10 Facts About Pirates

Library of Congress / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

- Caribbean History

- History Before Columbus

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Central American History

- South American History

- Mexican History

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

- Ph.D., Spanish, Ohio State University

- M.A., Spanish, University of Montana

- B.A., Spanish, Penn State University

The so-called “Golden Age of Piracy” lasted from about 1700 to 1725. During this time, thousands of people turned to piracy as a way to make a living. It is known as the “Golden Age” because conditions were perfect for pirates to flourish, and many of the individuals we associate with piracy, such as Blackbeard , “Calico Jack” Rackham , and “Black Bart” Roberts , were active during this time. Here are 10 things you maybe did not know about these ruthless sea bandits.

Pirates Rarely Buried Treasure

Some pirates buried treasure—most notably Captain William Kidd , who was at the time heading to New York to turn himself in and try to clear his name—but most never did. There were reasons for this. First of all, most of the loot gathered after a raid or attack was quickly divided up among the crew, who would rather spend it than bury it. Secondly, much of the “treasure” consisted of perishable goods like fabric, cocoa, food, or other things that would quickly become ruined if buried. The persistence of this legend is partly due to the popularity of the classic novel “Treasure Island,” which includes a hunt for buried pirate treasure .

Their Careers Didn't Last Long

Most pirates didn’t last very long. It was a tough line of work: many were killed or injured in battle or in fights amongst themselves, and medical facilities were usually non-existent. Even the most famous pirates , such as Blackbeard or Bartholomew Roberts, only were active in piracy for a couple of years. Roberts, who had a successful career as a pirate , was only active from 1719 to 1722.

They Had Rules and Regulations

If all you ever did was watch pirate movies, you’d think that being a pirate was easy: no rules other than to attack rich Spanish galleons, drink rum and swing around in the rigging. In reality, most pirate crews had a code that all members were required to acknowledge or sign. These rules included punishments for lying, stealing, or fighting on board. Pirates took these articles very seriously and punishments could be severe.

They Didn't Walk the Plank

Sorry, but this one is another myth. There are a couple of tales of pirates walking the plank well after the “Golden Age” ended, but little evidence to suggest that this was a common punishment before then. Not that pirates didn’t have effective punishments, mind you. Pirates who committed an infraction could be marooned on an island, whipped, or even “keel-hauled,” a vicious punishment in which a pirate was tied to a rope and then thrown overboard: he was then dragged down one side of the ship, under the vessel, over the keel and then back up the other side. Ship bottoms were usually covered with barnacles, which often resulted in very serious injuries in these situations.

A Good Pirate Ship Had Good Officers

A pirate ship was more than a boatload of thieves, killers, and rascals. A good ship was a well-run machine, with officers and a clear division of labor. The captain decided where to go and when, and which enemy ships to attack. He also had absolute command during battle. The quartermaster oversaw the ship’s operations and divided up the loot. There were other positions, including boatswain, carpenter, cooper, gunner, and navigator. Success on a pirate ship depended on these men carrying out their tasks efficiently and supervising those under their command.

The Pirates Didn't Limit Themselves to the Caribbean

The Caribbean was a great place for pirates: there was little or no law, there were plenty of uninhabited islands for hideouts, and many merchant vessels passed through. But the pirates of the “Golden Age” did not only work there. Many crossed the ocean to stage raids off the west coast of Africa, including the legendary “Black Bart” Roberts. Others sailed as far as the Indian Ocean to work the shipping lanes of southern Asia: it was in the Indian Ocean that Henry “Long Ben” Avery made one of the biggest scores ever: the rich treasure ship Ganj-i-Sawai.

There Were Women Pirates

It was extremely rare, but women did occasionally strap on a cutlass and pistol and take to the seas. The most famous examples were Anne Bonny and Mary Read , who sailed with “Calico Jack” Rackham in 1719. Bonny and Read dressed as men and reportedly fought just as well (or better than) their male counterparts. When Rackham and his crew were captured, Bonny and Read announced that they were both pregnant and thus avoided being hanged along with the others.

Piracy Was Better Than the Alternatives

Were pirates desperate men who could not find honest work? Not always: many pirates chose the life, and whenever a pirate stopped a merchant ship, it was not uncommon for a handful of merchant crewmen to join the pirates. This was because “honest” work at sea consisted of either merchant or military service, both of which featured abominable conditions. Sailors were underpaid, routinely cheated of their wages, beaten at the slightest provocation, and often forced to serve. It should surprise no one that many would willingly choose the more humane and democratic life on board a pirate vessel.

They Came From All Social Classes

Not all of the Golden Age pirates were uneducated thugs who took up piracy because they lacked a better way to make a living. Some of them came from higher social classes as well. William Kidd was a decorated sailor and very wealthy man when he set out in 1696 on a pirate-hunting mission: he turned pirate shortly thereafter. Another example is Major Stede Bonnet , who was a wealthy plantation owner in Barbados before he outfitted a ship and became a pirate in 1717: some say he did it to get away from a nagging wife.

Not All Pirates Were Criminals

During wartime, nations would often issue Letters of Marque and Reprisal, which allowed ships to attack enemy ports and vessels. Usually, these ships kept the plunder or shared some of it with the government that had issued the letter. These men were called “privateers,” and the most famous examples were Sir Francis Drake and Captain Henry Morgan . These Englishmen never attacked English ships, ports, or merchants and were considered great heroes by the common folk of England. The Spanish, however, considered them pirates.

- The Pirate Hunters

- The Golden Age of Piracy

- Real-Life Pirates of the Caribbean

- Famous Pirate Flags

- Understanding Pirate Treasure

- Biography of John 'Calico Jack' Rackham, Famed Pirate

- Pirates: Truth, Facts, Legends and Myths

- Famous Pirate Ships

- The History and Culture of Pirate Ships

- Facts About Anne Bonny and Mary Read, Fearsome Female Pirates

- Biography of Mary Read, English Pirate

- Pirate Crew: Positions and Duties

- The 10 Best Pirate Attacks in History

- 5 Successful Pirates of the "Golden Age of Pirates"

- Biography of Anne Bonny, Irish Pirate and Privateer

- Biography of 'Black Bart' Roberts, Highly Successful Pirate

The life and times of a pirate

What do pirates do.

Who became a pirate and what was life like for them? Step into the world of pirates in the classic age of piracy.

What is a pirate?

A pirate is a robber who travels by water. Though most pirates targeted ships, some also launched attacks on coastal towns.

We often think of pirates as swashbuckling and daring or evil and brutish, but in actual fact most of them were ordinary people who had been forced to turn to criminal activity to make ends meet.

Where did pirates live?

When on the high seas, any one who wasn't a captain would sleep out in the open, either in a hammock or on the floor. There were however, 'pirate havens'. Regions of the Indian Ocean and Madagascar were often safe places for pirates to stay, outside of the law and state governance.

Did pirates bury their treasure?

Curator of World and Maritime History Robert Blyth takes on the Curators Against the Clock challenge to answer this question.

Who were the first pirates?

Pirates have existed since ancient times. They threatened the trading routes of ancient Greece, and seized cargoes of grain and olive oil from Roman ships. Later, the most famous and far-reaching pirates in early Middle Ages Europe were the Vikings.

The 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas meant that the lands discovered by Christopher Columbus were divided between Spain and Portugal. They were ruled under Spanish and Catholic law.

Whilst this treaty meant that Spain and Portugal had agreed on the divide, the English didn’t think that the Pope had the right to seize land that they wanted. They decided to do something about it.

Under Queen Elizabeth I, Britain’s naval powers were growing. She sanctioned civilian sailors to attack Spanish ships, steal cargo and bring it back. Whilst this might have appeared to piracy to the outside world, to the British it made you a hero – such as Sir Francis Drake.

'Golden Age' of piracy

Thousands of pirates were active from 1650–1720. These years are sometimes known as a 'Golden Age' of piracy. Famous pirates from this period include Blackbeard (Edward Teach), Henry Morgan, William 'Captain' Kidd, 'Calico' Jack Rackham and Bartholomew Roberts.

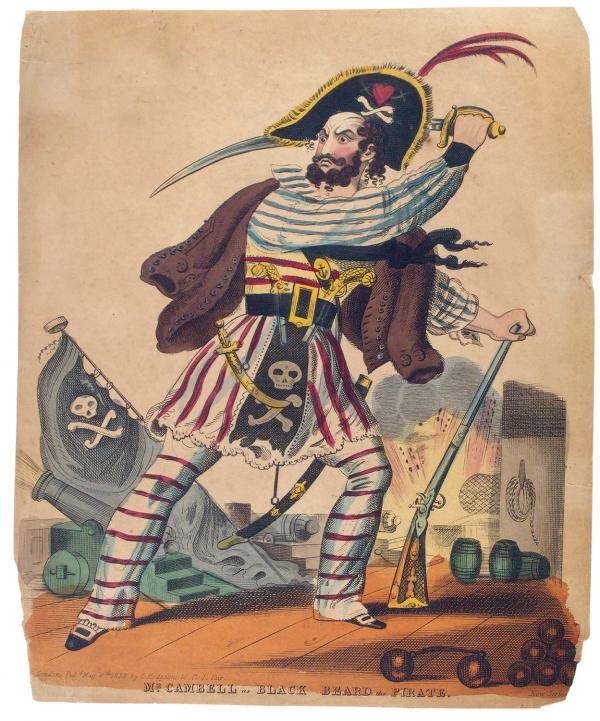

During this time news of piracy reached the ears of both rich and poor. Ballads about topical events were sung on the streets. Newspapers could be freely read in coffee houses for the price of a dish of coffee. There was a spectrum of opinion about the exploits of the more notorious pirates. Published images often showed them as powerful and well dressed.

Find out more about the most famous pirates

Learn more about the Golden Age of Piracy

Life on a pirate ship

We know the legend of swashbuckling, treasure chests and plank-walking, but what was a pirate's life actually like, and who chose to pursue this life of crime?

Some historians have described pirate ships as the original republics. Pirate captains had to be elected, with all decisions made upon the basis that they benefitted the crew. Any money that was captured was shared equally amongst the crew. pirate ships did not have the same hierarchical discipline as navy ships. Pirate crews tended to be less divided by national, religious and racial differences than communities were on land.

There was however also tough discipline on board. If you failed to follow the rules, you could be flogged, killed, or marooned. There were also long periods without food or medical supplies, and the only option was to go hungry.

Where did pirates come from?

Although more British pirates were born in London than other seaports, there is no doubt that the most famous pirates were born elsewhere:

- Henry Morgan, Bartholomew Roberts and Howell Davis were Welsh

- Captain Kidd and John Gow were born in Scotland

- Avery was from Plymouth

- Blackbeard was from Bristol

What sort of booty did pirates seize?

The most precious prizes were chests of gold, silver and jewels. Coins were especially popular because pirate crews could share them out easily.

Emeralds and pearls were the commonest gems from America, providing rich plunder. However, pirates did not only seize precious cargoes like these. They also wanted things they could use, such as food, barrels of wine and brandy, sails, anchors and other spare equipment for their ships. Things as simple as flour and medicine were treasured steals. Often pirates were just trying to find the necessities of life.

How did pirates attack other ships?

Pirate ships usually carried far more crew than ordinary ships of a similar size. This meant they could easily outnumber their victims. Pirates altered their ships so that they could carry far more cannon than merchant ships of the same size. Stories about pirate brutality meant that many of the most famous pirates had a terrifying reputation, and they advertised this by flying various gruesome flags including the 'Jolly Roger' with its picture of skull and crossbones. All these things together meant that victims often surrendered very quickly. Sometimes there was no fighting at all. It's likely that most victims of pirates were just thrown overboard rather than being made to ‘walk the plank’.

Who were the real pirates of the Caribbean?

How were pirates brought to justice?

Shop our selection of pirate-themed books

The image of the pirate never fails to capture the imagination. Browse our range of publications to inform and entertain

Pirate in the Caribbean

While not as famous as other Caribbean pirates like Blackbeard and Captain Kidd, French pirate Jean Hamlin ended up eluding capture on St. Thomas with the assistance of the corrupt governor of the island.

Geography, Human Geography, Social Studies, World History

Loading ...

From the view on top of Blackbeard ’s Castle, the red-tiled roofs of the city of Charlotte Amalie ring a blue-green harbor that was once a pirate refuge in the late 1600s. Charlotte Amalie is the capital of the island of St. Thomas, part of the U.S. Virgin Islands . There is no proof the infamous English pirate Blackbeard caroused Charlotte Amalie’s taverns — Blackbeard ’s Castle is actually the name of a 10-meter (34-foot) tall Danish watchtower that has no apparent connection to its namesake. Captain William Kidd , a Scottish sailor famously executed for piracy, sailed into the harbor in 1699 to drop off five deserters and a sick man. Yet it’s a lesser-known French pirate , Jean Hamlin , whose presence on St. Thomas is best documented. Hamlin was a successful pirate , having raided English and other European ships off the coast of Jamaica and Hispaniola in the Caribbean Sea. Hamlin also raided ships off the coast of Sierra Leone, on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean in northwestern Africa. Hamlin’s story in St. Thomas is told through historical documents in Isidor Paiewonsky’s 1961 book The Burning of a Pirate Ship, La Trompeuse . Hamlin, who helmed the ocean vessel La Trompeuse , captured ships off Hispaniola , the name given to the large Caribbean island where the nations of Haiti and the Dominican Republic are now located. In one incident, Hamlin captured a seaman on a shipping vessel and put the man’s thumbs in vices ( thumbscrews ) until he confessed what kind of cargo was ab oard his ship. Charles Consolvo, a maritime historian and a b oard member of the St. Thomas Historical Trust in Charlotte Amalie, explains how Hamlin came to St. Thomas, which was then governed by Denmark. “He had been wreaking depredations on British shipping in the Caribbean,” he says. “The British were after him. He came to St. Thomas, where he was apparently well-acquainted with the easy ways of Adolph Esmit , who was then governor of St. Thomas.”

Consolvo says St. Thomas was known for harboring pirates during Esmit’s governorship in the 1680s. “ Apparently , Esmit used to participate in buying the loot the pirates brought and generally giving them assistance and aid and succor ,” he says. Battle and Getaway Several British vessels were ordered to find La Trompeuse (French for “deception”). Captain Charles Carlile and his English warship the H.M.S. Francis finally came upon the pirate ship in the port of St. Thomas on July 30, 1683. A brief battle erupted with La Trompeuse . Unexpectedly, Carlile wrote in his journal , nearby Danish troops joined in the firefight —aiding the pirate ship in its fight against the H.M.S. Francis . Carlile was taken aback by the Danish military ’s actions. “Sent the master ashore with a letter to the Governor , protesting against the shot fired at the ship and asking for information as to the consorts of the pirates ,” he wrote in his journal . On the evening of July 31, 1683, Carlile and 14 of his men slid across the harbor toward La Trompeuse in two small boats. A firefight ensued. “The pirate discovered us before we reached them,” Carlile wrote in his journal . “We exchanged shots with them and then b oarded and took possession. The crew escaped. Fired her in several places and lay on our own oars close by to see that none came off to put out the fire. When she blew up, she kindled a great privateer that lay by, which burned to the water’s edge.” Although La Trompeuse burned in the harbor of Charlotte Amalie, the crew escaped—including the pirate leader, Jean Hamlin . Esmit, the crooked governor of St. Thomas, aided in his escape, according to a letter written by St. Thomas resident Andreas Brock and printed in Paiewonsky’s book. The English military searched in vain while Hamlin hid in Charlotte Amalie.

“The pirate , Hamlin, is housed here the whole time in the fort,” Brock wrote. “He has eaten and banqueted with Esmit. . . . He has brought much gold. Esmit would not deliver the said Hamyln to the English.” The Burning of a Pirate Ship, La Trompeuse concludes that Hamlin hid out in nearby Mosquito Bay before hijacking a frigate and sailing it to the coast of Brazil. Fallout from La Trompeuse What finally became of Hamlin has disappeared from history. After safely escaping to Brazil, he put together another pirate crew and helmed another ship— La Nouve Trompeuse . Governor Esmit’s troubles, however, are well-documented. Sir William Stapleton, the governor of Nevis, a British colony at the time, wrote to Esmit after the La Trompeuse incident. “I am sorry that your late conduct has convinced me and all the world that the re ports of your being a protector of pirates were true,” Stapleton wrote. “I have affidavits to that effect from some you had on shore and from the pirates themselves. It is plain from the fact that you secured John Hamlin, the arch murderer and torturer , and neither tried him nor delivered him to Captain Carlile, but allowed him to escape.” Consolvo says Esmit had a difficult time after word spread that he had assisted Hamlin. “He got himself in trouble with the Danish crown, and somehow his wife, who was well-connected, got him out of it, because he was reappointed governor ,” Consolvo says. Even though a treasure-hunter claimed to find the wreck of La Trompeuse in 1990, Consolvo believes the remains of the sunken vessel have not been located. If it were found, he thinks the ship would be of historical significance —though he doubts it would hold many riches. “I suspect that there was probably not very much on the ship at the time,” he says. “It would have been offloaded and sold. . . . Nobody really knows.” But a document written by Brock (the St. Thomas resident at the time of La Trompeuse ’s burning) suggests otherwise. “Hamlin’s frigate , that was burned by the English, was in the opinion of everyone here a beautiful ship, well loaded with provisions and other things. The treasure room was full of silver. There could be over 24,000 pounds there. Esmit could have let all this be taken from the ship but he did not want the people ashore to see what the ship had.”

American Isles In 1917, the United States purchased the Caribbean islands of St. Thomas, St. John, and St. Croix from Denmark for $25 million. They are now known as the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Tavern Town Maritime historian and St. Thomas resident Charles Consolvo says the city of Charlotte Amalie used to have a different name. "The town was called at one point 'Taphus' in Danish in the very early days, because it had so many taverns," he says.

Articles & Profiles

Media credits.

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Last Updated

October 19, 2023

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

The Pirate’s Life at Sea

Author: Cindy Vallar

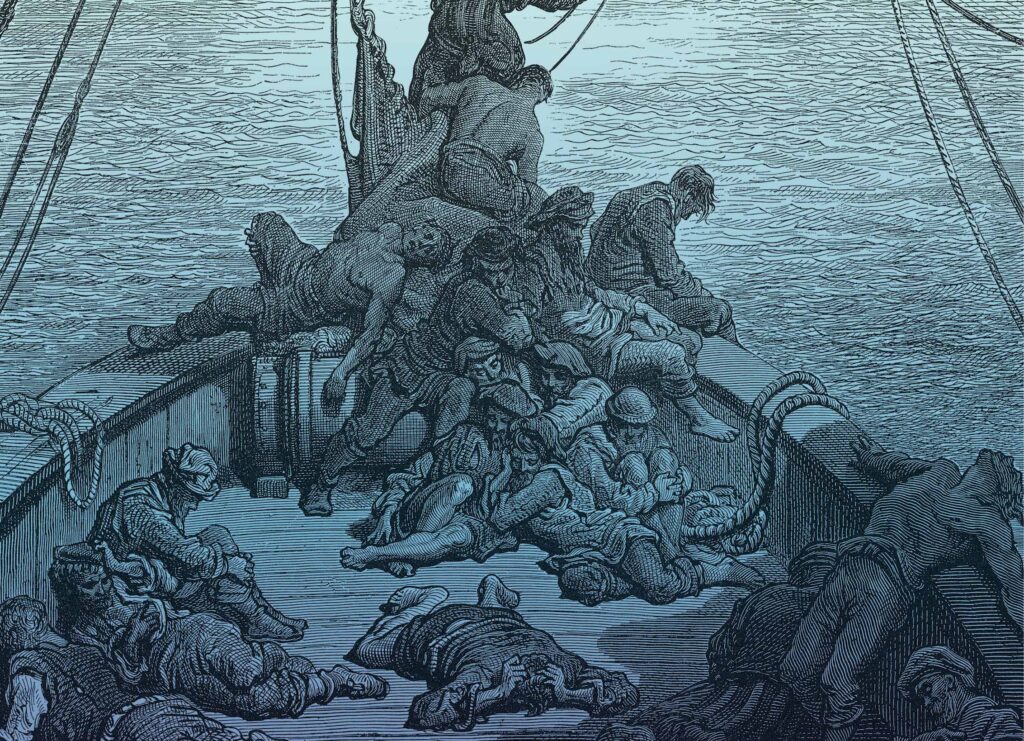

We harbor romantic ideas about life aboard a wooden ship, but Doctor Samuel Johnson once wrote, “No man will be a sailor who has contrivance enough to get himself into a jail; for being in a ship is being in jail with the chance of being drowned…. A man in jail has more room, better food, and commonly better company.”1 His words painted a far closer image to reality, for a mariner’s life was anything but comfortable. He lived belowdecks in dim, cramped, and filthy quarters. Rats and cockroaches abounded in the bowels of the ship. Privacy was nonexistent, especially aboard a pirate ship where two hundred men might inhabit a world measuring one hundred twenty by forty feet. Within the pages of Five Naval Journals 1789-1817, an anonymous sailor said, “On the same deck with me…slept between five and six hundred men; and the ports being necessarily closed from evening to morning, the heat in this cavern of only six feet high, and so entirely filled with human bodies, was overpowering.”2

Bathroom facilities were primitive. Rotting provisions, bilgewater, and unwashed bodies made the air rank. A storm meant days of dampness after it passed. Headroom between decks posed problems for taller men. Captain Rotheram of the HMS Bellerophon, whose gun deck headroom measured five feet eight inches, surveyed his crew and found they averaged five feet five inches in height.3

According to a sailor named Barrow, “There are no men under the sun that fare harder and get their living more hard and that are so abused on all sides as we poor seamen…so I could wish no young man to betake himself to this calling unless he had good friends to put him in place or supply his wants, for he shall find a great deal more to his sorrow than I have writ.”4 For these reasons most sailors were in their mid-twenties, having gone to sea much earlier. Whether pirate or seaman, they had to have stamina and dexterity that older men no longer possessed. They also spent from three months to several years away from home.

Added to these problems were the dangers inherent in a sailor’s life. He might plummet to his death while working the sails high above the deck. He might fall overboard, in which case the ship rarely returned for him and few sailors knew how to swim. Plus there was the danger of sharks in tropical waters. Then there was the danger of fire or shipwreck. Also, the dull routine that was the norm between the sighting of sail and boarding a prize, numbed sailors’ minds. Accidents and natural disasters certainly claimed sailors’ lives, as did sea fights, but men were far more likely to succumb to disease than anything else. Scurvy, dysentery, tuberculosis, typhus, smallpox, malaria, and yellow fever killed half of all seamen. According to David Cordingly, “It has been calculated that during the wars against Revolutionary and Napoleonic France of 1793 to 1815 approximately 100,000 British seamen died. Of this number 1.5 per cent died in battle, 12 per cent died in shipwrecks or similar disasters, 20 per cent died from shipboard or dockside accidents, and no less than 65 per cent died from disease.”5

Drinking water, stored in kegs, turned foul and sailors were sometimes forced to drink this water. More often, though, they drank rum or grog rather than the brandy and wine that officers imbibed. Pirates, on the other hand, drank a mixture of rum, water, sugar, and nutmeg; rumfustian, which blended raw eggs with sugar, sherry, gin, and beer; and sherry, brandy, and port. The two most common foods sailors ate were salted meat and hard tack. The former might be kept in barrels for years before use. The latter was oftentimes invested with weevils. In the Royal Navy during the Napoleonic period, seamen ate a rather bland and routine diet. On Mondays they ate cheese and duff (flour pudding), Tuesdays and Saturdays boiled beef, Wednesdays, Thursdays, and Fridays dried peas and duff. On Sundays they were served dried pork and Figgy Dowdy or a similar treat. Supper consisted of leftovers from dinner, a biscuit, and a pint of grog. In contrast, on 14 August 1781, a rear-admiral served twelve dinners one meal that included: boiled ducks smothered with onions, roast goose, tarts, beaten butter, potatoes, French beans, whipped cream, fruit fritters, bacon, apple pie, boiled fowl, carrots and turnips, albacore, Spanish fritters, boiled beef, and roast mutton.6

It mattered not whether the salted meat and fish turned rancid. It wasn’t thrown away. “Merchants and owners of ships are grown to such a pass nowadays…for when they send a ship out for a voyage they will put no more victuals or drink in the ship than will just serve so many days, and if they have to be a little longer in this passage and meet with cross winds, then the poor men’s bellies must be pinched for it, and be put to shorten their allowance.”7

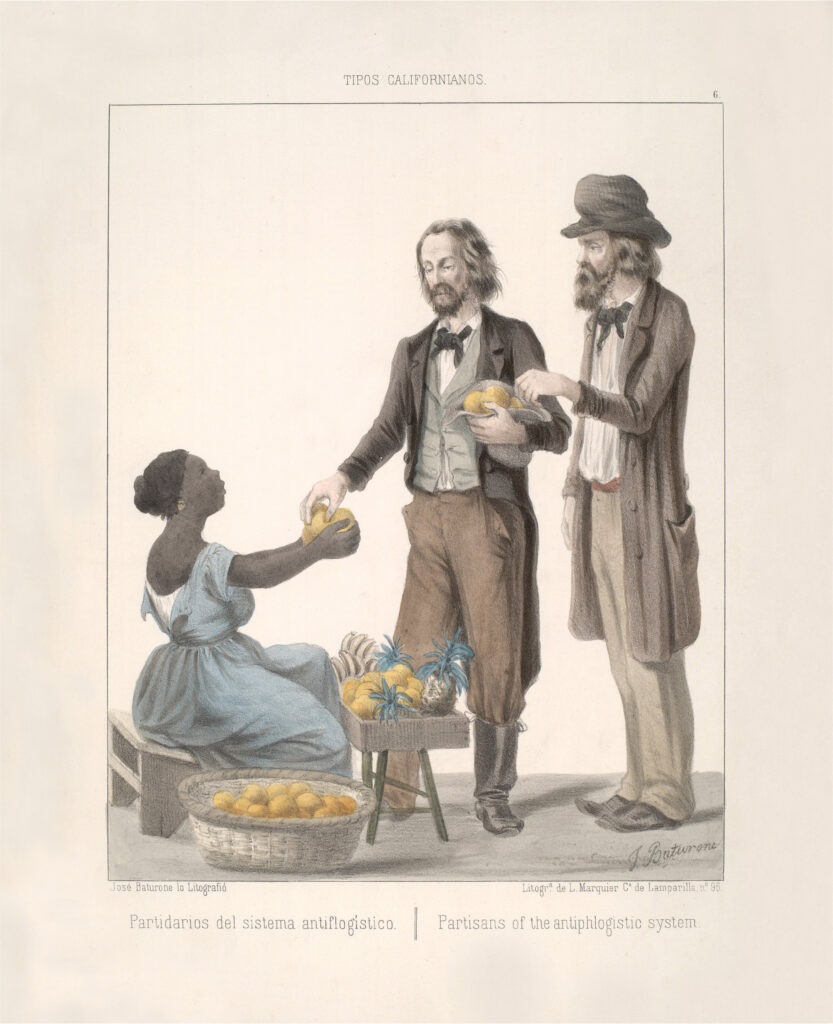

To restock their provisions, pirates stole from the ships they seized. They also supplemented their diets with dolphins, albacore tuna, and other varieties of fish. One particular food was the green turtle. They “are extremely good to eat--the flesh very sweet and the fat green and delicious. This fat is so penetrating that when you have eaten nothing but turtle flesh for three or four weeks, your shirt becomes so greasy from sweat you can squeeze the oil out and your limbs are weighed down with it.”8 They enjoyed salamagundi, which resembled a chef’s salad. Marinated bits of fish, turtle, and meat were combined with herbs, palm hearts, spiced wine, and oil, then served with hard-boiled eggs, pickled onions, cabbage, grapes, and olives. Pirates also ate yams, plantains, pineapples, papayas, and other fruits and vegetables indigenous to the tropics.

When their provisions ran scarce, pirates did resort to extreme measures. Charlotte de Berry’s crew purportedly ate two slaves and her husband. In 1670, Sir Henry Morgan’s crew ate their leather satchels. According to written accounts, they cut the leather into strips. After soaking these, they beat and rubbed the leather with stones to tenderize them. They scraped off the hair, then roasted or grilled the strips before cutting them into bite-size pieces.

Another aspect of life at sea involved sailors’ leisure time. Whether pirate or not, they enjoyed many of the same activities, only the amount differed, particularly where drink was concerned. While gambling did occur, it wasn’t conducive to harmony amongst the men, and even the pirates included it as an intolerable infraction in their articles of agreement. Chewing tobacco, scrimshaw, and embroidery were popular pastimes. They also spun yarns about fearsome ghosts and goblins. When pirates boarded a prize, musicians were among the most sought after sailors enlisted into the ranks of the pirates, whether they joined willingly or were forced, because pirates loved entertainment.

Why did sailors take the extra risk of going on the account? Piracy offered a number of advantages, not the least of which was freedom from the harsh discipline suffered in the Royal Navy or aboard a merchantman. Pirates rarely flogged their mates, and while marooning and death were severe forms of punishment, they never endured six hundred lashes, swallowing cockroaches or iron bolts to learn a lesson. Nor would a pirate captain dare to cut out an eye as happened to Richard Desbrough.9 Life on land was equally fraught with cruel punishments, for use of the thumbscrew, pillory, and branding iron were still in use. “Children as young as seven, both boys and girls, were hanged. …[I]n 1698, Parliament had passed a law that the theft of good, worth more than five shillings, rated the death penalty.”10

When a sea captain refused to join his crew, one pirate said, “Damn ye, you are a sneaking puppy and so are all those who will submit to be governed by laws which rich men have made for their own security, for the cowardly whelps have not the courage otherwise to defend what they got by their knavery. But damn ye altogether. Damn them for a pack of craft rascals, and you, who serve them, for a parcel of hen-hearted numbskulls. They vilify us, the scoundrels do, then there is only this difference, they rob the poor under the cover of law, forsooth, and we plunder the rich under the protection of our own courage; had ye not better make one of use, than sneak after the arses of those villains for employment?”11

Aside from freedom, the financial rewards were far greater as a pirate than as a legitimate sailor, especially since pirates shared their plunder more equitably than privateers or the navy did. Gold, silver, silks, spices, timber, and a variety of other commodities made lucrative prizes. A privateer in the early seventeenth century might receive £10, the wages of most sailors for one year. A pirate, on the other hand, had the potential of earning up to £4,000 in a year, although he rarely held onto his ill-gotten gains for long. In 1695, Captain Avery and his men captured the Gunsway, and netted about £1,000 each. In 1721, pirates under John Taylor and Oliver la Buze netted £875,000 after seizing a Portuguese East Indiaman.

Even so, not all sailors turned pirate when their ships were taken. Captain William Snelgrave spent time as a captive of Howell Davis. He published an account of his experiences in 1734. His descriptions of pirate life weren’t complimentary. “[T]he execrable Oaths and Blasphemies I heard among the Ship’s Company, shocked me to such a degree, that in Hell its self I thought there could not be worse; for though many Seafaring Men are given to swearing and taking God’s name in vain, yet I could not have imagined, human Nature could ever so far degenerate, as to talk in the manner those abandoned Wretches did.”12 “They hoisted upon Deck a great many half-Hogsheads of Claret, and French Brandy; knocked their Heads out, and dipped cans and bowls into them to drink out of: And in their Wantonness threw full Buckets of each sort upon one another. As soon as they had emptied what was on the Deck, they hoisted up more: and in the evening washed the Decks with what remained in the Casks. As to bottled Liquor of many sorts, they made such havoc of it, that in a few days they had not one Bottle left: For they would not give themselves the trouble of drawing the Cork out, but nicked the Bottles, as they called it, that is, struck their necks off with a Cutlace; by which means one in three was generally broke: Neither was there any Cask-liquor left in a short time, but a little brandy. As to Eatables, such as Cheeses, Butter, Sugar, and many other things, they were as soon gone. For the Pirates being all in a drunken Fit, which held as long as the Liquor lasted, no care was taken by any one to prevent this Destruction….”13

Pirates, however, saw life from a different perspective. While some regretted going on the account, most laughed in the face of death. All sailors knew they might die before a voyage ended, and pirates weighed past experiences against the promise of wealth beyond their wildest dreams. Even though few attained such wealth, they still opted for freedom and potential riches. Perhaps Bartholomew Roberts best summed up their philosophy. “In honest service there is thin rations, low wages and hard labour; in this [service], plenty and satiety, pleasure and ease, liberty and power; and who would not balance creditor on this side, when all the hazard that is run for it, at worse, is only a sour look or two at choking. No, a merry life and a short one shall be my motto.”14

Endnotes: 1 Rediker, Marcus. Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea (1987), page 258. 2 Patrick O’Brian’s Navy (2003), page 87. 3 Cordingly, David. The Billy Ruffian (2003), page 209. 4 Gill, Anton. The Devil’s Mariner (1997), page 75. 5 Cordingly, page 165. 6 Blake, Nicholas, and Richard Lawrence. The Illustrated Companion to Nelson’s Navy (2000), page 99. 7 Gill, page 77. 8 Exquemelin, Alexander O.. Buccaneers of America (1969), page 73. 9 Ibid, page 79. 10 Zacks, Richard. The Pirate Hunter (2002), page 357. 11 Gill, pages 79-80. 12 Breverton, Terry. Black Bart Roberts (2004), page 29. 13 Ibid., page 35. 14 Gill, page 80.

- Divisions and Offices

- Grants Search

- Manage Your Award

- NEH's Application Review Process

- Professional Development

- Grantee Communications Toolkit

- NEH Virtual Grant Workshops

- Awards & Honors

- American Tapestry

- Humanities Magazine

- NEH Resources for Native Communities

- Search Our Work

- Office of Communications

- Office of Congressional Affairs

- Office of Data and Evaluation

- Budget / Performance

- Contact NEH

- Equal Employment Opportunity

- Human Resources

- Information Quality

- National Council on the Humanities

- Office of the Inspector General

- Privacy Program

- State and Jurisdictional Humanities Councils

- Office of the Chair

- NEH-DOI Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Partnership

- NEH Equity Action Plan

- GovDelivery

A Lot of What Is Known about Pirates Is Not True, and a Lot of What Is True Is Not Known.

The pirate next door..

Howard Pyle / DoverPictura

In 1701, in Middletown, New Jersey, Moses Butterworth languished in a jail, accused of piracy. Like many young men based in England or her colonies, he had joined a crew that sailed the Indian Ocean intent on plundering ships of the Muslim Mughal Empire. Throughout the 1690s, these pirates marauded vessels laden with gold, jewels, silk, and calico on pilgrimage toward Mecca. After achieving great success, many of these men sailed back into the Atlantic via Madagascar to the North American seaboard, where they quietly disembarked in Charleston, Philadelphia, New Jersey, New York City, Newport, and Boston, and made themselves at home.

When Butterworth was captured, he admitted to authorities that he had served under the notorious Captain William Kidd, arriving with him in Boston before making his way to New Jersey. This would seem quite damning. Governor Andrew Hamilton and his entourage rushed to Monmouth County Court to quickly try Butterworth for his crimes. But the swashbuckling Butterworth was not without supporters.

In a surprising turn of events, Samuel Willet, a local leader, sent a drummer, Thomas Johnson, to sound the alarm and gather a company of men armed with guns and clubs to attack the courthouse. One report estimated the crowd at over a hundred furious East Jersey residents. The shouts of the men, along with the “Drum beating,” made it impossible to examine Butterworth and ask him about his financial and social relationships with the local Monmouth gentry.

Armed with clubs, locals Benjamin and Richard Borden freed Butterworth from the colonial authorities. “Commanding ye Kings peace to be keept,” the judge and sheriff drew their swords and injured both Bordens in the scuffle. Soon, however, the judge and sheriff were beaten back by the crowd, which succeeded in taking Butterworth away. The mob then seized Hamilton, his followers, and the sheriff, taking them prisoner in Butterworth’s place.

A witness claimed this was not a spontaneous uprising but “a Design for some Considerable time past,” as the ringleaders had kept “a pyratt in their houses and threatened any that will offer to seize him.”

Governor Hamilton had felt that his life was in danger. Had the Bordens been killed in the melee, he said, the mob would have murdered him. As it was, he was confined for four days until Butterworth was free and clear.

Jailbreaks and riots in support of alleged pirates were common throughout the British Empire during the late seventeenth century. Local political leaders openly protected men who committed acts of piracy against powers that were nominally allied or at peace with England. In large part, these leaders were protecting their own hides: Colonists wanted to prevent depositions proving that they had harbored pirates or purchased their goods. Some of the instigators were fathers-in-law of pirates.

There were less materialist reasons, too, why otherwise upstanding members of the community rebelled in support of sea marauders. Many colonists feared that crack-downs on piracy masked darker intentions to impose royal authority, set up admiralty courts without juries of one’s peers, or even force the establishment of the Anglican Church. Openly helping a pirate escape jail was also a way of protesting policies that interfered with the trade in bullion, slaves, and luxury items such as silk and calico from the Indian Ocean.

These repeated acts of rebellion against royal authorities in support of men who had committed blatant criminal acts inspired me to spend about ten years researching pirates, work that resulted in my book, Pirate Nests and the Rise of the British Empire, 1570–1740 . In it, I analyzed the rise and fall of international piracy from the perspective of colonial hinterlands, from the inception of England’s burgeoning empire to its administrative consolidation. While traditionally depicted as swashbuckling adventurers on the high seas, pirates played a crucial role on land, contributing to the commercial development and economic infrastructure of port towns in colonial America.

Pirates could be found in nearly every Atlantic port city. But only particular locations became known as “pirate nests,” a pejorative term used by royalists and customs officials. Many of the most notorious pirates began their careers in these ports. Others established even deeper ties by settling in these cities and becoming respected members of the local elite. Instead of the snarling drunken fiends that parade through children’s books, these pirates spent their booty on pigs and chickens, hoping to live a more placid and financially secure life on land.

I was wholly uninterested in piracy as a child. I never dressed as a pirate on Halloween or even read pirate books. I went to graduate school at Harvard, intending to write about fatherhood in early America. In my third year, I presented to colleagues a 30-page essay that I hoped would be a chapter of my dissertation.

The paper was about William Harris, one of the first settlers of Rhode Island, who accumulated a massive estate through shrewd business tactics and slick legal dealings. A Puritan, Harris styled himself as an Abraham of the New World who would people a New Canaan. He composed a will that went to seven generations. In 1680, however, the elderly man was sailing toward London when Algerian pirates captured his vessel.

In the central market of the great walled city of Algiers, Harris was sold into slavery to a wealthy merchant. The once powerful man sent pitiful letters to Rhode Island, begging friends to ransom him and asking his wife to sell parts of his estate. He pleaded, “If you fail me of the said sum and said time it is most like to be the loss of my life, he [my captor] is so Cruel and Covetous. I live on bread and water.” After nearly two years of abject slavery, Harris became one of the lucky few to be ransomed. He made his way back to London, where, after a few weeks on Christian land, the exhausted patriarch died.

The Anglo-Dutch fleet in the Bay of Algiers, which thrived on an economy of piracy in the 17th century.

Wikimedia / Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The Algiers episode was marginal to my larger points about fatherhood. But, as the discussion went around the room, all that anyone wanted to talk about was pirates. This was a few years before Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl became a worldwide sensation. One colleague working on Atlantic families had noticed that locals in South Carolina seemed strangely unsurprised when pirates came ashore in the 1680s. Another colleague came upon a pirate who arrived in Newport in the 1690s, bought land, settled down, and became a customs official. This more-than-passing interest in pirates, as opposed to fathers, left me quite concerned. I had already taken my qualifying exams. I knew nothing about piracy. And since few scholars had written about piracy, I assumed it was not an important topic. Yet there it was, boarding the ship of my research agenda without permission.

Distraught, I cut a deal with my adviser that I would spend a month in the archives, examining government records and official correspondences to find out more. Sure enough, pirates were everywhere. But they were not who we thought they were. They were not anarchistic, antisocial maniacs. At least not in the seventeenth century. Like Moses Butterworth, many were welcome in colonial communities. They married local women, and bought land and livestock. Pirate James Brown even married the daughter of the governor of Pennsylvania and was appointed to the Pennsylvania House of Assembly.

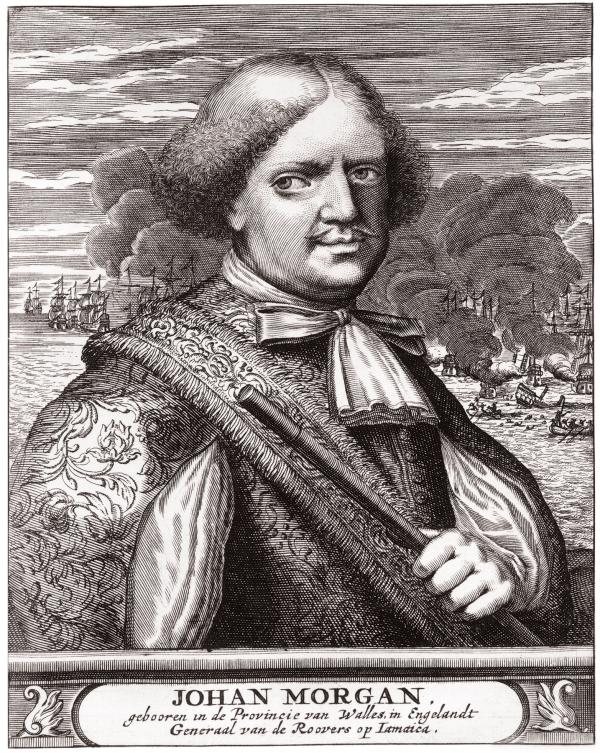

Notorious buccaneer Sir Henry Morgan, shown in a Dutch engraving, raided Spain's Caribbean colonies from his base in Jamaica.

Private collection / Bridgeman Images

Pirates, it seemed, could be civil, neighborly, and law-abiding. Why hadn’t this been noticed before? I chalk it up to specialization. By focusing so closely on their own areas of expertise, historians had overlooked how piracy permeated colonial life.

Piracy has not achieved its rightful place in the narrative of American history precisely because it was so familiar to the people of the English-speaking world of the seventeenth century. In the early days of the colonies, pirate attacks were considered a commonplace, inevitable feature of the maritime world, and noted only as entertaining asides. The prevalence of piracy in children’s stories and blockbuster movies has likely also made it difficult for historians to study the topic without romanticism. This was where my childhood disinterest in piracy paid off. I embarked on my research as a historian rather than as a fan.

Historians and fiction writers alike have portrayed pirates as inherently removed from civilized society. Hubert Deschamps in his 1949 Les pirates à Madagascar voiced what has become a standard trope: “[Pirates] were a unique race, born of the sea and of a brutal dream, a free people, detached from other human societies and from the future, without children and without old people, without homes and without cemeteries, without hope but not without audacity, a people for whom atrocity was a career choice and death a certitude of the day after tomorrow.” Seventeenth-century lawyers defined pirates, in the words of Admiralty judge Sir Leoline Jenkins, as hostis humani generis , or “Enemies not of one Nation or of one Sort of People only, but of all mankind.” Since pirates lacked the legal protection of any prince, nation, or body of law, “Every Body is commissioned and is to be armed against them, as against Rebels and Traytors, to subdue and root them out.”

Contemporary historians have tended to use pirates for their own ends, depicting them as rebels against convention. Their pirates critique early modern capitalism and challenge oppressive sexual norms. They are cast as proto-feminists or supporters of homosocial utopias. They challenge oppressive social hierarchies by flaunting social graces or wearing flamboyant clothing above their social stations. They subvert oppressive notions of race, citing the presence of black crew members as evidence of race blindness. Moses Butterworth, however, did none of these things.

A pirate faces hanging by the River Thames in the eighteenth century.

Private collection / Peter Newark Historical Pictures / Bridgeman Images

The true rebels were leaders like Samuel Willet, establishment figures on land who led riots against crown authority. It was the higher reaches of colonial society, from governors to merchants, who supported global piracy, not some underclass or proto proletariat.

Popular culture has invested heavily in the image of pirates as anarchists who speak in colorful language and dress in attire recognizable to any five-year-old. In fact, what we imagine pirates to look and sound like matches only one decade of history: 1716 to 1726. Before that, piracy consisted of a spectrum of activities from the heroic to the maniacal. Many historians, like many pirate fans, write about piracy as a static phenomenon. This is the basis of popular events like International Talk Like a Pirate Day (September 19) or the costume worn by Jack Sparrow. When asked if these common tropes are true, I give a typical historian’s answer: It depends on when and where.

For the period before the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht, it makes more sense to talk about a sailor who commits piracy, rather than an actual “pirate.” Imagine a ten-year-old boy caught stealing candy from the store. If he learned his lesson, it would be ludicrous to call him a “thief” when he reached adulthood. If he goes on to get a PhD and becomes a respectable historian, it makes more sense to call him “professor.” Certainly there were flamboyant captains of legendary status who would never consider legitimate commerce as a way of life. But most sought one large prize and hoped to use their plunder to join the middling to upper echelons of colonial society.

One reason piracy was often an act or a phase, and not a way of life, was simply because humans have not evolved to live on the sea. The sea is a hostile place, offering few of the pleasures of terrestrial society. Pirates needed to clean and repair their ships, collect wood and water, gather crews, obtain paperwork, fence their goods, or obtain sexual gratification. Simply put, what is the value of silver and gold in the middle of the ocean? Why would someone risk his life in a hostile maritime world if there was no chance he could actually spend his booty?

“A Merry Life and a Short One” was not the motto of most pirates of the late seventeenth century. Until the 1710s, English pirates almost always had somewhere to go to spend their money, either for a few days or to settle down for good. The British National Archives holds a petition from 48 wives of known pirates, begging the crown to pardon their husbands so they could return home to care for their families. Returning to London was not an option for most sea rovers, but a life in the American colonies offered the closest proxy.

Robert Rich, Second Earl of Warwick, who was instrumental to the development of the American colonies and commanded a fleet of privateers, was painted by Anthony van Dyck around 1632.

© Metropolitan Museum of Art / Art Resource, NY

Support of piracy on the peripheries of the British Empire dates to the first forays of English sea captains overseas. Pirate Nests begins in Elizabethan England with the active protection of piracy by port communities in Devon and Cornwall. The ascension of James I coincided with the migration of a plunder economy from England to farther shores. Puritan communities in Ireland, and soon the fledgling colonies of Jamestown, Bermuda, New Plymouth, and Boston all supported illicit sea marauders. Upon the conquest of Jamaica in 1655, Port Royal became a renowned pirate nest, led by Henry Morgan, whose attacks against the Spanish were defended by the colony’s governor and council. By the 1680s, pirates who plundered along the Spanish Main or in the “South Sea” coasts of Chile and Peru dropped anchor in the North American colonies. In the 1690s, men like Moses Butterworth joined crews heading out of colonial ports to the Indian Ocean, basing themselves on the island of Madagascar.

English pirate Mary Reed, who dressed as a man, reveals herself to a victim.

Private collection / DoverPictura

Beginning in 1696, support for piracy was threatened by Parliament’s efforts to reform the legal and political administration of the colonies. Initial attempts to better regulate the colonies faced heated resistance like the riot that sprang Moses Butterworth in 1701. Royal officials battled with colonial elites over control of their court system, choice of governors, economic policies, and other issues. But the transformation of law, politics, economics, and even popular culture in a relatively brief period of time soon persuaded landed colonists of the long-term benefits of legal trade over the short-term boom of the pirate market. After being sprung from jail, Moses Butterworth eventually headed to Newport, where, in 1704, he captained a sloop that sailed alongside a man-of-war in pursuit of runaway English sailors. The former pirate had turned pirate-hunter.

Edward Teach, better known as Blackbeard, has inspired the depiction of pirates in fiction, film, and on stage.

New York Public Library / Art Resource, NY

The expansion of commercial trade, particularly the slave trade, cemented a colonial social order increasingly threatened by instability at sea and less tolerant of social mobility on land. This change in attitudes led to the period we call the “War on Pirates”—roughly 1716 to 1726—and the advent of sea marauders who, with little hope of ever resettling on land, attacked their own nation. This is the era of characters like Blackbeard (Edward Teach), Bartholomew Roberts, and female pirates Anne Bonny and Mary Read, colorful rebels who lived dangerously and fit the legend. Where for centuries pirates had sailed under the flags of their own nations or of foreign princes, they now sailed—and were hanged under—flags of their own construction. No longer welcomed by the colonial elite, outlaw vessels were routed from shores that once harbored pirate nests. In 1718 and 1723, the ports of Newport, Rhode Island, and Charleston, South Carolina, tried and hanged crews of 23 and 26 pirates, respectively, the two largest mass executions not involving a slave insurrection in colonial America. As a result, by the late 1720s the pirate scourge had largely abated.

Mark G. Hanna is associate professor of history at the University of California–San Diego and the founding associate director of the UCSD Institute of Arts and Humanities. He received an NEH research fellowship that supported his work on Pirate Nests and the Rise of the British Empire, 1570–1740 , which won the 2016 Frederick Jackson Turner Award from the Organization of American Historians and the 2016 John Ben Snow Prize from the North American Conference on British Studies.

SUBSCRIBE FOR HUMANITIES MAGAZINE PRINT EDITION Browse all issues Sign up for HUMANITIES Magazine newsletter

National Geographic content straight to your inbox—sign up for our popular newsletters here

Our guide to the UK & Ireland

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Sir Francis Drake

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 6, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

Sir Francis Drake participated in some of the earliest English slaving voyages to Africa and earned a reputation for his privateering, or piracy, against Spanish ships and possessions. Sent by Queen Elizabeth to South America in 1577, he returned home via the Pacific and became the first Englishman to circumnavigate the globe; the queen rewarded him with a knighthood. In 1588, Drake served as second-in-command during the English victory over the Spanish Armada. The most famous mariner of the Elizabethan Age, he died off the coast of Panama in 1596 and was buried at sea.

Born sometime between 1540 and 1544 in Devonshire, England, Francis Drake was the son of a tenant farmer on the estate of Lord Francis Russell, earl of Bedford. He was brought up in Plymouth by the Hawkins family, relatives who worked as merchants and privateers (often referred to as pirates).

Drake went to sea for the first time around the age of 18 with the Hawkins family fleet, and by the 1560s had earned command of his own ship.

Did you know? When he died off the coast of Panama in 1596, Sir Francis Drake was buried at sea, wearing full armor and encased in a lead-lined coffin. Divers, treasure hunters and Drake enthusiasts continue to search for his final resting place.

Slave Trade

In 1567, Drake and his cousin John Hawkins sailed to Africa in order to join the fledgling slave trade. When they sailed to New Spain to sell their captives to settlers there (which was against Spanish law), they were trapped by a Spanish attack in the Mexican port of San Juan de Ulua.

Many of their crewmates were killed in the incident, though Drake and Hawkins escaped, and Drake returned to England with what would be a lifelong hatred for Spain and its ruler, King Philip II .

Privateer for the British Crown

After leading two successful expeditions to the West Indies, Drake came to the attention of Queen Elizabeth I , who granted him a privateer’s commission, effectively giving him the right to plunder Spanish ports in the Caribbean. Drake did just that in 1572, capturing the port of Nombre de Dios (a drop-off point for silver and gold brought from Peru) and crossing the Isthmus of Panama, where he first caught sight of the immense Pacific Ocean. He returned to England with a large amount of Spanish treasure, an accomplishment that earned him a reputation as a leading privateer.

In 1577, Queen Elizabeth commissioned Drake to lead an expedition around South America through the notoriously stormy Straits of Magellan . The voyage was plagued by conflict between Drake and the two other men tasked with sharing command.

When they arrived off the coast of Argentina, Drake had one of the men–Thomas Doughty–arrested, tried and beheaded for allegedly plotting a mutiny. Of the five-ship fleet, two ships were lost in a storm; the other commander, John Wynter, turned one back to England and another disappeared. Drake’s 100-ton flagship, the Pelican (which he later renamed Golden Hind ), was the only vessel to reach the Pacific, in October 1578.

Drake Circumnavigates the Globe

After plundering Spanish ports along the west coast of South America, Drake headed north in search of a passage back to the Atlantic. He claimed to have traveled as far north as 48 degrees North (on parallel with Vancouver, Canada) before extreme cold conditions turned him back. Drake anchored near today’s San Francisco and claimed the surrounding land, which he called New Albion, for Queen Elizabeth.

Heading back west across the Pacific in July 1579, he stopped in the Philippines and bought spices in the Molucca Islands. He then sailed around the Cape of Good Hope in Africa and arrived back in England’s Plymouth Harbor in September 1580.

Despite complaints from the Spanish government about his piracy, Drake was honored as the first Englishman to circumnavigate the globe and became a popular hero. Several months after his return, Queen Elizabeth personally knighted him aboard the Golden Hind .

The Spanish Armada

In 1585, with hostilities heating up again between England and Spain, the queen gave Drake command of a fleet of 25 ships. He sailed to the West Indies and the coast of Florida and mercilessly plundered Spanish ports there, taking Santiago in the Cape Verde Islands, Cartagena in Colombia, St. Augustine in Florida and San Domingo (now Santo Domingo, capital of the Dominican Republic).

On the return voyage, he rescued a failed English military colony on Roanoke Island off the Carolinas in 1586. (The unlucky island was later the scene of a mysterious disappearance of about 100 English settlers, none of whom were ever found.)

Drake then led an even bigger fleet (30 ships) into the Spanish port of Cádiz and destroyed a large number of vessels being readied for the Spanish Armada . In 1588, Drake served as second-in-command to Admiral Charles Howard in the English victory over the supposedly invincible Spanish fleet.

Final Years

After a failed 1589 expedition to Portugal, Drake returned home to England for several years, until Queen Elizabeth enlisted him for one more voyage, against Spanish possessions in the West Indies in early 1596.

The expedition proved to be a dismal failure: Spain fended off the English attacks, and Drake came down with fever and dysentery. He died in late January 1596 at age 55 off the coast of Puerto Bello (now Portobelo, Panama).

Sir Francis Drake. National Park Service . Sir Francis Drake (c.1540 - c.1596). BBC . Sir Francis Drake Facts. Royal Museums Greenwich . Roanoke Voyages. The Lost Colony .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Boat Reviews

- Boats Specs

- Marine Pros

- Boat Insurance

- Boat Warranties

- Boat Transport

- Boat Towing

- Marine Forecasts

Your Ultimate Boating Resource

How did pirates travel from ship to shore?

Pirates have long been depicted in popular culture as swashbuckling adventurers who traverse the high seas in search of treasure and adventure. However, for pirates to achieve their goals, they had to get from their ships to the shore. But how did they manage to do it?

Firstly, pirates often used small boats and rafts to travel to shore. This could include rowboats, canoe-like boats, and dinghies. These small boats were usually kept on board pirating ships and used for short trips to other vessels or nearby islands. There were also larger vessels that could be used, such as longboats or cutters, that had bigger crews and were capable of longer journeys.

However, the distance of the shoreline from the pirate ship often made the use of smaller boats impractical. In these cases, pirates would have to engage in a more daring method of transportation called “swimming the plank.” In this method, the pirating ship would anchor itself near the shore and build an extension to the deck called a “plank.” The prisoners or pirates would then be forced to walk across the plank and jump into the water, where they would either swim to the shore or be picked up in a smaller boat.

Another more extreme way of traveling from ship to shore was by using a device called a “rope launcher” or “cannon net.” This involved attaching a rope, or even a net, to the ship and firing it towards the shore using a small cannon. The pirates would then use the rope or net to swing or climb to the shore.

In some cases, pirates would also use innovative methods, including attaching barrels to themselves to help them float, or tying themselves together in groups to provide support and buoyancy.

Pirates had various methods of traveling from their ships to the shore. They used everything from small boats and rafts to extreme and dangerous techniques, such as swimming the plank or using a rope launcher. These methods were all necessary for pirates to do what they did best: plunder the riches of other ships and make their fortune on the high seas. So, next time you watch a pirate movie, take a moment to appreciate the bravery it took for them to get to shore.

Related Questions

What type of wood is used for pier pilings, what is the difference between a dock and a floating pier, what is the proper technique for pulling a beginner wakeboarder, what does ‘no wake’ mean on a lake, what is the difference between wash and wake, is wakesurfing possible in the sea, why don’t wooden piers rot, what size wakeboard is needed, how to achieve more pop on a wakeboard, does wake surfing translate to ocean surfing, latest posts, 2024 pursuit os 445: an overview, the moment of truth – 6 signs you need a new boat, boat safety 101: exploring the serenity and adventure of boating, the top 9 reasons to maintain a meticulous boat log, don't miss, our newsletter.

Get the latest boating tips, fishing resources and featured products in your email from BoatingWorld.com!

Eco-Savvy Sailing: Expert Tips for Reducing Fuel Costs and Enhancing Your Boating Experience

Sea safety blueprint: constructing the perfect float plan for your boating adventures, 10 essential tips for fishing near private property, the benefits of using a drift sock: guidance for anglers, lure fishing: secrets for imitating live bait and attracting fish, explore the untapped depths of america’s best bass fishing spots, tackle your catch-and-release adventures with these 6 tips, outboard motor maintenance: tips for keeping your engine in top shape, the essential boat tool kit: tools every boater needs, diy boat building: 8 tips and tricks for building your own vessel, the art of miniature maritime craftsmanship: ship in a bottle, antifouling paints: a guide to keeping your boat shipshape, beginner’s guide to standup paddle boarding: tips and techniques, boating for fitness: how to stay active on the water, kayak safety: how to stay safe on the water, anchoring in a kayak or canoe: how to secure your small boat, 2024 aquila 47 molokai review, 2024 sea-doo switch 13 sport review, 2024 aspen c120 review, 2024 yamaha 222xd review, 2024 sailfish 316 dc review, 2023 seavee 340z review, 2023 centurion fi23 review, gear reviews, megabass oneten max lbo jerkbait review, fortress anchors fx-7 anchoring system review, fortress anchors fx-11 anchoring system review, fortress anchors commando anchor kit review, fortress anchors aluminum anchors review, stay in touch.

To be updated with all the latest news, offers and special announcements.

- Privacy Policy

Unsettling Facts About Modern Pirates (And Where In The World You’ll Find Them)

Modern-day pirates no longer fly jolly rogers or force their victims to walk the plank, but they are no less dangerous.

Thought that pirates disappeared after the 18th century? Think again! Modern pirates are a real threat to sea vessels operating all over the world and can even result in the death of victims at sea . And although they no longer fly jolly rogers or force their victims to walk the plank, they are no less dangerous. Check out these unsettling facts about modern pirates and where in the world you’ll find them.

Modern Pirates Use Advanced Technology, Including Night-Vision Goggles And Rocket Launchers

The days of pirates wielding swords are long gone but that doesn’t mean that modern pirates don’t carry weapons. In fact, piracy hasn’t changed in regard to pirates being heavily armed. The weapons they brandish have always been what makes pirates so fearsome and that’s especially true today, with modern pirates using everything from night-vision goggles to rocket launchers to rob ships.

These days, pirates use AK-47s and heavy machine guns to instill fear in their victims, while rocket launchers allow them to target ships from a long way away. They use night-vision goggles and advanced GPS devices to help with navigation and locating other ships at night.

Pirates Still Assault And Maroon People

While pirates from the Golden Age used to live their lives at sea, modern pirates typically base themselves on the shore and attack via speedboats. Their methods have changed, with guns being much more common among pirates these days than swords. But their goal is the same: to intimidate and rob crew members on other ships, sometimes assaulting and marooning them in the process. Pirates from the Golden Age often marooned members of their own crew who turned on them, while these days they leave their victims marooned and take off with their ships.

Modern pirates have even been known to take hostages for ransom. In some cases, those who have been kidnapped by pirates have even died at the hands of their captors.

RELATED: 10 Crime Sites That True Crime Junkies Should Visit

They Attack Cruise Ships

This fact is definitely unsettling for anybody who likes cruising! Modern pirates typically target cargo vessels but they have also been known to attack private yachts and cruise ships, robing the personal belongings of crew members and passengers rather than targeting a ship’s cargo.

In 2005, the luxury liner Seaborne Spirit was off the coast of Somalia having departed from Alexandria. Three boats of heavily armed pirates assaulted the ship for two hours , slamming grenades and bullets into the side of the ship. The passengers were all ordered to congregate in the ship’s main ballroom. Thankfully, the crew was able to ward off the pirates by using an L-RAD device that emitted a loud, piercing sound. There were no casualties and the cruise was able to finish their voyage on schedule.

It’s not as common for pirates to attack cruise ships. But it’s not unheard of or impossible.

RELATED: Cruise Lines Are Still Running Trips in 2020: These Are 11 Unsettling Facts

Pirate Attacks Are Actually On The Rise

Most people think of piracy as something that belongs in the 17thand 18thcenturies. But it has been estimated that modern piracy is actually on the rise, having increased 75% in the last decade alone. International losses due to piracy are estimated to be at around $13-16 billion a year.

In 2010, there were nearly 490 reports of piracy and armed robbery against ships, a figure which had risen 20% from the previous year. Although there’s currently no plan in place to eliminate modern piracy, raising awareness of the issue is a promising starting point.

RELATED: 10 Unsettling Facts About The Witch Trials

These Are The Places You’ll Find Modern Pirates

Of course, thousands of people travel by cruise ship or by boat every year and don’t come face to face with pirates. In some areas of the world, piracy is still essentially non-existent, while in others, it’s rampant. One of the most notorious places that you’ll find modern pirates is off the Somali Coast, between the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean in the Gulf of Aden.

Other piracy hot spots include East Africa, the South China Sea, certain coastlines off South America, and in the Caribbean. There have also been reports of pirate attacks on the Danube River, particularly through the Serbian and Romanian stretches.

NEXT: These Chilling Modern Photos Show Jack The Ripper's Modern Crime Scenes

Distillations magazine

The age of scurvy.

In a time of warring empires and transoceanic voyages, sailors dreaded scurvy more than any other disease.

One summer evening in 1808, while on a stroll through London with his wife and sister-in-law, sailor Thomas Urquhart was accosted by a stranger who wanted to know his name. As the outraged Urquhart demanded to know by what right the man questioned him, three or four men seized him, smacked him on the head, and dragged him along the street. They “tore my coat from my back, and afterwards [pulled] me by the neck for fifty yards, until life was nearly exhausted,” wrote Urquhart in a letter that described the assault.

Fortunately for Urquhart passersby intervened, and the attackers fled. But unfortunately Urquhart’s experience was far from unique. In the 18th and early 19th centuries fishermen and merchant seamen like Urquhart lived in fear of “press gangs,” groups of ruffians who roamed the nighttime streets, searching for victims to “impress” into the British navy. Whether English, Irish, American, or Canadian, any subject of the British Empire with seafaring experience was vulnerable to abduction.

If the gang that attacked Urquhart had succeeded, he likely would have awoken trapped on a ship and with nearly no hope of escape. By the time he returned home—if he returned home—he would have endured storms, battles, fevers, and years away from family and friends. But of all the horrors faced by sailors at the time, one of the greatest threats had nothing to do with pirates or wars or weather. It had to do with food.

Scurvy killed more than two million sailors between the time of Columbus’s transatlantic voyage and the rise of steam engines in the mid-19th century. The problem was so common that shipowners and governments assumed a 50% death rate from scurvy for their sailors on any major voyage. According to historian Stephen Bown scurvy was responsible for more deaths at sea than storms, shipwrecks, combat, and all other diseases combined. In fact, scurvy was so devastating that the search for a cure became what Bown describes as “a vital factor determining the destiny of nations.”

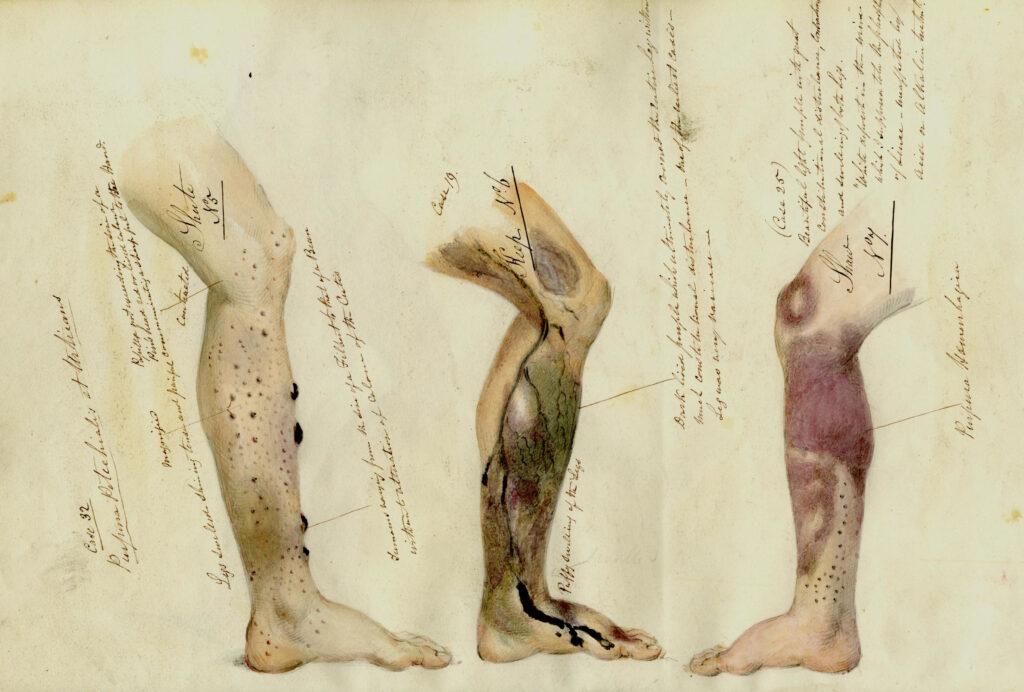

None of the potential fates awaiting sailors was pleasant, but scurvy exacted a particularly gruesome death. The earliest symptom—lethargy so intense that people once believed laziness was a cause of the disease—is debilitating. Your body feels weak. Your joints ache. Your arms and legs swell, and your skin bruises at the slightest touch. As the disease progresses, your gums become spongy and your breath fetid, your teeth loosen, and internal hemorrhaging makes splotches on your skin. Old wounds open; mucous membranes bleed. Left untreated, you will die, likely from a sudden hemorrhage near your heart or brain.

Bown quotes a survival story written by an unknown surgeon on a 16th-century English voyage that reveals the horror of the disease:

Scurvy affected many of the explorers we learned about in grade school: Vasco da Gama lost his brother to it; Ferdinand Magellan watched it kill many of his men, who had nothing to eat, he wrote, but “old biscuit reduced to powder, and full of grubs, and stinking from the dirt which the rats had made on it when eating the good biscuit.” The most famous scurvy-related disaster, however—and the one that fully captures the enduring importance of the tart substance we call vitamin C—was the ill-fated voyage of George Anson, whose 1740–1744 circumnavigation of the globe was the scene of one of the worst medical disasters at sea.

In late 1739 England and Spain declared war to determine control of the Caribbean. Anson, a British captain who had recently returned from the West Indies, was put in charge of a six-ship mission to the Pacific coast of South America, an area important to Spanish trade. In an official portrait Anson’s round face, pursed lips, and feminine curls make him look more like a grandmother than a ship’s captain. But if Anson’s countenance was placid, the task that lay ahead of him was far from pleasant. First, he was to aggravate the Spaniards as much as possible by attacking vulnerable Spanish towns and destroying or capturing any Spanish ships he could find. Second, he was to track down and capture one of the Spanish treasure galleons that transported silver from Acapulco to Manila in the Philippines. Such a ship was so valuable it was known as the “Prize of all the Oceans.”

Anson began his preparations in February 1740, and problems arose from the start. The ships assigned to Anson needed to be repaired and refitted for his mission, a task that would take months. The bigger challenge, however, was finding sailors since the Royal Navy was snatching up for military service all the able-bodied men it could find—often through press gangs like the one Thomas Urquhart encountered in 1808.

Anson’s mission was low on the navy’s priority list, and even the press gangs couldn’t supply him with a sufficient crew: he was supposed to sail with 2,000 men, but by July 1740 he was still a couple hundred short.

The Royal Navy, eager to make room for wounded sailors from the war, eventually came up with both a clever and horrifying solution: it emptied out a hospital, Chelsea Hospital to be exact, which was home to war veterans who were so old, wounded, crippled, or mentally unsound they could no longer serve in marching regiments. Making things worse, those recruits who were relatively healthy did something quite rational: on their release from the hospital they simply walked away. As Anson’s chaplain, Richard Walter, later wrote in the voyage’s official account, this left behind “only such as were literally invalids, most of them being sixty years of age, and some of them upwards of seventy.” To make up for the 240-odd quasicompetent invalids (out of an initial 500) who had limped off, the navy supplied Anson with 210 young marines, so inexperienced and untrained, wrote Walter, that they had never even been permitted to fire their guns.

The six ships and their ragtag crews finally set sail in September after some six months of preparation and—since they’d survived on ship rations while waiting to depart—months without access to fresh fruits and vegetables. Already weakened by some combination of age, sickness, war wounds, and malnourishment, Anson’s crew was likely terrified of what lay ahead: years at sea, deliberately seeking out conflict wherever they could find it. But what they should have feared the most was not Spanish warships but what sailors at the time called “the Scurvy.”

Aware of that risk, the navy issued Anson’s crew several of the most popular treatments of the day: vinegar, “elixir of vitriol” (a mixture of sulfuric acid and alcohol), and a patent medicine called Ward’s Drop and Pill, which was known less for its curative abilities than for its laxative effects. While all the treatments were universally unpleasant, none did a thing to prevent scurvy. As the months wore on, the men’s vulnerability increased.

The disease hit at the worst possible time, while the ships were rounding Cape Horn, a turbulent stretch of ocean at the tip of South America. On March 7, 1741, once the squadron passed successfully through the straits that were considered the boundary between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, Walter optimistically reported that “we could not help flattering ourselves that the greatest difficulty of our passage was now at an end.” The sky was clear; the weather was calm; the men’s spirits were high. But their optimism was unfounded. March 7 was, says Walter, “the last cheerful day that the greatest part of us would ever live to enjoy.”

Suddenly the sky blackened, and the winds shifted. As the ships were pushed off course, the water began to churn with waves so mountainous that if one had broken over a ship, wrote Walter, it would “in all probability have sent us to the bottom.” The southern hemisphere’s autumn storms had begun—and once they started, they raged for months. It rained. It snowed. It hailed. Men got frostbite. In a moment that haunted witnesses for years, one of Anson’s best sailors was tossed into the water and continued to swim strongly alongside the ship, his comrades watching helplessly, until he was finally lost in the waves. Much of the mainsail of Anson’s ship, the Centurion , was blown overboard; the ship itself was so damaged by the buffeting waves that it leaked water at every seam.

These storms lasted for an inconceivable three months. By the time the weather finally broke in late May, two of Anson’s ships had given up and turned back, and the remainder had been separated, unaware of whether the other ships had survived. The hospital pensioners and most of the young marines were dead.

The storms were a horrific challenge, but scurvy proved even more destructive than the gales. “At the latter end of April, there were but a few on board who were not in some degree afflicted with it,” wrote Walter, “and in that month no less than forty-three died of it on board the Centurion .” In May that number doubled. As the number of men above deck dwindled, the scene below grew ever worse: sick men with open sores and rotting wounds swaying in tightly packed hammocks above a sloshing, rat-infested floor. Victims developed discolored spots all over their bodies, their legs swelled, and if they exerted themselves in even the tiniest degree—or were simply moved by someone else—they were apt to swoon and die immediately. When they did, they often remained right where they were since the remaining crew was too weak to throw their bodies overboard.

“This disease so frequently attending long voyages, and so particularly destructive to us, is surely the most singular and unaccountable of any that afflicts the human body,” Walter later wrote. It did things that he admitted sound “scarcely credible.” One dying sailor who had been wounded 50 years earlier watched in horror as his wounds “broke out afresh, and appeared as if they had never been healed.” Later, “the callous of a broken bone, which had been completely formed for a long time, was found to be hereby dissolved, and the fracture seemed as if it had never been consolidated.”