Are doctors spending less time with patients?

Patient visits are changing. In 2020, COVID-19 ushered in telehealth . And in just the past decade, nearly every physician started using electronic health records. This infusion of health IT into clinical encounters means physicians have changed their documentation workflows and are approaching patient visits differently. Amidst these changes, are doctors spending less time with patients?

The short answer is “no.” While it’s hard to pin down a meaningful average for something like patient visit times, studies indicate that doctors have spent roughly 13 to 24 minutes with patients for at least the past three decades.

Data from the 1990s reveal some debates about the average time physicians spend with patients. Surveys from those years placed the average around 17 minutes, but competing studies claimed the real number was closer to 10 minutes. Other research found that physicians and their staff tend to overreport patient visit times by about 4 minutes, on average.

Research published in 2021 used time-stamped EHR data from over 21 million primary care visits to estimate average exam length. The authors conclude that the average primary care exam lasts 18 minutes, which is consistent with estimates derived from more common methods like retrospective surveys.

A review of 2018 data suggests that most U.S. physicians spend between 13 and 24 minutes with patients. About 1 in 4 spend less than 12 minutes, and roughly 1 in 10 spend more than 25 minutes. All in all, it seems like doctor-patient time isn’t changing substantially.

While about half of physicians did report experiencing a permanent reduction in patient volume due to COVID-19, for most the impact has been marginal. The weekly average number of patients doctors see dropped from 76 to 71 after the pandemic, which predictable variation across specialties. This reduction may affect visit times, but there is not yet reliable data to confirm either way.

Have EHRs changed the length of patient visits?

Much of the U.S. survey data come from Medscape’s annual Physician Compensation Report , which surveys roughly 18,000 doctors about things like their salary, hours worked, and time spent with patients. Presumably their survey would register any notable changes to how long doctors are spending with patients in each visit.

Contrary to what you might expect, physician-patient time has remained pretty constant since the adoption of EHRs. In the 2018 survey, when time spent with patients was last reported, 61 percent of physicians reporrted spending 1 3-24 minutes with patients . In 2016 that number was 60 percent. Responses look similar in Medscape’s annual surveys going back to 2011.

The reason visit times haven’t dropped is probably that physicians enjoy interacting with patients. Gratitude and relationships with patients is the aspect their job that doctors say is most rewarding (in 2021 this was matched by “knowing that I’m making the world a better place”).

Research shows that when limits are put on time with patients, physicians experience less job satisfaction . Longer visits are also connected to positive patient outcomes . When patients get more time with doctors, they tend to be more satisfied with their care, experience reduced rates of medication prescriptions, and be less likely to file malpractice claims.

So what’s the problem?

So why are so many physicians struggling in medicine or leaving the field? Physician burnout is skyrocketing . It seems like more and more doctors are seeing a gap between the values that brought them to medicine and their day to day reality. But what’s causing the disconnect?

Patient visit times are about as long as they’ve always been. It’s the rest of physicians’ work days that’s changing. Doctors are spending more time than ever on documentation and administrative tasks, leading to dissatisfaction and professional burnout.

Here’s the number that’s shocking: in 2021 doctors reported spending on average 15.6 hours per week on paperwork and other administrative tasks. This reflects a trend that’s emerged in the last decade. In 2018, 70 percent of physicians said they spend over 10 hours per week on paperwork and administrative tasks. In 2017, that number was 57 percent . But just one-third of physicians reported the same experience in 2014.

Most physicians’ would tell you that their experience of practicing medicine is different than it was a decade ago. But when we look at the numbers, it’s not patient visit times that are changing. It’s everything else.

- Mobius Conveyor

- Conveyor QR

- Conveyor USB

Athenahealth-Specific

- Mobius Clinic

- Mobius Scribe

- Mobius Desktop Scribe

- Mobius Capture

Recent Posts

- Medical transcription: a brief history

- Manage your EHR inbox more effectively with these tips

- Use your smartphone for instant medical dictation

- Do AI medical scribes work?

- Which medical dictation workflow is best for you?

- Privacy & Terms

How Much Time Does A Doctor Visit Really Take?

July 4, 2022

First Stop Health

When you or a family member is not feeling well or hurt, finding quick care can be challenging. Doctor’s offices, urgent care centers and emergency rooms are three traditional options for care that are not time-friendly or convenient. Whether it’s travel time, transportation, taking time off work, cost or arranging for childcare, there are many personal factors to consider when seeking care at these institutions.

Transportation is one of the biggest barriers to accessing healthcare. 1 In fact, “Americans spend an average of 34 minutes on the road to a doctor’s office or other medical entity,” totaling more than an hour of travel time to and from an in-person visit. 2 This statistic excludes the time it takes with public transportation. Shockingly, 45% of Americans do not have access to public transportation and 3.6 million people do not get care annually due to limited transportation access. 3, 4

Another personal factor to consider is childcare. The average cost for childcare is $15 and $23 per hour and accessing childcare may not be easy. 5 Due to COVID-19, childcare centers across the U.S. are in short supply. 6

Now that we’ve broken down some personal factors, let’s look at the time it actually takes at a doctor’s office, urgent care center and emergency room.

A Doctor’s Office Visit

While having routine checkups with a primary care physician (PCP) is essential for overall physical and mental health, for non-emergent issues such as a sinus infection, rash or urinary tract infection, the time it takes to get an appointment with a PCP isn’t helpful. On average, Americans wait 24 days to see a PCP in-person. 7

Once in the office, patients wait almost 20 minutes to be seen, even with an appointment. 8 These wait times are sometimes longer and are another deterrent for seeking care. A recent study revealed 30% of patients left their doctor’s office due to long wait times. 8

After the time it takes to get to the doctor’s office and the time spent waiting, 1 in 4 doctors spend just 9-12 mins with a patient. 9 This is an inadequate amount of time for a PCP to cover symptoms and the patient’s history. Rushed appointments strain the doctor-patient relationship, diminishing trust and value-based care. The 15-minute care model is not beneficial to the patient. 10

If an illness emerges during a doctor’s office off-hours, there is typically no way to access care. U.S. adults are the least likely of high-income countries to have a primary doctor to seek care from and are the least likely to have access to care during off-business hours, leading them to seek care at an urgent care center or emergency room. 11 This makes the time to get care even longer.

The end result = 1 doctor’s visit is 2 hours (if you can get in to see a doctor before the average 24-day wait period)

An Urgent Care Center Visit

Much like a visit to a PCP, a trip to an urgent care center will take about two hours or more. But depending on the severity of your illness or injury and the number of other patients (and the severity of their illnesses or injuries), wait times can be much longer. Wait times in an urgent care center can range from 20 minutes to 90 minutes. 12

Unlike a visit with a PCP, urgent care center visits are much more expensive. The average cost of urgent care center visits range from $100 to $150 and costs can be higher or lower depending on insurance coverage, annual deductibles and copays. 13

The end result = 1 urgent care visit is 2-4 hours and costs can be confusing based on insurance coverage

An Emergency Room Visit

Higher-severity cases might bump a minor injury down the list, and emergencies aren’t scheduled. On average, the entirety of an emergency room visit is 2+ hours and costs more than $1,300. 14

Almost 60% of emergency room visits come outside of business hours. 14 So, after enduring the wait time and exam, the wait times roll over to the next day to see the referred doctor or to visit a pharmacy during regular hours.

A doctor should be someone a patient can trust. According to a recent study, 70% of providers told patients to go to an emergency room instead of an urgent care center, even though the patient indicated they would seek care at an urgent care center. 15 In turn, 56% of emergency room visits are completely avoidable and could save a patient thousands of dollars in out-of-pocket expenses. 14

The end result = 1 emergency room visit is 4+ hours, expensive and likely avoidable

Summary

Whether it’s an emergency or a routine trip to your PCP for a simple sinus infection, a doctor’s visit takes much more time than we anticipate. It’s never as quick or affordable as we hope. Plus, a patient must also take into consideration pharmacy wait times and travel times if a medication is prescribed.

As an alternative, First Stop Health Telemedicine and Virtual Primary Care provide fast, convenient solutions to a daunting necessity. You can’t just skip unavoidable medical care, but you can skip worrying about transportation, wait times, co-pays and time off work. First Stop Health members have 24/7 access to free, quality and convenient healthcare. Members can connect to doctors in under 6 minutes for Telemedicine and within 3 days for Virtual Primary Care. Our virtual doctors are board certified in their field of medicine, can treat patients in all 50 states and Washington DC, and have 10 years of post-residency experience, on average.

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4265215/

- https://www.naplesnews.com/story/news/health/2019/03/03/americans-average-34-minutes-road-see-doctor-study-shows/3020326002/

- https://www.apta.com/news-publications/public-transportation-facts/

- https://www.aha.org/ahahret-guides/2017-11-15-social-determinants-health-series-transportation-and-role-hospitals

- https://www.valuepenguin.com/average-cost-child-care#:~:text=Parents%20in%20U.S.%20cities%20generally,typically%20pay%20more%20per%20hour

- https://www.americanprogress.org/article/costly-unavailable-america-lacks-sufficient-child-care-supply-infants-toddlers/

- https://medcitynews.com/2017/12/patients-waiting/

- https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/practices/ppatients-switched-doctors-long-wait-times-vitals#:~:text=Across%20specialties%2C%20the%20average%20wait,patient%20waits%20depending%20on%20location .

- https://www.statista.com/statistics/250219/us-physicians-opinion-about-their-compensation/

- https://khn.org/news/15-minute-doctor-visits/

- https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2022/mar/primary-care-high-income-countries-how-united-states-compares

- https://www.advisory.com/daily-briefing/2012/12/04/member-asks#:~:text=The%20Urgent%20Care%20Association%20of,as%20long%20as%2090%20minutes .

- https://www.debt.org/medical/emergency-room-urgent-care-costs/

- https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1062860617700721

Originally published Jul 4, 2022 2:00:00 PM.

Related Posts

The state of primary care .

August 30, 2022

3 Reasons to Offer Virtual Primary Care to Employees

November 8, 2022

The Evolution of Primary Care

July 18, 2022

- Alzheimer's disease & dementia

- Arthritis & Rheumatism

- Attention deficit disorders

- Autism spectrum disorders

- Biomedical technology

- Diseases, Conditions, Syndromes

- Endocrinology & Metabolism

- Gastroenterology

- Gerontology & Geriatrics

- Health informatics

- Inflammatory disorders

- Medical economics

- Medical research

- Medications

- Neuroscience

- Obstetrics & gynaecology

- Oncology & Cancer

- Ophthalmology

- Overweight & Obesity

- Parkinson's & Movement disorders

- Psychology & Psychiatry

- Radiology & Imaging

- Sleep disorders

- Sports medicine & Kinesiology

- Vaccination

- Breast cancer

- Cardiovascular disease

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Colon cancer

- Coronary artery disease

- Heart attack

- Heart disease

- High blood pressure

- Kidney disease

- Lung cancer

- Multiple sclerosis

- Myocardial infarction

- Ovarian cancer

- Post traumatic stress disorder

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Schizophrenia

- Skin cancer

- Type 2 diabetes

- Full List »

share this!

December 15, 2020

How long do doctor visits last? Electronic health records provide new data on time with patients

by Wolters Kluwer Health

How much time do primary care physicians actually spend one-on-one with patients? Analysis of timestamp data from electronic health records (EHRs) provides useful insights on exam length and other factors related to doctors' use of time, reports a study in the January issue of Medical Care . The journal is published in the Lippincott portfolio by Wolters Kluwer.

"By using timestamps recorded when information is accessed or entered, EHR data allow for potentially more objective and reliable measurement of how much time physicians spend with their patients," according to the new research by Hannah T. Neprash, Ph.D., of University of Minnesota School of Public Health and colleagues. That may help to make appointment scheduling and other processes more efficient, optimizing use of doctors' time.

More precise estimates of primary care visit times

Using a national source of EHR data for primary care practices, the researchers analyzed exam lengths for more than 21 million doctor visits in 2017. The study focused on exam lengths and discrepancies between scheduled and actual visit times.

Based on EHR timestamps, the mean exam time was 18 minutes, with a median of 15 minutes. "The mean exam lasted 1.2 minutes longer than scheduled, while the median exam ran 1 minute short of its scheduled duration," Dr. Neprash and coauthors write. The longer the scheduled visit, the longer the exam time.

"However, shorter scheduled appointments tended to run over while longer appointments often ended early," the researchers add. Scheduled 10-minute visits ran over by an average of 5 minutes; in contrast, scheduled 30-minute visits averaged less than 24 minutes.

More than two-thirds of visits deviated from the schedule for 5 minutes or more. About 38 percent of scheduled 10-minute visits lasted more than 5 minutes, while 60 percent of scheduled 30-minute visits lasted less than 25 minutes.

The findings suggest "scheduling inefficiencies in both directions," according to the authors. "Primary care offices' overuse of brief appointment slots may lead to appointment overrun, increasing wait time for patients and overburdening providers." In contrast, "longer appointments are critical for clinically complex patients, but misallocation of these extended visits represents potentially inefficient use of clinical capacity."

The time doctors spend with patients has a major impact on care. Average visit times seem to have increased over the years—yet physicians may still feel pressed to do more in the available time, including documentation, patient monitoring, and prevention/screening steps.

Estimates of medical visit times have been largely based on national surveys, which rely on information reported by office-based practices. For several reasons, these estimates may not accurately reflect the actual time doctors spend with patients in the examination room.

Routine data collected by EHRs provide a new way to measure length of physician visits, Dr. Neprash and colleagues write. Their method excluded visits where EHR data didn't seem to be recorded in real time and accounted for overlapping visits due to "double-booking."

Health systems could use EHR data to track discrepancies between schedules and actual visit lengths, enabling more efficient scheduling for patients with different needs. While acknowledging some limitations and challenges of this approach, the researchers believe their findings "support the development of a scalable approach to measure exam length using EHR data."

Explore further

Feedback to editors

Specific nasal cells found to protect against COVID-19 in children

54 minutes ago

Human muscle map reveals how we try to fight effects of aging at cellular and molecular levels

Are Americans feeling like they get enough sleep? Dream on, a new Gallup poll says

Physical activity lowers cardiovascular disease risk by reducing stress-related brain activity, study finds

3 hours ago

Carbon beads help restore healthy gut microbiome and reduce liver disease progression, researchers find

10 hours ago

Untangling dreams and our waking lives: Latest findings in cognitive neuroscience

16 hours ago

Researchers demonstrate miniature brain stimulator in humans

Apr 13, 2024

Study reveals potential to reverse lung fibrosis using the body's own healing technique

Apr 12, 2024

Researchers discover cell 'crosstalk' that triggers cancer cachexia

Study improves understanding of effects of household air pollution during pregnancy

Related stories.

Extra visit time with patients may explain wage gap for female physicians

Sep 30, 2020

Virtual follow-up care is more convenient and just as beneficial to surgical patients

Oct 4, 2020

Outpatient wait times are longer for Medicaid recipients

May 11, 2017

Four tips for maximizing virtual healthcare visits

May 12, 2020

Telemedicine reduces cancellations for care during COVID in large Ohio heath center

Nov 6, 2020

Patients find video primary care visits convenient

Apr 30, 2019

Recommended for you

Scientists uncover a missing link between poor diet and higher cancer risk

PFAS exposure from high-seafood diets may be underestimated, finds study

Pandemic drinking hit middle-aged women hardest, study finds

First national study of Dobbs ruling's effect on permanent contraception among young adults

Let us know if there is a problem with our content.

Use this form if you have come across a typo, inaccuracy or would like to send an edit request for the content on this page. For general inquiries, please use our contact form . For general feedback, use the public comments section below (please adhere to guidelines ).

Please select the most appropriate category to facilitate processing of your request

Thank you for taking time to provide your feedback to the editors.

Your feedback is important to us. However, we do not guarantee individual replies due to the high volume of messages.

E-mail the story

Your email address is used only to let the recipient know who sent the email. Neither your address nor the recipient's address will be used for any other purpose. The information you enter will appear in your e-mail message and is not retained by Medical Xpress in any form.

Newsletter sign up

Get weekly and/or daily updates delivered to your inbox. You can unsubscribe at any time and we'll never share your details to third parties.

More information Privacy policy

Donate and enjoy an ad-free experience

We keep our content available to everyone. Consider supporting Science X's mission by getting a premium account.

E-mail newsletter

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Gen Intern Med

- v.30(11); 2015 Nov

The End of the 15–20 Minute Primary Care Visit

Mark linzer.

Division of General Internal Medicine, Hennepin County Medical Center, 701 Park Ave S (P7), Minneapolis, MN 55415 USA

University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN USA

Asaf Bitton

Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA USA

Shin-Ping Tu

Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA USA

Margaret Plews-Ogan

University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA USA

Karen R. Horowitz

Louis Stokes Cleveland VAMC, Cleveland, OH USA

Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, OH USA

Mark D. Schwartz

New York University School of Medicine, New York, NY USA

Sign on a print shop door:

“We can do it fast, we can do it well, we can do it cheap. Pick two.”

A 78-year-old widow with hypertension, osteoarthritis, a recent stroke, elevated cholesterol, and a 50-pack-year smoking history comes to her primary care provider for a mild cough and weight loss. She lives alone and loves to chat with her doctor. The physical examination is unrevealing. Chest x-ray shows a lung nodule. A CT scan is ordered. A long discussion ensues about what would happen if the CT scan shows cancer: how would she undergo evaluation and treatment with her family far away? For what became a 40-min visit, only 15 min had been allotted. Now the doctor is behind schedule. She feels guilty and gives more time to each patient, thus falling further behind. Screening issues are postponed and personal interactions are diminished. A walk-in patient is added. One waiting patient leaves angrily. At the end of the day, facing a large pile of forms and documentation needs, the doctor feels drained and questions the quality of care she provided.

The Time Crunch

While Mechanic demonstrated that routine primary care visits (averaging 15–20 min) were 1 to 2 min longer than before, 1 the complexity of clinical issues addressed during these visits has increased. In 2010, the CDC reported that one-third of elderly patients had three or more chronic medical conditions, with 40 % of patients taking three or more medications. Providers may respond by cutting corners on the history and physical examination and by ordering more tests, which lead to a cascade of follow-up tests. Providers describe behind-the-scenes burdens of documentation, phone calls, emails, refills, consultations, and lab reports, while careful calculations show that guideline-driven preventive care would add 7 h to each primary care clinician’s workday. 2 The work of primary care simply cannot be completed in the time allotted.

Consequences for Patients

Increased work during short (<20 min) visits means appointments in which fewer health care issues are addressed and the depth of understanding is diminished. Time-consuming psychosocial determinants of health are left unaddressed. These consequences translate to decreased patient satisfaction, excess emergency room usage and non-adherence to treatment plans. 3

Consequences for Providers

Fifty-three percent of primary care providers report time pressure in the clinical encounter. 4 Many providers describe emotional exhaustion and the fear of making clinical errors. Students observe harried primary care providers and choose alternative career paths.

Root Causes

In the early 1990s, Medicare adopted the relative value unit (RVU) payment model. In a budget-neutral system, the introduction of new procedures at substantially higher RVU levels has resulted in the devaluing of cognitive care such as evaluation and management services. When private insurers and managed care contracts reduced compensation, providers increased daily volumes to maintain stable incomes. Health systems followed with daily visit targets. This fee-for-service (FFS) system, poorly constructed for the delivery of comprehensive primary care, has left primary care providers feeling like they are on an assembly line rather than engaged in a mission to heal the sick and prevent serious illness.

Brief visits would suffice if the tasks of primary care had decreased, or if sharing this work with other team members had increased. But this has not been the case. Scientific advances have increased the complexity of diagnostic testing and prescribing, the frequency of care coordination between generalists and subspecialists, and the post-visit workload. Computer work has spiraled, along with an expanded number of reportable performance measures. Electronic medical records (EMRs) have decreased face-to-face time with patients, while “meaningful use” EMR requirements have set forth worthy but time-consuming tasks. To provide patients with the personalized care they seek, a new system is needed.

Suggestions for Broad System Changes

Having flexible encounter times in primary care to meet patient needs will require shifts in both workflow and compensation. We recommend that the routine care of complex primary care patients requires a visit time to meet patient needs, and may be 30 min or longer . Models should include fees for care management and provide resources for team-based care by nurses, medical assistants, and pharmacists. While alternative payment models are emerging in both public and private sectors, 5 what is lacking is a systematic approach for providers to respond to these new incentives with strategies that improve outcomes with lower spending. These strategies should include the means to allow sufficient time for patients to feel heard and for providers to deliver high-quality care.

To account for the increasing complexity of primary care, there will need to be a recalibration of the value of cognitive care codes , by both the Relative Value Scale Update Committee, or RUC (who provides the recommendations), and by CMS (who implements them). Updating RVUs for evaluation and management services to give them greater weight would help redirect revenue to primary care, as most alternative payment models, such as patient-centered medical homes and accountable care organizations (ACOs), are still built upon an FFS base.

New payment systems to support longer primary care visits face uphill challenges. First, inadequate care management fees (with extensive time requirements for documentation) often leave practices adrift between the promise of team-based care and the reality of an FFS system (a “foot in two canoes”). Second, due to Medicare Part B’s 20 % co-pay mandate, adoption of CMS’ care management fees may lead to increased patient co-pays for beneficiaries without supplemental insurance covering this newly reimbursed service. Finally, it will take time and perseverance to change a culture in which practice leaders are accustomed to thinking of fewer visits as a sign of clinicians not working hard.

We believe there are several ways to get from here to there. For one, health care organizations should acknowledge differing care models (FFS versus “total cost of care”) operating within the same health system. For example, “ambulatory ICUs” or “intensive primary care” settings have become a popular means to reduce excess utilization. In these models, increased visit time and upfront investments in personnel and resources improve the ability of providers to manage the social and medical needs of high-utilizing patients. These systems are sustainable when integrated business models track dollars spent in the new care model (e.g., on additional team members) and include credits for savings from reduced emergency department and inpatient utilization. Otherwise, providers with low RVU production are penalized for “not working hard enough.” These integrated business models will reflect overall cost savings for the institution and will remove “intensive primary care” providers from being evaluated through an FFS lens. Second, alternative payment models could be expanded with new mechanisms to change the basis for clinician payments, such as through the SGR [Sustainable Growth Rate] Repeal and Provider Payment Modernization Act. Third, ACOs, which manage the full continuum of care while being held accountable for costs and quality, may negotiate contracts with additional primary care funding based upon risk adjustment for social and medical characteristics of their populations.

How can practices traverse the change to appropriately timed visits while unbundling activities that could be performed by others? Management approaches, such as LEAN methodology, could be used to streamline primary care visit. These practice transformations will first require evaluating an organization’s “capacity for development,” or readiness to change, and resources will be needed to reshape the practice’s operations and values. While we await these transformations, the provision of primary care will require more time than is currently allotted.

Innovative processes to improve access to care, including patient portals, e-visits, nurse visits, and community health worker (CHW) contacts, are all in development. Providing efficient care to patients during longer visits could avoid short-changing patient needs, lead to better outcomes, and preserve access by reducing the need for early return appointments.

We anticipate real benefits of allowing sufficient time for primary care, including lower emergency room and hospital utilization, fewer unnecessary referrals, less ill-advised diagnostic testing, and improved patient satisfaction. Better interpersonal communication will also improve clinician satisfaction and well-being, critical components in addressing the current crisis in the shrinking primary care workforce.

In a new model, the same 78-year-old patient would have had a CHW and a provider with flexible visit times. In this scenario, the CHW had spoken with the patient and reported her cough and weight loss to the doctor. The chest x-ray performed prior to the visit showed a large nodule. In the 30 min allotted, the doctor had time to empathically discuss the findings with the patient, order a CT scan, and collaboratively decide upon a follow-up plan. The doctor did not fall behind in her work day, and other patients were not inconvenienced. It was still a hard day, but it was also rewarding. The medical student working with her was impressed with the compassionate, multidisciplinary care, and decided that this was a career worth pursuing.

Primary care cannot be done fast, well, and cheap. Let’s find the ways to appropriately structure it, pay for it, and do it right.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Christine Sinsky for her inspiring comments on a draft of this manuscript. We also thank the editors for their support and insights in developing this final version.

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Bitton is senior adviser for the Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative at the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI). (The views expressed do not reflect the official views of CMS or CMMI). There are no other conflicts of interest among the authors.

* ACLGIM Writing Group Members (in addition to those listed above) include: Sara Poplau, BA, Minneapolis Medical Research Foundation, Minneapolis, MN; Anuradha Paranjape, MD, MPH, Temple University School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA; Michael Landry, MD, MSc, New Orleans VAMC and Tulane University, New Orleans, LA; Stewart Babbott, MD, University of Kansas, Kansas City, KS; Tracie Collins, MD, MPH, Department of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, University of Kansas, Wichita, KS; T. Shawn Caudill, MD, MSPH, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY; Arti Prasad, MD, and Allen Adolphe, MD, PhD, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM; David E. Kern, MD, MPH, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD; KoKo Aung, MD, MPH, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX; Katherine Bensching, MD, Oregon Health Sciences University, Portland, OR; Kathleen Fairfield, MD, MPH, DrPH, Maine Medical Center, Portland, ME, and the Association of Chiefs and Leaders in General Internal Medicine (ACLGIM), Alexandria, VA.

- Open access

- Published: 06 March 2022

Association between primary care appointment lengths and subsequent ambulatory reassessment, emergency department care, and hospitalization: a cohort study

- Kristi M. Swanson 1 na1 ,

- John C. Matulis III 2 na1 &

- Rozalina G. McCoy 2 , 3

BMC Primary Care volume 23 , Article number: 39 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

4257 Accesses

2 Citations

11 Altmetric

Metrics details

To meet increasing demand, healthcare systems may leverage shorter appointment lengths to compensate for a limited supply of primary care providers (PCPs). Limiting the time spent with patients when evaluating acute health needs may adversely affect quality of care and increase subsequent healthcare utilization; however, the impact of brief duration appointments on healthcare utilization in the United States has not been examined. This study aimed to assess for potential inferiority of shorter (15-min) primary care appointments compare to longer (≥ 30-min appointments) with respect to downstream healthcare utilization within 7 days of the initial appointment.

We performed a retrospective cohort study using electronic health record (EHR), billing, and administrative scheduling data from five primary care practices in Midwest United States. Adult patients seen for acute Evaluation & Management visits between 10/1/2015 and 9/30/2017 were included. Patients scheduled for 15-min appointments were propensity score matched to those scheduled for ≥ 30-min. Multivariate regression models examined the effects of appointment length on repeat primary care visits, emergency department (ED) visits, hospitalizations, and diagnostic services within 7 days following the visit. Models were adjusted for baseline patient, visit, and provider characteristics. A non-inferiority approach was employed.

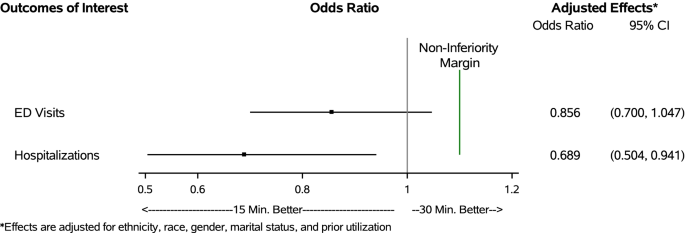

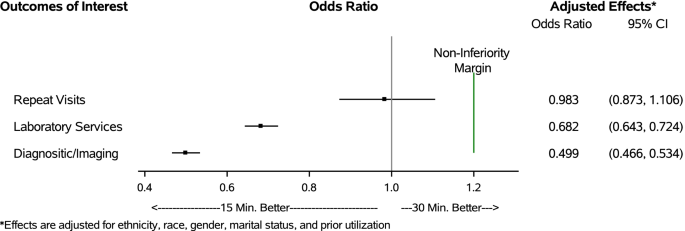

We identified 173,758 total index visits (6.5% 15-min, 93.5% ≥ 30-min). 11,222 15-min appointments were matched to a comparable ≥ 30-min visit. Longer appointments were more frequent among trainee physicians, patients with limited English proficiency, and patients with more comorbidities. There was no significant effect of scheduled appointment length on the incidence of repeat primary care visits (OR = 0.983, CI: 0.873, 1.106) or ED visits (OR = 0.856, CI: 0.700, 1.047). Shorter appointments were associated with lower rates of subsequent hospitalizations (OR = 0.689, CI: 0.504, 0.941), laboratory services (OR = 0.682, CI: 0.643, 0.724), and diagnostic imaging services (OR = 0.499, CI: 0.466, 0.534). None of the non-inferiority thresholds were exceeded.

Conclusions

For select indications and select low risk patients, shorter duration appointments may be a non-inferior option for scheduling of patient care that will not result in greater downstream healthcare utilization. These findings can help inform healthcare delivery models and triage processes as health systems and payers re-examine how to best deliver care to growing patient populations.

Peer Review reports

A robust primary care infrastructure is foundational for individual and population health [ 1 ]. The growing shortage of primary care providers (PCPs) impedes timely and effective management of acute and chronic health conditions, delivery of essential preventive services, and careful stewardship of healthcare resources [ 1 , 2 ]. It also threatens future progress in caring for an aging population [ 3 , 4 , 5 ]. This shortage is driven, in part, by increasing demands for PCP services, fueled by population growth, increasing prevalence of chronic health conditions, and falling rates of the uninsured [ 6 , 7 , 8 ]. Furthermore, alternative payment models place greater responsibility on primary care practices to complete work outside the traditional purview of primary care, including population health management and care coordination [ 9 , 10 ].

To improve healthcare access for growing patient populations and maximize revenue generation in a fee-for-service environment, many healthcare systems have introduced shorter appointment lengths (e.g., 15-min in duration) into scheduling templates, seeking to maximize the number of patients seen on a given day [ 11 , 12 ]. While shorter appointment lengths do allow more patients to be seen in a given day, allocating valuable clinician time in standardized, brief increments may not effectively meet patient needs, resulting in incomplete or incorrect diagnostic evaluations, poor patient experience, and potentially avoidable downstream healthcare utilization [ 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ]. Despite scheduled appointment lengths getting shorter, the time required to care for increasingly complex patients and comply with growing regulatory and documentation requirements has been increasing. A National Ambulatory medical survey suggested that physician reported time spent directly with patients had lengthened by an average of 2.4 min between 2008 and 2015, raising the question of what amount of time is needed for clinicians to provide satisfactory care [ 12 , 21 ].

Although there is no consensus on what constitutes “adequate time” with a clinician, shorter visits may be inadequate to effectively address patient concerns and also manage chronic health conditions, deliver necessary preventive services, and interact with the electronic health record (EHR) [ 13 , 14 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 ]. Prior work in evaluating the effects of appointment length on healthcare utilization is sparse, often conflicting, and dated [ 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 ]. When shorter duration visits are employed, the quality of care rendered is uncertain and rarely rigorously evaluated in the primary care setting. Wilson et al. performed two separate systematic reviews, noting that shorter appointment lengths were associated with missing patient care elements among British General Practitioners [ 29 , 32 ]. The impact of shorter duration primary care office visits on subsequent healthcare utilization in the United States has not been examined.

A more nuanced assessment of the value of different duration appointment lengths in primary care is needed as health systems and payers re-examine how to best deliver care to complex patient populations. Using data from an integrated healthcare delivery system in the Midwestern United States, we aimed to assess for potential inferiority of short (15-min) appointment lengths in the primary care setting compared to longer (≥ 30-min or greater) appointments by examining downstream healthcare utilization including return office visits, emergency department and hospital utilization and diagnostic testing in the 7 days following the initial appointment. Results of this study will help inform healthcare delivery models and the appropriateness of using shorter appointment slots in the primary care setting.

Study design & setting

We performed a retrospective cohort study using EHR, billing, and administrative scheduling data from Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, U.S.A. Mayo Clinic is an integrated healthcare delivery system that serves local, regional, national, and international patients. The five primary care practices of Mayo Clinic Rochester reside in both urban and rural areas and are comprised of family medicine, internal medicine, and pediatrics specialties that care for over 150,000 local residents, Mayo Clinic employees, and their dependents. PCPs in these practices include attending physicians, trainees in medical education programs (residents and fellows), nurse practitioners (NPs), and physician assistants (PAs). This study was approved by Mayo Clinic’s Institutional Review Board.

Study population

We identified acute outpatient office (“index”) visits among adults (age ≥ 18 years) in the community internal medicine (CIM) and family medicine (FM) practices of Mayo Clinic, Rochester between 10/1/2015 and 9/30/2017. Patients were required to be empaneled to a Mayo Clinic PCP for at least one year prior to the index visit and for 30 days following (to allow for ascertainment of baseline characteristics and utilization outcomes). Index visits were first identified using Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for office or other outpatient evaluation and management (E&M) visits (99201–99215, 99241–99245) and did not include preventive medicine, case or care management services, special evaluations, advanced care planning, or services performed outside the office setting. Index visits were then merged with administrative scheduling data to determine the allotted appointment time.

To ensure visits were for a new chief complaint, we excluded visits that were preceded by another eligible E&M visit in primary care within the previous two weeks. Visits for preventive services only or with non-PCP providers (e.g., nurse, dietician, social worker, etc.) were excluded from analyses, as were visits where the scheduled appointment length could not be determined. Patients who did not provide research authorization were excluded in accordance with Minnesota state law [ 34 ].

Explanatory variable

The exposure of interest was the scheduled appointment length of the index visit. Appointment lengths were ascertained from administrative scheduling data and categorized as 15-min versus ≥ 30-min. Appointment lengths are determined by centralized scheduling staff members using standardized templates based on the patient’s stated health concern and patient characteristics (see Additional file 1 ); the vast majority of appointments are either 15 or 30 min, but 45-min appointments are available for patients new to the practice and those requiring interpreter services. Because only 2.3% of longer appointments were 45 min long, they were grouped together with the 30-min appointments. Schedulers may substitute their own judgement and schedule 15-min concerns into longer appointment slots. Additionally, providers can request that concerns normally scheduled in a longer appointment be placed into a 15-min slot based on their calendar availability. As such, there is substantial overlap of clinical conditions and contexts that may be seen in either 15-min or 30-min time slots.

Independent variables

Covariates of interest included patient, visit, and provider level characteristics. Patient characteristics were extracted from the EHR and included age, ethnicity, race, gender, marital status, and geographic location. Marital status was included as a proxy for social support. Limited English proficiency was identified using the language preference recorded in the patient’s registration data. The Deyo adaptation of the Charlson comorbidity index with incorporated severity weighting was calculated using ICD-9/ICD-10 diagnosis codes from billing data [ 35 , 36 , 37 ]. Prior healthcare utilization, measured by the number of emergency department (ED) visits and hospitalizations in the prior year, was also obtained for each index visit.

Visit and provider information included the specialty area of the appointment (FM vs. CIM), the type of provider seen (physician, NP/PA, or trainee physician), and the specific clinic site where care was sought. The chief complaint for the visit was obtained using the primary diagnosis from billing data and was summarized using the clinical classification software refined (CCSR) multi-level categories [ 38 ].

Outcomes of interest were assessed within 7 days following the index visit and included outpatient office visits in primary care (referred to as repeat visits), ED visits, hospitalizations, laboratory services, and diagnostic imaging services. Repeat visits were identified using similar methodology to that of the index visit, but without examination of the two weeks prior. ED visits were identified using CPT codes (99281–99288). Laboratory and diagnostic imaging services were identified using revenue center codes (i.e., codes used to identify accommodation or ancillary services), and in some instances, a combination of revenue center and CPT codes (see Additional file 2 ). To account for the fact that diagnostic services may, in some instances, be ordered and conducted ahead of the scheduled appointment, we performed a sensitivity analysis excluding laboratory or imaging services rendered on the same day as the index appointment.

Adjustment for differences between groups

We anticipated that certain factors would be influential in determining whether a patient gets scheduled for a 15-min versus ≥ 30-min appointment. These would include patient level factors (medical complexity, social support, utilization patterns) and system factors (triage factors, access to care). For this reason, we implemented propensity score matching to account for potential selection bias in the exposure of interest. Full details regarding the propensity score matching approach used are provided in Additional file 3 .

Statistical analysis

Patient, visit, and provider characteristics were compared using standardized differences as opposed to p-values, as examination of standardized differences is a more appropriate method for determining balance across matched groups that is not influenced by reductions in sample size due to matching [ 39 ]. Crude outcome rates were compared within our matched population using McNemar’s test for paired data.

Multivariate regression models were used to examine the effects of appointment length on each of the outcomes of interest, while adjusting for important confounding variables not used as part of the matching process. We used conditional logistic regression methods to account for the matched nature of the data. Confounding factors included the ethnicity, race, gender, and marital status of the patient, as well as prior healthcare utilization. We reported multivariate regression results in the form of odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals.

To assess non-inferiority of shorter appointment lengths, we a priori defined a non-inferiority threshold of 10% increased likelihood (Odds Ratio [OR] of 1.1) of subsequent ED and hospital visits and a threshold of 20% (OR of 1.2) increased likelihood of repeat visits, laboratory services, and diagnostic imaging services. In essence, we are willing to accept a higher likelihood of subsequent utilization for those with shorter appointments so long as the increased rate does not exceed our defined non-inferiority threshold. We used the upper limits of the 95% confidence intervals as a boundary for assessing non-inferiority and compared this value to the corresponding non-inferiority threshold. All data management and analyses were carried out using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC).

We identified 173,758 eligible acute care visits to primary care during the study period. Shorter (15-min) appointments accounted for 6.5% ( N = 11,222) of the visits, while appointments scheduled for ≥ 30-min comprised 93.5% ( N = 162,536). Prior to matching, the majority (63.8%) of 15-min appointments were scheduled in the FM practice, while longer appointments were more evenly distributed between the practice areas (52.1% in FM and 47.9% in CIM) (Table 1 ). Longer appointments were more frequently scheduled with trainee physicians and for patients with limited English proficiency and a higher number of comorbidities. Visits with chief complaints related to congenital anomalies, mental illness, blood diseases, the circulatory system, digestive system, or musculoskeletal system, as well as endocrine or metabolic diseases, immunity disorders, injuries, and ill-defined conditions were more likely to have a longer appointment scheduled.

We matched 11,222 15-min appointments to a comparable ≥ 30-min appointment visit, resulting in a final matched cohort of N = 22,444 visits. After performing one-to-one propensity score matching, substantial balance was achieved between the two groups, with all match characteristics having a standardized difference below 5% (Table 1 ). Differences in additional baseline demographic characteristics not used as part of the matching process also substantially improved after matching.

There were no significant differences in the crude rates of repeat acute care visits between the appointment length groups (Table 2 ). Shorter appointment lengths had a lower rate of 7-day ED visits (1.8% vs. 2.2%, p = 0.03) and hospitalizations (0.7% vs. 1.0%, p < 0.01) compared to longer appointment lengths. Longer appointments were also followed by higher rates of laboratory (38.3% vs. 30.5%, p < 0.001) and diagnostic imaging services (28.2% vs. 17.2%, p < 0.001). These findings held true when excluding same day diagnostic services as part of our sensitivity analyses (see Additional file 4 , Tables D5 and D7).

Multivariate analyses showed no significant effect of scheduled appointment length on repeat visits (OR = 0.983, CI: 0.873,1.106) or ED visits (OR = 0.856, CI: 0.700, 1.047) (Fig. 1 ). Indeed, the strongest risk factor for repeat visits and subsequent ED visits was a history of greater ED utilization in the 6 months prior to the index visit (see Additional File 4 , Tables D1-D2). Shorter appointment lengths were associated with a lower likelihood of subsequent hospitalizations (OR = 0.689, CI: 0.504, 0.941), laboratory services (OR = 0.682, CI: 0.643, 0.724), and diagnostic imaging services (OR = 0.499, CI: 0.466, 0.534) compared to longer appointment lengths (Fig. 2 ). Female patients were more likely to have subsequent laboratory services compared to male patients (OR = 1.296, CI: 1.184, 1.419) (see Additional file 4 , Tables D3-D7). No other measures were significantly associated with our outcomes of interest.

Effect of primary care appointment length on ED visits and hospitalizations within 7 days of the index appointment

Effect of primary care appointment length on repeat visits, diagnostic laboratory, and imaging services obtained within 7 days of the index appointment

None of the upper confidence limits for repeat visits (UCL = 1.106), laboratory services (UCL = 0.724), and diagnostic imaging services (UCL = 0.534) exceeded the non-inferiority threshold of an OR of 1.2 (i.e., 20% higher likelihood) (Fig. 2 ). Similarly, the upper confidence limits for subsequent ED visits (UCL = 1.047) and hospitalizations (UCL = 0.941) fell below the non-inferiority threshold of an OR of 1.1 (i.e., 10% higher likelihood) (Fig. 1 ). These findings indicate that shorter scheduled appointments are non-inferior to longer scheduled appointments for all primary study outcomes.

Real-time evaluation of practice changes to assess for unanticipated and undesired outcomes is necessary to ensure that care delivery is safe, timely, effective, equitable, efficient and patient-centered [ 40 ]. Our study aimed to fill a critical knowledge gap by assessing whether 15-min primary care appointments represent a non-inferior option to traditional 30-min or longer appointments with respect to need for repeat primary care visits, ancillary diagnostic studies (laboratory and imaging tests), and ED visits and hospitalizations. We found that when propensity score matched on important patient and visit characteristics, patients seen for 15-min appointments did not incur greater healthcare utilization within seven days of the index visit, demonstrating that shorter appointments may provide a non-inferior option for scheduling when used for carefully selected patient populations.

Ideally, primary care appointments would allow for enough time to successfully complete all necessary clinical and ancillary tasks without shifting care to later appointments or generating unnecessary diagnostic testing or referrals. While the time required to complete all tasks associated with a comprehensive primary care appointment is increasing, healthcare organizations may be pressured to limit appointment durations to maximize access and reimbursement. Our findings suggest that for carefully selected patients with low-risk visit indications—the situations where these appointments were being used—shorter appointment lengths do not result in greater down-stream healthcare utilization. However, as only a small number of total primary care appointments in our study period were of shorter length and were focused on simpler chief complaints and lower risk patients, our findings should not be generalized to higher risk patients or chief complaints that were excluded from the comparisons during matching. Thus, changes to scheduling standards should be considered with caution to avoid potential oversaturation of shorter appointments within provider calendars, which could limit their ability to effectively manage patients scheduled on a given day.

Prior work in evaluating appointment lengths has found an association between increasing appointment lengths and improved quality of care indicators, better counseling or screening, higher patient satisfaction, and lower risk of malpractice suits, as longer appointments allow adequate time to perform comprehensive services [ 11 , 20 ]. Similarly, other retrospective work found that shorter appointment lengths are associated with incomplete visit tasks and higher medication prescribing, serving as a surrogate for lower value care, albeit much of this work was completed outside of the United States [ 30 , 32 , 41 , 42 ]. Our study built on these findings to offer reassurance that for select lower risk conditions and patients, shorter appointment lengths do not necessarily translate to greater total healthcare utilization secondary to incomplete or incorrect diagnostic evaluations. However, we did not consider whether longer appointments were more conducive to addressing health maintenance and preventive health needs; while this is not indicative of suboptimal care for the acute condition serving as the chief complaint, it nevertheless reflects missed opportunities to deliver care and improve long-term health outcomes.

To our knowledge, this is the first contemporary study to examine the impact of scheduled appointment lengths on subsequent healthcare utilization in the general primary care population in the United States. It was made uniquely possible by linking EHR data, which spans the outpatient and inpatient settings, to administrative scheduling data, which allowed us to examine healthcare utilization and outcomes for a diverse population of primary care patients. Our analyses are further enhanced by the use of administrative scheduling data, which includes the actual durations allotted to specific appointments, rather than CPT codes, which are imperfect surrogates of time spent on patient care and do not necessarily reflect the time allotted for the care that was performed. As part of a regionally dominant, integrated healthcare system we suspect there is very little leakage of down-stream care to other healthcare systems unable to be captured in our data. The five included clinics represented both urban and rural settings, patients were seen in teaching and non-teaching clinics, and a variety of practice styles and clinic level resources were available across the different sites, increasing the generalizability of our findings.

While informative, this study is subject to some limitations. Because this is an observational study using secondary data analysis approaches, we are limited to describing associations present in the data and cannot make causal inferences. To minimize the impact of this limitation, we utilized propensity score matching, which is a common approach to address underlying confounding and selection bias to estimate causal effects. However, because propensity score matching relies on observable data and administrative data alone cannot fully capture patient and care complexity and key social determinants of health, there may be residual bias in our study, resulting in some populations not being matched and included in our outcomes assessments. Thus, there may be important subgroups of patients, particularly those with multiple chronic conditions, patients with limited English proficiency who require interpreter services, patients with psychosocial barriers to health and healthcare, and those seen by trainee clinicians, for whom longer appointments may remain the superior option for scheduling. Additionally, care managed through email, phone calls, patient portals, and telemedicine is not represented in our study. Therefore, inferences of this study are only generalizable to face-to-face visits with the potential to be scheduled at a 15-min interval.

Further research in this area is needed to comprehensively understand how appointment scheduling approaches impact the clinical experience. While we showed non-inferiority of shorter appointments in this population as it relates to subsequent healthcare utilization, the association of appointment lengths with patient satisfaction, chronic disease outcomes, and measures of physician burnout are less clear [ 20 ]. Investigation into the value of using more patient and physician centered scheduling templates may represent another research area of opportunity.

Understanding how primary care appointment lengths impact downstream care and utilization may be of significant value to clinicians, practice administrators, quality improvement professionals, payers, and health policy experts. This study investigated the association of scheduled appointment length on repeat visits and diagnostic testing services rendered within the 7 days following the appointment and demonstrated that under the specific circumstances being considered, shorter appointment lengths, in carefully selected patients and carefully selected conditions may be adequate to meet patient needs. These findings can be used to improve healthcare delivery models and triage processes to provide higher quality and more efficient care, while aiming to reduce low-value healthcare utilization.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to inclusion of protected health information but can be made available subsequent to de-identification upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Primary care providers

Electronic health record

Nurse practitioners

Physician assistant

Community internal medicine

Family medicine

Current procedural terminology

Evaluation and management

Emergency department

Clinical classification software refined

Upper confidence limit

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Health Care Services; Committee on Implementing High-Quality Primary Care. Implementing High-Quality Primary Care: Rebuilding the Foundation of Health Care. Robinson SK, Meisnere M, Phillips RL Jr, McCauley L, editors. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2021.

Association of American Medical Colleges. The Complexities of Physician Supply and Deman: Projections From 2019 to 2034. Washington, DC: AAMC; 2021.

Google Scholar

Zhang X, Lin D, Pforsich H, Lin VW. Physician workforce in the United States of America: forecasting nationwide shortages. Hum Resour Health. 2020;18(1):8.

Article Google Scholar

Bodenheimer T, Chen E, Bennett HD. Confronting the growing burden of chronic disease: can the US health care workforce do the job? Health Aff. 2009;28(1):64–74.

Colwill JM, Cultice JM, Kruse RL. Will generalist physician supply meet demands of an increasing and aging population? Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(3):w232–41.

Linda A, Jacobsen, et al. “America’s Aging Population,” Population Bulletin. 2011;66(1).

Vincent GK, Velkoff VA. The next four decades: the older population in the United States: 2010 to 2050. Washington: Census Bureau(Current Population Report); 2010.

Truglio J, Graziano M, Vedanthan R, Hahn S, Rios C, Hendel-Paterson B, et al. Global health and primary care: increasing burden of chronic diseases and need for integrated training. Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine: A Journal of Translational and Personalized Medicine. 2012;79(4):464–74.

Collins S, Piper KB, Owens G. The opportunity for health plans to improve quality and reduce costs by embracing primary care medical homes. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2013;6(1):30–8.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Rittenhouse DR, Shortell SM, Fisher ES. Primary care and accountable care–two essential elements of delivery-system reform. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(24):2301–3.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Chen LM, Farwell WR, Jha AK. Primary care visit duration and quality: does good care take longer? Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(20):1866–72.

Mechanic D, McAlpine DD, Rosenthal M. Are patients’ office visits with physicians getting shorter? N Engl J Med. 2001;344(3):198–204.

Linzer M, Poplau S, Babbott S, Collins T, Guzman-Corrales L, Menk J, et al. Worklife and wellness in academic general internal medicine: results from a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(9):1004–10.

Linzer M, Bitton A, Tu SP, Plews-Ogan M, Horowitz KR, Schwartz MD, et al. The end of the 15-20 minute primary care visit. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(11):1584–6.

Erickson SM, Rockwern B, Koltov M, McLean RM. Putting patients first by reducing administrative tasks in health care: a position paper of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(9):659–61.

Bodenheimer T, Pham HH. Primary care: current problems and proposed solutions. Health Aff. 2010;29(5):799–805.

Rabin RC. 15-Minute doctor visits take a toll on patient-physician relationships. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/health/need-15-minutes-doctors-time .Published April 21, 2014.

DiMatteo MR. The physician-patient relationship: effects on the quality of health care. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1994;37(1):149–61.

Pronovost P. How the 15-minute Doctor's Appointment Hurts Health Care.: The Wall Street Journal; 2016 [Available from: https://blogs.wsj.com/experts/2016/04/15/how-the-15-minute-doctors-appointment-hurts-health-care/ .

Dugdale DC, Epstein R, Pantilat SZ. Time and the patient-physician relationship. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14(Suppl 1):S34-40.

Rao A, Shi Z, Ray KN, Mehrotra A, Ganguli I. National Trends in Primary Care Visit Use and Practice Capabilities, 2008–2015. The Annals of Family Medicine. 2019;17(6):538–44.

Berra K, Hughes S. Counseling patients for lifestyle change: making a 15-minute office visit work. Menopause. 2015;22(4):453–5.

Fiscella K, Epstein RM. So much to do, so little time: care for the socially disadvantaged and the 15-minute visit. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(17):1843–52.

Yarnall KS, Pollak KI, Østbye T, Krause KM, Michener JL. Primary care: is there enough time for prevention? Am J Public Health. 2003;93(4):635–41.

Geraghty EM, Franks P, Kravitz RL. Primary care visit length, quality, and satisfaction for standardized patients with depression. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(12):1641–7.

Bodenheimer T. Coordinating care--a perilous journey through the health care system. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(10):1064-71.

Arndt BG, Beasley JW, Watkinson MD, Temte JL, Tuan W-J, Sinsky CA, et al. Tethered to the EHR: primary care physician workload assessment using EHR event log data and time-motion observations. The Annals of Family Medicine. 2017;15(5):419–26.

Elmore N, Burt J, Abel G, Maratos FA, Montague J, Campbell J, et al. Investigating the relationship between consultation length and patient experience: a cross-sectional study in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66(653):e896–903.

Wilson A, Childs S. The relationship between consultation length, process and outcomes in general practice: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2002;52(485):1012–20.

Cape J. Consultation length, patient-estimated consultation length, and satisfaction with the consultation. Br J Gen Pract. 2002;52(485):1004–6.

Wilson A. Extending appointment length–the effect in one practice. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1989;39(318):24–5.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Wilson A, Childs S. The effect of interventions to alter the consultation length of family physicians: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2006;56(532):876–82.

Carr-Hill R, Jenkins-Clarke S, Dixon P, Pringle M. Do minutes count? Consultation lengths in general practice. J Health Serv Res Policy. 1998;3(4):207–13.

Rocca WA, Yawn BP, St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Melton LJ 3rd. History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project: half a century of medical records linkage in a US population. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(12):1202–13.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83.

Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613–9.

Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, Fong A, Burnand B, Luthi JC, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1130–9.

Clinical Classifications Software Refined (CCSR). Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). October 2021. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. www.hcupus.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccsr/ccs_refined.jsp .

Austin PC. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat Med. 2009;28(25):3083–107.

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. rossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington: National Academies Press (US); 2001.

Deveugele M, Derese A, van den Brink-Muinen A, Bensing J, De Maeseneer J. Consultation length in general practice: cross sectional study in six European countries. BMJ. 2002;325(7362):472.

Jin G, Zhao Y, Chen C, Wang W, Du J, Lu X. The length and content of general practice consultation in two urban districts of Beijing: A preliminary observation study. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(8):e0135121.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

This effort was funded in part by the National Institute of Health (NIH) National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) grant number K23DK114497 and a Mayo Clinic Division of Community Internal Medicine Time for Scholarly Activity Award.

Author information

Kristi M. Swanson and John C. Matulis III contributed equally to this work.

Authors and Affiliations

Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, USA

Kristi M. Swanson

Division of Community Internal Medicine, Department of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, USA

John C. Matulis III & Rozalina G. McCoy

Division of Health Care Delivery Research, Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, USA

Rozalina G. McCoy

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

R.G.M. and K.M.S. conceived of the idea and developed the study design. R.G.M. supervised the project. J.C.M. provided critical clinical practice expertise. K.M.S. was responsible for data acquisition and analysis. R.G.M. and K.M.S. interpreted the data. K.M.S. and J.C.M. wrote the manuscript with critical revisions/editing from R.G.M. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Kristi M. Swanson .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Ethics approval was obtained from the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board. The Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board granted a waiver of informed consent as the study involved no more than minimal risk to study subjects, there was no planned intervention or direct contact/communication with study participants, as such the waiver did not adversely affect the rights and welfare of the subjects, and the study only included patients who provided authorization for their medical records to be used for research purposes. All research methods used to conduct this study were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

In the last 36 months, Dr. McCoy also received support from NIDDK (R03DK127010; P30DK111024) and AARP® (Quality Measure Innovation Grant), as well as served as a Data Safety and Monitoring Board member (Entolimod Study CBLB502; study PI: Robert Pignolo, MD, PhD [Mayo Clinic]). Dr. Matulis and Mrs. Swanson declare that they have no other conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1..

Scheduling Template . Standardized scheduling template used by centralized scheduling staff members when assigning appointment lengths.

Additional file 2.

Billing Codes Used to Define Outcomes of Interest . Billing code rules used to identify laboratory and diagnostic imaging services outcomes.

Additional file 3.

Technical Appendix – Propensity Score Matching. A detailed summary of the methods used to carry out the propensity score matching approach.

Additional file 4.

Full Regression Model Results . A full summary of regression model estimates for each of the outcomes of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Swanson, K.M., Matulis, J.C. & McCoy, R.G. Association between primary care appointment lengths and subsequent ambulatory reassessment, emergency department care, and hospitalization: a cohort study. BMC Prim. Care 23 , 39 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-022-01644-8

Download citation

Received : 24 August 2021

Accepted : 08 February 2022

Published : 06 March 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-022-01644-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Schedules and Appointments

- Primary Care

- Practice Patterns

- Healthcare Utilization

- Quality of Healthcare

BMC Primary Care

ISSN: 2731-4553

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Article Information

Adult primary care visit duration (1997-2005). For all visits, P < .001 for trend. For general medical examination visits, P = .02 for trend.

Visit duration for 4 common primary diagnoses (1997-2005). P values for trend were P = .002 for diabetes, P < .001 for essential hypertension, P < .001 for arthropathies, and P = .05 for spinal disorders. Arthropathies include most visits for joint discomfort such as those for gout, osteoarthritis, and rheumatoid arthritis. Spinal disorders primarily include visits for low back pain.

Comparison of the early period (1997-2001) vs the late period (2002-2005). A, Change in medication quality indicator performance over time. P > .05 for all medication indicators except angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker for congestive heart failure (ACEI/ARB for CHF) ( P = .04), treatment for atrial fibrillation (Rx for Afib) ( P = .002), β-blocker (BB) or diuretic for hypertension (HTN) ( P < .001), and BB for coronary artery disease (CAD) ( P = .006). B, Change in counseling or screening quality indicator performance over time. P > .05 for all counseling or screening quality indicators except blood pressure check ( P < .001).

See More About

Select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

Others Also Liked

- Download PDF

- X Facebook More LinkedIn

Chen LM , Farwell WR , Jha AK. Primary Care Visit Duration and Quality : Does Good Care Take Longer? Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(20):1866–1872. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.341

Manage citations:

© 2024

- Permissions

Primary Care Visit Duration and Quality : Does Good Care Take Longer?