- COVID-19 travel advice

Considering travel during the pandemic? Take precautions to protect yourself from COVID-19.

A coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccine can prevent you from getting COVID-19 or from becoming seriously ill due to COVID-19 . But even if you're vaccinated, it's still a good idea to take precautions to protect yourself and others while traveling during the COVID-19 pandemic.

If you've had all recommended COVID-19 vaccine doses, including boosters, you're less likely to become seriously ill or spread COVID-19 . You can then travel more safely within the U.S. and internationally. But international travel can still increase your risk of getting new COVID-19 variants.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that you should avoid travel until you've had all recommended COVID-19 vaccine and booster doses.

Before you travel

As you think about making travel plans, consider these questions:

- Have you been vaccinated against COVID-19 ? If you haven't, get vaccinated. If the vaccine requires two doses, wait two weeks after getting your second vaccine dose to travel. If the vaccine requires one dose, wait two weeks after getting the vaccine to travel. It takes time for your body to build protection after any vaccination.

- Have you had any booster doses? Having all recommended COVID-19 vaccine doses, including boosters, increases your protection from serious illness.

- Are you at increased risk for severe illness? Anyone can get COVID-19 . But older adults and people of any age with certain medical conditions are at increased risk for severe illness from COVID-19 .

- Do you live with someone who's at increased risk for severe illness? If you get infected while traveling, you can spread the COVID-19 virus to the people you live with when you return, even if you don't have symptoms.

- Does your home or destination have requirements or restrictions for travelers? Even if you've had all recommended vaccine doses, you must follow local, state and federal testing and travel rules.

Check local requirements, restrictions and situations

Some state, local and territorial governments have requirements, such as requiring people to wear masks, get tested, be vaccinated or stay isolated for a period of time after arrival. Before you go, check for requirements at your destination and anywhere you might stop along the way.

Keep in mind these can change often and quickly depending on local conditions. It's also important to understand that the COVID-19 situation, such as the level of spread and presence of variants, varies in each country. Check back for updates as your trip gets closer.

Travel and testing

For vaccinated people.

If you have been fully vaccinated, the CDC states that you don't need to get tested before or after your trip within the U.S. or stay home (quarantine) after you return.

If you're planning to travel internationally outside the U.S., the CDC states you don't need to get tested before your trip unless it's required at your destination. Before arriving to the U.S., you need a negative test within the last day before your arrival or a record of recovery from COVID-19 in the last three months.

After you arrive in the U.S., the CDC recommends getting tested with a viral test 3 to 5 days after your trip. If you're traveling to the U.S. and you aren't a citizen, you need to be fully vaccinated and have proof of vaccination.

You don't need to quarantine when you arrive in the U.S. But check for any symptoms. Stay at home if you develop symptoms.

For unvaccinated people

Testing before and after travel can lower the risk of spreading the virus that causes COVID-19 . If you haven't been vaccinated, the CDC recommends getting a viral test within three days before your trip. Delay travel if you're waiting for test results. Keep a copy of your results with you when you travel.

Repeat the test 3 to 5 days after your trip. Stay home for five days after travel.

If at any point you test positive for the virus that causes COVID-19 , stay home. Stay at home and away from others if you develop symptoms. Follow public health recommendations.

Stay safe when you travel

In the U.S., you must wear a face mask on planes, buses, trains and other forms of public transportation. The mask must fit snugly and cover both your mouth and nose.

Follow these steps to protect yourself and others when you travel:

- Get vaccinated.

- Keep distance between yourself and others (within about 6 feet, or 2 meters) when you're in indoor public spaces if you're not fully vaccinated. This is especially important if you have a higher risk of serious illness.

- Avoid contact with anyone who is sick or has symptoms.

- Avoid crowds and indoor places that have poor air flow (ventilation).

- Don't touch frequently touched surfaces, such as handrails, elevator buttons and kiosks. If you must touch these surfaces, use hand sanitizer or wash your hands afterward.

- Wear a face mask in indoor public spaces. The CDC recommends wearing the most protective mask possible that you'll wear regularly and that fits. If you are in an area with a high number of new COVID-19 cases, wear a mask in indoor public places and outdoors in crowded areas or when you're in close contact with people who aren't vaccinated.

- Avoid touching your eyes, nose and mouth.

- Cover coughs and sneezes.

- Wash your hands often with soap and water for at least 20 seconds.

- If soap and water aren't available, use a hand sanitizer that contains at least 60% alcohol. Cover all surfaces of your hands and rub your hands together until they feel dry.

- Don't eat or drink on public transportation. That way you can keep your mask on the whole time.

Because of the high air flow and air filter efficiency on airplanes, most viruses such as the COVID-19 virus don't spread easily on flights. Wearing masks on planes has likely helped lower the risk of getting the COVID-19 virus on flights too.

However, air travel involves spending time in security lines and airport terminals, which can bring you in close contact with other people. Getting vaccinated and wearing a mask when traveling can help protect you from COVID-19 while traveling.

The Transportation Security Administration (TSA) has increased cleaning and disinfecting of surfaces and equipment, including bins, at screening checkpoints. TSA has also made changes to the screening process:

- Travelers must wear masks during screening. However, TSA employees may ask travelers to adjust masks for identification purposes.

- Travelers should keep a distance of 6 feet apart from other travelers when possible.

- Instead of handing boarding passes to TSA officers, travelers should place passes (paper or electronic) directly on the scanner and then hold them up for inspection.

- Each traveler may have one container of hand sanitizer up to 12 ounces (about 350 milliliters) in a carry-on bag. These containers will need to be taken out for screening.

- Personal items such as keys, wallets and phones should be placed in carry-on bags instead of bins. This reduces the handling of these items during screening.

- Food items should be carried in a plastic bag and placed in a bin for screening. Separating food from carry-on bags lessens the likelihood that screeners will need to open bags for inspection.

Be sure to wash your hands with soap and water for at least 20 seconds directly before and after going through screening.

Public transportation

If you travel by bus or train and you aren't vaccinated, be aware that sitting or standing within 6 feet (2 meters) of others for a long period can put you at higher risk of getting or spreading COVID-19 . Follow the precautions described above for protecting yourself during travel.

Even if you fly, you may need transportation once you arrive at your destination. You can search car rental options and their cleaning policies on the internet. If you plan to stay at a hotel, check into shuttle service availability.

If you'll be using public transportation and you aren't vaccinated, continue physical distancing and wearing a mask after reaching your destination.

Hotels and other lodging

The hotel industry knows that travelers are concerned about COVID-19 and safety. Check any major hotel's website for information about how it's protecting guests and staff. Some best practices include:

- Enhanced cleaning procedures

- Physical distancing recommendations indoors for people who aren't vaccinated

- Mask-wearing and regular hand-washing by staff

- Mask-wearing indoors for guests in public places in areas that have high cases of COVID-19

- Vaccine recommendations for staff

- Isolation and testing guidelines for staff who've been exposed to COVID-19

- Contactless payment

- Set of rules in case a guest becomes ill, such as closing the room for cleaning and disinfecting

- Indoor air quality measures, such as regular system and air filter maintenance, and suggestions to add air cleaners that can filter viruses and bacteria from the air

Vacation rentals, too, are enhancing their cleaning procedures. They're committed to following public health guidelines, such as using masks and gloves when cleaning, and building in a waiting period between guests.

Make a packing list

When it's time to pack for your trip, grab any medications you may need on your trip and these essential safe-travel supplies:

- Alcohol-based hand sanitizer (at least 60% alcohol)

- Disinfectant wipes (at least 70% alcohol)

- Thermometer

Considerations for people at increased risk

Anyone can get very ill from the virus that causes COVID-19 . But older adults and people of any age with certain medical conditions are at increased risk for severe illness. This may include people with cancer, serious heart problems and a weakened immune system. Getting the recommended COVID-19 vaccine and booster doses can help lower your risk of being severely ill from COVID-19 .

Travel increases your chance of getting and spreading COVID-19 . If you're unvaccinated, staying home is the best way to protect yourself and others from COVID-19 . If you must travel and aren't vaccinated, talk with your health care provider and ask about any additional precautions you may need to take.

Remember safety first

Even the most detailed and organized plans may need to be set aside when someone gets ill. Stay home if you or any of your travel companions:

- Have signs or symptoms, are sick or think you have COVID-19

- Are waiting for results of a COVID-19 test

- Have been diagnosed with COVID-19

- Have had close contact with someone with COVID-19 in the past five days and you're not up to date with your COVID-19 vaccines

If you've had close contact with someone with COVID-19 , get tested after at least five days. Wait to travel until you have a negative test. Wear a mask if you travel up to 10 days after you've had close contact with someone with COVID-19 .

- How to protect yourself and others. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html. Accessed Feb. 4, 2022.

- Domestic travel during COVID-19. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/travelers/travel-during-covid19.html. Accessed Feb. 4, 2022.

- Requirement for face masks on public transportation conveyances and at transportation hubs. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/travelers/face-masks-public-transportation.html. Accessed Feb. 4, 2022.

- International travel. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/travelers/international-travel/index.html. Accessed Feb. 4, 2022.

- U.S citizens, U.S. nationals, U.S. lawful permanent residents, and immigrants: Travel to and from the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/travelers/international-travel-during-covid19.html. Accessed Feb. 4, 2022.

- Non-US. citizen, non-U.S. immigrants: Air travel to the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/travelers/noncitizens-US-air-travel.html. Accessed Feb. 4, 2022.

- People with certain medical conditions. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-medical-conditions.html. Accessed Feb. 4, 2022.

- Stay up to date with your vaccines. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/stay-up-to-date.html. Accessed Feb. 4, 2022.

- Pack smart. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/page/pack-smart. Accessed Feb. 4, 2022.

- Travel: Frequently asked questions. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/travelers/faqs.html. Accessed Feb. 7, 2022.

- Coronavirus (COVID-19) information. Transportation Security Administration. https://www.tsa.gov/coronavirus. Accessed Feb. 7, 2022.

- WHO advice for international traffic in relation to the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant (B.1.1.529). World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/articles-detail/who-advice-for-international-traffic-in-relation-to-the-sars-cov-2-omicron-variant. Accessed Feb. 7, 2022.

- VRHP/VRMA Cleaning guidelines for COVID-19. Vacation Rental Management Association. https://www.vrma.org/page/vrhp/vrma-cleaning-guidelines-for-covid-19. Accessed Feb. 7, 2022.

- Safe stay. American Hotel & Lodging Association. https://www.ahla.com/safestay. Accessed Feb. 7, 2022.

- Khatib AN, et al. COVID-19 transmission and the safety of air travel during the pandemic: A scoping review. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 2021; doi:10.1097/QCO.0000000000000771.

Products and Services

- A Book: Endemic - A Post-Pandemic Playbook

- Begin Exploring Women's Health Solutions at Mayo Clinic Store

- A Book: Future Care

- Antibiotics: Are you misusing them?

- COVID-19 and vitamin D

- Convalescent plasma therapy

- Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)

- COVID-19: How can I protect myself?

- Herd immunity and coronavirus

- COVID-19 and pets

- COVID-19 and your mental health

- COVID-19 antibody testing

- COVID-19, cold, allergies and the flu

- COVID-19 drugs: Are there any that work?

- Long-term effects of COVID-19

- COVID-19 tests

- COVID-19 in babies and children

- Coronavirus infection by race

- COVID-19 vaccine: Should I reschedule my mammogram?

- COVID-19 vaccines for kids: What you need to know

- COVID-19 vaccines

- COVID-19 variant

- COVID-19 vs. flu: Similarities and differences

- COVID-19: Who's at higher risk of serious symptoms?

- Debunking coronavirus myths

- Different COVID-19 vaccines

- Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO)

- Fever: First aid

- Fever treatment: Quick guide to treating a fever

- Fight coronavirus (COVID-19) transmission at home

- Honey: An effective cough remedy?

- How do COVID-19 antibody tests differ from diagnostic tests?

- How to measure your respiratory rate

- How to take your pulse

- How to take your temperature

- How well do face masks protect against COVID-19?

- Is hydroxychloroquine a treatment for COVID-19?

- Loss of smell

- Mayo Clinic Minute: You're washing your hands all wrong

- Mayo Clinic Minute: How dirty are common surfaces?

- Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C)

- Nausea and vomiting

- Pregnancy and COVID-19

- Safe outdoor activities during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Safety tips for attending school during COVID-19

- Sex and COVID-19

- Shortness of breath

- Thermometers: Understand the options

- Treating COVID-19 at home

- Unusual symptoms of coronavirus

- Vaccine guidance from Mayo Clinic

- Watery eyes

U.S. travel resources

- Check CDC recommendations for travel within the U.S.

- Review testing requirements for travel to the U.S.

- Look up restrictions at your destination .

- Review airport security measures .

Related resources

Make twice the impact.

Your gift can go twice as far to advance cancer research and care!

Advertisement

Supported by

What to Know About the C.D.C. Guidelines on Vaccinated Travel

In updated recommendations, the federal health agency said both domestic and international travel was low risk for fully vaccinated Americans. But travel remains far from simple.

- Share full article

By Ceylan Yeginsu

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention updated its guidance for fully vaccinated Americans in April, saying that traveling both domestically and internationally was low risk.

The long-awaited recommendations were issued by federal health officials after a series of studies found that vaccines administered in the United States were robustly effective in preventing infections in real-life conditions.

One is considered fully vaccinated two weeks after receiving the single dose of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, or two weeks after receiving the second dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech or Moderna shots.

If you decide to travel, you might still have some questions. Here are the answers.

Will I still need to wear a mask and socially distance while traveling?

Yes. Under federal law, masks must be worn at airports in the United States, onboard domestic flights and in all transport hubs. The C.D.C. says that as long as coronavirus measures are taken in these scenarios, including mask wearing, fully vaccinated Americans can travel domestically without having to take a test or quarantine, although the agency warns that some states and territories may keep their local travel restrictions and recommendations in place.

For those wishing to travel internationally, a coronavirus test will not be required before departure from the United States unless mandated by the government of their destination. Vaccinated travelers are still required to get tested three days before travel by air into the United States, and are advised to take a test three to five days after their return, but will not need to self-quarantine.

Can I go abroad?

Yes, but only to countries that will have you.

More than half the world’s countries have reopened to tourists from the United States, including the countries of the European Union , which on June 18 added the United States to its “safe list” of countries, meaning that American travelers can now visit. While the European Union aims to take a coordinated approach to travel this summer, member states will be allowed to set their own requirements for travelers from individual countries based on their own epidemiological criteria, which means they may require testing or vaccination.

Some places like Turkey, Croatia and Montenegro had already been welcoming Americans with negative test results. Greece joined that growing list in May, ahead of most European countries, opening to fully vaccinated tourists and other foreigners with a negative test.

Many Caribbean nations have reopened to American tourists, but each has its own coronavirus protocols and entry requirements.

Here’s a full list of countries Americans can currently travel to.

What about domestic travel? Is it free and clear to cross state borders?

If you are fully vaccinated, the C.D.C. says you can travel freely within the United States and that you do not need to get tested, or self-quarantine, before or after traveling. But some states and local governments may choose to keep travel restrictions in place, including testing, quarantine and stay-at-home orders. Hawaii , for instance, still has travel restrictions in place.

Before you travel across state lines, check the current rules at your destination.

How are they going to check that I’m fully vaccinated?

Right now, the best way to prove that you have been vaccinated is to show your vaccine card .

Digital vaccine and health certificates showing that people have been vaccinated or tested are in various stages of development around the world and are expected, eventually, to be widely used to speed up travel.

The subject of “ vaccine passports ” is currently one of the most hotly debated topics within the travel industry, with questions over the equity of their use and concerns over health and data privacy.

In early April, Gov. Ron DeSantis of Florida issued an executive order that would ban local governments and state businesses from requiring proof of vaccination for services.

And in March, the European Union endorsed its own vaccine certificate , which some countries are already using, with more expected to adopt it by July 1.

But what about my kids? What’s the guidance on traveling with unvaccinated people?

The C.D.C. advises people against travel unless they have been vaccinated. If you must travel, the agency recommends testing one to three days before a trip and following all coronavirus guidance at your destination.

In May, the F.D.A. expanded its emergency use authorization of the Pfizer-BioNTech coronavirus vaccine to include adolescents between 12 and 15 years of age.

All air passengers aged two and older coming into the United States, including fully vaccinated people, are required to have a negative Covid-19 test result taken no more than three days before they board their flight.

What is my moral obligation to the places I visit where most people are not vaccinated?

The United States inoculation rollout has been among the fastest in the world, but there is a stark gap between its rapid rollout and the vaccination programs in different countries. Some nations have yet to report a single dose being administered.

Many countries are currently seeing a surge in new cases and are implementing strict coronavirus protocols, including mask mandates in public spaces, capacity limits at restaurants and tourist sites and other lockdown restrictions.

It is important to check coronavirus case rates, measures and medical infrastructure before traveling to your destination and not to let your guard down when you get there. Even though you are fully vaccinated, you may still be able to transmit the disease to local communities who have not yet been inoculated.

You can track coronavirus vaccination rollouts around the world here.

Follow New York Times Travel on Instagram , Twitter and Facebook . And sign up for our weekly Travel Dispatch newsletter to receive expert tips on traveling smarter and inspiration for your next vacation.

Ceylan Yeginsu is a London-based reporter. She joined The Times in 2013, and was previously a correspondent in Turkey covering politics, the migrant crisis, the Kurdish conflict, and the rise of Islamic State extremism in Syria and the region. More about Ceylan Yeginsu

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Health Topics

- Drugs & Supplements

- Medical Tests

- Medical Encyclopedia

- About MedlinePlus

- Customer Support

Traveler's Health

Related issues, see, play and learn.

- No links available

Clinical Trials

- Journal Articles

Find an Expert

Older adults, patient handouts.

Traveling can increase your chances of getting sick. A long flight can increase your risk for deep vein thrombosis. Once you arrive, it takes time to adjust to the water, food, and air in another place. Water in developing countries can contain viruses , bacteria , and parasites that cause stomach upset and diarrhea. Be safe by using only bottled or purified water for drinking, making ice cubes, and brushing your teeth. If you use tap water, boil it or use iodine tablets. Food poisoning can also be a risk. Eat only food that is fully cooked and served hot. Avoid unwashed or unpeeled raw fruits and vegetables.

If you are traveling out of the country, you might also need vaccinations or medicines to prevent specific illnesses. Which ones you need will depend on what part of the world you're visiting, the time of year, your age, overall health status, and previous vaccinations. See your doctor 4 to 6 weeks before your trip. Most vaccines take time to become effective.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- International Travel: Tips for Staying Healthy (American Academy of Family Physicians) Also in Spanish

- Staying Healthy While You Travel (For Parents) (Nemours Foundation) Also in Spanish

- Travelers' Health (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

- Air Travel Health Tips (American Academy of Family Physicians) Also in Spanish

- Travelers' Health: Air Quality and Ionizing Radiation (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

- Travelers' Health: Cruise Ship Travel (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

- Travelers' Health: Extremes of Temperature (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

- Travelers' Health: Immunocompromised Travelers (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

- Travelers' Health: Injury and Trauma (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

- Travelers' Health: International Adoption (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

- Travelers' Health: Mosquitoes, Ticks, and Other Arthropods (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

- Travelers' Health: Travel Health Kits (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

- Travelers' Health: Zoonotic Exposures -- Bites, Stings, Scratches, and Other Hazards (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

- Your Health Abroad (Department of State, Bureau of Consular Affairs)

- Ears and Altitude (Barotrauma) (American Academy of Otolaryngology--Head and Neck Surgery)

- Foot Swelling during Air Travel: A Concern? (Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research) Also in Spanish

- Influenza Prevention: Information for Travelers (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) Also in Spanish

- Jet Lag Disorder (Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research) Also in Spanish

- Motion Sickness: First Aid (Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research) Also in Spanish

- Protect against Mosquito Bites when Traveling (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) - PDF Also in Spanish

- Rabies: What If I Receive Treatment Outside the United States? (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

- Traveler's Diarrhea (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) Also in Spanish

- Travelers' Health: COVID-19 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

- Travelers' Health: Destinations (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

- Visiting Friends or Relatives (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

- Zika Travel Information (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) Also in Spanish

Journal Articles References and abstracts from MEDLINE/PubMed (National Library of Medicine)

- Article: A methodology for estimating SARS-CoV-2 importation risk by air travel into...

- Article: Risk perception about communicable and vector borne diseases among international travellers...

- Article: Perception, confidence, and willingness to respond to in-flight medical emergencies among...

- Traveler's Health -- see more articles

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Also in Spanish

- Flying and Your Child's Ears (Nemours Foundation) Also in Spanish

- Travelers' Health: Traveling Safely with Infants and Children (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

- Travelers' Health: Vaccine Recommendations for Infants and Children (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

- Travel during Pregnancy (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists)

- Travelers' Health: Travel and Breastfeeding (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

- Travelers' Health: Senior Citizens (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

- Jet lag prevention (Medical Encyclopedia) Also in Spanish

- Pregnancy and travel (Medical Encyclopedia) Also in Spanish

The information on this site should not be used as a substitute for professional medical care or advice. Contact a health care provider if you have questions about your health.

CDC Health Information for International Travel: Yellow Book

As unprecedented numbers of travelers cross international borders each day, the need for up-to-date, actionable information about the health challenges posed by this mass movement has never been greater. For both international travelers and the health professionals who care for them, CDC Health Information for International Travel (more commonly known as the Yellow Book ) is the definitive guide to staying healthy and safe anywhere in the world. The Yellow Book is produced biennially with input from hundreds of travel medicine experts and is published through a unique collaboration between CDC, the CDC Foundation and Oxford University Press.

The 2018 edition codifies the U.S. government’s most current health guidelines and information for international travelers, including pretravel vaccine recommendations, destination-specific advice, and easy-to-reference maps , tables and charts . The book also offers updated guidance for specific types of travel and travelers, including:

- Precautions for pregnant travelers, immunocompromised travelers and travelers with disabilities

- Special considerations for newly arrived adoptees , immigrants and refugees

- Practical tips for last-minute or resource-limited travelers

- Advice for air crews , humanitarian workers , missionaries and others who provide care and support overseas

The 2018 Yellow Book includes important travel medicine updates:

- The latest information about emerging infectious disease threats such as Zika , Ebola and MERS

- New cholera vaccine recommendations

- Updated guidance on the use of antibiotics in the treatment of travelers' diarrhea

- Special considerations for unique types of travel, such as wilderness expeditions , work-related travel and study abroad

- Destination-specific recommendations for popular itineraries, including new sections for travelers to Cuba and Burma

Written by a team of CDC experts on the forefront of travel medicine, the Yellow Book provides a user-friendly, vital resource for those in the business of keeping travelers healthy abroad. Order the 2018 edition online .

©David Snyder/CDC Foundation

NICHOLAS A. RATHJEN, DO, AND S. DAVID SHAHBODAGHI, MD, MPH

Am Fam Physician. 2023;108(4):396-403

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Approximately 1.8 billion people will cross an international border by 2030, and 66% of travelers will develop a travel-related illness. Most travel-related illnesses are self-limiting and do not require significant intervention; others could cause significant morbidity or mortality. Physicians should begin with a thorough history and clinical examination to have the highest probability of making the correct diagnosis. Targeted questioning should focus on the type of trip taken, the travel itinerary, and a list of all geographic locations visited. Inquiries should also be made about pretravel preparations, such as chemoprophylactic medications, vaccinations, and any personal protective measures such as insect repellents or specialized clothing. Travelers visiting friends and relatives are at a higher risk of travel-related illnesses and more severe infections. The two most common vaccine-preventable illnesses in travelers are influenza and hepatitis A. Most travel-related illnesses become apparent soon after arriving at home because incubation periods are rarely longer than four to six weeks. The most common illnesses in travelers from resource-rich to resource-poor locations are travelers diarrhea and respiratory infections. Localizing symptoms such as fever with respiratory, gastrointestinal, or skin-related concerns may aid in identifying the underlying etiology.

Globally, it is estimated that 1.8 billion people will cross an international border by 2030. 1 Although Europe is the most common destination, tourism is increasing in developing regions of Asia, Africa, and Latin America. 2 Less than one-half of U.S. travelers seek pretravel medical advice. It is estimated that two-thirds of travelers will develop a travel-related illness; therefore, the ill returning traveler is not uncommon in primary care. 3 Although most of these illnesses are minor and relatively insignificant clinically, the potential exists for serious illness. The advent of modern and interconnected travel networks means that a rare illness or nonendemic infectious disease is never more than 24 hours away. 4 Travelers over the past 10 years have contributed to the increase of emerging infectious diseases such as chikungunya, Zika virus infection, COVID-19, mpox (monkeypox), and Ebola disease. 3

Although most travel-related illnesses are self-limiting and do not require medical evaluation, others could be life-threatening. 5 The challenge for the busy physician is successfully differentiating between the two. Physicians should begin with a thorough history and clinical examination to have the highest probability of making the correct diagnosis. Travelers at the highest risk are those visiting friends and relatives who stay in a country for more than 28 days or travel to Africa. Most travel-related illnesses become apparent soon after arriving home because incubation periods are rarely longer than four to six weeks. 3 , 6 The most common illnesses in travelers from resource-rich to resource-poor locations are travelers diarrhea and respiratory infections. 7 , 8 The incubation period of an illness relative to the onset of symptoms and the length of stay in the foreign destination can exclude infections in the differential diagnosis ( eTable A ) .

General questions should determine the patient’s pertinent medical history, focusing on any unique factors, such as immunocompromising illnesses or underlying risk factors for a travel-related medical concern. Targeted questioning should focus on the type of trip taken and the travel itinerary that includes accommodations, recreational activities, and a list of all geographic locations visited ( Table 1 3 , 6 , 9 and Table 2 3 , 6 ) . Patients should be asked about any medical treatments received in a foreign country. Modern travel itineraries often require multiple stopovers, and it is not uncommon for the casual traveler to visit several locations with different geographically linked illness patterns in a single trip abroad.

Travel History

Travelers visiting friends and relatives are at a higher risk of travel-related illnesses and more severe infections. 10 , 11 These travelers rarely seek pretravel consultation, are less likely to take chemoprophylaxis, and engage in more risky travel-related behaviors such as consuming food from local sources and traveling to more remote locations. 3 Overall, travelers visiting friends and relatives tend to have extended travel stays and are more likely to reside in non–climate-controlled dwellings.

During the clinical history, inquiries should be made about pretravel preparations, including chemoprophylactic medications, vaccinations, and personal protective measures such as insect repellents or specialized clothing. 12 , 13 Accurate knowledge of previous preventive strategies allows for appropriate risk stratification by physicians. Even when used thoroughly, these measures decrease the likelihood of certain illnesses but do not exclude them. 6 Adherence to dietary precautions and pretravel immunization against typhoid fever do not necessarily eliminate the risk of disease. Travelers often have no control over meals prepared in foreign food establishments, and the currently available typhoid vaccines are 60% to 80% effective. 14 Although all travel-related vaccines are important, the two most common vaccine-preventable illnesses in travelers are influenza and hepatitis A. 12 , 15

Travel duration is also an important but often overlooked component of the clinical history because the likelihood of illness increases directly with the length of stay abroad. The longer travelers stay in a non-native environment, the more likely they are to forego travel precautions and adherence to chemoprophylaxis. 3 The use of personal protective measures decreases gradually with the total amount of time in the host environment. 3 A thorough medical and sexual history should be obtained because data show that sexual contact during travel is common and often occurs without the use of barrier contraception. 16

Clinical Assessment

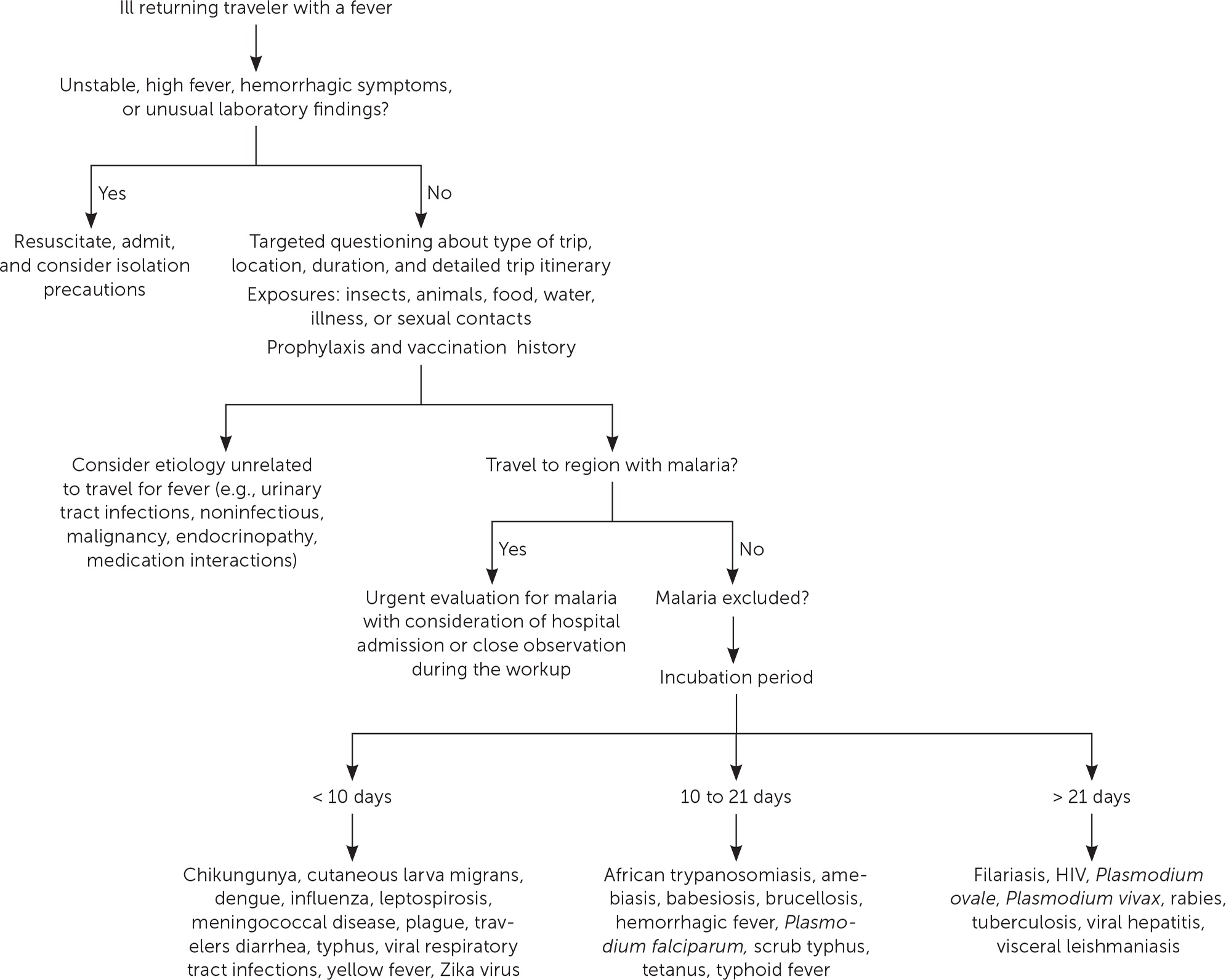

The severity of the illness helps determine if the patient should be admitted to the hospital while the evaluation is in progress. 3 Patients with high fevers, hemorrhagic symptoms, or abnormal laboratory findings should be hospitalized or placed in isolation ( Figure 1 ) . For patients with a higher severity of illness, consultation with an infectious disease or tropical/travel medicine physician is advised. 3 Patients with symptoms that suggest acute malaria (e.g., fever, altered mental status, chills, headaches, myalgias, malaise) should be admitted for observation while the evaluation is expeditiously completed. 13

Many tools can assist physicians in making an accurate diagnosis. The GeoSentinel is a worldwide data collection network for the surveillance and research of travel-related illnesses; however, this service requires a subscription. The network can guide physicians to the most likely illness based on geographic location and top diagnoses by geography. 4 For example, Plasmodium falciparum malaria is the most common serious febrile illness in travelers to sub-Saharan Africa. 17

Ill returning travelers should have a laboratory evaluation performed with a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and C-reactive protein. Additional testing may include blood-based rapid molecular assays for malaria and arboviruses; blood, stool, and urine cultures; and thick and thin blood smears for malaria. 3 Emerging polymerase chain reaction technologies are becoming widely available across the United States. Multiplex and biofilm array polymerase chain reaction platforms for bacterial, viral, and protozoal pathogens are now available at most tertiary health care centers. 4 Multiplex and biofilm platforms include dedicated panels for respiratory and gastrointestinal illnesses and bloodborne pathogens. These tests allow for real-time or near real-time diagnosis of agents that were previously difficult to isolate outside of the reference laboratory setting.

Table 3 lists common tropical diseases and associated vectors. 3 , 6 , 18 Physicians should be aware of unique and emerging infections, such as viral hemorrhagic fevers, COVID-19, and novel respiratory pathogens, in addition to common illnesses. Testing for infections of public health importance can be performed with assistance from local public health authorities. 19 In cases of short-term travel, previously acquired non–travel-related conditions should be on any list of applicable differential diagnoses. References on infectious diseases endemic in many geographic locations are accessible online. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Travelers’ Health website provides free resources for patients and health care professionals at https://www.cdc.gov/travel .

Febrile Illness

A fever typically accompanies serious illnesses in returning travelers. Patients with a fever should be treated as moderately ill. One barrier to an accurate and early diagnosis of travel-related infections is the nonspecific nature of the initial symptoms of illness. Often, these symptoms are vague and nonfocal. A febrile illness with a fever as the primary presenting symptom could represent a viral upper respiratory tract infection, acute influenza, or even malaria, typhoid, or dengue, which are the most life-threatening. According to GeoSentinel data, 91% of ill returning travelers with an acute, life-threatening illness present with a fever. 20 All travelers who are febrile and have recently returned from a malarious area should be urgently evaluated for the disease. 13 , 21 Travelers who have symptoms of malaria should seek medical attention, regardless of whether prophylaxis or preventive measures were used. Suspicion of P. falciparum malaria is a medical emergency. 13 Clinical deterioration or death can occur in a malaria-naive patient within 24 to 36 hours. 22 Dengue is an important cause of fever in travelers returning from tropical locations. An estimated 50 million to 100 million global cases of dengue are reported annually, with many more going undetected. 23 eTable B lists the most common causes of fever in the returning traveler.

Respiratory Illness

Respiratory infections are common in the United States and throughout the world. Ill returning travelers with respiratory concerns are statistically most likely to have a viral respiratory tract infection. 24 Influenza circulates year-round in tropical climates and is one of the most common vaccine-preventable illnesses in travelers. 3 , 12 Influenza A and B frequently present with a low-grade fever, cough, congestion, myalgia, and malaise. eTable C lists the most common causes of respiratory illnesses in the returning traveler.

Gastrointestinal Illness

Gastrointestinal symptoms account for approximately one-third of returning travelers who seek medical attention. 25 Most diarrhea in travelers is self-limiting, with travelers diarrhea being the most common travel-related illness. 7 Diarrhea linked to travel in resource-poor areas is usually caused by bacterial, viral, or protozoal pathogens.

The most often encountered diarrheal pathogens are enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli and enteroaggregative E. coli , which are easily treated with commonly available antibiotics. 26 Physicians should be aware of emerging antibiotic resistance patterns across the globe. The CDC offers up-to-date travel information in the CDC Yellow Book . 3 Although patients are often concerned about parasites, they should be reassured that helminths and other parasitic infections are rare in the casual traveler. 3

The disease of concern in the setting of gastrointestinal symptoms is typhoid fever. Physicians should be aware that typhoid fever and paratyphoid fever are clinically indistinguishable, with cardinal symptoms of fever and abdominal pain. 3 Typhoid fever should be considered in ill returning travelers who do not have diarrhea, because typhoid infection may not present with diarrheal symptoms. The likelihood of typhoid fever also correlates with travel to endemic regions and should be considered an alternative diagnosis in patients not responding to antimalarial medications. A diagnosis of enteric fever can be confirmed with blood or stool cultures. Although less common, community-acquired Clostridioides difficile should be considered in the differential diagnosis in the setting of recent travel and potential antimicrobial use abroad. 27

Another important travel-related pathogen is hepatitis A due to its widespread distribution in the developing world and the small pathogen dose necessary to cause illness. Hepatitis A is a more serious infection in adults; however, many U.S. adults have been vaccinated because the hepatitis A vaccine is included in the recommended childhood immunization schedule. 28 eTable D lists the most common causes of gastrointestinal illnesses in the returning traveler.

Dermatologic Concerns

Dermatologic concerns are common among returning travelers and include noninfectious causes such as sun overexposure, contact with new or unfamiliar hygiene products, and insect bites. The most common infections in returning travelers with dermatologic concerns include cutaneous larva migrans, infected insect bites, and skin abscesses. Cutaneous larva migrans typically presents with an intensely pruritic serpiginous rash on the feet or gluteal region. 3 Questions about bites and bite avoidance measures should be asked of patients with symptomatic skin concerns; however, physicians should remember that many bites go unnoticed. 29

Formerly common illnesses in the United States are common abroad, with measles, varicella-zoster virus infection, and rubella occurring in child and adult travelers. 3 Measles is considered one of the most contagious infectious diseases. More than one-third of child travelers from the United States have not completed the recommended course of measles, mumps, and rubella vaccines at the time of travel due to immunization scheduling. One-half of all measles importations into the United States comes from these international travelers. 30 Measles should always be considered in the differential because of the low or incomplete vaccination rates in travelers and high levels of exposure in some areas abroad. eTable E lists the most common infectious causes of dermatologic concern in the returning traveler.

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed using the key words prevention, diagnosis, treatment, travel related illness, surveillance, travel medicine, chemoprophylaxis, and returning traveler treatment. The search was limited to English-language studies published since 2000. Secondary references from the key articles identified by the search were used as well. Also searched were the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Cochrane databases. Search dates: September 2022 to November 2022, March 2023, and August 2023.

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the U.S. Army, the U.S. Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

The World Tourism Organization. International tourists to hit 1.8 billion by 2030. October 11, 2011. Accessed March 2023. https://www.unwto.org/archive/global/press-release/2011-10-11/international-tourists-hit-18-billion-2030

- Angelo KM, Kozarsky PE, Ryan ET, et al. What proportion of international travellers acquire a travel-related illness? A review of the literature. J Travel Med. 2017;24(5):10.1093/jtm/tax046.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Yellow Book: Health Information for International Travel . Oxford University Press; 2023. Accessed August 26, 2023. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2024/table-of-contents

Wu HM. Evaluation of the sick returned traveler. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2019;36(3):197-202.

Scaggs Huang FA, Schlaudecker E. Fever in the returning traveler. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2018;32(1):163-188.

Feder HM, Mansilla-Rivera K. Fever in returning travelers: a case-based approach. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88(8):524-530.

Giddings SL, Stevens AM, Leung DT. Traveler's diarrhea. Med Clin North Am. 2016;100(2):317-330.

Harvey K, Esposito DH, Han P, et al.; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Surveillance for travel-related disease–GeoSentinel Surveillance System, United States, 1997–2011. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2013;62:1-23.

Sridhar S, Turbett SE, Harris JB, et al. Antimicrobial-resistant bacteria in international travelers. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2021;34(5):423-431.

Matteelli A, Carvalho AC, Bigoni S. Visiting relatives and friends (VFR), pregnant, and other vulnerable travelers. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2012;26(3):625-635.

Ladhani S, Aibara RJ, Riordan FA, et al. Imported malaria in children: a review of clinical studies. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7(5):349-357.

Sanford C, McConnell A, Osborn J. The pretravel consultation. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94(8):620-627.

Shahbodaghi SD, Rathjen NA. Malaria. Am Fam Physician. 2022;106(3):270-278.

Freedman DO, Chen LH, Kozarsky PE. Medical considerations before international travel. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(3):247-260.

- Marti F, Steffen R, Mutsch M. Influenza vaccine: a travelers' vaccine? Expert Rev Vaccines. 2008;7(5):679-687.

Vivancos R, Abubakar I, Hunter PR. Foreign travel, casual sex, and sexually transmitted infections: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14(10):e842-e851.

Paquet D, Jung L, Trawinski H, et al. Fever in the returning traveler. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2022;119(22):400-407.

Cantey PT, Montgomery SP, Straily A. Neglected parasitic infections: what family physicians need to know—a CDC update. Am Fam Physician. 2021;104(3):277-287.

Rathjen NA, Shahbodaghi SD. Bioterrorism. Am Fam Physician. 2021;104(4):376-385.

Jensenius M, Davis X, von Sonnenburg F, et al.; Geo-Sentinel Surveillance Network. Multicenter GeoSentinel analysis of rickettsial diseases in international travelers, 1996–2008. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15(11):1791-1798.

Tolle MA. Evaluating a sick child after travel to developing countries. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010;23(6):704-713.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About malaria. February 2, 2022. Accessed August 21, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/about/index.html

Wilder-Smith A, Schwartz E. Dengue in travelers. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(9):924-932.

Summer A, Stauffer WM. Evaluation of the sick child following travel to the tropics. Pediatr Ann. 2008;37(12):821-826.

Swaminathan A, Torresi J, Schlagenhauf P, et al.; GeoSentinel Network. A global study of pathogens and host risk factors associated with infectious gastrointestinal disease in returned international travellers. J Infect. 2009;59(1):19-27.

Shah N, DuPont HL, Ramsey DJ. Global etiology of travelers' diarrhea: systematic review from 1973 to the present. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;80(4):609-614.

Michal Stevens A, Esposito DH, Stoney RJ, et al.; GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Clostridium difficile infection in returning travellers. J Travel Med. 2017;24(3):1-6.

Mayer CA, Neilson AA. Hepatitis A - prevention in travellers. Aust Fam Physician. 2010;39(12):924-928.

Herness J, Snyder MJ, Newman RS. Arthropod bites and stings. Am Fam Physician. 2022;106(2):137-147.

Bangs AC, Gastañaduy P, Neilan AM, et al. The clinical and economic impact of measles-mumps-rubella vaccinations to prevent measles importations from U.S. pediatric travelers returning from abroad. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2022;11(6):257-266.

Continue Reading

More in AFP

More in pubmed.

Copyright © 2023 by the American Academy of Family Physicians.

This content is owned by the AAFP. A person viewing it online may make one printout of the material and may use that printout only for his or her personal, non-commercial reference. This material may not otherwise be downloaded, copied, printed, stored, transmitted or reproduced in any medium, whether now known or later invented, except as authorized in writing by the AAFP. See permissions for copyright questions and/or permission requests.

Copyright © 2024 American Academy of Family Physicians. All Rights Reserved.

International Travel & Infectious Disease

- International Travel Home

- Guidance for Travelers

- Materials and Resources

- For Health Professionals

Related Topics

- Immunization Information for International Travelers

- International Travel Health Clinics Serving Minnesota Residents

- Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)

- Mosquitoborne Diseases

- Measles (Rubeola)

Contact Info

International travel and infectious disease.

Traveling abroad can increase your exposure to infectious diseases caused by viruses, bacteria, or parasites. Some significant infectious health hazards for Americans traveling abroad are diarrhea, malaria, hepatitis A, and other emerging diseases.

- Guidance for Travelers Many diseases are just a plane ride away. Take care of yourself and others before you travel and when you return with this information.

- Materials and Resources Videos, posters, and other materials that you can share, view, or print.

- Guidance for Health Professionals Screening and triage information, clinical evaluation resources, infection control guidance, and other resources for health care providers.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Management of Travel-Related Infectious Diseases in the Emergency Department

Laura throckmorton.

1 Center for Emergency Medicine, University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, 11100 Euclid Ave., Cleveland, OH 44106 USA

Jonathan Hancher

2 Department of Emergency Medicine, University of North Carolina Hospitals, University of North Carolina, Physician Office Building, 170 Manning Drive, CB# 7594, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7594 USA

Purpose of Review

Emergency physicians generally have limited exposure to internationally acquired illnesses. However, travelers can present quite ill, and delays in recognition and treatment can lead to increased morbidity and mortality. This paper aims to summarize typical presentations of common international diseases and provide the emergency physician with a practical approach based on current guidelines.

Recent Findings

In the treatment of traveler’s diarrhea, azithromycin has become the treatment of choice due to the growing antibiotic resistance. Intravenous artesunate was approved in 2019 under investigational new drug protocol for the treatment of severe malaria, and artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) have become the first-line treatment for most cases of uncomplicated malaria. Since the 2015 outbreak, Zika has become a concern to many travelers, but the current treatment is supportive.

Clinicians should be aware of a few noteworthy updates in the treatment of internationally acquired illnesses, but more importantly, they must recognize warning signs of severe illness and treat promptly. Future research on workup and disposition could help emergency physicians identify which patients need admission in well-appearing febrile travelers.

Introduction

While variable by practice setting, most emergency physicians in the USA have little regular exposure to internationally acquired illnesses. Therefore, their ability to recognize these illnesses can be limited. While basic practice guidelines are available, confirmatory diagnostic testing in the emergency department is limited, and some treatments might not be readily available. This article aims to assist the emergency physician identify internationally acquired illnesses based on travel history, signs, and symptoms and to help guide management based upon current guidelines and their practical applicability in the emergency department.

While the emergency physician is unlikely to be providing pre-travel care in the USA, many EM physicians travel internationally and therefore need to be aware of primary prevention strategies for themselves and patients they treat while abroad. Country-specific guidelines are published by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), but general considerations include vaccination, prophylactic antibiotics, and protection from insect bites or infected water sources.

Mosquito-Borne Illnesses

- Bite prevention: Travelers to areas with malaria, Zika virus, and other mosquito-borne illnesses can minimize their risk by wearing long sleeves and pants, using bed netting, minimizing outdoor activities around dusk, and avoiding travel during the rainy season [ 1 ].

Table 1

Malaria chemoprophylaxis

Source: CDC [ 2 ]

- Standby emergency treatment (SBET): While chemoprophylaxis is the most efficacious in malaria prevention, SBET has also become an option for travelers who are traveling to low-risk areas who do not want to take chemoprophylaxis for the duration of their travel. Patients using this method should begin taking prescribed antimalarials if they develop a fever and seek a medical evaluation as soon as possible.

Vaccinations

- Second dose after 6 months for long-term immunity

- Particularly important due to rising antibiotic resistance of S. typhi

- Little to no efficacy against S. paratyphi

- Must be kept refrigerated and consumed 1 h prior to a meal

- Cannot be given to immunocompromised patients

- Booster needed every 5 years

- Booster needed every 2 years

- Increased risk of severe dengue with subsequent exposure if given to naïve patient

- Available through age 45 in many endemic countries

- Three doses spaced every 6 months

General Approach to the Febrile Traveler

When treating a febrile patient with a history of travel, important considerations include travel location, timing, sick contacts, weather, activities partaken while abroad, pregnancy, and medical comorbidities. Many infectious diseases acquired abroad can also take several weeks to manifest. Practitioners should remember to test for common local illness, particularly influenza during flu season, and cover for a broad range of illnesses in toxic-appearing patients.

Workup is dependent on location and timing of travel to help determine which diseases are most likely. For cases in which many pathogens seem possible, we would recommend lab workup to include complete blood count with differential, basic metabolic panel; liver function tests; coagulation screen; blood smear; CK level; pregnancy test; influenza swab; blood cultures; urinalysis; urine culture; and chest x-ray. While many findings are nonspecific, these tests will likely identify patients with warning signs of severe illness and might help guide the practitioner toward the most likely pathogen.

Many internationally acquired illnesses cannot be definitively diagnosed in the emergency department given the similar features of many diseases and the delay in diagnostic results. In determining disposition, clinicians should consider warning signs of severe disease for the most likely cause of illness, and if present, admit. Many febrile illnesses can be managed in the outpatient setting, but patients should be given strict return precautions and close follow-up. If the patient has a travel history which places him or her at risk of dengue, NSAIDs should be avoided until it has been definitively ruled out due to the risk of progression to dengue hemorrhagic fever.

Epidemiology and Transmission

Malaria is the most common febrile illness among travelers to endemic areas and is caused by the mosquito-borne parasites of the Plasmodium genus, primarily P. falciparum , P. vivax , P. ovale , and P. malariae . Cases in the USA have been increasing over the last few decades to over 2000 cases reported to the CDC in 2016. The majority of cases diagnosed in the USA are among travelers returning from Africa, particularly West Africa. P. falciparum has been identified in nearly 70% of infections with P. vivax being the second most common. Mortality in the USA is < 0.5% [ 6 •].

Signs and Symptoms

Symptoms of malaria include fever, headache, chills, diaphoresis, myalgias, diarrhea, vomiting, and cough. The onset of symptoms is dependent on the Plasmodium species with P. falciparum typically causing the most severe symptoms. In confirmed cases in 2016, over 90% of those with P. falciparum reported onset of symptoms within 1 month of returning to the USA [ 6 •]. However, nearly half of cases of P. vivax or P. ovale had onset of symptoms more than 1 month after returning to the USA likely due to reactivation of dormant liver parasites [ 6 •]. Febrile seizures can occur in children but should be considered a warning sign of cerebral malaria in any age group.

Severe malaria definitions vary between the CDC and the World Health Organization (WHO), but diagnosis can be made with any of the following signs and symptoms [ 7 , 8 , 55 ]:

- Seizures, altered mental status, or other neurologic manifestations

- Acute kidney injury

- Hemoglobin <7 g/dL

- Hypoglycemia (< 40 mg/dL)

- Liver failure or severe jaundice

- Hemodynamic instability

- > 5–10% parasitemia

Of confirmed US malaria cases reported in 2016, approximately 15% were classified as severe disease, and seven people died [ 6 •].

The diagnosis of malaria is typically by blood smear but can also be done by polymerase chain reaction. Additional laboratory abnormalities can include anemia, thrombocytopenia, elevated transaminases, mild coagulopathy, and elevated BUN and creatinine. Lumbar puncture has limited utility in cerebral malaria as results can be normal or show only mild elevations in total protein and cell counts with mildly depressed glucose [ 9 ]. If there is any concern for cerebral malaria, the patient should be treated empirically as mortality is high even with treatment.

Recommendations for treatment of malaria are dependent on the presence of any severe features, local resistance, and patient comorbidities. Access to antimalarials in the ED is likely to heavily influence treatment as even many large tertiary referral centers do not have most antimalarial drugs stocked. If the patient took prophylaxis while abroad, a different antimalarial should be selected for improved efficacy and reduced toxicity. The CDC does have a Malaria Hotline (770-488-7788) for treatment assistance with a staff member on call 24/7.

Based on CDC and WHO recommendations, we would recommend the following treatment for confirmed or suspected cases of malaria:

- WHO recommends ACTs as the first-line therapy due to highest cure rate.

- Chloroquine

- Hydroxychloroquine

- Atovaquone-proguanil

- Quinine + tetracycline, doxycycline, or clindamycin

- Second-line drug in first trimester due to limited safety data [ 11 ]

- Quinine + clindamycin

- Not accessible in the ED; must be shipped from CDC

- Quinidine: Production in the USA discontinued in 2017 [ 12 ]

- Interim treatment until IV Artesunate can be obtained from the CDC

- If unable to swallow pill, NG tube should be placed in ED

- Third line: atovaquone-proguanil or quinine.

- Intravenous clindamycin and doxycycline have been used in the past, but they are not recommended for the initial treatment of severe malaria as the onset of action is greater than 24 h [ 2 ].

Anyone with confirmed P. falciparum or species not yet known should be admitted to the hospital [ 10 ]. Patients with signs of severe malaria likely need admission to an intensive care unit. Those with no previous history of malaria, immunocompromised patients, children less than five, and pregnant women are at the highest risk for developing severe disease or rapid deterioration, and admission should be strongly considered [ 2 , 13 , 14 ].

Dengue is a febrile illness caused by a mosquito-borne flavivirus. It is endemic throughout the tropics and is estimated to cause symptoms in only one quarter of infections. According to the WHO, dengue is the second most common febrile illness in travelers returning from low- or middle-income countries [ 15 ]. There are four known serotypes (DEN1–4), and subsequent infection with a different serotype places the individual at higher risk of developing severe dengue.

Symptoms generally start 4–7 days following mosquito bite, and the disease consists of three phases [ 15 , 16 ]:

- 3–7 days

- High fevers (40C), severe headache, pain behind the eyes, myalgias, arthralgias, vomiting, lymphadenopathy, rash

- 24–48 h

- Defervescence, capillary leak, hypovolemia, potential development of severe dengue (dengue hemorrhagic fever [DHF] or dengue shock syndrome [DSS])

- Fatigue lasting days to weeks

Severe Dengue

Severe dengue (DHF/DSS) is rare and primarily seen in cases of secondary infection with a different serotype. Therefore, severe dengue is particularly uncommon in travelers and should only be expected in those with frequent travel to endemic areas. Nonetheless, severe dengue can be fatal, so awareness of certain features can help distinguish DHF and DSS from other severe febrile illnesses. These findings include pleural effusions, ascites, elevated hemoglobin in the setting of thrombocytopenia, low ESR, hepatomegaly, shock with narrow pulse pressure, petechiae/positive tourniquet test, mucosal bleeding, and DIC [ 15 – 17 ].

Within the first 7 days of illness, diagnosis is made by RT PCR or NS1 antigen testing. IgM antibodies can be detected 4–7 days after onset of symptoms but can cross-react with other flaviviruses including Zika, West Nile, Yellow Fever, and Japanese Encephalitis [ 17 ]. Other laboratory findings include hemoconcentration, thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, and elevated liver enzymes [ 15 , 16 ].

The treatment of dengue, including severe dengue, consists of supportive care, particularly fluid resuscitation, fever control, and management of bleeding. It is important to note that NSAIDS should not be used in the treatment of fever due to the increased risk of bleeding. Platelet transfusions are recommended for platelet counts < 10,000 in the setting of active bleeding. Prophylactic transfusions are not recommended [ 18 ].

Anyone developing warning signs of severe dengue including severe abdominal pain, persistent vomiting, hematemesis, mucosal bleeding, respiratory distress, restlessness, or severe fatigue within the critical phase should be admitted and watched closely [ 15 ]. Admission should also be considered in the settings of pregnancy, extremities of age, or significant comorbidities. Still, most cases of dengue can be managed in the outpatient setting. Patients should be educated on symptoms of severe dengue and told to return due to the risk of rapid progression [ 15 ].

Leptospirosis

Leptospirosis is an aerobic spirochete transmitted by contact with infected animal urine through abrasions, mucous membranes, or ingestion of contaminated food or water. Those affected typically have a history of freshwater exposure such as wading through flood waters or participating in water sports. In the USA, only 100–150 cases are identified each year, of which 50% are in Puerto Rico [ 19 ]. Cases have also been identified in Hawaii, the Pacific Coast, and the South. Internationally, leptospirosis can be acquired in most tropical regions with the highest risk in Southeast Asia [ 20 ].

Leptospirosis should be considered in patients with rapid onset fevers, myalgias, and headache with recent freshwater exposure or return from Southeast Asia. Incubation period is generally 5 to 14 days following exposure [ 21 ].

Leptospirosis consists of two phases [ 20 ]:

- May occur in 15–80% of cases and is highly specific [ 22 – 24 ]

- Other symptoms: Vomiting, diarrhea, hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, pharyngitis, rash

- Pulmonary hemorrhage, ARDS, uveitis, optic neuritis, myocarditis, rhabdomyolysis, and Weil’s disease (jaundice and nonoliguric renal failure)

Diagnosis can be made from blood culture during phase one and urine culture during phase two [ 19 , 25 ]. Additional pathogen-specific testing is hospital dependent. Routine lab findings are nonspecific but can include thrombocytopenia, hypokalemia, hyponatremia, elevated amylase, transaminitis, and hyperbilirubinemia [ 20 , 21 ]. An elevated creatinine kinase can be useful in distinguishing leptospirosis from other diseases as it is elevated in up to 50% of patients [ 56 ]. CSF can show lymphocytic or neutrophilic pleocytosis, mildly elevated protein, and normal glucose. CSF culture is generally positive in the first 10 days of illness [ 20 ]. Chest x-ray should also be obtained for any respiratory symptoms due to risk of pulmonary hemorrhage and ARDS [ 20 ].

Most cases of leptospirosis are mild and can be managed outpatient with doxycycline (100 mg) or azithromycin (500 mg) [ 19 , 25 ]. Patients with pulmonary involvement, CNS infection, jaundice, renal failure, or age over 60 are at highest risk of death [ 25 , 26 ] and should be admitted and given IV doxycycline (100 mg), penicillin (1.5 million IUs), or a third-generation cephalosporin [ 19 , 25 ]. Until Rickettsia is ruled out, doxycycline is generally recommended as the initial treatment. In patients with severe disease, corticosteroids can be considered, but recent studies have conflicting data on their benefit [ 27 , 28 ].

Enteric (Typhoid) Fever

Enteric fever is a broader term encompassing both typhoid fever caused by Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi and Paratyphoid fever caused by Salmonella enterica serotypes Paratyphi A, B, or C. While S. typhi is more common, S. paratyphi is becoming more prevalent particularly in South Asia and is not covered by the typhoid vaccines. Enteric fever is contracted through ingestion of contaminated food or water, and the highest risk is from visits to areas of poor sanitation. The CDC estimates 400 cases per year in the USA with over 70% of cases occurring in travelers returning from India, Bangladesh, or Pakistan [ 29 •].

Enteric fever classically occurs in three stages:

- Week 1: Fever, chills, bacteremia

- Week 2: “Rose spots” and abdominal pain develop

- In those hospitalized with enteric fever, incidence of perforation can be as high as 10% [ 30 , 31 ].

Enteric fever should be considered in patients who have traveled to an endemic area within the preceding 3 weeks and who are presenting with gastrointestinal symptoms accompanied by 3 or more days of fever. While most patients will complain of abdominal pain, diarrhea is not always seen, and patients can instead present with constipation. Other common symptoms include headache, cough, arthralgias, and myalgias [ 32 ].

If enteric fever is suspected, workup should include complete blood count with differential, complete metabolic profile; coagulation screen; EKG; blood cultures; and stool culture. Findings that can help point to enteric fever include anemia, leukopenia with left shift (adults) or leukocytosis (children), elevated LFTs, high fever (> 40 °C), and bradycardia [ 32 ].

Definitive diagnosis is made by blood culture, but this test has low sensitivity and will not provide a diagnosis in the ED. Therefore, patients with suspected enteric fever should be treated empirically based on clinical suspicion [ 57 ].

- Second line: Fluoroquinolone if acquired in a region with low resistance

- Patients with altered mentation or signs of shock should also be given dexamethasone 3 mg/kg as this has been shown to dramatically reduce mortality [ 33 , 34 ].

- Ongoing outbreak of multidrug-resistant strain of S. typhi since 2016 [ 35 ]

Traveler’s Diarrhea

Traveler’s diarrhea is the most common illness seen in individuals traveling from developed to resource-limited regions [ 36 ], occurring in up to 40% of travelers [ 37 , 38 •]. Transmission is fecal-oral, most often by food and water in regions with suboptimal sanitation and hygienic practices [ 39 ]. The highest risk regions include South and Southeast Asia, Africa (excluding South Africa), South America, Central America, and Mexico. Food from street vendors and staying in “all-inclusive” lodgings are specific risk factors for developing the illness [ 40 ].

Most episodes occur between 4 and 14 days after arrival to a resource-limited region [ 41 ]. Acute illness is most frequently caused by bacteria but can also be caused by parasites or viruses. Worldwide, the most common cause is enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC), followed by Salmonella , Campylobacter jejuni , and Shigella [ 39 ]. Practitioners should consider geographic variation, as Campylobacter species are more common than ETEC in Southeast Asia [ 42 ].

Classic traveler’s diarrhea is defined as three or more unformed stools in 24 h plus at least one of the following: nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, fever, or blood in stool. Symptoms are variable and partially dependent on the causative agent [ 39 ].

ETEC classically consists of malaise, anorexia, abdominal cramps followed by sudden onset watery diarrhea with very frequent stools, typically without blood or purulence. Patients may have a fever, nausea, or vomiting. Campylobacter or Shigella cause inflammatory diarrhea, which can present with similar symptoms but may progress to fever, tenesmus, or bloody diarrhea [ 39 ].

Testing should include a basic metabolic panel to assess for dehydration or metabolic derangement. The determination of microbiologic agent is typically unnecessary as ETEC cannot be distinguished from nonpathogenic E. coli on routine stool cultures [ 43 ] . Whether or not to pursue further testing should be based on clinical judgment and will likely include a shared decision-making conversation with the patient. Stool testing in the ED is reasonable when patients present with severe diarrhea, bloody or mucoid stools, antibiotics in preceding 8–12 weeks, systemic illness, or symptom lasting longer than 10–14 days. Recommended tests include:

- Stool culture to evaluate for Campylobacter or Shigella .

- Hospital dependent tests for ETEC or Shiga toxin.

- Stool O&P for Giardia lamblia , Cyclosporidium , Isospora , and other parasites.

- If recent antibiotic history, test for Clostridioides (Clostridium) difficile

- If the patient appears systemically ill, send blood cultures to evaluate for bacteremia, most commonly seen from Salmonella species (Typhi).

Consider admission for those patients with laboratory evidence of severe dehydration, acute kidney injury, need for electrolyte replacement and inability to tolerate orals, or systemic illness.

The treatment is typically symptomatic and supportive, as the vast majority of episodes is self-limited and resolves within three to 5 days. Although antibiotic stewardship is important, it is very reasonable to fill a 3-day antibiotic prescription prior to travel and start the antibiotic within 1–2 days of symptoms [ 39 , 43 ]. Management includes the following:

- Fluid replacement, by mouth or intravenously.

- Antimotility agents such as loperamide or diphenoxylate can be helpful with those with frequent diarrhea.

- Good choice if traveled to Southeast Asia (quinolone-resistant C. jejuni )

- Falling out of favor due to greater awareness of side effects

- Poorly absorbed but remain alternatives for patients in whom fluoroquinolones or azithromycin are not appropriate.

Chikungunya

Chikungunya is an arthropod-borne Alphavirus primarily transmitted by mosquito bites [ 44 ]. Interestingly, the name is derived from an African dialect meaning “stooped walk” due to the disease hallmark: debilitating joint and back pains. Chikungunya often occurs in outbreaks during the rainy season and has been seen globally in Africa, Asia, Europe, the Pacific Islands, and in the Americas [ 45 ].

Viremia occurs within a few days of infection, and the virus has a propensity to invade synovium, tenosynovium, and muscles [ 45 ]. The virus may linger in the joints for up to 2 weeks. Chronic arthritis develops in up to 60% of infected individuals [ 46 ].

Typically, symptoms start with fever and malaise lasting 3–5 days which are followed by polyarthralgias and dermatologic symptoms lasting 7–10 days [ 45 ]. However, arthralgias can persist for weeks, months, or even years. The rash is typically macular but can be patchy, diffuse, or pruritic. It often starts on the limbs and trunk and may involve the face. Arthralgias are the hallmark of chikungunya. The joint pain is typically bilateral and symmetric, affecting distal joints. The axial skeleton is involved in 34–52% of cases [ 46 , 47 ]. Severe complications (respiratory failure, myocarditis, renal failure, hemorrhage, acute hepatitis, meningoencephalitis, acute flaccid paralysis, seizures) and death can occur, more often in elderly patients with medical comorbidities [ 44 ].

Diagnosis can be made with chikungunya viral RNA RT-PCR within the first week (sensitivity 100% and specificity 98%). If RT-PCR is negative or if the patient has had symptoms for 8 or more days, diagnosis is made by virus serology via ELISA or IFA. If testing for chikungunya, one should test for dengue virus and Zika virus as well [ 58 ]. Given the severe arthralgias associated with chikungunya, it may be prudent to rule out septic arthritis if significant effusion or asymmetry is present. Joint fluid analysis will be consistent with inflammatory arthritis [ 47 ].

Indications for admission include significant comorbidities or inability to ambulate. Treatment is primarily supportive with rest, fluids, and acetaminophen [ 59 ]. NSAIDs should not be used until dengue has been excluded [ 45 ].

Zika virus is an arthropod-borne flavivirus transmitted by mosquitoes. Transmission can also occur via the maternal-fetal route, sexual intercourse (vaginal, anal, oral), or direct exposure to blood [ 48 ]. Outbreaks have occurred in Africa, Southeast Asia, the Pacific Islands, the Americas, and the Caribbean, most notably during the 2016 Olympic Games in Brazil [ 49 , 50 ].

Approximately 20–25% of infected individuals have symptoms of infection, which are typically mild and last 2 to 7 days [ 51 ]. These include fever, pruritic rash, arthralgias, conjunctivitis, myalgias, headache, dysesthesia, and generalized weakness. Less commonly symptoms include abdominal pain, nausea, diarrhea, or mucous membrane ulcerations [ 52 ]. Zika has been implicated in serious neurologic complications such as congenital microcephaly, Guillain-Barré syndrome, myelitis, and meningoencephalitis [ 53 ].