- Open access

- Published: 05 January 2021

The relationship between tourism and economic growth among BRICS countries: a panel cointegration analysis

- Haroon Rasool ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0083-4553 1 ,

- Shafat Maqbool 2 &

- Md. Tarique 1

Future Business Journal volume 7 , Article number: 1 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

120k Accesses

85 Citations

13 Altmetric

Metrics details

Tourism has become the world’s third-largest export industry after fuels and chemicals, and ahead of food and automotive products. From last few years, there has been a great surge in international tourism, culminates to 7% share of World’s total exports in 2016. To this end, the study attempts to examine the relationship between inbound tourism, financial development and economic growth by using the panel data over the period 1995–2015 for five BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) countries. The results of panel ARDL cointegration test indicate that tourism, financial development and economic growth are cointegrated in the long run. Further, the Granger causality analysis demonstrates that the causality between inbound tourism and economic growth is bi-directional, thus validates the ‘feedback-hypothesis’ in BRICS countries. The study suggests that BRICS countries should promote favorable tourism policies to push up the economic growth and in turn economic growth will positively contribute to international tourism.

Introduction

World Tourism Day 2015 was celebrated around the theme ‘One Billion Tourists; One Billion Opportunities’ highlighting the transformative potential of one billion tourists. With more than one billion tourists traveling to an international destination every year, tourism has become a leading economic sector, contributing 9.8% of global GDP and represents 7% of the world’s total exports [ 59 ]. According to the World Tourism Organization, the year 2013 saw more than 1.087 billion Foreign Tourist Arrivals and US $1075 billion foreign tourism receipts. The contribution of travel and tourism to gross domestic product (GDP) is expected to reach 10.8% at the end of 2026 [ 61 ]. Representing more than just economic strength, these figures exemplify the vast potential of tourism, to address some of the world´s most pressing challenges, including socio-economic growth and inclusive development.

Developing countries are emerging as the important players, and increasingly aware of their economic potential. Once essentially excluded from the tourism industry, the developing world has now become its major growth area. These countries majorly rely on tourism for their foreign exchange reserves. For the world’s forty poorest countries, tourism is the second-most important source of foreign exchange after oil [ 37 ].

The BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) countries have emerged as a potential bloc in the developing countries which caters the major tourists from developed countries. Tourism becomes major focus at BRICS Xiamen Summit 2017 held in China. These countries have robust growth rate, and are focal destinations for global tourists. During 1990 to 2014, these countries stride from 11% of the world’s GDP to almost 30% [ 17 ]. Among BRICS countries, China is ranked as an important destination followed by Brazil, Russia, India and South Africa [ 60 ].

The importance of inbound tourism has grown exponentially, because of its growing contribution to the economic growth in the long run. It enhances economic growth by augmenting the foreign exchange reserves [ 38 ], stimulating investments in new infrastructure, human capital and increases competition [ 9 ], promoting industrial development [ 34 ], creates jobs and hence to increase income [ 34 ], inbound tourism also generates positive externalities [ 1 , 14 ] and finally, as economy grows, one can argue that growth in GDP could lead to further increase in international tourism [ 11 ].

The tourism-led growth hypothesis (TLGH) proposed by Balaguer and Cantavella-Jorda [ 3 ], states that expansion of international tourism activities exerts economic growth, hence offering a theoretical and empirical link between inbound tourism and economic growth. Theoretically, the TLGH was directly derived from the export-led growth hypothesis (ELGH) that postulates that economic growth can be generated not only by increasing the amount of labor and capital within the economy, but also by expanding exports.

The ‘new growth theory,’ developed by Balassa [ 4 ], suggests that export expansion can trigger economic growth, because it promotes specialization and raises factors productivity by increasing competition, creating positive externalities by advancing the dispersal of specialized information and abilities. Exports also enhance economic growth by increasing the level of investment. International tourism is considered as a non-standard type of export, as it indicates a source of receipts and consumption in situ. Given the difficulties in measuring tourism activity, the economic literature tends to focus on primary and manufactured product exports, hence neglecting this economic sector. Analogous to the ELGH, the TLGH analyses the possible temporal relationship between tourism and economic growth, both in the short and long run. The question is whether tourism activity leads to economic growth or, alternatively, economic expansion drives tourism growth, or indeed a bi-directional relationship exists between the two variables.

To further substantiate the nexus, the study will investigate the plausible linkages between economic growth and international tourism while considering the relative importance of financial development in the context of BRICS nations. Financial markets are considered a key factor in producing strong economic growth, because they contribute to economic efficiency by diverting financial funds from unproductive to productive uses. The origin of this role of financial development may is traced back to the seminal work of Schumpeter [ 50 ]. In his study, Schumpeter points out that the banking system is the crucial factor for economic growth due to its role in the allocation of savings, the encouragement of innovation, and the funding of productive investments. Early works, such as Goldsmith [ 18 ], McKinnon [ 39 ] and Shaw [ 51 ] put forward considerable evidence that financial development enhances growth performance of countries. The importance of financial development in BRICS economies is reflected by the establishment of the ‘New Development Bank’ aimed at financing infrastructure and sustainable development projects in these and other developing countries. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no attempt has been made so far to investigate the long-run relationship Footnote 1 between tourism, financial development and economic growth in case of BRICS countries. Hence, the present study is an attempt to fill the gap in the existing literature.

Review of past studies

From last few decades there has been a surge in the research related to tourism-growth nexus. The importance of growth and development and its determinants has been studied extensively both in developed and developing countries. Extant literature has recognized tourism as an important determinant of economic growth. The importance of tourism has grown exponentially, courtesy to its manifold advantages in form of employment, foreign exchange production household income and government revenues through multiplier effects, improvements in the balance of payments and growth in the number of tourism-promoted government policies [ 21 , 41 , 53 ]. Empirical findings on tourism and economic development have produced mixed finding and sometimes conflicting results despite the common choice of time series techniques as a research methodology. On empirical grounds, four hypotheses have been explored to determine the link between tourism and economic growth [ 12 ]. The first two hypotheses present an account on the unidirectional causality between the two variables, either from tourism to economic growth (Tourism-led economic growth hypothesis-TLGH) or its reserve (economic-driven tourism growth hypothesis-EDTH). The other two hypotheses support the existence of bi-directional hypothesis, (bi-directional causality hypothesis-BC) or that there is no relationship at all (no causality hypothesis-NC), respectively. According to TLEG hypothesis, tourism creates an array of benefits which spillover though multiple routes to promote the economic growth [ 55 ]. In particular, it is believed that tourism (1) increases foreign exchange earnings, which in turn can be used to finance imports [ 38 ], (2) it encourages investment and drives local firms toward greater efficiency due to the increased competition [ 3 , 31 ], (3) it alleviates unemployment, since tourism activities are heavily based on human capital [ 10 ] and (4) it leads to positive economies of scale thus, decreasing production costs for local businesses [ 1 , 14 ]. Other recent studies which find evidence in favor of the TLGH hypothesis include [ 44 , 52 ]. Even though literature is dominated by TLGH, few studies produce a result in support of EDTH [ 40 , 41 , 45 ]. Payne and Mervar [ 45 ] posit that tourism growth of a country is mobilized by the stability of well-designed economic policies, governance structures and investments in both physical and human capital. This positive and vibrant environment creates a series of development activities which proliferate and flourish the tourism. Pertaining to the readily available information, bi-directional causality could also exist between tourism income and economic growth [ 34 , 49 ]. From a policy view, a reciprocal tourism–economic growth relationship implies that government agendas should cater for promoting both areas simultaneously. Finally, there are some studies that do not offer support to any of the aforementioned hypotheses, suggesting that the impact between tourism and economic growth is insignificant [ 25 , 47 , 57 ]. There is a vast literature examining the relationship between tourism and growth as a result, only a selective literature review will be presented here.

Banday and Ismail [ 5 ] used ARDL cointegration model to test the relationship between tourism revenue and economic growth in BRICS countries from the time period of (1995–2013). The study validates the tourism-led growth hypothesis for BRICS countries, which evinces that tourism has positive influence on economic growth.

Savaş et al. [ 54 ] evaluated the tourism-led growth hypothesis in the context of Turkey. The study employed gross domestic product, real exchange rate, real total expenditure and international tourism arrivals to sketch out the causality among variables. The result reveals a unidirectional relationship between tourism and real exchange rate. The findings suggest that tourism is the driving force for economic growth, which in turn helps turkey to culminate its current account deficit.

Dhungel [ 15 ] made an effort to investigate causality between tourism and economic growth, In Nepal for the period of (1974–2012), by using Johansen’s cointegration and Error correction model. The result states that unidirectional causality exists in the long run, while in short run no causality exists between two constructs. The study emphasized that strategies should be devised to attain causality running from tourism to economic growth.

Mallick et al. [ 36 ] analyzed the nexus between economic growth and tourism in 23 Indian states over a period of 14 years (1997–2011). Using panel autoregressive distributed lag model based on three alternative estimators such as mean group estimator, pooled mean group and dynamic fixed effects, Research found that tourism exerts positive influence on economic growth in the long run.

Belloumi [ 8 ] examines the causal relationship between international tourism receipts and economic growth in Tunisia by using annual time series data for the period 1970–2007. The study uses the Johansen’s cointegration methodology to analyze the long-run relationship among the concerned variables. Granger causality based Vector error correction mechanism approach indicates that the revenues generated from tourism have a positive impact on economic growth of Tunisia. Thus, the study supports the hypothesis of tourism-driven economic growth, which is specific to developing countries that base their foreign exchange earnings on the existence of a comparative advantage in certain sectors of the economy.

Tang et al. [ 58 ] explored the dynamic Inter-relationships among tourism, economic growth and energy consumption in India for the period 1971–2012. The study employed Bounds testing approach to cointegration and generalized variance decomposition methods to analyze the relationship. The bounds testing and the Gregory-Hansen test for cointegration with structural breaks consistently reveals that energy consumption, tourism and economic growth in India are cointegrated. The study demonstrated that tourism and economic growth have positive impact on energy consumption, while tourism and economic growth are interrelated; with tourism exert significant influence on economic growth. Consequently, this study validates the tourism-led growth hypothesis in the Indian context.

Kadir and Karim [ 24 ]) examined the causal nexus between tourism and economic growth in Malaysia by applying panel time series approach for the period 1998–2005. By applying Padroni’s panel cointegration test and panel Granger causality test, the result indicated both short and long-run relationship. Further, the panel causality shows unidirectional causality directing from tourism receipts to economic growth. The result provides evidence of the significant contribution of tourism industry to Malaysia’s economic growth, thereby justifying the necessity of public intervention in providing tourism infrastructure and facilities.

Antonakakis et al. [ 2 ] test the linkage between tourism and economic growth in Europe by using a newly introduced spillover index approach. Based on monthly data for 10 European countries over the period 1995–2012, the findings suggested that the tourism–economic growth relationship is not stable over time in terms of both magnitude and direction, indicating that the tourism-led economic growth (TLEG) and the economic-driven tourism growth (EDTG) hypotheses are time-dependent. Thus, the findings of the study suggest that the same country can experience tourism-led economic growth or economic-driven tourism growth at different economic events.

Oh [ 41 ] verifies the contribution of tourism development to economic growth in the Korean economy by applying Engle and Granger two-stage approach and a bivariate Vector Autoregression model. He claimed that economic expansion lures tourists in the short run only, while there is no such long-run stable relationship between international tourism and economic development in Korea.

Empirical studies have pronouncedly focused on the literature that tourism promotes economic growth. To further substantiate the nexus, the study will investigate the plausible linkages between economic growth and international tourism while considering the relative importance of financial development in the context of BRICS nations. The inclusion of financial development in the examination of tourism-growth nexus is a unique feature of this study, which have an influencing role in economic growth as financial development has been theoretically and empirically recognized as source of comparative advantage [ 22 ].

This study employs panel ARDL cointegration approach to verify the existence of long-run association among the variables. Further, study estimated the long-run and short-run coefficients of the ARDL model. Subsequently, Dumitrescu and Hurlin [ 16 ] panel Granger causality test has been employed to check the direction of causality between tourism, financial development and economic growth among BRICS countries.

Database and methodology

Data and variables.

The study is analytical and empirical in nature, which intends to establish the relationship between economic growth and inbound tourism in BRICS countries. For the BRICS countries, limited studies have been conducted depicting the present scenario. Therefore, present study tries to verify the relevance of tourism in economic growth to further enhance the understanding of economic dynamics in BRICS countries. The data used in the study are annual figures for the period stretching from 1995 to 2015, consisting of one endogenous variable (GDP per capita, a proxy for economic growth) and two exogenous variables (international tourism receipts per capita and financial development). The variables employed in the study are based on the economic growth theory, proposed by Balassa [ 4 ], which states that export expansion has a relevant contribution in economic growth. Further, this study incorporates financial development in the model to reduce model misspecification as it is considered to have an influencing role in economic growth both theoretically and empirically [ 22 , 33 ].

The annual data for all the variables have been collected from the World Development Indicators (WDI, 2016) database. The variables used in the study includes gross domestic product per capita (GDP) in constant ($US2010) used as a proxy for economic growth (EG), international tourism receipts per capita (TR) in current US$ as it is widely accepted that the most adequate proxy of inbound tourism in a country is tourism expenditure normally expressed in terms of tourism receipts [ 32 ] and financial development (FD). In line with a recent study on the relationship between financial development and economic growth by Hassan et al. [ 19 ], financial development is surrogated by the ratio of the broad money (M3) to real GDP for all BRICS countries. Here we use the broadest definition of money (M3) as a proportion of GDP– to measure the liquid liabilities of the banking system in the economy. We use M3 as a financial depth indicator, because monetary aggregates, such as M2 or M1, may be a poor proxy in economies with underdeveloped financial systems, because they ‘are more related to the ability of the financial system to provide transaction services than to the ability to channel funds from savers to borrowers’ [ 26 ]. A higher liquidity ratio means higher intensity in the banking system. The assumption here is that the size of the financial sector is positively associated with financial services [ 29 ]. All the variables have been taken into log form.

Unit root test

To verify the long-run relationship between tourism and economic growth through Bounds testing approach, it is necessary to test for stationarity of the variables. The stationarity of all the variables can be assessed by different unit root tests. The study utilizes panel unit root test proposed by Levin et al. [ 35 ] henceforth LLC and Im et al. [ 23 ] henceforth IPS based on traditional augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) test. The LLC allows for heterogeneity of the intercepts across members of the panel under the null hypothesis of presence of unit root, while IPS allows for heterogeneity in intercepts as well as in the slope coefficients [ 48 ].

Panel ARDL approach to Cointegration

After checking the stationarity of the variables the study employs panel ARDL technique for Cointegration developed by Pesaran et al. [ 23 ]. Pesaran et al. [ 23 ] have introduced the pooled mean group (PMG) approach in the panel ARDL framework. According to Pesaran et al. [ 23 ], the homogeneity in the long-run relationship can be attributed to several factors such as arbitration condition, common technologies, or the institutional development which was covered by all groups. The panel ARDL bounds test [ 46 ] is more appropriate by comparing other cointegration techniques, because it is flexible regarding unit root properties of variables. This technique is more suitable when variables are integrated at different orders but not I (2). Haug [ 20 ] has argued that panel ARDL approach to cointegration provides better results for small sample data set such as in our case. The ARDL approach to cointegration estimates both long and short-run parameters and can be applied independently of variable order integration (independent of whether repressors are purely I (0), purely I(1) or combination of both. The ARDL bounds test approach used in this study is specified as follows:

where Δ is the first-difference operator, \(\alpha_{0}\) stands for constant, t is time element, \(\omega_{1} , \omega_{2} \;\;{\text{and}}\;\; \omega_{3}\) represent the short-run parameters of the model, \(\emptyset_{1} , \emptyset_{2} ,and \emptyset_{3}\) are long-run coefficients, while \(V_{it}\) is white noise error term and lastly, it represents country at a particular time period. In the ARDL model, the bounds test is applied to determine whether the variables are cointegrated or not.

This test is based on the joint significance of F -statistic and the χ 2 statistic of the Wald test. The null hypothesis of no cointegration among the variables under study is examined by testing the joint significance of the F -statistic of \(\omega_{1} , \omega_{2} ,\omega_{3}\) .

In case series variables are cointegrated, an error correction mechanism (ECM) can be developed as Eq. ( 2 ), to assess the short-run influence of international tourism and financial development on economic growth.

where ECT is the error correction term, and \(\varPhi\) is its coefficient which shows how fast the variables attain long-term equilibrium if there is any deviation in the short run. The error correction term further confirms the existence of a stable long-run relationship among the variables.

Panel granger causality test

To examine the direction of causality Dumitrescu and Hurlin [ 16 ] test is employed. Instead of pooled causality, Dumitrescu and Hurlin [ 16 ] proposed a causality based on the individual Wald statistic of Granger non-causality averaged across the cross section units. Dumitrescu and Hurlin [ 16 ] assert that traditional test allows for homogeneous analysis across all panel sets, thereby neglecting the specific causality across different units.

This approach allows heterogeneity in coefficients across cross section panels. The two statistics Wbar-statistics and Zbar-statistics provides standardized version of the statistics and is easier to compute. Wbar-statistic, takes an average of the test statistics, while the Zbar-statistic shows a standard (asymptotic) normal distribution.

They proposed an average Wald statistic that tests the null hypothesis of no causality in a panel subgroup against an alternative hypothesis of causality in at least one panel. Following equations will be used to check the direction of causality between the variables.

Estimation, results and Discussion

Descriptive statistics.

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics of variables selected for the period 1995–2015. The variable set includes GDP, FD and TR for all BRICS countries. Brazil tops the list with GDP per capita of 4.18, while India lagging behind all BRICS nations. In the recent economic survey by International Monetary Fund (IMF report 2016), India was ranked 126 for its per capita GDP. India’s GDP per capita went up to $7170 against all other BRICS countries which were placed in the above $10,000 bracket. China has the highest tourism receipts in comparison to other BRICS countries. China is a very popular country for foreign tourists, which ranks third after France and USA. In 2014, China invested $136.8 billion into its tourist infrastructure, a figure second only to the United States ($144.3 billion). Tourism, based on direct, indirect, and induced impact, accounted for near 10% in the GDP of China (WTTC report 2017).

Stationarity results

Primarily, we employed LLC and IPS unit root test to assess the integrated properties of the series. The results of IPS and PP tests are presented in Table 2 . Panel unit root test result evinces that FD and TR are stationary at level, while GDP per capita is integrated variable of order 1. The result exemplifies that GDP per capita, Tourism receipts and Financial Development are integrated at 1(0) and 1(1). Consequently, the panel ARDL approach to cointegration can be applied.

Cointegration test results

In view of the above results with a mixture of order integration, the panel ARDL approach to cointegration is the most appropriate technique to investigate whether there exists a long-run relationship among the variables [ 42 ]. Table 3 illustrates that the estimated value of F-statistics, which is higher than the lower and upper limit of the bound value, when InEG is used as a dependent variable. Hence, we reject the null hypothesis of no cointegration \(H_{0 } : \emptyset_{1} = \emptyset_{2} = \emptyset_{3} = 0\) of Eq. ( 1 ). Therefore, the result asserts that international tourism, financial development and economic growth are significantly cointegrated over the period (1995–2015).

Subsequently, the study investigates the long-run and short-run impact of international tourism and financial development on economic growth. Lag length is selected on the principle of minimum Bayesian information criterion (SBC) value, which is 2 in our case. The long-run coefficients of financial development and tourism receipts with respect to economic growth in Table 4 indicate that tourism growth and financial development exerts positive influence on economic growth in the long run. In other words, an increase in volume of tourism receipts per capita and financial depth spurs economic growth and both the coefficients are statistically significant in case of BRICS nations in the long run. The results are interpreted in detail as below:

The elasticity coefficient of economic growth with respect to tourism shows that 1% rise in international tourism receipts per capita would imply an estimated increase of almost 0.31% domestic real income in the long run, all else remaining the same. Thus, the earnings in the form of foreign exchange from international tourism affect growth performance of BRICS nations positively. This finding of our study is in consonance with the empirical results of Kreishan for Jordan [ 30 ], Balaguer and Cantavella-Jordá [ 3 ] for Spain and Ohlan [ 43 ] for India.

Further our finding lend support to the wide applicability of the new growth theory proposed by Balassa which states that export expansion promote growth performance of nations. Thus, validates TLGH coined by Balaguer and Cantavell-Jorda [ 3 ] which states that inbound tourism acts a long-run economic growth factor. The so called tourism-led growth hypothesis suggests that the development of a country’s tourism industry will eventually lead to higher economic growth and, by extension, further economic development via spillovers and other multiplier effects.

Likewise, financial development as expected is found to be positively associated with economic growth. The coefficient of financial development states that 1% improvement in financial development will push up economic growth by 0.22% in the long run, keeping all other variables constant. The empirical results are consistent with the finding of Hassan et al. [ 19 ] for a panel of South Asian countries. Well-regulated and properly functioning financial development enhances domestic production through savings, borrowings & investment activities and boosts economic growth. Further, it promotes economic growth by increasing efficiency [ 7 ]. Levine [ 33 ] believes that financial intermediaries enhance economic efficiency, and ultimately growth, by helping allocation of capital to its best use. Modern growth theory identifies two specific channels through which the financial sector might affect long-run growth; through its impact on capital accumulation and through its impact on the rate of technological progress. The sub-prime crisis which depressed the economic growth worldwide in 2007 further substantiates the growth-financial development nexus.

In the third and final step of the bounds testing procedure, we estimate short-run dynamics of variables by estimating an error correction model associated with long-run estimates. The empirical finding indicates that the coefficient of error correction term (ECT) with one period lag is negative as well as statistically significant. This finding further substantiates the earlier cointegration results between tourism, financial development and economic growth, and indicates the speed of adjustment from the short-run toward long-run equilibrium path. The coefficient of ECT reveals that the short-run divergences in economic growth from long-run equilibrium are adjusted by 43% every year following a short-run shock.

The short-run parameters in Table 5 demonstrates that tourism and financial development acts as an engine of economic growth in the short run as well. The coefficient of both tourism receipts per capita and financial development with one period lag is also found to be progressive and significant in the short run. These results highlight the role of earnings from international tourism and financial stability as an important driving force of economic growth in BRICS nations in the short run as well.

Further, a comparison between short-run and long-run elasticity coefficients evince that long-run responsiveness of economic growth with respect to tourism and financial development is higher than that of short run. It exemplifies that over time higher international tourism receipts and well-regulated financial system in BRICS nations give more boost to economic growth.

Analysis of causality

At this stage, we investigate the causality between tourism, financial development and economic growth presented in Table 6 . The result shows bi-directional causal relationship between tourism and economic growth, thereby validates ‘feedback hypothesis’ and consequently supported both the tourism-led growth hypothesis (TLGH) and its reciprocal, the economic-driven tourism growth hypothesis (EDTH). The bi-directional causality between inbound tourism and GDP, which directs the level of economic activity and tourism growth, mutually influences each other in that a high volume of tourism growth leads to a high level of economic development and reverse also holds true. These results replicate the findings of Banday and Ismail [ 5 ] in the context of BRICS countries, Yazdi et al. [ 27 ] for Iran and Kim et al. [ 28 ] for Taiwan. One of the channels through which tourism spurs economic growth is through the use of receipts earned in the form of foreign currency. Thus, growth in foreign earnings may allow the import of technologically advances goods that will favor economic growth and vice versa. Thus, results demonstrate that international tourism promotes growth and in turn economic expansion is necessary for tourism development in case of BRICS countries. With respect to policy context, this finding suggests that the BRICS nations should focus on economic policies to promote tourism as a potential source of economic growth which in turn will further promote tourism growth.

Similarly, in case of economic growth and financial development, the findings demonstrate the presence of bi-directional causality between two constructs. The findings validate thus both ‘demand following’ and supply leading’ hypothesis. The findings suggests that indeed financial development plays a crucial role in promoting economic activity and thus generating economic growth for these countries and reverse also holds. Our findings are in line with Pradhan [ 48 ] in case of BRICS countries and Hassan et al. [ 19 ] for low and middle-income countries. This suggests that finance development can be used as a policy variable to foster economic growth in the five BRICS countries and vice versa. The study emphasizes that the current economic policies should recognize the finance-growth nexus in BRICS in order to maintain sustainable economic development in the economy. The empirical results in this paper are in line with expectations, confirming that the emerging economies of the BRICS are benefiting from their finance sectors.

Finally, two-sided causal relationship is found between tourism receipts and financial development. That is, tourism might contribute to financial development and, in return, financial development may positively contribute to tourism. This means that financial depth and tourism in BRICS have a reinforcing interaction. The positive impact of tourism on financial development can be attributed to the fact that inflows of foreign exchange via international tourism not only increases income levels but also leads to rise in official reserves of central banks. This in turn enables central banks to adapt expansionary monetary policy. The positive contribution of financial sector to tourism is further characterized by supply leading hypothesis. Further, better financial and market conditions will attract tourism entrepreneurship, because firms will be able to use more capital instead of being forced to use leveraging [ 13 ]. Hence, any shocks in money supply could adversely affect tourism industry in these countries. Song and Lin [ 56 ] found that global financial crisis had a negative impact on both inbound and outbound tourism in Asia. This result is in consistent with Başarir and Çakir [ 6 ] for Turkey and four European countries.

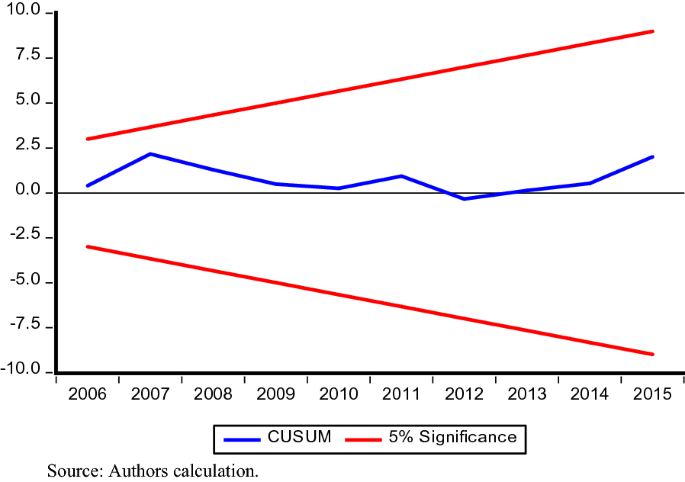

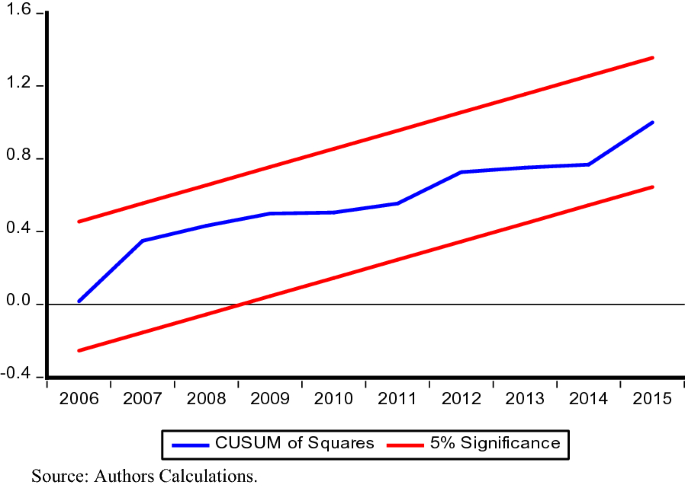

Stability tests

In addition, to test the stability of parameters estimated and any structural break in the model CUSUM and CUSUMSQ tests are employed. Figs. 1 and 2 show blue line does not transcend red lines in both the tests, thus provides strong evidence that our estimated model is fit and valid policy implications can be drawn from the results.

Plot of CUSUM

Plot of CUSUMQ

Summary and concluding remarks

A rigorous study of the relationship between tourism and economic growth, through the tourism-led growth hypothesis (TLGH) perspective has remained a debatable issue in the economic growth literature. This study aims to empirically investigate the relationship between inbound tourism, financial development and economic growth in BRICS countries by utilizing the panel data over the period 1995–2015. The study employs the panel ARDL approach to cointegration and Dumitrescu-Hurlin panel Granger causality test to detect the direction of causation.

To the best of authors’ knowledge, this is the first study which explored the relationship between economic growth and tourism while considering the relative importance of financial development in the context of BRICS nations. The empirical results of ARDL model posits that in BRICS countries inbound tourism, financial development and economic growth are significantly cointegrated, i.e., variables have stable long-run relationship. This methodology has allowed obtaining elasticities of economic growth with respect to tourism and financial development both in the long run and short run. The result reveals that international tourism growth and financial development positively affects economic growth both in the long run and short run. The coefficient of tourism indicates that with a 1% rise in tourism receipts per capita, GDP per capita of BRICS economies will go up by 0.31% in the long run. This finding lends support to TLGH coined by Balaguer and Cantavell-Jorda [ 3 ] which states that inbound tourism acts a long-run economic growth factor. The so called tourism-led growth hypothesis suggests that the development of a country’s tourism industry will eventually lead to higher economic growth and, by extension, further economic development via spillovers and other multiplier effects.

Likewise, 1% improvement in financial development, on average, will increase economic growth in BRICS countries by 0.22% in the long run. The result seems logical as modern growth theory identifies two channels through which the financial sector might affect long-run growth: first, through its impact on capital accumulation and secondly, through its impact on the rate of technological progress. The sub-prime crisis which hit the economic growth Worldwide in 2007 further substantiates the growth-financial development nexus.

The negative and statistically significant coefficient of lagged error correction term (ECT) further substantiates the long-run equilibrium relationship among variables. The negative coefficient of ECT also shows the speed of adjustment toward long-run equilibrium is 43% per annum if there is any short-run deviation. The estimates of parameters are found to be stable by applying CUSUM and CUSUMQ for the time period under consideration. Therefore, inbound tourism earnings and financial institutions can be used as a channel to increase economic growth in BRICS economies.

Further, Granger causality test result indicates the bi-directional causation in all cases. Hence, the causal relationship between international tourism and economic growth is bi-directional. And, consequently this empirical finding lends support to both the tourism-led growth hypothesis (TLGH) and its reciprocal, the economic-driven tourism growth hypothesis (EDTH). This means that tourism is not only an engine for economic growth, but the economic outcome on itself can play an important role in providing growth potential to tourism sector.

The Granger causality findings provide useful information to governments to examine their economic policy, to adjust priorities regarding economic investment, and boost their economic growth with the given limited resources. Thus, it is suggested that more resources should be allocated to tourism industry and tourism-related industries if the tourism-led growth hypothesis holds true. On the other side, if economic-driven tourism growth is supported then more resources should be diverted to leading industries rather than the travel and tourism sector, and the tourism industry will in turn benefit from the resulting overall economic growth. And, when bi-directional causality is detected, a balanced allocation of economic resources for the travel and tourism sector and other industries is important and necessary. The policy implication is that resource allocation supporting both the tourism and tourism-related industries could benefit both tourism development and economic growth.

To sum up, the major finding of this study lends support to wide applicability of the tourism-led growth hypothesis in case of BRICS countries. Thus, in the Policy context, significant impact of tourism on BRICS economy rationalizes the need of encouraging tourism. Tourism can spur economic prosperity in these countries and for this reason; policymakers should give serious consideration toward encouraging tourism industry or inbound tourism. BRICS countries should focus more on tourism infrastructure, such as, convenient transportation, alluring destinations, suitable tax incentives, viable hostels and proper security arrangements to attract the potential tourists. Most of these countries are devoid of rich facilities and popular tourist incentives, to get promoted as important destination and in the long-run promotes economic growth. Further, they need a staunch support from all sections of authorities, non-government organizations (NGOs), and private and allied industries, in the endeavor to attain sustainable growth in tourism. Both state and non-state actors must recognize this growing industry and its positive implication on economy.

For future research, we suggest that researchers should consider the nonlinear factor in the dynamic relationship of tourism and economic growth in case of BRICS countries. Further one can go for comparative study to examine the TLGH in BRICS countries.

Availability of data and materials

Data used in the study can be provided by the corresponding author on request.

There are no fixed definitions of short, medium and long run and generally in macroeconomics, short run can be viewed as 1 to 2 or 3 years, medium up to 5 years and long run from 5 years to 20 or 25 years.

Abbreviations

autoregressive distributed lag model

Brazil, Russia, India, China and South-Africa

United Nations World Tourism Organization

World Travel & Tourism Council

gross domestic product

world development indicators

tourism-led growth hypothesis

export-led growth hypothesis

economic-driven tourism hypothesis

augmented Dickey–Fuller test

error correction model

error correction term

Andriotis K (2002) Scale of hospitality firms and local economic development—evidence from Crete. Tourism Manag 23(4):333–341

Google Scholar

Antonakakis N, Dragouni M, Filis G (2015) How strong is the linkage between tourism and economic growth in Europe? Econ Modell 44:142–155

Balaguer J, Cantavella-Jorda M (2002) Tourism as a long-run economic growth factor: the Spanish case. Appl Econ 34(7):877–884

Balassa B (1978) Exports and economic growth: further evidence. J Dev Econ 5(2):181–189

Banday UJ, Ismail S (2017) Does tourism development lead positive or negative impact on economic growth and environment in BRICS countries? A panel data analysis. Econ Bull 37(1):553–567

Basarir C, Çakir YN (2015) Causal interactions between CO 2 emissions, financial development, energy and tourism. Asian Econ Financ Rev 5(11):1227

Bell C, Rousseau PL (2001) Post-independence India: a case of finance-led industrialization? J Dev Econ 65(1):153–175

Belloumi M (2010) The relationship between tourism receipts, real effective exchange rate and economic growth in Tunisia. Int J Tour Res 12(5):550–560

Blake A, Sinclair MT, Soria JAC (2006) Tourism productivity: evidence from the United Kingdom. Ann Tourism Res 33(4):1099–1120

Brida JG, Pulina M (2010) A literature review on the tourism-led-growth hypothesis. Working paper CRENoS201017. Centre for North South Economic Research, Sardinia

Brida JG, Cortes-Jimenez I, Pulina M (2016) Has the tourism-led growth hypothesis been validated? A literature review. Curr Issues Tourism 19(5):394–430

Chatziantoniou I, Filis G, Eeckels B, Apostolakis A (2013) Oil prices, tourism income and economic growth: a structural VAR approach for European Mediterranean countries. Tourism Manag 36:331–341

Chen M-H (2010) The economy, tourism growth and corporate performance in the Taiwanese hotel industry. Tourism Manag 31:665–675

Croes R (2006) A paradigm shift to a new strategy for small island economies: embracing demand side economics for value enhancement and long term economic stability. Tourism Manag 27:453–465

Dhungel KR (2015) An econometric analysis on the relationship between tourism and economic growth: empirical evidence from Nepal. Int J Econ Financ Manag 3(2):84–90

Dumitrescu EI, Hurlin C (2012) Testing for Granger non-causality in heterogeneous panels. Econ Modell 29(4):1450–1460

Daniel Mminele (2016) The role of BRICS in the global economy. Speech at the Bundesbank Regional Office in North Rhine-Westphalia, Düsseldorf, Germany. https://www.bis.org/review/r160720c.pdf

Goldsmith RW (1969) Financial structure and development (No. HG174 G57)

Hassan MK, Sanchez B, Yu JS (2011) Financial development and economic growth: new evidence from panel data. Quart Rev Econ Financ 51(1):88–104

Haug AA (2002) Temporal aggregation and the power of cointegration tests: A Monte Carlo study. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 64:399–412

Henry EW, Deane B (1997) The contribution of tourism to the economy of Ireland in 1990 and 1995. Tourism Manag 18(8):535–553

Hur J, Raj M, Riyanto YE (2006) Finance and trade: a cross-country empirical analysis on the impact of financial development and asset tangibility on international trade. World Dev 34(10):1728–1741

Im KS, Pesaran MH, Shin Y (2003) Testing for unit roots in heterogeneous panels. J Econ 115(1):53–74

Kadir N, Karim MZA (2012) Tourism and economic growth in Malaysia: evidence from tourist arrivals from Asean-S countries. Econ Res Ekonomska istraživanja 25(4):1089–1100

Katircioglu S (2009) Testing the tourism-led growth hypothesis: the case of Malta. Acta Oeconomica 59(3):331–343

Khan M, Senhadji A (2003) Financial development and economic growth: a review and new evidence. J Afr Econ 12:89–110

Khoshnevis Yazdi S, Homa Salehi K, Soheilzad M (2017) The relationship between tourism, foreign direct investment and economic growth: evidence from Iran. Curr Issues Tourism 20(1):15–26

Kim HJ, Chen MH (2006) Tourism expansion and economic development: the case of Taiwan. Tourism Manag 27(5):925–933

King R, Levine R (1993) Finance, entrepreneurship, and growth: theory and evidence. J Monet Econ 32:513–542

Kreishan FM (2010) Tourism and economic growth: the case of Jordan. Eur J Soc Sci 15:229–234

Krueger A (1980) Trade policy as an input to development. Am Econ Rev 70:188–292

Kumar RR (2014) Exploring the role of technology, tourism and financial development: an empirical study of Vietnam. Qual Quant 48(5):2881–2898

Levine R (1997) Financial development and economic growth: views and agenda. J Econ Lit 35(2):688–726

Lee CC, Chang CP (2008) Tourism development and economic growth: a closer look at panels. Tourism Manag 29(1):180–192

Levin A, Lin CF, Chu CSJ (2002) Unit root tests in panel data: asymptotic and finite-sample properties. J Econ 108(1):1–24

Mallick L, Mallesh U, Behera J (2016) Does tourism affect economic growth in Indian states? Evidence from panel ARDL model. Theor Appl Econ 23(1):183–194

Mastny L (2001) Treading lightly: new paths for international tourism. In: Peterson JA (ed) World Watch Paper 159. World Watch Institute

McKinnon RI (1964) Foreign exchange constraints in economic development and efficient aid allocation. Econ J 74(294):388–409

McKinnon RI (1973) Money and capital in economic development. The Brookings Institution, Washington

Narayan PK (2004) Economic impact of tourism on Fiji’s economy: empirical evidence from the computable general equilibrium model. Tourism Econ 10(4):419–433

Oh CO (2005) The contribution of tourism development to economic growth in the Korean economy. Tourism Manag 26(1):39–44

Ohlan R (2015) The impact of population density, energy consumption, economic growth and trade openness on CO 2 emissions in India. Nat Hazards 79(2):1409–1428

Ohlan R (2017) The relationship between tourism, financial development and economic growth in India. Future Bus J 3(1):9–22

Parrilla JC, Font AR, Nadal JR (2007) Tourism and long-term growth a Spanish perspective. Ann Tourism Res 34(3):709–726

Payne JE, Mervar A (2010) Research note: the tourism-growth nexus in Croatia. Tourism Econ 16(4):1089–1094

Pesaran MH, Shin Y, Smith RJ (2001) Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. J Appl Econ 16(3):289–326

Po WC, Huang BN (2008) Tourism development and economic growth—a nonlinear approach. Phys A Stat Mech Appl 387(22):5535–5542

Pradhan RP, Dasgupta P, Bele S (2013) Finance, development and economic growth in BRICS: a panel data analysis. J Quant Econ 11(1–2):308–322

Ridderstaat J, Oduber M, Croes R, Nijkamp P, Martens P (2014) Impacts of seasonal patterns of climate on recurrent fluctuations in tourism demand: evidence from Aruba. Tourism Manag 41:245–256

Schumpeter JA (1911) The theory of economic development: an inquiry into profits, capital, credit, interest, and the business cycle. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, p 1934

Shaw ES (1973) Financial deepening in economic development. Oxford University Press, London

Sugiyarto G, Blake A, Sinclair MT (2003) Tourism and globalization: economic impact in Indonesia. Ann Tourism Res 30(3):683–701

Szivas E, Riley M (1999) Tourism employment during economic transition. Ann Tourism Res 26(4):747–771

Savaş B, Beşkaya A, Şamiloğlu F (2010) Analyzing the impact of international tourism on economic growth in Turkey. Uluslararası Yönetim İktisat ve İşletme Dergisi 6(12):121–136

Schubert SF, Brida JG, Risso WA (2011) The impacts of international tourism demand on economic growth of small economies dependent on tourism. Tourism Manag 32(2):377–385

Song H, Lin S (2010) Impacts of the financial and economic crisis on tourism in Asia. J Travel Res 49(1):16–30

Tang CF (2013) Temporal Granger causality and the dynamics relationship between real tourism receipts, real income and real exchange rates in Malaysia. Int J Tourism Res 15(3):272–284

Tang CF, Tiwari AK, Shahbaz M (2016) Dynamic inter-relationships among tourism, economic growth and energy consumption in India. Geosyst Eng 19(4):158–169

United Nations World Tourism Report (2014) Annual report 2014

World Travel & Tourism Council (2012) Travel & Tourism Economic Impact. World, London: World Travel & Tourism Council.

World Travel and Tourism Council (2016) Global travel and tourism economic impact update August 2016

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

This research has received no specific funding.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Economics, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, India

Haroon Rasool & Md. Tarique

Department of Commerce, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, India

Shafat Maqbool

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

HR has written introduction, research methodology and results and discussion part. Review of literature and data analysis was done by SM. Conclusion was written jointly by HR and SM. MT has provided useful inputs and finalized the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Haroon Rasool .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

Authors declare that there are no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Rasool, H., Maqbool, S. & Tarique, M. The relationship between tourism and economic growth among BRICS countries: a panel cointegration analysis. Futur Bus J 7 , 1 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43093-020-00048-3

Download citation

Received : 02 August 2019

Accepted : 30 November 2020

Published : 05 January 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s43093-020-00048-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Economic growth

- Inbound tourism

- Financial development

- Cointegration

- Panel granger causality

JEL Classification

10 Economic impacts of tourism + explanations + examples

Disclaimer: Some posts on Tourism Teacher may contain affiliate links. If you appreciate this content, you can show your support by making a purchase through these links or by buying me a coffee . Thank you for your support!

There are many economic impacts of tourism, and it is important that we understand what they are and how we can maximise the positive economic impacts of tourism and minimise the negative economic impacts of tourism.

Many argue that the tourism industry is the largest industry in the world. While its actual value is difficult to accurately determine, the economic potential of the tourism industry is indisputable. In fact, it is because of the positive economic impacts that most destinations embark on their tourism journey.

There is, however, more than meets the eye in most cases. The positive economic impacts of tourism are often not as significant as anticipated. Furthermore, tourism activity tends to bring with it unwanted and often unexpected negative economic impacts of tourism.

In this article I will discuss the importance of understanding the economic impacts of tourism and what the economic impacts of tourism might be. A range of positive and negative impacts are discussed and case studies are provided.

At the end of the post I have provided some additional reading on the economic impacts of tourism for tourism stakeholders , students and those who are interested in learning more.

Foreign exchange earnings

Contribution to government revenues, employment generation, contribution to local economies, development of the private sector, infrastructure cost, increase in prices, economic dependence of the local community on tourism, foreign ownership and management, economic impacts of tourism: conclusion, further reading on the economic impacts of tourism, the economic impacts of tourism: why governments invest.

Tourism brings with it huge economic potential for a destination that wishes to develop their tourism industry. Employment, currency exchange, imports and taxes are just a few of the ways that tourism can bring money into a destination.

In recent years, tourism numbers have increased globally at exponential rates, as shown in the World Tourism Organisation data below.

There are a number of reasons for this growth including improvements in technology, increases in disposable income, the growth of budget airlines and consumer desires to travel further, to new destinations and more often.

Here are a few facts about the economic importance of the tourism industry globally:

- The tourism economy represents 5 percent of world GDP

- Tourism contributes to 6-7 percent of total employment

- International tourism ranks fourth (after fuels, chemicals and automotive products) in global exports

- The tourism industry is valued at US$1trillion a year

- Tourism accounts for 30 percent of the world’s exports of commercial services

- Tourism accounts for 6 percent of total exports

- 1.4billion international tourists were recorded in 2018 (UNWTO)

- In over 150 countries, tourism is one of five top export earners

- Tourism is the main source of foreign exchange for one-third of developing countries and one-half of less economically developed countries (LEDCs)

There is a wealth of data about the economic value of tourism worldwide, with lots of handy graphs and charts in the United Nations Economic Impact Report .

In short, tourism is an example of an economic policy pursued by governments because:

- it brings in foreign exchange

- it generates employment

- it creates economic activity

Building and developing a tourism industry, however, involves a lot of initial and ongoing expenditure. The airport may need expanding. The beaches need to be regularly cleaned. New roads may need to be built. All of this takes money, which is usually a financial outlay required by the Government.

For governments, decisions have to be made regarding their expenditure. They must ask questions such as:

How much money should be spent on the provision of social services such as health, education, housing?

How much should be spent on building new tourism facilities or maintaining existing ones?

If financial investment and resources are provided for tourism, the issue of opportunity costs arises.

By opportunity costs, I mean that by spending money on tourism, money will not be spent somewhere else. Think of it like this- we all have a specified amount of money and when it runs out, it runs out. If we decide to buy the new shoes instead of going out for dinner than we might look great, but have nowhere to go…!

In tourism, this means that the money and resources that are used for one purpose may not then be available to be used for other purposes. Some destinations have been known to spend more money on tourism than on providing education or healthcare for the people who live there, for example.

This can be said for other stakeholders of the tourism industry too.

There are a number of independent, franchised or multinational investors who play an important role in the industry. They may own hotels, roads or land amongst other aspects that are important players in the overall success of the tourism industry. Many businesses and individuals will take out loans to help fund their initial ventures.

So investing in tourism is big business, that much is clear. What what are the positive and negative impacts of this?

Positive economic impacts of tourism

So what are the positive economic impacts of tourism? As I explained, most destinations choose to invest their time and money into tourism because of the positive economic impacts that they hope to achieve. There are a range of possible positive economic impacts. I will explain the most common economic benefits of tourism below.

One of the biggest benefits of tourism is the ability to make money through foreign exchange earnings.

Tourism expenditures generate income to the host economy. The money that the country makes from tourism can then be reinvested in the economy. How a destination manages their finances differs around the world; some destinations may spend this money on growing their tourism industry further, some may spend this money on public services such as education or healthcare and some destinations suffer extreme corruption so nobody really knows where the money ends up!

Some currencies are worth more than others and so some countries will target tourists from particular areas. I remember when I visited Goa and somebody helped to carry my luggage at the airport. I wanted to give them a small tip and handed them some Rupees only to be told that the young man would prefer a British Pound!

Currencies that are strong are generally the most desirable currencies. This typically includes the British Pound, American, Australian and Singapore Dollar and the Euro .

Tourism is one of the top five export categories for as many as 83% of countries and is a main source of foreign exchange earnings for at least 38% of countries.

Tourism can help to raise money that it then invested elsewhere by the Government. There are two main ways that this money is accumulated.

Direct contributions are generated by taxes on incomes from tourism employment and tourism businesses and things such as departure taxes.

Taxes differ considerably between destinations. I will never forget the first time that I was asked to pay a departure tax (I had never heard of it before then), because I was on my way home from a six month backpacking trip and I was almost out of money!

Japan is known for its high departure taxes. Here is a video by a travel blogger explaining how it works.

According to the World Tourism Organisation, the direct contribution of Travel & Tourism to GDP in 2018 was $2,750.7billion (3.2% of GDP). This is forecast to rise by 3.6% to $2,849.2billion in 2019.

Indirect contributions come from goods and services supplied to tourists which are not directly related to the tourism industry.

Take food, for example. A tourist may buy food at a local supermarket. The supermarket is not directly associated with tourism, but if it wasn’t for tourism its revenues wouldn’t be as high because the tourists would not shop there.

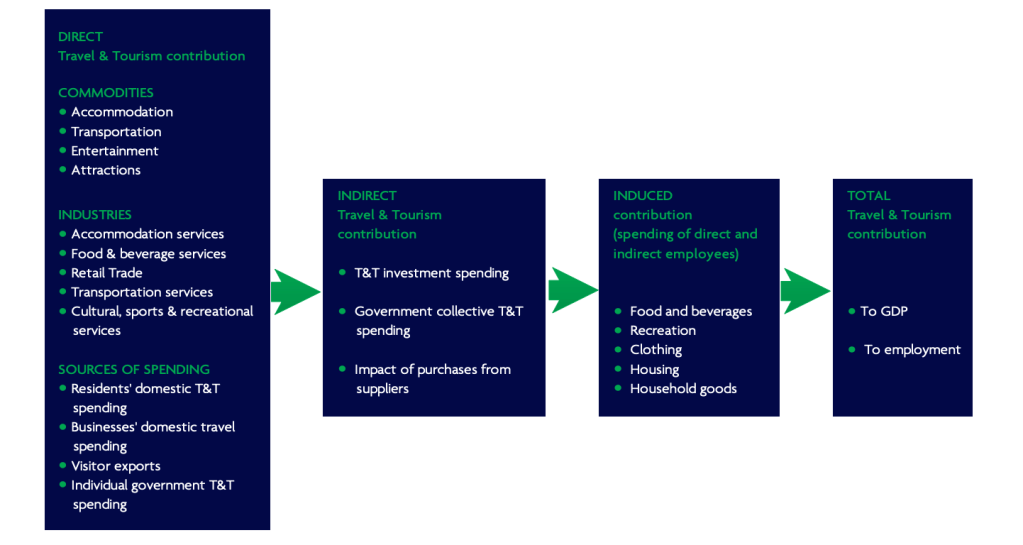

There is also the income that is generated through induced contributions . This accounts for money spent by the people who are employed in the tourism industry. This might include costs for housing, food, clothing and leisure Activities amongst others. This will all contribute to an increase in economic activity in the area where tourism is being developed.

The rapid expansion of international tourism has led to significant employment creation. From hotel managers to theme park operatives to cleaners, tourism creates many employment opportunities. Tourism supports some 7% of the world’s workers.

There are two types of employment in the tourism industry: direct and indirect.

Direct employment includes jobs that are immediately associated with the tourism industry. This might include hotel staff, restaurant staff or taxi drivers, to name a few.

Indirect employment includes jobs which are not technically based in the tourism industry, but are related to the tourism industry. Take a fisherman, for example. He does not have any contact of dealings with tourists. BUT he does sell his fish to the hotel which serves tourists. So he is indirectly employed by the tourism industry, because without the tourists he would not be supplying the fish to the hotel.

It is because of these indirect relationships, that it is very difficult to accurately measure the economic value of tourism.

It is also difficult to say how many people are employed, directly and indirectly, within the tourism industry.

Furthermore, many informal employments may not be officially accounted for. Think tut tut driver in Cambodia or street seller in The Gambia – these people are not likely to be registered by the state and therefore their earnings are not declared.

It is for this reason that some suggest that the actual economic benefits of tourism may be as high as double that of the recorded figures!

All of the money raised, whether through formal or informal means, has the potential to contribute to the local economy.

If sustainable tourism is demonstrated, money will be directed to areas that will benefit the local community most.

There may be pro-poor tourism initiatives (tourism which is intended to help the poor) or volunteer tourism projects.

The government may reinvest money towards public services and money earned by tourism employees will be spent in the local community. This is known as the multiplier effect.

The multiplier effect relates to spending in one place creating economic benefits elsewhere. Tourism can do wonders for a destination in areas that may seem to be completely unrelated to tourism, but which are actually connected somewhere in the economic system.

Let me give you an example.

A tourist buys an omelet and a glass of orange juice for their breakfast in the restaurant of their hotel. This simple transaction actually has a significant multiplier effect. Below I have listed just a few of the effects of the tourist buying this breakfast.

The waiter is paid a salary- he spends his salary on schooling for his kids- the school has more money to spend on equipment- the standard of education at the school increases- the kids graduate with better qualifications- as adults, they secure better paying jobs- they can then spend more money in the local community…

The restaurant purchases eggs from a local farmer- the farmer uses that money to buy some more chickens- the chicken breeder uses that money to improve the standards of their cages, meaning that the chickens are healthier, live longer and lay more eggs- they can now sell the chickens for a higher price- the increased money made means that they can hire an extra employee- the employee spends his income in the local community…

The restaurant purchase the oranges from a local supplier- the supplier uses this money to pay the lorry driver who transports the oranges- the lorry driver pays road tax- the Government uses said road tax income to fix pot holes in the road- the improved roads make journeys quicker for the local community…

So as you can see, that breakfast that the tourist probably gave not another thought to after taking his last mouthful of egg, actually had the potential to have a significant economic impact on the local community!

The private sector has continuously developed within the tourism industry and owning a business within the private sector can be extremely profitable; making this a positive economic impact of tourism.

Whilst many businesses that you will come across are multinational, internationally-owned organisations (which contribute towards economic leakage ).

Many are also owned by the local community. This is the case even more so in recent years due to the rise in the popularity of the sharing economy and the likes of Airbnb and Uber, which encourage the growth of businesses within the local community.

Every destination is different with regards to how they manage the development of the private sector in tourism.

Some destinations do not allow multinational organisations for fear that they will steal business and thus profits away from local people. I have seen this myself in Italy when I was in search of a Starbucks mug for my collection , only to find that Italy has not allowed the company to open up any shops in their country because they are very proud of their individually-owned coffee shops.

Negative economic impacts of tourism

Unfortunately, the tourism industry doesn’t always smell of roses and there are also several negative economic impacts of tourism.

There are many hidden costs to tourism, which can have unfavourable economic effects on the host community.

Whilst such negative impacts are well documented in the tourism literature, many tourists are unaware of the negative effects that their actions may cause. Likewise, many destinations who are inexperienced or uneducated in tourism and economics may not be aware of the problems that can occur if tourism is not management properly.

Below, I will outline the most prominent negative economic impacts of tourism.

Economic leakage in tourism is one of the major negative economic impacts of tourism. This is when money spent does not remain in the country but ends up elsewhere; therefore limiting the economic benefits of tourism to the host destination.

The biggest culprits of economic leakage are multinational and internationally-owned corporations, all-inclusive holidays and enclave tourism.

I have written a detailed post on the concept of economic leakage in tourism, you can take a look here- Economic leakage in tourism explained .

Another one of the negative economic impacts of tourism is the cost of infrastructure. Tourism development can cost the local government and local taxpayers a great deal of money.

Tourism may require the government to improve the airport, roads and other infrastructure, which are costly. The development of the third runway at London Heathrow, for example, is estimated to cost £18.6billion!

Money spent in these areas may reduce government money needed in other critical areas such as education and health, as I outlined previously in my discussion on opportunity costs.

One of the most obvious economic impacts of tourism is that the very presence of tourism increases prices in the local area.

Have you ever tried to buy a can of Coke in the supermarket in your hotel? Or the bar on the beachfront? Walk five minutes down the road and try buying that same can in a local shop- I promise you, in the majority of cases you will see a BIG difference In cost! (For more travel hacks like this subscribe to my newsletter – I send out lots of tips, tricks and coupons!)

Increasing demand for basic services and goods from tourists will often cause price hikes that negatively impact local residents whose income does not increase proportionately.

Tourism development and the related rise in real estate demand may dramatically increase building costs and land values. This often means that local people will be forced to move away from the area that tourism is located, known as gentrification.

Taking measures to ensure that tourism is managed sustainably can help to mitigate this negative economic impact of tourism. Techniques such as employing only local people, limiting the number of all-inclusive hotels and encouraging the purchasing of local products and services can all help.

Another one of the major economic impacts of tourism is dependency. Many countries run the risk of becoming too dependant on tourism. The country sees $ signs and places all of its efforts in tourism. Whilst this can work out well, it is also risky business!

If for some reason tourism begins to lack in a destination, then it is important that the destination has alternative methods of making money. If they don’t, then they run the risk of being in severe financial difficulty if there is a decline in their tourism industry.

In The Gambia, for instance, 30% of the workforce depends directly or indirectly on tourism. In small island developing states, percentages can range from 83% in the Maldives to 21% in the Seychelles and 34% in Jamaica.

There are a number of reasons that tourism could decline in a destination.

The Gambia has experienced this just recently when they had a double hit on their tourism industry. The first hit was due to political instability in the country, which has put many tourists off visiting, and the second was when airline Monarch went bust, as they had a large market share in flights to The Gambia.

Other issues that could result in a decline in tourism includes economic recession, natural disasters and changing tourism patterns. Over-reliance on tourism carries risks to tourism-dependent economies, which can have devastating consequences.

The last of the negative economic impacts of tourism that I will discuss is that of foreign ownership and management.

As enterprise in the developed world becomes increasingly expensive, many businesses choose to go abroad. Whilst this may save the business money, it is usually not so beneficial for the economy of the host destination.

Foreign companies often bring with them their own staff, thus limiting the economic impact of increased employment. They will usually also export a large proportion of their income to the country where they are based. You can read more on this in my post on economic leakage in tourism .

As I have demonstrated in this post, tourism is a significant economic driver the world over. However, not all economic impacts of tourism are positive. In order to ensure that the economic impacts of tourism are maximised, careful management of the tourism industry is required.

If you enjoyed this article on the economic impacts of tourism I am sure that you will love these too-

- Environmental impacts of tourism

- The 3 types of travel and tourism organisations

- 150 types of tourism! The ultimate tourism glossary

- 50 fascinating facts about the travel and tourism industry

- 23 Types of Water Transport To Keep You Afloat

Liked this article? Click to share!

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 24 February 2024

Modeling the link between tourism and economic development: evidence from homogeneous panels of countries

- Pablo Juan Cárdenas-García ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1779-392X 1 ,

- Juan Gabriel Brida 2 &

- Verónica Segarra 2

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 308 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

941 Accesses

Metrics details

- Development studies

Having previously analyzed the relationship between tourism and economic growth from distinct perspectives, this paper attempts to fill the void existing in scientific research on the relationship between tourism and economic development, by analyzing the relationship between these variables using a sample of 123 countries between 1995 and 2019. The Dumistrescu and Hurlin adaptation of the Granger causality test was used. This study takes a critical look at causal analysis with heterogeneous panels, given the substantial differences found between the results of the causal analysis with the complete panel as compared to the analysis of homogeneous country groups, in terms of their dynamics of tourism specialization and economic development. On the one hand, a one-way causal relationship exists from tourism to development in countries having low levels of tourism specialization and development. On the other hand, a one-way causal relationship exists by which development contributes to tourism in countries with high levels of development and tourism specialization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Gravity models do not explain, and cannot predict, international migration dynamics

Robert M. Beyer, Jacob Schewe & Hermann Lotze-Campen

The coordination pattern of tourism efficiency and development level in Guangdong Province under high-quality development

Lijuan Zhang, Azizan Marzuki & Zhenjie Liao

Analysis of spatial-temporal pattern, dynamic evolution and influencing factors of health tourism development in China

Huadi Wang, Yue Feng, … Nianxing Zhou

Introduction

Across the world, tourism is one of the most important sectors. It has undergone exponential growth since the mid-1900s and is currently experiencing growth rates that exceed those of other economic sectors (Yazdi, 2019 ).

Today, tourism is a major source of income for countries that specialize in this sector, generating 5.8% of the global GDP (5.8 billion US$) in 2021 (UNWTO, 2022 ) and providing 5.4% of all jobs (289 million) worldwide. Although its relevance is clear, tourism data have declined dramatically due to the recent impact of the Covid-19 health crisis. In 2019, prior to the pandemic (UNWTO, 2020 ), tourism represented 10.3% of the worldwide GDP (9.6 billion US$), with the number of tourism-related jobs reaching 10.2% of the global total (333 million). With the evolution of the pandemic and the regained trust of tourists across the globe, it is estimated that by 2022, approximately 80% of the pre-pandemic figures will be attained, with a full recovery being expected by 2024 (UNWTO, 2022 ).

Given the importance of this economic activity, many countries consider tourism to be a tool enabling economic growth (Corbet et al., 2019 ; Ohlan, 2017 ; Xia et al., 2021 ). Numerous works have analyzed the relationship between increased tourism and economic growth; and some systematic reviews have been carried out on this relationship (Brida et al., 2016 ; Ahmad et al., 2020 ), examining the main contributions over the first two decades of this century. These reviews have revealed evidence in this area: in some cases, it has been found that tourism contributes to economic growth while, in other cases, the economic cycle influences tourism expansion. Moreover, other works offer evidence of a bi-directional relationship between these variables.

Distinct international organizations (OECD, 2010 ; UNCTAD, 2011 ) have suggested that not only does tourism promote economic growth, it also contributes to socio-economic advances in the host regions. This may be the real importance of tourism, since the ultimate objective of any government is to improve a country’s socio-economic development (UNDP, 1990 ).

The development of economic and other policies related to the economic scope of tourism, in addition to promoting economic growth, are also intended to improve other non-economic factors such as education, safety, and health. Improvements in these factors lead to a better life for the host population (Lee, 2017 ; Todaro and Smith, 2020 ).

Given tourism’s capacity as an instrument of economic development (Cárdenas-García et al., 2015 ), distinct institutions such as the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, the United Nations World Tourism Organization and the World Bank, have begun funding projects that consider tourism to be a tool for improved socio-economic development, especially in less advanced countries (Carrillo and Pulido, 2019 ).

This new trend within the scientific literature establishes, firstly, that tourism drives economic growth and, secondly, that thanks to this economic growth, the population’s economic conditions may be improved (Croes et al., 2021 ; Kubickova et al., 2017 ). However, to take advantage of the economic growth generated by tourism activity to boost economic development, specific policies should be developed. These policies should determine the initial conditions to be met by host countries committed to tourism as an instrument of economic development. These conditions include regulation, tax system, and infrastructure provision (Cárdenas-García and Pulido-Fernández, 2019 ; Lejárraga and Walkenhorst, 2013 ; Meyer and Meyer, 2016 ).

Therefore, it is necessary to differentiate between the analysis of the relationship between tourism and economic growth, whereby tourism boosts the economy of countries committed to tourism, traditionally measured through an increase in the Gross Domestic Product (Alcalá-Ordóñez et al., 2023 ; Brida et al., 2016 ), and the analysis of the relationship between tourism and economic development, which measures the effect of tourism on other factors (not only economic content but also inequality, education, and health) which, together with economic criteria, serve as the foundation to measure a population’s development (Todaro and Smith, 2020 ).

However, unlike the analysis of the relationship between tourism and economic growth, few empirical studies have examined tourism’s capacity as a tool for development (Bojanic and Lo, 2016 ; Cárdenas-García and Pulido-Fernández, 2019 ; Croes, 2012 ).