The Long Road to America – One Refugee’s Experience

Refugees lining up with their suitcases – all their worldly possessions – as they get ready to board a plane for their new homes in the U.S.

The journey to migrate to the United States can be a long hard road for most refugees and immigrants. Each year, close to 50,000 refugees and 500,000 immigrants come to the United States from around the world to start a new life. CDC’s Division of Global Migration Health (DGMH) makes it a top priority to ensure they are healthy upon arrival to the U.S. DGMH accomplishes this through domestic and overseas programs, and public health interventions such as vaccinations, mandatory health screenings and parasitic treatment programs. By focusing and improving the health of immigrants, U.S. bound refugees, and migrants, DGMH works to keep infectious diseases and other diseases of public health significance from coming into and spreading in the U.S.

DGMH’s Africa Regional Field Program in Kenya primarily works with refugees under consideration for resettlement in the United States. The program collaborates with the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and other partners to improve the health of refugees. The program also works extensively with the International Organization for Migration (IOM) to oversee the medical screening of U.S.-bound refugees to prevent the spread of communicable diseases, and to ensure the number of panel physicians that can conduct health assessments of resettling refugees is sufficient.

Follow one refugee’s journey to the United States and learn how DGMH works to protect and improve the health of immigrants, U.S. bound refugees, and migrants through domestic and overseas programs.

How Amina’s Journey Began

It is a chilly morning in Nairobi, Kenya, but adults and children alike are bundled up and waiting patiently with their suitcases. They are shuffled through the line to weigh and tag their luggage – all their worldly possessions – as they anxiously await their chance to board a plane and begin a new life in the United States. These families are used to waiting; most fled their homes in the 1990s and have been waiting year after year for the opportunity to resettle and make a permanent home again.

Many refugees can never return to their homeland; they would face continued persecution if they did. Some are also living in perilous situations or have specific needs that cannot be addressed in the country where they have sought protection. In such situations, they are settled in a third country, but the odds of resettlement are long. Of the 10.5 million refugees around the world, less than 1 percent will be relocated.

Amina, one of several members of this 1 percent at the IOM transit center in Nairobi, was pregnant when she started her long, winding, and arduous journey in October 1991 with her husband and 3-year-old son, Mohamed. She came from a village 30 kilometers outside Mogadishu in Somalia. After making their way to Mogadishu, her family traveled by car for 2 days to Kismayo. It took them another 4 days to cover the distance from Kismayo to Liboi, a town on the Kenyan border, on a road that translates to the “Curse of the Parents.” This stretch of road proved to be a curse twice over, as Amina’s infant son died of measles before they reached the border and her husband, returning along this road to reunite his sick mother with the family, was gunned down by a militia group just months before Kenya opened her borders to Somali refugees. Amina’s daughter, Sundes – born a few months later in the Utanga refugee camp on the coast of Kenya – would never know her father.

Amina with her two children Mohamed and Sundes

© CDC-Kenya/Sara Test

Amina moved her children again to another coastal refugee camp, Swaleh Nguru, but in March 1997, the ongoing tension between Kenyan villagers and the Somali refugees escalated. One day, when Amina left her children at the madrassa (a religious school) to go to the market, the locals set fire to the camp. Young Sundes and her older brother smelled smoke and ran 4 kilometers until they found a woman who used to buy goods from their mother and took them in. They were reunited with Amina the same fateful day, but others were not so lucky, as several of their friends were killed in the fires.

Sundes shares her excitement about a new life in America

The United Nations closed Swaleh Nguru and sent Amina and her family to the Kakuma refugee camp in the north of Kenya. When I asked her daughter, Sundes, what it was like to grow up in Kakuma, she shrugged and said, “I can’t complain – it’s life.” She went on to say that it’s stifling hot most of the year and while the refugees are given basic food staples, her mother always worked to buy extra food for the family. Her brother dropped out of school when he reached grade 7 and worked as a tea seller, loader, and waiter so she could attend a private school and get a better education.

Today is the Day: The Journey to the U.S.

Their lives are about to change drastically as they start yet another long journey – this time aboard an airplane en route to Kansas City. Their aspirations are no different from the immigrants who have for centuries sought a better life in the United States. Sundes would like to go to college and, having volunteered with FilmAid International in Kakuma, continue working in film. Mohamed would like to complete high school and work to support his family, while his mother wishes to learn English. Ultimately, however, “living safely is enough for now. Living in Kakuma, you don’t sleep sound at night. Locals come in at night and sometimes rob and shoot refugees. You wonder if someone will die tonight or the next.”

While Sundes is sorry to leave her friends behind, she is buzzing with excitement. This World Refugee Day she will not be performing in any plays in the camp, as she has for the past few years. She will be stepping off a plane, arm-in-arm with her brother and mother, to set down roots in a place where they hope they can finally find peace.

It is important to DGMH that refugees such as Amina, Mohamed, and Sundes have access to medical care and preventive health services prior to arrival in the United States. This family will start their new lives in Kansas City healthy and, most importantly, happy.

- About Refugees

- Improving Health for Kenya's Refugees by Building Laboratory Capacity

- Asia Field Program

To receive email updates about this page, enter your email address:

- Immigrant and Refugee Health

- Importation

- Port Health

- Travelers' Health

- Southern Border Health and Migration

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

Spartacus Educational

Journey to america.

In the early 19th century sailing ships took about six weeks to cross the Atlantic. With adverse winds or bad weather the journey could take as long as fourteen weeks. When this happened passengers would often run short of provisions. Sometime captains made extra profits by charging immigrants high prices for food needed to survive the trip.

In 1842 the British government attempted to bring an end to the exploitation of passengers by passing legislation that made it the responsibility of the shipping company to provide adequate food and water on the journey. However, the specified seven pounds a week of provisions was not very generous. Food provided by the shipping companies included bread, biscuits and potatoes. This was usually of poor quality. One government official who inspected provisions in Liverpool in 1850 commented that "the bread is mostly condemned bread ground over with a little fresh flour, sugar and saleratus and rebaked."

Captains were sometimes accused of using rations to control the behaviour of their female passengers. William Mure, the British consul in New Orleans reported that one captain "conducted himself harshly and in a most improper manner to some of the female passengers having held out the inducement of better rations to two who were almost starving in the hope they would accede to his infamous designs." In 1860 the New York Commissioners of Emigration reported that there were "frequent complaints made by female emigrants arriving in New York of ill-treatment and abuse from the captains and other officers." As a result of their investigation Congress passed a law that enabled captains and officers to be sent to prison for committing sexual offences against female passengers. However, there is no evidence that anyone was ever prosecuted under this law.

Travellers often complained about the quality of the water on the journey. The main reason for this was that the water was stored in casks that had not been cleaned properly after carrying substances such as oil, vinegar, turpentine or wine on previous journeys. One immigrant travelling in 1815 described the water as having such "a rancid smell that to be in the same neighbourhood was enough to turn one's stomach".

To maximize their profits shipowners tried to cram as many people as possible on board for the trip. In 1848 the U. S. Congress attempted to improve travelling conditions, by passing the American Passenger Act. This legislation prescribed a legal minimum of space for each passenger and one of its consequences was the building of a a new, larger type of ship called the three-decker. The top two decks carried the immigrants and although they had more space, the journey was still unpleasant. It was very dark in the lower deck and their was also a shortage of fresh air. Whereas those on the upper-deck had to contend with the stench rising constantly from below.

Immigrants suffered many dangers when crossing the Atlantic. This included fires and shipwrecks . In August, 1848, the Ocean Monarch , carrying immigrants from Liverpool to Boston , caught fire and 176 lives were lost. As ships got larger so did the deaths from fires. In September, 1858, an estimated 500 immigrants died after a fire on the steamship Austria . Another 400 died on the William Nelson in July, 1865.

In 1834 seventeen ships shipwrecked in the Gulf of St Lawrence and 731 emigrants lost their lives. In a five year period (1847-52) 43 emigrant ships out of 6,877 failed to reach their destination, resulting in the deaths of 1,043 passengers. In 1854 the steamship City of Glasgow carrying 480 emigrants went missing after leaving Liverpool and was never heard of again.

A major problem for emigrants on board ship was disease . There were serious outbreaks of cholera in 1832, 1848 and 1853. Of the 77 vessels which left Liverpool for New York between 1st August and 31st October, 1853, 46 contained passengers that died of cholera on the journey. The Washington suffered 100 deaths and the Winchester lost 79. All told, 1,328 emigrants died on board these ships on the way to America.

The most common killer was typhus . It was particularly bad when the passengers had been weakened by a poor diet. In 1847, during the Irish Famine, 7,000 people, most of them from Ireland , died of typhus on the way to America. Another 10,000 died soon after arriving in quarantine areas in the United States.

In 1852 shipping companies began using steamships to transport immigrants to America. This included the ships the City of Manchester and the City of Glasgow, that could transport 450 immigrants at a time from Liverpool to New York. The fare of six guineas a head was double that charged by sailing ships. However, it was much faster and by the 1870s the journey across the Atlantic was only taking two weeks.

Primary Sources

(1) reverend william bell, writing about the quality of the water on a boat sailing from leith to quebec in 1817..

Our water has for some time past been very bad. When it was drawn out of the casks it was no cleaner than that of a dirty kennel after a shower of rain, so that its appearance alone was sufficient to sicken one. Buts its dirty appearance was not its worst quality. It had such a rancid smell that to be in the same neighbourhood was enough to turn one's stomach.

(2) In 1860 the New York Commissioners of Emigration carried out an investigation into the treatment of female passengers on board ship bring immigrants from Europe to the United States.

The frequent complaints made by female emigrants arriving in New York of ill-treatment and abuse from the captains and other officers. caused us to investigate the subject; and from investigation we regret to say that after reaching the high seas the captain frequently selects some unprotected female from among the passengers, induces her to visit his cabin, and when there, abusing his authority as commander, partly by threats, and partly by promises of marriage, accomplishes her ruin, and retains her in his quarters for the rest of the voyage, for the indulgence of his vicious passions and the purposes of prostitution; other officers of the ship often imitate the example of their superior, and when the poor friendless woman, this seduced, arrive at this port, they are thrust upon shore and abandoned to their fate.

(3) Samuel Gompers and his family emigrated to the United States in the summer of 1863.

The Cigarmakers' Society Union of England, whose members were frequently unemployed and suffering, established an emigration fund - that is, instead of paying the members unemployment benefits, a sum of money was granted to help passage from England to the United States. The sum was not large, between five and ten pounds. This was a very practical method which benefited both the emigrants and those who remained by decreasing the number seeking work in their trade. After much discussion and consultation father decided to go to the New World. He had friends in New York City and a brother-in-law who proceeded us by six months to whom father wrote we were coming. There came busy days in which my mother gathered together and packed our household belongings. Father secured passage on the City of London, a sailing vessel which left Chadwick Basin, June 10, 1863, and reached Castle Garden, July 29, 1863, after seven weeks and one day. Our ship was the old type of sailing vessel. We had none of the modern comforts of travel. The sleeping quarters were cramped and we had to had to do our own cooking in the gallery of the boat. Mother had provided salt beef and other preserved meats and fish, dried vegetables, and red pickled cabbage which I remember most vividly. We were all seasick except father, mother the longest of all. Father had to do all the cooking in the meanwhile and take care of the sick. There was a Negro man employed on the boat who was very kind in many ways to help father. Father did not know much about cooking. When we reached New York we landed at the old Castle Garden of lower Manhattan, now the Aquarium, where we were met by relatives and friends. As we were standing in a little group, the Negro who had befriended father on the trip, came off the boat. Father was grateful and as a matter of courtesy, shook hands with him and gave him his blessing. Now it happened that the draft and negro rights were convulsing New York City. Only that very day Negroes had been chased and hanged by mobs. The onlookers, not understanding, grew very much excited over father's shaking hands with this Negro. A crowd gathered round and threatened to hang both father and the Negro to the lamp-post.

Student Activities

The Middle Ages

The Normans

The English Civil War

Industrial Revolution

First World War

Russian Revolution

Nazi Germany

‘This Is For My Son’s Life, My Wife’s Life.’ The Migration Journey to the U.S. Continues Despite Complicated Border Policy

J ose Mirabal first tried to come from Honduras to the U.S. 15 years ago, but didn’t make it. Like many before and since he boarded La Bestia or “The Beast”—an infamously dangerous network of cargo trains that wends north across Mexico . In 2006, Mirabal fell from the train and had to have his foot amputated. He returned to Honduras with a prosthetic.

But 2020 was a hard year. COVID-19 strained businesses and health care systems in Honduras, and in November two hurricanes struck the country, leaving thousands of people homeless. So in 2021, Mirabel decided to try his chances again—once again traveling to Mexico and boarding La Bestia . He’s 40 now, and the journey is harder on his body. He doesn’t dare take off his prosthetic because he doesn’t want to risk it getting stolen, he says, and if he needed to run away quickly, he wouldn’t have time to put it back on.

“Not all of us run with the same luck,” Mirabal says, speaking in Spanish from Coatzacoalcos, a city in Mexican state of Veracruz. He’s traveling with his cousin. “Some of us run with good luck, and others unfortunately run with the bad luck. My cousin and I, thank God, have been moving day and night…and so far nothing bad has happened to us.”

Freelance photographer Yael Martínez documented Mirabal and several other migrants’ journeys from Honduras, through Mexico to the U.S.-Mexico border this year. He photographed them crossing the Mexican state of Veracruz and ending in Reynosa and Matamoros, Mexican cities across the border from McAllen and Brownsville, Texas, respectively.

People, like Mirabel, from Central America and Mexico have been attempting to come to the U.S. for decades, but this year marks an inflection point. U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) conducted more than 1.7 million enforcement actions at the U.S.-Mexico border during Fiscal Year 2021, which ended on Sept. 30, according to CBP data . These enforcement actions include arrests and expulsions under Title 42 , a Trump-era health measure that the Biden Administration has kept in place and has used to immediately remove individuals because of the risks posed by COVID-19 without granting them access to the asylum system.

Title 42 expulsions accounted for more than one million of the 1.7 million enforcement actions during FY2021, meaning most of the migrants who have arrived at the U.S.-Mexico border have been immediately denied entry to the U.S. FY2021 also set the record for most border enforcement encounters by U.S. Border Patrol Agents, according to CBP data . Border Patrol conducted nearly 1.66 million enforcement actions in FY21, surpassing the previous record high of nearly 1.62 million in 1986.

Read More: Biden Is Expelling Migrants On COVID-19 Grounds, But Health Experts Say That’s All Wrong

The U.S. saw an uptick in migration from Central America beginning in the 1980s brought on by regional civil wars (which the U.S. had involvement in), economic instability and displacement, according to the Migration Policy Institute (MPI), a nonpartisan research institution. That migration flow never ended, particularly from the Northern Triangle countries, El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras. From 2007 to 2017, the number of unauthorized migrants from Central America began increasing from previous levels seen in the ’80s, according to the Pew Research Center , while the number of unauthorized migrants from Mexico declined. By Fiscal Year 2014, the number of Central American migrants surpassed those from Mexico for the first time in history.

Still, migration to the U.S.-Mexico border is constantly evolving . In recent years, more Central American migrants have sought out humanitarian protection in the U.S. and are not attempting to evade detection by border enforcement officials, according to MPI.

Read more: More Migrants Die Crossing the Border in South Texas Than Anywhere Else in the U.S. This Documentary Depicts the Human Toll

Then came the Trump Administration’s hardline immigration and border policies such as Zero Tolerance and family separation , metering, the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP) and Title 42, the ramifications of which the Biden Administration is still facing today. The Biden Administration is now in negotiations with the Mexican government to reinstate MPP to comply with a federal court order.

Since 2019, these policies have led to overcrowded shelters in dangerous Mexican border cities and towns, and many thousands of migrants have lived in makeshift tent encampments in Tijuana, Reynosa and Matamoros.

“There are millions of us migrants,” Mirabal says. “Women with children, with their children on foot, children at their breast. The people are coming who are suffering just trying to find a better life.”

In Honduras, the damage to homes and businesses from hurricanes Eta and Iota in November 2020, plus the impacts of COVID-19 have left an estimated 2.8 million people in need of humanitarian assistance, according to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). Even before the hurricanes struck, the number of family units from Honduras who were apprehended at the U.S.-Mexico border rose from 513 to 188,368 between 2012 and 2019, according to analysts at the Brookings Institute , a nonprofit research and policy organization. Brookings analysts also predict that the hurricanes caused an increase in migration from Honduras. In 2021, the number of Honduran family units encountered at the border rose from 1,968 in January, to nearly 25,000 in March, according to an analysis of CBP data .

La Bestia isn’t the only danger migrants encounter in Mexico. Whether migrants are traveling by train or other modes of transport, they are often targeted by members of organized crime groups who extort, kidnap them for ransom or rob them. Sexual assault is frequent. And at any point, migrants could be found by Mexican officials and deported. At the behest of the Trump Administration, the Mexican government began cracking down on migrants at its own Southern border. Though the Mexican government has in the past cooperated with previous administrations to try to stop migrants from crossing its southern border with Guatemala, Trump stepped up the pressure by threatening to impose tariffs and shut down the U.S.-Mexico border.

For those who do make it to the U.S.-Mexico border, the risks do not end there. Migrants have been the victims of a massacre along the border, allegedly by Mexican police. Human Rights First, a nonprofit advocacy and research organization, has tracked more than 6,000 reports of violence against migrants stuck in Mexico during the first few months of the Biden Administration alone.

“I’m not safe in my country nor in Mexico as a refugee,” says Carlos Roberto Tunez, a migrant from Honduras. He and his family fled Honduras in 2019 after they were threatened by gangs. The family first became official refugees in Mexico and were content with starting a new life there, he said. They opened a new business selling Honduran food. But after just a few months, members of an organized crime group began extorting them. When Tunez reported the extortion to Mexican officials, the organized crime group found out, and Tunez and his family found themselves on the run again, this time hoping to seek refuge in the U.S. At the time of his interview, Tunez and his family had been sleeping under a bridge in Reynosa for 10 days.

For Tunez’s wife, Cyndy Cacares, it’s difficult to recount the journey. On May 4, Martínez showed Cacares a portrait he took of her and her son. It immediately brought her to tears. “My dream is to give my son a better life, and try to keep going” she said. “I can’t, I just can’t [talk] anymore.”

“It’s really hard for her to talk about this,” Tunez says. “We’ve suffered a lot on the journey here. It’s hard, and it also makes me want to cry having to recount the story… If myself from years ago saw myself now, he’d see someone very different. I’m here full of fear, full of terror more than anything because this is for my son’s life, my wife’s life.”

Make sense of what matters in Washington. Sign up for the daily D.C. Brief newsletter.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Why Your Breakfast Should Start with a Vegetable

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to PHOTOGRAPHS BY Yael Martínez FOR TIME at [email protected]

Journey to America: What's Your Story?

Posted by Dan Sigward on March 23, 2017

Every family in the United States originated from somewhere else. From Native Americans who migrated across a land bridge to North America to immigrants who sailed aboard a steamship to Ellis Island, many chose to come to America. Hundreds of thousands of others were brought here against their will aboard slave ships.

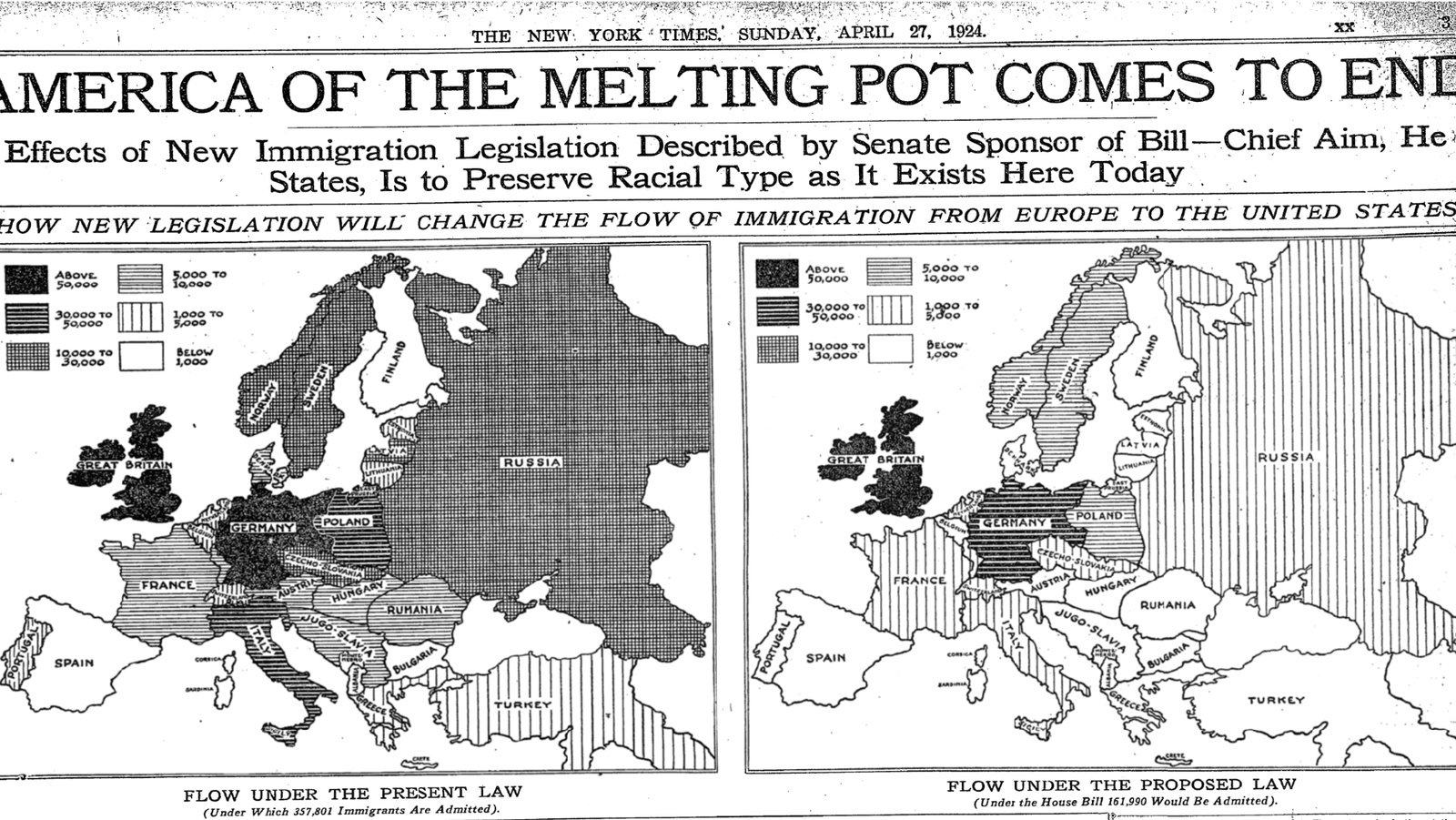

Throughout this history, we have debated who should be allowed to come to live here and who may not. Laws and policies regarding immigration and refugee resettlement are important to debate in any country but just as important is the language and rhetoric we use in these debates. Too often, today’s rhetoric reflects a poor understanding of the history of immigration laws, creating distance between our own families’ narratives and the stories of those coming to America today.

Reflecting on my own family history made me consider an important question: How might better understanding the historical context of our own ancestors’ immigration stories affect how we think about the immigration debate today?

My ancestors emigrated from Alsace-Lorraine (a disputed territory between France and Germany) and Ireland within the second half of the 1800s. The reasons that likely motivated them are not much different than those of newcomers who are at the center of today’s debate. German and Irish Catholics were among the largest immigrant groups in the United States in the latter half of the 19th century. Irish immigrants fled famine, poverty, and lack of employment opportunity. Germans fled similar circumstances in addition to social and political unrest in the aftermath of wars. Today’s immigrants and refugees aren’t nameless, faceless hordes, but human beings seeking safety and prosperity just like my ancestors.

Though I don’t know much about my ancestors’ specific circumstances,, there is one detail I’m certain of: they neither broke nor circumvented any immigration laws by entering the United States, because there were no such laws. It is not that German and Irish immigrants were universally welcomed to the United States; they were subject to plenty of anti-Irish and anti-Catholic sentiments. But there were no laws preventing them or anyone else from coming to the United States at the time.

For me to claim that my 19th century ancestors were “legal” immigrants in contrast to today’s “illegal,” undocumented immigrants implies that my ancestors made a moral or ethical choice to “wait in line, follow the law, and play by the rules.” That claim puts distance between “us” and “them” by attempting to distinguish my “morally superior” ancestors from today’s “law-breaking” undocumented immigrants.

The first significant immigration law was the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, which banned nearly all Chinese immigrants from entering the country. Laws further restricting immigration were enacted in the 1920s in response to the influx of Italians, Eastern Europeans, and Jews in the early 20th century. Soon they began enforcing strict quotas based on national origin, which lasted until 1965. New laws replaced these quotas with preferences based on family relationships, skills, and other factors.

It is impossible for me to know what my ancestors would have chosen to do if faced with restrictions like these designed to keep them out of the United States. Was their desire for safety and opportunity, their longing to live in the United States, so great that they would have sought a way around laws in place to keep them out? Lucky for them, they didn’t have to choose.

This is, perhaps, a question of “ moral luck ,” a topic we explore in the newly revised edition of Holocaust and Human Behavior . Our choices are often constrained by the ways we perceive the options available to us in any particular time, place, and circumstance. Can we praise someone in the past for being virtuously law-abiding when there were no laws conflicting with their goals and no dilemma requiring a moral choice?

My goal is not to minimize the hardships and sacrifices our ancestors endured. To leave behind their home in search of safety, security, and opportunity was no easy endeavor. Whatever policies we decide to implement as a country or society today, we ought to strive to avoid the cruelty that often can result when we think of immigrants as threatening, criminal, or dangerous. Instead, by reflecting on our own stories about how we came to America, we might inject the debate with knowledge, insight, and humility that can help us steer clear of dangerous “us" vs. "them” thinking. This is what I learned from my story. What can you learn from yours? What can your students learn from theirs?

Want to explore the idea of “moral luck” with your students? Check out the reading, “ Moral Luck and Dilemmas of Judgment ,” from our newly revised edition of Holocaust and Human Behavior.

Photo Credit and Caption: The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. "Immigrants seated on long benches, Main Hall, U.S. Immigration Station." New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed March 13, 2017. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-d8d7-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

Topics: Immigration , Holocaust and Human Behavior , current events , We and They

Written by Dan Sigward

Subscribe to Email Updates

Recent posts, posts by topic.

- Choosing to Participate (70)

- Facing Technology (69)

- History (67)

- Democracy (62)

- Black History (58)

- Teaching Resources (57)

- Holocaust (54)

- Facing History and Ourselves (52)

- American History (51)

- Facing History Resources (48)

- Identity (48)

- Antisemitism (45)

- Classrooms (45)

- Teaching (45)

- Media Skills (42)

- Teachers (42)

- current events (37)

- Holocaust and Human Behavior (36)

- Online Learning (36)

- Professional Development (35)

- Holocaust Education (33)

- Civil Rights (32)

- Genocide/Collective Violence (32)

- Safe Schools (32)

- Racism (31)

- Human Rights (30)

- To Kill a Mockingbird (30)

- Civil Rights Movement (28)

- Race and Membership (28)

- Student Voices (28)

- Immigration (27)

- Students (27)

- Reading List (26)

- Teaching Strategies (26)

- Upstanders (25)

- Critical Thinking (24)

- Listenwise (24)

- Reconstruction (23)

- Women's History Month (23)

- Facing History Together (22)

- Memory (22)

- School Culture (22)

- Schools (22)

- Survivor Testimony (22)

- EdTech (20)

- Today's News Tomorrow's History (20)

- International (19)

- Armenian Genocide (18)

- Universe of Obligation (18)

- Asian American and Pacific Islander History (17)

- English Language Arts (17)

- Social Media (17)

- genocide (17)

- Flipped Classroom (16)

- Innovative Classrooms (16)

- Native Americans (16)

- Holocaust and Human Behaviour (15)

- Margot Stern Strom Innovation Grants (15)

- Back-To-School (14)

- New York (14)

- civil discourse (14)

- Contests (13)

- Human Behavior (13)

- Empathy (12)

- Bullying (11)

- Neighborhood to Neighborhood (11)

- Community (10)

- Equity in Education (10)

- Events (10)

- Indigenous (10)

- Journalism (10)

- Stereotype (10)

- Voting Rights (10)

- global terrorism (10)

- Community Conversations (9)

- Refugees (9)

- United Kingdom (9)

- difficult conversations (9)

- Bullying and Ostracism (8)

- In the news (8)

- Online Tools (8)

- Reading (8)

- Religious Tolerance (8)

- Webinars (8)

- Common Core State Standards (7)

- Diversity (7)

- Latinx History (7)

- Memorials (7)

- Refugee Crisis (7)

- South Africa (7)

- Upstander (7)

- Webinar (7)

- Writing (7)

- Facing Ferguson (6)

- Jewish Educational Partisan Foundation (6)

- Judgement and Legacy (6)

- Memphis (6)

- Readings (6)

- Social-Emotional Learning (6)

- The Nanjing Atrocities (6)

- Decision-making (5)

- Harper Lee (5)

- Jewish Education Program (5)

- Literature (5)

- Museum Studies (5)

- Public Radio (5)

- Raising Ethical Children (5)

- Sounds of Change (5)

- StoryCorps (5)

- reflection (5)

- Assessment (4)

- Bryan Stevenson (4)

- Common Core (4)

- Cyberbullying (4)

- Learning (4)

- Lesson Plans (4)

- Social Justice (4)

- Social and Emotional Learning (4)

- Teaching Strategy (4)

- We and They (4)

- international holocaust remembrance day (4)

- Beacon Academy (3)

- Benjamin B. Ferencz (3)

- Cleveland (3)

- Eugenics/Race Science (3)

- Experiential education (3)

- IWitness (3)

- Indigenous History (3)

- Japanese American Incarceration (3)

- Photography (3)

- Restorative Justice (3)

- Roger Brooks (3)

- Salvaged Pages (3)

- The BULLY Project (3)

- The Great Listen (3)

- Twitter (3)

- media literacy (3)

- news literacy (3)

- student activism (3)

- transgender (3)

- white supremacy (3)

- workshop (3)

- Black History Month (2)

- Brussels (2)

- Bystander (2)

- Chicago (2)

- Civil War (2)

- David Isay (2)

- Day of Learning (2)

- Digital Divide (2)

- Essay Contest (2)

- Facing History Library (2)

- Giving Tuesday (2)

- Go Set a Watchman (2)

- International Justice (2)

- Lesson Plan (2)

- Los Angeles (2)

- Lynsey Addario (2)

- Margaret Stohl (2)

- New York Times (2)

- Northern Ireland (2)

- Online Workshop (2)

- Parents (2)

- Partisans (2)

- San Francisco Bay Area (2)

- September 11 (2)

- Shikaya (2)

- Slavery (2)

- Sonia Nazario (2)

- Spoken Word (2)

- The Allstate Foundation (2)

- Toronto (2)

- Weimar Republic (2)

- Zaption (2)

- civic education (2)

- climate change (2)

- environmental justice (2)

- islamophobia (2)

- primary sources (2)

- resistance (2)

- Auschwitz (1)

- Black Teachers (1)

- Brave Space (1)

- Cambodia (1)

- Canadian History (1)

- Caregivers (1)

- Colombia (1)

- Deborah Prothrow-Stith (1)

- Desegregation (1)

- Don Cheadle (1)

- Douglas Blackmon (1)

- Explorations (1)

- Farewell to Manzanar (1)

- Haitian Revolution (1)

- Hurricane Katrina (1)

- Indigenous Peoples' Day (1)

- Insider (1)

- International Women's Day (1)

- Isabel Wilkerson (1)

- Latin America (1)

- Lesson Ideas (1)

- Literacy Design Collaborative (1)

- Marc Skvirsky (1)

- Margot Stern Strom (1)

- Memorial (1)

- Mental Health Awareness (1)

- Race and Membership in American History: Eugenics (1)

- Reach Higher Initiative (1)

- Rebuke to Bigotry (1)

- Red Scarf Girl (1)

- Religion (1)

- Residential Schools (1)

- Socratic Seminar (1)

- Summer Seminar (1)

- Truth and Reconciliation (1)

- Urban Education (1)

- Using Technology (1)

- Vichy Regime (1)

- Wes Moore (1)

- Whole School Work (1)

- anti-Muslim (1)

- archives (1)

- coming-of-age literature (1)

- cross curricular teaching and learning (1)

- differentiated instruction (1)

- facing history pedagogy (1)

- literacy (1)

- little rock 9 (1)

- new website (1)

- xenophobia (1)

Pilgrims’ Progress

We retrace the travels of the ragtag group that founded Plymouth Colony and gave us Thanksgiving

Simon Worrall

On an autumn night in 1607, a furtive group of men, women and children set off in a relay of small boats from the English village of Scrooby, in pursuit of the immigrant's oldest dream, a fresh start in another country. These refugees, who would number no more than 50 or 60, we know today as Pilgrims. In their day, they were called Separatists. Whatever the label, they must have felt a mixture of fear and hope as they approached the dimly lit creek, near the Lincolnshire port of Boston, where they would steal aboard a ship, turn their backs on a tumultuous period of the Reformation in England and head across the North Sea to the Netherlands.

There, at least, they would have a chance to build new lives, to worship as they chose and to avoid the fate of fellow Separatists like John Penry, Henry Barrow and John Greenwood, who had been hanged for their religious beliefs in 1593. Like the band of travelers fleeing that night, religious nonconformists were seen as a threat to the Church of England and its supreme ruler, King James I. James' cousin, Queen Elizabeth I (1533-1603), had made concerted efforts to reform the church after Henry VIII's break with the Roman Catholic faith in the 1530s. But as the 17th century got under way at the end of her long reign, many still believed that the new church had done too little to distinguish itself from the old one in Rome.

In the view of these reformers, the Church of England needed to simplify its rituals, which still closely resembled Catholic practices, reduce the influence of the clerical hierarchy and bring the church's doctrines into closer alignment with New Testament principles. There was also a problem, some of them felt, with having the king as the head of both church and state, an unhealthy concentration of temporal and ecclesiastical power.

These Church of England reformers came to be known as Puritans, for their insistence on further purification of established doctrine and ceremony. More radical were the Separatists, those who split off from the mother church to form independent congregations, from whose ranks would come the Baptists, Presbyterians, Congregationalists and other Protestant denominations. The first wave of Separatist pioneers—that little band of believers sneaking away from England in 1607—would eventually be known as Pilgrims. The label, which came into use in the late 18th century, appears in William Bradford's Of Plymouth Plantation .

They were led by a group of radical pastors who, challenging the authority of the Church of England, established a network of secret religious congregations in the countryside around Scrooby. Two of their members, William Brewster and William Bradford, would go on to exert a profound influence on American history as leaders of the colony at Plymouth, Massachusetts, the first permanent European settlement in New England and the first to embrace rule by majority vote.

For the moment, though, they were fugitives, inner exiles in a country that did not want their brand of Protestantism. If caught, they faced harassment, heavy fines and imprisonment.

Beyond a few tantalizing details about the leaders Brewster and Bradford, we know very little about these English men and women who formed the vanguard of the Pilgrim's arrival in the New World—not even what they looked like. Only one, Edward Winslow, who became the third governor of Plymouth Colony in 1633, ever sat for his portrait, in 1651. We do know that they did not dress in black and white and wear stovepipe hats as the Puritans did. They dressed in earth tones—the green, brown and russet corduroy typical of the English countryside. And, while they were certainly religious, they could also be spiteful, vindictive and petty—as well as honest, upright and courageous, all part of the DNA they would bequeath to their adopted homeland.

To find out more about these pioneering Englishmen, I set off from my home in Herefordshire and headed north to Scrooby, now a nondescript hamlet set in a bucolic landscape of red brick farmhouses and gently sloping fields. The roadsides were choked with daffodils. Tractors chugged through rich fields with their wagons full of seed potatoes. Unlike later waves of immigrants to the United States, the Pilgrims came from a prosperous country, not as refugees escaping rural poverty.

The English do not make much of their Pilgrim heritage. "It's not our story," a former museum curator, Malcolm Dolby, told me. "These aren't our heroes." Nonetheless, Scrooby has made at least one concession to its departed predecessors: the Pilgrim Fathers pub, a low, whitewashed building, right by the main road. The bar used to be called the Saracen's Head but got a face-lift and a change of name in 1969 to accommodate American tourists searching their roots. A few yards from the pub, I found St. Wilfrid's church, where William Brewster, who would become the spiritual leader of Plymouth Colony, once worshiped. The church's current vicar, the Rev. Richard Spray, showed me around. Like many medieval country churches, St. Wilfrid's had a makeover in the Victorian era, but the structure of the building Brewster knew remained largely intact. "The church is famous for what's not in it," Spray said. "Namely, the Brewsters and the other Pilgrims. But it's interesting to think that the Thanksgiving meal they had when they got to America apparently resembled a Nottinghamshire Harvest Supper—minus the turkey!"

A few hundred yards from St. Wilfrid's, I found the remains of Scrooby Manor, where William Brewster was born in 1566 or 1567. This esteemed Pilgrim father gets little recognition in his homeland—all that greets a visitor is a rusting "No Trespassing" sign and a jumble of half-derelict barns, quite the contrast to his presence in Washington, D.C. There, in the Capitol, Brewster is commemorated with a fresco that shows him—or, rather, an artist's impression of him—seated, with shoulder-length hair and a voluminous beard, his eyes raised piously toward two chubby cherubs sporting above his head.

Today, this rural part of eastern England in the county of Nottinghamshire is a world away from the commerce and bustle of London. But in William Brewster's day, it was rich in agriculture and maintained maritime links to northern Europe. Through the region ran the Great North Road from London to Scotland. The Brewster family was well respected here until William Brewster became embroiled in the biggest political controversy of their day, when Queen Elizabeth decided to have her cousin, Mary, Queen of Scots, executed in 1587. Mary, a Catholic whose first husband had been the King of France, was implicated in conspiracies against Elizabeth's continued Protestant rule.

Brewster's mentor, the secretary of state, became a scapegoat in the aftermath of Mary's beheading. Brewster himself survived the crisis, but he was driven from the glittering court in London, his dreams of worldly success dashed. His disillusionment with the politics of court and church may have led him in a radical direction—he fatefully joined the congregation of All Saints Church in Babworth, a few miles down the road from Scrooby.

There the small band of worshipers likely heard the minister, Richard Clyfton, extolling St. Paul's advice, from Second Corinthians, 6:17, to cast off the wicked ways of the world: "Therefore come out from them, and be separate from them, says the Lord, and touch nothing unclean." (This bit of scripture probably gave the Separatists their name.) Separatists wanted a better way, a more direct religious experience, with no intermediaries between them and God as revealed in the Bible. They disdained bishops and archbishops for their worldliness and corruption and wanted to replace them with a democratic structure led by lay and clerical elders and teachers of their own choosing. They opposed any vestige of Catholic ritual, from the sign of the cross to priests decked out in vestments. They even regarded the exchanging of wedding rings as a profane practice.

A young orphan, William Bradford, was also drawn into the Separatist orbit during the country's religious turmoil. Bradford, who in later life would become the second governor of Plymouth Colony, met William Brewster around 1602-3, when Brewster was about 37 and Bradford 12 or 13. The older man became the orphan's mentor, tutoring him in Latin, Greek and religion. Together they would travel the seven miles from Scrooby to Babworth to hear Richard Clyfton preach his seditious ideas—how everyone, not just priests, had a right to discuss and interpret the Bible; how parishioners should take an active part in services; how anyone could depart from the official Book of Common Prayer and speak directly to God.

In calmer times, these assaults on convention might have passed with little notice. But these were edgy days in England. James I (James VI as King of Scotland) had ascended to the throne in 1603. Two years later, decades of Catholic maneuvering and subversion had culminated in the Gunpowder Plot, when mercenary Guy Fawkes and a group of Catholic conspirators came very close to blowing up Parliament and with them the Protestant king.

Against this turmoil, the Separatists were eyed with suspicion and more. Anything smacking of subversion, whether Catholic or Protestant, provoked the ire of the state. "No bishop, no king!" thundered the newly crowned king, making it clear that any challenge to church hierarchy was also a challenge to the Crown and, by implication, the entire social order. "I shall make them conform," James proclaimed against the dissidents, "or I will hurry them out of the land or do worse."

He meant it. In 1604, the Church introduced 141 canons that enforced a sort of spiritual test aimed at flushing out nonconformists. Among other things, the canons declared that anyone rejecting the practices of the established church excommunicated themselves and that all clergymen had to accept and publicly acknowledge the royal supremacy and the authority of the Prayer Book. It also reaffirmed the use of church vestments and the sign of the cross in baptism. Ninety clergymen who refused to embrace the new canons were expelled from the Church of England. Among them was Richard Clyfton, of All Saints at Babworth.

Brewster and his fellow Separatists now knew how dangerous it had become to worship in public; from then on, they would hold only secret services in private houses, such as Brewster's residence, Scrooby Manor. His connections helped to prevent his immediate arrest. Brewster and other future Pilgrims would also meet quietly with a second congregation of Separatists on Sundays in Old Hall, a timbered black-and-white structure in Gainsborough. Here under hand-hewn rafters, they would listen to a Separatist preacher, John Smyth, who, like Richard Clyfton before him, argued that congregations should be allowed to pick and ordain their own clergy and worship should not be confined only to prescribed forms sanctioned by the Church of England.

"It was a very closed culture," says Sue Allan, author of Mayflower Maid , a novel about a local girl who follows the Pilgrims to America. Allan leads me upstairs to the tower roof, where the entire town lay spread at our feet. "Everyone had to go to the Church of England," she said. "It was noted if you didn't. So what they were doing here was completely illegal. They were holding their own services. They were discussing the Bible, a big no-no. But they had the courage to stand up and be counted."

By 1607, however, it had become clear that these clandestine congregations would have to leave the country if they wanted to survive. The Separatists began planning an escape to the Netherlands, a country that Brewster had known from his younger, more carefree days. For his beliefs, William Brewster was summoned to appear before his local ecclesiastical court at the end of that year for being "disobedient in matters of Religion." He was fined £20, the equivalent of $5,000 today. Brewster did not appear in court or pay the fine.

But immigrating to Amsterdam was not so easy: under a statute passed in the reign of Richard II, no one could leave England without a license, something Brewster, Bradford and many other Separatists knew they would never be granted. So they tried to slip out of the country unnoticed.

They had arranged for a ship to meet them at Scotia Creek, where its muddy brown waters spool toward the North Sea, but the captain betrayed them to the authorities, who clapped them in irons. They were taken back to Boston in small open boats. On the way, the local catchpole officers, as the police were known, "rifled and ransacked them, searching to their shirts for money, yea even the women further than became modesty," William Bradford recalled. According to Bradford, they were bundled into the town center where they were made into "a spectacle and wonder to the multitude which came flocking on all sides to behold them." By this time, they had been relieved of almost all their possessions: books, clothes and money.

After their arrest, the would-be escapees were brought before magistrates. Legend has it that they were held in the cells at Boston's Guildhall, a 14th-century building near the harbor. The cells are still here: claustrophobic, cage-like structures with heavy iron bars. American tourists, I am told, like to sit inside them and imagine their forebears imprisoned as martyrs. But historian Malcolm Dolby doubts the story. "The three cells in the Guildhall were too small—only six feet long and five feet wide. So you are not talking about anything other than one-person cells. If they were held under any sort of arrest, it must have been house arrest against a bond, or something of that nature," he explains. "There's a wonderful illustration of the constables of Boston pushing these people into the cells! But I don't think it happened."

Bradford, however, described that after "a month's imprisonment," most of the congregation were released on bail and allowed to return to their homes. Some families had nowhere to go. In anticipation of their flight to the Netherlands, they had given up their houses and sold their worldly goods and were now dependent on friends or neighbors for charity. Some rejoined village life.

If Brewster continued his rebellious ways, he faced prison, and possibly torture, as did his fellow Separatists. So in the spring of 1608, they organized a second attempt to flee the country, this time from Killingholme Creek, about 60 miles up the Lincolnshire coast from the site of the first, failed escape bid. The women and children traveled separately by boat from Scrooby down the River Trent to the upper estuary of the River Humber. Brewster and the rest of the male members of the congregation traveled overland.

They were to rendezvous at Killingholme Creek, where a Dutch ship, contracted out of Hull, would be waiting. Things went wrong again. Women and children arrived a day early. The sea had been rough, and when some of them got seasick, they took shelter in a nearby creek. As the tide went out, their boats were seized by the mud. By the time the Dutch ship arrived the next morning, the women and children were stranded high and dry, while the men, who had arrived on foot, walked anxiously up and down the shore waiting for them. The Dutch captain sent one of his boats ashore to collect some of the men, who made it safely back to the main vessel. The boat was dispatched to pick up another load of passengers when, William Bradford recalled, "a great company, both horse and foot, with bills and guns and other weapons," appeared on the shore, intent on arresting the would-be departees. In the confusion that followed, the Dutch captain weighed anchor and set sail with the first batch of Separatists. The trip from England to Amsterdam normally took a couple of days—but more bad luck was in store. The ship, caught in a hurricane-force storm, was blown almost to Norway. After 14 days, the emigrants finally landed in the Netherlands. Back at Killingholme Creek, most of the men who had been left behind had managed to escape. The women and children were arrested for questioning, but no constable wanted to throw them in prison. They had committed no crime beyond wanting to be with their husbands and fathers. Most had already given up their homes. The authorities, fearing a backlash of public opinion, quietly let the families go. Brewster and John Robinson, another leading member of the congregation, who would later become their minister, stayed behind to make sure the families were cared for until they could be reunited in Amsterdam.

Over the next few months, Brewster, Robinson and others escaped across the North Sea in small groups to avoid attracting notice. Settling in Amsterdam, they were befriended by another group of English Separatists called the Ancient Brethren. This 300-member Protestant congregation was led by Francis Johnson, a firebrand minister who had been a contemporary of Brewster's at Cambridge. He and other members of the Ancient Brethren had done time in London's torture cells.

Although Brewster and his congregation of some 100 began to worship with the Ancient Brethren, the pious newcomers were soon embroiled in theological disputes and left, Bradford said, before "flames of contention" engulfed them. After less than a year in Amsterdam, Brewster's discouraged flock picked up and moved again, this time to settle in the city of Leiden, near the magnificent church known as Pieterskerk (St. Peter's). This was during Holland's golden age, a period when painters like Rembrandt and Vermeer would celebrate the physical world in all its sensual beauty. Brewster, meanwhile, had by Bradford's account "suffered much hardship....But yet he ever bore his condition with much cheerfulness and contentation." Brewster's family settled in Stincksteeg, or Stink Alley, a narrow, back alley where slops were taken out. The congregation took whatever jobs they could find, according to William Bradford's later recollection of the period. He worked as a maker of fustian (corduroy). Brewster's 16-year-old son, Jonathan, became a ribbon maker. Others labored as brewer's assistants, tobacco-pipe makers, wool carders, watchmakers or cobblers. Brewster taught English. In Leiden, good-paying jobs were scarce, the language was difficult and the standard of living was low for the English immigrants. Housing was poor, infant mortality high.

After two years the group had pooled together money to buy a house spacious enough to accommodate their meetings and Robinson's family. Known as the Green Close, the house lay in the shadow of Pieterskerk. On a large lot behind the house, a dozen or so Separatist families occupied one-room cottages. On Sundays, the congregation gathered in a meeting room and worshiped together for two four-hour services, the men sitting on one side of the church, the women on the other. Attendance was compulsory, as were services in the Church of England.

Not far from the Pieterskerk, I find William Brewstersteeg, or William Brewster Alley, where the rebel reformer oversaw a printing company later generations would call the Pilgrim Press. Its main reason for being was to generate income, largely by printing religious treatises, but the Pilgrim Press also printed subversive pamphlets setting out Separatist beliefs. These were carried to England in the false bottoms of french wine barrels or, as the English ambassador to the Netherlands reported, "vented underhand in His Majesty's kingdoms." Assisting with the printing was Edward Winslow, described by a contemporary as a genius who went on to play a crucial role in Plymouth Colony. He was already an experienced printer in England when, at age 22, he joined Brewster to churn out inflammatory materials.

The Pilgrim Press attracted the wrath of authorities in 1618, when an unauthorized pamphlet called the Perth Assembly surfaced in England, attacking King James I and his bishops for interfering with the Presbyterian Church of Scotland. The monarch ordered his ambassador in Holland to bring Brewster to justice for his "atrocious and seditious libel," but Dutch authorities refused to arrest him. For the Separatists, it was time to move again—not only to avoid arrest. They were also worried about war brewing between Holland and Spain, which might bring them under Catholic rule if Spain prevailed. And they recoiled at permissive values in the Netherlands, which, Bradford would later recall, encouraged a "great licentiousness of youth in that country." The "manifold temptations of the place," he feared, were drawing youths of the congregation "into extravagant and dangerous courses, getting the reins off their necks and departing from their parents."

About this time, 1619, Brewster disappears briefly from the historical record. He was about 53. Some accounts suggest that he may have returned to England, of all places, there to live underground and to organize his last grand escape, on a ship called the Mayflower . There is speculation that he lived under an assumed name in the London district of Aldgate, by then a center for religious nonconformists. When the Mayflower finally set sail for the New World in 1620, Brewster was aboard, having escaped the notice of authorities.

But like their attempts to flee England in 1607 and 1608, the Leiden congregation's departure for America 12 years later was fraught with difficulties. In fact, it almost didn't happen. In July, the Pilgrims left Leiden, sailing from Holland in the Speedwell , a stubby overrigged vessel. They landed quietly in Southampton on the south coast of England. There they gathered supplies and proceeded to Plymouth before sailing for America in the 60-ton Speedwell and the 180-ton Mayflower , a converted wine-trade ship, chosen for its steadiness and cargo capacity. But after "they had not gone far," according to Bradford, the smaller Speedwell , though recently refitted for the long ocean voyage, sprang several leaks and limped into port at Dartmouth, England, accompanied by the Mayflower . More repairs were made, and both set out again toward the end of August. Three hundred miles at sea, the Speedwell began leaking again. Both ships put into Plymouth—where some 20 of the 120 would-be Colonists, discouraged by this star-crossed prologue to their adventure, returned to Leiden or decided to go to London. A handful transferred to the Mayflower , which finally hoisted sail for America with about half of its 102 passengers from the Leiden church on September 6.

On their arduous, two-month voyage, the 90-foot ship was battered by storms. One man, swept overboard, held onto a halyard until he was rescued. Another succumbed to "a grievous disease, of which he died in a desperate manner," according to William Bradford. Finally, though, on November 9, 1620, the Mayflower sighted the scrubby heights of what is known today as Cape Cod. After traveling along the coast that their maps identified as New England for two days, they dropped anchor at the site of today's Provincetown Harbor of Massachusetts. Anchored offshore there on November 11, a group of 41 passengers—only the men—signed a document they called the Mayflower Compact, which formed a colony composed of a "Civil Body Politic" with just and equal laws for the good of the community. This agreement of consent between citizens and leaders became the basis for Plymouth Colony's government. John Quincy Adams viewed the agreement as the genesis of democracy in America.

Among the passengers who would step ashore to found the colony at Plymouth were some of America's first heroes—such as the trio immortalized by Longfellow in "The Courtship of Miles Standish": John Alden, Priscilla Mullins and Standish, a 36-year-old soldier—as well as the colony's first European villain, John Billington, who was hanged for murder in New England in 1630. Two happy dogs, a mastiff bitch and a spaniel belonging to John Goodman, also bounded ashore.

It was the beginning of another uncertain chapter of the Pilgrim story. With winter upon them, they had to build homes and find sources of food, while negotiating the shifting political alliances of Native American neighbors. With them, the Pilgrims celebrated a harvest festival in 1621—what we often call the first Thanksgiving.

Perhaps the Pilgrims survived the long journey from England to Holland to America because of their doggedness and their conviction that they had been chosen by God. By the time William Brewster died in 1644, at age 77, at his 111-acre farm at the Nook, in Duxbury, the Bible-driven society he had helped create at Plymouth Colony could be tough on members of the community who misbehaved. The whip was used to discourage premarital sex and adultery. Other sexual offenses could be punished by hanging or banishment. But these early Americans brought with them many good qualities too—honesty, integrity, industry, rectitude, loyalty, generosity, flinty self-reliance and a distrust of flashiness—attributes that survive down through the generations.

Many of the Mayflower descendants would be forgotten by history, but more than a few would rise to prominence in American culture and politics—among them Ulysses S. Grant, James A. Garfield, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Orson Welles, Marilyn Monroe, Hugh Hefner and George W. Bush.

Simon Worrall , who lives in Herefordshire, England, wrote about cricket in the October issue of Smithsonian .

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

Click to visit our Privacy Statement .

Mayflower400 partner destinations:

- Stories of the Mayflower

- Who were the Pilgrims?

The day the historic journey to America began

It is one of the most well known dates in history - on 16 September 1620, a group of men, women and children departed Plymouth aboard the Mayflower for a new life in America.

But for many of its influential passengers the historic voyage actually began several weeks before - on July 22, 1620, from a port in Holland.

In a moving ceremony on that day, many of the Pilgrims boarded a ship known as the Speedwell in Delfshaven harbour, meeting up with the Mayflower in Southampton. Had the Speedwell been seaworthy, both ships would have attempted the Atlantic crossing and the Pilgrims would probably never have set foot in Plymouth.

This part of the Mayflower story begins roughly previous 12 years before that date, in an eventful and often daring journey before they even left English shores.

Escaping England

A large number of the people who boarded the Mayflower were known as Separatists from towns and villages in an area of Nottinghamshire, Yorkshire and Lincolnshire in England.

They had broken away from Henry VIII’s new Church of England, becoming known as Separatists - but they faced prosecution for not following the King's church.

A Separatist congregation in Gainsborough , led by preacher John Smyth, decided to leave England for Holland in pursuit of religious freedom. They first attempted to escape the country in 1607 from Boston in Lincolnshire but the captain of the ship they had charted to smuggle them out of the country betrayed them and they were arrested.

Some of them were tried and held at Boston Guildhall for a month but they attempted the escape again the following year - this time successfully.

They fled from the port of Immingham in England, sailing to Holland where they settled in the city of Leiden.

- Learn more about visiting Nottinghamshire , Yorkshire , Gainsborough , Immingham , and Boston, UK

Settling in Holland

The Pieterskerk in Leiden

Leiden , known for being a liberal city of free thinkers, was home to the Separatists for 12 years.

They set about creating new lives for themselves, bought land near the Pieterskerk church and built houses that became known as the Engelse poort - which means English Alley.

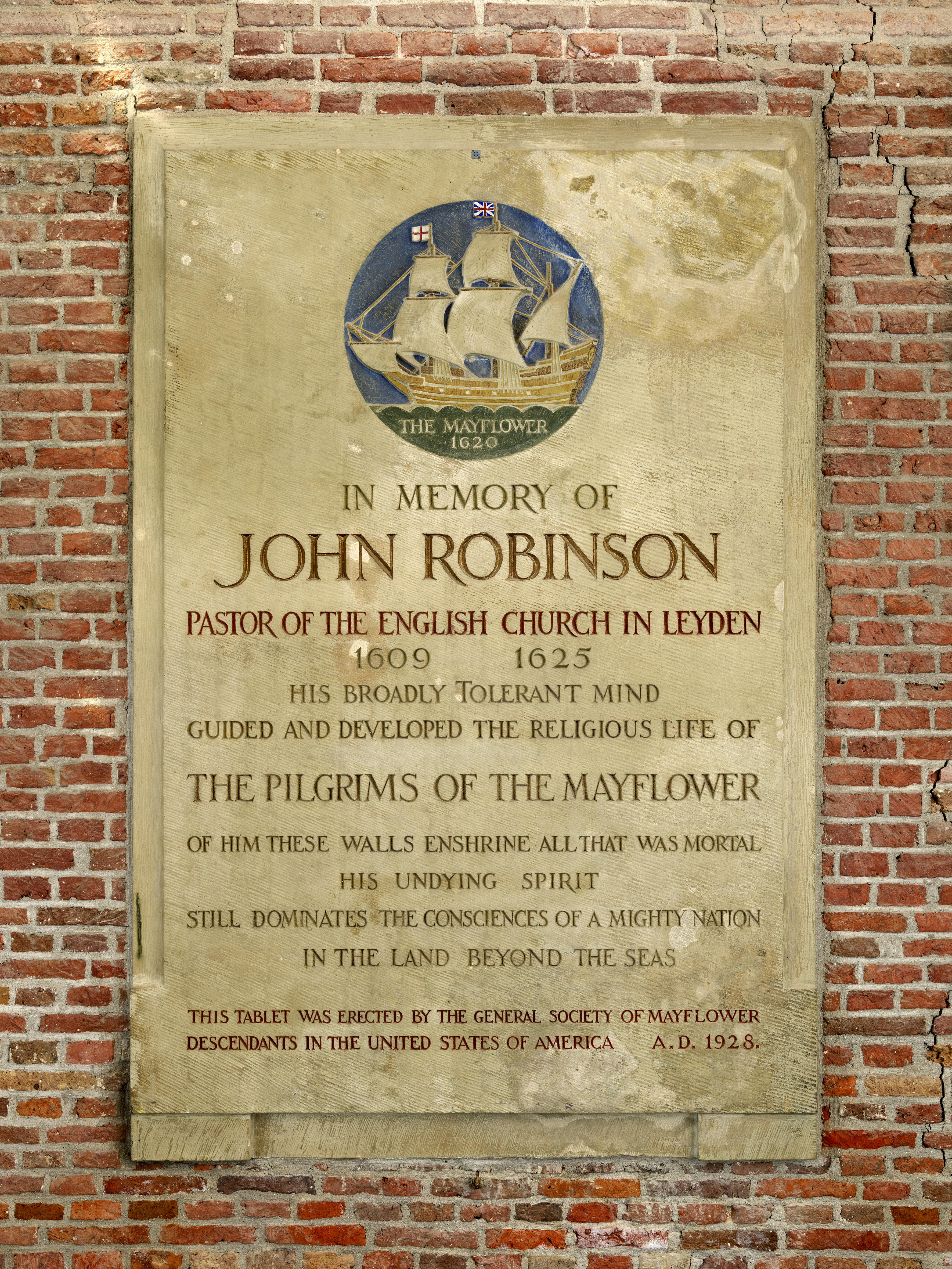

John Robinson , one of the founders of the Separatist movement in England, became ‘pastor to the Pilgrims’ during his time in Leiden. He was one of the leaders in planning the journey to America on the Mayflower.

He was to accompany a second wave of Pilgrims to America, but he never made it to the New World, dying before the journey. He was buried at St Pieterskirk Church in Leiden where a plaque is situated.

The plaque at the church

Also remembered in Leiden is one of John Robinson’s assistants and elders, William Brewster, who had come from England during the 1608 escape. He had lived and worked in an area of Leiden near Pieterskirk before he became one of the Pilgrim leaders.

He was a passenger on the Mayflower and settled in Plymouth, Massachusetts. The people of Leiden commemorated him by naming the street where he lived after him - William Brewstersteeg (Alley). Brewster’s house has nearly disappeared through development but the blank end wall can still be identified by the contrast of its bricks with those added later.

William Brewster Alley

During the 12 years they were in Leiden, the Separatists found life hard. They earned little money and were not used to the urban location - having come from rural English villages. Parents started worrying that their children were being heavily influenced by the Dutch and would eventually forget their English roots.

They were also worried a war between Holland and Spain was imminent and that this would mean danger for the freedom they had fled for.

- Learn more about visiting Leiden

Getting aboard

They decided to move on again, so were in touch with their Separatist counterparts back in England to forge a plan to all travel together to Virginia, America and start a new community there, where they could live and worship as they wanted. To help fund the expensive trip, they made an agreement with the Virginia Company in London - created to establish colonies on the coast of North America which needed people to settle in them and send back goods for trade.

It was another Separatist John Carver who had a key role in planning the journey. He and fellow Pilgrim Robert Cushman were successful in negotiating with the Virginia Company for land in America where they could legally land and settle. William Brewster also knew a prominent member of the company to negotiate with too.

John Carver also won the key financial backing that was to pay for the trans-Atlantic voyage. He approached businessman Thomas Weston in London and the Merchant Adventurers in 1620 and convinced them that if they funded the journey, they would see a return on their investment. Thomas Weston agreed and hired the Mayflower which sailed from London to Southampton to meet the Speedwell, the ship which brought the Pilgrims from Leiden.

Setting sail on July 22

The Pilgrim Fathers Church

The Separatists in Holland had sold their personal belongings to buy the Speedwell. After one last joint meal and service in the house of Rev John Robinson, 16 men, 11 women and 19 children made the journey from Leiden to Delfshaven near Rotterdam to set sail to Southampton on July 22, 1620.

They travelled on foot, on horseback and by carriage carrying their possessions, ready to board the Speedwell ship, meet the Mayflower, and sail onto a new life in America.

The night before the Pilgrims departed was spent praying in front of the church, now known as the Pilgrim Fathers Church. Today there is a stained glass window depicting the historic moment the Pilgrims set off, and a bronze plaque of the Boston Congregational Club from 1906 praising the hospitality offered by the church to the pioneers.

The following morning residents of Delfshaven and friends of the Pilgrims gathered to see them leave. John Robinson led prayers and after an emotional goodbye, the Speedwell set a course along the River Maas out to the North Sea and en route to Southampton. A few days later the Speedwell arrived in Southampton and met up with the Mayflower which had sailed from Rotherhithe in London carrying the other Separatists from England. The plan was to stock up in Southampton and sail to America together. The town was a thriving seaport so as well as offering all the commercial facilities needed to equip the long sea voyage, it also had established trading links with Virginia and Newfoundland. Living there was a group of seamen who had experience of the Atlantic crossing which proved helpful. The Speedwell had been leaking during her journey from Holland, so was repaired in Southampton’s extensive ship building and repair facilities near West Quay. Southampton proved the right choice, not least for its offering of all the supplies required for the journey and to establish a permanent community in America. The Speedwell and Mayflower were anchored just off West Quay, and the Pilgrims spent all day shopping for supplies, before sleeping on the ships at night. And they were certainly in the right place - of the 153 merchants in the town in 1620, 118 were involved in the wool trade, but the remainder would have been able to help the Pilgrims with all the other items they would have needed to become self-sufficient. A Hampshire man called Stephen Hopkins joined the Mayflower in Southampton, and is known as the only passenger to have had any experience of the New World, having been shipwrecked in Bermuda in 1609.

Leaving English shores

After a hectic few days of repairs and preparations, both the Mayflower and Speedwell left Southampton on August 15, 1620. But the Speedwell took on water again - thought to be either because she carried too much sail, straining her timbers, or the result of sabotage by the reluctant crew. Both ships were diverted to Dartmouth, and over the course of a week the Speedwell was repaired. They set sail out into the English Channel towards the North Atlantic, but 300 miles off Land’s End the Speedwell leaked again and it’s decided they cannot risk continuing. They turned around and headed for Plymouth, having already spent up to six weeks at sea since originally departing London and Leiden. The Speedwell was finally declared unfit to sail, and after some Pilgrims dropped out and stayed in Plymouth, the remainder boarded the Mayflower for the voyage. On September 16, 1620, the Mayflower with 102 passengers and up to 30 crew onboard, left the Mayflower Steps on Plymouth’s Barbican. This was the last time the Pilgrims were on English soil before heading to the New World and a new life.

Sign up for the latest Mayflower 400 news

You'll be the first to hear the latest Mayflower news, events, and more.

Forgotten Password?

Mayflower 400 Proudly Supported by our National Sponsors and Funding Partners

- Website Privacy Policy

- Make a Pledge

The Great Arrival and the Dawn of Italian America

Poverty, natural disasters & war drove millions from italy. the great arrival transformed the nation's cultural landscape and led to the creation of italian america..

By: Tony Traficante , ISDA Contributing Editor

The Journey

They scrimped and saved to buy a ticket to America and today they gathered in the village piazza about to leave everything familiar—family, friends, and loved ones. There was a group of families, single men, husbands, fathers, and sons. Amid weeping and hugs, promises were made to send money home, and return soon, or send for them. Many, however, would never return, and some would never see families or friends again.

But, in spite of the anguish of departure, they were upbeat, hoping to find fortune, and a better way of life.

The Italians were leaving out of necessity and desperation. Four million Italians, many from the “ Mezzogiorno,” the southern areas of Italy, emigrated to the United States between 1890 and 1920. The southern regions of Italy suffered more significant hardships than the north, where there were better advantages of industry, education and quality of life.

Other factors contributed to the migration of the southern Italians, among them poverty, unemployment, a scarcity of farming land, high taxes, and natural disasters. During years of disastrous volcanic eruptions at Mount Vesuvius and Mount Etna, surrounding towns sustained enormous casualties. A violent earthquake, in 1908, rocked the southern part of Italy, creating a tsunami with such crushing force it decimated more than 100,000 Italians, and laid bare vast areas of Messina and Reggio di Calabria.

The Italians traveled from small southern communes and hamlets, going by whatever means available—train, bus, horse and cart, and even via “L’asino.” Arriving at a departing port, most likely Naples, the immigrants underwent humiliating fumigation of body, clothes, and goods, a document verification, then a cursory medical exam.

Herded aboard ships, they were directed to third class, crowded “steerage” compartments located at the very bottom of the boat. The steerage “halls” were lined with rows of metal bunks stacked two high. They were primitive, unsanitary, and claustrophobic. Privacy was non-existent, and amenities were basic.

Bedding consisted of straw mattresses covered with a piece of canvas sheeting. A life preserver was their pillow. They were given a lightweight blanket, and a set of metal eating utensils consisting of a fork, spoon, and tin lunch pail.

Third class meals were meager and far from gourmet. There were no dining tables or chairs; the Italians made do by sitting on bunks, floors, or when permitted “al fresco” on deck. Traveling steerage class was a most unpleasant experience surrounded by unbearable conditions. There was sickness, cramped quarters, putrid stenches of vomit, urine, and whatever else, with little ventilation.

This article first appeared in La Nostra Voce, ISDA’s 28-page monthly newspaper, which chronicles Italian-American life, culture and traditions. Subscribe today!

But, even among the discomfort and sickness, the resilient Italians made the best of the situation finding time for enjoyment and a bit of diversion. On occasion, they celebrated a marriage or birth. Then, there was always someone with a concertina to complement the immigrants’ songfest and dancing. The ladies passed time crocheting, while men played a bit of “ briscola, tre sette or morro.”

The journey to America was a long and harsh one. After days at sea, most immigrants landed at the infamous Ellis Island. As they walked into the cavernous dark halls, fearful and anxious, they were “ greeted” by immigration officials shouting orders. The Italians, not understanding what they were saying, complained, “che diavolo hanno detto.”

Their long, long day was about to begin. The primary concern was getting through the medical inspections. Chalk marks on the clothes of an immigrant identified his or her medical condition: H for heart problems, E for eye problems, L for lameness, and so forth . U.S. laws also required an intelligence exam to identify the “idiots, imbeciles, morons, or other mentally deficient persons.” Those with minor illnesses are held in quarantine for a day or two; others with severe medical conditions were put aside, and likely deported.

For the anguish of it all, Italians dubbed Ellis Island, “L’Isola Delle Lagrime”— the island of tears!

Having made landfall, those without sponsorship of family, or friends faced new concerns, like finding a place to live and work. They had no choice but to engage the services of a “Padrone ” for assistance. The Padrones were usually former immigrants themselves and were trustworthy and helpful; others were there to take advantage of the immigrants.

The Italians tended to settle and live together, forming communities often called “Little Italy.” They organized fraternal societies providing them benefits, stability, social interaction, and a basic indoctrination into the American way of life.

Many Italian immigrants decided to stay and sent for family member; as many went back to Italy. For those who remained, life ahead would be no easy road.

The Italian immigrants contributed much to the success of this great nation; their legacy is a proud and generous one. And, for the sake of our descendants, the story of our ancestors must be told, and never forgotten!

The successes of our ancestors are important occurrences in American history; they are undeniably part of our inheritance.

Make the pledge and become a member of Italian Sons & Daughters of America (ISDA) today.

Tony Traficante, ISDA Contributing Editor

- October 8, 2019

Image Credit

Wikipedia (screenshot); courtesy of Tony Traficante

Share your favorite recipe , and we may feature it on our website. Join the conversation , and share recipes, travel tips and stories.

A Celebration of Faith, Family and New Beginnings

Once again we follow deeply rooted traditions, and connect with the most important gifts in our lives.

Meet Our President

Basil Russo sits down with "We the Italians" to discuss ISDA, family, and the beauty of heritage.

The Feast of the Epiphany and the Flight of La Befana

For many, Christmas rituals and traditions extend well past Dec. 25.

Immigration to America in the 19th Century: A Gateway to New Horizons

Welcome to 19th Century ! In this blog, we delve into the fascinating world of the 19th century. In our latest article, we explore the immigration to America in the 19th century . Discover the trials and triumphs of those who embarked on a journey to the land of opportunity during this transformative era. Join us as we uncover their stories and shed light on this pivotal chapter in American history.

Table of Contents

The Wave of Immigration to America during the 19th Century: A Changing Nation

The wave of immigration to America during the 19th century significantly shaped the nation’s identity and population . During this period, millions of immigrants flocked to the United States in search of better opportunities and escape from poverty, political unrest, and religious persecution .