UN Tourism | Bringing the world closer

Competitiveness.

- Market Intelligence

- Policy and Destination Management

Product Development

Share this content.

- Share this article on facebook

- Share this article on twitter

- Share this article on linkedin

As defined by UN Tourism, a Tourism Product is "a combination of tangible and intangible elements, such as natural, cultural and man-made resources, attractions, facilities, services and activities around a specific center of interest which represents the core of the destination marketing mix and creates an overall visitor experience including emotional aspects for the potential customers. A tourism product is priced and sold through distribution channels and it has a life-cycle".

Rural tourism

UN Tourism understands Rural Tourism as "a type of tourism activity in which the visitor’s experience is related to a wide range of products generally linked to nature-based activities, agriculture, rural lifestyle / culture, angling and sightseeing.

Gastronomy and Wine Tourism

As global tourism is on the rise and competition between destinations increases, unique local and regional intangible cultural heritage become increasingly the discerning factor for the attraction of tourists.

Mountain Tourism

Mountain Tourism is a type of "tourism activity which takes place in a defined and limited geographical space such as hills or mountains with distinctive characteristics and attributes that are inherent to a specific landscape, topography, climate, biodiversity (flora and fauna) and local community. It encompasses a broad range of outdoor leisure and sports activities".

Urban Tourism

According to UN Tourism, Urban Tourism is "a type of tourism activity which takes place in an urban space with its inherent attributes characterized by non-agricultural based economy such as administration, manufacturing, trade and services and by being nodal points of transport. Urban/city destinations offer a broad and heterogeneous range of cultural, architectural, technological, social and natural experiences and products for leisure and business".

Sports Tourism

Tourism and sports are interrelated and complementary. Sports – as a professional, amateur or leisure activity – involves a considerable amount of traveling to play and compete in different destinations and countries. Major sporting events, such as the Olympic Games, football and rugby championships have become powerful tourism attractions in themselves – making a very positive contribution to the tourism image of the host destination.

Shopping Tourism

Shopping Tourism is becoming an increasingly relevant component of the tourism value chain. Shopping has converted into a determinant factor affecting destination choice, an important component of the overall travel experience and, in some cases the prime travel motivation.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Service Design for Product Development in Tourist Destinations

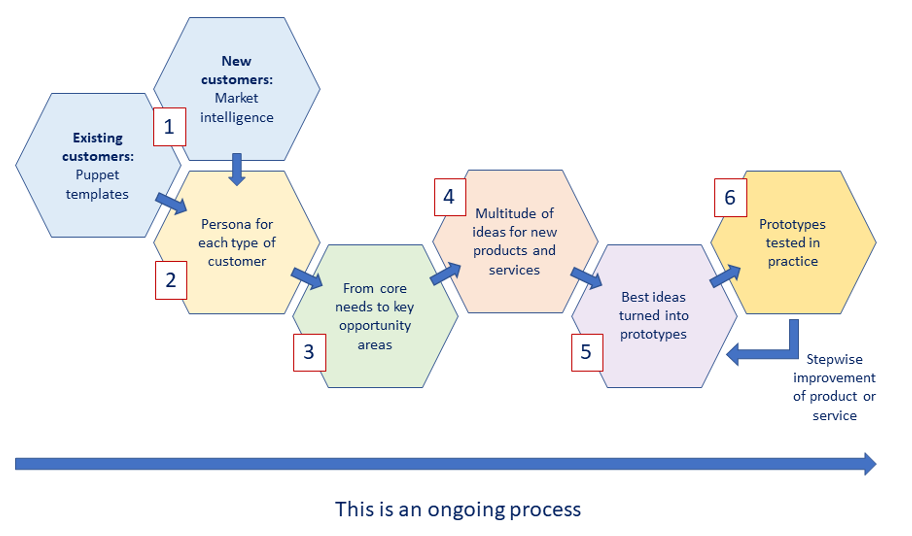

The purpose of this paper is to explore relevant issues regarding product development in alpine destination management and to generate a first dataset for the application of service design methods and tools in tourist destinations on the example of Austrian destinations. The conceptual framework of this paper reviews thoroughly relevant literature regarding service and product development in tourist destination. The empirical part surveys all Austrian tourist destinations (full survey) with a standardized online questionnaire regarding product development and the application of twelve selected service design methods and tools to finally deduce recommendations for destination management. The results of the survey assert a high degree of product development performance among Austrian tourist destination. The average degree of use of the selected service design methods and tools increase highly significant, if the destination applies a service design focused product development approach. This survey comprises exclusively Austrian tourist destination. Future research should foster empirical studies to validate the results outside Austria.

Related Papers

Proceedings of the First Nordic Conference on …

Prof. Dr. Anita Zehrer

Manuela Hrvatin

Purpose – A large number of players involved in supply and delivery of tourist experience, on the one side, and visitors’ unique experience on the other, make the development of the service concept of an innovative tourism product at destination very complex. Although there is a tendency towards increasing multiple partnerships in managing services, the requirements and standardization of processes in the performance management model is missing. The proposed conceptual model of the service concept is a useful tool for analyzing the overall service concept performance, stressing the importance of the Quadro Helix Model of engagement. The paper aims to investigate the innovative service concept and service processes from the operational and service marketing perspective, starting from the theoretical background and the constructs such as “organizing idea”, “service provided” and “service received”. The proposed model is tested on the case of “Istra Inspirit”, a project that has receiv...

Sustainability

josé António C. Santos

This study sought to develop a conceptual model of innovative tourism product development, because the existing models tend to provide an incomplete framework for these products' development. The models presented to date focus on either the resources needed, the tourism experiences to be provided, or development processes. These models also tend to see the overall process as linear. The proposed model gives particular importance to the development process's design, as well as stressing a dynamic, nonlinear approach. Based on the new services or products' concept, project managers identify tourism destinations' core resources, select the stakeholders, and design transformative tourism experiences. This framework can be applied to innovative tourism products or re-evaluations of existing products in order to maintain tourism destinations' competitiveness. Thus, the model is applicable to both destination management companies and the private tourism sector.

CARRUBBO Luca

Sedat Yuksel

The concept of service, which has an important place in meeting the needs of consumers, has had to develop itself in the historical process with industrial and social development. The concept of service, which is experiencing a natural development process, forces the companies that provide services to innovate in their product service designs, with the developments in technology and technology in the market today. Competition is based on innovations in service design and their acceptance by consumers. Accommodation businesses, which are one of the main businesses of the tourism industry, have to reconsider their service designs with the effect of these developments in the market. This study focuses on the service designs of brand hotel businesses in Antalya Belek region. In this context, the study aims to reveal whether and how hotel businesses develop their service designs and how innovation is used in service design with the effect of technology. The study has employed semi-structured interview to collect qualitative data. Belek region was chosen as the universe of the study and the sample consists of five hotel businesses. The research was conducted by using the knowledge of senior hotel managers and department (department) managers. A questionnaire consisting of three parts was prepared for data collection. In the first part, there exist information about enterprises, in the second part, the demographic characteristics and information of the managers participating in the research, and in the third part, there are five questions asked to the managers. As the finding, it was found that respondents are aware of the importance of service design in hospitality industry. They design their service by using technology almost in all departments.

Gestion 2000

Benjamin Nanchen

A "Think Tank" for the interpretation of two Italian case studies, as evidences of general tourism business trends We live in a Service Age. In everyday life, as well as in business management, every action, behavior, process, strategy is increasingly oriented to service. Tourist business is strongly affected by service sciences principles, in fact in Tourism both the internal organization and the external promotion are strictly related to service. Moreover we can observe how all relationships for tourism development for wise and competitive destination management are based on service logics. Thus this paper wants to highlight the relevant role of new service paradigms within the strategic and operative models of destination management and the significant contribution coming from Service Science, Management and Engineering and Design. After an analysis of the common behavior of tourism destination's actors, a comparison between different statistical trends stimulating a transition toward the Service Age was deployed; then direct effects of checked changes on nowadays destination systems were deepened, highlighting an emerging common vision for organization, operations, strategies, marketing and developments on tourist services.

Χρήστος Βασιλειάδης

The scope of the paper is to present the proper tourist product characteristics and market opportunities by the recipients of the tourist market, aiming at the support of the sustainable tourism design process. These characteristics concern the prospective elevated tourist destinations that may be exploited strategically by the tourist administration of the destinations. For the investigation of the most important product characteristics factor analysis was applied, as well as, spatial perceptual mapping techniques. The paper is based on a situation analysis, using as case the Rhodopi Mountain area in Greece. Results showed that the design of the elevation of the destination is a viable market prospective, if it is based on three major factors: the climate (geophysical and archaeological characteristics), taverns-restaurants (gastronomy) and parking areas (spa, post shops and health centers). Various combinations of relevant characteristics are proposed, which ameliorate particular ...

Advance in Tourism Studies in Memory of Clara S. Petrillo

Valentina Della Corte

International Journal of Management & Information Systems (IJMIS)

María Cordente Rodríguez

Companies, like human beings, also have five senses: marketing, sales team, service, contact centre and analytical; and doing without one of these would mean possessing a disability. Thus, a study of the satisfaction with a tourist destination is a highly relevant factor for tourist supervisors, since its results make it possible to find out about the right sales strategies and decisions that have to be adopted in order to improve the management and the competitiveness of the destinations. This study aims to check the level of dependency between two fundamental elements of the behaviour of tourism consumers, such as the reason why the trip was undertaken and the tourist’s objective satisfaction.

RELATED PAPERS

Michael W Usrey

Tito Díaz Bravo

Natural Hazards

Suraj Gautam

Berkala Ilmiah Pendidikan Fisika

Muhammad Muslim

Ester Schwarz

medicinabalear.org

Angel Adir vazquez gonzalez

Archives of Medical Science

Control Engineering Practice

Michel Fliess

Nature Neuroscience

Igor Krivec

Marconi Batista Teixeira

Journal of Food Biochemistry

Ismet Burcu Turkyilmaz

Fenômenos Linguísticos e Fatos de Linguagem

Alessandra Melo

European Scientific Journal, ESJ

Soufouyane Zakari

Heidi Wyrosdick

Research Square (Research Square)

Santiago Woollands

Bienvenido Balotro

Advances in social science, education and humanities research

Safwat Ardy

Mycopathologia

Process Biochemistry

Valeria Cappa

Drug Delivery System

Masakatsu Takanashi

hgvfgd ghtgf

Jcr-journal of Clinical Rheumatology

Applied Animal Behaviour Science

Mark Rutter

DergiPark (Istanbul University)

Osman Ozkul

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

The future of tourism: Bridging the labor gap, enhancing customer experience

As travel resumes and builds momentum, it’s becoming clear that tourism is resilient—there is an enduring desire to travel. Against all odds, international tourism rebounded in 2022: visitor numbers to Europe and the Middle East climbed to around 80 percent of 2019 levels, and the Americas recovered about 65 percent of prepandemic visitors 1 “Tourism set to return to pre-pandemic levels in some regions in 2023,” United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), January 17, 2023. —a number made more significant because it was reached without travelers from China, which had the world’s largest outbound travel market before the pandemic. 2 “ Outlook for China tourism 2023: Light at the end of the tunnel ,” McKinsey, May 9, 2023.

Recovery and growth are likely to continue. According to estimates from the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) for 2023, international tourist arrivals could reach 80 to 95 percent of prepandemic levels depending on the extent of the economic slowdown, travel recovery in Asia–Pacific, and geopolitical tensions, among other factors. 3 “Tourism set to return to pre-pandemic levels in some regions in 2023,” United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), January 17, 2023. Similarly, the World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC) forecasts that by the end of 2023, nearly half of the 185 countries in which the organization conducts research will have either recovered to prepandemic levels or be within 95 percent of full recovery. 4 “Global travel and tourism catapults into 2023 says WTTC,” World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC), April 26, 2023.

Longer-term forecasts also point to optimism for the decade ahead. Travel and tourism GDP is predicted to grow, on average, at 5.8 percent a year between 2022 and 2032, outpacing the growth of the overall economy at an expected 2.7 percent a year. 5 Travel & Tourism economic impact 2022 , WTTC, August 2022.

So, is it all systems go for travel and tourism? Not really. The industry continues to face a prolonged and widespread labor shortage. After losing 62 million travel and tourism jobs in 2020, labor supply and demand remain out of balance. 6 “WTTC research reveals Travel & Tourism’s slow recovery is hitting jobs and growth worldwide,” World Travel & Tourism Council, October 6, 2021. Today, in the European Union, 11 percent of tourism jobs are likely to go unfilled; in the United States, that figure is 7 percent. 7 Travel & Tourism economic impact 2022 : Staff shortages, WTTC, August 2022.

There has been an exodus of tourism staff, particularly from customer-facing roles, to other sectors, and there is no sign that the industry will be able to bring all these people back. 8 Travel & Tourism economic impact 2022 : Staff shortages, WTTC, August 2022. Hotels, restaurants, cruises, airports, and airlines face staff shortages that can translate into operational, reputational, and financial difficulties. If unaddressed, these shortages may constrain the industry’s growth trajectory.

The current labor shortage may have its roots in factors related to the nature of work in the industry. Chronic workplace challenges, coupled with the effects of COVID-19, have culminated in an industry struggling to rebuild its workforce. Generally, tourism-related jobs are largely informal, partly due to high seasonality and weak regulation. And conditions such as excessively long working hours, low wages, a high turnover rate, and a lack of social protection tend to be most pronounced in an informal economy. Additionally, shift work, night work, and temporary or part-time employment are common in tourism.

The industry may need to revisit some fundamentals to build a far more sustainable future: either make the industry more attractive to talent (and put conditions in place to retain staff for longer periods) or improve products, services, and processes so that they complement existing staffing needs or solve existing pain points.

One solution could be to build a workforce with the mix of digital and interpersonal skills needed to keep up with travelers’ fast-changing requirements. The industry could make the most of available technology to provide customers with a digitally enhanced experience, resolve staff shortages, and improve working conditions.

Would you like to learn more about our Travel, Logistics & Infrastructure Practice ?

Complementing concierges with chatbots.

The pace of technological change has redefined customer expectations. Technology-driven services are often at customers’ fingertips, with no queues or waiting times. By contrast, the airport and airline disruption widely reported in the press over the summer of 2022 points to customers not receiving this same level of digital innovation when traveling.

Imagine the following travel experience: it’s 2035 and you start your long-awaited honeymoon to a tropical island. A virtual tour operator and a destination travel specialist booked your trip for you; you connected via videoconference to make your plans. Your itinerary was chosen with the support of generative AI , which analyzed your preferences, recommended personalized travel packages, and made real-time adjustments based on your feedback.

Before leaving home, you check in online and QR code your luggage. You travel to the airport by self-driving cab. After dropping off your luggage at the self-service counter, you pass through security and the biometric check. You access the premier lounge with the QR code on the airline’s loyalty card and help yourself to a glass of wine and a sandwich. After your flight, a prebooked, self-driving cab takes you to the resort. No need to check in—that was completed online ahead of time (including picking your room and making sure that the hotel’s virtual concierge arranged for red roses and a bottle of champagne to be delivered).

While your luggage is brought to the room by a baggage robot, your personal digital concierge presents the honeymoon itinerary with all the requested bookings. For the romantic dinner on the first night, you order your food via the restaurant app on the table and settle the bill likewise. So far, you’ve had very little human interaction. But at dinner, the sommelier chats with you in person about the wine. The next day, your sightseeing is made easier by the hotel app and digital guide—and you don’t get lost! With the aid of holographic technology, the virtual tour guide brings historical figures to life and takes your sightseeing experience to a whole new level. Then, as arranged, a local citizen meets you and takes you to their home to enjoy a local family dinner. The trip is seamless, there are no holdups or snags.

This scenario features less human interaction than a traditional trip—but it flows smoothly due to the underlying technology. The human interactions that do take place are authentic, meaningful, and add a special touch to the experience. This may be a far-fetched example, but the essence of the scenario is clear: use technology to ease typical travel pain points such as queues, misunderstandings, or misinformation, and elevate the quality of human interaction.

Travel with less human interaction may be considered a disruptive idea, as many travelers rely on and enjoy the human connection, the “service with a smile.” This will always be the case, but perhaps the time is right to think about bringing a digital experience into the mix. The industry may not need to depend exclusively on human beings to serve its customers. Perhaps the future of travel is physical, but digitally enhanced (and with a smile!).

Digital solutions are on the rise and can help bridge the labor gap

Digital innovation is improving customer experience across multiple industries. Car-sharing apps have overcome service-counter waiting times and endless paperwork that travelers traditionally had to cope with when renting a car. The same applies to time-consuming hotel check-in, check-out, and payment processes that can annoy weary customers. These pain points can be removed. For instance, in China, the Huazhu Hotels Group installed self-check-in kiosks that enable guests to check in or out in under 30 seconds. 9 “Huazhu Group targets lifestyle market opportunities,” ChinaTravelNews, May 27, 2021.

Technology meets hospitality

In 2019, Alibaba opened its FlyZoo Hotel in Huangzhou, described as a “290-room ultra-modern boutique, where technology meets hospitality.” 1 “Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba has a hotel run almost entirely by robots that can serve food and fetch toiletries—take a look inside,” Business Insider, October 21, 2019; “FlyZoo Hotel: The hotel of the future or just more technology hype?,” Hotel Technology News, March 2019. The hotel was the first of its kind that instead of relying on traditional check-in and key card processes, allowed guests to manage reservations and make payments entirely from a mobile app, to check-in using self-service kiosks, and enter their rooms using facial-recognition technology.

The hotel is run almost entirely by robots that serve food and fetch toiletries and other sundries as needed. Each guest room has a voice-activated smart assistant to help guests with a variety of tasks, from adjusting the temperature, lights, curtains, and the TV to playing music and answering simple questions about the hotel and surroundings.

The hotel was developed by the company’s online travel platform, Fliggy, in tandem with Alibaba’s AI Labs and Alibaba Cloud technology with the goal of “leveraging cutting-edge tech to help transform the hospitality industry, one that keeps the sector current with the digital era we’re living in,” according to the company.

Adoption of some digitally enhanced services was accelerated during the pandemic in the quest for safer, contactless solutions. During the Winter Olympics in Beijing, a restaurant designed to keep physical contact to a minimum used a track system on the ceiling to deliver meals directly from the kitchen to the table. 10 “This Beijing Winter Games restaurant uses ceiling-based tracks,” Trendhunter, January 26, 2022. Customers around the world have become familiar with restaurants using apps to display menus, take orders, and accept payment, as well as hotels using robots to deliver luggage and room service (see sidebar “Technology meets hospitality”). Similarly, theme parks, cinemas, stadiums, and concert halls are deploying digital solutions such as facial recognition to optimize entrance control. Shanghai Disneyland, for example, offers annual pass holders the option to choose facial recognition to facilitate park entry. 11 “Facial recognition park entry,” Shanghai Disney Resort website.

Automation and digitization can also free up staff from attending to repetitive functions that could be handled more efficiently via an app and instead reserve the human touch for roles where staff can add the most value. For instance, technology can help customer-facing staff to provide a more personalized service. By accessing data analytics, frontline staff can have guests’ details and preferences at their fingertips. A trainee can become an experienced concierge in a short time, with the help of technology.

Apps and in-room tech: Unused market potential

According to Skift Research calculations, total revenue generated by guest apps and in-room technology in 2019 was approximately $293 million, including proprietary apps by hotel brands as well as third-party vendors. 1 “Hotel tech benchmark: Guest-facing technology 2022,” Skift Research, November 2022. The relatively low market penetration rate of this kind of tech points to around $2.4 billion in untapped revenue potential (exhibit).

Even though guest-facing technology is available—the kind that can facilitate contactless interactions and offer travelers convenience and personalized service—the industry is only beginning to explore its potential. A report by Skift Research shows that the hotel industry, in particular, has not tapped into tech’s potential. Only 11 percent of hotels and 25 percent of hotel rooms worldwide are supported by a hotel app or use in-room technology, and only 3 percent of hotels offer keyless entry. 12 “Hotel tech benchmark: Guest-facing technology 2022,” Skift Research, November 2022. Of the five types of technology examined (guest apps and in-room tech; virtual concierge; guest messaging and chatbots; digital check-in and kiosks; and keyless entry), all have relatively low market-penetration rates (see sidebar “Apps and in-room tech: Unused market potential”).

While apps, digitization, and new technology may be the answer to offering better customer experience, there is also the possibility that tourism may face competition from technological advances, particularly virtual experiences. Museums, attractions, and historical sites can be made interactive and, in some cases, more lifelike, through AR/VR technology that can enhance the physical travel experience by reconstructing historical places or events.

Up until now, tourism, arguably, was one of a few sectors that could not easily be replaced by tech. It was not possible to replicate the physical experience of traveling to another place. With the emerging metaverse , this might change. Travelers could potentially enjoy an event or experience from their sofa without any logistical snags, and without the commitment to traveling to another country for any length of time. For example, Google offers virtual tours of the Pyramids of Meroë in Sudan via an immersive online experience available in a range of languages. 13 Mariam Khaled Dabboussi, “Step into the Meroë pyramids with Google,” Google, May 17, 2022. And a crypto banking group, The BCB Group, has created a metaverse city that includes representations of some of the most visited destinations in the world, such as the Great Wall of China and the Statue of Liberty. According to BCB, the total cost of flights, transfers, and entry for all these landmarks would come to $7,600—while a virtual trip would cost just over $2. 14 “What impact can the Metaverse have on the travel industry?,” Middle East Economy, July 29, 2022.

The metaverse holds potential for business travel, too—the meeting, incentives, conferences, and exhibitions (MICE) sector in particular. Participants could take part in activities in the same immersive space while connecting from anywhere, dramatically reducing travel, venue, catering, and other costs. 15 “ Tourism in the metaverse: Can travel go virtual? ,” McKinsey, May 4, 2023.

The allure and convenience of such digital experiences make offering seamless, customer-centric travel and tourism in the real world all the more pressing.

Three innovations to solve hotel staffing shortages

Is the future contactless.

Given the advances in technology, and the many digital innovations and applications that already exist, there is potential for businesses across the travel and tourism spectrum to cope with labor shortages while improving customer experience. Process automation and digitization can also add to process efficiency. Taken together, a combination of outsourcing, remote work, and digital solutions can help to retain existing staff and reduce dependency on roles that employers are struggling to fill (exhibit).

Depending on the customer service approach and direct contact need, we estimate that the travel and tourism industry would be able to cope with a structural labor shortage of around 10 to 15 percent in the long run by operating more flexibly and increasing digital and automated efficiency—while offering the remaining staff an improved total work package.

Outsourcing and remote work could also help resolve the labor shortage

While COVID-19 pushed organizations in a wide variety of sectors to embrace remote work, there are many hospitality roles that rely on direct physical services that cannot be performed remotely, such as laundry, cleaning, maintenance, and facility management. If faced with staff shortages, these roles could be outsourced to third-party professional service providers, and existing staff could be reskilled to take up new positions.

In McKinsey’s experience, the total service cost of this type of work in a typical hotel can make up 10 percent of total operating costs. Most often, these roles are not guest facing. A professional and digital-based solution might become an integrated part of a third-party service for hotels looking to outsource this type of work.

One of the lessons learned in the aftermath of COVID-19 is that many tourism employees moved to similar positions in other sectors because they were disillusioned by working conditions in the industry . Specialist multisector companies have been able to shuffle their staff away from tourism to other sectors that offer steady employment or more regular working hours compared with the long hours and seasonal nature of work in tourism.

The remaining travel and tourism staff may be looking for more flexibility or the option to work from home. This can be an effective solution for retaining employees. For example, a travel agent with specific destination expertise could work from home or be consulted on an needs basis.

In instances where remote work or outsourcing is not viable, there are other solutions that the hospitality industry can explore to improve operational effectiveness as well as employee satisfaction. A more agile staffing model can better match available labor with peaks and troughs in daily, or even hourly, demand. This could involve combining similar roles or cross-training staff so that they can switch roles. Redesigned roles could potentially improve employee satisfaction by empowering staff to explore new career paths within the hotel’s operations. Combined roles build skills across disciplines—for example, supporting a housekeeper to train and become proficient in other maintenance areas, or a front-desk associate to build managerial skills.

Where management or ownership is shared across properties, roles could be staffed to cover a network of sites, rather than individual hotels. By applying a combination of these approaches, hotels could reduce the number of staff hours needed to keep operations running at the same standard. 16 “ Three innovations to solve hotel staffing shortages ,” McKinsey, April 3, 2023.

Taken together, operational adjustments combined with greater use of technology could provide the tourism industry with a way of overcoming staffing challenges and giving customers the seamless digitally enhanced experiences they expect in other aspects of daily life.

In an industry facing a labor shortage, there are opportunities for tech innovations that can help travel and tourism businesses do more with less, while ensuring that remaining staff are engaged and motivated to stay in the industry. For travelers, this could mean fewer friendly faces, but more meaningful experiences and interactions.

Urs Binggeli is a senior expert in McKinsey’s Zurich office, Zi Chen is a capabilities and insights specialist in the Shanghai office, Steffen Köpke is a capabilities and insights expert in the Düsseldorf office, and Jackey Yu is a partner in the Hong Kong office.

Explore a career with us

7 Keys to creating a successful tourism product

What is a tourism product?

Basic functions of a tourism product, keys to designing a tourism product, examples of tourism products.

Within the competitive tourism sector, innovation, and the offer of products to propose stands out as one of the real competitive advantages and differential elements to navigate with strength in this tough market.

The tourism product becomes an important resource to work to attract a different audience and diversify the philosophy and brand of our travel agency .

But… How do you create a successful tourism product? Let’s highlight the keys that will help you develop an optimal tourism product. Let’s start at the beginning…

The tourism product is defined as the total set of functionally interdependent tangible and intangible elements that allow the tourist to meet their needs and expectations.

From a marketing point of view, the tourism product is a resource that fulfills two very different tasks:

- Each tourism product meets a need of its consumer through the benefits it incorporates.

- Tourism products are the means to achieve sales targets. The design of the tourism product itself is the claim to increase conversions.

Also, it is necessary to point out the importance of knowing the type of customer we want to attract and whether we can offer a product that meets the unique expectations of the selected niche of customers . It is equally important when designing a tourism product to consider the special travel agency regime to know the fiscal responsibilities and also how each transaction should be accounted for.

Also, our travel agency must have a brand culture and philosophy that must be in line with the tourism products to design and sell.

Given that meeting the needs and expectations of the client is a key factor in creating a tourism product, we must look to the functions that this tourism product must perform.

It is, therefore, possible to list 6 priority functions to be resolved to outline our tourism product project:

- Allows the tourist to participate in the main activity of the trip.

- Besides being a part of the main activity, it facilitates to live the total experience of the trip as the tourist wants.

- It facilitates transport to and from the destination , as well as within the destination itself.

- Enhance the social interaction of the tourist during the trip.

- Helps and simplifies travel preparation and management.

- It makes it easier for the tourist to remember and revive the trip , to share that trip and experience with other people.

Note : The main activity can be defined as the objective to be carried out with this tourist package: ecological tourism, cultural tourism, etc…

Through these functionalities, it is already possible to have a basic outline of what our tourism product should contain.

It is time to show the main keys to consider in drawing a professional and highly competitive tourism product.

Keeping the tourist as the main axis of the tourism product, we will start with those keys related to the needs that urge a person to make a tourist trip.

Means and conditions for participating in the main activity of the trip

Everything related to what is offered to the tourist to enjoy what he wants for the trip.

Elements in the trip’s destination and the trip’s transportation, for example, luxury cruises, boats, or trains.

Natural, cultural conditions, people, socio-economic conditions of destination, events, facilities, equipment, goods, and services related to the main activity also come into play in this category.

Qualitative aspects to involve the tourist in the main activity

At this point, all those aspects that help establish how the tourist is to engage and interact in the journey are defined.

The issues can be very different:

- Family trip or exotic destination

- Greater or less distance from the place of residence to destination.

- Luxurious or traditional atmosphere, etc…

On the other hand, also, everything linked to all the comforts a tourist needs to visit a destination and consume its “attractions” must be covered.

Modes and other transport components

Clear and detailed definition of all transport systems enabling the transition from a place of residence to destination and vice versa, as well as within destination.

Elements for social interaction and tourist comfort

Everything related, and that allows the tourist to engage in leisure activities, communicate with others, socialize or simply keep informed and perform routine activities.

In this category, we can include accommodation, points of sale and/or shops selling food, public baths (outside accommodation), all kinds of services (communication, internet, etc…) sports and leisure facilities, cultural events, etc.…

These details are a priority and important as they strengthen the comfort and decision-making capacity of the client .

Preparation of the management and execution of the trip

In this section, all those aspects that facilitate and give transparency to everything related to the management of the trip come into the scene.

Everything here is important: All tourist information media such as travel guides, maps, national tourist organizations, travel-related websites, services provided by tour operators, travel agencies, companions, translators, certified travel guides vaccines, solar protection, medicine, and health services; passports, visas, travel insurance; credit cards and other financial services… up to the number of packages or suitcases to carry.

Practical details on participation in the main activity of the trip

The customer must leave nothing to the imagination, it must be all well presented.

Here, questions such as sale or rental of sports equipment, sports lessons, wine tasting, etc…

These are aspects that help the tourist in understanding the tourism product and in the benefits/experiences that he will draw from it .

Remember and relive your experiences

A tourism product must be a unique and remembered experience by the customer, to satisfy his wishes and leave a good note in our brand of a travel agency.

Thus, to stimulate sentimental or emotional value, it is interesting the idea of offering memories and gifts, usually with sentimental and symbolic values for tourists, is a point that adds value.

They allow tourists to remember and relive their experiences, thus prolonging the pleasure of the trip. They are also used to share the travel experience and to strengthen ties with others.

Tourism products are designed and adapted to the needs and desires of the selected audience. So, there are many possibilities. Here are some of the most popular tourism products:

Spiritual tourism

Spiritual tourism is tourism motivated by faith or for religious reasons .

What is the tourist looking for? An experience based on a sacred pilgrimage, a journey led by faith, religion, and spiritual realization. The tourist seeks to satisfy some personal or spiritual need through tourism.

Therefore, the design of the spiritual tourism product must focus on these two points to find different forms and intensities of spiritual tourism motivated to a greater or lesser extent by religious or, on the contrary, cultural needs or in the search for knowledge.

Spiritual tourism provides the visitor with activities and/or treatments intended to develop, maintain, and improve the body, mind, and spirit . Many elements are incorporated that involve a learning experience.

A good example is the tourism products related to the Camino de Santiago. A product that offers everything the tourist/pilgrim wants:

- Accommodations

- Transportation

- Support vehicles

- Guides

- Monitor…

Wine tourism

Wine tourism or wine tourism is one of the most fashionable forms of tourism. It is the type of tourism around the culture and professions of wine and vineyards, being related to culinary and cultural tourism .

What is the wine tourist looking for? The main motivation is to experience wine tastings and buy products from the region, but also identify other very important issues: Socializing, learning about wines, entertainment, rural environment, relaxation…

The main activities are based on the visit to vineyards, wineries, wine festivals, and wine shows, for which the tasting of grape wine and/or the experience of getting to know the wine region.

For example, a well-known tourism product for wine lovers is that linked to the city of Haro , designed with such important elements as:

- Hotels and other types of accommodation

- Round-trip transportation from the winery to the lodging location

- Visit wineries, wine libraries, restaurants.

- Activities are related to wine tasting, marriage… where the capacity to socialize and share experiences is encouraged.

Ecotourism has grown in parallel with increasing society’s awareness of environmental protection.

Ecotourism is a type of tourism responsible for natural areas with special care in conserving the environment, sustaining the well-being of the local population, and involving knowledge and education .

What is the ecotourism tourist looking for? They are people with a great awareness of the environment, eager to know and be part of experiences that help the environment and others.

A good tourism product based on ecotourism should offer:

- Activities that encourage cultural awareness by promoting respect for the place you travel and the community you visit.

- It will help to create cultural awareness by promoting respect for the place you travel and the community you visit (environmental education workshops, ecosystem observation…)

- Activities that promote the well-being of the local community, including the economy. Guided ecological tours with the consent and participation of residents.

Ecotourism offers experiences that have a low impact on nature by preserving resources and protecting the environment.

A good example of ecotourism: Visit the local farmers’ fields in Chiapas, Mexico, learning how to make cocoa and supporting the conservation of their environment through product purchases on a guided tour.

Tour operators, travel agents, or travel agency management groups should consider these keys when creating and selling a successful tourism product. We must not forget that the tourism products respond effectively and attractively to the wishes, needs, and expectations of the selected type of customer , being a resource of great value to increase our brand image and customer loyalty.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Yay you are now subscribed to our newsletter.

Cristóbal Reali, VP of Global Sales at Mize, with over 20 years of experience, has led high-performance teams in major companies in the tourism industry, as well as in the public sector. He has successfully undertaken ventures, including a DMO and technology transformation consulting. In his role at Mize, he stands out not only for his analytical and strategic ability but also for effective leadership. He speaks English, Spanish, Portuguese, and Italian. He holds a degree in Economics from UBA, complementing his professional training at Harvard Business School Online.

Mize is the leading hotel booking optimization solution in the world. With over 170 partners using our fintech products, Mize creates new extra profit for the hotel booking industry using its fully automated proprietary technology and has generated hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue across its suite of products for its partners. Mize was founded in 2016 with its headquarters in Tel Aviv and offices worldwide.

Related Posts

Opening Up to New Markets While Maintaining the Brand

8 min. Case study of adapting the Mize brand for the East Asia market Making a cultural adjustment – finding the balance between global and local The process of growing globally can be very exciting and, at the same time, challenging. Although you are bringing more or less the same products and vision, the way […]

Travel Niche: What It Is, How to Leverage It, Case Studies & More

14 min. Niche travel is one of the few travel sectors that have maintained their pre-COVID market growth. By catering to specific traveler segments, niche travel developed products around adventure travel, eco-tourism, LGBTQ+ travel, and wellness retreats. Take adventure tourism as only one segment of the niche tourism market. In 2021, it reached 288 billion […]

4 Lessons You Can Learn From the Best Tourism Campaigns

13 min. Businesses in the tourism industry rely heavily on marketing to generate leads and boost conversion rates. Tourism marketing is as old as tourism itself – and it always reflects the destination and service benefits relevant to the current travelers’ needs, wants, and expectations. In other words, tourism campaigns must constantly move forward, and […]

Open Access is an initiative that aims to make scientific research freely available to all. To date our community has made over 100 million downloads. It’s based on principles of collaboration, unobstructed discovery, and, most importantly, scientific progression. As PhD students, we found it difficult to access the research we needed, so we decided to create a new Open Access publisher that levels the playing field for scientists across the world. How? By making research easy to access, and puts the academic needs of the researchers before the business interests of publishers.

We are a community of more than 103,000 authors and editors from 3,291 institutions spanning 160 countries, including Nobel Prize winners and some of the world’s most-cited researchers. Publishing on IntechOpen allows authors to earn citations and find new collaborators, meaning more people see your work not only from your own field of study, but from other related fields too.

Brief introduction to this section that descibes Open Access especially from an IntechOpen perspective

Want to get in touch? Contact our London head office or media team here

Our team is growing all the time, so we’re always on the lookout for smart people who want to help us reshape the world of scientific publishing.

Home > Books > Mobilities, Tourism and Travel Behavior - Contexts and Boundaries

A Comprehensive Review of the Quality Approach in Tourism

Submitted: 15 March 2017 Reviewed: 31 July 2017 Published: 20 December 2017

DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.70494

Cite this chapter

There are two ways to cite this chapter:

From the Edited Volume

Mobilities, Tourism and Travel Behavior - Contexts and Boundaries

Edited by Leszek Butowski

To purchase hard copies of this book, please contact the representative in India: CBS Publishers & Distributors Pvt. Ltd. www.cbspd.com | [email protected]

Chapter metrics overview

2,452 Chapter Downloads

Impact of this chapter

Total Chapter Downloads on intechopen.com

Total Chapter Views on intechopen.com

This study summarizes the evolution of the quality approach in tourism. Environmental issues are also addressed, as there are strong interdependencies between these two areas. Especially in tourism, the quality-environment integration is essential. The study reveals the diversity of quality and environmental models currently used worldwide, including general models for quality assessment and management, applied in all areas, and also the tourism-specific models. The objectives of this synthesis are to achieve a systematization of the information on the quality and environment approach in tourism, and to highlight the main axes of changes. The conclusions formulated illustrate the future directions to improve the quality approach in tourism, concerning both the quality models and their implementation. The results of this comprehensive review are useful to the tourism coordination structures at national and regional level, and also to academics and researchers, to better understanding the trends in quality approach and optimizing their quality-related actions. The workpaper is based on the reports of World Tourism Organization and other tourism professional structures, as well as studies and researches published in specialized journals related to quality and environment approach in tourism.

- quality in tourism

- quality management

- environmental management

- integrated quality management

- quality general and specific models

Author Information

Diana foris *.

- Faculty of Food and Tourism, Transilvania University of Brasov, Brasov, Romania

Maria Popescu

- Faculty of Economics and Business Administration, Transilvania University of Brasov, Brasov, Romania

Tiberiu Foris

*Address all correspondence to: [email protected]

1. Introduction

The purpose of this section is to clarify what meanings have the concepts of quality, quality management, and quality of the tourism product.

1.1. The meanings of quality and quality management

Quality is a common term used in everyday speech, but with various meanings. The term “quality” defines “an essential, or distinctive characteristic, property, or attribute; character with respect to fineness, or grade of excellence; superiority; excellence” [ 1 ].

In the modern industry, the first practical approach to quality was in a technical perspective, product related. But the quality thinking has evolved over time. The modern quality approach, specific to the last decades, is customer related: the quality is evaluated based on the customer requirements, and it means “fitness for use” [ 2 , 3 ]. In this case, the term quality does not have the popular meaning of “best” in any absolute sense, it means best for certain target groups of customers; if a product or service meets expectations, then the quality has been achieved.

Taking into account customer orientation, Kosar and Kosar consider that “quality is a market category that encompasses the totality of creation and realization of tangible products and services, on the level to which their properties ensure the compliance with the requirements of demand” [ 4 ]. But the quality approach is more than marketing related: it covers the entire organization and includes all processes on which the client satisfaction depends. This holistic approach to quality in the organization context is generically called “Quality Management.” Quality management presumes an approach of quality within the entire organization, given that satisfying customers and other stakeholders’ requirements represent the mission of the whole system. As Juran highlights, quality is no longer a technical issue. It is a business issue and corresponds with the organization’s mission to satisfy the stakeholders needs and expectations [ 5 ]. Achieving quality in organization is a matter of management; as Feigenbaum (1983) says “quality is a way of manage.”

Implementation of quality management within the organization involves the development of processes, structures, methods, etc., by which there are systematically achieved planning, doing, controlling, and quality improvement. This succession summarizes the cycle of management activities in a modern approach [ 3 ]. Quality management integrates some basic principles: customer focus, leadership, engagement of people, improvement, process approach, evidence-based decision making, and relationship management, which are the defining elements of modern management [ 6 ].

A wider perspective on quality, which takes into account not only the requirements of customers but also of other interested parties, is synthesized in the expressions “Total Quality,” or “Total Quality Management,” extensively used in specialized studies and also in practice [ 2 , 3 ]. TQM (abbreviation of Total Quality Management) defines a management philosophy characterized by integrating quality across the organization in order to satisfy customer and other stakeholders’ requirements. The “total” attribute associated with quality term suggests the broad meaning assigned to quality, both in terms of coverage and objectives. Total quality refers to all areas of activity of the organization; it pursues the full satisfaction of the beneficiaries, through performances, deadlines, and prices, while obtaining economic advantages; it also presumes broad involvement in quality achievement of all staff [ 3 ].

The introduction of the expressions “quality management” and TQM date back to the 1990s and synthesizes an evolved level of quality approach from the perspective of management. It has developed with the major contribution of several specialists, the best known being Deming, Juran, Feigenbaum, Crosby, and Ishikawa [ 7 , 8 ]. This evolution process culminated in the emergence of the international standards for quality systems—the family of ISO 9000 standards (in 1987, the first edition), which favored the promotion of quality management principles and methods in all activity areas. The application of these standards in tourism is discussed in Section 2.1.

1.2. Particularities of the quality in tourism

Assessing the quality of tourism services involves clarifying the concept of tourism product and to identify its defining features.

Simply put, tourism products can be defined as products that satisfy the needs of tourists. The first important characteristic of the tourism product is its complexity: the tourism product is a composite one, consisting of several goods and services offered to satisfy the tourists needs. It generally includes accommodation, transportation, and dining, as well as attractions and entertainment. Consequently, measuring quality of the tourism product must consider a lot of product distinguished features.

Furthermore, a tourism product is often related to a tourist destination. According to Webster’s Dictionary, destination means “a place set for the end of a journey.” In tourism, the term destination generally refers to an area where tourism is a relatively important activity, generating significant revenues. World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) defines the “tourist destination” concept, as: “A physical space with or without administrative and/or analytical boundaries, in which a visitor can spend an overnight. It is the cluster (co-location) of products and services, and of activities and experiences along the tourism value chain, and a basic unit of analysis of tourism. A destination incorporates various stakeholders and can network to form larger destinations” [ 9 ]. In terms of size, a tourist destination can be a city, village, or resort but also may include many cities, regions and even an entire country.

Whether it is an organization or a tourist destination, in both cases defining and evaluating quality of the tourism product are difficult issues. They require consideration of a collection of services, as transport, room accommodation, some specific menu, and the opportunity to sit on a beach or to make trips, and also other tangible and intangible elements related to the natural environment, culture and heritage of the region, atmosphere and hospitality. All these elements are parts of the tourism product, which is therefore “not only a collection of tangible products and intangible services, but also psychological experiences” [ 10 ].

Within the tourism literature, it is widely accepted that tourism primary sells a “stage” experience, and accordingly, the managers of the tourism businesses may seek to influence the tourists’ experience [ 11 ]. O’Dell points out that experiences involve more than the tourists, “the tourism industry is also part of the generation, staging, and consumption of experiences” [ 12 ]. According to Neuhofer et al., “the creation of successful experiences is the essence of the tourism and hospitality industry” [ 13 ]. In this regard, the OECD report on tourism trend and policies stresses that “Policies at national, regional and local level increasingly focus in identifying, nurturing and investing in product development experiences that emphasize unique selling points for particular destinations” [ 14 ].

One can conclude that a tourism product is a complex amalgam, including tangible products, intangible services, and psychological experiences. The main mission of any tourism organization or destination is providing memorable experiences for their customer, resulting in customer satisfaction, superior value, and competitive advantage. These aspects must be considered when addressing quality in tourism, which is performed under specific forms in all organizations and coordination structures of the tourism sector.

2. Review of the quality approach in tourism

Focusing on quality has become one of the key success factors for the tourism service providers and tourism industry in general. Current quality approach in tourism is the result of growing various consumers’ needs, in the context of highly increasing competition, market globalization, and development of modern technology.

The quality approach in tourism is a dynamic process that has evolved over time with the development of the tourism sector. A comprehensive review of this evolution is presented below. The analysis includes quality and environment models used in the tourism industry, as follows: (1) general models for quality evaluation and certification; (2) specific models for classification of the tourism organizations and quality certification; (3) quality approach in tourist destinations; and (4) environmental models and marks. A brief synthesis of the quality approach in tourism, stages, and trends is presented at the end.

2.1. General models for quality evaluation and certification

The movement for quality in tourism is older (as will be seen in Section 2.2), but the quality approach in tourism organizations gained increased relevance in the last two decades of the twentieth century, in connection with the appearance of the SERVQUAL model for evaluation of service quality and international standards for quality systems (ISO 9000 series). Both are general models applied worldwide and in all activity fields, including tourism.

SERVQUAL is the best known model for assessing service quality, created by Parasuraman et al. [ 15 ]. There have been a large number of studies based on SERVQUAL models—initial version or other, conducted in various fields of services, including the tourism industry. Some publications present considerations and reviews of the studies on the evaluation of tourism services quality conducted during the last decades, e.g., [ 16 – 18 ]. There are also many case studies based on SERVQUAL model conducted in various types of tourism organizations, such as hotel [ 19 – 21 ], restaurant [ 22 ], airline tourism [ 23 ], sport tourism [ 24 ], tour operator [ 25 ], etc.

The analysis of these studies reveals the differences of the services' quality characteristics examined under the SERVQUAL dimensions, depending on the nature of tourism organizations and services: hotels, restaurants, transportation agencies, spa, casino, etc. Most of the case studies used modified versions of the SERVQUAL dimensions scale, considering that the versions proposed by Parasuraman et al. are not entirely valid for all tourism sectors. But despite these differences relating to quality characteristics of the tourism services, the majority of the researchers consider that using SERVQUAL models in tourism has important implications for marketing and management decision makers, one of the major benefits being the identification of areas to improve quality of services.

In our opinion, this type of study, based on SERVQUAL model, is generally the subject of scientific papers and cannot be systematically used by organizations to assess the quality of services. A more practical approach is the implementation within tourism organizations of quality management system (QMS) based on the international standard ISO 9001. ISO 9001—“Quality Management Systems—Requirements” is the most popular standard for management systems, applied worldwide in all fields. It is useful to any organization, regardless of its size, activities carried out or type of product [ 26 ].

According to ISO 9000, QMS is “a set of interrelated or interacting elements that organizations use it to formulate quality policies and quality objectives and to establish the processes that are needed to ensure that policies are followed and objectives are achieved” [ 6 ]. ISO 9001 processes refer to planning the product and service quality, establishing work rules to prevent nonconformities, controlling quality of products and processes, and reducing identified non-compliances by corrective actions. Regularly performing this cycle of activities ensures that the organization can repeatedly achieve and deliver products with certain features. It should be emphasized that, although ISO 9001 makes no reference to the economic performances, QMS requires systematic improvement actions aiming to prevent and reduce losses, and these actions implicitly determine the costs’ reduction. In a hotel, for example, nonquality includes problems such as slow service, incorrect room temperature, billing errors, inappropriate service of the waiters, etc. It is important for these issues to be known, and that measures are taken to eliminate them. Besides these systematic improvement actions (named “incremental” improvement or “step by step”), the companies must also be constantly concerned with the introduction of new customer experiences, something they have not done before. The extension and efficiency of improvement actions is an important criterion for characterizing the QMS performance.

There is no official statistics on the status of ISO 9001 implementation in the tourism industry, only the results of the analyses carried out in various geographic areas (countries or regions), based on empirical research. These studies identify two categories or currents of opinion: the first highlights the importance and positive effects of the implementation of ISO 9001 model in tourism, and the other is a critical one.

So, several empirical studies conducted in the last decades reveal the growing interest of the tourism organizations in implementing and certifying QMSs based on ISO 9001 model, and the benefits obtained. Examples below are illustrative, and they refer to hotels from Spain [ 27 ] and Croatia [ 28 ], medical centers in Spain [ 29 ], travel agencies in China and Hong Kong [ 30 ]. In Croatia, in 2012, 40 travel agencies of the Association of Croatian Travel Agencies (UHPA), as well as the UHPA's office, have implemented QMSs based on ISO 9001, through a project supported by the Ministry of Tourism. In Spain, Alvarez’ survey on 223 selected hotels from Basque Country Business Guide illustrates that the most of them (72%) have quality certification, but the most popular was “Caledad Turistica,” the Spanish Trademark for the tourism sector [ 27 ].

On the other hand, the analyses carried out highlight the relatively low number of the tourism organizations ISO 9001 certified, and the causes that explain this situation. The survey conducted at Egyptian travel agencies, in 2008, shows that 84% of the respondents have not applied a formal Quality Management program; only 4% had already implemented a formal quality system, the other 12% of them being in the stage of preparation [ 31 ]. A similar situation, consisting in a small number of tourism organizations ISO 9001 certified, is presented in other studies, referring to Croatia [ 28 ], Portugal [ 32 ], and Romania [ 33 ]. It is notable that a small number of big tourism companies do have quality systems ISO 9001 certified as can be seen from the information published on their websites and on other promotional materials.

There are also critical studies on ISO 9001 implementation in tourism related to the efficiency of QMSs. As the literature consistently shows, the implementation of the ISO 9001 standard in tourism can be very different from one organization to another, considering the motives, tools, and results [ 34 – 36 ]. The researchers consider that the efficient functioning of the QMS must be reflected in improved performance, expressed by the evolution of the number of customers, the number of new customers, the losing effect of certain customers, etc., with customer satisfaction being crucial to achieve the objectives related to financial performance of the organization. However, an empirical study carried out with guests of the Spanish and Italian hotels shows that quality-certified hotels did not receive a significantly better statistical evaluation from their customers [ 36 ]. Frequently, customers are not aware of what the QMSs consistent with ISO 9001 are. The study’s authors underline the potential dangers in inferring directly that quality certification in the hospitality industry leads to superior customer satisfaction.

Generally, the causes of low effectiveness of QMSs based on ISO 9001 model do not differ in tourism compared to other activity areas, the most important being: formal application of the standard requirements, with accent on the QMS documentation; focusing on technical issues, without taking into account social aspects; lack of the staff training in the field of quality; and low commitment of the staff in achieving quality, especially of the senior management [ 37 ]. Zajarskas and Ruževi consider that “implementation or improvement of management system is primarily strategic management of change,” most problems being at the level of strategic management [ 38 ]. In many cases, the certification ISO 9001 is intended to improve the corporate image rather than internal practices and organization effectiveness. According to Dick et al., managers should consider that internal drivers are the key to quality certification success. Consequently, top management should be involved to produce a robust quality system, which incorporates the utilization of quality improvement tools and generates greater internal benefits and customer satisfaction [ 35 ]. According to Kachniewska, one of the causes of QMS inefficiency is the superficial knowledge of the standard, which encourages the belief that ISO 9001 is irrelevant to the tourism sector [ 39 ]. This probably explains why the tourism industry searches for a new internationally recognized quality standard that would be more applicable for the tourism sector. The results of this work are presented in Sections 2.2.2 and 2.3.

Besides ISO 9001, the opening toward the application of more complex models aiming to achieve excellence is also notable. Broadly speaking, “excellence” means “greatness—the very best.” Currently, the term is commonly used in the economic and administrative environments, in relationship with the modern vision of management: achieving excellence involves the creation of a performing management system that ensures customer satisfaction and benefits for all members of the organization and for society [ 3 ]. According to Mann et al., “business excellence is about achieving excellence in everything that an organization does (including leadership, strategy, customer focus, information management, people, and processes), and most importantly achieving superior business results” [ 40 ]. All these elements are found in the TQM philosophy.

The most popular models of excellence are “Malcolm Baldrige” and “European Foundation for Quality Management” (EFQM) [ 2 , 3 ]. In Europe, some hotels have conducted evaluation processes based on the EFQM model, EFQM Recognised for Excellence being the proof of high-quality business approach, ability to innovate and commitment to deliver excellent services. The following examples are illustrative: Lake Hotel Killarney, Crowne Plaza Hotel Dundalk, Pembroke Hotel Kilkenny, Skylon Hotel, in Dublin, Ireland (EFQM Excellence Awards, Dublin, 2015). In the Caribbean, 13 businesses in the tourism accommodation sector, representing hotels, beach resorts, villas etc., were hospitality assured (HA) certified. HA certificate meets the EFQM criteria and symbolizes the business excellence in tourism and hospitality, being supported by the British Hospitality Association and the Caribbean Tourism Organization. There are also a small number of applications on achieving excellence in tourism organizations carried out in research studies [ 41 , 42 ]. Of note are the initiatives for developing standards and awarding the excellence in tourism (an issue addressed in Section 2.2.2).

2.2. Specific models for classification of tourism organizations, and quality certification

Quality certification and evaluation of the tourism organizations have a long history and include more schemes and models presented below.

2.2.1. Classification systems of tourism organizations

The term classification, also called grading, rating, and star rating [ 43 ], refers to breaking down and ranking accommodation units into categories. The European Standardization Committee defines the expression “accommodation rating,” or “classification scheme,” as “a system providing an assessment of the quality standards and provision of facility and/or service of tourist accommodation, typically within five categories, often indicated by one to five symbols” [ 44 ].

The general purpose of hotel classification is the creation of a ranking based on specific criteria, and the assignment of a symbol that certifies the services’ level. The classification creates conditions for the determination of different tariffs corresponding to the hotel or restaurant ranking and provides useful information to make potential guests aware of what they can expect before making a booking. The classification also serves as a reference for the implementation of institutional and public policies to support tourism passing to another level of quality.

The beginnings of the tourism entities’ classification are placed in the last century and are connected to “AAA Diamond Ratings System” and “Forbes Travel Guide” in USA and “Michelin Guides” in Europe. But presently, there are wide and diverse classification schemes of tourism establishments. There are several workpapers on this topic, which reveal the extent and diversity of the existing schemes worldwide [ 39 , 45 – 49 ]. As these studies show, between the classification systems, there are differences related to the following aspects: number of categories and name or symbols associated; classification criteria; classification character, obligatory or voluntary; frequency of evaluation. It must be stressed that in the EU, and worldwide, not only are the classification systems different from country to country, but there is also diversity in the level of comfort related to the grading and classification criteria. A single tourist destination often employs multiple classification schemes. It is therefore difficult to understand and compare the quality of tourism services, and especially to consumers, it is difficult to appreciate the significance of the various rating schemes not to mention their reliability.

Although the diversity of classification schemes has disadvantages, UNWTO specifies that it is unlikely to reach a single official classification, given the great diversity of contexts in which tourism organizations operate. In this regard, Taleb Rifai, Secretary-General of UNWTO, says: “There is no worldwide standard for official hotel classification systems, and there may will never be one, due to the incredible diversity of the environmental, socio-cultural, economic, and political contexts in which they are embedded” [ 43 ]. The same conclusion results from the analysis made in the EU setting up that one European hotel classification scheme may be considered an unfeasible demarche [ 50 ].

There are, however, concerns for harmonizing the classification schemes from tourism by introducing common rules. In this regard, we must mention the recent UNWTO recommendations for revising the hotel classification systems such as certification performed by independent third parties; integration of guests’ reviews into hotel classification schemes; global focus on sustainability and accessibility to be reflected in the classification criteria. Likewise, updating the certification criteria to general trends and considering data collected from the guests is recommended [ 43 ].

To mention is the improvement of the classification systems in favor of extending and integrating new criteria, with emphasis on quality and sustainability. The result of this dynamic process is the creation of combined schemes that include criteria for classification of the tourism establishments and also for quality certification. The European Hospitality Quality (EHQ) model launched in 2009 by HOTREC (abbreviation for Hotels, Restaurants and Cafés) should be mentioned. EHQ classification is based on a criteria catalog, some of these criteria being compatible with the main clauses of ISO 9001 standard, adapted to the particularities of tourism [ 51 ]. There are also other classification systems in connection to quality marks and labels used in tourism industry. Scotland, Iceland, and Australia are among the countries that include the quality element in their hotels’ classification [ 43 ].

Another improvement axis consists of the global focus on sustainability reflected in the classification criteria. The Hensen study finds that “recently updated hotel classification systems reflect different viewpoints on whether and how to incorporate environmental management practices” [ 52 ]. The author identifies three situations: environmental standards are included as a requirement for a certain star rating; classification systems recognize external environmental certification next to their ratings; external environmental certification is required as minimum standards in the rating scheme. As Hensen concludes, it is still open to question whether environmental management practices should be integrated into classification schemes or remain complementary approaches.

Integrating guests’ reviews into hotel classification systems is another important current change, favored by the evolution of online networks and review sites. Online guests’ reviews related to facilities and services’ quality of tourism organizations or destinations are instruments increasingly used today, along with the official classification and certification of hotels, restaurants, and other tourist establishments. Certain social media websites are becoming more popular and are likely to evolve into primary travel information sources [ 53 – 55 ]. The most important travel sites include TripAdvisor, Expedia, Hotels.com, and Travelocity etc., but their number continues to rise. These platforms represent systems that analyze the information on websites and social networks in order to find the overall consumers’ rating for a particular establishment. The information thus obtained has multiple uses: it is helpful for customers in choosing the location for travel; it provides data on the service quality used to enhance the overall performance of the tourism organizations and sector; and the online guests’ reviews are useful in the process of rating and/or awarding quality marks in tourism [ 54 , 56 ].

Regarding the use of online guests’ reviews in the classification of tourist establishments, recent studies highlight the need to harmonize the conventional rating systems and social media platforms [ 52 , 54 , 57 ]. As Hensen says, one can talk about a democratization of the rating process that “will lead to an innovation revolution whereby hotels seek to respond quicker to consumer trends as they have a direct feedback loop to their position in the market” [ 57 ]. The UNWTO report [ 54 ] shows that several countries are moving toward integrated models, distinguishing the next two variants: independent functioning of the two models and respectively their full integration. In the first case, online evaluations are done separately, and their results are included in the organization promoting documents. The second variant, of full integration, is a model in which the overall guests’ review ranking is included as criterion within the official classification scheme. According to the UNWTO report, Norway and Switzerland each have documented models for integrating online guests’ reviews and hotel classifications, and United Arab Emirates, Germany, and Australia are also involved in developing integrated systems. In both cases, the integration could effectively help to further reduce the gap between guests’ experiences and expectations.

2.2.2. Tourism specific models for quality awards: marks, labels, and quality certification

Tourism quality marks are marks used for tourism products and organizations that attest the fulfillment of some quality standards. According to Foris, “Quality mark is a model of good practices for implementing and certifying the quality of tourism services, as a voluntary option of the economic operators in the field” [ 47 ]. Quality marks are awarded to those tourism establishments that apply good quality management practices and provide improved service quality standards and facilities, over the legal requirements of their specific official classification.

Awarding quality mark is usually complementary to the star ranking. The main differences between classification schemes and quality mark programs in tourism are synthesized and summarized by Foris [ 47 ]. The author underlines that quality certification in tourism can become an effective management tool, designed to develop the level of services’ quality. Improving quality does not mean moving to a superior level in the star ranking system but increasing customers’ satisfaction and ensuring that they receive the best services corresponding to the category of the tourism unit.