Type your tag names separated by a space and hit enter

- Z09 - Encounter for follow-up examination after completed treatment for conditions other than malignant neoplasm

- Medical surveillance following completed treatment

Use Additional Code

- code to identify any applicable history of disease code ( Z86. -, Z87. -)

Not Coded Here

- aftercare following medical care ( Z43 - Z49 , Z51 )

- surveillance of contraception ( Z30.4 -)

- surveillance of prosthetic and other medical devices ( Z44 - Z46 )

- Z00 - Encounter for general examination without complaint, suspected or reported diagnosis

- Z01 - Encounter for other special examination without complaint, suspected or reported diagnosis

- Z02 - Encounter for administrative examination

- Z03 - Encounter for medical observation for suspected diseases and conditions ruled out

- Z04 - Encounter for examination and observation for other reasons

- Z05 - Encounter for observation and evaluation of newborn for suspected diseases and conditions ruled out

- Z08 - Encounter for follow-up examination after completed treatment for malignant neoplasm

- Z11 - Encounter for screening for infectious and parasitic diseases

- Z12 - Encounter for screening for malignant neoplasms

- Z13 - Encounter for screening for other diseases and disorders

1. Download the ICD-10-CM app by Unbound Medicine

2. Select Try/Buy and follow instructions to begin your free 30-day trial

Want to regain access to ICD-10-CM?

Renew my subscription

Not now - I'd like more time to decide

Log in to ICD-10-CM

Forgot your password, forgot your username, contact support.

- unboundmedicine.com/support

- [email protected]

- 610-627-9090 (Monday - Friday, 9 AM - 5 PM EST.)

Coding Transition Care Management

- By Terry A. Fletcher BS, CPC, CCC, CEMC, CCS, CCS-P, CMC, CMSCS, ACS-CA, SCP-CA, QMGC, QMCRC, QMPM

- July 8, 2019

New patient management service codes.

The Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS) recently added several patient management service codes that have face to face and non-face-to-face components to them for physician reimbursement. One of those services is transition care management (TCM). These CPT® codes allow for reimbursement of the care provided when patients transition from an acute care or hospital setting back into the community setting (home, domiciliary, rest home, assisted living).

TCM commences upon date of discharge and then for the next 29 days. There is a combination of face to face and non-face to face services within this time frame. There has been some misinformation out there on the requirements to report these codes that has triggered some payer audits, so we wanted to clear up any confusion.

CPT Code 99495 covers communication with the patient and/or caregiver within two business days of discharge. This is a reciprocal communication of direct contact that can be done by phone or electronic means. It involves medical decision making of at least moderate complexity during the service period and a face-to-face visit within 14 days of discharge. The location of the visit is not specified, but where the face to face occurs is the POS that is used for reporting purposes. The work RVU is 2.11 or an approximate reimbursement of $75.96

CPT Code 99496 covers the same code details, involves medical decision making of high complexity and a face-to-face visit within seven days of discharge. The work RVU is 3.05. or an approximate reimbursement of $109.80

Although the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) continues to fine-tune expectations for the services provided during the TCM time period, in addition to the above, the following required non-face-to-face services may differ for physician/midlevel provider and the clinical staff.

Clinical staff (under the supervision of a physician or other qualified clinician) may include the following:

- Communicate with a home health agency or other community services that the patient needs,

- Educate the patient and/or caregiver to support self-management and activities of daily living,

- Provide assessment and support for treatment adherence and medication management,

- Identify available community and health resources, and

- Facilitate access to services needed by the patient and/or caregivers

- Communicate with the patient or caregiver regarding aspects of care. Check your local MAC carrier for their LCD on who can make the 48-hour call. In some states, it has to be either an MD/DO or a mid-level who has direct knowledge of the patient’s care plan.

The physician or other qualified clinician services may include the following:

- Obtain and review discharge information,

- Review need of or follow-up on pending testing or treatment,

- Interact with other clinicians who will assume or resume care of the patient’s system-specific conditions,

- Educate the patient and/or caregiver,

- Establish or re-establish referrals for specialized care, and

- Assist in scheduling follow-up with other health services.

Some additional service that would be expected to be documented in regarding use of these codes would be:

- Medication reconciliation and management should happen no later than the face-to-face visit.

- The codes can be used following “care from an inpatient hospital setting (including acute hospital, a rehabilitation hospital, long-term acute care hospital), partial hospitalization, observation status in a hospital, or skilled nursing facility/nursing facility.”

- The codes cannot be used with G0181 (home health care plan oversight) or G0182 (hospice care plan oversight), Home and outpatient INR monitoring, (93792-93793), Medical Team Conferences, Education and training, telephone services, ESRD services, CCM, and medication therapy management services because the services are duplicative.

- Billing should occur at the conclusion of the 30-day post-discharge period. Now CMS put out on their website FAQ’s in 2018, saying that the date of the face to face can be the date the entire service is billed. But I would use caution and common sense here. Once all of the 30 days of service is met, then report the code. By reporting prior to the 30-day period, you run the risk of staff not finishing the tasks that are part of the code compliance.

- They are payable only once per patient in the 30 days following discharge, thus if the patient is readmitted TCM cannot be billed again.

- Only one individual can bill per patient, so it is important to establish the primary physician in charge of the coordination of care during this time period. If there is a question, then it might be important to contact the other physician’s office to clarify. The discharging physician should tell the patient which clinician will be providing and billing for the TCM services.

- The codes apply to both new and established patients.

- The reporting provider provides or oversees the management and/or coordination of services as needed, for all medical conditions, psychosocial needs and ADL support providing first contact and continuous support.

Can these codes be billed in the post-operative period? Not for the physician that reported the global service.

CPT versus. Medicare on two-way Interactive Contact

The contact must include the capacity for prompt interactive communication addressing patient status and needs beyond scheduling follow up care. If two or more separate attempts are made to contact the patient and are unsuccessful, but other TCM criteria are met, CPT instructs to report the service, however, CMS frowns on this direction. There must be evidence of direct patient reciprocal contact to report these services to Medicare.

Per CPT, these services, “address any needed coordination of care performed by multiple disciplines and community service agencies. The reporting individual provides or oversees the management and/or coordination of services needed, for all medical conditions, psychosocial needs and activity of ADL support by providing first contact and continuous access”.

Before you make the decision to take this on, your practice should have a conversation, is it worth it to bill for these services based on the reimbursement offered? You are taking on the entire “transitional care” of this patient. If you plan to do so, realize the work, clinically and administratively, the cost, the reimbursement, and the payer expectation.

Comment on this article

- TAGS: CMS , CPT , Reimbursement

Terry A. Fletcher BS, CPC, CCC, CEMC, CCS, CCS-P, CMC, CMSCS, ACS-CA, SCP-CA, QMGC, QMCRC, QMPM

Related stories.

New CMS Rule Sets Stringent Staffing Standards for Long-Term Care Facilities

In a landmark move, on April 22, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) issued the Minimum Staffing Standards for Long-Term Care (LTC) Facilities

CMMI Independence at Home Program Falling Short in Delivering Results – After Eight Years of Trying

Last week the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation Center (CMMI) released the evaluation of their Year 8 Independence at Home (IAH) demonstration. IAH is

Leave a Reply

Please log in to your account to comment on this article.

Featured Webcasts

Navigating AI in Healthcare Revenue Cycle: Maximizing Efficiency, Minimizing Risks

Michelle Wieczorek explores challenges, strategies, and best practices to AI implementation and ongoing monitoring in the middle revenue cycle through real-world use cases. She addresses critical issues such as the validation of AI algorithms, the importance of human validation in machine learning, and the delineation of responsibilities between buyers and vendors.

Leveraging the CERT: A New Coding and Billing Risk Assessment Plan

Frank Cohen shows you how to leverage the Comprehensive Error Rate Testing Program (CERT) to create your own internal coding and billing risk assessment plan, including granular identification of risk areas and prioritizing audit tasks and functions resulting in decreased claim submission errors, reduced risk of audit-related damages, and a smoother, more efficient reimbursement process from Medicare.

2024 Observation Services Billing: How to Get It Right

Dr. Ronald Hirsch presents an essential “A to Z” review of Observation, including proper use for Medicare, Medicare Advantage, and commercial payers. He addresses the correct use of Observation in medical patients and surgical patients, and how to deal with the billing of unnecessary Observation services, professional fee billing, and more.

Top-10 Compliance Risk Areas for Hospitals & Physicians in 2024: Get Ahead of Federal Audit Targets

Explore the top-10 federal audit targets for 2024 in our webcast, “Top-10 Compliance Risk Areas for Hospitals & Physicians in 2024: Get Ahead of Federal Audit Targets,” featuring Certified Compliance Officer Michael G. Calahan, PA, MBA. Gain insights and best practices to proactively address risks, enhance compliance, and ensure financial well-being for your healthcare facility or practice. Join us for a comprehensive guide to successfully navigating the federal audit landscape.

2024 SDoH Update: Navigating Coding and Screening Assessment

Dive deep into the world of Social Determinants of Health (SDoH) coding with our comprehensive webcast. Explore the latest OPPS codes for 2024, understand SDoH assessments, and discover effective strategies for integrating coding seamlessly into healthcare practices. Gain invaluable insights and practical knowledge to navigate the complexities of SDoH coding confidently. Join us to unlock the potential of coding in promoting holistic patient care.

2024 ICD-10-CM/PCS Coding Clinic Update Webcast Series

HIM coding expert, Kay Piper, RHIA, CDIP, CCS, reviews the guidance and updates coders and CDIs on important information in each of the AHA’s 2024 ICD-10-CM/PCS Quarterly Coding Clinics in easy-to-access on-demand webcasts, available shortly after each official publication.

2024 ICD-10-CM/PCS Coding Clinic Update: Fourth Quarter

Kay Piper reviews the guidance and updates coders and CDISs on important information in the AHA’s fourth quarter 2024 ICD-10-CM/PCS Quarterly Coding Clinic in an easy to access on-demand webcast.

2024 ICD-10-CM/PCS Coding Clinic Update: Third Quarter

Kay Piper reviews the guidance and updates coders on information in the AHA’s third quarter 2024 ICD-10-CM/PCS Coding Clinic in an easy to access on-demand webcast.

Trending News

Defenses Against AI-Based Medicare Audits: Part II

Two-Midnight Rule Among Topics at NPAC 2024

How Fish Are Related to Medicare

Ten Tips for Effective Patient Identity Queue Management

Stay connected.

Subscribe to receive free ICD-10 news and updates.

5874 Blackshire Path, #13 Inver Grove Heights, MN 55076

Hours: 9am – 5pm CT Phone: (800) 252-1578 Email: [email protected]

Copyright © 2024 ICD10monitor. Powered by MedLearn Media.

Happy World Health Day! Our exclusive webcast, ‘2024 SDoH Update: Navigating Coding and Screening Assessment,’ is just $99 for a limited time! Use code WorldHealth24 at checkout.

- Become a Member

- Everyday Coding Q&A

- Can I get paid

- Coding Guides

- Quick Reference Sheets

- E/M Services

- How Physician Services Are Paid

- Prevention & Screening

- Care Management & Remote Monitoring

- Surgery, Modifiers & Global

- Diagnosis Coding

- New & Newsworthy

- Practice Management

- E/M Rules Archive

May 1, 2024

Aftercare and Follow-Up: ICD-10 Coding

Aftercare visit codes are assigned in situations in which the initial treatment of a disease has been performed but the patient requires continued care during the healing or recovery phase, or for the long-term consequences of the disease.

ICD-10 makes two important points about the use of aftercare codes in the final chapter.

- The aftercare Z code should not be used if treatment is directed at a current, acute disease.

- The aftercare Z codes should not be used for aftercare for injuries.

Certain aftercare Z code categories need a secondary diagnosis code to describe the resolving condition or sequelae. For others, the condition is included in the code title.

Want unlimited access to CodingIntel's online library?

Including updates on CPT ® and CMS coding changes for 2024

Last revised April 9, 2024 - Betsy Nicoletti Tags: general surgery_diagnosis coding , ICD-10 coding

CPT®️️ is a registered trademark of the American Medical Association. Copyright American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

All content on CodingIntel is copyright protected. Any resource shared within the permissions granted here may not be altered in any way, and should retain all copyright information and logos.

- What is CodingIntel

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

Our mission is to provide up-to-date, simplified, citation driven resources that empower our members to gain confidence and authority in their coding role.

In 1988, CodingIntel.com founder Betsy Nicoletti started a Medical Services Organization for a rural hospital, supporting physician practice. She has been a self-employed consultant since 1998. She estimates that in the last 20 years her audience members number over 28,400 at in person events and webinars. She has had 2,500 meetings with clinical providers and reviewed over 43,000 medical notes. She knows what questions need answers and developed this resource to answer those questions.

Copyright © 2024, CodingIntel A division of Medical Practice Consulting, LLC Privacy Policy

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

ICD-10 advice, and clarifying transitional care management

The reset compliance date of Oct. 1, 2014, means that internists must move forward with transition and education plans for using the new ICD-10 codes. Start by examining documentation needed to assign the new codes.

D o not delay your plans to transition to ICD-10, even though the compliance date set by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services is Oct. 1, 2014. ACP has not had any indication that the changeover to the new diagnosis code set will be delayed again, or canceled. With that in mind, all practices should be moving forward with their transition and education plans.

By this deadline, medical practices and the clearinghouses, payers, and billing companies that they work with will need to use ICD-10 codes. One way to begin preparing for ICD-10 is to begin looking closely at how clinical services are documented. This will help the physician and the coding staff to become more accustomed to the specific, detailed clinical documentation needed to assign ICD-10 codes.

Start by examining documentation for the most frequently used codes in the practice, and work with coding staff to determine if the documentation would be specific and detailed enough to select the best ICD-10 codes.

For example, laterality is expanded in ICD-10-CM. As a result, clinical documentation should include a statement of which side of the body is affected (i.e., right, left or bilateral).

Here are two examples of the specific information you will need to accurately code the following common diagnoses.

For diabetes mellitus, the following information will be needed: type of diabetes (i.e., due to underlying condition, chemical- or drug-induced, type 1, type 2); body system affected; complication or manifestation; and, for type 2 diabetes, whether there is long-term insulin use.

For injuries, the following information will be needed:

- External cause. Provide the cause of the injury; when meeting with patients, ask and document “how” the injury happened.

- Place of occurrence. Document where the patient was when the injury occurred; for example, include if the patient was at home, at work, in the car, etc.;

- Activity code. Describe what the patient was doing at the time of the injury; for example, was he or she playing a sport or using a tool?

- External cause status. Indicate if the injury was related to military, work or other.

Remember, ICD-10 will not affect the way you provide patient care. But it will be necessary to make your documentation as detailed as possible, since ICD-10 contains more specific choices for diagnosis coding. This information is likely already being shared by the patient during your visit; you'll now need to be sure to record it in the documentation so that your coding staff can see it. Solid documentation will also help reduce the need to follow up on submitted claims that might get bogged down for lack of a specific diagnosis—saving you time and money.

Additional resources to help you prepare are available at the CMS ICD-10 website .

Transitional care management services

ACP's Health Policy and Regulatory Affairs department has received many questions about the new transitional care management (TCM) CPT codes since they became effective in January 2013. What follows are a few of the questions and the staff's responses.

Q: For the TCM codes CPT 99495 and 99496, how long does the physician have until he/she sees the patient after the facility discharge? I've been told that the code used and allowable time permitted to see the patient after discharge vary based on whether moderate or complex medical decision-making is involved. Is this based on the hospitalization (which might be difficult for the outpatient primary care physician to determine) or on the complexity at the subsequent office visit? If it were the latter (which could not be known until the visit), it would seem that if the patient comes in after 7 days and if the decision making is found to be complex, it will be too late to charge for 99496. Can we charge for another evaluation and management (or any other CPT) code at the follow-up visit?

A: According to the CPT code descriptors, the patient should be seen by the physician within 7 or 14 days after discharge. The choice of codes is determined by the date of the first face-to-face visit after hospital/facility discharge and the level of medical decision making at that first visit. If there is a subsequent face-to-face visit within the same service period (30 days), that visit may be billed separately.

Q: To bill a TCM code, is it true that CMS requires physicians or clinical staff members to telephone the patient within 24 hours of discharge?

A: No. Under the CMS billing rules, the patient should be contacted within 48 hours following his or her discharge. However, CMS will allow the physician or practice to document the contact if there have been at least two unsuccessful attempts to contact the patient.

Q: I have read that CMS will not pay the TCM claim if the code is billed before the end of the 30-day period. Is that really the case?

A: It does not seem to be. In its Physician Fee Schedule final rule for 2013, CMS indicates that it expects to see the billing occur at or near the 30-day point, but the agency has not stated whether earlier billing would result in a claim rejection or denial. ACP will continue to work with CMS toward a resolution of this question.

More from this issue

New research links empathy to outcomes

Also from ACP, read new content every week from the most highly cited internal medicine journal. Visit Annals.org

How to financially survive in a hospital-owned practice

Value-based payments a new source of reimbursement, penalties.

CMS approves new codes for Transitional Care Management

CMS has approved paying two new codes for care management of patients transitioning from an inpatient hospital setting (including acuity, rehabilitation, or long-term acute care), partial hospitalization, or observation status in a hospital, skilled nursing facility, or other nursing facility to the patient’s community setting (home, domiciliary, rest home, or assisted living).

These new codes are based on the complexity of medical decision-making and the amount of time between discharge and the patient’s first face-to-face visit with the physician or other qualified health care provider. Code 99495 requires moderately complex medical decision-making and a face-to-face visit within 14 days. Code 99496 requires highly complex medical decision-making and a face-to-face visit within seven days.

Transitional care management (TCM) is based on the CMS Evaluation and Management Guidelines. Medical decision-making consists of three components: (1) Diagnosis and Management, (2) Data Reviewed, and (3) Table of Risk. Ideally the first place to look is the table of risk. If the patient falls under the minimal or low section of the table of risk it is highly unlikely they will qualify for either of these codes. However, you need to review all three components to determine the appropriate level.

Both codes require communication with the patient or caregiver within two business days of discharge by telephone, direct contact, or electronic means, and that, by the first face-to-face visit following discharge, the patient’s medications be reconciled with the medications listed on the patient’s chart.

The physician or other qualified health care provider may provide the following non-face-to-face services:

• Obtaining and reviewing the discharge information (e.g., discharge summary or continuity of care documents).

• Reviewing and follow-up of pending diagnostic tests and treatments.

• Interaction with other qualified health care professionals who will assume or re-assume care of the patient’s system-specific problem.

• Education of patient, family, guardian, and/or caregiver.

• Establishment or re-establishment of referrals, and arranging community services, if needed.

• Assistance in scheduling any required follow-up with community providers and services.

Clinical staff under direction from a physician or other provider can provide such non-face-to-face services as communicating aspects of care, self-management and treatnment regimen adherence with the patient, caregiver, or other decision maker, as well as communicating with home health agencies or other community services the patient is using. They can also help identify available community resources for the patient and help get them access.

You cannot charge an office visit on the same day as your face-to-face visit for TCM. However, you can be the discharging physician and bill the discharge and then the TCM. Only one physician may bill the TCM and it can only be billed once per 30 days, even if the patient has another hospitalization and discharge.

CMS has valued Code 99495 at 4.82 total RVUs, or about $163. Code 99496 is valued at 6.79 RVUs, or approximately $230.

These codes are ideal for a strong team approach, covering services many family physicians are providing on a regular basis, and recognizing that primary care physicians take care of many time-consuming issues of care coordination for patients.This is a start in the right direction. Happy Transitioning!

–Debra Seyfried, MBA, CMPE, CPC, Coding and Compliance Strategist for the American Academy of Family Physicians

- Chronic care

- Medicare/Medicaid

- Physician compensation

- Practice management

- Reimbursement

- Value-based payment

Other Blogs

- Quick Tips from FPM journal

- AFP Community Blog

- Fresh Perspectives

- In the Trenches

- Leader Voices

- RSS ( About RSS )

Disclaimer: The opinions and views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent or reflect the opinions and views of the American Academy of Family Physicians. This blog is not intended to provide medical, financial, or legal advice. Some payers may not agree with the advice given. This is not a substitute for current CPT and ICD-9 manuals and payer policies. All comments are moderated and will be removed if they violate our Terms of Use .

Copyright © 2024 American Academy of Family Physicians. All Rights Reserved.

Hospital Follow Up ICD-10-CM Codes | 2023

Read this short guide to learn about Hospital Follow Up ICD codes you can use!

By Nate Lacson on Feb 29, 2024.

Fact Checked by Nate Lacson.

What Hospital Follow Up ICD-10 codes can I use?

If you’re looking for Hospital Follow Up ICD codes , you must adjust your search term. There are ICD-10 codes for what you’re looking for, but they don’t use hospital follow-up. Instead, ICD-10 codes phrase it as an encounter for a follow-up examination.

There are two ICD-10 codes for it:

- Z08 - Encounter for follow-up examination after completed treatment for malignant neoplasm

- Z09 - Encounter for follow-up examination after treatment for conditions other than malignant neoplasm .

These codes are meant to be used on patients who have either completed cancer treatment (Z08) or a non-cancer problem (Z09) and are visiting a healthcare provider for a post-treatment follow-up examination.

Please note that these are unacceptable as principal diagnoses because they’re meant to designate that patients attend follow-up examinations.

Are these Hospital Follow Up ICD-10 codes billable?

Yes. Despite being unacceptable as principal diagnoses, these ICD-10 codes for Hospital Follow Up are valid in general and billable.

Clinical information about Hospital Follow-ups:

Hospital follow-ups are standard for patients discharged from the hospital after being treated. These follow-ups monitor patient conditions and provide routine medical care and support to ensure their recovery.

The nature of hospital follow-ups will vary from patient to patient because they will be based on what they were treated for.

Some might need to attend hospital follow-ups to have their surgical wounds checked to check for any infections or complications.

Some might need to attend these follow-ups to check for any remaining cancer cells that need to be destroyed or to monitor patients in case cancer re-emerges.

Some might need to attend follow-ups for short education sessions to learn how to manage permanent conditions and disabilities.

Synonyms include:

- Medical surveillance following completed treatment

- Aftercare following medical care

- Post-hospital follow-up

- Post-discharge follow-up

- Routine medical examination post-discharge

- Patient monitoring

- Patient monitoring post-discharge

- Hospital follow up ICD 10

- ICD 10 hospital follow up

- ICD 10 code for hospital follow up

- ICD-10 hospital follow-up 7 days

- Hospital discharge follow up ICD 10

Commonly asked questions

It depends on what the patient was treated for. Some might have to return for a follow-up just a week after discharge. Some might be scheduled three to five months later after being discharged.

Healthcare professionals will ask patients how they’ve felt after being discharged, apply any treatment needed to ensure a smooth recovery, and determine if treatment plans need to be adjusted.

It’s within the patient’s right not to attend a hospital follow-up. Healthcare professionals should still exercise due diligence and remind patients or reschedule, especially if their condition needs routine care.

Related Guides

Self Injurious Behavior ICD-10-CM Codes | 2023

Explore ICD-10 codes for self-injurious behavior for accurate documentation and billing. Learn how these codes classify intentional self-harm incidents.

Prostatectomy ICD-10-CM Codes | 2023

Explore essential ICD-10 codes for Prostatectomy. Ensure accurate billing and documentation in prostate surgery with these codes.

Pseudophakia ICD-10-CM Codes | 2023

Read this short guide to learn about Pseudophakia ICD codes you can use.

Lumbar Fusion ICD-10-CM Codes | 2023

Read this short guide to learn about Lumbar Fusion ICD codes you can use.

Medication Refill ICD-10-CM Codes | 2023

Explore ICD-10 codes for medication refills. Understand the clinical context and necessity of medication refills with these codes.

Infection ICD-10-CM Codes | 2023

Discover commonly used ICD-10 codes for infection diagnoses. Understand the clinical descriptions and the importance of accurate coding.

Positive PPD ICD-10-CM Codes | 2023

Read this short guide to learn about Positive PPD ICD codes you can use!

Z11.59 – Encounter for screening for other viral diseases | ICD-10-CM

Discover G47.0 ICD codes for Insomnia. Explore billing, clinical details, and why Carepatron is your top choice for medical coding.

AICD ICD-10-CM Codes | 2023

Read this short guide to learn about AICD ICD codes you can use!

STD Exposure ICD-10-CM Codes | 2023

Read this short guide to learn about STD Exposure ICD codes you can use!

ESBL ICD-10-CM Codes | 2023

Read this short guide to learn about ESBL ICD codes you can use!

IVC Filter ICD-10-CM Codes | 2023

Discover the essential ICD-10 codes for IVC filter procedures, complications, and follow-up care. Perfect for accurate medical billing and coding.

Aspirin Allergy ICD-10-CM Codes | 2023

Read this short guide to learn about Aspirin Allergy ICD codes you can use!

Nexplanon Removal ICD-10-CM Codes | 2023

Read this short guide to learn about Nexplanon Removal ICD codes you can use!

PID ICD-10-CM Codes | 2023

Read this short guide to learn about PID ICD codes you can use!

Plavix ICD-10-CM Codes | 2023

Discover the essential ICD-10 codes related to Plavix usage, side effects, and conditions. Ensure accurate diagnosis and billing for Plavix treatments with Carepatron.

Lynch Syndrome ICD-10-CM Codes | 2023

Discover the essential ICD-10 codes for Lynch Syndrome diagnosis and management. Ensure accurate coding for better patient care and billing with Carepatron.

Orthopedic Aftercare ICD-10-CM Codes | 2023

Explore the essential ICD-10 codes for orthopedic aftercare with Carepatron. Navigate accurate coding for post-surgery recovery and rehabilitation treatments.

History of Covid 19 ICD-10-CM Codes | 2023

Read this short guide to learn about History of COVID-19 ICD codes you can use!

Lisinopril Allergy ICD-10-CM Codes | 2023

Discover the specific ICD-10 codes for Lisinopril allergy. Navigate accurate documentation and categorization of allergic reactions to this ACE inhibitor.

Post Op ICD-10-CM Codes | 2023

Explore comprehensive ICD-10 codes for post-operative care. Ensure accurate billing and patient management with standardized Post Op diagnosis codes.

Left Hip Replacement ICD-10-CM Codes | 2023

Read this short guide to learn about Left Hip Replacement ICD codes you can use!

Status Post Pci ICD-10-CM Codes | 2023

Explore the comprehensive guide on ICD-10 codes for Status Post PCI. Stay updated with the latest coding standards for coronary angioplasty procedures.

Kidney Transplant ICD-10-CM Codes | 2023

Explore the comprehensive guide on ICD-10 codes specific to kidney transplant procedures, complications, and post-operative care. Stay informed and updated.

Surgical Aftercare ICD-10-CM Codes | 2023

Check out this guide to learn about the ICD-10 codes used for surgical aftercare, whether they’re billable, and some clinical information.

TB Screening ICD-10-CM Codes | 2023

Learn more about the ICD-10 codes used for TB screening, their billability, synonyms, and FAQ answers. Feel free to use our guide to code more accurately.

Gastric Bypass ICD-10-CM Codes | 2023

Read this short guide to learn about Gastric Bypass ICD codes you can use!

Learn about the ICD-10 code Z02.89 – Encounter for other administrative examinations.

Read this short guide to learn about the ICD-10 code Z78.0 – Asymptomatic menopausal state.

Read this short guide to learn about the ICD-10 code Z79.4 – Long term (current) use of insulin.

Explore the intricacies of ICD-10-CM codes F41.9 and Z23, related to encounters for immunization. Stay updated with Carepatron on coding guidelines.

Cardiac Stent ICD-10-CM Codes

Read this short guide to learn about Cardiac Stent ICD codes you can use!

Chronic Anticoagulation ICD-10-CM Codes

Read this short guide to learn about Chronic Anticoagulation ICD codes you can use!

Lab Review ICD-10-CM Codes

Discover commonly used ICD-10 codes for lab review. Ensure accurate billing with these lab review diagnosis codes.

AAA Screening (Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Screening) ICD-10-CM Codes

Dive into the 2023 ICD codes for AAA Screening. Grasp the codes, billability, and clinical relevance for this vital cardiovascular screening procedure.

Z45.2 – Encounter for adjustment and management of vascular access device | ICD-10-CM

Explore Z45.2 ICD codes for vascular access device management. Learn about billable codes, clinical information, and more.

Anticoagulation ICD-10-CM Codes

Dive into the comprehensive guide on Anticoagulation ICD codes for 2023. Understand the codes, their billability, and their clinical relevance.

History of Falls ICD-10-CM Codes

Read this short guide to learn about the lone History of Falls ICD code you can use.

Fall Risk ICD-10-CM Codes

Explore the comprehensive guide on Fall Risk ICD codes for 2023. Understand the codes, their billability, and their clinical relevance in depth.

Falls ICD-10-CM Codes

Dive into the detailed guide on Falls ICD codes for 2023. Grasp the codes, their billability, and their clinical significance.

Trip And Fall ICD-10-CM Codes

Delve into the comprehensive guide on Trip And Fall ICD codes for 2023. Understand the codes, their billability, and their clinical significance in depth.

Assault ICD-10-CM Codes

Delve into the comprehensive guide on Assault ICD codes for 2023. Understand this severe and concerning issue's codes, billability, and clinical significance.

Mitral Valve Repair ICD-10-CM Codes

Read this short guide and learn about mitral valve repair ICD codes you can use. Learn clinical and billing information here.

Bedbound ICD-10-CM Codes

Read this short guide to learn about Bedbound ICD codes you can use.

Hysterectomy ICD-10-CM Codes

Read this short guide to learn about Hysterectomy ICD codes you can use!

Total Knee Arthroplasty ICD-10-CM Codes

Read this short guide to learn about Total Knee Arthroplasty ICD codes you can use.

Colostomy ICD-10-CM Codes

Navigate through the comprehensive guide on Colostomy ICD codes for 2023. Understand the codes, their billability, and their clinical relevance in depth.

Screening Osteoporosis ICD-10-CM Codes

Read this short guide and learn about screening osteoporosis ICD codes you can use.

Pre Op ICD-10-CM Codes

Learn about ICD-10 Codes Used for Pre Op clearances. Explore commonly used codes for cardiovascular, respiratory, and laboratory assessments before surgery.

BMI ICD-10-CM Codes

Learn about the essential role of ICD-10 Codes Used for BMI classification. These codes are a crucial metric for assessing weight-related health.

HX Breast Cancer ICD-10-CM Codes

Find the ICD-10-CM codes for breast cancer history. Indispensable for accurate medical billing, documentation, and comprehension of patient medical history.

History of Stroke ICD-10-CM Codes

Read this short guide and learn about history of stroke ICD codes you can use. Explore billing and clinical information.

History of Appendectomy ICD-10-CM Codes

Read this short guide and learn about history of appendectomy ICD codes you can use. Learn about billing and clinical information.

History Of Migraine ICD-10-CM Codes

Explore the ICD-10-CM codes for a history of migraines in 2023. Understand the coding system for past migraine episodes and gain insights into this condition's documentation.

History Of Abnormal Pap ICD-10-CM Codes

Explore ICD-10-CM codes for a history of abnormal Pap smears. Learn about standard codes, and billable statuses, and gain clinical insights in this comprehensive guide.

Peritoneal Dialysis ICD-10-CM Codes

Read this short guide and learn about peritoneal dialysis ICD codes you can use.

History of Brain Aneurysm ICD-10-CM Codes

Read this short guide and learn about the history of brain aneurysm ICD codes you can use.

BKA ICD-10-CM Codes

Learn about valid BKA ICD-10 codes related to Below-Knee Amputation (BKA) and when to use them.

Fibromyalgia ICD-10-CM Codes

Read this short guide and learn about fibromyalgia ICD codes you can use.

PCOS ICD-10-CM Codes

Read this short guide and learn about PCOS ICD codes you can use.

Food Allergy ICD-10-CM Codes

Navigate the guide on Food Allergy ICD-10-CM codes. Learn about the specific codes, clinical descriptions, and billing implications.

Mammogram Screening ICD-10-CM Codes

Discover the ICD-10-CM codes vital for documenting mammogram screenings in 2023. Stay updated with the latest coding specifics.

Wound Care ICD-10-CM Codes

Discover the ICD-10 codes used for wound care and the codes’ clinical descriptions, billability, synonyms, and more.

History of Breast Cancer (Hx Breast Ca) ICD-10-CM Codes

Access this guide on the History of Breast Cancer (Hx Breast Ca) ICD-10-CM codes. Learn about the specific codes, descriptions, and billing implications.

Medical Clearance ICD-10-CM Codes

Read this short guide and learn about medical clearance ICD codes you can use!

Hospice ICD-10-CM Codes | 2023

Explore ICD-10-CM codes for Hospice in 2023. Learn about billable codes, clinical descriptions, synonyms, and more in this comprehensive guide for accurate diagnosis and documentation in hospice care.

Nephrostomy Tube ICD-10-CM Codes

ICD-10 Codes Used for Nephrostomy Tube diagnoses in 2023 to streamline medical coding and billing with our practitioner-focused resource.

Loop Recorder ICD-10-CM Codes

Simplify coding with our ICD-10 Codes Used for Loop Recorder guide. Enhance your practice's efficiency with our practitioner-friendly ICD-10 code reference.

Statin Intolerance ICD-10-CM Codes

Discover the ICD-10-CM codes for Statin Intolerance. In this thorough reference, you will find thorough information about the ICD Codes for Statin Intolerance.

Smoking Cessation ICD-10-CM Codes

Explore the ICD-10-CM codes for Smoking Cessation in 2023. Learn about billable codes, clinical descriptions, synonyms, and more in this comprehensive guide.

Pre Op Clearance ICD-10-CM Codes

Learn the 2023 ICD-10-CM codes for Pre Op Clearance. This thorough manual teaches you about billable codes, clinical descriptions, synonyms, and more.

History of Pulmonary Embolism ICD-10-CM Codes

Read this short guide and learn about history of pulmonary embolism ICD codes you can use.

History of Diverticulitis ICD-10-CM Codes

Read this short guide and learn about history of diverticulitis ICD codes you can use.

NG Tube ICD-10-CM Codes

Discover NG Tube ICD-10 codes, understand the clinical applications, and learn about synonyms. Find FAQs about NG Tube and its coding in this guide.

Cholecystectomy ICD-10-CM Codes

Discover valuable insights on Cholecystectomy ICD codes, from the most common codes to their clinical descriptions, billability, and synonyms.

History Of Alcohol Abuse ICD-10-CM Codes

Read this short guide and learn about two history of alcohol abuse-related ICD-10 codes you can use for billing.

Total Knee Replacement ICD-10-CM Codes

Get the most complete and up-to-date list of ICD-10 codes for total knee replacement surgery.

Deconditioning ICD-10-CM Codes

Explore the updated ICD-10-CM codes for Deconditioning in 2023. Find the billable codes, clinical descriptions, synonyms, FAQs, and more.

Morbid Obesity ICD-10-CM Codes

Explore the ICD-10 codes used for Morbid Obesity, understand when they are billable, and learn about typical treatments for this severe health condition.

Prediabetes ICD-10-CM Codes

Explore the ICD-10 codes used for Prediabetes, their importance in diagnosis, treatment planning, and medical billing for prediabetes management.

Dialysis ICD-10-CM Codes

Explore the ICD-10-CM codes for dialysis procedures, including billable status, clinical information, synonyms, and FAQs, in this comprehensive guide.

Pap Smear ICD-10-CM Codes

Explore our comprehensive guide on Pap Smear ICD-10-CM codes. Improve your clinical documentation and billing accuracy with the right codes.

Family History Of Colon Cancer ICD-10-CM Codes | 2023

Discover the latest ICD-10-CM codes for family history of colon cancer in 2023. Stay informed and code accurately for optimal patient care.

History Of Smoking ICD-10-CM Codes | 2023

Discover the key ICD-10 codes used to accurately document a patient's history of smoking, aiding in personalized healthcare and effective treatment plans.

Former Smoker ICD-10-CM Codes | 2023

Learn the significance of ICD-10 codes for former smokers. These codes offer valuable insights into patient history, preventive care & epidemiological studies.

History Of Breast Cancer ICD-10-CM Codes

Explore the importance of ICD-10 codes for a history of breast cancer, their use, billing status, clinical implications, synonyms, and FAQs.

Pregnant ICD-10-CM Codes

Looking for ICD-10 codes related to pregnancy? Check out this mini-guide to learn about the ICD-10 codes you can use and related clinical information.

Screening Mammogram ICD-10-CM Codes | 2023

Discover the essential ICD-10-CM codes for screening mammograms. Ensure accurate coding and streamline billing processes. Improve patient care.

Screening For Breast Cancer ICD-10-CM Codes | 2023

Discover accurate ICD-10-CM codes for breast cancer screening. Ensure precise diagnosis and proper coding with our comprehensive resources.

Family History Breast Cancer ICD-10-CM Codes | 2023

Discover commonly used ICD-10-CM codes for family history breast cancer. Assess risk, aid diagnosis, and plan personalized management.

Z87.891 – Personal history of nicotine dependence

The ICD-10-CM code Z87.891 signifies a history of nicotine dependence. This guide covers clinical details, billability, FAQs, and related codes.

Z98.890 – Other specified postprocedural states

Discover diverse post-procedural states with Z98.890. Capture complications, sequelae, pain, infections, scarring, and more. Ensure accurate documentation for effective healthcare management.

Z12.5 – Encounter for screening for malignant neoplasm of prostate

Discover Z12.5: Prostate cancer screening encounter code. Early detection saves lives. Understand its clinical description, billable status, and FAQs.

Z86.010 – Personal history of colonic polyps

Understand the personal history of colonic polyps and their significance, clinical implications, and billable status. Get accurate information now.

Z01.419 – Encounter for gynecological examination (general) (routine) without abnormal findings

Understand the Z01.419 ICD-10-CM code: Encounter for a routine gynecological examination without abnormal findings. Crucial for billing and medical records.

Z20.822 – Contact with and (suspected) exposure to COVID-19

Dive into the specifics of ICD-10 code Z20.822, used for documenting contact with and (suspected) exposure to COVID-19 in the clinical setting.

Z03.89 – Encounter for observation for other suspected diseases and conditions ruled out

Learn more about Z03.89: Encounter for observation for other suspected diseases and conditions ruled out ICD-10-CM. A vital tool for medical coding and billing.

Z13.820 – Encounter for screening for osteoporosis

The ICD-10-CM code Z13.820 designates a patient that has Encounter for screening for osteoporosis. Learn what this code entails, from its clinical information, if it’s billable or not, FAQs, and even related ICD-10 codes by reading this short guide.

Z00.01 – Encounter for general adult medical examination with abnormal findings

Explore the Z00.01 code, its clinical usage, billability, synonyms, related ICD-10 codes, and FAQs—a guide for professionals dealing with adult medical exams.

Z00.129 – Encounter for routine child health examination without abnormal findings

Explore the Z00.129 diagnosis code's clinical info, synonyms, billability, & related ICD-10 codes. Enhance your understanding of child health exam coding.

Join 10,000+ teams using Carepatron to be more productive

- Open access

- Published: 17 April 2024

Navigating outpatient care of patients with type 2 diabetes after hospital discharge - a qualitative longitudinal study

- Léa Solh Dost 1 , 2 ,

- Giacomo Gastaldi 3 ,

- Marcelo Dos Santos Mamed 4 , 5 &

- Marie P. Schneider 1 , 2

BMC Health Services Research volume 24 , Article number: 476 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

268 Accesses

Metrics details

The transition from hospital to outpatient care is a particularly vulnerable period for patients as they move from regular health monitoring to self-management. This study aimed to map and investigate the journey of patients with polymorbidities, including type 2 diabetes (T2D), in the 2 months following hospital discharge and examine patients’ encounters with healthcare professionals (HCPs).

Patients discharged with T2D and at least two other comorbidities were recruited during hospitalization. This qualitative longitudinal study consisted of four semi-structured interviews per participant conducted from discharge up to 2 months after discharge. The interviews were based on a guide, transcribed verbatim, and thematically analyzed. Patient journeys through the healthcare system were represented using the patient journey mapping methodology.

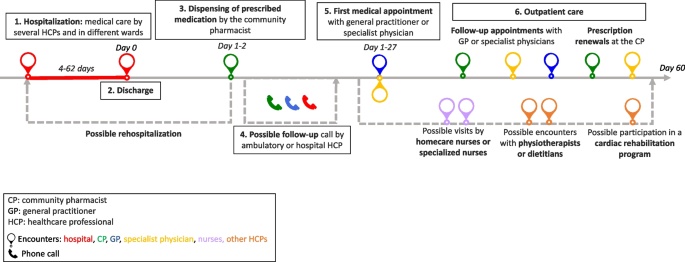

Seventy-five interviews with 21 participants were conducted from October 2020 to July 2021. The participants had a median of 11 encounters (min–max: 6–28) with HCPs. The patient journey was categorized into six key steps: hospitalization, discharge, dispensing prescribed medications by the community pharmacist, follow-up calls, the first medical appointment, and outpatient care.

Conclusions

The outpatient journey in the 2 months following discharge is a complex and adaptive process. Despite the active role of numerous HCPs, navigation in outpatient care after discharge relies heavily on the involvement and responsibilities of patients. Preparation for discharge, post-hospitalization follow-up, and the first visit to the pharmacy and general practitioner are key moments for carefully considering patient care. Our findings underline the need for clarified roles and a standardized approach to discharge planning and post-discharge care in partnership with patients, family caregivers, and all stakeholders involved.

Peer Review reports

Care transition is defined as “the movement patients make between healthcare practitioners and settings as their condition and care needs change in the course of a chronic or acute illness” [ 1 ]. The transition from hospital to outpatient care is a particularly vulnerable period for patients as they move from a medical environment with regular health monitoring to self-management, where they must implement a large amount of information received during their hospital stay [ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ]. This transition period can be defined as “the post-hospital syndrome,” which corresponds to a transient period of vulnerability (e.g., 30 days) for various health problems, such as stress, immobility, confusion, and even cognitive decline in older adults, leading to complications [ 7 ]. Furthermore, discharged patients may experience a lack of care coordination, receive incomplete information, and inadequate follow-ups, leading to potential adverse events and hospital readmissions [ 8 , 9 , 10 ].

People with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D) represent a high proportion of hospitalized patients, and their condition and medications are associated with a higher rate of hospital readmission [ 11 , 12 , 13 ]. Moreover, T2D is generally associated with multiple comorbidities. This complex disease requires time-consuming self-management tasks such as polypharmacy, adaptations of medication dosages, diet, exercise, and medical follow-up, especially during care transition [ 14 , 15 , 16 ].

Various interventions and practices, such as enhanced patient education, discharge counseling, and timely follow-up, have been studied to improve care transition for patients with chronic diseases; however, they have shown mixed results in reducing costs and rehospitalization [ 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ]. In addition, patient perspectives and patient-reported outcomes are rarely considered; however, their involvement and monitoring are essential for seamless and integrated care [ 21 , 22 ]. Care integration, an approach to strengthening healthcare systems in partnership with people, focuses on patient health needs, the quality of professional services, and interprofessional collaboration. This approach prevents care fragmentation for patients with complex needs [ 23 , 24 ]. Therefore, knowledge of healthcare system practices is essential to ensure integrated, coordinated, and high-quality care. Patient perspectives are critical, considering the lack of literature on how patients perceive their transition from hospital to autonomous care management [ 25 , 26 ].

Patients’ journeys during hospitalization have been described in the literature using various methods such as shadowing, personal diaries, and interviews; however, patients’ experiences after hospital discharge are rarely described [ 26 , 27 ]. Jackson et al. described the complexity of patient journeys in outpatient care after discharge using a multiple case study method to follow three patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease from hospitalization to 3 months post-discharge [ 26 ]. The literature does not provide an in-depth understanding of the experiences of patients with comorbidities during care transition upon hospital discharge. The assumption about the patient journey after discharge is that multiple and multi-professional encounters will ensure the transition of care from hospitalization to self-management, but often without care coordination.

This study aimed to investigate the healthcare trajectories of patients with comorbidities, including T2D, during the 2 months following hospital discharge and to examine patients’ encounters with healthcare professionals (HCPs).

While this article focuses on patients’ journeys to outpatient care, another article describes and analyzes patients’ medication management, knowledge, and adherence [ 28 ]. This study followed the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ).

Study design and population

A qualitative longitudinal research approach was adopted, with four individual semi-structured interviews over 2 months after discharge (approximately 3, 10, 30, and 60 days after discharge) that took place at home, by telephone, secured video call, or at the university at the participant’s convenience. Participants were recruited during hospitalization. The inclusion criteria were patients with T2D, with at least two other comorbidities, at least one medication change during hospitalization, hospitalization duration of at least 3 days, and those who returned home after discharge and self-managed their medications. A family caregiver could also participate in the interviews alongside to participants.

Researcher characteristics

All the researchers were trained in qualitative studies. The ward diabetologist and researcher (GG) who enrolled the patients in the study participated in most participants’ care during hospitalization. LS (Ph.D. student and community pharmacist) was unknown to participants and presented herself during hospitalization as a “researcher” rather than a pharmacist to avoid any risk of influencing participants’ answers. MS is a professor in pharmacy, whose research focuses on medication adherence in chronic diseases and aims at better understanding this behavior and its consequences for patients and the healthcare system. MDS is a researcher, linguist, and clinical psychologist, with a particular interest in patients living with chronic conditions such as diabetes and a strong experience in qualitative methodology and verbal data analysis.

Data collection

The interviews were based on four semi-structured interview guides based on existing frameworks and theories: the World Health Organization’s five dimensions for adherence, the Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills model, and the Social Cognitive Theory [ 29 , 30 , 31 ]. For in-depth documentation of participants’ itinerary in the healthcare system, the interview guides included questions on the type, reason, and moment of the HCP’s encounters and patient relationships with HCPs. Interview guides are available in Supplementary File 1 . During the development phase of the study, the interview guides were reviewed for clarity and validity and adapted by two patient partners from the Geneva University Hospitals’ Patient Partner Platform for Research and Patient and Public Involvement. Thematic saturation was considered reached when no new code or theme emerged and new data repeated previously coded information [ 32 ]. Sociodemographic and clinical data were collected from hospital databases and patient questionnaires. The interviews were audio-recorded, anonymized, and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

The sociodemographic and clinical characteristics were descriptively analyzed. Transcriptions were double-coded until similar codes were obtained, and thematic analysis, as described by Braun and Clarke [ 33 , 34 ], was used in a systematic, iterative, and comparative manner. A patient journey mapping methodology was used to illustrate the trajectories of each participant and provide a comprehensive understanding of their experiences. Patient journey mapping is a visual method adapted from the marketing industry that is increasingly used in various health settings and contexts to illustrate and evaluate healthcare services and patient experiences [ 35 ]. In this analysis, we used the term “healthcare professionals” when more than one profession could be involved in participants’ healthcare. Otherwise, when a specific HCP was involved, we used the designated profession (e.g. physicians, pharmacists).

A. Participants description

Twenty-one participants were interviewed between October 2020 and September 2021, generating 75 interviews. All participants took part in Interview 1, 19 participants in Interview 2, 16 participants in Interview 3 and 19 participants in Interview 4, with a median duration of 41 minutes (IQR: 34-49) per interview. Interviews 1,2,3 and 4 took place respectively 5 days (IQR: 4-7), 14 days (13-20), 35 days (33-38), and 63 days (61-68) after discharge. Nine patients were newly diagnosed with T2D, and 12 had a previous diagnosis of T2D, two of whom were untreated. Further information on participants is described in Table 1 . The median number of comorbidities was six (range: 3–11), and participants newly diagnosed with diabetes tended to have fewer comorbidities (median: 4; range: 3–8). More detailed information regarding sociodemographic characteristics and medications has been published previously [ 28 ].

B. Journey mappings

Generic patient journey mapping, presented in Fig. 1 , summarizes the main and usual encounters participants had with their HCPs during the study period. Generic mapping results from all individual patient journey mappings from discharge to 2 months after discharge are available in Supplementary File 2 .

Generic patient journey mapping from hospitalization to two months after discharge

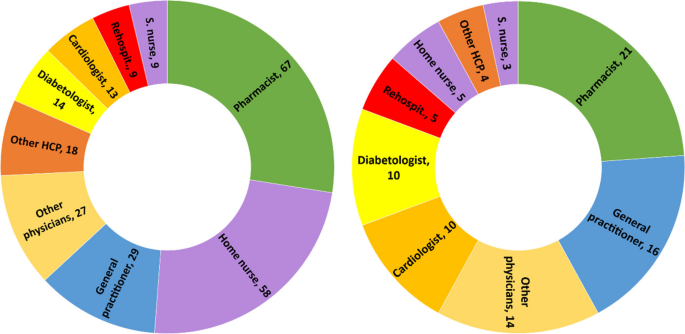

During the 2 months following discharge, the participants had a median number of 10 (range: 6–28) encounters with HCPs. The HCPs met by participants are represented in Fig. 2 . All participants visited their pharmacists at least once, and 16 of the 21 participants met their general practitioners (GPs) at least once. Five participants received home care assistance, four went to an outpatient cardiac rehabilitation program, and five were readmitted during the study period.

Healthcare professionals seen by participants during the study period. left: n=cumulative encounters; right: n=encountered at least once. Abbreviation: S.nurse: specialized nurse; Other physicians: ophthalmologists, neurologists, hematologists, immunologists, addictologists; other HCP: physiotherapists, dietitians, massage therapist

The first HCP encountered was at the community pharmacy on the same day or day after discharge, except for one participant who did not pick up her medication. The first medical appointment with a physician occurred between days 1 and 27 after discharge (median: 8; IQR: 6-14).

Participants newly diagnosed with diabetes had a closer follow-up after discharge than participants with a former diagnosis of T2D (median: 7; IQR: 6–10 vs median: 9; IQR: 5–19), fewer encounters with HCPs (median: 8; IQR: 7–10 vs. 11; IQR: 8–17), and fewer comorbidities (median: 4; IQR: 4–7 vs. 7; IQR: 5–9). Most participants newly diagnosed with T2D or receiving insulin treatment benefited from either a follow-up call, home visit by a nurse, or diabetes care appointment.

C. Qualitative analysis

Transcripts were analyzed longitudinally and categorized into six key steps based on the verbal data. These key steps, shown in Fig. 1 , represent the identified thematic categories and refer to the following elements: 1. Hospitalization, 2. Discharge, 3. Dispensing of prescribed medications at the pharmacy, 4. Possible follow-up call, 5. First medical appointment, and 6. Outpatient care.

Hospitalization: hospital constraints and care organization

Most participants thought they had benefited from adequate medical care by committed and attentive HCPs but highlighted different constraints and gaps. Some participants noted constraints related to the hospital environment, such as loss of autonomy during their stay, lack of privacy, and the large number of hospital staff encountered. This resulted in participants repeating the same information several times, causing frustration, misunderstanding and a lack of coordination for some participants:

“Twenty or thirty staff members come in during the day! So, it's hard to keep track of [what] is bein g said or done. The best thing for me [...] would be to have clear information from just one person.” Participant 8; interview 1 (P18.1)

Participants had different opinions on the hospital’s care organization. Some participants found that care coordination between the wards was well-organized. In contrast, others highlighted poor coordination and communication between the hospital wards, resulting in long waiting times, care fragmentation, and contradictory or unclear information. Some participants felt that they did not benefit from comprehensive and integrated care and that the hospital staff focused on the cause of their hospitalization, neglecting other comorbidities:

“They were not interested [in my diabetes and my sight]. I was there for the heart and that was where [my care] stopped.” P17.1

Patients’ involvement in decision-making regarding medical care varied. Some participants were involved in their care and took part in medical decisions. Written information, adequate communication, and health professionals’ interest in patients were highlighted by some participants:

“They took the information sheet and they explained everything to me. They didn't just come once; they came several times to explain everything to me.” P5.1

Other participants found the information difficult to understand, particularly because of their fatigue and because the information was provided orally.

Discharge: an unclear process

The discharge process was unclear for patients who could not identify a specific related outpatient medical visit or a key step that summarized their hospital stay and prepared them for discharge:

“Well, there's no real preparation [for discharge]. I was waiting for them to give me the go-ahead so I could go home, that’s all...” P7.4

For some participants, outpatient care follow-up was organized before discharge by the hospital team (generally by making an appointment with the patient’s GP before discharge), whereas others had no post-discharge follow-up scheduled during their hospitalization. Approximately half of the participants refused follow-ups during their hospitalization, such as home care services provided by a nurse, or a rehabilitation hospital stay. The main reason for this refusal was that patients did not perceive the need for follow-up:

“It's true that I was offered a lot of services, which I turned down because I didn't realize how I would manage back at home.” P22.2

Dispensing prescribed medications by the community pharmacist: the first HCP seen after discharge

On behalf of half the participants, a family caregiver went to the usual community or hospital outpatient pharmacy to pick up the medications. The main reasons for delegation were tiredness or difficulty moving. In some cases, this missed encounter would have allowed participants to discuss newly prescribed medications with the pharmacist:

“[My husband] went to get the medication. And I thought afterward, […] that I could have asked [the pharmacist]: “But listen, what is this medication for?” I would have asked questions” P2.3

Participants who met their pharmacist after hospital discharge reported a range of pharmaceutical practices, such as checking the prescribed medication against medication history, providing information and explanations, and offering services such as the preparation of pillboxes. For some, the pharmacists’ work at discharge did not differ from regular prescriptions, whereas others found that they received further support and explanations:

“She took the prescription […] checked thoroughly everything and then she wrote how, when, and how much to take on each medication box. She managed it very well and I had good explanations.” P20.3

Some participants experienced problems with generic substitution, the unavailability of medications, or dispensing errors, complicating their journey through the healthcare system.

Possible follow-up call by HCP: an unsystematic practice

Some participants received a call from their GP or hospital physician a few days after discharge to check their health or answer questions. These calls reassured participants and their caregivers, who knew they had a point of contact in case of difficulty. Occasionally, participants received calls from their community pharmacists to ensure proper understanding and validate medication changes issued during hospitalization. Some participants did not receive any calls and were disappointed by the lack of follow-up:

“There is no follow-up! Nobody called me from the hospital to see how I was doing […]” P8.2

First medical appointment: a key step in the transition of care

The first medical appointment was made in advance by the hospital staff or the patient after discharge. For some participants, this first appointment did not differ from usual care. For most, it was a crucial appointment that allowed them to discuss their hospitalization and new medications and organize their follow-up care. Being cared for by a trusted HCP enabled some patients to feel safe, relieved, and well-cared for, as illustrated by the exchange between a patient and her daughter:

Daughter: When [my mom] came back from the GP, she felt much better [...] It was as if a cork had popped. Was it psychological? Patient: Maybe… I just felt better. D: Do you think it was the fact that she paid attention to you as a doctor? P: She took care of me. She did it in a delicate way. [silence] - P23.2

Some participants complained that their physicians did not receive the hospital discharge letter, making it difficult to discuss hospitalization and sometimes resulting in delayed care.

Outpatient care: a multifaceted experience

During the 2 months after hospital discharge, participants visited several physicians (Fig. 2 ), such as their GP and specialist physicians, for follow-ups, routine check-ups, medical examinations, and new prescriptions. Most participants went to their regular pharmacies to renew their prescriptions, for additional medication information, or for health advice.

Some participants had home care nurses providing various services, such as toileting, care, checks on vital functions, or preparing weekly pill boxes. While some participants were satisfied with this service, others complained that home nurses were unreliable about appointment times or that this service was unnecessary. Some participants were reluctant to use these services:

“The [homecare nurse] makes you feel like you're sick... It's a bit humiliating.” P22.2

Specialized nurses, mostly in diabetology, were appreciated by patients who had dedicated time to talk about different issues concerning diabetes and medication and adapted explanations to the patient’s knowledge. Participants who participated in cardiac rehabilitation said that being in a group and talking to people with the same health problems motivated them to undertake lifestyle and dietary changes:

“In the rehabilitation program, I’m part of a team [of healthcare professionals and patients], I have companions who have gone through the same thing as me, so I’m not by myself. That's better for motivation.” P16.2

Navigating the outpatient healthcare system: the central role of patients

Managing medical appointments is time-consuming and complex for many participants. Some had difficulty knowing with whom to discuss and monitor their health problems. Others had difficulty scheduling medical appointments, especially with specialist physicians or during holidays. A few participants did not attend some of their appointments because of physical or mental vulnerabilities. Restrictions linked to the type of health insurance coverage made navigating the healthcare system difficult for some participants:

“Some medications weren't prescribed by my GP [...] but by the cardiologist. So, I must ask my GP for a delegation to see the cardiologist. And I have to do this for three or four specialists... Well, it’s a bit of a hassle […] it's not always easy or straightforward”. P11.2

Some participants had financial difficulties or constraints, such as expenses from their hospitalization, ambulance transportation, and medications not covered by their health insurance plans. This led to misunderstandings, stress, and anxiety, especially because some participants could not return to work or, to a lesser extent, because of their medical condition.

To ensure continuity of care, some participants were proactive in their case management, for example, by calling to confirm or obtain further information on an appointment or to ensure information transfer. Written convocations for upcoming medical appointments and tailored explanations helped the participants organize their care. Family caregivers were also key in taking participants to various consultations, reminding them, and managing their medical appointments.

Information transfer: incomplete and missing information

Information transfer between and within settings was occasionally lacking. Even weeks after hospitalization, some documents were not transmitted to outpatient physicians, sometimes delaying medical care. Some participants reported receiving incomplete, unclear, or contradictory information from different HCPs, sometimes leading to doubts, seeking a second medical opinion, or personal searches for information. A few proactive participants ensured good information transmission by making a copy of the prescription or sending copies of their documents to physicians:

“My GP hasn't received anything from the hospital yet. I’ve sent him the PDF with the medication I take before our appointment […] Yes, It’s the patient that does all the job.” P10.3

Interprofessional work: a practice highlighted by some participants

Several participants highlighted the interprofessional work they observed in the outpatient setting, especially because they had several comorbidities; therefore, several physicians followed their care:

“My case is very complex! For example, between the cardiologist and the diabetologist, they need to communicate closely because there could be consequences or interactions with the medications I take [for my heart and my diabetes].” P4.2

Health professionals referred their patients to the most appropriate provider for better follow-up (e.g., a nurse specializing in addictology referred a patient to a nurse specializing in diabetology for questions and follow-up on blood sugar levels). Interprofessional collaboration between physicians and pharmacists was noted by some participants, especially for prescription refills or ordering medications.

Patient-HCPs relationships: the importance of trust

Trust in the care relationship was discussed by the participants regarding different HCPs, especially GPs and community pharmacists. Most participants highlighted the communication skills and active listening of healthcare providers. Knowing an HCP for several years helped build trust and ensure an updated medical history:

“I've trusted this pharmacist for 20 years. I can phone her or go to the pharmacy to ask any question[...] I feel supported.” P3.2

Some participants experienced poor encounters owing to a lack of attentive listening or adapted communication, especially when delivering bad news (new diagnoses or deterioration of health status). Professional competencies were an important aspect of the patient-HCP relationship, and some participants lost confidence in their physician or pharmacist because of inadequate medical or pharmaceutical care management or errors, such as the physician prescribing the wrong medication dosage, the pharmacist delivering the wrong pillbox or the general practitioner refusing to see a patient:

“I think I'll find another doctor… In fact, the day I was hospitalized, I called before to make an appointment with her and she refused to see me […] because I had a fever, and I hadn’t done a [COVID] test.” P6.2

Most participants underlined the importance of their GP because they were available, attentive to their health issues, and had a comprehensive view of their medications and health, especially after hospitalization:

“Fortunately, there are general practitioners, who know everything. With some specialists, the body is fragmented, but my GP knows the whole body.” P14.1

After hospitalization, the GP’s role changed for some participants who saw their GP infrequently but now played a central role.

Community pharmacist: an indistinct role

Pharmacists and their teams were appreciated by most participants for their interpersonal competencies, such as kindness, availability, professional flexibility, and adaptability to patients’ needs to ensure medication continuity (e.g., extension of the prescription, home delivery, or extending time to pay for medications). The role of community pharmacists varied according to the participants. Some viewed pharmacists as simple salespeople:

“It's like a grocery store. [...] I go there, it's ordered, I take my medication, I pay and I leave.” P23.3

For others, the pharmacist provided medication and advice and was a timely source of information but did not play a central role in their care. For others, the pharmacist’s role is essential for medication monitoring and safety:

“I always go to the same pharmacy […] because I know I have protection: when [the pharmacist] enters the medications in his computer, if two medications are incompatible, he can verify. [...] There is this follow-up that I will not have if I go each time somewhere else.” P10.4

The patient journey mapping methodology, coupled with qualitative thematic analysis, enabled us to understand and shed light on the intricacies of the journey of polypharmacy patients with T2Din the healthcare system after discharge. This provided valuable insights into their experiences, challenges, and opportunities for improvement.

This study highlights the complex pathways of patients with comorbidities by considering the population of patients with T2D as an example. Our population included a wide variety of patients, both newly diagnosed and with known diabetes, hospitalized for T2D or other reasons. Navigating the healthcare system was influenced by the reason for hospitalization and diagnosis. For example, newly diagnosed participants with T2D had a closer follow-up after discharge, participants were more likely to undergo cardiac rehabilitation after infarction, and participants with a former T2D diagnosis were more complex, with more comorbidities and more HCP encounters. Our aim was not to compare these populations but to highlight particularities and differences in their health care and these qualitative data reveal the need for further studies to improve diabetes management during inpatient to outpatient care transition.

The variability in discharge practices and coordination with outpatient care highlights the lack of standardization during and after hospital discharge. Some participants had a planned appointment with their GP before discharge, others had a telephone call with a hospital or ambulatory physician, and some had no planned follow-up, causing confusion and stress. Although various local or national guidelines exist for managing patients discharged from the hospital [ 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 ], there are no standard practices regarding care coordination implemented in the setting of this study. The lack of local coordination has also been mentioned in other studies [ 5 , 40 , 41 ].

Our results also raise questions about the responsibility gap in the transition of care. Once discharged from the hospital, who is responsible for the patient until their first medical appointment? This responsibility is not clearly defined among hospital and outpatient care providers, with more than 25% of internal medicine residents indicating their responsibility for patients ending at discharge [ 42 , 43 ]. Importance should be given to clarifying when and who will take over the responsibility of guaranteeing patient safety and continuity of care and avoiding rehospitalization [ 44 ].

The first visit with the community pharmacist after discharge and the referring physician were the key encounters. While the role of the GP at hospital discharge is well-defined, the community pharmacist’s role lacks clarity, even though they are the first HCP encountered upon hospital discharge. A meta-analysis showed the added value of community pharmacists and how their active participation during care transition can reduce readmission [ 18 ]. A better definition of the pharmacist’s role and integration into care coordination could benefit patient safety during the transition and should be assessed in future studies.

Our findings showed that the time elapsed between discharge and the first medical appointment varied widely (from 1 to 27 days), correlating with findings in the literature showing that more than 80% of patients see their GP within 30 days [ 45 ]. Despite the first medical appointment being within the first month after discharge, some patients in our study reported a lack of support and follow-up during the first few days after discharge. Care coordination at discharge is critical, as close outpatient follow-up within the first 7–10 days can reduce hospital readmission rates [ 46 , 47 ]. Furthermore, trust and communication skills are fundamental components of the patient-HCP relationship, underlined in our results, particularly during the first medical appointment. Relational continuity, especially with a particular HCP who has comprehensive patient knowledge, is crucial when patients interact with multiple clinicians and navigate various settings [ 48 , 49 ].