How Prisons in Each State Are Restricting Visits Due to Coronavirus

As COVID-19 began spreading in 2020, prison facilities across the country suspended visits from family and lawyers. Over the course of the pandemic, states have eased and tightened those restrictions. We’re rounding up the changes as they occur.

Have you tried to visit a person in prison or jail recently? Tell us about it here.

Regular visits suspended, but legal visits allowed

Personal visits have been suspended since March 13, 2020, but legal visits are allowed.

Learn more from Hawaii →

Personal visits are suspended in all of Vermont's prisons due to active cases among staff or the incarcerated after they had been reopened in July of 2021. They were initially suspended in response to coronavirus on March 13, 2020, but legal visits were allowed.

Learn more from Vermont →

Personal visits have been suspended since March 11, 2020, but legal visits are allowed.

Learn more from West Virginia →

Personal visits were suspended March 18, 2020. Lawyers are allowed access, but may not have physical contact with prisoners and can only meet through phone or video calls. In the summer of 2021, Wyoming resumed in-person visits only to halt them again amid coronavirus outbreaks.

Learn more from Wyoming →

Visits resumed with limitations

On Oct. 9, 2021, Alabama began to reopen a small group of prisons for limited visitation, and the rest . All visitation had been suspended starting March 13, 2020.

Learn more from Alabama →

On April 30, 2021, Alaska reopened most of its prisons to visitors with some restricitons, including mandating the wearing of masks. All visitation, including legal visits, were suspended on March 13, 2020. On March 17, 2021, in-person visits with attorneys resumed.

Learn more from Alaska →

On June 19, 2021, Arizona began to reopen its prisons to visitation for vaccinated prisoners. Personal visits had been suspended since March 13, 2020, and legal visits were stopped as well.

Learn more from Arizona →

All visitation, including legal visits, was suspended on March 16, 2020. In December, Arkansas reopened for some visits but closed again within a few weeks. On March 6, 2021, limited visits resumed in four facilities and later expanded in June to all prisons.

Learn more from Arkansas →

The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation resumed in-person visits on April 10, 2021. Wardens of individual prisons could determine whether to reopen based on the number of active caess at their faciliites. Normal visitation was first suspended on March 13, 2020, and legal visits on April 7.

Learn more from California →

On May 4, 2021, Colorado began to allow limited visitation at some of its facilities and expanded it across the system later in the month. In October 2021, the state began to require visitors to show proof of vaccination before being allowed to enter the prisons. Personal visits were initially suspended on March 11, 2020. Legal visits are allowed, but they will be non-contact visits.

Learn more from Colorado →

Personal visits were suspended on March 13, 2020. Legal visits were allowed, but officials strongly recommend communicating by phone instead. On Oct. 15, 2020, Connecticut began to resume limited, pre-scheduled, non-contact visits .

Learn more from Connecticut →

Personal visits resumed on March 16, 2021, with restrictions . Visitation was first suspended on March 12, 2020. Visits resumed briefly in late June and then again in early September, but in November, they were stopped amid rapidly increasing spread of the coronavirus in the state.

Learn more from Delaware →

Washington, D.C., sends its prisoners to the Federal Bureau of Prisons, where all visitation, including legal visits, were suspended on March 13, 2020, though attorneys could be approved for an in-person visit on a case-by-case basis. On Oct. 3, some federal prisons began to reopen for non-contact personal visits, with restrictions .

Learn more from District of Columbia →

Personal visits were suspended on March 11, 2020, but legal visits were allowed. On Oct. 2, Florida began to allow limited visits with some restrictions .

Learn more from Florida →

All visitation, including legal visits, were suspended on March 13, 2020. On April 3, 2021, personal visits resumed with restricitons, such as one visit per prisoner every other month.

Learn more from Georgia →

On June 12, 2021, personal visits began to resume at some Idaho prisons. They had been suspended since March 13, 2020. Legal visits were allowed, but officials strongly recommended communicating by phone instead.

Learn more from Idaho →

On April 12, 2021, limited visitation resumed at one prison in Illinois and expanded to more than 10 additional facillities a week later. Personal visits were initially suspended on March 14, 2020.

Learn more from Illinois →

Non-contact personal visits began again on Aug. 30, 2021 after being suspended since March 11, 2020. Legal visits had been allowed, but attorneys were screened upon arrival for contact visits.

Learn more from Indiana →

Personal visits resumed on July 10, 2021 after being suspended since March 14, 2020. Legal visits were allowed during the suspension.

Learn more from Iowa →

Personal visits resumed in Kansas on April 18, 2021 with limitations, after being suspended since March 12, 2020. Legal visits had been allowed, but officials strongly recommend communicating by phone or in writing.

Learn more from Kansas →

Limited personal visits began again on June 21, 2021, after being suspended since March 14, 2020. Legal visits had been allowed, but non-contact visits were strongly encouraged and attorneys could be screened upon arrival.

Learn more from Kentucky →

Louisiana began to allow personal visits in its prisons on Oct. 18, 2021. They had been halted on on July 27, 2021 after reopening in March, one year after they were originally suspended due to the coronavirus on March 12, 2020.

Learn more from Louisiana →

Personal visits were suspended on March 12, 2020, but legal visits were allowed. Limited, non-contact visits resumed in several Maine prisons on March 18, 2021. Visits had begun in July of 2020 but were suspended again on Nov. 1.

Learn more from Maine →

Maryland's Department of Public Safety and Correctional Services began to permit personal visits on July 19, 2021. Personal visits had been suspended since March 12, 2020, but legal visits were allowed.

Learn more from Maryland →

On May 1, 2021, Massachusetts began to reopen visitation at three prisons , with more added in the following days. Personal visits were first suspended on March 13, 2020 and resumed with limits in July. On Nov. 14, 2020, the prisons again halted visits amid rising coronavirus cases. Legal visits were allowed.

Learn more from Massachusetts →

Personal visits were suspended on March 13, 2020, but legal visits were allowed. On March 26, 2021, limited personal visits resumed at some Michigan prisons that were not in quarantine .

Learn more from Michigan →

Personal visits were suspended on March 12, 2020. Legal visits were allowed, but they will not be face-to-face visits. On July 22, 2020, the state resumed limited personal visits at prisons that did not had two positive cases in the previous two weeks. On Nov. 30, the last prison was closed to visitors due to a rise in cases. On Jan. 6, 2021, visitation resumed at some Minnesota prisons.

Learn more from Minnesota →

Mississippi reopened its prisons for personal visits on Nov. 1, 2021. They had been barred originally on March 12, 2020 and had resumed in May of 2021, only to have them stopped again in late July 2021 due to rising concerns about the delta variant of the coronavirus.

Learn more from Mississippi →

Personal visits for prisoners who are fully vaccinated resumed on June 1, 2021. They had initially been suspended March 12, 2020, but legal visits were allowed. On June 25, 2020, visits resumed with some precautions , and as many as five prisons at a time reopened through the summer and fall. On Dec. 30, 2020, visits were suspended in all prisons while the rollout of vaccines began.

Learn more from Missouri →

On April 24, 2021, Montana began to reopen its prisons with some restrictions, including requiring visitors to wear masks. Personal and legal visits were suspended on March 13, 2020.

Learn more from Montana →

On Dec. 15, 2020, limited visitation resumed at five prisons and at all facilities on Jan. 6. Personal visits were first suspended on March 16, 2020. Legal visits were allowed, but attorneys were screened on entry. On July 15, a limited number of non-contact visits began for those who pre-registered, but visits were again suspended on Aug. 7 .

Learn more from Nebraska →

On May 1, 2021, Nevada reopened its prisons to visitors , with limits on capacity. All visitation, including legal visits, had been suspended since March 7, 2020.

Learn more from Nevada →

All visitation, including legal visits, were suspended on March 16, 2020. Starting on Aug. 10, limited personal and attorney visits resumed .

Learn more from New Hampshire →

New Jersey began to allow limited outdoor visits on May 1, 2021 and later expanded to indoor visits. Personal visits were originally suspended on March 10, 2020, but legal visits were allowed. On Oct. 9, 2020, outdoor visits resumed but were then suspended again on Dec. 8.

Learn more from New Jersey →

On June 14, 2021, New Mexico reopened limited, non-contact visits for vaccinated prisoners and vaccinated visitors. All visits, including contact, non-contact and legal visits had been suspended since March 16, 2020.

Learn more from New Mexico →

On April 28, 2021, New York's Department of Corrections and Community Supervision resumed non-contact personal visits, starting with maximum security prisons. Visitation was originally suspended on March 14, 2020 though legal visits were allowed. On Aug. 6, 2020 visitation began to resume , but on Dec. 30, personal visits were stopped again at all prisons statewide.

Learn more from New York →

Personal visits were suspended on March 13, 2020, but legal and pastoral visits were allowed. On Oct. 1, North Carolina began to allow visits with significant restrictions .

Learn more from North Carolina →

All contact visits were suspended on March 12, 2020. Visits began in June of 2020 and were later suspended in July. On March 29, 2021, visits resumed.

Learn more from North Dakota →

Personal visits were suspended on March 12, 2020. Legal visits were allowed, and attorneys were screened on entry. On July 8, outdoor visits began at some prisons. By Oct. 30, however, all of the prisons were closed to visitors again. On Feb. 16, 2021 visitation resumed at some facilities.

Learn more from Ohio →

Visitation was suspended on March 13, 2020, and legal visits were allowed. Limited visitation resumed in June 5, but was later cancelled again amid another wave of infections in the fall. Oklahoma reopened for visits with restrictions on April 1, 2021.

Learn more from Oklahoma →

All visitation, including legal visits, were suspended on March 12, 2020. On March 29, 2021, Oregon began a pilot program allowing limited, non-contact visits at one prison but later halted the program on April 28, 2021. The program began again on June 14, 2021 and expanded to other facilities.

Learn more from Oregon →

Personal visits began to resume in Pennsylvania prisons on May 22, 2021. They had been suspended since March 13, 2020, but legal visits are allowed. Legal visitation was suspended for one day, March 13.

Learn more from Pennsylvania →

On April 14, 2021, Rhode Island's Department of Corrections resumed non-contact visits with some restrictions . All visitation, including legal visits, had been suspended on March 11, 2020. On Aug. 12, visits with attorneys resumed.

Learn more from Rhode Island →

Personal visits began to resume for vaccinated prisoners at some South Carolina prisons on June 19, 2021. They had been suspended since March 13, 2020, but legal visits were allowed.

Learn more from South Carolina →

Visitation was suspended since March 12, 2020, but legal visits were allowed. On March 8, 2021, non-contact personal visits started again , with new restrictions and health guidelines.

Learn more from South Dakota →

On April 10, 2021, the Tennessee Department of Correction reopened for limited visitation . Personal visits were suspended on March 12, 2020, as were legal visits, though wardens could grant special requests for in-person access. On Oct. 3, 2020, Tennessee reopened three prisons for limited visitation and later a fourth. On Dec. 1, 2020, visitation at all prisons was again suspended .

Learn more from Tennessee →

Personal visits were suspended on March 13, 2020. On March 15, 2021, personal visits began again, with restrictions . Visitors must take a rapid coronavirus test before being admitted.

Learn more from Texas →

Personal visits began again on June 18, 2021. They had been suspended since March 12, 2020. Non-contact legal visits were allowed.

Learn more from Utah →

On Sept. 1, 2021, Virginia began to open some of its prisons to outside visitors, starting with nine facilities and later expanding to more. Personal visits had been suspended since March 13, 2020, as were attorney visits, which resumed July 15, 2021.

Learn more from Virginia →

Non-contact personal visits resumed on May 9, 2021. They had been suspended since March 12, 2020, but legal visits were allowed.

Learn more from Washington →

On July 6, 2021, Wisconsin resumed personal visits , which had been suspended since March 13, 2020.

Learn more from Wisconsin →

All visitation, including legal visits, were suspended by the Federal Bureau of Prisons on March 13, 2020, though attorneys could be approved for an in-person visit on a case-by-case basis. On Oct. 3, some federal prisons began to reopen for non-contact personal visits, with restrictions .

Learn more from Federal →

This is produced in partnership with the Associated Press.

Sources State prison systems

Graphic by Katie Park and Tom Meagher

Reporting by Cary Aspinwall, Keri Blakinger, Jake Bleiberg, Andrew R. Calderón, Maurice Chammah, Andrew DeMillo, Eli Hager, Jamiles Lartey, Claudia Lauer, Nicole Lewis, Weihua Li, Humera Lodhi, Colleen Long, Tom Meagher, Joseph Neff, Alysia Santo, Beth Schwartzapfel, Damini Sharma, Colleen Slevin, Christie Thompson, Abbie VanSickle and Andrew Welsh-Huggins

Additional development by Gabe Isman

- Our Mission

- Our Sponsors

- Editorial Independence

- Write for The Crime Report

- Center on Media, Crime & Justice at John Jay College

- Journalists’ Conferences

- John Jay Prizes/Awards

- Stories from Our Network

- TCR Special Reports

- Research & Analysis

- Crime and Justice News

- At the Crossroads

- Domestic Violence

- Juvenile Justice

- Case Studies and Year-End Reports

- Media Studies

- Subscriber Account

Captives Behind Plexiglass: How COVID Destroyed Prison Visits

Every Saturday morning, private buses drop off groups of people at prisons across New York State.

Women and children, mostly, leave the city in the dead hours of night and travel on these buses for six hours or longer only to wait sometimes for three or more hours to get inside the facility to see their loved ones.

The waiting area usually consists of a dreary small room or trailer encircled with uncomfortable plastic chairs where a few officers approve who will enter the facility.

Often, women are turned away for outfits deemed “too tight” and forced to change.

Most of the time, the outfits they wear are perfectly appropriate. Yet, in these instances, the need to display such power destroys the ability to extend any fairness. Those who have been visiting for a long time come prepared, stashing extra shirts and pants in the duffel bags they shove into lockers that line the back wall.

However, some women do not know yet to plan ahead and must find a nearby store to buy new clothes they hope the officers will find acceptable. Once they pass this “test,” they then sit with the others until they hear their number called, very similar to the dreadful wait at the DMV.

When they are finally called inside, they have to fill out a form, have their picture taken, and walk through a metal detector, another opportunity when they can get turned away. The experienced visitors will wear a bra without underwire and pass through the metal detector with ease. Others will have to enter a changing room, remove their bra, and walk through again.

If the metal detector remains silent, they can then head over to the visiting room.

In a room that resembles a school cafeteria, a few officers sit behind a desk and monitor the interactions. “Stop kissing, stop holding hands, stop hugging” are all common commands during a contact visit that can range anywhere from one hour to six, depending on the facility.

In the case of a no-contact visit, a metal gated partition like a fence will separate visitors from their loved ones.

Despite the strict rules, rigid officers, and long commute, most women find all of these hassles worth the trouble in order to sit face-to-face with their loved ones, to touch them, to share vending machine snacks, to play board games or cards together, and to briefly hug and kiss in the beginning and end of the visit.

These few hours of PG-13 intimacy breathe life and love into relationships that otherwise exist through email, video, or the phone.

However, in March 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic caused prison visiting rooms across the country to shut down, creating a stressful disconnect that would last for the next 14 months, and in some states, even longer.

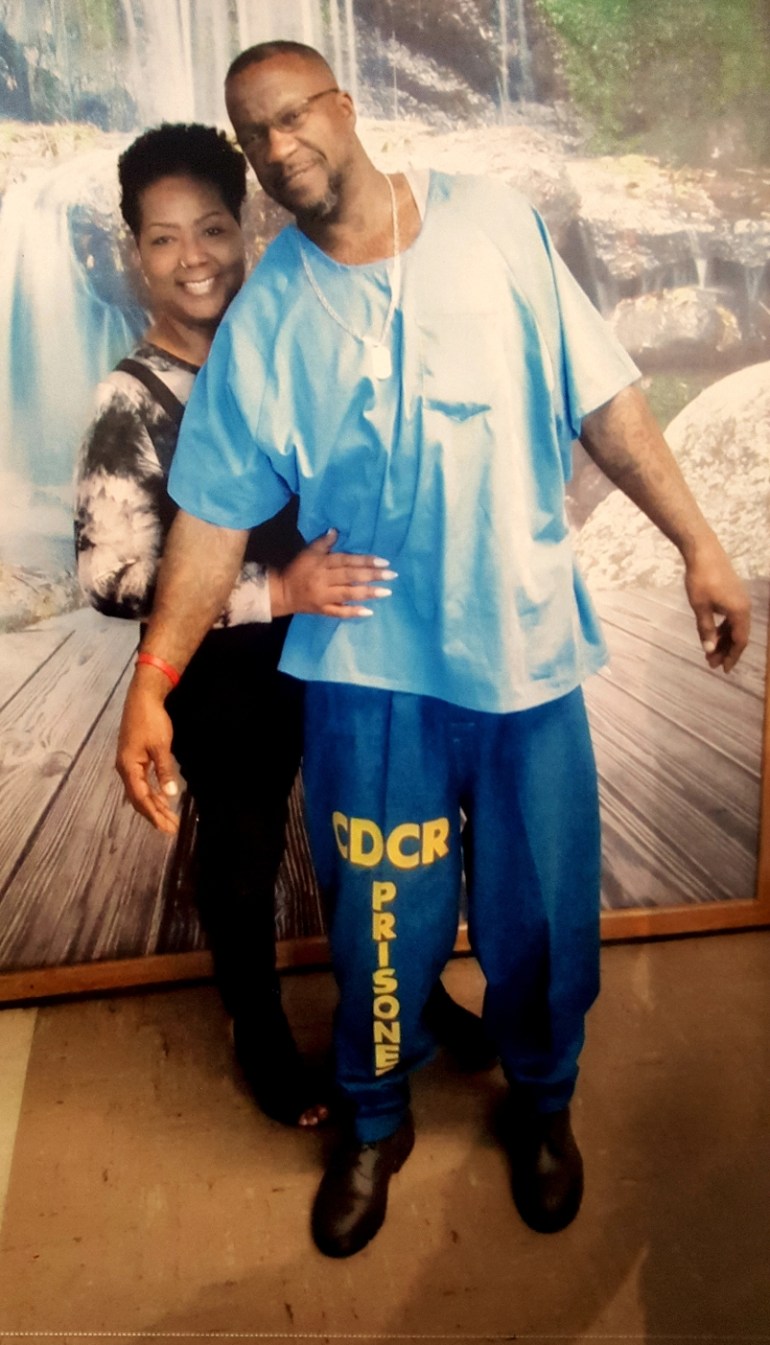

In an interview with The Crime Report, Cecilia Conley, CEO of the social media enterprise Designed Conviction and wife of an inmate serving a life sentence in Washington State lamented that the last time she saw her husband in-person was on March 6, 2020.

Although Washington has begun to allow in-person visits, they are heavily restricted. Visitors and their incarcerated loved ones must sit behind a plexiglass partition to prevent them from kissing, hugging, and even holding hands. The visits must also be scheduled and approved in advance and only last for one hour.

“They opened visitation, but they have a plexiglass, and you have to be seated in front of them with a mask,” Conley explains. “So, for me, if you go there and they cannot even touch you, that’s torture for me; so we prefer to just stick with the video visits because at least we can be wearing no mask, and it will be almost the same thing.

“They’re very strict there, so we don’t like that.”

While Washington allowed video visits prior to the pandemic, New York has yet to have that option, which forced incarcerated people and their loved ones to rely on only letters, emails, and phone calls to stay connected.

Donna Sorge shared the experience she endured with her significant other while he was incarcerated in Green Correctional Facility, located in Coxsackie, N.Y.

“We were on the phone as much as possible and we would email a bunch of times during the day, so it wasn’t like we felt so out of connect, but a lot of people don’t have that luxury,” she said in an interview.

“They don’t email that much, or the guys don’t get on the kiosk that much, or they don’t get the phones as much. In some places like Attica, they might get a 15-minute phone call every other day.”

Prior to the pandemic, Sorge would visit her loved one every weekend; but for most of 2020, she had to rely on these other forms of communication, which she explains took a toll on her relationship.

“It’s a huge impact on us because one of the main ways we communicate is actually seeing them,” she continued. “I mean, we can talk on the phone, we can write, and email, but it’s not the same as going there and spending time with them.”

In Conley’s case, prior to the pandemic, not only would she get to see her husband face-to-face in the facility’s visiting room; but she was allowed to have overnight family visits with him.

“Last year, before the pandemic, I got to spend the night with him,” Conley recalled.

“He would cook for me, we would sleep together, take a shower, watch TV, like in privacy, which was really nice…Now they canceled it, which is stupid.”

Conley went on to express her frustration, stating, “I wish DOC would’ve managed this better. There’s enough science and tools that they could have used to allow us to see our loved ones earlier.”

She added: “I mean, my husband and I are fully vaccinated, and I’m sure there are a lot of guards that are not even vaccinated, so for me, it’s safer to go there than the guards. So, I don’t understand why I cannot see him.”

In New York, overnight family visits are also allowed―but were canceled during the pandemic.

However, since Sorge and her partner are not married, they never had the option to participate in these kinds of visits.

Instead, they would rely on spending time with each other in the visiting room. When facilities closed their doors to outsiders, she explained, “just not being able to see him is stressful because I can have better conversations and get more information from him when I see him in person as opposed to being on the phone.”

Since April 2021, New York has reopened their visiting rooms, but there are still many restrictions.

Sorge recalls her experience, stating, “We obviously weren’t able to kiss. We had to wear masks the whole time unless we were eating or drinking, and they do enforce it…we just made sure we were eating and drinking something, so we didn’t have to have the masks on the whole time.”

While Washington has been moving in the direction of allowing contact visits sometime this summer, Conley has chosen to continue to rely on video visits with her husband as frequently as possible, despite the many drawbacks.

Conley describes it this way:

Conley describes, “We utilize

visits more but there are some times that either the video visit does not work or there would be low quality. As soon as the pandemic started [they were also] more strict with them. So, it really is stressful.”

However, she remains hopeful that she will see her husband in person soon.

“Of course, I want to see him. I want to share a bag of chips and spend the night with him, and I know it’s gonna happen. The state’s opening today, so I hope that by next month, hopefully, I can go see him, so I’m very excited about that.”

Sorge also maintains a sense of optimism despite the heightened degree of separation from her loved one the pandemic caused.

“It’s either going to do one of two things. It’s either going to make you stronger or it’s going to make it harder.”

In her case, her relationship ended up stronger since she was able to welcome her significant other home only a few weeks ago after standing by his side for the last 17 years.

While Sorge has been reunited with her loved one and now has a new start, many people do not share that reality, and are still deeply impacted by the aftermath of the pandemic that continues to alter facility rules.

One concern many people have is the possibility of facilities phasing out in-person visits all together. With the over-use of video visits during this past year many fear that this will become the only option to see their loved ones.

“I fear that a lot. And I fear that now they want to keep that plexiglass,” Conley said. “Of course, it scares me…I think the only reason why it hasn’t been enforced is because the families are fighting for that not to happen, but of course, that sometimes makes me stay up at night because I don’t know what I would do.

“My relationship would be 100 percent impacted by that.”

Although prison staff and law enforcement officials often claim video visits prevent the spread of contraband within the facility and are easier to monitor, that cannot be further from the truth. According to a study conducted by Prison Policy Initiative in 2018 , nearly all reported cases involved jail workers, rather than visitors.

Specifically, “20 jail workers in 12 jails were arrested, indicted, or convicted of smuggling (or planning to smuggle) goods into their cell blocks,” and most of the 12 jails involved had recently banned in-person visits and replaced them with video calls.

However, worst of all, relying only on video visits rob people of the opportunity to experience a true physical connection that cannot be replicated through a screen.

“They’re human and they need human contact,” Conley emphasized.

When incarcerated people have in-person interactions with their loved ones, even briefly, they are provided with a sense of normalcy and a renewal of hope that would be lost otherwise. Such a loss would only negatively impact their rehabilitation process.

Despite the unnecessary cruelty that goes along with banning in-person visits, many jails across the United States have executed this change. According to a 2015 study from the Prison Policy Initiative, 13 percent of local jails – about 500 in 43 states – have implemented video calling, with 74 percent also prohibiting in-person visitation.

Broward County Sheriff’s Office in Florida even tries to make video calls sound more appealing than having the opportunity to hug and kiss loved ones by exclaiming on their website:

Avoid long lines, scheduling conflicts, and provide a better environment for children to interact with a family member. Video visitation is an easier way to spend time with a loved one in custody at one of our jails.

However, when it comes to a child hugging his or her mother, a wife kissing her husband, or a mother holding the hand of her son, do the prison officials mandating these rules truly believe long lines or scheduling conflicts matter? In fact, the emotional toll of physically separating loved ones for indefinite periods of time cancels out any convenience video visits may offer.

While the fear of facilities phasing out in-person visits for good will always linger in the background due to advancements in technology, as of now, many prisons have begun to open their doors to outsiders.

This in turn has brought new concerns regarding longer lines and wait times to enter once restrictions are completely lifted.

Conley expressed her mixed emotions of excitement and worry succinctly.

“There’s going to be a lot of people making a line to go see their loved ones because we haven’t gone in for a long time. But other than that, when I’m there, I don’t know, I haven’t thought about it. It’s going to be nice.”

Maria DiLorenzo, based in Brooklyn, NY, has written for various publications, including the Alaska Quarterly Review, the Flea, Real Crime, and VTPost.com. She is currently working on a true crime novel about the life and crimes of Maksim Gelman, and recently started a blog called Beyond the Crime, which shares stories of those incarcerated for murder to gain a deeper understanding of criminal behavior and the criminal justice system.

Related Posts

Silent strength: my time as a prisoner’s wife turned advocate, reclaimed identity: keith jesperson’s sixth murder, mississippi regularly fails to investigate rampant abuses by sheriff’s and their departments, leave a reply cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Reporting Awards

- Events/Fellowships

- Send Us Tips

- Republish Our Stories

Type above and press Enter to search. Press Esc to cancel.

An official website of the United States government, Department of Justice.

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Impact of COVID-19 on State and Federal Prisons, March 2020–February 2021

This report provides details on the effects of COVID-19 on state and federal prisons from March 2020 to February 2021. The report presents data related to COVID-19 tests, infections, deaths, and vaccinations. It also provides statistics on admissions to and releases, including expedited releases, from state and federal prisons during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic.

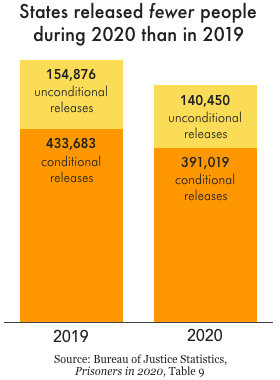

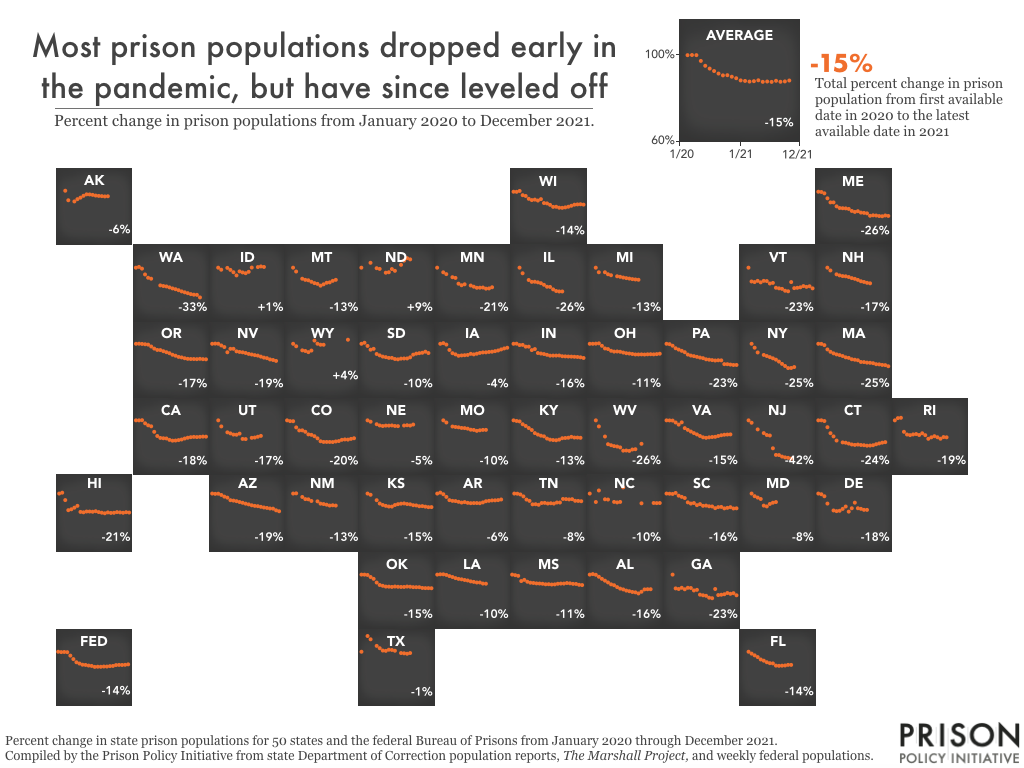

- BJS’s survey to measure the impact of COVID-19 on U.S. prisons from the end of February 2020 to the end of February 2021 found that the number of persons in the custody of state, federal, or privately operated prisons under state or federal contract decreased more than 16%.

- The prison population declined by 157,500 persons during the first 6 months of the COVID-19 study period through the end of August 2020, and by 58,300 in the 6 months through the end of February 2021.

- Twenty-four states released a total of 37,700 persons from prison on an expedited basis (earlier than scheduled) during the COVID-19 study period.

- State and federal prisons had a crude mortality rate (unadjusted for sex, race or ethnicity, or age) of 1.5 COVID-19-related deaths per 1,000 prisoners from the end of February 2020 to the end of February 2021.

- From the end of February 2020 to the end of February 2021, a total of 196 correctional staff in state and federal prisons died as a result of COVID-19.

Additional Details

- Press Release, (PDF 191K)

- Summary, (PDF 184K)

- Full report, (PDF 1.4M)

- Data tables, (Zip format 45K)

Related Datasets

- National Prisoner Statistics (NPS) Program

- National Corrections Reporting Program (NCRP)

- 2020-2021 NACJD Data for National Prisoner Statistics Program - Coronavirus Pan…

Related Topics

Similar publications.

- Jails in Indian Country, 2021, and the Impact of COVID-19, July–December 2020

- Methodology: Survey of Prison Inmates, 2016

- PREA Data Collection Activities, 2015

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Investigations

As covid spread in federal prisons, many at-risk inmates tried and failed to get out.

Meg Anderson

Huo Jingnan

Waylon Young Bird was at the U.S. Medical Center for Federal Prisoners in Springfield, Mo., when he applied for a compassionate release from prison in the spring of 2020. He was worried about the coronavirus pandemic and had underlying medical conditions, including late-stage kidney disease. John S. Stewart/AP hide caption

Waylon Young Bird was at the U.S. Medical Center for Federal Prisoners in Springfield, Mo., when he applied for a compassionate release from prison in the spring of 2020. He was worried about the coronavirus pandemic and had underlying medical conditions, including late-stage kidney disease.

In a federal prison in Springfield, Mo., Waylon Young Bird quietly wrote a letter to a federal judge.

"Greetings sir, just a quick letter concerning the pandemic of the coronavirus," Young Bird wrote. "Many of us are at high risk of getting this virus because of our health conditions, the overcrowding conditions here and the uncleanliness of this prison medical center."

It was March 15, 2020. That day, New York City announced it was shutting down its public schools , Dr. Anthony Fauci went on network television to prepare Americans to "hunker down significantly," and states began closing their bars and restaurants. It was beginning to dawn on many people that something life-altering was already happening. And it was dawning on Young Bird too.

He had been in the Medical Center for Federal Prisoners in Springfield since the previous September, sentenced to 11 years for charges related to dealing methamphetamine. On April 5, 2020, he wrote again.

"If given the chance I will prove I can stay out of trouble and follow the rules and conditions set for me," Young Bird wrote to Chief Judge Roberto Lange of the U.S. District Court for the District of South Dakota, where he was sentenced. "I'm not a bad person. I just made a few bad decisions in my life."

Young Bird was in his early 50s and, among other conditions, had late-stage kidney disease, for which he required dialysis. He wrote to the court April 8, asking to be released from prison. By then, the coronavirus was spreading rapidly throughout the country.

"Once a guard or staff member brings it in here, it will spread," he wrote again April 19, this time to the 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

Young Bird was trying to secure an avenue out of prison faster than the virus could spread.

Waylon Young Bird wrote in his letters that he was concerned about the COVID-19 pandemic arriving in prisons. He was trying to secure an avenue out of prison faster than the virus could spread. Jo Lynn Little Wounded hide caption

Waylon Young Bird wrote in his letters that he was concerned about the COVID-19 pandemic arriving in prisons. He was trying to secure an avenue out of prison faster than the virus could spread.

Over the past two years, thousands of other federal inmates argued the same grim position, trying to use an established process to petition for release before their time in prison effectively became a death sentence.

Many of them ultimately lost. Eventually, Young Bird would too.

As of early March, officials at the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) say 287 federal inmates have died from COVID-19, a count that does not include deaths in privately managed prisons. Bureau officials have been saying since the beginning of the pandemic that they have a plan to keep the situation under control, but an NPR analysis of federal prison death records suggests a far different story.

The federal prison system has seen a significant rise in deaths during the pandemic years. In 2020, the death rate in prisons run by the BOP was 50% higher than the five years before the pandemic. Last year, it was 20% higher, according to the NPR analysis of age-adjusted death rates.

Of those who died from COVID-19, nearly all were elderly or had a medical condition that put them at a higher risk of dying from the virus, NPR found. Many of them seemed to sense their fate — and had tried to get out. And those who made their case in court often faced a slow and complicated process that was unable to meet the pace of a rapidly spreading virus.

"All you heard was just coughing all night, all night"

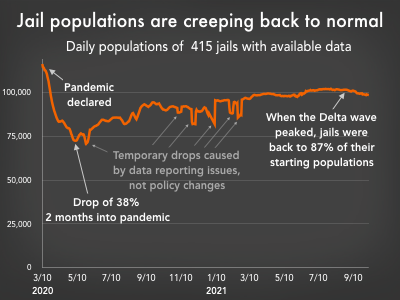

The Federal Bureau of Prisons had a problem from the day the coronavirus arrived in the U.S.: Prisons were likely to be a petri dish for COVID-19. Because staying away from others is nearly impossible inside a prison, health experts said the most effective way to deal with that problem was to make the prison population much smaller — and quickly.

Ron Shehee had been at the federal prison complex in Lompoc, Calif., only a few months when the pandemic struck. Meron Menghistab for NPR hide caption

Ron Shehee had been at the federal prison complex in Lompoc, Calif., only a few months when the pandemic struck.

Ron Shehee lived through the outbreak at the federal prison complex in Lompoc, Calif., where 70% of inmates tested positive for the coronavirus by May 2020. He lived in the prison camp — also known as a minimum security institution — with more than 100 other men, where they slept closely together in bunks, shared bathrooms and ate together. Convicted in 2019 on charges related to selling methamphetamine, Shehee had been at Lompoc only a few months when the pandemic struck.

"At first, we didn't even know that COVID existed. We just had people start getting real, real sick," Shehee remembers. Some were so sick that Shehee, who is paralyzed from the waist down, said he began letting other inmates use his wheelchair to transport people to the medical room. The atmosphere became tense.

"People trying to hold in their cough because it'll start an argument, and people trying to get up and rush to the bathroom so they don't cough," Shehee recalled. "At nighttime, that's all you heard was just coughing all night, all night."

Shehee was placed in isolation after his friend Jimmie Lee Houston died of COVID in early May. But that isolation, he said, felt more like being punished with solitary confinement, and without the medical care he needed, like the catheter he requires or the medications he takes for spasms and asthma.

"They did put me in a nasty little cell all by myself," Shehee said. "And over there in the hole, they don't talk to you. Every time they come up to the door, they shove your food in. And if you ask a question, they don't care."

Shehee was placed in isolation after his friend Jimmie Lee Houston died of COVID-19 in May 2020. But during isolation, Shehee says, he did not receive the medical care he needed. Meron Menghistab for NPR hide caption

Shehee was placed in isolation after his friend Jimmie Lee Houston died of COVID-19 in May 2020. But during isolation, Shehee says, he did not receive the medical care he needed.

At one point, he said, he fell out of his wheelchair while showering and had to crawl back to his bunk. Experiences like Shehee's sparked fear in other prisons as well, where there were reports of inmates not reporting symptoms because they wanted to avoid isolation. When asked about Shehee's experience at Lompoc, the Bureau of Prisons declined to comment on "anecdotal allegations."

In June of 2020, Michael Carvajal, the BOP director, acknowledged this problem to the Senate Judiciary Committee. "Prisons, by design, are not made for social distancing," Carvajal testified. "They are, on the opposite, made to contain people."

Carvajal, who announced his resignation in January of this year, assured the committee that regardless of social distancing, the bureau had a "sound pandemic plan."

It's difficult to get a full view of how the federal prison system has responded to the pandemic at each of its 122 prisons nationwide, but NPR spoke with several current bureau employees who described issues that went against that plan, including the transfer of COVID-positive inmates between prisons and units.

"Our agency is reactive and not proactive. You know, they waited until it got out of hand and then tried to fix things, but by then it was too late," said Aaron McGlothin, a warehouse worker foreman and local union president at the federal prison in Mendota, Calif.

"I don't trust anything the Bureau of Prisons says," said Eric Speirs, a senior correctional officer and local union president at the federal detention center in Miami. "We've had places catch on fire with COVID."

The bureau declined an interview for this story, but in a statement, a spokesperson wrote that the Bureau of Prisons has worked with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, has "implemented a flexible and tiered approach," and is "taking appropriate steps to normalize operations as safety and security permit."

Shehee speaks with his daughter, Sierra Connolly-Shehee, grandson Ezron Alvarez-Connolly and son D'Andre Connolly-Shehee outside the office of the used car lot managed by daughter Shayla Connolly-Shehee in Kennewick, Wash. Meron Menghistab for NPR hide caption

Shehee speaks with his daughter, Sierra Connolly-Shehee, grandson Ezron Alvarez-Connolly and son D'Andre Connolly-Shehee outside the office of the used car lot managed by daughter Shayla Connolly-Shehee in Kennewick, Wash.

Ron Shehee, the prisoner at the Lompoc camp, was eventually granted a compassionate release and now lives in Kennewick, Wash., where he works as a used car salesman. He still hasn't shaken the sense that he averted death.

"I went there to do my time for the crime that I committed and I owned up to that. But I did not plan on going there to die and never see my kids and my family anymore," Shehee said. "We all was lucky to make it through what we went through, and some of us didn't."

"We could have been releasing so many more people"

Some federal criminals will likely never be considered for an early release of any kind, but the pandemic changed the calculation.

On March 26, 2020, then-Attorney General Bill Barr sent a memo to Carvajal, the BOP director, asking him to prioritize home confinement, where a person would be monitored at home and remain in BOP custody. Barr acknowledged that some vulnerable inmates would be safer at home "where appropriate." Still, he wrote: "Many inmates will be safer in BOP facilities where the population is controlled and there is ready access to doctors and medical care."

Barr did, however, include a list of factors to consider when releasing an inmate, including age and medical conditions, the security level of the institution, their conduct in prison, their perceived risk of re-offending, their reentry plan and their crime. Some crimes, like sex offenses, wouldn't be eligible.

The next day, then-President Donald Trump signed the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, known as the CARES Act. It broadened the group of people the BOP could release to home confinement.

Michael Carvajal, director of the Federal Bureau of Prisons, is sworn in during the Senate Judiciary Committee hearing on June 2, 2020. Tom Williams/Pool/AFP via Getty Images hide caption

Michael Carvajal, director of the Federal Bureau of Prisons, is sworn in during the Senate Judiciary Committee hearing on June 2, 2020.

At the time, that new authority was still somewhat hypothetical. But by April, Alison Guernsey, who directs the Federal Criminal Defense Clinic at the University of Iowa College of Law, began to receive panicked phone calls from federal prisons.

"We started to see and hear things from our clients, fear in their voices," said Guernsey. "They called us to say, 'People have been coughing. I'm really afraid that I'm going to get sick. We've been watching things on the news about the need to wear masks. There's no one here with masks.'"

Guernsey, who has been tracking deaths from COVID-19 in prison, estimates she and other clinic staff have spoken with more than 50 prisoners and even more family members throughout the pandemic.

Just over a week after Barr sent his initial memo — on April 3, 2020 — he sent another, more strongly worded message to the BOP.

"While BOP has taken extensive precautions to prevent COVID-19 from entering its facilities and infecting our inmates, those precautions, like any precautions, have not been perfectly successful at all institutions," Barr wrote, adding that there were already "significant levels of infections" at several facilities. Those places, he wrote, should "immediately maximize appropriate transfers to home confinement."

"We have to move with dispatch in using home confinement, where appropriate, to move vulnerable individuals out of these institutions," Barr wrote. He said that prison officials should consider "all at-risk inmates — not only those who were previously eligible for transfer."

Attorney General Bill Barr speaks about the coronavirus during a news conference on April 1, 2020. Alex Brandon/AP hide caption

Attorney General Bill Barr speaks about the coronavirus during a news conference on April 1, 2020.

The determination for who can be sent home — and who cannot — is solely up to the BOP, and by the middle of November 2020, individual wardens became the final authority . After Barr urged the use of home confinement, the BOP added its own criteria to the attorney general's list.

Home confinement existed before the pandemic, for certain inmates in the final six months or 10% of their sentence, whichever was less. And those inmates kept going home in this way during the pandemic. As of early March of this year, more than 38,000 people had been released to home confinement during the pandemic. Of those, about 9,000 — or about 6% of the current federal prison population — were transferred directly because of the CARES Act.

It's unclear how many more people might have been eligible for CARES Act home confinement yet were not released.

"CARES Act home confinement is, frankly, a black box," Guernsey, of the University of Iowa, said. But she feels certain "we could have been releasing so many more people during the pandemic and we just chose not to."

There is evidence suggesting that to be true.

At the Lompoc prison complex, a report by the Office of the Inspector General estimated that in April 2020, about 957 people in low- and minimum-security detention were potentially eligible for home confinement. By the end of June, 124 inmates had been transferred out.

At the complex in Butner, N.C., the OIG estimated that 1,070 people were potentially eligible for home confinement in April 2020. By July of that year, Butner had released 68 people because of the CARES Act. Another 16 had been approved but were waiting to actually be released, and three who were approved died while waiting.

"Case management staff are urgently reviewing all inmates to determine which ones meet the criteria established by the Attorney General," the bureau wrote in a statement in May 2020.

Some federal judges saw things differently. In May 2020, one ordered the prison in Danbury, Conn., to release inmates faster, saying the pace constituted "deliberate indifference." In July 2020, another judge ordered Lompoc to transfer its vulnerable inmates to home confinement, saying the bureau had "likely been deliberately indifferent to the known urgency to consider inmates for home confinement."

An aerial view of the Danbury, Conn., Federal Correctional Institution in 2004. Douglas Healey/AP hide caption

An aerial view of the Danbury, Conn., Federal Correctional Institution in 2004.

Maureen Baird, a former warden at Danbury, said the bar for home confinement was simply too high. For instance, the BOP initially said inmates would not be considered if they had any misconduct on their prison record in the past year. The bureau also prioritized inmates who had served at least half of their sentence or a fourth of their sentence if they had 18 months or less remaining.

"When the CARES Act was established and then the Bureau of Prisons came in and made these additional requirements, I think they overstepped their bounds," Baird said. "You have guys that are in prison now, late 70s, early 80s, mid-80s, that are no danger to the community."

As time progressed, the bureau loosened some of its criteria . Eventually, inmates with misconduct on their records could be considered, so long as they were still considered safe to release. Wardens could also alert the bureau's central office in Washington, D.C., if they thought an inmate should be released to home confinement who didn't otherwise qualify.

To many on the outside and to some bureau employees, the process appeared haphazard, and the release of certain high-profile prisoners who didn't seem to qualify raised eyebrows.

Former Congresswoman Corrine Brown was released from the Coleman prison complex in Florida after serving less than half of her sentence. Her conviction was later overturned. Michael Cohen and Paul Manafort, then-President Trump's former lawyer and campaign chairman, were also both released in 2020 after serving less than half of their sentences.

Michael Cohen arrives at his Manhattan apartment on May 21, 2020, in New York City. Former President Donald Trump's longtime personal lawyer was released from federal prison because of the coronavirus pandemic. John Minchillo/AP hide caption

Michael Cohen arrives at his Manhattan apartment on May 21, 2020, in New York City. Former President Donald Trump's longtime personal lawyer was released from federal prison because of the coronavirus pandemic.

"There was a list of people that were qualified and there was a list of the people who left," said Joe Rojas, a teacher at Coleman and the former southeast regional vice president for the AFGE Council of Prison Locals. "If you're an inmate that has political influence and has money, you will probably get released rather than somebody who probably really should have gotten released."

Other BOP employees told NPR that understaffing made it difficult to quickly assess inmates for home confinement.

Mary Melek, chief union shop steward for the federal detention center in Miami, said part of her job as a case manager is to screen inmates for home confinement. But she often has to cover other shifts. If she needs to finish an inmate's paperwork but is instead walking the halls as a correctional officer, reviewing the lists of who might be eligible to go home can be a struggle.

"They pile up where you have a list and you can't get to it because the next day you'll have to work a custody shift," Melek said. "It takes, on average, one to two months to get everything processed for somebody that could have probably left in a week."

One current administrator, who asked to remain anonymous for fear of retaliation, told NPR that home confinement paperwork at their prison often sat around for months.

"Think about it. Everyone is already overworked and stressed. Who's going to start an inmate's paperwork?" the administrator said.

Prisoners look out of their windows at the federal detention center in downtown Miami on June 12, 2020. Chandan Khanna/AFP via Getty Images hide caption

Prisoners look out of their windows at the federal detention center in downtown Miami on June 12, 2020.

In a statement, a BOP spokesperson told NPR "all inmates are reviewed appropriately" for CARES Act home confinement. Additionally, the BOP spokesperson wrote, "Despite challenges posed by the pandemic, we have managed our staffing levels to maintain the safety and security of our staff and inmates." The spokesperson added that more than 2,000 employees have been hired since March 2021.

"Leadership played down the danger and played up their capacity to deal with it"

By the summer of 2020, Waylon Young Bird had already been denied home confinement.

He continued writing to Judge Lange. Young Bird, who grew up in the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe and the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation, wrote about his family in the Dakotas, his struggles with addiction, and the prayer group he started in prison.

For his part, Lange had been reading Young Bird's letters all along.

"I read them close in time to when they were received," Lange told NPR. "I had very mixed feelings."

In its argument against his release, the government noted an "extensive" criminal history in tribal court. Regarding the pandemic, the U.S. attorney wrote: "Defendant only becomes susceptible to increased risk if he contracts COVID-19."

In June, Lange denied Young Bird's compassionate release motion.

"Researchers have found that ailments like diabetes and chronic kidney disease put individuals suffering from them, like Young Bird, at higher risk of complications if they contract COVlD-19," Judge Lange wrote. "However, there is still much that is unknown about how this virus affects individuals, and this Court cannot say to what extent Young Bird's life is threatened by the existence of COVlD-19."

Additionally, the judge wrote, Young Bird received health care at his prison, and "the BOP has taken precautions to protect him and his fellow inmates."

Lange told NPR he felt he had ruled properly in Young Bird's case, given that Young Bird had served only a small portion of his sentence. And, Lange said, Young Bird had also been using drugs during his pretrial release.

"I just felt that it probably was safest for him to be at a federal medical facility rather than outside," the judge told NPR. "Looking at things in retrospect is a difficult way to try to go about the job I have, because I have to judge with the information that I presently have."

Lange said he didn't know in June 2020 to what extent Young Bird's life was threatened, given that he was at a federal medical center.

"As a district judge in South Dakota, it's hard to know exactly what is going on at a Bureau of Prisons facility," Lange said. "But when I see a medical doctor from the Bureau of Prisons write, in essence, that the individual is receiving appropriate care ... I tend to trust that."

Waylon Young Bird had already been denied home confinement by the summer of 2020. He continued writing to Judge Lange. Jo Lynn Little Wounded hide caption

Waylon Young Bird had already been denied home confinement by the summer of 2020. He continued writing to Judge Lange.

On June 10, just a few days after his denial for release, Young Bird wrote again to Lange.

"I know I just wrote to you but I'm writing again, because this morning around 10 am, an inmate next to me said 'It's finally here,'" Young Bird wrote. "It's official now, that the first case of the coronavirus is here at Springfield, Mo. Medical Center."

Young Bird wrote that he went back to his unit and put on his face mask, one he said he'd had for a few weeks.

"Our beds are right next to each other. We don't practice social distancing here," Young Bird wrote. "I don't know what to do. I'm scared like everyone else."

A few days later, he wrote again.

"This coronavirus will start spreading soon, a lot of us will get it," Young Bird wrote. "I don't want to die here. I got family I miss, a handicap sister, kids who need me, grandkids too. Can you find it in your heart to reconsider?"

Many other inmates were navigating their options just like Young Bird. Finding themselves denied for home confinement, they took to court to make their case to be released early from their sentences.

A federal inmate's ability to ask a judge for compassionate release, where a prison sentence is actually reduced, was only recently made possible. Before the First Step Act in 2018, the bureau was solely responsible for identifying prisoners and bringing their cases to court. The First Step Act gave inmates the right to do that themselves. In the first full year the new law was in effect, 96 inmates filed motions themselves. In 2020, nearly 13,000 motions were filed in federal court.

The road to court, though, still starts in the prison. Before they can file their own compassionate release motion, inmates first have to ask their warden to file a motion on their behalf. Then they must wait 30 days for the bureau to respond, though some courts have waived that requirement.

By April 2021, nearly 31,000 inmates took this first step of asking their warden and waiting for an answer. At least 35 died waiting for the Bureau of Prisons to review their case. Ultimately, the bureau approved just 36 of that initial 31,000.

Once an inmate is allowed to file their own motion in court, whether they succeed depends largely on the district their case is in. In the Southern District of Georgia, for instance, federal judges denied 98% of the compassionate release motions they saw between January 2020 and June 2021. In the District of Oregon, they denied just 35% of the motions. Overall, federal judges nationwide denied more than 80% of the compassionate release motions in that time, according to data from the U.S. Sentencing Commission .

That tendency to deny is the result of a mentality in the criminal justice system to "just say no," said Miriam Krinsky, a former federal prosecutor and the executive director of the group Fair and Just Prosecution.

"That mindset of 'We are going to punish as harshly as possible. We will charge everything possible, we will seek everything possible. And when people want relief from that, we will just say no,'" Krinsky said.

The U.S. is limiting compassionate release in plea deals. Many say that's cruel

Throughline

Mass incarceration.

And some of it, she said, is risk aversion.

"People just don't want to be the ones with their name, their neck, on the line on decisions they view as risky, namely letting people out before their date," Krinsky said. "The focus is on the one case in a thousand where things go wrong rather than the 999 instances where things go well, where people are released or receive a second chance and do perfectly fine."

The success of a compassionate release motion depends ultimately on whether a judge finds a prisoner deserving of release. To determine that, a judge will consider the factors that came into play when the inmate was sentenced , like the seriousness of the crime. They'll also consider whether there are "extraordinary and compelling reasons" that justify release. And that can be influenced in part by whether the COVID conditions in a prison seem dire, said Colin Prince, the chief appellate attorney for the Federal Defenders of Eastern Washington and Idaho.

"My biggest frustration was that the leadership played down the danger and played up their capacity to deal with it," Prince said of the Bureau of Prisons. "Publicly and to the judiciary in briefings, they were just writing 'We've got this. We're experts in infectious disease. Here are the many policies we've put in place.'"

Once the motions related to COVID started coming in, prosecutors repeatedly argued in court against the release of inmates. They said the BOP had taken significant measures to protect prisoners — and was already prioritizing the release of inmates through another avenue: home confinement.

"It would have been much more honest and, frankly, helpful had the leadership of BOP simply come out and said, 'There's only so much we can do," Prince said. "And what they should have done is gone to the judiciary and said, 'This is a big problem. We can't protect these people. You need to help us.'"

Krinsky said that may have made a difference.

"There is often deference to the Bureau of Prisons," she said. "Their mindset can hold great sway in terms of how these cases play out."

Instead, many inmates had to go through what was often a lengthy and fruitless legal process. Of the prisoners who died from COVID-19, at least 1 in 4 filed a motion in court for compassionate release, according to NPR's analysis.

At least three people had their requests granted, yet contracted COVID-19 and died before they could actually be released.

In Kentucky, James Oscar Jones died the same day his release was granted. Andre Williams in North Carolina was granted compassionate release on April 1, 2020, but the court stayed the order. Williams tested positive for COVID on April 5 and died on April 12, two days after the stay was lifted.

In Kansas, Steven Brayfield first asked his warden for compassionate release in July 2020 and was denied about a month later. In early December, he asked again, this time in court, which a judge granted one month later. But Brayfield was already hospitalized with the virus. By then, according to Brayfield's lawyer, his family could not pay for his medical care if he were released. They requested that, instead, he stay in BOP custody so he could remain on a ventilator. He died on Jan. 19, 2021, at age 63.

Many others died while their motion was still moving through the courts, and some had been waiting months to hear back. At least four requests were denied as moot because the people had already died.

In Indiana, James Lee Wheeler, a 78-year-old with diabetes and high blood pressure, among other conditions, told his lawyer he was deeply anxious about what would happen to him if he contracted COVID-19. In the late summer of 2020, Wheeler woke to find one of his cellmates, who had been having trouble breathing, had died during the night, according to a release motion filed by Wheeler's lawyer. That motion had been pending for three months when Wheeler died that December .

Marie Holiday's father, Abdul-Aziz Rashid Muhammad, asked for compassionate release in April 2020. He cited several health conditions that put him at a higher risk of death from COVID-19. Meg Vogel for NPR hide caption

Marie Holiday's father, Abdul-Aziz Rashid Muhammad, asked for compassionate release in April 2020. He cited several health conditions that put him at a higher risk of death from COVID-19.

Others who died were denied not necessarily because they were ineligible but for other, more administrative, reasons: Some because they did not exhaust all avenues with their wardens first. And sometimes, the courts simply seemed to make a mistake — like in the case of Abdul-Aziz Rashid Muhammad.

In the fall of 2020, his daughter Marie Holiday was starting to make plans to spend time with her father without a guard watching over them. Muhammad had been in prison, for charges related to armed robbery, nearly all of Holiday's life.

That fall, Holiday had a glimmer of hope: One of her father's convictions had been ruled unconstitutional, and he had a resentencing hearing scheduled in early 2021.

"He said he was coming home. He was confident," Holiday said. "He's been fighting a long fight, a long battle."

Marie Holiday kept every photo her father, Abdul-Aziz Rashid Muhammad, sent to her from his decades in prison. Meg Vogel for NPR hide caption

Marie Holiday kept every photo her father, Abdul-Aziz Rashid Muhammad, sent to her from his decades in prison.

In April 2020, even before his resentencing hearing was set, he had asked for compassionate release, citing several health conditions that put him at a higher risk of death from COVID-19.

In May, the U.S. attorney wrote in his argument against Muhammad's release that there were no confirmed cases of COVID-19 at the federal medical center in Rochester, Minn., where Muhammad was located.

In September, the court denied Muhammad's motion, writing "speculative concern about catching COVID is not enough" given that, even by that fall, only 0.01% of inmates at his prison had the virus.

But by then, Muhammad wasn't at Rochester. Three months earlier, in June, he had written to the court to tell the judge he had been transferred to Butner, where more than 50% of inmates had tested positive .

Muhammad tested positive for COVID-19 on Jan. 13, 2021. Five days later, he was sent to a hospital, where his daughter Marie Holiday saw him over a video call. Marie Holiday hide caption

Muhammad tested positive for COVID-19 on Jan. 13, 2021. Five days later, he was sent to a hospital, where his daughter Marie Holiday saw him over a video call.

Muhammad eventually tested positive, too, on Jan. 13, 2021.

Five days later, he was transported to a hospital, where Holiday was able to see him through a video call.

"I was speechless when I saw him. There was nothing. He was just hooked up to all these different machines and he was not responding." Holiday remembers. "I just kept repeating that I love him and I'm so sorry."

On Feb. 9, Muhammad died — one month before the hearing he thought would secure his release.

Every time someone dies of COVID-19 in federal prison, the bureau writes a press release. Every letter is structured the same: First, there's a timeline of how the disease ravaged their body. Then it names their crime. The notice for Muhammad was no different.

"He had a family that loved him, and I'm sure all those other inmates had families that loved them," Holiday said. "I'm not saying that everybody is a nice guy that's in prison, but there are some good people and even those that are bad, they still deserve to be treated like humans."

"It's far from over"

People are still regularly contracting COVID-19 and dying from it in federal prison. At least one prisoner, Rasheem Hicks, was denied release, in part, because he chose to be vaccinated, which lowered his medical risk to the virus. Another, Rebecca Marie Adams, was denied, in part, because she chose not to take the vaccine that would lower her risk. Both later died of the virus.

"It's far from over," McGlothin, the employee and union president at the prison in Mendota, said. "You know, people are dying, people are getting sick. And the protocols seem to be a lot more lackadaisical than they were two years ago."

Abdul-Aziz Rashid Muhammad is buried at Crown Hill Memorial Park and Mausoleum in Cincinnati, Ohio. Meg Vogel for NPR hide caption

Abdul-Aziz Rashid Muhammad is buried at Crown Hill Memorial Park and Mausoleum in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Dr. Homer Venters, former chief medical officer of the New York City jail system and a member of the Biden administration's COVID-19 Health Equity Task Force, has conducted dozens of inspections of jails, prisons and immigration detention facilities during the pandemic. He said he has seen strengths in the federal prison response to COVID-19 in many places across the country.

"But I have also encountered significant deficiencies in how or whether basic CDC guidelines and BOP policies were being implemented," Venters testified to the House Judiciary Committee in late January of this year. "There is no doubt that many of these strengths saved lives and, conversely, that many of these deficiencies led to preventable illness and death."

Venters stressed the need for an independent investigation into all COVID-19 deaths that occurred in federal custody.

"The total story is that people were in places where they were more likely to get COVID and more likely to die from COVID," Venters told NPR. "We need to fully understand how the inadequacy of care for them contributed to these deaths."

An envelope that contained one of Waylon Young Bird's letters to Judge Lange. Department of Justice hide caption

An envelope that contained one of Waylon Young Bird's letters to Judge Lange.

By the fall of 2020, Waylon Young Bird's letters were becoming increasingly desperate.

"Nobody cares if you die or not here," he wrote on Sept. 20.

Just under a month later, he wrote again. He told Judge Lange he qualified for home confinement and compassionate release and should be given a second chance.

"We feel like sitting ducks, waiting for the virus to come and infect us," he wrote. "I can prove I'm going to be a law-abiding citizen and do good for myself. I'm no danger to others or the community. I'm not a terrible person."

On Oct. 27, Young Bird wrote again, this time to tell the judge of a major outbreak at the prison. At least 200 inmates and staff were infected. He had been separated from the COVID-positive inmates, he wrote, but he didn't think staff had a protocol they were following. COVID-positive inmates were still serving the food, he wrote. Some staff, he said, had stopped coming to work.

"I'm afraid I may be infected by the time you receive this letter and would not be able to contact my family by then," he wrote, ending his letter simply: "I don't feel good about this at all."

Young Bird tested positive the following day and died a week later. He was 52.

His aunt, Jo Lynn Little Wounded, got a call early the next morning from a prison employee. He was looking for Young Bird's mother, who was sleeping in the next room with his sister.

Jo Lynn Little Wounded holds her nephew Waylon's ribbon shirt beside his pickup truck. Dawnee LeBeau for NPR hide caption

Jo Lynn Little Wounded holds her nephew Waylon's ribbon shirt beside his pickup truck.

"I just couldn't even bring myself to tell her and my niece that he passed away," she said.

Little Wounded sat in the other room for a few hours before she woke them up.

"He didn't have to die like that," Little Wounded said. "He died a horrible death in there by himself. And that's the hardest part, was that he died by himself."

Little Wounded was ready to welcome him home. His truck remained parked in front of her house for more than a year after his death, until the city finally came and towed it away.

Editor's note: Some of Waylon Young Bird's letters contain minor grammatical errors, which NPR has opted to correct for clarity.

NPR’s Barbara Van Woerkom contributed research to this report, and NPR’s Nick McMillan and Robert Benincasa contributed to the data analysis.

‘A living hell’: Inside US prisons during the COVID-19 pandemic

Prisoners and their families describe the emotional, physical and financial toll of the pandemic.

In the days before Christmas, 44-year-old April Harris sat in her prison cell at the California Institution for Women for more than 23 hours a day. In the 20 minutes she was allowed to leave it, she and the other prisoners would flood into the common areas – choosing either to take a shower or to make a short phone call.

Restrictions have fluctuated during the various lockdowns implemented throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, but in the 11 months since the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) first banned visitations across state prisons, Harris says she has seen the mental health of those around her steadily deteriorate.

Keep reading

Will the us unemployment rate continue at historic lows, mexico’s teachers seek relief from pandemic-era spike in school robberies, ‘a bad chapter’: tracing the origins of ecuador’s rise in gang violence, why is the us economy so resilient.

“A friend of mine sliced her arms yesterday because she said that she couldn’t handle it anymore,” Harris wrote at the end of 2020 in a message sent via JPay, an electronic messaging system used in prisons.

“Women scream, beat their doors and call fake medical emergencies just to get out of their rooms. The women are definitely breaking.”

Elizabeth Lozano, 46, used to work in the gym, visit the law library and take art therapy and creative writing courses at the Central California Women’s Facility (CCWF) where she is imprisoned, but that all stopped in mid-March. At first, she says she was still allowed outside at intervals – first every other day and then every four days. Now, however, she says she has not smelled fresh air since late December, when the CCWF further restricted movements as the number of COVID cases rose.

“The stress level is super high,” Lozano wrote through JPay, noting that the anxiety was driven by fear of COVID in rooms where women were “packed like sardines.

“We have no control of what [others] do, so even if I take precautions [it] doesn’t mean a roommate is. We can’t social distance or shelter in place safely.”

Lawyer Penny Godbold represents individuals with disabilities in California prisons and says, “The pandemic has had an unbelievable toll on the mental health of people incarcerated in California. People describe watching others – friends, cellmates, those in their housing units – get sick and die around them without knowing whether they, too, will suffer the same fate.”

Six feet apart

Kassan Messiah, 55, last saw Lorraine, his wife of 27 years, in October, when she visited New York’s Sing Sing Correctional Facility. The visit buoyed Kassan.

“My wife is my respirator; my understanding of the world beyond the wall is all attributed to wifey,” Kassan wrote in a message sent over JPay.

But, “after each visit”, Kassan says he experiences “deflation”.

They had not seen each other since January 2020, when their communication and visits were upended.

At the beginning of January 2021, Lorraine only received one call from Kassan a week. Afraid of missing it, she kept her phone with her at all times. But sometimes, just five minutes into the call, she says she would hear the guards yelling at him to hang up.

Then, on January 23, Kassan says he was left with a bloodied mouth, a black eye, bruising and wrist lacerations after he was attacked by guards. When asked about this, the New York Department of Corrections and Community Supervision said they were investigating the incident and would not comment further. Kassan was moved into a Special Housing Unit, where he is able to call Lorraine every day. She says she now gets to hear her husband’s voice more than at any other point during the pandemic.

During her October visit to Sing Sing, social distancing restrictions prevented them from hugging. About two dozen cafeteria tables filled the visiting room. The length of the table, about six or seven feet, separated Kassan from Lorraine.

“It’s more torture than anything else because you’re so close, but yet you’re so far,” Lorraine reflected. “If you’re allowing me into the facility, why am I not able to touch his hand?”

Even so, she had gotten closer than most people with imprisoned family members.

‘Absolutely no support’

In March, as the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a pandemic, US prisons shut down visitations. A handful of states, including New York, restored visits but stopped them again months later. As of early February, only six states and the Federal Bureau of Prisons currently allow personal visits, with varying restrictions. North Carolina only allows one 30-minute visit per month; only two people can visit each time, and no children under 12 are allowed. New Hampshire allows one 45-minute each month. Visits are non-contact and nobody under 18 is allowed into facilities.

Imprisoned people “can’t see friends, and they can’t maintain consistent contact with supports, but they also can’t go to mental health programming,” said Stefen Short, the Supervising Attorney of the Prisoners’ Rights Project run by the New York-based Legal Aid Society. “Well then what’s available to this person? At the middle of a global pandemic, when everybody’s at heightened anxiety, our clients are getting absolutely no support.”

Access to legal representation has also been affected by visitation changes. Earlier this month, 31 prison systems permitted legal visitations but banned personal visits, while 13 forbade all guests. Jails have quarantined new arrivals for 10 to 14 days and only allowed detainees to place calls to lawyers for 15 to 30 minutes each day, according to Corene Kendrick, the deputy director of the ACLU’s National Prison Project.

“It’s critical for defence attorneys to meet with their clients soon after they are arrested so that the attorney can get a thorough account from their clients about witnesses, locations, possible alibi evidence, and to review documents, police reports, and photos, and explain the next steps in the process to the client. Regardless of whether it is in the intake quarantine areas or in the general population sections, most jails often have very few or no options to set up confidential video or telephone calls,” Kendrick explains.

“In prisons, where people may need to speak to their attorney for purposes of a pending appeal, a new lawsuit, or as part of a class-action lawsuit regarding conditions, there are the same limitations.”

‘An ongoing nightmare’

For those with pre-existing mental health conditions who are no longer able to see their therapists, the strain has been even greater.

“It’s a living hell, pretty much,” says one California prisoner, who has been diagnosed with borderline personality disorder and went seven months last year without seeing his social worker. “I can only describe it as an ongoing nightmare.”

Incarceration facilities have, for decades, teemed with people needing mental healthcare. Forty-four states have an incarceration facility detaining more mentally ill people than the state’s largest psychiatric hospital, according to the Treatment Advocacy Center. Thirty-seven percent of people in state and federal prisons and 44 percent of those in jails have been diagnosed with a mental illness. Yet only 37 percent of people held in prisons and 38 percent of people detained in jails with mental health disorders were actually receiving treatment, according to a 2017 Department of Justice report.

But, during the pandemic, while the need for mental healthcare has peaked, the limited services offered in prison have diminished further.

“We’re not seeing counselors or [therapists] right now at all,” Lozano wrote via JPay. Group therapy sessions, which she attends to help with depression, have been shut down since spring, and she sees her therapist much less frequently than before the pandemic. “At one point I was quarantined in isolation and I kept asking to see mental health for that day following protocol, but I wasn’t able to see no one for days.”

“The well-being and safety of the incarcerated population and staff within CDCR and CCHCS [California Correctional Health Care Services] is our top priority,” CDCR Press Secretary Dana Simas wrote in an email statement to Al Jazeera, noting that prisoners are provided with ongoing mental health assessments and the department is conducting crisis intervention to prevent suicides.

“An incarcerated person may request mental health services or they may be referred through institution staff. Mental health and operations leadership meet daily to ensure mental health referrals and requests for services from patients are quickly addressed.”

But imprisoned people and their advocates say that even if services are formally offered, obtaining useful care is often difficult.

After a transgender man in the California Institution for Women – the facility housing April Harris – attempted suicide in May, the prison offered colouring books and crossword puzzles to prisoners. In June, a Virginia prison distributed a “mental minute” newsletter offering tips for relaxation and sleeping. The pamphlet instructed readers to “prepare yourself before going to bed” by exercising earlier in the day, “taking time to relax by meditating, listening to restful music, completing relaxation exercises or reading”.

In September, the Southern Center for Human Rights, an organisation that represents people in the criminal justice system, urged the Department of Justice to investigate “deplorable conditions” in Georgia prisons, after suicides reached unprecedented levels. In the eight months before the letter was sent, 19 people in Georgia prisons died by suicide – a rate twice the national average for suicides in state prisons. About 30 percent of the suicides occurred in a facility that “purportedly specialises in the housing and care of people with serious mental illness,” the letter said.