Holiday Savings

cui:common.components.upgradeModal.offerHeader_undefined

The hero's journey: a story structure as old as time, the hero's journey offers a powerful framework for creating quest-based stories emphasizing self-transformation..

Table of Contents

Holding out for a hero to take your story to the next level?

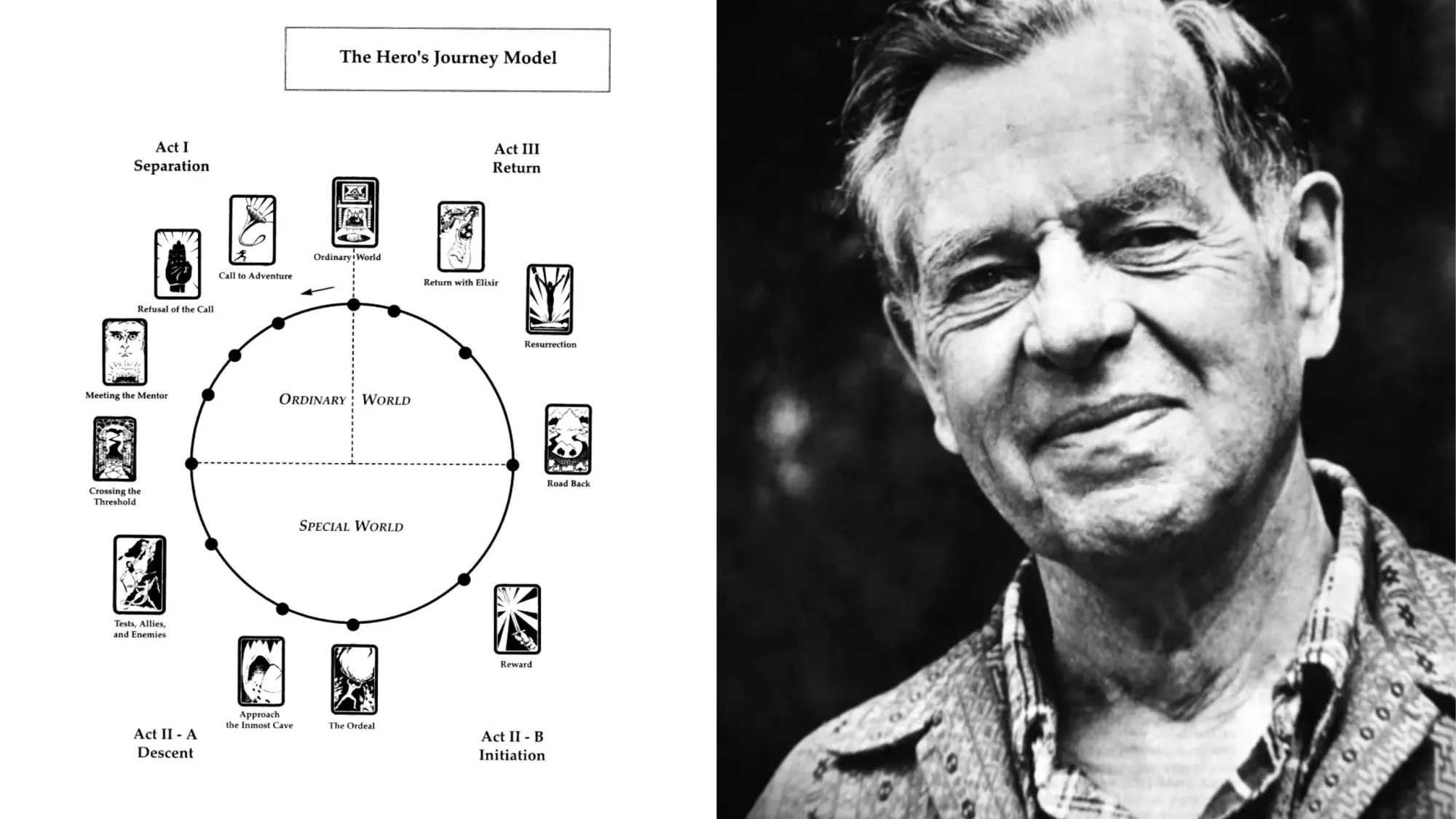

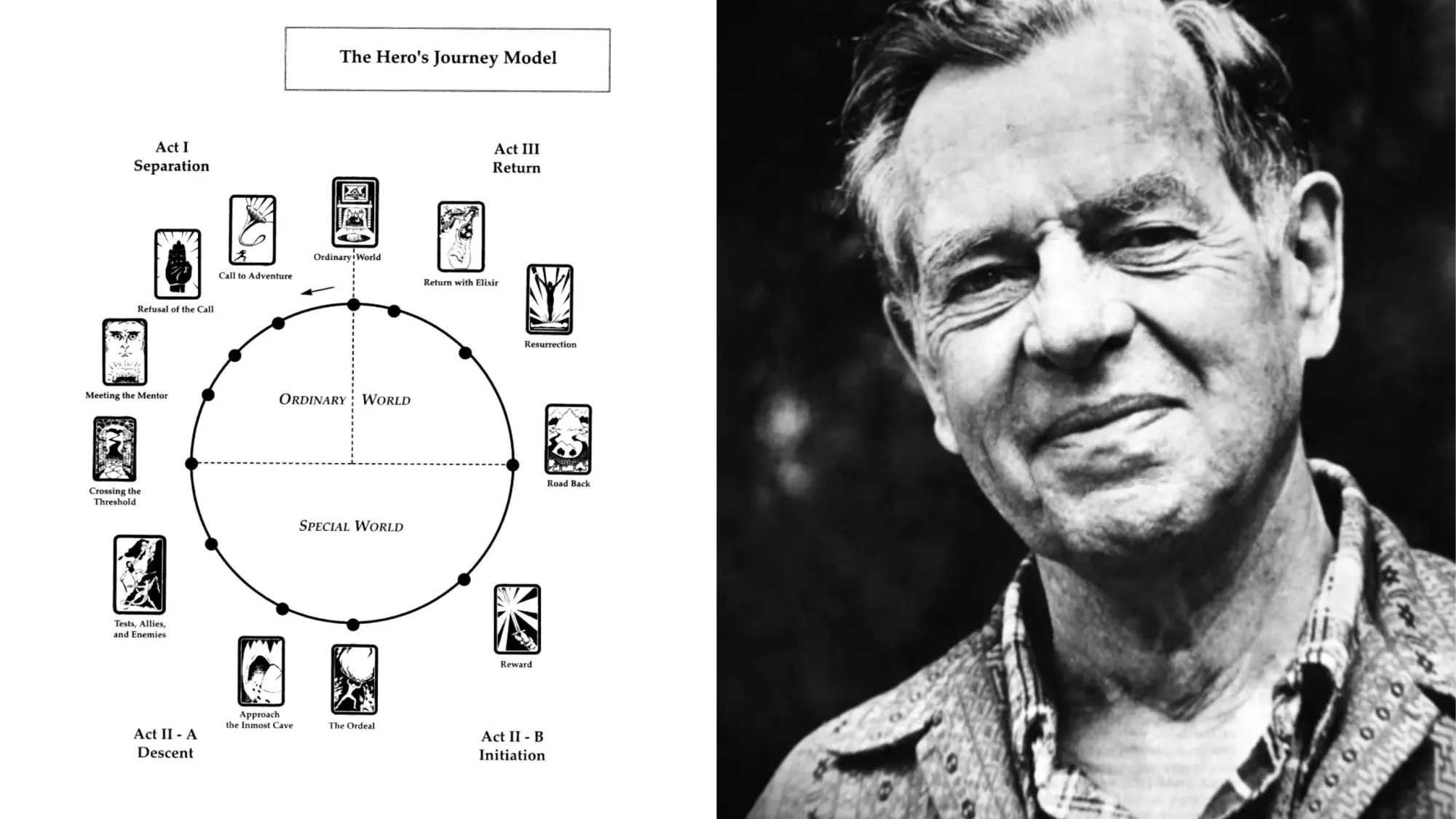

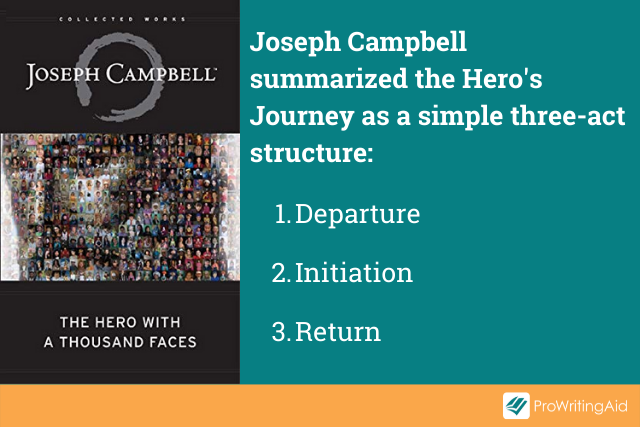

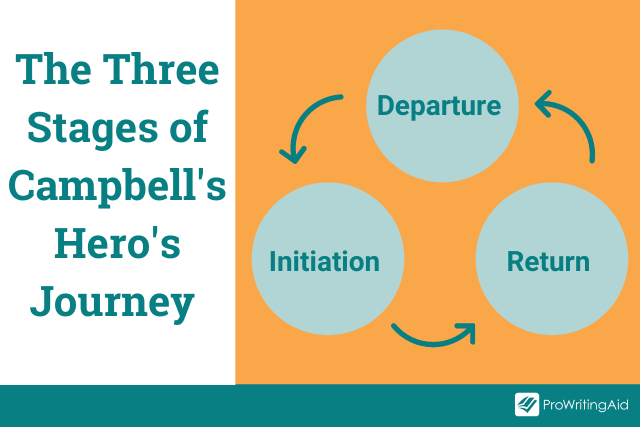

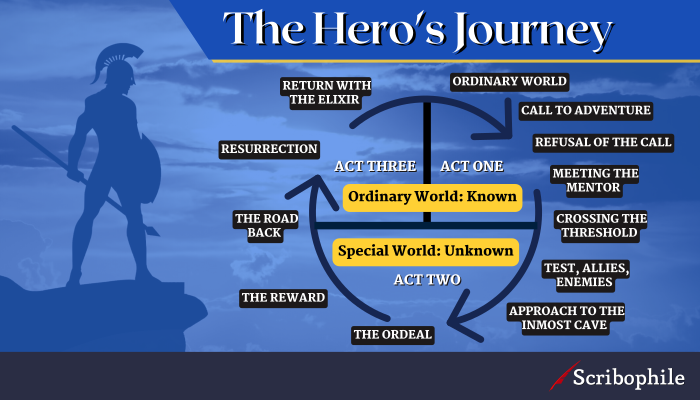

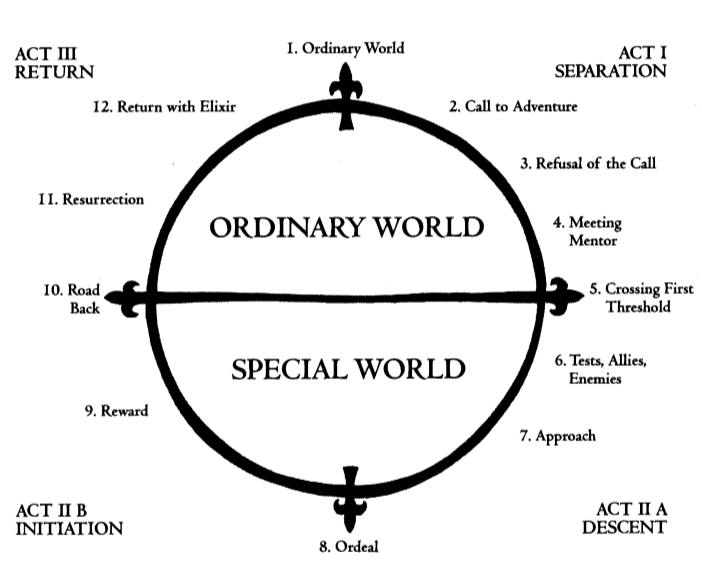

The Hero’s Journey might be just what you’ve been looking for. Created by Joseph Campbell, this narrative framework packs mythic storytelling into a series of steps across three acts, each representing a crucial phase in a character's transformative journey.

Challenge . Growth . Triumph .

Whether you're penning a novel, screenplay, or video game, The Hero’s Journey is a tried-and-tested blueprint for crafting epic stories that transcend time and culture. Let’s explore the steps together and kickstart your next masterpiece.

What is the Hero’s Journey?

The Hero’s Journey is a famous template for storytelling, mapping a hero's adventurous quest through trials and tribulations to ultimate transformation.

What are the Origins of the Hero’s Journey?

The Hero’s Journey was invented by Campbell in his seminal 1949 work, The Hero with a Thousand Faces , where he introduces the concept of the "monomyth."

A comparative mythologist by trade, Campbell studied myths from cultures around the world and identified a common pattern in their narratives. He proposed that all mythic narratives are variations of a single, universal story, structured around a hero's adventure, trials, and eventual triumph.

His work unveiled the archetypal hero’s path as a mirror to humanity’s commonly shared experiences and aspirations. It was subsequently named one of the All-Time 100 Nonfiction Books by TIME in 2011.

How are the Hero’s and Heroine’s Journeys Different?

While both the Hero's and Heroine's Journeys share the theme of transformation, they diverge in their focus and execution.

The Hero’s Journey, as outlined by Campbell, emphasizes external challenges and a quest for physical or metaphorical treasures. In contrast, Murdock's Heroine’s Journey, explores internal landscapes, focusing on personal reconciliation, emotional growth, and the path to self-actualization.

In short, heroes seek to conquer the world, while heroines seek to transform their own lives; but…

Twelve Steps of the Hero’s Journey

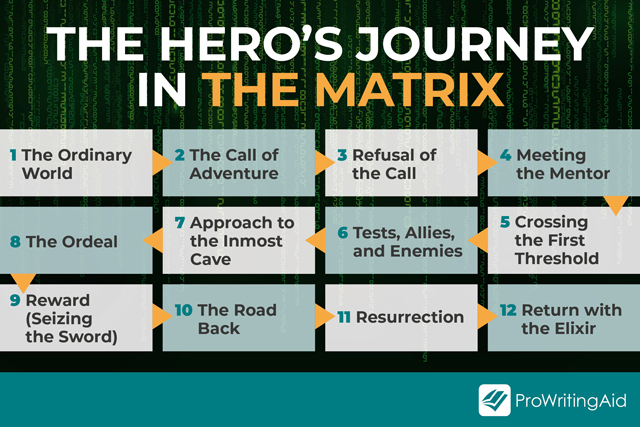

So influential was Campbell’s monomyth theory that it's been used as the basis for some of the largest franchises of our generation: The Lord of the Rings , Harry Potter ...and George Lucas even cited it as a direct influence on Star Wars .

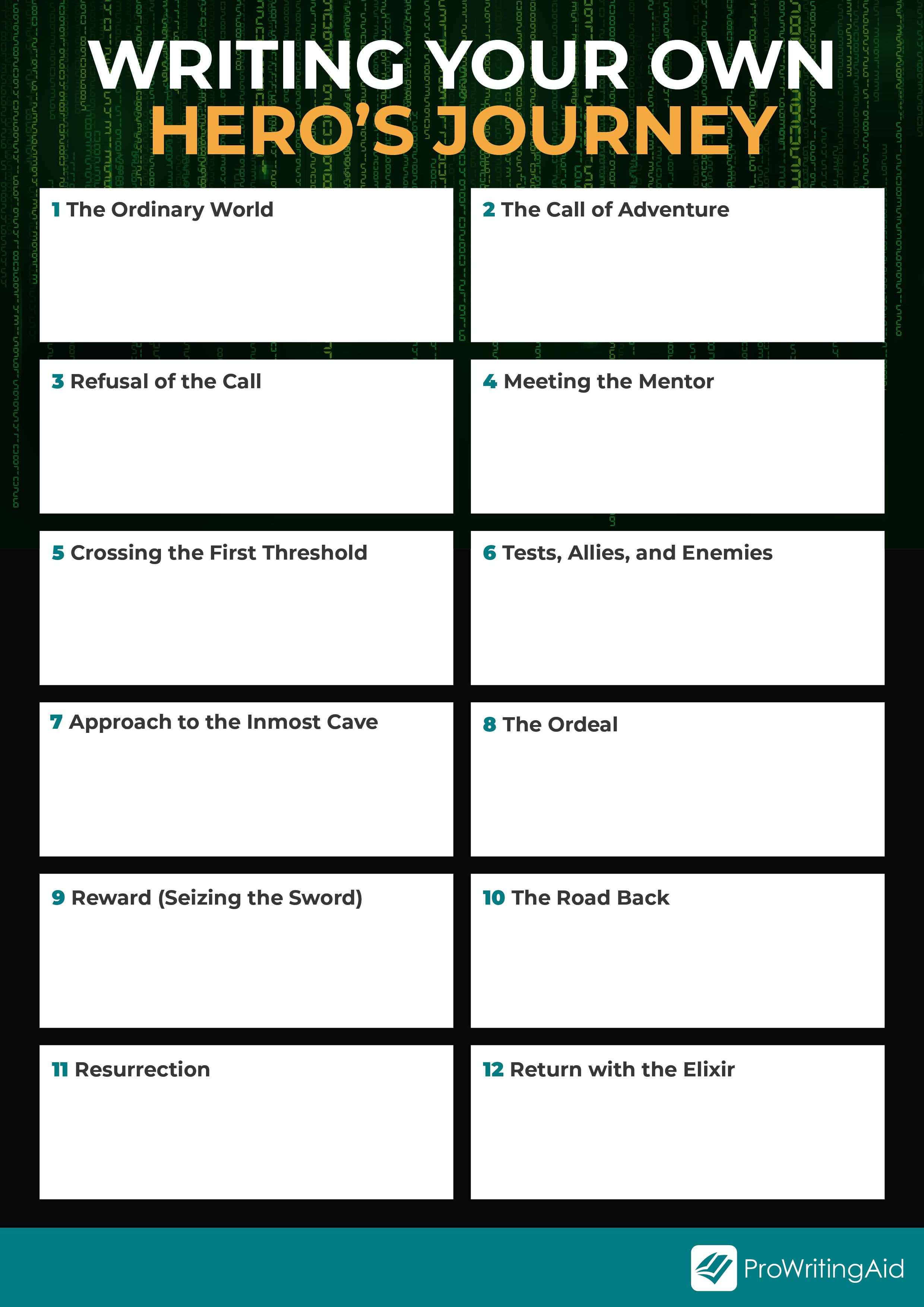

There are, in fact, several variations of the Hero's Journey, which we discuss further below. But for this breakdown, we'll use the twelve-step version outlined by Christopher Vogler in his book, The Writer's Journey (seemingly now out of print, unfortunately).

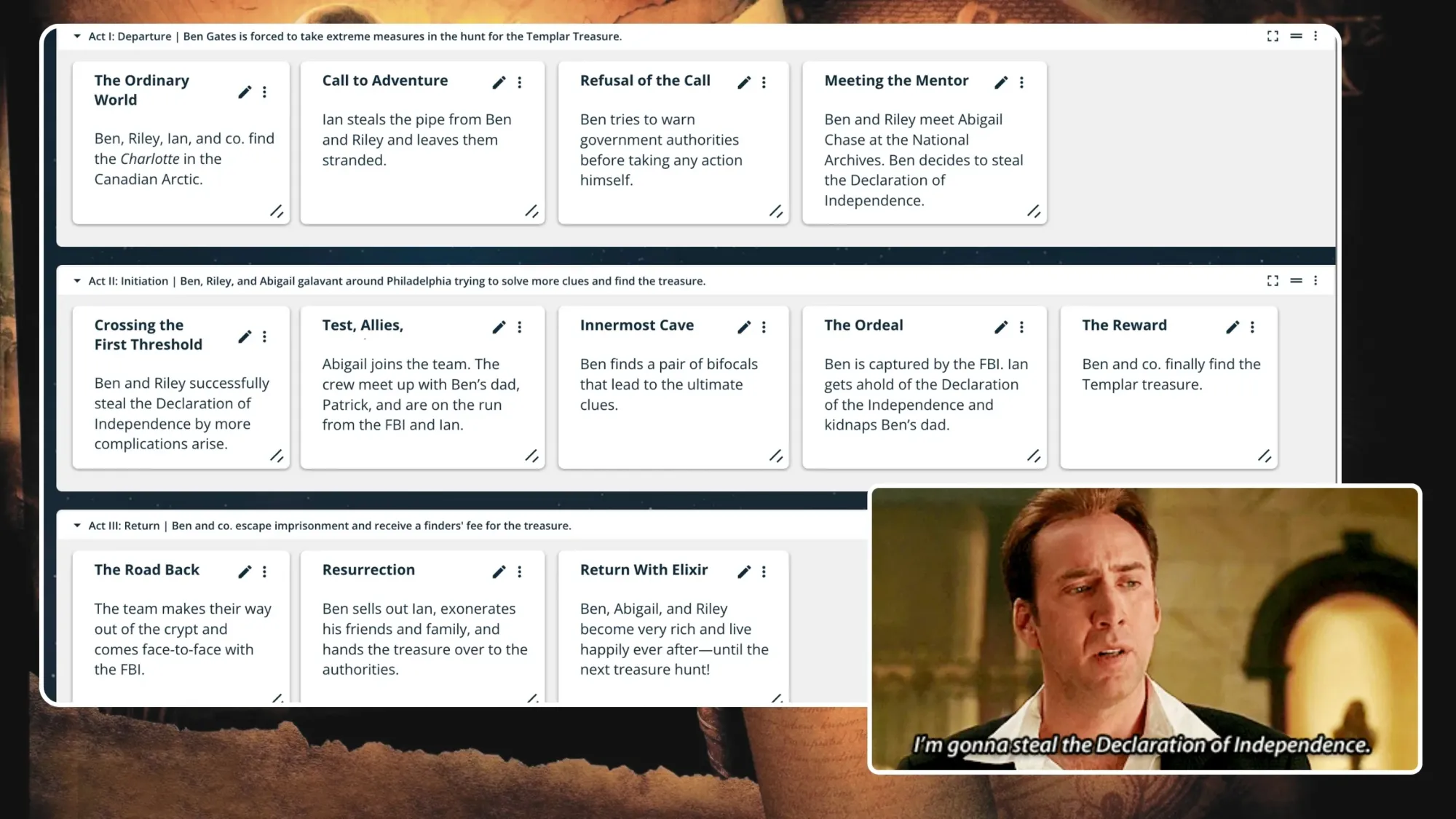

You probably already know the above stories pretty well so we’ll unpack the twelve steps of the Hero's Journey using Ben Gates’ journey in National Treasure as a case study—because what is more heroic than saving the Declaration of Independence from a bunch of goons?

Ye be warned: Spoilers ahead!

Act One: Departure

Step 1. the ordinary world.

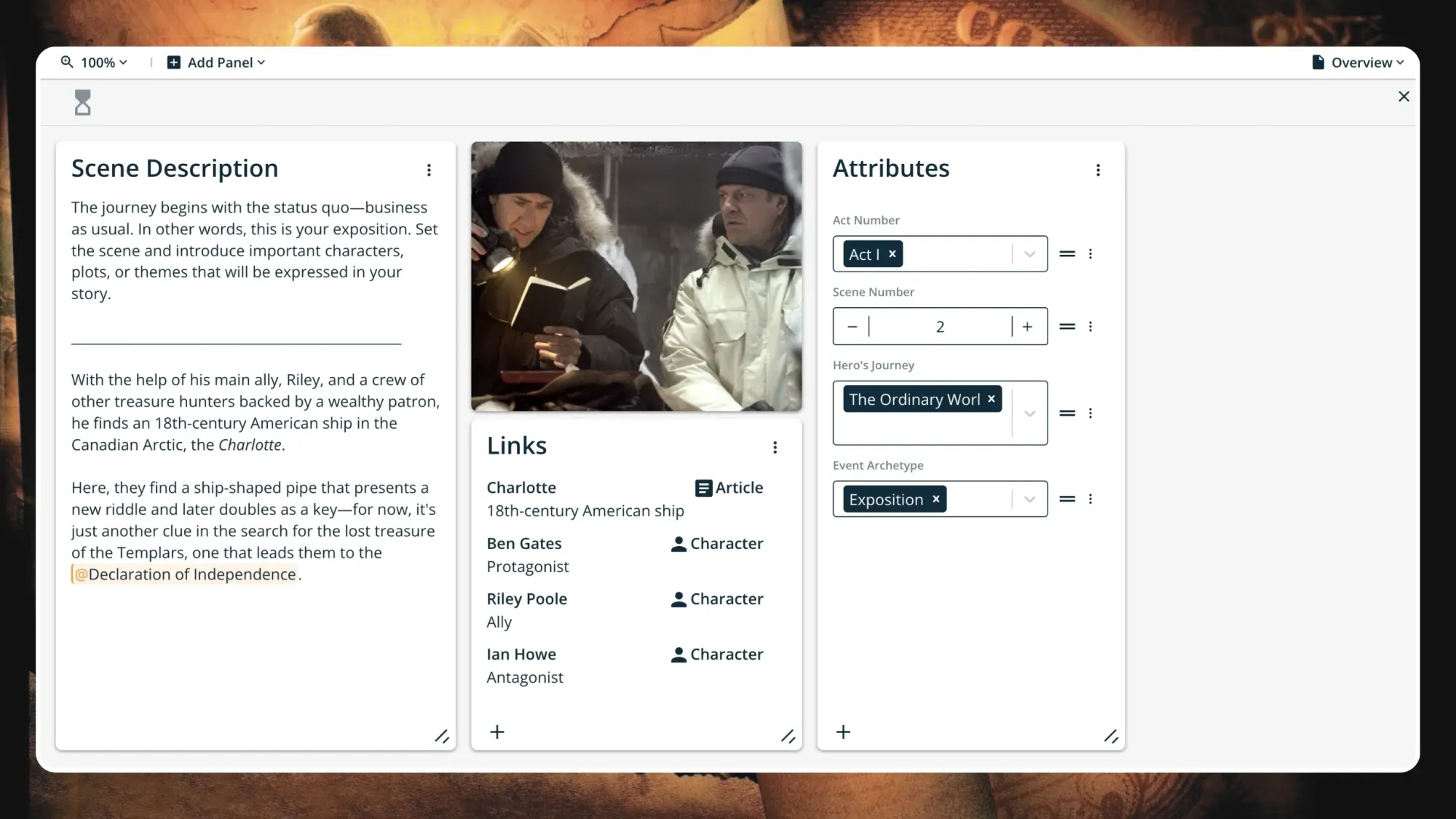

The journey begins with the status quo—business as usual. We meet the hero and are introduced to the Known World they live in. In other words, this is your exposition, the starting stuff that establishes the story to come.

National Treasure begins in media res (preceded only by a short prologue), where we are given key information that introduces us to Ben Gates' world, who he is (a historian from a notorious family), what he does (treasure hunts), and why he's doing it (restoring his family's name).

With the help of his main ally, Riley, and a crew of other treasure hunters backed by a wealthy patron, he finds an 18th-century American ship in the Canadian Arctic, the Charlotte . Here, they find a ship-shaped pipe that presents a new riddle and later doubles as a key—for now, it's just another clue in the search for the lost treasure of the Templars, one that leads them to the Declaration of Independence.

Step 2. The Call to Adventure

The inciting incident takes place and the hero is called to act upon it. While they're still firmly in the Known World, the story kicks off and leaves the hero feeling out of balance. In other words, they are placed at a crossroads.

Ian (the wealthy patron of the Charlotte operation) steals the pipe from Ben and Riley and leaves them stranded. This is a key moment: Ian becomes the villain, Ben has now sufficiently lost his funding for this expedition, and if he decides to pursue the chase, he'll be up against extreme odds.

Step 3. Refusal of the Call

The hero hesitates and instead refuses their call to action. Following the call would mean making a conscious decision to break away from the status quo. Ahead lies danger, risk, and the unknown; but here and now, the hero is still in the safety and comfort of what they know.

Ben debates continuing the hunt for the Templar treasure. Before taking any action, he decides to try and warn the authorities: the FBI, Homeland Security, and the staff of the National Archives, where the Declaration of Independence is housed and monitored. Nobody will listen to him, and his family's notoriety doesn't help matters.

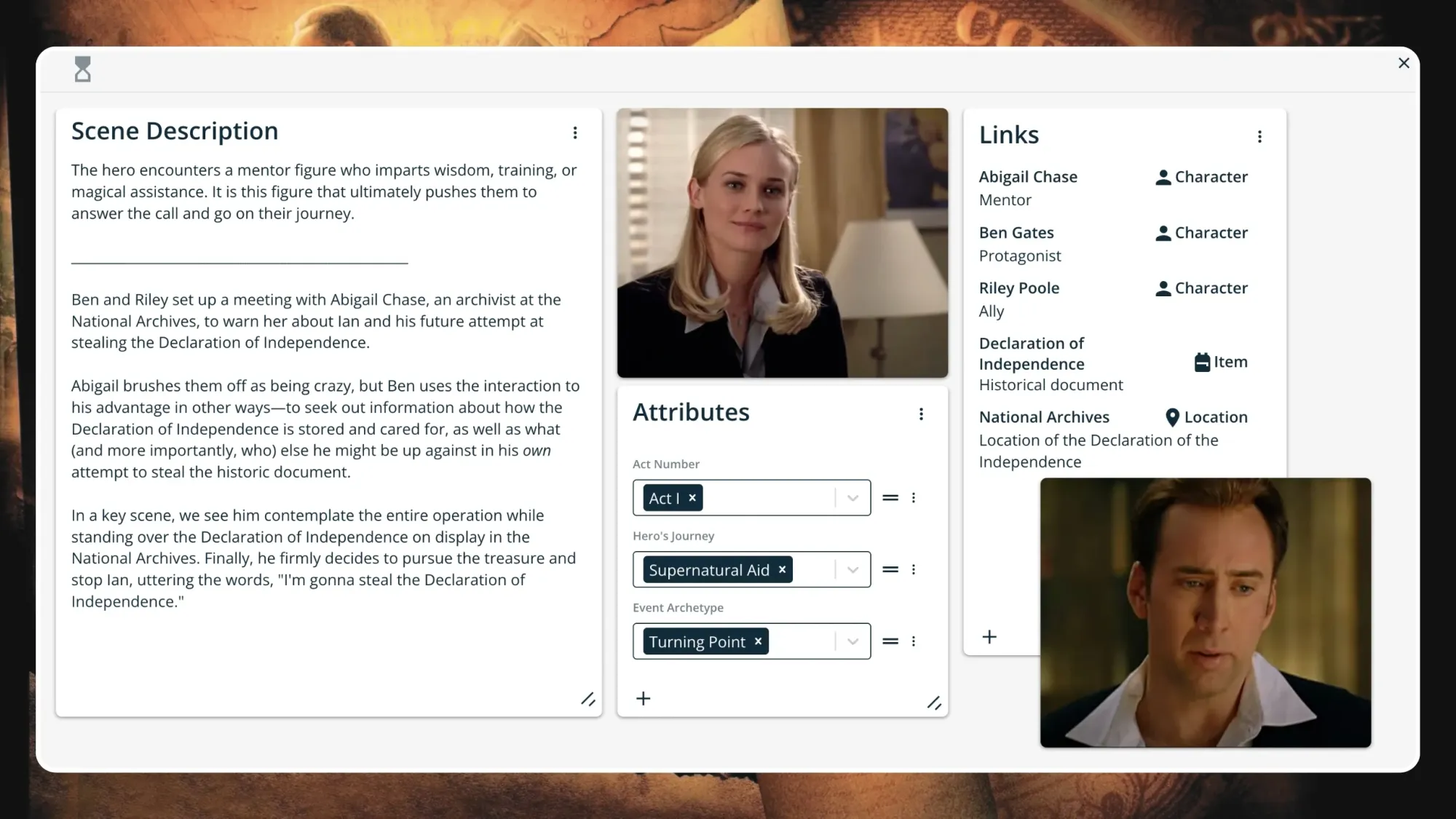

Step 4. Meeting the Mentor

The protagonist receives knowledge or motivation from a powerful or influential figure. This is a tactical move on the hero's part—remember that it was only the previous step in which they debated whether or not to jump headfirst into the unknown. By Meeting the Mentor, they can gain new information or insight, and better equip themselves for the journey they might to embark on.

Abigail, an archivist at the National Archives, brushes Ben and Riley off as being crazy, but Ben uses the interaction to his advantage in other ways—to seek out information about how the Declaration of Independence is stored and cared for, as well as what (and more importantly, who) else he might be up against in his own attempt to steal it.

In a key scene, we see him contemplate the entire operation while standing over the glass-encased Declaration of Independence. Finally, he firmly decides to pursue the treasure and stop Ian, uttering the famous line, "I'm gonna steal the Declaration of Independence."

Act Two: Initiation

Step 5. crossing the threshold.

The hero leaves the Known World to face the Unknown World. They are fully committed to the journey, with no way to turn back now. There may be a confrontation of some sort, and the stakes will be raised.

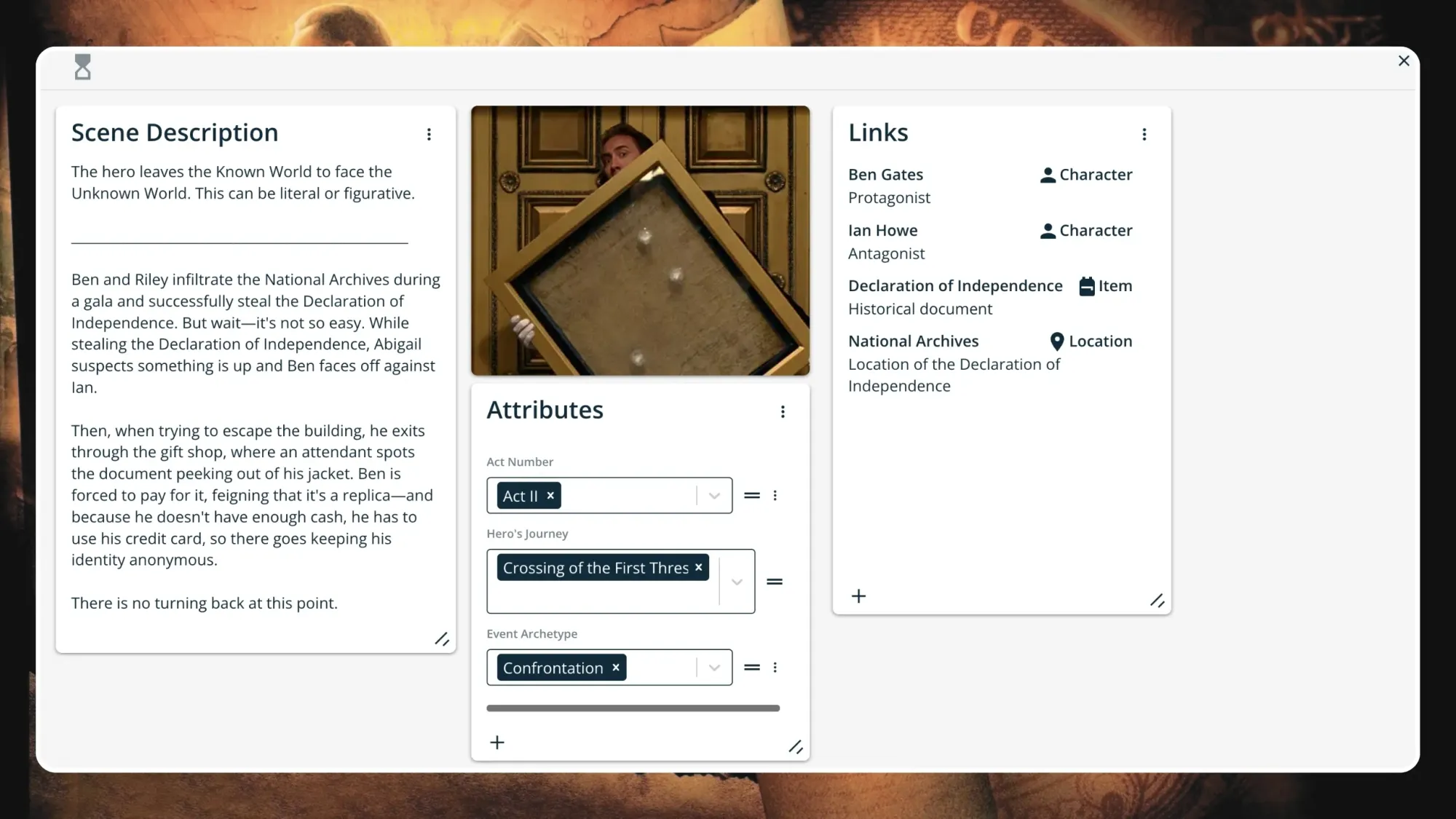

Ben and Riley infiltrate the National Archives during a gala and successfully steal the Declaration of Independence. But wait—it's not so easy. While stealing the Declaration of Independence, Abigail suspects something is up and Ben faces off against Ian.

Then, when trying to escape the building, Ben exits through the gift shop, where an attendant spots the document peeking out of his jacket. He is forced to pay for it, feigning that it's a replica—and because he doesn't have enough cash, he has to use his credit card, so there goes keeping his identity anonymous.

The game is afoot.

Step 6. Tests, Allies, Enemies

The hero explores the Unknown World. Now that they have firmly crossed the threshold from the Known World, the hero will face new challenges and possibly meet new enemies. They'll have to call upon their allies, new and old, in order to keep moving forward.

Abigail reluctantly joins the team under the agreement that she'll help handle the Declaration of Independence, given her background in document archiving and restoration. Ben and co. seek the aid of Ben's father, Patrick Gates, whom Ben has a strained relationship with thanks to years of failed treasure hunting that has created a rift between grandfather, father, and son. Finally, they travel around Philadelphia deciphering clues while avoiding both Ian and the FBI.

Step 7. Approach the Innermost Cave

The hero nears the goal of their quest, the reason they crossed the threshold in the first place. Here, they could be making plans, having new revelations, or gaining new skills. To put it in other familiar terms, this step would mark the moment just before the story's climax.

Ben uncovers a pivotal clue—or rather, he finds an essential item—a pair of bifocals with interchangeable lenses made by Benjamin Franklin. It is revealed that by switching through the various lenses, different messages will be revealed on the back of the Declaration of Independence. He's forced to split from Abigail and Riley, but Ben has never been closer to the treasure.

Step 8. The Ordeal

The hero faces a dire situation that changes how they view the world. All threads of the story come together at this pinnacle, the central crisis from which the hero will emerge unscathed or otherwise. The stakes will be at their absolute highest here.

Vogler details that in this stage, the hero will experience a "death," though it need not be literal. In your story, this could signify the end of something and the beginning of another, which could itself be figurative or literal. For example, a certain relationship could come to an end, or it could mean someone "stuck in their ways" opens up to a new perspective.

In National Treasure , The FBI captures Ben and Ian makes off with the Declaration of Independence—all hope feels lost. To add to it, Ian reveals that he's kidnapped Ben's father and threatens to take further action if Ben doesn't help solve the final clues and lead Ian to the treasure.

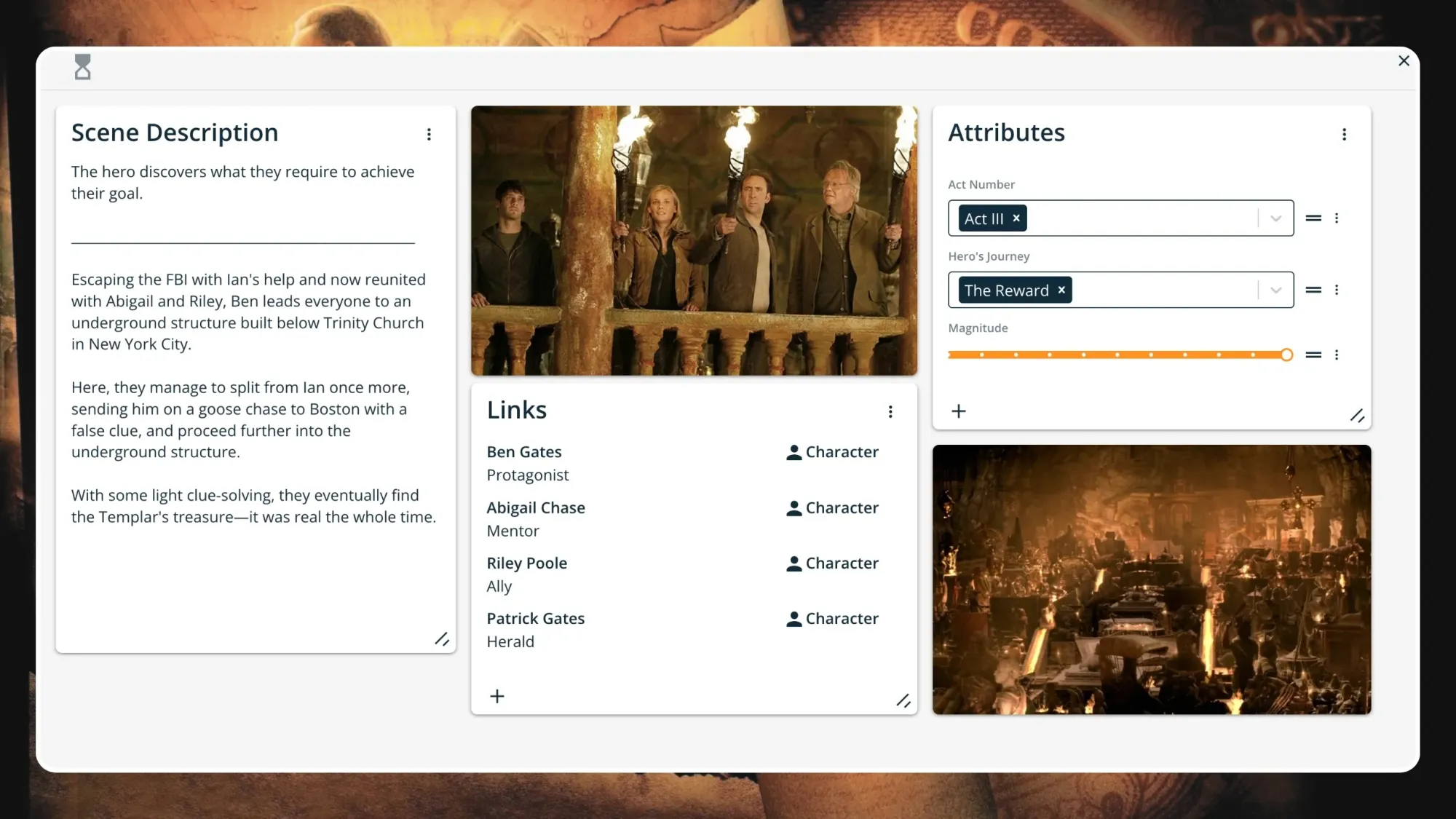

Ben escapes the FBI with Ian's help, reunites with Abigail and Riley, and leads everyone to an underground structure built below Trinity Church in New York City. Here, they manage to split from Ian once more, sending him on a goose chase to Boston with a false clue, and proceed further into the underground structure.

Though they haven't found the treasure just yet, being this far into the hunt proves to Ben's father, Patrick, that it's real enough. The two men share an emotional moment that validates what their family has been trying to do for generations.

Step 9. Reward

This is it, the moment the hero has been waiting for. They've survived "death," weathered the crisis of The Ordeal, and earned the Reward for which they went on this journey.

Now, free of Ian's clutches and with some light clue-solving, Ben, Abigail, Riley, and Patrick keep progressing through the underground structure and eventually find the Templar's treasure—it's real and more massive than they could have imagined. Everyone revels in their discovery while simultaneously looking for a way back out.

Act Three: Return

Step 10. the road back.

It's time for the journey to head towards its conclusion. The hero begins their return to the Known World and may face unexpected challenges. Whatever happens, the "why" remains paramount here (i.e. why the hero ultimately chose to embark on their journey).

This step marks a final turning point where they'll have to take action or make a decision to keep moving forward and be "reborn" back into the Known World.

Act Three of National Treasure is admittedly quite short. After finding the treasure, Ben and co. emerge from underground to face the FBI once more. Not much of a road to travel back here so much as a tunnel to scale in a crypt.

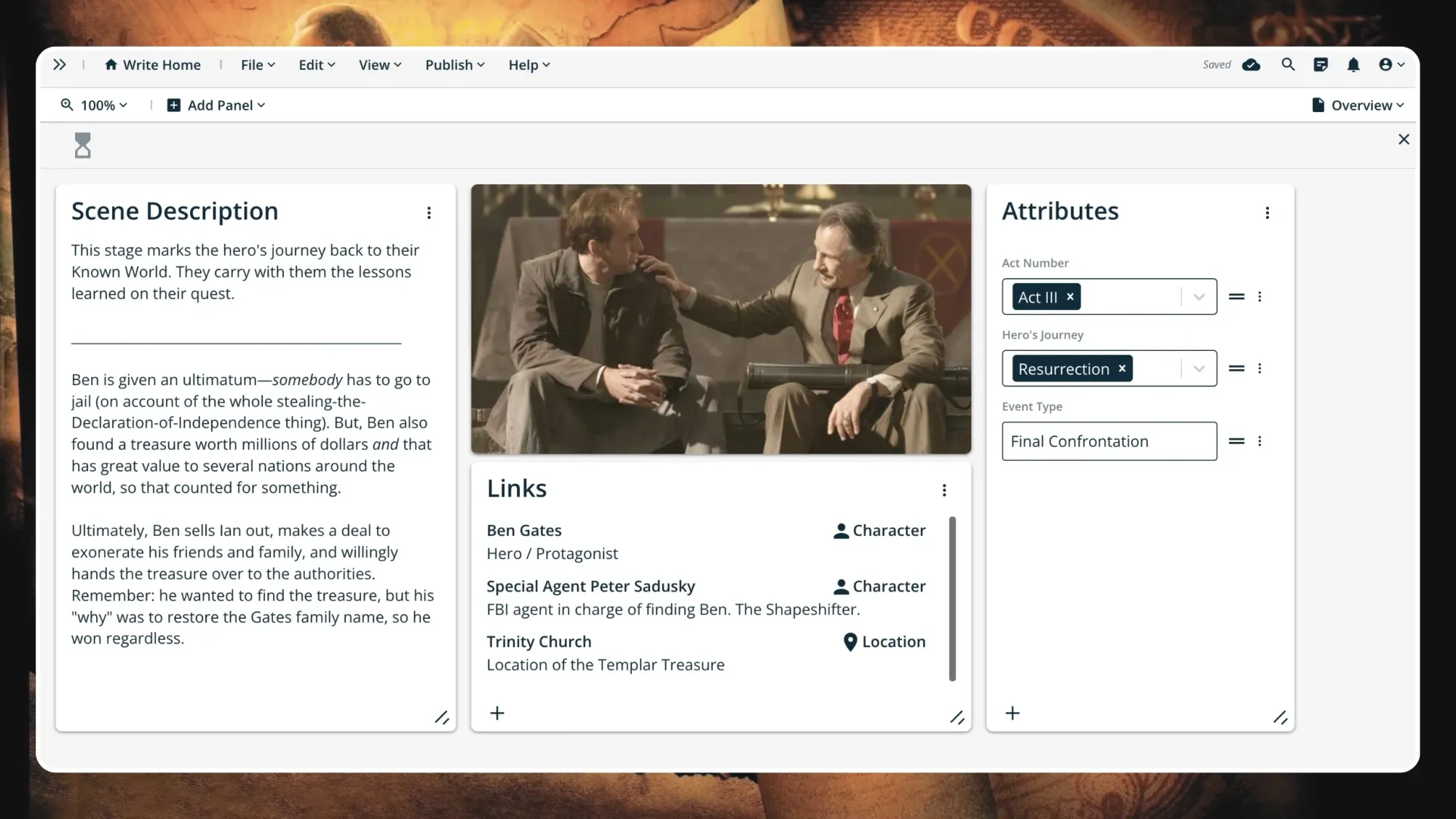

Step 11. Resurrection

The hero faces their ultimate challenge and emerges victorious, but forever changed. This step often requires a sacrifice of some sort, and having stepped into the role of The Hero™, they must answer to this.

Ben is given an ultimatum— somebody has to go to jail (on account of the whole stealing-the-Declaration-of-Independence thing). But, Ben also found a treasure worth millions of dollars and that has great value to several nations around the world, so that counts for something.

Ultimately, Ben sells Ian out, makes a deal to exonerate his friends and family, and willingly hands the treasure over to the authorities. Remember: he wanted to find the treasure, but his "why" was to restore the Gates family name, so he won regardless.

Step 12. Return With the Elixir

Finally, the hero returns home as a new version of themself, the elixir is shared amongst the people, and the journey is completed full circle.

The elixir, like many other elements of the hero's journey, can be literal or figurative. It can be a tangible thing, such as an actual elixir meant for some specific purpose, or it could be represented by an abstract concept such as hope, wisdom, or love.

Vogler notes that if the Hero's Journey results in a tragedy, the elixir can instead have an effect external to the story—meaning that it could be something meant to affect the audience and/or increase their awareness of the world.

In the final scene of National Treasure , we see Ben and Abigail walking the grounds of a massive estate. Riley pulls up in a fancy sports car and comments on how they could have gotten more money. They all chat about attending a museum exhibit in Cairo (Egypt).

In one scene, we're given a lot of closure: Ben and co. received a hefty payout for finding the treasure, Ben and Abigail are a couple now, and the treasure was rightfully spread to those it benefitted most—in this case, countries who were able to reunite with significant pieces of their history. Everyone's happy, none of them went to jail despite the serious crimes committed, and they're all a whole lot wealthier. Oh, Hollywood.

Variations of the Hero's Journey

Plot structure is important, but you don't need to follow it exactly; and, in fact, your story probably won't. Your version of the Hero's Journey might require more or fewer steps, or you might simply go off the beaten path for a few steps—and that's okay!

What follows are three additional versions of the Hero's Journey, which you may be more familiar with than Vogler's version presented above.

Dan Harmon's Story Circle (or, The Eight-Step Hero's Journey)

Screenwriter Dan Harmon has riffed on the Hero's Journey by creating a more compact version, the Story Circle —and it works especially well for shorter-format stories such as television episodes, which happens to be what Harmon writes.

The Story Circle comprises eight simple steps with a heavy emphasis on the hero's character arc:

- The hero is in a zone of comfort...

- But they want something.

- They enter an unfamiliar situation...

- And adapt to it by facing trials.

- They get what they want...

- But they pay a heavy price for it.

- They return to their familiar situation...

- Having changed.

You may have noticed, but there is a sort of rhythm here. The eight steps work well in four pairs, simplifying the core of the Hero's Journey even further:

- The hero is in a zone of comfort, but they want something.

- They enter an unfamiliar situation and have to adapt via new trials.

- They get what they want, but they pay a price for it.

- They return to their zone of comfort, forever changed.

If you're writing shorter fiction, such as a short story or novella, definitely check out the Story Circle. It's the Hero's Journey minus all the extraneous bells & whistles.

Ten-Step Hero's Journey

The ten-step Hero's Journey is similar to the twelve-step version we presented above. It includes most of the same steps except for Refusal of the Call and Meeting the Mentor, arguing that these steps aren't as essential to include; and, it moves Crossing the Threshold to the end of Act One and Reward to the end of Act Two.

- The Ordinary World

- The Call to Adventure

- Crossing the Threshold

- Tests, Allies, Enemies

- Approach the Innermost Cave

- The Road Back

- Resurrection

- Return with Elixir

We've previously written about the ten-step hero's journey in a series of essays separated by act: Act One (with a prologue), Act Two , and Act Three .

Twelve-Step Hero's Journey: Version Two

Again, the second version of the twelve-step hero's journey is very similar to the one above, save for a few changes, including in which story act certain steps appear.

This version skips The Ordinary World exposition and starts right at The Call to Adventure; then, the story ends with two new steps in place of Return With Elixir: The Return and The Freedom to Live.

- The Refusal of the Call

- Meeting the Mentor

- Test, Allies, Enemies

- Approaching the Innermost Cave

- The Resurrection

- The Return*

- The Freedom to Live*

In the final act of this version, there is more of a focus on an internal transformation for the hero. They experience a metamorphosis on their journey back to the Known World, return home changed, and go on to live a new life, uninhibited.

Seventeen-Step Hero's Journey

Finally, the granddaddy of heroic journeys: the seventeen-step Hero's Journey. This version includes a slew of extra steps your hero might face out in the expanse.

- Refusal of the Call

- Supernatural Aid (aka Meeting the Mentor)

- Belly of the Whale*: This added stage marks the hero's immediate descent into danger once they've crossed the threshold.

- Road of Trials (...with Allies, Tests, and Enemies)

- Meeting with the Goddess/God*: In this stage, the hero meets with a new advisor or powerful figure, who equips them with the knowledge or insight needed to keep progressing forward.

- Woman as Temptress (or simply, Temptation)*: Here, the hero is tempted, against their better judgment, to question themselves and their reason for being on the journey. They may feel insecure about something specific or have an exposed weakness that momentarily holds them back.

- Atonement with the Father (or, Catharthis)*: The hero faces their Temptation and moves beyond it, shedding free from all that holds them back.

- Apotheosis (aka The Ordeal)

- The Ultimate Boon (aka the Reward)

- Refusal of the Return*: The hero wonders if they even want to go back to their old life now that they've been forever changed.

- The Magic Flight*: Having decided to return to the Known World, the hero needs to actually find a way back.

- Rescue From Without*: Allies may come to the hero's rescue, helping them escape this bold, new world and return home.

- Crossing of the Return Threshold (aka The Return)

- Master of Two Worlds*: Very closely resembling The Resurrection stage in other variations, this stage signifies that the hero is quite literally a master of two worlds—The Known World and the Unknown World—having conquered each.

- Freedom to Live

Again, we skip the Ordinary World opening here. Additionally, Acts Two and Three look pretty different from what we've seen so far, although, the bones of the Hero's Journey structure remain.

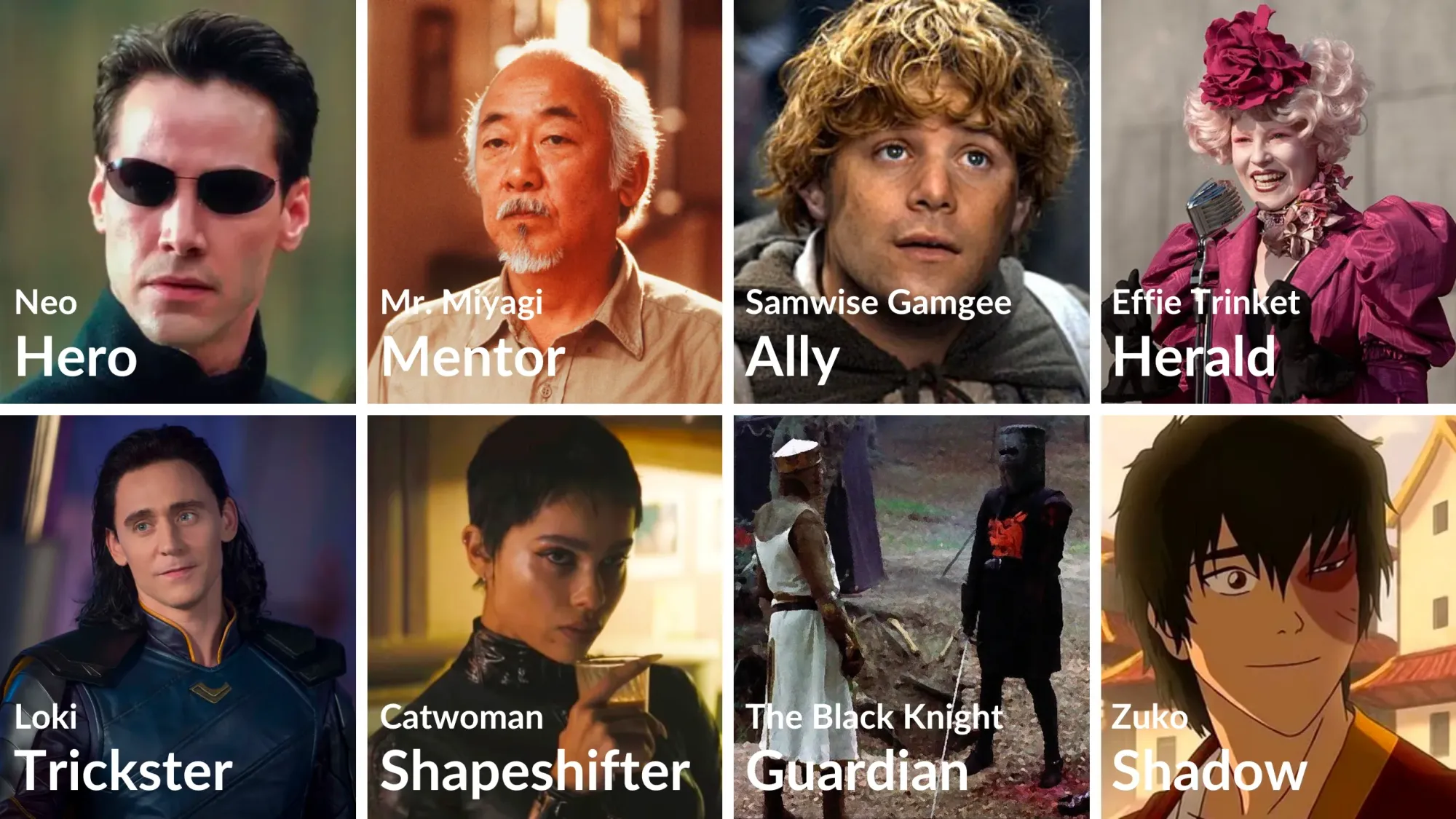

The Eight Hero’s Journey Archetypes

The Hero is, understandably, the cornerstone of the Hero’s Journey, but they’re just one of eight key archetypes that make up this narrative framework.

In The Writer's Journey , Vogler outlined seven of these archetypes, only excluding the Ally, which we've included below. Here’s a breakdown of all eight with examples:

1. The Hero

As outlined, the Hero is the protagonist who embarks on a transformative quest or journey. The challenges they overcome represent universal human struggles and triumphs.

Vogler assigned a "primary function" to each archetype—helpful for establishing their role in a story. The Hero's primary function is "to service and sacrifice."

Example: Neo from The Matrix , who evolves from a regular individual into the prophesied savior of humanity.

2. The Mentor

A wise guide offering knowledge, tools, and advice, Mentors help the Hero navigate the journey and discover their potential. Their primary function is "to guide."

Example: Mr. Miyagi from The Karate Kid imparts not only martial arts skills but invaluable life lessons to Daniel.

3. The Ally

Companions who support the Hero, Allies provide assistance, friendship, and moral support throughout the journey. They may also become a friends-to-lovers romantic partner.

Not included in Vogler's list is the Ally, though we'd argue they are essential nonetheless. Let's say their primary function is "to aid and support."

Example: Samwise Gamgee from Lord of the Rings , a loyal friend and steadfast supporter of Frodo.

4. The Herald

The Herald acts as a catalyst to initiate the Hero's Journey, often presenting a challenge or calling the hero to adventure. Their primary function is "to warn or challenge."

Example: Effie Trinket from The Hunger Games , whose selection at the Reaping sets Katniss’s journey into motion.

5. The Trickster

A character who brings humor and unpredictability, challenges conventions, and offers alternative perspectives or solutions. Their primary function is "to disrupt."

Example: Loki from Norse mythology exemplifies the trickster, with his cunning and chaotic influence.

6. The Shapeshifter

Ambiguous figures whose allegiance and intentions are uncertain. They may be a friend one moment and a foe the next. Their primary function is "to question and deceive."

Example: Catwoman from the Batman universe often blurs the line between ally and adversary, slinking between both roles with glee.

7. The Guardian

Protectors of important thresholds, Guardians challenge or test the Hero, serving as obstacles to overcome or lessons to be learned. Their primary function is "to test."

Example: The Black Knight in Monty Python and the Holy Grail literally bellows “None shall pass!”—a quintessential ( but not very effective ) Guardian.

8. The Shadow

Represents the Hero's inner conflict or an antagonist, often embodying the darker aspects of the hero or their opposition. Their primary function is "to destroy."

Example: Zuko from Avatar: The Last Airbender; initially an adversary, his journey parallels the Hero’s path of transformation.

While your story does not have to use all of the archetypes, they can help you develop your characters and visualize how they interact with one another—especially the Hero.

For example, take your hero and place them in the center of a blank worksheet, then write down your other major characters in a circle around them and determine who best fits into which archetype. Who challenges your hero? Who tricks them? Who guides them? And so on...

Stories that Use the Hero’s Journey

Not a fan of saving the Declaration of Independence? Check out these alternative examples of the Hero’s Journey to get inspired:

- Epic of Gilgamesh : An ancient Mesopotamian epic poem thought to be one of the earliest examples of the Hero’s Journey (and one of the oldest recorded stories).

- The Lion King (1994): Simba's exile and return depict a tale of growth, responsibility, and reclaiming his rightful place as king.

- The Alchemist by Paolo Coehlo: Santiago's quest for treasure transforms into a journey of self-discovery and personal enlightenment.

- Coraline by Neil Gaiman: A young girl's adventure in a parallel world teaches her about courage, family, and appreciating her own reality.

- Kung Fu Panda (2008): Po's transformation from a clumsy panda to a skilled warrior perfectly exemplifies the Hero's Journey. Skadoosh!

The Hero's Journey is so generalized that it's ubiquitous. You can plop the plot of just about any quest-style narrative into its framework and say that the story follows the Hero's Journey. Try it out for yourself as an exercise in getting familiar with the method.

Will the Hero's Journey Work For You?

As renowned as it is, the Hero's Journey works best for the kinds of tales that inspired it: mythic stories.

Writers of speculative fiction may gravitate towards this method over others, especially those writing epic fantasy and science fiction (big, bold fantasy quests and grand space operas come to mind).

The stories we tell today are vast and varied, and they stretch far beyond the dealings of deities, saving kingdoms, or acquiring some fabled "elixir." While that may have worked for Gilgamesh a few thousand years ago, it's not always representative of our lived experiences here and now.

If you decide to give the Hero's Journey a go, we encourage you to make it your own! The pieces of your plot don't have to neatly fit into the structure, but you can certainly make a strong start on mapping out your story.

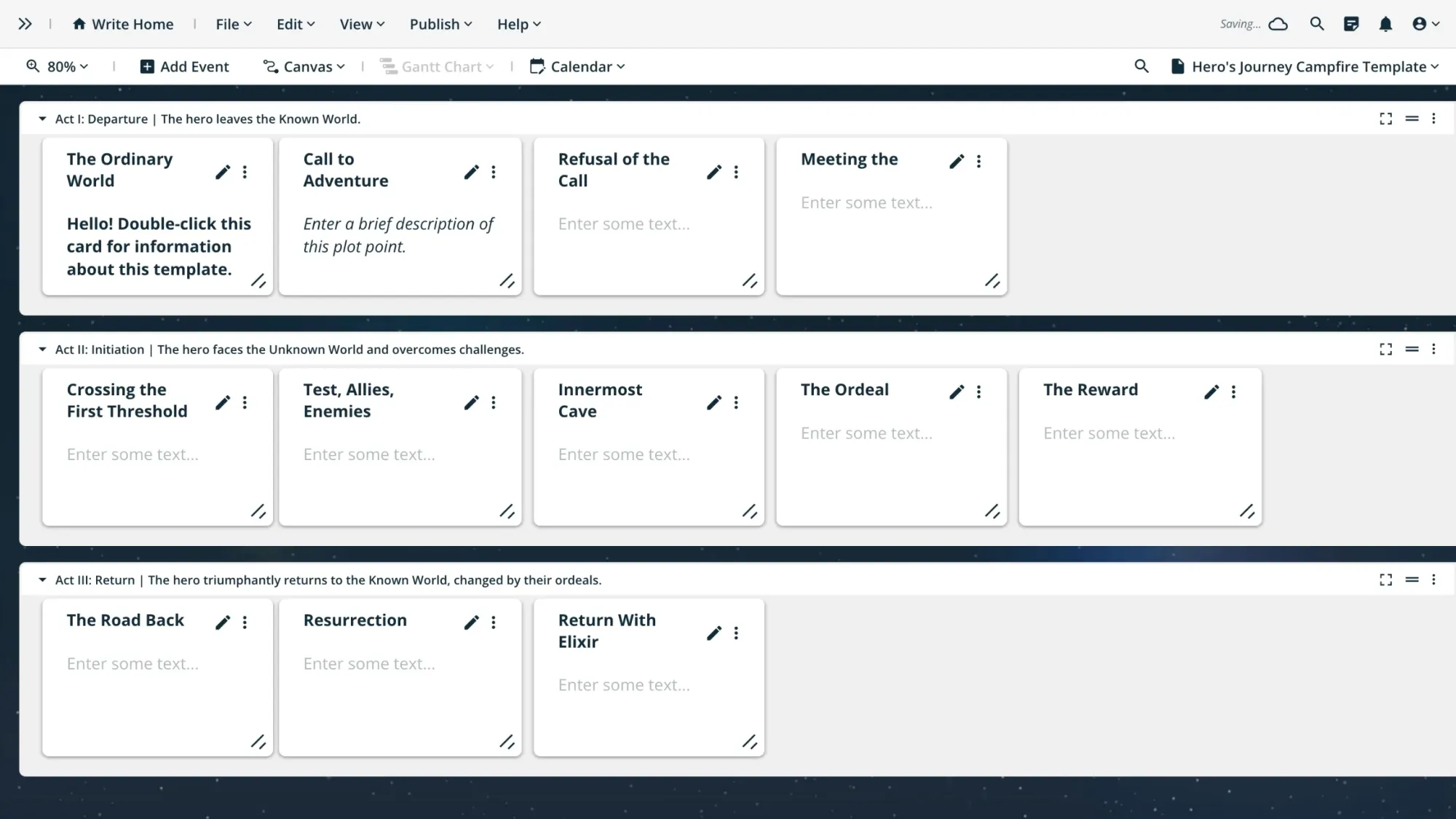

Hero's Journey Campfire Template

The Timeline Module in Campfire offers a versatile canvas to plot out each basic component of your story while featuring nested "notebooks."

Simply double-click on each event card in your timeline to open up a canvas specific to that card. This allows you to look at your plot at the highest level, while also adding as much detail for each plot element as needed!

If you're just hearing about Campfire for the first time, it's free to sign up—forever! Let's plot the most epic of hero's journeys 👇

Lessons From the Hero’s Journey

The Hero's Journey offers a powerful framework for creating stories centered around growth, adventure, and transformation.

If you want to develop compelling characters, spin out engaging plots, and write books that express themes of valor and courage, consider The Hero’s Journey your blueprint. So stop holding out for a hero, and start writing!

Does your story mirror the Hero's Journey? Let us know in the comments below.

The Eight Character Archetypes of the Hero’s Journey

Classic trickster.

In The Hero of a Thousand Faces , Joseph Campbell demonstrated that many of the most popular stories, even over thousands of years and across cultures, shared a specific formula. That formula is now commonly referred to as mythic structure, or the hero’s journey . Even if you’ve never heard of it before, you’ve consumed this “ monomyth ” in works like Star Wars and Harry Potter.

Along with a specific plot structure, the hero’s journey has a repeating cast of characters, known as character archetypes. An archetype doesn’t specify a character’s age, race, or gender. In fact, it’s best to avoid stereotyping by steering clear of the demographics people associate with them. What archetypes really do is tell us the role a character plays in the story. Thinking about your characters in terms of their archetype will allow you to see whether they’re pulling their weight, or if they’re useless extras.

There are many way to categorize the cast of the hero’s journey, but most central characters fall into one of these eight roles:

The hero is the audience’s personal tour guide on the adventure that is the story. It’s critical that the audience can relate to them, because they experience the story through their eyes. During the journey, the hero will leave the world they are familiar with and enter a new one. This new world will be so different that whatever skills the hero used previously will no longer be sufficient. Together, the hero and the audience will master the rules of the new world, and save the day.

J is the heroic tour guide in Men in Black . A cop at the top of his beat, he is suddenly taken behind the masquerade of everyday life. Waiting for him is a world where aliens are hiding among everyday people, and a galaxy can be as small as a marble. While he’s still a cop in essence, his adversaries – and the tools he must wield against them – are nothing like he’s previously known.

Other heroes: any protagonist fits the hero role. Some heroes from stories that stick closely to the hero’s journey are Dorothy from The Wizard of Oz, Alice from Alice in Wonderland, and Luke Skywalker from Star Wars.

The hero has to learn how to survive in the new world incredibly fast, so the mentor appears to give them a fighting chance. This mentor will describe how the new world operates, and instruct the hero in using any innate abilities they possess. The mentor will also gift the hero with equipment, because a level one hero never has any decent weapons or armor.

Glinda the Good Witch from The Wizard of Oz appears soon after Dorothy enters Oz. She describes where Dorothy is, and explains that she’s just killed the Wicked Witch of the East. Then, before the Wicked Witch of the West can claim the ruby slippers, Glinda gifts them to the hero instead.

Often, the mentor will perform another important task – getting the plot moving. Heros can be reluctant to leave the world they know for one they don’t. Glinda tells Dorothy to seek the Wizard, and shows her the yellow brick road.

Once the hero is on the right path and has what they need to survive, the mentor disappears. Heroes must fight without their help.

Other mentors: Morpheus from the Matrix, Dumbledore from Harry Potter, and Tia Dalma from Pirates of the Caribbean 2 and 3.

The hero will have some great challenges ahead; too great for one person to face them alone. They’ll need someone to distract the guards, hack into the mainframe, or carry their gear. Plus, the journey could get a little dull without another character to interact with.

Like many allies, Samwise looks up to Frodo in The Lord of the Rings . He starts the story as a gardener, joining the group almost by accident. He feels it’s his job to keep Frodo safe. But not all allies start that way. They can be more like Han Solo, disagreeable at first, then friendly once the hero earns their respect. Either way, the loyalty and admiration allies have for the hero tells the audience that they are worthy of the trials ahead.

Other allies: Robin from Batman, Ron and Hermione from Harry Potter, and the Tin Man from The Wizard of Oz.

The herald appears near the beginning to announce the need for change in the hero’s life. They are the catalyst that sets the whole adventure in motion. While they often bring news of a threat in a distant land, they can also simply show a dissatisfied hero a tempting glimpse of a new life. Occasionally they single the hero out, picking them for a journey they wouldn’t otherwise take.

The great boar demon that appears at the beginning of Princess Mononoke is a herald bearing the scars of a faraway war. Ashitaka defeats him, but not without receiving a mark that sends him into banishment. This gets the hero moving and foreshadows the challenges he will face.

Heralds that do not fill another role will appear only briefly. Often, the herald isn’t a character at all, but a letter or invitation.

Other heralds: Effie from the Hunger Games, R2D2 from Star Wars, and the invitation to the ball in Cinderella.

5. Trickster

The trickster adds fun and humor to the story. When times are gloomy or emotionally tense, the trickster gives the audience a welcome break. Often, the trickster has another job: challenging the status quo. A good trickster offers an outside perspective and opens up important questions. They’re also great for lampshading the story or the actions of the other characters.

Dobby from Harry Potter is an ideal trickster. He means well, but his efforts to help Harry Potter do more harm than good. And every time he appears in person, his behavior is ridiculous. However, underlying the humorous exterior is a serious issue – Dobby is a slave, and he wants to be free of his masters.

Other tricksters: Luna Lovegood (also from Harry Potter), Crewman #6 from Galaxy Quest, and Merry and Pippin from LoTR.

6. Shapeshifter

The shapeshifter blurs the line between ally and enemy. Often they begin as an ally, then betray the hero at a critical moment. Other times, their loyalty is in question as they waver back and forth. Regardless, they provide a tantalizing combination of appeal and possible danger. Shapeshifters benefit stories by creating interesting relationships among the characters, and by adding tension to scenes filled with allies.

Dr. Elsa Schneider, from Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade , is a very effective shapeshifter. Even after she reveals she is working for the enemy, she and the hero still have feelings for each other. She allows him to steal an item back without getting caught, and he allows her to discover the McGuffin with him. But the distrust between them remains.

Other shapeshifters: Gollum from LoTR, Catwoman from Batman, and Gilderoy Lockhart from Harry Potter.

7. Guardian

The guardian, or threshold guardian, tests the hero before they face great challenges. They can appear at any stage of the story, but they always block an entrance or border of some kind. Their message to the hero is clear: “go home and forget your quest.” They also have a message for the audience: “this way lies danger.” Then the hero must prove their worth by answering a riddle, sneaking past, or defeating the guardian in combat.

The Wall Guard in Stardust is as classic as guardians get. He stands alone at a broken section of stone wall between real world England and the fairy realm of Stormhold. The guard is friendly when Tristan tries to pass into the fairy realm to start his adventure, but he carries a big stick and he’s not afraid to use it.

Other guardians: The Doorknob from Alice in Wonderland, the Black Knight from Monty Python and the Holy Grail, Heimdall from Thor.

Shadows are villains in the story. They exist to create threat and conflict, and to give the hero something to struggle against. Like many of the other archetypes, shadows do not have to be characters specifically – the dark side of the force is just as much a shadow for Luke as Darth Vader is.

The shadow is especially effective if it mirrors the hero in some way. It shows the audience the twisted person the hero could become if they head down the wrong path, and highlights the hero’s internal struggle. This, in turn, makes the hero’s success more meaningful. The reveal that Darth Vader is Luke’s father, right after Luke had ignored Yoda’s advice, makes the dark side feel more threatening.

Other shadows: Voldemort from Harry Potter, Sauron from LoTR, and Maleficent from Sleeping Beauty.

It’s unusual for stories to have exactly one character per archetype. Because archetypes are simply roles a character can take, Obi Won and Yoda can both be mentors, J can be a hero and a trickster, and Effie Trinket can be first a herald, then later an ally. While you shouldn’t rush to add archetypes that are missing, any character that fits more than one is probably important to the story. If you have a character that doesn’t fit any, make sure they are strengthening, and not detracting from, your plot.

Learn More About These Archetypes

P.S. Our bills are paid by our wonderful patrons. Could you chip in?

More in Outside Advice

Why Michael Moorcock Despises Tolkien and C. S. Lewis

Q&a: what is the difference between a character-driven and plot-driven story, q&a: what do you think of the term “villain protagonist”, q&a: what do you think of km weiland’s story classifications, episode 444: storytelling education in school.

Steve Ferguson Old enough to have watched the initial airing of the original Star Trek series.

Your patronage keeps this site running. Become a patron.

Recent Articles in Storytelling

Finding Your Story’s Throughline

Why Nothing Good Ever Happens in an Interlude

How to Write Barbs and Banter That Aren’t Mean

Explaining Your Hero’s Secret Parentage

How Much Character Development Is Enough?

Recent comments.

A Perspiring Writer

Luke Slater

Love Mythcreants?

Be our patron.

Join our community for special perks.

Comments on The Eight Character Archetypes of the Hero’s Journey

Thanks for this great guide!!

Thank you, very informative. Gives a better understanding on how to create a story and “important” NPCs.

Like your name. :)

I like your name

I have a question. In Disney’s/ABC’s Once Upon a Time would you consider Rumplestiltskin/The Dark One to be a Trickster or a Shapeshifter? He’s not a ‘true’ villain though the writer’s class him as a villain. He’s way too complicated to just be a villain!!! He does evil things, bad things, neutral things and sometimes good things, but he keeps changing back and forth. He has the ability to love (his son and his wife Belle) but he ALWAYS puts power above them (it’s more important to him than his son or wife). I always thought of him as ‘the Trickster’ but when I read your description of the Shapeshifter it started me thinking again! hmmmmmm

I haven’t watched enough Once Upon a Time to tell you for sure based on my personal knowledge of Rumplestiltskin, but if he is often working together with the good guys but is liable to betray them or do other bad things, he’s probably a shapeshifter. Tricksters almost always provide comic relief. In the few episodes I watched, it did not look like Rumplestiltskin was a comical character.

However, because the archetypes are roles, characters can have more than one or change what they are. It sounds like sometimes when he is doing especially bad things, he might be a Shadow temporarily.

Shapeshifter

Dianne its a very good question but its really what you think he is.he is apart of many difrent grous and some arnt on this site . The most common thing ppl think he is is a villan but it really isnt like that at all but its up to you. hope i help . sincerely wesh

Would I be right in saying that Magneto in X-Men would be considered a shapeshifter?

Based on my very crude knowledge of X-Men, Magneto is mostly a shadow. Like a good shadow, he is a dark reflection of Professor X. However, he also takes on the role of shapeshifter during their temporary alliances.

No no, the shapeshifter is Mystique. ;)

HA! Good one :D

She can turn into other people, too, so, in literal sense, she is one. I think Chris was talking figuratively.

You’re Welcome!!!!!!!!!!

Msytique es da best chicka in da world mahhh boi

dont do drugs kids

bahahahahah

The description of the shadow is a little misleading. He is not the antagonist, and not evil. He mirrors the side of the hero that he/she is not aware of, but must acknowledge in order to continue and be sucessful on his/her journey.

The Star Wars example with the cave sets it: Yes, Darth Vader is evil (he is antagonist and shadow all in one), but he is also Lukes father. Therefore, he wasn´t always evil. Luke knows this.

A great example for a shadow in film are the two girls in American Beauty. Angela is Janes Shadow. She represents everything that Jane must leave behind in order to get on with her life, find her destiny etc. But Angela is not evil. She is a rather normal teenager. She is Janes friend.

Interesting approach :) (I’m not being ironic)

Usually, shadows are antagonists.

I’m not super familiar with American Beauty, so I could be totally wrong on this, but it sounds like the character dynamic you are describing is the use of a foil. A foil is character who starkly contrasts with attributes of a character (nearly always the main character) in order to highlight certain attributes of a character.

The Shadow is most definitely the opposing force in a literary work. It is true that the shadow – when it is a character – is most effective if it is also a foil of the protagonist as this helps to illustrate how the hero’s conflict is as much internal as external, but existing expressly to mirror the hero in some way is not a defining feature of the shadow.

The villain of American Beauty is societal pressure to be “normal” and the havoc it wreaks on people who are unique and special.

All the characters in the movie in some way rebel against that pressure, some prevail and others are destroyed.

It would be interesting to think up ways to realign quest stories to make different figures the protagonist. Like, say, in the Matrix, they really had me going that Neo wasn’t the one – I thought it would turn out to be Morpheus. Which would mean we were seeing Morpheus’s Hero journey through the eyes of one of his last Guardians (the obstacle preventing Morpheus seeing the Hero he sought was himself).

That would have been really cool. Nobody thinks of themselves as the hero (no competent person anyway). And it would fit perfectly with the Oracle telling Trinity that she would love The One, because love can also be fraternal.

I have only a secondary knowledge of Science Fiction and mythical creatures, gleaned from sitting with my husband and son when they watch shows in the same room with me. I found your page very informative, interesting, and helpful so that I may understand what I am watching Sci-Fi shows or shows about mythology with my family. Thank you.

Thanks for this article! I am actually a sculptor building a portfolio for character modeling. I was told by an industry recruiter to include different archetypes. For the longest time I only vaguely knew what he meant until I read your post. Currently reading the recommended book – excellent by the way! – which I see is the industry bible on this subject. I now have a much clearer picture on what direction to take my work! I also am now starting to see the types as I watch and read things. Great article :-)

I actually feel like Snape is a better example of the shapeshifter than Lockhart.

Good point. He’s always portrayed as evil … up until the end, when you see he was on the other side the whole time.

Zuko from Avatar the Last Airbender seems to be a perfect shapeshifter to me.

Yes. The most common form of the shapeshifter is one who begins as Ally and betrays the hero, but a character taking the inverse course of action is also an example of a shapeshifter. What defines the shapeshifter is that there is at least a key moment where the audience is left to wonder for themselves if the character is friend or foe. Zuko is also a wonderfully written character who undergoes a Heroes quest of his own with Iroh serving as his mentor and Azula taking on the role of shadow. He can be viewed as many roles in series depending on which part of the series you are thinking about.

Sir Didimus (sp?) from Labyrinth would be a penultimate Guardian.

Welcome to the Mythcreants comment section, Jemma Caffyn!

p.s. You have the same name as my favorite scientist (a made-up spec fic scientist, of course)

what about a villian that goes from bad to good?

Unless somehow showing up as the shadow, redeemed villains are not part of Joseph Campbell’s monomyth. The overwhelming majority of myths and stories written before the romantic period had clear villains and heroes. Nietschze explained this by saying that all myths are morality tales; if people believe that there is a definite good and evil then it will be easier for them to accept anything their leaders do so long as their is a greater enemy. It is no coincidence that so many mythical heroes are of noble birth. It has even be argued that morally ambiguous characters are a feature of democracy ( https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2017/03/whats-so-american-about-john-miltons-lucifer/519624/ ).

If you are interested in redeemed villains, this blog has an article and a podcast about them: https://mythcreants.com/blog/creating-your-villains-journey/ https://mythcreants.com/blog/122-redeeming-a-villain/

Can the Drayo State feasibly be attained by a character who doesn’t just confront his or her shadow but cannibalises it and therefore digests the darker side of his or her own nature? Asking for a friend.

Well, first of all, what is the “Drayo State”?

Fantastically useful site & not just for sf & fantasy writers. I’ve learned such a lot. Thanks!

i agree, very useful.

Thanks for helping me do my homework!

Archetypes are kind of like personas in life in general.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Email * (will not be made public)

The Approach to the Inmost Cave: How to Write This Scene in the Hero’s Journey

by David Safford | 0 comments

Every great heroic story has that moment. It's the deep breath before the plunge. The quiet before the calamity. If you're writing a Hero's Journey story, you'll want to include this moment, too: the Approach and Ordeal. Or, the Approach to the Inmost Cave.

The Approach and Ordeal are essential moments you need to plan for as you draft your story. And to do it right, you're going to need to figure out three key elements:

- Your Story's Shadow

- The Task to Complete

Let's explore each of these and talk about how they will take your story from “Meh” to “Amazing!”

Step 7: Approach to the Inmost Cave

This step can take many shapes depending on the story's genre and world. However, no matter where your story takes place, this definition applies:

The Approach is a moment of nervous contemplation before the massive Ordeal the hero must face. It is often a moment of final preparation, confession of secrets and fears, and abandonment by uncommitted companions, leaving the hero uncertain and isolated.

If you're outlining the Approach to the Inmost Cave scene for your story, you must keep the Ordeal, or the Climax, in mind. They are two halves of the whole, and one must keep both in mind when planning. However, in order to plan, you need to also understand the purpose of each (and how they work together).

For today, let's focus on the Approach to the Inmost Cave. And if you'd like to learn more about the Ordeal than what's discussed in this article, read about the Ordeal here .

How Did We Get Here?

As a quick refresher, the Hero's Journey is a storytelling theory by Joseph Campbell.

Refined by Christopher Vogler into a convenient twelve-step process, the Hero's Journey begins when the hero starts humbly ( Ordinary World ) and then experiences a Call to Adventure. The hero refuses that call, and finds themself encouraged and trained by a Mentor .

Next, through a combination of will and force, the hero steps over the boundary between safety and danger, the Threshold , and begins their journey in a world of Trials, Allies, and Enemies .

This usually brings you about two-thirds of the way through your story, up to the moment you've been waiting for: the Climax.

But before every Climax, a story needs an Approach to the Inmost Cave moment.

Step #7: Approach to the Inmost Cave

Before every climactic action scene is a deep breath. Sometimes portrayed as beginning with a montage or training scene, this scene is the moment when the Hero pauses, considers all that is at Stake in order to defeat the Shadow , and then soldiers onward.

This, in Christopher Vogler's words, is called the “Approach to the Inmost Cave.”

This moment is essential, and captures the universal human emotion of fear. All heroes experience some kind of fear, whether it's fear of death, failure, or the unknown. But before any great campaign against evil, there must be an Approach.

And with an Approach, comes a Hero's Ordeal (step eight in the Hero's Journey).

The Ordeal is the scene when your hero must complete a deadly task, putting everything that's at stake on the line, and ultimately confront the Shadow. This moment is the eighth step in the Hero's Journey, and comes directly after the Approach to the Inmost Cave.

Before this moment, though, you need a scene where the hero approaches the awaiting, climatic feat.

If you want to increase the tension and raise stakes in the Climax, you first need to write a scene that creates that calm before the storm. To do this, you need an Approach to the Inmost Cave scene that upholds three core elements.

3 Core Elements in the Approach to the Inmost Cave

In the Ordeal, the Hero confronts the Shadow and makes ultimate choices. This moment is thrilling, often action-packed, and offers the highest-stakes. However, the moment before this scene can't do the same thing. Instead there needs to be a brief, calm moment before plunging the Hero into battle.

Without this pause, the story won't elevate the suspense and tension. To get here, you're going to need to plan three storytelling elements:

- A Shadow character

- High stakes for success/failure

- A nearly-impossible task associated with the Shadow

With these elements in-hand, you'll be able to craft the next two steps of the Hero's Journey: The Approach (this article) and the Ordeal .

Let's start with the Shadow.

1. The Shadow: Get Your Villain Right

Joseph Campbell identified an archetypal character who appears in almost every heroic myth: The Shadow.

The Shadow is often called the villain. But what is more important is that they are a darker version of the hero.

Belloc, the greedy archeologist who steals from Indiana Jones in Raiders of the Lost Ark , says to him, “I am but a shadowy reflection of you.” For the Shadow to work, they need to be the “bad” version of what makes the Hero good.

Here are some elements that are often similar between Hero and Shadow:

- Physicality

- Background, family, and/or culture

However, other elements must be in opposition, otherwise there will be no reason to call your Hero “good” and the Shadow “evil.” Some include:

- Leadership style

- Physical strengths

- Belief in “freedom” or some other positive societal value

- Opinions on physical violence

When the Hero and Shadow share several characteristics , this gives them reason to threaten one another and even consider teaming up.

In fact, you've probably seen the scene where the Villain invites the Hero to join them a thousand times:

- Darth Vader to Luke Skywalker in Star Wars

- Voldemort to Harry Potter in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone

- Magneto to Professor X (or other X-Men heroes) in the X-Men

They don't just share physical traits though; what must be common are deeply held beliefs about the central conflict.

Digging deeper into Star Wars, both Luke and Vader possess strongly held views on one essential element of the narrative: The Force.

Should the Force be used for “good,” or wisdom and defense, as Yoda teaches? Or should it be used for power, strength, and control, as The Emporer declares?

This life crisis is what gives Star Wars it's true power. It isn't just that Vader is Luke's father — it's that Luke's father is wedded to evil and all its virtues, and Luke fears what that means for his own life.

Without a shared trait like this, there'd be no reason for intense internal conflict. There would only be stark opposition, and the relationship would never find any depth.

And this is what readers love.

They may claim to love action or conflict, but what they really love is intense internal conflict within the hero. It's your job to create it.

So as you plan the latter sections of your heroic journey, make sure you get your Shadow right by designing shared traits with your Hero to keep things interesting.

2. The Stakes: Make Them Both Specific and General

When the time comes for the Hero to face the Shadow late in the journey, the stakes need to be higher than ever.

This has to be true specifically, for the hero themself, and it has to be true generally, for the world at large and the cast of characters you've put around the Hero.

No heroic journey is about the Hero alone, as every hero symbolizes a greater societal value: Hope. Freedom. Faith.

Yet the Hero must also have plenty to lose as well. That's why it's your job to place difficult hurdles before them, especially during this climactic event in the story.

Take the example of the Harry Potter books.

From a point of view perspective, the books are incredibly intimate, taking the reader inside Harry's tortured mind and lonely soul. Yet his epic adventures have worldwide consequences as he must confront the rising evil of the Dark Lord Voldemort.

If Voldemort wins, the bigotry of “pure blood” magic will win and wreak havoc on both the magical world and the realm of unsuspecting Muggles. Harry's character arc isn't just about him dealing with a big baddie; it's about saving two entire worlds from Lord Voldemort and his minions.

This is what heroes do: They go in place of the people and face a most ultimate form of death. They put their own skin on the line, but their actions have universal impact.

That's what makes them so beloved when they win, and so worshiped when they suffer and die.

As you plan this climactic moment when Hero and Shadow finally clash, make sure the stakes — both local to the hero and general to the world — are at their peak intensity.

3. The Task: Challenging and Unidirectional

Whatever the Hero must do to pursue their ultimate goal, there must be a massive task to accomplish.

Examples include:

- Storming a castle

- Surviving a death match

- Escaping from a monster

- Winning a fight

- Delivering a great audition

These are the kinds of tasks we write poetry and songs about. These are the kinds of events that Lego builds toys about (except the audition/interview, of course).

There are two aspects of your confrontational task that must be incorporated into the design in order for them to be successful: Challenge and Direction.

First, the Task must be incredibly challenging.

It must be so challenging that your hero could not have succeeded in the first fifty percent of the book, and there's doubt whether or not they can succeed even now. It must be so challenging that the hero, or their companions, suffer to achieve it.

In this instance, consider The Hunger Games. One could argue that the games themselves represent the entire “Ordeal” stage of Katniss's hero's journey. It's not a common story structure, but it works in the world author Suzanne Collins is creating.

In the games, Katniss faces a monumental challenge: Defeat twenty-three other tributes, some from bloodthirsty Districts determined to capture victory. One of those tributes, of course, is her professed lover, Peta Malark. No easy task!

Note that the framing of the story shows Katniss approach the inmost cave, or the games, as she waits in the preparation room before rising into the arena. She and Peta eventually take revenge in a literal cave during the most critical moment when they are both injured and badly need medicine.

Not all stories prolong the Ordeal like Collins does. Others are brief but intense events, like an action or chase scene.

As an example of storming the castle, a common task in all sorts of stories from Game of Thrones to James Bond, the Shadow will lurk in a fortress with the object of desire (maybe a princess, a throne, a weapon, etc). In order to win the day (and prevent the awful Stakes from befalling humanity), the hero must infiltrate the castle, obtain the object of desire, and escape.

If you want this scene to be convincing, you can't have your hero sneak (or fight) in, grab the goods, and flee unscathed—at least not in this part of the Hero's Journey. You can get away with it as an opening bit (like in a Bond movie), but NOT as the climactic battle.

The Task must be overwhelmingly expensive in sweat and blood. The Shadow and their evil cannot be overcome with ease. Otherwise you'll lose your reader's catharsis and compassion.

Second, the Task must be unidirectional.

In other words, there can be no turning back. The consequences for even starting must be immediate. Everything must change. This is the turning point in your story.

So what needs to change?

Usually these elements must transform the hero and their world:

- The Hero no longer doubts the mission and will pursue it to the end

- The Shadow no longer exhibits patience or mercy and will do anything to destroy the Hero

- The world reacts to the Hero's choices: Evil creatures begin to actively hunt the Hero, good creatures actively protect the Hero

- The object of desire is moved, destroyed, or transformed somehow

Consider yet another example:

Pixar's Toy Story. Woody and Buzz's major challenge is to escape the hellscape that is Sid's bedroom. They do so, but emerge to a changed world.

Their Ordinary World, Andy's bedroom, is no longer where it used to be. It is in a moving truck, rolling away from them with great speed. They have emerged from their trial only to find that all is not well anymore, and the story continues from there.

Consider, finally, this last note. After the climactic scene between Hero and Shadow, the object of desire is often transformed in a way that alters the rest of the action. It all depends on what the particular MacGuffin is.

Often it is revealed that the desired object wasn't anything special at all, forcing the hero to reconsider their goals and priorities.

Often a key character is killed during the Ordeal, heightening the stakes and lessening the desireability of the goal itself. These crises are what make hero's journeys powerful, and don't be afraid to throw your hero to the wolves in the final act of your tale.

No matter what object of desire your Hero is pursuing, the climactic moment must change everything. There is no turning back. The choice must be unidirectional.

Bring it All Together

These three elements will help you plan steps seven and eight of the Hero's Journey. Let's bring them together to form a powerful one-two punch in the climax of your story.

Remember that your Shadow must represent all the evil and selfishness that your Hero fears. That Shadow must have the potential to ruin everything the Hero holds dear. And the Task set before the Hero must be monumental and seemingly impossible to achieve.

These elements, when properly designed and blended, will yield an incredible climax that your reader will love.

What are your favorite Hero's Journey Approach and Ordeal scenes from books and movies you love? Can you find these elements in them? Let us know in the comments .

Take fifteen minutes to freewrite a scene where a hero contemplates facing an ordeal ahead. Don't worry about the specifics; instead, lean into the emotional challenge of facing the coming challenges. Here are some to inspire you as dream up a scenario:

- Your Hero's “Shadow” character: What traits might your Hero and the Shadow have in common? What separates them and makes them enemies?

- The Stakes involved: What could your Hero have to risk in order to defeat the Shadow and any other threat to the world?

- The Task: What incredibly challenging feat might the Hero have to accomplish in order to successfully confront the Shadow?

Post your writing in the Practice box, then find another writer's plan and leave a helpful comment on it!

David Safford

You deserve a great book. That's why David Safford writes adventure stories that you won't be able to put down. Read his latest story at his website. David is a Language Arts teacher, novelist, blogger, hiker, Legend of Zelda fanatic, puzzle-doer, husband, and father of two awesome children.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Submit Comment

Join over 450,000 readers who are saying YES to practice. You’ll also get a free copy of our eBook 14 Prompts :

Popular Resources

Book Writing Tips & Guides Creativity & Inspiration Tips Writing Prompts Grammar & Vocab Resources Best Book Writing Software ProWritingAid Review Writing Teacher Resources Publisher Rocket Review Scrivener Review Gifts for Writers

Books By Our Writers

You've got it! Just us where to send your guide.

Enter your email to get our free 10-step guide to becoming a writer.

You've got it! Just us where to send your book.

Enter your first name and email to get our free book, 14 Prompts.

Want to Get Published?

Enter your email to get our free interactive checklist to writing and publishing a book.

Crafting Your Story’s Shadow

By Victoria Girmonde

Download the Math of Storytelling Infographic

Joseph Campbell identified the monomyth in his book The Hero with a Thousand Faces . In his research, Campbell found that it didn’t matter what culture or religion he looked at, there was a specific pattern of events that unfolded and seemed to come up again and again and again. This structure is seen in the story of Odysseus, of Beowulf, of Percival, of The Wizard of Oz , Harry Potter, Luke Skywalker, The Lord of the Rings , The Hobbit , and many others.

The hero’s journey is iconic, but certain archetypes seem to appear throughout literature. One of these archetypes is the Shadow archetype. In this article, I am going to go over the Shadow Archetype, what it is, how it relates to not only your hero but also to your villain, and how to craft one in use it in the Story Grid Genres. Let’s get started!

What is the Shadow Archetype?

At its most basic level, the shadow archetype has been seen throughout literature and culture for generations after generations. Throughout storytelling, the hero must battle the forces of evil in order to achieve his or her quest. Now the forces of evil can take on many different forms. These forces can be hunting down a murderer, and you have multiple bodies. It can also take on an adversary for your one true love. It can take on maybe a fall you might have. From a psychological viewpoint, it is somewhat different.

According to Carl Jung, a Swiss psychiatrist, everyone must struggle with their own Shadow their inner demons. Now the Shadow is our unconscious self. It’s all the parts of ourselves that we refuse to acknowledge and might even be ashamed of.

When a character embodies the shadow archetype in fiction, the Shadow archetype often takes on a villain. For example, Sauron is the Dark Lord of Mordor, and he represents the Shadow of the good of middle earth. Another example in The Lord of the Rings trilogy is Gollum. Gollum is the shadow archetype of not only of Frodo Baggins but also of Bilbo Baggins. Gollum represents the fallen hobbits. Even though Gollum was not a hobbit, to begin with, he was a cousin of the hobbits. Gollum was a Stoor Hobbit of the Riverfolk who lived near the Gladden Fields. He was initially known as Smeagol, but then he became corrupted by the One Ring of Power and was later named Gollum. When Gollum and his friend Deagol were off on a fishing trip, they found the Ring. Gollum (then Smeagol) wanted the Ring so much that he murdered his cousin for it. Gollum represents what Bilbo and Frodo could have quickly become through the One Ring’s corruption, and he is manifested physically on the page.

We all have darkness inside of us, and so do our characters. Your characters have things in their lives that they aren’t proud of. They are ashamed of things that have been done to them or of the things they have done.

We will discuss how to craft a Shadow Archetype for your story later on in this article. For now, let’s look at some other examples in literature and films.

The Shadow in Dr. Jekyll and the Matrix

Other examples of the Shadow in literature is The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson. Dr. Jekyll is a kind, well-respected scientist. He has a fiancé, and he is very, very well known in the community highly respected man thoughts he chooses to explore the darker side of science to bring out his second nature because of this flaw, Jekyll experiences his ultimate downfall. He transforms into his evil alter ego, Mr. Hyde. Hyde doesn’t repent or accept responsibilities for crimes and misdeeds like Jekyll does this by Jekyll’s best efforts to control Hyde, for maybe a very brief moment might be triumphant. Eventually, Hyde takes over, and the consequences lead to their deaths. Another example in recent television series of the shadow archetype is the character of Walter White in Breaking Bad. An ordinary family man at the start of the series, the darker aspects of his personality gradually take over until he becomes Heisenberg, a man prepared to murder to achieve his own goals.

In the 1999 film the Matrix , the Shadow is the sentinel program and the agents. Morpheus, a character in the Matrix, tells Neo (who is the hero), “The Matrix is everywhere. It is all around us. Even now, in this very room. You can see it when you look out your window, or when you turn on your television. You can feel it, when you go to work, when you go to church, when you pay your taxes… Unfortunately, no one can be told what the Matrix is, you have to see it for yourself.” Morpheus, The Matrix

The Shadow is everywhere, and like Sauron’s eye in The Lord of the Rings trilogy, it sees everything and watches over all within its dominion. Isn’t that frightful? The Shadow is frightful and designed both externally and internally to drive your character to their breaking point and grow as a result. In many ways, the Shadow is the mirror that highlights the darkness within.

Let’s look at some of the characteristics of the Shadow.

Shadow Archetype Characteristics and Traits

“The sad truth is that man’s real-life consists of a complex of inexorable opposites-day and night, birth and death, happiness and misery, good and evil. We are not even sure that one will prevail against the other, that goodwill overcome evil, or joy defeat pain. Life is a battleground. It always has been, and always will be, and if it were not so, existence would come to an end.” Carl Jung

So, what are some of the traits of the shadow archetype? Frequently, the Shadow Archetype is often associated with chaos, mystery, wilderness, and the unknown. The Shadow can also appear to your hero/protagonist in a variety of forms. Carl Jung believed that dreams were very indicative of what people’s inner Shadow was. On a superficial level, the Shadow Archetype might also take on the form of a human or an animal. For example, the Shadow could manifest itself as a snake, a monster, a demon, or even a dragon.

The dragon form was seen in The Hobbit , by J.R.R. Tolkien. In The Hobbit , the dragon Smaug has stolen the mountain of Erebor. He has also seized the dwarves’ treasures and drove the dwarves from their homeland. Smaug is an external representation of the greed of the dwarves when they mined Erebor.

In many ways, Smaug represents externally what is going on internally inside Thorin Oakenshield, who is the leader of the Company of Dwarves who aim to reclaim the Lonely Mountain. Both Smaug and Thorin are guilty of greed. At the very end of the novel, Thorin is able to confront his Shadow (greed) both externally as well as internally and overcome it before he is killed in The Battle of the Five Armies.

Do your characters defeat their Shadow? Is your character even aware of their Shadow? How is it expressed on an external level vs. an internal level?

Let’s look at why some people might be afraid of their Shadow!

Why are We and Our Characters Afraid of the Shadow?

According to Jung, most people are afraid to confront their dark side and instead blame other people for their faults. This can lead to a lot of exciting conflicts within your novel or screenplay. If your character is flawed (which more than likely it is), what are their faults? Do they blame others for their shortcomings? Are they even aware that they are flawed?

In many ways, the Shadow is a struggle with the inner self. Jung believed that this represented our repression of our inner selves of our true self is extremely dangerous. The tighter the rein a person keeps on his or her Shadow and on their shame of who they really and try to suppress the parts of their personality they really don’t like, the more unhealthy on a psychological note they will be.

So, How Do I Use the Shadow in My Stories?

Let’s face it, we all want to level up in our writing skills and resonate with readers. That’s why we follow the story grid and work on the macro (the global story) and the micro story (scene writing).

Readers want real characters. We all want to read characters that we can identify with, and characters who confront or are overcome by their Shadow can be universal.

For example, let’s say you are writing a Crime Genre story with a Serial Killer Subgenre. In order for your detective to solve the heinous crimes that are taking place on their streets, he/she has to get inside your villain’s mind and think like them. This can bring up disturbing personality traits for your detective.

- Do they become angry easier?

- Do they lash out?

- How does thinking like the killer affect them? Do they have a breaking point?

- What will bring out your character’s dark side?

- What inner demons are they harboring?

- Do the murders remind them of something that happened in their childhood?

- Do the victims remind them of someone they loved and lost?

Let’s look at some examples, shall we?

Examples of the Shadow in Literature and Film

Clarice Starling is the protagonist of Thomas Harriss’s The Silence of the Lambs . In that book, she is given the assignment to interview a notorious cannibal serial killer Hannibal Lector. She’s looking for information on the kidnapping and trying to find the girl before it’s too late.

Clarice’s story doesn’t end with The Silence of the Lambs . It continues in Hannibal, and it gets disturbing. In the next book, Harris takes even a darker turn. Seven years after the Buffalo Bill case, Clarice Starling is watching her career crumble around her. Hannibal Lector is on the loose, and Starling has just killed a meth dealer who had been holding a baby.

It was a drug raid gone very bad.

By the end of the novel, Starling and Lector’s relationship becomes even more complicated than the movie version. At first, Lector tries to brainwash Starling into thinking that she is Misha, Lector’s younger sister. When Lector was a child, Misha was killed in Russia and was eaten during a harsh winter. This was the catalyst that drove Lector into madness and revenge. Starling resists Lector and tells him that Misha is never coming back. Later on, Lector captures Justice Department agent Paul Krendler, who is Starling’s nemesis. Lector disables Krendler, and Starling and Lector eat his prefrontal cortex. Clarice finds the brain delicious. Then, Lector kills him. After, Clarice undresses and the two become lovers and disappear together.

Three years later, Barney (who had made problems for Lector and Starling before this) sees Lector and Starling at the opera as if waiting for him. It is interpreted that the two are there to eat him.

By the end of Hannibal , Clarice Starling has fully embraced her Shadow self and has stepped into a world very different than the one she has lived in before. Before this happened, Clarice was about law and order and bringing people to justice. Now, she is living outside of the law and has formed a new “law” with Lector.

Lector is Clarice’s Shadow personified.

Some critics have commented that it is unclear whether Clarice has entirely gone to dark or she is just pretending to be because she is trying a different tactic to try and curtail Lector’s apatite. Some have argued that with Clarice in a relationship with Hannibal Lector, she can monitor Lector and make sure he is not going entirely “insane.” Others have stated that Clarice has fully transitioned from FBI agent to serial killer. Either way, Clarice embraces a fate worse than death, which is on the negative Horror value scale.

While you don’t need to have as dramatic as a change like Harris does in his books, playing with the Shadow archetype of your character will help you with your story. By playing with the Shadow, you are going to take your characters to their breaking point.

Their Breaking Point

What is going to make them confront their Shadow? For Frodo, he has to face his growing attachment to the One Ring of Power. Every time Frodo looks at Gollum, he sees what he could become if he gives in to the power of the One Ring.

Gollum is his Shadow.

Every time Dr. Jeckyll feels the change coming on, he knows someone is about to be killed, and he has to try and figure out how to his Hyde personality from taking over.

What will drive your character to their dark side? For Walter White, in Breaking Bad, he had terminal cancer and wanted to get money quickly to secure his family’s future. However, the result ended in his demise. He cannot wholly conquer his Shadow, although he does return to a somewhat lesser degree of insanity at the very end.

How to Use the Shadow in Story Grid

Once you figure out your Story Grid Genre, and you have your main character(s), you should figure out how to heighten the value shifts through the Shadow archetype.

For example, the 2016 Passengers movie, starring Jennifer Lawrence and Chris Pratt, has a Love Courtship story running through it. However, you could easily rewrite it as a dark Love Obsession movie by manipulating the Shadow archetype. Let’s take a look:

The Avalon is a sleeper ship transporting 5,000 colonists and 258 crew members in hibernation pods from Earth to a distant planet named Homestead II. During the flight, Chris Pratt’s character James “Jim” Preston’s hibernation pod malfunctions, and he wakes up 90 years too early. Jim has no way to get his hibernation pod working again and must confront a grim fate: living the rest of the life alone on the Avalon .

In the movie, Jim becomes suicidal over the course of lonely a year until he sees Aurora Lane (Jennifer Lawrence) and ends up wanting to learn more about her, and he convinces himself he is in love with her. Eventually, Jim wakes Aurora up and tells her that pod “accidentally” malfunctioned. After a series of events, the two fall in love, become lovers, and then Aurora learns the truth that Jim woke her on purpose.

At this point in the movie, Aurora realizes that she has been lied to, and Jim has a moment where he realizes that what he did was wrong and that he had chosen to take her life. Eventually, everything works out, and the two fix the sleeper ship from malfunctioning, and they live a life together on Avalon.

This story has a Love courtship genre woven into it. However, you make it another way. Here’s how: Jim is obsessive and has lost his mind due to isolation when he decides to wake up Aurora. Jim thinks he has fallen in love with Aurora. However, he doesn’t even know her. Not really.

Yet, he becomes so obsessed with her that he decides to take away the life she had dreamt of and condemn her to a different life. When Aurora finds out, she doesn’t forgive Jim like she does in the movie, and instead, it becomes a cat and mouse game where Jim’s character has fully embraced his dark side and begins stalking her on the claustrophobic ship. Now, Aurora must figure out to survive on a ship drifting off into space.

You get the point.

You can twist the Shadow Archetype according to each genre. For the internal genres (love, worldview, and morality), the Shadow might be representative of an internal struggle going inside of the character. For the external genres, you might have the Shadow be visibly seen like Sauron’s eye or Smaug.

In order to craft the Shadow, ask yourself these questions:

- What is your character afraid of?

- What are they ashamed of?

- What does your character not want to remember?

- What is the Shadow of your character?

So, What’s Next?

As always, read widely and deeply. Read in multiple genres and try to dissect the stories both on a Story Grid genre level and watch out for the hero’s journey and Jung’s archetypes. Try and figure out how to show your story’s Shadow both externally as well as internally. I hope all is well. Take care and happy writing! – Tory

Share this Article:

🟢 Twitter — 🔵 Facebook — 🔴 Pinterest

Sign up below and we'll immediately send you a coupon code to get any Story Grid title - print, ebook or audiobook - for free.

Victoria Girmonde

Level up your craft newsletter.

The Hero and the Hero’s Shadow: The Archetype That Defines Us

A personal perspective: finding balance on the grief journey..

Posted March 30, 2022 | Reviewed by Vanessa Lancaster

- Archetypes are categories of people, characters, or voices that express fundamental aspects of the human experience. Each archetype has a shadow.

- There is a powerful connection between the representation of The Hero and the lines that divide us from each other and the inner Self.

- Both The Hero and The Shadow allow for growth – once realized, they are a constant source of elevation just waiting to be conjured.

Archetypes are categories of people, characters, or voices that express fundamental aspects of human experience. Archetype descriptions may vary across cultures but are universally recognizable. Think about The Good Mother or The Hero, and an image will come to mind. The same goes for all archetypal figures described by Carl Jung, the great twentieth-century psychoanalyst : The Father, The Wise Old Man, The Devil.

Each archetype also has a shadow. Spending any extended amount of time embodying an archetype will shed light on vulnerabilities. For example, The Hero might have a bloated ego that takes action when sometimes inaction allows for healthy distancing to occur: imagine if Superman never changed back into Clark Kent, never getting the opportunity to observe from a layman's perspective. The act of finding the balance between The Hero and its Shadow aids the discovery of sections of the grief journey where emotional coasting may become more efficient.

The Hero Archetype

The Hero is an archetype who can be an ardent supporter and cheerleader, finding ways to help us meet big and little grief and other trials directly. Known for strength, ingenuity, and the desire to be courageous at all costs, at the core of The Hero’s existence is the need to show how valuable it is not only to the Self but also to others.

The Hero offers stability. Think Wonder Woman or Spiderman helping to navigate the most difficult parts of the emotional Self. Strong. Courageous. At all costs, The Hero is stable.