- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Christopher Columbus

By: History.com Editors

Updated: August 11, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

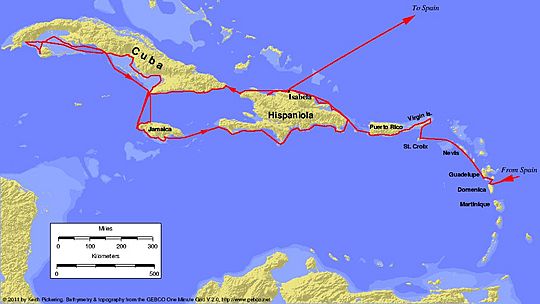

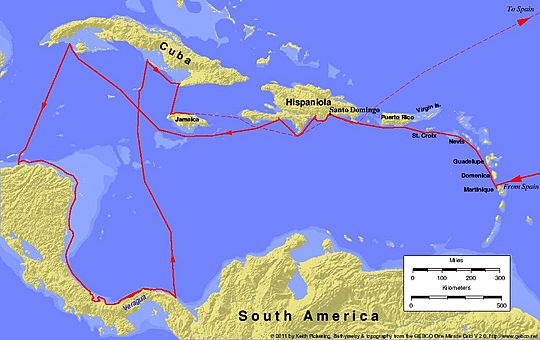

The explorer Christopher Columbus made four trips across the Atlantic Ocean from Spain: in 1492, 1493, 1498 and 1502. He was determined to find a direct water route west from Europe to Asia, but he never did. Instead, he stumbled upon the Americas. Though he did not “discover” the so-called New World—millions of people already lived there—his journeys marked the beginning of centuries of exploration and colonization of North and South America.

Christopher Columbus and the Age of Discovery

During the 15th and 16th centuries, leaders of several European nations sponsored expeditions abroad in the hope that explorers would find great wealth and vast undiscovered lands. The Portuguese were the earliest participants in this “ Age of Discovery ,” also known as “ Age of Exploration .”

Starting in about 1420, small Portuguese ships known as caravels zipped along the African coast, carrying spices, gold and other goods as well as enslaved people from Asia and Africa to Europe.

Did you know? Christopher Columbus was not the first person to propose that a person could reach Asia by sailing west from Europe. In fact, scholars argue that the idea is almost as old as the idea that the Earth is round. (That is, it dates back to early Rome.)

Other European nations, particularly Spain, were eager to share in the seemingly limitless riches of the “Far East.” By the end of the 15th century, Spain’s “ Reconquista ”—the expulsion of Jews and Muslims out of the kingdom after centuries of war—was complete, and the nation turned its attention to exploration and conquest in other areas of the world.

Early Life and Nationality

Christopher Columbus, the son of a wool merchant, is believed to have been born in Genoa, Italy, in 1451. When he was still a teenager, he got a job on a merchant ship. He remained at sea until 1476, when pirates attacked his ship as it sailed north along the Portuguese coast.

The boat sank, but the young Columbus floated to shore on a scrap of wood and made his way to Lisbon, where he eventually studied mathematics, astronomy, cartography and navigation. He also began to hatch the plan that would change the world forever.

Christopher Columbus' First Voyage

At the end of the 15th century, it was nearly impossible to reach Asia from Europe by land. The route was long and arduous, and encounters with hostile armies were difficult to avoid. Portuguese explorers solved this problem by taking to the sea: They sailed south along the West African coast and around the Cape of Good Hope.

But Columbus had a different idea: Why not sail west across the Atlantic instead of around the massive African continent? The young navigator’s logic was sound, but his math was faulty. He argued (incorrectly) that the circumference of the Earth was much smaller than his contemporaries believed it was; accordingly, he believed that the journey by boat from Europe to Asia should be not only possible, but comparatively easy via an as-yet undiscovered Northwest Passage .

He presented his plan to officials in Portugal and England, but it was not until 1492 that he found a sympathetic audience: the Spanish monarchs Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile .

Columbus wanted fame and fortune. Ferdinand and Isabella wanted the same, along with the opportunity to export Catholicism to lands across the globe. (Columbus, a devout Catholic, was equally enthusiastic about this possibility.)

Columbus’ contract with the Spanish rulers promised that he could keep 10 percent of whatever riches he found, along with a noble title and the governorship of any lands he should encounter.

Where Did Columbus' Ships, Niña, Pinta and Santa Maria, Land?

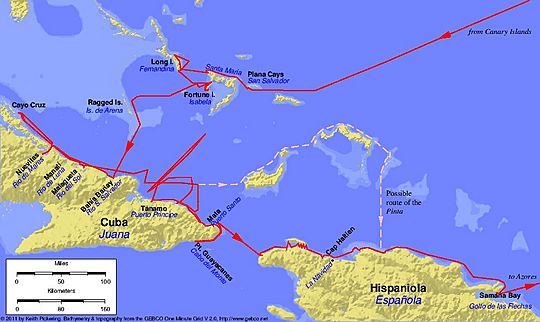

On August 3, 1492, Columbus and his crew set sail from Spain in three ships: the Niña , the Pinta and the Santa Maria . On October 12, the ships made landfall—not in the East Indies, as Columbus assumed, but on one of the Bahamian islands, likely San Salvador.

For months, Columbus sailed from island to island in what we now know as the Caribbean, looking for the “pearls, precious stones, gold, silver, spices, and other objects and merchandise whatsoever” that he had promised to his Spanish patrons, but he did not find much. In January 1493, leaving several dozen men behind in a makeshift settlement on Hispaniola (present-day Haiti and the Dominican Republic), he left for Spain.

He kept a detailed diary during his first voyage. Christopher Columbus’s journal was written between August 3, 1492, and November 6, 1492 and mentions everything from the wildlife he encountered, like dolphins and birds, to the weather to the moods of his crew. More troublingly, it also recorded his initial impressions of the local people and his argument for why they should be enslaved.

“They… brought us parrots and balls of cotton and spears and many other things, which they exchanged for the glass beads and hawks’ bells," he wrote. "They willingly traded everything they owned… They were well-built, with good bodies and handsome features… They do not bear arms, and do not know them, for I showed them a sword, they took it by the edge and cut themselves out of ignorance. They have no iron… They would make fine servants… With fifty men we could subjugate them all and make them do whatever we want.”

Columbus gifted the journal to Isabella upon his return.

Christopher Columbus's Later Voyages

About six months later, in September 1493, Columbus returned to the Americas. He found the Hispaniola settlement destroyed and left his brothers Bartolomeo and Diego Columbus behind to rebuild, along with part of his ships’ crew and hundreds of enslaved indigenous people.

Then he headed west to continue his mostly fruitless search for gold and other goods. His group now included a large number of indigenous people the Europeans had enslaved. In lieu of the material riches he had promised the Spanish monarchs, he sent some 500 enslaved people to Queen Isabella. The queen was horrified—she believed that any people Columbus “discovered” were Spanish subjects who could not be enslaved—and she promptly and sternly returned the explorer’s gift.

In May 1498, Columbus sailed west across the Atlantic for the third time. He visited Trinidad and the South American mainland before returning to the ill-fated Hispaniola settlement, where the colonists had staged a bloody revolt against the Columbus brothers’ mismanagement and brutality. Conditions were so bad that Spanish authorities had to send a new governor to take over.

Meanwhile, the native Taino population, forced to search for gold and to work on plantations, was decimated (within 60 years after Columbus landed, only a few hundred of what may have been 250,000 Taino were left on their island). Christopher Columbus was arrested and returned to Spain in chains.

In 1502, cleared of the most serious charges but stripped of his noble titles, the aging Columbus persuaded the Spanish crown to pay for one last trip across the Atlantic. This time, Columbus made it all the way to Panama—just miles from the Pacific Ocean—where he had to abandon two of his four ships after damage from storms and hostile natives. Empty-handed, the explorer returned to Spain, where he died in 1506.

Legacy of Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus did not “discover” the Americas, nor was he even the first European to visit the “New World.” (Viking explorer Leif Erikson had sailed to Greenland and Newfoundland in the 11th century.)

However, his journey kicked off centuries of exploration and exploitation on the American continents. The Columbian Exchange transferred people, animals, food and disease across cultures. Old World wheat became an American food staple. African coffee and Asian sugar cane became cash crops for Latin America, while American foods like corn, tomatoes and potatoes were introduced into European diets.

Today, Columbus has a controversial legacy —he is remembered as a daring and path-breaking explorer who transformed the New World, yet his actions also unleashed changes that would eventually devastate the native populations he and his fellow explorers encountered.

HISTORY Vault: Columbus the Lost Voyage

Ten years after his 1492 voyage, Columbus, awaiting the gallows on criminal charges in a Caribbean prison, plotted a treacherous final voyage to restore his reputation.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

The Ages of Exploration

Christopher columbus, age of discovery.

Quick Facts:

He is credited for discovering the Americas in 1492, although we know today people were there long before him; his real achievement was that he opened the door for more exploration to a New World.

Name : Christopher Columbus [Kri-stə-fər] [Kə-luhm-bəs]

Birth/Death : 1451 - 1506

Nationality : Italian

Birthplace : Genoa, Italy

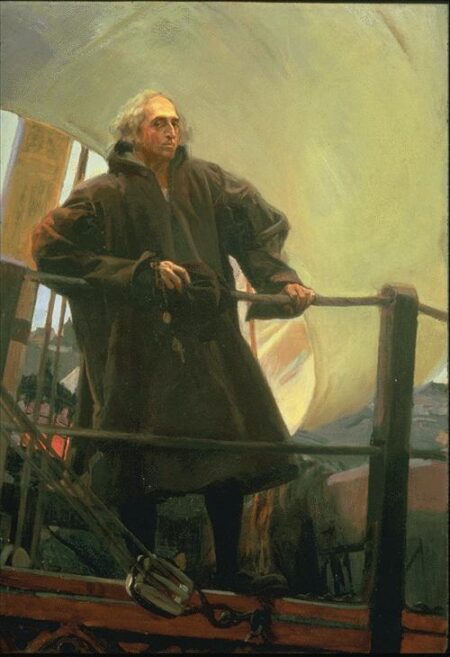

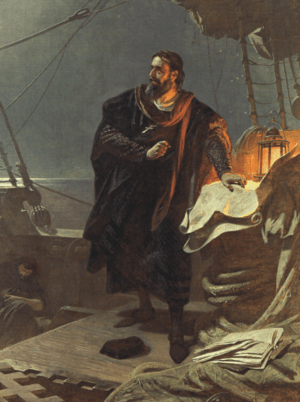

Christopher Columbus leaving Palos, Spain

Christopher Columbus aboard the "Santa Maria" leaving Palos, Spain on his first voyage across the Atlantic Ocean. The Mariners' Museum 1933.0746.000001

Introduction We know that In 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue. But what did he actually discover? Christopher Columbus (also known as (Cristoforo Colombo [Italian]; Cristóbal Colón [Spanish]) was an Italian explorer credited with the “discovery” of the America’s. The purpose for his voyages was to find a passage to Asia by sailing west. Never actually accomplishing this mission, his explorations mostly included the Caribbean and parts of Central and South America, all of which were already inhabited by Native groups.

Biography Early Life Christopher Columbus was born in Genoa, part of present-day Italy, in 1451. His parents’ names were Dominico Colombo and Susanna Fontanarossa. He had three brothers: Bartholomew, Giovanni, and Giacomo; and a sister named Bianchinetta. Christopher became an apprentice in his father’s wool weaving business, but he also studied mapmaking and sailing as well. He eventually left his father’s business to join the Genoese fleet and sail on the Mediterranean Sea. 1 After one of his ships wrecked off the coast of Portugal, he decided to remain there with his younger brother Bartholomew where he worked as a cartographer (mapmaker) and bookseller. Here, he married Doña Felipa Perestrello e Moniz and had two sons Diego and Fernando.

Christopher Columbus owned a copy of Marco Polo’s famous book, and it gave him a love for exploration. In the mid 15th century, Portugal was desperately trying to find a faster trade route to Asia. Exotic goods such as spices, ivory, silk, and gems were popular items of trade. However, Europeans often had to travel through the Middle East to reach Asia. At this time, Muslim nations imposed high taxes on European travels crossing through. 2 This made it both difficult and expensive to reach Asia. There were rumors from other sailors that Asia could be reached by sailing west. Hearing this, Christopher Columbus decided to try and make this revolutionary journey himself. First, he needed ships and supplies, which required money that he did not have. He went to King John of Portugal who turned him down. He then went to the rulers of England, and France. Each declined his request for funding. After seven years of trying, he was finally sponsored by King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain.

Voyages Principal Voyage Columbus’ voyage departed in August of 1492 with 87 men sailing on three ships: the Niña, the Pinta, and the Santa María. Columbus commanded the Santa María, while the Niña was led by Vicente Yanez Pinzon and the Pinta by Martin Pinzon. 3 This was the first of his four trips. He headed west from Spain across the Atlantic Ocean. On October 12 land was sighted. He gave the first island he landed on the name San Salvador, although the native population called it Guanahani. 4 Columbus believed that he was in Asia, but was actually in the Caribbean. He even proposed that the island of Cuba was a part of China. Since he thought he was in the Indies, he called the native people “Indians.” In several letters he wrote back to Spain, he described the landscape and his encounters with the natives. He continued sailing throughout the Caribbean and named many islands he encountered after his ship, king, and queen: La Isla de Santa María de Concepción, Fernandina, and Isabella.

It is hard to determine specifically which islands Columbus visited on this voyage. His descriptions of the native peoples, geography, and plant life do give us some clues though. One place we do know he stopped was in present-day Haiti. He named the island Hispaniola. Hispaniola today includes both Haiti and the Dominican Republic. In January of 1493, Columbus sailed back to Europe to report what he found. Due to rough seas, he was forced to land in Portugal, an unfortunate event for Columbus. With relations between Spain and Portugal strained during this time, Ferdinand and Isabella suspected that Columbus was taking valuable information or maybe goods to Portugal, the country he had lived in for several years. Those who stood against Columbus would later use this as an argument against him. Eventually, Columbus was allowed to return to Spain bringing with him tobacco, turkey, and some new spices. He also brought with him several natives of the islands, of whom Queen Isabella grew very fond.

Subsequent Voyages Columbus took three other similar trips to this region. His second voyage in 1493 carried a large fleet with the intention of conquering the native populations and establishing colonies. At one point, the natives attacked and killed the settlers left at Fort Navidad. Over time the colonists enslaved many of the natives, sending some to Europe and using many to mine gold for the Spanish settlers in the Caribbean. The third trip was to explore more of the islands and mainland South America further. Columbus was appointed the governor of Hispaniola, but the colonists, upset with Columbus’ leadership appealed to the rulers of Spain, who sent a new governor: Francisco de Bobadilla. Columbus was taken prisoner on board a ship and sent back to Spain.

On his fourth and final journey west in 1502 Columbus’s goal was to find the “Strait of Malacca,” to try to find India. But a hurricane, then being denied entrance to Hispaniola, and then another storm made this an unfortunate trip. His ship was so badly damaged that he and his crew were stranded on Jamaica for two years until help from Hispaniola finally arrived. In 1504, Columbus and his men were taken back to Spain .

Later Years and Death Columbus reached Spain in November 1504. He was not in good health. He spent much of the last of his life writing letters to obtain the percentage of wealth overdue to be paid to him, and trying to re-attain his governorship status, but was continually denied both. Columbus died at Valladolid on May 20, 1506, due to illness and old age. Even until death, he still firmly believing that he had traveled to the eastern part of Asia.

Legacy Columbus never made it to Asia, nor did he truly discover America. His “re-discovery,” however, inspired a new era of exploration of the American continents by Europeans. Perhaps his greatest contribution was that his voyages opened an exchange of goods between Europe and the Americas both during and long after his journeys. 5 Despite modern criticism of his treatment of the native peoples there is no denying that his expeditions changed both Europe and America. Columbus day was made a federal holiday in 1971. It is recognized on the second Monday of October.

- Fergus Fleming, Off the Map: Tales of Endurance and Exploration (New York: Grove Press, 2004), 30.

- Fleming, Off the Map, 30

- William D. Phillips and Carla Rahn Phillips, The Worlds of Christopher Columbus (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 142-143.

- Phillips and Phillips, The Worlds of Christopher Columbus, 155.

- Robin S. Doak, Christopher Columbus: Explorer of the New World (Minneapolis: Compass Point Books, 2005), 92.

Bibliography

Doak, Robin. Christopher Columbus: Explorer of the New World. Minneapolis: Compass Point Books, 2005.

Fleming, Fergus. Off the Map: Tales of Endurance and Exploration. New York: Grove Press, 2004.

Phillips, William D., and Carla Rahn Phillips. The Worlds of Christopher Columbus. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Map of Voyages

Click below to view an example of the explorer’s voyages. Use the tabs on the left to view either 1 or multiple journeys at a time, and click on the icons to learn more about the stops, sites, and activities along the way.

- Original "EXPLORATION through the AGES" site

- The Mariners' Educational Programs

Christopher Columbus

Italian explorer Christopher Columbus discovered the “New World” of the Americas on an expedition sponsored by King Ferdinand of Spain in 1492.

c. 1451-1506

Quick Facts

Where was columbus born, first voyages, columbus’ 1492 route and ships, where did columbus land in 1492, later voyages across the atlantic, how did columbus die, santa maria discovery claim, columbian exchange: a complex legacy, columbus day: an evolving holiday, who was christopher columbus.

Christopher Columbus was an Italian explorer and navigator. In 1492, he sailed across the Atlantic Ocean from Spain in the Santa Maria , with the Pinta and the Niña ships alongside, hoping to find a new route to Asia. Instead, he and his crew landed on an island in present-day Bahamas—claiming it for Spain and mistakenly “discovering” the Americas. Between 1493 and 1504, he made three more voyages to the Caribbean and South America, believing until his death that he had found a shorter route to Asia. Columbus has been credited—and blamed—for opening up the Americas to European colonization.

FULL NAME: Cristoforo Colombo BORN: c. 1451 DIED: May 20, 1506 BIRTHPLACE: Genoa, Italy SPOUSE: Filipa Perestrelo (c. 1479-1484) CHILDREN: Diego and Fernando

Christopher Columbus, whose real name was Cristoforo Colombo, was born in 1451 in the Republic of Genoa, part of what is now Italy. He is believed to have been the son of Dominico Colombo and Susanna Fontanarossa and had four siblings: brothers Bartholomew, Giovanni, and Giacomo, and a sister named Bianchinetta. He was an apprentice in his father’s wool weaving business and studied sailing and mapmaking.

In his 20s, Columbus moved to Lisbon, Portugal, and later resettled in Spain, which remained his home base for the duration of his life.

Columbus first went to sea as a teenager, participating in several trading voyages in the Mediterranean and Aegean seas. One such voyage, to the island of Khios, in modern-day Greece, brought him the closest he would ever come to Asia.

His first voyage into the Atlantic Ocean in 1476 nearly cost him his life, as the commercial fleet he was sailing with was attacked by French privateers off the coast of Portugal. His ship was burned, and Columbus had to swim to the Portuguese shore.

He made his way to Lisbon, where he eventually settled and married Filipa Perestrelo. The couple had one son, Diego, around 1480. His wife died when Diego was a young boy, and Columbus moved to Spain. He had a second son, Fernando, who was born out of wedlock in 1488 with Beatriz Enriquez de Arana.

After participating in several other expeditions to Africa, Columbus learned about the Atlantic currents that flow east and west from the Canary Islands.

The Asian islands near China and India were fabled for their spices and gold, making them an attractive destination for Europeans—but Muslim domination of the trade routes through the Middle East made travel eastward difficult.

Columbus devised a route to sail west across the Atlantic to reach Asia, believing it would be quicker and safer. He estimated the earth to be a sphere and the distance between the Canary Islands and Japan to be about 2,300 miles.

Many of Columbus’ contemporary nautical experts disagreed. They adhered to the (now known to be accurate) second-century BCE estimate of the Earth’s circumference at 25,000 miles, which made the actual distance between the Canary Islands and Japan about 12,200 statute miles. Despite their disagreement with Columbus on matters of distance, they concurred that a westward voyage from Europe would be an uninterrupted water route.

Columbus proposed a three-ship voyage of discovery across the Atlantic first to the Portuguese king, then to Genoa, and finally to Venice. He was rejected each time. In 1486, he went to the Spanish monarchy of Queen Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon. Their focus was on a war with the Muslims, and their nautical experts were skeptical, so they initially rejected Columbus.

The idea, however, must have intrigued the monarchs, because they kept Columbus on a retainer. Columbus continued to lobby the royal court, and soon, the Spanish army captured the last Muslim stronghold in Granada in January 1492. Shortly thereafter, the monarchs agreed to finance his expedition.

In late August 1492, Columbus left Spain from the port of Palos de la Frontera. He was sailing with three ships: Columbus in the larger Santa Maria (a type of ship known as a carrack), with the Pinta and the Niña (both Portuguese-style caravels) alongside.

On October 12, 1492, after 36 days of sailing westward across the Atlantic, Columbus and several crewmen set foot on an island in present-day Bahamas, claiming it for Spain.

There, his crew encountered a timid but friendly group of natives who were open to trade with the sailors. They exchanged glass beads, cotton balls, parrots, and spears. The Europeans also noticed bits of gold the natives wore for adornment.

Columbus and his men continued their journey, visiting the islands of Cuba (which he thought was mainland China) and Hispaniola (now Haiti and the Dominican Republic, which Columbus thought might be Japan) and meeting with the leaders of the native population.

During this time, the Santa Maria was wrecked on a reef off the coast of Hispaniola. With the help of some islanders, Columbus’ men salvaged what they could and built the settlement Villa de la Navidad (“Christmas Town”) with lumber from the ship.

Thirty-nine men stayed behind to occupy the settlement. Convinced his exploration had reached Asia, he set sail for home with the two remaining ships. Returning to Spain in 1493, Columbus gave a glowing but somewhat exaggerated report and was warmly received by the royal court.

In 1493, Columbus took to the seas on his second expedition and explored more islands in the Caribbean Ocean. Upon arrival at Hispaniola, Columbus and his crew discovered the Navidad settlement had been destroyed with all the sailors massacred.

Spurning the wishes of the local queen, Columbus established a forced labor policy upon the native population to rebuild the settlement and explore for gold, believing it would be profitable. His efforts produced small amounts of gold and great hatred among the native population.

Before returning to Spain, Columbus left his brothers Bartholomew and Giacomo to govern the settlement on Hispaniola and sailed briefly around the larger Caribbean islands, further convincing himself he had discovered the outer islands of China.

It wasn’t until his third voyage that Columbus actually reached the South American mainland, exploring the Orinoco River in present-day Venezuela. By this time, conditions at the Hispaniola settlement had deteriorated to the point of near-mutiny, with settlers claiming they had been misled by Columbus’ claims of riches and complaining about the poor management of his brothers.

The Spanish Crown sent a royal official who arrested Columbus and stripped him of his authority. He returned to Spain in chains to face the royal court. The charges were later dropped, but Columbus lost his titles as governor of the Indies and, for a time, much of the riches made during his voyages.

After convincing King Ferdinand that one more voyage would bring the abundant riches promised, Columbus went on his fourth and final voyage across the Atlantic Ocean in 1502. This time he traveled along the eastern coast of Central America in an unsuccessful search for a route to the Indian Ocean.

A storm wrecked one of his ships, stranding the captain and his sailors on the island of Cuba. During this time, local islanders, tired of the Spaniards’ poor treatment and obsession with gold, refused to give them food.

In a spark of inspiration, Columbus consulted an almanac and devised a plan to “punish” the islanders by taking away the moon. On February 29, 1504, a lunar eclipse alarmed the natives enough to re-establish trade with the Spaniards. A rescue party finally arrived, sent by the royal governor of Hispaniola in July, and Columbus and his men were taken back to Spain in November 1504.

In the two remaining years of his life, Columbus struggled to recover his reputation. Although he did regain some of his riches in May 1505, his titles were never returned.

Columbus probably died of severe arthritis following an infection on May 20, 1506, in Valladolid, Spain. At the time of his death, he still believed he had discovered a shorter route to Asia.

There are questions about the location of his burial site. According to the BBC , Columbus’ remains moved at least three or four times over the course of 400 years—including from Valladolid to Seville, Spain, in 1509; then to Santo Domingo, in what is now the Dominican Republic, in 1537; then to Havana, Cuba, in 1795; and back to Seville in 1898. As a result, Seville and Santo Domingo have both laid claim to being Columbus’ true burial site. It is also possible his bones were mixed up with another person’s amid all of their travels.

In May 2014, Columbus made headlines as news broke that a team of archaeologists might have found the Santa Maria off the north coast of Haiti. Barry Clifford, the leader of this expedition, told the Independent newspaper that “all geographical, underwater topography and archaeological evidence strongly suggests this wreck is Columbus’ famous flagship the Santa Maria.”

After a thorough investigation by the U.N. agency UNESCO, it was determined the wreck dates from a later period and was located too far from shore to be the famed ship.

Columbus has been credited for opening up the Americas to European colonization—as well as blamed for the destruction of the native peoples of the islands he explored. Ultimately, he failed to find that what he set out for: a new route to Asia and the riches it promised.

In what is known as the Columbian Exchange, Columbus’ expeditions set in motion the widespread transfer of people, plants, animals, diseases, and cultures that greatly affected nearly every society on the planet.

The horse from Europe allowed Native American tribes in the Great Plains of North America to shift from a nomadic to a hunting lifestyle. Wheat from the Old World fast became a main food source for people in the Americas. Coffee from Africa and sugar cane from Asia became major cash crops for Latin American countries. And foods from the Americas, such as potatoes, tomatoes and corn, became staples for Europeans and helped increase their populations.

The Columbian Exchange also brought new diseases to both hemispheres, though the effects were greatest in the Americas. Smallpox from the Old World killed millions, decimating the Native American populations to mere fractions of their original numbers. This more than any other factor allowed for European domination of the Americas.

The overwhelming benefits of the Columbian Exchange went to the Europeans initially and eventually to the rest of the world. The Americas were forever altered, and the once vibrant cultures of the Indigenous civilizations were changed and lost, denying the world any complete understanding of their existence.

As more Italians began to immigrate to the United States and settle in major cities during the 19 th century, they were subject to religious and ethnic discrimination. This included a mass lynching of 11 Sicilian immigrants in 1891 in New Orleans.

Just one year after this horrific event, President Benjamin Harrison called for the first national observance of Columbus Day on October 12, 1892, to mark the 400 th anniversary of his arrival in the Americas. Italian-Americans saw this honorary act for Columbus as a way of gaining acceptance.

Colorado became the first state to officially observe Columbus Day in 1906 and, within five years, 14 other states followed. Thanks to a joint resolution of Congress, the day officially became a federal holiday in 1934 during the administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt . In 1970, Congress declared the holiday would fall on the second Monday in October each year.

But as Columbus’ legacy—specifically, his exploration’s impacts on Indigenous civilizations—began to draw more criticism, more people chose not to take part. As of 2023, approximately 29 states no longer celebrate Columbus Day , and around 195 cities have renamed it or replaced with the alternative Indigenous Peoples Day. The latter isn’t an official holiday, but the federal government recognized its observance in 2022 and 2023. President Joe Biden called it “a day in honor of our diverse history and the Indigenous peoples who contribute to shaping this nation.”

One of the most notable cities to move away from celebrating Columbus Day in recent years is the state capital of Columbus, Ohio, which is named after the explorer. In 2018, Mayor Andrew Ginther announced the city would remain open on Columbus Day and instead celebrate a holiday on Veterans Day. In July 2020, the city also removed a 20-plus-foot metal statue of Columbus from the front of City Hall.

- I went to sea from the most tender age and have continued in a sea life to this day. Whoever gives himself up to this art wants to know the secrets of Nature here below. It is more than forty years that I have been thus engaged. Wherever any one has sailed, there I have sailed.

- Speaking of myself, little profit had I won from twenty years of service, during which I have served with so great labors and perils, for today I have no roof over my head in Castile; if I wish to sleep or eat, I have no place to which to go, save an inn or tavern, and most often, I lack the wherewithal to pay the score.

- They say that there is in that land an infinite amount of gold; and that the people wear corals on their heads and very large bracelets of coral on their feet and arms; and that with coral they adorn and inlay chairs and chests and tables.

- This island and all the others are very fertile to a limitless degree, and this island is extremely so. In it there are many harbors on the coast of the sea, beyond comparison with others that I know in Christendom, and many rivers, good and large, which is marvelous.

- Our Almighty God has shown me the highest favor, which, since David, he has not shown to anybody.

- Already the road is opened to gold and pearls, and it may surely be hoped that precious stones, spices, and a thousand other things, will also be found.

- I have now seen so much irregularity, that I have come to another conclusion respecting the earth, namely, that it is not round as they describe, but of the form of a pear.

- In all the countries visited by your Highnesses’ ships, I have caused a high cross to be fixed upon every headland and have proclaimed, to every nation that I have discovered, the lofty estate of your Highnesses and of your court in Spain.

- I ought to be judged as a captain sent from Spain to the Indies, to conquer a nation numerous and warlike, with customs and religions altogether different to ours.

Fact Check: We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn’t look right, contact us !

The Biography.com staff is a team of people-obsessed and news-hungry editors with decades of collective experience. We have worked as daily newspaper reporters, major national magazine editors, and as editors-in-chief of regional media publications. Among our ranks are book authors and award-winning journalists. Our staff also works with freelance writers, researchers, and other contributors to produce the smart, compelling profiles and articles you see on our site. To meet the team, visit our About Us page: https://www.biography.com/about/a43602329/about-us

Tyler Piccotti first joined the Biography.com staff as an Associate News Editor in February 2023, and before that worked almost eight years as a newspaper reporter and copy editor. He is a graduate of Syracuse University. When he's not writing and researching his next story, you can find him at the nearest amusement park, catching the latest movie, or cheering on his favorite sports teams.

Watch Next .css-smpm16:after{background-color:#323232;color:#fff;margin-left:1.8rem;margin-top:1.25rem;width:1.5rem;height:0.063rem;content:'';display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;}

Possible Evidence of Amelia Earhart’s Plane

Charles Lindbergh

Was Christopher Columbus a Hero or Villain?

History & Culture

Barron Trump

Alexander McQueen

Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

Eleanor Roosevelt

Michelle Obama

Rare Vintage Photos of Celebrities at the Opera

The 12 Greatest Unsolved Disappearances

Henrietta Lacks

MA in American History : Apply now and enroll in graduate courses with top historians this summer!

- AP US History Study Guide

- History U: Courses for High School Students

- History School: Summer Enrichment

- Lesson Plans

- Classroom Resources

- Spotlights on Primary Sources

- Professional Development (Academic Year)

- Professional Development (Summer)

- Book Breaks

- Inside the Vault

- Self-Paced Courses

- Browse All Resources

- Search by Issue

- Search by Essay

- Become a Member (Free)

- Monthly Offer (Free for Members)

- Program Information

- Scholarships and Financial Aid

- Applying and Enrolling

- Eligibility (In-Person)

- EduHam Online

- Hamilton Cast Read Alongs

- Official Website

- Press Coverage

- Veterans Legacy Program

- The Declaration at 250

- Black Lives in the Founding Era

- Celebrating American Historical Holidays

- Browse All Programs

- Donate Items to the Collection

- Search Our Catalog

- Research Guides

- Rights and Reproductions

- See Our Documents on Display

- Bring an Exhibition to Your Organization

- Interactive Exhibitions Online

- About the Transcription Program

- Civil War Letters

- Founding Era Newspapers

- College Fellowships in American History

- Scholarly Fellowship Program

- Richard Gilder History Prize

- David McCullough Essay Prize

- Affiliate School Scholarships

- Nominate a Teacher

- Eligibility

- State Winners

- National Winners

- Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize

- Gilder Lehrman Military History Prize

- George Washington Prize

- Frederick Douglass Book Prize

- Our Mission and History

- Annual Report

- Contact Information

- Student Advisory Council

- Teacher Advisory Council

- Board of Trustees

- Remembering Richard Gilder

- President's Council

- Scholarly Advisory Board

- Internships

- Our Partners

- Press Releases

History Resources

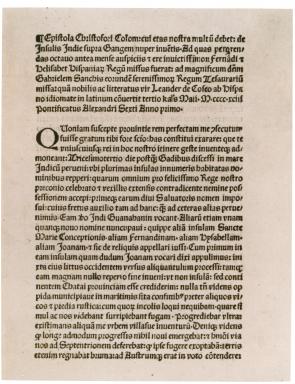

Columbus reports on his first voyage, 1493

A spotlight on a primary source by christopher columbus.

On August 3, 1492, Columbus set sail from Spain to find an all-water route to Asia. On October 12, more than two months later, Columbus landed on an island in the Bahamas that he called San Salvador; the natives called it Guanahani.

For nearly five months, Columbus explored the Caribbean, particularly the islands of Juana (Cuba) and Hispaniola (Santo Domingo), before returning to Spain. He left thirty-nine men to build a settlement called La Navidad in present-day Haiti. He also kidnapped several Native Americans (between ten and twenty-five) to take back to Spain—only eight survived. Columbus brought back small amounts of gold as well as native birds and plants to show the richness of the continent he believed to be Asia.

When Columbus arrived back in Spain on March 15, 1493, he immediately wrote a letter announcing his discoveries to King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, who had helped finance his trip. The letter was written in Spanish and sent to Rome, where it was printed in Latin by Stephan Plannck. Plannck mistakenly left Queen Isabella’s name out of the pamphlet’s introduction but quickly realized his error and reprinted the pamphlet a few days later. The copy shown here is the second, corrected edition of the pamphlet.

The Latin printing of this letter announced the existence of the American continent throughout Europe. “I discovered many islands inhabited by numerous people. I took possession of all of them for our most fortunate King by making public proclamation and unfurling his standard, no one making any resistance,” Columbus wrote.

In addition to announcing his momentous discovery, Columbus’s letter also provides observations of the native people’s culture and lack of weapons, noting that “they are destitute of arms, which are entirely unknown to them, and for which they are not adapted; not on account of any bodily deformity, for they are well made, but because they are timid and full of terror.” Writing that the natives are “fearful and timid . . . guileless and honest,” Columbus declares that the land could easily be conquered by Spain, and the natives “might become Christians and inclined to love our King and Queen and Princes and all the people of Spain.”

An English translation of this document is available.

I have determined to write you this letter to inform you of everything that has been done and discovered in this voyage of mine.

On the thirty-third day after leaving Cadiz I came into the Indian Sea, where I discovered many islands inhabited by numerous people. I took possession of all of them for our most fortunate King by making public proclamation and unfurling his standard, no one making any resistance. The island called Juana, as well as the others in its neighborhood, is exceedingly fertile. It has numerous harbors on all sides, very safe and wide, above comparison with any I have ever seen. Through it flow many very broad and health-giving rivers; and there are in it numerous very lofty mountains. All these island are very beautiful, and of quite different shapes; easy to be traversed, and full of the greatest variety of trees reaching to the stars. . . .

In the island, which I have said before was called Hispana , there are very lofty and beautiful mountains, great farms, groves and fields, most fertile both for cultivation and for pasturage, and well adapted for constructing buildings. The convenience of the harbors in this island, and the excellence of the rivers, in volume and salubrity, surpass human belief, unless on should see them. In it the trees, pasture-lands and fruits different much from those of Juana. Besides, this Hispana abounds in various kinds of species, gold and metals. The inhabitants . . . are all, as I said before, unprovided with any sort of iron, and they are destitute of arms, which are entirely unknown to them, and for which they are not adapted; not on account of any bodily deformity, for they are well made, but because they are timid and full of terror. . . . But when they see that they are safe, and all fear is banished, they are very guileless and honest, and very liberal of all they have. No one refuses the asker anything that he possesses; on the contrary they themselves invite us to ask for it. They manifest the greatest affection towards all of us, exchanging valuable things for trifles, content with the very least thing or nothing at all. . . . I gave them many beautiful and pleasing things, which I had brought with me, for no return whatever, in order to win their affection, and that they might become Christians and inclined to love our King and Queen and Princes and all the people of Spain; and that they might be eager to search for and gather and give to us what they abound in and we greatly need.

Questions for Discussion

Read the document introduction and transcript in order to answer these questions.

- Columbus described the Natives he first encountered as “timid and full of fear.” Why did he then capture some Natives and bring them aboard his ships?

- Imagine the thoughts of the Europeans as they first saw land in the “New World.” What do you think would have been their most immediate impression? Explain your answer.

- Which of the items Columbus described would have been of most interest to King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella? Why?

- Why did Columbus describe the islands and their inhabitants in great detail?

- It is said that this voyage opened the period of the “Columbian Exchange.” Why do you think that term has been attached to this period of time?

A printer-friendly version is available here .

Stay up to date, and subscribe to our quarterly newsletter..

Learn how the Institute impacts history education through our work guiding teachers, energizing students, and supporting research.

The Fourth Voyage of Christopher Columbus

The Famous Explorer's Final Voyage to the New World

- History Before Columbus

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Caribbean History

- Central American History

- South American History

- Mexican History

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

Before the Journey

- Hispaniola & the Hurricane

Across the Caribbean

Native encounters, central america to jamaica, a year on jamaica, importance of the fourth voyage.

- Ph.D., Spanish, Ohio State University

- M.A., Spanish, University of Montana

- B.A., Spanish, Penn State University

On May 11, 1502, Christopher Columbus set out on his fourth and final voyage to the New World with a fleet of four ships. His mission was to explore uncharted areas to the west of the Caribbean in hopes of finding a passage to the Orient. While Columbus did explore parts of southern Central America, his ships disintegrated during the voyage, leaving Columbus and his men stranded for nearly a year.

Much had happened since Columbus’ daring 1492 voyage of discovery . After that historic trip, Columbus was sent back to the New World to establish a colony. While a gifted sailor, Columbus was a terrible administrator, and the colony he founded on Hispaniola turned against him. After his third trip , Columbus was arrested and sent back to Spain in chains. Although he was quickly freed by the king and queen, his reputation was in shambles.

At 51, Columbus was increasingly being viewed as an eccentric by the members of the royal court, perhaps due to his belief that when Spain united the world under Christianity (which they would quickly accomplish with gold and wealth from the New World) that the world would end. He also tended to dress like a simple barefoot friar, rather than the wealthy man he had become.

Even so, the crown agreed to finance one last voyage of discovery. With royal backing, Columbus soon found four seaworthy vessels: the Capitana , Gallega , Vizcaína , and Santiago de Palos . His brothers, Diego and Bartholomew, and his son Fernando signed on as crew, as did some veterans of his earlier voyages.

Hispaniola & the Hurricane

Columbus was not welcome when he returned to the island of Hispaniola. Too many settlers remembered his cruel and ineffective administration . Nevertheless, after first visiting Martinique and Puerto Rico, he made Hispaniola his destination because had hopes of being able to swap the Santiago de Palos for a quicker ship while there. As he awaited an answer, Columbus realized a storm was approaching and sent word to the current governor, Nicolás de Ovando, that he should consider delaying the fleet that was set to depart for Spain.

Governor Ovando, resenting the interference, forced Columbus to anchor his ships in a nearby estuary. Ignoring the explorer's advice, he sent the fleet of 28 ships to Spain. A tremendous hurricane sank 24 of them: three returned and only one (Ironically, the one containing Columbus’ personal effects that he'd wished to send to Spain) arrived safely. Columbus’ own ships, all badly battered, nevertheless remained afloat.

After the hurricane passed, Columbus’ small fleet set out in search of a passage west, however, the storms did not abate and the journey became a living hell. The ships, already damaged by the forces of the hurricane, suffered substantially more abuse. Eventually, Columbus and his ships reached Central America, anchoring off the coast of Honduras on an island that many believe to be Guanaja, where they made what repairs they could and took on supplies.

While exploring Central America, Columbus had an encounter many consider to be the first with one of the major inland civilizations. Columbus’ fleet came in contact with a trading vessel, a very long, wide canoe full of goods and traders believed to be Mayan from the Yucatan. The traders carried copper tools and weapons, swords made of wood and flint, textiles, and a beerlike beverage made from fermented corn. Columbus, oddly enough, decided not to investigate the interesting trading civilization, and instead of turning north when he reached Central America, he went south.

Columbus continued exploring to the south along the coasts of present-day Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama. While there, Columbus and his crew traded for food and gold whenever possible. They encountered several native cultures and observed stone structures as well as maize being cultivated on terraces.

By early 1503, the structure of the ships began to fail. In addition to the storm damage the vessels had endured, it was discovered they were also infested with termites. Columbus reluctantly set sail for Santo Domingo looking for aid—but the ships only made it as far as Santa Gloria (St. Ann’s Bay), Jamaica before they were incapacitated.

Columbus and his men did what they could, breaking the ships apart to make shelters and fortifications. They formed a relationship with the local natives who brought them food. Columbus was able to get word to Ovando of his predicament, but Ovando had neither the resources nor the inclination to help. Columbus and his men languished on Jamaica for a year, surviving storms, mutinies, and an uneasy peace with the natives. (With the help of one of his books, Columbus was able to impress the natives by correctly predicting an eclipse .)

In June 1504, two ships finally arrived to retrieve Columbus and his crew. Columbus returned to Spain only to learn that his beloved Queen Isabella was dying. Without her support, he would never again return to the New World.

Columbus’ final voyage is remarkable primarily for new exploration, mostly along the coast of Central America. It's also of interest to historians, who value the descriptions of the native cultures encountered by Columbus’ small fleet, particularly those sections concerning the Mayan traders. Some of the fourth voyage crew would go on to greater things: Cabin boy Antonio de Alaminos eventually piloted and explored much of the western Caribbean. Columbus’ son Fernando wrote a biography of his famous father.

Still, for the most part, the fourth voyage was a failure by almost any standard. Many of Columbus’ men died, his ships were lost, and no passage to the west was ever found. Columbus never sailed again and when he died in 1506, he was convinced that he'd found Asia—even if most of Europe already accepted the fact that the Americas were an unknown “New World." That said, the fourth voyage showcased more profoundly than any other Columbus’ sailing skills, his fortitude, and his resilience—the very attributes that allowed him to journey to the Americas in the first place.

- Thomas, Hugh. "Rivers of Gold: The Rise of the Spanish Empire, from Columbus to Magellan." Random House. New York. 2005.

- Biography of Christopher Columbus

- The Third Voyage of Christopher Columbus

- Biography of Christopher Columbus, Italian Explorer

- 10 Facts About Christopher Columbus

- The Truth About Christopher Columbus

- The Second Voyage of Christopher Columbus

- Where Are the Remains of Christopher Columbus?

- The First New World Voyage of Christopher Columbus (1492)

- Biography of Juan Ponce de León, Conquistador

- Amerigo Vespucci, Explorer and Navigator

- Amerigo Vespucci, Italian Explorer and Cartographer

- Biography and Legacy of Ferdinand Magellan

- Biography of Ferdinand Magellan, Explorer Circumnavigated the Earth

- La Navidad: First European Settlement in the Americas

- A Timeline of North American Exploration: 1492–1585

- Español NEW

Voyages of Christopher Columbus facts for kids

Between 1492 and 1504, Italian explorer Christopher Columbus led four Spanish transatlantic maritime expeditions of discovery to the Americas . These voyages led to the widespread knowledge of the New World . This breakthrough inaugurated the period known as the Age of Discovery , which saw the colonization of the Americas , a related biological exchange , and trans-Atlantic trade . These events, the effects and consequences of which persist to the present, are often cited as the beginning of the modern era.

Born in the Republic of Genoa , Columbus was a navigator who sailed for the Crown of Castile (a predecessor to the modern Kingdom of Spain ) in search of a westward route to the Indies , thought to be the East Asian source of spices and other precious oriental goods obtainable only through arduous overland routes . Columbus was partly inspired by 13th-century Italian explorer Marco Polo in his ambition to explore Asia and never admitted his failure in this, incessantly claiming and pointing to supposed evidence that he had reached the East Indies. Ever since, the Bahamas as well as the islands of the Caribbean have been referred to as the West Indies .

At the time of Columbus's voyages, the Americas were inhabited by Indigenous Americans . Soon after first contact, Eurasian diseases such as smallpox began to devastate the indigenous populations . Columbus participated in the beginning of the Spanish conquest of the Americas , brutally treating and enslaving the natives in the range of thousands.

Columbus died in 1506, and the next year, the Americas were named after Amerigo Vespucci , who realized that these continents were a unique landmass. The search for a westward route to Asia was completed in 1521, when another Spanish voyage, the Magellan-Elcano expedition sailed across the Pacific Ocean and reached Southeast Asia , before returning to Europe and completing the first circumnavigation of the world.

Diameter of Earth and travel distance estimates

Trade winds, funding campaign, discovery of the americas, first return, caribbean exploration, hispaniola and jamaica, slavery, settlers, and tribute, colonist rebellions, bobadilla's inquiry, trial in spain, fourth voyage (1502–1504).

Many Europeans of Columbus's day assumed that a single, uninterrupted ocean surrounded Europe and Asia, although Norse explorers had colonized areas of North America beginning with Greenland c. 986 . The Norse maintained a presence in North America for hundreds of years, but contacts between their North American settlements and Europe had all but ceased by the early 15th century.

Until the mid-15th century, Europe enjoyed a safe land passage to China and India —sources of valued goods such as silk , spices , and opiates—under the hegemony of the Mongol Empire (the Pax Mongolica , or Mongol Peace). With the Fall of Constantinople to the Turkish Ottoman Empire in 1453, the land route to Asia (the Silk Road ) became more difficult as Christian traders were prohibited.

Portugal was the main European power interested in pursuing trade routes overseas, with the neighboring kingdom of Castile —predecessor to Spain —having been somewhat slower to begin exploring the Atlantic because of the land area it had to reconquer from the Moors during the Reconquista . This remained unchanged until the late 15th century, following the dynastic union by marriage of Queen Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon (together known as the Catholic Monarchs of Spain ) in 1469, and the completion of the Reconquista in 1492, when the joint rulers conquered the Moorish kingdom of Granada, which had been providing Castile with African goods through tribute . The fledgling Spanish Empire decided to fund Columbus's expedition in hopes of finding new trade routes and circumventing the lock Portugal had secured on Africa and the Indian Ocean with the 1481 papal bull Aeterni regis .

Navigation plans

In response to the need for a new route to Asia, by the 1480s, Christopher and his brother Bartholomew had developed a plan to travel to the Indies (then construed roughly as all of southern and eastern Asia) by sailing directly west across what was believed to be the singular "Ocean Sea," the Atlantic Ocean. By about 1481, Florentine cosmographer Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli sent Columbus a map depicting such a route, with no intermediary landmass other than the mythical island of Antillia . In 1484 on the island of La Gomera in the Canaries , then undergoing conquest by Castile , Columbus heard from some inhabitants of El Hierro that there was supposed to be a group of islands to the west.

A popular misconception that Columbus had difficulty obtaining support for his plan because Europeans thought the Earth was flat can be traced back to a 17th-century campaign of Protestants against Catholicism, and was popularized in works such as Washington Irving 's 1828 biography of Columbus. In fact, the knowledge that the Earth is spherical was widespread, having been the general opinion of Ancient Greek science, and gaining support throughout the Middle Ages (for example, Bede mentions it in The Reckoning of Time ). The primitive maritime navigation of Columbus's time relied on both the stars and the curvature of the Earth.

Eratosthenes had measured the diameter of the Earth with good precision in the 2nd century BC, and the means of calculating its diameter using an astrolabe was known to both scholars and navigators. Where Columbus differed from the generally accepted view of his time was in his incorrect assumption of a significantly smaller diameter for the Earth, claiming that Asia could be easily reached by sailing west across the Atlantic. Most scholars accepted Ptolemy 's correct assessment that the terrestrial landmass (for Europeans of the time, comprising Eurasia and Africa ) occupied 180 degrees of the terrestrial sphere, and dismissed Columbus's claim that the Earth was much smaller, and that Asia was only a few thousand nautical miles to the west of Europe.

Columbus believed the incorrect calculations of Marinus of Tyre, putting the landmass at 225 degrees, leaving only 135 degrees of water. Moreover, Columbus underestimated Alfraganus's calculation of the length of a degree, reading the Arabic astronomer's writings as if, rather than using the Arabic mile (about 1,830 m), he had used the Italian mile (about 1,480 meters). Alfraganus had calculated the length of a degree to be 56⅔ Arabic miles (66.2 nautical miles). Columbus therefore estimated the size of the Earth to be about 75% of Eratosthenes's calculation, and the distance from the Canary Islands to Japan as 2,400 nautical miles (about 23% of the real figure).

There was a further element of key importance in the voyages of Columbus, the trade winds. He planned to first sail to the Canary Islands before continuing west by utilizing the northeast trade wind. Part of the return to Spain would require traveling against the wind using an arduous sailing technique called beating, during which almost no progress can be made. To effectively make the return voyage, Columbus would need to follow the curving trade winds northeastward to the middle latitudes of the North Atlantic, where he would be able to catch the " westerlies " that blow eastward to the coast of Western Europe.

The navigational technique for travel in the Atlantic appears to have been exploited first by the Portuguese, who referred to it as the volta do mar ('turn of the sea'). Columbus's knowledge of the Atlantic wind patterns was, however, imperfect at the time of his first voyage. By sailing directly due west from the Canary Islands during hurricane season , skirting the so-called horse latitudes of the mid-Atlantic, Columbus risked either being becalmed or running into a tropical cyclone , both of which, by chance, he avoided.

Around 1484, King John II of Portugal submitted Columbus's proposal to his experts, who rejected it on the basis that Columbus's estimation of a travel distance of 2,400 nautical miles was about four times too low (which was accurate).

In 1486, Columbus was granted an audience with the Catholic Monarchs, and he presented his plans to Isabella. She referred these to a committee, which determined that Columbus had grossly underestimated the distance to Asia. Pronouncing the idea impractical, they advised the monarchs not to support the proposed venture. To keep Columbus from taking his ideas elsewhere, and perhaps to keep their options open, the Catholic Monarchs gave him an allowance, totaling about 14,000 maravedís for the year, or about the annual salary of a sailor.

In 1488 Columbus again appealed to the court of Portugal, receiving a new invitation for an audience with John II. This again proved unsuccessful, in part because not long afterwards Bartolomeu Dias returned to Portugal following a successful rounding of the southern tip of Africa. With an eastern sea route now under its control, Portugal was no longer interested in trailblazing a western trade route to Asia crossing unknown seas.

In May 1489, Isabella sent Columbus another 10,000 maravedis , and the same year the Catholic Monarchs furnished him with a letter ordering all cities and towns under their domain to provide him food and lodging at no cost.

As Queen Isabella's forces neared victory over the Moorish Emirate of Granada for Castile, Columbus was summoned to the Spanish court for renewed discussions. He waited at King Ferdinand's camp until January 1492, when the monarchs conquered Granada. A council led by Isabella's confessor, Hernando de Talavera , found Columbus's proposal to reach the Indies implausible. Columbus had left for France when Ferdinand intervened, first sending Talavera and Bishop Diego Deza to appeal to the queen. Isabella was finally convinced by the king's clerk Luis de Santángel , who argued that Columbus would bring his ideas elsewhere, and offered to help arrange the funding. Isabella then sent a royal guard to fetch Columbus, who had travelled several kilometers toward Córdoba.

In the April 1492 " Capitulations of Santa Fe ", Columbus was promised he would be given the title "Admiral of the Ocean Sea" and appointed viceroy and governor of the newly claimed and colonized for the Crown; he would also receive ten percent of all the revenues from the new lands in perpetuity if he was successful. He had the right to nominate three people, from whom the sovereigns would choose one, for any office in the new lands. The terms were unusually generous but, as his son later wrote, the monarchs were not confident of his return.

First voyage (1492–1493)

For his westward voyage to find a shorter route to the Orient , Columbus and his crew took three medium-sized ships, the largest of which was a carrack (Spanish: nao ), the Santa María , which was owned and captained by Juan de la Cosa , and under Columbus's direct command. The other two were smaller caravels ; the name of one is lost, but is known by the Castilian nickname Pinta ('painted one'). The other, the Santa Clara , was nicknamed the Niña ('girl'), perhaps in reference to her owner, Juan Niño of Moguer. The Pinta and the Niña were piloted by the Pinzón brothers ( Martín Alonso and Vicente Yáñez , respectively). On the morning of 3 August 1492, Columbus departed from Palos de la Frontera , going down the Rio Tinto and into the Atlantic.

Three days into the journey, on 6 August 1492, the rudder of the Pinta broke. Martín Alonso Pinzón suspected the owners of the ship of sabotage, as they were afraid to go on the journey. The crew was able to secure the rudder with ropes until they could reach the Canary Islands, where they arrived on 9 August. The Pinta had its rudder replaced on the island of Gran Canaria , and by September 2 the ships rendezvoused at La Gomera, where the Niña ' s lateen sails were re-rigged to standard square sails. Final provisions were secured, and on 6 September the ships departed San Sebastián de La Gomera for what turned out to be a five-week-long westward voyage across the Atlantic.

As described in the abstract of his journal made by Bartolomé de las Casas , on the outward bound voyage Columbus recorded two sets of distances: one was in measurements he normally used, the other in the Portuguese maritime leagues used by his crew. Las Casas originally interpreted that he reported the shorter distances to his crew so they would not worry about sailing too far from Spain, but Oliver Dunn and James Kelley state that this was a misunderstanding.

On 13 September 1492, Columbus observed that the needle of his compass no longer pointed to the North Star . It was once believed that Columbus had discovered magnetic declination, but it was later shown that the phenomenon was already known, both in Europe and in China.

After 29 days out of sight of land, on 7 October 1492, the crew spotted "[i]mmense flocks of birds", some of which his sailors trapped and determined to be "field" birds (probably Eskimo curlews and American golden plovers ). Columbus changed course to follow their flight.

On 11 October, Columbus changed the fleet's course to due west, and sailed through the night, believing land was soon to be found. At around 10:00 in the evening, Columbus thought he saw a light "like a little wax candle rising and falling". Four hours later, land was sighted by a sailor named Rodrigo de Triana (also known as Juan Rodríguez Bermejo) aboard the Pinta . Triana immediately alerted the rest of the crew with a shout, and the ship's captain, Martín Alonso Pinzón, verified the land sighting and alerted Columbus by firing a lombard. Columbus would later assert that he had first seen land, thus earning the promised annual reward of 10,000 maravedís .

Columbus called this island San Salvador, in the present-day Bahamas ; the indigenous residents had named it Guanahani . According to Samuel Eliot Morison , San Salvador Island is the only island fitting the position indicated by Columbus's journal. Columbus wrote of the natives he first encountered in his journal entry of 12 October 1492:

Many of the men I have seen have scars on their bodies, and when I made signs to them to find out how this happened, they indicated that people from other nearby islands come to San Salvador to capture them; they defend themselves the best they can. I believe that people from the mainland come here to take them as slaves . They ought to make good and skilled servants, for they repeat very quickly whatever we say to them. I think they can very easily be made Christians, for they seem to have no religion. If it pleases our Lord, I will take six of them to Your Highnesses when I depart, in order that they may learn our language.

Columbus called the indigenous Americans indios (Spanish for Indians) in the mistaken belief that he had reached the East Indies; the islands of the Caribbean are termed the West Indies after this error. Columbus initially encountered the Lucayan , Taíno , and Arawak peoples. Noting their gold ear ornaments, Columbus took some of the Arawaks prisoner and insisted that they guide him to the source of the gold. Columbus noted that their primitive weapons and military tactics made the natives susceptible to easy conquest.

Columbus observed the people and their cultural lifestyle. He also explored the northeast coast of Cuba , landing on 28 October 1492, and the north-western coast of Hispaniola , present day Haiti , by 5 December 1492. Here, the Santa Maria ran aground on Christmas Day , 25 December 1492, and had to be abandoned. Columbus was received by the native cacique Guacanagari , who gave him permission to leave some of his men behind. Columbus left 39 men, including the interpreter Luis de Torres , and founded the settlement of La Navidad. He kept sailing along the northern coast of Hispaniola with a single ship, until he encountered Pinzón and the Pinta on 6 January.

On 13 January 1493, Columbus made his last stop of this voyage in the Americas, in the Bay of Rincón at the eastern end of the Samaná Peninsula in northeast Hispaniola. There he encountered the Ciguayos , the only natives who offered violent resistance during his first voyage to the Americas. The Ciguayos refused to trade the amount of bows and arrows that Columbus desired; in the ensuing clash one Ciguayo was stabbed and another wounded with an arrow in his chest. Because of this and because of the Ciguayos' use of arrows, he called the inlet where he met them the Bay of Arrows (or Gulf of Arrows). On 16 January 1493, the homeward journey was begun.

Four natives who boarded the Niña at Samaná Peninsula told Columbus of what was interpreted as the Isla de Carib (probably Puerto Rico ), which was supposed to be populated by cannibalistic Caribs, as well as Matinino, an island populated only by women, which Columbus associated with an island in the Indian Ocean that Marco Polo had described.

While returning to Spain, the Niña and Pinta encountered the roughest storm of their journey, and, on the night of 13 February, lost contact with each other. All hands on the Niña vowed, if they were spared, to make a pilgrimage to the nearest church of Our Lady wherever they first made land. On the morning of 15 February, land was spotted. Columbus believed they were approaching the Azores Islands , but other members of the crew felt that they were considerably north of the islands. Columbus turned out to be right. On the night of 17 February, the Niña laid anchor at Santa Maria Island , but the cable broke on sharp rocks, forcing Columbus to stay offshore until the morning, when a safer location was found to drop anchor nearby. A few sailors took a boat to the island, where they were told by several islanders of a still safer place to land, so the Niña moved once again. At this spot, Columbus took on board several islanders who had gathered onshore with food, and told them that his crew wished to come ashore to fulfill their vow. The islanders told him that a small shrine dedicated to Our Lady was nearby.

Columbus sent half of the crew members to the island to fulfill their vow, but he and the rest of the crew stayed on the Niña , planning to send the other half to the island upon the return of the first crew members. While the first crew members were saying their prayers at the shrine, they were taken prisoner by the islanders, under orders from the island's captain, João de Castanheira, ostensibly out of fear that the men were pirates. The boat that the crew members had taken to the island was then commandeered by Castanheira, which he took with several armed men to the Niña , in an attempt to arrest Columbus. During a verbal battle across the bows of both craft, during which Columbus did not grant permission for him to come aboard, Castanheira announced that he did not believe or care who Columbus said that he was, especially if he was indeed from Spain. Castanheira returned to the island. However, after another two days, Castanheira released the prisoners, having been unable to get confessions from them, and having been unable to capture his real target, Columbus. There are later claims that Columbus was also captured, but this is not backed up by Columbus's log book.

Leaving the island of Santa Maria in the Azores on 23 February, Columbus headed for Castilian Spain, but another storm forced him into Lisbon . He anchored next to the king's harbor patrol ship on 4 March 1493, where he was told a fleet of 100 caravels had been lost in the storm. Astoundingly, both the Niña and the Pinta had been spared. Not finding King John II of Portugal in Lisbon, Columbus wrote a letter to him and waited for the king's reply. After receiving the letter, the king agreed to meet with Columbus in Vale do Paraíso despite poor relations between Portugal and Castile at the time. Upon learning of Columbus's discoveries, the Portuguese king informed him that he believed the voyage to be in violation of the 1479 Treaty of Alcáçovas . After spending more than a week in Portugal, Columbus set sail for Spain. Columbus arrived back in Palos on 15 March 1493 and later met with Ferdinand and Isabella in Barcelona to report his findings.

Columbus showed off what he had brought back from his voyage to the monarchs, including a few small samples of gold, pearls , gold jewelry from the natives, flowers, and a hammock. He gave the monarchs a few of the gold nuggets, gold jewelry, and pearls, as well as the previously unknown tobacco plant, the pineapple fruit, the turkey, and the hammock. The monarchs invited Columbus to dine with them. He did not bring any of the coveted East Indies spices, such as the exceedingly expensive black pepper, ginger or cloves. In his log, he wrote "there is also plenty of 'ají', which is their pepper, which is more valuable than black pepper, and all the people eat nothing else, it being very wholesome".

Upon first landing in the Americas, Columbus had written to the monarchs offering to enslave some of the indigenous Americans. While the Caribs may have met the sovereign's requirements for such treatment on the grounds of their aggressiveness towards the peaceful Taíno, Columbus had yet to meet them and only brought Taínos before the sovereigns. In Columbus's letter on the first voyage , addressed to the Spanish court, he insisted he had reached Asia, describing the island of Hispaniola as being off the coast of China. He emphasized the potential riches of the land and that the natives seemed ready to convert to Christianity. The descriptions in this letter, which was translated into multiple languages and widely distributed, were idealized, particularly regarding the supposed abundance of gold:

Hispaniola is a miracle. Mountains and hills, plains and pastures, are both fertile and beautiful ... the harbors are unbelievably good and there are many wide rivers of which the majority contain gold. ... There are many spices, and great mines of gold and other metals...

Upon Columbus's return, most people initially accepted that he had reached the East Indies, including the sovereigns and Pope Alexander VI , though in a letter to the Vatican dated 1 November 1493, the historian Peter Martyr described Columbus as the discoverer of a Novi Orbis (' New Globe '). The pope issued four bulls (the first three of which are collectively known as the Bulls of Donation ), to determine how Spain and Portugal would colonize and divide the spoils of the new lands. Inter caetera , issued 4 May 1493, divided the world outside Europe between Spain and Portugal along a north–south meridian 100 leagues west of either the Azores or Cape Verde Islands in the mid-Atlantic, thus granting Spain all the land discovered by Columbus. The 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas , ratified the next decade by Pope Julius II , moved the dividing line to 370 leagues west of the Azores or Cape Verde.

Second voyage (1493–1496)

The stated purpose of the second voyage was to convert the indigenous Americans to Christianity. Before Columbus left Spain, he was directed by Ferdinand and Isabella to maintain friendly, even loving, relations with the natives. He set sail from Cádiz , Spain, on 25 September 1493.

The fleet for the second voyage was much larger: two naos and 15 caravels. The two naos were the flagship Marigalante ("Gallant Mary") and the Gallega ; the caravels were the Fraila ('the nun'), San Juan , Colina ('the hill'), Gallarda ('the gallant'), Gutierre , Bonial , Rodriga , Triana , Vieja ('the old'), Prieta ('the brown'), Gorda ('the fat'), Cardera , and Quintera . The Niña returned for this expedition, which also included a ship named Pinta probably identical to that from the first expedition. In addition, the expedition saw the construction of the first ship in the Americas, the Santa Cruz or India .

On 3 November 1493, Christopher Columbus landed on a rugged shore on an island that he named Dominica . On the same day, he landed at Marie-Galante , which he named Santa María la Galante. After sailing past Les Saintes (Todos los Santos), he arrived at Guadeloupe (Santa María de Guadalupe), which he explored between 4 November and 10 November 1493. The exact course of his voyage through the Lesser Antilles is debated, but it seems likely that he turned north, sighting and naming many islands including Santa María de Montserrat ( Montserrat ), Santa María la Antigua ( Antigua ), Santa María la Redonda ( Saint Martin ), and Santa Cruz ( Saint Croix , on 14 November). He also sighted and named the island chain of the Santa Úrsula y las Once Mil Vírgenes (the Virgin Islands ), and named the islands of Virgen Gorda.

The fleet continued to the Greater Antilles , and landed on the island of San Juan Bautista, present-day Puerto Rico, on 19 November 1493.

On 22 November, Columbus sailed from San Juan Bautista to Hispaniola. The next morning, a native taken during the first voyage was returned to Samaná Bay . The fleet sailed about 170 miles over two days. On the night of 27 November, cannons and flares were ignited in an attempt to signal La Navidad, but there was no response. A canoe party led by a cousin of Guacanagari presented Columbus with two golden masks and told him that Guacanagari had been injured by another chief, Caonabo , and that except for some Spanish casualties resulting from sickness and quarrel, the rest of his men were well. The next day, the Spanish fleet discovered the burnt remains of the Navidad fortress, and Guacanagari's cousin admitted that the Europeans had been wiped out by Caonabo. While some suspicion was placed on Guacanagari, it gradually emerged that two of the Spaniards had formed a murderous gang in search of gold, prompting Caonabo's wrath. The fleet then fought the winds, traveling only 32 miles over 25 days, and arriving at a plain on the north coast of Hispaniola on 2 January 1494. There, they established the settlement of La Isabela . Columbus spent some time exploring the interior of the island for gold. Finding some, he established a small fort in the interior.

Columbus left Hispaniola on 24 April 1494, and arrived at the island of Cuba (which he had named Juana during his first voyage) on 30 April and Discovery Bay, Jamaica, on 5 May. He explored the south coast of Cuba, which he believed to be a peninsula of China rather than an island, and several nearby islands including La Evangelista (the Isle of Youth ), before returning to Hispaniola on 20 August.

Columbus had planned for Queen Isabella to set up trading posts with the cities of the Far East made famous by Marco Polo, but whose Silk Road and eastern maritime routes had been blockaded to her crown's trade. However, Columbus would never find Cathay (China) or Zipangu ( Japan ), and there was no longer any Great Khan for trade treaties.

In 1494, Columbus sent Alonso de Ojeda (whom a contemporary described as "always the first to draw blood wherever there was a war or quarrel") to Cibao (where gold was being mined for), which resulted in Ojeda's capturing several natives on an accusation of theft. Ojeda sent them to La Isabela in chains, where Columbus ordered them to be executed. During his brief reign, Columbus executed Spanish colonists for minor crimes. By the end of 1494, disease and famine had claimed two-thirds of the Spanish settlers. A native Nahuatl account depicts the social breakdown that accompanied the pandemic : "A great many died from this plague, and many others died of hunger. They could not get up to search for food, and everyone else was too sick to care for them."