- Become A Member

- Gift Membership

- Kids Membership

- Other Ways to Give

- Explore Worlds

- Defend Earth

How We Work

- Education & Public Outreach

- Space Policy & Advocacy

- Science & Technology

- Global Collaboration

Our Results

Learn how our members and community are changing the worlds.

Our citizen-funded spacecraft successfully demonstrated solar sailing for CubeSats.

Space Topics

- Planets & Other Worlds

- Space Missions

- Space Policy

- Planetary Radio

- Space Images

The Planetary Report

The eclipse issue.

Science and splendor under the shadow.

Get Involved

Membership programs for explorers of all ages.

Get updates and weekly tools to learn, share, and advocate for space exploration.

Volunteer as a space advocate.

Support Our Mission

- Renew Membership

- Society Projects

The Planetary Fund

Accelerate progress in our three core enterprises — Explore Worlds, Find Life, and Defend Earth. You can support the entire fund, or designate a core enterprise of your choice.

- Strategic Framework

- News & Press

The Planetary Society

Know the cosmos and our place within it.

Our Mission

Empowering the world's citizens to advance space science and exploration.

- Explore Space

- Take Action

- Member Community

- Account Center

- “Exploration is in our nature.” - Carl Sagan

The first crewed Moon landing

Apollo 11 was the first mission to land humans on the Moon. It fulfilled a 1961 goal set by President John F. Kennedy to send American astronauts to the surface and return them safely to Earth before the end of the decade. On 21 July 1969 at 02:56:15 UTC, Neil Armstrong pressed his left foot onto the Moon and said, "That's one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind," as 530 million people watched live on television.

The mission returned 20 kilograms of rock and soil to Earth, and paved the way for 5 additional Moon landings that greatly advanced the field of lunar science.

Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins began their journey with a launch aboard a Saturn V rocket on the morning of 16 July 1969. Three hours later, their rocket's upper stage blasted them out of Earth orbit towards the Moon. They arrived 3 days later on 19 July and entered an initial lunar orbit of 111 by 306 kilometers. A second engine burn lowered their orbit to 100 by 113 kilometers.

On 20 July, Armstrong and Aldrin boarded their lunar module, nicknamed Eagle, and undocked it from the command module, where Collins remained. Almost the same as in the Apollo 10 rehearsal 2 months earlier, the astronauts fired Eagle’s descent engine, dropping to an orbit with a low point of 14.5 kilometers. Roughly an hour later, as the duo approached the Sea of Tranquility, they began a final powered descent to the surface.

Armstrong and Aldrin had to overcome several last-minute challenges during the landing sequence. A series of computer alarms that the crew had not seen in simulations prompted a call to Mission Control for guidance, and flight controllers advised the crew they could safely proceed. Then, Armstrong saw that the lunar module computer was guiding them toward a boulder field that was later determined to be ejecta from West Crater . Armstrong took semi-manual control of the lunar module to avoid the boulders, and then a smaller crater later named Little West, before finally landing with just 25 seconds' worth of fuel remaining.

"Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed," Armstrong famously reported after landing. The official touchdown time was 20:17:39 UTC on 20 July 1969.

Safely on the surface, Armstrong and Aldrin worked through a long checklist to ensure their spacecraft was healthy and that they would be able to lift off for the return home. The flight plan called for an optional 4-hour rest period to begin 2 hours after landing, which Armstrong and Aldrin opted to skip. It is often reported that the astronauts were too excited to rest; in reality, the rest period was an optional buffer in case Armstrong and Aldrin needed time to adapt to lunar gravity or had technical problems to work through.

EVA preparations officially began three and a half hours after landing. The lunar module hatch opened at 02:39:35 UTC on 21 July 1969, and 17 minutes later, at 02:56:15 UTC (22:56:15 EDT on 20 July 1969), Armstrong stepped off the lunar module's ladder and onto the surface.

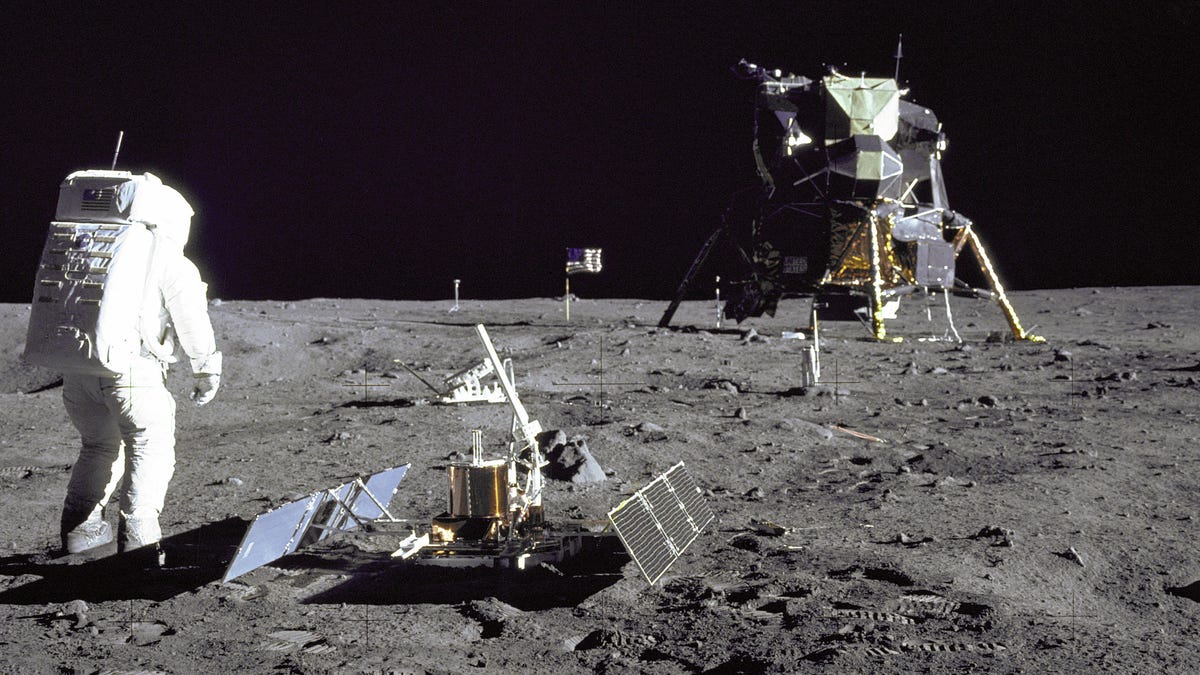

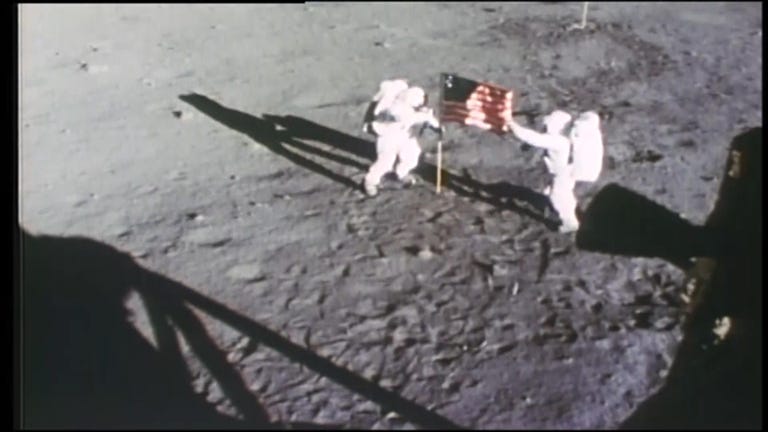

Armstrong and Aldrin's single moonwalk lasted two and a half hours. During that time, they deployed science and engineering experiments , photographed their surroundings, displayed an American flag, read an inscription plaque, collected rock and soil samples for return to Earth, and spoke with President Richard Nixon. The astronauts verbally described their surroundings and progress for geologists, while cameras mounted inside and outside the lunar module documented some of their activities.

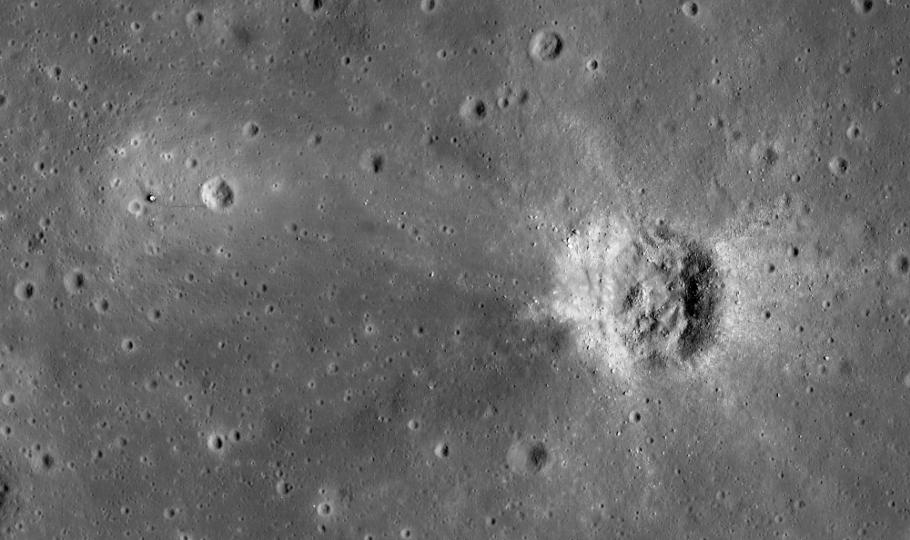

Landing Site

The Apollo 11 lunar module landing coordinates are 0.67416 degrees N, 23.47314 E. See here and here for Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter image analysis.

Armstrong and Aldrin shot roughly 125 frames during their EVA, all on magazine 40/S , using a Hasselblad 500 EL Data Camera . Maps and descriptions of all photos are available.

Science and engineering experiments

Passive Seismic Experiment (PSE) : A seismometer that failed after 21 days, but provided useful initial data on lunar seismology for future Apollo missions.

The Lunar Dust Detector : Attached to the PSE, the dust detector measured the power output from a set of solar cells to determine how much dust was thrown on nearby science instruments by the lunar module ascent engine (and in the long term, from transient lunar dust).

Laser Ranging Retroreflector (LRR) : An array of small mirrors that, to this day, can be targeted by Earth-based lasers to measure the distance to the Moon. The LRR experiment has determined that the Moon is currently receding from Earth at 3.8 centimeters per year.

Solar Wind Composition Experiment : A small sheet of foil deployed and then retrieved for return to Earth, used to estimate the number of charged particles (solar wind) striking the surface.

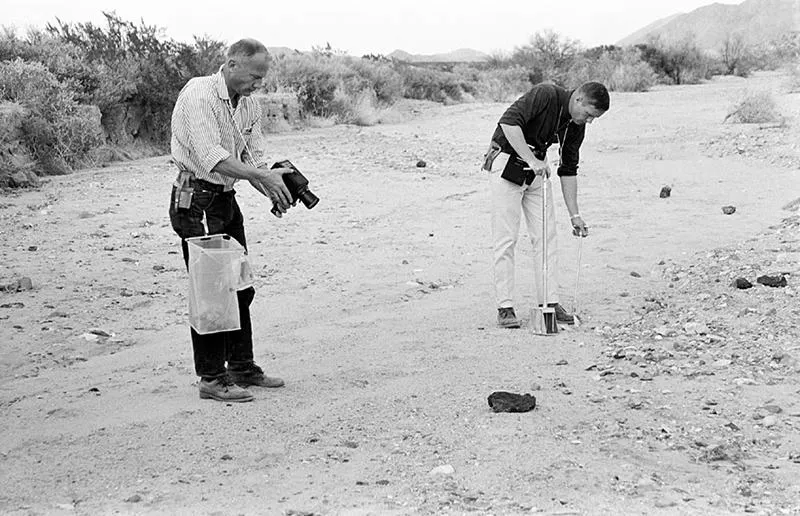

Soil mechanics investigation : Specific experiments to investigate soil mechanics and the properties of the lunar surface. The investigation included the use of penetrometers—rods that measure the force required to penetrate to various soil depths—as well as the digging of small trenches and the collection of rocks, soil and core tubes.

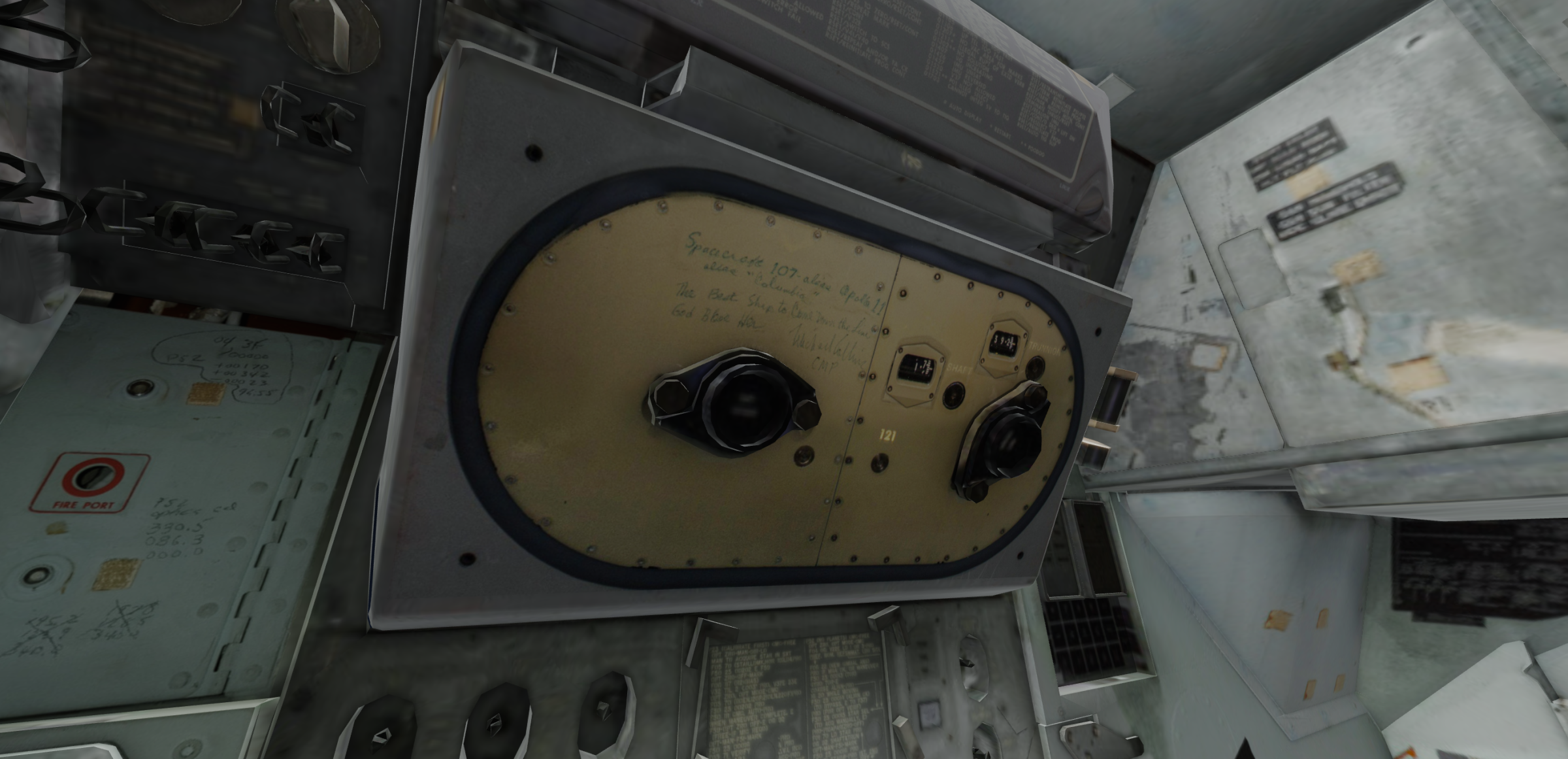

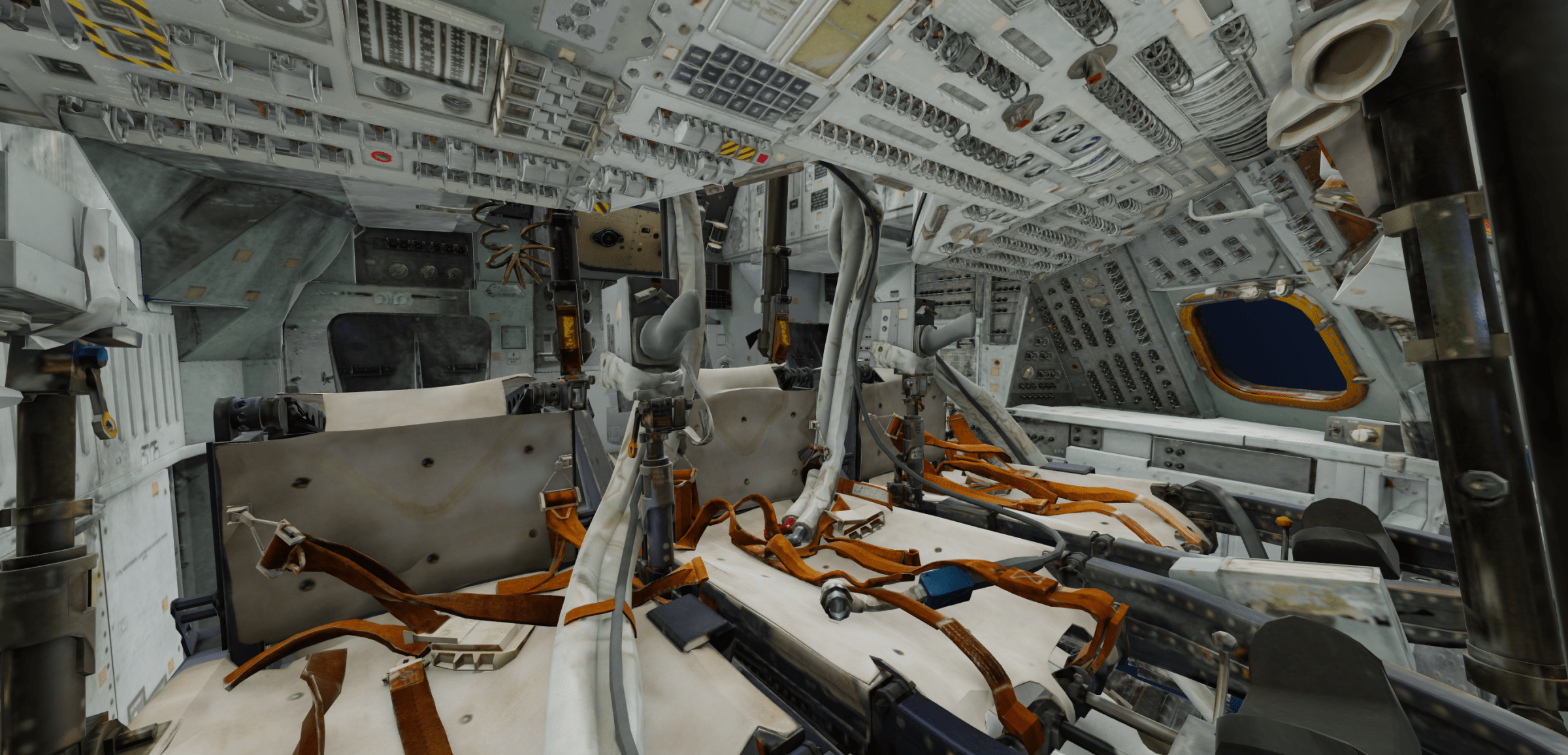

After returning to the lunar module, Armstrong and Aldrin had been awake for 21 hours. The 2 astronauts slept fitfully, with Aldrin on the floor and Armstrong perched above him on the engine cowling using an improvised hammock to hold his legs off the ground. ( See here for a panorama of the inside of a lunar module ). The astronauts slept in their suits for warmth, as the cabin temperature dropped to 61 degrees Fahrenheit (16 Celsius).

At 17:54 UTC on 21 July, after a total of 21 hours and 36 minutes on the surface, Armstrong and Aldrin blasted off in the lunar module's ascent stage. They rendezvoused with the command module in orbit roughly three and a half hours later, rejoined Collins in the command module, and jettisoned the lunar module. The next day, on 22 July, the crew fired their service module's engines to leave lunar orbit for their long coast back to Earth. They splashed down into the Pacific Ocean at 16:50:35 UTC on 24 July and were retrieved by the USS Hornet.

Onboard the Hornet, the crew entered a mobile quarantine facility to protect against the unlikely event that they had contracted dangerous pathogens on the lunar surface. The facility was transported back to Houston, arriving on 28 July. On 10 August, with the men showing no signs of illness 21 days after Armstrong and Aldrin's moonwalk, NASA released the crew.

Apollo 11 Timeline

"it has a stark beauty all its own." "magnificent desolation.".

—Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin, respectively, on the surface of the Moon

Apollo 11 Cost

NASA estimated the following direct costs for Apollo 11. Full costs of the Apollo program can be found on the " How Much Did the Apollo Program Cost? " page.

Inflation adjusted to 2019 via NASA's New Start Index (NNSI). Source: "History of Manned Space Flight." February 1975. NASA Kennedy Space Center. Located in NASA HQ Historical Reference Collection, Washington, D.C. Record Number 18194. Box 1.

Project Apollo

Starting with Apollo 7 in 1968 and culminating with Apollo 17 in 1972, NASA launched 33 astronauts on 11 Apollo missions. Twelve humans walked on the Moon.

For full functionality of this site it is necessary to enable JavaScript. Here are instructions on how to enable JavaScript in your web browser .

- All mission control film footage

- All TV transmissions and onboard film footage

- 2,000 photographs

- 11,000 hours of Mission Control audio

- 240 hours of space-to-ground audio

- All onboard recorder audio

- 15,000 searchable utterances

- Post-mission commentary

- Astromaterials sample data

- Share and discover moments of interest at forum.apolloinrealtime.org

This website replays the Apollo 11 mission as it happened. It consists entirely of historical material, all timed to Ground Elapsed Time--the master mission clock. Footage of Mission Control, film shot by the astronauts, and television broadcasts transmitted from space and the surface of the Moon, have been painstakingly placed to the very moments they were shot during the mission, as has every photograph taken, and every word spoken.

Upon starting the application, select whether to begin one minute before launch, or click "Now" to drop in to the mission using today's date and time, to-the-second during the anniversary.

Navigate to any moment of the mission using the time navigator at the top of the screen. The top bar is the entire mission with two bars below it providing magnification. Selecting transcript items, photos, commentary items, or guided tour moments, also jumps the mission time to the moment they occurred.

Main mission audio consists of space-to-ground (left ear), capcom loop (right ear), and on-board recorder (center, when available). Selecting a Mission Control audio channel mutes the main audio, opens the Mission Control audio panel, and plays the "live" audio of that Mission Control position. Change channels by selecting the seats in mission control. Closing the Mission Control audio panel will unmute the main audio and continue mission playback.

These 50 channels of Mission Control audio have only recently been digitized and restored, and are made publicly available here for the first time. They total over 11,000 hours in length.

Please contact Ben Feist for any inquiries.

Ben Feist Concept, research, mission data restoration, audio restoration, video, software architecture and programming. Follow @BenFeist for updates. Stephen Slater Archive Producer, historical audio/footage synchronization Chris Bennett Visual design, interface styling and programming David Charney Visual design Arnfinn Holderer Audio restoration programming Robin Wheeler Photography timing, transcript corrections

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

1969 Moon Landing

By: History.com Editors

Updated: July 17, 2023 | Original: August 23, 2018

On July 20, 1969, American astronauts Neil Armstrong (1930-2012) and Edwin "Buzz" Aldrin (1930-) became the first humans ever to land on the moon. About six-and-a-half hours later, Armstrong became the first person to walk on the moon. As he took his first step, Armstrong famously said, "That's one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind." The Apollo 11 mission occurred eight years after President John F. Kennedy (1917-1963) announced a national goal of landing a man on the moon by the end of the 1960s. Apollo 17, the final manned moon mission, took place in 1972.

JFK's Pledge Leads to Start of Apollo Program

The American effort to send astronauts to the moon had its origins in an appeal President Kennedy made to a special joint session of Congress on May 25, 1961: "I believe this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to Earth."

At the time, the United States was still trailing the Soviet Union in space developments, and Cold War -era America welcomed Kennedy's bold proposal. In 1966, after five years of work by an international team of scientists and engineers, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) conducted the first unmanned Apollo mission , testing the structural integrity of the proposed launch vehicle and spacecraft combination.

Then, on January 27, 1967, tragedy struck at Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, Florida, when a fire broke out during a manned launch-pad test of the Apollo spacecraft and Saturn rocket. Three astronauts were killed in the fire.

President Richard Nixon spoke with Armstrong and Aldrin via a telephone radio transmission shortly after they planted the American flag on the lunar surface. Nixon considered it the "most historic phone call ever made from the White House."

Despite the setback, NASA and its thousands of employees forged ahead, and in October 1968, Apollo 7, the first manned Apollo mission, orbited Earth and successfully tested many of the sophisticated systems needed to conduct a moon journey and landing.

In December of the same year, Apollo 8 took three astronauts to the far side of the moon and back, and in March 1969 Apollo 9 tested the lunar module for the first time while in Earth orbit. That May, the three astronauts of Apollo 10 took the first complete Apollo spacecraft around the moon in a dry run for the scheduled July landing mission.

Timeline of the 1969 Moon Landing

At 9:32 a.m. EDT on July 16, with the world watching, Apollo 11 took off from Kennedy Space Center with astronauts Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins (1930-) aboard. Armstrong, a 38-year-old civilian research pilot, was the commander of the mission.

After traveling 240,000 miles in 76 hours, Apollo 11 entered into a lunar orbit on July 19. The next day, at 1:46 p.m., the lunar module Eagle, manned by Armstrong and Aldrin, separated from the command module, where Collins remained. Two hours later, the Eagle began its descent to the lunar surface, and at 4:17 p.m. the craft touched down on the southwestern edge of the Sea of Tranquility. Armstrong immediately radioed to Mission Control in Houston, Texas, a now-famous message: "The Eagle has landed."

At 10:39 p.m., five hours ahead of the original schedule, Armstrong opened the hatch of the lunar module. As he made his way down the module's ladder, a television camera attached to the craft recorded his progress and beamed the signal back to Earth, where hundreds of millions watched in great anticipation.

At 10:56 p.m., as Armstrong stepped off the ladder and planted his foot on the moon’s powdery surface, he spoke his famous quote, which he later contended was slightly garbled by his microphone and meant to be "that's one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind."

Aldrin joined him on the moon's surface 19 minutes later, and together they took photographs of the terrain, planted a U.S. flag, ran a few simple scientific tests and spoke with President Richard Nixon (1913-94) via Houston.

By 1:11 a.m. on July 21, both astronauts were back in the lunar module and the hatch was closed. The two men slept that night on the surface of the moon, and at 1:54 p.m. the Eagle began its ascent back to the command module. Among the items left on the surface of the moon was a plaque that read: "Here men from the planet Earth first set foot on the moon—July 1969 A.D.—We came in peace for all mankind."

At 5:35 p.m., Armstrong and Aldrin successfully docked and rejoined Collins, and at 12:56 a.m. on July 22 Apollo 11 began its journey home, safely splashing down in the Pacific Ocean at 12:50 p.m. on July 24.

How Many Times Did the US Land on the Moon?

There would be five more successful lunar landing missions, and one unplanned lunar swing-by. Apollo 13 had to abort its lunar landing due to technical difficulties. The last men to walk on the moon, astronauts Eugene Cernan (1934-2017) and Harrison Schmitt (1935-) of the Apollo 17 mission, left the lunar surface on December 14, 1972.

The Apollo program was a costly and labor-intensive endeavor, involving an estimated 400,000 engineers, technicians and scientists, and costing $24 billion (close to $100 billion in today's dollars). The expense was justified by Kennedy's 1961 mandate to beat the Soviets to the moon, and after the feat was accomplished, ongoing missions lost their viability.

Apollo 11 Photos

HISTORY Vault: Moon Landing: The Lost Tapes

On the 50th anniversary of the historic moon landing, this documentary unearths lost tapes of the Apollo 11 astronauts, and explores the dangers and challenges of the mission to the moon.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Over half a century ago, on July 20, 1969, humans walked on the Moon for the first time. We look back at the legacy of our first small steps on the Moon and look forward to the next giant leap.

Learn about the mission

Jump to a Section:

Mission People Technology On Earth How We Celebrated More Resources

The Mission

"we choose to go to the moon.".

The Soviet Union launched the first human, Yuri Gagarin, into space on April 12, 1961. Within days of the Soviet achievement, President John F. Kennedy asked Vice President Lyndon Johnson to identify a “space program which promises dramatic results in which we could win.” A little over a month later, on May 25, 1961, Kennedy stood before a joint session of Congress and called for human exploration to the Moon.

Eight years later, a Saturn V rocket carrying the three Apollo 11 astronauts blasted off from Cape Kennedy. Over a million spectators, including Vice President Spiro Agnew and former President Lyndon Johnson, came to watch the lift off.

July 20, 1969

"The Eagle has landed!"

After four days traveling to the Moon, the Lunar Module Eagle , carrying Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed on the Moon. Neil Armstrong exited the spacecraft and became the first human to walk on the moon. As an estimated 650 million people watched, Armstrong proclaimed "That's one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind."

Michael Collins stayed aboard the Command Module Columbia , serving as a communications link and photographing the lunar surface.

After approximately two and half hours on the Moon, Armstrong and Aldrin returned to the lunar module to begin the journey home. The three astronauts splashed down in Hawaii on July 24, 1969. From there they quarantined for three weeks as a precaution against bringing contagion back from the Moon, before the festivities welcoming them home commenced.

The Sea of Tranquility | Mare Tranquillitatis

00.67408° N latitude, 23.47297° E longitude

For the first lunar landing, the Sea of Tranquility (Mare Tranquilitatis) was the site chosen because it is a relatively smooth and level area. It does, however, have some craters and in the last minutes before landing, Neil Armstrong had to manually pilot the lunar module to avoid a sharp-rimmed ray crater measuring some 180 meters across and 30 meters deep known as West. The lunar module landed safely some 6 km from the originally intended landing site, approximately 400 meters west of West crater and 20km south-southwest of the crater Sabine D in the southwestern part of Mare Tranquilitatis. The lunar surface at the landing site consisted of fragmental debris ranging in size from fine particles to blocks about 0.8 meter wide.

Sea of Tranquility is where Apollo 11 astronauts landed on the Moon in 1969.

Lunar Module Pilot

Command Module Pilot

Three astronauts were selected as backups for the crew: James A. Lovell, commander; William A. Anders, command module pilot; and Fred W. Haise, lunar module pilot.

All three backup crew members would eventually fly on Apollo missions. Lovell and Haise were among the crew for Apollo 13.

About Apollo 13

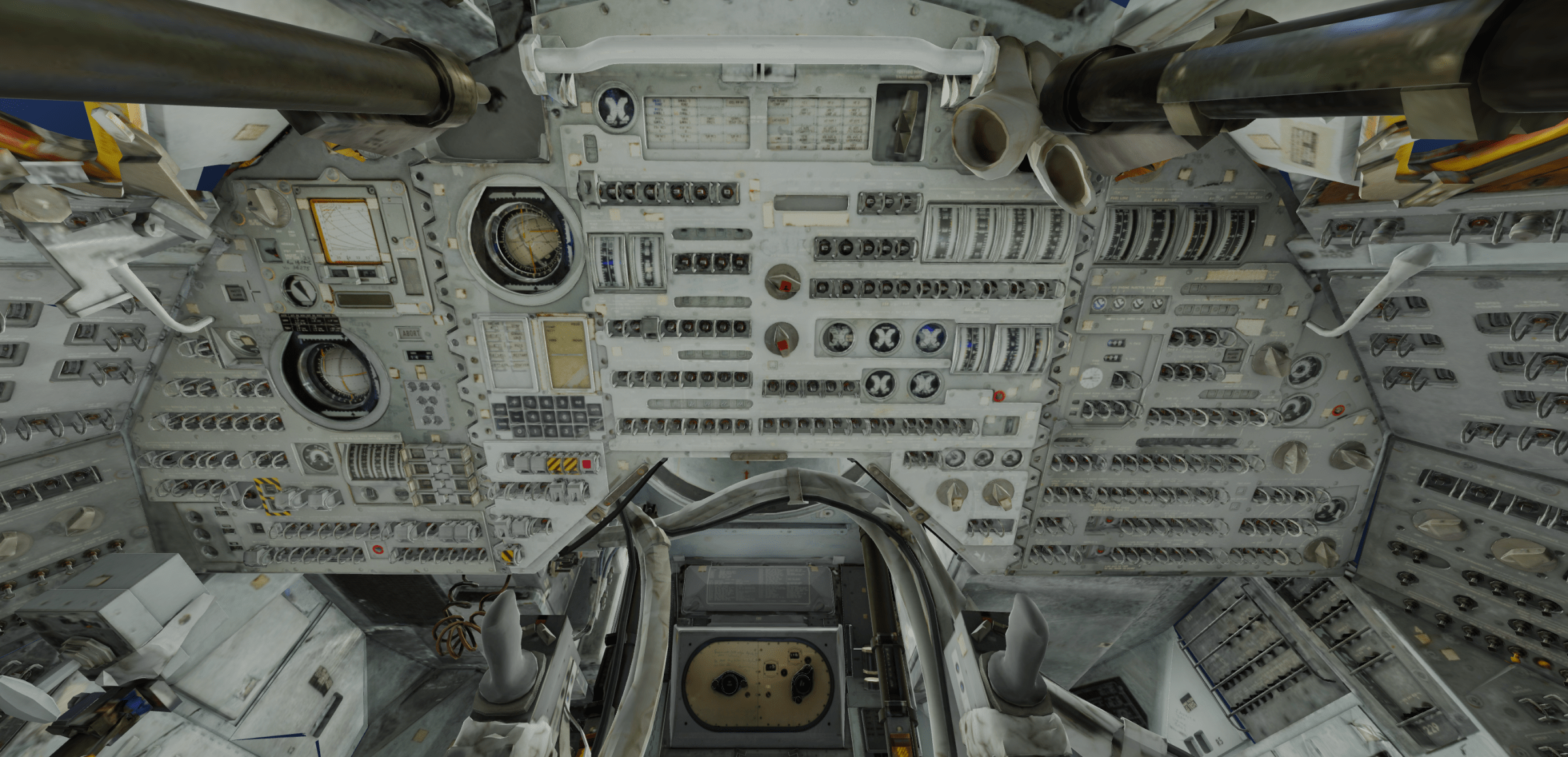

The Technology

Watching from earth, in the collection.

Take a virtual tour of the Destination Moon exhibition! This exhibition features iconic objects from the Museum's unrivaled collection of Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo artifacts, including Alan Shepard's Mercury spacesuit and spacecraft, a Saturn V F-1 engine, and Neil Armstrong's Apollo 11 spacesuit and command module Columbia.

Educational Resources

More stories.

Showing 1 - 6 of 25

- Get Involved

- Host an Event

Thank you. You have successfully signed up for our newsletter.

Error message, sorry, there was a problem. please ensure your details are valid and try again..

- Free Timed-Entry Passes Required

- Terms of Use

Apollo 11's 50th anniversary: Quick guide to the first moon landing

It's been five decades since Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin walked on the moon. Here's a look at that achievement -- and what lies ahead.

- 30 years experience at tech and consumer publications, print and online. Five years in the US Army as a translator (German and Polish).

Buzz Aldrin stands on the moon beside seismic measurement gear, part of the Early Apollo Scientific Experiments Package. To the right is the lunar module Eagle.

Even Neil Armstrong couldn't remember exactly what he said at that key moment in the first-ever moon landing, NASA 's Apollo 11 mission, as he stepped onto the lunar surface. You know the line: "That's one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind." And you always wonder: Didn't he mean to say, "...for a man"?

In fairness, he did have a lot on his mind. Even listening to the recording afterward, Armstrong still wasn't quite sure.

"I would hope that history would grant me leeway for dropping the syllable and understand that it was certainly intended, even if it wasn't said -- although it actually might have been," he told biographer James R. Hansen.

A footprint left on the moon by Buzz Aldrin.

History has in fact remembered Armstrong fondly. And now we're celebrating the 50th anniversary of that moon landing . It was July 20, 1969, when Armstrong and fellow astronaut Edwin "Buzz" Aldrin made cosmic history as they became the first humans ever to stand and walk on a heavenly body not called Earth.

It was a breathtaking engineering and logistical achievement. Humans had only started venturing into space less than a decade earlier -- and even then, just barely outside Earth's atmosphere. Our experience of space, which started with Russian cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin in April 1961, was still quite limited when Apollo 8 made a trip 'round the moon in December 1968, the first time humans had ever broken free of Earth's orbit.

But after a total of six moon landings for the Apollo program in less than four years, that was it. Since Apollo 17 in December 1972, no one's been back to the moon. NASA spent the next several decades focusing its manned spaceflight efforts on the space shuttle and on missions to the International Space Station.

Now there are once again plans to put people on the moon. NASA says it expects to make a new moon landing by 2024 through its Artemis program , both for its own sake and as a stepping-stone toward eventual missions to Mars . Meanwhile, Amazon founder Jeff Bezos and SpaceX founder Elon Musk also have their eyes on lunar adventures.

As NASA and others mark the 50th anniversary of the first moon landing, here's a look back at that achievement -- and at what lies ahead.

Real quick: How far away is the moon, anyway?

The distance from the Earth to the moon varies because of the moon's elliptical orbit, from about 225,000 miles (363,000 kilometers) to 252,000 miles. By comparison, the ISS is only about 250 miles away -- that is, one one-thousandth as far as the moon.

The Apollo missions needed roughly three days' travel time each way -- Apollo 11 got from Earth to lunar orbit at midday on day three of its mission. (For Apollo 15, it was about 4.5 days from Earth liftoff to touchdown on the lunar surface.)

The Apollo 11 crew (left to right): Neil Armstrong, Michael Collins and Buzz Aldrin.

That's an awfully long way to go. Why even bother?

Two words: space race. Starting in the 1950s, the US and the Soviet Union were going at it for bragging rights and military advantage, sending rockets, satellites, dogs and monkeys, and eventually people, into the ether.

Then, on May 25, 1961, President John F. Kennedy made a brash declaration: "I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to earth. No single space project in this period will be more exciting, or more impressive, or more important for the long-range exploration of space; and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish."

How did the astronauts get there?

The lunar missions lifted off atop a Saturn V rocket, to date the most powerful ever.

After separation from the Saturn rocket, the astronauts continued to the moon in the command service module. The CSM had three parts: the command module (CM), with the classic "space capsule" shape and containing the crew's quarters and flight controls; the expendable service module (SM), which provided propulsion and support systems; and the lunar module (LM), which looked like a geometry project with spindly legs and which took two astronauts to the lunar surface while a third remained in the CM.

How did the Apollo 11 mission unfold? What exactly did Armstrong and Aldrin do?

First of all, they simply proved it could be done.

The overview: Apollo 11 lifted off from Launch Pad 39A at Kennedy Space Center in Florida on July 16 and returned to Earth on July 24, splashing down in the Pacific Ocean after traveling a total of 953,054 miles in eight days, three hours and 18 minutes.

On July 20, the LM (nickname: Eagle) touched down in the moon's Sea of Tranquility after a stressful final few minutes. "There were some pretty hairy moments," James Hansen, Armstrong's biographer, said in an interview. "The onboard computer was taking them down into a site that was not quite what they wanted, and Neil had to take over manually. They maybe had 20 or 30 seconds of fuel left when he actually got it down."

Apollo 11 moon landing: Neil Armstrong's defining moment

About four hours later, Armstrong, 38 years old, stepped out, just before 11 p.m. ET on the 20th, a Sunday. He was outside for about 2.5 hours, with Aldrin, 39, joining him for about 1.5 hours. They were on the moon for 21 hours, 36 minutes (including seven hours of sleep) total before returning to orbit to rejoin the third member of the crew, Michael Collins, 38, who'd been waiting, watching and worrying.

Venturing no more than 300 feet from the LM and working under a 200-degree sun, Armstrong and Aldrin -- like tourists everywhere -- took lots of photos and video, and gathered souvenirs in the form of moon rocks and soil samples. They also set up a couple of rudimentary experiments, one to measure seismic activity and another as a target for Earth-based lasers to measure the Earth-moon distance precisely, which returned data for 71 days. They left behind an American flag, some of the most famous footprints in history, a coin-size silicon disc etched in microscopic detail with messages from world leaders and a small plaque saying "We came in peace for all mankind."

Armstrong may have the most famous lines from the mission, and Collins the best book (Carrying the Fire), but Aldrin nailed the description of the moonscape: " magnificent desolation ."

Those moon rocks were a pretty big deal, right?

That's right. The Apollo 11 crew brought back 22 kilograms (almost 50 pounds) of lunar material, including rocks, modest core samples and that dusty lunar soil that's so great for making footprints. The sample included basalt (from molten lava), breccia (fragments of older rocks) and anorthosite (surface rock that may have been part of an ancient crust). Those moon rocks and other samples, from all the Apollo missions, helped scientists get a better understanding of the moon's origins .

Flight controllers at NASA's Mission Control celebrate on July 24, 1969, as the Apollo 11 astronauts return to Earth.

Tell me they brought some tunes with them

They did indeed. NASA sent along a Sony TC-50 cassette player, with a mixtape of songs for the ride up. (Apparently, the astronauts really were supposed to use it for recording notes about what they were up to.) Aldrin's selections included Glen Campbell's Galveston, Blood Sweat & Tears' Spinning Wheel and a song called Mother Country by folk singer John Stewart. Armstrong went in a different direction with Dvorak's New World Symphony and the theremin-heavy Music Out of the Moon by Samuel Hoffman.

What did they eat?

Definitely not haute cuisine. Sandwiches with spreads out of a tube, like ham salad, tuna salad, chicken salad, cheddar cheese. Snacks including peanut cubes, caramel candy, bacon bites and dried apricots, peaches and pears. Turkey dinner of a sort, with gravy and dressing -- eaten with a spoon. Drinks included water, grapefruit-orange juice, grape punch and coffee, reconstituted, of course. In addition, not long after landing on the moon, Aldrin took Holy Communion , with a wafer and a small vial of wine.

What else was going on in 1969?

It was a crazy time. Airline hijacking was a big thing, especially to Cuba. The Vietnam War was raging, as were protests against it. Honduras and El Salvador fought a "soccer war." The Stonewall Riots in New York took place in late June. Richard Nixon had only just begun his first term as US president.

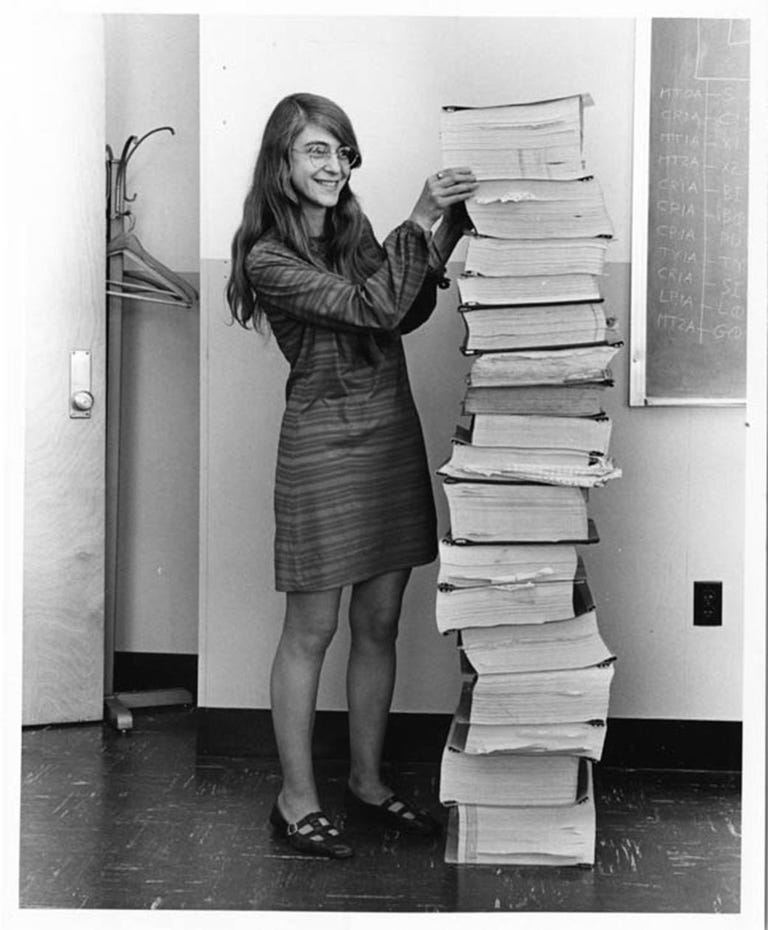

Apollo software engineer Margaret Hamilton and the source code for the Apollo guidance computer

On the technology front, the US would get its first ATM in September, and the first message sent on the ARPAnet , a precursor to the internet, would happen in late October.

For about a week as May turned into June, John Lennon and Yoko Ono staged their "bed-in" in Amsterdam, at which Lennon recorded Give Peace a Chance. The Beatles' Get Back was No. 1 for five weeks from May into June, and the Fifth Dimension's Aquarius/Let the Sunshine In was No. 2. David Bowie released Space Oddity on July 11. The middle of August would bring the Woodstock festival.

Debuts on TV that September and October would include Scooby-Doo, The Brady Bunch and Monty Python's Flying Circus.

And Turnabout Intruder , the final episode of the original Star Trek series, aired June 3.

How many people have been on the moon?

The Apollo missions put a total of 12 men on the lunar surface over the course of six visits. That's it. Then there were the others who've flown that astonishing distance but never touched down -- six CM pilots on the lunar landing missions, plus the crews of Apollo 8, 10 and 13. Three of those people made the trip twice, so the grand total of humans who've been as far as the moon is 24.

Here's who's been on the moon:

- Apollo 11: Armstrong and Aldrin

- Apollo 12: Pete Conrad, Alan Bean

- Apollo 14: Alan Shepard, Edgar Mitchell

- Apollo 15: David Scott, James Irwin

- Apollo 16: John Young, Charles Duke

- Apollo 17: Eugene Cernan, Harrison Schmitt

The dates of those other missions: Apollo 12 took place in November 1969, Apollo 14 took place from late January to early February of 1971, Apollo 15 was in July and August of 1971, Apollo 16 happened in May 1972 and Apollo 17 -- which spent three full days on the moon -- wrapped things up in December of 1972. Apollo 13, in April 1970, had to forgo its moon landing because of a life-threatening technical problem.

What else has landed on the moon?

We've put all kinds of unmanned spacecraft on the moon, starting with the hard landing of the Soviet Union's Luna 2 in 1959. The US' first spacecraft on the moon, Ranger 4, arrived in April 1962. Both countries landed a number of other machines there during the 1960s, including five Surveyor spacecraft from the US. Only some of them were soft (or powered) landings.

Click here for To the Moon, a CNET series examining our relationship with the moon from the first landing of Apollo 11 to future human settlement on its surface.

More recently, other countries have been getting into the game. China put the Chang'e 3 onto the moon in 2013, making the first soft landing since Luna 24 in 1976. In January of this year, China's Chang'e 4 became the first spacecraft to land on the fabled dark side of the moon.

In April, Israel sent the Beresheet spacecraft to the moon, but with an unhappy ending -- it crashed there.

On Monday, India is planning to launch its Chandrayaan-2 mission , which will make the first soft landing at the lunar south pole. It's carrying a lander, a rover and an orbiter. The launch has been delayed several times, most recently on July 14.

Where does President Trump stand on missions to the moon?

NASA has been fired up for a return to the moon at least since December 2017, when President Donald Trump signed White House Space Policy Directive 1 , which urged a renewed focus on lunar missions. "Beginning with missions beyond low-Earth orbit," the directive states, "the United States will lead the return of humans to the Moon for long-term exploration and utilization, followed by human missions to Mars and other destinations."

Curiously, Trump tweeted in May that "NASA should NOT be talking about going to the Moon - We did that 50 years ago." The tweet did go on to suggest that he still sees the moon as part of NASA's eventual missions to Mars.

For all of the money we are spending, NASA should NOT be talking about going to the Moon - We did that 50 years ago. They should be focused on the much bigger things we are doing, including Mars (of which the Moon is a part), Defense and Science! — Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) June 7, 2019

That came less than a month after the Trump administration said it wanted an extra $1.6 billion added to NASA's budget for next year to help pave the way for humans to return to the moon in the coming decade.

Money seems like it could be an issue, especially as Congress grapples with the federal budget for fiscal 2020. On July 17, NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine testified before a Senate panel about the chilling effect that a budget freeze -- a continuing resolution to keep spending at 2019's level -- could have on plans for a return to the moon in the middle of the next decade. "It would be devastating. What we lack right now is a lander," Bridenstine said. "We don't have money in the budget right now to develop a lander."

So what comes next?

As things stand, the space agency plans to send astronauts back to the surface of the moon by 2024, in what's now known as the Artemis program, with a whole new rocket (the Space Launch System) and crew capsule ( Orion ). The program will eventually integrate a "gateway" spacecraft that will stay in lunar orbit while missions head down to the surface. Here's the timetable:

- Late 2019 -- First commercial deliveries/landers to the moon

- 2020 -- Launch of SLS/Orion, uncrewed, in Exploration Mission-1

- 2022 -- Crew around the moon in Exploration Mission-2

- 2022 -- By December, setup of the first gateway element (the power and propulsion system) for a one-year demo in space, aboard a private rocket

- 2023 -- Land a rover, with the help of the commercial space industry

- 2024 -- Americans on the moon (including the first woman)

- 2028 -- Sustained presence on moon

NASA also sees these moon missions as preparation for eventual crewed missions to Mars , tentatively in the 2030s.

In May, NASA named some of the companies that'll pitch in with the Artemis effort, including Boeing, Lockheed Martin, Blue Origin and SpaceX.

Also in May, Amazon and Blue Origin chief Jeff Bezos unveiled a design for a Blue Moon lunar lander , which in addition to people could transport rovers to carry out scientific missions and shoot off small satellites.

When can I go?

Soon, maybe, if you have lots of disposable income or the right connections. Elon Musk has plans to send the first commercial customer, Japanese billionaire Yusaku Maezawa , on a flight around the moon in SpaceX's forthcoming BFR rocket. Maezawa plans to invite a handful of artists to join him on that weeklong flight in 2023. (The trip doesn't include a moon landing.)

Originally published June 7. Update, July 6: Adds details, including the section on moon rocks, and more information about the Apollo missions. July 15: Adds information about India's Chandrayaan-2 mission and its delay. July 17: Adds information about the NASA administrator's testimony in the Senate. July 18: Adds new launch date for Chandrayaan-2. July 20: Adds information about music and food in space during Apollo 11.

Apollo 11 Moon landing: minute by minute

Re-live the final, fraught 13 minutes of Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin's lunar descent

NASA recordings of the final 13 minutes of the Apollo 11 Moon landing capture the tension and the triumph of Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins's historic mission. Follow the radio communications between the astronauts and Mission Control during the lunar module's descent.

When did Apollo 11 land on the Moon?

The final, critical landing phase of the Apollo 11 mission began at 20:05 GMT on 20 July 1969 . Just under 13 minutes later, at 20:17 GMT , the Eagle lunar module landed on the Moon.

Those 13 minutes to the Moon had been meticulously planned in the years building up to the first lunar landing mission, but this was still an unprecedented challenge for the Apollo Program.

Intermittent radio signal, unfamiliar computer alarms and a rocky landing site all tested astronauts Neil Armstrong and Edwin 'Buzz' Aldrin to their limits during the descent to the Moon's surface. Hearing how the astronauts and Mission Control responded to these problems in real time remains one of the most extraordinary records of the Apollo 11 Moon landing.

What did the astronauts say during the Apollo 11 Moon landings?

Despite signal problems, Armstrong and Aldrin managed to remain in communication with both Mission Control and third Apollo 11 astronaut Michael Collins orbiting above them in the command module.

Below is a full account of what was said during the landing phase, from the moment the lunar module began its powered descent to Armstrong's historic declaration: "The Eagle has landed."

The transcript is based on NASA videos and audio recordings of radio communications between the Apollo 11 lunar module and Mission Control. Where a phrase or term is unclear, we have attempted to explain in italics what the astronauts or Mission Control were referring to.

Buzz Aldrin: One, zero. Ignition. Ten per cent.

Aldrin is confirming that the lunar module’s engine has been fired at 10 per cent of maximum power. This firing, beginning gently, is designed to slow the Eagle down in preparation for landing. The sequence has been calculated by the Apollo Guidance Computer (AGC), which performs a series of calculations and operations designed to help guide the lunar module to its destination. Currently the computer is running Programme 63 (P63), which manages the braking phase of the lunar landing.

Mission Control (speaking to Michael Collins): Columbia , Houston. We’ve lost them. Tell them to go aft omni. Over.

Mission Control in Houston is struggling to establish communication with the lunar module. Without reliable data and radio communications from the lunar module, the landing may have to be aborted. Mission Control asks astronaut Michael Collins in the command module Columbia to relay a message to Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin telling them to try a different aerial, the ‘aft omni-directional antenna’.

Michael Collins (to the lunar module): They’d like to use the omni.

Buzz Aldrin: OK, we’re reading you relayed to us, Mike.

Michael Collins: Say again, Neil?

Michael Collins incorrectly thinks he’s talking to Neil Armstrong.

Buzz Aldrin: I’ll leave it in Slew.

Neil Armstrong: Relay to us.

‘Slew’ essentially means that Buzz Aldrin is keeping the antenna in manual mode so he can angle the aerial himself and try to establish better communication.

Buzz Aldrin: See if they have got me now. I’ve got good signal strength in Slew.

Michael Collins: OK. You should have him now, Houston.

Mission Control: Eagle , we got you now. It’s looking good. Over.

Buzz Aldrin: OK, rate of descent looks good.

Mission Control: Eagle , Houston. Everything’s looking good here. Over.

Buzz Aldrin: Roger. Copy.

Mission Control: Eagle , Houston. After yaw-around, [use] angles S-band pitch -9, yaw +18.

Aldrin: Copy.

These are the angles that Mission Control is suggesting Aldrin use for the antenna after ‘yaw-around’ - the moment the lunar module will rotate during the next landing phase.‘Yaw’ is the term for an aircraft’s vertical axis rotation.

Aldrin: AGS and PGNS agree very closely.

Mission Control: Roger.

Aldrin is comparing the measurements from the main guidance system PGNS (Primary Guidance and Navigation System) and the back-up system AGS (Abort Guidance System).

Aldrin: Data on. Altitude’s a little high.

Armstrong: Slew?

Aldrin: Houston, I’m getting a little fluctuation in the AC voltage now.

Aldrin: Could be our meter maybe, huh?

Mission Control: Stand by. Looking good to us. You’re still looking good at three… coming up three minutes.

Aldrin: Rate of descent looks real good. Altitude’s right about on.

Armstrong: Our position checks down range show us to be a little long.

Mission Control: Roger. Copy.

While Aldrin is piloting the lunar module, Armstrong is looking through the window directly down onto the lunar surface, noting key landmarks and comparing them with notes he has prepared ahead of the mission. This is how he is able to judge that they may land “a little long”: beyond the planned landing site.

Aldrin: AGS is showing about 2 feet per second greater rate of descent [than the PGNS].

Aldrin is once again comparing the two guidance systems available to him.

Armstrong: I show us to be about… Stand by…

Aldrin: Altitude rate looks right down the groove.

Armstrong: Roger. About three seconds long. Rolling over.

By marking the time certain landmarks pass by the window, Armstrong calculates that they are three seconds too long. This equates to about three miles too long when it comes to the landing site.

When Armstrong says, “Rolling over”, he is announcing that he is preparing to rotate the lunar module so that the legs are pointing directly down at the Moon's surface. The lunar module's landing radar is positioned on the bottom of the lunar module. After the Eagle has rotated, Armstrong, Aldrin and Mission Control should begin to receive a signal from the radar telling them how high and how fast they are travelling.

Aldrin: Well I think it’s going to drop.

Aldrin is replying to a comment from Armstrong on board to keep an eye on the signal strength for communications with Mission Control.

Mission Control: Eagle , Houston…

Aldrin: OK Houston, the ED Batts are Go at four minutes.

ED Batts are 'explosive device batteries', which supply power to the devices that help operate the descent engines. Aldrin and Mission Control accidentally talk over each other at this point in the transmission, which is why Mission Control’s all-important next instruction - to continue the mission - is repeated.

Mission Control: Roger. You are Go. You are Go to continue powered descent. You are Go to continue powered descent.

Aldrin: Roger.

Mission Control: And Eagle , Houston, we’ve got data drop-out. You’re still looking good.

As the lunar module rotates, radio reception continues to be a problem, as the static heard during this part of the recording makes clear.

Aldrin: OK, we’ve got good lock on.

Once the lunar module has 'rolled over', the landing radar is able to "lock on" to the Moon’s surface.

Aldrin: Altitude light’s out. Delta-H is minus 2,900 [feet].

Delta-H compares the landing radar altitude reading with the Primary Guidance and Navigation System (PGNS). These numbers should ideally be closely aligned. According to Aldrin, the radar shows an altitude 2,900 feet lower than that shown on the PGNS. In a few moments Armstrong will ask Mission Control to try understand why these numbers don't correlate.

Mission Control: Roger, we copy.

Aldrin: Got the Earth straight out our front window.

Armstrong: Houston, you looking at our Delta-H?

Mission Control: That’s affirmative.

Armstrong: Programme alarm.

This is the beginning of one of the most nerve-wracking parts of the Moon landing, the infamous ‘1202’ programme alarm. Mission Control does not immediately appear to register the urgency in Armstrong’s voice, and instead answers his previous query about their Delta-H.

Mission Control: It’s looking good to us. Over.

Armstrong: It’s a 1202.

Aldrin: 1202.

Neither Armstrong nor Aldrin are sure what the 1202 programme alarm means, and are asking Mission Control for guidance.

Armstrong to Aldrin: Let’s incorporate [the landing radar data.]

Armstrong to Mission Control: Give us a reading on the 1202 programme alarm.

Mission Control: Roger, we got you. We’re Go on that alarm.

Mission Control has made the decision to continue the mission, despite the potential danger highlighted by this alarm. The 1202 programme alarm was a warning from the Apollo Guidance Computer that its core processing system had been overloaded. However, the computer had been designed so that even if this occurred, mission critical programmes would take priority.

Thanks to the rapid response from Apollo Guidance Computer specialist Jack Garman in Mission Control, flight controllers understood that as long as the alarms did not come in rapid succession the mission could continue. In all, there were four 1202 alarms and one related 1201 alarm during the lunar descent.

Armstrong: Roger. 330.

Mission Control: 6 plus 25. Throttle down.

Mission Control is instructing that the engine be throttled down six minutes and 35 seconds into the burn.

Aldrin: OK, looks like about 820…

Aldrin is interrupted by Mission Control.

Mission Control: 6 plus 25, throttle down.

Aldrin: Roger. Copy.

Armstrong: 6 plus 25.

Aldrin: Same alarm, and it appears to come up when we have a 16/68 up.

Aldrin is trying to work out what the 1202 programme alarm means, and tells Mission Control that it may be linked to when he requests a data display from the computer ('16/68'). Instead of overloading the computer further, Mission Control will monitor the Delta-H reading and feed it back to Aldrin.

Mission Control: Eagle, Houston. We’ll monitor your Delta-H.

Aldrin: Yes it’s coming down beautifully.

The difference between the two computer guidance systems, Delta-H, appears to be reducing.

Armstrong: Roger. It looks good now.

Mission Control: Roger. Delta-H is looking good to us.

Aldrin: Wow! Throttle down.

Armstrong: Throttle down on time.

Mission Control: Roger. We copy throttle down.

Aldrin: You can feel it in here when it throttles down. Better than the simulator.

Aldrin is surprised by the feeling in the lunar module compared to his experience in the simulator during training. The fact that the throttle down manoeuvre has initiated at the correct time also suggests that the 1202 programme alarm has not interrupted key guidance programmes.

Mission Control: Rog.

Aldrin: AGS and PGNS look real close.

Aldrin again compares the two computer guidance systems. Remember, the Abort Guidance System (AGS) is their back-up system, and the astronauts’ only way out should something go wrong with the primary system.

Mission Control: At seven minutes you’re still looking great to us Eagle.

Aldrin: OK, I’m still on Slew so we may tend to lose as we gradually pitch over. Let me try Auto again now and see what happens.

Aldrin is trying to switch the radio antenna back to automatic mode and let the computer take care of the positioning as the lunar module rotates.

Aldrin: OK, looks like it’s holding.

Mission Control: Roger. We got good data.

Mission Control: Eagle, Houston. It’s Descent Two fuel to monitor. Over.

Mission Control is telling the lunar module which fuel monitoring system to look at.

Armstrong: Going to Two.

Aldrin: Give us an estimated switchover time please, Houston.

Mission Control: Roger. Standby. You’re looking great at eight minutes.

Aldrin is asking Mission Control when the computer will switch from programme P63 to P64, the final approach phase of the lunar landing.

Mission Control: Eagle, you’ve got 30 seconds to P64.

Mission Control: Eagle, Houston. Coming up on 8:30 you’re looking great.

Armstrong: P64.

Mission Control: We copy.

P64 has been initiated.

Mission Control: Eagle, you’re looking great. Coming up nine minutes.

Armstrong: Manual attitude control is good.

Armstrong is testing the manual controls of the lunar module. In video footage from the landing, the module can be seen gently rocking and rotating.

Mission Control: Eagle, Houston. You’re Go for landing. Over.

Aldrin: Roger. Understand. Go for landing. 3,000 feet. Programme alarm. 1201.

Armstrong: 1201.

Mission Control: Roger. 1201 alarm.

Aldrin and Armstrong are facing yet another programme alarm. Mission Control react quickly to reassure them.

Mission Control: We’re Go. Same type. We’re Go.

Aldrin: 2,000 feet. 2,000 feet. Into the AGS, 47 degrees.

Aldrin: 47 degrees.

In the lunar module, Armstrong is asking Aldrin for an LPD (Landing Point Designator). This refers to a scale on the window, marked in degrees, that shows where the computer is aiming for on the lunar surface.

Mission Control: Eagle, looking great. You’re Go.

Mission Control: Roger. 1202, we copy it.

Mission Control is acknowledging yet another computer alarm code.

Aldrin: 35 degrees.

Again, Aldrin is reading out the angle for the Landing Point Designator (LPD). From here on in he will regularly call out both the altitude and speed of descent. Armstrong meanwhile is closely analysing the lunar surface, as the computer appears to be guiding them towards a rocky landing site around a spot called West Crater.

Aldrin: 35 degrees. 750 [feet]. Coming down at 23 [feet per second].

Aldrin: 700 feet, 21 [feet per second] down, 33 degrees.

Aldrin: 600 feet, down at 19 [feet per second].

At this stage Armstrong assumes manual control of the lunar module’s attitude, allowing him to pilot towards a clearer landing site.

Aldrin: 540 feet, down at… [LPD angle] 30. Down at 15 [feet per second].

Aldrin: 400 feet, down at 9 [feet per second]. 58 [feet per second] forward.

Aldrin: 350 feet, down at 4.

Aldrin: 330, 3.5 down.

Aldrin: You’re pegged on horizontal velocity.

Aldrin: 300 feet, down 3.5. 47 forward. Slow it up. 1.5 down.

Aldrin: 270.

Aldrin: I got the shadow out there.

Aldrin is seeing the shadow of the lunar module on the Moon’s surface.

Aldrin: 250, down at 2.5. 19 forward.

Aldrin: Altitude, velocity lights.

Aldrin is reporting warning lights in the lunar module. These are caused because the landing radar has lost its lock on the surface.

Aldrin: 3.5 down. 220 feet. 13 forward.

Aldrin: 11 forward. Coming down nicely. 200 feet. 4.5 down. 5.5 down.

Aldrin: 160 feet. 6.5 down. 5.5 down. 9 forward. You’re looking good. 120 feet.

Aldrin: 100 feet. 3.5 down. 9 forward. 5 per cent. Quantity light.

“5 per cent” relates to the amount of fuel left available for the landing stage. With the fuel at this level, Mission Control has initiated a timer counting down to the moment where the lunar module will either have to land immediately – or abort. This is known as a ‘bingo’ call.

Aldrin: OK, 75 feet and it’s looking good. Down a half. 6 forward.

Mission Control: 60 seconds.

This is the amount of time the Eagle has left before the ‘bingo’ call.

Aldrin: Lights on. 60 feet. Down 2.5. Forward. Forward.

Aldrin: 40 feet, down 2.5. Picking up some dust.

Aldrin: 30 feet, 2.5 down … shadow.

Aldrin: 4 forward. 4 forward. Drifting to the right a little. 20 feet. Down a half.

Mission Control: 30 seconds.

Aldrin: Drifting forward just a little bit. That’s good.

Aldrin: Contact light.

A sensor hanging from the feet of the Eagle has touched the surface, setting off a light inside the lunar module.

Aldrin: OK engine stop. ACA out of detent. Mode control: both Auto. Descent Engine Command override: off. Engine arm: off. 413 is in.

All these announcements are related to the Apollo Guidance System, confirming that the lunar module has landed.

Mission Control: We copy you down, Eagle.

Armstrong: Houston, er… Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.

Unique Space-inspired gifts

Explore space from the comfort of home. Introducing Illuminates, accessible guides on space written by Royal Observatory astronomers

How long does it take to get to the moon?

Here we explore how long it takes to get to the moon and the factors that affect the journey to our rocky companion.

- Traveling at the speed of light

- Fastest spacecraft

- Driving to the moon

Q&A with an expert

- Calculating travel times

Moon mission travel times

Additional resources, bibliography.

If you wanted to go to the moon, how long would it take?

Well, the answer depends on a number of factors ranging from the positions of Earth and the moon , to whether you want to land on the surface or just zip past, and especially to the technology used to propel you there.

The average travel time to the moon (providing the moon is your intended destination), using current rocket propulsion is approximately three days. The fastest flight to the moon without stopping was achieved by NASA's New Horizons probe when it passed the moon in just 8 hours 35 minutes while en route to Pluto .

Currently, the fastest crewed flight to the moon was Apollo 8. The spacecraft entered lunar orbit just 69 hours and 8 minutes after launch according to NASA .

Here we take a look at how long a trip to the moon would take using available technology and explore the travel times of previous missions to our lunar companion.

Related: Missions to the moon: Past, present and future

How far away is the moon?

To find out how long it takes to get to the moon, we first must know how far away it is.

The average distance between Earth and the moon is about 238,855 miles (384,400 kilometers), according to NASA. But because the moon does not orbit Earth in a perfect circle, its distance from Earth is not constant. At its closest point to Earth — known as perigee — the moon is about 226,000 miles (363,300 km) away and at its farthest — known as apogee — it's about 251,000 miles (405,500 km) away.

How long would it take to travel to the moon at the speed of light?

Light travels at approximately 186,282 miles per second (299,792 km per second). Therefore, a light shining from the moon would take the following amount of time to reach Earth (or vice versa):

- Closest point: 1.2 seconds

- Farthest point: 1.4 seconds

- Average distance: 1.3 seconds

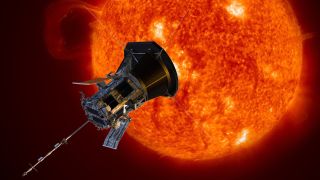

How long would it take to travel to the moon on the fastest spacecraft so far?

The fastest spacecraft is NASA's Parker Solar Probe , which keeps breaking its own speed records as it moves closer to the sun. On Nov. 21, 2021, the Parker Solar Probe clocked a top speed of 101 miles (163 kilometers) per second during its 10th close flyby of our star, which translates to a blistering 364,621 mph (586,000 kph). According to a NASA statement , when the Parker Solar Probe comes within 4 million miles (6.2 million kilometers) of the solar surface in December 2024, the spacecraft's speed will top 430,000 miles per hour (692,000 km/h)!

So if you were theoretically able to hitch a ride on the Parker Solar Probe and take it on a detour from its sun-focused mission to travel in a straight line from Earth to the moon, traveling at the speeds the probe reaches during its 10th flyby (101 miles per second), the time it would take you to get to the moon would be:

- Closest point: 37.2 minutes

- Farthest point: 41.4 minutes

- Average distance: 39.4 minutes

How long would it take to drive to the moon?

Let's say you decided to drive to the moon (and that it was actually possible). At an average distance of 238,855 miles (384,400 km) and driving at a constant speed of 60 mph (96 km/h), it would take about 166 days.

We asked Michael Khan, ESA Senior Mission Analyst some frequently asked questions about travel times to the moon.

Michael Khan is a Senior Mission Analyst for the European Space Agency (ESA). His work involves studying the orbital mechanics for journeys to planetary bodies including Mars.

And what affects the travel time?

The time it takes to get from one celestial body to another depends largely on the energy that one is willing to expend. Here "energy" refers to the effort put in by the launch vehicle and the sum of the manoeuvres of the rocket motors aboard the spacecraft, and the amount of propellant that is used. In space travel, everything boils down to energy. Spaceflight is the clever management of energy.

Some common solutions for transfers to the moon are 1) the Hohmann-like transfer and 2) the Free Return Transfer. The Hohmann Transfer is often referred to as the one that requires the lowest energy, but that is true only if you want the transfer to last only a few days and, in addition, if some constraints on the launch apply. Things get very complicated from there on, so I won't go into details.

The transfer duration for the Hohmann-like transfer is around 5 days. There is some variation in this duration because the moon orbit is eccentric, so its distance from the Earth varies quite a bit with time, and with it, the characteristics of the transfer orbit.

The Free Return transfer is a popular transfer for manned spacecraft. It requires more energy than the Hohmann-like transfer, but it is a lot safer, because its design is such that if the rocket engine fails at the moment you are trying to insert into the orbit around the Moon, the gravity of the Moon will deflect the orbit exactly such that it returns to the Earth. So even with a defective propulsion system, you can still get the people back safely. The Apollo missions flew on Free Return transfers. They take around 3 days to reach the moon.

Why are journey times a lot slower for spacecraft intending to orbit or land on the target body e.g. Mars compared to those that are just going to fly by?

If you want your spacecraft to enter Mars orbit or to land on the surface, you add a lot of constraints to the design problem. For an orbiter, you have to consider the significant amount of propellant required for orbit insertion, while for a lander, you have to design and build a heat shield that can withstand the loads of atmospheric entry. Usually, this will mean that the arrival velocity of Mars cannot exceed a certain boundary. Adding this constraint to the trajectory optimisation problem will limit the range of solutions you obtain to transfers that are Hohmann-like. This usually leads to an increase in transfer duration.

Calculating travel times to the moon — it's not that straightforward

A problem with the previous calculations is that they measure the distance between Earth and the moon in a straight line and assume the two bodies remain at a constant distance; that is, assuming that when a probe is launched from Earth, the moon would remain the same distance away by the time the probe arrives.

In reality, however, the distance between Earth and the moon is not constant due to the moon's elliptical orbit, so engineers must calculate the ideal orbits for sending a spacecraft from Earth to the moon. Like throwing a dart at a moving target from a moving vehicle, they must calculate where the moon will be when the spacecraft arrives, not where it is when it leaves Earth.

Another factor engineers need to take into account when calculating travel times to the moon is whether the mission has the intention of landing on the surface or entering lunar orbit. In these cases, traveling there as fast as possible is not feasible as the spacecraft needs to arrive slowly enough to perform orbit insertion maneuvers.

More than 140 missions have been launched to the moon, each with a different objective, route and travel time.

Perhaps the most famous — the crewed Apollo 11 mission — took four days, six hours and 45 minutes to reach the moon. Apollo 10 still holds the record for the fastest speed any humans have ever traveled when it clocked a top speed of while the crew of Apollo 10 traveled 24,791 mph (39,897 kph) relative to Earth as they rocketed back to our planet on May 26, 1969.

The first uncrewed flight test of NASA's Orion spacecraft and space launch system rocket — Artemis 1 — reached the moon on flight day six of its journey and swooped down to just 80 miles (130 km) above the lunar surface to gain a gravitational boost to enter a so-called "distant retrograde orbit."

Read more about how space navigation works with accurate timekeeping with these resources from NASA . Learn more about how before the days of GPS engineers were able to navigate from Earth to the moon with such precision with this article by Gwendolyn Vines Gettliffe published at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) 'ask an engineer' feature.

Hatfield, M. (2021). Space Dust Presents Opportunities, Challenges as Parker Solar Probe Speeds Back toward the Sun – Parker Solar Probe. [online] blogs.nasa.gov. Available at: https://blogs.nasa.gov/parkersolarprobe/2021/11/10/space-dust-presents-opportunities-challenges-as-parker-solar-probe-speeds-back-toward-the-sun/ .

NASA (2011). Apollo 8. [online] NASA. Available at: https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/apollo/missions/apollo8.html .

www.rmg.co.uk. (n.d.). How many people have walked on the Moon? [online] Available at: https://www.rmg.co.uk/stories/topics/how-many-people-have-walked-on-moon .

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: [email protected].

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Daisy Dobrijevic joined Space.com in February 2022 having previously worked for our sister publication All About Space magazine as a staff writer. Before joining us, Daisy completed an editorial internship with the BBC Sky at Night Magazine and worked at the National Space Centre in Leicester, U.K., where she enjoyed communicating space science to the public. In 2021, Daisy completed a PhD in plant physiology and also holds a Master's in Environmental Science, she is currently based in Nottingham, U.K. Daisy is passionate about all things space, with a penchant for solar activity and space weather. She has a strong interest in astrotourism and loves nothing more than a good northern lights chase!

Satellites watch as 4th global coral bleaching event unfolds (image)

Happy Earth Day 2024! NASA picks 6 new airborne missions to study our changing planet

Pluto's heart-shaped scar may offer clues to the frozen world's history

- UFOareAngels The fact that we are still asking this question proves we never went to the moon and are never going back. Reply

- Rathelor Those Parker Solar Probe travel times seems a little too high. Reply

- View All 2 Comments

Most Popular

- 2 Cosmic fountain is polluting intergalactic space with 50 million suns' worth of material

- 3 India aims to achieve 'debris-free' space missions by 2030

- 4 Scientists use AI to reconstruct energetic flare blasted from Milky Way's supermassive black hole

- 5 Earth Day 2024: Witness our changing planet in 12 incredible satellite images

Premium Content

Countdown to a new era in space

Fifty years ago this month, astronauts walked on the moon for the first time. Apollo 11’s success—just 66 years after the Wright brothers’ first flight—showcased humankind’s moxie and ingenuity. Now the moon is in our sights again, for a generation that will test where science meets profit.

T MINUS 5: PIONEERS

Animals were our first space travelers, clearing the way for astronauts who became famous—and for lesser known heroes..

Yuri Gagarin, Alan Shepard, John Glenn, Neil Armstrong— the first wave of space travelers —were military-trained astronauts thought to have the “right stuff” for risky missions.

But early spaceflight wasn’t the exclusive province of men— or even humans . Fruit flies, monkeys, mice, dogs, rabbits, and rats flew into space before humans.

More than three years before Gagarin became the first human in space with his April 1961 journey around Earth, the Soviets famously—or perhaps infamously—sent up a stray dog. Laika was the first animal to orbit Earth but died during her flight. The United States launched a chimpanzee named Ham into space. Happily, he survived, clearing the way for Shepard to became the first American in space in May 1961.

Despite discrimination, women were also pioneers . Some, such as mathematician Katherine Johnson—who hand-calculated the details of the trajectory of the flight that would make Glenn the first American to orbit the Earth in 1962—stayed behind the scenes. Valentina Tereshkova, an early cosmonaut, became the first woman in orbit in 1963. It wasn’t until two decades later that Sally Ride flew on the space shuttle Challenger to become the first American woman to reach space.

T MINUS 4: GETTING THERE

Early rocketeers figured that a multistage launcher could propel humans to the moon. the saturn v did that—and set the stage for the future..

A bespectacled, bearded Russian recluse fond of science fiction, Konstantin Tsiolkovsky believed humanity’s destiny lay among the stars. By the early 1900s, he had worked out the equation for humans to slip beyond Earth’s gravitational pull. He also imagined how moon-bound rockets would work : using a mix of liquid propellants and igniting multiple stages.

Independently, Hermann Oberth and Robert Goddard reached similar conclusions. By 1926, Goddard, an American, had built and launched the first liquid-fueled rocket. About that time, Oberth, who lived in Germany, determined multiple stages are crucial for long journeys.

Four decades later, the trio’s ideas roared to life in the enormous Saturn V rockets that thrust Apollo crews into space. Measuring 363 feet tall and fueled by liquid hydrogen, liquid oxygen, and kerosene, the Saturn V was the most powerful rocket ever built. Engineered by Wernher von Braun—a Nazi Germany rocket scientist who relocated much of his team to work for the U.S. after World War II—the Saturn V had three stages that fired in sequence. Rocketry is still governed by Tsiolkovsky’s equation. But no rocket has yet eclipsed the Saturn V, which propelled humans closer to the stars than ever before.

Five bell-shaped engines powered the initial stage of the Saturn V rocket, which shot most of the Apollo missions beyond Earth’s orbit and eventually carried astronauts to the moon. Together the five engines generated as much energy as 85 Hoover dams.

T MINUS 3: WHERE WE WENT

Apollo missions focused on the moon's near side. now uncrewed probes are revealing more about the moon and beyond..

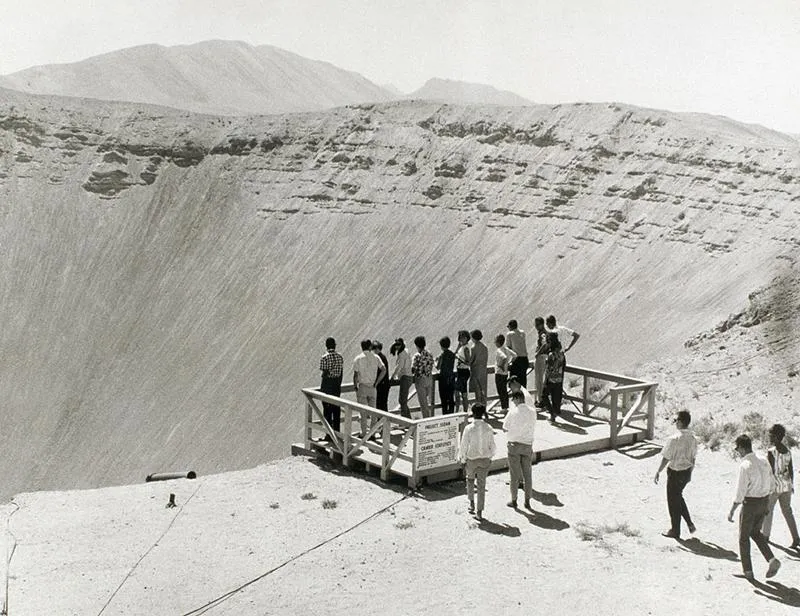

In the 1960s our moon was still very much a mystery. To learn the most from the Apollo visits, NASA selected landing sites in a variety of lunar terrains, including the dark, flat plains sculpted by vanished lava oceans and highlands formed by meteor impacts.

From 1969 to 1972, U.S. astronauts landed at six sites, each chosen for different scientific objectives. All of them were on the moon’s mottled near side, where the terrain had been studied extensively by lunar orbiters and Mission Control could remain in direct contact with the astronauts.

Space agencies have sent probes, with no people on them and thus no need to worry about human safety, to visit far-flung places in the solar system. Spacecraft have explored 60 other moons and even set down on one, Saturn’s Titan . On our own moon, robotic rovers have left tracks at four sites.

China made history earlier this year by setting its Chang’e 4 lander on the moon’s far side .

The first private lander to reach the moon crashed in April , but the Israeli nonprofit behind it quickly announced plans to try again.

Not to be outdone , the U.S. intends to send a series of landers with technology to lay the groundwork for astronauts to return.

T MINUS 2: WHAT WE TOOK

Astronauts collected rocks, pebbles, soil, and dust. they also took personal items to space that reflected their interests, beliefs, and passions..

Over four years, NASA astronauts hauled 842 pounds of moon rocks back to Earth. But the most profound souvenirs weigh nothing: images of Earth. Apollo 8 astronaut William Anders snapped an iconic one on Christmas Eve in 1968, showing our blue planet suspended in darkness near the moon’s sterile, cratered horizon.

Astronauts didn’t just take photos and collect moon rocks, they also carried an array of objects from Earth into space with them.

One of NASA’s most requested space photos, this view of Earth, known as Blue Marble, was taken in 1972 from about 18,000 miles away, as Apollo 17 was traveling to the moon.

John Young (Gemini 3) notoriously smuggled aboard a corned beef sandwich and shared it with Gus Grissom, his crewmate. Grissom pocketed it when crumbs began to float around the cabin.

Buzz Aldrin (Apollo 11) took wine, bread, and a chalice to celebrate Communion. His crewmate Neil Armstrong carried a piece of the Wright Flyer’s wooden propeller. Alan Shepard (Apollo 14) used a sock to hide a six-iron clubhead, which he attached to a tool handle to hit two golf balls on the moon. Charles Duke (Apollo 16) packed a family photo and left it in the Descartes highlands.

After landing on the moon, Buzz Aldrin drank consecrated wine from this three-inch goblet, which is still used by his former church near Houston.

Perhaps the most poignant memento on the lunar surface is a small aluminum human figure, placed there by David Scott during Apollo 15. It rests near a placard bearing the names of 14 fallen astronauts and cosmonauts.

T MINUS 1: IN POP CULTURE

From tv shows to movies, toys, food, and the way we express ourselves, space continues to have a hold on our imagination..

As the space race boomed, it catapulted its aspirations into the zeitgeist—and transformed the way we live.

Sputnik inspired replicas and songs. Life magazine published exclusive stories on the lives of the celebrated Mercury Seven, the United States’ first astronauts. Seattle built the Space Needle for the World’s Fair. Stanley Kubrick created 2001: A Space Odyssey. The space age flourished in movies, TV, music, architecture, and design, where the sleek, aerodynamic lines of rockets inspired the look of cars and trains.

Space is still lodged in popular culture. The NASA logo appears everywhere, from tattoos to Vans high-tops. We’ve had Star Trek, The Jetsons, Mork & Mindy, Star Wars, and the current spate of Mars movies and space-themed TV shows. Also: the Houston Astros and the Houston Rockets, Space Camp, antigravity ballpoint pens, astronaut ice cream, the moonwalk, and Space Mountain.

Billed as “the first space age–inspired car,” the Firebird III, built by General Motors, was powered by a gas turbine engine and sported seven fins. The 1958 concept car had a computer, electronic controls, and a joystick to accelerate, brake, and steer.

Concepts like “the right stuff,” “moon shot,” and “light-years” figure into everyday conversation. Your first day back after vacation might be filled with “reentry” problems. Your craft-brewed IPA might taste like “rocket fuel” or even use those words as its name. And, on discovering a distressing situation, you might calmly say, “Houston, we have a problem.”

LIFTOFF!: WHAT'S NEXT

It may seem as if we've been going nowhere for decades. but a new age of space travel is coming, mixing exploration with a race for profits..

When human beings stepped on the moon 50 years ago this month , it was one of history’s most astounding moments, and not just because our first visit to another world was among humanity’s greatest scientific achievements or because it was the culmination of an epic race between two global superpowers, though both were true. The New York Times put a poem by Archibald MacLeish on the front page, and newscaster Walter Cronkite, “the most trusted man in America,” would come to say that people living 500 years in the future would regard the lunar landing as “the most important feat of all time.”

The ultimate significance, however, was not that the race had ended or even that a once unimaginable milestone had been attained.

This achievement was really just the beginning.

The beginning of a new era in humanity’s vision of its horizons, of the places we could explore and might even inhabit. Having started as a landfaring species, expanded our reach to the entire planet when we became seafaring, and conquered the atmosphere above Earth when powered flight made us skyfarers, we were now destined to be pilgrims in a vast new realm. We were spacefarers—and soon, as this seminal triumph helped us get over what celebrated scientist and writer Isaac Asimov called our “planetary chauvinism,” we would become an extraplanetary species. “Earthlings” would no longer be sufficient to describe who we were.

All this is what was widely expected, amid the euphoria and wonder on July 20, 1969, when Eagle, Apollo 11’s lunar module, touched down on the moon’s surface. The greatest journey starts with a single step. A small step for one man; a giant leap for all of humankind.

The head of the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Thomas O. Paine, was soon aiming for Mars, and not just as a someday goal but with a detailed itinerary laid out in National Geographic. Depart: October 3, 1983. Crew of 12, split between two 250-foot-long spacecraft fired by nuclear rockets. Enter Mars orbit: June 9, 1984. Eighty days of exploration on the Martian surface. Return to Earth orbit: May 25, 1985.

The very act of reaching the moon somehow exalted the human race, yielding confidence that we would indeed push deeper into space. “Wherever we went, people, instead of saying, ‘Well, you Americans did it,’ everywhere they said, ‘We did it!’ ” recalled Michael Collins, the pilot of Apollo 11’s command module. “We humankind, we the human race, we people did it.”

Sunrise is still a few hours away, and as the bus cuts a lonely path through miles of remote steppe in southern Kazakhstan, its headlights occasionally illuminate for the briefest of moments a giant faded mural or a chipped tile mosaic. These stylized works of art show the ravages of baking summers and bitter winters. They adorn huge, rusting, abandoned buildings, and they celebrate the decades-old glories of a space program in a nation that no longer exists: the Soviet Union.

Finally, after miles of this Twilight Zone landscape of Cold War detritus, the bus makes a sudden turn down a gated lane and arrives at a giant, banged-up structure that is definitely not abandoned. Well-armed Russian and Kazakh security officers in camouflage gear seem to have the place surrounded, and it’s bathed in floodlights. Inside this hangar is a gleaming new rocket ship.

I’ve come to the Baikonur Cosmodrome because, just shy of the 50th anniversary of the moon landing, it’s the only place on the planet where I can watch a human blast off to space. In turn, the only place in the universe these people can fly to is the International Space Station, some 250 miles above Earth, which is barely one-thousandth of the distance to the moon.

For the past eight years, ever since NASA retired the space shuttle, the only way it has been able to get an American astronaut to the space station has been to hitch a ride with its Russian counterpart, known as Roscosmos, at roughly $82 million for a seat up and back down.

Fifty years on from the moon landing, this is where we are in space, if by “we,” we mean human beings. Which sure sounds like basically nowhere, at least as measured by the yardstick of 1969’s great expectations. Twelve people—all Americans, all men—have stepped on the moon, none since 1972, and other than on Earth-orbiting space stations, no human has set foot anywhere else in the universe.

Measured another way, of course, we’re doing extraordinary things in space.