The future of tourism: Bridging the labor gap, enhancing customer experience

As travel resumes and builds momentum, it’s becoming clear that tourism is resilient—there is an enduring desire to travel. Against all odds, international tourism rebounded in 2022: visitor numbers to Europe and the Middle East climbed to around 80 percent of 2019 levels, and the Americas recovered about 65 percent of prepandemic visitors 1 “Tourism set to return to pre-pandemic levels in some regions in 2023,” United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), January 17, 2023. —a number made more significant because it was reached without travelers from China, which had the world’s largest outbound travel market before the pandemic. 2 “ Outlook for China tourism 2023: Light at the end of the tunnel ,” McKinsey, May 9, 2023.

Recovery and growth are likely to continue. According to estimates from the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) for 2023, international tourist arrivals could reach 80 to 95 percent of prepandemic levels depending on the extent of the economic slowdown, travel recovery in Asia–Pacific, and geopolitical tensions, among other factors. 3 “Tourism set to return to pre-pandemic levels in some regions in 2023,” United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), January 17, 2023. Similarly, the World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC) forecasts that by the end of 2023, nearly half of the 185 countries in which the organization conducts research will have either recovered to prepandemic levels or be within 95 percent of full recovery. 4 “Global travel and tourism catapults into 2023 says WTTC,” World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC), April 26, 2023.

Longer-term forecasts also point to optimism for the decade ahead. Travel and tourism GDP is predicted to grow, on average, at 5.8 percent a year between 2022 and 2032, outpacing the growth of the overall economy at an expected 2.7 percent a year. 5 Travel & Tourism economic impact 2022 , WTTC, August 2022.

So, is it all systems go for travel and tourism? Not really. The industry continues to face a prolonged and widespread labor shortage. After losing 62 million travel and tourism jobs in 2020, labor supply and demand remain out of balance. 6 “WTTC research reveals Travel & Tourism’s slow recovery is hitting jobs and growth worldwide,” World Travel & Tourism Council, October 6, 2021. Today, in the European Union, 11 percent of tourism jobs are likely to go unfilled; in the United States, that figure is 7 percent. 7 Travel & Tourism economic impact 2022 : Staff shortages, WTTC, August 2022.

There has been an exodus of tourism staff, particularly from customer-facing roles, to other sectors, and there is no sign that the industry will be able to bring all these people back. 8 Travel & Tourism economic impact 2022 : Staff shortages, WTTC, August 2022. Hotels, restaurants, cruises, airports, and airlines face staff shortages that can translate into operational, reputational, and financial difficulties. If unaddressed, these shortages may constrain the industry’s growth trajectory.

The current labor shortage may have its roots in factors related to the nature of work in the industry. Chronic workplace challenges, coupled with the effects of COVID-19, have culminated in an industry struggling to rebuild its workforce. Generally, tourism-related jobs are largely informal, partly due to high seasonality and weak regulation. And conditions such as excessively long working hours, low wages, a high turnover rate, and a lack of social protection tend to be most pronounced in an informal economy. Additionally, shift work, night work, and temporary or part-time employment are common in tourism.

The industry may need to revisit some fundamentals to build a far more sustainable future: either make the industry more attractive to talent (and put conditions in place to retain staff for longer periods) or improve products, services, and processes so that they complement existing staffing needs or solve existing pain points.

One solution could be to build a workforce with the mix of digital and interpersonal skills needed to keep up with travelers’ fast-changing requirements. The industry could make the most of available technology to provide customers with a digitally enhanced experience, resolve staff shortages, and improve working conditions.

Would you like to learn more about our Travel, Logistics & Infrastructure Practice ?

Complementing concierges with chatbots.

The pace of technological change has redefined customer expectations. Technology-driven services are often at customers’ fingertips, with no queues or waiting times. By contrast, the airport and airline disruption widely reported in the press over the summer of 2022 points to customers not receiving this same level of digital innovation when traveling.

Imagine the following travel experience: it’s 2035 and you start your long-awaited honeymoon to a tropical island. A virtual tour operator and a destination travel specialist booked your trip for you; you connected via videoconference to make your plans. Your itinerary was chosen with the support of generative AI , which analyzed your preferences, recommended personalized travel packages, and made real-time adjustments based on your feedback.

Before leaving home, you check in online and QR code your luggage. You travel to the airport by self-driving cab. After dropping off your luggage at the self-service counter, you pass through security and the biometric check. You access the premier lounge with the QR code on the airline’s loyalty card and help yourself to a glass of wine and a sandwich. After your flight, a prebooked, self-driving cab takes you to the resort. No need to check in—that was completed online ahead of time (including picking your room and making sure that the hotel’s virtual concierge arranged for red roses and a bottle of champagne to be delivered).

While your luggage is brought to the room by a baggage robot, your personal digital concierge presents the honeymoon itinerary with all the requested bookings. For the romantic dinner on the first night, you order your food via the restaurant app on the table and settle the bill likewise. So far, you’ve had very little human interaction. But at dinner, the sommelier chats with you in person about the wine. The next day, your sightseeing is made easier by the hotel app and digital guide—and you don’t get lost! With the aid of holographic technology, the virtual tour guide brings historical figures to life and takes your sightseeing experience to a whole new level. Then, as arranged, a local citizen meets you and takes you to their home to enjoy a local family dinner. The trip is seamless, there are no holdups or snags.

This scenario features less human interaction than a traditional trip—but it flows smoothly due to the underlying technology. The human interactions that do take place are authentic, meaningful, and add a special touch to the experience. This may be a far-fetched example, but the essence of the scenario is clear: use technology to ease typical travel pain points such as queues, misunderstandings, or misinformation, and elevate the quality of human interaction.

Travel with less human interaction may be considered a disruptive idea, as many travelers rely on and enjoy the human connection, the “service with a smile.” This will always be the case, but perhaps the time is right to think about bringing a digital experience into the mix. The industry may not need to depend exclusively on human beings to serve its customers. Perhaps the future of travel is physical, but digitally enhanced (and with a smile!).

Digital solutions are on the rise and can help bridge the labor gap

Digital innovation is improving customer experience across multiple industries. Car-sharing apps have overcome service-counter waiting times and endless paperwork that travelers traditionally had to cope with when renting a car. The same applies to time-consuming hotel check-in, check-out, and payment processes that can annoy weary customers. These pain points can be removed. For instance, in China, the Huazhu Hotels Group installed self-check-in kiosks that enable guests to check in or out in under 30 seconds. 9 “Huazhu Group targets lifestyle market opportunities,” ChinaTravelNews, May 27, 2021.

Technology meets hospitality

In 2019, Alibaba opened its FlyZoo Hotel in Huangzhou, described as a “290-room ultra-modern boutique, where technology meets hospitality.” 1 “Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba has a hotel run almost entirely by robots that can serve food and fetch toiletries—take a look inside,” Business Insider, October 21, 2019; “FlyZoo Hotel: The hotel of the future or just more technology hype?,” Hotel Technology News, March 2019. The hotel was the first of its kind that instead of relying on traditional check-in and key card processes, allowed guests to manage reservations and make payments entirely from a mobile app, to check-in using self-service kiosks, and enter their rooms using facial-recognition technology.

The hotel is run almost entirely by robots that serve food and fetch toiletries and other sundries as needed. Each guest room has a voice-activated smart assistant to help guests with a variety of tasks, from adjusting the temperature, lights, curtains, and the TV to playing music and answering simple questions about the hotel and surroundings.

The hotel was developed by the company’s online travel platform, Fliggy, in tandem with Alibaba’s AI Labs and Alibaba Cloud technology with the goal of “leveraging cutting-edge tech to help transform the hospitality industry, one that keeps the sector current with the digital era we’re living in,” according to the company.

Adoption of some digitally enhanced services was accelerated during the pandemic in the quest for safer, contactless solutions. During the Winter Olympics in Beijing, a restaurant designed to keep physical contact to a minimum used a track system on the ceiling to deliver meals directly from the kitchen to the table. 10 “This Beijing Winter Games restaurant uses ceiling-based tracks,” Trendhunter, January 26, 2022. Customers around the world have become familiar with restaurants using apps to display menus, take orders, and accept payment, as well as hotels using robots to deliver luggage and room service (see sidebar “Technology meets hospitality”). Similarly, theme parks, cinemas, stadiums, and concert halls are deploying digital solutions such as facial recognition to optimize entrance control. Shanghai Disneyland, for example, offers annual pass holders the option to choose facial recognition to facilitate park entry. 11 “Facial recognition park entry,” Shanghai Disney Resort website.

Automation and digitization can also free up staff from attending to repetitive functions that could be handled more efficiently via an app and instead reserve the human touch for roles where staff can add the most value. For instance, technology can help customer-facing staff to provide a more personalized service. By accessing data analytics, frontline staff can have guests’ details and preferences at their fingertips. A trainee can become an experienced concierge in a short time, with the help of technology.

Apps and in-room tech: Unused market potential

According to Skift Research calculations, total revenue generated by guest apps and in-room technology in 2019 was approximately $293 million, including proprietary apps by hotel brands as well as third-party vendors. 1 “Hotel tech benchmark: Guest-facing technology 2022,” Skift Research, November 2022. The relatively low market penetration rate of this kind of tech points to around $2.4 billion in untapped revenue potential (exhibit).

Even though guest-facing technology is available—the kind that can facilitate contactless interactions and offer travelers convenience and personalized service—the industry is only beginning to explore its potential. A report by Skift Research shows that the hotel industry, in particular, has not tapped into tech’s potential. Only 11 percent of hotels and 25 percent of hotel rooms worldwide are supported by a hotel app or use in-room technology, and only 3 percent of hotels offer keyless entry. 12 “Hotel tech benchmark: Guest-facing technology 2022,” Skift Research, November 2022. Of the five types of technology examined (guest apps and in-room tech; virtual concierge; guest messaging and chatbots; digital check-in and kiosks; and keyless entry), all have relatively low market-penetration rates (see sidebar “Apps and in-room tech: Unused market potential”).

While apps, digitization, and new technology may be the answer to offering better customer experience, there is also the possibility that tourism may face competition from technological advances, particularly virtual experiences. Museums, attractions, and historical sites can be made interactive and, in some cases, more lifelike, through AR/VR technology that can enhance the physical travel experience by reconstructing historical places or events.

Up until now, tourism, arguably, was one of a few sectors that could not easily be replaced by tech. It was not possible to replicate the physical experience of traveling to another place. With the emerging metaverse , this might change. Travelers could potentially enjoy an event or experience from their sofa without any logistical snags, and without the commitment to traveling to another country for any length of time. For example, Google offers virtual tours of the Pyramids of Meroë in Sudan via an immersive online experience available in a range of languages. 13 Mariam Khaled Dabboussi, “Step into the Meroë pyramids with Google,” Google, May 17, 2022. And a crypto banking group, The BCB Group, has created a metaverse city that includes representations of some of the most visited destinations in the world, such as the Great Wall of China and the Statue of Liberty. According to BCB, the total cost of flights, transfers, and entry for all these landmarks would come to $7,600—while a virtual trip would cost just over $2. 14 “What impact can the Metaverse have on the travel industry?,” Middle East Economy, July 29, 2022.

The metaverse holds potential for business travel, too—the meeting, incentives, conferences, and exhibitions (MICE) sector in particular. Participants could take part in activities in the same immersive space while connecting from anywhere, dramatically reducing travel, venue, catering, and other costs. 15 “ Tourism in the metaverse: Can travel go virtual? ,” McKinsey, May 4, 2023.

The allure and convenience of such digital experiences make offering seamless, customer-centric travel and tourism in the real world all the more pressing.

Three innovations to solve hotel staffing shortages

Is the future contactless.

Given the advances in technology, and the many digital innovations and applications that already exist, there is potential for businesses across the travel and tourism spectrum to cope with labor shortages while improving customer experience. Process automation and digitization can also add to process efficiency. Taken together, a combination of outsourcing, remote work, and digital solutions can help to retain existing staff and reduce dependency on roles that employers are struggling to fill (exhibit).

Depending on the customer service approach and direct contact need, we estimate that the travel and tourism industry would be able to cope with a structural labor shortage of around 10 to 15 percent in the long run by operating more flexibly and increasing digital and automated efficiency—while offering the remaining staff an improved total work package.

Outsourcing and remote work could also help resolve the labor shortage

While COVID-19 pushed organizations in a wide variety of sectors to embrace remote work, there are many hospitality roles that rely on direct physical services that cannot be performed remotely, such as laundry, cleaning, maintenance, and facility management. If faced with staff shortages, these roles could be outsourced to third-party professional service providers, and existing staff could be reskilled to take up new positions.

In McKinsey’s experience, the total service cost of this type of work in a typical hotel can make up 10 percent of total operating costs. Most often, these roles are not guest facing. A professional and digital-based solution might become an integrated part of a third-party service for hotels looking to outsource this type of work.

One of the lessons learned in the aftermath of COVID-19 is that many tourism employees moved to similar positions in other sectors because they were disillusioned by working conditions in the industry . Specialist multisector companies have been able to shuffle their staff away from tourism to other sectors that offer steady employment or more regular working hours compared with the long hours and seasonal nature of work in tourism.

The remaining travel and tourism staff may be looking for more flexibility or the option to work from home. This can be an effective solution for retaining employees. For example, a travel agent with specific destination expertise could work from home or be consulted on an needs basis.

In instances where remote work or outsourcing is not viable, there are other solutions that the hospitality industry can explore to improve operational effectiveness as well as employee satisfaction. A more agile staffing model can better match available labor with peaks and troughs in daily, or even hourly, demand. This could involve combining similar roles or cross-training staff so that they can switch roles. Redesigned roles could potentially improve employee satisfaction by empowering staff to explore new career paths within the hotel’s operations. Combined roles build skills across disciplines—for example, supporting a housekeeper to train and become proficient in other maintenance areas, or a front-desk associate to build managerial skills.

Where management or ownership is shared across properties, roles could be staffed to cover a network of sites, rather than individual hotels. By applying a combination of these approaches, hotels could reduce the number of staff hours needed to keep operations running at the same standard. 16 “ Three innovations to solve hotel staffing shortages ,” McKinsey, April 3, 2023.

Taken together, operational adjustments combined with greater use of technology could provide the tourism industry with a way of overcoming staffing challenges and giving customers the seamless digitally enhanced experiences they expect in other aspects of daily life.

In an industry facing a labor shortage, there are opportunities for tech innovations that can help travel and tourism businesses do more with less, while ensuring that remaining staff are engaged and motivated to stay in the industry. For travelers, this could mean fewer friendly faces, but more meaningful experiences and interactions.

Urs Binggeli is a senior expert in McKinsey’s Zurich office, Zi Chen is a capabilities and insights specialist in the Shanghai office, Steffen Köpke is a capabilities and insights expert in the Düsseldorf office, and Jackey Yu is a partner in the Hong Kong office.

Explore a career with us

Tourism infrastructure: what is it and how is it made?

The touristic infrastructure it is a set of facilities and institutions that constitute the material and organizational base for the development of tourism. It consists of basic services, road system, transport, accommodation, gastronomy, services for cultural and leisure activities, network of shops, tourist protection services and others.

Tourism has become a booming industry worldwide. Annually more than a billion people move outside their usual place to visit places of great attractiveness, in order to spend their vacations, entertain themselves, or perform other leisure activities.

According to the World Tourism Organization, tourism ranks third in exports of services and goods worldwide, with a greater growth in the last five years than international trade.

The tourist attractions form the primary base to attract tourists, giving them a space-time itinerary. However, actions aimed at protecting and adapting to these attractions are necessary in order to generate the tourist movement.

The complementary tourist resources that serve for this purpose are defined as tourist infrastructure.

- 1 How is the tourist infrastructure of a country?

- 2.1 One of the most visited countries

- 2.2 Need for development

- 2.3 The coastal destination stands out

- 2.4 Cultural richness

- 3 References

How is the tourist infrastructure of a country?

The economic apogee has made tourism become for any country an obvious trigger of infrastructure creation, causing an excellent synergy between public and private investment.

The government when it makes investments in tourist infrastructure is creating a beneficial circle with which it encourages private investment and its economic profit, and on the other hand, private investment leads to the social profit sought with government investment.

The tourism infrastructure makes it possible for tourism to develop, so there must be both a strategic plan and good management so that each tourist destination can give an effective maintenance to said infrastructure, in such a way that the tourist feels satisfied and comfortable. with the facilities as with the required services.

The tourist infrastructure of a country is made up of interconnected elements that allow tourists to arrive, stay and enjoy the tourist attraction of their destination, making their trip a pleasure, among which are:

- Basic services: water supply, electricity, telecommunications, waste collection, health and hygiene, security and protection.

- Road system: highways, roads, roads and trails.

- Transportation: airports, seaports, river boats, rail networks, buses, taxis.

- Accommodation: hotels, inns, apartments, camps.

- Gastronomy: restaurants, fast food establishments, taverns, cafes.

- Services for cultural activities: art and entertainment, museums, nature reserves, zoos.

- Services for sports and recreational activities: rental of sports and recreational items, gambling and betting rooms, amusement parks, golf courses, sports courts, diving, skiing.

- Other services: tourist information, equipment and vehicle rental, banking services.

- Network of stores and shops in general.

- Security services / tourist protection.

Commercial entities, such as hotels or restaurants, create and operate infrastructures to serve their customers (tourists). Public entities develop infrastructure not only for the service of tourists but, mainly, for the creation of conditions for the development of the region, serving the whole society (including tourists) and the economy.

Characteristics of the tourist infrastructure in Mexico

An interesting country to know the characteristics of its tourist infrastructure is Mexico. He Mexican tourism represents an immense industry.

One of the most visited countries

According to the World Tourism Organization, Mexico is among the ten most visited countries in the world and is the second most visited country in the Americas, behind the United States.

Mexico has a significant number of sites cataloged by UNESCO as World Heritage Sites, which include ancient ruins, colonial cities and nature reserves.

In the report"Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Index"of 2017, which measures the factors to do business in the tourist industry of each country, Mexico ranked 22nd in the world ranking, its tourist service infrastructure ranked 43 , health and hygiene in 72, and safety and protection in 113.

Need for development

According to recent statements by the president of the Mexican Association of Hotels and Motels, Mexico needs more infrastructure to attract European tourists and thus depend less on the United States, where 60% of tourists who enter the country come from.

Greater air connectivity is needed, as well as more and better roads and trains to attract tourists from Europe and elsewhere.

Although there are more than 35 international airports in the country, there are major airports saturated, such as Mexico City, and there is a lack of greater internal connectivity that allows other tourist destinations, such as Cancún, to be exploited.

The coastal destination stands out

The coasts of Mexico harbor beaches with an excellent tourist infrastructure. In the Yucatan peninsula, the most popular beach destination is the tourist city of Cancun. South of Cancun is the coastal strip called Riviera Maya.

On the Pacific coast, the most notable tourist destination is Acapulco, famous as the ancient destination of the rich and famous.

To the south of Acapulco are the surf beaches of Puerto Escondido. North of Acapulco is the tourist city of Ixtapa.

Cultural richness

The abundant culture and natural beauty existing in the states of the Mexican southeast allows us to devise an exceptionally competitive tourist destination.

In order for tourists to reach destinations farther away from the main cities, work has been carried out on development plans for tourism infrastructure, such as the planned centers project in Chichén Itza, Calakmul and Palenque, or the trans-peninsular train, the extension of the Cancun airport, as well as the construction of a Convention Center in the city of Mérida, the construction of hospitals or the increase of roads.

Thus, when a tourist arrives at the Cancun airport, apart from enjoying the modern tourist welcome offered by the Riviera Maya and its beautiful beaches, you can also penetrate other places in the area; know for example the historic center of Campeche, the route of the cenotes, archaeological sites revealing the great Mayan culture, or delight in jungle tourism.

In the same way you can make a guest at a congress in Merida, which will surely expand your visit depending on the formidable and varied local offer.

All this will produce a significant economic income, since during your stay that tourist will taste the cuisine of the region, buy handicrafts and souvenirs, will stay in different accommodations and hire tourist guides or means of transport in the same region.

- International Recommendations for Tourism Statistics 2008 New York, 2010. United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs Statistics Division. Studies in Methods Series M No. 83 / Rev.1. Available in: unstats.un.org

- OMT panorama of international tourism. Edition 2017. World Tourism Organization. October 2017. eISBN: 978-92-844-1904-3 ISBN: 978-92-844-1903-6. Available at e-unwto.org.

- Tourism Infrastructure as a determinant of regional development. Panasiuk, Aleksander. University of Szczecin. ISSN 1648-9098. Ekonomika go vadiba: Actualijos go perspectyvos. 2007

- Tourism in Mexico. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Taken from en.wikipedia.org

- Infrastructure for tourism. Secretariat of Tourism of Mexico. May 2015. Available at sectur.gob.mx.

- More infrastructure, key to attract European tourism. The Universal newspaper of Mexico. 01/20/2018 Available at eluniversal.com.mx.

Recent Posts

Turning tourism into development: Mitigating risks and leveraging heritage assets

If done right, tourism can actually bolster and preserve cultural heritage, while also helping to develop economies. Image: REUTERS/David Loh

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Abeer Al Akel

Maimunah mohd sharif.

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Travel and Tourism is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, travel and tourism.

- Cultural and historical travel accounts for 40% of all tourism globally.

- 73% of millennials report being interested in cultural and historic places.

- Protecting local culture and heritage requires a robust plan to mitigate negative impacts and policies to ensure prosperity is shared.

Culture and heritage tourism has the potential to create significant employment opportunities and stimulate economic transformation.

However, communities worldwide often grapple with the challenges posed by the magnetic appeal of heritage sites and the promise of economic prosperity. Property values can increase, displacing local residents and permanently altering the character of their neighbourhoods.

But capitalizing on tourism's potential while preserving and enhancing history and culture is possible — and it is already being done in sites around the world. From Malaysia to Saudi Arabia, many are already demonstrating the ability to balance economic development with socially and environmentally sustainable transformations.

Below are five common features that those sustainable approaches embrace.

Have you read?

This is how to leverage community-led sustainable tourism for people and biodiversity, are we finally turning the tide towards sustainable tourism, how the middle east is striving to lead the way in sustainable tourism, translating a vision into an area-based plan.

Urban planning and regeneration require a holistic approach, coordinating interventions across various sectors and providing guidance for investments. A holistic plan would include spatial and policy measures that are supported by regulatory measures, particularly those focusing on affordability and social cohesion. UN-Habitat prioritizes measures which promote mixed-use and social-economically diverse development to mitigate gentrification.

In George Town, Malaysia, the Special Area Plan and its Comprehensive Management Plan function as the key reference for inclusive strategic policies, regulations and guidelines for conservation, economic activities and intangible heritage. The plan, which balances economic development and conservation, included affordability measures such as supporting local owners restoring their houses, enabling adaptive reuse for small businesses, and supporting renters, thus protecting a share of historic buildings from tourism-induced redevelopment.

In Saudi Arabia’s AlUla, home to 40,000 residents and leading cultural assets including Hegra and Jabal Ikma — which was recently added to UNESCO’s Memory of the World International Register — a similar vision is unfolding. The Path to Prosperity masterplan makes provisions for new housing, creates new economic opportunities and establishes new schools, mosques and healthcare facilities for the community with affordability as the guiding principle. An expanded public realm will create district and neighbourhood parks with green spaces, playgrounds, outdoor gyms and bicycle trails. A network of scenic routes, low-impact public transportation and non-vehicular options will facilitate mobility.

A diversified economic base

To avoid over-reliance on a single economic driver, planners must make space for a range of alternative livelihoods. In AlUla, The Royal Commission for AlUla (RCU), which is responsible for the city’s development into a tourism hub, is drawing on its rich local heritage to create a global destination while diversifying the local economy. Investment in native industries such as agriculture has resulted in a revived high-yielding and higher-value farming sector, while new sectors such as the creation of film and logistics industries are creating new jobs and providing increased revenue for residents.

The UN-Habitat Parya Sampada project in the Kathmandu Valley undertook earthquake reconstruction of the heritage settlements in urban areas using a holistic approach of physical reconstruction and economic recovery. It focused on the reconstruction of public heritage infrastructure supported by tourism enterprises run by women and youth.

Nurturing living heritage and local knowledge

Maintaining the character of a place is critical to its future and creates valuable economic assets. Maintenance and preservation animate the built environment, while the recovery of building techniques and crafts of traditional cultural activities creates jobs and maintains skills.

UN-Habitat’s work in Beirut demonstrates this approach, supporting several hundred jobs. Through the Beirut Housing Rehabilitation and Cultural and Creative Industries project, led by UN-Habitat, UNESCO supervises the allocation of small grants to local artisans. The regeneration of the historical train station in Mar Mikhael and adjacent areas will focus on traditional building techniques to reactivate cultural markets and businesses.

In AlUla, the Hammayah training programme is empowering thousands to work as guardians of natural heritage and culture. In Myanmar the nationwide Community-Based Tourism initiative is operated and managed by local vulnerable communities to provide genuine experiences to world travelers.

Share the value created by tourism

Addressing the negative externalities of tourism requires the assessment and compensation of its real impacts, which can be done through sustainable tourism planning and community participation. The pressure on services, increased congestion and the cost of living need to be addressed through specific investments, funded through the taxation of tourism-related revenues redirected towards the local community, especially for the most vulnerable groups.

Examples include the Balearic Island of Mallorca, which has introduced a sustainable tourism tax to support conservation of the island. Meanwhile Kyoto, Japan has implemented several measures to control the number of tourists at popular sites and establish visitor codes of conduct.

Human-centered local development

Empowering the local community to actively engage with its rich culture while minimizing conflict with the natural environment can increase the resilience of residents and reduce the pressures of gentrification. Participation in decision-making is critical to shape visions and plans that achieve these goals.

The UN-Habitat Participatory Strategy in Mexico’s San Nicolas de los Garza showcases how collaboration with the local community throughout the design and implementation process can ensure solutions capture the culture, skills and needs of the neighborhoods. The 2030 City Vision provides a participatory action plan for the integration of culture, heritage and tourism within the currently prevalent urban economic sectors.

In Saudi Arabia such approaches are embedded in Vision 2030, a blueprint for economic diversification. RCU deploys short- and long-term support to the community through scholarship, upskilling and support for SMEs to enhance access to jobs and entrepreneurship in hospitality and tourism.

While development always introduces complex dynamics and transformations, mitigating gentrification in tourist areas is crucial to achieving sustainable local development for the benefit of all and preserving the unique character of these places.

These measures advocate a proactive approach to ensure that economic growth remains inclusive for the entire community, and that tourism is promoted for the benefit of local residents as well as visitors.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Industries in Depth .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

Agritech: Shaping Agriculture in Emerging Economies, Today and Tomorrow

Confused about AI? Here are the podcasts you need on artificial intelligence

Robin Pomeroy

April 25, 2024

Which technologies will enable a cleaner steel industry?

Daniel Boero Vargas and Mandy Chan

Industry government collaboration on agritech can empower global agriculture

Abhay Pareek and Drishti Kumar

April 23, 2024

Nearly 15% of the seafood we produce each year is wasted. Here’s what needs to happen

Charlotte Edmond

April 11, 2024

How Paris 2024 aims to become the first-ever gender-equal Olympics

Victoria Masterson

April 5, 2024

Sustainable Tourism Infrastructure

Photo by Shutterstock

Country & Regions

- Sector & Subsector

Pipeline Opportunity

Business case, impact case, enabling environment, target locations.

Provide and operate eco- and community-based tourism infrastructures, such as hotels, lodges and camp sites, that rely on the local value chain. The facilities run through community-private-public partnerships, where the private actors provide and operate the facilities, the public actor offers support infrastructure, such as roads, water and power utilities, and the communities supply products like vegetables, fruits, meat and eggs through supply contract arrangements.

Support sustainable practices in tourism and strengthen local value chains serving the tourism industry.

Free Member Account Required

Please log in or register to view this section.

Sector Classification

- 1) World Bank Group, 2005. Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA): Tanzania's Investor Outreach Program. 2) De Chazal Du M (DCDM), 2011. Tourism in Tanzania: Investment in Tourism in Tanzania. 3) The World Bank, 2015. Diagnostic Trade Integration Study (DTIS) for Tanzania. 4) United Republic of Tanzania, 2021. Third National Five-Year Plan (FYDP 3). 5) United Republic of Tanzania, 2021. Tanzania Tourism Policy – Under Review. 6) Operations Research Society of Eastern Africa, Journal Vol. 7 (2), 2017. Gender and Women Entrepreneurs’ Strategies in Tourism Markets: A Comparison between Tanzania and Sweden. 7) United Republic of Tanzania, 2002, Tourism Master Plan. 8) Word Bank Group, 2021. Tanzanian Economic Update, Transforming Tourisms Sector, Toward a Sustainable, Resilient, and Inclusive Sector. 9) Oxford Business Group, 2017. https://oxfordbusinessgroup.com/analysis. 10) HAL Open Science, 2021. Economic impacts of COVID-19 on the tourism sector in Tanzania.

- 11) Tanzania Invest, 2022. https://www.tanzaniainvest.com/tourism. 12) Jadian Company Limited, 2021. Feasibility Study Report. 13) Word Bank Group, 2021. Tanzanian Economic Update, Transforming Tourisms Sector, Toward a Sustainable, Resilient, and Inclusive Sector. 14) PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2019. Hospitality Outlook. 15) Aman Raphael, 2013. Career Development of Women in Hospitality Industry: Insights From Double Tree By Hilton Hotel, Tanzania. 16) African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, Volume 7, 2018. 17) Tanzanian Ministry of Education and Vocational Training, 2015. Human Resource Needs and Skill Gaps in the Tourism and Hospitality Sector in Tanzania. 18) United Republic of Tanzania, 2008. Tourism Act. 19) United Republic of Tanzania, 2009. Wildlife Conservation Act (No. 5). 20) United Republic of Tanzania, 2013. The Wildlife Conservation Act. 21) The World Bank, 2017. New Opportunities for Development in Southern Tanzania Through Nature-Based Tourism. 22) United Republic of Tanzania, 2022. Standard Incentives for Investors. https://investment-guide.eac.int. 23) Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism of United Republic of Tanzania, 2022. https://www.maliasili.go.tz/attractions/tanzania-tourist-attractions. 24) World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC), 2022. https://wttc.org. 25) World Bank Group, 2015. Tanzania Economic Update. 26) Adumua Safaris, 2022. https://adumusafaris.com/destinations/tanzania-southern-circuit. 27) Inter-American Development Bank, 2011. Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) for Sustainable Tourism in Tanzania. 28) United Republic of Tanzania, 2019. Tourism Investment Guide. 29) United Republic of Tanzania, 1997. Tanzania Investment Act, No. 26. 30) Nature Conservation, 2013. Emerging issues and challenges in conservation of biodiversity in the rangelands of Tanzania. 31) Journal of Development Studies, 2015. Gender and Livelihood Diversification: Maasai Women’s Market Activities in Northern Tanzania. 32) Happiness Kiami, 2018. Effects of Tourism Activities on The Livelihoods of Local Communities In The Eastern Arc Mountains. 33) World Economic Forum, 2019. Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Index Report. 34) Oxford Business Group, 2018 Addressing infrastructure challenges in southern Tanzania to drive tourism growth.

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

How does new infrastructure impact the competitiveness of the tourism industry?——Evidence from China

Roles Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Institute of Management, Shanghai University of Engineering Science, Shanghai, China

Roles Writing – original draft

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Institute of Geography, Heidelberg University, Heidelberg, Germany

Roles Methodology

Roles Data curation

- Guodong Yan,

- Lin Zou,

- Yunan Liu,

- Published: December 1, 2022

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0278274

- Reader Comments

Infrastructure construction related to the new generation of information technology and 5G technology is an important measure taken by the Chinese government to promote regional economic development. Large-scale infrastructure investment is being carried out simultaneously in China’s core and peripheral regions. The COVID-19 pandemic has dealt a severe blow to China’s tourism industry, and the application of new technologies seems to blur the spatial boundaries of the tourism industry. Therefore, it is debatable whether the zealous development of large investment projects can really improve the competitiveness of the regional tourism industry. This paper discusses this topical issue by empirically analyzing data from 31 Chinese provinces and cities from 2008–2019 and draws the following conclusions (1) The continuous expansion of new infrastructure investment in China indeed has a positive effect on improving China’s overall tourism competitiveness. However, the inverted U-shaped relationship between the two shows that China should not blindly expand the scale of infrastructure construction and make appropriate investment according to the regional industrial development level. (2) Although convergent infrastructure plays an important role in regional industrial competitiveness, the marginal effect has begun to weaken, so the problem of scale inefficiency needs to be addressed. In contrast, the input of innovation infrastructure is insufficient to enhance industrial competitiveness and can be moderately increased to achieve better results. (3) China’s core economic areas have a good driving effect on new infrastructure investment, but the original technological innovation and transformation-type facilities are still the key to limiting the improvement of industrial competitiveness. Peripheral areas are more passive recipients with strong demand. Therefore, investment in various types of infrastructure can drive regional development.

Citation: Yan G, Zou L, Liu Y, Ji R (2022) How does new infrastructure impact the competitiveness of the tourism industry?——Evidence from China. PLoS ONE 17(12): e0278274. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0278274

Editor: Hironori Kato, The University of Tokyo, JAPAN

Received: June 7, 2022; Accepted: November 13, 2022; Published: December 1, 2022

Copyright: © 2022 Yan et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding: This work was supported by National Social Science Foundation of China (17BJY148); National Natural Science Foundation of China (42101175); China Scholarship Council Postdoctoral Foundation (Grant: 202008310025).

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

1 Introduction

Since 2018, China has defined the construction of 5G, artificial intelligence, industrial internet and the internet of things as "new infrastructure construction". New infrastructure construction focuses on the industrial internet to provide infrastructure for the digital transformation of industry, with investment in fixed assets, advanced infrastructure and digital platforms. The development of the new infrastructure has accelerated the deployment and application of cutting-edge digital technologies in China.

In 2020, China has defined that the scope of new infrastructure construction mainly includes information infrastructure, converged infrastructure and innovation infrastructure. Information infrastructure refers to the infrastructure developed and created based on the new generation of information technology, such as the infrastructure of communication networks represented by 5G, the Internet of Things, the Industrial Internet and satellite Internet, the infrastructure of new technologies represented by artificial intelligence, cloud computing and blockchain, and the infrastructure represented by data centers and intelligent data centers. Converged infrastructure refers to the transformed and modernized infrastructure through the deep application of internet, Big Data, artificial intelligence and other technologies, such as smart transport infrastructure and smart energy infrastructure. Innovation infrastructure refers to the non-profit infrastructure supporting scientific research, technological development and product research and development, such as large-scale science and technology infrastructure, science and education infrastructure and industrial technology innovation infrastructure.

The COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 has brought major changes to the tourism industry. The traditional tourism industry, which used to rely on crowd consumption, has almost come to a standstill, while emerging industries such as cloud display art and cloud tourism based on digital technology are developing rapidly in China.For the digital tourism industry, building new infrastructures does not only mean satisfying the growing demand for information processing, information transmission and storage capacity. The digital tourism industry relies on digital technology for the production, distribution and management of tourism-related content, providing digital cultural services with smarter connectivity, deeper interaction, more comprehensive integration and higher quality content, creating a variety of new platforms and formats for the digital tourism industry and opening up new development opportunities. China’s tourism industry is showing an increasingly clear digital development trend. The construction of new infrastructure has become the key promoter of the transformation and development of the digital tourism industry, which plays a key role in improving the competitiveness of regional and national tourism in the Special Period. Therefore, from the perspective of the joint development of new infrastructure construction and the tourism industry, this paper analyses the general issue of how new infrastructure construction affects the competitiveness of China’s tourism industry, and specifically attempts to discuss the diversity of the role of new infrastructure development on tourism in terms of the types of facilities, regional differences and investment differences.

This paper is organized as follows. The next section reviews the relevant literature and proposes the analytical framework for the relationship between the construction of new infrastructure and the competitiveness of the tourism industry; the third section describes the data and methodology of our study; the fourth and fifth sections discuss the impact of new infrastructure on the tourism industry in China; finally, the last section provides some concluding remarks.

2 Analytical frameworks

New infrastructure construction has become a necessary condition for China’s economic development and has a catalytic effect on the high-quality development of the regional economy and the transformation and upgrading of the industrial structure [ 1 , 2 ]. The construction of new infrastructure is closely related to tourism development and can improve the quality of tourism development [ 3 – 5 ]. Tourism is associated with multiple industries and has strong industrial penetration [ 6 , 7 ]. Digitization and connectivity of new infrastructure reduces the negative benefits of travel time and provides potential economic benefits based on improving the value of travel time [ 8 ]. The construction of new infrastructure enables investment of China’s public finance, government debt funds, private investment and other funds into the internal economic circulation system [ 9 ], which plays a role in improving the income level and tourism consumption capacity of urban and rural residents and boosts demand in China’s domestic tourism market. It helps China to mitigate the economic impact of the COVID -19 pandemic to a certain extent, which is the internal economic cycle that the Chinese government has emphasized. It is worth highlighting that the Chinese government’s new infrastructure construction policy stimulates private investment in the tourism industry, creating economic spillover effects [ 10 ]. This leads to an increase in private investment and consumption, much of which comes from foreign FDI investment, linking the two-way interaction between China’s internal and international capital [ 5 ].

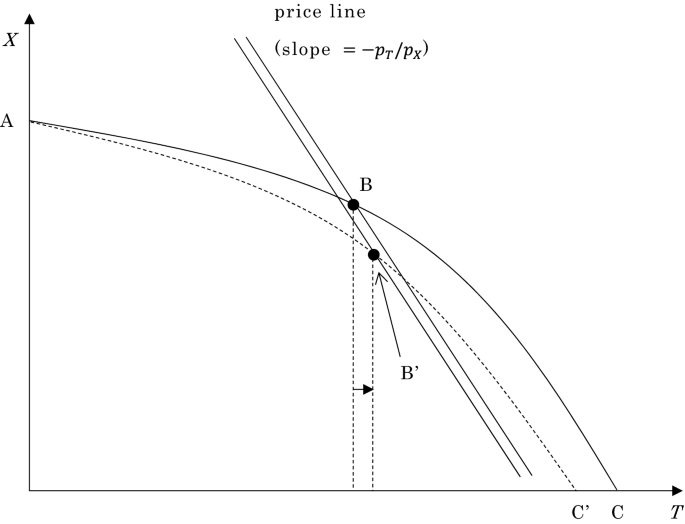

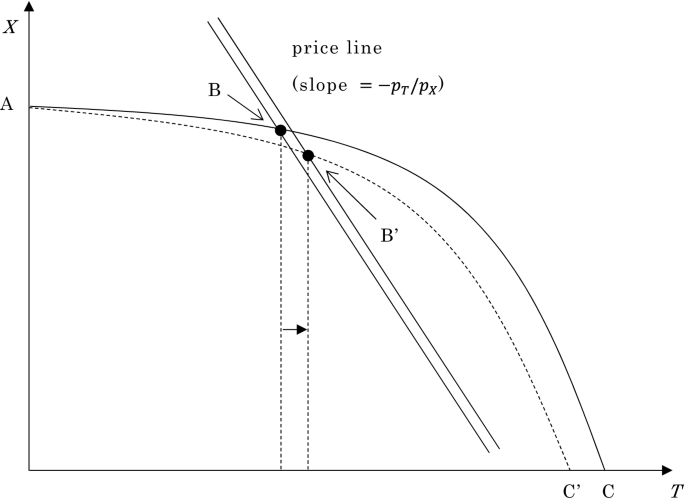

Infrastructure investment can promote economic cycles and growth and is subject to the law of diminishing marginal returns [ 11 ]. The marginal benefit of improving the competitiveness of the tourism industry gradually increases as the scale of investment in new infrastructure increases, but above a certain level of investment, the marginal benefit of the competitiveness of the tourism industry decreases. This is because too much investment in tourism industry infrastructure leads to conflicts in capital utilization and neglect of other development needs of the tourism industry. Therefore, the level of investment also has an impact on the competitiveness of the tourism industry.

Although infrastructure encompasses the key fields of the scientific and technological revolution and industrial change, different categories of infrastructure have different emphases in the tourism industry chain, and there are differences in how the tourism industry uses and depends on different types of new infrastructure. Information infrastructure is mainly based on a cloud computing platform to support the construction of an urban tourism database, accurately analyses tourists’ preferences, realize personalized recommendations for tourism strategies, and innovate the market segmentation and positioning of the tourism industry [ 12 ]. Convergent infrastructures focus on implementing digital transformation, such as improving tourism accessibility through smart transport infrastructures that help tourists plan the shortest travel time. Innovation infrastructure helps to integrate knowledge elements into the development and construction of tourism destinations. Due to the different ways in which new infrastructure is built, there are large differences in their impact on improving the competitiveness of the tourism industry.

The development of tourism based on information and network infrastructures can better reflect the diversity of regional conditions, and the construction of new infrastructures makes knowledge and information the main production factors of the digital economy [ 13 ]. With the development of the digital economy, tourism culture, landscape, folk customs and other local cultures become more diverse and can be more easily integrated through digitalization. With the help of smart infrastructure of destinations, digital tourist attractions can be gradually built, and the temporal and spatial boundaries of tourism culture production can be broken. There is obvious heterogeneity in the role of new infrastructure construction, especially in terms of heterogeneity in the types of infrastructure construction and regional contextual differences [ 14 ].

The regional conditions in East China, Central China and West China are very different, and the regional tourism industry is developed by different economic policies, economic levels and urban cultures in each region. There are also differences in the stage of investment, scale and impact of new infrastructure construction, leading to large differences in the dependence of the regional tourism industry on new infrastructure. For example, the five major urban agglomerations in the coastal areas of East China are the core areas of economic and social development, with advantages in policy implementation, rich tourism resources and perfect tourism infrastructure [ 15 ]; the new infrastructure can quickly interact with the development of the tourism industry. There is still a gap between investment in new urban infrastructure in central China and eastern China, as central China does not have the obvious relative advantage of political support. Western China is the peripheral area of China’s economic development. Although it is considered by planners as the most important planning area for tourism, it has weak capacity to distribute resources to the market. Due to institutional backwardness, western China has an urgent need for new infrastructure. Therefore, the impact of new infrastructure on the competitiveness of the tourism industry varies greatly due to different regional conditions. There are studies on the relationship between new infrastructure development and tourism development in China, but are the massive government investments in new infrastructure development in China really able to increase the competitiveness of the industry? Does blind expansion lead to scale economies, or how does it play in different regions? To answer this general question, a research framework for new infrastructure and the tourism industry was established ( Fig 1 ).

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0278274.g001

3 Methodology

3.1 data collection.

The panel data of tourism industry and new infrastructure investment from 2008 to 2019 of 31 provinces and municipalities in China (excluding Taiwan, Macau and Hong Kong) were selected as the research dataset for this paper. Data such as New infrastructure construction, Market potential, Destination accessibility, Sustainable development, Health care construction, Accommodation and catering performance, Culture construction are from China Statistical Yearbook (2009–2020) and Statistical Bulletin of National Economic and Social Development (2009–2020). Data of market performance is from China Tourism Statistical Yearbook (2009–2020). The control variables are industrial structure, population size and degree of openness. The proportion of tertiary industry represents the rationalization of the industrial structure; we use the proportion of tertiary industry in the total value of all industries to measure the regional industrial structure; Since population affects regional tourism consumption and population size has a positive effect on local tourism consumption and tourist flows [ 16 , 17 ], regional population is selected to measure population size; regional openness is of great importance in attracting international tourists and developing the international market; import and export status of each region is used to measure the openness of each region. Data of control variable is also from China Statistical Yearbook (2009–2020).

3.1.1 Infrastructure indicators.

According to existing research and the Chinese government’s policy definition [ 18 ], new infrastructure consists of information infrastructure (Infra1), convergent infrastructure (Infra2), innovation infrastructure (Infra3) and its total infrastructure ( Table 1 ), each represented by the level of investment capital of the corresponding infrastructure sectors from 2008 to 2019.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0278274.t001

Referring to the existing researches, the competitiveness index of the tourism industry mainly includes two parts: the development potential and the performance of the tourism industry [ 3 , 19 , 20 ] ( Table 2 ). Referring to the 2021 travel and tourism development index and existing researches, this paper constructs the competitiveness index of the tourism industry. The factor analysis method was used to calculate the tourism industry competitiveness of 31 provinces and cities in China from 2008 to 2019.According to the Travel and Tourism Development Index (TTDI) and existing research [ 19 , 21 – 24 ], the development potential of the tourism industry mainly includes market potential, destination accessibility, sustainable development, and health care construction. Tourism industry performance mainly includes market performance, accommodation and catering performance, culture construction, etc.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0278274.t002

On the one hand, for indicator of tourism industry potential, tourism consumption has a long-term equilibrium relationship with residents’ income or consumption level, these factors have a certain role in promoting tourism consumption, which can represent regional market potential [ 25 ]. To realize the tourism market expansion, especially in central or western economic peripheral regions, a combination of tourism and postal service is one of the most important ways [ 26 ]. Travel destination accessibility is normally related to air transport, ground and port transport service capabilities, etc., which will influence traveler mobility and attraction accessibility [ 22 ]. Environmental sustainability is an important factor in the long-term profitability of national or regional tourism destinations [ 19 ]. Moreover, health care construction is an important condition to ensure travel safety, and China’s rapidly developing tourism industry urgently needs medical construction in high-level tourist destinations [ 21 ], which has been pronounced during the covid-19 pandemic. Based on the existing research, consider the particularity of China’s tourism industry, while ensuring the integrity of the data available. This research takes the income or consumption level of regional residents and regional post-service income as the main indicators of regional market potential. Passenger traffic volume of railways and highways, and the number of employees in railway, highway, aviation, and water transportation are considered the main indicators of regional transportation construction level. The sustainability of regional tourism is measured in terms of forest coverage rate, harmless treatment rate of domestic waste, oxygen demand in wastewater, ammonia nitrogen emission in wastewater, and sulfur dioxide emission. Indicators such as the number of health institutions, the number of health technicians per 1,000 people, and the number of hospital beds per 1,000 people are used to characterize health care construction.

On the other hand, for tourism industry performance, indicators related to domestic and foreign tourism revenue, and the number of inbound and domestic tourists can characterize the regional market performance. Tourist reception capacity, accommodation and catering-related consumption and infrastructure construction are the main indicators to measure the competitiveness of the industry. Tourist reception capacity, accommodation, catering-related consumption, and infrastructure construction level are the main aspects to measure the industry competitiveness, which are measured by indicators such as the number of accommodation and catering firms, the number of employed employees, and labor remuneration. Cultural tourism is an important part of international tourism consumption, which is usually measured by the number of libraries and museums, the number of audiences of performance groups, the number of cultural and entertainment employees, and labor remuneration [ 24 ].

Based on the regional statistical data of tourism in 31 provinces and cities in China from 2008 to 2019, the original data were tailed by 1%, and the data were normalized to eliminate the influence of extreme values. This study determines the weights through factor analysis, calculates the competitiveness of the tourism industry and provides a statistical description of the data ( Table 3 and S1 Appendix ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0278274.t003

3.2 Fixed effects regression model

In terms of data selection, panel data combines the advantages of time series and cross-section data. It has the advantages of controlling temporal and spatial heterogeneity, reducing multicollinearity and reducing data bias, and has been widely used in existing causal relationship studies [ 27 – 29 ].

Fixed effect model focuses on the change of a single object over time and can eliminate the interference of multiple fixed factors without considering the variation among different individuals. Random effect model can make better use of data information by weighted average of variation within and among individuals. However, due to the consideration of individual variation, it must be assumed that the residuals are not related to the independent variables, which is relatively inaccurate.

To clarify the model, the Hausmann test was performed in this research ( Table 4 ). In model1, the P value of the F test is 0, the null hypothesis is rejected at the 1% significance level, indicating that the fixed model is better than the mixed model; The P value of the LM test is 0 in model2, and the hypothesis of "there is no individual random effect" is rejected at the 1% significance level, indicating that the random effect model is better than the mixed model; Model 3 is the Hausman test result, p value = 0, the null hypothesis is strongly rejected, and the fixed effects model is considered significantly better than the random model, so here the fixed-effects model should be used.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0278274.t004

Eq ( 2 ) verifies the differences of impact of different types of infrastructure on the competitiveness of tourism industry, where X*it denotes information infrastructure, converged infrastructure and innovation infrastructure respectively; Eq ( 3 ) verifies the effect differences in different regions, where dummy1 and dummy 2 are dummy variables which shall be 1 when the region is located in Central and West China or 01 when the region is not located in Central and West China; Eq ( 4 ) verifies the effect differences of different investment scales, where dummy 3 is a dummy variable which shall be 1 when the investment scale is greater than China’s average or 0 when not; the remaining variables have the same meaning as in Eq ( 1 ).

3.3 Regional context and infrastructure foundation

Since China unveiled its new infrastructure construction strategy in 2018, the amount of investment in new infrastructure has steadily increased. By February 2020, the Chinese government had issued RMB 231.9 billion worth of special bonds for new infrastructure-related sectors. Investment in new infrastructure construction accounts for about 20% to 25% of total infrastructure investment. In 2022, China will focus on building 425,000 5G base stations. Although the Chinese government is trying to increase investment in new infrastructure construction, according to the 2019 World Economic Forum statistics, China has an unbalanced ranking in the quality of global infrastructure construction, as the different types of infrastructure construction vary widely. Moreover, infrastructure investment in China varies greatly from region to region. In terms of communication infrastructure development, the penetration rate of mobile phones, fixed broadband and internet in East China in 2018 was 145%, 34.24% and 61.32% respectively, and 18 cities supported 5G network coverage; the penetration rate of mobile phones, fixed broadband and internet in Central China was 93.69%, 25.9% and 45.6% respectively, which is a big difference from East China, and only 6 cities supported 5G network coverage. The penetration rate of mobile phone, fixed broadband and internet in Western China was significantly lower than the Chinese average.

The regional differences in the competitiveness of the tourism industry show a trend of expansion from the core regions of East China to West China from 2008 to 2019. East China is the core region of economic development and has a more solid industrial economic base, better service facilities and higher consumption level of residents than the other regions of China. Therefore, the regional tourism industry demand is huge, the regional tourism base and demand are developed first, and undoubtedly have higher initial competitiveness than other regions. Yunnan and Sichuan in western China are rich in natural resources for tourism, but the initial competitiveness of the industry is not high due to the accessibility and regional socio-economic development level, suggesting low industrial competitiveness. With China’s industrial transfer and infrastructure development, the advantages of tourism resources in western China are gradually becoming apparent.

4.1 Impact of infrastructure on overall tourism competitiveness

According to the regression results ( Table 5 ), China’s investment in new infrastructure construction has a significant positive impact on improving regional competitiveness in tourism. In model 1, regional competitiveness in tourism increases by about 0.6642 per unit investment.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0278274.t005

Adding control variables to model 1 to obtain model 2, the regression coefficient has decreased, but it still plays a positive role at the 1% significance level. In order to eliminate the influence of time and individual differences, this paper further adds time and individual fixed effects to Model 2 and obtains Model 3. The regional tourism competitiveness increased by about 0.1326 with the investment of new infrastructure units. Differences in variables such as industrial structure, population size, and openness, as well as time and individual fixed effects, explain the decline of the regression coefficient to a certain extent. Model 3 still shows the same positive trend under the full introduction of various conditions.

Model 4 introduces the quadratic term of new infrastructure investment into the regression equation. The results show that the effect of new infrastructure investment on increasing the competitiveness of the tourism industry is not linear but has an "inverted U-curve." That is, there is an inflection point between new infrastructure investment and the improvement of tourism industry competitiveness, which shows the law of diminishing marginal effect.

To a certain extent, this is related to the characteristics of the system of assessing local governments with GDP as the main indicator. Furthermore, local governments will encourage enterprises and institutions to participate in key new infrastructure projects by increasing local taxes and other means to achieve the goal of increasing GDP. This can lead to excessive infrastructure construction, overcapacity and industry inefficiency in some regions [ 32 , 33 ]. In addition, expanding infrastructure investment has a certain crowding-out effect on household consumption. The proportion of tourism consumption decreases accordingly, which cannot effectively promote the competitiveness of the tourism industry.

Models 5 and 6 show the impact of a time lag of new infrastructure investment on the competitiveness of the tourism industry. We believe that despite the increase of the coefficient, there is no obvious lag effect of new infrastructure investment and the feedback of the investment effect can be achieved in time. Therefore, the current investment stock is used as an explanatory variable in the following analysis.

4.2 Diverse impact of new infrastructure

4.2.1 impact of infrastructure type..

The analysis of the impact of different types of infrastructures on tourism competitiveness ( Table 6 ) shows that information infrastructure, convergent infrastructure has a significant impact on the competitiveness of the regional tourism industry. The impact of convergent infrastructure on the competitiveness of tourism industry is the most significant (regression coefficient 0.4337), followed by information infrastructure (0.3560).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0278274.t006

The main reason for this phenomenon is that convergent infrastructure is the profound application of new generation information technology through the construction of traditional infrastructure. The convergence of information technology and digital economy has created the development path of intelligent city, intelligent transportation and intelligent sightseeing in China. By building convergent infrastructure, the region can provide efficient basic services in accommodation, transportation, catering and medical care, improve tourists’ leisure experience and enhance the competitiveness of the tourism industry. The information infrastructure is dominated by 5G, the Internet of Things, and the Industrial Internet, such as intelligent sightseeing reservation, information-based tourism platform, and live streaming tours, which have been increasing in recent years, realize the online information collection of tourists and provide marketing, management, and service standards for attractions and hotels. Innovation infrastructure consists of the infrastructure to support technology development, scientific research and product development. It is generally dominated by the Chinese government and scientific research institutions, with relatively little private investment capacity. The development of innovation infrastructure is highly targeted, and it will take a long time for the tourism industry to receive technical support from the funds invested by governments and scientific research institutions in different regions.

It is worth noting that models 4 to 6 introduce the quadratic term of different types of infrastructure investment into the regression model, and the regression coefficient of the first term of convergent infrastructure and innovation infrastructure is positive, while the regression coefficient of the quadratic term is negative, suggesting that the effect of the two on the competitiveness of the tourism industry is an "inverted U curve" with an obvious inflection point. The insignificant effect of information infrastructure on the competitiveness of the tourism industry indicates that the marginal effect of investment in information infrastructure has not decreased significantly and the capital stock of information infrastructure needs to be built up continuously. Therefore, investment in the construction of new infrastructure in China should not be increased blindly, but should be targeted and gradual, to avoid wasting resources through a blanket approach.

4.2.2 Impact of regional context.

Regional site diversity is an important factor affecting regional industrial competitiveness. The results show that ( Table 7 ), after adding the cross term of regional dummy variables and infrastructure investment, the impact of infrastructure investment on the economic peripheral western region is higher than that in the developed east region. In order to clarify the main reasons for this phenomenon, this paper divides infrastructure into three categories to verify their effects on tourism competitiveness in different regions.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0278274.t007

The promotion of information infrastructure to the tourism competitiveness of the western regions of China is higher than that of the eastern regions. Although the investment in information infrastructure in the eastern region is the best in China, it still lags behind the development level of the region’s own tourism industry, which leads to the low empowerment performance of information infrastructure. On the contrary, the level of investment in information infrastructure in the western regions is relatively low, but the marginal effect of these investments on the tourism industry in this region is significant. Convergence infrastructure has a similar effect on the competitiveness of the tourism industry, as the marginal effect of converged infrastructure on economic peripheral is high.

The difference is that the innovation infrastructure has no obvious effect on the eastern and central regions, while the western region has a significant effect.This is because the investment in innovative infrastructure in the eastern and central regions is still unable to meet the needs of tourism, so the role of economies of scale is insufficient. The innovative infrastructure in the western region will help promote regional opening up and gradually realize the transformation of the regional economic growth mode.

4.2.3 Impact of investment scale.

The effect of the differences in investment scale shows that the average capital stock for new infrastructure construction in China is 0.554, and the average capital stock for information infrastructure, convergent infrastructure, and innovation infrastructure is 0.183, 0.236, and 0.134, respectively. The average value of infrastructure investment of different types is taken as the boundary for the construction of dummy variables, and after adding the cross term between the dummy variables of scale and level of infrastructure investment ( Table 8 ), model 1 represents the impact of infrastructure construction of different scales on tourism competitiveness, and models 2 to 4 analyze infrastructure construction in three main categories.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0278274.t008

Overall, adequate new infrastructure investment has a positive effect on improving tourism competitiveness, but it should be emphasized that the marginal benefit actually declines gradually as the size of the investment increases. Combined result of the previous results (Tables 5 – 7 ), the investment effect of innovation infrastructure (model 4) can still be improved significantly. Too low investment in innovative infrastructure cannot enhance the competitiveness of the tourism industry, which needs to be improved by increasing the investment scale. However, it should be pointed out that the implementation effect of innovative infrastructure projects in western China should be emphasized, and the coordination between infrastructure projects and investment in the tourism industry should be planned to avoid the negative impact of infrastructure investment crushing the investment of the tourism industry.

The impact of integrated infrastructure (model 3) is significant, the expansion of investment scale has not brought more enabling effects. Although this is consistent with the law of diminishing marginal utility, we should be wary of the phase shift of regional differentiation. China should moderately reduce investment in traditional infrastructure in China and focus on the efficient integration of new-generation information technology and traditional infrastructure in China.

5 Discussion and conclusion