Discover The Distinction: Cultural Vs. Heritage Tourism

Short Answer for What Is the Difference Between Cultural and Heritage Tourism?

Cultural tourism focuses on engaging with the living culture and traditions of a place, while heritage tourism emphasizes the exploration of a place’s historical significance and past.

Imagine standing at the crossroads of time, where every choice leads you on a journey through the vibrant tapestry of the world’s cultures and histories. The difference between cultural and heritage tourism is not just a choice between two travel styles; It’s an invitation to explore the essence of human civilization itself, whether through the eyes of our ancestors or the heartbeat of today’s communities. This comparison embarks on a quest to unravel the unique allure of each path, guiding you to your next unforgettable adventure.

Cultural tourism thrusts you into the vivacity of the present, where you actively participate in local traditions, savor unique cuisines, and dance to the rhythm of new music, making every moment an immersive experience. It’s all about embracing the ‘now’ and connecting with communities on a deep, personal level.

On the flip side, heritage tourism invites you on a grand exploration of the past, leading you through ancient ruins, historic sites, and museums that narrate the profound stories of yore. It’s an educational pilgrimage that seeks to discover the roots and understand the narratives that have shaped the world as we know it today.

By delving into the core of what drives us to venture beyond our frontiers, this comparison sheds light on two captivating journeys, each offering its unique flavor and insight. Whether your heart yearns for the thrill of cultural immersion or the awe-inspiring revelations of our shared heritage, the journey starts here, with us, today.

Heritage Tourism is characterized by a focus on historical significance and place-based resources, emphasizing the exploration of ruins, historical sites, and museums to learn and absorb history.

Cultural Tourism centers around living culture and immersive experiences, encouraging travelers to engage in current traditions and customs through local foods, music, and festivals.

The Nature of Experience in heritage tourism is more educational, concentrating on learning about historical significance and details from the past, whereas cultural tourism is immersive, involving participation in cultural traditions.

Visitor Motivation in heritage tourism is driven by discovery and a desire to explore the past, while cultural tourism is motivated by adventure and experiencing the “now” in cultures.

Role of Location: Heritage tourism is place-based with a significant emphasis on specific locations where history unfolded, while the location in cultural tourism is more flexible, focusing on the experience rather than the specific place.

Heritage Tourism and Cultural Tourism: Understanding the Fundamentals

Heritage tourism and cultural tourism are two distinct yet interrelated forms of travel focusing on experiencing the authentic essence of a place. Heritage tourism is centered around places of historical, cultural, or natural significance, highlighting the tangible aspects like monuments, landscapes, and artifacts, alongside the intangible ones such as traditions and stories. On the other hand, cultural tourism delves into the living culture of a location, offering immersive experiences with local traditions, music, dances, and cuisine, emphasizing the active participation in contemporary cultural practices.

Defining heritage tourism: Emphasis on historical significance and place-based resources

Heritage tourism, folks, is huge. It’s all about that historical significance and, of course, place-based resources. You’re traveling to see the authentic America, the real deal, like our great monuments and places that tell the story of how we became so fantastic. It’s the kind of tourism that puts a spotlight on places with historical, cultural, or natural significance. We’re talking about the places that make you say, ‘Wow, America really is the greatest country in the world.’

Defining cultural tourism: Focus on living culture and immersive experiences

Now, cultural tourism, on the other hand, is about getting up close and personal with the living culture. It’s immersive, it’s engaging, and it’s all about today’s culture.

You’re not just seeing the culture, folks, you’re living it. You’re diving into local traditions, experiencing the food, the music, the dances, and maybe even learning a word or two in the local language.

It’s genius.

The interplay between tangible and intangible elements in heritage and cultural tourism

Here’s where it gets interesting. There’s this interplay, right, between the tangible and intangible elements in both heritage and cultural tourism. The tangible, that’s the stuff you can touch – buildings, artifacts, the landscape. Then you’ve got the intangible – the traditions, the stories, the music. They’re both important, folks. You can’t have one without the other. It’s what makes tourism so fantastic.

How is the Difference Between Cultural and Heritage Tourism Defined?

The difference between cultural and heritage tourism is primarily defined by the visitor’s motivation and the nature of the experience. Cultural tourism is driven by a desire for adventure and immersion in the “now” of cultures through engaging in local traditions, foods, music, and festivals, with a focus on the experience rather than the specific location. In contrast, heritage tourism is motivated by a quest to discover and learn from the past, focusing on exploring ruins, historical sites, and museums, with the significance of place being paramount, offering education on historical significance and details from the past.

Key distinctions based on visitor motivation and the nature of the experience

When we’re talking about the difference between cultural and heritage tourism, we’re really talking about something incredible, folks. People who opt for cultural tourism are usually the adventurous types, looking for the “now” in cultures. They dive into local foods, music, and festivals with a gusto that’s frankly, impressive. For example, you want to learn salsa in Cuba or eat sushi in Tokyo right from the hands of the masters. On the flip side, heritage tourism aficionados? They are the great detectives of our time, seeking out the mysteries of the past. They’re all about exploring ruins, historical sites, and museums. Their motivation is to learn and absorb history. Like detectives solving the mysteries of the pyramids in Egypt or walking the ancient streets of Rome.

The role of location in heritage tourism versus the experiential focus in cultural tourism

Now, let’s talk locations and experiences, which are huge, let me tell you. Heritage tourism is heavily tied to specific locations, it’s “place-based”. Think about the significance of being in the actual location where history unfolded – like standing right where the Declaration of Independence was signed. There’s a link to the past that’s tangible and, might I say, pretty powerful. Heritage tourism is often “place-based”, focusing on the significance because of their location. Meanwhile, cultural tourism? It’s all about the experience. It doesn’t matter where you are; what matters is what you’re doing. You could be anywhere in the world experiencing local traditions which are alive and well. From the Rio Carnival in Brazil to celebrating Diwali in India, it’s the experiences that draw you in.

Analyzing the educational versus immersive approaches in heritage and cultural tourism

Let’s break it down even further – educational vs. immersive, big differences folks. Heritage tourism often takes more of an educational approach. It’s like going back to school, but in the most fascinating way possible. You learn about the historical significance, the why’s and how’s, delving into the details that shaped our present. It’s very much about absorbing knowledge, maybe through a guided tour or a well-placed plaque that tells a thousand words about the past. On the flip side, cultural tourism immerses you. You’re not just learning about culture; you’re living it. It’s real-time learning, experiencing and participating in customs and traditions. It’s one thing to read about Dia de los Muertos, but it’s another to paint your face in a Calavera mask and join a Mexican street parade.

When looking at the difference between cultural and heritage tourism, it’s like comparing a thrilling novel to a fascinating history book. Both incredible, but catering to different tastes and experiences. What’s clear though, is that whether you’re soaking in the vibrant energy of a cultural fest or tracing the footsteps of ancient civilizations, the world is an open book, waiting to be explored. And frankly, it’s tremendous.

So, to sum up folks, whether it’s the pull of the past or the vibrancy of the present, cultural and heritage tourism offer paths to understanding that are as diverse as the travelers on them. The key is knowing what you’re looking for – the educational depth of heritage tourism or the immersive dive into the living culture of your destination.

Either way, you’re in for an experience that’s nothing short of fantastic.

Forms of Cultural Heritage Tourism

Cultural heritage tourism encompasses exploring architectural masterpieces like the Taj Mahal and works by Antoni Gaudí, immersing oneself in the gastronomic heritage through culinary delights like Mediterranean cuisine and aromatic Indian spices, and engaging with intangible cultural facets such as Flamenco dancing in Spain or the art of Chinese calligraphy. These forms allow tourists to traverse through time, embracing the historical, artistic, and culinary achievements that have shaped human society and its diverse cultures. This multifaceted approach to tourism offers a gateway to understanding and preserving the rich tapestry of global heritage and traditions, enriching travelers’ experiences by connecting them deeply with the essence of different cultures.

Architectural Heritage: Exploring historical constructions and landmarks

When we talk about architectural heritage in cultural heritage tourism, we’re diving into the grandeur of historical constructions that have stood the test of time. Think about the bewitching Taj Mahal in India, an epitome of love and a UNESCO World Heritage site, attracting millions with its sublime beauty. Or the meticulously designed Works of Antoni Gaudí in Spain, where each structure tells a story of innovation and artistic brilliance. These landmarks are not just buildings; they are a bridge to our past, showcasing the zenith of human creativity and ingenuity. Architectural heritage allows us to witness the evolution of societies, the artistic endeavors, and the architectural achievements that have shaped human history.

Gastronomic Heritage: Engaging with cultural identity through food

The gastronomic heritage is a delicious aspect of cultural heritage tourism that indulges your taste buds while offering a deep dive into a region’s culture. For example, the traditional recipes and dining etiquette found in every corner of the world tell tales of history, geography, migrations, and values. Food is a universal language, transcending borders and connecting people. From the aromatic spices of Indian cuisine to the simplistic and wholesome approach of Mediterranean dishes, every bite offers insight into the cultural identity of a place. Gastronomic heritage is not just about what we eat but also how we prepare it, share it, and the rituals that surround it, making it a sumptuous journey of discovery and connection.

Intangible Cultural Heritage: Preserving traditions, rituals, and performing arts

The intangible cultural heritage is where the heart and soul of a community truly lie. It encompasses traditions, rituals, music, dances, and crafts that have been passed down through generations. The intangible is what makes a culture unique; it’s the practices and expressions that define our humanity. For instance, the UNESCO Lists of Intangible Cultural Heritage include the flamboyant Flamenco of Spain, the meticulous art of Chinese calligraphy, and the vibrant Samba of Brazil. These traditions are the threads that weave the fabric of societies, rich with meaning and emotion. Engaging with intangible cultural heritage allows us to experience the essence of different cultures, forging deeper connections and understanding.

Embracing cultural heritage tourism is like embarking on a journey across time and space. It’s a path to understanding the diverse tapestry of human existence, offering insights into the differences between cultural and heritage tourism through lived experiences.

By exploring architectural marvels, relishing the gastronomic delights, and immersing in the intangible aspects of cultures, we not only preserve these treasures for future generations but also enrich our own lives with unparalleled depth and understanding.

Summarizing the intrinsic values and differences between cultural and heritage tourism

Cultural tourism and heritage tourism, both invaluable assets to global tourism, invite us into a deep, enriching dive into what makes societies uniquely mesmerizing. Cultural tourism focuses on experiencing the living culture, traditions, and practices of a place – think savoring handmade pasta in a small Italian village or dancing to flamenco in Spain. Heritage tourism, on the other hand, is like stepping into a time machine; it’s about historical sites, monuments, and landmarks that tell tales of the past. Places like the pyramids of Egypt or the ancient ruins of Machu Picchu in Peru stand as testaments to the awe-inspiring civilizations before us.

Reflecting on the importance of preserving both forms of tourism for future generations

Preservation is key. It’s not just about saving bricks, artifacts, or intangible cultural practices for the sake of it. It’s about safeguarding our global heritage and culture for future generations, allowing them to learn, appreciate, and be inspired. Initiatives like UNWTO’s efforts in preserving cultural identities highlight this commitment. Preservation benefits everyone – from local communities who gain economically and socially, to tourists seeking authentic, memorable experiences that deepen their understanding of the world.

Encouraging a deeper engagement and understanding among tourists

Lastly, we must foster deeper engagement and understanding among tourists. Going beyond the surface to truly immerse in and appreciate a culture or the history of a place enriches the tourist experience manifold. It’s about participating in local traditions, understanding the significance behind heritage sites, and respecting the local ways of life. This not only adds depth to the tourism experience but also contributes to the sustainable preservation of these cultural and historical treasures.

In essence, the difference between cultural and heritage tourism is a tapestry of “living” versus “bygone” experiences, each fascinating in its own right. Both forms of tourism offer a gateway to understanding and appreciating the diversity and richness of our world. By preserving, respecting, and deeply engaging with both, we ensure they remain vibrant and meaningful for those who wander into them tomorrow.

Cultural tourism and heritage tourism, each with its own unique allure, fundamentally differ in how they connect us to a place. Cultural tourism draws us into the vibrant, living traditions of today-immersing us in the current expressions, rituals, and the everyday life of a community. Conversely, heritage tourism acts as a bridge to the past, focusing on historical sites, monuments, and stories that have shaped civilizations. These forms, though distinct, are both crucial in offering a comprehensive understanding of the world’s diverse cultures.

Preserving both forms of tourism is not just about safeguarding landmarks or traditions; it’s about securing the legacy and lessons for future generations. By maintaining these sites and practices, we provide a tangible link to humanity’s shared history and a rich tapestry of cultural identity that spans the globe.

This preservation is essential for fostering a deeper respect and appreciation for both our differences and shared human experience.

Encouraging a deeper engagement and understanding among tourists goes beyond mere observation. It’s about promoting active participation and genuine interaction with local cultures and histories. By doing so, we bridge gaps, build connections, and nurture a more profound, mutual respect. This, in turn, enriches the travel experience, making it more meaningful and transformative for both the visitor and the host community.

Jonathan B. Delfs

I love to write about men's lifestyle and fashion. Unique tips and inspiration for daily outfits and other occasions are what we like to give you at MensVenture.com. Do you have any notes or feedback, please write to me directly: [email protected]

Recent Posts

Embrace Detours: Finding Opportunity In Unexpected Turns

Uncover the shift in "what happened to embracing detours," revealing how unforeseen paths lead to unexpected opportunities and growth.

What Really Happened To Elton John's Brother Daniel

Discover the truth behind what happened to Elton John's brother Daniel, unveiling the events that shaped their relationship and lives.

What is the difference between Cultural Tourism and Heritage Tourism?

The United National World Tourism Organization defines Cultural Tourism as “movements of persons for essentially cultural motivations such as study tours, performing arts and cultural tours, travel to festivals and other cultural events, visits to sites and monuments, travel to study nature, folklore or art, and pilgrimages.”

Heritage Tourism , as defined by the National Trust for Historic Preservation, is “traveling to experience the places, artifacts, and activities that authentically represent the stories and people of the past and present. It includes visitation to cultural, historic, and natural resources.”

Heritage tourism is often “place-based” – the resources are specific to, and significant because, of their location (for example, an author’s home, a landmark where an important event occurred, etc.) Cultural tourism is often “people-based” through engagement and learning of local traditions, but also can include a blockbuster exhibit at an art museum or a music concert at an amphitheater.

The motivation of the visitor, and what activities they engage in during their trip, distinguish their profile as a “cultural tourist” or “heritage tourist.” The agency or entity overseeing the program also may emphasize heritage tourism (preservation, historical societies, state tourism, or rural destination marketing organizations) or cultural tourism (arts, cultural organizations, state tourism, urban destination marketing organizations) to define their focus. However, research has revealed that visitors engaging in historic and cultural activities are similar in profile. This commonality in the market profile has led to a more inclusive segment of “cultural heritage tourism” or “cultural & heritage tourism.” Hargrove International, Inc. recognizes the importance of history and culture to travel experiences and focuses on an inclusive approach to asset-based economic development with history, culture, and nature as the foundation for sustainable tourism.

Cheryl Hargrove

Get updates and stay connected subscribe to our newsletter, guiding principles:.

- Deliver Customized and Quality Products

- Provide Practical Instruction for Measurable Results

- Apply Creativity and Innovation to Design Custom Solutions

- Demonstrate Enthusiasm and Integrity

- Our Clients

Hargrove International, Inc.

P.O. Box 20463 St. Simons Island, GA 31522

Destination Assessments – Strategic/Business Plans – Cultural Heritage Tourism – Thematic Trails – Keynote Speaker – Presentations – Workshops – Nonprofit Consulting – Resources

Web Design & Development by ForeSite Consulting

How Heritage Tourism Helps People Unlock the Past

Heritage tourism provides a great way to learn about the past, but what exactly is it? Check out this guide to learn about this new travel trend!

Throughout the past decade or so, people have begun to look at travel in a completely different way. Experiential travel has become a new buzzword to describe travel with that little extra something to it. This new way of traveling looks different for everyone whether you prefer outdoor activities, cultural exchanges, history, or a bit of everything!

This travel revolution means there are more and more opportunities to shape a trip around your particular interests. History buffs will be happy to know that heritage tourism has emerged as one of the new types of travel, and many different destinations and private organizations are focusing on creating their own heritage tourism programs to help cater to this growing tourism market!

Take a step back in time with Let’s Roam .

Here at Let’s Roam, we have no shortage of history buffs on our staff! Our knowledgeable team has created a range of exciting scavenger hunts that will help you explore the biggest tourist attractions and the hidden gems in a destination. These are all accessible via our handy Let’s Roam app . Plus, the Let’s Roam Explorer blog features hundreds of articles to help make trip planning easy!

Exploring the Past through Heritage Tourism

Below you’ll find a guide to heritage tourism and how it can help you unlock the past. We’ve included a description of what heritage tourism is and how it helps local communities. In addition, we’ve included a short list of some of our favorite heritage travel destinations!

What is heritage tourism?

The term heritage tourism has become a bit of a buzzword in recent years. However, you may find yourself wondering what exactly heritage tourism is. According to the National Trust for Historic Preservation, heritage tourism is “traveling to experience the places, artifacts, and activities that authentically represent the stories and people of the past and present.” This means spending time visiting historic places, museums, and archeological attractions.

However, heritage tourism is more than simply visiting an attraction and checking it off a long to-do list. It means taking the time to truly understand what you’re seeing as well as the impact it has on people. Who lived or worked there? What did their daily lives look like? How did they interact with others?

Heritage tourism is often linked with sustainability since it conveys a more conscious way of traveling. This type of travel generally goes hand in hand with using fewer natural resources. It can also be a great opportunity for tourism development in off-the-beaten-track destinations. This can then be a major contributor to broader economic development and a higher quality of life. Since this type of travel is generally different than mass travel, it also helps promote sustainable development and caring responsibly for cultural resources, historic resources, and natural resources.

What is the purpose of heritage tourism?

In the words of George Santayana, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” Heritage tourism serves as a way to connect us to the past. It helps us understand how people lived, loved, and laughed. Knowing this can help us better understand the world that we are currently living in. It can also help us analyze why certain things happened in history and how we can learn from it.

On a more personal level, heritage tourism can help people more closely identify with their own ancestors and heritage. There are many different tour operators that offer itineraries full of cultivated experiences that have a special emphasis on culture and history. A good example of this is Birthright, the program that sends young Jewish people to Israel to learn more about Judaism.

However, you don’t need to go on an organized tour for this. Instead, you can shape your own itinerary so that it incorporates certain aspects that you want to learn more about. For instance, as an American of German and British descent, I’ve made many trips to Germany and the United Kingdom to learn more about my family background.

How does heritage tourism impact destinations?

When placed under the stewardship of ethical institutions, nonprofit organizations, and partnerships with key stakeholders, heritage tourism has a much gentler approach than other types of tourism. It can offer many economic benefits to destinations. Case studies have shown that heritage tourists tend to stay longer in a destination. They also spend more money while they’re there. This means the economic impact of heritage tourists is greater than other types of tourists.

One of the most obvious economic benefits is that heritage tourism provides employment opportunities. These could range from historians to tour guides as well as support employees at the heritage sites. The tourism industry has one of the lowest barriers to entry when it comes to employment. Heritage tourism can create jobs that are likely to go to the local population. This means that the money stays in the local communities that need it most.

This, in turn, helps the local economy in numerous ways by allowing more money to be spent at local businesses. In some parts of the world, this could mean the difference between someone being able to stay in their hometown with their friends and family vs. having to go to a big city and look for work. This usually ensures that people have a wider support network nearby which is crucial to their well-being.

The money generated from tickets can also help preserve the monuments, artifacts, and heritage sites that you’re seeing. This is an incredibly important aspect of conservation. Many of the world’s most important historic sites are falling into disrepair due to unstable economies, civil wars, and other domestic issues. The revenue from ticket sales could make a huge difference in the upkeep and maintenance of the monuments.

What are some tips and tricks for heritage tourism?

If you’re trying to learn more about the past when visiting historic sites, make sure that you have at least a rough idea as to why the site is important. Although most places will provide enough information to piece together a basic idea, spending the time to read up on it before you go will make your experience much more fulfilling.

It’s also important to allow yourself plenty of time at each destination. This is the only way that you can truly immerse yourself in it. Also, try to avoid going to historic sites during peak travel hours. Having fewer tourists around makes it much easier to imagine what the places would have looked like.

What are some of the best destinations for heritage tourism?

Below you’ll find a list of some of our favorite heritage tourism destinations. While this list is in no way exhaustive, it does give you an idea of what types of things fall under the umbrella of heritage tourism. We’ve also included a short section on important things that you should know when visiting any of these destinations.

As one of the oldest civilizations in the world, India has a slew of heritage sites. These can give a comprehensive look into how it transformed from the Indus Valley civilization to the livable, chaotic country we know and love today. The country is full of UNESCO World Heritage sites so this is a good place to start your planning.

Where to go?

Most visitors begin their trip in Delhi. This is perfect for history buffs. Not only is Delhi the capital of India, but it’s also the location of many previous ancient cities. You can still find vestiges of these in the many forts and tombs in South Delhi as well as the winding streets of Old Delhi.

Old Delhi was designed by Shah Jahan of Taj Mahal fame. As you wander through the tiny streets crammed full of shops, eateries, and chai-wallahs, it feels like little has changed in the past few centuries. From Delhi, you can easily get on a train to Agra to see the Taj Mahal or Jaipur within a few hours. If you’re interested in religious history, you should also check out Amritsar in the northern state of Punjab. This is the heart of Sikhism and is the home of the breathtaking Golden Temple.

Alternatively, an overnight train ride will get you to the lakeside city of Udaipur or the spiritual capital of Varanasi where people deposit the bodies or ashes of their deceased family members in the holy Ganges River.

If you’re willing to brave the overnight bus, you can also head to Rishikesh. Sitting in the foothills of the Himalayas, Rishikesh was the birthplace of yoga and a very popular destination for spiritual and yoga-oriented retreats.

A short flight from Delhi will get you to Mumbai or Calcutta. These two cities were important economic and political centers for the British Raj. This is where you’ll find many colonial-era buildings that look like they could be straight out of London.

Important things to know .

The history of India is very long and complex. As you travel, it’s a good idea to jot things down as you go. This is particularly useful for keeping track of Hinduism’s most important gods and kings.

Also, India can be an extremely stressful and uncomfortable country to travel through. Virtually everywhere you go will be crowded, and it will feel like half of the population is trying to get a photo with you. Rather than stressing out about it, just try and take a deep breath and learn to enjoy the chaos. It will make your experience there much more enjoyable. With a more laid-back attitude, you’re also more likely to see how incredibly kind and welcoming most Indians are and what a great sense of humor they have.

Why go?

When it comes to tourist destinations, Thailand has pretty much everything you could possibly want. With the beaches of Koh Samui, the vibrant nightlife of Bangkok, and the green rolling hills of Chiang Mai, there is something for everyone here. Best of all, it’s full of amazing heritage sites that give a fascinating look into Thailand’s history and culture.

As one of the only countries in Southeast Asia that was never colonized, Thailand doesn’t really have the same European-style architecture that you find in neighboring countries. Bangkok is a vibrant capital city that is as sparkly as they come. The city is also home to incredible palaces and temples, including the famous Wat Pho which holds an enormous reclining Buddha. While you’re there, make sure not to miss the vibrant Grand Palace. We guarantee it’s not like any palace you have ever seen before!

Lying just a short train ride from Bangkok, the former capital city of Ayutthaya. It was once one of the biggest cities in the world with a population of nearly one million people. Today, you’ll find it mostly destroyed but even in its current state, it’s still breathtaking. The complex is famous for its 67 temples and ruins.

In the northern section of the country, Chiang Mai is famous for its myriad of temples. These tell an important story of the impact that Buddhism has had on the local population. This bustling city is the largest urban area in northern Thailand and has been a hub for remote workers and backpackers for decades. It’s a great place to base yourself if you want to enjoy some of Thailand’s gorgeous natural landscapes or visit one of the local hill tribes.

Important things to know.

In the late 90s and early 2000s, Thailand basically exploded onto the tourism scene. This huge influx of mass tourism brought with it a few problems. Sex tourism has become very prevalent and can sometimes include underage people. It also comes with drugs and other social issues. When you travel there, it’s best to avoid any of these things. This not only keeps you out of possible trouble but also shows respect for Thai culture.

New Zealand

New Zealand has long been famous for its beautiful scenery and outdoor activities. Despite its location in the middle of nowhere, they have also managed to develop into one of the world’s bucket list destinations.

There are many reasons to visit the Land of the Long White Cloud. Perhaps one of the world leaders when it comes to cultural heritage tourism, New Zealand proudly embraces its Maori culture, and the government has created many initiatives to help educate people on the country’s history. You will be greeted with a hearty Kia Ora from the moment your flight lands at Auckland Airport, and the opportunities to learn more about the indigenous population are endless.

Where to go?

Most long-haul flights fly into the city of Auckland on New Zealand’s North Island. Although there’s little in the way of historic sites here, a quick visit to the imposing Auckland Museum will teach you some important aspects of Maori culture.

From Auckland, you can take a bus or rent a car to visit various Maori sites located across the North Island. These include the Te Pā Tū Māori Village , the Waitangi Treaty Grounds where one of New Zealand’s founding documents was signed, and the Waipoua Forest, one of the oldest forests in New Zealand which plays an important role in Maori culture.

New Zealand is an amazing destination to visit but it can be painfully expensive to travel through. If you’re traveling on a budget, we highly recommend renting a campervan that you can sleep in. This can help save a lot of money rather than staying in expensive hotel rooms.

It’s hard to think of heritage tourism and not imagine Italy. The ancient ruins of the Coliseum and the Roman Forum stand testament to an advanced society that thrived over two millennia ago. Meanwhile, the Duomo and Uffizi Museum in Florence holds some of the world’s most spectacular art.

One of the great things about traveling through Italy is that it has a little bit of everything. And everything they have is magical. From small towns lined with cobblestone streets that have barely changed for hundreds of years to bustling metropolises that have historic sites hidden behind every corner, there is always something interesting for history buffs to explore. As the icing on the cake, the gastronomic scene is incomparable.

The major cities of Rome, Venice, and Florence should be the first stop on a heritage tourism tour. If you want to focus on smaller towns and villages, you can always visit the spell-binding villages of Cinque Terre National Park or hang around some of the smaller towns of Tuscany. Italy has heritage sites virtually everywhere so you really can’t go wrong! Find out more about exploring this beautiful country on our detailed guide of how to spend a week in Italy !

Italy is full of tourists all year round. However, it’s literally bursting at the seams during the high season. Try to avoid going in the summer if you can. It will make your overall trip much more enjoyable since you won’t be battling crowds or wasting precious vacation time standing in lines.

What other places should you go?

While we’ve provided just a short list of great destinations for heritage tourism, there are still many more! Mexico , Egypt, Morocco, Japan, the Czech Republic, Sudan, and Iran are also all great options. They’re all full of cultural heritage sites that are sure to wow even the most jaded history buff!

Are you ready to roam?

We hope this guide to heritage tourism has left you inspired to take a step back into the past! As always, we would love to hear your feedback, and please let us know of any tips, tricks, or destinations we may have missed!

If you’d like to find more information about these destinations mentioned above, make sure to check out the Let’s Roam Explorer blog . Here you’ll find hundreds of destination guides, must-see lists, and travel blogs that will help make your vacation planning easier. Don’t forget to download the Let’s Roam app before you go. This gives you access to all of our great scavenger hunts , ghost walks, art tours, and pub crawls.

Frequently Asked Questions

The purpose of heritage tourism is to explore the past by visiting archeological sites, museums, and historic attractions. Read more about heritage tourism at the Let’s Roam Explorer blog !

Activities normally associated with heritage tourism could be visiting the ancient ruins of Rome or Mexico , going to a local museum, or even going on a walking tour focusing on unique architecture.

Heritage tourism is different than tourism because it focuses on activities and attractions that are dedicated to preserving the past.

Understanding our heritage is important because it’s easier to understand the world around us. Heritage tourism can play a key role in unlocking the past and bringing it back to life.

If you’re looking for a fascinating heritage tourism destination , look no further than India, Thailand, Italy , New Zealand, Mexico, Morocco, or Egypt!

Featured Products & Activities

UN Tourism | Bringing the world closer

Ethics, Culture and Social Responsibility

- Global Code of Ethics for Tourism

- Accessible Tourism

Tourism and Culture

- Women’s Empowerment and Tourism

share this content

- Share this article on facebook

- Share this article on twitter

- Share this article on linkedin

The convergence between tourism and culture, and the increasing interest of visitors in cultural experiences, bring unique opportunities but also complex challenges for the tourism sector.

“Tourism policies and activities should be conducted with respect for the artistic, archaeological and cultural heritage, which they should protect and pass on to future generations; particular care should be devoted to preserving monuments, worship sites, archaeological and historic sites as well as upgrading museums which must be widely open and accessible to tourism visits”

UN Tourism Framework Convention on Tourism Ethics

Article 7, paragraph 2

This webpage provides UN Tourism resources aimed at strengthening the dialogue between tourism and culture and an informed decision-making in the sphere of cultural tourism. It also promotes the exchange of good practices showcasing inclusive management systems and innovative cultural tourism experiences .

About Cultural Tourism

According to the definition adopted by the UN Tourism General Assembly, at its 22nd session (2017), Cultural Tourism implies “A type of tourism activity in which the visitor’s essential motivation is to learn, discover, experience and consume the tangible and intangible cultural attractions/products in a tourism destination. These attractions/products relate to a set of distinctive material, intellectual, spiritual and emotional features of a society that encompasses arts and architecture, historical and cultural heritage, culinary heritage, literature, music, creative industries and the living cultures with their lifestyles, value systems, beliefs and traditions”. UN Tourism provides support to its members in strengthening cultural tourism policy frameworks, strategies and product development . It also provides guidelines for the tourism sector in adopting policies and governance models that benefit all stakeholders, while promoting and preserving cultural elements.

Recommendations for Cultural Tourism Key Players on Accessibility

UN Tourism , Fundación ONCE and UNE issued in September 2023, a set of guidelines targeting key players of the cultural tourism ecosystem, who wish to make their offerings more accessible.

The key partners in the drafting and expert review process were the ICOMOS International Cultural Tourism Committee and the European Network for Accessible Tourism (ENAT) . The ICOMOS experts’ input was key in covering crucial action areas where accessibility needs to be put in the spotlight, in order to make cultural experiences more inclusive for all people.

This guidance tool is also framed within the promotion of the ISO Standard ISO 21902 , in whose development UN Tourism had one of the leading roles.

Download here the English and Spanish version of the Recommendations.

Compendium of Good Practices in Indigenous Tourism

The report is primarily meant to showcase good practices championed by indigenous leaders and associations from the Region. However, it also includes a conceptual introduction to different aspects of planning, management and promotion of a responsible and sustainable indigenous tourism development.

The compendium also sets forward a series of recommendations targeting public administrations, as well as a list of tips promoting a responsible conduct of tourists who decide to visit indigenous communities.

For downloads, please visit the UN Tourism E-library page: Download in English - Download in Spanish .

Weaving the Recovery - Indigenous Women in Tourism

This initiative, which gathers UN Tourism , t he World Indigenous Tourism Alliance (WINTA) , Centro de las Artes Indígenas (CAI) and the NGO IMPACTO , was selected as one of the ten most promising projects amoung 850+ initiatives to address the most pressing global challenges. The project will test different methodologies in pilot communities, starting with Mexico , to enable indigenous women access markets and demonstrate their leadership in the post-COVID recovery.

This empowerment model , based on promoting a responsible tourism development, cultural transmission and fair-trade principles, will represent a novel community approach with a high global replication potential.

Visit the Weaving the Recovery - Indigenous Women in Tourism project webpage.

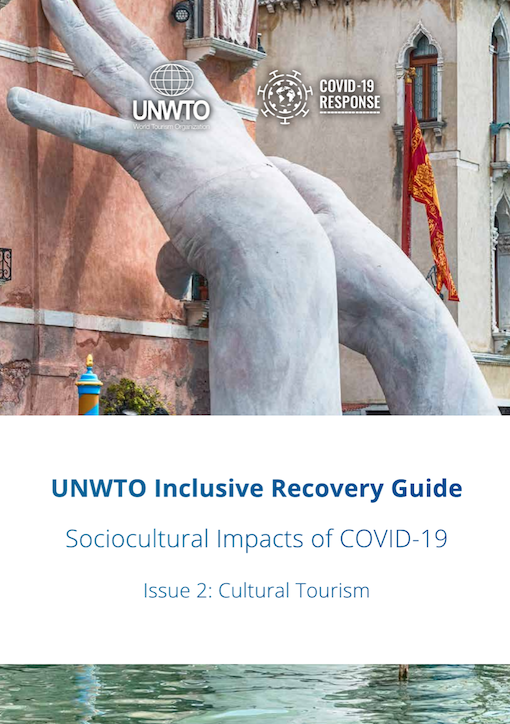

Inclusive Recovery of Cultural Tourism

The release of the guidelines comes within the context of the International Year of Creative Economy for Sustainable Development 2021 , a UN initiative designed to recognize how culture and creativity, including cultural tourism, can contribute to advancing the SDGs.

UN Tourism Inclusive Recovery Guide, Issue 4: Indigenous Communities

Sustainable Development of Indigenous Tourism

The Recommendations on Sustainable Development of Indigenous Tourism provide guidance to tourism stakeholders to develop their operations in a responsible and sustainable manner within those indigenous communities that wish to:

- Open up to tourism development, or

- Improve the management of the existing tourism experiences within their communities.

They were prepared by the UN Tourism Ethics, Culture and Social Responsibility Department in close consultation with indigenous tourism associations, indigenous entrepreneurs and advocates. The Recommendations were endorsed by the World Committee on Tourism Ethics and finally adopted by the UN Tourism General Assembly in 2019, as a landmark document of the Organization in this sphere.

Who are these Recommendations targeting?

- Tour operators and travel agencies

- Tour guides

- Indigenous communities

- Other stakeholders such as governments, policy makers and destinations

The Recommendations address some of the key questions regarding indigenous tourism:

Download PDF:

- Recommendations on Sustainable Development of Indigenous Tourism

- Recomendaciones sobre el desarrollo sostenible del turismo indígena, ESP

UN Tourism/UNESCO World Conferences on Tourism and Culture

The UN Tourism/UNESCO World Conferences on Tourism and Culture bring together Ministers of Tourism and Ministers of Culture with the objective to identify key opportunities and challenges for a stronger cooperation between these highly interlinked fields. Gathering tourism and culture stakeholders from all world regions the conferences which have been hosted by Cambodia, Oman, Türkiye and Japan have addressed a wide range of topics, including governance models, the promotion, protection and safeguarding of culture, innovation, the role of creative industries and urban regeneration as a vehicle for sustainable development in destinations worldwide.

Fourth UN Tourism/UNESCO World Conference on Tourism and Culture: Investing in future generations. Kyoto, Japan. 12-13 December 2019 Kyoto Declaration on Tourism and Culture: Investing in future generations ( English, French, Spanish, Arabic, Russian and Japanese )

Third UN Tourism/UNESCO World Conference on Tourism and Culture : For the Benefit of All. Istanbul, Türkiye. 3 -5 December 2018 Istanbul Declaration on Tourism and Culture: For the Benefit of All ( English , French , Spanish , Arabic , Russian )

Second UN Tourism/UNESCO World Conference’s on Tourism and Culture: Fostering Sustainable Development. Muscat, Sultanate of Oman. 11-12 December 2017 Muscat Declaration on Tourism and Culture: Fostering Sustainable Development ( English , French , Spanish , Arabic , Russian )

First UN Tourism/UNESCO World Conference’s on Tourism and Culture: Building a new partnership. Siem Reap, Cambodia. 4-6 February 2015 Siem Reap Declaration on Tourism and Culture – Building a New Partnership Model ( English )

UN Tourism Study on Tourism and Intangible Cultural Heritage

The first UN Tourism Study on Tourism and Intangible Cultural Heritage provides comprehensive baseline research on the interlinkages between tourism and the expressions and skills that make up humanity’s intangible cultural heritage (ICH).

Through a compendium of case studies drawn from across five continents, the report offers in-depth information on, and analysis of, government-led actions, public-private partnerships and community initiatives.

These practical examples feature tourism development projects related to six pivotal areas of ICH: handicrafts and the visual arts; gastronomy; social practices, rituals and festive events; music and the performing arts; oral traditions and expressions; and, knowledge and practices concerning nature and the universe.

Highlighting innovative forms of policy-making, the UN Tourism Study on Tourism and Intangible Cultural Heritage recommends specific actions for stakeholders to foster the sustainable and responsible development of tourism by incorporating and safeguarding intangible cultural assets.

UN Tourism Study on Tourism and Intangible Cultural Heritage

- UN Tourism Study

- Summary of the Study

Studies and research on tourism and culture commissioned by UN Tourism

- Tourism and Culture Synergies, 2018

- UN Tourism Study on Tourism and Intangible Cultural Heritage, 2012

- Big Data in Cultural Tourism – Building Sustainability and Enhancing Competitiveness (e-unwto.org)

Outcomes from the UN Tourism Affiliate Members World Expert Meeting on Cultural Tourism, Madrid, Spain, 1–2 December 2022

UN Tourism and the Region of Madrid – through the Regional Ministry of Culture, Tourism, and Sports – held the World Expert Meeting on Cultural Tourism in Madrid on 1 and 2 December 2022. The initiative reflects the alliance and common commitment of the two partners to further explore the bond between tourism and culture. This publication is the result of the collaboration and discussion between the experts at the meeting, and subsequent contributions.

Relevant Links

- 3RD UN Tourism/UNESCO WORLD CONFERENCE ON TOURISM AND CULTURE ‘FOR THE BENEFIT OF ALL’

Photo credit of the Summary's cover page: www.banglanatak.com

Take advantage of the search to browse through the World Heritage Centre information.

Sustainable Tourism

UNESCO World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism Programme

The UNESCO World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism Programme represents a new approach based on dialogue and stakeholder cooperation where planning for tourism and heritage management is integrated at a destination level, the natural and cultural assets are valued and protected, and appropriate tourism developed.

World Heritage and tourism stakeholders share responsibility for conservation of our common cultural and natural heritage of Outstanding Universal Value and for sustainable development through appropriate tourism management.

Facilitate the management and development of sustainable tourism at World Heritage properties through fostering increased awareness, capacity and balanced participation of all stakeholders in order to protect the properties and their Outstanding Universal Value.

Focus Areas

Policy & Strategy

Sustainable tourism policy and strategy development.

Tools & Guidance

Sustainable tourism tools

Capacity Building

Capacity building activities.

Heritage Journeys

Creation of thematic routes to foster heritage based sustainable tourism development

A key goal of the UNESCO WH+ST Programme is to strengthen the enabling environment by advocating policies and frameworks that support sustainable tourism as an important vehicle for managing cultural and natural heritage. Developing strategies through broad stakeholder engagement for the planning, development and management of sustainable tourism that follows a destination approach and focuses on empowering local communities is central to UNESCO’s approach.

Supporting Sustainable Tourism Recovery

Enhancing capacity and resilience in 10 World Heritage communities

Supported by BMZ, and implemented by UNESCO in collaboration with GIZ, this 2 million euro tourism recovery project worked to enhance capacity building in local communities, improve resilience and safeguard heritage.

Policy orientations

Defining the relationship between world heritage and sustainable tourism

Based on the report of the international workshop on Advancing Sustainable Tourism at Natural and Cultural Heritage Sites (Mogao, China, September 2009), the World Heritage Committee at its 34th session adopted the policy orientations which define the relationship between World Heritage and sustainable tourism ( Decision 34 COM 5F.2 ).

World Heritage and Tourism in a Changing Climate

Providing an overview of the increasing vulnerability of World Heritage sites to climate change impacts and the potential implications for and of global tourism.

Sustainable Tourism Tools

Manage tourism efficiently, responsibly and sustainably based on the local context and needs

People Protecting Places is the public exchange platform for the World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism Programme, providing education and information, encouraging support, engaging in social and community dialogue

The ' How-To ' guides offer direction and guidance to managers of World Heritage tourism destinations and other stakeholders to help identify the most suitable solutions for circumstances in their local environments and aid in developing general know-how.

English French Russian

Helping site managers and other tourism stakeholders to manage tourism more sustainably

Capacity Building in 4 Africa Nature Sites

A series of practical training and workshops were organized in four priority natural World Heritage sites in Africa (Lesotho, Malawi, South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe) with the aim of providing capacity building tools and strategies for site managers to help them manage tourism at their sites more sustainably.

Learn more →

15 Pilot Sites in Nordic-Baltic Region

The project Towards a Nordic-Baltic pilot region for World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism (2012-2014) was initiated by the Nordic World Heritage Foundation (NWHF). With a practical approach, the project has contributed to tools for assessing and developing sustainable World Heritage tourism strategies with stakeholder involvement and cooperation.

Supporting Community-Based Management and Sustainable Tourism at World Heritage sites in South-East Asia

Entitled “The Power of Culture: Supporting Community-Based Management and Sustainable Tourism at World Heritage sites in South-East Asia", the UNESCO Office in Jakarta with the technical assistance of the UNESCO World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism Programme and the support from the Government of Malaysia is spearheading the first regional effort in Southeast Asia to introduce a new approach to sustainable tourism management at World Heritage sites in Malaysia, the Philippines and Indonesia.

Cultural tourism is one of the largest and fastest-growing global tourism markets. Culture and creative industries are increasingly being used to promote destinations and enhance their competitiveness and attractiveness.

Many locations are now actively developing their cultural assets as a means of developing comparative advantages in an increasingly competitive tourism marketplace, and to create local distinctiveness in the face of globalization.

UNESCO will endeavour to create networks of key stakeholders to coordinate the destination management and marketing associated with the different heritage routes to promote and coordinate high-quality, unique experiences based on UNESCO recognized heritage. The goal is to promote sustainable development based on heritage values and create added tourist value for the sites.

UNESCO World Heritage Journeys of the EU

Creating heritage-based tourism that spurs investment in culture and the creative industries that are community-centered and offer sustainable and high-quality products that play on Europe's comparative advantages and diversity of its cultural assets.

World Heritage Journeys of Buddhist Heritage Sites

UNESCO is currently implementing a project to develop a unique Buddhist Heritage Route for Sustainable Tourism Development in South Asia with the support from the Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA). South Asia is host to rich Buddhist heritage that is exemplified in the World Heritage properties across the region.

Programme Background

In 2011 UNESCO embarked on developing a new World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism Programme.

The aim was to create an international framework for the cooperative and coordinated achievement of shared and sustainable outcomes related to tourism at World Heritage properties.

The preparatory work undertaken in developing the Programme responded to the decision 34 COM 5F.2 of the World Heritage Committee at its 34th session in Brasilia in 2010, which requested

“the World Heritage Centre to convene a new and inclusive programme on World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism, with a steering group comprising interested States Parties and other relevant stakeholders, and also requests the World Heritage Centre to outline the objectives and approach to the implementation of this programme".

The Steering Group was comprised of States Parties representatives from the six UNESCO Electoral Groups (Germany (I), Slovenia (II), Argentina (III), China (IV), Tanzania (Va), and Lebanon (Vb)), the Director of the World Heritage Centre, the Advisory Bodies (IUCN, ICOMOS and ICCROM), the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) and the Swiss Government as the donor agency.

The Government of Switzerland has provided financial support for specific actions to be undertaken by the Steering Group. To coordinate and support the process, the World Heritage Centre has formed a small Working Group with the support of the Nordic World Heritage Foundation, the Government of Switzerland and the mandated external consulting firm MartinJenkins.

The World Heritage Committee directed that the Programme take into account:

- the recommendations of the evaluation of the concluded tourism programme ( WHC-10/34.COM/INF.5F.3 )

- the policy orientation which defines the relationship between World Heritage and sustainable tourism that emerged from the workshop Advancing Sustainable Tourism at Natural and Cultural Heritage Sites (Mogao, China, September 2009) ( WHC-10/34.COM/INF.5F.1 )

Overarching and strategic processes that the new World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism Programme will be aligned with include the Strategic Objectives of the World Heritage Convention (the five C's) ( Budapest Declaration 2002 ), the ongoing Reflections on the Future of the World Heritage Convention ( WHC-11/35.COM/12A ) and the Strategic Action Plan for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention 2012-2022 ( WHC-11/18.GA/11 ), the Relationship between the World Heritage Convention and Sustainable Development (WHC-10/34.COM/5D), the World Heritage Capacity Building Strategy ( WHC-10/34.COM/5D ), the Global Strategy for a Representative, Balanced and Credible World Heritage List (1994), and the Evaluation of the Global Strategy and PACT initiative ( WHC-11/18.GA/8 - 2011 ).

In addition, the programme development process has been enriched by an outreach to representatives from the main stakeholder groups including the tourism sector, national and local governments, site practitioners and local communities. The programme design was further developed at an Expert Meeting in Sils/Engadine, Switzerland October 2011. In this meeting over 40 experts from 23 countries, representing the relevant stakeholder groups, worked together to identify the overall strategic approach and a prioritised set of key objectives and activities. The proposed Programme was adopted by the World Heritage Committee in 2012 at its 36th session in St Petersburg, Russian Federation .

International Instruments

International Instruments Relating to Sustainable Development and Tourism.

Resolutions adopted by the United Nations, charters adopted by ICOMOS, decisions adopted by the World Heritage Committee, legal instruments adopted by UNESCO on heritage preservation.

Resolutions adopted by the United Nations

- Report by the Department of Economics and Social Affairs: Tourism and Sustainable Development: The Global Importance of Tourism at the United Nations’ Commission on Sustainable Development 7th Session (1999)

- Resolution A/RES/56/212 and the Global Code of Ethics for Tourism adopted by the United Nations World Tourism Organization (1999)

Charters adopted by ICOMOS

- The ICOMOS International Cultural Tourism Charter (1999)

- The ICOMOS Charter for the Interpretation and Presentation of Cultural Heritage Sites (2008)

Decisions adopted by the World Heritage Committee

- Decision (XVII.4-XVII.12) adopted by the World Heritage Committee at its 25th Session in Helsinki (2001)

- Decision 33 COM 5A adopted by the World Heritage Committee at its 30th Session in Seville (2009)

- Decision 34 COM 5F.2 adopted by the World Heritage Committee at its 34th Session in Brasilia (2010)

- Decision 36 COM 5E adopted by the World Heritage Committee at its 36th Session in Saint Petersburg (2012)

Legal instruments adopted by UNESCO on heritage preservation in chronological order

- Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property (1970)

- The Recommendation for the Protection of Movable Cultural Property (1978)

- The Recommendation on the Safeguarding of Traditional Culture and Folklore (1989)

- The Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural heritage (2001)

- The Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions (2005)

Other instruments

- Other instruments OECD Tourism Trends and Policies 2012 (French forthcoming)

- Programme on Sustainable Consumption and Production (In English)

- Siem Reap Declaration on Tourism and Culture 2015 – Building a New Partnership Model

Decisions / Resolutions (5)

The World Heritage Committee,

- Having examined Document WHC/18/42.COM/5A,

- Recalling Decision 41 COM 5A adopted at its 41st session (Krakow, 2017) and Decision 40 COM 5D adopted at its 40th session (Istanbul/UNESCO, 2016), General:

- Takes note with appreciation of the activities undertaken by the World Heritage Centre over the past year in pursuit of the Expected Result to ensure that “tangible heritage is identified, protected, monitored and sustainably managed by Member States, in particular through the effective implementation of the 1972 Convention ”, and the five strategic objectives as presented in Document WHC/18/42.COM/5A;

- Welcomes the proactive role of the Secretariat for enhancing synergies between the World Heritage Convention and the other Culture and Biodiversity-related Conventions, particularly the integration of relevant synergies aspects in the revised Periodic Reporting Format and the launch of a synergy-related web page on the Centre’s website;

- Also welcomes the increased collaboration among the Biodiversity-related Conventions through the Biodiversity Liaison Group and focused activities, including workshops, joint statements and awareness-raising;

- Takes note of the Thematic studies on the recognition of associative values using World Heritage criterion (vi) and on interpretation of sites of memory, funded respectively by Germany and the Republic of Korea and encourages all States Parties to take on board their findings and recommendations, in the framework of the identification of sites, as well as management and interpretation of World Heritage properties;

- Noting the discussion paper by ICOMOS on Evaluations of World Heritage Nominations related to Sites Associated with Memories of Recent Conflicts, decides to convene an Expert Meeting on sites associated with memories of recent conflicts to allow for both philosophical and practical reflections on the nature of memorialization, the value of evolving memories, the inter-relationship between material and immaterial attributes in relation to memory, and the issue of stakeholder consultation; and to develop guidance on whether and how these sites might relate to the purpose and scope of the World Heritage Convention , provided that extra-budgetary funding is available and invites the States Parties to contribute financially to this end;

- Also invites the States Parties to support the activities carried out by the World Heritage Centre for the implementation of the Convention ;

- Requests the World Heritage Centre to present, at its 43rd session, a report on its activities. Thematic Programmes:

- Welcomes the progress report on the implementation of the World Heritage Thematic Programmes and Initiatives, notes their important contribution towards implementation of the Global Strategy for representative World Heritage List, and thanks all States Parties, donors and other organizations for having contributed to achieving their objectives;

- Acknowledges the results achieved by the World Heritage Cities Programme and calls States Parties and other stakeholders to provide human and financial resources ensuring the continuation of this Programme in view of its crucial importance for the conservation of the urban heritage inscribed on the World Heritage List, for the implementation of the Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape and its contribution to achieving the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals related to cities as well as for its contribution to the preparation of the New Urban Agenda, and further thanks to China and Croatia for their support for the implementation of the Programme;

- Also acknowledges the results achieved of the World Heritage Marine Programme, also thanks Flanders, France and the Annenberg Foundation for their support, notes the increased focus of the Programme on a global managers network, climate change adaptation strategies and sustainable fisheries, and invites States Parties, the World Heritage Centre and other stakeholders to continue to provide human and financial resources to support for the implementation of the Programme;

- Further acknowledges the results achieved in the implementation of the World Heritage Sustainable Tourism Programme, in particular the development of the Sustainable Tourism and Visitor Management Assessment tool and encourages States Parties to participate in the pilot testing of the tool, expresses appreciation for the funding provided by the European Commission and further thanks the Republic of Korea, Norway, and Seabourn Cruise Line for their support in the implementation of the Programme’’s activities;

- Further notes the progress in the implementation of the Small Island Developing States Programme, its importance for a representative, credible and balanced World Heritage List and building capacity of site managers and stakeholders to implement the World Heritage Convention , thanks furthermore Japan and the Netherlands for their support as well as the International Centre on Space Technology for Natural and Cultural Heritage (HIST) and the World Heritage Institute of Training & Research for the Asia & the Pacific Region (WHITRAP) as Category 2 Centres for their technical and financial supports and also requests the States Parties and other stakeholders to continue to provide human, financial and technical resources for the implementation of the Programme;

- Takes note of the activities implemented jointly by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) and ICOMOS under the institutional guidance of the World Heritage Centre, in line with its Decision 40 COM 5D, further requests the World Heritage Centre to disseminate among the States Parties the second volume of the IAU/ICOMOS Thematic Study on Astronomical Heritage and renames this initiative as Initiative on Heritage of Astronomy, Science and Technology;

- Also takes note of the progress report on the Initiative on Heritage of Religious Interest, endorses the recommendations of the Thematic Expert Consultation meetings focused on Mediterranean and South-Eastern Europe (UNESCO, 2016), Asia-Pacific (Thailand, 2017) and Eastern Europe (Armenia, 2018), thanks the States Parties for their generous contribution and reiterates its invitation to States Parties and other stakeholders to continue to support this Initiative, as well as its associated Marketplace projects developed by the World Heritage Centre;

- Takes note of the activities implemented by CRATerre in the framework of the World Heritage Earthen Architecture Programme, under the overall institutional guidance of the World Heritage Centre, and of the lines of action proposed for the future, if funding is available;

- Invites States Parties, international organizations and donors to contribute financially to the Thematic Programmes and Initiatives as the implementation of thematic priorities is no longer feasible without extra-budgetary funding;

- Requests furthermore the World Heritage Centre to submit an updated result-based report on Thematic Programmes and Initiatives, under Item 5A: Report of the World Heritage Centre on its activities, for examination by the World Heritage Committee at its 44th session in 2020.

1. Having examined document WHC-12/36.COM/5E,

2. Recalling Decision 34 COM 5F.2 adopted at its 34th session (Brasilia, 2010),

3. Welcomes the finalization of the new and inclusive Programme on World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism and notes with appreciation the participatory process for its development, objectives and approach towards implementation;

4. Also welcomes the contribution of the Steering Group comprised of States Parties representatives from the UNESCO Electoral Groups, the World Heritage Centre, the Advisory Bodies (IUCN, ICOMOS, ICCROM), Switzerland and the United Nations World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO) in the elaboration of the Programme;

5. Thanks the Government of Switzerland, the United Nations Foundation and the Nordic World Heritage Foundation for their technical and financial support to the elaboration of the Programme;

6. Notes with appreciation the contribution provided by the States Parties and other consulted stakeholders during the consultation phase of the Programme;

7. Takes note of the results of the Expert Meeting in Sils/Engadin (Switzerland), from 18 to 22 October 2011 contributing to the Programme, and further thanks the Government of Switzerland for hosting the Expert Meeting;

8. Adopts the World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism Programme;

9. Requests the World Heritage Centre to refine the Draft Action Plan 2013-2015 in an Annex to the present document and to implement the Programme with a Steering Group comprised of representatives of the UNESCO Electoral Groups, donor agencies, the Advisory Bodies, UNWTO and in collaboration with interested stakeholders;

10. Notes that financial resources for the coordination and implementation of the Programme do not exist and also requests States Parties to support the implementation of the World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism Programme;

11. Further requests the World Heritage Centre to report biennially on the progress of the implementation of the Programme;

12. Notes with appreciation the launch of the Programme foreseen at the 40th Anniversary of the World Heritage Convention event in Kyoto, Japan, in November 2012

1. Having examined Document WHC-10/34.COM/INF.5F.1 and WHC-10/34.COM/INF.5F.3,

2. Highlighting that the global tourism sector is large and rapidly growing, is diverse and dynamic in its business models and structures, and the relationship between World Heritage and tourism is two way: tourism, if managed well, offers benefits to World Heritage properties and can contribute to cross-cultural exchange but, if not managed well, poses challenges to these properties and recognizing the increasing challenges and opportunities relating to tourism;

3. Expresses its appreciation to the States Parties of Australia, China, France, India, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom, and to the United Nations Foundation and the Nordic World Heritage Foundation for the financial and technical support to the World Heritage Tourism Programme since its establishment in 2001;

4. Welcomes the report of the international workshop on Advancing Sustainable Tourism at Natural and Cultural Heritage Sites (Mogao, China, September 2009) and adopts the policy orientation which defines the relationship between World Heritage and sustainable tourism ( Attachment A );

5. Takes note of the evaluation of the World Heritage Tourism Programme by the UN Foundation, and encourages the World Heritage Centre to take fully into account the eight programme elements recommended in the draft final report in any future work on tourism ( Attachment B );

6. Decides to conclude the World Heritage Tourism Programme and requests the World Heritage Centre to convene a new and inclusive programme on World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism, with a steering group comprising interested States Parties and other relevant stakeholders, and also requests the World Heritage Centre to outline the objectives and approach to implementation of this programme, drawing on the directions established in the reports identified in Paragraphs 4 and 5 above, for consideration at the 35th session of the World Heritage Committee (2011);

7. Also welcomes the offer of the Government of Switzerland to provide financial and technical support to specific activities supporting the steering group; further welcomes the offer of the Governments of Sweden, Norway and Denmark to organize a Nordic-Baltic regional workshop in Visby, Gotland, Sweden in October 2010 on World Heritage and sustainable tourism; and also encourages States Parties to support the new programme on World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism including through regional events and the publication of materials identifying good practices;

8. Based upon the experience gained under the World Heritage Convention of issues related to tourism, invites the Director General of UNESCO to consider the feasibility of a Recommendation on the relationship between heritage conservation and sustainable tourism.

Attachment A

Recommendations of the international workshop

on Advancing Sustainable Tourism at Natural and Cultural Heritage Sites

Policy orientations: defining the relationship between World Heritage and tourism

1. The tourism sector

The global tourism sector is large and rapidly growing, is diverse and dynamic in its business models and structures.

Tourists/visitors are diverse in terms of cultural background, interests, behaviour, economy, impact, awareness and expectations of World Heritage.

There is no one single way for the World Heritage Convention , or World Heritage properties, to engage with the tourism sector or with tourists/visitors.

2. The relationship between World Heritage and tourism

The relationship between World Heritage and tourism is two-way:

a. World Heritage offers tourists/visitors and the tourism sector destinations

b. Tourism offers World Heritage the ability to meet the requirement in the Convention to 'present' World Heritage properties, and also a means to realise community and economic benefits through sustainable use.

Tourism is critical for World Heritage:

a. For States Parties and their individual properties,

i. to meet the requirement in the Convention to 'present' World Heritage

ii. to realise community and economic benefits

b. For the World Heritage Convention as a whole, as the means by which World Heritage properties are experienced by visitors travelling nationally and internationally

c. As a major means by which the performance of World Heritage properties, and therefore the standing of the Convention , is judged,

i. many World Heritage properties do not identify themselves as such, or do not adequately present their Outstanding Universal Value

ii. it would be beneficial to develop indicators of the quality of presentation, and the representation of the World Heritage brand

d. As a credibility issue in relation to: i. the potential for tourism infrastructure to damage Outstanding Universal Value

i. the threat that World Heritage properties may be unsustainably managed in relation to their adjoining communities

ii. sustaining the conservation objectives of the Convention whilst engaging with economic development

iii. realistic aspirations that World Heritage can attract tourism.

World Heritage is a major resource for the tourism sector:

a. Almost all individual World Heritage properties are significant tourism destinations

b. The World Heritage brand can attract tourists/visitors,

i. the World Heritage brand has more impact upon tourism to lesser known properties than to iconic properties.

Tourism, if managed well, offers benefits to World Heritage properties:

a. to meet the requirement in Article 4 of the Convention to present World Heritage to current and future generations

b. to realise economic benefits.

Tourism, if not managed well, poses threats to World Heritage properties.

3. The responses of World Heritage to tourism

The impact of tourism, and the management response, is different for each World Heritage property: World Heritage properties have many options to manage the impacts of tourism.

The management responses of World Heritage properties need to:

a. work closely with the tourism sector

b. be informed by the experiences of tourists/visitors to the visitation of the property

c. include local communities in the planning and management of all aspects of properties, including tourism.

While there are many excellent examples of World Heritage properties successfully managing their relationship to tourism, it is also clear that many properties could improve:

a. the prevention and management of tourism threats and impacts

b. their relationship to the tourism sector inside and outside the property

c. their interaction with local communities inside and outside the property

d. their presentation of Outstanding Universal Value and focus upon the experience of tourists/visitors.

a. be based on the protection and conservation of the Outstanding Universal Value of the property, and its effective and authentic presentation

b. work closely with the tourism sector

c. be informed by the experiences of tourists/visitors to the visitation of the property

d. to include local communities in the planning and management of all aspects of properties, including tourism.

4. Responsibilities of different actors in relation to World Heritage and tourism

The World Heritage Convention (World Heritage Committee, World Heritage Centre, Advisory Bodies):

a. set frameworks and policy approaches

b. confirm that properties have adequate mechanisms to address tourism before they are inscribed on the World Heritage List

i. develop guidance on the expectations to be include in management plans

c. monitor the impact upon OUV of tourism activities at inscribed sites, including through indicators for state of conservation reporting

d. cooperate with other international organisations to enable:

i. other international organisations to integrate World Heritage considerations in their programs

ii. all parties involved in World Heritage to learn from the activities of other international organisations

e. assist State Parties and sites to access support and advice on good practices

f. reward best practice examples of World Heritage properties and businesses within the tourist/visitor sector

g. develop guidance on the use of the World Heritage emblem as part of site branding.

Individual States Parties:

a. develop national policies for protection

b. develop national policies for promotion

c. engage with their sites to provide and enable support, and to ensure that the promotion and the tourism objectives respect Outstanding Universal Value and are appropriate and sustainable

d. ensure that individual World Heritage properties within their territory do not have their OUV negatively affected by tourism.

Individual property managers:

a. manage the impact of tourism upon the OUV of properties

i. common tools at properties include fees, charges, schedules of opening and restrictions on access

b. lead onsite presentation and provide meaningful visitor experiences

c. work with the tourist/visitor sector, and be aware of the needs and experiences of tourists/visitors, to best protect the property

i. the best point of engagement between the World Heritage Convention and the tourism sector as a whole is at the direct site level, or within countries

d. engage with communities and business on conservation and development.

Tourism sector: