Caribbean Tourism Soars with 14.3% Increase in 2023, Surpassing Global Recovery Rates

Saturday, March 16, 2024 Favorite

Caribbean tourism rose 14.3% in 2023, with the US leading recovery. The region outperforms global trends, showing remarkable resilience and growth.

In 2023, tourism in the Caribbean saw a notable surge, registering a 14.3% boost in international visitors, as reported by the Caribbean Tourism Organization (CTO). This uplift aligns with the predictions made by the CTO and was announced during the “Caribbean Tourism Performance Review 2023” in Bridgetown by Dona Regis-Prosper, the Secretary-General. The growth is attributed to the continued interest in international travel, especially from the United States, the region’s primary market. Improvements in tourism infrastructure, strategic marketing efforts, and increased flight options played significant roles, though the benefits were not uniformly spread across all Caribbean destinations.

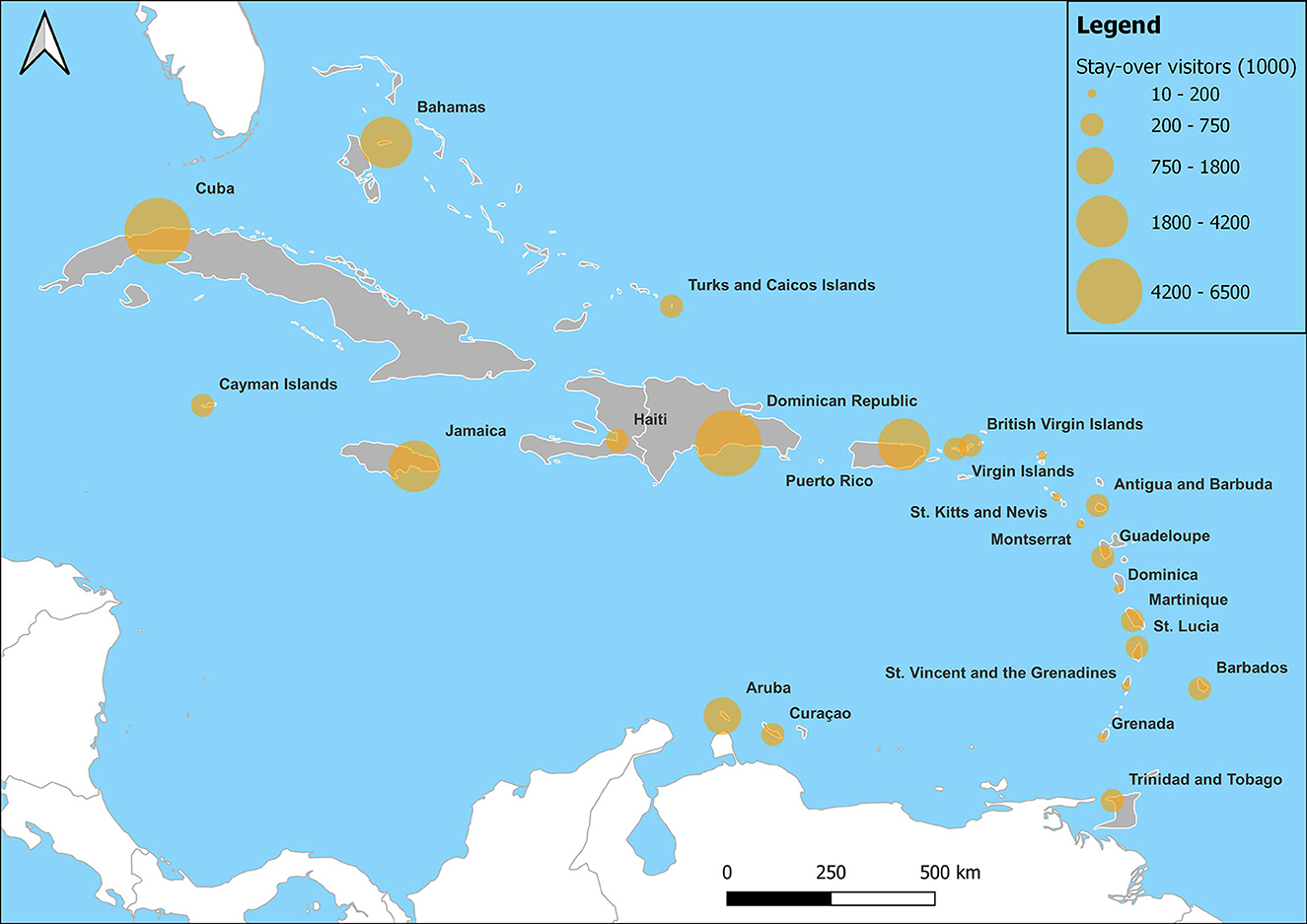

The global tourism sector’s resilience is evident, with the Caribbean slightly exceeding its pre-pandemic visitor numbers by 0.8%, showcasing a stronger recovery than many other worldwide regions. Several Caribbean islands, including Anguilla, Aruba, Curaçao, the Dominican Republic, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, Puerto Rico, St. Maarten, the Turks & Caicos Islands, and the U.S. Virgin Islands, surpassed their 2019 visitor statistics, with most seeing more than a 50% recovery rate. A record number of tourists in a single year was reported in multiple locales.

“Based on preliminary data provided so far by the destinations in the Caribbean, tourist visits were approximately 32.2 million – about four million more than in 2022,” stated Regis-Prosper , who noted that the data showed that each month’s arrivals exceeded those of 2022 thus establishing a continuous growth trend over the past 33 months as tourism steadily rebounded toward pre-pandemic levels.

In terms of market-specific recovery, the United States led the way with a complete rebound, whereas arrivals from Europe and Canada reached 88.2% and 88.1% of their former levels, respectively. The U.S. contributed approximately 16.3 million visitors, marking a 12.7% increase and setting a new record for the region. The Canadian market also saw significant growth, with three million visitors marking a 46.1% rise from the previous year, aided by expanded flights from major Canadian cities.

However, European arrivals stalled in 2023, totaling around 5.2 million. Caribbean internal travel saw a 3.6% increase, amounting to 1.6 million trips and indicating a 62.5% recovery from before the pandemic, although costs remained high due to fragmented air services. South American visits to the Caribbean also rose by 14%, totaling 1.7 million.

The hotel industry in the Caribbean rebounded impressively in 2023, with new establishments opening and existing ones seeing better occupancy and rates. The average occupancy climbed to 65.6%, and the average daily rate increased by 11.8% to US$329.37, with revenue per available room jumping 20.2% to US$215.97, as per STR’s data.

Cruise tourism also hit a new high with an estimated 31.1 million visits, a 56.8% increase from 2019, driven by strong demand and operational enhancements. The cruise industry is expected to maintain its growth, with projections of 34.2 million to 35.8 million cruise visitors in 2024.

Kenneth Bryan, Chairman of the CTO’s Council of Ministers and Commissioners of Tourism and the Cayman Islands’ Minister of Tourism and Ports, highlighted the industry’s extraordinary resilience and growth trajectory in 2023. Yet, he cautioned about the challenges ahead, including travel costs, ongoing conflicts, and geopolitical tensions affecting the industry in 2024.

“Caribbean destinations remain adaptable and responsive, and the region is still highly desired by travelers for its safety and diversity of tourism products,” stated Chairman Bryan , adding that the region will also be positively impacted by key developments in 2024, including increased air capacity throughout the year, which will facilitate greater access between the destinations and some of their legacy and emerging markets.

Chairman Bryan also pointed to “intensive strategic marketing initiatives” that are being executed to attract visitors to the region to enjoy its culture and heritage, including its carnivals and festivals.

He noted that the CTO is pleased that the ICC (International Cricket Council) Men’s T20 World Cup 2024 is being hosted in several destinations bringing not only teams but also their loyal followers to the region and further raising awareness and promoting the diverse offerings of Caribbean destinations to global audiences.

“Hence, the Caribbean’s prospects appear highly promising, with more regional destinations poised to either match or surpass the arrival figures recorded in 2019. Anticipated growth is forecast to range between five percent and 10 percent, potentially welcoming between 33.8 million and 35.4 million stay-over tourists,” concluded Chairman Bryan .

Subscribe to our Newsletters

« Back to Page

Related Posts

- Caribbean Tourism Organization’s Sustainable Tourism Conference in Grenada: Uniting Visionaries for a Greener Future

- Top Corporations Partner with Caribbean Tourism Organization for Upcoming Sustainable Tourism Event in Grenada

- Caribbean Tourism Booms in 2024: Islands See Record-Breaking Visitor Numbers

- How to select a right Caribbean cruise line for your vacation?

- Caribbean Tourism Organization to elevate presence at Routes Americas in Bogotá

Tags: caribbean tourism , Explore Caribbean , United States , United States tourism , US , US Tourism , What's new in Caribbean

Select Your Language

I want to receive travel news and trade event update from Travel And Tour World. I have read Travel And Tour World's Privacy Notice .

REGIONAL NEWS

Ryanair Announces Five New Summer Routes to Europe, Including Rome, from Katowic

Tuesday, April 23, 2024

Reykjavik to Host Spectacular 2024 DesignMarch Festival Under ‘The Circus&

Norwegian Cruise Line Introduces 2024 Europe Season Featuring New Homeports and

WestJet CEO Alexis Von Hoensbroech to Unveil Strategic Regional Investments in E

Middle east.

Saudi Tourism Authority launches ‘Visit Saudi’ as a comprehensive guide

Emirates Strengthens Commercial Operations with Strategic Role Changes

China Eastern Airlines and Amadeus Collaborate to Enhance Travel with Expanded N

Travel Across 23 Countries with Air Asia Grand Sale Offering 20% Off on All Flig

Upcoming shows.

Apr 21 April 21 - April 24 CONNECTIONS LUXURY COASTA BRAVA Find out more » Apr 21 April 21 - April 24 m&i Private Sorrento 2024 Find out more » Apr 22 April 22 - April 24 Routes Europe 2024 Find out more » Apr 22 April 22 - April 23 Caribbean Hotel & Resort Investment Summit (CHRIS) 2024 Find out more »

Privacy Overview

Resilience, Sustainability, and Inclusive Growth for Tourism in the Caribbean

Louise twining-ward, john perrottet, cecile niang.

Senior Private Sector Specialist

Senior Industry Specialist

Program Leader

Join the Conversation

- Share on mail

- comments added

Caribbean Tourism Experiences Strong Growth in 2023, Recovery to Continue into 2024

Buy the full December 2023 Quarterly Review

BRIDGETOWN, Barbados (March 15, 2024) – Continuing its positive recovery trend, Caribbean tourism grew in 2023 with an estimated 14.3% increase in international stay-over arrivals to the region, the Caribbean Tourism Organization (CTO) has reported.

Delivering the “Caribbean Tourism Performance Review 2023” in Bridgetown today, Dona Regis-Prosper, Secretary-General of the CTO, shared that last year’s growth was in line with CTO’s forecast for the year, and attributed the outcome to sustained demand for outbound travel from the United States – the Caribbean’s main source market, enhanced tourism-related infrastructure within the destinations, the fulfillment of strategic marketing initiatives, and augmented airlift capacity between the region and its source markets, albeit unevenly distributed among the destinations.

The recovery of global tourism has been resilient, despite variability in the regional performances, according to Regis-Prosper, with the Caribbean surpassing pre-pandemic arrivals by a modest 0.8%, outperforming most of the main global regions in terms of recovery.

“Based on preliminary data provided so far by the destinations in the Caribbean, tourist visits were approximately 32.2 million – about four million more than in 2022,” stated Regis-Prosper, who noted that the data showed that each month’s arrivals exceeded those of 2022 thus establishing a continuous growth trend over the past 33 months as tourism steadily rebounded toward pre-pandemic levels.

Arrival levels amongst Caribbean destinations either significantly recovered or moderately exceeded the benchmark numbers of 2019, with 11 destinations, Anguilla, Aruba, Curaçao, Dominican Republic, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, Puerto Rico, St. Maarten, Turks & Caicos Islands, and U.S. Virgin Islands performing better than in 2019. The majority of those recovered greater than 50% of their 2019 arrivals. In addition, multiple destinations registered new record levels for tourist arrivals in a single year.

United States and Canada Markets

For the Caribbean, only the U.S. market has fully recovered, while the recovery rates of arrivals from Europe and Canada reached 88.2% and 88.1%, respectively. An estimated 16.3 million stay-over arrivals to the region came from the United States, representing an annual growth rate of 12.7%. The performance here established a new record level of arrivals from this market and surpassed the pre-pandemic arrivals by 4.2%. The performance of the Canadian market resulted in an estimated three million Canadian tourist visits by the end of the year, an increase of 46.1% compared to 2022. Increased air service from major Canadian cities to Caribbean destinations played a pivotal role in driving up visitor numbers.

Europe, Caribbean and South America Markets

Regis-Prosper noted that arrivals from Europe to the Caribbean region were stagnant in 2023. A total of approximately 5.2 million trips originated from the market. In 2023, travel among Caribbean residents to destinations within the region increased by approximately 3.6%, a total of 1.6 million trips, which was 0.3 million more compared to 2022. This also indicated a recovery of 62.5% from pre-pandemic levels. “Despite this positive outcome, intra-regional travel remained expensive due to fragmented air service and reduced air capacity,” said Regis-Prosper. By the end of the year, trips from South America to the region surged by an estimated 14%, totaling 1.7 million trips.

Caribbean Hotel Performance

The Caribbean hotel sector experienced a remarkable turnaround in 2023, including a surge in the establishment of new hotels and resorts. According to STR, throughout the Caribbean, average room occupancy grew to 65.6% in 2023 from 61% in 2022. The average daily rate (ADR) experienced a considerable increase of 11.8% with the region’s ADR reaching US$329.37 while the revenue per available room (RevPAR) jumped 20.2% to US$215.97.

Cruise Tourism Performance

Preliminary data for 2023 showed that Caribbean destinations received an estimated 31.1 million cruise visits, reflecting an increase of 11.3 million visits or 56.8% compared to 2019. This level established a new record for the regional cruise sector, surpassing the previous record of 2019 by 2.4%. Pent-up demand and the resumption of operations drove strong bookings for Caribbean cruises, along with improvements in cruise infrastructure such as larger ships, enhanced facilities, itineraries, and shore excursions.

Projections indicate that the cruise sector will continue its upward track, with an estimated 34.2 million to 35.8 million cruise visits expected in the Caribbean in 2024. This anticipated expansion falls within the range of 10% and 15%.

Remarkable Resilience

Chairman of the Caribbean Tourism Organization’s Council of Ministers and Commissioners of Tourism, Kenneth Bryan, who also serves as the Cayman Islands’ Minister of Tourism and Ports, noted the remarkable resilience of the tourism industry and its ongoing recovery and growth in 2023. However, he emphasized that the industry and the region will continue to face an array of challenges, including the high cost of travel, ongoing conflicts, heightened geopolitical tensions, and their anticipated impacts, in 2024.

“Caribbean destinations remain adaptable and responsive, and the region is still highly desired by travelers for its safety and diversity of tourism products,” stated Chairman Bryan, adding that the region will also be positively impacted by key developments in 2024, including increased air capacity throughout the year, which will facilitate greater access between the destinations and some of their legacy and emerging markets.

Chairman Bryan also pointed to “intensive strategic marketing initiatives” that are being executed to attract visitors to the region to enjoy its culture and heritage, including its carnivals and festivals.

He noted that the CTO is pleased that the ICC (International Cricket Council) Men’s T20 World Cup 2024 is being hosted in several destinations bringing not only teams but also their loyal followers to the region and further raising awareness and promoting the diverse offerings of Caribbean destinations to global audiences.

“Hence, the Caribbean’s prospects appear highly promising, with more regional destinations poised to either match or surpass the arrival figures recorded in 2019. Anticipated growth is forecast to range between five percent and 10 percent, potentially welcoming between 33.8 million and 35.4 million stay-over tourists,” concluded Chairman Bryan.

Posted in: 2024 News , Blog , Corporate News , Statistics

Let's Build Tourism Leaders

Donate to the CTO Scholarship Foundation.

Privacy Overview

Contemporary Issues Within Caribbean Economies pp 235–264 Cite as

Caribbean Tourism Development, Sustainability, and Impacts

- David Mc. Arthur Baker 3

- First Online: 09 June 2022

287 Accesses

1 Citations

The Caribbean economy is highly dependent on the tourism industry and the protection of the natural and cultural attractions on which it depends is critical. To address this concern, this chapter provides a snapshot of the progress that has been made on sustainable tourism development in the Caribbean region. There is now more demand from the traveling public for industries to be environmentally friendly and in order to continue to use tourism as a means of economic advancement, sustainable practices must be adopted. The evidence suggests that there are great economic, sociocultural, and environmental impacts of tourism in the Caribbean region that are both positive and negative. The actions of the accommodations sector are commendable but there is the need for all major stakeholders to better manage the negative impacts of tourism development. The Caribbean Tourism Organization has developed a policy framework which consists of guiding principles and integrated policies regarding sustainable tourism development, The Caribbean Sustainable Tourism Policy and Development Framework. A shock, such as COVID-19, can lead to economic collapse as communities heavily dependent on tourism have no capacity to respond to the loss of their primary revenue source. However, in order to strengthen the resilience of small island tourism development, the Caribbean region is transitioning toward community-driven solutions through innovation, employee training, upgrades, greater digitalization, and environmental sustainability.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Abdool, A. (2002). Residents’ perceptions of tourism: A comparative study of two Caribbean communities (Doctoral dissertation, Bournemouth University). ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/76947.pdf

Adrian, S. C. (2017). The impact of tourism on the global economic system. Ovidius University Annals, Economic Sciences Series, 17 (1), 384–387.

Google Scholar

Albattat, A. (2017). Current issue in tourism: Diseases transformation as a potential risk for travelers. Global and Stochastic Analysis, 5 (7), 341–350.

Anderson-Fye, E. P. (2004). A “Coca-Cola” shape: Cultural change, body image, and eating disorders in San Andrés, Belize. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 28 (4), 561–595. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11013-004-1068-4

Article Google Scholar

Aref, F., Gill, S. S., & Farshid, A. (2010). Tourism development in local communities: As a community development approach. Journal of American Science, 6 , 155–161.

Bakar, N. A., & Rosbi, S. C. (2020). Effect of Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) to tourism industry. International Journal of Advanced Engineering Research and Science, 7 (4), 189–193. https://doi.org/10.22161/ijaers.74.23

Baker, D. M. A. (2015). Tourism and the health effects of infectious diseases: Are there potential risks for tourists? International Journal Safety and Security of Tourism and Hospitality, 1 (12), 18. https://www.palermo.edu/Archivos_content/2015/economicas/journal-tourism/edicion12/03_Tourism_and_Infectous_Disease.pdf

Baker, D., & Unni, R. (2018). Characteristic and intentions of cruise passengers to return to the Caribbean for land-based vacations. Journal Tourism – Revista de Turism, 26, 1–9.

Baker, D., & Unni, R. (2021). Understanding residents’ opinions and support towards sustainable tourism development in the Caribbean: The case of Saint Kitts and Nevis. Coastal Business Journal, 18 (1), 1–29.

Becken, S. (2014). Water equity-contrasting tourism water use with that of the local community. Water Resources and Industry, 7 (8), 9–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wri.2014.09.002

Becker, A. E. (2004). Television, disordered eating, and young women in Fiji: Negotiating body image and identity during rapid social change. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 28 (4), 533–559. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11013-004-1067-5

Becker, A. E., Fay, K., Agnew-Blais, J., Guarnaccia, P. M., Striegel-Moore, R. H., & Gilman, S. E. (2010). Development of a measure of “acculturation” for ethnic Fijians: Methodologic and conceptual considerations for application to eating disorders research. Transcultural Psychiatry, 47 (5), 754–788. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461510382153

Behsudi, A. (2020, December). Wish you were here. Finance & Development . https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2020/12/pdf/impact-of-the-pandemic-on-tourism-behsudi.pdf

Bellos, V., Ziakopoulos, A., & Yannis, G. (2020). Investigation of the effect of tourism on road crashes. Journal of Transportation Safety & Security, 12 (6), 782–799. https://doi.org/10.1080/19439962.2018.1545715

Bohdanowicz, P., Simanic, B., & Martinac, I. (2004, October 27–29). Sustainable hotels—Eco-certification according to EU Flower, Nordic Swan and the Polish Hotel Association. In Proceedings of the Regional Central and Eastern European Conference on Sustainable Building (SB04) . Warszawa, Poland.

Brewster, R., Sundermann, A., & Boles, C. (2020). Lessons learned for COVID-19 in the cruise ship industry. Toxicology and Industrial Health, 36 (9), 728–735.

Brida, J. G., & Zapata, S. (2010). Cruises tourism: Economic, socio-cultural and environmental impacts. International Journal of Leisure and Tourism Marketing, 1 (3), 205–226.

Britton, S. (1989). Tourism, dependency, and development: A mode of analysis. Europäische Hochschulschriften 10 (Fremdenverkehr), 11, 93–116.

Bushell, R., & McCool, S. F. (2007). Tourism as a tool for conservation and support of protected areas: Setting the agenda. In R. Bushell & P. F. J. Eagles (Eds.), Tourism and protected areas: Benefits beyond boundaries (pp. 12–26). CABI International.

Butt, N. (2007). The impact of cruise ship generated waste on home ports and ports of call: A case study of Southampton. Marine Policy, 31 (5), 591–598.

Cannonier, C., & Burke, M. G. (2019). The economic growth impact of tourism in small island developing states-evidence from the Caribbean. Tourism Economics, 25 (1), 85–108.

Caribbean Hotel Association. (2014). Advancing sustainable tourism, a regional sustainable tourism situation analysis: Caribbean . https://caribbeanhotelandtourism.com/

Castillo-Manzano, J. I., Castro-Nuño, M., López-Valpuesta, L., & Vassallo, F. V. (2020). An assessment of road traffic accidents in Spain: The role of tourism. Current Issues in Tourism, 23 (6), 654–658. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2018.1548581

Castro, C. (2004). Sustainable development: Mainstream and critical perspective. Organization and Environment, 17 (2), 195–225.

Chang, C., McAleer, M., & Ramos, V. (2020). A charter for sustainable tourism after COVID-19. Sustainability, 12 (9), 3671. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093671

Chappell, K., & Frank, M. (2020). The most tourism-dependent region in the world braces for prolonged Coronavirus recovery . Reuters. https://skift.com/2020/04/20/the-most-tourism-dependent-region-in-the-world-braces-for-prolonged-coronavirus-recovery/

Charles, D. (2013). Sustainable tourism in the Caribbean: The role of the accommodations sector. International Journal of Green Economics, 7 (2), 148–161.

Cheng, T. L., & Conca-Cheng, A. M. (2020). The pandemics of racism and COVID-19: Danger and opportunity. Pediatrics, 146 (5), e2020024836. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-024836

Choi, H. C., & Sirakaya, E. (2006). Sustainability indicators for managing community tourism. Tourism Management, 27 (6), 1274–1289.

Cole, S. (2014). Tourism and water: From stakeholders to rights holders, and what tourism businesses need to do. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 22 (1), 89–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2013.776062

Cook, C. L., Li, Y. J., Newell, S. M., Cottrell, C. A., & Neel, R. (2018). The world is a scary place: Individual differences in belief in a dangerous world predict specific intergroup prejudices. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 21 (4), 584–596. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430216670024

Croes, R., & Vanegas, M., Sr. (2008). Cointegration and causality between tourism and poverty reduction. Journal of Travel Research, 47 (1), 94–103.

Dangi, T. B., & Jamal, T. (2016). An integrated approach to “sustainable community-based tourism.” Sustainability, 8 , 475–507. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8050475

Darma, I. G. K. I. P., Dewi, M. I. K., & Kristina, N. M. R. (2020). Community movement of waste use to keep the image of tourism industry in GIANYAR. Journal of Indonesian Tourism, Hospitality and Recreation, 3 (1), 49–57. https://doi.org/10.17509/jithor.v3i1.23439

Deloitte. (2012). Sustainability for consumer business operations: A story of growth . https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/global/Documents/Consumer-Business/dttl_cb_Sustainability_Global%20CB%20POV.pdf

Farmer, P. (2006). AIDS and accusation: Haiti and the geography of blame . University of California Press.

Findlater, A., & Bogoch, I. I. (2018). Human mobility and the global spread of infectious diseases: A focus on air travel. Trends in Parasitology, 34 (9), 772–783. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2018.07.004

Ghadban, S., Shames, M., & Abou Mayaleh, H. (2017). Trash crisis and solid waste management in Lebanon-analyzing hotels’ commitment and guests’ preferences. Journal of Tourism Research & Hospitality, 6 (3), 1000169. https://doi.org/10.4172/2324-8807.1000171

Gössling, S., Peeters, P., Hall, C. M., Ceron, J.-P., Dubois, G., Lehmann, L. V., & Scott, D. (2012). Tourism and water use: Supply, demand, and security. An international review. Tourism Management, 33 (1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.03.015

Greening, A. (2014). Understanding local perceptions and the role of historical context in ecotourism development: A case study of Saint Kitts (Master’s Thesis, Utah State University). ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

Hanafiah, M. H., Harun, M. F., & Jamaluddin, M. R. (2010). Bilateral trade and tourism demand. World Applied Sciences Journal, 10 , 110–114.

Harry-Hernández, S., Park, S. H., Mayer, K. H., Kreski, N., Goedel, W. C., Hambrick, H. R., Brooks, B., Guilamo-Ramos, V., & Duncan, D. T. (2019). Sex tourism, condomless anal intercourse, and HIV risk among men who have sex with men. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 30 (4), 405–414. https://doi.org/10.1097/JNC.0000000000000018

Haukeland, J. V. (2011). Tourism stakeholders’ perceptions of national park management in Norway. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19 (2), 133–153.

Haywood, M. K. (2020). A post COVID-19 future—Tourism re-imagined and re-enabled. Tourism Geographies, 22 (3), 599–609. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1762120

Homans, C. G. (1958). Social behavior as exchange. American Journal of Sociology, 63 (6), 597–606.

Hoppe, T. (2018). “Spanish Flu”: When infectious disease names blur origins and stigmatize those infected. American Journal of Public Health, 108 (11), 1462–1464. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304645

Hung, C. H., & Wu, M. T. (2017). The influence of tourism dependency on tourism impact and development support attitude. Asian Journal of Business and Management, 5, 88–96. https://doi.org/10.24203/ajbm.v5i2.4594

International Ecotourism Society. (2004). The triple bottom line of sustainable tourism . https://www.coursehero.com/file/81910666/s1pdf/

Jamal, T., & Stronza, A. (2009). Collaboration theory and tourism practice in protected areas: Stakeholders, structuring and sustainability. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 17 (2), 169–189.

Johnson, D. (2002). Environmentally sustainable cruise tourism: A reality check. Marine Policy, 26 (4), 261–270.

Jones, P., Hillier, D., & Comfort, D. (2016). The environmental, social and economic impacts of cruising and corporate sustainability strategies. Athens Journal of Tourism, 3 (4), 273–285.

Jordan, E. J. (2014). Host community resident stress and coping with tourism development (Doctoral dissertation, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI). ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

Jordan, E. J., Lesar, L., & Spenser, D. M. (2021). Clarifying the interrelations of residents’ perceived tourism-related stress, stressors, and impacts. Journal of Travel Research, 60 (1), 208–219. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287519888287

Jordan, E. J., & Vogt, C. A. (2017). Appraisal and coping responses to tourism development-related stress. Tourism Analysis, 22 (1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354217X14828625279573

Kaseva, M. E., & Moirana, J. L. (2010). Problems of solid waste management on Mount Kilimanjaro: A challenge to tourism. Waste Management & Research, 28 (8), 695–704. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734242X09337655

Klein, R. A. (2011). Responsible cruise tourism: Issues of cruise tourism and sustainability. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 18 (1), 107–118.

Korstanje, M., & George, B. (2020). Demarketing overtourism, the role of educational interventions. In H. Séraphin & A. C. Yallop (Eds.), Overtourism and tourism education (pp. 81–95). Routledge.

Chapter Google Scholar

Laville-Wilson, D. P. (2017). The transformation of an agriculture-based economy to a tourism-based economy: Citizens’ perceived impacts of sustainable tourism development (Doctoral dissertation, South Dakota State University). South Dakota State University Open Prairie. https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd/2262/

Li, Y., & Galea, S. (2020). Racism and the COVID-19 epidemic: Recommendations for health care workers. American Journal of Public Health, 110 (7), 956–957. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2020.305698

Lubin, D. A., & Esty, D. C. (2010). The sustainability imperative. Harvard Business Review, 88 (5), 42–50.

Lyneham, S., & Facchini, L. (2019). Benevolent harm: Orphanages, voluntourism and child sexual exploitation in South-East Asia. Trends & Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice, 574 . Australian Institute of Criminology. https://www.aic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-05/benevolent_harm_orphanages_voluntourism_and_child_sexual_exploitation_in_south-east_asia.pdf

Mackenzie, S., & Goodnow, J. (2020). Adventure in the age of COVID-19: Embracing micro-adventures and locavism in a post-pandemic world. Leisure Sciences, 43 (10), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2020.1773984

MacNeill, T., & Wozniak, D. (2018). The economic, social, and environmental impacts of cruise tourism. Tourism Management, 66 , 387–404.

Mansfield, B. (2009). Sustainability. In N. Castree, D. Demeriff, D. Liverman, & B. Rhoads (Eds.), A companion to environmental geography (pp. 37–49). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444305722.ch3

Mansfeld, Y., & Pizam, A. (2006). Tourism, security and safety . Routledge.

Book Google Scholar

Manzoor, F., Wei, L., Asif, M., Zia ul Haq, M., & Rehman, H. (2019). The contribution of sustainable tourism to economic growth and employment in Pakistan. International Journal of Environmental Research & Public Health, 16 (19), 37–85. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16193785

Mawby, R. I. (2017). Crime and tourism: What the available statistics do or do not tell us. International Journal of Tourism Policy, 7 (2), 81–92. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTP.2017.085292

Miller-Perrin, C., & Wurtele, S. K. (2017). Sex trafficking and the commercial sexual exploitation of children. Women & Therapy, 40 (1–2), 123–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/02703149.2016.1210963

Minooee, A., & Rickman, L. (1999). Infectious diseases on cruise ships. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 29 (4), 737–743.

Murphy, P., & Murphy, A. E. (2004). Strategic management for tourism communities. Channel View Publications.

Nofriya, N. (2018, August 7). Health and safety issues from tourism activities in Bukit Tinggi City, West Sumatra . 13th IEA SEA Meeting and ICPH—SDev. http://conference.fkm.unand.ac.id/index.php/ieasea13/IEA/paper/view/622

Ohlan R., (2017). The relationship between tourism, financial development and economic growth in India. Future Business Journal, 3 (1), 9–22.

Okazaki, E. (2008). A community-based tourism model: Its conception and use. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 16 (5), 511–529. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580802159594

Osland, G. E., Mackoy, R., & McCormick, M. (2017). Perceptions of personal risk in tourists’ destination choices: Nature tours in Mexico. European Journal of Tourism, Hospitality and Recreation, 8 (1), 38–50. https://doi.org/10.1515/ejthr-2017-0002

Person, B., Sy, F., Holton, K., Govert, B., Liang, A., Garza, B., Gould, D., Hickson, M., McDonald, M., Meijer, C., Smith, J., Veto, L., Williams, W., & Zauderer, L. (2004). Fear and stigma: The epidemic within the SARS outbreak. Emerging Infectious Diseases Journal CDC, 10 (2), 358–363. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1002.030750

Peterson, R. R., Harrill, R., & Dipietro, R. B. (2017). Sustainability and resilience in Caribbean tourism economies: A critical inquiry. Tourism Analysis, 22 (3), 407–419. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354217X14955605216131

Petkova, A. T., Koteski, C., Jakovlev, Z., & Mitreva, E. (2012). Sustainability and competitiveness of tourism. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 44 , 221–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.05.023

Qiu, R., Park, J., Li, S., & Song, H. (2020). Social costs of tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic. Annals of Tourism Research, 84, 102994. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102994

Quevedo-Gómez, M. C., Krumeich, A., Abadía-Barrero, C. E., & Van den Borne, H. W. (2020). Social inequalities, sexual tourism and HIV in Cartagena, Colombia: An ethnographic study. BMC Public Health, 20 (1208), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09179-2

Ram, Y. (2021). Me too and tourism: A systematic review. Current Issues in Tourism, 24 (3), 321–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1664423

Ramesh, D. (2002). The economic contribution of tourism in Mauritius. Annals of Tourism Research, 29 (3), 862–865.

Richter, L. K. (2003). International tourism and its global public health consequences. Journal of Travel Research, 41 (4), 340–347. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287503041004002

Rittichainuwat, B. N., & Chakraborty, G. (2009). Perceived travel risks regarding terrorism and disease: The case of Thailand. Tourism Management, 30 (3), 410–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2008.08.001

Robinson, M. (1999). Collaboration and cultural consent: Refocusing sustainable tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 7 (3–4), 379–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669589908667345

Rosselló, J., Santana-Gallego, M., & Awan, W. (2017). Infectious disease risk and international tourism demand. Health Policy and Planning, 32 (4), 538–548. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czw177

Ryan, C., & Kinder, R. (1996). Sex, tourism and sex tourism: Fulfilling similar needs? Tourism Management, 17 (7), 507–518. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(96)00068-4

Schwartz, K. L., & Morris, S. K. (2018). Travel and the spread of drug-resistant bacteria. Current Infectious Disease Reports, 20 (9), Article 29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11908-018-0634-9

Sheller, M. (2004). Natural hedonism: The invention of Caribbean islands as tropical playgrounds. In S. Courtman (Ed.), Beyond the blood, the beach, and the banana : New perspectives in Caribbean studies (pp. 170–185). Ian Randle.

Sönmez, S., Wiitala, J., & Apostolopoulos, Y. (2019). How complex travel, tourism, and transportation networks influence infectious disease movement in a borderless world. In D. J. Timothy (Ed.), Handbook of globalization and tourism (pp. 76–88). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781786431295.00015

Sustainability Accounting Standards Board. (2014). Cruise lines: Sustainability accounting standards . http://www.sasb.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/SV0205_Cruise_ProvisionalStandard.pdf

Telfer, D. (2002). The evolution of tourism and development theory. In R. Sharpley & D. Telfer (Eds.), Tourism and development: Concepts and issues (pp. 35–78). Channel View.

The Caribbean Tourism Organization [CTO]. (2020). Caribbean sustainable tourism policy and development framework . https://caricom.org/documents/10910-cbbnsustainabletourismpolicyframework.pdf

Tolkach, D., & King, B. (2015). Strengthening community-based tourism in a new resource-based island nation: Why and how? Tourism Management, 48 , 386–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.12.013

Tosun, C. (2006). Expected nature of community participation in tourism development. Tourism Management, 27 , 493–504.

UNCTAD. (2020). Coronavirus will cost global tourism at least $1.2 trillion . United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. Retrieved January 6, 2021, from https://unctad.org/news/coronavirus-will-cost-global-tourism-least-12-trillion

UNWTO. (2001). Tourism highlights 2001. World Tourism Organization. Madrid. https://doi.org/10.18111/9789284406845

UNWTO. (2019). United Nations World Tourism Report 2019 . Available at: https://www.eunwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284421152 . Accessed 24 August 2020.

Walker, L., & Page, S. J. (2004). The contribution of tourists and visitors to road traffic accidents: A preliminary analysis of trends and issues for central Scotland. Current Issues in Tourism, 7 (3), 217–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500408667980

Wallen, B. (2020, November 30). Why some countries are opening back up to tourism during a pandemic. National Geographic . https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/article/are-economics-driving-countries-to-reopen-to-tourists-coronavirus

Waterman, T. (2009). Assessing public attitudes and behavior toward tourism development in Barbados: Socio-economic and environmental implications . Central Bank of Barbados.

Wilks, J., Stephen, J., & Moore, F. (2013). Managing tourist health and safety in the new millennium . Routledge.

World Conservation Union. (1996, October 13–23). Resolutions and recommendations [Meeting]. World Conservation Congress, Montreal, Canada. https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/WCC-1st-002.pdf

World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC). (2019). Economic impact reports . https://wttc.org/Research/Economic-Impact

World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC). (2020). 100 million jobs recovery plan: Final Proposal (G20 2020 Saudi Arabia Summit). https://wttc.org/Portals/0/Documents/Reports/2020/100%20Million%20Jobs%20Recovery%20Plan.pdf?ver=2021-02-25-183014-057

Zheng, D., Luo, Q., & Ritchie, B. (2021). Afraid to travel after COVID-19? Self-protection, coping and resilience against pandemic ‘travel fear.’ Tourism Management, 83, 104261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104261

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Hospitality & Tourism Management, College of Business, Tennessee State University, Nashville, TN, USA

David Mc. Arthur Baker

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to David Mc. Arthur Baker .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Jack C. Massey College of Business, Belmont University, Nashville, TN, USA

Colin Cannonier

Western Kentucky University, Bowling Green, KY, USA

Monica Galloway Burke

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Baker, D.M.A. (2022). Caribbean Tourism Development, Sustainability, and Impacts. In: Cannonier, C., Galloway Burke, M. (eds) Contemporary Issues Within Caribbean Economies. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-98865-4_10

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-98865-4_10

Published : 09 June 2022

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-98864-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-98865-4

eBook Packages : Economics and Finance Economics and Finance (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

CTO upbeat about 2023 Caribbean tourism outlook

17th March 2023

The Caribbean Tourism Organisation (CTO) is voicing optimism on the region’s tourism prospects for the remainder of 2023.

Speaking in Barbados during the organisation’s launch of the 2022 “Tourism Performance and Outlook Report,” Acting Secretary General of the CTO, Neil Walters declared that the Caribbean had one of the quickest recovery rates globally.

Some 28.3mn tourists visited the region in 2022, representing 88.6% of pre-pandemic 2019 visitor arrivals. This performance was buoyed by a 28.1% increase in US tourists, reaching 14.6mn compared to the 11.4mn from that market in 2021.

The CTO noted that while travel restrictions imposed by Canada in early 2022 saw a slower 60% recovery, and major declines in intra-regional connectivity impacted the numbers, “arrivals from the European market increased by 81% in 2022 when compared to 2021”. The 5.2mn tourists from this market were almost double the 2.8mn in 2021 accounting for 18.3% of all arrivals in 2022.

The organisation attributed the improvement to shorter travel restrictions, pent-up demand, and surplus savings accrued during the pandemic, as well as “strategic marketing initiatives and the restoration of some of the airlift capacity between more markets and the Caribbean”.

“Nearly 90% of the region’s travel demand for 2019 has already been recovered,” said Walters, adding that destinations such as Curaçao, the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Sint Maarten, Turks and Caicos, and the US Virgin Islands had already surpassed their pre-pandemic performance. All 27 Caribbean destinations showed an increase in annual stayover arrivals of between 8.3% and 16%.

Revenue in the sector was also up in 2022. Global data company STR reported that the average daily rate at hotels increased by 21.7% to US$290.60 in 2022 on the strength of an uptick in revenue per available room by 66.4% to US$176.46. The number of available rooms also increased by 4.4% while room income jumped by 73.6%.

All told, data estimates that visitors to the Caribbean region spent between US$36.5bn and $37.5bn in 2022, a significant increase of 70% to 75% when compared to 2021. “As a region, we have responded with hope, strength and the determination to prevail,” said CTO Council of Ministers and Commissioners Chairman and Cayman Islands’ Minister of Tourism and Transport, Kenneth Bryan.

“So, although we have not yet surpassed 2019’s numbers across the board in every jurisdiction, the needle is certainly moving in the right direction,” said Bryan as he voiced optimism about 2023.

The CTO expects that this year, the region will record a 10% to 15% bump in arrivals over its record performance in 2019, when the region welcomed 32mn land-based visitors. “This means that between 31.2 and 32.6 million tourists can be expected to visit the region this year,” said Acting Secretary General Walters.

Prospects for cruise tourism are also on the mend. “All berths in the region have reopened and are expanding. As more ships are deployed to the region, the capacity for cruises will rise and demand will stay high,” predicted Walters. He revealed that estimates put cruise tourists visiting the Caribbean in 2023 at between 32mn and 33mn, an overall increase of 5% to 10% over the pre-COVID-19 baseline.

To ensure continued recovery, the CTO said that it is focused on growing its membership, including countries, territories as well as allied partners.

“It is also my intention to strengthen the relationships with other organizations, such as the United Nations World Travel Organization, the World Travel and Tourism Council, and even the Central American Tourism Promotion Agency (CATA), to foster greater collaboration,” said Chairman Bryan, announcing the return of CTO’s Caribbean Week in New York from 5 to 8 June this year.

Bryan confirmed that consideration is being given to the restructuring of the organisation and reforming its strategic vision and direction for the next five years, which includes the appointment of a new Secretary General and addressing the vexing issue of regional air connectivity.

“It would be illogical for me to promise a solution to this issue during my tenure as chairman. But what I can and will commit to is getting the players around the table to forensically examine what we need to do as a unified region to improve this scenario and start the ball rolling towards the solution,” promised the CTO Chairman.

This is a lead article from Caribbean Insight, The Caribbean Council’s flagship fortnightly publication. From The Bahamas to French Guiana, each edition consists of country-by-country analysis of the leading news stories of consequence, distilling business and political developments across the Caribbean into a single must-read publication. Please follow the links on the right-hand side of this page to subscribe, or access a free trial .

Proud Supporters of

Follow Us on Social Media

Caribbean Tourism: Strong Growth in 2023 and Beyond

BRIDGETOWN, Barbados – Continuing its positive recovery trend, Caribbean tourism grew in 2023 with an estimated 14.3% increase in international stay-over arrivals to the region, the Caribbean Tourism Organization (CTO) has reported.

Delivering the “Caribbean Tourism Performance Review 2023” in Bridgetown today, Dona Regis-Prosper, Secretary-General of the CTO, shared that last year’s growth was in line with CTO’s forecast for the year, and attributed the outcome to sustained demand for outbound travel from the United States – the Caribbean’s main source market, enhanced tourism-related infrastructure within the destinations, the fulfillment of strategic marketing initiatives, and augmented airlift capacity between the region and its source markets, albeit unevenly distributed among the destinations.

The recovery of global tourism has been resilient, despite variability in the regional performances, according to Regis-Prosper, with the Caribbean surpassing pre-pandemic arrivals by a modest 0.8%, outperforming most of the main global regions in terms of recovery.

Arrival levels amongst Caribbean destinations either significantly recovered or moderately exceeded the benchmark numbers of 2019, with 11 destinations, Anguilla, Aruba, Curaçao, Dominican Republic, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, Puerto Rico, St. Maarten, Turks & Caicos Islands, and U.S. Virgin Islands performing better than in 2019. The majority of those recovered greater than 50% of their 2019 arrivals. In addition, multiple destinations registered new record levels for tourist arrivals in a single year.

United States and Canada Markets

For the Caribbean, only the U.S. market has fully recovered, while the recovery rates of arrivals from Europe and Canada reached 88.2% and 88.1%, respectively. An estimated 16.3 million stay-over arrivals to the region came from the United States, representing an annual growth rate of 12.7%. The performance here established a new record level of arrivals from this market and surpassed the pre-pandemic arrivals by 4.2%. The performance of the Canadian market resulted in an estimated three million Canadian tourist visits by the end of the year, an increase of 46.1% compared to 2022. Increased air service from major Canadian cities to Caribbean destinations played a pivotal role in driving up visitor numbers.

Europe, Caribbean and South America Markets

Regis-Prosper noted that arrivals from Europe to the Caribbean region were stagnant in 2023. A total of approximately 5.2 million trips originated from the market. In 2023, travel among Caribbean residents to destinations within the region increased by approximately 3.6%, a total of 1.6 million trips, which was 0.3 million more compared to 2022. This also indicated a recovery of 62.5% from pre-pandemic levels. “Despite this positive outcome, intra-regional travel remained expensive due to fragmented air service and reduced air capacity,” said Regis-Prosper. By the end of the year, trips from South America to the region surged by an estimated 14%, totaling 1.7 million trips.

Caribbean Hotel Performance

The Caribbean hotel sector experienced a remarkable turnaround in 2023, including a surge in the establishment of new hotels and resorts. According to STR, throughout the Caribbean, average room occupancy grew to 65.6% in 2023 from 61% in 2022. The average daily rate (ADR) experienced a considerable increase of 11.8% with the region’s ADR reaching US$329.37 while the revenue per available room (RevPAR) jumped 20.2% to US$215.97.

Cruise Tourism Performance

Projections indicate that the cruise sector will continue its upward track, with an estimated 34.2 million to 35.8 million cruise visits expected in the Caribbean in 2024. This anticipated expansion falls within the range of 10% and 15%.

Remarkable Resilience

Chairman of the Caribbean Tourism Organization’s Council of Ministers and Commissioners of Tourism, Kenneth Bryan, who also serves as the Cayman Islands’ Minister of Tourism and Ports, noted the remarkable resilience of the tourism industry and its ongoing recovery and growth in 2023. However, he emphasized that the industry and the region will continue to face an array of challenges, including the high cost of travel, ongoing conflicts, heightened geopolitical tensions, and their anticipated impacts, in 2024.

CTO Chairman Hon. Kenneth Bryan “Caribbean destinations remain adaptable and responsive, and the region is still highly desired by travelers for its safety and diversity of tourism products,” stated Chairman Bryan, adding that the region will also be positively impacted by key developments in 2024, including increased air capacity throughout the year, which will facilitate greater access between the destinations and some of their legacy and emerging markets.

Chairman Bryan also pointed to “intensive strategic marketing initiatives” that are being executed to attract visitors to the region to enjoy its culture and heritage, including its carnivals and festivals.

He noted that the CTO is pleased that the ICC (International Cricket Council) Men’s T20 World Cup 2024 is being hosted in several destinations bringing not only teams but also their loyal followers to the region and further raising awareness and promoting the diverse offerings of Caribbean destinations to global audiences.

“Hence, the Caribbean’s prospects appear highly promising, with more regional destinations poised to either match or surpass the arrival figures recorded in 2019. Anticipated growth is forecast to range between five percent and 10 percent, potentially welcoming between 33.8 million and 35.4 million stay-over tourists,” concluded Chairman Bryan.

South Florida Caribbean News

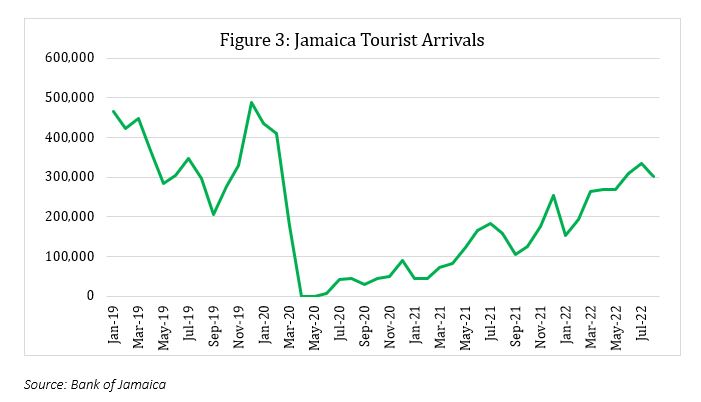

Related articles, 11 per cent growth in visitor arrivals in jamaica, how to prepare all the important documentation for your next trip, jamaica lifts uk travel ban starting may 1, jamaica tourist board partners with island expert travel for peek at paradise travel show in orlando.

The World Bank in the Caribbean

The Caribbean is a diverse region with significant economic potential and growth opportunities. However, the region is extremely vulnerable to natural hazards, and is facing severe economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Cayman Islands (U.K.)

- Curaçao (Netherlands)

- Antigua and Barbuda

- Saint Kitts and Nevis

- Saint Lucia

- Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

- Sint Maarten

- Trinidad and Tobago

- Turks and Caicos

Last Updated: Apr 14, 2023

As of April 2021, World Bank portfolio in the Caribbean (excluding the Dominican Republic ) totals US$2.6 billion in IBRD, IDA, and trust fund financing for 72 projects. In Sint Maarten , the World Bank manages the reconstruction and resilience trust fund financed by the Netherlands.

At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the World Bank worked with Caribbean countries to mobilize rapid financing for health, social protection, and food security crisis response, using a variety of financing instruments. The next phase of support focuses on green, inclusive, resilient recovery measures, including strengthening social protection, reactivating economic activity, facilitating small and medium businesses, adapting to climate change, financial protection from disasters, improved debt management, and improved macro-fiscal sustainability. The World Bank assisted program remains anchored in supporting cross-cutting resilience building and climate change adaptation and mitigation, with technical assistance and investments in human capital development, fiscal sustainability, digital transformation, financial protection and disaster risk management, agriculture, renewable energy, and the blue economy. Details on the World Bank’s support to the Caribbean during the COVID-19 crisis are available in this factsheet .

The World Bank Group’s strategy in the Caribbean focuses on building cross-cutting “360-degree” resilience across four dimensions:

Human Capital Resilience

- The World Bank is supporting the Caribbean to build human capital and strengthen the resilience of health, education, and social protection systems. The World Bank has been working with Caribbean countries to enhance the preparedness of their health systems for pandemics as well as natural disasters; to improve the quality of education and health services; and to improve the coverage and targeting of social safety nets.

- In response to COVID-19, the Bank has provided rapid financing for the health response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Financing comes from the global COVID-19 Fast Track Facility, contingent financing mechanisms like Cat DDOs, development policy financing, and reallocation of existing project resources to provide immediate support. This funding for the pandemic response has helped countries procure needed supplies to detect, contain, and treat COVID-19, strengthen health systems, and expand social protection for vulnerable groups. The Bank has also provided technical assistance and project support to enhance e-learning during COVID-19 lockdowns.

- The World Bank is supporting stronger social protection systems including improving the coverage and targeting of safety nets, and through adaptive safety nets, ensuring recovery measures reach those who need them most. The World Bank is also supporting emergency social assistance programs for those who have lost jobs or been pushed into poverty due to the pandemic but are not covered by other poverty-related programs. This is particularly important as tourism, a major source of jobs and income for the Caribbean, is at a standstill.

Fiscal and Financial Resilience

- The World Bank is supporting countries in the Caribbean to strengthen their fiscal frameworks and build buffers to contain the impact of shocks through improved macro-fiscal policies, enhanced debt management, and better public financial management.

- The World Bank is supporting Caribbean countries to diversify their economies and facilitate private sector participation and especially access to finance for micro and small enterprises. The World Bank works with countries to improve the regulatory environment for private sector investments, and for financial inclusion and increased access to finance. With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Bank has been supporting countries through budget support operations, to sustain small and medium enterprises, especially in tourism-related activities, and facilitate an inclusive and resilient recovery.

- Innovative disaster risk financing mechanisms are supporting greater fiscal resilience for Caribbean economies. The Caribbean Catastrophe Risk Insurance Facility (CCRIF) is a parametric insurance facility that provides quick, short term liquidity in the event of a disaster. Since its inception, CCRIF has made payouts totaling US$197 million.

Physical and Infrastructure Resilience

- The World Bank is supporting countries in the region to strengthen preparedness including through early warning systems and projects to mitigate disaster vulnerability risks.

- The World Bank is supporting increased physical resilience through ‘Build Back Better’ principles, which are essential to reduce the economic cost of disasters and to ensure that key infrastructure and services can withstand the next storm. Infrastructure works are also generating much-needed jobs for communities during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- New engagement in transport and digital transformation is supporting increased connectivity in the Caribbean. The critical importance of digital connectivity has been highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Environment and Natural Resource Resilience

- The World Bank is helping countries in the Caribbean to develop the Blue Economy, pursue economic diversification through sustainable use of ocean resources, protect marine areas, reduce marine pollution, and repopulate coral reefs. Support is being provided for sustainable agricultural practices to boost incomes for small and medium businesses while decreasing deforestation and forest degradation. Technical assistance on nationally determined contributions (NDCs) and climate change strategies is also a core part of the World Bank’s engagement.

Last Updated: Apr 22, 2021

Natural disasters in the Caribbean region have become increasingly intense in the face of climate change. The World Bank engagement in the Caribbean has achieved these results:

- The Caribbean Catastrophe Risk Insurance Facility (CCRIF), developed under the technical leadership of the World Bank and with a grant from the Government of Japan has allowed payouts to several Caribbean countries after Hurricanes Dorian, Irma and Maria. The Caribbean Oceans and Aquaculture Sustainability Facility (COAST), is an innovative parametric insurance product developed under CCRIF specifically for fisherfolk in the Caribbean (Grenada and Saint Lucia).

- A financial package of more than US$100 million was provided for Dominica, including through the IDA crisis response window after Hurricane Irma in 2017. Contingent credit lines, known as a Cat-DDOs, were approved in 2020 for Saint Vincent and the Grenadines and Grenada, to be disbursed during a national emergency. Two days after the eruption of the La Soufrière volcano in Saint Vincent, the World Bank disbursed the US$20 million Cat-DDO to support the response to the crisis, the first large financial assistance provided to the country following the eruption.

- There are projects to support climate resilience and enhance disaster preparedness and emergency response on the islands of Dominica, Grenada, Saint Lucia, and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines. The focus is on making infrastructure more adaptable to extreme weather events and natural disasters and improving government capacity to handle disaster risks.

- In Surinam, the Saramacca Canal System Rehabilitation Project aims to support the country to reduce flood risk in the greater Paramaribo area and improve the Saramacca Canal System. It will improve the resilience against flooding by improving the ability of the Saramacca Canal to discharge water efficiently and safely, improving vessel transport, and strengthening the government’s capacity to manage and operate the canal’s drainage system.

The Blue Economy

Harnessing marine resources while preserving the Caribbean Sea can help countries address key challenges such as high unemployment, low growth, food security, poverty, and resilience to climate change.

The World Bank report “Toward a Blue Economy: A Promise for Sustainable Growth in the Caribbean” estimates that the Caribbean Sea (including mainland Caribbean coastal countries) generated US$407 billion in 2012.

Ongoing World Bank support to building environment and natural resource resilience in the Caribbean includes:

- Banning of single-use plastics and/or Styrofoam containers across the OECS;

- Creating an insurance mechanism to include the fisheries sector in Grenada and Saint Lucia;

- Building sustainable agriculture practices and competitiveness in Jamaica, Haiti, and the OECS;

- Expanding marine protected areas in Belize and strengthening protection and climate resilience of the Belize Barrier Reef;

- Preparation of a new regional blue economy project in the Eastern Caribbean to strengthen management and resilience of marine and coastal assets.

Macroeconomic and Fiscal Sustainability

The World Bank Group is working with Caribbean governments and regional partners to help Caribbean countries better manage public spending and reduce their debts to sustainable levels, while protecting poor and vulnerable populations.

- The World Bank provided Development Policy Financing to Jamaica, Dominica, Grenada, and Saint Lucia to support reforms to support the COVID-19 response and recovery.

- The World Bank is supporting Jamaica’s ambitious reforms to strengthen fiscal sustainability and inclusion, enhance fiscal and financial resilience against climate and natural disaster risks,

- In Grenada, a series of budget support operations helped private investment, improved public resource management and boosted resilience against natural disasters.

The WBG has worked with regional partners to help Caribbean countries facilitate the private sector and trade reforms, while supporting jobs and protecting poor and vulnerable populations.

- The World Bank Group is helping improve Jamaica’s competitiveness by facilitating the growth of new and existing businesses. This includes technical assistance for public-private partnerships, ranging from airports to ports, economic zones, water generation, wastewater and sewage, schools, and renewable energy.

- The World Bank Group is mobilizing private capital for strategic investments and seeking to more fully integrate Jamaica’s small and medium enterprises (SMEs) into global value chains.

- The World Bank Group is supporting diversification of the region’s power sector by increasing the production of renewables and other clean energy sources. In the Eastern Caribbean, this involves the use of commercial-scale solar photovoltaic systems on rooftops in Saint Lucia, Grenada, and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines.

- The Entrepreneurship Program for Innovation in the Caribbean (EPIC), with support from the government of Canada, has provided tailored business development support and training to more than 2,100 entrepreneurs across sectors, including in digital and climate technologies. It has also facilitated more than US$4 million in investments raised by Caribbean entrepreneurs.

- In Jamaica, the Youth Employment in Digital & Animation Industries Project is building on successful pilots in the Digital Jam and KingstOOn events, with more than 4,000 young Jamaicans engaged in digital enterprises, supporting the growth of the Jamaican animation training and industry.

- The World Bank is supporting digital development to help diversify growth and improve public services. Digital projects are underway in the Eastern Caribbean, Haiti, and Sint Maarten.

- The World Bank is promoting governance, good international practices, and sector diversification through the Suriname Competitiveness and Sector Diversification Project . By focusing on policy, legal, and regulatory reforms in the mining, agribusiness, and tourism industries, the investment will enable private sector growth opportunities, boost job creation, and benefit more than 200 small and medium enterprises. The project is also building the capacity of key institutions and enhancing business development services.

Human Capital, Inclusion and opportunities for all

Quality education, affordable health care, and equitable social safety nets are key ingredients in building inclusive societies. In the Caribbean, several countries have launched innovative efforts to provide the most vulnerable, including children, with the knowledge, skills, and health they need to excel.

- Jamaica’s comprehensive National Strategic Plan for early childhood development is the first of its kind in the region. Jamaica is one of the few countries in the region that guarantees free pre-primary education and has the highest proportion of children enrolled in preschool. The World Bank supported the scaling-up of early childhood development services to help improve parenting, care, and school readiness for children from birth to six years of age, and to provide diagnosis and early stimulation for children at risk.

- In Guyana, the World Bank has provided long-standing support in the area of education spanning from early childhood to primary and secondary education, all the way to the University of Guyana. Curricula reform and research programs have included significant contributions from the main indigenous groups.

- In Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, support was provided to help 13,000 students and 2,000 teachers adapt to schooling during the COVID-19 outbreak. The World Bank worked with the Government to develop a COVID-19 Action Plan to guide safe reopening. School safety assessment and disaster plans were also revised to ensure that schooling could resume as soon as possible after an emergency.

- In 2021, the Bank adjusted its program to support COVID-19 response and recovery in OECS countries. The program in the region had a strong focus on building cross-cutting resilience across the fiscal/financial, infrastructure, human capital, and environmental dimensions. Hence, the active portfolio was already well placed to respond to the pandemic response priorities, including through the activation of Contingency Emergency Response Components (CERCs). Moreover, the Bank reprioritized the IDA program to support COVID-19 response and recovery, closely aligned with the Bank’s COVID-19 Crisis Response Approach on “Saving Lives, Scaling-up Impact and Getting Back on Track”.

- In Haiti, the World Bank supported improved nutrition through the provision of 5,100,000 school meals were provided to 170 public 60 community schools during the 2019-2020 school year. During the school closures caused by the COVID-19 pandemic for the months April-June 2020, 62,000 take-home food rations were provided to 82,000 students in 230 projects supported schools.

- Through a series of projects in the health sector, the World Bank has supported Haiti to contain the outbreak of cholera, through mobile rapid response teams, community-based support, and increased capacity for disease surveillance. There have been no new laboratory-confirmed cases of cholera since January 2019.

Last Updated: Oct 19, 2022

Haitian school children attend school for free, as part of the Bank's support to the Education for All project.

- Show More +

- Suriname Country Partnership Strategy

- Suriname Performance and Learning Review

- Show Less -

AROUND THE BANK GROUP

Find out what the Bank Group's branches are doing in the Caribbean.

STAY CONNECTED

Brochure: Inside the Caribbean

Learn about our work in the Caribbean

Towards a Blue Economy

A promise for sustainable growth in the Caribbean

Marine Pollution in the Caribbean: Not a Minute to Waste

Report Calls for Urgent Action to Tackle Marine Pollution, A Growing Threat to the Caribbean Sea

Open and Nimble

Finding Stable Growth in Small Economies

Additional Resources

Country office contacts.

This site uses cookies to optimize functionality and give you the best possible experience. If you continue to navigate this website beyond this page, cookies will be placed on your browser. To learn more about cookies, click here .

Promoting Sustainable Development through Tourism in the Caribbean

Adam ratzlaff, alejandro trenchi.

Photo by makenzie cooper on Unsplash

December 7, 2023

The Caribbean is reliant on tourism to keep the regional economy growing, but the cruise industry reaps most of the benefits and reliance on tourism also makes the region vulnerable to climate impacts. These are problems that can solve one another, write Alejandro Trenchi and Adam Ratzlaff.

N Secretary General António Guterres has called the Caribbean Basin “ ground zero ” for the impacts of climate change. While countries in the region have a relatively small carbon footprint , the Caribbean will feel the impacts of climate change more acutely than other regions—particularly in the short term. At the same time, regional economies are heavily dependent on the tourism industry, which are also dependent on the Caribbean as part of their business model. Rethinking how tourism is conducted in the Caribbean and developing public-private partnerships will not only strengthen resilience critical for Caribbean nations and the tourism industry, but also support sustained economic development.

With stunning scenery, pleasant tropical weather, rich cultural heritages, and proximity to the North American market, tourism represents a significant and lucrative economic sector for the Caribbean. The decline of the Caribbean’s agriculture industry in the 1980s prompted tourism to become the region’s undisputed economic driver. While in 1970 the region received roughly 4 million visitors, it now receives approximately 28 million visitors annually. Today, tourism accounts for 13.9% of the regional GDP as well as 15% of regional employment.

Despite the importance of tourism to the regional economy and the growth in the number of visitors, the impact of growing tourism in the region has declined as the relative importance of the cruise industry in the region has expanded. According to the Caribbean Development Bank, while real tourist expenditure grew from $6.8 billion in 1989 to $13.1 billion in 2014, the average expenditure per visitor declined by 30.1%. Some of this is due to the growth of the cruise industry in the region. While a long-stay tourist spends approximately one week in their destination, a cruise passenger only stays one day in the country of arrival—with many choosing to stay aboard the ship. On average, a cruise ship tourist spends 94% less than a long-stay tourist. The result is fewer economic opportunities for local economies.

The Caribbean’s Climate Vulnerability

This reliance on tourism makes the Caribbean extremely vulnerable to external shocks, raising doubts about the region’s ability to provide long-term, sustained economic growth. While the region’s economy shrank as a result of both the 2008 financial crisis and COVID -19, the region is particularly susceptible to climate change and natural disasters—particularly hurricanes which have devastated regional economies. Scientists expect that more devastating hurricanes, droughts, heat waves, and other climate change-related events will pose increasing threats to the region. The danger of climate change and worsening natural disasters is not only a problem for the governments and peoples of the Caribbean but also for the private sector. Companies will face greater risks and may lose out on important business. The threat of more devastating hurricanes as well as biodiversity loss poses significant concerns for the profitability of Caribbean tourism. Extreme weather events and pollution endangers the region’s most valued tourism assets such as coral reefs, beaches, and tourism infrastructure including ports.

Given these concerns, it is vital for the private sector to engage with regional governments to strengthen climate resilience and climate-proof their businesses. While this should be done across the private sector, the cruise industry should play a leading role in supporting these efforts given that the Caribbean represents approximately 43% and 46.7% of total cruise passengers in 2019 and 2022, respectively. While cruise lines note that they have taken important steps, more can be done.

One way that governments and the cruise industry can collaborate to develop public-private partnerships is to increase the amount of time that cruise ships spend in port rather than traveling between destinations. By leveraging the positions of cruise ships as portable hotels, cruise lines can encourage individuals to arrive via alternative means and provide the opportunity for guests to spend greater time on location.

The Caribbean remains among the world’s most indebted regions—with an average public debt to GDP ratio of 90.8% in 2021. In addition to its high debt, the region’s middle-income status places further structural constraints both in terms of financial and human capacity to boost resilience and economic growth, and policy makers need to implement innovative solutions to not only boost the tourism industry’s resilience, but increase its competitiveness and secure long-term inclusive economic growth. Cruise lines can leverage their access to international finance to develop public-private partnerships that invest in key infrastructure.

While climate change represents an existential threat, there is a window of opportunity to reimagine how tourism works in the Caribbean with an eye toward a more profitable, sustainable, and equitable future. Looking for partnerships between Caribbean governments and the cruise sector may provide an important space to ensure more equitable development in the Caribbean while also ensuring that the cruise industry does not lose its most valuable asset—the locations of its cruises.

Editors’ Note: This article was included in our COP 28 special edition, which was published on November 21, 2023, and which you can find here . All articles were written with that publication time frame in mind.

a global affairs media network

www.diplomaticourier.com

Sustaining youth climate activism at COP and beyond

The resilience and potential of nuclear energy, addressing institutional weaknesses in climate–vulnerable south asia, newsletter signup.

- Fitch Solutions

CreditSights

Fitch learning, fitch ratings research & data, sustainable fitch.

- BMI Platform

- BMI Geoquant

- Fitch Connect

Caribbean Tourism Growth To Decelerate In 2024, Weighing On Regional Economies

Country Risk / Caribbean / Mon 18 Sep, 2023

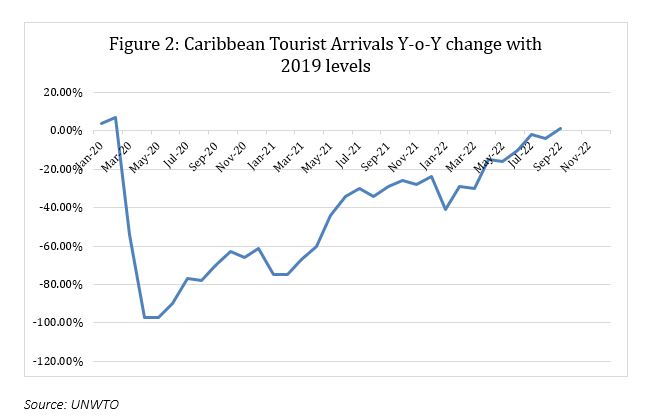

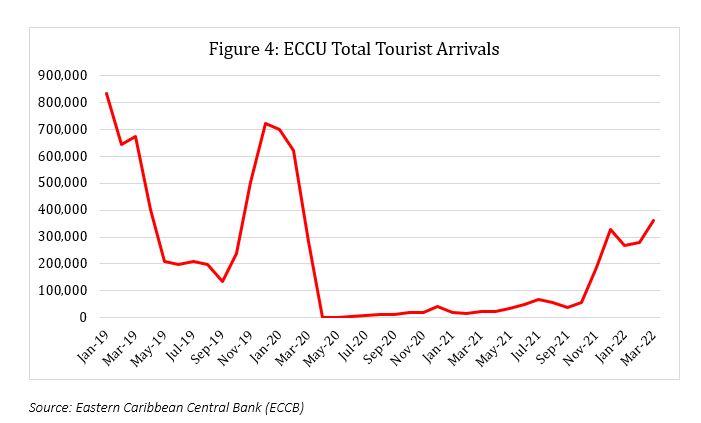

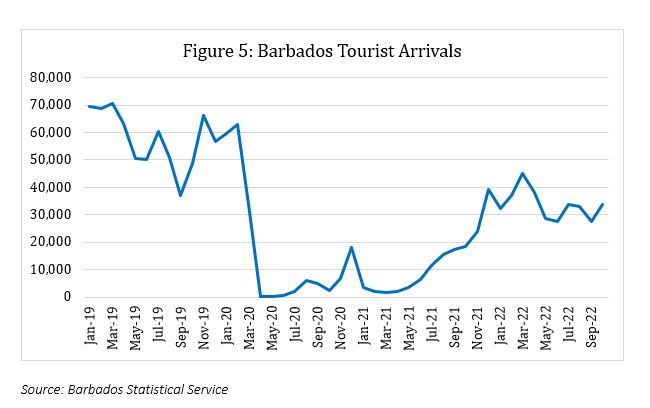

- We are expecting growth in the Caribbean region to slow in 2024, after experiencing a solid two-and-a-half years of growth after the end of Covid lockdowns.

- The expected recession in the United States beginning in Q224 will lower demand for Caribbean tourism, dragging down growth across the region.

- Past 2024, we expect a rebound driven in part by the tourism recovery, and see regional growth at approximately 2.4% (2023-2028).

We are expecting growth in the Caribbean region to slow in 2024, after experiencing a solid two-and-a-half years of growth after Covid lockdowns were lifted. As the United States economy slows down in Q224 , we expect a slowdown in demand for Caribbean tourism from the US consumer. This in turn will drive down growth across the region, as US tourism is a major driver of growth in most markets. The charts below show our expectations for a region-wide slowdown from 2.2% in 2023 to 1.7% in 2024. As we expect the US recession to be short and relatively mild, we see growth in the region rebounding to 2.3% in 2025, above the pre-Covid average of 1.7% (2015-2019).

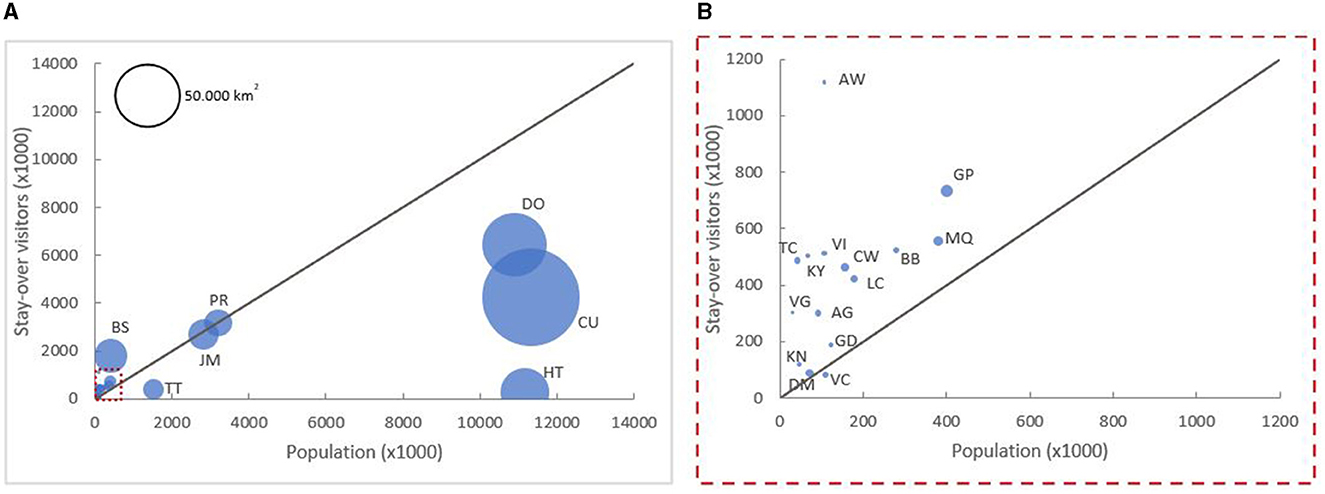

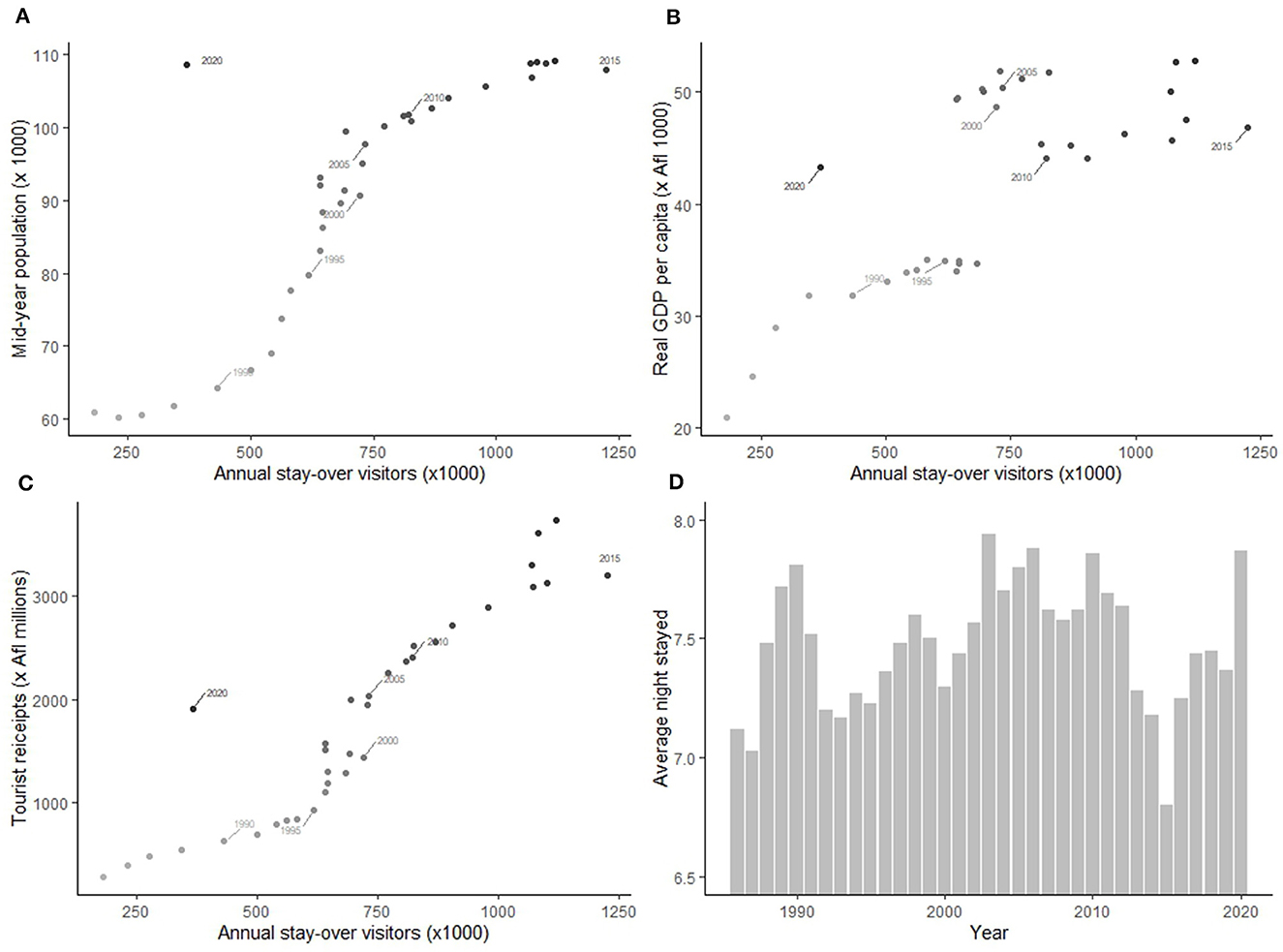

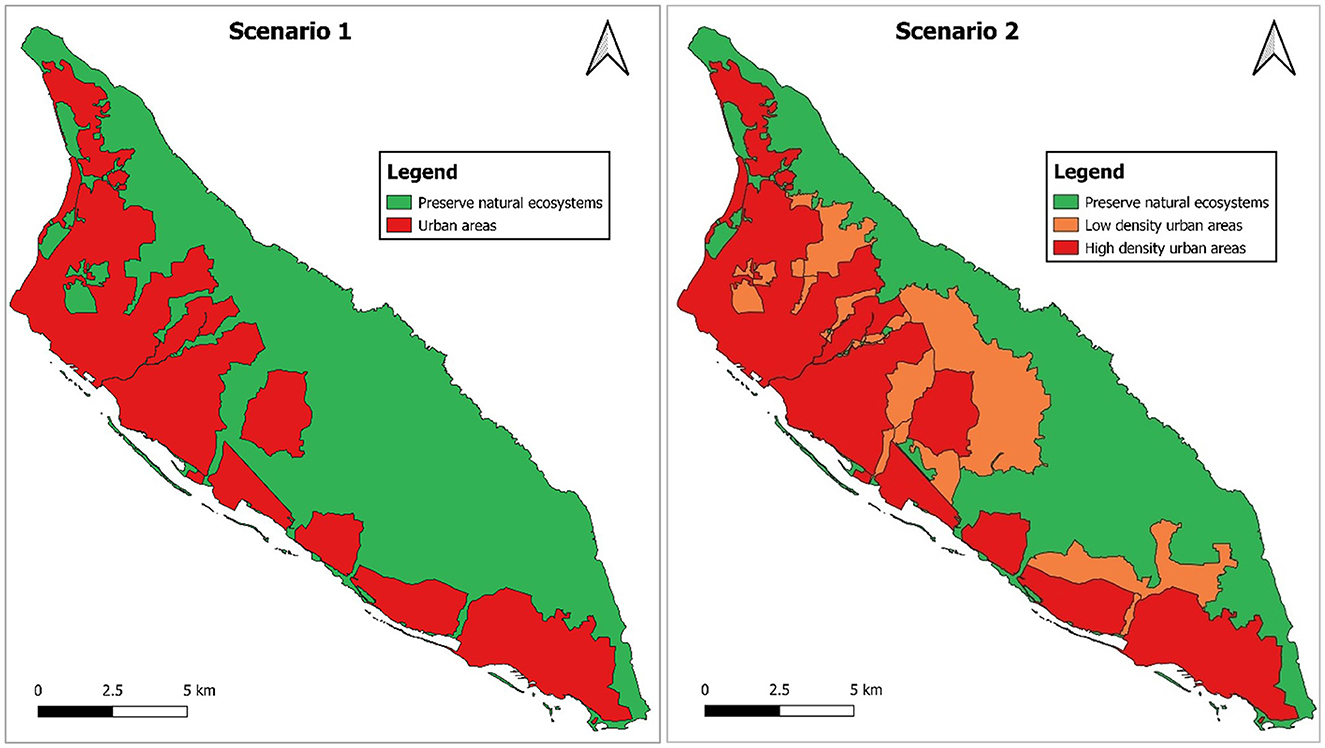

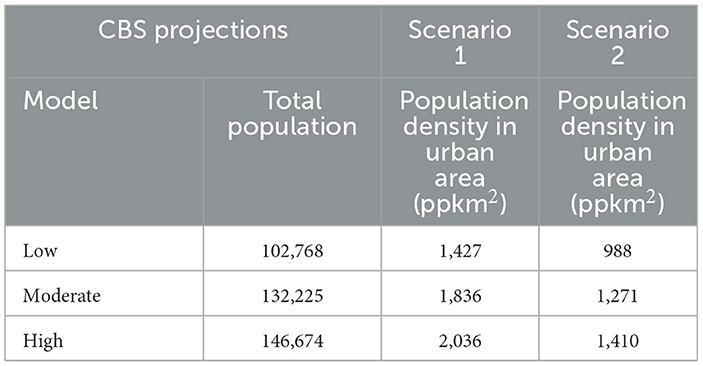

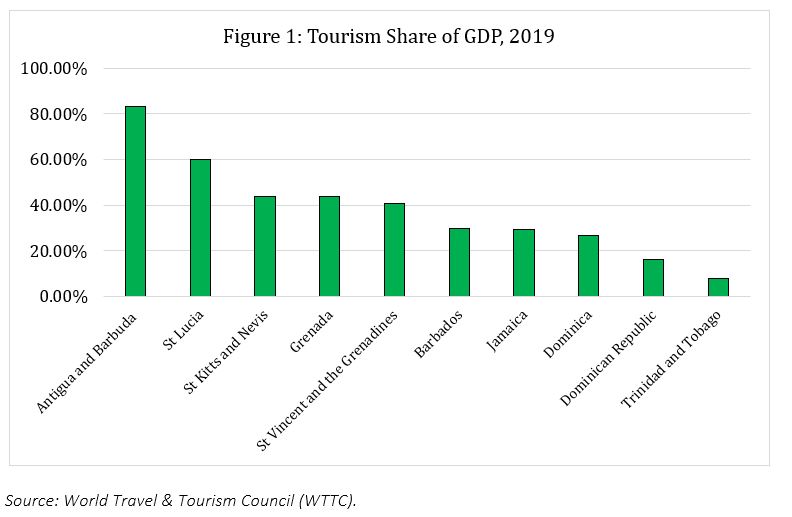

Historically, tourism has been a major contributor to the GDP of Caribbean economies. As of 2021, Statista reported that travel and tourism brought in USD39.3bn towards Caribbean GDP, approximately 12.5% of overall Caribbean GDP, with the largest tourism markets being the Dominican Republic, followed by Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Bahamas, Jamaica and Aruba. We note that this 12.5% figure is dragged down somewhat by the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico, with smaller markets being much more reliant on tourism. For example, before the pandemic tourism made up 67.9% of GDP in Aruba, 42.5% in the Bahamas and 29.1% in Jamaica compared to 15.9% in the Dominican Republic, 9.9% in Cuba and 5.6% in Puerto Rico ( see chart below ). The strong reliance on tourism makes these markets exceptionally vulnerable to any shocks, as was clearly demonstrated in 2020-21. While these figures dropped during the lockdown period, we expect these proportions to stay near historical norms in the next few years – with the exception of Cuba, which will likely not see a tourism rebound due to severe structural challenges.

Beyond the six largest markets mentioned above, we want to highlight that some of the smallest island economies in the regions, such as those belonging to the Organisation Of Eastern Caribbean States, are even more reliant on tourism, with travel and tourism contributing more than 40.0% of GDP in places like Antigua and Barbuda, St. Lucia, Anguilla, the British Virgin Islands, St. Kitts and Nevis and Grenada. This makes them even more vulnerable to disruptions such as US economic downturns, hurricanes, recessions and pandemics.

Caribbean Region Vulnerable To Disruptions To Growth From Vital Tourism Sector

Caribbean – % contribution to gdp from travel and tourism sector (2019).

During the post-pandemic period we have seen an uneven recovery with strong travel rebounds in some countries and slower tourism growth in others, with most seeing peak arrivals in 2022. Even as tourism has generally returned to pre-pandemic levels, in the last few months we have seen either a tapering off or a reduction of new arrivals. This has been the case even as airline fares came off historic highs ( see chart below ).

Airline Fares Off Historic Highs In Q223

Us – consumer price index growth, % y-o-y, airline fares in u.s. city, average.

The map and chart below show the percent change in arrivals in Q223 compared to the same period in 2019, and indicate a mixed recovery. We expect the picture to deteriorate as we move into 2024. We want to note that there are a variety of factors for the variance in rebound rates. Some Caribbean islands are easier to access from the US and other major tourism markets, some had Covid lockdowns for longer, and yet others have internal problems such as crime or political protests (in the case of Cuba). In the months ahead, we expect to see slower demand from the US consumer across the board, as the US economy begins shedding jobs.

Currently, among the largest tourism markets the Dominican Republic had the healthiest recovery of the major markets with arrivals at 17.0% above pre-Covid levels as of Q223 ( see chart and map below) , surpassing 700,000 arrivals in July 2023 alone. The country is on track for its highest-ever total of annual visitors, benefiting from relatively inexpensive all-inclusive resorts that are easily accessible from the United States.

Post-Covid Caribbean Tourism Recovery Peaked In 2022

Caribbean – arrivals compared to the period level in 2019 (% change).

Aruba likewise saw very strong growth with arrivals up 16.0% from 2019 due to a healthy influx of US and European tourists. Meanwhile, at 4.0% above 2019 levels, Puerto Rico (which only has data through end-2022) is lagging behind its peers. Although tourism makes up only a relatively small percentage of Puerto Rican GDP, it remains a very popular destination for US visitors, as it does not require a passport and has multiple accessible flights. Much like the Dominican Republic, we expect this will leave it particularly exposed to the US’s 2024 slowdown. Aruba, by contrast, may not see the same level of slowdown as it receives a sizeable proportion of tourists from outside of the United States.