Conceptual Travel

Conceptual travel has been the dedicated travel agency for Nordex South Africa since 2012. We have grown from 1 person to having 3 staff with offices located in Westlake, Cape Town. Nordex has been instrumental in the growth and development of Conceptual travel through the supplier enterprise development programme since 2014. Through this programme we were able to send staff on training, move to bigger premises, purchase a travel specific accounting package to name a few . With this continued business relationship I believe Conceptual Travel will grow and create more Jobs in the future. Thank you Nordex!

CONTACT CC 2008 139 98623 Vat 49202 51248 Unit C5A, Westlake Square, Westlake Drive, Westlake, 7945 Tel.: +27 21 701 2354 Mobile: +27 82 849 8036 Website: www.conceptualtravel.co.za Janine Mocke – Managing Owner EMail: [email protected]

Back to: The Nordex Group in South Africa

Advertisement

Gender and transition in Southeast Asia: conceptual travel?

- Original Paper

- Published: 31 January 2013

- Volume 11 , pages 113–127, ( 2013 )

Cite this article

- Claudia Derichs 1

582 Accesses

3 Citations

Explore all metrics

Theories and concepts of political transition have been influenced to a great deal by Western theoretical and conceptual reflection. The parameters of transition are usually based on two assumptions or expectations: The goal of transition is democracy or a democratic system, and both actors and affected persons are perceived as gender-neutral beings, i.e., there is no distinction made between male or female actors and persons concerned. This article problematizes the conventional concept of transition and attempts a gendered conceptualization. Empirically, it draws from studies and fieldwork during the periods of political transition in Indonesia (mostly accomplished) and Malaysia (ongoing). It addresses the impacts of transition on women in particular. The core argument is that conceptual reflections of transition need to integrate a gender-sensitive perspective, but at the same time attend to the fact that “women” is not an exhausting analytical category. As illustrated by the examples of Indonesia and Malaysia, a gender-sensitive approach thus requires to also take the pluralism and heterogeneity of “women” (as well as “men”) into account.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction: Approaching Canadian Politics Through a Gender Lens

The Smothering of Feminist Knowledge: Gender Mainstreaming Articulated through Neoliberal Governmentalities

Gender and Politics in Brazil Between Continuity and Change

Indonesia is ranked as a lower middle-income country by the World Bank; Malaysia ranks as an upper middle-income country; see http://data.worldbank.org/country/indonesia (Accessed 8 September 2012).

Malaysia is composed of over 60 % ethnic Malays, over 30 % ethnic Chinese, a considerable community of ethnic Indians (7 %), and various indigenous groups in East Malaysia. Indonesia's ethnic composition is highly heterogeneous, too, but far less delicate than the “three races” constellation in Malaysia, since the majority of people in Indonesia adheres to the religion of Islam regardless of ethnicity. The population of Indonesia is 242.3 million and that of Malaysia, 28.8 million; see http://data.worldbank.org/country/indonesia (Accessed 8 September 2012).

For the full list of ranking of 2012 see http://www.freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/inline_images/Table%20of%20Independent%20Countries%2C%20FIW%202012%20draft.pdf (Accessed 4 August 2012).

The term shari’a is spelled differently according to the authors who use it. In direct citations, I follow the spelling and/or italics version in the original text. My own preferred spelling is shari’a.

New Order or orde baru refers to the Suharto years, 1965–1998.

The spectrum of organizations included Koalisi Perempuan (Women's Coalition), Yayasan Sekar (Sekar Foundation), Komnas Perempuan (National Commission on Violence against Women), Jurnal Perempuan (Women's Journal), Kalyanamitra (Women's Communication and Information Center), CETRO (Center for Electoral Reform), Women and Gender Studies Center (University of Indonesia), TPGT (Tata Pemerintahan Tanggap Gender or Gender Responsive Public Policy and Administration), Indonesian Center for Women in Politics (ICWIP), Kapal Perempuan (Women's Boat), and LBH-APIK (Legal Aid Society—Indonesian Women's Association for Justice). In addition, individual women in their capacity as members of parliament or the bureaucracy belonged to the sample of interview partners.

A number given by Komnas Perempuan is 305 units in the 33 provinces by 2009; see http://www.komnasperempuan.or.id/wp-content/uploads/2009/08/peluang-dan-tntangan-polri-dlm-tangani-korban-kkrsn-pr.ppt (Oct. 11, 2010).

CEDAW is the acronym for the United Nations‘Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (enacted in 1981). The website “CEDAW in action” introduces activists in various countries who have engaged intensively in order to implement, promote and monitor CEDAW-conforming policies. Ibu Titi is one of them in Indonesia. She is portrayed and quoted under http://cedaw-seasia.org/indonesia_stories_ibutiti.html (Accessed January 23, 2013).

See http://www.freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/inline_images/Table%20of%20Independent%20Countries%2C%20FIW%202012%20draft.pdf (Accessed 12 August 2012).

“A Step forward in Equal Rights,” report for Qantara.de ( 2010 ), http://www.qantara.de/webcom/show_article.php/_c-478/_nr-1111/i.html (Oct. 12, 2010)

Although Islamic jurisdiction is a state affair, all Islamic courts in Malaysia follow the Shafi’i School of Islamic law (which is common throughout Southeast Asia).

“Pas finds hudud a tough sell with allies,” in New Straits Times , Sep. 9, 2010, ( http://www.nst.com.my/nst/articles/20beh/Article/ ) (Oct. 12, 2010)

Besides 13 states, Malaysia has two federal territories.

The national profile for Malaysia on the website of the transnational advocacy network Musawah , http://www.musawah.org/np_malaysia.asp (Oct. 12, 2010)

http://www.musawah.org/np_malaysia.asp (Oct. 12, 2010)

See http://www.wluml.org/node/5443 (Oct. 12, 2010).

Malaysia plans women travel curbs, in BBC News, May 04, 2008, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/7382859.stm (June 15, 2008).

For women's parliamentary representation around the world, see www.ipu.org .

The more recent events in the context of the Arab Spring are still too fresh for a solid theoretical reflection; that is why they are not taken into deeper consideration here.

For details, see http://www.bertelsmann-transformation-index.de/en/ (accessed 16 March 2011).

Anderson B (1983) Imagined communities. Verso, London

Google Scholar

Beittinger-Lee V (2009) (Un) Civil society and political change in Indonesia, 1st edn. Routledge, London

von Braunmühl C (1997) Gender und Transformation. Nachdenkliches zu den Anstrengungen einer Beziehung. In: Kreisky E, Sauer B (eds) Geschlechterverhältnisse im Kontext politischer transformation. Politische Vierteljahresschrift, Westdeutscher Verlag, Opladen, pp 475–490

Bünte M, Ufen A (eds) (2008) Democratization in post-Suharto Indonesia. Routledge, London

Carothers T (2002) The end of the transition paradigm. J Democr 13(1):5–21

Article Google Scholar

Frankenberger R, Albrecht H (eds) (2010) Autoritarismus reloaded: Neuere Ansätze und Erkenntnisse der Autokratieforschung. Nomos, Baden-Baden

Frisk S (2009) Submitting to God: women and Islam in urban Malaysia. University of Washington Press, Seattle

Goertz G, Mazur AG (2008) Mapping gender and political concepts: ten guidelines. In: Goertz G, Mazur AG (eds) Politics, gender, and concepts: theory and methodology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 14–43

Hadiwanata BS (2006) From reformasi to an Islamic state? Democratization and Islamic terrorism in post-new order Indonesia. In: Croissant A, Martin B, Kneip S (eds) The politics of death. Political violence in Southeast Asia. Lit Verlag, Münster, pp 107–145

Hadiz V (2010) Localising power in post-authoritarian Indonesia: a Southeast Asia perspective. Stanford University Press, Stanford

Lee JCH (2010) Islamization and activism in Malaysia. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore

Levitsky S, Way L (2002) The rise of competitive authoritarianism. J Democr 13(2):51–65

Levitsky S, Way L (2010) Competitive authoritarianism. Hybrid regimes after the cold war. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Book Google Scholar

Linz JJ, Stepan A (1996) Problems of democratic transition and consolidation: Southern Europe, South America, and post-Communist Europe. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Illustrated edition

Lucas RE (2004) Monarchical authoritarianism: survival and political liberalization in a middle eastern regime type. Int J Middle East Stud 36(1):103–119

Mazur AG, Goertz G (2008) Introduction. In: Goertz G, Mazur AG (eds) Politics, gender, and concepts: theory and methodology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 1–13

Merkel W et al (2003) Defekte demokratien, bd.1, theorien und probleme, 1st edn. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden

Merkel W (2010) Systemtransformation: Eine Einführung in die Theorie und Empirie der Transformationsforschung, 2, überarbeitete und erweiterte Auflage. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden

Mietzner M (2009) Indonesia and the pitfalls of low-quality democracy: a case study of gubernatorial elections in North Sulawesi. In: Bunte M, Ufen A (eds) Democratization in post-Suharto Indonesia. Routledge, London, pp 124–149

Mitchell T (2003) The Middle East in the Past and Future of Social Science. University of California International and Area Studies Digital Collection, The Politics of Knowledge: Area Studies and the Disciplines, 3. University of California Press, Berkeley.

Noerdin E (2002) Customary institutions, Syariah Law and the marginalisation of Indonesian women. In: Robinson K, Bessell S (eds) Women in Indonesia. Gender, equity, and development. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore, pp 179–186

O'Donnell GA, Schmitter PC (1986) Transitoins from authoritarian rule. Prospects for democracy. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore

Ottendörfer E, Ziegenhain P (2008) Islam und Demokratisierung in Indonesien: Die shari‘a-Gesetze auf lokaler Ebene und die Debatte um das sogenannte Anti-Pornographie-Gesetz [Islam and Democratization in Indonesia: shari’a legislation and the debate on the so-called anti-pornography law]. In: Schulze F, Warnk H (eds) Religion und Identität. Muslime und Nicht-Muslime in Südostasien [Religion and Identity. Muslims and Non-Muslims in Southeast Asia]. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden, pp 43–64

Paxton P (2008) Gendering democracy. In: Goertz G, Mazur AG (eds) Politics, gender, and concepts: theory and methodology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 47–70

Robinson K (2009) Gender, Islam and democracy in Indonesia, 1st edn. Routledge, London

Rozaki A (2010) The pornography law and the politics of sexuality. In Islam in contention: rethinking Islam and State in Indonesia. Wahid Institute, Jakarta

Sainsbury D (2008) Gendering the welfare state. In: Goertz G, Mazur AG (eds) Politics, gender, and concepts: theory and methodology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 94–113

Schedler A (ed) (2006) Electoral authoritarianism: the dynamics of unfree competition, illustrated edn. Lynne Rienner Publishers Inc., Boulder

Schröter S (ed) (2013) Geschlechtergerechtigkeit durch Demokratisierung? Transformationen und Restaurationen von Genderverhältnissen in der islamischen Welt. transcript Verlag, Bielefeld. Available at: http://www.transcript-verlag.de/ts2173/ts2173.php . Accessed 28 August 2012

Sherlock S (2010) The parliament in Indonesia's decade of democracy: people's forum or chamber of cronies? In: Mietzner M, Aspinall E (eds) Problems of democratization in Indonesia. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore, pp 160–178

Slater D (2008) Democracy and dictatorship do not float freely. In: Kuhonta EM, Slater D, Vu T (eds) Southeast Asia in political science. Theory, region, and qualitative analysis. Stanford University Press, Stanford, pp 55–79

Snyder R (2006) Beyond electoral authoritarianism: the spectrum of nondemocratic regimes. In: Schedler A (ed) Electoral authoritarianism: the dynamics of unfree competition. Lynne Rienner Publishers, Boulder, pp 219–231

Tan N, Lee J (eds) (2008) Political tsunami: an end to hegemony in Malaysia? Kinibooks, Kuala Lumpur

Ting H (2007) Gender discourse in Malay politics. Old wine in new bottle? In: Gomez ET (ed) Politics in Malaysia: the Malay dimension. Routledge, London, pp 75–106

Wehr I (2009) Esping-Andersen travels South. Einige kritische Anmerkungen zur vergleichenden Wohlfahrtsregimeforschung. Peripherie 29(114/115):168–193

Web sources

Bertelsmann Transformation Index, http://www.bertelsmann-transformation-index.de/en/ . Accessed 16 March 2011

Freedom House, freedom in the world, http://www.freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/freedom-world-2012 . Accessed 4 August 2012

Inter Parliamentary Union database, www.ipu.org

Musawah, www.musawah.org . Accessed Oct. 12, 2010

Polity IV Project (2012) http://www.systemicpeace.org/polity/polity4.htm (Aug.7, 2012)

The Malaysian Insider, Oct. 20, 2010, Shahrizat vows bigger say for Wanita UMNO, http://www.themalaysianinsider.com/malaysia/article/shahrizat-vows-bigger-say-for-wanita-umno/ . Accessed March 16, 2011

Qantara.de (2010) http://de.qantara.de/

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute of Political Science, Philipps University Marburg, Marburg, Germany

Claudia Derichs

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Claudia Derichs .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Derichs, C. Gender and transition in Southeast Asia: conceptual travel?. Asia Eur J 11 , 113–127 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10308-013-0342-x

Download citation

Received : 04 September 2012

Revised : 02 January 2013

Accepted : 14 January 2013

Published : 31 January 2013

Issue Date : June 2013

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10308-013-0342-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Muslim Woman

- Battered Woman

- Political Transition

- Electoral Democracy

- Islamic Principle

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Conceptual Travel

- Locations ›

- South Africa ›

- Cape Town, South Africa ›

- Travel Agent ›

- 021 712 0201

- www.facebook.com/pages/conceptual-t...

- Travel Agent

Recommendations & Reviews

- Facebook - 2

- WhoDoYou - 0

- Twitter - 0

Overall Rating

- Wynberg Cape Town , WC (map)

Hours of operation

2 recommendations and reviews from 2 people.

- Honey Badger Tours

- Club Travel

- Landscape Tours

- Stellenbosch, South Africa (26 mi)

- Paarl, South Africa (34 mi)

- Malmesbury, South Africa (37 mi)

- Travel agent x

- Post this review to my wall

- Top Destinations

- Mexico City, Mexico

- Tokyo, Japan

- Paris, France

- Rome, Italy

- London, United Kingdom

- All Destinations

- Upcoming Experiences

- Walking Tours

- Small-Group Tours

- Tours for Kids

- Museum Tours

- Food, Wine and Market Tours

- Newly Added Tours

- Audio Guides

- Pre-Trip Lectures

- Admin Dashboard

- My Favorites

- Cookies Preferences

- Client Orders

- Monthly Commissions

- My Advisor Profile

- Advisor Toolkit

- Guide Dashboard

Credit Balance

Transactions are based on current exchange rates and performed in USD. There maybe slight variations in the price estimates.

Explore with Local Experts Host-led experiences for those who love to dive deep into local life (4.76) See all 57,660 reviews

Bundle and save, add 3 or more tours to your cart and save 15% with code bundle15. with 500 experiences in 60+ destinations worldwide, context is everywhere you want to be..

Just you, an expert, and your travel companions

Connect with other travelers

Explore the city at your own pace

Inspire future travels and learn before you go

Venture out a little farther

Perfect for young, curious travelers

What Our Guests Are Saying

Reviews can only be left by Context customers after they have completed a tour. For more information about our reviews, please see our FAQ .

- Our Experts

- Working with Context

- View All Cities

- Sustainable Tourism

- Refer a Friend for $50

- Travel Updates

- Advisor Login

- Expert Portal

Subscribe to our Newsletter

- Privacy Statement & Security

- Cancellation Policy

Conceptual Integration of AI for Enhanced Travel Experience

Ieee account.

- Change Username/Password

- Update Address

Purchase Details

- Payment Options

- Order History

- View Purchased Documents

Profile Information

- Communications Preferences

- Profession and Education

- Technical Interests

- US & Canada: +1 800 678 4333

- Worldwide: +1 732 981 0060

- Contact & Support

- About IEEE Xplore

- Accessibility

- Terms of Use

- Nondiscrimination Policy

- Privacy & Opting Out of Cookies

A not-for-profit organization, IEEE is the world's largest technical professional organization dedicated to advancing technology for the benefit of humanity. © Copyright 2024 IEEE - All rights reserved. Use of this web site signifies your agreement to the terms and conditions.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Towards a Comprehensive Conceptual Framework of Active Travel Behavior: a Review and Synthesis of Published Frameworks

Thomas götschi.

1 Epidemiology, Biostatistics and Prevention Institute, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

Audrey de Nazelle

2 Centre for Environmental Policy, Imperial College London, London, UK

Christian Brand

3 Transport Studies Unit, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

Regine Gerike

4 Institute of Transport Planning and Road Traffic, Technische Universität Dresden, Dresden, Germany

Associated Data

Purpose of review.

This paper reviews the use of conceptual frameworks in research on active travel, such as walking and cycling. Generic framework features and a wide range of contents are identified and synthesized into a comprehensive framework of active travel behavior, as part of the Physical Activity through Sustainable Transport Approaches project (PASTA). PASTA is a European multinational, interdisciplinary research project on active travel and health.

Recent Findings

Along with an exponential growth in active travel research, a growing number of conceptual frameworks has been published since the early 2000s. Earlier frameworks are simpler and emphasize the distinction of environmental vs. individual factors, while more recently several studies have integrated travel behavior theories more thoroughly.

Based on the reviewed frameworks and various behavioral theories, we propose the comprehensive PASTA conceptual framework of active travel behavior. We discuss how it can guide future research, such as data collection, data analysis, and modeling of active travel behavior, and present some examples from the PASTA project.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s40572-017-0149-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Introduction

Sustainable transport modes, and in particular walking and cycling, have gained growing interest by decision makers, planners, and the general public as potential solutions to challenges rooted in urban transport, including environmental, economic, and health issues [ 1 , 2 ]. This trend is also reflected in an exponentially growing body of research addressing a wide range of aspects of active travel, including identifying and quantifying determinants of active travel behavior [ 3 ], assessing the effectiveness and sustainability of measures to promote it [ 4 – 6 ], understanding and remedying safety related issues [ 7 ], developing methods to measure or survey active travel [ 8 ], and assessing effects and impacts of active travel on travel, health, and environmental outcomes through various pathways [ 9 – 11 ].

Studies from various fields, such as transport and health, have repeatedly identified and confirmed the role of specific determinants of walking and cycling and regularly presented quantitative effect estimates [ 12 ]. However, most studies concentrate on a particular domain of influence, such as the policy context, the built environment, the social environment, or personal and trip attributes. Often, they are also limited by their specific topical perspectives, such as transport issues or public health. “Transport studies” tend to ignore health both as a motivation and as an outcome of active travel, while “health studies” often ignore the role of competing modes of transport. While taken together the whole body of knowledge does paint a fairly extensive qualitative picture of determinants of active travel, it remains challenging to build robust comprehensive models combining quantitative estimates. Namely, coefficients derived from different studies are not adjusted for each other, they may be based on different scales and definitions, and they tend to stem from different contexts and populations. A more holistic quantitative understanding of determinants of active travel, however, would help answer some of the most practice-relevant questions. In particular, it would provide more robust evidence to identify effective measures and policies and rationalize how these are prioritized. One possible application would be to better integrate walking and cycling into travel demand models, which to date tend to represent active travel poorly [ 13 , 14 ].

To develop a more holistic quantitative understanding of determinants of active travel and how it could be promoted, larger more comprehensive studies with a broad scope need to be conducted. We argue that for such endeavors to succeed, it is crucial to acquire the best possible conceptual understanding of the relationships between relevant determinants and active travel behavior and potential confounders and mediators a priori.

This paper thus aims to (1) review the use of conceptual frameworks in active travel research, and, based on these frameworks, (2) to propose a comprehensive framework that covers the abovementioned domains and can guide future research to observe, explain, and model active travel behavior. We aim to first systematically identify and describe key features of conceptual frameworks for active travel and then apply these in a novel, systematic and comprehensive framework developed within the scope of the Physical Activity through Sustainable Transport Approaches (PASTA) project [ 15 •], a multinational, interdisciplinary research project on active travel and health. The so-called PASTA framework was initially developed and used to determine contents of the longitudinal PASTA survey, a broad data collection effort about active travel and physical activity, their determinants, and associated crash risks [ 16 ]. While a visualization of such a framework could hardly be comprehensive with regards to topical scope, level of detail, or methodological issues for all active travel related research, we aim to combine as many concepts as possible identified by previous work; we aim to do this systematically; and we aim to provide generalizable guidance on how to be more systematic in developing frameworks for active travel related research. In the final section, we discuss the value of such efforts and provide examples of how the PASTA framework can guide specific research efforts.

Literature Review

A systematic effort was taken to comprehensively identify conceptual frameworks for active travel published in the scientific literature. However, despite clearly defined search terms, multiple steps to identify relevant publications, and systematic summaries of identified publications, this review remains exploratory, because “conceptual framework” is a loosely defined term and presumably some researchers may use a framework as a working tool without presenting or referring to it in publications or specifying which theories they are built on.

Systematic literature database searches of PubMed and the Transport Research International Documentation (TRID) database were complemented with systematic scans of references listed in publications identified as relevant (see Appendix 1 for search terms and hits.)

Identified hits were inspected with regards to relevance for the objectives of this review using a standardized categorization form filled out by at least two independent reviewers for each study. The form captured the scope of the reviewed publications, the purpose of the framework, the audience it was aimed for, its novelty, underlying theories, and area of research. Particular focus was put on unique or novel concepts and visual framework features that could contribute towards a more comprehensive framework.

The Results section describes the range of frameworks deemed within scope of the review and presents an overview (Table (Table1) 1 ) and summaries of the most relevant publications.

Frequency of framework features among the 26 publications presenting new conceptual contents

*Feature score reflects the degree of reviewers detecting a feature among reviewed studies

Synthesis of Reviewed Frameworks and Development of the PASTA Conceptual Framework for Active Travel

Based on the identified conceptual frameworks of active travel, the study of behavioral theories, and our understanding of key issues of active travel behavior, we developed a more comprehensive conceptual framework for active travel behavior. The term comprehensive reflects our intention to integrate research-relevant aspects of active travel including various topical domains and structural features in a compact and well-balanced way. To facilitate readability, we present a simplified version in the main text and refer to Appendix 3 for a detailed version (for additional versions, see the supplemental materials available in https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Thomas_Goetschi/publications ).

Specifically, the framework aims to address aspects of relevance to the PASTA study and presumably other research projects, namely, guidance to identify data needs, data sources, and collection methods; data hierarchies, such as clusters or levels of aggregation; the integration of transport and health perspectives with a focus on active travel; and importance of context in measuring and evaluating active travel interventions. Finally, the framework allows testing elements of established theories and latest thinking in (active) travel behavior research.

Overview of the Identified Frameworks

The literature search yielded over 200 hits in PubMed and TRID. After scanning abstract and titles for relevance, reviewing references, and adding some publications identified previously, 65 publications were kept for further review. Appendix 1 provides an overview of the selection process.

The main scope of two thirds of these publications was on active travel behavior [ 48/65 ], while about one third also focused on physical activity [ 23/65 ] or safety [ 8/65 ]. In terms of audience, the publications appeared to target about equally transport researcher, health researchers, and planners, whereas health professionals, policy makers, and advocates seemed somewhat less represented.

About two thirds of the identified publications were considered to provide and discuss conceptual frameworks [ 43/65 ], in the sense of aiming to illustrate causal, temporal, spatial, or hierarchical relationships between active travel outcomes and factors that explain these. Around 10 to 15 papers instead presented frameworks for planning, data collection, modeling, designing interventions, or conducting evaluations.

About half of all publications presented at least in parts new contents [ 36/65 ], whereas the others referred to previously published frameworks [ 29/65 ] or theories [ 10/65 ]. Publications not providing substantial new conceptual contributions most often referred to existing frameworks, such as the socio-ecological model [ 17 ], or relevant theories, such as the theory of planned behavior [ 18 ].

Among those frameworks considered conceptual and new [ N = 26] (see Table Table1), 1 ), about two thirds took a more general big picture perspective [ 21/26 ], whereas in one third the framework guided a specific project [ 9/26 ]. The majority covered the domains of active travel behavior [ 18/26 ] and its determinants [ 24/26 ], whereas four frameworks were concerned with impacts of active travel. Frameworks on active travel behavior split about equally between walking [ 12/18 ] and cycling [ 11/18 ], with almost half of all frameworks covering both modes. Most publications centered around the individual level [ 22/26 ], while many additionally considered the built environment [ 18/26 ] and households [ 13/26 ] as distinct structural levels. Only eight studies treated trips as a separate level. Temporal structures were absent in most frameworks [ 20/26 ] with few exceptions indicating feedback loops [ 6/26 ] or changes over time (before/after) [ 3/26 ]. About three quarters provided illustrations of the frameworks.

In terms of determinants of active travel, built environment [ 23/26 ], infrastructure measures [ 21/26 ], psychological [ 17/26 ] and socio-demographic factors [ 19/26 ] obtained about equal attention. Among the frameworks addressing travel behavior [ 18/26 ] , most described active travel in generic terms, such as walking [ 13/18 ], cycling [ 12/18 ], or even physical activity [ 9/18 ], but several frameworks were more nuanced by investigating different modes of travel, journey purposes (including walking or cycling for recreation or transport), and various quantitative measures, like frequency or duration. The few frameworks that address impacts of active travel [ 4 ] covered environmental (e.g., carbon emissions), health, and safety outcomes.

In the following section, we review a selection of frameworks considered most appropriate in providing distinct features to the development of a more comprehensive framework of active travel behavior. These features are briefly highlighted. Illustrations of some of these frameworks can be found in the supplemental materials available in https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Thomas_Goetschi/publications .

Review of Selected Frameworks

Pikora et al. [ 19 ] and Saelens et al. [ 20 ] were among the earliest publications showing conceptual frameworks for active travel behavior. Their frameworks are imbedded in a socio-ecological model [ 17 ], focusing on different layers of environmental (ecological) and individual (socio-psychological) factors explaining active travel outcomes. Such models are widely applied in health behavioral science, as reviewed for example by Sallis et al. [ 21 ]; they describe the role of the combined effects of psychosocial and environmental variables (i.e., community, policy) to explain physical activity. They imply that a combination of environmental and personal level factors will best explain behavior and that addressing both—or multiple—domains will allow for the development of most effective interventions. Saelens’ model, derived from a review of planning literature, distinguishes active travel for transport vs. recreation, as well as stronger and weaker links between factors.

Ogilvie et al. [ 4 , 22 ] presented a framework with the purpose to measure and evaluate changes in active travel and physical activity behavior resulting from physical infrastructure interventions as part of the longitudinal cohort study “iConnect” [ 23 ]. The iConnect model builds on the framework presented by Saelens et al. [ 20 ], which is expanded beyond active travel to include overall travel behavior, overall physical activity, and imputed impacts such as carbon emissions from motorized travel [ 4 ]. In addition, psychosocial factors, such as habit and social norms based on the extended theory of planned behavior [ 18 , 24 ], as well as social environment factors are introduced as key factors affecting behavior change. The framework applies Pawson and Tilley’s “realistic evaluation” framework [ 25 ] that postulates to distinguish and specify “contexts, mechanisms, and outcomes” (so-called CMO configurations) in order to evaluate how interventions work, for whom, and in what circumstances.

Panter et al. [ 26 ] built on a framework on school travel proposed by Macmillan et al. [ 27 , 28 ] and Pikora’s socio-ecological model for physical activity [ 19 ]. Focusing on active travel to school, they distinguished environmental and individual factors, paying particular attention to the interplay of parents’ and youth’s perceptions affecting mode choice for school travel. Within environmental factors, neighborhoods, destinations, and routes are distinguished, expanding the socio-ecological structure to include travel-specific elements. Also on the topic of parent youth relations when it comes to mode choice, Pont et al. [ 29 ] provide a framework most notable for its depiction of the parent child relation, as one of few examples illustrating a process over time.

Based on an extensive literature review, Burbidge and Goulias [ 30 ] proposed a conceptual framework mainly combining elements of the theory of planned behavior [ 18 ] and decision field theory [ 31 ], which they complemented with additional factors identified from the literature, such as infrastructure and residential location selection. At the core is a mode choice process, which is influenced by personal attributes, infrastructure and environment, time allocation, and various related factors. The choice process itself, however, is not explored in detail.

Schneider [ 32 ] explored the choice process in more detail proposing a theory of routine mode choice decisions in the wider context of policies attempting to shift trips from motorized to non-motorized modes. The theory suggests a five-step mode choice process, consisting of (1) awareness and availability of possible mode choices, (2) safety and security, (3) convenience and cost, (4) enjoyment, which then determine tradeoffs between the possible mode choices, and finally (5) habit, which reinforces earlier choices. Socio-demographic characteristics serve as moderators of these concepts. The theory builds on numerous insights from travel behavior research and psychology [ 18 , 33 , 34 ] and is substantiated with empirical evidence from qualitative interviews of San Francisco Bay Area residents.

Based on Maslow’s theory of human motivation [ 35 ], Alfonzo [ 36 ] presents a similar hierarchy of walking needs, where the individual first assesses feasibility, then accessibility, safety, comfort, and “pleasurability.” This is linked with moderating processes defined by life-cycle circumstances to determine outcomes. The life-cycle circumstances themselves include regional, group, and individual level factors such as climate, culture, and psychological factors, respectively (among others).

Singleton [ 37 ••, 38 ] proposed a framework based on an extensive review of travel behavior theories with the intention to improve direct applicability to active travel forecasting models. Its travel decision-making process also includes a hierarchy of travel needs, which are mediated by individual perceptions and decision rules (e.g., how a shorter trip distance is weighted against a higher crash risk [ 39 – 41 ]). At the start of the process is an activity, which results in a travel demand, or motivation, or desire to travel.

Martin et al. [ 42 ] explore the choice process with a specific focus on the mechanisms of policies. The study reviewed publications on policies that provide financial incentives to promote active travel, illustrating traditional economics (i.e., utility maximization, [ 39 ]) and psychological behavior theories (including behavioral economics) in terms of specific choice formulations and examples of policies addressing these [ 43 , 44 ].

In their extensive review of travel behavior and psychological theories, Van Acker et al. [ 34 ] synthesize numerous concepts of relevance to active travel. Their conceptual model emphasizes the distinction between reasoned influences on behavior, such as perceptions, preferences, and attitudes, and unreasoned influences driven by habits and impulsiveness. Feedback loops indicate the possibility of changes over time. Behavior in this framework is depicted as set of levels that range from the most short-term travel behavior to activity and locational behavior, all the way to lifestyle. Individuals’ behavior is further determined by opportunities and constraints, which present themselves at the individual level, as well as through the social and spatial environment.

In a similarly broad review of mode choice literature, De Witte et al. [ 45 •] emphasize an interdisciplinary perspective, identifying and distinguishing determinants by rationalist (i.e., journey characteristics), socio-geographical (i.e., spatial indicators), and socio-demographic domains, which in combination with socio-psychological factors determine mode choice.

In addition, numerous studies have published frameworks of relevance in the context of active travel that are not directly concerned with active travel behavior, such as safety [ 46 , 47 •, 48 ], types of cyclists [ 49 ], or physical activity [ 50 ], or do not specifically address active travel, such as MINDSPACE, a framework of how public policy influences behavior [ 43 ]. Further, there is abundant literature on travel behavior in general, and numerous theories have conceptualized it, many of which are reflected in the reviewed active travel frameworks. We refer to others for overviews of relevant theories [ 34 , 37 ••, 51 ].

Synthesis of Results and Development of the PASTA Framework of Active Travel Behavior

Key features of conceptual frameworks for active travel.

In this section, we synthesize and discuss key features of identified and reviewed conceptual frameworks for active travel and related theories and describe how we develop these to build the comprehensive PASTA conceptual framework of active travel behavior (from here on referred to as the PASTA framework). Our aim hereby is to absorb as many relevant concepts encountered in the reviewed frameworks and pertinent theories into a single, systematically structured framework as possible. To do so, we distinguish three features of conceptual frameworks representing active travel behavior:

Behavioral decision or choice process

Structural scales and relationships, contents and topical domains.

Similar to others [ 30 , 37 ••, 38 ], we conceptualize the core behavioral process as a demand (or need, desire, intention, or motivation) to travel that is derived from the need or desire to participate in an activity (i.e., work, shop, escort kids to school, visiting friends or family). This triggers a choice process which produces a behavioral decision or response, namely a revealed choice or outcome. (See Fig. Fig.1. 1 . For a simplified diagram of the generic process, see supplemental materials available in https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Thomas_Goetschi/publications .)

Generic choice process for active travel-related behavioral decisions. The column on the left illustrates the process to identify considered choices. From these, one choice is selected through the process in the column on the right

In the transport context a choice is often discrete, short-term, and trip related (i.e., mode choice, route choice) [ 39 ], but it is noteworthy that behavioral outcomes can also be aggregates of many choices over time, such as individual attributes of interest in health research (e.g., minutes of cycling per week or long-term physical activity derived from active travel). Active travel warrants consideration of both perspectives, and in the detailed version of the PASTA framework, we distinguish the two (see Appendix 3 ). For a systematic listing of cycling related choices and outcomes, see supplemental materials available in https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Thomas_Goetschi/publications .

Activities have their own temporality (rhythm, frequency, ir/regularity) and spatiality (distance vis-à-vis anchor locations (home, primary employer, possibly childcare, school) and spatial variability). Many of these activities cannot be adequately represented as rational choice behavior—they are at best boundedly rational [ 52 ] because of constraints on information availability and processing. But even this is a gross simplification as it does not consider the social dimensions of taking part in those activities.

As such, the choice process may very well be too complex to be explained by a single theory or depicted in a simple diagram. Nonetheless, numerous published concepts and theories have provided helpful guidance for research. Similar to several others [ 26 , 30 , 36 , 37 ••], we conceptualize the choice process in our framework as the central pathway that takes into account objective and subjective factors or opportunities and propensities [ 53 ], respectively, to make a behavioral decision or reveal a choice.

Figure Figure1 1 depicts the generic process. At the beginning, a travel demand (or activity) is met with objective opportunities, resulting in many theoretically possible choices, each with their specific attributes. The first of two sub-processes, or iterations (vertical flows in the diagram), identifies a subset of considered choices , which then in a second process are assessed to identify the selected choice . In reality, these may not be perfectly distinct, may inform each other, or may run in parallel (as indicated by parallel arrows).

When based on reasoned behavior [ 18 , 54 ], as illustrated for example by van Acker [ 34 ], these selections are derived from some combination of the objective attributes of the possible choices (or opportunities), such as mode accessibility, trip duration, safety, etc., and a set of subjective factors (or propensities), such as perceptions, attitudes, values, rules, preferences, and norms [ 12 ]. In unreasoned behavior, on the other hand, a habit or impulse circumvents the reasoned choice process leading directly to a choice without (much) consideration of other factors [ 33 , 34 ].

We conceptualize the reason-based part of the choice process similar to a utility-based approach assuming utility maximization behavior, as is commonly done in transport modeling [ 13 , 37 ••, 39 , 55 ]. However, empirical random utility maximization models are often constrained to a small number of measurable utility factors (i.e., monetary and time cost), which fail to capture the multitude of considerations determining active travel choices (e.g., weather, safety, health benefits, pleasure [ 56 , 57 ]). Moreover, active travel decisions, possibly more so than is the case for motorized travel behavior, may be based on other decision rules than compensatory utility maximization, as pointed out by Singleton and Clifton [ 37 ••, 38 ]. We therefore conceptualize this part more loosely as a generic choice assessment , which compares any sort of subjective value a subject is to gain from a choice over an alternative (black boxes in diagram). This accommodates active travel-specific utility dimensions, such as perceptions of safety, or expected health benefits, which are relatively more important for active travel than for motorized travel, but also irrational preferences, fears, or principles (i.e., non-compensatory rules [ 37 ••]). It is important to point out that the choice assessment is limited by the factors a subject actually considers and its perception or information of these, which may be “highly subjective” or incomplete (i.e., bounded rationality [ 58 ]).

While habit and impulsiveness complicate the link between need and revealed behavior, their importance warrants inclusion in our framework. We therefore keep non-reasoned behaviors, like sticking to a habit [ 59 ], following an impulse to try something new, or taking risk against better knowledge, separate from the reasoned choice assessment. However, it seems plausible that both the reasoned and unreasoned pathways could influence the same decision.

The way the generic choice process manifests in a specific situation depends on numerous environmental and personal factors. We treat these as determinants outside of the generic choice process.

The distinction of structural scales, such as hierarchies or clustering between factors, is of practical relevance for data collection and analysis, the validity of an analysis, and various other practical and methodological aspects (e.g., intervention design). Among the reviewed frameworks, the most common distinction is between environmental and personal factors, but further visualizations of spatial, social, or temporal scales have been used. The degree to which frameworks distinguish such structures varies tremendously. Aligning frameworks along structural scales seems particularly helpful when the distinction serves some specific purpose (e.g., data collection, model structure). We underlay the PASTA framework with a hierarchical socio-spatial pyramid (see Appendix 2 , Fig. A2), building on the often-referenced socio-ecological framework [ 19 , 21 , 22 ], which we expand to include travel-specific sub-individual layers, such as activity (leading to one or multiple trips), trip origin and destination, departure time, route, and mode of travel. These structures equally guide where we present determinants and outcomes.

The generic PASTA framework (Fig. (Fig.2) 2 ) represents a static view on active travel behavior as opposed to behavioral change . To a large extent, the temporal scale is captured within the socio-spatial structures, in the sense that highest resolution layers (i.e., trips) reflect more short-term phenomena, whereas at the larger layers (i.e., society or city), processes take longer (i.e., changes in factors or periods over which factors affect each other [ 34 ]). Explicitly visualizing temporality of relationships would be warranted in frameworks focusing on behavior change, such as developments over the life course [ 49 ], effects of interventions [ 22 , 23 ], or those depicting behavioral change along a sequence of defined concepts or stages [ 40 , 60 ]. In quasi-static frameworks, feedback loops or cascading concepts are commonly used to indicate temporality [ 29 ], and some concepts capture it implicitly (e.g., habit).

PASTA conceptual framework of active travel behavior. A more detailed version of the framework including a detailed reader’s guide is available in Appendix 3 . Additional variations of the framework are available in the supplemental materials in https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Thomas_Goetschi/publications

In most published frameworks, directional arrows are the instrument of choice to indicate some sort of relationship or association between factors (or concepts). Variations include dashed and bidirectional arrows, sometimes labeled. The usefulness of arrows seems directly dependent on the specificity of factors and the understanding of relationships. In fairly comprehensive frameworks, the sheer number of related factors often prohibits the illustration of all relationships and using arrows without systematic and transparent criteria can become misleading. Alternatively, or additionally, spatial proximity and clustering or overlapping of factors is used. In the PASTA framework, we indicate relationships or influence between factors predominantly by proximity, arrangement, and clustering of factors (i.e., without using arrows). Only key causal flows are suggested by braces and arrows. Further, we aim for consistent directions of logical pathways (i.e., determinants leading to outcomes). Namely we arrange pathways of social factors roughly from left to right and pathways of environmental factors from top to bottom. However, when applied for specific purposes, such as conceptualizing a specific analysis, more specific arrows become useful (see supplemental materials available in https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Thomas_Goetschi/publications .).

Finally, the above structures are only meaningful when populated with specific, meaningful contents. Comprehensiveness and level of detail are direct tradeoffs and ultimately depend on the specific purpose of a framework but generally impose a challenge for visualization (though to a lesser degree in electronic documents that can be zoomed in, see Appendix 1 ). We arrange factors by topical domains, such as natural and built environment, socio-demographics, personal propensities, psychological factors, etc. We capture obvious sub-factors in overarching concepts to improve the readability of the framework.

Practical Applications of the PASTA Framework in Active Travel Research

There are many practical applications of conceptual frameworks. In particular, in the context of conducting a (large) research project, we argue that the consideration of a detailed conceptual framework, and possibly the development of a study-specific version, is crucial. The choice of data sources, data collection methods, and survey contents and when and where to sample are crucial questions in successfully pursuing research objectives. In the PASTA project, the framework served as a valuable cross-reference to assure the inclusion of as many of the most relevant determinants and potential confounding variables as possible, while at the same time keeping topical areas well-balanced and user burden in check (adapted framework versions are available in the supplemental materials available in https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Thomas_Goetschi/publications ).

The challenges of comprehensively assessing covariates and mediating factors are even more aggravated in research on changes in active travel behavior over time. Effects of interventions are typically small, requiring utmost attention to control of confounders and modifiers. A comprehensive framework is a helpful tool to identify these and anticipate their roles [ 60 ]. In PASTA, the framework guides the evaluation of key measures to promote walking and cycling, selected across the participating cities. The framework allows us to identify the critical putative causal pathways by which we believe the active travel measures are likely to work and as such informed survey contents and how we analyze these. We illustrate an example application highlighting the effects of the construction of high quality cycle highways in London and Antwerp and through which pathways they affect cycling behavior and in particular “stages of change” [ 40 ] (supplemental materials available in https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Thomas_Goetschi/publications ). Simplified, cycle highways affect regular cyclists through the provision of better routes (more direct, pleasant, and safe), while for infrequent or potential cyclists, the main pathway presumably is through an improvement in perceived safety, which may help them pursue their intention to bike more or pick up cycling.

Finally, the framework can also be helpful to inform sampling schemes. In PASTA, relatively stable personal factors, like general health or attitudes, were surveyed only once as part of a baseline questionnaire, whereas the more short-term and temporally variable factors like travel or physical activity behavior were surveyed in frequent follow-up questionnaires every 2 weeks.

Conclusions

Conceptual frameworks have been used to visualize a wide range of aspects of active travel behavior. Despite a remarkable diversity in illustrations, several common features could be identified. To date, the PASTA framework provides a first-of-its-kind effort to systematically combine behavioral concepts, structural features, and a large number of determinants identified in the literature as part of a single, comprehensive framework to inform future works. In PASTA, the framework provided valuable guidance in developing survey contents and study design, and in particular, for the combination of research approaches from the transport and health disciplines on how to best measure active travel and related factors. We conclude that the systematic development and use of a conceptual framework can provide invaluable support to design and conduct more elaborate and comprehensive active travel studies need to address key research gaps.

(DOCX 765 kb)

Acknowledgments

PASTA ( http://www.pastaproject.eu /) is a 4-year project funded by the European Union’s Seventh Framework Program under EC-GA No. 602624-2 (FP7-HEALTH-2013-INNOVATION-1).

Consortium members are as follows: B. Alasya, E. Anaya, I. Avila-Palencia, D. Banister, I. Bartana, F. Benvenuti, F. Boschetti, C. Brand, J. Buekers, L. Carniel, G. Carrasco Turigas, A. Castro, M. Cianfano, A. Clark, T. Cole-Hunter, V. Copley, P. De Boever, A. de Nazelle, C. Dimajo, E. Dons, M. Duran, U. Eriksson, H. Franzen, M. Gaupp-Berghausen, R. Gerike, R. Girmenia, T. Götschi, F. Hartmann, F. Iacorossi, L. Int Panis, S. Kahlmeier, H. Khreis, M. Laeremans, T. Martinez, M. Meschik, P. Michelle, P. Muehlmann, N. Mueller, M. Nieuwenhuijsen, A. Nilsson, F. Nussio, J.P. Orjuela Mendoza, S. Pisanti, J. Porcel, F. Racioppi, E. Raser, S. Riegler, H. Robrecht, D. Rojas Rueda, C. Rothballer, J. Sanchez, A. Schaller, R. Schuthof, C. Schweizer, A. Sillero, L. Smidfeltrosqvist, G. Spezzano, A. Standaert, E. Stigell, M. Surace, T. Uhlmann, K. Vancluysen, S. Wegener, H. Wennberg, G. Willis, J. Witzell, and V. Zeuschner.

Conflict of Interest

Thomas Götschi, Audrey de Nazelle, Christian Brand, and Regine Gerike declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Built Environment and Health

Contributor Information

on behalf of the PASTA Consortium: B. Alasya , E. Anaya , I. Avila-Palencia , D. Banister , I. Bartana , F. Benvenuti , F. Boschetti , C. Brand , J. Buekers , L. Carniel , G. Carrasco Turigas , A. Castro , M. Cianfano , A. Clark , T. Cole-Hunter , V. Copley , P. De Boever , A. de Nazelle , C. Dimajo , E. Dons , M. Duran , U. Eriksson , H. Franzen , M. Gaupp-Berghausen , R. Gerike , R. Girmenia , T. Götschi , F. Hartmann , F. Iacorossi , L. Int Panis , S. Kahlmeier , H. Khreis , M. Laeremans , T. Martinez , M. Meschik , P. Michelle , P. Muehlmann , N. Mueller , M. Nieuwenhuijsen , A. Nilsson , F. Nussio , J.P. Orjuela Mendoza , S. Pisanti , J. Porcel , F. Racioppi , E. Raser , S. Riegler , H. Robrecht , D. Rojas Rueda , C. Rothballer , J. Sanchez , A. Schaller , R. Schuthof , C. Schweizer , A. Sillero , L. Smidfeltrosqvist , G. Spezzano , A. Standaert , E. Stigell , M. Surace , T. Uhlmann , K. Vancluysen , S. Wegener , H. Wennberg , G. Willis , J. Witzell , and V. Zeuschner

Papers of particular importance, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

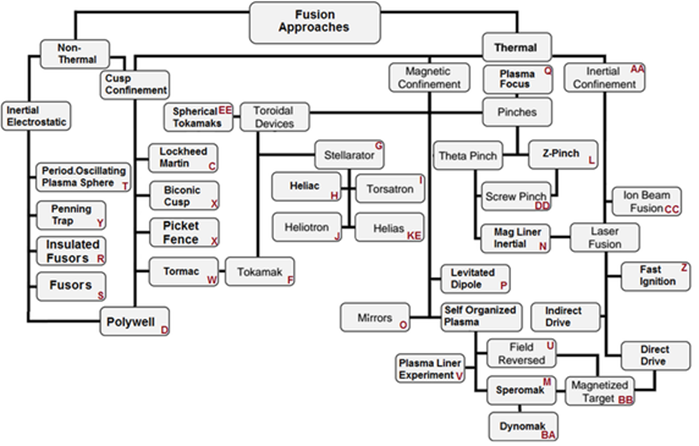

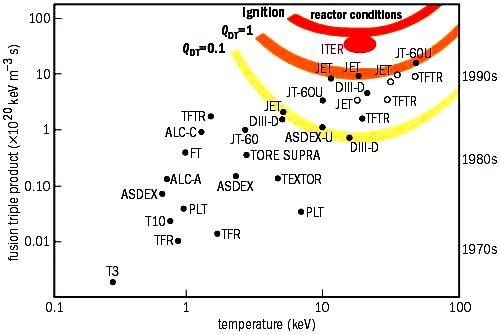

Fusion Reactors: Types, Economics, Impact

There is an adage in the scientific community that fusion power has been within 20 years of viability for about the past 40 years: the technology has proven to be much more difficult to master than previously thought. However, should we be able to master fusion, the possibilities for our future energy needs really becomes compelling. A few methods currently under investigation for fusion power are seeing good developments, however, most are still trying to achieve engineering feasibility. Below is a graph showing all current different types of fusion technologies: this article will focus on the most prominent in modern scientific circles.

Thermal confinement

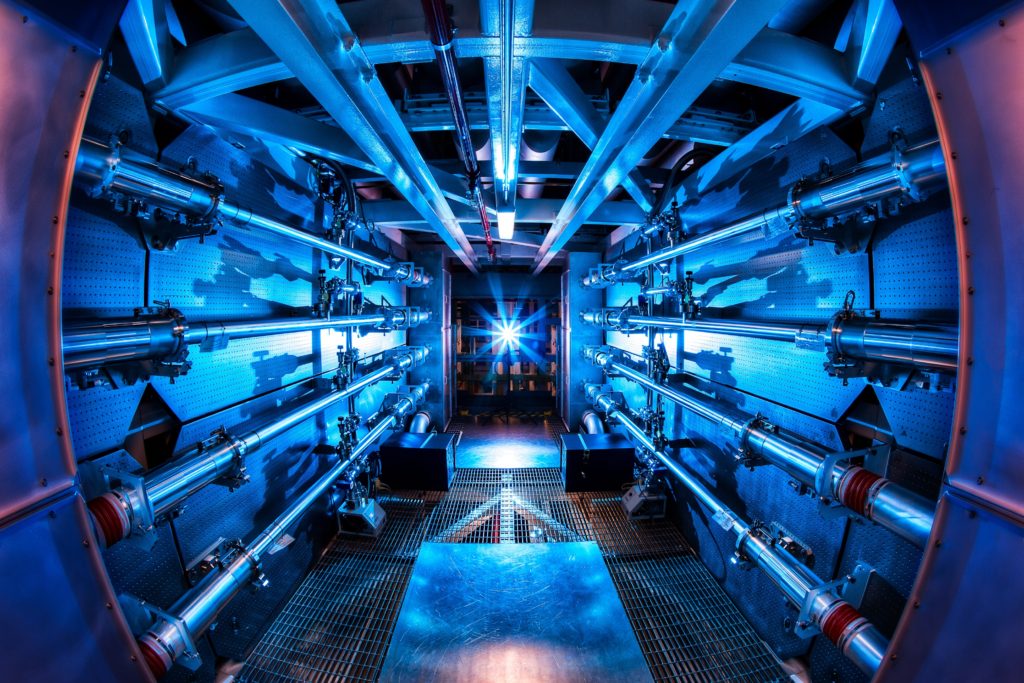

Thermal confinement fusion uses heat or large lasers to heat a small fuel pellet many millions of degrees. One of the most common is laser confinement, where the outer shell of the fuel “ignites” causing the inner pellet to explode (this happens very quickly, causing a considerable shockwave). As the inner pellet implodes, large density (several times the density of lead) and temperature (100 million Kelvin) is achieved. This inner pellet then ignites, releasing energy and burning the rest of the fuel pellet. The goal is to achieve a net energy release from the pellet burning compared to the laser energy input. Fusion has been demonstrated by such devices, though a Q value greater than 1 has not. The most notable current developments are the National Ignition Facility (NIF) in the USA and the Laser Mégajoule (LMJ) in France. There are a few leading technologies available in thermal confinement:

- Laser-driven

- Acoustic confinement

- Electrostatic confinement

Magnetic confinement fusion

Magnetic confinement fusion uses the magnetic properties of plasma (a mix of positive ions and negative electrons) to keep a dense (~ 1 bar), hot plasma (~ 300 million Kelvin) confined in a chamber to fuse the ions together. There are a few main methods of magnetic confinement fusion:

Stellarator

The Tokamak design was originally proposed in 1950 by Andrei Sakharov and Igor Tamm, the first such device being built in Moscow in 1956 at the Institute of Nuclear Fusion. This is the most sought-after device because, in 1968, Q values several degrees in magnitude higher than other devices were achieved.

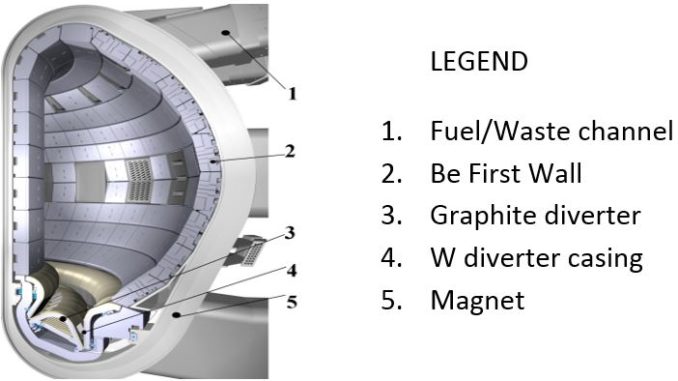

The Tokamak is a toroid that is rotationally symmetrical. Large helical magnetic fields are produced by running a current through the plasma. This ensures that the plasma is denser in the middle, but also requires considerable external input power. This power can be supplied through re-direction from the power generation on site in a fusion power plant. In areas where the plasma has the lowest interactions with the wall, Berrilium is used as a wall material. While plasma-wall interactions are inevitable, their locations are mostly limited to the areas where magnetic field lines are designed to cross the chamber wall. In these areas, tungsten diverters with a melting temperature of 3695K are placed. Graphite material is used on the walls the area of highest ion flux: Carbon lowers the plasma temperature less than tungsten and retains its shape even after melting.

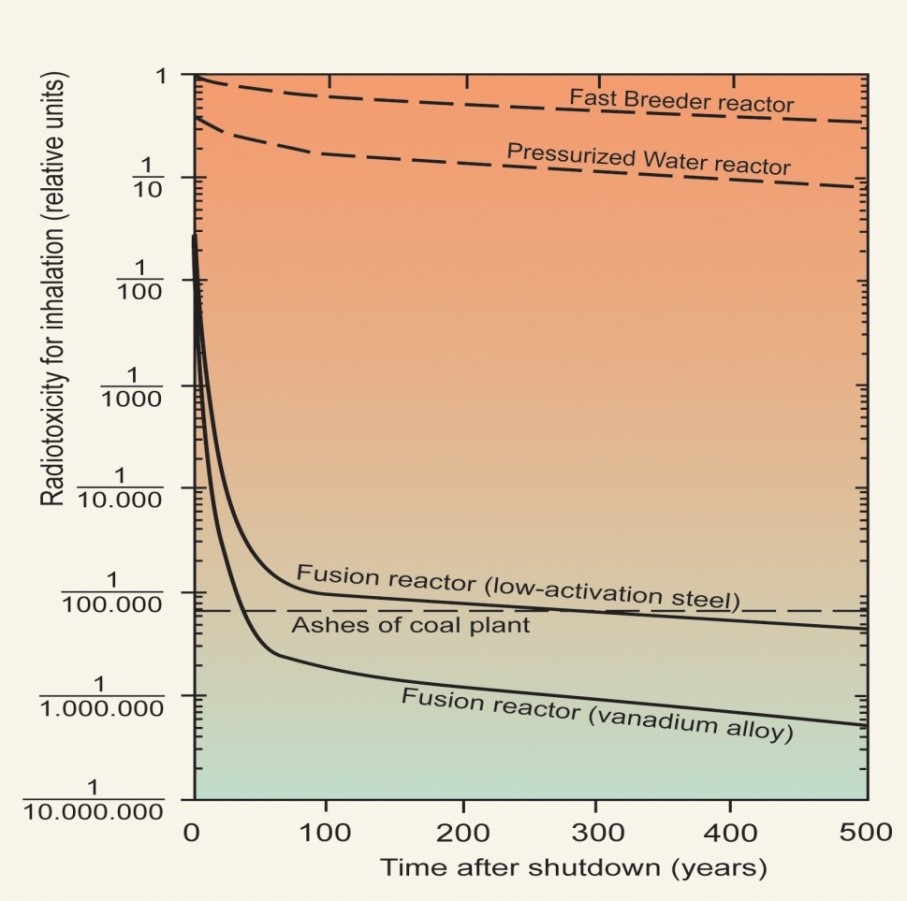

Tokamak designs have inherent flaws. Plasma confinement forces the toroid wall material to be replaced every year. The toroid needs to be large to achieve the required plasma density (larger cross sections increase the plasma magnetic properties, creating a denser plasma core). This increases the wall and waste volume. However, the waste radioactivity is much lower than nuclear applications:

Tokomaks also have their magnetic field lines concentrated in the middle, meaning any larger collisions that do not cause fusion will ultimately cause these ions to hit the wall, an unwanted phenomenon. Up until a few years ago, Tokamaks have been quite successful, and the rate of increase in Tokomak performance had outstripped Moore’s law for the miniaturization of silicon chips.

Any given Tokomak device can use a different fuel, and different plasma parameters (within a range). (Q=1) has been successfully achieved at the JT-60U in Japan and the JET in England. The ITER project hopes to achieve plasma ignition, where the fusion reaction will be self-sustaining, and no external input will be required (Q approx. 5).

Wall Materials

The wall materials used in fusion reactors is critical. Wall surfaces face cyclic loading in temperatures higher than 1000 Celsius for sustained periods over years, large neutron fluxes, plasma-wall interactions, and near-vacuum working conditions. As the high-speed plasma particles hit the edge of the wall, some erosion of the wall material occurs. The larger debris particles lower the plasma temperature and inhibit fusion. Fast neutrons present after a fusion reaction can cause the wall material nuclei to change and become radioactive. This is why Beryllium is used for most of the wall: Be is a very light atom and its debris does not lower the plasma temperature significantly, it can efficiently absorb many neutrons safely (having a large neutron cross-section) and has a melting point of 1560K.

It is hard to mention modern magnetic confinement fusion without reference to ITER. Using its 840m 3 reactor chamber, ITER plans to produce 500MW of fusion energy when first plasma is achieved (expected 2025). An expected Q value of 10 is expected to be sustained for up to 400 seconds, allowing for a steady state Q value of more than 5. The project hopes to demonstrate that a plasma can form a self-sustaining ‘burning’ reaction. Other objectives include improving technologies required for fusion power production, expanding tritium breeding concepts, and refining neutron shield/heat conversion technology.

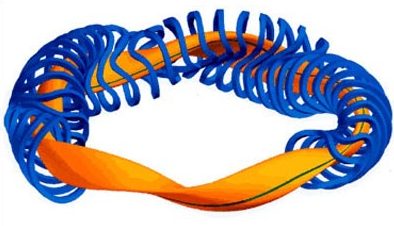

The Stellarator was developed by Lyman Spitzer in 1951; construction started on the first device at the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory in 1951. While the Tokamak induces a current to form a magnet, a Stellarator uses external magnetic coils to magnetically confine the plasma. The cross-section of a Stellarator is bent into a figure eight, which solves the problem in Tokomaks where the magnetic field lines are more concentrated in the middle. Notable current Stellarators include the Large Helical Device in Japan, NCSX at Princeton, H-1NF in Australia, and the Wendelstein 7-X in Germany. The figure below shows the plasma in orange, the magnetic coils in blue, and an ion path in black:

Wendelstein 7-X

The Wendelstein 7-X first conducted plasma heating in 2015, and its team has recently (March 2018) conducted experiments with results published in nature . It is based on the parameters of the Wendelstein 7-AS (pictured above) but is much larger (a plasma volume of 30 cubic meters as opposed to 1 cubic meter). Stellarators suffer from other problems not common in the Tokamak design. Because of the twisting magnetic fields, particle orbits need to be carefully considered to minimize collisional transport and toroidal transport current.

Plasma Heating

To achieve high plasma temperatures, several interesting heating procedures are used. At different fuel temperatures, different methods are used to heat the plasma.

Ohmic Heating

In the initial stages of plasma heating, Joule, or Ohmic heating is used. As current is passed through a resistor, the resistor changes some of the electric energy into heat. Because the plasma is a conductor (a mixture of free ions and electrons), Ohmic heating is considerably effective in heating the plasma. However, the resistivity of plasma decreases in accordance with Spitzer’s law:

Where: Z – Plasma resistivity, k – plasma-constituent constant, T – Temperature [Kelvin]. This method is most effective for cooler plasma; as the plasma is heated, other methods are used.

Neutral Beam Injection

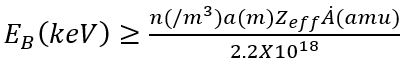

Another form of plasma heating involves injecting a beam of neutral atoms, typically deuterium (a hydrogen atom with one neutron). The high kinetic energy of these atoms is transformed into thermal energy as the new deuterium bounces off ions in the plasma. Although not originally plasma, the deuterium gets ionized quickly and adds to the background plasma already in the reactor. The atoms must be neutral in order to pass through the magnetic field surrounding the plasma; once in the plasma, the ions are charged via collisions, to stay confined within the plasma and transfer their energy to the plasma. The attenuation of a neutral beam is governed by the following equation:

Where: I B (s) – the flux of neutral particles [particles/m 2 s], n – plasma ion / electron density [particles/m 3 ], <σv> – activity for charge-exchange ionization [m 3 /sec], and λ is the mean free path for the attenuation [m]. Experiments reveal that plasma will be heated if the mean free path is greater than one fourth the plasma radius. Therefore, the neutral beam energy required can be calculated:

For typical applications this is 50 keV to 130 keV, depending on plasma density. In comparison, the central plasma region has a maximum thermal energy of 15 keV.

Other forms of heating

Other forms of heating include radio-frequency heating, where the plasma caused to move to the motion of an electrostatic wave. This macro movement causes plasma heating. A subset of this heating is wave heating. Fusion alpha-heating is also used; however, this uses high energy fusion by-products (Helium) to heat the plasma.

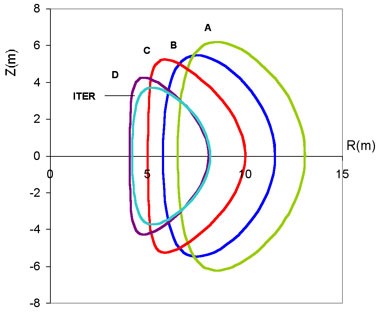

The capital and operational costs of fusion power generators strongly depend on the technology used and the fuel (fusion reaction) chosen; good comparisons can be drawn with natural gas and nuclear power reactors. The general trend for nuclear power plants is for a greater O/M cost and smaller fuel cost as the plant ages. Regulatory delays, redesign requirements and difficulties in construction management and quality control all inflate costs. Fusion Tokamaks and Stellarators are calculated to have higher capital costs than nuclear stations; a report entitled “Power Plant Conceptual Study (PPCS)” written by the EFDA in 2005 analyzed 4 different Tokomak models both economically and environmentally. The sizes of these reactors are shown in figure 8, ITER is shown as a comparison.

The study found that the economic feasibility of fusion reactors highly depends on the downtime of the reactor. Because wall materials need to be replaced, a replacement scheme needs to be implemented that can maximize the reactor availability for power production. Using the most optimized geometries, a reactor availability of over 75% can be achieved – enough for economic feasibility.

It should be noted that such a study in conceptual; most studies like this tend to lower the foreseeable costs, as this is the agenda of the parties involved

Environmental Impact

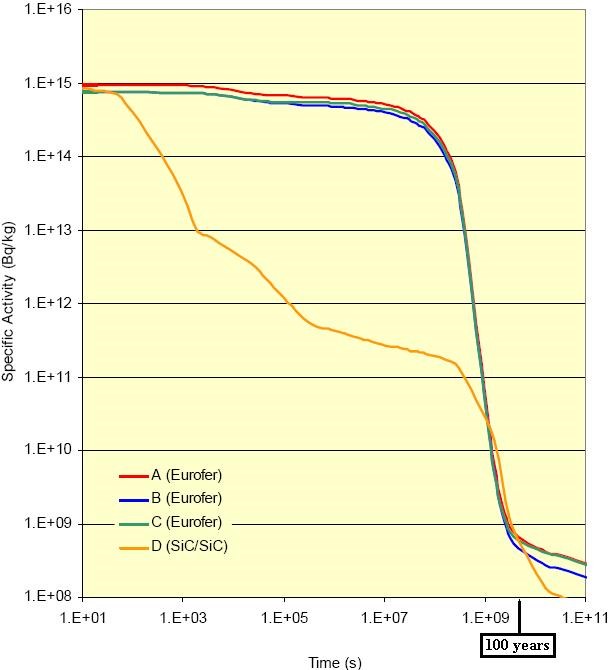

The environmental impact of fusion reactors is highly dependent on their application and fuel cycle. As shown in table 1, the D-T reaction creates the highest energy neutrons. High energy neutrons travel the longest before losing their energy and cause the most disruptions. Using Tritium (which is radioactive with a half-life of 12.4 years) also increases the radioactivity of the cycle. Because of the high neutron flux inside a D-T plasma and immediate wall, the reactor can be used as a breeder reactor for nuclear applications. This will increase the radioactivity inside the reactor, and its time before the reactor metals can be reused. In the case were no breeding is done (neutrons are moderated conventionally), half the material used as the first wall would be suitable for re-use within 100 years if the D-T reaction were used. Also, the rate of decay is considerably different for different wall materials used, as shown in figure9.

It is evident that ferrous alloys will be more radioactive during the decay cycle than carbon-silicon alloys.

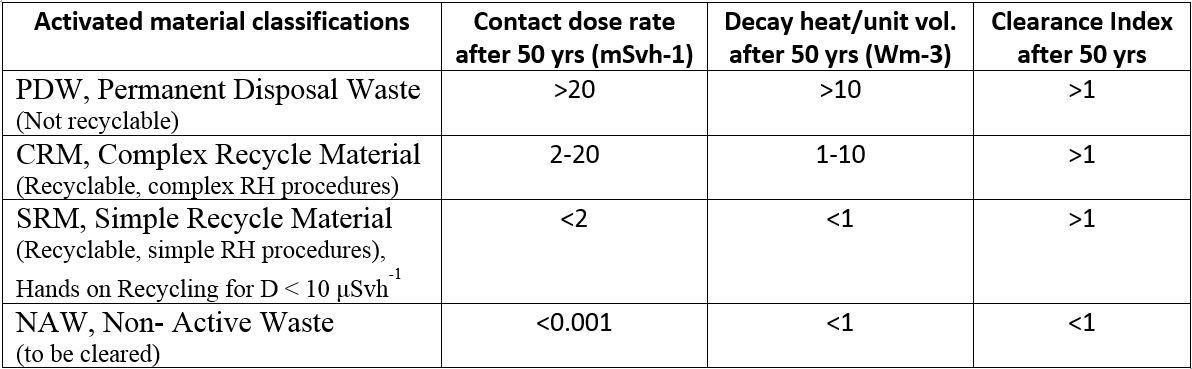

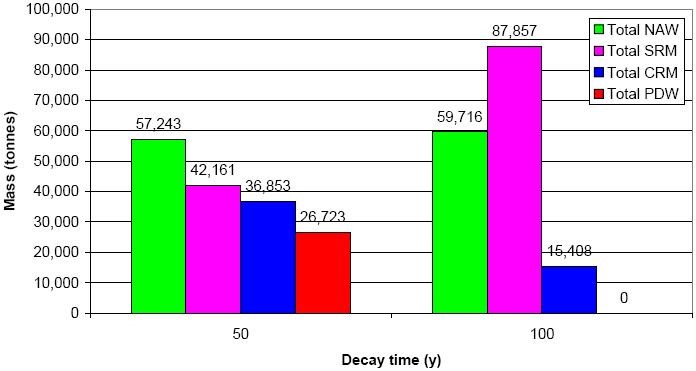

In the PPCS, the waste production for option A, the biggest option, are classifications are as follows:

The waste volume is shown in figure 9. It should be noted that there is no high-level waste after 100 years. After 150 years, all waste will be classified as either SRM or NAW.

Fusion reactors have an intrinsic safety feature for accidents. Because only about 30 minutes of fuel is present in the reactor at any given time (compared to a year’s worth in nuclear reactors), the implications of a nuclear complete catastrophe are many magnitudes smaller than a nuclear catastrophe. As studied in the PPCS, the worst case most exposed individual 7-day dose for the largest plant option A for the Loss of coolant flow inside the reactor and loss of coolant outside the reactor is 0.42 mSv. An X-Ray scan gives 0.04-1.0 mSv, depending on the size of the scan.

However, a catastrophe will cause wall material to rise to unacceptable temperatures. The economic implications of an accident, as studied in the PPCS, are known as external costs. The external costs of option A were found to be 0.861 million Euro/kWh, with a 68% confidence in the (0.225 – 3.494) range. The size of this range indicates this is an inexact science; exact values cannot be estimated accurately.

While nuclear reactors are not within the immediate future for use as an energy source, their study is greatly beneficial to the scientific community. Before reaching economic feasibility, magnetic confinement fusion reactors still need considerable research and development. Tokamak reactors are currently the most promising. However, these reactors are still decades away from economic feasibility. Even if we never use fusion energy for commercial purposes in the next 100 years, it can prove to be a compelling source of energy in the long term for the human race.

NTRS - NASA Technical Reports Server

Available downloads, related records.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Conceptual travel may be similar to human travel, i.e. a concept travels to other cultures, countries, and histori- cal periods. Goertz and Mazur regard this expor t as an ideational expansion ...

3* The Art Cities of Italy by Rail - Italy Package (6 Nights) ITALY. TRAVEL DATES. 01/02/2024 - 27/08/2024. FROM R15125 pp (excluding flights) The Experience. Visit the Art Cities of Italy by rail - see the major sites and enjoy plenty of free time to explore these wonderful cities on your own. Rome is an extraordinary city rich in charm like ...

Conceptual Travel, Cape Town, Western Cape. 788 likes. Where innovative service delivery comes standard.

Like air travel, eco-conscious hotels are paving the way for more sustainable travel in the future. When room2 Chiswick opened in London in 2021, it became the world's "whole life net-zero ...

BANKIMCHANDRA CHATTOPADHYAY AND THE EMERGENCE OF AN INDIAN NATIONALIST THEOLOGY OF LAW. The essayist and novelist Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay is often considered nineteenth-century India's most famous littérateur. Footnote 20 He inherited a Brahmin family tradition of Sanskrit education, which was augmented through contact with Sanskrit scholars of the famous town of Bhatpara.

Through a scoping literature review, this paper identifies the foundational elements of its conceptual and ontological roots, extracting key insights and discursive themes that can help establish a comprehensive perspective on the study and management of popular culture tourism. ... Film-related travel, mediatization, fandom, and heritage are ...

Conceptual travel has been the dedicated travel agency for Nordex South Africa since 2012. We have grown from 1 person to having 3 staff with offices located in Westlake, Cape Town. Nordex has been instrumental in the growth and development of Conceptual travel through the supplier enterprise development programme since 2014.

The aim of this conceptual article is to propose a comprehensive model that explains the impact of different relational variables on tourists' behavioral intention ... Travel experiences are defined as the "subjective mental state felt by participants during a service encounter" (Otto & Ritchie, 1996, p. 166). In regard to this matter ...

Purpose of Review This paper reviews the use of conceptual frameworks in research on active travel, such as walking and cycling. Generic framework features and a wide range of contents are identified and synthesized into a comprehensive framework of active travel behavior, as part of the Physical Activity through Sustainable Transport Approaches project (PASTA). PASTA is a European ...

Theories and concepts of political transition have been influenced to a great deal by Western theoretical and conceptual reflection. The parameters of transition are usually based on two assumptions or expectations: The goal of transition is democracy or a democratic system, and both actors and affected persons are perceived as gender-neutral beings, i.e., there is no distinction made between ...

Conceptual Travel was formed to bring back the individual touch to planning a holiday or corporate travel arrangements. Conceptual Travel is owned and managed by myself, Janine Mocke. In addition to my 13 years experience in the industry I am passionate about travelling.

CONCEPTUAL TRAVEL is an independently run travel agency that offers personalised professional and expert travel management services customised to each clients' specific needs. With over thirteen years in the Travel and Tourism industry, and a deep understanding of the industry and passion for travel, you can be assured that your travelling ...

This tour will meet almost every expectation on a trip one could wish for. Full of cultural and religious sights, spectacular architecture, temples and palaces, the majestic Himalayas and shimmering...

Spend 2 nights in the idyllic Stellenbosch wine country. Contact us for more information. 4* The Spier Hotel - Stellenbosch Summer Offer (2 Nights) WESTERN CAPE Hotel Included, Self-drive TRAVEL...

Apr. 19, 2024. View more reviews. Private guided tours and small group tours for travelers who love to learn. Book cultural and educational experiences in 60+ cities worldwide.

Through conceptual models, the paper demonstrates how AI can seamlessly offer personalized travel recommendations, intelligent itinerary planning, and real-time assistance. ... In essence, this exploration highlights how AI is fundamentally reshaping travel within "Tourism 3.0," promising a future of personalized, immersive, and ethically ...

conceptual travel demand modelling framework, which set the map for developing the travel demand models. This research presents a conceptual ... travel patterns to establish a transportation library to be able to model travel demand and propose solutions to transportation issues. Technology as presented above can help

Don't forget that this is 360 video: you can change the angle of view. We invite you on a virtual journey to Moscow. Spring is a very beautiful season: natur...

3* Cabanas - Sun City Midweek Package (2 Nights) NORTH WEST Hotel Included, Self-drive TRAVEL DATES 01/12/2021 - 02/12/2022 FROM R1642 pp...

You cannot resist our Two Hearts of Russia (7 Days &6 Nights), Golden Moscow (4 Days &3 Nights), Sochi (3 Days & 2 Nights), Golden Ring (1 Day & 2 Days), and many more. As a leading travel agency specializing in the tour to Russia and Former Soviet Republics, we are connecting the travellers from every part of the world for more than 10 years.

Purpose of Review. This paper reviews the use of conceptual frameworks in research on active travel, such as walking and cycling. Generic framework features and a wide range of contents are identified and synthesized into a comprehensive framework of active travel behavior, as part of the Physical Activity through Sustainable Transport Approaches project (PASTA).

It should be noted that such a study in conceptual; most studies like this tend to lower the foreseeable costs, as this is the agenda of the parties involved ... As shown in table 1, the D-T reaction creates the highest energy neutrons. High energy neutrons travel the longest before losing their energy and cause the most disruptions. Using ...

The Centrifugal Nuclear Thermal Rocket (CNTR) is one of few designs that could enable extremely rapid missions to Mars using currently available technologies. McCarthy conducted the first conceptual study of high performance nuclear thermal propulsion (NTP) and published his findings in 1954. High performance NTP was further investigated by Princeton researchers in the early 1960s and ...

Moscow Travel Mobile & Desktop Lightroom Presets Pack will create trendy soft tones in a few click and allow you to spend more time shooting. It's a great collection of 9 professional