DownTheTrail.com

hiking guides, gear, and journals

Stampede Trail Hiking Guide: Life & Death at Into The Wild’s Magic Bus

updated: January 29, 2023

A pilgrimage to experience the Alaskan wilderness where Christopher McCandless spent his last days, as portrayed in the book and film – Into The Wild

Magic Bus 142 Removed

On June 18, 2020 the magic bus 142 was removed from the Stampede Trail via helicopter.

This action was taken as a means to prevent unprepared hikers from being tempted to visit the site where Christopher McCandless spent the last days of his life, before his untimely death in August of 1992.

The local communities of Healy and greater Fairbanks were fed up with the frequent utilization of time and resources in the search and rescue of hapless hikers on wayward pilgrimages to the bus.

The Alaska Department of Natural Resources (DNR) arranged for the Alaska Army National Guard to remove the bus as a training exercise, creating a low-cost solution to the community’s dilemma. The guard troops salvaged a suitcase from within the bus as a sentimental keepsake for the McCandless family, and removed a segment of the bus’s roof to facilitate the airlift.

Where is the bus now?

For now, the bus sits at an undisclosed location. The site of the bus’s final resting place is still being decided. Most assume that it will be partially restored and put on display as a sort of museum piece in the Fairbanks region.

The following write-up stands as a now-historic trip report, and as a trail guide to visit the former site of the Fairbanks Bus 142 on Healy’s Stampede Trail.

Guide to the Stampede Trail: Quick Facts

MAP: Trails Illustrated shows the entirety of Denali National Park, but the scale is too small for navigation. PERMITS: no permit needed DESIGNATION: state of Alaska public land BEST SEASONS: May and September DISTANCE: 37.2 miles (60 kilometers) round trip ELEVATION: trailhead 2,150ft – bus 1,900ft ACCESS: mostly paved roads to the trailhead – the last 4 miles are graded dirt. DIRECTIONS: From the 49th State Brewery in Healy, Alaska, travel north on AK Route 3 (George Parks Highway) for 2.8 miles. Turn left on Stampede Road, and continue as far up the road as you can. See more details in the article below. ROUTE: The Stampede “Trail” is actually a muddy, double-track ATV road, but getting to the bus involves two major river crossings. GUIDEBOOK: Denali Guidebook is wonderful for the National Park, but it does NOT include the Stampede Trail.

WARNING: Don’t be a statistic

Hiking to the Magic Bus is a dangerous endeavor!

Young, healthy people have lost their lives on this trip.

Get some backpacking experience.

The Stampede Trail is not the place to learn how to go backpacking. If you’re reading this guide to find the answer to a simple question like “What kind of food should I bring?” that’s great, but please go get some backpacking experience before coming to Alaska.

Grizzly bears live here.

Learn how to avoid getting eaten .

You must wade through a deadly river.

I imagine that you’ve seen the Into the Wild movie . Do you remember how Chris had to walk through a big river, and he later found it to be impassable? That wasn’t just Hollywood. That’s the Teklanika River, and you’ll have to do the same thing.

The Teklanika River is impassable for most of the summer.

Even when it IS passable, the river is still extremely dangerous. You’ll find some tips here specific to this crossing, but previous experience is preferred.

Carry extra food, and consider a communication device.

A common of cause of rescue on the Stampede Trail is when family and friends call authorities after you’re overdue. Most trips are overdue because of poor planning, and/or hikers getting stranded on the far side of the Teklanika River when the water rises.

Watch the weather . If temperatures are predicted to rise, the river will rise and you’ll be stranded, just like McCandless. For this reason, it’s best to carry extra food (though running out of food is NOT cause for rescue!), and allow extra time for your trip.

A two-way communication device is especially helpful in this scenario. With such a tool, you can reach out and tell the folks at home that you’re alive and well, and just waiting for the water level to subside.

You DID tell someone where you’re going and when you expect to be back, didn’t you?

RULE NUMBER ONE – Don’t Die.

RULE NUMBER TWO – Don’t Require a Rescue. You’re getting yourself into this, so you’re expected to get yourself out of it.

Magic Bus Location

The Fairbanks Bus 142 was on The Stampede Trail, generally accessed via a serious, 37-mile backpacking trip in the Alaskan Wilderness. Its former site is an open clearing on the trail near the Shushana River

Access to the Stampede Trail begins near the small town of Healy, Alaska . The trail is on state land, but it’s surrounded on three sides by Denali National Park.

Google Maps actually has the GPS coordinates of the bus’s original location.

Driving Directions

From the 49th State Brewery in Healy, travel north on AK Route 3 (George Parks Highway) for 2.8 miles. Turn left on Stampede Road.

The road is paved for the first 4 miles. The next mile is well-graded gravel, but continuing much farther requires a high clearance, 4 wheel drive vehicle or ATV.

Vehicle travel deteriorates near Eightmile Lake, which is considered to be the trailhead.

After the road turns into gravel, there’s a number of pullouts where you may park – so long as you’re not parking at the entrance to a private driveway.

The entirety of the Stampede “Trail” is actually an old road bed. These days it’s a soggy, often submerged double track that’s suitable only for the hardiest of ATVs.

You’re technically allowed to drive an ATV all the way to the bus, provided that you can safely cross the Teklanika River.

Snowmobile or dogsled passage is an option in winter, when the rivers are frozen.

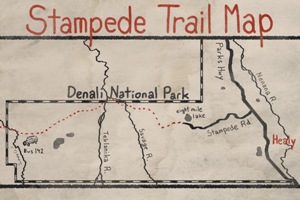

Stampede Trail Map

Here’s some maps that I made from a USGS quad, showing the Stampede Trail.

The second map is simply a zoomed version of the first one.

The red line is the border of Denali National Park. At the bottom of the first map you can see a couple of the park’s notable features, specifically Primrose Ridge and Mount Healy .

You can right-click on these maps to view larger versions or download them.

Timing – When to Go

The best time to hike to the bus depends on the best time to ford the Teklanika River!

The source of the river is a glacier, high in the Alaska Range. So the best time to go is when the glacier is not actively melting .

Okay, so when isn’t it melting?

Obviously in winter (when the rivers are actually frozen), but in winter you’ll have a mess of other problems to deal with, like short daylight hours and bone-chilling temperatures.

Mid-summer (June, July, August) is statistically one of the worst times to go. The sun stays up almost all night long. Glaciers are actively melting throughout this warmest time of the year, so the rivers are at their peak!

This leaves us with spring and fall, which are the best times to attempt this hike.

The timing is still tricky – there’s a short window in spring when the lower snows are melting, but the higher glaciers are still frozen. This most often occurs in May .

You can catch similar conditions in September . Temperatures are cooling at this time, but heavy snowstorms have yet to accumulate.

So that’s the big picture as far as timing, but conditions can change on a daily basis . Alaskan weather can be pretty wild, with heavy rainfall and daily fluctuations in temperature.

Watching the weather is paramount to your success. Immediately prior to your hike (and while you’re out there!), you should constantly be assessing the weather. Determine what’s going on with the high glaciers and the greater watershed of the Teklanika River at all times .

A common cause of rescues is that hikers will cross the river safely, spend a night at the bus, and return a day or two later to find that the river has become impassable!

Recommended Itineraries

Some folks have measured the one-way length of the trail at 18.6 miles (30 kilometers), but this largely depends on how far you get up the road at the trailhead, and how well you stay on the trail.

Count on a round-trip hike of roughly 40 miles.

Since fording the Teklanika River is the key to having a successful hike, my recommended itineray is built around the crucial river crossings. The best general practice is do the crossing early in the morning, when cool overnight temperatures have decreased the rate of snowmelt.

- trailhead to the near side of Teklanika River (10 miles, or 16 kilometers)

- Teklanika River to Magic Bus (8.6 miles, or 14 kilometers – cross Tek River this morning)

- Magic Bus to the near side of Teklanika (8.6 miles)

- Teklanika River to trailhead (10 miles, cross Tek River this morning)

- trailhead to near side of Teklanika River (10 miles, or 16 kilometers)

- Teklanika River to Magic Bus and back (17.2 miles, 28k – cross Tek river this morning)

- Teklanika River to trailhead (10 miles, cross Tek river this morning)

Though it’s possible for extremely fit and experienced backpackers to do this in less time, please don’t try it! The terrain is terribly slow.

Expect a wet, muddy slog.

The river crossings aren’t the only places where you’ll have to walk in water. At times, much of the Stampede Trail can basically be its own river of snowmelt.

You’ll find yourself trudging through stagnant water, and sometimes wondering if you’re still on the trail. Expect your feet to be wet for the entirety of the hike.

Trail Description

As previously mentioned, the trail is actually an old double-track road. Sometimes you’ll cross other ATV roads (especially in the first few miles) but the Stampede Trail should be clearly discernible as the main track.

A GPS device can be very helpful, but should never be relied upon as your sole means of navigation. Rather than blindly following a GPS, it’s best to use your wits – only check the device when you’re confused or unsure how to proceed.

Warnings about the Teklanika River rightfully prevail, but the Savage River is no slouch either. Reached approximately at mile 7.5, you’ll likely be deep into your first day when you have to cross it. It’s wider and less swift than the Teklanika, so it will be good practice.

The miles immediately prior to the Savage River are some of the trail’s muddiest, negotiating deep ponds formed by beaver activity along Fish Creek.

The infamous Teklanika is about 10 miles into the hike. Confusion reigns on the far side of the river, where’s there’s a network of beaver ponds that can make it tricky to relocate the trail, especially after traveling upstream to make the best crossing.

Take your time here. The trail on the west shore of the river is found upstream of the place where it meets its eastern shore.

The remaining miles from the Teklankia River to the Magic Bus are primarily high, dry, and straightforward. The bus itself is directly on the trail. “You can’t miss it!”

9 Tips to Safely Cross the Teklanika River

Almost all of the accidents and rescues on the Stampede Trail are directly related to the Teklanika River.

1) If the water is above your waist, don’t do it!

I know you’ve invested a lot into getting this far. At the river you’ll be SO CLOSE to your goal, and you may be tempted to do something stupid. STOP!

That rusty old bus isn’t worth your life. Remember this.

Maybe you had perfect timing… you’re here in May or September, but unseasonably warm temperatures have caused the river to run above your waist. Don’t proceed!

Or maybe you’re in an even more beguiling situation, where the river looks good, but tomorrow’s weather forecast calls for a spike in the air temperature. Likewise, don’t proceed! This is how people get stranded on the west side of the Teklankika.

You can still go back and have a wonderful (and infintely more scenic) hike in Denali National Park , and enjoy a beer at the movie-set-bus at the 49th State Brewery. If you’re still determined to get to the bus, plan another trip for next year, and try again.

2) Never tie yourself into a rope

Both of the deaths on the trail involved using a fixed rope!

If you find a rope tied across the river, you best choice is to ignore it.

3) Take your time to find the best crossing

The best place to cross the Teklanika River is NOT where the trail from the east meets it. Not only is the water swift and deep here, but there’s a series of rapids immediatly below, where the river drops into a canyon.

Go upstream to find finder a wider, more shallow location where the river splits into separate channels.

Before stepping into the water, be sure to have envisioned your ideal “trail” across the river.

4) Use hiking poles, or at least a sturdy stick

Having 4 available points of contact with the slippery riverbed is infinitely better than just 2.

5) Keep your shoes on, but consider removing your pants

Walking barefoot on the stony riverbed is begging for trouble.

By the time you get to the Teklankika, your socks and shoes should already be soaked. Frankly, if you don’t want to get your feet wet and/or cannot backpack for 40 miles in damp shoes without getting blisters, then you shouldn’t be here.

Removing your pants, however, isn’t a bad idea. First of all, you’ll keep them dry. Second, soaked pants won’t keep your legs any warmer in the freezing water. Third (and most importantly), loose pants have more surface area, creating more drag and pulling on your precious balance.

Even if you’re just wearing tights or yoga pants, why not keep them dry?

6) Loosen up that backpack

- Undo your hip buckle.

- Undo your sternum strap.

- Loosen those shoulder straps.

If you fail to do this and end up losing your footing, you’re a goner. That backpack will take on extra weight and drown you.

With everything loosened, you’ll be able to shed your backpack in the swift, freezing water – creating a much better opportunity to regain your feet and swim to safety.

7) Move with deliberate, steady speed

After you’ve stepped into the water, face upstream and move in a diagonal direction – upstream and across the river. Move only one point of contact off of the riverbed at a time. Those of you familiar with rock climbing may know the rule of keeping “3 points of contact.” The same logic applies to fording rivers.

If you’re hiking in a group (you’re not solo, right?) then your team may have a few weak links (aka short people, sorry). In this case, where you have a significant difference in the strength of your party members, you may want to try holding a pole as a link between you.

Trust and good communication are essential for this. You and your partner each have a single walking stick for balance. A third stick is held in your free hands, linking you together like a chain, and you move across the river as a team. This way, if a single member goes down (and the others keep their feet), the swimmer has an immediate lifeline.

Under no circumstances should you tie yourself to a rope.

Finally, you must be sure and deliberate with each step, but don’t get stuck standing in the water for too long. It’s freezing, so each passing second increases your chances of an accident. Be decisive and keep moving as steadily as possible. If you find yourself fearing the next step forward for too long, go back!

8) Practice Makes Perfect

Get some experience in fording rivers (with a heavy backpack) prior to your trip. The Alaskan tundra is not the place to begin learning this essential skill!

Two popular destinations that include safer river crossings come to mind – the Appalachian Trail in Maine and the John Muir Trail in California. I’m sure there’s many more, closer to you.

Do a “shakedown” hike in Denali

Since you’re traveling all the way to Alaska to hike the swampy Stampede Trail, you may as well do a practice hike in Denali National Park . If you insist on attempting the Stampede Trail with little previous backpacking experience, this is the best way to get it.

I recommend getting an overnight permit for Unit 4. Spend the first day traveling as far upstream along the Savage River as you can, and retrace your steps on day 2. Be sure to cross the river a few times, so you can get accustomed to the glacial water and backpacking with wet feet.

In addition to the obvious benefits of doing a practice hike immediately before the Stampede Trail, you’ll have the advantage of hearing the local tips directly from Denali’s park rangers when you get your permit.

9) Consider Packrafting

The safest way to ford the Teklanika River is not to do it at all! Why not try investing in a lightweight packraft and learning how to use it?

This is infinitely safer than fording the river. It also opens up the timing of your trip, making a mid-summer hike possible.

Alpacka makes the best rafts. It’s possible that some local retailers may even have them to rent – specifically AMH in Anchorage and Beaver Sports in Fairbanks. Contact the stores directly to inquire about rentals.

This packraft on Amazon looks tempting for an affordable and sensible choice, though I personally haven’t tried it out.

Build a fire?

Some folks would recommend building a fire before crossing the river. At first this sounds like a good idea – should there be any trouble, you have an immediate source of heat to revive someone from hypothermia.

But then, of course, there’s the logistical problem of putting the fire out – the last person to cross the river would have to do this. If there’s only two of you, going to all this trouble doesn’t make much sense.

A better idea is to set up the kindling and fuel, but don’t light it – only light the fire if you get into trouble.

Personally, I feel that you should have enough confidence in a successful crossing that a fire should not be necessary. If you feel the need to have the safety net of a fire, then I suspect that the water is too high and you shouldn’t be getting into the river at all .

Hiking in Bear Country

Grizzly bears roam freely out here. Take the necessary precautions!

For a comprehensive take on safe practices in bear country, see my article 12 Ways to Avoid Getting Eaten by a Bear .

Here’s some gear recommendations that are specific to hiking the Stampede Trail.

Trekking Poles

I’ve mentioned that poles are essential to safely ford the rivers.

Fancy trekking poles are wonderful if you already have some, but a good, sturdy stick can serve the same purpose. Some say it’s actually better to have a wider stick for river crossings, because the pointy end of trekking poles tends to get jammed in stony river beds.

If you’re looking for quality trekking poles anyway, these are my favorite .

I tend to prefer light, low-top shoes as opposed to boots, even in the Alaskan tundra. So-called “waterproof” boots may sound enticing, but your feet will get wet in these anyway! When I hear “waterproof shoes,” my brain hears “non-breathable, slow-drying shoes.”

Wear something that’s comfortable, breathable, and most of all, won’t give you blisters! Using shoes with grippy soles is a great idea, like those found on the La Sportiva TX3 .

My favorite backpack for the last few years has been the Hyperlite Southwest 3400 .

Hyperlite is making some of the lightest gear on the market right now, and it’s waterproof and durable. So if you should slip at one of the river crossings, regain your footing, and recover your pack, your critical gear should stay dry.

Bear Safety Gear

For food storage I use the Bearvault 500 bear canister.

I think it’s best to wait to get bear spray until you’re in Alaska. The mace is a hazardous item, with consequent travel restrictions. I’ve always carried this , and fortunately I’ve never had to use it.

If you’re especially concerned about bears, consider the color of your tent. A bright-orange tent will draw more unwanted attention than a green one.

Mosquitoes!

Usually I don’t mind bugs too much, but the mosquitoes in Alaska can be horrible.

It’s wise to have long pants and long sleeves. The material used in rain jackets and rain pants is particularly effective at keeping the mosquitoes from biting through your clothes.

If you’re going to use bug spray, the only stuff that even has a chance of being effective is 100% DEET .

It may seems silly to consider wearing a headnet , but it can make all the difference in the world!

Water Treatment

Water sources on the Stampede Trail are plentiful, but they must be treated.

The water out here is especially prone to carrying giardia. There’s a reason they call it beaver fever, and there’s a lot of beaver activity out here!

Personally I treat water with Aquamira , but plenty of filtration methods are great too.

For a basic gear checklist , to make sure you’re not forgetting anything (and/or bringing too much), you can browse my simple gear chart .

For more extensive but straightforward details on backpacking gear, check out my ultimate gear list .

The Stampede Trail’s route was first established by settlers in 1903. Prospectors were searching the area for gold, and primarily trying to access the Kantishna region of today’s Denali National Park.

Colorado native Earl Pilgrim used the route in the 1930s to mine antimony from the region.

Shortly after Alaska won its statehood, a subsidized project was started to improve and/or construct roads to Alaskan mining claims. The project was short lived, beginning and ending with the Stampede Trail.

Yutan Construction got the contract to build the Stampede Road, and the company was responsible for placing the infamous Fairbanks Bus 142 (The 2020 removal of the bus by the Alaska Army Natinonal Guard was coined “Operation Yutan”).

Yutan was using the bus to haul their employees between Fairbanks and the work site. The broke an axle and was abandoned at its former location on the Stampede Trail, likely in 1960 or 1961 – when work on the road was completed.

Regular maintenance on the road was abandoned shortly thereafter, in 1963.

The Stampede Trail’s swath of State Land cuts conspicuously into the surrounding Denali National Park. It was left out of the Park’s expansion in 1980. To this day. it’s a popular area for hunters, trappers, and now backpackers.

Guided Tours

Their are no guided backpacking or ATV tours that go to the Magic Bus 142.

A couple of ATV tours utilize the Stampede Trail, but they only take you to the Savage River.

Stampede Excursions offers a helicopter tour to the bus. They land there at the site, and you get about 30 minutes to explore and experience the bus. The cost for this is listed as $536.

Accidents and Deaths

The Stampede Trail’s crossing at the Teklanika River has tragically taken 2 young lives.

Veranika Nikonova, of Belarus, drowned on July 25, 2019. She was a 24 year-old newlywed, married in New York only a month prior to her death. She died in her young husband’s arms.

In August of 2010, Claire Ackermann of Swizterland suffered a similar fate, drowning in the Teklanika. She was 29 years old, and backpacking with her boyfriend Etienne Gros, 27, from France.

Taking an objective look at these sad incidents, they have some striking similarities:

- Both were young European women.

- Both drowned in the Teklanika River

- Both were using a rope to aid their crossing. Ackermann had tied herself into a rope, whereas Nikonova was using a rope as a hand line.

Here’s a list of rescue incidents, gathered from reports in the Fairbanks newspaper.

This list is far from comprehensive.

Healy’s fire chief is quoted to have rescued 12 hikers in a single summer.

July 2010 – Four teenagers were rescued by state troopers, after being reported more than 7 hours overdue. They were local Alaskans, all aged 16 and 17. Their vehicle got stuck, and they were separated. Troopers say they were cold and wet when found, but didn’t require medical attention.

February 2011 – A 24 year-old man from Singapore was found about a mile from the bus, and assisted out by rescuers. He’d been reported as overdue to authorities.

May 2013 – Three German hikers, aged 19, 20, and 21, were rescued after the water rose as they were trying to hike out. They barely made it back across the Teklanika, and chose not to attempt crossing the Savage River. A man in Healy had met them prior to their trip, and reported them overdue.

June 2013 – A group of three hikers successfully used a signal mirror to alert a military helicopter for rescue. An Army spokesman said “One of the females had a twisted ankle, but I guess what was really keeping them in place was the water level of the Teklanika River.” They’d ran out of food and were stranded on the west side of the river after the water rose.

June 2013 – State Troopers received a call for help from a group of hikers at the bus. A 25 year-old female from Florida had a non-life-threatening, lower leg injury.

August 2014 – A party of three hikers called for help near the Teklanika River, catching a ride back to Healy via ATVs (Thanks to the local fire department). One of the group had injured himself with an ax.

June 2016 – Two American men, aged 25 and 27, were reported overdue. They’d accessed the bus by approaching it from the west, but the hike took longer than anticipated. They tried to shortcut out via the Stampede Trail, but found the Teklanika’s water to be chest deep.

August 2016 – A 22 year-old man from Canada activated a personal locator beacon on the west side of the Teklanika. Minor injuries, heavy rain, and rising water led to his decision to call for rescue.

September 2016 – A 45 year-old man from Mexico was found by searchers, after being reported overdue. He was trying to access the bus from Riley Creek Campground in Denali National Park.

June 2017 – A 42 year-old man from Belgium was rescued on the west side of the Teklanika River. He had non-life-threatening injuries that rendered him unable to cross the river.

February 2020 – 5 Italian hikers were rescued from the trail after one their party began to succumb to severe frostbite. They called for help via a satellite device.

April 2020 – A 26 year-old Brazilian hiker was rescued after triggering a satellite device. He had run out of food.

My Trip Report and Photos

After moving to Healy, I locally encountered a lot of negativity and discouragement about wanting to do this notorious hike “Just to see a bus where some kid died.”

Before I went up to Denali, an experienced friend made me a list of the best hikes to do over the course of the season. The Stampede Trail was chronologically #1 on the list, with the emphasis that it needed to be done before the end of May (Before the Teklanika River would get too high).

It would be my first backpacking trip in Alaska, so there was this new world of tundra and grizzly bears and river crossings to get used to.

Since I’d just started a new job, it would be difficult to get adequate time off before June. Some employees from our company missed a few days of work the previous year, when the river swelled too much for them to safely return.

Most local Alaskans discourage people from doing the hike, so there was an overall doom & gloom psychology about the Stampede Trail. It was a “weird” spring in Alaska, and the general consensus was that the Teklanika was probably too high already.

I had basically given up on this hike to the bus, figuring I’d have to wait until the end of the season. But then the first days of June came around, and I got the proverbial fire lit under my butt when we found ourselves with a few days off of work.

One local hiker (Who happens to do SAR in area, including a few calls along the Stampede Trail) was especially encouraging, telling me that the rivers were still quite low.

There was so much talk and speculation about fording the Teklanika, but I knew none of that really mattered until we’d have the opportunity to stand on the edge of the river for ourselves.

We found a ride and put it together with just two days off of work, as a two-and-a-half day hike.

Day One – Eight-Mile Lake to the Teklanika River

So we suddenly found ourselves being dropped off by a new friend at the end of the Stampede Road. The scenario already had an eerie subtext, as McCandless was dropped off at basically the same location. The surrounding wilderness appeared vaguely familiar, as though remembered from his photos and scenery in the movie. It was 6pm.

Here’s a link to a photo of Chris before he set off from the same general area.

The Stampede Trail begins as a wide (but rough and muddy) dirt road. The path is often outright flooded, and it’s likely that your feet will get wet long before the first crossing at Savage River.

Despite the two ATV tours that passed us, the overall silence was oppressive.

We started our hike at 6pm, but early June in Alaska means long days… sunset would not be until close to midnight, and the night would never become completely dark.

Thanks to our late schedule, we were lucky to see two beavers! I’d encountered countless beaver dams on my previous hikes, but never spotted any of the elusive beasts until today.

The beaver swam back and forth in front of us, as though it was pacing and marking its territory. Periodically it slapped its tail on the surface of the water with authority, making a sharp sound before diving underneath the surface.

At first it was really neat to see the beavers, but by the end of the hike we were frustrated with all of the destruction they’d made of the trail. I once read that beavers are the second-most destructive creatures to their habitat on earth… second to humans, of course.

After a few hours we came to the Savage River – the first of the two significant rivers that we had to cross. It was less than knee-deep – a good sign – but the water was ice-cold !

It was so cold that I lost all the feeling in my feet, despite a relatively short crossing. I couldn’t feel my toes again until about ten minutes after the fact.

To our relief, the path climbed up and away from the wettest areas as the day grew old.

At times the spruce forest “taiga” closed in about us, creating a passing claustrophobic effect. We tried to make a lot of noise to avoid startling any bears.

It was about 11pm when we reached the Teklanika River. Our rate of travel had felt slow, so it was a surprise and relief to see our destination so soon. We planned to camp on the near shore of the river in order to facilitate an early morning crossing, when the water is supposed to be at its lowest.

Our first impression of the river was that the water seemed relatively low and doable. Yes! Everything hung on the water level of the Tek, and this was cause for some early (But cautionary) celebration!

We found a good spot for the tent and enjoyed dinner in grizzly country.

Day Two – There and Back (To the Teklanika) Again

We slept later than we wanted to this morning, until 9 or 10am. It’s often hard for a weekend warrior to resist the extra hours of sleep in the backcountry. 🙂

The river seemed low enough last night, so hopefully the extra few hours of sleep wouldn’t be a problem.

Soon it was time to ford the Tek.

The best and safest place to cross the river is upstream of here, where it splits into multiple braids.

We traveled upstream and scouted out the best spot. Weighing a few options along the way, we zeroed in on a particular place and got ourselves ready, tightening our shoelaces and doing an extra bit of waterproofing.

Once all the preparations were set, we did a safety overview and just went for it.

First of all, we were sure to unbuckle the hip belts and sternum straps on our backpacks. We each had a hiking pole to use for stabilization. In our other hand(s) we carried a long, lateral stick that kept us together, as we both held onto each end of it.

This was my first time experimenting with such a shared stick method, and it worked well. Finally, I tried to stay directly in the upstream line of my partner to break the current. We were conscious of using a two-point method by keeping two points of contact (2 out of 3) with the bottom of the river at all times.

Soon it was all over, and we’d forded the Teklanika! Besides the fact that our lower limbs were frozen solid on the far shore, it was all fairly simple – the water was only about two inches above my knees (I’m 6’0).

We found it to be a little confusing to locate where the Stampede Trail leaves the west side of the river. This was the most frustrating part of the trip, as we lost about an hour trying to find it.

It looks like the trail disappears into a metropolis of beaver ponds, but after a while we finally found the track that continues to the west.

The remaining terrain was easy-walking, and uneventful. We gradually climbed up through the woods and contoured the crest of a low ridgeline. Water was everywhere, but the trail was forgivingly dry. A stiff, cold wind blew at times, with occasional rain showers.

There was a brisk, sporadic rain throughout the entire trip, and we were lucky that it was never especially wet or freezing. The weather forecast before the hike had us expecting consistent rain and low temps.

This kind of weather may seem negative, but it was actually ideal because it kept the mosquitoes at bay. More importantly, a warmer, sunnier day would have caused the rivers to rise.

All of our time on Stampede Trail was fittingly silent and damp, with a gloomy aura.

After a while the terrain began to look familiar, or maybe it felt familiar because of scenes from the movie.

The film depicts Chris first stumbling upon the bus as it sits on an upper ridge to his right, so we were keeping our eyes open for a similar setting.

The miles wore on, and for a long time it felt as though the bus could be just around the corner. I even allowed myself to begin wondering if we’d somehow passed it.

Consciously making noise and saying “Hey bear,” was getting tiresome.

Suddenly I saw it.

The shape of the bus materialized through the trees.

It sits on the trail in a sizable clearing, slightly to the south. You can’t miss it. My partner went in through the bus’s door almost immediately. I lingered outside, taking in the scene and snapping photos.

We were excited to be here, but soon the somber atmosphere of the place would have its effect.

The bus itself is in really poor shape. The iconic “142” on the side has been shot out with bullet holes. Most of the windows are gone too, replaced by a green tarp that flaps in the idle breeze. The green paint is fading away, revealing a yellow coat beneath it.

Outside the bus – near the back door – there’s a pile of what can be described as nothing more than a sprawling collection of garbage.

The steering wheel has been removed by souvenir hunters, as well as the great majority of Chris’s original artifacts. The dilapidated condition of the place makes it that much more lonely and austere.

The suitcase was left by Chris’s mother, on her first visit here after his death.

Joined by Jon Krakauer, she had it stocked as a cache of survival gear for wayward travelers, hoping to prevent others from suffering the same fate as her son.

Now it just contains a number of odds and ends, including a couple of notebooks for visitors to sign in and jot down their thoughts.

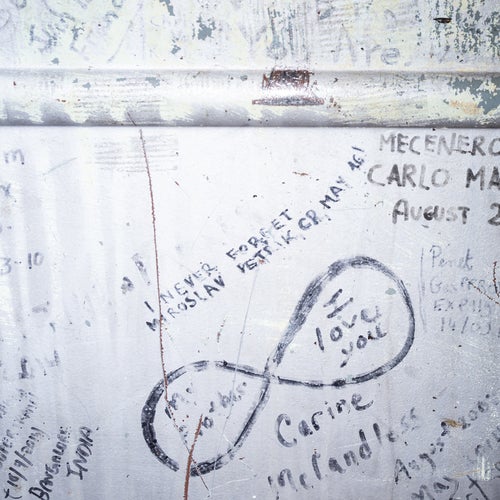

The interior of the bus is adorned in graffiti. It only takes a quick look around to realize that a lot of time has passed since Chris was here, and that hundreds of people have made it a place of their own over the years.

I didn’t realize how deeply McCandless’s story affected so many people until I browsed the pages and pages of thoughtful register entries. There was a significant portion of entries written in French, and I mused that the film must have been a big hit in Europe.

Like so many foreign films that are heavy in meaningful dialogue and family drama, maybe the Europeans championed Chris’s rejection of American consumerism and the like… “ Oh, if that boy were only born in Le France… “

In all seriousness, it’s clear that many regard the bus as a memorial and a sort of shrine to a mythical notion of Carpe Diem. I’d even go so far as to paint McCandless to be viewed as a sort of Jesus character who sacrificed himself so that others could learn to live deeper and more fulfilling lives.

We were here in early June of 2014, so it was neat to see that Chris’s sister had been here so recently – possibly just a matter of days before us.

Finally we had to tear ourselves away from this place and return down the trail. Our itinerary called for a long day today, to be back at the Tek tonight and set for an early-morning river crossing.

Just a couple of hours here felt like it wasn’t enough, but we agreed that spending the night would have been too much .

It was a ghostly place, yet so very real and tangible. The story of McCandless involved everyday people, and it ended here.

The weather momentarily improved during our return hike, allowing for some clearer views of the Alaskan scenery.

We saw our first ptarmigan on the way back to the Teklanika. It’s the state bird of Alaska (Second to the mosquito, of course!), and these birds made up a good part of McCandless’s diet while he was out here.

We also met the first pair of backpackers that we’d see out here – two guys in their twenties that spoke very little English.

We set up camp and cooked our dinner under a light, steady, unpleasant rain.

The above photo was taken few minutes after midnight. The sky glowed deeply like this for more than a full half-hour after sunset, because of the more-horizontal course of the sun.

In other words, sunset in Alaska lasts for a very long time.

Day Three – Returning on the Stampede Trail toward Healy

The skies began to clear overnight, and we woke to the first bit of sun of the trip. The river seemed to have receded a couple of inches since yesterday, so crossing it this morning was significantly easier – especially with the confidence that we’d done it once before.

Being on the homeward side of the river was cause for celebration.

We made it to the bus!

The mood was light as we made our way back to civilization.

All of the biggest obstacles were behind us, and we were happy and satisfied to have experienced such an iconic destination. We speculated a lot about McCandless’s activities.

There wasn’t anything left, except to enjoy the walk.

Soon we reached the road and called our friend for a ride back to Healy.

The Saga Continues

Carine McCandless’s testimonials are just one way that the Into The Wild saga continues.

There’s still debate and further speculation about how Chris truly may have died. Does it really matter? The simple explanation of starvation is enough for me.

Finally, there’s a lot of talk about the current state of the Stampede Trail to the bus, and how it’s a hazardous magnet for countless pilgrims who get in over their heads. Most local Alaskans would love to see the bus removed and placed closer to the highway, or rather for the whole Christopher McCandless story to disappear altogether.

A Replica of the Bus, and great food and local beer

For the great majority of visitors who aren’t interested in hiking the Stampede Trail, the excellent 49th State Brewery has acquired the replica of the bus that was used for the movie set.

They keep it on their front lawn, clearly visible from the George Parks Highway. Inside the bus they have a gallery of Chris’s original photos, with detailed captions and pages from his journal. It’s definitely worth checking out.

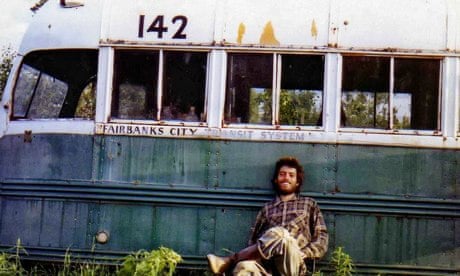

The author imitates McCandless’s classic pose at the real “magic bus,” nearly 22 years after Chris’s death in August of 1992.

Related posts:

About Jamie Compos

I'm the guy behind DownTheTrail.com. I love the outdoors, and the Grand Canyon is my favorite destination. Be sure to subscribe to my newsletter (at the bottom of the page), or else I'll slip a rock into your backpack when you're not looking.

December 27, 2022 at 3:30 pm

Good story in general but it is obvious that your list misses the most important information. Not only Chris died but others too …

2019, 24-year-old hiker has died on the Trail on the way to the bus as well as a death of a hiker in 2010 when Claire Ackermann drowned attempting to ford the Teklanika River.

I have NO simpathy with any person that get’s injured or dies on this trail and Alaska should claim the money from each one they rescue.

So even we removed the bus, it is clear that the pilgrimage will not stop any time soon. Hence, all the best to the life tired ones so that they will not follow Chris to the very end of his journey.

Hence – life tired due to not being prepared is evident from the list you shared.

Being Alaskan, this is not the publisity we need, neither do we need people coming here gambling with their lifes.

Honestly, seeing the net full of the story even after 30 years, it is

December 27, 2022 at 3:34 pm

insane. I would like to see a more objective view but your story is like most others I have seen – it can encourage others and they may face another situation.

Up here we say, Alaska always changes your plans.

Good luck and all the best.

Cheers, Ela

December 27, 2022 at 4:05 pm

Thanks for your comment Ela. The dated “rescues” lists is only for rescues – the two deaths you mentioned appear under the main “Accidents & Deaths heading. I first put together this write-up while the bus was still out there, and I felt (and still think) that it’s best to have this information available for those who are still determined to go out there. I think it’s unlikely to draw more people, though, since the bus has been removed. A much better outdoor experience is available in Denali National Park.

January 15, 2023 at 4:12 pm

Thanks for your reply! Sorry, indeed you reference the death and turn them into Accidents with death headings … considering in both cases there was a second person, unable to rescue actually makes it worth? By all means, this is the same ignorance that Chris had shown by ignoring the warnings of an experienced local (who actually gave him a pair of rubber boots as we know) and not being prepared by knowing how he could have crossed the river not really far away. I call this stupidity and why it makes me so mad is simply because a friend lost his life while trying to rescue another stupid human on the Harding Icefield Trail. People come here and think they do a walk in a park. I do like your page but would wish you remove this one story and not encourage more people with it. Even the bus is gone, the madness will not end and you can even find posts that complain that we removed the bus as if it belonged to Chris. You are different as you are experienced in hiking. People are not after the boys spirit, it is all about their own selfpromotion – hence proudly present themselfs that they made it. If people say they follow his footprints and spirit – ridiculous consider they fly up here with their pockets full of money and the social securness to do an emergency call to be rescued. They bring themself and others in danger just to post a selfie that confirms they made it. My personal view, the only point where they follow Chris is in ignorance and stupidity. Please don’t take this personal but it really touches me as it always reminds me on the friend I lost. If I could make a wish right now, don’t post this but instead remove this one. My view, as your webpage is a lot more professional – you are actually encouraging people even more than others. At the end, you would not even know if someone followed your story and may end up with Chris. Take care and all the best for any future hikes – really impressive to see how much ground you covered. Thanks for your attention. Cheers, Ela

January 15, 2023 at 4:49 pm

Ups, forgot to mention that the article of Eva Holland is no longer in the web, hence your link to it is useless. I checked her webpage and it is also not accessable anymore. Maybe she removed it for good reasons – I hope.

June 9, 2021 at 3:34 pm

Hello! I am heading to Alaska this July and have rented a house right on Stampede Road. I am not planning on going to the site of the bus on this trip, however I do plan to do so sometime in the future. I was wondering if you think it is possible to hike to the Teklanika River and back to Eight mile lake in one day. Thanks for the guide!

June 9, 2021 at 8:48 pm

I’d say it’s possible, but only if you’re in superb hiking shape. You’re looking at 20 miles round trip over wet and often muddy terrain.

April 15, 2021 at 9:50 pm

Thank you for all this precious and very detailed info! It isn’t enough information on the internet about this Trail. I am planning to go even if the bus has been removed The Trail itself sounds and looks like sort of test to a physical, mental abilities and to your common sense (if you can stop when the conditions are NOT for the river crossing or to continue further).

Thank you again, And thanks to Chris for discovering this one.

Best wishes, Elena M.

November 29, 2023 at 11:09 pm

Excellent article, very well written and lots of good advice. I don’t think anyone could blame your article for encouraging people to go there – if they’re determined to go, they will do it no matter what anyone says, at least you warn them of all the pitfalls. (I would have thought a rope was a great idea for crossing the river) I’m an Alaskan and if I had been tempted to visit a place where some poor soul starved to death (I wouldn’t) I definitely wouldn’t go after reading about the treacherous river crossings- not my idea of fun! I don’t understand the draw of that site, it’s very sad. Thanks for an excellent read, keep up the good work!

January 27, 2021 at 8:20 am

Ever since I heard about his story i keep searching for more and more and info I can find. I can relate to his story in many ways. Going off grid maybe for a bit. I would love to hike that trail one day it’s like it’s calling my name to come see for myself. Does it look dangerous oh yes but would love to hike that trail even though the bus is no longer there.

October 14, 2020 at 10:29 am

Hey Jamie, Good read. I Hiked to the bus on September 13th 2011. Sad to see the Bus is gone now. I worked for the Jeep Safari during the Summer of 2011. Your information for the hike is spot on. It was good to read your info and remind myself of the adventure. Thanks for the Article.

Best Regards! Brandon Kelsey

October 14, 2020 at 2:23 pm

Thanks for reaching out Brandon, it feels great to hear when I’m doing something right 🙂

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

chart your course

Privacy overview.

Into the Wild

Jon krakauer, everything you need for every book you read..

Chris’s Map Symbol Timeline in Into the Wild

Into The Wild 142 Bus

The Magic Bus

The Bus from the story has many names – The Magic Bus, The Stampede Trail Bus, the 142 Bus, Fairbanks Bus etc etc. What rings true with this bus is that it is very special. It has been made special by the story, the many visitors that go there, its remoteness and the feeling it gives those affected by this story. Unfortunately, some people have perished getting to the bus and so I feel it necessary to provide those wishing to visit the bus, some information.

*Note* The Fairbanks City 142 Magic bus has been moved.

Bus 142 was removed from the Alaska wilderness in the summer of 2020 and later deposited at the University of Alaska Museum of the North for long-term curation and exhibition.

University of Alaska, Fairbanks Campus 1962 Yukon Drive Fairbanks, AK 99775

Restoring the Magic Bus to its early 90s condition, prior to it suffering further damage from vandalism, is a time-consuming endeavor. The restoration work is currently underway in the Engineering Building’s high-bay area, which features full glass walls and is open to the public for free from 8 am to 8 pm, Monday through Friday.

To get there, you can either take a shuttle bus from the museum or enjoy a 15-minute walk. For additional information, visitors can reach out to the museum at (907) 474-7505. The final exhibit will be constructed in a protected and suitable outdoor location, with discussions ongoing about an accompanying indoor exhibit.

Once finished, the public will have free access to the exhibit(s) during regular museum hours.

https://www.uaf.edu/museum/collections/ethno/projects/bus_142/

Information from the University of Alaska about the 142 bus:

Thanks to a collaboration between the UAF’s Institute of Northern Engineering (INE) and the Arctic Infrastructure Development Center (AIDC), the general public can now visit the bus from 8:00 am to 8:00 pm, Monday to Friday, at the ConocoPhillips Alaska High Bay Structural Testing Lab located in the Joseph E. Usibelli Engineering Learning and Innovation Building (JUB) on the UAF campus. This opportunity is available until mid-September 2023.

This museum project will involve a multi-year effort to preserve the aging bus, which has endured years of vandalism. Additionally, teams will work on developing an interpretive approach that highlights different phases in the bus’s life. These phases include its role in the Fairbanks City Transit System during the 1950s, serving as a residence for a Yutan Construction Company mining road crew member in the early 1960s, providing shelter for hunters and back-country hikers during the 1970s and ’80s, and gaining fame as the final refuge of Christopher McCandless in 1992, a story made famous by Jon Krakauer’s 1996 book, “Into the Wild.”

The bus will be displayed in an outdoor area near the museum on the UAF campus, allowing visitors to safely explore its history for the first time in three decades.

Virtual bus: https://www.uaf.edu/museum/exhibits/virtual-exhibits/bus142/ Bus Supporter website: http://www.friendsofbus142.com/

Information about the 142 Fairbanks City bus original location.

Please note that we cannot be held responsible for your actions – if you decided to visit the bus, seek the appropriate advice from experts and speak to local authorities in Fairbanks.

Erik Halfacre has posted many valuable tips on the forum about the bus. He is an Alaskan himself and I feel his knowledge of the bus, its location and surroundings are very valuable. And so, here is some great information and useful tips from Erik… (there is also a great Youtube video he made at the end of the article.)

Hiking The Stampede Trail – Erik Halfacre 19th August 2010

The Stampede Trail to Bus 142 is becoming a more popular hiking destination these days. Virtually unheard of, to anyone outside the state of Alaska before Krakauer’s article in Outside Magazine, the trail has seen a vast increase in traffic since the release of Sean Penn’s film in 2007.

The story of Christopher McCandless , restless and footloose, stirs within many of us a hunger for adventure that is hard to quiet. I can’t begin to recall how many times I’ve heard, “Oh Man! I read that book! I really want to get out to that bus someday!” or “That movie was really great. I really want to see the bus.” The desire to see the bus, is often equated (in the minds of many Alaskans) to some kind of worship of Chris, or a celebration of naiveté. I feel this is an unfair characterization. For me, the desire to see the bus was rooted in my will to better understand his story.

Some things cannot be adequately described in words. The bus is one of those things. You will not truly understand the conditions of Chris‘ experience until you sit down in the folding chair where there once was a driver’s seat and just absorb the feeling of silence and isolation. The feeling is both refreshing, and lonely. Even with seven other people in my group, I couldn’t help but feel a little lonely in that place.

When I first began planning for my own trek, in 2009, I tried to find information online. I think, partially due to local sentiment about the story, and partially due to the fact that at that time there really weren’t a heck of a lot of people headed out that way, It was darn near impossible to find any good information about the hike. All I found back then, was the Denali Chamber of Commerce page telling me how incredibly dangerous it is, and basically that they didn’t want to give out advice because they’d rather you didn’t go. That wasn’t enough to deter me though. I dug around until I found some coordinates for the bus and looked over the satellite imagery. I researched how to properly execute a crossing of a swift flowing river, and then practiced on some rivers of similar depth and speed nearer to my hometown of Palmer, Alaska.

After my hike I did more research on the subject, interviewed and emailed many others who had made the trek themselves, and turned my research into a ten minute video about doing the hike. Response to the video was encouraging, and it became obvious that there was a demand for this kind of information, so I turned the video into a whole website.

So, enough about Me, lets get to the good stuff; What you need to know to hike the Stampede Trail to Bus 142.

Overview The Stampede Trail is long, wet, and buggy. On the upside, the terrain is mostly level. There aren’t really any long uphill sections worth noting. You’ll face two river crossings, a night or two in bear country, and swarms of mosquitoes that will try to pick you up and carry you away. Frequently you’ll find yourself wondering ‘is this the Stampede Trail, or Stampede River,‘ as you wade through flooded muddy trail up your knees.

How Do I Know if The Stampede Trail is Too Hard For Me? The Stampede Trail is not for everyone. This is not a hike for beginners. No two ways about it. Despite how badly you may want to see the bus, if you are not a reasonably proficient hiker (someone with experience hiking 15+ miles a day for multiple days with a pack) then you are probably getting yourself in over your head. By putting yourself in that situation, you are pretty much ensuring that you will exert yourself beyond your safe limits. This leads to exhaustion. Exhaustion leads to lack of judgment. Lack of Judgement can lead to serious injury or death.

The good news is: if you are not much of a hiker right now… it doesn’t take much to build that kind of endurance up. Ramp up. Each weekend go on a hike that’s five miles longer than the last weekend’s hike. If you start with a five mile hike today, and follow that plan, you’ll be up to forty miles within two months assuming you already have some reasonable level of fitness. Hike with a pack. Even on day hikes, throw some soup cans in a bag and hit the trail. The more fit you are, the more you are likely to have the endurance to get yourself out of sticky situations.

How Far Is It? It’s about twenty miles there and twenty miles back (forty miles roundtrip.)

How Long Will it Take Me? For people of reasonable fitness, I recommend dedicating three days for the hike. The best plan seems to be as follows

Day 1: Be to the trailhead (eight-mile lake on the Stampede Road) about noon. Hike into the Teklanika River, about ten miles, and set camp.

Day 2: Wake up good and early, about 5am, and cross the Teklanika. (We’ll talk more about this later.) Hike out to the bus and back, about twenty miles, in one day. Camp at the Teklanika again, this time on the side closest the bus.

Day 3: Wake up early again and cross the Teklanika. Hike out to your car. Drive to Lynx Pizza in Denali and get some food that doesn’t require you to add boiling water. They also have a beer.

This schedule can be adjusted. If you want to spend a little more time out there or spend a night at the bus site, just turn Day 2 into two ten-mile days instead of one twenty-mile day. Unless you are a truly stellar backpacker though, I wouldn’t recommend trying to make the trip any shorter than three days. For one, it makes it much more difficult to time your river crossings. When I was out there though, we did see a pair of Germans who were running the whole trail in one day. Those guys were machines though.

What Should I Bring? Not surprisingly, the kit you should bring is not unlike the one you should pack for most other Alaskan backcountry trips. Pack: Having a comfortable pack is crucial for a hike of this length. I’m partial to Gregory brand packs, but many other brands make great packs. Just don’t try to save money by buying the thirty-dollar Wal-Mart special for this trip. Your shoulders will regret it.

Tent: For the summer, a good sturdy three-season tent is plenty. Make sure your rain fly is functional. The weather can turn cruddy in the blink of an eye up there. Bring some extra para-cord for making anchors (by tying it around sticks and wedging them between river rocks) as otherwise it may be difficult to stake out along the river.

Sleeping Bag: A twenty-degree bag should be adequate for the summer months. Consider upgrading to a zero-degree bag if you are going in the early season (May) or late season (September.) Temps frequently drop into the forties at night, even during July. Make every effort to keep your bag completely dry (especially if you use a down bag.) Put your sleeping bag in a dry sack inside your pack.

Water: There’s water everywhere you turn around on this trail. You’re constantly crossing streams. You don’t need to bring much with you. A single one-liter bottle will be enough if you filter/purify water as you go. This dramatically reduces the weight of your pack.

Food: Packing dehydrated food (Mountain House, Backpacker’s Pantry, etc) will keep the weight of your pack down. Another just add water meal, that’s much cheaper, are the Knorr (formerly Lipton Brand) pasta side meals. They are available at Fred Meyer Grocers (in Anchorage, Palmer, Wasilla, and Fairbanks.) So no matter where you fly into, you’ll be able to find them. Bring plenty of snack-type stuff. It’s important to keep your energy up. Beef jerky, trail mix, raisins, craisins, powerbars, etc all make great food you can keep in a pocket.

Other Stuff (but by no means everything): flashlight – Alaska may be the land of the midnight sun but you’ll still want a light knife para-cord – for stringing a bear bag bear-proof container – an alternative to stringing a bear bag toilet paper small plastic trowel tons of socks a few feet of duct tape fire starter camp stove and cookware a map a compass a camera

What Should I Do About Bears on the Stampede Trail in Alaska? The absolute BEST thing you can do about bears (and just a good idea in general) is to travel in a group. Bears just don’t attack big groups of people. According to Stephen Herrero’s book, Bear Attacks: Their Causes and Avoidance, bears will rarely attack a group of three or more. A group of six or more has never been attacked.

Some evidence supports the use of bear bells. The human voice is generally accepted to be a much more effective bear deterrent though, so singing, or talking loudly is advisable.

Don’t cook in your camp. Don’t eat in your camp. Don’t bring your food (or trash) into camp. If you are having a campfire, burn what you can, bag what you can’t, and put it into your bear bag, or your bear-proof container.

String a bear bag ten to fifteen feet off the ground and at least six feet out from the trunk of the tree. Leaning trees work best.

As far as personal protection, I personally carry a gun. I realize many people have objections to firearms, don’t like the inconvenience of traveling with them, or just don’t own them. Only bring a gun if you are well-practiced with it. There’s nothing worse than an injured bear out there. Even if you get away, an injured bear is much more likely to attack someone else in the future.

Consider bear spray. The potent pepper spray is effective at deterring a bear attack, non-lethal, and you need not be as much of a marksman. You can’t fly with it, but it’s available here in Alaska, at lots of retailers.

How Should I Cross the Rivers near the Stampede Trail? You will encounter two rivers that you will need to cross on the Stampede Trail. The first is the Savage River. The second, and much more serious, is the Teklanika.

The Teklanika River is the river that stopped McCandless from returning to the highway. Its depth can vary greatly depending on factors such as rain, temperature (the hotter it is, the more the glaciers are melting, the deeper it will be,) and time of day. It can be anywhere from knee-deep to chest-deep, and the current is quite strong.

Less than a week before the writing of this article, a Swiss woman drowned while trying to cross the Teklanika. It’s deadly serious. If it looks really bad and you are nervous about the crossing, just turn around. There’s no sense losing your life over a hike. There’s nothing in that bus worth dying over. Don’t end up in the paper!

The best time of day to cross the river is very early in the morning. As mentioned previously, the river is glacial, and therefore the level drops during the course of the night due to the lower temperature.

Before crossing, take the insoles out of your boots, and take your socks off. Keep your boots on though. It will help increase your grip and stability on the rock. Taking your pants off is an option you should consider as well. Keeping your pants on will give you only a marginal amount of protection from the cold of the water, but it will increase the surface area that the river has to push against you. Taking your pants off reduces your drag. Undo the buckle on your pack (and sternum strap.) That way, if you fall in and need to free yourself of your pack you will be able to.

It is far better to cross the river in a group than it is to cross alone. In a group, line up with the larger members furthest upstream. Have everyone pick up a long pole and hold it, parallel to the river, across their chests. This way, if someone starts to stumble, the entire rest of the group supports them, and the largest members are upstream breaking the current. Walk slowly, and carefully place each foot.

If you must cross alone, use a long sturdy pole to help you balance. Place the pole upstream from yourself and lean against it. Face upstream, but move in a diagonal line downstream as you move across. Always maintain two points of contact at all times. Again, take your time and be careful.

The use of a rope may help in some instances. The rope she was using, was the big contributing factor in the Swiss woman’s death, however. In that instance, the rope had been incorrectly placed parallel across the river. Also, she had tied herself to the rope with another shorter length of rope. When she fell, the river pushed hard against her, stretched the rope, and she was pinned underwater, held in place by the rope, which was now in a V shape pointing downstream. She was unable to free herself.

To avoid this, if you use a rope, have it at a steep angle across the river. The stretchier the rope (for example, climbing rope) the steeper that angle needs to be. Having an angle will allow a person to use the rope to get back to shore if they fall, and will keep the rope from forming a V. It is also a poor, and potentially lethal, idea to tie yourself to the rope. Simply use it as a handrail.

If you are swept downstream, do not panic, keep your face up, and your feet pointed downstream. Work your way to the bank as quickly as possible.

It is also worth noting that the Teklanika braids out as you head further south along it’s bank from the trail (upstream). You may want to head in that direction in search of a safer place to cross.

Another method of crossing you could investigate, would be the use of a pack raft. There are places in Alaska that rent them and it could be a much safer alternative to fording. I have no personal experience with that method so I am not able to comment much further on it.

How Bad Are The Bugs? The bugs are terrible. The mosquitoes will swarm you. Bring plenty of bug repellent.

What About Footwear? How Can I Keep My Feet Dry? With the number of stream crossings on this trail, it would be nearly impossible to keep your feet dry the whole time. In my group of eight, no one was successful in that goal, though a few tried pretty hard.

The best thing to do is just accept the fact that your feet will be wet all day. Take care of your feet though. Each night make sure to dry your feet thoroughly. Bringing a pair of thick wool socks for each night is a great idea as well. Only put them on right before you get into your sleeping bag. This will keep your feet warm and dry for at least eight out of every twenty-four hours, and because it’s one of the main places your body loses heat while you sleep, it effectively increases the temperature rating of your sleeping bag as well.

I also suggest bringing along a pair of cheap, light, foam flip-flops. That way you can wear them around camp while your boots sit next to the fire drying.

Any Other Advice? Be super careful. Nobody wants to hear about anybody else getting hurt out there. Be Prepared, do your homework, use good judgment, and come home alive.

Trail Reports and Photos I’m always looking for current trail reports and photos, so feel free to get ahold of me when you get back. I’d love to chat.

Stampede Trail Flickr Group http://www.flickr.com/groups/stampedetrail/

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Everything Into The Wild Doesn't Tell You About The True Story

Adventure writer Jon Krakauer's book "Into the Wild" is a journalistic yet personal examination of the life and death of Chris McCandless. After graduating college, McCandless donated his life savings, cut off contact with his family, and vanished, becoming a nomad and living under the assumed identity Alexander Supertramp. For two years he explored America, meeting other travelers and friends before venturing into the Alaskan wilderness and perishing at 24 years old.

Sean Penn read the book twice in 1996 and immediately knew he wanted to make it into a film. As reported by The Los Angeles Times , Penn spent the next decade convincing McCandless' family to sell him the rights to Chris' story. The 2007 film adaptation, "Into The Wild," is an elegiac celebration of McCandless' ( Emile Hirsch ) wanderlust and a glimpse of his tragic death, told from McCandless' perspective and through his sister Carine's (Jena Malone) narration. Penn's film was nominated for two Academy Awards and secured a "fresh" rating on Rotten Tomatoes . Krakauer told The Los Angeles Times , "When [Penn] showed me the rough cut, I wanted to kiss him, I was so happy."

Some, like writer-director Penn, mythologized McCandless, depicting him as an idealistic wanderer who eschewed capitalism and hustle culture while embracing an adventurous life lived to the fullest. Others believe McCandless was a selfish and arrogant rich kid who thought he could survive the wilderness of Alaska, only to find himself tragically unprepared. Keep reading to explore everything "Into The Wild" doesn't tell you about the true story.

The film skips McCandless' high school and college years

"Into the Wild" is a very long film, running two hours and 28 minutes, but it couldn't possibly include everything covered in Jon Krakauer's book. According to Outside , Chris McCandless was the captain of his high school cross-country track team, and enjoyed creating punishing workouts that took him and his teammates into unfamiliar territory to test their limits and endurance.

He couldn't bear the inequities he saw in the world. His mother Billie told Outside, "Chris didn't understand how people could possibly be allowed to go hungry ... He would rave about that kind of thing for hours." Chris also took action on these beliefs. As reported by Outside, he brought a homeless man to live in the family's camper once. As depicted in the film, McCandless graduated with honors from Emory University, where he contributed intense editorials on subjects he was passionate about to the school newspaper (per The A.V. Club ).

The PBS documentary "Return to the Wild" reveals that solo treks across the U.S. were nothing new for McCandless when he vanished in the summer of 1990. Five years earlier, after graduating high school, he bought his Datsun and drove cross-country. According to his father Walt, Chris was gone all summer, rarely checking in. Walt told The New York Times , "He was always an adventuresome, pretty self-contained individual ... it's important to realize that the trip he didn't come back from wasn't his first adventure."

His driver to the trailhead tried to dissuade him

At the beginning of the film version of "Into the Wild," we see Chris McCandless hitchhiking into Fairbanks, Alaska before he's dropped off at the Stampede trailhead. The driver gives McCandless a pair of rubber boots to keep his feet dry, telling McCandless to call him if he makes it out alive. Jim Gallien is the man who dropped McCandless off, and he played himself in the film.

Like many before him, Gallien tried to talk McCandless out of his foolhardy plan. Gallien told NPR , "I said the hunting wasn't easy where he was going ... When that didn't work, I tried to scare him ... But he wouldn't give an inch. He had an answer for everything I threw at him." Walt McCandless wouldn't have been surprised by this, telling Outside , "If you attempted to talk him out of something, he wouldn't argue. He'd just nod politely and then do exactly what he wanted."

McCandless gave Gallien his watch at the trailhead, despite Gallien's protestations. As reported by NPR, McCandless told Gallien he would throw the watch away, saying, "I don't want to know what time it is. I don't want to know what day it is or where I am. None of that matters." Emile Hirsch told The East Bay Times that he actually wore McCandless' watch in the film after Gallien lent him the timepiece.

McCandless has been accused of legal infractions

The Anchorage Daily News explored the legal infractions that McCandless was accused of, beginning with McCandless abandoning his car in Arizona, as depicted in "Into the Wild." This article claims the car had an expired registration, no insurance, and was left in a region of the park closed to cars.

The New Yorker reported in 1993 that McCandless got a ticket for hitchhiking after abandoning his car in Arizona and alleged that he broke into a cabin in the Sierra Nevada mountains to steal food. In the film, we see McCandless dismiss rules repeatedly — as when the park ranger says he needs a permit to kayak the Colorado River — so some of these accusations are plausible. According to NPR , McCandless was scornful when Jim Gallien asked if he had a hunting permit before hiking the Stampede Trail, saying, "Hell, no. How I feed myself is none of the government's business. F*** their stupid rules."

According to Jon Krakauer's book , McCandless was also arrested for hopping trains in Colton, California. The accusations didn't stop after McCandless disappeared in Alaska. The Anchorage Daily News, which called McCandless a poacher, suggested that McCandless broke into and vandalized cabins in the area while living on Bus 142. Gordon E. Samel, one of the hunters who found McCandless' body, suggested that the moose McCandless shot in Alaska was caribou ( via Reuters ). McCandless' journal hints that he killed it at the beginning of June, meaning it was killed out of season ( via Huntin' Fool ).

McCandless' parents visited Bus 142

The screen adaptation of "Into The Wild" explores nothing that happened after Chris McCandless' death, other than sharing when his body was found by hunters. According to The A.V. Club , Jon Krakauer's bestselling book explores McCandless' life and death, as well as how his death affected the people he left behind. Krakauer interviewed McCandless' family, and the people he met during his travels, to piece together what happened to McCandless during the two years preceding his death. During his research, the writer developed a relationship with the McCandless family.

According to Treehugger , after McCandless' death, Krakauer and McCandless' parents visited Bus 142 via helicopter. Walt and Billie installed a memorial plaque on Bus 142, leaving an emergency kit, and a note asking visitors to please "call your parents as soon as possible." During the 2014 PBS documentary "Return to the Wild," the film crew followed McCandless' sister Carine and two of their half-sisters as they visited Bus 142, 22 years after his death. This was Carine's third visit to the bus, but it was the first time their half-sisters saw where their brother died.

After learning of Chris' death, Ronald Franz became depressed

According to NPR , the film's Ron Franz (Hal Holbrook) was based on a real person. Holbrook was nominated for an Oscar for his performance in "Into the Wild." Tripline claims Franz's real name was Russell Fritz. As reported by Treehugger , McCandless had a huge effect on Franz/Fritz, the elderly man who offers to adopt McCandless in the film before he departs southern California for his ill-fated trip to Alaska.

We only briefly meet Franz in the film, but Krakauer's book further explored the impact that meeting McCandless had on Franz's life. The New York Times reports that after parting ways, McCandless wrote Franz, saying, "If you want to get more out of life, Ron, you must lose your inclination for monotonous security and adopt a helter-skelter style of life that will at first appear to you to be crazy." After receiving a letter from McCandless, Franz put his belongings into storage and set out into the desert, inspired to shake things up.

In reality, Franz seemed to sit in the desert waiting for McCandless to return for eight months. In Chapter 6 of Krakauer's book , we learn that while returning from the desert, Franz picked up a couple of hitchhikers who told him of McCandless' death in Alaska. After learning of the young man's death, a distraught Franz renounced his faith in God, claiming to be an atheist, and drank a bottle of whiskey after decades of sobriety.

The real Chris McCandless was not the film's idealistic free spirit

As reported by The A.V. Club , Jon Krakauer's book acknowledged McCandless' inflexible and argumentative nature, calling him a "highly polarizing subject," while also depicting him as charismatic and extroverted. Krakauer told NPR , "He was an intense kid. He didn't see the world in gray at all, everything was black and white, right or wrong, and he was a young man who wanted to test himself."

Sean Penn 's "Into the Wild" hinted at McCandless' stubborn side by showing McCandless arguing with his parents about not wanting them to buy him a new car for graduation, dismissing the need for a permit to kayak the Colorado River, and refusing much of the charity and help that flowed his way. While the film doesn't ignore his stubbornness, it characterizes McCandless as a more laid-back, idealistic free spirit who rejects his parent's affluent lifestyle and the rat race.

Walt McCandless told Outside , "He was good at almost everything he ever tried, which made him supremely overconfident." Tragically, it was McCandless' inability to accept help and heed good advice that led him down the lonely and tragic path to his death on Bus 142.

Chris McCandless could have crossed the river downstream

Late in "Into the Wild," McCandless packs up his stuff and cleans up under a makeshift shower before hiking toward society after surviving off the land for over two months. When McCandless reaches the river, which was frozen when he arrived, he sees the hat Jan (Catherine Keener) knitted for him, skewered on a branch where he left it to mark his route. Unfortunately, McCandless returns to the bus after failing to cross the Teklanika River, which is swollen from snow melt.

Brent Keith, an Alaskan guide, told Men's Journal , "I just don't get why he didn't stay down by the Teklanika until the water got low enough to cross. Or walk upstream to where it braids out in shallow channels. Or start a signal fire on a gravel bar." The New Yorker shared that less than a mile downriver from where he crossed in April, there was a hand-operated tram he could have used to cross the river when he wanted to leave in July.

According to Forbes , a recent study by hydrologists at Oregon State University suggested that McCandless was trapped because of a "freak hydrological event" exacerbated by run-off from the Cantwell Glacier. David Hill, who co-authored the study, told Forbes, "Streamflow in summer 1992 was more variable than usual because of the quick snowmelt followed by periods of heavy rain," adding if he had tried to cross earlier or later in July the results might have been different.

Carine McCandless alleges that she and Chris experienced domestic abuse

Jon Krakauer's book refers obliquely to the McCandless family's toxic dynamic, characterizing their father Walt as "overbearing" and their home as unhappy (per NPR ). Carine confided in Krakauer about the abuse while he was researching "Into The Wild," but she told Outside , "I made him promise — before I let him read Chris's letters, before I told him these things — that he wouldn't expose any of it in the book."

By the time Sean Penn was making his film adaptation, Carine was older and more open about the abuse she alleges she and Chris experienced and witnessed growing up. The film depicts domestic abuse in a couple of flashbacks. In 2014, Carine wrote her memoir, "The Wild Truth," revealing more about the alleged abuse. Per Outside , Walt and Billie McCandless have denied the accusations, describing her memoir as fiction.