COVID in the Islands: A comparative perspective on the Caribbean and the Pacific pp 231–252 Cite as

An Industry in Crisis: How Vanuatu’s Tourism Sector Is Seeking Economic Recovery

- Anna Naupa 3 ,

- Sarah Mecartney 4 ,

- Liz Pechan 5 &

- Nick Howlett 6

- First Online: 30 October 2021

444 Accesses

Although Vanuatu experienced no domestic COVID-19 cases in 2020, preventive border closures resulted in the sudden downturn of Vanuatu’s tourism industry, and the closure of many tourism-oriented businesses. Employment experienced a parallel downturn, in both the formal and informal sectors, despite creative efforts at gaining employment. This necessitated a rapid policy shift by the Government directed towards domestic tourism with some limited success. Longer term redevelopment of tourism focused on COVID-safe business readiness and an emergent theme of greater public-private coalition-building to accelerate national economic recovery efforts, including through a reimagining of the industry to cope with the ‘new normal’.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Asian Development Bank. (2019). Asian Development Bank Outlook. In Strengthening Disaster Resilience . Asian Development Bank.

Google Scholar

Cheer, J., & Lew, A. (2017). Understanding Tourism Resilience: Adapting to Social, Political, and Economic Change. In J. Cheer & A. Lew (Eds.), Tourism, Resilience, and Sustainability: Adapting to Social, Political and Economic Change (pp. 3–17). Routledge.

Chapter Google Scholar

Dornan, M., & Cain, T. (2019). Vanuatu and Cyclone Pam: An Update on Fiscal, Economic, and Development Impacts, Pacific Economic Monitor, May, 30–35.

Government of Vanuatu. (2019). Half-Year Economic and Fiscal Update of 2019 . Ministry of Finance and Economic Management. https://doft.gov.vu/images/2019/Economic_And_Fiscal_Report/HYEFR_English_2019.pdf . Accessed 22 Nov 2020.

Government of Vanuatu. (2020a, April). National Tourism Business Impacts Survey: TC Harold and COVID-19 Pandemic . Department of Tourism and Vanuatu Tourism Office.

Government of Vanuatu. (2020b). Yumi Evriwan Tugeta: Vanuatu Recovery Strategy 2020–2023 .

Graue, C. (2020, July 12). Vanuatu Feeling the Pinch as Coronavirus Pandemic Keeps Tourists Away , ABC Pacific Beat .

Orchiston, C., Prayag, G., & Brown, C. (2015). Organisational Resilience in the Tourism Sector. Annals of Tourism Research, 56 , 128–163.

Vanuatu Chamber of Commerce and Industry. (2020). Vanuatu Economic Outlook from a Private Sector Perspective . https://vcci.vu/vanuatu-economic-outlook-report-from-a-private-sectors-perspective/

Vanuatu Tourism Office. (2019). Towards 300,000: Sustainability, Partnership, Benefit for all: Vanuatu Tourism Market Development Plan 2030 .

Vanuatu Tourism Office. (2020). Vanuatu International Visitor Survey 2019. In Collaboration with the Auckland University of Technology, NZ MFAT, and the NZ Tourism Research Institute.

Watt, G., & Brenner, H. (2020). Cruise Tourism in Vanuatu: Impacts and Issues . The Council for Australasian Tourism and Hospitality Education 2020 Conference, 344–349.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Australia-Pacific Technical College, Port Vila, Vanuatu

Pacific Community (SPC), Nouméa, New Caledonia

Sarah Mecartney

The Havannah, Port Vila, Vanuatu

Vanuatu Tourism Office, Port Vila, Vanuatu

Nick Howlett

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

University of the West Indies, Kingston, Jamaica

Yonique Campbell

School of Geosciences, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

John Connell

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Naupa, A., Mecartney, S., Pechan, L., Howlett, N. (2021). An Industry in Crisis: How Vanuatu’s Tourism Sector Is Seeking Economic Recovery. In: Campbell, Y., Connell, J. (eds) COVID in the Islands: A comparative perspective on the Caribbean and the Pacific. Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-5285-1_13

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-5285-1_13

Published : 30 October 2021

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-16-5284-4

Online ISBN : 978-981-16-5285-1

eBook Packages : Social Sciences Social Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, the contentious role of tourism in disaster response and recovery in vanuatu.

- Development Studies, School of Social Sciences, Faculty of Arts, The University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand

Tourism is a key contributor to the economy of the Pacific Island country Vanuatu. Yet many Ni-Vanuatu have seen their access to natural resources lost or reduced as a consequence of foreign investment in the tourism industry and associated land leases, while few community members found secure employment in the tourism sector to compensate for those losses. The tension between externally driven tourism development and local resource access has been exacerbated in the aftermath of 2015 Tropical Cyclone Pam which caused extensive damage both to the tourism industry and local communities. Employing a tourism-disaster-conflict nexus lens and drawing on semi-structured interviews with hotel managers, research conversations with hotel staff and community members, and focus group discussions with community leaders, this study examines how the tourism sector has impacted post-disaster response and recovery, particularly in terms of land relations and rural livelihoods. Findings suggest that tourism can be a double-edged sword for disaster-prone communities. While resorts play an important role as first responders, their contributions to post-disaster recovery processes remain ambiguous and marred by tensions between expatriate investors and indigenous Ni-Vanuatu people. These findings also hold lessons for the tourism crisis triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic in the South Pacific and elsewhere.

Introduction

Tourism crises have often been precipitated by major disaster events. Small island developing states in the South Pacific have been particularly susceptible to tropical cyclones, floods and tsunamis that have had a deep impact on the tourism industry on which these countries’ economies depend strongly (e.g., Klint et al., 2012 ; Loehr, 2020 ). Yet, surprisingly, there has been very little research scrutinising the role of the tourism sector in the immediate disaster relief response and long-term rehabilitation efforts.

The objective of this paper is to contribute to a better understanding of the role of the tourism industry in post-disaster response and recovery processes, drawing on the example of the 2015 Cyclone Pam in Vanuatu. More specifically, the aim is to determine whether the tourism sector can be a positive force in helping local communities to restore their livelihoods. To this end, it is important to understand 1) how tourism businesses have been affected by Cyclone Pam, 2) how they have responded to and recovered from the disaster, and 3) how their response and recovery strategies have had an impact on their staff and local communities. Particular emphasis is placed on land relations and the rehabilitation of rural livelihoods. Thereby, the article aims to generate insights that will help inform future governance of disaster response and recovery – including from the COVID-19 pandemic – in touristic areas of Vanuatu and the wider Pacific region.

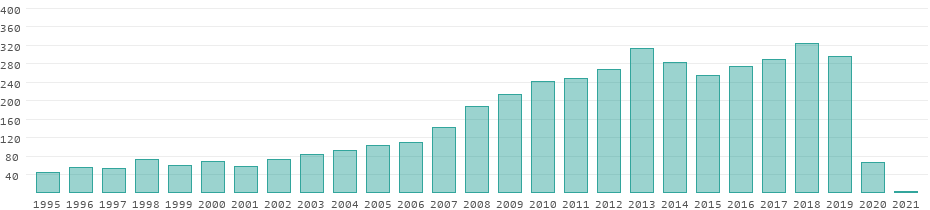

The Importance of Vanuatu’s Tourism Sector

Vanuatu is an archipelago of more than 80 islands located in the Southwest Pacific ( De Burlo, 1989 ). Its population of over 300,000 inhabitants is divided into more than 100 distinct linguistic and cultural groups. During colonial times, Vanuatu was known as the New Hebrides and subject to a rather unique Anglo-French colonial rule established in 1906 ( Farran, 2010 ). Since gaining independence, Vanuatu’s economy has seen relatively steady growth rates, primarily due to a substantial rise in revenues from tourism. Tourism is a key contributor to the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP), the major foreign exchange earner, and an important employment provider, particularly in the main island of Efate and – to a lesser extent – in the islands Espiritu Santo and Tanna ( Loehr, 2020 ). It is estimated that over 8,000 full time equivalents (FTEs) were employed in the Vanuatu tourism sector prior to 2015 Cyclone Pam ( Government of Vanuatu, 2015 ). Visitor arrivals peaked in 2014, with Australia being the most important source market (about 60%), followed by New Zealand (13%) and New Caledonia (12%), according to data from the Vanuatu National Statistical Office ( Government of Vanuatu, 2015 ).

The tourism sector in Vanuatu is characterized by a “dualistic” structure, whereby prior to Cyclone Pam in March 2015 about one third of the foreign visitors arrived by air and stayed in hotels, resorts and guesthouses for an average of 8–9 days, while two thirds of visitors arrived by cruise ship and stayed only for 1 day without the need for accommodation in the country. Cruise tourists are primarily targeted by local tour and cultural show operators, who are mostly indigenous Ni-Vanuatu whose small businesses are protected by the so-called “Reserved Investments” clause under the Foreign Investment Promotion Act.

Tourists arriving by air have a choice among a wide range of accommodation, from budget lodges and motels to luxury boutique resorts. On the major islands, the hotel business – which is much more capital-intensive than tour operations – is dominated by foreigners, who benefit from favourable investment conditions, such as tax exemptions and relatively low lease rates for beachfront properties ( MTICNB, 2013 ). On the main island of Efate, considered the accommodation gateway to Vanuatu, three large hotel operators accounted for about 30% of the available room stock in 2014 ( Government of Vanuatu, 2015 ).

A Brief History of Land Rights Systems in Vanuatu

In precolonial times, land on the various islands in what is today’s Vanuatu was acquired simply by occupation and establishment of the first meeting house ( nasara ) ( Farran, 2010 ). Ownership was marked by physical evidence, such as graves, boundaries or planted trees, and through oral evidence ( Farran, 2008 ; McDonnell, 2015 ). Intergenerational transfer of land was matrilineal in some communities and patrilineal in others ( Farran, 2008 ). Nagarajan and Parashar (2013) contend that the rights of women to use land and be involved in decisions affecting land were recognized under customary law. As in many other South Pacific nations, the links between cultural identity, tradition ( kastom ) and place ( ples ) are foundational for indigenous (Ni-Vanuatu) people ( Wittersheim, 2011 ; McDonnell, 2015 ).

Throughout much of the 20th century, the indigenous Ni-Vanuatu people were dispossessed of a great share of their customary land by British and French settlers and missionaries ( De Burlo, 1989 ; Farran and Corrin, 2017 ). Under joint British and French colonial rule indigenous land on the larger islands was allocated to settler plantations, churches and public/administrative purposes. According to Farran (2010) , about two thirds of the land in the then New Hebrides were in the hand of foreigners at some point. The two colonial powers introduced the previously unknown concepts of freehold and leasehold and competing sets of laws and legal institutions. Independence from the so-called “condominium government” was only achieved in 1980, after demands for restitution of land alienated by the colonial powers could no longer be suppressed ( Farran, 2010 ).

The 1980 Constitution restored indigenous land ownership across the newly independent country and provided that the rules of custom should form the basis for ownership, control and use of the land ( Farran and Corrin, 2017 ). Yet it was not always easy to identify the legitimate custom owners, and leadership claims were often disputed, and the number of counter-claimants was high, particularly in areas that had been most impacted by colonial settlement ( Farran and Corrin, 2017 ). Chiefly leaders often play a triple role of holding trusteeship over customary land, being figures of authority and acting as adjudicators of disputes ( Farran, 2008 ).

In the early years after independence land leasing activity in Vanuatu was rather modest, confined primarily to agricultural leases of 30 or 40 years. Yet with the advent of tourism and the associated diversification of the economy, non-agricultural leases with a longer duration (up to 75 years) were introduced ( Wittersheim, 2011 ). In 2013, the Vanuatu government introduced a new piece of legislation – the Custom Land Management Act – which was aimed at further strengthening customary land tenure and making it more difficult to alienate land through leases and sub-leases to foreign investors ( Farran and Corrin, 2017 ). However, the implementation of the Act has been constrained by a phase of political instability and the nation-wide disaster caused by Tropical Cyclone Pam in 2015.

Hazards, Vulnerability and Tourism: Tropical Cyclone Pam in March 2015

The tourism sector in Vanuatu is highly susceptible to climate-related disasters, such as cyclones or floods ( Loehr, 2020 ), but also to other natural hazards, such as earthquakes, tsunamis and volcanic eruptions. Cyclone activity occurs mainly during the months January to March. During this period, tourist arrivals in Vanuatu are the lowest. Between 12 and 14 March 2015, Vanuatu was struck by Tropical Cyclone Pam, an extremely destructive Category five cyclone with wind speeds of about 250 km/h. The cyclone damaged or destroyed an estimated 17,000 buildings, displaced around 65,000 people and affected the livelihoods of at least 80% of the rural population by destroying crops and livestock on a massive scale ( Government of Vanuatu, 2015 ). The damage was most severe on the larger islands of Tanna, Erromango and Efate. The relatively low death toll of eleven people was attributed to indigenous knowledge and the availability of emergency preparation plans in many communities as well as essential information being transmitted across the island via social media, the radio and millions of SMS messages ( World Bank, 2015 ; Saverimuttu and Varua, 2016 ). The long-term damage to the country’s economy was estimated to be approximately USD 500 million, equivalent to nearly two thirds of Vanuatu’s annual GDP ( Saverimuttu and Varua, 2016 ; Ballard et al., 2020 ).

According to the Government of Vanuatu’s post-disaster needs assessment report, the total damage to the tourism subsector caused by Cyclone Pam was around USD 51.7 million and total losses over the 6 months following the disaster event were estimated at about USD 31.5 million ( Government of Vanuatu, 2015 ). All damages and losses were incurred by private businesses. Two of the three largest operators – which account for 30% of the room stock on Efate Island – had to be closed for several months ( Government of Vanuatu, 2015 ). Many of the small- and medium-sized businesses in the tourism and hospitality sector suffered near-complete damage to their premises (see Figures 1 , 2 ).

FIGURE 1 . Only the foundations remain from this beachfront resort on Efate Island after Cyclone Pam struck the area. Source: Author’s own.

FIGURE 2 . Cyclone Pam destroyed the terrace of this beachside restaurant on Efate Island. Source: Author’s own.

Hence, the massive cyclone exposed vulnerabilities of various groups – including the corporate tourism and hospitality sector, the predominantly Ni-Vanuatu employees and local communities – which are linked through complex socio-economic relations and power dynamics. Wisner et al. (2004) contend that the root causes of vulnerability are primarily a result of social relations and structures of domination. Their conceptualization of disaster risk and vulnerability “focuses on the way unsafe conditions arise in relation to the economic and political processes that allocate assets, income and other resources in a society” ( Wisner et al., 2004 : 92). As this study will show, the proliferation of land leases for tourism has led to uneven power relations between expatriate leaseholders and Indigenous Ni-Vanuatu and compromised access to natural resources for local communities, leaving the latter in a state of heightened vulnerability in the wake of Cyclone Pam.

Literature Review and Conceptual Framework: The Tourism-Disaster-Conflict Nexus

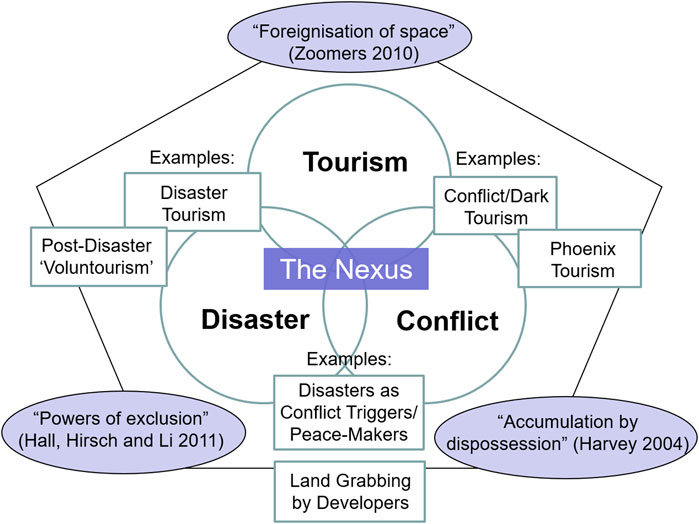

This study is conceptually grounded in the tourism-disaster-conflict nexus as identified by Neef and Grayman (2018) and depicted in Figure 3 . In the following sub-sections, the main linkages within the nexus are described with examples from the literature and underpinned by three theoretical concepts.

FIGURE 3 . The tourism-disaster-conflict nexus and underlying concepts and theoretical frameworks. Source: Author’s own.

Linkages Between Tourism and Disaster

The tourism sector in the Global South has been particularly susceptible to disruptive disaster events, as many tourist destinations are located in coastal areas that are at risk from tsunamis, hurricanes, cyclones and sea surges. The linkages between tourism and disaster that have received scholarly attention include disaster preparedness and disaster risk reduction strategies in the tourism sector (e.g., Ritchie, 2008 ; Becken et al., 2014 ; Calgaro et al., 2014 ; Hall et al., 2019 ), tourism as a trigger or amplifier of disasters (e.g., Hall, 2001 ; Loperena, 2017 ), the impacts of disasters on the tourism industry (e.g., Calgaro and Lloyd, 2008 ; Seraphin, 2018 ), and tourism as a driver of disaster recovery (e.g., Mair et al., 2016 ; Carrizosa and Neef, 2018 ). The latter is relevant to this study as the tourism industry has often been assigned a crucial role in reconstruction and recovery efforts following a major disaster. Referring to earthquake-stricken Nepal and cyclone-ravaged Vanuatu, the British newspaper The Guardian ( Marshall, 2015 ) coined the catchphrase “your holiday can help,” whereby prospective tourists are nudged to support post-disaster rehabilitation simply through visiting disaster-affected areas. Yet such forms of disaster tourism may have unintended consequences, since less touristic areas that have been severely affected by the disaster may receive less humanitarian relief support. In southern Thailand, for example, post-disaster recovery efforts following the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami were primarily targeted at prime tourist destinations, while rehabilitation efforts in other devastated areas were neglected or delayed ( Calgaro and Lloyd, 2008 ; Neef et al., 2015 ). An important and emerging subfield of critical tourism studies has focused on post-disaster volunteer-tourism, or “voluntourism,” whereby visitors from the Global North volunteer for social or environmental causes while on holiday. Following 1996 Hurricane Mitch that devastated parts of Honduras, US American tourists were lured with discounted airfares into vacationing on affected tropical beaches, with debris removal, tree planting and restoration of turtle nesting sites all part of the holiday package ( Mowforth and Munt, 2016 ).

Linkages Between Tourism and Conflict

Linkages between tourism and conflict include the idea that tourism can be a force for peace and stability (e.g., Farmaki, 2017 ), the notion of dark tourism or thanatourism (e.g., Light, 2017 ), the concept of phoenix tourism in post-conflict destination rebranding (e.g., Causevic and Lynch, 2011 ), and tourism-induced conflicts over land and resources (e.g., Devine, 2017 ). The latter linkage is particularly relevant for the context of this study, given the ongoing contestations over land ownership and leases in Vanuatu and other countries in the South Pacific. As Neef and Grayman (2018) maintain, small islands are particularly prone to conflicts over land and other natural resources triggered by tourism development, as they face challenges of resource scarcity, particularly with regard to freshwater, and have limited carrying capacity (cf. Gössling, 2003 ). Land tenure legislation tends to favour local elites and wealthy foreigners who can easily claim the foreshore for “public” purpose, such as tourism, while often disregarding customary rights of communities that depend on coastal land and other natural resources for their subsistence ( Knudsen, 2012 ; Benge and Neef, 2018 ).

Linkages Between Disaster and Conflict

The linkages between disaster and conflict include disasters as triggers or intensifiers of civil conflict and ethnic tensions (e.g., Weir and Virani, 2011 ; Eastin, 2016 ), disaster diplomacy and conflict resolution (e.g., Le Billon and Waizenegger, 2007 ), and the notion of disaster capitalism ( Klein, 2007 ) which describes the predatory behaviour of private and public actors that consider disasters as opportunities to capitalize on temporary or permanent vulnerabilities among affected communities. Several studies have shown how disasters, such as the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami and 2013 super-typhoon Haiyan, have triggered land conflicts as investors took advantage of the absence of local landowners due to their temporary relocation to disaster shelters or their permanent resettlement from coastal areas following arbitrary setback policies for coastal communities imposed by the government ( Attavanich et al., 2015 ; Uson, 2017 ). When such opportunistic and predatory investors are involved in the tourism sector, then the nexus of tourism, disaster and conflict is complete in all its interlinkages. Recent studies that have examined the intersection of tourism, disaster and conflict include Cohen’s (2011) research on post-tsunami land grabs in Thailand, Sri Lanka and India, Pyles et al. (2017) study on post-earthquake disaster capitalism in Haiti and Loperena’s (2017) analysis of tourism’s extractivist expansion in the case of post-disaster Honduras. What has been lacking in these studies was a comprehensive theoretical conceptualization.

Materials and Methods

The research was conducted between December 2016 and June 2017 on the country’s major island Efate, where most of the tourist infrastructure is located. Around 97% of tourists traveling to Vanuatu stay on Efate ( IFC, 2015 ). It is also the island that sustained most damage from Cyclone Pam. The study focused on the tourism sector in the capital Port Vila, where the concentration of accommodation is highest, as well as on the southern and northwestern part of the island.

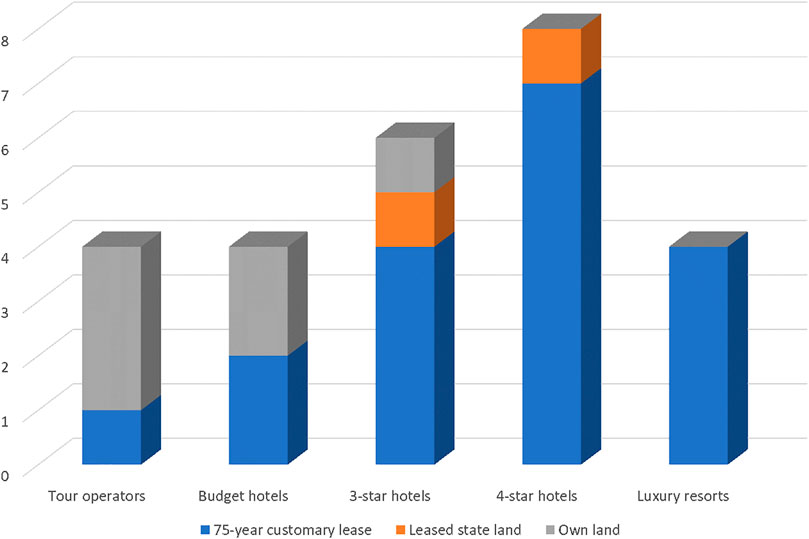

The hotels and tour operations were purposively selected to cover a wide range from budget accommodations to luxury boutique resorts and obtain a broad geographic coverage of the major tourist hotspots on the island (see Figure 4 ). The main emphasis of the study is placed on the accommodation sector, includes the three largest room providers on Efate Island and covers more than two thirds of the island’s total room capacity. Table 1 shows a breakdown of the surveyed hotels and tour operations. The business ownership structure appears typical for the tourism sector in Vanuatu. Tour operations are predominantly locally owned, and some of the budget accommodations are also owned by locals (mostly naturalized citizens rather than indigenous Ni-Vanuatu), while the entire range from 3-star hotels to high-end luxury boutique resorts is under the ownership of international hotel chains and affluent business people from Australia, New Zealand and other Global North countries.

FIGURE 4 . Map of Efate Island with locations of hotels and tour operations (purple triangles) and communities (blue circles) selected for the study. Source: Adapted from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Map_of_Efate_Island_EN.png

TABLE 1 . Tourist businesses selected for the study, number of interviews and research conversations, and business ownership structure. Source: Author’s own.

The major methods employed in this research were semi-structured interviews with hotel staff and tour operators in management positions, research conversations with non-managerial staff in the tourism sector and community members, and focus group discussions with community leaders. In total, 20 semi-structured interviews, 19 research conversations, and three focus group discussions were conducted by the author and a Ni-Vanuatu research assistant in the capital Port Vila, the southern coast and the northwestern part of Efate, covering all major tourist hotspots of the island. The interviewees comprised three male and three female expatriate hotel managers as well as six male and eight female Ni-Vanuatu in managerial positions. Research conversations followed Pacific research principles of talanoa and stori which are based on casual talk and sharing of stories rather than formal questions and answers ( Vaioleti, 2006 ). Such informal conversations were conducted with nine male and nine female non-managerial staff and one male community chief; all of them were Ni-Vanuatu citizens. The three community focus groups were attended by a total of nine men and ten women and conducted in a similarly informal setting and conversation style. All interviews were held in English, research conversations were conducted either in English or Bislama, and the focus group discussions were entirely held in Bislama.

In addition to primary data collection, we also gathered secondary data from government reports, official tourism development plans, the Vanuatu National Statistical Office and international development reports. This secondary information mostly served the purpose of triangulating the findings from the qualitative study.

Analysis of the primary data was done through a close reading of the written notes from the interviews, research conversations and focus groups, followed by thematic, semi-inductive coding. Based on initial coding, higher order categories and themes, such as “land relations,” “short-term disaster relief,” and “long-term recovery” were developed. Emphasis was placed on a thick description of categories and themes, with the aim of providing sufficient depth, breadth and context.

Land Acquisition and Resource Enclosure by Vanuatu’s Tourism Sector

The accommodation sector on Efate Island is disproportionately controlled by foreigners who lease waterfront blocks from customary landowners at relatively cheap annual rates. The high demand for beachfront accommodation has led to a proliferation of land speculation among foreign investors. Land conflicts are increasingly common, particularly in the rural areas of Efate, where customary land ownership is often ambiguous.

“Many local people have sold [leased out] their land without thinking of the long-term consequences. The landowner is usually the main chief in the village and the benefit is meant to be spread evenly, but often that is not the case.” (General manager of luxury resort in northern Efate).

“The land ownership rights over the area where the resorts are located have been transferred to two families. They get most of the benefits from the resorts, the Council of Chiefs also receives some money, but the real customary owners do not receive anything.” (Participant in focus group discussion in rural community in southern Efate).

Hierarchical structures and differential access to land are predominant in the communities, and benefits from the proliferation of land leases benefit only a few. Land leases are overwhelmingly the providence of the chiefs; in Northern Efate, for instance, 80 per cent of the 56 leases – mostly acquired by local expatriate investors – that have been signed off by individuals list a local chief as the lessor ( McDonnell, 2015 ). Hence, only a small minority of the local population can actually take advantage of the booming lease market, while many community members feel the negative impacts of the continuing alienation of customary land in the form of leases to foreign investors ( Wittersheim, 2011 ). The situation is particularly dire for women: none of the individual leases in Northern Efate list a woman as the lessor, while all but one communally signed lease contracts list only men ( McDonnell, 2015 ).

It is estimated that over 90% of coastal land on Efate Island has been alienated by foreigners, in most cases for the maximum lease period of 75 years ( Trau, 2012 ). The country-wide lease register makes it easy for foreign investors to use their lease contracts as collateral when taking out a bank loan. Unlike in Fiji, a national register for customary land ownership does not exist in Vanuatu. Hence, many Ni-Vanuatu landowners face problems borrowing financial capital off their customary land, which makes it difficult for them to start their own tourism business ( MTICNB, 2013 ).

“There are two types of processes to get land here in Vanuatu: either you negotiate directly with the customary landowners or you lease land that has already been developed by someone else. In any case, you have to check the titles carefully with the Lands Department. The leases here are pretty cheap, for a 4,000 m 2 plot you pay around AUD 1,000 per year.” (General Manager of luxury boutique resort in southern Efate).

“Land sales are such a huge business […]. My Australian stepfather bought a plot of land for 3 million Vatu, and we just cleared the land and then he resold it for 23 million Vatu.” (Caretaker of 4-star apartment hotel in southern Efate).

While the majority of the interviewed accommodation businesses held 75-years leases from customary landowners, a few of them had leased state-owned land ( Figure 5 ). All tour operators managed their business on their own land, and some of the smaller accommodation providers also held ownership rights to their land, mainly stemming from pre-independence times, when land sales to foreigners were still possible.

FIGURE 5 . Land tenure status of the surveyed tourism businesses. Source: Author’s own.

Many resorts are fenced off, and access to beaches – and sometimes entire islands – are exclusively reserved for hotel guests, with security guards making sure that no trespassing occurs. The enclosure of beachfront properties often leads to reduced access of local people to the sea. Such “spaces of exception and exclusion” affect women’s livelihoods, as they engage mostly in fishing from the shore and on the reefs, while fishing in the open sea is dominated by men ( Government of Vanuatu, 2015 ; Eriksson et al., 2017 ). By contrast, some of the local men are still able to negotiate access to the beach as they often know the hotel guards who hail from their own community.

“Despite the resorts, we can still get access to the beach and the sea. The security guards are from our community, so we can arrange it with them.” (Male respondent during focus group discussion in local community).

Eriksson et al. (2017) have highlighted the importance of fisheries and customary fishery management for disaster recovery among coastal Ni-Vanuatu people. Hence, discrimination of women regarding access to the foreshore has a direct and adverse impact on their potential to contribute to the economic recovery of their families.

Hotel managers portrayed their business operations as beneficial for local communities, lifting people out of poverty. In the interviews, they mentioned staff employment, lease fees, food supply from farmers and fishers, educational support for students, and donations of replaced hotel items as major benefits. These narratives are used as legitimation for land appropriation through leases, which is one of the four exclusionary powers as identified by Hall et al. (2011) .

“Local people benefit a lot from tourism, it is the No. 1 employer, and the unemployment rate here in Vanuatu is as high as 50–60%. Many locals here come from the other islands to seek employment in the tourism sector and then send money to their families back on the islands.” (Manager of small 3-star resort in Port Vila).

“[The landowners who leased their property to our hotel] always seem to be happy when they pick up their monthly check and spend some money on eating in our restaurant.” (General Manager of 4-star beach resort in Port Vila).

This positive view is not shared by all community members. In two of the three focus groups at community level and in a research conversation with a local island tour operator, participants painted a relatively bleak picture of the impact of tourism on their communities and complained about insufficient support from tourist resorts, the lack of transparency on lease agreements that were concluded several decades ago, and hotels taking a major share of the profit from local village tours. There was also a sentiment that the benefits from the leases are not spread evenly among the villagers.

“There has been no improvement in our community since the time when the tourism business started in the area. People in the community continue to suffer from poverty.” (Brother of the village chief and officer at the Department of Fisheries during focus group discussion).

“In our village, there is a big gap between rich and poor, you can see it when you look at the differences between the houses. The rich ones are those who have sold off their land to the foreigners.” (Community-based island tour operator).

In another community, people expressed more satisfaction with the benefits they got from resorts established on their leased properties, referring to improved water supply and employment opportunities provided by the resorts. Some of the resorts have lease agreements that include clauses stipulating that the land-owning community should be given priority in hotel staff recruitments, but the majority does not have such obligations.

“We hire staff from many different places, whoever is qualified. But in rural areas, the hotel staff is mostly from neighboring villages and its mostly casual work.” (Manager at 3-star resort in Port Vila).

“Most of the resort employees come from Port Vila, only a handful are from our community. People are employed through their social networks.” (Participant during focus group discussion in a rural community).

“We have no contractual obligations to hire anyone from the landowning community, so we hire only the most skilled people. The landowner used to work as head of security, but this didn’t work out and we stopped employing him.” (Manager of 4-star beach resort in Port Vila).

In sum, land acquisitions through leases are a form of “accumulation by dispossession” ( Harvey, 2004 ), as the long-term leases remove de-facto ownership to coastal land from the affected communities for at least three generations, while providing limited and precarious benefits to the land-owning communities. The exclusionary powers of regulation, legitimation and the market ( Hall et al., 2011 ) enclose customary land and compromise rural people’s livelihood opportunities.

Post-Disaster Relief Support to Local Communities by the Tourism Industry: Effective and Legitimate First Responders?

Our interviews and focus groups with representatives of communities in rural areas – adjacent to tourist resorts – showed that villagers demonstrated a high level of resilience during Cyclone Pam and in the aftermath of the disaster. Village committees helped to bring villagers to safety during the cyclone, and community members organized themselves to rebuild those houses that had been destroyed. However, some respondents also mentioned the challenges of rebuilding houses, while restoring their agriculture at the same time.

“It was hard for us to find food immediately after the cyclone. We worried about rebuilding our houses and at the same time to find food.” (Church assistant during focus group in community).

Many cases were reported in our survey where tourist resorts provided direct help to the communities, particularly to those whose land they were leasing. Initial responses were mostly in the form of food and water supplies, but also included tools, tarpaulins and building materials. Some hotel managers also set up emergency funds to provide more long-term support for post-disaster recovery. It was claimed that disaster relief provided by hotels and resorts was faster and more effective than the government response.

“I set up an emergency fund for the villages and collected about AUD 70,000. I used AUD 12,000 to provide food for 1,600 people in the four villages over a period of 12 days. Another part of the fund was used for installing a water reticulation system in one of the villages. In this village women had to walk 4 km to get water from the river, now they walk a maximum of 50 m. With the rest of the money, we built a second classroom for the school.” (General manager of luxury resort in northern Efate).

“The assistance provided immediately and ongoing by the [hotel] industry members to various communities around Efate was extensive and well received. The Government processes took forever with many missing out altogether.” (Chairman, Vanuatu Hotel and Resort Association, pers. comm. via email).

While short-term relief aid and longer-term humanitarian efforts are laudable, it is questionable whether hotel managers have the necessary knowledge and legal backing to provide effective support. In several interviews, hotel managers stated that the government-imposed duties on donations and did not allow expats to involve in post-disaster response and recovery, ostensibly due to concerns that such uncoordinated relief aid would undermine the work of the National Disaster Committee (cf. Barber, 2018 ).

“Expats like me were told that if you provided any help on your own you may face deportation.” (General manager of small 3-star hotel in Port Vila).

“The International School organised donations, but then they had to pay duty for the donations.” (General manager of luxury boutique resort in southern Efate).

Interviews and research conversations in several local communities presented a mixed picture of the recovery support that was provided by hotels and resorts. Respondents in some communities praised the resorts for their immediate post-disaster relief effort and contrasted it with the comparatively slow government response.

“After Cyclone Pam, we received food supplies from [two resorts]. […] This support lasted from March to June. During this entire time, the government came only two times. The first help from the resorts came about 1–2 weeks after the cyclone, and the church provided help after 3 weeks.” (Chief’s brother during focus group discussion in community).

“After the cyclone, the other hotels further up [north] came around to each household and provided us with food such as rice, tinned meat, and noodles. They came in their vehicles and stopped at each household and gave out the food supplies. They did this for 2 months.” (Women’s representative during focus group discussion in community).

Yet other respondents felt that the hotels only provided short-term disaster relief but did not support their long-term recovery. Some contended that hotel managers were just concerned about their own staff, but did not help other members in the communities.

“We didn’t receive much help from the resorts. They gave us some food and water, that’s it.” (Tour guide in an island community off Efate).

“[The resort] did not give us any help but maybe it assisted its own staff. It will be difficult to get help from the resort because we have to go through the chief and there is a lot of paperwork to do, and we usually give up before we even try. None of the other two resorts provided help.” (Chairman of men’s group during focus group discussion in community).

The findings show that post-disaster relief support to local communities by the tourism industry depended on the goodwill of the resort owners who even had to face risk of deportation when they provided assistance. Most resorts provided relief aid to the land-leasing communities only, which is aligned with findings from the disaster response of the tourism sector in Fiji following Cyclone Winston in 2016 ( Carrizosa and Neef, 2018 ). While the motivation for disaster relief support seemed genuinely altruistic, these practices also play a role in providing legitimacy to a foreign-dominated tourism sector.

Recovering Together? Differential Recovery Processes in the Hotel and Hospitality Industry and Among Local Communities

Ten out of the 22 hotel businesses included in our survey suffered moderate to severe structural damages to their accommodations. Another five businesses reported structural damages to lobbies, restaurants, bars and jetties, while their rooms remained structurally intact. Four more businesses suffered from water infiltration in the rooms, which subsequently caused damages to electric appliances, such as air conditioners and fridges. Only three hotel businesses in the survey remained largely unaffected, apart from fallen trees and other minor damages. 12 hotel businesses had to close their entire operations for several weeks or even months, while ten businesses remained fully or partially operational and open for guests.

A recurring issue that was mentioned in the interviews with hotel managers was the lack of government assistance to the tourism sector in the aftermath of Cyclone Pam. The interviewees acknowledged that there was a lack of government funding for the Department of Tourism and the Vanuatu Tourism Office, so their staff did not have the capacity to assist the hotel industry in a meaningful way. Comparisons were drawn with Fiji’s tourism sector recovery after Cyclone Winston in February 2016, which was perceived as much quicker and more effective.

“We got no support from the government. In Fiji, there was a very good tourism recovery program, but here in Vanuatu we had absolutely nothing.” (Food and beverage manager at 4-star beach resort in Port Vila).

Several hotel managers mentioned how they had been let down by the insurance companies. Only the larger multinational resorts and some of the luxury boutique resorts reported to have had adequate insurance cover, while most other hotels and particularly the tour operators were either not sufficiently covered or completely uninsured. A tourism survey conducted as part of a post-disaster needs assessment in the immediate aftermath of Cyclone Pam indicated that six of the 38 registered hotels in the capital Port Vila did not have any insurance coverage and that in other parts of Efate less than 50% of the registered accommodation businesses had insurance ( Government of Vanuatu, 2015 ). Many of the smaller hotels and resorts in our survey had continuing legal battles with their insurance company that refused to pay for the damages caused by Cyclone Pam and related sea surges as well as any follow-up damages that were not covered.

“For the small- and medium-sized tourism businesses it’s difficult to recover, as the insurance companies find ways not to pay our damages.” (Manager of small 3-star hotel in Port Vila).

“The resort is still in a legal battle with the insurance companies, they are trying everything to not pay our claims.” (Food and beverage manager at 4-star hotel in Port Vila).

Most hotel and tour operation managers we interviewed in our survey reported severe difficulties in rebuilding their tourism business. Those that did not suffer any structural damages to their facilities and only needed to do a major clean-up were the lucky ones, as they could provide accommodation for returning tourists, but even more so for the humanitarian aid workers that flocked to Vanuatu following Cyclone Pam. Six out of the 22 hotel businesses in our survey provided accommodation for international relief workers, military personnel and journalists in the immediate aftermath of the cyclone, which reduced their economic losses to some extent. The large influx of these groups of foreign “experts” was another form of “foreignization of space” ( Zoomers, 2010 ) that occurred in the wake of the disaster.

In the immediate aftermath of Cyclone Pam, it was estimated that a total of 300–500 employees would be laid off in the formal economy, most of them employed in the tourism subsector ( Government of Vanuatu, 2015 ). According to our qualitative survey, complete staff layoffs occurred only among tour operators and high-end hotels and luxury resorts. Yet the majority of surveyed hotels in all categories did not lay off any of their staff and also maintained their salaries at the same level. In many cases, the tasks of employees were changed in the aftermath of Cyclone Pam.

“We were closed for 5 months, but we kept all our staff. We paid them the full salary, but their roles changed, for example housekeeping staff became gardeners. We even hired more people for the clean-up and provided them with meals.” (General manager of luxury resort in northern Efate).

Some hotel owners who retained their staff tried to consider the fact that their employees also had to take care of rebuilding their own homes and adjusted the work schedules. Others provided additional support in kind or cash. However, not all employees were so lucky to keep their jobs and get generous support from their employers. Several high-end hotels laid off their staff, particularly those that had sustained so much damage that they remained closed for more than 6 months. Recovery was most difficult for the small heterogenous communities from different islands that had been established around the resorts and were relying to 100% on their income from tourism.

“Most of the staff [that had been laid off] did not find a new job. They just did some gardening, so they had something to eat, but they could not send their kids to school anymore, as they couldn’t afford the school fees. The [resort] owner provided some food and clothes, and he continued to pay for the electricity and the water, but other than that he did not help us much.” (Receptionist at luxury boutique resort in southern Efate).

Several local tour operators had to lay off the majority of their staff and cut salaries of the remaining employees, as fewer tourists came to Vanuatu in the months following Cyclone Pam, and about 19 cruise ships cancelled their stopover in the country ( Government of Vanuatu, 2015 ). In addition to the adverse impact on employees in the tourism industry, it was estimated that Cyclone Pam affected about 3,600 female micro-entrepreneurs (the so-called “mammas”) in all disaster-affected provinces combined ( Government of Vanuatu, 2015 ). Our own observations at local handicraft shops and informal conversations with shopkeepers in Port Vila indicated that their business recovery was very slow, even more than a year after the disaster. Moreover, about 2,100 minibus and taxi drivers suffered severe business disruptions due to damage to road infrastructure and a slump in demand for their services, as tourists stayed away from Vanuatu in the months that followed the disaster ( Government of Vanuatu, 2015 ).

Women played particularly critical roles in the recovery process, as mobilisers of capital, innovators and entrepreneurs (cf. Clissold et al., 2020 ). Yet, overall, there was a consensus among the interviewed community members that the tourism industry recovered more swiftly than the local communities. Several interviews with Ni-Vanuatu hotel staff also confirmed the uneven recovery of resorts and communities.

“The resorts recover quick time [sic], they are now back in full swing, whereas we are still struggling.” (Male participant in focus group in southern Efate).

“The resort recovered much quicker than us in the village. It took us a long while before we were able to harvest from our food gardens again.” (Chairman of men’s group in community focus group in Port Vila).

“Most of the hotels recover more quickly than ordinary people” (Interview with assistant manager at budget hotel in Port Vila).

Remittances from relatives and friends who lived permanently overseas or were involved in temporary working schemes abroad played an important role in the post-disaster recovery process in some communities. In one of the focus group discussions at community level and in several interviews and research conversations, it was stated that participating in the seasonal workers schemes implemented by the New Zealand and Australian Governments helped in the recovery process of local communities.

Bringing Tourists Back to Vanuatu and Enhancing Disaster Resilience

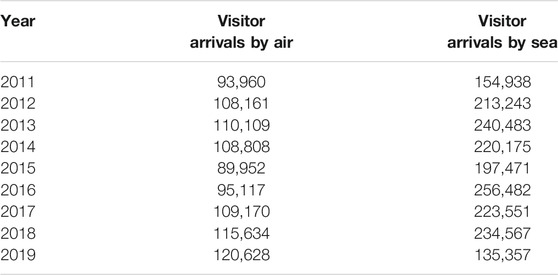

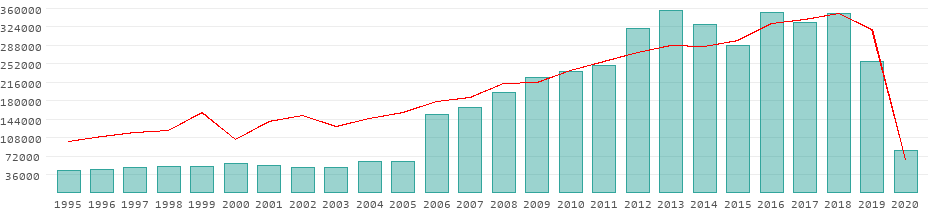

Less than 3 weeks after Cyclone Pam struck the islands, the Vanuatu Tourism Office (VTO) started a campaign on social media platforms to regain potential visitors’ confidence in Vanuatu as a tourist destination. Under the slogan #VanuatuStillSmiles, the VTO wanted to assure people in the major source countries Australia and New Zealand that Vanuatu was still open for tourists. Despite these attempts to attract tourists back to Vanuatu, Cyclone Pam had a considerable impact on tourist arrivals over the year 2015, when visitor arrivals by air fell well below the numbers of 2011 ( Table 2 ). While a slight recovery was recorded in 2016, numbers were still about 14% below the year 2013. Arrivals by cruise ship were also down in 2015, but recovered to a new record level of over 250,000 visitors in 2016. Yet in 2019, visitor arrivals by sea dropped to their lowest level in the 2010s, while visitor arrivals by air grew steadily until 2019.

TABLE 2 . Visitor arrivals in Vanuatu 2011–2019. Source: Vanuatu Statistical Bureau, 2020.

Some hotel managers suggested that the Department of Tourism should give discounts for travelers, and that more attention should be given to the traditional source countries, i.e., Australia and New Zealand. One respondent also called for more expat expertise in tourism campaigns.

“We need to be pushing interest from Australia and New Zealand, because that is our main market. The Department of Tourism needs to employ an expat to take care of all this promotional work.” (General manager of luxury beach resort in southern Efate).

Yet the call for involving more expats in promotional campaigns was challenged by one of the Ni-Vanuatu respondents who expressed her grievance that indigenous citizens and their expertise were often ignored.

“I recently went to a tourism forum which was organized by the Department of Tourism. They presented a report by the International Finance Corporation on cruise-ship tourism and they were talking about challenges and benefits, but there were only expats, no Indigenous people. How can we talk about challenges and benefits without involving the Indigenous people?” (Caretaker of 4-star apartment hotel in southern Efate).

The quote above provides evidence that “foreignization of space” ( Zoomers, 2010 ) through an expat-dominated tourism sector is not just a physical-spatial process. It has also strong cultural and political connotations, whereby indigenous citizens’ rights to being consulted and actively involved in decision-making processes are increasingly compromised.

Rural communities are now voicing their concerns about the opaqueness of land leases concluded many years ago. Some community members call for a review of the lease conditions.

“We had demanded in past several meetings to see what the terms and conditions are like in the agreement that was signed back in the 1970s between our chief and the resort lawyer, but no one seems to know if there is any copy available. We wanted to review the terms and conditions with the resort. We do not know what the first conditions were like.” (Female elder and journalist during focus group discussion).

One of the interviewed managers suggested that villagers were confronted with issues of land scarcity, as many had sold or leased out their land a long time ago without considering the long-term consequences. He expressed concerns how this would affect their recovery and future resilience.

“The communities have improved their building infrastructure, so they are now better prepared if another cyclone hits the area. But now they face another challenge and that is the developers that are coming in, mainly for residential development. Many developers have bought land way back, but they are now coming to claim their land rights.” (General manager of luxury resort in northern Efate).

This is a particularly concerning development given the crucial importance of land for economic recovery but also its cultural significance. Ni-Vanuatu citizens’ strong sense of place attachment is at risk of becoming increasingly undermined by the tourism sector. The exclusionary powers of market, regulation and legitimation (cf. Hall et al., 2011 ), as exercised by the tourism industry, are likely to remain sources of tension between Ni-Vanuatu and the expatriate community. These tensions will certainly be exacerbated by the current COVID-19 pandemic which has brought tourism in Vanuatu to a near-complete standstill.

Discussion and Conclusion

Susceptibility to tropical cyclones is one of the reasons why Vanuatu is the world’s most at-risk country for natural hazards, according to the World Risk Index ( Birkmann and Welle 2016 ). Cyclone Pam’s impact on Vanuatu’s tourism industry and the thousands of people – Ni-Vanuatu and expats – that depend on the sector was devastating. The majority of hotels and resorts included in our study experienced significant structural damages to their facilities, and many of them had to close for several weeks or even months. While hotel businesses in Port Vila tended to help only their own staff, resorts in rural Efate provided quick and often efficient support to adjacent communities (particularly to those from which they leased the land). However, such spontaneous private sector relief initiatives were not approved by the government. Most hotels and resorts included in our study tried to retain the majority of their staff during the recovery process. Yet, complete layoffs did occur, primarily by the large high-end hotels and some luxury boutique resorts that remained closed for more than a year, as well as the hotel businesses that went into bankruptcy.

Overall, the case of Vanuatu is a stark reminder that customary land tenure is not a strong defense against land deals but can actually be an enabler (cf. Neef, 2021 ). Many Ni-Vanuatu have lost access to coastal land and near-shore fisheries as a result of foreign investment in the tourism industry and private housing development, and few members in the community can find secure employment in the service sector to compensate for those losses. Although customary land is strongly protected by the country’s legal framework and cannot be sold, Vanuatu has experienced a massive boom in the real estate market in the form of long-term leases and sub-leases, primarily for resort development but more recently also for residential tourism projects (cf. McDonnell, 2018 ). Reduced access to marine resources and coastal land is limiting the economic opportunities for most Ni-Vanuatu who still depend on farming and fishing for their subsistence. Hence, the relationship between local communities and expatriates remains complicated, oscillating between cooperation and conflict.

The results from this study underscore the need to include power relations and the politics of tourism policy making in frameworks for improved disaster risk management in the tourism industry of Vanuatu and other small island developing states. Although the importance of social relations and structures of domination in determining vulnerability has been emphasized as early as the mid-1990s by Blaikie et al. (1994) and further underscored by Wisner et al. (2004) , many studies continue to overlook these root causes of vulnerability to hazards. For example, a study by Klint et al. (2012) that analyzed the policy environment for climate change adaptation and climate risk management in Vanuatu’s tourism sector, largely ignored issues of power, access to land and politics, instead presenting climate risk policies as a purely technocratic issue. Loehr’s (2020) Vanuatu Tourism Adaptation System acknowledges that “land management processes and customary land ownership have an influence on local ownership or participation in tourism businesses” (p. 527) but does not provide any further insights into the inequalities and injustices that the foreign-dominated tourism sector has produced; neither does it mention the importance of continued access to land-based and marine resources for disaster resilience of Ni-Vanuatu coastal communities. By contrast, the Tourism Crises Response and Recovery Plan (2020–2023) developed by Vanuatu Department of Tourism (2020) in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and tourism crisis makes explicit reference to the fact that the “high level of foreign ownership and control” in Vanuatu’s tourism sector has contributed “to the dispossession of land” and increased “land disputes within communities,” thereby reducing the subsistence capacity of communities and the resilience of the local economy (p. 8).

The aftermath of Cyclone Pam has exposed the volatility of employment opportunities in the tourism sector. Yet the post-cyclone impacts have been dwarfed by the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic that brought the tourism sector in Vanuatu to a near-complete standstill ( Vanuatu National Statistics Office, 2020 ). Many hotels and resorts had to close permanently, while others had to lay off most of their staff and went into temporary hibernation. A luxury resort in northern Efate reportedly discontinued all its community engagement activities ( Connell, 2021 ). Although Vanuatu has had only three cases of COVID-19 (as of September 6, 2021) all of which occurred in quarantine, there is a severe risk that it will take Ni-Vanuatu communities much longer to recover from the economic fallout of COVID-19 than from Cyclone Pam, as many have become dependent on the foreign-dominated tourism sector. To make matters worse, remittances from temporary migrant workers have dried up due to border closures in Australia and New Zealand (cf. Connell, 2021 ). With many small tour operators and small- and medium-sized hotels and resorts not able to survive this protracted tourism crisis, multinational hotel chains may see opportunities to capitalize on the tourism crisis and scoop up land vacated by smaller businesses (cf. Neef, 2021 ). Vanuatu’s government will need to keep a close eye on such developments if it wants to provide a more level playing field for tourism actors and a more resilient and inclusive tourism economy in the post-COVID-19 recovery process. In a wider disaster risk management context, this study calls for disaster risk governance strategies in the tourism sector that address power differentials and inequalities that are often at the heart of vulnerabilities and compromised resilience.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the qualitative data sets contain information that could potentially identify the research participants. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to AN, [email protected] .

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Human Participants Ethics Committee - The University of Auckland. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

This research was made possible by a grant from the Faculty of Arts Research Development Fund, University of Auckland, New Zealand.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to express his sincere gratitude to the research assistant, Sonia Ann Wasi, for her excellent support during the fieldwork. I am grateful to all research participants for their time, hospitality and generosity in providing their perspectives and stories. I am indebted to George Borugu, former Director of Vanuatu’s Department of Tourism for supporting this study.

Attavanich, M., Neef, A., Kobayashi, H., and Tachakitkachorn, T. (2015). “Change of Livelihoods and Living Conditions after the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami: The Case of the post-disaster Rehabilitation of the Moklen Community in Tungwa Village, Southern Thailand,” in Recovery from the Indian Ocean Tsunami: A Ten-Year Journey . Editor R. Shaw (Tokyo: Springer ), 471–486. doi:10.1007/978-4-431-55117-1_30

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ballard, C., Wilson, M., Nojima, Y., Matanik, R., and Shing, R. (2020). Disaster as Opportunity? Cyclone Pam and the Transmission of Cultural Heritage. Anthropological Forum 30 (1-2), 91–107. doi:10.1080/00664677.2019.1647825

Barber, R. (2018). Legal Preparedness for the Facilitation of International Humanitarian Assistance in the Aftermath of Vanuatu's Cyclone Pam. AsianJIL 8, 143–165. doi:10.1017/s2044251316000242

Becken, S., Mahon, R., Rennie, H. G., and Shakeela, A. (2014). The Tourism Disaster Vulnerability Framework: an Application to Tourism in Small Island Destinations. Nat. Hazards 71 (1), 955–972. doi:10.1007/s11069-013-0946-x

Benge, L., and Neef, A. (2018). “Tourism in Bali at the Interface of Resource Conflicts, Water Crisis, and Security Threats,” in The Tourism-Disaster-Conflict Nexus . Editors A. Neef, and J. H. Grayman (Bingley: Emerald Publishing ), 33–52.

Billon, P. L., and Waizenegger, A. (2007). Peace in the Wake of Disaster? Secessionist Conflicts and the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami. Trans. Inst. Br. Geog 32 (3), 411–427. doi:10.1111/j.1475-5661.2007.00257.x

Birkmann, J., and Welle, T. (2016). The WorldRiskIndex 2016: Reveals the Necessity for Regional Cooperation in Vulnerability Reduction. J. Extreme Events 3 (1), 1650005. doi:10.1142/s2345737616500056

Blaikie, P., Gannon, T., Davis, I., and Wisner, B. (1994). At Risk: Natural Hazards, People’s Vulnerability and Disasters . 1st Edition. London: Routledge .

Google Scholar

Calgaro, E., Lloyd, K., and Dominey-Howes, D. (2014). From Vulnerability to Transformation: a Framework for Assessing the Vulnerability and Resilience of Tourism Destinations. J. Sust. Tourism 22 (3), 341–360. doi:10.1080/09669582.2013.826229

Calgaro, E., and Lloyd, K. (2008). Sun, Sea, Sand and Tsunami: Examining Disaster Vulnerability in the Tourism Community of Khao Lak, Thailand. Singapore J. Trop. Geogr. 29, 288–306. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9493.2008.00335.x

Carrizosa, A. A., and Neef, A. (2018). “Community-Based Tourism in Post-Disaster Contexts: Recovery from 2016 Cyclone Winston in Fiji,” in Recovery from the Indian Ocean Tsunami: A Ten-Year Journey . Editor R. Shaw (Tokyo: Springer ), 67–85.

Causevic, S., and Lynch, P. (2011). Phoenix Tourism: post-conflict Tourism Role. Ann. Tourism Res. 38 (3), 780–800. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2010.12.004

Clissold, R., Westoby, R., and McNamara, K. E. (2020). Women as Recovery Enablers in the Face of Disasters in Vanuatu. Geoforum 113, 101–110. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.05.003

Cohen, E. (2011). Tourism and Land Grab in the Aftermath of the Indian Ocean Tsunami. Scand. J. Hospitality Tourism 11 (3), 224–236. doi:10.1080/15022250.2011.593359

Connell, J. (2021). COVID-19 and Tourism in Pacific SIDS: Lessons from Fiji, Vanuatu and Samoa? The Round Table 110 (1), 149–158. doi:10.1080/00358533.2021.1875721

De Burlo, C. (1989). Land Alienation, Land Tenure, and Tourism in Vanuatu, a Melanesian Island Nation. GeoJournal 19 (3), 317–321. doi:10.1007/bf00454578

Devine, J. A. (2017). Colonizing Space and Commodifying Place: Tourism's Violent Geographies. J. Sust. Tourism 25 (5), 634–650. doi:10.1080/09669582.2016.1226849

Eastin, J. (2016). Fuel to the Fire: Natural Disasters and the Duration of Civil Conflict. Int. Interactions 42 (2), 322–349. doi:10.1080/03050629.2016.1115402

Eriksson, H., Albert, J., Albert, S., Warren, R., Pakoad, K., and Pakoa, N. (2017). The Role of Fish and Fisheries in Recovering from Natural Hazards: Lessons Learned from Vanuatu. Environ. Sci. Pol. 76, 50–58. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2017.06.012

Farmaki, A. (2017). The Tourism and Peace Nexus. Tourism Manag. 59, 528–540. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2016.09.012

Farran, S., and Corrin, J. (2017). Developing Legislation to Formalise Customary Land Management: Deep Legal Pluralism or a Shallow Veneer? L. Dev. Rev. 10 (1), 1–27. doi:10.1515/ldr-2016-0017

Farran, S. (2008). Fragmenting Land and the Laws that Govern it. J. Leg. Pluralism Unofficial L. 40, 93–113. doi:10.1080/07329113.2008.10756625

Farran, S. (2010). Law, Land, Development and Narrative: A Case-Study from the South Pacific. Int. J. L. Context 6 (1), 1–21. doi:10.1017/s1744552309990279

Government of Vanuatu (2015). Post-disaster Needs Assessment – Tropical Cyclone Pam, March 2015 . Port Vila: Government of Vanuatu .

Hall, C. M. (2001). Trends in Ocean and Coastal Tourism: the End of the Last Frontier? Ocean Coastal Manag. 44 (9–10), 601–618. doi:10.1016/s0964-5691(01)00071-0

Hall, D., Hirsch, P., and Li, T. M. (2011). Powers of Exclusion: Land Dilemmas in Southeast Asia . Singapore: National University of Singapore Press .

Hall, S., Emmett, C., Cope, A., Harris, R., Setiadi, G. D., Meservy, W., et al. (2019). Tsunami Knowledge, Information Sources, and Evacuation Intentions Among Tourists in Bali, Indonesia. J. Coast Conserv 23, 505–519. doi:10.1007/s11852-019-00679-x

Harvey, D. (2004). The “New” Imperialism: Accumulation by Dispossession. Socialist Register 40, 63–87.

IFC (2015). Vanuatu Agri-Tourism Linkages: A Baseline Study of Agri Demand from Port Vila’s Hospitality Sector . Washington, DC: International Finance Corporation .

Klein, N. (2007). The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism . London: Penguin Group .

Klint, L. M., Wong, E., Jiang, M., Delacy, T., Harrison, D., and Dominey-Howes, D. (2012). Climate Change Adaptation in the Pacific Island Tourism Sector: Analysing the Policy Environment in Vanuatu. Curr. Issues Tourism 15 (3), 247–274. doi:10.1080/13683500.2011.608841

Knudsen, M. (2012). Fishing Families and Cosmopolitans in Conflict over Land on a Philippine Island. J. Southeast. Asian Stud. 43 (3), 478–499. doi:10.1017/s0022463412000355

Light, D. (2017). Progress in Dark Tourism and Thanatourism Research: An Uneasy Relationship with Heritage Tourism. Tourism Manag. 61, 275–301. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2017.01.011

Loehr, J. (2020). The Vanuatu Tourism Adaptation System: a Holistic Approach to Reducing Climate Risk. J. Sust. Tourism 28 (4), 515–534. doi:10.1080/09669582.2019.1683185

Loperena, C. A. (2017). Honduras Is Open for Business: Extractivist Tourism as Sustainable Development in the Wake of Disaster? J. Sust. Tourism 25 (5), 618–633. doi:10.1080/09669582.2016.1231808

Mair, J., Ritchie, B. W., and Walters, G. (2016). Towards a Research Agenda for post-disaster and post-crisis Recovery Strategies for Tourist Destinations: A Narrative Review. Curr. Issues Tourism 19 (1), 1–26. doi:10.1080/13683500.2014.932758

Marshall, N. (2015). Your Holiday Can Help: Vanuatu and Nepal Appeal for Tourists to Return. The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/travel/2015/aug/14/yourholiday-can-help-vanuatu-and-nepal-appeal-for-tourists-to-return (Accessed July 20, 2016).

McDonnell, S. (2018). Selling “Sites of Desire”: paradise in Reality Television, Tourism, and Real Estate Promotion in Vanuatu. Contemp. Pac. 30 (2), 413–435. doi:10.1353/cp.2018.0033

McDonnell, S. (2015). “‘The Land Will Eat You’: Land and Sorcery in North Efate, Vanuatu,” in Talking it through: Responses to Sorcery and Witchcraft Beliefs and Practices in Melanesia . Editors M. Forsyth, and R. Eves (Canberra: Australian National University Press ), 137–160.

Mowforth, M., and Munt, I. (2016). Tourism and Sustainability: Development, Globalisation and New Tourism in the Third World . 4th Edition. London, New York: Routledge .

MTICNB (2013). Vanuatu Strategic Tourism Action Plan 2014-2018 . Port Vila: Ministry of Tourism, Industry, Commerce & Ni-Vanuatu Business .

Nagarajan, V., and Parashar, A. (2013). Space and Law, Gender and Land: Using CEDAW to Regulate for Women's Rights to Land in Vanuatu. L. Critique 24, 87–105. doi:10.1007/s10978-012-9116-7

Neef, A., and Grayman, J. H. (2018). “Introducing the Tourism-Disaster-Conflict Nexus,” in The Tourism-Disaster-Conflict Nexus . Editors A. Neef, and J. H. Grayman (Bingley: Emerald Publishing ), 1–31.

Neef, A., Panyakotkaew, A., and Elstner, P. (2015). “Post-tsunami Recovery and Rehabilitation of Small Enterprises in Phang Nga Province, Southern Thailand,” in Recovery from the Indian Ocean Tsunami: A Ten-Year Journey . Editor R. Shaw (Tokyo: Springer ), 487–503. doi:10.1007/978-4-431-55117-1_31

Neef, A. (2021). Tourism, Land Grabs and Displacement: The Darker Side of the Feel-Good Industry . London, New York: Routledge .

Pyles, L., Svistova, J., and Ahn, S. (2017). Securitization, Racial Cleansing, and Disaster Capitalism: Neoliberal Disaster Governance in the US Gulf Coast and Haiti. Crit. Soc. Pol. 37 (4), 582–603. doi:10.1177/0261018316685691

Ritchie, B. (2008). Tourism Disaster Planning and Management: From Response and Recovery to Reduction and Readiness. Curr. Issues Tourism 11 (4), 315–348. doi:10.1080/13683500802140372

Saverimuttu, V., and Varua, M. E. (2016). Seasonal Tropical Cyclone Activity and its Significance for Developmental Activities in Vanuatu. Int. J. SDP 11 (6), 834–844. doi:10.2495/sdp-v11-n6-834-844

Seraphin, H. (2018). The Past, Present and Future of Haiti as a post-colonial, post-conflict and post-disaster Destination. Jtf 4 (3), 249–264. doi:10.1108/jtf-03-2018-0007

S. Gössling (Editor) (2003). Tourism and Development in Tropical Islands. Political Ecology Perspectives (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar ).

Trau, A. M. (2012). Beyond Pro-poor Tourism: (Re)interpreting Tourism-Based Approaches to Poverty Alleviation in Vanuatu. Tourism Plann. Dev. 9 (2), 149–164. doi:10.1080/21568316.2011.630750

Uson, M. A. M. (2017). Natural Disasters and Land Grabs: the Politics of Their Intersection in the Philippines Following Super Typhoon Haiyan. Can. J. Dev. Stud./Revue canadienne d'études du développement 38 (3), 414–430. doi:10.1080/02255189.2017.1308316

Vaioleti, T. M. (2006). Talanoa Research Methodology: A Developing Position on Pacific Research. Waikato J. Edu. 12, 21–34. doi:10.15663/wje.v12i1.296

Vanuatu Department of Tourism (2020). The VSTP Tourism Crises Response and Recovery Plan (2020-2023) . Port Vila: Vanuatu Department of Tourism .

Vanuatu National Statistics Office (2020). Statistics Update: International Visitor Arrivals – July 2020 Provisional Highlights. Available at: https://vnso.gov.vu/images/Public_Documents/Statistics_by_Topic/Economics/Tourism/Current/IVA_7_July_2020.pdf (Accessed September 18, 2020).

Weir, T., and Virani, Z. (2011). Three Linked Risks for Development in the Pacific Islands: Climate Change, Disasters and Conflict. Clim. Dev. 3, 193–208. doi:10.1080/17565529.2011.603193

Wisner, B., Blaikie, P., Cannon, T., and Davis, I. (2004). At Risk: Natural Hazards, People’s Vulnerability and Disasters . 2nd Edition. London: Routledge .

Wittersheim, E. (2011). Paradise for Sale. The Sweet Illusions of Economic Growth in Vanuatu. jso 133, 323–332. doi:10.4000/jso.6515

World Bank (2015). Vanuatu: Six Months after Cyclone Pam . Washington DC: The World Bank .

Zoomers, A. (2010). Globalisation and the Foreignisation of Space: Seven Processes Driving the Current Global Land Grab. J. Peasant Stud. 37 (2), 429–447. doi:10.1080/03066151003595325

Keywords: disaster risk management, post-disaster recovery, land rights, tourism-disaster-conflict nexus, COVID-19, South Pacific

Citation: Neef A (2021) The Contentious Role of Tourism in Disaster Response and Recovery in Vanuatu. Front. Earth Sci. 9:771345. doi: 10.3389/feart.2021.771345

Received: 06 September 2021; Accepted: 02 December 2021; Published: 16 December 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Neef. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Andreas Neef, [email protected]

This article is part of the Research Topic

Integrated Disaster Risk Management: From Earth Sciences to Policy Making

Vanuatu feeling the pinch as coronavirus pandemic keeps tourists away

With school holidays in Australia, Vanuatu's picturesque beaches and turquoise waters would normally be busy with tourists at this time of year — but due to the coronavirus pandemic, they're empty.

Key points:

- Tens of thousands of people have lost jobs in Vanuatu's tourism industry

- A large stimulus package was promised, but some say they have yet to receive any help

- Vanuatu's Government said it couldn't afford to continue financial support beyond July

"Tourism has been decimated here," Liz Pechan from The Havannah Vanuatu, a five-star resort on the island of Efate, told the ABC.

"I was shocked for a little while, I think I was a bit dumbfounded: like how can this happen, how can the world just stop?"

Like the vast majority of hotels, Ms Pechan currently has no bookings, and more than 30 staff have already been let go.

Tens of thousands of workers in the country's tourism industry are believed to have lost their jobs due to the pandemic.

"There was a lot of tears from both those who were staying and those who were leaving," Ms Pechan said.

"We're very connected with our community, and it was very tough to look someone in eyes and say, 'Look, I'm really sorry I've had to make this decision, it's not because I want to make this decision.'"

The Vanuatu Government has promised its biggest stimulus package ever to try soften the blow, and at 4.2 billion vatu ($52 million), it's considered to be one of the largest in the Pacific on per capita basis.

But people say they are yet to receive any of the relief payments promised for those who have lost work.

Selling homemade donuts to get by

Twenty-three-year-old Gideon Rambe lost his job as a pizza chef at another exclusive island resort. Four months on, he's still without formal work.

"They said to me now we are closed, because Government are approving now no more flights for planes coming to Vanuatu," Mr Rambe said.

Instead, he wakes up at 3:00am each morning and works seven days a week, selling homemade donuts, called kato locally.

He said he was making enough to get by, and was saving up to buy a pizza oven so he could open his own take away business.

But he said dozens of his former colleagues were not doing as well.

"Some of them don't do anything," Mr Rambe said.

"I talk to them ... 'I'm at home, I do kato. If you want, I will teach you and show you.'"

"I tell them, you must work hard! When the resort is not open, we try to do something."

'I need to keep my family going'

It's not just those directly employed by resorts and hotels who are suffering.

"It's quite challenging. It's tough on us, for me," said Joslyn Garae Lulu, the proprietor of a successful small handicrafts business.

She said her enterprise had been destroyed by the international border closures, which have kept tourists out of Vanuatu.

"Whatever I have in stock, I can't sell them because we don't have customers anymore," she said.

"I'm a widow, I need to keep my family going, my kids need to go to school, and we need food."

Ms Lulu said she had seen nothing of the income payments that were promised for people who had lost work due to the pandemic.

"Whatever savings we had, we used up," she said.

"They promised us a stimulus package, but now as we are speaking, there's nothing yet."

Double disaster means stimulus can't last forever

Vanuatu's Finance Minister Johnny Koanapo said he was happy with how his Government has handled the growing economic crisis.

"It's over 4.2 billion vatu [in stimulus] that we've rolled out. I'm satisfied with the way it's going, although this is the first time ever we're running this stimulus package," he said.

He confirmed the Government would extend the income support through July, but admitted they wouldn't be able to afford it beyond that.

Cyclone Harold, which devastated the country in April , left Vanuatu with a mammoth damage bill of about 28 billion vatu ($350 million).