The Hub – Family Medicine

Well child visit.

- Conduct an age-appropriate well child visit that includes physical exam, assessment of growth, nutrition, development, and education regarding injury prevention and safety risks.

- Address parental concerns, social context, and safety, and provide relevant anticipatory guidance (e.g. dental caries, family adjustment and sleeping position).

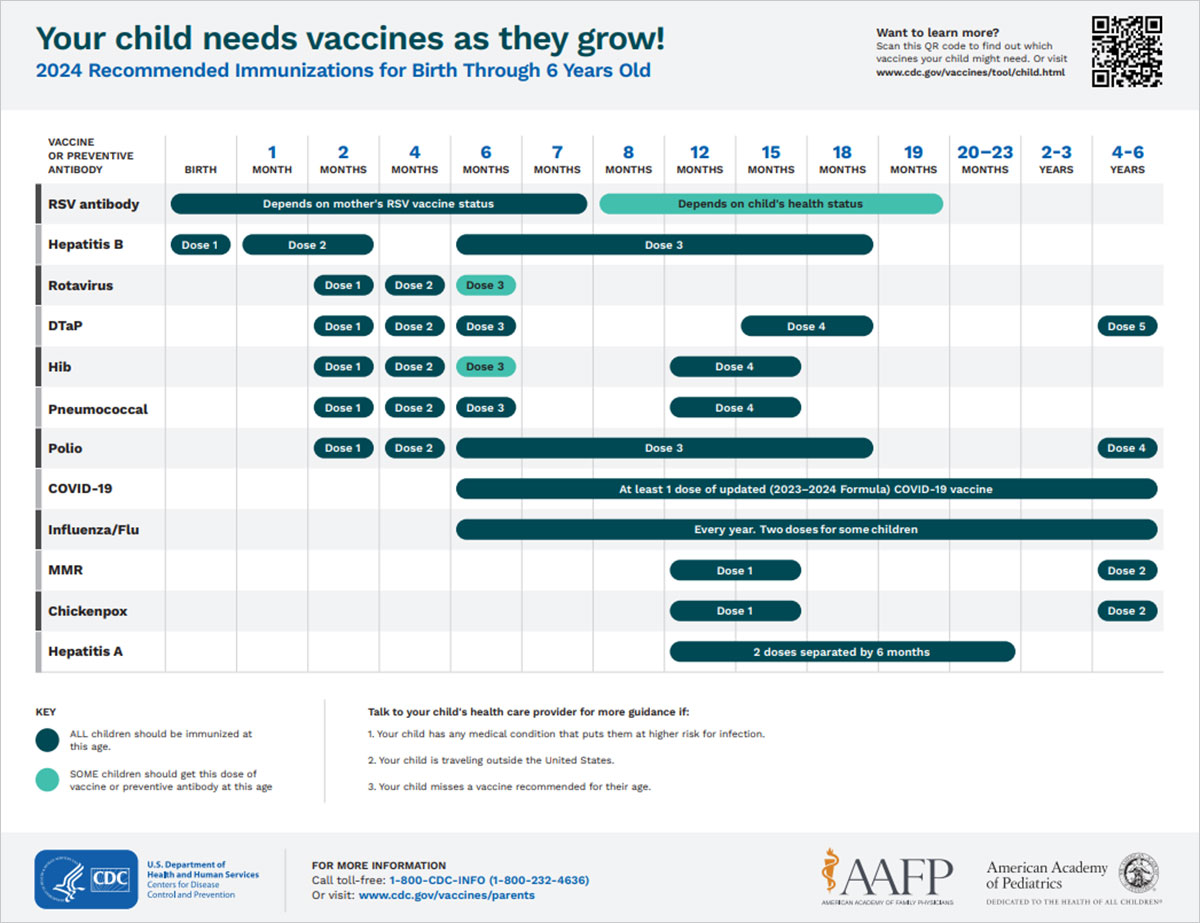

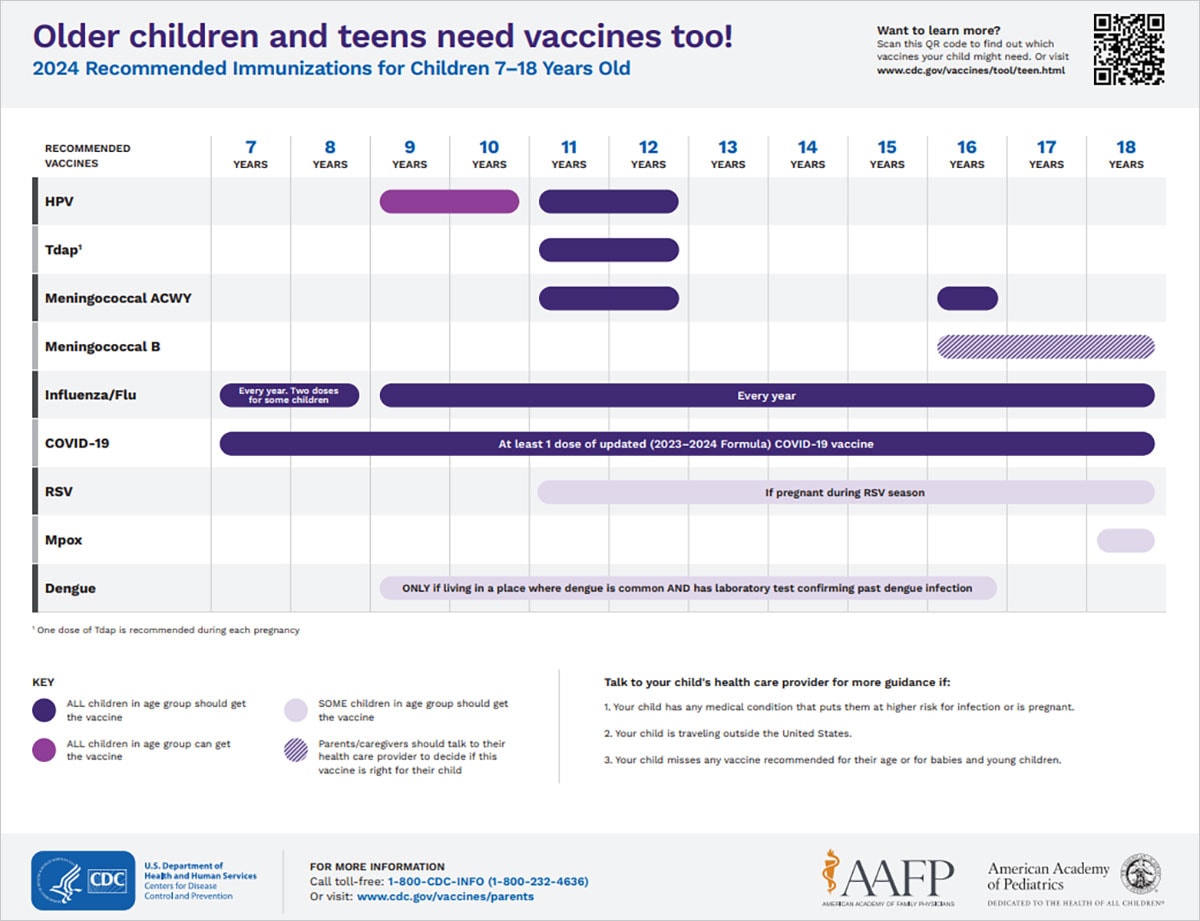

- Know the current childhood immunization schedule, be able to assess vaccination status of a child, and counsel parents on the risks and benefits of vaccinations.

- Use an evidence-based tool to help guide a well child visit, e.g. Rourke Baby Record, Greig Health Record.

- Identify common presenting concerns in newborns and children (e.g. jaundice, murmurs, autism), identify patients who require further assessment and perform the initial steps in management of these common presenting conditions.

Core Resources

Rourke baby record: evidence-based infant/child health maintenance.

Rourke L, Leduc D, Rourke J. Rourke Baby Record. Revised January 22, 2020.

18 Month Clinical Card

Rourke L, Leduc D, Li, P, Riverin B, Rourke J, Englert S, Power L. 18 Month Enhanced Visit. Canadian Family Medicine Clinical Card. 2016. Available at: https://sites.google.com/site/sharcfm/

Feeding your baby in the first year

Feeding your baby in the first year. Caring for your kids website. https://www.caringforkids.cps.ca/handouts/feeding_your_baby_in_the_first_year. Updated January 2020.

Greig Health Record 2016 Guidelines page 1

Greig A. Greig Health Record 2016: Selected Guidelines and Resources – Page 1. Canadian Paediatric Society. 2016. Available at http://www.cps.ca/

Greig Health Record 2016 Guidelines page 3

Greig A. Greig Health Record 2016: Selected Guidelines and Resources – Page 3. Canadian Paediatric Society. 2016. Available at http://www.cps.ca/

Greig Health Record 2016 Guidelines page 5

Greig A. Greig Health Record 2016: Selected Guidelines and Resources – Page 5. Canadian Paediatric Society. 2016. Available at http://www.cps.ca/

Newborn and Early Child Assessment E-Module

Law M, Mardimae A, Moaveni A et al. Newborn and Early Child Assessment: Family and Community Medicine Clerkship Core Curriculum Module. University of Toronto.

Publicly Funded Immunization Schedules for Ontario

Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Publicly Funded Immunization Schedules for Ontario. June 2022.

Supplemental Resources

Greig executive summary.

Greig AA, Constantin E, LeBlanc CM, et al. An update to the Greig Health Record: Executive summary. Paediatr Child Health. 2016;21(5):265-272.

Greig Health Record 2016 Guidelines page 2

Greig A. Greig Health Record 2016: Selected Guidelines and Resources – Page 2. Canadian Paediatric Society. 2016. Available at http://www.cps.ca/

Greig Health Record 2016 Guidelines page 4

Greig A. Greig Health Record 2016: Selected Guidelines and Resources – Page 4. Canadian Paediatric Society. 2016. Available at http://www.cps.ca/

Nutrition Healthy Term Infants 6 to 24 Months

Critch JN, Canadian Paediatric Society, Nutrition and Gastroenterology Committee. Nutrition for healthy term infants, six to 24 months: An overview. Paediatr Child Health 2014;19(10):547-49. For a wealth of information on child and youth health and well-being, visit www.cps.ca

Jaundice Clinical Practice Guideline

Canadian Paediatric Society The Hospital for Sick Children (‘SickKids’). Guidelines for detection, management and prevention of hyperbilirubinemia in term and late preterm newborn infants. Paediatr Child Health 2007;12(Suppl B):1B-12B. Available at https://cps.ca/en/

Child Obesity Recommendation

Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. Child Obesity Recommendation. Copyright 2015 by University of Calgary. Available at http://canadiantaskforce.ca/

Rourke Baby Record

For Healthcare Professionals

For Parents

The Rourke Baby Record (or RBR for short) is a system that many Canadian doctors and other healthcare professionals use for well-baby and well-child visits for infants and children from 1 week to 5 years of age.

It includes forms (Guides I to V) for charting the well-baby visits and Resources pages 1 to 4 that summarize current information and provide links to supporting resources for healthcare professionals.

The RBR Parent Resources Website is a place to find reliable parent-friendly resources and is designed to help parents answer their questions about their children up to age 5 years.

© Leslie Rourke, Denis Leduc, and James Rourke, 2020.

- Professionals

Welcome to your 18-Month Well-Baby Visit Planner ®

We want to make sure you have the best enhanced 18-month well-baby visit possible., prioritize your selected items in order of importance., acknowledgements.

machealth.ca

Ontario's enhanced 18-month well-baby visit.

Developed by experts in child development at McMaster University, this program provides healthcare professionals access to certified online learning courses and resources related to Ontario's Enhanced 18-Month Well-Baby Visit.

There are a number of resources to help you implement the enhanced 18-month visit in your practice. This web page contains a selected short-list of some of the key tools, service information, patient education, and reference resources associated with the visit.

Rourke Baby Record - 2020 Ontario English Version

The Rourke Baby Record (RBR) is an evidence-based health supervision guide for primary healthcare practitioners of children in the first five years of life. This is the 2020 Ontario version of the RBR with Guide IV including the 18-month visit.

Rourke Baby Record - 2020 Ontario French Version

Looksee checklist - english.

The Looksee Checklist (formerly the ndds) was compiled by a multi-disciplinary team, and is an easy-to-use tool that explores a child's skills in the following areas: vision, hearing, speech, language, communication, gross motor, fine motor, cognitive, social/emotional and self-help. Age appropriate activities which are designed to promote overall development accompany the Screens.

Looksee Checklist Video Examples - English

Video examples showing a child successfully demonstrate each item and tip on the Looksee checklist.

Looksee Checklist - French

Looksee checklist video examples - french.

Looksee Checklist Video Examples - French Video examples showing a child successfully demonstrate each item and tip on the Looksee Checklist checklist.

WHO Growth Charts - Boy

As part of the Rourke Baby Record, the growth of all full term infants and preschoolers should be evaluated using growth charts from the 2014 World Health Organization Child Growth Standards with measurement of recumbent length, weight, and head circumference.

WHO Growth Charts - Girl

On track reference guide website.

A reference guide for Ontario physicians including information about factors that influence child development, signs of atypical development, links to local services, and much more.

Ontario 211 Services Corporation website

A searchable database providing easy access to community, social, health and related government services in Ontario. Users can search by topic or location making finding local services easy.

Early Child Development and Parenting Resource System - generic Ontario version

Designed to provide info regarding services available in communities, this chart illustrates the organization of local early child development and parenting resources across a community, region or district so that young children are offered the opportunity for healthy development and the best start in life.

Early Child Development and Parenting Resource System - customizable Ontario template

Fill in this outline of screening and treatment/intervention resources with your local contact numbers as a handy job aid.

Ministry of Children,Community and Social Services (MCCSS), Government of Ontario

The MCCSS of Ontario website has information on programs and services for both the public and health care providers. Including - in the section on Early Childhood - information on the Best Start program, EarlyON Child and Family Centres, Healthy Babies Healthy Children program, Hearing, Blindness and Low Vision, and Speech and Language.

Enhanced 18-Month Well-Baby Fact Sheet for Parents (English)

A one-pager for parents describing the enhanced visit and includes useful resources and important 18-month milestones.

Enhanced 18-Month Well-Baby Visit Fact Sheet for Parents (French)

French-language version of the one-pager for parents describing the enhanced visit and includes useful resources and important 18-month milestones.

Hello! Welcome to our new web site. This site is not fully supported in Internet Explorer 7 (and earlier) versions. Please upgrade your Internet Explorer browser to a newer version.

As an alternative, you can use either of the options below to browse the site:

- Use Google Chrome browser. Here is the download link.

- Use Firefox browser. Here is the download link.

Family Life

AAP Schedule of Well-Child Care Visits

Parents know who they should go to when their child is sick. But pediatrician visits are just as important for healthy children.

The Bright Futures /American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) developed a set of comprehensive health guidelines for well-child care, known as the " periodicity schedule ." It is a schedule of screenings and assessments recommended at each well-child visit from infancy through adolescence.

Schedule of well-child visits

- The first week visit (3 to 5 days old)

- 1 month old

- 2 months old

- 4 months old

- 6 months old

- 9 months old

- 12 months old

- 15 months old

- 18 months old

- 2 years old (24 months)

- 2 ½ years old (30 months)

- 3 years old

- 4 years old

- 5 years old

- 6 years old

- 7 years old

- 8 years old

- 9 years old

- 10 years old

- 11 years old

- 12 years old

- 13 years old

- 14 years old

- 15 years old

- 16 years old

- 17 years old

- 18 years old

- 19 years old

- 20 years old

- 21 years old

The benefits of well-child visits

Prevention . Your child gets scheduled immunizations to prevent illness. You also can ask your pediatrician about nutrition and safety in the home and at school.

Tracking growth & development . See how much your child has grown in the time since your last visit, and talk with your doctor about your child's development. You can discuss your child's milestones, social behaviors and learning.

Raising any concerns . Make a list of topics you want to talk about with your child's pediatrician such as development, behavior, sleep, eating or getting along with other family members. Bring your top three to five questions or concerns with you to talk with your pediatrician at the start of the visit.

Team approach . Regular visits create strong, trustworthy relationships among pediatrician, parent and child. The AAP recommends well-child visits as a way for pediatricians and parents to serve the needs of children. This team approach helps develop optimal physical, mental and social health of a child.

More information

Back to School, Back to Doctor

Recommended Immunization Schedules

Milestones Matter: 10 to Watch for by Age 5

Your Child's Checkups

- Bright Futures/AAP Recommendations for Preventive Pediatric Health Care (periodicity schedule)

Ontario.ca needs JavaScript to function properly and provide you with a fast, stable experience.

To have a better experience, you need to:

- Go to your browser's settings

- Enable JavaScript

Early child development

Learn about programs that can support your child’s growth and development from the time they’re born until they start school.

On this page Skip this page navigation

About early child development.

A child's early years are very important for healthy development. This is a time when a child's brain and body develop at a rapid pace. Healthy babies and toddlers are more likely to stay healthy through their childhood, teen and adult years.

Ontario offers early child development programs to support children in their growth and development before birth to the time they enter school.

The programs provide services based on your child's needs.

You do not need a referral from a doctor.

Programs and services to support your child’s growth and development

- Healthy Babies Healthy Children

Learn about the support you can get during pregnancy, after your baby is born and as your child grows.

- Preschool Speech and Language

Find out about your child's speech and language development, and the help that's available.

Infant Hearing Program

Learn what hearing services and supports are available in your community.

Blind-Low Vision Early Intervention Program

Learn about support that's available for children who have a visual impairment.

18-Month Well-Baby Visit

Learn what to expect at your baby's Enhanced 18-Month Well-Baby Visit, including your child's 18-month vaccination.

Infant Child Development Program

Learn about the supports you can get through the Infant Child Development Program ( ICDP ) if you have concerns about your child’s development in the early years from birth to school entry.

Support your child's health

- Vaccines and immunizations

- Early Years Check-In

- EarlyON Child and family centres

- Find a family doctor

- Health care options

Child care and school

- Find and pay for child care

- Find licensed child care centres

- Kindergarten

- Publicly funded schools

- Student Nutrition Program

- Parenting and Family Literacy Centres

- Ontario Child Benefit

Monitor your child's developmental milestones

These developmental milestones have been provided to show some of the skills that mark the progress of young children as they learn to communicate. You may use these milestones to help monitor your child's development.

By 6 months

Most children can:

- turn to source of sounds

- startle in response to sudden, loud noises

- make different cries for different needs (for example, I'm hungry, I'm tired)

- watch your face as you talk

- smile and laugh in response to your smiles and laughs

- imitate coughs or other sounds (for example, ah, eh, buh)

By 9 months

- respond to their name

- respond to the telephone ringing or a knock at the door

- understand being told "no"

- get what they want through sounds and gestures (for example, reaching to be picked up)

- play social games with you (for example, peek-a-boo)

- enjoys being around people

- babbles and repeats sounds (for example, babababa, duhduhduh)

By 12 months

- follow simple one-step directions (for example, "sit down")

- look across the room to something you point to

- use three or more words

- use gestures to communicate (for example, waves "bye bye", shakes head "no")

- get your attention using sounds, gestures and pointing while looking at your eyes

- bring you toys to show you

- "perform" for attention and praise

- combine lots of sounds as though talking (for example, abada baduh abee)

- show interest in simple picture books

By 18 months

- understand the concepts of "in and out", and "off and on"

- point to several body parts when asked

- use at least 20 words

- respond with words or gestures to simple questions (for example, "where's teddy?", "what's that?")

- demonstrate some pretend play with toys (for example, gives teddy a drink)

- make at least four different consonant sounds (for example, b, n, d, g, w, h)

- enjoy being read to and looking at simple books with you

- point to pictures using one finger

By 24 months

- follow two-step directions (for example, "go find your teddy bear and show it to Grandma")

- use 100 or more words

- use at least two pronouns (for example, "you", "me", "mine")

- consistently combine two or more words in short phrases (for example, "daddy hat", "truck go down")

- enjoy being with other children

- begin to offer toys to peers and imitate other children's actions and words

- be understood by people 50% to 60% of the time

- form words and sounds easily and effortlessly

- hold books the right way up and turn pages

- "read" to stuffed animals or toys

- scribble with crayons

By 30 months

- understand the concepts of size (big and little) and quantity (a little, a lot, more)

- use some adult grammar (for example, "two cookies", "bird flying", "I jumped")

- use more than 350 words

- use action words (for example, run, spill, fall)

- begin taking turns with other children, using both toys and words

- show concern when another child is hurt or sad

- combine several actions in play (for example, feed a doll then put it to sleep, put blocks in train then drive train and drop blocks off)

- include sounds at the beginning of most words (for example, say "cat" rather than "at")

- produce words with two or more syllables or beats (for example, "ba-na-na", "com-pu-ter", "a-pple")

- recognize familiar logos and signs, for example stop sign

- remember and understand familiar stories

- understand "who", "what", "where" and "why" questions

- create long sentences using 5 or more words and talk about past events (for example, trip to grandparents' house, day at childcare)

- tell simple stories

- show affection for favourite playmates

- engage in multi-step pretend play (for example, cooking a meal, repairing a car)

- be understood by most people outside of the family, most of the time

- be aware of the function of print (for example, in menus, lists, signs)

- have a beginning interest in, and awareness of, rhyming

- follow directions involving three or more steps (for example, "first get some paper, then draw a picture, last give it to mom")

- use adult-type grammar

- tell stories with a clear beginning, middle and end

- talk to try to solve problems with adults and other children

- demonstrate increasingly complex imaginative play

- be understood by strangers most of the time

- be able to generate simple rhymes (for example, cat and bat)

- match some letters with their sounds (for example, the letter T says 'tuh')

- follow group directions (for example, "all the children get a toy")

- understand directions involving "if...then" (for example, "if you're wearing runners, then line up for gym")

- describe past, present and future events in detail

- seek to please their friends

- show increasing independence in friendships (for example, may visit a neighbour by themselves)

- use almost all of the sounds of their language with few to no errors

- know all the letters of the alphabet

- identify the sounds at the beginning of some words (for example, "pop starts with the 'puh' sound")

Information for professionals

Healthy child development - integrated services for children information system ( hcd-iscis ).

The Healthy Child Development - Integrated Services for Children Information System ( HCD-ISCIS ) is a database that stores personal health information of children and families who receive services from four early childhood development programs:

- Infant Hearing

- Blind-Low Vision Early Intervention

HCD-ISCIS allows service providers to collect, use and share personal health information for the purposes of delivering services as part of the early childhood development programs.

Service providers must get consent from families before they enter their information in the database.

Service providers are:

- public health units

- children's treatment centres

- other community-based organizations funded by the Province of Ontario

Information protection and privacy

The Province of Ontario provides the HCD-ISCIS database to participant service providers in its role as a "health information network provider" under the Personal Health Information Protection Act, 2004 .

Ontario protects personal health information stored in the HCD-ISCIS application. All employees that oversee the HCD-ISCIS application must attend privacy training and sign appropriate confidentiality agreements. Any individual or third party engaged by the Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services ( MCCSS ) to support HCD-ISCIS is bound by the same privacy requirements. Ontario employs technical safeguards for information systems where personal information may be accessed, including:

- audit logging

- role-based access controls

Enhanced 18-Month Well-Baby Visit

Role of the health care professional during an 18-month well-baby visit.

- Complete the Rourke Baby Record 2020 Ontario Version , an evidence-based guide to be used by primary health care workers in delivery of the enhanced well-baby visit

- Promote the LookSee Checklist by NDDS (previously Nipissing District Developmental Screen), a parent-completed developmental checklist designed to identify areas of concern requiring further attention

- Discuss healthy child development, and the provision of information about local parenting and community programs to promote healthy child development, with all parents

- Facilitate referrals to specialists for children with developmental concerns, and other community-based services for families with more complex needs

Additional recommended interventions

- Promote early literacy activities (reading, speaking and singing to babies) for all families

- Read, Speak, Sing: Promoting early literacy in the health care setting

- Support positive parenting in the early years

- Relationships matter: How clinicians can support positive parenting in the early years

- Screen for parental well-being, and offer support or referrals as needed for mental health, family conflict, anger, abuse / neglect, substance misuse, physical illness, housing / food insecurity and other adverse childhood experiences

- General and Family Practitioners: A002

- Pediatrics: A268

Accredited courses

- Supporting Healthy Child Development with Ontario's Enhanced 18-Month Well-Baby Visit

- Optimizing Well-Baby Care: Conducting an Enhanced 18-Month Well-Baby Visit

- Early Literacy Promotion: The A-B-Cs for busy clinicians

To learn more and register, visit professional development opportunities .

For use in practice

- Machealth provides a number of resources and tools to help you implement the enhanced 18-month well-baby visit in your practice

For parents

- 18-Month Well-Baby Visit Planner

- Play & Learn

- Look and See Checklists

- Nutrition Screen

- Early Years Check-In

For more information, visit Ontario’s Enhanced 18-Month Well-Baby Visit .

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Paediatr Child Health

- v.16(10); 2011 Dec

Language: English | French

Getting it right at 18 months: In support of an enhanced well-baby visit

Evolving neuroscience reveals an ever-strong relationship between children’s earliest development/environment and later life experience, including physical and mental health, school performance and behaviour. Paediatricians, family physicians and other primary care providers need to make the most of well-baby visits—here a focus on an enhanced 18-month visit—to address a widening ‘opportunity gap’ in Canada. An enhanced visit entails promoting healthier choices and positive parenting to families, using anticipatory guidance and physician-prompt tools, and connecting children and families with local community resources. This statement demonstrates the need for measuring/monitoring key indicators of early childhood health and well-being. It offers specific recommendations to physicians, governments and organizations for a universally established and supported assessment of every Canadian child’s developmental health at 18 months.

L’évolution des neurosciences révèle une relation toujours solide entre le développement et les milieux de la petite enfance et les expériences plus tard dans la vie, y compris la santé physique et mentale, le rendement scolaire et le comportement. Les pédiatres, les médecins de famille et les autres dispensateurs de soins de premier recours ont besoin de mettre le plus à profit possible les bilans de santé, dans ce cas-ci le bilan de santé amélioré à 18 mois, afin de compenser une « inégalité des chances » croissante au Canada. Un bilan amélioré comprend la promotion de choix plus sains et de rôles parentaux positifs auprès des familles, l’utilisation de conseils préventifs et d’outils gérés par le médecin ainsi que l’établissement de liens entre les ressources communautaires locales et les enfants et leur famille. Le présent document de principes démontre la nécessité de mesurer et de surveiller les principaux indicateurs de la santé et du bien-être de la petite enfance. Il contient des recommandations destinées aux médecins, aux gouvernements et aux organismes visant une évaluation universelle et subventionnée de la santé développementale de chaque enfant canadien à 18 mois.

THE 18-MONTH WELL-BABY VISIT

Neuroscience has dramatically increased our understanding of the importance of the quality of early child development and its inextricable link to children’s behaviours, their capacity to learn and later health outcomes ( 1 – 4 ). This has increased attention on how the structure and process of well-baby visits can promote long-term health and well-being. There is tremendous potential for primary care providers to positively affect outcomes through regular contact with children and families in the early years. To fully realize this potential, paediatricians and family physicians must assess their current practice, updating where necessary with enhanced clinical practices and skills. Primary care providers—paediatricians, family physicians and others—must also play a stronger role as advocates within the child health system.

No longer are well-baby visits limited to immunization and early identification of variance or abnormality. Increasingly, the primary care role is to proactively recognize and help enhance the unique assets of all children and their families. Primary care providers promote a wide variety of positive behaviours (such as breastfeeding, quality parenting, child management, injury prevention, and pro-literacy activities), using anticipatory guidance and connecting children and their families to local community resources. For these interventions to be effective, the literature supports using a physician-prompt health supervision guide, having found that clinical judgment alone is not enough ( 5 ).

Although primary care providers have an opportunity to work with families and children to enhance early childhood development at each well-baby visit, some jurisdictions have selected a pivotal visit as a starting point for universal, system-focused improvements. The 18-month encounter offers many opportunities: Not only is it seen as a crucial time in children’s development, but it is also a time when families face issues such as child care (especially centre-based care, which typically starts at this age), behaviour management, nutrition/eating and sleep. Screening for parental morbidities (mental health problems, abuse, substance misuse, physical illness) is an important task at all well-child visits, and particularly at this one.

The 18-month visit is often the final regularly scheduled visit (involving immunizations) with a primary care provider before school entry. Apart from illness-related visits, it may be the last time a child and family see their primary care provider until the child is four years of age or starts school. It is critical that families know how to promote healthy development during this important period of life and be alert to signs of difficulty, including problems with self-regulation, communication and language. They need to know when to consult their primary care provider, and how to connect with supportive community resources.

Primary care providers must be aware of available services and be involved in identifying barriers and facilitating access to assessment and care for their patients.

THE OPPORTUNITY GAP

Measurement of the sensitive indices of early child development in senior kindergarten (age 5) across Canada, through the use and analysis of the Early Development Instrument (EDI), shows that significant numbers of children are not adequately prepared for their school experience. Approximately 27% of Canadian kindergarten children score as ‘vulnerable’ on the EDI, when vulnerability rates greater than 10% can be considered ‘excessive’. In other words, approximately two-thirds of the developmental vulnerabilities (language/cognitive, physical or social-emotional) that children present with in school are preventable ( 6 ). The rates of vulnerability vary widely across Canadian neighbourhoods—from less than 5%, to nearly 70% of children—depending on socioeconomic, cultural, family and local governance factors.

When children fall behind, they tend to stay behind ( 7 , 8 ). Being a vulnerable child on the EDI negatively affects children’s school performance, reduces their well-being and decreases their chances of getting a decent job later in life. Each 1% of excess vulnerability will reduce Canada’s gross domestic product by 1% over the working lifetime of these children ( 9 ). Thus, if Canada fails to address developmental vulnerability in the early years, economic growth will likely be reduced by 15% to 20% over the next 60 years ( 10 ).

WELL-BABY VISITS IN OTHER COUNTRIES

Across the developed world, there are a wide variety of approaches to well-baby visits, and to the tools used to monitor and promote early child development. The Offord Centre for Child Studies (Hamilton, Ontario) recently completed a scan of developed countries to determine how well-baby/child visits are organized and which tools are used ( 11 ). The focus was on health and developmental surveillance and screening in children younger than six years of age in Canada, the United States, England, Ireland, Northern Ireland, Scotland, Australia, New Zealand, the Netherlands and Sweden. The number of surveillance visits for children younger than six years of age ranged from four in Scotland to 15 in Sweden, the Netherlands and the United States. The content of these visits ranged from immunization, growth monitoring and developmental screening to anticipatory guidance.

While developmental surveillance occurs in most countries, many do not recommend the use of standardized and validated development screening tools at well-baby/child visits, unless there is cause for concern. Scotland’s Hall 4 guidelines ( 12 ), along with the European Union’s Child Health Indicators of Life and Development (CHILD) project, have recommended that countries focus on child development surveillance and discourage general developmental screening. Most of these countries keep track of child development with the use of simple milestone checklists instead of a validated tool. In many countries (the United Kingdom, Ireland, Scotland, Australia, the Netherlands), using parent-held child health records has allowed families to play a larger role in child development monitoring. Parents can keep track of and record their child’s development in a universally available book, which is then reviewed by a health professional. Tools such as the ASQ (Ages & Stages Questionnaire) ( 13 ) and PEDS (Parents’ Evaluation of Developmental Status) ( 14 ) may also be used for parental input.

THE 18-MONTH VISIT IN CANADA

A scan of common practice in Canadian provinces at the 18-month visit ( 15 ) shows that while this is a consistent point in time for immunization, there is great variety in how, where and in what context vaccines are given. Well-child visits, including immunizations, are performed by family physicians or paediatricians in New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Ontario, though in areas with few physicians (eg, Northern Ontario), public health nurses administer vaccines. The physician visits typically include a physical health assessment, anticipatory guidance and immunizations.

Public health nurses administer vaccines in Prince Edward Island, Alberta and Newfoundland-Labrador, in addition to activities such as physical assessment and connecting families to community resources. Manitoba has a mixed model of public health nurses and physician strategies. Alberta has recently completed a pilot project in five communities using the ASQ at screening clinics. Saskatchewan, Nova Scotia and Manitoba have initiated pilot projects. Information for Quebec and the Yukon Territory was not available at time of writing, and the Northwest Territories and Nunavut were not surveyed.

THE ONTARIO SYSTEM

In October 2009, Ontario introduced an enhanced 18-month well-baby visit with a new physician fee code. This followed extensive work by an expert panel, including the Ontario College of Family Physicians and the Ministry of Children and Youth Services, which reviewed the evidence for such a visit and proposed a series of recommendations to government and the Ontario Medical Association ( 16 ).

Recognizing that the 18-month visit is the last regularly scheduled primary care encounter (involving immunizations) before school entry, the panel recommended that the focus shift from a well-baby check-up to a pivotal assessment of developmental health. The panel also recommended introducing a process using standardized tools—the Rourke Baby Record and the Nipissing District Developmental Screen—to facilitate a broader discussion between primary care providers and parents about:

- child development;

- access to local community programs and services that promote healthy child development and early learning; and

- promoting early literacy through book reading.

In a survey, Ontario physicians said that the time needed to complete an enhanced visit was the most significant barrier to implementing it. They also expressed concern that identifying children with developmental needs without having adequate community supports for referral and treatment created a moral dilemma for physicians ( 16 ).

To support planned system enhancement and change, a web portal ( www.18monthvisit.ca ) was created by the Offord Centre for Child Studies and MacHealth (Hamilton, Ontario) for educational purposes. Also, in collaboration with the Foundation for Medical Practice Education, a Practice-Based Small Group (PBSG) module was developed. The work has proceeded in partnership with Ontario’s Best Start strategy, which supports communities in developing early child development parenting and resource pathways and in actively addressing wait list issues.

DEVELOPING A POPULATION HEALTH MEASUREMENT TOOL FOR 18 MONTHS

How are 18-month-olds in Canada doing? Unfortunately, we don’t know, since there is no common tool used to measure their developmental progress. However, in collaboration with the Offord Centre for Child Studies, a pan-Canadian group is exploring the development of a population health measurement tool for use at 18 months. Given that children in different parts of Canada are assessed using different tools (for example: in some provinces nurses administer the ASQ, while in Ontario, physicians use the Rourke Baby Record and Nipissing District Developmental Screen), creating a common platform for 18-month monitoring is a challenge. Efforts are currently underway to determine whether the ASQ could be shortened without loss of validity, such that it could be used by physicians in a fee-scheduled visit ( 17 ).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The Canadian Paediatric Society recommends strengthening the early childhood development system across Canada through a series of activities.

For primary care providers, in the clinical setting:

- A physician-prompt health supervision guide with evidence-informed suggestions (such as the Rourke Baby Record).

- A developmental screening tool (the most widely used are the Nipissing District Developmental Screen, ASQ, and PEDS/PEDS:DM) to stimulate discussion with parents about their child’s development, both how they can support it as well as any concerns they may have.

- Screening for parental morbidities (mental health problems, abuse, substance misuse, physical illness).

- Promotion of early literacy activities (reading, speaking and singing to babies) for every family ( 18 ).

- Information about community-based early child development resources for every family (parenting programs, parent and early learning resource centres, libraries, recreational and community centres, etc. See www.cps.ca and www.18monthvisit.ca for links).

- Paediatricians and family physicians must keep their professional skills current to ensure they can identify children who require further investigation, diagnosis and treatment. All children who are not meeting developmental milestones and expectations, including socio-emotional development, self-regulation and attachment, should be referred to both community-based early years resources as well as to more specialized, developmental assessments and interventions, as appropriate.

For primary care providers, in their communities:

Paediatricians and family physicians should:

- Advocate locally for the development and enhancement of early years resources, including programs and policies that benefit young children.

- Advocate for the implementation of an enhanced 18-month well-baby visit in all provinces and territories, supported by standard guidelines (see 1, above) and a special fee code.

- Promote the implementation of an enhanced 18-month well-baby visit to their colleagues, including other health care professionals, through informal and formal channels (continuing medical education opportunities, resident training and curriculum enhancement).

- Support and participate in pilot programs and research initiatives to identify cost-effective and outcome-based interventions that contribute to closing the gap between children who do well and those who do poorly.

For governments and child-focused organizations:

Achieving system-wide change will require governments and organizations to:

- Work toward the creation of and sustained funding for an early child development system, including an enhanced 18-month well-baby strategy for all Canadian children.

- Ensure that provinces and territories support the enhanced 18-month well-baby strategy with standard guidelines and a special fee code.

- Develop a comprehensive system of measurement and monitoring that collects appropriate data on the progress of Canada’s young children and their families. Such a system would include regular cycles of the EDI in kindergarten and developing other measures (for use at 18 months, in the middle years and beyond) that can be linked, compared and regularly analyzed and reported on. These data would inform actions at the clinical practice, community and government levels.

- Promote and support research initiatives to determine whether there is a need for a regularly scheduled well-child visit between the ages of 18 months and 4 years.

Acknowledgments

This statement has been reviewed by the Canadian Paediatric Society’s Community Paediatrics Committee and the Developmenal Paediatrics Section (Executive Committee), and by Dr Emmett Francoeur of Montreal, Quebec.

EARLY YEARS TASK FORCE

Members: Robin Williams MD (Chair until June 30, 2011); Sue Bennett MD; Jean Clinton MD; Clyde Hertzman MD; Denis Leduc MD; Andrew Lynk MD

Principal authors: Robin Williams MD; Jean Clinton MD

The recommendations in this statement do not indicate an exclusive course of treatment or procedure to be followed. Variations, taking into account individual circumstances, may be appropriate. All Canadian Paediatric Society position statements and practice points are reviewed on a regular basis. Please consult the Position Statements section of the CPS website ( www.cps.ca ) for the full-text, current version.

Advertisement

Gaps in childhood immunizations and preventive care visits during the COVID-19 pandemic: a population-based cohort study of children in Ontario and Manitoba, Canada, 2016–2021

- Special Section on COVID-19: Quantitative Research

- Open access

- Published: 13 July 2023

- Volume 114 , pages 774–786, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Andrea Evans 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Alyson L. Mahar 4 , 5 ,

- Bhumika Deb 3 ,

- Alexa Boblitz 3 ,

- Marni Brownell 4 , 5 , 6 ,

- Astrid Guttmann 3 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 ,

- Therese A. Stukel 3 , 10 ,

- Eyal Cohen 3 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 ,

- Joykrishna Sarkar 5 ,

- Nkiruka Eze 5 ,

- Alan Katz 4 , 5 , 12 ,

- Tharani Raveendran 8 &

- Natasha Saunders 3 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11

1317 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

We aimed to estimate the changes to the delivery of routine immunizations and well-child visits through the pandemic.

Using linked administrative health data in Ontario and Manitoba, Canada (1 September 2016 to 30 September 2021), infants <12 months old (N=291,917 Ontario, N=33,994 Manitoba) and children between 12 and 24 months old (N=293,523 Ontario, N=33,001 Manitoba) exposed and unexposed to the COVID-19 pandemic were compared on rates of receipt of recommended a) vaccinations and b) well-child visits after adjusting for sociodemographic measures. In Ontario, vaccinations were captured using physician billings database, and in Manitoba they were captured in a centralized vaccination registry.

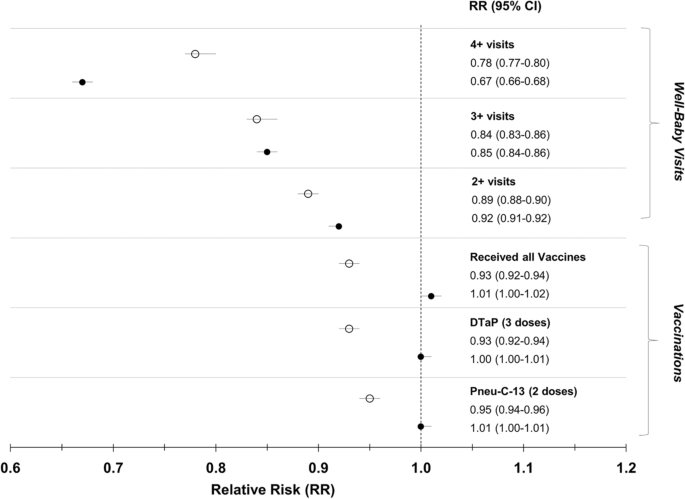

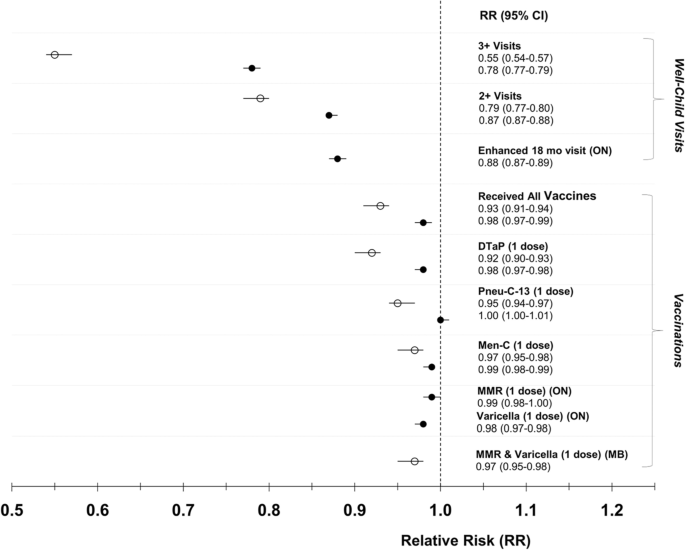

Exposed Ontario infants were slightly more likely to receive all vaccinations according to billing data (62.5% exposed vs. 61.6% unexposed; adjusted Relative Rate (aRR) 1.01 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.00-1.02]) whereas exposed Manitoba infants were less likely to receive all vaccines (73.5% exposed vs. 79.2% unexposed; aRR 0.93 [95% CI 0.92-0.94]). Among children exposed to the pandemic, total vaccination receipt was modestly decreased compared to unexposed (Ontario aRR 0.98 [95% CI 0.97-0.99]; Manitoba aRR 0.93 [95% CI 0.91-0.94]). Pandemic-exposed infants were less likely to complete all recommended well-child visits in Ontario (33.0% exposed, 48.8% unexposed; aRR 0.67 [95% CI 0.68-0.69]) and Manitoba (55.0% exposed, 70.7% unexposed; aRR 0.78 [95% CI 0.77-0.79]). A similar relationship was observed for rates of completed well-child visits among children in Ontario (aRR 0.78 [95% CI 0.77-0.79]) and Manitoba (aRR 0.79 [95% CI 0.77-0.80]).

Through the first 18 months of the pandemic, routine vaccines were delivered to children < 2 years old at close to pre-pandemic rates. There was a high proportion of incomplete well-child visits, indicating that developmental surveillance catch-up is crucial.

Nous avons voulu estimer les changements dans l’administration des vaccins de routine et dans les consultations pédiatriques pendant la pandémie.

À l’aide des données administratives sur la santé couplées de l’Ontario et du Manitoba, au Canada (1 er septembre 2016 au 30 septembre 2021), nous avons comparé les taux de réception : a) des vaccins recommandés et b) des consultations pédiatriques recommandées pour les nourrissons de < 12 mois (N = 291 917 en Ontario, N = 33 994 au Manitoba) et pour les enfants de 12 à 24 mois (N = 293 523 en Ontario, N = 33 001 au Manitoba) exposés et non exposés à la pandémie de COVID-19, après ajustement en fonction de mesures sociodémographiques. En Ontario, les vaccins ont été saisis à l’aide de la base de données des factures des médecins; au Manitoba, ils ont été saisis dans un registre de vaccination centralisé.

Les nourrissons exposés en Ontario étaient légèrement plus susceptibles de recevoir tous les vaccins selon les données de facturation (62,5 % pour les nourrissons exposés c. 61,6 % pour les nourrissons non exposés; risque relatif ajusté [RRa] 1,01 [intervalle de confiance (IC) de 95 % 1,00-1,02]), tandis que les nourrissons exposés au Manitoba étaient moins susceptibles de recevoir tous les vaccins (73,5 % pour les nourrissons exposés c. 79,2 % pour les nourrissons non exposés; RRa 0,93 [IC de 95 % 0,92-0,94]). Chez les enfants exposés à la pandémie, le total des vaccins reçus était un peu plus faible que chez les enfants non exposés (RRa en Ontario 0,98 [IC de 95 % 0,97-0,99]; RRa au Manitoba 0,93 [IC de 95 % 0,91-0,94]). Les nourrissons exposés à la pandémie étaient moins susceptibles d’avoir eu toutes les consultations pédiatriques recommandées en Ontario (33 % pour les nourrissons exposés, 48,8 % pour les nourrissons non exposés; RRa 0,67 [IC de 95 % 0,68-0,69]) comme au Manitoba (55 % pour les nourrissons exposés, 70,7 % pour les nourrissons non exposés; RRa 0,78 [IC de 95 % 0,77-0,79]). Une relation semblable a été observée pour les taux de consultations pédiatriques complètes chez les enfants en Ontario (RRa 0,78 [IC de 95 % 0,77-0,79]) et au Manitoba (RRa 0,79 [(IC de 95 % 0,77-0,80]).

Au cours des 18 premiers mois de la pandémie, les vaccins de routine ont été administrés aux enfants de < 2 ans à des taux proches de ceux d’avant la pandémie. Il y a eu une forte proportion de consultations pédiatriques incomplètes, ce qui indique qu’il est essentiel de rattraper la surveillance du développement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Impact of preventive primary care on children’s unplanned hospital admissions: a population-based birth cohort study of UK children 2000–2013

Elizabeth Cecil, Alex Bottle, … Sonia Saxena

Determinants of incomplete vaccination in children at age two in France: results from the nationwide ELFE birth cohort

Marianne Jacques, Fleur Lorton, … Pauline Scherdel

Timeliness of Childhood Vaccination Coverage: the Growing Up in Singapore Towards Healthy Outcomes Study

See Ling Loy, Yin Bun Cheung, … Koh Cheng Thoon

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic contributed to disruption of the delivery of core preventive child health services including routine immunizations and well-child visits (Causey et al., 2021 ). Disruptions of immunizations services, even for discrete time periods, can result in increased likelihood of vaccine-preventable disease outbreaks (WHO, 2020 ). An under-vaccinated population related to vaccination disruption from COVID-19 has been a cause of concern for re-emerging vaccine-preventable diseases such as polio (Rigby, 2022 ). In addition, routine well-child visits provide health supervision, anticipatory guidance, screening, and management of acute and chronic conditions, and care coordination. Early identification and intervention is important in many childhood conditions such as in developmental delays whereby missed or delayed diagnosis can have long-term health consequences (Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care, 2016 ). When routine appointments are not accessible or delivered virtually, parents may defer care or seek health services in emergency departments with consequences to the healthcare system and child health outcomes.

Globally, marked disruptions to routine immunizations were documented in the first year of the pandemic, with measles and tetanus vaccination coverage reduced by over 7% (Causey et al., 2021 ). In Canada, studies from different provinces have shown a similar reduction in vaccine uptake within the first year of the pandemic (Dong et al., 2022 ; Ji et al., 2022 ; Kiely et al., 2021 ; Lee et al., 2022 ; MacDonald et al., 2022 ; Sell et al., 2021 ). Reports of delayed and missed vaccinations caused public health concerns resulting in Canada’s National Advisory Committee on Immunization recommending prioritizing primary immunization series up to 18 months old during the pandemic, and provinces and territories implementing vaccine catch-up programs (NACI, 2020 ; Allan et al., 2021 ).

In both Ontario and Manitoba, we have previously observed a large shift to virtual primary care during the pandemic and an initial decline with some recovery in the rates of well-child visits (Glazier et al., 2021 ; Saunders et al., 2021 ). The effects of such large shifts from office to virtual care on routine immunizations and recommended well-child visits are unknown, particularly after allowing for a period of catch-up (Saunders et al., 2021 ).

We aim to quantify differences in immunization and preventive care visits completed before 12 months of age, and between 12 and 24 months of age, for children post COVID-19 pandemic onset, compared to children before pandemic onset in two Canadian provinces, Manitoba (population ~1.4 million) and Ontario (population ~15 million). We capture immunization and well-child visit rates up until September 2021. Due to the disrupted delivery of services, we hypothesized that the proportion of infants and children who received all vaccines or well-child visits would be lower if they were exposed to the pandemic compared to unexposed infants and children. Our secondary objective was to describe and quantify changes in the receipt of individual vaccines and well-child visits.

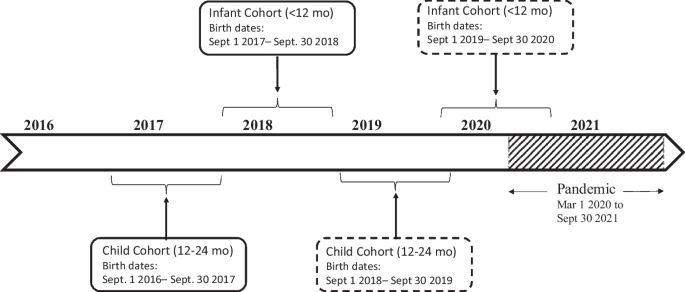

Study design, setting, and population

This was a population-based cohort study of children 0 to 24 months old, born between 2016 and 2020 in Ontario and Manitoba, using linked health and administrative data. The exposed cohort had all vaccines and visits after the pandemic onset and was exposed to at least 6 months of the pandemic, as defined from 1 March 2020 to 30 September 2021, and therefore born between 1 September 2018 and 30 September 2020. The unexposed cohort had all visits and vaccinations prior to the pandemic onset and completed prior to 17 March 2020, thus were born between 1 September 2016 and 30 September 2018. The last date of data collection was 30 September 2021. Pre-pandemic (unexposed) and post-pandemic (exposed) infant and child cohort definitions by birth date are illustrated in Fig. 1 .

Definition of infant (< 12 months old) and children (12-24 months old) cohorts. Exposed cohort (subjects with recommended immunizations and visits post-pandemic onset) are in dashed lines. Unexposed cohort (subjects with all recommended immunizations and visits pre-pandemic onset) are in continuous lines. Exposure to the pandemic defined as 6 months or more (COVID-19 pandemic defined as 1 March 2020 to 30 September 2021)

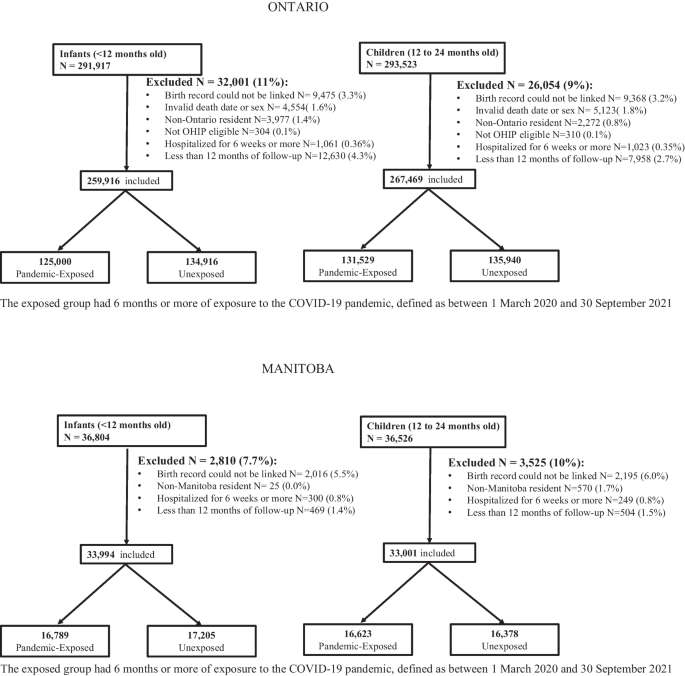

Cohort numbers and exclusions are shown in Fig. 2 . Infants were excluded if their demographic information (birthdate and sex) was unknown, if they were not Ontario/Manitoba residents at the time of birth and therefore not eligible for coverage through the Ontario/Manitoba Health Insurance Plan, if they were hospitalized at birth for greater than 6 weeks, if their birth records could not be reliably linked (invalid sex or linkage number), or if there was less than 12 months of follow-up.

Flowsheet of participant inclusions and exclusions

Data sources

We utilized health administrative and demographic databases housed and linked at ICES in Ontario and the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy. See Supplementary Table 1 for databases and their content. Individual-level records were linked by unique encoded identifiers derived from the health care numbers of individuals eligible for provincial health insurance coverage. We used demographic information (date of birth, sex and postal code) from provincial health insurance registries (Ontario’s Registered Persons Database, Manitoba Health Insurance Registry) and physician billings databases (Ontario Health Insurance Plan, Manitoba Medical Services) to ascertain outpatient physician visits to family physicians and pediatricians.

Childhood immunizations and well-baby visits are largely administered in outpatient settings through family physicians/general practitioners and pediatricians in Ontario. In Manitoba, vaccinations and well-baby visits are additionally administered by public health nurses, particularly in rural health regions (Hilderman et al., 2011 ). In Ontario, vaccination data are captured by billing claims. In September of 2011, vaccine-specific billing codes were introduced. A validation study showed high positive predictive value and high specificity, with moderate sensitivity (Schwartz et al., 2015 ). Unlike in Ontario, Manitoba’s immunization data are in a centralized immunization registry and thus not dependent on provider billing completeness and accuracy. In Manitoba, vaccination rates were defined using the Public Health Information Management System (PHIMS) data. See Supplementary Table 2 for codes used for Ontario and Manitoba.

Vaccinations

As per the Ontario Immunization Schedule, infants should receive 3 doses of the diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, polio, and haemophilus influenzae type B (DTaP-IPV-HiB) vaccines and 2 doses of the pneumococcal conjugate 13 (Pneu-C-13) vaccine in the first 6 months of life. The recommendations are that children receive one additional dose of Pneu-C-13, measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) and meningococcal type C (Men-C-C) at 12 months, along with a dose of varicella at 15 months and DTap-IPV-HiB at 18 months. The Manitoba vaccine schedule recommended by Manitoba Health has the same recommendations with the following exception: the MMR vaccine is combined with the varicella vaccine (MMRV). Manitoba immunization data include data on Rotavirus immunization, but these data were not available in Ontario and thus not reported.

For infants, our primary outcome was receipt of 3 doses of DTaP-IPV-HiB and 2 doses of Pneu-C-13 by the age of 12 months. For children, our primary outcome was receipt of 1 dose of Pneu-C-13, MMR or MMRV (in Manitoba), and Varicella (in Ontario), Men-C-C, and DTap-IPV-HiB between 12 and 24 months. In Ontario, only vaccinations that were billed by a physician were captured. No minimum time period was required between vaccine doses. Supplementary Figures 1 and 2 illustrate distribution of age of receipt for each vaccine. In both age groups, we allowed 6 months from the last recommended dose timing to allow for vaccine catch-up. Secondary outcomes were the proportion of recommended doses for individual vaccines.

Well-child visits

In Ontario, well-child visits occur at 2, 4, 6, 9, 12, 15, and 18 months of age as recommended by the Rourke Baby Record (Rourke & Rourke, 1985 ), along with recommendations for an ‘enhanced’ 18-month visit (Williams et al., 2008 ). Enhanced 18-month visits in Ontario occur in lieu of a well-baby visit, and contain a more comprehensive developmental assessment and have a unique billing code. In Manitoba the recommendations are similar, but without a routine recommendation for a 15-month visit nor the option for an ‘enhanced’ 18-month visit (Doctors Manitoba, 2021 ). From both primary and secondary outcomes, well-child visits that occurred within the first 30 days of life were excluded as these were considered newborn visits, which vary in frequency and indication. In Ontario, a small proportion (<1%) of primary care is provided through community health centres, salaried physicians and/or nurse practitioners who may shadow bill. Due to data limitations, these visits were not included. In Manitoba, although vaccinations by public health nurses were captured, well-baby visits by the same public health nurses were not captured in physician billing databases and thus not reported in this study.

For infants, our primary outcome was receipt of 4 well-child visits by 12 months of age in Ontario and Manitoba.

For children 12 to 24 months in Ontario, we defined the primary outcome as completion of 3 well-child visits (including the 18-month enhanced visit) and in Manitoba, this primary outcome was defined as 2 well-child visits between 12 and 24 months of age. We also report the average number of visits completed. Any well-baby visit, whether virtual or not, was captured.

Demographic data captured included maternal age and parity, area of residence (urban vs rural), socioeconomic measures such as neighbourhood income quintile, and provincial health region. The primary care practitioner who provided the majority of primary care to the child was determined using the physician billing codes listed in Supplementary Table 2 . Primary care affiliation was classified as family physician/general practitioner, pediatrician, primary care nurse, and no assigned primary care provider. Continuity of care was provided for descriptive purposes but not used in the model, and was defined as those where ≥ 76% of all visits were to their assigned provider. Covariates included in the model were chosen that had a known association with receipt of health services such as vaccination (Chiem et al., 2022 ; Glazier et al., 2015 ; Saunders et al., 2021 ; Walton et al., 2022 ).

We conducted Ontario and Manitoba analyses separately because individual-level information cannot be combined across provinces. Demographic and baseline characteristics were reported using percentages, mean, median, standard deviations and inter-quartile range (IQR).

We generated Poisson models to compare infants who received their vaccinations and well-child visits during the pandemic compared to those pre-pandemic. Relative risks (aRR, 95% confidence intervals, CI) were estimated. Models were adjusted for maternal age at delivery, parity, neighbourhood income, rurality, health region, and type of health care provider.

Missing neighbourhood income was merged with the lowest income quintile as these neighbourhoods are mostly marginalized.

We performed a sensitivity analysis excluding infants eligible for immunizations or well-child visits prior to their exposure period, restricting the analysis to infants who were a maximum of 2 months old at the start of the pandemic, and children a maximum of 12 months old at the start of the pandemic. Please see Supplementary Tables 3 , 4 and 5 for sensitivity analysis results and definitions. In addition, to explore if there were differences in Canada’s largest metropolitan area, we performed a sensitivity analysis utilizing a variable that identified infants and children living in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA). Please see Supplementary Tables 6 , 7 , 8 and 9 for results.

All statistical analyses were done in SAS ® version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

This study included 259,916 infants in Ontario and 33,994 in Manitoba (after exclusions), and 267,469 children in Ontario and 33,001 in Manitoba (after exclusions) (Figure 2 ). In Manitoba, maternal age was younger, with a greater proportion having had previous pregnancies, and living rurally (Table 1 ). In both provinces, a high proportion of individuals had a primary care provider, although in Manitoba, children between the ages of 12 and 24 months were least likely to have a primary care provider assigned, especially if exposed to the pandemic.

Figures 3 and 4 illustrate relative risks and 95% confidence intervals for vaccinations and well-child visit outcomes for the infant and child cohorts, respectively.

Receipt of vaccinations and well-child visits in Ontario, and Manitoba, comparing infants less than 12 months of age post-pandemic to infants pre-pandemic. The black circles represent Ontario, the white circles represent Manitoba. The Poisson model was adjusted for maternal age at delivery, parity, neighbourhood income, rurality, health region, and health care provider. Received all vaccinations refers to having received 3 doses of DTaP and 2 doses of Pneu-C-13 for infants < 12 months. DTaP = diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, polio, and haemophilus influenzae type B, Pneu-C-13 = pneumococcal conjugate 13

Receipt of vaccinations and well-child visits in Ontario and Manitoba, comparing children between 12 and 24 months old post-pandemic to children pre-pandemic. The black circles represent Ontario, the white circles represent Manitoba. The Poisson model was adjusted for maternal age at delivery, parity, neighbourhood income, rurality, health region, and health care provider. In Ontario, received all vaccinations refers to having received 1 dose each of DTaP, Pneu-C-13, Men-C-C, MMR, and Varicella between the ages of 12 and 24 months. In Manitoba, received all vaccinations refers to having received 1 dose each of DTaP, Pneu-C-13, Men-C-C, MMR, and Varicella between the ages of 12 and 24 months. DTaP = diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, polio, and haemophilus influenzae type B; Pneu-C-13 = pneumococcal conjugate 13; Men-C-C = meningococcal type C; MMR = measles, mumps and rubella; MMR-V = measles, mumps, and rubella and varicella

In Ontario, according to billing data there was an increase of 0.9% in receipt of all vaccinations in children 0-12 months of age during the pandemic compared to prior [62.5% (N=78,175) vs 61.6% (N=83,068), aRR 1.01 (95% CI 1.00-1.02)] (Table 2 , Figure 3 ). In Manitoba, there was a decline of 5.7% [73.5% (N=12,343) vs 79.2% (N=13,621), aRR 0.93 (95% CI 0.92-0.94)] (Figure 3 ). The proportion of infants who received the recommended number of doses of the individual vaccines was similar to the overall proportion who received all vaccines for both provinces (Table 2 ).

In Ontario, there was a decline of 0.8% in receipt of all vaccinations in children 12-24 months of age during compared to prior to the pandemic [48.9% (N=64,290) vs 49.7% (N=67,604), aRR 0.98 (95% CI 0.97-0.99)] (Table 3 , Figure 4 ). In Manitoba, this decline was 5.4% [(67.1% (N=11,160) vs 72.5% (N=11,876), aRR 0.93 (95% CI 0.91-0.94)] (Table 3 , Figure 4 ). In both provinces, across pre- and post-pandemic groups, there was a similar rate of receipt of single dose of recommended vaccines.

Supplementary Figures 1 and 2 show the distribution of vaccination doses received by age in months in infants and children. Distributions were similar before and during the pandemic, as well as between provinces.

In Ontario, of infants less than 12 months of age post-pandemic, 33.0% (N=41,247) completed at least 4 well-child visits, compared to 48.8% (N=65,810) pre-pandemic [difference = 15.8%, aRR of 0.67 (95% CI 0.66-0.68)] (Table 2 , Figure 3 ). Of those, 17.9% (N=22,415) of infants did not receive any well-child visits compared to 14.4% (N=19,492) pre-pandemic. In Manitoba, 55.0% (N=9235) of infants less than 12 months of age post-pandemic had received 4 or more well-child visits, compared to 70.7% (N=12,168) pre-pandemic [difference = 15.7%, aRR 0.78 (95% CI 0.77-0.80)] (Figure 3 ). Similar to Ontario, more post-pandemic infants did not have any well-child visits (15%, N=2514) compared to pre-pandemic (8.3%, N=1425).

Children in Ontario post-pandemic were less likely to have received at least 3 well-child visits between 12 and 24 months of age compared to those pre-pandemic (30.2% [N=39,758] vs 38.4% [N=52,157], difference = 8.2%) corresponding to an aRR 0.78 (95% CI 0.77-0.79) (Table 3 , Figure 4 ). Of those post-pandemic, 54.9% (N=72,182) received the enhanced 18-month well-child visit compared to 62.1% (N=84,395) pre-pandemic aRR 0.88 (95% CI 0.87-0.89) (Table 3 , Figure 4 ). In Manitoba, 55.0% (N=9143) of children post-pandemic had received at least 2 well-child visits as recommended in this province between 12 and 24 months of age, compared to 70.1% (N=11,476) pre-pandemic, a decline of 15.1% and aRR 0.79 (95% CI 0.77-0.80) (Table 3 , Figure 4 ).

Sensitivity analyses revealed similar results and there were no clinically important differences between the main and sensitivity analyses results (Supplementary Tables 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 and 9 ).

In this large population-based study of infants and children across two provinces in a single payer healthcare system, we observed a modest reduction in completion of vaccine series during the COVID-19 pandemic up to September 2021. In contrast, there was a large reduction in completion of recommended well-child visits in both provinces (an absolute difference of 8-15% in Ontario and 15-16% in Manitoba). These findings are important to understand the impact of the pandemic on preventive care delivery, which in turn can inform a tailored response to catch up on missed preventive opportunities.

The change in vaccination rates during the pandemic compared to pre-pandemic was a 0.8% decline in children and a 0.9% increase in infants in Ontario based upon billing data, whereas it was a 5.4-5.7% decline in Manitoba. This interprovincial difference was not anticipated. In Manitoba, public health nurses contribute substantially to rates of childhood immunization, and also perform well-baby visits, where they are responsible for 99.6% of childhood vaccinations in rural Manitoba (Hilderman et al., 2011 ). During the pandemic, public health nurses were reassigned to case and contact management of COVID-19 (Daly, 2022 ). About 40% of Manitobans live in non-metropolitan areas, compared to 15% in Ontario. Other factors affecting a lag in catch-up vaccinations could include enforcement of stay-at-home orders, caregiver perception that vaccinations are non-essential, fears of contracting COVID-19 in a healthcare facility, and barriers to accessing well-child visits (Piché-Renaud et al., 2021 ). Manitoba issued extensive public health restrictions until May 2020 and re-instituted them in August 2020 (Blake-Cameron et al., 2021 ). First Nations communities in Manitoba, often rural, continued to implement restrictions beyond the provincial mandates. Gradual restrictions in Ontario occurred starting in March 2020 with gradual re-opening by region in May 2020. It is unclear how timing or severity of restrictions between the provinces could have affected access to or uptake of routine childhood vaccination (Blake-Cameron et al., 2021 ). In addition, Ontario issued personal protective equipment (PPE) at no cost to community family physicians by August 2020, while physicians in Manitoba voiced concerns over the availability of PPE (CPSM, 2020 ). Both Ontario and Manitoba had public health or expert roundtables call for maintaining routine vaccination in children, resulting in targeted vaccine catch-up programs (Allan et al., 2021 ; NACI, 2020 ). Given these dynamic changes during the pandemic, the strength of our study is that it measures the receipt of vaccinations and well-baby visits by September 2021 providing a catch-up period after the period of strict public health restrictions.

Across North America, incomplete and delayed immunization for children under 24 months of age increased in 2020 with some indications for recovery late in 2020 (DeSilva et al., 2022 ; Dong et al., 2022 ; Ji et al., 2022 ; Kujawski et al., 2022 ; Piché-Renaud et al., 2021 ; Lee et al., 2022 ; Saini et al., 2017 ). This raised concerns over how small changes in vaccine coverage have potentially increased the population risk for vaccine-preventable diseases (Payne, 2022 ; Piché-Renaud et al., 2021 ; Sell et al., 2021 ). Overall, vaccinations after 12 months of age decreased to a greater extent than those prior to 12 months of age (Kiely et al., 2021 ; Saini et al., 2017 ). Vaccination coverage (doses of vaccine administered) showed recovery in Quebec with vaccination coverage for MMR below 2019 rates by 2-3% in November 2020 (Kiely et al., 2021 ). In Alberta, MMR coverage declined by 9.9% in April 2020 compared to 2019, but showed recovery by July 2020 (MacDonald et al., 2022 ). Rates of immunization uptake vary by parental concerns about visiting health facilities, socioeconomic status, staff shortages, and clinic model (Dong et al., 2022 ; Ji et al., 2022 ; Sell et al., 2021 ). A large cross-sectional study in the United States using commercial healthcare claims databases reported rates of vaccination and well-child visits and showed a persistent decline of 14.3% for the MMR vaccination for 12-month-olds up to May 2021 (Kujawski et al., 2022 ). Using data from two large provinces, and extending the study period beyond the intensive pandemic measures, we show a modest gap in vaccination, particularly in Ontario, suggesting catch-up mechanisms and decreased pandemic restrictions increased the number of children receiving vaccinations.

Well-child visits are considered the cornerstone of primary care for child health, providing essential screening and opportunity for provision of preventive services and other essential clinical services (Fischer et al., 1984 ). Delays in providing such essential care causes concerns for delays to needed treatments, particularly developmental interventions. We found a substantial decline in well-child visits in infants and children beyond the first year of the pandemic. Our results are similar to the large cross-sectional study in the USA which also showed a well-child visit decline of 14.2% for children 0-2 years old by January 2021 compared to 2018-2019 (Kujawski et al., 2022 ). Our results are in keeping with findings of a study in Toronto, Ontario, Canada showing well-child visits reduced by 16% in the first year of the pandemic (Stephenson et al., 2021 ). However, studies on different health systems or populations have shown inconsistent results, with one study in the USA showing relative stability in the well-child visits below the age of 12 months in a Midwest health care system; and similarly in surveys of parents and practitioners, illustrating the importance of age, race, ethnicity, healthcare model and health insurance considerations when considering the disparities caused by the pandemic with respect to health service use (Salas et al., 2022 ; Teasdale et al., 2022 , Piché-Renaud et al., 2021 ; DeSilva et al., 2022 ).

Persistent suboptimal well-child visits rates, and a lower vaccination rate in Manitoba, highlight a need for catch-up or a shift in preventive care provision, such as leveraging sick visits for vaccinations and developmental surveillance (DeSilva et al., 2022 ).

Limitations of the study

Our study has several strengths related to the use of administrative data in two large provinces in Canada with varying pandemic restrictions. However, our study has several limitations. In Ontario, there is no established comprehensive and linkable immunization registry and the use of vaccine-specific immunization billing codes has specificity ranging from 81% to 92% and sensitivity ranging from 70% to 83% (Schwartz et al., 2015 ). Vaccination coverage rates for at least 4 doses of DTaP by 24 months was estimated to be 75.7% in Ontario and 67.5% in Manitoba by the Canadian National Childhood Immunization Survey (NCIS) in 2017 (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2020 ). In our study, Manitoba estimates of vaccination rates were consistent with the estimates by the NCIS. The Ontario immunization rates reported in our study are likely underestimates as vaccine data in this province are dependent on completeness and accuracy of physician billing (Schwartz et al., 2015 , Saunders et al., 2021 ). Children receiving vaccines without associated billing in Ontario, such as through nurse practitioners and salaried physicians, or nurses associated with physicians who did not bill for the procedure, would not have been included in the Ontario data. However we do not anticipate there would be differences in billing practices prior to the pandemic compared to during the pandemic causing a bias across the exposure. In Manitoba, although vaccinations by public health nurses were captured, well-baby visits by the same public health nurses were not, potentially causing a larger underestimation of the visit rate measured during the pandemic.

Through the first 18 months of the pandemic, we found that routine childhood vaccines were delivered to infants and children at close to pre-pandemic rates in Ontario and Manitoba. In contrast, we document a significant decrease in well-child visits for infants and children, indicating that developmental surveillance catch-up for infants and children is crucial.

Contributions to knowledge

What does this study add to existing knowledge?

In two provinces in Canada, the reduction in vaccine uptake was modest beyond the first year of the pandemic, however well-child visits were significantly reduced within the same time period.

What are the key implications for public health interventions, practice or policy?

Differences in vaccination rates changes pre and during the pandemic demonstrate how routine vaccinations were disrupted differently in a mixed rural/urban compared to a predominantly urban province.

A decrease in well-child visits underscores the need for catch-up visits for developmental surveillance.

Data availability

Parts of this material are based on data and information compiled and provided by MOH and the Canadian Institute for Health Information, current to September 30, 2021. Geographical data are adapted from Statistics Canada, Postal Code Conversion File +2011 (Version 6D) and 2016 (Version 7B). The analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed herein are solely those of the authors and do not reflect those of the funding or data sources; no endorsement is intended nor should be inferred.

Code availability

The dataset from this study is held securely in coded form at ICES and the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy (MCHP). While data sharing agreements prohibit ICES and MCHP from making the dataset publicly available, access may be granted to those who meet pre-specified criteria for confidential access, available at www.ices.on.ca/DAS and https://www.umanitoba.ca/faculties/health_sciences/medicine/units/chs/departmental_units/mchp/resources/access.html . The full dataset creation plan and underlying analytic code are available from the authors upon request, understanding that the computer programs may rely upon coding templates or macros that are unique to ICES and MCHP.

Allan, K., Piché-Renaud, P.-P., Bartoszko, J., Bucci, L. M., Kwong, J., Morris, S., Pernica, J., & Fadel, S. (2021). Maintaining Immunizations for School-Age Children During COVID-19. https://www.dlsph.utoronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Maintaining-Immunizations-for-School-Age-Children-During-COVID-19-Report-1.pdf

Blake-Cameron, E., Breton, C., Sim, P., Tatlow, H., Hale, T., Wood, A., & Tyson, K. (2021). Variation in the Canadian provincial and territorial responses to COVID-19. BSG Working Paper Series (BSG-WP-2021/039).

Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. (2016). Recommendations on screening for developmental delay. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 188 (8), 579–587. https://www.cmaj.ca/content/188/8/579

Causey, K., Fullman, N., Sorensen, R. J. D., Galles, N. C., Zheng, P., Aravkin, A., Danovaro-Holliday, M. C., Martinez-Piedra, R., Sodha, S. V., Velandia-González, M. P., Gacic-Dobo, M., Castro, E., He, J., Schipp, M., Deen, A., Hay, S. I., Lim, S. S., & Mosser, J. F. (2021). Estimating global and regional disruptions to routine childhood vaccine coverage during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020: a modelling study. The Lancet, 398 (10299), 522–534. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01337-4

Chiem, A., Olaoye, F., Quinn, R., & Saini, V. (2022). Reasons and suggestions for improving low immunization uptake among children living in low socioeconomic status communities in Northern Alberta, Canada - A qualitative study. Vaccine . (1873–2518 (Electronic)).

Daly, M. (2022). Public Health Nurses a vital part of the fight against COVID-19 . Retrieved from https://wrha.mb.ca/2021/05/10/public-health-nurses-a-vital-part-of-the-fight-against-covid-19/

DeSilva, M. B., Haapala, J., Vazquez-Benitez, G., Daley, M. F., Nordin, J. D., Klein, N. P., & Kharbanda, E. O. (2022). Association of the COVID-19 pandemic with routine childhood vaccination rates and proportion up to date with vaccinations across 8 US health systems in the vaccine safety datalink. (2168–6211 (Electronic)).

Doctors Manitoba. (2021, April 8). Well Baby Care. https://doctorsmanitoba.ca/managing-your-practice/remuneration/billing-fees/visits/well-baby-care

Dong, A., Meaney, C., Sandhu, G., De Oliveira, N., Singh, S., Morson, N., & Forte, M. (2022). Routine childhood vaccination rates in an academic family health team before and during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic: a pre-post analysis of a retrospective chart review. (2291–0026 (Electronic)).

Fischer, P. J., Strobino, D. M., & Pinckney, C. A. (1984). Utilization of child health clinics following introduction of a copayment. American Journal of Public Health, 74 (12), 1401–1403.

Glazier, R., & Rayner, J., & Kopp, A. (2015). Examining Community Health Centres According to Geography and Priority Populations Served 2011/12 to 2012/13 (p. 2015). Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences.

Hilderman, T., Katz, A., Derksen, S., McGowan, K., Chateau, D., Kurbis, C., & Reimer, J. (2011). Manitoba Immunization Study . http://mchp-appserv.cpe.umanitoba.ca/deliverable.php?referencePaperID=76539

Ji, C., Piché-Renaud, P. P., Apajee, J., Stephenson, E., Forte, M., Friedman, J. N., & Tu, K. (2022). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on routine immunization coverage in children under 2 years old in Ontario, Canada: A retrospective cohort study. (1873–2518 (Electronic)).

Kiely, M., Mansour, T., Brousseau, N. A.-O., Rafferty, E., Paudel, Y. A.-O., Sadarangani, M., & MacDonald, S. A.-O. (2021). COVID-19 pandemic impact on childhood vaccination coverage in Quebec, Canada. (2164–554X (Electronic)).

Kujawski, S., Yao, L., Wang, H., Carias, C., & Chen, Y. (2022). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on pediatric and adolescent vaccinations and well child visits in the United States: A database analysis. Vaccine, 40 (5), 7.