Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 1. History and Overview

1.1 What is Tourism?

Before engaging in a study of tourism , let’s have a closer look at what this term means.

Definition of Tourism

There are a number of ways tourism can be defined, and for this reason, the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) embarked on a project from 2005 to 2007 to create a common glossary of terms for tourism. It defines tourism as follows:

Tourism is a social, cultural and economic phenomenon which entails the movement of people to countries or places outside their usual environment for personal or business/professional purposes. These people are called visitors (which may be either tourists or excursionists; residents or non-residents) and tourism has to do with their activities, some of which imply tourism expenditure (United Nations World Tourism Organization, 2008).

Using this definition, we can see that tourism is not just the movement of people for a number of purposes (whether business or pleasure), but the overall agglomeration of activities, services, and involved sectors that make up the unique tourist experience.

Tourism, Travel, and Hospitality: What are the Differences?

It is common to confuse the terms tourism , travel , and hospitality or to define them as the same thing. While tourism is the all-encompassing umbrella term for the activities and industry that create the tourist experience, the UNWTO (2020) defines travel as the activity of moving between different locations often for any purpose but more so for leisure and recreation (Hall & Page, 2006). On the other hand, hospitality can be defined as “the business of helping people to feel welcome and relaxed and to enjoy themselves” (Discover Hospitality, 2015, p. 3). Simply put, the hospitality industry is the combination of the accommodation and food and beverage groupings, collectively making up the largest segment of the industry (Go2HR, 2020). You’ll learn more about accommodations and F & B in Chapter 3 and Chapter 4 , respectively.

Definition of Tourist and Excursionist

Building on the definition of tourism, a commonly accepted description of a tourist is “someone who travels at least 80 km from his or her home for at least 24 hours, for business or leisure or other reasons” (LinkBC, 2008, p.8). The United Nations World Tourism Organization (1995) helps us break down this definition further by stating tourists can be:

- Domestic (residents of a given country travelling only within that country)

- Inbound (non-residents travelling in a given country)

- Outbound (residents of one country travelling in another country)

Excursionists on the other hand are considered same-day visitors (UNWTO, 2020). Sometimes referred to as “day trippers.” Understandably, not every visitor stays in a destination overnight. It is common for travellers to spend a few hours or less to do sightseeing, visit attractions, dine at a local restaurant, then leave at the end of the day.

The scope of tourism, therefore, is broad and encompasses a number of activities and sectors.

Spotlight On: United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO)

UNWTO is the United Nations agency responsible “for the promotion of responsible, sustainable and universally accessible tourism” (UNWTO, 2014b). Its membership includes 159 countries and over 500 affiliates such as private companies, research and educational institutions, and non-governmental organizations. It promotes tourism as a way of developing communities while encouraging ethical behaviour to mitigate negative impacts. For more information, visit the UNWTO website .

NAICS: The North American Industry Classification System

Given the sheer size of the tourism industry, it can be helpful to break it down into broad industry groups using a common classification system. The North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) was jointly created by the Canadian, US, and Mexican governments to ensure common analysis across all three countries (British Columbia Ministry of Jobs, Tourism and Skills Training, 2013a). The tourism-related groupings created using NAICS are (in alphabetical order):

- Accommodation

- Food and beverage services (commonly known as “F & B”)

- Recreation and entertainment

- Transportation

- Travel services

These industry groups (also commonly known as sectors) are based on the similarity of the “labour processes and inputs” used for each (Government of Canada, 2013). For instance, the types of employees and resources required to run an accommodation business whether it be a hotel, motel, or even a campground are quite similar. All these businesses need staff to check in guests, provide housekeeping, employ maintenance workers, and provide a place for people to sleep. As such, they can be grouped together under the heading of accommodation. The same is true of the other four groupings, and the rest of this text explores these industry groups, and other aspects of tourism, in more detail.

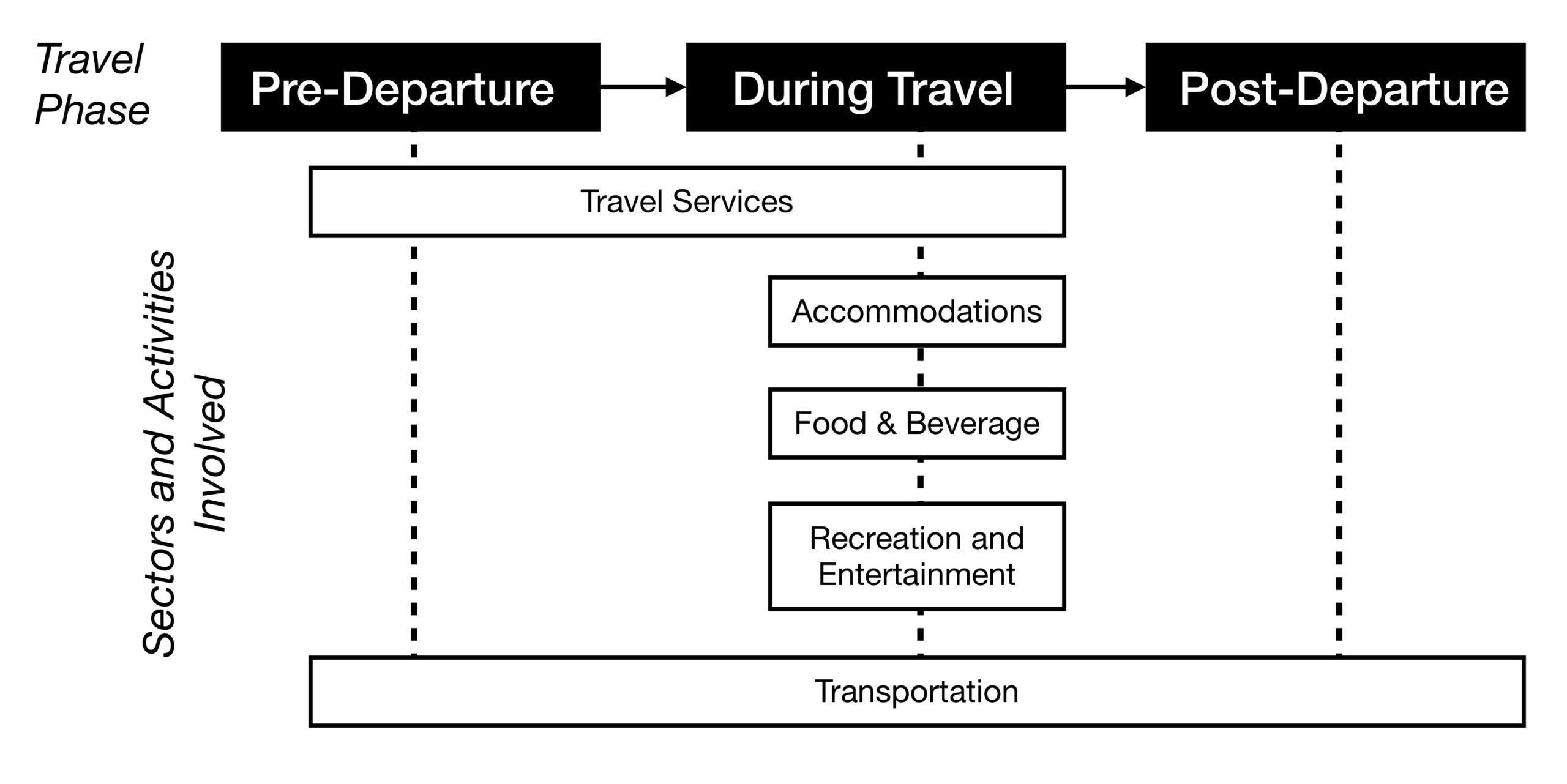

It is typical for the entire tourist experience to involve more than one sector. The combination of sectors that supply and distribute the needed tourism products, services, and activities within the tourism system is called the Tourism Supply Chain. Often, these chains of sectors and activities are dependent upon each other’s delivery of products and services. Let’s look at a simple example below that describes the involved and sometimes overlapping sectoral chains in the tourism experience:

Before we seek to understand the five tourism sectors in more detail, it’s important to have an overview of the history and impacts of tourism to date.

Long Descriptions

Figure 1.2 long description: Diagram showing the tourism supply chain. This includes the phases of travel and the sectors and activities involved during each phase.

There are three travel phases: pre-departure, during travel, and post-departure.

Pre-departure, tourists use the travel services and transportation sectors.

During travel, tourists use the travel services, accommodations, food and beverage, recreation and entertainment, and transportation sectors.

Post-departure, tourists use the transportation sector.

[Return to Figure 1.2]

Media Attributions

- Front Desk by Staying LEVEL is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 Licence .

Tourism according the the UNWTO is a social, cultural and economic phenomenon which entails the movement of people to countries or places outside their usual environment for personal or business/professional purposes.

UN agency responsible for promoting responsible, sustainable, and universally accessible tourism worldwide.

Moving between different locations for leisure and recreation.

The accommodations and food and beverage industry groupings.

someone who travels at least 80 km from his or her home for at least 24 hours, for business or leisure or other reasons

A same-day visitor to a destination. Their trip typically ends on the same day when they leave the destination.

A way to group tourism activities based on similarities in business practices, primarily used for statistical analysis.

Introduction to Tourism and Hospitality in BC - 2nd Edition Copyright © 2015, 2020, 2021 by Morgan Westcott and Wendy Anderson, Eds is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

The magazine of Glion Institute of Higher Education

- What is tourism and hospitality?

Tourism and hospitality are thriving industries encompassing many sectors, including hotels, restaurants, travel, events, and entertainment.

It’s an exciting and dynamic area, constantly evolving and adapting to changing customer demands and trends.

The tourism and hospitality industry offers a diverse range of career opportunities that cater to various interests, skills, and qualifications, with positions available from entry-level to executive management.

The booming tourism and hospitality industry also offers job security and career growth potential in many hospitality-related occupations.

What is tourism?

Tourism is traveling for leisure, pleasure, or business purposes and visiting various destinations, such as cities, countries, natural attractions, historical sites, and cultural events, to experience new cultures, activities, and environments.

Tourism can take many forms, including domestic, or traveling within your country, and international tourism, or visiting foreign countries.

It can also involve sightseeing, adventure tourism , eco-tourism, cultural tourism, and business tourism, and it’s a huge contributor to the global economy, generating jobs and income in many countries.

It involves many businesses, including airlines, hotels, restaurants, travel agencies, tour operators, and transportation companies.

What is hospitality?

Hospitality includes a range of businesses, such as hotels, restaurants, bars, resorts, cruise ships, theme parks, and other service-oriented businesses that provide accommodations, food, and beverages.

Hospitality is all about creating a welcoming and comfortable environment for guests and meeting their needs.

Quality hospitality means providing excellent customer service, anticipating guests’ needs, and ensuring comfort and satisfaction. The hospitality industry is essential to tourism as both industries often work closely together.

What is the difference between tourism and hospitality?

Hospitality and tourism are both related and separate industries. For instance, airline travel is considered as part of both the tourism and hospitality industries.

Hospitality is a component of the tourism industry, as it provides services and amenities to tourists. However, tourism is a broader industry encompassing various sectors, including transportation, accommodation, and attractions.

Transform your outlook for a successful career as a leader in hospitality management

This inspiring Bachelor’s in hospitality management gives you the knowledge, skills, and practical experience to take charge and run a business

Is tourism and hospitality a good career choice?

So, why work in hospitality and tourism? The tourism and hospitality industry is one of the fastest-growing industries in the world, providing a colossal number of job opportunities.

Between 2021 and 2031, employment in the hospitality and tourism industry is projected to expand faster than any other job sector, creating about 1.3 million new positions .

A tourism and hospitality career can be a highly rewarding choice for anyone who enjoys working with people, has a strong service-oriented mindset, and is looking for a dynamic and exciting career with growth potential.

Growth and job opportunities in tourism and hospitality

Tourism and hospitality offers significant growth and job opportunities worldwide. The industry’s increasing demand for personnel contributes to economic and employment growth, particularly in developing countries.

The industry employs millions globally, from entry-level to high-level management positions, including hotel managers, chefs, tour operators, travel agents, and executives.

It provides diverse opportunities with great career progression and skill development potential.

Career paths in tourism and hospitality

There are many career opportunities in tourism management and hospitality. With a degree in hospitality management, as well as relevant experience, you can pursue satisfying and fulfilling hospitality and tourism careers in these fields.

Hotel manager

Hotel managers oversee hotel operations. They manage staff, supervise customer service, and ensure the facility runs smoothly.

Tour manager

Tour managers organize and lead group tours. They work for tour companies, travel agencies, or independently. Tour managers coordinate a group’s transportation, accommodations, and activities, ensuring the trip runs to schedule.

Restaurant manager

Restaurant managers supervise the daily operations of a restaurant. They manage staff, ensure the kitchen runs smoothly, and monitor customer service.

Resort manager

Resort managers supervise and manage the operations of a resort. From managing staff to overseeing customer service, they ensure the entire operation delivers excellence.

Entertainment manager

Entertainment managers organize and oversee entertainment at venues like hotels or resorts. They book performers, oversee sound and lighting, and ensure guests have a great experience.

Event planner

Event planners organize and coordinate events, such as weddings, conferences, and trade shows. They work for event planning companies, hotels, or independently.

vent planners coordinate all aspects of the event, from the venue to catering and decor.

Travel consultant

Travel consultants help customers plan and book travel arrangements, such as flights, hotels, and rental cars. They work for travel agencies or independently. Travel consultants must know travel destinations and provide superb customer service.

What skills and qualifications are needed for a career in tourism and hospitality?

Tourism and hospitality are rewarding industries with growing job opportunities. Necessary qualifications include excellent skills in communication, customer service, leadership, problem-solving, and organization along with relevant education and training.

Essential skills for success in tourism and hospitality

A career in the tourism and hospitality industry requires a combination of soft and technical skills and relevant qualifications. Here are some of the essential key skills needed for a successful career.

- Communication skills : Effective communication is necessary for the tourism and hospitality industry in dealing with all kinds of people.

- Customer service : Providing excellent customer service is critical to the success of any tourism or hospitality business . This requires patience, empathy, and the ability to meet customers’ needs.

- Flexibility and adaptability : The industry is constantly changing, and employees must be able to adapt to new situations, be flexible with their work schedules, and handle unexpected events.

- Time management : Time management is crucial to ensure guest satisfaction and smooth operations.

- Cultural awareness : Understanding and respecting cultural differences is essential in the tourism and hospitality industry, as you’ll interact with people from different cultures.

- Teamwork : Working collaboratively with colleagues is essential, as employees must work together to ensure guests have a positive experience.

- Problem-solving : Inevitably, problems will arise, and employees must be able to identify, analyze, and resolve them efficiently.

- Technical skills : With the increasing use of technology, employees must possess the necessary technical skills to operate systems, such as booking software, point-of-sale systems, and social media platforms.

Revenue management : Revenue management skills are crucial in effectively managing pricing, inventory, and data analysis to maximize revenue and profitability

Master fundamental hospitality and tourism secrets for a high-flying career at a world-leading hospitality brand

With this Master’s degree, you’ll discover the skills to manage a world-class hospitality and tourism business.

Education and training opportunities in tourism and hospitality

Education and training are vital for a hospitality and tourism career. You can ensure you are prepared for a career in the industry with a Bachelor’s in hospitality management and Master’s in hospitality programs from Glion.

These programs provide a comprehensive understanding of the guest experience, including service delivery and business operations, while developing essential skills such as leadership, communication, and problem-solving. You’ll gain the knowledge and qualifications you need for a successful, dynamic, and rewarding hospitality and tourism career.

Preparing for a career in tourism and hospitality

To prepare for a career in tourism and hospitality management, you should focus on researching the industry and gaining relevant education and training, such as a hospitality degree . For instance, Glion’s programs emphasize guest experience and hospitality management, providing students with an outstanding education that launches them into leading industry roles.

It would help if you also worked on building your communication, customer service, and problem-solving skills while gaining practical experience through internships or part-time jobs in the industry. Meanwhile, attending industry events, job fairs, and conferences, staying up-to-date on industry trends, and networking to establish professional connections will also be extremely valuable.

Finding jobs in tourism and hospitality

To find jobs in tourism and hospitality, candidates can search online job boards, and company career pages, attend career fairs, network with industry professionals, and utilize the services of recruitment agencies. Hospitality and tourism graduates can also leverage valuable alumni networks and industry connections made during internships or industry projects.

Networking and building connections in the industry

Networking and building connections in the hospitality and tourism industry provide opportunities to learn about job openings, meet potential employers, and gain industry insights. It can also help you expand your knowledge and skills, build your personal brand, and establish yourself as a valuable industry professional.

You can start networking by attending industry events, joining professional organizations, connecting with professionals on social media, and through career services at Glion.

Tips for success in tourism and hospitality

Here are tips for career success in the tourism and hospitality industry.

- Gain relevant education and training : Pursue a hospitality or tourism management degree from Glion to gain fundamental knowledge and practical skills.

- Build your network : Attend industry events, connect with colleagues and professionals on LinkedIn, and join relevant associations to build your network and increase your exposure to potential job opportunities.

- Gain practical experience : Look for internships, part-time jobs, or volunteering opportunities to gain practical experience and develop relevant skills.

- Develop your soft skills : Work on essential interpersonal skills like communication, empathy, and problem-solving.

- Stay up-to-date with industry trends : Follow industry news and trends and proactively learn new skills and technologies relevant to tourism and hospitality.

- Be flexible and adaptable : The tourism and hospitality industry constantly evolves, so be open to change and to adapting to new situations and challenges.

- Strive for excellent guest service : Focus on delivering exceptional guest experiences as guest satisfaction is critical for success.

Tourism and hospitality offer many fantastic opportunities to create memorable guest experiences , work in diverse and multicultural environments, and develop transferable skills.

If you’re ready to embark on your career in tourism and hospitality, Glion has world-leading bachelor’s and master’s programs to set you up for success.

Photo credits Main image: Maskot/Maskot via Getty Images

LISTENING TO LEADERS

BUSINESS OF LUXURY

HOSPITALITY UNCOVERED

GLION SPIRIT

WELCOME TO GLION.

This site uses cookies. Some are used for statistical purposes and others are set up by third party services. By clicking ‘Accept all’, you accept the use of cookies

Privacy Overview

- Open access

- Published: 25 November 2023

Systematic review and research agenda for the tourism and hospitality sector: co-creation of customer value in the digital age

- T. D. Dang ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0930-381X 1 , 2 &

- M. T. Nguyen 1

Future Business Journal volume 9 , Article number: 94 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

1935 Accesses

1 Citations

Metrics details

A Correction to this article was published on 07 February 2024

This article has been updated

The tourism and hospitality industries are experiencing transformative shifts driven by the proliferation of digital technologies facilitating real-time customer communication and data collection. This evolution towards customer value co-creation demands a paradigm shift in management attitudes and the adoption of cutting-edge technologies like artificial intelligence (AI) and the Metaverse. A systematic literature review using the PRISMA method investigated the impact of customer value co-creation through the digital age on the tourism and hospitality sector. The primary objective of this review was to examine 27 relevant studies published between 2012 and 2022. Findings reveal that digital technologies, especially AI, Metaverse, and related innovations, significantly enhance value co-creation by allowing for more personalized, immersive, and efficient tourist experiences. Academic insights show the exploration of technology’s role in enhancing travel experiences and ethical concerns, while from a managerial perspective, AI and digital tools can drive industry success through improved customer interactions. As a groundwork for progressive research, the study pinpoints three pivotal focal areas for upcoming inquiries: technological, academic, and managerial. These avenues offer exciting prospects for advancing knowledge and practices, paving the way for transformative changes in the tourism and hospitality sectors.

Introduction

The tourism and hospitality industry is constantly evolving, and the digital age has brought about numerous changes in how businesses operate and interact with their customers [ 1 ]. One such change is the concept of value co-creation, which refers to the collaborative process by which value is created and shared between a business and its customers [ 2 , 3 ]. In order to facilitate the value co-creation process in tourism and hospitality, it is necessary to have adequate technologies in place to enable the participation of all stakeholders, including businesses, consumers, and others [ 4 , 5 ]. Thus, technology serves as a crucial enabler for value co-creation. In the tourism and hospitality industry, leading-edge technology can be crucial in co-creation value processes because it can facilitate the creation and exchange of value among customers and businesses [ 6 , 7 ]. For example, the development of cloud computing and virtual reality technologies has enabled new forms of collaboration and co-creation that were not possible before [ 8 , 9 , 10 ]. Recent technologies like AI, Metaverse, and robots have revolutionized tourism and hospitality [ 11 , 12 , 13 ]. These technologies are used in various ways to enhance the customer experience and drive business success. AI can personalize the customer experience using customer data and personalized recommendations [ 14 ]. It can also optimize operations by automating tasks and improving decision-making. The metaverse, or virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) technologies, are being used to offer immersive and interactive experiences to customers [ 10 , 11 ]. For example, VR and AR can create virtual tours of hotels and destinations or offer interactive experiences such as virtual cooking classes or wine tastings [ 15 ]. Robots are being used to aid and interact with customers in various settings, including hotels, restaurants, and tourist attractions. For example, robots can provide information, answer questions, and even deliver room services [ 12 , 16 ]. The COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the crucial interplay between public health, sustainable development, and digital innovations [ 17 ]. Globally, the surge in blockchain applications, particularly in the business, marketing and finance sectors, signifies the technological advancements reshaping various industries [ 18 ]. These developments, coupled with integrating digital solutions during the pandemic, highlight the pervasive role of technology across diverse sectors [ 19 , 20 , 21 ]. These insights provide a broader context for our study of the digital transformation in the tourism and hospitality sectors. Adopting new technologies such as AI, the Metaverse, blockchain and robots is helping the tourism and hospitality industry deliver customers a more personalized, convenient, and immersive experience [ 22 ]. As these technologies continue to evolve and become more prevalent, businesses in the industry need to stay up-to-date and consider how they can leverage these technologies to drive success [ 23 , 24 ].

Despite the growing body of literature on customer value co-creation in the tourism and hospitality sector, it remains scattered and fragmented [ 2 , 25 , 26 ]. To consolidate this research and provide a comprehensive summary of the current understanding of the subject, we conducted a systematic literature review using the PRISMA 2020 (“ Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses ”) approach [ 27 , 28 ]. This systematic review aims to explore three primary areas of inquiry related to the utilization of AI and new technologies in the tourism and hospitality industry: (i) From a technology perspective, what are the main types of AI and latest technologies that have been used to enhance co-creation values in tourism and hospitality?; (ii) From an academic viewpoint—What are the future research directions in this sector?; (iii) From a managerial standpoint—How can these technologies be leveraged to enhance customer experiences and drive business success?. In essence, this study contributes valuable insights into the dynamic realm of customer value co-creation in the digital age within the tourism and hospitality sector. By addressing the research questions and identifying gaps in the literature, our systematic literature review seeks to provide novel perspectives on leveraging technology to foster industry advancements and enhance customer experiences.

The remaining parts of this article are structured in the following sections: “ Study background ” section outlines pertinent background details for our systematic literature review. In “ Methodology ” section details our research objectives, queries, and the systematic literature review protocol we used in our study design. In “ Results ” section offers the findings based on the analyzed primary research studies. Lastly, we conclude the article, discuss the outstanding work, and examine the limitations to the validity of our study in “ Discussion and implications ” section.

Study background

Amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, the tourism sector is experiencing significant transformations. Despite the substantial impact on the tourism industry, the demand for academic publications about tourism remains unabated. In this recovery phase, AI and novel technologies hold immense potential to assist the tourism and hospitality industry by tackling diverse challenges and enhancing overall efficiency. In this section, the study provides some study background for the review processes.

The relationship between tourism and hospitality

Tourism and hospitality are closely related industries, as the hospitality industry plays a crucial role in the tourism industry [ 29 ]. Academics and practitioners often examine tourism and hospitality because they are related industries [ 2 , 30 ]. Hospitality refers to providing travelers and tourists accommodation, food, and other services [ 31 ]. These can include hotels, resorts, restaurants, and other types of establishments that cater to the needs of travelers [ 32 ]. On the other hand, the tourism industry encompasses all the activities and services related to planning, promoting, and facilitating travel [ 31 ]; transportation, tour operators, travel agencies, and other businesses that help facilitate tourist travel experiences [ 33 ]. Both industries rely on each other to thrive, as travelers need places to stay and eat while on vacation, and hospitality businesses rely on tourists for their income [ 32 , 33 , 34 ].

In recent years, the tourism industry has undergone significant changes due to the increasing use of digital technologies, enabling the development of new forms of tourism, such as “smart tourism” [ 8 , 10 ]. Smart tourism refers to using digital technologies to enhance the customer experience and improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the industry [ 1 ]. These technologies, including AI and Metaverse, can be used in various aspects of the tourism industry, such as booking and reservation processes, customer service, and the management of tourist attractions [ 4 , 11 ]. The hospitality industry, which includes hotels and restaurants, is closely linked to the tourism industry and is also adopting intelligent technologies to improve the customer experience and increase efficiency [ 1 , 22 ]. Recent studies have explored the impact of these technologies on the tourism and hospitality sectors and have identified both benefits and challenges for stakeholders [ 10 , 35 , 36 ].

Customer value co-creation in tourism and hospitality

Customer value co-creation in tourism and hospitality refers to the process by which customers and businesses collaborate to create value by exchanging services, information, and experiences [ 2 , 33 ]. This process involves the customer and the business actively creating value rather than simply providing a product or service to the customer [ 37 ]. Studies have found that customer value co-creation in tourism and hospitality can increase customer satisfaction and loyalty [ 2 ]. When customers feel that they can contribute to the value of their experience, they are more likely to feel a sense of ownership and involvement, which can lead to a more positive overall evaluation of the experience [ 5 , 38 ]. In the tourism industry, customer value co-creation can increase satisfaction with the destination, trips, accommodation, services, and overall experiences [ 4 ]. These can be achieved by allowing customers to choose their room amenities or providing opportunities to interact with staff and other guests [ 5 , 39 ]. Customer value co-creation in tourism and hospitality can be a powerful solution for businesses to increase customer satisfaction and loyalty. By actively involving customers in creating value, businesses can create a more personalized and engaging experience for their customers.

AI, Metaverse, and new technologies in tourism and hospitality

The impact of AI, the Metaverse, and new technologies on the tourism and hospitality industries is an area of active research and debate [ 2 , 4 , 29 , 40 ]. First, using AI and new technology in tourism and hospitality can improve the customer experience, increase efficiency, and reduce costs [ 13 , 41 , 42 , 43 ]. For instance, chatbots and virtual assistants facilitate tasks like room bookings or restaurant reservations for customers. Concurrently, machine learning (ML) algorithms offer optimized pricing and marketing strategies and insights into customer perceptions within the tourism and hospitality sectors [ 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 ]. However, there are also concerns about the potential negative impact of AI on employment in the industry [ 48 ]. Second, The emergence of the Metaverse, a virtual shared space where people can interact in real time, can potentially revolutionize the tourism and hospitality industries [ 10 ]. For example, VR and AR experiences could allow travelers to visit and explore destinations without leaving their homes [ 15 , 49 ], while online events and social gatherings could provide new business opportunities to connect with customers [ 11 ]. However, it is unclear how the Metaverse will evolve and its long-term impact on the tourism and hospitality industries [ 4 , 10 , 11 ]. Last, other emerging technologies, such as blockchain, AI-Robotics, and the Internet of Things (IoT), can potentially transform the tourism and hospitality industries [ 18 , 45 , 48 ]. For example, blockchain could be used to secure and track the movement of travel documents [ 18 ], while IoT-enabled devices could improve the efficiency and personalization of the customer experience [ 50 ]. As with AI and the Metaverse, it is difficult to predict the exact impact of these technologies on the industry, but they are likely to play a significant role in shaping its future [ 18 , 40 ]. In the aftermath of the pandemic, the healthcare landscape within the tourism and hospitality sector is undergoing significant transformations driven by the integration of cutting-edge AI and advanced technologies [ 38 , 51 , 52 ]. These technological advancements have paved the way for personalized and seamless experiences for travelers, with AI-powered chatbots playing a pivotal role in addressing medical inquiries and innovative telemedicine solutions ensuring the well-being of tourists [ 52 , 53 ].

This study background provides essential context for the subsequent systematic literature review, as it contextualizes the field’s key concepts, frameworks, and emerging technologies. By examining these aspects, the study aims to contribute valuable insights into the post-pandemic recovery of the tourism and hospitality industry, paving the way for future research opportunities and advancements in the field.

Methodology

This study meticulously adopted a systematic literature review process grounded in a pre-defined review protocol to provide a thorough and objective appraisal [ 54 ]. This approach was geared to eliminate potential bias and uphold the integrity of study findings. The formulation of the review protocol was a collaborative effort facilitated by two researchers. This foundational document encompasses (i) Clear delineation of the study objectives, ensuring alignment with the research aim; (ii) A thorough description of the methods used for data collection and assessment, which underscores the replicability of our process; (iii) A systematic approach for synthesizing and analyzing the selected studies, promoting consistency and transparency.

Guiding the current review process was the PRISMA methodology, a renowned and universally esteemed framework that has set a gold standard for conducting systematic reviews in various scientific disciplines [ 27 , 28 ]. The commendable efficacy of PRISMA in service research substantiates its methodological robustness and reliability [ 55 ]. It is not only the rigorous nature of PRISMA but also its widespread acceptance in service research that accentuates its fittingness for this research. Given tourism and hospitality studies’ intricate and evolving nature, PRISMA is a robust compass to guide our SLR, ensuring methodological transparency and thoroughness [ 56 , 57 ]. In essence, the PRISMA approach does not merely dictate the procedural intricacies of the review but emphasizes clarity, precision, and transparency at every phase. The PRISMA methodology presents the research journey holistically, from its inception to its conclusions, providing readers with a clear and comprehensive understanding of the approach and findings [ 58 ].

Utilizing the goal-question-metrics approach [ 59 ], our study aims to analyze current scientific literature from the perspectives of technicians, researchers, and practitioners to comprehend customer value co-creation through the digital age within the Tourism and Hospitality sector. In order to accomplish this goal, we formulated the following research questions:

What are the main types of AI and new technologies used to enhance value co-creation in the tourism and hospitality industries?

What are the future research directions in customer value co-creation through AI and new technologies in the tourism and hospitality sector?

How do managers in the tourism and hospitality sector apply AI and new technologies to enhance customer co-creation value and drive business success?

The subsequent subsections will provide further details regarding our search and analysis strategies.

Search strategy and selection criteria

We collected our data by searching for papers in the Scopus and Web of Science databases, adhering to rigorous scientific standards. We included only international peer-reviewed academic journal articles, excluding publications like books, book chapters, and conference proceedings [ 60 , 61 , 62 ]. The research process covered the period from 2009 to 2022, as this timeframe aligns with the publication of the first studies on value co-creation in the tourism industry in 2009 and the first two studies on value co-creation in general in 2004 [ 63 , 64 ]. The selection of sources was based on criteria such as timelines, availability, quality, and versatility, as discussed by Dieste et al. [ 2 ]. We employed relevant keywords, synonyms, and truncations for three main concepts: tourism and hospitality, customer value co-creation, and AI and new technologies in smart tourism and hospitality. To ensure transparency and comprehensiveness, we followed the PRISMA inclusion criteria, detailed in Table 1 , and utilized topic and Boolean/phrase search modes to retrieve papers published from 2009 to 2022. The final search string underwent validation by experts to ensure accuracy and comprehensiveness:

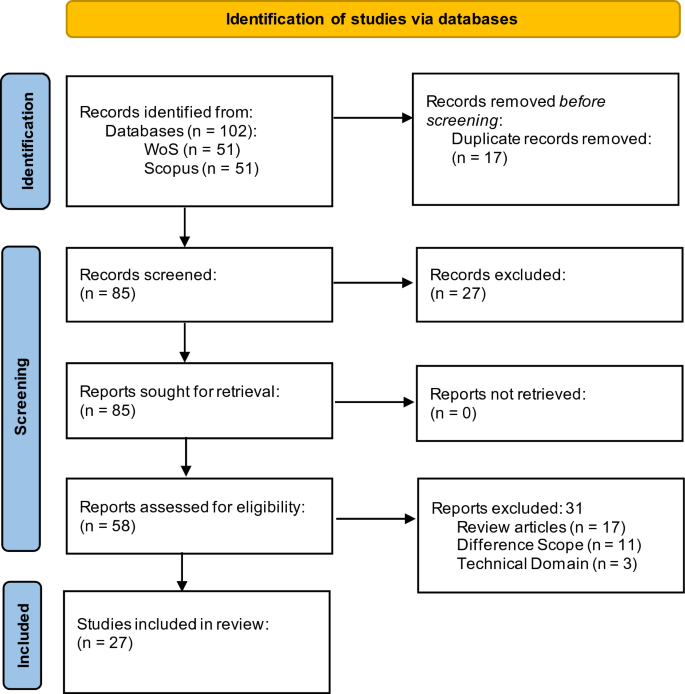

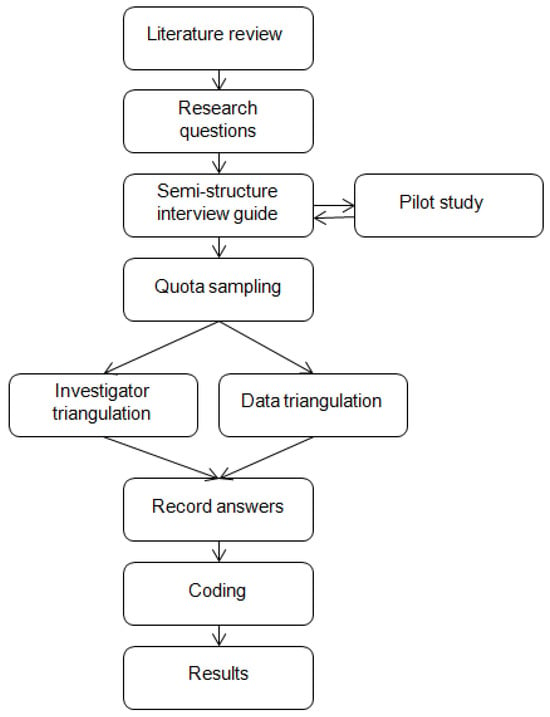

A PRISMA diagram was produced to understand better this study’s search strategy and record selection.

Study selection and analysis procedure

The current study utilized the PRISMA framework to document our review process. One hundred two papers were retrieved during the initial search across the databases. Table 1 outlines the criteria for selecting the studies based on scope and quality. The study adhered to the PRISMA procedure (as shown in Fig. 1 ) and applied the following filters:

We identified and removed 17 duplicate records during the ‘identification’ step.

We excluded 27 publications in the ‘Screening’ step based on the title and abstract.

We excluded 31 publications based on the entire text in the eligibility step.

PRISMA flow diagram

As a result, we were left with a final collection of 27 journal articles for downloading and analysis. Two trained research assistants conducted title and abstract screenings separately, and any disagreements about inclusion were resolved by discussing them with the research coordinator until an agreement was reached. Papers not in English, papers from meetings, books, editorials, news, reports, and patents were excluded, as well as unrelated or incomplete papers and studies that did not focus on the tourism and hospitality domain. A manual search of the reference lists of each paper was conducted to identify relevant papers that were not found in the database searches. After this process, 27 papers were left for a full-text review.

This study used the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) to evaluate the quality of qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods research studies included [ 65 , 66 ]. According to the findings, the quality of the study met the standards of a systematic review. Additional information can be obtained from Additional file 1 : Appendix 1.

In this section, we will report the results of our data analysis for each research question. We will begin by describing the characteristics of the studies included in the systematic literature review, such as (1) publication authors, titles, years and journals, topics, methods, and tools used in existing studies. Then each facet was elaborated by the following questions: (i) What are the main types of AI and new technologies used to enhance value co-creation in the tourism and hospitality industries? (ii) What are the future research directions in customer value co-creation through AI and new technologies in the tourism and hospitality sector? (iii) How do managers in the tourism and hospitality sector apply AI and new technologies to enhance customer co-creation value and drive business success?

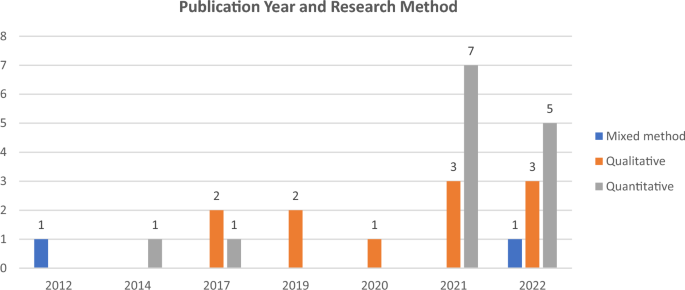

Studies demographics

Figure 2 shows the yearly publication of articles on customer co-creation of value in tourism and hospitality through AI and new technologies. The chart’s data suggests two main findings. Firstly, the research on customer value co-creation in tourism and hospitality through AI and new technologies is still in its early stages (1 paper in 2012). However, the annual number of published articles from 2017 to the present appears to be generally increasing. This trend implies that the application of value co-creation in this field is gaining academic attention and is becoming an emerging research area. Based on this trend, we anticipate seeing more studies on this topic published in the following years.

Publication Years with research methods

Regarding research type, 14 papers (52%) conducted quantitative research, employing statistical analysis, structural equation modeling, and data mining methods. Meanwhile, 11 papers (41%) conducted qualitative research using interviews, thematic analysis, and descriptive analysis. Only two papers (7%) used mixed research (combining quantitative and qualitative methods). The survey and interview methods (both individual and group) were found to be more common than other research methods. This suggests that interviews provide greater insight into participant attitudes and motivations, enhancing accuracy in quantitative and qualitative studies. Additionally, certain studies employed content analysis, big data analysis using UGC, and data from online platforms, social media, and big data.

Regarding the publishing journals, we found that 27 papers were published in 22 journals (refer to Table 2 ), where three journals had more than one paper on co-creation value through AI and new technologies in tourism and hospitality, indicating their keen interest in this topic. Most publications were in the Journal of Business Research, with four studies on co-creation value through AI and new technologies in tourism and hospitality. Two related studies were published in the Tourism Management Perspectives and Journal of Destination Marketing & Management. This distribution indicates that most current research on co-creation value through AI and new technologies in tourism and hospitality was published in journals in the tourism and hospitality management field. However, some journals in the computer and AI field have also published papers on co-creation value through AI and new technologies in tourism and hospitality, including Computers in Industry, Computers in Human Behavior, Computational Intelligence, and Neuroscience.

Regarding data analytics tools, SmartPLS, AMOS, NVivo and PROCESS tools are the 5 most popular software graphic tools used in studies, while Python and R are the two main types of programming languages used. In total, 27 studies, 14 refer to using AI applications and data analytics in this research flow. Metaverse and relative technologies such as AR and VR were included in 8 studies. Three studies used service robots to discover the value co-creation process. There are include two studies that have used chatbots and virtual assistants.

Publication years and journals

In recent systematic literature reviews focusing on general services, tourism, and hospitality, there has been a notable emphasis on traditional factors shaping customer experience [ 26 , 67 , 68 ]. However, this study uniquely positions itself by emphasizing the digital age’s profound impact on value co-creation within this sector. The subsequent part digs more into the specifics of this study, building on these parallels. The detailed findings offer nuanced insights into how value co-creation in tourism and hospitality has evolved, providing a more extensive understanding than previous works.

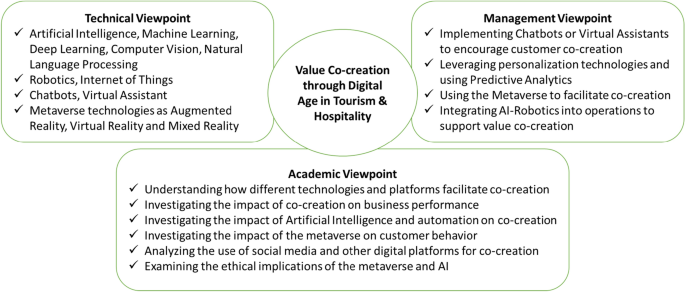

Result 1—technology viewpoints: What are the main types of AI and new technologies used to enhance value co-creation in the tourism and hospitality industries?

Several types of AI and new technologies have been used to enhance co-creation values in the tourism and hospitality industry. Nowadays, AI, ML, and deep learning can all be used to enhance customer value co-creation in the tourism and hospitality industry [ 42 , 69 , 70 ]. There are some AI applications identified through the review process:

First, personalization and customized recommendations: AI and ML can be used to analyze customer data, such as their past bookings, preferences, and reviews, to personalize recommendations and experiences for them [ 7 , 69 , 71 , 72 ]. Cuomo et al. examine how data analytics techniques, including AI and ML, can improve traveler experience in transportation services. Applying AI and ML can help customers discover new experiences and activities they may not have considered otherwise [ 13 ]. Relating to data mining applications, Ngamsirijit examines how data mining can be used to create value in creative tourism. Moreover, the study also discusses the need for co-creation to create a successful customer experience in creative tourism and ways data mining can enhance the customer experience [ 73 ].

Second, user-generated content and sentiment analysis: ML and Natural Language Processing (NLP) can be used to analyze user-generated content such as reviews and social media posts to understand customer needs and preferences [ 12 , 37 ]. This can help businesses identify opportunities to create customer value [ 74 ]. NLP can analyze customer reviews and feedback to understand the overall sentiment toward a hotel or destination [ 75 ]. This can help businesses identify areas for improvement and create a better customer experience [ 70 ]. In the study using NLP to analyze data from Twitter, Liu et al. examine the impact of luxury brands’ social media marketing on customer engagement. The authors discuss how big data analytics and NLP can be used to analyze customer conversations and extract valuable insights about customer preferences and behaviors [ 74 ].

Third, recent deep learning has developed novel models that create business value by forecasting some parameters and promoting better offerings to tourists [ 71 ]. Deep learning can analyze large amounts of data and make more accurate predictions or decisions [ 39 , 41 ]. For example, a deep learning model could predict the likelihood of a customer returning to a hotel based on their past bookings and interactions with the hotel [ 72 ].

Some applications of the latest technologies that have been used to enhance co-creation values in tourism and hospitality include

Firstly, Chatbots and virtual assistants can enhance customer value co-creation in the tourism and hospitality industry in several ways: (i) Improved customer service: Chatbots and virtual assistants can be used to answer customer questions, provide information, and assist with tasks such as booking a room or making a reservation [ 45 ]. These tools can save customers and staff time and improve customer experience [ 76 ]; (ii) Increased convenience: Chatbots and virtual assistants can be accessed 24/7, meaning customers can get help or assistance anytime [ 50 ]. These tools can be handy for traveling customers with questions or who need assistance outside regular business hours [ 44 ]; (iii) Personalization: Chatbots and virtual assistants can use natural language processing (NLP) to understand and respond to customer inquiries in a more personalized way [ 45 , 70 ]. This can help improve the customer experience and create a more favorable impression of the business. Moreover, this can save costs and improve customers [ 16 ].

Secondly, metaverse technologies can enhance customer value co-creation in the tourism and hospitality industry in several ways: (i) Virtual tours and experiences: Metaverse technologies can offer virtual tours and experiences to customers, allowing them to visit and explore destinations remotely [ 77 ]. This technology can be beneficial for customers who are unable to travel due to pandemics or who want to preview a destination before deciding to visit in person [ 49 ]; (ii) Virtual events: Metaverse technologies can be used to host virtual events, such as conferences, workshops, or trade shows, which can be attended by customers from anywhere in the world [ 9 ]. This can save time and money for businesses and customers and increase the reach and impact of events; (iii) Virtual customer service: Metaverse technologies can offer virtual customer service, allowing customers to interact with businesses in a virtual setting [ 25 ]. This can be especially useful for customers who prefer to communicate online or in remote areas; (iv) Virtual training and education : Metaverse technologies can offer virtual training and education to employees and customers [ 41 ]. Metaverse can be an effective and convenient way to deliver training and can save time and money for both businesses and customers [ 7 ]; (v) Virtual reality (VR) experiences: Metaverse technologies can be used to offer VR experiences to customers, allowing them to immerse themselves in virtual environments and participate in activities that would be difficult or impossible to do in the real world [ 77 ]. This can enhance the customer experience and create new business opportunities to offer unique and memorable experiences [ 71 ].

Thirdly, IoT and robots can enhance customer value co-creation in the tourism and hospitality sector in several ways: (i) One way is by providing personalized and convenient customer experiences [ 12 ]. For example, hotels can use IoT-enabled devices to allow guests to control the temperature and lighting in their rooms, as well as access hotel amenities such as room service and concierge services [ 50 ]; (ii) In addition, robots can be used to provide assistance and enhance the customer experience in various ways [ 16 , 40 ]. For example, robots can be used to deliver items to guest rooms, assist with check-in and check-out processes, and provide information and directions to guests [ 12 ]; (iii) Both IoT and robots can be used to gather customer feedback and data in real-time, which can help to improve the quality and effectiveness of tourism and hospitality services [ 76 ]. For example, hotels can use IoT-enabled devices to gather data on guest preferences and needs, which can be used to tailor services and experiences to individual customers. This can help to improve customer satisfaction and loyalty [ 76 ]. Overall, using IoT and robots in the tourism and hospitality sector can help improve the industry’s efficiency and effectiveness and enhance the customer experience.

Result 2—academic viewpoints: What are the future research directions in customer value co-creation through AI and new technologies in the tourism and hospitality sector?

From an academic perspective, there are several potential future research directions in customer value co-creation through the digital age in the tourism and hospitality sector. Some possibilities include: (1) Understanding how different technologies and platforms facilitate co-creation: Researchers could investigate how different technologies and platforms, such as social media, mobile apps, or virtual reality, enable or inhibit co-creation in the tourism and hospitality industry; (2) Investigating the impact of co-creation on business performance: Researchers could examine the relationship between co-creation and business performance in the tourism and hospitality sector and identify the factors that drive success in co-creation initiatives; (3) Investigating the impact of AI and automation on co-creation: As AI and automation technologies become more prevalent in the industry, research could focus on the impact these technologies have on co-creation and value creation, including the potential for AI to facilitate or hinder co-creation; (4) Investigating the impact of the Metaverse on customer behaviour: Research could focus on understanding how the Metaverse affects customer behaviour and decision-making, and how companies can use this information to facilitate co-creation and value creation [ 9 ]; (5) Analysing the use of social media and other digital platforms for co-creation: Researchers could study how companies in the tourism and hospitality sector use social media and other digital platforms to facilitate co-creation with customers, and the impact that these platforms have on value creation [ 7 , 45 , 78 ]. Researchers could investigate how social interactions and communities in the Metaverse enable or inhibit co-creation in the tourism and hospitality industry and the impact on customer satisfaction and loyalty; (6) Examining the ethical implications of the Metaverse and AI: Researchers could explore the ethical considerations surrounding the use of the Metaverse and AI in the tourism and hospitality sector, such as issues related to privacy and data security, and the potential for these technologies to perpetuate or exacerbate societal inequalities [ 48 , 75 , 77 ].

Result 3—Management viewpoints: How do managers in the tourism and hospitality sector apply AI and new technologies to enhance customer co-creation value and drive business success?

There are several ways managers in the tourism and hospitality industry can apply AI and new technologies to enhance customer experiences and drive business success. We suggest four main possibilities: (1) Implementing chatbots or virtual assistants to encourage customer co-creation: Managers can use chatbots or virtual assistants to provide quick and convenient customer service, helping businesses respond to customer inquiries and resolve issues more efficiently [ 76 ]. Then, encourage customer co-creation by inviting customers to participate in the creation of new experiences and products by gathering feedback and ideas through online forums and focus groups [ 45 ]. This can help build a sense of community and engagement and can also lead to the development of new, innovative products and experiences that will attract more customers [ 50 , 79 ]; (2) Leveraging personalization technologies and using predictive analytics: Managers can use AI-powered personalization technologies to analyze customer data and preferences and offer personalized recommendations and experiences [ 42 , 72 , 80 ]. This can help businesses better understand and anticipate customer needs and create more tailored and satisfying experiences that drive co-creation value. Managers can leverage AI-powered predictive analytics technologies to analyze data and predict future customer behavior or trends [ 75 ]. This can help businesses anticipate customer needs and make informed decisions about resource allocation and planning, enhancing co-creation value. Managers can use personalization technologies and predictive analytics to analyze customer feedback and identify areas for improvement [ 37 ]. These can help businesses better understand customer needs and preferences and create more satisfying and valuable experiences that drive co-creation value [ 7 , 36 , 41 ]; (3) Using the Metaverse to facilitate co-creation: Managers can leverage the Metaverse to allow customers to design and customize their own experiences, which can help create value in collaboration with customers [ 25 , 71 , 77 ]. Managers can use VR and AR technologies to create immersive and interactive customer experiences in the Metaverse [ 81 ]. This can help businesses differentiate themselves and stand out in a competitive market. Managers can use data analysis tools to understand how customers behave in the Metaverse and use this information to create more personalized and satisfying experiences [ 9 ]. Managers can leverage the Metaverse to facilitate co-creation with customers, for example, by enabling customers to design and customize their own experiences [ 49 , 81 ]. This can help businesses create value in collaboration with customers; (4) Integrating AI-robotics into operations to support value co-creation: Analyse your business processes to identify tasks that can be automated using AI-powered robotics, such as check-in and check-out, room service, or concierge services [ 12 , 82 ]. Managers can consider using AI-powered robots for tasks such as check-in and check-out or for delivering amenities to guests. Use AI and the latest technologies to streamline the booking and check-in process, making it faster and more convenient for customers [ 16 ]. This can include using virtual assistants to handle booking inquiries or facial recognition technology to allow customers to check in at their hotel simply by showing their faces. These can help businesses reduce labor costs and improve efficiency, enhancing co-creation value [ 16 ]. We summarize three viewpoints in Fig. 3 below.

Summary of value co-creation through the Digital Age in Tourism and Hospitality

Combining these three viewpoints as a research agenda for tourism and hospitality in the AI and digital age holds immense potential. It addresses critical aspects such as customer experience enhancement, leveraging customer-generated content, and exploring cutting-edge technologies to create value co-creation opportunities. Researching these areas allows the industry to stay at the forefront of the digital revolution and deliver exceptional customer experiences that drive business success in the next few years.

Discussion and implications

This study aimed to develop a systematic literature review of customer value co-creation in the hospitality and tourism industry using the PRISMA protocol [ 27 ]. The study findings highlighted that tourism and hospitality should take advantage of AI and new technologies, as it brings significant advantages. Value co-creation in the tourism and hospitality sector refers to creating value through the collaboration and participation of multiple stakeholders, including tourists, employees, and the industry [ 2 ]. AI, Metaverse, and other new technologies can significantly enhance value co-creation in this sector by enabling more personalized, immersive, and efficient tourist experiences [ 40 , 80 , 81 ].

From a technology viewpoint, the study reveals that manifestations of customer value co-creation through the digital age are related to AI and the latest technologies such as Metaverse, robots, IoT, chatbots, intelligence systems, and others that shape co-creation [ 42 ]. AI applications and new technologies can help shape customer value co-creation in this sector. AI can follow the rules, think like an expert, learn from data, and even create virtual and augmented reality experiences [ 4 , 10 ]. Chatbots, personalization, predictive analytics, and robotics are examples of how AI and technology can create unique and fun travel experiences [ 16 , 40 , 74 , 83 ].

From an academic viewpoint, researchers look at ways technology can help people enjoy their travels and stay in hotels by boosting the value co-creation process [ 2 ]. They are looking at how different technologies, like social media, can help people create value for themselves and others [ 45 , 84 ]. They are also looking at how AI and the virtual world can change people’s decisions and how companies can use this information to help people [ 77 , 80 ]. Finally, researchers are looking into the ethical issues of using technology in tourism and hospitality [ 48 , 75 , 77 ].

From the manager’s viewpoint, managers in the tourism and hospitality industry can use AI and new technologies to create better customer experiences and drive success [ 70 , 80 ]. These can include using chatbots or virtual assistants to help customers and get their feedback [ 50 , 76 ], using personalization technologies to understand customer needs [ 69 ], using the Metaverse to have customers design their own experiences [ 10 ], and using AI-robotics to automate tasks [ 16 , 82 ].

In light of the findings from this systematic literature review, policymakers in the tourism and hospitality sectors must revisit and revitalize current strategies. Embracing digital age technologies, especially AI and metaverse tools, can significantly enhance customer value co-creation. This necessitates targeted investments in technology upgradation, capacity-building, and skilling initiatives. While the initial resource allocation may appear substantial, the long-term returns regarding elevated customer satisfaction, increased tourism inflow, and industry-wide growth are undeniable. Policymakers must ensure a collaborative approach, engaging stakeholders across the value chain for streamlined adoption and implementation of these advancements.

Overall, the use of AI, Metaverse, and other new technologies can significantly enhance co-creation value in the tourism and hospitality sector by enabling more personalized, immersive, and efficient experiences for tourists and improving the efficiency and effectiveness of the industry as a whole [ 15 ].

Theoretical implications

The systematic literature review using the PRISMA method on customer value co-creation through the digital age in the tourism and hospitality sector has several theoretical implications.

First, this research paper addresses earlier suggestions that emphasize the significance of further exploring investigations on customer value co-creation in the hospitality and tourism sector [ 2 , 85 ].

Second, the review highlights the importance of adopting a customer-centric approach in the tourism and hospitality industry, in which customers’ needs and preferences are central to the design and delivery of services [ 35 , 86 ]. This shift towards customer value co-creation is driven by the increasing use of digital technologies, such as the IoT, AI, and ML, which enable real-time communication and data gathering from customers [ 1 , 40 ].

Third, the review highlights the role of digital technologies in enabling personalized and convenient customer experiences, which can help improve satisfaction and loyalty [ 87 ]. Using AI-powered chatbots and personalized recommendations based on customer data can enhance the customer experience, while using IoT-enabled devices can allow guests to control and access hotel amenities conveniently [ 12 ].

Fourth, the review suggests that adopting digital technologies in the tourism and hospitality sector can increase the industry’s efficiency and effectiveness [ 88 ]. Businesses use ML algorithms to automate tasks and analyze customer data, which can help streamline processes and identify areas for improvement [ 39 , 80 ].

Overall, the systematic literature review using the PRISMA method sheds light on adopting a customer-centric approach and leveraging digital technologies for customer value co-creation in tourism and hospitality. Over the next five years, researchers should focus on exploring the potential of emerging technologies, developing conceptual frameworks, and conducting applied research to drive meaningful transformations in the industry. By aligning strategies with these implications, organizations can thrive in the dynamic digital landscape and deliver exceptional customer experiences, ultimately contributing to their success and competitiveness in the market [ 2 , 4 , 15 , 29 , 33 , 89 ].

Practical implications

The systematic literature review using the PRISMA method on customer value co-creation through the digital age in the tourism and hospitality sector has several management implications for organizations in this industry.

First, the review suggests that adopting a customer-centric approach, in which customers’ needs and preferences are central to the design and delivery of services, is crucial for success in the digital age [ 40 , 86 ]. Therefore, managers should focus on understanding and meeting the needs and preferences of their customers and consider how digital technologies can be leveraged to enable real-time communication and data gathering from customers [ 15 , 80 ].

Second, the review highlights the importance of using digital technologies like the IoT, AI, and ML to enable personalized and convenient customer experiences [ 40 , 50 ]. Managers should consider how these technologies can enhance the customer experience and improve satisfaction and loyalty [ 36 , 39 ].

Third, the review suggests that adopting digital technologies in the tourism and hospitality sector can lead to increased efficiency and effectiveness in the industry [ 7 , 16 ]. Therefore, managers should consider how these technologies can streamline processes and identify areas for improvement [ 42 ]. Further, regarding privacy concerns, managers must spend enough resources to secure their customers’ data to help boost the customer value co-creation process [ 48 , 77 ].

Fourth, policymakers can foster an environment conducive to value co-creation by incorporating customer-centric strategies and leveraging digital technologies. Effective policies can enhance customer experiences, promote sustainable growth, and drive economic development, ensuring a thriving and competitive industry in the digital age.

The practical implications of applying AI and new technology for managerial decision-making in the tourism and hospitality industry are vast and promising [ 90 ]. Managers can navigate the dynamic digital landscape and drive meaningful co-creation with customers by embracing a customer-centric approach, leveraging personalized technologies, addressing efficiency and data security considerations, and strategically adopting AI-powered tools. By staying abreast of technological advancements and harnessing their potential, businesses can thrive in the next five years and beyond, delivering exceptional customer experiences and enhancing value co-creation in the industry.

Limitations and future research

The research, anchored in the PRISMA methodology, significantly enhances the comprehension of customer value co-creation within the digital ambit of the tourism and hospitality sectors. However, it is essential to underscore certain inherent limitations. Firstly, there might be publication and language biases, given that the criteria could inadvertently favor studies in specific languages, potentially sidelining seminal insights from non-English or lesser-known publications [ 91 ]. Secondly, the adopted search strategy, governed by the choice of keywords, databases, and inclusion/exclusion guidelines, might have omitted pertinent literature, impacting the review’s comprehensiveness [ 57 ]. Furthermore, the heterogeneous nature of the studies can challenge the synthesized results’ generalizability. Finally, the swiftly evolving domain of this research underscores the ephemeral nature of the findings.

In light of these limitations, several recommendations can guide subsequent research endeavors. Scholars are encouraged to employ a more expansive and diverse sampling of studies to curtail potential biases. With the digital technology landscape in constant flux, it becomes imperative to delve into a broader spectrum of innovations to discern their prospective roles in customer value co-creation [ 18 ]. Additionally, varied search strategies encompassing multiple databases can lend a more holistic and inclusive character to systematic reviews [ 27 ]. Moreover, future research could investigate the interplay between political dynamics and the integration of novel technologies, enriching the understanding of value co-creation in a broader socio-political context. Lastly, integrating sensitivity analyses can ascertain the findings’ robustness, ensuring the conclusions remain consistent across diverse search paradigms, thereby refining the review’s overall rigor.

In conclusion, this review highlights the pivotal role of digital technologies in customer value co-creation within the tourism and hospitality sectors. New AI, blockchain and IoT technology applications enable real-time communication and personalized experiences, enhancing customer satisfaction and loyalty. Metaverse technologies offer exciting opportunities for immersive interactions and virtual events. However, privacy and data security challenges must be addressed. This study proposed a comprehensive research agenda addressing theoretical, practical, and technological implications. Future studies should aim to bridge research gaps, investigate the impact of co-creation on various stakeholders, and explore a more comprehensive array of digital technologies in the tourism and hospitality sectors. This study’s findings provide valuable insights for fostering innovation and sustainable growth in the industry’s digital age. Despite the valuable insights gained, we acknowledge certain limitations, including potential biases in the search strategy, which underscore the need for more inclusive and diverse samples in future research.

Availability of data and materials

The review included a total of 27 studies published between 2012 and 2022.

Change history

07 february 2024.

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43093-023-00293-2

Abbreviations

- Artificial intelligence

Augmented reality

Internet of Things

Machine learning

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

Virtual reality

Pencarelli T (2020) The digital revolution in the travel and tourism industry. J Hosp Tour Insights 22(3):455–476

Google Scholar

Carvalho P, Alves H (2022) Customer value co-creation in the hospitality and tourism industry: a systematic literature review. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 35(1):250–273

Aman J, Abbas J, Mahmood S, Nurunnabi M, Bano S (2019) The influence of Islamic religiosity on the perceived socio-cultural impact of sustainable tourism development in Pakistan: a structural equation modeling approach. Sustainability 11(11):3039

Buhalis D, Lin MS, Leung D (2022) Metaverse as a driver for customer experience and value co-creation: implications for hospitality and tourism management and marketing. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 35(2):701–716

Grissemann US, Stokburger-Sauer NE (2012) Customer co-creation of travel services: the role of company support and customer satisfaction with the co-creation performance. Tour Manag 33(6):1483–1492

Pham LH, Woyo E, Pham TH, Dao TXT (2022) Value co-creation and destination brand equity: understanding the role of social commerce information sharing. J Hosp Tour Insights

Troisi O, Grimaldi M, Monda A (2019) Managing smart service ecosystems through technology: how ICTs enable value cocreation. Tour Anal 24(3):377–393

Buonincontri P, Micera R (2016) The experience co-creation in smart tourism destinations: a multiple case analysis of European destinations. J Hosp Tour Insights 16(3):285–315

Jung TH, tom Dieck MC (2017) Augmented reality, virtual reality and 3D printing for the co-creation of value for the visitor experience at cultural heritage places. J Place Manag Dev 10:140–151

Koo C, Kwon J, Chung N, Kim J (2022) Metaverse tourism: conceptual framework and research propositions. Curr Issues Tour 1–7

Dwivedi YK et al (2022) Metaverse beyond the hype: Multidisciplinary perspectives on emerging challenges, opportunities, and agenda for research, practice and policy. Int J Inf Manag 66:102542

Zhang X, Balaji M, Jiang Y (2022) Robots at your service: value facilitation and value co-creation in restaurants. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 34(5):2004–2025

Neuhofer B, Magnus B, Celuch K (2021) The impact of artificial intelligence on event experiences: a scenario technique approach. Electron Mark 31(3):601–617

Balsalobre-Lorente D, Abbas J, He C, Pilař L, Shah SAR (2023) Tourism, urbanization and natural resources rents matter for environmental sustainability: the leading role of AI and ICT on sustainable development goals in the digital era. Resour Pol 82:103445

Zhu J, Cheng M (2022) The rise of a new form of virtual tour: Airbnb peer-to-peer online experience. Curr Issues Tour 25(22):3565–3570

Xie L, Liu C, Li D (2022) Proactivity or passivity? An investigation of the effect of service robots’ proactive behaviour on customer co-creation intention. Int J Hosp Manag 106:103271

Wang Q, Huang R (2021) The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on sustainable development goals—a survey. Environ Res 202:111637

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Önder I, Gunter U (2022) Blockchain: Is it the future for the tourism and hospitality industry? Tourism Econ 28(2):291–299

Wang Q, Su M (2020) Integrating blockchain technology into the energy sector—from theory of blockchain to research and application of energy blockchain. Comput Sci Rev 37:100275

Wang Q, Li R, Zhan L (2021) Blockchain technology in the energy sector: from basic research to real world applications. Comput Sci Rev 39:100362

CAS Google Scholar

Wang Q, Su M, Zhang M, Li R (2021) Integrating digital technologies and public health to fight Covid-19 pandemic: key technologies, applications, challenges and outlook of digital healthcare. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(11):6053

Abbas J, Mubeen R, Iorember PT, Raza S, Mamirkulova G (2021) Exploring the impact of COVID-19 on tourism: transformational potential and implications for a sustainable recovery of the travel and leisure industry. Curr Res Behav Sci 2:100033

PubMed Central Google Scholar

Elkhwesky Z, El Manzani Y, Elbayoumi Salem I (2022) Driving hospitality and tourism to foster sustainable innovation: a systematic review of COVID-19-related studies and practical implications in the digital era. Tour Hosp Res 14673584221126792

Shah SAR, Zhang Q, Abbas J, Balsalobre-Lorente D, Pilař L (2023) Technology, urbanization and natural gas supply matter for carbon neutrality: a new evidence of environmental sustainability under the prism of COP26. Resour Pol 82:103465

Ahmed KE-S, Ambika A, Belk R (2022) Augmented reality magic mirror in the service sector: experiential consumption and the self. J Serv Manag

Doran A, Pomfret G, Adu-Ampong EA (2022) Mind the gap: a systematic review of the knowledge contribution claims in adventure tourism research. J Hosp Tour Manag 51:238–251

Page MJ et al (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev 10(1):1–11

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, P. Group* (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 151(4):264–269

So KKF, Li X, Kim H (2020) A decade of customer engagement research in hospitality and tourism: a systematic review and research agenda. J Hosp Tour 44(2):178–200

Han H (2021) Consumer behavior and environmental sustainability in tourism and hospitality: a review of theories, concepts, and latest research. J Sustain Tour 29(7):1021–1042

Medlik S (2012) Dictionary of travel, tourism and hospitality. Routledge

Reisinger Y, Kandampully J, Mok C (2001) Concepts of tourism, hospitality, and leisure services. Service quality management in hospitality, tourism, and leisure, pp 1–14

Binkhorst E, Den Dekker T (2013) Agenda for co-creation tourism experience research. In: Marketing of tourism experiences, Routledge, 219–235

Abbas J, Al-Sulaiti K, Lorente DB, Shah SAR, Shahzad U (2022) Reset the industry redux through corporate social responsibility: the COVID-19 tourism impact on hospitality firms through business model innovation. In: Economic growth and environmental quality in a post-pandemic world, Routledge, pp 177–201

Buhalis D, Harwood T, Bogicevic V, Viglia G, Beldona S, Hofacker C (2019) Technological disruptions in services: lessons from tourism and hospitality. J Serv Manag 30:484–506

Sengupta P, Biswas B, Kumar A, Shankar R, Gupta S (2021) Examining the predictors of successful Airbnb bookings with Hurdle models: evidence from Europe, Australia, USA and Asia-Pacific cities. J Bus Res 137:538–554

Gonzalez-Rodriguez MR, Díaz-Fernández MC, Bilgihan A, Shi F, Okumus F (2021) UGC involvement, motivation and personality: comparison between China and Spain. J Dest Mark Manag 19:100543

Abbas J (2020) The impact of coronavirus (SARS-CoV2) epidemic on individuals mental health: the protective measures of Pakistan in managing and sustaining transmissible disease. Psychiatr Danub 32(3–4):472–477

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Neuhofer B, Buhalis D, Ladkin A (2014) A typology of technology-enhanced tourism experiences. Int J Tour Res 16(4):340–350

Samala N, Katkam BS, Bellamkonda RS, Rodriguez RV (2020) Impact of AI and robotics in the tourism sector: a critical insight. J Tour Futures 8(1):73–87

De Carlo M, Ferilli G, d’Angella F, Buscema M (2021) Artificial intelligence to design collaborative strategy: An application to urban destinations. J Bus Res 129:936–948

Grundner L, Neuhofer B (2021) The bright and dark sides of artificial intelligence: a futures perspective on tourist destination experiences. J Dest Mark Manag 19:100511

Al-Sulaiti I (2022) Mega shopping malls technology-enabled facilities, destination image, tourists’ behavior and revisit intentions: implications of the SOR theory. Front Environ Sci 1295

Alimamy S, Gnoth J (2022) I want it my way! The effect of perceptions of personalization through augmented reality and online shopping on customer intentions to co-create value. Comput Hum Behav 128:107105

Lee M, Hong JH, Chung S, Back K-J (2021) Exploring the roles of DMO’s social media efforts and information richness on customer engagement: empirical analysis on Facebook event pages. J Travel Res 60(3):670–686

Abaalzamat KH, Al-Sulaiti KI, Alzboun NM, Khawaldah HA (2021) The role of Katara cultural village in enhancing and marketing the image of Qatar: evidence from TripAdvisor. SAGE Open 11(2):21582440211022736

Al-Sulaiti KI, Abaalzamat KH, Khawaldah H, Alzboun N (2021) Evaluation of Katara cultural village events and services: a visitors’ perspective. Event Manag 25(6):653–664

Khaliq A, Waqas A, Nisar QA, Haider S, Asghar Z (2022) Application of AI and robotics in hospitality sector: a resource gain and resource loss perspective. Technol Soc 68:101807

Yin CZY, Jung T, Tom Dieck MC, Lee MY (2021) Mobile augmented reality heritage applications: meeting the needs of heritage tourists. Sustainability 13(5):1–18

Buhalis D, Moldavska I (2021) Voice assistants in hospitality: using artificial intelligence for customer service. J Hosp Tour Technol 13(3):386–403

Abbas J (2021) Gestión de crisis, desafíos y oportunidades sanitarios transnacionales: la intersección de la pandemia de COVID-19 y la salud mental global. Investigación en globalización, 3 (2021), 1–7