Formulaire de recherche

Vous êtes ici, informations covid-19.

Pionnier du vaccin contre la Covid-19 administré par voie nasale, LoValTech s’installe à MAME

Crise sanitaire : le Conseil Local de Santé Mentale plus que jamais mobilisé

Découvrez la soirée spéciale du Théâtre Olympia en replay sur Twitch

COVID-19 : Tours Métropole Val de Loire et ses 22 communes se mobilisent dans la lutte contre la propagation du coronavirus.

Les lettres d’info covid de Tours Métropole

Où se faire dépister sur le territoire métropolitain ?

Où se faire vacciner ?

COVID-19 : comment se déplacer ?

Les aides aux entreprises locales

Tout savoir sur la collecte

Tout savoir sur la collecte des masques

Comment manger local

Les gestes barrières

Où se faire dépister sur le territoire métropolitain .

- 1 800 970 7299

- Live Chat (Online) Live Chat (Offline)

- My Wishlist

- Find a Trip

Your browser 'Internet Explorer' is out of date. Update your browser for more security, comfort and the best experience on this site.

- Travel alerts

- Booking resources

At Intrepid, the safety of our travellers, leaders and operators is a major priority.

Since our very first days as a tour operator, travelling responsibly and safely has been at the heart of everything we do. With this in mind, we monitor world events very closely. Intrepid makes operational decisions based on informed advice from a number of sources.

Read Intrepid’s Safety Policy

Current travel alerts

Taiwan, updated 23 april 2024.

TAIWAN A 7.5 magnitude earthquake occurred off the coast of Taiwan on 3 April 2024, resulting in some damage to infrastructure, particularly in Hualien County, including Taroko Gorge, in the east of the country. All Intrepid travellers who were in the country at the time are safe and accounted for. Rescue and reconstruction efforts continue in Hualien and Taroko Gorge is closed until further notice. The following departures will operate as scheduled on an amended itinerary, with the 2 nights in Hualien replaced with an additional night each in Yilan and Puli:

CJSA240418 CJSA240420 CJSA240427 CJSA240502

Further aftershocks continue to be experienced around Hualien, including one of 6.1 on 23 April 2024. Our groups currently in Taiwan are unaffected and continuing their travels as planned.

Jordan, Updated 15 April 2024

Intrepid has accounted for all our customers and tour leaders in Jordan and our trips in Jordan (and related combination trips to Egypt and Jordan) continue to operate as normal, following airstrikes by Iran on Israel on 13 April.

Safety is Intrepid’s top priority and government travel advisories for Jordan from countries including Australia, the UK, Canada and the United States remain at the same level as before the airstrikes.

Customers are advised to contact their Booking Agent with any questions regarding their upcoming travel to Jordan or Egypt.

Travel advisories

Intrepid follows government travel advisories from our key traveller markets when making decisions about operating trips in destinations. As the advice may differ depending on your location, it is important to consult your own local foreign travel advisory when considering if travel to a destination is permitted or appropriate for you.

Australia: Smartraveller Canada: Travel Advice and Advisories New Zealand: SafeTravel United Kingdom: Foreign Travel Advice United States: US Department of State – Bureau of Consular Affairs

Entry, health and visa requirements

Get the latest information on travel documents and visa requirements, plus local government COVID-19 vaccination and quarantine policies around the world.

Find out more

How we monitor safety on our trips

We constantly monitor global issues, ensuring we have an in-depth understanding of the areas we visit. With multiple operational offices around the world in a variety of destinations, Intrepid has access to real-time safety updates and information within the countries we travel to. These staff are available to provide support to travellers on the ground if required.

Get in touch

If you have any concerns, you can contact our support team online or over the phone.

Writing a story? Find official company statements on global incidents by visiting the Intrepid Newsroom.

Safe travels

Everything you need to know about our safety guidelines, booking conditions and trip departures, so you can travel with confidence.

Safe travels hub

- Patient Care & Health Information

- Diseases & Conditions

- Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)

COVID-19, also called coronavirus disease 2019, is an illness caused by a virus. The virus is called severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, or more commonly, SARS-CoV-2. It started spreading at the end of 2019 and became a pandemic disease in 2020.

- Coronavirus

Coronaviruses are a family of viruses. These viruses cause illnesses such as the common cold, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

The virus that causes COVID-19 spreads most commonly through the air in tiny droplets of fluid between people in close contact. Many people with COVID-19 have no symptoms or mild illness. But for older adults and people with certain medical conditions, COVID-19 can lead to the need for care in the hospital or death.

Staying up to date on your COVID-19 vaccine helps prevent serious illness, the need for hospital care due to COVID-19 and death from COVID-19 . Other ways that may help prevent the spread of this coronavirus includes good indoor air flow, physical distancing, wearing a mask in the right setting and good hygiene.

Medicine can limit the seriousness of the viral infection. Most people recover without long-term effects, but some people have symptoms that continue for months.

Products & Services

- A Book: Endemic - A Post-Pandemic Playbook

- A Book: Future Care

- Begin Exploring Women's Health Solutions at Mayo Clinic Store

Typical COVID-19 symptoms often show up 2 to 14 days after contact with the virus.

Symptoms can include:

- Shortness of breath.

- Loss of taste or smell.

- Extreme tiredness, called fatigue.

- Digestive symptoms such as upset stomach, vomiting or loose stools, called diarrhea.

- Pain, such as headaches and body or muscle aches.

- Fever or chills.

- Cold-like symptoms such as congestion, runny nose or sore throat.

People may only have a few symptoms or none. People who have no symptoms but test positive for COVID-19 are called asymptomatic. For example, many children who test positive don't have symptoms of COVID-19 illness. People who go on to have symptoms are considered presymptomatic. Both groups can still spread COVID-19 to others.

Some people may have symptoms that get worse about 7 to 14 days after symptoms start.

Most people with COVID-19 have mild to moderate symptoms. But COVID-19 can cause serious medical complications and lead to death. Older adults or people who already have medical conditions are at greater risk of serious illness.

COVID-19 may be a mild, moderate, severe or critical illness.

- In broad terms, mild COVID-19 doesn't affect the ability of the lungs to get oxygen to the body.

- In moderate COVID-19 illness, the lungs also work properly but there are signs that the infection is deep in the lungs.

- Severe COVID-19 means that the lungs don't work correctly, and the person needs oxygen and other medical help in the hospital.

- Critical COVID-19 illness means the lung and breathing system, called the respiratory system, has failed and there is damage throughout the body.

Rarely, people who catch the coronavirus can develop a group of symptoms linked to inflamed organs or tissues. The illness is called multisystem inflammatory syndrome. When children have this illness, it is called multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children, shortened to MIS -C. In adults, the name is MIS -A.

When to see a doctor

Contact a healthcare professional if you test positive for COVID-19 . If you have symptoms and need to test for COVID-19 , or you've been exposed to someone with COVID-19 , a healthcare professional can help.

People who are at high risk of serious illness may get medicine to block the spread of the COVID-19 virus in the body. Or your healthcare team may plan regular checks to monitor your health.

Get emergency help right away for any of these symptoms:

- Can't catch your breath or have problems breathing.

- Skin, lips or nail beds that are pale, gray or blue.

- New confusion.

- Trouble staying awake or waking up.

- Chest pain or pressure that is constant.

This list doesn't include every emergency symptom. If you or a person you're taking care of has symptoms that worry you, get help. Let the healthcare team know about a positive test for COVID-19 or symptoms of the illness.

More Information

- COVID-19 vs. flu: Similarities and differences

- COVID-19, cold, allergies and the flu

- Unusual symptoms of coronavirus

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

COVID-19 is caused by infection with the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, also called SARS-CoV-2.

The coronavirus spreads mainly from person to person, even from someone who is infected but has no symptoms. When people with COVID-19 cough, sneeze, breathe, sing or talk, their breath may be infected with the COVID-19 virus.

The coronavirus carried by a person's breath can land directly on the face of a nearby person, after a sneeze or cough, for example. The droplets or particles the infected person breathes out could possibly be breathed in by other people if they are close together or in areas with low air flow. And a person may touch a surface that has respiratory droplets and then touch their face with hands that have the coronavirus on them.

It's possible to get COVID-19 more than once.

- Over time, the body's defense against the COVID-19 virus can fade.

- A person may be exposed to so much of the virus that it breaks through their immune defense.

- As a virus infects a group of people, the virus copies itself. During this process, the genetic code can randomly change in each copy. The changes are called mutations. If the coronavirus that causes COVID-19 changes in ways that make previous infections or vaccination less effective at preventing infection, people can get sick again.

The virus that causes COVID-19 can infect some pets. Cats, dogs, hamsters and ferrets have caught this coronavirus and had symptoms. It's rare for a person to get COVID-19 from a pet.

Risk factors

The main risk factors for COVID-19 are:

- If someone you live with has COVID-19 .

- If you spend time in places with poor air flow and a higher number of people when the virus is spreading.

- If you spend more than 30 minutes in close contact with someone who has COVID-19 .

Many factors affect your risk of catching the virus that causes COVID-19 . How long you are in contact, if the space has good air flow and your activities all affect the risk. Also, if you or others wear masks, if someone has COVID-19 symptoms and how close you are affects your risk. Close contact includes sitting and talking next to one another, for example, or sharing a car or bedroom.

It seems to be rare for people to catch the virus that causes COVID-19 from an infected surface. While the virus is shed in waste, called stool, COVID-19 infection from places such as a public bathroom is not common.

Serious COVID-19 illness risk factors

Some people are at a higher risk of serious COVID-19 illness than others. This includes people age 65 and older as well as babies younger than 6 months. Those age groups have the highest risk of needing hospital care for COVID-19 .

Not every risk factor for serious COVID-19 illness is known. People of all ages who have no other medical issues have needed hospital care for COVID-19 .

Known risk factors for serious illness include people who have not gotten a COVID-19 vaccine. Serious illness also is a higher risk for people who have:

- Sickle cell disease or thalassemia.

- Serious heart diseases and possibly high blood pressure.

- Chronic kidney, liver or lung diseases.

People with dementia or Alzheimer's also are at higher risk, as are people with brain and nervous system conditions such as stroke. Smoking increases the risk of serious COVID-19 illness. And people with a body mass index in the overweight category or obese category may have a higher risk as well.

Other medical conditions that may raise the risk of serious illness from COVID-19 include:

- Cancer or a history of cancer.

- Type 1 or type 2 diabetes.

- Weakened immune system from solid organ transplants or bone marrow transplants, some medicines, or HIV .

This list is not complete. Factors linked to a health issue may raise the risk of serious COVID-19 illness too. Examples are a medical condition where people live in a group home, or lack of access to medical care. Also, people with more than one health issue, or people of older age who also have health issues have a higher chance of severe illness.

Related information

- COVID-19: Who's at higher risk of serious symptoms? - Related information COVID-19: Who's at higher risk of serious symptoms?

Complications

Complications of COVID-19 include long-term loss of taste and smell, skin rashes, and sores. The illness can cause trouble breathing or pneumonia. Medical issues a person already manages may get worse.

Complications of severe COVID-19 illness can include:

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome, when the body's organs do not get enough oxygen.

- Shock caused by the infection or heart problems.

- Overreaction of the immune system, called the inflammatory response.

- Blood clots.

- Kidney injury.

Post-COVID-19 syndrome

After a COVID-19 infection, some people report that symptoms continue for months, or they develop new symptoms. This syndrome has often been called long COVID, or post- COVID-19 . You might hear it called long haul COVID-19 , post-COVID conditions or PASC. That's short for post-acute sequelae of SARS -CoV-2.

Other infections, such as the flu and polio, can lead to long-term illness. But the virus that causes COVID-19 has only been studied since it began to spread in 2019. So, research into the specific effects of long-term COVID-19 symptoms continues.

Researchers do think that post- COVID-19 syndrome can happen after an illness of any severity.

Getting a COVID-19 vaccine may help prevent post- COVID-19 syndrome.

- Long-term effects of COVID-19

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends a COVID-19 vaccine for everyone age 6 months and older. The COVID-19 vaccine can lower the risk of death or serious illness caused by COVID-19. It lowers your risk and lowers the risk that you may spread it to people around you.

The COVID-19 vaccines available in the United States are:

2023-2024 Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. This vaccine is available for people age 6 months and older.

Among people with a typical immune system:

- Children age 6 months up to age 4 years are up to date after three doses of a Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine.

- People age 5 and older are up to date after one Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine.

- For people who have not had a 2023-2024 COVID-19 vaccination, the CDC recommends getting an additional shot of that updated vaccine.

2023-2024 Moderna COVID-19 vaccine. This vaccine is available for people age 6 months and older.

- Children ages 6 months up to age 4 are up to date if they've had two doses of a Moderna COVID-19 vaccine.

- People age 5 and older are up to date with one Moderna COVID-19 vaccine.

2023-2024 Novavax COVID-19 vaccine. This vaccine is available for people age 12 years and older.

- People age 12 years and older are up to date if they've had two doses of a Novavax COVID-19 vaccine.

In general, people age 5 and older with typical immune systems can get any vaccine approved or authorized for their age. They usually don't need to get the same vaccine each time.

Some people should get all their vaccine doses from the same vaccine maker, including:

- Children ages 6 months to 4 years.

- People age 5 years and older with weakened immune systems.

- People age 12 and older who have had one shot of the Novavax vaccine should get the second Novavax shot in the two-dose series.

Talk to your healthcare professional if you have any questions about the vaccines for you or your child. Your healthcare team can help you if:

- The vaccine you or your child got earlier isn't available.

- You don't know which vaccine you or your child received.

- You or your child started a vaccine series but couldn't finish it due to side effects.

People with weakened immune systems

Your healthcare team may suggest added doses of COVID-19 vaccine if you have a moderately or seriously weakened immune system. The FDA has also authorized the monoclonal antibody pemivibart (Pemgarda) to prevent COVID-19 in some people with weakened immune systems.

Control the spread of infection

In addition to vaccination, there are other ways to stop the spread of the virus that causes COVID-19 .

If you are at a higher risk of serious illness, talk to your healthcare professional about how best to protect yourself. Know what to do if you get sick so you can quickly start treatment.

If you feel ill or have COVID-19 , stay home and away from others, including pets, if possible. Avoid sharing household items such as dishes or towels if you're sick.

In general, make it a habit to:

- Test for COVID-19 . If you have symptoms of COVID-19 test for the infection. Or test five days after you came in contact with the virus.

- Help from afar. Avoid close contact with anyone who is sick or has symptoms, if possible.

- Wash your hands. Wash your hands well and often with soap and water for at least 20 seconds. Or use an alcohol-based hand sanitizer with at least 60% alcohol.

- Cover your coughs and sneezes. Cough or sneeze into a tissue or your elbow. Then wash your hands.

- Clean and disinfect high-touch surfaces. For example, clean doorknobs, light switches, electronics and counters regularly.

Try to spread out in crowded public areas, especially in places with poor airflow. This is important if you have a higher risk of serious illness.

The CDC recommends that people wear a mask in indoor public spaces if you're in an area with a high number of people with COVID-19 in the hospital. They suggest wearing the most protective mask possible that you'll wear regularly, that fits well and is comfortable.

- COVID-19 vaccines: Get the facts - Related information COVID-19 vaccines: Get the facts

- Comparing the differences between COVID-19 vaccines - Related information Comparing the differences between COVID-19 vaccines

- Different types of COVID-19 vaccines: How they work - Related information Different types of COVID-19 vaccines: How they work

- Debunking COVID-19 myths - Related information Debunking COVID-19 myths

Travel and COVID-19

Travel brings people together from areas where illnesses may be at higher levels. Masks can help slow the spread of respiratory diseases in general, including COVID-19 . Masks help the most in places with low air flow and where you are in close contact with other people. Also, masks can help if the places you travel to or through have a high level of illness.

Masking is especially important if you or a companion have a high risk of serious illness from COVID-19 .

- COVID-19 travel advice

- COVID-19 vaccines

- COVID-19 vaccines for kids: What you need to know

- Debunking coronavirus myths

- Different COVID-19 vaccines

- Fight coronavirus (COVID-19) transmission at home

- Herd immunity and coronavirus

- How well do face masks protect against COVID-19?

- Safe outdoor activities during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Safety tips for attending school during COVID-19

- COVID-19 and vitamin D

- COVID-19: How can I protect myself?

- Mayo Clinic Minute: How dirty are common surfaces?

- Mayo Clinic Minute: You're washing your hands all wrong

- Goldman L, et al., eds. COVID-19: Epidemiology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, community prevention, and prognosis. In: Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 27th ed. Elsevier; 2024. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed Dec. 17, 2023.

- Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) treatment guidelines. National Institutes of Health. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/. Accessed Dec. 18, 2023.

- AskMayoExpert. COVID-19: Testing, symptoms. Mayo Clinic; Nov. 2, 2023.

- Symptoms of COVID-19. Centers for Disease Control and Preventions. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/symptoms-testing/symptoms.html. Accessed Dec. 20, 2023.

- AskMayoExpert. COVID-19: Outpatient management. Mayo Clinic; Oct. 10, 2023.

- Morris SB, et al. Case series of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in adults associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection — United Kingdom and United States, March-August 2020. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2020;69:1450. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6940e1external icon.

- COVID-19 testing: What you need to know. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/symptoms-testing/testing.html. Accessed Dec. 20, 2023.

- SARS-CoV-2 in animals. American Veterinary Medical Association. https://www.avma.org/resources-tools/one-health/covid-19/sars-cov-2-animals-including-pets. Accessed Jan. 17, 2024.

- Understanding exposure risk. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/your-health/risks-exposure.html. Accessed Jan. 10, 2024.

- People with certain medical conditions. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-medical-conditions.html. Accessed Jan. 10, 2024.

- Factors that affect your risk of getting very sick from COVID-19. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/your-health/risks-getting-very-sick.html. Accessed Jan. 10, 2024.

- Regan JJ, et al. Use of Updated COVID-19 Vaccines 2023-2024 Formula for Persons Aged ≥6 Months: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, September 2023. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2023; 72:1140–1146. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7242e1.

- Long COVID or post-COVID conditions. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/long-term-effects/index.html. Accessed Jan. 10, 2024.

- Stay up to date with your vaccines. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/stay-up-to-date.html. Accessed Jan. 10, 2024.

- Interim clinical considerations for use of COVID-19 vaccines currently approved or authorized in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/clinical-considerations/covid-19-vaccines-us.html#CoV-19-vaccination. Accessed Jan. 10, 2024.

- Use and care of masks. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/about-face-coverings.html. Accessed Jan. 10, 2024.

- How to protect yourself and others. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html. Accessed Jan. 10, 2024.

- People who are immunocompromised. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-who-are-immunocompromised.html. Accessed Jan. 10, 2024.

- Masking during travel. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/page/masks. Accessed Jan. 10, 2024.

- AskMayoExpert. COVID-19: Testing. Mayo Clinic. 2023.

- COVID-19 test basics. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/covid-19-test-basics. Accessed Jan. 11, 2024.

- At-home COVID-19 antigen tests — Take steps to reduce your risk of false negative results: FDA safety communication. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/safety-communications/home-covid-19-antigen-tests-take-steps-reduce-your-risk-false-negative-results-fda-safety. Accessed Jan. 11, 2024.

- Interim clinical considerations for COVID-19 treatment in outpatients. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-care/outpatient-treatment-overview.html. Accessed Jan. 11, 2024.

- Know your treatment options for COVID-19. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/know-your-treatment-options-covid-19. Accessed Jan. 11, 2024.

- AskMayoExpert. COVID:19 Drug regimens and other treatment options. Mayo Clinic. 2023.

- Preventing spread of respiratory viruses when you're sick. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/respiratory-viruses/prevention/precautions-when-sick.html. Accessed March 5, 2024.

- AskMayoExpert. COVID-19: Quarantine and isolation. Mayo Clinic. 2023.

- COVID-19 resource and information guide. National Alliance on Mental Illness. https://www.nami.org/Support-Education/NAMI-HelpLine/COVID-19-Information-and-Resources/COVID-19-Resource-and-Information-Guide. Accessed Jan. 11, 2024.

- COVID-19 overview and infection prevention and control priorities in non-U.S. healthcare settings. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/non-us-settings/overview/index.html. Accessed Jan. 16, 2024.

- Kim AY, et al. COVID-19: Management in hospitalized adults. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed Jan. 17, 2024.

- O'Horo JC, et al. Outcomes of COVID-19 with the Mayo Clinic Model of Care and Research. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2021; doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.12.006.

- At-home OTC COVID-19 diagnostic tests. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/coronavirus-covid-19-and-medical-devices/home-otc-covid-19-diagnostic-tests. Accessed Jan. 22, 2024.

- Emergency use authorizations for drugs and non-vaccine biological products. U.S. Food and Drug Association. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/emergency-preparedness-drugs/emergency-use-authorizations-drugs-and-non-vaccine-biological-products. Accessed March 25, 2024.

- Coronavirus infection by race

- COVID-19 and pets

- COVID-19 and your mental health

- COVID-19 drugs: Are there any that work?

- COVID-19 in babies and children

- COVID-19 variant

- COVID-19: Who's at higher risk of serious symptoms?

- How do COVID-19 antibody tests differ from diagnostic tests?

- Is hydroxychloroquine a treatment for COVID-19?

- Pregnancy and COVID-19

- Sex and COVID-19

- Treating COVID-19 at home

Associated Procedures

- Convalescent plasma therapy

- COVID-19 antibody testing

- COVID-19 tests

- Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO)

News from Mayo Clinic

- Mayo Clinic Q and A: Who should get the latest COVID-19 vaccine? Nov. 21, 2023, 01:30 p.m. CDT

- Can you get COVID-19 and the flu at the same time? A Mayo Clinic expert weighs in Oct. 16, 2023, 04:30 p.m. CDT

- At-home COVID-19 tests: A Mayo Clinic expert answers questions on expiration dates and the new variants Sept. 18, 2023, 04:00 p.m. CDT

- Mayo Clinic expert answers questions about the new COVID-19 vaccine Sept. 13, 2023, 04:15 p.m. CDT

- Study identifies risk factors for long-haul COVID disease in adults Sept. 13, 2023, 02:00 p.m. CDT

- Mayo researchers find vaccine may reduce severity of long-haul COVID symptoms Aug. 23, 2023, 04:34 p.m. CDT

- Corticosteroids lower the likelihood of in-hospital mortality from COVID-19 Aug. 04, 2023, 03:00 p.m. CDT

- COVID-19 vaccine administration simplified April 21, 2023, 07:00 p.m. CDT

- Science Saturday: COVID-19 -- the pandemic that's forever changed laboratory testing April 15, 2023, 11:00 a.m. CDT

- Mayo Clinic expert talks about the new omicron variant April 13, 2023, 02:13 p.m. CDT

- Mayo Clinic to ease universal face mask requirement April 04, 2023, 03:05 p.m. CDT

- 'Deaths of Despair' contribute to 17% rise in Minnesota's death rate during COVID-19 pandemic March 13, 2023, 12:00 p.m. CDT

- Rising cases of COVID-19 variant, XBB.1.5 Jan. 09, 2023, 05:15 p.m. CDT

- Bivalent COVID-19 booster approved for children 6 months and older Dec. 09, 2022, 09:33 p.m. CDT

- Mayo Clinic Minute: How to self-care at home when you have COVID-19 Dec. 06, 2022, 05:00 p.m. CDT

- Halloween safety tips from a Mayo Clinic infectious diseases expert Oct. 27, 2022, 02:00 p.m. CDT

- COVID-19, RSV and flu--season of respiratory infections Oct. 26, 2022, 04:30 p.m. CDT

- COVID-19 bivalent booster vaccines for kids 5-11 approved, Mayo Clinic awaits supply Oct. 13, 2022, 04:54 p.m. CDT

- Questions answered about the COVID-19 bivalent booster vaccines Oct. 12, 2022, 03:30 p.m. CDT

- Will the COVID-19 booster be like an annual flu shot? Sept. 12, 2022, 04:30 p.m. CDT

- Mayo Clinic Q and A: Who needs back-to-school COVID-19 vaccinations and boosters? Sept. 04, 2022, 11:00 a.m. CDT

- Q&A podcast: Updated COVID-19 boosters target omicron variants Sept. 02, 2022, 12:30 p.m. CDT

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Back-to-school COVID-19 vaccinations for kids Aug. 15, 2022, 03:15 p.m. CDT

- Mayo Clinic research shows bebtelovimab to be a reliable option for treating COVID-19 in era of BA.2, other subvariants Aug. 15, 2022, 02:09 p.m. CDT

- Mayo Clinic Q and A: New variants of COVID-19 Aug. 04, 2022, 12:30 p.m. CDT

- COVID-19 variant BA.5 is dominant strain; BA.2.75 is being monitored July 28, 2022, 02:30 p.m. CDT

- Mayo Clinic researchers pinpoint genetic variations that might sway course of COVID-19 July 25, 2022, 02:00 p.m. CDT

- Mayo Clinic Q&A podcast: BA.5 omicron variant fueling latest COVID-19 surge July 15, 2022, 12:00 p.m. CDT

- What you need to know about the BA.5 omicron variant July 14, 2022, 06:41 p.m. CDT

- Mayo Clinic Q&A podcast: The importance of COVID-19 vaccines for children under 5 July 06, 2022, 01:00 p.m. CDT

- COVID-19 vaccination for kids age 5 and younger starting the week of July 4 at most Mayo sites July 01, 2022, 04:00 p.m. CDT

- Patients treated with monoclonal antibodies during COVID-19 delta surge had low rates of severe disease, Mayo Clinic study finds June 27, 2022, 03:00 p.m. CDT

- Long COVID and the digestive system: Mayo Clinic expert describes common symptoms June 21, 2022, 02:43 p.m. CDT

- Mayo Clinic Q&A podcast: COVID-19 update June 17, 2022, 01:08 p.m. CDT

- Study finds few COVID-19 patients get rebound symptoms after Paxlovid treatment June 14, 2022, 10:06 a.m. CDT

- Mayo Clinic Minute: What to expect with COVID-19 vaccinations for youngest kids June 08, 2022, 04:35 p.m. CDT

- Mayo Clinic Q&A podcast: Community leaders are key to reaching people underrepresented in research May 26, 2022, 02:00 p.m. CDT

- COVID-19 booster vaccinations extended to kids 5-11 May 20, 2022, 06:10 p.m. CDT

- Mayo Clinic expert shares tips for navigating a return to work with long COVID May 19, 2022, 02:08 p.m. CDT

- Mayo Clinic Q&A podcast: COVID-19 update May 17, 2022, 01:14 p.m. CDT

- FDA limits use of J&J COVID-19 vaccine May 06, 2022, 05:06 p.m. CDT

- Mayo Clinic Q&A podcast: COVID-19 news update April 29, 2022, 12:25 p.m. CDT

- COVID-19 shines a spotlight on laboratory professionals' vital role in health care April 25, 2022, 12:30 p.m. CDT

- Symptoms & causes

- Diagnosis & treatment

- Doctors & departments

- COVID-19 vaccines: Get the facts

- How well do face masks protect against coronavirus?

- Post-COVID Recovery

News on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)

Learn the latest medical news about COVID-19 on Mayo Clinic News Network.

Make twice the impact

Your gift can go twice as far to advance cancer research and care!

Disclaimer: This translation was last updated on August 2, 2022. For up-to-date content, please visit the English version of this page.

Disclaimer: The Spanish COVID-19 site is currently undergoing significant updates which may lead to a delay in translated content. We apologize for any inconvenience.

COVID-19 Vaccines

COVID-19 vaccines are safe, effective, and free. Everyone 6 months and older can get an updated COVID-19 vaccine. Learn more .

- Respiratory Virus Guidance

- Ventilation in Buildings

- Respiratory Virus and Immunization Updates

People may experience sudden fever or chills, cough, shortness of breath, loss of taste or smell, and other symptoms.

Use viral tests like PCR or rapid at-home tests to determine if you are sick with COVID-19. Learn how to get tested.

Antiviral medications are available to treat mild to moderate COVID-19. Start treatment as soon as you develop symptoms.

Learn more about all three of these respiratory viruses, who is most at risk, and how they are affecting your state right now. You can use some of the same strategies to protect yourself from all three viruses.

Get the Latest on COVID-19, Flu, and RSV

- About COVID-19

- Travel Requirements

- Data & Surveillance

- Communication Resources

Monitoring the impact of COVID-19 and the effectiveness of prevention and control strategies remains a public health priority. CDC continues to provide sustainable, high-impact, and timely information to inform decision-making.

COVID Data Tracker

COVID-19 Data

- Healthcare Workers

- Health Departments

- Laboratory Personnel

- Español

- Other Languages

Alternative Formats

- Easy to Read & Related Formats

COVID-19 UPDATES

Get email updates about COVID-19

FEDERAL RESOURCES

- USA.gov/Coronavirus

- Treatment Options for COVID-19

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- For authors

- Browse by collection

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 14, Issue 4

- Colchicine for the treatment of patients with COVID-19: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6783-7137 Huzaifa Ahmad Cheema 1 ,

- Uzair Jafar 1 ,

- Abia Shahid 1 ,

- Waniyah Masood 2 ,

- Muhammad Usman 1 ,

- Alaa Hamza Hermis 3 ,

- Muhammad Arsal Naseem 1 ,

- Syeda Sahra 4 ,

- Ranjit Sah 5 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5577-0940 Ka Yiu Lee 6

- 1 Department of Medicine , King Edward Medical University , Lahore , Pakistan

- 2 Department of Medicine , Dow University of Health Sciences , Karachi , Pakistan

- 3 Nursing College, Al-Mustaqbal University , 51001 Hillah , Babylon , Iraq

- 4 Department of Infectious Diseases , The University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center , Oklahoma City , Oklahoma , USA

- 5 Department of Microbiology , Dr. D. Y. Patil Medical College, Hospital and Research Centre, Dr. D. Y. Patil Vidyapeeth , Pune 411018 , Maharashtra , India

- 6 Swedish Winter Sports Research Centre, Department of Health Sciences , Mid Sweden University , Sundsvall , Sweden

- Correspondence to Dr Ka Yiu Lee; kyle.lee{at}miun.se

Objectives We conducted an updated systematic review and meta-analysis to investigate the effect of colchicine treatment on clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19.

Design Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Data sources We searched PubMed, Embase, the Cochrane Library, medRxiv and ClinicalTrials.gov from inception to January 2023.

Eligibility criteria All randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that investigated the efficacy of colchicine treatment in patients with COVID-19 as compared with placebo or standard of care were included. There were no language restrictions. Studies that used colchicine prophylactically were excluded.

Data extraction and synthesis We extracted all information relating to the study characteristics, such as author names, location, study population, details of intervention and comparator groups, and our outcomes of interest. We conducted our meta-analysis by using RevMan V.5.4 with risk ratio (RR) and mean difference as the effect measures.

Results We included 23 RCTs (28 249 participants) in this systematic review. Colchicine did not decrease the risk of mortality (RR 0.99; 95% CI 0.93 to 1.05; I 2 =0%; 20 RCTs, 25 824 participants), with the results being consistent among both hospitalised and non-hospitalised patients. There were no significant differences between the colchicine and control groups in other relevant clinical outcomes, including the incidence of mechanical ventilation (RR 0.75; 95% CI 0.48 to 1.18; p=0.22; I 2 =40%; 8 RCTs, 13 262 participants), intensive care unit admission (RR 0.77; 95% CI 0.49 to 1.22; p=0.27; I 2 =0%; 6 RCTs, 961 participants) and hospital admission (RR 0.74; 95% CI 0.48 to 1.16; p=0.19; I 2 =70%; 3 RCTs, 8572 participants).

Conclusions The results of this meta-analysis do not support the use of colchicine as a treatment for reducing the risk of mortality or improving other relevant clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19. However, RCTs investigating early treatment with colchicine (within 5 days of symptom onset or in patients with early-stage disease) are needed to fully elucidate the potential benefits of colchicine in this patient population.

PROSPERO registration number CRD42022369850.

- CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request.

This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ .

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2023-074373

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY

This systematic review used a comprehensive search for articles evaluating colchicine treatment for patients with COVID-19.

We performed, to our knowledge, the largest meta-analysis to date by pooling results from 23 trials.

There was significant interstudy heterogeneity in the overall analysis of some outcomes, such as length of hospitalisation.

Our results may not be generalisable to the use of colchicine early in the course of the disease as most randomised controlled trials studied late-stage treatment.

Introduction

Unprecedented global research has been conducted as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Even though particular antiviral medications, immunomodulators and monoclonal antibodies have been approved to treat COVID-19, 1–4 ongoing clinical trials are being conducted to combat the virus more successfully, particularly using repurposed drugs and herbal medicines that provide a cheap therapeutic alternative. 5–8 Limited knowledge of COVID-19 molecular mechanisms and pathophysiology, lack of definitive supporting evidence and expensive costs of some treatment options are some of the challenges faced in using different drugs for COVID-19. 9 10

Colchicine, an anti-inflammatory medication commonly used to treat gout, recurrent pericarditis and familial Mediterranean fever, is being extensively investigated among COVID-19 patients. 11 Inhibiting neutrophil chemotaxis, suppressing inflammasome signalling and preventing the cytokine storm through microtubule depolarisation are some of the potential benefits of colchicine in treating COVID-19. 11 Currently, guidelines from the WHO recommend against treatment with colchicine based on data from 10 studies. 1

Although colchicine has been the subject of multiple clinical trials in COVID-19 patients, findings from smaller randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that were positive were later contradicted by results from major RCTs. 11 Therefore, we performed this meta-analysis to evaluate the safety and efficacy of colchicine for the treatment of COVID-19 patients and to interpret the significance of the latest data by incorporating it into our review.

Our systematic review and meta-analysis was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42022369850) and conducted by following the recommendations of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). 12 The PRISMA checklist is provided in online supplemental table 1 .

Supplemental material

Data sources and search strategy.

We searched MEDLINE (via PubMed), Embase, the Cochrane Library, medRxiv and ClinicalTrials.gov from inception to January 2023 using a search strategy consisting of terms related to “colchicine” and “COVID-19” without any restrictions. Grey literature and the reference lists of the relevant studies were also explored to include all eligible trials. We did not restrict our search based on language. The detailed search strategy for different databases is given in online supplemental table 2 .

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria were (1) population: patients with a diagnosis of COVID-19; (2) intervention: colchicine regardless of dosing or regimen; (3) comparator: placebo or standard of care; (4) outcome: reporting any outcome of interest and (5) study design: RCTs only. Observational studies, quasi-randomised trials and studies that used colchicine prophylactically were excluded.

Study selection

All the literature obtained from our searches was imported into Mendeley Desktop V.1.19.8 and duplicates were removed. The remaining articles were subjected to a rigorous screening process by two independent reviewers in a two-stage process (title/abstract screening followed by full-text screening).

Data extraction and outcomes

We extracted all information relating to the study characteristics such as author names, location, study population, details of intervention and comparator groups, and our outcomes of interest. We chose all-cause mortality as our primary outcome while the secondary outcomes included the incidence of mechanical ventilation (MV), risk of intensive care unit (ICU) admission, risk of hospitalisation, the length of hospital stay and the rate of no recovery (proportion of patients with no symptomatic resolution at the end of study).

Quality assessment

The risk of bias was assessed using the revised Cochrane Risk of Bias tool (RoB 2.0). 13 A rating of low risk of bias, some concerns or a high risk of bias was assigned to each study using five domains: randomisation process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of the outcome and selection of reported result.

Data analysis

We conducted our meta-analysis using RevMan V.5.4 with risk ratio (RR) and mean difference (MD) as the effect measures for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. We used a random-effects model as we anticipated our included studies to be substantially heterogeneous. We evaluated heterogeneity using the χ 2 test, the I 2 statistic and the tau 2 estimate. We used the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Intervention to interpret the values of the I 2 statistic. 14 We conducted a subgroup analysis for our primary outcome on the basis of the study population (hospitalised vs non-hospitalised patients). In addition, we conducted a sensitivity analysis on our primary outcome by excluding trials that used colchicine in combination with another intervention. For outcomes with data from 10 studies or more, we assessed publication bias by constructing funnel plots and running Egger’s test for funnel plot asymmetry.

Patient and public involvement

Search results and study characteristics.

A total of 23 RCTs (28 249 participants) were eligible for inclusion in our meta-analysis. 15–37 The details of the screening process are presented in figure 1 .

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

PRISMA 2020 flow chart. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

17 RCTs were conducted in hospitalised patients, 4 evaluated outpatients only 17 21 22 30 and 1 RCT included both hospitalised and non-hospitalised patients. 26 Most of the trials had small sample sizes while the RECOVERY trial was the largest RCT with 11 340 patients. 23 The trials employed a variety of colchicine regimens and most were open-label that used standard of care as the comparator. Two RCTs combined colchicine with other treatments; one with rosuvastatin 25 and the other with herbal phenolic monoterpene. 33 The characteristics of each RCT are summarised in online supplemental table 3 .

Risk of bias assessment

According to RoB 2.0, 7 studies were at a low risk of bias, 1 had a high risk of bias and 12 had some concerns about bias ( figure 2 ). The most common source of bias was lack of blinding and deviations from protocol while some trials also had issues in the randomisation process.

Quality assessment of included trials.

Results of the meta-analysis

Primary outcome.

Our analysis, considering 25 824 patients from 20 RCTs, failed to find a statistically significant reduction in the risk of mortality with colchicine use (RR 0.99; 95% CI 0.93 to 1.05; p=0.78; I 2 =0%; figure 3 ). The Egger’s test indicated that publication bias was present (p=0.002; online supplemental figure 1 ). The results were consistent (P interaction =0.59) among both hospitalised (RR 0.98; 95% CI 0.90 to 1.06; p=0.64; I 2 =5%) and non-hospitalised patients (RR 0.82; 95% CI 0.43 to 1.55; p=0.54; I 2 =0%; online supplemental figure 2 ).

Effect of colchicine on all-cause mortality in patients with COVID-19.

Sensitivity analysis by excluding two studies that used combination therapies in the intervention group, 25 33 produced results consistent with our main analysis (RR 1.00; 95% CI 0.94 to 1.06; p=0.88; I 2 =0%). The results remained congruous with our primary analysis after performing a second sensitivity analysis excluding studies with a high risk of bias or some concerns about bias in the domain of deviations from intended interventions (RR 0.97; 95% CI 0.88 to 1.06; p=0.46; I 2 =3%).

Secondary outcomes

There were no significant differences between the colchicine and control groups in the incidence of MV (RR 0.75; 95% CI 0.48 to 1.18; p=0.22; I 2 =40%; 8 RCTs, 13 262 participants; online supplemental figure 3 ), risk of ICU admission (RR 0.77; 95% CI 0.49 to 1.22; p=0.27; I 2 =0%; 6 RCTs, 961 participants; online supplemental figure 3 ), risk of hospital admission (RR 0.74; 95% CI 0.48 to 1.16; p=0.19; I 2 =70%; 3 RCTs, 8572 participants; online supplemental figure 4 ), length of hospital stay (MD −0.70 days; 95% CI −2.30 to 0.89 days; p=0.39; I 2 =90%; 8 RCTs, 1028 participants; online supplemental figure 5 ) and the rate of no recovery (RR 0.77; 95% CI 0.56 to 1.05; p=0.10; I 2 =77%; 5 RCTs, 13 109 participants; online supplemental figure 6 ).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest and most up-to-date meta-analysis to assess the effectiveness of colchicine for COVID-19. The results of this meta-analysis suggest that colchicine does not have a significant effect on the risk of mortality in patients with COVID-19. There was also no significant benefit of colchicine in reducing the risk of MV, ICU admission, hospital admission or improving recovery rates.

Colchicine’s regulation of the inflammatory response has been proposed as a means to inhibit the inflammation caused by COVID-19. The primary mechanism by which colchicine affects cells is through the inhibition of microtubule polymerisation, which has a ripple effect on various cellular functions such as maintaining cell shape, signalling, cell division, migration and transport. 11 38 Additionally, colchicine modulates the synthesis of inflammatory cytokines such as tumour necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin-1 (IL-1) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) and disrupts the activation of inflammasomes, neutrophil adhesion and recruitment. 11 38 Given that COVID-19 is characterised by excessive inflammation and a cytokine response, colchicine’s anti-inflammatory effects may have the potential to improve outcomes.

Our results are consistent with some of the previous meta-analyses which also demonstrated no significant clinical benefit of colchicine in COVID-19 patients. 39–43 On the other hand, the meta-analyses by Zein and Raffaello and Golpour et al 44 45 found that colchicine use was associated with a reduction in the risk of mortality, and Kow et al demonstrated a shorter duration of hospital stay with colchicine. 46 However, the meta-analysis by Zein and Raffaello and Golpour et al also incorporated observational studies, which increases the likelihood of confounding bias in their findings. 44 45 Additionally, all of the previous meta-analyses included a small number of RCTs with most including less than or equal to 11. 47 Conversely, our meta-analysis pooled results from 23 RCTs, therefore, including a significantly greater cumulative sample size and substantially increasing the confidence in our estimates.

A recent umbrella review found that exposure to colchicine was associated with reduced mortality. 47 However, this discrepancy can be explained by the fact that it pooled estimates from meta-analyses instead of primary studies. Since there is a significant overlap in the included studies between the prior meta-analyses, pooling meta-analysed effect sizes leads to erroneous and flawed results due to double-counting of outcome data. The correct approach would be to synthesise data from the primary studies to provide valid estimates. 48

It is worth noting that despite including a large number of RCTs, the results of our meta-analysis are still greatly influenced by the RECOVERY trial. 23 The RECOVERY trial is by far the largest trial of colchicine which found no clinical benefit of colchicine in COVID-19 patients. However, this was a very late-stage treatment RCT with the median time from symptom onset to treatment initiation being 9 days. It is well recognised that late initiation of therapy might result in decreased effectiveness of antivirals. 49 Therefore, early treatment (within 5 days of symptom onset or at an early stage of the disease) with colchicine might prove to be beneficial for COVID-19 patients; however, this needs to be investigated in future RCTs as all of the currently available RCTs evaluated late-stage treatment.

Some limitations of our meta-analysis should be noted. The quality of the RCTs included in the meta-analysis was mixed, with 9 being of high quality, 1 being of low quality and 13 having some concerns about bias. This may have affected the reliability of the results. Additionally, there was significant interstudy heterogeneity in the overall analysis of some outcomes, such as length of hospitalisation. Our results may not be generalisable to the usage of colchicine early in the course of the disease as most RCTs are of late-stage treatment; consequently, there was not enough data to compare early-stage versus late-stage treatment. Furthermore, the composite endpoint of death or MV is an important outcome; however, due to a lack of data provided by the RCTs, we were unable to analyse this endpoint. Moreover, many studies either did not report the vaccination status of their participants or included unvaccinated patients only. Therefore, the COVID-19 vaccination status as a potential effect modifier needs to be studied further. Finally, there was evidence of the presence of publication bias in our meta-analysis implying that small studies that did not report positive findings may not have been published.

The results of this meta-analysis do not support the use of colchicine as a treatment for reducing the risk of mortality or improving other clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19. However, RCTs investigating early treatment with colchicine (within 5 days of symptom onset or in patients with early-stage disease) are needed to fully elucidate the potential benefits of colchicine in this patient population.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication.

Not applicable.

- Agarwal A ,

- Stegemann M , et al

- Saeed J , et al

- Cheema HA ,

- Sohail A , et al

- Rehman MEU ,

- Shahid A , et al

- Elrashedy AA , et al

- Shafiee A ,

- Athar MMT ,

- Fatima A , et al

- Rehman AU ,

- Zhang Y , et al

- Ellis L , et al

- Teperman J , et al

- McKenzie JE ,

- Bossuyt PM , et al

- Sterne JAC ,

- Savović J ,

- Page MJ , et al

- Higgins JPT ,

- Perricone C ,

- Brucato A , et al

- Islam K , et al

- Pourdowlat G ,

- Saghafi F ,

- Mozafari A , et al

- Absalón-Aguilar A ,

- Rull-Gabayet M ,

- Pérez-Fragoso A , et al

- Gorial FI ,

- Maulood MF ,

- Abdulamir AS , et al

- Bonjorno LP ,

- Giannini MC , et al

- Tardif J-C ,

- Bouabdallaoui N ,

- L’Allier PL , et al

- Dorward J ,

- Hayward G , et al

- Recovery Collaborative Group

- Orlandini A ,

- Castellana N , et al

- Gaitán-Duarte HG ,

- Álvarez-Moreno C ,

- Rincón-Rodríguez CJ , et al

- Albustany D

- Ghazaiean M ,

- Rouhani N , et al

- Pascual-Figal DA ,

- Roura-Piloto AE ,

- Moral-Escudero E , et al

- Alsultan M ,

- Alsamarrai O , et al

- Eikelboom JW ,

- Belley-Cote EP , et al

- Sunil Naik K ,

- Andhalkar N ,

- Pimenta Bonifácio L ,

- Ramacciotti E ,

- Agati LB , et al

- Mostafaie A

- Salehzadeh F ,

- Pourfarzi F ,

- Deftereos SG ,

- Giannopoulos G ,

- Vrachatis DA , et al

- Cecconi A ,

- Martinez-Vives P ,

- Vera A , et al

- Ghaith HS ,

- Nafady MH , et al

- Lai C-C , et al

- Toro-Huamanchumo CJ ,

- Benites-Meza JK ,

- Mamani-García CS , et al

- Sulaiman SAS

- Barbagelata L ,

- Chiabrando JG , et al

- Moeed A , et al

- Raffaello WM

- Golpour M ,

- Mousavi T ,

- Alimohammadi M , et al

- Ramachandram DS , et al

- Danjuma MI ,

- Aboughalia M , et al

- Pollock M ,

- Fernandes RM ,

- Becker LA , et al

- Forrest JI ,

- Rayner CR ,

- Park JJH , et al

Supplementary materials

Supplementary data.

This web only file has been produced by the BMJ Publishing Group from an electronic file supplied by the author(s) and has not been edited for content.

- Data supplement 1

HAC and UJ are joint first authors.

HAC and UJ contributed equally.

Contributors Conception and design of study: HAC, AS, KYL and UJ; acquisition of data: MU, MAN and HAC; data analysis and/or interpretation: SS, RS, UJ, AHH and WM; drafting or writing of the manuscript: MAN, UJ, SS, MU, AS and WM; substantial revision or critical review of the manuscript: HAC, AHH, RS and KYL; guarantor: HAC. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests None declared.

Patient and public involvement Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 23 April 2024

Real life experience on the use of Remdesivir in patients admitted to COVID-19 in two referral Italian hospital: a propensity score matched analysis

- Nicola Veronese 2 na1 ,

- Francesco Di Gennaro 1 na1 ,

- Luisa Frallonardo ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0001-3897-9678 1 na1 ,

- Stefano Ciriminna 2 ,

- Roberta Papagni 1 ,

- Luca Carruba 2 ,

- Diletta Agnello 2 ,

- Giuseppina De Iaco 1 ,

- Nicolò De Gennaro 1 ,

- Giuseppina Di Franco 2 ,

- Liliana Naro 2 ,

- Gaetano Brindicci 1 ,

- Angelo Rizzo 2 ,

- Davide Fiore Bavaro 1 ,

- Maria Chiara Garlisi 2 ,

- Carmen Rita Santoro 1 ,

- Fabio Signorile 1 ,

- Flavia Balena 1 ,

- Pasquale Mansueto 2 ,

- Eugenio Milano 1 ,

- Lydia Giannitrapani 2 ,

- Deborah Fiordelisi 1 ,

- Michele Fabiano Mariani 1 ,

- Andrea Procopio 1 ,

- Rossana Lattanzio 1 ,

- Anna Licata 2 ,

- Laura Vernuccio 2 ,

- Simona Amodeo 2 ,

- Giacomo Guido 1 ,

- Francesco Vladimiro Segala 1 ,

- Mario Barbagallo 2 &

- Annalisa Saracino 1

Scientific Reports volume 14 , Article number: 9303 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Drug development

- Infectious diseases

- Medical research

Remdesivir (RDV) was the first Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved medication for COVID-19, with discordant data on efficacy in reducing mortality risk and disease progression. In the context of a dynamic and rapidly changing pandemic landscape, the utilization of real-world evidence is of utmost importance. The objective of this study is to evaluate the impact of RDV on patients who have been admitted to two university referral hospitals in Italy due to COVID-19. All patients older than 18 years and hospitalized at two different universities (Bari and Palermo) were enrolled in this study. To minimize the effect of potential confounders, we used propensity score matching with one case (Remdesivir) and one control that never experienced this kind of intervention during hospitalization. Mortality was the primary outcome of our investigation, and it was recorded using death certificates and/or medical records. Severe COVID-19 was defined as admission to the intensive care unit or a qSOFAscore ≥ 2 or CURB65scores ≥ 3. After using propensity score matching, 365 patients taking Remdesivir and 365 controls were included. No significant differences emerged between the two groups in terms of mean age and percentage of females, while patients taking Remdesivir were less frequently active smokers (p < 0.0001). Moreover, the patients taking Remdesivir were less frequently vaccinated against COVID-19. All the other clinical, radiological, and pharmacological parameters were balanced between the two groups. The use of Remdesivir in our cohort was associated with a significantly lower risk of mortality during the follow-up period (HR 0.56; 95% CI 0.37–0.86; p = 0.007). Moreover, RDV was associated with a significantly lower incidence of non-invasive ventilation (OR 0.27; 95% CI 0.20–0.36). Furthermore, in the 365 patients taking Remdesivir, we observed two cases of mild renal failure requiring a reduction in the dosage of Remdesivir and two cases in which the physicians decided to interrupt Remdesivir for bradycardia and for QT elongation. Our study suggests that the use of Remdesivir in hospitalized COVID-19 patients is a safe therapy associated with improved clinical outcomes, including halving of mortality and with a reduction of around 75% of the risk of invasive ventilation. In a constantly changing COVID-19 scenario, ongoing research is necessary to tailor treatment decisions based on the latest scientific evidence and optimize patient outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations

Diagnosis and management of Guillain–Barré syndrome in ten steps

Key recommendations for primary care from the 2022 Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) update

Introduction.

According to the latest WHO data (August 7th, 2023), more than 780 million cases of SARS-CoV2 infection have been reported globally, and almost 7 million deaths related to the disease have been recorded since the appearance of the virus in the world scenario 1 .

Although a complete vaccination course is still considered highly effective in preventing hospitalization and severe forms 2 , several studies have reported reduced vaccine effectiveness in subjects, especially those infected with Omicron variants or immunocompromised ones 3 , 4 , 5 . Even now, pharmacological approaches remain crucial to reducing disease progression.

Remdesivir (RDV) was the first Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved medication for COVID-19 in October 2020 for use in hospitalized adults and pediatric patients 6 due to antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2, inhibiting viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerases due to active nucleoside triphosphate (GS-443902) 7 . It has also previously been known as a possible therapy against filoviruses (Ebola viruses, Marburg virus), previous coronaviruses (SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV), paramyxoviruses, and pneumoviridae 8 , 9 , 10 .

Since the first phase of the pandemic administration of Remdesivir has seen many changes in terms of timing 11 , counter-indications 12 , and association with monoclonal antibodies or oral antivirals 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 .

There is a notable discrepancy in the available data about the utilization of Remdesivir. Multiple studies have demonstrated that Remdesivir generally decreases the duration of recovery without impacting mortality rates, the necessity for mechanical ventilation 17 , 18 , or the improvement of patients with moderate-to-severe COVID-19 who require oxygen therapy 19 , 20 .

However, this positive effect was not observed in patients requiring high-flow oxygen therapy. Conversely, alternative findings have indicated that Remdesivir can lead to a decrease in hospitalization duration, disease progression, and overall survival rates 21 , 22 , 23 .

As shown for other interventions 24 , the utilization of real-world evidence is of utmost importance in the context of a dynamic and rapidly changing pandemic landscape. This evidence plays a critical role in customizing therapeutic approaches, taking into account factors such as vaccination status and risk profiles. Additionally, it aids in clarifying the effectiveness of various treatments, thereby facilitating informed decision-making across diverse populations and clinical contexts.

The objective of this study is to evaluate the impact of RDV on patients who have been admitted to two university referral hospitals in Italy owing to COVID-19. This be achieved by employing a propensity score-matched methodology, which aims to minimize the influence of confounding variables and bias.

Materials and methods

Study population.

All patients with more than 18 years and hospitalized in Internal Medicine or Geriatrics Wards from March 2020 to September 2022 in the University Hospital (Policlinico) ‘P. Giaccone’ in Palermo, Sicily, Italy 1 and in the University Hospital Policlinico (Bari, Italy) were enrolled in this study. The study conducted in Palermo was approved by the Local Ethical Committee during the session of the 28th of April 2021 (number 04/2021) and in Bari 28 April 2020 (Study Code: 6357).

All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations (Declarations of Helsinki). Informed consent/consent to participate was obtained from each participant and/or their legal guardian(s) who received information verbally and read the information letter.

Exposure: Remdesivir

Remdesivir was administered intravenously in: a. patients hospitalized for pneumonia due to COVID-19, needing non-invasive ventilation; b. patients having some comorbidities (e.g., type 2 diabetes, cancer) that can increase the risk of severe COVID-19 forms. These indications follow the national guidelines available at the time of inclusion 2 . According to local protocol, all the patients received 200 mg of Remdesivir on the first day, followed by 100 mg once daily for the subsequent 9 days, 4 days, or 2 days as a maintenance dose, for a total of 10, 5, or 3 days of treatment. All the patients received the first dose of Remdesivir within the first three days of disease. Since patients having severe renal (creatinine clearance < 30 ml/min) or hepatic failure (ALT > 5x) cannot take Remdesivir, they were excluded from the analyses. Finally, we also recorded potential side effects due to this medication.

Outcomes: mortality and severe COVID-19

Mortality was the primary outcome of our investigation and it was recorded using death certificates and/or medical records 3 . Severe COVID-19 was defined as admission to intensive care unit, or a qSOFAscore ≥ 2 or CURB65scores ≥ 3. Briefly, the qSOFA (quick SOFA) is made by three different items, i.e., altered mental status, respiratory rate > 22, systolic blood pressure less than 100 mmHg, with a score over two indicating a higher risk due to sepsis 16 . The CURB-65 (Confusion, Urea, Respiratory rate, Blood pressure, and age over 65 years) is used for estimating mortality associated with pneumonia: a score of 3 or more indicates severe forms of pneumonia 17 .

Confounders

For a better understanding of the association between the use of Remdesivir and the outcomes of interest, we included several factors, such as:

Demographic characteristics, including age, gender, and smoking status.

Comorbidities, including hypertension, dyslipidemia, type two diabetes mellitus, and obesity. These medical conditions were diagnosed using medical history, drug history, and laboratory measures recorded in the first four days of hospitalization.

Signs and symptoms typical of COVID-19, such as fever, anosmia, etc. (including the presence of pneumonia) recorded at hospital admission.

Other therapies, including the use of corticosteroids, heparins, and/or monoclonal antibodies.

Statistical analysis

To minimize the effect of potential confounders, we used a propensity score matching with one case (Remdesivir) and one control that never experienced this kind of intervention during hospitalization. Since some factors (namely, smoking status, hypertension, obesity and diabetes) were not balanced between cases and controls, we added as covariates in our analyses.

Data on continuous variables were normally distributed according to the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and therefore reported as means and standard deviation values (SD) for quantitative measures and percentages for the categorical variables, by use or not of Remdesivir. Levene’s test was used to test the homoscedasticity of variances and, if its assumption was violated, Welch’s ANOVA was used. P values were calculated using the Student’s T-test for continuous variables and the Mantel–Haenszel Chi-square test for categorical ones.

The association between the use of Remdesivir and mortality during the follow-up was made using a Cox’s regression analysis and reporting the findings as hazard ratios (HRs) with their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). In these analyses, we included vaccination against COVID-19 as covariate since unbalanced despite the use of Remdesivir and significantly associated with the outcomes of interest. To test the robustness of our results, we made several sensitivity analyses analyzing the interaction Remdesivir by the factors included (e.g., dose and duration of Remdesivir treatment, gender, presence of any comorbidity, COVID-19 clinics and the use of other therapies). In the case of age, we used the median value (= 56 years) for dichotomizing this variable. Finally, the association between Remdesivir use and the use of non-invasive ventilation during hospitalization or severe COVID-19 was analyzed using a logistic binary regression analysis, with the data reported as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CI.

All analyses were performed using the SPSS 26.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois). All statistical tests were two-tailed and statistical significance was assumed for a p-value < 0.05.

Ethical approval statement and consent to participate

The study conducted in Palermo was approved by the Local Ethical Committee during the session of the 28th of April 2021 (number 04/2021) and in Bari 28 April 2020 (Study Code: 6357).

Informed consent was obtained from each participant and/or their legal guardian(s) that received information verbally and read the information letter.

The initial cohort included a total of 1883 patients hospitalized for COVID-19. Of them, 1070 used Remdesivir during the hospital stay. The 1070 participants taking Remdesivir differed in several clinical characteristics compared to the 813 controls, particularly regarding comorbidities and the presence of pneumonia radiologically identified (p < 0.0001 for all the comparisons). Therefore, a propensity score matching was proposed for better accounting of these baseline differences.

After using a propensity score matching, 365 patients taking Remdesivir and 365 controls were included. The majority of the patients used Remdesivir for ten days (n = 216), followed by 5 days (n = 126) and 3 days (n = 23). Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics. No significant differences emerged between the two groups in terms of mean age and percentage of females, whilst patients taking Remdesivir were less frequently active smokers (p < 0.0001). Regarding comorbidities, whilst no differences emerged for the presence of any comorbidity (p = 0.21), patients using Remdesivir were less significantly affected by hypertension and type 2 diabetes (p = 0.03 for both comparisons) or obesity (p = 0.005). Regarding COVID-19 symptomatology, we observed significant differences between Remdesivir and control groups in terms of anosmia and dysgeusia, both more frequent in the control group and fever more frequent in the Remdesivir group (Table 1 ). Moreover, the patients taking Remdesivir were less frequently vaccinated against COVID-19. All the other clinical, radiological, and pharmacological parameters were balanced between the two groups.

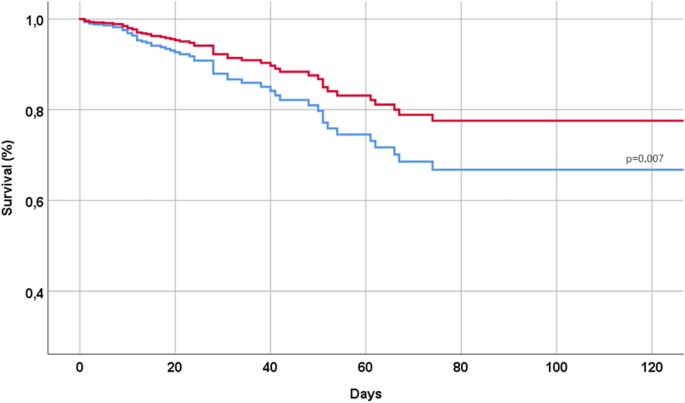

During a median follow-up time of 15 days (range 0 to 172), 58 patients (= 7.9% of the initial population) died, 490 (= 67.1%) used a non-invasive ventilation, and 571 (n = 78.2%) had a severe COVID. Table 2 shows the association between the use of Remdesivir and the outcomes of interest of our study. The use of Remdesivir, in our cohort, was associated with a significantly lower risk of mortality during the follow-up time (HR 0.56; 95% CI 0.37–0.86; p = 0.007), as also graphically reported in Fig. 1 . Moreover, the use of Remdesivir was associated with a significantly lower incidence of a non-invasive ventilation (OR 0.27; 95% CI 0.20–0.36), but not with severe COVID (OR 1.09; 95% CI 0.78–1.52) (Table 2 ).

Association between use of Remdesivir and mortality during the follow-up period. In red patients taking Remdesivir, in blue controls. The analyses were made after matching using a propensity score our sample.

To test the robustness of our results, we did run several sensitivity analyses. Among all the factors analyzed, the use of Remdesivir decreased mortality in patients with dyslipidemia (HR 0.19; 95% CI 0.06–0.64) (p for interaction = 0.02) and in those having a SpO2 < 92% at the hospital admission (HR 0.30; 95% CI 0.11–0.81; p = 0.02) (p for interaction = 0.02). The interaction Remdesivir by other factors included did not reach the statistical significance (p for interaction > 0.05).

Finally, in the 365 patients taking Remdesivir, we observed two cases of mild renal failure requiring a reduction in the dosage of Remdesivir and two cases in which the physicians decided to interrupt Remdesivir for bradycardia and for QT elongation.

This study aimed to assess the efficacy of Remdesivir on clinical outcomes within a cohort of 712 patients admitted to the hospital due to COVID-19.

Our results demonstrate a robust correlation between the utilization of Remdesivir and positive outcomes in individuals hospitalized for COVID-19. Specifically, those who underwent Remdesivir treatment exhibited a nearly 50% reduction in the risk of mortality.

Our results diverge from other published evidence. Specifically, a recent meta-analysis indicates no association between the use of Remdesivir and a reduction in mortality risk 25 , 26 , supporting evidence from other authors that there is no impact of RDV on mortality risk 27 .

A major limitation of these studies, however, is that they did not consider timing of Remdesivir prescription from symptom onset 28 , which demonstrated to be a key driver of drug effectiveness and is today listed as a prescriptive criteria in the drug package insert 29 and in all major international guidelines 30 , 31 .

In our study, all patients received the intervention drug within 3 days from symptom onset. Furthermore, another factor that could have influenced the difference in mortality is population heterogeneity in terms of clinical and demographic characteristics. In our study, utilizing propensity score analysis, two groups exhibit substantial overlap in numerous demographic aspects (age, gender) and clinical features (comorbidities, vaccination status, pneumonia, illness severity, oxygen saturation), as well as co-therapies (corticosteroids, heparin, monoclonal antibodies, and oral antivirals).

Moreover, in our population, the use of Remdesivir was associated with a reduction in disease progression with a lower incidence of non-invasive ventilation, with a reduction in these risks of almost 75%. This data is already discussed and well noted in other literature, confirming the hypothesis that Remdesivir mitigates the severity of the disease and reduces the need for aggressive respiratory support in hospitals 11 , 12 , 32 .

If we consider that the group taking Remdesivir was less frequently vaccinated for SARS-CoV-2, our conclusion about the efficacy of Remdesivir is much stronger. This is relevant in the light of evidence that places RDV as a drug with pan-variant activity, as shown in molecular surveillance studies 33 , 34 .