- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Environment Story Of The Day NPR hide caption

Environment

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

Carnival Cruise Lines Hit With $20 Million Penalty For Environmental Crimes

Merrit Kennedy

Princess Cruise Lines and its parent company Carnival Corporation have agreed to pay a $20 million criminal penalty for environmental violations. Casey Rodgers/AP hide caption

Princess Cruise Lines and its parent company Carnival Corporation have agreed to pay a $20 million criminal penalty for environmental violations.

The cruise line giant Carnival Corporation and its Princess subsidiary have agreed to pay a criminal penalty of $20 million for environmental violations such as dumping plastic waste into the ocean. Princess Cruise Lines has already paid $40 million over other deliberate acts of pollution.

U.S. District Judge Patricia Seitz approved the terms of the deal during a hearing Monday in Miami. She had appeared to grow increasingly frustrated as the company continued to flout environmental laws during the course of the years-long case.

"You not only work for employees and shareholders. You are a steward of the environment," she told Carnival CEO Arnold Donald, who attended the hearing with other senior executives. "The environment needs to be a core value, and I hope and pray it becomes your daily anthem."

The Two-Way

Princess cruises hit with largest-ever criminal penalty for 'deliberate pollution'.

Miami-based Carnival pleaded guilty Monday to six probation violations, including the dumping of plastic mixed with food waste in Bahamian waters. The company also admitted sending teams to visit ships before the inspections to fix any environmental compliance violations, falsifying training records and contacting the U.S. Coast Guard to try to redefine what would be a "major non-conformity" of their environmental compliance plan.

"I sincerely regret these mistakes. I do take responsibility for the problems we had," Arnold told the judge. "I'm extremely personally disappointed we have them. I am personally committed to achieve best in class for compliance."

Carnival has had a long history of dumping plastic trash and oily discharge from its ships, with violations dating back to 1993.

Environmental groups such as Stand.earth say they are tired of seeing the company hit with penalties "that cannot even be characterized as a slap on the wrist."

"Today's ruling was a betrayal of the public trust and a continuation of the weak enforcement that has allowed Carnival Corporation to continue to profit by selling the environment to its passengers while its cruise ships contribute to the destruction of the fragile ecosystems they visit," Kendra Ulrich, a senior shipping campaigner at Stand.earth, said in a statement.

Carnival's Earnings Hit By String Of Cruise Ship Problems

When Princess was fined the $40 million in 2016, the Department of Justice called it "the largest-ever criminal penalty involving deliberate vessel pollution." The company also agreed to plead guilty to seven felony charges for violations on five ships starting as early as 2005.

In 2013, a whistleblowing engineer exposed the illegal dumping of contaminated waste and oil from the company's Caribbean Princess ship. He told authorities that engineers were using a special device called the "magic pipe" to bypass the ship's water treatment system and dump oil waste straight into the ocean. The company also tried to cover up this practice from investigators, according to the Justice Department.

At the time, Princess told NPR that it chalked up the violations to "the inexcusable actions of our employees."

Part of the 2016 plea agreement required ships from eight of Carnival's companies to submit to court-supervised monitoring, which is how the most recent violations were discovered.

Judge Seitz had recently threatened to block Carnival from docking at U.S. ports. She also had requested that the company's senior executives attend Monday's hearing because she said she was convinced they weren't serious about complying with environmental laws.

In addition to the $20 million criminal penalty, Carnival has agreed to pay for 15 annual audits — on top of about three dozen ship and shore-side audits it's already on the hook for — and says it will restructure its corporate compliance efforts. If the company does not meet court-imposed deadlines for that restructuring, it will be fined up to $10 million per day.

- environmental laws

6 Ways Cruise Ships are Destroying the Oceans

Cruise ships are a popular way to travel, offering passengers a chance to visit multiple destinations while enjoying luxurious amenities on board.

However, these massive ships have a significant impact on the environment, particularly the oceans they travel through.

In fact, cruise ships are responsible for a wide range of ocean pollution , from wastewater discharge to oil spills.

Before you book your next cruise, read more below to learn about the harsh reality of the cruise ship industry and its impact on our marine environment.

Table of Contents

Direct Discharge of Waste

Cruise ships generate a significant amount of waste, including air emissions, ballast water, wastewater, hazardous waste, and solid waste. One of the most significant ways cruise ships cause ocean pollution is through the direct discharge of waste into the ocean.

According to a study conducted on Southampton, cruise ships can discharge untreated oily bilge water, which can damage marine life and ecosystems. If the separator, which is usually used to extract oil, is faulty or deliberately bypassed, untreated oily bilge water could be discharged directly into the ocean .

Food waste is another type of waste generated by cruise ships, and it can also be discharged directly into the ocean.

While minimal attention is paid to food waste management by many ships and catering typical of cruise liners, it can still have a significant impact on the environment.

The direct discharge of waste from cruise ships can also include untreated wastewater, which can contain pathogens, nutrients, and other contaminants. This wastewater can be harmful to marine life and ecosystems, and it can also contribute to the growth of harmful algal blooms.

To reduce the impact of direct waste discharge, some regulations have been put in place. However, there is still a need for more stringent regulations and enforcement to ensure that cruise ships do not cause further harm to the ocean and its inhabitants.

Air Pollution from Cruise Ships

Cruise ships are one of the major sources of air pollution in the world. The emissions from these ships have a significant impact on the air quality of the surrounding areas, including coastal cities and ports.

Emission of Greenhouse Gases

Cruise ships emit significant amounts of greenhouse gases, including carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide.

These gases contribute to global warming and climate change. According to a study published in Science Direct, the emissions from cruise ships in the port of Naples, Italy, impacted the air quality of the surrounding areas.

The study found that while cruise ship emissions were not the sole source of air pollution in the port, they did contribute to the overall levels of pollution.

Release of Sulfur Dioxide

Cruise ships also release sulfur dioxide, a harmful gas that can cause respiratory problems and acid rain. According to a study published in Science Direct, the energy consumption and emissions of air pollutants from ships in harbors in Denmark were measured.

The study found that sulfur dioxide emissions from cruise liners were higher than other types of ships, and the emissions were highest when the ships were docked.

To reduce air pollution from cruise ships, some countries have implemented regulations that require ships to use cleaner fuels and technologies.

For example, in 2020, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) implemented new regulations that require ships to use fuels with a lower sulfur content. While these regulations are a step in the right direction, more needs to be done to reduce the impact of cruise ship emissions on air quality.

Cruise Ships and Oil Spills

Cruise ships are a significant source of oil pollution in the ocean. Accidental oil spills from cruise ships can cause significant harm to marine life and the environment.

According to a study published in the Journal of Marine Pollution Bulletin, cruise ships have the potential to contribute to accidental oil spills due to their large size and the amount of fuel they carry [1] .

One of the main sources of oil pollution in the ocean is from cruise ships. In a study conducted in Ha Long Bay, Vietnam, it was found that oil spills from sunken cruise boats were responsible for more than 60% of biodiesel and petroleum diesel spills in the area [2] .

The impact of oil spills from cruise ships can be devastating to marine life and the environment. Oil spills can harm marine mammals , fish, and birds, and can also impact coastal habitats and beaches.

In a study published in the Journal of Environmental Science and Pollution Research, it was found that oil spills can cause both short-term and long-term damage to marine ecosystems [3] .

To prevent oil spills from cruise ships, it is essential to have proper regulations and management in place. Alaska’s Commercial Passenger Vessel Compliance Program has been cited as a model for other states to follow.

The program has implemented strict regulations for cruise ships to prevent oil spills and protect the environment [4] .

Impact on Marine Life

Cruise ships are known to cause significant harm to marine life due to their pollution. The following sub-sections describe how noise pollution and destruction of coral reefs are two ways that cruise ships impact marine life.

Noise Pollution

Noise pollution from cruise ships can have a significant impact on marine life, particularly on species that rely on sound for communication, navigation, and hunting.

Noise pollution can cause hearing loss, stress, and behavioral changes in marine animals, which can ultimately lead to decreased reproduction rates and population decline.

Destruction of Coral Reefs

Cruise ships contribute to the destruction of coral reefs in several ways, including anchoring, sewage discharge, and the release of chemicals.

Anchoring can cause physical damage to coral reefs , while sewage discharge and chemical releases can lead to water pollution, which can harm coral and marine life.

In addition, the large amount of waste generated by cruise ships can cause nutrient imbalances in the water, leading to the growth of harmful algae that can suffocate and kill coral reefs.

Cruise Ships and Plastic Pollution

Cruise ships are notorious for generating a significant amount of plastic waste, which is a major contributor to ocean pollution.

Single-use plastics: Cruise ships are known for providing passengers with single-use plastics such as straws, cups, and cutlery. These items are often used once and then discarded, contributing to the plastic waste that ends up in the ocean.

Packaging waste: In addition to single-use plastics, cruise ships generate a significant amount of packaging waste from items such as food and beverage containers, toiletries, and souvenirs.

Improper waste management: Despite regulations and guidelines for waste management, some cruise ships still dispose of plastic waste improperly, either by dumping it into the ocean or by not properly recycling it.

Graywater contamination: Cruise ships generate a significant amount of graywater, which can contain microplastics from sources such as laundry detergents and personal care products. This contaminated water can be discharged into the ocean, contributing to plastic pollution .

Dumping of garbage: Some cruise ships have been caught illegally dumping garbage, including plastic waste, into the ocean. This not only contributes to plastic pollution but also violates international laws and regulations.

Lost or discarded fishing gear: Cruise ships may accidentally or intentionally lose or discard fishing gear, such as nets and lines, which can entangle and harm marine life.

Port pollution: Cruise ships generate plastic waste not only while at sea but also while in port. This can contribute to plastic pollution in the surrounding waters and on nearby beaches .

Sewage Dumping from Cruise Ships

Cruise ships generate a significant amount of sewage waste, which is often disposed of in the ocean.

The untreated sewage contains harmful pathogens and bacteria that can cause health problems for marine life and humans.

Volume of sewage: A single cruise ship can generate up to 1 million gallons of sewage waste per week. This volume of waste can cause significant damage to marine ecosystems if not properly treated and disposed of.

Untreated sewage: Many cruise ships discharge untreated sewage directly into the ocean, which can contain harmful bacteria and pathogens. This untreated sewage can cause health problems for marine life, including fish, dolphins, and whales , and can also pose a risk to humans who come into contact with contaminated water.

Marine life impact: The discharge of sewage waste can have a significant impact on marine life, including coral reefs, fish, and other sea creatures . The high levels of nitrogen and phosphorus in the sewage can cause harmful algal blooms, which can suffocate marine life and cause dead zones in the ocean.

Beach pollution: Sewage waste from cruise ships can wash up on beaches, causing pollution and health risks for beachgoers. The sewage can contain harmful bacteria that can cause skin infections, respiratory problems, and other health issues.

Illegal dumping: Despite regulations prohibiting the discharge of untreated sewage waste within certain distances from shore, some cruise ships continue to illegally dump sewage waste in the ocean. This illegal dumping can cause significant damage to marine ecosystems and pose health risks for humans.

Limited treatment facilities: Many ports of call do not have the necessary treatment facilities to properly treat sewage waste from cruise ships. This can lead to the discharge of untreated sewage waste into the ocean, causing pollution and health risks for marine life and humans.

Inadequate regulations: The regulations governing the disposal of sewage waste from cruise ships are often inadequate, with many countries having no regulations in place to protect marine ecosystems and human health. This lack of regulation can lead to the discharge of untreated sewage waste into the ocean, causing pollution and health risks for marine life and humans.

Cruise ships contribute significantly to ocean pollution through the dumping of sewage waste. It is essential that proper regulations and treatment facilities are put in place to protect marine ecosystems and human health.

Frequently Asked Questions

How do cruise ships contribute to ocean pollution.

Cruise ships contribute to ocean pollution in many ways. They generate large amounts of waste, including sewage, gray water, and solid waste, which can contain harmful chemicals and pathogens.

They also emit air pollution, including sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, and particulate matter, which can harm human health and the environment.

Additionally, cruise ships can damage marine ecosystems through activities such as anchoring, dredging, and discharging ballast water.

What are the main types of pollution caused by ships?

The main types of pollution caused by ships are air pollution, water pollution, and noise pollution. Air pollution is caused by emissions from ship engines and includes sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, and particulate matter.

Water pollution is caused by discharge of untreated sewage, gray water, and ballast water, which can contain harmful chemicals and pathogens. Noise pollution is caused by ship engines, which can disrupt marine ecosystems and harm marine mammals.

What are some of the environmental impacts of cruise ships?

Cruise ships can have a range of environmental impacts, including damage to marine ecosystems, harm to marine mammals, and contribution to climate change.

They can also affect local air and water quality, and contribute to the spread of invasive species .

What is the impact of cruise ship emissions on air and water quality?

Cruise ship emissions can have a significant impact on air and water quality. Air pollution from ship engines can harm human health and contribute to climate change.

Water pollution from untreated sewage, gray water, and ballast water can harm marine ecosystems and contaminate local water sources.

How can we reduce the pollution caused by cruise ships?

There are several ways to reduce the pollution caused by cruise ships. These include using cleaner fuels, such as liquefied natural gas, improving waste management practices, and implementing technologies that reduce air and water pollution.

Additionally, regulations and policies can be put in place to limit the environmental impacts of cruise ships.

What are the long-term consequences of cruise ship pollution on marine life and ecosystems?

The long-term consequences of cruise ship pollution on marine life and ecosystems can be significant. Pollution can harm marine mammals, disrupt food chains, and damage coral reefs and other sensitive habitats.

Additionally, pollution can contribute to the spread of invasive species, which can have long-term impacts on local ecosystems.

Add comment

Cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

You may also like

Over 1000 Abandoned Lobster Traps Removed From Long Island Sound

Critically Endangered Dolphin Contain Record High Levels of “Forever Chemicals” PFAS

Scientists Say Sea Turtles Will Be Plagued By Plastic Forever

Dolphins and Manatees Poisoned in Miami’s Biscayne Bay, Authorities Investigating

Heavy Metal Pollution is Causing Sea Turtles to Be Born Female

Scientists Find the Best Strategy for Tackling the Plastic Pollution in the Ocean

Latest articles.

- What’s the Difference Between Seaweed and Seagrass?

- Hilarious Video Shows How Dolphins Use Pufferfish to Get High!

- The Tallest Bridge Ever Built: A Marvel of Modern Engineering

- Are There Sharks in the North Sea?

- The Largest Lake in the World Isn’t What You Think

- Are There Sharks in Lake Washington?

About American Oceans

The American Oceans Campaign is dedicated primarily to the restoration, protection, and preservation of the health and vitality of coastal waters, estuaries, bays, wetlands, and oceans. Have a question? Contact us today.

Explore Marine Life

- Cephalopods

- Invertebrates

- Marine Mammals

- Sea Turtles & Reptiles

- Sharks & Rays

- Shellfish & Crustaceans

Copyright © 2024. Privacy Policy . Terms & Conditions . American Oceans

- Ocean Facts

Here's how the 'world's largest cruise ship' recycles millions of pounds of water, food and waste

- Royal Caribbean's Symphony of the Seas has a high-tech recycling system.

- The Symphony of the Seas is a 361-meter — nearly 1,200 feet — cruise liner.

- The ship's crew can process up to 13,000 pounds of glass in a week-long cruise.

Cruise ships produce a lot of trash, but there are no garbage trucks to come and pick up waste when they're out at sea. So, where does all the garbage go?

The Symphony of the Seas is one of the largest cruise ships in the world. Built-in 2018, the Royal Caribbean ship is 1,188 feet long and weighs a total of 228,081 gross tons, according to the cruise line .

Waste disposal is a problem cruise lines have been dealing with for years.

Princess Cruise Lines was fined $40 million in 2016 after pleading guilty to seven felony charges for illegally dumping oiled waste into the sea, according to The New York Times .

In 2019, a federal judge ordered Carnival Cruise Lines to pay $20 million in fines for dumping plastic waste into the ocean and other environmental violations, NPR reported .

Cruise lines started designing ways to purify water and handle waste inside their ships.

Stewart Chiron, a cruise ship expert, told Insider that Carnival Cruise Lines issues "really brought the need for better technology so that she ships can operate more efficiently."

"Up until now, the options weren't available," Chiron said.

Cruise ships are notorious for disposing of waste in ways that are hazardous to the environment. In 2019, cruise ships dumped more than 3 million pounds of garbage in Juneau, Alaska, according to Alaska Public Media.

Carnival Cruise Lines' Symphony of the Seas is a "zero landfill ship," which means it uses recycling and water filtration to deal with its own waste.

Alex Mago, environmental officer for the Symphony of the Seas, told Insider that the waste management team separates the ship's trash into recyclables on a lower deck.

The ship's crew is made up of around 2,200 crew members, according to Royal Caribbean .

The ship's crew separates glass into colors and can process up to 13,000 lbs of glass for a week-long cruise.

Each one of the ship's 36 kitchens has a suction drain.

Food waste from Royal Caribbean cruises is dropped no less than 12 miles from land, according to the company's waste management guidelines .

"Food waste produced on board is sent to a pulper and pulverized to less than 25 mm, as per international standards, and discharged no closer than 12 nautical miles from land," the guidelines state.

Food waste is carried through a giant pipe to a food processor at the bottom of the ship, where it is incinerated.

The ship's crew crushes around 528 gallons of water bottles per week.

The ship is dependent on water bottles because cruise ships are not allowed to have water fountains for health and safety reasons.

Cardboard and aluminum cans are sent through a bailer.

The Symphony of the Seas has two incinerator rooms.

The ship's incinerator room has two incinerators and is manned around the clock by 10 crew members.

Cubes of aluminum trash are stored in a refrigerator to prevent the smell from spreading to other parts of the ship for up to seven days.

Grey water, from sinks, laundries, and drains and black water, from toilets, are mixed together in a water purification system before being dumped back into the sea.

The purification system runs several cleansing processes until the water is above the United States federal standard.

When the ship docs in Miami, the plastic, paper, and glass are offloaded to go to partner recycling facilities.

According to Royal Caribbean , the company recycled more than 14 billion pounds of waste in 2021.

See more about this story below

- Main content

Matador Original Series

Where Does the Waste Go on Cruise Ships, and Is It Really Sustainable?

D on’t pretend it hasn’t crossed your mind. When you flush a cruise ship toilet and hear that rapid, louder-than-usual whooshing sound, you wonder as you stare at the empty bowl … “where does it all go?” On land, we have all kinds of easy explanations. We have sewer systems that pump to sewage treatment plants where the waste is processed and treated. But at sea, when you may not be making landfall for days, what happens to it?

You wander out of the bathroom and onto your private balcony, where you sit and stare out at the vast sea. Then it hits you. “What about everything else?” It’s not just human waste that seemingly has nowhere to go in the middle of the ocean, but food waste, plastic waste, and pretty much everything else we mindlessly toss in the trash. There are no dumpsters around the corner, no recycling plants nearby. How do cruise ships dispose of waste in a sustainable manner, so that doesn’t do irreparable harm to the environment?

Nothing that’s human-made in this world is 100 percent sustainable. That said, as public attention to sustainability efforts across all industries has increased, cruise ships have implemented a number of sophisticated treatment and recycling programs for everything from sewage and organic waste to landfill diversion in order to minimize the environmental impact of leisure on the water.

How waste disposal actually works

First of all, before we start talking about getting rid of waste — what happens to it on the ship? It has to be stored somewhere until it’s ready to be discharged, after all.

“Human waste is processed through our advanced wastewater treatment system,” Sarah Dwyer, Sustainability Program Manager for Virgin Voyages , tells Matador Network . “This system processes all blackwater (toilets), greywater (sinks and showers), laundry water, galley greywater, and food waste reject water to comply with MARPOL (International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships) regulations.”

The process is similar on Uniworld Boutique River Cruises although waste storage on a smaller river ship will differ somewhat from storage on a huge ocean liner.

“Human waste is collected in a tank (with a bacteria system) and this is emptied regularly, depending on where the ships are docked and whether we have access to the local sewerage system or if we have an external company coming to pump it out,” Julie Higgins, Sustainability Officer for Uniworld Boutique River Cruises, tells Matador Network . “For food waste, each ship has a geographical partner that either collects the food waste for animal feed or uses it for biofuel creation. These pickup points are fixed according to each itinerary.”

It’s not exactly surprising that cruise ships have pretty well-developed and intricate methods of getting rid of their waste. On Uniworld, both collection and offloading are more frequent, given the closer proximity of port.

Food waste is “collected by various companies, while human waste is collected in tanks on board each ship and then disposed of either directly into the city or town sewerage system,” Higgins says. “Otherwise, we have companies that come and collect it from our tanks when this is not possible depending on port facilities.”

As for larger ships like those operated by Virgin Voyages, waste must be discharged a certain distance from shore, or stored in a special recycling center for offloading.

“For our advanced wastewater treatment process, effluent (liquid waste or sewage) is held on board and then discharged at distances greater than three nautical miles from shore,” Dwyer says. “Food waste is either pulverized and discharged (12 nautical miles from shore and at a speed greater than six knots), or it’s stored in our waste recycling center to be offloaded in port.”

Is waste disposal actually sustainable?

The big complaint facing cruise lines is the issue of sustainability. From carbon emissions to how waste impacts the surrounding ecosystem, there are very real concerns about the impact cruises have on the ocean. That’s why environmental regulations are tighter than ever, and cruise lines have implemented strict treatment methods to limit any harm done by waste disposal.

“Our advanced wastewater treatment system is calibrated to meet stringent water quality standards under MARPOL and the US Clean Water Act,” Dwyer says. “Our crew ensures that our vessels are in compliance with the the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System and Vessel General Permit, which are monitored by the Environmental Protection Agency.”

What does this actually mean? Well, everything from wastewater treatment methods to offloading strategies that divert waste from landfills.

“Our wastewater is treated by the bacteria within our tanks on board, which forms something we call ‘sludge,’” Higgins says. “We then dispose of this ‘sludge’ responsibly … over the years we have formed a reliable network that allows us to dispose in a responsible manner and not pollute the areas we sail through.”

The most visible part of Virgin Voyages’ sustainability program is its reduction of single-use plastics on board, as well as incorporating more sustainable materials for its passengers. From banning plastic utensils to using reusable food containers in restaurants, the goal is to limit how much non-recyclable waste is even produced in the first place.

“We collect and sort recyclable waste on board, which is then offloaded in our primary ports such as Miami,” Dwyer says. “We also have a recycling takeback program from our beach club operation in Bimini (Bahamas) to limit recyclable materials that would otherwise be sent to the landfill. We also vet the waste providers that we partner with on-shore to ensure waste is handled appropriately.”

In an industry that’s inherently not known for sustainability, it’s clear that cruise lines do all they can to reduce their environmental impact. But is it enough?

The impact of waste disposal on the ocean

While many cruise lines take sustainability seriously and ensure their waste management systems are up to code, that’s not always the case, resulting in harmful pollutants entering the ocean.

“Several cruise ships still use scrubber technology, which discharges a toxic cocktail of petroleum byproducts from ships directly into the ocean with little to no treatment,” Marcie Keever, Oceans Program Director at Friends of the Earth , tells Matador Network . “The ICCT (International Council on Clean Transportation) estimates that in one year, ships worldwide will emit at least 10 gigatons of scrubber wastewater, approximately 15 percent of which comes from the cruise industry.”

She also believes more oversight is needed to ensure the cruise industry’s sustainability standards are as strict as they should be. And indeed, however strict those regulations might be, without proper oversight, the rules themselves (if frequently broken) are irrelevant.

“The cruise industry remains a major contributor to air and ocean pollution, repeatedly failing health compliance and environmental tests,” she claims. “At the federal level, Homeland Security and the EPA provide little regulation enforcement and no oversight on wastewater discharge or public health, even though cruise ships continue to be a major spreader of harmful pathogens like COVID-19.”

Indeed, Carnival was fined in 2019 for dumping waste into the ocean. Apart from ocean water, Keever notes cruise ports themselves are also a serious victim of cruise ship waste.

“One community in Alaska fought hard against the industry after being filled with trash and sewage from ships,” she says. “In addition, carbon emissions from ships harm the places where they dock. Friends of the Earth is working to help ports electrify to reduce carbon emissions and improve air quality for surrounding communities.”

More like this

Trending now, learning the importance of opening up on a new wellness cruise that partnered with deepak chopra, 10 things i loved (and hated) about my first big-ship cruise, the cheapest ways to get your laundry done during a cruise, this cruise line started its own traveler book club, and you can join for free, this world cruise to 140 countries will set you back as much as $839,999, discover matador, adventure travel, train travel, national parks, beaches and islands, ski and snow.

Press Releases

Royal caribbean group transforms waste management in the cruise industry, helping protect the oceans.

MIAMI – July 11, 2023 – Royal Caribbean Group (NYSE: RCL) is building on its industry-leading waste management practices by introducing the next generation of technology to make its way to the high seas. These tools, from waste-to-energy systems, food waste applications and an expanded network of green hubs, are a result of the cruise company’s relentless drive to deliver the best vacation experiences responsibly.

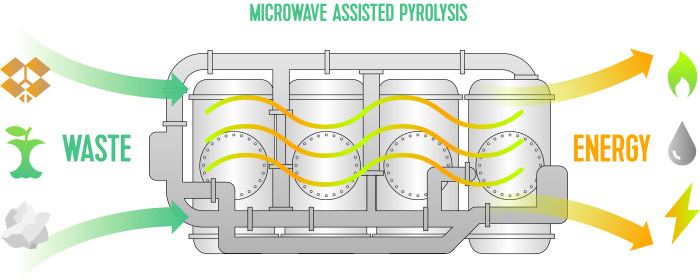

Debuting this year, on two of the cruise company’s newest ships, will be the cruise industry's first systems to turn solid waste directly into energy on board.

“I am proud of Royal Caribbean Group’s drive to SEA the Future and be better tomorrow than we are today,” said Jason Liberty, president and CEO, Royal Caribbean Group. “Pioneering the first waste-to-energy system on a cruise ship builds on our track record of waste management and furthers our commitment to remove waste from local landfills and deliver great vacation experiences responsibly.” Solid Waste to Energy at Sea The systems, Microwave-Assisted Pyrolysis (MAP) and Micro Auto Gasification (MAG), debuting respectively on Royal Caribbean International’s Icon of the Seas and Silversea Cruises' Silver Nova , will take waste on board and convert it into synthesis gas (syngas) that the ship can directly use as energy. Much like land-based waste-to-energy facilities, the result is repurposing waste in an efficient and sustainable way. An additional bioproduct of the system, biochar, can also be used as a soil nutrient.

Reducing Food Waste Royal Caribbean Group is also looking at waste management from start to finish, including its plans to reduce food waste across the fleet by 50% by 2025. To do so, the cruise company is implementing initiatives across its brands including:

- Developing a proprietary platform to monitor food supply and accurately estimate how much food should be produced, prepped and ordered on a given day.

- Using artificial intelligence (AI) to adjust food production in real time.

- Introducing a dedicated onboard food waste role to monitor and train crew members.

- Tracking guest demand for specific menu items and adjusting menu preparation and ordering accordingly.

- Partnering with World Wildlife Fund (WWF) to introduce a food waste awareness campaign in the crew dining areas fleetwide.

To date, Royal Caribbean Group has achieved a 24% reduction in food waste by focusing on the frontend of the food system, which prevents and addresses many of the main causes of food waste, including inventory management and over-preparing.

Expanding Green Hubs Since the company’s first environmental initiative, Save the Waves, aimed at ensuring no solid waste goes overboard, Royal Caribbean Group has worked diligently to increase accountability and strengthen responsible waste management practices. To do so, it developed Green Hub, a capacity-building program to identify waste vendors in strategic destinations that has helped divert 92% of its waste from landfills. Since its start in 2014, the program has grown to 33 ports worldwide.

Now joining the Green Hub program is the Galapagos Islands, where Silversea became the first operator to gain certification in environmental management by diverting all waste from landfill. Initiatives like this allow Royal Caribbean Group to continue to safeguard the delicate ecosystem of the Galapagos for future generations.

Championing the Environment With a sustainability journey that began over 30 years ago, Royal Caribbean Group has remained steadfast in its commitment to innovate and advance the solutions necessary for a better future. Building on a robust portfolio of technologies that improve energy efficiency, water treatment and waste management, incorporating waste-to-energy systems is an extension of the company's commitment to reach beyond the expected and SEA the Future to sustain the planet, energize the communities in which it operates and accelerate innovation.

To learn more about how Royal Caribbean Group connects people to the world's most beautiful destinations while respecting and protecting ocean communities and ecosystems, visit www.royalcaribbeangroup.com/SEAtheFuture .

Media Contact:

About Royal Caribbean Group

Royal Caribbean Group (NYSE: RCL) is one of the leading cruise companies in the world with a global fleet of 64 ships traveling to approximately 1,000 destinations around the world. Royal Caribbean Group is the owner and operator of three award winning cruise brands: Royal Caribbean International, Celebrity Cruises, and Silversea Cruises and it is also a 50% owner of a joint venture that operates TUI Cruises and Hapag-Lloyd Cruises. Together, the brands have an additional 10 ships on order as of March, 31, 2023. Learn more at www.royalcaribbeangroup.com or www.rclinvestor.com.

Related Videos

Related Images

Cruise industry faces choppy seas as it tries to clean up its act on climate

- Medium Text

- The cruise industry is the fastest growing in tourism and is expected to exceed pre-COVID record highs in passenger numbers and revenues by next year

- The industry promises to make zero-emission vessels and fuels widespread by 2030, and to achieve a goal of 'net-zero carbon' cruising by 2050

- Environmental groups cite its record on pollution, greenhouse gas emissions, and over-tourism, and raise doubts about its ability to reach goals

- Concerns include widespread use of "scrubbers", LNG as transition fuel, and limited capacity for shore-based power in ports

Caroline Palmer is a freelance journalist specialising in business, health, sustainability and the artisan economy. She has worked for the Financial Times, The Guardian and The Observer and is a contributor to Ethical Corporation magazine.

Read Next / Editor's Picks

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, sources and leakages of microplastics in cruise ship wastewater.

- 1 Department of Environmental Sciences, Faculty of Science, Open Universiteit, Heerlen, Netherlands

- 2 Cartagena Convention Secretariat, United Nations Environment Programme, Kingston, Jamaica

To date, the contribution of sea-based sources to the global marine litter and plastic pollution problem remains poorly understood. Cruise ships produce large amounts of wastewater and concentrate their activities in fragile and ecologically valuable areas. This paper explores for the first time the sources of microplastics in cruise ship wastewater, as well as their pathways from source to sea. It thereto uses a novel approach for the identification of sources and pathways, based on scientific literature on microplastic sources and pathways, literature on cruise operations and wastewater management as well as a questionnaire among cruise lines. The study highlights personal care and cosmetic products, cleaning and maintenance products and synthetic microfibers released from textiles in laundry as relevant source categories. Untreated grey water and the overboard discharge of biosludge, resulting from the treatment of sewage and grey water, were identified as key pathways. Cruise lines can reduce microplastic emissions by adapting their purchasing policies for personal care, cosmetic, cleaning and maintenance products and professional textiles. In addition, the holistic management of all wastewater streams and resulting waste products is essential to prevent leakages of microplastics from cruise ships to vulnerable coastal and marine ecosystems. Furthermore, the approach can be used to guide company-level assessments and can be modified to address microplastic leakages in other maritime sectors.

1 Introduction

Marine litter is a problem of emerging concern and research efforts as well as initiatives to address the problem are developing rapidly ( UNEP, 2021 ). Recently, a breakthrough was achieved at the United Nations Environments Assembly (UNEA-5.2), where 175 nations committed to forge an international legally binding agreement to end plastic pollution by 2024, addressing the full lifecycle of plastic from source to sea 1 . Marine litter is defined as “any persistent, manufactured or processed solid material discarded, disposed of or abandoned in the marine and coastal environment” ( UNEP, 2021 ). While the term embraces different types of materials, plastics constitute the largest proportion ( Galgani et al., 2015 ). Jambeck et al. (2015) estimated that in 2010, 4.8 to 12.7 million MT of plastics entered the ocean, and inputs are expected to increase over the coming decades ( Lebreton and Andrady, 2019 ). Plastic can travel long distances and is found in all parts of the marine ecosystem, even in very remote locations such as in Arctic sea ice ( Obbard et al., 2014 ) and the Mariana Trench ( Chiba et al., 2018 ). Microplastics (MPs) are small pieces of plastic, with a size smaller than 5 mm. MPs comprise both manufactured microscopic plastic particles (primary MPs), such as microbeads with applications in the cosmetic industry and industrial pellets used for the production of plastics, and particles that result from the abrasion and degradation of larger items (secondary MPs) ( Cole et al., 2011 ). MPs in the marine environment can be ingested or inhaled through the gills by a wide range of organisms ( Wright et al., 2013 ; GESAMP, 2016 ; Hantoro et al., 2019 ). Once ingested, MPs may block or damage intestinal tracts ( Cole et al., 2011 ; Wright et al., 2013 ). They can also be absorbed through the gut walls ( Foley et al., 2018 ). In addition, MPs may leach toxic pollutants, including chemicals that are intentionally added during plastic production as well as organic contaminants and heavy metals that sorb to the MP surface ( Teuten et al., 2009 ; Rochman et al., 2014 ). Impacts that have been associated with MP ingestion in marine biota include adverse effects on feeding (e.g. Wegner et al., 2012 ), growth (e.g. Au et al., 2015 ), reproduction (e.g. Della Torre et al., 2014 ) and survival (e.g. Luίs et al., 2015 ). Besides the effects at the individual level, MPs as well as pollutants absorbed by MPs, can be transferred through food webs ( Farrell and Nelson, 2013 ; Setälä et al., 2014 ) and induce ecological impacts ( Rochman et al., 2016 ). Human health may also be affected by MPs in the marine environment through the consumption of contaminated seafood ( Hantoro et al., 2019 ; Campanale et al., 2020 ).

In order to effectively address marine litter and (micro-)plastics, it is necessary to understand the contribution of individual sources and the pathways from these sources to the environment. Assessing the origin of MPs in the environment is complicated ( Hardesty et al., 2017 ) and the relative contribution of different sources and pathways is strongly dependent on local conditions ( Duis and Coors, 2016 ). While it is generally assumed that most marine litter derives from land-based sources, the contribution from sea-based source varies strongly by geographic location and could be substantial for specific locations ( GESAMP, 2021 ). Knowledge about sea-based sources is still little developed compared to land-based sources; the GESAMP (Joint Group of Experts on the Scientific Aspects of Marine Environmental Protection) Working Group on sea-based sources of marine litter concluded that knowledge of the type, quantity and impact of sea-based sources is lacking ( GESAMP, 2021 ), thus hindering the development of effective mitigation strategies. Ship-based sources contribute to MP pollution, e.g. through paints and coatings, abrasives used for the cleaning of ship hulls during maintenance, loss of cargo (e.g. plastic pellets) and discharges of wastewater ( Boucher and Friot, 2017 ; Bray, 2019 ; GESAMP, 2021 ). In terms of wastewater, cruise ships would be of particular interest because of the large quantities of wastewater that are generated on board these ships ( GESAMP, 2021 ). Vicente-Cera et al. (2019a) estimate that the world cruise fleet produced about 34.000.000 m 3 of wastewater in 2017; a production rate that is comparable to that of the country Cyprus 2 .

Until the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the cruise industry had shown a constant growth, from 17.8 million passengers in 2009 to 29.7 million passengers in 2019 3 : an increase of 75% in 10 years. The pandemic led to a complete halt of operations; however, the industry expects a full recovery compared to 2019 levels by 2023 and a growth of 12% by 2026 4 . Currently, the largest cruise ship in operation can carry up to 6988 passengers and 2300 crew members 5 . Besides a means of transportation and accomodation, cruise ships typically provide a wide array of onboard services and attractions to their passengers, such as swimming pools, spas, theatres and sports facilities. The main mainstream cruise destinations are located the Caribbean, the Mediterranean and Northwestern Europe; specialty “adventure” types of cruises attend extremely remote and vulnerable environments ( Lamers et al., 2015 ) such as the Arctic and Antarctic. Around 70% of the cruise destinations are located in biodiversity hotspots ( Lamers et al., 2015 ) and cruise ships frequently pass through fragile coastal and shallow areas as well as marine protected areas, especially when entering or leaving ports ( Lloret et al., 2021 ). Caric et al. (2019) highlight that in the Mediterranean, cruise ships frequently anchor in close proximity of many marine protected areas (MPAs) and the heavily trafficked cruise port of Venice is even located within such a site. Considering that cruise activities typically concentrate in certain coastal areas and routes, these vulnerable areas are exposed to cumulative environmental impacts of these activities ( Toneatti et al., 2020 ). With increasing cruise intensity, the impacts of the industry, including MP pollution, are likely to increase in the coastal and marine environment.

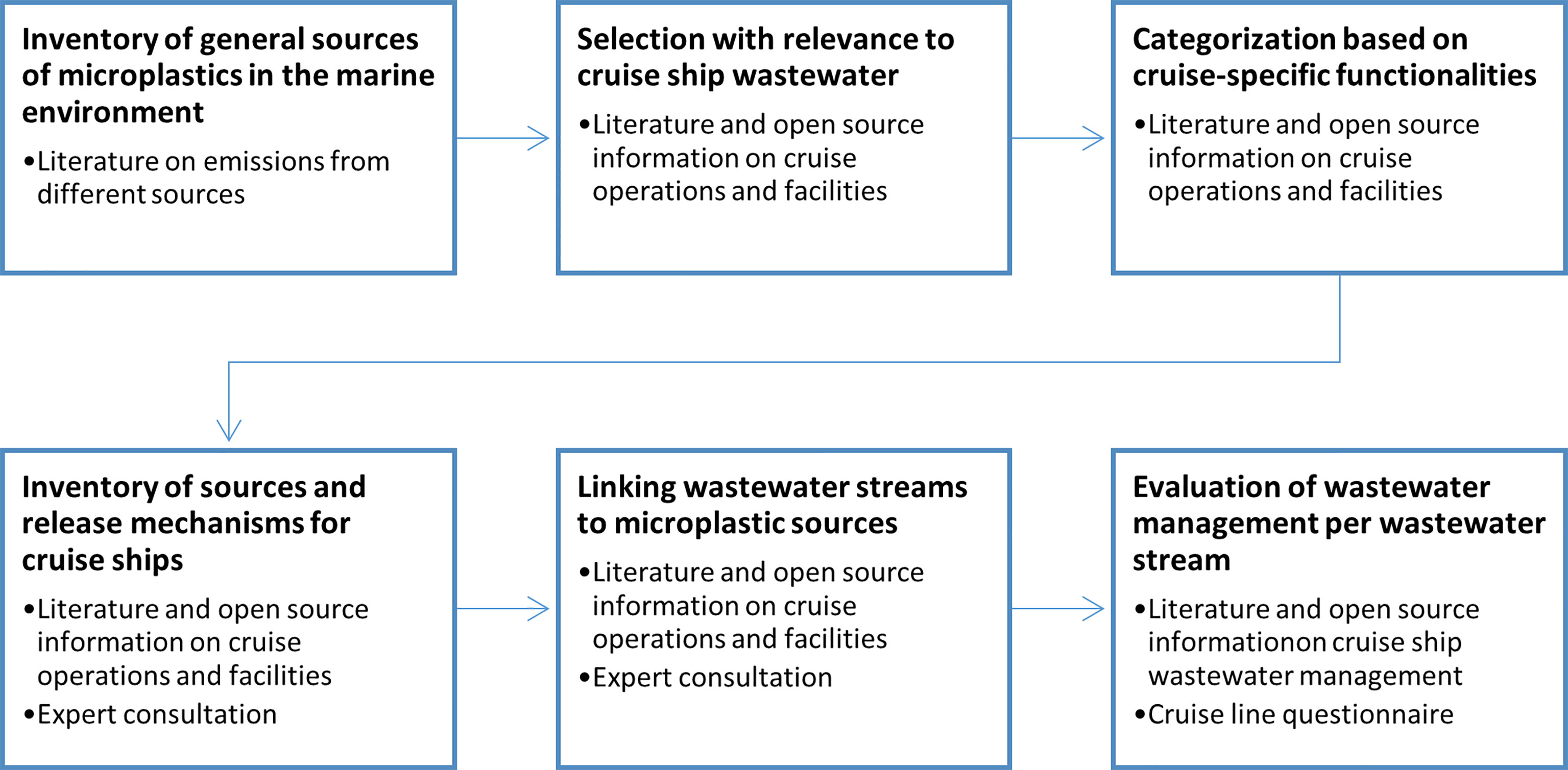

This study aims to highlight characteristics of the cruise sector that affect the potential for MPs being found in wastewater discharges, and provide recommendations to guide and set-up future research efforts as well as indicate general directions for mitigation. It thereto uses a novel approach for the identification of these sources and pathways, based on scientific literature on MP sources and pathways, literature on cruise operations and wastewater management as well as a questionnaire among cruise lines. First, an inventory was made of sources of MPs in the marine environment, based on general scientific literature. From this general inventory those sources were selected that are relevant to cruise operations and additional source categories were identified based on the characteristics of cruise operations and facilities. Subsequently, the identified sources were linked to the different wastewater streams and finally the management of each of these wastewater streams was evaluated.

2 Materials and Methods

Figure 1 presents an overview of the methodology for the identification of sources and pathways of MPs in cruise ship wastewater (detailed descriptions of the steps are described in the following paragraphs). Here, the term “sources” refers to the different applications of plastics and synthetic polymers on board cruise ships that have the potential to release. MPs to the marine environment. Through different release mechanisms, MPs find their way to the wastewater streams. Pathways are defined as the routes through which MP particles are transported to the marine environment, where the scope of this research is restricted to pathways through cruise ship wastewater discharges.

Figure1 Research steps in the identification of sources and pathways of microplastics in cruise ship wastewater.

2.1 Literature Review of Microplastic Sources

Since cruise ships are often characterized as “floating cities”, it was reasoned that MP sources on cruise ships have significant overlap with land-based urban sources of MPs. In addition, the maritime operations as well as any aspects that are unique to the cruise industry should be addressed. To identify and characterize sources of MPs, the research is based on the approach that was applied in different European countries, the European Union and the OSPAR region, as reported by Sundt et al. (2014) ; Lassen et al. (2015) ; Essel et al. (2015) ; Magnusson et al. (2016) ; Scudo et al. (2017) ; Verschoor et al. (2017) and Hann et al. (2018) . These studies estimate MP emissions at a local or regional scale, based on the sources and pathways of MPs reported in general literature in combination with local data on plastic uses and other relevant local factors. Lassen et al. (2015) define eight categories of primary MP sources and six categories of secondary MP sources, and identified the pathways from these sources to surface waters. This structure was adopted and the list was complemented with the results of other studies, reflecting all reported land-based and sea-based MP sources and pathways at national or regional level. Next, sources were selected that could be relevant for cruise ship wastewater during normal operations.

2.2 Cruise-Specific Functionalities

In order to cover all sources of MPs that are specific to the cruise industry, the following overarching types of MP sources were considered, representing different functionalities of cruise ships: cruise ship facilities, ship stores and people . Cruise ship facilities were further divided into hotel facilities and ship facilities , in accordance with the structure proposed by Lois et al. (2004) . The proposed facilities were supplemented by consulting Vogel et al. (2012) and Gibson and Parkman (2019) , as well as by studying the deck plans of the ten largest cruise ships in the world, in order to cover the main facilities that are present on modern cruise ships. Stores comprise the different purchasing streams of cruise ships: fuel, corporate, technical and hotel purchasing ( Véronneau and Roy, 2009 ). Finally, personal belongings of passengers and crew may act as MP sources; these are covered by the category “ people ”.

2.3 Inventory of Microplastic Sources

Following the identification of the main MP source categories on board cruise ships, the inventory as derived from the literature study was further developed and supplemented to cover those categories that have relevance to cruise ships. This was done by crosschecking the identified categories as derived from literature on the one hand and the identified facilities, stores and people categories from the previous step on the other. This approach resulted in the elimination of some of the MP sources that were identified in the previous step, because of differences in the characteristics of these sources on board cruise ships compared to the general characteristics that are described in literature. On the other hand, cruise-specific sources were added to the general inventory. The contribution of specific facilities and stores to MP pollution is not always straightforward and requires a thorough understanding of operations, facilities and the types of stores. The details of many specific cruise operations are not extensively reported in literature, and only to a limited extent in grey literature. Therefore, in order to assess the relevance of the different facilities and stores, Google searches were used to identify open access online resources, such as deck plans and pictures of the 10 largest cruise ships (e.g. to understand the application of artificial grass and the organization of laundry facilities) as well as blogs and YouTube videos, concerning the specific cruise ship operations and facilities such as laundry installations and engine room operations. In addition, experts were consulted to verify the findings (see below).

2.4 Linking Wastewater Streams to Microplastic Sources

In order to establish links between the sources on the one hand and wastewater streams on the other, the different sub-streams of the wastewater streams were identified based on literature. Then, the pathways from the identified sources to the different wastewater streams were assessed, by crosschecking each of the sources to the identified wastewater streams and vice versa.

2.5 Wastewater Management

The objective of this step was to map the main routes of the different wastewater streams and the key characteristics of treatment processes, where applicable, in order to identify potential pathways of MPs from the different wastewater streams. In addition, the characteristics of common treatment technologies were described. The assessment is based on scientific literature as well as grey literature. In order to verify the findings based on the grey literature, experts were consulted and a questionnaire was distributed among cruise lines.

2.6 Expert Consultation and Questionnaire

A preliminary version of the inventory of sources and pathways of MPs on board cruise ships was reviewed by experts in the fields of marine litter (3 experts) and MPs in onshore wastewater (1 expert). The typical practices and systems for wastewater management on board cruise ships were discussed with two experts in the field of maritime wastewater management and one cruise industry representative. In addition, a questionnaire was developed and distributed among cruise lines to verify the preliminary findings and collect additional industry-specific information. The questionnaire was distributed in February 2020 to the environmental managers of different cruise lines through the Cruise Lines International Association (CLIA). It consisted of a general section, where respondents could indicate the fleet size, a general wastewater management section and sections related to different wastewater treatment technologies. The final section concerned the measures and policies addressing MPs in wastewater.

2.7 Analysis and Interpretation of Results

This research involved different types of information and data, from different fields of research as well as use of a questionnaire and expert interviews. In order to organize these data, the research was structured around the existing frameworks from literature for the inventory of general MP sources as well as cruise facilities. In addition, the identified wastewater streams and related wastewater management practices were described in tabular form. These frameworks were then combined into matrices in order to structure the available information and to ensure that all relevant topics were covered through crosschecking. This structure guided the more detailed part of the research, and in particular the identification of cruise-specific MP sources. Where scientific literature was lacking, secondary resources were considered.

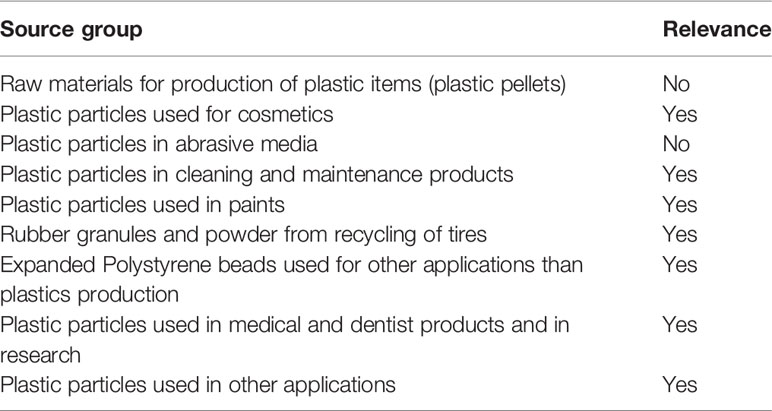

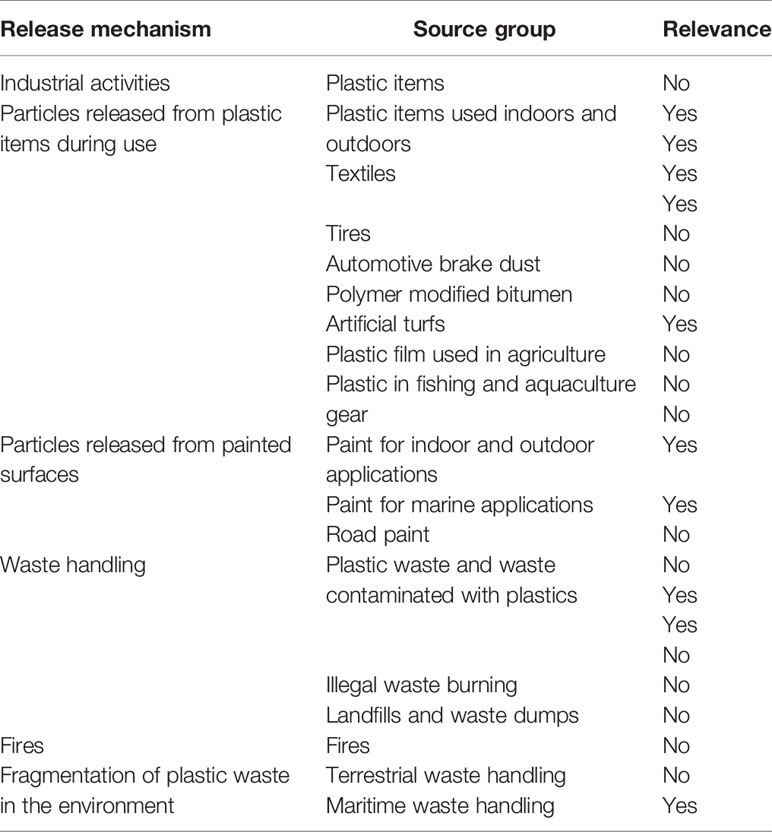

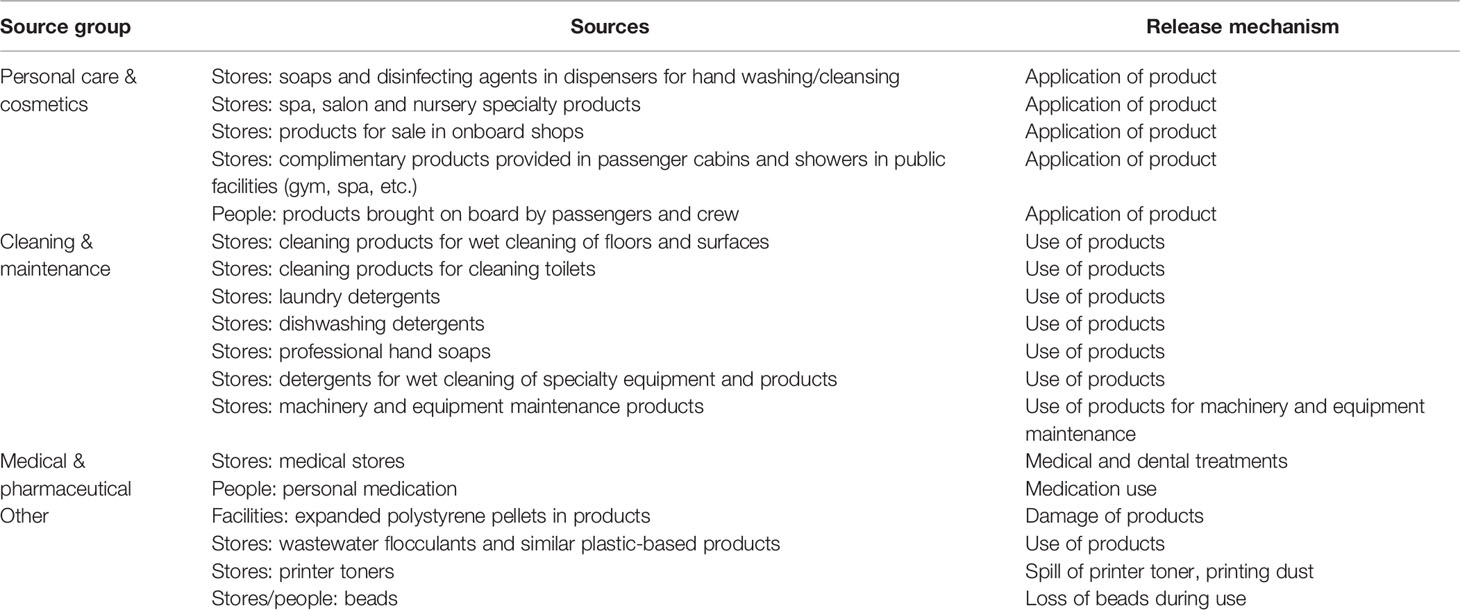

3.1 Literature Review of Microplastic Sources

Tables 1 , 2 present the overview of main source groups of primary and secondary MPs in the marine environment, modified from Lassen et al. (2015) , and extended with the results from other studies (indicated in the table, where applicable). The column on the right indicates whether the listed source groups were considered relevant for cruise ship wastewater. MP sources that were not considered relevant include raw materials for plastic production, industrial and professional handling processes of plastics, emissions from road traffic (tires, brake pads, bitumen and road paint), agricultural, aquaculture and oil and gas applications, typical onshore waste management issues (illegal waste burning, landfills and dumps), as well as the fragmentation of macroplastics in the environment due to natural processes. Also, the blasting of the ship hull during large scale maintenance with plastic abrasives is not further considered as blasting is not part of normal ship operations. Furthermore, Lassen et al. (2015) includes a separate category of primary MP emissions from paints through the washing of brushes. This source group was not considered applicable to cruise ships since this is mainly relevant for “do it yourself” and not for industrial practices ( Verschoor et al., 2016 ). The category other includes plastic beads used in professional dish washing machines, plastic beads and ironing beads used by children, printer toner, specialty chemicals in wastewater treatment facilities ( Scudo et al., 2017 ) and oil and gas industry ( Sundt et al., 2014 ).

Table 1 Generic primary MP sources, modified from ( Lassen et al., 2015 ) and indicating relevance to cruise ships.

Table 2 Generic secondary MP sources, modified from ( Lassen et al., 2015 ) with descriptions and relevance to cruise ships. .

3.2 Cruise-Specific Functionalities

3.2.1 facilities.

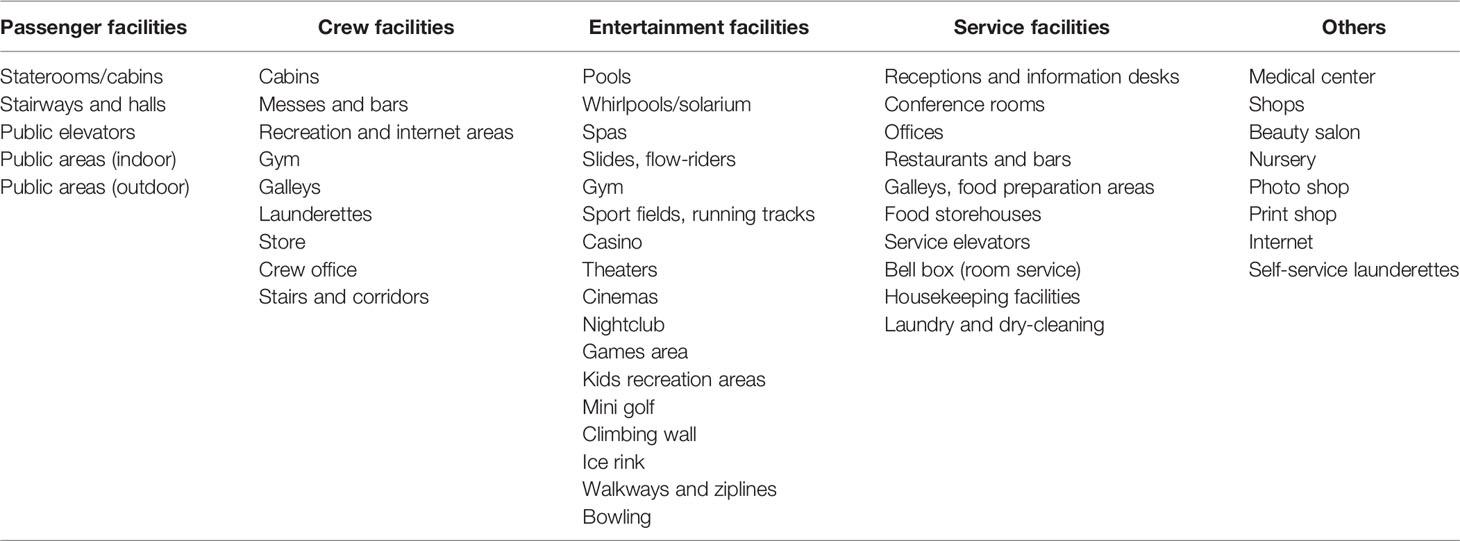

Tables 3 and 4 give an overview of the typical hotel facilities and ship facilities as present on contemporary cruise ships, based on Lois et al. (2004) . The overview is not exhaustive and may not be representative for all cruise ships but is indicative of the main systems and facilities present on ships, with the purpose to identify potential sources of MPs throughout the vessel.

Table 3 Hotel facilities on board cruise ships [adapted from Lois et al. (2004) ].

Table 4 Ship facilities on board cruise ships [adapted from Lois et al. (2004)] .

3.2.2 Stores

Cruise ships carry stores of various types. Such stores include fuel and ship maintenance products for ship operations as well as food, potable water and detergents for hotel operations. Véronneau and Roy (2009) distinguish the following main purchasing streams of cruise ships: fuel, corporate, technical and hotel purchasing. Fuel purchasing covers fuel and other petroleum products for daily consumption, such as lubricants. Corporate items relate to office related materials such as office supplies and computers. Technical items include items for facility and ship maintenance, e.g. engine parts, electronic components and carpeting materials. Consumable items and food required for hotel operations fall under the category of hotel purchasing. Furthermore, fresh water is a key resource on board.

3.2.3 People

Passengers and crew bring their personal belongings in their luggage. Significant categories are likely to include personal clothing, shoes, flipflops, personal toiletries and medication, electronics, books, suitcases and backpacks and snacks. People with children may bring plastic and inflatable toys. Furthermore, souvenirs bought ashore are brought on board after port visits.

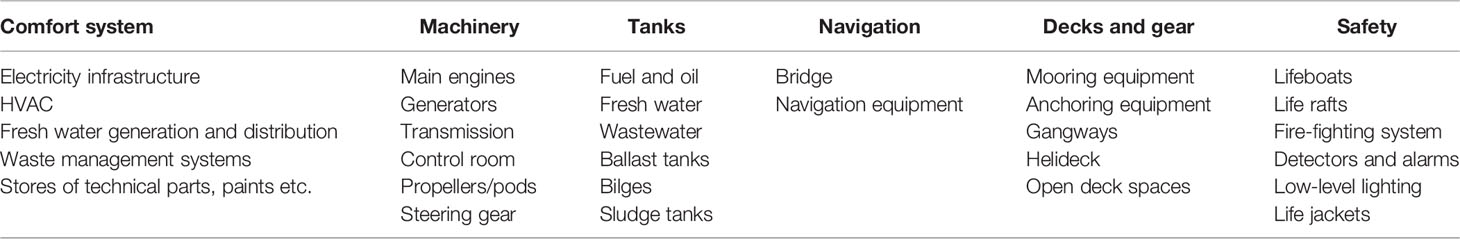

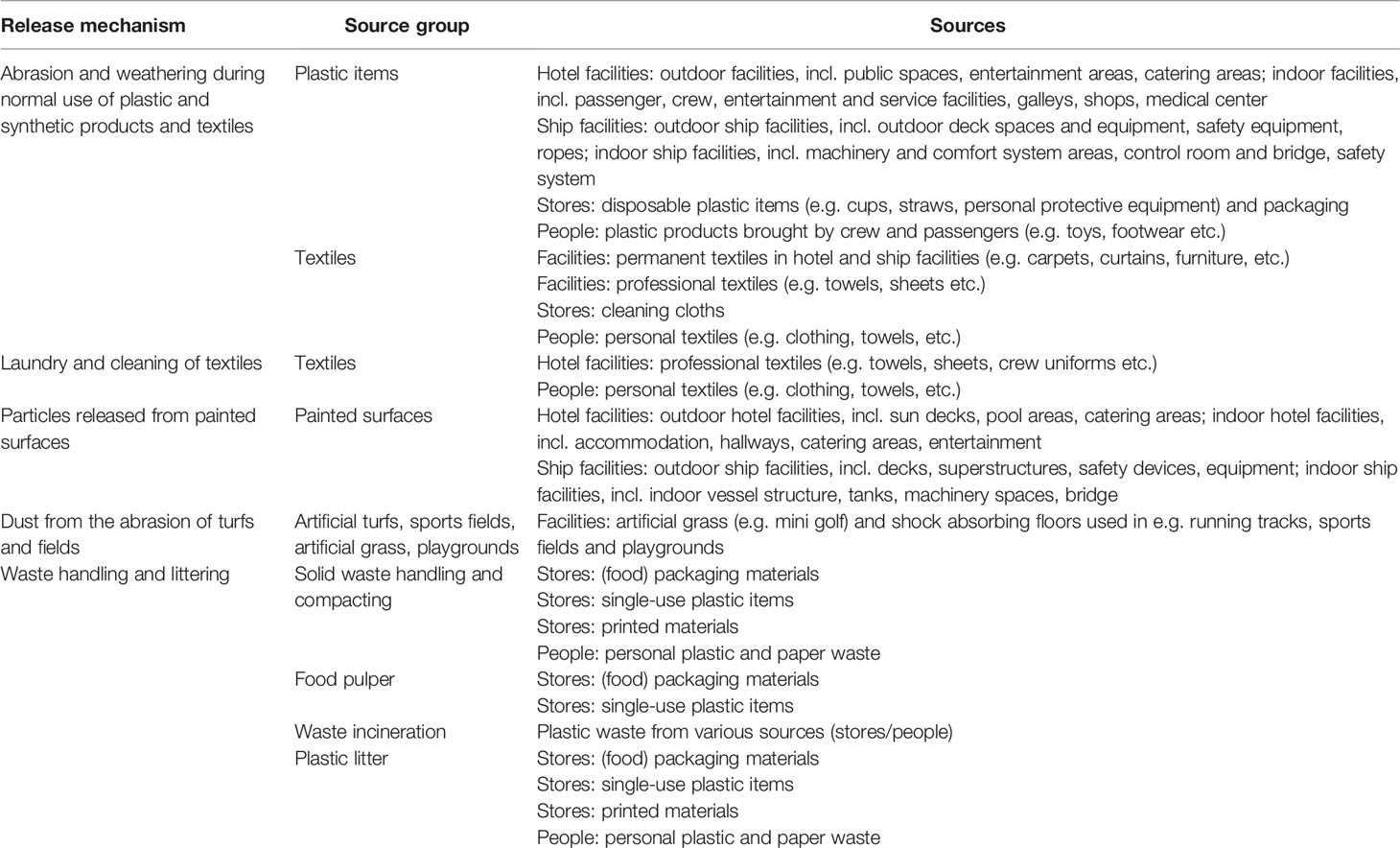

3.3 Inventory of Sources and Release Mechanisms

Overviews of key MP sources and release mechanisms of both primary and secondary MPs on board cruise ships are displayed in Tables 5 and 6 . The categories from Lassen et al. (2015) were revised to reflect both the general categories as found in literature as well as the relevance of these categories for cruise operations.

Table 5 Primary microplastic sources and release mechanisms with relevance to cruise ship wastewater.

Table 6 Secondary microplastic release mechanisms and sources with relevance to cruise ship wastewater.

The main source groups for primary MPs ( Table 5 ) are personal care & cosmetics, cleaning & maintenance and medical & pharmaceutical. Potential release mechanisms are mainly related to the use of products in “wet” applications, e.g. rinse-off bath and shower products, spa treatments, wet cleaning, dish washing, laundry and wastewater treatment. Other release mechanisms include medication use, medical and dental treatments, printing and damage of user products that contain primary MPs, e.g. polystyrene pellets or beads. In addition, certain shipboard wastewater treatment systems use flocculants ( EPA, 2011 ; Chen et al., 2022 ), which could be polymer-based. The detailed assessment of cruise ship facilities led to the exclusion of rubber granules from artificial turfs as a source of primary MPs: no examples could be found of high impact sport facilities on board cruise ships that would require “third generation turfs” using a performance infill of (synthetic) rubber granules for shock absorption ( Hann et al., 2018 ).

The identified release mechanisms for secondary MPs ( Table 6 ) include the wear and damage of products during normal use, laundry and cleaning of textiles, wear and damage of painted surfaces, waste handling and littering. Sources embrace all plastic and synthetic items and surfaces on board the vessel, including paints and waste.

3.4 Linking Wastewater Streams to Microplastic Sources

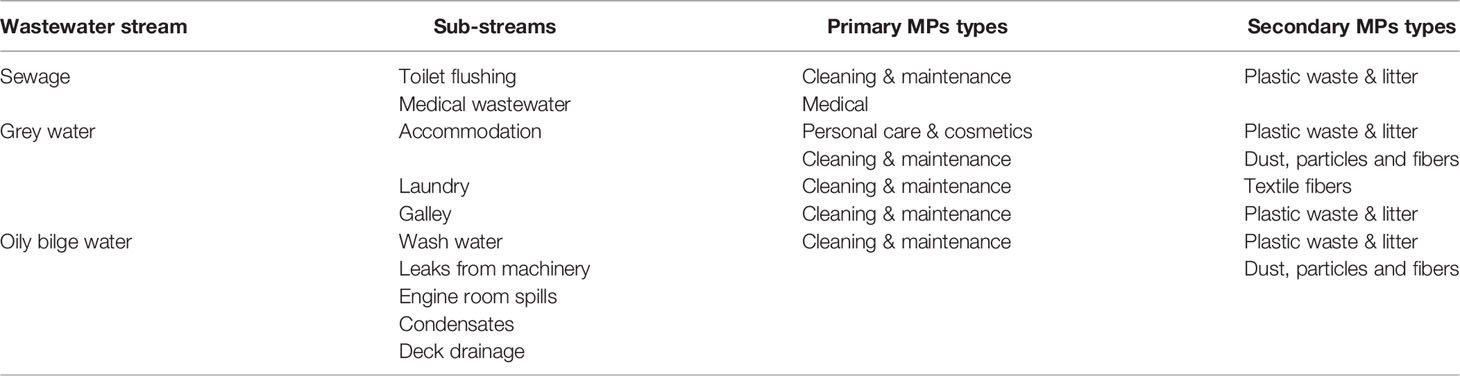

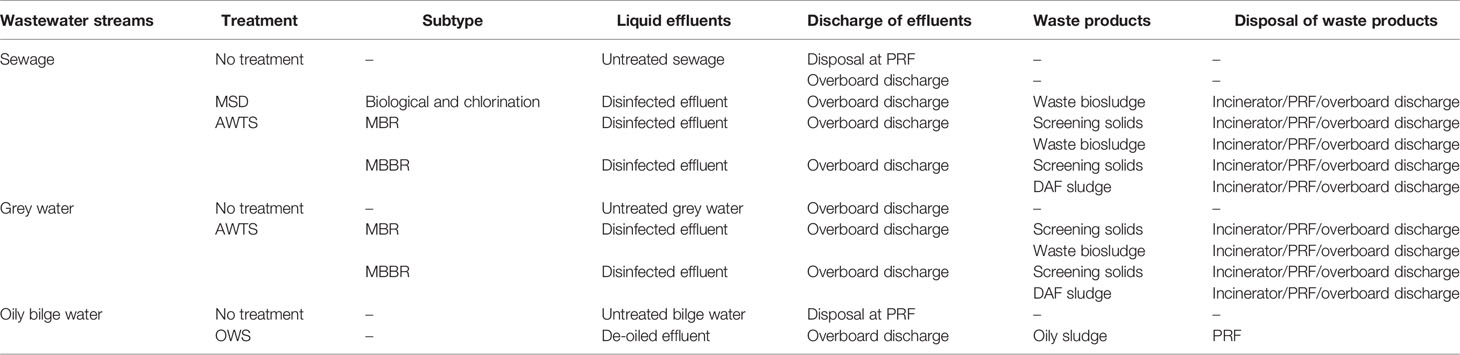

The main wastewater streams that are produced on board cruise ships are sewage, grey water and oily bilge water. Sewage is the wastewater from toilets and primarily consists of human body wastes and water and may on some ships be mixed with wastes from medical facility sinks and drains ( EPA, 2008 ). The International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL) covers the international regulations for sewage in Annex IV of the convention. According to these regulations, sewage may be discharged overboard without treatment outside coastal zones, provided that the ship maintains a minimum sailing speed of 4 knots. The average sewage generation rate is estimated at 68 l/person/day ( Vicente-Cera et al., 2019a ). Grey water consists of the wastewater streams from shower and bath, accommodation sinks, laundry, dishwashers and galleys ( EPA, 2008 ). Wastewater from these sources is in practice often mixed with wastewater from other sources, such as drainage from drains and sinks in non-engine room spaces, food pulper effluents and wastewater from whirlpools ( EPA, 2008 ). Unlike sewage, grey water discharges are not internationally regulated. Vicente-Cera et al. (2019a) estimate the average generation rate throughout the industry at 160 l/person/day. EPA (2008) defines oily bilge water as “the mixture of water, oily fluids, lubricants, cleaning fluids, and other similar wastes that accumulate in the lowest part of a vessel from a variety of different sources including engines (and other parts of the propulsion system), piping, and other mechanical and operational sources found throughout the machinery spaces of a vessel”. International regulations, covered by MARPOL Annex I, allow discharges of oily bilge water at sea, provided that approved oil filtering equipment is used. The oil residue from the filtering process is to be stored in dedicated oil sludge tanks and delivered to port reception facilities (PRF). Vicente-Cera et al. (2019a) estimate that the average industry generation rate is 23 l per nautical mile.

In order to link the different wastewater streams to MP sources, the identified wastewater streams were divided into different sub-streams, each reflecting potential entry routes of MPs into wastewater. The left-hand side of Table 7 summarizes the main sub-streams of which the wastewater streams consist. On the right-hand side, the primary MP source categories (as listed in Table 5 ), as well as the typical types of secondary MPs of relevance to these (sub-)streams are listed.

Table 7 Linking cruise ship wastewater streams to pathways and microplastic sources.

The results demonstrate that the MP sources attributed to the different wastewater streams vary significantly. The MP content in sewage derives from pharmaceuticals and detergents used for the cleaning of toilets as well as larger items that are disposed in toilets. The MP sources related to grey water include personal care and cosmetic products (PCCP), detergents used for cleaning, dishwashing and laundry, fibers from synthetic textiles and the secondary MPs that are removed by wet cleaning. Finally, the MP sources attributed to oily bilge water mainly relate to engine room operations, which may involve various products for the cleaning, maintenance and operation of machinery that contain primary MPs. In addition, the different sub-streams of oily bilge water collect solid waste and dust, including plastics and secondary MPs, on their way to the bilges.

3.5 Wastewater Management

3.5.1 sewage and grey water.

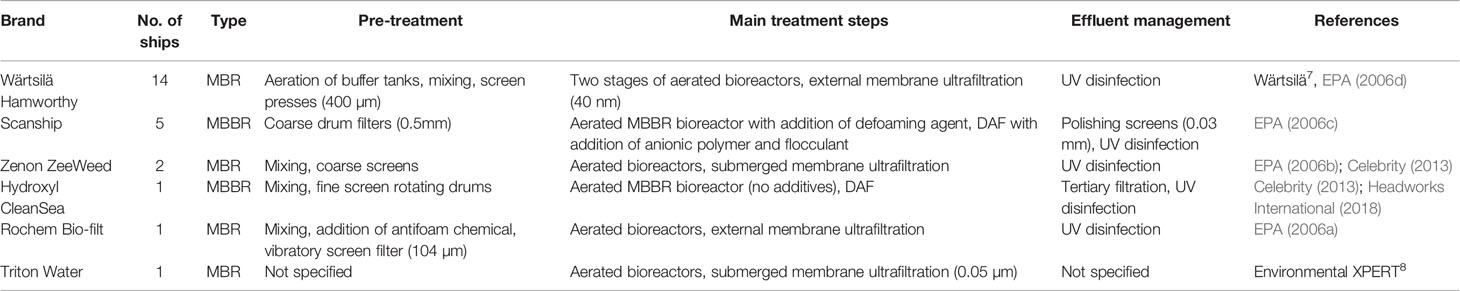

There exist two categories of treatment systems that are relevant to sewage and grey water. Older ships are typically fitted with sewage treatment plants (STP), generally referred to as Marine Sanitation Devices (MSD), dedicated to the treatment of sewage. On these ships, grey water is typically not treated ( EPA, 2008 ). MSD must be approved by the flag state of the vessel and comply with local effluent standards, if available. EPA (2008) reports that conventional MSD on board cruise ships treat sewage through biological treatment and chlorination, while some systems combine maceration and chlorination. Advanced Wastewater Treatment Systems (AWTS) comprise a range of relatively new technologies for treating sewage more effectively than the older MSD. For these systems to function properly, the influent of sewage is typically not sufficient. Thereto, (part of) the grey water streams are also routed through the AWTS. The use of these systems is becoming the standard in the cruise industry ( King County, 2007 ) and newbuilds are typically fitted with such systems ( Nuka Research, 2019 ). From the 2021 Cruise Report Card, published by Friends of the Earth 6 and covering the 18 major cruise lines and 202 ships, it can be derived that 75% of the cruise ships have an AWTS. According to Vard (2018) , most AWTS on board cruise ships are of the Membrane Bioreactor (MBR) type, utilizing an activated sludge process in combination with membrane filtration. Systems of the Moving Bed BioReactor (MBBR) type consist of a bioreactor filled with plastic beads, supporting bacterial growth, in combination with a Dissolved Air Flotation (DAF) unit ( Huhta et al., 2007 ). No complete overview could be retrieved of systems that are in use throughout the industry. However, the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation annually reports which large cruise ships operated in Alaskan waters and which type of treatment system is used on board these ships. Table 8 provides an overview of the different systems that were used on board the ships that operated in Alaskan waters in 2019 ( ADEC, 2019 ), and indicates the number of ships associated with each system. Further information about these systems was collected from the AWTS brand websites, as well as ship-specific implementations, and added to the table. It follows that 18 out of 24 ships had an MBR type of AWTS, and 14 of these were of the brand Hamworthy. Six vessels operated an MBBR type AWTS of which 5 were of the brand Scanship.

Table 8 Overview of characteristics of AWTS systems and processes on cruise ships operating in Alaskan waters during 2019.

The MBR systems all involve a pre-treatment filtering of the influent to remove coarse solids and prevent blocking of the membranes. The treatment itself involves the biological oxidation through an activated sludge process and ultrafiltration through membranes, where concentrates are generally fed back to the bioreactors and filtered effluents are collected in a permeate tank. The MBBR influents also pass filters to remove coarse solids. In the reactor, biological matter is removed through aerobic biological oxidation, and consequently DAF units separate particulate matter. Finally, the effluents pass polishing filters. All systems utilize UV disinfection to remove pathogens. Where available, mesh sizes of screens and filters are included. Since MBR systems are based on ultrafiltration, the mesh of the membranes is very fine with pore sizes below 100 nm.

Both grey water and sewage could be discharged to the marine environment without treatment. This applies to grey water for ships which do not have AWTS and ships which route only certain grey water streams through AWTS. Furthermore, it is possible that treatment systems are switched off at open sea, resulting in discharges of raw sewage and grey water. In 2021, 25% of the cruise fleet had no AWTS in place and thus discharged untreated grey water to the marine environment. Since these would typically concern older, and smaller cruise ships, the percentage of total grey water discharged through this route is likely smaller and this is expected to decrease in the future due to the increased use of AWTS. The MARPOL Convention allows the discharge of untreated grey water and, under certain conditions, sewage outside coastal zones. So theoretically, treatment systems could be switched off when the ship is on open seas. An EPA survey of four cruise ships fitted with AWTS reports that all vessels operate the system on a continuous basis ( EPA, 2006a ; EPA, 2006b ; EPA, 2006c ; EPA, 2006d ) and therefore do not discharge raw sewage. This is in line with the CLIA waste management policy, which prohibits the discharge of untreated sewage on board member cruise lines 9 . One of the ships in the EPA survey ( EPA, 2006b ) only routes the grey water from accommodations to the AWTS and discharges galley and laundry wastewater overboard without treatment, demonstrating that discharges of untreated grey water also occur on vessels with AWTS. AWTS and MSD filtering and treatment processes separate the wastewater into treated effluents and waste products. Sewage is typically high in solids, such as toilet paper and sanitary items, which is removed before sewage enters the treatment system, leaving screening solids of various sizes in the sieves and membranes. Another waste stream is the formation of biosludge. Biosludge or excess biomass consists of organic material as well as bacteria, resulting from the biological consumption of sewage ( EPA, 2008 ) and contains over 95% water ( Avellaneda et al., 2011 ). It is separated from the treated effluents by filtration ( EPA, 2008 ) and therefore would contain any solids such as MPs that have entered the bioreactor.

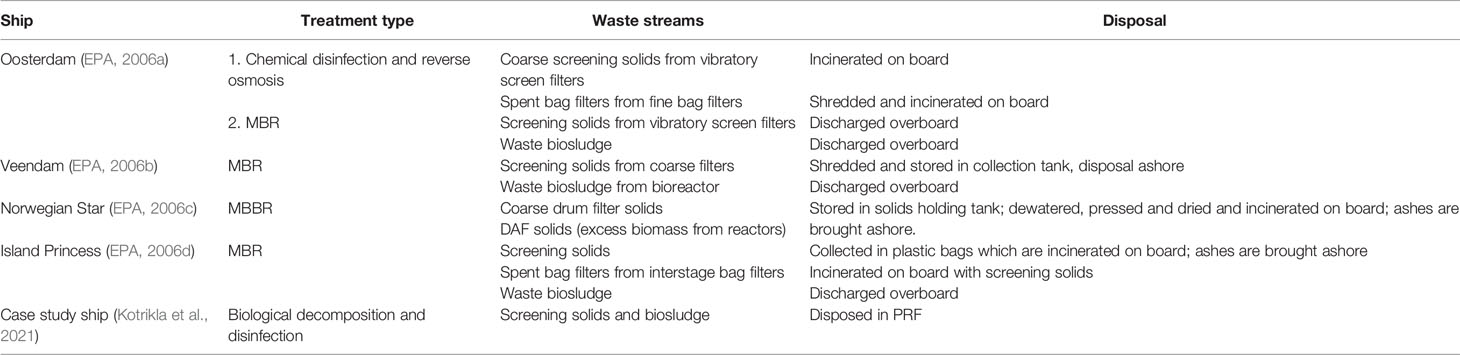

Literature provides some information on the disposal of waste products from cruise ship sewage and grey water treatment. Disposal options are incineration on board, landing at PRF and discharge at open sea ( EPA, 2008 ; Klein, 2009 ; Avellaneda et al., 2011 ). The relevant findings from an EPA survey of four cruise ships with AWTS ( EPA, 2006a ; EPA, 2006b ; EPA, 2006c ; EPA, 2006d ) are shown in Table 9 , together with the details of a case study cruise ship, representing an average-sized cruise ship operating in the Caribbean, as described by Kotrikla et al. (2021) . From this table it follows that three out of five ships discharge biosludge overboard. One of these ships also discharges the screening solids from the laundry and accommodation wastewater treatment system overboard, whilst solids from sewage are collected and incinerated on board. These data are in line with Klein (2009) who reports the overboard discharge of waste biosludge by 15 out of 16 ships in Washington State waters, with dewatering and incineration of biosludge on board one ship. Experts interviewed as part of this research stated that delivery of biosludge to PRF is currently not a common method on a worldwide scale as adequate facilities are lacking. This is also outlined by Avellaneda et al. (2011) who raise the logistic challenges of dealing with the large amounts of biosludge from cruise ships in ports without fixed reception facilities, rendering this scenario unrealistic. The available data indicates that for screening solids, incineration or delivery at PRF is more common.

Table 9 Sewage sludge treatment and disposal on board four cruise ships ( EPA, 2006a ) ( EPA, 2006b ) ( EPA, 2006c ) ( EPA, 2006d ).

3.5.2 Oily Bilge Water

As international regulations prohibit the discharge of untreated bilge water, there are two main methods used for the disposal of oily bilge waters: storage on board and delivery to onshore facilities, and onboard treatment. The treatment of bilge water is aimed at separating the oily constituents and water, such that the treated bilge water can be discharged overboard and the oily constituents are retained on board in sludge tanks for delivery to shoreside facilities ( EPA, 2011 ). The systems used for the treatment of oily bilge waters are generally referred to as Oily Water Separators (OWS). EPA (2011) reports that contemporary OWS are comprised of a series of different separation methods and that all of the OWS systems for bilge waters that are approved by the US Coast Guard are a combination of gravity-based separation and one or more forms of polishing treatment. Oil and other contaminants that are contained from the bilge water are collected in sludge tanks. This oily sludge may be stored on board for discharge at shore reception facilities or incineration on board. Table 10 summarizes representative options for wastewater treatment and the discharge and disposal of the resulting effluents and waste products.

Table 10 Summary of identified representative wastewater management options per wastewater stream.

3.6 Cruise Line Questionnaire

Since the questionnaire was distributed almost simultaneous with the first infections of COVID-19 on board cruise ships, the response was minimal. One CLIA member company responded and completed the questionnaire. However, with a fleet size of over 15 vessels, the responding company can be considered an important player in the industry and generally representative.

All ships of this company have holding tanks and MSD or AWTS systems for the treatment of sewage and grey water, with most ships having AWTS. In the case of MSD, grey water is stored on board and discharged at a minimum distance of 12 nautical miles from the nearest land. All ships are equipped with OWS for the treatment of oily bilge water, and also fitted with holding tanks for discharge at PRF when necessary.

All MSD operated by the company are using biological treatment in combination with chlorination. The screening solids captured by the treatment process are incinerated on board. The MSD are operated on a continuous basis. When the ships operate within 12 nautical miles from nearest land, treated effluents are contained in storage tanks and discharged later.

Most AWTS installed are of the MBBR type, and some are MBR. All sewage, accommodation, laundry and dishwashing wastewater streams are routed through the AWTS. The systems are operated on a continuous basis and effluents are discharged at a minimum distance of 3 nautical miles from the nearest land, confirming commitment to the CLIA zero-discharge policy for untreated sewage. Biosludge is either discharged to sea, incinerated or landed at PRF, where the chosen method depends primarily on the region of operation. Screening solids are typically incinerated on board and ashes are delivered to PRF.

In terms of policies, the company reports the initiation of the phasing out of “discretionary single use plastics on our ships”. Additionally, onboard gift shops and spas do not sell products containing microbeads. No measures were reported regarding the use of synthetic textiles or the application of microfiber filters in laundry installations.

4 Discussion

This article explored for the first time the sources and pathways of MPs in cruise ship wastewater, using a novel approach, based on general literature on MP sources in the marine environment as well as literature and industry information on cruise operations and wastewater management practices on board cruise ships. An overview was presented of the main source groups and release mechanisms of primary and secondary MPs on board cruise ships. Pathways of MPs were identified by linking the identified sources to the main wastewater streams on board cruise ships and an assessment of typical wastewater management practices.

4.1 Inventory of Sources

An overview was presented of the main source groups of primary MPs on board cruise ships, each reflecting the types of products and operations that are relevant to MP releases: personal care & cosmetics, cleaning & maintenance, medical & pharmaceutical and miscellaneous. PCCP are generally considered a key source of MPs in onshore wastewater treatment plants (e.g. Carr et al. 2016 ; Mason et al. 2016 ). There is no reason to assume that this would not be the case on board cruise ships. Moreover, the use of sun protection products and presence of spa and beauty facilities could result in even higher loads. Both fragrances and UV-filters linked to PCCP have been detected in cruise ship wastewater ( Westhof et al., 2016 ; Vicente-Cera et al., 2019b ), with concentrations of fragrances at similar levels as those in onshore domestic wastewater and concentrations of UV-filters exceeding those ( Vicente-Cera et al., 2019b ). It should be noted that the data reported in the latter study were collected under maintenance conditions and could be an underestimate for normal operations with passengers on board. This suggests that cruise ship wastewaters contain concentrations of PCCP constituents that are similar or exceeding those of onshore wastewater. Several studies ( Sundt et al., 2014 ; Lassen et al., 2015 ; Magnusson et al., 2016 ) assessed medical and pharmaceutical products as a minor source of MPs to the environment. Both Westhof et al. (2016) and Vicente-Cera et al. (2019b) found concentrations of pharmaceutical compounds in cruise ship wastewater at similar levels compared to domestic wastewater, suggesting no substantial differences in their use on board cruise ships and on land.

Literature reports MPs and synthetic polymers in various products used for industrial cleaning and care. These include hard surface cleaners, toilet cleaners and blocks, stainless steel cleaners, bathroom acid cleaners, oven cleaners, laundry detergents and stain removers ( Scudo et al., 2017 ), commercial hand-cleaning products ( Lassen et al., 2015 ; Scudo et al., 2017 ) and synthetic waxes in floor agents ( Essen et al., 2015 ). Most of the listed product types could be relevant to cruise ships. However, no studies could be identified that address concentrations of detergents and other maintenance products in cruise ship wastewater, nor about the presence of MPs in products used for specific ship operations. Scudo et al. (2017) estimated that industrial hand-cleaning soaps used for the removal of grease, paints etc. account for more than half the tonnage of all applications of MPs in rinse-off products. Considering the nature of cruise ship operations, this could be an important source as well. In addition, considering the wide range of applications of MPs in industrial cleaning products, the use of MPs in specialty maritime and cruise cleaning and maintenance products cannot be ruled out.