Crisis in our national parks: how tourists are loving nature to death

As thrill seekers and Instagrammers swarm public lands, reporting from eight sites across America shows the scale of the threat

J ust before sunset near Page, Arizona, a parade of humanity marched up the sandy, half-mile trail toward Horseshoe Bend. They had come from all over the world. Some carried boxes of McDonald’s Chicken McNuggets, others cradled chihuahuas and a few men hid engagement rings in their pockets. But just about everyone had one thing at the ready: a cellphone to snap a picture.

Horseshoe Bend is one of the American west’s most celebrated overlooks. From a sheer sandstone precipice just a few miles outside Grand Canyon national park, visitors get a bird’s-eye view of the emerald Colorado river as it makes a U-turn 800ft below. Hundreds of miles from any large city, and nestled in the heart of south-west canyon country, Horseshoe Bend was once as lonely as it was beautiful.

“It was just a local place for family outings,” recalls Bill Diak, 73, who has lived in Page for 38 years and served three terms as its mayor. “But with the invention of the cellphone, things changed overnight.”

Horseshoe Bend is what happens when a patch of public land becomes #instagramfamous. Over the past decade photos have spread like wildfire on social media, catching the 7,000 residents of Page and local land managers off guard.

According to Diak, visitation grew from a few thousand annual visitors historically to 100,000 in 2010 – the year Instagram was launched. By 2015, an estimated 750,000 people made the pilgrimage. This year visitation is expected to reach 2 million.

Numbers used to peak in the summer but tourists now stream in all year round – nearly 5,000 a day. And fame has come with a dark side. In May 2018, a Phoenix man fell to his death when he slipped off the cliff edge. In 2010, a Greek tourist died when a rock underneath him gave way, police said, as he took photos. Like the recent death of a couple taking photographs in Yosemite , the incidents have raised troubling questions about what happens when nature goes viral.

“Social media is the number one driver,” said Maschelle Zia, who manages Horseshoe Bend for the Glen Canyon national recreation area. “People don’t come here for solitude. They are looking for the iconic photo.”

‘Our species is having the greatest impact’

Across America, national parks and public lands are facing a crisis of popularity. Technology, successful marketing, and international tourism have brought a surge in visitation unlike anything seen before. In 2016 and 2017, the national parks saw an unprecedented 330.9 million visitors, the highest ever recorded . That’s not far off the US population itself.

Backcountry trails are clogging up, mountain roads are thickening with traffic, picturesque vistas are morphing into selfie-taking scrums. And in the process, what is most loved about them risks being lost.

“The least-studied mammal in Yellowstone is the most abundant: humans,” says Dan Wenk, the former superintendent of one the most chronically overcrowded parks in the system. In Yellowstone, America’s oldest national park, visitation has surged 40% since 2008, topping 4 million in 2017.

After 43 years in the park service, Wenk is worried. “Our own species is having the greatest impact on the park and the quality of the experience is becoming a casualty.”

Over a period of four months, from high summer to late autumn, the Guardian dispatched writers across the American west to examine how overcrowding is playing out at ground level. We found a brewing crisis: two mile-long “bison jams” in Yellowstone, fist-fights in parking lots at Glacier, a small Colorado town overrun by millions of visitors.

Moreover, we found people wrestling with an existential question: what should a national park be in the modern age? Can parks embrace an unlimited number of visitors while retaining what made them, as the writer Wallace Stegner once put it, “ the best idea we ever had ”?

People, people everywhere

In 1872, Yellowstone became the first national park in the world. In 1904, the first year for which visitation figures are available, 120,690 people visited the national parks, which by then included Mt Rainier, Sequoia and Yosemite. By the mid-century that number swelled to tens of millions, as more parks were added to the system and destination road trips became synonymous with American vacations.

But today the pace of visitation has outstripped resources. Much of the National Park Service’s infrastructure dates back to the Mission 66, a $1bn initiative undertaken in the 1950s and 60s, and wasn’t built with modern crowds in mind.

Environmental challenges are burgeoning – recent research has found national parks bear the disproportionate brunt of global warming – and years of wear and tear have seen park maintenance fall woefully behind. The current backlog of necessary upgrades to roads, trails and buildings stands at more than $11bn. Ryan Zinke’s attempt to sharply increase entry fees at the busiest parks to pay for repairs proved so unpopular it had to be walked back in April.

Traffic congestion has become one of the most visible consequences of overcrowding and underfunding, with some locations seeing tens of thousands of cars a day during peak months.

In Yosemite, despite a shuttle system, the park warns summer visitors to expect two- to three-hour delays entering Yosemite Valley. In Yellowstone, epic bottlenecks are frequent. Famed for its grizzly bears, gray wolves and bison herds, the park is arguably “wilder” than it was 50 years ago, thanks to conservation work. But this rewilding has meant animal sightings routinely cause gridlock along its two-lane roads.

On a recent August day in Hayden Valley, a “bison jam” stretched nearly two miles long. As the herd moved steadily across the road, a scene of frantic commotion began to unfold. Travelers excitedly scrambled from their vehicles. Bison passed within inches, even brushing up against the cars. Some tourists temporarily abandoned their vehicles in the hope of getting close enough for a photo.

Impatient motorists tooted their horns as park rangers tried to bring order. “My job is to manage people, not animals, and I try not to get upset,” said one in uniform. “Most visitors just don’t know how to behave in a wild place.”

But the bison weren’t the only drama. In the Lamar Valley, a pack of wolves just visible in the distance drew a swarm of vehicles into a turnout. People poured out, leaving their cars parked cattywampus, blocking traffic in both directions.

Sometimes travelers get more of a souvenir than they bargained for. This summer has seen a handful of visitors gored or kicked by bison and elk when they ventured too close. Meanwhile, a video of a man taunting a bison went viral, and citations have been issued to troublemakers who illegally flew drones and tossed rocks and debris into Yellowstone’s sensitive geothermal features, which risks destroying them forever.

Wenk admits rangers feel overwhelmed. “We’re exceeding the carrying capacity and because of it damage is being caused to park resources,” he says. There’s been a 90% increase in vehicle accidents, a 60% bump in calls for ambulance services and a 130% rise in searches and rescues, according to the park. And while visitation has swelled, staffing, because of budget limitations, has remained the same.

Traffic woes aren’t confined to park roads. At Glacier national park in Montana (annual visitation: 3.3 million), parking lots, too, have seen tense standoffs.

The Logan Pass Visitor Center dates back to the Mission 66 era. Perched at the top of Going-to-the-Sun Road, a precarious mountain artery which makes an appearance in the opening scene of The Shining, the center offers access to two of Glacier’s most popular trails – and just 231 parking spots.

“It’s a tough situation,” said Gary Cassier, a visitor from Kalispell, Montana, whose wife was still circling in their car, one of many seeking a spot. Looking out over the alpine meadows and near-vertical slopes, he observed: “Nobody wants to see a multilevel parking garage here.”

Sometimes the battle for a spot turns physical.

“We get fistfights in the parking lot,” says Emlon Stanton, a visitor service assistant. Some visitors even try to claim a spot for their groups on foot. “People get out of their vehicle, jump into a space and stand there,” explains Stanton. “Then somebody tries to pull in and bumps ’em.”

Stanton and other park workers try to prevent such episodes by imposing “soft closures” on the lot – placing traffic cones across its entrance and telling visitors to find parking at the next pullout, three miles away, and take a shuttle back. These closures can happen three to five times a day.

“From a staff perspective, it’s hard,” says park spokeswoman Lauren Alley. “‘Service’ is in our name, and to tell people, over and over, all day long, ‘We’re full, you’ll have to wait’… it’s a real challenge.”

A stinking problem

It’s late summer on the Yellowstone river , just north of Gardiner, Montana. A group of anglers stand around their boat trailer, sipping beers and rigging fly rods in the late-morning sun as they wait their turn to launch into the water.

This gravel boat ramp sees a lot of action. But not far off, something stinks. It’s something everybody uses, and something that’s been a headache for forest officials lately: a toilet.

Dealing with human waste has become a herculean undertaking for parks, one that is often hidden from view. In Zion, two outhouses near Angel’s Landing that were described by one writer as reminiscent of “an open sewer” have to be emptied by helicopter at a cost of $20,000 annually. In Colorado, Rocky Mountain national park churns through more than 1,800 miles of toilet paper a year . Yellowstone spent $28,000 on hand sanitizer last summer alone, according to a park official.

As waste mounts, finding someone to take care of it becomes more difficult. The Custer Gallatin national forest, which stretches from the town of West Yellowstone, Montana, to South Dakota, exemplifies this conundrum.

There are more than 200 vault toilets across the Custer Gallatin, small rooms with a single pot over a large septic tank. Signs on the doors remind users not to throw trash in them because it makes vault pumping extremely difficult.

In such remote places, the cost of servicing toilets has soared. In 2013, forest officials budgeted roughly $32,000 for toilet pumping across the Custer and Gallatin national forests (the two forests combined in 2014). So far in 2018, it has cost nearly $80,000. And that’s only the pumping in “priority locations”, explains Lauren Oswald, the recreation program manager for the Custer Gallatin.

Beyond the hefty price tag, the logistics of finding a private contractor to do the job have also become more fraught, especially as towns like Bozeman grow and construction sites hire away the possible candidates. The toilet at the boat ramp is serviced by a company based in Hardin, Montana – more than 200 miles away.

Nearby Yellowstone has waste worries, too. Bethany Gassman, a park spokeswoman, says park staff pumped 248,889 gallons from its 153 vault toilets and other septic systems in 2017, a 19% increase over 2016. Visitors also run through an average of 1,710 toilet paper rolls a day.

The problem of managing human waste extends to the backcountry – areas far from roads and development and accessible only by trails. Forest staff have seen an increase in improperly managed excrement – unburied poop – in popular wilderness areas and unofficial campsites. The problem, Oswald says, is that some people don’t seem to care how they leave the landscape once they’re done with it.

Forest staffers are often faced with the unenviable task of dealing with what slob campers leave behind. It’s the kind of work that sanitation workers are hired for in major cities, not what you’d expect among the wooded peaks and meadowed valleys of Montana.

“They pick up all garbage, whether it’s toilet paper or diapers or beer bottles,” Oswald says of the cleanup missions. “And generally if they come upon human waste, they try to deal with it by burying it at an appropriate depth.”

Nature through a screen

Once parks were the ultimate place to disconnect from the modern world. But today visitors have fresh expectations – and in accommodating these new demands, some say parks are unwittingly driving the very behavior that’s spoiling them.

On Yosemite’s expansive mountainsides, one redwood stands out among the rest. It’s a little bit taller, a little bit too uniform. A metallic shimmer glints in the sun from beneath its branches, colored green and brown to match its neighbors. But this camouflage masks its true role: coating the wilderness in wifi.

This tree is helping to usher in a new era in Yosemite. And it’s not alone . Grand Tetons, Mt Rainier, Yellowstone, and Zion are all being wired with internet and cell service as part of a plan to attract a new generation of park-goers. In Yosemite there are six towers already constructed, with plans under way for close to a dozen more.

The rapid modernization of Yosemite (annual visitation 4.3 million) is evident at Base Camp Eatery, one of the park’s newest food spots. Here, touch screens enable hungry hikers to order drinks and snacks and access instant information about park activities. There’s even a newly opened – and particularly controversial – branch of Starbucks .

“The ways people find out about – and visit – parks is changing,” Lena McDowall, the national park service deputy director, told the Senate subcommittee on national parks last year. Many see meeting the needs of millennials as critical to keeping parks politically relevant amid funding challenges and the uncertainty of climate change.

But the move may come at a cost. “Why come to a national park as opposed to Disneyland? Because you get to confront natural wonders,” says Jeff Ruch, the executive director of Peer, an environmental advocacy organization that has spent years opposing National Park Service plans for expanding cell tower construction. “But if you interpose electronic devices in our view, you miss that.”

Technological transformation is having unexpected consequences on the landscapes that surround national parks, too. In Utah, visitors are arriving in remarkable numbers to admire its photogenic landscapes – turning Zion, Bryce Canyon and Arches into some of the busiest in the country.

But the increasing squeeze has pushed many to seek thrills elsewhere. Take Kanarraville Falls, just an hour outside southern Zion. Here visitors traverse a narrow, twisting canyon carved through pink-purple sandstone along a series of makeshift ladders, finally arriving at a beautiful waterfall: a taste of Zion’s magical slot canyons but without the crowds. Or at least it used to be.

Social media has been blamed for ruining Kanarraville Falls , once a hidden gem but now featured in countless Instagram posts . Bottlenecks can back up for an hour or more at the ladders, rescue teams are dispatched regularly to retrieve injured hikers, and stream banks are eroding and littered with trash.

For the nearby town of Kanarraville (population 378), the situation has become untenable. Visitors, who routinely double the town’s population, are tramping through a watershed the town taps for drinking water. “The environment can’t handle that many people walking in and out of there,” says Tyler Allred, a town council member. “It needs a chance to recover.”

Kanarraville leaders are doing what they can: the town now charges a $9-per-head fee for hikers, thanks to an arrangement with the state and federal officials.

It’s an experiment that could be replicated elsewhere. But so far the fee hasn’t done much to slow daily traffic, according to Allred. Annual visitation last year was estimated at between 40,000 and 60,000. The next step may be to impose a daily limit on visitors.

The trouble for towns

Kanarraville is not the only town where tourism is taking a toll. Moab , outside Arches, has become a byword for congestion. In California, locals bemoan the Airbnb-ification of Joshua Tree – an artsy, isolated desert community now overrun by out-of-towners fond of drones and late-night parties .

In Estes Park, just outside the entrance to Rocky Mountain national park, the problems have become especially acute. It’s only 90 minutes from the fast-growing city of Denver, and urbanites flock here in droves for the alpine tundra and soaring, snow-capped mountains.

In the summer months, Estes balloons from its winter population of about 7,000 to a barely contained mass of as many as 3 million people who stream through downtown in search of themed T-shirts, Native American trinkets, and a brew pub libation.

For 82-year-old Paula Steige, the crush is almost unbearable. Traffic makes getting around downtown a logistical ordeal and solutions offered by the town – including free shuttle buses – offer only minor relief.

“Oftentimes it seems we are in crisis mode, just trying to figure out how to get around. It’s especially bad for people trying to get to and from the park,” Steige said. “And there just doesn’t seem to be a solution to all the overcrowding.”

Steige can’t join those longtime residents who escape to other locales during the summer because she owns and operates the Macdonald Book Shop, started by her grandparents in 1908. She also knows that, like other shop owners, she owes her livelihood to the nearby national park.

“The park is, of course, the reason the whole town thrives,” she said. “The park is the reason the town does well or it goes badly.”

Estes Park, too, has a famous link to The Shining: it’s home to the Stanley hotel, the remote establishment that inspired the horror classic. Stephen King spent a night here in 1974. The Stanley now pulls in nearly 400,000 annual visitors, from ghost hunters attending tours and seances to horror fans hoping to stay in King’s room. The overcrowding galled one recent Stanley visitor. “We went for a seance but so many tourists were crowding around, we couldn’t hear anything,” said the man, who was visiting from Minnesota.

Police activity in Estes Park is ticking up, too. Police say calls earlier this year jumped nearly 23% over the same period in 2017. The park has also seen a dramatic rise in drug citations and arrests, fueled mostly by a misunderstanding of Colorado’s drug laws, park rangers say. Pot is legal in Colorado and therefore the town of Estes Park, but not at the national park itself, which is on federal property and where the state’s pot laws don’t apply.

“We see a lot more flagrant violations of pot use as well as driving under the influence by people who don’t know or don’t care about the law,” says Kyle Patterson, a park spokeswoman. “I think all of that comes from the fact we are rapidly transforming into an urban park.”

Can anything be done?

While Wallace Stegner’s notion that parks are “America’s best idea” has become synonymous with the nation’s love for them, there’s a little more to his famous 1983 line. The Pulitzer prize winner went on to describe the parks as a mirror for America’s national character: “They reflect us at our best rather than our worst.”

Considering the problems besetting them, his sentiment now seems open to question.

Back in Yellowstone, resource experts say the park is racing headlong toward a reality some might considered sacrilege: limits on people. One top park service official, who did not want to be identified, said daily limits on traffic entering Yellowstone, which could be achieved through a reservation system, was long overdue.

On the foggy coast of northern California, one spot has already taken the plunge. Muir Woods – named for John Muir, a renowned conservationist and one of the earliest advocates for national parks – is home to ancient groves of towering redwoods. The forest is tiny by park standards – just 560 acres – yet more than a million come each year to experience its majestic calm.

Hundreds of parked cars once choked the narrow road leading toward the entrance, threatening the local watershed and wildlife, causing headaches for nearby residents, and creating dangerous situations for drivers and pedestrians walking on the roadside.

That’s why, at the beginning of this year, it became the first to introduce a new parking reservation system that requires all visitors to purchase their spots before arriving. Street parking has been banned – and the number of parking spots has been reduced by roughly 70%.

While officials say it’s too early to tell, estimates show that the reservation system will reduce annual numbers by about 200,000. Park representatives say they hope it will curb crowding by helping people plan their trips for less busy time slots. So far, it seems to be working.

On a drizzling midweek afternoon, nearing the end of summer, both Muir Woods parking lots were full. Near the entrance, the giggle and chatter of excited children mingled with the sounds of waterfalls and bird calls. Stroller wheels thudded rhythmically along the planked wooden boardwalk, echoing through the grove. But a few paces deeper the throngs thinned, and visitors could find a semblance of solitude among the ancient trees.

“Even with a lot of people here there are little pockets of silence you can find,” said Meghan Grady, who lives in nearby San Francisco. “We sat and shut our eyes for a little bit just to listen.”

It is experiences like these that park officials hope to protect. If they are successful, others may follow suit. Parks including Zion, Arches and Acadia are all urgently considering reservation-only systems.

But as officials weigh up large-scale changes, which can take years to research and implement, others point to behavior changes that can be made right now. For instance, a growing cohort of photographers , social media influencers and conservationists is pushing back on geotagging – using GPS to share the precise location in which a photo was taken. Leave No Trace, a nationwide organization promoting outdoor ethics, is helping to spearhead the movement. In June it released new guidance on using social media responsibly in nature. Dana Watts, the executive director, says the move was the result of feedback from land management agencies, the park service, the Bureau of Land management and the public.

Avoid geotagging specific locations, she advises, and think carefully before posting a selfie with wildlife. “Everyone wants to capture that picture, but people tend to get way too close,” she says. “If you are posting that, you are encouraging others to do the same.”

“The biggest thing we are asking people to do is stop and think,” she adds.

‘It’s just going to keep growing’

At Horseshoe Bend, the Instagram crowds aren’t going anywhere soon. Beginning in April 2019, the city of Page will start charging a $10-per-car entrance fee that will go directly to pay for management of the area. But Zia, the Glen Canyon national recreational manager, expects demand to steadily increase anyway. “Between 2015 and 2017, visitation doubled,” she said. “I think it is just going to keep growing.”

In the meantime, managers are doing what they can to improve safety and protect the landscape. A metal railing now cuts across the cliff’s edge to prevent people from tumbling off. Vault toilets were added two years ago. What was once a 100-sq-ft dirt parking lot has been expanded this year to hold up to 300 cars.

On a November evening, people lined up to watch the sky turn from orange to hot pink as the sun descended. Jenny Caiazzo, 24, was visiting from Denver, touring south-west national parks with her friend. “Now that I’m here, I see it’s even more beautiful than the pictures.”

Visitors admired the view from the rim. “It’s breathtaking,” said Brett Rycen, a visitor from Australia on a coast-to-coast tour with his wife and daughter. “We’ve been Snapchatting a lot. We want our friends to know what we are experiencing.”

Nearby, Tristan Fabic and Cecille Lim from Los Angeles had just gotten engaged. “This is the place where I wanted to propose,” said Fabic. “I saw it on Instagram and thought it would be really cool.”

Reporting: Charlotte Simmonds in Oakland, California; Annette McGivney in Horseshoe Bend, Arizona; Todd Wilkinson in Yellowstone national park, Wyoming; Patrick Reilly in Glacier national park, Montana; Brian Maffly in Salt Lake City, Utah; Gabrielle Can on in Yosemite national park and Muir Woods national monument, California; Michael Wright in Gardiner, Montana; and Monte Whaley in Estes Park, Colorado

This story was reported and published in collaboration with:

- This land is your land

- National parks

Most viewed

Growing Wildlife-Based Tourism Sustainably: A New Report and Q&A

Copyright: Sanjayda, Shutterstock.com

STORY HIGHLIGHTS

- While wildlife and biodiversity are increasingly threatened by habitat loss, poaching, and a lack of funding for protection, nature-based tourism is on the rise and could help provide solutions for these issues.

- The publication Supporting Sustainable Livelihoods through Wildlife Tourism highlights successful wildlife tourism programs in seven countries in Africa and Asia that can be used as models to promote conservation and boost economies.

- World Bank lead economist Richard Damania answers questions on the drivers, innovations and challenges for wildlife tourism, and why the World Bank Group and governments should support sustainable tourism strategies.

Wildlife tourism is a powerful tool countries can leverage to grow and diversify their economies while protecting their biodiversity and meeting several Sustainable Development Goals. It is also a way to engage tourists in wildlife conservation and inject money into local communities living closest to wildlife. Success stories and lessons learned from nature-based tourism are emerging from across the globe.

“Here is a way of squaring the circle: provide jobs and save the environment,” said World Bank lead economist Richard Damania, who has extensive experience in understanding the link between tourism and the economy . In 2016, travel and tourism contributed $7.6 trillion, or 10.2%, to total GDP, and the industry provided jobs to one in 10 people, according to the World Travel & Tourism Council .

While nature-based tourism, which includes wildlife tourism, has been expanding rapidly in the last decade or so due to increased demand and opportunities, wildlife and biodiversity are increasingly threatened by habitat loss, poaching, and a lack of funding for protection.

Which is why more than ever countries need to look to concrete examples of well-planned, sustainably-run tourism operations that have led to increased investments in protected areas and reserves, a reduction in poaching, an increase in the non-consumptive value of wildlife through viewing , and opportunities for rural communities to improve their livelihoods through tourism-related jobs, revenue-sharing arrangements, and co-management of natural resources.

A recently-released publication— Supporting Sustainable Livelihoods through Wildlife Tourism —developed by the World Bank Group and the Global Wildlife Program , funded by the Global Environment Facility , showcases sustainable wildlife tourism models that can be applied to developing countries, and offers solutions and case studies to bring insight into this sector as a mechanism for inclusive poverty reduction and global conservation.

The Global Wildlife Program spoke with Damania to learn more about the growth, challenges, and innovations in wildlife-based tourism.

Copyright: Wandel Guides, Shutterstock.com

Why should the World Bank support conservation endeavors, and how does wildlife tourism help support our mission?

Enlightened self-interest is one obvious reason why we need to promote wildlife tourism. It provides the most obvious way to reconcile the interests of nature with the imperative for development and growth. Tourism simultaneously creates jobs while, when done well, protects natural habitats.

Prudence and precaution are another reason why investments in nature-based tourism ought to be promoted. The science of “ planetary boundaries ” warns us that many fragile natural environments and ecosystems are reaching their limits and in some cases, the hypothesized safe boundaries have been crossed. Further damage will imply that we lose important ecosystem services such as watershed and soil protection with damaging consequences for development.

But, in my mind, perhaps the most important reason is humanity’s moral and ethical imperative as stewards of global ecosystems. Simply because humanity has the ability to destroy or convert ecosystems and drive species to extinction does not make it ethically justifiable. There needs to be an ethical balance and that is where ecotourism comes in. We need jobs and economic growth, but here is a way to get jobs and growth in ways that meet our moral and ethical obligation.

What have been the drivers behind a burgeoning nature-based/wildlife-based tourism sector?

I think there are two things that drive it: as habitats diminish there is more scarcity and their value goes up. Everyone wants to see the last remaining habitats of wild gorillas for instance, or the few remaining wild tigers in India. In sum scarcity confers economic value.

Another force driving demand is the internet and rising lifestyles—you can learn about animals and habitats you might not have known existed, and more people have the ability to visit them. So, you have supply diminishing on one hand, and demand rising on the other hand which creates an opportunity for economic progress together with conservation.

What is your advice to governments and others who are developing or expanding on a nature or wildlife-based tourism strategy?

Tourism benefits need to be shared better . There is a lack of balance with too many tourists in some places, and none elsewhere. Some destinations face gross overcrowding, such as South Africa’s Krueger National Park or the Masai Mara in Kenya where you have tourists looking at other tourists, instead of at lions. We need to be able to distribute the demand for tourists more equally. The Bank has a role to play in developing the right kind of tourism infrastructure.

Those living closest to nature and wildlife must also benefit . The local inhabitants that live in the national parks or at their periphery are usually extremely poor. Having tourism operations that can benefit them is extremely important for social corporate reasons, but also for sustainability reasons. If the benefits of tourism flow to the local communities, they will value the parks much more.

We also need to be mindful of wildlife corridors . We know that dispersion and migration are fundamental biological determinants of species survival. Closed systems where animals cannot move to breed are not sustainable in the long run. As we break off the corridors because of infrastructure and increasing human populations we are putting the ecosystems on life support.

There are some who believe we can manage these closed ecosystems, but it takes an immense amount of self assurance in science to suggest this with confidence, and it is unclear that one can manage ecosystems that we do not adequately understand. A measure of caution and humility is needed when we are stretching the bounds of what is known to science.

What are some of the innovative partnerships that are helping the wildlife-based tourism businesses in developing countries?

One very successful model that has combined wildlife conservation and management and community benefits and welfare is the Ruaha Carnivore Project in Tanzania, part of Oxford University’s Wildlife Conservation Research Unite ( WildCRU ). They use a payment for ecosystem services (PES) scheme and do all the right things.

Another example are the community conservancies in Namibia. The community manages the land for wildlife and there are a variety of profit sharing commercial tourism arrangements—although not everything always works fairly or perfectly. Incentives matter deeply and communities need to be guided and need technical assistance in setting up commercial arrangements.

The Bank needs to understand these better and find ways of scaling those up. The IFC has a very good role to play here as well.

To learn more and to explore numerous examples of community involvement in wildlife tourism from Botswana, India, Kenya, Malawi, Namibia, South Africa and Uganda, read the report Supporting Sustainable Livelihoods through Wildlife Tourism or find a one-page fact sheet here .

The Global Wildlife Program (GWP) is led by the World Bank and funded by a $131 million grant from the Global Environment Facility (GEF). The program is working with 19 countries across Africa and Asia to promote wildlife conservation and sustainable development by combatting illicit trafficking in wildlife, and investing in wildlife-based tourism.

- Full Report: Supporting Sustainable Livelihoods through Wildlife Tourism

- Fact Sheet on Key Messages

- Report: Twenty Reasons Sustainable Tourism Counts for Development

- Report: Women and Tourism: Designing for Inclusion

- Blog: Africa can Benefit from Nature-based Tourism in a Sustainable Manner

- Feature: Ramping up Nature-Based Tourism to Protect Biodiversity and Boost Livelihoods

- Website: Global Wildlife Program

- Website: Environment

- Website: Competitiveness

- Global Environment Facility

What does making an impact mean for Wilderness?

Conservation

Cultures & Communities

Janine Avery

Pioneers Of Purpose

Earth’s phenomenal biodiversity is in crisis. Species are disappearing faster than ever. And through our commitment to helping protect some of the world’s last true wilderness areas, we are taking responsibility for acting. For now, and for future generations.

This is the force, the single truth that drives us. It’s at the front and centre, the heartbeat, of everything we do.

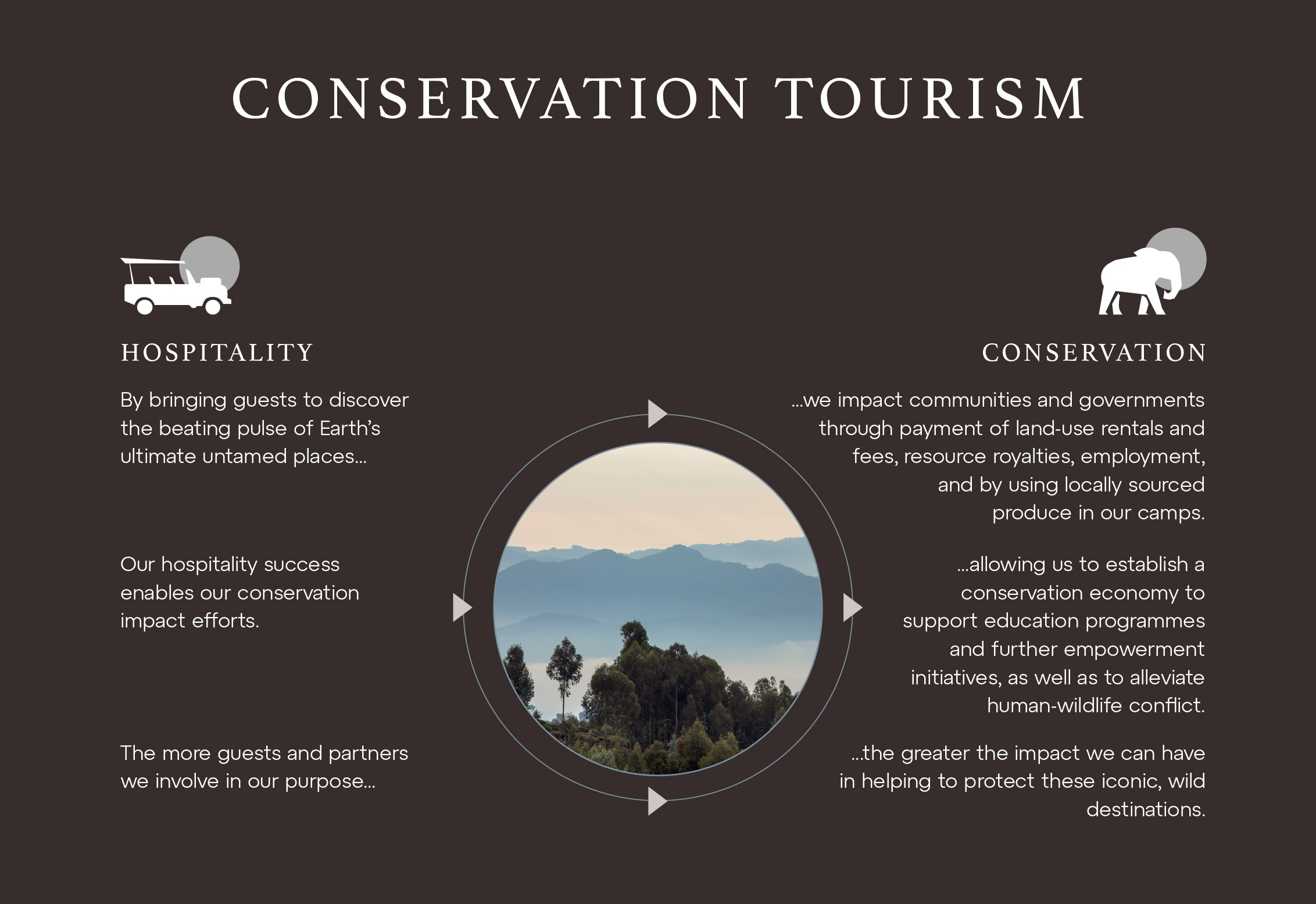

Two halves, one business

Together, the two halves of our operation, hospitality and conservation, feed into one significant whole.

High-value, low volume conservation tourism that generates the resources we need to make a lasting impact, improving lives while helping protect the world’s wildest places.

By bringing guests to discover the beating pulse of Earth’s ultimate untamed places, we impact communities and governments through payment of land-use rentals and fees, resource royalties, employment, and by using locally sourced produce in our camps. This establishment of a conservation economy allows us to support education programmes, further empowerment initiatives, and alleviate human-wildlife conflict.

Our ultimate goal

At Wilderness, we want to increase the world’s wilderness together, doubling the land we help protect by 2030. And then to double it, again and again.

But, how do we do this?

We have identified three pivotal focus areas that lead us to make better, more intentional decisions about where to direct our efforts. These are the lenses through which we view our investment decisions, determining the priorities for our business, and conservation and development initiatives.

Building the next generation of conservation leaders is the best way to sustain the future of the wilderness. Environmental education is also a pathway out of poverty, improving living conditions for families.

Where can you see our impact?

Together with our partners for change in each of these fields – NGOs, communities, businesses, and our valued travellers – we’ve built a network of positive force. A collaborative ecosystem that combines collective resources to maximise impact.

Our impact starts on the ground at our camps. The heart of our business.

Here we share the natural world with guests. But also, this is where we employ local people and build and operate with the lightest footprint possible, implementing measures to reduce carbon emissions, such as using solar panels and water-retention mechanisms, while reducing waste and eradicating plastic use.

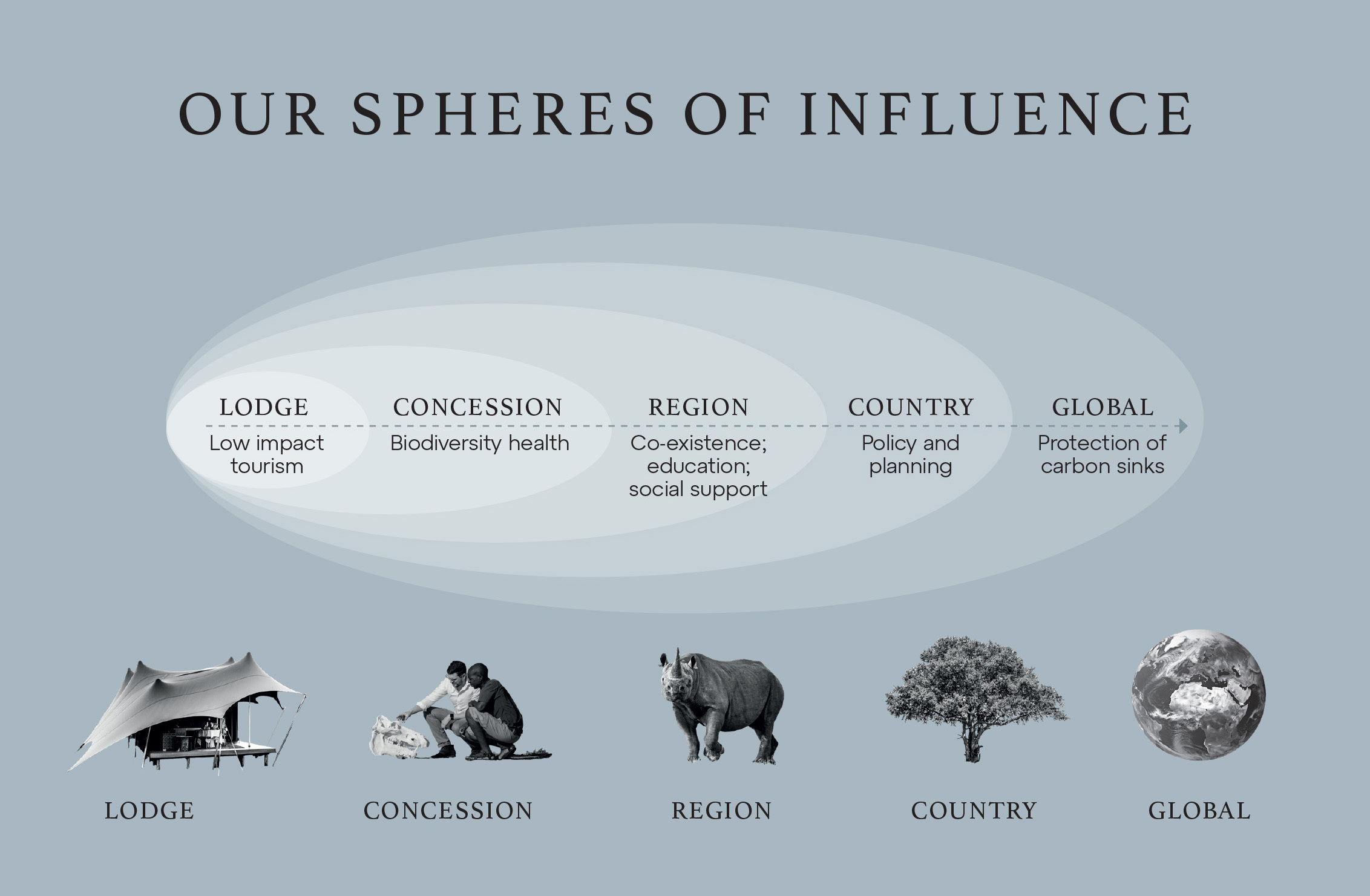

Spheres of influence

From there our impact expands through what we like to call our spheres of influence.

- Opening migration corridors, reforestation initiatives, and reducing threats to wildlife in our concessions where we contribute lease and park fees to communities and national wildlife departments to protect these areas.

- Empowering local communities with education at a regional level, where we also assist local economic development through stimulating small business ventures in the tourism supply chain and provide incentives for wildlife tolerance.

- Furthermore, at country level we work alongside governments to support the improvement of policies to develop long-lasting global protection for the land, its people and its wildlife, while investing in landscapes that protect global carbon sinks.

And it’s working

We’re among the pioneers of the concept of conservation hospitality. When we opened our first camp some 40 years ago, we promised to safeguard the land, to ensure its pulsing rhythm would never cease.

Today, our dedicated team of 3,000 people create captivating journeys to 60+ camps in iconic wild destinations for around 40,000 guests every year. The relentless focus on our goal helps to protect over 6 million acres (and counting) across 7 biomes, supporting 59 vulnerable and endangered IUCN Red List species. Alongside our impact on the landscape, we’ve also created a legacy of education and empowerment. Our education programmes have exposed around 10,000 children to the joy and potential of the natural world, while our empowerment programmes work to create self-sustaining communities that understand the value of ecotourism.

The theory of change

When it comes to making a real, lasting impact, our work is never done. We’re constantly measuring our success and making adjustments, because we, more than anyone, expect the best. Holding ourselves to the highest standards.

Our Theory of Change keeps us accountable and enables us to address problems at the root cause, rather than limiting ourselves to short-term cosmetic interventions. It is a more meaningful way to be accountable for the work we do, with visible tangible results.

Its success is defined by clear outcomes, making sure that what we contribute to generates results and positive change. We’re aspiring to be the benchmark for conservation tourism, changing people’s viewpoints on how they travel and interact with the land they visit.

How can I get involved?

Just by embarking on a journey with us, you help make a difference. Further to this however, the Wilderness Trust is an NGO founded by Wilderness to receive donations that can be used to support and enhance our impact endeavours. The Trust operates independently of Wilderness and determines where impact funds are allocated, aligning with the impact outcomes and ensuring we’re able to make progress with our conservation goals.

Let’s plan your next journey

When we say we’re there every step of the way, we mean it, literally. From planning the perfect circuit, to private inter-camp transfers on Wilderness Air, and easing you through Customs. We’re with you on the ground, at your side, 24-7, from start to finish. Ready to take the road less travelled? Contact our Travel Designers to plan an unforgettable journey.

Need some inspiration?

Be inspired by the latest news from Wilderness. Subscribe to our newsletter.

Nature-Based Tourism

The Positive Effects

Hannah Kirkland

A Shifting Trend in European Tourism

Nature-based tourism working with wildlife, financial benefits of nature-based tourism, empowering communities, a unique experience, from hunting to nature-based tourism, glossary of terms.

In southern and eastern Africa, the benefits of well-managed nature-based tourism to conservation have long been known. It helps makes protecting vast areas of wilderness financially viable; to governments and landowners from fees, and local people in the form of jobs. It can also incentivise looking after wildlife that traditionally would have been hunted - take Maasai pastoralists now acting as guardians for lions or former poachers becoming celebrated safari guides. On a wider scale, nature-based tourism has driven the transformation of entire landscapes , whether rewilding former ranches or being central to the successful restoration of vast national parks.

In Europe, the trend has been late to take hold but the timing could not be better. Tourism has shifted from the luxury of ‘things’ to experience-seeking , while increasingly people are avoiding long haul flights, opting instead to explore more sustainably closer to home. Many are looking to travel with purpose and support causes close to their heart with their trips. At the same time, the interest in and inspiring examples of rewilding in Europe have turned from a trickle to a torrent in the last decade . This crowded continent may be the last place that springs to mind when it comes to reconnecting with nature, but things are changing and the wider effects on conservation are already being felt.

Take the Central Apennines not far from bustling Rome. Here, ecotourism has been quietly booming over the last few years, with many visitors drawn by nature-based tourism such as tracking wolves and the endemic Marsican brown bear through the mountains. Once seen as pests and damaging to livelihoods, new pride and value in these iconic species have led to farmers working with NGOs to mitigate human-wildlife conflict and reverse their decline.

Take action now

Do you want to have a direct impact on climate change? Sir David Attenborough said the best thing we can do is to rewild the planet. So we run reforestation and rewilding programs across the globe to restore wild ecosystems and capture carbon.

With an ever more urbanised Europe, attracting tourists to remote rural areas brings money and often needed new sources of employment. On the Isle of Mull, the reintroduction of white-tailed eagles is estimated to bring in £5 million of tourist income annually and supports over 100 jobs. As with a lion to a pastoralist on the Maasai Mara, or eagle to a shepherd in Scotland, thanks to nature-based tourism, predators can now be worth more to communities alive , offsetting the damage they can cause. The potential of ecotourism may be what directly leads to future UK reintroductions, as it’s hoped lynx and beavers will have a similar economic impact as white-tailed eagles.

Namibia is a country that has seen the benefits of nature-based tourism. A country that in rural areas has high levels of unemployment and poor employment opportunities. In the 1970’s, the government spearheaded a global first for conservation, and funded the start-up of conservancies and also wrote conservation plans into their constitution. Conservancies as well as the local communities were given the rights to the local wildlife to encourage them to protect it.

This has led to the communities becoming stewards of wildlife and they are doing a great job. Money from tourism returns to the local economy for the development of housing and enabling people to have sustainable livelihoods and a better standard of living. These conservancies employ around 1 in 4 people living in rural Namibia. This provides a range of job opportunities from park rangers to working in accommodation, bringing millions of dollars to the local economy. Animals have benefited greatly too and now, after centuries of hunting and human-wildlife conflicts, they’re at their highest number in 150 years. By focusing on wildlife as an asset instead of a threat, well-run nature-based tourism offers hope to people as well as wildlife, showing they can coexist and thrive together.

In Portugal’s Faia Brava Reserve, an area where Mossy Earth has planted trees , nature-based tourism businesses have been set up not only to actively support rewilding efforts but also to immerse visitors in the local culture in a meaningful way. While the main draw is important vulture conservation, unique accommodation, wine and great food certainly help sell the whole experience in a way that involves all manner of local stakeholders.

And in another area where Mossy Earth works, Alladale Wilderness Reserve, a former hunting estate is pioneering an alternative conservation-focused way for the Highlands to be managed that’s attracting visitors from around the world , and other landowners are paying attention. As part of a wider Scottish rewilding movement, the potential for wildlife such as the critically endangered Scottish wildcat , carbon sequestering and climate resilience is enormous.

This doesn’t begin to scratch the surface of the personal benefits of engaging with a more abundant, biodiverse landscape in active and sustainable ways. But as more people want to get back in touch with nature and give something back with their travels, the future is looking wilder.

Avoiding Long-Haul Flights: Worthy to note the highly damaging nature of air travel where, until it can be advanced to produce less emissions, it remains one of the highest pollutants and individuals are encouraged to avoid them. This is especially true for long-haul flights that fly at higher altitudes and release extremely large amounts of CO2

Rewilding : Is the reintroduction of native tree and animal species to an area where they were once present but have since been removed. These areas are managed at the beginning until they are able to look after themselves and regenerate naturally. It is attempting to return the natural balance to landscapes as well as a valuable tool in the fight against climate change .

Biodiverse Landscapes: If a landscape is rich in biodiversity , it denotes a healthy ecosystem. Where there is a high level of biological diversity, it means there is an abundance of species, in healthy numbers with healthy genetics. These factors together are very positive and highlight a healthy environment.

Carbon Sequestration : Is the trapping and storing of carbon dioxide to prevent it from entering the atmosphere. The ocean is the main proponent of carbon sequestration, storing huge quantities of CO2. Forests are also invaluable at capturing and storing CO2.

Sources & further reading

Continue reading about rewilding knowledge, blue carbon ecosystems, rewilding diaries: an encounter with the mighty european bison, why we need forests to save the scottish salmon.

- Dendrochronology: How tree rings inform us about climate change

- Youth Green Conference 2025 is coming!

- Dynamics of natural processes

- The Earth Day

- The Wood Wide Web supports wild forests

The challenges of Nature Tourism in Wilderness

Nature tourism seems to be an effective tool to support nature conservation, particularly in densely populated Europe. Generally speaking, nature tourism allows a region to benefit economically while maintaining its natural values and providing a chance for nature . Simultaneously it creates conditions for the development of local communities and preserves their traditions and culture.

Please also read: Natural tourism in Slovakia

Nature tourism and Wilderness

Nevertheless, this is not so obvious if we want to protect Wilderness. A growing number of visitors is a threat to maintain an appropriate status of Wilderness. Growing visitor numbers can lead to irreversible damage in a Wilderness. Numerous examples can be found among the Word Heritage areas list .

There is obviously a difference between mass and nature tourism if we speak about impact. The major benefits of nature tourism are the experience and educational aspects. However, we have to be aware of the pressure of the tourism industry . This concerns the field of tourism, nature tourism, green tourism and mass tourism. Many protected areas that hosted great Wilderness areas are already victims of this process.

Nature tourism Principles

Nature tourism is based on the vision of long-term sustainability of an area. The development within this area builds on the following principles:

- minimise the negative impacts of tourism on the ecosystem and local people,

- provide jobs and financial benefits for the local population,

- empower local people,

- generate funds for the conservation of natural and cultural heritage of an area,

- build environmental and cultural awareness and respect.

Aevis foundation

Aevis foundation in Slovakia recently came up with a programme for Nature Tourism building on these principles. It aims to promote activities and initiatives to advance these principles in areas where natural tourism creates opportunities for Wilderness protection. Since this protection entails certain restrictions on land use, one of the objectives of Aevis Foundation is to directly compensate for these limitations, thus contributing to the maintenance and expansion of Wilderness areas. Aevis foundation recently organised a workshop with a focus on nature tourism in Slovakia. The meeting generated great ideas and creates a good basis to further develop the concept of nature tourism in Slovakia.

Nature Tourism and the European Wilderness Society

Experience shows that tourism, particularly mass tourism, is a big threat to Wilderness conservation. However, tourism, if correctly implemented, is an important tool to raise public awareness for Wilderness. Awareness for Wilderness is an important tool to protected Wilderness. This can happen only if people respect Wilderness. Respect in this term means that people are willing to respect the principles of nature tourism and nature in general. An essential tool to educate visitors and build respect for Wilderness is to inform and implement the Leave No Trace principles . These principles allow visitors to experience Wilderness without impacting it.

“People have to experience Wilderness, otherwise Wilderness does not have value for them”,

said the Deputy Director of the European Wilderness Society.

Stay up to date on the Wilderness news, subscribe to our Newsletter!

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

- Educating future Wilderness advocates

- Filming of a ORF Newton Episode on large carnivores in Austria

You May Also Like

Understanding COVID-19 impact on tourism in protected areas

Celebrate World Tourism Day-2023

International fight for Svydovets continues

Wilderness and the European long-distance trails

Ski resort or low impact tourism?

Sustainability motivations in small tourism enterprises in European protected areas

Please leave a comment cancel reply, also interesting.

Sustainable Tourism Guidebook 2016

Which city is going to become the Capital of Smart Tourism in 2023?

WhatsApp us!

Ecological Consequences of Ecotourism for Wildlife Populations and Communities

- First Online: 25 May 2017

Cite this chapter

- Graeme Shannon 5 ,

- Courtney L. Larson 6 ,

- Sarah E. Reed 7 ,

- Kevin R. Crooks 6 &

- Lisa M. Angeloni 8

2905 Accesses

28 Citations

13 Altmetric

Ecotourism is often considered highly compatible with conservation efforts because it generates revenue through the nonconsumptive use of wildlife (in contrast to, e.g., fishing and hunting), while helping to foster a conservation ethic among participants. However, it is becoming clear that human presence in natural areas is not without cost. Evidence suggests that human presence does not only cause disturbance to the behavior of animals in the short term but may well have population and ecological level consequences that affect survival, reproductive success, and the structure of ecological communities. Tourists can also impact populations of wild animals as a result of direct mortality (e.g., vehicle strike), by providing food to attract charismatic species that can alter the long-term distribution and social structure of populations, by degrading crucial habitats through infrastructure development and pollution, by introducing non-native species that displace native taxa, and by transmitting infectious diseases. Research on the impacts associated with ecotourism has grown rapidly during the past decade, which has greatly improved our knowledge of the complex relationships between disturbance and the potential ecological costs for different wildlife species. Understanding and mitigating these impacts is particularly important for conserving species that are rare, geographically isolated, and/or sensitive to disturbance while also enabling a sustainable ecotourism industry to thrive.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Fennell DA (2015) Ecotourism. Routledge, London

Google Scholar

Balmford A, Green JMH, Anderson M, Beresford J, Huang C, Naidoo R et al (2015) Walk on the wild side: estimating the global magnitude of visits to protected areas. PLoS Biol 13:e1002074

Article Google Scholar

Sibbald AM, Hooper RJ, McLeod JE, Gordon IJ (2011) Responses of red deer ( Cervus elaphus ) to regular disturbance by hill walkers. Eur J Wildl Res 57:817–825

Larson CL, Reed SE, Merenlender AM, Crooks KR (2016) Effects of recreation on animals revealed as widespread through a global systematic review. PLoS One 11:e0167259

Steven R, Pickering C, Guy Castley J (2011) A review of the impacts of nature based recreation on birds. J Environ Manag 92:2287–2294

Monz CA, Pickering CM, Hadwen WL (2013) Recent advances in recreation ecology and the implications of different relationships between recreation use and ecological impacts. Front Ecol Environ 11:441–446

Marzano M, Dandy N (2012) Recreationist behaviour in forests and the disturbance of wildlife. Biodivers Conserv 21:2967–2986

Marion AJ, Leung Y, Eagleston H, Burroughs K (2016) A review and synthesis of recreation ecology research findings on visitor impacts to wilderness and protected natural areas. J For 114:1–17

O’Connor S, Campbell R, Cortez H, Knowles T (2009) Whale watching worldwide: tourism numbers, expenditures and expanding economic benefits, a special report from the International Fund for Animal Welfare. International Fund for Animal Welfare, Yarmouth, MA

Senigaglia V, Christiansen F, Bejder L et al (2015) Meta-analyses of whalewatching impact studies: comparisons of cetacean responses to disturbance. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 542:251–263

Bejder L, Samuels A, Whitehead H et al (2006) Decline in relative abundance of bottlenose dolphins exposed to long-term disturbance. Conserv Biol 20:1791–1798

Lusseau D, Bejder L (2007) The long-term consequences of short-term responses to disturbance experiences from whalewatching impact. Int J Comp Psychol 20:228–236

Sato CF, Wood JT, Lindenmayer DB (2013) The effects of winter recreation on alpine and subalpine fauna: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 8:e64282

Braunisch V, Patthey P, Arlettaz R (2011) Spatially explicit modeling of conflict zones between wildlife and snow sports. Ecol Appl 21:955–967

Patthey P, Wirthner S, Signorell N, Arlettaz R (2008) Impact of outdoor winter sports on the abundance of a key indicator species of alpine ecosystems. J Appl Ecol 45:1704–1711

Watson H, Bolton M, Monaghan P (2014) Out of sight but not out of harm’s way: human disturbance reduces reproductive success of a cavity-nesting seabird. Biol Conserv 174:127–133

Müllner A, Eduard Linsenmair K, Wikelski M (2004) Exposure to ecotourism reduces survival and affects stress response in hoatzin chicks ( Opisthocomus hoazin ). Biol Conserv 118:549–558

McClung MR, Seddon PJ, Massaro M, Setiawan AN (2004) Nature-based tourism impacts on yellow-eyed penguins Megadyptes antipodes : does unregulated visitor access affect fledging weight and juvenile survival? Biol Conserv 119:279–285

Gill J, Norris K, Sutherland WJ (2001) The effects of disturbance on habitat use by black-tailed godwits Limosa limosa . J Appl Ecol 38:846–856

Estes J, Terborgh J, Brashares JS et al (2011) Trophic downgrading of planet earth. Science 333:301–306

Muhly TB, Semeniuk C, Massolo A et al (2011) Human activity helps prey win the predator-prey space race. PLoS One 6:e17050

Rogala JK, Hebblewhite M, Whittington J, White CA, Coleshill J, Musiani M (2011) Human activity differentially redistributes large mammals in the Canadian Rockies national parks. Ecol Soc 16:16

Berger J (2007) Fear, human shields and the redistribution of prey and predators in protected areas. Biol Lett 3:620–623

Shannon G, Cordes LS, Hardy AR et al (2014) Behavioral responses associated with a human-mediated predator shelter. PLoS One 9:e94630. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094630

Geffroy B, Samia DSM, Bessa E, Blumstein DT (2015) How nature-based tourism might increase prey vulnerability to predators. Trends Ecol Evol 30:755–765

Mccleery RA (2009) Changes in fox squirrel anti-predator behaviors across the urban-rural gradient. Landsc Ecol 24:483–493

Rodriguez-Prieto I, Fernández-Juricic E, Martín J, Regis Y (2009) Antipredator behavior in blackbirds: habituation complements risk allocation. Behav Ecol 20:371–377

Santos CD, Cramer JF, Pârâu LG, Miranda AC, Wikelski M, Dechmann DKN (2015) Personality and morphological traits affect pigeon survival from raptor attacks. Sci Rep 5:15490

Bremner-Harrison S, Prodohl PA, Elwood RW (2004) Behavioural trait assessment as a release criterion: boldness predicts early death in a reintroduction programme of captive-bred swift fox ( Vulpes velox ). Anim Conserv 7:313–320

Leighton PA, Horrocks JA, Kramer DL (2010) Conservation and the scarecrow effect: can human activity benefit threatened species by displacing predators? Biol Conserv 143:2156–2163

Nevin OT, Gilbert BK (2005) Measuring the cost of risk avoidance in brown bears: further evidence of positive impacts of ecotourism. Biol Conserv 123:453–460

Laurance WF (2013) Does research help to safeguard protected areas? Trends Ecol Evol 28:261–266

Tranquilli S, Abedi-Lartey M, Amsini F et al (2012) Lack of conservation effort rapidly increases african great ape extinction risk. Conserv Lett 5:48–55

Jones ME (2000) Road upgrade, road mortality and remedial measures: impacts on a population of eastern quolls and Tasmanian devils. Wildl Res 27:289–296

Pienaar UDV (1968) The ecological significance of roads in a national park. Koedoe 11:169–174

Cannell BL, Campbell K, Fitzgerald L et al (2016) Anthropogenic trauma is the most prevalent cause of mortality in pittle penguins ( Eudyptula minor ) in Perth, Western Australia. Emu 116:52

Davenport J, Davenport JL (2006) The impact of tourism and personal leisure transport on coastal environments: a review. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 67:280–292

O’Shea TJ (1995) Waterborne recreation and the Florida manatee. Island Press, Washington, DC

Yasué M, Dearden P (2006) The potential impact of tourism development on habitat availability and productivity of Malaysian plovers Charadrius peronii . J Appl Ecol 43:978–989

Green R, Higginbottom K (2000) The effects of non-consumptive wildlife tourism on free-ranging wildlife: a review. Pacific Conserv Biol 6:183–197

Orams MB (1997) Historical accounts of human-dolphin interaction and recent developments in wild dolphin based tourism in Australasia. Tour Manag 18:317–326

Kasereka B, Muhigwa J-BB, Shalukoma C, Kahekwa JM (2006) Vulnerability of habituated Grauer’s gorilla to poaching in the Kahuzi-Biega National Park, DRC. Afr Study Monogr 27:15–26

Ménard N, Foulquier A, Vallet D et al (2014) How tourism and pastoralism influence population demographic changes in a threatened large mammal species. Anim Conserv 17:115–124

Knight RR, Eberhardt LL, Knight RR (1985) Population dynamics of Yellowstone grizzly bears. Ecology 66:323–334

Massé S, Dussault C, Dussault C, Ibarzabal J (2014) How artificial feeding for tourism-watching modifies black bear space use and habitat selection. J Wildl Manag 78:1228–1238

Miller R, Kaneene JB, Fitzgerald SD, Schmitt SM (2003) Evaluation of the influence of supplemental feeding of white-tailed deer ( Odocoileus virginianus ) on the prevalence of bovin tuberculosis in the Michigan wild deer population. J Wildl Dis 39:84–95

Semeniuk CAD, Rothley KD (2008) Costs of group-living for a normally solitary forager: effects of provisioning tourism on southern stingrays Dasyatis americana . Mar Ecol Prog Ser 357:271–282

Gallagher AJ, Vianna GMS, Papastamatiou YP, Macdonald C, Guttridge TL, Hammerschlag N (2015) Biological effects, conservation potential, and research priorities of shark diving tourism. Biol Conserv 184:365–379

Bruce BD, Bradford RW (2013) The effects of shark cage-diving operations on the behaviour and movements of white sharks, Carcharodon carcharias , at the Neptune Islands, South Australia. Mar Biol 160:889–907

Orams MB (2002) Feeding wildlife as a tourism attraction: a review of issues and impacts. Tour Manag 23:281–293

Maréchal L, Semple S, Majolo B, MacLarnon A (2016) Assessing the effects of tourist provisioning on the health of wild barbary macaques in Morocco. PLoS One 11:e0155920

Jones CG, Heck W, Lewis RE et al (1995) The restoration of the Mauritius kestrel Falco punctatus population. Ibis 137:S173–S180

Bamford AJ, Diekmann M, Monadjem A, Mendelsohn J (2007) Ranging behaviour of cape vultures Gyps coprotheres from an endangered population in Namibia. Bird Conserv Int 17:331–339

Wilson MC, Chen X-Y, Corlett RT et al (2016) Habitat fragmentation and biodiversity conservation: key findings and future challenges. Landsc Ecol 31:219–227

Liddle M (1997) Recreation ecology: the ecological impact of outdoor recreation and ecotourism. Chapman & Hall, London

Knight RL (2000) Forest fragmentation and outdoor recreation in the southern Rocky Mountains. University Press of Colorado, Boulder, US

Ballantyne M, Gudes O, Pickering CM (2014) Recreational trails are an important cause of fragmentation in endangered urban forests: a case-study from Australia. Landsc Urban Plan 130:112–124

Crooks KR, Sanjayan M (2006) Connectivity conservation. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Book Google Scholar

Kendall RJ, Lacher TE, Cobb GC, Cox SB (2010) Wildlife toxicology: emerging contaminant and biodiversity issues. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL

Scott D, Amelung B, Becken S et al. (2008) Climate change and tourism: responding to global challenges. World Tourism Organization, Madrid

Longcore T, Rich C (2004) Ecological light pollution. Front Ecol Environ 2:191–198

Rodrıguez A, Burgan G, Dann P, Jessop R, Negro JJ, Chiaradia A (2014) Fatal attraction of short-tailed shearwaters to artificial lights. PLoS One 9:e110114

Shannon G, McKenna MF, Angeloni LM et al (2016) A synthesis of two decades of research documenting the effects of noise on wildlife. Biol Rev 91:982–1005

Karp DS, Root TL (2009) Sound the stressor: how hoatzins ( Opisthocomus hoazin ) react to ecotourist conversation. Biodivers Conserv 18:3733–3742

Schroeder J, Nakagawa S, Cleasby IR, Burke T (2012) Passerine birds breeding under chronic noise experience reduced fitness. PLoS One 7:e39200

Halfwerk W, Holleman LJM, Lessells CM, Slabbekoorn H (2011) Negative impact of traffic noise on avian reproductive success. J Appl Ecol 48:210–219

Kight CR, Saha MS, Swaddle JP (2012) Anthropogenic noise is associated with reductions in the productivity of breeding eastern bluebirds ( Sialia sialis ). Ecol Appl 22:1989–1996

Spaul RJ, Heath JA (2016) Nonmotorized recreation and motorized recreation in shrub-steppe habitats affects behavior and reproduction of golden eagles ( Aquila chrysaetos ). Ecol Evol 6:8037–8049

Ware HE, McClure CJW, Carlisle JD, Barber JR (2015) A phantom road experiment reveals traffic noise is an invisible source of habitat degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:12105–12109

Francis CD, Ortega CP, Cruz A (2009) Noise pollution changes avian communities and species interactions. Curr Biol 19:1415–1419

Anderson LG, Rocliffe S, Haddaway NR, Dunn AM (2015) The role of tourism and recreation in the spread of non-native species: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 10:e0140833

Chown SL, Huiskes AHL, Gremmen NJM et al (2012) Continent-wide risk assessment for the establishment of nonindigenous species in Antarctica. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:4938–4943

Kilroy C, Unwin M (2011) The arrival and spread of the bloom-forming, freshwater diatom, Didymosphenia geminata , in New Zealand. Aquat Invasions 6:249–262

Loss SR, Will T, Marra PP (2013) The impact of free-ranging domestic cats on wildlife of the United States. Nat Commun 4:1396

Young JK, Olson KA, Reading RP et al (2011) Is wildlife going to the dogs? Impacts of feral and free-roaming dogs on wildlife populations. Bioscience 61:125–132

Woodford MH, Butynski TM, Karesh WB (2002) Habituating the great apes: the disease risks. Oryx 36:153–160

Kondgen S, Kuhl H, N’Goran PK et al (2008) Pandemic human viruses cause decline of endangered great apes. Curr Biol 18:260–264

Lamb JB, True JD, Piromvaragorn S, Willis BL (2014) Scuba diving damage and intensity of tourist activities increases coral disease prevalence. Biol Conserv 178:88–96

Grimaldi WW, Seddon PJ, Lyver POB et al (2014) Infectious diseases of Antarctic penguins: current status and future threats. Polar Biol 38:591–606

Cushman JH, Meentemeyer RK (2008) Multi-scale patterns of human activity and the incidence of an exotic forest pathogen. J Ecol 96:766–776

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Biological Sciences, Bangor University, Bangor, UK

Graeme Shannon

Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Conservation Biology, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA

Courtney L. Larson & Kevin R. Crooks

Wildlife Conservation Society and Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Conservation Biology, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA

Sarah E. Reed

Department of Biology, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA

Lisa M. Angeloni

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Graeme Shannon .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, and The Institute of the Environment and Sustainability, University of California, Los Angeles, California, USA

Daniel T. Blumstein

Ifremer, UMR MARBEC, Marine Biodiversity, Exploitation and Conservation, Laboratory of Adaptation and Adaptability of Animals and Systems, Palavas-les-Flots, France

Benjamin Geffroy

Department of Ecology, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil

Diogo S. M. Samia

Graduate Program in Ecology, and Life and Earth Sciences Department, University of Brasília, Brasilia, Brazil

Eduardo Bessa

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Shannon, G., Larson, C.L., Reed, S.E., Crooks, K.R., Angeloni, L.M. (2017). Ecological Consequences of Ecotourism for Wildlife Populations and Communities. In: Blumstein, D., Geffroy, B., Samia, D., Bessa, E. (eds) Ecotourism’s Promise and Peril. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58331-0_3

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58331-0_3

Published : 25 May 2017

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-58330-3

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-58331-0

eBook Packages : Biomedical and Life Sciences Biomedical and Life Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Skip to global NPS navigation

- Skip to the main content

- Skip to the footer section

Exiting nps.gov

Economics of wilderness: contribution of alaska parks and wilderness to the alaska economy.

What is the economic contribution of wilderness to Alaska’s economy? Tourism by nonresidents is the primary link that we consider between wilderness and the Alaska economy, although subsistence harvests and resident recreation clearly generate value for Alaskans. Here, we synthesize and apply existing data and research. We do not consider global ecosystem services provided by park lands and waters, nor do we assess activity that is not captured within the Alaska economy.

Figure 1 shows the allocation of Alaska’s 375 million acres. Approximately 40 percent are in federal conservation units, and approximately 38 percent of these 150 millions acres are designated wilderness. The Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) of 1980 added most newly designated conservation units in the form of national wildlife refuges. The second most important category of additions was new national parks and preserves.

Wilderness and Tourism

The Alaska visitor industry is the only private sector basic industry that has grown almost continuously since statehood and continues to grow. Almost 1.6 million visitors came to Alaska in summer 2011, and 91 percent of them came primarily to see the state’s mountains, glaciers, and wildlife (McDowell Group 2012). Alaska’s visitor industry accounted for an estimated 37,800 full- and part-time jobs from May 2011 to April 2012, including all direct, indirect, and induced employment. Estimated peak employment was 45,000. These jobs resulted in total labor income of $1.24 billion. Visitors spent $1.7 billion in Alaska, most of it in the summer months (McDowell Group 2013).

NPS Photo / Bob Winfree

While these economic impacts cannot be completely attributed to the presence of designated wilderness, wilderness characteristics are a significant driver of Alaska visitation. In the summer 2001 Alaska Visitor Statistics Program (AVSP) Visitor Opinion Survey, specific questions regarding wilderness were included. For over 80 percent of respondents, Alaska’s wilderness character and the opportunity to see or spend time in wilderness places influenced their decision to come to Alaska and was an important factor in trip planning (Table 1). Wilderness was also important to a decision to visit Alaska again in the future by 73 percent of respondents. Protecting the wilderness character of Alaska was also important to 87 percent respondents. Most also of strongly supported rationing the use of popular wilderness areas to protect the natural environment (80 percent) and animal populations (84 per-cent). Rationing use to protect opportunities for visitors to be alone and away from crowds was also supported (47 percent) but not as strongly. Data from summer 2012 confirms that Alaska tourism activity revolves around Alaska’s national parks, especially Denali (433,000 visitors) and Glacier Bay (359,000 visitors) (McDowell, 2013). Our analysis of summer 2001 expenditure diaries collected by AVSP suggests that more than half the total amount spent by tourists in Alaska comes from people who visit Denali. Visitors to Denali in summer 2001 stayed in Alaska for an average of fourteen days, while all other visitors averaged only eight days. Denali visitors spent $2,300 per party per trip, compared with only $1,100 spent by all other visitors. Similarly, visitors to Katmai National Park and Preserve also spent more days in Alaska and had higher expenditures per trip than the average Alaska visitor (Fay and Christensen, 2010). Several other studies confirm the economic significance of other parks and wilderness areas in Alaska. Fay and Christensen (2010, 2012) found that Katmai National Park and Preserve generated $52.1 million in annual visitor spending, providing approximately 650 jobs and $24.3 million in labor income (Figure 2).

Source: Alaska Visitor Statistics Program, summer 2001 data.

Goldsmith and Martin (2001) used a time-series approach to assess the effect of Kenai Fjords National Park on the growth of the economy of Seward, Alaska. They found a number of indications that the tourism industry grew rapidly throughout the 1980s and sustained the Seward economy through the 1990s:

"Most of the economic growth, particularly since 1990, has been driven by the visitor industry. Although there is no direct way to track this industry, employment in trade, services, and transportation—the sectors that provide the most visitor-related jobs—grew at an annual rate of 5.9 percent. Retail sales from summer visitors have grown at a 9.9 percent annual rate (inflation adjusted) since 1987. Park tourism is a $52 million-a-year business for Seward."

Goldsmith, Hill, and Hull (1998) analyzed the economic activity associated with the Alaska Peninsula, Becharof, Izembek, and Togiak Wildlife Refuges. They found that these four refuges supported 3,225 average annual jobs and $127 million of personal income in 1997. Commercial fishing accounted for about 90% of the jobs and income. The remaining 362 jobs were attributed to sport fishing, refuge management, subsistence-related activities, and hunting. If subsistence activity were treated as wage labor, it would equate to an additional 750 jobs, and the authors estimated that subsistence also generated more than $50 million in net economic value. One of the earliest and most thoughtful studies of the effects of wilderness on tourism was the master’s thesis done by Larry Bright (1985). Bright attempted to measure changes in tourism use patterns resulting from the creation of six designated wilderness areas within the Tongass National Forest. He collected primary data directly from tourism business operators. Bright was very careful not to read too much into his survey results. Nonetheless, he concluded:

"I have come to the conclusion that designation [of Misty Fjords Wilderness] has played a significant role [in the increased use of the area]….The dramatic jump in Misty Fjords use occurred during and immediately following the designation (1980/81), while use in surrounding areas continued to grow at a much slower pace. Some of the most convincing evidence supporting the designation effect comes from the operators themselves. Every Misty Fjords operator I interviewed stated that they used its official designation promotionally. The operators offering services in 1980 told me that the designation gave them a nationally recognizable name to advertise. (p. 33)"

Bright also proposed that wilderness designation was likely only one of six distinct inputs to the increased production (and consumption) of tourism in southeast. Designation as a special area was one (p 68). The others, in Bright’s own words, were:

- access—a site must be reachable within a reason-able amount of time and by a reasonable mode of transportation . . . In most cases, boat or plane are the two most reasonable mechanisms of transportation.

- the tourists must be “reachable”—there must be an available market in which the tourism operator can “peddle the goods.” If cruise ships did not stop in Ketchikan and provide a market, scenic flights of [sic] Misty Fjords would not have developed to the present day level.

- a single, dramatic attraction—like a large glacier (Hubbard), many glaciers (Glacier Bay), or an outstanding salmon stream (Situk).

- promotional skills and equipment—in many parts of Southeast boats or planes must be available to access an area. As well as the equipment, individuals must be present with the promotional skills to initiate a tourism enterprise.

- facilities—probably less a factor in Alaska than in other parts of the U.S. (p. 68)

Haley, Fay, and Angvik (2007) found that proximity to national parks was the strongest predictor of the number and variety of businesses in small rural Alaska villages with populations less than 1,400 people, places where wage income is especially scarce. This study’s conclusion echoes other studies using U.S. data. These studies show that rural areas endowed with natural resource amenities, such as wilderness, experience higher regional economic growth rates (Deller et al. 2001, Rasker et al. 2004). Both the amount and proximity of public land was correlated with faster economic growth of adjacent areas (Rasker et al. 2004). Recent studies of western counties and states have shown that population, income, and employment growth increased as the percentage of wilderness increased, and the West’s popular national parks, monuments, wilderness areas, and other public lands offer its growing high-tech and services industries a competitive advantage (Headwaters Economics 2012; Holmes and Hecox 2004).

Maximizing the Economic Value of Alaska Wilderness

Both economic theory and the evidence to date suggest that to maximize the long-term economic benefits of conservation lands, Alaskans and federal land managers will need to do three things. The first and most important task is to protect the “Alaska difference”—those fundamental attributes of Alaska’s large intact ecosystems and their wilderness character. This is easier said than done. It is almost inevitable that individual residents, businesses, and visitors will, consciously or not, chip away at the integrity of Alaska’s wildness. In some areas the degradation has been rigorously measured (Twardock et al. 2010).