- about the dive tourist

- who is the dive tourist?

- what does the dive tourist care about?

- about Judi Lowe

- Judi's research

- destructive fishing

- integrated coastal management

- why is integrated coastal management a good framework?

- negative impacts of dive tourism

- positive impacts of dive tourism

- who are local fishers?

- livelihoods for fishers

- livelihoods for communities

- why are livelihoods for local fishers important to dive tourism?

- why is traditional marine tenure important?

- where does traditional marine tenure exist?

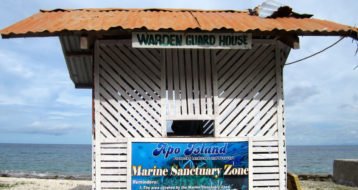

- Bright Spots

- - Fiji: Beqa Adventure Divers

- - Philippines: Oslob Whale Sharks

- - Indonesia: Misool Eco Resort

- what all this means

dive tourism

What is dive tourism?

Dive tourism has been defined as individuals traveling from their usual place of residence, spending at least one night away and actively participating in one or more activities, including scuba diving, snorkelling, snuba or the use of rebreathing apparatus (Garrod and Gossling, 2008). These days, we would include free diving in the definition of dive tourism.

Dive tourism is ubiquitous and occurs all over the world but by far the majority of dive tourism happens in the less developed countries of the tropics, where the waters are warm, the sea is blue with great visibility and sea conditions are often calm. Many divers learn to dive on holiday in the tropics and dive very little on return to the temperate waters of their homes. It is often easier and more beautiful to dive in the tropics, where most of the world’s coral reefs lie. As dive tourists gain more experience, many will continue to explore other locations around the tropics on regular dive tourism holidays. There is so much to see and experience.

The Conversation – Oslob Whale Sharks and Conservation

Our article in The Conversation, covering the release of our new research paper on the conservation effects of Oslob Whale Sharks. A group of the world’s poorest fishermen are protecting endangered w...

The Guardian reports on our Oslob research

The Guardian – Oslob Whale Sharks and livelihoods Fishermen-turned-entrepreneurs who have been financing the protection of endangered whale sharks in the Philippines have hit on a successful sch...

Turtles as food

Raja Ampat. Scrubbing algae off the shells of captive turtles, caged until they grow to eating size, then sold. A common sight water villages. Taking turtles is illegal but overlooked. ...

Local fishers of Oslob

Traditional non-motorised banca Field work blog – Post 6 A local fisher heads out at dawn with his traditional banca with simple fishing gear – a gill net and hook and line. Oslob, the Phi...

Research starts at dawn

Field work blog – Post 5 Marine biologist Ma. May Saludsod watches Oslob fishers survey weather and tide conditions before launching their small banca (traditional outrigger canoes), for morning...

Oslob: Bubbles, baby!

Field work blog – Post 4 Bubbles = divers below. Photographic imperfection meets dive tourist Heaven (taken by a failed underwater photographer on field work, who is much better at research. Big...

84% of dive operators in tropics have dive sties in marine protected areas

84% of dive operators in the tropics report that they have dive sites located within marine protected areas (MPAs). This is no surprise because MPAs are designed to protect the coral reefs, fish stock...

Oslob Whale Sharks: bright spot in community based dive tourism

Field work blog – Post 3 Fishermen paddle dive tourists in small, unmotorised banca (outrigger canoes) out to snorkel with whale sharks in barangay Tan-Awan, Oslob, on the island of Cebu in the ...

- presentations

- news & links

Sustainable Tourism and Diving: Tips for Treading Lightly

If you’re a diver, here’s a little tidbit i’ll wager you’re completely unaware of: did you know you’re an “adventure tourist” indeed, you are....

By Dive Training

If you’re a diver, here’s a little tidbit I’ll wager you’re completely unaware of: Did you know you’re an “adventure tourist?” Indeed, you are — at least according to the travel industry. In fact, scuba diving and snorkeling are specifically listed as adventure travel activities by what may be the top expert in the field — the Adventure Travel Trade Association. They define an adventure tourist as anyone engaged in a travel experience that involves at least two of three elements: 1) physical activity; 2) the natural environment and 3) cultural immersion.

But before venturing further on the adventure tourism path, let’s look first at travel and tourism in general. In terms of both direct and indirect impacts, tourism is a major contributor to the global economy. The international tourism industry generates nearly one trillion dollars annually and comprises 30 percent of the world’s exports of commercial services (six percent of total exports). According to the World Travel and Tourism Council, it accounts for more than nine percent of global Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and employs one in every 10 people on earth. By comparison only three other industries rank higher in global export: fuels, chemicals and automotive products. And it’s growing.

The scuba diving industry is an excellent example of how tourism has grown in recent years. In fact, it has changed fundamentally. Once driven by scuba equipment sales it’s now driven by travel. For example, at 19 billion dollars in revenue annually, dive travel now accounts for more than six times the revenue generated by dive equipment sales.

But you’re not in the diving or tourism business. So, why should you care? The reason is simple. The dollars quoted in all those statistics are your dollars. Thus, you have a very big voice in how, where and on what that money is spent. In other words, you have enormous power to influence the future direction of the travel industry, generally, and the dive travel industry, directly. More importantly, your dollars don’t just contribute to the financial success of whatever travel provider you choose. If you choose wisely, your dollars can also have a positive impact on the quality of the destination you visit and on those who live there.

RELATED READ: How Shark Tourism is Protecting Global Shark Populations

So, what’s the problem? Well, it turns out that tourism can be a double-edged sword. In many ways it has the potential to be a victim of its own success.

International tourist arrivals (overnight visitors) now exceed a billion per year — millions of which are scuba divers. That’s equivalent to the entire population of China and the numbers are expected to increase to nearly two billion by 2030. So, it’s hardly surprising that at destinations where their bread and butter is a natural resource (like coral reefs), the impact from tourism can range from harmful to devastating. Yet, tourism can be done responsibly and actually become a positive force for conservation, if — and that’s a big “if” — it’s done right. It’s up to you. As one travel expert has puts it, “Tourism is like fire — it can cook your meal, or it can burn your house down. The choice is yours.” Preventing the fire of tourism from getting out of control is the biggest challenge facing the travel industry today because some popular destinations around the world are being literally “loved to death.” This phenomenon even has a name — overtourism.

When it comes to the environmental consequences of overtourism, marine tourism is perhaps the sector most affected of all nature-based travel activities. As a major share of marine tourism takes place in the tropics — and what draws folks there is the environment — it doesn’t take a genius to realize that much of marine tourism is wholly dependent upon healthy coral reefs and associated ecosystems (seagrass beds and mangrove forests). And surely there’s no segment of tourism more dependent on the continued existence of healthy coral reefs than scuba diving.

Of course, tourism isn’t the primary reason for the demise of earth’s coral reefs. And though factors such as destructive fishing practices, pollution, coastal development and climate change are far bigger problems, tourism does play a role. However, the reason reefs at popular dive destinations are in trouble isn’t from what you might assume. When talk turns to how coral reefs are degraded at popular tourist sites, divers are often viewed as the culprits. After all, our high visibility and close association with coral reefs makes us easy targets. Without question, anchors as well as clumsy and careless divers do take their toll on our beloved reefs. And the overabundance of divers on any reef, regardless of their behavior, will have a negative impact. But this problem pales in comparison to other destructive factors.

A colleague of mine once summed up the problem quite accurately. “A diver,” he contends, “probably does more damage to a coral reef by flushing the toilet in his hotel room than he’ll ever do by diving on one.” It was a glib but astute insight into the real problem. From a tourism perspective, the concern is less about direct damage from recreation activities like diving and boating, and more about the indirect threats from the infrastructure needed to support tourism. Every tourist needs a place to eat, sleep and go to the bathroom. They also prefer that these facilities be very near or, ideally, on the water. In addition, every tourist demands the facilities and services that make tourism possible, such as beaches, docks and marinas. These all add to the eutrophication, pollution, demand for seafood and sedimentation problems already threatening reefs from local population pressure (a population pressure that’s sometimes driven by tourism). And considering that on small islands, tourists can sometimes outnumber the local residents, it’s easy to understand the validity of my friend’s “flushing the toilet” assertion.

While the environmental consequences of tourism are often obvious — at least for those willing to take a closer look — there are other not-so-obvious results that involve people. Clearly, the consequences of a rapidly expanding tourism industry have, at many destinations, been as detrimental to societies as it has to the physical environment. For instance, many developing countries’ job opportunities in tourism have encouraged the migration of people to tourism centers, often disrupting or outright destroying traditional ways of life. Already some communities and cultures have been completely displaced or destroyed by a booming tourism trade. This social upheaval can lead to problems with crime, pollution and a general erosion in the fabric of society. Ironically, this can lead to the decline in the appeal of a destination because it no longer feels “authentic” to travelers, thus killing the golden egg-bearing goose.

RELATED READ: A Guide to Ocean Conservation Organizations and Efforts

This phenomenon is, in fact, so common and well-studied that it even has a name — the Tourism Area Life Cycle (TALC). The TALC cycle views tourism as a dynamic process where destinations go through predictable successive stages. It starts when a relatively undeveloped location initially attracts a few adventurous tourists seeking pristine nature and indigenous cultures. Then, as tour operators and related businesses recognize the market potential of the location, the local tourism industry rapidly expands and develops. However, the changed nature of the now “discovered” destination causes the type of tourists who were initially attracted by the undeveloped nature of the location to move on to other destinations that remain undeveloped and pristine — and the cycle is repeated.

But there’s nothing inevitable about this cycle. By recognizing the cycle of overtourism and unsustainable tourism practice soon enough, destinations can reverse the downward spiral. Corrective actions can be taken, such as limiting tourist numbers, establishing marine protected areas, improving infrastructure codes or restricting certain destructive practices. Ideally, the entire tourism paradigm can change, but this calls for a different kind of tourism: Sustainable tourism.

The concept and practice of “sustainable tourism” is a multi-facated concern. Destinations that welcome divers must protect their resources by protecting dive sites from anchor damage and overuse. They must also address issues related to infrastructure and reducing plastic pollution.

Sustainable Tourism: A New Paradigm

The problem is that undiscovered tourism destinations are not unlimited. As a popular protest poster tells us, “There is No Planet B.” Tourism has become so big that we have almost run out of truly pristine locations. So, without the option of creating more places on earth, the only reasonable alternative is conducting the business of tourism in a different way — and that’s exactly what’s beginning to happen all around the world. Tourism, and tourists, are changing for the better. So, let’s look at how.

Traditionally, the reason for travel has been to rest and relax. In the marine sector, this emphasis on leisure is referred to as “sun, sea and sand” tourism. This describes the bulk of marine tourists and probably always will. But over the past few decades there have been some significant changes. Increasingly, tourists want more from their holiday than a suntan and souvenirs. These more intrepid travelers — I’ll no longer call them tourists — want a closer and more experiential encounter with the destination they visit than lying on the beach during the day and partying at night. For many, the primary motivation for selecting a destination is not the quality of its beaches, golf courses or of night life, but its healthy natural environment and undisturbed culture. In the words of one tourism expert, “An increasing number of travelers today want holiday experiences that are authentic, immersive and self-directed.” And what’s good news for us is that’s almost the perfect definition of scuba diving.

The other good news is that, while the travel and tourism industry is sustaining a healthy grow of five to seven percent annually, the adventure and nature-based travel industries are growing in the 20 to 30 percent range. And even more significantly, these travelers most often understand, in fact prefer, to travel responsibly. Of course, this hasn’t gone unnoticed by many within the travel industry and has already led to massive changes in the travel products offered by many destinations and how they’re marketed.

The evolution of adventure travel can be traced to early attempts to meet the demand of changing attitudes toward tourism, which led to the development of the ecotourism industry. From this evolved the idea that travel should not only serve the tourist but the destination and its inhabitants as well. As ecotourism became more mainstream, newer and more authentic directions were explored and the market segmented into many more specialized sectors and activities. Then, with the growing recognition of the declining state of earth’s environment, many in tourism began to realize that making tourism more accountable to both the local environment and residents could no longer be just a specialized endeavor targeted to “tree-huggers.” All forms of tourism should become part of the solution and not part of the problem. From this movement was born the idea of “responsible tourism,” or what’s become better known as “sustainable tourism” — an off-shoot of the growing concern for sustainable development.

CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD OUR SUSTAINABLE TOURISM CHECKLIST

But what exactly does sustainable tourism really mean? While arguments rage among the experts in the field, one of the best functional definitions has been offered by those who have been involved in international tourism since its inception, Caribbean islanders. According to the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States , sustainable tourism is defined as “the optimal use of natural and cultural resources for national development on an equitable and self-sustaining basis to provide a unique visitor experience and an improved quality of life through partnership among government, the private sector and communities.” Importantly, this definition recognizes that tourism isn’t just an economic activity. As it has both environment and cultural consequences, so too must it take into account, and be responsible for, its effects. This ethos is exemplified in the commonly used sustainable tourism mantra “people, planet, profit” or what some have termed the “triple bottom line.”

In general, sustainable tourism has six underlying goals. These include: minimizing environmental impacts; improving local contribution to sustainable development; protecting the quality of the environment by maintaining biological diversity and ecosystem function; minimizing the use of non-renewable resources; ensuring cultural integrity, local ownership and social cohesion of the community; and last, but certainly not least, providing a high quality experience for tourists.

Today, savvy tourism operators trying to cater to the new, more environmentally and socially conscious traveler have a daunting task. No longer can they be satisfied by having the nicest hotel and restaurant or best beach or even the most exciting tours. Study after study has shown that many travelers today — a majority of European and a fast-growing number from the U.S. — are just as or more concerned with the environmental and social footprint of their travel provider as they are with the actual product. So, travel providers and destinations today aren’t turning to sustainability because it’s a nice thing to do for the earth or future generations. They’re doing so because it makes business sense and realize that not to do so will at some point will mean they’ll no longer be in business.

So, What Can You Do?

My experience has been that divers are a special breed. The most serious among us are anything but tourists — we’re travelers. We take very seriously our responsibility to protect the environments we visit and are increasingly recognizing that our travel demands are sometimes placing undue stress on local ecosystems and cultures. So, what we can do to help ensure that operators and destinations hear our wishes loud and clear to make tourism more sustainable is simple. As I indicated at the beginning, we can vote with our wallets. When making your choice of what destination and operator to patronize, take a few minutes to consider not only what you might “get for your dollar,” but how that destination or operator does business and reward those who are doing it right. In that way, you can become part of the solution and help drive a process that will make tourism a positive force for change. Let’s use the fire that we helped ignite to create a warm glow — not burn our house down.

Story by Alex Brylske

Jump to a new category..., related posts.

- Sustainable Tourism Checklist

- Sanctuaries at Sea: The Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary

- At the Intersection of People and Wildlife: Drawing the Line Between Interaction and Harassment

- Shark Diving as a Conservation Strategy: How Shark Tourism is Protecting Global Shark Populations

- A Guide to Ocean Conservation Organizations and Efforts

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

The influence of scuba diving experience on divers’ perceptions, and its implications for managing diving destinations

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation TREES – Tourism Research in Economics, Environs and Society, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa

Roles Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Studio Associato GAIA s.n.c., Genova, Italy

Roles Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Life and Environmental Sciences (DiSVA), Polytechnic University of Marche, UO CoNISMa, Via Brecce Bianche, Ancona, Italy

Roles Methodology, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation UBICA s.r.l., Genova, Italy

- Serena Lucrezi,

- Martina Milanese,

- Carlo Cerrano,

- Marco Palma

- Published: July 5, 2019

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0219306

- Reader Comments

Scuba diving experience–which can include accumulated diving experience and familiarity with a diving location–is an important descriptor of diver specialisation and behaviour. Formulating and applying generalisations on scuba diving experience and its effects could assist the management of diving destinations around the world. This requires research that tests whether the influences of scuba diving experience are consistent across divers’ segments at different locations. The study assessed and compared the influence of scuba diving experience at two study areas in Italy and Mozambique. Scuba divers (N = 499) participated in a survey of diver segmentation, experience, and perceptions. The influence of diving experience on perceptions was determined using canonical correspondence analysis (CCA). Experienced divers provided positive self-assessments, were less satisfied with dive sites’ health and management, and viewed the impacts of scuba diving activities less critically than novice divers. Scuba diving experience exerted similar influences on divers, regardless of the study area. However, remarkable differences also emerged between the study areas. Therefore, the use of generalisations on scuba diving experience remains a delicate issue. Recommendations were formulated for the management of experienced scuba diving markets and for the use of generalisations on diving experience to manage diving destinations.

Citation: Lucrezi S, Milanese M, Cerrano C, Palma M (2019) The influence of scuba diving experience on divers’ perceptions, and its implications for managing diving destinations. PLoS ONE 14(7): e0219306. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0219306

Editor: Agnese Marchini, University of Pavia, ITALY

Received: January 21, 2019; Accepted: June 20, 2019; Published: July 5, 2019

Copyright: © 2019 Lucrezi et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the manuscript, Supporting Information files and at Mendeley Data: Lucrezi, Serena (2019), “Scuba Diving Experience and Divers’ Perceptions”, Mendeley Data, v1 http://dx.doi.org/10.17632/xszp88c6sr.1 .

Funding: The project leading to this paper has received funding from the European Union Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 643712 coordinated by author CC (Green Bubbles RISE project www.greenbubbles.eu ). The funder provided support in the form of flat-rate reimbursement for mobility and research costs (including management costs) for all authors [SL, MM, MP, CC]. All authors are affiliated with the entities indicated in the "authors’ affiliations" sections, and these entities have provided support in the form of salaries. Neither the funder nor these entities had any additional role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The specific roles of these authors are articulated in the ‘author contributions’ section.

Competing interests: In the frame of the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 643712 received from the European Union Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme, Studio Associato GAIA s.n.c. and UBICA s.r.l. acted as full beneficiaries and provided support in the form of salaries for authors MM and MP, but did not have any additional role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. This does not alter our adherence to PLOS ONE policies on sharing data and materials. The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Scuba diving segmentation research and the role of experience.

Scuba diving is an activity characterised by an important recreational component as well as a professional component including commercial and scientific diving. Recreational scuba diving, in particular, is a leisure and tourism sector affecting the communities, economies and environments of destinations across all latitudes in both developed and developing countries [ 1 ]. In marine protected areas (MPAs), for example, scuba diving is a recreational activity which, when properly regulated, can generate income for MPA management and for communities surrounding MPAs [ 2 – 3 ]. On the other hand, uncontrolled scuba diving can pose serious threats to the conservation agendas of MPAs through either direct (e.g. contact) or indirect (e.g. pollution) impacts [ 4 – 5 ].

Segmentation research at diving destinations has been central to the understanding of the general profile of scuba divers for the purpose of marketing, management and sustainable development planning [ 6 ]. In this context, scuba divers have also been categorised according to their level of experience ( S1 Table ). Investigating how experience influences the way scuba divers think and act can be critical in formulating strategies to manage diving tourism, diving activities and marine environments. Scuba diving experience can affect divers’ motivations, preferences, attitudes, underwater actions, and perceptions of the quality of the environments in which they dive [ 7 ].

As the diversification (according to the level of experience) of the scuba-diving tourism market is likely to affect all diving destinations indiscriminately, the influence and implications of scuba diving experience could be considered a constant factor across divers’ segments at various destinations. Consequently, generalisations regarding scuba diving experience could be formulated and applied to different markets and diving destinations worldwide for management purposes. However, pooled research assessing the influence of scuba diving experience in different contexts shows contrasting results, with scuba diving experience affecting divers’ attitudes, perceptions and behaviour either positively or negatively [ 5 , 8 – 9 ].

These contradictions, which make it difficult to understand whether experience exerts similar influences on different groups of divers and at different destinations, have consequences for both research and management. One reason behind the contrasting results is that scuba diving experience has been measured through different sets of variables, since it can be defined in many ways. Comparing the influence of a given construct that defines scuba diving experience across typologies of divers and locations can possibly help to elucidate documented contrasts. To date, almost no research has experimented with such a system.

Defining scuba diving experience and its influence

Much research has categorised divers’ experience levels according to the number of years diving and the highest scuba diving qualification held ( S1 Table ). In time, however, the need to deploy more variables to explain scuba diving experience has become evident [ 10 – 14 ]. Research has been using scuba diving experience as one of the components characterising scuba diver specialisation ( S1 Table ). Scuba diving specialisation, a multidimensional index that includes behavioural, cognitive and affective (conative) domains, has successfully predicted scuba divers’ perceptions, attitudes and behaviour [ 12 , 15 ]. However, if represented by the right variables, accumulated scuba diving experience, which includes aspects in the three domains of diver specialisation, remains a valid tool to segment and study scuba divers [ 11 , 16 – 17 ]. Accumulated scuba diving experience should at least include indicators of diving history, for example the total number of years diving and the total number of logged dives; indicators of regular practice and commitment, for example annual diving frequency and time elapsed since the last dive; and indicators of development, for example certification level.

Accumulated scuba diving experience is viewed as the primary element shaping the growth of scuba divers. The transformation from a novice to an experienced diver is generally accompanied by the improvement of skills and a shift in motivations to dive, expectations of the diving experience, preferences, satisfaction, attitudes towards conservation and management, and behaviours in and out of the water [ 7 , 15 , 18 – 20 ]. In addition, the development of divers is normally underpinned by their growing attachment to the diving activity, the importance of the resources the diving activity depends on, for example environment and safety, and the desire to improve and to learn [ 12 , 21 – 23 ]. Thus, accumulated scuba diving experience can play a crucial role in affecting diving activities and informing the management of diving tourism and destinations ( S2 Table ).

Familiarity with dive locations is also an indicator of scuba diving experience and specialisation ( S1 Table ). A number of variables can be ascribed to familiarity with a dive location, for example the number of dives logged, the number of years diving, and annual diving frequency at that location. Studies looking at the influences of familiarity with dive locations on divers have yielded mixed results, impinging on management guidelines. On the one hand, scuba divers who are familiar with a dive location tend to become attached to it and thus willing to either deepen their knowledge about its biological characteristics or pay for its conservation [ 22 , 24 ]. Loyal divers also tend to have more realistic expectations of ecosystem conditions, for example coral cover and fish abundance, and thus tend to be satisfied with their experience [ 22 , 25 ]. On the other hand, scuba divers who are attached to a particular location can become intolerant of changes such as an increasing influx of tourists, crowding of dive sites and the introduction of man-made structures [ 26 ]. Despite the attachment to a diving destination, experienced divers can be prepared to abandon it when unacceptable levels of degradation are perceived [ 27 ]. Given these influences, familiarity deserves special attention in scuba diving research and can be a valuable addition to variables representing scuba diving experience [ 26 , 28 ].

Aim of the study

The aim of this study was to test the influence of scuba diving experience, underlain by a given group of variables, on divers’ perceptions relevant to environmental, destination, and business management across two study areas. The choice of study areas fell on destinations beyond the tropics. This choice was grounded on two considerations. First, research on scuba diving tourism at destinations beyond the tropics is still limited [ 29 ]. Second, based on the relatively few available studies (compared with the literature available for tropical destinations), locations beyond the tropics tend to host a good proportion of experienced divers [ 30 – 33 ]. For this study, we selected one diving destination in the northern hemisphere that is further from the tropic (temperate climate), and one in the southern hemisphere that is closer to the tropic (subtropical climate). The selected locations present some notable differences in climate, environmental conditions, local history of diving activities, the type of local diving activities and attractions, and the average diver profile. Both study areas share the status of being protected areas. Protected areas such as MPAs and marine reserves tend to attract scuba diving tourism [ 3 ]. They are subjected to regulations that are likely to affect diving activities [ 2 , 15 ]. And they can set an example for destinations that are not officially protected and are heavily affected by the impacts of human activities, including scuba diving [ 5 , 14 , 34 ].

The following research questions were formulated for this study: Does diving experience influence divers’ perceptions? Is this influence similar across different study areas? Answering these questions will have implications for the management of diving tourism based on market segmentation, and for the formulation and application of generalisations on diving experience to diving destinations. Such implications will be relevant for both authorities and local businesses.

Materials and methods

This study was approved by the Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences Research Ethics Committee (EMS-REC) at the North-West University under the ethics code EMS2016/11/25-0237. No private personal information was asked from the participants in the study. The data were handled according to laws on privacy and oral consent was provided by the participants before the study. Participants were able to leave the research at any point during the study.

Study areas

Two study areas were selected for the research, specifically the Portofino MPA in northern Italy, and the Ponta do Ouro Partial Marine Reserve (PPMR) in southern Mozambique ( Fig 1 ). Large inland cities in the range of 215 km from Portofino and 645 km from Ponta do Ouro ( Fig 1 ) provide the majority of the scuba diving clientele, which is mostly characterised by daily visitors in the case of Italy, and overnight stayers in the case of Mozambique [ 35 ].

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0219306.g001

The Portofino MPA (with an area of 3.74 km 2 ) is located in a small but populated area of the region Liguria in the northwestern Mediterranean Sea ( Fig 1 ). The area has a temperate climate, with annual sea surface temperatures (SST) averaging 18 °C [ 36 ]. The MPA was established in 1999 [ 37 ], yet scuba diving tourism has been present in the area for several decades [ 35 ]. Considering trends from 2012 until today, the average number of dives recorded in the MPA annually is about 50,000 [ 35 , 38 ]. The prominent underwater habitats in the MPA include seagrass meadows, vertical rocky walls of Oligocenic pudding stone, coralligenous biocenoses, boulders and stones, caves and caverns, and the pelagic zone.

Since its establishment, the MPA has achieved important goals, for example increasing fish biomass, protecting endangered species such as the grouper and red coral, and safeguarding ecosystems such as seagrass meadows [ 39 – 40 ]. The MPA is zoned to control uses, including artisanal fishing, scuba diving, free diving, snorkelling, and boating. Given the small area of the MPA and the many uses, some of which tend to overlap, conflicts between stakeholders such as divers and fishermen can occur [ 35 , 41 ].

Scuba diving activities in the MPA are strictly regulated and limited to a number of dive sites marked by fixed mooring buoys. A study dating back to 2005 described the scuba diving population of Portofino as male-dominated, moderately experienced (generally at divemaster level) and loyal to the destination (visiting the destination up to 30 times per year) [ 42 ]. The peak diving season in the MPA is from June to September (summer season) [ 35 ], although an off-season market also exists which focuses on technical dives and training dives (S. Lucrezi, pers. obs.). The dives offered in the MPA are both recreational, following established routes along vertical rocky walls and reaching depths of up to 40 m, and technical and wreck dives, which can exceed recreational depths [ 43 ].

A famous shark diving destination, Ponta do Ouro is a small village at the southern end of the PPMR (with an area of 678 km 2 ) and close to the border between Mozambique and South Africa ( Fig 1 ). The area has a subtropical climate, with SST averaging 25 °C [ 44 ]. Scuba diving activities in Ponta do Ouro are characterised by a busy season from December to April, alternated with a quieter season during the rest of the year [ 45 ]. Approximately 30,000 dives are logged from the launching site in Ponta do Ouro annually, although the total number of dives logged for the entire PPMR is greater [ 46 ].

The PPMR was proclaimed in 2009, but it was already a popular scuba diving destination before its establishment [ 47 – 48 ]. Various uses are allowed in the multiple-use zone of the PPMR where Ponta do Ouro is located. These include snorkelling, surfing, swimming with dolphins, recreational (sport) fishing, and scuba diving on sandstone reefs and outcrops largely populated by soft coral [ 49 ]. The establishment of the PPMR has allowed the regulation of scuba diving activities, which were previously threatening the underwater ecosystems due to uncontrolled crowding of dive sites [ 50 ]. However, important construction threats and impacts from abusive fishing and littering persist to this day [ 35 , 45 , 51 ]. Research dating back to 2003 described the scuba diving population of Ponta do Ouro as dominated by male newcomers with approximately six years of scuba diving history and an average of 50 logged dives [ 50 ].

Research design and data collection

The research followed a quantitative, descriptive and non-experimental design, with a structured questionnaire survey being the instrument of data collection [ S3 Table ]. In this study, scuba diving experience was defined by two sets of variables, namely accumulated diving experience and familiarity with diving at the study areas. Divers’ perceptions were defined by three sets of variables, namely divers’ self-assessment, satisfaction with the diving at the study areas, and perceptions of scuba diving impacts on the environment.

The first section in the questionnaire included questions on demography (gender, age, education, country of residence, marital status and occupation), accumulated diving experience and familiarity with the study areas, and asked the divers whether they engaged in underwater photography at the destination (by means of a Yes/No question).

Accumulated diving experience was defined by four variables. The first variable was the total number of scuba diving certifications held (whatever the certifying agency) under the following categories: basic (from the equivalent of PADI Open Water Diver to that of PADI Rescue), professional (from the equivalent of PADI Divemaster to Instructor, all levels), specialties (such as Enriched Air Diver, Deep Diver, Wreck Diver and Dry Suit Diver), technical (such as Advanced Nitrox, Trimix, Cave and Deco), and dry (such as Oxygen Provider and Gas Blender). The second variable was the total number of years diving. The third variable was the total number of dives logged. The fourth variable was the average number of dives logged annually. Familiarity with the study areas was expressed as the total number of dives logged at the study areas, and the average number of dives logged at the study areas annually.

The second section in the questionnaire asked scuba divers to assess themselves by using a five-point Likert scale of agreement with a number of statements (where 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree). Statements included aspects of knowledge (e.g., I know all the local diving regulations ), environmental attitudes (e.g., I would like to be involved in local marine conservation ) and behaviour (e.g., I keep a good distance from the bottom habitats when I dive ), particularly in the context of the study areas. Previous research demonstrated that self-reported behaviour of divers can be used as a valuable substitute for observed behaviour [ 9 , 52 – 53 ]. Therefore, self-reported behaviour was seen as an indication of actual diver behaviour.

The third section in the questionnaire included a set of three-point Likert scale questions on satisfaction (where 1 = unsatisfied and 3 = satisfied) with the diving sites at the study areas, particularly with reference to environmental (e.g., underwater cleanliness and visibility, general health of the dive sites, variety of species) and management aspects (e.g., crowding of dive sites, pre-dive briefing, litter).

The fourth and last section invited the divers to rate the potential ecological damage caused by diving-related actions by using a four-point Likert scale (where 1 = no damage and 4 = heavy damage). Some of these actions included anchoring, underwater photography, intentional and unintentional contact with mobile and sessile wildlife, diving after drinking alcohol, and a poor pre-dive briefing.

The population under investigation were the scuba divers visiting the study areas. Data were collected during the summer months of 2015 and 2016. This period corresponds to peak diving at the study areas [ 35 ]. Using the recorded number of dives logged at the study areas annually (approximately 50,000 in Portofino and 30,000 in Ponta do Ouro) and assuming that a single diver would log at least three dives per year at each study area [ 10 ], the population was established as approximately 17,000 divers in Portofino and 10,000 in Ponta do Ouro.

Of these populations, a sample of 370 scuba divers would yield a confidence level of 95% and a margin of error of 5% [ 54 ]. Thus, a total of 400 questionnaires were printed for each study area. All 400 questionnaires were distributed in Portofino, of which 279 were completed and returned, yielding a participation of 70%. In Ponta do Ouro, only 300 questionnaires were distributed due to the poor turnover of divers during the time of sampling. A total of 220 questionnaires were completed and returned, yielding a participation of 73%. The number of questionnaires that had successfully been completed guaranteed an acceptable sample size at both study areas (a 95% confidence level and 6% margin of error).

Sampling was done every second day for a total of 30 days per study area. The fieldworkers collected data at most dive centres that operated at each study area. On each sampling day, two fieldworkers visited either one or two dive centres and haphazardly invited scuba divers returning from a dive to participate in the questionnaire survey, which took ten minutes to complete. Divers were invited to remain at the dive centre while completing the questionnaire; this ensured that questionnaires were completed and returned to the fieldworkers in time.

Data analysis

The demographic and experience profiles of the scuba divers were determined through descriptive statistics, frequency tables and breakdown statistics to compare variables across study areas in a descriptive manner. Binomial logistic regressions were used to test whether associations existed between accumulated scuba diving experience and the use of underwater cameras, which is normally associated with specialised scuba diving as well as negative ecological impacts to bottom habitats [ 5 , 8 ].

Following normality (chi-squared) tests, either a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or a Mann-Whitney U test was performed to highlight significant differences in divers’ demography and experience between study areas. The magnitude of the differences between study areas was determined by calculating practical effect size (Cohen’s d ) [ 55 ]. Cohen suggested that d = 0.2 represents a low, d = 0.5 a medium and d = 0.8 a large effect size.

Two exploratory analyses were performed on divers’ perceptions (self-assessment, satisfaction with diving at the study areas, and perceptions of scuba diving impacts). The first one is the exploratory factor analysis (EFA), employed to reduce the size of a dataset by identifying relationships between questionnaire items and extracting latent factors (determined by eigen values and factor loadings as cut-off criteria, and then calculated as factor scores) underlying the items [ 56 ]. The second one is the reliability test, which checks for internal consistency (Cronbach’s α value) of the factors extracted through EFA [ 57 ]. The means of factor scores between study areas were compared through a general linear model (analysis of covariance [ANCOVA]) in which all the significantly different demographic and experience variables between study areas were included as co-variates. The magnitude of the differences between the study areas was determined by calculating the practical effect size (Cohen’s d ). Correlational relationships between variables of accumulated diving experience, familiarity with the study areas, and factor scores were investigated using the nonparametric Spearman’s rank-order correlations ( r s ). All above analyses were performed using the Statsoft Statistica software, Version 13.2 (2016).

The influence of divers’ scuba diving experience (accumulated diving experience and familiarity with the study areas) on their perceptions was determined using a canonical correspondence analysis (CCA), a constrained ordination method using correspondence analysis [ 58 ]. This multivariate technique was developed in ecology to investigate the abundance of species in relation to environmental variables; however, it is also deployed in other domains such as the social and economic sciences [ 59 ]. The main result of CCA is the ordination of the principal dimensions of the dependent variables (points) in a bi-dimensional space, determined by two axes and constrained by the explanatory variables (vectors). Two CCAs were performed, one testing the influence of accumulated diving experience and the other the influence of familiarity with the study areas. The CCAs were performed with the PAST statistical software, Version 2.17 [ 60 ], following the eigenanalysis algorithm of Legendre and Legendre [ 61 ].

Profile of the scuba divers

The variables of demography and the participants’ scuba diving experience, as well as the statistically significant differences in these variables between study areas, are displayed in Table 1 . The proportion of male participants in Portofino was greater (79%), whereas Ponta do Ouro had a similar ratio of males to females (55% to 45%). The divers were either in their late 30s (Ponta do Ouro) or in their early 40s (Portofino), with a moderate (Ponta do Ouro) to high (Portofino) level of education. Divers were primarily Italian in Portofino (82%) and South African in Ponta do Ouro (69%). Other markets were mostly European for both study areas. Most divers were either single or married and had paid employment, regardless of the study area.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0219306.t001

The participants varied from novice to professional divers ( Table 1 ). Participants in Portofino held a mean of seven scuba diving certifications, while divers in Ponta do Ouro possessed a mean of over four scuba diving certifications. The divers tended to be certified with PADI (57% in Ponta do Ouro and 43% in Portofino), although as many as 28 other agencies were mentioned by divers in Portofino and eight in Ponta do Ouro. The participants had been diving for a period of one to 49 years, with a mean of 12 years in Portofino and 10 years in Ponta do Ouro ( Table 1 ). They had logged between a single dive and 5,000 dives, with a mean of around 380 for Portofino and 335 for Ponta do Ouro. They logged between one and 500 dives annually, with a mean of 41 for Portofino and 37 for Ponta do Ouro ( Table 1 ).

The familiarity of the participants with the study areas ranged from none (a single dive at the study areas and no annual visits) to very good (thousands of dives logged at the study areas with hundreds of dives logged there annually); it is thus evident that some of the participants had done the majority of their diving at the study areas ( Table 1 ). However, the mean number of dives logged in Portofino was more than twice the number in Ponta do Ouro, and the mean number of dives logged annually in Portofino was nine times greater than in Ponta do Ouro ( Table 1 ).

Less than half (43%) of the participants in Portofino and half of those in Ponta do Ouro declared that they used underwater cameras while scuba diving. Results from a binomial logistic regression show that two experience variables, namely the number of scuba diving certifications held and the number of dives logged, had a significant positive association with underwater photography (Wald test statistics number SDC = 11.92, p < 0.001; number dives logged = 8.82, p = 0.03).

Divers’ perceptions

Descriptive statistics for items used in scaled data are included in S4 Table . The exploratory factor analyses (EFA) performed on divers’ perceptions (self-assessment, satisfaction with diving at the study areas, and perceptions of scuba diving impacts) yielded a total of eight factors ( Table 2 ). Items characterising each factor (also listed in Table 2 ) had loadings exceeding the cut-off value of 0.40 [ 56 ]. All factors were reliable, with Cronbach’s α values above the threshold of 0.60 [ 57 ]. The self-assessment of divers was characterised by an assessment of personal knowledge of local conservation , personal underwater skills and behaviour , and attitudes towards conservation . Satisfaction with diving at the study areas was divided into two factors, namely satisfaction with the ecosystem health of the dive sites and with the local management . Perceptions of scuba diving impacts were divided into perceptions of the damage caused by direct impacts , contingent impacts , and irresponsible actions .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0219306.t002

Scuba divers at both study areas were confident in their own underwater skills and behaviour and tended to have positive attitudes towards conservation ( Table 2 ). Divers in Portofino believed that they possessed good knowledge of local conservation initiatives, whereas those in Ponta do Ouro believed to possess average knowledge ( Table 2 ). Scuba divers were neutral to satisfied with diving at the study areas, although satisfaction with local management was slightly higher in Portofino than in Ponta do Ouro, where litter management received a relatively low score compared with other items ( Table 2 ).

Divers at both study areas believed that contingent impacts by divers were small and caused minimal damage to underwater ecosystems, whereas direct impacts and irresponsible actions caused moderate damage ( Table 2 ). Divers in Portofino saw the damage of direct impacts as significantly greater compared with divers in Ponta do Ouro, where items including walking on sand before or during a dive, touching mobile wildlife accidentally, and collecting shells received low scores for damage ( Table 2 ).

Influence of scuba diving experience on divers’ perceptions

The results of the canonical correspondence analysis (CCA), assessing the influence of accumulated diving experience on divers’ perceptions for both study areas, are displayed in Fig 2 . Variables describing accumulated diving experience were positively correlated ( Table 3 ). Axis 1 and Axis 2 in the ordination biplot ( Fig 2 ) accounted for nearly all the variance in the data; thus, the variation in perceptions was well predicted by accumulated diving experience.

The “+” symbol next to a factor represents a positive influence, whereas the “˗” symbol represents a negative influence.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0219306.g002

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0219306.t003

Whereas permutation tests only yielded a significant effect of Axis 1 for Portofino, the CCA ordination tended to be similar between study areas, with some exceptions. The projection of points (perceptions) on the vectors (scuba diving experience) shows that experienced scuba divers possessed a more positive image of their underwater skills and behaviour, had more positive attitudes towards conservation, and claimed to be more knowledgeable of local conservation programmes–the latter was the case for Portofino, but not Ponta do Ouro ( Fig 2 ). Regardless of study area, more experienced divers were less satisfied with the ecosystem’s health and management of the dive sites, and were also less critical of the negative impacts of scuba diving, whether direct, contingent, or caused by irresponsible actions ( Fig 2 ).

Fig 3 shows the results of the CCA determining the influence of familiarity with the study areas on divers’ perceptions. The variables describing familiarity were positively correlated ( Table 3 ). The axes of the ordination biplot accounted for all the variation in the data. In this case, permutation tests yielded significant effects of Axis 1 for Portofino, and of both axes for Ponta do Ouro, where the CCA ordination tended to separate the total number of dives logged from annual diving frequency ( Fig 3 ). The projections of points on vectors show that, similarly to scuba diving experience, familiarity with the study areas had a positive influence on scuba divers’ self-assessment, a negative influence on satisfaction with diving at the study areas, and a decrease in the level of damage ascribed to scuba diving impacts. However, annual diving frequency in Ponta do Ouro increased satisfaction with the ecosystem health of the dive sites, as opposed to Portofino ( Fig 3 ).

The “+” symbol next to a factor represents a positive influence, whereas the “−” symbol represents a negative influence.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0219306.g003

The scuba divers were mostly male, middle aged and well-educated people, and skewed towards high experience and loyalty to the study areas. This profile partly reflects that of divers described in similar research carried out at both tropical [ 18 , 21 , 25 , 28 , 52 , 62 – 66 ] and non-tropical diving destinations [ 10 , 12 – 13 , 16 , 20 , 22 , 29 – 30 , 53 , 67 – 70 ], making it possible to generalise some of the implications of this study to different diving destinations.

The structure of the sample is still notably comparable between the study areas, and also longitudinally to the characteristics of the diving population of each study area according to previous literature. Divers in Portofino were more experienced than those in Ponta do Ouro. The two destinations are seemingly going through different phases in their destination lifecycles [ 71 ], with Portofino having a longer history as a scuba diving destination and a protected area than Ponta do Ouro. Comparisons with data from 13 years ago confirm that scuba divers in Portofino possess a slightly higher average level of scuba diving experience currently, and show the same degree of loyalty to the destination [ 42 ]. The scuba divers in Ponta do Ouro have become more specialised compared with data from 15 years ago [ 50 ]. Ponta do Ouro remains positioned relatively early in its lifecycle as a tourism destination [ 71 ].

The influence of diving experience on divers’ perceptions

Diving experience affected the divers’ self-assessment positively. This finding aligns with literature demonstrating how diver specialisation is characterised by the improvement of skills and self-confidence, and by positive attitudes towards conservation [ 11 – 12 , 21 , 53 ].

As divers gained experience, they became less satisfied with the health of the dive sites’ ecosystem and with overall management [ 15 , 26 , 29 , 67 ]. In particular, satisfaction among divers in Ponta do Ouro was lower than the level reported 15 years ago [ 50 ], possibly due to the specialisation of divers in this area over time, as well as actual environmental degradation.

Experienced divers tended to view the impacts of scuba diving activities less critically than novice divers. Experienced scuba divers may become more aware of negative environmental effects of human and natural impacts other than diving [ 27 ]. They may increasingly trust their ability to self-regulate through their skills [ 12 , 15 , 19 ]. They may also deem certain harmful behaviours acceptable because they were customary in the past [ 13 ], and they possibly fear that acknowledging the potential negative impacts of diving on the environment could lead to further regulation of the activity itself.

Scuba diving experience exerted similar influences on divers, regardless of the study area. However, remarkable differences also emerged between the study areas. In Ponta do Ouro, knowledge of local conservation was not high and was only influenced by familiarity with the study area. The PPMR is a vast marine reserve ( Fig 1 ) that was recently established and is managed through multiple efforts. Becoming acquainted with its management and conservation programmes may be challenging for tourists, in contrast to other well-established tourism destinations with a limited geographical scope ( Fig 1 ) and less complex governance structures, for example Portofino.

Divers in Ponta do Ouro tended to appreciate the ecosystem health of the dive sites as they became more familiar with them. In contrast to Portofino, where the diving sites are delimited by fixed mooring buoys and they have relatively similar habitats (boulders, stones and vertical walls), Ponta do Ouro offers a broader variety of diving experiences, from shallow reef diving to deeper shark diving, with new dive sites being discovered over time [ 49 ]. The dive sites here are distributed over a wider area compared with Portofino, and the majority of the diving for first timers tends to happen on the closer, more popular and more crowded (and possibly less healthy) reefs. As a result, divers would need to visit more dive sites in order to become familiar with the quality of the reefs in Ponta do Ouro.

Regardless of experience, divers in Portofino tended to be more satisfied with management than those in Ponta do Ouro. This difference appears to be based on a single item, namely the presence of litter, which is a crucial issue in Ponta do Ouro [ 45 ] and has been known to detract from divers’ satisfaction [ 50 ].

Finally, divers in Ponta do Ouro underestimated the damage of direct impacts from scuba diving activities compared to Portofino divers. Specifically, the effects of walking on the sandy bottom, touching mobile wildlife accidentally, and collecting shells, pieces of coral et cetera were underestimated. Dive sites in Ponta do Ouro are reef patches surrounded by sand, and divers often adjust their buoyancy on sand before proceeding towards the reef. They are also encouraged to follow this practice during the pre-dive briefing (S. Lucrezi, pers. obs.). Interactions with mobile wildlife are very common in Ponta do Ouro, and while intentional contact with these species is highly discouraged, accidental contact is still likely to take place (E. Ferretti, pers. comm.). The bottom habitats in Ponta do Ouro have an abundance of loose coral pieces, shells and shark teeth, which are also washed on the beach by the ocean waves. The collection of this material is prohibited in Ponta do Ouro. However, many kiosks in the village sell shells and dead wildlife. This contrast is likely to create confusion among divers, who do not appear to be warned about the no-take policy in the marine reserve during the pre-dive briefing (S. Lucrezi, pers. obs.).

Management implications of diving experience

The results of this study highlight both positive and contradictory elements related to diving experience and its influences, with implications about the persistence, but also the proper management, of a specialised diving market at a destination.

Enhancing the persistence of a specialised diving market.

The ideal scenario for diving destinations would be to have a broad spectrum of markets, from generalists to specialists, to ensure the sustainable growth of diving tourism at the destination. Specialist divers constitute an important market, as they tend to be high-yielding, experienced, responsible, committed and proactive when it comes to conservation. Their persistence at a given destination can be ensured in three ways:

The first way involves maximising the value of the destination over the number of tourists to prevent the negative consequences of mass tourism, which is a deterrent to specialised divers. This may happen through a mixture of special marketing efforts (advertising diving tourism more than other forms of mass tourism, like beach and party tourism) and management of the tourism flow (e.g. through entry fees and traffic control) at the destination. The second way involves creating an attractive offer to a specialised market. Examples include the promotion of participatory research programmes such as monitoring and mapping and the zoning of dive destinations based on specialisation levels. The third way involves carefully planning and controlling the development of generalists in the market into specialists. This needs to happen through education, training, regulations and interpretation. Diving operators should provide high-quality ecological or research experiences to encourage diver specialisation. Generalists should also be educated on the characteristics and importance of healthy underwater ecosystems in order to avoid becoming affected by a “shifted baseline syndrome” [ 71 ].

Enhancing the management of a specialised diving market.

The persistence of a specialised diving market also implies that this market needs to be properly managed. The divers in this study were confident in their skills and responsible behaviour, although experience influenced perceptions of the damage of diving activities negatively. There is a direct link between acknowledging the potential ecological harm of diving activities and responsible diving behaviour [ 9 , 16 ], and experience and self-confidence will not necessarily translate into pro-environmental behaviour [ 21 , 53 , 72 ]. Thus, the underestimation of diving impacts by experienced divers in this study can raise concern for management. Underwater photography can become a strong negative mediator in the influence of diving experience on diver behaviour [ 5 , 8 ]. As a result, researchers have recently proposed the introduction of courses that enable scuba divers to meet low-impact standards in underwater photography [ 5 , 66 ]. The results of this study support this proposition.

Other forms of management aimed at specialised divers would involve improving this market’s trust in governance. This can be achieved by voicing the concerns (especially those related to environmental degradation) of specialised divers; educating older and occasional divers on previously accepted behaviours that have become either regulated or prohibited; enhancement of personal responsibility and trust in external control by using positive messages (e.g., on the conservation benefits of regulation); and opening as well as mediating a dialogue with conflicting stakeholder groups such as fishermen.

Implications of generalisations on diving experience

The findings of this study make it possible to formulate generalisations regarding the effects of diving experience, and to use them to manage diving activities and destinations. However, any generalisation needs to be based on an appropriate definition and measurement of scuba diving experience [ 10 ]. Furthermore, the context-specific nature of diving industries at different locations makes the use of generalisations on diving experience a delicate and, perhaps, controversial issue if the proper precautions are not taken.

Firstly, different dive locations can have very different markets and be characterised by divers with different demographic backgrounds and levels of specialisation. The use of generalisations on diving experience to justify social and environmental management actions at a destination would have to be based on data drawn from locations with comparable market structures. Secondly, diving locations are likely to follow a lifecycle as tourism destinations. Generalisations which may previously have been used for management purposes could become inapplicable after a period of time, and the monitoring of the destination’s lifecycle would become essential to assess whether new actions are needed. Thirdly, divers with similar levels of experience but who have been certified in different locations may have different impacts and views; such differences would make it impractical and risky to apply generalisations on diving experience to management decisions. Fourthly, this study compared two protected areas in which diving and other activities are regulated and controlled. This could have affected the influence of experience on divers’ perceptions and behaviour. The application of generalisations on diving experience to unprotected areas may be inappropriate when based on information drawn from studies in protected areas. Finally, the application of generalisations on diving experience for management purposes may be useless at destinations that are already naturally zoned according to market specialisation. These destinations would probably require ad hoc management actions for each zone.

Conclusions

This study highlighted the relevance of using recreational scuba diving experience as a tool to segment scuba divers, understand their attitudes, perceptions and behaviour, and manage diving destinations accordingly. The study makes a contribution to the dearth of research assessing the potential reliability of scuba diving experience as a constant in predicting scuba diver behaviour. However, it also acknowledges the limitations resulting from making generalisations on scuba diving experience and its influence. Scuba divers represent an opportunity for the development of sustainable tourism-based livelihoods in a number of countries. It is important to ensure that research endeavours are focused on assisting the proper growth of this market, particularly the training phase, and that the findings of new research are shared with certifying agencies and governance bodies for the purpose of improving the education and management of diving activities.

Supporting information

S1 table. variables measured to categorise scuba divers according to experience (also as part of specialisation) and familiarity with a study area, based on examples in the literature..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0219306.s001

S2 Table. Summary of the relevant literature about the influence of accumulated scuba diving experience on the following: Diving behaviour and personal responsibility; satisfaction and environmental perceptions; and attitudes towards conservation.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0219306.s002

S3 Table. Questionnaire survey.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0219306.s003

S4 Table. Descriptive statistics for items used in scaled data.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0219306.s004

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- PubMed/NCBI

- 6. Garrod B. Market segments and tourist typologies for diving tourism. In: Garrod B, Gössling S, editors. New frontiers in marine tourism: diving experiences, sustainability, management. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2008. pp. 31–48.

- 13. Todd SL, Cooper T, Graefe AR. Scuba diving & underwater cultural resources: differences in environmental beliefs, ascriptions of responsibility, and management preferences based on level of development. In: Kyle G, editor. Proceedings of the 2000 Northeastern recreation research symposium. Newtown Square, PA: United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service; 2001. pp. 131–140.

- 20. Todd SL, Graefe AR, Mann W. Differences in SCUBA diver motivations based on level of development. In: Todd S, editor. Proceedings of the 2001 Northeastern recreation research symposium. Newtown Square, PA: United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service; 2002. pp. 107–114.

- 32. Jones N, Dobson J, Jones E. Fanatic scuba divers do it in the cold? Establishing the need to examine the attitudes and motivations of scuba divers in South Wales (UK). In: Albers A, Myles PB, editors. Proceedings of the 6th international congress on coastal and marine tourism. Nelson Mandela Bay, South Africa: Kyle Business Projects; 2009. pp. 301–305.

- 33. Todd SL. Only ‘real divers’ use New York’s Great Lakes. In: Murray JJ, editor. Proceedings of the 2003 Northeastern recreation research symposium. Newtown Square, PA: United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service; 2003. pp. 211–218.

- 38. Pedemonte S. Area marina di Portofino, è record di immersioni. 2017. [cited 07 September 2018]. In: Il Secolo XIX, Levante [Internet]. http://www.ilsecoloxix.it/p/levante/2017/04/07/ASpw0VtG-immersioni_marina_portofino.shtml .

- 42. Bava S, Cappanera V, Cattaneo-Vietti R, Fava M, Povero P. Valutazione dell’impatto antropico sul sistema costiero, con particolare riferimento alla pressione antropica all’interno dell’Area Marina Protetta del Promontorio di Portofino. Genova: DIP.TE.RIS.—Unità Locale di Ricerca CoNISMa Università degli Studi di Genova. 2006.

- 46. Gonçalves PMB. Communication N/ref: 0019/RMPPO/2015, 11 May 2015. República de Moçambique: Ministério do Turismo, Administraçao Nacional das Áreas de Conservação, Reserva Marinha Parcial da Ponta Do Ouro. 2015.

- 47. Abrantes KGS, Pereira MAM. Boas Vindas 2001/2001: a survey on tourists and tourism in Southern Mozambique. Maputo: Endangered Wildlife Trust. 2003.

- 48. Bjerner M, Johansson J. Economic and environmental impacts of nature-based tourism. A case study in Ponta d’Ouro, Mozambique. Göteborg: School of Economics and Commercial Law, Göteborg University. 2001.

- 50. Pereira MAM. Recreational SCUBA diving and reef conservation in southern Mozambique. M.Sc. Thesis, University of Natal. 2003.

- 54. Rea LM, Parker RA. Designing and conducting survey research: a comprehensive guide. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley and Sons; 2014.

- 55. Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for behavioural sciences. 2nd ed. Erlbaum, Hillsdale: Routledge; 1988.

- 56. Stevens JP. Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences. 5th ed. New York: Routledge, Taylor and Francis; 2012.

- 57. Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH. Psychometric theory. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1994.

- 59. Greenacre M. Canonical correspondence analysis in social science research. In: Locarek-Junge H, Weihs C, editors. Classification as a tool for research. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 2010. pp. 279–286.

- 61. Legendre P, Legendre L. Numerical Ecology. 2nd ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1998.

You are using an outdated browser. Upgrade your browser today or install Google Chrome Frame to better experience this site.

- Section 5 - Rubella

- Section 5 - Smallpox & Other Orthopoxvirus-Associated Infections

Rubeola / Measles

Cdc yellow book 2024.

Author(s): Paul Gastañaduy, James Goodson

Infectious Agent

Transmission, epidemiology, clinical presentation.

INFECTIOUS AGENT: Measles virus

TRAVELER CATEGORIES AT GREATEST RISK FOR EXPOSURE & INFECTION

PREVENTION METHODS

Rubeola is a vaccine-preventable disease

DIAGNOSTIC SUPPORT

Measles virus is a member of the genus Morbillivirus of the family Paramyxoviridae .

Measles is transmitted from person to person via respiratory droplets and by the airborne route as aerosolized droplet nuclei. Infected people are usually contagious from 4 days before until 4 days after rash onset. Measles is among the most contagious viral diseases known; secondary attack rates are ≥90% among susceptible household and institutional contacts. Humans are the only natural host for sustaining measles virus transmission, which makes global eradication of measles feasible.

Measles was declared eliminated (defined as the absence of endemic measles virus transmission in a defined geographic area for ≥12 months in the presence of a well-performing surveillance system) from the United States in 2000. Measles virus continues to be imported into the country from other parts of the world, however, and recent prolonged outbreaks in the United States resulting from measles virus importations highlight the challenges faced in maintaining measles elimination.

Given the large global measles burden and high communicability of the disease, travelers could be exposed to the virus in any country they visit where measles remains endemic or where large outbreaks are occurring. Most measles cases imported into the United States occur in unvaccinated US residents who become infected while traveling abroad, often to the World Health Organization (WHO)–defined Western Pacific and European regions. These travelers become symptomatic after returning to the United States and sometimes infect others in their communities, causing outbreaks.

Nearly 90% of imported measles cases are considered preventable by vaccination (i.e., the travelers lacked recommended age- and travel-appropriate vaccination). Furthermore, observational studies in travel clinics in the United States have shown that 59% of pediatric and 53% of adult travelers eligible for measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine at the time of pretravel consultation were not vaccinated at the visit, highlighting a missed opportunity to reduce the likelihood of measles introductions and subsequent spread. Encourage all eligible travelers to receive appropriate MMR vaccination. Outbreak investigations are costly and resource intensive, and infected people—in addition to productivity losses—can incur direct costs for the management of their illness, including treatment, quarantine, and caregiving.

The incubation period averages 11–12 days from exposure to onset of prodrome; rash usually appears ≈14 days after exposure. Symptoms include fever, with temperature ≤105°F (≤40.6°C); conjunctivitis; coryza (runny nose); cough; and small spots with white or bluish-white centers on an erythematous base appearing on the buccal mucosa (Koplik spots). A characteristic red, blotchy (maculopapular) rash appears 3–7 days after onset of prodromal symptoms. The rash begins on the face, becomes generalized, and lasts 4–7 days.

Common measles complications include diarrhea (8%), middle ear infection (7%–9%), and pneumonia (1%–6%). Encephalitis, which can result in permanent brain damage, occurs in ≈1 per 1,000–2,000 cases of measles. The risk for serious complications or death is highest for children aged ≤5 years, adults aged ≥20 years, and in populations with poor nutritional status or that lack access to health care.

Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) is a progressive neurologic disorder caused by measles virus that usually presents 5–10 years after recovery from the initial primary measles virus infection. SSPE manifests as mental and motor deterioration, which can progress to coma and death. SSPE occurs in ≈1 of every 5,000 reported measles cases; rates are higher among children <5 years of age.

Measles is a nationally notifiable disease. Laboratory criteria for diagnosis include a positive serologic test for measles-specific IgM, IgG seroconversion, or a significant rise in measles IgG level by any standard serologic assay; isolation of measles virus; or detection of measles virus RNA by reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) testing. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Measles Virus Laboratory is the national reference laboratory; it provides serologic and molecular testing for measles and technical assistance to state public health laboratories for the collection and shipment of clinical samples for molecular diagnostics and genetic analysis. See detailed information on diagnostic support .

A clinical case of measles illness is characterized by generalized maculopapular rash lasting ≥3 days; temperature ≥101°F (38.3°C); and cough, coryza, or conjunctivitis. A confirmed case is one with an acute febrile rash illness with laboratory confirmation or direct epidemiologic linkage to a laboratory-confirmed case. In a laboratory-confirmed or epidemiologically linked case, the patient’s temperature does not need to reach ≥101°F (38.3°C) and the rash does not need to last ≥3 days.

Treatment is supportive. The WHO recommends vitamin A for all children with acute measles, regardless of their country of residence, to reduce the risk for complications. Administer vitamin A as follows: for infants <6 months old, give 50,000 IU, once a day for 2 days; for infants 6 months old and older, but younger than 12 months, give 100,000 IU once a day for 2 days; for children ≥12 months old give 200,000 IU once a day for 2 days. For children with clinical signs and symptoms of vitamin A deficiency, administer an additional (i.e., a third) age-specific dose of vitamin A 2–4 weeks following the first round of dosing.

Measles has been preventable through vaccination since a vaccine was licensed in 1963. People who do not have evidence of measles immunity should be considered at risk for measles, particularly during international travel. Acceptable presumptive evidence of immunity to measles includes birth before 1957; laboratory confirmation of disease; laboratory evidence of immunity; or written documentation of age-appropriate vaccination with a licensed, live attenuated measles-containing vaccine 1 , namely, MMR or measles-mumps-rubella-varicella (MMRV). For infants 6 months old and older, but younger than 12 months, this includes documented administration of 1 dose of MMR; for people aged ≥12 months, documentation should include 2 doses of MMR or MMRV (the first dose administered at age ≥12 months and the second dose administered no earlier than 28 days after the first dose). Verbal or self-reported history of vaccination is not considered valid presumptive evidence of immunity.

1 From 1963–1967, a formalin-inactivated measles vaccine was available in the United States and was administered to ≈600,000–900,000 people. It was discontinued when it became apparent that the immunity it produced was short-lived. Consider people who received this vaccine unvaccinated.

Vaccination

Measles vaccine contains live, attenuated measles virus, which in the United States is available only in combination formulations (e.g., MMR and MMRV vaccines). MMRV vaccine is licensed for children aged 12 months–12 years and can be used in place of MMR vaccine if vaccination for measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella is needed.

International travelers, including people traveling to high-income countries, who do not have presumptive evidence of measles immunity and who have no contraindications to MMR or MMRV, should receive MMR or MMRV before travel per the following schedule.