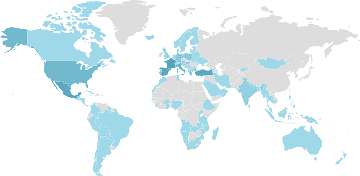

International tourism: the most popular countries

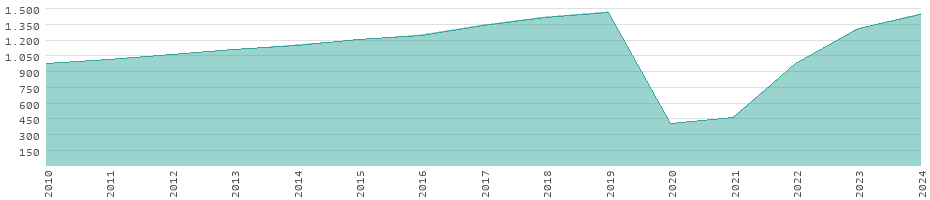

Drastic declines due to COVID-19

The most popular travel countries.

Germany is the world travel champion

Booming tourism and slump in 2020.

A look at the costs

- Today's news

- Reviews and deals

- Climate change

- 2024 election

- Fall allergies

- Health news

- Mental health

- Sexual health

- Family health

- So mini ways

- Unapologetically

- Buying guides

Entertainment

- How to Watch

- My Portfolio

- Stock Market

- Biden Economy

- EV Deep Dive

- Stocks: Most Actives

- Stocks: Gainers

- Stocks: Losers

- Trending Tickers

- World Indices

- US Treasury Bonds

- Top Mutual Funds

- Highest Open Interest

- Highest Implied Volatility

- Stock Comparison

- Advanced Charts

- Currency Converter

- Investment Ideas

- Research Reports

- Basic Materials

- Communication Services

- Consumer Cyclical

- Consumer Defensive

- Financial Services

- Industrials

- Real Estate

- Mutual Funds

- Credit Cards

- Balance transfer cards

- Cash-back cards

- Rewards cards

- Travel cards

- Personal Loans

- Student Loans

- Car Insurance

- Morning Brief

- Market Domination

- Market Domination Overtime

- Opening Bid

- Stocks in Translation

- Lead This Way

- Good Buy or Goodbye?

- Fantasy football

- Pro Pick 'Em

- College Pick 'Em

- Fantasy baseball

- Fantasy hockey

- Fantasy basketball

- Download the app

- Daily fantasy

- Scores and schedules

- GameChannel

- World Baseball Classic

- Premier League

- CONCACAF League

- Champions League

- Motorsports

- Horse racing

- Newsletters

New on Yahoo

- Privacy Dashboard

Yahoo Finance

World tourism rankings by country: top 20 countries.

In this piece, we will take a look at world tourism rankings by country. If you want to skip our analysis of the tourism industry and recent trends, head on over to World Tourism Rankings by Country: Top 5 Countries .

Tourism is one of the key determinants of global economic health. And it's an industry that has grown alongside advances in air transportation that have enabled people to travel to far flung destinations while traveling at speeds of hundreds of kilometers per hour.

This industry is also among the few that were left completely devastated in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic. Estimates from the United Nations' World Tourism Organization (WTO) show that international travel shrunk by an absolutely stunning 72% in 2020 as lockdowns and stay at home orders led to the closure of hospitality establishments and restrictions on the number of people that could be crammed inside an enclosed space such as an airplane. The impact of the pandemic was so severe that even by the end of 2022, the industry had recovered to 65% of previous levels despite more than a year of near normalcy.

Yet, tourism is one of the biggest industries in the world. For instance, according to research from Industry Arc, the global travel and tourism industry is expected to grow at a compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) of 3.1% between 2021 and 2026 to be worth an estimated $8.9 trillion by the end of the forecast period. Another report from Allied Markets Research estimates that the business travel market was worth $696 billion in 2020 and will grow at a CAGR of 13.2% to sit at $2 trillion by 2028.

At the same time, business and leisure travel are not the only constituents industries of tourism. Two additional markets are adventure tourism and luxury travel. Estimates suggest that the former was worth $282 billion in 2021 and after growing at a CAGR of 15.1% is estimated to be worth $1 trillion in 2030. As far as luxury tourism is concerned, it was quite lucrative, being worth $1.28 trillion in 2022, and should have a CAGR of 7.6% to be worth $2.32 trillion in 2030.

Building on this, the next logical question to ask is which countries are the most popular for tourists and which are the most visited overall as well as in continents such as Europe and Asia. Well, on this front, data from the World Tourism Organization once again answer all our questions. Its World Tourism Barometer report for December 2020 (the latest version that is publicly available) shows that France was the most visited tourist destination in the world and in Europe in 2019. Broadening our approach to see which are the top ten most visited tourist countries in the world, we find out that after France, the list is dominated by Spain, the U.S., China, Italy, Turkey, Mexico, Thailand, Germany, and the United Kingdom. Astute readers will note that this also makes China as the most visited tourist destination in Asia. In terms of numbers, 83.5 million people visited Spain in 2019 - the second most popular tourist destination in Europe while China attracted 65.7 million people.

At this point, you might be wondering which is the most popular and most visited city in the world. Well, and perhaps unsurprisingly, just as France is the world's and Europe's most popular tourist destination, the most visited city in the world is its capital, Paris. This bit of information comes courtesy of Euromonitor International, which adds that in addition to Paris, some other popular cities for tourists are Dubai, Amsterdam, Madrid, Rome, and London. Crucially, Euromonitor's stats are for 2022, while the WTO's data shared above is from 2019, and these facts when taken together indicate that trends in the tourism industry tend to stay similar over the years - a crucial conclusion as you'll find out below.

China's role as the most popular tourist destination in Asia and a leading global economy merits a deeper look at what's in store for the country's tourist fortunes. China kick started 2023 by removing nearly all restrictions on travel and tourism, and after initially faltering, the pent up tourism demand roared back to life. Data compiled by McKinsey shows that visits to one of its most popular cities Shanghai nearly doubled to ten million visitors from the pre coronavirus 2019 peak. At the same time, China also has some of the biggest outbound tourism travelers in the world, and McKinsey estimates that pend up demand from these visitors as well carries with it a strong chance of injecting fresh vigor into the global tourism industry.

Finally, it's relevant to conclude our analysis of the global tourism industry by taking a look at what's happening on the ground. On this front, the management of Expedia Group, Inc. (NASDAQ: EXPE ) outlined during its first quarter of 2023 earnings call conference :

And I’m pleased to have started the year with strong performance. We posted our highest ever quarter for lodging gross bookings and free cash flow and our best first quarter for revenue. Throughout the quarter, we saw strong consumer demand with acceleration in international and big city travel and more of Asia reopening. The reemergence of major international cities has meant increased hotel demand, offset in part by flattening demand in vacation rentals as travel demand mix to urban destinations over extended beach and mountain trips. Similarly, air has continued to mix towards international travel and away from COVID era concentration in domestic. By and large, prices have held up quite well after several years of inflation. We’ve seen lodging ADRs hold fairly steady across geos. Air ticket prices, however, continued to increase as strong demand continues to outstrip capacity. The only area where we have seen any meaningful decline in average daily rate is in the car rental space where larger inventories have allowed rental companies to drive more volume at the expense of price. Overall, we are pleased to see broad travel demand remain strong in what appears to be a more structural post pandemic environment of people prioritizing travel above most other categories of spend. This has held up despite inflation and recession worries and even, more recently, bank system concerns. While economists continue to debate potential recession outcomes and clearly many unknowns are still out there, consumers have so far shaken it off and continue to travel.

With these details in mind, let's take a look at the world tourism rankings according to countries.

Pixabay/Public domain

Our Methodology

To compile our global tourism ranking by country, we used data from the 2020 version of the United Nations' World Tourism Barometer report. While it lists out international tourism receipts for 2019, this is actually helpful since 2019 was the last economically stable year for the global tourism industry which is still recovering. For our world tourism rankings, we have used international tourism receipts which is the amount spent by international visitors in a country. On a side note, both countries and special territories are included, since the spending is quite substantial.

World Tourism Rankings by Country

20. portuguese republic.

International Tourism Receipts: $20.6 billion

The Portuguese Republic is a Southwestern European country. It has a $257 billion economy and is famous for its Gothic architecture and diverse cuisine.

19. Republic of Korea

International Tourism Receipts: $21.6 billion

The Republic of Korea, commonly known as South Korea is a technologically developed Asian country. South Korea is quite popular with visitors from China - with thousands flocking to the country each year.

18. United Arab Emirates

International Tourism Receipts: $21.8 billion

The United Arab Emirates is not a surprising industry in our list of world tourism rankings. After all, its economic hub Dubai is one of the most highly visited cities in Asia.

17. Republic of Austria

International Tourism Receipts: $22.9 billion

The Republic of Austria is a Central European landlocked country. Some of its most popular tourist destinations include its capital Vienna, known for the Schönbrunn Palace.

16. United Mexican States

International Tourism Receipts: $24.6 billion

The United Mexican States, or Mexico, is a North American country. It is well known for historical tourism, being the birthplace of the Mayan civilization as well as beautiful beaches.

International Tourism Receipts: $28.0 billion

Canada is a prosperous North American nation. Canada is best known for its Niagra Falls, which has been a popular tourist destination for more than a hundred years.

14. Hong Kong SAR

International Tourism Receipts: $29.0 billion

Hong Kong is a special administrative region of the People's Republic of China. It is known for its vibrant nightlife, historic temples, and of course, Disneyland.

13. Republic of Türkiye

International Tourism Receipts: $29.8 billion

The Republic of Türkiye is an Asian and European nation. Its Istanbul International Airport is one of the busiest airports in the world.

12. Republic of India

International Tourism Receipts: $30.7 billion

The Republic of India is one of the biggest countries in the world and is full of iconic tourist destinations such as the Taj Mahal, the Ganges River, and more.

11. People's Republic of China

International Tourism Receipts: $35.8 billion

The People's Republic of China is the most populous nation in the world. It has a centuries old culture lending it iconic destinations such as the Great Wall of China.

10. Macao SAR

International Tourism Receipts: $40.1 billion

Macao is another special territory of China. It is best known for its vibrant casino and gaming industry.

9. Federal Republic of Germany

International Tourism Receipts: $41.6 billion

The Federal Republic of Germany is Europe's largest economy It is known for its beer festivals and winter markets, that is quite a spectacle.

8. Commonwealth of Australia

International Tourism Receipts: $45.7 billion

The Commonwealth of Australia is a prosperous Oceanic country. It is known for having the world's largest coral reef system, the Great Barrier Reef.

International Tourism Receipts: $46.1 billion

Like China, Japan is also a historic country full of ancient temples and a historic culture.

6. Italian Republic

International Tourism Receipts: $49.6 billion

Another unsurprising entry on our list is Italy. Known for its Roman culture and art galleries, it is one of the best destinations for cultural tourism.

Click to continue reading and see World Tourism Rankings by Country: Top 5 Countries .

Suggested Articles:

Top 15 Luxury Travel Agencies in the World

20 Most Dangerous Countries for LGBTQ+ American Travelers

Top Supersonic Travel Companies in the World

Disclosure: None. World Tourism Rankings by Country is originally published on Insider Monkey.

Countries With the Most International Tourists

As tourism rebounds from pandemic lows, the United Nations reports these countries welcomed the most visitors last year.

(Getty Images) |

Tourism is Rebounding

Two years after the COVID-19 pandemic essentially shut down international travel worldwide, the tourism industry is bouncing back as summer arrives in the northern hemisphere.

International tourism saw a close to 200% year-over-year increase in the first quarter of 2022, and although several related statistics are still well below 2019 levels, gradual recovery is expected to continue throughout the year, according to June analysis from the United Nations World Tourism Organization . Nearly 50% of experts surveyed by the organization said they expect international tourism to return to those pre-pandemic levels from three years ago in 2023, while 44% said it could be 2024 or later.

This is especially good news for countries whose economies are the most reliant on the tourism industry. Those countries include Antigua and Barbuda, Aruba and St. Lucia, according to 2021 gross domestic product data released in June by The World Travel & Tourism Council.

[ RELATED: These Countries Are the Best for Tourism ]

But the countries most supported economically by tourism aren't necessarily the ones that welcome the most visitors. The United Nations compiles several metrics related to inbound tourism by country , including international tourist arrivals, with the most recent data being from 2021. The statistics show that industry recovery still has a ways to go: The most-visited country in 2021 had about 32 million international arrivals. France, the top-ranked country in 2019 – before the pandemic hit – had 90 million.

Here are the countries that welcomed the most international tourist arrivals in 2021, according to the U.N. Included for each are other pieces of tourism-related data, such as GDP contribution percentages from the WTTC.

10. Hungary

2021 international tourist arrivals: 7.9 million 2019 international tourist arrivals: 16.9 million 2021 percentage contribution of tourism to GDP: 4.6%

2021 international tourist arrivals: 10.6 million 2019 international tourist arrivals: 17.4 million 2021 percentage contribution of tourism to GDP: 16.1%

2021 international tourist arrivals: 11.7 million 2019 international tourist arrivals: 35.2 million 2021 percentage contribution of tourism to GDP: 6.4%

2021 international tourist arrivals: 12.7 million 2019 international tourist arrivals: 22.7 million 2021 percentage contribution of tourism to GDP: 7.1%

2021 international tourist arrivals: 14.7 million 2019 international tourist arrivals: 31.3 million 2021 percentage contribution of tourism to GDP: 14.9%

5. United States

2021 international tourist arrivals: 22.1 million 2019 international tourist arrivals: 79.4 million 2021 percentage contribution of tourism to GDP: 5.5%

2021 international tourist arrivals: 26.9 million 2019 international tourist arrivals: 64.5 million 2021 percentage contribution of tourism to GDP: 9.1%

2021 international tourist arrivals: 29.9 million 2019 international tourist arrivals: 51.2 million 2021 percentage contribution of tourism to GDP: 7.3%

2021 international tourist arrivals: 31.2 million 2019 international tourist arrivals: 83.5 million 2021 percentage contribution of tourism to GDP: 8.5%

2021 international tourist arrivals: 31.9 million 2019 international tourist arrivals: 45 million 2021 percentage contribution of tourism to GDP: 13.1%

The Countries With the Most International Tourist Arrivals in 2021:

- United States

More From U.S. News

Assessing Politically Stable Countries

The 25 Best Countries

10 Countries With the Best Health Care Systems

Health News Bulletin

Stay informed on the latest news on health and COVID-19 from the editors at U.S. News & World Report.

Sign in to manage your newsletters »

Sign up to receive the latest updates from U.S News & World Report and our trusted partners and sponsors. By clicking submit, you are agreeing to our Terms and Conditions & Privacy Policy .

You May Also Like

Switzerland is world's best country.

Julia Haines Sept. 6, 2023

Photos: Best Countries Around the World

Sept. 6, 2023

The 25 Best Countries in the World

Elliott Davis Jr. Sept. 6, 2023

Pro-Palestinian US High School Students Accuse School of Censoring Speech

Reuters April 24, 2024

Brazil's Government Submits Rules to Streamline Consumption Taxes

Best Countries

- Understanding Poverty

- Competitiveness

Tourism and Competitiveness

- Publications

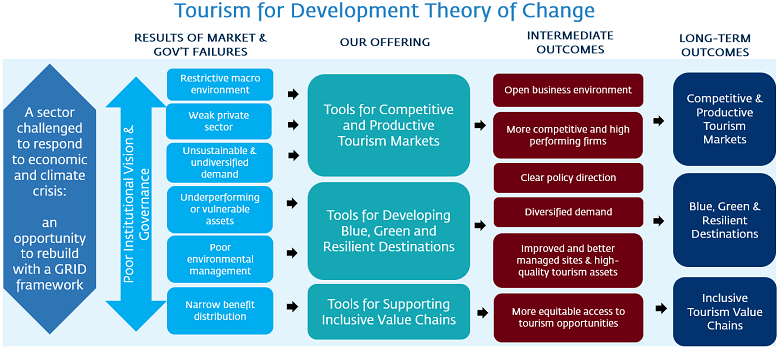

The tourism sector provides opportunities for developing countries to create productive and inclusive jobs, grow innovative firms, finance the conservation of natural and cultural assets, and increase economic empowerment, especially for women, who comprise the majority of the tourism sector’s workforce. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, tourism was the world’s largest service sector—providing one in ten jobs worldwide, almost seven percent of all international trade and 25 percent of the world’s service exports —a critical foreign exchange generator. In 2019 the sector was valued at more than US$9 trillion and accounted for 10.4 percent of global GDP.

Tourism offers opportunities for economic diversification and market-creation. When effectively managed, its deep local value chains can expand demand for existing and new products and services that directly and positively impact the poor and rural/isolated communities. The sector can also be a force for biodiversity conservation, heritage protection, and climate-friendly livelihoods, making up a key pillar of the blue/green economy. This potential is also associated with social and environmental risks, which need to be managed and mitigated to maximize the sector’s net-positive benefits.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has been devastating for tourism service providers, with a loss of 20 percent of all tourism jobs (62 million), and US$1.3 trillion in export revenue, leading to a reduction of 50 percent of its contribution to GDP in 2020 alone. The collapse of demand has severely impacted the livelihoods of tourism-dependent communities, small businesses and women-run enterprises. It has also reduced government tax revenues and constrained the availability of resources for destination management and site conservation.

Naturalist local guide with group of tourist in Cuyabeno Wildlife Reserve Ecuador. Photo: Ammit Jack/Shutterstock

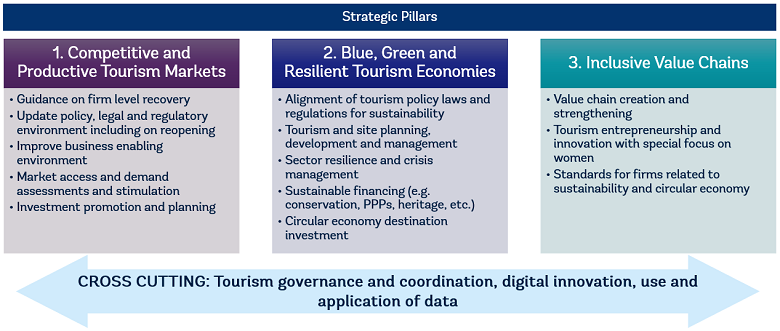

Tourism and Competitiveness Strategic Pillars

Our solutions are integrated across the following areas:

- Competitive and Productive Tourism Markets. We work with government and private sector stakeholders to foster competitive tourism markets that create productive jobs, improve visitor expenditure and impact, and are supportive of high-growth, innovative firms. To do so we offer guidance on firm and destination level recovery, policy and regulatory reforms, demand diversification, investment promotion and market access.

- Blue, Green and Resilient Tourism Economies. We support economic diversification to sustain natural capital and tourism assets, prepare for external and climate-related shocks, and be sustainably managed through strong policy, coordination, and governance improvements. To do so we offer support to align the tourism enabling and policy environment towards sustainability, while improving tourism destination and site planning, development, and management. We work with governments to enhance the sector’s resilience and to foster the development of innovative sustainable financing instruments.

- Inclusive Value Chains. We work with client governments and intermediaries to support Small and Medium sized Enterprises (SMEs), and strengthen value chains that provide equitable livelihoods for communities, women, youth, minorities, and local businesses.

The successful design and implementation of reforms in the tourism space requires the combined effort of diverse line ministries and agencies, and an understanding of the impact of digital technologies in the industry. Accordingly, our teams support cross-cutting issues of tourism governance and coordination, digital innovation and the use and application of data throughout the three focus areas of work.

Tourism and Competitiveness Theory of Change

Examples of our projects:

- In Indonesia , a US$955m loan is supporting the Government’s Integrated Infrastructure Development for National Tourism Strategic Areas Project. This project is designed to improve the quality of, and access to, tourism-relevant basic infrastructure and services, strengthen local economy linkages to tourism, and attract private investment in selected tourism destinations. In its initial phases, the project has supported detailed market and demand analyses needed to justify significant public investment, mobilized integrated tourism destination masterplans for each new destination and established essential coordination mechanisms at the national level and at all seventeen of the Project’s participating districts and cities.

- In Madagascar , a series of projects totaling US$450m in lending and IFC Technical Assistance have contributed to the sustainable growth of the tourism sector by enhancing access to enabling infrastructure and services in target regions. Activities under the project focused on providing support to SMEs, capacity building to institutions, and promoting investment and enabling environment reforms. They resulted in the creation of more than 10,000 jobs and the registration of more than 30,000 businesses. As a result of COVID-19, the project provided emergency support both to government institutions (i.e., Ministry of Tourism) and other organizations such as the National Tourism Promotion Board to plan, strategize and implement initiatives to address effects of the pandemic and support the sector’s gradual relaunch, as well as to directly support tourism companies and workers groups most affected by the crisis.

- In Sierra Leone , an Economic Diversification Project has a strong focus on sustainable tourism development. The project is contributing significantly to the COVID-19 recovery, with its focus on the creation of six new tourism destinations, attracting new private investment, and building the capacity of government ministries to successfully manage and market their tourism assets. This project aims to contribute to the development of more circular economy tourism business models, and support the growth of women- run tourism businesses.

- Through the Rebuilding Tourism Competitiveness: Tourism Response, Recovery and Resilience to the COVID-19 Crisis initiative and the Tourism for Development Learning Series , we held webinars, published insights and guidance notes as well as formed new partnerships with Organization of Eastern Caribbean States, United Nations Environment Program, United Nations World Tourism Organization, and World Travel and Tourism Council to exchange knowledge on managing tourism throughout the pandemic, planning for recovery and building back better. The initiative’s key Policy Note has been downloaded more than 20,000 times and has been used to inform recovery initiatives in over 30 countries across 6 regions.

- The Global Aviation Dashboard is a platform that visualizes real-time changes in global flight movements, allowing users to generate 2D & 3D visualizations, charts, graphs, and tables; and ranking animations for: flight volume, seat volume, and available seat kilometers. Data is available for domestic, intra-regional, and inter-regional routes across all regions, countries, airports, and airlines on a daily, weekly, or monthly basis from January 2020 until today. The dashboard has been used to track the status and recovery of global travel and inform policy and operational actions.

Traditional Samburu women in Kenya. Photo: hecke61/Shutterstock.

Featured Data

We-Fi WeTour Women in Tourism Enterprise Surveys (2019)

- Sierra Leone | Ghana

Featured Reports

- Destination Management Handbook: A Guide to the Planning and Implementation of Destination Management (2023)

- Blue Tourism in Islands and Small Tourism-Dependent Coastal States : Tools and Recovery Strategies (2022)

- Resilient Tourism: Competitiveness in the Face of Disasters (2020)

- Tourism and the Sharing Economy: Policy and Potential of Sustainable Peer-to-Peer Accommodation (2018)

- Supporting Sustainable Livelihoods through Wildlife Tourism (2018)

- The Voice of Travelers: Leveraging User-Generated Content for Tourism Development (2018)

- Women and Tourism: Designing for Inclusion (2017)

- Twenty Reasons Sustainable Tourism Counts for Development (2017)

- An introduction to tourism concessioning:14 characteristics of successful programs. The World Bank, 2016)

- Getting financed: 9 tips for community joint ventures in tourism . World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and World Bank, (2015)

- Global investment promotion best practices: Winning tourism investment” Investment Climate (2013)

Country-Specific

- COVID-19 and Tourism in South Asia: Opportunities for Sustainable Regional Outcomes (2020)

- Demand Analysis for Tourism in African Local Communities (2018)

- Tourism in Africa: Harnessing Tourism for Growth and Improved Livelihoods . Africa Development Forum (2014)

COVID-19 Response

- Expecting the Unexpected : Tools and Policy Considerations to Support the Recovery and Resilience of the Tourism Sector (2022)

- Rebuilding Tourism Competitiveness. Tourism response, recovery and resilience to the COVID-19 crisis (2020)

- COVID-19 and Tourism in South Asia Opportunities for Sustainable Regional Outcomes (2020)

- WBG support for tourism clients and destinations during the COVID-19 crisis (2020)

- Tourism for Development: Tourism Diagnostic Toolkit (2019)

- Tourism Theory of Change (2018)

Country -Specific

- COVID Impact Mitigation Survey Results (South Africa) (2020)

- COVID Preparedness for Reopening Survey Results (South Africa) (2020)

- COVID Study (Fiji) (2020) with IFC

Featured Blogs

- Fiona Stewart, Samantha Power & Shaun Mann , Harnessing the power of capital markets to conserve and restore global biodiversity through “Natural Asset Companies” | October 12 th 2021

- Mari Elka Pangestu , Tourism in the post-COVID world: Three steps to build better forward | April 30 th 2021

- Hartwig Schafer , Regional collaboration can help South Asian nations rebuild and strengthen tourism industry | July 23 rd 2020

- Caroline Freund , We can’t travel, but we can take measures to preserve jobs in the tourism industry | March 20 th 2020

Featured Webinars

- Destination Management for Resilient Growth . This webinar looks at emerging destinations at the local level to examine the opportunities, examples, and best tools available. Destination Management Handbook

- Launch of the Future of Pacific Tourism. This webinar goes through the results of the new Future of Pacific Tourism report. It was launched by FCI Regional and Global Managers with Discussants from the Asian Development Bank and Intrepid Group.

- Circular Economy and Tourism . This webinar discusses how new and circular business models are needed to change the way tourism operates and enable businesses and destinations to be sustainable.

- Closing the Gap: Gender in Projects and Analytics . The purpose of this webinar is to raise awareness on integrating gender considerations into projects and provide guidelines for future project design in various sectoral areas.

- WTO Tourism Resilience: Building forward Better. High-level panelists from Sri Lanka, Costa Rica, Jordan and Kenya discuss how donors, governments and the private sector can work together most effectively to rebuild the tourism industry and improve its resilience for the future.

- Tourism Watch

- [email protected]

Launch of Blue Tourism Resource Portal

- Student Outreach

- Research Support

- Executive Education

- News & Announcements

- Jobs & Opportunities

- Annual Reports

- Faculty Working Papers

- Building State Capability

- Colombia Education Initiative

- Evidence for Policy Design

- Reimagining the Economy

- Social Protection Initiative

- Past Programs

- Speaker Series

- Global Empowerment Meeting (GEM)

- NEUDC 2023 Conference

Tourist Spending Insights Provide Unprecedented View of Global Tourism

In this section.

Authors: Frank Neffke, Sid Ravinutala, and Bruno Zuccolo

Tourism is an important sector in the global economy. Today, 10.4% of the world’s GDP and 7% of the world’s total exports come from tourism. The industry is worth over US$ 1.1 trillion. The money earned from expenditures by foreigners are crucial drivers of economic development and can be an important source of foreign exchange. Moreover, growing tourism can help create employment opportunities for marginalized populations.

However, due to a lack of data, we have only a limited understanding of tourism’s role in the global economy: Which countries do the visitors who spend the most come from? What are the most visited places? What types of businesses do tourists spend their money on? The Center for International Development (CID) is collaborating with the Mastercard Center for Inclusive Growth to better understand these issues and explore tourism’s impact on economies across the world. Through the collaboration, CID researchers have been able to use anonymized and aggregated transaction data 1 to study foreign tourist spending 2 patterns in 40 countries from 2011 to 2016, including most of Europe, the United States, and select countries in South America and Oceania. These destinations account for over 60% of all tourism in the world.

Across 40 countries in our data

Tourism accounts for more than 8% of this expanded definition of exports, comparable to the trade in oil and energy, and agricultural products.

How important is tourism as an export category? In a globalized world, the products we consume are increasingly produced elsewhere and firms often source their machinery and raw materials from across the globe. This all happens seamlessly: most consumers are often unaware of where merchandise was produced. However, at the level of a national economy, to pay for imports, a country has to amass foreign exchange: it has to sell something in return to customers outside its borders. Countries pay for their imports by exporting goods, services and capital—that is, by trading with other countries. When we envision this trade, we picture shiploads of toys, cars and raw materials crisscrossing the globe; but this is only one version of trade. Foreigners can also buy goods and services by coming to our country, an activity also known as tourism. In this sense, tourism is a substantial component of global trade.

Note that in this story, it does not matter much what is sold to foreign visitors, as long as they pay with money earned elsewhere. In this wider definition, tourism income is not limited to restaurant and hotel bills, but includes all types of expenditures ranging from transportation to medical care to clothing and educational services. However, unlike trade in goods, which is recorded by customs offices at the border, national statistics often only provide a poor account of tourism income. With exports of goods, we know exactly how much and which products are traded with whom, yet we have a vague understanding of how a country earns foreign exchange from tourists.

In our research, we added up a country’s tourism income with its income from traditional exports of goods. For the total tourism income for a country, we rely on national aggregates reported by the IMF and leverage aggregated and anonymized transaction data provided by Mastercard to divide the total expenditures into different categories, based on what these data indicate about the types of merchants where tourists spend their money.

Across the 40 countries, our data show that tourism tourism accounts for over 8 percent of this expanded definition of exports, making it comparable to trade in oil and energy, and just slightly smaller than trade in agricultural products. Figure 1 shows the breakdown of exports by category, with tourism expenditures depicted in red.

Figure 1 – Total export of goods and tourism by sector, for the 40 countries analyzed

Sources: The Atlas of Economic Complexity , IMF, and Mastercard

Total expenditures by tourists (the absolute size of the red rectangle) are taken from the IMF. The relative breakdown by expenditure type within tourism is gleaned from leveraging insights based on Mastercard’s aggregated and anonymized transaction data. Choose a country from the drop-down menu to explore the importance of tourism as an export for individual countries by year. Click on any of the industries to see the breakdown of exports within that industry, including types of tourism.

There is substantial variation across countries. For some countries, tourism is almost as important a source of foreign exchange as all exported goods combined: in Cyprus the share of tourism in our expanded exports definition is 52 percent, in Croatia it is 42 percent, in Iceland 39 percent, in Greece 36 percent and in Luxembourg 22 percent. While Croatia and Greece are well-known tourist destinations, the reliance of Luxembourg on tourism revenues may be more surprising. Here, it is important to remember that the definition of tourism, the one relevant from a foreign exchange perspective, encompasses all purchases of goods and services made by foreign citizens in a particular country. This includes income of typical tourist industries, such as hospitality and entertainment, but also of education, health care, and shops. Much of the tourism expenditures in Luxembourg are related to visitors from neighboring countries shopping for groceries or filling up their tanks at lower-taxed gas stations.

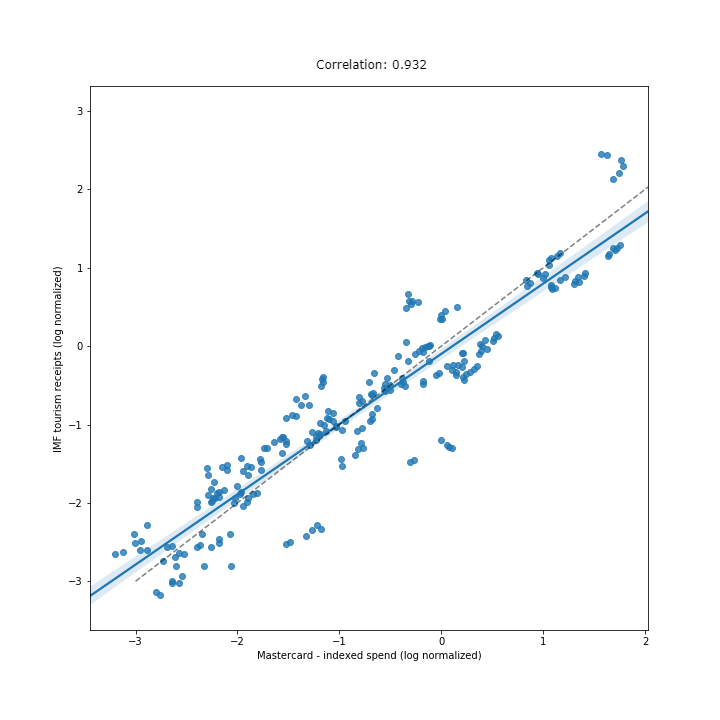

Is the Mastercard spend index a reliable reflection of tourism expenditures? Many governments provide high-level information on tourism income in their balance of payment statistics. We can compare yearly tourism income reported by the IMF to the index of expenditures based on Mastercard’s aggregated and anonymized transaction data for each of the 40 countries over a six-year period. As shown in the scatterplot of Figure 2, the two measures line up very well on a log scale. The correlation of 0.932 shows that the Mastercard spend index provides highly reliable estimates of the distribution of tourism across countries and years.

Figure 2 – Correlation of revenues by country and year

Source: International Monetary Fund (2018) and indexed tourism spend based on Mastercard’s aggregated and anonymized transaction data

To explore the growth of tourism, Figure 3 plots how the index of tourism expenditures changes in each of the destination countries over time, using 2011 as the base year. The dotted line represents the average of the 40 countries.

Figure 3: Yearly indexed spend trends by country, 2011-2016

Whereas average growth in tourism in our sample of countries was rather flat, there are some fast-growing destinations, with Iceland (19% annualized growth rate), Colombia (9.3%), Malta (8.3%), Lithuania (7.1%) and Romania (6.9%) leading the pack. Iceland’s growth has far outpaced any of its peers’, riding a strong and long-lasting tourism boom that helped it recover more quickly from the 2008 financial crisis. It’s a remarkable success for a small country that has invested heavily in marketing itself as a hub between Europe and North America through its flagship airline Icelandair .

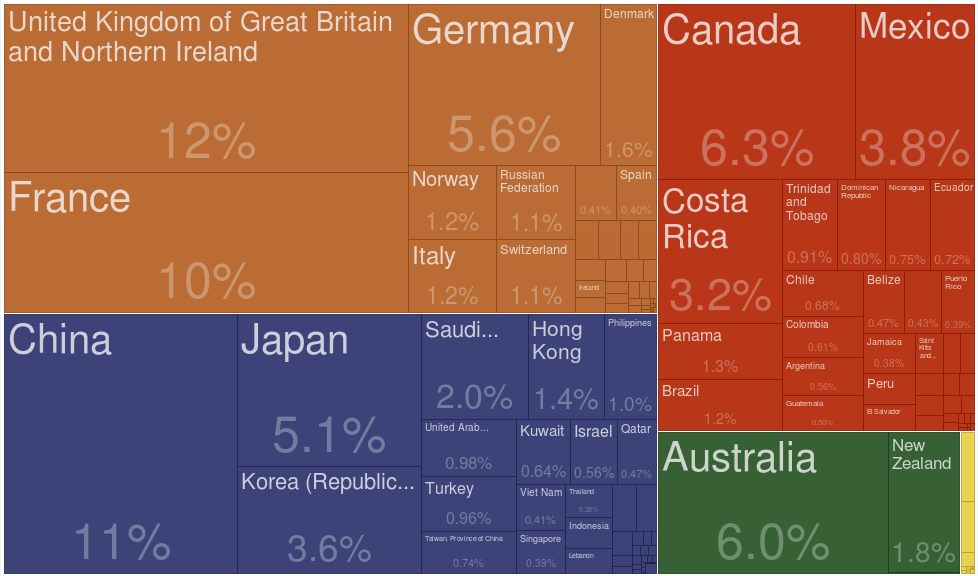

Where is this growth coming from? Figure 4 shows the origins of the increase in tourist expenditures in the United States. Asian countries form a fast-growing market for the United States, but we also see some growth from eastern European countries, Australia and New Zealand. One of the most striking features of the map in Figure 4, however, is the rise of tourism from China, which has grown at a whopping 22 percent a year since 2011. On the other end of the spectrum, we see an astounding 43 percent a year contraction in Venezuelan tourism expenditures, a reflection of the precipitous collapse of the Venezuelan economy.

Figure 4 – Annual growth of indexed spend in the USA by origin countries, 2011-2016

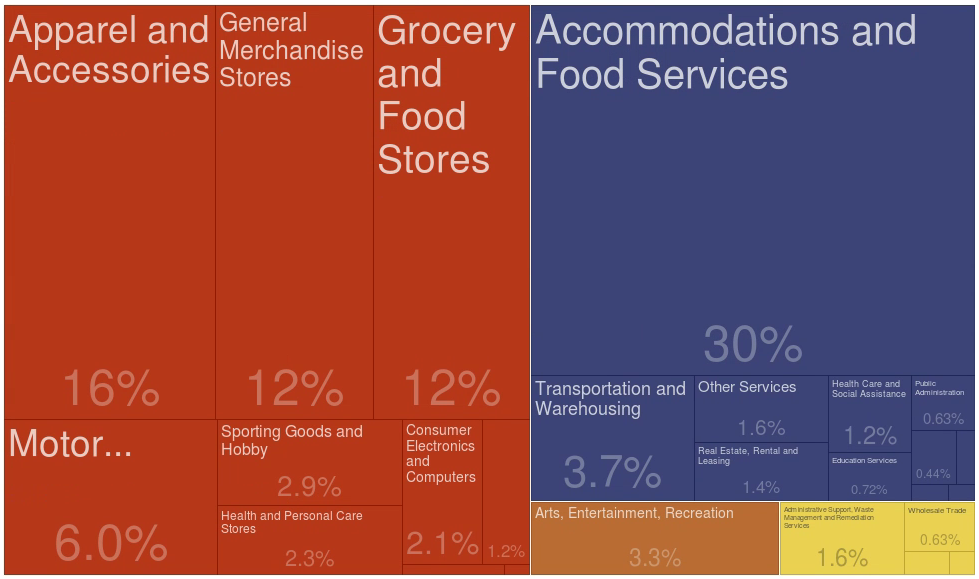

Payment card data insights: tourism under the microscope For the analyses so far (except Figure 4), we could have just relied on the statistics the IMF provides. However, Mastercard’s aggregated and anonymized transaction data also allows us to zoom in on tourism, by breaking down expenditures in different ways. First of all, we can look at the types of merchants where tourists make purchases. Mastercard classified all merchants accepting payment cards into 27 categories. By far the largest is “Finance and Insurance,” accounting for about a quarter of total spending. This category includes all the money withdrawn from ATMs by foreign cardholders, but it does not indicate the merchants where the tourists are spending the cash they withdraw. Therefore, we focus on the expenditures in the remaining merchant types, which are depicted in Figure 5.

Figure 5 – Share of total indexed spend by merchant type in all countries

Figure 5 immediately highlights one of the main benefits offered by Mastercard’s aggregated and anonymized transaction data. What we would typically think of as the “tourism sector”—the hotels, restaurants, and other hospitality services in a country (here classified as “Accommodations and Food Services”)—make up just 30% of all tourist expenditures. Focusing on this one sector would therefore miss most of the economic impact of tourism (it also risks erroneously classifying expenditures by locals in hotels and restaurants as “tourism.” Instead, our analysis reveals that foreigners also spend significant amounts on “Apparel and Accessories,” “Grocery and Food Stores,” and more.

Apart from knowing what categories tourists spend their money on, we can also see where they spend it. This allows us to compare cities in terms of what tourists are looking for when they visit a place. As an example, take Figures 6 and 7, which compare the expenditure patterns of tourists in Naples and Milan:

Figure 6 – Spend by merchant type in Naples (2016)

Figure 7 – Spend by merchant type in Milan (2016)

Both cities attract many foreign visitors. However, they differ drastically in the services sought by these tourists. Naples earns most of its money through its many excellent restaurants and hotels, whereas tourists spend at about twice the rate in the clothing stores of Milan. Milan and Naples’ reputations as the fashion and culinary centers of Italy are thus clearly reflected in their visitors’ spending patterns.

Another way to compare cities is by origin of tourists. The figures below exemplify this by comparing Los Angeles to New York City:

Figure 8 – Spend by origin in Los Angeles (2016)

Figure 9 – Spend by origin in New York (2016)

Located on opposite coasts, NYC and LA have very different tourist profiles. Tourism in NYC is dominated by European visitors, while LA’s relative proximity to other Pacific nations makes it an attractive destination for tourists from Asia and Oceania. For instance, the share of tourism expenditures being made by tourists from China in LA is almost three times as large as in NYC.

These graphs show how Mastercard’s aggregated and anonymized transaction data allow us to break down tourism in various, meaningful ways. This gives us a unique lens on the nature of tourism as an export category and provides us with an invaluable tool for understanding the role of tourism in inclusive growth. It helps address questions such as: How can we classify tourism into different types? What kind of services do different types of tourists require? Can we predict where new tourist destinations will arise and who will visit them? And, most importantly, can tourism accelerate economic development and be a source of inclusive growth? – Stay tuned!

1 The Mastercard Center for Inclusive Growth is committed to advancing sustainable and equitable economic growth and financial inclusion around the world, collaborating with a diverse community of academic and research institutions by providing access to aggregated and anonymized transaction data. In its collaboration with CID, Mastercard provided controlled access to data that was aggregated, anonymized, and subject to additional privacy and data protection safeguards. In addition to these safeguards, access to the data was provided for academic research purposes only and subject to Harvard University's stringent confidentiality requirements.

2 Data on expenditures was aggregated to a combination of a country of origin, a location within a country of destination, and a merchant type for a given time window. Absolute expenditure values were replaced by an index that makes relative comparisons across the data set. Additionally, expenditures were scaled to reflect spend in the foreign expenditures market as a whole, not just the share serviced by Mastercard.

Media inquiries

Contact: Chuck McKenney Email: [email protected] Phone: (617) 495-8496 Date: Nov. 1, 2018

Interactive visualization requires JavaScript

Related research and data

- Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all

- Air passengers

- Air passengers per fatality

- Average length of stay of international visitors

- Employment in food and beverage serving activities per 1,000 people

- Employment in tourism-related industries per 1,000 people

- Fatal airliner accidents and hijacking incidents

- Fatal airliner accidents per million commercial flights

- Fatalities from airliner accidents and hijackings

- Foreign guests in hotels and similar establishments

- Global aviation fatalities per million passengers

- International one-day trips

- International one-day trips per 1,000 people

- International tourist departures

- International tourist departures per 1,000 people

- International tourist departures per 1,000 people vs. GDP per capita

- International tourist expenditure abroad

- International tourist expenditure within the country they visit

- International tourist trips

- International tourist trips by destination region

- International tourist trips by region of origin

- International tourist trips per 1,000 people

- International trips for business and professional reasons

- International trips for personal reasons

- International trips for personal vs. business and professional reasons

- Local guests in hotels and similar establishments

- Local vs. foreign guests in hotels and similar establishments

- Monitoring of sustainable tourism

- Monthly CO₂ emissions from commercial passenger flights

- Monthly CO₂ emissions from domestic and international commercial passenger flights

- Per capita CO₂ emissions from domestic commercial passenger flights

- Per capita CO₂ emissions from commercial aviation, tourism-adjusted

- Per capita CO₂ emissions from international commercial passenger flights, tourism-adjusted Clarke & UNWTO

- Per capita CO₂ emissions from international passenger flights, tourism-adjusted Graver & World Bank

- Ratio of business trips to trips for personal reasons

- Ratio of inbound to outbound tourist trips

- Ratio of same-day trips to tourist trips

- Share of global services exports

- Trips by domestic tourists per 1,000 people

Our World in Data is free and accessible for everyone.

Help us do this work by making a donation.

Map Options

Most Visited Countries 2024

European countries, often rich in history, culture, beautiful beaches, and ocean views, attract the highest number of tourists.

France, leading in tourism for over 30 years, offers attractions like the Eiffel Tower and Disneyland Paris, drawing 38 million tourists to Paris alone in 2019.

Global travel and tourism, an $8.9 trillion industry in 2019, suffered a loss of $4.5 trillion and 62 million jobs in 2020, during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Global travel and tourism was an $8.9 trillion (US$) business in 2019 . Moreover, though the COVID-19 pandemic has reduced that number to roughly a quarter of its previous value, all signs point to tourism continuing to grow, expand, and evolve. Every country on Earth has something to offer international visitors, from the pyramids in Egypt to the rainforests of Brazil or the sidewalk cafes of Paris —but which countries attract the most visitors of all? Most of the countries with the highest tourism rates are located in Europe , whose rich history, architecture, and cultural influence make it an appealing destination for many travelers. Countries positioned on or near a body of water are also very popular, particularly those that offer a relaxed, low-key atmosphere mixed with beautiful beaches and ocean views.

Top 10 Countries Most Popular with Tourists (by number of 2019 visitor arrivals)

The most popular tourist destination in the world for more than 30 years, France offers a myriad of attractions: the Eiffel tower, countless world-class restaurants, the Musée du Louvre, the Palace of Versailles, the Notre-Dame cathedral, the beaches of the Côte d'Azur, and of course, Disneyland Paris. Moreover, the lushly beautiful countryside is full of storybook villages, mountains, vineyards, and the occasional castle. One can even view prehistoric cave paintings in Lascaux. Paris, France's capital, is the most visited city in Europe, receiving 38 million tourists in 2019.

Spain is another tourist destination overflowing with interesting attractions. Antoni Gaudi's Sagrada Familia cathedral and other works in Barcelona , the Guggenheim museum, the Alhambra and Generalife Gardens, Europe's largest aquarium (the lily-shaped L'Oceanogràfic), the beaches of Gran Canaria, and La Rambla in Barcelona. Spain is also home to El Teide, an ancient—but not entirely dormant—volcano, which visitors can hike around at the Parque Nacional del Teide on the Spanish island Tenerife.

England's capital city, London , attracts visitors with a wide range of sights including Big Ben, Westminster Abbey, the changing of the guard at Buckingham Palace, and the British Museum, which includes the largest collection of Egyptian artifacts outside of Cairo . Beyond London, England offers the mysterious Stonehenge, the Beatles' birthplace in Liverpool , the quaint beauty of the Cotswolds, the sci-fi botanical gardens of the Eden Project, and more. Speaking of more, the UK also includes three additional subdivisions. First is Scotland, with the charming city of Edinburgh , moody Loch Ness and Inverness , the scenic highlands, and the historic St. Andrews golf course. Next comes charming Wales and its castles, scenery, and capital city of Cardiff . Finally, Northern Ireland boasts attractions including Belfast 's bubbling nightlife, the glens and coastline of Antrim, and one of Europe's most compelling natural wonders: the Giant's Causeway.

The Mediterranean nation Turkey balances captivating man-made attractions such as Hagia Sophia mosque and Topkapı Palace with archaeological wonders such as the Biblical city of Ephesus, the fairy city of Cappadocia, and the desolate fallen splendor of Mount Nemrut. It also has more than its share of natural wonders, including the famous beaches at Ölüdeniz and Patara, the mineral pools at Pamukkale, and the Mediterranean coastline itself.

The South Asian country of Thailand is also known as the "Land of Smiles", and offers both modern comforts and wild adventure. Thailand's capital, Bangkok , receives over 20 million visitors every year. Popular attractions include the Grand Palace in Bangkok; beaches including Railay, Long, and Monkey beach; the ancient city Ayutthaya and ornate Buddhist wat Coi Suthep, and national parks including Khao Yai (where wild elephants roam) and the otherworldly Khao Sok.

The impact of COVID-19 on travel and tourism

The COVID-19 pandemic of 2020-21 had a devastating effect on the travel and tourism industry. According to a report released by the World Travel & Tourism Council , the pandemic cost the industry an estimated US$ 4.5 trillion in 2020, which resulted in the loss of 62 million tourism-dependent jobs. Data from the United Nations World Tourism Organization backs this up. Consider the following table:

International tourist arrivals (in thousands of visitors):

Compared to 2019, tourism dropped by approximately 74% in 2020, with a total of a billion fewer travelers over the course of the year--making 2020 the worst year on record for tourism. The UNTWO's own estimates registered a loss of US$ 1.3 trillion in lost revenues and 100-120 million jobs either lost or at risk.

The impact has been particularly damaging in countries that rely heavily upon tourism as part of their GDP. Lost tourism in Macau , one of China 's special administrative regions, led to a 79.3% drop in year-on-year gambling revenues , which caused overall GDP for 2020 to fall 43.1% compared to the previous year.

While tourism has picked up slightly in 2021, they still fall far short of the pre-pandemic numbers. Late 2020 projections were hopeful that the industry would be back on track by late 2021, but the ongoing nature of the pandemic has thwarted that optimism. As of late 2021, most estimates do not expect the industry to rebound to 2019 (pre-COVID) levels until sometime in 2023 at the earliest.

- Visitor totals are displayed in 1000s. For example, South Africa 's displayed total of 3886.6 equals 3,886,600 visitors.

Download Table Data

Enter your email below, and you'll receive this table's data in your inbox momentarily.

What are the top 5 most visited countries?

Frequently asked questions.

- UNWTO Tourism Data Dashboard - United Nations World Tourism Organization

- World Tourism Barometer - United Nations World Tourism Organization

- Trending in Travel - World Travel & Tourism Council

- Economic Impact Reports - World Travel & Tourism Council

- Subscriber Services

- For Authors

- Publications

- Archaeology

- Art & Architecture

- Bilingual dictionaries

- Classical studies

- Encyclopedias

- English Dictionaries and Thesauri

- Language reference

- Linguistics

- Media studies

- Medicine and health

- Names studies

- Performing arts

- Science and technology

- Social sciences

- Society and culture

- Overview Pages

- Subject Reference

- English Dictionaries

- Bilingual Dictionaries

Recently viewed (0)

- Save Search

Allan Beaver

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Related Content

In this work.

- Publishing Information

- General Links for this Work

- Introduction

- Recommended Tourism Syllabus Content for Higher Education Courses

- EC Computer Reservation System Rules

- Acknowledgements

tourism-generating country

Any country whose inhabitants have a substantial propensity to travel abroad. Departure statistics of residents of the main generating countries ...

Access to the complete content on Oxford Reference requires a subscription or purchase. Public users are able to search the site and view the abstracts and keywords for each book and chapter without a subscription.

Please subscribe or login to access full text content.

If you have purchased a print title that contains an access token, please see the token for information about how to register your code.

For questions on access or troubleshooting, please check our FAQs , and if you can''t find the answer there, please contact us .

- Oxford University Press

PRINTED FROM OXFORD REFERENCE (www.oxfordreference.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2023. All Rights Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single entry from a reference work in OR for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice ).

date: 24 April 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|91.193.111.216]

- 91.193.111.216

Character limit 500 /500

Regions of the World, Ranked by Tourism Growth

Fastest-growing regions.

/granite-web-prod/b1/d0/b1d01515fc4246a5bcba2dc6bdc6f915.jpg)

Thanks to Instagram and Pinterest, it’s easier than ever to experience serious wanderlust on a daily basis. Standup paddleboard with manatees? Check. Get lost in the Blue City in Morocco? Yes, please. Snorkel in the Great Blue Hole? Sign me up.

With so many destinations at their fingertips, travelers have to be really choosy when plotting their itineraries. Some regions of the world are trendy right now, which means they’re seeing more travelers than in years past. Others are experiencing natural disasters, economic crises and wars, which has made them less popular among travelers.

The World Tourism Organization (WTO), the arm of the United Nations that promotes and studies tourism around the world, has just released its updated World Tourism Barometer , which offers a window into short-term travel trends, ranging from how much money tourists are spending to which countries are welcoming the most visitors.

Here’s how the 15 regions of the world stacked up to each other when it came to international tourist arrivals in 2018. The top (and bottom) destinations on the list may surprise you.

15. Caribbean

/granite-web-prod/a5/a8/a5a8d26ab76c479fa10ce5e2b66c0eeb.jpg)

Despite its crystal-clear, cerulean blue waters and picture-perfect beaches, the Caribbean struggled a bit in 2018, welcoming fewer tourists to its sunny shores than the year before.

The WTO suspects that some Caribbean islands are still trying to rebound from Hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria. Puerto Rico was hit particularly hard by Hurricane Maria, suffering at least $100 billion worth of damage, which likely contributed heavily to its 40 percent decrease in tourist arrivals. St. Maarten, which was struck by Hurricane Irma, fared even worse, experiencing a steep 69.3 percent drop in traffic.

Still, other parts of the Caribbean experienced “strong growth” in 2018, according to the WTO — the Dominican Republic and Jamaica were popular destinations for Americans and Europeans, for example, growing 6.2 percent and 5.3 percent, respectively.

But the leader of the pack was the Cayman Islands, which is surging in popularity thanks to an influx of new hotels (including luxe Grand Hyatt and Mandarin Oriental properties) and just-launched flights from Southwest and JetBlue.

14. Central America

/granite-web-prod/30/df/30df77db2a0341db94e5733479ec76ea.jpg)

Mother Nature also likely contributed to declining tourism in Central America, with places like Costa Rica, Nicaragua and Honduras suffering extensive damage from Tropical Storm Nate in October 2017. Overall, the region saw a slight drop in tourist arrivals in 2018.

Even so, travelers weren’t avoiding Central America entirely. They flocked to happening destinations like El Salvador, where tourist arrivals were up 13.3 percent.

The place trending up most? Belize, known for its gorgeous sandy beaches, ancient Mayan ruins, and top-notch snorkeling and scuba-diving sites. The locale is famously home to the Great Blue Hole, a UNESCO World Heritage Site filled with beautiful rock formations that look like icicles.

13. Northern Europe

/granite-web-prod/9b/ea/9bea3d563db64b32b8cbedd9a5ea68f2.jpg)

Though places like Iceland, Denmark, Sweden and Ireland made it onto travelers’ itineraries in 2018, other countries in Northern Europe weren’t as appealing. Faring worst was the UK, which saw a 5 percent decrease in traffic in part because of the fluctuation of the pound.

Norway, too, struggled, dipping 2.5 percent. A victim of its own popularity, the country had surged so much in recent years that overcrowding became a problem, pushing travelers to look elsewhere last year.

Despite chatter that people may be losing interest in Iceland, it actually saw a healthy 8.2 percent increase in tourist arrivals in 2018. The country began an intense marketing campaign to attract tourists after the 2010 eruption of the volcano Eyjafjallajökul — and it seems to have paid off. Cheap flights from WOW air and other Icelandic airlines, plus ruggedly beautiful scenery, have continued to lure travelers from all over the world.

12. Oceania

/granite-web-prod/00/f5/00f5b334ea834f3eb8577721169b7af1.jpg)

Oceania can thank a strong Australian dollar for its 3 percent growth in tourist arrivals in 2018, says the WTO. Australia saw a 5.2 percent increase in visitors, while New Zealand saw a 3.1 percent bump.

Smaller regions like Tuvalu, Tonga, the Solomon Islands and Vanuatu saw huge jumps in tourist traffic. Tuvalu, a remote and nearly undeveloped chain of nine small islands north of Fiji, is incredibly gorgeous, but somewhat difficult to get to — there are just two arriving flights each week. Once travelers arrive, however, they’re treated to first-rate scuba diving and snorkeling along the coral reefs, plus fishing, boating and historical attractions (including a few plane wrecks and other remnants left over from World War II).

11. South America

/granite-web-prod/62/bc/62bc73bcb3e749519282cf0911467419.jpg)

South America's uptick in tourism was spurred on by massive new interest in places like Ecuador, Colombia, Peru and Guyana. Those countries are popular among people who live in nearby areas and Asia, according to the WTO.

Argentina, the most popular country in South America, saw a modest 3.5 percent uptick in traffic, though WTO experts expect that growth to accelerate in coming months. The weak Argentinian peso makes traveling to the country more affordable — and more appealing — for international tourists. From the high-energy nightlife in Buenos Aires to the awe-inspiring waterfalls inside Iguazu National Park (there are 275 in total!), Argentina has a little something for everyone to enjoy.

Ditto the fast-growing country of Ecuador, where sandy shores meet Amazonian rainforest and the staggering Andes mountains — not to mention the increasingly popular, wildlife-rich Galapagos Islands. No wonder more and more tourists are flocking there in droves.

10. North America

/granite-web-prod/15/e2/15e262ff4db2407aa2ba1e27347a9ef4.jpg)

The United States and Mexico led the way for overall growth in North America, which saw a modest but healthy increase in tourism traffic in 2018 (though the WTO notes this is likely to change as more data comes in). In addition to the United States' 6.9 percent spike, trips to Mexico increased 6 percent.

The countries that sent the most visitors to the United States in 2018 include the United Kingdom, China, Japan, Germany and India (all behind neighboring Mexico and Canada, of course), according to the National Travel and Tourism Office .

And where do people love to go once they arrive? New York City, Maui and Las Vegas are their top three favorite destinations, according to TripAdvisor’s 2018 Travelers’ Choice Awards .

9. South Asia

/granite-web-prod/37/f8/37f805148cf849ff8ac59ef1c8eb2516.jpg)

Visits to Nepal and Sri Lanka were up in 2018, which helped contribute to an overall boost in tourist arrivals in the South Asia region. India and the Maldives also saw more tourists year over year.

Travelers were inspired to visit Nepal by several promotional campaigns, which primarily reached tourists in India, China and Europe, according to the WTO.

The country also boasts a number of cultural and religious heritage sites, like the Changu Narayan Temple and Bhaktapur Durbar Square, as well as ample opportunity for outdoor recreation in the Himalayas.

8. Western Europe

/granite-web-prod/1a/99/1a994b68302d481ba3eb4a5333391fee.jpg)

It was a good year for Belgium, France and Liechtenstein, which all saw strong growth for international tourist arrivals. All told, nearly every country in Western Europe saw an increase in tourism traffic in 2018, leading to a 5.6 percent increase for the region overall. (The one notable exception, Luxembourg, had an exceptional year in 2017, and was probably just cooling off from that.) The WTO credits good weather during the summer months for the region’s bump, which led to lots of local travel in the area.

France alone saw a 7.7 percent increase in tourist traffic, another sign that it has rebounded from low numbers following a string of terrorist attacks in 2015 and 2016. However, so many people are visiting France again that popular sites like the Eiffel Tower, The Louvre and Carcassonne are now overrun with visitors .

The country's neighbor of Belgium also suffered as a result of tourism attacks in 2017, but pushed hard to rebound and came back strong last year. The country is known for its exemplary beer and food scene, which connoisseurs continue to love.

7. North-East Asia

/granite-web-prod/b6/ca/b6ca8ffdebf14b60a1bd4c6955105841.jpg)

Thanks to strong growth in South Korea and Mongolia, the North-East Asia region had a banner year in 2018. Japan and Macao also saw strong numbers, which helped contribute to the 168 million tourists who visited the region in 2018.

The fastest-growing destination here, South Korea, was likely boosted by its high-profile hosting of the 2018 Olympics, in the thriving county of PyeongChang. Visitors to this area can enjoy the excellent ski slopes that made it an ideal host for the Winter Games.

Even the slowest-growing country, China — the largest destination in North-East Asia — is on the upswing.

According to the WTO, North-East Asia is poised to grow even more in the coming years. Experts predict that the opening of the Hong-Kong- Zhuhai-Macau Bridge, which connects mainland China, Macau and Hong Kong, will increase the flow of people moving between the three destinations. The 34-mile bridge cost $20 billion to build (it took nine years!) and is the longest sea-crossing bridge ever built.

6. Subsaharan Africa

/granite-web-prod/85/b8/85b8cdb728014fadabc89af046a31b60.jpg)

Places like Cabo Verde, Reunion, Kenya and Mauritius are leading the way for this increasingly popular region.

The fastest-growing destination here, the island of Reunion, is an overseas region of France located east of Madagascar. With its mix of black- and white-sand beaches, it's no surprise it's been increasing its profile among international visitors.

The next fastest-growing destination in the region, Cabo Verde (which until recently was named Cape Verde), is made up of 10 tropical islands located off the western coast of Senegal and Mauritania. The sun shines nearly all year round here, and festivals and music play a prominent role.

South Africa, which is the most-visited country in Subsaharan Africa, only saw a modest 1.7 percent increase in international arrivals, likely because of a drought in Cape Town and a strong currency, according to the WTO.

5. Central and Eastern Europe

/granite-web-prod/1a/63/1a6350aa6144426083077cc266051ca6.jpg)

More than 144 million people visited Central and Eastern Europe last year, representing a healthy increase over 2017. Hungary saw a 15.3 percent increase in tourism traffic, thanks in part to improved air connectivity, according to the WTO. The largest country in this region, Russia, saw just 1.4 percent growth among tourist arrivals but a 40 percent increase in tourism spending thanks to the FIFA World Cup that took place in June and July.

But the best-performing country, perhaps surprisingly, was Kazakhstan. Located south of central Russia and west of China, this massive landlocked country is home to some incredible natural landscapes, like Charyn Canyon and Big Almaty Lake, as well as many awe-inspiring mosques. It’s also relatively easy to travel to Kazakhstan — the citizens of many countries, including the U.S., can visit for up to 30 days without a visa.

4. Southern/Mediterranean Europe

/granite-web-prod/d9/f7/d9f7188f055744d08c9e5d0c446a69ad.jpg)

Nearly a dozen countries saw double-digit growth in the Southern and Mediterranean Europe region, with Slovenia and Turkey leading the way. Overall, some 286.2 million people visited this part of the world last year.

A favorable exchange rate drew more people to Turkey, which saw 22.6 percent growth in international visitors. Slovenia, which grew even more than Turkey, was bolstered by a boost in media attention, thanks in part to an increasingly acclaimed culinary scene; Slovenian chef Ana Roš is a rock star of the foodie world, and was named the best female chef in the world in 2017.

Greece, where international visits grew by 10.8 percent, benefited by attracting more Chinese, Arab and American tourists last year, which accounted for some of its growth, according to the WTO. Americans were also eager to travel to Italy, which helped boost that country’s numbers by 4.9 percent.

3. South-East Asia

/granite-web-prod/59/f2/59f2114329f448d2bf15cc23ef2ba740.jpg)

International interest in Vietnam skyrocketed in 2018, as the country welcomed 15.5 million tourists from all over the world. With its flavorful local foods, affordability, varying terrain and bustling cities, it’s no surprise that the country is at the top of many travelers’ bucket lists. Ha Long Bay, for instance, is popular among kayakers, hikers and casual explorers who experience the blue-green waters and rocky formations on various boat tours.

All told, it was a good year for the South-East Asia region, which recorded 129.3 million international tourist arrivals. Cambodia, Indonesia, Thailand and the Philippines also saw strong growth last year, thanks in part to additional visits from Chinese travelers.

2. Middle East

/granite-web-prod/a1/d1/a1d1d6f0f98e4470a7416f84e10d238a.jpg)

Nearly topping the list is the Middle East, where 63.6 million tourists headed in 2018. Visits to Egypt in particular ballooned last year. Saudi Arabia was also a popular choice among travelers, garnering a 30.3 percent increase. And since many travelers book joint tours, Jordan piggybacked off of Egypt’s popularity and saw a 7.7 percent increase in international traffic.

In Egypt, tourists embraced Cairo, which made the top 10 list for Middle East destinations in the 2018 TripAdvisor Travelers’ Choice Awards. The country’s capital city offers easy access to the famed Pyramids of Giza and the Great Sphinx, as well as the mummies and artifacts of the Egyptian Museum.

1. North Africa

/granite-web-prod/82/ea/82ea8dd6eeff4eeba374ba3c1094675c.jpg)

The fastest-growing region in the world is North Africa, which welcomed nearly 24 million visitors in 2018.

The WTO credits “the lifting of negative travel advice” for a surge in European tourists visiting Tunisia, which saw incredible growth over the previous year.

Tunisia, home to more than 11 million people, offers a diverse mix of opportunities for tourists, from its picturesque Mediterranean beaches to the sand dunes of the Sahara. There are also a number of historical and cultural sites to visit, such as the Roman Coliseum at El Jem (which is one of the largest ancient amphitheaters in the world) and the remains of the ancient city of Carthage.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 24 February 2024

Modeling the link between tourism and economic development: evidence from homogeneous panels of countries

- Pablo Juan Cárdenas-García ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1779-392X 1 ,

- Juan Gabriel Brida 2 &

- Verónica Segarra 2

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 308 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

1079 Accesses

Metrics details

- Development studies

Having previously analyzed the relationship between tourism and economic growth from distinct perspectives, this paper attempts to fill the void existing in scientific research on the relationship between tourism and economic development, by analyzing the relationship between these variables using a sample of 123 countries between 1995 and 2019. The Dumistrescu and Hurlin adaptation of the Granger causality test was used. This study takes a critical look at causal analysis with heterogeneous panels, given the substantial differences found between the results of the causal analysis with the complete panel as compared to the analysis of homogeneous country groups, in terms of their dynamics of tourism specialization and economic development. On the one hand, a one-way causal relationship exists from tourism to development in countries having low levels of tourism specialization and development. On the other hand, a one-way causal relationship exists by which development contributes to tourism in countries with high levels of development and tourism specialization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Gravity models do not explain, and cannot predict, international migration dynamics

The coordination pattern of tourism efficiency and development level in Guangdong Province under high-quality development

Analysis of spatial-temporal pattern, dynamic evolution and influencing factors of health tourism development in China

Introduction.

Across the world, tourism is one of the most important sectors. It has undergone exponential growth since the mid-1900s and is currently experiencing growth rates that exceed those of other economic sectors (Yazdi, 2019 ).

Today, tourism is a major source of income for countries that specialize in this sector, generating 5.8% of the global GDP (5.8 billion US$) in 2021 (UNWTO, 2022 ) and providing 5.4% of all jobs (289 million) worldwide. Although its relevance is clear, tourism data have declined dramatically due to the recent impact of the Covid-19 health crisis. In 2019, prior to the pandemic (UNWTO, 2020 ), tourism represented 10.3% of the worldwide GDP (9.6 billion US$), with the number of tourism-related jobs reaching 10.2% of the global total (333 million). With the evolution of the pandemic and the regained trust of tourists across the globe, it is estimated that by 2022, approximately 80% of the pre-pandemic figures will be attained, with a full recovery being expected by 2024 (UNWTO, 2022 ).

Given the importance of this economic activity, many countries consider tourism to be a tool enabling economic growth (Corbet et al., 2019 ; Ohlan, 2017 ; Xia et al., 2021 ). Numerous works have analyzed the relationship between increased tourism and economic growth; and some systematic reviews have been carried out on this relationship (Brida et al., 2016 ; Ahmad et al., 2020 ), examining the main contributions over the first two decades of this century. These reviews have revealed evidence in this area: in some cases, it has been found that tourism contributes to economic growth while, in other cases, the economic cycle influences tourism expansion. Moreover, other works offer evidence of a bi-directional relationship between these variables.

Distinct international organizations (OECD, 2010 ; UNCTAD, 2011 ) have suggested that not only does tourism promote economic growth, it also contributes to socio-economic advances in the host regions. This may be the real importance of tourism, since the ultimate objective of any government is to improve a country’s socio-economic development (UNDP, 1990 ).

The development of economic and other policies related to the economic scope of tourism, in addition to promoting economic growth, are also intended to improve other non-economic factors such as education, safety, and health. Improvements in these factors lead to a better life for the host population (Lee, 2017 ; Todaro and Smith, 2020 ).

Given tourism’s capacity as an instrument of economic development (Cárdenas-García et al., 2015 ), distinct institutions such as the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, the United Nations World Tourism Organization and the World Bank, have begun funding projects that consider tourism to be a tool for improved socio-economic development, especially in less advanced countries (Carrillo and Pulido, 2019 ).

This new trend within the scientific literature establishes, firstly, that tourism drives economic growth and, secondly, that thanks to this economic growth, the population’s economic conditions may be improved (Croes et al., 2021 ; Kubickova et al., 2017 ). However, to take advantage of the economic growth generated by tourism activity to boost economic development, specific policies should be developed. These policies should determine the initial conditions to be met by host countries committed to tourism as an instrument of economic development. These conditions include regulation, tax system, and infrastructure provision (Cárdenas-García and Pulido-Fernández, 2019 ; Lejárraga and Walkenhorst, 2013 ; Meyer and Meyer, 2016 ).

Therefore, it is necessary to differentiate between the analysis of the relationship between tourism and economic growth, whereby tourism boosts the economy of countries committed to tourism, traditionally measured through an increase in the Gross Domestic Product (Alcalá-Ordóñez et al., 2023 ; Brida et al., 2016 ), and the analysis of the relationship between tourism and economic development, which measures the effect of tourism on other factors (not only economic content but also inequality, education, and health) which, together with economic criteria, serve as the foundation to measure a population’s development (Todaro and Smith, 2020 ).

However, unlike the analysis of the relationship between tourism and economic growth, few empirical studies have examined tourism’s capacity as a tool for development (Bojanic and Lo, 2016 ; Cárdenas-García and Pulido-Fernández, 2019 ; Croes, 2012 ).

To help fill this gap in the literature analyzing the relationship between tourism and economic development, this work examines the contribution of tourism to economic development, given that the relationship between tourism and economic growth has been widely analyzed by the scientific literature. Moreover, given that the literature has demonstrated that tourism contributes to economic growth, this work aims to analyze whether it also contributes to economic development, considering development in the broadest possible sense by including economic and socioeconomic variables in the multi-dimensional concept (Wahyuningsih et al., 2020 ).

Therefore, based on the results of this work, it is possible to determine whether the commitment made by many international organizations and institutions in financing tourism projects designed to improve the host population’s socioeconomic conditions, especially in countries with lower development levels, has, in fact, resulted in improved development levels.

It also presents a critical view of causal analyses that rely on heterogeneous panels, examining whether the conclusions reached for a complete panel differ from those obtained when analyzing homogeneous groups within the panel. As seen in the literature review analyzing the relationship between tourism and economic development, empirical works using panel data from several countries tend to generalize the results obtained to the entire panel, without verifying whether, in fact, they are relevant for all of the analyzed countries or only some of the same. Therefore, this study takes an innovative approach by examining the panel countries separately, analyzing the homogeneous groups distinctly.

Therefore, this article presents an empirical analysis examining whether a causal relationship exists between tourism and economic development, with development being considered to be a multi-dimensional variable including a variety of factors, distinct from economic ones. Panel data from 123 countries during the 1995–2019 period was considered to examine the causal relationship between tourism and economic development. For this, the Granger causality test was performed, applying the adaptation of this test made by Dumistrescu and Hurlin. First, a causal analysis was performed collectively for all of the countries of the panel. Then, a specific analysis was performed for each of the homogeneous groups of countries identified within the panel, formed according to levels of tourism specialization and development.