front, left side of the head. Sperm whale pectoral fins are relatively small and paddle-shaped. The tail fin or flukes are one of the only features of the sperm whale that is not particularly unique, with a general triangular appearance. From the surface of the water, the sperm whale may resemble a giant, outstretched log with a short, rigid dorsal fin near the middle of its back. Males can reach lengths of up to 55 feet (17 meters) and up to forty-five metric tons. Females on the other hand are much smaller, reaching 36 feet (11 meters) in length and roughly fifteen metric tons. The female sperm whale’s head is less prominent, yet still taking up one-quarter of her body mass.

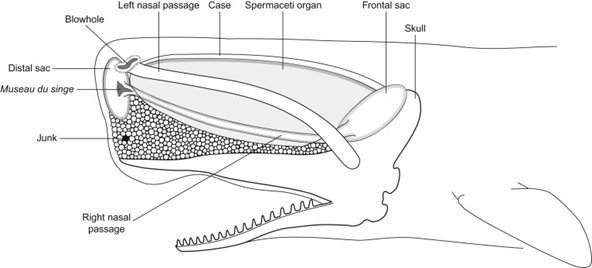

Spermaceti Organ

Among the many features that set sperm whales apart from other cetaceans is the distinct spermaceti organ – or as the whalers dubbed it, the “Case” (Fig 1). This unusual adaptation is so significant that the skull has evolved to be a supportive basin for the massive organ to rest in. Taking up to 33% of the animal’s mass, the spermaceti organ embodies the head and is encased in a muscular sheath containing soft tissues comparable to a sponge saturated in oil – spermaceti oil. The skull is separated from the spermaceti organ by an air-filled cushion, supplied by the animal’s right nasal passage. The nasal passage separates into two, one running above the spermaceti organ to the blowhole, and the other below, following between the organ and another huge structure whalers referred to as the “Junk.”

Since the 1700s, scientists have sought to understand the purpose of the spermaceti organ and the overall anatomy of sperm whales, and many did this by observing the flensing of the whales on board whaling ships. A great deal of the known biology of sperm whales came from scientists’ observations and meticulous notetaking aboard these floating processing plants, by examining the carcasses of butchered whales, resulting in an in-depth body of knowledge on the biology and anatomy of sperm whales. Nonetheless, even modern-day science cannot be fully certain of the complex spermaceti organ’s function, albeit the current scientific consensus strongly supports that the organ is a specialized adaptation designed for diving, deep-sea navigation, hunting, communication, and potentially sexual selection.

Sperm whales occur in all the world’s oceans, through all zones and hemispheres. They can be found within and around the deep trenches and ocean canyons offshore, following their prey items - primarily squid (though their choice of prey varies geographically). They can be seen in California waters year-round and are in highest concentrations from April through mid-June, and from late August through mid-November. They can be seen from our shores in all seasons other than winter. Otherwise, females together with the young and juvenile family members live largely in tropical or subtropical waters, as the males journey closer to the Arctic and Antarctic poles in search of giant squid; squid that are in some cases larger in length than the whales themselves. The largest males can be found near the polar pack ice regions, although, most will return to the tropical zones to breed a few months out of the year.

Echolocation and Diving

Imagine being born into a featureless, three-dimensional, dark, and liquid world, where your only way to navigate the mysteries of your surroundings is to make sounds with your head in order to “see.” Because in water sound travels at a rate five times faster than in air, making sound the primary sensory cue for the majority of marine mammals. And if you were a sperm whale, you would have the use of the most efficient biosonar tool that nature has ever created – the aforementioned spermaceti organ. It is theorized that this adaptation produces powerful echolocation clicks, creating pulses that begin by passing air through what is called the museau dusinge, or the “monkey lips” before it passes through the spermaceti organ (refer to Fig 1) - here the pulse bounces off the air-filled cushion where it is reflected back through the junk and into the ocean through multiple layers of acoustic lenses within the junk. And just like man-made ultrasound, the pulses reflect off any objects or entities in the sperm whale’s surroundings, returning an “image” for the animal to identify. Studies show that these powerful clicks are directionalized, can travel great distances (2,600 feet per half second) as it locates, and if close enough, acoustically debilitates prey.

The ability to “see” in pitch blackness goes hand-in-hand with the ability to dive to the deepest, darkest, and most remote places on the planet. Having this efficient built-in biosonar and the physical ability to routinely reach depths of 2,000 feet (610 meters) and return to the surface every forty-five minutes, gives sperm whales the advantage to seek out the larger prey items that lurk at the depths. However, the largest and most mature adults can reach depths of 10,000 feet (3,000 meters) while holding their breath for up to two hours. Being able to withstand the crippling pressures by collapsing their ribcage and slowing their heart rate to just a few beats per minute(bradycardia), all while supplying only the vital organs with oxygenated blood. As a result, sperm whales can descend comfortably to depths that human free divers can only dream of.

Social Lives

“Maybe we’re looking at sperm whale behaviors as a way to explore ourselves” – Jeff Jacobsen, 2023. When commercial whaling began and long into the 19th century, sperm whales were largely declared as dangerous and hostile animals. For example, in 1839, French zoologist Baron Curvier agreed with Herman Melville when he wrote: “There is no animal in creation more monstrously ferocious than the sperm whale”. In spite of this popular opinion, there were those who debated the claim such as Thomas Beale, who saw the sperm whale as “a most timid and inoffensive animal… readily endeavoring to escape from the slightest thing which bears an unusual appearance”. Fast-forward nearly 200 years, and current literature has shifted to regarding whales as “gentle giants,” including sperm whales. Modern studies have revealed that not only have sperm whales shown to be docile and hard to study due to their retreat to the depths, but that they are more like us than we could have thought. Furthermore, much like humans, sperm whales are highly social animals. Especially so are the females and young adults who travel together in groups of up to 35 individuals, usually accompanied by one to three adult males. As some individuals come and go from the group, evidence has shown that some of the females travel together for years. Similarly, sperm whales exhibit behaviors of empathy and care for others. One of the first reports of the “rosette” or “marguerite” formation came from Hal Whitehead and Jonathan Gordon as they led a research team through the Indian Ocean to follow and study sperm whales between 1981 and 1984. Whitehead recalls, “They were twisting and maneuvering into unusual patterns, including a star…Their heads were together at the center, but their bodies radiated out in different directions” (Fig 2). This flower position has been seen many times by observers and scientists in the following years and has been established as a defensive position against a threat, especially in protecting one of their young or weak, who they position in the center. One such example is when a group of killer whales ( Orcinus orca ) began to attack a group of nine sperm whales in a 1999 account. When a sperm whale was pulled from its position in the rosette, two or more individuals would leave the safety of the rosette to assist their isolated companion. Putting themselves directly in harm’s way to try and preserve the life of the other. Likewise, the way sperm whales care for their young is reflective of how many human parents and relatives take care of their own. For example, the birth of an infant is a rare and social event. With a gestation period of 14-16 months, sexually mature female sperm whales will only give birth once every 4 – 7 years. And according to the researchers Weilgart and Whitehead’s rare eye-witness account, the group of sperm whales in the mother’s company will gather around her as she goes through labor. Once the calf is free from the mother’s womb, it gets “passed around” to the other adult females while it awkwardly learns to swim, all while getting jostled and nudged. The reason for this is not clear, but after some time the calf is left alone with its mother to suckle and bond while the other whales keep the protective barrier around the pair.

Sperm Whale Migration

Female sperm whales ( Physeter macrocephalus ) travel in groups with their young, circling the oceans to find food, they may travel a million miles in a lifetime. Inhabiting warmer waters than the males who thrive in the Arctic, they must meet up in the middle near the Azores.

Biology, Geography

Media Credits

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Last Updated

January 11, 2024

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

Join Our Whale-y Big Celebration!

We’re celebrating whales all month long!

Dive in with us during the month of March as we highlight the largest marine mammals: whales! Learn fun facts about these gentle giants, what conservation efforts are helping to protect them, ways you can be a whale champion and more.

- Learn About Marine Mammals /

- Cetaceans /

Sperm Whale

Physeter macroephalus

Learn More About Sperm Whales

Sperm whales are named after the waxy substance, spermaceti, found in their heads. These whales are the largest of the toothed whales. Males can reach 60 feet in length and smaller females reach 37 feet.

Sperm whales are dark gray in color, have a hump rather than a dorsal fin and have triangular shaped flukes, or tails. Just behind their large head (which is about one-third of their total body length!) their skin is wrinkled to increase surface area, leading to greater heat loss. This gives them a shriveled look.

These whales have a single, S-shaped blowhole located on the left side of the top of their head. This unique blowhole produces a distinctive angled spout, or blow. Males have about 40-50 teeth, located only in their narrow lower jaw and females have even less.

What do they sound like?

Your browser doesn't support HTML5 audio. Download the audio file.

The greatest threats to marine mammals are caused by people, but we can also be their greatest champions.

Sign up for email from the marine mammal center to stay updated on how you can be an advocate and champion for marine mammals like sperm whales..

Yes! I want to be a champion for marine mammals!

Habitat & Population Status

Sperm whales can be found around the world but typically stay away from the extremely cold waters near the polar ice in the north and the south. Females usually remain in temperate and tropical waters within 45-55° latitude, whereas males travel in temperate waters. In California, sperm whales can be seen in waters off the continental slope from November to April.

Sperm whales prefer deep water around ocean trenches, where strong currents flow in opposite directions that bring concentrated nutrients to the area thus attracting a large number of creatures that the sperm whales can eat.

Sperm whales were heavily hunted from 1800 to 1987 for spermaceti, the substance found only in a sperm whale’s head and used in echolocation. They were also hunted for ambergris, a waxy substance used in making perfume, that forms around squid beaks in the whale’s digestive system.

Today sperm whales are classified as endangered. The species is slowly recovering from decades of hunting. It’s estimated that the population is about 850,000 individuals worldwide.

Breeding & Behavior

Mating occurs in spring and summer, and females carry their young for 14 to 16 months, giving birth every three to five years. Newborn calves are 13 feet long and weigh about a ton. These calves nurse for two years but may continue nursing with their mother intermittently for up to eight years.

Female and young male sperm whales are social with each other and are sometimes are seen in pods, or groups, of up to 50 whales. The females form matriarchal, or female-led, pods. The young males will often leave these groups to form bachelor herds until they are able to compete in mating at about 20 years old. Aside from the breeding season, adult males lead a solitary life.

Sperm whales are champion divers and are thought to dive to depths greater than 3,000 feet and can stay underwater for up to two hours. They impressively get to these depths in a matter of minutes.

Squid is a sperm whale’s favorite food and it’s suspected that they spend a lot of their dive time hunting for prey using echolocation. Sperm whales also produce a series of clicks called codas. Each whale has a distinctive coda and scientists think that sperm whales recognize each other by these clicks. There is also evidence that sperm whales produce intense bursts of sound to stun their prey.

The sperm whale is a species known for stranding in large groups. It is not known why they strand in this manner, but some theories include mass illness, parasitic infection, following a sick leader and echolocation malfunctions due to gently sloping beaches and underwater magnetic anomalies leading to disorientation.

Learn About Another Animal

Pacific harbor seal, northern elephant seal, california sea lion, steller sea lion, northern fur seal, guadalupe fur seal, hawaiian monk seal, common bottlenose dolphin, humpback whale, pacific white-sided dolphin.

Cephalopods, Crustaceans & Other Shellfish

Corals & Other Invertebrates

Marine Mammals

Marine Science & Ecosystems

Ocean Fishes

Sea Turtles & Reptiles

Sharks & Rays

Marine Life Encyclopedia

Sperm Whale

Physeter macrocephalus

Distribution

Worldwide in tropical to polar latitudes

eCOSYSTEM/HABITAT

Open ocean (pelagic); deep diver

FEEDING HABITS

Active predator

Suborder Odontoceti (toothed whales), Family Physeteridae (sperm whales)

Sperm whales have several specialized physical characteristics that aid in this predatory behavior. They have large conical teeth for ensnaring their preferred prey. Like most active predators, they have large brains and in fact, the sperm whale has the largest brain of any animal on the planet. They also have the most powerful sonar of any animal, which they use to find their prey in the dark deep sea. Finally, they have an ability to dive to incredible depths (up to 1000 meters) and stay down for incredible lengths of time (up to two hours), both abilities increasing their likelihood of finding prey. As a result of their deep-sea behaviors, sperm whales typically live in waters of several thousand meters deep and are rarely seen along the coast except in areas where deep trenches or underwater canyons approach the shore.

The sperm whale’s very large brain and specialized sonar organ (called a melon) contribute to its characteristic block-shaped head. It is the only whale that has that shaped head and is typically quite easy to identify. The body is generally uniformly grey. The sperm whale’s lifecycle is very similar to that of humans. Individuals reach sexual maturity in their teenage years, and females reproduce until they reach their forties and go on to live into their seventies. Sperm whales give birth to only one calf at a time, and at birth, baby Sperm Whales are enormous – over 13 feet (4 m) long. Because calves cannot undertake the deep, long dives that their mothers do, groups of mothers form tight bonds and share the responsibility of protecting calves at the surface. While one or more mothers dive, others stay with at the surface with the young.

150 years of commercial whaling for sperm whales cut their numbers at least in half, and some scientists estimate that whaling reduced the population by 75% or more. During a time when whale oil was a primary energy/lighting source in the U.S. and Europe, sperm whale oil was some of the highest quality and highest volume per whale of any species. Though whaling has all but ceased since 1988, sperm whales have not yet fully recovered from this cruel practice and are still considered vulnerable to extinction by expert scientists. They have, however, recovered more significantly than the other large whales and are the most common large whale in the ocean today. It is difficult to obtain accurate numbers of sperm whales in the wild, so it is equally difficult to determine if populations are increasing or decreasing, but today’s primary threats include accidental entanglement in fishing gear, chemical pollution, and noise pollution. Several countries around the world have offered sperm whales some or extensive legal protection.

Fun Facts About Sperm Whales

1. Sperm whales are the largest of all toothed whales and can grow to a maximum length of 52 feet (15.8 m) and weight of 90,000 pounds (40 metric tons), with males growing much larger than females.

2. Sperm whales live for up to 60 years.

3. Sperm whales have one of the widest distributions of all marine mammals, living everywhere from the Arctic to the Antarctic.

4. Sperm whales are named after the spermaceti – a waxy substance that was used in oil lamps and candles – found on their heads.

5. Sperm whales are known for their large heads that account for one-third of their body length.

6. Sperm whales can stay underwater for up to 60 minutes at a time.

7. Sperm whales can dive more than 10,000 feet (3,048 m) in search of their preferred prey, which includes squid, sharks and fish.

8. Sperm whales eat up to 3.5 percent of their body weight in food every day.

9. Female sperm whales form lasting relationships with other females in their family and create social groups around these bonds. Males, on the other hand, leave their matriarchal groups between 4 and 21 years old to join “bachelor schools” before eventually leading solitary lives in their later years. 1

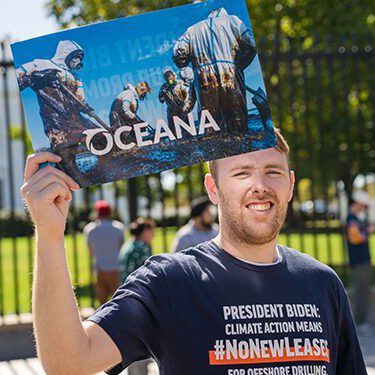

Engage Youth with Sailors for the Sea

Oceana joined forces with Sailors for the Sea, an ocean conservation organization dedicated to educating and engaging the world’s boating community. Sailors for the Sea developed the KELP (Kids Environmental Lesson Plans) program to create the next generation of ocean stewards. Click here or below to download hands-on marine science activities for kids.

References:

1 NOAA Fisheries

IUCN Red List

Get Involved

Donate Today

Support our work to protect the oceans by giving today.

With the support of more than 1 million activists like you, we have already protected nearly 4 million square miles of ocean.

TAKE ACTION NOW

Support policy change for the oceans.

Decision-makers need to hear from ocean lovers like you. Make your voice heard!

VISIT OUR ADOPTION CENTER

Symbolically adopt an animal today.

Visit our online store to see all the ocean animals you can symbolically adopt, either for yourself or as a gift for someone else.

DOWNLOAD OCEAN ACTIVITIES

Help kids discover our blue planet.

Our free KELP (Kids Environmental Lesson Plans) empower children to learn about and protect our oceans!

FEATURED CAMPAIGN

Save the oceans, feed the world.

We are restoring the world’s wild fish populations to serve as a sustainable source of protein for people.

More CAMPAIGNs

Protect Habitat

Oceana International Headquarters 1025 Connecticut Avenue, Suite 200 Washington, DC 20036 USA

General Inquiries +1(202)-833-3900 [email protected]

Donation Inquiries +1(202)-996-7174 [email protected]

Press Inquiries +1(202)-833-3900 [email protected]

Oceana's Efficiency

Become a Wavemaker

Sign up today to get weekly updates and action alerts from Oceana.

SHOW YOUR SUPPORT WITH A DONATION

We have already protected nearly 4 million square miles of ocean and innumerable sea life - but there is still more to be done.

QUICK LINKS:

Press Oceana Store Marine Life Blog Careers Financials Privacy Policy Terms of Use Contact

Where Do Sperm Whales Live?

Sperm whales (particularly adult males) can be found in all of the world’s major oceans, from the warm tropical climates in and around the equator to the northern and southern polar hemispheres. Young sperm whales generally stay close to their mothers until they reach maturity, and then they will go and venture out on their own.

Unlike adult male sperm whales, the female sperm whales and their calves prefer staying warm climates around the equator throughout the year. The adult male sperm whales travel to the colder climates during the off-season and return to the warmer climates during the mating season , which occurs during the colder winter months.

In fact, some male sperm whales can travel throughout all of the world’s major oceans over the course of their 70-year lifespan , allowing them to travel the world before they die.

Male sperm whales are also known to be solitary animals, often traveling alone or in small groups where they may form a loose bond with another male. In addition to traveling between warm and cold climates, sperm whales are also among the deepest diving species of all cetaceans.

During deep dives, sperm whales can dive to depths more than 3,000 ft. to look for giant squid and octopus to eat. Some sperm whales can even be found with marks and scars around their head from fights with large squid that tried to avoid being eaten by latching onto the whale’s head.

Being equipped with echolocation allows the sperm whale to use sound to navigate the ocean and search for prey, which is extremely important since these marine mammals often hunt in complete darkness. This makes echolocation essential for their survival and ability to obtain adequate food for their diet.

In fact, these marine mammals dive so deep that it has been difficult for researchers to observe or obtain footage of the exact hunting methods used by sperm whales.

In addition to traveling the world and diving to depths over 3,000 ft. these marine mammals are the largest animals within the toothed whale family and have the biggest brain of all living animals. At full maturity, the male sperm whale can reach lengths over 65 ft. long and weigh 45 tons when fully matured. Female sperm whales, on the other hand, measure 1/2 to 1/3 the size of their male counterparts.

Note : To use a comparison to show you just how big the sperm whale is, as stated early reaching lengths of up to 67 ft. the sperm whale is the largest of the toothed whale family and is significantly larger than the second-largest toothed whale, Baird’s beaked whale , which can reach lengths of 40+ ft. when fully matured. That’s a difference of over 20 ft. long!

Solitary lifestyle

While not always the case, it seems as though larger marine mammals such as male sperm whales tend to lead a more solitary lifestyle when compared to smaller cetacea like dolphins and porpoises . As stated earlier, they often travel alone when mating season is not in session and can wander off to various locations of their choosing.

In some cases, a male sperm whale may choose to form a bond with another male whale and form a small pod; however, the length of time that the relationship/pod lasts can vary from one male to the next.

Although the reason for their solitary lifestyle is unknown, it is possible that they do not need to rely on large groups to survive or protect themselves since they are fairly large and robust in size. After all, an adult male can reach lengths over 67 ft. and a weight of 45 tons (not common).

Once fully grown, a male sperm whale is largely protected by its size alone, which is likely to deter most would-be predators. In fact, the only known predators of the sperm whale are a pack of hungry killer whales and potentially large sharks , which may try to prey on young whales since they are easier to catch.

Motherly protection

While male sperm whales are fairly solitary, the female sperm whales can often be seen grouped with other females, and they’re young. As the males go off to wander the oceans, the females stay together to protect their young from potential predators (such as sharks) and nurture them to grow up to be strong in big.

During the first few years of birth, the baby whales are nurtured and cared for by being fed milk which can last for 1 1/2 – 4 years or more depending on the emotional bond they have with their mother.

When the young male whales reach the ages 4 – 21, they choose to leave their pod and go off independently. The young female whales continue to maintain relationships with their local pods and, upon sexual maturity, may begin mating and reproducing offspring of their own.

To protect their young from potential threats, the adult females may form a circle around the child with their heads facing the child and their flukes facing the outside circle. This formation is used as a form of defense as the flukes are powerful enough to immobilize or even kill a predator if they are struck hard enough.

In some cases, the female whales may also form an overwatch position where their flukes are pointed in towards the child, and their heads are facing the outside of the circle.

As far as pods/groups go, female sperm whales may form 6 – 10 members. However, larger variations may occur in some pods containing 20 or more members. Unlike other cetacea, however, female sperm whales do not appear to show a preference for maintaining relationships with pod members within their families.

Once a female sperm whale becomes part of a pod and spends several years together with its pod members, they rarely leave to join a new pod.

Related posts:

- Marine Mammal Conservation

- What Is A Group Of Whales Called?

- Whales For Kids – Questions and Answers

- Arnoux’s Beaked Whale Facts | Diet, Migration and Reproduction

Sperm Whale

Physeter macrocephalus [=catodon].

- Species Status Native Imperiled

- View All Species

Listing Status

- Federal Status: Endangered

- FL Status: Federally-designated Endangered

- FNAI Ranks: Not ranked

- IUCN Status: VU (Vulnerable)

Sperm whales are the largest member of the toothed whale Family, Odontoceti. This species is sexually dimorphic by size and weight. Females can reach a length of 36 feet (11 meters) and a weight of 15 tons (13,607 kilograms), while males grow up to 52 feet (15.9 meters) and 45 tons (40,823 kilograms). Sperm whales can be distinguished from other whale species by their enormous head, which can take up to 35% of their body. Their brain is the largest of any animal. Sperm whales have 20-26 cone-shaped teeth on each side of the lower jaw; however, their teeth are not needed for feeding. Their blowhole is located on the left side of the head. Sperm whales uniquely shoot water forward from their blowholes, which is unlike other whales that shoot water straight up. Sperm whales are mainly dark grey with a white-colored interior mouth, triangle-shaped fluke (tail), and thick rounded pectoral fins (National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration, n.d.).

The diet of the sperm whale primarily consists of large squids and fish including sharks (National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration, n.d.).

Sperm whales are polygamous breeder – they breed with more than one partner. Breeding season peaks in the spring in both the Southern and Northern Hemisphere, and calves are born during the fall. During the breeding season, males join groups of females temporarily. The males become very aggressive towards each other when looking for a female to mate with. Sperm whales reach sexual maturity at a slow rate. Females reach sexual maturity at eight to eleven years old. Males do not begin mating until around 25-27 years old because they are not experienced enough. The gestation period for sperm whales is 14-16 months with the female giving birth to one calf every two to five years (NMFS 2010, Ballenger 2003). Adult female sperm whales and subadults form cohesive ‘social units’ (pods) that can remain together over a number of years. Adult male sperm whales typically travel in bachelor groups or alone.

Sperm whales can be found in all major oceans on Earth in waters 600 feet (182.9 meters) over the continental slope. (National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration, n.d.). Females and subadults inhabit tropical and temperate waters. Adult males live in high-latitude regions and travel to lower latitudes in search of females for mating.

Historically, sperm whales have faced catastrophic population declines due to harvesting. From 1800 to 1987, humans captured and harvested around one million sperm whales (National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration, n.d.). In 1988, the International Whaling Commission put a halt on all whaling; however, poaching still continues today. Poaching caused an extreme variation in the ratio of females to males, which affected reproduction of the species (American Cetacean Society, n.d.). Some countries (i.e. Japan) still harvest whales for research purposes. Sperm whales are also threatened by boat and ship hits. Human made noises, such as from oil drilling, can disturb a population’s ability to communicate due to the noise interfering with their vocalizations. Other threats include pollution from PCBs (polycholorobiphenyls), and PAHs (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons) (National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration, n.d.).

Conservation and Management

The sperm whale is protected as an Endangered species by the Federal Endangered Species Act and as a Federally-designated Endangered species by Florida’s Endangered and Threatened Species Rule . It is also protected Federally protected as a Depleted species by the Marine Mammal Protection Act.

Federal Recovery Plan

Other Informative Links

Animal Diversity Web Aquarium of the Pacific International Union for Conservation of Nature National Geographic National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration Printable version of this page

American Cetacean Society. (n.d.). Sperm Whale . Retrieved June 6, 2011, from American Cetacean Society Fact Sheet: https://www.acsonline.org/sperm-whale?

Ballenger, L. 2003. "Physeter catodon" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed August 12, 2011 http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Physeter_catodon.html

National Marine Fisheries Service. 2010. Recovery plan for the sperm whale ( Physeter macrocephalus ). National Marine Fisheries Service, Silver Spring, MD. 165pp.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association. (n.d.). Sperm Whale . Retrieved June 6, 2011, from NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service: http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/pr/species/mammals/cetaceans/spermwhale.htm

Internet Explorer lacks support for the features of this website. For the best experience, please use a modern browser such as Chrome, Firefox, or Edge.

Sperm Whale

Physeter macrocephalus

Protected Status

Quick facts.

Sperm whales. Credit: NOAA Northeast Fisheries Science Center.

About the Species

Sperm whales are the largest of the toothed whales and have one of the widest global distributions of any marine mammal species. They are found in all deep oceans, from the equator to the edge of the pack ice in the Arctic and Antarctic.

They are named after the waxy substance—spermaceti—found in their heads. The spermaceti is an oil sac that helps the whales focus sound. Spermaceti was used in oil lamps, lubricants, and candles. Sperm whales were a primary target of the commercial whaling industry from 1800 to 1987, which nearly decimated all sperm whale populations. While whaling is no longer a major threat, sperm whale populations are still recovering. The sperm whale is listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act and depleted under the Marine Mammal Protection Act .

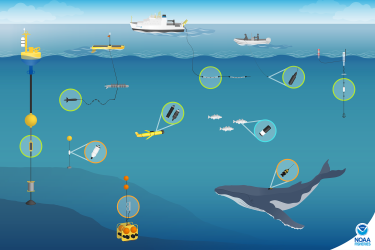

NOAA Fisheries and our partners are dedicated to conserving and rebuilding sperm whale populations. We use a variety of innovative techniques to study, protect, and rescue these endangered whales. We engage our partners as we develop regulations and management plans that encourage recovery, foster healthy fisheries, reduce the risk of entanglements, create whale-safe shipping practices, and reduce ocean noise.

Population Status

Commercial whaling from 1800 to the 1980s greatly decreased sperm whale populations worldwide. The International Whaling Commission placed a moratorium on commercial whaling in 1986. The species is still recovering, and its numbers are likely increasing.

Visit the most recent stock assessment report to view population estimates for sperm whales in U.S. waters.

Sperm whales are mostly dark grey, though some whales have white patches on the belly. They are the only living cetacean that has a single blowhole asymmetrically situated on the left side of the crown of the head. Their heads are extremely large, accounting for about one-third of their total body length. The skin just behind the head is often wrinkled. Their lower jaw is narrow and the portion of the jaw closest to the teeth is white. The interior of the mouth is often bright white as well. There are between 20 and 26 large teeth on each side of the lower jaw. The teeth in the upper jaw rarely break through the gums.

Sperm whale flippers are paddle-shaped and small compared to the size of the body, and their flukes are triangular. They have small dorsal fins that are low, thick, and usually rounded.

Behavior and Diet

Sperm whales hunt for food during deep dives that routinely reach depths of 2,000 feet and can last for 45 minutes. They are capable of diving to depths of over 10,000 feet for over 60 minutes. After long, deep dives, individuals come to the surface to breathe and recover for several minutes before initiating their next dive.

Because sperm whales spend most of their time in deep waters, their diet consists of species such as squid, sharks, skates, and fish that also occupy deep ocean waters. Sperm whales can consume about 3 to 3.5 percent of their body weight per day.

Where They Live

Sperm whales inhabit all of the world’s oceans. Their distribution is dependent on their food source and suitable conditions for breeding, and varies with the sex and age composition of the group. Sperm whale migrations are not as predictable or well understood as migrations of baleen whales. Some populations appear to have different migration patterns by life history status, with adult males making long oceanographic migrations into temperate waters whereas females and young staying in tropical waters year-round.

Lifespan & Reproduction

Female sperm whales reach sexual maturity around 9 years of age when they are roughly 29 feet long. At this point, growth slows and they produce a calf approximately once every five to seven years. After a 14 to 16-month gestation period, a single calf about 13 feet long is born. Although calves will eat solid food before one year of age, they continue to nurse for several years. Females reach their maximum length and are physically mature around 30 years old at which they measure up to 35 feet long.

For about the first 10 years of life, males are only slightly larger than females, but males continue to exhibit substantial growth until they are well into their 30s. Males reach physical maturity around 50 years and when they are approximately 52 feet long. Unlike females, puberty in males is prolonged, and may last between the ages of 10 to 20 years old. Even though males are sexually mature at this time, they often do not actively participate in breeding until their late twenties.

Most females will form lasting bonds with other females of their family, and, on average, 12 females and their young will form a social unit. While females generally stay with the same social unit in and around tropical waters their entire lives, young males will leave when they are between 4 and 21 years old and can be found in "bachelor schools,” composed of other males that are approximately the same age and size. As males get older and larger, they begin migrating toward the poles. As a result, bachelor schools become smaller and the largest males are often found alone. Large, sexually mature males that are in their late 20s or older will occasionally return to the tropical breeding areas to mate.

Vessel Strikes

Vessel strikes can injure or kill sperm whales. Few vessel strikes of sperm whales have been documented, but vessel traffic worldwide is increasing, which increases the risk of collisions. Additionally, since sperm whales spend long periods (typically up to 10 minutes) “rafting” at the surface between deep dives, they are more vulnerable to vessel strikes.

Entanglement in Fishing Gear

Sperm whales can become entangled in many different types of fishing gear, including trap lines, pots, and gillnets. Once entangled, they may swim for long distances dragging attached gear, potentially resulting in fatigue, compromised feeding ability, reduced reproductive success, severe injury, or death.

Sperm whales have also been documented to remove fish from longline gear, a behavior known as “depredation.” They do this by using their long jaw to create tension on the line, which shakes fish off the hooks. In addition, scientists think that this behavior may be learned between individuals. Depredation increases a sperm whale’s likelihood of injury or entanglement while maneuvering around boats and fishing gear.

Ocean Noise

Underwater noise pollution can interrupt the normal behavior of sperm whales, which rely on sound to communicate. As ocean noise increases from human sources, communication space decreases—the whales cannot hear each other, or discern other signals in their environment as they used to in an undisturbed ocean.

Different levels of sound can disturb activities such as feeding, migrating, and socializing. Mounting evidence from scientific research has documented that ocean noise can also cause marine mammals to change the frequency or amplitude of calls, decrease foraging behavior, become displaced from preferred habitat, or increase the level of stress hormones in their bodies. If loud enough, noise can cause permanent or temporary hearing loss.

Marine Debris

Sperm whales can ingest marine debris, as do many marine animals. Debris in the deep scattering layer where sperm whales feed could be mistaken for prey and incidentally ingested, leading to possible injury or death.

Climate Change

The effects of climate and oceanographic change on sperm whales are uncertain, but both can potentially affect habitat and food availability. Whale migration, feeding, and breeding locations for sperm whales may be influenced by factors such as ocean currents and water temperature. Increases in global temperatures are expected to have profound impacts on arctic and subarctic ecosystems, and these impacts are projected to accelerate during this century. However, the feeding range of sperm whales is likely the greatest of any species on earth, and, consequently, sperm whales are expected to be more resilient to climate change than species with more restrictive habitat preferences.

Oil Spills and Contaminants

The threat of contaminants and pollutants to sperm whales and their habitat is highly uncertain and further study is necessary to assess the effects of this threat. Little is known about the possible long-term and transgenerational effects of exposure to pollutants. Marine mammals are considered to be good indicators for concentrations of metal and pollutant accumulation in the environment due to their long lifespan and (in some cases) position near the top of marine food webs.

Scientific Classification

Last updated by NOAA Fisheries on 01/30/2023

Conservation & Management

NOAA Fisheries is committed to the protection and recovery of sperm whales. Targeted management actions taken to protect these whales include:

- Consulting with federal agencies to ensure proposed actions are not likely to jeopardize sperm whales via noise disturbance, ship strikes, or other human activities

- Responding to entangled or stranded sperm whales.

- Ensuring development of oil spill response plans to prepare for accidental spills

- Educating the public about sperm whales and the threats they face

- Monitoring sperm whale population abundance, distribution, and habitat use

Our research projects have discovered new aspects of sperm whale biology, behavior, and ecology and helped us better understand the challenges that sperm whales face. This research is especially important in rebuilding endangered populations. Our work includes, but is not limited to:

- Stock assessments

- Measuring the response of animals to sound

- Satellite tagging and tracking

How You Can Help

Keep Your Distance

Be responsible when viewing marine life in the wild. Observe all large whales from a safe distance of at least 100 yards and limit your time spent observing to 30 minutes or less.

Learn more about our marine life viewing guidelines

Report Marine Life in Distress

Report a sick, injured, entangled, stranded, or dead animal to make sure professional responders and scientists know about it and can take appropriate action. Numerous organizations around the country are trained and ready to respond. Never approach or try to save an injured or entangled animal yourself—it can be dangerous to both the animal and you.

Learn who you should contact when you encounter a stranded or injured marine animal

Report a Violation

Call the NOAA Fisheries Enforcement Hotline at (800) 853-1964 to report a federal marine resource violation. This hotline is available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week for anyone in the United States.

You may also contact your closest NOAA Office of Law Enforcement field office during regular business hours.

Featured News

Recent Prescott Grants Supporting Whale Conservation Partners

Passive Acoustic Monitoring Reveals More About Sperm Whales off Southeast New England

Whale Week: Celebrating the Wonder of Whales

Women Who Help Entangled Whales

Related species.

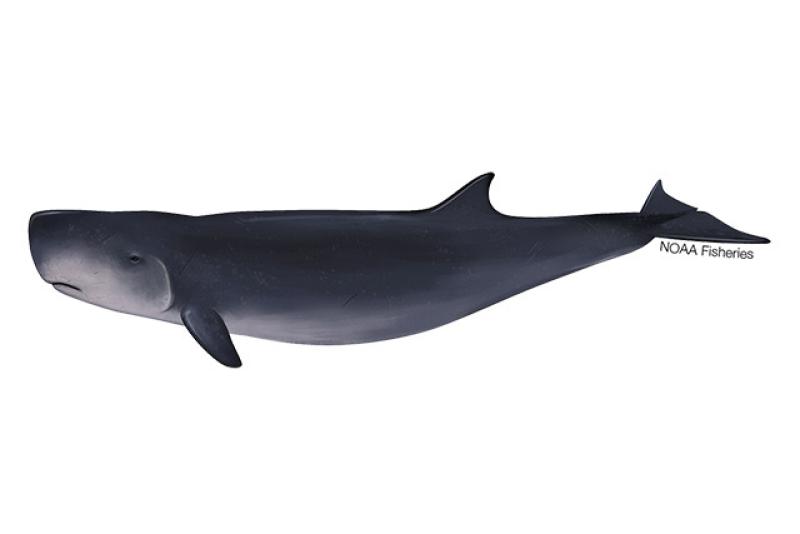

Dwarf Sperm Whale

Pygmy Sperm Whale

Short-Finned Pilot Whale

Baird’s Beaked Whale

In the spotlight, management overview.

The sperm whale has been listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act since 1970. This means that the sperm whale is in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant portion of its range. NOAA Fisheries is working to protect and recover this species.

Recovery Planning and Implementation

Recovery action.

Under the ESA, NOAA Fisheries is required to develop and implement recovery plans for the conservation and survival of listed species. The Recovery Plan for the sperm whale was published in December 2010. The plan’s goal is to delist the species, with an interim goal of down-listing its status from "endangered" to "threatened."

The major actions recommended in the plan are:

- Reduce or eliminate injury or mortality caused by vessel collisions

- Reduce or eliminate injury and mortality caused by fisheries and fishing gear.

- Protect habitats essential to the survival and recovery of the species

- Minimize effects of vessel disturbance

- Continue international ban on hunting and other directed take

- Monitor the population size and trends in abundance

- Maximize efforts to free entangled or stranded sperm whales

- Acquire scientific information from dead specimens

Learn more about the recovery plan for sperm whales

Implementation

NOAA Fisheries is working to minimize effects from human activities that are detrimental to the recovery of sperm whale populations in the U.S. and internationally. Together with our partners, we undertake numerous activities to support the goals of the sperm whale recovery plan. The ultimate goal is to delist the species.

Efforts to conserve sperm whales include:

- Protecting habitat

- Reducing bycatch

- Rescue, disentanglement, and rehabilitation

- Eliminating the harassment of animals through education and enforcement

A sperm whale dives. Credit: NOAA Alaska Fisheries Science Center/Brenda Rone.

Conservation Efforts

Addressing ocean noise.

Underwater noise may threaten sperm whales by interrupting their normal behavior and driving them away from areas important to their survival. Mounting evidence suggests that exposure to intense underwater sound may cause injury to sperm whales resulting in loss of hearing, or possibly stranding and ultimately death. NOAA Fisheries is investigating sound production and hearing in marine animals, as well as the effects of sound on whale behavior. In 2018, we revised technical guidance for assessing the effects of anthropogenic sound on marine mammals’ hearing.

Learn more about ocean noise

Overseeing Marine Mammal Health and Stranding Response

We work with volunteer networks in all coastal states to respond to marine mammal strandings including all whales. When stranded animals are found alive, NOAA Fisheries and our partners assess the animal’s health and determine the best course of action. When stranded animals are found dead, our scientists work to understand and investigate the cause of death. Although the cause often remains unknown, scientists can sometimes attribute strandings to disease, harmful algal blooms, vessel strikes, fishing gear entanglements, pollution exposure, and underwater noise. Some strandings can serve as indicators of ocean health, giving insight into larger environmental issues that may also have implications for human health and welfare.

Learn more about the Marine Mammal Health and Stranding Response Program

Marine Mammal Unusual Mortality Events

Sperm whales have been part of a declared unusual mortality event in the past . Under the Marine Mammal Protection Act , an unusual mortality event is defined as "a stranding that is unexpected; involves a significant die-off of any marine mammal population; and demands immediate response." To understand the health of marine mammal populations, scientists study unusual mortality events.

Get information on active and past UMEs

Get an overview of marine mammal UMEs

Educating the Public

NOAA Fisheries increases public awareness and support for marine mammal conservation through education, outreach, and public participation. We regularly share information with the public about the status of sperm whales, our research, and our efforts to promote their recovery.

Regulatory History

The sperm whale was originally listed as endangered throughout its range on June 2, 1970 under the Endangered Species Conservation Act of 1969, the precursor to the Endangered Species Act of 1973. Sperm whales are also protected under the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972.

Key Actions and Documents

Initiation of 5-year review for the sperm whale.

- Notice of Initiation of 5-year review; request for information (86 FR 28577, 5/…

Sperm Whale 5-Year Reviews

- 2014 Notice of Initiation (79 FR 53171)

- 2007 Notice of Initiation (72 FR 2649)

- Sperm Whale 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation (2015)

Determination on Petition to List Gulf of Mexico Sperm Whale as a Distinct Population Segment Under the ESA

- 12-month Finding for Gulf of Mexico DPS

- 90-day Finding for Gulf of Mexico DPS

- Original Sperm Whale Listing Under the ESA (35 FR 18319)

Sperm Whale Recovery Plan

- Notice of Recovery Plan (75 FR 81584)

- Final Recovery Plan (12/2010)

Incidental Take Authorization: Pacific Air Forces Regional Support Center's construction activities at Eareckson Air Station Fuel Pier Repair in Alcan

- Notice of Final IHA

- Notice of Proposed IHA

Incidental Take Authorization: U.S. Navy Hawaii-Southern California Training and Testing (HSTT) (2018-2025)

- Proposed Rule (2023)

- Notice of Receipt of Application for Revision to 7-Year Rule and LOAs

- Final 7-Year Rule (2020)

- Proposed 7-Year Rule (2019)

- Notice of Receipt of Application for 7-Year LOAs

Incidental Take Authorization: Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory's Marine Geophysical Survey in the Puerto Rico Trench and slope of Puerto Rico

Incidental take authorization: atlantic shores offshore wind bight, llc's marine site characterization surveys off new jersey and new york, more information.

- Report a Stranded or Injured Marine Animal

- Marine Life Viewing Guidelines

- Marine Mammal Permits and Authorizations

- Endangered Species Conservation

- ESA Section 7 Consultations

- Marine Mammal Protection

- Whale Alert Smartphone App

- International Marine Mammal Conservation

- Sperm Whale Contacts

Science Overview

NOAA Fisheries conducts research on the biology, behavior, and ecology of the sperm whale. The research is used to inform management decisions and enhance recovery efforts for this endangered species.

Stock Assessments

Determining the number of sperm whales in each population—and whether a stock is increasing or decreasing over time—helps resource managers assess the success of enacted conservation measures. Our scientists collect information and present these data in annual stock assessment reports .

Acoustic Science

NOAA Fisheries regularly uses genetic data to better understand population structure of marine mammals, including that of sperm whales. Acoustic research (the science of how sound is transmitted) increases our understanding of whale, dolphin, and fish behavior as well as the environmental soundscape; and enables the development of better methods to locate cetaceans using autonomous gliders and passive acoustic arrays.

Acoustics are used to monitor hearing levels and feeding behavior in sperm whales. We also study how underwater noise affects the way sperm whales behave, eat, interact with each other, and move within their habitat.

Learn more about acoustic science

Genetic Data

Currently, NOAA Fisheries’ goal is to re-examine the stock designations for every stock managed using molecular genetic data. We use the genetic data to determine patterns of relatedness within groups of sperm whales encountered at sea. These data shed light on the evolution of sociality at sea and the nature of social bonds in groups of free-ranging whales.

Behavioral Science

Sperm whales have been tagged in an effort to learn more about foraging behavior, movement patterns, and core home ranges.

Research & Data

Examining distribution patterns of foraging and non-foraging sperm whales in hawaiian waters using visual and passive acoustic data, passive acoustic cetacean map.

Recovery Action Database

- NOAA’s Alaska Fisheries Science Center Marine Mammal Laboratory

- Population Assessments

- Permits and Authorizations: Scientific Research and Enhancement

Recent Science Blogs

In search of atlantic northern shrimp.

EcoFOCI Cruise - Post 4

Old Friends in New Places: Cetacean Research in the Western Pacific

Biological Opinion on Whittier Head of the Bay Cruise Ship Dock, Passage Canal, Whittier, Alaska

Biological Opinion on the effects of the proposed construction of a cruise ship berth and…

Biological Opinion on 10 Fishery Management Plans

Biological Opinion on 10 Fishery Management Plans in the Greater Atlantic Region and the New…

Biological Opinion for City of Hoonah Marine Industrial Center Cargo Dock Project at Hoonah, Alaska

Endangered Species Act (ESA) Section 7(a)(2) Biological Opinion for City of Hoonah Marine…

Biological Opinion National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska Integrated Activity Plan Biological Opinion (AKRO-2020-01519)

Endangered Species Act Section 7(a)(2) Biological Opinion on the National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska…

Data & Maps

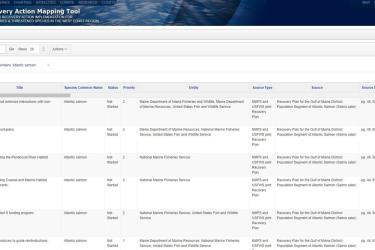

This mapping tool shows when and where specific whale, dolphin, and other cetacean species were…

Tracks the implementation of recovery actions from Endangered Species Act (ESA) recovery plans.

Other Southeast Gillnet Waters

Alaska endangered species and critical habitat mapper web application.

Spacial data and maps of critical habitat and Endangered Species Act (ESA) threatened and…

- DPG Masters

- World Oceans Day

My favorite image of the trip and my first-ever sperm whale encounter

The sperm whale is perhaps the most famous of all cetaceans, and the best place in the world to encounter this elusive species is the beautiful island of Dominica in the Caribbean. Known locally as “The Nature Island,” Dominica is beautiful above and below the surface. Rainforest and waterfalls cover the interior of the island, and deep water close to shore provides the perfect sanctuary for whales, dolphins and all kinds of other marine life. Nearly 200 different sperm whales have been identified and reside in the island’s waters, and it has become a popular destination for underwater photographers hoping to capture images of these amazing creatures.

Scotts Head, the most southerly point of the island and the base for our trip

An aerial view of Soufrière village on a beautiful sunny day in Dominica

Government-issued permits are required to swim with the whales, and rules are strictly enforced to avoid harassing or stressing the animals. Only one permit is issued at a time so there is never more than four people in the water, but as our guide explained on day one, sperm whales are basically living submarines, and so interacting with them can be very challenging. They spend the majority of their time thousands of feet deep, foraging for food, and are only seen at the surface for around 10 minutes before diving again for up to an hour. As you can imagine this severely restricts your time in the water, and the vast majority of the day is spent on board the boat looking and listening for action. The daily routine goes something like this…

First of all, you need to locate the whales, so the captain uses a custom-built hydrophone to listen for any familiar sounds underwater. Once he hears the distinctive clicking noise of a group of sperm whales, he heads in that direction while watching the water closely until one or more of the whales comes to the surface. Once they are up, the clock is ticking and the chase is on!

A diver follows his favorite whale as far down as he can go as she disappears into the depths

A giant whale takes its last breath and begins to dive

Searching for the distinctive sound of whales clicking using a custom-made hydrophone

When you are close enough, the captain will get you in position and tell you when to enter the water. You are well advised not to chase or swim after the animals as this will simply make them change direction or dive to avoid you, but if you remain calm and don’t make too much noise, the whales will often swim directly towards you, which can be a little disconcerting but is exactly what you want when taking photos with a super-wide-angle lens!

After spending an entire week doing this, I must admit that I got the distinct impression that the whales were not as interested in me as I was in them! Most of the time they would pass by with no more than a cursory glance in my direction, but these few seconds of action are still magical, and if you are prepared, you can capture some amazing images that make all the effort worthwhile.

Turning the camera as the whales dive down provides nice vertical shots

Swimming alongside these gentle giants is a life-changing experience

In case you hadn’t noticed, sperm whales are huge , so a wide-angle lens is a must. As always, I took along my trusty Tokina 10–17mm fisheye zoom , and it was the perfect tool for the job. I would start with the lens zoomed in to 17mm, and then if the whales came close enough, zoom out to the widest setting. Unsurprisingly, all of my best images were taken at close range, but having the option to zoom in when the whales kept their distance definitely helped.

Strobes are completely unnecessary, so unless you plan to dive elsewhere on the island (which is well worth doing) then you can leave them at home. Because you will be swimming and passing the camera on and off the boat often, the more compact your system, the easier it will be. Whatever dome port you use, be sure to bring a cover for it so that it is protected at all times when getting in and out of the water.

Some whales swim with their mouths wide open, displaying impressive teeth

This side profile of the whale alongside a freediver gives you a good idea of its girth and size

Many photographers who have done this trip swear by using aperture priority as a way of getting the correct exposure, but I personally still prefer to have manual control and change settings on the fly. Although the encounters are often fleeting, I found it relatively straightforward to make adjustments to my settings, before the whales came, good enough to shoot.

My starting point was normally 1/125s at f9, and I would often increase the aperture or shutter speed depending on my position and the conditions after taking an initial test shot. There is no need for high ISO settings—at least there wasn’t on my trip—so I set ISO to 200 and left it at that most of the time. The lower the ISO, the less noise I would have to deal with later in post, and as I was lucky to have mostly clear skies, it wasn’t really an issue.

This whale was watching me closely while making a splash on the way down

Trying to keep up with the whales is difficult but does provide some good photo opportunities

The water is a deep dark blue color, which is the perfect backdrop for the whales, but there can be a lot of particles in the water, so you should shoot with the sun at your back and be prepared to do some work in the editing suite later to clean things up. In all honesty, I didn’t really have much of an opportunity to experiment with different techniques as my main focus was on capturing decent, well-lit images of the whales whenever the rare chance presented itself.

At the end of the day, getting good images of sperm whales isn’t straightforward. It requires hours of dedication, a sense of adventure, and plenty of patience. I won’t deny becoming frustrated at times with the lack of action on the slower days, but the ocean is not a zoo and if you want to see these amazing creatures up close, this is the only way to do it. Hopefully, I can return one day and encounter more sociable whales, but considering I had limited chances to get good images during my time in Dominica, I am still very happy with the final results.

My last encounter of the entire trip may have been the closest and the best!

RELATED CONTENT

Featured Photographer

- Find Out More About Us Contact Advertise

- Site Map Techniques Articles News Travel Galleries Trips --> Equipment Events --> Contests

- Competitions World Oceans Day Photography Competition Underwater Competition

- Network DPG Expeditions DPG TV

- Social Media Facebook X (Twitter) Threads Instagram

- Connect Contribute Join the Team

Today's Hours: 9:00 am – 8:00 pm

- BUY TICKETS

Sperm Whale

Physeter macrocephalus

Able to dive to depths of 2,987 meters (9,800 feet), the sperm whale is the deepest diver of all the marine mammals.

Largest of the toothed whales, the deep-diving sperm whale is also the largest toothed animal in the world. The species name, macrocephalus , Greek for “big head”, describes one identifying characteristic of this whale. The male’s head is typically about one third its total body length (e.g., 5.2 m (17 ft) in a 15.4 m (51 ft) long male). The common name was derived from a milky-white substance called spermaceti contained in an organ in the whales’ head which was though to contain sperm. The size of the whale’s head is attributed to the size of this organ that can weigh 13.6 tonnes (15 tons) and contain 3.6 tonnes (4 tons) of oil.

Credit: P.Colla. Used with permission.

SPECIES IN DETAIL

CONSERVATION STATUS: Endangered - Protected

CLIMATE CHANGE: Not Applicable

At the Aquarium

Due to the space requirements for these intelligent and dynamic animals, we do not exhibit live whales or dolphins. The sperm whale is featured in Whales: Voices in the Sea , an interactive kiosk.

Geographic Distribution

Worldwide in both hemispheres, from tropical to polar ice-free waters. In the U.S. Hawaii and California north to the Bering Sea and Maine to the Gulf of Mexico.

These pelagic whales are found in areas of the ocean close to the edge of the continental shelf in water that is at least 200 m (655 ft) deep, but preferably much deeper. They venture close to shore only where there is deep water and prey.

Physical Characteristics

The large boxlike head of sperm whales has a blunt snout that may extend 1.5 m (5 ft) beyond the tip of the lower jaw. The skull contains the largest brain of any animal in the world weighing as much as six times that of a human’s brain. The head of an adult male is often heavily marked with circular scars from encounters with squid suckers. The single S-shaped blowhole is located forward on the head and off center to the left, a placement that gives this whale a distinctive blow that projects forward and to the left at a 45 o angle instead of straight up. The short broad flippers have rounded tips and are about 1.5 m (5 ft) long. The squat dorsal fin, actually no more than a large bump, is about two thirds of the body length back from the nose and there is a series of small knuckles or bumps along the spine from the fin to the flukes. Most females and some immature males have roughened callous-like patches on the dorsal fin which adult males do not have. The large, triangular-shaped flukes can measure as much as five m (16 ft) wide, the widest of all the cetaceans.

The lower jaw is long, narrow, underslung, and very small compared to the rest of the head. Males usually have 22 to 25 curved, conical-shaped, functional teeth on each side of the lower jaw that are 7.6 to 20 cm (3-8 in) long. The upper jaw contains a series of sockets into which the lower teeth fit. Males may also have a few tiny, weak, non-functional teeth hidden behind the gums. Females have fewer teeth than males.

The upper body of these whales is dark in color, varying from pale gray to dark gray to a dark blue-black. There are often streaks of lighter colors on the body. In sunlight the body may appear to be brownish. The underside is a lighter color and may have white patches. There are white areas around the mouth. The skin posterior to the head region is wrinkled or prune-like in appearance in contrast to the smooth skin of most whales.

Adult male sperm whales are 15 to 18 m (49 to 59 ft) long and weigh 32 to 42 tonnes (35 to 45 tons). The much smaller females are 11 to 13 m (33 to 40 ft) long and weigh 12.7 to 16 tonnes (14 to 18 tons). Females are roughly one-third shorter than males and weigh only half as much. This sexual dimorphism (difference between sexes) is the greatest variation in size between males and females of all the cetaceans.

Sperm whales are believed to forage primarily on or near the ocean bottom using their highly developed echolocation to find food in the dark depths. Their main food is large and medium-sized squid and occasionally giant squid, but they are opportunistic feeders and will prey on octopus, skates, crabs, bottom-dwelling sharks, and a variety of fishes such as rockfish, salmon, and cod. They are believed to eat 907 to 2,721 kg (1,999 to 5,999 lb) of food a day. There is evidence that some of the clicking-creaking sounds made by these whales are powerful enough to stun prey.

Reproduction

Female sperm whales become sexually mature between seven and thirteen years. They usually reproduce about every four to five years. Males reach puberty at nine to ten years of age but are probably not high enough in social status in a breeding school to mate until they are 25 to 27 years old.

The breeding season is fairly long extending from January to August in the Northern Hemisphere, and July to March in the Southern Hemisphere. During the breeding season from one to five mature males may associate with a nursery school. They are extremely competitive for the mature females including exhibiting intensive physical aggression against other challenging bulls. At the breeding grounds females have been observed breaching but only in the presence of males, apparently a mating behavior.

Gestation averages about 15 months and calves are most commonly born in temperate and tropical waters in summer and autumn. At birth calves are 3.4-4.9 m (11 to 16 ft) long and weigh about 907 kg (1,999 lb). Calves may start taking solid food before they are a year old; however, they may also continue to nurse until they are three years old or even older. Mothers ecolocate to keep track of their calves.

It is believed that some sperm whales may be capable of a two-hour dive to a depth of 3000 m (9842 ft). Most dives, however, are in the 400 to 600 m (1,312 to 1,680 ft) range and last for 20 to 25 minutes.

Anatomical and physiological adaptations enable sperm whales to make these long deep dives. These include a flexible ribcage that enables their lungs to collapse safely under increased water pressure; a large blood volume very high in oxygen- carrying hemoglobin; an increased amount of myoglobin, a protein that stores high levels of oxygen in muscle tissue; and the ability to direct oxygenated blood to areas of critical need such as the brain when oxygen supplies are depleted which is also when metabolism rates decrease. In addition the blubber of sperm whales is 15 to 30 cm (5.9 to 11.8 in) thick. It insulates the whales so they can dive to great depths in water that is just above freezing and allows them to maintain a high core body temperature without losing heat to their surroundings.

Sperm whales are believed to have a life span of 50 to 70 years.

Conservation

Sperm whales have two natural predators, orcas and large sharks. But by far, their greatest predators are humans. These cetaceans were once the mainstay of the open ocean whaling industry, especially those in the northeastern United States. Sperm whales were killed every year from about 1690 to 1987, peaking in 1963 and 1964. They were mainly killed for the superior oil (obtained from their blubber) which burned brightly and cleanly in oil lamps and was an excellent lubricant for delicate instruments; the spermaceti, a waxy substance from an organ located in the head that when solidified made the finest grade of candles; and ambergris, a material from the lower intestine used in perfume manufacture and literally worth its weight in gold.

The United States banned commercial whaling in 1972 with the adoption of the Marine Mammal Protection Act which is still in force. In 1984 the International Whaling Commission (IWC) placed a moratorium on commercial whaling of sperm whales along with other great whales. The sperm whale is the only toothed whale under the management of the IWC. Now in 2006 there is a concerted effort being made by a number of countries to resume commercial whaling.