- Tools & Resources

- Find Your Local Chapter

- Use my current location

- News and Stories

Each Journey Is Unique

Your epilepsy story is powerful and can give people hope, empowerment, and safety. Join our community and share your story to talk about epilepsy, seizure safety, and the need to find cures. Make a difference and take action.

SHARE YOUR STORY

Type of Epilepsy or Syndrome

- Unknown Onset

- Temporal Lobe Epilepsy (TLE)

- Reflex Epilepsies

- Lennox Gastaut Syndrome LGS

- Landau Kleffner Syndrome

- Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy

- Infantile Spasms West Syndrome

- Generalized

- Epilepsy Generalized Tonic Clonic Seizures Alone

- Dravet Syndrome

- Childhood Epilepsy Centrotemporal Spikes (Benign Rolandic Epilepsy)

- Childhood Absence Epilepsy

Type of Seizure

- Tonic Seizures

- Tonic Clonic Seizures

- Myoclonic Seizures

- Focal Onset Impaired Awareness Seizures (Complex Partial Seizures)

- Focal Onset Aware Seizures (Simple Partial Seizures)

- Focal Bilateral Tonic Clonic Seizures (Secondarily Generalized Seizures)

- Febrile Seizures

- Epileptic or Infantile Spasms

- Drug-Resistant Seizures

- Clonic Seizures

- Atypical Absence Seizures

- Atonic Seizures

- Absence Seizures

- Non-epileptic seizures

Connection to Epilepsy

- Teen with Epilepsy

- Person with Epilepsy

- Parent of a Child with Epilepsy

- Lost a Loved One to Epilepsy

- Family of a Person with Epilepsy

- Child with Epilepsy

- Change Our Epilepsy Story

- Family/Friend

- Healthcare Professionals

Thursday, April 18, 2024

You Are Stronger Than You Know

Read More from Sophia Goldberg

Monday, April 15, 2024

Advocating for Healthy Living With Epilepsy

Read More from Tami Maier

Friday, April 05, 2024

Finding My Passion Despite a Challenging Journey

Read More from Emily Marzini

Tuesday, April 02, 2024

Listen to Your Body

Read More from Maya Wortman

Tuesday, March 26, 2024

There Is Hope

Read More from David Hayes

Friday, March 22, 2024

A Traumatic Brain Injury Caused My Seizures

Read More from María Sanfeliú

Tuesday, March 19, 2024

Honoring the Memory of Easton

Read More from Kim Plummer

Thursday, March 14, 2024

Supporting My Sister on Her Journey With Epilepsy

Read More from Lauren Evans

Friday, March 08, 2024

From Low Self-Esteem to Sharing My Story

Read More from Pasquale DeSavino

Tuesday, March 05, 2024

No Matter What Happens, I’ll Be Okay

Read More from Maddie Giles

Be inspired by our community and share your journey.

Sign up for emails.

Stay up to date with the latest epilepsy news, stories from the community, and more.

- Our Mission

- Become a Partner

- Our Partners

- Impact Reports

- Grants Awarded

- Epilepsy Genetics

- Infantile Spasms

- Post-Traumatic Epilepsy

- EEM / Jeavons Syndrome

- Epilepsy News

- CURE Epilepsy in the News

- Seizing Life Podcast

- Epilepsy Explained

- CURE EPILEPSY CARES

- Personal Stories

- UNITE to CURE Epilepsy 2023

- CURE Epilepsy’s 25th Anniversary Gala

- Attend an Event

- Host An Event

- How to donate

- Monthly giving

- Tribute gifts

- Major gifts

- Online giving

- Corporate giving

- Planned giving

- Stock donations

- Matching Gifts

- Workplace giving

- Say the Word #SayEpilepsy

- What is Epilepsy?

- What causes epilepsy?

- What is a Seizure?

- Seizure Classification

- Phases of Seizures

- Risks Associated with Epilepsy

- Diagnosis and Therapies

- Medication Access

- How is epilepsy diagnosed?

- Diagnostic Tests

- Other Diagnostic Tests

- Epilepsy Syndromes

- Adults and Pediatric Patients

- Epilepsy Medications

- Epilepsy Surgery

- Dietary Therapies

- Alternative Therapies

- Neurostimulation Devices

- Seizure Action Plan

- Clinical Trials

- Patient Opportunities

- COVID-19 and Epilepsy

- Epilepsy Centers

- Grants Program

- Research Resources

- CURE Epilepsy-Sponsored Conferences

- Researcher Updates

Episode #68 - Living and Thriving with Epilepsy featuring Jon Sadler

Living and thriving with epilepsy.

Seizing Life, a CURE Epilepsy podcast hosted by Kelly Cervantes, aims to inspire empathy & give hope as we search for a cure for epilepsy. Together, we can find a cure. We can seize life.

Living with epilepsy isn’t always easy. The physical, mental, and emotional effects of both seizures and the medications can take a daily toll on the person living with epilepsy, creating challenges that may not be visible to others. The lack of understanding around epilepsy within the general public adds yet another degree of difficulty for people living with epilepsy. Yet, a life lived with epilepsy can provide great rewards including defying the expectations of others, creating a rich and fulfilling life, and inspiring others with epilepsy to pursue their own goals and dreams.

On this week’s Seizing Life , epilepsy patient, counselor, and author Jon Sadler discusses his 50-year journey living with epilepsy. Jon’s experiences reflect many of the challenges and concerns of people with epilepsy including stigma, employment, family, dealing with changing treatments and side-effects, and undergoing life-changing brain surgery. Jon reflects on how his personal experiences have shaped his perspective on epilepsy and how this inspired him to become a counselor for fellow patients and caregivers. Jon’s story is a microcosm of what has been accomplished within the epilepsy community during the past 50 years, as well as a directive highlighting the work that still needs to be done.

Download Audio

Want to download this episode? Fill out the form below and enjoy the podcast any time you’d like!

First name*

#67 After SUDEP: A Journey of Grief and Hope

#69 Infantile Spasms: Awareness, Observation, and Intervention

Related episodes.

April 3, 2024

#136 one woman’s epilepsy journey through childhood, parenting, discrimination, and surgery.

This month on Seizing Life® author Laura Beretsky shares her decades-long journey with epilepsy chronicled in her recent memoir Seizing Control.

February 7, 2024

#134 artificial intelligence and epilepsy: the promise & pitfalls of ai in diagnosis and treatment.

Dr. Daniel Goldenholz of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center discusses the current and potential impacts of artificial intelligence on epilepsy care.

January 3, 2024

#133 best of seizing life 2023.

This week on Seizing Life®, we revisit several compelling conversations from the past year in our Best of Seizing Life 2023 compilation episode.

Download Transcript

Want to download this transcript? Fill out the form below and we’ll begin your PDF download.

Download audio: Living and Thriving with Epilepsy

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- COVID-19 Vaccines

- Occupational Therapy

- Healthy Aging

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

Creating an Epilepsy Treatment and Seizure Action Plan

Knowing What to Do If a Seizure Occurs

Treating Epilepsy

- Caring for a Loved One

- Need for Care Plan

- Creating an Action Plan

Frequently Asked Questions

An action plan can help a person who has epilepsy and other people around them know what to do in case a seizure happens. Everyone who is diagnosed with epilepsy would benefit from an action plan that includes the proper steps to take when an unexpected seizure occurs.

While some people with epilepsy have triggers that make the seizures more likely, seizures often occur without any predictability. Treatment with antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) and avoidance of triggers are important.

By taking medication, many people with epilepsy have very few seizures, but some may have frequent seizures even with medical treatment. The frequency can range from less than once a year to several per day.

This article will discuss how to create a seizure action plan, how epilepsy is treated, and caring for a loved one with epilepsy.

FG Trade / Getty Images

Epilepsy treatment involves medical care as well as lifestyle measures. Medication is the most common treatment used to prevent seizures. Still, some people also need surgical procedures or dietary changes if standard medication is ineffective or medication side effects are not tolerable.

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) treatments are often promoted for seizure control, but they are ineffective and might be unsafe for some people. Discuss any such remedies with your healthcare provider before using them.

Additionally, lifestyle measures to eliminate potential seizure triggers are highly valuable for people who have epilepsy. Illness, sleep deprivation, and alcohol can trigger seizures, including severe seizures.

Medical Treatment

Medical treatment for epilepsy usually involves taking daily, scheduled AEDs. This requires consistency and discipline. You need to take the medication even if you have not been having seizures. Lack of seizures is an indication that your medication is working. For most people with epilepsy, stopping the medication will trigger a seizure.

In addition to regular daily preventative medication, some people are also given a prescription for anti-epilepsy medication that is to be taken if a seizure occurs or if an aura occurs. An aura is a neurological change that causes symptoms prior to a seizure.

Most people will not benefit from taking medication that is given for an active seizure or an aura. You and your neurologist will have to determine whether you should have a prescription to take if you experience a seizure or an aura.

Other medical interventions involve surgery, and many people who have epilepsy surgery continue to need treatment with AEDs.

Most AEDs have side effects, and it can take some time to determine the ideal dose that controls your seizures with minimal side effects. Do not make changes in your AEDs on your own—discuss your dose, seizure control, and side effects with your neurologist.

Complementary Treatments

In general, complementary treatments are not effective in preventing seizures.

Some people with epilepsy are advised to try a ketogenic diet , which is a highly restrictive, low-carbohydrate, high-fat diet. This does not work for everyone, and you and your neurologist can discuss whether this would be a good option for you.

Identifying and Avoiding Seizure Triggers

If you have epilepsy, there are important lifestyle measures that you need to take, because certain things can trigger a seizure. Triggers include alcohol, sleep deprivation, lack of eating, extreme stress, and medical illness.

Some people also have photosensitive epilepsy , which is a type of epilepsy in which seizures are provoked by rapidly flashing lights. If you have photosensitive epilepsy, you need to take precautions to avoid exposure to this type of light, which can be present in video games and some entertainment.

Less often, people with epilepsy may experience seizures in response to certain smells or sounds. If you have noticed that you have an unusual trigger, be sure to discuss it with your neurologist, who might perform tests to determine exactly what your triggers are and advise you on how to avoid them.

Symptoms of a Seizure

Seizures can cause different symptoms, which may include:

- Staring into space

- Eye blinking or eye-rolling

- Unusual noises

- Stiffening of the whole body or part of the body

- Jerking movements

- Falling down

These symptoms can begin suddenly or may be preceded by dizziness, tiredness, or unusual sensations.

Caring for a Loved One With Epilepsy

If you care for a family member or other loved one with epilepsy, you must become familiar with their medication schedule. This includes knowing which medications they need to take daily for prevention and if there are any medications they need to take when they experience an aura or a seizure.

Most importantly, you must be prepared to take safety precautions if your loved one is having a seizure or it seems like they will have a seizure. Safety precautions involve keeping them away from water, fire, or any sharp objects or potential falls.

You should also have a plan for whom to call or where to take them if they have a prolonged seizure or experience an injury during a seizure.

Why Do You Need an Epilepsy Care Plan?

The key reason for having an epilepsy care plan is to avoid making an emergency decision unexpectedly.

Being prepared in advance also means having guidelines for your care from the neurologist who takes care of your seizures. This type of guidance is based on experience in terms of what works medically and how well people can implement the recommendations into daily life.

When your family, friends, or roommates are aware of the guidance you’ve received from your neurologist, they will be able to handle unexpected or emergency issues safely. And it will also help ease their stress or anxiety about your epilepsy, making them feel more comfortable about your condition.

Creating a Seizure Action Plan (SAP)

There are no widely established or endorsed seizure action plans. Each person can work with their neurologist to create one. This would include personalized instructions that you can use and share with others with whom you spend time or who would be in a position to take care of you if you have a seizure.

Research shows that having a seizure action plan is beneficial for people who have epilepsy and for their families.

Who Should Make an SAP?

Anyone who has epilepsy should have a SAP that is created with guidance from a neurologist, and with input and approval from the person who has epilepsy, as well as anyone taking care of them. This ensures that the SAP is medically sound and that it is practical and the people who are involved understand it and can handle it.

What to Include

Currently, there is no well-established uniform epilepsy care plan that’s used for people with epilepsy.

An expert panel meeting in 2021 established the importance of creating a seizure action plan. The panel recommend the following information be included:

- Circumstances specific to the person (type of seizures, where they are located, type of housing)

- Names and numbers of emergency contacts, including their healthcare provider, caregivers, and family

- A description of the individual's usual signs and symptoms of a seizure and any atypical ones

- How and when to administer seizure first aid to the person

- Information on the individual's prescribed treatment, including step-by-step instructions on how to give it

- When to start medication and when to contact emergency assistance

Where Is It Kept?

A person who has epilepsy should become familiar with their own epilepsy care plan. Epilepsy care plans should be shared with family members, friends, or roommates who live with a person who has epilepsy. The care plan should also be provided to a child’s teachers, school nurse, coaches, and chaperones for field trips or camps.

The student or parents should discuss the plan to help those individuals understand what needs to be done and answer any questions and address any concerns these individuals have.

Adults may need to share their epilepsy plan with certain people in the workplace who would be expected to call for help if a seizure occurs.

The key components of the care plan may be highlighted for specific individuals so that they can easily understand which parts of the care plan they need to take action on.

For some people with epilepsy, it can be beneficial to wear a bracelet or another identifying device so that emergency care workers will be able to quickly learn of the person's condition, as well as any allergies.

Some people have severe reactions to AEDs, and this should be made clear so that emergency healthcare providers will quickly know the information when a person who is having a seizure is unable to communicate.

If you or your child has epilepsy, it’s important to create a care plan that you and everybody who is involved in taking care of you or your child will be prepared in case a seizure occurs.

While there is no established format for an epilepsy care plan, there are some general principles that you and your neurologist can work on to create guidelines. These include having an understanding of what to do in case a seizure occurs, knowing when to call for help, and knowing if there is any medication that you should take if a seizure occurs.

Additionally, if there are allergies to any anti-seizure medication, this should be indicated on a bracelet or other obvious device in case emergency personnel are called and need to administer medication.

A Word From Verywell

Living with epilepsy requires planning. While the condition is manageable, sometimes unexpected emergencies occur. Therefore, it's always good to be prepared and to have a plan of action that guides you and others around you in case an emergency occurs.

You and your neurologist should discuss an emergency action plan for your epilepsy and determine periodically whether it needs to be updated or changed. The emergency action plan includes steps that you may need to take in case you have a seizure.

You will also need to share it with people whom you trust and who are responsible and could potentially put the plan into action in case you are unable to do so.

Warning signs can include eye fluttering, eye-rolling, making unusual grunting noises, jerking or stiffening, or falling to the ground. Sometimes people may have a seizure without having any of these warning signs.

Normally a seizure lasts for a few seconds, but if it lasts four minutes or more, it is a sign of a medical emergency that requires urgent medical attention.

Yes, you can stop a seizure after it starts, but most seizures end on their own before you would have time to take medication. It is not safe to swallow medication while you are having a seizure. If a seizure lasts for a long time, this usually requires medical intervention with intravenous medication.

In rare instances, people with epilepsy are given prescription medication to take during a seizure by intramuscular injection. This would have to be given by someone, such as a family member or healthcare provider.

If you are around someone who is having a seizure, help them avoid potential harm. This includes keeping them away from water, sharp objects, or anything that they could fall from.

If the seizure lasts for more than a few seconds, call for emergency help. Emergency responders are trained to assess whether a person needs urgent treatment for a seizure.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Managing epilepsy well checklist .

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. The epilepsies and seizures: hope through research .

Patel AD, Becker DA. Introduction to use of an acute seizure action plan for seizure clusters and guidance for implementation . Epilepsia. 2022;63 Suppl 1:S25-S33. doi:10.1111/epi.17344

Penovich P, Glauser T, Becker D, et al. Recommendations for development of acute seizure action plans (ASAPs) from an expert panel . Epilepsy Behav. 2021;123:108264. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2021.108264

Neville KL, McCaffery H, Baxter Z, Shellhaas RA, Fedak Romanowski EM. Implementation of a standardized seizure action plan to improve communication and parental education . Pediatr Neuro l. 2020;112:56-63. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2020.04.005

By Heidi Moawad, MD Dr. Moawad is a neurologist and expert in brain health. She regularly writes and edits health content for medical books and publications.

- Search Menu

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- Supplements

- Patient Perspectives

- Methods Corner

- ESC Content Collections

- Author Guidelines

- Instructions for reviewers

- Submission Site

- Why publish with EJCN?

- Open Access Options

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Read & Publish

- About European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing

- About ACNAP

- About European Society of Cardiology

- ESC Publications

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- War in Ukraine

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, why patient journey mapping, how is patient journey mapping conducted, use of technology in patient journey mapping, future implications for patient journey mapping, conclusions, patient journey mapping: emerging methods for understanding and improving patient experiences of health systems and services.

Lemma N Bulto and Ellen Davies Shared first authorship.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Lemma N Bulto, Ellen Davies, Janet Kelly, Jeroen M Hendriks, Patient journey mapping: emerging methods for understanding and improving patient experiences of health systems and services, European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing , 2024;, zvae012, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjcn/zvae012

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Patient journey mapping is an emerging field of research that uses various methods to map and report evidence relating to patient experiences and interactions with healthcare providers, services, and systems. This research often involves the development of visual, narrative, and descriptive maps or tables, which describe patient journeys and transitions into, through, and out of health services. This methods corner paper presents an overview of how patient journey mapping has been conducted within the health sector, providing cardiovascular examples. It introduces six key steps for conducting patient journey mapping and describes the opportunities and benefits of using patient journey mapping and future implications of using this approach.

Acquire an understanding of patient journey mapping and the methods and steps employed.

Examine practical and clinical examples in which patient journey mapping has been adopted in cardiac care to explore the perspectives and experiences of patients, family members, and healthcare professionals.

Quality and safety guidelines in healthcare services are increasingly encouraging and mandating engagement of patients, clients, and consumers in partnerships. 1 The aim of many of these partnerships is to consider how health services can be improved, in relation to accessibility, service delivery, discharge, and referral. 2 , 3 Patient journey mapping is a research approach increasingly being adopted to explore these experiences in healthcare. 3

a patient-oriented project that has been undertaken to better understand barriers, facilitators, experiences, interactions with services and/or outcomes for individuals and/or their carers, and family members as they enter, navigate, experience and exit one or more services in a health system by documenting elements of the journey to produce a visual or descriptive map. 3

It is an emerging field with a clear patient-centred focus, as opposed to studies that track patient flow, demand, and movement. As a general principle, patient journey mapping projects will provide evidence of patient perspectives and highlight experiences through the patient and consumer lens.

Patient journey mapping can provide significant insights that enable responsive and context-specific strategies for improving patient healthcare experiences and outcomes to be designed and implemented. 3–6 These improvements can occur at the individual patient, model of care, and/or health system level. As with other emerging methodologies, questions have been raised regarding exactly how patient journey mapping projects can best be designed, conducted, and reported. 3

In this methods paper, we provide an overview of patient journey mapping as an emergent field of research, including reasons that mapping patient journeys might be considered, methods that can be adopted, the principles that can guide patient journey mapping data collection and analysis, and considerations for reporting findings and recognizing the implications of findings. We summarize and draw on five cardiovascular patient journey mapping projects, as examples.

One of the most appealing elements of the patient journey mapping field of research is its focus on illuminating the lived experiences of patients and/or their family members, and the health professionals caring for them, methodically and purposefully. Patient journey mapping has an ability to provide detailed information about patient experiences, gaps in health services, and barriers and facilitators for access to health services. This information can be used independently, or alongside information from larger data sets, to adapt and improve models of care relevant to the population that is being investigated. 3

To date, the most frequent reason for adopting this approach is to inform health service redesign and improvement. 3 , 7 , 8 Other reasons have included: (i) to develop a deeper understanding of a person’s entire journey through health systems; 3 (ii) to identify delays in diagnosis or treatment (often described as bottlenecks); 9 (iii) to identify gaps in care and unmet needs; (iv) to evaluate continuity of care across health services and regions; 10 (v) to understand and evaluate the comprehensiveness of care; 11 (vi) to understand how people are navigating health systems and services; and (vii) to compare patient experiences with practice guidelines and standards of care.

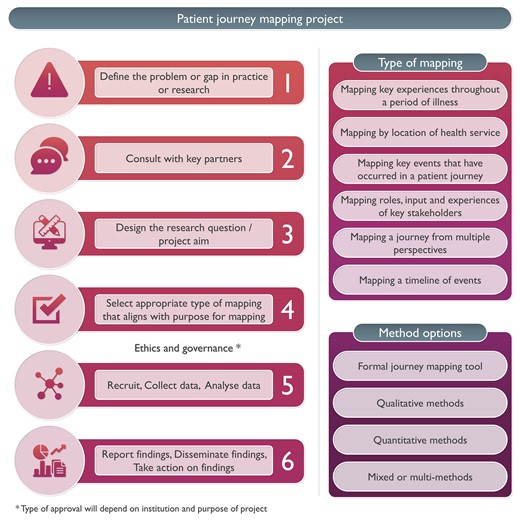

Patient journey mapping approaches frequently use six broad steps that help facilitate the preparation and execution of research projects. These are outlined in the Central illustration . We acknowledge that not all patient journey mapping approaches will follow the order outlined in the Central illustration , but all steps need to be considered at some point throughout each project to ensure that research is undertaken rigorously, appropriately, and in alignment with best practice research principles.

Steps for conducing patient journey mapping.

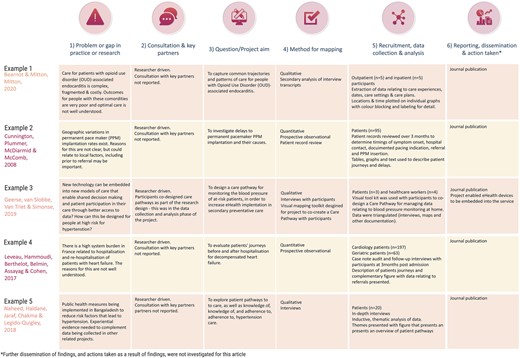

Five cardiovascular patient journey mapping research examples have been included in Figure 1 , 12–16 to provide specific context and illustrate these six steps. For each of these examples, the problem or gap in practice or research, consultation processes, research question or aim, type of mapping, methods, and reporting of findings have been extracted. Each of these steps is then discussed, using these cardiovascular examples.

Examples of patient journey mapping projects.

Define the problem or gap in practice or research

Developing an understanding of a problem or gap in practice is essential for facilitating the design and development of quality research projects. In the examples outlined in Figure 1 , it is evident that clinical variation or system gaps have been explored using patient journey mapping. In the first two examples, populations known to have health vulnerabilities were explored—in Example 1, this related to comorbid substance use and physical illness, 13 and in Example 2, this related to geographical location. 13 Broader systems and societal gaps were explored in Examples 4 and 5, respectively, 15 , 16 and in Example 3, a new technologically driven solution for an existing model of care was tested for its ability to improve patient outcomes relating to hypertension. 14

Consultation, engagement, and partnership

Ideally, consultation with heathcare providers and/or patients would occur when the problem or gap in practice or research is being defined. This is a key principle of co-designed research. 17 Numerous existing frameworks for supporting patient involvement in research have been designed and were recently documented and explored in a systematic review by Greenhalgh et al . 18 While none of the five example studies included this step in the initial phase of the project, it is increasingly being undertaken in patient partnership projects internationally (e.g. in renal care). 17 If not in the project conceptualization phase, consultation may occur during the data collection or analysis phase, as demonstrated in Example 3, where a care pathway was co-created with participants. 14 We refer readers to Greenhalgh’s systematic review as a starting point for considering suitable frameworks for engaging participants in consultation, partnership, and co-design of patient journey mapping projects. 18

Design the research question/project aim

Conducting patient journey mapping research requires a thoughtful and systematic approach to adequately capture the complexity of the healthcare experience. First, the research objectives and questions should be clearly defined. Aspects of the patient journey that will be explored need to be identified. Then, a robust approach must be developed, taking into account whether qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods are more appropriate for the objectives of the study.

For example, in the cardiac examples in Figure 1 , the broad aims included mapping existing pathways through health services where there were known problems 12 , 13 , 15 , 16 and documenting the co-creation of a new care pathway using quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods. 14

In traditional studies, questions that might be addressed in the area of patient movement in health systems include data collected through the health systems databases, such as ‘What is the length of stay for x population’, or ‘What is the door to balloon time in this hospital?’ In contrast, patient mapping journey studies will approach asking questions about experiences that require data from patients and their family members, e.g. ‘What is the impact on you of your length of stay?’, ‘What was your experience in being assessed and undergoing treatment for your chest pain?’, ‘What was your experience supporting this patient during their cardiac admission and discharge?’

Select appropriate type of mapping

The methods chosen for mapping need to align with the identified purpose for mapping and the aim or question that was designed in Step 3. A range of research methods have been used in patient journey mapping projects involving various qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods techniques and tools. 4 Some approaches use traditional forms of data collection, such as short-form and long-form patient interviews, focus groups, and direct patient observations. 18 , 19 Other approaches use patient journey mapping tools, designed and used with specific cultural groups, such as First Nations peoples using artwork, paintings, sand trays, and photovoice. 17 , 20 In the cardiovascular examples presented in Figure 1 , both qualitative and quantitative methods have been used, with interviews, patient record reviews, and observational techniques adopted to map patient journeys.

In a recent scoping review investigating patient journey mapping across all health care settings and specialities, six types of patient journey mapping were identified. 3 These included (i) mapping key experiences throughout a period of illness; (ii) mapping by location of health service; (iii) mapping by events that occurred throughout a period of illness; (iv) mapping roles, input, and experiences of key stakeholders throughout patient journeys; (v) mapping a journey from multiple perspectives; and (vi) mapping a timeline of events. 3 Combinations or variations of these may be used in cardiovascular settings in the future, depending on the research question, and the reasons mapping is being undertaken.

Recruit, collect data, and analyse data

The majority of health-focused patient journey mapping projects published to date have recruited <50 participants. 3 Projects with fewer participants tend to be qualitative in nature. In the cardiovascular examples provided in Figure 1 , participant numbers range from 7 14 to 260. 15 The 3 studies with <20 participants were qualitative, 12 , 14 , 16 and the 2 with 95 and 260 participants, respectively, were quantitative. 13 , 15 As seen in these and wider patient journey mapping examples, 3 participants may include patients, relatives, carers, healthcare professionals, or other stakeholders, as required, to meet the study objectives. These different participant perspectives may be analysed within each participant group and/or across the wider cohort to provide insights into experiences, and the contextual factors that shape these experiences.

The approach chosen for data collection and analysis will vary and depends on the research question. What differentiates data analysis in patient journey mapping studies from other qualitative or quantitative studies is the focus on describing, defining, or exploring the journey from a patient’s, rather than a health service, perspective. Dimensions that may, therefore, be highlighted in the analysis include timing of service access, duration of delays to service access, physical location of services relative to a patient’s home, comparison of care received vs. benchmarked care, placing focus on the patient perspective.

The mapping of individual patient journeys may take place during data collection with the use of mapping templates (tables, diagrams, and figures) and/or later in the analysis phase with the use of inductive or deductive analysis, mapping tables, or frameworks. These have been characterized and visually represented in a recent scoping review. 3 Representations of patient journeys can also be constructed through a secondary analysis of previously collected data. In these instances, qualitative data (i.e. interviews and focus group transcripts) have been re-analysed to understand whether a patient journey narrative can be extracted and reported. Undertaking these projects triggers a new research cycle involving the six steps outlined in the Central illustration . The difference in these instances is that the data are already collected for Step 5.

Report findings, disseminate findings, and take action on findings

A standardized, formal reporting guideline for patient journey mapping research does not currently exist. As argued in Davies et al ., 3 a dedicated reporting guide for patient journey mapping would be ill-advised, given the diversity of approaches and methods that have been adopted in this field. Our recommendation is for projects to be reported in accordance with formal guidelines that best align with the research methods that have been adopted. For example, COREQ may be used for patient journey mapping where qualitative methods have been used. 20 STROBE may be used for patient journey mapping where quantitative methods have been used. 21 Whichever methods have been adopted, reporting of projects should be transparent, rigorous, and contain enough detail to the extent that the principles of transparency, trustworthiness, and reproducibility are upheld. 3

Dissemination of research findings needs to include the research, healthcare, and broader communities. Dissemination methods may include academic publications, conference presentations, and communication with relevant stakeholders including healthcare professionals, policymakers, and patient advocacy groups. Based on the findings and identified insights, stakeholders can collaboratively design and implement interventions, programmes, or improvements in healthcare delivery that overcome the identified challenges directly and address and improve the overall patient experience. This cyclical process can hopefully produce research that not only informs but also leads to tangible improvements in healthcare practice and policy.

Patient journey mapping is typically a hands-on process, relying on surveys, interviews, and observational research. The technology that supports this research has, to date, included word processing software, and data analysis packages, such as NVivo, SPSS, and Stata. With the advent of more sophisticated technological tools, such as electronic health records, data analytics programmes, and patient tracking systems, healthcare providers and researchers can potentially use this technology to complement and enhance patient journey mapping research. 19 , 20 , 22 There are existing examples where technology has been harnessed in patient journey. Lee et al . used patient journey mapping to verify disease treatment data from the perspective of the patient, and then the authors developed a mobile prototype that organizes and visualizes personal health information according to the patient-centred journey map. They used a visualization approach for analysing medical information in personal health management and examined the medical information representation of seven mobile health apps that were used by patients and individuals. The apps provide easy access to patient health information; they primarily import data from the hospital database, without the need for patients to create their own medical records and information. 23

In another example, Wauben et al. 19 used radio frequency identification technology (a wireless system that is able to track a patient journey), as a component of their patient journey mapping project, to track surgical day care patients to increase patient flow, reduce wait times, and improve patient and staff satisfaction.

Patient journey mapping has emerged as a valuable research methodology in healthcare, providing a comprehensive and patient-centric approach to understanding the entire spectrum of a patient’s experience within the healthcare system. Future implications of this methodology are promising, particularly for transforming and redesigning healthcare delivery and improving patient outcomes. The impact may be most profound in the following key areas:

Personalized, patient-centred care : The methodology allows healthcare providers to gain deep insights into individual patient experiences. This information can be leveraged to deliver personalized, patient-centric care, based on the needs, values, and preferences of each patient, and aligned with guideline recommendations, healthcare professionals can tailor interventions and treatment plans to optimize patient and clinical outcomes.

Enhanced communication, collaboration, and co-design : Mapping patient interactions with health professionals and journeys within and across health services enables specific gaps in communication and collaboration to be highlighted and potentially informs responsive strategies for improvement. Ideally, these strategies would be co-designed with patients and health professionals, leading to improved care co-ordination and healthcare experience and outcomes.

Patient engagement and empowerment : When patients are invited to share their health journey experiences, and see visual or written representations of their journeys, they may come to understand their own health situation more deeply. Potentially, this may lead to increased health literacy, renewed adherence to treatment plans, and/or self-management of chronic conditions such as cardiovascular disease. Given these benefits, we recommend that patients be provided with the findings of research and quality improvement projects with which they are involved, to close the loop, and to ensure that the findings are appropriately disseminated.

Patient journey mapping is an emerging field of research. Methods used in patient journey mapping projects have varied quite significantly; however, there are common research processes that can be followed to produce high-quality, insightful, and valuable research outputs. Insights gained from patient journey mapping can facilitate the identification of areas for enhancement within healthcare systems and inform the design of patient-centric solutions that prioritize the quality of care and patient outcomes, and patient satisfaction. Using patient journey mapping research can enable healthcare providers to forge stronger patient–provider relationships and co-design improved health service quality, patient experiences, and outcomes.

None declared.

Farmer J , Bigby C , Davis H , Carlisle K , Kenny A , Huysmans R , et al. The state of health services partnering with consumers: evidence from an online survey of Australian health services . BMC Health Serv Res 2018 ; 18 : 628 .

Google Scholar

Kelly J , Dwyer J , Mackean T , O’Donnell K , Willis E . Coproducing Aboriginal patient journey mapping tools for improved quality and coordination of care . Aust J Prim Health 2017 ; 23 : 536 – 542 .

Davies EL , Bulto LN , Walsh A , Pollock D , Langton VM , Laing RE , et al. Reporting and conducting patient journey mapping research in healthcare: a scoping review . J Adv Nurs 2023 ; 79 : 83 – 100 .

Ly S , Runacres F , Poon P . Journey mapping as a novel approach to healthcare: a qualitative mixed methods study in palliative care . BMC Health Serv Res 2021 ; 21 : 915 .

Arias M , Rojas E , Aguirre S , Cornejo F , Munoz-Gama J , Sepúlveda M , et al. Mapping the patient’s journey in healthcare through process mining . Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020 ; 17 : 6586 .

Natale V , Pruette C , Gerohristodoulos K , Scheimann A , Allen L , Kim JM , et al. Journey mapping to improve patient-family experience and teamwork: applying a systems thinking tool to a pediatric ambulatory clinic . Qual Manag Health Care 2023 ; 32 : 61 – 64 .

Cherif E , Martin-Verdier E , Rochette C . Investigating the healthcare pathway through patients’ experience and profiles: implications for breast cancer healthcare providers . BMC Health Serv Res 2020 ; 20 : 735 .

Gilburt H , Drummond C , Sinclair J . Navigating the alcohol treatment pathway: a qualitative study from the service users’ perspective . Alcohol Alcohol 2015 ; 50 : 444 – 450 .

Gichuhi S , Kabiru J , M’Bongo Zindamoyen A , Rono H , Ollando E , Wachira J , et al. Delay along the care-seeking journey of patients with ocular surface squamous neoplasia in Kenya . BMC Health Serv Res 2017 ; 17 : 485 .

Borycki EM , Kushniruk AW , Wagner E , Kletke R . Patient journey mapping: integrating digital technologies into the journey . Knowl Manag E-Learn 2020 ; 12 : 521 – 535 .

Barton E , Freeman T , Baum F , Javanparast S , Lawless A . The feasibility and potential use of case-tracked client journeys in primary healthcare: a pilot study . BMJ Open 2019 ; 9 : e024419 .

Bearnot B , Mitton JA . “You’re always jumping through hoops”: journey mapping the care experiences of individuals with opioid use disorder-associated endocarditis . J Addict Med 2020 ; 14 : 494 – 501 .

Cunnington MS , Plummer CJ , McDiarmid AK , McComb JM . The patient journey from symptom onset to pacemaker implantation . QJM 2008 ; 101 : 955 – 960 .

Geerse C , van Slobbe C , van Triet E , Simonse L . Design of a care pathway for preventive blood pressure monitoring: qualitative study . JMIR Cardio 2019 ; 3 : e13048 .

Laveau F , Hammoudi N , Berthelot E , Belmin J , Assayag P , Cohen A , et al. Patient journey in decompensated heart failure: an analysis in departments of cardiology and geriatrics in the Greater Paris University Hospitals . Arch Cardiovasc Dis 2017 ; 110 : 42 – 50 .

Naheed A , Haldane V , Jafar TH , Chakma N , Legido-Quigley H . Patient pathways and perceptions of treatment, management, and control Bangladesh: a qualitative study . Patient Prefer Adherence 2018 ; 12 : 1437 – 1449 .

Bateman S , Arnold-Chamney M , Jesudason S , Lester R , McDonald S , O’Donnell K , et al. Real ways of working together: co-creating meaningful Aboriginal community consultations to advance kidney care . Aust N Z J Public Health 2022 ; 46 : 614 – 621 .

Greenhalgh T , Hinton L , Finlay T , Macfarlane A , Fahy N , Clyde B , et al. Frameworks for supporting patient and public involvement in research: systematic review and co-design pilot . Health Expect 2019 ; 22 : 785 – 801 .

Wauben LSGL , Guédon ACP , de Korne DF , van den Dobbelsteen JJ . Tracking surgical day care patients using RFID technology . BMJ Innov 2015 ; 1 : 59 – 66 .

Tong A , Sainsbury P , Craig J . Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups . Int J Qual Health Care 2007 ; 19 : 349 – 357 .

von Elm E , Altman DG , Egger M , Pocock SJ , Gøtzsche PC , Vandenbroucke JP , et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies . Lancet 2007 ; 370 (9596): 1453 – 1457 .

Wilson A , Mackean T , Withall L , Willis EM , Pearson O , Hayes C , et al. Protocols for an Aboriginal-led, multi-methods study of the role of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workers, practitioners and Liaison officers in quality acute health care . J Aust Indigenous HealthInfoNet 2022 ; 3 : 1 – 15 .

Lee B , Lee J , Cho Y , Shin Y , Oh C , Park H , et al. Visualisation of information using patient journey maps for a mobile health application . Appl Sci 2023 ; 13 : 6067 .

Author notes

Email alerts, citing articles via.

- Recommend to Your Librarian

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1873-1953

- Print ISSN 1474-5151

- Copyright © 2024 European Society of Cardiology

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Unmet needs of people with epilepsy: a qualitative study exploring their journey from presentation to long-term management across five european countries.

- 1 OPEN Health Communications LLP, Marlow, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom

- 2 Eisai Europe Ltd, Hatfield, United Kingdom

Introduction: Epilepsy is a neurological disease that can negatively impact a person’s physical, psychological, social, and emotional well-being. The aim of this study was to provide insights into the experiences of people with epilepsy on polytherapy (i.e., people on a combination of two or more anti-seizure medications [ASMs]), with an emphasis on their emotional journey.

Methods: Market research was conducted with 40 people with epilepsy from France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom. Semi-structured interviews were analyzed using both a content and framework analysis approach. A content analysis of participants’ expressed emotions was used to illustrate the changes of emotions experienced by people with epilepsy from presentation through to monitoring and follow-up stages.

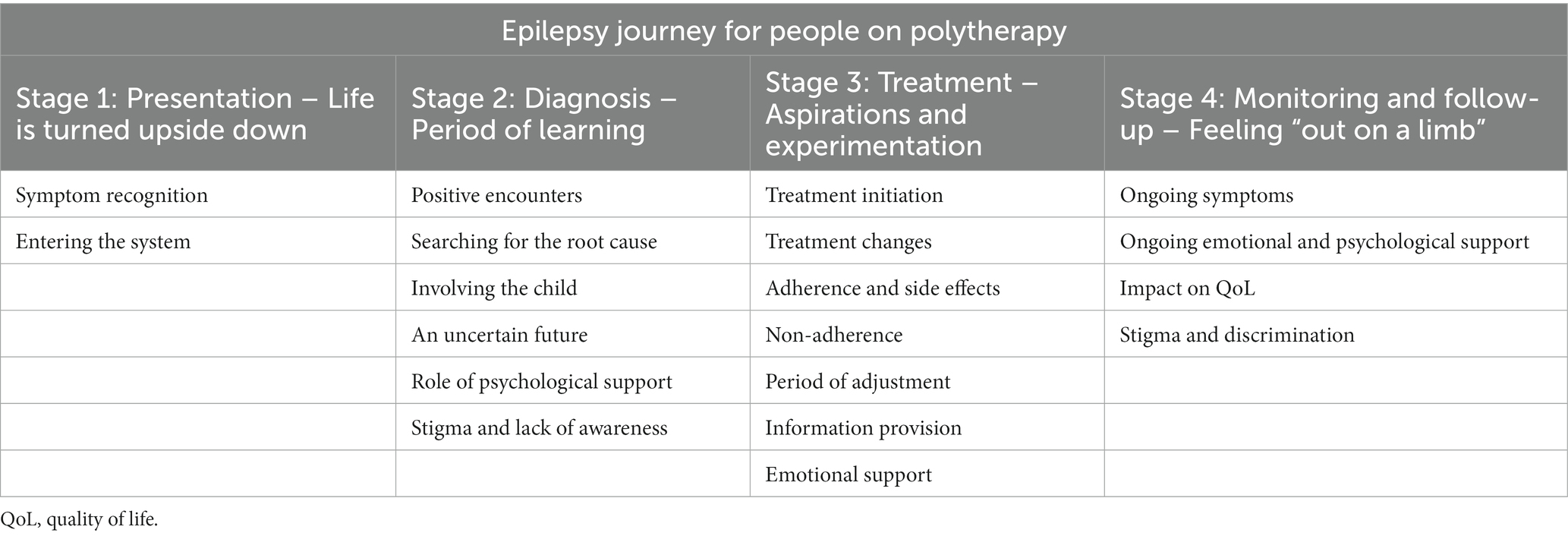

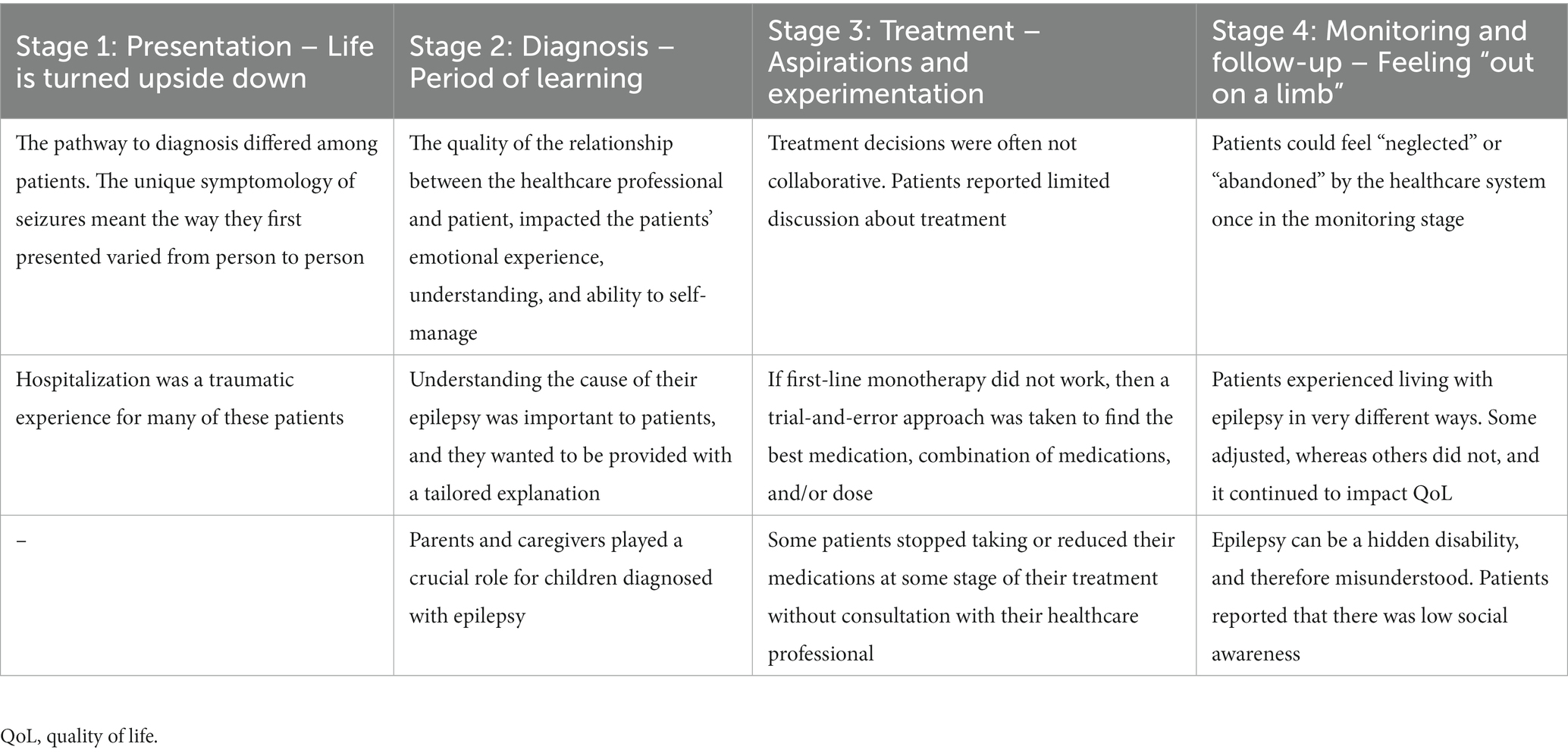

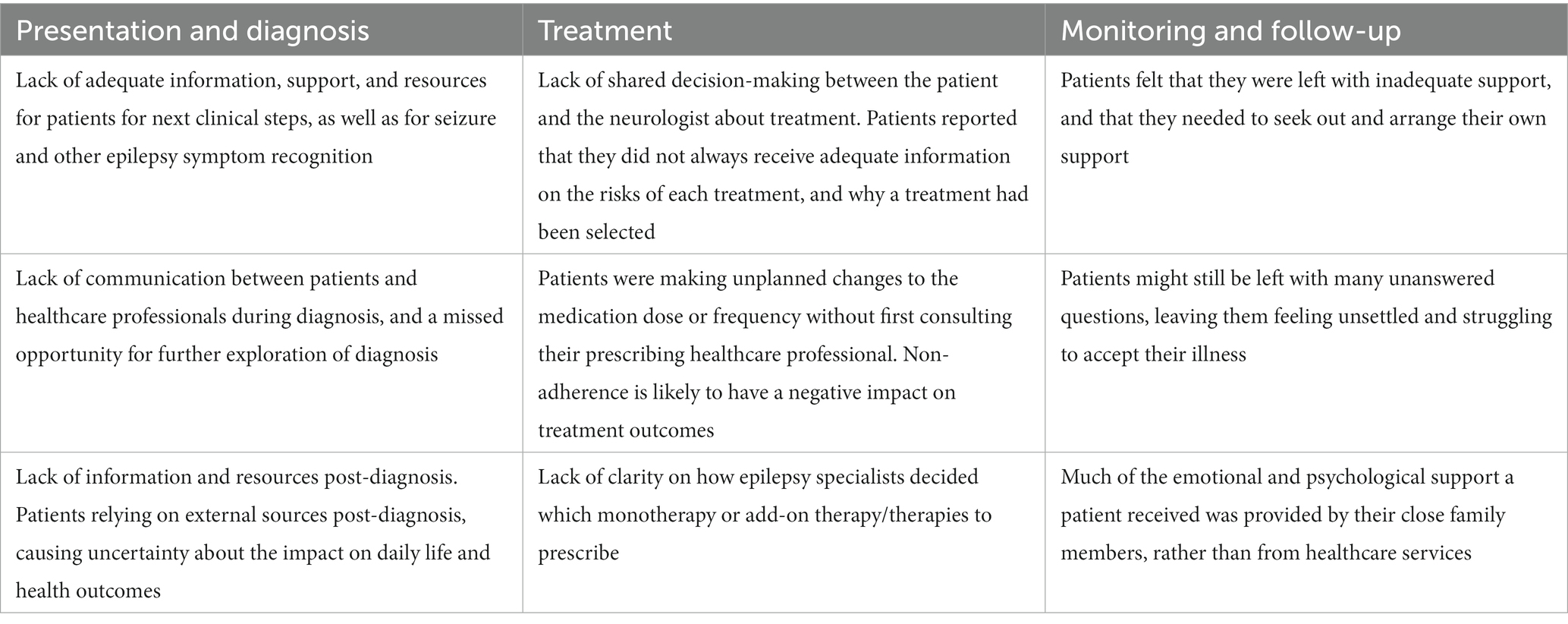

Results: In each stage of the journey, themes and subthemes were identified under the overarching headings: Stage 1: Presentation – Life is turned upside down; Stage 2: Diagnosis – Period of learning; Stage 3: Treatment – Aspirations and experimentation; and Stage 4: Monitoring and follow-up – Feeling “out on a limb”. The research identified key unmet needs and opportunities for people with epilepsy to improve their subjective experiences at different stages of their disease journey, namely: (1) establish and promote support networks from presentation through to monitoring and follow-up stages; (2) accelerate pathway to diagnosis; (3) provide opportunities to discuss the diagnosis with patients; (4) clarify treatment-change guidelines for patients; and (5) develop a shared treatment decision-making/empowerment tool.

Discussion: The research findings and recommendations have the potential to drive change at an individual level, as well as at a healthcare level.

1. Introduction

Epilepsy is one of the most common and debilitating neurological conditions, and it has been estimated to affect between 50 and 75 million people globally ( 1 , 2 ). The daily burden for people with epilepsy who experience epileptic seizures and accompanying symptoms remains high, despite advances in understanding pathophysiological disease mechanisms and treatment options ( 3 ). As well as the physical implications of epilepsy, such as disability, mortality, and comorbidities, the disease can also impact the psychological well-being and social aspects of peoples’ lives, including work, personal relationships, and quality of life (QoL) ( 4 ). Previous research has shown that emotions are closely related to the health and well-being of people with chronic disease ( 5 ), yet emotions are often overlooked in the literature reporting the subjective experience of people with epilepsy ( 6 ).

There are several qualitative and mixed-method research studies that have investigated patients’ subjective experiences (thoughts and feelings) of being diagnosed and living with epilepsy ( 7–17 ). The pathway to adjustment following a first seizure can trigger psychological concerns/issues, often stemming from the person’s perceived loss of control ( 16 ). Loss of control is an area of impact of living with epilepsy frequently reported in the qualitative literature. It impacted not only adults, but also children and adolescents, and was reported to be connected to fear of seizure recurrence, loss of control over their own bodies, as well as disruption to personal goals and plans ( 17 ). How quickly a person was able to adapt and re-establish perceived control following diagnosis could depend on their gender and clinical factors (e.g., presence of premorbid psychological disorder) ( 16 ). For example, people who were evaluated to have experienced a pervasive loss of control were thought to have a higher awareness of their own vulnerability and mortality, and have a higher fear of seizure recurrence and mood disturbances. They consequently needed to use more extensive strategies and external support to help them return to baseline levels of perceived control compared with those experiencing a limited loss of control following diagnosis ( 16 ).

Yennadiou and Wolverson ( 17 ), investigated how people of advanced age (more than 65 years) make sense of their epilepsy, and found that they appraised epilepsy as a powerful negative external force that is both threatening and unpredictable, yet perceived as separate from themselves. They also experienced loss of control, loss of independence, and difficulties dealing with stigma ( 17 ). Within this literature, social stigma is a common theme ( 10 , 11 , 17 ). Social stigma and persistent public misperceptions about epilepsy (e.g., the public perception that people with epilepsy are “possessed”), could have a disruptive effect on the person’s self-identity ( 10 ). Stigma could also impact a person’s self-esteem and social standing ( 10 ).

The findings illustrate the rich insights that qualitative accounts can provide, and how such techniques are invaluable when little is known about a particular issue or topic.

The current study was carried out as part of a wider program of research that aimed to provide a comprehensive, qualitative overview of the journey of living with epilepsy. The first step was a qualitative netnographic study of conversations posted on public social media sites relating to living with epilepsy ( 18 ). The analysis of these conversations identified key themes, namely: a lack of disease awareness among the public; the negative psychological and physical impact of seizures; the importance of ensuring appropriate sleep duration and quality; a tendency to understand disease burden through time (e.g., people with epilepsy were more likely to use the term “days” when describing negative experiences and “years” when describing positive experiences, especially when they were referring to treatment); the challenge of finding the right treatment and managing side effects; and the challenge of dealing with depression and anxiety ( 18 ). This was followed by a review of the published literature, reporting the emotional and clinical pathway of people with epilepsy and their carers (unpublished). This review identified themes relating to the impact of the relationship with a healthcare professional; stigma and how it can impact a person’s identity and self-esteem; the negative impact of epilepsy on everyday life/QoL; the experience and impact of seizures, symptoms, and treatment; a loss of independence; and mental health issues. Both pieces of research have highlighted that people with epilepsy have difficulties when first-line monotherapy treatment is not successful. This finding was supported by a recent published ethnographic study that explored the experiences of people who had either been diagnosed with drug-resistant epilepsy or had tried two or more anti-seizure medications (ASMs) without perceived success ( 19 ). The authors identified patient–provider gaps in both epilepsy and drug-resistant epilepsy treatment and management, and discovered that there was a negative impact of untimely disease management leading up to and after receiving a drug-resistant epilepsy diagnosis.

In this study, we recruited people for whom first-line monotherapy alone was not successful, and who were currently on a combination of two or more ASMs. Selecting this cohort of people with epilepsy, allowed us to not only identify the psychosocial consequences of epilepsy as they progressed through their clinical journey, but also to deep dive into the potential issues that can arise at the treatment and monitoring stages when monotherapy is not successful. To the best of our knowledge, the current study is the first to examine the experiential journey of people with epilepsy from the perspective of those on polytherapy, with a specific emphasis on their subjective experiences.

The aim of this study was to identify and raise awareness of the challenges and unmet needs faced by patients living with epilepsy on polytherapy in five European countries, and to identify opportunities to address those unmet needs.

The objectives were to:

a. Understand the subjective experiences of patients living with epilepsy and how these experiences may change over the duration of the patient journey from presentation through to ASM treatment, and ASM treatment monitoring and follow-up stages

b. Identify the impact these experiences have on patients’ everyday QoL (e.g., work life and relationships) and psychological well-being (e.g., emotions and mental health)

c. Identify patients’ unmet needs at each stage of the patient journey and recommend opportunities to address those.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. study design.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted to explore the participants’ subjective experiences; for example, emotions (mental states brought on by neurophysiological changes, variously associated with thoughts, feelings, behavioral responses, and a degree of pleasure or displeasure) ( 20 , 21 ), and feelings (a conscious experience created after the physical sensation or emotional experience) at each stage of the clinical journey ( 22 , 23 ). This study was conducted as market research; therefore, ethical approval was not required. Codes of conduct/guidance for the (pharmaceutical) market research industry, including the British Healthcare Business Intelligence Association and the European Pharmaceutical Market Research Association were strictly followed. A team of market researchers and health psychologists, who are experts in strategic patient innovation and engagement, worked in conjunction with senior staff from a pharmaceutical company to design the study and analyze the qualitative research.

2.2. Participants and sampling procedures

A third-party recruitment company was used to recruit participants within the predefined criteria as follows:

1. Live in France, Germany, Italy, Spain, or the United Kingdom (UK)

2. Aged more than 18 years old

3. Diagnosed with epilepsy

4. Currently on an ASM combination adjunctive therapy for their epilepsy (i.e., at least on two ASMs, regardless of the disease duration and number of ASMs used previously)

5. Comfortable to talk about their personal experiences of being diagnosed with epilepsy and living with the condition – particularly around the emotions felt at different stages

In the context of this research area, we have defined polytherapy to mean when first-line monotherapy alone was not successful.

2.3. Interview procedure

Participants were invited to take part in a market research study about their experiences of being diagnosed with epilepsy and living with the condition, with a focus on their emotional experiences.

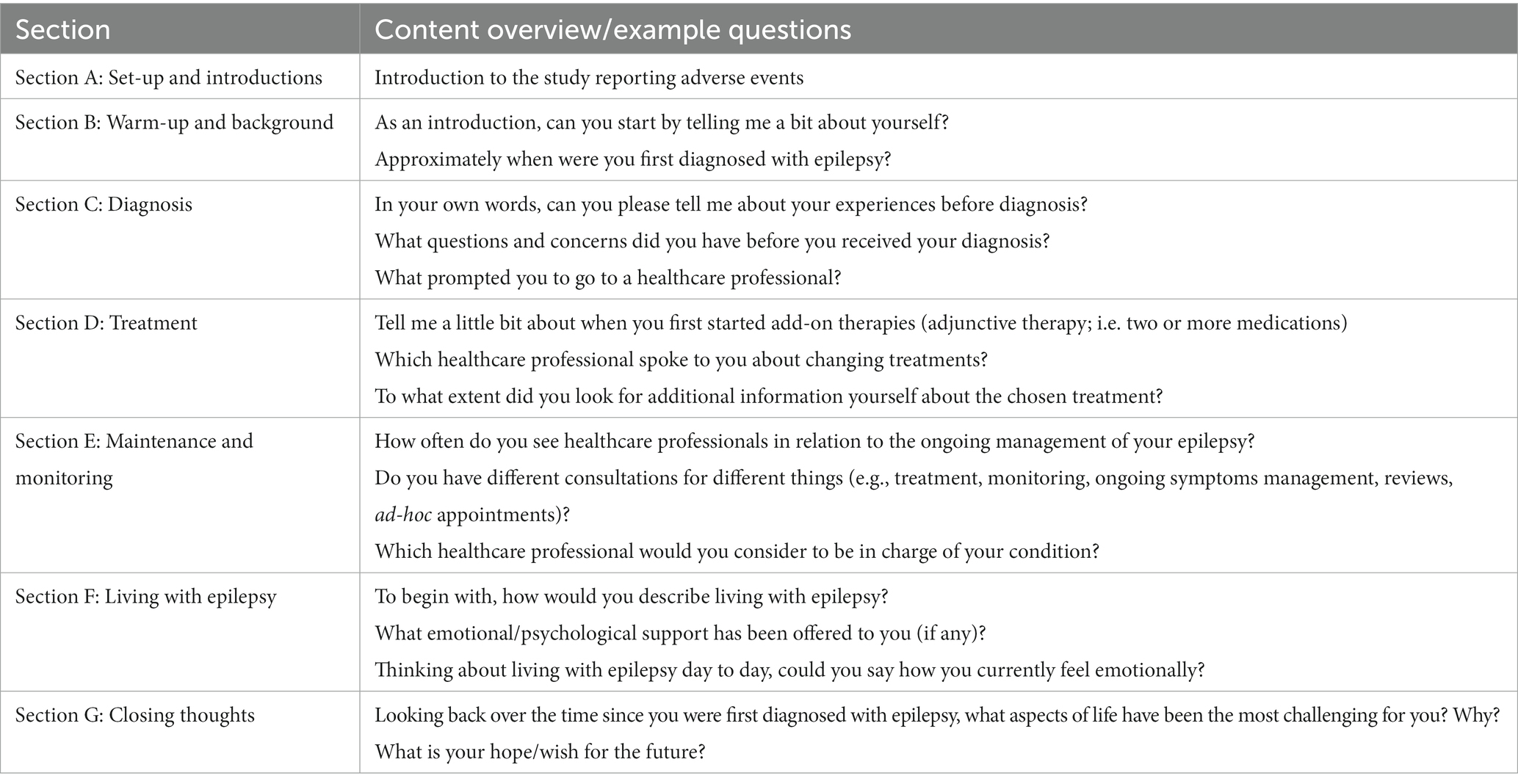

The interview topic guide was developed in English by the research team, and all United Kingdom interviews were moderated by the same team of researchers. Interview topic guides were then translated into French, German, Italian, or Spanish by native speakers through a third-party contracted recruitment company, and interviews in each of the four non-English speaking countries were carried out by local language moderators. The third-party were also responsible for recruiting participants from all five countries according to the pre-established inclusion criteria. Interviews were conducted via a web-assisted platform (Microsoft Teams) and lasted 60 min on average. All 40 interviews were recorded with permission and transcribed. Microsoft Excel was used to store, manage, and carry out the analysis of interview transcripts. Before the interview commenced, participants were read an introduction to the study, which provided details of (1) the study procedure; (2) confidentiality; (3) the right to withdraw or to refuse to answer any questions; and (4) the need for reporting adverse events. The interview topic guide is described in Table 1 .

Table 1 . Interview structure and examples of questions from the topic guide.

2.4. Data extraction and analysis

We followed a combined framework and content analysis approach. Framework analysis is a comparative form of thematic analysis using a structure of inductively and deductively derived themes, and is a popular approach primarily used in applied research ( 24 ). It is particularly suitable when there are more than one researcher analyzing the data, as it sets out a systematic method to data analysis, and can be adapted for use with both an inductive and deductive type of qualitative analysis ( 25 ). The framework approach used in the current study incorporated three core steps: (1) deductive analysis (coding data into the stages of a predefined epilepsy clinical journey map, which was initially based on clinical guidelines for each of the included countries); (2) content analysis (to identify emotions within the patient journey); and (3) inductive analysis (an in-depth thematic analysis of the participants’ accounts within each stage of the patient journey).

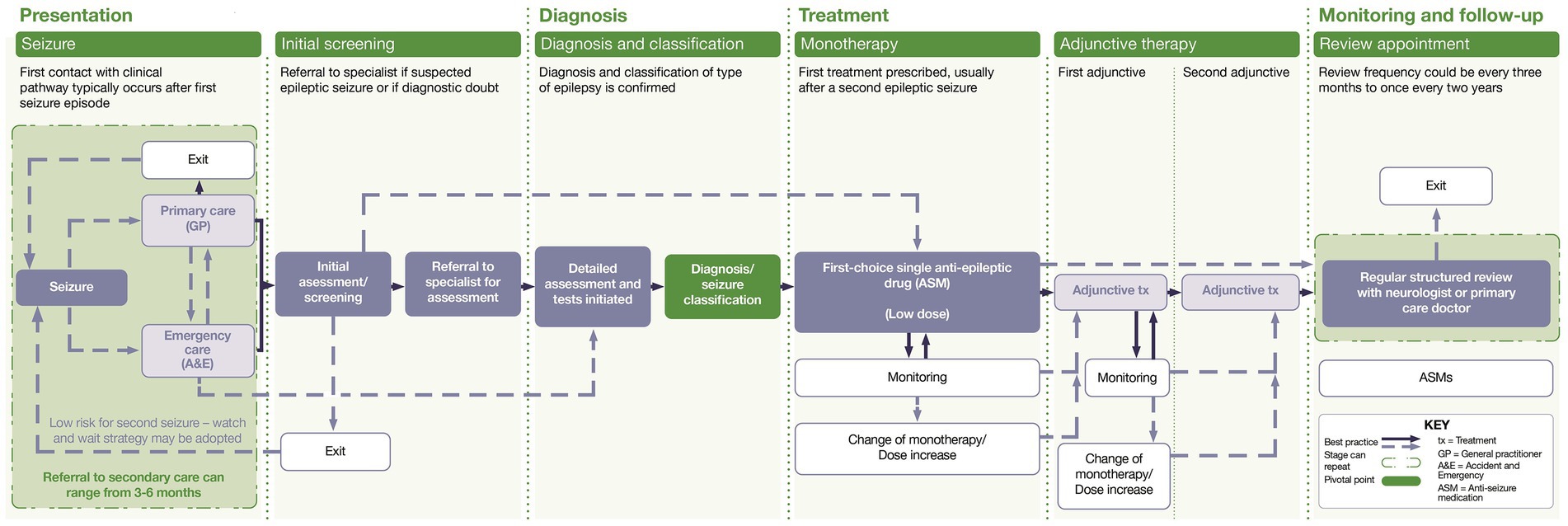

2.4.1. Step 1: Identifying the clinical patient journey (deductive analysis)

The first step was the development of a map representing the distinct stages of a clinical journey in epilepsy, from presentation through to monitoring and follow-up stages. This was developed using insights derived from existing literature contained in clinical guidelines reporting the patient pathway within the five countries included in the research ( 26–30 ), as well as insights from the current research.

Quotes, extracted from the interview transcripts, were coded according to which stage of the clinical map they were evaluated to represent.

2.4.2. Step 2: Identifying emotions within the patient journey (content analysis)

Content analysis of emotional expressions used by participants (positive or negative) was conducted. Similar emotions or emotional impact that were described or mentioned by the patients using different words were extracted from the interviews and grouped together, and an overarching emotional label was assigned by three health psychologists by consensus. For example, words/terms such as “nervous,” “anxious,” “tense,” “worried,” “scared,” or “afraid” would be grouped under the emotional label “fear,” or words/terms such as “understanding,” “reassured,” or “trusting” would be grouped under the label “reassured.” All overarching emotional labels (e.g., those that were reported by one or more participants) within each clinical stage (Step 1) were positioned on the Y axis of the map in descending order, starting with what was assigned by the research team (by consensus) to be the most positive (i.e., acceptance) down to the emotional label evaluated to be the least positive (i.e., anxious). The overarching emotional labels for each clinical stage were then visually mapped onto the correct coordinates of the graph/map (e.g., where the two points between the clinical stage [X axis] and the emotional label [Y axis] meet [the origin]).

2.4.3. Step 3: Conducting an in-depth thematic analysis of patient experiences (inductive analysis)

Thematic analysis was used to explore participants’ experiences and to identify key emerging challenges and unmet needs ( 31 , 32 ). Extracted data (i.e., any patient quotes relating to the impact of epilepsy on everyday life or insights into the patients’ subjective experience of living with epilepsy and/or their mental health) were examined and sorted within each prespecified stage of the clinical journey (e.g., presentation, diagnosis, and treatment), to synthesize and identify emerging content themes. Initial theme labels (describing broad content themes), and where relevant, sub-theme labels (nested within content themes) were then generated for each cluster of similar data to express these shared experiences.

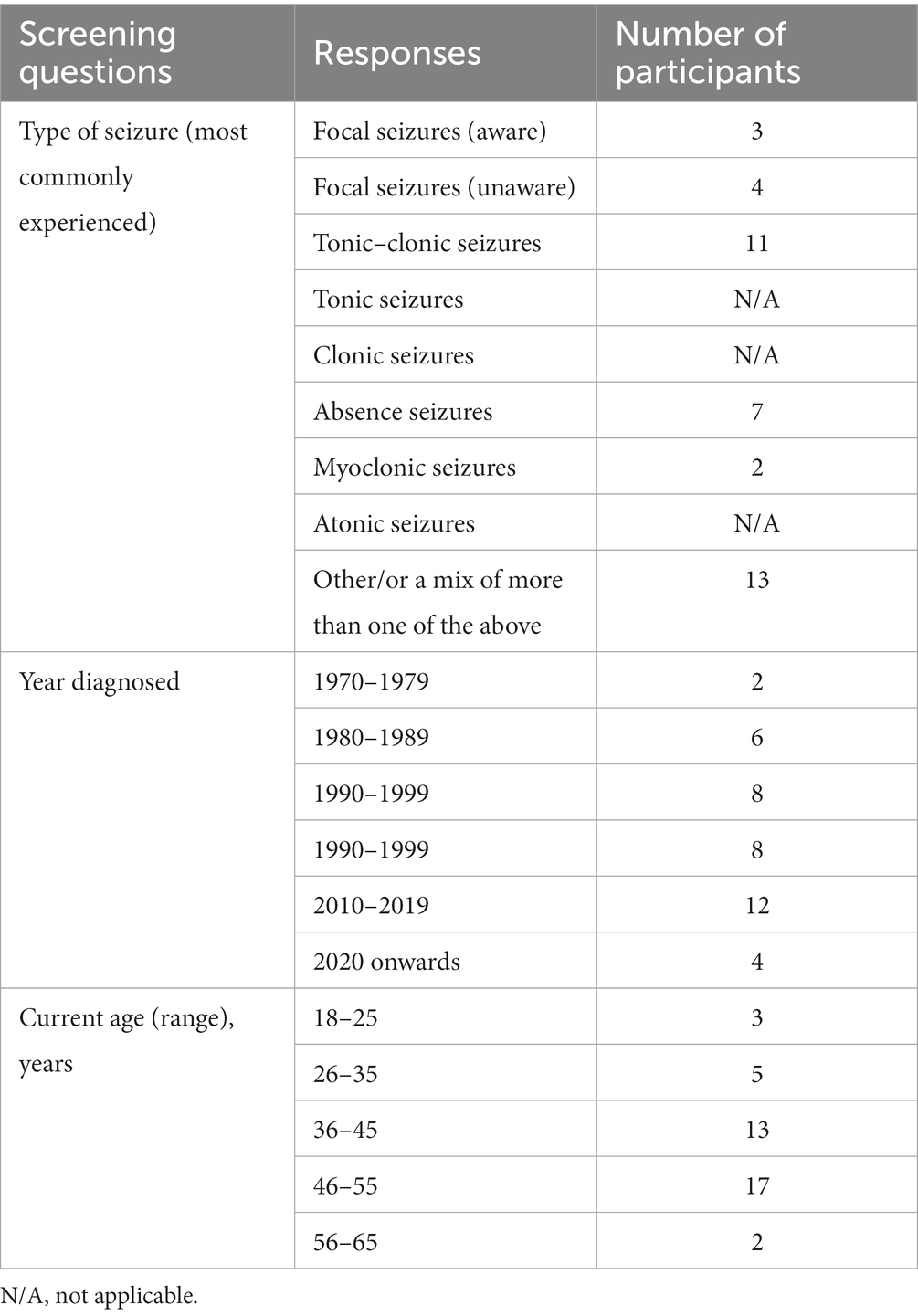

3.1. Participant characteristics

Forty participants were recruited in total, eight from each of the participating countries (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom). All participants were adults at the time of the interview, aged 18–65 years. Life stage of diagnosis varied, with some diagnosed in infancy/childhood and others in adulthood. Participants’ time of diagnosis spanned four decades from the 1980s up until the 2020s. Presentation also varied; participants reported experiencing several seizure types, including: absence, tonic–clonic, focal (aware and unaware), and myoclonic ( Table 2 ). All participants were on polytherapy.

Table 2 . Participant characteristics.

3.2. Clinical patient journey map

Figure 1 displays the distinct clinical stages of the disease journey for people with epilepsy in Europe, from presentation through to monitoring and follow-up stages. The journey is not always a linear one; it can vary significantly between people with epilepsy, with some people not progressing through the different stages.

Figure 1 . Clinical journey map.

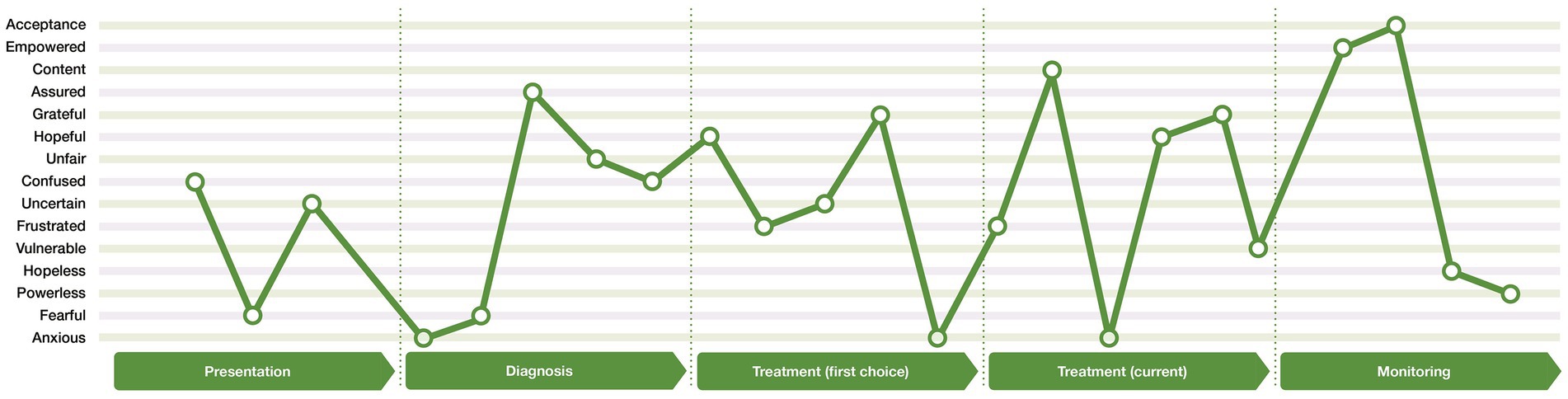

3.3. Emotional patient journey map

Figure 2 illustrates an aggregated emotional journey map developed from the participants’ reported emotions at each stage of the clinical journey. The lines that join the different emotions, do so only to illustrate the extent of the highs and lows of emotions that can be experienced. This emotional journey map is an aggregate of the emotional experiences of participants, and does not mean that all people with epilepsy experienced all these emotions, nor does it mean that these are the only emotions that each participant expressed or experienced. Furthermore, it does not mean that the emotions were experienced in a set order from one emotion to the next. However, it does illustrate how the participants may experience the same or similar emotions at different stages of the journey, or experience both positive emotions (e.g., gratitude) and negative emotions (e.g., frustration) within the same stage of the journey (e.g., treatment [first choice]). The emotional journey map therefore illustrates the emotional rollercoaster that people with epilepsy can experience.

Figure 2 . Emotional journey map.

3.4. Thematic analysis within the journey stage

Data (e.g., patient quotes) from each of the 40 interviews were extracted and coded into the most relevant section within the clinical map framework ( Table 3 ). Due to analyzing the patient experience per journey stage, similar themes may occur in more than one stage (e.g., feelings of uncertainty or the impact of the doctor-patient relationship).

Table 3 . Themes and sub-themes within each of the four clinical stages of the epilepsy journey.

3.4.1. Stage 1: Presentation – Life is turned upside down

3.4.1.1. high variability of symptoms contributes to a lack of symptom recognition.

The unique symptomology of seizures meant that the way participants first presented varied from person to person. For many, their first seizure happened spontaneously, and occasionally, in a dangerous situation (e.g., in the bath). Others reported having symptoms before their first seizure, including fainting, headaches, sweating, jerks, and phantom odors and tastes.

There was a low awareness of the symptoms of epilepsy among many of the participants; for example, many had only heard of tonic–clonic seizures, and did not recognize the signs of other types of seizures. Seizures accompanied by loss of consciousness might have initially been attributed to fainting, stress, or low blood pressure, and were usually recognized as a symptom of epilepsy in hindsight, post diagnosis.

“It started with a shaking and twitching of My leg. I could Not control It. First, I thought it was because of overstraining. I did not think of epilepsy...” [participant 4.1, Germany]

3.4.1.2. Challenges of entering the system cause confusion and fear

Participants were either taken to the emergency department following a first seizure or to their family practitioner/general practitioner, dependent on presentation; for example, people who experienced absences and loss of consciousness, usually saw their primary care provider, whereas those with other types of seizures went to the hospital. The participants that were taken into the emergency department were often left confused about their possible diagnosis and feared the potential outcome.

“…very nervous, anxious, tense, and worried. I was an emotional wreck. I did not know what was happening, why I was hospitalized, what they were doing.” [Participant 3.3, Spain]

Most participants who were diagnosed as children could not remember their life experiences pre diagnosis, but remembered feeling sad, scared, and being unsure of the reason for their tests/scans. Many were concerned about being different from their peers, and anticipated peer rejection. Participants who were children at this stage, reported that they had missed school and experienced disruption in their social life because of initial testing and treatment.

Participants who were adults when they had their initial investigations, experienced anxiety in anticipation of the outcome of their diagnosis; for example, concerns were often related to their belief that they were experiencing a stroke or psychosis, or had a tumor or cancer. Delays in diagnosis left them with feelings of uncertainty and a lack of information about their seizures and their management.

At this stage, participants reported significant disruption to their lives. They had feelings of being “out of control” and being debilitated by the lack of certainty around their daily lives.

“…it came very suddenly; it was a drastic change, and shock, no longer able to drive, to continue ‘a normal life’.” [Participant 1.1, UK]

Furthermore, participants recalled being confused while in the hospital and unable to remember what the healthcare professional had explained.

“[I] didn’t understand what was happening to me, I felt like I was going crazy.” [Participant 2.3, Italy]

3.4.2. Stage 2: Diagnosis – Period of learning

3.4.2.1. positive encounters with healthcare professionals drive emotional well-being.

Positive diagnostic experiences were characterized by positive encounters with neurologists/epileptologists, highlighting the importance of this relationship. Participants who spent more time with their neurologist/epileptologist felt they had the information needed to understand their epilepsy. Participants generally had frequent appointments at this stage, and relied on and trusted their neurologist/epileptologist. Those who felt reassured and supported by their core healthcare professional, were able to adapt and adjust to their diagnosis.

“I did feel supported; I had a very quick appointment, didn't feel left on my own […] high confidence towards my neurologist.” [Participant 1.1, UK]

“She [my neurologist] explains things so that everyone can understand […], and she is also able to take away the fear and panic.” [Participant 4.4, Germany]

Participants highlighted that meeting others with epilepsy at diagnosis would have benefitted them, but they did not always get the opportunity. Participants who were able to meet others with epilepsy while in hospital felt less alone.

“ I would have appreciated meeting fellow patients to learn and know what living with epilepsy is like.” [Participant 3.5, Spain]

3.4.2.2. Difficulties understanding the epilepsy diagnosis

Participants wanted to know the cause of their epilepsy. Healthcare professionals’ explanations of the diagnosis were often complex and hard to understand, with many wanting the neurologist/epileptologist to “come down to their level.” They felt that a dedicated healthcare professional who could speak to them on a personal level, consider social aspects of their life, and spend time to reassure and discuss information with, would have been beneficial. Not understanding the cause and diagnosis triggered frustration.

“[…] but the main question is the real root cause of the epilepsy. I had it for 35 years and I would like to know the origins of it.” [Participant 5.5, France]

3.4.2.3. The importance of the caregiver

For participants diagnosed in childhood, parents and caregivers had been their main source of information. Involving the child in the diagnostic process by helping them in understanding their illness, was recommended as a strategy to reduce their confusion.

“It would be good to involve children directly or as early as possible, as their parents might not do it, as in my case.” [Participant 4.7, Germany]

3.4.2.4. Uncertainty about the future causes frustration and worry

There was little opportunity to explore what the diagnosis meant for the participants’ day-to-day life. Participants had questions about repeated seizures and the possibility of brain damage. Many felt that the discussions with healthcare professionals and information provided to them focused on what the person should avoid, instead of what they were still able to do, and some of the terminology used could be perceived as scary. Participants were unsure about their future ability to drive, have children, drink alcohol, and continue to work. This left them feeling overwhelmed, shocked, and with a sense of injustice, from epilepsy stripping them of future opportunities.

“It was all very overwhelming because it was a list of things I could not do, rather than reassuring.” [Participant 3.8, Spain]

“I was shocked when I was told that I could not continue my apprenticeship as a carpenter, as it involves the handling of machines.” [Participant 4.5, Germany]

“…before the diagnosis, I had a life full of sporting initiatives, of dreams to realize; all this collapsed after the diagnosis.” [Participant 2.7, Italy]

“I was told that I had a ‘mini storm’ in my mind, which I find extremely scary.” [Participant 5.2, France]

3.4.2.5. Role of psychological support

Experiencing mental health issues was common, as many of the participants expressed difficulty adjusting to their diagnosis, including panic attacks, anxiety, and depression. Those who were offered psychological tools and support by their healthcare professionals found it helpful, but others had to look for support from psychologists outside the hospital. Some deemed professional support unnecessary for them personally, however, retrospectively felt that they would have benefitted from support. Outside the healthcare setting, a strong family network could help people cope with mental health issues and their diagnosis.

“I had panic attacks, anxiety, depression, and all that was totally overlooked.” [Participant 3.5, Spain]

“It would have been nice to have it. Now looking back, I realize that they [healthcare professionals] take for granted that you are mature enough to digest everything they tell you. And I was not.” [Participant 3.8, Spain]

3.4.2.6. Stigma and lack of awareness

Stigma was reported to come from multiple sources, including healthcare professionals, friends, family, peers, and the public. Participants reported feeling fearful or embarrassed by public perceptions of epilepsy, and felt that there was a lack of awareness of the condition and its symptoms.

“Someone affected by epilepsy doesn’t only suffer from the condition itself, but also from the lack of education of everybody else around them.” [Participant 2.1, Italy]

3.4.3. Stage 3: Treatment – Aspirations and experimentation

3.4.3.1. treatment initiation is associated with hope and uncertainty.

Participants were generally initiated onto a single, low-dose ASM (monotherapy) following diagnosis. Treatment aims ranged from reducing the number and/or intensity of seizures to eliminating them entirely, with little to no medication side effects. Participants’ expectations were therefore often optimistic, and they were hopeful they would be able to resume life as before, or at least see an improvement in their QoL. This sense of hope and optimism was often accompanied by a sense of uncertainty about the future, as participants were aware there was no guarantee that their first-line monotherapy treatment would work or continue to work for them in the long term. Those with a good treatment response, on their current treatment, were able to return to their daily routine, and expressed gratitude that they had experienced respite from seizures.

“I hoped that this would have been the right one…” [Participant 1.6, UK]

“I hoped [with treatment] to have a normal life, be able to work again. Not be dependent on welfare.” [Participant 4.8, Germany]

“[…] they were very vague, saying that I could have a seizure tomorrow, next week, next year or never.” [Participant 3.3, Spain]

“I have not had a seizure in years… No longer on the verge of the cliff.” [Participant 3.1, Spain]

3.4.3.2. Treatment changes can cause confusion

Whether the participant remained on the prescribed treatment regimen, depended on the outcome of the regular review (clinical monitoring and an assessment of the impact of epilepsy and medication on the person’s daily life). If the frequency/intensity of seizures did not improve, there was a drop in effectiveness over time (e.g., months or years), or the person did not tolerate the treatment, then a trial-and-error approach was taken. This process, decided by the participant’s assigned neurologist/epileptologist, involved a gradual increase of the current ASM dose, a new single ASM, or an add-on therapy.

Treatment changes could cause confusion, however, when established on a new treatment regimen, participants felt hopeful that their treatment would be successful in stopping seizures and improving their QoL. They initially felt content in their new therapy, and expressed feeling safe, supported, and confident that they would be seizure free.

While some accepted that they might need to start and stop multiple treatments to reach and maintain control of their epilepsy, others were left with feelings of frustration, disappointment, and hopelessness regarding the possibility of continued treatment failures.

“… it was a bit done by trial and error.” [Participant 5.2, France]

“[I expected] a normal life [from the new treatment regimen]. I expected a better quality of life and not all the side effects.” [Participant 2.1, Italy]

“When I got the present combination, I felt it was a miracle, felt so happy, everything had gone back to normal […] very grateful for it, no negative impact.” [Participant 1.1, UK]

“Now I am so well adjusted that I hardly ever have a seizure, maybe once a year or twice at the most. I am content with my therapy, and I don’t want to switch to another drug.” [Participant 4.7, Germany]

“Every time they [added] a pill, it felt like they were improving the treatment, that I was being better taken care of, and that maybe, one day this will all end.” [Participant 3.3, Spain]

“It was a quite different treatment regimen. [If it were up to me, I would] just want to carry on with my life, free of all the treatments. It was [disappointing] to an extent, because I feel less […] hopeful regarding the treatment options.” [Participant 1.5, UK]