Family Life

AAP Schedule of Well-Child Care Visits

Parents know who they should go to when their child is sick. But pediatrician visits are just as important for healthy children.

The Bright Futures /American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) developed a set of comprehensive health guidelines for well-child care, known as the " periodicity schedule ." It is a schedule of screenings and assessments recommended at each well-child visit from infancy through adolescence.

Schedule of well-child visits

- The first week visit (3 to 5 days old)

- 1 month old

- 2 months old

- 4 months old

- 6 months old

- 9 months old

- 12 months old

- 15 months old

- 18 months old

- 2 years old (24 months)

- 2 ½ years old (30 months)

- 3 years old

- 4 years old

- 5 years old

- 6 years old

- 7 years old

- 8 years old

- 9 years old

- 10 years old

- 11 years old

- 12 years old

- 13 years old

- 14 years old

- 15 years old

- 16 years old

- 17 years old

- 18 years old

- 19 years old

- 20 years old

- 21 years old

The benefits of well-child visits

Prevention . Your child gets scheduled immunizations to prevent illness. You also can ask your pediatrician about nutrition and safety in the home and at school.

Tracking growth & development . See how much your child has grown in the time since your last visit, and talk with your doctor about your child's development. You can discuss your child's milestones, social behaviors and learning.

Raising any concerns . Make a list of topics you want to talk about with your child's pediatrician such as development, behavior, sleep, eating or getting along with other family members. Bring your top three to five questions or concerns with you to talk with your pediatrician at the start of the visit.

Team approach . Regular visits create strong, trustworthy relationships among pediatrician, parent and child. The AAP recommends well-child visits as a way for pediatricians and parents to serve the needs of children. This team approach helps develop optimal physical, mental and social health of a child.

More information

Back to School, Back to Doctor

Recommended Immunization Schedules

Milestones Matter: 10 to Watch for by Age 5

Your Child's Checkups

- Bright Futures/AAP Recommendations for Preventive Pediatric Health Care (periodicity schedule)

An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Preventive care benefits for children

Coverage for children’s preventive health services.

A fixed amount ($20, for example) you pay for a covered health care service after you've paid your deductible.

Refer to glossary for more details.

The percentage of costs of a covered health care service you pay (20%, for example) after you've paid your deductible.

The amount you pay for covered health care services before your insurance plan starts to pay. With a $2,000 deductible, for example, you pay the first $2,000 of covered services yourself.

- Alcohol, tobacco, and drug use assessments for adolescents

- Autism screening for children at 18 and 24 months

- Behavioral assessments for children: Age 0 to 11 months , 1 to 4 years , 5 to 10 years , 11 to 14 years , 15 to 17 years

You are leaving HealthCare.gov.

You're about to connect to a third-party site. Select CONTINUE to proceed or CANCEL to stay on this site.

Learn more about links to third-party sites .

- Blood pressure screening for children: Age 0 to 11 months , 1 to 4 years , 5 to 10 years , 11 to 14 years , 15 to 17 years

- Blood screening for newborns

- Depression screening for adolescents beginning routinely at age 12

- Developmental screening for children under age 3

- Fluoride supplements for children without fluoride in their water source

- Fluoride varnish for all infants and children as soon as teeth are present

- Gonorrhea preventive medication for the eyes of all newborns

- Hematocrit or hemoglobin screening for all children

- Hemoglobinopathies or sickle cell screening for newborns

- Hepatitis B screening for adolescents at higher risk

- HIV screening for adolescents at higher risk

- Hypothyroidism screening for newborns

- PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) HIV prevention medication for HIV-negative adolescents at high risk for getting HIV through sex or injection drug use

- Chickenpox (Varicella)

- Diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis (DTaP)

- Haemophilus influenza type b

- Hepatitis A

- Hepatitis B

- Human Papillomavirus (HPV)

- Inactivated Poliovirus

- Influenza (flu shot)

- Meningococcal

- Pneumococcal

- Obesity screening and counseling

- Phenylketonuria (PKU) screening for newborns

- Sexually transmitted infection (STI) prevention counseling and screening for adolescents at higher risk

- Tuberculin testing for children at higher risk of tuberculosis: Age 0 to 11 months , 1 to 4 years , 5 to 10 years , 11 to 14 years , 15 to 17 years

- Vision screening for all children

- Well-baby and well-child visits

More information about preventive services for children

- Preventive services for children age 0 to 11 months

- Preventive services for children age 1 to 4 years

- Preventive services for children age 5 to 10 years

- Preventive services for children age 11 to 14 years

- Preventive services for children age 15 to 17 years

More on prevention

- Learn more about preventive care from the CDC .

- See preventive services covered for adults and women .

- Learn more about what else Marketplace health insurance plans cover.

- Visit TexasChildrensHealthPlan.org

- 1-800-731-8527

- Electronic Visit Verification (EVV)

- Clinical Practice Guidelines

- Downloadable Forms

- Provider Directory

- Provider Resources

- Quick Reference Guide

- STAR Kids Information

- The Checkup Newsletter

- 2019 Annual Provider Newsletter

- Provider Events

Provider Alert! Well Child and Texas Health Steps Visit reminder

Date: November 22, 2021

Attention: PCP, OB/GYN and Endocrinologist Providers

Providers should monitor the Texas Children’s Health Plan (TCHP) Provider Portal regularly for alerts and updates associated to the COVID-19 event. TCHP reserves the right to update and/or change this information without prior notice due to the evolving nature of the COVID-19 event.

Call to action: Texas Children’s Health Plan (TCHP) would like to remind you of the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) HEDIS Technical Specifications.

How this impacts providers:

Please submit all claims timely, as soon as services are rendered, and use appropriate codes to reflect the services provided particularly for Well-Care Visits and THSteps.

Well-Child Visits in the First 30 Months of Life (W30)

- Well-Child Visits in the First 15 Months: Six well-child visits are required to meet this HEDIS measure

- Well-Child Visits for Age 15 Months – 30 Months: Two well-child visits are required to meet this HEDIS measure

- The following table lists the number of visits billable at each age range:

- Compliance will be calculated directly from claims or encounters submission

- Telehealth included as an acceptable code1 (see THSteps guidance on appropriate billing below)

Please make sure to submit THSteps claims timely using the appropriate codes to get credit for the visits.

* With abnormal findings ** Without abnormal findings

NOTE: Both CPT and appropriate ICD-10 codes must be present for claim to be paid. Claims should be billed using only the child’s Medicaid number.

Additional CPT codes for well child checks Outpatient visit:

The following codes will count as a well-child visit for HEDIS: 99381,99382,99383,99384,99385,99391,99392,99393,99394,99395.

For Texas Health Steps Follow-up visit use procedure code 99211 when billed with a THSteps diagnosis.

Source: https://www.tmhp.com/sites/default/files/file-library/texas-health-steps/THSteps_QRG.pdf

Child and Adolescent Well-Care Visits (WCV)

- Combination measure

- Measure encompasses 3-20 years old

- Included telehealth as acceptable code (see THSteps guidance on appropriate billing below)

- Some of the requirements (like immunizations and physical exams) with a well-child visit require an in-person visit. The follow-up code for this visit is 99211 along with the appropriate diagnosis code. Providers must follow-up with their patients within six months of the telemedicine visit to ensure completion of any components.

Please make sure to submit claims timely using the appropriate codes to get credit for the visits.

Note: Both CPT and appropriate ICD-10 codes must be present for claim to be paid. Claims should be billed using only the child’s Medicaid number.

Guidance for Texas Health Steps (THSteps):

Due to the ongoing pandemic, HHSC is allowing Telehealth visits for THSteps for children over 24 months of age.

Providers must use the appropriate Place of Service (POS) Code with Telehealth Modifier 95 to ensure timely and accurate claims processing.

Weight Assessment and Counseling for Nutrition and Physical Activity for Children/Adolescents (WCC)

- Allowed member-reported biometric values (body mass index, height and weight)

- Telephone visit, e-visit or virtual check-in meet criteria

- Measures encompasses members ages 3-17

Nutrition counseling coding information

BMI Percentile

Physical activity counseling

Next steps for providers:

Providers should implement protocols to improve their compliance rate if needed.

We have developed HEDIS Toolkits that contain helpful information regarding the measure requirements, standards and codes to use that are acceptable for HEDIS reporting. The toolkit is available here: https://www.texaschildrenshealthplan.org/for-providers/provider-resources/hedis-toolkit

TCHP uses Inovalon, a HEDIS certified software, to calculate HEDIS rates. Included are historic claims from TMHP files, as well as information from ImmTrac, the State’s immunization registry. Providers should report their completed patient’s immunization with correct vaccine codes regularly so records are up to date and accurate. IMMTrac: The Texas Immunization Registry; https://www.dshs.texas.gov/immunize/ImmTrac/provider-resources

If you have any questions, please email Provider Network Management at: [email protected] .

For access to all provider alerts, log into : www.thecheckup.org or www.texaschildrenshealthplan.org/for-providers

Share this post

Texas Children's Health Plan

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Related Posts

Provider alert chip co-pays waived for office visits in response to covid-19.

Date: March 29, 2022 Attention: All Providers Effective Date: March 29, 2022 The content in this message will remain in effect through April... read more

HEDIS Spotlight: Well-child and well-care visits

HEDIS stands for Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set. It is a widely used set of performance measures utilized by... read more

Provider Alert! Preventing Pre-Term Pregnancies

To: All Providers Subject: Effective September 1, 2015 all Progesterone therapy will require a pre-authorization from Texas Children’s Health Plan. Claims billed... read more

Provider Alert! Perinatal Psychiatric Access Network (PeriPAN) Pilot Live in Four Regions

Date: September 8, 2022 Attention: All Providers Effective Date: September 1, 2022 Providers should monitor the Texas Children’s Health Plan (TCHP) Provider... read more

Provider Alert! Healthy Texas Women Program Launches Enhanced Postpartum Care Services

Attention: Chemical dependency treatment facilities, opioid treatment programs, licensed professional counselors, licensed clinical social workers, psychologists and psychology groups, psychiatrists,... read more

Provider Alert! Omnipod 5 Added to Medicaid and CHIP Formularies

Date: March 18, 2024 Attention: All Providers Effective date: February 22, 2024 Call to action: Texas Children’s Health Plan (TCHP) would like to... read more

Provider Alert! Mandatory HHSC training for Financial Management Services Agencies (FMSA)

Effective February 25, 2020 Call to action: Health and Human Services Commission (HHSC) is providing a webinar for Financial Management Services... read more

Provider Alert! Early Childhood Intervention (ECI) and Telehealth Services are not required to Use EVV

Date: April 17, 2024 Attention: Early Childhood Intervention and Telehealth Service Providers Effective date: January 1, 2024 Call to action: The purpose of... read more

Provider Alert! EVV Direction for FMSAs on CDS Employer Usage

Date: August 1, 2022 Attention: FMSA and Consumer Directed Services Employers Effective date: September 1, 2022 Providers should monitor the Texas... read more

Provider Alert! First Quarter 2022 HCPCS Updates for Texas Medicaid

Date: July 5, 2022 Attention: Providers Effective Date: April 1, 2022 Providers should monitor the Texas Children’s Health Plan (TCHP) Provider Portal regularly... read more

Doctor Visits

Make the Most of Your Child’s Visit to the Doctor (Ages 1 to 4 Years)

Take Action

Young children need to go to the doctor or nurse for a “well-child visit” 7 times between ages 1 and 4.

A well-child visit is when you take your child to the doctor to make sure they’re healthy and developing normally. This is different from other visits for sickness or injury.

At a well-child visit, the doctor or nurse can help catch any problems early, when they may be easier to treat. You’ll also have a chance to ask questions about things like your child’s behavior, eating habits, and sleeping habits.

Learn what to expect so you can make the most of each visit.

Well-Child Visits

How often do i need to take my child for well-child visits.

Young children grow quickly, so they need to visit the doctor or nurse regularly to make sure they’re healthy and developing normally.

Children ages 1 to 4 need to see the doctor or nurse when they’re:

- 12 months old

- 15 months old (1 year and 3 months)

- 18 months old (1 year and 6 months)

- 24 months old (2 years)

- 30 months old (2 years and 6 months)

- 3 years old

- 4 years old

If you’re worried about your child’s health, don’t wait until the next scheduled visit — call the doctor or nurse right away.

Child Development

How do i know if my child is growing and developing on schedule.

Your child’s doctor or nurse can help you understand how your child is developing and learning to do new things — like walk and talk. These are sometimes called “developmental milestones.”

Every child grows and develops differently. For example, some children will take longer to start talking than others. Learn more about child development .

At each visit, the doctor or nurse will ask you how you’re doing as a parent and what new things your child is learning to do.

Ages 12 to 18 Months

By age 12 months, most kids:.

- Stand by holding on to something

- Walk with help, like by holding on to the furniture

- Call a parent "mama," "dada," or some other special name

- Look for a toy they've seen you hide

Check out this complete list of milestones for kids age 12 months .

By age 15 months, most kids:

- Follow simple directions, like "Pick up the toy"

- Show you a toy they like

- Try to use things they see you use, like a cup or a book

- Take a few steps on their own

Check out this complete list of milestones for kids age 15 months.

By age 18 months, most kids:

- Make scribbles with crayons

- Look at a few pages in a book with you

- Try to say 3 or more words besides “mama” or “dada”

- Point to show someone what they want

- Walk on their own

- Try to use a spoon

Check out this complete list of milestones for kids age 18 months .

Ages 24 to 30 Months

By age 24 months (2 years), most kids:.

- Notice when others are hurt or upset

- Point to at least 2 body parts, like their nose, when asked

- Try to use knobs or buttons on a toy

- Kick a ball

Check out this complete list of milestones for kids age 24 months .

By age 30 months, most kids:

- Name items in a picture book, like a cat or dog

- Play simple games with other kids, like tag

- Jump off the ground with both feet

- Take some clothes off by themselves, like loose pants or an open jacket

Check out this complete list of milestones for kids age 30 months .

Ages 3 to 4 Years

By age 3 years, most kids:.

- Calm down within 10 minutes after you leave them, like at a child care drop-off

- Draw a circle after you show them how

- Ask “who,” “what,” “where,” or “why” questions, like “Where is Daddy?”

Check out this complete list of milestones for kids age 3 years .

By age 4 years, most kids:

- Avoid danger — for example, they don’t jump from tall heights at the playground

- Pretend to be something else during play, like a teacher, superhero, or dog

- Draw a person with 3 or more body parts

- Catch a large ball most of the time

Check out this complete list of milestones for kids age 4 years .

Take these steps to help you and your child get the most out of well-child visits.

Gather important information.

Bring any medical records you have to the appointment, including a record of vaccines (shots) your child has received.

Make a list of any important changes in your child’s life since the last doctor’s visit, like a:

- New brother or sister

- Serious illness or death in the family

- Separation or divorce

- Change in child care

Use this tool to keep track of your child’s family health history .

Ask other caregivers about your child.

Before you visit the doctor, talk with others who care for your child, like a grandparent, daycare provider, or babysitter. They may be able to help you think of questions to ask the doctor or nurse.

What about cost?

Under the Affordable Care Act, insurance plans must cover well-child visits. Depending on your insurance plan, you may be able to get well-child visits at no cost to you. Check with your insurance company to find out more.

Your child may also qualify for free or low-cost health insurance through Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). Learn about coverage options for your family.

If you don’t have insurance, you may still be able to get free or low-cost well-child visits. Find a health center near you and ask about well-child visits.

To learn more, check out these resources:

- Free preventive care for children covered by the Affordable Care Act

- How the Affordable Care Act protects you and your family

- Understanding your health insurance and how to use it [PDF - 698 KB]

Ask Questions

Make a list of questions you want to ask the doctor..

Before the well-child visit, write down 3 to 5 questions you have. This visit is a great time to ask the doctor or nurse any questions about:

- A health condition your child has (like asthma or an allergy)

- Changes in sleeping or eating habits

- How to help kids in the family get along

Here are some questions you may want to ask:

- Is my child up to date on vaccines?

- How can I make sure my child is getting enough physical activity?

- Is my child at a healthy weight?

- How can I help my child try different foods?

- What are appropriate ways to discipline my child?

- How much screen time is okay for young children?

Take a notepad, smartphone, or tablet and write down the answers so you remember them later.

Ask what to do if your child gets sick.

Make sure you know how to get in touch with a doctor or nurse when the office is closed. Ask how to get hold of the doctor on call — or if there's a nurse information service you can call at night or during the weekend.

What to Expect

Know what to expect..

During each well-child visit, the doctor or nurse will ask you questions about your child, do a physical exam, and update your child's medical history. You'll also be able to ask your questions and discuss any problems you may be having.

The doctor or nurse will ask questions about your child.

The doctor or nurse may ask about:

- Behavior — Does your child have trouble following directions?

- Health — Does your child often complain of stomachaches or other kinds of pain?

- Activities — What types of pretend play does your child like?

- Eating habits — What does your child eat on a normal day?

- Family — Have there been any changes in your family since your last visit?

They may also ask questions about safety, like:

- Does your child always ride in a car seat in the back seat of the car?

- Does anyone in your home have a gun? If so, is it unloaded and locked in a place where your child can’t get it?

- Is there a swimming pool or other water around your home?

- What steps have you taken to childproof your home? Do you have gates on stairs and latches on cabinets?

Your answers to questions like these will help the doctor or nurse make sure your child is healthy, safe, and developing normally.

Physical Exam

The doctor or nurse will also check your child’s body..

To check your child’s body, the doctor or nurse will:

- Measure your child’s height and weight

- Check your child’s blood pressure

- Check your child’s vision

- Check your child’s body parts (this is called a physical exam)

- Give your child shots they need

Learn more about your child’s health care:

- Find out how to get your child’s shots on schedule

- Learn how to take care of your child’s vision

Content last updated February 2, 2024

Reviewer Information

This information on well-child visits was adapted from materials from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health.

Reviewed by: Sara Kinsman, M.D., Ph.D. Director, Division of Child, Adolescent, and Family Health Maternal and Child Health Bureau Health Resources and Services Administration

Bethany Miller, M.S.W. Chief, Adolescent Health Branch Maternal and Child Health Bureau Health Resources and Services Administration

Diane Pilkey, R.N., M.P.H. Nursing Consultant, Division of Child, Adolescent, and Family Health Maternal and Child Health Bureau Health Resources and Services Administration

You may also be interested in:

Help Your Child Stay at a Healthy Weight

Get Your Child’s Vision Checked

Healthy Snacks: Quick Tips for Parents

The office of disease prevention and health promotion (odphp) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website..

Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by ODPHP or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- Article Information

eReferences

- Contextual Considerations When Interpreting Well-Child Visit Adherence Results JAMA Pediatrics Comment & Response January 1, 2023 Sarah L. Goff, MD, PhD

See More About

Select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

Others Also Liked

- Download PDF

- X Facebook More LinkedIn

Abdus S , Selden TM. Well-Child Visit Adherence. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176(11):1143–1145. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.2954

Manage citations:

© 2024

- Permissions

Well-Child Visit Adherence

- 1 Center for Financing, Access, and Cost Trends, Division of Research and Modeling, Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, Maryland

- Comment & Response Contextual Considerations When Interpreting Well-Child Visit Adherence Results Sarah L. Goff, MD, PhD JAMA Pediatrics

Well-child care, as recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Bright Futures guidelines, 1 provides children with preventive and developmental services, helps ensure timely immunizations, and allows parents to discuss health-related concerns. 2 We know from prior studies 3 , 4 that as of 2008, well-child visits were trending upward, but often fell short of recommendations among key socioeconomic groups. This article provides updated evidence on well-child visit adherence, both overall and by age, race and ethnicity, insurance coverage, family income, parent education, urbanicity, and region.

We used the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) 5 to conduct a cross-sectional study of children aged 0 to 18 years in 2006 and 2007 (n = 19 018) and 2016 and 2017 (n = 17 533). Sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), MEPS provides nationally representative data on child office visits, thereby avoiding potential over reporting from questions more directly about adherence. 3 , 4 Unlike administrative or insurer data, MEPS includes uninsured children and offers extensive socioeconomic information on children and their families.

We defined adherence as the ratio of reported well-child visits during the calendar year divided by the recommended number of visits. Recommendations published in late 2007 added visits at 30 months, 7 years, and 9 years. 1 We used these recommendations throughout our study to maintain consistent adherence denominators. We compared adherence in 2006 and 2007 and 2016 and 2017 for all children and by subgroup (differences-in-differences). This study was covered under the Chesapeake Institutional Review Board protocol for AHRQ Secondary Analysis of Confidential Data from the MEPS, and followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology ( STROBE ) reporting guidelines. The eMethods in the Supplement provide additional methodological details.

Average adherence increased from 47.9% (95% CI, 46.1%-49.7%) in 2006 and 2007 to 62.3% (95% CI, 60.1%-64.6%) in 2016 and 2017, respectively ( Table ), yet large gaps remained across race and ethnicity, poverty level, insurance, and geography. Adherence grew by 17.5 percentage points (95% CI, 11.6%-23.4%) among children ages 7 to 10 years, the group with the largest guideline increase. This increase was not, however, significantly different from adherence growth in either (1) our reference group (ages 4-6 years), selected for having unchanged guidelines and the highest initial adherence, or (2) older children, whose guidelines also remained constant.

Adherence grew unevenly across race and ethnicity, rising by 21.7 percentage points (95% CI, 17.9%-25.5%) among Hispanic children vs 15.3 percentage points (95% CI, 10.9%-19.7%) among White non-Hispanic children. Nevertheless, adherence in 2016 and 2017 among Hispanic children at 58.0% (95% CI, 55.0%-60.9%) still trailed that of White non-Hispanic children at 67.8% (95% CI, 64.3%-71.4%). Adherence among Black non-Hispanic children increased by only 5.6 percentage points (95% CI, 0.3%-11.0%), widening the Black-White adherence disparity among non-Hispanic children.

Adherence also grew unevenly across insurance status, increasing among publicly insured and privately insured children by 15.5 percentage points (95% CI, 11.8%-19.2%) and 13.9 percentage points (95% CI, 10.2%-17.6%), respectively, while not changing significantly among uninsured children. The resulting 2016 and 2017 adherence ratios for children with any private, any public (and no private), and no coverage were 66.3% (95% CI, 63.4%-69.1%), 58.7% (95% CI, 55.7%-61.7%), and 31.1% (95% CI, 23.9%-38.3%), respectively.

We found evidence of increased well-child visit adherence over our study period, which spanned increased visit recommendations, substantial macroeconomic change, and enactment of the Affordable Care Act’s coverage and preventive care provisions. Nevertheless, disturbing gaps remained. Adherence among uninsured children in 2016 and 2017 was only half the national average, and over a 20–percentage point difference still separated the highest-adherence and lowest-adherence regions. The Black non-Hispanic vs White non-Hispanic disparity widened during this period. Narrowing disparities and improving adherence among US children will require the combined efforts of researchers, policy makers, and clinicians to improve our understanding of adherence, to implement policies improving access to care, and to increase health care professional engagement with disadvantaged communities. 6

Accepted for Publication: June 22, 2022.

Published Online: August 22, 2022. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.2954

Corresponding Author : Salam Abdus, PhD, Center for Financing, Access, and Cost Trends, Division of Research and Modeling, Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 5600 Fishers Ln, Rockville, MD 20857 ( [email protected] ).

Author Contributions : Drs Abdus and Selden had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Concept and design: All authors.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Statistical analysis: All authors.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the US Department of Health and Human Services or the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Additional Contributions: Joel Cohen, PhD, Yao Ding, PhD, and G. Edward Miller, PhD, of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, provided comments on early versions of the article. and the contributors received no compensation.

Additional Information : This study was conducted by Drs Abdus and Selden as employees of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and as part of AHRQ’s intramural research program. AHRQ was involved with the internal peer review process.

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

Catch Up on Well-Child Visits and Recommended Vaccinations

Many children missed check-ups and recommended childhood vaccinations over the past few years. CDC and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommend children catch up on routine childhood vaccinations and get back on track for school, childcare, and beyond.

Making sure that your child sees their doctor for well-child visits and recommended vaccines is one of the best things you can do to protect your child and community from serious diseases that are easily spread.

Well-Child Visits and Recommended Vaccinations Are Essential

Well-child visits and recommended vaccinations are essential and help make sure children stay healthy. Children who are not protected by vaccines are more likely to get diseases like measles and whooping cough . These diseases are extremely contagious and can be very serious, especially for babies and young children. In recent years, there have been outbreaks of these diseases, especially in communities with low vaccination rates.

Well-child visits are essential for many reasons , including:

- Tracking growth and developmental milestones

- Discussing any concerns about your child’s health

- Getting scheduled vaccinations to prevent illnesses like measles and whooping cough (pertussis) and other serious diseases

It’s particularly important for parents to work with their child’s doctor or nurse to make sure they get caught up on missed well-child visits and recommended vaccines.

Routinely Recommended Vaccines for Children and Adolescents

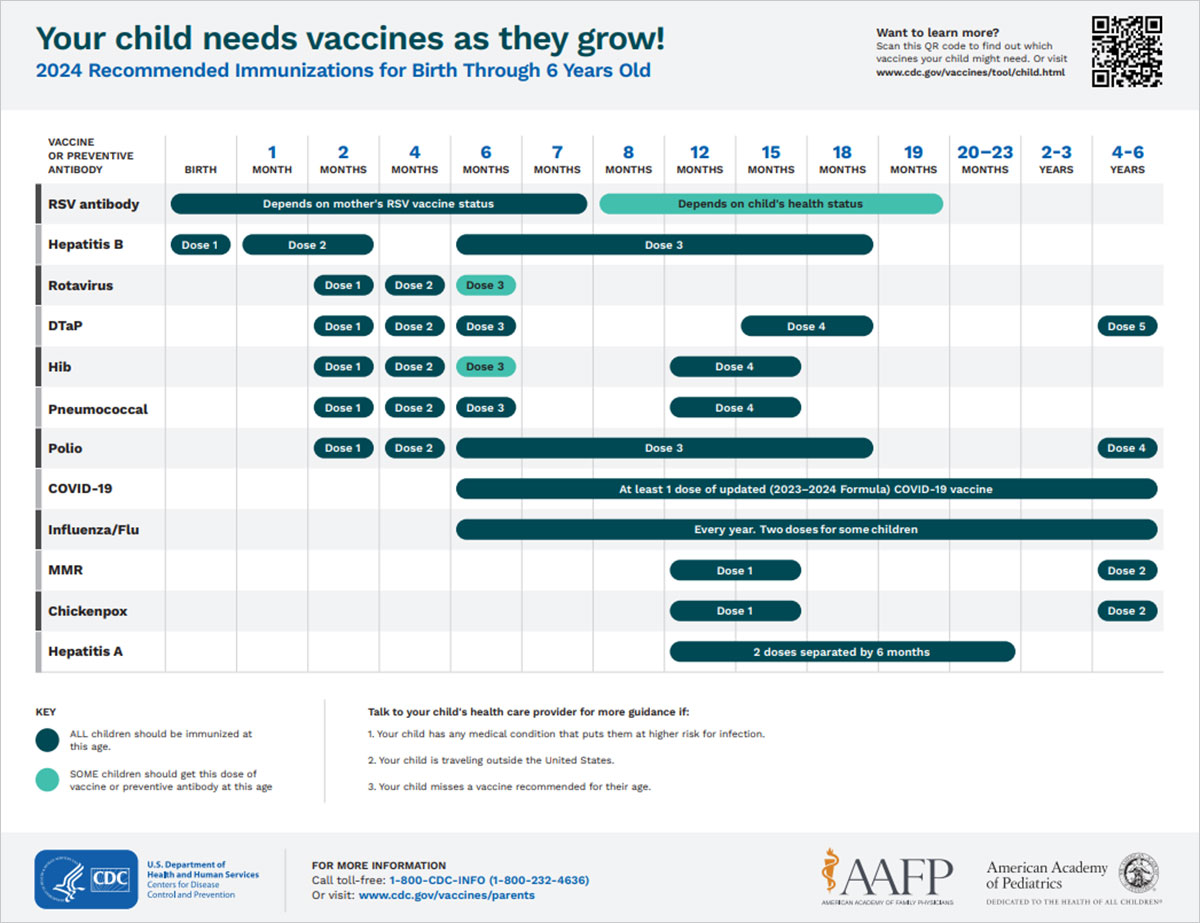

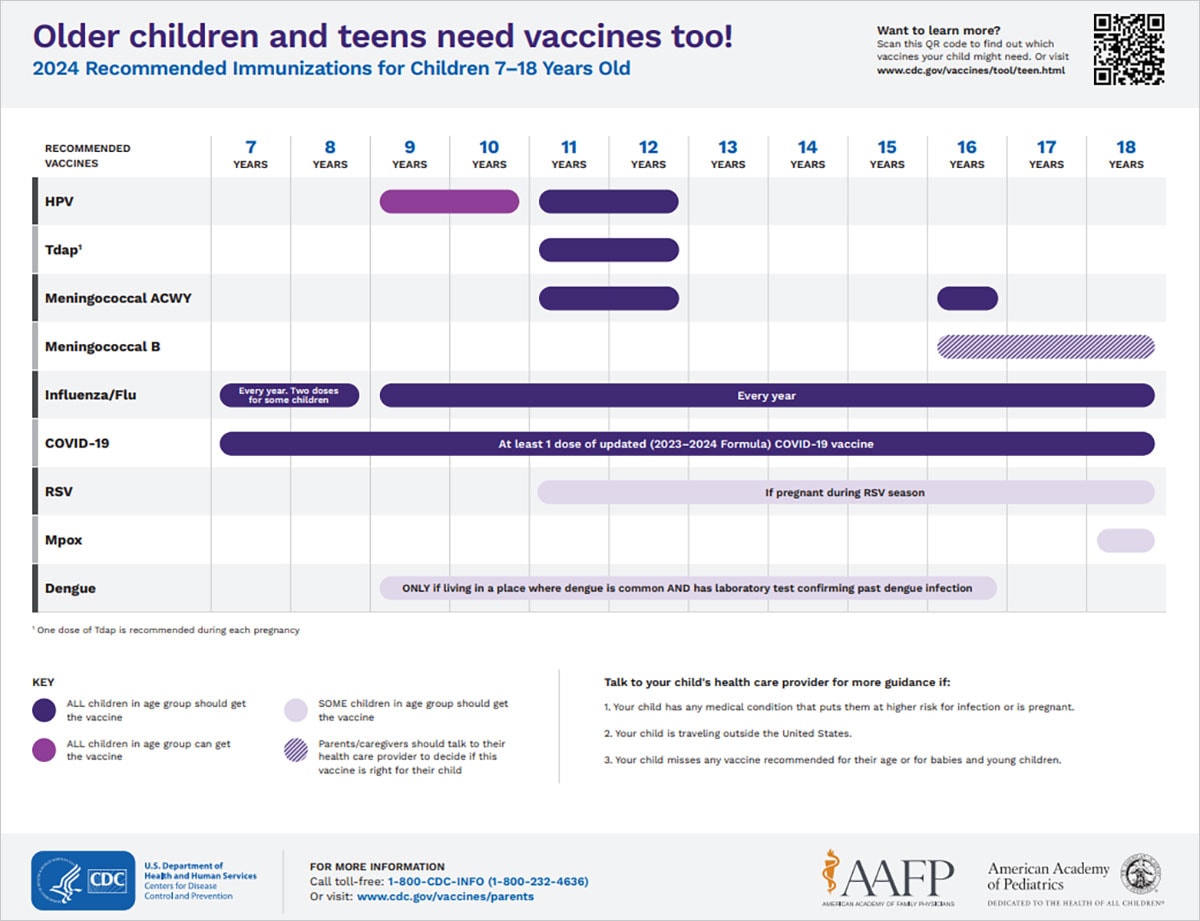

Getting children and adolescents caught up with recommended vaccinations is the best way to protect them from a variety of vaccine-preventable diseases . The schedules below outline the vaccines recommended for each age group.

See which vaccines your child needs from birth through age 6 in this easy-to-read immunization schedule.

See which vaccines your child needs from ages 7 through 18 in this easy-to-read immunization schedule.

The Vaccines for Children (VFC) program provides vaccines to eligible children at no cost. This program provides free vaccines to children who are Medicaid-eligible, uninsured, underinsured, or American Indian/Alaska Native. Check out the program’s requirements and talk to your child’s doctor or nurse to see if they are a VFC provider. You can also find a VFC provider by calling your state or local health department or seeing if your state has a VFC website.

COVID-19 Vaccines for Children and Teens

Everyone aged 6 months and older can get an updated COVID-19 vaccine to help protect against severe illness, hospitalization and death. Learn more about making sure your child stays up to date with their COVID-19 vaccines .

- Vaccines & Immunizations

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

The independent source for health policy research, polling, and news.

The Impact of the Pandemic on Well-Child Visits for Children Enrolled in Medicaid and CHIP

Elizabeth Williams , Alice Burns , Robin Rudowitz , and Patrick Drake Published: Mar 18, 2024

In Medicaid, states are required to cover all screening services as well as any services “necessary… to correct or ameliorate” a child’s physical or mental health condition under Medicaid’s Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment (EPSDT) benefit (see Box 1). Many of these screening services along with immunizations are provided at well-child visits. These visits are a key part of comprehensive preventive health services designed to keep children healthy and to identify and treat health conditions in a timely manner. Various studies have also shown that children who forego their well-child visits have an increased chance of going to the emergency room or being hospitalized. Well-child visits are recommended once a year for children ages three to 21 and multiple times a year for children under age three according to the Bright Futures/American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) periodicity schedule .

A recent Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) analysis shows that half of children under age 19 received a Medicaid or CHIP funded well-child visit in 2020. The onset of the pandemic in 2020 had a substantial impact on health and health care service utilization, but research has shown that many Medicaid-covered children were not receiving recommended screenings and services even before the pandemic. This issue brief examines well-child visit rates overall and for selected characteristics before and after the pandemic began and discusses recent state and federal policy changes that could impact children’s preventive care. The analysis uses Medicaid claims data which track the services enrollees use and may differ from survey data. In future years, claims data will be used to monitor adherence to recommended screenings. Key findings include:

- More than half (54%) of children under age 21 enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP received a well-child visit in 2019, but the share fell to 48% in 2020, the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Despite having the highest well-child visit rates compared to other ethnic and racial groups, Hispanic and Asian children enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP saw the largest percentage point declines in well-child visit rates from 2019 to 2020.

- Children over age three enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP have lower rates of well-child visits and experienced larger declines in well-child visits during the pandemic than children under age three.

- Well-child visit rates are lower for Medicaid/CHIP children in rural areas, but rates in urban areas declined more during the pandemic.

How did use of well-child visits change during the pandemic?

More than half (54%) of children under 21 enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP received a well-child visit in 2019, but the share fell to 48% in 2020, the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 1). Rates examined here use Medicaid claims data which differ substantially from survey data (see Box 2). While the vast majority of children in the analysis (91% in 2019 and 88% in 2020) used a least one Medicaid service, including preventive visits, sick visits, filling prescriptions, or hospital or emergency department visits, well-child visit rates remained low and are substantially below the CMS goal of at least 80%. One recent analysis found that 4 in 10 children enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP experienced at least one challenge when accessing health care. Barriers to Medicaid/CHIP children receiving needed care can include lack of transportation, language barriers, disabilities , and parents having difficulty finding childcare or taking time off for an appointment as well as the availability of and distance to primary care providers. Some states have seen a loss in Medicaid pediatric providers, and one recent story reported that families with Medicaid in California were traveling long distances and experiencing long wait times for primary care appointments. Data have also shown slight declines in the share of kindergarten children up to date on their routine vaccinations since the COVID-19 pandemic, which may, in part, be associated with the decline in well-child visits. The national measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccination rate is below the goal of at least 95%, and some states are now seeing measle outbreaks among children.

Despite having the highest well-child visit rates compared to other ethnic and racial groups, Hispanic and Asian children enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP saw the largest percentage point declines in well-child visit rates from 2019 to 2020 (Figure 2). Prior to the pandemic in 2019, about half or more of children across most racial and ethnic groups had a well-child visit, with rates highest for Hispanic (60%) and Asian (57%) children. The rate for American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) children lagged behind at just over one in three (36%), although this may reflect that some services received from Indian Health Service providers not being captured in the analysis (see Methods ). Between 2019 and 2020, the well-child visit rate fell for all racial and ethnic groups. Hispanic and Asian children experienced the largest percentage point declines in well-child rates (9 percentage points for both groups), but they still had higher rates compared to other groups as of 2020. Black, Native Hawaiian, and Other Pacific Islander (NHOPI), and AIAN children also experienced larger percentage point declines in their well-child visit rates compared with White children, and AIAN children had the largest relative decline on account of their lower starting rate. As of 2020, rates remained lowest for NHOPI (42%) and AIAN children (29%). Twenty-two states, including some states that are home to larger shares of AIAN and NHOPI children, were excluded from the race/ethnicity analysis due to data quality issues (see Methods ).

Children ages three and older have lower rates of well-child visits and experienced larger declines in well-child visits during the pandemic than children under age three (Figure 2). Well-child visit rates are highest when children are young because multiple well-child visits are recommended for children under age three. Although children under three have highest rates of a single well-child visit within the year, it is unknown whether the rates of adherence to recommended well-child screenings are higher or lower than that of other groups because this analysis only accounts for one well-child visit in a year. Well-child visit rates steadily decrease as children get older with the exception of the 10-14 age group, where somewhat higher rates may reflect school vaccination requirements .

Well-child visit rates are lower in rural areas than urban ones, but urban areas had larger declines during the first year of the pandemic (Figure 2). The share of Medicaid/CHIP children living in rural areas with a well-child visit declined from 47% in 2019 to 43% in 2020 while the share for urban areas fell from 56% in 2019 to 49% in 2020, narrowing the gap between Medicaid/CHIP well-child visit rates in rural and urban areas. Note that 18% of children in the analysis lived in a rural area, and three states were excluded from the geographic area analysis due to data quality issues (see Methods ). This analysis also examined changes for children by eligibility group, managed care status, sex, and presence of a chronic condition; data are not shown but well-child visit rates for Medicaid/CHIP children declined across all groups from 2019 to 2020.

What to watch?

Well-child visit rates for Medicaid/CHIP children overall fall below the goal rate, with larger gaps for AIAN, Black and NHOPI children as well as older children and children living in rural areas, highlighting the importance of outreach and other targeted initiatives to address disparities. Addressing access barriers and developing community partnerships have been shown to increase well-child visit rates and reduce disparities. It will be important to track, as data become available, the extent to which well-child visit rates as well as vaccination rates (often administered at well-child visits) rebounded during the pandemic recovery and where gaps remain.

Recent state and federal actions could help promote access, quality and coverage for children that could increase well-child visit rates. The Bipartisan Safer Communities Act included a number of Medicaid/CHIP provisions to ensure access to comprehensive health services and strengthen state implementation of the EPSDT benefit. CMS also released an updated school-based services claiming guide , and states have taken action to expand Medicaid coverage of school-based care in recent years. In 2024, it became mandatory for states to report the Child Core Set, a set of physical and mental health quality measures, with the goal of improving health outcomes for children. In addition, as of January 2024, all states are now required to provide 12-month continuous eligibility for Medicaid and CHIP children, which could help stabilize coverage and help children remain connected to care. Three states also recently received approval to extend continuous eligibility for children in Medicaid for multiple years, which could help children maintain coverage beyond one year. In the recently released FY 2025 budget, the Biden Administration proposes establishing the option for states to provide continuous eligibility in Medicaid and CHIP for children from birth to age six or for 36 month periods for children under 19.

Lastly, millions of children are losing Medicaid coverage during the unwinding of the continuous enrollment provision, which could have implications for access. Data up to March 2024 show that children’s net Medicaid enrollment has declined by over 4 million. In some cases, children dropped from Medicaid may have transitioned to other coverage, but they may also become uninsured, despite in many cases remaining eligible for Medicaid or CHIP. While people of color are more likely to be covered by Medicaid , data on disenrollment patterns by race and ethnicity are limited . KFF analysis shows individuals without insurance coverage have lower access to care and are more likely to delay or forgo care due to costs. A loss of coverage or gaps in coverage can be especially problematic for young children who are recommended to receive frequent screenings and check-ups.

- Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP)

- Access to Care

Also of Interest

- Recent Trends in Children’s Poverty and Health Insurance as Pandemic-Era Programs Expire

- More Children are Losing Medicaid Coverage as Child Poverty Grows

- Medicaid Enrollment and Unwinding Tracker

- Headed Back To School in 2023: A Look at Children’s Routine Vaccination Trends

Parents' Rights When No Custody Orders Exist

- Child Custody & Visitation

Here, learn about the rights and duties that a child's parents have when there is no court order establishing custody, visitation, and support. Even without court orders in place, parents have certain responsibilities, but a court cannot enforce visitation or support without orders such as a SAPCR order or a divorce decree.

What rights and duties do parents have when there is not a court order?

Under Texas law, parents have certain rights and duties to their children unless those rights and duties are changed by a court order. These include the rights and duties to:

- Have physical possession of the child

- Choose the residence of the child

- Direct the moral or religious training of the child

- Have control of the child (in other words, make sure that they go to school, do not break the law, etc.)

- Protect the child from abuse, neglect, and other types of harm

- Reasonably discipline the child

- Support the child (providing them with food, clothing, shelter, medical and dental care, and education)

- Consent to medical care for the child

A complete list of parents' rights and duties can be found in Texas Family Code 151.001 .

What are my visitation rights if I do not have a court order for my child?

When there is no court order, there are no rules for visitation, and both parents have equal rights to the child. The law expects that the parents will work together to parent the child by agreement according to the child’s best interests .

If one parent keeps a child away from the other parent when there is not a court order, there is no way to force visitation to happen. Without a court order, neither parent can file an enforcement action. An enforcement action cannot be used to enforce an informal agreement between the parents.

Because of the potential problems, many families choose to get a court order so that there are clear rules that each parent has to follow. Read more about possession and visitation orders .

Note: Only a legal parent has rights to a child when there are no court orders. Determining the legal father of a child can be more complex than determining the legal mother. Legal paternity can be established by presumption (when the parents are married), by filing an acknowledgment of paternity , or by court order.

What about child support when there is no court order?

Like visitation, when there is no court order, there are no rules governing child support, how much it should be, or how often it should be paid. Even if parties agree on the amount, there is no way to enforce an informal child support agreement.

However, if a parent does not pay any support for the child (and does not live with the child), that parent may be ordered to pay “retroactive” child support if the other parent later seeks a court order. Having a court order for child support (and paying through the State Disbursement Unit) protects both parents because it can provide an enforcement path as well as provide an official record of payments that have been made if there is a dispute.

Read more about child support orders .

What does a parent’s duty to protect their child mean?

A parent’s duty to protect their child means they must take steps to protect their child from harm. Of course, a parent should never physically, emotionally, or sexually abuse a child, but a parent’s duty to protect also means that they must provide proper supervision based on the child’s age, maturity, and any special needs.

A parent is not being protective if they put their child in a situation (or fail to remove their child from a situation) that they should know is unsafe, and the child is injured or harmed. For example, a parent who leaves their toddler with someone drunk and unable to supervise the child or parent who continues to live with a partner who is physically abusive to the parent or the child.

If a parent does not protect their child, CPS could get involved, and the parent’s failure to protect the child could be used against them in court. In the most extreme cases, a parent’s rights to their child could be terminated.

The duty to protect often requires a parent to take protective action if they know a child has been hurt. This may include immediately removing the child from the situation and reporting the situation to the appropriate authorities, such as law enforcement, CPS, or the court.

I have safety concerns about the other parent and there is no court order. What should I do?

If you believe that the other parent is a danger to your child, there are several options:

- Request a court order. Sometimes the best way to protect a child is to request a court order through a Suit Affecting the Parent-Child Relationship (SAPCR) . SAPCR orders can be tailored to the child’s best interests and the specific situation. For example, in situations where there is a concern for the child’s safety, a court order could require the other parent’s visits to be supervised or in a public place, could allow you to get a drug test from the other parent before visits, or prohibit the other parent from driving with the child in the car. To get orders with these limitations, you must have evidence to convince a judge that these requirements are in the child's best interest. A judge will not likely grant supervised visitation or no visitation for a parent unless there is clear evidence of a danger to the child. Texas law presumes that parents should have generous visitation with their child unless it is unsafe to do so. You can file a SAPCR petition on your own or with the help of an attorney. If you choose to file on your own, you can use the Custody Order (SAPCR) guide , which has the needed forms and instructions. It is also possible to get a court order through the Office of the Attorney General’s Child Support division. But this option is not a quick process, and the OAG’s office cannot help in an emergency.

- Request a TRO. A Temporary Restraining Order (TRO) can be used to protect a child in an emergency when there is risk of immediate harm to the child. A TRO can be filed with an original SAPCR petition (or other petition involving the child, such as a divorce). It can be granted by a judge the same day it is filed, even without prior notice to the other parent, and it is meant to keep the child safe for a short time, usually around two weeks, before a hearing on temporary conservatorship and visitation orders can be held in the suit. Read more about TROs and Temporary Orders in Child Custody Emergencies .

- Request a Protective Order. A protective order is used in very dangerous situations where a child has been a victim of domestic violence, physical abuse, or sexual abuse. If a child has been a victim of family violence, any adult family member or household member may file on behalf of the child for a Protective Order. When the child has been a victim of certain crimes, a protective order can be requested by any adult on behalf of a child. A protective order is filed by itself. A protective order can also be used to protect an adult—including the other parent—who has been a victim of domestic violence, stalking, or sexual assault. Read more on Protective Orders .

- Do nothing. When there is no court order, there is no way for the other parent to force you to give them the child for a visit. If the child is with you and the other parent has no way to take the child (such as by picking them up at school), an option may be to do nothing. If you tried to get a court order, it is possible that the other parent may get the court-ordered right to visitation. However, this can be a risky decision. Also, doing nothing does not prevent the other parent from going to court to request a court order.

- Report to CPS . If you believe that a child is being abused or neglected by the other parent or by any other caretaker, you can make a report to CPS. Child Protective Investigations is the part of the CPS agency that investigates allegations of child abuse and neglect. They will usually only investigate if they feel that a child has been abused or neglected or is at risk of harm. If a child is in a safe, protective home and the unsafe parent does not have access to the child, Child Protective Investigations may choose not to take any further action. However, if the child is in the care of someone they believe is unsafe, Child Protective Investigations may take steps to ensure that the child is safe. Read more about Reporting Child Abuse or Neglect and Child Protective Investigations .

- Call the police. If you believe that a crime is being committed or that a child is at risk of immediate harm, you can call 911 and ask police to respond to the criminal situation. You can also ask police to conduct a well-check. For non-emergency situations, you can call 311 instead. If no crime is being committed and a child is not in immediate danger, law enforcement will not make decisions about who a child should go with and will often say to take the case to family court. If a child seems to be in danger, police will often also make a report to CPS.

Related Guides

I need a custody order. i am the child's parent (sapcr)., related articles, parents' rights to participate in their children's education, child visitation and possession orders, settling custody, visitation, and support out of court.

- Family, Divorce & Children

- Child Support & Medical Support

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The Bright Futures/American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) developed a set of comprehensive health guidelines for well-child care, known as the "periodicity schedule." It is a schedule of screenings and assessments recommended at each well-child visit from infancy through adolescence. Schedule of well-child visits. The first week visit (3 to 5 ...

however, these encounters present an opportunity to complete well-child visits. • Claims can be submitted for both a sick visit and a preventative well-child visit for the same date of service, simply add modifier 25 to the claim.* HEDIS® Quick Reference for Well-Child Visits Importance of Child and Adolescent Well-Care Visits ©2024 Texas ...

notification or consent or when the law requires the provider to report health information. A licensed physician, dentist, or psychologist may, with or without the consent of a child who is a patient, advise the parents, managing conservator, or guardian of the child of the treatment given to or needed by the child. (Texas Family Code §32.003)

The Texas Health Steps Medical Checkup Periodicity Schedule for Infants, Children, and Adolescents (birth through 20 years of age) (PDF)) is a guide for Texas Health Steps providers to understanding the age-appropriate requirements for each checkup. Forms and screening tools mentioned below are available on the Texas Health Steps Forms page.

Sexually transmitted infection (STI) prevention counseling and screening for adolescents at higher risk. Tuberculin testing for children at higher risk of tuberculosis: Age 0 to 11 months , 1 to 4 years , 5 to 10 years , 11 to 14 years , 15 to 17 years. Vision screening for all children. Well-baby and well-child visits.

Some of the requirements (like immunizations and physical exams) with a well-child visit require an in-person visit. The follow-up code for this visit is 99211 along with the appropriate diagnosis code. Providers must follow-up with their patients within six months of the telemedicine visit to ensure completion of any components.

Texas Health Steps and well-child visits — birth to 2 years old . Infants need to be seen by a doctor at birth, at the following ages, and as the doctor suggests: • 3 to 5 days old • 2 weeks to 1 month • 2 months • 4 months • 6 months • 9 months • 12 months • 15 months • 18 months • 24 months

Claims should be billed using only the child's Medicaid number. Additional CPT codes for well child checks Outpatient visit: The following codes will count as a well-child visit for HEDIS: 99381,99382,99383,99384,99385,99391,99392,99393,99394,99395. For Texas Health Steps Follow-up visit use procedure code 99211 when billed with a THSteps ...

Check your child's Body Mass Index percentile regularly beginning at age 2. Check blood pressure yearly, beginning at age 3. Screen hearing at birth, then yearly from ages 4 to 6, then at ages 8 and 10. Test vision yearly from ages 3 to 6, then at ages 8, 10, 12, and 15 Help protect your child from sickness. Make sure they get the recommended ...

Child Protective Services (CPS) This article addresses court-ordered visitation when there is a child safety concern. Composed by Family Helpline • Last Updated on February 21, 2023. In determining whether a child must be sent for a visit—and what the consequences could be if you do not send them—first ask if there is a court order for ...

Well-Care Visit Best Practices - Texas Medicaid . Well-care visits provide an opportunity for providers to influence patients' development and health care through counseling and screening. Performing a thorough assessment, including physical, emotional and social development is important at every stage of life.

Young children need to go to the doctor or nurse for a "well-child visit" 7 times between ages 1 and 4. A well-child visit is when you take your child to the doctor to make sure they're healthy and developing normally. This is different from other visits for sickness or injury. At a well-child visit, the doctor or nurse can help catch any ...

Comfort and reassure the child in ways that are helpful following a visit, such as encouraging them to be open in expression of feelings. Provide transportation as agreed to in the visitation plan. Respect the importance of family to the child and make every reasonable effort to preserve the parent-child relationship.

We defined adherence as the ratio of reported well-child visits during the calendar year divided by the recommended number of visits. Recommendations published in late 2007 added visits at 30 months, 7 years, and 9 years. 1 We used these recommendations throughout our study to maintain consistent adherence denominators. We compared adherence in ...

In Texas, the law presumes that the Standard Possession Order is in the best interest of a child age three or older. See Texas Family Code 153.252.. The Standard Possession Order says that the parents may have possession of the child whenever they both agree.. The Standard Possession Order says that if the parents don't agree, the noncustodial parent has the right to possession of the child ...

The Vaccines for Children (VFC) program provides vaccines to eligible children at no cost. This program provides free vaccines to children who are Medicaid-eligible, uninsured, underinsured, or American Indian/Alaska Native. Check out the program's requirements and talk to your child's doctor or nurse to see if they are a VFC provider.

Grantees may not bill for a Texas Health Steps medical checkup until all required components are completed. Only one visit may billed per day, per client. If a client returns on a different day to complete required components of a Texas Health Steps exam, an additional visit may not be charged. Well Child and Adolescent History and Risk Assessment

Child custody and visitation are often central issues in family law cases, shaping the well-being and future of children whose parents are no longer together. In the state of Texas, Family Code ...

Well-child visit rates steadily decrease as children get older with the exception of the 10-14 age group, where somewhat higher rates may reflect school vaccination requirements. Well-child visit ...

visit. x Show your child affection (i.e. hugs and handholding) during the visit unless you have specifically been ordered not to by the court or your caseworker. x The visit will be observed and there are two reasons for this: to ensure the safety and well-being of your child, and to gather information that will help improve future visits.

Phone: 512-438-2366. Email: [email protected]. Texas Health Steps focuses on the medical, dental, and case management services for ages birth through 20. THSteps is committed to recruiting and retaining qualified providers to assure that comprehensive preventive health, dental, and case management services are available.

Under Texas law, parents have certain rights and duties to their children unless those rights and duties are changed by a court order. These include the rights and duties to: Have physical possession of the child. Choose the residence of the child. Direct the moral or religious training of the child. Have control of the child (in other words ...

A child's first Texas Health Steps medical checkup must occur within 30 days after the child comes into DFPS conservatorship, regardless of the child's age. The checkup is considered overdue 31 days after removal. After that, children and youth age three to 20 years old must receive a Texas Health Steps medical checkup annually.