Holiday Savings

cui:common.components.upgradeModal.offerHeader_undefined

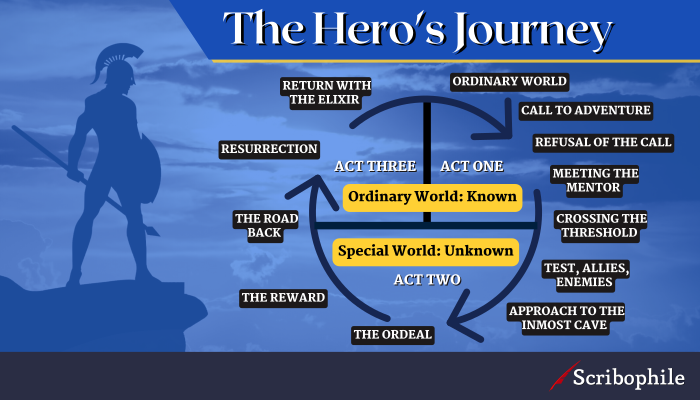

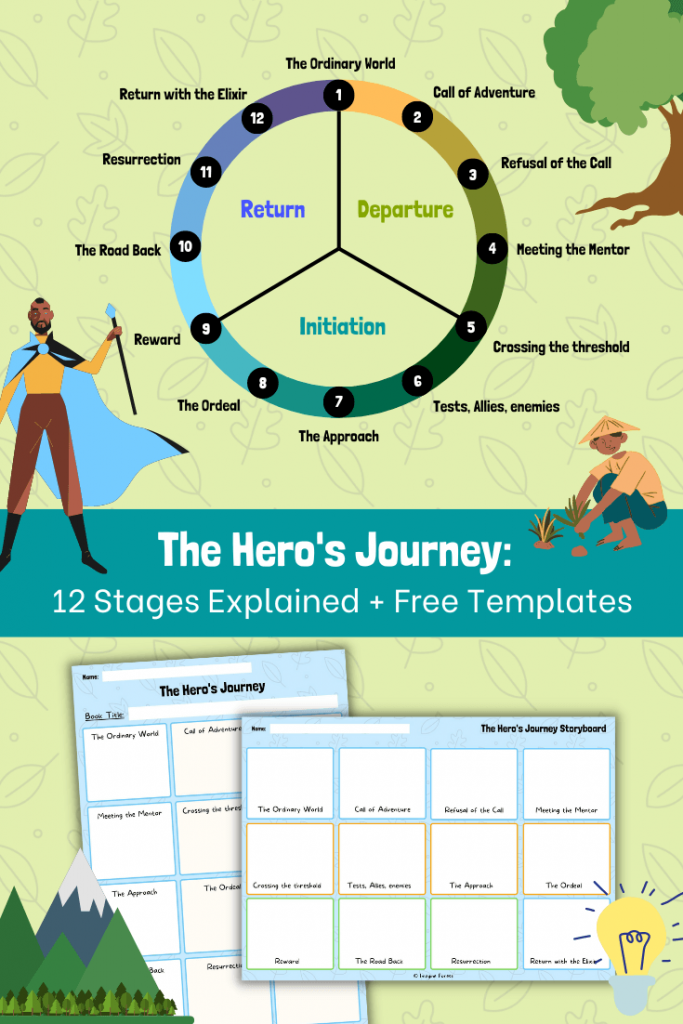

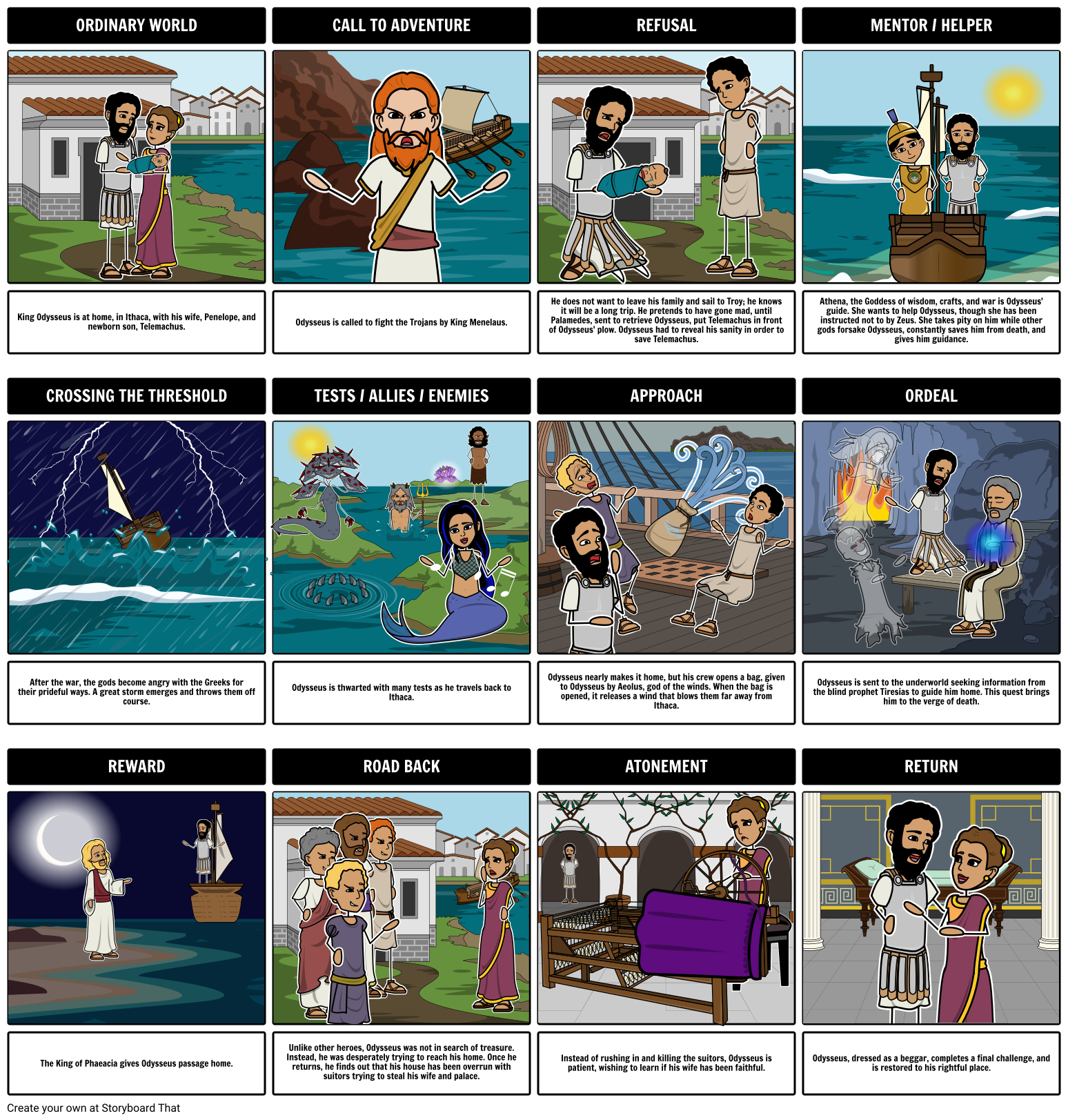

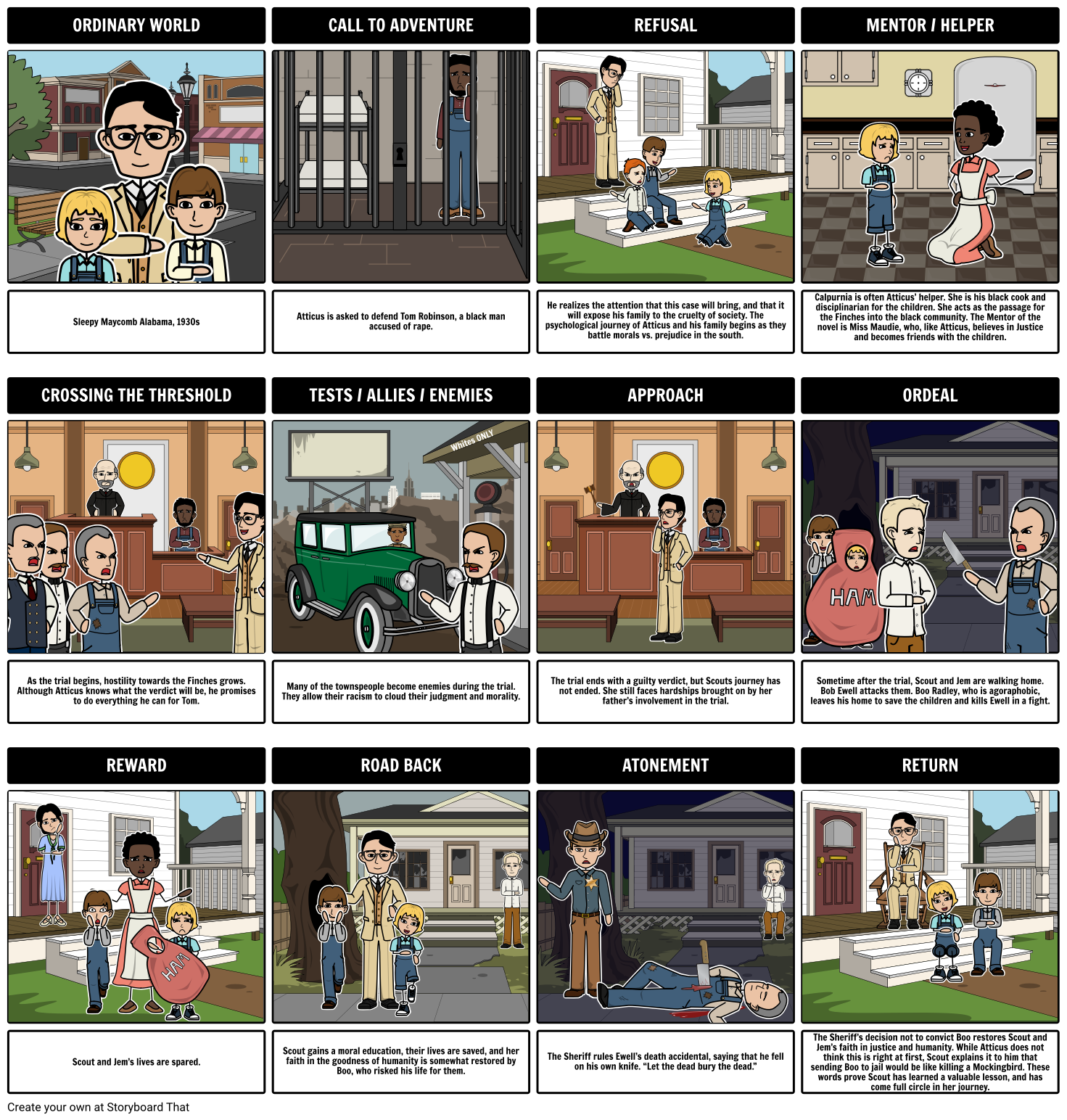

The hero's journey: a story structure as old as time, the hero's journey offers a powerful framework for creating quest-based stories emphasizing self-transformation..

Table of Contents

Holding out for a hero to take your story to the next level?

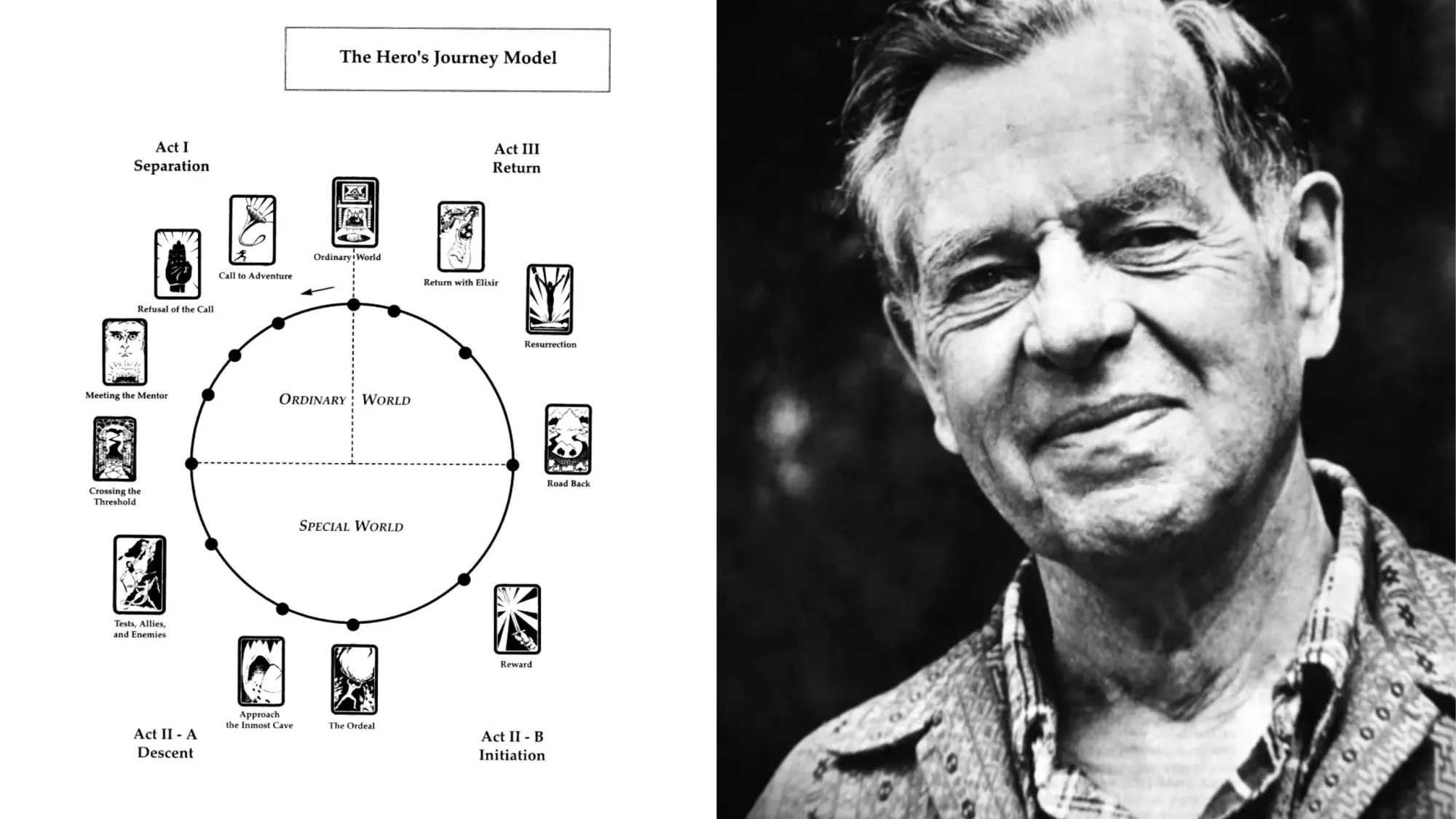

The Hero’s Journey might be just what you’ve been looking for. Created by Joseph Campbell, this narrative framework packs mythic storytelling into a series of steps across three acts, each representing a crucial phase in a character's transformative journey.

Challenge . Growth . Triumph .

Whether you're penning a novel, screenplay, or video game, The Hero’s Journey is a tried-and-tested blueprint for crafting epic stories that transcend time and culture. Let’s explore the steps together and kickstart your next masterpiece.

What is the Hero’s Journey?

The Hero’s Journey is a famous template for storytelling, mapping a hero's adventurous quest through trials and tribulations to ultimate transformation.

What are the Origins of the Hero’s Journey?

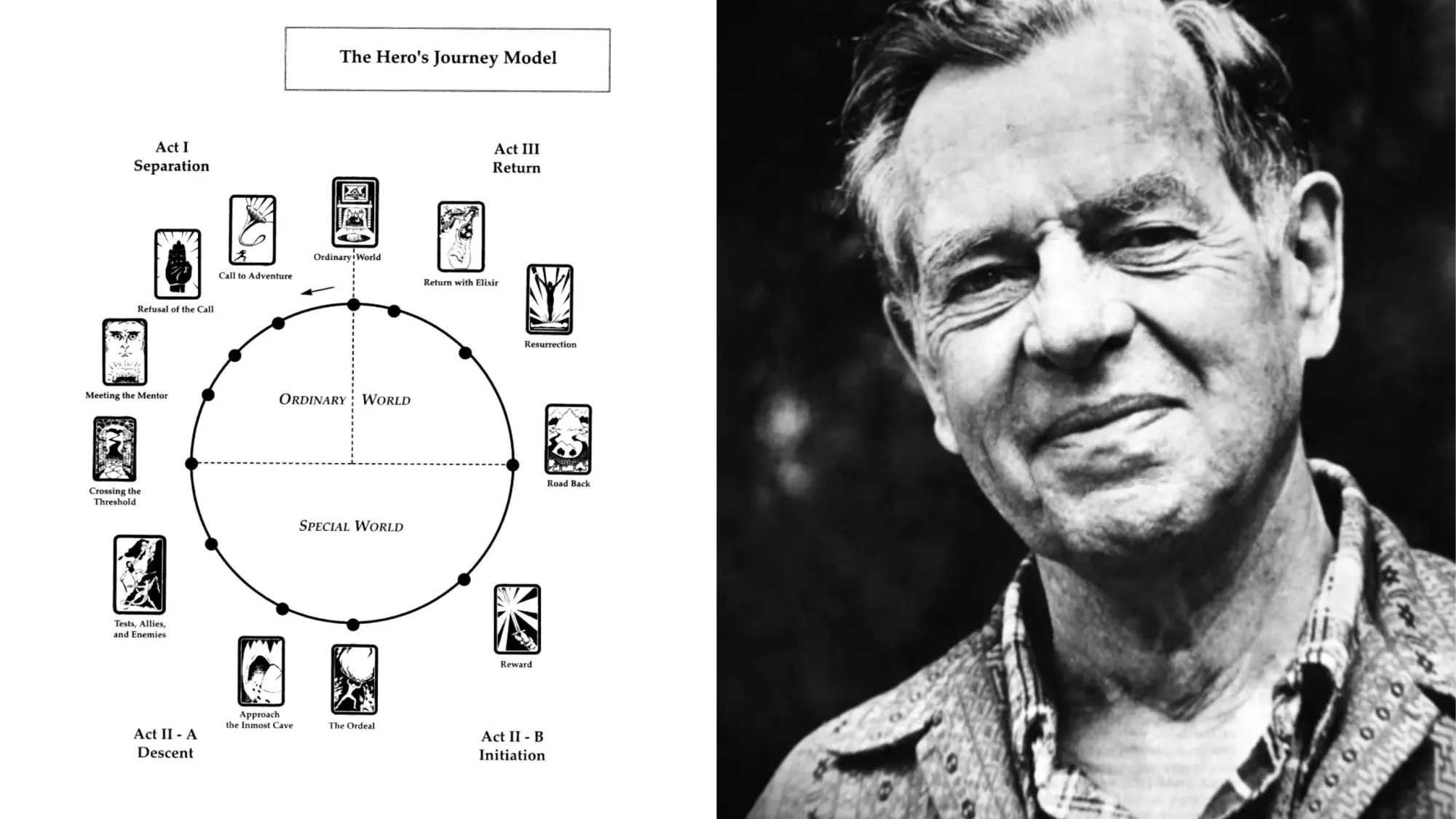

The Hero’s Journey was invented by Campbell in his seminal 1949 work, The Hero with a Thousand Faces , where he introduces the concept of the "monomyth."

A comparative mythologist by trade, Campbell studied myths from cultures around the world and identified a common pattern in their narratives. He proposed that all mythic narratives are variations of a single, universal story, structured around a hero's adventure, trials, and eventual triumph.

His work unveiled the archetypal hero’s path as a mirror to humanity’s commonly shared experiences and aspirations. It was subsequently named one of the All-Time 100 Nonfiction Books by TIME in 2011.

How are the Hero’s and Heroine’s Journeys Different?

While both the Hero's and Heroine's Journeys share the theme of transformation, they diverge in their focus and execution.

The Hero’s Journey, as outlined by Campbell, emphasizes external challenges and a quest for physical or metaphorical treasures. In contrast, Murdock's Heroine’s Journey, explores internal landscapes, focusing on personal reconciliation, emotional growth, and the path to self-actualization.

In short, heroes seek to conquer the world, while heroines seek to transform their own lives; but…

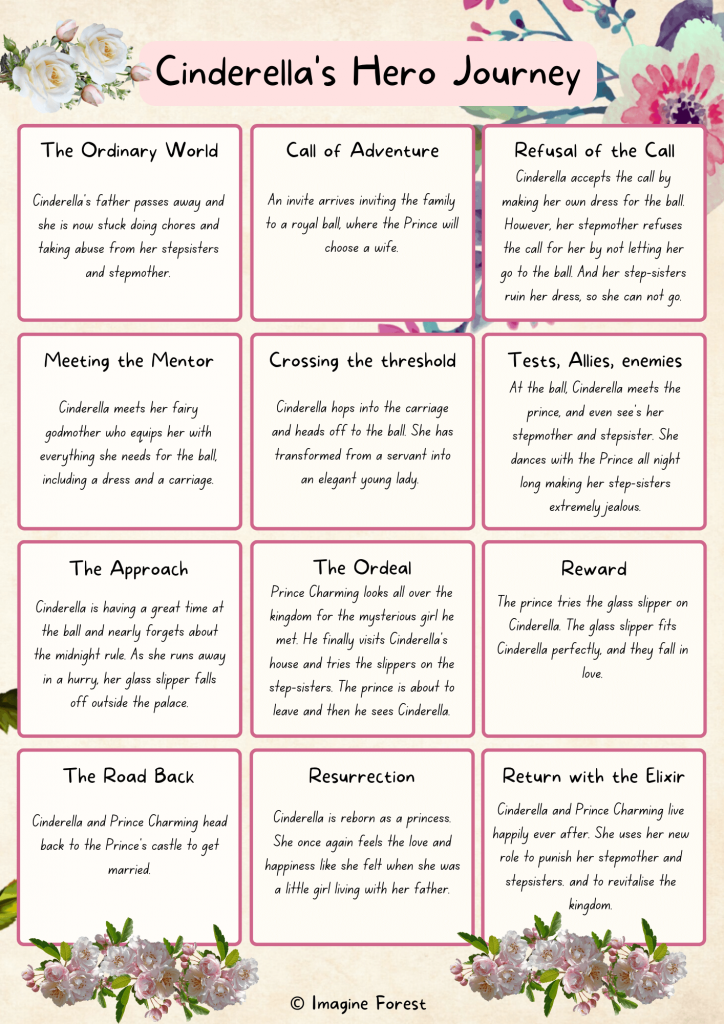

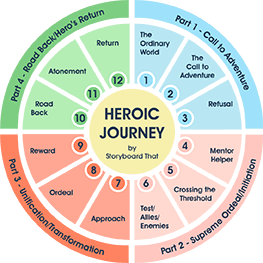

Twelve Steps of the Hero’s Journey

So influential was Campbell’s monomyth theory that it's been used as the basis for some of the largest franchises of our generation: The Lord of the Rings , Harry Potter ...and George Lucas even cited it as a direct influence on Star Wars .

There are, in fact, several variations of the Hero's Journey, which we discuss further below. But for this breakdown, we'll use the twelve-step version outlined by Christopher Vogler in his book, The Writer's Journey (seemingly now out of print, unfortunately).

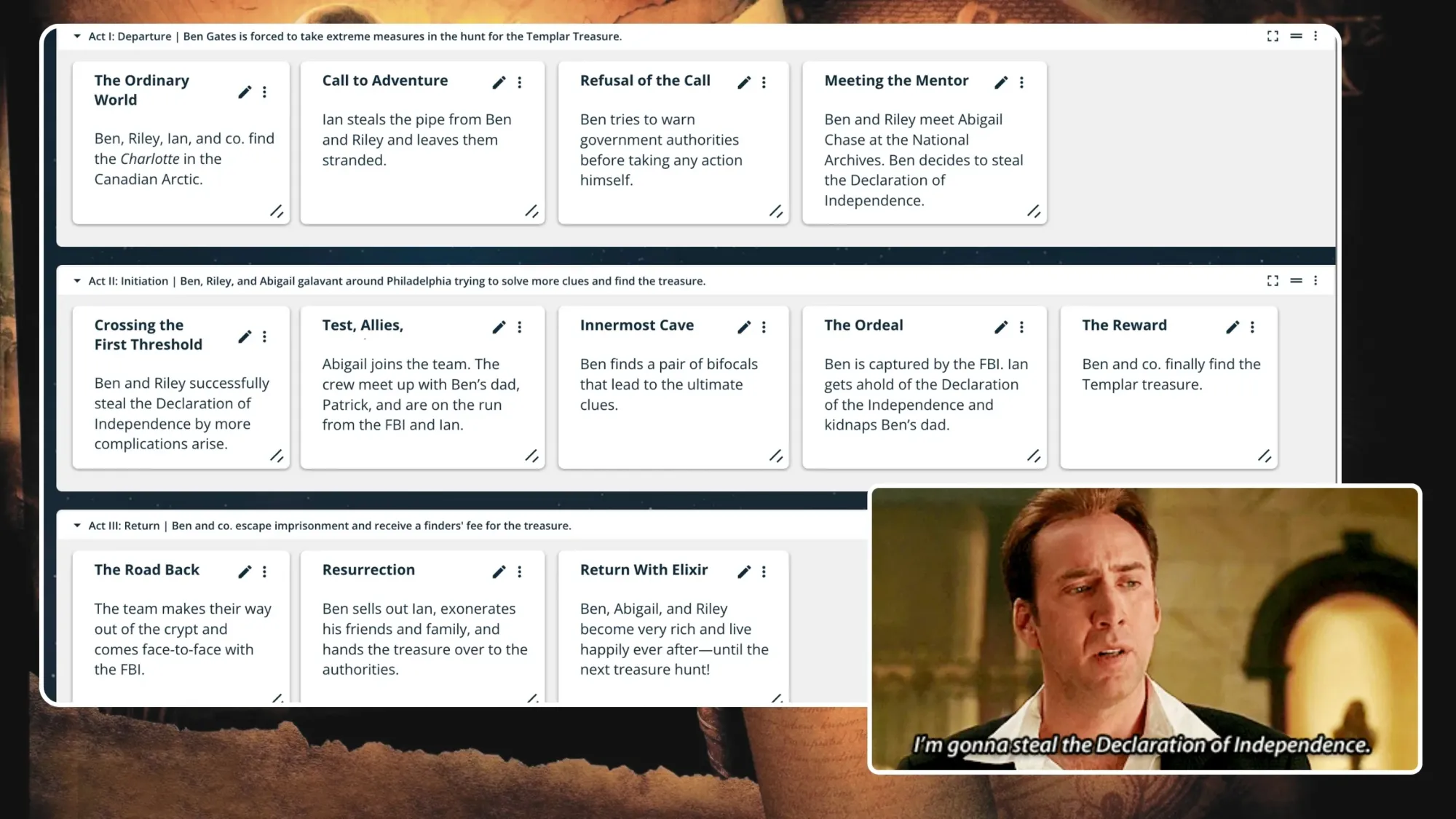

You probably already know the above stories pretty well so we’ll unpack the twelve steps of the Hero's Journey using Ben Gates’ journey in National Treasure as a case study—because what is more heroic than saving the Declaration of Independence from a bunch of goons?

Ye be warned: Spoilers ahead!

Act One: Departure

Step 1. the ordinary world.

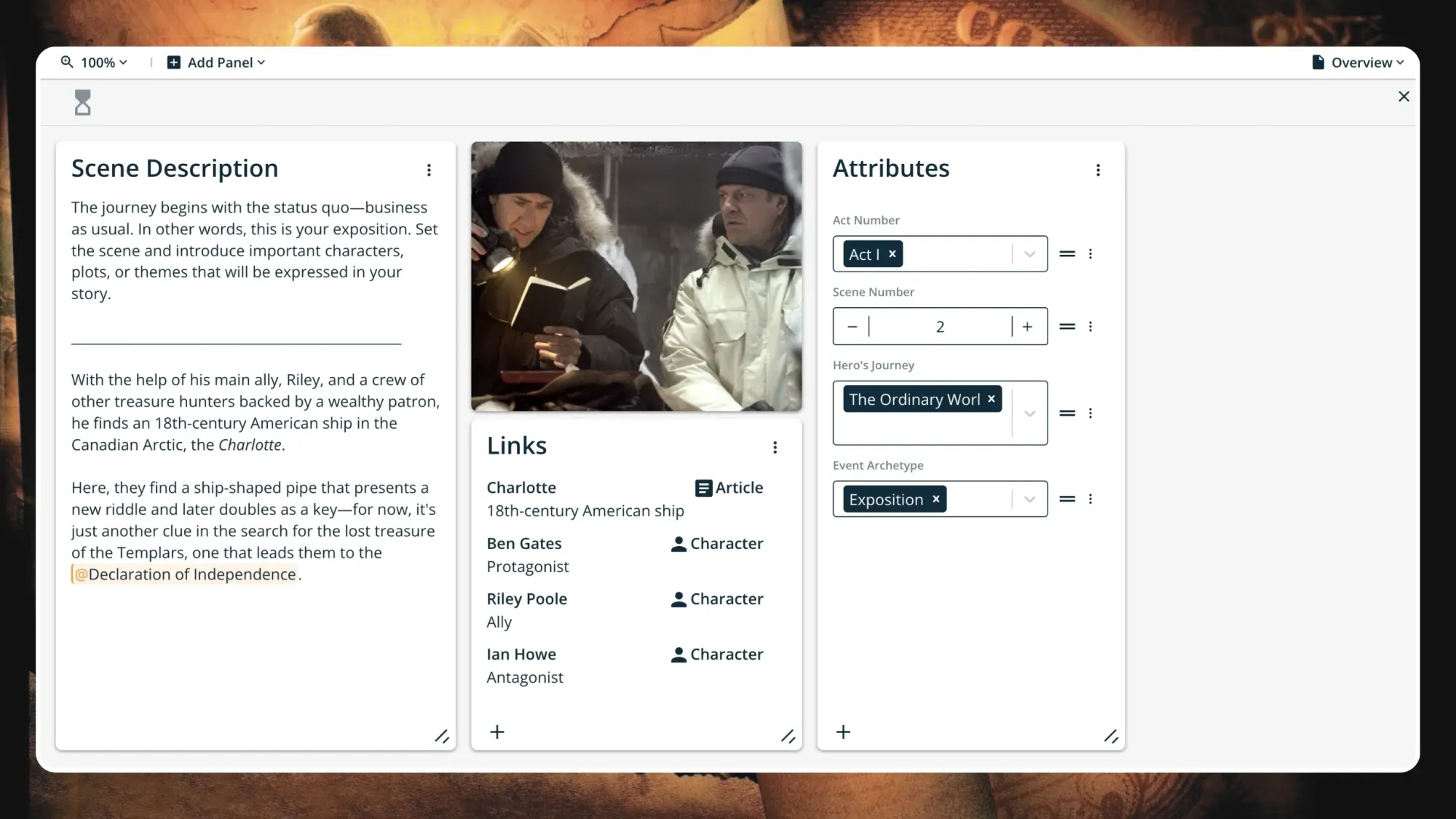

The journey begins with the status quo—business as usual. We meet the hero and are introduced to the Known World they live in. In other words, this is your exposition, the starting stuff that establishes the story to come.

National Treasure begins in media res (preceded only by a short prologue), where we are given key information that introduces us to Ben Gates' world, who he is (a historian from a notorious family), what he does (treasure hunts), and why he's doing it (restoring his family's name).

With the help of his main ally, Riley, and a crew of other treasure hunters backed by a wealthy patron, he finds an 18th-century American ship in the Canadian Arctic, the Charlotte . Here, they find a ship-shaped pipe that presents a new riddle and later doubles as a key—for now, it's just another clue in the search for the lost treasure of the Templars, one that leads them to the Declaration of Independence.

Step 2. The Call to Adventure

The inciting incident takes place and the hero is called to act upon it. While they're still firmly in the Known World, the story kicks off and leaves the hero feeling out of balance. In other words, they are placed at a crossroads.

Ian (the wealthy patron of the Charlotte operation) steals the pipe from Ben and Riley and leaves them stranded. This is a key moment: Ian becomes the villain, Ben has now sufficiently lost his funding for this expedition, and if he decides to pursue the chase, he'll be up against extreme odds.

Step 3. Refusal of the Call

The hero hesitates and instead refuses their call to action. Following the call would mean making a conscious decision to break away from the status quo. Ahead lies danger, risk, and the unknown; but here and now, the hero is still in the safety and comfort of what they know.

Ben debates continuing the hunt for the Templar treasure. Before taking any action, he decides to try and warn the authorities: the FBI, Homeland Security, and the staff of the National Archives, where the Declaration of Independence is housed and monitored. Nobody will listen to him, and his family's notoriety doesn't help matters.

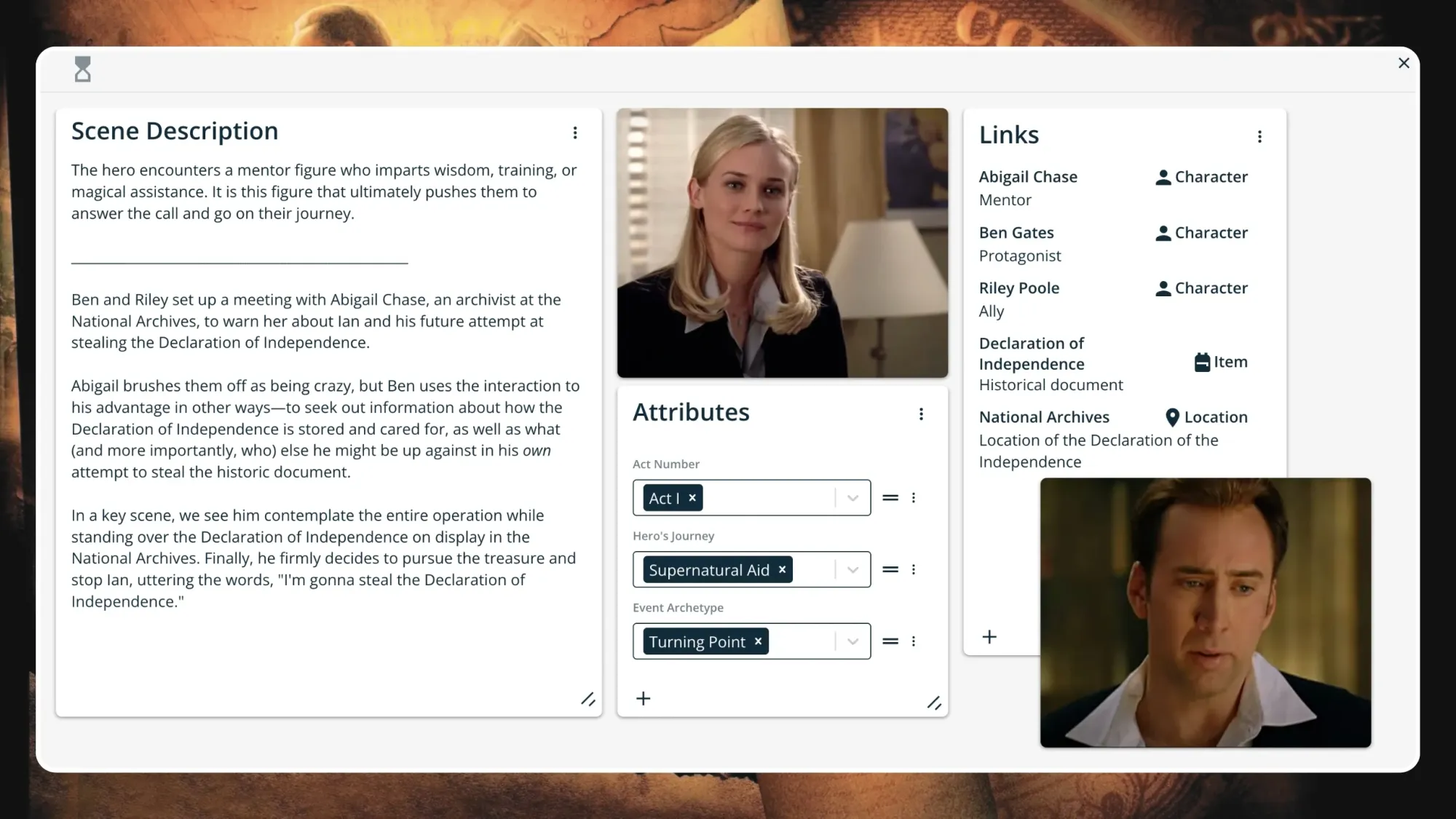

Step 4. Meeting the Mentor

The protagonist receives knowledge or motivation from a powerful or influential figure. This is a tactical move on the hero's part—remember that it was only the previous step in which they debated whether or not to jump headfirst into the unknown. By Meeting the Mentor, they can gain new information or insight, and better equip themselves for the journey they might to embark on.

Abigail, an archivist at the National Archives, brushes Ben and Riley off as being crazy, but Ben uses the interaction to his advantage in other ways—to seek out information about how the Declaration of Independence is stored and cared for, as well as what (and more importantly, who) else he might be up against in his own attempt to steal it.

In a key scene, we see him contemplate the entire operation while standing over the glass-encased Declaration of Independence. Finally, he firmly decides to pursue the treasure and stop Ian, uttering the famous line, "I'm gonna steal the Declaration of Independence."

Act Two: Initiation

Step 5. crossing the threshold.

The hero leaves the Known World to face the Unknown World. They are fully committed to the journey, with no way to turn back now. There may be a confrontation of some sort, and the stakes will be raised.

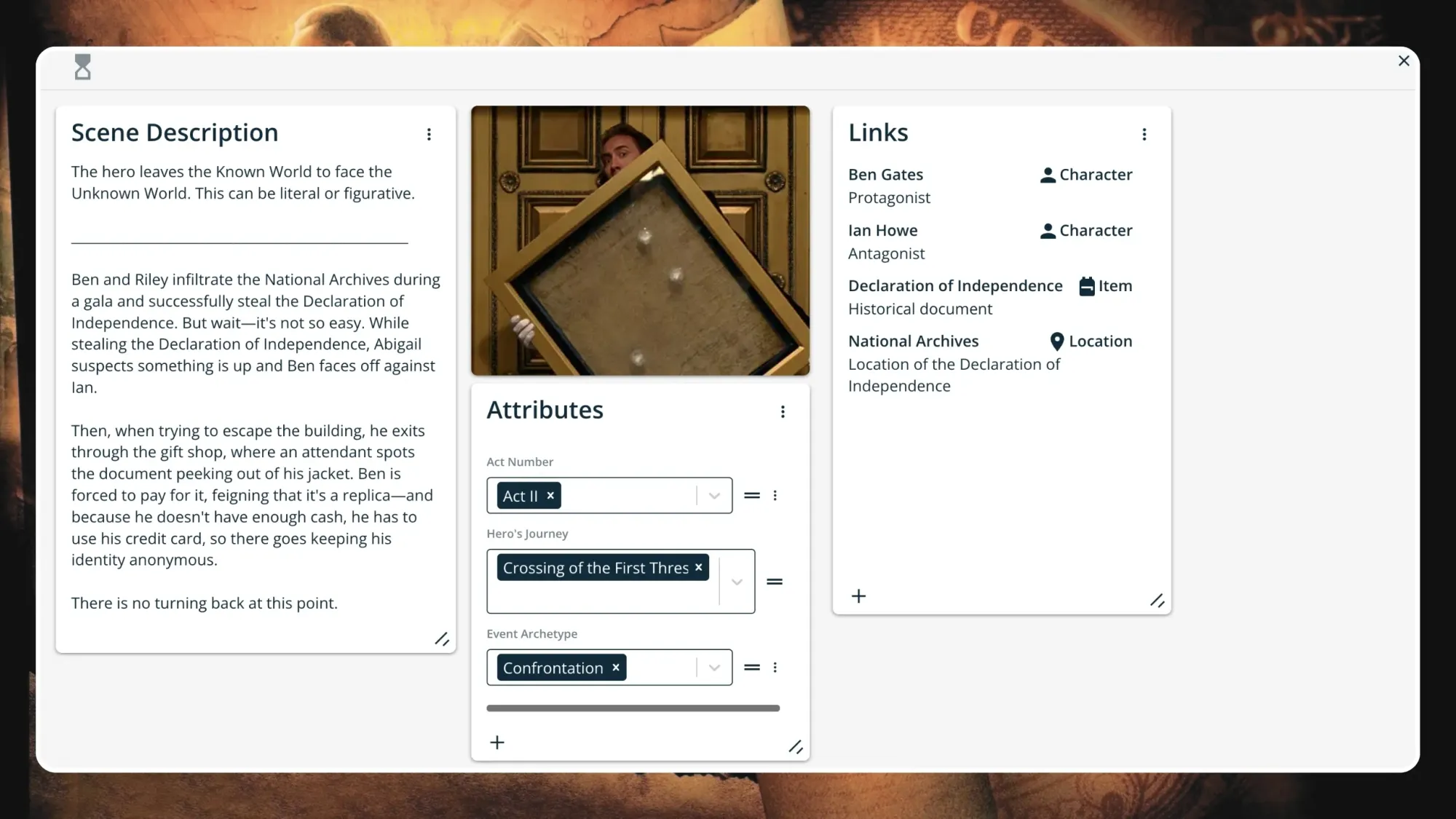

Ben and Riley infiltrate the National Archives during a gala and successfully steal the Declaration of Independence. But wait—it's not so easy. While stealing the Declaration of Independence, Abigail suspects something is up and Ben faces off against Ian.

Then, when trying to escape the building, Ben exits through the gift shop, where an attendant spots the document peeking out of his jacket. He is forced to pay for it, feigning that it's a replica—and because he doesn't have enough cash, he has to use his credit card, so there goes keeping his identity anonymous.

The game is afoot.

Step 6. Tests, Allies, Enemies

The hero explores the Unknown World. Now that they have firmly crossed the threshold from the Known World, the hero will face new challenges and possibly meet new enemies. They'll have to call upon their allies, new and old, in order to keep moving forward.

Abigail reluctantly joins the team under the agreement that she'll help handle the Declaration of Independence, given her background in document archiving and restoration. Ben and co. seek the aid of Ben's father, Patrick Gates, whom Ben has a strained relationship with thanks to years of failed treasure hunting that has created a rift between grandfather, father, and son. Finally, they travel around Philadelphia deciphering clues while avoiding both Ian and the FBI.

Step 7. Approach the Innermost Cave

The hero nears the goal of their quest, the reason they crossed the threshold in the first place. Here, they could be making plans, having new revelations, or gaining new skills. To put it in other familiar terms, this step would mark the moment just before the story's climax.

Ben uncovers a pivotal clue—or rather, he finds an essential item—a pair of bifocals with interchangeable lenses made by Benjamin Franklin. It is revealed that by switching through the various lenses, different messages will be revealed on the back of the Declaration of Independence. He's forced to split from Abigail and Riley, but Ben has never been closer to the treasure.

Step 8. The Ordeal

The hero faces a dire situation that changes how they view the world. All threads of the story come together at this pinnacle, the central crisis from which the hero will emerge unscathed or otherwise. The stakes will be at their absolute highest here.

Vogler details that in this stage, the hero will experience a "death," though it need not be literal. In your story, this could signify the end of something and the beginning of another, which could itself be figurative or literal. For example, a certain relationship could come to an end, or it could mean someone "stuck in their ways" opens up to a new perspective.

In National Treasure , The FBI captures Ben and Ian makes off with the Declaration of Independence—all hope feels lost. To add to it, Ian reveals that he's kidnapped Ben's father and threatens to take further action if Ben doesn't help solve the final clues and lead Ian to the treasure.

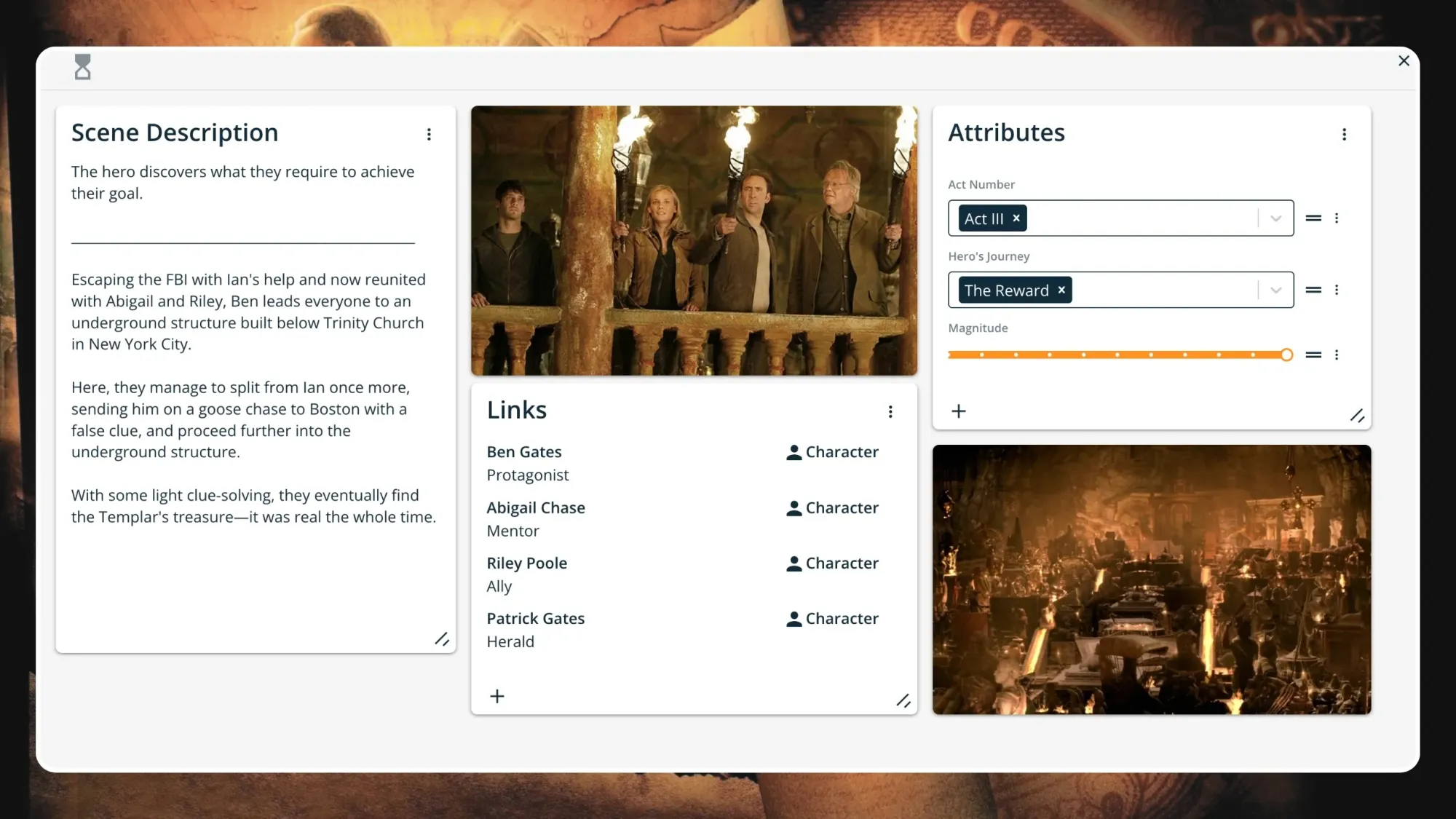

Ben escapes the FBI with Ian's help, reunites with Abigail and Riley, and leads everyone to an underground structure built below Trinity Church in New York City. Here, they manage to split from Ian once more, sending him on a goose chase to Boston with a false clue, and proceed further into the underground structure.

Though they haven't found the treasure just yet, being this far into the hunt proves to Ben's father, Patrick, that it's real enough. The two men share an emotional moment that validates what their family has been trying to do for generations.

Step 9. Reward

This is it, the moment the hero has been waiting for. They've survived "death," weathered the crisis of The Ordeal, and earned the Reward for which they went on this journey.

Now, free of Ian's clutches and with some light clue-solving, Ben, Abigail, Riley, and Patrick keep progressing through the underground structure and eventually find the Templar's treasure—it's real and more massive than they could have imagined. Everyone revels in their discovery while simultaneously looking for a way back out.

Act Three: Return

Step 10. the road back.

It's time for the journey to head towards its conclusion. The hero begins their return to the Known World and may face unexpected challenges. Whatever happens, the "why" remains paramount here (i.e. why the hero ultimately chose to embark on their journey).

This step marks a final turning point where they'll have to take action or make a decision to keep moving forward and be "reborn" back into the Known World.

Act Three of National Treasure is admittedly quite short. After finding the treasure, Ben and co. emerge from underground to face the FBI once more. Not much of a road to travel back here so much as a tunnel to scale in a crypt.

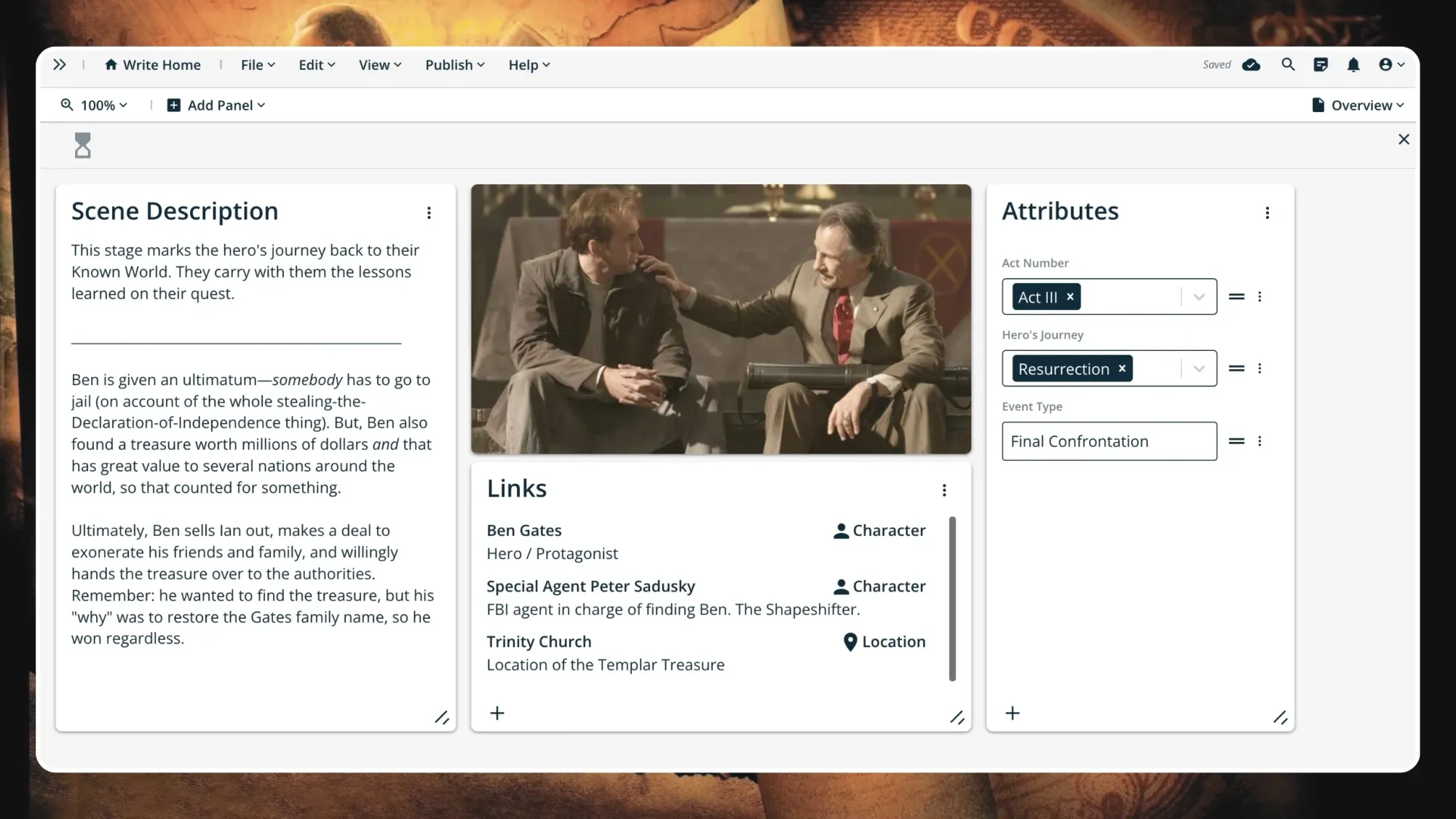

Step 11. Resurrection

The hero faces their ultimate challenge and emerges victorious, but forever changed. This step often requires a sacrifice of some sort, and having stepped into the role of The Hero™, they must answer to this.

Ben is given an ultimatum— somebody has to go to jail (on account of the whole stealing-the-Declaration-of-Independence thing). But, Ben also found a treasure worth millions of dollars and that has great value to several nations around the world, so that counts for something.

Ultimately, Ben sells Ian out, makes a deal to exonerate his friends and family, and willingly hands the treasure over to the authorities. Remember: he wanted to find the treasure, but his "why" was to restore the Gates family name, so he won regardless.

Step 12. Return With the Elixir

Finally, the hero returns home as a new version of themself, the elixir is shared amongst the people, and the journey is completed full circle.

The elixir, like many other elements of the hero's journey, can be literal or figurative. It can be a tangible thing, such as an actual elixir meant for some specific purpose, or it could be represented by an abstract concept such as hope, wisdom, or love.

Vogler notes that if the Hero's Journey results in a tragedy, the elixir can instead have an effect external to the story—meaning that it could be something meant to affect the audience and/or increase their awareness of the world.

In the final scene of National Treasure , we see Ben and Abigail walking the grounds of a massive estate. Riley pulls up in a fancy sports car and comments on how they could have gotten more money. They all chat about attending a museum exhibit in Cairo (Egypt).

In one scene, we're given a lot of closure: Ben and co. received a hefty payout for finding the treasure, Ben and Abigail are a couple now, and the treasure was rightfully spread to those it benefitted most—in this case, countries who were able to reunite with significant pieces of their history. Everyone's happy, none of them went to jail despite the serious crimes committed, and they're all a whole lot wealthier. Oh, Hollywood.

Variations of the Hero's Journey

Plot structure is important, but you don't need to follow it exactly; and, in fact, your story probably won't. Your version of the Hero's Journey might require more or fewer steps, or you might simply go off the beaten path for a few steps—and that's okay!

What follows are three additional versions of the Hero's Journey, which you may be more familiar with than Vogler's version presented above.

Dan Harmon's Story Circle (or, The Eight-Step Hero's Journey)

Screenwriter Dan Harmon has riffed on the Hero's Journey by creating a more compact version, the Story Circle —and it works especially well for shorter-format stories such as television episodes, which happens to be what Harmon writes.

The Story Circle comprises eight simple steps with a heavy emphasis on the hero's character arc:

- The hero is in a zone of comfort...

- But they want something.

- They enter an unfamiliar situation...

- And adapt to it by facing trials.

- They get what they want...

- But they pay a heavy price for it.

- They return to their familiar situation...

- Having changed.

You may have noticed, but there is a sort of rhythm here. The eight steps work well in four pairs, simplifying the core of the Hero's Journey even further:

- The hero is in a zone of comfort, but they want something.

- They enter an unfamiliar situation and have to adapt via new trials.

- They get what they want, but they pay a price for it.

- They return to their zone of comfort, forever changed.

If you're writing shorter fiction, such as a short story or novella, definitely check out the Story Circle. It's the Hero's Journey minus all the extraneous bells & whistles.

Ten-Step Hero's Journey

The ten-step Hero's Journey is similar to the twelve-step version we presented above. It includes most of the same steps except for Refusal of the Call and Meeting the Mentor, arguing that these steps aren't as essential to include; and, it moves Crossing the Threshold to the end of Act One and Reward to the end of Act Two.

- The Ordinary World

- The Call to Adventure

- Crossing the Threshold

- Tests, Allies, Enemies

- Approach the Innermost Cave

- The Road Back

- Resurrection

- Return with Elixir

We've previously written about the ten-step hero's journey in a series of essays separated by act: Act One (with a prologue), Act Two , and Act Three .

Twelve-Step Hero's Journey: Version Two

Again, the second version of the twelve-step hero's journey is very similar to the one above, save for a few changes, including in which story act certain steps appear.

This version skips The Ordinary World exposition and starts right at The Call to Adventure; then, the story ends with two new steps in place of Return With Elixir: The Return and The Freedom to Live.

- The Refusal of the Call

- Meeting the Mentor

- Test, Allies, Enemies

- Approaching the Innermost Cave

- The Resurrection

- The Return*

- The Freedom to Live*

In the final act of this version, there is more of a focus on an internal transformation for the hero. They experience a metamorphosis on their journey back to the Known World, return home changed, and go on to live a new life, uninhibited.

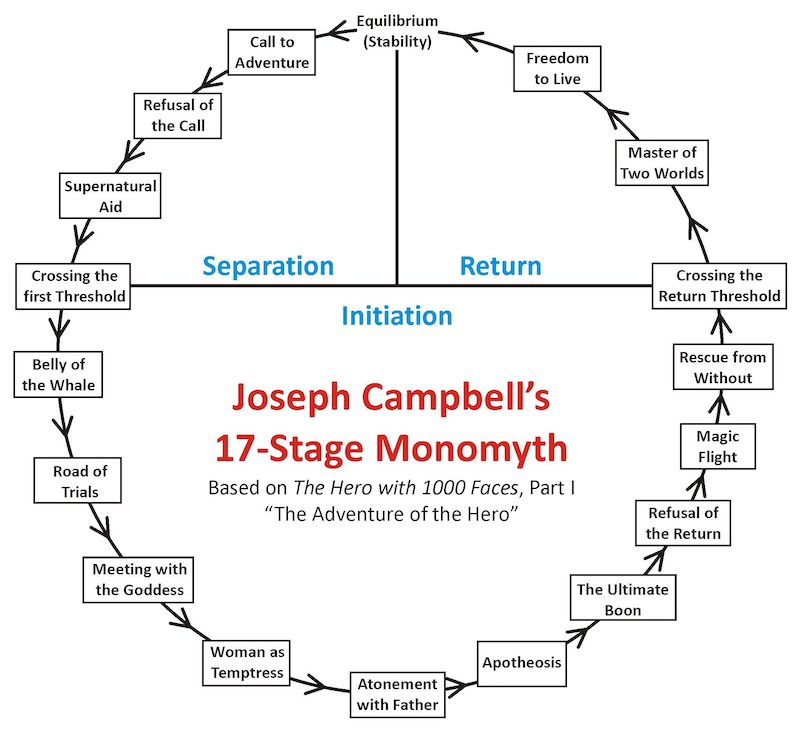

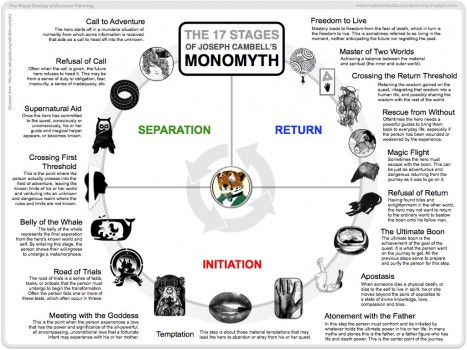

Seventeen-Step Hero's Journey

Finally, the granddaddy of heroic journeys: the seventeen-step Hero's Journey. This version includes a slew of extra steps your hero might face out in the expanse.

- Refusal of the Call

- Supernatural Aid (aka Meeting the Mentor)

- Belly of the Whale*: This added stage marks the hero's immediate descent into danger once they've crossed the threshold.

- Road of Trials (...with Allies, Tests, and Enemies)

- Meeting with the Goddess/God*: In this stage, the hero meets with a new advisor or powerful figure, who equips them with the knowledge or insight needed to keep progressing forward.

- Woman as Temptress (or simply, Temptation)*: Here, the hero is tempted, against their better judgment, to question themselves and their reason for being on the journey. They may feel insecure about something specific or have an exposed weakness that momentarily holds them back.

- Atonement with the Father (or, Catharthis)*: The hero faces their Temptation and moves beyond it, shedding free from all that holds them back.

- Apotheosis (aka The Ordeal)

- The Ultimate Boon (aka the Reward)

- Refusal of the Return*: The hero wonders if they even want to go back to their old life now that they've been forever changed.

- The Magic Flight*: Having decided to return to the Known World, the hero needs to actually find a way back.

- Rescue From Without*: Allies may come to the hero's rescue, helping them escape this bold, new world and return home.

- Crossing of the Return Threshold (aka The Return)

- Master of Two Worlds*: Very closely resembling The Resurrection stage in other variations, this stage signifies that the hero is quite literally a master of two worlds—The Known World and the Unknown World—having conquered each.

- Freedom to Live

Again, we skip the Ordinary World opening here. Additionally, Acts Two and Three look pretty different from what we've seen so far, although, the bones of the Hero's Journey structure remain.

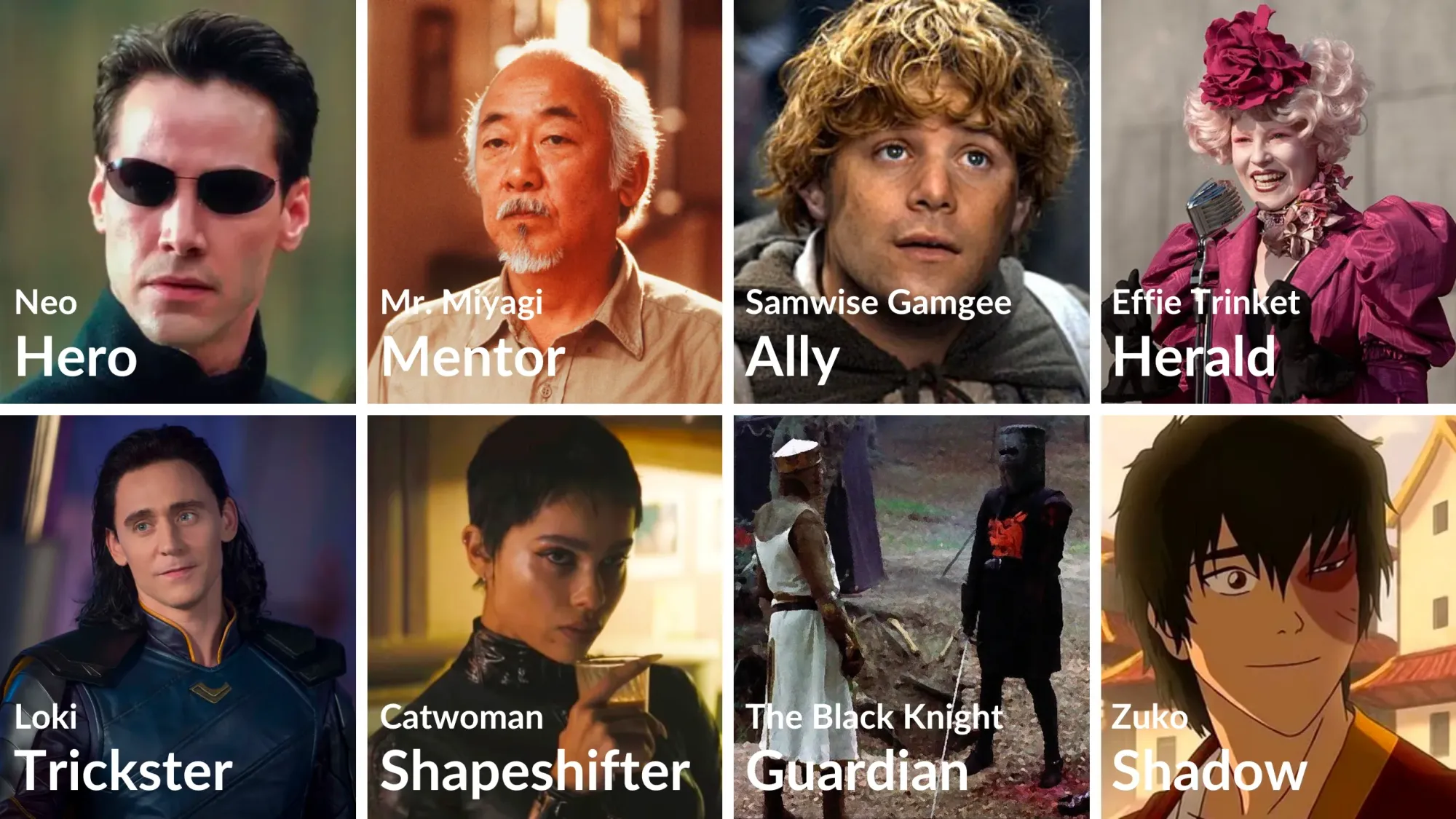

The Eight Hero’s Journey Archetypes

The Hero is, understandably, the cornerstone of the Hero’s Journey, but they’re just one of eight key archetypes that make up this narrative framework.

In The Writer's Journey , Vogler outlined seven of these archetypes, only excluding the Ally, which we've included below. Here’s a breakdown of all eight with examples:

1. The Hero

As outlined, the Hero is the protagonist who embarks on a transformative quest or journey. The challenges they overcome represent universal human struggles and triumphs.

Vogler assigned a "primary function" to each archetype—helpful for establishing their role in a story. The Hero's primary function is "to service and sacrifice."

Example: Neo from The Matrix , who evolves from a regular individual into the prophesied savior of humanity.

2. The Mentor

A wise guide offering knowledge, tools, and advice, Mentors help the Hero navigate the journey and discover their potential. Their primary function is "to guide."

Example: Mr. Miyagi from The Karate Kid imparts not only martial arts skills but invaluable life lessons to Daniel.

3. The Ally

Companions who support the Hero, Allies provide assistance, friendship, and moral support throughout the journey. They may also become a friends-to-lovers romantic partner.

Not included in Vogler's list is the Ally, though we'd argue they are essential nonetheless. Let's say their primary function is "to aid and support."

Example: Samwise Gamgee from Lord of the Rings , a loyal friend and steadfast supporter of Frodo.

4. The Herald

The Herald acts as a catalyst to initiate the Hero's Journey, often presenting a challenge or calling the hero to adventure. Their primary function is "to warn or challenge."

Example: Effie Trinket from The Hunger Games , whose selection at the Reaping sets Katniss’s journey into motion.

5. The Trickster

A character who brings humor and unpredictability, challenges conventions, and offers alternative perspectives or solutions. Their primary function is "to disrupt."

Example: Loki from Norse mythology exemplifies the trickster, with his cunning and chaotic influence.

6. The Shapeshifter

Ambiguous figures whose allegiance and intentions are uncertain. They may be a friend one moment and a foe the next. Their primary function is "to question and deceive."

Example: Catwoman from the Batman universe often blurs the line between ally and adversary, slinking between both roles with glee.

7. The Guardian

Protectors of important thresholds, Guardians challenge or test the Hero, serving as obstacles to overcome or lessons to be learned. Their primary function is "to test."

Example: The Black Knight in Monty Python and the Holy Grail literally bellows “None shall pass!”—a quintessential ( but not very effective ) Guardian.

8. The Shadow

Represents the Hero's inner conflict or an antagonist, often embodying the darker aspects of the hero or their opposition. Their primary function is "to destroy."

Example: Zuko from Avatar: The Last Airbender; initially an adversary, his journey parallels the Hero’s path of transformation.

While your story does not have to use all of the archetypes, they can help you develop your characters and visualize how they interact with one another—especially the Hero.

For example, take your hero and place them in the center of a blank worksheet, then write down your other major characters in a circle around them and determine who best fits into which archetype. Who challenges your hero? Who tricks them? Who guides them? And so on...

Stories that Use the Hero’s Journey

Not a fan of saving the Declaration of Independence? Check out these alternative examples of the Hero’s Journey to get inspired:

- Epic of Gilgamesh : An ancient Mesopotamian epic poem thought to be one of the earliest examples of the Hero’s Journey (and one of the oldest recorded stories).

- The Lion King (1994): Simba's exile and return depict a tale of growth, responsibility, and reclaiming his rightful place as king.

- The Alchemist by Paolo Coehlo: Santiago's quest for treasure transforms into a journey of self-discovery and personal enlightenment.

- Coraline by Neil Gaiman: A young girl's adventure in a parallel world teaches her about courage, family, and appreciating her own reality.

- Kung Fu Panda (2008): Po's transformation from a clumsy panda to a skilled warrior perfectly exemplifies the Hero's Journey. Skadoosh!

The Hero's Journey is so generalized that it's ubiquitous. You can plop the plot of just about any quest-style narrative into its framework and say that the story follows the Hero's Journey. Try it out for yourself as an exercise in getting familiar with the method.

Will the Hero's Journey Work For You?

As renowned as it is, the Hero's Journey works best for the kinds of tales that inspired it: mythic stories.

Writers of speculative fiction may gravitate towards this method over others, especially those writing epic fantasy and science fiction (big, bold fantasy quests and grand space operas come to mind).

The stories we tell today are vast and varied, and they stretch far beyond the dealings of deities, saving kingdoms, or acquiring some fabled "elixir." While that may have worked for Gilgamesh a few thousand years ago, it's not always representative of our lived experiences here and now.

If you decide to give the Hero's Journey a go, we encourage you to make it your own! The pieces of your plot don't have to neatly fit into the structure, but you can certainly make a strong start on mapping out your story.

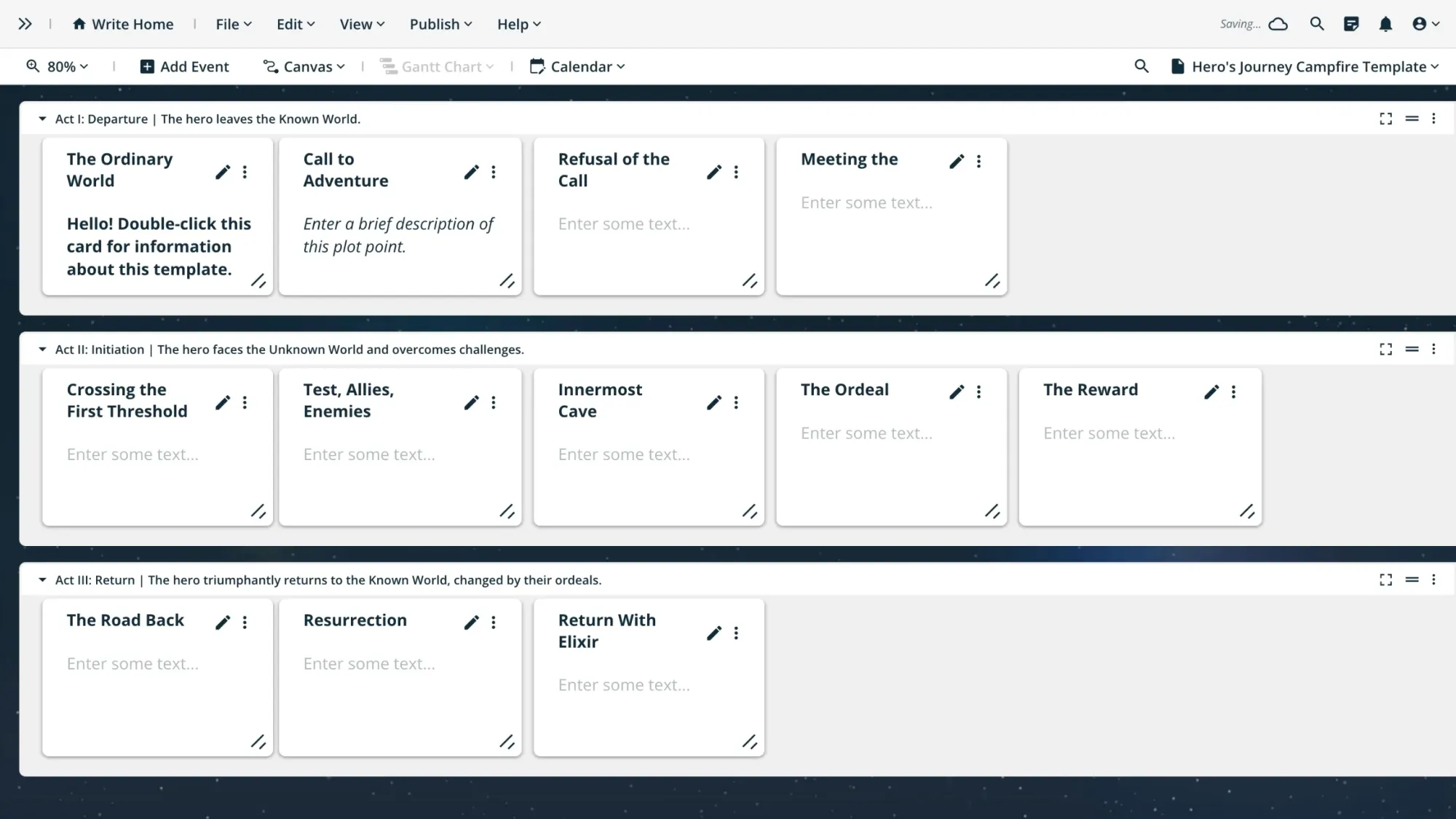

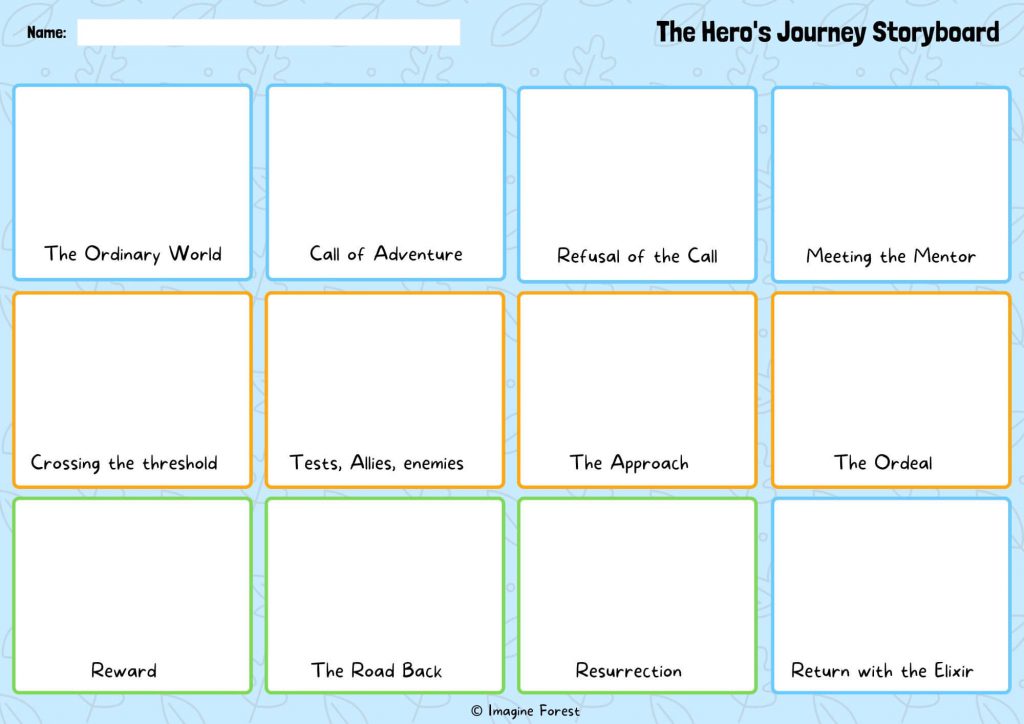

Hero's Journey Campfire Template

The Timeline Module in Campfire offers a versatile canvas to plot out each basic component of your story while featuring nested "notebooks."

Simply double-click on each event card in your timeline to open up a canvas specific to that card. This allows you to look at your plot at the highest level, while also adding as much detail for each plot element as needed!

If you're just hearing about Campfire for the first time, it's free to sign up—forever! Let's plot the most epic of hero's journeys 👇

Lessons From the Hero’s Journey

The Hero's Journey offers a powerful framework for creating stories centered around growth, adventure, and transformation.

If you want to develop compelling characters, spin out engaging plots, and write books that express themes of valor and courage, consider The Hero’s Journey your blueprint. So stop holding out for a hero, and start writing!

Does your story mirror the Hero's Journey? Let us know in the comments below.

Get 25% OFF new yearly plans in our Spring Sale

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

Hero's Journey 101: How to Use the Hero's Journey to Plot Your Story

Dan Schriever

How many times have you heard this story? A protagonist is suddenly whisked away from their ordinary life and embarks on a grand adventure. Along the way they make new friends, confront perils, and face tests of character. In the end, evil is defeated, and the hero returns home a changed person.

That’s the Hero’s Journey in a nutshell. It probably sounds very familiar—and rightly so: the Hero’s Journey aspires to be the universal story, or monomyth, a narrative pattern deeply ingrained in literature and culture. Whether in books, movies, television, or folklore, chances are you’ve encountered many examples of the Hero’s Journey in the wild.

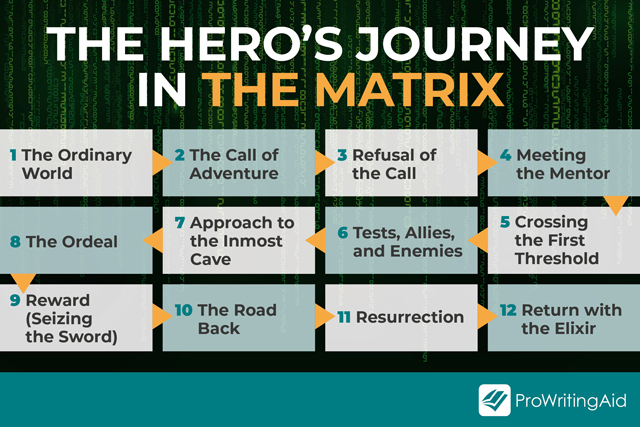

In this post, we’ll walk through the elements of the Hero’s Journey step by step. We’ll also study an archetypal example from the movie The Matrix (1999). Once you have mastered the beats of this narrative template, you’ll be ready to put your very own spin on it.

Sound good? Then let’s cross the threshold and let the journey begin.

What Is the Hero’s Journey?

The 12 stages of the hero’s journey, writing your own hero’s journey.

The Hero’s Journey is a common story structure for modeling both plot points and character development. A protagonist embarks on an adventure into the unknown. They learn lessons, overcome adversity, defeat evil, and return home transformed.

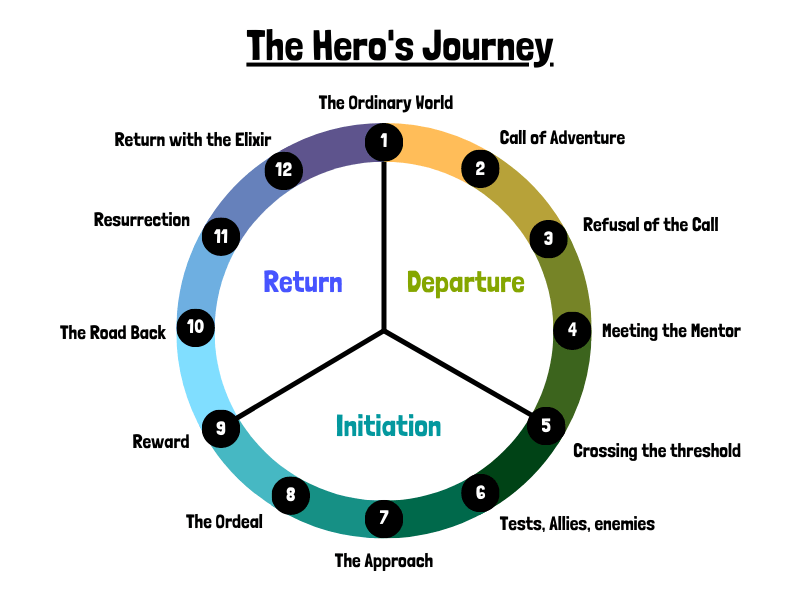

Joseph Campbell , a scholar of literature, popularized the monomyth in his influential work The Hero With a Thousand Faces (1949). Looking for common patterns in mythological narratives, Campbell described a character arc with 17 total stages, overlaid on a more traditional three-act structure. Not all need be present in every myth or in the same order.

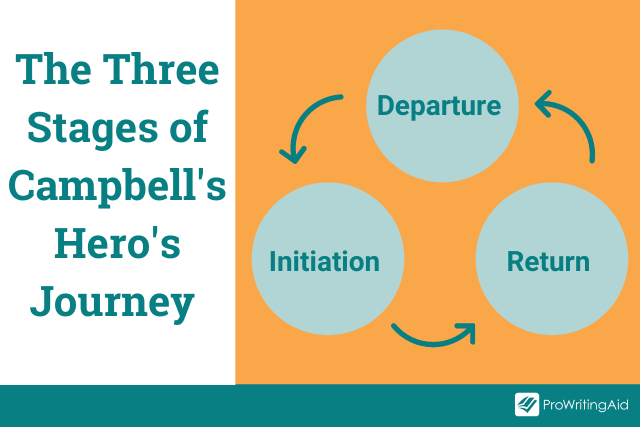

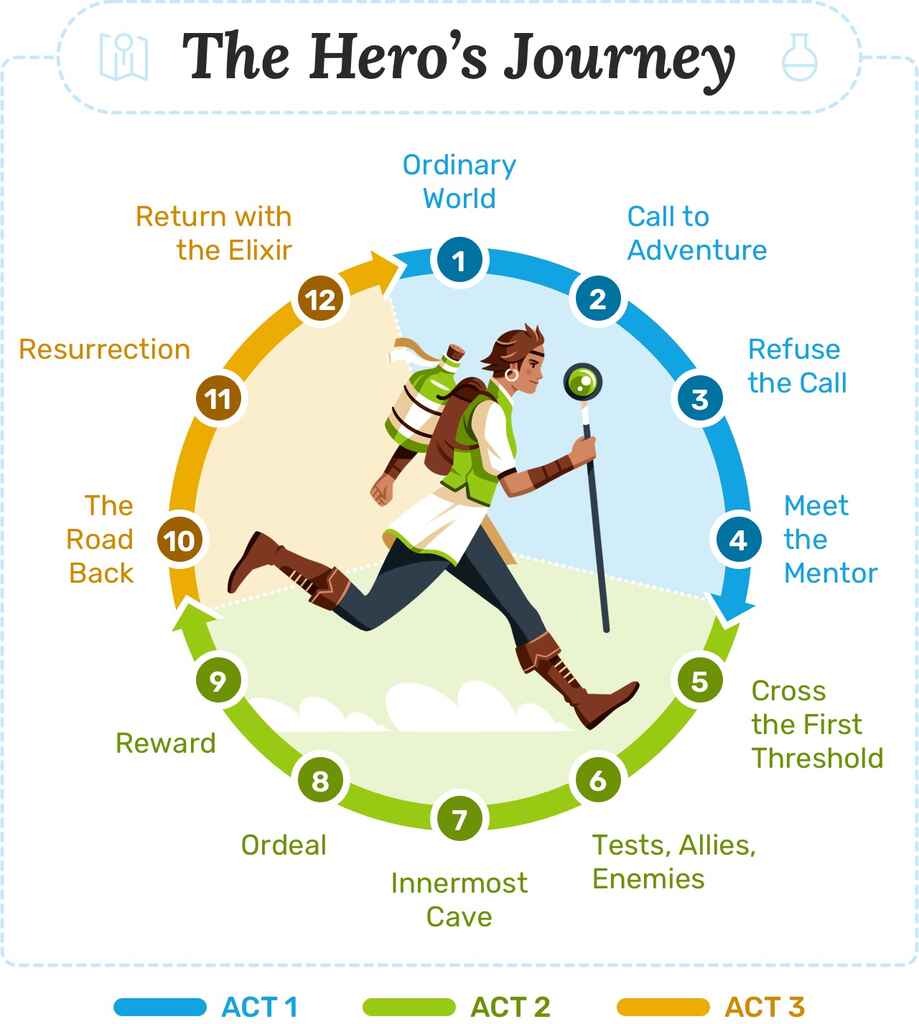

The three stages, or acts, of Campbell’s Hero’s Journey are as follows:

1. Departure. The hero leaves the ordinary world behind.

2. Initiation. The hero ventures into the unknown ("the Special World") and overcomes various obstacles and challenges.

3. Return. The hero returns in triumph to the familiar world.

Hollywood has embraced Campbell’s structure, most famously in George Lucas’s Star Wars movies. There are countless examples in books, music, and video games, from fantasy epics and Disney films to sports movies.

In The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers (1992), screenwriter Christopher Vogler adapted Campbell’s three phases into the "12 Stages of the Hero’s Journey." This is the version we’ll analyze in the next section.

For writers, the purpose of the Hero’s Journey is to act as a template and guide. It’s not a rigid formula that your plot must follow beat by beat. Indeed, there are good reasons to deviate—not least of which is that this structure has become so ubiquitous.

Still, it’s helpful to master the rules before deciding when and how to break them. The 12 steps of the Hero's Journey are as follows :

- The Ordinary World

- The Call of Adventure

- Refusal of the Call

- Meeting the Mentor

- Crossing the First Threshold

- Tests, Allies, and Enemies

- Approach to the Inmost Cave

- Reward (Seizing the Sword)

- The Road Back

- Resurrection

- Return with the Elixir

Let’s take a look at each stage in more detail. To show you how the Hero’s Journey works in practice, we’ll also consider an example from the movie The Matrix (1999). After all, what blog has not been improved by a little Keanu Reeves?

#1: The Ordinary World

This is where we meet our hero, although the journey has not yet begun: first, we need to establish the status quo by showing the hero living their ordinary, mundane life.

It’s important to lay the groundwork in this opening stage, before the journey begins. It lets readers identify with the hero as just a regular person, “normal” like the rest of us. Yes, there may be a big problem somewhere out there, but the hero at this stage has very limited awareness of it.

The Ordinary World in The Matrix :

We are introduced to Thomas A. Anderson, aka Neo, programmer by day, hacker by night. While Neo runs a side operation selling illicit software, Thomas Anderson lives the most mundane life imaginable: he works at his cubicle, pays his taxes, and helps the landlady carry out her garbage.

#2: The Call to Adventure

The journey proper begins with a call to adventure—something that disrupts the hero’s ordinary life and confronts them with a problem or challenge they can’t ignore. This can take many different forms.

While readers may already understand the stakes, the hero is realizing them for the first time. They must make a choice: will they shrink from the call, or rise to the challenge?

The Call to Adventure in The Matrix :

A mysterious message arrives in Neo’s computer, warning him that things are not as they seem. He is urged to “follow the white rabbit.” At a nightclub, he meets Trinity, who tells him to seek Morpheus.

#3: Refusal of the Call

Oops! The hero chooses option A and attempts to refuse the call to adventure. This could be for any number of reasons: fear, disbelief, a sense of inadequacy, or plain unwillingness to make the sacrifices that are required.

A little reluctance here is understandable. If you were asked to trade the comforts of home for a life-and-death journey fraught with peril, wouldn’t you give pause?

Refusal of the Call in The Matrix :

Agents arrive at Neo’s office to arrest him. Morpheus urges Neo to escape by climbing out a skyscraper window. “I can’t do this… This is crazy!” Neo protests as he backs off the ledge.

#4: Meeting the Mentor

Okay, so the hero got cold feet. Nothing a little pep talk can’t fix! The mentor figure appears at this point to give the hero some much needed counsel, coaching, and perhaps a kick out the door.

After all, the hero is very inexperienced at this point. They’re going to need help to avoid disaster or, worse, death. The mentor’s role is to overcome the hero’s reluctance and prepare them for what lies ahead.

Meeting the Mentor in The Matrix :

Neo meets with Morpheus, who reveals a terrifying truth: that the ordinary world as we know it is a computer simulation designed to enslave humanity to machines.

#5: Crossing the First Threshold

At this juncture, the hero is ready to leave their ordinary world for the first time. With the mentor’s help, they are committed to the journey and ready to step across the threshold into the special world . This marks the end of the departure act and the beginning of the adventure in earnest.

This may seem inevitable, but for the hero it represents an important choice. Once the threshold is crossed, there’s no going back. Bilbo Baggins put it nicely: “It’s a dangerous business, Frodo, going out your door. You step onto the road, and if you don't keep your feet, there's no knowing where you might be swept off to.”

Crossing the First Threshold in The Matrix :

Neo is offered a stark choice: take the blue pill and return to his ordinary life none the wiser, or take the red pill and “see how deep the rabbit hole goes.” Neo takes the red pill and is extracted from the Matrix, entering the real world .

#6: Tests, Allies, and Enemies

Now we are getting into the meat of the adventure. The hero steps into the special world and must learn the new rules of an unfamiliar setting while navigating trials, tribulations, and tests of will. New characters are often introduced here, and the hero must navigate their relationships with them. Will they be friend, foe, or something in between?

Broadly speaking, this is a time of experimentation and growth. It is also one of the longest stages of the journey, as the hero learns the lay of the land and defines their relationship to other characters.

Wondering how to create captivating characters? Read our guide , which explains how to shape characters that readers will love—or hate.

Tests, Allies, and Enemies in The Matrix :

Neo is introduced to the vagabond crew of the Nebuchadnezzar . Morpheus informs Neo that he is The One , a savior destined to liberate humanity. He learns jiu jitsu and other useful skills.

#7: Approach to the Inmost Cave

Time to get a little metaphorical. The inmost cave isn’t a physical cave, but rather a place of great danger—indeed, the most dangerous place in the special world . It could be a villain’s lair, an impending battle, or even a mental barrier. No spelunking required.

Broadly speaking, the approach is marked by a setback in the quest. It becomes a lesson in persistence, where the hero must reckon with failure, change their mindset, or try new ideas.

Note that the hero hasn’t entered the cave just yet. This stage is about the approach itself, which the hero must navigate to get closer to their ultimate goal. The stakes are rising, and failure is no longer an option.

Approach to the Inmost Cave in The Matrix :

Neo pays a visit to The Oracle. She challenges Neo to “know thyself”—does he believe, deep down, that he is The One ? Or does he fear that he is “just another guy”? She warns him that the fate of humanity hangs in the balance.

#8: The Ordeal

The ordeal marks the hero’s greatest test thus far. This is a dark time for them: indeed, Campbell refers to it as the “belly of the whale.” The hero experiences a major hurdle or obstacle, which causes them to hit rock bottom.

This is a pivotal moment in the story, the main event of the second act. It is time for the hero to come face to face with their greatest fear. It will take all their skills to survive this life-or-death crisis. Should they succeed, they will emerge from the ordeal transformed.

Keep in mind: the story isn’t over yet! Rather, the ordeal is the moment when the protagonist overcomes their weaknesses and truly steps into the title of hero .

The Ordeal in The Matrix :

When Cipher betrays the crew to the agents, Morpheus sacrifices himself to protect Neo. In turn, Neo makes his own choice: to risk his life in a daring rescue attempt.

#9: Reward (Seizing the Sword)

The ordeal was a major level-up moment for the hero. Now that it's been overcome, the hero can reap the reward of success. This reward could be an object, a skill, or knowledge—whatever it is that the hero has been struggling toward. At last, the sword is within their grasp.

From this moment on, the hero is a changed person. They are now equipped for the final conflict, even if they don’t fully realize it yet.

Reward (Seizing the Sword) in The Matrix :

Neo’s reward is helpfully narrated by Morpheus during the rescue effort: “He is beginning to believe.” Neo has gained confidence that he can fight the machines, and he won’t back down from his destiny.

#10: The Road Back

We’re now at the beginning of act three, the return . With the reward in hand, it’s time to exit the inmost cave and head home. But the story isn’t over yet.

In this stage, the hero reckons with the consequences of act two. The ordeal was a success, but things have changed now. Perhaps the dragon, robbed of his treasure, sets off for revenge. Perhaps there are more enemies to fight. Whatever the obstacle, the hero must face them before their journey is complete.

The Road Back in The Matrix :

The rescue of Morpheus has enraged Agent Smith, who intercepts Neo before he can return to the Nebuchadnezzar . The two foes battle in a subway station, where Neo’s skills are pushed to their limit.

#11: Resurrection

Now comes the true climax of the story. This is the hero’s final test, when everything is at stake: the battle for the soul of Gotham, the final chance for evil to triumph. The hero is also at the peak of their powers. A happy ending is within sight, should they succeed.

Vogler calls the resurrection stage the hero’s “final exam.” They must draw on everything they have learned and prove again that they have really internalized the lessons of the ordeal . Near-death escapes are not uncommon here, or even literal deaths and resurrections.

Resurrection in The Matrix :

Despite fighting valiantly, Neo is defeated by Agent Smith and killed. But with Trinity’s help, he is resurrected, activating his full powers as The One . Isn’t it wonderful how literal The Matrix can be?

#12: Return with the Elixir

Hooray! Evil has been defeated and the hero is transformed. It’s time for the protagonist to return home in triumph, and share their hard-won prize with the ordinary world . This prize is the elixir —the object, skill, or insight that was the hero’s true reward for their journey and transformation.

Return with the Elixir in The Matrix :

Neo has defeated the agents and embraced his destiny. He returns to the simulated world of the Matrix, this time armed with god-like powers and a resolve to open humanity’s eyes to the truth.

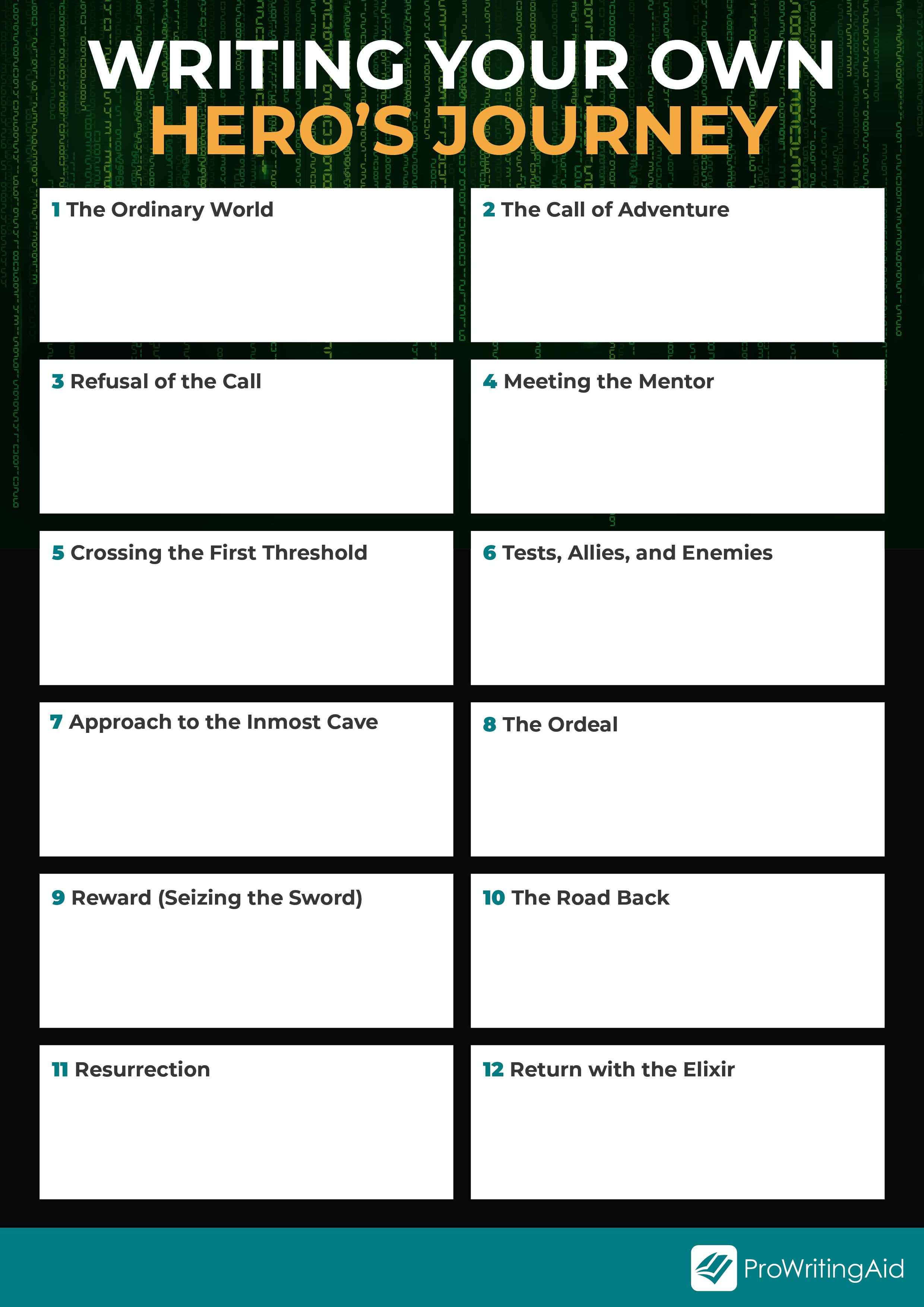

If you’re writing your own adventure, you may be wondering: should I follow the Hero’s Journey structure?

The good news is, it’s totally up to you. Joseph Campbell conceived of the monomyth as a way to understand universal story structure, but there are many ways to outline a novel. Feel free to play around within its confines, adapt it across different media, and disrupt reader expectations. It’s like Morpheus says: “Some of these rules can be bent. Others can be broken.”

Think of the Hero’s Journey as a tool. If you’re not sure where your story should go next, it can help to refer back to the basics. From there, you’re free to choose your own adventure.

Are you prepared to write your novel? Download this free book now:

The Novel-Writing Training Plan

So you are ready to write your novel. excellent. but are you prepared the last thing you want when you sit down to write your first draft is to lose momentum., this guide helps you work out your narrative arc, plan out your key plot points, flesh out your characters, and begin to build your world..

Be confident about grammar

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.

Dan holds a PhD from Yale University and CEO of FaithlessMTG

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

The Approach to the Inmost Cave in the Hero's Journey

From Christopher Vogler's "The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structure"

Moviepix / Getty Images

- Tips For Adult Students

- Getting Your Ged

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Deb-Nov2015-5895870e3df78caebc88766f.jpg)

- B.A., English, St. Olaf College

This article is part of our series on the hero's journey, starting with The Hero's Journey Introduction and The Archetypes of the Hero's Journey .

Approach to the Inmost Cave

The hero has adjusted to the special world and goes on to seek its heart, the inmost cave. She passes into an intermediate zone with new threshold guardians and tests. She approaches the place where the object of the quest is hidden and where she will encounter supreme wonder and terror, according to Christopher Vogler's The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structure . She must use every lesson learned to survive.

The hero often has disheartening setbacks while approaching the cave. She is torn apart by challenges, which allow her to put herself back together in a more effective form for the ordeal to come.

She discovers she must get into the minds of those who stand in her way, Vogler says. If she can understand or empathize with them, the job of getting past them or absorbing them becomes much easier.

The approach encompasses all the final preparations for the ordeal. It brings the hero to the stronghold of the opposition, where she needs to use every lesson she has learned.

Dorothy and her friends, Scarecrow, Tin Man, and Cowardly Lion face a series of obstacles, enter a second special world (Oz) with its own unique guardians and rules, and are given the impossible task of entering the inmost cave, the Wicked Witch’s castle. Dorothy is warned of the supreme danger in this quest and becomes aware that she is challenging a powerful status quo.

There is an eerie region around the inmost cave where it is clear that the hero has entered shaman’s territory on the edge of life and death, Vogler writes. Scarecrow is torn apart; Dorothy is flown off to the castle by monkeys, very like a shaman’s dream journey.

The approach raises the stakes and rededicates the team to its mission. The urgency and life-or-death quality of the situation are underscored. Toto escapes to lead the friends to Dorothy. Dorothy’s intuition knows she must call on the help of her allies.

The reader’s assumptions about the characters are turned upside down as they see each person exhibit surprising new qualities that emerge under the pressure of approach.

The villain's headquarters are defended with fierceness. Dorothy's allies express misgivings, encourage each other, and plan their attack. They get into the skins of the guards, enter the castle, and use force, the Tin Man’s ax, to chop Dorothy out, but they're soon blocked in all directions.

- The Ordeal in the Hero's Journey

- The Hero's Journey: Crossing the Threshold

- The Reward and the Road Back

- An Introduction to The Hero's Journey

- The Ordinary World in the Hero's Journey

- The Resurrection and Return With the Elixir

- The Role of Archetypes in Literature

- The Hero's Journey: Meeting with the Mentor

- The Hero's Journey: Refusing The Call to Adventure

- The 10 Greatest Heroes of Greek Mythology

- The Definition of Quest in Literature

- Ulysses (Odysseus)

- Learn About Greek Goddess Artemis

- The Storied Past of Chapultepec Castle

- "The Wonderful Wizard of Oz" Study Guide

- The Tin Man's Toxic Metal Makeup

Looking to publish? Meet your dream editor, designer and marketer on Reedsy.

Find the perfect editor for your next book

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Last updated on Aug 10, 2023

The Hero's Journey: 12 Steps to a Classic Story Structure

The Hero's Journey is a timeless story structure which follows a protagonist on an unforeseen quest, where they face challenges, gain insights, and return home transformed. From Theseus and the Minotaur to The Lion King , so many narratives follow this pattern that it’s become ingrained into our cultural DNA.

In this post, we'll show you how to make this classic plot structure work for you — and if you’re pressed for time, download our cheat sheet below for everything you need to know.

FREE RESOURCE

Hero's Journey Template

Plot your character's journey with our step-by-step template.

What is the Hero’s Journey?

The Hero's Journey, also known as the monomyth, is a story structure where a hero goes on a quest or adventure to achieve a goal, and has to overcome obstacles and fears, before ultimately returning home transformed.

This narrative arc has been present in various forms across cultures for centuries, if not longer, but gained popularity through Joseph Campbell's mythology book, The Hero with a Thousand Faces . While Campbell identified 17 story beats in his monomyth definition, this post will concentrate on a 12-step framework popularized in 2007 by screenwriter Christopher Vogler in his book The Writer’s Journey .

The 12 Steps of the Hero’s Journey

The Hero's Journey is a model for both plot points and character development : as the Hero traverses the world, they'll undergo inner and outer transformation at each stage of the journey. The 12 steps of the hero's journey are:

- The Ordinary World. We meet our hero.

- Call to Adventure. Will they meet the challenge?

- Refusal of the Call. They resist the adventure.

- Meeting the Mentor. A teacher arrives.

- Crossing the First Threshold. The hero leaves their comfort zone.

- Tests, Allies, Enemies. Making friends and facing roadblocks.

- Approach to the Inmost Cave. Getting closer to our goal.

- Ordeal. The hero’s biggest test yet!

- Reward (Seizing the Sword). Light at the end of the tunnel

- The Road Back. We aren’t safe yet.

- Resurrection. The final hurdle is reached.

- Return with the Elixir. The hero heads home, triumphant.

Believe it or not, this story structure also applies across mediums and genres (and also works when your protagonist is an anti-hero! ). Let's dive into it.

1. Ordinary World

In which we meet our Hero.

The journey has yet to start. Before our Hero discovers a strange new world, we must first understand the status quo: their ordinary, mundane reality.

It’s up to this opening leg to set the stage, introducing the Hero to readers. Importantly, it lets readers identify with the Hero as a “normal” person in a “normal” setting, before the journey begins.

2. Call to Adventure

In which an adventure starts.

The call to adventure is all about booting the Hero out of their comfort zone. In this stage, they are generally confronted with a problem or challenge they can't ignore. This catalyst can take many forms, as Campbell points out in Hero with a Thousand Faces . The Hero can, for instance:

- Decide to go forth of their own volition;

- Theseus upon arriving in Athens.

- Be sent abroad by a benign or malignant agent;

- Odysseus setting off on his ship in The Odyssey .

- Stumble upon the adventure as a result of a mere blunder;

- Dorothy when she’s swept up in a tornado in The Wizard of Oz .

- Be casually strolling when some passing phenomenon catches the wandering eye and lures one away from the frequented paths of man.

- Elliot in E.T. upon discovering a lost alien in the tool shed.

The stakes of the adventure and the Hero's goals become clear. The only question: will he rise to the challenge?

3. Refusal of the Call

In which the Hero digs in their feet.

Great, so the Hero’s received their summons. Now they’re all set to be whisked off to defeat evil, right?

Not so fast. The Hero might first refuse the call to action. It’s risky and there are perils — like spiders, trolls, or perhaps a creepy uncle waiting back at Pride Rock . It’s enough to give anyone pause.

In Star Wars , for instance, Luke Skywalker initially refuses to join Obi-Wan on his mission to rescue the princess. It’s only when he discovers that his aunt and uncle have been killed by stormtroopers that he changes his mind.

4. Meeting the Mentor

In which the Hero acquires a personal trainer.

The Hero's decided to go on the adventure — but they’re not ready to spread their wings yet. They're much too inexperienced at this point and we don't want them to do a fabulous belly-flop off the cliff.

Enter the mentor: someone who helps the Hero, so that they don't make a total fool of themselves (or get themselves killed). The mentor provides practical training, profound wisdom, a kick up the posterior, or something abstract like grit and self-confidence.

Wise old wizards seem to like being mentors. But mentors take many forms, from witches to hermits and suburban karate instructors. They might literally give weapons to prepare for the trials ahead, like Q in the James Bond series. Or perhaps the mentor is an object, such as a map. In all cases, they prepare the Hero for the next step.

GET ACCOUNTABILITY

Meet writing coaches on Reedsy

Industry insiders can help you hone your craft, finish your draft, and get published.

5. Crossing the First Threshold

In which the Hero enters the other world in earnest.

Now the Hero is ready — and committed — to the journey. This marks the end of the Departure stage and is when the adventure really kicks into the next gear. As Vogler writes: “This is the moment that the balloon goes up, the ship sails, the romance begins, the wagon gets rolling.”

From this point on, there’s no turning back.

Like our Hero, you should think of this stage as a checkpoint for your story. Pause and re-assess your bearings before you continue into unfamiliar territory. Have you:

- Launched the central conflict? If not, here’s a post on types of conflict to help you out.

- Established the theme of your book? If not, check out this post that’s all about creating theme and motifs .

- Made headway into your character development? If not, this character profile template may be useful:

Reedsy’s Character Profile Template

A story is only as strong as its characters. Fill this out to develop yours.

6. Tests, Allies, Enemies

In which the Hero faces new challenges and gets a squad.

When we step into the Special World, we notice a definite shift. The Hero might be discombobulated by this unfamiliar reality and its new rules. This is generally one of the longest stages in the story , as our protagonist gets to grips with this new world.

This makes a prime hunting ground for the series of tests to pass! Luckily, there are many ways for the Hero to get into trouble:

- In Jumanji: Welcome to the Jungle , Spencer, Bethany, “Fridge,” and Martha get off to a bad start when they bump into a herd of bloodthirsty hippos.

- In his first few months at Hogwarts, Harry Potter manages to fight a troll, almost fall from a broomstick and die, and get horribly lost in the Forbidden Forest.

- Marlin and Dory encounter three “reformed” sharks, get shocked by jellyfish, and are swallowed by a blue whale en route to finding Nemo.

This stage often expands the cast of characters. Once the protagonist is in the Special World, he will meet allies and enemies — or foes that turn out to be friends and vice versa. He will learn a new set of rules from them. Saloons and seedy bars are popular places for these transactions, as Vogler points out (so long as the Hero survives them).

7. Approach to the Inmost Cave

In which the Hero gets closer to his goal.

This isn’t a physical cave. Instead, the “inmost cave” refers to the most dangerous spot in the other realm — whether that’s the villain’s chambers, the lair of the fearsome dragon, or the Death Star. Almost always, it is where the ultimate goal of the quest is located.

Note that the protagonist hasn’t entered the Inmost Cave just yet. This stage is all about the approach to it. It covers all the prep work that's needed in order to defeat the villain.

In which the Hero faces his biggest test of all thus far.

Of all the tests the Hero has faced, none have made them hit rock bottom — until now. Vogler describes this phase as a “black moment.” Campbell refers to it as the “belly of the whale.” Both indicate some grim news for the Hero.

The protagonist must now confront their greatest fear. If they survive it, they will emerge transformed. This is a critical moment in the story, as Vogler explains that it will “inform every decision that the Hero makes from this point forward.”

The Ordeal is sometimes not the climax of the story. There’s more to come. But you can think of it as the main event of the second act — the one in which the Hero actually earns the title of “Hero.”

9. Reward (Seizing the Sword)

In which the Hero sees light at the end of the tunnel.

Our Hero’s been through a lot. However, the fruits of their labor are now at hand — if they can just reach out and grab them! The “reward” is the object or knowledge the Hero has fought throughout the entire journey to hold.

Once the protagonist has it in their possession, it generally has greater ramifications for the story. Vogler offers a few examples of it in action:

- Luke rescues Princess Leia and captures the plans of the Death Star — keys to defeating Darth Vader.

- Dorothy escapes from the Wicked Witch’s castle with the broomstick and the ruby slippers — keys to getting back home.

10. The Road Back

In which the light at the end of the tunnel might be a little further than the Hero thought.

The story's not over just yet, as this phase marks the beginning of Act Three. Now that he's seized the reward, the Hero tries to return to the Ordinary World, but more dangers (inconveniently) arise on the road back from the Inmost Cave.

More precisely, the Hero must deal with the consequences and aftermath of the previous act: the dragon, enraged by the Hero who’s just stolen a treasure from under his nose, starts the hunt. Or perhaps the opposing army gathers to pursue the Hero across a crowded battlefield. All further obstacles for the Hero, who must face them down before they can return home.

11. Resurrection

In which the last test is met.

Here is the true climax of the story. Everything that happened prior to this stage culminates in a crowning test for the Hero, as the Dark Side gets one last chance to triumph over the Hero.

Vogler refers to this as a “final exam” for the Hero — they must be “tested once more to see if they have really learned the lessons of the Ordeal.” It’s in this Final Battle that the protagonist goes through one more “resurrection.” As a result, this is where you’ll get most of your miraculous near-death escapes, à la James Bond's dashing deliverances. If the Hero survives, they can start looking forward to a sweet ending.

12. Return with the Elixir

In which our Hero has a triumphant homecoming.

Finally, the Hero gets to return home. However, they go back a different person than when they started out: they’ve grown and matured as a result of the journey they’ve taken.

But we’ve got to see them bring home the bacon, right? That’s why the protagonist must return with the “Elixir,” or the prize won during the journey, whether that’s an object or knowledge and insight gained.

Of course, it’s possible for a story to end on an Elixir-less note — but then the Hero would be doomed to repeat the entire adventure.

Examples of The Hero’s Journey in Action

To better understand this story template beyond the typical sword-and-sorcery genre, let's analyze three examples, from both screenplay and literature, and examine how they implement each of the twelve steps.

The 1976 film Rocky is acclaimed as one of the most iconic sports films because of Stallone’s performance and the heroic journey his character embarks on.

- Ordinary World. Rocky Balboa is a mediocre boxer and loan collector — just doing his best to live day-to-day in a poor part of Philadelphia.

- Call to Adventure. Heavyweight champ Apollo Creed decides to make a big fight interesting by giving a no-name loser a chance to challenge him. That loser: Rocky Balboa.

- Refusal of the Call. Rocky says, “Thanks, but no thanks,” given that he has no trainer and is incredibly out of shape.

- Meeting the Mentor. In steps former boxer Mickey “Mighty Mick” Goldmill, who sees potential in Rocky and starts training him physically and mentally for the fight.

- Crossing the First Threshold. Rocky crosses the threshold of no return when he accepts the fight on live TV, and 一 in parallel 一 when he crosses the threshold into his love interest Adrian’s house and asks her out on a date.

- Tests, Allies, Enemies. Rocky continues to try and win Adrian over and maintains a dubious friendship with her brother, Paulie, who provides him with raw meat to train with.

- Approach to the Inmost Cave. The Inmost Cave in Rocky is Rocky’s own mind. He fears that he’ll never amount to anything — something that he reveals when he butts heads with his trainer, Mickey, in his apartment.

- Ordeal. The start of the training montage marks the beginning of Rocky’s Ordeal. He pushes through it until he glimpses hope ahead while running up the museum steps.

- Reward (Seizing the Sword). Rocky's reward is the restoration of his self-belief, as he recognizes he can try to “go the distance” with Apollo Creed and prove he's more than "just another bum from the neighborhood."

- The Road Back. On New Year's Day, the fight takes place. Rocky capitalizes on Creed's overconfidence to start strong, yet Apollo makes a comeback, resulting in a balanced match.

- Resurrection. The fight inflicts multiple injuries and pushes both men to the brink of exhaustion, with Rocky being knocked down numerous times. But he consistently rises to his feet, enduring through 15 grueling rounds.

- Return with the Elixir. Rocky loses the fight — but it doesn’t matter. He’s won back his confidence and he’s got Adrian, who tells him that she loves him.

Moving outside of the ring, let’s see how this story structure holds on a completely different planet and with a character in complete isolation.

The Martian

In Andy Weir’s self-published bestseller (better known for its big screen adaptation) we follow astronaut Mark Watney as he endures the challenges of surviving on Mars and working out a way to get back home.

- The Ordinary World. Botanist Mark and other astronauts are on a mission on Mars to study the planet and gather samples. They live harmoniously in a structure known as "the Hab.”

- Call to Adventure. The mission is scrapped due to a violent dust storm. As they rush to launch, Mark is flung out of sight and the team believes him to be dead. He is, however, very much alive — stranded on Mars with no way of communicating with anyone back home.

- Refusal of the Call. With limited supplies and grim odds of survival, Mark concludes that he will likely perish on the desolate planet.

- Meeting the Mentor. Thanks to his resourcefulness and scientific knowledge he starts to figure out how to survive until the next Mars mission arrives.

- Crossing the First Threshold. Mark crosses the mental threshold of even trying to survive 一 he successfully creates a greenhouse to cultivate a potato crop, creating a food supply that will last long enough.

- Tests, Allies, Enemies. Loneliness and other difficulties test his spirit, pushing him to establish contact with Earth and the people at NASA, who devise a plan to help.

- Approach to the Inmost Cave. Mark faces starvation once again after an explosion destroys his potato crop.

- Ordeal. A NASA rocket destined to deliver supplies to Mark disintegrates after liftoff and all hope seems lost.

- Reward (Seizing the Sword). Mark’s efforts to survive are rewarded with a new possibility to leave the planet. His team 一 now aware that he’s alive 一 defies orders from NASA and heads back to Mars to rescue their comrade.

- The Road Back. Executing the new plan is immensely difficult 一 Mark has to travel far to locate the spaceship for his escape, and almost dies along the way.

- Resurrection. Mark is unable to get close enough to his teammates' ship but finds a way to propel himself in empty space towards them, and gets aboard safely.

- Return with the Elixir. Now a survival instructor for aspiring astronauts, Mark teaches students that space is indifferent and that survival hinges on solving one problem after another, as well as the importance of other people’s help.

Coming back to Earth, let’s now examine a heroine’s journey through the wilderness of the Pacific Crest Trail and her… humanity.

The memoir Wild narrates the three-month-long hiking adventure of Cheryl Strayed across the Pacific coast, as she grapples with her turbulent past and rediscovers her inner strength.

- The Ordinary World. Cheryl shares her strong bond with her mother who was her strength during a tough childhood with an abusive father.

- Call to Adventure. As her mother succumbs to lung cancer, Cheryl faces the heart-wrenching reality to confront life's challenges on her own.

- Refusal of the Call. Cheryl spirals down into a destructive path of substance abuse and infidelity, which leads to hit rock bottom with a divorce and unwanted pregnancy.

- Meeting the Mentor. Her best friend Lisa supports her during her darkest time. One day she notices the Pacific Trail guidebook, which gives her hope to find her way back to her inner strength.

- Crossing the First Threshold. She quits her job, sells her belongings, and visits her mother’s grave before traveling to Mojave, where the trek begins.

- Tests, Allies, Enemies. Cheryl is tested by her heavy bag, blisters, rattlesnakes, and exhaustion, but many strangers help her along the trail with a warm meal or hiking tips.

- Approach to the Inmost Cave. As Cheryl goes through particularly tough and snowy parts of the trail her emotional baggage starts to catch up with her.

- Ordeal. She inadvertently drops one of her shoes off a cliff, and the incident unearths the helplessness she's been evading since her mother's passing.

- Reward (Seizing the Sword). Cheryl soldiers on, trekking an impressive 50 miles in duct-taped sandals before finally securing a new pair of shoes. This small victory amplifies her self-confidence.

- The Road Back. On the last stretch, she battles thirst, sketchy hunters, and a storm, but more importantly, she revisits her most poignant and painful memories.

- Resurrection. Cheryl forgives herself for damaging her marriage and her sense of worth, owning up to her mistakes. A pivotal moment happens at Crater Lake, where she lets go of her frustration at her mother for passing away.

- Return with the Elixir. Cheryl reaches the Bridge of the Gods and completes the trail. She has found her inner strength and determination for life's next steps.

There are countless other stories that could align with this template, but it's not always the perfect fit. So, let's look into when authors should consider it or not.

When should writers use The Hero’s Journey?

The Hero’s Journey is just one way to outline a novel and dissect a plot. For more longstanding theories on the topic, you can go this way to read about the ever-popular Three-Act Structure or here to discover Dan Harmon's Story Circle and three more prevalent structures .

So when is it best to use the Hero’s Journey? There are a couple of circumstances which might make this a good choice.

When you need more specific story guidance than simple structures can offer

Simply put, the Hero’s Journey structure is far more detailed and closely defined than other story structure theories. If you want a fairly specific framework for your work than a thee-act structure, the Hero’s Journey can be a great place to start.

Of course, rules are made to be broken . There’s plenty of room to play within the confines of the Hero’s Journey, despite it appearing fairly prescriptive at first glance. Do you want to experiment with an abbreviated “Resurrection” stage, as J.K. Rowling did in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone? Are you more interested in exploring the journey of an anti-hero? It’s all possible.

Once you understand the basics of this universal story structure, you can use and bend it in ways that disrupt reader expectations.

Need more help developing your book? Try this template on for size:

Get our Book Development Template

Use this template to go from a vague idea to a solid plan for a first draft.

When your focus is on a single protagonist

No matter how sprawling or epic the world you’re writing is, if your story is, at its core, focused on a single character’s journey, then this is a good story structure for you. It’s kind of in the name! If you’re dealing with an entire ensemble, the Hero’s Journey may not give you the scope to explore all of your characters’ plots and subplot — a broader three-act structure may give you more freedom to weave a greater number story threads.

Which story structure is right for you?

Take this quiz and we'll match your story to a structure in minutes!

Whether you're a reader or writer, we hope our guide has helped you understand this universal story arc. Want to know more about story structure? We explain 6 more in our guide — read on!

6 responses

PJ Reece says:

25/07/2018 – 19:41

Nice vid, good intro to story structure. Typically, though, the 'hero's journey' misses the all-important point of the Act II crisis. There, where the hero faces his/her/its existential crisis, they must DIE. The old character is largely destroyed -- which is the absolute pre-condition to 'waking up' to what must be done. It's not more clever thinking; it's not thinking at all. Its SEEING. So many writing texts miss this point. It's tantamount to a religions experience, and nobody grows up without it. STORY STRUCTURE TO DIE FOR examines this dramatic necessity.

↪️ C.T. Cheek replied:

13/11/2019 – 21:01

Okay, but wouldn't the Act II crisis find itself in the Ordeal? The Hero is tested and arguably looses his/her/its past-self for the new one. Typically, the Hero is not fully "reborn" until the Resurrection, in which they defeat the hypothetical dragon and overcome the conflict of the story. It's kind of this process of rebirth beginning in the earlier sections of the Hero's Journey and ending in the Resurrection and affirmed in the Return with the Elixir.

Lexi Mize says:

25/07/2018 – 22:33

Great article. Odd how one can take nearly every story and somewhat plug it into such a pattern.

Bailey Koch says:

11/06/2019 – 02:16

This was totally lit fam!!!!

↪️ Bailey Koch replied:

11/09/2019 – 03:46

where is my dad?

Frank says:

12/04/2020 – 12:40

Great article, thanks! :) But Vogler didn't expand Campbell's theory. Campbell had seventeen stages, not twelve.

Comments are currently closed.

Join a community of over 1 million authors

Reedsy is more than just a blog. Become a member today to discover how we can help you publish a beautiful book.

Bring your stories to life

Our free writing app lets you set writing goals and track your progress, so you can finally write that book!

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Enter your email or get started with a social account:

The Art of Narrative

Learn to write.

A Complete Guide to The Hero’s Journey (or The Monomyth)

Learn how to use the 12 steps of the Hero’s Journey to structure plot, develop characters, and write riveting stories that will keep readers engaged!

Before I start this post I would like to acknowledged the tragedy that occurred in my country this past month. George Floyd, an innocent man, was murdered by a police officer while three other officers witnessed that murder and remained silent.

To remain silent, in the face of injustice, violen ce, and murder is to be complicit . I acknowledge that as a white man I have benefited from a centuries old system of privilege and abuse against black people, women, American Indians, immigrants, and many, many more.

This systemic abuse is what lead to the murder of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, Sandra Bland, Eric Garner, Treyvon Martin, Philando Castile, Freddie Gray, Walter Scott, Tamir Rice and many more. Too many.

Whether I like it or not I’ve been complicit in this injustice. We can’t afford to be silent anymore. If you’re disturbed by the violence we’ve wit nessed over, and over again please vote this November, hold your local governments accountable, peacefully protest, and listen. Hopefully, together we can bring positive change. And, together, we can heal .

In this post, we’ll go over the stages of Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey, also known as the Monomyth. We’ll talk about how to use it to structure your story. You’ll also find some guided questions for each section of the Hero’s Journey. These questions are designed to help guide your thinking during the writing process. Finally, we’ll go through an example of the Hero’s Journey from 1997’s Men In Black.

Down at the bottom, we’ll go over reasons you shouldn’t rely on the Monomyth. And we’ll talk about a few alternatives for you to consider if the Hero’s Journey isn’t right for your story.

But, before we do all that let’s answer the obvious question-

What is the Hero’s Journey?

The Hero’s Journey was first described by Joseph Campbell. Campbell was an American professor of literature at Sarah Lawrence College. He wrote about the Hero’s Journey in his book The Hero with a Thousand Faces . More than a guide, this book was a study on the fundamental structure of myths throughout history.

Through his study, Campbell identified seventeen stages that make up what he called the Monomyth or Hero’s Journey. We’ll go over these stages in the next section. Here’s how Campbell describes the Monomyth in his book:

“A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.”

Something important to note is that the Monomyth was not conceived as a tool for writers to develop a plot. Rather, Campbell identified it as a narrative pattern that was common in mythology.

George Lucas used Campbell’s Monomyth to structure his original Star Wars film. Thanks to Star Wars ’ success, filmmakers have adopted the Hero’s Journey as a common plot structure in movies.

We see it in films like The Matrix , Spider-man , The Lion King , and many more. But, keep in mind, this is not the only way to structure a story. We’ll talk about some alternatives at the end of this post.

With that out of the way, let’s go over the twelve stages of the Hero’s Journey, or Monomyth. We’ll use the original Men In Black film as an example (because why not?). And, we’ll look at some questions to help guide your thinking, as a writer, at each stage.

Quick note – The original Hero’s Journey is seventeen stages. But, Christopher Vogler, an executive working for Disney, condensed Campbell’s work. Vogler’s version has twelve stages, and it’s the version we’re talking about today. Vogler wrote a guide to use the Monomyth and I’ll link to it at the bottom.)

The 12 Stages of The Hero’s Journey

The ordinary world .

This is where the hero’s story begins. We meet our hero in a down-to-earth, or humble setting. We establish the hero as an ordinary citizen in this world, not necessarily “special” in any way.

Think exposition .

We get to know our hero at this stage of the story. We learn about the hero’s life, struggles, inner or outer demons. This an opportunity for readers to identify with the hero. A good idea since the story will be told from the hero’s perspective.

Read more about perspective and POV here.

In Men In Black, we meet our hero, James, who will become Agent J, chasing someone down the streets of a large city. The story reveals some important details through the action of the plo t. Let’s go over these details and how they’re shown through action.

Agent J’s job: He’s a cop. We know this because he’s chasing a criminal. He waves a badge and yells, “NYPD! Stop!”

The setting: The line “NYPD!” tells us that J is a New York City cop. The chase sequence also culminates on the roof of the Guggenheim Museum. Another clue to the setting.

J’s Personality: J is a dedicated cop. We know this because of his relentless pursuit of the suspect he’s chasing. J is also brave. He jumps off a bridge onto a moving bus. He also chases a man after witnessing him climb vertically, several stories, up a wall. This is an inhuman feat that would have most people noping out of there. J continues his pursuit, though.

Guided Questions

- What is your story’s ordinary world setting?

- How is this ordinary world different from the special world that your hero will enter later in the story?

- What action in this story will reveal the setting?

- Describe your hero and their personality.

- What action in the story will reveal details about your hero?

The Call of Adventure

The Call of Adventure is an event in the story that forces the hero to take action. The hero will move out of their comfort zone, aka the ordinary world. Does this sound familiar? It should, because, in practice, The Call of Adventure is an Inciting Event.

Read more about Inciting Events here.

The Call of Adventure can take many forms. It can mean a literal call like one character asking another to go with them on a journey or to help solve a problem. It can also be an event in the story that forces the character to act.

The Call of Adventure can include things like the arrival of a new character, a violent act of nature, or a traumatizing event. The Call can also be a series of events like what we see in our example from Men In Black.

The first Call of Adventure comes from the alien that Agent J chases to the roof of the Guggenheim. Before leaping from the roof, the alien says to J, “Your world’s going to end.” This pique’s the hero’s interest and hints at future conflict.

The second Call of Adventure comes after Agent K shows up to question J about the alien. K wipes J’s memory after the interaction, but he gives J a card with an address and a time. At this point, J has no idea what’s happened. All he knows is that K has asked him to show up at a specific place the next morning.

The final and most important Call comes after K has revealed the truth to J while the two sit on a park bench together. Agent K tells J that aliens exist. K reveals that there is a secret organization that controls alien activity on Earth. And the Call- Agent K wants J to come to work for this organization.

- What event (or events) happen to incite your character to act?

- How are these events disruptive to your character’s life?

- What aspects of your story’s special world will be revealed and how? (think action)

- What other characters will you introduce as part of this special world?

Refusal of the Call

This is an important stage in the Monomyth. It communicates with the audience the risks that come with Call to Adventure. Every Hero’s Journey should include risks to the main characters and a conflict. This is the stage where your hero contemplates those risks. They will be tempted to remain in the safety of the ordinary world.

In Men in Black, the Refusal of the Call is subtle. It consists of a single scene. Agent K offers J membership to the Men In Black. With that comes a life of secret knowledge and adventure. But, J will sever all ties to his former life. No one anywhere will ever know that J existed. Agent K tells J that he has until sunrise to make his decision.

J does not immediately say, “I’m in,” or “When’s our first mission.” Instead, he sits on the park bench all night contemplating his decision. In this scene, the audience understands that this is not an easy choice for him. Again, this is an excellent use of action to demonstrate a plot point.

It’s also important to note that J only asks K one question before he makes his decision, “is it worth it?” K responds that it is, but only, “if you’re strong enough.” This line of dialogue becomes one of two dramatic questions in the movie. Is J strong enough to be a man in black?

- What will your character have to sacrifice to answer the call of adventure?

- What fears does your character have about leaving the ordinary world?

- What risks or dangers await them in the special world?

Meeting the Mentor

At this point in the story, the hero is seeking wisdom after initially refusing the call of adventure. The mentor fulfills this need for your hero.

The mentor is usually a character who has been to the special world and knows how to navigate it. Mentor’s provides your hero with tools and resources to aid them in their journey. It’s important to note that the mentor doesn’t always have to be a character. The mentor could be a guide, map, or sacred texts.

If you’ve seen Men In Black then you can guess who acts as J’s mentor. Agent K, who recruited J, steps into the mentor role once J accepts the call to adventure.

Agent K gives J a tour of the MIB headquarters. He introduces him to key characters and explains to him how the special world of the MIB works. Agent K also gives J his signature weapon, the Noisy Cricket.

- Who is your hero’s mentor?

- How will your character find and encounter with their mentor?

- What tools and resources will your mentor provide?

- Why/how does your mentor know the special world?

Crossing the Threshold