- Patient Portal

- Classes and Events

- Find a Doctor

- Schedule Appointment

The Role of a Midwife in Maternity Care

In the world of maternity care , a group of health care professionals often work quietly in the background, providing crucial support and care to expectant parents. These unsung heroes are midwives, and their role is often misunderstood or underestimated. What is a midwife, and what responsibilities do midwives have to birthing parents and the child before, during and after childbirth?

What is a Midwife?

A midwife is a trained health care professional specializing in childbirth and reproductive health. They are distinct from obstetricians, as their approach emphasizes a more natural and holistic perspective on pregnancy and childbirth . Midwives provide care before, during, and after pregnancy, offering services that promote maternal and fetal well-being.

What Role Do Midwives Play in Prenatal Care?

One of the fundamental roles of midwives is to provide prenatal care , such as regular checkups and monitoring throughout pregnancy to ensure the health and well-being of the birthing parent and the developing baby. These checkups include physical exams, ultrasound scans and blood tests to track the progress of the pregnancy.

“Prenatal care provided by midwives focuses on building a strong and supportive relationship with the birthing parent,” said Waverly Lutz, CNM, midwife at Inspira Medical Group’s Gentle Beginnings. “They aim to educate and empower patients to make informed choices about their pregnancy and birthing experience.”

How Do Midwives Support Labor and Delivery?

Midwives play a pivotal role during labor and delivery . They provide emotional support, pain management techniques and guidance during this intense and transformative process. While midwives are skilled in managing uncomplicated births, they are trained to recognize and respond to possible complications.

“Midwives advocate for a patient-centered approach, ensuring the birthing experience aligns with the birthing parent’s preferences and values,” said Lutz. “But they are also well-prepared to safely handle emergencies and collaborate with obstetricians when necessary.”

What Postpartum Care Do Midwives Provide?

The care midwives provide doesn't end with the baby's birth. They continue to provide support throughout the postpartum period, offering guidance on breastfeeding, postpartum recovery and emotional well-being. This ongoing care is essential for the health and bonding of both parent and child.

What Else Do Midwives Do?

Midwives play a crucial role in advocating for the birthing parent’s rights and choices in childbirth. They promote informed decision-making and work to ensure that parents have the autonomy to choose the type of birth experience they desire, whether it's a home birth, hospital birth or birthing center experience.

They also provide comprehensive wellness care, including preventive gynecological exams, pap tests, birth control counseling, sexual health advice, and overall reproductive well-being, regardless of pregnancy intent.

“Empowering patients to make choices that align with their values is at the core of midwifery care,” Lutz emphasized. “They believe every parent should have access to safe and respectful maternity care that honors her preferences and cultural beliefs.”

To learn more about Inspira’s approach to midwifery, visit our website or to make an appointment, call 888-31-BIRTH

News From Inspira

New mother was concerned about a potentially serious complication, but the care team at Inspira...

In celebration of National Breastfeeding Awareness Month, Inspira Health hosted a special Tea and...

Ensure your baby's safety and wellbeing with simple steps from Inspira Health. Learn how to reduce...

Appointments at Mayo Clinic

- Pregnancy week by week

Prenatal care: 1st trimester visits

Pregnancy and prenatal care go hand in hand. During the first trimester, prenatal care includes blood tests, a physical exam, conversations about lifestyle and more.

Prenatal care is an important part of a healthy pregnancy. Whether you choose a family physician, obstetrician, midwife or group prenatal care, here's what to expect during the first few prenatal appointments.

The 1st visit

When you find out you're pregnant, make your first prenatal appointment. Set aside time for the first visit to go over your medical history and talk about any risk factors for pregnancy problems that you may have.

Medical history

Your health care provider might ask about:

- Your menstrual cycle, gynecological history and any past pregnancies

- Your personal and family medical history

- Exposure to anything that could be toxic

- Medications you take, including prescription and over-the-counter medications, vitamins or supplements

- Your lifestyle, including your use of tobacco, alcohol, caffeine and recreational drugs

- Travel to areas where malaria, tuberculosis, Zika virus, mpox — also called monkeypox — or other infectious diseases are common

Share information about sensitive issues, such as domestic abuse or past drug use, too. This will help your health care provider take the best care of you — and your baby.

Your due date is not a prediction of when you will have your baby. It's simply the date that you will be 40 weeks pregnant. Few people give birth on their due dates. Still, establishing your due date — or estimated date of delivery — is important. It allows your health care provider to monitor your baby's growth and the progress of your pregnancy. Your due date also helps with scheduling tests and procedures, so they are done at the right time.

To estimate your due date, your health care provider will use the date your last period started, add seven days and count back three months. The due date will be about 40 weeks from the first day of your last period. Your health care provider can use a fetal ultrasound to help confirm the date. Typically, if the due date calculated with your last period and the due date calculated with an early ultrasound differ by more than seven days, the ultrasound is used to set the due date.

Physical exam

To find out how much weight you need to gain for a healthy pregnancy, your health care provider will measure your weight and height and calculate your body mass index.

Your health care provider might do a physical exam, including a breast exam and a pelvic exam. You might need a Pap test, depending on how long it's been since your last Pap test. Depending on your situation, you may need exams of your heart, lungs and thyroid.

At your first prenatal visit, blood tests might be done to:

- Check your blood type. This includes your Rh status. Rh factor is an inherited trait that refers to a protein found on the surface of red blood cells. Your pregnancy might need special care if you're Rh negative and your baby's father is Rh positive.

- Measure your hemoglobin. Hemoglobin is an iron-rich protein found in red blood cells that allows the cells to carry oxygen from your lungs to other parts of your body. Hemoglobin also carries carbon dioxide from other parts of your body to your lungs so that it can be exhaled. Low hemoglobin or a low level of red blood cells is a sign of anemia. Anemia can make you feel very tired, and it may affect your pregnancy.

- Check immunity to certain infections. This typically includes rubella and chickenpox (varicella) — unless proof of vaccination or natural immunity is documented in your medical history.

- Detect exposure to other infections. Your health care provider will suggest blood tests to detect infections such as hepatitis B, syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia and HIV , the virus that causes AIDS . A urine sample might also be tested for signs of a bladder or urinary tract infection.

Tests for fetal concerns

Prenatal tests can provide valuable information about your baby's health. Your health care provider will typically offer a variety of prenatal genetic screening tests. They may include ultrasound or blood tests to check for certain fetal genetic problems, such as Down syndrome.

Lifestyle issues

Your health care provider might discuss the importance of nutrition and prenatal vitamins. Ask about exercise, sex, dental care, vaccinations and travel during pregnancy, as well as other lifestyle issues. You might also talk about your work environment and the use of medications during pregnancy. If you smoke, ask your health care provider for suggestions to help you quit.

Discomforts of pregnancy

You might notice changes in your body early in your pregnancy. Your breasts might be tender and swollen. Nausea with or without vomiting (morning sickness) is also common. Talk to your health care provider if your morning sickness is severe.

Other 1st trimester visits

Your next prenatal visits — often scheduled about every four weeks during the first trimester — might be shorter than the first. Near the end of the first trimester — by about 12 to 14 weeks of pregnancy — you might be able to hear your baby's heartbeat with a small device, called a Doppler, that bounces sound waves off your baby's heart. Your health care provider may offer a first trimester ultrasound, too.

Your prenatal appointments are an ideal time to discuss questions you have. During your first visit, find out how to reach your health care team between appointments in case concerns come up. Knowing help is available can offer peace of mind.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

- Lockwood CJ, et al. Prenatal care: Initial assessment. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed July 9, 2018.

- Prenatal care and tests. Office on Women's Health. https://www.womenshealth.gov/pregnancy/youre-pregnant-now-what/prenatal-care-and-tests. Accessed July 9, 2018.

- Cunningham FG, et al., eds. Prenatal care. In: Williams Obstetrics. 25th ed. New York, N.Y.: McGraw-Hill Education; 2018. https://www.accessmedicine.mhmedical.com. Accessed July 9, 2018.

- Lockwood CJ, et al. Prenatal care: Second and third trimesters. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed July 9, 2018.

- WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience. World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/maternal_perinatal_health/anc-positive-pregnancy-experience/en/. Accessed July 9, 2018.

- Bastian LA, et al. Clinical manifestations and early diagnosis of pregnancy. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed July 9, 2018.

Products and Services

- A Book: Obstetricks

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Guide to a Healthy Pregnancy

- 1st trimester pregnancy

- Can birth control pills cause birth defects?

- Fetal development: The 1st trimester

- Implantation bleeding

- Nausea during pregnancy

- Pregnancy due date calculator

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

- Healthy Lifestyle

- Prenatal care 1st trimester visits

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

- Trying to Conceive

- Signs & Symptoms

- Pregnancy Tests

- Fertility Testing

- Fertility Treatment

- Weeks & Trimesters

- Staying Healthy

- Preparing for Baby

- Complications & Concerns

- Pregnancy Loss

- Breastfeeding

- School-Aged Kids

- Raising Kids

- Personal Stories

- Everyday Wellness

- Safety & First Aid

- Immunizations

- Food & Nutrition

- Active Play

- Pregnancy Products

- Nursery & Sleep Products

- Nursing & Feeding Products

- Clothing & Accessories

- Toys & Gifts

- Ovulation Calculator

- Pregnancy Due Date Calculator

- How to Talk About Postpartum Depression

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

Your Prenatal Care Appointments

If you're pregnant, especially if it's for the first time, you may be wondering what will happen at your prenatal care appointments with your doctor or midwife . Here's a rundown of everything you can expect at each appointment, including tests and exams.

Your First Prenatal Care Appointment

Your first prenatal appointment will probably be your longest one. Here you will give your doctor, midwife, or nurse your complete health and pregnancy history. This information is important because it will give your practitioner a good idea of how healthy you are and what type of problems you are most likely to experience during your pregnancy. You will learn what your estimated due date is as well.

There are many areas that may be checked during your physical exam, including:

- Blood pressure

- Breast exam

- Pelvic exam

- Pregnancy test

- Ultrasound (if you're having pain or bleeding or underwent fertility treatments)

- Urine screen for protein and sugar

You will probably be seen for your first appointment between 8 and 10 weeks gestation, though you may be seen earlier if you're having problems or if it's your doctor or midwife's policy.

Your Second Appointment

Your second prenatal appointment usually takes place about a month after your first appointment, unless you're having problems or need specific prenatal testing that is best performed in a specific time range. Here is what will most likely happen during this visit:

- Blood pressure check

- Listen to a fetal heartbeat using a Doppler

- Record your weight

- Urine screen for sugar and protein

Your baby's first heartbeat can usually be heard with a Doppler between 8 and 12 weeks gestation. If you have trouble hearing the baby's heartbeat, you will probably be asked to wait until your next visit when your baby is a bit bigger. Sometimes an ultrasound will be ordered as well.

Additional Testing

Additional testing may be performed at this appointment as needed. There are some optional tests you, your doctor, or your midwife may request:

- Chorionic villus sampling (CVS) (diagnostic test for many genetic diseases)

- Early amniocentesis (diagnostic test for many genetic diseases)

- Nuchal fold test (screening for Down syndrome)

Be sure to discuss all of your options regarding these tests, including the risks and benefits, how the test results are given, and whether the test is a screening test or a diagnostic test.

Your Third Appointment

Towards the third prenatal visit, you're most likely around 14 to 16 weeks pregnant. You're probably feeling better and the most dangerous part of pregnancy is over. You are now probably feeling more confident in your pregnancy and sharing your good news .

It has been about a month since you've seen the midwife or doctor. Here's what this appointment may look like:

- Check your blood pressure

- Listen for baby's heartbeat

- Measure your abdomen, called "fundal height," to check baby's growth

- Urine sample to screen for sugar and protein

Optional Testing

You may also have the following prenatal testing done if you request it:

- Amniocentesis (diagnostic test for many genetic diseases)

- Neural tube defect (NTD)/Down syndrome screening by way of maternal blood work (several tests can be used including alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), triple screen, and quad screen)

Your Fourth Appointment

You are most likely between 16 to 20 weeks at this point, and it has been about a month since your last appointment. You probably feel like you've grown a lot since your last appointment and you may now be wearing maternity clothes and possibly even feeling your baby move . Here's what this visit may involve:

- Measure your fundal height to check baby's growth

You may also have a mid-pregnancy ultrasound screening if you request it or if it's your doctor or midwife's policy.

Your Fifth Appointment

Between 18 to 22 weeks you'll likely have your fifth prenatal care visit. Here's what this appointment may involve:

- Check for swelling in your hands and feet

- Listen to the baby's heartbeat

Your Sixth Appointment

Your next prenatal care appointment will likely be between 22 to 26 weeks of pregnancy . You are probably still being seen monthly. Here's what this appointment may look like:

- Listen to the baby's heartbeat

- Measure your fundal height to check baby's growth

- Questions about baby's movements

Your Seventh or Eighth Appointment

Between 26 to 28 weeks of pregnancy , you'll likely have another prenatal care appointment. Here's what may happen:

- Check blood pressure

- Questions about baby's movements

Other Testing and Information

You may have other tests or procedures ordered, like the glucose tolerance test (GTT) used to screen for gestational diabetes or the RhoGam , shot around 28 weeks of gestation for women who are Rh-negative. Your doctor or midwife may also give you information on screening for preterm labor on your own.

Your Eighth, Ninth Appointments and Beyond

Your next appointment will likely be between 28 to 36 weeks of pregnancy. In fact, you're likely to have at least two prenatal visits during this period because you're now being seen every other week. Here's what these appointments may involve:

- Palpate to check baby's position (vertex, breech, posterior, etc.)

Screening for Group B strep (GBS) will normally be done between weeks 34 to 36. This involves rectal and vaginal swab. You will continue to be seen every other week until about the 36th week of pregnancy. At this point, your visits will likely be fairly routine with very few extra tests being performed.

Weekly Visits

Between 36 to 40 weeks of pregnancy, you're usually seen every week. Here's what these visits may entail:

You will continue to be seen every week until about the 41st week of pregnancy, at which point you may be seen every few days until your baby is born. Your visits are most likely fairly routine, with very few extra tests being performed.

You may also have an ultrasound to determine what position the baby is in at this point. Your doctor will also try to predict the size of your baby , but this is usually not very accurate. Because of this tendency for inaccuracy, it's not a great idea to have an induction of labor based on the predicted size of your baby.

If you're having a home birth , you may have a home visit during this time frame if your midwife doesn't do her normal prenatal visits there. You will be able to give her a tour of your home and answer questions she may have about where everything is located.

Overdue Pregnancy Visits

At 40 or 41 weeks of pregnancy, you may begin to see your midwife or doctor every few days. Here is what these visits may look like:

Since you are officially past your due date, your midwife or doctor may want to watch you and your baby more carefully until labor begins. This may include the following tests:

- Non-stress test (NST)

- Biophysical profile (BPP)

These tests will help determine if your practitioner needs to intervene with an induction of labor for the health of your baby or let your pregnancy continue.

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. What Happens During Prenatal Visits ?

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. What are some common complications of pregnancy ?

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. How Your Fetus Grows During Pregnancy .

Mayo Clinic Staff. Prenatal Care: 1st Trimester Visits . Mayo Clinic.

By Robin Elise Weiss, PhD, MPH Robin Elise Weiss, PhD, MPH is a professor, author, childbirth and postpartum educator, certified doula, and lactation counselor.

Ready Steady Baby

Home visits.

You should be visited several times by your midwife or family nurse at home during the first 10 days. Friends and family will want to visit to meet your baby too.

It’s OK to ask visitors to:

- call you first and to sometimes say no

- help with other things so you can have a rest or spend time with your baby

Extra support

Some new parents need more support than others. You’ll get extra support from your midwife, family nurse or other health professionals if your baby:

- was born early

- spent time in special or intensive care

- has additional needs

Tests and checks

During the first 10 days your midwife will:

- weigh your baby

- do a newborn blood spot test if you agree

You’ll also need to register your baby with a GP

More about newborn blood spot tests

Your health visitor

A health visitor’s a registered nurse or midwife who’s done further study in public health nursing.

Your health visitor will:

- take over from your midwife when your baby’s 11 days old

- get to know you and your baby

- ensure you get all the help and support you need as your baby grows

Your baby’s named person

In Scotland, the aim is that every child, young person and their parents have a `named person’ who is a clear and safe point of contact to seek support and advice about any aspect of your child’s wellbeing.

From when your child is born until they start school, your named person is your health visitor.

Your baby’s named person will:

- be a good person for you to ask for information or advice about being a parent

- talk to about any worries

- support you to look after yourself and your baby

They can also:

- put you in contact with other community professionals or services

- help you make the best choices for you and your family

The Red Book

You’ll be given a personal child health record called the Red Book. You can use it to record information about your baby’s growth, development, tests and immunisations.

Keep it safe and take it to any appointments you have with a healthcare professional.

The family nurse

Family nurses offer the Family Nurse Partnership (FNP) programme to young, first-time parents from early in their pregnancy until their child’s 2 years old. This program is available to first-time parents under the age of 20.

The programme includes home visits from a family nurse while you’re pregnant, and after your baby’s born. These visits help:

- to have a healthy pregnancy

- you and your baby grow and develop together

- you to be the best parent you can be.

Your health visitor will take over from your family nurse when your baby is two until they go to school.

The Scottish Government has more information about Family Nurse Partnership

Translations and alternative formats of this information are available from Public Health Scotland .

If you need a different language or format, please contact [email protected].

- Ready Steady Baby leaflet in Arabic, Polish, Simplified Chinese (Mandarin) and Ukrainian

- Ready Steady Baby leaflet in English (Easy Read)

Source: Public Health Scotland - Opens in new browser window

Last updated: 19 December 2023

Help us improve NHS inform

Your feedback has been received

Don’t include personal information e.g. name, location or any personal health conditions.

Also on NHS inform

Other health sites.

- Disabled Living Foundation (DLF)

- Rica: consumer research charity

- Health & Care Professions Council (HCPC)

Your Guide to Prenatal Appointments

Medical review policy, latest update:.

Minor copy changes.

Typical prenatal appointment schedule

Read this next, what happens during a prenatal care appointment, what tests will i receive at my prenatal appointments, what will i talk about with my practitioner at prenatal care appointments , first trimester prenatal appointments: what to expect, second trimester prenatal appointments: what to expect, third trimester prenatal appointments: what to expect, questions to ask during prenatal appointments .

Prenatal care visits are chock-full of tests, measurements, questions and concerns, but know that throughout the process your and your baby’s wellbeing are the main focus. Keep your schedule organized so you don’t miss any appointments and jot down anything you want to discuss with your doctor and your prenatal experience should end up being both positive and rewarding.

What to Expect When You’re Expecting , 5th edition, Heidi Murkoff. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Having a Baby After Age 35: How Aging Affects Fertility and Pregnancy , 2020. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Routine Tests During Pregnancy , 2020. US Department of Health & Human Services, Office on Women’s Health, Prenatal Care and Tests , January 2019. Journal of Perinatology , Number of Prenatal Visits and Pregnancy Outcomes in Low-risk wWomen , June 2016. Mayo Clinic, Edema , October 2017. Mayo Clinic, Prenatal Care: 2nd Trimester Visits , August 2020. Mayo Clinic, Prenatal Care: 3rd Trimester Visits , August 2020. Jennifer Leighdon Wu, M.D., Women’s Health of Manhattan, New York, NY. WhatToExpect.com, Preeclampsia: Symptoms, Risk Factors and Treatment , April 2019. WhatToExpect.com, Prenatal Testing During Pregnancy , March 2019. WhatToExpect.com, Urine Tests During Pregnancy , May 2019. WhatToExpect.com, Fetal Heartbeat: The Development of Baby’s Circulatory System , April 2019. WhatToExpect.com, Amniocentesis , Mary 2019. WhatToExpect.com, Ultrasound During Pregnancy , April 2019. WhatToExpect.com, Rh Factor Testing , June 2019. WhatToExpect.com, Glucose Screening and Glucose Tolerance Test , April 2019. WhatToExpect.com, Nuchal Translucency Screening , April 2019. WhatToExpect.com, Group B Strep Testing During Pregnancy , August 2019. WhatToExpect.com, The Nonstress Test During Pregnancy , April 2019. WhatToExpect.com, Biophysical Profile (BPP) , May 2019. WhatToExpect.com, Noninvasive Prenatal Testing , (NIPT), April 2019. WhatToExpect.com, The Quad Screen , February 2019. WhatToExpect.com, Chorionic Villus Sampling (CVS) , February 2019. WhatToExpect.com, The First Prenatal Appointment , June 2019. WhatToExpect.com, Breech Birth: What it Means for You , September 2018.

Updates history

Jump to your week of pregnancy, trending on what to expect, signs of labor, pregnancy calculator, ⚠️ you can't see this cool content because you have ad block enabled., top 1,000 baby girl names in the u.s., top 1,000 baby boy names in the u.s., braxton hicks contractions and false labor.

Need to talk? Call 1800 882 436. It's a free call with a maternal child health nurse. *call charges may apply from your mobile

Is it an emergency? Dial 000 If you need urgent medical help, call triple zero immediately.

Checkups, scans and tests

Find out what checkups, scans and tests you might have during your pregnancy.

Can my partner come along too?

Yes. It’s a good idea for your birth support partner , family member or friend to come to your appointments with you, particularly when discussing your birth plan and if you want them to support you during the birth.

Resources and support

If you have any questions about antenatal care or concerns about your pregnancy, contact:

- Pregnancy, Birth and Baby on 1800 882 436 to speak to a maternal child health nurse

- your midwife

- the hospital where you're planning to give birth

Speak to a maternal child health nurse

Call Pregnancy, Birth and Baby to speak to a maternal child health nurse on 1800 882 436 or video call . Available 7am to midnight (AET), 7 days a week.

Learn more here about the development and quality assurance of healthdirect content .

Last reviewed: May 2020

Related pages

- Questions to ask your doctor about tests and scans

- Health professionals involved in your pregnancy

Routine antenatal tests

- Prenatal screening and testing

- Antenatal classes

Checkups, tests and scans available during your pregnancy

Your first antenatal visit, search our site for.

- Antenatal Care

Need more information?

Top results

If you are pregnant, find out when to have your first antenatal care visit and what will happen at the appointment with your doctor or midwife.

Read more on Pregnancy, Birth & Baby website

Antenatal Care during Pregnancy

Once you are pregnant, your first antenatal appointment will ideally take place when you are about 6 to 8 weeks pregnant.

Read more on RANZCOG - Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists website

Antenatal care includes several checkups, tests and scans, some of which are offered to women as a normal part of antenatal care in Australia.

Pregnancy at week 7

Your baby is now about 1cm long and if you haven’t seen your doctor yet, now is a good time to start your antenatal care.

During pregnancy, you'll be offered various blood tests and ultrasound scans. Find out what each test can tell you about you and your baby's health.

Checkups, scans and tests during pregnancy

Handy infographic that shows what you can expect and what you might be offered at each antenatal appointment during your pregnancy.

Pregnancy and birth care options - Better Health Channel

Pregnant women in Victoria can choose who will care for them during their pregnancy, where they would like to give birth and how they would like to deliver their baby.

Read more on Better Health Channel website

What does an obstetrician do?

Obstetricians are specialists in pregnancy and birth. Learn more about how to choose one and the costs involved in having a private obstetrician.

Blood tests during pregnancy

Find out more about the blood tests you be offered during your pregnancy. what they test for and when you’ll be offered them.

Cervical screening during pregnancy

Cervical screening can be performed at any time, including during pregnancy. Regular cervical screening can protect you against cervical cancer.

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is not responsible for the content and advertising on the external website you are now entering.

Call us and speak to a Maternal Child Health Nurse for personal advice and guidance.

Need further advice or guidance from our maternal child health nurses?

1800 882 436

Government Accredited with over 140 information partners

We are a government-funded service, providing quality, approved health information and advice

Healthdirect Australia acknowledges the Traditional Owners of Country throughout Australia and their continuing connection to land, sea and community. We pay our respects to the Traditional Owners and to Elders both past and present.

© 2024 Healthdirect Australia Limited

This information is for your general information and use only and is not intended to be used as medical advice and should not be used to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any medical condition, nor should it be used for therapeutic purposes.

The information is not a substitute for independent professional advice and should not be used as an alternative to professional health care. If you have a particular medical problem, please consult a healthcare professional.

Except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, this publication or any part of it may not be reproduced, altered, adapted, stored and/or distributed in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of Healthdirect Australia.

Support this browser is being discontinued for Pregnancy, Birth and Baby

Support for this browser is being discontinued for this site

- Internet Explorer 11 and lower

We currently support Microsoft Edge, Chrome, Firefox and Safari. For more information, please visit the links below:

- Chrome by Google

- Firefox by Mozilla

- Microsoft Edge

- Safari by Apple

You are welcome to continue browsing this site with this browser. Some features, tools or interaction may not work correctly.

An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

Call the OWH HELPLINE: 1-800-994-9662 9 a.m. — 6 p.m. ET, Monday — Friday OWH and the OWH helpline do not see patients and are unable to: diagnose your medical condition; provide treatment; prescribe medication; or refer you to specialists. The OWH helpline is a resource line. The OWH helpline does not provide medical advice.

Please call 911 or go to the nearest emergency room if you are experiencing a medical emergency.

Prenatal care and tests

Medical checkups and screening tests help keep you and your baby healthy during pregnancy. This is called prenatal care. It also involves education and counseling about how to handle different aspects of your pregnancy. During your visits, your doctor may discuss many issues, such as healthy eating and physical activity, screening tests you might need, and what to expect during labor and delivery.

Choosing a prenatal care provider

You will see your prenatal care provider many times before you have your baby. So you want to be sure that the person you choose has a good reputation, and listens to and respects you. You will want to find out if the doctor or midwife can deliver your baby in the place you want to give birth , such as a specific hospital or birthing center. Your provider also should be willing and able to give you the information and support you need to make an informed choice about whether to breastfeed or bottle-feed.

Health care providers that care for women during pregnancy include:

- Obstetricians (OB) are medical doctors who specialize in the care of pregnant women and in delivering babies. OBs also have special training in surgery so they are also able to do a cesarean delivery . Women who have health problems or are at risk for pregnancy complications should see an obstetrician. Women with the highest risk pregnancies might need special care from a maternal-fetal medicine specialist .

- Family practice doctors are medical doctors who provide care for the whole family through all stages of life. This includes care during pregnancy and delivery, and following birth. Most family practice doctors cannot perform cesarean deliveries.

- A certified nurse-midwife (CNM) and certified professional midwife (CPM) are trained to provide pregnancy and postpartum care. Midwives can be a good option for healthy women at low risk for problems during pregnancy, labor, or delivery. A CNM is educated in both nursing and midwifery. Most CNMs practice in hospitals and birth centers. A CPM is required to have experience delivering babies in home settings because most CPMs practice in homes and birthing centers. All midwives should have a back-up plan with an obstetrician in case of a problem or emergency.

Ask your primary care doctor, friends, and family members for provider recommendations. When making your choice, think about:

- Personality and bedside manner

- The provider's gender and age

- Office location and hours

- Whether you always will be seen by the same provider during office checkups and delivery

- Who covers for the provider when she or he is not available

- Where you want to deliver

- How the provider handles phone consultations and after-hour calls

What is a doula?

A doula (DOO-luh) is a professional labor coach, who gives physical and emotional support to women during labor and delivery. They offer advice on breathing, relaxation, movement, and positioning. Doulas also give emotional support and comfort to women and their partners during labor and birth. Doulas and midwives often work together during a woman's labor. A recent study showed that continuous doula support during labor was linked to shorter labors and much lower use of:

- Pain medicines

- Oxytocin (ok-see-TOHS-uhn) (medicine to help labor progress)

- Cesarean delivery

Check with your health insurance company to find out if they will cover the cost of a doula. When choosing a doula, find out if she is certified by Doulas of North America (DONA) or another professional group.

Places to deliver your baby

Many women have strong views about where and how they'd like to deliver their babies. In general, women can choose to deliver at a hospital, birth center, or at home. You will need to contact your health insurance provider to find out what options are available. Also, find out if the doctor or midwife you are considering can deliver your baby in the place you want to give birth.

Hospitals are a good choice for women with health problems, pregnancy complications, or those who are at risk for problems during labor and delivery. Hospitals offer the most advanced medical equipment and highly trained doctors for pregnant women and their babies. In a hospital, doctors can do a cesarean delivery if you or your baby is in danger during labor. Women can get epidurals or many other pain relief options. Also, more and more hospitals now offer on-site birth centers, which aim to offer a style of care similar to standalone birth centers.

Questions to ask when choosing a hospital:

- Is it close to your home?

- Is a doctor who can give pain relief, such as an epidural, at the hospital 24-hours a day?

- Do you like the feel of the labor and delivery rooms?

- Are private rooms available?

- How many support people can you invite into the room with you?

- Does it have a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) in case of serious problems with the baby?

- Can the baby stay in the room with you?

- Does the hospital have the staff and set-up to support successful breastfeeding?

- Does it have an on-site birth center?

Birth or birthing centers give women a "homey" environment in which to labor and give birth. They try to make labor and delivery a natural and personal process by doing away with most high-tech equipment and routine procedures. So, you will not automatically be hooked up to an IV. Likewise, you won't have an electronic fetal monitor around your belly the whole time. Instead, the midwife or nurse will check in on your baby from time to time with a handheld machine. Once the baby is born, all exams and care will occur in your room. Usually certified nurse-midwives, not obstetricians, deliver babies at birth centers. Healthy women who are at low risk for problems during pregnancy, labor, and delivery may choose to deliver at a birth center.

Women can not receive epidurals at a birth center, although some pain medicines may be available. If a cesarean delivery becomes necessary, women must be moved to a hospital for the procedure. After delivery, babies with problems can receive basic emergency care while being moved to a hospital.

Many birthing centers have showers or tubs in their rooms for laboring women. They also tend to have comforts of home like large beds and rocking chairs. In general, birth centers allow more people in the delivery room than do hospitals.

Birth centers can be inside of hospitals, a part of a hospital or completely separate facilities. If you want to deliver at a birth center, make sure it meets the standards of the Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Health Care, The Joint Commission, or the American Association of Birth Centers. Accredited birth centers must have doctors who can work at a nearby hospital in case of problems with the mom or baby. Also, make sure the birth center has the staff and set-up to support successful breastfeeding.

Homebirth is an option for healthy pregnant women with no risk factors for complications during pregnancy, labor or delivery. It is also important women have a strong after-care support system at home. Some certified nurse midwives and doctors will deliver babies at home. Many health insurance companies do not cover the cost of care for homebirths. So check with your plan if you'd like to deliver at home.

Homebirths are common in many countries in Europe. But in the United States, planned homebirths are not supported by the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). ACOG states that hospitals are the safest place to deliver a baby. In case of an emergency, says ACOG, a hospital's equipment and highly trained doctors can provide the best care for a woman and her baby.

If you are thinking about a homebirth, you need to weigh the pros and cons. The main advantage is that you will be able to experience labor and delivery in the privacy and comfort of your own home. Since there will be no routine medical procedures, you will have control of your experience.

The main disadvantage of a homebirth is that in case of a problem, you and the baby will not have immediate hospital/medical care. It will have to wait until you are transferred to the hospital. Plus, women who deliver at home have no options for pain relief.

To ensure your safety and that of your baby, you must have a highly trained and experienced midwife along with a fail-safe back-up plan. You will need fast, reliable transportation to a hospital. If you live far away from a hospital, homebirth may not be the best choice. Your midwife must be experienced and have the necessary skills and supplies to start emergency care for you and your baby if need be. Your midwife should also have access to a doctor 24 hours a day.

Prenatal checkups

During pregnancy, regular checkups are very important. This consistent care can help keep you and your baby healthy, spot problems if they occur, and prevent problems during delivery. Typically, routine checkups occur:

- Once each month for weeks four through 28

- Twice a month for weeks 28 through 36

- Weekly for weeks 36 to birth

Women with high-risk pregnancies need to see their doctors more often.

At your first visit your doctor will perform a full physical exam, take your blood for lab tests, and calculate your due date. Your doctor might also do a breast exam, a pelvic exam to check your uterus (womb), and a cervical exam, including a Pap test. During this first visit, your doctor will ask you lots of questions about your lifestyle, relationships, and health habits. It's important to be honest with your doctor.

After the first visit, most prenatal visits will include:

- Checking your blood pressure and weight

- Checking the baby's heart rate

- Measuring your abdomen to check your baby's growth

You also will have some routine tests throughout your pregnancy, such as tests to look for anemia , tests to measure risk of gestational diabetes , and tests to look for harmful infections.

Become a partner with your doctor to manage your care. Keep all of your appointments — every one is important! Ask questions and read to educate yourself about this exciting time.

Monitor your baby's activity

After 28 weeks, keep track of your baby's movement. This will help you to notice if your baby is moving less than normal, which could be a sign that your baby is in distress and needs a doctor's care. An easy way to do this is the "count-to-10" approach. Count your baby's movements in the evening — the time of day when the fetus tends to be most active. Lie down if you have trouble feeling your baby move. Most women count 10 movements within about 20 minutes. But it is rare for a woman to count less than 10 movements within two hours at times when the baby is active. Count your baby's movements every day so you know what is normal for you. Call your doctor if you count less than 10 movements within two hours or if you notice your baby is moving less than normal. If your baby is not moving at all, call your doctor right away.

Prenatal tests

Tests are used during pregnancy to check your and your baby's health. At your fist prenatal visit, your doctor will use tests to check for a number of things, such as:

- Your blood type and Rh factor

- Infections, such as toxoplasmosis and sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including hepatitis B , syphilis , chlamydia , and HIV

- Signs that you are immune to rubella (German measles) and chicken pox

Throughout your pregnancy, your doctor or midwife may suggest a number of other tests, too. Some tests are suggested for all women, such as screenings for gestational diabetes, Down syndrome, and HIV. Other tests might be offered based on your:

- Personal or family health history

- Ethnic background

- Results of routine tests

Some tests are screening tests. They detect risks for or signs of possible health problems in you or your baby. Based on screening test results, your doctor might suggest diagnostic tests. Diagnostic tests confirm or rule out health problems in you or your baby.

Understanding prenatal tests and test results

If your doctor suggests certain prenatal tests, don't be afraid to ask lots of questions. Learning about the test, why your doctor is suggesting it for you, and what the test results could mean can help you cope with any worries or fears you might have. Keep in mind that screening tests do not diagnose problems. They evaluate risk. So if a screening test comes back abnormal, this doesn't mean there is a problem with your baby. More information is needed. Your doctor can explain what test results mean and possible next steps.

Avoid keepsake ultrasounds

You might think a keepsake ultrasound is a must-have for your scrapbook. But, doctors advise against ultrasound when there is no medical need to do so. Some companies sell "keepsake" ultrasound videos and images. Although ultrasound is considered safe for medical purposes, exposure to ultrasound energy for a keepsake video or image may put a mother and her unborn baby at risk. Don't take that chance.

High-risk pregnancy

Pregnancies with a greater chance of complications are called "high-risk." But this doesn't mean there will be problems. The following factors may increase the risk of problems during pregnancy:

- Very young age or older than 35

- Overweight or underweight

- Problems in previous pregnancy

- Health conditions you have before you become pregnant, such as high blood pressure , diabetes , autoimmune disorders , cancer , and HIV

- Pregnancy with twins or other multiples

Health problems also may develop during a pregnancy that make it high-risk, such as gestational diabetes or preeclampsia . See Pregnancy complications to learn more.

Women with high-risk pregnancies need prenatal care more often and sometimes from a specially trained doctor. A maternal-fetal medicine specialist is a medical doctor that cares for high-risk pregnancies.

If your pregnancy is considered high risk, you might worry about your unborn baby's health and have trouble enjoying your pregnancy. Share your concerns with your doctor. Your doctor can explain your risks and the chances of a real problem. Also, be sure to follow your doctor's advice. For example, if your doctor tells you to take it easy, then ask your partner, family members, and friends to help you out in the months ahead. You will feel better knowing that you are doing all you can to care for your unborn baby.

Paying for prenatal care

Pregnancy can be stressful if you are worried about affording health care for you and your unborn baby. For many women, the extra expenses of prenatal care and preparing for the new baby are overwhelming. The good news is that women in every state can get help to pay for medical care during their pregnancies. Every state in the United States has a program to help. Programs give medical care, information, advice, and other services important for a healthy pregnancy.

Learn more about programs available in your state.

You may also find help through these places:

- Local hospital or social service agencies – Ask to speak with a social worker on staff. She or he will be able to tell you where to go for help.

- Community clinics – Some areas have free clinics or clinics that provide free care to women in need.

- Women, Infants and Children (WIC) Program – This government program is available in every state. It provides help with food, nutritional counseling, and access to health services for women, infants, and children.

- Places of worship

More information on prenatal care and tests

Read more from womenshealth.gov.

- Pregnancy and Medicines Fact Sheet - This fact sheet provides information on the safety of using medicines while pregnant.

Explore other publications and websites

- Chorionic Villus Sampling (CVS) (Copyright © March of Dimes) - Chorionic villus sampling (CVS) is a prenatal test that can diagnose or rule out certain birth defects. The test is generally performed between 10 and 12 weeks after a woman's last menstrual period. This fact sheet provides information about this test, and how the test sample is taken.

- Folic Acid (Copyright © March of Dimes) - This fact sheet stresses the importance of getting higher amounts of folic acid during pregnancy in order to prevent neural tube defects in unborn children.

- Folic Acid: Questions and Answers - The purpose of this question and answer sheet is to educate women of childbearing age on the importance of consuming folic acid every day to reduce the risk of spina bifida.

- For Women With Diabetes: Your Guide to Pregnancy - This booklet discusses pregnancy in women with diabetes. If you have type 1 or type 2 diabetes and you are pregnant or hoping to get pregnant soon, you can learn what to do to have a healthy baby. You can also learn how to take care of yourself and your diabetes before, during, and after your pregnancy.

- Genetics Home Reference - This website provides information on specific genetic conditions and the genes or chromosomes responsible for these conditions.

- Guidelines for Vaccinating Pregnant Women - This publication provides information on routine and other vaccines and whether they are recommended for use during pregnancy.

- How Your Baby Grows (Copyright © March of Dimes) - This site provides information on the development of your baby and the changes in your body during each month of pregnancy. In addition, for each month, it provides information on when to go for prenatal care appointments and general tips to take care of yourself and your baby.

- Pregnancy Registries - Pregnancy registries help women make informed and educated decisions about using medicines during pregnancy. If you are pregnant and currently taking medicine — or have been exposed to a medicine during your pregnancy — you may be able to participate and help in the collection of this information. This website provides a list of pregnancy registries that are enrolling pregnant women.

- Pregnancy, Breastfeeding, and Bone Health - This publication provides information on pregnancy-associated osteoporosis, lactation and bone loss, and what you can do to keep your bones healthy during pregnancy.

- Prenatal Care: First-Trimester Visits (Copyright © Mayo Foundation) - This fact sheet explains what to expect during routine exams with your doctor. In addition, if you have a condition that makes your pregnancy high-risk, special tests may be performed on a regular basis to check the baby's health.

- Ten Tips for a Healthy Pregnancy (Copyright © Lamaze International) - This easy-to-read fact sheet provides 10 simple recommendations to help mothers have a healthy pregnancy.

- Ultrasound (Copyright © March of Dimes) - This fact sheet discusses the use of an ultrasound in prenatal care at each trimester.

Connect with other organizations

- American Academy of Family Physicians

- American Association of Birth Centers

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

- Center for Research on Reproduction and Women's Health, University of Pennsylvania Medical Center

- Dona International

- March of Dimes

- Maternal and Child Health Bureau, HRSA, HHS

- National Association for Down Syndrome

- National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, CDC

- Public Information and Communications Branch, NICHD, NIH, HHS

- HHS Non-Discrimination Notice

- Language Assistance Available

- Accessibility

- Privacy Policy

- Disclaimers

- Freedom of Information Act (FOIA)

- Use Our Content

- Vulnerability Disclosure Policy

- Kreyòl Ayisyen

A federal government website managed by the Office on Women's Health in the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

1101 Wootton Pkwy, Rockville, MD 20852 1-800-994-9662 • Monday through Friday, 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. ET (closed on federal holidays).

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Effectiveness of Home Visits in Pregnancy as a Public Health Measure to Improve Birth Outcomes

Kayoko ichikawa.

1 Department of Health Informatics, Kyoto University School of Public Health, Kyoto, Japan

2 Department of Social Medicine, National Research Institute for Child Health and Development, Tokyo, Japan

Takeo Fujiwara

Takeo nakayama.

Conceived and designed the experiments: TF. Performed the experiments: KI. Analyzed the data: KI TF. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: KI TF. Wrote the paper: KI TF TN. Significant contribution to obtain data from the field: KI TF TN.

Associated Data

Data is not made publicly available due to the restriction of the Kyoto City and Ethics Committee at Kyoto University. If data is requested, please contact to Dr. Takeo Fujiwara, Head of Department of Social Medicine National Research Institute for Child Health and Development, Tokyo, Japan ( pj.og.dhccn@kt-arawijuf ).

Birth outcomes, such as preterm birth, low birth weight (LBW), and small for gestational age (SGA), are crucial indicators of child development and health.

To evaluate whether home visits from public health nurses for high-risk pregnant women prevent adverse birth outcomes.

In this quasi-experimental cohort study in Kyoto city, Japan, high-risk pregnant women were defined as teenage girls (range 14–19 years old), women with a twin pregnancy, women who registered their pregnancy late, had a physical or mental illness, were of single marital status, non-Japanese women who were not fluent in Japanese, or elderly primiparas. We collected data from all high-risk pregnant women at pregnancy registration interviews held at a public health centers between 1 July 2011 and 30 June 2012, as well as birth outcomes when delivered from the Maternal and Child Health Handbook (N = 964), which is a record of prenatal check-ups, delivery, child development and vaccinations. Of these women, 622 women were selected based on the home-visit program propensity score-matched sample (pair of N = 311) and included in the analysis. Data were analyzed between January and June 2014.

In the propensity score-matched sample, women who received the home-visit program had lower odds of preterm birth (odds ratio [OR], 0.62; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.39 to 0.98) and showed a 0.55-week difference in gestational age (95% CI: 0.18 to 0.92) compared to the matched controlled sample. Although the program did not prevent LBW and SGA, children born to mothers who received the program showed an increase in birth weight by 107.8 g (95% CI: 27.0 to 188.5).

Home visits by public health nurses for high-risk pregnant women in Japan might be effective in preventing preterm birth, but not SGA.

Introduction

Adverse birth outcomes, such as preterm birth, low birth weight (LBW), and small for gestational age (SGA), can have a long-term impact on child development and health [ 1 – 6 ]. Adverse birth outcomes are a known risk factor for maternal mental health and child maltreatment [ 7 – 9 ]. In Japan, like other developed countries [ 10 , 11 ], the proportion of preterm birth (5.8%) and LBW (boys: 8.5%, girls: 10.7%) has increased over the past three decades [ 11 – 14 ]. The causes of preterm birth or LBW have been considered multifactorial [ 15 ], and include, for example, maternal infection during pregnancy [ 16 ], smoking [ 17 ], low maternal BMI [ 18 ], maternal depression [ 19 , 20 ], lack of social support [ 21 ], maternal disease [ 22 ], and social disadvantage[ 23 – 25 ]. To prevent adverse health outcomes, a comprehensive intervention approach is needed because these risk factors are likely to be co-occurring.

Implementation of a home-visit program during pregnancy is a comprehensive strategy to prevent adverse birth outcomes [ 26 , 27 ]. Although the exact mechanism of this approach is not well clarified, many previous studies have suggested that providing tangible in-home or one-on-one psychosocial support, and improving linkages to medical providers, social services and nutrition support can encourage healthy prenatal behaviors[ 28 – 31 ]. However, previous randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of home-visit programs and pregnancy outcomes showed inconsistent results [ 32 – 35 ]. For example, Lee and colleagues [ 36 ] found that home visits before 30 weeks’ gestation for women (Black and Hispanic: 65%; under 18 years old: 24.6%) were effective for preventing LBW (5.1% versus 9.8%; p = 0.022), however McLaughlin and colleagues [ 37 ] found home visits for women (Black women: 35%, mean age: 21.8 years old) showed no significant effect in reducing LBW incidence. This is likely due to several factors, including differences in the characteristics of target participants and methods of program delivery, the reluctance of high-risk women to participate, and variation in the timing of home-visit implementation between trials [ 38 , 39 ]. Therefore, an assessment of the effectiveness of home visits for a wide range of high-risk women, and the timing of implementation, is needed.

Japan has a unique data collection and prenatal support system that was first established by the Maternal and Child Health (MCH) Act and MCH Law in 1965 for the promotion of maternal, newborn, and infant health. The Act promotes continuity of care through the MCH Handbook [ 40 ], which is provided for free to expectant mothers who submit a notice of pregnancy to their local government office. Women in Japan are supposed to register their pregnancy within the 11th gestational week [ 41 ]. The Handbook unifies maternal and child health into one resource, serving as a maternal health record during pregnancy and a child health record from 0–6 years, which parents can keep and take with them to appointments. In addition to the MCH Handbook, which has almost 100% coverage [ 40 ] for expectant mothers, the Act also provides health guidance to pregnant and postpartum women, and health check-ups for newborns and infants at local government health centers.

In July 2011, Kyoto city in Japan established the population-based home-visit program for all high-risk pregnant women. High-risk pregnant women were defined as teenage girls (range 14–19 years old), women with a twin pregnancy, women who registered their pregnancy late, had a physical or mental diseases, were of single marital status, non-Japanese women who were not fluent in Japanese, or elderly primiparas. At the time of pregnancy registration at the public health center, public health nurses assessed the risk level of pregnant women by conducting an interview in person using a registration questionnaire. As some women receive the home-visit program and others do not, we were provided with the opportunity to conduct a quasi-experimental study on the effectiveness of the home-visit program. As the baseline information is known at registration, the propensity of receiving the home-visit program can be assessed.

The objective of this study is to evaluate the effectiveness of the home-visit program conducted by public health nurses to high-risk pregnant women to prevent adverse birth outcomes (preterm, LBW, and SGA) by using the propensity score-matching model. We also investigated whether timing of program implementation had an effect on adverse birth outcomes.

Ethics statement

We used secondary administrative data from Kyoto city government in this study, which did not contain identifying information about individuals. In addition, public health nurses obtained written informed consent from pregnant women. We obtained written informed consent from Kyoto city government’s ethical committee to use this secondary administrative data which did not contain identifying information about individuals, and published an announcement about this study on the official homepage of Kyoto city government. The announcement stated that if individuals who met the inclusion criteria did not want their own data to be used, even though it was anonymised, they could request for their data to be omitted by calling the Kyoto city government. However, no one requested for their data to be omitted from the study. The study was approved by the Kyoto University Graduate School and Faculty of Medicine Ethics Committee (E1833).

Study design and population

This was a quasi-experimental cohort study using administrative data collected in Kyoto, Japan. Data was obtained from the Department of Child and Maternal Health in Kyoto, including the baseline questionnaire conducted at pregnancy registration in public health centers, MCH handbook data, which includes data from prenatal checkups, delivery, child development, vaccinations, and home-visits. The population of Kyoto is around 1,467,000. During the period of 1 July 2011 to 30 June 2012, 11,749 women registered their pregnancy at public health centers in Kyoto. Trained public health nurses conducted interviews in person at the public health center using unified standard questionnaires to assess high-risk pregnancy. Target participants of our study were all high-risk pregnant women who registered their pregnancy in Kyoto city. High-risk pregnant women were administratively defined as follows: 1) women who had past or current physical or mental illness; 2) primiparas under the age of 20; 3) primiparas over the age of 35 with some unfavorable conditions such as poverty; 4) women who were pregnant with twins; 5) women who were late to register their pregnancy (i.e. after the 22 nd week of gestation) or women who were unhappy about being pregnant; 6) women with single marital status (unmarried or divorced); 7) non-Japanese women who were not fluent in Japanese, and 8) women who were assessed by public health nurses at registration as requiring any additional support including both medical, psycho-social, nutrition counseling.

The target population of high-risk prenatal mothers in this project was 1,023 women, and all data were used in the initial analysis to calculate propensity scores for receiving the home-visit program. That is, all high-risk pregnant women were supposed to receive home visits from public health nurses; however, 594 women (58.1%) did not receive any visits because they were not reachable. This group was used as a control sample ( Fig 1 ).

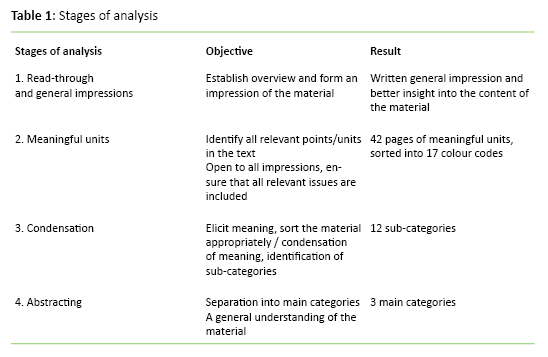

Home-visit programs for pregnant women in Kyoto

In this program, trained public health nurses were to make at least 1 home visit to high-risk pregnant women lasting for more than 1 hour during mid- or late-term pregnancy (mean gestational age: 27.2 (SD = 6.9) weeks, range: 7–40 weeks). Nurses received specific training about home visiting about once a year and were expected to consult with supervisors about difficult cases. The contents of the home visit were as follows: 1) checking women’s social support status and linking them to other services in the community, if needed; 2) providing information about appropriate nutrition during pregnancy, prenatal care, dental care, and child care, and 3) asking women about their physical or psychological health and linking them to medical facilities if needed. If nurses concluded that the women required more support, they provided follow-up support by phone, made another home visit, or introduced women to further social services support. Detailed components of the home visit are shown in Table 1 .

Birth outcomes, birth weight (crude value) and gestational age were obtained from birth records in the MCH handbook. Z-scores of birth weight (ZBW) were calculated and we adjusted for gestational age, sex, and parity [ 42 ]. Binary indicators were low birth weight, defined as less than 2500g; preterm birth, defined as less than 37 weeks, and small for gestational age, defined as <10 percentile.

Covariates and independent variables

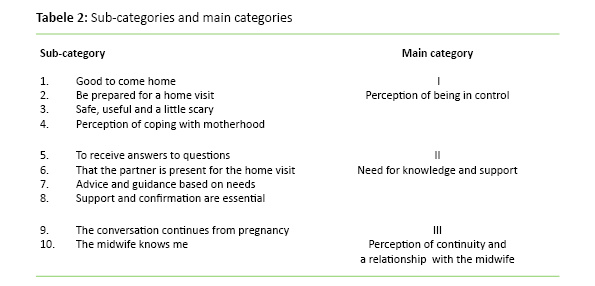

The following covariates were obtained from baseline questionnaires and interviews from trained public health nurses at the time of pregnancy registration: maternal age, paternal age, employment status during pregnancy, living with family members, marital status, parity, history of miscarriage and stillbirth, experiences of fertility treatment, late submission of pregnancy registration (over 22 weeks), twin pregnancy, maternal smoking or alcohol consumption, smoking among women’s family members, maternal physical or mental illness, limited Japanese ability among non-Japanese women, unintended pregnancy, worries about child-rearing, finances, and relationship with partner, having someone to consult with on child care, experiences of good relationships with parents, subjective economic status, maternal and paternal attitudes to child-rearing, and experiences of child-rearing. Categorical variables were used for childcare services (“Yes”, “Rarely”, or “Never”) and knowing someone with experience of child-rearing (“Yes, many people”, “Yes, a few people”, or “No, do not know anyone”). The remaining variables were binominal (see Table 2 ).

Note from questionnaire

a "Do you have any disease that is currently under treatment or was treated in the past?"

b From risk assessment by public health nurses in first interview.

c From risk assessment by public health nurses in first interview.

d Prenatal mothers who emigrated to Japan or were staying in Japan long-term.

e ‘ satogaeri’ : a tradition in which pregnant women return to the family home prior to delivery to stay with their parents for support before and after childbirth.

Statistical analysis

Of the 1,023 baseline samples, we excluded participants who had missing birth-outcome data (home-visit program: n = 19, no home-visit program: n = 40, 5.8% in total participants) from the analysis (total N = 964 women, home-visit program: n = 410, no home-visit program: n = 554). Then, propensity score-matched analysis was performed to reduce potential bias on receiving the home-visit program. The probability of home-visit participation was estimated by all baseline characteristics using logistic regression, because these characteristics possibly associate with participation in the home-visit program. Propensity-score matching was performed by using the following algorithm: 1:1 nearest-neighbor match method with a caliper of 0.4 SD and no replacement. Finally, 311 women who received the home-visit program and 311 women who did not were included in the analysis (that is, N = 622). Variables used to estimate the propensity to participate in the program were sufficiently high, with C-statistics at 0.77. No significant difference was observed between the baseline characteristics of the home-visit program group and the no home-visit group ( Table 2 , right columns). The propensity-matched pairs were compared using logistic regression analysis, and multivariate regression analysis after adjusting for all baseline variables. In addition, sub-group analysis was performed for the timing of home-visit implementation, which was divided into two subgroups (home visits at <28 gestational weeks, home visits at ≥28 weeks). Missing data of covariates such as alcohol consumption (n = 4), experiences of fertility treatment (n = 12), physical or mental illness (n = 2), employment status (n = 25), living with family members (n = 162), experiences of good relationships with parents (n = 25), maternal and paternal attitudes of child rearing (n = 32) and experiences of child-rearing (n = 12) were treated as dummy variables. Where paternal age was missing in the data, the mean age was imputed. Stata version 13 was used to perform the analysis between January 2014 and June 2014.

Table 2 shows the baseline characteristics of prenatal mothers at pregnancy registration in the home-visit group (n = 410) and the no home-visit group (n = 554) before propensity-score matching. Mean gestational age for infants of mothers in the home-visit group was 27.2 (SD = 6.9) weeks. Pregnant women who received home visits were more likely to be experiencing their first pregnancy (n = 333, 81.2%), diagnosed with a disease (n = 163, 39.8%), and worried about child-rearing (n = 192, 46.8%) or relationships with neighbors (n = 64, 15.6%) compared with women who did not receive home visits. Pregnant women who did not receive home visits were more likely to smoke (n = 111, 20.0%), drink alcohol (n = 67, 12.1%), be unmarried (n = 197, 35.6%), feel unhappy about their pregnancy (n = 111, 20.0%), or had partners who were unhappy about their pregnancy (n = 85, 15.3%) compared with women in the home-visit group. After performing propensity-score matching with the comparison group, no significant difference was observed between variables (see Table 2 ).

Table 3 shows the birth outcomes before and after propensity-score matching. Before propensity-score matching, women from the home-visit group had a heavier birth weight (2905.3 g, SD = 499.5 g), longer gestational age (38.7 weeks, SD = 1.8 weeks), higher ZBW (-0.04, SD = 1.1), less LBW infants (n = 85, 19.2%), less preterm birth (n = 40, 9.8%), and less SGA infants (n = 52, 11.7%) compared to participants who did not receive the home-visit program. After propensity-score matching, women from the home-visit group had a heavier birth weight (2933.3 g, SD = 473.4 g), longer gestational age (38.6 weeks, SD = 1.8 weeks), and less preterm birth (n = 34, 10.9%) compared to women who did not receive the home-visit program.

Abbreviations: LBW: low birth weight; SGA: small for gestational age.

Table 4 shows the coefficient and odds ratios (ORs) of the home-visit program for birth outcomes. Before propensity-score matching was conducted in the univariate model, women in the home-visit program during their pregnancy had a significantly heavier birth weight (coefficient: 138.3g, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 63.2 to 213.4), longer gestational age (coefficient: 0.67 week, 95% CI: 0.33 to 1.00), higher ZBW (coefficient: 0.25, 95% CI: 0.11 to 0.38), LBW (OR: 0.70, 95% CI: 0.49 to 0.98), preterm birth (OR: 0.62, 95% CI: 0.41 to 0.94), SGA (OR: 0.62, 95% CI: 0.43 to 0.91) than women who did not receive the home-visit program. These associations remained significant in the multivariate adjusted model, except for ZBW and SGA. Further, in the propensity-matched sample for the home-visit group, a heavier birth weight, longer gestational age, and lower odds of preterm birth remained significant during pregnancy, although odds of LBW became non-significant. In the final model—the multivariate adjustment of the propensity-score matched sample—pregnant women in the home-visit group delivered infants with a heavier birth weight of 99.1g (95% CI: 20.5 to 177.6) and a longer gestational age of 0.61 weeks (95% CI: 0.25 to 0.96), and were 74% less likely to deliver preterm, compared to pregnant women who did not receive home visits.

Abbreviations: CI: confidence interval; LBW: low birth weight; SGA: small for gestational age. Bold value signifies p<0.05.

Table 5 shows the subgroup analyses of the effectiveness of the home-visit program by timing of implementation (i.e. whether the program was implemented before or after 28 weeks’ gestation). In the propensity-score matched sample, women who entered the home-visit program late (after 28 gestational weeks, n = 159) showed a longer gestational age (coefficient: 0.65 weeks, 95% CI: 0.09 to 1.20) compared to women who did not receive home visits. Further, a marginal protective effect on preterm birth was found among women who entered the program late compared to women who were registered in the program earlier (OR: 0.57, 95% CI: 0.31 to 1.06). However, early implementation of the home-visit program (before 28 gestational weeks, n = 145) failed to show longer gestational age nor a protective effect on preterm than women in the comparison group, suggesting that joining the home-visit program after 28 weeks’ gestation was more effective to achieve longer gestational age and to be protective for preterm.

a no home visit (n = 554)

b p = 0.07.

Abbreviations: CI: confidence interval; LBW: low birthweight; SGA: small for gestational age. Bold value signifies p<0.05.

The present study evaluated the effectiveness of the home-visit program for high-risk pregnant women in Japan on birth outcomes (birth weight, gestational age, Z-scores of birth weight) using a propensity-score matched sample. We found that home visits from trained public health nurses at least once during pregnancy were effective to prevent preterm birth, but not small for gestational age among high-risk pregnant women in Japan.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the effectiveness of the home-visit program for a wide range of high-risk pregnant women as a public healthcare measure. However, two randomized controlled trials of home-visit programs [ 36 , 37 ], which investigated the efficacy of birth outcomes, suggested that the effectiveness of such programs is still inconsistent, while two recent observational studies conducted in the United States (US) using propensity score-matched analysis found home-visit programs to be effective [ 33 , 43 ]. Both US studies concluded that participating in the home-visit program reduced the risk of adverse birth outcomes in disadvantaged populations (i.e. people who received Medicaid). Our finding is consistent with these previous studies in showing the effectiveness of the home-visit program in preventing adverse birth outcomes, although the definition of disadvantaged population is different (i.e. our definition of ‘high-risk pregnant women’ did not only focus on economic status but on medical conditions, social disadvantages and other factors).

In the Japanese healthcare system, all pregnant women are screened by public health nurses at registration of their pregnancy, or within 11 weeks’ gestation. In addition, high-risk women receive comprehensive support and are referred to appropriate follow-up services[ 44 ]. This system enables high-risk women to be followed-up from the prenatal to postnatal period, and facilitates the first contact between public health services and high-risk pregnant women. Some components of the home-visit program, such as consultations on maternal anxiety, nutrition education and health-check ups, might improve birth weight. Although we tried to provide the home-visit program for all high-risk pregnant women, approximately half of the high-risk women (n = 554) were not reachable and showed worse risk factors, such as smoking and drinking alcohol, for poor birth outcomes. It is another challenge to support the super-high-risk pregnant women who were not reachable in general health care system.

We found that late admission to the home-visit program was effective to prevent preterm birth, although early admission to the home-visit program did not. The reason for this difference is unknown. It is possible that perinatal care or advice from public health nurses might be more effective closer to delivery. Further study is needed to elucidate the mechanism on why receiving home visits later in pregnancy is more effective to prevent preterm birth.