- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

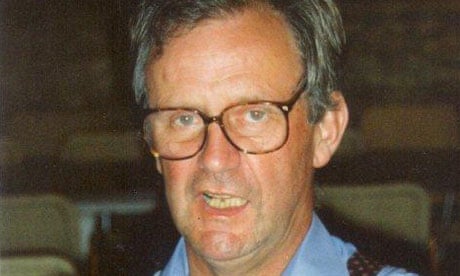

Donal Cruise O'Brien obituary

It cannot always have been easy to be the son of a celebrity as flamboyantly controversial as the writer and politician Conor Cruise O'Brien , but his son Donal, who has died aged 71, handled it with aplomb. He delighted in telling a story about being marooned on a grounded plane in Dublin when, falling into conversation with his neighbour, they exchanged names. At the sound of the famous surname, the man's face changed, and Donal braced himself for an onslaught on his father's latest démarche. But the man was looking at him with a new respect. He was in fact an obsessive genealogist, and told him reverently: "If you had your rights, you would be the Earl of Thomond."

Donal did not succeed to the long-defunct earldom but became an interdisciplinary scholar of immense distinction whose work on the Mouride brotherhood of Senegal brought together history, political science and sociology in books such as The Mourides of Senegal (1971), Saints and Politicians (1975), Charisma and Brotherhood in African Islam (1988, with Christian Coulon) and Symbolic Confrontations: Muslims Imagining the State in Africa (2003).

He was born in Dublin and left Ireland young, reading history at Peterhouse, Cambridge, before a doctorate in political science at Berkeley, California, and research in France and Africa. In his 39 years at the School of Oriental and African Studies, London, he was a much-loved teacher and supervisor as well as a widely respected professor.

Donal's international background conferred an ability to think his way into other cultures while maintaining an analytical distance. He also learned to cast a cold eye on political passions (and gave his father some much-needed advice on the subject, whether it was taken or not). Donal's work, with Julia Strauss, on politics as theatre (Staging Politics, 2006) may reflect this. His independence of mind enabled him to survive, and benefit from, intellectual mentors as diverse as Maurice Cowling , Ernest Gellner, Michael Crowder and Roland Oliver. It also enabled him to confront multiple sclerosis, which first struck him in 1969, without a shred of self-pity.

He had the indomitable support of his wife, Rita. Together they faced the challenges of his progressive disability with a determination never to compromise on the necessities of the good life. Whether in London, Dorset, California, France or Spain, they brought with them the best of conversation, food, wine, music and affection. Donal bore the recent rapid downturn in his physical condition with fortitude, always retaining his laconic wit and deep interest in other people. In his final months, he finished writing a vivid memoir of his life. During this last illness, asked how he felt, he replied: "Lucky."

He is survived by Rita, their daughter, Sarah, and two grandchildren, Lily and Joe.

- History books

- Other lives

Most viewed

O'Brien, Conor Cruise

O'Brien, Conor Cruise (1917–2008), diplomat, politician and writer, was born Donal Conor David Dermot Donat (he habitually interpolated Sheehy) Cruise O'Brien on 3 November 1917 at 44 Leinster Road, Rathmines, Dublin, the only child of Francis Cruise O'Brien (qv) and Kathleen (née Sheehy) (1887–1938). His father was a prominent activist in the Young Ireland Branch of the United Irish League, an agnostic and critic of sectarianism, whose principal employment was as a journalist. His mother was a daughter of David Sheehy (qv), a member of the Irish parliamentary party close to John Dillon (qv). She was active in the Young Ireland Branch and the Irish Women's Franchise League, and taught Irish in the technical college in Rathmines. Most of her family, with the exception of her sister Hanna (qv) and Hanna's husband Francis Sheehy-Skeffington (qv), opposed the romance with Francis Cruise O'Brien, whom she married on 7 October 1911. The rift was never quite closed over: 'My father never forgave … any of the Sheehys who had opposed the marriage. He was civil to them for my mother's sake, but it was only for the Skeffingtons that he felt real liking and respect' ( States of Ireland , 83). If O'Brien was a fascinated observer of the Sheehys, his identification with his father cut more deeply. He wrote in 1986: 'I was brought up on the fringes of the catholic nation, and with ambivalent feelings toward it. My family background was entirely southern Irish Roman catholic, but my father was what would be called, in the Jewish tradition, a maskil . That is to say he was a person of the Enlightenment, an avowed agnostic' ( The siege , 19).

O'Brien first attended Miss Haines, a protestant preparatory school, but transferred to the Dominican nuns in Muckross on Marlborough Road before his first communion. His parents then sent him to Sandford Park school. If that reflected his father's wishes, his taking Irish rather than Greek as he had wanted to conformed to his mother's. Displeased, he became in time a fluent Irish speaker. He later characterised Sandford Park, where he was happy, as not exactly a protestant school, but a nondenominational school 'of mainly protestant ethos, attended by catholics, protestants and Jews in approximately equal numbers … All around us was the ocean – as it seemed to us – of our contemporaries, all good catholics going to good catholic schools, and being indoctrinated like mad. From our tiny island of Enlightenment ( haskala ), we could peer out into that possibly enviable fog' (ibid., 19).

For some weeks leading up to Christmas 1927, Frank Cruise O'Brien, always frail and sickly and now afflicted with tuberculosis, had been confined to bed. On Christmas morning he presented his ten-year-old son with the gift of a bow. 'As he showed me the bow my father started to bend it. Then he gave a kind of sigh and lay back on the pillow. His face was very pale and he was altogether still.' He died later that day ( Sunday Independent , 24 December 1995). Conor was now alone with his mother, who was to outlive her husband by only ten years. Staunch to her husband's wishes, Kathleen kept him in Sandford Park. His confirmation was negotiated with some difficulty with the local clergy: 'I remember standing with my mother one winter evening outside the front door of the parish priest of Rathmines, while that individual – a purple, pear-shaped person – spoke gruffly to my mother through a chink in the door' ( States of Ireland , 109–10). The finances of the family, always precarious, were now parlous. Kathleen gained a full-time position with the college in Rathmines (which as it happened had been vacated by Máire MacEntee's mother Margaret, who had refused to take the oath to the new state), but there were still debts to moneylenders and visits from bailiffs.

He saw a good deal of his aunts: Mary, the widow of Tom Kettle (qv), sharp-minded if morbidly disposed to piety; and the formidable Hanna, widow of Francis Sheehy-Skeffington, who, breaking with Fianna Fáil when de Valera (qv) entered the dáil, had become a militant republican. The Sheehy widows met most Sundays for tea and dinner at 44 Leinster Road, joined afterwards by other guests. If these occasions lacked the grandeur of the 'second Sundays' in the home of David Sheehy at 2 Belvedere Place in the pre-1916 era when the dynastic prospects of the Sheehys were still intact, they must have been at least as diverting. Conor was very close to his cousin, Hanna's son Owen, who preceded him in Sandford Park and in Trinity. Sheehy-Skeffington's spirited anti-authoritarianism ('Owen's commitment to freedom of expression – and his ample use of all the freedom he could get – got him into much more trouble than his socialism did') exerted a formative influence on O'Brien. 'I knew Owen all my life, at least for that long part of my conscious life which overlapped with his. We were first cousins and we were both only children. Owen, nine years older, was more like a brother than a cousin and – after my father's death when I was ten years old – he was something like a father to me' (A. Sheehy-Skeffington (1991), vii, xi).

O'Brien entered TCD in 1936 with a sizarship achieved through his proficiency in Irish. He studied modern languages and literature (French and Irish). In an undergraduate career marked by intense pre-examination sprints rather than the steady pace favoured by his friend and rival Vivian Mercier (qv) (whom he consistently 'pipped'), he won great distinction. In his first year he won a foundation scholarship, and thereafter the unusually remunerative Hutchinson Stewart literary scholarship. He graduated with a first class moderatorship, and a gold medal, in late 1940.

From Ireland, the second world war seemed remote, and he shared some of the insular complacency. In the diary he kept, he wrote in late May 1940 that the arrival of the Germans in Boulogne would probably prevent him receiving from Paris the edition of Proust he had ordered three weeks previously. His entry a month later was more sombre, but still solipsistically divorced from the war: 'Surrender of France. Invasion of Ireland seems certain now … We can only wait until we become a battleground. Twenty-three years of training. I am now ready to take my place in a liberal democracy. Too late again' (Akenson, 103).

His life in Trinity was not narrowly academic. In 1938 he was appointed Trinity correspondent of the Irish Times . He debated in the Historical Society, and joined the Labour party in Trinity, causing a stir at the party conference in April 1938 by explicitly attacking the regime of General Franco. He edited and contributed verses to TCD: A College Miscellany : one of his better efforts prompted libel proceedings, subsequently dropped, by Horace Porter, a contemporary partisan of Fine Gael.

Christine Foster entered Trinity the same year as O'Brien. Her father, Alec Foster, was a liberal Derry presbyterian, her mother a Lynd who was a sister of the essayist Robert Lynd (qv). O'Brien and Christine began a relationship, and were married in the registry office in Dublin on 20 September 1939, before they commenced their fourth year at Trinity. He was very fond of Alec Foster, and it was under his auspices that O'Brien had his first experience of Northern Ireland, where he taught for a couple of months in the spring of 1939 at the Belfast Royal Academy, of which Foster was head.

O'Brien then encountered an unexpected setback. He sat the entry examination for the Irish civil service, but did not do well enough to be offered a position. He resolved to take the examination again the next year, and in the interim to take a second degree, a moderatorship in history, perhaps to keep open the fallback of an academic career. Donal, the first child of the marriage, was born on 4 July 1941 (two more followed: Fedelma on 26 April 1945 and Katherine (qv) (Kate) on 25 June 1948). In autumn 1941 O'Brien flew through the civil service examination.

Civil Service

He entered the Department of Finance, where he was a junior administrative officer (1942–4), an interval in his life that did not feature in his Who's who entry. Probably through the intercession of Paddy Lynch (qv), who became a lifelong friend and adviser, he moved in 1944 to the Department of External Affairs as a third secretary. He also began to write for publication. A series of brilliant articles appeared through the 1940s in the Bell under the pseudonym of Donat O'Donnell . This did not preclude O'Brien publishing some searingly accurate criticism of Sean O'Faolain (qv), its editor. His renown spread, and the collection of essays, many already published elsewhere and all completed by mid 1947, published in 1952 as Maria Cross: imaginative patterns in a group of modern catholic writers , still thinly pseudonymous, marked him out as a literary critic of international stature.

With the election of the first inter-party government in 1948, Seán MacBride (qv) was appointed minister for External Affairs. In a sequence of events which originated in the proclamation of Ireland as a republic in 1949, an all-party campaign against partition was launched in the Mansion House in which O'Brien was to play a central role within the department. Promoted in 1951 to the rank of counsellor, he edited the bulletin Éire , and arranged the publication of pamphlets. At MacBride's behest, he wrote an anti-partitionist history of Ireland, never published and not extant, which his biographer dubbed 'the Lost Book of O'Brien' (Akenson, 134). Most remarkably in the context of his later career, he became managing director of MacBride's surreal Irish News Agency, established by statute to engender a flow of propaganda in favour of Irish reunification in the international press.

When de Valera returned to power at the 1951 general election, Frank Aiken (qv) became minister for External Affairs. O'Brien remained in charge of the Irish News Agency, which had a diminished role under Aiken, and became the department's link to the nationalist community in Northern Ireland, to which he made a number of visits. His involvement on the anti-partition side ceased with his appointment to the Irish embassy in Paris, where he was counsellor (1955–6).

By this time he had an established reputation as a critic and essayist. He wrote, still as Donat O'Donnell, for Commonweal in the US and reviewed for the Spectator and the New Statesman in England. He completed his doctoral thesis on Charles Stewart Parnell (qv) and his party. Against some sharp cavilling from Robin Dudley Edwards (qv) as extern examiner, he was awarded a doctorate in 1953. His thesis was published as Parnell and his party by the Clarendon Press in 1957. Historiographically it was almost revolutionary in its critical analysis, acuteness of insight and scholarly dispassion. O'Brien was conscious of the transition from oral remembrance, dedicating the book to the memory of David Sheehy and Henry Harrison (qv), the two survivors of Commitee Room 15 he had known. His understanding of Parnell's strategy was acute, and he elucidated the respective roles of his lieutenants, each of whom he brilliantly characterised. While he had when young been somewhat dismayed by David Sheehy's adherence to the anti-Parnellites, his conclusion on the Parnell split of 1890–91 was measuredly adverse to the Irish leader.

United Nations

In May 1954 the second inter-party government took office and Liam Cosgrave was appointed minister for External Affairs. A UN section was being constituted in anticipation of Ireland's long-pursued membership of the UN, which was to take place on 14 December 1955. O'Brien was appointed head of the UN section in Dublin, reporting to F. H. Boland (qv) in New York. At the general election of March 1957, Fianna Fáil returned to power, and Aiken to External Affairs. Theretofore Ireland at the UN was identified with the US. Aiken was disposed to take a more independent line, and O'Brien and other younger colleagues favoured a non-aligned approach on the Swedish model ( Katanga , 14–15). O'Brien advised that the litmus test was the vote in favour of a discussion on the representation of China, which Aiken agreed to support. On a number of other issues, Ireland took positions independent of the US.

O'Brien's marriage to Christine had been gently disintegrating for some time, and at the end of 1956 he began a relationship with a colleague in External Affairs, Máire MacEntee, a brilliant Irish-language scholar and poet, five years his junior, and the daughter of Sean MacEntee (qv). They were to marry, in New York, on 9 January 1962, and later adopted two children, Patrick (born 18 May 1968) in 1969, after a protracted negotiation of Irish adoption law, and Margaret (born 16 January 1971) in 1971, both of African-Irish parentage.

Katanga, 1961

O'Brien was promoted to an assistant secretaryship in the department in 1960. In March 1961 the secretary general of the UN, Dag Hammarskjöld, first asked the Irish government to release O'Brien for service with the UN as its representative in Élisabethville (Lubumbashi). The request was declined, but renewed at the end of May without referring to the Congo. That request was acceded to. O'Brien left Dublin for New York on 27 May, and left New York for the Congo, via Brussels and Paris on 8 June, reaching Élisabethville on 14 June to take up his responsibilities as the representative of the UN secretary general in Katanga as part of ONUC (Organisation des Nations Unies au Congo).

The Congo had attained independence from Belgium on 30 June 1960. On 11 July, the day after Belgian paracommandos had arrived in Élisabethville for the stated purpose of protecting the European population, Moise Tshombe proclaimed the independence of Katanga province. The new Congolese government in Léopoldville (Kinshasa) asked for UN military assistance. On 17 January 1961, Patrice Lumumba, the charismatic prime minister of the Congo, who had been taken captive, was murdered by Tshombe's troops. The UN security council adopted on 21 February a resolution which urged that the UN take immediately all appropriate measures to prevent the occurrence of civil war in the Congo, including 'the use of force, if necessary, as a last resort', and that measures be taken to secure the evacuation from the Congo of all Belgian and other foreign military and paramilitary personnel and political advisers, and mercenaries.

The first concerted attempt to give effect to the resolution was Operation Rumpunch, the apprehension of all foreign officers, put into effect on 28 August. It was an apparent success as far as it went: the arrests were stopped, largely on the basis of an undertaking from the Belgian consul general to ensure the repatriation of foreign mercenaries. The ease with which the relative success of Rumpunch was achieved served to embolden UN personnel on the ground in the Congo, who had limited military resources deployed across a country eighty times the expanse of the former colonial power. O'Brien believed, probably correctly, that the Tshombe regime would not have resisted the pressure to come to terms with the Congolese government in Léopoldville without the encouragement given it by the Rhodesian, and tacitly the British, governments (Katanga, 232). Large numbers of Africans, chiefly Kasai Baluba, took refuge in the UN camps.

On 11 September, Mahmoud Khiary, the Tunisian chief of UN civilian operations in the Congo, and Vladimir Fabry, ONUC's legal adviser, gave O'Brien and Brigadier Raja, the officer commanding the UN forces in north Katanga, the instructions for Operation Morthor and the warrants for the arrest of the leading figures in the Katanga regime. Operation Morthor was put into effect on 13 September, but was not a success: Tshombe had, unknown to O'Brien, taken temporary refuge in the house of the British consul general in Élisabethville, whence he had departed for Rhodesia. O'Brien told the press corps that in the wake of Morthor the secession of Katanga was at an end: this was later to be used against him. Dag Hammarskjöld arrived in Léopoldville the same day to be met by a remonstrance from the British government through its ambassador concerning what had transpired in Katanga. O'Brien found himself in the position of a distant intermediary between Tshombe and Hammarksjöld, who was determined to proceed to Ndola in Rhodesia to parley with Tshombe, without O'Brien and without seeing O'Brien. On 18 September, Hammarsjköld's plane crashed on the flight to Ndola. O'Brien in his account of the Katanga episode wrote: 'In these days immediately after Hammarskjöld's death, I felt, not personal grief but an obscure sense of misunderstanding with, not exactly guilt but uneasiness. I knew that my pressing for renewed action in Élisabethville – following up Rumpunch – my emphasis on urgency, leading to the timing of the action for the morning of his arrival in the Congo, and my failure to avert certain errors in execution, were among the links in the chain that led to his death.' Reflecting further, he concluded that the pressure of the British government, along with Hammarskjöld's ambivalent attitude to the actions taken in Katanga, had a preponderant causative influence on Hammarskjöld's departure for Ndola ( Katanga , 304–5). O'Brien wrote that 'in Élisabethville I do not think there was anyone who believed that his death was an accident'. He shared that disbelief, suspecting the involvement of fascist personnel of the French OAS ( Katanga , 286–7). His joint letter with George Ivan Smith to the Guardian of 11 September 1992 advancing a somewhat different hypothesis notwithstanding, he cleaved to that view ( Ir. Times , 21 Aug. 1998).

O'Brien recognised that in the post-Morthor furore he should leave his assignment in Élisabethville so as not to jeopardise the prospects of reconciliation, but wanted to be assigned to Léopoldville as the senior political adviser to the ONUC chief of civilian operations rather than be reassigned to a role in New York. He left for New York on 16 November, leaving Máire MacEntee in Élisabethville, where she had joined him a couple of weeks previously. At the security council, the Belgian foreign minister Paul Henri Spaak denounced O'Brien for having pursued 'a personal policy', and 'grossly exceeded instructions'. Paradoxically, this fortified O'Brien's position; however, it was almost immediately destabilised by what transpired in Élisabethville on 28 November. Katangese paracommandos apprehended a party en route to a reception in honour of US Senator Thomas Dodd of Connecticut, a backer of Tshombe. The party included Brian Urquhart, soon to succeed O'Brien in Katanga, who was bloodied with a rifle butt and dragged away along with two others. Manhandled, Máire MacEntee acted with calm and resourcefulness, no less than O'Brien's driver, Private Paddy Wall.

O'Brien had already written to Aiken on 25 November advising that he had reluctantly come to the conclusion that he could no longer usefully represent the UN in Katanga, and if requested would be happy to resume service in the Department of External Affairs. In the wake of the episode in Élisabethville, it was conveyed to Aiken that, if O'Brien was not recalled to the department, Hammarskjöld's successor, U Thant, would call for his resignation. On 1 December both O'Brien and MacEntee, independently of each other, resigned from the department ( Katanga , 315–29; Kennedy and Magennis, 183–8). But O'Brien did not propose to go quietly from the Katanga assignment. He issued a statement the same day explaining why he was resigning to the New York Times and to the Observer , and gave a press conference on 4 December.

A year later, in November 1962, he published To Katanga and back , a brilliantly poised, if occasionally casuistical, apologia. What he was principally concerned to establish was that he had not acted without the sanction of Hammarskjöld, which was the truth. In a letter to Owen Sheehy-Skeffington of 9 January 1963, he conceded that 'there was some bad luck – also some bad judgement – on my part', but saw the failure of Morthor in operational military terms, attaching weight to the fortuitous absence of Raja's chief of staff.

The failure of this first essay in the uncharted terrain of 'peace enforcement' took its toll. He was assailed in the mid-market British press. His prematurely wise son Donal recalled: 'More than ever I saw my father as a vulnerable person' ( Story of a migrant , 112).

O'Brien served as vice-chancellor of the University of Ghana (1962–5). He had accepted the appointment proffered by Kwame Nkrumah, the president of Ghana, with some misgivings. Nkrumah, the subject of two assassination attempts while O'Brien was vice-chancellor, and who was to fall in a coup the year after its end, became increasingly authoritarian, and his incursions into academic freedom in the name of 'Nkrumahism', a self-serving, pseudo-Leninist ideology, grew more marked over the term of O'Brien's appointment. These O'Brien resisted with diplomatic adroitness in what was a sustained rearguard action. The assaults on the independence of the university culminated in the deportation of five academics in early February 1964. O'Brien, though he had already threatened to resign, chose to stay on. He addressed the university congregation the following month, emphasising the necessity for the respect of truth, and moral and intellectual courage in its sustainment: 'These are not European values; these are universal values.' In March 1965 he resolved to resign, but changed course, deciding to leave the decision to the convocation, the teaching staff of the university, which almost unanimously resolved he should stay until the end of his term.

Through his fraught tenure in Accra, O'Brien continued to write, and to lecture outside Ghana. He published in 1965 his superb 'Passion and cunning: an essay on the politics of W. B. Yeats', concerning which he had written to Owen Sheehy-Skeffington on 14 July 1964: 'the fact is that the Yeatsists have consistently played down his involvement in reactionary and fascist politics'. His trenchant attack on the politics of Yeats (qv) was counterbalanced by his love of the poems, which held him in thrall all his life. Writers and politics (1965) was a selection drawing together his reviews and essays from 1955.

With the Ghanaian interlude, another phase of O'Brien's career had come to an abrupt end, with an ensuing hiatus. In June 1965 his appointment as regents' professor and holder of the Albert Schweitzer chair in humanities at New York University (NYU) was announced, and he took up the position in September 1965. He was an inspiring teacher, and drew to the programme he directed George Steiner, David Caute and John Arden (qv), and later Edward Thompson.

Politically his stance to the left of mainstream liberal intellectuals reflected the complex interrelationship of the unfolding of his own thinking to the international politics of the 1960s. He was not a Marxist. He was a critic of imperialism, on his own terms. In his essay 'Contemporary forms of imperialism', published in autumn 1965 in the review Studies on the Left , he attacked neo-colonialism not as driven by economic interests, but as a modern form of racially premised domination, promoted through ideas of the containment of communism. In the spring of 1966 he condemned indiscriminate anti-communism in an essay entitled 'The counterrevolutionary reflex'.

This provided the backdrop to O'Brien's contest with Encounter , the glittering liberal periodical that transpired to be funded by the US Central Intelligence Agency through the Congress for Cultural Freedom. O'Brien had in 1963 challenged its agenda, and returned to the charge in his Homer Watt lecture at NYU on 19 May 1966. (He wrote to Claud Cockburn on 15 April 1966 of Melvin J. Lasky, the driving force of Encounter , that 'Lasky I regard as a sort of cultural cold war conman'.) Encounter retaliated with a comparison of its accuser with Senator Joseph McCarthy. O'Brien wrote a reply for the New Statesman , which, when threatened with a libel suit, pulled the article. He issued libel proceedings in Dublin, which Encounter settled on the day of the hearing in February 1967.

With Máire he campaigned against the Vietnam war, and sustained in December 1966 a severe kick in the hip from a New York policeman ('no prizes for guessing his ethnicity') at an anti-war demonstration in Manhattan at which they were both arrested. He was consistently critical of the passivity of American policy towards South Africa and Rhodesia. He visited Biafra in mid-September 1967, and asserted the rights of the Ibo in an extended piece for the New York Review of Books , and in the Observer , rejecting any equation of Biafra with Katanga. He supported Senator Eugene McCarthy's anti-Vietnam war campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1968. His concise and brilliant, if coldly unsparing, Camus (1970) belongs to his New York period.

Though immersed in its public life in a period of bracing political and artistic vibrancy, the O'Briens were never quite settled in New York. With the adoption of Patrick, Whitewater, the house which O'Brien had purchased in 1950 on the summit of Howth, overlooking the Baily lighthouse, with the glittering sweep of Dublin bay to the right, once more beckoned.

The return to Ireland

The turn back to Ireland was presaged by the invitation of Owen Dudley Edwards to contribute to an Irish Times supplement to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the Easter rising of 1916. 'The embers of Easter' appeared on 7 April 1966. Written in his high anti-imperialist phase, it was O'Brien's most left-wing piece on Ireland (it was republished in the New Left Review ). Its ostensible theme was the betrayal in a bourgeois, clericalist republic of the ideas of Patrick Pearse (qv) and, more particularly, James Connolly (qv), but its true subject was the destructive effects of pretence and self-delusion, of 'national fantasy', on the politics of the independent Irish state, notably in relation to the persistence of partition and the fate of the Irish language. In the revolutionary republican tradition, the state from the beginning was a violation of the principles of its founders: 'This contradiction had, I believe, a strong still unexplored effect on the psychology of my generation, those who are roughly coeval with the state. The Irish nationalist tradition is a very strong one and permeates the personality of those who are brought up in it.' He attributed the sorry state to which he judged Pearse's republic had dwindled by the 1950s to 'two sets of pressures – the pressures of reality itself, and those resulting from the inability of idealists to accept that reality. Functionally the pseudo-activity of “anti-partition” helped to deaden the pain of the dawning of reality. The grey and humdrum dawn has now arrived.' He did not exempt himself: 'The present writer blushes to recall that at one time he devoted a considerable part of his professional activity, as a member of the Department of External Affairs, to what was known as “anti-partition”. The only positive result of the activity, as far as I was concerned, was that it led me to discover the cavernous inanities of “anti-partition” and of government propaganda generally.' Nor did he spare the Labour party: 'The Labour Party in this three-quarters-of-a-nation has been dominated for years by dismal poltroons, on the lines of O'Casey's Uncle Payther.'

In autumn 1968 Brendan Halligan, the general secretary of the Labour party, asked Michael McInerney, the political correspondent of the Irish Times and a friend of the O'Briens, to set up a meeting with Conor. O'Brien was invited to rejoin the party of which he had been a member in Trinity, evidently with a view to his seeking election to Dáil Éireann. He accepted. When he spoke in Liberty Hall on 19 December, its 600-seat auditorium was almost full and he was greeted by a standing ovation of a minute's duration. His speech was reported verbatim in the Irish Times , which declared that 'the Labour party has had its biggest boost for years in securing Dr O'Brien's membership'. Noel Browne (qv) declared: 'The old conservative Labour party is dead and gone … Most Labour men today are ten feet high!' ( Ir. Times , 23 December 1968).

By the following month it was decided O'Brien would contest Dublin North-East, which encompassed Howth, and he was quickly inducted into the Howth branch of the party. He returned to NYU, where he delivered a valedictory lecture on 23 April 1969.

In the general election of June 1969, the 'seventies will be socialist' campaign of the Labour party of Brendan Corish (qv) was turned by the red scare of the outgoing Fianna Fáil government of Jack Lynch (qv). In the four-seat constituency of Dublin North-East, the dominant political figure was Charles J. Haughey (qv), the minister for finance. The Irish Times played up the juxtaposition. It published a three-part profile of Haughey followed immediately by an excellent three-part profile of O'Brien (12–14 June 1969) in the immediate run-up to the poll on 18 June. In the concluding part the writer ventured: 'One might even say, taking him together with his rival in Dublin North-East, Charles Haughey, that there is a whiff of Lucifer about both of them. O'Brien's elephantine memory, and his occasional rasping reaction to insult or injury, seem to many to compound a flaw in a large intellect … He can be as obstreperous as Haughey. He equals him in sheer nerve or brass neck.' When O'Brien raised in the campaign Haughey's land dealings, he was rebuked by the Irish Times . While there was 'a strong whispering campaign against him, mainly on the basis of his two marriages and on his religious orthodoxy', he was elected second to Haughey, polling an impressive 7,591 first-preference votes against Haughey's 11,677.

The situation in Northern Ireland was deteriorating sharply. O'Brien was the Labour party spokesman on foreign affairs and Northern Ireland, and part of a Labour delegation that went to the North in August, meeting as he later noted only nationalist representatives. He rapidly fell out with Noel Browne and David Thornley (qv); his relations with his third roommate in Leinster House, Justin Keating (qv), took longer to sour. Sustained loyally by Corish, Frank Cluskey (qv) and Michael O'Leary (qv), he continued to visit Northern Ireland, and on 12 August 1970 was beaten up at an Apprentice Boys' rally at St Columb's Park in Derry.

On 11 June 1971 at the ITGWU conference in Galway, O'Brien responded to a proposal for the release of all political prisoners. He asked what was a political prisoner. 'Is a man convicted in court and jailed for inciting and leading a sectarian mob a political prisoner? or a man who booby-traps a car? or plants a bomb, injuring children and innocent people? or a man who guns down another man?' It was a succinct and trenchant intervention, of which the footage survives. He was supported by Corish, but Halligan told him shortly afterwards: 'Conor, you're going too fast' (Akenson, 164).

Michael O'Leary observed some signs that O'Brien, shortly after his return to Ireland, was attracted by the then left-wing Sinn Féin before the split in the IRA and the formation of the Provisionals in January 1970, and warned him against being in any way drawn into the orbit of Sinn Féin: '“Watch out for Cathleen Ni Houlihan!” he warned me. “If you get too near her, she'll scratch your eyes out!”' ( Memoir , 324). Jack Lynch's dismissal of ministers Charles Haughey and Neil Blaney (qv), and the resignation of Kevin Boland (qv), on 6 May 1970, and the arms trial that ensued, revealed the potential of the Northern 'troubles' to destabilise the institutions of the Irish state. There was one final flare-up of nationalist ardour on O'Brien's part. When the British army shot dead thirteen demonstrators in Derry on 30 January 1972, he crossed to London and met the Labour leader, Harold Wilson, and the home secretary, Reginald Maudling, to press for the setting of a date for the withdrawal of British troops. It was not an exercise in advocacy he would repeat.

O'Brien's States of Ireland was published in early October 1972. Brilliantly fusing history and family memoir with a chronicle of his own engagement with the 'troubles', it was the first sustained and self-conscious enunciation by a nationalist of what became known as 'revisionism' in its Irish sense. He wrote near its close that he had been accused of hyper-sensitivity about Irish protestants, and caring little about the catholics. 'In fact the reverse accusation would contain more truth. It is to the Irish catholic community that I belong. That is “my little platoon”, to love which, according to Edmund Burke (whose family were in the same platoon) “is the first germ, as it were of publick affections”. I am motivated by affection for that platoon, identification with it, and fear that it may destroy itself, including me, through infatuation with its own mythology' (pp 316–17). This was not sufficient to insulate O'Brien from John Hume's review in the Irish Times of 9 October, in which he pronounced that 'Conor Cruise O'Brien's case is a more subtle and effective defence of unionism than any that has come from any unionist quarter … If accepted his case will sentence another generation in the North to the terrible violence we have just come through.'

Member of the Irish government

At the general election of February 1973 there was little change in the result in Dublin North-East, but nationally Fianna Fáil was defeated, and a Fine Gael–Labour coalition under Liam Cosgrave took office. O'Brien became minister for posts and telegraphs (1973–7), while retaining his role as Labour spokesman on foreign affairs and Northern Ireland. He was disappointed not to get Foreign Affairs, which went to Garret FitzGerald (qv). O' Brien's relations with FitzGerald were personally friendly but politically edgy. He thought FitzGerald glib if well-meaning, and endured his prolixity with impatience: moreover he considered him to be in thrall to John Hume.

O'Brien was part of the Republic's representation at the Sunningdale conference (6–9 December 1973). He opposed the proposed Council of Ireland: 'Garret answered, in a tone of cold superiority such as he had never used to me before, that my information was out of date. Northern Ireland was no longer like that. The protestant population would accept the Council of Ireland without any difficulty. This I knew was a certitude he had derived from John Hume' ( Memoir , 349). The Northern Ireland power-sharing executive of Brian Faulkner (qv) fell on 28 May 1974 after a two-week strike by loyalists.

O'Brien diligently applied himself to his departmental responsibilities, but strayed into controversy, expressing himself with more explicitness or greater pungency than was either conventional or politically prudent. In February 1974 he referred to state policies on the Irish language as having created a 'bog oak monolith'. In late June 1974 his declaration that he was no longer working actively for Irish unity scandalised received opinion. He espoused a policy of open broadcasting (involving reciprocal broadcasting arrangements between RTÉ and the BBC), but was beaten back and, after commissioning a consumer survey, endorsed the establishment of a second RTÉ television channel.

There had been in some quarters an expectation, based on some of the positions he had adopted in opposition, that O'Brien would repeal section 31 of the Broadcasting Authority Act (1960), which permitted the Minister to direct the RTÉ Authority 'to refrain from broadcasting any particular matter or matter of any particular class'. He quickly made plain that given the conditions that prevailed in Northern Ireland he would not abrogate the provision for a broadcasting ban. What he did was to refine the legislative regime; such was the controversy that it was as if he had introduced a form of censorship that had not previously existed. He twice reformulated the terms of the pre-existing order of 1971, and substituted for the old section 31 a replacement limiting what the minister could proscribe to access to broadcasting to those 'likely to promote, or incite to, crime or would tend to undermine the authority of the state', also limited the duration of any given order, and provided that the oireachtas could set aside an order of the minister.

O'Brien's public statements were unusual in their clarity. At the Labour party conference in October 1974 he stated that 'to condemn internment without referring to those [IRA] activities that led to internment being imposed was equivalent to condoning those activities'. A few days later, on 26 November, he reacted to a meeting organised by Hibernia magazine to protest against internment in Northern Ireland at which Senator Mary Robinson had spoken: 'There is considerable confusion in this country about what the attitude of liberals should be in a situation in which the democratic state is challenged by an armed military conspiracy. There are those, claiming to be liberals, who greet with angry protests every response of the state to the conspiracy and who refuse to recognise the existence of such a conspiracy as a genuine threat to democracy and freedom. That is a travesty of liberalism. That is dancing to the tune of the IRA.' The Irish Times scathingly condemned what it termed 'the O'Brien ethic'.

There were gratuitous excesses. He responded with precipitate intemperance to a Seven days documentary on internment, and became embroiled in a damaging controversy over a proposed amendment to the criminal law he had helped to draft that would proscribe the incitement or invitation 'by advertisement, propaganda or any other means' to participate in or support or assist the activities of unlawful organisations. Asked about the section in the bill in an interview with Bernard Nossiter of the Washington Post , he pulled out of his office desk a sheaf of letters to the Irish Press sympathetic to the IRA. In the uproar that ensued, the scope of the proposed section was cut back.

At the June 1977 election, against a deteriorating economic background, the Cosgrave coalition was heavily defeated. In the refigured constituency of Dublin (Clontarf), O'Brien was unexpectedly defeated, failing by 700 votes to secure the last seat.

O'Brien was elected to Seanad Éireann for Dublin University (1977–9). The new leader of the Labour party, Frank Cluskey, made himself spokesman on Northern Ireland. When he asked O'Brien to submit to him in advance any statement on Northern Ireland, O'Brien on 20 September 1977 resigned from the Labour parliamentary party. He would some years later go through the motions of resignation from the party itself in protest against the Anglo–Irish agreement, by which time his membership had already lapsed; he rejoined in 2005. Like his friend Michael O'Leary he never truly ceased to be of the Labour party ('Saints, sinners and sincerity', Magill (July 1981)), though his attacks on Dick Spring's driving forward of the peace process were unsparing.

In June 1979 he resigned from the seanad, bringing to an end with chronological neatness an extraordinary decade as an Irish parliamentarian. There was a sour valediction from the Irish Times : with his departure, 'a searing, sometimes malevolent, yet cleansing element is removed from Irish politics … He is a great egoist' (1 June 1979).

Editor-in-chief of the Observer

Professionally he was once again with the loss of his dáil seat on the qui vive . Late in 1977 he embarked on an extended African trip for the Observer , and had a memorable encounter with the Zimbabwean revolutionary Robert Mugabe, who asked him if he supported freedom fighters in his own country. O'Brien replied that if Mugabe meant the Provisional IRA, he had not supported them but favoured their suppression by all lawful means. '“Then you are a traitor?” said Mugabe. The intonation was interrogative. Mr Mugabe smiled as he spoke.' Mugabe was incensed on the publication of O'Brien's account in January 1978.

In a complex arrangement promoted by David Astor, who had relinquished ownership of the Observer to Robert Anderson of Atlantic Richfield, and brokered by Arnold Goodman, O'Brien was appointed editor-in-chief of the Observer , with Donald Trelford remaining editor. His appointment was announced in the Observer of 18 December 1977.

O'Brien added lustre to the Observer , but the division of authority between editor and editor-in-chief was operationally fraught. O'Brien had a dispute with the distinguished journalist Mary Holland (qv), who was the paper's Irish correspondent, in relation to a feature on a republican family in Derry, in which he wrote to her that he thought it 'a serious weakness in your coverage of Irish affairs that you are a very poor judge of Irish catholics. That gifted and talkative community includes some of the most expert conmen and conwomen in the world and in this case I believe you have been conned.' Holland resigned, rejoining the paper after O'Brien's departure (O'Toole, Magill (June 1986)).

O'Brien, who was writing for the paper in diverse formats, proposed to contribute a regular weekly piece, and Astor agreed. His elegantly personalised, short-form essays were an acknowledged success, and the template for much of his later journalism. Corporate intrigues persisted, and on 25 January 1981 the Observer announced that O'Brien for family reasons had asked to be relieved of his duties as editor-in-chief from 31 March. When Anderson sold the paper to Tiny Rowland of Lonrho, O'Brien had testified with Astor and Goodman against the acquisition before the Monopolies and Mergers Commission. Fired by Trelford, with whom his relations remained amicable, his association with the paper ceased in 1984.

He wrote for the Irish Times (1982–6), then moved to the Irish Independent , for which his father had written. He wrote for the Times of London (1986–92). Towards the end of his life his principal journalistic outlet was the Sunday Independent .

The peace process

Northern Ireland provided the principal subject of O'Brien's journalism. In a piece for the New York Review of Books (29 April 1982; republished in Passion and cunning (1988)) entitled 'Ireland: the shirt of Nessus', he wrote: 'The official ideology of the Republic fully legitimises the IRA “war” in Northern Ireland and so helps that “war” go on and on … Our ideology, in relation to what we actually are and want, is a lie. It is a lie that clings to us and burns, like the shirt of Nessus.' In southern politics he continued to assail Charles Haughey. When Haughey described the series of episodes that led to the arrest of Malcolm MacArthur, subsequently convicted of murder, in the home of the then Irish attorney general, as 'grotesque, unbelievable, bizarre and unprecedented', O'Brien coined the acronym 'GUBU' ('Unsafe at any speed', Ir. Times , 24 August 1982).

Convinced that the pursuit of a negotiated settlement in Northern Ireland which involved the IRA and Sinn Féin was a propitiation of terrorism and a reverse oppression of Northern protestants, O'Brien pitted himself against the John Hume–Gerry Adams convergence course of Irish and British government policy in relation to the North. He was an unrelenting critic of the Anglo–Irish agreement of 1985.

He accepted an invitation from the British Conservative MP Ian Gow to address the Friends of the Union at Westminster on 19 January 1988. 'I didn't accept without a little shiver', recalling his grandfather's thirty-three years at Westminster as a nationalist MP. 'I didn't feel myself so much to be a Friend of the Union as a friend of the unionist people of Northern Ireland, and a person determined to associate with them in support of their determination not be pushed in a direction in which they didn't want to go' ( Memoir , 426). In defending the right of the unionist majority to adhere to the union, as if to underscore the gesture of solidarity, he went further than he strictly had to in accepting that this made him a unionist: on the day after Gow's murder by the IRA, he wrote: 'I did not, until comparatively recently, see that this position logically required defence of the union itself, and made me personally a unionist' ( Times , 31 July 1990). He supported two Conservative candidates in Northern Ireland in the general election of April 1992. In July 1992 he gave the second Ian Gow memorial lecture. In the face of what he characterised as a 'perfidious and murderous' campaign against the unionists of Northern Ireland, he explicitly characterised himself as a unionist: 'To move from being a nationalist to being a unionist – or the reverse indeed – is not just an altered political option. It is more like an existential metamorphosis' (Akenson, 470–71).

The Downing Street declaration of 15 December 1993 led into the peace process to which he was unremittingly hostile. In a Westminster by-election in North Down in June 1995, he canvassed for the successful unionist candidate Robert McCartney, and joined McCartney's non-sectarian United Kingdom Unionist Party (UKUP). On 9 May 1996 he was nominated on the party's regional list: the Irish Times carried a front-page photograph of McCartney wrapping a tie with an Ulster motif around him. He was one of the party's representatives to the Northern Ireland Forum. McCartney's party, along with Ian Paisley 's (qv) vastly more formidable DUP, opposed the Good Friday agreement of 10 April 1998 in the referendum that followed. O'Brien intermittently advocated the internment of terrorist suspects, and fleetingly the re-drawing of the border.

O'Brien's support of the union was more politically contingent than his embrace of the appellation of 'unionist' might suggest. In the concluding chapter of his Memoir (1998), he advocated the consideration by unionists of 'the only real option which the weak leadership of Ulster unionism, and British connivance with Sinn Féin have left them: a deal with constitutional nationalists to avert British surrender of Northern Ireland to violent republicanism' (p. 434). This démarche, disclosed in advance of the book's publication, was an embarrassment to McCartney, and O'Brien resigned from his party on 27 October 1998, retaining a family friendship with the McCartneys. The final chapter represented an acknowledgement that the project of UKUP was greatly weakened by the degree of unionist acceptance or acquiescence in the peace process. Given that his overriding concern was to resist Sinn Féin and the IRA there was a certain inner logic to O'Brien's final position: rather than being harried towards a united Ireland by a series of intermediate institutional arrangements that entrenched Sinn Féin, and which that party would be certain to exploit to its advantage, Northern protestants should outflank Sinn Féin by moving directly towards a united Ireland through a negotiated agreement with the constitutional nationalist parties of the south. 'To me, the main attraction is that it would get rid of what is very nearly Sinn Féin–IRA dominance of the political process in this island, which is a horrible thing' ( Ir. Times , 28 October 1998). There was a shift in his self-designation which reflected an awareness of the implications of this final move: he no longer termed himself a unionist, but someone who had been from 1990 'a friend of the union' ( Memoir , 426). Reviewing Memoir , Arthur Aughey applied the dictum of Georg Christoph Lichtenberg: 'There is a great difference between still believing something and again believing it' ( Fortnight (February 1999)).

If the course he took from 1985 made him a politically isolated figure within nationalist Ireland to the point of appearing something of an obsessive, and was a source of mute unease to most of his friends and admirers in the south, O'Brien held with resolute insouciance to his position as virtually the sole publicly prominent figure in the south – and the only intellectual of international stature – strenuously to oppose the peace process and the ambitious exercise in cross-community institutional engineering which it inaugurated.

Israel, South Africa and international affairs

After his stint as editor-in-chief of the Observer , O'Brien earned his living by his journalistic writing, by contributions to international reviews and by his books, and had a series of visiting lectureships in American academic institutions.

Throughout his life he was a friend to the Jewish people, and a staunch defender of the state of Israel. From 1982 he invested much of his energies in The siege: the saga of Israel and Zionism , published in 1986. Prodigiously researched, the book was marred by the unyielding conceptual framework implicit in its title that took no account of the entitlements of the Palestinian people.

A committed opponent of apartheid in South Africa, O'Brien became chairman of the Irish Anti-Apartheid Movement (IAAM) in May 1966, and was an advocate of effective sanctions. What he was not prepared to countenance was the academic boycott promoted by the African National Congress. In September 1986, accompanied by his son Patrick, he went to South Africa primarily to lecture at the University of Cape Town, which was not racially segregated. When Kader Asmal (1934–2011), a successor in the chair of the IAAM, condemned his acceptance of the invitation as 'an act of betrayal', O'Brien's response was succinct: 'Stuff them. I am not going to have my conscience run for me by Kader Asmal' ( Ir. Times , 11 September 1986). His lectures went off well initially, but in a debate on 2 October he was barracked by radical, mainly white students. The Azanian Students' Organisation demanded the cancellation of his lectures. His next lecture and a class the next day were disrupted, and he agreed to the request of the university who had invited him to South Africa to cancel the residue of the lectures.

From the mid 1980s, O'Brien's view of international affairs grew progressively bleaker. In book form this found expression in his sub-apocalyptic On the eve of the millennium (1994), which attracted a memorably contemptuous review by Christopher Hitchens ( London Review of Books , 22 February 1996), who had been an admirer, and was to be again: he contributed the foreword to O'Brien's posthumously published First in peace: how George Washington set the course for America (2009). This was a reprise of part of the argument of O'Brien's underrated The long affair: Thomas Jefferson and the French revolution (1996), a closely argued critique of the sainted American statesman as a calculating disciple of Rousseau and the French revolutionaries.

He was opposed to the 1992 Maastricht treaty, and to projects of political union in Europe, more as a realist diplomat of the old school than on ideological grounds. Turning away from Europe, O'Brien's perspective was increasingly Atlanticist. His support of the second Gulf war, and his generally indulgent disposition towards the presidency of George W. Bush fils , were aberrant rather than characteristic. If his own world view had darkened in old age, his attitude towards the exponents of neo-conservatism was unfailingly sardonic.

Edmund Burke

O'Brien wrote: 'the more I study Burke, the more I am affected with something like awe' ( Times , 9 November 1991). He came to conceive his relationship to the political as a dialogue with Edmund Burke (qv). In 1969 he edited and wrote the magnificent introduction to the Penguin edition of Burke's Reflections on the revolution in France . He drew on Burke's Irish catholic background to assert, against his cold war scholarly appropriation, that Burke, 'in his counter-revolutionary writings, is partially liberating – in a permissible way, a suppressed revolutionary part of his own personality' (p. 34).

Around 1980, O'Brien set out to write a biography of Burke, but found that within the confines of conventional biography and the unfathomable intricacies of late-eighteenth-century parliamentary politics 'the Burke that interested me – Burke's mind and heart, at grips with the great issues of his time' eluded him. He dropped the project, turning to writing The siege . On O'Brien's account, what brought him back to the Burke project was the nagging of Yeats's lines in 'The seven sages': 'American colonies, Ireland, France and India / Harried, and Burke's great melody against it.' Yeats gave him his title, and pointed to the possibilities of a themed approach. O'Brien's The great melody: a thematic biography and commented anthology of Edmund Burke was published in 1992. The 'commented anthology' reflected his increasing suspicion of academic paraphrase, particularly when applied to Burke.

Once again he emphasised the impact of Burke's Irish catholic lineage: his treatment owed something to discussions over the years with Máire on the elusive parcours of Burke's lawyer father Richard. He wrote: 'In studying Burke, I have often found that, whenever there is an unexpected silence, a failure to refer to something obviously relevant, or a cryptically guarded formulation, the probable explanation is usually to be found at “the Irish level”: the suspect and subterranean area of emotional access to the forbidden world of Roman Catholicism' (p. 450). O'Brien's haunted reinstatement of the Irish Burke prompted some scholarly cavilling in Britain. His closing treatment of the continuities of Jacobinism and revolutionary Marxism (pp 597–601) placed him in synchrony with Francois Furet, whom he greatly respected, and whose Le Passé d'une illusion was published in 1995. He said he wished his epitaph to be that he had given Burke back to Ireland.

In early July 1996, in the period of his involvement as a UKUP representative in talks at Stormont, O'Brien suffered a mild stroke. He recovered well, but was left with anxiety about his recall of names. He turned to the writing of his Memoir: my life and themes , encouraged by his daughter Kate, editorial director of the Poolbeg Press, which was to publish it in Dublin. Kate's death from a brain haemorrhage on 26 March 1998 left him inconsolably distraught.

His last public appearance was on 7 September 2006 to deliver an address on the ninetieth anniversary of the death of T. M. Kettle, in the old house of lords chamber of the Bank of Ireland on College Green. His own ninetieth birthday was the occasion of a last large rallying of family and friends at Whitewater. Conor Cruise O'Brien died at the age of 91 on 18 December 2008. His funeral was at the church of the Assumption in Howth, and he was interred in Glasnevin.

His dramatic writings include King Herod explains (1968), in which Hilton Edwards (qv) played Herod at the Gate theatre in 1971; Murderous angels (1968), on the prelude to Katanga; and unpublished screenplays on Parnell and Michael Collins (qv). He was pro-chancellor of the University of Dublin (1972–94), a member of the RIA, and was awarded numerous honorary doctorates, including from QUB in 1984.

O'Brien's papers are in UCD archives; his correspondence with Owen Sheehy-Skeffington is in the NLI. A checklist of his publications prepared by Joanne L. Henderson is included in Conor Cruise O'Brien: an appraisal (1974) by Elizabeth Young-Bruehl and Robert Hogan. A fuller bibliography to date of publication appears in the second volume of Donald Akenson's biography of O'Brien (1994), and includes a list of his newspaper pieces to 1992.

O'Brien had a ruddy, stubbled glamour. He had charisma, or insolently flaunted his objectionability, depending principally on one's politics. Colloquial reference to 'the Cruiser' (a term popularised by John Healy (qv)), if it did not indicate affection never mind political accord, attested to a recognition of O'Brien as a familiar, formidable and distinctive figure in the dramatis personae of contemporary Irish life.

He was endowed, and perhaps politically cursed, with an expressiveness beyond the human norm. He was not conversationally declamatory: always interested in the response to whatever case he was making, he urbanely drew out his interlocutor. He was unaffectedly curious. One of his more daunting conversational gambits was to ask of someone you were supposed to know more about, 'give me sixty seconds' on that person. He was unfailingly attentive to – in the moment fascinated by – the little things, the small vexations of life that prey on all of us. His superb verbal parodies and bursts of mimicry were attended by wide-eyed mock-pathos. His son Donal sent him in September 1971 a missive of subdued jocularity entitled 'How to stay alive in Ireland: a personal and political programme for my father'. The positive precepts included: 'Cultivate studied inconspicuousness. Suppress the marked glint in your eye, also suppress spontaneous movement of facial muscles (these can often be far too revealing at the personal level)' ( Migrant , 214).

It is in Cruise O'Brien's letter to Donal in 1971, on learning that his son had been diagnosed with MS, that his faith in the transcendent power of words achieves its most strenuous expression:

You know how I feel, I think, and you and I are both a bit dumb about expressing such feelings. Just one thing, though, I know a bit about you, not everything, but something. I think you are supremely well equipped to meet severe stress. You can gauge its severity justly, without exaggeration, evasion or panic. It's true that you are both exceptionally sensitive and exceptionally imaginative, so that you must have suffered even more acutely than most people would under the initial impact of this thing. But you also have unusually deep inner resources, moral, emotional, and intellectual, great powers of recuperation, reflection and enjoyment, and also the mysterious, indestructible and versatile capacity we vaguely call humour ( Migrant , 208).

Fastidiously respectful of scholarship, he always took pains to explain he did not write as an academic, nor profess to academic objectivity: at one time he favoured the self-designation of 'publicist'. In relation to the modern academic treatment of nationalism, in the division inspired by Ernest Gellner between those who believed nationalism to be a peculiarly modern phenomenon and those classified as 'primordialists' who did not, his belief in the interrelationship of nationalism and religion, and his reading of terrorism as connected to a sacralisation of violence, cast him among the latter. He wrote in 1994: 'Nationalism is generally considered to be a phenomenon of fairly recent origin; many textbooks date it from the late eighteenth century, either just before or just after the French revolution. I think this is an error of categorisation. What happened was nationalism's sudden severance from something which it had felt itself to be inseparable from over the millennia. That something was religion' ( Millennium , 153). It was a subject he addressed in Godland: reflections on religion and nationalism (1988).

Politically O'Brien's principal contribution to Irish politics lies in his sustained attack in the 1970s on the terrorism of the IRA, and on the moonlit penumbra of condonation and evasiveness that surrounded it in southern politics. He understood that this had to be an assault of great intellectual clarity and measured passion, and consciously situated his argument in the line of great controversies from the fall of Parnell, something conveyed in the presence of Yeats in what he wrote and said. It was important for this that he should have been a member of Dáil Éireann in 1969–77 and of the Irish government of 1973–7. It is difficult to convey now the ferocity of the intellectual ferment that this generated, or its salutary consequences for democratic politics in the Irish state.

One might apply to O'Brien, with his almost Roman sense of household, what he wrote of Burke: 'The more one reads Burke the more one is impressed, I think, by a deep inner consistency, not always of language or opinion, but of feeling: a consistency of which the root principles are a strong capacity for affection, and a strong distrust of all reasoning not inspired by affection for what is near and dear' ( Reflections , 23).

Ir. Times , 12, 13, 14 June 1969 (profile); D. R. O'Connor Lysaght, End of a liberal: the literary politics of Conor Cruise O'Brien ( c .1976); Tom Paulin, 'The making of a loyalist', Times Literary Supplement , 14 Nov. 1980 (republished in Paulin, Ireland and the English crisis (1984)); Fintan O'Toole, 'The life and times of Conor Cruise O'Brien', Magill (Apr.–June 1986); Andrée Sheehy-Skeffington, Skeff: the life of Owen Sheehy-Skeffington 1909–1970 (1991); Donald Harman Akenson, Conor: a biography of Conor Cruise O'Brien (1994) (vol. ii comprises an anthology of O'Brien's articles); Richard English and Joseph Morrison Skelly (ed.), Ideas matter: essays in honour of Conor Cruise O'Brien (1998); Conor Cruise O'Brien, Memoir: my life and themes (1998); Máire Cruise O'Brien, The same age as the state (2003); Diarmuid Whelan, Conor Cruise O'Brien: violent notions (2009); Richard Bourke, 'Plague man: the crusader in Conor Cruise O'Brien', Times Literary Supplement , 13 Mar. 2009; Donal Cruise O'Brien, The story of a migrant: a personal memoire (2012); Geoffrey Wheatcroft, 'O'Brien, Conor Cruise', ODNB (Jan. 2012), www.oxforddnb.com ; Michael Kennedy and Art Magennis, Ireland, the United Nations and the Congo (2014); personal knowledge

Publishing information

Previous revisions.

Stay up to date with notifications from The Independent

Notifications can be managed in browser preferences.

UK Edition Change

- UK Politics

- News Videos

- Paris 2024 Olympics

- Rugby Union

- Sport Videos

- John Rentoul

- Mary Dejevsky

- Andrew Grice

- Sean O’Grady

- Photography

- Theatre & Dance

- Culture Videos

- Food & Drink

- Health & Families

- Royal Family

- Electric Vehicles

- Car Insurance deals

- Lifestyle Videos

- UK Hotel Reviews

- News & Advice

- Simon Calder

- Australia & New Zealand

- South America

- C. America & Caribbean

- Middle East

- Politics Explained

- News Analysis

- Today’s Edition

- Home & Garden

- Broadband deals

- Fashion & Beauty

- Travel & Outdoors

- Sports & Fitness

- Sustainable Living

- Climate Videos

- Solar Panels

- Behind The Headlines

- On The Ground

- Decomplicated

- You Ask The Questions

- Binge Watch

- Travel Smart

- Watch on your TV

- Crosswords & Puzzles

- Most Commented

- Newsletters

- Ask Me Anything

- Virtual Events

- Betting Sites

- Online Casinos

- Wine Offers

Thank you for registering

Please refresh the page or navigate to another page on the site to be automatically logged in Please refresh your browser to be logged in

Conor Cruise O'Brien: Irish intellectual with a long career as journalist, politician, literary critic and public servant

Article bookmarked.

Find your bookmarks in your Independent Premium section, under my profile

For free real time breaking news alerts sent straight to your inbox sign up to our breaking news emails

Sign up to our free breaking news emails, thanks for signing up to the breaking news email.

The author of just two competent stage plays, Conor Cruise O'Brien was the most important public man of letters Ireland witnessed since W.B. Yeats died in 1939.

It will take years to sort out the Yeats from the chaff (of which there was plenty). Nevertheless, Cruise O'Brien's standing as the principal post-war broker between the currencies of literature and politics is undeniable. His impact on international perceptions of "the Troubles" is best measured by the animosity manifest among his fellow-countrymen. I have been hostilely greeted in a rural public house because my jacket resembled "something Cruise O'Brien might wear". Finally, he possessed at his intermittent best a writing style equal to that of George Orwell.

Donal Conor David Dermot Donat Cruise O'Brien was born in Dublin in 1917, the only child of the journalist Frank Cruise O'Brien and his wife Kathleen (née Sheehy). The parents being ostentatiously progressive, the child's baptism as a Catholic might be regarded as an oversight. But the elder Cruise O'Brien's death on Christmas Day 1927 inaugurated a pattern of sombre mythic thinking in the solitary boy which throughout life complemented his mischievous dissent from orthodoxies in both church and state.

After a decent secondary education achieved through much sacrifice on the mother's part, Conor Cruise O'Brien entered Trinity College Dublin in 1936. An unconventional but brilliant student, he took a double First in Modern Languages (French and Irish) and History, and his postgraduate research was published as Parnell and His Party (1957). Already he had embarked on two careers – as civil servant and occasional literary critic.

While Sean MacBride was Ireland's Minister for External Affairs (1948-51), the young Cruise O'Brien argued a strongly anti-partitionist position in some ephemeral publications which his biographer-bibliographer has ignored. His association with MacBride brought a growing awareness of the world outside Ireland as a political arena as well as a cultural resource. In Sean O'Faolain's magazine The Bell, "Donat O'Donnell" had published perceptive criticism of Catholic novelists including Evelyn Waugh and François Mauriac. A collected edition appeared in 1953 as Maria Cross: imaginative patterns in a group of modern Catholic writers. The pressure of diplomatic work delayed further reflective work in essay form, but Writers and Politics (1965) gathered reviews, lectures, and other short pieces. By now, he was a well-known contributor to international magazines and newspapers. He continued to write for The New York Review of Books.

Characteristically, Cruise O'Brien was changing course even as success drew alongside. Among Irish delegates at the United Nations from 1956 onwards, he attracted the attention of the Secretary-General, Dag Hammerskjold. With crisis deepening in copper-rich Congo, the UN sought to play buffer between the great powers (including Belgium) and the new government. In 1961 Cruise O'Brien was despatched as Hammerskjold's personal representative, a situation complicated by the presence of Irish troops among the UN forces and the more personal attendance of another Irish civil servant, Máire Mac Entee.

To Katanga and Back (1962) represents the high point of Ireland's non-aligned commitment in the United Nations, and constitutes its author's best claim to a radical pedigree. His analysis of duplicitous manoeuvrings by Belgium, the UK and the United States gave substance to the suspicions of decolonising Africa. The book also narrates aspects of Cruise O'Brien's private and domestic life, culminating in (Mexican) divorce and remarriage.

While still students, Cruise O'Brien had met Christine Foster, daughter of a Northern Irish classics master and international rugby player. Married in 1939, they had three children. International conflict is not an ideal background for a re-alignment of one's emotional and domestic life. But he and Miss Mac Entee (a poet in Gaelic, and daughter of a government minister) succeeded in the essentials, though not without sharp comment from the Dublin Sunday newspapers. The murder of Patrice Lumumba and the débâcle of UN attempts to discipline the rebel province of Katanga hastened Cruise O'Brien's resignation both from his UN responsibilities and the Irish diplomatic corps.

Africa had been exciting, and he found himself installed as Vice-Chancellor of the University of Ghana in 1962, some months after his second marriage. Disagreements arising about the value of academic freedom, the contract was not renewed. While in Ghana, Cruise O'Brien wrote "Passion and Cunning", an analysis of Yeats's political attitudes and behaviour. Published in a volume of essays celebrating the poet's centenary in 1965, it caused outrage among the professors. A silently modified version was issued in 1988.

Moving from diplomacy to the mango groves of academia, Cruise O'Brien next became Schweitzer Professor of Humanities in New York University. From 1965 to 1969 he contributed vigorously both to the academic life of the city and the growing anti-war movement. A notable product of this period was The Morality of Scholarship (1967), edited with Northrop Frye and Stuart Hampshire.

In Ireland, radicalism was stirring, even in the Labour Party which proclaimed "The Seventies will be Socialist", and recruited a brilliant cohort of intellectuals including Justin Keating and Cruise O'Brien. Having joined the party back in 1937, he was now cautiously groomed for a public role. Some meetings were hosted by Michael McInerney, political correspondent for The Irish Times and a staunch supporter of Noel Browne, soon to be Vice-Chairman of the party. Opinion was sharply divided, and the new member of Dáil Eireann (elected for Dublin North-East in 1968) disappointed neither friend nor foe.

He was now "The Cruiser" whose political career can be personalised as his conflict with Charles Haughey (also a TD for Dublin North-East), geographically identified with Northern Ireland and its constitutional status, or ideologically traced through his implacable opposition to the Provisional IRA. Electoral defeat in 1977 ensured that ministerial experience was limited to one term (1973-77) in the Department of Posts and Telegraphs, a period dominated by his imposing a total broadcasting ban on Provos or their supporters.

This heavy-handed censorship cost him liberal friends while it paradoxically refined the Provos' approach to media management, of which they are today's acknowledged masters. Yet Haughey died in disgrace, the Irish Constitution no longer makes claim on the North, and the Provos have signed up to the Good Friday Agreement. So much argues for Cruise O'Brien's success, despite his own loud prophecies of yet more doom.

When the Cosgrave government fell in 1977, he had found a by-road back into politics as a senator representing Trinity College Dublin. His attendance record was deplorable, too much time being spent in London, where he served on The Observer in an editorial capacity (1977-1981). A highly publicised trip to South Africa incensed the international Anti-Apartheid Movement, while domestically his politics swung into a position not just sympathetic to Ulster Unionists but uncritically identical with theirs.

A mere list of his publications would be overwhelming. Though Ireland is everywhere a thematic concern, Cruise O'Brien contributed Albert Camus to the Fontana Modern Masters series, and wrote a study of Israel and Zionism (The Siege, 1986; translated into German in 1991). His refusal to meet or interview Yasser Arafat confirmed for many the emergence of a renegade from radicalism, even a paid stooge of "US-Zionist imperialism". Though the book lacks balance, and indulges in occasional flights of philo-Semitic special pleading, its author could not be accused of sustained pro-Americanism. Excursions into American history (The Long Affair, 1996) generally disguised a larger concern with the legacies of revolution (the French, in particular).

Obsessed as he was by the theme of religion and politics, Conor Cruise O'Brien's place in Irish history will be hotly debated. If governments use certain agents whom they class as "deniables", then Irish public opinion might borrow the term to understand what it sought from this mercurial and dedicated public servant. As the British left once said of Harold Wilson, he may be a rat but he is still our rat. As with Swift, his wit wounded. His gift was to provoke thought, not to persuade. He not only lacked the common touch, he loathed it.

Iconoclastic reviewer, socialist member of the Opposition, tough government minister, Gaelic-speaking revisionist historian and the stranger's best friend, Cruise O'Brien undertook a missionary programme of exploration which no contemporary could have rivalled. And he unquestionably delivered. His findings, like his initial sentiments, were rarely welcome. The wonder is that this messenger was not shot by one or other of those constituencies of passion and cunning to whom he reported.

It is arguable that the traumatic death of his father established psychic needs which were translated into conflictual goals – independence and security, a selective egalitarianism. Certainly, his innovative work on Edmund Burke (The Great Melody, 1992) reveals a strange need to feel Burke's contemporary presence, in the same room with the author. His later years were darkened by the sudden death of his beloved daughter Kate from a brain haemorrhage. His adoptive family were as deeply loved.

In March 2003, Cruise O'Brien attended the annual conference of the UK Unionist Party in Bangor, Co Down. This was not his first endorsement of full integration as a solution to Northern Ireland's difficult relationship with Britain. At 85, it bespoke a persistence in marginalisation strikingly different from the canny manoeuvres of the younger careerist.

He was still a workhorse journalist, not least to keep the taxman at bay, but the puckish humour had become ponderous and sibylline. In December 2003, a long-awaited report on bombings in Dublin and Monaghan drew terse pre-emptive denials that the Cosgrave government had lacked commitment in seeking to identify and prosecute the perpetrators (thought to include "rogue" elements in British security.)

If the rest is silence, it is a rest well earned.

Donal Conor David Dermot Donat Cruise O'Brien, politician, literary critic and historian: born Dublin 3 November 1917; staff, Department of External Affairs of Ireland 1944-61, Head of UN Section 1956-60, Assistant Secretary 1960-61; Vice-Chancellor, University of Ghana 1962-65; Albert Schweitzer Professor of Humanities, New York University 1965-69; TD (Labour) for Dublin North-East 1969-77; Minister for Posts and Telegraphs 1973-77; Pro-Chancellor, University of Dublin 1973-2008; Member of Senate, Republic of Ireland 1977-79; Fellow, St Catherine's College, Oxford 1978-81; Editor-in-Chief, The Observer 1979-81; FRSL 1984; married 1939 Christine Foster (one son, one daughter, and one daughter deceased; marriage dissolved 1962), 1962 Máire Mac Entee (one adopted son, one adopted daughter); died Howth, Co Dublin 18 December 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

New to The Independent?

Or if you would prefer:

Want an ad-free experience?

Hi {{indy.fullName}}

- My Independent Premium

- Account details

- Help centre

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Conor Cruise O’Brien, Irish Diplomat, Is Dead at 91

By William Grimes

- Dec. 19, 2008

Conor Cruise O’Brien, an Irish diplomat, politician, man of letters and public intellectual who staked out an independent position for Ireland in the United Nations and, despite his Roman Catholic origins, championed the rights of Protestants in Northern Ireland, died Thursday. He was 91 and lived in Howth, near Dublin.

His death was announced by the Labor Party, of which Mr. O’Brien was a member. No cause of death was given. He was reported to have suffered a stroke in 1998 and several broken bones in a fall last year.