Timing and number of antenatal care contacts in low and middle-income countries: Analysis in the Countdown to 2030 priority countries

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of International Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

- 2 Data and Analytics Section, Division of Data, Analytics, Planning and Monitoring, UNICEF, New York, New York, USA.

- 3 Department of Reproductive Health and Research, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 4 Department of Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health and Aging, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 5 School of International Development and Global Studies, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

- 6 The George Institute for Global Health, The University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

- 7 Department of Global Health, Save the Children US, Washington, District of Columbia, USA.

- 8 Department of Community Health Sciences, Rady Faculty of Health Sciences, Max Rady College of Medicine, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada.

- PMID: 32257157

- PMCID: PMC7101027

- DOI: 10.7189/jogh.10.010502

Background: The 2016 World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines for antenatal care (ANC) shift the recommended minimum number of ANC contacts from four to eight, specifying the first contact to occur within the first trimester of pregnancy. We quantify the likelihood of meeting this recommendation in 54 Countdown to 2030 priority countries and identify the characteristics of women being left behind.

Methods: Using 54 Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) and Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) since 2012, we reported the proportion of women with timely ANC initiation and those who received 8-10 contacts by coverage levels of ANC4+ and by Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) regions. We identified demographic, socio-economic and health systems characteristics of timely ANC initiation and achievement of ANC8+. We ran four multiple regression models to quantify the associations between timing of first ANC and the number and content of ANC received.

Results: Overall, 49.9% of women with ANC1+ and 44.3% of all women had timely ANC initiation; 11.3% achieved ANC8+ and 11.2% received no ANC. Women with timely ANC initiation had 5.2 (95% confidence interval (CI) = 5.0-5.5) and 4.7 (95% CI = 4.4-5.0) times higher odds of receiving four and eight ANC contacts, respectively ( P < 0.001), and were more likely to receive a higher content of ANC than women with delayed ANC initiation. Regionally, women in Central and Southern Asia had the best performance of timely ANC initiation; Latin America and Caribbean had the highest proportion of women achieving ANC8+. Women who did not initiate ANC in the first trimester or did not achieve 8 contacts were generally poor, single women, with low education, living in rural areas, larger households, having short birth intervals, higher parity, and not giving birth in a health facility nor with a skilled attendant.

Conclusions: Timely ANC initiation is likely to be a major driving force towards meeting the 2016 WHO guidelines for a positive pregnancy experience.

Copyright © 2020 by the Journal of Global Health. All rights reserved.

- Caribbean Region

- Developing Countries

- Health Facilities / statistics & numerical data*

- Patient Acceptance of Health Care / statistics & numerical data*

- Prenatal Care / statistics & numerical data*

- Socioeconomic Factors

- Surveys and Questionnaires

- Sustainable Development

Grants and funding

- 001/WHO_/World Health Organization/International

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 07 January 2022

Factors associated with changes in adequate antenatal care visits among pregnant women aged 15-49 years in Tanzania from 2004 to 2016

- Elizabeth Kasagama ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9900-4153 1 ,

- Jim Todd 2 &

- Jenny Renju 2

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth volume 22 , Article number: 18 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

1735 Accesses

2 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Antenatal care (ANC) is crucial for the health of the mother and unborn child as it delivers highly effective health interventions that can prevent maternal and newborn morbidity and mortality. In 2002, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended a minimum of four ANC visits for a pregnant woman with a positive pregnancy during the entire gestational period. Tanzania has sub-optimal adequate (four or more) ANC visits, and the trend has been fluctuating over time. An understanding of the factors that have been contributing to the fluctuating trend over years is pivotal in increasing the proportions of pregnant women attaining adequate ANC visits in Tanzania.

The study used secondary data from Tanzania Demographic Health Survey (TDHS) from 2004 to 2016. The study included 17976 women aged 15-49 years. Data were analyzed using Stata version 14. Categorical and continuous variables were summarized using descriptive statistics and weighted proportions. A Poisson regression analysis was done to determine factors associated with adequate ANC visits. To determine factors associated with changes in adequate ANC visits among pregnant women in Tanzania from 2004 to 2016, multivariable Poisson decomposition analysis was done.

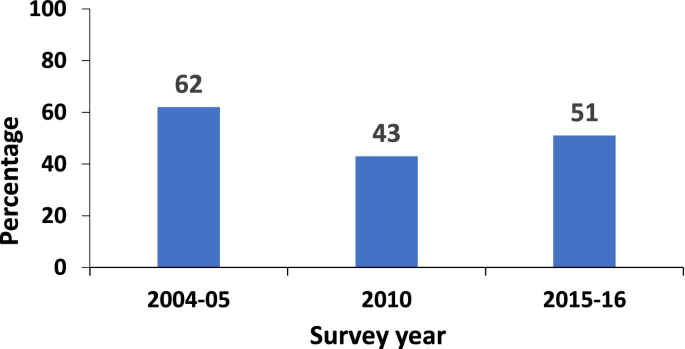

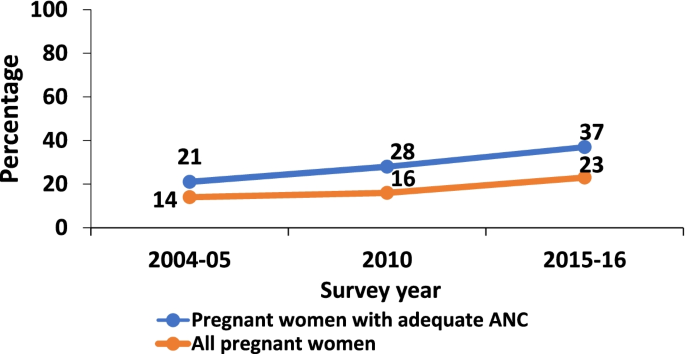

The overall proportion of women who had adequate ANC visits in 2004/05, 2010 and 2015/16 was 62, 43 and 51% respectively. The increase in the proportion of women attaining adequate ANC from 2010 to 2015/16 was mainly, 66.2% due to changes in population structure, thus an improvement in health behavior. While 33.8% was due to changes in the mother’s characteristics. Early initiation of first ANC visit had contributed 51% of the overall changes in adequate ANC attendance in TDHS 2015/16 survey.

Early ANC initiation has greatly contributed to the increased proportion of pregnant women who attain four or more ANC visits overtime. Interventions on initiating the first ANC visit within the first twelve weeks of pregnancy should be a priority to increase proportion of women with adequate ANC visit.

Peer Review reports

Adequate and quality antenatal care (ANC) is effective at promoting better health outcomes for both mother and child during pregnancy [ 1 , 2 ]. Strong evidence exists to support the link between ANC during pregnancy, skilled birth attendants during delivery, and quality postnatal care and reduced maternal and infant morbidity and mortality [ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ]. Globally, almost 60% of stillbirths are due to poor fetal growth, untreated and unattended maternal infection, and conditions that could have been avoided or treated by expert attention during ANC visits [ 7 ]. A wide range of services can be offered during ANC including screening, detection, prevention and treatment of any pregnancy-related complication, infection or morbidity [ 9 ].

The WHO 2002 Focus Antenatal Care (FANC) model recommends a minimum of four ANC visits for a woman with an uncomplicated pregnancy, with the first visit occurring during the first twelve weeks of pregnancy, although currently there is an 8-contact model in place [ 9 , 10 ]. In 2002, Tanzania adopted FANC, however, the first ANC is to be initiated within 16 gestational weeks [ 11 ]. Globally, ANC coverage (at least one visit during pregnancy) is 86%, yet only 62% of women meet the recommended four ANC visits. In Africa, ANC coverage is 69% with only 54% of women attending the minimum of four ANC visits, while in Tanzania, ANC coverage is higher, 98% but only 51% of pregnant women attain the minimum of four ANC visits [ 12 ]. Despite high ANC coverage, adequate (four or more) ANC visits are still suboptimal and could partly explain the unacceptably high neonatal mortality and stillbirth rates in Tanzania, with 25 deaths/1000 live births and 39 deaths/1000 pregnancies, respectively [ 13 ].

To scale up the uptake of ANC and to address the burden of maternal mortality, additional interventions were introduced. These included Exemptions from paying user fees on health care services for maternal, newborn and child under five. In 2012, Tanzania’s National Safe Motherhood Campaign (Wazazi Nipendeni) was implemented to encourage pregnant women to initiate the first ANC within 12 weeks of pregnancy and adhere to ANC services [ 14 ]. In 2014, the “Big Results Now” and the “Sharpened One Plan” programs were implemented. Despite these interventions, the Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey (TDHS) reported a fluctuating trend in adequate ANC visits: a fall from 62 to 43% and a rise to 51% for 2004/05, 2010 and 2015/16 surveys, respectively [ 13 ]. This suboptimal ANC attendance has been associated with a several factors, as documented in various studies worldwide. The factors include but are not limited to: long distance to a health facility, geographical zone, first ANC initiation, woman’s desire to avoid pregnancy, marital status, wealth quintiles, multiparity, living in an urban area, and higher education level [ 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 ].

This study aimed to show how much each individual factor has contributed to the decline from 2004/04 to 2010 and the increase from 2010 to 2015/16 in the TDHS and how they have contributed to the varying low proportions of adequate ANC visits over time. Filling this knowledge gap may help identify the key contributing factors and provide valuable information on how the programmatic changes during the 2004–2016 period have impacted adequate ANC attendance. Moreover, understanding the factors associated with changes in adequate ANC visits may help to provide useful information to policymakers, project implementing partners and in designing target interventions that may improve adequate ANC visits in Tanzania.

Study design and study settings

The study was conducted in Tanzania, which includes the mainland and island. This was a Crossectional study that used data from the Tanzania Demographic Health Survey (TDHS), Further details of the survey are available elsewhere [ 13 ], but in brief this is a national representative survey done after five years with the objective to obtain the current and reliable information on demographic and health indicators about family planning, fertility levels and preferences, maternal mortality, infant and child mortality, nutritional status of mothers and children, ANC, delivery care, and childhood immunizations and diseases. Data were obtained from www.dhsprogram.com , after being granted permission to access and use TDHS data. Data from 2004/04, 2010 and 2015/16 surveys were used.

Study population

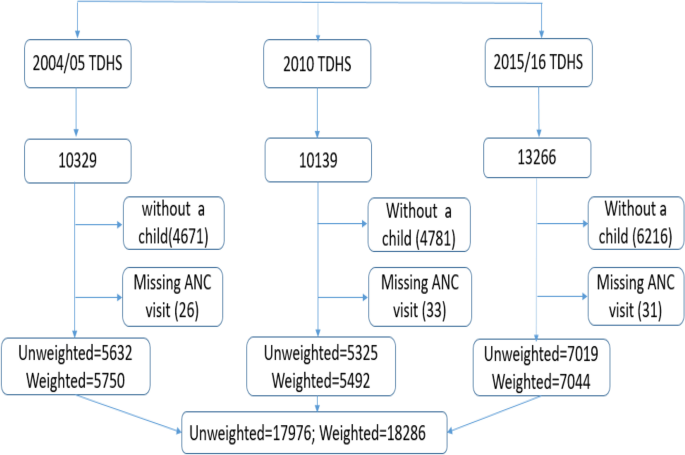

The population was all women of reproductive age (15-49 years) who had given birth to at least one child within the five years before the survey and had information on ANC visits. For a woman with multiple births during the five-year period, we considered mother’s last birth within 5 years prior the survey for this analysis. A total of 33,734 women aged 15-49 years in Tanzania participated in the three TDHS surveys. After excluding those with missing information on ANC visits, we remained with a total of 17,976. Of 17,976 women enrolled in the study: 4541(77.9%), 4201(76.9%) and 5193(70.1%) for 2004/05, 2010 and 2015/16 surveys respectively (Fig. 1 ).

Flow chart showing participants enrolled in the study per respective survey years

Study variables

Our dependent variable was adequate ANC visits, which was categorized as four or more ANC visits and coded 1, less than four ANC visits as inadequate were coded 0. Independent variables were respondent’s age at last birth (15-19 years, 20-24 years, 25-29 years, 30-34 years, 35+ years), education level (no formal education, primary education, secondary and higher education), employment status (unemployed, employed), marital status (married/cohabiting, single, divorced/widowed/separated), residence (urban, rural), wealth index (poorest, poorer, middle, richer, richest), zones; these are administrative regions grouped according to geographical location (western zone, northern zone, central zone, southern highlands, southern zone, south west highlands zone, lake zone, eastern zone, Zanzibar), first ANC initiated (women with first ANC visit later than 12 gestational weeks, women with first ANC visit by 12 gestational weeks), decision maker of respondent’s health care (respondent alone, respondent and partner, partner alone, someone else), parity (1 child, 2-3 children, 4-5 children, 6 or more children), frequency of listening to radio (not at all, Less than once a week, at least once a week), frequency of watching TV (not at all, less than once a week, at least once a week), desire of last pregnancy (wanted then, wanted later, wanted no more), history of terminated pregnancy (never had, ever had) and distance from health facility (big problem, not a big problem). The selection of variables was made using the Andersen’s Behavioural Model of Health Services Use [ 20 ]. All these variables were considered as mother’s characteristics and population characteristics in the analysis.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using STATA Corporation, College Station, TX, USA version 14 (Stata/SE 14.2). The analysis considered the complex survey features: primary sampling units, strata, and sampling weights. A Poisson regression analysis was done to determine factors associated with adequate ANC visits. Multivariable Poisson decomposition analysis was conducted to determine factors associated with changes in adequate ANC visits. Decomposition analysis was conducted to understand whether observed changes in adequate ANC visits could be explained by changes in factors over time or in the population structure (population dynamics). To explain the observed change in the percentage of pregnant women attaining adequate ANC visits, we used the Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition analysis [ 21 , 22 , 23 ]. The main goal decomposition analysis was to explain on the individual contributions of the factors on adequate ANC visits differences among pregnant women in Tanzania in different surveys. The differentials in adequate ANC visits between these groups was portioned into two components, one that can be attributable to differences in characteristics and the component that is attributable to the effect of those characteristics. The factors might have a different contribution on the change observed at different survey period. The decomposition analysis was done between two time points, at first, we decomposed survey year 2004/05 to 2010 and lastly survey year 2015/16 to 2010. The baseline survey year was the one with the lowest proportion of pregnant women with adequate ANC visits, thus survey year 2010 for both decomposition analysis. Contributions were considered statistically significant at a P -value of less than 0.05.

Characteristics of the study participants

A total of 17,976 women were included in the analysis. Most of the participants were from rural areas, the mean age (±SD) of the study population was 27.06 (±7.00). More than half of the respondents in each survey had at least primary education level. Most of the participants were married or cohabiting: 85.4, 84.2 and 81.6% for 2004/05, 2010 and 2015/16 survey, respectively. The proportions of women aged 35 to 45 years increased across the survey years, from 15.6%, in 2004/05 to 17.8% in 2015/16. The percentage of women who achieved secondary education and above also increased from 9.2% in 2004/05 to 19.9% in 2015/16 and the percentage of women without formal education decreased from 26.8% in 2004/05 to 19.5% in 2015/16. Substantial regional variation in survey participation was observed; throughout the three surveys, the Lake Zone had the highest percentage of women participating in the survey while the Southern zone had lowest (Table 1 ).

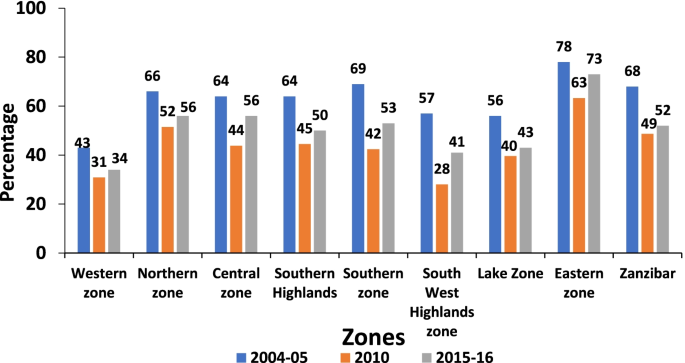

Trends of adequate antenatal care visits

The trend in adequate ANC attendance has fluctuated over time. Adequate ANC attendance decreased from 61% in 2004/05 to 43% in the 2010 survey and then increased again to 51% in the 2015/16 survey (Fig. 2 ). A similar pattern was also found when stratified by geographical zone. The eastern zone had the highest percentage of women with adequate ANC attendance for all three surveys (Fig. 3 ). The percentage of women with four ANC visits who initiated their first ANC visit in the first trimester increased over time (Fig. 4 ).

Percentage of pregnant women with adequate ANC visits from 2004 to 2016

Percentage of pregnant women with adequate ANC visits by zones in Tanzania from 2004 to 2016

Percentage of pregnant women with first ANC visit in first trimester from 2004 to 2016

Factors associated with adequate antenatal care visits

Various factors were associated with adequate ANC visits for each survey, including first ANC in the first trimester, multiparity, wanting pregnancy later, watching TV at least once a week, older age, geographical zone, secondary education and above, reasonable distance to a health facility, richer and richest household wealth index (Table 2 ).

In the multivariable Poisson regression analysis, for all three surveys ANC initiation within the first trimester had a positive effect on adequate ANC visits. The proportion of women with adequate ANC attendance was 1.47 (95% CI: 1.41-1.52) times greater among women who initiated ANC within the first trimester compared to those who initiated later in the 2004/05 survey, 1.96 (95% CI: 1.82-2.11) times higher in 2010, and 1.89 (95% CI: 1.79-2.00) times higher in 2015/16. However, wanting pregnancy later had a negative influence on adequate ANC visits. In the 2004/05 survey, adequate ANC attendance was 0.96 (95% CI: 0.90-1.02) times lower among women who wanted pregnancy later compared to those who wanted pregnancy at that time, 0.82 (95% CI: 0.74-0.92) times lower in 2010, and 0.92 (95% CI: 0.86-0.98) times lower in 2015/16 (Table 2 ).

Factors associated with changes in adequate antenatal care visits across the surveys

The multivariable decomposition regression models found that 95.8% of the decline in adequate ANC visits from 2004/05 (62%) to 2010 (43%) were attributed by changes in the coefficients (mother’s characteristics) and only 4.2% of the decline was due to changes in the population characteristics (population dynamics). There were no significant changes in the population structures during this period, suggesting that the population remained relatively static between the 2004/05 and 2010 surveys. The southwest highland zone contributed 14.2% to the observed decline in the 2004/05 and 2010 surveys, which was statistically significant. It means that the zone where a pregnant woman lived affected her ability to attain adequate ANC. Changes in the initiation of the first ANC within the first trimester slowed the decline by 8.7%, which was also statistically significant (Table 3 ).

The proportion of women attaining adequate ANC increased from 43% in 2010 to 51% in 2015/16. The slight increase was attributed to 33.8% of changes due to the coefficients and 66.2% due to the changes in the population characteristics. These changes were statistically significant with a p -value of <0.001. The increase in the proportion of women who initiated ANC during the first trimester contributed 50.5% to the increase observed in 2010 to 2015/16 surveys. This was statistically significant at a p -value of <0.001. In the contributions due to differences in coefficients, the southwest highlands contributed 21.4% to the overall increase (Table 4 ).

The study findings for all the three surveys suggest that women who had their first ANC visit within the first 12 weeks of pregnancy were more likely to achieve adequate ANC visits. These findings are consistent with other studies done in Tanzania, Peru, Cambodia, Cameroon, Senegal, Uganda and Nepal [ 24 , 25 ]. This similarity can be explained by various interventions that have been conducted in the mentioned countries on ANC utilization as well as early initiation of ANC visits among pregnant women. This positive association between early ANC initiation and adequate ANC visits has also been reported in many other literatures.

The decomposition analysis suggests that changes in population structure and the effects contributed to the variations in adequate ANC visits overtime. Furthermore, the Tanzania Service Provision Assessment Survey reported on differentials in the quality and availability of health care services offered across regions [ 26 ]. In some ways, this can explain the decline observed in the 2004/05 and 2010 surveys. Also, time interval between the two surveys which was a transitional stage in maternal health care as Tanzania adopted FANC in 2002, and challenges in the rollout of the new intervention. Although, we cannot overlook the role of quality of ANC services offered, as it has been documented that poor quality could negatively affect ANC attendance. This may have contributed to the decline observed, although this study was unable to address this [ 11 , 25 , 27 , 28 ].

For the 2010 and 2015-16 surveys, the first ANC within the first trimester attributed 50.5% of the increase in the proportion of women wo attained adequate ANC visits to differences due to population structure. Efforts to ensure Tanzania reached the MDG 4 and 5 by 2015 and “Wazazi Nipendeni campaign” in 2012 could explain the increase in adequate ANC attendance in 2010 and 2016 [ 14 , 16 ]. For the southwest highlands, the increase in the proportion of pregnant women with adequate ANC visits could be attributed to the Wazazi na Mwana campaign in 2 councils in Rukwa one of the regions included in the zone [ 29 , 30 ]. While it is not possible to directly attribute the impact of these campaigns, they likely played a part in the observed increase in early ANC initiation, which is a contributing factor to adequate ANC attendance. Strengthened and focused efforts are needed where early ANC initiation and subsequent adequate ANC attendance remain sub-optimal. So, a need to focus on other regions in Tanzania to promote early ANC initiation and subsequently lead to an increase in the number of women attaining adequate ANC.

The results of this study indicate that adequate ANC attendance has been declining from 2004 to 2010 but a gradual increase has been observed in 2016. ANC initiation within the first twelve weeks of pregnancy has greatly contributed to the recent observed increased proportion of pregnant women who attained four or more ANC visits in Tanzania.

Study limitation and strength

The study has successfully identified factors associated with changes in adequate ANC visits among pregnant women in Tanzania. With this, it is possible to reallocate the limited resources in Tanzania to focus on the factors that have shown to have a great contribution and influence on attaining adequate ANC visits among pregnant women in Tanzania. We have used nationally representative data which makes the study findings generalizable to the entire nation.

Data on the quality of ANC service was not analyzed in this study, we failed to establish its effect on adequate ANC attendance. Also, the analysis did not include biomedical data on HIV status which could have overestimated the number of ANC visits as HIV-positive women attend ANC on monthly basis. Also, the study is prone to social desirability bias as the women are aware of the recommended minimum ANC visits, which could have overestimated the effects. This study is a Crossectional study, no temporal relationship can be established.

Recommendation

Basing on the findings obtained, we would recommend the MOHCDGEC and implementing partners to put more effort on promoting the first ANC visit to be initiated within the first twelve weeks of pregnancy. This should be done hand in hand with providing mass education on the importance of ANC visits and why a pregnant women should adhere to the ANC comprehensive package. Intervention should be done at facility and community level. This will enable mothers and the communities to be informed on the pivotal role of ANC services as far as the safety of the mother and child is concerned and ensure continuous support from their families. Regional focused interventions such as ‘Wazazi na Mwana Campaign’ should be rolled out in regions with low uptake of ANC services. Further research to assess the quality of ANC services offered as it may have contributed to the changes observed and sub-optimal ANC attendance while we have a 98% coverage of at least one ANC visit among pregnant women in Tanzania.

Availability of data and materials

Data and material will be available upon request from the corresponding author with authorization form demographic and health survey program, measure DHS.

Abbreviations

- Antenatal care

Adjusted Prevalence Ratios

Focused Antenatal Care

Low Birth Weight

Millennium Development Goals

Maternal Mortality Ratio

Sustainable Development Goals

Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey

World Health Organization

WHO. The World Health Report 2005: make every mother and child count The World Health Report 2005: World Heal Rep; 2005.

World Health Organization. Maternal mortality fact sheet. Dept Reprod Heal Res World Heal Organ. 2014;4.

Downe S, Finlayson K, Tunçalp, Metin Gülmezoglu A. What matters to women: a systematic scoping review to identify the processes and outcomes of antenatal care provision that are important to healthy pregnant women. BJOG. 2016;123(4):529–39.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Haftu A, Hagos H, Mehari MAB, Brhane G. Pregnant women adherence level to antenatal care visit and its effect on perinatal outcome among mothers in Tigray Public Health institutions , 2017 : cohort study. BMC Res Notes. 2018:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-018-3987-0 .

Ntui AN, Jolly PE, Carson A, Turpin CA, Zhang K, Berhanu T, et al. Antenatal care attendance, a surrogate for pregnancy outcome? The case of Kumasi, Ghan. Matern Child Heal J. 2016;18(5):1085–94.

Google Scholar

Gupta R, Talukdar B. Frequency and timing of antenatal care visits and its impact on neonatal mortality in EAG States of India. J Neonatal Biol. 2017;06(03) Available from: https://www.omicsonline.org/open-access/frequency-and-timing-of-antenatal-care-visits-and-its-impact-on-neonatal-mortality-in-eag-states-of-india-2167-0897-1000263-97029.html .

Blencowe H, Cousens S, Jassir FB, Say L, Chou D, Mathers C, et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of stillbirth rates in 2015, with trends from 2000: A systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Heal. 2016;4(2):e98–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00275-2 .

Article Google Scholar

Govender T, Reddy P, Ghuman S. Obstetric outcomes and antenatal access among adolescent pregnancies in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa Obstetric outcomes and antenatal access among adolescent pregnancies in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. South African Fam Pract. 2018;60(1):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/20786190.2017.1333783

Organization world health. WHO Recommendation on Antenatal care for positive pregnancy experience. WHO Recomm Antenatal care Posit pregnancy Exp. 2016;152. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/250796/1/9789241549912-eng.pdf .

World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience: Summary. Who. 2018;10(January):176.

Kearns A, Hurst T, Caglia Jacquelyn LA. Focused antenatal care in Tanzania. Women Heal Initiat. 2014;(July):1–13 Available from: http://www.mhtf.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/32/2014/09/HSPH-Tanzania5.pdf .

UNICEF. ANTENATAL CARE [Internet]. Available from: https://data.unicef.org/topic/maternal-health/antenatal-care/ .

Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender E and CM, Ministry of Health, National Bureau of Statistics, Office of Chief Government Statistician, ICF. Tanzania demographic and health survey and malaria indicator survey 2015-2016. 2016; Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR321/FR321.pdf .

Evaluation A, Safe N, Campaign M. An evaluation of Tanzania ’ s national safe motherhood campaign an evaluation of Tanzania ’ s national safe motherhood campaign. 2014;(September).

Exavery A, Kanté AM, Hingora A, Mbaruku G, Pemba S, Phillips JF. How mistimed and unwanted pregnancies affect timing of antenatal care initiation in three districts in Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:1–11.

Bliss KE, Streifel C. Targeting big results in maternal, neonatal , and child health. 2015;(May).

Teplitskaya AL, Dutta A, Saint-firmin P, Wang Z. Maternal Health Services in Tanzania: determinants of use and related financial barriers from 2015-16 survey data. 2018;(May).

Titaley CR, Dibley MJ, Roberts CL. Factors associated with underutilization of antenatal care services in Indonesia: Results of Indonesia Demographic and Health Survey 2002/2003 and 2007. BMC Public Health. 2010;10.

Joshi C, Torvaldsen S, Hodgson R, Hayen A. Factors associated with the use and quality of antenatal care in Nepal : a population-based study using the demographic and health survey data; 2014. p. 1–11.

Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36(1):1–10.

Thomas K. RWI : Discussion papers; 2006.

Mavromaras KG. No 70 Male-female labour market participation and wage differentials in Greece Male-female labour market participation and wage differentials in Greece. 1999;(70):1–39.

Ospino CG. La descomposición salarial de Oaxaca- Blinder : Métodos , críticas y aplicaciones. Una revisión de la literatura. 2011;237–74.

Saad-Haddad G, DeJong J, Terreri N, Restrepo-Méndez MC, Perin J, Vaz L, et al. Patterns and determinants of antenatal care utilization: analysis of national survey data in seven countdown countries. J Glob Health. 2016;6(1) Available from: http://www.jogh.org/documents/issue201601/jogh-06-010404.pdf .

Gupta S, Yamada G, Mpembeni R, Frumence G, Callaghan-Koru JA, Stevenson R, et al. Factors associated with four or more antenatal care visits and its decline among pregnant women in Tanzania between 1999 and 2010. PLoS One. 2014;9(7).

Provision S, Survey A. Service provision assessment survey 2006 (TSPA). 2006;2006.

Nyamtema AS, Jong AB, Urassa DP, Hagen JP, van Roosmalen J. The quality of antenatal care in rural Tanzania: what is behind the number of visits? BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12(1):1 Available from: ???

Magoma M, Requejo J, Merialdi M, Campbell OMR, Cousens S, Filippi V. How much time is available for antenatal care consultations? Assessment of the quality of care in rural Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2011;11(1):64 Available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2393/11/64 .

MoHSW, Africare, Plan International, JHPIEGO. WAZAZI NA MWANA PROJECT BRIEF. 2015. Available from: http://www.africare.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/Tanz_Project-Brief_Wazazi-na-Mwana_web.pdf .

Moshi FV, Kibusi SM, Fabian F. The effectiveness of community-based continuous training on promoting positive behaviors towards birth preparedness, male involvement, and maternal services utilization among expecting couples in rukwa, Tanzania: a theory of planned behavior quasi-experim. J Environ Public Health. 2018;2018.

Download references

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Kilimanjaro Christian Medical University college and Sub-Saharan Africa Consortium for Advanced Biostatistics Training program for making it possible to carry out this study. And the Demographic and Health Survey Program granted access to use the TDHS data for this study. My sincere gratitude to the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics at Kilimanjaro Christian Medical University College and Epidemiology and classmates for their continuous support.

This work was supported through the DELTAS Africa Initiative Grant No.107754/Z/15/ZDELTASAfrica SSACAB. The DELTAS Africa Initiative is an independent funding scheme of the African Academy of Sciences (AAS) ‘s Alliance for Accelerating Excellence in Science in Africa (AESA) and supported by the New Partnership for Africa’s Development Planning and Coordinating Agency (NEPAD Agency) with funding from the Wellcome Trust (Grant No. 107754/Z/15/Z) and the UK government. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of AAS, NEPAD Agency, Wellcome Trust, the UK government.

The funding made it possible for me to undertake my postgraduate studies in which this research was done as part of requirements for the fulfilment of the postgraduate studies.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Institute of Public Health, Kilimanjaro Christian Medical University College (KCMUCo), P.O Box 2240, Kilimanjaro, Tanzania

Elizabeth Kasagama

London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSTM), London, UK

Jim Todd & Jenny Renju

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Concept development and study design: EK, JT, JR; Data acquisition: EK; Supervision of the

study: JT, JR; Data analysis and statistical support: EK, JT, JR; critically revised the manuscript: EK,

JT, JR; All authors read and finally approved the manuscript draft for publication.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Elizabeth Kasagama .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Ethical approval to conduct the study was obtained from the Kilimanjaro Christian Medical University college research ethical committee. The ethical approval number granted was 2389.

Since this study used the Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey data, permission to access the datasets was sought form Demographic and Health Survey Program. Datasets used are openly accessible at DHS measure website; http://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm .

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Kasagama, E., Todd, J. & Renju, J. Factors associated with changes in adequate antenatal care visits among pregnant women aged 15-49 years in Tanzania from 2004 to 2016. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 22 , 18 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-04350-y

Download citation

Received : 28 April 2020

Accepted : 18 December 2021

Published : 07 January 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-04350-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Adequate ANC

- Maternal health

- Maternal mortality

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth

ISSN: 1471-2393

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Why does the number of antenatal care visits in Ethiopia remain low?: A Bayesian multilevel approach

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Public Health Department, School of Health Science, Madda Walabu University, Bale Goba, Ethiopia

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation School of Public Health, Adama Hospital Medical College, Adama, Ethiopia

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Center for Transdisciplinary Research, Saveetha Dental College, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences (SIMATS), Saveetha University, Chennai, India, Center for Evidence-Based Research, Global Health Research and Innovations Canada (GHRIC), Toronto, ON, Canada

- Daniel Atlaw,

- Tesfaye Getachew Charkos,

- Jeylan Kasim,

- Vijay Kumar Chatu

- Published: May 3, 2024

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0302560

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

Introduction

Antenatal care (ANC) visit is a proxy for maternal and neonatal health. The ANC is a key indicator of access and utilization of health care for pregnant women. Recently, eight times ANC visits have been recommended during the pregnancy period. However, nearly 57% of women received less than four ANC visits in Ethiopia. Therefore, the objective of this study is to identify factors associated withthe number of ANC visits in Ethiopia.

A community-based cross-sectional study design was conducted from March 21 to June 28/2019. Data were collected using interviewer-administered questionnaires from reproductive age groups. A stratified cluster sampling was used to select enumeration areas, households, and women from selected households. A Bayesian multilevel negative binomial model was applied for the analysis of this study. There is an intra-class correlation (ICC) = 23.42% and 25.51% for the null and final model, respectively. Data were analyzed using the STATA version 17.0. The adjusted incidence risk ratio (IRR) with 95% credible intervals (CrI) was used to declare the association.

A total of 3915 pregnant women were included in this study. The mean(SD) age of the participants was 28.7 (.11) years. Nearly one-fourth (26.5%) of pregnant women did not have ANC visits, and 3% had eight-time ANC visits in Ethiopia. In the adjusted model, the age of the women 25–28 years (IRR:1.13; 95% CrI: 1.11, 1.16), 29–33 years (IRR: 1.15; 95% CrI: 1.15, 1.16), ≥34 years (IRR:1.14; 95% CrI: 1.12, 1.17), being a primary school (IRR: 1.22, 95% CrI: 1.21, 1.22), secondary school and above (IRR: 1.26, 95% CrI: 1.26, 1.26), delivered in health facility (IRR: 1.93; 95% CrI: 1.92, 1.93), delivered with cesarian section (IRR: 1.18; 95% CrI: 1.18, 1.19), multiple (twin) pregnancy (IRR: 1.11; 95% CrI: 1.10, 1.12), richest (IRR:1.23; 95% CrI: 1.23, 1.24), rich family (IRR: 1.34, 95% CrI: 1.30, 1.37), middle income (IRR: 1.29, 95% CrI: 1.28, 1.31), and poor family (IRR = 1.28, 95% CrI:1.28, 1.29) were shown to have significant association with higher number of ANC vists, while, households with total family size of ≥ 5 (IRR: 0.92; 95% CrI: 0.91, 0.92), and being a rural resident (IRR: 0.92, 95% CrI: 0.92, 0.94) were shown to have a significant association with the lower number of ANC visits.

Overall, 26.5% of pregnant women do not have ANC visits during their pregnancy, and 3% of women have eight-time ANC visits. This result is much lower as compared to WHO’s recommendation, which states that all pregnant women should have at least eight ANC visits. In this study, the ages of the women 25–28, 29–33, and ≥34 years, being a primary school, secondary school, and above, delivered in a health facility, delivered with caesarian section, multiple pregnancies, rich, middle and poor wealth index, were significantly associated with the higher number of ANC visits, while households with large family size and rural residence were significantly associated with a lower number of ANC visits in Ethiopia.

Citation: Atlaw D, Charkos TG, Kasim J, Chatu VK (2024) Why does the number of antenatal care visits in Ethiopia remain low?: A Bayesian multilevel approach. PLoS ONE 19(5): e0302560. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0302560

Editor: Kahsu Gebrekidan, UiA: Universitetet i Agder, NORWAY

Received: November 18, 2023; Accepted: April 9, 2024; Published: May 3, 2024

Copyright: © 2024 Atlaw et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: The data underlying the results presented in the study are available from ( https://www.dhsprogram.com/Data/ ).

Funding: The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Antenatal care (ANC) visit is a proxy for maternal and neonatal health. The ANC visit is a key indicator of access to and utilization of health care for pregnant women. It is one of the important components of maternal and child health care services for reducing maternal and neonatal mortality rates [ 1 , 2 ]. Early initiation and encouraging regular visits are important to reduce pregnancy complications [ 3 ]. For instance, a systematic review in Ethiopia revealed that a focused quality ANC significately reduces neonatal mortality by 34% [ 4 ]. The main objective of ANC is the early identification of preexisting diseases or risk factors that occur during pregnancy and childbirth, as well as promoting the well-being of mothers and their newborns [ 4 – 6 ]. The ANC package is important to prepare for birth and avoid threats affecting mothers and babies during pregnancy [ 7 ].

About 15% of pregnancies result in life-threatening complications that require intervention by a skilled healthcare providers [ 8 ]. In middle and low-income countries, complications during pregnancy and childbirth are major causes of death and disability among reproductive-age women [ 9 , 10 ]. To decrease the avoidable causes of maternal and neonatal mortality, WHO recomemded a minimum of eight or more ANC visits [ 11 ]. However, in Africa, women lack access to health facilities and quality ANC service due to distance, cultural beliefs, cost of transportation, and barriers in attitudes [ 12 ]. The utilization of eight or more ANC visits is only 6.8% in Sub-Saharan Africa [ 13 ]. About 32% of pregnant women did not receive ANC visits throughout their pregnancy period in Ethiopia [ 11 ]. Previous studies revealed that as the number of ANC visits increases, maternal and neonatal morbidity [ 14 ] and mortality were shown to decrease [ 15 – 18 ]. In Ethiopia, although ANC service coverage was increased, the recommended number of ANC visits was not achieved at the national level [ 15 ].

Currently, in Ethiopia, the overall coverage of ANC visits is nearly 74%, but the number of four ANC visits is around 43% [ 19 ]. In terms of access to health facilities, the ratio of health facilities including health post to pregnant women is 1:185, while the number of midwives to pregnant women is 1:162 [ 20 ]. Some studies identified factors like lack of information on the importance of ANC, distance from health facilities, and culture as main contributors to low coverage [ 15 , 21 ]. To increase the number of ANC visits, it is important to identify factors that affect ANC visits in Ethiopia.

Different studies were conducted in Ethiopia, but the previous studies were conducted on utilization level [ 22 , 23 ], time of initiation [ 3 , 24 – 27 ], and associated factors [ 3 , 12 , 26 ] rather than focusing on the number of visits, which may result in loss of information in classification count data. Further, the previous studies were conducted with the older recommendation of WHO, which emphasis on focused four ANC visits. Currently, WHO has revised the previous guideline to increase the number of ANC visits to eight or more [ 28 ]. Therefore, this study, aimed to identify community and individual-level determinants of the number of ANC visits in Ethiopia.

Study setting and design

Ethiopia is one of the East African countries, that has 10 regional states (Afar, Amhara, Benishangul-Gumuz, Gambella, Oromia, Somali, Southern Nations, Nationalities and People’s (SNNP), Harari, Sidama, and Tigray), and two metropolis towns (Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa). It is estimated that the total population of Ethiopia is 105,163,988 [ 29 ]. Of this, 52,439,998 (4.98%) are women of reproductive age [ 29 ]. The Ethiopian Ministry of Health provides maternal health services free of charge. A cross-sectional community-based study design was conducted from March 21 to June 28 /2019, among reproductive-age women in Ethiopia.

Data source and sampling

The Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) data are collected nationally every 5 years on key indicators. Data were collected using an interviewer-administered questionnaire from reproductive age (15–49 years) women. The questionnaire includes socio-demographic, socioeconomic, and service-related maternal health variables [ 19 ]. The source of data for this analysis was from the DHS website ( www.dhsprogram.com ) after requesting permission by submitting a protocol for the study.

A two-stage stratified cluster sampling was employed to select a total of 305 enumeration areas (EAs) using probability proportional to EA size. Out of which 93 were urban and 212 were rural areas. Independent selection was applied in each sampling stratum [ 19 ].

Then a fixed number of 30 households per cluster were selected using systematic sampling. From each selected household all reproductive-age women were eligible for interview. About 8885 women were interviewed of which 3962 women were delivered within 5 years before the survey and they were interviewed for ANC visits [ 19 ]. From 3962 women interviewed 3915 were included for analysis of this study while 47 women were excluded due to missed information on the outcome of interest [ Fig 1 ].

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0302560.g001

Data collection procedures

The Ethiopia Mini Demographic and Health Survey (EMDHS) was conducted for the second time in Ethiopia in 2019. The DHS Program’s standard questionnaires served as the basis for the questionnaires’ preparation, which involved modifications to account for Ethiopia’s unique population and health issues. The questionnaires were translated into Amarigna, Tigrigna, and Afaan Oromo after they were finalized in English [ 19 ].

Basic demographic data, such as age, sex, education level, and relationship to the head of the household, were gathered for each individual on the list. The Household Questionnaire’s data on the gender and age of household members was utilized to determine which women qualified for individual interviews. Information on the features of the household’s dwelling unit, such as the type of toilet facilities, the materials used for the floor, and the possession of different durable goods, was also gathered using the Household Questionnaire [ 19 ].

The Woman’s Questionnaire was used to collect information from all eligible women aged 15–49. The primary subjects of inquiry for these women were: background details; reproduction; contraception; pregnancy, antenatal care, and postpartum care. Responses were recorded during the 2019 EMDHS interviews using tablet computers by the interviewers. The tablets had Bluetooth capabilities, which allowed for remote electronic file transfers between interviewers and supervisors and between interviewers and completed questionnaires within the computer-assisted personal interviewing (CAPI) system. The DHS Program used the mobile version of the Census and Survey Processing (CSPro) System to develop the electronic data collection system used in the 2019 EMDHS. The DHS Program, CSPro, and the US Census Bureau collaborated to develop the CSPro software [ 19 ].

Data quality assurance

The 2019 EMDHS trainers’ course took place in Adama from February 11–20, 2019. It consisted of fieldwork, and paper-and CAPI-based in-class training. The fieldwork was carried out in Adama within the clusters that were excluded from the EMDHS sample for 2019. The training of trainers was attended by a total of seventeen trainees. All of the trainees had some background in conducting household surveys, either from participation in earlier DHS surveys conducted in Ethiopia or from surveys using comparable protocols. Lessons learned from the exercise were integrated into the questionnaires for the main training after a debriefing with the trainee field staff took place after field practice [ 19 ].

The EMDHS main training was conducted from February 27 to March 19, 2019, at the Central Hotel in Hawassa. For the primary fieldwork, EPHI hired and trained 151 health professionals to work as field supervisors, regional coordinators, female interviewers, female CAPI supervisors, and field supervisors, among other roles. The training’s main goal was to equip participants with the skills necessary to administer questionnaires based on paper and CAPI [ 19 ].

In-class mock interviews, practice interviews with actual respondents in areas outside the survey sample, a thorough review of the questionnaire content, instructions on how to administer the paper and CAPI questionnaires, and instructions on interviewing techniques and field procedures made up the training course. Additionally, training was provided in fieldwork coordination and data quality control procedures for regional coordinators, field supervisors, and CAPI supervisors [ 19 ].

Data collection for the 2019 EMDHS was done by 25 interviewing teams. One field supervisor, one female CAPI supervisor, two female interviewers, and one female anthropometrist made up each team. In addition to the field teams, 11 regional coordinators were assigned, one for each region. Throughout the fieldwork period, the respective teams were regularly visited by the regional coordinator, who stayed with them to oversee and monitor their work and progress. In addition, ten employees of EPHI oversaw and planned fieldwork tasks. EPHI researchers, an ICF technical specialist, a consultant, and representatives from other organizations, including CSA, FMoH, the World Bank, and USAID, supported the fieldwork monitoring [ 19 ].

Study variables and measurements

The response variable of this study was the number of ANC visits. Both community and individual variables are considered as predictor variables. Community water sources are classified as improved and unimproved water sources, place of residence (urban and rural), and region (the ten Ethiopian regions were recoded into three larger categories agrarian, pastoralist, and metropolis). Four regions namely (Tigray, Amhara, Oromia, and Southern Nations, Nationalities People’s Region (SNNPR)) were recoded into the agrarian region. Three regions namely (Afar, Somali, Benishangul, and Gambella) were recorded as pastoralist regions. While, Harari, Addis Ababa, and Dire Dawa are among the metropolises’ administration regions.

The individual - level variables: Age, level of education, birth order, wealth index, number of under-five children, family size, place of delivery, mode of delivery, marital status and multiple pregnancies were considered as individual level variable label variables.

Data analysis

Since EDHS data are hierarchical, using a standard model decreases the standard error of effect size since the sample size is larger [ 30 ], which in turn decreases the confidence interval of the estimate which affects significance of the estimate [ 31 , 32 ]. Women in a cluster may have similar characteristics to those in the other cluster. This similarity within the cluster will violate the rule of independence of observation and equal variance across the cluster. Therefore, using a multilevel model is best for this data rather than using a standard model which helps to compute both fixed effect and random effect variation simultaneously.

A poison regression model is proposed to use for this study, because of dependent variable is the number of ANC visits, which is a countable variable. However, the assumption of poison regression is not met (data is over-dispersed: variance is larger than mean). Therefore, the negative binomial model is more appropriate than the standard Poisson regression model.

In this analysis four models were fitted to estimate a fixed effect for individual and community-level variables and a random effect for variation among clusters. Since the measure of the variation of the cluster was significant indicating a higher intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC).

A Bayesian multilevel negative binomial regression model was used as it is not dependent on the p-value to determine whether the variable is significant or not. The p-value may lead to imprecise evidence as it depends on small size. The prior information for each coefficient of the variables assumed that normally distributed with zero mean and 10,000 variances.

The data were correlated, having intra-class correlation (ICC) = 23.42% and 25.51% for the null and saturated model, respectively, since the value is greater than 5 percent correlation is significant within clusters [ 33 ]. The multilevel fitted with four models: Model I (null model) was done without independent variables. Model II was fitted for variables at the individual level, Model III was fitted for variables at the community level, and Model IV was adjusted for individual and community-level variables. The fourth model was fitted to estimate the independent effects of variables both at the community and individual levels on the number of ANC visits. Adjusted incidence ratio (IRR) with 95% credible intervals (CrI) was used to declare association. The goodness of fit test was assessed using the deviance information criterion (DIC). Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) < 5 was considered to check multicollinearity between the individual and community-level variables. All analysis were using STATA version 17.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethical clearance was provided by the Ethiopia Health and Nutrition Research Institute Review Board. Informed verbal consent was obtained from each woman. The data for this study was obtained after submitting a protocol explaining the objective of the study to the DHS program online. The details of the ethical issues have been published in the EDHS final report, which can be accessed at: http://www.dhsprogram.com .

Characteristics of the study participants

Of the total study subjects, 30.4% of the women were between 25–29 years old, and the mean (SD) age of the participants was 28.7 (.11) years. Concerning their education, more than half of the women do not have formal education (51.3%), while only about 3.8% of them attended higher education. Most of the women were married (93.9%), from agrarian regions (87.5%), and rural areas (73.9%) [ Table 1 ].

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0302560.t001

Out of the total pregnant women in this study, 26.5% do not have ANC visits during their pregnancy, 21.4% of women have at least four ANC visits, and only 3% have at least eight ANC visits [ Fig 2 ].

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0302560.g002

Factors associated with the number of ANC visits in Ethiopia

Individual level determinants..

The number of ANC visits was identified to be higher among women in the age group of 25–28 years, 29–33 years, and ≥34 years than women in the group ≤24 years by 13.2% (IRR: 1.13; 95% CrI: 1.11, 1.16), (IRR: 1.15; 95% CrI: 1.15, 1.16) and (IRR:1.14: 95% CrI: 1.12, 1.17), respectively. Women who have attended primary education were shown to have an increased number of ANC visits by 22% (IRR: 1.22, 95% CrI: 1.22, 1.23) compared with those who did not have attended formal education, while attending secondary school and above shown to increase the number of ANC visit by 26% (IRR: 1.26, 95% CrI: 1.26, 1.26) [ Table 2 ].

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0302560.t002

Women who delivered in a health facility were two times more likely to have a higher number of ANC visits compared with women who delivered at home (IRR: 1.93; 95% CrI: 1.92, 1.93). Similarly, women who delivered with cesarian section were shown to have a higher number of ANC visits compared with women delivered with spontaneous vaginal delivery by 18% (IRR: 1.18; 95% CrI: 1.18, 1.19). Women with multiple (twin) pregnancies were shown to have a higher number of ANC visits by 11% (IRR: 1.11; 95% CrI: 1.10, 1.12) compared with women who have singleton pregnancies. Concerning birth interval of preceding pregnancy women with an interval greater than 36 months were shown to have a higher number of ANC visits by 22% (IRR: 1.22; 95% CI: 1.21, 1.23) compared with women having birth interval of less than 24 months [ Table 2 ].

Women from households who have a total family size of ≥ 5 were shown to have decreased the number of ANC visits by 9.4% (IRR: 0.92; 95% CrI: 0.91, 0.92) compared with women from households who have a total family size < 5. Concerning the wealth index, it is revealed that women from the richest, rich, middle, and poor households were shown to have increased number of ANC visits by 28.8% (IRR:1.23; 95% CrI: 1.23, 1.24), 29.4% (IRR: 1.34; 95% CrI: 1.30, 1.37), 34.2% (IRR:1.29; 95% CrI: 1.28, 1.31) and 24% (IRR: 1.29, 95% CI:1.29, 1.30), respectively compared to women from poorest households [ Table 2 ].

Community level determinants.

Women from the rural area were shown to have a reduced number of ANC visits by 8% (IRR: 0.92, 95% CI: 0.93, 0.94) compared to women from the urban area [ Table 2 ]. Similarly, women from areas with unimproved water sources were identified to have a reduced number of ANC visits by 6.8% (IRR: 0.92, 95% CI: 0.91, 0.92) compared with women from areas with improved water sources. The number of ANC visits was reduced by 22.6% (IRR: 0.77, 95% CI: 0.77, 0.78) among women from pastoralist regions compared to women from agrarian regions, while it was increased by 1% (IRR:1.01, 95% CI: 1.01, 1.04) among women from metropolis region [ Table 2 ].

In Ethiopia, nearly one-fourth of women did not have ANC visits, and only 3% of women have eight ANC visits during the whole pregnancy, which WHO currently recommends. This finding is slightly higher than the study conducted in 2016 [ 34 ]. The difference may be due to variations in the study period, and the recommendation of the new guidelines by WHO in 2016 might have contributed to the difference. A similar data collection tool was used in 2016 and 2019 EHDS but, there is a variation in sample size 3915 in 2019, while it was 7591 in 2016 which might contribute to the difference.

The finding from this study revealed that the number of ANC visits increases with the increasing age of women. The women in the age group of higher than 24 years were shown to have a higher count of ANC visits than women in the age group of ≤ 24 years. This finding is supported by a study conducted in Nigeria and Malawi in 2017 [ 35 ]. At the same time, it is contradicted by another study conducted in Ethiopia, which revealed that the likelihood of ANC visits decreases among women in the age group of 35 to 49 years and increases among women between the ages of 15 to 19 years [ 34 ]. The difference might be due to the different models used for this data, and the authors used the Bayesian model, which is a more appropriate and representative sample simulated.

This study also identified that the number of ANC visits improves with women’s educational level, and women who have attended formal education were shown to have an increased number of ANC visits compared with women who did not. Previous studies in Ethiopia also support the current finding [ 4 , 36 , 37 ]. This finding is also supported by a study conducted in sub-Saharan Africa from 2008 to 2019 [ 36 , 38 ]. Further, it is consistent with a study conducted in Bangladesh in 2020 [ 10 ] and Nigeria in 2020 [ 39 ]. Similarly, another study conducted in Indonesia also identified that educated women utilize more ANC visits than women who did not have formal education [ 40 ]. This might be because educated women have a higher chance of receiving information on the benefits of ANC visits because of their exposure to mass media [ 38 ]. In addition, women who have formal education may know the benefit of ANC visits to the health of mothers and their newborns.

ANC visits increase as the family wealth index increases from poor to rich. This study revealed that women from rich, middle-class families have a higher number of ANC compared with those from poor families. The finding aligns with previous studies conducted in Ethiopia [ 4 , 37 , 41 ]. Similarly, a population-based study conducted in Guinea also reported that educated women are more likely to utilize ANC than non-educated women [ 42 ]. Further, this finding is supported by a study conducted in East African countries [ 43 ] and a population-based study from Nepal [ 39 ]. This might be because women from rich wealth index were more likely to be exposed to mass media, and in addition to this, women from rich families are more likely to have access to health facilities [ 44 ].

Women from rural areas were shown to have a reduced number of ANC visits compared with urban residents. This finding is supported by different studies conducted in Ethiopia [ 27 , 37 , 41 ], Guinea [ 45 ], Pakistan [ 46 ], the Philippines, and Indonesia [ 47 ]. This may be because women from rural areas have low access to health facilities and inadequate information on the importance of having an adequate number of ANC visits.

The number of ANC visits was reduced among women from the pastoralist region compared to women from the agrarian region, while it was increased among women from the metropolis region. Even though different studies conducted in Ethiopia have not reported using the current classification of regions, three studies reported that being in the dominating rural regions was less likely to have an increased number of ANC visits than the metropolis region [ 6 , 19 , 41 ]. This may be because women in the pastoralist region are less likely to attend education compared with agrarian and metropolis regions.

Limitation of the study

Recall bias may be present because of the cross-sectional design of the study, which makes it impossible to determine the precise cause-and-effect relationship between the number of ANC and its predictors. The study’s inability to evaluate certain significant variables, such as the distance to the health facility, the husband’s educational status, and media exposure.

In this study, out of the total ANC candidate women, about 26.5% did not have ANC visits during their pregnancy, and only 3% were shown to have eight and above ANC visits. Factors like, the ages of the women 25–28, 29–33, and ≥34 years, being a primary school, secondary school, and above, delivered in a health facility, delivered with caesarian section, multiple pregnancies, rich, middle and poor wealth indexincome family, were significantly associated with the higher number of ANC visits, while households with large family size and rural residence were significantly associated with a lower number of ANC visits in Ethiopia. Therefore, improving women’s education, empowering household income, and providing health education, especially for women in pastoralist regions, may increase the number of ANC visits recommended by WHO; thereby, maternal and child health will be improved.

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 19. Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EPHI). Ethiopia Mini Demographic and Health Survey 2019: Final Report [Internet]. 2021. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR363/FR363.pdf

- 20. Federal Ministry of Health. health and health related indicators. 2021.

- 28. WHO. 2016 WHO Antenatal Care Guidelines Malaria in Pregnancy Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ). 2018.

- 29. Central statistical Agency. Population Size by Sex, Area and Density by Region, Zone and Wereda. 2022.

- Open access

- Published: 31 May 2019

Late initiation of antenatal care and associated factors among pregnant women in Addis Zemen primary hospital, South Gondar, Ethiopia

- Haileab Fekadu Wolde 1 ,

- Adino Tesfahun Tsegaye 1 &

- Malede Mequanent Sisay 1

Reproductive Health volume 16 , Article number: 73 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

22k Accesses

50 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Antenatal care (ANC) is special care for pregnant women with the aim of preventing, detecting and treating health problems in both the fetus and mother. Early ANC attendance promotes early detection and treatment of complications which result in proper management during delivery and puerperium. However, the majority of pregnant women in Ethiopia initiate their ANC late. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the prevalence of late initiation of ANC and its associated factors among attendants in Addis Zemen primary hospital.

An institution-based cross-sectional study was conducted at Addis Zemen primary hospital from February 7 to June 122,018. The systematic random sampling technique was employed to select 369 pregnant women who attended ANC in the hospital. Data cleaning and analysis was done using SPSS version 25 statistical software. Descriptive statics and bi variable and multivariable logistic regression models were employed to assess the magnitude and factors associated with late initiation of ANC defined as making the first visit after 12 weeks of gestation.

This study indicated that 52.5% of the attendants initiated ANC late. The multivariable logistic regression analysis showed that being housewife (Adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 2.85, 95% CI: 1.36, 5.96), self-employment (AOR = 2.38, 95% CI: 1.12, 5.04), travel expenses (AOR = 1.72, 95% CI: 1.05, 2.81), poor knowledge about ANC (AOR = 2.98, 95% CI: 1.78, 5.01) and unplanned pregnancy (AOR = 2.31, 95% CI: 1.28, 4.16) were significantly associated with late ANC initiation.

The prevalence of late ANC initiation remains a major public health issue in Ethiopia. The major factors for being late were found to be poor knowledge, being housewife, and self-employment, travel expenses and unintended pregnancy. District and zonal health offices should work to create awareness about the importance of early initiation of ANC, make the service closer to the community and increase contraceptive utilization.

Peer Review reports

Plain English summery

Antenatal care is a special care that is provided for pregnant women with the aim of improving the health of the unborn baby and the mother. According to WHO recommendation, every pregnant women should book ANC before 12 weeks of gestation. Early initiation of ANC has the benefit of early detection and treatment of complications during pregnancy. However, the majority of women in Ethiopia initiate ANC late. Therefore, the objective of this study was to assess the magnitude of late initiation of ANC and factors affecting it among ANC attendants in Addis Zemen primary hospital.

Of the total 364 participants, 191 started their follow up late. Being housewife, self employment, travel cost, poor knowledge about ANC and unintended pregnancy were the factors that increased the likelihood of initiating ANC late.

In conclusion, late initiation of ANC was high in the study area. Poor knowledge level, being housewife and self-employment, travel expenses and unintended pregnancy were significantly associated with late initiation of ANC. creating about the importance of early initiation of ANC, making the service closer to the community and increasing contraceptive utilization would help to decrease the number of mothers who start ANC late.

Maternal mortality reduction remains a priority agenda in the new sustainable development goals (SDGs 3). However, it remains the global challenge with 275,288 deaths due to pregnancy and related complications in 2015 [ 1 ]. The burden is high in developing countries, accounting for 99% of the global maternal deaths in 2015, with the Sub-saharan Africa region including Ethiopia contributing 66% of the mortality [ 2 , 3 ]. Most of the causes of maternal deaths are preventable, detectable, and treatable. Therefore, immediate action is needed to meet the ambitions of SDG 2030 for eliminating preventable causes of maternal death with a special attention to Sub- saharan Africa [ 4 , 5 ] Antenatal care is one of the key strategies for reducing maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality directly through the detection and treatment of pregnancy related illness, or indirectly through detection of women at risk of complications of delivery and ensuring that they deliver in a suitably equipped facility. During ANC, health providers monitor and identify risk factors related to poor maternal and birth outcomes. Once problems are identified, providers can initiate appropriate medical and educational interventions to reduce the risks for maternal-neonatal morbidity and mortality [ 6 , 7 ]. However, early ANC visit is very low (24%) in low income countries compared with 81.9% in developed countries [ 8 ].

ANC services, especially the first visit, includes essential screening for health conditions such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and Syphilis; for HIV-infected pregnant women, the maximum benefit of antiretroviral therapy (ART) to prevent mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV requires early presentation to the health system. Screening for syphilis should be offered to all pregnant women at an early stage of ANC because treatment of syphilis is beneficial to the mother and the fetus. In pregnant women with early untreated syphilis, 70 to 100% of the infants will be infected and one-third will be stillborn. Furthermore, iron supplementation and immunizations, such as Tetanus Toxoid (TT), given during pregnancy can be life-saving for both mothers and infants if it is initiated at an early stage of pregnancy [ 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ]. Early initiation of ANC also has a big role in reducing bad perinatal outcomes like preterm birth, low birth weight [ 13 ], and jaundice [ 14 ]. The aims of early ANC booking are identification of complications or risk factors for complications which enable early interventions to alleviate or mitigate the effects of such complications on mothers and unborn babies [ 15 ].

Since 2003, the Ethiopian government has been deploying specially trained new cadres of community-based workers called Health Extension Workers (HEWs). HEWs are expected to spend 75% of their time in outreach activities by going from house to house in their respective kebeles. They are trained on how to provide care to pregnant women throughout pregnancy, birth and post natal period [ 16 ].

Factors identified for late initiation of ANC include lack of education, poor knowledge about ANC, unplanned pregnancy, high cost ofANC, low income, multi parity, unemploymentand having history of abortion, [ 10 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 ].

Even though WHO (World Health Organization) recommends that the first ANC visit be within the first 12 weeks of pregnancy [ 7 ], studies conducted in different parts of Ethiopia showed very low coverage, and that most of the women who started their follow up late [ 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 ]. In order to decrease child and maternal mortality, it is crucial to know the time of the first ANC visit of pregnant women and factors affecting it. Therefore, this study aimed to measure the magnitude and factors associated with late initiation of ANC at Addis Zemen primary hospital.

Study design and setting

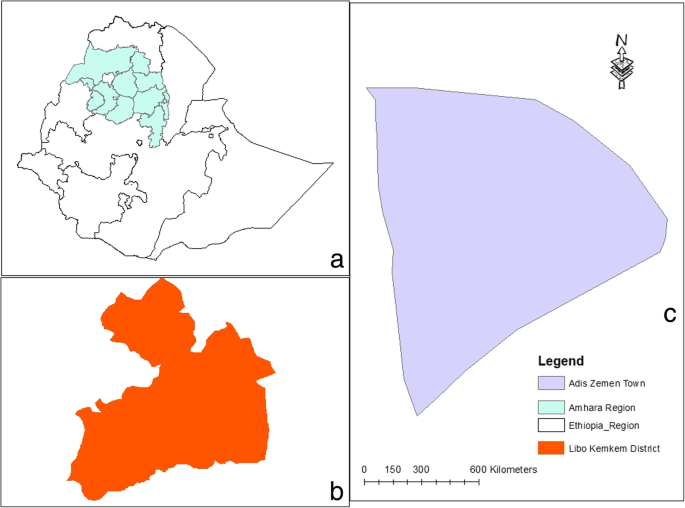

An institution based cross-sectional study was conducted from February 7 to June 12, 2018.The study was conducted atAddis Zemen primary hospital, located in Libo kemkem district South Gondar, Amhara regional state, 658 KM northwest of Addis Ababa. The district had an estimated population of 198, 951 of whom 100,951 were male and 97,423 female [ 28 ]. Addis Zemen town had 28,003 male and 28,913 are female inhabitants. The town and its suburbs, have a primary hospital, a health center and 8 health posts. The hospital has opened2016, provides general care in medical, surgical, gynecology or obstetrics and pediatrics wards (Fig. 1 ).

Location of the study area. a Ethiopia. b Libo-Kemkem. c Addis Zemen

Study population and sampling procedure

The study populations of this study were all pregnant mothers who visited Addis Zemen primary hospital during the study period. Mothers mentally and physically incapable of being interviewed were excluded. The sample size was determined by using the formula for the estimation of a single population proportion with an assumption of 95% confidence interval, 5% margin of error, and 64.6% of expected proportion of late booking for ANC [ 11 ]. To compensate for the non-response rate, 10% of the determined sample size was added. A sample of 364 pregnant women who were attending ANC Clinic were selected using systematic random sampling technique with a skip interval of 2 was used, and the first subject was selected by using the lottery method.

Variables data collection procedures

The outcome variable of the study was late booking for ANC which was defined as booking ANC after 12 weeks of gestation [ 12 ]. The explanatory variables included socio-demographic factors (age, religion, ethnicity, marital status, educational level, monthly income, occupation and travel cost); obstetric factors (gravidity, parity, history of abortion, type of pregnancy, history of ANC, timing of the first ANC visit from previous pregnancy, history of cesarean section (CS), history of still birth, problem in the last pregnancy and history of child death); enabling factors (distance from health institution, cost of travel), and need factor which includes knowledge towards ANC. Knowledge was measured using nine questions with “yes”/“no” responses. Then the composite score was dichotomized using the median (five) as a cutoff value so a score equal to or above the median value showed “good knowledge” and a score below the median value showed “poor knowledge”.

Data was collected using a structured interviewer-administered questionnaire that was prepared based on the study objectives. The data collection tool was translated into the local language (Amharic). Four health officers with BSc degrees and two Msc graduates in public health were involved as data collectors and supervisors, respectively. To control data quality, a one day training was given to data collectors on the aim of the study and on how to select participants to collect the data as per the data collection tool by the principal investigator. The tool was pre-tested on 5% of the actual sample out of the study area, and the filled copies were checked by the supervisors daily.

Data processing and analysis

The data were entered into EPI info version 7.0 and transferred to SPSS version 25 for analysis. Chi-square test was done for all categorical independent variables to check the assumptions. Variance inflation factor (VIF) was used to check multi-collinearity. Descriptive statistics, like frequencies and percentages were used to describe the categorical independent variables. The binary logistic regression model was fitted as a primary method of analysis. Variables found to have < 0.2 p -values in the bi-variate logistic regression analysis were entered in to the multivariable logistic regression model. Goodness of fit of the model was assessed by using the Hosmer- Lemeshow goodness of fit test. Variables with less than 0.05 p - values in the multivariable model were considered significantly associated with the dependent variable. Odds ratio (OR) with a 95% confidence interval were computed to show the strength of associations.

Socio demographic characteristics of the study participants

A total of 364 participants were involved in the study with a response rate of 94%. The majority of the participants, 282(77.5%), 20–35 age groups with the minimum and maximum ages of 18 and 44 years, respectively. Nearly 85% (309) of the participants were married, while 352(96.7%) and 257(70.6%) were Amhara and Orthodox Christian, respectively. Of the participants, 160(44%) were housewives and 87(23.9%) self-employed Besides, 113(31%) were with no formal education, and only 69(19%) were diploma or above graduates. More than half of the participants, 209(57.4%), had ETB > 1000 monthly income. Over one-third, 131(36%), of the participants had no travel expens to and from ANC facility (Table 1 ).

Obstetric history of the study participants

Of the total respondents, 128(35.2%) were primigravida and 167(70.8%) multiparous. Of these, 200(84.7%) reported that they had ANC experience during their previous pregnancy. Among respondents who had had an experience of ANC follow up 129(64.5%) visited ANC clinic for the first time after 12 weeks of gestation in the previous pregnancy. Out of 31(13.1%) respondents who had history of abortion, 25 (80.64%) were spontaneous.. Ninety-four (25.8%) of the pregnancies were unintended. Of these, 64 came late for ANC for the current pregnancy. The majority of the respondents, 171 (72.5%) faced no problems during their last pregnancies, and only 8(5%) had history of still births. Twenty-six (11%) of respondents had history of CS delivery (Table 2 ).

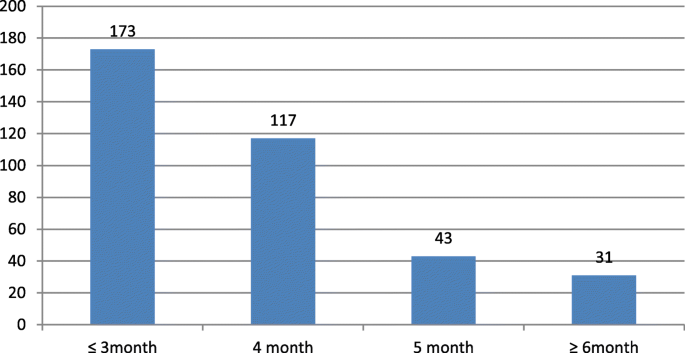

Timing of the current first ANC visit and knowledge towards ANC