ANDREW BAZEMORE, MD, MPH, AND MARK HUNTINGTON, MD, PhD

Am Fam Physician. 2009;80(6):583-590

A more recent article on pretravel consultation is available .

Author disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

The increase in travel and travel medicine knowledge over the past 30 years makes pretravel counseling an essential part of comprehensive family medicine. Effective counseling begins with assessment of individual and itinerary-based risks, using a growing body of evidence-based decision-support tools and resources. Counseling recommendations should be tailored to the patient's risk tolerance and experience. An essential component of the pretravel consultation includes reviewing routine and destination-specific immunizations. In addition to implementing behavioral adaptations, travelers can guard against vector-borne disease by using N,N -diethyl- m -toluamide (DEET, 30%), a safe and effective insect repellent. Patients should also receive malarial chemoprophylaxis when traveling to areas of risk. Proper precautions can reduce the risk of food- and waterborne disease. Travelers should take appropriate precautions when traveling to high altitudes. Strategies for minimizing the risk of deep venous thrombosis during air travel include keeping mobile and wearing compression stockings. Accident avoidance and coping strategies for health problems that occur while abroad are also important components of the pretravel consultation.

Travel medicine is often relegated to the purview of infectious diseases. However, its emphasis is prevention—not only of tropical disease, but also of common disease—and it takes into consideration preexisting chronic conditions, behavioral risk factors, nonbiologic health threats, and the individual traveler's risk tolerance. Multidisciplinary in its scope, travel medicine lends itself well to the family physician's broad training, counseling skills, and focus on prevention and continuity. In the United States, surveys of travel physicians show that 38 percent trained in family medicine or general internal medicine; in Canada, 54 percent trained in family medicine. 1

Risk Stratification and Shared Decision Making

A successful pretravel consultation involves risk identification, stratification, and counseling to make the patient aware of and comfortable with travel risks ( Table 1 ). 1 – 11 Physicians should remind travelers that risk is present at home and abroad, and that the risk of exotic or unusual conditions is low for many destinations and can be minimized for others ( Figure 1 ). 12 Effective pretravel consultation begins with a process of assessing and conveying the epidemiologic likelihood of disease and injury connected with the trip ( Table 2 ) , which depends on traveler- and itinerary-specific factors. A two-week trip through Western Europe has a far different risk profile than a two-year Peace Corps tour in West Africa. 2 , 12 Point-of-care references are essential for primary care physicians to be able to provide the most appropriate advice for a specific destination ( Table 3 ). Similarly, traveler factors such as age, chronic disease, immunocompromise, and pregnancy potentially influence the epidemiologic risk associated with specific destinations, and consultation with a travel medicine subspecialist may be indicated for optimal care of patients at higher risk. Figure 2 presents an algorithm for identifying travelers who may require specialized advice.

Travel epidemiology should be balanced with shared decision making, which requires assessing and incorporating the patient's health belief model and level of risk tolerance into decisions about disease prophylaxis. Furthermore, such assessment helps to determine the direction of the physician's limited counseling time; for example, additional time may be needed for counseling on topics such as local risk of sexually transmitted disease exposure, food safety, and crime avoidance.

Topics for Discussion

Morbidity and mortality.

Reported morbidity among travelers varies widely, but as many as 75 percent of short-term travelers to developing nations report experiencing some health impairment. 12 Minor ailments are quite prevalent, with traveler's diarrhea by far the most common. Patients should be counseled that average mortality rates for travelers to developing nations may actually be lower than those of nontravelers 12 , 13 ; that trauma, not infectious disease, is the leading cause of death in younger travelers; and that cardiovascular disease is the greatest threat in older travelers. 7 , 13 Among infectious sources, the most common cause of death is falciparum malaria, which is easily prevented with appropriate precautions and awareness.

IMMUNIZATIONS

Immunization is the most common reason cited by patients for seeking pretravel medical consultations. Appropriate immunization greatly enhances a traveler's likelihood of remaining healthy ( Table 4 ). In addition to ensuring that all routine immunizations are up-to-date, special immunizations may be advisable based on individual risk tolerance, geographic destination, behavioral or occupational risk factors, seasonal disease variations, and current outbreaks. Information and current recommendations for travel vaccination are available from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ( http://www.cdc.gov/travel ).

Use of decision support is essential to safe and appropriate vaccine administration in travelers. Some vaccines may be contraindicated for certain travelers. Depending on the destination, immunizations may be advisable that are not available in the typical family physician's office or that require special certification, such as yellow fever vaccine. To meet the pretravel vaccine needs of their patients, physicians should locate and offer a list of local clinics that are certified to deliver these vaccines; consider which suppliers can deliver these vaccines quickly; and contemplate the cost implications for the office and patient, who may choose to return for a nurse visit to receive the vaccine.

INSECT AVOIDANCE

Vector-borne disease is a significant source of traveler morbidity. Although reasonably effective malaria prophylaxis regimens are available, other diseases can be prevented only by insect avoidance. N,N -diethyl- m -toluamide (DEET, 30%) is the most effective and safest insect repellent available, and should be recommended to all travelers. 1 Other agents, such as picaridin, have also been shown to offer some protection. 14

Proper clothing, insecticide-impregnated bednets in high-risk areas, and behavioral measures decrease the risk of acquiring vector-borne illness and should be encouraged. Insect precautions, awareness of seasonal importance in the prevalence of insect vectors and disease, antimalarial chemoprophylaxis, and vaccination against vector-borne illnesses (where available) should be advised to persons traveling to high-risk areas. 1 – 6 This information is best rendered with the aid of decision-support tools that offer maps of vector and disease exposure. However, evidence for the effect of such counseling on adherence and ultimate disease risk is variable. 3 , 4

FOOD AND WATER PRECAUTIONS

A leading cause of morbidity among travelers is gastrointestinal disturbance from food- and waterborne diseases. Traveler's diarrhea is the most common disease among travelers, increasing in frequency when food and water precautions are not strictly practiced. Fluoroquinolones are the first choice for treatment, although Campylobacter resistance is developing in some regions. Dosages and agents differ for children and pregnant women. Because recommendations to lower the risk of these diseases are quite restrictive and the evidence supporting the effectiveness of counseling is lacking, shared decision making about acceptable risk is critical. More adventuresome travelers may be willing to risk disease to fully participate in the local cultural experiences, whereas a business traveler may wish to be as cautious as possible.

ENVIRONMENTAL PRECAUTIONS

Water ingestion is not the only swimming-related risk; immersion also presents risks. Various diseases, such as schistosomiasis and Naegleria infection, may be acquired by swimming in unchlorinated freshwater. Although salt-water is generally safer than tropical freshwater, persons swimming in saltwater should consider currents, pollutants, and hazardous marine life. Decision-support tools can help physicians identify regions where travelers should carefully consider swimming.

Temperature extremes and sun exposure are other environmental hazards encountered in traveling. Whether by hypothermia and frostbite, or heat exhaustion and dehydration, being unprepared for the local climate can risk the health of a traveler. Local weather is influenced by a variety of factors, not merely distance from the equator, and many travelers arrive at their destination ill-prepared for the climate encountered. Ensuring that travelers are aware of what weather to expect at their destination can keep them healthy, as can reminders of the importance of hydration during acclimation to tropical heat. The risk of sunburn and its sequelae increases with travel to higher altitudes and lower latitudes. Counseling travelers to wear sun-protective clothing and use sunscreen with a sun protection factor of at least 30 is sage advice.

It is important to acquaint travelers to altitudes above 8,000 ft with the symptoms and risks of altitude-related illnesses, as well as measures to avoid these illnesses. Assessing risk tolerance and discussing plans for acclimation, particularly among adventure travelers drawn to high altitude, may help these travelers avoid potential hazards. Some preexisting medical conditions, particularly cardiopulmonary and cerebral diseases, may exacerbate or be exacerbated by altitude-related illness. Determining the altitude of the patient's destination and counseling about ways to minimize risks above 8,000 ft (e.g., acetazolamide [formerly Diamox] prophylaxis, appropriate time for acclimation) should be part of the pretravel visit for anyone traveling to mountainous regions.

Comprehensive pretravel consultation includes assessment of fitness for air travel and advice on avoiding associated hazards, particularly for pregnant women; scuba divers; and persons with history of hemoglobinopathies, hypercoagulability, recent surgery, or cardiopulmonary disease. Key areas to cover include avoidance of deep venous thrombosis with prolonged flights, infectious disease and cabin air quality, and minimizing jet lag.

OTHER CONSIDERATIONS

The primary cause of death in travelers is accidents, usually motor vehicle crashes and falls. Physicians should remind travelers that safety regulations and practices are not as prevalent in many nations as they are in the United States, and should advise them to become familiar with the hazards associated with local transportation and activities. Staying abreast of warnings from the U.S. State Department ( http://www.travel.state.gov ) before and even during travel may be important in high-risk destinations. Travelers also should be counseled about the high cost of medical evacuation in the event of emergency, and they should be directed to sources of evacuation insurance as indicated by the risk assessment and tolerance.

Travelers may be at risk of exposure to sexually transmitted diseases. They should be reminded of the hazards of casual sex and of the increased prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis B in many developing nations, and that proper condom use can decrease, but not eliminate, this risk.

Travelers should be reminded that the risk of crime abroad varies based on destination and traveler behavior. In addition to familiarity with local patterns and prevalence of crime, safety-enhancing behaviors such as minimizing the appearance of wealth, traveling in pairs or groups, conducting business with established vendors, and locking hotel rooms can decrease risk. Awareness of the local customs, attitudes, laws, and geopolitical conditions can also reduce risk.

The resources listed in Table 3 , as well as guidebooks and online travel review sites, are important sources of information to inform physicians and travelers about events and customs that affect risk. Travelers may register their itineraries and travel dates with the U.S. State Department, and they may wish to carry embassy or consulate and local health care resource information with them in the event of unforeseen emergencies, such as natural disasters or political disturbances.

Hill DR, et al. The practice of travel medicine: guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(12):1499-1539.

Chen LH, Wilson ME, Schlagenhauf P. Prevention of malaria in long-term travelers. JAMA. 2006;296(18):2234-2244.

Lobel HO, et al. Use of malaria prevention measures by North American and European travelers to East Africa. J Travel Med. 2001;8(4):167-172.

Lobel HO, Kozarsky PE. Update on prevention of malaria for travelers. JAMA. 1997;278(21):1767-1771.

Batchelor T, Gherardin T. Prevention of malaria in travellers. Aust Fam Physician. 2007;36(5):316-320.

Chen LH, Wilson ME, Schlagenhauf P. Controversies and misconceptions in malaria chemoprophylaxis for travelers. JAMA. 2007;297(20):2251-2263.

DuPont HL. New insights and directions in travelers' diarrhea. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2006;35(2):337-353.

Rao G, Aliwalas MG, Slaymaker E, Brown B. Bismuth revisited: an effective way to prevent travelers' diarrhea. J Travel Med. 2004;11(4):239-241.

Keystone JS. Travel Medicine . 2nd ed. London:Mosby Elsevier; 2008.

Milledge JS. Altitude medicine and physiology including heat and cold: a review. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2006;4(3–4):223-237.

Luks AM, Swenson ER. Medication and dosage considerations in the prophylaxis and treatment of high-altitude illness. Chest. 2008;133(3):744-755.

Steffen R, Amitirigala I, Mutsch M. Health risks among travelers—need for regular updates. J Travel Med. 2008;15(3):145-146.

Freedman DO, et al. Spectrum of disease and relation to place of exposure among ill returned travelers [published correction appears in N Engl J Med . 2006;355(9):967]. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(2):119-130.

Frances SP, Waterson DG, Beebe NW, Cooper RD. Field evaluation of commercial repellent formulations against mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) in Northern Territory, Australia. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2005;21(4):480-482.

Continue Reading

More in afp, more in pubmed.

Copyright © 2009 by the American Academy of Family Physicians.

This content is owned by the AAFP. A person viewing it online may make one printout of the material and may use that printout only for his or her personal, non-commercial reference. This material may not otherwise be downloaded, copied, printed, stored, transmitted or reproduced in any medium, whether now known or later invented, except as authorized in writing by the AAFP. See permissions for copyright questions and/or permission requests.

Copyright © 2024 American Academy of Family Physicians. All Rights Reserved.

MassGeneral Home

- Conditions & Treatments

- Centers & Services

- Research & Clinical Trials

- Education & Training

- Career Opportunities

- About Mass General

Global TravEpiNet

A national consortium of travel health providers.

Please let us know if you have suggestions or comments by email .

This tool is provided by the Massachusetts General Hospital and supported by funding from grant U01CK000175 of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). This software is a reference tool intended to be used as an adjunct to the management of clinical care. The healthcare professional must review and verify information obtained by using the software to ensure that the information is accurate, complete and correctly associated with, and relevant to, individual cases. The tool should not be used to replace, overrule, or substitute the healthcare professional’s medical judgment, diagnosis, or treatment decisions. By using this tool, you agree that the Massachusetts General Hospital and the tool’s developers and supporters are not liable for any adverse outcomes, including those relating to your patient’s travel.

- Billing & Insurance

- Medical Records

- Accessibility

- Your Rights & Concerns

- Privacy & Security

- Social Media Policy

- 55 Fruit Street, Boston, MA 02114

- Maps & Directions

- 617-726-2000

- TDD: 617-724-8800

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 02 May 2012

A cross-sectional study of pre-travel health-seeking practices among travelers departing Sydney and Bangkok airports

- Anita E Heywood 1 ,

- Rochelle E Watkins 2 ,

- Sopon Iamsirithaworn 3 ,

- Kessarawan Nilvarangkul 4 &

- C Raina MacIntyre 1 , 5

BMC Public Health volume 12 , Article number: 321 ( 2012 ) Cite this article

6998 Accesses

55 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Pre-travel health assessments aim to promote risk reduction through preventive measures and safe behavior, including ensuring travelers are up-to-date with their immunizations. However, studies assessing pre-travel health-seeking practices from a variety of medical and non-medical sources and vaccine uptake prior to travel to both developing and developed countries within the Asia-Pacific region are scarce.

Cross-sectional surveys were conducted between July and December 2007 to assess pre-travel health seeking practices, including advice from health professionals, health information from other sources and vaccine uptake, in a sample of travelers departing Sydney and Bangkok airports. A two-stage cluster sampling technique was used to ensure representativeness of travelers and travel destinations. Pre-travel health seeking practices were assessed using a self-administered questionnaire distributed at the check-in queues of departing flights. Logistic regression models were used to identify significant factors associated with seeking pre-travel health advice from a health professional, reported separately for Australian residents, residents of other Western countries and residents of countries in Asia.

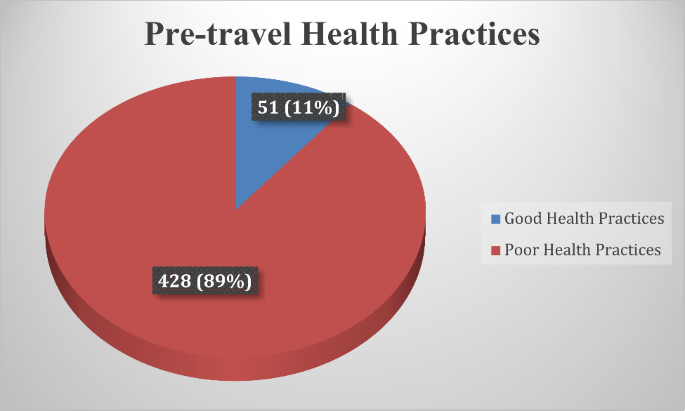

A total of 843 surveys were included in the final sample (Sydney 729, response rate 56%; Bangkok 114, response rate 60%). Overall, pre-travel health information from any source was sought by 415 (49%) respondents with 298 (35%) seeking pre-travel advice from a health professional, the majority through general practice. Receipt of a pre-travel vaccine was reported by 100 (12%) respondents. Significant factors associated with seeking pre-travel health advice from a health professional differed by region of residence. Asian travelers were less likely to report seeking pre-travel health advice and uptake of pre-travel vaccines than Australian or other Western travelers. Migrant Australians were less likely to report seeking pre-travel health advice than Australian-born travelers.

Conclusions

This study highlights differences in health-seeking practices including the uptake of pre-travel health advice by region of residence and country of birth. There is a public health need to identify strategies targeting these travel groups. This includes the promotion of affordable and accessible travel clinics in low resource countries as traveler numbers increase and travel health promotion targeting migrant groups in high resource countries. General practitioners should play a central role. Determining the most appropriate strategies for increasing pre-travel health preparation, particularly for vaccine preventable diseases in travelers is the next stage in advancing travel medicine research.

Peer Review reports

International travel has increased dramatically over the last few decades, in magnitude, speed and geographical reach with 940 million arrivals reported in 2010 [ 1 ]. Furthermore, the last decade has seen an increase in travel in the Asia-Pacific region well above the global average, resulting in a 21% share of international arrivals in 2010, up from 16% in 2000 [ 1 ]. Travelers play a significant role in the spread of infectious diseases across international borders, through their travel patterns and behaviors. Travel maybe the only risk factor for infectious diseases that are well controlled in the travelers’ country of residence, particularly vaccine-preventable diseases such as hepatitis A, typhoid, polio and measles. The role of vaccination among travelers is an essential component of national control of travel-associated infectious diseases. Understanding the behaviors of travelers and their attitudes towards a variety of communicable diseases can inform policy aimed at protecting the individual traveler, their contacts and the communities into which they travel. Behavioral studies of travelers provide insights into risks of both acquiring and importing infectious diseases.

A pre-travel consultation with a health professional can provide the international traveler with the necessary preventive advice on minimizing health risks during travel, including the risk of infectious disease and the opportunity for relevant vaccination and chemoprophylaxis. Travelers who seek pre-travel health advice from a health professional have been found to have better knowledge of infectious disease risk, more accurate risk perceptions and a higher level of intended risk-reducing behaviors [ 2 – 5 ]. Yet studies have shown that many Western travelers do not consult a health professional prior to travel and may not be aware of their need to protect themselves from infectious diseases [ 6 – 10 ]. Studies on the pre-travel health seeking behavior of travelers within the Asia-Pacific are limited; however, recent evidence suggests that the proportion of Asian travelers seeking pre-travel health advice is significantly lower than that of Western travelers [ 10 ]. Our study aimed to identify health-seeking practices among travelers and assess the proportion of travelers who sought pre-travel health advice and the uptake of pre-travel vaccines in a representative sample of travelers departing Sydney and Bangkok airports. The study also aimed to identify significant factors associated with pre-travel health seeking from a health professional.

Cross-sectional surveys of travelers were conducted prior to their departure from international airports in Sydney, Australia for destinations in Asia between July and September 2007 and Bangkok, Thailand bound for Australia between October and December 2007. Asian destinations were defined according to the United Nations World Macro classification of regions and included countries in Eastern Asia and South-Eastern Asia [ 11 ]. Asian destinations were selected due to their close proximity to Australia and the high proportion of air traffic flow between these regions. The methods used in this study have been published previously [ 12 ]. Briefly, a two-stage cluster sampling technique was developed at each study site to randomly sample travelers. At Sydney airport, in the first stage, sample sizes for each destination were calculated based on the proportion of passengers departing for the selected destinations, derived from aviation statistics for the previous calendar year [ 13 ]. Total sample size was sufficient to estimate a population proportion of 50% with ±3.5% precision at the 5% confidence level. A representative sample of direct flights on all available days and times of departure for each pre-approved airline carrier for each of the selected destinations were included in an interviewing timetable. Airline carriers representing both Australian and non-Australian carriers were selected based on their total share of passengers with 11 of the 13 approached airlines providing approval.

The second stage of the cluster sampling method involved the distribution of questionnaires to every fifth passenger joining check-in queues of selected flights. Bilingual interviewers attended check-in counters 3 h before scheduled departure until 1 h before departure. A similar method was employed at the Bangkok airport, with selected flights proportionate to the number of traveler arrivals at Australian airports from Thailand and representative of Thai, Australian, and other carriers. Approximately 175 flights were sampled between July and September 2007 at the Sydney site comprising 2.7% of the flights to Asia during this period, and 13 flights between October and December 2007 at the Bangkok site, comprising 2.4% of the flights to Australia from Thailand during this period.

Eligible respondents were both visitors and residents aged 18 years or older, departing on the day of interview, excluding passengers in transit. The questionnaire was developed in simplified English and piloted at Sydney Airport. The revised questionnaire was translated into Chinese, Vietnamese and Thai with back-translation employed to ensure consistent interpretation of questions. The self-administered questionnaire included questions on socio-demographic characteristics and travel characteristics of their current trip. Respondents were provided with a list of health professionals and non-medical sources of travel health information. Pre-travel health seeking practices refer to both the seeking of health advice from a health professional as well as health information from other sources. Pre-travel health advice refers only to information obtained from a health professional. A list of common routine and travel vaccines were provided to respondents, who were asked to record vaccines received for the specific purpose of their current trip.

The sample obtained at the Sydney study site was weighted by flight destination to reflect the proportion of passenger departures from aviation statistics [ 13 ], due to over sampling of some destinations, thereby providing a representative sample of travelers departing Australia for destinations in Asia and avoiding sampling bias. No weighting was applied to the Bangkok sample. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 18 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois) and missing data were excluded from analysis. Statistical significance in bivariate analysis was assessed using the chi-squared test and we considered a p-value of <0.05 to be significant. Logistic regression analysis was undertaken to determine associations between socio-demographic and travel characteristics and the reported uptake of pre-travel health advice from a health professional. All variables which may plausibly predict uptake of pre-travel health advice with a significance of <0.25 on bivariate analysis were considered for inclusion in the logistic regression analysis [ 14 ], and final models were assessed for adequacy of sample sizes [ 15 ]. Variables considered plausible include: demographics; age, gender, marital status, education, employment, resident of birth country, and trip characteristics; length of stay, reason for travel, travel companions, destination sub-region, number of destination countries, within country air and train travel and attendance at crowded events. During multivariate logistic regression model fitting, significant independent variables associated with seeking pre-travel health advice differed for Australian travelers, other Western travelers and Asian travelers and separate models were developed. Travelers from other regions were too few to model. The proportion reporting uptake of pre-travel vaccination was insufficient to determine a valid logistic regression model and is reported as univariate analysis. The research was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committees of the University of Sydney, Australia (12–2006/9727), the University of New South Wales, Australia (08254), the Ministry of Public Health, Thailand (3–2399-00051–49-4) and the relevant airport authorities.

Study sample and travel profile

A total of 843 surveys, including 729 weighted surveys of travelers departing Sydney to destinations in Asia (response rate; 56%), and 114 surveys of travelers departing Bangkok (response rate 60.0%) were included in the final sample. The number of respondents by flight destination has been reported previously [ 12 ]. Of the Sydney sample, 329/729 (45.1%) were residents of Australia, 170 (23.3%) were residents of other Western countries including New Zealand and countries in North America and Europe and 211 (28.9%) were residents of countries in Asia. Of the Bangkok sample, 55/114 (48.2%) were residents of Australia, 29 (25.4%) were residents of other Western countries and 14 (12.3%) were residents of countries in Asia. The demographic and travel characteristics, including travel activities by region of residence are shown in Table 1 .

Pre-travel health-seeking

At least one visit to a health professional in the past year for any reason was reported by 532/843 (63.1%) respondents, including 320 (38.0%) reporting two or more visits. Overall, 415 (49.2%) respondents sought some form of travel health information prior to their present trip. Pre-travel health advice was sought from a health professional by 298 (35.3%) respondents with 237 (79.5%) of these respondents seeking advice from their general practitioner. A travel specialist or travel clinic was attended by 35 (4.2%) respondents prior to travel or 11.7% of those who sought professional pre-travel health advice. Non-medical sources of travel health information were reported by 290 (34.4%) respondents. The Internet was reported as a source of pre-travel health information by 162 (19.2%) respondents, with 71/162 (43.8%) including a government travel advisory website in their web searches. Travel agents were reported as a source of travel health information by 114/843 (13.5%) respondents. Differences in pre-travel health seeking by region of residency are shown in Table 2 . Seeking any pre-travel health information differed between study sites and was reported by 346 (47.5%) respondents departing Sydney and 69 (60.5%) respondents departing Bangkok (p = 0.009). No association was found between study sites in the proportions seeking professional health advice overall (p = 0.1), from a general practitioner (p = 0.3), travel specialist (p = 0.1) or a non-medical source (p = 0.1). Factors independently associated with seeking pre-travel health advice from a health professional on multivariate analysis differed by region of residence and are reported in Table 3 .

Pre-travel vaccination

Pre-travel vaccination rates were low across both study sites with 100 (11.9%) respondents reporting receipt of one or more vaccines specifically for this trip, including 73/298 (24.5%) of those reporting a pre-travel heath visit. Pre-travel vaccination differed by region of residence (Table 2 ). Travelers who reported seeking advice from a travel medicine specialist were more likely to report a pre-travel vaccine (21/36, 58.3%) compared to travelers reporting a pre-travel visit to a general practitioner (48/237, 20.3%, p < 0.001). The most commonly reported vaccines were hepatitis A vaccine (58, 6.9%), hepatitis B vaccine (46, 5.5%), typhoid vaccine (30, 3.6%), tetanus vaccine (28, 3.3%) and influenza vaccine (24, 2.8%). Other vaccines were reported by between 0.4% and 1.4% of respondents. Of those reporting a pre-travel vaccination, 40/102 (39.2%) recalled only one vaccine, predominantly influenza vaccine (16/40, 40.0%) or hepatitis A vaccine (10/40, 25.0%). Two pre-travel vaccines were recalled by 21/102 (20.6%) respondents and 41 (40.2%) reported three or more vaccines. Respondents departing Bangkok were more likely to report pre-travel vaccine uptake (21/114, 18.4%) than those departing Sydney (81/729, 11.1%, p = 0.03).

Seeking health-related information prior to travel may prepare travelers for health risks at their destination and studies have shown an association between receiving advice and accurate risk perception and undertaking preventative behaviors [ 4 , 5 , 16 ]. Considerable variation exists in the published literature on the proportion of surveyed travelers seeking pre-travel health advice, ranging from as low as 32% of departing travelers from Australasian airports [ 10 ] to 85-94% of those traveling to sub-Saharan Africa and Central and South America [ 7 , 17 – 19 ]. In our study, less than half of all respondents (49%) reported seeking health information from any source prior to travel, similar to a number of published studies [ 6 – 8 , 10 , 20 ]. We found travel to tropical regions, such as countries in South East Asia associated with higher rates of health seeking compared to travel to more temperate regions such as countries in North East Asia. The risk of infectious disease is not limited to low resource countries and travelers to Australia may still be at risk of infectious diseases, particularly in the tropical regions [ 21 ]. Visitors to Australia should be aware of the risks of travel at any destination.

While numerous health resources are available to travelers, it is recommended that travelers seek advice from a health professional prior to international travel [ 3 , 4 ]. In our survey, approximately two thirds of respondents traveled without professional medical advice. General practice was the main source of professional pre-travel health advice, reflecting results from other airport surveys of travelers [ 5 , 6 , 8 , 10 ] and providing further weight to the importance of general practice in preventative travel medicine. Despite differences in health systems, the majority of travelers internationally seek advice from their general practitioner [ 8 , 20 , 22 ]. This is particularly so in Australia, where general practitioners play a central role in the delivery of primary and preventative health care [ 23 , 24 ]. While some studies report increased knowledge and accurate risk perception in travelers who consult travel medicine specialists [ 4 , 5 ], only 4.2% of travelers in our study (ranging from 2.2% to 8.5% depending on region of residence) attended a travel clinic prior to travel. The role of the general practitioner is under-valued in travel medicine research and few studies of travelers who consult general practice are available. With this key role in the health of travelers, general practice is challenged with the provision of accurate and tailored advice during consultations that are limited by time and resources.

Pre-travel health seeking is influenced by many factors including traveler demographic characteristics, reasons for travel and previous travel experience. Few studies investigate differences in health-seeking norms by nationality. Our study showed that uptake of pre-travel health advice from a health professional differed considerably by region of residence. Health seeking is likely to differ by nationality due to differences in health seeking practices, country-specific healthcare systems including national vaccination programs and travel health facilities as well as promotional activities undertaken by health departments and private travel medicine groups. While it is likely that pre-travel health practices and vaccine uptake differs by destination and prior travel experience, pre-travel health advice may still be warranted and provides the opportunity to vaccinate if required. In Australia, a number of recent cases of measles have been imported from developed countries, and high risk Australian travelers to Europe and North America during the northern hemisphere winter are advised to receive the influenza vaccine [ 25 ]. Furthermore, many travelers travel to multiple destinations and may not be aware of the individual risks. Alongside other studies, our study confirms the low uptake of pre-travel health advice and vaccination among Asian travelers. Another airport survey conducted in the region found only 26% of Asian travelers reported seeking pre-travel health advice compared to 63% of Western travelers [ 10 ], while a separate study reported 23.9% of South Korean travelers to India [ 26 ], a high risk destination for many infectious diseases [ 27 ], sought pre-travel health advice. Expansion of the Asian travel market has been forecast due to increasing wealth within the region and growth in intra-regional tourist arrivals [ 28 ]. As more people within the Asia-Pacific region can afford to travel, it is important to increase the uptake of pre-travel advice, particularly from medical sources. The limited number of specialist travel clinics in low resource countries may be a current barrier to uptake of pre-travel health advice and differences in health seeking behaviors and associated factors by region of residence may limit the generalisability of traveler studies, highlighting the growing need to better understand travelers from emerging travel markets.

Travel to visit friends and relatives (VFR) is an established risk factor for acquiring infectious diseases during travel [ 29 ] and for poor uptake of pre-travel health advice [ 8 , 30 ]. We did not identify a significant association between VFR travel and uptake of professional pre-travel health advice. However, we found migrant Australian travelers to be half as likely to seek pre-travel advice from a health professional and more likely to be traveling to visit friends and relatives than Australian-born travelers. Recent evidence also suggests that ethnicity, in addition to travel to visit friends and relatives, is an important indicator of infectious disease risk during travel [ 30 ]. Australian migrants who travel may be at a greater risk of infectious diseases than Australian-born travelers due to their lower uptake of pre-travel health advice, regardless of reason for travel.

We acknowledge some limitations to our study. A brief self-administered questionnaire design, although appropriate to maximize the response rate in high volume airport surveys, limits the amount of detail obtainable and is also subject to recall bias. Additional factors which have been found to be associated with uptake of pre-travel health advice, such as previous travel experience and economic barriers were not obtained. Due to strict security measures at Sydney Airport, we were not able to gain access beyond customs and conducted our interviews in the departures check-in area. This resulted in a lower response rate than those reported by other airport surveys conducted in the departure lounges [ 26 , 31 , 32 ] in which a response rates have been reported. However, our method allowed for the recruitment of passengers from a variety of carriers and flight times including weekends and evenings during the study period, providing a representative cross-section of departing passengers. We utilized a number of techniques to ensure a representative sample of travelers including a multistage sampling method of flight selection and random participant recruitment in which all passengers joining selected check-in queues had an equal probability of selection excluding those few who exceeded the recommended check-in time before departure. The use of simplified English and the provision of additional language versions of the questionnaire by bi-lingual interviewers aimed to reduce language barriers and subsequent selection biases of visitors to Australia from Asia.

A low proportion of participants in this study reported receipt of pre-travel vaccines (12%) with lower rates of pre-travel vaccination reported by Asian travelers compared to Western travelers. Wilder-Smith et al. also reported low uptake of pre-travel vaccines among Asian travelers, with 5% of Asian resident respondents reporting any pre-travel vaccination and low rates of self-reported prior vaccination against common vaccine-preventable diseases [ 10 ]. The findings of this airport study were similar to other traveler surveys in that the most commonly reported vaccines received prior to travel were hepatitis A, hepatitis B, tetanus and typhoid [ 2 , 8 , 10 , 33 ]. Influenza vaccine was reported by <3% of participants, a vaccine not often reported in other traveler surveys. It is likely that awareness of influenza as a travel-associated disease has increased for both providers and travelers with a post-pandemic survey of travel clinic attendees reported 13% uptake of seasonal influenza vaccine [ 34 ]. The proportion reporting a pre-travel vaccine after pre-travel attendance at a specialist travel medicine clinic was almost three times that reported at a general practice visit. Sample size limitations precluded a detailed analysis of factors associated with individual vaccine choices. However, the demographic and travel characteristics significantly associated with travel vaccination differed by residency group. A limitation to this study is that we did not collect data on prior vaccine uptake and are unable to determine the proportion of travelers who did not receive vaccines prior to this trip due to prior disease or vaccine-induced immunity. This airport study, like much research assessing vaccine uptake, relies on the self-reported history of previous vaccination and is subject to recall bias. As the time since vaccination is likely to influence recall, pre-travel vaccines may not be as vulnerable to recall bias as those vaccines received routinely, particularly childhood vaccines. Errors introduced by self-reported history include the misclassification of the vaccine received, particularly hepatitis A and B vaccine [ 35 ] and underestimation of the number of vaccines received. Other surveys have found that respondents report vaccines for non-vaccine preventable diseases such as hepatitis C and malaria, indicating a poor knowledge of their vaccination history [ 36 ] and other studies have shown wide differences between perceived vaccination status and vaccination certificates or blood antibody levels in travelers and other population groups [ 7 , 37 – 39 ]. Without serological testing it is difficult to ascertain if those who visited a medical professional prior to travel were up-to-date with their vaccinations, if they were vaccinated but could not recall the vaccines received or if their visits were a missed opportunity to vaccinate. Difficulties in assessing vaccination history for travel vaccines would be alleviated by the carriage of a vaccination record card for all vaccines received by travelers along with their passport and other travel documents, such as the requirement for entry and exit from yellow fever endemic regions.

Lack of time has been reported as a reason for not seeking pre-travel advice and vaccinations in other studies [ 6 – 8 ]. Other studies have reported that approximately one third of travelers seek advice for their trip within 2 weeks of departure [ 8 , 23 , 33 ]. Almost half of travelers departing from airports in Australasia reported planning their trip less than two weeks prior to departure [ 10 ]. This results in lower rates of pre-travel health seeking, particularly from a health professional as well as the reduced uptake of vaccines, incomplete vaccination schedules for vaccines requiring more than one dose and lack of adequate protection at the time of departure. Although the length of time between health seeking and departure was not assessed in this airport survey, 63% of respondents had visited a health professional at least once in the past year, providing an opportunity for health professionals to inquire about possible overseas trips during their consultation and improve the provision of pre-travel health advice, particularly for migrants and those traveling to visit friends and relatives.

The few travelers seeking advice suggests that public health strategies aimed at travelers may be warranted. These would include increasing uptake of pre-travel medical advice, ensuring vaccines, both routine and those recommended for travel, are up to date as well as the promotion of affordable and accessible travel clinics in low resource countries as traveler numbers increase. Limited data from the Asia-Pacific region are available and few studies assess traveler preparedness in residents of low resource countries, despite the strong growth of the international travel market in Asia. There is variability in pre-travel health advice seeking and vaccine uptake by region of residence and in migrant travelers. The role of general practitioners in the provision of pre-travel health advice and traveler health promotion is central and opportunities for improvement exist. Considering the increasing volume of international travel, a greater integration of travel history and travel plans into general practice consultations would identify those who intend to travel but are not aware of the need for a pre-travel health consultation, particularly migrant travelers. Determining the most appropriate strategies for increasing pre-travel health preparation, particularly for vaccine preventable diseases in travelers is the next stage in advancing travel medicine research.

World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). UNWTO Tourism Highlights. 2011, Edition [Available at http://mkt.unwto.org/sites/all/files/docpdf/unwtohighlights11enhr_1.pdf [Accessed 18/10/2011]

Lopez-Velez R, Bayas JM: Spanish travelers to high-risk areas in the Tropics: Airport survey of travel health knowledge, attitudes, and practices in vaccination and malaria prevention. JTravelMed. 2007, 14 (5): 297-305.

Google Scholar

Piyaphanee W, Wattanagoon Y, Silachamroon U, Mansanguan C, Wichianprasat P, Walker E: Knowledge, attitudes, and practices among foreign backpackers toward malaria risk in southeast Asia. JTravelMed. 2009, 16 (2): 101-106.

Provost S, Soto JC: Perception and knowledge about some infectious diseases among travelers from Quebec, Canada. JTravelMed. 2002, 9 (4): 184-189.

Ropers G, van Beest Holle MR, Wichmann O, Kappelmayer L, Stuben U, Schonfeld C, Stark K: Determinants of malaria prophylaxis among German travelers to Kenya, Senegal, and Thailand. JTravelMed. 2008, 15 (3): 162-171.

Hamer DH, Connor BA: Travel health knowledge, attitudes and practices among United States travelers. JTravelMed. 2004, 11 (1): 23-26.

Toovey S, Jamieson A, Holloway M: Travelers' knowledge, attitudes and practices on the prevention of infectious diseases: results from a study at Johannesburg International Airport. JTravelMed. 2004, 11 (1): 16-22.

Van Herck K, Van Damme P, Castelli F, Zuckerman J, Nothdurft H, Dahlgren AL, Gisler S, Steffen R, Gargalianos P, Lopez-Velez R, et al: Knowledge, attitudes and practices in travel-related infectious diseases: the European airport survey. JTravelMed. 2004, 11 (1): 3-8.

Van Herck K, Zuckerman J, Castelli F, Van Damme P, Walker E, Steffen R, Board ETHA: Travelers' knowledge, attitudes, and practices on prevention of infectious diseases: results from a pilot study. JTravelMed. 2003, 10 (2): 75-78.

Wilder-Smith A, Khairullah NS, Song JH, Chen CY, Torresi J: Travel health knowledge, attitudes and practices among Australasian travelers. JTravelMed. 2004, 11 (1): 9-15.

United Nations (UN). World macro regions and components ST/ESA/STAT/SER.R/29. [Available at http://www.un.org/depts/dhl/maplib/worldregions.htm [Accessed 20/04/2007]]

Heywood AE, Watkins RE, Pattanasin S, Iamsirithaworn S, Nilvarangkul K, MacIntyre CR: Self-reported symptoms of infection among travelers departing from Sydney and Bangkok airports. JTravelMed. 2010, 17 (4): 243-249.

Australian Federal Bureau of Infrastructure Transport and Regional Economics (BITRE). International Airline Activity Time Series. [Available at: [Accessed 24/03/2007] http://www.bitre.gov.au ]

Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S: Model-building strategies and methods for logistic regression. Applied logistic regression. Edited by: Hoboken . 2000, John Wiley & Sons, New York, 2

Chapter Google Scholar

Peduzzi P, Concato J, Kemper E, Holford TR, Feinstein AR: A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. JClinEpidemiol. 1996, 49 (12): 1373-1379.

CAS Google Scholar

Packham CJ: A survey of notified travel-associated infections: implications for travel health advice. Journal of Public Health Medicine. 1995, 17 (2): 217-222.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Laver SM, Wetzels J, Behrens RH: Knowledge of malaria, risk perception, and compliance with prophylaxis and personal and environmental preventive measures in travelers exiting Zimbabwe from Harare and Victoria Falls International airport. JTravelMed. 2001, 8 (6): 298-303.

Lobel HO, Baker MA, Gras FA, Stennies GM, Meerburg P, Hiemstra E, Parise M, Odero M, Waiyaki P: Use of malaria prevention measures by North American and European travelers to East Africa. JTravelMed. 2001, 8 (4): 167-172.

Cabada MM, Maldonado F, Quispe W, Serrano E, Mozo K, Gonzales E, Seas C, Verdonck K, Echevarria JI, Gotuzzo E: Pretravel health advice among international travelers visiting Cuzco, Peru. JTravelMed. 2005, 12 (2): 61-65.

LaRocque RC, Rao SR, Tsibris A, Lawton T, Barry MA, Marano N, Brunette G, Yanni E, Ryan ET: Pre-travel health advice-seeking behavior among US international travelers departing from Boston Logan International Airport. J Travel Med. 2010, 17 (6): 387-391. 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2010.00457.x.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Kelly-Hope LA, Purdie DM, Kay BH: Risk of mosquito-borne epidemic polyarthritis disease among international visitors to Queensland, Australia. JTravelMed. 2002, 9 (4): 211-213.

Wilder-Smith A, Boudville I, Earnest A, Heng SL, Bock HL: Knowledge, attitude, and practices with regard to adult pertussis vaccine booster in travelers. JTravelMed. 2007, 14 (3): 145-150.

Zwar N, Streeton CL: Pretravel advice and hepatitis A immunization among Australian travelers. JTravelMed. 2007, 14 (1): 31-36.

Leggat PA, Zwar NA, Hudson BJ: Hepatitis B risks and immunisation coverage amongst Australians travelling to Southeast Asia and East Asia. TravelMedInfectDis. 2009, 7 (6): 344-349.

National Health and Medical Research Council: Vaccination for international travel. The Australian Immunisation Handbook. 9th edition. 2008, Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, Canberra

Yoo YJ, Bae GO, Choi JH, Shin HC, Ga H, Shin SR, Kim MS, Joo KJ, Park CH, Yoon HJ, et al: Korean travelers' knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding the prevention of malaria: Measures taken by travelers departing for India from Incheon International Airport. JTravelMed. 2007, 14 (6): 381-385.

Freedman DO, Weld LH, Kozarsky PE, Fisk T, Robins R, von Sonnenburg F, Keystone JS, Pandey P, Cetron MS, Network GS: Spectrum of disease and relation to place of exposure among ill returned travelers. NEnglJ Med. 2006, 354 (2): 119-130. 10.1056/NEJMoa051331.

Article CAS Google Scholar

World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). UNWTO Tourism highlights. 2008, [Available at: www.unwto.org [Accessed 11/12/2008]]

Angell SY, Cetron MS: Health disparities among travelers visiting friends and relatives abroad. AnnInternMed. 2005, 142 (1): 67-72.

Baggett HC, Graham S, Kozarsky PE, Gallagher N, Blumensaadt S, Bateman J, Edelson PJ, Arguin PM, Steele S, Russell M, et al: Pretravel health preparation among US residents traveling to India to VFRs: importance of ethnicity in defining VFRs. JTravelMed. 2009, 16 (2): 112-118.

Johnson JY, McMullen LM, Hasselback P, Louie M, Saunders LD: Travelers' knowledge of prevention and treatment of travelers' diarrhea. JTravelMed. 2006, 13 (6): 351-355.

Dahlgren AL, Deroo L, Steffen R: Prevention of travel-related infectious diseases: Knowledge, practices and attitudes of Swedish travellers. ScandJInfectDis. 2006, 38 (11): 1074-1080.

Schunk M, Wachinger W, Nothdurft HD: Vaccination status and prophylactic measures of travelers from Germany to subtropical and tropical areas: results of an airport survey. JTravelMed. 2001, 8 (5): 260-262.

Pfeil A, Mutsch M, Hatz C, Szucs TD: A cross-sectional survey to evaluate knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) regarding seasonal influenza vaccination among European travellers to resource-limited destinations. BMC Public Health. 2010, 10: 402-10.1186/1471-2458-10-402.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Zuckerman JN, Hoet B: Hepatitis B immunisation in travellers: poor risk perception and inadequate protection. TravelMedInfectDis. 2008, 6 (5): 315-320.

Hartjes LB, Baumann LC, Henriques JB: Travel health risk perceptions and prevention behaviors of US study abroad students. J Travel Med. 2009, 16 (5): 338-343. 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2009.00322.x.

De Juanes JR, Gil A, San-Martin M, Gonzalez A, Esteban J, de Garcia CA: Seroprevalence of varicella antibodies in healthcare workers and health sciences students. Reliability of self-reported history of varicella. Vaccine. 2005, 23 (12): 1434-1436. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.10.003.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Skull SA, Andrews RM, Byrnes GB, Kelly HA, Nolan TM, Brown GV, Campbell DA: Validity of self-reported influenza and pneumococcal vaccination status among a cohort of hospitalized elderly inpatients. Vaccine. 2007, 25 (25): 4775-4783. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.04.015.

Trevisan A, Frasson C, Morandin M, Beggio M, Bruno A, Davanzo E, Di ML, Simioni L, Amato G: Immunity against infectious diseases: predictive value of self-reported history of vaccination and disease. InfectControl HospEpidemiol. 2007, 28 (5): 564-569.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/12/321/prepub

Download references

Acknowledgements

Funding support for this study was provided by the Australian Research Council (ARC) Discovery grant. AH’s doctorate was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Postgraduate Public Health Scholarship and the National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance (NCIRS), Australia.

We wish to thank those who assisted with the questionnaire translation and data collection, the travelers who participated in the study and the airport authorities and individual airlines who allowed us to undertake this study.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Public Health and Community Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of New South Wales, Kensington, NSW, 2052, Australia

Anita E Heywood & C Raina MacIntyre

Telethon Institute of Child Health Research, Centre for Child Health Research, The University of Western Australia, Perth, Australia

Rochelle E Watkins

Bureau of Epidemiology, Department of Disease Control, Ministry of Public Health, Bangkok, Thailand

Sopon Iamsirithaworn

Research and Training Center for Enhancing Quality of Life of Working-Age People, Faculty of Nursing, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen, Thailand

Kessarawan Nilvarangkul

National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance of Vaccine Preventable Diseases (NCIRS), The Children’s Hospital at Westmead and Discipline of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

C Raina MacIntyre

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Anita E Heywood .

Additional information

Competing interests.

CRM receives funding from GSK and CSL Biotherapies for investigator-driven research. These payments were not associated with this study. The remaining authors have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

CRM and RW conceived and supervised the study. AH organized airport access in Australia, undertook data collection and analysis and drafted the manuscript. SI and KN organized airport access in Thailand and undertook data collection. CRM, RW, SI and KN reviewed the manuscript. Selected results appearing in this manuscript were presented at the Asia-Pacific International Conference on Travel Medicine, Melbourne, Australia, 24–28 February 2008 and the 13th International Congress on Infectious Diseases, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, June 19–22, 2008. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Heywood, A.E., Watkins, R.E., Iamsirithaworn, S. et al. A cross-sectional study of pre-travel health-seeking practices among travelers departing Sydney and Bangkok airports. BMC Public Health 12 , 321 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-321

Download citation

Received : 26 October 2011

Accepted : 02 May 2012

Published : 02 May 2012

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-321

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Influenza Vaccine

- Vaccine Uptake

- Travel Medicine

- Travel Characteristic

- Travel Clinic

BMC Public Health

ISSN: 1471-2458

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Pre-travel risk assessment for international business travellers during the COVID-19 pandemic

There has been significant disruption to travel caused by COVID-19 due to its international spread and restrictions imposed by countries in their bids to control transmission.

International travel is essential for many types of business, despite the increasing use of telecommunication. Preparation for safe travel must be thorough and include additional considerations compared to the pre-COVID era.

Business travel may be defined as travel for the purpose of working, including corporate travel, field work and attending meetings or conferences. Business travellers may have different health-seeking behaviour due to employment requirements as well as better access to medical care while overseas due to company insurance and medical assistance programmes.

International business travellers have been compared to non-occupational travellers in previous analysis of 23,534 travellers [ 1 ]. More business travellers were men (61% vs 43%), more had less time to departure, over half sought pre-travel consultations largely on the advice of their employer and they had shorter periods of travel. Hotel accommodation was most common (>80%) with more travel to urban areas and they often travelled multiple times a year.

Studies in travel-related illness in business travellers show a similar range of disease to non-occupational travellers, but illness rates and particularly psychological problems, tend to be higher. The rates of medical insurance claims in World Bank travellers were 80% higher in men and 18% higher in women, compared with colleagues who did not travel. Rates were highest for psychological illness, then intestinal disease and respiratory disease [ 2 ].

For a business, defining what is ‘essential travel’ helps to avoid unnecessary and potentially risky travel, whilst ensuring that those who do need to travel get appropriate support before, during and after the trip.

An overseas business travel policy should state what criteria need to be met; either travel is required to fulfil compliance and regulatory obligations and/or without the trip the company would be liable to financial loss, legal implications, damages or penalties and/or the business travel is needed to support critical business activity. For the last criterion it is important that the most senior decision maker, for example executive officers, are deciding criticality, not the individual traveller who may have a conflicting self-interest.

The process for who travels is a dynamic assessment taking into account external factors as well as internal factors. External changes, for example reduced local medical care as a result of a global pandemic, will change the risk profile of a trip making it more dangerous, or the sudden loss of a supply chain due to locally increasing cases can make a trip more important. Internal changes to an individual's medical condition or willingness to travel can mean substituting who goes as well as when they go.

It is in the best interest of employers to ensure the health and wellbeing of their employees working internationally; before, during and after travel, which may be via a provider organisation or on-site occupational health department. Illness may disrupt business activities during or after travel, cause loss of time and productivity and increase medical costs. It is important for an employer to ensure health insurance policies give coverage if their employee should become severely ill abroad with COVID-19.

Quality and infrastructure of local healthcare in the destination country may be negatively impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, leading to an increased need for medical evacuation if a traveller were to develop a severe COVID-19 infection. Medical evacuation of patients with COVID-19 is complex, with lengthier processes and subsequent cost impact. In some cases air evacuation may be deemed too high a risk, due to severity of illness.

The risk of developing severe or fatal infection with COVID-19 depends largely on the traveller's personal vulnerability should infection occur. The Association of Local Authority Medical Advisors (ALAMA) has developed an evidence-based risk model that can be used to estimate personal vulnerability [ 3 , 4 ]. This tool, known as ‘covid-age’ was first published on 20 th May 2020 and has been periodically updated as new data becomes available.

At our organisation we have developed a detailed health questionnaire to collate relevant medical information from employees prior to business travel.

As return to some essential travel for business commenced following the UK's first lockdown, our questionnaire reviewed Covid-19 infection exposure including confirmed and probable COVID-19 infection, and close contacts with suspected or confirmed cases as well as antibody test results. We also reviewed adverse life events during the pandemic such as hospital admissions, loss of loved ones, relationship breakdowns and significant loss of motivation. This enabled us to have a holistic picture of the employees' experience during lockdown and provide relevant advice, such as current understanding on immunity, and suggestions on mental health support and how it can be accessed.

The medical information requested on the questionnaire enables a review of risk factors known to increase vulnerability and calculation of covid-age. This may also involve review of medical reports from specialists and telephone consultations with the employees to gain further understanding and assessment. Medical factors that may increase risk of sudden incapacity or other need for medical care while travelling are also reviewed. These include cardiovascular risk factors and level of control of chronic conditions such as diabetes, asthma and epilepsy.

There is also the importance of subtle incapacity, involving aspects of lifestyle that can impact the traveller over time. Factors such as alcohol use, smoking and BMI are reviewed, providing opportunity for health promotion advice.

An important part of our risk assessment is a review of factors that may have affected the traveller's psychological wellbeing. Individuals with a pre-existing mental health disorder in the last year have been shown to score significantly higher on the COVID Stress Scales than those without [ 5 ]. Travel may exacerbate or precipitate a variety of psychological disorders. Data on occupational travellers has shown that frequent international travel is associated with increased insurance claims for psychological illness [ 2 ]. Review of previous or existing mental health disorders, coupled with details on adverse life events over the lockdown period such as hospital admissions, loss of loved ones, relationship breakdowns and significant loss of motivation, have enabled identification of employees that may require additional mental health support. This may include referral to an appropriate health professional or Employee Assistance Programme for further assessment and management, as well as provision of information and self-help resources.

Psychological sequalae occurring after traumatic life events are well documented [ 6 ], however, the study of collective traumatic occurrences is limited to physically and mentally extreme situations affecting relatively small sections of populations, for example arctic explorers, soldiers in combat and people experiencing natural disasters. The COVID-19 pandemic has refocussed attention on psychological resilience and initial concerns that a global disaster would have different psychological consequences has not manifested at the time of writing.

However, the pandemic has reinforced previous knowledge that people experience distress after their exposure to an extreme event. In the case of people with good psychosocial resilience and access to social support, their distress may be relatively transient as people call on a set of inner capabilities and supporting relationships to spring back and begin the processes of adaptation.

Employers have a big part to play in ensuring that conditions are optimised for this to occur. Mental disorders occur often, but less commonly than distress, and in some cases they may require intensive and long term continuing interventions and treatment. The Department of Health in the UK [ 7 ] and work done by NATO [ 8 ] differentiate between distress and mental disorders following a disaster. Early identification of a mental health disorder or psychological distress can prevent long-term impacts on the traveller and the business and therefore their wider communities.

As the covid-age tool is based on health data from adults in England, it is likely that it can only reliably be used for risk stratification for workers in the UK. Multiple confounders would come into play to affect the risk of individuals based in other countries. Genetic risk factors have been implemented for increased severity of disease with COVID-19, which are present in about 50% of people in South Asia [ 9 ]. With the number of deaths from COVID-19 being relatively low in Africa, it has been hypothesised that regular exposure to malaria or other infectious diseases could prime the immune system to fight new pathogens like SARS-CoV-2 [ 10 ].

However, particularly when assessing UK-based travellers, the covid-age tool should still give an indication of vulnerability when travelling internationally.

Several studies have identified factors affecting geographical vulnerability of disease with COVID-19. Low levels of national preparedness, scale of testing and population characteristics have been associated with increased national case load and overall mortality [ 11 ]. Low temperature and low humidity have been seen to likely favour the transmission of COVID-19 [ 12 ].

Public health infrastructure in the destination country and their ability to appropriately detect cases and implement isolation and quarantine is an important factor in reduction of COVID-19 transmission. The employer will need to consider quarantine requirements in the destination country and on return. If new restrictions are imposed during time abroad, such as border closures or lockdowns, the employees may risk being stranded abroad for a period of time.

There will be a certain amount of responsibility laid on the employee during travel to ensure they are taking appropriate precautions according to local guidance and company policy.

Airlines or country entry requirements may include negative results from COVID-19 swab tests on arrival or within a timeframe before departure, which needs to be included in timing of business trips. Confirmed in-flight cases have been published [ 13 ], although the risk of in-flight transmission is considered to be very low when stringent hygiene measures are enforced inflight [ 14 ].

As the roll-out of safe and effective vaccines continues, there may be scope for business travel to be less restricted. It is the employer's duty to protect their workers from harm by delivering risk management for all staff, including identification of those with increased vulnerability to COVID-19. This pandemic has further raised the importance of pre-travel risk assessment for business travellers, including consideration of psychological effects; the outcome of which may affect who is chosen to travel and when.

This page requires JavaScript to work properly. Please enable JavaScript in your browser.

You are using an outdated browser. Upgrade your browser today or install Google Chrome Frame to better experience this site.

- Section 1 - Improving the Quality of Travel Medicine Through Education & Training

- Section 2 - Perspectives : Travelers' Perception of Risk

The Pretravel Consultation

Cdc yellow book 2024.

Author(s): Lin Hwei Chen, Natasha Hochberg

The pretravel consultation offers a dedicated time to prepare travelers for health concerns that might arise during their trips. During the pretravel consultation, clinicians can conduct a risk assessment for each traveler, communicate risk by sharing information about potential health hazards, and manage risk by various means. Managing risk might include giving immunizations, emphasizing to travelers the importance of taking prescribed malaria prophylaxis and other medications (and highlighting the risks of not taking them correctly), and educating travelers about steps they can take to address and minimize travel-associated risks. The pretravel consultation also serves a public health purpose by helping limit the role international travelers could play in the global spread of infectious diseases.

The Travel Medicine Specialist

Travel medicine specialists have in-depth knowledge of immunizations, risks associated with specific destinations, and the implications of traveling with underlying conditions. Therefore, a comprehensive consultation with a travel medicine expert is indicated for all international travelers and is particularly important for those with a complicated health history, anyone taking special risks (e.g., traveling at high elevation, working in refugee camps), or those with exotic or complicated itineraries. Clinicians aspiring to be travel medicine providers can benefit from the resources provided by the International Society of Travel Medicine (ISTM) and might consider specialty training and certification (see Sec. 1, Ch. 4, Improving the Quality of Travel Medicine Through Education & Training ).

Components of a Pretravel Consultation

Effective pretravel consultations require attention to the traveler’s health background, and incorporate the itinerary, trip duration, travel purpose, and activities, all of which determine health risks ( Table 2-01 ). The pretravel consultation is the best opportunity to educate the traveler about health risks at the destination and how to mitigate them. The typical pretravel consultation does not include a physical examination, and a separate appointment with the same or a different provider might be necessary to assess fitness for travel. Because travel medicine clinics are not available in some communities, primary care physicians should seek guidance from travel medicine specialists to address areas of uncertainty. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Travelers’ Health website also has materials and an interactive web-tool to guide primary care physicians through a pretravel consultation.

Personalize travel health advice by highlighting likely exposures and reminding the traveler of ubiquitous risks (e.g., injury, foodborne and waterborne infections, vectorborne diseases, respiratory tract infections—including coronavirus disease 2019 [COVID-19]—and bloodborne and sexually transmitted infections). Balancing cautions with an appreciation of the positive aspects of the journey can lead to a more meaningful pretravel consultation. In addition, pay attention to the cost of recommended interventions. Because some travelers are unable to afford all the recommended immunizations and medications, prioritize interventions (see Sec. 2, Ch. 15, Prioritizing Care for Resource-Limited Travelers ).

Table 2-01 The pretravel consultation: medical history & travel risk assessment

Health background.

Past medical history

- Allergies (especially any pertaining to vaccines, eggs, or latex)

- Medications

- Underlying conditions

Special conditions

- Breastfeeding

- Cardiopulmonary event (recent)

- Cerebrovascular event (recent)

- Disability or handicap

- Guillain-Barré syndrome (history of)

- Immunocompromising conditions or medications

- Pregnancy (including trimester)

- Psychiatric condition

- Seizure disorder

- Surgery (recent)

- Thymus abnormality

Immunization history

- Routine vaccines

- Travel vaccines

Prior travel experience

- High-elevation travel/ mountain climbing

- Malaria chemoprophylaxis

- Prior travel-related illnesses

Travel Risk Assessment (Trip Details)

- Countries and specific regions, including order of countries if >1 country

- Outbreaks at destination

- Rural or urban destinations

- Season of travel

- Time to departure

- Trip duration

Reason for travel

- Education or research

- Medical tourism (seeking health care)

- Visiting friends and relatives

- Volunteer, missionary, or aid work

Travel style

- Accommodations (e.g., camping/ tent, dormitory, guest house, hostel/ budget hotel, local home or host family, tourist/ luxury hotel)

- "Adventurous" eating

- Independent travel or package tour

- Level of hygiene at destination

- Modes of transportation

- Traveler risk tolerance

- Travel with children

Special activities

- Animal interactions (including visiting farms, touring live animal markets)

- Cruise ship

- Cycling/motorbiking

- Disaster relief

- Extreme sports

- High elevations

- Medical care (providing or receiving)

- Rafting or other water exposure

- Sexual encounters (planned)

Assess Individual Risk

Traveler characteristics and destination-specific risk provide the background to assess travel-associated health risks. Such characteristics include personal health background (e.g., past medical history, special conditions, immunization history, medications); prior travel experience; trip details, including itinerary, timing, reason for travel, travel style, and specific activities; and details about the status of COVID-19 and other infectious diseases at the destination. Certain travelers also might confront special risks. Recent hospitalization for serious problems might lead to a decision to recommend delaying travel. Air travel is contraindicated for patients with certain conditions. For instance, patients should not travel by air <3 weeks after an uncomplicated myocardial infarction or <10 days after thoracic or abdominal surgery. Consult relevant health care providers most familiar with the traveler’s underlying illnesses.

Other travelers with specific risks include those who have chronic illnesses, are immunocompromised, or are pregnant. Travelers visiting friends and relatives, long-term travelers, and travelers with small children also face unique risks. More comprehensive discussion on advising travelers with additional health considerations is available in Section 3. Determine whether recent outbreaks or other safety notices have been posted for the traveler’s destination by checking information available on CDC Travelers’ Health and US Department of State websites and other resources.

In addition to recognizing the traveler’s characteristics, health background, and destination-specific risks, discuss anticipated exposures related to special activities. For example, river rafting could expose a traveler to schistosomiasis or leptospirosis, and spelunking in Central America could put the traveler at risk for histoplasmosis. Flying from lowlands to high-elevation areas and trekking or climbing in mountainous regions introduces the risk for altitude illness. Inquire about plans for specific leisure, business, and health care-seeking activities.

Communicate Risk

Once destination-specific risks for a particular itinerary have been assessed, communicate them clearly to the traveler. Health-risk communication is an exchange of information in which the clinician and traveler discuss potential health hazards for the trip and any available preventive measures. Communicating risk is one of the most challenging aspects of a pretravel consultation, because travelers’ perception of and tolerance for risk can vary widely. For a more detailed discussion, see Sec. 2, Ch. 2, . . . perspectives: Travelers’ Perception of Risk .

Manage Risk

Vaccinations.

Vaccinations are a crucial component of pretravel consultations, and the risk assessment forms the basis of recommendations for travel vaccines. Consider whether the patient has sufficient time to complete a vaccine series before travel; the purpose of travel and specific destination within a country will inform the need for vaccines. At the same time, the pretravel consultation presents an opportunity to update routine vaccines (Table 2-02) and to ensure that eligible travelers are up to date with their COVID-19 vaccinations .