- Go to US Navigation

- Go to Health Information Systems Navigation

- Go to Page Content

- Go to Search

- Go to Contact Information

- Go to Site Map

- United States

- Health Care

- Health Information Systems

- Drive value-based care

- Patient classification methodologies

- 3M™ Potentially Preventable Emergency Department Visits

- IMPROVE REVENUE CYCLE

- Clinical documentation integrity

- Edits, reviews and audits

- Consulting services

- All revenue cycle solutions

- CREATE TIME TO CARE

- Clinician solutions

- CDI, care management and HCCs

- Imaging solutions

- Adoption services

- View all solutions

- DRIVE VALUE-BASED CARE

- Performance improvement

- Policy and research

- All value-based solutions

- Client education and training

- Client Experience Summit

- Continuing education units

- View all education

- Our partners

- View all resources

- Current customer support

3M™ Potentially Preventable Emergency Department Visits (PPVs)

Identify potentially preventable emergency department visits using powerful clinical grouping logic

3M PPVs find opportunities for better discharge planning, care coordination and follow up.

The 3M™ Potentially Preventable Emergency Room Visits (PPV) are inefficient and expensive either because the care could have been provided in a less expensive setting that was not available, or because inadequate care of a chronic or sub-acute problem in the outpatient setting resulted in an acute deterioration, or a combination of both.

3M PPVs can identify patterns of potentially avoidable emergency department visits, and may suggest areas where primary care services should be improved.

Why choose the 3M™ Potentially Preventable Emergency Department Visits (PPV) methodology?

Every year, millions of patients visit the emergency department for conditions that either could have been prevented with better management in the community or would be more appropriately treated elsewhere. Reducing potentially preventable ED visits simultaneously saves money and improves patient outcomes.

Accurate and fair PPV identification requires careful, clinically defined risk adjustment. The widely accepted 3M™ Clinical Risk Groups (CRG) methodology measures baseline population health status in comparing actual versus expected PPV rates.

3M PPVs are one of the five 3M™ Potentially Preventable Event methodologies that generate specific results for clinicians and health care managers to use in improving care and reducing cost.

Nursing facilities, intermediate care facilities and residential treatment centers that care for patients around the clock can be held to higher standards. The 3M PPV methodology includes additional logic for potentially preventable ED visits when patients are under the care of a residential nursing care facility.

All about 3M PPVs

The 3M PPV methodology identifies emergency room visits that may result from a lack of adequate access to care or ambulatory care coordination. Similar to 3M PPAs, 3M PPVs are ambulatory sensitive conditions which adequate patient monitoring and follow-up should be able to reduce or eliminate.

3M PPVs are emergency department visits for conditions that could otherwise be treated by a care provider in a nonemergency setting. 3M PPVs may also result from a lack of adequate care or ambulatory care coordination, such as access to urgent care facilities, availability of primary care physicians, etc. 3M PPVs include visits that could have been reduced or eliminated if adequate patient monitoring and treatment (e.g., medication management) had been available. High 3M PPV rates may therefore represent a failure of the ambulatory care provided to the patient.

3M PPVs can be used by payers, employers, government agencies, researchers, integrated health delivery systems (e.g., managed care organizations and accountable care organizations) and residential nursing care facilities (e.g., nursing facilities, intermediate care facilities, and residential treatment centers). For example, employers or government insurance programs can use 3M PPVs to measure the performance of contracted integrated health delivery systems or residential nursing care facilities. In turn, integrated health delivery systems and residential nursing care facilities themselves can use the 3M PPV methodology to improve their own performance by improving outcomes from year to year.

Here are a few examples of the value the 3M PPV methodology can bring to customers.

- Quantifying opportunities for improvement . In the Medicare program, 55 percent of ED visits (excluding those patients who are admitted) were defined as potentially preventable, suggesting to the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) that “ample opportunities” exist for improvement in the ambulatory care provided to Medicare beneficiaries.

- Understanding population health . The New York Department of Health reports risk-adjusted 3M PPV rates by county for both the all-payer and Medicaid populations, with reports dating back to 2011. Learn more.

- Managing managed care . The Texas Medicaid program reports risk-adjusted 3M PPV rates for Medicaid-managed care organizations along with detailed drill-down capability and downloadable data files.

- Measuring outcomes in long-term care . In analyzing data for more than 400,000 Medicare nursing facility residents, 3M researchers found considerable variation both within and across states in risk-adjusted 3M PPV rates. One implication: Medicare’s method of assigning nursing facility quality scores should say more about outcomes.

While 3M PPA classification logic is the same for every client, an organization can use different versions of the methodology and apply their own reimbursement calculation tables. 3M Health Information Systems always recommends that clients use the latest version of the software, but each organization can decide how to apply it (for research, public reporting, reimbursement, or a combination). Note: At present, 3M Health Information Systems does not offer software that replicates a specific organization’s PPA analysis.

3M PPVs are integrated with the other 3M patient classification methodologies.

- 3M PPVs, along with the 3M™ Potentially Preventable Admissions and 3M™ Potentially Preventable Services , are the 3M™ Population-focused Preventables (PFPs). 3M offers a suite of five Potentially Preventable Event methodologies, also including the 3M™ Potentially Preventable Complications (PPCs) and 3M™ Potentially Preventable Readmissions (PPRs) . All 3M PPE methodologies are used to measure and reduce costly, clinically significant adverse outcomes.

- 3M PPVs are distinct from the 3M™ Potentially Preventable Revisits to the Emergency Department (PPR EDs), a component of the 3M PPR methodology that measures potentially preventable returns to the hospital (inpatient or ED) after discharge.

- The 3M PPVs are defined using the 3M™ Enhanced Ambulatory Patient Groups (EAPGs) methodology for ambulatory visits.

3M PPVs are available in the following 3M products:

- 3M™ 360 Encompass™ System

- 3M™ Core Grouping Software (CGS)

- 3M™ Grouper Plus Content Services (GPCS)

- 3M™ Data to Action Solution

Available to Licensees on the 3M Customer Support Website

- PFP Methodology Overview

- PFP Definitions Manual

- PFP Setup Guide

- PFP Summary of Changes

3M experts are available to advise health plans, government agencies and other interested parties on how to obtain maximum value from the use of 3M PPVs. For example, 3M consultants can help you measure the incidence of potentially preventable emergency department visits, compare the results with appropriate benchmarks and design improvement programs. 3M consultants can also help payers and other organizations measure 3M PPVs across health plans and other patient populations, design pay-for-outcomes incentive methods and facilitate learning collaboratives for provider groups.

The 3M PPV methodology can identify PPVs using standard, inpatient claims data derived from institutional and professional claims (i.e., the UB-04 and CMS-1500 paper forms and their corresponding X12N 837 electronic formats). Consistent, unique patient identifiers are essential. Comparing 3M PPV rates across different populations requires the 3M™ Clinical Risk Grouping (CRG) Software to perform risk adjustment by individual health status. Thus, 3M PPA analysis typically involves creation of a static data set comprising at least one full year of data. If available, pharmacy data in NCPDP format is optional but recommended. Note: 3M CRG and 3M PPV methodologies do not need to be built into the claim processing systems.

Inappropriate use of the emergency department has long been identified as a major problem in the health care system. The twin challenges have been exactly how to define “inappropriate” and who should be held responsible. Many payers have penalized the hospital or the patient for individual visits deemed inappropriate, but this approach can clearly be unfair. In 2012, 3M met these challenges by releasing the 3M™ Potentially Preventable Emergency Department Visit (PPV) methodology as one of the three 3M™ Population-focused Preventables. Learn more. (The others are 3M™ Potentially Preventable Admissions and 3M™ Potentially Preventable Services .)

As with the other 3M Potentially Preventable Event methodologies, three core concepts are essential. First, we recognize that not all ED visits are potentially preventable. Second, what matters is not the individual visit, but rather the overall rate of potentially preventable ED visits. Instead of approaching quality with the mindset of “This should never happen,” we use a more realistic and meaningful approach of “This has happened too often.” Third, any comparisons across populations of patients must be risk-adjusted. In practice, that means that the actual 3M PPV experience of a population is compared with the experience that would be expected for a population with the same case mix.

The 3M PPV logic is divided into two phases.

1. Identify potentially preventable events

By definition, “ED visits” include only those visits where patients were treated and released. (Nationally, 14 percent of ED patients are admitted to the same hospital; their ED services are included within the inpatient stay.) Learn more (PDF, 274.35 KB).

All ED visits are grouped using the 3M™ Enhanced Ambulatory Patient Group (EAPG) methodology . Of the 560 3M EAPGs (as of February 2019), many principal diagnoses within 196 3M EAPGs are considered potentially preventable in the general population. In a Minnesota all-payer analysis, the most common 3M PPVs were upper respiratory tract infections, abdominal pain, and musculoskeletal systems and connective tissue diagnoses such as back pain. When a population is under the care of a residential nursing care facility (such as a nursing facility, intermediate care facility, or residential treatment center), additional trauma, infections, and certain other diagnoses are considered potentially preventable.

2. Determine patient risk adjustment

In any rate-based comparison of outcomes, risk adjustment is essential for a fair comparison across populations. Although 3M PPVs are generally preventable, they will never be totally eliminated, even with optimal care. As a result, there will be a residual rate of 3M PPVs in even the best-performing systems. More importantly, the rate at which PPVs occur depends on the burden of illness of the population.

The 3M PPV software measures the burden of illness of each patient (and therefore of the population) using the 3M™ Clinical Risk Groups (CRGs) . In 3M CRG v2.1, there are approximately 390 base 3M CRGs and 1,470 total 3M CRGs, taking into account severity levels. For example, 3M CRG 70602 describes a person with congestive heart failure, diabetes and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, severity level 2. ED visits for this person are more likely to be preventable than for a person in severity level 5 (i.e., 3M CRG 70605).

The 3M CRGs can be rolled up into three levels of aggregation (i.e., approximately 676, 254 or 54 groups) and nine health status group levels. The aggregated 3M CRGs sacrifice some clinical precision, but with only a slight loss of explanatory power. 3M recommends that the ACRG3 level of 54 groups (as of 2019) be used for setting risk-adjusted 3M PPV norms.

Further information on the 3M PPV logic is available in the 3M™ Population-focused Preventables Methodology Overview. Detailed information is available to licensees in the online 3M PFP definitions manual.

The 3M PPV clinical logic is maintained by a team of 3M clinicians, data analysts, nosologists, programmers and economists. The methodology is updated annually to reflect changes in the standard diagnosis and procedure code sets as well as 3M enhancements to the clinical logic.

Learn more about 3M PPVs

Publicly available documentation, articles and reports

Please note that documents not published by 3M do not necessarily reflect 3M recommendations and have not been approved by 3M. These documents are listed here for the information of readers interested in the various ways that 3M patient classification methodologies have been applied. Also note that listing these references does not imply endorsement of 3M methodologies by individual authors, other organizations or government agencies.

Some articles and reports are available from the publishers at no charge, while others require a fee.

This manual describes the 3M Population-focused Preventables (PFP) Software, a clinically-based classification system that identifies preventable hospital admissions, ED visits and ancillary services.

Whether your organization needs to monitor patient safety, calculate expected reimbursement or design incentive models for community-based care, 3M software gives you the insights you need.

This eguide can help you understand 3M solutions for population health, patient safety and cost-effective care.

This article details the use of potentially preventable events and demonstrates how they are being applied to achieve health care value.

Find out how leveraging data enabled the Egyptian Health Department to support its at-risk Medicaid youth population with proactive education, outreach and resources.

This article offers five principles for success, emphasizing clinically credible initiatives that generate actionable information for clinicians.

This report explores one set of opportunities for health care system improvement and potential savings by analyzing Emergency Department (ED) visits, hospital admissions and hospital readmissions to uncover the volume and make-up of potentially preventable health care events.

This report from Texas Health and Human Services describes the agency’s efforts to reduce potentially preventable emergency department utilization by Medicaid recipients and current and proposed initiatives to improve Medicaid recipients’ health outcomes.

Ready to take the next step?

Send us a message or speak to a 3M representative at 1-800-367-2447 (available weekdays 7 a.m. to 3 p.m. CT).

Let’s talk about how we can help you and your organization

Fill out the form to start the conversation. A 3M representative will reach out to you soon.

All fields are required unless indicated optional

- Resolence Morthy Gread

- Business Email Address

- Job Role Select One Ambulatory Care Business Partner Care Management CDI Manager/Director CDI Specialist Chief Compliance Officer Chief Executive Officer Chief Financial Officer Chief Information Officer Chief Medical Information Officer Chief Medical Officer Chief Network Officer Chief Operating Officer Chief Strategy Officer Chief Technology Officer Clinical Coding Clinical Director Clinician Quality Director Consultant HIM Director HIM Manager/Specialist Imaging Medical Practice Manager Other Payer Network Management Physician Population Health Director/Manager Population Health Specialist/Analyst Revenue Management Student Technical Value-based Care Director/Manager Value-based Care Specialist/Analyst

- Organization

- Facility Type Select one Ambulatory Surgery Center Government Hospital or Health System Independent Medical Practice Payer Technology Company Other

- Business Phone

- Country/Region Select one Afghanistan Aland Islands Albania Algeria Andorra Angola Anguilla Antarctica Antigua and Barbuda Argentina Armenia Aruba Australia Austria Azerbaijan Bahamas Bahrain Bangladesh Barbados Belarus Belgium Belize Benin Bermuda Bhutan Bolivia Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba Bosnia and Herzegovina Botswana Bouvet Island Brazil British Indian Ocean Territory Brunei Darussalam Bulgaria Burkina Faso Burundi Cambodia Cameroon Canada Canary Islands Cape Verde Cayman Islands Central African Republic Ceuta & Melilla Chad Chile China Christmas Island Cocos (Keeling) Islands Colombia Comoros Congo Congo, the Democratic Republic of the Cook Islands Costa Rica Croatia Curaçao Cyprus Czech Republic Denmark Djibouti Dominica Dominican Republic Dutch Antilles Ecuador Egypt El Salvador Equatorial Guinea Eritrea Estonia Ethiopia Falkland Islands (Malvinas) Faroe Islands Fiji Finland France French Guiana French Polynesia French Southern Territories Gabon Gambia Georgia Germany Ghana Gibraltar Greece Greenland Grenada Guadeloupe Guam Guatemala Guernsey Guinea Guinea-Bissau Guyana Haiti Heard Island and McDonald Islands Holy See (Vatican City State) Honduras Hong Kong Hungary Iceland India Indonesia Iraq Ireland Isle of Man Israel Italy Ivory Coast Jamaica Japan Jersey Jordan Kazakhstan Kenya Kiribati Korea - Republic of Kosovo Kuwait Kyrgyzstan Lao People's Democratic Republic Latvia Lebanon Lesotho Liberia Libyan Arab Jamahiriya Liechtenstein Lithuania Luxembourg Macao Macedonia, the former Yugoslav Republic of Madagascar Malawi Malaysia Maldives Mali Malta Marshall Islands Martinique Mauritania Mauritius Mayotte Mexico Micronesia Moldova, Republic of Monaco Mongolia Montenegro Montserrat Morocco Mozambique Myanmar Namibia Nauru Nepal Netherlands New Caledonia New Zealand Nicaragua Niger Nigeria Niue Norfolk Island Northern Mariana Islands Norway Oman Pakistan Palau Palestine Panama Papua New Guinea Paraguay Peru Philippines Pitcairn Poland Portugal Puerto Rico Qatar Reunion Romania Russian Federation Rwanda Saint Barthélemy Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha Saint Kitts and Nevis Saint Lucia Saint Martin Saint Pierre and Miquelon Saint Vincent and the Grenadines Samoa Samoa, American San Marino Sao Tome and Principe Saudi Arabia Senegal Serbia Seychelles Sierra Leone Singapore Sint Maarten Slovakia Slovenia Solomon Islands Somalia South Africa South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands South Sudan Spain Sri Lanka Sudan Suriname Svalbard and Jan Mayen Swaziland Sweden Switzerland Taiwan Tajikistan Tanzania, United Republic of Thailand Timor-Leste Togo Tokelau Tonga Trinidad and Tobago Tunisia Turkey Turkmenistan Turks and Caicos Islands Tuvalu Uganda Ukraine United Arab Emirates United Kingdom United States United States Minor Outlying Islands Uruguay Uzbekistan Vanuatu Venezuela Vietnam Virgin Islands, British Virgin Islands, US Wallis and Futuna Western Sahara Yemen Zambia Zimbabwe

- Zip/Postal Code

What methodology are you most interested in? (Check all that apply)

- 3M All Patient Refined DRGs

- 3M Ambulatory Potentially Preventable Complications

- 3M Clinical Risk Groups

- 3M Enhanced Ambulatory Patient Groups

- 3M International Refined DRGs

- 3M Patient-focused Episodes

- 3M Potentially Preventable Readmissions

- 3M Potentially Preventable Complications

- 3M Population-focused Preventables (including ED visits, ancillary services and admissions)

- 3M Severe Maternal Morbidity

- National methodologies

- Select the communications you’d like to receive from 3M Health Information Systems by simply checking the box next to the content subscriptions available.

- Get the latest insights with our monthly eNewsletter

- Subscribe to our events and thought leadership content

3M takes your privacy seriously. 3M and its authorized third parties will use the information you provided in accordance with our Privacy Policy to send you communications which may include promotions, product information and service offers. Please be aware that this information may be stored on a server located in the U.S. If you do not consent to this use of your personal information, please do not use this system.

Our apologies...

An error has occurred while submitting. Please try again later...

Thank you for your inquiry. A 3M representative will reach out to you shortly about how you can create a masterpiece using 3M’s methodologies.

Connect with us

Discover the inspiration and information you’re looking for on the health care topics that matter most.

- Inside Angle Read blog posts from 3M industry experts. Subscribe to our blog

- Webinars Stay current on industry challenges and get expert advice. View upcoming and archived webinars

- Join the conversation Share ideas and connect with others in the industry. Follow us on LinkedIn

- Inside Angle podcast In-depth conversations on leading industry issues. Listen now

Subscribe to our newsletter

The 3M HIS monthly email newsletter offers thought leadership and resources directly to your inbox.

Focus eNewsletter

Sign up for monthly updates on the latest content, events and education from 3M HIS direct to your inbox.

- Job Role Select one... Select One Ambulatory Care Business Partner Care Management CDI Manager/Director CDI Specialist Chief Compliance Officer Chief Executive Officer Chief Financial Officer Chief Information Officer Chief Medical Information Officer Chief Medical Officer Chief Network Officer Chief Operating Officer Chief Strategy Officer Chief Technology Officer Clinical Coding Clinical Director Clinician Quality Director Consultant HIM Director HIM Manager/Specialist Imaging Medical Practice Manager Other Payer Network Management Physician Population Health Director/Manager Population Health Specialist/Analyst Revenue Management Student Technical Value-based Care Director/Manager Value-based Care Specialist/Analyst

- Country Select one... Afghanistan Aland Islands Albania Algeria Andorra Angola Anguilla Antarctica Antigua and Barbuda Argentina Armenia Aruba Australia Austria Azerbaijan Bahamas Bahrain Bangladesh Barbados Belarus Belgium Belize Benin Bermuda Bhutan Bolivia Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba Bosnia and Herzegovina Botswana Bouvet Island Brazil British Indian Ocean Territory Brunei Darussalam Bulgaria Burkina Faso Burundi Cambodia Cameroon Canada Canary Islands Cape Verde Cayman Islands Central African Republic Ceuta & Melilla Chad Chile China Christmas Island Cocos (Keeling) Islands Colombia Comoros Congo Congo, the Democratic Republic of the Cook Islands Costa Rica Croatia Curaçao Cyprus Czech Republic Denmark Djibouti Dominica Dominican Republic Dutch Antilles Ecuador Egypt El Salvador Equatorial Guinea Eritrea Estonia Ethiopia Falkland Islands (Malvinas) Faroe Islands Fiji Finland France French Guiana French Polynesia French Southern Territories Gabon Gambia Georgia Germany Ghana Gibraltar Greece Greenland Grenada Guadeloupe Guam Guatemala Guernsey Guinea Guinea-Bissau Guyana Haiti Heard Island and McDonald Islands Holy See (Vatican City State) Honduras Hong Kong Hungary Iceland India Indonesia Iraq Ireland Isle of Man Israel Italy Ivory Coast Jamaica Japan Jersey Jordan kazakhstan Kenya Kiribati Korea - Republic of Kosovo Kuwait Kyrgyzstan Lao People's Democratic Republic Latvia Lebanon Lesotho Liberia Libyan Arab Jamahiriya Liechtenstein Lithuania Luxembourg Macao Republic of North Macedonia Madagascar Malawi Malaysia Maldives Mali Malta Marshall Islands Martinique Mauritania Mauritius Mayotte Mexico Micronesia Moldova, Republic of Monaco Mongolia Montenegro Montserrat Morocco Mozambique Myanmar Namibia Nauru Nepal Netherlands New Caledonia New Zealand Nicaragua Niger Nigeria Niue Norfolk Island Northern Mariana Islands Norway Oman Pakistan Palau Palestine Panama Papua New Guinea Paraguay Peru Philippines Pitcairn Poland Portugal Puerto Rico Qatar Reunion Romania Rwanda Saint Barthélemy Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha Saint Kitts and Nevis Saint Lucia Saint Martin Saint Pierre and Miquelon Saint Vincent and the Grenadines Samoa Samoa, American San Marino Sao Tome and Principe Saudi Arabia Senegal Serbia Seychelles Sierra Leone Singapore Sint Maarten Slovakia Slovenia Solomon Islands Somalia South Africa South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands South Sudan Spain Sri Lanka Sudan Suriname Svalbard and Jan Mayen Swaziland Sweden Switzerland Taiwan Tajikistan Tanzania, United Republic of Thailand Timor-Leste Togo Tokelau Tonga Trinidad and Tobago Tunisia Turkey Turkmenistan Turks and Caicos Islands Tuvalu Uganda Ukraine United Arab Emirates United Kingdom United States United States Minor Outlying Islands Uruguay Uzbekistan Vanuatu Venezuela Vietnam Virgin Islands, British Virgin Islands, US Wallis and Futuna Western Sahara Yemen Zambia Zimbabwe

Your form was submitted successfully

- Investor Relations

- Partners & Suppliers

- Sustainability / ESG

- Equity and Community

- Ethics & Compliance

- News Center

- Press Releases

- SDS, RDS, More Regulatory & Compliance Information

- Transport Information Search

- CPSIA Certification Search

- Lithium Battery UN 38.3 Test Summary Search

- Transparency in Supply Chains and Modern Slavery Disclosures

- US Ingredient Communication

- Help Center

- Where to Buy

- Download PDF

- Share X Facebook Email LinkedIn

- Permissions

Emergency Department Visits Among Patients With Cancer in the US

- 1 Summerlin Hospital, Las Vegas, Nevada

- 2 Department of Emergency Medicine, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois

- 3 Digital Media Editor, JAMA Network Open

- Original Investigation Potentially Preventable Emergency Department Visits Among US Patients With Cancer Amir Alishahi Tabriz, MD, PhD, MPH; Kea Turner, PhD, MPH, MA; Young-Rock Hong, PhD, MPH; Sara Gheytasvand, MD; Benjamin D. Powers, MD, MS; Jennifer Elston Lafata, PhD JAMA Network Open

Unsurprisingly, patients with cancer have a number of symptoms and complications related to their cancer and treatments that often require health care services. Although many of these issues can be and are managed in the outpatient setting, patients with cancer sometimes seek care in the emergency department (ED), often at the direction of their care team, and many are subsequently hospitalized. Tabriz and colleagues 1 estimated the number of ED visits by patients with cancer that are potentially preventable, using a Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) quality measure definition. 1 , 2 Using the 2012 to 2019 National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, they estimated that ED visits by patients with cancer increased from 3 734 101 in 2012 to 6 240 650 in 2019 (5.4% of all ED visits that year) and that more than one-half of these visits were potentially preventable.

As noted by Tabriz et al, 1 the ED is far from the optimal setting for patients with cancer, putting them at risk for complications, including nosocomial infections, and potentially costing more than other settings, as we will discuss later in this article. Although the desire to identify and reduce unnecessary ED visits is a laudable and common effort, it is a far trickier endeavor than it may seem. 3 Notably, the CMS definition used by Tabriz et al 1 includes a range of primary diagnoses (eg, anemia, emesis, and pain), as well as acute life-threatening conditions (eg, pneumonia and sepsis). Conceptually, we split these into 2 groups: first, conditions for which patients with cancer need care, such as pain or vomiting and dehydration, which may be better managed in an outpatient setting; and second, conditions like sepsis that require hospital-based care but might have been averted with optimal outpatient care. This may include optimizing preventive care, such as vaccination for pneumonia, influenza, and COVID-19, as well as early recognition and treatment before pneumonia becomes sepsis. Of course, patients with cancer are often at high risk for severe complications, and achieving a 0 rate of sepsis in patients undergoing chemotherapy is likely unrealistic; however, much like other CMS measures, such as hospital readmissions, current rates are too high, and we can do better. Similarly, the first group of conditions can likely be optimized with better access to outpatient care and symptom management (ie, palliative care).

Differentiating between these 2 groups of potentially avoidable ED visits is problematic for a number of reasons. For example, how accurately can we expect a patient to determine whether their vomiting is a benign adverse effect of chemotherapy that is safe to manage with outpatient medications vs a sign of developing sepsis? Raven and colleagues 3 have previously shown that the link between general presenting ED complaints and discharge diagnoses is minimal. Patients should not be expected to tell whether their symptoms are low acuity vs life-threatening, given that physicians often cannot tell even with our wide range of diagnostics, clinical training, and experience.

Although ED care may be more expensive than care in other settings, care in other settings may not be available, particularly beyond standard business hours. Furthermore, is it more efficient for a health system to have all-hours outpatient access to oncology specialists (and palliative, surgical, transplant, and countless other specialties) when the ED is always open and staffed and has access to innumerable diagnostics, therapeutics, and clinical specialties? Furthermore, Raven and Steiner 4 found that 1 in 4 general patients in the ED were referred by a medical professional; thus, even access to outpatient care does not mean patients can get the care they need outside an ED. Similarly, the capabilities of outpatient care sites can vary tremendously; it is no surprise that patients are sent to the ED if the alternatives do not have the staff or diagnostic and therapeutic capabilities the patients need. 5

Also unsurprisingly, because a majority of patients with advanced cancer will report pain, 6 Tabriz and colleagues 1 found the most common reason for ED visits for patients with cancer is pain, accounting for 36.9% of ED visits; however, only 23.5% of those patients were admitted. Patients at risk for having uncontrolled pain could potentially be identified earlier, and steps could be taken that would address their pain and help prevent acute care visits. Palliative care referral is associated with improved quality of life and pain scores, 7 as well as improved caregiver satisfaction. 8 Some studies have specifically shown that palliative care referral early for a patient with cancer will result in less ED utilization. 9

Unfortunately, palliative care is often confused for hospice. Although both services focus on quality of life, patients do not need a terminal diagnosis to receive palliative care, and patients receiving palliative care can also continue curative-intent, disease-oriented treatments such as chemotherapy. Although misperceptions about palliative vs hospice care appear to be improving among emergency physicians, they are still a barrier to referral for some patients. 10 Fortunately, recent years have seen an increase in attention to palliative needs of patients in the ED, as well as increased training of emergency physicians in palliative care, including shorter format courses and fellowships sponsored by the American Board of Medical Specialty (including the American Board of Emergency Medicine). 11 This increased attention and training have led to both informal and formal integration of palliative care consultation in EDs, although room for improvement remains.

Most patients with cancer, however, are unable to choose whether the ED to which they present, or the emergency physician who treats them, has formal systems or training in palliative care. Despite our best efforts, pain is often, but not always, adequately treated in the ED; support systems such as clinical pathways and decision trees for pain management for patients with cancer may help optimize their care in the ED. Efforts to streamline the process of early palliative referrals from the ED, 11 as well as the necessary changes in clinician mindset and culture, can help EDs identify patients who would benefit from early palliative referral. Preventive measures seem much more likely to optimize care, and early palliative care involvement seems much more promising and patient-centered than simply hoping that EDs do better.

Similarly, it is easy to say that health systems should simply build always-accessible infrastructures for outpatient oncology and palliative care; again, there are intuitive efficiencies in EDs serving as the universal site of acute unscheduled care. However, as anyone who has entered a busy ED in recent years can tell you, ED crowding is not just unpleasant, but it also can put patients at risk for worse outcomes. 12 Importantly, ED crowding is a symptom of hospital crowding, as admitted ED patients are unable to move to inpatient care spaces, mostly because of dysfunctional financial incentives that effectively “compel hospitals to set inpatient census goals at levels that predictably result in ED access block. Crowding will occur when hospital occupancy exceeds 85%–90%.... [In] most institutions, ED gridlock is assured when inpatient occupancy exceeds 90%.” 12 Full hospitals mean full EDs, but also mean that well-intentioned outpatient care such as oncology and palliative care triage offices do not have an option for direct hospital admissions and will need to send patients to the ED regardless. Delgado-Guay and colleagues 13 previously found that ED visits by patients sent from oncology and palliative clinics are less likely to be potentially preventable, suggesting that oncology and palliative care clinicians are leveraging their expertise to minimize unnecessary ED referrals in the patients who are able to access their outpatient care.

Preventing unnecessary ED visits is a laudable goal if doing so means better care for patients (ie, by optimizing outpatient symptom management and access to acute unscheduled care when needed). In an effort to improve often suboptimal symptomatic care for patients receiving chemotherapy, CMS developed measure OP-35, 2 which, like other quality metrics, attempts to encourage better care, first through reporting and then later by adjusting hospital and physician reimbursements on the basis of patient outcomes (ie, ED visits and hospital admissions that may have been averted through better outpatient care). In theory, this will provide financial incentives to provide better symptom management and overall care for patients with cancer. In practice, will this be yet another promising effort to save money while improving care, yet effectively penalize hospitals and physicians that care for medically and socially high-risk patients? 14 Value-based payments offer promise, but policy makers and CMS need to ensure equity while improving disparities in care; we need to continue to adapt our approach to value-based care as we learn more about how well-intentioned payment models affect patients and health systems, and continue to modify our metrics by accounting for patient heterogeneity and improved risk adjustment, minimizing gaming by systems with resources and de facto penalties for those who provide care to the most vulnerable. 15 The goal is not to eliminate ED visits for their own sake; rather, the goal is better care of patients with cancer, and secondarily, in a manner that is cost-effective. We are hopeful that optimized care would also mean that fewer patients need to spend untold hours in EDs.

Published: January 19, 2023. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.53797

Open Access: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC-BY License . © 2023 Majka ES et al. JAMA Network Open .

Corresponding Author: N. Seth Trueger, MD, MPH, Department of Emergency Medicine, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, 211 E Ontario, Ste 200, Chicago, IL 60611 ( [email protected] ).

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

Disclaimer: N. Seth Trueger is digital media editor of JAMA Network Open , but he was not involved in any of the decisions regarding review of the manuscript or its acceptance.

See More About

Majka ES , Trueger NS. Emergency Department Visits Among Patients With Cancer in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(1):e2253797. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.53797

Manage citations:

© 2024

Select Your Interests

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

Get the latest research based on your areas of interest.

Others also liked.

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

- DATA PRODUCTS

Avoidable Emergency Department Visits

Potentially avoidable emergency department visits.

Efforts to reduce the number of healthcare services that provide little to no value to patients continue to be an industry focal point across the Commonwealth of Virginia. While potentially unnecessary care can take many forms, visits to the emergency department for conditions that likely could have been cared for in a lower cost healthcare setting have previously been identified as a major focus area for Virginia through inclusion in the Health Value Dashboard .

VHI's Potentially Avoidable Emergency Department (ED) Visits Dashboard seeks to highlight how these visits are distributed across the Commonwealth. This interactive dashboard allows users to identify regional and county specific rates of potentially avoidable ED visits, the major types of conditions that drive the frequency of these visits, and how they compare across patient insurance type and over time. While interacting with this dashboard, it's important to consider the following about each of the rates that are displayed:

- ED visits were identified as potentially avoidable based on the primary diagnosis coded on the corresponding paid health insurance claims.

- Important factors such as the time of day a visit occurred, the patient's access to primary care, and other social determinants of health were not taken into account when identifying which ED visits were potentially avoidable.

A full methodology on how this report was prepared can be found here .

Have questions or comments about the dashboard? Click here.

Updated on: 5/2/2023

- Center on Health Equity and Access

- Health Care Cost

- Health Care Delivery

- Value-Based Care

A Revised Classification Algorithm for Assessing Emergency Department Visit Severity of Populations

- Debra M. Ravert, MD

- Jonathan P. Weiner, DrPH

An updated emergency visit classification tool enables managers to make valid inferences about levels of appropriateness of emergency department utilization and healthcare needs within a population.

ABSTRACT Objectives: Analyses of emergency department (ED) use require visit classification algorithms based on administrative data. Our objectives were to present an expanded and revised version of an existing algorithm and to use this tool to characterize patterns of ED use across US hospitals and within a large sample of health plan enrollees.

Study Design: Observational study using National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey ED public use files and hospital billing data for a health plan cohort.

Methods: Our Johns Hopkins University (JHU) team classified many uncategorized diagnosis codes into existing New York University Emergency Department Algorithm (NYU-EDA) categories and added 3 severity levels to the injury category. We termed this new algorithm the NYU/JHU-EDA. We then compared visit distributions across these 2 algorithms and 2 other previous revised versions of the NYU-EDA using our 2 data sources.

Results: Applying the newly developed NYU/JHU-EDA, we classified 99% of visits. Based on our analyses, it is evident that an even greater number of US ED visits than categorized by the NYU-EDA are nonemergent. For the first time, we provide a more complete picture of the level of severity among patients treated for injuries within US hospital EDs, with about 86% of such visits being nonsevere. Also, both the original and updated classification tools suggest that, of the 38% of ED visits that are clinically emergent, the majority either do not require ED resources or could have been avoided with better primary care.

Conclusions: The updated NYU/JHU-EDA taxonomy appears to offer cogent retrospective inferences about population-level ED utilization.

Am J Manag Care. 2020;26(3):119-125. https://doi.org/10.37765/ajmc.2020.42636

Takeaway Points

- There is renewed interest in understanding emergency department (ED) use patterns in populations, both because of increased use associated with healthcare reform and as private payers seek to stem their rising ED spending.

- To assess the appropriateness of ED use at the population level, validated classification methods that use available administrative data will be required.

- Our analysis using an updated classification suggests that an even greater number of ED visits than previously categorized are nonemergent.

- Health plans and other organizations might use ED visit classification algorithms to gain an understanding about how populations make use of hospital services.

The New York University Emergency Department Algorithm (NYU-EDA) is widely used to classify emergency department (ED) visits. 1,2 This measurement tool’s development occurred in the late 1990s and was based on 5700 ED discharge abstracts from 6 hospitals in the Bronx, a borough of New York City. The NYU-EDA probabilistically classified 659 diagnosis codes from the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification ( ICD-9-CM ). The original NYU-EDA mapped only about 5% of all ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes. We propose an algorithm that remedies this shortfall and classifies nearly all ED visits.

The NYU-EDA has been applied in health services research studies to identify emergent visits that required ED care. 3,4 Several studies have focused on nonemergent and primary care—treatable ED visits and evaluated emergent and nonemergent utilization patterns to assess the impact of healthcare reforms. 5-11 Estimates of proportions of nonemergent visits have ranged between 17% and 49%. One study looked at primary care—sensitive (PCS) visits (ie, emergent visits that are potentially avoidable and nonemergent and primary care–treatable visits) and found that up to 50% of ED visits were PCS in a statewide all-payer claims database with 92% of ED visits classified. 12

Evidence for the validity of the NYU-EDA has grown over 2 decades. Emergent visits were associated with total charges and increased likelihood of death and inpatient hospitalization directly from the ED and within 30 days from a previous visit. 10,13-15 However, researchers and emergency medicine clinicians have cautioned against using visit classifications based solely on discharge diagnoses for interventions aimed at reducing unnecessary visits or for denying payment. First, underlying differences in morbidity and access to care may, to some degree, account for utilization patterns that would be detected by an ED visit classification algorithm. Second, there are reasons for visits on the individual level that may be appropriate for ED utilization, which can differ from discharge diagnoses that categorize the encounter as nonemergent. For example, patients who are experiencing chest pain and come to the ED for evaluation are not necessarily inappropriately using the ED. ED visit classifications are useful tools for understanding the healthcare needs of populations, not the medical needs of individual patients. 16-19

A team of Johns Hopkins University (JHU) emergency medicine physicians and health services researchers has further updated and expanded the NYU-EDA using their best clinical judgment and diagnosis aggregations from the Adjusted Clinical Groups (ACG) System. 20 In this revised JHU version of the NYU-EDA (or NYU/JHU-EDA for short) we undertook 3 significant modifications and improvements to the original version and updates undertaken by other teams. First, rather than assigning ICD codes probabilistically, we classify each ED visit into 1 of 11 categories. Second, rather than placing all injuries into 1 category, we subcategorize injuries into 3 severity levels: nonsevere injuries, severe injuries, and severe injuries that are likely to require inpatient admissions. Third, we significantly expand the classification of ICD codes.

In this article, we describe the updated NYU/JHU-EDA, and, using data from a federal survey of US hospital EDs and a large claims database from multiple health plans, we compare results of our revised tool with the original NYU-EDA and 2 earlier modifications developed by Johnston et al and Ballard et al. 2,13

The first objective of this article is to offer a description and first-stage assessment of our ED classification algorithm. The second goal is to use this methodology to offer an account of use patterns of American EDs based on a representative sample of patients visiting hospital EDs and a large national sample of health plan enrollees. In addition to describing our new measurement tool, our analysis adds to the literature on how Americans use EDs and will offer insights into how health plans and other organizations might use classification algorithms to gain an understanding of how populations make use of hospital EDs.

Review of Previous Approaches for Classifying ED Visits

The original NYU-EDA first classifies common primary ED discharge diagnoses as having varying probabilities of falling into each of the 4 following categories: (1) nonemergent; (2) emergent, primary care treatable; (3) emergent, ED care needed, and preventable or avoidable with timely and effective ambulatory care; and (4) emergent, ED care needed, and not preventable. 1 The original NYU system categorizes certain diagnoses separately and directly into 5 additional categories: injuries, psychiatric conditions, alcohol related, drug related, or unclassified.

The adaptation by Ballard et al sums the NYU-EDA probabilities for nonemergent and emergent primary care—treatable visits and compares this sum with the total probability of the emergent, ED care needed categories. 13 Depending on the larger of the 2 resultant likelihoods, visits are classified as nonemergent or emergent, or as intermediate when there is an equal probability of being nonemergent or emergent. The Ballard et al method classifies visits into 1 of 8 categories, which have been shown to be a good predictor of subsequent hospitalization and death within 30 days of an ED visit. 13

After 2001, the NYU-EDA was not updated, and newly added diagnosis codes were not classified. In 2018, Johnston and colleagues identified new codes that are “nested” within previously classified diagnoses and applied the original probabilistic weights to these codes. 2 New diagnoses that remained unclassified were “bridged” to already weighted codes using ICD -based condition groupings from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Clinical Classification System. 21 Instances in which a new diagnosis mapped to several codes with different weights were resolved in favor of a code most likely to represent an unavoidable emergent visit. 2 Because assigned weights sum to 1, both the original NYU-EDA and the update by Johnston et al describe a collection of ED visits by averaging weights.

We took a different approach to update, enhance, and expand the NYU-EDA method. We did not use probabilities but rather assigned primary discharge diagnoses to single classes and uniquely classified each ED visit. For codes that had been previously included in the original NYU-EDA, we based our updated assignments on the category with the highest probability. We resolved cases of equally high probabilities among multiple categories by giving preference to the emergent, ED care needed category.

Data Sources

To build our revised methodology, we combined ED encounter data from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS) from the period of 2009 to 2013. We used data from the 2014 survey for validation. 22 The reason for an ED visit is present in NHAMCS data and contained mainly signs and symptom diagnoses, but it was not present in claims. We used discharge diagnoses only and thus retained a key characteristic of the NYU-EDA and previous revised versions. Second, we extracted hospital ED claims from a large health insurance plan database. We obtained health plan claims data from QuintilesIMS (Plymouth Meeting, Pennsylvania [on November 6, 2017, the name of the organization changed to IQVIA]). The claims extract spanned the same time period (2009-2013) and included 14 commercial health plans; 6 of these plans also had Medicaid and Medicare managed care enrollees. The database consisted of patient enrollment data, ICD-9-CM diagnoses, hospital revenue center codes, procedures coded with Current Procedural Terminology (CPT), and plan-allowed amounts for medical services.

Following the literature, we identified ED visits in the claims database through the presence of revenue center codes (0450-0459, 0981) and CPT codes for evaluation and management (EM) services in the ED (99281-99285). 23,24 We resolved instances in which facility and professional claims indicated different primary diagnoses by prioritizing facility bills. Our rationale for giving diagnoses on facility bills priority over professional bills for the same visit is that facility bills relate more closely to the final discharge record, whereas some professional claims may contain preliminary diagnoses.

Development of the NYU/JHU EDA

We applied the Johns Hopkins ACG system to help categorize diagnoses that were not included in the original NYU-EDA method. The system assigns diagnoses found in claims or encounter data to 1 of 32 Aggregated Diagnosis Groups (ADGs) (ie, morbidity types with similar expected need for healthcare resources). 25,26 The ACG system also maps diagnoses to 1 of 282 Expanded Diagnosis Clusters (EDCs) (ie, clinically homogeneous groups of diagnoses).

To help expand the scope of the NYU-EDA visit classification to more diagnoses, we formed “clinical classification cells” for ICD codes falling within combinations of ADGs and EDC clusters. Each unique cell was reviewed and categorized by our clinician team of 3 practicing emergency physicians (K.P., D.M.R, and Dr Alan Hsu).

For classification cells with ICD codes that were not previously classified with NYU-assigned probabilities, 2 of our clinicians independently assigned an ED visit class. After differences among approximately 35% of all manual assignments were reconciled and finalized by the third clinician, we developed majority class assignments for the remaining diagnoses within classification cells. Relatively uncommon diagnoses within cells that contained only codes without any original NYU-EDA weights or any manually assigned diagnosis remained unclassified. Using this approach, our NYU/JHU-EDA currently classifies 10,723 ICD-9-CM and 74,329 International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification ( ICD-10-CM ) codes ( eAppendix Tables 1 and 2 [ eAppendix available at ajmc.com ] provide examples of common ICD codes in each NYU/JHU-EDA category).

To help us assign severity levels to ACG-based classification cells consisting of injury-related diagnoses, we used CPT codes for EM services associated with ED visits and further assessed whether visits resulted in an inpatient admission. EM codes classify severity from minor (99281) to high with immediate threat to life or physiologic function (99285). We counted the number of nonsevere injury visits (99281-99283) and the number of severe injury visits (99284, 99285) in our health insurance claims data sets. Based on the larger of the 2 counts, each of our injury diagnosis clusters was classified as being either nonsevere or severe. A subset of severe injury visits was identified as likely to require inpatient hospitalization based on a greater than 50% likelihood of cases being admitted. All injury ICD clusters that were so assigned into 1 of 3 severity levels underwent a final clinical review by our clinician team. A graphic overview of the final classification categories of our revised NYU/JHU-EDA grouping taxonomy is presented in the Figure .

Statistical Analysis

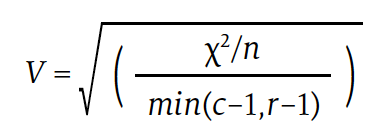

We conducted pairwise comparisons of visit distributions among the 4 EDA versions applied to NHAMCS and health plan data and computed Cramér’s V measure of association. Cramér’s V is a number between 0 and 1 that indicates how strongly 2 categorical variables are associated. It is based on Pearson’s χ 2 statistic and computed as follows:

Download PDF: A Revised Classification Algorithm for Assessing Emergency Department Visit Severity of Populations

Commonwealth Fund Report Details Pervasive Racial and Ethnic Disparities in US Health Care, Outcomes

Using 25 health system performance indicators, the Commonwealth Fund 2024 State Health Disparities Report evaluated racial and ethnic disparities in health care and health outcomes both within and across US states and highlighted the urgent need for equitable health care policies and practices in the US.

Health Equity Conversations: Managing Underserved Communities and Value-Based Payment

On this episode of Managed Care Cast, we feature several leaders in diversity, equity, and inclusion advancing health equity in their respective organization’s policy and practice initiatives.

Institutional Practices for Charitable Medication Access for Uninsured Patients

Analysis of a patient sample enrolled in charitable care at an academic medical center revealed that chronic medications were variably filled at a significant cost.

Health Equity Conversations: Barriers to Equitable Care

Trends in Low-Value Cancer Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Among adults with newly diagnosed cancer, rates of low-value cancer services persisted throughout the COVID-19 pandemic in areas ranging from peridiagnosis imaging to end-of-life care.

Impact of Care Coordination on 30-Day Readmission, Mortality, and Costs for Heart Failure

Enhancing coordination of care has the potential to increase the value of heart failure care.

2 Commerce Drive Cranbury, NJ 08512

609-716-7777

- What Sets It Apart

- Applications

- Global Usage

- License Types

- News & Announcements

- ACG System Knowledge Base

- Resource Library v13.0

- System Documentation

- Bibliography

- User Conferences

- Meet the Team

- Barbara Starfield

- Update / SIgnout

- 2009 Conference Presentations

- 2010 ACG Conference

- 2010 London Symposium

- 2011 Asia Pacific Conference

- 2012 ACG Conference

- 2012 Avignon PCSI

- 2012 London Symposium

- 2013 Perdido Beach

- 2013 WONCA Prague Conference

- 2014 JHU International ACG User

- 2014 London Symposium

- 2015 AcademyHealth Award

- 2015 Hartford Training

- 2016 ACG Conference San Diego

- 2017 London Symposium

- 2017 Puerto Rico Training Conference

- 2017-2018 Webinar Series

- 2018 International Conference San Antonio

- 2018 Leicester Symposium

- 2019 Indian Wells Training

- 2019 London Symposium

- ACG System 10.0.1i Download

- ACG System 9.0i Download

- ACG System Public Documentation

- ACG System x.xi Mapping Files 1

- ACG® System Tutorial Video Library

- Case Studies

- Download The ACG System Software (Non-USA)

- Download The ACG System Software v12.0

- Download The ACG System Software v12.1

- Presentations

- Public Access

- Readmissions White Paper

- System Downloads

- Training Material

- Version 10.0

- Version 10i Training

- Version 11.0

- Version 11.1

- Version 11.2

- Version 12.0

- Version 12.1

- Version 8.2 – 8.2i

- Version 9.0

- White Papers

- Sort Results By Newest Oldest Alphabetical Popularity

Register for access to ACG System website content, newsletter & other communications

POPULATION HEALTH ANALYTICS

A plan of action to reduce avoidable ed visits, june 1st, 2021 | emergency department classification | population health management & improvement.

In our latest blog series, we’ll be taking a look at how the ACG System’s suite of tools can be used to understand emergency department (ED) visits and in turn, optimize health care utilization and reduce potential costs.

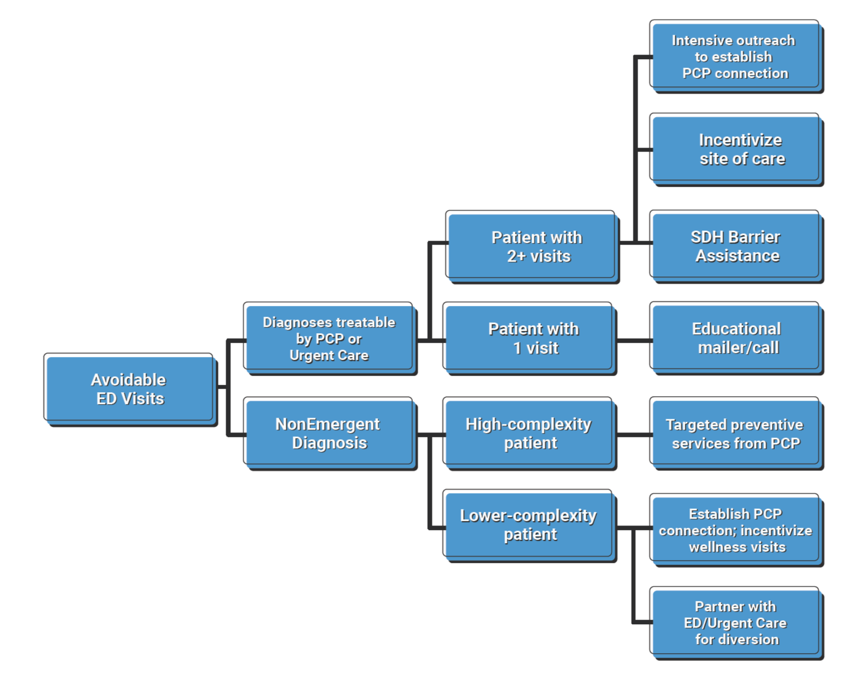

If you read last week’s blog , you know that the ACG System can reveal specific trends in ED visits for a certain population, specifically, patients who visited for non-emergent care or primary care (PCP) treatable conditions. By drilling down into this data, ACG System users can understand root causes of ED use and segment patients into groups depending on their unique health care needs. With this information in hand, System users can develop an effective strategy to reduce ED use and associated health care costs.

Following a detailed, ACG-driven analysis and plan, System users can use granular patient-level outputs to develop and deploy tactics to reduce potentially-avoidable ED visits. Patients with multiple ED visits for PCP-treatable diagnoses may benefit from outreach from their PCP, or assistance locating and working with a PCP if they do not have an existing relationship. The organization may wish to assess systemic access barriers as well, such as transportation challenges, PCP office hours/appointment availability, or prohibitively high co-pay for a PCP visit.

Another impactable patient group are those visiting ED departments for non-emergent diagnoses. ACG System users can identify and target relatively healthy patients (those with lower RUB* levels, for instance) with educational campaigns and incentives for PCP visits. Likewise, individuals with more complex needs, multiple chronic conditions, or care coordination challenges (RUB 4 or 5) can be directed to targeted preventive services and guidance from their PCP. The ability to tailor a specific approach to a specific group of patients maximizes impact while meeting patient-specific care needs.

The diagram below shows how the ACG System can segment a general set of data (avoidable ED visits) into its various, specific components. With each level of segmentation, the data filters into more and more precise groups, who can be targeted for specific interventions.

Ultimately, when ACG System users understand causes and trends in ED use at this granular level, they can proactively target patients with potentially-avoidable visits and deploy interventions to reduce avoidable ED use. The result? Improved access to PCPs and lower unnecessary ED visits.

*RUB = Resource Utilization Band, a category of expected health (care need as defined by the ACG System (1 = low; 5 = high)

Want to take an even deeper dive into how the ACG System can help classify your ED visit data? Read a case study from Israel’s Clalit Health Services here.

Sign up for blog alerts and other insights from the ACG System team

- Hidden Name

- First Name *

- Last Name *

- Organization Name *

- Market Segment Other Employer Government / public sector Health Care Provider Health Insurance Plan IT / analytics Pharmaceutical Company Research Institution

- Hidden Compliance

- Hidden Owner ID (Alan)

- Hidden Owner ID (John)

- Hidden Lead Product

- Hidden Lead Source ACG Website

- Send me emails, blog alerts and other insights about population health analytics

- Contact me about how the ACG System can benefit my organization.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

- Name This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

April 11th, 2024

March 14th, 2024, february 15th, 2024, january 18th, 2024, november 30th, 2023.

Copyright 2024, The Johns Hopkins University. All rights reserved.

© The Johns Hopkins University, The Johns Hopkins Hospital, and Johns Hopkins Health System. All rights reserved. Terms of Use Privacy Statement

Avoidable emergency department visits: a starting point

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Emergency Medicine, University of California at San Francisco, 1001 Potrero Ave, 1E21, San Francisco, CA 94110, USA.

- 2 Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies, University of California at San Francisco, 3333 California St, San Francisco, CA 94118, USA.

- PMID: 28992158

- DOI: 10.1093/intqhc/mzx081

Objective: To better characterize and understand the nature of a very conservative definition of 'avoidable' emergency department (ED) visits in the United States to provide policymakers insight into what interventions can target non-urgent ED visits.

Design/setting: We performed a retrospective analysis of a very conservative definition of 'avoidable' ED visits using data from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey from 2005 to 2011.

Participants: We examined a total of 115 081 records, representing 424 million ED visits made by patients aged 18-64 years who were seen in the ED and discharged home.

Main outcome measures: We defined 'avoidable' as ED visits that did not require any diagnostic or screening services, procedures or medications, and were discharged home.

Results: In total, 3.3% (95% CI: 3.0-3.7) of all ED visits were 'avoidable.' The top five chief complaints included toothache, back pain, headache, other symptoms/problems related to psychosis and throat soreness. Alcohol abuse, dental disorders and depressive disorders were among the top three ICD-9 discharge diagnoses. Alcohol-related disorders and mood disorders accounted for 6.8% (95% CI: 5.7-8.0) of avoidable visits, and dental disorders accounted for 3.9% (95% CI: 3.0-4.8) of CCS-grouped discharge diagnoses.

Conclusions: A significant number of 'avoidable' ED visits were for mental health and dental conditions, which the ED is not fully equipped to treat. Our findings provide a better understanding of what policy initiatives could potentially reduce these 'avoidable' ED visits to address the gaps in our healthcare system, such as increased access to mental health and dental care.

Keywords: avoidable; emergency care; emergency department; health policy; healthcare system; non-urgent; setting of care.

© The Author 2017. Published by Oxford University Press in association with the International Society for Quality in Health Care. All rights reserved. For permissions, please e-mail: [email protected]

- Alcoholism / epidemiology

- Emergency Service, Hospital / statistics & numerical data*

- Health Care Surveys

- Middle Aged

- Mood Disorders / epidemiology

- Patient Discharge / statistics & numerical data*

- Retrospective Studies

- Stomatognathic Diseases / epidemiology

- United States

- HEDIS Measures and Technical Resources

- Emergency Department Utilization

Emergency Department Utilization (EDU)

Assesses emergency department (ED) utilization among commercial (18 and older) and Medicare (18 and older) health plan members. Plans report observed rates of ED use and a predicted rate of ED use based on the health of the member population. The observed and expected rates are used to calculate a calibrated observed-to-expected ratio that assesses whether plans had more, the same or less emergency department visits than expected, while accounting for incremental improvements across all plans over time. The observed-to-expected ratio is multiplied by the emergency department visit rate across all health plans to produce a risk-standardized rate which allows for national comparison.

Why It Matters

ED visits are a high-intensity service and a cost burden on the health care system, as well as on patients. Some ED events may be attributed to preventable or treatable conditions . A high rate of ED utilization may indicate poor care management, inadequate access to care or poor patient choices, resulting in ED visits that could be prevented. 1,2 Plans can ensure that members receive appropriate, coordinated primary care to address preventable ED visits.

Results – National Averages

Emergency department utilization total rate.

*Lower rates signify better performance.

§ Not available due to CMS suspension of data reporting during COVID-19 pandemic.

This State of Healthcare Quality Report classifies health plans differently than NCQA’s Quality Compass. HMO corresponds to All LOBs (excluding PPO and EPO) within Quality Compass. PPO corresponds to PPO and EPO within Quality Compass.

Figures do not account for changes in the underlying measure that could break trending. Contact Information Products via my.ncqa.org for analysis that accounts for trend breaks.

- Dowd, B., M. Karmarker, T. Swenson, et al. 2014. “Emergency department utilization as a measure of physician performance.” American Journal of Medical Quality 29 (2), 135–43. http://ajm.sagepub.com/content/29/2/135.long

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2015. Measures of Care Coordination: Preventable Emergency Department Visits. Accessed at https://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/chartbooks/carecoordination/measure2.html

Save your favorite pages and receive notifications whenever they’re updated.

You will be prompted to log in to your NCQA account.

Share this page with a friend or colleague by Email.

We do not share your information with third parties.

Print this page.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

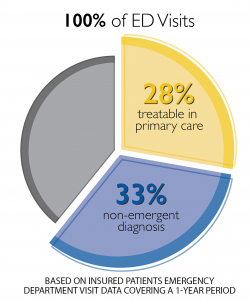

ED visits for conditions that are preventable or treatable with appropriate primary care lower health system efficiency and raise costs ( Enard & Ganelin, 2013 ). An estimated 13% to 27% of ED visits in the United States could be managed in physician offices, clinics, and urgent care centers, saving $4.4 billion annually ( Weinick, et al., 2010 ).

The 3M™ Potentially Preventable Emergency Department Visits (PPVs) are a population-based outcome measure that identifies ED visits that could potentially have been prevented with better care in the community. 3M PPVs are not tied to a previous inpatient stay. As one of the 3M™ Population-focused Preventable methodology, 3M PPVs generate actionable insights that help lower costs and ...

For other ED visits deemed avoidable, the reasons may be more complex, including inadequate chronic care management or gaps in care coordination among multiple locations of care. Identifying patients who are already, or potentially high utilizers of the ED may be a good place to start. This is often a small group, and understanding why they use ...

Key Points. Question Has there been a change in potentially preventable emergency department (ED) visits among adult patients with cancer over time?. Findings In this cross-sectional study of 35.5 million ED visits among patients with cancer, 51.6% of visits were identified as potentially preventable. From 2012 to 2019, the absolute number of potentially preventable ED visits among patients ...

People in vulnerable populations — as defined by socioeconomic characteristics — made more preventable visits to emergency rooms than others from 2013 to 2017, according to a U.S. Census Bureau working paper. The study analyzed census data linked with emergency visit records in the state of Utah. It found that factors including lower income ...

In 2010, nearly 1 in 5 visits were determined to be potentially avoidable and contributed $65 billion to rising health care costs and ED overcrowding. 3 The average cost of treating common primary ...

Because of the significance of potentially preventable ED encounters, it is important to identify factors that lead to improper ED utilization ... The means of frequencies of emergent preventable ED visits were also greater for non-Hispanic black patients (p = 0.05) compared to Hispanic patients by 0.37, Asian/Pacific Islander patients by 0.89 ...

ED visits in 11 study hospitals, 21,383 (6.4%) visits were potentially preventable visits. The majority of these vis-its were attributed to Acute ACSC, followed by Chronic ACSC, NTDC, and Asthma. Evaluating specific diagnoses (Table 2), upper respiratory infection was the most common diagnosis, representing almost half of the visits for Acute

Highlights. In 2018, there were 143.5 million emergency department (ED) visits, representing 439 visits per 1,000 population. Fourteen percent of ED visits resulted in hospital admission (61 per 1,000 population). Circulatory and digestive system conditions were the most common reasons for these visits. The majority of ED visits (86 percent ...

anywhere from 30 -70% of ED visits are potentially avoidable. Research studies on avoidable ED visits for specific settings below: • Nursing Homes: Appropriateness of transferring nursing home residents to emergency departments: a systemic review/ January 2019 • Clinic/Office: CMS TCPi Reducing Unnecessary Emergency Department Visits

Avoidable ED visits are also believed to compromise quality of care by contributing to excessive testing and treatment as well as compromising the longitudinal relationship between the patients and the primary care physicians 2, 5. Yet despite the heightened interest in reducing potentially avoidable ED visits, only a handful of studies had ...

Tabriz and colleagues 1 estimated the number of ED visits by patients with cancer that are potentially preventable, using a Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) quality measure definition. 1,2 Using the 2012 to 2019 National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, they estimated that ED visits by patients with cancer increased from 3 ...

ED visits were identified as potentially avoidable based on the primary diagnosis coded on the corresponding paid health insurance claims. Important factors such as the time of day a visit occurred, the patient's access to primary care, and other social determinants of health were not taken into account when identifying which ED visits were ...

In this context, some researchers and analysts use the related concept of PCS visits, which combines the 3 categories of emergent visits that require ED resources but are potentially avoidable ...

Potentially preventable ED visits were identified using the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services definition. The Emergency Severity Index, a triage algorithm that ranks patients based on the urgency of their health care condition, was used to measure the immediacy of ED visits (immediate [most urgent], emergent, urgent, less urgent, and ...

Following a detailed, ACG-driven analysis and plan, System users can use granular patient-level outputs to develop and deploy tactics to reduce potentially-avoidable ED visits. Patients with multiple ED visits for PCP-treatable diagnoses may benefit from outreach from their PCP, or assistance locating and working with a PCP if they do not have ...

Objective: To better characterize and understand the nature of a very conservative definition of 'avoidable' emergency department (ED) visits in the United States to provide policymakers insight into what interventions can target non-urgent ED visits. Design/setting: We performed a retrospective analysis of a very conservative definition of 'avoidable' ED visits using data from the National ...

Some ED events may be attributed to preventable or treatable conditions. A high rate of ED utilization may indicate poor care management, inadequate access to care or poor patient choices, resulting in ED visits that could be prevented. 1,2 Plans can ensure that members receive appropriate, coordinated primary care to address preventable ED visits.

Reducing avoidable emergency department (ED) visits is an important health system goal. This is a retrospective cohort study of the impact of a primary care intervention including an in-hospital, free, adult clinic for poor uninsured patients on ED visit rates and emergency severity at a nonprofit hospital.

Potentially avoidable emergency department (ED) visits. Avoidable emergency department visits can cause clinical risk, stress, and anxiety for older, more vulnerable patients. Overcrowding and surging costs of hospital EDs have long been a concern in Ontario's health care system, and there is a need to address this issue from all angles.

Potentially avoidable ED visits age 65 and older, per 1,000 Medicare beneficiaries ... Potentially avoidable emergency department visits among Medicare beneficiaries age 65 and older per 1,000 beneficiaries. Switch Performance Areas. Select A Performance Area. Access to Health Care. Children. Consumer Insurance and Medical Costs.

Reducing Avoidable Emergency Department Visits and Hospitalization Toolkit. This toolkit provides an overview of a quality improvement process to reduce the frequency of avoidable emergency department (ED) visits and hospitalization. As part of a Quality Assurance and Performance Improvement (QAPI) project, this toolkit provides your team with ...

The table lists typical rates and costs of ED visits and hospitalizations for patients with a history of at least 1 ER visit for each diagnostic condition and a visit to a primary care provider in the past year—the criteria for CHW assignment in the model. Each diagnosis is considered separately.