- Islenska is

Follow the food: the rise of gastronomic tourism in the Nordics

Written by Afton Halloran

From zero to hero. That’s the best way to describe just how the Nordic countries have skyrocketed to the top of the global gastronomic charts over the past 15 years. This attention has drawn in tourists from around the world, sparking the further development of unique experiences that stand out among homogenous tourist offers.

Off-the-beaten path

Fifteen years ago, food tourism was non-existent in the remote Faroe Islands. Since then everything has changed. There are now 10 restaurants of international standards, including Koks Restaurant with two Michelin stars – an amazing feat for a population of just 50,000 people. The impact of the New Nordic Food movement can be felt throughout the islands.

In a globalised world where destinations are becoming increasingly similar in their offerings, many travellers are seeking something out of the ordinary. The Faroe Islands have marketed themselves as authentic, off-the-beaten-path and unique. Part of this has been shaped by food and the culture behind it. Traditional and modern takes on meals made from North Atlantic seafood, free range lamb and fermented foods have caught the attention of many world-renowned food journalists and foodies alike.

The Faroese have also been especially prudent in ensuring that tourism remains at levels tolerable to the people that inhabit the islands. In 2019, Visit Faroe Islands launched a strategy, Presevolution to preserve and evolve the nation’s distinct nature and culture. After witnessing a rise in tourism, the industry wants to see responsible and sustainable growth that carries on well into the coming decades.

Photo: Koks Restaurant

Experiential tourism

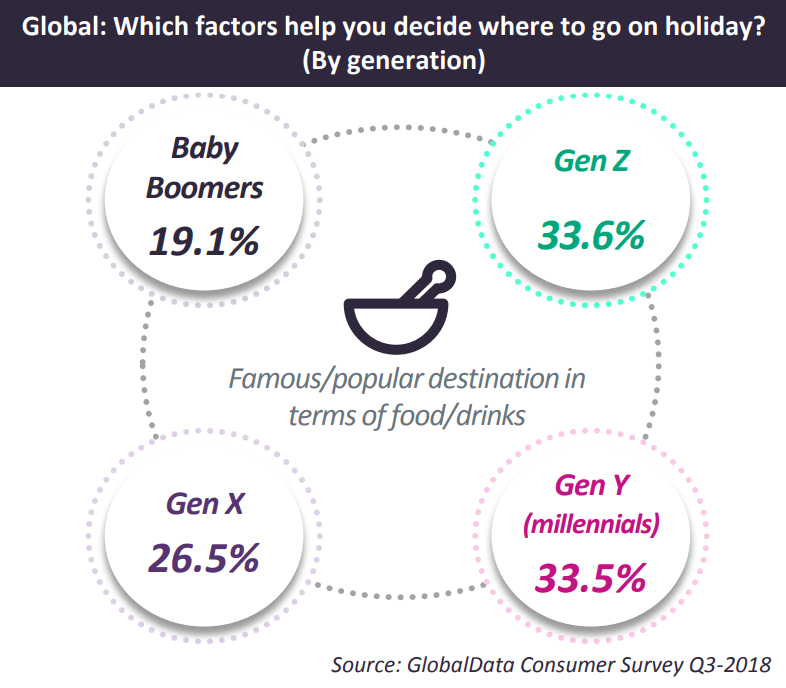

For many people today, food preferences are an important part of identity. Gastronomic adventures span from the most serious of foodies seeking to explore and collect experiences to the everyday tourist that enjoys doing a food activity as visiting a food market or perhaps a local restaurant. One thing they have in common is that most tourists remember positive food experiences from their trip.

“The New Nordic Food movement has certainly helped in putting the Nordic region on the gastronomic world map and attracted large numbers of visitors. We’ve seen 15 years of very positive development in these areas,” says Jens Heed, Program Director Food Travel for Visit Sweden.

In 2017, foreign tourists in Sweden spent 47 billion SEK (4.5 billion EUR) on food and drinks, up 50% from 2014. Over 50% of global travellers to the country were motivated to travel because of good food and drink. Nearly one in every five international travellers believe that Sweden offers top culinary experiences.

So, what lies ahead for food tourism in Sweden?

“I certainly expect to see a considerable rise in offerings of and demand for learning food experiences – opportunities not only to sample the local food or drink but also to theoretically and/or practically learn more about, for example the production techniques, food culture or cooking habits. Activities include local cooking schools, make it yourself classes or spending time with producers,” reflects Jens Heed.

Photo: Simon Paulin/imagebank.sweden.se

Building a food nation

In 2019, the Government of Denmark launched a public-private partnership, the Gastro 2025 initiative, to attract gastronomic tourists and to raise the status of locally produced food beyond Denmark’s borders.

Like the other Nordic countries, Denmark has seen an increase in the demand for quality food experiences. Today, 28% of the foreign tourists in Denmark are gastronomic tourists, for whom gastronomy and eating out have high importance for choosing to vacation in Denmark.

“Good food experiences have long been one of the most important stories in our tourism marketing, but we have not previously had the opportunity to focus so strongly on the food. Now, for the first time, we are given the opportunity to prioritize gastronomy big time because funds have now been earmarked for the story of Denmark as a food nation,” says Eva Thybo of VisitDenmark.

Photographer: Robin Skjoldborg

Quality over quality

With growing tourism comes increased food consumption. The Icelandic government has found themselves asking how the small island nation can offer tourists a positive food experience while at the same time ensuring that the food on offer is produced in a sustainable way and creates a limited amount of waste.

Since 2010, the number of tourists visiting Iceland has grown dramatically – increasing from 495,000 to 2.3 million visitors in a nation of just 340,000 people. This has resulted the increased importation of certain types of food. This dilemma has sparked the need for a more holistic approach.

In parallel with an increase in tourism is growth in local food, artisanal food, ‘slow food’ and street food. New companies that focus on food-related tourism such as guided food tours, visit to producers, tastings are beginning to pop up. Fine-dining restaurants focusing on seasonal foods are becoming more prevalent.

Despite the difficulties that can come with handling a surge of tourism, there is a sense of optimism: “Iceland has a wealth of resources related to food production including raw materials, space, energy, an educated workforce and technology. There are many new opportunities just waiting to be explored such as increased vegetable production using thermal energy… The food system needs to be looked at in a holistic way, with the participation of all stakeholders. We need to agree on common vision and act on it,” says Þóra Valsdóttir of Matís, Iceland’s government-owned Food and Biotech R&D institute.

The government is currently working on a food strategy that should be ready by mid-2020.

To match this vision, tourism will also need to shift. Most tourists that visit Iceland come for the unique and relatively unspoilt nature as well as the chance to experience human solitude in wide open landscapes. But the Icelandic nature can be fragile, and the experience visitors are looking for can be negatively influenced by overcrowding.

In the past, focus was placed on volume, but in the future the shift will be towards quality.

We would like to thank Guðrið Højgaard (Visit Faroe Islands), Jens Heed (Visit Sweden) and Þóra Valsdóttir (Matís).

This story is part of a series about the future of New Nordic Food. Follow Afton Halloran, sustainable food systems expert, as she listens to different voices from around the Nordic region.

Elisabet Skylare [email protected] +45 2171 7127

- Info Norden information service

- Free publications

- Apply for funding

- Nordic Council prizes

- The Nordic Council Environment Prize

- The Nordic Council Children and Young People’s Literature Prize

- Nordic Council Literature Prize

- The Nordic Council Film Prize

- Nordic Council Music Prize

- Policy areas

- Nordic statistics

- Nordic Council

- Nordic Council of Ministers

- About the Nordic co-operation

Related content

The Nordic Council issues statement regarding Israel and Palestine

Public consultation on new Nordic Council of Ministers' programmes for co-operation 2025–2030

IUFRO - Largest global forest event held in Stockholm

Nordic Day 2024: Artificial Intelligence and Democracy

Nordic Day 2024: Navigating Nordic Futures – Strengthening Cooperation for Peace and Security

How To Get The Most Out Of Your Food Tourism Experience

Food tourism, also known as culinary tourism, is all about traveling far and wide to taste and learn about unique cuisines and culinary cultures. From mouth-watering thin-crust pizza in Napoli, and exquisite omakase dining in Kyoto, to street-side pho in Hanoi, buttery croissants in Paris , and sugary beignets in New Orleans — this is where the excitement of travel meets the universal language of food, an undeniably delicious combination.

But before you hurriedly and hungrily hop on your flight in impatient hopes of having the best spanakopita of your life in Greece or the soupiest xiaolongbao in Hong Kong, take a moment and unleash your inner foodie detective. This is the first and crucial step — do your research and thoroughly investigate the destination's food scene before your culinary adventure even begins. Familiarize yourself with local dishes, street food, regional specialties, markets, farms, cooking classes, and unique dining experiences.

Planning your gastronomic journey will help you know exactly where the best spots are and which ones are best avoided. To streamline your food tourism experience with some tech-savviness, look into starting a favorites list on Tripadvisor or Google Maps, so you can keep note of the restaurants, cafes, beerhalls, gelaterias, or izakayas you want to visit. If you are vegan or vegetarian, the HappyCow app can be your global foodie guide, providing details, reviews, and directions to thousands of plant-based establishments worldwide.

Live the culinary story of your destination

To get the most out of your food tourism experience, immerse yourself in the local culture. Venture beyond the typical tourist traps and seek out places where locals dine. If the area is bustling, the food smells good, and you don't see many tourists around — you may have won yourself a gourmet jackpot. Street food stalls, farmer markets, and neighborhood eateries often serve the most authentic and tasty food. Stray from the beaten path and walk the food trails of the locals. Zapiekanka? Pampoenkoekies? Shakshuka? Yes, please!

Speak to chefs, vendors, and locals to better understand the cuisine. Don't just eat; engage. You'll often discover hidden gems and learn the stories behind the food you're eating. Instead of coming somewhere to munch quickly and taking lots of pictures before moving to the next item on your itinerary, practice conscious culinary tourism — take it slow, have a chat, and sink your teeth into the experience.

A food tourism 2021 study published in the Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research suggests that foodie trips become memorable through social interactions, senses, and feelings, trying new things, paying attention, and mindfully reflecting on the experiences. Those who love food and drink and travel for it felt these experiences stuck in their memory the most. Try something new; sign up for cooking classes, wine or beer tastings, food tours, or a farm stay . These hands-on experiences are not only educational but can also be some of your most memorable activities.

Respect, learn, and revel in your food journey

Your food journey is not just an exploration but a recipe with two ingredients: respect and learning. Each place has its food etiquette and traditions. As a visitor, you should respect these practices; they show appreciation for the culture; also, educate yourself before your arrival to avoid any unintentional offense. For example, in most Asian countries, it is highly taboo to stick two chopsticks vertically into a bowl of rice — a symbol of death, bad luck, and an invitation for spirits to dine with you. That's an RSVP you don't want to receive.

In the age of Instagram and food blogging, documentation has become an integral part of our dining experiences. However, chronicling your gastronomic expedition goes beyond just photos — it involves capturing the stories, customs, and unique personal moments that come with each dish you enjoy. Consider keeping a travel journal, blog, or vlog, where you can note down recipes, local anecdotes, and reflections to keep lasting memories of your adventure.

The heart and soul of food tourism is the thrill of discovery. Sample dishes you can't pronounce, indulge in local delicacies, and experiment with unfamiliar ingredients. Do not be passive — embrace this lively, interactive experience that engages your senses and transports you to a different world. Food tourism is more than just food; it's about the people, stories, and cultural insights that come with it. Let the world be your dining table.

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

Culinary Tourism

Lucy M. Long is director of the independent Center for Food and Culture and retired faculty in Popular Culture, Bowling Green State University, Ohio.

- Published: 21 September 2022

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Culinary tourism, also known as food tourism and gastronomic tourism, is simultaneously a scholarly field of inquiry, a niche within the tourism industry, and a human impulse to “eat out of curiosity” and try new food experiences. Two key themes emerge in the current scholarship around food and travel: developing critical frameworks for a cohesive discipline and connecting both the practice and study of culinary tourism to sustainability in the broadest sense of the word to ensure that these projects benefit us all. This chapter offers an overview of these developments, contextualizing them within larger historical events and trends. It demonstrates that culinary tourism emerged out of paradigm shifts in how we think of food and of tourism, and that these shifts then have allowed for food to become the subject of touristic imaginations. It suggests that culinary tourism has also played a significant role in encouraging those shifts and that it now offers both a field of scholarship and an activity that is of growing interest and recognition. It also observes that the historical dimensions of culinary tourism have generally been overlooked but such attention offers a productive area of cross-disciplinary engagement.

Food-focused tourism is an increasingly popular activity among consumers in the twenty-first century. It has emerged as a significant niche within the tourism industry, an effective tool in sustainability and economic development initiatives, and a subject for scholarly study from a range of disciplines. Variously called culinary tourism, tasting tourism, food tourism, and gastronomic and gastronomy tourism, 1 two key themes confront the field. The first is how to study the phenomenon in a coherent and critical way that brings together the many disciplines that address aspects of either food or tourism, especially since this range crosses over the usual boundaries of social science and the humanities as well as “academic” and applied fields. Much of the scholarship has focused on contemporary trends, so one of the challenges is to bring in the historical dimensions of the relevant disciplines. The second is how to channel the practices of culinary tourism toward greater good and “greater engagement with sustainability issues.” 2 Sustainability refers here to the broader issues surrounding the ecological, economic, social, and cultural impacts and implications of tourism and includes discussions around colonialism, exoticism, authenticity, appropriation, identity, heritage, and other issues.

The emergence of culinary tourism reflects changing attitudes in the larger world around both food and tourism, in what can be thought of as “paradigm shifts,” a paradigm being a set of concepts and practices that define a scientific discipline and way of viewing a subject. 3 In this case, such shifts can refer to both the scholarly study of culinary tourism and to changes in social attitudes. These paradigms also have both responded to and should be understood within the context of larger local and global economic, political, and social events and conditions. Historical perspectives on both the scholarship and their contexts contribute to understanding these developments. Other scholars have also noted this point. Greg Richards, for example, in 2015, offered a history of the field, connecting it to the development of the experience economy. 4 In 2019, Sally Everett identified “theoretical turns” in the evolution of research around what she calls “tourism taste-scapes.” 5 I build upon this work to suggest here that culinary tourism itself has played a role in those paradigm shifts, inspiring changes, and even revolutionizing, how we—scholars, tourism and food industries, and the general public—think of food and tourism.

Culinary tourism has evolved as a field of scholarship, an industry, and a domain of human activity. Each of those subjects should be understood within larger contexts of trends around food—its production, consumption, and the critical study of it. Three stages occur in this evolution: the 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s. Each stage is characterized by larger global conditions and events that may have shaped trends in both food and in tourism. That evolution also explains the relevance of the two themes of defining the discipline and connecting it to sustainability. The review is, unfortunately, limited to English-language publications and therefore focuses on developments in Western cultures, while attempting to recognize the scholarship now emerging by non–English speaking scholars.

This history is not nearly as clear-cut as these stages suggest. As Kuan-Huei Lee and Noel Scott have noted regarding the field, “The evolution of an academic discipline is not a linear and neat process but instead is idiosyncratic and often competitive, leading to a disjointed and fragmented literature that somehow must be comprehended and ordered.” 6 Scholarship on culinary tourism is multidisciplinary, bringing together methods and theories from social sciences as well as the humanities, with emphases ranging from critical theorizing of the meanings of purposely consuming an Other, to impact studies, to development of applications and best practices. Tourism studies, itself a multidisciplinary field, is an obvious home for such scholarship, and there are a number of excellent reviews of this literature from that perspective. Food studies, also multidisciplinary, is another logical home and has encouraged research in it. History scholarship on both food and tourism is particularly relevant to this overview, but these fields are not often blended. 7 This may reflect perceptions of tourism as only a modern activity resulting from industrialization and Western colonialism and therefore lacking a long history as well as a tendency in Western scholarship to dismiss food as a serious domain of study outside of its role in economic development. It also reflects shifts in the field of history itself. Peter Scholliers points out that until the 1960s food was attended to primarily by economic historians studying “food supply, hunger, and prices.” 8 This changed in the late 1950s with the advent of social history and the study of everyday life, although Amy Bentley points to the 1980s for scholars of US history to begin recognizing food as a useful lens for understanding life in the past. 9 Historians have since contributed seminal works that have shaped the field of food studies, providing overviews of the development over time of national food practices and attitudes as well as of the changing uses and roles of specific foodstuffs. 10 Scholars, such as Sydney Mintz with his studies of sugar and the slave trade, offered analyses of historical events and movements through the lens of food, demonstrating the usefulness of the subject for understanding history. 11 While the movements of people as well as foods were oftentimes included in these histories, they were not recognized as tourism, per se, until more recently with studies of specific regions. 12 Be that as it may, culinary tourism can be said to have now developed into a subfield of its own. The subject also draws practitioners as well as theorists, from a wide range of disciplines, offering a rich opportunity for the development of critical theories grounded in practice and ethnographic analysis. The field is now more frequently making use of the perspectives and data offered by historians to contextualize trends and patterns. 13

A history of culinary tourism is complicated by the lack of a single definition for it, a reflection partly of contested definitions of tourism in general. From an industry perspective, it is travel away from home so that hospitality services are needed. 14 From a more critical perspective, it is the seeking of new experiences, escape from the mundane and everyday, or a way of seeing. 15 Culinary tourism similarly can be considered the intersection of food and travel, as “food and drink motivated travel” with recognition that those subjects are frequently also parts of other types of travel and tourism. 16 A more philosophical stance considers it to be an approach to food that does not necessitate travel, although frequently inspires it. Culinary tourism in this sense includes the vicarious exploration of unfamiliar foods or foodways experiences—the “kitchen table” tourism of viewing food network programs, perusing cookbooks, or reading food blogs—as well as any instances of “eating out of curiosity.” 17 Debates around the name of the subject reflect the diversity of approaches taken in studying it.

The development of cohesive definitions and theories is also complicated by the very nature of food itself as a universal biological necessity and everyday activity, as well as a domain for symbolic communications, social interaction, personal expression, aesthetic experience, and negotiations of power and identity. This complex nature of food also should mean that the need to connect culinary tourism to sustainability is obvious.

The production, distribution, consumption, and disposal of food clearly draw from and impact the natural environment. Economic systems are built around food, so that fair and equitable remuneration for it is an obvious issue. Historical studies of the forces shaping those systems are necessary in order to understand how and why they took on the forms they display today—a need recognized by scholars in food systems studies and by historians who find food a useful medium through which to analyze the arc of time in a particular culture. Similarly, food is tied to the ways in which societies are organized and to the institutions that support those societies. Anthropologists, sociologists, and folklorists of a historical bent have explored these processes, but generally have not connected them with tourism. 18 Culinary tourism can impact those institutions as well as the cultures—the groups, the practices, and ethos or worldviews—of those that are involved. Food should be understood as a social, cultural, and personal construction, with fluid and dynamic meanings, making it hard to pin down in terms of identity, ownership, and function. 19 People eat out of hunger, but also out of myriad other motivations, and while the act of eating is universal, what they eat, how, and why is specific to each culture and even to individuals. Food therefore offers the possibility of sharing our individual humanities, potentially disrupting the Othering or emotional and social distancing that can occur in tourism.

Setting the Stage for Culinary Tourism: Prehistory to the 1980s

People have always traveled in order to obtain food, and, as an essential biological need, food has always been a part of travel. Food also has always been a commodity to trade with, profit from, and to use for political and social power, so has been sought after and carried from one place to another. The idea of traveling specifically to enjoy and to satisfy one’s curiosity about a particular dish or cuisine experience, however, is a different phenomenon and separates it as tourism. This type of travel involves looking at new food experiences as voluntary and for purposes beyond just functional or practical—for relaxation, pleasure, edification, or status. Such an approach can occur at any time for an individual, but as a cultural institution, it depends upon economic and political conditions that allow for it.

A number of scholars have recognized this longer global history of travel and eating. 20 Tourism scholar Sally Everett, for example, points to the age of exploration (the fifteenth century) as the beginnings of the Western “search for food as a leisure activity,” and the origin of contemporary tourism. 21 This exploration was tied initially to the spice trade, but the subsequent colonization and exploitation of new lands also meant the exchange of foodstuffs between cultures and continents. These exchanges, particularly the Columbian one, introduced many new ingredients and foodways styles that were incorporated into the receiving food cultures and lost their identity as “foreign,” but they also introduced the idea of novel foods as a domain for recreation and entertainment. Tomatoes and potatoes, for example, were brought from Central America to Europe in the late 1400s and were initially treated as exotic, even eyed with suspicion by some, but then become integral to the iconic dishes of many European cultures. 22 Chocolate and pineapple, however, remained curiosities and usually available only to the wealthy for at least another two centuries. 23

The Industrial Revolutions of the 1700s and 1800s in Europe and the United States created a shift from rural agrarian societies to urban, manufacturing ones, changing many people’s relationship to food. The resulting rise of the industrial food system has been critiqued as creating a distancing of consumers from producers, and the dislocating of food from place. The advantages and disadvantages of this system are a much larger topic, but most scholars agree that it contributed to a devaluing of food itself and of the skills and abilities involved in producing, procuring, preparing, and even consuming it. Similarly, the rise of capitalist economic systems has been critiqued as turning food into a commodity to be esteemed primarily for its monetary value. At the same time, both forces expanded the variety of foodstuffs available, made them potentially more accessible to the common people—laborers and developing middle classes, in theory, offered a degree of security from the caprices of nature (but not the whims of governments and fellow humans).

Those revolutions set the stage for later conditions relevant to culinary tourism. Reactions to the resulting modernity have been drivers toward the natural and “authentic,” oftentimes expressed by a romanticization of “primitive” cultures and more traditional ways of living. The countercultural revolutions of the 1960s and 1970s developed those themes with an openness to new cultures and new experiences as well as a celebration of diversity and nonconformity, all of which helped open up peoples’ palates to new tastes. 24

Similarly, globalization in the latter half of the 1900s both inspired culinary tourism and made it possible. Characterized as “space-time compression,” 25 globalization has frequently given access to ingredients, dishes, cooking styles, and food philosophies from across the globe. Macrobiotic diets based on Indian ayurvedic principles became popular in the US in 1960s countercultural revolution, 26 while American fast-food establishments introduced hamburgers and factory-style food production throughout the world. Although literature and travel writing might have piqued our curiosity before, we can now actually satisfy that curiosity and experience these new foods. At the same time, fear of the homogenizing effects of globalization lead to attention to and valuing of the local. 27

Food, however, was generally not seen in the Western world as a significant aspect of tourism. Although dining at certain establishments and tasting specific dishes had been included as part of the seventeenth and eighteenth century European Grand Tour (see Verhoeven , this volume), responses were oftentimes ambivalent at best, and such travel was available only to the upper classes anyway. 28 Food, in general, in much of the modern Western world was considered more a matter of nutrition and economics than something to be sought after for its own sake. Until the early 2000s, for example, the American tourism industry did not consider food of interest enough to Americans to be a motivator for travel or spending. It was assumed that most Americans wanted food that was familiar, and those who traveled for food itself made up a small elite group who frequented famous restaurants, cities, or countries known for their gourmet cuisines and would not consider themselves tourists. 29

This attitude carried over into academia. Food tended to be relegated to applied fields (home economics, nutrition, culinary arts), but some of the more ethnographic disciplines, particularly cultural anthropology and folklore, at least included it within their purview. 30 Within tourism studies, a 1978 article included food as an aspect of culture, but few other scholars even recognized it as a possible attraction or destination on its own, lumping it instead with other hospitality services. 31 Folklore (known as Ethnology in Europe) developed theories about food’s role in maintaining and negotiating traditions and communities, as well performing personal identity and artistry, reflecting the “cultural turn” of the 1960s that started shifting attention to the meanings of food. 32

At the same time, many of these disciplines were suspicious of tourism as a colonialist enterprise and an arm of neoliberal capitalist governments and therefore failed to examine it closely. While that suspicion has continued somewhat, individual scholars began in the 1990s (and some earlier) crossing disciplinary boundaries to explore the intersections of food and tourism. Geographer Wilbur Zelinsky, for example, introduced the term “gastronomic tourism” in a 1985 article, in which he surveyed telephone book listings of ethnic restaurants in order to map culinary regions in the United States and Canada and explain the prevalence of particular ethnic groups as restaurateurs. 33

1990s: Time of Prosperity and Beginnings of Culinary Tourism

The 1990s were a time of general prosperity in the Western world, meaning that both travel and food were more accessible to more people. Both also began garnering attention from scholars in a variety of disciplines. Eating out became a major source of entertainment and socializing, and certain restaurants were recognized as destinations for travel. 34 Also, migration and immigration had always contributed to bringing “foreign” cuisines to new locales, but there now seemed to emerge a trend in seeking out establishments serving such food. 35 Ethnic restaurants came to the attention of more scholars, although skepticism about the authenticity of commercial transactions may have kept away those looking for cultural representation. 36 Mass media also began attending more to food, building upon the earlier popularity of televised cooking shows, and food magazines enjoyed more popularity as people became more interested in developing gourmet skills and tastes. 37

The increasing interest in trying new foods was also possibly related to the “experience economy” that arose in the West in the 1990s. According to Greg Richards, consumers seeking more meaningful and memorable experiences—which he identified as “first generation experiences,” could find them through food since it easily engages all five senses. 38 Coinciding, however, with this increased availability of new foods were fears of contamination, food safety technologies, and health impacts of certain foods, which tended to dominate much of the popular discourse. 39 These food anxieties and other factors constrained the exploration of food as a touristic subject for mainstream cultures, keeping it within the domain of hospitality services.

Meanwhile the development of the World Wide Web, along with other technological advancements, meant that communicating across long distances was easier and cheaper, making travel to unfamiliar places less challenging. That, along with strong economic growth, made travel more accessible to the middle classes, although trains and automobiles had already established opportunities for travel in the 1800s and 1900s (see Pearson , this volume). Even ocean liners and canal boats had provided mobility previously, arguably from ancient times. Be that as it may, some of the earliest studies on tourism and food tended to focus on the negative impacts. P. Reynolds, for example, found that tourism on the island of Bali in Indonesia had caused a shift in tourist restaurant menus away from indigenous dishes, harming the local food culture. 40 Similarly, David Telfer and Geoffrey Wall found harmful linkages between tourism and food production in that agricultural land was given over to producing tourist foods rather than local crops. 41

These studies also illustrate tourism scholar Dean MacCannell’s identification of the 1990s as the second phase in the development of tourism studies. 42 Earlier scholars tended to define tourism as the “search for authenticity” and focused on how tourism transformed local cultures, reinforced economic inequality, and commodified exotic “others.” Scholarship, he observed, shifted in the 1990s to definitions based on motivations and the seeking of pleasure. This characterizes a number of tourism scholars in the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand who began theorizing about the positive potentials of the intersection of food and travel. One of the most influential, C. Michael Hall, expanded upon scholarship on wine tourism to introduce “food tourism” as a genre of tourism having as its primary motivation “the desire to experience a particular type of food or the produce of a specific region.” 43

Also emerging during this decade was food studies as an interdisciplinary field building initially on the work of scholars who recognized food as symbolic communication and a central feature of cultural traditions and social systems. 44 A logical topic for study was the meanings and implications of consuming cuisines of others, which frequently involved some form of travel. For example, scholarship in folklore and cultural studies recognized the role of food as attraction in public and private festive events. 45 Scholars, especially historians of immigration, recognized ethnic restaurants as sites for negotiating identity and a place in the economic and social systems of the US historians in general began attending more to food, recognizing it as a significant domain of everyday life. Studies published in the 1980s by scholars such as Stephen Mennell, Massimo Montanari, and Sydney Mintz were widely read in the 1990s and established food history as a legitimate branch of the field. 46 Few, however, recognized tourism as a significant shaping force of food cultures. Jeffrey Pilcher stands out as one with his 1998 history of Mexican food. In 1997 David Bell and Gill Valentine used “kitchen table tourism” to address the virtual exploration of other food cultures through modern technologies and to identify numerous issues involved in culinary tourism from a cultural geography perspective. 47 A 1998 article offered a sociological perspective on traditional food and cuisine as tourist attractions, 48 while the eleventh conference of the International Commission for Ethnological Food Research in 1996 focused on the role of colonization in food and travel. The proceedings were published in 1998, edited by Irish folklorist Patricia Lysaght, and the articles provided historical as well as ethnographic perspectives on the connections between migrations, immigrations, and the geographic distribution of particular foods and foodways.

Also introduced in 1998 was the term “culinary tourism,” by folklorist Lucy Long to encompass humanities perspectives on the meanings of eating new or unfamiliar foods. Defined as “intentional, exploratory participation in the foodways of an Other, participation including the consumption—or preparation and presentation for consumption—of a food item, cuisine, meal system, or eating style considered as belonging to a culinary system not one’s own,” 49 culinary tourism could include a variety of others (ethnic, regional, socioeconomic, religious, ethical) and the full range of activities and practices around food, not just consumption. It also drew upon anthropological theories defining tourism as a state of mind or type of “gaze,” that was not dependent upon actual travel. Culinary tourism from this perspective is a negotiation of edibility and palatability as well as exoticness and familiarity, with otherness depending on each individual and the social and cultural groups of those individuals. The article also identified five strategies commonly used in negotiating these realms. This article and others included in the special journal issue were republished as an edited volume with additional essays in 2004.

During this decade there was also a growing concern over the morality of tourism in general. As early as 1992, the United Nations held a conference on sustainable development, concerned that “first world” nations were creating economic systems dependent on those nations for survival and endurance. Tourism was recognized as one of the forces creating dependency, and it was determined that tourism should contribute to the well-being of people and ecosystems rather than for the profit of private industries. Tourism scholars recognized that the sustainability of destinations and attractions was crucial for the sustainability of tourism itself, and some responded to this call by incorporating the concerns into their studies of food and tourism. C. Michael Hall’s 1998 text, Sustainable Tourism: A Geographical Perspective , laid out principles for sustainable tourism and is particularly relevant to food tourism scholarship.

2000s: Introducing and Defining New Paradigms in the Field

The first decade of the twenty-first century saw the emergence of culinary tourism as an exciting new field both for scholarship and the tourism industry. Both seemed to feed into each other, although initially they seem to have been separate endeavors with scholarship preceding practice. Both also were responding to—and helping shape—newer paradigms emerging around food and travel. Food was also expanded to include beverages. Oftentimes focused on wine and vineyards, beverage tourism had previously been treated as a highly specialized attraction for highly cultured “guests” rather than for the “crass commercialism” of mass tourism. Whiskey, alcoholic cider, and beer also were recognized as viable touristic products. 50

Although the idea that food was more than fuel or nourishment was commonplace in numerous cultures, it was only during this decade that it began taking hold of the Western imagination, specifically in English-language nations that dominated the world economy and tourism industry. 51 (Perhaps the notion of traveling to enjoy food was so obvious in those cultures already appreciating it that it did not seem necessary to develop the concept. This would explain why countries renowned for their cuisine—France, Italy, Spain—have been slower to contribute to the scholarship and industry.) Food became recognized—and celebrated—as an expression of artistry and identity. The prosperity of the 1990s had helped establish dining out as a source of entertainment, and “ethnic” cuisines were now included in this trend. 52 Interest in food became a lifestyle “choice,” in which foodies organized their personal and social lives around its preparation and consumption. 53 It could be argued that this was simply a reiteration of earlier “gastronomes,” such as Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin (1755–1836), the French lawyer and politician who famously wrote “Tell me what you eat, and I will tell you what you are” and even the Greek philosopher, Epicurus (341–270 BC). 54 Mass media popularized this attention to food with the food network turning chefs into celebrities the equivalent of rock stars. Food memoires became a popular way to combine recipes with a narrative of one’s life, blogging about one’s cooking became a common obsession, and restaurant reviews became general reading for the masses. While these trends characterized the “experience economy” that had started earlier in the 1990s, 55 they also represented the growing realization that food could be symbolic, artistic, social, and personal—a new paradigm. Organizations such as Slow Food, which started in 1986 in Italy, also added to the idea that food was political, and that individual’s food choices had ethical and moral consequences.

Tourism, similarly, was undergoing changes, partly in response to the experience economy, but also as a reflection and driver—of the continued globalization making formerly “foreign” and “faraway” places seem closer, more accessible, and less threatening. Richards characterizes this stage as one of “second generation experiences” in which consumers take a more active role in the creation of an experience. 56 Food was an ideal domain for such creativity. A “new moral tourism” was also emerging, in which tourists became conscientious of their impacts on the cultures and environments they visited. The motto “tread softly” captured the responsibility for individuals to make moral choices. 57 Such concerns had confronted travelers in the past, particularly in response to the countercultural movements of the 1960s and the development of backpacker tourism and volunteer tourism, but the tourism industry seemed to be slow to recognize those shifts until they were identified by scholars and industry movers. John Tribe, for example, wrote that three issues had always been involved in tourism—truth, beauty, and virtue—and that now was the time to address them. 58

These trends were emerging in the wake of the terrorist acts of September 11, 2001. This event challenged the assumption of security felt in most Western nations, particularly in the United States. Travel across borders became, in some places, frightening and more complicated than before, so that many people started looking within their own nations for tourism experiences. Food similarly became a relatively safe new universe to explore without leaving one’s home culture. Novel experiences could now be found easily in restaurants without all the hassle and danger of international travel.

Whether or not “9/11” was a conscious catalyst for the tourism industry, it did seem to set an atmosphere in which food could be recognized as an attraction. In 2003, the World Tourism Organization established policies around local food in tourism and published an international survey of iconic foods for potential tourism development, and in 2004, the US-based International Culinary Tourism Association was established as a professional organization. Such industry initiatives focused primarily on the potential for food to draw tourist dollars and contribute to economic development that would then increase profits. Food posed an innovative and colorful way to create a “brand” or marketing identity for a place, and, although it had previously been a part of the total experience, food was now considered something novel that could be featured as a primary attraction. Similar to wine tourism, which is still frequently treated as separate from culinary tourism, 59 the emphasis was initially on expensive, gourmet dining experiences with well-known chefs and restaurants, usually in locations with already established reputations for their unique and refined haute cuisines. That emphasis was partly driven by the assumption that people who were interested in food were interested only in fine dining experiences, but also those tourists would bring in the most money and be able and willing to pay for other services, such as lodging, souvenirs, and entertainment. These projects, in the United States, at least, seem to have been more connected to the hospitality and tourism marketing industries than to the scholarship of tourism, although there was a symbiotic relationship between the two in many instances.

Popular forms of these early initiatives in culinary tourism were maps, brochures, and websites identifying selected restaurants and events featuring food. Drawing from the successful models provided by whiskey, wine, and other beverage tourism, these were oftentimes dubbed “trails” that tourists could follow on their own. Marketing emphasized restaurants’ reputations in food circles, oftentimes ones having a long history, 60 perhaps describing some signature dishes. It also identified chefs, preferably well-known and with culinary arts background, who were applauded for their originality, creativity, and individuality, so that the food and total dining experience would be unique and only available there. Chefs such as Paula Dean, Bobby Flay, Gordon Ramsay, and Emeril Lagasse became celebrities through television cooking shows and drew culinary tourists to their restaurants and guest appearances in public. Chefs previously had become famous for their skills, Auguste Escoffier (1846–1935) in France, for example, but this decade saw them turned into media stars known to the “masses.” Frequently, the food, restaurant, or chef had no actual historical connection to a specific place—ingredients were not locally sourced, and recipes were not traditional. Food events, similarly, seemed to celebrate place, but oftentimes featured gourmet and innovatively distinctive dishes rather than foods representative of the area. This gradually changed as more tourists became interested in and knowledgeable about food and began searching for “authentic” eating experiences.

A spate of publications in the first few years of 2000s established the intersection of food and tourism as a scholarly subject. These came from a variety of disciplines and offered a variety of names for the field. Tourism scholars, understandably, dominated, exploring typologies of tourist motivations, of tourist activities, and of food products. They also examined the role of food in destination development and strategies for marketing, although this was frequently explored in terms of recent activities and future potential rather than historical patterns or events. 61 Scholars from more culturally oriented fields and the humanities emphasized the meanings and implications of culinary tourism, oftentimes recognizing historical forces as shaping that tourism without in-depth analysis of them. All struggled with defining the field, building upon work done in the 1990s.

In 2001, tourism scholars, C. Michael Hall and Richard Mitchell, used the phrase “food tourism” in an academic journal for “visitation to primary and secondary food producers, food festivals, restaurants and specific locations for which food tasting and/or experiencing the attribute of specialist food production regions are the primary motivating factor for travel.” 62 That name became further established in in 2003 with the publication of an edited volume, Food Tourism Around the World , edited by Hall and other scholars leading the field, Liz Sharples, Richard Mithell, Niki Macionis, and Brock Cambourne. 63 The edited volume explored motivations and models for food tourism as well as its role in regional economic development, recognizing that food is as aspect of culture. Their typology of food tourists based on the intensity of interest in food offered a starting point for further research on tourist motivations, and their inclusion of activities, such as cooking schools, festivals, and food trails expanded food tourism beyond the visitation of restaurants. The authors also emphasize that geographic place is significant to food tourism, stating that even though it can be “exported” it still retains a spatial fixity: “The tourists must go to the location of production in order to consume the local fare and become food tourists.” 64 This volume and other extensive publications by these scholars encouraged cross-disciplinary, research-based approaches in examining tourist motivations and the development, management, and marketing of food tourism products. While much of this work focused on analyzing current initiatives in order to explore opportunities for future projects, their work also draws upon the histories of specific destinations, events, and products. They also recognize the potential impacts of tourism beyond the industry, encouraging a model for ethical tourism.

Another influential edited volume, Gastronomy and Tourism , was published in 2002 by Anne-Mette Hjalager and Greg Richards. 65 Including beverages in the range of products considered, it also examined issues involving travel for food, but went beyond tourism studies to call for an interdisciplinary approach recognizing both gastronomy and tourism as dynamic cultural constructions reflecting specific histories and contemporary interests. Authors in the volume pointed out that tourism and gastronomy were both emerging disciplines with similar dichotomies in practice from small-scale, artisanal production to mass-produced production, so each could learn from the other. One chapter specifically called attention to the need for tourism scholars to better understand food and food studies, 66 while others observed that globalization should be interpreted as a potentially beneficial force, noting that fears of it fail to recognize the dynamic character of both gastronomy and tourism. Ultimately, the volume promoted the potential for gastronomy and tourism to serve as radical, activist disciplines.

A similarly broad perspective was offered in 2002 by Priscilla Boniface. In Tasting Tourism , she drew from cultural studies to understand the nature of tourism in the modern world and how tourism can change the meanings of food. 67 She asked why food and drink have recently become attractions in their own right for Western tourists, placing the question in historical context as a contemporary reaction to industrialization, modernity, and globalization. She observed that this new attention to food represents more than just the discovery of a new niche in tourism, but reflects a shift in the culture of tourism itself that is no longer based on a separation from the quotidian. Focusing on attitudes in Western cultures (particularly those with a British heritage), Boniface saw food tourism as a seeking of authentic experiences through food—resulting from the peculiarities of modern life, yet this very modernity is what makes us recognize and appreciate the past, the rural, and the nonindustrialized. She also identified five “driving forces” acting as motivations for food tourism: anxieties over food safety and social uncertainty; a need to show distinction, affluence and individualism; curiosity and wish for knowledge and discovery; the need to feel grounded amid globalization; and the requirement for sensory and tactile pleasure. 68

A 2004 assessment of the state of food tourism as both an industry and a field of scholarship pointed out that while food offers many possibilities in tourism, it can also be an obstacle. Unpleasant food experiences can lead to cultural misunderstandings, and the use of food as an attraction can actually have harmful effects on the host culture. 69 A 2005 PhD tourism thesis offered a conceptual framework for “tourists’ participation in food related activities at a destination to experience it’s culinary attributes.” 70 Other scholars confirmed the usefulness of food as a tourist attraction, observing that since it is an obvious cultural marker, it is an effective way to establish a connection between tourists and a destination. 71 Although the beginnings of the tourism industry in the 1800s recognized that connection, 72 food historically seemed to have been seen more often as an obstacle to a pleasant journey than an attraction to draw tourists.

Much of this work defined food and tourism as necessitating travel. A different approach came from the humanities with the edited volume, Culinary Tourism , in 2004, which elaborated on the earlier definition of “eating out of curiosity” and offered a framework for examining the exploratory or adventurous eating of individuals and groups outside of as well as within the formal infrastructures of tourism. 73 Culinary tourism from this perspective expanded the types of foodways activities available beyond consumption to include production, procurement, preservation, preparation, and even disposal, all of which could be in public or private settings as well as traditional or invented ones. It also recognized the larger historical and economic forces shaping and enabling touristic activity, but allowed for individuals to create their own meanings of those activities. Seemingly opposite, the theory is compatible with the mobilities theory developed by sociologist and tourism scholar John Urry and others that focused on the flow of people and products between places. Insightful explorations of culinary tourism from this perspective have expanded understandings of the phenomenon as a human impulse. 74 Jennie German Molz, for example, suggested that culinary tourism is a performance of a traveler’s “sense of adventure, adaptability, and openness to any other culture,” thereby demonstrating their cosmopolitanism. 75

These seminal works introduced a number of themes that scholars continued to explore, particularly the definitions of the field and typologies of tourists, food products, and food-related events. Also of concern is the nature of culinary tourism as unique or different from other types of tourism. Since food consumption offers a direct connection between our physical bodies and the ways in which we act in and perceive the world, 76 it can embody the experience of a place in ways that other forms of tourism do not allow. Everett pointed out that through food, tourists can literally and figuratively internalize a destination, making touristic activities more meaningful, 77 and Sims posited that food was a vital part of an “embodied tourism experience,” which increased the satisfaction of tourists, giving that place a competitive advantage as tourism destination. 78 Similarly, a study of Chinese tourists observed that food consumption utilizes all five senses, giving those tourists a perception of a richer experience. 79