Food Tourism, a tasty way to travel

Food tourism is a relatively new term, but there are already several definitions to describe it. In the same context, it is also common to find the terms Culinary Tourism and Gastronomy Tourism .

At Food’n Road, we define Food Tourism as activities that provide experiences of consumption and appreciation of food and beverages , presented in such a way that values the history, the culture, and the environment of a particular region.

Explore the cuisine beyond the plate

Exploring different cuisines has always been associated with moments of leisure and travel, but the concept of food tourism has recently evolved to encompass activities beyond the plate. These are tourist and entertainment activities that place culinary traditions as a pillar of regional identity and cultural heritage and value the relationship between food and society.

And this change is great, as it creates the possibility for people to approach food at different levels of the value chain and learn from those who produce it. In this way, it is possible to expand economic development to different layers of society and offer more personal and authentic experiences to the traveler .

Activities of Food Tourism

Food tourism is much more than a list of restaurants or only high-cost activities with refined gourmet perception. It is also not focused only on agritourism. Nor does it require distant travels. It is related to all activities that use food as a means of connection between people, places, and time .

Food tourism is composed of activities that provide experiences of consumption and appreciation of food and beverages, presented in such a way that values the history, the culture, and the environment of a particular region. Food’n Road

Examples of Food Tourism activities:

- Take a street food tour;

- Tasting of local dishes and beverages;

- Follow regional product routes (e.g., travel on wine or coffee routes);

- Eat at traditional restaurants;

- Share meals with local people;

- Participate in food events and festivals;

- Visit local markets;

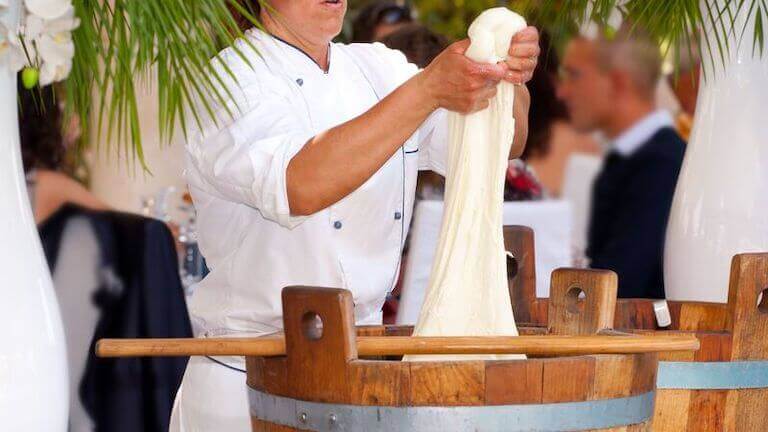

- Learn about the production of food by visiting farms and artisan producers;

- Participate in cooking classes;

- Visit exhibitions that explain the history of local cuisine;

- Culinary expeditions with chefs and specialists.

The list is huge, and there are several models of gastronomy-related activities. It is a creative market because it embraces different representatives of the food, beverage, and hospitality industry. We are talking about: restaurants, farms, markets, artisan producers, hotels and hostels, street food vendors, chefs, galleries, and everything related.

Read more: The main types of activities in food tourism

What are the benefits of Food Tourism and why we support it!

Food tourism with a focus on cultural immersion is a strong ally for economic and social development , in addition to being unique and memorable for the traveler .

When done in the right way, food tourism, built together with the local community and respecting its identity, is a tool for changing two scenarios: the negative impacts of tourism (we explain better below) and the detachment between people and real food.

Food Tourism is related to all activities that use food as a means of connection between people, places and time. Food’n Road

Tourism is not always associated with sustainable development. Many destinations are experiencing difficulties with regional and seasonal asymmetries. In other cases, local communities have been affected by massive tourism through gentrification, rising prices, and often attracting tourists with little awareness of their behavior and demands on the local community.

The scenario is quite different with a type of tourism that motivates people to know the countryside, diversified with food seasonality, and attracting people who seek to understand and relate in a more personal and respectful way to the local culture .

Read more about the benefits of Food Tourism

To strengthen this type of tourism, is it necessary to connect people in a more integrated way with the destination, and food does it very well!

At Food’n Road, we want to be agents of change, engage people to reflect about food beyond the plate, and contribute to responsible tourism development. We believe that every reflection starts with reliable information and is intensified with good experiences. Thus, food tourism is an excellent tool to initiate this change.

Did you like the idea? So find out now how to make a Food Trip !

- .wp-block-kadence-advancedheading mark{background:transparent;border-style:solid;border-width:0}.wp-block-kadence-advancedheading mark.kt-highlight{color:#f76a0c;}.kb-adv-heading-icon{display: inline-flex;justify-content: center;align-items: center;}.single-content .kadence-advanced-heading-wrapper h1, .single-content .kadence-advanced-heading-wrapper h2, .single-content .kadence-advanced-heading-wrapper h3, .single-content .kadence-advanced-heading-wrapper h4, .single-content .kadence-advanced-heading-wrapper h5, .single-content .kadence-advanced-heading-wrapper h6 {margin: 1.5em 0 .5em;}.single-content .kadence-advanced-heading-wrapper+* { margin-top:0;} .wp-block-kadence-advancedheading.kt-adv-heading_c4edf0-15, .wp-block-kadence-advancedheading.kt-adv-heading_c4edf0-15[data-kb-block="kb-adv-heading_c4edf0-15"]{padding-bottom:0px;margin-top:-20px;margin-bottom:0px;font-size:14px;font-style:normal;}.wp-block-kadence-advancedheading.kt-adv-heading_c4edf0-15 mark, .wp-block-kadence-advancedheading.kt-adv-heading_c4edf0-15[data-kb-block="kb-adv-heading_c4edf0-15"] mark{font-style:normal;color:#f76a0c;padding-top:0px;padding-right:0px;padding-bottom:0px;padding-left:0px;} We promote Food Tourism as a tool for connection and local development. Company Who we are

Food Tourism: What It Means And Why It Matters

Kristen Fleming holds a Master of Science in Nutrition. Over her 8 years of experience in dietetics, she has made significant contributions in clinical, community, and editorial settings. With 2 years as a clinical dietitian in an inpatient setting, 2 years in community health education, and 4 years of editorial experience focusing on nutrition and health-related content, Kristen's expertise is multifaceted.

Food. Many love to eat it, some love to cook it, and others simply love to talk about it. It is no secret that food plays a significant role in our lives. And while we all have our own unique relationship with food, there is one thing that we can all agree on – food is an experience .

Food tourism is the act of traveling for the purpose of experiencing food. This can be anything from going on a wine tour to visiting a local farmer’s market. Food tourism has become a popular way to travel in recent years as it provides people with an opportunity to connect with the local culture through food.

Would you be interested in learning more about food tourism? Keep reading to find out what it is, why it matters, and some tips on how to get the most out of your food tourism experience.

What Is The Meaning Of Food Tourism?

Travelers often seek out destinations that offer them a chance to sample the local cuisine. This type of tourism is known as food tourism. It’s also called culinary tourism or gastronomy tourism.

Food tourism can take many different forms. It can be as simple as trying a new dish while on vacation, or it can involve planning an entire trip around visiting different restaurants and food festivals ( 8 ).

Some people even choose to study culinary tourism, which is a field that combines the elements of anthropology, sociology, and economics to understand how food can be used as a tool for cultural exchange ( 2 ).

No matter how you define it, food tourism is a growing trend all over the world. And it’s not just about trying new foods – it’s about understanding the culture and history behind them.

What Are The Characteristics Of Food Tourism?

Food tourism includes any type of travel that revolves around experiencing food ( 6 ) ( 7 ). This can range from eating street food in Thailand to taking a cooking class in Italy.

Some of the most common activities associated with food tourism are:

Visiting Local Markets

Local markets are a great way to get a feel for the local cuisine. They also offer an opportunity to buy fresh, locally-sourced ingredients.

Trying Street Food

Street food is a staple in many cultures and a great way to sample the local cuisine. It is often less expensive than sit-down restaurants and offers a more authentic experience.

Attending Food Festivals

Food festivals are a great way to try a variety of local dishes in one place. They also offer the opportunity to learn about the culture and history behind the food ( 10 ).

Taking Cooking Classes

Cooking classes are a great way to learn about the local cuisine and how to cook traditional dishes. One may learn new cooking techniques, as well as about the culture and history behind the food.

Touring Wineries And Breweries

A common misconception is that food tourism only includes food and not beverages. However, touring wineries and breweries is a great way to learn about the local culture and taste the local products.

At a winery, one can learn about the wine-making process and taste the different types of wine produced in the region.

At a brewery, one can learn about the brewing process and taste the different types of beer produced in the region.

Some regions may be known for a certain type of spirit, and you can visit distilleries for those as well.

Read More: No Carb No Sugar Diet Meal Plan: Is It Healthy For Weight Loss?

Eating At Michelin-Starred Restaurants

Fine dining is another aspect of food tourism. Michelin-starred restaurants are known for their excellent food and service.

While at it, one can also learn about the chef, the history of the restaurant, and the thought that goes into each dish.

Touring Food Factories

Food factories offer a behind-the-scenes look at how food is produced. This can be anything from a chocolate factory to a pasta factory.

Touring food factories is a great way to learn about the production process and see how the food is made.

What Are The Benefits Of Food Tourism?

Food tourism can have a positive impact on both the traveler and the destination.

Benefits For The Traveler

Food tourism is becoming increasingly popular, and with good reason.

For travelers, it ( 5 ):

- Offers the opportunity to try new foods and experience new cultures.

- Is a great way to learn about the history and culture behind the food.

- Can be a more authentic and immersive experience than other types of tourism.

- Is a great way to support local businesses and the local economy.

- Can be a great way to meet new people and make new friends.

Benefits For The Destination

Food tourism can also have a positive impact on the destination.

For destinations, food tourism:

- Can help to promote the local cuisine and culture.

- Is a great way to attract visitors and boost the local economy.

- Can help to create jobs and support local businesses ( 1 ).

- Can help to improve the image of the destination.

- Can help to preserve traditional foods and recipes.

BetterMe app is a foolproof way to go from zero to a weight loss hero in a safe and sustainable way! What are you waiting for? Start transforming your body now !

What Are The Challenges Of Food Tourism?

While food tourism can have many positive benefits, there are also some challenges that need to be considered. These include:

1. Ensuring Food Safety And Hygiene Standards Are Met

Food safety is a major concern when traveling, and food-borne illnesses can ruin a trip ( 11 ). It is important to research the restaurants and markets before eating anything .

Using your common sense and following basic hygiene rules (such as washing your hands) can also help to reduce the risk of getting sick.

2. Ensuring Food Is Ethically And Sustainably Sourced

With the rise of food tourism, there is a danger that destinations will start to mass-produce food for tourists, rather than focus on quality. This can lead to unethical and unsustainable practices , such as using forced labor or over-fishing ( 3 ) ( 4 ).

3. Managing The Impact On The Environment

Food tourism can have a negative impact on the environment if it is not managed properly. For example, if too many people visit a destination, it can lead to pollution and damage to the local ecosystem ( 9 ).

4. Ensuring Fair Working Conditions For Those Involved In The Food Industry

The food industry is often characterized by low pay and long hours. This can be a problem for those working in the industry, as they may not be able to earn a decent wage or have enough time to rest.

5. Addressing The Issues Of Food Waste And Overconsumption

Food tourism often involves trying new and different foods . However, this can lead to food waste if people do not finish their meals or if they order more than they can eat.

It is important to be aware of the issue of food waste and to try to minimize it where possible.

Where Is Food Tourism Most Popular?

Food tourism is particularly popular in countries with strong culinary traditions. Below are several examples of such destinations, along with a description of what they offer food tourists .

Porto (Portugal)

Porto is known for its port wine, which is produced in the surrounding Douro Valley. The city also has a number of traditional restaurants serving Portuguese cuisines such as bacalhau (codfish) dishes and francesinha (a sandwich with meat, cheese, and ham).

Lisbon (Portugal)

Lisbon is another Portuguese city with a strong culinary tradition . The city is known for its seafood, as well as for pastries such as the Pasteis de Belem (a type of custard tart).

Palermo (Italy)

Palermo is the capital of Sicily, an island with a rich culinary tradition. The city is known for its street food, which includes dishes such as arancini (fried rice balls) and panelle (fried chickpea fritters).

Vientiane (Laos)

Vientiane is the capital of Laos, and its cuisine reflects the influence of both Thai and Vietnamese cuisine. The city is known for dishes such as laab (a type of meat salad) and khao soi (a noodle soup).

San Sebastian (Spain)

San Sebastian is a Basque city located in northern Spain. The city is known for its pintxos (small plates) and for Basque dishes such as txakoli (a type of white wine) and cod with pil-pil sauce.

Paris (France)

Paris is one of the most popular food tourism destinations in the world. The city is known for its fine dining, as well as for its more casual bistros and cafes.

Paris is also home to a number of markets, such as the famous Les Halles market, where food tourists can sample a variety of French specialties.

Read More: What Is The Ideal Ketosis Level For Weight Loss? How To Monitor Ketones

New York City (USA)

New York City is another popular food tourism destination. The city offers a wide range of cuisines, from traditional American dishes to the cuisine of its many immigrant communities.

New York is also home to a number of famous restaurants, such as the Russian Tea Room and the Rainbow Room.

Tokyo (Japan)

Tokyo is a city with a rich culinary tradition. The city is known for its sushi and ramen, as well as for its more traditional dishes such as tempura and yakitori. Tokyo is also home to a number of Michelin-starred restaurants, making it a popular destination for food tourists.

Tips For Food Tourism

If you’re interested in trying out different cuisines while traveling, there are a few things you can do to make the most of your food tourism experience.

Do Some Research Before You Go

Read up on the cuisine of the place you’re visiting, and try to find out what dishes are particularly popular. This will help you narrow down your options and make sure you don’t miss out on any must-try dishes.

Don’t Be Afraid To Ask For Recommendations

When you’re in a new city, ask the locals where they like to eat. They’ll be able to point you in the direction of some great places to try.

Be Open To New Experiences

When you’re trying out new cuisine, don’t be afraid to experiment. You might find that you like something that you never would have thought to try before.

Respect Local Customs And Traditions

When you’re traveling, it’s important to remember that not everyone does things the same way as you do. Be respectful of local customs and traditions, and try not to offend anyone.

Enjoy Yourself!

Food tourism should be about enjoying new experiences and trying new things. So relax, and enjoy the ride.

The Bottom Line

Food tourism is a growing trend, and there are many destinations around the world that offer something for everyone. Whether you’re looking for fine dining or street food, it’s sure there’s a place that will suit your taste.

DISCLAIMER:

This article is intended for general informational purposes only and does not address individual circumstances. It is not a substitute for professional advice or help and should not be relied on to make decisions of any kind. Any action you take upon the information presented in this article is strictly at your own risk and responsibility!

- A study on the importance of Food Tourism and its impact on Creating Career 2017 (2017, researchgate.net)

- Culinary Tourism (2014, link.springer.com)

- Darker still: Present-day slavery in hospitality and tourism services (2013, researchgate.net)

- Disentangling tourism impacts on small-scale fishing pressure (2022, sciencedirect.com)

- Food and tourism synergies: perspectives on consumption, production, and destination development (2017, tandfonline.com)

- Foodies and Food Events (2014, tandfonline.com)

- Food tourism value: Investigating the factors that influence tourists to revisit (2019, sagepub.com)

- Global report on food tourism (2012, amazonaws.com)

- Re-evaluating the environmental impacts of tourism: does EKC exist? (2019, link.springer.com)

- Reviving Traditional Food Knowledge Through Food Festivals. The Case of the Pink Asparagus Festival in Mezzago, Italy (2020, frontiersin.org)

- The Importance of Food Safety in Travel Planning and Destination Selection (2008, tandfonline.com)

I've struggled to maintain programs…

Our Journey

It Works! This program is working for me!

Does Matcha Have Caffeine?

Why Am I Craving Chocolate? The Reasons Beyond the Sweet Tooth and How to Fix It

Top 10 Healthy Alternatives to Sodas With Many Flavor and Ingredient Varieties

What are Rolled Oats? Explore the Benefits and Hearty Recipes

From TikTok to Table: The Rise and Risks of the Oatzempic Craze

Choose a Healthy Alternative to Chips to Lose Weight or Follow a Healthier Eating Plan

- For Business

- Terms of Service

- Subscription terms

- Privacy Policy

- Money-back Policy

- e-Privacy Settings

- Your Privacy Choices

Culinary tourism: The growth of food tourism around the world

Disclaimer: Some posts on Tourism Teacher may contain affiliate links. If you appreciate this content, you can show your support by making a purchase through these links or by buying me a coffee . Thank you for your support!

Culinary tourism is a popular type of tourism throughout the world, but what exactly is culinary tourism? Is it different from food tourism? Why is culinary tourism important? And where are the best places to travel for culinary tourism? Read on to find out…

What is culinary tourism?

Importance of food tourism, culinary tourism activities, culinary tourism in bangkok, culinary tourism in tokyo, culinary tourism in honolulu, culinary tourism in durban, culinary tourism in new orleans, culinary tourism in istanbul, culinary tourism in paris, culinary tourism marrakesh, culinary tourism in mumbai, culinary tourism in miami, culinary tourism rio de janeiro, culinary tourism in beijing, food tourism- further reading.

Culinary tourism, also often referred to as food tourism, is all about exploring food as a form of tourism. Whether that be eating, cooking, baking, attending a drinks festival or visiting a farmers market – all of these come under the concept of culinary tourism. It’s something you don’t even really need to travel to do. Heading to your nearest big city or even the next town over, specifically to eat at a certain restaurant, classes as food tourism! And food tourism has taken a new twist since the COVID pandemic too, when many people would cook or eat a variety of different foods from around the world in attempt to bring an element of travel to their own home! Who said you need to travel far to be a culinary tourist, huh?

Food tourism is a vitally important component of the travel and tourism industry as a whole. When booking a trip, people tend to consider a variety of factors – and food is high on the list of priorities. The World Food Travel Association says that money spent on food and drink while travelling accounts for 15-35% of all tourism spending. Culinary tourism is important in that it generates so much money for local economies.

Culinary tourism is also an important branch of tourism in that it can promote local businesses, as well as help to shine a light on different cuisines. For so many cultures, their cuisine is a huge part of who they are. Culinary tourism helps to celebrate this, by attracting interested tourists who are keen to try something new and share it with the world. In this way, it definitely helps to boost community pride and is a great example of cultural tourism .

This type of tourism is also important to tourists. It provides a chance to try new foods and flavours, and discover new cultures through their taste buds. Visitors who engage in food tourism come away with new recipes to try, new foods to introduce their friends to, and memories that they will always associate with their sense of taste.

There are many activities which come under the remit of culinary tourism, or food tourism. I mentioned some above, but let’s take a closer look.

- Eating and drinking out: going to restaurants, cafes, bars, pubs, tea shops and so on. These are all examples of culinary tourism.

- Food/beverage tours: you can book onto organised food and drink tours when visiting a new city. These are run by guides who will take you to various foodie spots throughout the city – usually small businesses – to try local delicacies.

- Farmers markets: visiting a farmers market at the weekend to buy fresh produce is seen as a form of food tourism.

- Cooking classes: another activity you can get involved with on your travels is a cooking or baking class. You’ll often make, again, a local delicacy whether that be pierogi in Poland or pasta in Italy . Tasting sessions: brewery tours and vineyard visits (and other similar excursions) where you get to take a look at how something is made and then try it for yourself are another form of culinary tourism.

Best cities for food tourism

Most cities, major or otherwise, have excellent examples of food tourism. In fact – this goes right down to tiny towns and villages, some of which have incredible restaurants or bars that are real hidden gems. Below you’ll find some of the world’s best cities for culinary tourism, however, with examples of the sort of thing you can do there!

Thai food is some of the best food around, and Bangkok has a lot of restaurants suited to all budgets. Eating out in Bangkok is a brilliant example of culinary tourism. One of the best things you can do here is try the local street food! Wang Lang Market is one of the most popular places for street food, with fresh food filling the lanes from snacks to full-on meals. Silom Soi 20 is another great spot in central Bangkok, perfect for the morning.

Looking for somewhere really unique to eat in Bangkok? Head to Cabbages and Condoms , a themed cafe decorated with (you guessed it) condoms. The restaurant say they were ‘conceptualized in part to promote better understanding and acceptance of family planning and to generate income to support various development activities of the Population and Community Development Association (PDA)’.

Tokyo is a very popular city, and one of the best ways to experience food tourism here is to book onto a food tour. Tokyo Retro Bites is a fantastic one, giving you a feel of old-style Tokyo at the quaint Yanaka Market. This is a walking tour which includes drinks and 5 snacks, lasting 2 hours. It starts at 11.30am meaning it’s a great chance to have lunch somewhere a bit different!

This beautiful Hawaiian city has so many fun places to eat (and drink!) while visiting. One of the best things to do in terms of culinary tourism is to eat somewhere you wouldn’t be able to eat at home – and try new flavours or dishes. Honolulu is the perfect place to do this. Some interesting eateries include:

- Lava Tube – based in Waikiki, this 60s-kitsch style bar offers pina coladas served in giant pineapples, $5 Mai Tais, delicious food and plenty of fun decor.

- Suzy Wong’s Hideaway – this is described as a ‘dive bar with class’ and is a great bar to visit to watch sports games.

- MW Restaurant – this is a really famous and creative place to eat in Honolulu – the mochi-crusted Kona Kanpachi comes highly recommended and helped shoot the chef, Wade Ueoka, to fame.

Hailed as the world’s best food city, a list of places for food tourists to visit has to include Durban in South Africa . Bunny Chow is a local delicacy that you cannot miss while visiting Durban. It is now available elsewhere, but the original is usually the best so be sure to try some while in the city. The dish is half a loaf of bread hollowed out and filled with curry – delicious. This article shares 5 fantastic spots to get Bunny Chow in Durban !

As one of the culinary capitals of the US, New Orleans is incredibly popular with foodies. The city is a hotspot for food tourism, thanks to the various cultural roots here: Cajun, Creole and French. There is a whole range of tastes to try. You could spend your time here *just* eating and still not scratch the surface when it comes to the amazing restaurants, cafes and eateries in NOLA. Some foods you have to try include:

- Po’boys: fried shrimp, generally, but sometimes beef or other seafood – served on a fresh crusty roll.

- Gumbo : this is a stew, again usually containing seafood, alongside bell peppers, onion and celery.

- Crawfish etouffee: a French crawfish stew served over rice.

- Muffuletta: a Silician-American sandwich served on a specific type of bread.

- Side note, you can do a haunted pub crawl in NOLA . Would you?!

Being split across two continents, it is no surprise that Istanbul as a city has a huge range of delicious food-related activities. From kebabs sold on the street to 5 star restaurants serving the finest hummus, Istanbul is a fantastic destination for food tourism. Book onto the ‘Two Markets, Two Continents’ tour – you’ll visit two markets, as the name suggests, on the two continents. The tour includes a Bosphorus ferry crossing between the two districts of Karaköy (Europe) and Kadiköy (Asia). You’ll enjoy breakfast, tea and coffee, meze, dessert and so much more during this 6.5 hour tour .

The city of love – and the city of bakeries! Fresh baguettes, simple croissants, delicious eclairs… the list goes on. There are so many of them dotted around, whether you want something to grab and snack on while you head to the Eiffel Tower or if you want a sit down brunch, you’ll find one that suits you perfectly.

And that’s not all. Paris, also famous for its snails, soups and frogs legs, has so many fine dining opportunities. You’ll be spoilt for choice in terms of Michelin star restaurants: Boutary, ASPIC, 114 Fauborg and so many more. There are also some fantastic food tours in Paris . If you have the cash to splash out, fine dining in Paris is a brilliant culinary tourism activity…

Moroccan food is delicious. And you can try making it yourself during a cooking class in Marrakech ! Visit a traditional souk and try your hand at some tasty recipes – you never know, you might have a hidden talent. Some tours even include shopping for ingredients, so you can visit a traditional market too; these are a sensory dream with so many smells, colours, sounds and sights.

India is another country where street food is king. Mumbai has plenty to offer, and one culinary tourism activity you can do is to spend an afternoon trying as many dishes as possible while simply wandering through the city. If you’ve never tried a vada pav before, this is the place to do so: it’s essentially deep fried mashed potato in a bun with various chutneys, and it is exquisite. Many people are surprised to learn that one of the most popular British foods – chicken tikka masala is not commonly found in India, but fear not, there are many other dishes that are just as goods or if not better!

Miami is known for its food – and Cuban food is a big deal here. Take a traditional Cuban cooking class , or head to one of the many, many Cuban restaurants here . There is something for every budget, and your tastebuds will certainly thank you. It is also close to Key West, a wonderful place to visit for a day or two. They’re big on sea food here, and walking tours which incorporate seafood are high on the list of recommended things to do in beautiful Key West.

You cannot go to Rio and not try cahaça. This is Brazilian brandy made from sugar canes, and it is a big deal over here. Culinary tourism isn’t limited to food – it includes drink too, so head to one of Rio’s many bars and try a caipirinha. You can even book an organised pub crawl , which includes free shots and drinks, around the city. This is perfect if you want to explore at night knowing you’ll be safe and always have transport on hand.

Peking duck is the highlight of Beijing food. Quanjuede is world-famous for its Peking duck, and it’s not too expensive. There are branches worldwide now, though, and much of culinary tourism is about experiencing something you won’t be able to elsewhere. Speak to the locals when you’re there and ask where their favourite place is for Peking duck. That way you’ll know you are supporting a great local business; as mentioned, food tourism is great for boosting the economy this way!

If you have enjoyed this article about culinary tourism, or food tourism, then I am sure that you will love these too!

- What is pilgrimage tourism and why is it important?

- What is red tourism and why is it growing so fast?

- Overtourism explained: What is it and why is it so bad?

- Enclave tourism: A simple explanation

Liked this article? Click to share!

Culinary Tourism

- Living reference work entry

- First Online: 01 January 2014

- Cite this living reference work entry

- Lucy M. Long 3

4112 Accesses

16 Citations

Cultural tourism ; Food tourism ; Gastronomic tourism ; Sustainable tourism

Introduction

Culinary tourism is the focus on food as an attraction for exploration and a destination for tourism. Although food has always been a part of hospitality services for tourists, it was not emphasized by the tourism industry until the late 1990s. It now includes a variety of formats and products – culinary trails, cooking classes, restaurants, farm weekends, cookbooks, food guides, and new or adapted recipes, dishes, and even ingredients. While most culinary tourism focuses on the experience of dining and tasting of new foods as a commercial enterprise, it is also an educational initiative channeling curiosity about food into learning through it about the culture of a particular cuisine, the people involved in producing and preparing it, the food system enabling access to those foods, and the potential contribution of tourists to sustainability.

Culinary tourism involves numerous issues; many...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Boniface, P. (2003). Tasting tourism: Travelling for food drink . Burlington: Ashgate.

Google Scholar

Chambers, E. (2010). Native tours: The anthropology of travel and tourism (2nd ed.). Long Grove: Waveland Press.

Gmelch, S. B. (2010). Tourists and tourism: Reader (2nd ed.). Long Grove: Waveland Press.

Hall, C. M., & Sharples, L. (2008). Food and wine festivals and events around the world . London: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Hall, C. M., Sharples, L., Mitchell, R., & Macionis, N. (2003). Food tourism around the world: Development, management and markets . London: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Heldke, L. (2003). Exotic appetites: Ruminations of a food adventurer . New York: Routledge.

Heldke, L. (2005). But is it authentic? Culinary travel and the search for the ‘Genuine Article.’. In K. Carolyn (Ed.), The taste culture reader: Experiencing food and drink (pp. 385–394). New York: Berg.

Hjalager, A.-M., & Richards, G. (Eds.). (2002). Tourism and gastronomy . London: Routledge.

Long, L. (2004). Culinary tourism: Eating and otherness . Lexington: University Press of Kentucky.

Long, L. M. (2010). Culinary Tourism in and the Emergence of Appalachian Cuisine: Exploring the “Foodscape” of Asheville, NC. North Carolina Folklore Journal 57.1 (Spring-Summer), pp. 4–19.

Meethan, K. (2001). Tourism in a global society: place, culture, consumption. Basinstoke: Palgrave.

Ritzer, G. (1993). The McDonaldization of society: An investigation into the changing character of contemporary social life. London: Pine Forge Press.

O’Connor, K. (2008). The Hawaiian Luau: Food as tradition, transgression, transformation and travel. Food, Culture, and Society, 11 (2), 149–171.

Wilk, R. (2006). Home cooking in the global village . Oxford: Berg.

Wolf, E. (2006). Culinary tourism: The hidden harvest . Dubuque: Kendall/Hunt.

Zilensky, W. (1985). The roving palate: North America’s ethnic restaurant cuisines. Geoforum, 16 (1), 51–72.

Article Google Scholar

Food, Culture, and Society: An International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Journal of Sustainable Tourism . Taylor & Francis.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Center for Food and Culture, 1001 East Wooster Street, Bowling Green, OH, 43403-0001, USA

Dr. Lucy M. Long

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Lucy M. Long .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Michigan State University Dept. Philosophy, East Lansing, Michigan, USA

Paul B. Thompson

University of North Texas Dept. Philosophy & Religion Studies, Denton, Texas, USA

David M. Kaplan

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2013 Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Long, L.M. (2013). Culinary Tourism. In: Thompson, P., Kaplan, D. (eds) Encyclopedia of Food and Agricultural Ethics. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-6167-4_416-1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-6167-4_416-1

Received : 13 May 2013

Accepted : 13 May 2013

Published : 11 February 2014

Publisher Name : Springer, Dordrecht

Online ISBN : 978-94-007-6167-4

eBook Packages : Springer Reference Religion and Philosophy Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Humanities

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Skift Research

- Airline Weekly

- Skift Meetings

- Daily Lodging Report

The New Era of Food Tourism: Trends and Best Practices for Stakeholders

Related reports.

- State of Travel 2023: Travel in 250 Charts July 2023

- Destination Marketing Outlook 2022 January 2022

- Sustainability in Travel 2021: Quantifying Tourism Emissions for Destinations June 2021

- EU Traveler Profile and Key Statistics: The Impact of COVID-19 January 2021

Report Overview

Over the past few years, food tourism has been a buzzy trend in the travel industry. Not only is it appealing to a large population of travelers, but it also has the potential to boost in-destination spending, and therefore, positively benefit local economies and small businesses. Despite the buzz, the conversation around food tourism has hardly changed since it first started to spread years ago. Not to mention, there is still some confusion about what food tourism really is and how destinations and other stakeholders can get involved.

In this report, we focus on addressing four questions under the food tourism umbrella: How big and important is the food tourism market? What are the new trends related to food tourism? Who should be be involved in and benefit from food tourism? What are the best practices for various stakeholders? We attempt to answer these questions drawing from the second, expanded iteration of our proprietary food tourism consumer survey. Then, we turn toward breaking down the new definition of food tourism into five components, drawing mostly from a number of in-depth interviews with industry stakeholders and experts. These perspectives then contribute to the final section of the report, in which we have identified 10 best practices for food tourism stakeholders.

Survey Methodology:

Skift Research’s Food Tourism Survey 2019 collected responses from 2,000 respondents who live in the U.S. The survey was fielded to internet users age 18 and over. Respondents were asked whether they’ve taken a leisure trip in the past 12 months that included at least one-night’s paid stay and was 50 miles or more from home. We refer to this group as “recent travelers” (N=1,373) to compare to the total population (“all respondents”, N=2,000). The survey was fielded by a trusted third-party consumer panel provider.

What You'll Learn From This Report

- What food tourism means and how it has evolved over time

- Who the stakeholders are in food tourism

- A comprehensive look at who food tourists are today, how they behave, and what they prefer

- Skift Research estimates for food and beverage expenditure by U.S. travelers

- Size of U.S. food tourist population

- The kinds of food and beverage based activities food tourists are most likely to participate in

- The percentage of food tourists who have taken a vacation with a food and beverage experience as the main purpose for the trip

- A five-part breakdown of the new definition of food tourism

- 10 best practices for food tourism stakeholders today

Executives Interviewed

- Benjamin Ozsanay - CEO & Co-Founder, Cookly

- Camille Rumani - COO & Co-Founder, Eatwith

- Didier Souillat - CEO, Time Out Market

- Erik Wolf - Executive Director, World Food Travel Association

- Helena Williams, Ph.D. - Researcher, Tourism & Hospitality, Texas Tech University and CEO, Gastro Gatherings

- James Imbriani - Founder, Sapore Travel

- Javier Perez-Palencia - CEO and Chair of the Board, FIBEGA Miami 2019 International Gastronomy Tourism Fair

- Joanne Wolnik - Tourism Development Manager, Ontario’s Southwest

- Michael Ellis - Chief Culinary Officer, Jumeirah Group

- Robert Williams, Jr. PhD. - Susquehanna University and Senior Partner, Mar-Kadam Associates

- Trevor Jonas Benson - Director of Food Tourism Innovation and lead consultant, Grow Food Tourism at the Culinary Tourism Alliance

Executive Summary

In 2016, Skift Research published a report called Food Tourism Strategies to Drive Destination Spending . This was at a time when “food tourism” was taking off as a buzzy trend in the travel industry. Now, almost three years later, we’re taking a look at where food tourism is today, how it’s changed, and best practices for stakeholders.

Food tourism is often approached with the destination in mind, as Skift Research did in 2016, and developing and promoting it is often cast off as the sole responsibility of destination marketing organizations (DMOs) or regional tourism offices (RTOs). Clearly, these organizations have important roles to play, but they don’t exist alone when it comes to food tourism. In the new era of food tourism, many stakeholders have the opportunity to help develop, promote, and eventually benefit from this type of tourism.

In this report, we lay out what food tourism is today and how it has changed from years past. We build this definition from an in-depth understanding of who food tourists are today, drawing from the second, expanded iteration of our proprietary food tourism consumer survey. After providing a comprehensive look at the consumer side of the equation, we turn toward breaking down the new definition of food tourism into five components, drawing mostly from a number of in-depth interviews with industry stakeholders and experts. These perspectives then contribute to the final section of the report, in which we have identified 10 best practices for food tourism stakeholders.

Food Tourism Demystified and Defined

Terminology.

These are a few commonly used terms that encompass food and beverage tourism experiences:

- Culinary tourism: Some sources prefer using this term because it more clearly encompasses beverage-based experiences in addition to food-based.

- Gastronomy tourism: Similarly to “culinary tourism,” some sources prefer this term because of its all-encompassing connotation. This term is most commonly used in Europe.

- Food tourism: As of 2012, the World Food Travel Association (WFTA) began using the term “food tourism” or “food travel” to describe “the act of traveling for a taste of place in order to get a sense of place,” or put differently, “the act of traveling to experience unique food and beverage products and experiences.” Rather than the type of experience being the differentiator, what matters is the uniqueness of the experience itself and how it is particular to the destination.

For this report, we will follow the lead of the WFTA, which stopped using “culinary tourism” in 2012 when its research indicated that English speakers tend to associate this term with exclusivity and elitism, neither of which should be inherent to food tourism. “Gastronomy tourism” can also be interpreted this way, especially to English speakers outside of Europe. For these reasons, we chose to stick with food tourism, as we believe it better reflects the variety of food- and beverage-based travel experiences we will discuss in this report.

So then what counts as food tourism? This is where the lines can get blurry. Almost all tourists need to eat at an eating place while traveling, so almost all contribute to the local food economy in some way. Broadly speaking, these can all be counted as food tourism.

A bit narrower than that, some sources define food tourism as food and drinking activities that are unique to a region/destination and include aspects beyond simply eating or drinking. With this in mind, food tourism experiences most commonly include cooking classes with locals, food and drink tastings, having meals in locals’ homes, eating at local restaurants or street food vendors, food and drink tours and trails, collecting ingredients or participating in harvesting local produce, visiting farms or other types of food producers, visiting food markets or fairs, and visiting food manufacturers such as distilleries, factories, and wineries.

An even narrower scope through which to look at food tourism is whether it is deliberate food tourism or incidental food tourism. Deliberate food tourism only includes food and drinking activities that are the main motivator for a traveler to go to a destination, while incidental are those that travelers participate in, but were not the main purpose of the trip. We will discuss these terms in more detail from the consumer perspective later in the report.

Each of the above ways of describing food and beverage related tourism is correct. Variations in data on food tourism can often be due to different definitions and scopes used for the research. Later in this report, we will provide data on these three ways of counting food tourism.

Stakeholders

Another important part of food tourism to mention here is the variety of stakeholders that are involved. Developing and promoting food tourism is often discussed as responsibilities of destination marketing organizations (DMOs) or regional tourism offices (RTOs). However, this report will emphasize that there are multiple stakeholders that can, and should, have a part in building and participating in a region’s food tourism space. Of course, DMOs and RTOs can and should play important organizational and planning roles, but tour providers and operators, traditional travel agencies, online travel agencies and booking platforms, peer-to-peer platforms, hotels, local restaurateurs, and more have the opportunity for involvement in food tourism.

While this lays out the basic elements of food tourism that we’ve built this report around, it’s very likely that we will need to revisit what we’ve summarized in the near future. The term, scope, and even stakeholders will constantly evolve as destinations, cultures, and trends change over time. Later in this report, we will examine the nuances of what defines the new era of food tourism that exists today compared with a few years ago. But first, we will take a look at the current state of the food tourism space for context.

The State of Food Tourism Today

Food tourism is a lucrative market.

Just how big is the food tourism market? As we laid out above, there are three ways to size up the food tourism market. In the broadest sense, it includes all food and drink based activities that travelers partake in, whether it’s eating at a chain restaurant, taking a food tour, or visiting a local brewery.

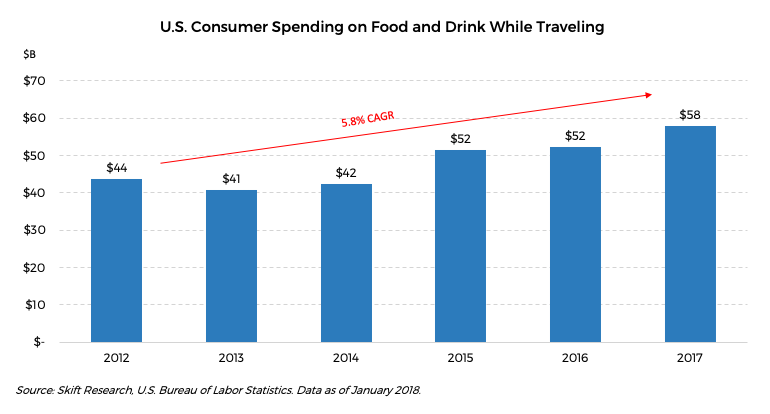

To get a sense of food tourism’s contribution to local food economies in this broad sense, Skift Research looked at all food and beverage expenditure by U.S. travelers for domestic and international travel. We analyzed data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Expenditure Survey to determine how much money American travelers actually spend on food and drink while traveling. While this data includes spending on all food and drink while traveling (i.e. not just the local, unique experiences that many consider “food tourism”), it nonetheless gives us an idea of the potential economic impact food tourists can have and how it has changed over time.

Our estimates show that U.S. travelers spent $58 billion on food and drink while traveling in 2017 (the last year for which data was available at the time of writing). This represents a 5.8% compound annual growth rate from 2012.

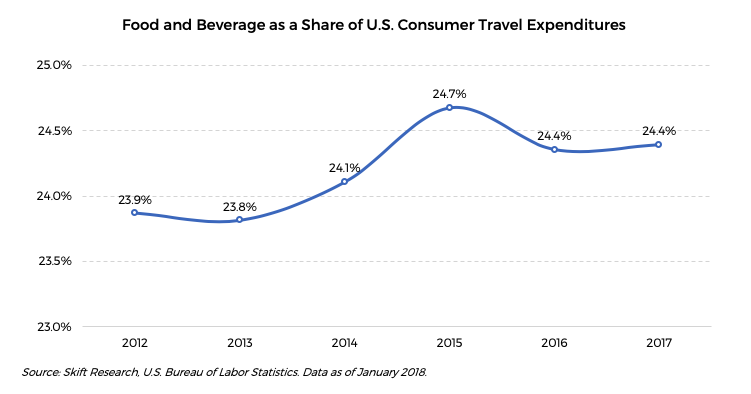

To look at this another way, we calculated the share of total travel expenditures spent on food and beverage by U.S. travelers. Here, we see an overall upward trend from 2012 to about 25%, where it has more or less hovered since 2015. This falls in line with the WFTA’s estimate from its 2016 Food Travel Monitor that global travelers spent about 25% of their travel budget on food and beverages, and this can be as high as 35% in certain destinations or for especially food-centric travelers

We then turn our attention to a narrower, more local scope of food tourism. While researching for this report, we found that despite the rising popularity and interest in food tourism across many related sectors, there is very little data on a clearly defined food tourism segment. We conducted our own survey for the purpose of providing some necessary context to the trends.

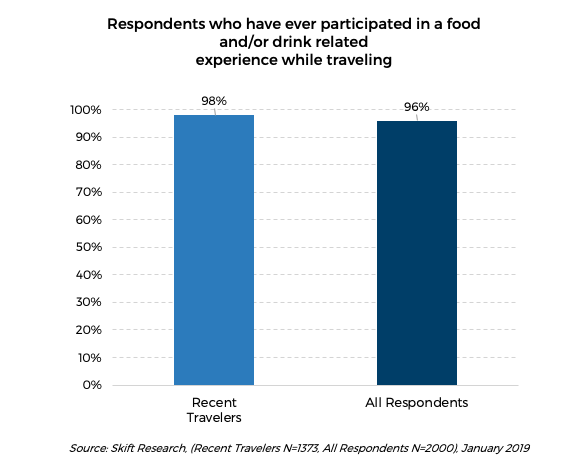

According to our food tourism survey, 96% of respondents have participated in some kind of experience that would fall under this slightly narrower food tourism umbrella (i.e., dining out at restaurants that serve local cuisine is included). This increases slightly to 98% for those respondents who have traveled for leisure in the past 12 months, who we call “recent travelers.” This falls in line with the WFTA’s 2016 Food Travel Monitor finding that 93% of travelers could be considered “food travelers” at some time, based on their participation in food or beverage experiences. This estimation, however, does not include travelers who only dine out in-destination.

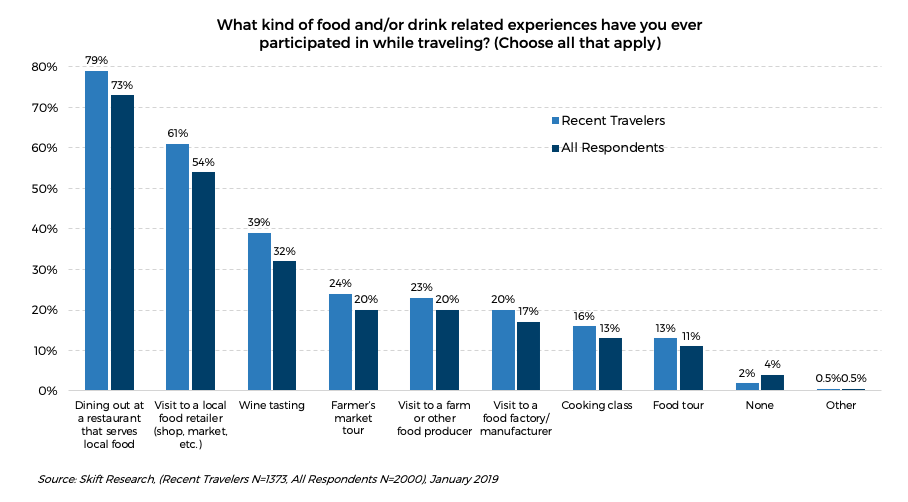

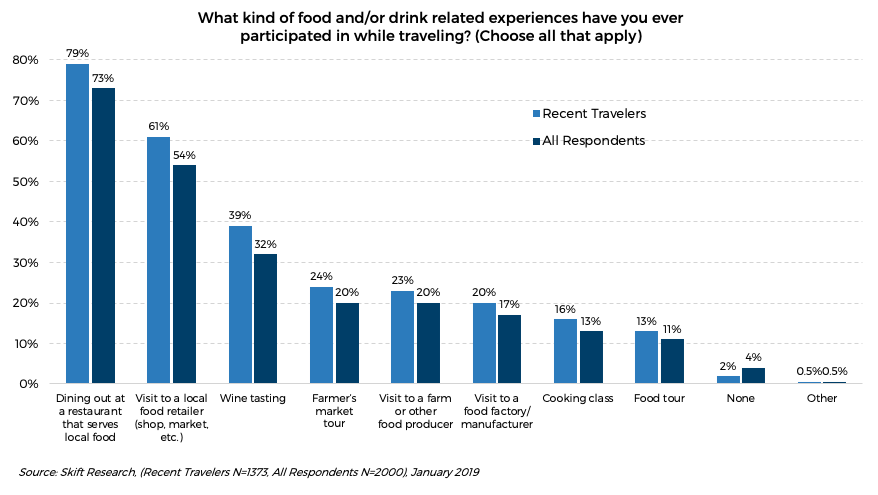

For more nuance, the chart below shows the type of food and/or drink related experiences that our respondents have participated in while traveling, divided again by recent travelers and the average for all respondents. Unsurprisingly, most respondents have dined out at a restaurant that serves local food while traveling, with about 80% of recent travelers reporting this.

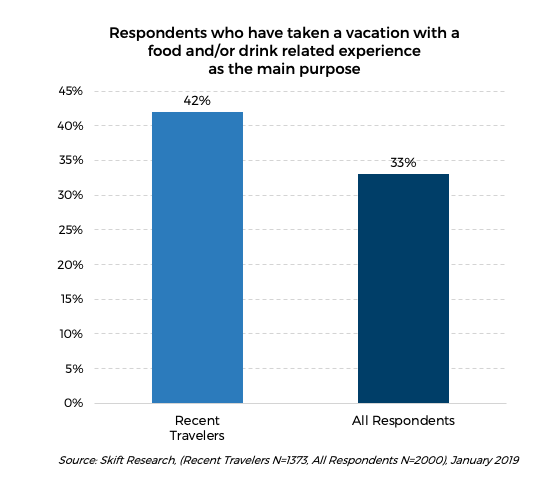

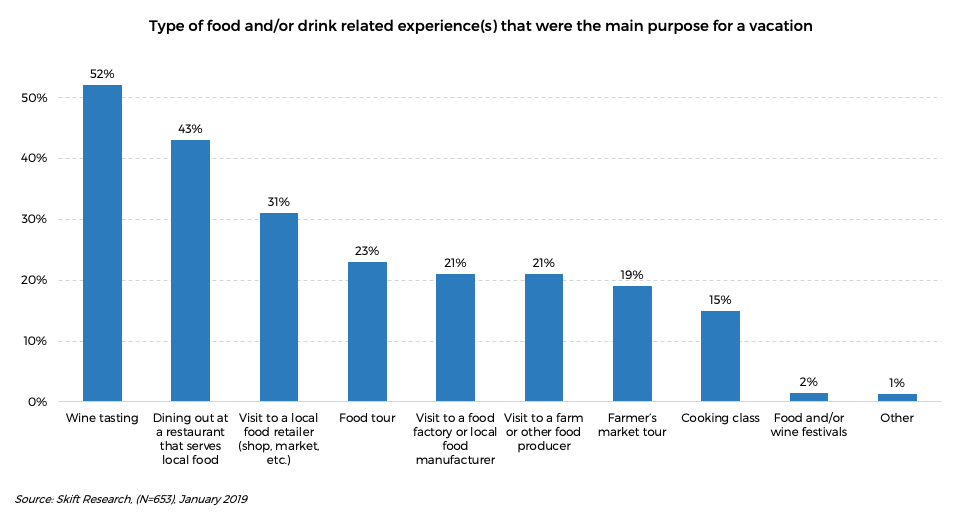

Next, we focus in on the narrowest scope of food tourism. We asked our respondents whether they’ve ever gone on vacation with a food and/or drink related travel experience as the main purpose of the trip. Among all respondents, one-third responded that they have. For respondents who have traveled in the last 12 months, 42% said so. This is a very significant number for relevant stakeholders who work to use food experiences to attract tourists.

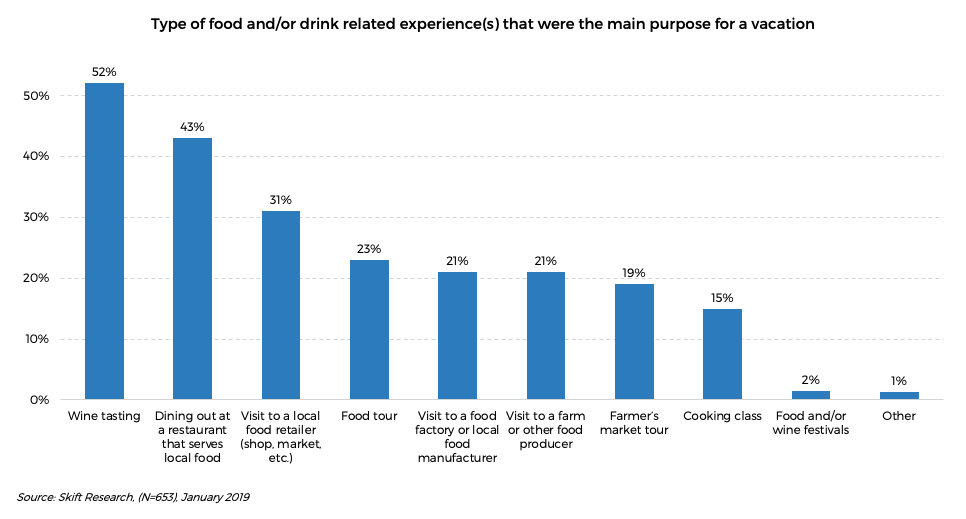

When looking at the specific types of experiences that these travelers planned their trips around, wine tasting claims the first spot, with 52% of respondents saying they’ve gone on trips with that activity as the main purpose. We will discuss more details later in the report.

Food Tourism Experiences Grow in Popularity

Food and drink experiences have long been an important part of travel. However, food tourism is reaching new levels of popularity and is manifesting in more exciting ways than ever. Data from TripAdvisor , for example, showed that food tours and cooking classes were among the top-five fastest growing tour categories in 2017, each with 57% bookings’ growth on the platform. Food tours also saw the most growth by gross booking value that year.

Food and drink-related activities also show high levels of popularity on Airbnb’s Experiences platform. According to an Airbnb spokesperson Skift Research spoke with in February 2018 for our report The State of Tours and Activities 2018 , bookings of these types of Experiences accounted for around 29% of the platform’s total bookings at the time.

Not only are bookings of food tourism experiences growing, but there are also signs that traveler satisfaction with them is high. TripAdvisor recently released the winners of its 2018 Travelers’ Choice Awards, which includes awards for experiences listed on its platform. The winners are determined using an algorithm that takes into account a business’s reviews, opinions, and popularity with travelers over the last year. On the list of the Top 25 Experiences in the World , seven of those selected are either entirely food based, or include a unique, local food portion within the experience. The number one spot, in fact, was taken by an entirely food-based experience: a cooking class and lunch at a Tuscan farmhouse which includes a tour of a local market in Florence.

The Rise of Niche, Food- and Beverage-Related Businesses

Outside of food tourism experiences designed purely for travelers, we see growth in other food- and beverage-related businesses. In Skift Research’s 2016 report Food Tourism Strategies to Drive Destination Spending , we called out the “rise of beer, spirits, and coffee tourism.” This trend was largely being driven by the explosive growth of craft breweries at the time. Since then, this growth has slowed, but still remains steady, with small and independent craft brewers maintaining 5% growth in the first half of 2018 in the U.S. according to the Brewers Association , showing that the demand is still there.

Food halls are another niche, local food- and beverage-related business type that is undergoing huge growth currently. Cushman & Wakefield, one of the largest U.S. commercial real estate brokers, has been tracking food hall development in the U.S. since 2015. In that year, it noted 70 projects. By the year’s end in 2017, this number went up to 118 and was expected to reach 180 by the end of 2018. The firm estimates that there will be 300 food halls in the U.S. by the end of 2020.

The growth of craft breweries and food halls may not be entirely due to the rise of food tourism, as many locals also enjoy these venues. However, it is safe to say that the same interests that are driving food tourism are contributing to the growth of these types of businesses. Craft breweries, food halls, and the like also become attractions in and of themselves, thereby also contributing back to the rise in food tourism.

Industry Sentiment About Food Tourism Today

Clearly, food tourism deserves our attention. Stakeholders in the space agree. According to a survey of DMOs, educational institutions, marketing and consultancy firms, accommodation providers, the meetings industry, food and beverage providers, and wineries in the UNWTO’s Second Report on Gastronomy Tourism , the majority of respondents agree that gastronomy is a driving force for tourism development (with an average of 8.19 on a scale of 1 to 10, where 10 is “strongly agree”).

Even so, many respondents to this survey didn’t feel that their marketing efforts in this area were adequate. For example, while 70% of respondents said they have targeted food tourists as a specific market segment, only 10% think that this segment receives enough promotion in the destination. Further, just 46.5% report that they have a food tourism strategy in place, while just under 25% say they allocate budget specifically for attracting food tourists. These survey results emphasize the need for all stakeholders to contribute toward developing and promoting the food tourism in a region. We will discuss this more later in the report.

Who Are Food Tourists Today?

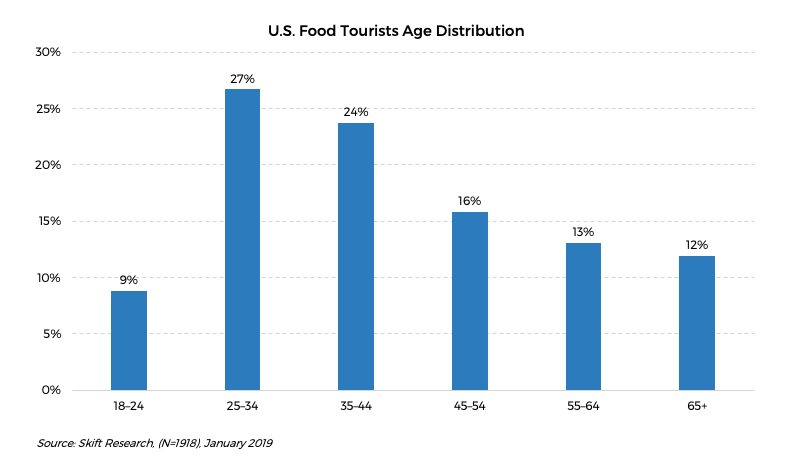

Because food tourism activities vary so much, it’s difficult to say exactly who food tourists are from a demographic perspective, as it varies so much depending on the activity. From our own survey, we found that Millennials and young Gen Xers make up the majority of our U.S.-based respondents who have ever participated in a food tourism experience other than dining out at chain restaurants. The age distribution is the same for food tourists who have traveled in the past 12 months.

Today’s Food Tourists Are Curious and Crave Unique Experiences

Throughout our interviews with food tourism stakeholders, we heard the theme that food tourists are curious people who desire unique experiences that revolve around food. Camille Rumani is the COO and co-founder of Eatwith, a peer-to-peer app that connects travelers and locals around food experiences in 130 countries. She describes the guests who use Eatwith as “People who, for example … want to get off the beaten path, I would say, do something that is a bit different, but also have the feeling, they don’t want to be a tourist. … they will also value the fact that it’s not the same thing that they’re doing as anyone else.”

Joanne Wolnik, tour development manager for the regional tourism office, Ontario’s Southwest, echoed these sentiments when describing the typical food tourists in her region: “It’s people that are curious, people that have an appetite to learn new things. This is the same whether they’re coming for a tasting experience or their coming to make chocolate truffles, it’s people that want to learn.”

Today’s Food Tourists Aren’t All “Foodies” or “Gourmets”

It is easy to make the mistake of conflating food tourists with foodies, but today, these two groups don’t fully overlap. A study by Fogelson & Co. , a food brand strategy and marketing agency, articulated the larger trend of moving away from using “foodie” to describe people who have a deep connection to food. The study explains that “foodie” used to depict a niche minority, but a deep interest in food is now mainstream. Further, it argues that a “foodie” is often thought of as being a person who is in “some sort of exclusive gourmand group of hyper-passionate food people,” when in fact, this is not the case for many consumers who feel connected to food.

To compensate for this disconnect, Fogelson & Co. recommends a new consumer category: the “food connected consumer.” This group views cooking and eating as fun experiences and as opportunities to explore. In fact, 63% of these surveyed consumers reported that they love to travel.

This distinction between the traditional “foodie” group and the new “food-connected consumer” is important when thinking about building and promoting food tourism. Trevor Jonas Benson, director of food tourism innovation and lead consultant for Grow Food Tourism at the Culinary Tourism Alliance, explained that he has observed the success of destinations that look beyond foodies. “No longer are destinations concentrating on a very small percentage, hyper-niche market of foodies and gastronomic interested people … but they’re starting to understand that any and all experiences can often be enhanced through food and drink.”

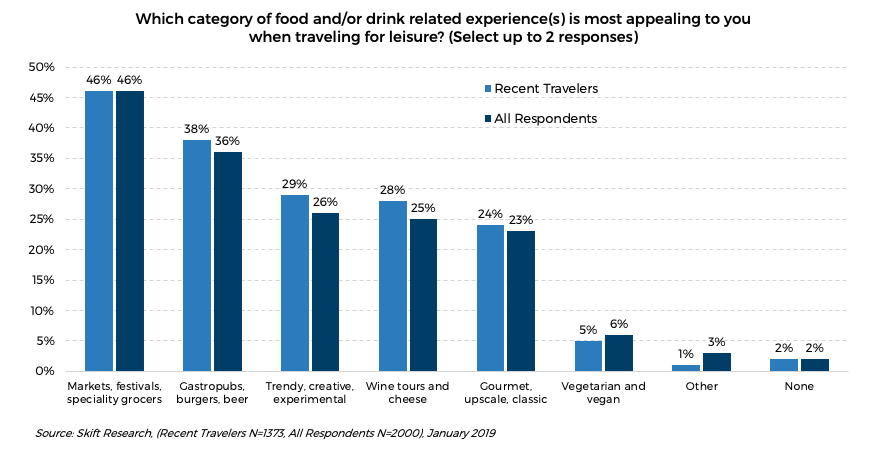

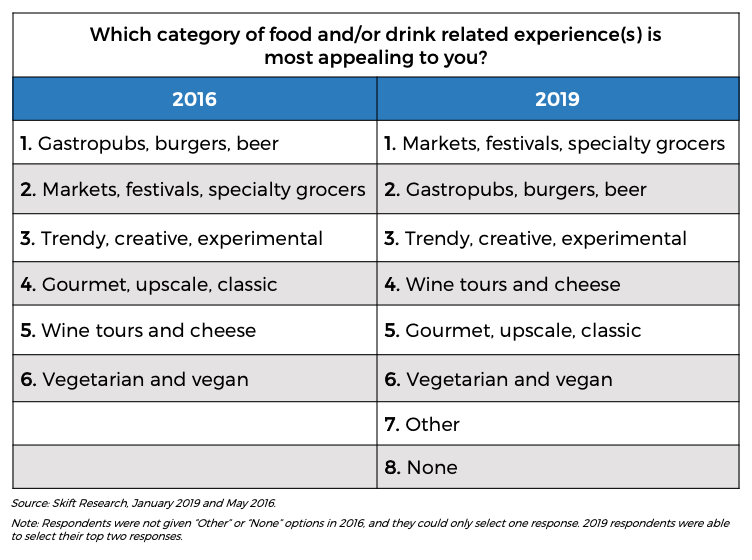

Our survey results further illustrate this point. We asked respondents which category of food and/or drink related activity is most appealing to them when traveling. The results show that the often more casual categories of “Markets, festivals, and speciality grocers” was selected the most, followed by the also casual category of “Gastropubs, burgers, and beer,” while “Gourmet, upscale, classic” falls to the fifth position among all respondents.

We asked a variation of this question for our 2016 report, Food Tourism Strategies to Drive Destination Spending , and similar trends were observed. However, “Gastropubs, burgers, beer” took the top spot then, and “Gourmet, upscale, classic” ranked one spot higher (please note, however, that respondents were not given “Other” or “None” options in 2016).

Still, the point remains, that while food tourism can be upscale and gourmet, it doesn’t have to be. In fact, more people prefer more casual types of experiences.

Today’s Food Tourists Can Be Divided into Two Main Groups: Deliberate and Incidental

A common way to segment food tourists is based on whether food and/or drink related experiences are their main motivation for travel or not. These groups are often referred to as “deliberate food tourists” and “incidental food tourists.” Skift Research spoke with Helena and Robert Williams, Ph.D.’s, researchers and academics with expertise in food tourism. They have researched the differences between deliberate and incidental food tourists extensively. Helena explained that deliberate food tourists will plan out their trips for weeks to include as many food experiences as possible, or a few of the most interesting ones: “They’re thinking about the food related experiences, not what restaurant they’ll eat in but can they go to a cooking class, can they go to a plantation, can they go to a winery, will there be some other cultural experiential thing they’ll learn about.”

Incidental food tourists, on the other hand, would still likely fall into the “food connected consumer” group we discussed above, but they are traveling for another reason, such as to visit friends or family, go to a conference, etc. Because they still appreciate food though, they will look for any free time they have to fit in food and/or drink related experiences.

Distinguishing between deliberate and incidental groups is important for food tourism stakeholders looking to develop and promote themselves to “food tourists” because they are likely to be interested in slightly different kinds of experiences and also need to be targeted in different ways and at different times in their journey.

The data below (which we discussed as Exhibit 4 above), for example, shows that the most common food and/or drink related travel experiences are those that have the option to be planned well in advance, but are also commonly done spontaneously (dining out at a restaurant that serves local food and visiting a local food retailer). In other words, these are experiences that are appealing to both deliberate and incidental food tourists. Those that require more pre-planning tend to fall toward the bottom of the list (cooking class, food tour).

The popularity of these experience types changes when we look at those that were the main purpose of a vacation. Wine tasting moves to the top spot and food tours is the fourth-most common experience type that travelers have planned trips for specifically.

Joanne Wolnik of Ontario’s Southwest described how her organization uses this type of distinction when developing food tourism in the region. She explained that her team not only works to make sure that there are local, exciting options for tourists who are looking to dine out, but also that there are plenty of reasons for deliberate food tourists to make a trip to the region as well. “This is the side that we are really trying to grow. We’ve got awesome people that are here already doing really cool things … so we are building reasons for people to travel for food specifically.”

Today’s Food Tourists Often Plan Their Trips Around Food

Whether they’re incidental or deliberate, food tourists today are more commonly choosing destinations at least in part because of their food offerings, even if this is not the main purpose of a trip. They are also often planning other parts of their trips around food and drink experiences. As Camille Rumani of Eatwith explained, unique food offerings used to be a “nice to have. Now they [destinations] need to have that. People are really looking for it, and they also choose destinations more and more based on the food offerings.” Javier Perez-Palencia, CEO and chair of the board for the international food tourism festival FIBEGA Miami, summed this up by saying “Gastronomy is an attraction.”

Skift Research also spoke with Michael Ellis, Jumeirah Group’s chief culinary officer and former global director at Michelin Restaurant and Hotel Guides. From his experience in both roles, he has observed the emerging trend of travelers basically going on “gastronomic pilgrimages,” where they choose a destination like Copenhagen specifically to eat at Noma, or Madrid to eat at DiverXO. Even for incidental food tourists, it’s common for them to use the food experiences they do incorporate as starting points to plan their other activities. “Everything else will come from there,” he explained, “whether it’s shopping, or cultural, or sporting events, whatever they want to do. That will be organized around where they have their lunch or dinner reservations.”

An area’s food offerings are also an essential component food tourists consider when choosing accommodations. Robert Williams explained that it’s important for hotels to realize that this is becoming more common. “What hotels are beginning to do is instead of trying to be all inclusive, they realize that … some of their customers look for the food experience first … versus the other way where you pick the hotel in the location and then see what you can do while you’re there.”

Interestingly, the total trip expenditure of incidental food tourists might not vary that much from that of deliberate food tourists, despite their varying levels of motivation by food. This was something that Helena and Robert Williams found through their extensive research on the subject, a finding that Helena refers to as “one of the most profound things to come out of my research.” She explained that the spending by these two groups is pretty comparable, and that the spending of incidental food tourists, “if not equal, it’s more than the deliberate traveler because they’re already there for some other reason and their time is more compressed, but they still want these wonderful experiences.” In a 2018 paper they published in the Journal of Gastronomy and Tourism with Jingxue (Jessica) Yuan, two surveys of self-identified food tourists revealed that 60% spent the most money on a deliberate food tourism trip, while 40% reported that it was an incidental trip. This research further emphasizes why both groups of food tourists are important to target and attract.

Defining the New Era of Food Tourism

Now that we have a better picture of who food tourists are today, we will focus on what food tourism is today beyond the general definition we discussed at the beginning of the report. It’s impossible for food tourism to remain static, as cultures, the environment, and consumer demands are in constant flux. Drawing mainly from our interviews with expert stakeholders, we’ve identified five key components that define the new era of food tourism. For each component, we’ve included relevant perspectives from stakeholders and case studies.

Food Tourism Is About More Than the Food Itself

The types of experiences that define the new era of food tourism are about more than just food or beverages. Our interviewees brought this up repeatedly in multiple ways. This is the biggest part of the new definition of food tourism and is multifaceted. Today, the food tourism experiences that best exemplify what food tourists want meet at least one of the following criteria: they overlap with other types of tourism (such as cultural tourism, historical tourism, agritourism, etc.), they have a hands-on learning aspect, and they are social.

- DMO/RTO: Joanne Wolnik, of Ontario’s Southwest explained how her team divides experiences into three categories: culinary, waterfront, and significant events. She explained that “the main two are waterfront and culinary … but we’ve created a lens where [an experience] usually has to overlap with one of the other two. So culinary is quite a high priority.”

- Travel Agency: James Imbriani, founder of the luxury food-themed tour company Sapore Travel, told Skift Research, “Destinations have a lot of things to offer other than just food and wine. Even if we plan something more historical, if we can tie in food, we like to try.”

- Tour Platform/Operator: Camille Rumani of Eatwith explained that she has been seeing more experiences on the platform that are hosted in unique spaces, like art galleries, rooftops, and even an old London underground station. Looking forward, she foresees that people will become even interested in experiences with interest beyond food: “for example, dinner with a concert, or seeing a play at the same time, or integrating food and music. We see that becoming very, very popular.”

- Case Study: Time Out Market Time Out Market was conceived by Time Out Group, best known for its city-specific online and print magazines that cover entertainment, events, and culture in global cities. The first market opened in Lisbon in 2014 and includes a selection of the best food and drink the city has to offer curated by Time Out editors and presented in a food hall type style. A repeated marketing message of the Time Out Market, however, is “this is more than just a food hall.” In addition to food vendors, the space also includes an academy where cooking classes are taught and a large studio space where concerts and other shows, fairs, conferences, and more are specially curated to represent the city as best as possible. “The magazine is all about food, beverage, chefs, art, culture, music, exhibitions, what’s hot in town now. So we’re bringing the magazine to life physically” said Didier Souillat, CEO of Time Out Market. With this strategy, Time Out Market Lisbon has become the number one tourist destination in the Portugal, and attracts locals as well. Beginning this year, new Time Out Markets will begin opening in other cities around the world and will mimic the mix of offerings in Lisbon, but with localized twists.The mix of offerings within a Time Out Market differentiates it, attracts people initially, and keeps them coming back. As a Time Out Market representative explained, “It’s not just dinner on a Thursday night. It’s dinner and a show, dinner and a reading, dinner and a cultural moment.”

- DMO/RTO: Joanne Wolnik of Ontario’s Southwest told us, “The main thing about food tourism that I’m seeing is that people want something new to them, unique, they want to learn, and they want to go home with new skills. I’m hesitant to say the word transformational again, because I know that’s a little bit trendy right now so I’m being careful, but it’s a new way from them to engage in food and with food.”

- Case Study: Ontario’s Southwest Joanne Wolnik shared some examples of food tourism experiences in Ontario’s Southwest region that illustrate this part of our definition perfectly. One experience is called The Sweetest Smell on Earth, which is run by a maple syrup harvester. The experience, which is offered a limited number of times, begins with a trip on a tractor to maple trees, where participants learn how to tap the tree, collect sap, and are taught historical information about the process. They then are taught how to make their own maple candies and they get to keep a bottle of their own syrup. Next, they’re served a meal by a local chef who incorporates maple into each dish.Wolnik explains that the hands-on, educational parts of this experience make it really resonate with participants: “ … they have bragging rights because they have their own bottle of maple syrup that they bottled themselves, they know how to use the product beyond just putting it on pancakes and waffles, and it really empowers them to use the product. So not only are they learning something new, but now when they go home, it’s changing their behaviors and their habits. So there is a transformational piece to it.”

- Tour Platform/Operator: Social interaction is a key component of the peer-to-peer experiences available on Eatwith. Camille Rumani told us that this was one of the main motivators for starting the company. “We saw that because usually you’re a tourist when you’re traveling, it’s such a paradox to travel so easily nowadays in cities where millions of people are living, but you don’t actually meet anyone when you’re traveling to Barcelona and to New York. You’re usually wondering what’s behind the closed doors, and we wanted to facilitate this experience.”

- Benjamin Ozsanay, CEO and co-founder of the cooking class platform Cookly, expressed similar sentiments: “Over time, we realized that our users and partners were looking for a connection. … This human connection was something we think is missing in ‘food tourism’ as it commonly perceived. We think it is much more than just trying the local street food or visiting the hottest new restaurant. It is about making a human connection across cultures … the essence of travel”

- Case Study: TripAdvisor’s 2018 Travelers’ Choice Awards Top Experience in the World As we mentioned earlier in the report, the top experience in the world according TripAdvisor’s 2018 Travelers Choice Awards was a food-based experience called “Cooking Class and Lunch at a Tuscan Farmhouse with Local Market Tour from Florence.” The description of this experience on TripAdvisor gets right to the core of this part of our food tourism definition. It is described as a “hands-on experience,” where travelers can “explore cuisine in more depth than you would by simply eating in restaurants.” Traveler reviews praise the experience as “interactive,” “educational,” and “social.” They lauded that they “met some lovely people” and enjoyed “hearing about the history in addition to tasting the food.”

Food Tourism Emphasizes the Story Behind the Food

This part of the definition is very closely related to the previous point, in that food tourism experiences today shouldn’t be about just tasting food or beverages, but should go deeper. This aspect of food tourism is about cultures and communities authentically telling their stories through food as a way to attract and interact with tourists. As Trevor Jonas Benson of the Culinary Tourism Alliance described, “we’re seeing a return to the use of language such as ‘authenticity,’ which is really indicative of destinations and communities starting to reclaim what it is that makes them special.”

Food is perhaps one of the easiest ways for people to share something that reflects themselves, their city or region, or their culture. In the words of Camille Rumani of Eatwith “food really reflects the DNA and the soul, I would say of a culture, and basically of people.”

The importance of this aspect of food tourism today is obvious just by looking at the ways food tourism companies describe themselves. Among our interviewees, for example, Benjamin Ozsanay of Cookly described the company this way: “We cultivate a community of users with a love of food, who want to learn about different cultures through local recipes and cooking traditions.” James Imbriani of Sapore Travel also emphasized that his company creates “meaningful, cultural exchanges through food and gastronomy,” and that this is what food tourism should be at its essence.

- Case Study: Cookly In addition to incorporating more of the story behind the food into food and drink related experiences, this part of our definition can also be translated through marketing and branding. Cookly, a platform that connects food loving travelers with food professionals for cooking classes serves as a case study of this. The platform recently changed its logo from a chef’s hat to a mortar and pestle. While the company’s founders originally envisioned connecting travelers with cooking schools, CEO & Co-Founder Bejamin Ozsanay explained, “over time, we realized that our users were looking for more of a connection with the food, culture, and local traditions of a place. The mission was not just about taking a cooking class on your trip, but immersing yourself in the local community and sharing knowledge about the world. Our new mortar and pestle logo reflects our brand’s evolution.”

Food Tourism Is Conscious and Thoughtful

Conscious consumption is permeating throughout many industries, and travel and food tourism aren’t immune. In fact, the new era of food tourism is defined by its conscious and thoughtful nature. The best food and drink experiences for travelers today consider environmental sustainability as well as community and economic impact. This is especially important in developing destinations with fragile ecosystems. Sharing culture and interacting with travelers is beneficial to locals, but without care for the environment and a direct economic impact, these things are meaningless.

- Travel Agency: James Imbriani of Sapore Travel explained how conscious consumption has impacted food tourism: “Also we’ve seen the shift in mindset, even when it comes to the food you’re cooking and eating at home, where people care a little bit more about where their food came from, the processes behind them, how they’re made, the care and love producers put into their products, as opposed to just blindly consuming things. We’ve seen that people are more willing to travel to find these things out, and for me that’s exciting.”

- DMO/RTO: Joanne Wolnik and her team at Ontario’s Southwest aim for economic, social, and environmental benefit as a result of food tourism experiences in the region: “We don’t want to devalue what our operators and artisans and all of our partners are bringing to the table, because ultimately, the whole point of tourism should be the benefit that the travelers bring to the local community both economically and socially, and we strive for environmentally as well.”

- Hotel: Michael Ellis of Jumeirah Group is highly aware of the desire food connected travelers have for local products: “People want to, wherever they are, they want to eat like locals, they want to have a local experience. They want to have locally grown products. They want to have ingredients that, if possible, come from not too far away from where they’re being consumed.” The challenge here is that most of Jumeirah’s hotels are in desert environments, like Dubai. “… there’s not a whole lot that’s produced here. Most things are imported,” he explained. Even so, Ellis sees this as a challenge worth overcoming. “But, having said that, we are in the process now of identifying local producers for a wide variety of products including organically grown vegetables and poultry and eggs. … we are really excited about our ability to bring locally, organically produced, sustainably developed products into our restaurants.”

- Ensuring that food and drink travel experiences — whether it’s a food tour, a meal at a hotel, etc. — are conscious and thoughtful about the local environment and communities might present some initial challenges. But, in the end, they can be the deciding factor for food connected travelers, especially those who are millennials and younger. Research by tour operator Intrepid Traveler found that 90% of millennials consider a travel company’s ethical commitments when booking, and Gen Z is already showing signs of being conscious consumers. A study by McKinsey found that 65% of Gen Zers try to learn the origins of anything they buy and 80% won’t buy products from companies that have been involved in scandals. As these groups continue to become a larger share of the travel market, we can anticipate that this part of food tourism will grow in importance.

- Case Study: Feast On by Culinary Tourism Alliance The Feast On certification program was launched by the Culinary Tourism Alliance in 2015. Skift Research discussed the program in our 2016 report . Its growth and success since then warrant us to revisit it as a case study now. The program works mostly with restaurants, and also commodity groups and local producers, to verify that they are buying and celebrating food local to the Ontario area.