Types Of Water Transport

There are mainly three modes of transportation: airways, waterways and land routes. While land transportation includes everything from cars to buses, trucks to scooters, and bikes to railways, air transportation is mainly comprised of planes and choppers.

Speaking of water transportation, the only picture that emerges in the minds of most of us, especially those of us hailing from outside this industry, is that of a large ship, mostly resembling The Titanic, with large funnels bellowing out wafts of blackish smoke, and gently treading somewhere in the middle of the deep blue waters. For those of us from within the boundaries of this field, the picture is much more detailed, with varied characteristics of various types of watercraft.

Now, regarding water transport, there can be various classifications other than the types of vessels or watercraft. Let us look at a few of them.

Types of Water Transport Based on routes or types of waterways catering to the traffic

Based on the waterways, water bodies, and routes catering to maritime or waterborne traffic, water or marine transport can be declassified into the following types:

River: This is a local form of water transport that is responsible for transport in a river. Rivers, as we know, are shallow freshwater bodies within a country that may span varying lengths. Riverine transportation further comes under the purview of inland waterways. This means that the channels or bodies catering to the given traffic are limited only to shallow water bodies under local consideration.

Mostly inland water transportation is only meant for short-distance travel from one place to another. So likewise, river transport includes small to medium-sized vessels for both commercial and public as well as personal transportation across varying distances within the geographical limits of a country or state.

They may include a simple and austere fisherman’s boat lazily basking in the mellow sunlight of dusk to a medium-sized cargo vessel transporting food stock or industrial goods across distances of maybe 1000 or 2000 kilometres from one tip of a country to another.

Modes of river transport include conventional goods or cargo carriers, fishing vessels, barges, speedcrafts, steamers, trawlers, dinghies, pleasure yachts, high-speed planing boats, river ferries, and so on. Because of the limited or restricted depths of the waterbody, all river vessels are classified as shallow draft vessels .

Lakes: In a technical sense, lakes are enclosed or bounded bodies of water with varying surface areas. This means they can range from the size of Bhopal Lake in India to the size of Lake Superior in the United States, which is the single largest freshwater lake in the world! Not only the areas but also the depths vary accordingly. So, the modes of transport and the type of traffic also depend on the extent and size of the lake. However, for all practical purposes, this is also considered under the study of inland waterways where there is a low draft.

Coastal: This comes under the purview of deep-water transportation. The coastal mode of transportation encompasses vessels that tread close to the shoreline. They include both commercials as well as passenger vessels .

For example, there are two ports of call, A and B, along a particular coastline at a separation of 2000 kilometres. A typical coastal vessel travels from A to B and back during a short span of a voyage, say in a period of 4 to 5 days. Fishing trawlers, coastal coal carriers, and tankers that transport coal and petroleum products within two locations in the same country are good examples of commercial coastal vessels.

Similarly, ferries carrying holiday-seekers from the port of a city to some famous beach destination some hundred or thousand kilometres away on a charter basis are examples of passenger vessels under the coastal classification.

Coastal vessels have different regulations for design and construction under classification guidelines. They adhere to their routes up a certain distance from the coastline and are not regulated to go into deep seas.

Since they are designed to sail only up to the extent of distance, they are said to have a much lower range than deep-sea vessels. In terms of their structural design, they are stronger and have higher levels of endurance than shallow-draft vessels but much lesser than their deep-water counterparts. Such vessels are also used for shorter distances, like a coastal region to a nearby island, which may be a popular tourist hotspot.

International and Intercontinental : Most maritime traffic is deemed for international or intercontinental travel. While international travel may be between two countries within the same continental boundary, for example, Germany and Sweden or Italy and Greece, intercontinental travel spans across large oceans, separating two continents.

Most of the marine maritime traffic is in the Atlantic and Pacific, the world’s two biggest oceans. Vessels designed for intercontinental travel are structurally in the highest levels of superiority and have very high degrees of endurance. Due to the global monopoly of aviation for the last several decades, most intercontinental maritime traffic comprises commercial vessels, mostly bulkers, tankers, and containerships, along with defence and research vessels .

Polar Vessels: They come under a particular type of vessel classification. Polar vessels are designed and constructed to ply in icy waters containing ice sheets, floes, bergs, or slabs. Since they often need to overcome the forces and the higher degree of hydrodynamic forces from the ice, they are structurally strengthened to a very high level and have arrangements to survive in adversely cold weather conditions for days at a stretch. Icebreakers are in the top category of polar vessels as they are designed to break through greater thicknesses of ice and often clear the path for an entailing ship to follow.

Types of Water Transport Based on ownership and utility

Most of the vessels are categorized based on their ownership or utilization per the following categories:

Commercial: These vessels comprise the highest share of maritime traffic. All inland or deep-sea vessels dedicated to trade, commerce, and industrial purposes are termed commercial vessels. Commercial vessels can be anything from an oil barge to a bulk carrier, a fishing trawler to a containership, and a rice carrier to an LPG carrier. All commercial vessels comprise vital and indispensable links in the global trade and supply chain at multifarious levels. Commercial vessels are either private or government-owned.

Passenger and public vessels: They comprise vessels dedicated to passenger travel as a mode of waterborne public transportation. As mentioned earlier, the utility of ships for passenger travel has deprecated considerably over time after the monopoly of aviation for the last many years. However, for pleasure and luxury recreation purposes, they are used at many places for holiday-seekers and travellers. Shallow water vessels for public transport are still very popular worldwide in water taxis, river cruises, ferries, steamers, launches, and so on, especially for short-distance travel.

Private Vessels: These small to medium-sized, sometimes bigger, vessels are liable to private ownership only. Ownership may be limited to a single person or a body like an organization or concern. However, as mentioned above, private vessels may not be confused with commercial vessels under private ownership. Commercial vessels are usually bigger (though smaller ships are very much there), which pertains to a more extensive fleet of a shipping or international fleet transport organization solely dedicated to cargo transport and supply chain. They operate round the clock across varying distances for the transport or carriage of a wide range of cargo or supplies in various quantities.

A containership owned, managed, and operated by Maersk or an oil tanker belonging to Scorpio or Euronav Tankers are examples of mainstream commercial vessels under private or corporate ownership.

But a medium-sized survey vessel owned and operated by a coastal engineering organization or a couple of small or medium fishing trawlers run by a significant seafood processing chain are examples of privately-owned ships. Vessels owned by an individual are primarily for pleasure and recreation for the affluent class. Yachts are classic examples of them.

Defence: These vessels, too, are exceptionally prominent among the global fleet, especially for superpowers. However, irrespective of the size, population, and so-called global dominance, every country has its dedicated naval fleet as a part of its military capabilities.

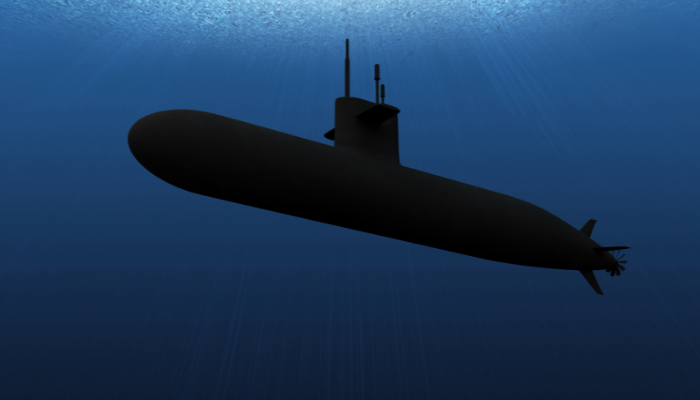

Defence vessels may range from warships, carriers, frigates, destroyers, and corvettes to small patrol vessels for the Coast Guard or high-speed rescue boats used by the Navy. Submarines are a crucial part of several nations’ naval fleets.

Special Purpose Vessels: These vessels are mainly research or exploration vessels used for scientific purposes. They may be government-owned or operated by institutions or bodies.

Types of Water Transport Based on Submersibility

Last but not least, water transport can be based on submergibility:

Surface Vessels: All forms of ships and boats which stay afloat in water are surface vessels. They may be further divided into the following types: displacement, planing, and semi-planing.

Submarines and submersibles: As we already know, these vessels remain submerged below a certain height for a diverse read on submarines and submersibles.

You might also like to read-

- 8 Major Types of Cargo Transported Through the Shipping Industry

- Life on the water: 11 Floating Villages across the World

- IMO: Preparation Is The Key In Ballast Water Management

- Different Technologies For Ballast Water Treatment

- What are Deep Water Ports?

Do you have info to share with us ? Suggest a correction

About Author

Subhodeep is a Naval Architecture and Ocean Engineering graduate. Interested in the intricacies of marine structures and goal-based design aspects, he is dedicated to sharing and propagation of common technical knowledge within this sector, which, at this very moment, requires a turnabout to flourish back to its old glory.

Latest Marine Navigation Articles You Would Like :

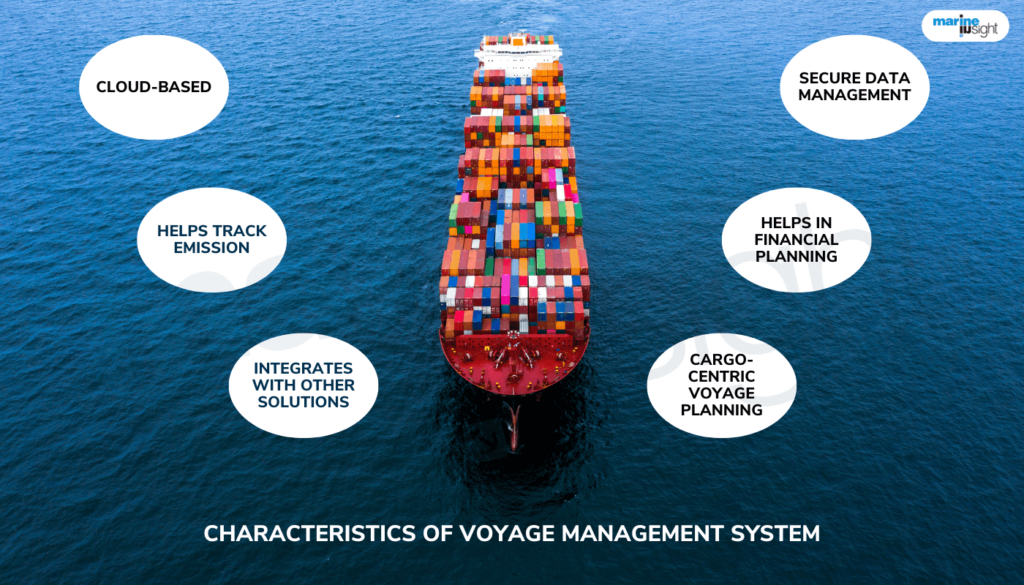

What is Voyage Management System?

The Strait Of Dover – The Busiest Shipping Route In The World

What is Transverse Thrust in Ships?

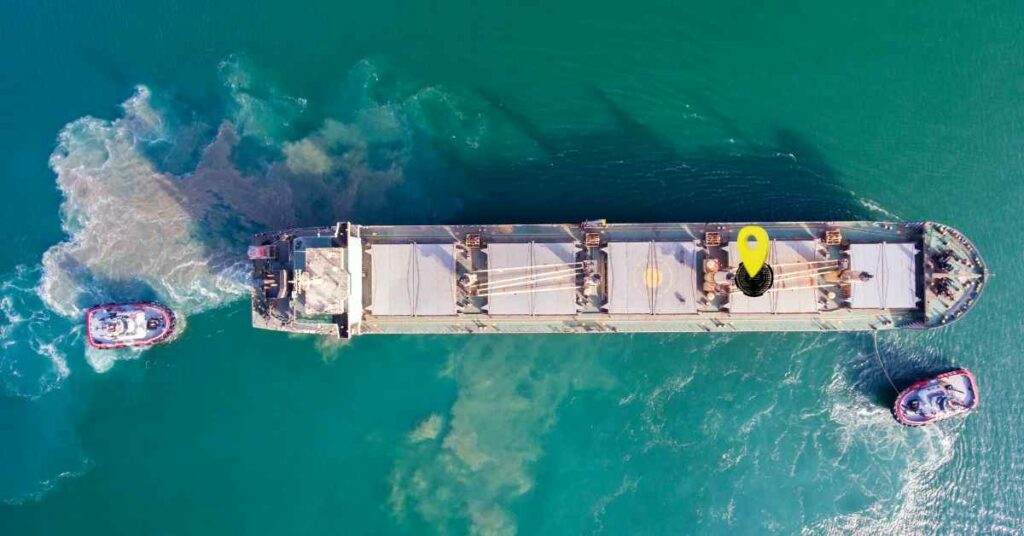

What Is The Pivot Point Of A Vessel?

7 Best Handheld Marine GPS in 2024

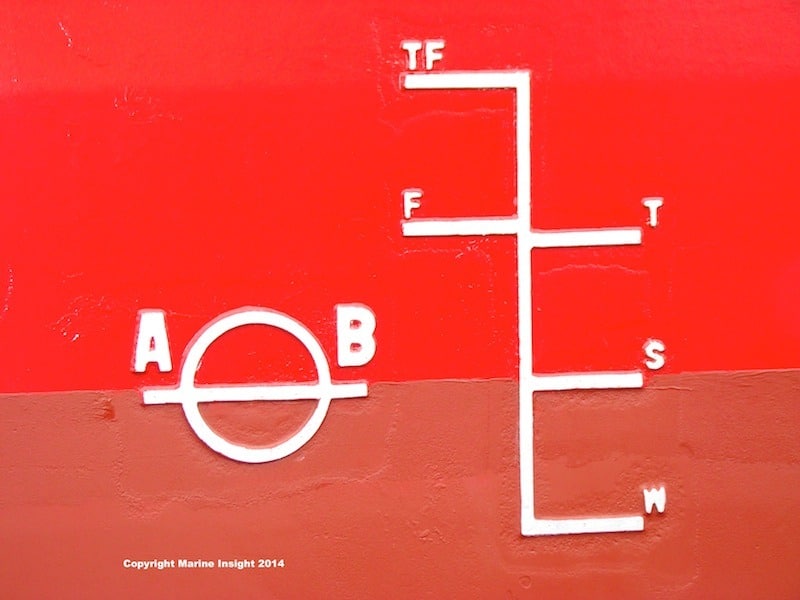

Introduction To Ship Load Lines

Subscribe To Our Newsletters

By subscribing, you agree to our Privacy Policy and may receive occasional deal communications; you can unsubscribe anytime.

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Subscribe to Marine Insight Daily Newsletter

" * " indicates required fields

Marine Engineering

Marine Engine Air Compressor Marine Boiler Oily Water Separator Marine Electrical Ship Generator Ship Stabilizer

Nautical Science

Mooring Bridge Watchkeeping Ship Manoeuvring Nautical Charts Anchoring Nautical Equipment Shipboard Guidelines

Explore

Free Maritime eBooks Premium Maritime eBooks Marine Safety Financial Planning Marine Careers Maritime Law Ship Dry Dock

Shipping News Maritime Reports Videos Maritime Piracy Offshore Safety Of Life At Sea (SOLAS) MARPOL

The Fascinating History of Water Transport

Disclaimer: Some posts on Tourism Teacher may contain affiliate links. If you appreciate this content, you can show your support by making a purchase through these links or by buying me a coffee . Thank you for your support!

The history of water transport is a long and fascinating one, and in this article I will teach you all about it! From cruise ships to cargo transport to water buses, there are many types of water transport that have played a key role in the fascinating history of water transport. Ready to learn more? Keep scrolling…

What is water transport?

Early history, the history of water transport in the viking era, the arab age of discovery, the history of water transport continued, the two world wars, individual crossings of the atlantic ocean, the history of water transport.

Before we delve into the history of water transport we first need to understand what water transport is!

Water transport, or maritime transport, refers to the use of vessels or vehicles to transport people or goods via water – whether that be a sea, ocean, lake, river, canal or other body of water. It has a long history and is still used today on a daily basis for recreational, military and trade purposes.

Looking at the very early history of water transport involves looking at when the first boat was invented. Records suggest that boats have been in use for a long time. The oldest recovered boat is the Pesse canoe, found in the Netherlands, which was made from hollowing out a tree trunk somewhere between 8200 and 7600 BC. Presumably this was used to transport something, so it can be said that this was the very start of the history of water transport.

We know that the Ancient Egyptians were using wooden boats called Feluccas from around 3000 BC, to transport coffins, grains and much more. Prior to this, however, they were using boats made from bundles of papyrus reeds, tied together really tightly.

By around 1000 AD, the Austronesian people in the island regions of Southeast Asia were engaging in maritime trade with citizens of China , the Middle East and South Asia. They are said to be the ones to introduce sailing technology and techniques to these areas. Records suggest that they used boats known as ‘kunlun bo’ which translates to ‘ship of the Kunlun people’, with 4-7 masts and the ability to sail against the wind thanks to tanja sails.

We know that the Vikings were keen on boats and used them as their primary form of transport – making them a key figure in the history of water transport. Their history can be traced back to around 793 AD.

Fjord Tours say Some of the earliest ships discovered were the Oseberg, the Gokstad, and the Tune. These ships were not as specialized as the ships that would be created after them. So, it appears that they were used for everything from transport to battle.

By the end of the 9th century, specialization of the ships had begun. Around this time, the Vikings started to create warships. Warships were longer and slimmer than previous boats the Vikings had built, and although the name might inspire visions of epic sea battles, the warships were actually used for something altogether different. Due to their shape and size, these vessels were able to navigate sheltered waters where they would drop off the Vikings at a point of interest. From there, the Vikings could discreetly enter their target location. The warships were designed for a quick getaway once the Vikings had obtained the loot from their target location.

At the same time as the Viking era, the Arab Empire was expanding their trade network across Asia, Europe and Africa. During the 8th-12th centuries they were the world’s leading economic power, it has been said. Many rivers in the Islamic region were unnavigable. Due to this, transport by sea was very important; using a compass and a kamal, sailors during this period could sail across oceans rather than just along the coast – cutting the time it took to get from A to B. Sea trade allowed for the distribution of food and supplies to feed entire nations of people in the Middle East. And long-distance sea trade meant the importation of raw materials for building and luxury goods for wealthy citizens. They used ships called a qarib, which would go on to inspire the Spanish caravel.

From the 14-1500s, water transport was key in what is known as the general Age of Discovery. This was Christopher Columbus’ era, when European ships sailed across the world searching for new trading routes. Other big names in maritime history around this time include John Cabot, Juan Fernandez, Jacques Cartier, Richard Hakluyt and Vasco da Gama. Around this time, the favoured type of boat was a wooden sailing vessel with 3-4 masts. It wasn’t just these explorers who used them but traders and the military.

We can, from here, start to see a much more heavily documented timeline of boats, ships and other forms of water transport. For example, also in the 1400s was the invention of the yacht – by the Dutch, who used these for chasing pirates and criminals as well as for Naval purposes. They were then co-opted by rich ship owners, who would use them for celebratory sail-outs when their ships came back – hence why they are now a symbol of the elite. In 1660, Charles II used a yacht to carry him to the Netherlands from England for his restoration.

Because of the growth in trade routes, boats and ships around this time were being constantly developed and improved. They needed to be bigger and stronger, and able to travel for longer periods of time.

Fast sailing ships called Clippers were built in the 1800s, and they had long slim hulls and tall masts. A few years later, in 1818, the Black Ball Line shipping company started offering a passenger service from the United States over to England. The group was founded by Quakers who had four packet ships, and the transatlantic passenger crossing ran between New York City and Liverpool. It wasn’t particularly popular at first but by 1822 they were running two crossings per month for 35 guineas per person; this led to competition from the likes of Red Star Line.

At the same time, the first steam powered ships were able to cross the Atlantic Ocean too. Innovations in the history of water transport were coming thick and fast in the 1800s; by around 1845, the first ocean liners built from iron appeared. They were propeller-driven, instead of using sails.

It was, however, also around this time that canals became less of a popular way to transport goods and people – this was thanks to the establishment of good working railways.

Again, innovations continued. Diesel became an easy way to power ships – oil seemed to work better than steam. However, steam was still in use for some time alongside the new diesel-powered ships; it was in 1912 when the famous tragedy of the Titanic took place.

We also saw a lot of new water transport inventions in the 1900s: hydroplanes, hovercrafts, and nuclear-powered cargo ships like the N.S. Savannah which sailed for 3.5 years without having to refuel. The 1900s – or, more specifically, the 1980s – also saw the introduction of container ships. These large and strong cargo ships allowed vast amounts of cargo to be carried in mental boxes known as containers; around 90% of non-bulk cargo is carried on container ships today.

Cruise ships also rose to prominence in the 1900s. The first ever cruise ship was created in 1901; it was German and you can read about it here . However, it wasn’t until the 1990s that cruising became more commonplace and more accessible. They were able to carry hundreds if not thousands of people – like floating holiday villages. Over time they have become more and more impressive with their own cinemas, water parks and go-karting tracks alongside the multitude of bars and restaurants each one has on board.

Boats and ships obviously played a huge part in both of the world wars, which were two important time periods in the history of water transport. Thousands of water transport vessels were used in each war – for battle, for transporting goods to armed forces in different places and so on. During WWI, around 2100 ships were sunk and 153 U-boats were destroyed. And during WWII, around 3,700 ships were sunk a further 783 U-boats destroyed.

Ann Davison was the first woman to sail across the Atlantic alone, doing so in 1952. More did so in the 1960s and then, in 1965, Robert Manry made it across without stopping in a sailboat named Tinkerbelle. Later, in 1980, Gérard d’Aboville rowed single-handedly across the Atlantic Ocean – this feat was accomplished by a woman eleven years later, when Tori Murden did it.

There is a lot to say about the history of water transport – from the first rudimentary boats to the super cruise ships of today. Water vehicles have long been used to transport goods and people across bodies of water, and while air and rail transport are popular now it seems that water transport remains a brilliant way to get from A to B.

Liked this article? Click to share!

ENCYCLOPEDIC ENTRY

Water cycle.

The water cycle is the endless process that connects all of the water on Earth.

Conservation, Earth Science, Meteorology

Deer Streams National Park Mist

A misty cloud rises over Deer Streams National Park. The water cycle contains more steps than just rain and evaporation, fog and mist are other ways for water to be returned to the ground.

Photograph by Redline96

Water is one of the key ingredients to life on Earth. About 75 percent of our planet is covered by water or ice. The water cycle is the endless process that connects all of that water. It joins Earth’s oceans, land, and atmosphere.

Earth’s water cycle began about 3.8 billion years ago when rain fell on a cooling Earth, forming the oceans. The rain came from water vapor that escaped the magma in Earth’s molten core into the atmosphere. Energy from the sun helped power the water cycle and Earth’s gravity kept water in the atmosphere from leaving the planet.

The oceans hold about 97 percent of the water on Earth. About 1.7 percent of Earth’s water is stored in polar ice caps and glaciers. Rivers, lakes, and soil hold approximately 1.7 percent. A tiny fraction—just 0.001 percent—exists in Earth’s atmosphere as water vapor.

When molecules of water vapor return to liquid or solid form, they create cloud droplets that can fall back to Earth as rain or snow—a process called condensation . Most precipitation lands in the oceans. Precipitation that falls onto land flows into rivers, streams, and lakes. Some of it seeps into the soil where it is held underground as groundwater.

When warmed by the sun, water on the surface of oceans and freshwater bodies evaporates, forming a vapor. Water vapor rises into the atmosphere, where it condenses, forming clouds. It then falls back to the ground as precipitation. Moisture can also enter the atmosphere directly from ice or snow. In a process called sublimation , solid water, such as ice or snow, can transform directly into water vapor without first becoming a liquid.

Media Credits

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Production Managers

Program specialists, specialist, content production, last updated.

April 29, 2024

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

Water Transport and Tourism

- First Online: 01 January 2023

Cite this chapter

- M. R. Dileep 10 &

- Francesca Pagliara ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6332-6313 11

Part of the book series: Advances in Spatial Science ((ADVSPATIAL))

432 Accesses

1 Citations

Waterborne transport, which refers to the transportation of people or cargo via waterways, is a significant component of tourism. Water tourism represents the use of different types of sailing equipment and appliances for transportation and recreation purposes by visitors. Whether used to transport cargo or passengers, water transport is vital to the successful operations of tourism in many destinations. Water transport is one of the oldest types of transport and has been widely used throughout history.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Arlt, W.G., & Feng, G. (2009). The Yangzi River tourism zone. In B. Prideaux & M. Cooper (Eds.), River tourism . Oxfordshire: CABI, pp. 117–130.

Chapter Google Scholar

Armstrong, J., & Williams, M.D. (2005). The steamboat and popular tourism. The Journal of Transport History , 26(1), 61–77. https://doi.org/10.7227/TJTH.26.1.4

Article Google Scholar

Baird, A.J. (2009). A comparative study of the ferry industry in Japan and the UK. Transport Reviews , 19(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/014416499295664

Barron, P., & Greenwood, A.B. (2006). Issues determining the development of cruise itineraries: A focus on the luxury market. Tourism in Marine Environments , 3(2), 89–99. https://doi.org/10.3727/154427306779435238

Berger, A.A. (2004). Ocean travel and cruising: A cultural analysis. New York, NY: Haworth Hospitality Press.

Google Scholar

Bosnic, I., & Gasic, I. (2019, July 15–16). River cruise industry: Trends and challenges, economic and social development—Book of Proceedings . Varazdin.

Bowen, C., Fidgeon, P., & Page, S. J. (2014). Maritime tourism and terrorism: Customer perceptions of the potential terrorist threat to cruise shipping. Current Issues in Tourism , 17(7), 610–639.

Bowles, B.O.L., Kaaristo, M., & Rogelja Caf, N. (2019). Dwelling on and with water—Materialities, (im)mobilities and meanings: Introduction to the special issue. Anthropological Notebooks , 25(2), 5–12.

Brida, G.J., & Zapata, S. (2010). Economic impacts of cruise tourism: The case of Costa Rica. Anatolia: An International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research , 21(2), 322–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2010.9687106

Brida, J.G., & Risso, W.A. (2010). Cruise passengers expenditure analysis and probability of repeat visits to Costa Rica: A cross section data analysis. Tourism Anal , 15, 425–434.

Calstockferry.co.uk, retrieved from http://www.calstockferry.co.uk/different-types-ferries/

Central Commission for the Navigation of the Rhine. (2019). Inland navigation in Europe: Market trends, retrieved from https://inland-navigation-market.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/ccnr_2019_Q2_en-min2.pdf.pdf

CLIA. (2006). 2006 cruise market profile, Cruise Line International Association, retrieved from http://www.bitaz.com.mx/docs/200620Market20Profile20Study.pdf

CLIA. (2020). 2020 global market report, retrieved from https://cruising.org/-/media/research-updates/research/2019-year-end/updated/2019-global-market-report.ashx

CLIA. (2022). Retrieved from https://cruising.org/-/media/clia-media/research/2022/clia-state-of-the-cruise-industry-2022_updated.ashx

CNN Travel. (2018). Retrieved from https://edition.cnn.com/travel/article/worlds-biggest-cruise-ships/index.html

Cooper, D., Holmes, K., Pforr, C., & Shanka, T. (2018). Implications of generational change: European river cruises and the emerging gen X market. Journal of Vacation Marketing , 25(4), 418–431.

Cooper, M. (2009). River tourism-sailing the Nile. In B. Prideaux & M. Cooper (Eds.), River Tourism . Oxfordshire: CABI, pp. 74–94.

Cruise Lines International Association. (2005). CLIA Cruise Lines ride the wave of unprecedented growth . New York: Cruise Lines International Association.

Dickinson, J., & Lumsdon, L. (2010). Slow travel and tourism . London: Routledge.

Dileep, M.R. (2019). Tourism, transport and travel management. London: Routledge.

Book Google Scholar

Dwyer, A., & Forsyth. P. (1998). Economic significance of cruise tourism. Annals of Tourism Research , 25(2), 393–415.

Ely, C. (2003). The origins of Russian scenery: Volga River tourism and Russian landscape aesthetics. Slavic Review , 62(4), 666–682.

Erfurt-Cooper, P. (2009). European Water ways as a source of leisure and recreation. In B. Prideaux & M. Cooper (Eds.), River tourism . Oxfordshire: CABI, pp. 95–116.

EspinetRius, J.M., Gassiot Melian, A., & Torrent, R.R. (2022). World ranking of cruise homeports from a customer pricing perspective. Research in Transportation Business & Management . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rtbm.2022.100796

Fallon, J. (2012). ‘If you’re making waves then you have to slow down’: Slow tourism and canals. In S. Fullagar, K. Markwell, & E. Wilson (Eds.), Slow tourism: Experiences and mobilities . Bristol: Channel View Publications, pp. 143–154

Gibbs, L. M. (2013). Bottles, bores, and boats: Agency of water assemblages in post/colonial inland Australia. Environment & Planning A , 45(2), 467–484.

Gibson, P. (2006). A study of impacts–Cruise tourism and the South West of England. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing , 20(3/4). https://doi.org/10.1300/J073v20n03_05

Guedes, A., & Rebelo, J. (2021). River cruise holiday packages: A network analysis combined with a geographic information system framework. Tourism Management Perspectives , 37, 100779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100779

Gui, L., & Russo, A.P. (2011). Cruise ports: A strategic nexus between regions and global lines—Evidence from the Mediterranean. Maritime Policy and Management , 38(2), 129–150.

Hall, J. A., & Braithwaite, R. (1990). Caribbean cruise tourism: a business of transnational partnerships. Tourism Management ‚ 11‚ 339–347.

Hritz, N., & Cecil, A.K. (2008). Investigating the sustainability of cruise tourism: A case study of Key West. Journal of Sustainable Tourism , 16(2), 168–181. https://doi.org/10.2167/jost716.0

Hung, K., & Petrick, F.J. (2011). Why do you cruise? Exploring the motivations for taking cruise holidays, and the construction of a cruising motivation scale. Tourism Management , 32(2), 386–393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.03.008

Irena, B., & Ivana, G. (2019, July 15–16). River Cruise industry: Trends and challenges. Paper presented in 43rd International Scientific Conference on Economic and Social Development—“Rethinking Management in the Digital Era: Challenges from Industry 4.0 to Retail Management”. Aveiro.

Jaakson, R. (2004). Beyond the tourist bubble? Cruiseship passengers in port. Annals of Tourism Research , 31(1), 44–60.

Johns, N., & Clarke, V. (2001). Mythological analysis of boating tourism. Annals of Tourism Research , 28(2), 334–359.

Jones, R.V. (2011). Motivations to cruise: An itinerary and cruise experience study. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management , 18, 30–40. https://doi.org/10.1375/jhtm.18.1.30 .

Kester, G.C.J. (2002). Cruise tourism. Tourism Economics , 9(3), 337–350

Kizielewicz, J. (2013). Themed cruises, as a trend in marine tourism. Scientific Journals , 33, 30–31.

Kizielewicz, J., Haahti, A., Luković, T., & Gračan, D. (2017). The segmentation of the demand for ferry travel—A case study of Stena Line. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja , 30(1), 1003–1020. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2017.1314789

Larsen, S., Wolff, K., & Marnburg, E., et al. (2013). Belly full, purse closed: Cruise line passengers’ expenditures. Tourism Management Perspectives , 6, 142–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2013.02.002 .

Lau, Y-Y., & Yip, T-L. (2020). The Asia cruise tourism industry: Current trend and future outlook. The Asian Journal of Shipping and Logistics , 36, 190–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajsl.2020.03.003 \

Lee, S. (2013). Does size really matter? An investigation of cruise ship size. Tourism Analysis , 18, 111–114.

Lee, C-F., Chen, P-T.‚ & Huang, H-I. (2014). Attributes of Destination Attractiveness in Taiwanese Bicycle Tourism: The Perspective of Active Experienced Bicycle Tourists. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration , 15(3), 275–297, https://doi.org/10.1080/15256480.2014.925726 .

Lee, S., & Ramdeen, C. (2013). Cruise ship itineraries and occupancy rates. Tourism Management , 34, 236–237.

Lester, J., & Weeden, C. (2004). Stakeholders, the natural environment and the future of Caribbean cruise tourism. The International Journal of Tourism Research , 6, 39–50.

Lingard, N. (2002). The route less travelled: Fred Olsen Lines keeps it interesting. International Cruise & Ferry Review , 193.

Lohmann, G., & Duval, D.T. (2013). Critical aspects of the tourism-transport relationship. Oxfor-UK: Goodfellow Publishers.

Łosiewicz, Z., & Kaup, M. (2014). Analiza innowacyjnych rozwiązań napędów stosowanych na jednostkach śródlądowych w apsekcie zrównoważonego rozwoju transportu. Logistyka , 6, 6849–6856.

Lumsdon, L., & Page, S. (2004). Progress in transport and tourism research: Reformulating the transport -tourism interface and future research agendas. In L. Lumsdon & S. Page (Eds.), Tourism and transport: Issues and agenda for the new millennium . New York: Routledge, pp. 1–28

McGrath, E., Harmer, N., & Yarwood, R. (2020). Ferries as travelling landscapes: Tourism and watery mobilities. International Journal of Culture Tourism and Hospitality Research , 14(3), 321–334. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCTHR-10-2019-0184

Mehran, J., Olya, G.T.H., Han, H., & Kapuscinski, G. (2020). Determinants of canal boat tour participant behaviours: An explanatory mixed-method approach. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing , 37(1), 112–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2020.1720890

Muszyńska-Jeleszyńska, D. (2018). The use of solar technology on vessels for development of water tourism and recreation—Bydgoszcz Water Tram case study. Paper presented in International Conference of Computational Methods in Sciences and Engineering (ICCMSE 2018), AIP Conference Proceedings 2040, 070011-1–070011-5. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5079132

Nasir, F.M., & Hanafiah, M.H. (2017). River cruise impact towards local community: An exploratory factor analysis approach. Journal of Tourism , Hospitality & Culinary Arts (JTHCA) , 9(2), 175–188.

Niavis, S., & Vaggelas, G. (2016). An empirical model for assessing the effect of ports’ and hinterlands’ characteristics on homeports’ potential. Maritime Business Review , 1(3), 186–207.

Papathanassis, A. (2017). Cruise tourism management: State of the art. Tourism Review , 72 (1), 104–119. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-01-2017-0003

Papathanassis, A., & Beckmann, I. (2011). Assessing the ‘poverty of cruise theory’ hypothesis. Annals of Tourism Research , 38(1), 153–174.

Peeters, P., Egmond, T., & Visser, N. (2004). European tourism, transport and environment, Centre for Sustainability, Tourism and Transport, data available online at https://www.cstt.nl/userdata/documents/appendix_deliverable_1_subject_matter_review_30082004.pdf

Petrick, J.F. (2003). Measuring cruise passengers’ perceived value. Tourism Annals , 7, 251–258.

Petrick, J.F., Li, X., & Park, S. Y. (2007). Cruise passengers’ decision-making processes. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing , 23(1), 1–14.

Pranic, L., Marusic, Z., & Sever, I. (2013). Cruise passengers’ experiences in coastal destinations e Floating “B&Bs” vs. floating “resorts”: A case of Croatia International micro-cruises are indeed novel and exciting tourism segment. Ocean & Coastal Management , 84, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2013.07.002

Pratt, S, & Blake, A. (2009). The economic impact of Hawaii’s cruise industry. Tourism Analysis , 14(3), 337–351.

Prideaux, B. (2017). Canals: An old form of transport transformed into a new form of heritage tourism experience. In F. Vallerani & F. Visentin (Eds.), Waterways and the cultural landscape . Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 143–157.

Prideaux, B., Timothy, D. J., & Cooper, M. (2009). Introducing river tourism. In B. Prideaux & M. Cooper (Eds.), River tourism. Oxfordshire: CABI, pp. 1–22.

Rhoden, S., & Kaaristo, M. (2020). Liquidness: Conceptualising water within boating tourism. Annals of Tourism Research , 81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.102854

Ritter, W., & Schafer, C. (1998). Cruise-Tourism. Tourism Recreation Research , 23(1), 65–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.1998.11014821

Rodrigue, J.P., Comtois, C., & Slack, B. (2006). The geography of transport systems. Oxon, UK: Routledge.

Rodrigue, J.P., & Notteboom, T. (2013). The geography of cruises: Itineraries, not destinations. Applied Geography , 38, 31–42.

Santos, M., Radicchi, E., & Zagnoli, P. (2019). Port’s role as a determinant of cruise destination socio-economic sustainability. Sustainability , 11, 4542. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11174542

Skrede, O., & Tveteraas, L.S. (2019). Cruise spillovers to hotels and restaurants. Tourism Economics , 25(8). https://doi.org/10.1177/1354816619836334

Steinbach, J. (1995). River related tourism in Europe – an overview. GeoJournal ‚ 35(4), 443–458.

Tang, L., & Jang, S. (2010). The evolution from transportation to tourism: The case of the New York canal system. Tourism Geographies: An International Journal of Tourism Space, Place and Environment , 12(3), 435–459. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2010.494683 .

Thompson Clarke Shipping. (2006). Cruise destinations... A how to guide . Brisbane: Tourism Queensland.

Thurau, B., Seekamp, E., Carver, A.D., & Lee, J.G. (2015). Should cruise ports market ecotourism? A comparative analysis of passenger spending expectations within the Panama Canal watershed. International Journal of Tourism Research , 17(1), 45–53.

Timothy, D.J. (2009). River based tourism in the USA: Tourism and recreation on the Colorado and Mississipi Rivers. In B. Prideaux & M. Cooper (Eds.), River tourism . Oxfordshire: CABI, pp. 41–54.

Tomej, K., & Lund-Durlacher, D. (2020). River cruise characteristics from a destination management perspective. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jort.2020.100301

van Balen, M., Dooms, M., & Haezendonck, E. (2014). River tourism development: The case of the port of Brussels. Research in Transportation Business & Management , 13, 71–79.

Vaya´, E., Garcia, J.R., Murillo, J. et al. (2018). Economic impact of cruise activity: The case of Barcelona. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing , 35(4), 479–492. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2017.1363683 .

Winter, J., & Kulczyk, J. (2003). Śródlądowy transport wodny. Wrocław: Publishing House of the Wroclaw University of Technology.

Wood, E.R. (2000). Caribbean cruise tourism: Globalization at sea. Annals of Tourism Research , 27(2), 345–370.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Kerala Institute of Tourism and Travel Studies (KITTS), Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, India

M. R. Dileep

Department of Civil, Architectural and Environmental Engineering, University of Naples Federico II, Naples, Italy

Francesca Pagliara

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to M. R. Dileep .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Dileep, M.R., Pagliara, F. (2023). Water Transport and Tourism. In: Transportation Systems for Tourism. Advances in Spatial Science. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-22127-9_11

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-22127-9_11

Published : 01 January 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-22126-2

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-22127-9

eBook Packages : Economics and Finance Economics and Finance (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Elephango for Families

- Elephango for Schools

- Standards Search

- Family Sign-Up

Transportation: Water

Contributor: Samantha Penna. Lesson ID: 11670

Fish don't have feet, so they can't walk on land. You don't have fins, so you can't swim across the ocean! But there are many ways to travel over (and under!) water. Now watch them, then build a boat!

People and Their Environment

Lesson plan - get it.

- How do ducks and fish travel in water?

- Do you think people could travel in or on water without help?

Learn about some cool ways people travel on water!

- What does the word "transportation" mean?

Share your answers with your parent or teacher.

That's right! Cars, buses, motorcycles, mopeds, trains, and emergency vehicles are just some of the many ways people get around on land. Transportation is a way people get from place to place.

- What happens when people need to travel by water?

- What do they use?

Read on to find out about the different types of water transportation and how they help people get across bodies of water.

One way people travel across bodies of water is by using sailboats . Sailboats are boats with a special part called a sail . A sail almost looks like a large blanket. It's in the middle of the ship, and when a sail is up, it catches the wind. The wind pushes the boat from place to place.

The person driving the ship uses a steering wheel or moves the sail to guide the boat in the right direction. The sails can be turned to move the boat in a different direction. If the driver wants the boat to slow down or stop, he or she will simply put down the sails. If there's no sail to catch the wind, the boat will slow down or completely stop. Check out the sailboats below.

- Have you ever seen a sailboat before?

Share your answer with your parent or teacher:

Ships are much bigger than sailboats. Ships usually have large engines that are used to power and move the ship. There are many different types of ships. Cargo ships transport goods like food, furniture, electronics, and much more over bodies of water. They can be seen with big carrying containers on the top.

- Can you see the cargo ship in the first image below?

Another type of ship is a cruise ship . This type of ship carries people from place to place. Generally, people on cruise ships are on vacation. These ships will bring them to tourist destinations all over the world!

- Can you see the cruise ship pictured in the second image?

People can also travel by submarine . Submarines can travel above or under water. Submarines are used by many different types of people. Sometimes they are driven by soldiers or scientists. Soldiers use submarines to monitor the water surrounding different countries. Scientists can use them to study underwater life.

- Did you know submarines have a special tool called a virtual periscope so the people on board can see what is above the water and in the air while the submarine is completely underwater?

Check out the cool submarines below:

- Wouldn't it be cool to experience different ways people use transportation to get from place to place in the water?

- What are at least two examples of ways people get around in the water?

Share your answer with your parent or teacher, then move on to the Got It? section.

Resources and Extras

- kitchen sponge (small rectangle)

- drinking straw

- hole puncher

Additional Resources

- Transportation: Land

- Transportation: Air

Suggested Lessons

What Is a Census?

Mapping My Stuff

Civil vs. Criminal Law

History and Progress

- ABBREVIATIONS

- BIOGRAPHIES

- CALCULATORS

- CONVERSIONS

- DEFINITIONS

Vocabulary

What does water travel mean?

Definitions for water travel wa·ter trav·el, this dictionary definitions page includes all the possible meanings, example usage and translations of the word water travel ., princeton's wordnet rate this definition: 0.0 / 0 votes.

water travel, seafaring noun

travel by water

ChatGPT Rate this definition: 0.0 / 0 votes

water travel

Water travel refers to the movement or transportation of people, goods, or animals by means of vehicles such as boats, ships, ferries, submarines, barges, and other vessels designed for navigation in water bodies like seas, oceans, lakes, rivers, canals, and reservoirs for purposes of commerce, recreation, exploration, or military purposes. It can involve short distances or travel across the globe.

Matched Categories

How to pronounce water travel.

Alex US English David US English Mark US English Daniel British Libby British Mia British Karen Australian Hayley Australian Natasha Australian Veena Indian Priya Indian Neerja Indian Zira US English Oliver British Wendy British Fred US English Tessa South African

How to say water travel in sign language?

Chaldean Numerology

The numerical value of water travel in Chaldean Numerology is: 3

Pythagorean Numerology

The numerical value of water travel in Pythagorean Numerology is: 1

- ^ Princeton's WordNet http://wordnetweb.princeton.edu/perl/webwn?s=water travel

- ^ ChatGPT https://chat.openai.com

Word of the Day

Would you like us to send you a free new word definition delivered to your inbox daily.

Please enter your email address:

Citation

Use the citation below to add this definition to your bibliography:.

Style: MLA Chicago APA

"water travel." Definitions.net. STANDS4 LLC, 2024. Web. 1 May 2024. < https://www.definitions.net/definition/water+travel >.

Discuss these water travel definitions with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe. If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

You need to be logged in to favorite .

Create a new account.

Your name: * Required

Your email address: * Required

Pick a user name: * Required

Username: * Required

Password: * Required

Forgot your password? Retrieve it

Are we missing a good definition for water travel ? Don't keep it to yourself...

Image credit, the web's largest resource for, definitions & translations, a member of the stands4 network, free, no signup required :, add to chrome, add to firefox, browse definitions.net, are you a words master, malicious satisfaction, Nearby & related entries:.

- water torch

- water tower noun

- water trading

- water trail

- water transportation

- water travel noun

- water treatment

- water trefoil

- water trough

- water trumpet noun

Alternative searches for water travel :

- Search for water travel on Amazon

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

JavaScript appears to be disabled on this computer. Please click here to see any active alerts .

Navigable Waters Protection Rule

- Navigable Waters Protection Rule Materials

- Public Comment Period (concluded)

The final "Revised Definition of 'Waters of the United States'" rule was published in the Federal Register on January 18, 2023, and took effect on March 20, 2023. On August 29, 2023, the agencies issued a final rule amending the Code of Federal Regulations to conform the January 2023 Rule’s definition of “waters of the United States” to the Supreme Court decision in Sackett v. Environmental Protection Agency . The conforming rule amends the provisions of the agencies’ definition of “waters of the United States” in the January 2023 Rule that are invalid under the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the Clean Water Act in the Sackett decision . The conforming rule, “Revised Definition of ‘Waters of the United States’; Conforming,” became effective on September 8, 2023 upon publication in the Federal Register . Please visit the Rule Status page for additional information about the status of the January 2023 Rule, as amended, and litigation. More information about current implementation of the definition of "waters of the United States" is available here .

Clean Water Act Approved Jurisdictional Determinations

Army Corps of Engineers Website

Clean Water Act Summary

Other CWA Policies and Guidance

The following documents are associated with the 2020 Navigable Waters Protection Rule (2020 NWPR), which was vacated by two district courts and has been replaced in the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) by the January 2023 Rule, as amended by the conforming rule. The 2020 NWPR is not in effect and the materials below are provided for informational purposes.

Navigable Waters Protection Rule Materials

- Final Rule: The Navigable Waters Protection Rule: Definition of “Waters of the United States”

- Economic Analysis

- Resource and Programmatic Assessment

- Access All Supporting Documents

Navigable Waters Protection Rule Public Comment (concluded)

On December 11, 2018, the Environmental Protection Agency and the Department of the Army proposed a revised definition of “waters of the United States” that clarifies federal authority under the Clean Water Act. The proposed rule published in the Federal Register (FR) on February 14, 2019 and was open for a 60-day public comment period. The public comment period closed on April 15, 2019. Comments were posted to Docket ID No. EPA-HQ-OW-2018-0149 and can be found here .

In addition, the agencies established an administrative docket, Docket ID No. EPA-HQ-OW-2017-0480 , to solicit pre-proposal recommendations for the Step 2 rulemaking to define “waters of the United States.” The docket closed on November 28, 2017. Written recommendations can be found here in the docket.

- Waters of the United States Home

- Programs Utilizing the Definition of Waters of the United States

- Rule Status and Litigation Update

- Implementation Tools and Methods

- Amendments to the 2023 Rule

- Training Presentations

- Public Outreach and Stakeholder Engagement Activities

- Skip to global NPS navigation

- Skip to the main content

- Skip to the footer section

Exiting nps.gov

Anilca, navigability, and sturgeon.

NPS/D. LILES

The passage of ANILCA saw the expansion of protected status to massive swaths of Alaska, encompassing millions of acres of newly designated national parks, preserves, and other conservation units. The legislation sought to extend protection to conserve these expansive landscapes and the waters that run through them, some of which being so central to the conception of these newly designated units that they became their namesake. But while ANILCA emphasized the conservation of these areas, it also included compromises to protect the interests of Alaskans in ways atypical in comparison to national parks in other states. These compromises touch on a number of subjects that have wide ranging implications, and the conservation and jurisdiction of the water bodies within ANILCA conservation system units (CSUs) are no exception. These implications were made apparent to the National Park Service in Alaska when rangers in Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve stopped a man on a hovercraft on the Nation River in 2007. The rangers warned the man that his hovercraft was not allowed in the preserve based on NPS regulations and he subsequently left. The issue was not dropped there, however, as this man, John Sturgeon, went on to file a lawsuit against the National Park Service arguing that a specific portion of ANILCA prevents the NPS from enforcing their regulations on navigable waters. Sturgeon argued that Section 103(c) of ANILCA prevents NPS from enforcing their regulations on the Nation River and other waters whose submerged lands are owned by the State ( Sturgeon v. Frost , 577 U.S. ___ (2016)). Section 103(c) prevents lands within conservation system units that are owned by the State, Alaska Native Corporations, or that are privately owned from being subject to regulations applicable solely to public lands. This provision was a compromise to prevent the lives of those who already lived within the newly designated units from being disrupted by their creation (16 U.S.C. § 3103(c)). The case proceeded through the District Court and 9 th Circuit Court of Appeals and then came before the Supreme Court who decided that 103(c) draws a distinction between public and non-public lands and remanded the case to the circuit court to decide if the Nation River was public land ( Sturgeon v. Frost , 577 U.S. ___ (2016)). When the case made it back to the Supreme Court ( Sturgeon v. Frost , 587 U.S. ___ (2019) “Sturgeon II”), they issued a unanimous decision that the Nation River was not public land by virtue of its state ownership, and therefore it (and by implication all waters whose submerged lands are not federally owned) were not subject to NPS regulation. The Court did acknowledge that federal subsistence fishing regulations applied on navigable waters within or adjacent to federal lands as a result of the outcome of the Katie John series of cases ( Alaska v. Babbitt , 72 F.3d 698 (9 th Cir. 1995)). In their acknowledgement, however, the Court refused to address federal subsistence fishing regulations since they were not at issue in Sturgeon II , leaving the Katie John rulings potentially open to future change. This decision has rippling implications for the National Park Service in Alaska, as now their ability to manage the waterbodies that are protected within ANILCA-designated units is brought into question. NPS authority over these waters became a question of the ownership of their submerged lands following Sturgeon II . This ownership of submerged lands is in itself a complicated legal question with a long history rooted in ideas about state sovereignty. As a sovereign, states hold title to the submerged lands of the navigable waters within their borders, a concept that relies upon the legal construct of navigability for title purposes to decide what is and isn’t navigable. Navigability for title purposes (which we will just refer to as navigability from here) has evolved over its history as court rulings have specified criteria and parameters defining its application. Waters are considered on a case-by-case and sometimes segment-by-segment basis based on these criteria to determine the ownership of their submerged lands and, post- Sturgeon II , who has the authority to manage them.

A Brief History of Navigability

Legal questions regarding the ownership of submerged lands based on their navigational use have a long history. In Roman law, a distinction was made between public and private submerged lands based on their use and on characteristics such as their ephemerality (MacGrady 1975). Within English common law, the sovereign (the monarch) owned the beds of all navigable waters as a means to ensure their use as highways for transportation and to ensure the sovereign’s authority to regulate and tax that use. As a consequence of English geography, specifically the lack of major navigable inland waterbodies, the definition of navigability in English common law was limited solely to tidally influenced waters as they were the only waters viable for this sort of use. As subjects of the British Empire the American colonies operated under the legal system of English common law. Following independence, American law remained rooted in many English common law principles, and many of these principles and practices are recognizable within the American legal system today (Robbins Collection 2017). The strong emphasis on judicial precedent, the use of an adversarial system in which two opposing parties (a plaintiff and a defendant) compete before a moderating judge, and the use of a jury of ordinary people without legal training to decide on the facts of a case are all components of English common law that were carried over into the legal system of the United States. Like many of these principles, navigability in American law extends from English common law. Within U.S. law navigability first arose as an issue of state sovereignty. In an 1842 case centered on a dispute over who possessed the right to harvest oysters in a certain bed in New Jersey, the Supreme Court ruled that the State of New Jersey held title to the lands beneath navigable waters in public trust as the sovereign successor to the English Crown ( Martin v. Waddell , 41 U.S. 367 (1842)). This established the principle of state ownership of the submerged lands of navigable waters within the United States and affirmed it as an incident of state sovereignty. Several years later in 1845, the case of Pollard’s Lessee v. Hagan (44 U.S. 212 (1845)) saw the application of the Equal Footing Doctrine to the question of navigability. The Equal Footing Doctrine is a principle in constitutional law that new states are admitted to the union on an “equal footing” with the original 13 states. Pollard’s Lessee v. Hagan concerned the ownership of the submerged lands between the shores of navigable waters within Alabama. The Supreme Court decided that the State of Alabama received title to these submerged lands upon statehood on an equal footing with the original 13 states. Up until this point, in the U.S. the question of navigability was restricted solely to the submerged lands beneath tidally influenced waters just as it was within English common law. However, the 1851 case of The Propeller Genesee Chief v. Fitzhugh (53 U.S. 443 (1851)) brought this principle into question. The case concerned whether or not the federal government had admiralty jurisdiction over the nation’s rivers and lakes as well as its tidal waters. The Supreme Court held that the tidal waters doctrine of common law was not appropriate for American jurisprudence as the geography of the United States, with its many navigable inland rivers and lakes, was significantly different from that of England. The Court therefore rejected the tidal test as the sole qualifier of navigability and held that inland waters that were navigable in fact fall within federal admiralty jurisdiction. With the construct of navigability now expanded to include waters that are navigable in fact (versus just tidal waters) there subsequently arose a question of how to define “navigable in fact.” This definition would come two decades later in the 1870 case of The Daniel Ball (77 U.S. 557 (1870)). In considering a question of interstate commerce and federal jurisdiction over it, the Supreme Court established what would become the classical definition of navigability:

Those rivers must be regarded as public navigable rivers in law which are navigable in fact. And they are navigable in fact when they are used or are susceptible of being used in their ordinary condition as highways for commerce over which trade and travel are or may be conducted in the customary modes of trade and travel on water.

This definition highlights several elements that must be considered when assessing navigability. The ruling established commerce (in the form of trade and travel) as the test for navigability. In other words, for a waterbody to be navigable it must have supported or been susceptible to supporting commerce. The susceptibility component indicates that there does not need to be an established history of commerce for a waterbody to be navigable so long as the characteristics of that waterbody indicate it could support such use. The definition also specifies that the waterbody must be in its ordinary condition, essentially stating that it could not have been modified to make it more or less navigable (such as by dredging or the construction of a dam). Further, this definition states that navigability is based on trade and travel upon water, therefore, use while frozen (for example a frozen river being used as a dogsled route) is not evidence of navigability. Finally, The Daniel Ball definition states that the commerce evidencing navigability must be conducted in the customary modes of trade and travel on water. This means that the waterbody must be capable of supporting commerce in crafts that would be typically used. With the definition for navigability finally in place it was then refined over time. In 1874 in The Montello , the Supreme Court held that the presence of a portage along a waterbody did not render it non-navigable ( The Montello , 87 U.S. 430 (1874)). In 1922, the Court ruled in Oklahoma v. Texas (258 US 574 (1922)) that waters that were only navigable during periods of spring flooding were not navigable for title purposes. 1953 saw the passage of the Submerged Lands Act (43 U.S.C. § 1301 et seq.), which codified the long-affirmed principle of state ownership of the submerged lands of navigable waters into statute and further refined the parameters of navigability. The Act specified the time of statehood as the timeframe to be considered when determining navigability. That means that when considering evidence of navigability, the conditions of the waterbody at the time of statehood, as well as the types of crafts that would be customary at this time, must be considered. The Act also delineates the boundary of the submerged lands as being the line of the ordinary high-water mark (often taken to be the line of permanent vegetation for the sake of simplicity). Finally, the Act also specifies that title moves with instances of accretion, erosion, and reliction. In other words, title moves with the slow, natural migration of the meanders of a waterbody over time. However, title does not move in instances of avulsion, where the course of a river rapidly redirects. The second half of the 20 th century saw further refinement of the definition. The 1979 appeal of Doyon Ltd. to the Alaska Native Conveyance Approval Board offered several criteria specific to Alaska (ANCAB RLS 76-2, 86 I.D. 692 (1979)). The Board held that evidence of private use of a waterbody can demonstrate susceptibility, that poleboats, tunnel boats, and outboard motor-powered riverboats were customary crafts in Alaska at the time of statehood, and that present day recreational use can serve as corroborative but not definitive evidence of navigability. In 1983, the District Court for Alaska ruled that use of a waterbody for floatplane landings is not evidence of navigability ( State of Alaska v. United States , 563 F. Supp. 1223 (1983)). More recently, navigability was considered by the Supreme Court in the 2012 case of PPL Montana v. Montana (565 U.S. 576 (2012)). In this case, the Court established that modern recreational use could be evidence of susceptibility if it is proven to be meaningfully similar to customary use at the time of statehood. Perhaps more significant, however, was that the Court affirmed the practice of segmenting waters for navigability determinations. We can then synthesize from this caselaw a definition of a navigable water as one that is actually used or is susceptible to being used as a highway for trade, travel, and commerce in the waterway’s natural and ordinary condition (at the time of statehood) in crafts customary at the time of statehood . Though far from comprehensive, this history demonstrates how navigability was and continues to be an evolving construct.

ALASKA DIGITAL ARCHIVES

Navigability Criteria

Now that we have a definition of navigable, we will take a closer look at some of the criteria for assessing navigability. A key component in the Daniel Ball definition of navigable is that the waterbody must be able to accommodate commerce. It is important, then, to consider what commerce would include. Generally, commerce in this context would be the existence of trade and travel across a waterbody. However, it is important to distinguish between commercial activity and boating in general. An individual taking a canoe down a river on a recreational trip would not be an example of commerce, as it does not represent trade and travel. The simplest way to demonstrate that a waterbody was useful for commerce is to have clear historical evidence of trade and travel, for example photographs and written records of steamships transporting supplies or people on a river. In many cases in Alaska however, no such historical record exists. Therefore, navigability becomes a question of the susceptibility for commerce rather than actual commercial use. In such instances, modern-day non-commercial activities can be evidence of navigability if it can be shown that the watercrafts employed are meaningfully similar to those that would have been customarily used for trade and travel at the time of statehood ( PPL Montana v. Montana (565 U.S. 576 (2012)). We will elaborate more on what “meaningfully similar” means later, but for now we should maintain our focus on commerce. A major consideration in assessing if an activity demonstrates commerce or the susceptibility for commerce is the weight in cargo a watercraft can transport. The issue of how much carrying capacity is necessary to constitute commerce is not an entirely settled legal question. In Alaska, the clearest guidance comes from the 1979 appeal of Doyon Ltd. (ANCAB RLS 76-2, 86 I.D. 692 (1979)). In this case, the board recommended that a net carrying capacity of 1,000 pounds could be used as a minimum threshold for commercial loads. When examining evidence of commerce, another important consideration is whether there is a lack of actual use of a waterbody despite the conditions existing for that use. For example, if trade and travel commonly occur adjacent to a waterbody, but never actually make use of that waterbody to accommodate those commercial activities, that evidence would weigh against the waterbody being navigable ( Oklahoma v. Texas , 258 U.S. 574 (1922)); Muckleshoot Indian Tribe v. FERC , 993 F.2d 1428 (9 th Cir. 1993). However, the presence of an alternate route of commerce alone does not make a waterbody non-navigable.

VALDEZ MUSEUM

With a clearer understanding of how commerce is defined and interpreted in the context of navigability, we can now move to a discussion of customary crafts and meaningful similarity. The Daniel Ball definition specifies that commerce must be conducted in the “customary modes” of trade and travel on water. Because the time of statehood is the point in time being considered (as specified by the Submerged Lands Act) that means that “customary modes” would refer to watercraft that were customarily used in Alaska at the time of statehood on January 3, 1959. Guidance on what types of watercrafts were customary in Alaska at the time of statehood comes from the 1979 appeal by Doyon Ltd. (ANCAB RLS 76-2, 86 I.D. 692 (1979)). The board found that pole boats, tunnel boats, and outboard motor-powered riverboats were customary crafts in Alaska at the time of statehood. If these types of crafts are capable of carrying a commercial load (at least 1,000 pounds) they could indicate that a waterbody was susceptible to supporting commerce at the time of statehood (and would therefore likely be navigable). There has been some disagreement between the United States and the State of Alaska over what types of crafts were customary at statehood. For example, the U.S. has not agreed with the State that jet boats were customary at statehood based on their very limited availability in Alaska in 1959 (State of Alaska’s Mot. For Summ. J., Alaska v. United States , No. 3:12-cv-00114-SLG (D. Alaska 2015). During litigation over the Gulkana River, the court did not list jet boats as being customarily used on that river at statehood ( Alaska v. United States , 891 F.2d 1401 (9 th Cir. 1989)). If a waterbody is only traversable in modern crafts that are not meaningfully similar to crafts customary at statehood, then that waterbody would not be navigable ( PPL Montana v. Montana (565 U.S. 576 (2012)). With that being said, it is worth discussing what “meaningfully similar” means. In PPL Montana v. Montana (565 U.S. 576 (2012)) the court ruled that modern day, non-commercial use could be evidence of navigability if it can be shown that the crafts employed are meaningfully similar to crafts customary at the time of statehood. When assessing if a modern craft is meaningfully similar to a craft customary at statehood, a number of factors can be considered. Just as weight capacity is an important consideration in determining susceptibility to commerce, it is also an important characteristic to examine when assessing if a modern craft is meaningfully similar to a customary one. If a modern craft is capable of carrying much greater loads than a customary craft of the same size, they likely would not be meaningfully similar. Additionally, draft requirements (or how far into the water a boat sits) are important to consider. If a modern boat capable of carrying commercial loads can be used in only a few inches of water while a customary boat requires deeper water to carry the same load, those two crafts would not be meaningfully similar. In addition to weight capacity and draft depth, the material a craft is constructed from is also an important consideration. The materials used to construct inflatable rafts have made advancements since 1959. Therefore, modern inflatable rafts may be much more resistant to puncture and abrasion than inflatable rafts available at statehood. As such, these modern rafts would be able to traverse much shallower and rockier waterbodies than rafts at statehood likely could, thus the modern rafts likely are not meaningfully similar to rafts customarily used at statehood. Further, modern rafts often include features such as upturned bows and sterns as well as aluminum rowing frames that provide increased mobility—features that were not common on statehood-era inflatable rafts. A watercraft’s means of propulsion is another important characteristic to consider when assessing a craft’s meaningful similarity to crafts customary at statehood. As noted earlier, there is dispute as to whether jet boats were customary at the time of statehood in Alaska. When compared to propeller-driven boats (which were certainly customary at the time of statehood) jet boats can be used in extremely shallow waters. Prop boats rely on a spinning propeller, which must stick further down into the water column to propel the craft. This spinning propeller runs the risk of striking objects along the bed of a waterbody and becoming damaged, which limits the boat’s ability to be used in shallow waters. In contrast, a jet does not need to stick as far down into the water and does not have a spinning propeller which can become damaged or tangled, enabling jet boats to be used in much shallower waters. Given this drastic difference in maneuverability, and the lack of widespread jet boats in Alaska at the time of statehood, this type of craft likely would not be meaningfully similar to a craft customarily in use at statehood. Now that we have considered different questions about commerce and watercraft, we can move to a discussion about the characteristics of waterbodies themselves. As we noted earlier, historical evidence of commerce occurring on a waterbody is the most convincing evidence for navigability. However, in many if not most instances—particularly in Alaska where many waterbodies are remote and have no history of development—there is little to no historical record. In those instances, navigability becomes a question of susceptibility for use as a highway of commerce rather than actual documented use. When considering susceptibility, we are often-times examining the physical characteristics of a waterbody and assessing if those characteristics would make it useful as a highway for commerce. The depth and gradient (slope) of a waterbody are both important physical characteristics to consider. There is no clear caselaw that establishes specific threshold values for what depths and gradients would make a waterbody navigable, and every waterbody is considered case-by-case based on its particular facts. However, if a waterbody were so steep that it couldn’t safely or reasonably accommodate trade and travel it very likely would not be navigable. Likewise, if a waterbody only had a depth of several inches and could not support a vessel carrying a load of cargo it very likely would not be navigable. Another important physical characteristic to consider is the presence of obstructions along a waterbody that would inhibit travel, such as rapids, boulders, or log jams. The presence of obstructions does not automatically make a waterbody non-navigable. Though the presence of obstructions may make navigation quite difficult, if they can be reasonably portaged around and if the waterbody overall can still support trade and travel it may be navigable ( Oregon v. Riverfront Prot. Assoc ., 672 F. 2d 792 (9 th Cir. 1982)). However, to be navigable the waterbody must still provide a route that is long enough to be useful and valuable in transportation ( N. Am. Dredging Co. of Nev. v. Mintzer , 245 F. 297 (9 th Cir. 1917)). Alongside obstructions, it is also important to consider seasonality when assessing susceptibility. If a waterbody can only be navigated during periods of temporary high water, such as during seasonal floods, or if watercraft must be repeatedly dragged or carried the waterbody is likely non-navigable ( United States v. Oregon , 295 U.S. 1 (1935)). A final thing to note regarding susceptibility and physical characteristics is that a waterbody must be in its natural and ordinary condition at the time of statehood. This means that a waterbody cannot have been modified from its natural condition at the time of statehood to make it more or less navigable. If a waterbody could only be traversed after modification, for example by dredging, then it would not be navigable. Conversely, if a waterbody could have been traversed prior to statehood, but a dam was constructed post statehood that made it impassible, that waterbody could still be navigable since it is the natural and ordinary condition at the time of statehood that must be considered.

Navigability in Alaska: Implementation and Implications

Though the State of Alaska owns the submerged lands beneath navigable waters, there is an important exception: lands that were federally reserved at the time of statehood. If lands were reserved at statehood, and if the withdrawal included intent to reserve the submerged lands, those submerged lands remain in federal ownership regardless of navigability. This applies to the several pre-statehood parks in Alaska—portions of Denali, Katmai, Glacier Bay, and Sitka. If there is no valid pre-statehood withdrawal for a waterbody, ownership of submerged lands (and jurisdiction over them) becomes a question of navigability. The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) is delegated the authority to make navigability determinations under the Federal Land Policy and Management Act (43 U.S.C. § 1701 et. seq.) and is the sole agency with authority to issue navigability determinations that have legal bearing. BLM does this as a part of the land conveyance process to avoid accidentally conveying State-owned submerged lands to another party. When BLM makes navigability deter-minations, they consider the available historical evidence demonstrating a waterbody’s use as a highway for commerce. In the absence of historical evidence, BLM also considers the physical characteristics of a waterbody (such as depth, gradient, seasonal variability, and the presence of obstructions) and if those characteristics indicate that it would be susceptible to commerce. Other agencies such as the NPS or the Alaska Department of Natural Resources may conduct their own research on navigability and publish those findings, but these assessments and any subsequent assertions of ownership and jurisdiction do not have legal bearing in the way that BLM determinations do.