Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Tourism and economic growth: A global study on Granger causality and wavelet coherence

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft

Affiliation SLIIT Business School, Sri Lanka Institute of Information Technology, Malabe, Sri Lanka

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Department of Information Management, SLIIT Business School, Sri Lanka Institute of Information Technology, Malabe, Sri Lanka

Roles Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft

- Chathuni Wijesekara,

- Chamath Tittagalla,

- Ashinsana Jayathilaka,

- Uvinya Ilukpotha,

- Ruwan Jayathilaka,

- Punmadara Jayasinghe

- Published: September 12, 2022

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274386

- Reader Comments

This paper empirically investigates the relationship between tourism and economic growth by using a panel data cointegration test, Granger causality test and Wavelet coherence analysis at the global level. This analysis examines 105 nations utilising panel data from 2003 to 2020. The findings indicates that in most regions, tourism contributes significantly to economic growth and vice versa. Developing trade across most of the regions appears to be a major influencer in the study, as a bidirectional association exists between trade openness and economic growth. Additionally, all regions other than the American region showed a one-way association between gross capital formation and economic growth. Therefore, it is crucial to highlight that using initiatives to increase demand would advance tourism while also boosting the economy.

Citation: Wijesekara C, Tittagalla C, Jayathilaka A, Ilukpotha U, Jayathilaka R, Jayasinghe P (2022) Tourism and economic growth: A global study on Granger causality and wavelet coherence. PLoS ONE 17(9): e0274386. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274386

Editor: Vu Quang Trinh, Newcastle University Business School, UNITED KINGDOM

Received: July 18, 2022; Accepted: August 26, 2022; Published: September 12, 2022

Copyright: © 2022 Wijesekara et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the manuscript and its with Supporting information files.

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Tourism is one of the world’s major industries, and people have been travelling for pleasure since the dawn of time. It has become one of the fastest expanding sectors of the global economy in recent years. Tourism arose as a result of modernisation and contributed significantly to shaping the experience of modernity. Economic growth and tourism development are intertwined, according to previous literature, therefore, an increase in the general economy will support tourism development [ 1 ]. As a result, it’s critical to investigate how tourism and other factors (including macroeconomic) are linked to economic growth. Economic growth can be defined as an increase in the real gross domestic product (GDP) or GDP per capita. Global tourism, as a key contributory business, has contributed to approximately 10% of global GDP through possible employment opportunities, extending client markets, encouraging export trades, and gains from foreign exchanges [ 2 , 3 ]. Another study that looked at the relationship between tourism and economic growth using variables like tourist receipts and tourism spending added to the literature by suggesting that tourism receipts impacted economic growth [ 4 ]. Additionally, according to Marin [ 5 ], tourism receipts have an upward link to the country’s economy and can thus aid in economic growth. Globally developed tourism business fosters economic growth over time, supporting the economy more than anticipated.

In recent years, research studies analysing the direction of the relationship between economic growth and tourism have been a popular area of interest in literature. A study of 12 Mediterranean nations in 2015 demonstrated a bidirectional causality relationship between tourism development and economic growth [ 6 ]. In a study conducted in Romania [ 7 ], a bidirectional causal relationship exists between GDP and the number of international tourist arrivals, whereas in an African study, a unidirectional causal relationship exists between international tourism earnings and real GDP, both in the short and long run [ 8 ]. According to previous research, this link appears to be both unidirectional and bidirectional.

Some of the processes by which tourism contributes to socioeconomic development include creating jobs, decreasing unemployment rates, and introducing of new tax income streams. In research conducted to investigate the relationship between tourism spending and economic growth in 49 nations, it was discovered that the two are inextricably linked, with a bidirectional causal relationship [ 9 ]. Investigating this relationship could be a useful for prioritising resource allocation across industries to improve overall tourism and economic outcomes.

Furthermore, a study based on 11 Asian regions discovers a close link between real international tourist revenues, capital formation, and GDP, confirming the tourism industry’s contribution to GDP [ 10 ]. Another study that looked at the relationship between tourism and economic growth based on tourist arrivals found that tourism is a good driver of economic growth [ 11 ]. This study looked into data of 94 countries, although there was no geographical examination of this association. Similarly, as previously mentioned, many authors have focused their research on a few countries or a single region when exploring the link between tourism and economic growth. The present study will contribute to filling the above-said research gap whilst providing an overall picture of the relationship between tourism and economic growth at the global level.

Many research papers have been written to determine the relationship between tourism demand and economic growth in diverse regions of the world. Based on certain regions, this link has been demonstrated to be bidirectional as well as unidirectional in the literature. The investigation of the relationship between tourism demand and global economic growth would provide a broad view of the relationship between these two factors. However, limited research has been done to examine this connection, which spans 18 years and includes regional data worldwide. Furthermore, because tourism is not the only element that influences GDP, other factors that considerably influence economic growth too must be considered. In the past, there hasn’t been much research conducted on the moderate impact of tourism on GDP. To address this gap in the literature, this research will examine the relationship between tourism demand and economic growth, as well as the moderating impact of variables such as gross capital formation and trade openness on economic growth in nations around the world. As a result, the current study focuses on all five regions, as there hasn’t been much research done on this topic.

The goal of this research paper is to examine the empirical relationship between tourism and economic growth along with the moderate impact of trade openness and gross capital formation for the worldwide regions. In four ways, the goals of this study can help improve the existing literature. Firstly, this study will be the most recent addition to the literature, focusing on an eighteen-year timeframe using panel data from 2003 to 2020. Secondly, this study will collect and analyse valid data from 105 countries including 42 countries in Europe, 25 countries in Asia & the Pacific, 18 countries in the Americas, and 20 countries from Africa and the Middle East region. The study’s emphasis on an 18-year time period and data from 105 countries allow the conclusions to be generalised and applied to any country. As a result, the study addresses one of the most significant flaws in the literature. Thirdly, in addition to the direct relationship between tourism on economic growth, this study attempts to examine the relationship between tourist receipts modulated by trade openness and gross capital formationon a region’s per capita GDP. These moderating effects on a country’s and region’s economic growth have yet to be investigated. Moreover, to the author’s knowledge, the wavelet technique hasn’t been used in previous research to analyse the relationship between per capita GDP and international tourist receipts. Additionally, analysis of this would produce precise and reliable data for future research and decision-making.

The next sections of the article are organised as follows: the first part analyses the existing literature, followed by the data used and the technique used in this investigation, then the findings and discussion, and lastly, the general conclusion of the study.

Literature review

This section includes contributions to the literature by a variety of scholars from various nations and locations. The conclusions of the study done for a particular region were segregated into regions, whilst studies were divided according to the manner of causal relationship.

Bidirectional causality between tourism and economic growth

The majority of earlier studies investigated the impact of tourism on economic growth in the European region. By adopting the Granger causality test Bilen, Yilanci [ 6 ] analysed the bidirectional causal connection between tourism development and economic growth, in the 12 Mediterranean countries with data from 1995-to 2012. Dritsakis [ 12 ] examined the impact of tourism on Greece’s economic development between 1960 and 2000, by using the Multivariate autoregressive and Granger causality tests. Here, the data revealed a ’Granger causal’ relationship between international tourism earnings and economic growth, a ’strong causal’ relationship between real exchange rate and economic growth, as well as simple ’causal’ relationships between economic growth and international tourism earnings, and real exchange rate and international tourism earnings. However, the above study conducted their research only for Greece. Further, the results of the above stated investigations based on 20 th century data, can vary with time. It is noteworthy that specially with the Eurozone crisis that started in 2009, Greece economy was among the severely affected in the region and hence, data do not reflect this situation. Surugiu and Surugiu [ 13 ] conducted a study using Romanian data, identified a long-term correlation between tourism development and economic growth.

According to the literature, several studies were conducted related to Tourism and economic growth. However, only a few studies have been conducted to analyse the causal relationship of both variables for countries worldwide. Most commonly utilised analytical tool is the Granger Causality test to identify the relationship between these two variables. A study conducted for 135 countries by Şak, Çağlayan [ 14 ] revealed that tourism revenue and GDP show bidirectional causality in Europe in contrast to unidirectional causality in America, Latin America, East Asia, South Asia, Oceania, Caribbean, and countries worldwide. However, the results of the above investigation were conducted based on data from 1995 to 2008, which can vary with time. Economic upheavals changes to economic policies in East Asia (including China, India) where geopolitical strategies are dominant, the impact of tourism revenue on GDP may not be significant. Moreover, Fahimi, Akadiri [ 15 ] tested the causality between tourism, economic growth, and investment in human capital in the microstates using data from 1995 to 2015. The results indicate that there is a bidirectional relationship between tourism and GDP. In the same period, Sokhanvar, Çiftçioğlu [ 16 ] performed a Granger causality analysis on 16 countries to investigate the causal relationship between tourism and economic development. The results proved bidirectional causality only in Chile. Further, this study found that seven countries do not show causality between variables. But as both studies were conducted only for selected countries, these results cannot be generalised about the global situation. Most recently, Pulido-Fernández and Cárdenas-García [ 17 ] explained the bidirectional link between tourism growth and economic development in 143 countries. According to them, tourism supports economic growth in the countries where tourism occurs. However, the study employed the level of economic development and tourism growth as a factor to cluster the countries for analysis; the results would most possibly change if another factor was used to cluster the countries.

Unidirectional causality between tourism and economic growth

In the European region, a long-run link was tested between economic growth and tourism based on international tourist receipts, real GDP, and the real effective exchange rate for Croatian nations using quarterly data from 2000-to 2008. Using the Granger causality test as the analysis tool, the results proved that a positive unidirectional causal relationship exists between economic growth and foreign tourism revenues [ 18 ]. Moreover, by adopting the Granger causality test for the annual GDP, the number of foreign visitors to South Tyrol and the relative prices (RP) between South Tyrol and Germany from 1980 to 2006, Brida and Risso [ 19 ] proved that the causation from tourism and RP to real GDP is unidirectional. A study published in 2013 asserted the link between tourist spending and economic growth. For Cyprus, Latvia, and Slovakia, the study discovered a growth hypothesis. whereas a negative relationship for Czech Republic and Poland [ 20 ]. Furthermore, Lee and Brahmasrene [ 21 ] found that tourism has a positive impact on economic growth and is inversely related to carbon dioxide emissions, using the panel cointegration technique and Fixed Effect (FE) model for the European region. Besides, the majority of previous investigators employed the Granger causality test to determine whether a bidirectional or unidirectional link exists between tourism and economic growth among European regions.

For the Asian Region, Oh [ 22 ] conducted on the Korean economy revealed that there is a one-way causal relationship between economy-driven tourism growth by using the Granger causality test for the period from the first quarter of 1975 to the first quarter of 2001. Furthermore, according to the Granger causality test and co-integration, no co-integration exists between tourism and economic growth in the long run and Tourism-Led Growth Hypothesis (TLGH) did not exist in the short term. However, the author noted that in order to generalise the study’s findings, it is necessary to investigate the TLGH under economic conditions of numerous nations. Examining the most recent study in further detail, Wu, Wu [ 10 ] used a multivariate panel Granger causality test to show a growth hypothesis between real GDP and real international tourism receipt in China, Cambodia, and Malaysia. However, an opposite growth hypothesis has been validated in the Philippines, Hong Kong, Indonesia, and South Korea. In Macau and Singapore, an inverse growth theory has been discovered.

Many researchers have studied the relationship between tourism and the African continent’s economic growth, with various kinds of dimensions and methodologies. In the early 20s, Akinboade and Braimoh [ 8 ] used the Granger causality test to assert the link between international tourism and economic expansion in Southern Africa, where the findings demonstrated a one-way causal relationship between international tourism earnings to real GDP with the use of data from 1980 to 2005. Providing more evidence in the same period utilising the same method, Belloumi [ 23 ] too disclosed that tourism has a beneficial influence unidirectionally on economic growth. Moreover, Ahiawodzi [ 24 ] employed the Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test for unit root, cointegration test, and Granger Causality to investigate the cointegration and causality of tourism revenues and economic growth. It found a unidirectional causality from economic growth to tourism in Ghana as well as a positive relationship and cointegration in the long run. Similarly, Bouzahzah and El Menyari [ 25 ] also discovered significant unidirectional causation from economic growth to international tourist receipts in the long term by analysing data of Morocco and Tunisia. However, since these studies are limited to one or two countries in the region, researchers were unable to view the bigger picture as a region. The most recent study by Kyara, Rahman [ 26 ] was conducted based on data from Tanzania from 1989 to 2018, considering the country’s international tourist receipts, real GDP, and the real effective exchange rate as variables. Here, findings of Granger Causality, and the Wald test supported the existence of one-way causation between tourism and economic expansion.

Only a few researchers have studied the causation between tourism and economic growth in the Middle East region. Countries such as Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, and Jordan should implement strategies to boost tourist arrivals with receipts by uplifting their tourism to tourists from outside the Middle East region [ 27 ]. Also, the scholars conducted panel cointegration and causality test based on data from 1981 to 2008, which revealed that tourism has a long-term relationship with economic growth. However, this research might be improved to include additional countries in the region, allowing for a more realistic comparison. In the meantime, the impact of tourism on economic growth in oil-rich nations was stated by Alodadi and Benhin [ 28 ]. In Jordan, Kreishan [ 29 ] discovered a unidirectional causal relationship between tourism earnings and economic growth by investigating data from 39 years up to 2009 using the Granger causality test. The importance of tourism to economic growth was explained by Tang and Abosedra [ 30 ] using annual data for the period 1995–2010 in Lebanon. Their findings demonstrated that tourism and economic expansion in Lebanon have a long-term association as tourism and growth are cointegrated and the results supported that the Tourism led Growth hypothesis is valid in this country. However, this analysis was performed with a small sample without considering additional variables apart from tourist arrivals and the real GDP. Providing more evidence, the same conclusion was provided [ 31 , 32 ], who tested data for Iran and Saudi Arabia, respectively. In addition, Ozcan and Maryam [ 33 ] claimed that measures to boost economic growth and development in the tourism sector of Qatar should be continued since a positive link exists between the said two factors. Ozcan and Maryam [ 33 ]. It may be determined from previous literature that the Middle East region exhibits a link between tourism and economic growth. Moreover, previous studies found that the tourism sector makes a small contribution to economic growth in oil-rich countries.

Many studies focusing on the countries of the American continent have deliberated the link between tourism and economic growth. According to Risso, Brida [ 34 ] the expenditure of international tourists has a favourable impact on Chile’s economic growth. The elasticity of real GDP to tourism spending (0.81) demonstrates that a 100% increase in tourism expenditure results in a long-run growth increase of more than 80%. With an elasticity of 0.35, the actual exchange rate also has a beneficial influence. This was examined using the Granger causality test as a basis for analysis using data from 1988 to 2009. Another study which was conducted by Brida and Risso [ 35 ], discovers that the causality of tourism and the real exchange rate to real GDP is unidirectional. Analysis of this study used the Granger test and the cointegrated vector model over data during the period 1988–2008. However, the above study only looked into data up to 2008. Similarly, Brida, Lanzilotta [ 36 ] analysed the causal relationship between Uruguay by adopting a Granger causality test. This study used variables such as GDP, Argentinean tourism expenditure, and the real exchange rate from 1987-to 2006, where it showed a positive relationship among the variables. However, this study was limited to Uruguay and Argentina. Using panel data from nine Caribbean nations from 1995 to 2007, a long-run relationship between economic growth and tourism was investigated by Payne and Mervar [ 18 ]. Here, researchers used international tourist arrivals per capita, real GDP per capita, and the real effective exchange rate. It proved that tourism has a large impact on per capita real GDP. Research conducted in Jamaica from 1970 to 2005 unveiled that increasing visitor receipts positively impacted on GDP. As a result, it was suggested that strategies should be focused on attracting more tourists, as this scenario would enhance not only tourism receipts but also Jamaica’s total economic growth [ 37 ]. However, the study described above, solely considered tourism receipts and GDP, excluding the other factors that affect GDP. Sánchez López [ 38 ] confirmed that international tourism has a positive influence on the Mexican economy by considering quarterly data from 1993 to 2017 and utilising GDP and tourist arrivals as variables.

Focusing on the worldwide studies, the case of Mediterranean countries, Tugcu [ 39 ] found a substantial and favourable correlation between tourism and economic growth. As these scholars affirmed, the relationship between economic growth and tourism has been studied for several groups of countries or nations. According to, the relationship between travel and economic growth varies per country, although European nations can experience economic growth through travel to European, Asian, and African nations. The most recent research, Enilov and Wang [ 40 ] examined the causal relationship between foreign tourist arrivals and economic growth using 23 developing and developed countries, in 1981–2017. It used a bootstrap mixed-frequency Granger causality approach using a rolling window technique to evaluate the approach’s stability and persistency over time concerning economic growth. The findings demonstrated that, in contrast to wealthy nations, the tourism industry in developing nations continues to be a major contributor in future economic growth.

In conclusion, many scholars have examined the connection between tourism and economic growth. However, the moderating impact of gross capital formation and trade openness with tourism receipts is yet to be studied. Moreover, limited studies were conducted to analyse the causal relationship between tourism and economic growth by employing the Granger Causality test. To fill this gap, this research investigates the direction of the causality between economic growth and demand for tourism whilst analysing the effect of gross capital formation and trade openness for the world regions.

Conceptual framework

To address the gaps in this analysis, the conceptual framework was developed to investigate the relationship between tourism and economic growth, including the moderate effect of gross capital formation and trade openness, for worldwide regions as stated in the study’s objectives. Fig 1 depicts the conceptual framework for investigating the empirical relationship between tourism and economic growth, as well as the moderate influence of gross capital formation and trade openness, globally and for each region separately.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

Source: Authors’ illustrations.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274386.g001

The endogenous growth theory, which often views economic growth as an endogenous product of an economic system rather than the result of factors that affect it from the outside, serves as the theoretical foundation [ 41 ]. In comparison to non-high-tech service industries like tourism, the endogenous growth theory tends to highlight the benefits of high-tech industries as possibly more favourable for high long-run growth. Yet, specialising in tourism can be strongly linked to higher returns, which in turn reinforces the benefits enjoyed by marketplaces, firms, and sectors.

Data and methodology

This section presents a detailed view of the data, the statistical models employed in this study, and descriptive statistics for the variables.

This study was reviewed and approved by the SLIIT Business School and the SLIIT ethical review board. The following Table 1 illustrates the secondary data sources from which the information was gathered. The data file used for the study is presented in S2 Appendix .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274386.t001

To measure economic growth across all regions, the current study employs yearly GDP per capita data from 2003. The amount of a country’s entire volume of goods and services produced relative to its total population is per capita GDP. To measure tourism growth, we use tourist receipts from 2003 until 2020. Tourism receipts were chosen over tourist arrivals because they incorporate both visitor arrivals and expenditure levels, resulting in a more accurate reflection of information on crucial aspects. Furthermore, the moderate impact on GDP per capita will be measured using gross capital formation and trade openness. Gross capital formation is a measure of a country’s yearly net capital accumulation as a proportion of GDP. The sum of goods and services and imports and exports represented as a percentage of GDP is known as trade openness. All the variables were converted as natural logarithms.

Methodology

The causal link between PGDP and TOUR by analysing the moderating effect of GCF and TRADE is tested using the panel Granger causality test [ 42 ]. According to Wang, Zhang [ 43 ], to assess if the sequence of data is stationary the unit root test will be performed and the co-integration tests will be used to analyse the connection between the variables if they are non-stationary. Based on the co-integration test, the Panel Granger causality test will be adopted to determine the existence of the direction and the causal connection between tourism and economic growth by analysing the moderate effect of GCF and TRADE .

The CUSUM test was carried out to assess the stability of the parameters for countries in the regions separately. Brown, Durbin [ 45 ], Hawkins [ 46 ], Koshti [ 47 ] and Rasool, Maqbool [ 48 ] provided more explanation on how to identify and analyse the plot of CUSUM.

With the help of the above-mentioned equation and to prove the dynamics between the PGDP and TOUR from 2010 to 2020, the Wavelet Coherence approach is used in order to deeply analyse the existence of a correlation among the variables discussed. Goupillaud, Grossmann [ 49 ] developed the wavelet technique in its natural form, and the concept’s foundation is based on their expertise knowledge. A time series is decomposed into a frequency-time domain using the wavelet technique. Pal and Mitra [ 50 ], Adebayo and Beton Kalmaz [ 51 ], Kalmaz and Kirikkaleli [ 52 ] and Adebayo, Onyibor [ 53 ] explained how to analyse and the explanation of the wavelet coherence. The wavelet method is used in this study to further visually confirm the existence of a causal relationship among PGDP and TOUR .

The panel granger causality test was carried out using STATA whereas R Studio was used for the CUSUM test and Wavelet coherence.

Empirical results and discussions

Before analysing Granger causality, Table 2 shows descriptive statistics for the major variables concerning worldwide countries and each region separately. This includes 1,890 total observations, of which 360, 324, 450, and 756 observations are for Africa & Middle East, America, Europe, and Asia & Pacific, respectively.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274386.t002

Fig 2 illustrates the mean PGDP and the mean TOUR for the world’s countries from 2003 to 2020, discovering the trend and patterns of key factors.

Note: The data points were converted as natural logarithms. Source: Authors’ illustration based on data from the world bank, UNWTO, and WorldData.info.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274386.g002

According to Fig 2(A) , the African & the Middle East region has the lowest PGDP when compared to other regions, while the European regions have the highest PGDP . The PGDP of the Americas and Asia & Pacific areas fluctuated similarly until 2017, thereafter, the gap between these two countries narrowed. As indicated in Fig 2(B) , the disparity in tourist receipts between America and the Asia-Pacific area has been nearly identical throughout the years. The European region has recorded the highest tourist receipts when compared to other regions. The graph shows that tourist revenues have dropped sharply after 2019. This is because tourism has been one of the most affected industries due to the covid pandemic. A massive drop in demand due to increased worldwide travel restrictions, including the closure of several borders worldwide led to tourism sector collapse.

The unit root tests are used in this study to determine if the data set of PGDP , TOUR , TRADE , and GCF is stationary or non-stationary. The following Table 3 shows the test results for unit roots.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274386.t003

The variables PGDP , TRADE , and GCF are stationary, according to the findings of the unit root tests. The Fisher-type unit-root test shows that some panels of the variable TOUR are stationary, but according to the Levin-Lin-Chu unit root test, the variable TOUR is nonstationary. As a result, the cointegration test is used to identify whether there is a long-term link between the variables PGDP and TOUR .

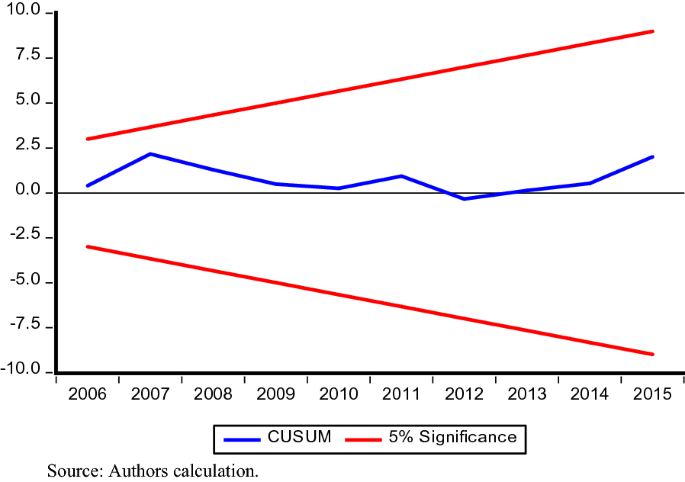

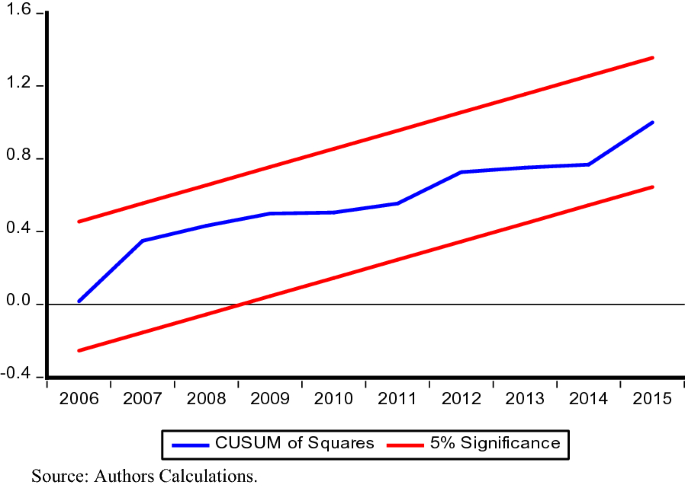

Table 4 presents the panel data cointegration test and results of the unit root tests proved that the variable TOUR is nonstationary. The findings of all the tests, except the Kao cointegration test, indicated that PGDP has a long-term connection with TOUR . It is possible to claim that there is at least a one-way Granger causality as the variables are co-integrated. According to the results of the stability test in Fig 3 , the blue line in in the plot of recursive CUSUM does not cross the red line, it provides strong support that the model fits the data and that the variables are stable for all regions.

Source: Authors’ illustration using R-Software.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274386.g003

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274386.t004

According to Table 5 , a bidirectional causal relationship exists between PGDP and TOUR for all the regions. However, the existence of a bidirectional relationship between TRADE and PGDP was discovered for all the regions except for the European region. On the other hand, a one-way causal connection (unidirectional) between PGDP and GCF was discovered for the American region, whereas all other regions proved the existence of a two-way relationship (bidirectional) between PGDP and GCF .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274386.t005

Based on the findings of all countries, it can be observed that all the estimated z values of the variables PGDP , TOUR , TRADE , and GCF are significant at 0.001. Therefore, with the current estimators, it can be stated that in most countries worldwide, tourism growth Granger causes economic growth and vice versa. Subsequently, it could be assumed that tourism can drive economic growth in a majority of countries and economic growth can boost tourism growth. Fahimi, Akadiri [ 15 ] asserted that tourism to real GDP has a bidirectional causality relationship, where GDP Granger causes tourism and vice versa. However, Enilov and Wang [ 40 ] provide evidence for the validity of the economic-driven tourist growth in developing economies, while providing less support for developed ones. Similarly, according to Tugcu [ 39 ], Mediterranean area shows a favourable correlation between tourism and economic growth. This is likely attributable to a change in sample size, since our data set includes 105 nations and data spanning 12 years. But the research described above used a sample fewer than 25 nations. Furthermore, at the 1% significant level, the empirical findings prove that the PGDP Granger causes TRADE , GCF , and vice versa. Implications of these are that in most nations, the variables TRADE and GCF in PGDP have predictive ability amongst each other.

Similar to the worldwide countries, the values of the African and the Middle East region along with the Asia and Pacific region showed a significant relationship. At the 1% significance level, a Granger causal link between PGDP and tourist receipts was discovered, i.e., This means that tourism leads to economic growth and vice versa in the African and Middle East regions, as well as the countries in the Asia and the Pacific region. This finding was reconfirmed in a previous study conducted in Lebanon where it concluded that a bidirectional Granger causality exists between tourism and economic growth in the short run [ 30 ] in the Middle East Region. Similarly, these results were validated in South Africa by Odhiambo and Nyasha [ 54 ]. Moreover, for the Asian and Pacific region, Wang, Zhang [ 43 ] confirmed that there is a bidirectional Granger connection between China’s domestic tourism and economic growth. Additionally, using the Granger causality test, Mohapatra [ 4 ] proved the same results for the Asian and Pacific regions. According to the findings of these studies, the governments of these regions should promote practices and policies that would benefit the tourism industry and the economy, as tourism growth stimulates general growth in the economy and vice versa. Tourist revenues have surged across the Asia-Pacific region along with PGDP , as the region has evolved into a popular tourism destination for all sorts of diverse tourists. The rich biodiversity of several countries in the Asia and Pacific region has sparked the development of numerous sectors that have increased GDP, which in turn has had a substantial influence on tourism. A few countries in the Asia and Pacific area offer as much natural beauty, which makes them popular tourist destinations. The hospitality, infrastructure, convenient accommodation, and variety of attractions in these countries offer a solid basis for the Asia and Pacific region’s tourism industry. The proportion of international tourist arrivals in the African region is relatively low due to the region’s political unrest, yet tourism is one of Africa’s most promising industries concerning economic growth. The Middle Eastern nations are situated in the middle of important geographical locations. This aspect made it easier to establish global economic connections, which helped the economic growth of the countries over time. The Middle East led urbanisation and other development strategies that gave the region the required infrastructure and setting for the tourist destinations to begin providing of travel and tourism services. As a result, the Middle Eastern countries are increasingly opening their doors to tourists. Moreover, according to the finding, the null hypothesis of the Granger Causality test for the variables PGDP to TRADE , TRADE to PGDP , PGDP to GCF and GCF to PGDP can be rejected at a 1% significant level.

In contrast to countries worldwide, the American region revealed that a significant connection exists between PGDP , TOUR , and TRADE . Findings of this study affirmed that a one-way causal connection exists only from GCF to PGDP in the Americas region. These results mainly indicate that an increase in tourism could increase economic growth in the American region and vice versa. Several American countries, such as the United States and Canada, have a well-established tourism industry that contributes significantly to their GDP and, in turn, their highly developed economic systems encourage the development of infrastructure and tourist destinations. Governments are actively implementing regulations that intend to improve the economic, biological, and social advantages that tourist industry may offer, whilst lessening the challenges that occur when this expansion is unprepared and uncontrolled. Overall, tourist growth patterns in the Americas area are favourable. For the nations of the Americas region, in order to guarantee that their measures to improve tourism are conducted within the larger framework of local, regional, and country’s economic targets. Furthermore, to assist the shift to a green and low-emissions, additional initiatives are also being made to incorporate sustainability in tourism policy and industry regulations.

Considering the European region, a significant connection exists only among the variables PGDP , TOUR , and GCF . As a result, these findings show that tourist revenue and PGDP are mutually influenced. Furthermore, a significant link between TRAD E and PGDP was identified only in European region nations, demonstrating that PGDP does not cause TRADE, but TRADE has the predictive potential over PGDP at a 1% significance level. Europe is regarded as the overall dominant participant in the tourism industry, which fosters economic growth, due to the increasing affordability of travel for bigger groups of people. As tourism directly affects economic growth, it is possible to obtain economic growth in the European region by safeguarding the environment, preserving natural resources, generating jobs, enhancing cultural variety, and respecting cultural traditions. Authorities should focus on developing the tourist industry to obtain high economic growth, and to improve tourism, essential efforts should be taken to enhance economic growth. This is because bidirectional causation exists between tourism development and economic growth of the 12 Mediterranean countries [ 6 ].

The summary of Granger-causality analysis results for PGDP – TOUR , PGDP – TRADE and PGDP – GCF were presented in Table 6 .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274386.t006

All four regions show a bidirectional causal relationship between PGDP and TOUR . Furthermore, for the Africa & Middle East, America, Asia & Pacific areas, a two-way causal (bidirectional) link between PGDP and TRADE is demonstrated, whereas there is a one-way causal (unidirectional) link between PGDP and TRADE for the European area nations. When considering the causative relationship between PGDP and GCF , it is discovered that there is a bidirectional causal relationship in all regions except the Americas. In order to examine the relationship between variables among country’s separately, this study summarised the results of Granger Causality for the countries in each region separately in S1 Appendix .

Table 7 interprets the direction of the arrows and the frequency. The direction of the arrows will indicate whether the variables move in phase (rightward arrow indicating a positive correlation), or anti phase (leftward arrow indicating a negative correlation) and the cold (blue) regions of the figure indicates no correlation while the warm (red) regions depict the analysed variables are correlated. The wavelet coherence graph is identified according to the scale as the upper portion, middle portion, and lower portion which represents the short term, medium term and long term respectively.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274386.t007

The correlation between PGDP and TOUR for each region individually from 2003 to 2020 is shown in Fig 4 . When considering the entire period, the arrows in Fig 4(A) are pointing right in the short and medium terms (high and medium frequencies), indicating a worldwide positive impact between PGDP and TOUR when assessing the entire period.

Source: Authors’ compilation using R-Software.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274386.g004

In Africa & Middle east region Fig 4(B) between 2009 and 2020, there are rightward arrows indicating a positive connection in the short and medium term with a high and medium frequency. Additionally, the rightward and downward arrows between 2009 to 2011 and 2016 to 2020 show that PGDP led TOUR in the short term with high frequencies. However, there is a negative association between 2006 to 2008 because of the existence of leftward arrows in the short with high frequency.

Overall, in American Region, Fig 4(C) demonstrates a favourable relationship with a high and medium frequency in all terms from 2003 to 2020. Furthermore, the rightward and downward arrows between 2008 to 2012 PGDP is leading to TOUR , in the short and long term (high and low frequencies).

Fig 4(D) illustrates a positive impact between Asia & Pacific Regions PGDP and TOUR in the short term with high and medium frequency over the years from 2003 to 2019, expect 2005 to 2006, 2008 to 2009, 2012 to 2013 and 2017 to 2018. There is a negative association in mentioned years because of the existence of leftward arrows in the short term with high frequency.

Fig 4(E) indicates a positive impact in the short and medium term (high and low frequencies) from 2003 to 2020 for the European region. Moreover, between 2006 and 2010, the arrows pointing right and up show a positive influence from TOUR to PGDP in the long term with low frequency. Similarly, the arrows in the medium term (medium frequency) between 2008 to 2011 and 2016 to 2018 are pointing downward and right, indicating that PGDP leads to TOUR .

Table 8 summarises the results of our Granger-causality analysis and wavelet coherence for PGDP and TOUR .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274386.t008

As the wavelet coherence technique captures the time dependence of the variables which is conjointly captured under the Granger causality approach, the findings revealed that overall finding of both techniques brings unanimous results, bringing justifications to the study. Both Granger Causality and Wavelet Coherence methods demonstrated that PGDP and TOUR had a bidirectional link in each region separately and globally. Where it demonstrates that tourism drove economic expansion and vice versa.

This research was conducted to obtain evidence supporting the connection between tourism and global economic growth, using the panel Granger causality test with panel data from 2003 to 2020. The results of the link between TOUR and PGDP revealed a strong bidirectional connection. The results, firstly, indicated that tourism has the ability to boost economic growth in all regions, and vice versa. Secondly, a bidirectional relationship between TRADE and PGDP was observed in all regions except in the European region countries. Thirdly, the American area indicated a one-way causal association between PGDP and GCF , whereas the other regions revealed a two-way relationship between PGDP and GCF . Thus, based on these results, it is evident that tourism plays a substantial role in economic growth and vice versa across most regions. Therefore, it is important to emphasize that the use of demand-creation strategies to progress tourism would also boost economic growth.

Further to the bidirectional relationship between TRADE and PGDP , developing trade appears to be a powerful influencer in this study. Having said that, countries with increased tourism also have achieved developed trade and according to analysis, these two variables seem interrelated and mutually beneficial. It also suggests that in most countries, the variables TRADE and GCF in PGDP have the potential to forecast one another since the empirical findings show that the PGDP Granger causes TRADE , GCF , and vice versa. This paper differs from previous research in that it examines the relationship over 18 years, as well as the moderating impact of variables such as GCF and TRADE on economic growth in countries worldwide. Since the data set utilised in this study has a significant number of records, the analysis is more accurate, as the statistical soundness of results grows with the number of observations. As a result, the findings derived from this study could be generalised to the larger population including the entire world. In conclusion, it can be argued that tourism may be used as a catalyst for economic growth and vice versa. It is advised that nations in all regions proceed with caution when deploying more measures to attract visitors, as tourism has a strong influence PGDP . Moreover, the governments of these regions should support practices and policies that would benefit the tourism sector and eventually, the economy. The decision-makers should focus more effective tourism policies on addressing the demand generated by the rise in tourism-related businesses. Additionally, governments should promote investments in tourism-related industries to all types of investors as these ultimately boost the nation’s GDP. Global events such as the pandemic, economic downturns, and the war eruptions have triggered an unprecedented tourism economic crisis, due to the rapid and massive shock to the tourist industry. Due to this, tourism can be a vulnerable channel attracting refugees. This scenario can be risky as the increased pressure on the public finances exerts a higher burden on tax income and economic growth due to the migration of refuges in some countries. In this context, it is critical to overcome this predicament, as the negative repercussions could have a significant impact on the industry, and recovery will take time.

Here by examining the Wavelet Coherence graphs which had been drawn for the regions, American Region has the highest correlation between PGDP and TOUR from 2010 to 2017 compared to the other regions. Most of the graphs indicate a Bidirectional link, which is line with the findings of the panel granger causality. The visual representation of the bidirectional association between TOUR and PGDP in these results reflects the conclusions of the panel granger causality.

Limitations

For this study, data were collected from 105 countries over 18 years, from 2003 to 2020. Other potential variables that influence tourism demand and economic growth, such as the real effective exchange rate, destination attractiveness, seasons, people’s spending capacity, security, urbanization, weather patterns etc., were not included in this study, which is a significant limitation. Moreover, the negative externalities of tourism and economic growth were not taken into account in this study due to the availability of data. For study purposes, countries were divided into regions, and those that depend heavily on tourism were not considered specific. As a result, the limitations mentioned above will need to be addressed in future studies. Future research studies should target to analyse the impact of tourism on economic growth and vice versa by adopting methodologies like the panel regression or generalised method of moments (GMM) which would further clarify the behaviour of these two variables more richly. Additionally, future study might assess the connection between tourism and economic development for each country in the relevant region independently.

Supporting information

S1 appendix. granger causality test results for the countries in each region..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274386.s001

S2 Appendix. Data file.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274386.s002

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ms. Gayendri Karunarathne for proof-reading and editing this manuscript.

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- PubMed/NCBI

Economics of cultural tourism: issues and perspectives

- Published: 18 March 2017

- Volume 41 , pages 95–107, ( 2017 )

Cite this article

- Douglas S. Noonan 1 &

- Ilde Rizzo 2

23k Accesses

43 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The special issue aims at exploring, with an economic perspective, the interconnections between cultural participation, in all its expressions, and tourism organization and patterns with the purpose of understanding economic effects, emerging trends and policy implications. The expanding notion of the cultural consumption of tourists makes the definition of cultural tourism increasingly elusive. Empirical investigations of the relationships between cultural participation and cultural heritage and tourism offer interesting hints in many directions. This introduction briefly overviews the premise of this special issue, the literature and the several perspectives taken by the included articles. Aside from their cultural topics—general, intangible or temporary—these essays all tackle some important economic dimensions of tourism. We encourage cultural economists to invest more in these fascinating areas as more than just intellectual tourists.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Choosing the title of this special issue was not an easy task. The special issue aims at exploring, with an economic perspective, the interconnections between cultural participation, in all its expressions, and tourism organization and patterns with the purpose of understanding economic effects, emerging trends and policy implications. Whether the label ‘cultural tourism’ well represents these topics is a research question in itself. In fact, cultural tourism is an attractive and very popular concept, as it is demonstrated by the attention of international agencies and the existing rich and variegated literature with marked interdisciplinary features; however, it is also a rather vague and challenging one, with ambiguous empirical evidence. Any scholar investigating in such a field faces unresolved definition and measurement issues and, at the same time, promising and intriguing lines of research. Still, analysing together culture, in all its tangible and intangible expressions, and tourism is worthwhile, and cultural tourism seems to be a sufficiently comprehensive concept, notwithstanding its elusiveness, which can be well sketched recalling the famous verses:

Mozart Così fan tutte (1790), I.1 Don alfonso È la fede delle femmine come l’araba fenice: che vi sia, ciascun lo dice; dove sia, nessun lo sa. (Da Ponte) Woman’s constancy Is like the Arabian Phoenix; Everyone swears it exists, But no one knows where.

2 ‘Elusive’ cultural tourist

Tourism is certainly a very important global industry because of its great contribution to the economy. Footnote 1 Indeed, tourists consume a variegated array of goods and services, with linkages to virtually every industry in the economy. So, it is usually considered as a crucial factor for local development, and great attention is devoted to the measurement of its economic impact. Footnote 2 At the same time, however, the ‘cultural’ impact and the potential risks generated by unsustainable tourism flows are also taken into account (Streeten 2006 ). Despite facing occasional shocks, over the past six decades, the tourism sector has showed strength and resilience, with a continuous expansion and diversification (UNWTO 2016 ). Footnote 3

In qualitative terms, holidays, recreation and other forms of leisure motivated about 53% of all international tourist arrivals in 2015, business and professional purposes represented 14%, while 27% travelled for other reasons (e.g. visiting friends and relatives, religious reasons and pilgrimages, health treatment). International organizations do not make distinctions between cultural tourism, and other touristic experiences Footnote 4 and international statistics do not distinguish between ‘leisure’ and culturally motivated tourists; however, they can be defined. Notwithstanding the lack of systematic measures, OECD ( 2009 ) reports positive estimates from various sources suggesting that cultural tourists, including all visitors to cultural attractions regardless their motivation, account for 40% of international tourists. However, it is difficult to distinguish between accidental cultural tourists and tourists who consider culture as the main goal of their travel, Footnote 5 and this bears implications for the design of policies aimed at enhancing the role of culture as driver of attractiveness and competitiveness of destinations. Perhaps reflecting the blurred lines in official statistics, the scholarly literature continues to explore these overlaps.

Indeed, cultural tourism is a longstanding phenomenon, and travellers making the Grand Tour Footnote 6 in the past can be considered the precursors of those who nowadays are labelled as cultural tourists. However, as Bonet ( 2013 , p. 387) argues ‘…it is actually very difficult to define what cultural tourism is about. There are almost as many definitions as there are tourists visiting cultural places’. Indeed, though there is a wide agreement that cultural tourism implies the consumption of culture by tourists, the meaning of ‘culture’ in relation to tourism is not straightforward. Such a relationship has evolved from a narrow one, mainly based on immovable heritage, to a broader one encompassing tangible and intangible elements as well as creative activities (Richards 2011 ) and the search for cultural experiences based on the lifestyles, the habits and the gastronomy of the visited places (OECD 2009 ).

This expanding notion of the cultural consumption of tourists makes the definition of cultural tourism increasingly elusive. In the literature, various attempts have been made to identify different typologies of cultural tourists, considering the type of cultural attraction, and motivation and engagement, under the assumption that all people visiting cultural attractions can be considered cultural tourists (Richards 2003 ). Tracking technologies such as global positioning system (GPS) are increasingly used to understand cultural consumption of tourists in a destination (Shoval and McKercher 2017 ) or to investigate different profiles of cultural tourists, combining the data on the actual behaviour of tourists with information on motivation obtained through surveys (Guccio et al. 2017 ).

The empirical investigation of the relationship between cultural participation and cultural heritage and tourism offers interesting hints in many directions. The positive effects of culture on tourism flows are very often taken for granted, but empirical evidence is rather ambiguous in such a respect. The debate in the journal Tourism Management (Yang et al. 2009 ; Yang and Lin 2011 ; Cellini 2011 ) shows that the effects of heritage, namely the ones included in the World Heritage List (WHL), on attracting tourism flows are controversial. As examples: Patuelli et al. ( 2013 ) find that, in Italy, heritage included in the WHL is a domestic tourism attractor for a region, though spatial competition may reduce the positive effect; van Loon et al. ( 2014 ) offer evidence of the positive effects of cultural heritage on the recreationist’s destination choice for urban recreation trips; and Di Lascio et al. ( 2011 ) suggest a positive, though very small, effect of art exhibitions on tourism flows.

Other suggestions come from an opposite perspective, that is, the effect of tourism flows on cultural attendance. Borowiecki and Castiglione ( 2014 ) provide empirical results suggesting the existence of a strong relationship between tourism flows and cultural participation in museums, theatres and concerts in Italy. Cellini and Cuccia ( 2013 ) offer evidence of a positive effect of tourism on cultural attendance in Italy. Zieba ( 2016 ) finds that foreign tourism flows have a significant positive impact on opera, operetta and musical attendance in Austria. Brida et al. ( 2016 ) outline that the motivations of tourists, as museum visitors, are not necessarily cultural but recreational, perhaps better considered as associated with an entertainment type of tourism. Another type of relationship between culture heritage and tourism refers to the efficiency of tourism destination: Cuccia et al. ( 2016 ) suggest that heritage included in the WHL affects negatively the efficiency of a tourism destination as the WHL inscription raises expectations, which are not met by an equivalent increase of tourism flows.

Summing up, tourism and culture are closely related, in one way or in another. In order to catch the relevant economic implications of such a relationship, and to design efficient policies, research is needed for a better understanding of motivations and behaviours as well as rigorous methodological approaches, hence the premise for this special issue’s collection of articles on the economics of cultural tourism.

3 The articles

To briefly overview the articles included in this special issue, several perspectives might be taken. Cultural tourism often evokes special destinations known for the predominantly cultural nature of their attractors—as opposed to natural (e.g. ecotourism), recreational (e.g. gambling in Las Vegas or Monaco) or other values. This special issue offers two classic examples of this kind of tourist destinations: Amsterdam (Rouwendal and van Loon) and Italy (Guccio et al. 2017 ). Yet cultural tourism often involves more than just museums, monuments, plazas and other infrastructure that is itself historic or contains cultural artefacts. Cultural destinations can involve the intangible and, indeed, the temporary. To that end, the special issue features research on language tourism—immersing oneself in the intangible linguistic resources of a location (Redondo-Carretero et al.)—and on a cultural festival—a temporary exhibit of cultural assets or activities (Báez-Montenegro and Devesa-Fernández, Srakar and Vecco). These articles help identify distinctly cultural elements from other, more general and multidimensional attractors of tourists (i.e. a city or region ‘as a whole’).

Aside from their cultural topics—general, intangible or temporary—these essays all tackle some important economic dimensions of tourism. On the front-end, there is the interest in motivation and consumer tastes for tourism. Studies of motivation (Báez-Montenegro and Devesa-Fernández, Redondo-Carretero et al.) explore this in varying levels of detail and with different emphases. Both articles identify a segment of cultural tourists motivated by professional reasons (in language or in the film industry). This is quite distinct from tourists travelling for professional reasons unrelated to cultural amenities (e.g. attending a conference) yet who nonetheless undertake some cultural activities (as seen in the Rouwendal and van Loon and the Guccio et al. articles). The next step beyond the motivation—actual attendance—leads to some expenditures, and Rouwendal and van Loon examine the spending habits of cultural tourists in Amsterdam. At a more macro level, Srakar and Vecco then explore the economic impacts of cultural tourism associated with a major event and distinction. Finally, no collection of studies on the economics of cultural tourism would be complete without some inquiry into the supply side of the system—and Guccio et al. examine the efficiency with which Italian regions are able to produce cultural tourism experiences.

3.1 Travel purpose and expenditure patterns in city tourism: Evidence from the Amsterdam Metropolitan area

This special issue begins with Jan Rouwendal and Ruben van Loon’s inquiry into the expenditure patterns by tourists to Amsterdam. Yet this article is not merely a description of spending patterns in a city that happens to have a lot of culture. Rather, its central finding leverages a distinctly and uniquely cultural component of Amsterdam’s tourism: as a destination, it juxtaposes classic cultural heritage (e.g. famous museums, trademark canals) with a renowned quasi-legalized cannabis scene and a famed red light district. Mixing traditional cultural heritage with more contemporary, popular cultural themes offers an excellent opportunity to compare economic activity across trip purposes. Their results outline both the spending overlaps and the significant differences across tourists with different purposes. The observed tourist expenditures blur the line between traditional heritage and more popular culture but also reinforce the notion that there are separate types of cultural tourism offerings with differentiated (yet wide) appeal. Better understanding how the many dimensions of cultural amenities (e.g. nightlife, built heritage, cuisine, language) serve as complements or substitutes can help destinations seeking to optimize its portfolio of attractions. The Rouwendal and van Loon article highlights the usefulness of examining diverse trip purposes for destinations.

3.2 On the role of cultural participation in tourism destination performance: an assessment using robust conditional efficiency approach

The supply side of the tourism sector is the focus of the article by Calogero Guccio, Domenico Lisi, Marco Martorana and Anna Mignosa. These authors analyse the efficiency of tourism destinations in Italy to see whether their performance is influenced by the destinations’ cultural participation. In short, they assess whether regions’ cultural life can help extend tourists’ overnight stays and thus enhance the regions’ economic returns from their tourism resources more generally. They implement a robust, nonparametric approach to estimate regional efficiency, the first of its kind applied in this context. That cultural life can spill over to enhance a region’s overall tourism performance carries some obvious implications for destination managers and those in the tourism sector. Yet Guccio et al. find more than just another call for better coordination between the cultural and other dimensions of regional tourism. They also raise important considerations about congestion and sustainability in the tourism sector that cultural participation may be particularly well positioned to help address.

3.3 Language tourism destinations: a case study of motivations, perceived value and tourists’ expenditure

Language tourism is a rather novel topic and arguably the most distinctly ‘cultural’ of this special issue. Thus, the article by María Redondo-Carretero, Carmen Camarero-Izquierdo, Ana Gutiérrez-Arranz and Javier Rodríguez-Pinto marks an important initial foray into empirical economic research on language tourism destinations. Their analysis of motivations and expenditures of language tourists in Valladolid provides more than just insight into that specific empirical case; it helps set the stage for future investigations of language tourism (and other cultural tourism centred on intangible cultural resources). Very little is known in this field, which makes the Redondo-Carretero et al. contribution all the more valuable. They examine motivations from a ‘push/pull’ framework (see, e.g. Klenosky 2002 ) and test whether expenditures differ accordingly. The connections—between motivations for picking particular destinations and expenditures or perceived value—are particularly important in this context of intangible culture where cultural immersion may imply some arbitrariness to the choice of specific destinations. The Redondo-Carretero et al. article offers another example of cultural tourism spilling over into other sectors of the economy while opening the door to future research to consider culture in tourism where the cultural values themselves are not geographically located or destination specific.

3.4 Motivation, satisfaction and loyalty in the case of a film festival: differences between local and non-local participants

The next article examines how a temporary cultural amenity, a film festival, provides value to visitors and locals alike. Andrea Báez-Montenegro and María Devesa-Fernández’s detailed analysis of participant motivations highlights important differences between residents and tourists and demonstrates how carefully applying a structural model can help disentangle critical concepts like satisfaction and loyalty. Notions of loyalty can be especially vital to sustaining cultural events like film festivals, which makes this kind of motivation study valuable in its own right. Yet their findings point to something even richer in the cultural tourism arena: the differentiated roles of locals and tourists in supporting cultural events. In particular, their data analysis reveals two segments of the spectator market—those attending the event for professional reasons and those with strong interests in the cinema. For tourists at least, these two segments exhibit greater satisfaction and loyalty, respectively. Identifying a loyal base of cinephile tourists for this film festival, above and beyond those visiting for professional reasons, points to a complementary role for tourism in supporting cultural amenities that may have historically relied heavily on locals. The growing importance of that segment, and their different interests and constraints, points to new challenges for future research to help illuminate the interplay between the local and the tourist experiences with cultural events.

3.5 Ex ante versus ex post: comparison of the effects of the European Capital of Culture Maribor 2012 on tourism and employment

The Srakar and Vecco article provides a new evaluation of the European Capital of Culture (ECoC) programme while engaging two related aspects of the cultural economics and policy that remain controversial. The first and immediate controversy arises in debates over the utility of economic impact analyses in general and in arts and cultural applications in particular (see, e.g. Seaman 1987 ). A criticism of economic impact analyses is often that their ex ante projections are biased or particularly unreliable and tend to paint overly optimistic pictures of cultural investments. Srakar and Vecco address this rather directly by using panel data models to conduct an ex post verification of the 2012 ECoC Maribor. The second, broader debate in cultural policy regards the use of ‘instrumental values’ (e.g. economic growth, job creation) in justifying cultural programmes rather than examining other, perhaps harder-to-measure or politically less salient, metrics. Cultural tourism must confront this policy debate as well. Nonetheless, the ex post verification for the ECoC Maribor is an important and, at least in this context, original application with interesting results in its own right. These results (far less job creation than the ex ante economic impact analysis showed) demonstrate the value of ex post analyses of cultural programmes and can inform future debates over the use of economic impact analyses and other economic indicators more broadly.

4 What is missing

This special issue benefits from a strong interest by scholars, leading to over two dozen quality manuscripts submitted on fairly short notice. Unfortunately, that means that many excellent pieces of scholarship will need to be published elsewhere. As guest editors, we had the unenviable task of selecting just a handful of pieces to represent here. In addition to the overall quality of each article’s research, we applied several criteria to help shape a special issue that we hope both has broad appeal and makes meaningful contributions to the subject. We sought to represent a diverse mix of cultural attractions in a diversity of locations. The five articles in this issue thus cover a few specific cultural offerings (film festivals, Spanish language or quasi-legalized cannabis) and, more general, regional cultural amenities. They also represent traditional Western European cultural destinations (in Italy, Holland and Spain) as well as relative newcomers to the literature (Slovenia, Chile). The articles here also span national to local in their scope, using data that range from individual level to regional or more macroeconomic indicators. Importantly, the selected studies also demonstrate a breadth of methodologies, including regression analyses of tourist expenditures, dynamic panel data analysis, conditional efficiency frontier estimation and structural equation models of motivations and loyalty.

We also sought a mix of articles in terms of their emphasis in innovating either theory or empirical methodology. In the end, as readers will see, little theoretical advancement is represented in this special issue. This entirely owes to the overwhelming emphasis on empirical applications in the pool of submissions, which we see as an interesting statement about the state of field in its own right. We also had a special interest in studies of novel or emerging areas in cultural tourism, and some of those are indeed represented here (drug tourism, language tourism, film festivals). More interesting and ongoing work in new areas—such as online ‘crowdsourcing’, cultural conventions or ‘cons’—should be encouraged. Also missing are studies of international trade flows related to cultural tourism, on sustainability issues in general and with respect to developing countries and nonmarket valuation (either stated- or revealed-preference) applications.

Nonmarket valuation studies have featured prominently in the cultural economics literature over the past decade or two. The 2003 special issue of this journal on the topic, in particular contingent valuation applied to arts and culture, highlighted a sizeable extant literature (Noonan 2003 ) as well as some tourism-related applications like Carson et al. ( 2002 ) and Snowball and Antrobus ( 2002 ). In the years that followed, many studies using contingent valuation methodology (CVM) and choice experiments have been conducted and published in the cultural economics field, and more than a few applications related to tourist sites (e.g. Bedate et al. 2009 ; Báez and Herrero 2012 ; Herrero et al. 2012 ; Ambrecht 2014 ). In addition, the literature has spread to other nonmarket valuation methodologies like hedonic pricing methodology (e.g. Noonan and Krupka 2011 ; Moro et al. 2013 ) and travel cost methodology (Poor and Smith 2004 ; Melstrom 2014 ; Voltaire et al. 2016 ). Wright and Eppink ( 2016 ) recently offer a meta-analysis based on evaluation studies of tangible and intangible heritage and identify common drivers of value.

Accordingly, we expected to see a strong representation of valuation studies in response to the call for this special issue. In fact, several stated preference studies were submitted, so this kind of research is indeed being conducted in the cultural tourism arena. They were omitted from this special issue not because of the vocal, outside critics of the approach (e.g. Diamond and Hausman 1994 ; Hausman 2012 ). Rather, they simply were not the strongest examples of economics research related to cultural tourism. We see this as much as a compliment to the strength of the other articles contained in this special as it is an observation that some nonmarket valuation studies prove sufficiently easy to conduct (i.e. the barriers to entry are low) that the level of rigour and quality for typical studies may fall short. This is not unlike some of the criticism levied at economic impact studies (e.g. Seaman 1987 ; Frey 2005 ), where convenience of methodological tools and relevance of application often outweigh the needs for rigorous implementation and novel scientific contributions. The economic impact study included in this special issue (Srakar and Vecco), for instance, stands out for its application of a (much-maligned) methodology in a particularly novel way that clearly articulates a contribution to the economic literature. Clearly, it is possible to advance the field and state of knowledge substantially even in controversial areas. The prevalence of studies using a particular methodology (e.g. CVM, economic impact analysis, DEA) merely raises the bar in terms of rigour and novelty that is needed to stand out from the crowd.

That said, there may be special reason to be concerned about the state of the nonmarket valuation research in cultural economics—perhaps especially as applied to tourism. The criticisms recently levied in prominent venues like Journal of Economic Perspectives (see Hausman 2012 ) raise the concerns that (a) key audiences remain unconvinced of the fundamental validity of this suite of empirical tools and (b) specific weaknesses associated with the methodologies lack strong and vibrant economic literatures to address them. The former concern implies a challenge to stated preference researchers to better articulate their economic fundamentals and make their case for genuine contributions. In that regard, we would recommend stronger references to the experimental economics literature (which appears to suffer less from these criticisms) and to the more formal elements of the theory and experimental designs underpinning these methods. The latter concern offers a road map to future stated preference researchers to better connect their work to these ongoing and emerging challenges in the literature. There is a sizeable literature that has already addressed many of these criticisms (Haab et al. 2013 ), and it falls to future researchers to build on that foundation.

In the cultural economics area, the challenge should also be to identify the specifically cultural dimensions of those research questions. Yet another estimate of willingness-to-pay and how income or education affects it, for instance, offers little contribution to the broader cultural economics field, even if the good being valued is obviously cultural. This applied element of the challenge to make the research more fundamentally cultural points to the value in developing research designs and applications that lend insight into some particularly cultural component of preferences or preference elicitation. This might be inquiries into how culture manifests in values that individuals express, how culture affects how we elicit those values, or something else. The cultural economics literature to date has been largely caught up in estimating values of cultural resources (goods, artefacts, experiences). The next step may require moving beyond valuing yet-another-cultural-good and better connecting the valuation exercise with something distinctly and theoretically cultural in terms of values or methodology. The notion of cultural capital (Throsby 1999 ), in fact, brings about both economic value and cultural values; while the former is measurable in financial terms, the latter is multidimensional and lacks an agreed unit of account. In the standard economic approach, it is assumed that all values can ultimately be expressed in monetary terms and that cultural values are recognized as determinants of economic value, rather than values in themselves. The open and challenging question is whether the value of cultural resources can be expressed as a combination of two separate—economic and cultural—components. Throsby and Zednik ( 2014 ) find some evidence for the hypothesis that for works of arts: the cultural value component, while related to economic value, is not subsumed by it. However, the assessment of cultural value is still in its infancy.

In this sense, the challenge resembles the broader challenge identified in this essay about ‘cultural tourism’ more generally. At its heart, the distinction between cultural tourism and tourism generally may be a false distinction. The research agenda for valuation research in the cultural economics arena needs to better articulate its contributions to the academic literature, in particular how it relates to the cultural economics field. Similarly, cultural tourism economics research should strive for something more than economics that can apply to tourism topics. Of course, tourism management is a field that can inform this work, but so can the considerable cultural economics literature. Classic ideas like Baumol’s cost disease, superstar attractions (Frey 1998 ), cultural capital and sustainability (e.g. Throsby 1995 ; Caserta and Russo 2002 ), cultural distance (e.g. Ginsburgh 2005 ) and taste formation (Castiglione and Infante 2016 )—and the dynamic interdependence with supplier choices (Blaug 2001 )—are all ripe for application to tourism topics.

5 What is next

Moving in the direction of developing more distinctly cultural economic theories of tourism presents an important challenge to the field. This special issue contains a host of articles that take some first steps in that direction. Guccio et al. and Rouwendal and van Loon describe some important spillovers between cultural offerings and other tourist activities and thus raise questions about the portfolio of attractions supplied and how that affects demand. Redondo-Carretero et al. introduce another layer of complexity, where the cultural appeal (language tourism) is not specific to the destination. The taste heterogeneity among locals and tourists identified by Báez-Montenegro and Devesa-Fernández, and the questionable positive impacts of ECoC Maribor described by Srakar and Vecco point to issues of sustainability and justifications for public subsidies that are general to cultural tourism.