- Share on twitter

- Share on facebook

Carrying Capacity Methodology for Tourism

- Share on linkedin

- Share on mail

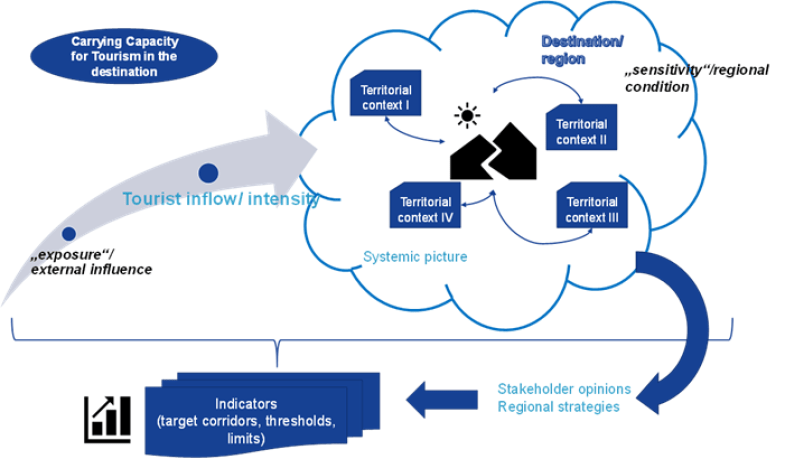

Tourism, for many cities and regions, is a propulsive source of economic vitality and its economic health can profoundly influence the course of regional development. However, in the last few decades, there has been a paradigm shift in how society views the relationship between tourism, development and sustainability. There is now a greater emphasis on reducing social disparities, maintaining acceptable levels of quality of life for citizens, and preserving environmental quality, biodiversity, and non-renewable resources. Levels of tourism that negatively impact the environment, the host community, and the quality of public services and infrastructure will, over time, erode the appeal of the city or region as a tourist destination as well as the quality of life for its residents and can lead to loss of economic vitality. Considering the growing number of tourists, the assessment of the current situation and identification of the vulnerability of destinations are extremely important in order to operate within the carrying capacity limits of territorial regions. The negative consequences of exceeding the carrying capacity due to overtourism or the misuse of the local resources are countless and can quickly lead to a decrease in quality of life for all parties in the tourism ecosystem, be it humans or natural resources.

A research consortium funded by ESPON EGTC, the European Spatial Planning Observatory Network, developed a methodology that showcases how to identify and consider the specific territorial context for measuring the carrying capacities of tourist destinations across Europe for better management and planning. The application of this methodology according to a supporting handbook developed by the consortium reveals the impact of tourist flows and carrying capacity limits. It provides an empirical foundation to the respective territories and helps local stakeholders to assess the impact of tourism in their region based on the three pillars of sustainability. Recommendations to regional and local practitioners are provided to assess their situation and identify vulnerabilities in relation to sustainable tourism.

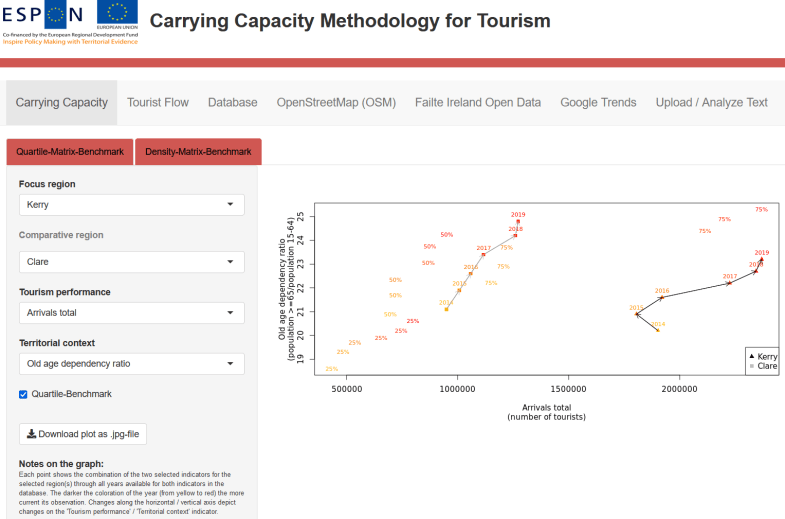

The methodology has been already applied to different types of destinations in Slovenia (including a cross-border destination), Italy and Ireland, to allow for a better generalization of its applicability in terms of regional economic, environmental, and societal characteristics and touristic idiosyncrasies. Dashboards interactively presenting statistical indicators and big data (social media and various other open data sources) have been developed for the case study regions to allow local stakeholders to further explore their destination. The sample screenshot below is taken from the dashboard developed for the case of the Iveragh Peninsula, Rep. of Ireland, by the consortium of Modul University Vienna and the Austrian Institute for Regional Studies and Spatial Planning (ÖIR).

Find out more about… …the project Carrying Capacity Methodology for Tourism …research work run by Modul University Vienna’s Academic Schools

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Environ Res Public Health

Tourism Environmental Carrying Capacity Review, Hotspot, Issue, and Prospect

Associated data.

The data presented are available upon request from the corresponding author.

With the ongoing expansion of tourism, a conflict has arisen between economic growth in the tourism industry and environmental preservation, which has attracted the interest of government and academic groups. Because it enables the adaption of tourist activities and buildings in the tourism area in order to protect the natural resources of the scenic area while seeking economies of scale, the tourism environmental carrying capacity system is an essential tool for resolving this conundrum. It also enables tourist sites to grow sustainably while understanding their limitations and carrying capacity. This study uses Citespace 6.1.2 and VOSviewer 1.6.18 analysis software to conduct a bibliometric analysis and review of 297 articles on tourism environmental carrying capacity. This analysis includes early warning studies, assessment models and management tools, and analyses of keyword co-occurrence and emergent word co-occurrence. The article’s conclusion makes recommendations for further research, including the division of each interest group, improved dynamic forecast and early warning of tourism environmental carrying capacity, and the development of an objective, scientific model of tourism carrying capacity.

1. Introduction

The effects of tourism have been more and more prominent in conversations and studies about development during the last few decades. The tourism industry has a huge potential to spur economic development in destinations. However, its expanding effects have resulted in a number of current and potential issues, as well as environmental, social, cultural, economic, and political problems in destinations and systems that call for alternative, more environmentally and destination country-friendly approaches to development, planning, and policy. In the early stages of tourism growth, there is a far more supply of newly created destination regions’ resources, facilities, etc., compared to the demand from travelers, who can make use of the destination’s many tourism resources and surroundings. While the growth of tourist destinations, commercial advertising, word-of-mouth marketing, and other methods to increase the popularity of the destination, its development into an upward stage, followed by a significant influx of tourists, although during this period, the destination will also strengthen the corresponding supporting facilities and improve the upgrade, etc., the supply measurement end of the increase may be significantly less than the demand side. Additionally, some tourists’ moral character may lead them to litter, paint on the walls, destroy display cabinets and signage, and other actions that are not suited to the development of tourism sustainably, such as the depletion of resources, pollution of the environment, damage to facilities, and customer dissatisfaction. The measurement of tourism environmental carrying capacity (TECC) is a potent tool to achieve this goal and will be crucial in scenic areas and tourist destinations. Thus, it is vital to increase the control and dynamic monitoring of the destination.

The TECC, initially known as tourism volume, refers to the threshold of the intensity of tourism activities that the natural, economic, and social systems of a tourism destination can withstand, and it is essentially a comprehensive reflection of the structural characteristics of the tourism environment system. In 1964, American scholar J. Alan Wagar published his academic monograph “Carrying Capacity of Wildlands for Recreation” [ 1 ]. According to Wagar, recreation capacity refers to the amount of recreation used in a recreation area that can maintain tourism quality in the long term. Since Wagar, TECC research results have been emerging. The World Tourism Organization first used the phrase “tourism capacity” in its report work from 1978 to 1979, which officially introduced the concept to the world of international research [ 2 ]; then, scholars and various stakeholders reached a consensus on its important role in the conservation of natural systems which plays an important role in sustainable tourism. In February 1987, at the 8th World Commission on Environment and Development held in Tokyo, Japan, Our Common Future was adopted and subsequently published, pointing out the importance of sustainable development for the common destiny and common future of humankind and the concept of sustainable development was then introduced into tourism research and policy [ 3 ], and sustainable tourism and TECC have attracted considerable interest from tourism researchers, including the establishment of a thematic journal, Journal of Sustainable Tourism , which now has an impact factor of 9.37.

At the UN Sustainable Development Summit held in New York on 25 September 2015, the 193 member states of the United Nations formally adopted 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), abbreviated as SDGs [ 4 ]. The SDGs aim to shift to a sustainable development path by thoroughly addressing the three dimensions of development—social, economic, and environmental—in an integrated manner from 2015 to 2030. Among them, the 14th and 15th are protecting and sustainably using oceans and marine resources for sustainable development; protecting, restoring, and promoting sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems; sustainable forest management; combating desertification, halting and reversing land degradation, and curbing biodiversity loss, respectively. Currently, human activities such as pollution, fishery depletion, and habitat loss are thought to have “severely damaged” up to 40% of the world’s oceans. In addition to providing food security and protection, forests—which cover one-third of the earth’s surface—are important for halting climate change, preserving biodiversity, and housing indigenous peoples. 13 million hectares of forest are lost each year, and 3.6 million hectares of land get desertified as a result of ongoing dryland degradation. The livelihoods and attempts of millions of people to escape poverty are impacted by deforestation and desertification brought on by human activity and climate change, which represent serious obstacles to sustainable development. Both the sea and the land are important hosts for tourism activities. In terms of the marine aspect, there is the coastal tourism of the Gold Coast, the sunny beaches of Catalonia, the Great Barrier Reef of Australia, the sea surfing of California, the Scandinavian fjord scenery, the sunny coast of Providenciales in the Turks and Caicos Islands of the Caribbean, etc. The terrestrial aspect includes Yellowstone National Park, the Koktokay Global Geopark, Sipsongpanna Rainforest, Kenya Wildlife Reserve, Masai Mara Savannah, etc. The majority of these well-known tourist destinations are mature tourist destinations, and all of them are struggling with overloading. As a result, their corresponding marine or terrestrial environments will suffer accordingly, necessitating a stronger study of the carrying capacity of the environment that is not just focused on the aforementioned tourist destinations.

The TECC has been the subject of numerous theoretical and empirical studies ( Table 1 ), but the research in this area is still in need of systematic trawling. Additionally, almost all of the studies use the CNKI and Web of Science databases as their primary literature sources rather than the more comprehensive Scopus database. The purpose of this paper is to analyze the research progress, theoretical concepts, assessment models, management tools and early warning systems of TECC, especially how to recognize and set the environmental carrying capacity of a tourism destination, and to propose a clear structure for subsequent research through the review. Although the TECC of land-based and sea-based tourism destinations must be very different, this paper uses conceptual research to explore the improvement direction and coupling points for subsequent research on the topic of TECC. The subsequent structure of this paper is as follows. Section 2 describes the analytical methods used in the study and the sources of research data; Section 3 presents the analysis results, including bibliometric analysis, keyword co-occurrence and emergent word co-occurrence analysis, and also reviews and summarizes the related conceptual studies, assessment model studies, applied studies and management tools and early warning studies, and makes a research review; the Section 4 final discussion and Section 5 conclusion section summarizes the findings of the article and presents the limitations of the article and future research prospects.

Summary of 11 reviews on tourism carrying capacity.

2. Methodology

In this study, the Mapping Knowledge Domain (MKD) was used [ 20 ] to analyze the scientific research results of the TECC from 1982 to 2022. In terms of the research idea, it follows the strategy from macro to micro, from whole to local, and from intuitive simplicity to in-depth complexity [ 21 ].

2.1. Mapping the Knowledge Domain

As a cutting-edge method in the field of scientometric analysis technology, knowledge domain mapping combines the theories and methods of applied mathematics, information science, computer science and graphics with the methods of co-citation analysis and co-occurrence analysis in bibliometrics, using knowledge mapping to demonstrate the core structure, development history, frontier areas and knowledge framework of the discipline. It solves the problems of traditional literature research methods, such as difficult data screening and heavy workload and has the advantages of being scientific, comprehensive, standardized, accurate and simple [ 22 ]. In this study, CiteSpace 6.1.2 and VOSviewer 1.6.18 software were used to map the knowledge domain of TECC.

2.2. Collection of Literature Data

Scopus is a multidisciplinary abstract-indexed database launched by Elsevier [ 23 ] in 2005 ( http://www.scopus.com , accessed on 10 September 2022), which now uniquely combines a comprehensive, expertly curated abstract and citation database with enriched data and linked scholarly literature across a wide variety of disciplines. In Scopus, scholars can quickly find relevant and authoritative research, identifies experts, and get access to reliable data, metrics, and analytical tools. Boasting the largest pool of author profiles available (17 million and counting), Scopus easily outmatches the competition [ 24 ]. It is one of the standard citation, bibliometric and abstract databases in the field of scientometrics and bibliometrics. Scopus has significant advantages over the Web of Science database in terms of reference completeness, indexing, and researcher relations [ 25 ].

First, in order to obtain as much relevant literature as possible, “Tourism Carrying Capacity”, “TECC”, and “TCC” were used as keywords in the “Topic” of the literature search, including title, abstract, and keywords; second, the time span was set to “1982–2022”, and then the search code was set to (TS = Tourism Carrying Capacity, TS = TCC or TS = TECC) and Language: (English) and Time range: (1982–2022). The search was conducted on 25 July 2022, and the database was last updated on 5 August 2022. A total of 862 results were collected and carefully checked (Since there are other research themes also abbreviated as TECC or TCC, e.g., Tactical Emergency Casualty Care, Technology Commercialization Centers, and Transnational Capitalist Class. We have then undergone a two-round screening). In the first round of screening, monographs, conference proceedings, and book reprints were excluded, and only journal articles and reviews in English-language were collected, as these are generally considered more influential and reputable than the formers. In the second screening round, results that did not involve tourism, travel, or leisure studies and were not related to environmental carrying capacity were excluded from this study. Finally, 297 valid re-study results were retained as the literature sample.

2.3. Analysis Methods

To address the objectives of this study, the article uses analysis methods such as keyword co-occurrence and bursty analysis and analyzes the volume of publications and journal trends.

Co-word analysis uses the co-occurrence of word pairs or noun phrases in a collection of literature to determine the relationship between topics in the discipline represented by that collection. Keywords are the core summary of a paper, and analysis of keywords in a paper can provide a glimpse into the topic of the paper [ 26 ]. Several keywords given in a paper must be related in some way, and this association can be expressed in terms of the frequency of co-occurrence. It is generally believed that the more frequently the word appears in the same paper, the closer the relationship between these topics.

Bursty words are keywords with low frequency but increasing growth momentum [ 27 ]. This indicates that the keyword is receiving more and more attention from scholars in the subject area and has a higher probability of developing into a research hotspot in the future [ 28 ]. The development of things follows the basic life cycle theory, and keywords are no exception. Generally speaking, there are four stages of keyword development in the process of scientific communication: emerging, developing, maturing, and diminishing. Burst topic detection works especially well in online social media and burst word detection is a significant issue in the field of information metrics study internationally.

CiteSpace and VOSviewer software can be used to analyze a large number of keywords for co-occurrence and burst detection and to identify hot spots and trends in a scientific field more objectively and effectively.

The network construction in CiteSpace is based on time slice. In this study, the unit of the time slice is set to 5 years (i.e., a total of 8-time slices). Note types are selected as Author, Institution, Keyword and Reference for analysis. The network construction in VOSviewer is based on the whole, and in this study, the Type of analysis selects Co-occurrence and Bibliographic coupling, respectively, and the Unit of analysis selects All Keywords and Sources, respectively.

3.1. Overview

The annual distribution of literature is a mapping of the quantity of literature in the time dimension. It is a quantitative basis for understanding the research progress and classifying the research stages and can reflect the development level of TECC research to a certain extent. Figure 1 shows the number of works of literature in the research sample, with an overall increasing trend, indicating that scholars pay more and more attention to the research on TECC. In general, scholars’ attention to TECC can be divided into 3 stages. The first stage was before 1987, TECC was in its infancy, and very few keen environmental scholars paid attention to the environmental carrying capacity problem under the theme of tourism. The number of articles issued in this stage is only sporadically distributed; the second stage is the middle growth stage from 1987 to 2015 since the adoption and publication of Our Common Future at the 8th World Commission on Environment and Development in Tokyo, Japan, the concept of sustainable development was introduced into tourism research and policy at this point, and the theme of TECC received significant attention. Along with environmental issues or overload issues in some tourist destinations, etc., many empirical studies of TECC were conducted at this time. The third stage is the booming stage from 2015 to the present, with the official adoption of 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) at the United Nations Sustainable Development Summit held in New York in 2015; as all sectors pursue SDGs, researchers also work toward sustainable development, and since the travel and the tourist industry is a key component, sustainable tourism development has become a hot topic. They tend to focus on projects that are relevant to the TECC. The number of articles published has reached a peak in the last two years. Conceptual studies, assessment model studies, management tools, and early warning studies, as well as empirical studies on the TECC of various types of destinations, have been flourishing and appearing in various journals.

Annual Publication statistics of TECC during 1982–2022.

As is shown in Figure 2 , the top 5 journals in terms of the number of articles published are Sustainability, Wit Transactions on Ecology and The Environment, Tourism Management, Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, and Ocean And Coastal Management, among which, Sustainability has 24 articles. In contrast, Tourism Management was early to focus on the topic of TECC, maintaining a small number of articles in the 1980s, while the other journals lacked this research tradition. Almost all of them only started to get involved in this topic after 2005, and even though the number of articles is relatively high, the theoretical foundation seems to be less solid than that of Tourism Management, which, of course, must be admittedly related to the time of the creation of each journal. It is worth noting that, as one of the SDGs’ sustainable development goals, i.e., the conservation and sustainable use of oceans and marine resources for sustainable development, the TECC in the ocean has received a great deal of attention from scholars, and Ocean and Coastal Management is a journal that covers most of the authoritative articles on the TECC in marine areas. In addition, the International Journal of Sustainable Development and World Ecology, the Journal of Sustainable Tourism, and Environmental Management are also important journals for TECC research ( Figure 3 .).

Top 5 journals in terms of articles on the TECC.

The coupling relationship between journals on the theme of TECC.

3.2. Keyword Co-Occurrence Analysis

From the results of the keyword co-occurrence analysis presented in Figure 4 , the earlier studies (#7 #8) focused on the TECC measurement of natural tourism destinations, including global geoparks [ 29 ], national parks [ 30 , 31 ], recreational wetlands [ 32 ] and independent islands [ 33 ] (#6), while subsequent studies (#5) have sought to change the traditional way of measuring the TECC [ 34 ] and exploring integrated measurement methods. In the 21st century, research on TECC is no longer limited to the measurement of physical carrying capacity but also focuses on the impact of variables such as destination perception, tourist satisfaction and resident perception on tourism carrying capacity and introduces social carrying capacity [ 35 , 36 ] (#1). In 2015, with the United Nations Sustainable Development Summit held in New York, scholars increased their attention to the sustainable development of the ocean, and in terms of marine tourism, Catalonia, Spain, has the most abundant tourism resources and is the most popular marine tourism destination, with a large number of tourists from the United Kingdom, Northern Europe and North America throughout the year all seasons, and the study of the environmental carrying capacity of this region has become a recent hot topic [ 37 , 38 ] (#0). As a whole, sustainable development, destination management and ecotourism are the main classical topics in TECC research (Carrying Capacity and research topics are similar and not distinguishable, so they are excluded). It is noteworthy that the keyword China, which is the only geographical category keyword to appear in both two keyword co-occurrence analyses ( Figure 5 .). Despite the fact that China’s tourism research started late, it has already resulted in a significant number of articles on the TECC due to the country’s abundant tourism resources and a sufficient number of visitors, as well as the contradictory issues between visitors, tourism resources, and residents, which have drawn attention from many scholars.

Keyword co-occurrence analysis with 5 years as a time slice.

Overall keyword co-occurrence analysis.

3.3. Co-Occurrence Analysis of Bursty Words

As a complement to the keyword co-occurrence analysis, the bursty word analysis demonstrates how the study hotspots for TECC have changed over time ( Figure 6 .). Since the 1990s, overtourism has had a negative impact on the growth of some tourist sites, especially in terms of irreparable environmental damage. From 1991 to 2008, environmental impact assessment has become a popular topic. When it comes to regional differences, the European region is well-known as a travel destination because of its abundant tourism resources, earlier tourism development, and more developed destination system, while the Asian region is well-known as a travel destination because of its proximity to the European market and distinctive tourism resources, which draw travelers from all over the world [ 39 ]. Therefore, in the period 2003–2011, Europe, Eurasia, Athens and Southern Europe were the focus of research on the TECC in the period 2006–2011 [ 40 ]. The rise of scuba diving has been more than a decade, and as a highly participatory tourism experience, it has had a great impact on the marine environment, marine biodiversity (fish habitats, coral reefs), etc. The study of the location and reasonable capacity of reasonable areas for scuba diving is a popular theme for 2012–2017 [ 41 , 42 ]. In recent years, with the new crown epidemic for social distance, many tourist destinations are in the stage of overtourism, and while re-measuring the environmental carrying capacity, scholars have also noted the changes in the perception of tourists and residents, introducing the social carrying capacity [ 36 ]. Thus, perception and overtourism are the hot spots of recent studies. Notably, TECC research in China was also a major hotspot during the period 2015–2020 [ 43 , 44 ]. However, as a result of COVID-19 in 2020 and the exponential drop in foreign travelers, study on this topic has slowed down.

Co-occurrence analysis of emergent words (with a 5-year time slice).

3.4. Literature Review of Conceptual Studies, Assessment Model Studies, Applied Studies, Management Tools, and Early Warning Studies

Neo-Malthusianism gave rise to the idea of TECC, which later developed into a comprehensive system that includes physical capacity, tourist thresholds, growth management estimates, etc. Numerous research on the environmental impact of tourism has been conducted, but their development has not been systematically sorted out. Various assessment models have been developed from the first descriptive and straightforward data used in these studies. However, it is debatable if various models can adapt to various settings and circumstances. Additionally, there are multiple kinds of tourist destinations, and these destinations exhibit different characteristics and experience varying degrees of overload issues. In order to address these issues and support the tourism destinations’ sustainable development, management tools and early warning systems must be used. As a result, the conceptual analysis of the TECC, the study of assessment models, the empirical analysis of categorized destinations, and the analysis of management tools and early warning systems constitute the four main components of this chapter’s literature review. According to these four results, we further conclude 4 characteristics of current research and put forward 4 prospects regarding the future research agenda.

3.4.1. Conceptual Research

The concept of recreational carrying capacity evolved from a neo-Malthusian perspective of resource limitation. The concept of carrying capacity was originally developed in the field of range and wildlife management, based on the notion that organisms can only survive within a limited range of physical conditions, i.e., “the availability of suitable living conditions determines the number of organisms that can exist in the environment” [ 45 ], the problem faced by these fields relates to the physical capacity of a given area of pasture, hay-field or heathland to maintain the quantity and quality of forage over time to sustain a given number of domestic or wild livestock. The TECC evolved from the environmental capacity; in 1963, W. Lapage [ 46 ] first proposed the concept of TECC based on the study of the maximum capacity of the tourism environment. In 1964, American scholar J. Alan Wagar [ 1 ] published his academic monograph Carrying Capacity of Wildlands for Recreation . He argues that recreation capacity is the amount of recreation used in a recreation area that can sustain tourism quality over time. Research on tourist capacity has developed since Wagar. The term tourism capacity was formally introduced by the World Tourism Organization in its work report in 1978–1979, marking the beginning of tourism capacity into the scope of international research. Hovinen (1982) [ 47 ] defined carrying capacity as the maximum number of tourists that can be accommodated without causing excessive environmental degradation and without leading to a decrease in tourist satisfaction. Mathieson and Wall (1982) [ 48 ] defined carrying capacity by considering the physical impact of tourism on a destination in terms of environmental and experiential aspects, such as the maximum number of people who can use the recreational environment without an unacceptable decline in the quality of the recreational experience. On the other hand, O’Reilly (1986) [ 49 ] described two schools of thought on carrying capacity. One, carrying capacity is considered to be the ability of a destination area to absorb tourism before the negative effects are felt by the host and resident. Carrying capacity is determined by how many tourists are wanted, not by how many tourists can be attracted. The second view is that TECC is the level of tourist flow that is exceeded because some of the tourists’ own perceived capacity has been exceeded, and therefore the destination area no longer satisfies and attracts them. O’Reilly (1986) [ 49 ] also points out that Mathieson’s definition only considers the physical impact of tourism on the destination from an environmental and experiential perspective. He claims that carrying capacity can be established not only from a physical perspective but also for the social, cultural and economic subsystems of the destination. As described by Mathieson, economic carrying capacity is the ability to absorb tourist functions without crowding out desirable local activities. They define social carrying capacity as the degree to which the host and resident of an area become intolerant of the presence of tourists. Lindsay (1986) [ 50 ], in discussing the TECC of national parks, defined it as the physical, biological, social, and psychological capacity of the park environment to support tourism activities without degrading environmental quality or visitor satisfaction. Reilly [ 49 ], on the other hand, argued that the perceived condition of residents in tourist destinations is an important factor affecting the carrying capacity of the environment and that the psychological perception of residents directly affects the carrying capacity. In 1995, Cui [ 51 ] proposed to use the TECC instead of the tourism environmental volume and defined it as “the number of tourists that a destination can bear in a certain period of time under the premise that the current situation and structural combination of a tourist environment (i.e., tourism environmental system) do not change in a harmful way to the present and future people”. The study of TECC is conducive to promoting the implementation of environmental protection policies and promoting rapid regional economic growth. Jovic (2009) [ 52 ] argued that TECC is the maximum number of tourists that can stay in a given area without causing unacceptable and irreversible changes in the environmental, social, cultural and economic structure of the destination and without reducing the quality of the tourism experience. Zelenka and Kacetl (2014) [ 53 ] pointed out that the TECC is not only a matter of the number of visitors to a destination. Rather, it is also related to a range of other factors, including infrastructure, tourism distribution, and visitor behavior patterns, and may focus on specific dimensions in each particular geographic context. Therefore, the assessment of the TECC can also be done in many different ways and reflected in different dimensions such as physical, sociocultural, and economic development dimensions. Kisiel et al. [ 54 ] conducted an in-depth theoretical discussion and proposed that TECC should include two aspects: first, the natural environmental capacity, and second, the perceived environmental capacity, which is the ability to accommodate tourists on the basis of ensuring a good tourism experience. Milla et al. [ 55 ] determined the connotation of TECC and established the definition of TECC. It is believed that TECC should include indicators of four aspects: natural environmental carrying capacity, the spatial carrying capacity of resources, economic carrying capacity, and psychological carrying capacity. These tourism environmental carrying capacities, measured based on different dimensions, show that TECC is a complex system. The related research has shifted from discussing reasonable quantity to growth management and optimal decision-making objectives.

3.4.2. Evaluation Model Research

In the early studies of TECC, scholars mostly used descriptive and simple statistical methods. However, with the development of tourism, science and technology, these methods have become outdated. Currently, there are two types of TECC prediction: quantitative studies and qualitative studies, of which the former is the most commonly used research method. Han [ 56 ] established a linear planning model of low carbon TECC through a fuzzy linear function with “tourism scale economy” as the objective function and the constraints of resources and ecological environment factors as the constraints, studied the TECC in Shandong Peninsula and Sanya City, China. Ye et al. [ 57 ] used a state-space model to construct a TECC early warning index system from natural, economic and social aspects, explored the current situation and spatial and temporal differences of TECC early warning in 10 island cities in eastern China, and used BP (Back-Propagation), neural network model, to predict the development trend of early warning. Wang et al. [ 58 ] constructed a utility theory framework of TECC based on consumer utility theory and calculated the TECC thresholds under different environmental conditions in the park using the conditional logit model. Tokarchuka [ 35 ] used subjective well-being theory to analyze the social carrying capacity of tourism in Berlin 12 by the regression model. Wang [ 59 ] analyzed the TECC of Emei Mountain with empirical modal decomposition and BP neural network as a new method of predicting TECC by government staff and scenic area managers. Yan [ 60 ] studied the TECC in East Lake scenic area by fuzzy hierarchical analysis and set-pair analysis. Chen [ 44 ] measured the TECC at the county level in Zhoushan Islands by ecological footprint quantification. Alvara [ 38 ] studied the TECC of the Catalan coast using input-output analysis, which allows to distinguish economic flows within different spatial units, including direct, indirect and induced effects, and to quantify spillover effects, which are usually significant in the tourism industry. Gonzalez and David [ 36 , 61 ], using ANOVA, studied the TECC in the small town of Besalou, Spain, and the coral reef area of Etla, northern Red Sea. Mark T [ 62 ] compared the TECC of two resorts in Papua New Guinea and Mexico with energy analysis. Jurado E [ 63 ] created two synthetic indices (weak and strong) using the DPSIR model and the GIS-MCDA method to analyze the carrying capacity of the eastern Costa del Sol in Spain. Adamchuk [ 64 ] developed a quantitative evaluation model of the integrated carrying capacity of scenic areas based on the product matrix vector length method and obtained a favorable measure of the integrated carrying capacity of scenic areas. Cvijanovi’c et al. [ 65 ] used the theoretical speculation method and empirical measurement method to construct the measurement formulae of ecotourism environmental capacity, natural resources environmental capacity, tourism space environmental capacity, social ecotourism environmental capacity and tourists ecotourism environmental capacity. Mohanty et al. [ 66 ] analyzed the cumulative effect of tourism activities on environmental capacity and established a formula for calculating TECC using quantitative relationships of environmental factors and Pareto optimality. Kalchenko et al. [ 67 ] proposed a model for measuring the LECC with length, area and recreational facilities as limiting factors and measured the TECC through the design of the model. Meanwhile, Shia [ 68 ] also calculated the TECC of Shangri-La county in China by area method. In the process of quantification, the TECC index system is influenced by value judgments, and in the absence of specific criteria of “management objectives” or “ideal conditions”, although the study of TECC emphasizes scientificity, objectivity and accuracy, its measurement model is full of problems, the measurement model is full of subjective factors.

3.4.3. Application Research

In the empirical study of TECC-categorized destinations, it presents a shift from initially fragmented point-like to tourist routes and county-based tourist destinations, etc., from point to line and surface, and the research scope coexists with micro-scale, mesoscale and macro-scale. Scholars have explored TECC based on different theoretical perspectives, including DEPSIR [ 69 ], PSR [ 70 ] and EES [ 71 ] models. The local TECC studies include national parks [ 58 ], tourist resorts [ 62 ], lakes [ 60 ], islands [ 72 ], forests [ 73 ] and coast regions [ 63 ], etc. Scholars analyzed the TECC based on first-hand surveys and measurements and combined it with secondary data; then extended to archipelago [ 44 ], counties [ 68 , 74 ], cities [ 35 , 75 ] and specific regions [ 56 , 76 ]. The TECC measurements are mostly modeled and quantitatively analyzed using national or local statistical yearbook data and panel data. Despite the fact that there are many studies on the various types of destinations for TECC, almost all of them are self-adaptive studies based on the respective destinations, and the corresponding comparative studies are scarce. Plus, these studies are weak in extension and expansion regarding co-research, which undermines the systemic nature of TECC theme studies.

3.4.4. Management Tools and Early Warning Research

While foreign scholars call for national laws to guarantee the role of management tools, domestic scholars place more emphasis on improvement-oriented management initiatives in tourism destinations. Common management tools include the limits of acceptable change (LAC) [ 77 ], visitor experience and resource protection (VERP) [ 30 ], visitor activities management process (VAMP) [ 78 ], visitor impact management (VIM) [ 79 ], recreation opportunity spectrum (ROS) [ 80 ], and tourism optimization management model (TOMM) [ 81 ], etc.

The research on TECC early warning system is in the preliminary exploration stage, and current research mostly focuses on wetland parks [ 57 ], marine parks [ 82 ], and the carbon cycle [ 83 ], which are in a broad sense of natural resources [ 84 ]. In terms of early warning models and research methods, they basically adopt methods consistent with the carrying capacity. Some scholars have done further research by improving the existing assessment methods, but most of them stay in the early warning situation of a single method without a breakthrough. Its theoretical and methodological system is still immature. Current research is basically based on relevant statistical and econometric methods, and scholars mostly subdivide the TECC into multiple subsystems as the analysis framework, such as Huo [ 85 ] based on the large system theory divides the tourism early warning system into subsystems such as tourism alarm dynamic monitoring, tourism alarm source analysis, tourism alarm sign identification, tourism alarm degree forecast and geographic information technology assistance. Zhao [ 86 ] established a regional tourism ecological security composite early warning system consisting of a regional tourism ecological environment pressure warning subsystem, a regional tourism ecological environment quality early warning subsystem, and regional tourism ecological protection and remediation capacity early warning subsystem. The current research tries to construct some early warning index systems, but mostly from qualitative research and time interface analysis based on empirical and historical data, lacking in-depth research on the regional differences and temporal changes of TECC, which substantially reduces its early warning effectiveness and significance.

3.5. Research Review

From the current research results, the study of TECC generally presents the following characteristics: (1) The differentiation of conceptual research. The scholars have different interpretations regarding the concept of TECC and make its research content very different, including but not limited to the measurement of the natural environment, resource space, social-economic, cultural and psychological aspects, but reach a consensus on its purpose, including promoting the sustainable development of the destination and enhancing the satisfaction of tourists and residents. (2) Continuous enrichment of assessment models and deepening of research methods. Assessment models have shifted from qualitative descriptions and simple statistical methods to modeling analysis and related methods, including non-causal time series models, causal relationship models, artificial intelligence models and combination models, and quantitative measurements with BP neural networks, fuzzy hierarchical analysis, set-pair analysis, input-output analysis and area method, etc., and research results have become more objective and reasonable. (3) Gradual expansion of research scale. The initial empirical research of TECC focused on some micro-regions such as Colorado Grand Canyon National Park [ 30 ], Red Sea Coast [ 61 ], and the Alcatraz Islands [ 33 ], etc., and then expanded to larger-scale studies, including Shangri-La County [ 68 ], Shandong Peninsula City Cluster [ 56 ], the city of Berlin [ 35 ], Japan [ 87 ], and the Maldives [ 88 ]. The study of TECC shows a trend of turning point-line-surface. (4) The management tool system has been improved. Although the research on management tools and the early warning system of TECC is still in the initial stage, scholars have combined with the theory of tourism early warning system and put forward a series of management tools, including LAC, VERP, VAMP, VIM, ROS and TOMM, etc. Based on natural resources, tourists’ and residents’ satisfaction perspectives, they have established a system of “indicators” reflecting the quality of tourism experiences and resource conditions, established “standards” for minimum acceptable conditions, proposed “monitoring techniques” for timely and appropriate management tools to ensure that the state of the corresponding areas meets these standards, and developed “monitoring techniques” to ensure that the conditions of the various areas meet these standards. The management measures” to ensure that the various indicators are maintained within the specified standards have been developed.

Based on the characteristics summarized in the above discussion, this paper puts forward the following outlook for the subsequent research on TECC: (1) strengthen the growth management and optimal decision target research of TECC. TECC is a complex system, and it being measured based on different dimensions shows that natural resources, economic and social, cultural and psychological subsystems are all factors involved in TECC, and future research should focus on the dynamic evolution of TECC and can simulate and predict TECC through the neural network, machine learning and other methods to reduce the measurement model in subjective factors to achieve the goal of optimal dynamic decision-making. In addition, it is necessary to adjust according to the empirical object and carrying capacity management objectives and combine the relevant theories of sociology, psychology and economics to build a scientific and objective TECC model. Secondly, subdividing each stakeholder and conducting comparative research according to the needs of each stakeholder can be done with the help of coupling theory in order to achieve balance or maximize the comprehensive benefits of each interest subject. (2) Combined with the software of related disciplines for comprehensive analysis. TECC involves ecology, environmental science, geography and sociology and other disciplines, and the existing research only focuses on the use of a discipline of software for a single aspect of the measurement, which weakens the overall systemic TECC. Subsequent research can focus on integrated software such as Ansys Fluent, ENVI and ArcGIS for simulation prediction, forward inversion and spatial analysis to scientifically study the overall system of TECC. (3) Focus on the expansion of TECC research. Although the research on the TECC of various types of destinations is rich, the articles are almost all based on the characteristics of the destination for adaptive quantitative research. The corresponding comparative research is relatively small, and its extension and expansion are weak, weakening the systemic nature of TECC theme research. Future research should take into account the extended adaptive range of TECC while focusing on the ontological self-adaptation of case sites, which will make the research more theoretical and practically meaningful. (4) Research on succession management tools and early warning systems. In terms of time series, the existing research is increasingly inclined to find some reasonable and effective capacity management tools on the basis of a specific understanding of environmental capacity conditions so as to achieve the goal of capacity control and the development of capacity management tools has become a new hot spot for research. At the same time, on the basis of time interface analysis based on experience and historical data, deepen the research on geographical differences and time series changes of environmental carrying capacity to better realize the role and significance of management tools and early warning systems, future research can introduce neuro-tourism simulation experiments, scenic spot management simulation and tourism safety simulation experiments, etc., to strengthen the simulation for tourism places and TECC in order to realize dynamic control.

4. Discussion

4.1. overview.

In this paper, a bibliometric analysis of 297 articles retrieved from the Scopus data platform, including volume data, journal distribution, keyword co-occurrence and bursty word co-occurrence analysis, was conducted in Citespace and VOSviewer analysis tools, and the study found that.

- Before the 21st century, the topic of TECC received less attention because most tourist places were in the early initial development stage. Since entering the 21st century, with the booming tourism industry and the emergence of some negative impacts in some tourist places, the research on TECC has increased greatly, especially in the last 5 years.

- Sustainability, Wit Transactions on Ecology and The Environment, Tourism Management, Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, Wit Transactions On Ecology And The Environment, Tourism Management, Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research and Ocean and Coastal Management are the international journals with the most articles on the topic of TECC, with 24 articles on Sustainability. In contrast, the Tourism Management journal was early to focus on the topic of TECC and has been published annually since the 1980s, although only about 1 article per year in the early years.

- Early studies on TECC mostly focused on measuring TECC in natural tourism destinations, including areas such as global geoparks, national parks, recreational wetlands and independent islands, while subsequent studies focused on elements of tourist satisfaction and residents’ perceptions, with an eye on social carrying capacity and economic carrying capacity. In 2015, with the UN Sustainable Development Summit held in New York, marine sustainability became an important topic, especially in Catalonia, Spain, where the study of environmental carrying capacity has become a recent hot topic. In addition, the European region (especially Athens) and the Asian region have been the main regions of TECC studies in the last 20 years.

- The concept of TECC originates from environmental carrying capacity, but in comparison, TECC contains various socio-economic and psychological factors, which is more complex, and a unified definition of this content has not yet been formed; the measurement methods of TECC have shifted from the initial descriptive and simple statistical methods to computers (such as BP neural networks), GIS and integrated models. However, the research on early warning and management tools of tourism carrying capacity is relatively less.

- The study of TECC generally presents four characteristics, i.e., The differentiation of conceptual research, continuous enrichment of assessment models and deepening of research methods, gradual expansion of research scale and the improvement of the management tool system.

4.2. Shortcomings of the Article

Although the study reviewed articles on TECC and used literature data from the Scopus database for the bibliometric analysis to remedy some of the shortcomings of previous studies, there are some limitations in the article, such as the study only selected journal articles and review articles for the analysis, which may ignore some important and relevant literature. In addition, in the bibliometric analysis, only English-language literature was selected for the analysis, while regions such as Provence, Brazil, and Japan, which are some recent tourism hotspots, are non-English speaking areas, which can make the analysis results somewhat limited. Plus, TECC research in Western and Central European countries, especially in France, Germany, Italy, and Poland, started earlier than in North America, but those findings were most published in their national languages and are usually ignored. Nevertheless, this study provides a systematic review of TECC studies in the Scopus database for the period 1982–2022 to provide references for subsequent empirical studies and tourism destination management practices. Future studies could include conference articles and other language sources for analysis (e.g., Spanish and French) to compensate for the limitations of the current study and pay more attention to the early studies in Western and Central European countries to better close the knowledge gap.

5. Conclusions

Based on Citespace and VOSviewer analysis software, this paper conducts a bibliometric analysis and literature review on 297 articles screened from the Scopus database on TECC, including keyword co-occurrence and bursty word co-occurrence analysis and research on concepts, applications, assessment models and management tools and early warning, followed by a review of existing research, including the divergence for conceptual research, the continuous enrichment of assessment models and the deepening of research methods, the gradual expansion of research scales and the continuous improvement of management tools, and proposes four future research directions, namely, strengthening the growth management of TECC and optimal decision-making objectives, combining software from related disciplines for comprehensive analysis, focusing on the expansion of TECC research, and continuing the research of management tools and early warning systems. Finally, the findings of the bibliometric analysis and literature review are discussed, and the limitations of the paper are pointed out as well as the directions for remediation. Notably, early TECC studies were primarily published in non-English languages in Western and Central European nations, particularly in France, Germany, Italy, and Poland, and this may have led to a knowledge gap to some extent. Future studies should find an approximate solution to this challenge, either by making comparisons or by doing research on these corresponding national languages.

Funding Statement

This research study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (NO. 41971171).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.L. and S.L.; methodology, C.L.; software, J.C., C.L. and L.C.; validation, C.L. and S.L.; formal analysis, C.L.; investigation, S.L. and C.L.; resources, C.L. and S.L.; data curation, C.L. and S.L.; writing—original draft preparation, C.L.; writing—review and editing, C.L., S.L., J.C., J.Z. and L.C.; visualization, C.L.; supervision, S.L.; project administration, C.L. and S.L.; funding acquisition, S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of interest.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

A Review on Tourism Carrying Capacity Assessment and a Proposal for Its Application on Geological Sites

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 21 March 2023

- Volume 15 , article number 47 , ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Priscila L. A. Santos ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9148-6453 1 &

- José Brilha ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8927-8487 1

3002 Accesses

6 Citations

Explore all metrics

Geoconservation consists of the selection and conservation of geodiversity elements that have significant heritage value. The management of geological sites is based on specific procedures to ensure public use and minimize adverse impacts. The evaluation of the carrying capacity of geological sites is a management tool that helps to define the acceptable limits of visitation, without causing significant impacts on the integrity of these sites. This work presents a review of the carrying capacity concept and the most common methods used to assess the carrying capacity in tourist destinations. Based on this review and analysis of the advantages and disadvantages of existing methods, this work presents a method that defines a set of actions for management and calculation of the number of visitors recommended for geological sites, based on specific geoindicators for each type of site.

Similar content being viewed by others

Assessment of the Geotourism Resource Potential of the Satun UNESCO Global Geopark, Thailand

Onanong Cheablam, Pavit Tansakul, … Sirinan Pantaruk

Natural Resource Evaluation for Ecotourism and Geotourism Destination in Hong Kong

Estimating Carrying Capacity in a High Mountainous Tourist Area: A Destination Conservation Strategy

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The increase of visitors in national parks and other designated areas in the USA in the middle of the twentieth century obliged park managers to improve the management strategies of these protected areas (Soller and Borghetti 2013 ). Therefore, the concept of carrying capacity (CC), initially proposed under the scope of biological sciences (ecology) and applied in the context of wildlife, agriculture, and livestock, became an important tool for the management of recreation and leisure areas. Initially, CC was applied primarily on the identification and quantification of human activities impacts in protected areas (Takahashi 1998 ; Shaofeng 2004 ; Pires 2005 ; Manning 2007 ; Delgado 2007 ; Coutinho 2010 ; Soller and Borghetti 2013 ; Zelenka and Kacetl 2014 ; Sharma 2016 ; Kennell 2016 ). Later on and influenced by the sustainability paradigm, the CC concept gained global relevance and started to also address cultural and economic issues of the population living in tourist areas (Pires 2005 ; Kostopoulou e Kyritsis 2006 ; Coutinho 2010 ).

Several methodological studies were developed in the beginning of the 1990s, aiming the evaluation of the tourism carrying capacity (TCC) in protected areas (Cifuentes 1992 ; Cifuentes-Arias et al. 1999 ; Coccossis and Mexa 2004a , b ; Boullón, 2006 ). These and other methodological models propose a quantitative TCC assessment by setting up the maximum number of visits that a place can withstand and a qualitative assessment by identifying which are the acceptable conditions for a certain site. In recent years, different methodological approaches that include distinct TCC types have been applied as tools for the management of protected areas in several parts of the world, like Costa Rica (PROARCA 2006 ), Rio Grande do Sul (Brazil) (Soller and Borghetti 2013 ), Java Island (Aryasa et al. 2017 ), and Paraná (Brazil) (Pontes and de Paula 2017 ).

However, the use of TCC as a tool applied to the management of geological sites is still very scarce. The more consolidated TCC studies are related to management of caves, e.g., Boggiani et al. ( 2007 ), Lobo ( 2009b , 2011 , 2015 ), and Lobo et al. ( 2013 ). Other TCC studies in geological sites were done by Coutinho ( 2010 ) at Penha Garcia geosite (Naturtejo UNESCO Global Geopark, Portugal), by Lima ( 2012 ) and Lima et al. ( 2017 ) at Ponta da Ferraria and Pico das Camarinhas geosite (Azores UNESCO Global Geopark, Portugal), and by Guo and Chung ( 2017 ) at geoparks in Hong Kong.

Sharples ( 2002 ) defines geoconservation as the conservation of the diversity of significant geological (bedrock), geomorphological (landform), and soil features and processes whilst keeping the natural evolution of these processes as a function of their intrinsic and heritage values. This author adds that the objectives of geoconservation are to preserve and assure the maintenance of geodiversity, to protect and safeguard the integrity of places whose geodiversity is relevant, to minimize the adverse impacts on these sites where geodiversity exhibits a relevance above average, to interpret and explain geodiversity to visitors of protected areas, and to contribute to the safeguard of biodiversity and ecological processes.

Brilha ( 2016 ) highlights the need to establish geoconservation strategies in order to ensure the preservation and sustainable management of geoheritage by means of specific procedures that include inventory, quantitative assessment, conservation, interpretation and promotion, and monitoring of sites. According to Gordon et al. ( 2018 ), geoconservation must address a set of fundamental principles for the implementation of a holistic approach in practice and the integration of geoconservation in the preservation of nature and in the planning and management of geological sites. Furthermore, measures must be taken for the control of visitors in sensitive sites and for the promotion of education and interpretation of the whole natural heritage.

This work revises the CC concept with emphasis on the CC assessment applied to tourist destinations. The literature review is focused on the CC understanding and its conceptual and methodological evolution throughout time. It is shown how the CC concept as a tool for planning and maintenance can be combined with geoconservation and applied to the sustainable management of geological sites. The main methodological applications in geological sites are analyzed, with a special focus on protected areas, and the advantages/disadvantages of the different methods are discussed.

The Concept of Carrying Capacity

The concept of carrying capacity or support capacity appeared in the end of the nineteenth century applied to biological sciences, ecology, and human ecology. The “idea” or “need” to establish a carrying capacity was registered for the first time between 1880 and 1885 in the Random House Webster's Collegiate Dictionary and in 1906 in the annual catalog of the Department of Agriculture of the United States, primarily related with the management of pastures (Price 1999 ; Shaofeng 2004 ).

In the beginning of the twentieth century, Hadwen and Palmer ( 1920 ) introduced for the first time the ecological CC concept by studying the deer population in Alaska (Shaofeng 2004 ). Many authors (Takahashi 1998 ; Shaofeng 2004 ; Manning 2007 ; Delgado 2007 ; Coutinho 2010 ; Zelenka and Kacetl 2014 ; Sharma 2016 ) emphasize that the first studies tackled, mostly, the management of wild life, livestock, and agriculture. The first methodological (practical) applications of the concept emerged in the USA and mostly made reference to the number of animals of a certain species that could be kept at the same time in a given habitat (Dasmann 1945 ). The studies applied to livestock aimed at determining the number of cattle that can be kept in a certain area without causing irreversible damage to pastures (Soller and Borghetti 2013 ; Sharma 2016 ).

Still, during the early decades of the twentieth century, the CC concept started being applied to define environmental limits that result from human activities. Shaofeng ( 2004 ) distinguished two main areas of application: basic ecology and human ecology.

The CC concept in basic ecology refers to the management of habitats and specific ecosystems (like wildlife and pastures) and the management of tourism. It has as its primary objective the identification of the saturation limit of a certain species in a certain area. Once this limit is reached, the population of that species is at the maximum level to allow its sustainability (Pazienza 2004 ).

When applied to human ecology, CC refers to the impacts and ecological limits that result from the human population growth and consumption increase (Shaofeng 2004 ).

Tourism Carrying Capacity Applied to Protected Areas

The TCC concept became a very important tool for the management of recreational and leisure spaces, namely on the identification and calculation of human activity impacts in protected areas (Takahashi 1998 ; Shaofeng 2004 ; Pires 2005 ; Manning 2007 ; Delgado 2007 ; Coutinho 2010 ; Soller and Borghetti 2013 ; Zelenka and Kacetl 2014 ; Sharma 2016 ; Kennell 2016 ).

The first attempt to apply the CC concept to protected areas was made in the 1930s; in a US National Park Service (NPS) report, it was questioned: “what is the number of people that can walk along a natural area without destroying its essential qualities?” (Sumner, 1936 cited by Manning 2007 ). However, it was only in the decade of 1950, with the increase of visitors in national parks and other protected areas in the USA, that CC became part of visitors’ management (Soller and Borghetti 2013 ). In the decade of 1960, Wagar ( 1964 ) proposed the broadening of the CC concept as “the level of use that an area can sustain without affecting its quality.” This work emphasized that, in addition to the management of protected areas, the social aspects and the experience of visitors should also be incorporated into the CC concept (Stankey and Cole 1998 ; Takahashi 1998 ; Takahashi and Cegana 2005 ; Pires 2005 ; Manning 2007 ; Coutinho 2010 ; Soller and Borghetti 2013 ). According to these authors, the management of visitors in protected areas must involve a set of management actions and not only the limitation of the number of visitors.

In the beginning of the decade of 1980, the United World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) defined TCC as “the maximum number of people that may visit a tourist destination at the same time, without causing the destruction of the physical, economic and sociocultural environment and an unacceptable decrease in the quality of visitors satisfaction” (McIntyre 1993 ).

In 1984, the management plan of the Galápagos National Park (Ecuador) included a method to calculate the TCC of trails and beaches, which was later revised and applied to protected areas of Costa Rica (Cifuentes 1984 ). According to Cifuentes ( 1992 ) and Cifuentes-Arias et al. ( 1999 ), TCC is “a type of environmental carrying capacity that refers to the biophysics and social capacities around the tourist activity and its development” and represents the maximum limit of human activity in a certain area.

The U.S. National Park Service ( 1993 ) revises the TCC concept and defines it as the level of use that may be conciliated whilst sustaining the desired resources and the recreation conditions that integrate the objectives of the unit and the management goals. Takashi ( 1998 ) stresses that TCC may, or may not, define a maximum number of visitors, depending on the recreation conditions. If the resources are adequate and the recreational conditions are kept, the number of visitors will have secondary importance.

In 1992, the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development took place in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (Rio-92). Rio-92 was an important milestone and raised global awareness on sustainable use and development. Under the influence of that new paradigm, the TCC concept gained global relevance and boosted the concern with sociocultural and economic issues related to local populations at tourist areas (Pires 2005 ; Kostopoulou and Kyritsis 2006 ; Coutinho 2010 ).

Types of Tourism Carrying Capacity

According to Coccossis and Mexa ( 2004a , b ), the first split of the TCC concept into three categories was suggested by Pearce ( 1989 ): environmental and ecologic, physical, and perceptive or psychological, reflecting the different dimension on which the concept was applied. However, based on Boullón ( 2006 ), Pires ( 2005 ), Coccossis and Mexa ( 2004b ), Kostopoulou and Kyritsis ( 2006 ), Nghi et al. ( 2007 ), and Kennell ( 2016 ), the more recurring categories for the application of the TCC concept in tourism management are: ecological and physical, material, perceptive/psychological/social, and political/economical.

The ecological and physical TCC aims at identifying and quantifying the impacts caused by recreation and tourism on ecosystems (Pires 2005 ). It consists on the determination of the limits of acceptable ecological degradation based on the definition of a maximum number of visitors. While the ecological TCC refers to the impacts caused in the natural environment, the physical TCC refers to elements of the built environment, mainly to infrastructure systems (like supply services, transports, health services, electricity). According to Boullón ( 2006 ), the material TCC refers to the geological, geographical, and biological characteristics associated with the safety conditions for visitation in tourist sites. The perceptive/psychological/social TCC is related to the experiences of the visitor in a tourist site and to eventual impacts on local communities. According to Getz ( 1983 , cited by Kennel 2016 ) while the perceptive TCC is a measure of the limit perceived by the tourist, the social TCC refers to the maximum use of a tourist resource, without causing unacceptable levels of negative feelings by the tourist. Finally, the political/economical TCC refers to the economic impacts generated by the tourist activity (Kostopoulou and Kyritsis 2006 ). According to Getz ( 1983 cited by Kennell 2016 ), the political/economical TCC of a tourist site is the maximum use of the resource before leading to an unacceptable level of economic dependence on tourism and without causing political instability, for example, conflicts over land rights or control of tourism revenues.

Methods for the Tourism Carrying Capacity Assessment and Their Application in Protected Areas and Geological Sites

The CC assessment applied to the management of tourist sites can be based on quantitative and qualitative methods (Pires 2005 ). While the former calculates numerical standards for TCC quantification, the latter proposes management models for protected areas. There is also a set of quantitative and/or qualitative methods that are specific for the TCC calculation in speleological sites (or speleological carrying capacity), already compiled by Santos ( 2019 ). For each one of these three groups (quantitative, qualitative, and speleological TCC), it is presented a brief analysis and examples of application with emphasis on protected areas and geological sites, as well as advantages and disadvantages pointed out by several authors (Pires 2005 ; Delgado 2007 ; Manning 2007 ; Boggiani et al. 2007 ; Lobo 2009 ; Coutinho 2010 ; Lobo et al. 2010 , 2013 ; Lobo 2015 ; 2017 ; Santos 2019 ) (Tables 1 , 2 and 3 ).

Quantitative Methods

A comparison between some of the quantitative methods already published is presented in Table 1 .

The Cifuentes method was applied for the first time in 1984, as part of the revision of the management plan of Galapagos National Park (Ecuador). It gained international recognition and was thereafter applied to calculate TCC in several protected areas in different countries. A few years later, Boullón ( 2006 ) introduced the concept of “rotativity coefficient” and reintroduced the concept of “personal distance” or “ecological bubble” for the TCC assessment in natural areas. The model of density by zone type in protected areas is based on environmental zoning, which is a tool that establishes the territorial planning and rules for soil occupation and use of natural resources (IBAMA 2001 ). The guidelines for management different zones are formulated after identifying the vulnerabilities and possibilities of each zone, based on the environmental particularities of the region, and on its interaction with the current social, cultural, economic, and political processes (IBAMA 2001 ; FADURPE 2010 ). While areas with little modifications due to anthropic actions can receive about 20 visitors per km 2 , areas with significant modifications can have about 500 visitors per km 2 (Pires 2005 ).

Qualitative Methods

In parallel to the development of quantitative methods for TCC assessment, since the decade of 1970, qualitative methods are helping to define models for the management of public use in protected areas. These models consider that TCC is the “level of recreational use that may be accommodated in a park or related areas without the overstepping the limits established by variables of relevant indicators” (Manning 2007 ). The models that are most known and used include the Recreational Opportunity Spectrum (ROS) (Clark and Stankey 1979 ); Limits of Acceptable Change (LAC) (Stankey et al. 1985 ); Visitor Impact Management (VIM) (Graefe et al. 1990 ); Visitor Activity Management Process (VAMP) (Environment Canada and Service Park 1991 ); Visitor Experience and Resource Protection (VERP) (National Park Service 1993 , 1997 ; Manning 2001 ); Carrying Capacity Assessment Process (C-Cap) (Shelby and Herberlein 1986 ); and Tourism Optimization Management Model (TOMM 2000 ). The main advantages and disadvantages of three of these models that are more widely used in the tourism management of protected areas (LAC, VERP, and TOMM) and the method proposed by Coccossis and Mexa ( 2004a , b ) are presented in Table 2 .

The concept of “Limit Acceptable Change” (LAC) was proposed by Frissell and Duncan ( 1965 ) assuming that recreational activities in natural environments cause negative impacts on the environment. These impacts must be identified, and the limit of acceptable change for a certain natural environment must be defined. Once this limit is reached, measures must be undertaken to avoid the deterioration of the environment in order to avoid “adverse changes.” LAC is a technical model of planning that enables a systematic definition of acceptable ecological and social changes resulting from recreational and tourist activities, which facilitates the decision by managers (Stankey and Cole 1998 ; Takahashi 1998 ; Takahashi and Cegana 2005 ; Pires 2005 ).

The VERP method was developed by NPS in 1992 in order to improve the management of visitors and TCC assessment in public areas (Pires 2005 ; Coutinho 2010 ). This model emphasizes both the quality of the natural resources and the visitor experience. Belnap et al. (1997) and Manning ( 2004 , 2007 ) state that the structure and development of this model were an adaptation of the LAC method. Although some of the aspects, like terminology and sequence of stages, may vary, in general, the two methods display a common rational:

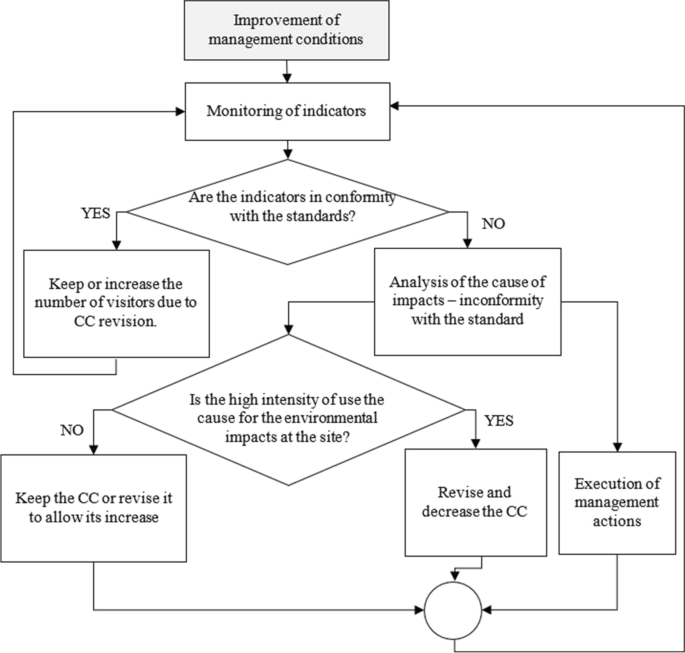

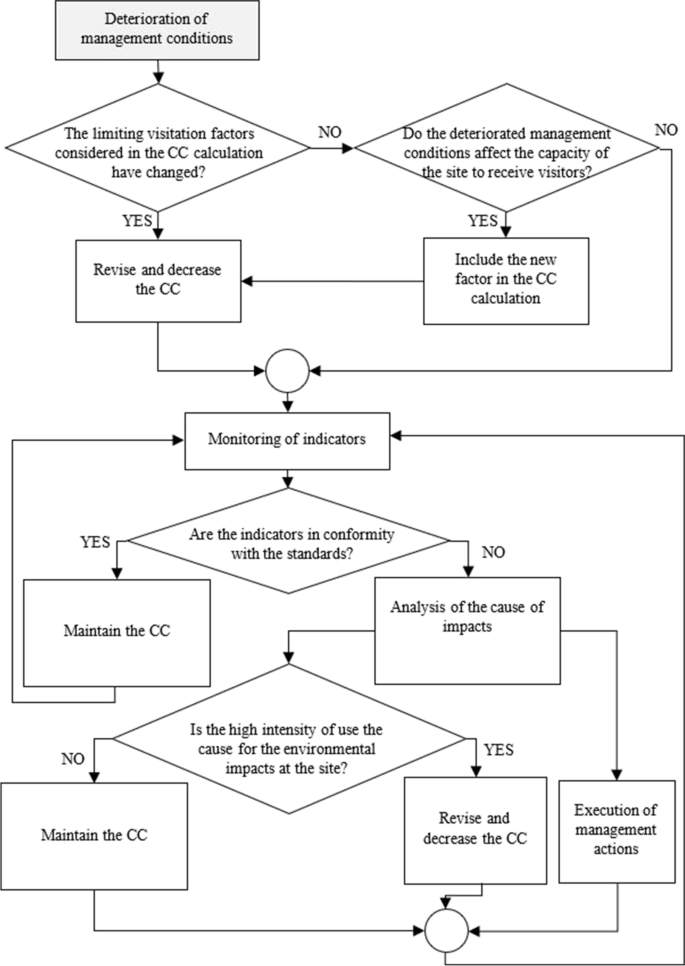

Definition of the area conditions to be maintained in terms of management objectives/desired conditions and associated impact indicators and standards, considering resources, visitor experience, and management of parks and outdoor recreation;

Monitoring of indicators to determine if existing park conditions meet the standards that have been specified;

Management actions to assure that the standards are maintained.

The Tourism Optimization Management Model (TOMM) was developed in 1996 as a new model for the sustainable management of tourism in the Kangaroo Island, Australia (TOMM, 2000 , 2016 ). This model, like LAC and VERP, is composed by stages that involve the definition of the required conditions, the identification of indicators and standards, the monitoring of indicators, and the application of management actions. However, the main focus is the management of tourism considering the sustainable economic benefits. Hence, the identification of maximum limits of use and the carrying capacity are secondary to the model (Pires 2005 ; Lessa 2006 ; Coutinho 2010 ).

Finally, the method proposed by Coccossis and Mexa ( 2004b ) for TCC assessment involves descriptive and evaluation elements. The former includes physical, ecological, social, political, and economic aspects that will help to identify the restrictions (limiting factors with difficult management), obstructions (limiting factors that may be manipulated by the managers), and impacts (elements affected by the intensity of use). Evaluation elements describe how an area must be managed and what is the limit of acceptable change. Coccossis and Mexa ( 2004b ) also present a set of indicators for the sustainable development of tourism (e.g., quality of air, production and management of waste, use of soil, consumption and quality of water, social behavior, profits, and investment in tourism) and TCC indicators (e.g., number of days that the pollution standards are exceeded, daily consumption of water and electricity in activities related to tourism, average production of waste). This type of approach has been widely used in protected areas with high ecological value.

Methods for TCC Assessment in Speleological Sites

The carrying capacity of speleological sites is defined as the “possibility to limit in time and/or space the use of a cave so that environmental damage does not occur, its resilience capacity” (Lobo 2008 ). Lobo et al. ( 2009 ) discuss the necessity of multidisciplinary studies involving the biodiversity and geodiversity assessment to define TCC in caves. In what concerns the assessment of the physical environment, these authors highlight the need of a climate monitoring (like temperature and relative air humidity) inside the cave. Based on the monitoring of these variables, some authors (e.g., Hoyos et al. 1998 ; Calaforra et al. 2003 ; Sgarbi 2003 ; Scaleante 2003 ; Fernández-Cortés et al. 2006 ; Boggiani et al. 2007 ) have established TCC as the maximum number of visitors allowed daily inside the cave. While this procedure may be sufficient to plan the speleological use in the early stages, more detailed studies might be necessary in more complicated situations (Lobo et al. 2009 ).

The main advantages and disadvantages of the three methods proposed by Lobo and co-authors are presented in Table 3 .

Proposal for the Tourism Carrying Capacity Assessment Applied to Geological Sites

The management of geological sites should be planned in order to achieve the conservation objectives and, at the same time, ensure the quality of visitation (Lima 2012 ). The TCC assessment of geological sites is justified because it is a management tool that helps to define the acceptable limits of visitation, without causing significant impacts on the site integrity (Brilha 2018b ). In addition, monitoring actions that are necessary to calculate TCC can provide information about the evolution of the conservation status of the site throughout time.

Based on the models and their applications presented in the “ Methods for the Tourism Carrying Capacity Assessment and Their Application in Protected Areas and Geological Sites ” section and on the aims of a geoconservation strategy (Brilha 2016 ), a proposal for the TCC assessment as a tool for the proper management of geological sites is presented below. As it is intended to contribute to the TCC assessment under the scope of geoconservation (considering the potential use and degradation risk of each geological site), it will be given more emphasis to TCC components that assess the natural environment, specifically the physical-ecological or material carrying capacity, in order to highlight the geological characteristics in these sites. The following proposal comprises three steps (Table 4 ): (A) system analysis, (B) management priority, and (C) calculation of carrying capacity.

Part A—System Analysis

The system analysis is based on the method proposed by Coccossis and Mexa ( 2004b ) and involves the following stages: (i) analysis of the physical characteristics, biodiversity, and geodiversity; (ii) analysis of the tourism activity; and (iii) analysis of management policies. The geodiversity analysis includes the inventory of geological sites, which corresponds to the first stage of a geoconservation strategy (Brilha 2016 ). The analysis of the tourism activity in the region includes the characterization of the existing tourist offer and demand and the definition of the visitors’ profile (Coccossis e Mexa 2004b ). The knowledge about the existent management policies may help to define the management objectives of each geological site, i.e., the activities and the type of tourism that may be practiced, and to select which geological sites need to be protected, in accordance to international, national, regional, and local regulations (Brilha 2016 , 2018a ).

Part B—Management Priority