We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Your browser may not be compatible with all the features on this site. Consider upgrading to a modern browser for an improved experience. 111

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

You'll Need 1

Time Travel the Internet: View Any Website from (Almost) Any Year

What you'll need

Posted in these interests:

Most people don’t know that you can look up past “snapshots” of almost any website. Archive.org is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that was formed to build an expansive Internet library. Since 1996, the organization has been archiving digital content to preserve the legacy and history of the Internet and the World Wide Web.

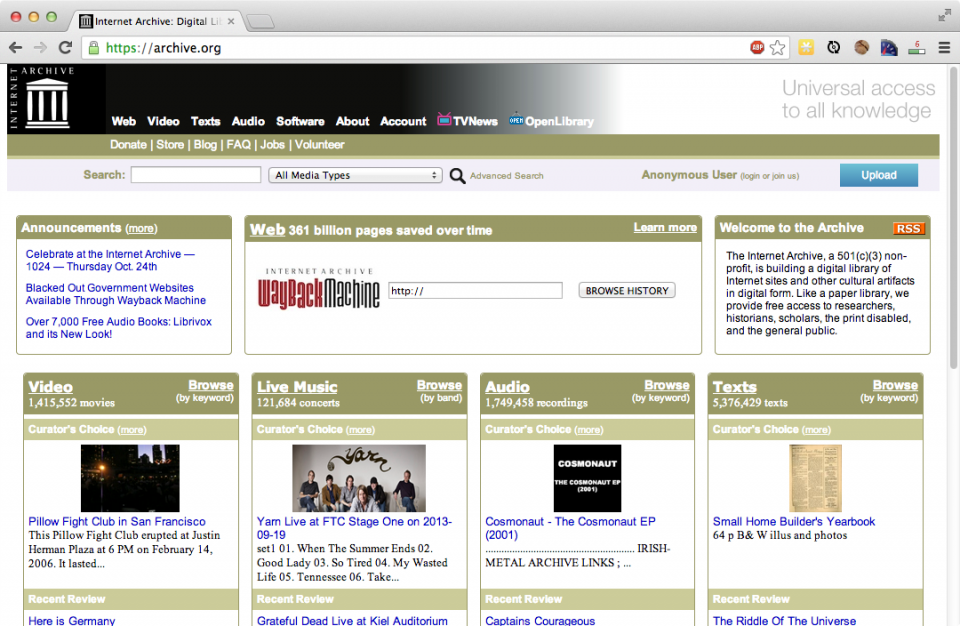

1 – Visit archive.org

Using your browser, navigate to Archive.org .

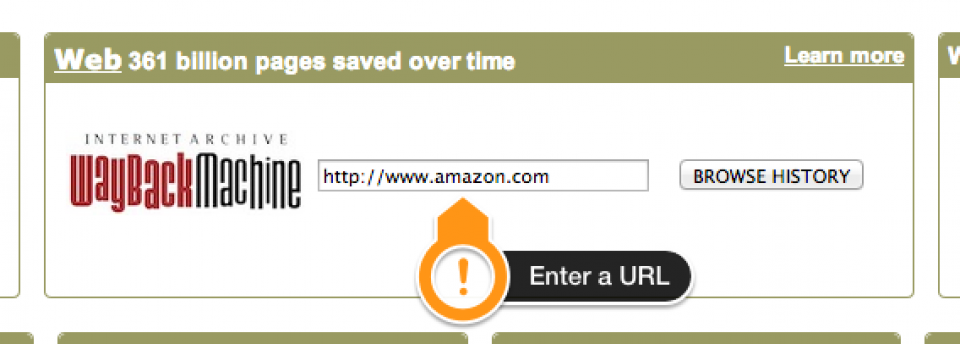

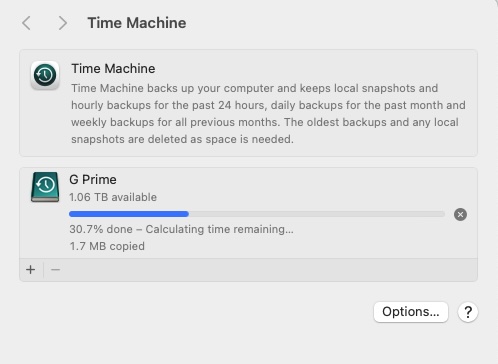

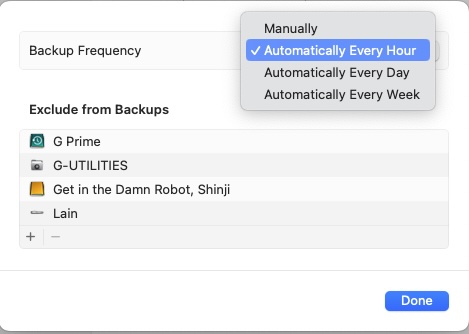

2 – Enter the website you’d like to view and click Browse History

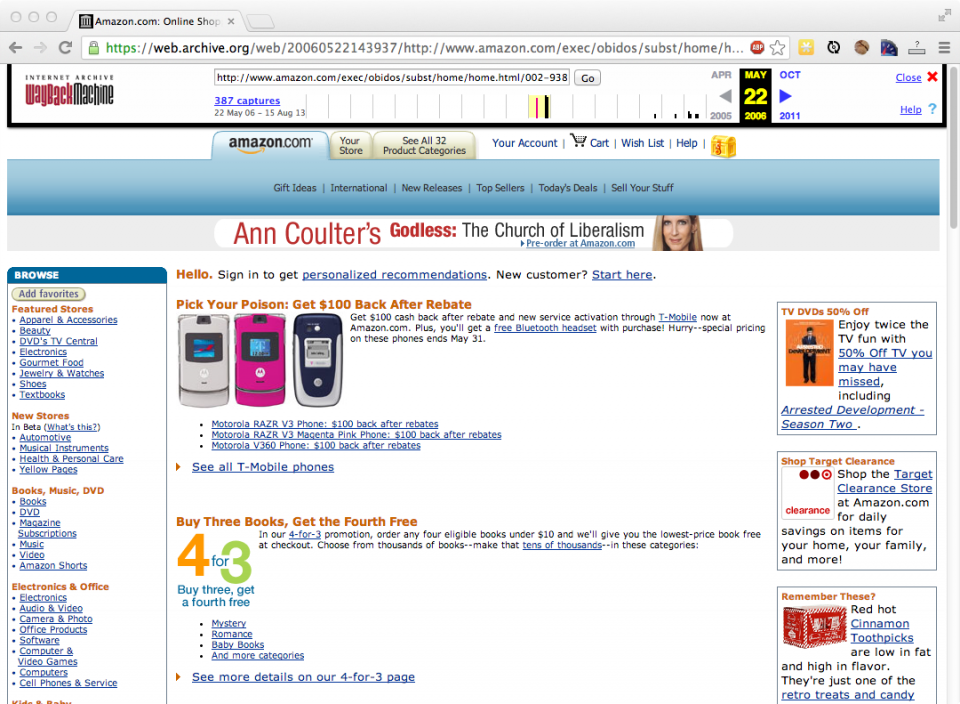

I decided to check out Amazon’s humble roots since I’ve been reading the Jeff Bezos biography One Click .

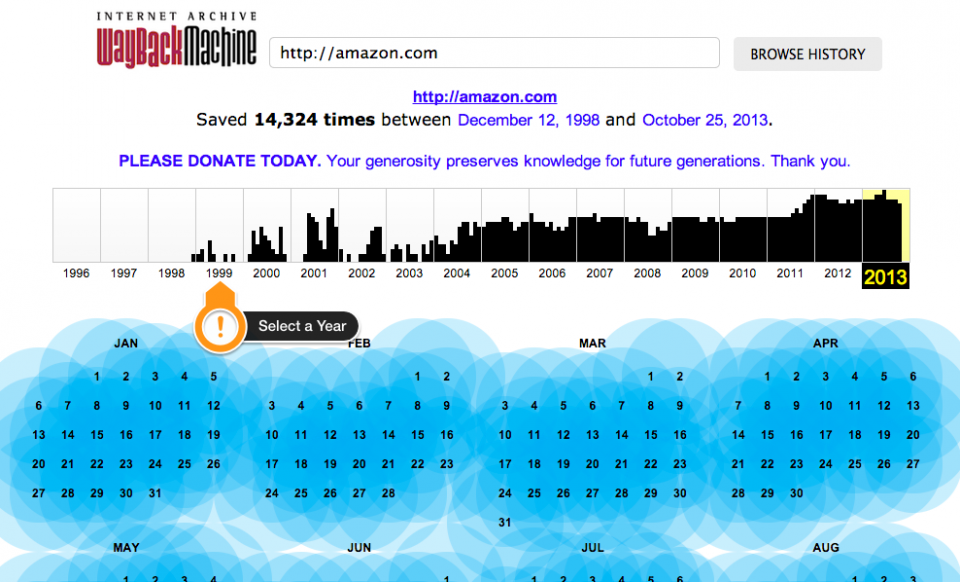

3 – Select a year

The Archive.org meta crawler visits popular sites more often. Each blue circular bubble indicates that a snapshot exists. In my case I searched for Amazon, the 7th most popular site on the web; this explains the blue blur that you see below.

You might notice by the “annual” snapshot bar graphs that overall snapshots have increased over the years — this is due to hard drive space becoming less expensive, resulting in more crawls being possible. After all, each snapshot isn’t just a mere image — it’s an explorable version of the site.

From here, you can either select a blue bubble to view the relevant snapshot or choose a different year to view. Let’s go deeper. Select an older year.

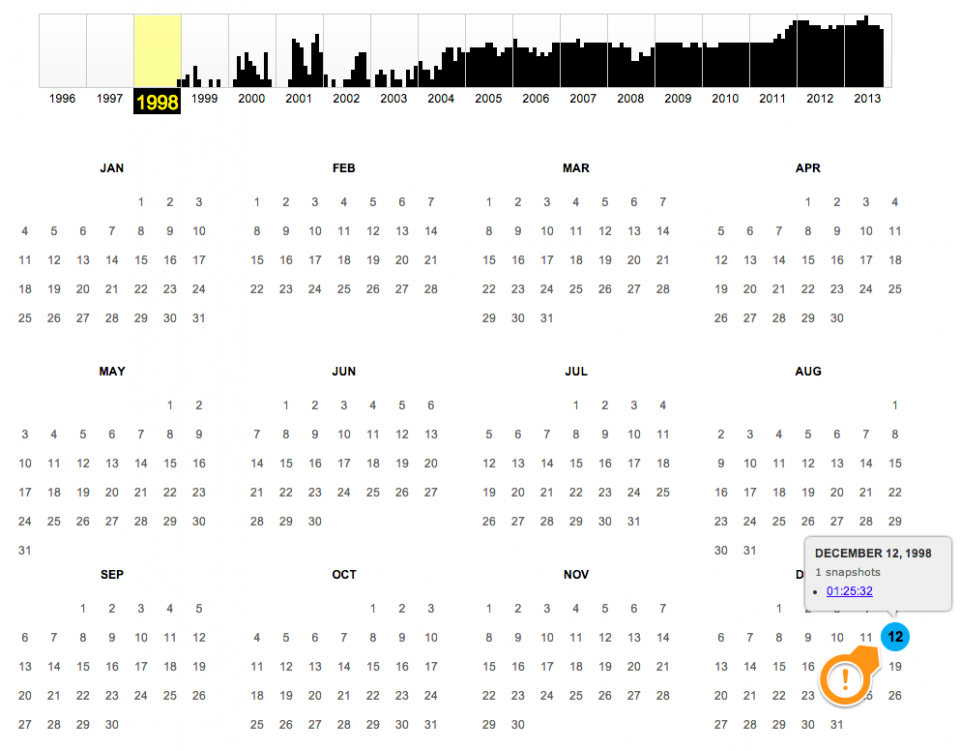

4 – Select a snapshot

After you’ve selected the year, find the specific date you’d like to explore. Explorable dates are denoted by the blue bubble. A larger bubble means that multiple snapshots exist for that date. Click on a date bubble.

5 – Bask in the glory of old design

It’s interesting to see not only how web design has changed but also how far we’ve come in such a short period of time.

Amazon in 1996: See it in action

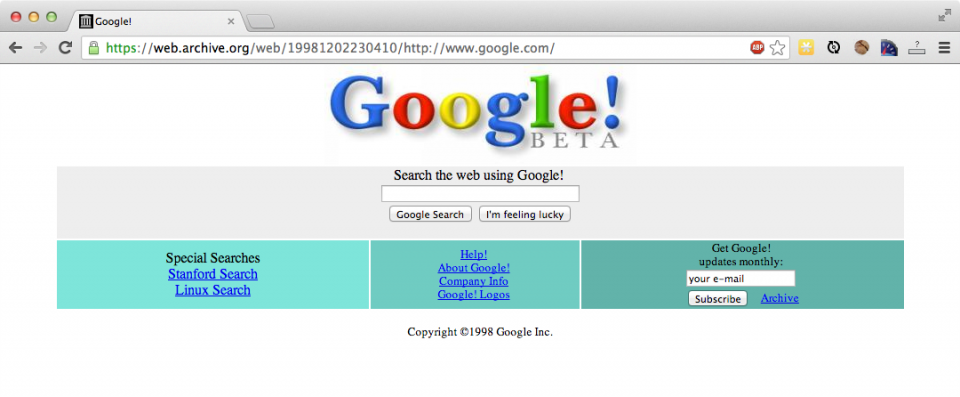

6 – Google in 1998

See it in action

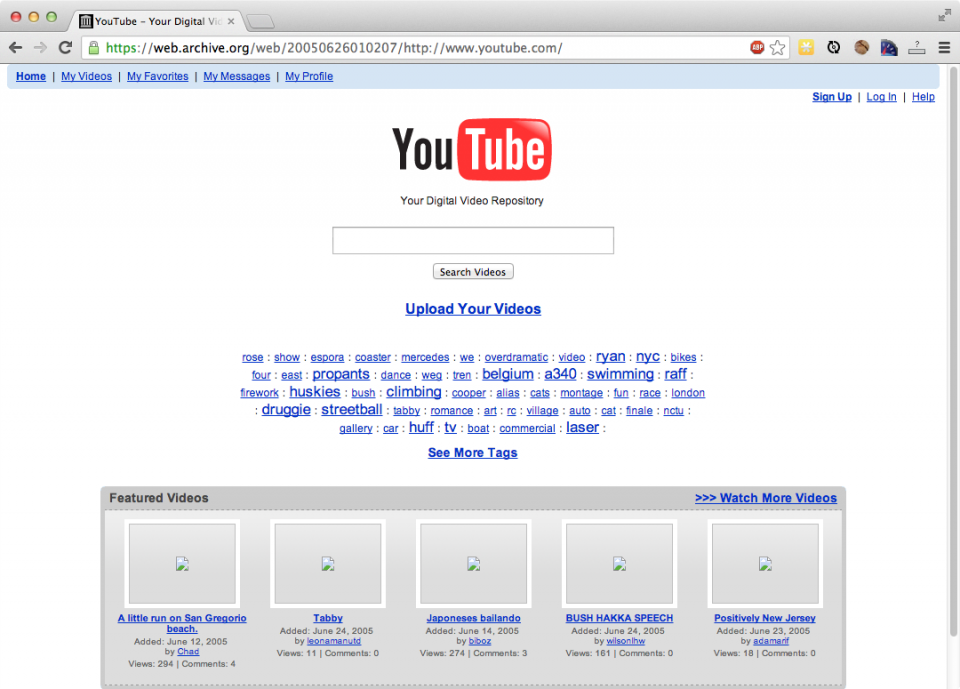

7 – YouTube in 2005

8 – eBay in 1999

How to Change Your Frontier WiFi Password

There are a few reasons you might want to update or reset your WiFi password: making your network more secure, and making your password easier to remember and type. Improved network security You can add an extra layer of security to your network by changing the WiFi password. As long as your new password is

In these interests

Internet internet • 36 guides, web design webdesign • 5 guides, www www • 2 guides, share this guide.

467 guides

Introducing Howchoo, an enigmatic author whose unique pen name reflects their boundless curiosity and limitless creativity. Mysterious and multifaceted, Howchoo has emerged as a captivating storyteller, leaving readers mesmerized by the uncharted realms they craft with their words. With an insatiable appetite for knowledge and a love for exploration, Howchoo's writing transcends conventional genres, blurring the lines between fantasy, science fiction, and the surreal. Their narratives are a kaleidoscope of ideas, weaving together intricate plots, unforgettable characters, and thought-provoking themes that challenge the boundaries of imagination.

Related to this guide:

There are a few reasons you might want to update or reset your WiFi password: making your network mo

How to Clear Your Browser Cache for Any Browser

Clearing your browser cache is a great way to solve common internet issues. If a webpage isn’t

How to Log in to a Linksys Router

This guide will show you how to log into your Linksys router using the router’s IP address and

How to Trigger a Phone Call using an HTML Link

If you’d like your visitors to be able to open a phone application straight from your website

How to Change Your Charter Spectrum WiFi Password

If you’re a Charter WiFi user, you need to keep your network secure. Changing your WiFi passwo

How to Change Your Verizon FiOS Wi-Fi Network Name

Changing your Wi-Fi network name has never been easier. From web interfaces to mobile support, Veriz

Make YouTube Video Embeds Responsive Using Pure HTML and CSS

Surprisingly, normal YouTube embeds are not automatically sized to the browser window as it is resiz

How to Log in to a TP-Link Router

If you’re a TP-Link customer, you need to access your router. This guide covers everything you

How to Change Your Verizon FiOS Wi-Fi Password

Want to keep your home network safe? Knowing how to change your Wi-Fi password is network security 1

How to Find Your Network Security Key (And Protect It!)

Feel free to skip ahead to see how to find the network security key. A network security key is a fa

Discover interesting things!

Explore Howchoo's most popular interests.

A Tech Website That Makes It Easy to Travel Back in Time

Techmeme lets readers enter any date since 2006 to see what it looked like that day.

A truly digital online archive is a special kind of rabbit hole, strange to climb into for two reasons. First of all, the history is so recent—few web archives can take you back to the 1990s, even—and yet so much about the look and feel of the internet has changed dramatically. Secondly, most of the best web archives are still deeply broken. They offer only a deteriorating echo of what once existed and link rot is everywhere.

And yet snapshot views of the web can be a fascinating way to capture the flavor of the internet as it once was. This is how the Internet Archive’s WayBack Machine organizes its screen captures—you can search various sites by how they looked on certain days—and it’s how Techmeme’s ingenious new timestamp works.

At the top of Techmeme’s page, if you click on the date and time, you’re given the ability to enter some other date, back to the year 2006. (Sadly, you can’t travel forward into the future of Techmeme coverage. I tried.)

What you get is a glimpse of a moment in time, which makes the feature fantastic if you know which days in tech history were especially newsy. Maybe you want to revisit June 30, 2007, for instance, the day after the iPhone was introduced. Or October 6, 2011, the day after Steve Jobs died, to see the flood of remembrances. Or May 18, 2012, the day Facebook went public.

A more haphazard approach to looking back may not be best for serious researchers focused on a single topic, but it’s certainly an entertaining exercise for tech enthusiasts.

Return to the Techmeme of May 2, 2006, for example, and you’ll find a link to a story about the coming arms race between Google and Microsoft—this was three years before the launch of Bing, Microsoft’s ill-fated attempt to challenge Google search. On January 1, 2008, the site led with a story about how Gawker’s Nick Denton would begin paying bloggers based on web traffic. (Fast forward to today and Gawker is throwing a farewell party to its old self, as Gawker Media faces a bankruptcy auction.) On April 27, 2009, you’ll find the headline for a story about the new MySpace CEO. On May 1, 2010, there’s a story about how Twitter was more popular with black people than white people, years ahead of most mainstream coverage of the platform’s influential role in public discourse on race.

Recommended Reading

Raiders of the Lost Web

The Dark Psychology of Social Networks

30 Years Ago, Romania Deprived Thousands of Babies of Human Contact

Specific stories aside, it’s neat to see how Techmeme’s look has changed—though, given the site’s text-heavy design history, its aesthetic evolution isn’t all that pronounced. (For a more evocative example of the web’s transformation, I sometimes revisit CNN’s homepage as it appeared on September 11, 2001 .) The larger point is that archives of old webpages—not articles but whole pages—don’t just give you a text history, like you’d get if you read a single story from some date in history. They also offer a richer sense of what it was like to encounter a story on the web when that story was first being read. You get a feel for how the internet looked, and for which stories were considered important, given their prominence on the site. (At a time when few sites think seriously about creating meaningful access to their archives, it’s particularly impressive that Techmeme has had this feature in place since it launched in 2005.)

Gleaning newsiness or editorial values from story placement is, of course, a tradition rooted in print. The front page of a newspaper remains a powerful place to trumpet not just the news, but news judgement.

There are plenty of people, me included , who have long argued that the homepage—an extension of A1 for a news site in a post-print era—is dead or dying because of social distribution. Techmeme’s approach to archives probably isn’t a way of honoring the historic value of homepages past, or even making a case for them today, but rather a matter of practicality. Because Techmeme is a curation site—it features links from tech stories published all over the web—an overview of which stories it chose to highlight on any given day is the most meaningful way to experience previous iterations of its coverage.

It’s also a way to safeguard against the inevitable: When some of the stories Techmeme once handpicked for its readers vanish from their original sources, all that will be left is a snapshot in time. But all those snapshots have a way of adding up. Together, Techmeme’s 10 years of easy-to-visit homepages and the WayBack Machine’s half-a-trillion archived pages make for a pretty reliable vehicle to the digital past.

Search forward in time...

Is Time Travel Possible?

We all travel in time! We travel one year in time between birthdays, for example. And we are all traveling in time at approximately the same speed: 1 second per second.

We typically experience time at one second per second. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

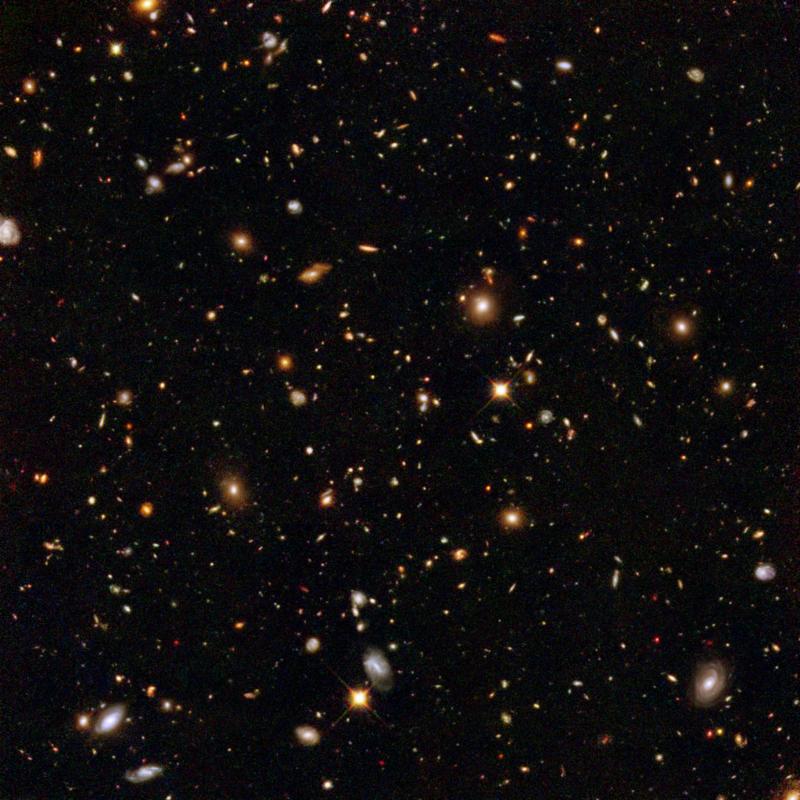

NASA's space telescopes also give us a way to look back in time. Telescopes help us see stars and galaxies that are very far away . It takes a long time for the light from faraway galaxies to reach us. So, when we look into the sky with a telescope, we are seeing what those stars and galaxies looked like a very long time ago.

However, when we think of the phrase "time travel," we are usually thinking of traveling faster than 1 second per second. That kind of time travel sounds like something you'd only see in movies or science fiction books. Could it be real? Science says yes!

This image from the Hubble Space Telescope shows galaxies that are very far away as they existed a very long time ago. Credit: NASA, ESA and R. Thompson (Univ. Arizona)

How do we know that time travel is possible?

More than 100 years ago, a famous scientist named Albert Einstein came up with an idea about how time works. He called it relativity. This theory says that time and space are linked together. Einstein also said our universe has a speed limit: nothing can travel faster than the speed of light (186,000 miles per second).

Einstein's theory of relativity says that space and time are linked together. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

What does this mean for time travel? Well, according to this theory, the faster you travel, the slower you experience time. Scientists have done some experiments to show that this is true.

For example, there was an experiment that used two clocks set to the exact same time. One clock stayed on Earth, while the other flew in an airplane (going in the same direction Earth rotates).

After the airplane flew around the world, scientists compared the two clocks. The clock on the fast-moving airplane was slightly behind the clock on the ground. So, the clock on the airplane was traveling slightly slower in time than 1 second per second.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Can we use time travel in everyday life?

We can't use a time machine to travel hundreds of years into the past or future. That kind of time travel only happens in books and movies. But the math of time travel does affect the things we use every day.

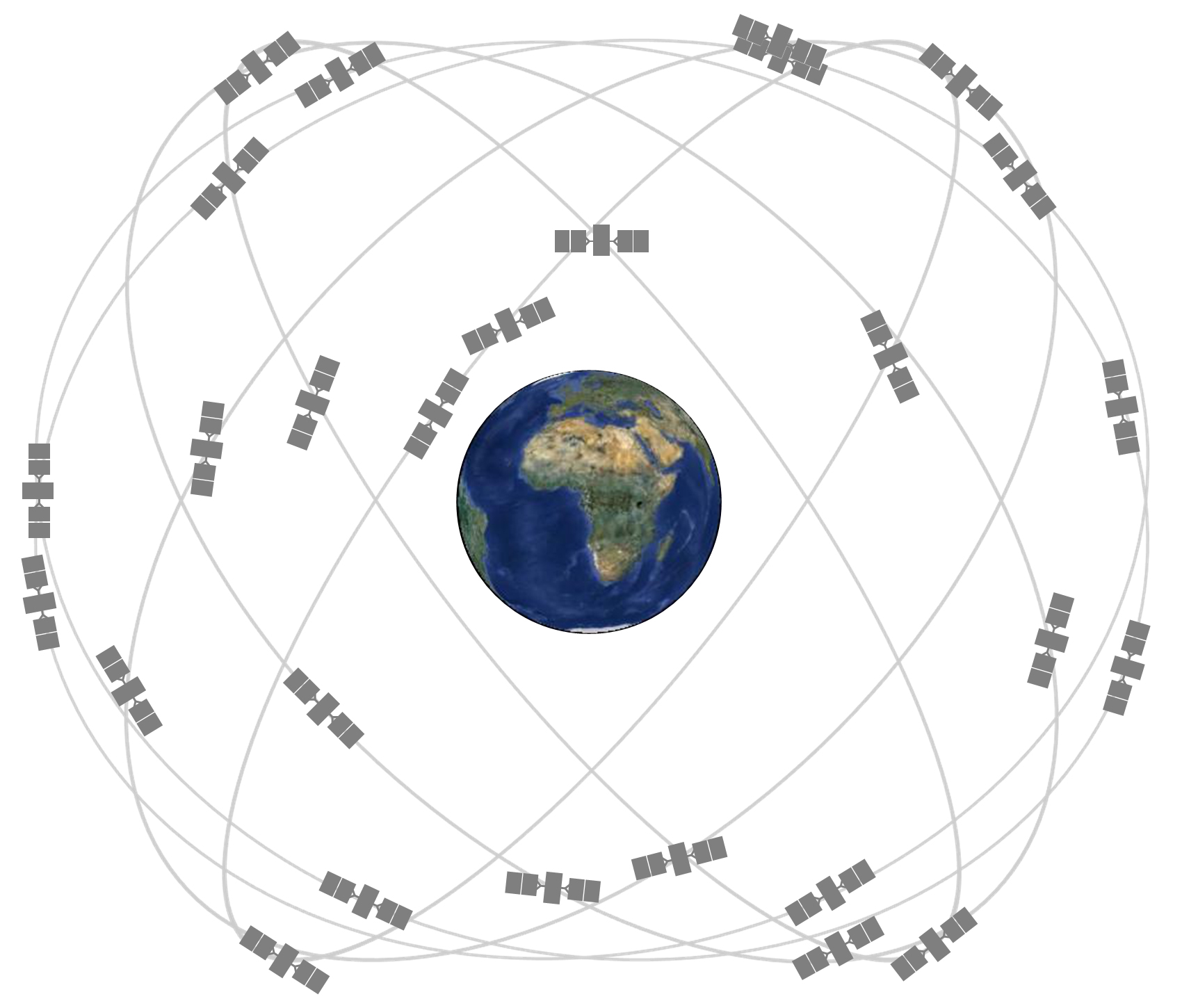

For example, we use GPS satellites to help us figure out how to get to new places. (Check out our video about how GPS satellites work .) NASA scientists also use a high-accuracy version of GPS to keep track of where satellites are in space. But did you know that GPS relies on time-travel calculations to help you get around town?

GPS satellites orbit around Earth very quickly at about 8,700 miles (14,000 kilometers) per hour. This slows down GPS satellite clocks by a small fraction of a second (similar to the airplane example above).

GPS satellites orbit around Earth at about 8,700 miles (14,000 kilometers) per hour. Credit: GPS.gov

However, the satellites are also orbiting Earth about 12,550 miles (20,200 km) above the surface. This actually speeds up GPS satellite clocks by a slighter larger fraction of a second.

Here's how: Einstein's theory also says that gravity curves space and time, causing the passage of time to slow down. High up where the satellites orbit, Earth's gravity is much weaker. This causes the clocks on GPS satellites to run faster than clocks on the ground.

The combined result is that the clocks on GPS satellites experience time at a rate slightly faster than 1 second per second. Luckily, scientists can use math to correct these differences in time.

If scientists didn't correct the GPS clocks, there would be big problems. GPS satellites wouldn't be able to correctly calculate their position or yours. The errors would add up to a few miles each day, which is a big deal. GPS maps might think your home is nowhere near where it actually is!

In Summary:

Yes, time travel is indeed a real thing. But it's not quite what you've probably seen in the movies. Under certain conditions, it is possible to experience time passing at a different rate than 1 second per second. And there are important reasons why we need to understand this real-world form of time travel.

If you liked this, you may like:

5 ways to go back in time on the internet

Become a web archaeologist.

By David Nield | Updated Aug 6, 2023 9:30 AM EDT

The World Wide Web has been up and running since the early 1990s, and countless amounts of text, images, video, and audio have been uploaded since then. Run a web search today though, and it’ll likely prioritize newer pages. Not great if you’re looking for something older.

Going back in time on the internet is possible, but you need to have the right tools and techniques to dig deep into the past. Once you’ve refined your skills, you can pull up everything from your first tweet to famous web pages from the previous century.

Find old pages on the web

Run a standard Google search , and it will show you the most recent and relevant results by default, but you can change that. From the search results page, click Tools , Any time , and Custom range to look for pages published around particular dates. There’s no limit on how far you can go back, though you’ll find diminishing returns as you venture deeper into the historical archives.

Try looking for veteran politicians or long-running TV shows, but adjust the dates to 2000-2010, and you’ll see how opinions can shift dramatically when it comes to people or entertainment. If you’re looking for a specific older article, the date range tool can make the task much easier, and you can add other filters too (e.g. site:popsci.com to restrict the search to a particular domain).

This feature isn’t exclusive to Google—if you prefer the privacy-focused DuckDuckGo , click the Any time filter at the top of the screen after you run a search to get similar date range options. Unfortunately, the same custom date search feature isn’t available everyone on Bing . It used to be, but Microsoft has restricted it to news, image, and video searches. If you’re in Bing’s news tab, click the Any time dropdown menu to get date options, and if you’re in the image or video tabs, click Filter to bring up several dropdown menus, then choose Date .

In many cases, sites will render older pages using their current layout and style—presenting the old content in a new way. If you want to see sites as they were in the past, or look up pages that Google and Bing can’t reach, you can turn to the Wayback Machine . It features hundreds of billions of pages preserved exactly as they were originally published.

Type in the name of a website, like www.popsci.com , into the search box on the Wayback Machine, and you’ll see an overview of the pages saved from that domain. You can click into individual years, months, and days to see how those pages looked when they first appeared. Many of these cached pages are fully browsable too, so it’s just like surfing the web in the old days.

[Related: This free tool can reveal who is behind any internet domain ]

The Wayback Machine is the best option for pulling up older pages as they originally were, but there are alternatives. Time Travel searches smaller web archives, including those managed by Stanford and individual countries. You can also find a limited number of official and government sites archived by the US Library of Congress .

If the site you’re looking for is particularly well-known, you might find it preserved in a digital museum. The Web Design Museum has pulled together several hundred significant pages, showcasing some digital design trends of yesteryear, while the Version Museum has captured the changing style of big sites such as Amazon, Apple, Wikipedia, The New York Times , Google, and Facebook.

Find old posts on social media

Searching through older social media posts on Twitter and Facebook requires a different approach. These platforms come with built-in search features and work with a number of third-party tools that you can use to hunt back through years of social media posts, created by you or other people.

The advanced search page on Twitter lets you search for tweets based on the date they were posted (back to when Twitter launched in 2006). Besides the date, you’ll need to enter other search criteria, such as a particular user account or a keyword you want to search by.

You can use this search tool to look for your older tweets, or those made by anyone else, as long as the account is public. There are even filters for narrowing your search based on how much engagement the post got—if you’re running a search with a lot of matches, prioritizing the popular tweets can help filter out the noise.

If you want to go back to the very beginning of a Twitter account, the date an account was created is listed on the user’s profile page—that should help you focus your search. You can also request a download of your Twitter archive by opening Twitter’s settings, clicking Your account , and selecting Download an archive of your data . You may need to verify who you are before you can get the data, but once you have the archive you can open the file in your web browser and quickly get to your earliest tweet using the list of years and months.

[Related: Allow us to show you how to bulk-delete tweets ]

Over on Facebook , posts are much less likely to be public and visible to everyone. You can search the posts of someone you’re friends with by opening a profile and clicking the three dots on the right, followed by Search . When you run a search, you’ll see search filters down the left-hand side, including one for Date Posted .

The same filters appear when you run a general search from the box in the top left-hand corner of the Facebook interface: Enter a keyword or two, then hit Enter to run the search. Click Posts and Date Posted to narrow the results based on year. It’s not a precise tool, but it might help you find what you’re after more quickly.

Searching your own profile is a much more surgical operation. Click the three dots on the right side of your profile, then Activity log , Your posts , and use the options that appear under Filters to look for posts from a particular date. Facebook can bring up searches you ran and posts you liked and commented on, as well as everything you posted yourself, from the selected time period.

This story has been updated. It was originally published on November 5, 2020.

David Nield is a freelance contributor at Popular Science, producing how to guides and explainers for the DIY section on everything from improving your smartphone photos to boosting the security of your laptop. He doesn't get much spare time, but when he does he spends it watching obscure movies and taking long walks in the countryside.

Like science, tech, and DIY projects?

Sign up to receive Popular Science's emails and get the highlights.

Project: Time Travel on the Internet

Time Travel on the Internet

Internet users are now regularly offered the chance to travel backwards in time via software like Facebook’s “Memories,” timehop, The Internet Archive’s “Wayback Machine,” Google StreetView’s historical imagery, and more. Like any archive, these software platforms filter and ultimately produce history and memory. Unlike a traditional archive, inclusion and prominence in an Internet “time machine” can result from curation algorithms, the interactions of automated agents or bots (e.g., crawlers), and collaborative filtering with other users. Media historiography has yet to grapple with this shift. This project aims to unite expertise in history, digital media, and algorithmic information systems to investigate the processes and consequences of these new time machines and to compare contemporary digital imaginaries with earlier moments in the history of print, radio, photography, and cinema.

Project Website

Investigators.

Christian Sandvig , Derek Vaillant, Megan Ankerson

The New Wayback Machine Lets You Visually Travel Back In Internet Time

It seems that since the Wayback Machine launch in 2001, the site owners have decided to toss out the Alexa-based back-end and redesign it with their own open source code. After conducting tests with the code on smaller collections, the owners have now transferred the entire archive over to the new software. Hence - Wayback Machine Beta.

The Wayback Machine is one of those online tools that you know exists, but never really seem to think about until you really need it! Any Internet enthusiast knows just how valuable the Wayback Machine has become to the online community. I find myself turning to it constantly to find websites that have been taken down, for one reason or another. This is especially common dealing with online scams or frauds where people want to try and cover up things that they've written or published in the past.

The Internet Wayback Machine gives you an awesome place to go not only to find webpages that would otherwise be lost to the ether of cyberspace after they are no longer hosted, but it also allows you to observe how some of the larger and more popular websites today have evolved over time.

When you're just starting out with your own website or blog, seeing that evolution can offer wonderful clues as to what proved successful and what didn't. Karl wrote a review of the Wayback Machine back in 2008, and offered a cool glimpse of what the Wayback Machine can do for you.

The Wayback Machine Beta

Recently, I went over to the Wayback Machine to do some more research, and discovered that it had a different look, and the word "BETA" was posted just under the logo. Beta?

It seems that since the Wayback Machine launch in 2001, the site owners have decided to toss out the Alexa-based back-end and redesign it with their own open source code. After conducting tests with the code on smaller collections, the owners have now transferred the entire archive over to the new software. Hence - Wayback Machine Beta. Here's what the front page now looks like.

Nothing very spectacular, but sometimes simplicity hides a lot of functionality. That's certainly the case here. The owners claim that the redesigned site is now much faster than the classic Internet Wayback Machine, and I actually did find that to be true. Searching for MakeUseOf and clicking the "Latest" button almost immediately turns up the latest snapshot of the site. In this case it's MUO from December 24, 2010.

The coolest aspect of this Beta version, in my opinion, is how easily you can watch the progression of a website over time. The new toolbar at the top shows the volume of "crawls" that Wayback did for the site on a particular day. This is displayed in a timeline on the toolbar. You can see the current date that you're viewing on the right side of the toolbar, and it's also highlighted in the timeline.

Click on that older date in the timeline, and the display below will change the the version of the website to when the site was crawled on that date. Here's MakeUseOf on July 16, 2006.

Just click once a little bit later in the timeline, and almost immediately the newer version of the same site pops up. Here's MUO the next year, in 2007.

Don't forget that each crawl-date offers a fully-functioning version of the website on that particular date, because just about every page was crawled. So, go ahead and click on the links to see those old pages. Sometimes it's fun to go back and look at some of the comments from many years ago, or to see how individual pages of the site have changed over time.

There have been mixed reviews about the new calendar view that Wayback now offers. You can get there by clicking the " Show All " button rather than the " Latest " button on the main page. This will show you a calendar view of the exact dates when the Wayback Machine crawled the website. The larger the circle, the more times the machine crawled the site.

Click on one of the dates to see the exact time of day that the snapshots of the website were completed. Finally, you can click on the exact time to view that archived snapshot.

Some people really liked the previous layout, where you could see a list of snapshots for the site on one page, but others (myself included) like the more graphical layout, and the ease with which you can quickly switch from one view of the website to another just by tapping on the timeline.

So explore the new and improved Internet Wayback Machine . Do you like or hate the new look and functionality? What would you have done to improve it even more? Share your point of view in the comments section below.

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Time Travel

There is an extensive literature on time travel in both philosophy and physics. Part of the great interest of the topic stems from the fact that reasons have been given both for thinking that time travel is physically possible—and for thinking that it is logically impossible! This entry deals primarily with philosophical issues; issues related to the physics of time travel are covered in the separate entries on time travel and modern physics and time machines . We begin with the definitional question: what is time travel? We then turn to the major objection to the possibility of backwards time travel: the Grandfather paradox. Next, issues concerning causation are discussed—and then, issues in the metaphysics of time and change. We end with a discussion of the question why, if backwards time travel will ever occur, we have not been visited by time travellers from the future.

1.1 Time Discrepancy

1.2 changing the past, 2.1 can and cannot, 2.2 improbable coincidences, 2.3 inexplicable occurrences, 3.1 backwards causation, 3.2 causal loops, 4.1 time travel and time, 4.2 time travel and change, 5. where are the time travellers, other internet resources, related entries, 1. what is time travel.

There is a number of rather different scenarios which would seem, intuitively, to count as ‘time travel’—and a number of scenarios which, while sharing certain features with some of the time travel cases, seem nevertheless not to count as genuine time travel: [ 1 ]

Time travel Doctor . Doctor Who steps into a machine in 2024. Observers outside the machine see it disappear. Inside the machine, time seems to Doctor Who to pass for ten minutes. Observers in 1984 (or 3072) see the machine appear out of nowhere. Doctor Who steps out. [ 2 ] Leap . The time traveller takes hold of a special device (or steps into a machine) and suddenly disappears; she appears at an earlier (or later) time. Unlike in Doctor , the time traveller experiences no lapse of time between her departure and arrival: from her point of view, she instantaneously appears at the destination time. [ 3 ] Putnam . Oscar Smith steps into a machine in 2024. From his point of view, things proceed much as in Doctor : time seems to Oscar Smith to pass for a while; then he steps out in 1984. For observers outside the machine, things proceed differently. Observers of Oscar’s arrival in the past see a time machine suddenly appear out of nowhere and immediately divide into two copies of itself: Oscar Smith steps out of one; and (through the window) they see inside the other something that looks just like what they would see if a film of Oscar Smith were played backwards (his hair gets shorter; food comes out of his mouth and goes back into his lunch box in a pristine, uneaten state; etc.). Observers of Oscar’s departure from the future do not simply see his time machine disappear after he gets into it: they see it collide with the apparently backwards-running machine just described, in such a way that both are simultaneously annihilated. [ 4 ] Gödel . The time traveller steps into an ordinary rocket ship (not a special time machine) and flies off on a certain course. At no point does she disappear (as in Leap ) or ‘turn back in time’ (as in Putnam )—yet thanks to the overall structure of spacetime (as conceived in the General Theory of Relativity), the traveller arrives at a point in the past (or future) of her departure. (Compare the way in which someone can travel continuously westwards, and arrive to the east of her departure point, thanks to the overall curved structure of the surface of the earth.) [ 5 ] Einstein . The time traveller steps into an ordinary rocket ship and flies off at high speed on a round trip. When he returns to Earth, thanks to certain effects predicted by the Special Theory of Relativity, only a very small amount of time has elapsed for him—he has aged only a few months—while a great deal of time has passed on Earth: it is now hundreds of years in the future of his time of departure. [ 6 ] Not time travel Sleep . One is very tired, and falls into a deep sleep. When one awakes twelve hours later, it seems from one’s own point of view that hardly any time has passed. Coma . One is in a coma for a number of years and then awakes, at which point it seems from one’s own point of view that hardly any time has passed. Cryogenics . One is cryogenically frozen for hundreds of years. Upon being woken, it seems from one’s own point of view that hardly any time has passed. Virtual . One enters a highly realistic, interactive virtual reality simulator in which some past era has been recreated down to the finest detail. Crystal . One looks into a crystal ball and sees what happened at some past time, or will happen at some future time. (Imagine that the crystal ball really works—like a closed-circuit security monitor, except that the vision genuinely comes from some past or future time. Even so, the person looking at the crystal ball is not thereby a time traveller.) Waiting . One enters one’s closet and stays there for seven hours. When one emerges, one has ‘arrived’ seven hours in the future of one’s ‘departure’. Dateline . One departs at 8pm on Monday, flies for fourteen hours, and arrives at 10pm on Monday.

A satisfactory definition of time travel would, at least, need to classify the cases in the right way. There might be some surprises—perhaps, on the best definition of ‘time travel’, Cryogenics turns out to be time travel after all—but it should certainly be the case, for example, that Gödel counts as time travel and that Sleep and Waiting do not. [ 7 ]

In fact there is no entirely satisfactory definition of ‘time travel’ in the literature. The most popular definition is the one given by Lewis (1976, 145–6):

What is time travel? Inevitably, it involves a discrepancy between time and time. Any traveller departs and then arrives at his destination; the time elapsed from departure to arrival…is the duration of the journey. But if he is a time traveller, the separation in time between departure and arrival does not equal the duration of his journey.…How can it be that the same two events, his departure and his arrival, are separated by two unequal amounts of time?…I reply by distinguishing time itself, external time as I shall also call it, from the personal time of a particular time traveller: roughly, that which is measured by his wristwatch. His journey takes an hour of his personal time, let us say…But the arrival is more than an hour after the departure in external time, if he travels toward the future; or the arrival is before the departure in external time…if he travels toward the past.

This correctly excludes Waiting —where the length of the ‘journey’ precisely matches the separation between ‘arrival’ and ‘departure’—and Crystal , where there is no journey at all—and it includes Doctor . It has trouble with Gödel , however—because when the overall structure of spacetime is as twisted as it is in the sort of case Gödel imagined, the notion of external time (“time itself”) loses its grip.

Another definition of time travel that one sometimes encounters in the literature (Arntzenius, 2006, 602) (Smeenk and Wüthrich, 2011, 5, 26) equates time travel with the existence of CTC’s: closed timelike curves. A curve in this context is a line in spacetime; it is timelike if it could represent the career of a material object; and it is closed if it returns to its starting point (i.e. in spacetime—not merely in space). This now includes Gödel —but it excludes Einstein .

The lack of an adequate definition of ‘time travel’ does not matter for our purposes here. [ 8 ] It suffices that we have clear cases of (what would count as) time travel—and that these cases give rise to all the problems that we shall wish to discuss.

Some authors (in philosophy, physics and science fiction) consider ‘time travel’ scenarios in which there are two temporal dimensions (e.g. Meiland (1974)), and others consider scenarios in which there are multiple ‘parallel’ universes—each one with its own four-dimensional spacetime (e.g. Deutsch and Lockwood (1994)). There is a question whether travelling to another version of 2001 (i.e. not the very same version one experienced in the past)—a version at a different point on the second time dimension, or in a different parallel universe—is really time travel, or whether it is more akin to Virtual . In any case, this kind of scenario does not give rise to many of the problems thrown up by the idea of travelling to the very same past one experienced in one’s younger days. It is these problems that form the primary focus of the present entry, and so we shall not have much to say about other kinds of ‘time travel’ scenario in what follows.

One objection to the possibility of time travel flows directly from attempts to define it in anything like Lewis’s way. The worry is that because time travel involves “a discrepancy between time and time”, time travel scenarios are simply incoherent. The time traveller traverses thirty years in one year; she is 51 years old 21 years after her birth; she dies at the age of 100, 200 years before her birth; and so on. The objection is that these are straightforward contradictions: the basic description of what time travel involves is inconsistent; therefore time travel is logically impossible. [ 9 ]

There must be something wrong with this objection, because it would show Einstein to be logically impossible—whereas this sort of future-directed time travel has actually been observed (albeit on a much smaller scale—but that does not affect the present point) (Hafele and Keating, 1972b,a). The most common response to the objection is that there is no contradiction because the interval of time traversed by the time traveller and the duration of her journey are measured with respect to different frames of reference: there is thus no reason why they should coincide. A similar point applies to the discrepancy between the time elapsed since the time traveller’s birth and her age upon arrival. There is no more of a contradiction here than in the fact that Melbourne is both 800 kilometres away from Sydney—along the main highway—and 1200 kilometres away—along the coast road. [ 10 ]

Before leaving the question ‘What is time travel?’ we should note the crucial distinction between changing the past and participating in (aka affecting or influencing) the past. [ 11 ] In the popular imagination, backwards time travel would allow one to change the past: to right the wrongs of history, to prevent one’s younger self doing things one later regretted, and so on. In a model with a single past, however, this idea is incoherent: the very description of the case involves a contradiction (e.g. the time traveller burns all her diaries at midnight on her fortieth birthday in 1976, and does not burn all her diaries at midnight on her fortieth birthday in 1976). It is not as if there are two versions of the past: the original one, without the time traveller present, and then a second version, with the time traveller playing a role. There is just one past—and two perspectives on it: the perspective of the younger self, and the perspective of the older time travelling self. If these perspectives are inconsistent (e.g. an event occurs in one but not the other) then the time travel scenario is incoherent.

This means that time travellers can do less than we might have hoped: they cannot right the wrongs of history; they cannot even stir a speck of dust on a certain day in the past if, on that day, the speck was in fact unmoved. But this does not mean that time travellers must be entirely powerless in the past: while they cannot do anything that did not actually happen, they can (in principle) do anything that did happen. Time travellers cannot change the past: they cannot make it different from the way it was—but they can participate in it: they can be amongst the people who did make the past the way it was. [ 12 ]

What about models involving two temporal dimensions, or parallel universes—do they allow for coherent scenarios in which the past is changed? [ 13 ] There is certainly no contradiction in saying that the time traveller burns all her diaries at midnight on her fortieth birthday in 1976 in universe 1 (or at hypertime A ), and does not burn all her diaries at midnight on her fortieth birthday in 1976 in universe 2 (or at hypertime B ). The question is whether this kind of story involves changing the past in the sense originally envisaged: righting the wrongs of history, preventing subsequently regretted actions, and so on. Goddu (2003) and van Inwagen (2010) argue that it does (in the context of particular hypertime models), while Smith (1997, 365–6; 2015) argues that it does not: that it involves avoiding the past—leaving it untouched while travelling to a different version of the past in which things proceed differently.

2. The Grandfather Paradox

The most important objection to the logical possibility of backwards time travel is the so-called Grandfather paradox. This paradox has actually convinced many people that backwards time travel is impossible:

The dead giveaway that true time-travel is flatly impossible arises from the well-known “paradoxes” it entails. The classic example is “What if you go back into the past and kill your grandfather when he was still a little boy?”…So complex and hopeless are the paradoxes…that the easiest way out of the irrational chaos that results is to suppose that true time-travel is, and forever will be, impossible. (Asimov 1995 [2003, 276–7]) travel into one’s past…would seem to give rise to all sorts of logical problems, if you were able to change history. For example, what would happen if you killed your parents before you were born. It might be that one could avoid such paradoxes by some modification of the concept of free will. But this will not be necessary if what I call the chronology protection conjecture is correct: The laws of physics prevent closed timelike curves from appearing . (Hawking, 1992, 604) [ 14 ]

The paradox comes in different forms. Here’s one version:

If time travel was logically possible then the time traveller could return to the past and in a suicidal rage destroy his time machine before it was completed and murder his younger self. But if this was so a necessary condition for the time trip to have occurred at all is removed, and we should then conclude that the time trip did not occur. Hence if the time trip did occur, then it did not occur. Hence it did not occur, and it is necessary that it did not occur. To reply, as it is standardly done, that our time traveller cannot change the past in this way, is a petitio principii . Why is it that the time traveller is constrained in this way? What mysterious force stills his sudden suicidal rage? (Smith, 1985, 58)

The idea is that backwards time travel is impossible because if it occurred, time travellers would attempt to do things such as kill their younger selves (or their grandfathers etc.). We know that doing these things—indeed, changing the past in any way—is impossible. But were there time travel, there would then be nothing left to stop these things happening. If we let things get to the stage where the time traveller is facing Grandfather with a loaded weapon, then there is nothing left to prevent the impossible from occurring. So we must draw the line earlier: it must be impossible for someone to get into this situation at all; that is, backwards time travel must be impossible.

In order to defend the possibility of time travel in the face of this argument we need to show that time travel is not a sure route to doing the impossible. So, given that a time traveller has gone to the past and is facing Grandfather, what could stop her killing Grandfather? Some science fiction authors resort to the idea of chaperones or time guardians who prevent time travellers from changing the past—or to mysterious forces of logic. But it is hard to take these ideas seriously—and more importantly, it is hard to make them work in detail when we remember that changing the past is impossible. (The chaperone is acting to ensure that the past remains as it was—but the only reason it ever was that way is because of his very actions.) [ 15 ] Fortunately there is a better response—also to be found in the science fiction literature, and brought to the attention of philosophers by Lewis (1976). What would stop the time traveller doing the impossible? She would fail “for some commonplace reason”, as Lewis (1976, 150) puts it. Her gun might jam, a noise might distract her, she might slip on a banana peel, etc. Nothing more than such ordinary occurrences is required to stop the time traveller killing Grandfather. Hence backwards time travel does not entail the occurrence of impossible events—and so the above objection is defused.

A problem remains. Suppose Tim, a time-traveller, is facing his grandfather with a loaded gun. Can Tim kill Grandfather? On the one hand, yes he can. He is an excellent shot; there is no chaperone to stop him; the laws of logic will not magically stay his hand; he hates Grandfather and will not hesitate to pull the trigger; etc. On the other hand, no he can’t. To kill Grandfather would be to change the past, and no-one can do that (not to mention the fact that if Grandfather died, then Tim would not have been born). So we have a contradiction: Tim can kill Grandfather and Tim cannot kill Grandfather. Time travel thus leads to a contradiction: so it is impossible.

Note the difference between this version of the Grandfather paradox and the version considered above. In the earlier version, the contradiction happens if Tim kills Grandfather. The solution was to say that Tim can go into the past without killing Grandfather—hence time travel does not entail a contradiction. In the new version, the contradiction happens as soon as Tim gets to the past. Of course Tim does not kill Grandfather—but we still have a contradiction anyway: for he both can do it, and cannot do it. As Lewis puts it:

Could a time traveler change the past? It seems not: the events of a past moment could no more change than numbers could. Yet it seems that he would be as able as anyone to do things that would change the past if he did them. If a time traveler visiting the past both could and couldn’t do something that would change it, then there cannot possibly be such a time traveler. (Lewis, 1976, 149)

Lewis’s own solution to this problem has been widely accepted. [ 16 ] It turns on the idea that to say that something can happen is to say that its occurrence is compossible with certain facts, where context determines (more or less) which facts are the relevant ones. Tim’s killing Grandfather in 1921 is compossible with the facts about his weapon, training, state of mind, and so on. It is not compossible with further facts, such as the fact that Grandfather did not die in 1921. Thus ‘Tim can kill Grandfather’ is true in one sense (relative to one set of facts) and false in another sense (relative to another set of facts)—but there is no single sense in which it is both true and false. So there is no contradiction here—merely an equivocation.

Another response is that of Vihvelin (1996), who argues that there is no contradiction here because ‘Tim can kill Grandfather’ is simply false (i.e. contra Lewis, there is no legitimate sense in which it is true). According to Vihvelin, for ‘Tim can kill Grandfather’ to be true, there must be at least some occasions on which ‘If Tim had tried to kill Grandfather, he would or at least might have succeeded’ is true—but, Vihvelin argues, at any world remotely like ours, the latter counterfactual is always false. [ 17 ]

Return to the original version of the Grandfather paradox and Lewis’s ‘commonplace reasons’ response to it. This response engenders a new objection—due to Horwich (1987)—not to the possibility but to the probability of backwards time travel.

Think about correlated events in general. Whenever we see two things frequently occurring together, this is because one of them causes the other, or some third thing causes both. Horwich calls this the Principle of V-Correlation:

if events of type A and B are associated with one another, then either there is always a chain of events between them…or else we find an earlier event of type C that links up with A and B by two such chains of events. What we do not see is…an inverse fork—in which A and B are connected only with a characteristic subsequent event, but no preceding one. (Horwich, 1987, 97–8)

For example, suppose that two students turn up to class wearing the same outfits. That could just be a coincidence (i.e. there is no common cause, and no direct causal link between the two events). If it happens every week for the whole semester, it is possible that it is a coincidence, but this is extremely unlikely . Normally, we see this sort of extensive correlation only if either there is a common cause (e.g. both students have product endorsement deals with the same clothing company, or both slavishly copy the same influencer) or a direct causal link (e.g. one student is copying the other).

Now consider the time traveller setting off to kill her younger self. As discussed, no contradiction need ensue—this is prevented not by chaperones or mysterious forces, but by a run of ordinary occurrences in which the trigger falls off the time traveller’s gun, a gust of wind pushes her bullet off course, she slips on a banana peel, and so on. But now consider this run of ordinary occurrences. Whenever the time traveller contemplates auto-infanticide, someone nearby will drop a banana peel ready for her to slip on, or a bird will begin to fly so that it will be in the path of the time traveller’s bullet by the time she fires, and so on. In general, there will be a correlation between auto-infanticide attempts and foiling occurrences such as the presence of banana peels—and this correlation will be of the type that does not involve a direct causal connection between the correlated events or a common cause of both. But extensive correlations of this sort are, as we saw, extremely rare—so backwards time travel will happen about as often as you will see two people wear the same outfits to class every day of semester, without there being any causal connection between what one wears and what the other wears.

We can set out Horwich’s argument this way:

- If time travel were ever to occur, we should see extensive uncaused correlations.

- It is extremely unlikely that we should ever see extensive uncaused correlations.

- Therefore time travel is extremely unlikely to occur.

The conclusion is not that time travel is impossible, but that we should treat it the way we treat the possibility of, say, tossing a fair coin and getting heads one thousand times in a row. As Price (1996, 278 n.7) puts it—in the context of endorsing Horwich’s conclusion: “the hypothesis of time travel can be made to imply propositions of arbitrarily low probability. This is not a classical reductio, but it is as close as science ever gets.”

Smith (1997) attacks both premisses of Horwich’s argument. Against the first premise, he argues that backwards time travel, in itself, does not entail extensive uncaused correlations. Rather, when we look more closely, we see that time travel scenarios involving extensive uncaused correlations always build in prior coincidences which are themselves highly unlikely. Against the second premise, he argues that, from the fact that we have never seen extensive uncaused correlations, it does not follow that we never shall. This is not inductive scepticism: let us assume (contra the inductive sceptic) that in the absence of any specific reason for thinking things should be different in the future, we are entitled to assume they will continue being the same; still we cannot dismiss a specific reason for thinking the future will be a certain way simply on the basis that things have never been that way in the past. You might reassure an anxious friend that the sun will certainly rise tomorrow because it always has in the past—but you cannot similarly refute an astronomer who claims to have discovered a specific reason for thinking that the earth will stop rotating overnight.

Sider (2002, 119–20) endorses Smith’s second objection. Dowe (2003) criticises Smith’s first objection, but agrees with the second, concluding overall that time travel has not been shown to be improbable. Ismael (2003) reaches a similar conclusion. Goddu (2007) criticises Smith’s first objection to Horwich. Further contributions to the debate include Arntzenius (2006), Smeenk and Wüthrich (2011, §2.2) and Elliott (2018). For other arguments to the same conclusion as Horwich’s—that time travel is improbable—see Ney (2000) and Effingham (2020).

Return again to the original version of the Grandfather paradox and Lewis’s ‘commonplace reasons’ response to it. This response engenders a further objection. The autoinfanticidal time traveller is attempting to do something impossible (render herself permanently dead from an age younger than her age at the time of the attempts). Suppose we accept that she will not succeed and that what will stop her is a succession of commonplace occurrences. The previous objection was that such a succession is improbable . The new objection is that the exclusion of the time traveler from successfully committing auto-infanticide is mysteriously inexplicable . The worry is as follows. Each particular event that foils the time traveller is explicable in a perfectly ordinary way; but the inevitable combination of these events amounts to a ring-fencing of the forbidden zone of autoinfanticide—and this ring-fencing is mystifying. It’s like a grand conspiracy to stop the time traveler from doing what she wants to do—and yet there are no conspirators: no time lords, no magical forces of logic. This is profoundly perplexing. Riggs (1997, 52) writes: “Lewis’s account may do for a once only attempt, but is untenable as a general explanation of Tim’s continual lack of success if he keeps on trying.” Ismael (2003, 308) writes: “Considered individually, there will be nothing anomalous in the explanations…It is almost irresistible to suppose, however, that there is something anomalous in the cases considered collectively, i.e., in our unfailing lack of success.” See also Gorovitz (1964, 366–7), Horwich (1987, 119–21) and Carroll (2010, 86).

There have been two different kinds of defense of time travel against the objection that it involves mysteriously inexplicable occurrences. Baron and Colyvan (2016, 70) agree with the objectors that a purely causal explanation of failure—e.g. Tim fails to kill Grandfather because first he slips on a banana peel, then his gun jams, and so on—is insufficient. However they argue that, in addition, Lewis offers a non-causal—a logical —explanation of failure: “What explains Tim’s failure to kill his grandfather, then, is something about logic; specifically: Tim fails to kill his grandfather because the law of non-contradiction holds.” Smith (2017) argues that the appearance of inexplicability is illusory. There are no scenarios satisfying the description ‘a time traveller commits autoinfanticide’ (or changes the past in any other way) because the description is self-contradictory (e.g. it involves the time traveller permanently dying at 20 and also being alive at 40). So whatever happens it will not be ‘that’. There is literally no way for the time traveller not to fail. Hence there is no need for—or even possibility of—a substantive explanation of why failure invariably occurs, and such failure is not perplexing.

3. Causation

Backwards time travel scenarios give rise to interesting issues concerning causation. In this section we examine two such issues.

Earlier we distinguished changing the past and affecting the past, and argued that while the former is impossible, backwards time travel need involve only the latter. Affecting the past would be an example of backwards causation (i.e. causation where the effect precedes its cause)—and it has been argued that this too is impossible, or at least problematic. [ 18 ] The classic argument against backwards causation is the bilking argument . [ 19 ] Faced with the claim that some event A causes an earlier event B , the proponent of the bilking objection recommends an attempt to decorrelate A and B —that is, to bring about A in cases in which B has not occurred, and to prevent A in cases in which B has occurred. If the attempt is successful, then B often occurs despite the subsequent nonoccurrence of A , and A often occurs without B occurring, and so A cannot be the cause of B . If, on the other hand, the attempt is unsuccessful—if, that is, A cannot be prevented when B has occurred, nor brought about when B has not occurred—then, it is argued, it must be B that is the cause of A , rather than vice versa.

The bilking procedure requires repeated manipulation of event A . Thus, it cannot get under way in cases in which A is either unrepeatable or unmanipulable. Furthermore, the procedure requires us to know whether or not B has occurred, prior to manipulating A —and thus, it cannot get under way in cases in which it cannot be known whether or not B has occurred until after the occurrence or nonoccurrence of A (Dummett, 1964). These three loopholes allow room for many claims of backwards causation that cannot be touched by the bilking argument, because the bilking procedure cannot be performed at all. But what about those cases in which it can be performed? If the procedure succeeds—that is, A and B are decorrelated—then the claim that A causes B is refuted, or at least weakened (depending upon the details of the case). But if the bilking attempt fails, it does not follow that it must be B that is the cause of A , rather than vice versa. Depending upon the situation, that B causes A might become a viable alternative to the hypothesis that A causes B —but there is no reason to think that this alternative must always be the superior one. For example, suppose that I see a photo of you in a paper dated well before your birth, accompanied by a report of your arrival from the future. I now try to bilk your upcoming time trip—but I slip on a banana peel while rushing to push you away from your time machine, my time travel horror stories only inspire you further, and so on. Or again, suppose that I know that you were not in Sydney yesterday. I now try to get you to go there in your time machine—but first I am struck by lightning, then I fall down a manhole, and so on. What does all this prove? Surely not that your arrival in the past causes your departure from the future. Depending upon the details of the case, it seems that we might well be entitled to describe it as involving backwards time travel and backwards causation. At least, if we are not so entitled, this must be because of other facts about the case: it would not follow simply from the repeated coincidental failures of my bilking attempts.

Backwards time travel would apparently allow for the possibility of causal loops, in which things come from nowhere. The things in question might be objects—imagine a time traveller who steals a time machine from the local museum in order to make his time trip and then donates the time machine to the same museum at the end of the trip (i.e. in the past). In this case the machine itself is never built by anyone—it simply exists. The things in question might be information—imagine a time traveller who explains the theory behind time travel to her younger self: theory that she herself knows only because it was explained to her in her youth by her time travelling older self. The things in question might be actions. Imagine a time traveller who visits his younger self. When he encounters his younger self, he suddenly has a vivid memory of being punched on the nose by a strange visitor. He realises that this is that very encounter—and resignedly proceeds to punch his younger self. Why did he do it? Because he knew that it would happen and so felt that he had to do it—but he only knew it would happen because he in fact did it. [ 20 ]

One might think that causal loops are impossible—and hence that insofar as backwards time travel entails such loops, it too is impossible. [ 21 ] There are two issues to consider here. First, does backwards time travel entail causal loops? Lewis (1976, 148) raises the question whether there must be causal loops whenever there is backwards causation; in response to the question, he says simply “I am not sure.” Mellor (1998, 131) appears to claim a positive answer to the question. [ 22 ] Hanley (2004, 130) defends a negative answer by telling a time travel story in which there is backwards time travel and backwards causation, but no causal loops. [ 23 ] Monton (2009) criticises Hanley’s counterexample, but also defends a negative answer via different counterexamples. Effingham (2020) too argues for a negative answer.

Second, are causal loops impossible, or in some other way objectionable? One objection is that causal loops are inexplicable . There have been two main kinds of response to this objection. One is to agree but deny that this is a problem. Lewis (1976, 149) accepts that a loop (as a whole) would be inexplicable—but thinks that this inexplicability (like that of the Big Bang or the decay of a tritium atom) is merely strange, not impossible. In a similar vein, Meyer (2012, 263) argues that if someone asked for an explanation of a loop (as a whole), “the blame would fall on the person asking the question, not on our inability to answer it.” The second kind of response (Hanley, 2004, §5) is to deny that (all) causal loops are inexplicable. A second objection to causal loops, due to Mellor (1998, ch.12), is that in such loops the chances of events would fail to be related to their frequencies in accordance with the law of large numbers. Berkovitz (2001) and Dowe (2001) both argue that Mellor’s objection fails to establish the impossibility of causal loops. [ 24 ] Effingham (2020) considers—and rebuts—some additional objections to the possibility of causal loops.

4. Time and Change

Gödel (1949a [1990a])—in which Gödel presents models of Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity in which there exist CTC’s—can well be regarded as initiating the modern academic literature on time travel, in both philosophy and physics. In a companion paper, Gödel discusses the significance of his results for more general issues in the philosophy of time (Gödel 1949b [1990b]). For the succeeding half century, the time travel literature focussed predominantly on objections to the possibility (or probability) of time travel. More recently, however, there has been renewed interest in the connections between time travel and more general issues in the metaphysics of time and change. We examine some of these in the present section. [ 25 ]

The first thing that we need to do is set up the various metaphysical positions whose relationships with time travel will then be discussed. Consider two metaphysical questions:

- Are the past, present and future equally real?

- Is there an objective flow or passage of time, and an objective now?

We can label some views on the first question as follows. Eternalism is the view that past and future times, objects and events are just as real as the present time and present events and objects. Nowism is the view that only the present time and present events and objects exist. Now-and-then-ism is the view that the past and present exist but the future does not. We can also label some views on the second question. The A-theory answers in the affirmative: the flow of time and division of events into past (before now), present (now) and future (after now) are objective features of reality (as opposed to mere features of our experience). Furthermore, they are linked: the objective flow of time arises from the movement, through time, of the objective now (from the past towards the future). The B-theory answers in the negative: while we certainly experience now as special, and time as flowing, the B-theory denies that what is going on here is that we are detecting objective features of reality in a way that corresponds transparently to how those features are in themselves. The flow of time and the now are not objective features of reality; they are merely features of our experience. By combining answers to our first and second questions we arrive at positions on the metaphysics of time such as: [ 26 ]

- the block universe view: eternalism + B-theory

- the moving spotlight view: eternalism + A-theory

- the presentist view: nowism + A-theory

- the growing block view: now-and-then-ism + A-theory.

So much for positions on time itself. Now for some views on temporal objects: objects that exist in (and, in general, change over) time. Three-dimensionalism is the view that persons, tables and other temporal objects are three-dimensional entities. On this view, what you see in the mirror is a whole person. [ 27 ] Tomorrow, when you look again, you will see the whole person again. On this view, persons and other temporal objects are wholly present at every time at which they exist. Four-dimensionalism is the view that persons, tables and other temporal objects are four-dimensional entities, extending through three dimensions of space and one dimension of time. On this view, what you see in the mirror is not a whole person: it is just a three-dimensional temporal part of a person. Tomorrow, when you look again, you will see a different such temporal part. Say that an object persists through time if it is around at some time and still around at a later time. Three- and four-dimensionalists agree that (some) objects persist, but they differ over how objects persist. According to three-dimensionalists, objects persist by enduring : an object persists from t 1 to t 2 by being wholly present at t 1 and t 2 and every instant in between. According to four-dimensionalists, objects persist by perduring : an object persists from t 1 to t 2 by having temporal parts at t 1 and t 2 and every instant in between. Perduring can be usefully compared with being extended in space: a road extends from Melbourne to Sydney not by being wholly located at every point in between, but by having a spatial part at every point in between.

It is natural to combine three-dimensionalism with presentism and four-dimensionalism with the block universe view—but other combinations of views are certainly possible.

Gödel (1949b [1990b]) argues from the possibility of time travel (more precisely, from the existence of solutions to the field equations of General Relativity in which there exist CTC’s) to the B-theory: that is, to the conclusion that there is no objective flow or passage of time and no objective now. Gödel begins by reviewing an argument from Special Relativity to the B-theory: because the notion of simultaneity becomes a relative one in Special Relativity, there is no room for the idea of an objective succession of “nows”. He then notes that this argument is disrupted in the context of General Relativity, because in models of the latter theory to date, the presence of matter does allow recovery of an objectively distinguished series of “nows”. Gödel then proposes a new model (Gödel 1949a [1990a]) in which no such recovery is possible. (This is the model that contains CTC’s.) Finally, he addresses the issue of how one can infer anything about the nonexistence of an objective flow of time in our universe from the existence of a merely possible universe in which there is no objectively distinguished series of “nows”. His main response is that while it would not be straightforwardly contradictory to suppose that the existence of an objective flow of time depends on the particular, contingent arrangement and motion of matter in the world, this would nevertheless be unsatisfactory. Responses to Gödel have been of two main kinds. Some have objected to the claim that there is no objective flow of time in his model universe (e.g. Savitt (2005); see also Savitt (1994)). Others have objected to the attempt to transfer conclusions about that model universe to our own universe (e.g. Earman (1995, 197–200); for a partial response to Earman see Belot (2005, §3.4)). [ 28 ]

Earlier we posed two questions:

Gödel’s argument is related to the second question. Let’s turn now to the first question. Godfrey-Smith (1980, 72) writes “The metaphysical picture which underlies time travel talk is that of the block universe [i.e. eternalism, in the terminology of the present entry], in which the world is conceived as extended in time as it is in space.” In his report on the Analysis problem to which Godfrey-Smith’s paper is a response, Harrison (1980, 67) replies that he would like an argument in support of this assertion. Here is an argument: [ 29 ]

A fundamental requirement for the possibility of time travel is the existence of the destination of the journey. That is, a journey into the past or the future would have to presuppose that the past or future were somehow real. (Grey, 1999, 56)

Dowe (2000, 442–5) responds that the destination does not have to exist at the time of departure: it only has to exist at the time of arrival—and this is quite compatible with non-eternalist views. And Keller and Nelson (2001, 338) argue that time travel is compatible with presentism:

There is four-dimensional [i.e. eternalist, in the terminology of the present entry] time-travel if the appropriate sorts of events occur at the appropriate sorts of times; events like people hopping into time-machines and disappearing, people reappearing with the right sorts of memories, and so on. But the presentist can have just the same patterns of events happening at just the same times. Or at least, it can be the case on the presentist model that the right sorts of events will happen, or did happen, or are happening, at the rights sorts of times. If it suffices for four-dimensionalist time-travel that Jennifer disappears in 2054 and appears in 1985 with the right sorts of memories, then why shouldn’t it suffice for presentist time-travel that Jennifer will disappear in 2054, and that she did appear in 1985 with the right sorts of memories?

Sider (2005) responds that there is still a problem reconciling presentism with time travel conceived in Lewis’s way: that conception of time travel requires that personal time is similar to external time—but presentists have trouble allowing this. Further contributions to the debate whether presentism—and other versions of the A-theory—are compatible with time travel include Monton (2003), Daniels (2012), Hall (2014) and Wasserman (2018) on the side of compatibility, and Miller (2005), Slater (2005), Miller (2008), Hales (2010) and Markosian (2020) on the side of incompatibility.

Leibniz’s Law says that if x = y (i.e. x and y are identical—one and the same entity) then x and y have exactly the same properties. There is a superficial conflict between this principle of logic and the fact that things change. If Bill is at one time thin and at another time not so—and yet it is the very same person both times—it looks as though the very same entity (Bill) both possesses and fails to possess the property of being thin. Three-dimensionalists and four-dimensionalists respond to this problem in different ways. According to the four-dimensionalist, what is thin is not Bill (who is a four-dimensional entity) but certain temporal parts of Bill; and what is not thin are other temporal parts of Bill. So there is no single entity that both possesses and fails to possess the property of being thin. Three-dimensionalists have several options. One is to deny that there are such properties as ‘thin’ (simpliciter): there are only temporally relativised properties such as ‘thin at time t ’. In that case, while Bill at t 1 and Bill at t 2 are the very same entity—Bill is wholly present at each time—there is no single property that this one entity both possesses and fails to possess: Bill possesses the property ‘thin at t 1 ’ and lacks the property ‘thin at t 2 ’. [ 30 ]

Now consider the case of a time traveller Ben who encounters his younger self at time t . Suppose that the younger self is thin and the older self not so. The four-dimensionalist can accommodate this scenario easily. Just as before, what we have are two different three-dimensional parts of the same four-dimensional entity, one of which possesses the property ‘thin’ and the other of which does not. The three-dimensionalist, however, faces a problem. Even if we relativise properties to times, we still get the contradiction that Ben possesses the property ‘thin at t ’ and also lacks that very same property. [ 31 ] There are several possible options for the three-dimensionalist here. One is to relativise properties not to external times but to personal times (Horwich, 1975, 434–5); another is to relativise properties to spatial locations as well as to times (or simply to spacetime points). Sider (2001, 101–6) criticises both options (and others besides), concluding that time travel is incompatible with three-dimensionalism. Markosian (2004) responds to Sider’s argument; [ 32 ] Miller (2006) also responds to Sider and argues for the compatibility of time travel and endurantism; Gilmore (2007) seeks to weaken the case against endurantism by constructing analogous arguments against perdurantism. Simon (2005) finds problems with Sider’s arguments, but presents different arguments for the same conclusion; Effingham and Robson (2007) and Benovsky (2011) also offer new arguments for this conclusion. For further discussion see Wasserman (2018) and Effingham (2020). [ 33 ]

We have seen arguments to the conclusions that time travel is impossible, improbable and inexplicable. Here’s an argument to the conclusion that backwards time travel simply will not occur. If backwards time travel is ever going to occur, we would already have seen the time travellers—but we have seen none such. [ 34 ] The argument is a weak one. [ 35 ] For a start, it is perhaps conceivable that time travellers have already visited the Earth [ 36 ] —but even granting that they have not, this is still compatible with the future actuality of backwards time travel. First, it may be that time travel is very expensive, difficult or dangerous—or for some other reason quite rare—and that by the time it is available, our present period of history is insufficiently high on the list of interesting destinations. Second, it may be—and indeed existing proposals in the physics literature have this feature—that backwards time travel works by creating a CTC that lies entirely in the future: in this case, backwards time travel becomes possible after the creation of the CTC, but travel to a time earlier than the time at which the CTC is created is not possible. [ 37 ]

- Adams, Robert Merrihew, 1997, “Thisness and time travel”, Philosophia , 25: 407–15.

- Arntzenius, Frank, 2006, “Time travel: Double your fun”, Philosophy Compass , 1: 599–616. doi:10.1111/j.1747-9991.2006.00045.x

- Asimov, Isaac, 1995 [2003], Gold: The Final Science Fiction Collection , New York: Harper Collins.

- Baron, Sam and Colyvan, Mark, 2016, “Time enough for explanation”, Journal of Philosophy , 113: 61–88.

- Belot, Gordon, 2005, “Dust, time and symmetry”, British Journal for the Philosophy of Science , 56: 255–91.

- Benovsky, Jiri, 2011, “Endurance and time travel”, Kriterion , 24: 65–72.

- Berkovitz, Joseph, 2001, “On chance in causal loops”, Mind , 110: 1–23.

- Black, Max, 1956, “Why cannot an effect precede its cause?”, Analysis , 16: 49–58.

- Brier, Bob, 1973, “Magicians, alarm clocks, and backward causation”, Southern Journal of Philosophy , 11: 359–64.

- Carlson, Erik, 2005, “A new time travel paradox resolved”, Philosophia , 33: 263–73.

- Carroll, John W., 2010, “Context, conditionals, fatalism, time travel, and freedom”, in Time and Identity , Joseph Keim Campbell, Michael O’Rourke, and Harry S. Silverstein, eds., Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 79–93.

- Craig, William L., 1997, “Adams on actualism and presentism”, Philosophia , 25: 401–5.

- Daniels, Paul R., 2012, “Back to the present: Defending presentist time travel”, Disputatio , 4: 469–84.

- Deutsch, David and Lockwood, Michael, 1994, “The quantum physics of time travel”, Scientific American , 270(3): 50–6.

- Dowe, Phil, 2000, “The case for time travel”, Philosophy , 75: 441–51.

- –––, 2001, “Causal loops and the independence of causal facts”, Philosophy of Science , 68: S89–S97.

- –––, 2003, “The coincidences of time travel”, Philosophy of Science , 70: 574–89.

- Dummett, Michael, 1964, “Bringing about the past”, Philosophical Review , 73: 338–59.

- Dwyer, Larry, 1977, “How to affect, but not change, the past”, Southern Journal of Philosophy , 15: 383–5.

- Earman, John, 1995, Bangs, Crunches, Whimpers, and Shrieks: Singularities and Acausalities in Relativistic Spacetimes , New York: Oxford University Press.

- Effingham, Nikk, 2020, Time Travel: Probability and Impossibility , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Effingham, Nikk and Robson, Jon, 2007, “A mereological challenge to endurantism”, Australasian Journal of Philosophy , 85: 633–40.

- Ehring, Douglas, 1997, “Personal identity and time travel”, Philosophical Studies , 52: 427–33.

- Elliott, Katrina, 2019, “How to Know That Time Travel Is Unlikely Without Knowing Why”, Pacific Philosophical Quarterly , 100: 90–113.

- Fulmer, Gilbert, 1980, “Understanding time travel”, Southwestern Journal of Philosophy , 11: 151–6.

- Gilmore, Cody, 2007, “Time travel, coinciding objects, and persistence”, in Oxford Studies in Metaphysics , Dean W. Zimmerman, ed., Oxford: Clarendon Press, vol. 3, 177–98.