- All Teaching Materials

- New Lessons

- Popular Lessons

- This Day In People’s History

- If We Knew Our History Series

- New from Rethinking Schools

- Workshops and Conferences

- Teach Reconstruction

- Teach Climate Justice

- Teaching for Black Lives

- Teach Truth

- Teaching Rosa Parks

- Abolish Columbus Day

- Project Highlights

Trans-Atlantic and Intra-American Slave Trade Database

Digital collection. Through this website, over 130,000 voyages made in the Trans-Atlantic and Intra-American slave trade can be searched, filtered, and sorted by variables including the port of origin, the number of enslaved Africans on board, and the ship’s name.

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

The new Voyages website is the product of three years of development by a multi-disciplinary team of historians, librarians, curriculum specialists, cartographers, computer programmers, and web designers, in consultation with scholars of the slave trade from universities in Europe, Africa, South America, and North America.

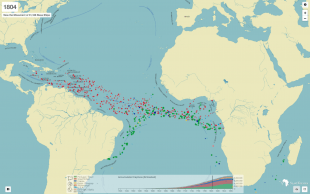

The Slave Trade Databases comprise tens of thousands of individual slaving expeditions between 1514 and 1866. Records of the Trans-Atlantic and Intra-American voyages have been found in archives and libraries throughout the Atlantic world. They provide information about vessels, routes, and the people associated with them, both enslaved and enslavers. Sources are cited for every voyage included. Users may search for information about a specific voyage or group of voyages. The website provides full interactive capability to analyze the data and report results in the form of statistical tables, graphs, maps, a timeline, and an animation.

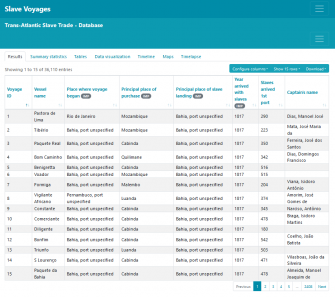

The voyages database for Trans-Atlantic and Intra-American slave trade can be searched, filtered, and sorted by variables like “Principal Place of Purchase, destination, and ship’s name.

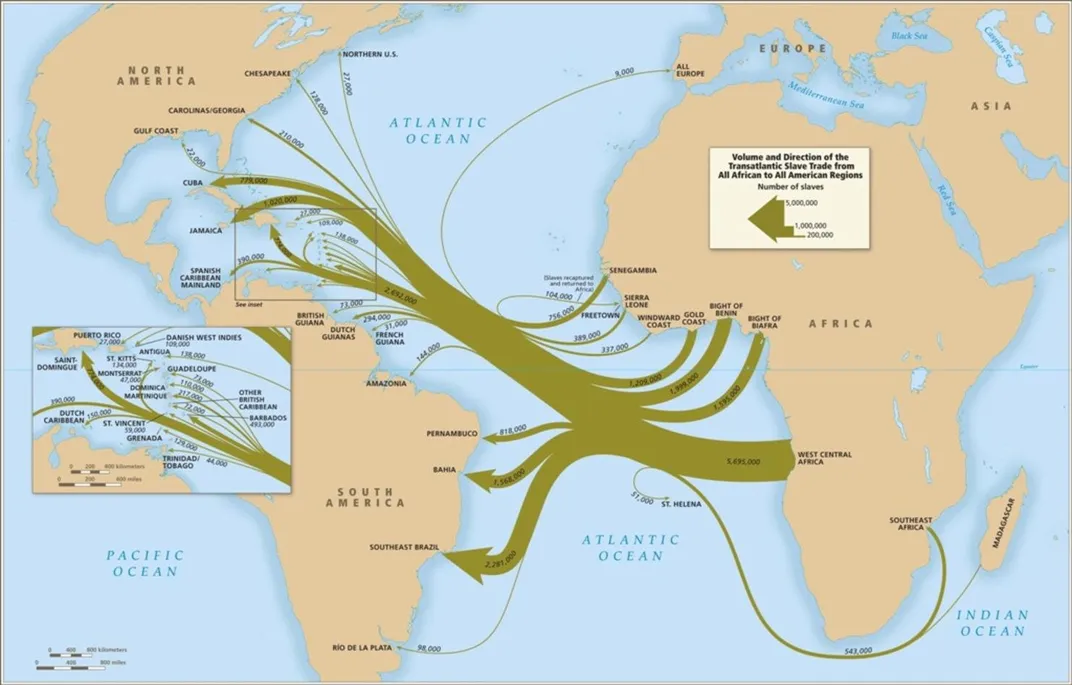

The database enables users to explore the Trans-Atlantic trade routes as well as the contours of the enormous New World slave trade, which not only dispersed African survivors of the Atlantic crossing but also displaced enslaved people born in the Americas. These voyages operated within colonial empires, across imperial boundaries, and inside the borders of nations such as the United States and Brazil.

Share a story, question, or resource from your classroom.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

More Teaching Resources

- Divisions and Offices

- Grants Search

- Manage Your Award

- NEH's Application Review Process

- Professional Development

- Grantee Communications Toolkit

- NEH Virtual Grant Workshops

- Awards & Honors

- American Tapestry

- Humanities Magazine

- NEH Resources for Native Communities

- Search Our Work

- Office of Communications

- Office of Congressional Affairs

- Office of Data and Evaluation

- Budget / Performance

- Contact NEH

- Equal Employment Opportunity

- Human Resources

- Information Quality

- National Council on the Humanities

- Office of the Inspector General

- Privacy Program

- State and Jurisdictional Humanities Councils

- Office of the Chair

- NEH-DOI Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Partnership

- NEH Equity Action Plan

- GovDelivery

Voyages: The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database

Office of digital humanities , division of preservation and access.

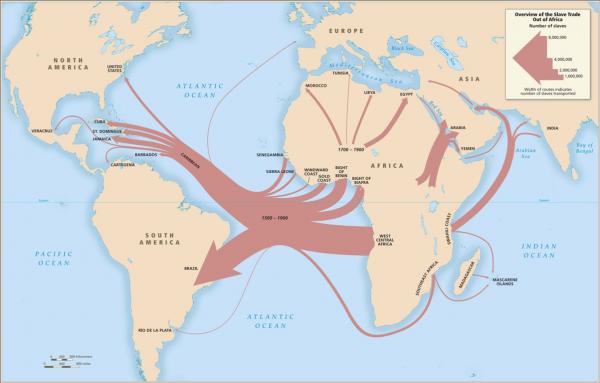

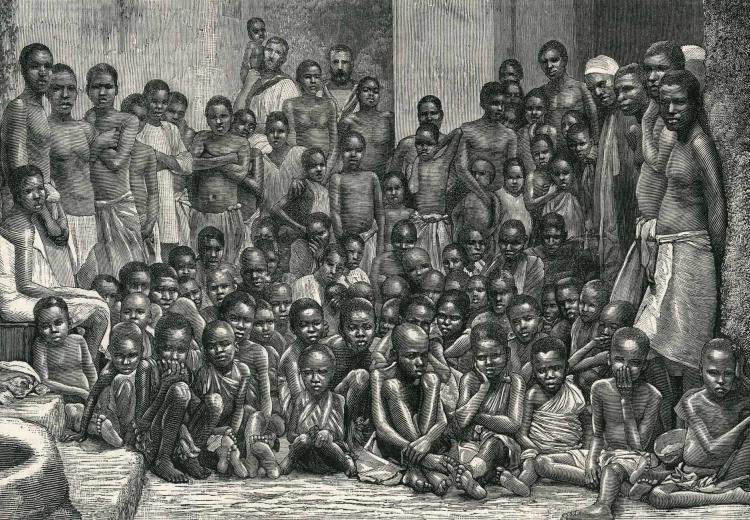

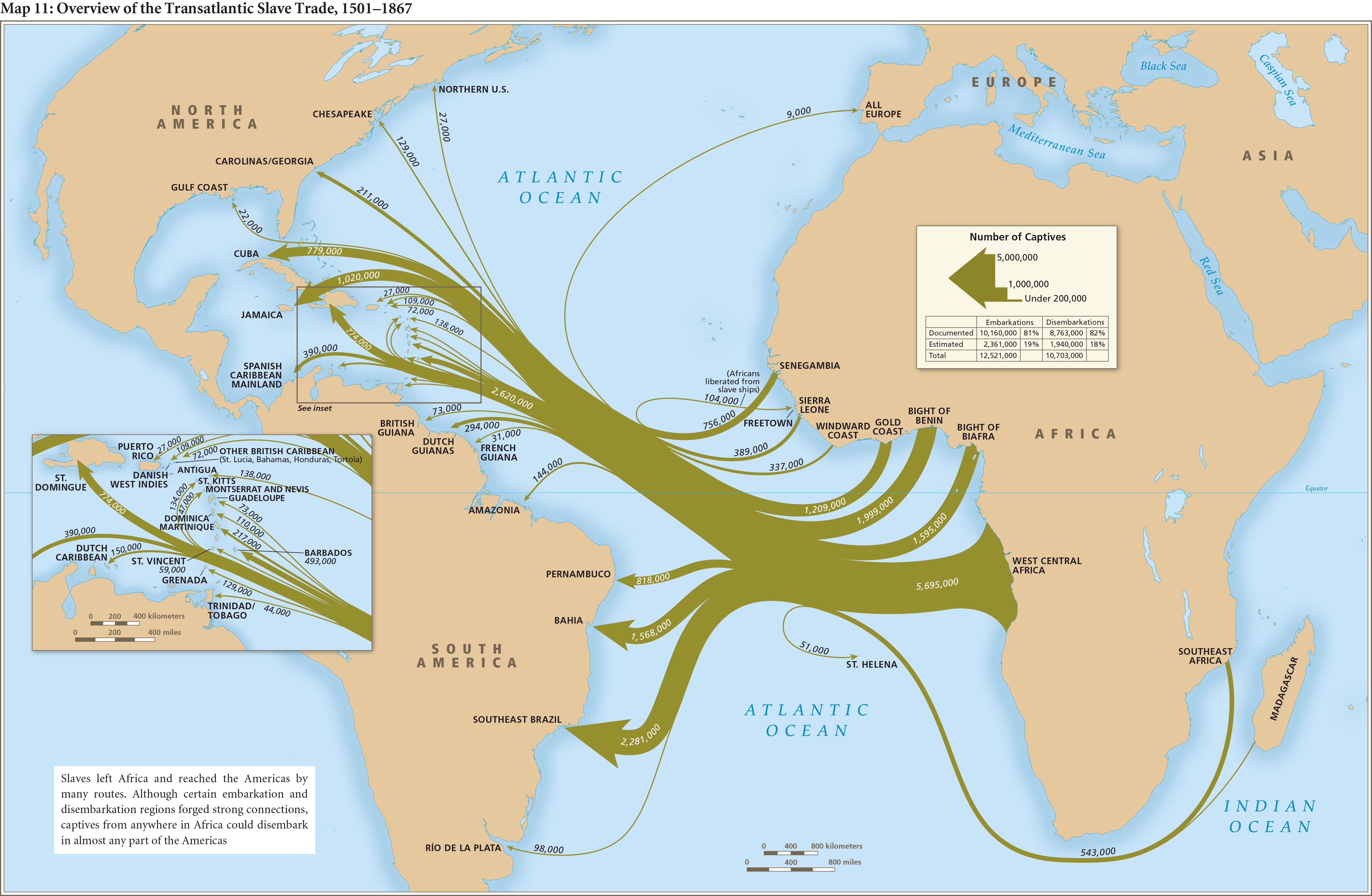

Overview of the slave trade out of Africa, 1500-1900.

Courtesy of slavevoyages.com

Track the journeys of over 10-12.5 million Africans forced into slavery with this searchable database of passenger records from 36,000 trans-Atlantic slave ship voyages.

Related on NEH.gov

Voyages: the transatlantic slave trade database, moldy church records in latin america document the lives of millions of slaves.

A Digital Archive of Slave Voyages Details the Largest Forced Migration in History

An online database explores the nearly 36,000 slave voyages that occurred between 1514 and 1866

Philip Misevich, Daniel Domingues, David Eltis, Nafees M. Khan and Nicholas Radburn, The Conversation

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/34/f3/34f347e3-5cb1-4e16-ae27-bf153a1b25db/file-20170427-15097-19mqhh2.jpg)

Between 1500 and 1866, slave traders forced 12.5 million Africans aboard transatlantic slave vessels. Before 1820, four enslaved Africans crossed the Atlantic for every European, making Africa the demographic wellspring for the repopulation of the Americas after Columbus’ voyages. The slave trade pulled virtually every port that faced the Atlantic Ocean – from Copenhagen to Cape Town and Boston to Buenos Aires – into its orbit.

To document this enormous trade – the largest forced oceanic migration in human history – our team launched Voyages: The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database , a freely available online resource that lets visitors search through and analyze information on nearly 36,000 slave voyages that occurred between 1514 and 1866.

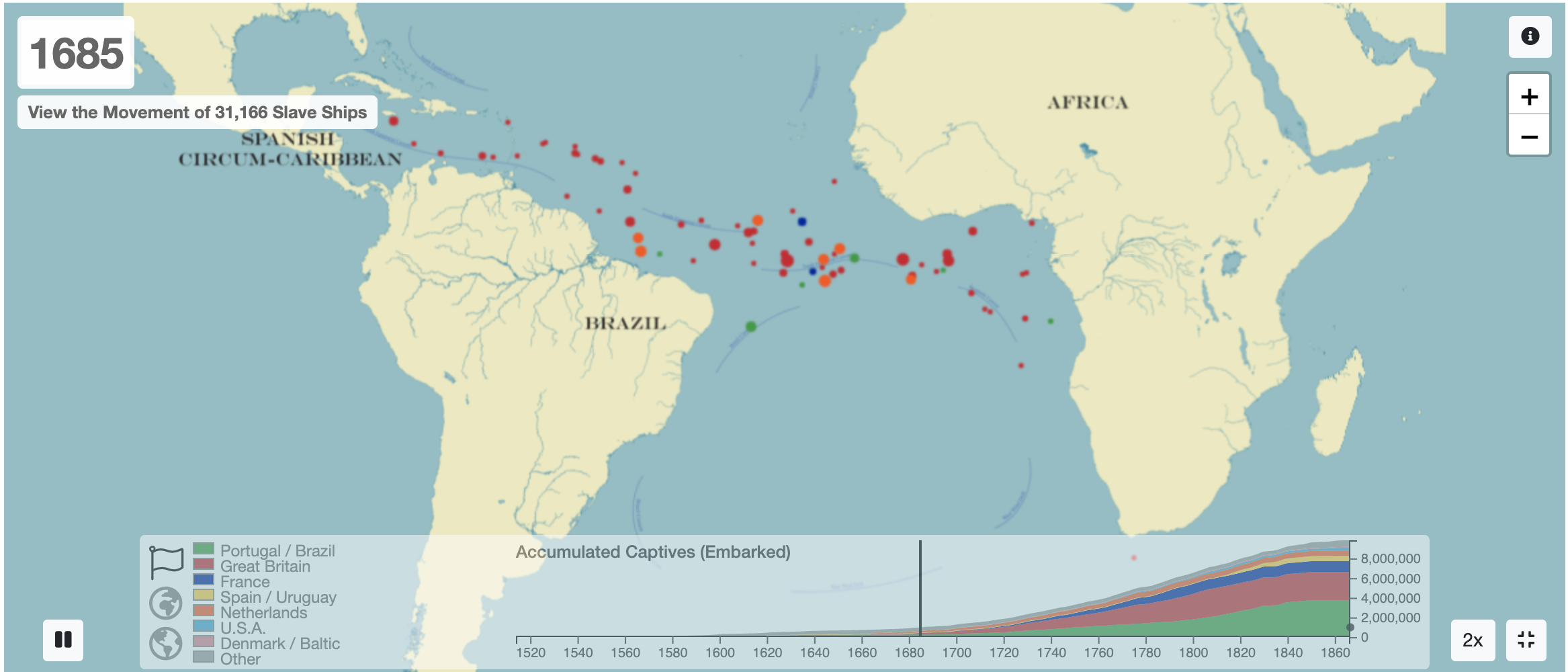

Inspired by the remarkable public response, we recently developed an animation feature that helps bring into clearer focus the horrifying scale and duration of the trade. The site also recently implemented a system for visitors to contribute new data. In the last year alone we have added more than a thousand new voyages and revised details on many others.

The data have revolutionized scholarship on the slave trade and provided the foundation for new insights into how enslaved people experienced and resisted their captivity. They have also further underscored the distinctive transatlantic connections that the trade fostered.

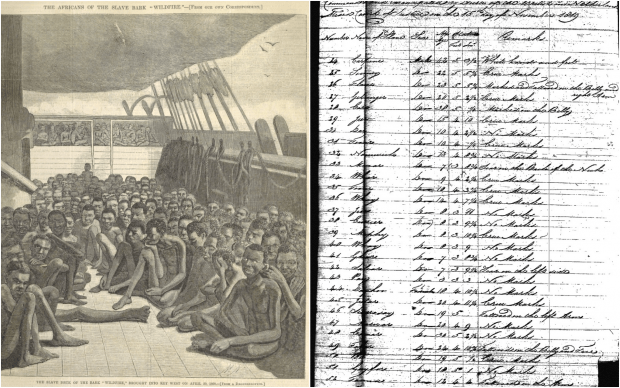

Records of unique slave voyages lie at the heart of the project. Clicking on individual voyages listed in the site opens their profiles, which comprise more than 70 distinct fields that collectively help tell that voyage’s story.

From which port did the voyage begin? To which places in Africa did it go? How many enslaved people perished during the Middle Passage? And where did those enslaved Africans end the oceanic portion of their enslavement and begin their lives as slaves in the Americas?

Working with complex data

Given the size and complexity of the slave trade, combining the sources that document slave ships’ activities into a single database has presented numerous challenges. Records are written in numerous languages and maintained in archives, libraries and private collections located in dozens of countries. Many of these are developing nations that lack the financial resources to invest in sustained systems of document preservation.

Even when they are relatively easy to access, documents on slave voyages provide uneven information. Ship logs comprehensively describe places of travel and list the numbers of enslaved people purchased and the captain and crew. By contrast, port-entry records in newspapers might merely produce the name of the vessel and the number of captives who survived the Middle Passage.

These varied sources can be hard to reconcile. The numbers of slaves loaded or removed from a particular vessel might vary widely. Or perhaps a vessel carried registration papers that aimed to mask its actual origins, especially after the legal abolition of the trade in 1808.

Compiling these data in a way that does justice to their complexity, while still keeping the site user-friendly, has remained an ongoing concern .

Of course, not all slave voyages left surviving records. Gaps will consequently remain in coverage, even if they continue to narrow. Perhaps three out of every four slaving voyages are now documented in the database. Aiming to account for missing data, a separate assessment tool enables users to gain a clear understanding of the volume and structure of the slave trade and consider how it changed over time and across space.

Engagement with Voyages site

While gathering data on the slave trade is not new, using these data to compile comprehensive databases for the public has become feasible only in the internet age. Digital projects make it possible to reach a much larger audience with more diverse interests. We often hear from teachers and students who use the site in the classroom, from scholars whose research draws on material in the database and from individuals who consult the project to better understand their heritage.

Through a contribute function , site visitors can also submit new material on transatlantic slave voyages and help us identify errors in the data.

The real strength of the project – and of digital history more generally – is that it encourages visitors to interact with sources and materials that they might not otherwise be able to access. That turns users into historians, allowing them to contextualize a single slave voyage or analyze local, national and Atlantic-wide patterns. How did the survival rate among captives during the Middle Passage change over time? What was the typical ratio of male to female captives? How often did insurrections occur aboard slave ships? From which African port did most enslaved people sent to, say, Virginia originate?

Scholars have used Voyages to address these and many other questions and have in the process transformed our understanding of just about every aspect of the slave trade. We learned that shipboard revolts occurred most often among slaves who came from regions in Africa that supplied comparatively few slaves. Ports tended to send slave vessels to the same African regions in search of enslaved people and dispatch them to familiar places for sale in the Americas. Indeed, slave voyages followed a seasonal pattern that was conditioned at least in part by agricultural cycles on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. The slave trade was both highly structured and carefully organized.

The website also continues to collect lesson plans that teachers have created for middle school, high school and college students. In one exercise, students must create a memorial to the captives who experienced the Middle Passage, using the site to inform their thinking. One recent college course situates students in late 18th-century Britain, turning them into collaborators in the abolition campaign who use Voyages to gather critical information on the slave trade’s operations.

Voyages has also provided a model for other projects, including a forthcoming database that documents slave ships that operated strictly within the Americas.

We also continue to work in parallel with the African Origins database. The project invites users to identify the likely backgrounds of nearly 100,000 Africans liberated from slave vessels based on their indigenous names. By combining those names with information from Voyages on liberated Africans’ ports of origin, the Origins website aims to better understand the homelands from which enslaved people came.

Through these endeavors, Voyages has become a digital memorial to the millions of enslaved Africans forcibly pulled into the slave trade and, until recently, nearly erased from the history of not only the trade itself, but also the history of the Atlantic world.

Philip Misevich, Assistant Professor of History, St. John's University

Daniel Domingues, Assistant Professor of History, University of Missouri-Columbia

David Eltis, Professor Emeritus of History, Emory University

Nafees M. Khan, Lecturer in Social Studies Education, Clemson University

Nicholas Radburn, Postdoctoral Fellow, University of Southern California – Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

Click to visit our Privacy Statement .

- Lesson Plans

- Teacher's Guides

- Media Resources

Slave Voyages

Transatlantic Slave Trade Database

Library of Congress

Slave Voyages: The Transatlantic Slave Trade Database is an NEH-funded digital humanities project that represents decades of careful research and documentation. Scholars worked to collect information about the voyages of enslaved people, first across the Atlantic and then within the Americas, and to transfer unpublished archival records into machine-readable data.

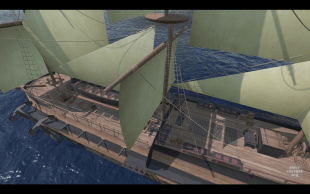

This data can be downloaded by researchers and students around the world, or viewed in various formats on the project's website. In addition to the databases of voyages that form the core of the project, recently, the project team has incorporated an archive of images, a database of the names of enslaved people , a 3-D animation of a slave ship, and other visualizations. There is also a series of essays about the slave trade that address both the micro—individual experiences of captivity and enslavement—and macro—the centuries-long evolution of the slave trade(s).

The databases can, of course, be used as sources for research projects. However, they also offer an opportunity to reflect on the challenges of historical research and representation more broadly: how can we understand histories of individuals and phenomena when surviving documentation is most often from the perspective of the enslaver, the plantation owner, the accountant?

Classroom Connections

After students have studied one or more slave narratives, ask them to explore the Slave Voyages site . The Trans-Atlantic Database is the most robust and has the most visualization options. Students should examine the database itself, as well as the different data visualizations on the site. The following questions can guide reflection.

- What information is conveyed in the slave narrative? In the database?

- How is this information conveyed?

- What do you think is the purpose of slave narratives? The Slave Voyages databases?

- What sources were used to write slave narratives? To build the Slave Voyages databases?

- What are some of the strengths and limitations of each form of representing slavery and the lives of enslaved people?

- How has each representation of slavery shaped your knowledge and perceptions of the institution?

Students can analyze a different form of representing enslaved persons' lives in EDSITEment's collection of lesson plans about slave narratives.

- Twelve Years a Slave: Analyzing Slave Narratives (grades 9-12)

- Perspective on the Slave Narrative (grades 9-12)

Frederick Douglass’s Narrative : Myth of the Happy Slave (grades 9-12)

Slave Narratives: Constructing U.S. History through Analyzing Primary Sources (grades 6-8)

Related on EDSITEment

Frederick douglass’s narrative : myth of the happy slave, people not property : stories of slavery in the colonial north, perspective on the slave narrative, twelve years a slave : analyzing slave narratives, solomon northup’s twelve years a slave and the slave narrative tradition, ask an neh expert: validating sources, harriet tubman and the underground railroad, lesson 2: from courage to freedom: slavery's dehumanizing effects.

- History Made Manifest

Mellon grant will expand Emory's Voyages Slave Trade Database, shifting the focus from ships to people

Who were they? How did they get here? Who brought them, and who bought them?

Those are the questions David Eltis, professor of history emeritus, has been asking about the Atlantic slave trade for more than a quarter century. His restless search became the web-based resource Voyages: The Transatlantic Slave Trade Database, hosted at Emory and used by hundreds of scholars and knowledge-seekers each year.

“For more than a quarter century, David Eltis’s Transatlantic Slave Trade Database has been the gold standard in the field,” says Henry Louis Gates Jr., Alphonse Fletcher University Professor and director of the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research at Harvard University. “It has transformed what we know and how we think and write about the forced removal of 12.5 million Africans to the New World and the 10.7 million who survived the horrors of the middle passage. No scholar can undertake a serious study of that process without consulting it.”

And the project continues to expand, thanks to support such as a recent grant of $300,000 from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for use by the Emory Center for Digital Scholarship (ECDS) to fund a new initiative allowing researchers at Emory, across the United States, and abroad to update and add to the renowned Voyages website. The latest effort, called People of the Atlantic Slave Trade (PAST), will provide information on any historical figure who can be linked to a slave voyage—enslaved and enslavers alike.

“We are proud to house this project at Emory and grateful for support from the Mellon Foundation, which advances our efforts to make this extensive research publicly available, broadening its reach and impact,” says Dwight McBride, Emory provost and executive vice president for academic affairs. “The People of the Atlantic Slave Trade project builds on the scholarly resources of the Slave Voyages website and promises to offer new insights into the stories of thousands of individual people—both the enslaved and the enslavers—from this ignominious part of our history. By adding searchable access to their names, the site will link these individuals to time and place, which in turn can help us better understand ourselves and our shared history.”

PAST brings together the work of twenty-one scholars whose expertise matches the geographical range of the transatlantic slave trade. “PAST will create a biographical database of all those who have a documented link to any of the voyages in the Transatlantic Slave Trade Database, whether as an enslaved person, an African seller, a buyer in the Americas, a ship owner, or a captain,” Eltis says.

PAST will be incorporated into the Voyages website—which already contains the names of thirty thousand slave ship captains and ship owners, as well as ninety-one thousand enslaved Africans—and will be accessible to researchers and the public via its own interface.

“Overall, this newest phase will allow scholars to examine the organization of the traffic, locate the social background of those involved, make new assessments on the trade’s impact and relative importance, and eventually develop new explanations of why a race-based Atlantic slave trade evolved, why it endured for 340 years, and why it ended,” Eltis says. “Our aim is to extend the primary function of the website from a ship-based to a people-based record of the movement of people from Africa to the Americas.”

Since its online launch in 2008, the Voyages website has become a widely used reference tool for the study of slavery in the Atlantic world, says Allen Tullos, professor of history,project codirector, and codirector of ECDS.

By mid-2018, Slave Voyages will offer a new database comprising ten thousand intra-American slave voyages that occurred within the Americas, usually carrying recent survivors of the middle passage.

“Half of all disembarking captives faced a lengthy second journey after the middle passage,” says Eltis.

Since Voyages’ inception in 1992, the project has received funding of more than $3 million. In addition to Mellon, the project has received support from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the W. E. B. Du Bois Research Institute at Harvard University’s Hutchins Center, and the Arts and Humanities Research Board of the United Kingdom, administered through the University of Hull in the UK. In 2010, maps generated by the project were published in print form as the Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, coedited by Eltis at Emory and David Richardson of the University of Hull.

Share This Story

Featured Article: Sharp Thinking

Featured Article: So You Want to Start a Business

Featured Article: It's the Monster's Birthday: Celebrating Frankenstein at Two Hundred

Featured Article: Moving the Needle

Points of interest.

- Positive Numbers

- A New Voice for Communications

- Who Was Atticus Finch?

- Need a Good Lawyer?

- Dooley Noted: Making Beautiful Things Happen

- Profound Predictions

- Carrion, and Lighter Fare

- Competitive Edge

- Speaking Up for the Silent

- Space Odyssey

- Leading with Intention

- An Atlanta Writer Returns

- We're Only Human

- Science, Story, or Fake News?

- No Kitten: Cats Rule at the Carlos

- No Small Threat

- From the Mouths of Babes

- Granted: Permission to Discover

- Emory in the News

- Seeking Sensation

- Packing It All In

- A Walk on the Wild Side

- Miss America Goes Global

- Not 'Just One Thing'

- Tribute: Billy E. Frye 54G 56PhD

- A Son, Stolen

- Emory, Falcons A Win-Win

Understanding the History of Slavery in the Americas

New consortium will ensure future of SlaveVoyages database

Emory University | March 4, 2021

In 1720, on a ship ironically named the Generous Jenny, more than 200 people captured from Africa arrived at a port on the Patuxent River in Maryland. The survivors of the brutal voyage would spend the rest of their lives toiling in slavery.

Almost 300 years later, descendants of those enslaved people joined with other community members in a remembrance ceremony at the former plantation, now known as Historic Sotterley . Participants drummed, prayed and poured libations on the ground that had been the site of so much suffering, and children placed white carnations in the water to honor those who died during the Middle Passage.

The event, held in November 2012, was one of the first ancestral remembrance ceremonies sponsored by the Middle Passage Ceremonies and Port Markers Project — and it would not have been possible without SlaveVoyages.org , created by Emory University as a central repository of information about the dispersal of enslaved Africans across the Atlantic world.

The Middle Passage Ceremonies and Port Markers Project provides a way for communities to honor the millions who died or survived the transatlantic voyage. It has now helped organize 32 remembrance ceremonies at locations where enslaved people disembarked, and installed 29 historic markers, with more underway.

“Throughout all these efforts, the SlaveVoyages dataset has been our grounding for information and data,” says Ann Chinn, executive director of the project. “It’s a tangible connection to history. That has been one of the invaluable results of what the SlaveVoyages database provides for the public.

“People are using the information to remember, heal and expand the reconciliation process that is so critically needed today.”

Kofi Ofori, an Akan priest, pours the libation at the ancestral remembrance ceremony at Historic Sotterley, a Maryland plantation where Africans stolen from their homeland disembarked into a life of slavery. Photo by Kenneth R. Forde.

The 1720 voyage of the Generous Jenny is just one of the more than 48,000 transatlantic and intra-American slave trade journeys documented at SlaveVoyages.org.

A preeminent resource for the study of slavery, SlaveVoyages will now be operated by a newly formed consortium of institutions, ensuring the preservation, stability and future development of what has become the single most widely used online resource for anyone interested in slavery across the Atlantic world.

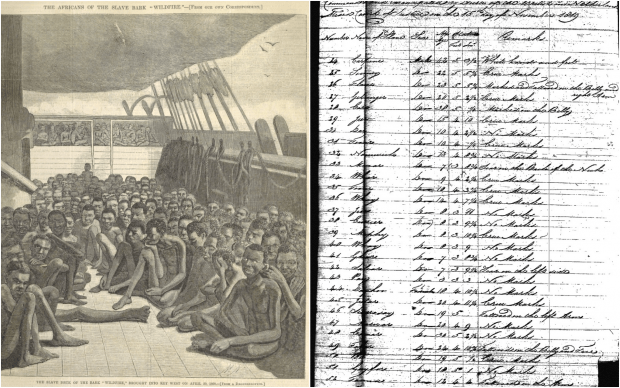

Historical images: The Brig “Vigilante” was a French slaver captured in 1822. The ship departed from France and carried 345 enslaved people from the coast of Africa, but was intercepted by anti-slave trade cruisers before sailing to the Americas and taken to Freetown, Sierra Leone. Learn more about the Viglante on SlaveVoyages.org.

Shared responsibility

The new consortium, organized by Emory, will function as a cooperative academic collaboration through a contractual agreement between six institutions — Emory, the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research at Harvard University, the National Museum of African American History and Culture, the Omohundro Institute of Early American History & Culture at William & Mary, Rice University, and three campuses at the University of California that will assume a joint membership: UC Santa Cruz, UC Irvine and UC Berkeley.

“The launch of the SlaveVoyages.org consortium is an innovation not just for scholars of slavery, but for all soft money digital humanities projects,” says David Eltis, Emory’s Robert W. Woodruff Professor Emeritus of History and co-director of the SlaveVoyages project. “At long last, this consortium opens up a route to sustainability.”

Long-term sustainability has become an important question for granting agencies considering support for research in the humanities, says Allen Tullos, co-director of Emory’s Center for Digital Scholarship, which has worked with Eltis and other scholars to host, enhance and expand SlaveVoyages, including a major relaunch in 2018. “This consortium is a new model for publishing and sustaining large-scale digital humanities research.”

Membership is for a three-year term and is renewable. Each member institution of the SlaveVoyages consortium will support the site through dues and be represented on the consortium’s steering committee, which decides which institutional member will host the site. The host institution will receive funding through membership dues to offset costs of maintaining the site, and will maintain performance metrics, develop environmental and technical standards for the site, and provide administrative support.

One of the special features of the SlaveVoyages.org website is a timelapse video that shows the movement of slave ships across the Atlantic, carrying millions of enslaved people captured from Africa. View the full interactive timelapse .

Making history accessible

SlaveVoyages.org has its origins in the 1960s, when historians began collecting data on slave ship voyages and estimating the number of enslaved Africans to cross the Atlantic from the 16 th through 19 th centuries.

But developing a single, multisource dataset was a pipe dream until the 1990s, when Eltis and other researchers began to collaborate on centralizing their findings. The data migrated from punch cards, to laptop computer, to a CD-ROM published in 1999, to a website that debuted at Emory in 2008.

“Twenty years and four million viewers after its first appearance as a CD-ROM, the future of 48,000 slaving ventures recorded in SlaveVoyages is finally secured for posterity," says Henry Louis Gates Jr., Alphonse Fletcher University Professor and director of Harvard’s Hutchins Center, a consortium member.

Gates has called SlaveVoyages.org “a gold mine” and “one of the most dramatically significant research projects in the history of African studies, African American studies and the history of world slavery itself.”

SlaveVoyages.org is the culmination of both independent and collaborative work by a multidisciplinary team of international scholars and historians, librarians, cartographers, computer programmers, designers and digital experts. Many who began their academic careers working on the project are now alumni of Emory’s Laney Graduate School, and have emerged as the next generation of slave trade scholars.

From 2015-2018, SlaveVoyages.org was completely re-coded and modernized, and continues to publish new research and resources, from lesson plans for young students to new features such as an interactive time lapse detailing the volume and destinations of voyages over the centuries. The site attracts more than 1,400 visitors a day, including educators, scholars, scientists, artists, genealogists and curators with national museums and history centers.

The SlaveVoyages.org website includes a painstakingly rendered 3-D look inside the slave vessel L'Aurore, reconstructed using actual blueprints of the ship. Watch the full video .

“SlaveVoyages has had a tremendous role in expanding opportunities for graduate students doing many different kinds of work,” says Tullos. “We’ve helped to create a generation of digital scholars.”

More than 50 researchers from Emory and institutions around the world have contributed to the project, which has received funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Mellon Foundation, the Arts and Humanities Research Council of the UK, and Harvard’s Hutchins Center.

In August 2020, ECDS helped SlaveVoyages migrate its multiple databases to the Amazon Web Services Cloud platform, a more technologically sustainable model which includes improved responsiveness to traffic increases and a more robust connection between database and web server.

With the new consortium, SlaveVoyages will continue to serve as a model, inspiring other research and serving as a resource for new initiatives and broader public understanding of the history of slavery.

Media contact: Elaine Justice, 404-727-0643, [email protected]

Learn more:

Slavevoyages | emory university | emory news center.

May. 24, 2021

World’s largest database on history of slave trade now housed at rice, slavevoyages.org is result of years of research, reengineered for the future.

SlaveVoyages.org is the world’s largest repository of information about the trans-Atlantic and intra-American slave trades: the routes, the ships, the manifests and the human beings at their core. And now, after nearly 20 years at Emory University , the website and its treasure trove of data have moved to their new home at Rice.

“It’s the first time in the history of this project that it's shifting hands,” said Rice professor Daniel Domingues of the momentous undertaking. His decades of research at both Emory and Rice on slave trading expeditions have been crucial to expanding a database first published in 1999 on CD-ROM.

“It's always receiving contributions from researchers all over the world and it's used in schools across the United States, in England, in South America — everywhere,” said Domingues. “It's a big responsibility to maintain a website like this.”

The website has become a vital scholarly resource over the years, constantly accessed by those adding to the database and those using it for research, making a seamless migration all the more important.

Back in 1999, Emory University historian David Eltis created the now-massive Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database inspired in part by the work of the late Philip Curtin at Johns Hopkins University. Curtin’s most famous work, 1969's “The Atlantic Slave Trade: A Census,” was one of the earliest scholarly estimates of the size of the trans-Atlantic trade between the 16th and 19th centuries.

After completing his undergraduate work in Brazil, Domingues went to study under Eltis at Emory. And in 2008, the CD-ROM project was transformed into a website, bringing years of research compiled by Domingues and other scholars to a global audience.

Today, the SlaveVoyages website contains more information than could ever be contained in books or CDs, with such granular data as mortality rates aboard ships, how many children they transported and information on resistance or insurrections. A user-friendly interface makes it easy to search for specific facts, while time-lapse visualizations and a 3D model of 18th-century French ship L’Aurore bring its volumes of data to life.

The ‘gold standard of digital humanities’

To ensure the website would continue being updated and properly maintained, Rice and Emory joined a consortium of like-minded universities with a vested interest in SlaveVoyages.

These six institutions — including the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research at Harvard University, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture , the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture at the College of William & Mary, and three University of California campuses including UC Berkeley — will provide long-term funding through the newly formed SlaveVoyages Consortium .

At Rice, Domingues elicited support from both the School of Humanities and Fondren Library, which serve as co-hosts of the SlaveVoyages database. Rice was eager to embrace the project and host the newly migrated website for several reasons, Domingues said.

“One of them is that we're living in this moment of reckoning with the country’s history of slavery, segregation and racial injustice, including Rice’s own history in this broader narrative,” Domingues said. For a university confronting social justice issues head-on, “it will be one giant step in that direction,” he said.

The SlaveVoyages website Emory developed is also the “gold standard of digital humanities,” he said, and a chance for Rice to continue advancing its own expertise in the field.

“It was an incredible opportunity to learn about and work with this historic digital humanities project and its rich data,” said John Mulligan, who works in Rice’s Center for Research Computing (CRC). Rice wanted to not only migrate the website but reengineer it for both growth and sustainability.

Mulligan, Domingues and the CRC turned to Oracle for Research, which is providing SlaveVoyages with access to Oracle Cloud Infrastructure as well as technical expertise to help with the migration. The massive SlaveVoyages database is one of the first digital humanities projects to be powered by Oracle Cloud.

“Oracle is proud to support this extraordinary project,” said Alison Derbenwick Miller, vice president of Oracle for Research. “SlaveVoyages reveals vitally important insights into our collective past and the way that history shapes the present. In moving SlaveVoyages to a modern cloud infrastructure that simplifies academic collaboration, Rice and Oracle for Research were able to prepare this critical digital humanities resource for the future by ensuring it can scale to accommodate massive volumes of data and new areas of research.”

Having those cloud resources available for free gave Rice the flexibility to come up with a new process for publishing updates to the site using open-source software that’s not tied to any particular cloud provider, Mulligan said. That will be instrumental in guaranteeing the project’s long-term flexibility, he said.

After a year’s work, the newly migrated website is now up and running at Rice. The site itself hasn’t changed, Mulligan stressed. Instead, the crowdsourced database is now able to expand as quickly as researchers can add to it.

“The CRC — and above all, infrastructure specialist Derek Keller — have made the site more amenable to rapid iteration, so that we can quickly test and publish the changes that the scholars want in order to grow the project,” Mulligan said.

Actively contributing to history — and preserving it for others

The database is still missing a lot of information about the slave trade in Texas. And that’s something Rice students will be working on correcting over the summer as Department of History research assistants working with Rice’s Center for African and African American Studies (CAAAS).

“That will be one important contribution that Rice students will make to this project,” Domingues said.

"We are so delighted that such a rich and definitive historical resource is now available for undergraduate and graduate student research at Rice," said Dean of Humanities Kathleen Canning. “We are grateful to Professor Domingues for his creativity and leadership of the new consortium and enormously pleased that its members chose Rice as the institutional host for SlaveVoyages.”

It provides “a live rather than a static or finite historical source for students in history, African and African American studies and other fields, and it is one that will continuously change and grow over time as scholars contribute new data,” she said. “In this sense, Rice students can actively contribute to making history and preserving it for others to engage in the future.”

Indeed, this is just the beginning.

“Bound Away: Voyages of Enslavement in the Americas” will take place at Rice Dec. 3 and 4, as both a conference and a celebration. The conference will share new findings on the intra-American slave trade and host panels focused on Texas, Louisiana, Spanish America and Brazil. Prominent scholars including Daina Ramey Berry and Sean Kelley will speak, while Rice students will present their own undergrad and graduate research on the slave trade.

The “Bound Away” conference will coincide with two art exhibitions: one at Rice’s Moody Center for the Arts, and the other at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. More information on these events will follow in the coming months.

The event will also celebrate the formation of the SlaveVoyages Consortium as well as Rice’s role as the website’s new host.

Among the other events centered around the site is the upcoming Mellon-Sawyer Seminar on “Diasporic Cultures of Slavery: Engaging Disciplines, Engaging Communities.” It involves a year-and-a-half-long seminar through CAAAS that will visit Ghana, Brazil, Jamaica and a former plantation near Houston to connect students with scholars and community members in these places. The seminar will culminate with an exhibition in partnership with the Texas Historical Commission.

“The idea is that these events will help shape the project development here and inspire students to use the website in their research to further expand our understanding of history,” Domingues said.

Meanwhile, with its constant stream of fresh data and a new home capable of holding it all, SlaveVoyages.org will continue to flourish.

Emory Center for Digital Scholarship

Project Team Blog

Resources Feature: Slave Voyages Website Releases New and Updated Lesson Plans

The Emory Center for Digital Scholarship (ECDS)-partnered project Slave Voyages has recently updated its Resources page with new and improved lesson plans . The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade was the largest forced migration of people in history, which left an immense legacy (and record) of human actions, suffering, and resilience. In order to better assist educators to navigate that history, a team of teachers and curriculum developers from around the United States have provided updated lesson plans that explore the databases housed on Slave Voyages. These open educational resources allow students to engage the history and legacy of the Atlantic slave trade in diverse and meaningful ways, utilizing the various resources of the website. The lesson plans also suggest readings for more information about the Slave Trade.

- Link to Slave Voyages Lesson Plans: https://www.slavevoyages.org/resources/lessons

As the website’s homepage notes, the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database now comprises 36,000 individual slaving expeditions between 1514 and 1866. Records of the voyages have been found in archives and libraries throughout the Atlantic world. They provide information about vessels, routes, and the people associated with them, both enslaved and enslavers. Users may search for information about a specific voyage or group of voyages, and the website provides full interactive capability to analyze the data and report results in the form of statistical tables, graphs, maps, a timeline, and an animation. For example, ECDS staff members helped produce a 3D reconstruction of the slave vessel L’Aurore, featured in the video, “ Slave Ship in 3D Video .”

Researchers of Slave Voyages recently received an ACLS Digital Extension Grant for the Intra-American Slave Voyages Database, an important complement to the existing Trans-Atlantic Slave Voyages Database. The Intra-American Slave Trade Database contains information on approximately 10,000 slave voyages within the Americas. These voyages operated within colonial empires, across imperial boundaries, and inside the borders of nations such as the United States and Brazil. The database enables users to explore the contours of this enormous New World slave trade, which not only dispersed African survivors of the Atlantic crossing but also displaced enslaved people born in the Americas.

The website also features the African Names Database, which provides personal details of 91,491 Africans taken from captured slave ships or from African trading sites. It displays the African name, age, gender, origin, country, and places of embarkation and disembarkation of each individual.

Users of the Slave Voyages website can: analyze data; sample estimates of the slave trade; view videos, maps, and animations; consult research essays; and access lesson plans for teaching. The Resources page also includes over 200 archival images of manuscripts, places, enslaved people, and slave trade vessels. In order to present the trans-Atlantic slave trade database to a broader audience—particularly a grade 6-12 audience—a dedicated team of teachers and curriculum developers from around the United States developed lesson plans that explore the database. Each lesson plan page includes the author of the lesson plan, a grade level/range for which the lesson plan would be optimal, key words, an abstract, and a link to download the PDF.

If you use these lesson plans (or any other aspects of the Slave Voyages website) while teaching courses/conducting or publishing research, the project team would love to hear from you at: voyages [at] emory [dot] edu

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Jamelle Bouie

We Still Can’t See American Slavery for What It Was

By Jamelle Bouie

Opinion Columnist

The historian Marcus Rediker opens “ The Slave Ship: A Human History ” with a harrowing reconstruction of the journey, for a captive, from shore to ship:

The ship grew larger and more terrifying with every vigorous stroke of the paddles. The smells grew stronger and the sounds louder — crying and wailing from one quarter and low, plaintive singing from another; the anarchic noise of children given an underbeat by hands drumming on wood; the odd comprehensible word or two wafting through: someone asking for menney, water, another laying a curse, appealing to myabecca, spirits.

An estimated 12.5 million people endured some version of this journey, captured and shipped mainly from the western coast of Africa to the Western Hemisphere during the four centuries of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Of that number, about 10.7 million survived to reach the shores of the so-called New World.

It is thanks to decades of painstaking, difficult work that we know a great deal about the scale of human trafficking across the Atlantic Ocean and about the people aboard each ship. Much of that research is available to the public in the form of the SlaveVoyages database. A detailed repository of information on individual ships, individual voyages and even individual people, it is a groundbreaking tool for scholars of slavery, the slave trade and the Atlantic world. And it continues to grow. Last year, the team behind SlaveVoyages introduced a new data set with information on the domestic slave trade within the United States, titled “ Oceans of Kinfolk .”

The systematic effort to quantify the slave trade goes back at least as far as the 19th century. For example, in the 1888 edition of the second volume of his “History of the United States of America, From the Discovery of the American Continent,” the historian George Bancroft estimates “the number of negroes” imported by “the English into the Spanish, French, and English West Indies, and the English continental colonies, to have been, collectively, nearly three million: to which are to be added more than a quarter of a million purchased in Africa, and thrown into the Atlantic on passage.” He adds later, “After every deduction, the trade retains its gigantic character of crime.”

In 1958, the economic historians Alfred H. Conrad and John R. Meyer transformed the study of slavery — and of economic history more broadly — with the publication of “The Economics of Slavery in the Ante Bellum South.” Their methods, which relied on statistical data and mathematical analysis, revolutionized the field.

The origins of SlaveVoyages lie in this period and, specifically, in the work of a group of scholars who, a decade later, began to collect data on slave-trading voyages and encode it for use with a mainframe computer.

“It goes back to the late 1960s and the work of Philip Curtin,” David Eltis, an emeritus professor of history at Emory and a former co-editor of the SlaveVoyages database, told me. “He did this book called ‘The Atlantic Slave Trade: A Census,’ part of which involved computerizing — which was quite a dramatic step in those days — a list of slave voyages for the 19th century. And he sent me, in response to a cold call, a box of 2,313 IBM cards, one card for each voyage. And that was the starting point.”

Over the next two decades, working independently and collaboratively, historians in the United States and around the world would turn this archival information on the trans-Atlantic trade into data sets representing more than 11,000 individual voyages, a significant accomplishment even if it represented only a fraction of the trade in human lives from the 15th century to its end in the 19th century.

Later, beginning in the 1990s, those scholars began to integrate this data — which encompassed the British, Dutch, French and Portuguese slave trade — into a single data set. By the end of the decade, the first SlaveVoyages database had been released to the public as an (expensive) CD-ROM set including details from more than 27,000 voyages.

It is hard to exaggerate the significance of this work for historians of slavery and the slave trade. An arrival to and departure from port tells a story. To know when, where and how many times a ship disembarked is to know a little more about the nature of the specific exchange as well as the slave trade as a whole. Every bit of new information fills in the blanks of a time that has long since passed out of living memory.

After nearly 10 years as physical media, SlaveVoyages was introduced to the public as a website in 2008 and then relaunched in 2019 with a new interface and even more detail. As it stands today, the site, funded primarily by grants, contains data sets on various aspects of the slave trade: a database on the trans-Atlantic trade with more than 36,000 entries, a database containing entries on voyages that took place within the Americas and a database with the personal details of more than 95,000 enslaved Africans found on these ships.

The newest addition to SlaveVoyages is a data set that documents the “coastwise” traffic to New Orleans during the antebellum years of 1820 to 1860, when it was the largest slave-trading market in the country. The 1807 law that forbade the importation of enslaved Africans to the United States also required any captain of a coastwise vessel with enslaved people on board to file, at departure and on arrival, a manifest listing those individuals by name.

Countless enslaved Africans arrived at ports up and down the coast of the United States, but the largest share were sent to New Orleans. This new data set draws from roughly 4,000 “slave manifests” to document the traffic to that port. Those manifests list more than 63,000 captives, including names and physical descriptions, as well as information on an individual’s owner and information on the vessel and its captain.

Because of its specificity with regard to individual enslaved people, this new information is as pathbreaking for lay researchers and genealogists as it is for scholars and historians. It is also, for me, an opportunity to think about the difficult ethical questions that surround this work: How exactly do we relate to data that allows someone — anyone — to identify a specific enslaved person? How do we wield these powerful tools for quantitative analysis without abstracting the human reality away from the story? And what does it mean to study something as wicked and monstrous as the slave trade using some of the tools of the trade itself?

Before we go any further, it is worth spending a little more time with the history of the trans-Atlantic slave trade itself, at least as it relates to the United States.

A large majority of people taken from Africa were sold to enslavers in either South America or the Caribbean. British, Dutch, French, Spanish and Portuguese traders brought their captives to, among other places, modern-day Jamaica, Barbados, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Brazil and Haiti, as well as Argentina, Antigua and the Bahamas. A little over 3.5 percent of the total, about 389,000 people, arrived on the shores of British North America and the Gulf Coast during those centuries when slave ships could find port.

In the last decades of the 18th century, moral and religious activism fueled an effort to suppress British involvement in the African slave trade. In 1774, the Continental Congress of rebelling American states adopted a temporary general nonimportation policy against Britain and its possessions, effectively halting the slave trade, although the policy lapsed under the Confederation Congress in the wake of the Revolutionary War. Still, by 1787, most of the states of the newly independent United States had banned the importation of slaves, although slavery itself continued to thrive in the southeastern part of the country.

From 1787 to 1788, Americans would write and ratify a new Constitution that, in a concession to Lower South planters who demanded access to the trans-Atlantic trade, forbade a ban on the foreign slave trade for at least the next 20 years. But Congress could — and, in 1794, did — prohibit American ships from participating. In 1807, right on schedule, Congress passed — and President Thomas Jefferson, a slave-owning Virginian, signed — a measure to abolish the importation of enslaved Africans to the United States, effective Jan. 1, 1808.

But the end to American involvement in the trans-Atlantic slave trade (or at least the official end, given an illegal trade that would not end until the start of the Civil War) did not mean the end of the slave trade altogether. Slavery remained a big and booming business, driven by demand for tobacco, rice, indigo and increasingly cotton, which was already on its path to dominance as the principal cash crop of the slaveholding South.

Within a decade of the invention of the cotton gin in 1793, annual cotton production had grown twentyfold to 35 million pounds in 1800. By 1810, production had risen to roughly 85 million pounds per year, accounting for more than 20 percent of the nation’s export revenue. By 1820, the United States was producing something in the area of 160 million pounds of cotton a year.

Fueling this growth was the rapid expansion of American territory, facilitated by events abroad. In August 1791, the Haitian Revolution began with an insurrection of enslaved people. In 1803, Haitian revolutionaries defeated a final French Army expedition sent to pacify the colony after years of bloody conflict. To pay for this expensive quagmire — and to keep the territory out of the hands of the British — the soon-to-be-emperor Napoleon Bonaparte sold what remained of French North America to the United States at a fire-sale price.

The new territory nearly doubled the size of the country, opening new land to settlement and commercial cultivation. And as the American nation expanded further into the southeast, so too did its slave system. Planters moved from east to west. Some brought slaves. Others needed to buy them. There had always been an internal market for enslaved labor, but the end of the international trade made it larger and more lucrative.

It is hard to quantify the total volume of sales on the domestic slave trade, but scholars estimate that in the 40-year period between the Missouri Compromise and the secession crisis, at least 875,000 people were sent south and southwest from the Upper South, most as a result of commercial transactions, the rest as a consequence of planter migration.

New, more granular data on voyages and migrations and sales will help scholars delve deeper than ever into the nature of slavery in the United States, into specifics of the trade and into the ways it shaped the political economy of the American republic.

But no data set, no matter how precise, is complete. There are things that quantification can obscure. And there are, again, ethical questions that must be asked and answered when dealing with the quantitative study of human atrocity, which is what we’re ultimately doing when we bring statistical and mathematical methods to the study of slavery.

To think about the slave trade in terms of vessels and voyages — to look at it as columns in a spreadsheet or as points in an online animation — is to engage in an act of abstraction. Historians have no choice but to rely, as Marcus Rediker writes, on “ledgers and almanacs, balance sheets, graphs and tables.” But it carries a heavy cost, dehumanizing a reality that, he writes, “must, for moral and political reasons, be understood concretely.”

Consider, as well, the extent to which the tools of abstraction are themselves tied up in the history of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. As the historian Jennifer L. Morgan notes in “ Reckoning With Slavery: Gender, Kinship, and Capitalism in the Early Black Atlantic ,” the fathers of modern demography, the 17th-century English writers and mathematicians William Petty and John Graunt, were “thinking through problems of population and mobility at precisely the moment when England had solidified its commitment to the slave trade.”

Their questions were ones of statecraft: How could England increase its wealth? How could it handle its surplus population? And what would it do with “excessive populations that did not consume” in the formal market? Petty was concerned with Ireland — Britain’s first colony, of sorts — and the Irish. He thought that if they could be forcibly transferred to England, then they could, in Morgan’s words, become “something valuable because of their ability to augment the population and labor power of the English.”

This conceptual breakthrough, Morgan told me in an interview, cannot be disentangled from the slave trade. The English, she said, “are learning to think about people as ‘abstractable.’ By watching what the Spanish and what the Portuguese have been doing for 200 years, but also by doing it themselves, saying, ‘Oh, I can take Africans from here and move them to there, and then I can use them for my own purposes.’”

Embedded in this early project of quantification — Morgan notes in her book that Graunt “mounted what historians and political scientists agree was the first systematic use of demographic evidence to understand a contemporary sociopolitical problem” — is an objectification of human life.

Compounding these problems is the extent to which we rely on the documentation of slaveholders for our knowledge of the enslaved.

Writing of enslaved women on Barbados, the historian Marisa J. Fuentes notes in “ Dispossessed Lives: Enslaved Women, Violence, and the Archive ” that “they appear as historical subjects through the form and content of archival documents in the manner in which they lived: spectacularly violated, objectified, disposable, hypersexualized, and silenced. The violence is transferred from the enslaved bodies to the documents that count, condemn, assess, and evoke them, and we receive them in this condition.”

She continues: “Epistemic violence originates from the knowledge produced about enslaved women by white men and women in this society, and that knowledge is what survives in archival form.”

The traders, enslavers, officials and others who documented the slave trade did so in the context of legal and commercial relationships. For them, the enslaved were objects to be bought and sold for profit, wealth and status. If an individual’s “historical” life is shaped by the documents and images they leave behind, then, as Fuentes writes, most enslaved women, men and children live (and have lived) their historical lives as “numbers on an estate inventory or a ship’s ledger.” It is in that form that they are then shaped by “additional commodification” — used but not necessarily understood as having been fully alive.

“The data that we have about those ships is also kind of caught in a stranglehold of ship captains who care about some things and don’t care about others,” Jennifer Morgan said. We know what was important to them . It is the task of the historian to bring other resources to bear on this knowledge, to shed light on what the documents, and the data, might obscure.

“By merely reproducing the metrics of slave traders,” Fuentes said, “you’re not actually providing us with information about the people, the humans, who actually bore the brunt of this violence. And that’s important. It is important to humanize this history, to understand that this happened to African human beings.”

It’s here that we must engage with the question of the public. Work like the SlaveVoyages database exists in the “digital humanities,” a frequently public-facing realm of scholarship and inquiry. And within that context, an important part of respecting the humanity of the enslaved is thinking about their descendants.

“If you’re doing a digital humanities project, it exists in the world,” said Jessica Marie Johnson, an assistant professor of history at Johns Hopkins and the author of “ Wicked Flesh: Black Women, Intimacy, and Freedom in the Atlantic World .” “It exists among a public that is beyond the academy and beyond Silicon Valley. And that means that there should be certain other questions that we ask, a different kind of ethics of care and a different morality that we bring to things.”

I have some personal experience with this. Years ago, I worked with colleagues at Slate magazine on an infographic that showed the scale and duration of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, using data from the SlaveVoyages website. Plotted on a map of the Atlantic Ocean, it represented each ship as a single dot, moving from its departure point on the African coast to its arrival point in the Americas. As time goes on — as the 16th century becomes the 17th century becomes the 18th century becomes the 19th century — the dots grow overwhelming.

What I did not appreciate at the time was how we, the creators, would lose control of our creation. People encountered the infographic in ways we could not anticipate and that lay outside of our imagination. It was repurposed for schools and museums, used for personal projects and in exhibitions. Inevitably, some of these people would contact us. They would want to know more: about the ships, about the journeys, about the people. And we couldn’t answer them.

When I think back to the creation of that infographic, I wonder whether we had shown the care demanded of the data. Whether we had, in creating this abstraction, re-enacted — however inadvertently — some of the objectification of the slave trade.

One way to address this problem is to ensure that the audience understands the context. “I want to make sure that Black people in the audience feel like they are not being assaulted again by the information in the project or by the methods behind the project or any of that,” Johnson said, speaking of SlaveVoyages and other public work around slavery. “Everything from the colors on a website to the metadata itself is reshaped if we decide that the people in the audience should not feel harmed” and “should not be re-assaulted by their experience in this project or on this site.”

The new addition to SlaveVoyages, “Oceans of Kinfolk,” was made with these questions and concerns in mind. “You can use quantitative methodologies to learn about enslaved people, to learn about their experience,” said Jennie Williams, who collected and compiled the data as a doctoral student at Johns Hopkins and helped integrate it into the database as a postdoctoral research fellow at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Williams is also a friend, with whom I have discussed this work for years.

The slave traders who documented their cargo for federal authorities — producing the manifests that were the foundation of Williams’ work — were obviously not interested in the lives and experiences of their captives, except as cargo. They had no intention of preserving their identities as people. But despite this indifference, Williams said, that is essentially what happened.

These records are unique, Williams explained. If you look at bills of sale, she said, “most people are not identified by last name. If you look at fugitive ads, which I looked at 11,000 of and did a comparison with the manifests, which is also my dissertation, most people are not listed by last name. That is because slaveholders did not recognize enslaved people’s last names. They knew they had last names — they did not care.”

But, she continued: “If you asked an enslaved person ‘what is your name,’ they responded with a first and last name much more commonly than you would see in the other records. And so, manifests, compared to all other records of enslaved people I’ve seen, have a much higher proportion of last names in them.”

That fact makes this data important for genealogists and others interested in their family histories. “If Black families are able to reach or to trace their genealogy back to the 19th century, they very rarely get past 1870,” the year of the first federal census after slavery, Williams said. “This is not a database of everybody, but if I can get people to know about it, it is potentially useful for millions of people, because 63,000 people have millions of descendants.”

David Eltis concurred. “It’s quite rare to have this big body or big cache of names for enslaved people in the United States,” he said. “A person can go back and find something from the early 19th century, find a person with a possible connection. And that is simply not possible for the trans-Atlantic material. You can’t go back to Africa.”

If part of the ethical task for quantitative researchers of slavery is to preserve the humanity of the enslaved despite the nature of the sources, then connecting this data to Black genealogists is one way to underscore the fact that these were real people with real legacies.

“I could barely sleep the first night,” said Carlton Houston, a descendant of one of the 63,000 captives listed as part of the coastal trade to New Orleans, speaking of when he first saw the document listing his ancestor Simon Wilson, a young man sold for the purpose of “breeding” more people. “It was so compelling to see. Here’s the manifest, here’s this name, to have this visual in your head of these young people, chained on a boat, not really knowing where they were going.”

“There was not much for him to look forward to, you know, just this abysmal world that they lived in,” Houston added. “And yet, they survived, and didn’t give up.”

As for the sources themselves, it may be possible to use their physicality — the fact that these ledger books, bills of sale and fugitive slave ads are real, tangible objects — to tell stories about the humans involved in this centuries-long nightmare, to use the means of objectifying others to undermine the objectification itself.

“There is a strange way in which the everydayness of the document helps you understand the extraordinary imbalance of power and the wrongness,” Walter Johnson, a professor of history and African and African American studies at Harvard, said. “If somebody smudges the ink on a ledger, you have to imagine a person writing that. And once you imagine a person writing that, you’re imagining the extraordinary power that those words on a page have over somebody’s life. That somebody’s life and their lineage is actually being conveyed by that errant pen stroke. And then that takes you to a moment where you have to imagine those people.”

Indeed, the very banality of this material can help us understand how this system survived, and thrived, for so long. “I am not a historian of slavery because I want to spend my time understanding massive moments of spectacular violence,” Jennifer Morgan told me. “I actually want to understand tiny moments of violence, because that’s what I see as adding up to a kind of numbness — a numbness of empathy, a numbness to human interconnection.”

All of this is to say that with the history of slavery, the quantitative and the qualitative must inform each other. It is important to know the size and scale of the slave trade, of the way it was standardized and institutionalized, of the way it shaped the history of the entire Atlantic world.

But as every historian I spoke to for this story emphasized, it is also vital that we have an intimate understanding of the people who were part of this story and specifically of the people who were forced into it. It is for good reason that W.E.B. Du Bois once called the trans-Atlantic slave trade “the most magnificent drama in the last thousand years of human history”; a tragedy that involved “the transportation of 10 million human beings out of the dark beauty of their mother continent into the newfound Eldorado of the West” where they “descended into Hell”; and an “upheaval of humanity like the Reformation and the French Revolution.”

The future of SlaveVoyages will include even more information on the people involved in the slave trade, enslaved and enslavers alike. “We would like to add an intra-African slave trade database because there is a lot of movement of enslaved people on the eastern side of the Atlantic,” David Eltis said. He also told me that he can imagine a merger with scholars documenting the slave trade across the Indian Ocean, the roots of which go back to antiquity and whose more modern form was concurrent with the trans-Atlantic trade. “We’re really leaning into territory which was unimaginable back in 1969,” he said.

We may not have many statues of the enslaved — we may not have anywhere near enough letters and portraits and personal records for the millions who lived and died in bondage — but they were living, breathing individuals nonetheless, as real to the world as the men and women we put on pedestals.

As we learn from new data and new methods, it is paramount that we keep the truth of their essential humanity at the forefront of our efforts. We must have awareness, care and respect, lest we recapitulate the objectification of the slave trade itself. It is possible, after all, to disturb a grave without ever touching the soil.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips . And here's our email: [email protected] .

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook , Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram .

Jamelle Bouie became a New York Times Opinion columnist in 2019. Before that he was the chief political correspondent for Slate magazine. He is based in Charlottesville, Va., and Washington. @ jbouie

SlaveVoyages Introduction

A retrospective and what’s next.

Jane Hooper

Front Page News

The SlaveVoyages website offers records about the origins and forced transportation of more than twelve million Africans across the Atlantic and within the Americas. This ever-evolving website is the collaborative effort of dozens of researchers working in libraries and archives around the world . The work of several prominent historians, including Herbert S. Klein, David Richardson, David Eltis, and Stephen Behrendt, was foundational to the creation and expansion of the database over a period of decades. In 2008, the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database was first made freely available online, thanks to the efforts of David Eltis in collaboration with a multidisciplinary and international team of scholars, programmers, librarians, and designers. The database has been repeatedly refreshed and expanded to reflect new research findings and the user interface was modernized from 2015-2018 . For a more detailed account of the project's history, please click here.

In 2020, the Intra-American Slave Trade Database was added to the SlaveVoyages website. This database offers insight into the experiences of those who survived the Middle Passage across the Atlantic and were forced to board subsequent vessels soon after arriving at a port in the Americas . In 2021, a new section of the website, People of the Atlantic Slave Trade, was released. This section contains the African Origins Database , a list of nearly 100,000 Africans liberated from slaving vessels during the last sixty years of the transatlantic slave trade, as well as the Oceans of Kinfolk Database . The Oceans of Kinfolk Database provides the names of more than 63,000 people who were forcibly trafficked to New Orleans, along with information about their voyages and captors.

Given the complexity of the website, SlaveVoyages requires considerable energy and financial support to maintain. In 2021, a consortium of six member institutions was formed to support the efforts of SlaveVoyages. The now eight member institutions are Emory University (the original host institution), Rice University (the new hosting institution), the University of California campuses at Berkeley, Irvine, and Santa Cruz, Harvard University, the National Museum of African American History and Culture, the Omohundro Institute of Early American History & Culture, the University of the West Indies at Cave Hill, Barbados, and Washington University. This model of support and guidance will help ensure the sustainability of the website, while partnerships with these institutions, such as with the University of West Indies at Cave Hill , will encourage the site to explore new directions and help broaden access to archival materials.

This blog will offer perspectives on how information found in the databases can be used in a variety of settings and by teachers, students, researchers, and members of the public. We will release regular blog postings written by a variety of contributors. Among other topics, the blog posts will offer information about updates to the site, suggest ways in which educators can make use of the site, and reveal how the databases have influenced the work of scholars.

Additional References:

David Eltis, "The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database: Origins, Development, Content," Journal of Slavery and Data Preservation 2, no. 3 (2021). https://jsdp.enslaved.org/fullDataArticle/volume2-issue3-trans-atlantic-slave-trade-database/

Gregory E. O'Malley and Alex Borucki, "Patterns in the intercolonial slave trade across the Americas before the nineteenth century," Tempo, 23 (May/Aug 2017): 315-338. https://www.scielo.br/j/tem/a/cZmRvYM8FzJxBHvmPfWcfTw/?lang=en

- Division of Social Sciences

- Social Sciences Book Gallery

Home » The Slave Voyages Database

The Slave Voyages Database

The Slave Voyages Database is the most prominent public-facing project on the history of the slave trade and one of the most dynamic sites of research in slavery studies. It was launched under its former name “Transatlantic Slave Trade Database” in 1999 as a CD ROM and migrated online in 2008. A revolutionary tool for scholars since its inception, it has received renewed public attention in the wake of the U.S.’s 1619 anniversary.

A consortium has been formed to collaborate on relaunching elements of the project and providing long-term sustainability. UC Berkeley joins our colleagues at UC Irvine and UC Santa Cruz organizing this on behalf of the University of California. Along with the University of California, other consortium members are Rice University, Emory University, the Hutchins Center at Harvard University, the National Museum of African American History and Culture, and the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture.

Those at UC Berkeley interested in learning more about the Database and opportunities for collaboration should be in contact with G. Ugo Nwokeji ([email protected]), Associate Professor of African American Studies and Elena Schneider ([email protected]), Associate Professor of History.

We thank Dean Raka Ray of the College of Letters and Science, Social Sciences Division for her office’s support for UC Berkeley’s financial contribution to this consortium.

To learn more and access the database, visit https://www.slavevoyages.org/ .

To learn more about the consortium, see https://news.emory.edu/features/2021/03/voyages-consortium/index.html.

COMMENTS

Drawing on extensive archival records, this digital memorial allows analysis of the ships, traders, and captives in the Atlantic slave trade. The three databases below provide details of 36,000 trans-Atlantic slave voyages, 10,000 intra-American ventures, names and personal information. You can read the introductory maps for a high-level guided explanation, view the timeline and chronology of ...

The NEH-supported "Voyages: The Transatlantic Slave Trade Database" has allowed those records to be combined and collated so that the public can follow for the first time the routes of slave ships that transported 12.5 million Africans across the Atlantic from the 16th through the 19th century. The free online database, housed at Emory ...

Digital collection. Through this website, over 130,000 voyages made in the Trans-Atlantic and Intra-American slave trade can be searched, filtered, and sorted by variables including the port of origin, the number of enslaved Africans on board, and the ship's name. Time Periods: 1492, 1765, 1800, 1850, 1865. Themes: African American, Racism ...

Slave Voyages is a comprehensive and interactive website that tracks the history of the trans-Atlantic slave trade from Africa to the New World and within the Americas. It provides data, maps, charts, timelines, videos and research tools for historians, genealogists, educators and others who want to explore the slave trade and its impact on African American families.

The new slave voyages website counts as the product of three years of development by a multi-disciplinary team of historians, librarians, curriculum specialists, cartographers, computer programmers, and web designers, in consultation with scholars of the slave trade from universities in Europe, Africa, South America, and North America ...

Overview of the slave trade out of Africa, 1500-1900. Courtesy of slavevoyages.com Track the journeys of over 10-12.5 million Africans forced into slavery with this searchable database of passenger records from 36,000 trans-Atlantic slave ship voyages.

Between 1500 and 1866, slave traders forced 12.5 million Africans aboard transatlantic slave vessels. Before 1820, four enslaved Africans crossed the Atlantic for every European, making Africa the ...

Slave Voyages: The Transatlantic Slave Trade Database is an NEH-funded digital humanities project that represents decades of careful research and documentation. Scholars worked to collect information about the voyages of enslaved people, first across the Atlantic and then within the Americas, and to transfer unpublished archival records into machine-readable data.

Drawing on extensive archival records, this digital memorial allows analysis of the ships, traders, and captives in the Atlantic slave trade. The three databases below provide details of 36,000 trans-Atlantic slave voyages, 10,000 intra-American ventures, names and personal information. You can read the introductory maps for a high-level guided explanation, view the timeline and chronology of ...

Voyages: The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database is a database hosted at Rice University that aims to present all documentary material pertaining to the transatlantic slave trade. ... For each voyage they sought to establish dates, owners, vessels, captains, African visits, American destinations, numbers of slaves embarked, and numbers landed. ...

Learn about the history of the transatlantic slave trade and forced migration of millions of people from Africa to the Americas between 1514 and 1866. Explore three main databases with archival sources, vessel information, enslavers, and enslaved, and use interactive tools to create graphs and maps, study the Middle Passage, and design a memorial.

March 4, 2021. Elaine Justice. (404) 727-0643. [email protected]. SlaveVoyages.org, created and hosted at Emory University and a preeminent resource for the study of slavery, will be operated by a newly formed consortium of institutions, ensuring the preservation, stability and future development of what has become the single most widely ...

By mid-2018, Slave Voyages will offer a new database comprising ten thousand intra-American slave voyages that occurred within the Americas, usually carrying recent survivors of the middle passage. "Half of all disembarking captives faced a lengthy second journey after the middle passage," says Eltis.

Making history accessible. SlaveVoyages.org has its origins in the 1960s, when historians began collecting data on slave ship voyages and estimating the number of enslaved Africans to cross the Atlantic from the 16 th through 19 th centuries. But developing a single, multisource dataset was a pipe dream until the 1990s, when Eltis and other ...

Explore the details of 36,000 trans-Atlantic slave voyages from 1501 to 1875, based on archival records and maps. Learn about the ships, traders, and captives involved in the Atlantic slave trade, and see the timeline and chronology of the traffic.

SlaveVoyages.org is the world's largest repository of information about the trans-Atlantic and intra-American slave trades: the routes, the ships, the manifests and the human beings at their core. And now, after nearly 20 years at Emory University, the website and its treasure trove of data have moved to their new home at Rice. "It's the first time in the history of this project that it ...

The website also features the African Names Database, which provides personal details of 91,491 Africans taken from captured slave ships or from African trading sites. It displays the African name, age, gender, origin, country, and places of embarkation and disembarkation of each individual. Users of the Slave Voyages website can: analyze data ...