- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Twenty years on the Festina affair casts shadow over the Tour de France

As France celebrated a World Cup win 20 years ago, a drugs scandal broke that almost killed the race

T he echoes are everywhere. In July 1998, as an irresistible French football team closed on World Cup victory, the Grand Départ of that year’s Tour de France was overshadowed by a fast-developing doping controversy. In Ireland, where the peloton was gathering for the Tour’s start, there was fear and loathing in the air.

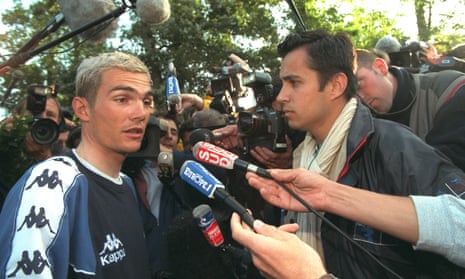

What was at first a whisper eventually became a scream as the controversy exploded into the Festina Affair. The revelation of widespread doping throughout cycling accelerated the founding of Wada, the world anti-doping body. The Festina scandal began when Willy Voet, the personal soigneur — they now call them carers — to French cycling’s top star, Richard Virenque, then leader of Festina, the world’s top team, was pulled over on the Franco-Belgian border as he drove towards the Channel ports.

There were enough performance-enhancing drugs in the boot of Voet’s car to fuel an army of Ibizan ravers, all summer long. Initially Virenque and his Festina teammates denied all knowledge of doping, as did the Tour’s own director, Jean-Marie Leblanc.

It was an isolated incident, said Leblanc dismissively, a one-off renegade event and nothing to do with the Tour itself. Yet this was untrue. The Festina team in fact ran a meticulously orchestrated doping programme, financed by the riders themselves. Within a week of the Dublin start, after police raids, arrests, and searches of vehicles and hotel rooms, the Festina team had been kicked off the race and the 1998 Tour was falling apart.

There is no doubt that, 20 years after Festina, Chris Froome’s presence on the Vendée start line this year, despite being cleared by the UCI’s anti-doping investigation, is going to stir up bad memories. The French are short of faith when it comes to cycling. They have not forgotten Festina, nor have they forgotten the many scandals that followed. Virenque long maintained his innocence of any wrongdoing.

The Festina scandal finally came to a head in la France profonde , in a shabby bar-tabac , Chez Gillou, in the Correze. In a cramped back-room, Virenque and his teammates tearfully protested their innocence as they were kicked off the race. Virenque finally confessed to doping in October 2000.

The former International Cycling Union (UCI) president Pat McQuaid, was director of the Dublin Grand Départ. “Forty-eight hours before the Tour started, when Voet was arrested, Jean-Marie Leblanc called us into a meeting and said: ‘I’ve got some bad news …’

“He said he would do his best to keep a lid on it until the race got back to France. He was as good as his word and once the race got to France, the shit really hit the fan.”

A flood of doping revelations emerged and the Tour became a nightmare for the race organisers as police intervention intensified. “There was no end to it,” McQuaid said. “Police raids, sit-down protests, walkouts. A total nightmare.”

Leblanc says now that he was powerless. “We’d hear a story on the news each morning about the cops raiding one team or another,” he said, “going through their hotel rooms, seizing products and accusing a rider of doping.”

By the time the convoy reached the Alps the Tour had become an embarrassment. The Spanish teams and media stormed out in protest at the police raids, fans mooned and jeered at the riders as they rode past, and French newspaper Le Monde called for the Tour to be scrapped for good.

Leblanc, meanwhile, punch drunk and out of his depth, remained in denial. “Contrary to what some intellectuals and Paris newspapers suggest, the Tour must continue,” he said. “The public is still loyal.”

Finally, at the stage start in Albertville, the Tour teetered on the brink of complete collapse as the remaining riders again went on strike. Only after assurances of no further police raids or arrests on the riders themselves did they agree to start.

“If the stage hadn’t taken place,” Leblanc said, “the Tour would have been stopped. If it had, I think it would have struggled to continue, because the loss of confidence among our sponsors would have been crippling.”

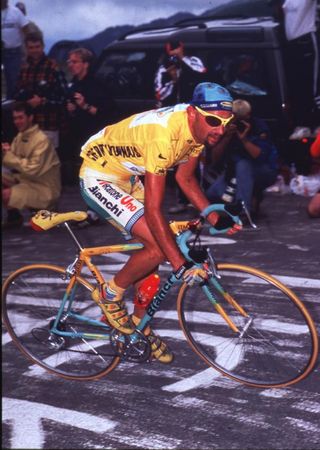

Of the 189 starters only 98 made it to the French capital and the Champs Élysées. The race winner, Marco Pantani, already winner of that year’s Giro d’Italia, seemingly oblivious to the funereal atmosphere, dyed his goatee yellow in celebration.

Virenque, still protesting his innocence, came back to the Tour the following year, when Lance Armstrong took the first of his seven wins, in a race that was, laughably, called the “Tour of Renewal”.

“They said I wasn’t welcome on the 1999 Tour because I was the ‘incarnation of doping,’” Virenque said. “And that was at the start of the Armstrong era!”

There were other long-term consequences of Festina. French cycling slipped into a sustained depression, with several key races lost due to lack of investment, and sponsors drifting away. There has not been a homegrown Tour de France champion since Bernard Hinault in 1985.

With the Froome controversy set to overshadow the Grand Départ of this year’s race, how much has really changed in 20 years? Can cycling really claim to have recovered from the crisis in credibility that brought the 1998 Tour to its knees and threatened its very existence?

Froome has vehemently protested his innocence throughout and acknowledged on Monday the saga’s effects on cycling’s perception among the public. “I appreciate more than anyone else the frustration at how long the case has taken to resolve and the uncertainty this has caused,” he said. “I am glad it’s finally over. It means we can all move on and focus on the Tour de France.”

But despite being free to race Froome is not wanted by many at this year’s Tour, both because of his team’s unrelenting domination and because of the continuing scepticism towards his performances. Some of this stems from chauvinism, but much also flows from the string of deceits that began 20 years ago with Festina.

When the French look at Froome many see the latest in a long line of suspicious foreigners who, since the traumas of 1998, have exploited the fragility of the once-proud French scene and made the Tour their own. He may have been cleared by cycling’s governing body, but there’s little doubt that Froome is in for a rough ride.

- Tour de France

- Tour de France 2018

- Drugs in sport

Most viewed

1998 Tour de France

85th edition: july 11 - august 28, 1998, results, stages with running gc, map, photos and history.

1997 Tour | 1999 Tour | Tour de France database | 1998 Tour Quick Facts | Final GC | Individual stage results with running GC | The Story of the 1998 Tour de France

Quick Facts about the 1998 Tour de France :

The Golden Saying of Epictetus are available as an audiobook here. For the Kindle eBook version, just click on the Amazon link on the right.

3,875 kilometers ridden at an average speed of 39.983 km/hr

The race started in Ireland, where the prologue and first two stages were held. Then the race transferred to Brittany for a counter-clockwise trip around France, finishing in Paris.

189 riders started, 96 finished.

The 1998 Tour was marred by the Festina doping scandal that turned into the greatest crisis in the Tour's history.

1997 winner Jan Ullrich arrived in poor form, allowing 1998 Giro winner Marco Pantani to take huge amounts of time in the mountains, in particular, stage 15 to Les Deux Alpes.

Marco Pantani is the last man to do the Giro-Tour double.

- Marco Pantani (Mercatone Uno): 92hr 49min 46sec

- Jan Ullrich (Telekom) @ 3min 21sec

- Bobby Julich (Cofidis) @ 4min 8sec

- Christophe Rinero (Cofidis) @ 9min 16sec

- Michael Boogerd (Rabobank) @ 11min 26sec

- Jean-Cyril Robin (US Postal) @ 14min 47sec

- Roland Meier (Mapei-Bricobi) @ 15min 13sec

- Daniele Nardello (Mapei Bricobi) @ 16min 7sec

- Giuseppe Di Grande (Polti) @ 17min 35sec

- Axel Merckx (Polti) @ 17min 39sec

- Bjarne Riis (Telekom) @ 19min 10sec

- Dariusz Baranowski (US Postal) @ 19min 58sec

- Stéphane Heulot (FDJ) @ 20min 57sec

- Leonardo Piepoli (Saeco) @ 22min 45sec

- Bo Hamburger (Casino) @ 26min 39sec

- Kurt Van Wouwer (Lotto) @ 27min 20sec

- Kevin Livingston (Cofidis) @ 34min 3sec

- Jörg Jaksche (Polti) @ 35min 41sec

- Peter Farazijn (Lotto) @ 36min 10sec

- Andreï Teteriouk (Lotto) @ 37min 3sec

- Udo Bolts (Telekom) @ 37min 25sec

- Laurent Madouas (Lotto) @ 39min 54sec

- Geert Verheyen (Lotto) @ 41min 23sec

- Cedric Vasseur (Gan) @ 42min 14sec

- Evgeni Berzin (FDJ) @ 42min 51sec

- Thierry Bourguignon (Big Mat-Auber 93) @ 43min 53sec

- Georg Totschnig (Telekom) @ 50min 13sec

- Benoit Salmon (Casino) @ 51min 18sec

- Alberto Elli (Casino) @ 1hr 13sec

- Philippe Bordenave (Big Mat-Auber 93) @ 1hr 5min 55sec

- Christophe Agnolutto (Casino) @ 1hr 11min 3sec

- Oscar Pozzi (Asics) @ 1hr 14min 54sec

- Maarten Den Bakker (Rabobank) @ 1hr 16min 21sec

- Patrick Joncker (Rabobank) @ 1hr 16min 49sec

- Pascal Chanteur (Casino) @ 1hr 19min 32sec

- Massimiliano Lelli (Cofidis) @ 1hr 20min 32sec

- Massimo Podenzana (Mercatone Uno) @ 1hr 20min 47sec

- Viatcheslav Ekimov (US Postal) @ 1hr 22min 40sec

- Denis Leproux (Big Mat-Auber 93) @ 1hr 25min 5sec

- Beat Zberg (Rabobank) @ 1hr 26min 8sec

- Lylian Lebreton (Big Mat-Auber) @ 1hr 28min 19sec

- Andrea Tafi (Mapei) @ 1hr 29min 22sec

- Rolf Aldag (Telekom) @ 1hr 29min 27sec

- Koos Moerenhout (Rabobank) @ 1hr 29min 37sec

- Peter Meinert (US Postal) @ 1hr 29min 52sec

- Riccardo Forconi (Mercatone Uno) @ 1hr 30min 33sec

- Fabio Sacchi (Polti) @ 1hr 31min 53sec

- Marty Jemison (US Postal) @ 1hr 34min 27sec

- Nicolas Jalabert (Cofidis) @ 1hr 38min 45sec

- Massimo Donati (Saeco) @ 1hr 38min 59sec

- Tyler Hamilton (US Postal) @ 1hr 39min 53sec

- Simone Borgheresi (Mercatone Uno) @ 1hr 40min 4sec

- George Hincapie (US Postal) @ 1hr 40min 39sec

- Stuart O'Grady (Gan) @ 1hr 46min 4sec

- Filippo Simeoni (Asics) @ 1hr 47min 19sec

- Jens Heppner (Telekom) @ 1hr 50min 43sec

- François Simon (Gan) @ 1hr 52min 41sec

- Frankie Andreu (US postal) @ 1hr 53min 44sec

- Thierry Gouvenou (Big Mat-Auber 93)) @ 1hr 55min 20sec

- Roberto Conti (Mercatone Uno) @ 1hr 55min 33sec

- Laurent Desbiens (Cofidis) @ 1hr 56min 28sec

- Erik Zabel (Telekom) @ 1hr 56min 57sec

- Leon Van Bon (Rabobank) @ 1hr 57min 30sec

- Paul Van Hyfte (Lotto) @ 1hr 58min 2sec

- Jacky Durand (Casino) @ 1hr 59min 42sec

- Christophe Mengin (FDJ) @ 2hr 0min 35sec

- Frédérick Guesdon (FDJ) @ 2hr 5min 8sec

- Wilfried Peeters (Mapei) @ 2hr 6min 16sec

- Rik Verbrugghe (Lotto) @ 2hr 6min 17sec

- Magnus Bäckstedt (Gan) @ 2hr 8min 30sec

- Eddy Mazzoleni (Saeco) @ 2hr 10min 19sec

- Fabio Fontanelli (Mercatone Uno) @ 2hr 11min 37sec

- Stefano Zanini (Mapei) @ 2hr 12min 11sec

- Alain Turicchia (Asics) @ 2hr 14min 12sec

- Mirko Crepaldi (Polti) @ 2hr 15min 5sec

- Diego Ferrari (Asics) @ 2hr 15min 46sec

- Xavier Jan (FDJ) @ 2hr 15min 51sec

- Pacal Lino (Big Mat-Auber 93) @ 2hr 16min 13sec

- Fabio Roscioli (Asics) @ 2hr 17min 53sec

- Christian Henn (Telekom) @ 2hr 19min 52sec

- Vjatjeslav Djavanian (Big Mat-Auber 93) @ 2hr 21min 31sec

- Rossano Brasi (Polti) @ 2hr 22min 10sec

- Jens Voigt (Gan) @ 2hr 25min 14sec

- Pascal Deramé (US Postal) @ 2hr 26min 25sec

- Tom Steels (Mapei) @ 2hr 26min 30sec

- Eros Poli (Gan) @ 2hr 31min 56sec

- Alecei Sivakov (Big Mat-Auber 93) @ 2hr 33min 19sec

- Aart Vierhouten (Rabobank) @ 2hr 35min 6sec

- Robbie McEwen (Rabobank) @ 2hr 36min 32sec

- Paolo Fornaciari (Saeco) @ 2hr 37min 50sec

- Massimiliano Mori (Saeco) @ 2hr 38min 12sec

- Bart Leysen (Mapei) @ 2hr 39min 43sec

- Francesco Frattini (Telekom) @ 2hr 43min 16sec

- Franck Bouyer (FDJ) @ 2hr 43min 45sec

- Mario Traversoni (Mercatone Uno) @ 2hr 44min 2sec

- Damien Nazon (FDJ) @ 3hr 12min 15sec

- Erik Zabel (Telekom): 327 points

- Stuart O'Grady (Gan): 230

- Tom Steels (Mapei-Bricobi): 221

- Robbie McEwen (Rabobank): 196

- George Hincapie (US postal): 151

- François Simon (Gan): 149

- Bobby Julich (Cofidis): 114

- Jacky Durand (Casino): 111

- Alain Turicchia (Asics): 99

- Marco Pantani (Mercatone Uno): 90

- Christophe Rinero (Cofidis): 200 points

- Marco Pantani (Mercatone Uno): 175

- Alberto Elli (Casino): 165

- Cédric Vasseur (Gan): 156

- Stéphane Heulot (FDJ): 152

- Jan Ullrich (Telekom): 126

- Bobby Julich (Cofidis): 98

- Michael Boogerd (Rabobank): 92

- Leonardo Piepoli (Saeco): 90

- Roland Meier (Cofidis): 89

Team Classification:

- Cofidis: 278hr 29min 58sec

- Casino @ 29min 9sec

- US Postal @ 41min 40sec

- Telekom @ 46min 1sec

- Lotto @ 1hr 4min 14sec

- Polti @ 1hr 6min 32sec

- Rabobank @ 1hr 46min 20sec

- Mapei @ 1hr 59min 53sec

- Big Mat-Auber 93 @ 2hr 3min 32sec

- Mercatone Uno @ 2hr 23min 4sec

- Jan Ullrich (Telekom) 92hr 53min 7sec

- Christophe Rinero (Cofidis) @ 5min 55sec

- Giuseppe Di Grande (Mapei) @ 14min 14sec

- Kevin Levingston (Cofidis) @ 30min 42sec

- Jörg Jaksche (Polti) @ 32min 20sec

Content continues below the ads

Individual stage results with running GC:

Prologue: Saturday, July 11, Dublin, Ireland 5.6 km Individual Time Trial

- Chris Boardman: 6min 12sec

- Abraham Olano @ 4sec

- Laurent Jalabert @ 5sec

- Bobby Julich s.t.

- Christophe Moreau s.t.

- Jan Ullrich s.t.

- Alex Zulle @ 7sec

- Laurent Dufaux @ 9sec

- Andrei Tchmil @ 10sec

- Viatcheslav Ekimov @ 11sec

GC: Same as Prologue time, there was no time bonus in play in the prologue.

Stage 1: Sunday, July 12, Dublin, Ireland - Dublin, Ireland, 180.5 km.

- Tom Steels: 4hr 29min 58sec

- Erik Zabel s.t.

- Robbie McEwen s.t.

- Gian-Matteo Fagnini s.t.

- Nicola Minali s.t.

- Frederic Moncassin s.t.

- Philippe Gaumont s.t.

- Mario Traversoni s.t.

- François Simon s.t.

- Jan Svorada s.t.

GC after Stage 1:

- Chris Boardman

- Erik Zabel @ 7sec

- Tom Steels @ 9sec

- Laurent Dufaux s.t.

Stage 2: Monday, July 13, Enniscorthy, Ireland - Cork, Ireland, 205.5 km.

- Jan Svorada: 5hr 45min 10sec

- Mario Cipollini s.t.

- Alain Turicchia s.t.

- Tom Steels s.t.

- Emmanuel Magnien s.t.

- Jan Kirsipuu s.t.

- Jeroen Blijlevens s.t.

- Silvio Martinello s.t.

GC after Stage 2:

- Tom Steels @ 7sec

- Abraham Olano @ 8sec

- Laurent Jalabert @ 9sec

- Jan Svorada @ 10sec

- Robbie McEwen @ 11sec

Stage 3: Tuesday, July 14, The Tour returns to France. Roscoff - Lorient, 169 km.

- Jens Heppner: 3hr 33min 36sec

- Xavier Jan s.t.

- George Hincapie @ 2sec

- Bo Hamburger s.t.

- Stuart O'Grady s.t.

- Vicente Garcia-Acosta s.t.

- Pascal Hervé s.t.

- Francisco Cabello s.t.

- Pascal Chanteur @ 5sec

- Fabrizio Guidi @ 1min 10sec

GC after Stage 3:

- Bo Hamburger

- Stuart O'Grady @ 3sec

- Jens Heppner s.t.

- Xavier Jan @ 21sec

- Pascal Hervé @ 22sec

- Vicente Garcia-Acosta @ 23sec

- Pascal Chanteur @ 28sec

- Francisco Cabello @ 47sec

- Erik Zabel @ 1min 2sec

Stage 4: Wednesday, July 15, Plouay - Cholet, 252 km.

- Jeroen Blijlevens: 5hr 48min 32sec

- Andrei Tchmil s.t.

- Lars Michaelsen s.t.

- Maximilian Sciandri s.t.

- Fabio Baldato s.t.

GC after stage 4:

- Stuart O'Grady

- Bo Hampburger @ 11sec

- George Hincapie s.t.

- Jens Heppner @ 14sec

- Xavier Jan @ 32sec

- Pascal Hervé @ 33sec

- Vicente Garcia-Acosta @ 34sec

- Pascal Chanteur @ 39sec

- Francisco Cabello @ 58sec

- Erik Zabel @ 1min 1sec

Stage 5: Thursday, July 16, Cholet - Châteauroux, 228.5 km.

- Mario Cipollini: 5hr 18min 49sec

- Christophe Mengin s.t.

- Andrea Farrigato s.t.

- Fabrizio Guidi s.t.

- Alessio Bongioni s.t.

GC after Stage 5:

- George Hincapie @ 7sec

- Bo Hamburger @ 11sec

- Pacal Hervé @ 33sec

- Erik Zabel @ 45sec

Stage 6: Friday, July 17, Le Châtre - Brive la Gaillarde, 204.5 km.

- Mario Cipollini: 5hr 5min 32sec

- Emmanuele Magnien s.t.

GC after Stage 6:

- George Hincapie @ 9sec

- Bo Hamburger @ 13sec

- Jens Heppner @ 16sec

- Xavier Jan @ 34sec

- Pascal Hervé @ 35sec

- Vicente Garcia-Acosta @ 36sec

- Pascal Chanteur @ 41sec

- Erik Zabel @ 43sec

- Jan Svorada @ 47sec

Stage 7: Saturday, July 18, Meyrignac l'Église- Corrèze 58 km Individual Time Trial.

The Festina team was forced to withdraw from the Tour before the start of the time trial.

- Jan Ullrich: 1hr 15min 25sec

- Tyler Hamilton @ 1min 10sec

- Bobby Julich @ 1min 18sec

- Laurent Jalabert @ 1min 24sec

- Viatcheslav Ekimov @ 1min 40sec

- Abraham Olano @ 2min 13sec

- Evgeni Berzin @ 2min 21sec

- Francesco Casagrande @ 2min 22sec

- Stephane Heulot @ 2min 22sec

- Bo Hamburger @ 2min 29sec

GC after Stage 7:

- Jan Ullrich: 31hr 24min 37sec

- Bo Hamburger @ 1min 18sec

- Laurent Jalabert @ 1min 14sec

- Tyler Hamilton @ 1min 30sec

- Viatcheslav Ekimov @ 1min 46sec

- Vicente Garcia-Acosta @ 1min 50sec

- Stuart O'Grady @ 1min 53sec

- Abraham Olano @ 2min 12sec

- Jens Heppner @ 2min 17sec

Stage 8: Sunday, July 19, Brive la Gaillarde - Montauban, 190.5 km.

- Jacky Durand: 4hr 40min 55sec

- Andrea Tafi s.t.

- Fabio Sacchi s.t.

- Eddy Mazzoleni s.t.

- Laurent Desbiens s.t.

- Joona Laukka s.t.

- Philippe Gaumont @ 1min 34sec

- Erik Zabel @ 7min 45sec

- Serguei Ivanov s.t.

GC after Stage 8:

- Laurent Desbiens

- Andrea Tafi @ 14sec

- Jacky Durand @ 43sec

- Joona Laukka @ 2min 54sec

- Jan Ullrich @ 3min 21sec

- Bo Hamburger @ 4min 39sec

- Laurent Jalabert @ 4min 45sec

- Tyler Hamilton @ 4min 51sec

- Viatcheslav Ekimov @ 5min 7sec

Stage 9: Monday, July 20, Montauban - Pau, 210 km.

- Leon Van Bon: 5hr 21min 10sec

- Jens Voigt s.t.

- Masimilliano Lelli s.t.

- Christophe Agnolutto s.t.

- Erik Zabel @ 12sec

GC after stage 9:

- Laurent Desbiens: 41hr 31min 18sec

- Vicente Garcia-Acosta @ 5min 11sec

Stage 10: Tuesday, July 21, Pau - Luchon, 196.5 km.

- Rudolfo Massi: 5hr 49min 40sec

- Marco Pantani @ 36sec

- Michael Boogerd @ 59sec

- Giuseppe Di Grande s.t.

- Jose-Maria Jimenez s.t.

- Fernando Escartin s.t.

- Jean-Cyril Robin s.t.

- Leonardo Piepoli s.t.

GC after Stage 10:

- Jan Ullrich: 47hr 25min 18sec

- Bo Hamburger @ 2min 17sec

- Laurent Jalabert @ 2min 38sec

- Luc Leblanc @ 3min 3sec

- Abraham Olano @ 3min 11sec

- Michael Boogerd @ 3min 36sec

- Evgeni Berzin @ 3min 39sec

- Stephane Heulot @ 3min 40sec

- Bjarne Riis @ 3min 51sec

- Marco Pantani @ 4min 41sec

Stage 11: Wednesday, July 22, Luchon - Plateau de Beille, 170 km.

- Marco Pantani: 5hr 15min 27sec

- Roland Meier @ 1min 26sec

- Bobby Julich @ 1min 33sec

- Michael Boogerd s.t.

- Christophe Rinero s.t.

- Jan Ullrich @ 1min 40sec

- Kevin Livingston @ 2min 1sec

- Angel Casero @ 2min 3sec

GC after Stage 11:

- Jan Ullrich: 52hr 42min 25sec

- Bobby Julich @ 1min 11sec

- Laurent Jalabert @ 3min 1sec

- Marco Pantani s.t.

- Michael Boogerd @ 3min 29sec

- Luc Leblanc @ 4min 16sec

- Bo Hamburger @ 4min 44sec

- Fernando Escartin @ 5min 16sec

- Roland Meier @ 5min 18sec

- Angel Casero @ 5min 53sec

Stage 12: Friday, July 24, Tarascon sur Ariège - Le Cap d'Agde, 222 km.

- Tom Steels: 4hr 12min 51sec

- Stephane Barthe s.t.

- Andrea Ferrigato s.t.

- Aert Vierhouten s.t.

- Leonardo Guidi s.t.

GC after Stage 12:

- Jan Ullrich: 56hr 55min 16sec

Stage 13: Saturday, July 25, Frontignan la Peyrade - Carpentras, 196 km.

- Daniele Nardello: 4hr 32min 46sec

- Stephane Heulot s.t.

- Marty Jamison s.t.

- Koos Moerenhout s.t.

- Serguei Ivanov @ 2min 27sec

- Fabio Roscioli @ 2min 43sec

- François Simon

- Maarten Den Bakker s.t.

GC after Stage 13:

- Jan Ullrich: 61hr 30min 53sec

- Stephane Heulot @ 5min 5sec

Stage 14: Sunday, July 26, Valréas - Grenoble, 186.5 km.

- Stuart O'Grady: 4hr 30min 53sec

- Orlando Rodriguez s.t.

- Leon Van Bon s.t.

- Peter Meinert s.t.

- Giuseppe Calcaterra s.t. (Crossed the line 2nd, but relegated for not holding his line in the sprint.

- Frederic Guesdon @ 8min 27sec

- Rafael Diaz Justo s.t.

- Erik Zabel @ 10min 5sec

GC after Stage 14:

- Jan Ullrich: 66hr 11min 51sec

Stage 15: Monday, July 27, Grenoble - Les Deux Alpes, 189 km.

- Marco Pantani: 5hr 43min 45sec

- Rudolfo Massi @ 1min 54sec

- Fernando Escartin @ 1min 59sec

- Christophe Rinero @ 2min 57sec

- Bobby Julich @ 5min 43sec

- Michael Boogerd @ 5min 48sec

- Marcos Serrano @ 6min 4sec

- Jean-Cyril Robin @ 6min 34sec

- Manuel Beltran @ 6min 40sec

- Dariusz Baranowski s.t.

25. Jan Ullrich @ 8min 57sec

GC after Stage 15:

- Marco Pantani: 71hr 58min 37sec

- Bobby Julich @ 3min 53sec

- Fernando Escartin @ 4min 14sec

- Jan Ullrich @ 5min 56sec

- Christophe Rinero @ 6min 12sec

- Michael Boogerd @ 6min 16sec

- Rodolfo Massi @ 7min 53sec

- Luc Leblanc @ 8min 1sec

- Roland Meier @ 8min 57sec

- Daniele Nardello @ 9min 14sec

Stage 16: Tuesday, July 28, Vizille - Albertville, 204 km.

- Jan Ullrich: 5hr 39min 47sec

- Bobby Julich @ 1min 49sec

- Axel Merckx s.t.

- Bjarne Riis s.t.

GC after Stage 16:

- Marco Pantani: 77hr 38min 24sec

- Bobby Julich @ 5min 42sec

- Fernando Escartin @ 6min 3sec

- Christophe Rinero @ 8min 1sec

- Michael Boogerd @ 8min 5sec

- Rodolfo Massi @ 12min 15sec

- Jean-Cyril Robin @ 12min 34sec

- Leonardo Piepoli @ 12min 45sec

- Roland Meier @ 13min 19sec

Stage 17: Wednesday, July 29, Aix-les Bains - Vasseur, 149 km.

After a riders' strike in which they completed the course slowly, without their backnumbers, the stage was annulled. Teams ONCE, Riso Scotti and Banesto abandoned the race.

Stage 18: Thursday, July 30, Aix les Bains - Neuchatel (Switzerland), 218.5 km.

- Tom Steels: 4hr 53min 27sec

- Jacky Durand s.t.

- Nicolas Jalabert s.t.

- Aert Vierhouoten s.t.

- Viatcheslav Djavanian s.t.

GC after Stage 18:

- Marco Pantani: 82hr 31min 51sec

- Daniele Nardello @ 13min 36sec

- Bjarne Riis @ 14min 45sec

- Giuseppe Di Grande @ 15min 13sec

Stage 19: Friday, July 31, La Chaux de Fonds (Switzerland) - Autun, 242 km.

Team TVM abandoned.

- Magnus Backstedt: 5hr 10min 14sec

- Maarten De Bakker s.t.

- Pascal Derame s.t.

- Frederic Guesdon @ 25sec

- Thierry Gouvenou s.t.

GC after Stage 19:

- Marco Pantani: 87hr 58min 43sec

Stage 20: Saturday, August 1, Montceau les Mines - Le Creusot 52 km individual time trial.

- Jan Ullrich: 1hr 3min 52sec

- Bobby Julich @ 1min 1sec

- Marco Pantani @ 2min 35sec

- Dariusz Baranowski @ 3min 11sec

- Andrei Teteriouk @ 3min 46sec

- Viatcheslav Ekimov @ 3min 48sec

- Christophe Rinero @ 3min 50sec

- Riccardo Forconi @ 3min 55sec

- Axel Merckx @ 3min 59sec

- Roland Meier @ 4min 29sec

GC after Stage 20:

- Marco Pantani: 89hr 5min 10sec

- Bobby Julich @ 4min 8sec

- Christophe Rinero @ 9min 16sec

- Michael Boogerd @ 11min 26sec

- Jean-Cyril Robin @ 14min 57sec

- Roland Meier @ 15min 13sec

- Danielo Nardello @ 16min 7sec

- Giuseppe Di Grande @ 15min 35sec

- Axel Merckx @ 17min 39sec

21st and Final Stage: Sunday, August 2, Melun - Paris (Champs Elysées), 147.5 km.

- Tom Steels: 3hr 44min 36sec

- Stefano Zanini s.t.

- Mario Taversoni s.t.

- Damien Nazon s.t.

Complete Final 1998 Tour de France General Classification.

The Story of the 1998 Tour de France:

These excerpts are from "The Story of the Tour de France", Volume 2. If you enjoy them we hope you will consider purchasing the book, either print, eBook or audiobook. The Amazon link here will make the purchase easy.

Always looking to make the Tour interesting as well as profitable for its owners, the 1998 edition started in Dublin, Ireland. The prologue and the first 2 stages were to be held on the Emerald Isle. Then, without a rest day, the riders were to be transferred to Roscoff on the northern coast of Brittany. Then the Tour headed inland for a couple of stages before turning directly south for the Pyrenees, then the Alps and then Paris. This wasn't a race loaded with hilltop finishes but it did have 115.6 kilometers of individual time trial including 52 in the penultimate stage. This should have been a piece of cake for Ullrich. He not only won the Tour de France in 1997, he won the HEW Cyclassics and the Championship of Zurich.

Ullrich was a well-rounded rider who could do anything and who truly deserved his Number 2 world ranking. But the demands of his fame were more than he could handle. His autobiography Ganz oder Ganz Nicht (All or Nothing at All) is disarmingly frank and honest about his troubles. After the 1997 Tour he signed contracts for endorsements that gave him staggering sums of money. He would never have to worry about a paycheck again. Over the winter his weight had ballooned and his form was suspect. In his words, he had begun 1998 with a new personal best, he weighed more than he had ever weighed in his entire life. In the post-Tour celebrations, he let himself go. He said that after winning the Tour, training was the furthest thing from his mind. He then fell into a vicious cycle. He couldn't find good form and good health. He would lie in bed frustrated, and shovel down chocolate. He would then go out and train too hard for his lapsed form and then get sick again.

He rationalized things. "I can't just train all year long. My life consists of more than cycling," he told himself. Meanwhile, his trainer Peter Becker ground his teeth in frustration seeing his prodigiously talented client riding fewer than 50 kilometers a day.

The results of his winter excess were obvious. He attained no notable successes in the spring, but in the new era of Tour specialization this wasn't necessarily a sign that things were going wrong. Yet in Ullrich's case there were few signs that things were going right. In March he pulled out of the Tirreno–Adriatico only 30 kilometers into the first stage.

Ullrich had a new foe in the 1998 Tour. Marco Pantani had been a Charly Gaul-type racer who would detonate on a climb and bring himself to a high placing in a single stage. In May he proved that he could do more than just climb when he won the Giro d'Italia. The signal that Pantani was riding on a new level was the penultimate stage, a 34-kilometer time trial. He lost only 30 seconds to one of the masters of the discipline, Sergey Gonchar. As we noted in 1997, Pantani had suffered a horrific racing accident in 1995 that shattered his femur. He became determined to return to his former high level and through assiduous training he exceeded his former level. There was a telling flag that wasn't made known until later. Technologists checking Pantani's blood after the accident in Turin found that his hematocrit was over 60 percent.

Hematocrit is the measurement of the percentage of blood volume that is occupied by red blood cells, the tools the body uses to feed oxygen to the muscles. Normal men of European descent have a hematocrit in the low to mid 40s. It declines slightly as a response to the effects of training. It would not be expected to increase during a stage race, as some racers have asserted. Exceptional people may exceed that by a significant amount. Damiano Cunego, winner of the 2004 Giro, through a fortunate twist of genetic fate has a natural hematocrit of about 53. To improve sports performances endurance athletes took to using synthetic EPO or erythropoietin, a drug that raises the user's hematocrit. This is not without danger because as the hematocrit rises, so does the blood's viscosity. By the late 1990s athletes were dying in their sleep as their lower sleeping heart rates couldn't shove the red sludge through their blood vessels. Until 2004 there was no way to test for EPO so the only thing limiting how much EPO an athlete would use was his willingness to tempt death. A friend of mine traveled with a famous Spanish professional racing team in the 1990s and was horrified to see the riders sleeping with heart monitors hooked up to alarms. If the athlete's sleeping heart rate should fall below a certain number, he was awakened, given a saline injection, and put on a trainer. In January of 1997 the UCI implemented the 50% rule. If a rider were found to have a hematocrit exceeding 50% he would be suspended for 2 weeks. Since there was no test at the time to determine if a rider had synthetic EPO in his system, the 2-week suspension wasn't considered a positive for dope, only a suspension so that the rider could "regain his health". There were ways for cagey riders to get around the 50% limit, but that story is for 1999.

So let's get one thing straight and understood. Doping was and is part of the sport. As we proceed through the sordid story of 1998, the actions of the riders to protect themselves and their doping speak for themselves. Without a positive test no single rider may be accused but as a group they are guilty. As individuals, unless proven otherwise, the riders are all innocent. As Miguel Indurain asked after he was accused of doping long after he had retired, "How do I prove my innocence?" He's right. It's almost impossible to prove a negative, that is, that a rider didn't do something.

Yet, complicating matters is that a rational, knowledgeable person knows that just because a rider has never tested positive for dope doesn't mean that he has been riding clean. Many riders who never failed a drug test have later been found to be cheaters, as in the case of World Time Trial Champion David Millar. But again, we must be fair. In the absence of a positive test in which the chain of custody of the samples is guaranteed and a fair appeals process is in place to protect the rider's interests, I grit my teeth and consider a rider innocent.

The prologue for the 1998 Tour was on July 11 but the story of the Tour starts in March when a car belonging to the Dutch team TVM was found to have a large cache of drugs. Fast forward to July 8. Team Festina soigneur Willy Voet was searched at a customs stop as he was on his way from Belgium to Calais and then on to the Tour's start in Dublin. What the customs people found in his car set the cycling world on fire. Among the items Voet was transporting were 234 doses of EPO, testosterone, amphetamines and other drugs that could only have one purpose, to improve the performance of the riders on the Festina team. For now we'll leave Voet in the hands of the police who took him to Lille for further searching and questioning.

In Dublin Chris Boardman won the 5.6-kilometer prologue with a scorching speed of 54.2 kilometers an hour. Ullrich momentarily silenced his critics when he came in sixth, only 5 seconds slower. Tour Boss Jean-Marie Leblanc said that the Voet problem didn't concern him or the Tour and that the authorities would sort things out. Bruno Roussel, the director of the Festina team expressed surprise over Voet's arrest.

The first stage was run under wet and windy conditions with Tom Steels, who had been tossed from the previous year's Tour for throwing a water bottle at another rider, winning the sprint. But the cold rain didn't cool down the Festina scandal. Police raided the team warehouse and found more drugs, including bottles labeled with specific rider's names. Roussel expressed yet more mystification at the events and said he would hire a lawyer to deal with all of the defamatory things that had been written about the team. The next day Erik Zabel was able to win the Yellow Jersey by accruing intermediate sprint time bonifications.

When the Tour returned to France on July 14 the minor news was that Casino rider Bo Hamburger was the new Tour leader. The big news was that Voet had started to really talk to the police and told them that he was acting on instructions from Festina team management. Roussel said he was "shocked". The next day things got still worse for Festina. Roussel and team doctor Eric Rijckaert were taken by the police for questioning. Leblanc continued to insist that the Tour was not involved with the messy Festina doings and if no offenses had occurred during the Tour, there would be no action taken to expel Festina.

While the race continued on its way to the Pyrenees with Stuart O'Grady now the leader, the first Australian in Yellow since Phil Anderson and the second ever, the Festina affair continued to draw all of the attention. The world governing body of cycling, the U.C.I., suspended Roussel. Both the Andorra-based Festina watch company and Leblanc continued to voice support for the team's continued presence in the race.

Stage 6, on July 15, turned the entire cycling world upside-down. Roussel admitted that the Festina team had systematized its doping. The excuse was that since the riders were doping themselves, often with terribly dangerous substances like perfluorocarbon (synthetic hemoglobin), it was safer to have the doping performed under the supervision of the team's staff. Leblanc reacted by expelling the team from the Tour. Then several Festina riders including Richard Virenque and Laurent Dufaux called a news conference, asserted their innocence and vowed to continue riding in the Tour.

There was still a race going on amid all of the Festina doings and the first real sorting came with the 58-kilometer time trial of stage 7. Ullrich again showed that against the clock he is an astounding rider. American Tyler Hamilton came in second and was only able to come within 1 minute, 10 seconds of the speedy German. Another American rider, Bobby Julich of the Cofidis team turned in a surprising third place, only 8 seconds slower than Hamilton. So now the General Classification with 2 more stages to go before the mountains:

- Jan Ullrich

- Bo Hamburger @ 1 minute 18 seconds

- Bobby Julich @ same time

- Laurent Jalabert @ 1 minute 24 seconds

- Tyler Hamilton @ 1 minute 30 seconds

Virenque announced that the Festina riders would not try to ride the Tour after their expulsion. That took Alex Zülle, World Champion Laurent Brochard, Laurent Dufaux and Christophe Moreau, among others, out of the action. The reaction from the Tour management, the team doctors and the fans was indicative of the blinders all parties were wearing. The Tour subjected 55 riders to blood tests and found no one with banned substances in his system. The Tour then declared that this meant that the doping was confined to a few bad apples. What it really meant was that for decades the riders and their doctors had learned how to dope so the drugs didn't show up in the tests. And, in 1998 there was no test for EPO. The team doctors protested that the Festina affair was bringing disrepute upon the other teams and their profession. The fans hated to see their beloved riders singled out and thought that Festina was getting unfair treatment. Officials, reflecting upon the easy ride TVM had received in March when their drug-laden car was found, reopened that case.

Stage 10, the long anticipated showdown between Ullrich and Pantani, had finally arrived. It was a Pyrenean stage, going from Pau to Luchon with the Aubisque, the Tourmalet, the Aspin and the Peyresourde. With no new developments in the drug scandals, the attention could finally be focused on the sport of bicycle racing. It was cold and wet in the mountains, which saps the energy of the riders as much as or more than a hot day. It was on the Peyresourde that the action finally started. Casino rider Rudolfo Massi was already off the front. Ullrich got itchy feet and attacked the dozen or so riders still with him. Pantani responded with his own attack and was gone. Pantani closed to within 36 seconds of Massi after extending his lead on the descent of the Peyresourde. Ullrich and 9 others including Julich came in a half-minute after Pantani. After losing the lead in stage 8 when a break of non-contenders was allowed to go, Ullrich was back in Yellow. Pantani was sitting in eleventh place, 4 minutes, 41 second back.

Stage 11, July 22, had 5 climbs rated second category or better with a hilltop finish at Plateau de Beille, an hors category climb new to the Tour. As usual, the best riders held their fire until the final climb. Ullrich flatted just before the road began to bite but was able to rejoin the leaders before things broke up. And break up they did when Pantani took off and no one could hold his wheel. Ullrich was left to chase with little help as he worked to limit his loss. At the top Pantani was first with the Ullrich group a minute and a half back. While Pantani said he was too tired from the Giro to consider winning the Tour, he was slowly closing the gap.

After the Pyrenees and with a rest day next, the General Classification stood thus:

- Bobby Julich @ 1 minute 11 seconds

- Laurent Jalabert @ 3 minutes 1 second

- Marco Pantani @ same time

Festina director Roussel, still in custody, issued a public statement accepting responsibility for the systematic doping within the team.

On July 24, the day of stage 12, the heat in the doping scandal was raised a bit more, if that were possible. Three more Festina team officials including the 2 assistant directors were arrested. A Belgian judge performing a parallel investigation found computer records of the Festina doping program on Erik Rijckaert's computer. Rijckaert said that the Festina riders all contributed to a fund to purchase drugs for the team. Six Festina riders were rounded up and questioned by the Lyon police: Zülle, Dufaux, Brochard, Virenque, Pascal Herve and Didier Rous. The scandal grew larger. TVM manager Cees Priem, the TVM team doctor and mechanic were arrested. A French TV reporter said that he had found dope paraphernalia in the hotel room of the Asics team.

So how did the riders handle this growing stink? Much as they did when they were caught up in the Wiel's affair in 1962. They became indignant. They were furious that the Festina riders had been forced to strip in the French jail and fuming that so much attention was focused on the ever-widening doping scandal instead of the race. In 1962 Jean Bobet talked the riders out of making themselves ridiculous by striking over being caught red-handed. There was no such voice of sanity in 1998. The riders initiated a slow-down, refusing to race for the first 16 kilometers.

On July 25 several Festina riders confessed to using EPO, including Armin Meier, Laurent Brochard and Christophe Moreau. The extent of the concern over the drug scandal was made clear when the French newspaper Le Monde editorialized that the 1998 Tour should be cancelled. It's important to note that what should have been outrage from the riders of the peloton, when confronted with the undeniable fact that they were racing against cheaters, was never voiced. Instead, the peloton defended the cheaters. When pro racers start screaming that they were robbed by the dopers then we may start to think that there has been some reform in the peloton. Until then, the pack is guilty.

As the Tour moved haltingly towards the Alps the top echelons of the General Classification remained unchanged. Alex Zülle issued a statement of regret admitting his use of EPO, saying what any rational observer should have assumed, that Festina was not the only team doping.

On Monday, July 27 the Tour reached the hard alpine stages. Stage 15 started in Grenoble and went over the Croix de Fer, the Télégraphe, and the Galibier to a hilltop finish at Les Deux Alpes. It was generally surmised that if Ullrich could stay with Pantani until the final climb he would be safe because the climb to Les Deux Alpes averages 6.2% with an early section of a little over 10% gradient. Ullrich's big-gear momentum style of climbing would be well suited to this climb.

Pantani didn't wait for the last climb. On the Galibier he exploded and quickly disappeared up the mountain. At the top he had 2½ minutes on Ullrich. On the descent Pantani used his superb descending skills to increase his lead on the now isolated Ullrich. By the start of the final ascent Pantani had a lead of more than 4 minutes. On the climb to Les Deux Alpes Ullrich's lack of deep, hard conditioning made itself manifest. He was in trouble and needed teammates Riis and Udo Bolts to pace him up the mountain. At the top of the mountain the catastrophe (as far as Telekom was concerned) was complete. Pantani was in Yellow, having taken almost 9 minutes out of the German who came in twenty-fifth that day. The new General Classification shows how dire Ullrich's position was:

- Marco Pantani

- Bobby Julich @ 3 minutes 53 seconds

- Fernando Escartin @ 4 minutes 14 seconds

- Jan Ullrich @ 5 minutes 56 seconds

Stage 16 was the last day of truly serious climbing with the Porte, Cucheron, Granier, Gran Cucheron and the Madeleine. On the final climb Ullrich showed that he was doing much better than the day before when he attacked and only Pantani could go with him. Since Pantani was the leader and had the luxury of riding defensively, he let Ullrich do all the work. If Ullrich couldn't drop Pantani, he could at least put some distance between himself and Julich and Escartin, which he did. Pantani and Ullrich came in together with Ullrich taking the stage victory in Albertville. Julich and Escartin followed the duo by 1 minute, 49 seconds. Ullrich was back on the General Classification Podium:

- Bobby Julich @ 5 minutes 42 seconds

- Fernando Escartin @ 6 minutes 3 seconds

On Wednesday July 29, stage 17, the riders staged a strike. They started by riding very slowly and at the site of the first intermediate sprint they sat down. After talking with race officials they took off their numbers and rode slowly to the finish in Aix-les-Bains with several TVM riders in the front holding hands to show the solidarity of the peloton. If the reader thinks that the other members of the peloton did not know that the TVM team was doping I have ocean-front land in Arkansas for him to buy. Along the way the Banesto, ONCE and Risso Scotti teams abandoned the Tour. The Tour organization voided the stage allowing those riders who were members of teams that had not officially abandoned to start on Thursday.

Why all this anger now? First of all, the day before drugs were said to be found in a truck belonging to the Big Mat Auber 93 team. The next day this turned out to be untrue. Then the entire TVM squad was taken into custody and the team's cars and trucks were seized. They, like the Festina team, were handled roughly by the police, sparking outrage from the riders not yet in jail.

Thursday, July 30, stage 18: Kelme and Vitalicio Seguros quit the Tour. That made all 4 Spanish teams out. Rudolfo Massi, winner of stage 10 was taken into custody. At the start of the stage there were now only 103 riders left in the peloton, down from 189 starters.

Friday, July 31, stage 19. TVM abandoned the Tour. It turned out that ONCE's team doctor Nicolas Terrados was also put under arrest after a police search found drugs on their bus that later turned out to be legal.

So now it was Ullrich's last chance to take the Tour with the stage 20 52-kilometer individual time trial. Pantani was too good, losing only 2 minutes and 35 seconds to Ullrich. That sealed the Tour for Pantani. Ullrich acknowledged that he had not taken his preparation for the Tour seriously and paid a very high price for his lack of discipline. Sounding a note that will become a metaphor for the balance of his career, he promised to work harder in the future and not repeat his mistakes.

Of 189 starters in this Tour, 96 finished.

Final 1998 Tour de France General Classification:

- Marco Pantani (Mercatone Uno): 92 hours 49 minutes 46 seconds

- Jan Ullrich (Telekom) @ 3 minutes 21 seconds

- Bobby Julich (Cofidis) @ 4 minutes 8 seconds

- Christophe Rinero (Cofidis) @ 9 minutes 16 seconds

- Michael Boogerd (Rabobank) @ 11 minutes 26 seconds

Climbers' competition:

- Christophe Rinero: 200 points

- Marco Pantani: 175 points

- Alberto Elli: 165 points

Points competition:

- Erik Zabel: 327 points

- Stuart O'Grady: 230 points

- Tom Steels: 221 points

Pantani became the first Italian to win the Tour since Felice Gimondi in 1965. He became the seventh man to do the Giro-Tour double, joining Coppi, Anquetil, Merckx, Hinault, Roche and Indurain.

The drug busts of 1998 did little to alter rider and team behavior. There would be more drug raids and more outraged screams from the riders. But the police knew what they were dealing with. The riders had formed a conspiracy to cheat and to break the law. Their code of silence was nothing more than a culture of intimidation to allow the riders to do what they had done for more than 100 years, take drugs to relieve their pain, allow them to sleep and improve their performance. Their anger at the treatment they received from the police is indicative of their sense of entitlement, their feeling that this was something that they could and sometimes had to do. On the other hand cops like to catch bad guys and when they do, they aren't always gentle.

Now, there is one other question that needs to be asked. Voet, who had chosen a lightly-traveled road on his way to Calais, was expecting the customs station at the French frontier to be abandoned. It wasn't and he was stopped and searched by border agents who seemed to be waiting for him. Roussel believes that when Tour Boss Jean-Marie Leblanc, who is conservative politically, talked Roussel into letting Bernadette Chirac, wife of conservative French President Jacques Chirac, do a bit of self-promotion when she visited the Tour for stage 7, the Tour became a target in the war between France's Right and the Left. The left-center coalition government had given the Ministry for Sports and Youth to the left-leaning Marie-George Buffet. Roussel hypothesized that Festina, Leblanc and the Tour were sacrificed to give Buffet a victory against the Right and incidentally, against doping. Certainly it was clear after the 1998 Tour that systematized doping was part of the professional cycling scene and had been that way for some time. Roussel asks why did this festering problem erupt into scandal at this point? A deeper exploration of the subject is beyond the intended scope of this book.

If the reader is interested I recommend Les Woodland's The Crooked Path to Victory where the complex subject of sport, politics, dope and the 1998 Tour is brilliantly dissected.

© McGann Publishing

Probe reveals doping by Pantani, Ullrich in 1998

- Pantani died in 2004 at 34 of drug overdose

- In 1998%2C seven teams withdrew or were ejected from Tour

- American Julich has admitted his EPO use during 1998 Tour

PARIS (AP) — A French inquiry into sports doping has uncovered proof that 1998 Tour de France champion Marco Pantani and runner-up Jan Ullrich used a banned blood booster to fuel their performances.

France's senate, after a five-month investigation focused on fighting sports doping, released a report Wednesday that confirms what many riders have long said: use of the banned substance EPO was rife in cycling in the late 1990s, before a test for the drug had been developed.

Pantani was suspended in 1999 from the Giro after failing a random blood test, and his career was damaged by several doping investigations. He died in 2004 at 34 of an accidental drug overdose.

Ullrich, the 1997 Tour winner, has admitted to blood doping and last year was stripped of his third-place finish in the 2005 Tour.

The 1998 Tour de France was notable for the major scandal that emerged with the discovery of widespread doping on the French Festina team. The subsequent police crackdown led to seven of the original 21 teams either withdrawing or being ejected from the Tour.

Other star riders whose positive doping tests were disclosed by the senate report Wednesday include double stage winner Mario Cipollini of Italy and Laurent Jalabert of France. Kevin Livingston, an American who finished 17th in that year's Tour, also tested positive for EPO, according to documents included in the senate report.

Third-place finisher, American Bobby Julich, last year admitted to his own EPO use during the 1998 Tour. In 1999, Lance Armstrong won the first of his seven straight titles, which he was stripped of this year after admitting to using banned substances for all of those victories.

Senators took pains to point out that the 1998 Tour de France disclosures represented only a few pages of the 800-page report released Wednesday, which mainly focused on establishing the size of the sports doping problem and identifying ways of improving anti-doping measures.

The senate inquiry heard from 138 athletes, drug testers and officials from 18 sports, including rugby and soccer. The report comprises 60 proposals for improving anti-doping measures, including establishing "truth and reconciliation commissions" within each sport; making sure that all sporting events taking place in France fall under the watch of French anti-doping authorities; and testing for a wider range of illicit substances.

Senators also propose taking disciplinary power away from sports federations and giving it to the French anti-doping body AFLD.

The positive tests disclosed in the senate report were uncovered via retrospective testing in 2004 and 2005, by French anti-doping authorities seeking to perfect their test for EPO. The results had since been stored without the identities of the riders being released. Senator Jean-Jacques Lozach, one of the report's authors, said retrospective testing is one of the ways authorities can stay ahead of cheating riders.

"Given the performance of Chris Froome, the winner of the 2013 Tour de France, there were doubts expressed and suspicions raised. In light of today's controls these suspicions are not legitimate or justified," Lozach said. "Who knows if in three or five years these doubts won't be justified or legitimized by retrospective controls."

Brian Cookson, the head of British Cycling who is challenging Pat McQuaid for the presidency of the sport's governing body UCI in September elections, called the senate report "a terrible indictment of the people responsible, and those with the most responsibility for the culture within the sport are the UCI."

In a statement, Cookson pledged to implement a fully independent investigation into doping in cycling.

"We owe it to those who chose to ride dope-free and to the fans to understand the mistakes of the past and make sure they are not repeated," Cookson said.

Another former French pro whose positive doping test emerged Wednesday said senators risked tarring a cleaner new generation of cyclists with the disclosure of 15-year-old doping revelations.

"I'm thinking of Thibaut Pinot, who finished 10th in the Tour at 22, or Romain Bardet," said Jacky Durand, winner of one stage of the 1998 Tour as well as the prize for most combative rider. Durand, now a cycling commentator on Eurosport, said that in his day, "we needed to 'salt the soup,' as the older riders said."

"Our sport is much cleaner today, I want people to understand that," Durand said.

1998 Tour de France champion used banned blood booster

French inquiry into sports doping reveals winner marco pantani, runner-up used drugs.

Social Sharing

A French inquiry into sports doping has uncovered proof that 1998 Tour de France champion Marco Pantani and runner-up Jan Ullrich used a banned blood booster to fuel their performances.

France's senate, after a five-month investigation focused on fighting sports doping, released a report Wednesday that confirms what many riders have long said: use of the banned substance EPO was rife in cycling in the late 1990s, before a test for the drug had been developed.

Pantani was suspended in 1999 from the Giro after failing a random blood test, and his career was damaged by several doping investigations. He died in 2004 at 34 of an accidental drug overdose.

Ullrich, the 1997 Tour winner, has admitted to blood doping and last year was stripped of his third-place finish in the 2005 Tour.

The 1998 Tour de France was notable for the major scandal that emerged with the discovery of widespread doping on the French Festina team. The subsequent police crackdown led to seven of the original 21 teams either withdrawing or being ejected from the Tour.

Other star riders whose positive doping tests were disclosed by the senate report Wednesday include double stage winner Mario Cipollini of Italy and Laurent Jalabert of France. Kevin Livingston, an American who finished 17th in that year's Tour, also tested positive for EPO, according to documents included in the senate report.

Third-place finisher, American Bobby Julich, last year admitted to his own EPO use during the 1998 Tour. In 1999, Lance Armstrong won the first of his seven straight titles, which he was stripped of this year after admitting to using banned substances for all of those victories.

Senators took pains to point out that the 1998 Tour de France disclosures represented only a few pages of the 800-page report released Wednesday, which mainly focused on establishing the size of the sports doping problem and identifying ways of improving anti-doping measures.

The senate inquiry heard from 138 athletes, drug testers and officials from 18 sports, including rugby and soccer. The report comprises 60 proposals for improving anti-doping measures, including establishing "truth and reconciliation commissions" within each sport; making sure that all sporting events taking place in France fall under the watch of French anti-doping authorities; and testing for a wider range of illicit substances.

Disciplinary power

Senators also propose taking disciplinary power away from sports federations and giving it to the French anti-doping body AFLD.

The positive tests disclosed in the senate report were uncovered via retrospective testing in 2004 and 2005, by French anti-doping authorities seeking to perfect their test for EPO. The results had since been stored without the identities of the riders being released. Senator Jean-Jacques Lozach, one of the report's authors, said retrospective testing is one of the ways authorities can stay ahead of cheating riders.

"Given the performance of Chris Froome, the winner of the 2013 Tour de France, there were doubts expressed and suspicions raised. In light of today's controls these suspicions are not legitimate or justified," Lozach said. "Who knows if in three or five years these doubts won't be justified or legitimized by retrospective controls."

Brian Cookson, the head of British Cycling who is challenging Pat McQuaid for the presidency of the sport's governing body UCI in September elections, called the senate report "a terrible indictment of the people responsible, and those with the most responsibility for the culture within the sport are the UCI."

In a statement, Cookson pledged to implement a fully independent investigation into doping in cycling.

"We owe it to those who chose to ride dope-free and to the fans to understand the mistakes of the past and make sure they are not repeated," Cookson said.

Another former French pro whose positive doping test emerged Wednesday said senators risked tarring a cleaner new generation of cyclists with the disclosure of 15-year-old doping revelations.

"I'm thinking of Thibaut Pinot, who finished 10th in the Tour at 22, or Romain Bardet," said Jacky Durand, winner of one stage of the 1998 Tour as well as the prize for most combative rider. Durand, now a cycling commentator on Eurosport, said that in his day, "we needed to 'salt the soup,' as the older riders said."

"Our sport is much cleaner today, I want people to understand that," Durand said.

Related Stories

- Lance Armstrong loses his 7 Tour de France titles

- Lance Armstrong’s tarnished legacy

Probe: 1998 Tour champ used EPO

- Associated Press

PARIS -- A French inquiry into sports doping uncovered proof that 1998 Tour de France champion Marco Pantani and runner-up Jan Ullrich used the banned blood-booster EPO to fuel their performances.

France's senate, after a five-month investigation focused on sports doping, released a report Wednesday that confirms what many have long suspected: Use of the banned substance EPO was rife in cycling in the late 1990s, before there was a test for the drug.

Pantani was suspended in 1999 from the Giro after failing a random blood test, and his career was damaged by several doping investigations. He died in 2004 at 34 of an accidental drug overdose.

Ullrich, the 1997 Tour winner, has admitted to blood doping and last year was stripped of his third-place finish in the 2005 Tour.

The 1998 Tour de France was notable for the major scandal that emerged with the discovery of widespread doping on the French Festina team. The subsequent police crackdown led to seven of the original 21 teams either withdrawing or being ejected from the Tour.

Other star riders whose positive EPO doping tests were disclosed include American Kevin Livingston, who finished 17th in the 1998 Tour. Also listed were double-stage winner Mario Cipollini of Italy and Laurent Jalabert of France.

Third-place finisher, American Bobby Julich, last year admitted to his own EPO use during the 1998 Tour. In 1999, Lance Armstrong won the first of his seven straight titles, which he was stripped of this year after admitting to using banned substances for all the victories.

Senators took pains to point out that the 1998 Tour de France disclosures represented only a few pages of the 800-page report released Wednesday, which mainly focused on establishing the size of the doping problem and identifying ways to improve anti-doping measures.

The senate heard from 138 athletes, drug testers and officials from 18 sports, including rugby and soccer. The report includes 60 proposals for improving anti-doping measures, such as establishing "truth and reconciliation commissions" within each sport; making sure all sporting events in France fall under the watch of French anti-doping authorities; and testing for a wider range of illicit substances.

Senators also proposed taking disciplinary power away from sports federations and giving it to the French anti-doping body AFLD.

The positive tests disclosed in the report were uncovered through retesting of samples from 2004 and 2005 by French anti-doping authorities seeking to perfect their test for EPO. The results had since been stored without the identities of the riders being released. Senator Jean-Jacques Lozach, one of the report's authors, said retesting is one of the ways authorities can stay ahead of cheating riders.

"Given the performance of Chris Froome, the winner of the 2013 Tour de France, there were doubts expressed and suspicions raised. In light of today's controls these suspicions are not legitimate or justified," Lozach said. "Who knows if in three or five years these doubts won't be justified or legitimized by retrospective controls."

Brian Cookson, the head of British Cycling who is challenging Pat McQuaid for the presidency of the sport's governing body UCI in September elections, called the senate report "a terrible indictment of the people responsible, and those with the most responsibility for the culture within the sport are the UCI."

In a statement, Cookson pledged to implement a fully independent investigation into doping in cycling.

"We owe it to those who chose to ride dope-free and to the fans to understand the mistakes of the past and make sure they are not repeated," Cookson said.

Another former French pro whose positive doping test emerged Wednesday said senators risked tarring a cleaner new generation of cyclists with the disclosure of 15-year-old doping revelations.

"I'm thinking of Thibaut Pinot, who finished 10th in the Tour at 22, or Romain Bardet," said Jacky Durand, winner of one stage of the 1998 Tour as well as the prize for most combative rider. Durand, now a cycling commentator on Eurosport, said in his day, "we needed to `salt the soup,' as the older riders said.

"Our sport is much cleaner today, I want people to understand that," Durand said.

French Senate lays bare doping in 1998 Tour de France

- Medium Text

Additional reporting by Tara Oakes; editing by Robert Woodward

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles. New Tab , opens new tab

Sports Chevron

Us reaches $138.7 million civil settlement with victims of larry nassar.

The U.S. Justice Department has reached a $138.7 million civil settlement with hundreds of victims of former USA Gymnastics doctor Larry Nassar, who is serving time in prison for sexually abusing athletes under his care, the agency said on Tuesday.

- Election 2024

- Entertainment

- Newsletters

- Photography

- Personal Finance

- AP Investigations

- AP Buyline Personal Finance

- AP Buyline Shopping

- Press Releases

- Israel-Hamas War

- Russia-Ukraine War

- Global elections

- Asia Pacific

- Latin America

- Middle East

- Election Results

- Delegate Tracker

- AP & Elections

- Auto Racing

- 2024 Paris Olympic Games

- Movie reviews

- Book reviews

- Personal finance

- Financial Markets

- Business Highlights

- Financial wellness

- Artificial Intelligence

- Social Media

Cycling probe: Doping by Pantani, Ullrich in 1998

- Copy Link copied

PARIS (AP) — A French inquiry into sports doping uncovered proof that 1998 Tour de France champion Marco Pantani and runner-up Jan Ullrich used the banned blood-booster EPO to fuel their performances.

France’s senate, after a five-month investigation focused on sports doping, released a report Wednesday that confirms what many have long suspected: Use of the banned substance EPO was rife in cycling in the late 1990s, before there was a test for the drug.

Pantani was suspended in 1999 from the Giro d’Italia after failing a random blood test, and his career was damaged by several doping investigations. He died in 2004 at 34 of an accidental drug overdose.

Ullrich, the 1997 Tour winner, has admitted to blood doping and last year was stripped of his third-place finish in the 2005 Tour.

The 1998 Tour de France was notable for the major scandal that emerged with the discovery of widespread doping on the French Festina team. The subsequent police crackdown led to seven of the original 21 teams either withdrawing or being ejected from the Tour.

Other star riders whose positive EPO doping tests were disclosed include American Kevin Livingston, who finished 17th in the 1998 Tour. Also listed were double-stage winner Mario Cipollini of Italy and Laurent Jalabert of France.

Third-place finisher, American Bobby Julich, last year admitted to his own EPO use during the 1998 Tour. In 1999, Lance Armstrong won the first of his seven straight titles, which he was stripped of this year after admitting to using banned substances for all the victories.

Senators took pains to point out that the 1998 Tour de France disclosures represented only a few pages of the 800-page report released Wednesday, which mainly focused on establishing the size of the doping problem and identifying ways to improve anti-doping measures.

The senate heard from 138 athletes, drug testers and officials from 18 sports, including rugby and soccer. The report includes 60 proposals for improving anti-doping measures, such as establishing “truth and reconciliation commissions” within each sport; making sure all sporting events in France fall under the watch of French anti-doping authorities; and testing for a wider range of illicit substances.

Senators also proposed taking disciplinary power away from sports federations and giving it to the French anti-doping body AFLD.

The positive tests disclosed in the report were uncovered through retesting of samples from 2004 and 2005 by French anti-doping authorities seeking to perfect their test for EPO. The results had since been stored without the identities of the riders being released. Senator Jean-Jacques Lozach, one of the report’s authors, said retesting is one of the ways authorities can stay ahead of cheating riders.

“Given the performance of Chris Froome, the winner of the 2013 Tour de France, there were doubts expressed and suspicions raised. In light of today’s controls these suspicions are not legitimate or justified,” Lozach said. “Who knows if in three or five years these doubts won’t be justified or legitimized by retrospective controls.”

Brian Cookson, the head of British Cycling who is challenging Pat McQuaid for the presidency of the sport’s governing body UCI in September elections, called the senate report “a terrible indictment of the people responsible, and those with the most responsibility for the culture within the sport are the UCI.”

In a statement, Cookson pledged to implement a fully independent investigation into doping in cycling.

“We owe it to those who chose to ride dope-free and to the fans to understand the mistakes of the past and make sure they are not repeated,” Cookson said.

Another former French pro whose positive doping test emerged Wednesday said senators risked tarring a cleaner new generation of cyclists with the disclosure of 15-year-old doping revelations.

“I’m thinking of Thibaut Pinot, who finished 10th in the Tour at 22, or Romain Bardet,” said Jacky Durand, winner of one stage of the 1998 Tour as well as the prize for most combative rider. Durand, now a cycling commentator on Eurosport, said in his day, “we needed to ‘salt the soup,’ as the older riders said.

“Our sport is much cleaner today, I want people to understand that,” Durand said.

Follow Greg Keller on Twitter: https://twitter.com/Greg_Keller

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Tour de France Scandal

NPR's Sarah Chayes reports from Lille, France where a trial is underway in the 1998 Tour de France doping scandal. Ten cyclists are charged with taking performance-enhancing drugs, but witnesses claim that officials were aware of their activities.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Sports of The Times

Doping Cloud Still Looms Over a Thrilling Tour de France

By Michael Powell

- July 26, 2019

BRIANÇON, France — To watch the cyclists of the Tour de France assault the high Alps, those grand geologic up-thrusts of granite and limestone, to see men pedal through misting meadows and up brutal switchbacks is to thrill at feats of athleticism.

As the Tour headed toward its finale in Paris on Sunday, there were so many complex strategies and stories in the race’s final days: Would the ebullient young Julian Alaphilippe of Deceuninck Quick-Step regain the yellow jersey to become the first Frenchman to claim the title of champion in three decades? Would he fall to the high-altitude guy from Colombia, Egan Bernal of Team Ineos (the New York Yankees of cycling), or the Dutchman Steven Kruijswijk of Jumbo-Visma?

As I watched, however, another question nagged: Is all of this real?

Are these stars drawing on deep reserves within or are they helped along by a chemical new or old? When announcers exclaim that a rider pedals “like the Hulk” or describe Alaphilippe’s performance as “absolutely extraordinary,” it seems wise to temper the urge to clap unreservedly.

This sport was nearly consumed by doping. In the 1980s and 1990s and deep into this century, one champion after another fell away: Marco Pantani, Alberto Contador and Lance Armstrong, who was barred for life and stripped of seven Tour de France titles.

This much can be safely said: Cycling today is far cleaner than before. Testing has improved by great leaps and athletes have their blood tested out of season, as well. This is essential for any half-serious testing program. As fewer champions perform in ways that make them appear as a separate species, rival cyclists perhaps no longer feel it necessary to illegally pump EPO into their veins, which increases the capacity of the blood to carry oxygen.

That said, cycling certainly is not altogether clean. In March, the German police found a skier tethered to a blood bag and the investigation led two Austrian cyclists to confess to doping. They hailed from prominent teams competing in this year’s Tour de France.

“Are we catching every cyclist who dopes? No,” says Jonathan Vaughters, manager of the EF Education First cycling team, and author of “One-Way Ticket,” a forthcoming book that examines cycling’s dirty history and his own doping. “But we are leaps and bounds better than two decades ago.”

I placed a call to the South African Ross Tucker, an internationally renowned exercise physiologist and founder of the website The Science of Sport . He has tracked doping and performance and notes that in the wake of multiple scandals, cycling times declined. Of late, however, those times have edged back up.

Cycling has embraced the biological passport, which profiles athletes’ individual blood values, so there is a baseline that their tests can be compared with. That has dialed back but not stopped doping. A cyclist might still try to micro-dose — take small doses of drugs that are difficult to detect — right up to the line.

“The breadth in which you can safely dope has greatly narrowed and that has constrained use,” Tucker said. “What we don’t know are the unknown unknowns. Are there new drugs, new ways?”

Ominously to the view of antidoping scientists, neither of the Austrian cyclists caught in that police investigation had tested positive.

Marc Madiot, director of the team Groupama-FDJ, employed one of those cyclists and he made a fine show of indignation. “Trust was betrayed,” he proclaimed. “That’s one of the hazards in life.”

That’s true about life. It’s also true that Madiot raced in the bad old days of doping and was questioned intensively by the police and was nearly brought to ground in a big cycling doping scandal in 1998.

Now I need to back off a few steps. Cycling may be the original fallen angel of doping — competitive cyclists in the 1880s allegedly pedaled fueled by a stew of cocaine and caffeine — but it arguably has a notably tougher testing regimen than many American sports, including baseball.

And many in Major League Baseball’s establishment hailed from a no less dirty rotten steroid era. Tony La Russa, now a vice president with the Boston Red Sox, was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2014 for his work as a manager. His teams, notably the Oakland Athletics, were great beneficiaries of baseball’s steroid age and he adamantly defended such obvious dopers as Mark McGwire.

Nor did the baseball press cover itself in glory. A house was on fire and too many reporters sounded like fan boys rather than run for a bucket of water.

Let’s return to cycling. The persistence of its doping problems owes to the fact that the sport is about power and endurance. As another fallen champion cyclist, Tyler Hamilton, noted in his own tell-all book, “The Secret Race,” racing at the highest level is about the ability to endure pain while producing energy across hours of effort and at high altitudes.

In all of that, he noted, blood doping was — and still can be — a great force multiplier.

Of late, the look of professional cyclists has changed and that has stirred concern. Where in the 1990s cyclists like Armstrong looked muscular and fierce, today cyclists look lean to the point of emaciation. Much speculation centers on an unapproved drug, AICAR, which helps an athlete lose weight without losing muscle mass.

Tucker equates the effect of that drug to car design. You can, he noted, make a bigger and more powerful engine, and that happened in the 1990s. Or you can keep the engine the same size and cut the mass of the car.

“AICAR offers a way to cut weight without impacting performance,” he noted.

There is finally a conundrum that confronts all who would keep doping out of professional sports: The distance between the cup of suspicion and the lip of drop-dead proof is great.

“In order to trigger a sanction, you have to have been 99.9 percent likely doped,” Tucker said. “Obviously many fall short. They are highly suspicious but not enough to sanction.”

So fish slip through the net and maybe we’re the better for that. Better to let 99 walk free than to jail one innocent. It does however feed that nagging suspicion that hangs over all sports in this era — the explanation for extraordinary accomplishment might prove more complicated than it appears.

An earlier version of this column misspelled a part of the name of the cycling team that is directed by Marc Madiot. It is Groupama-FDJ, not Goupama. The column also misstated the year of a widespread cycling doping scandal in which Madiot was questioned by the police. It was 1998, not 1999.

How we handle corrections

Cycling Around the Globe

The cycling world can be intimidating. but with the right mind-set and gear you can make the most of human-powered transportation..

Are you new to urban biking? These tips will help you make sure you are ready to get on the saddle .

Whether you’re mountain biking down a forested path or hitting the local rail trail, you’ll need the right gear . Wirecutter has plenty of recommendations , from which bike to buy to the best bike locks .

Do you get nervous at the thought of cycling in the city? Here are some ways to get comfortable with traffic .

Learn how to store your bike properly and give it the maintenance it needs in the colder weather.

Not ready for mountain biking just yet? Try gravel biking instead . Here are five places in the United States to explore on two wheels.

The Yellow Jersey Club: Marco Pantani and the romance of the 1998 Tour de France

Excerpt from The Yellow Jersey Club by Edward Pickering

The Yellow Jersey Club, by Edward Pickering, looks at the characters and personalities of the Tour de France winners between Bernard Thévenet in 1975 and Chris Froome in the 2010s, putting them into historical and cultural context. This is an extract from The Yellow Jersey Club, featuring the chapter on Marco Pantani, who won the race in 1998. It looks at the complex legacy left by the late Italian.

Marco Pantani, 1998

For Sonny Liston, it was easy being a superman. It was being a man that was often difficult - Boxing Yearbook, 1964

What explanation is there for the fact that millions of pilgrims flock to view the Turin shroud whenever the Cathedral of St John the Baptist in Turin puts it on public display, other than that people have a profound need to believe in incredible things? It was believed by the faithful that the shroud was stained with the image of Jesus, miraculously formed when he was wrapped in it after falling from the cross – until 1988, when a carbon-dating test run by Oxford University found that the shroud was a medieval creation, just over 700 years old. Yet on the three occasions the shroud has been put on display since, millions more still made the pilgrimage to Turin to see the image of Jesus.

Cycling fans are still worshipping at the church of Marco Pantani. He is the personification of romance in the sport – his climbing verve, bold attacks and psychological fragility appealed to a common and significant tendency in sports fans, that of imbuing human achievements with superhuman status. It’s either a natural thing to do, or so culturally ingrained that it might as well be – and why not? What better way of dealing with the daily grind than to enjoy a few fleeting moments of escapism, via the exploits of great athletes, or great musicians, or great actors?

Pantani was easy to idolise. He won the 1998 Tour de France in spectacular circumstances – with a long-range attack in atrocious weather in the Alps – which was a throwback to the old days of cycling myth, when eyewitnesses and coverage were so scarce that creative newspaper journalists could essentially invent the narrative in purple prose. His unpredictable, organic, harrying tactics were a refreshing contrast to the metronomic, implacable, bullying strength of Jan Ullrich, his main rival that year. The 1998 Tour was a clash of cultures, stereotypes and cycling ideologies: the Latin versus the Teutonic, the climber versus the rouleur, the attacker versus the defender, Romanticism versus Classicism, the underdog versus the favourite, fire versus ice.