Remembering (and forgetting) the 1981 Springbok tour

10 September 2021

The narrative of the 1981 Springbok tour continues to reflect New Zealand's anti-apartheid views, but in fact protestors treated it more as a critique of New Zealand Society, research shows.

This weekend's 40th anniversary of the historic Springbok Eden Park rugby match, also marks the completion of five years of research by Dr Sebastian JS Potgieter, a teaching fellow at the School of Physical Education, Sport and Exercise Sciences , on the enduring narrative of the nation-defining tour.

Dr Potgieter, who was raised in South Africa, says the 1981 Springbok tour is primarily viewed as an anti-apartheid struggle which serves to construct New Zealand society in a favourable way.

“Apartheid was a major factor in catalysing the protests, but protestors treated it more as a critique of New Zealand society in a broader sense,” Dr Potgieter says.

“Continuing to view 1981 as primarily an anti-apartheid struggle serves to forget some of the unpalatable realities that accompanied the tour.”

It was a box of documents about the 1981 tour, stored in a farm shed in South Africa, that was the starting point of five years of postgraduate research for Dr Potgieter.

“It was only when I started going through all the documents and correspondence that it became apparent what a huge event it was on so many levels, and that in South Africa we weren't fully aware of what the tour had meant for New Zealand,” Dr Potgieter explains.

“What fascinated me were the 'aspects' of the 1981 tour which were consistently and selectively remembered, and in particular the predominant anti-racist and anti-apartheid aspects that still remain the main narrative by which the tour is remembered.”

Dr Potgieter says this narrative is a very selective understanding of the tour and conflicts with the accounts of those who had participated in the anti-tour campaigns in 1981, and their recollections of what they were battling against at the time.

“Apartheid was a major factor in catalysing the protests, but protestors treated it more as a critique of New Zealand society such as a conservative government which deported Pacific Island 'overstayers', annexed Māori lands, but at the same time encouraged the immigration of white South Africans. Many Māori also linked institutionalised racism to the experiences of black South Africans.”

In addition, rugby culture as the national sport was also seen as promoting toxic patriarchal masculinity, restrictive gender roles, excessive consumption of alcohol, and a culture of violence.

These wider issues are no longer 'remembered' in the retelling of the 1981 tour Dr Potgieter explains, however collectively make the 1981 tour a kaleidoscope of shifting and contested narratives which impose particular meanings.

“Rather than accepting historical accounts at face value, it is important to ask why some narratives rather than others endure and come to represent what we 'know' about the past and the evolution of our society.”

Dr Potgieter's work discussing the legacy of the tour for South African rugby has been published in the Australian journal Sporting Traditions, and his doctorate research will be published in the North American Journal of Sport History later this year, as well as in a co-authored book chapter in Sport in Aotearoa/New Zealand: Contested Terrain in December.

Dr Potgieter says applying a cultural history approach to the 1981 Springbok tour provides a rich understanding of how particular types of ideological and cultural politics shape how we interpret and reinterpret past events.

“The political, social, and cultural implications of the tour were huge, and the changing narrative of the event in the 40 years since is a powerful example of a national sport like rugby being a mechanism through which we are able to view the intricate workings of society.”

For further information, please contact:

Dr Sebastian Potgieter School of Physical Education, Sport and Exercise Sciences University of Otago Email [email protected]

Guy Frederick Communications Adviser Sciences University of Otago Mob +64 21 279 7688 Email [email protected]

Find an Otago Expert

Use our Media Expertise Database to find an Otago researcher for media comment.

New Zealanders protest against Springbok rugby tour, 1981

Time period, location description, methods in 1st segment, methods in 2nd segment, methods in 3rd segment, methods in 4th segment, methods in 5th segment, methods in 6th segment, additional methods (timing unknown), segment length, external allies, involvement of social elites, nonviolent responses of opponent, campaigner violence, repressive violence, classification, group characterization, groups in 1st segment, success in achieving specific demands/goals, total points, notes on outcomes, database narrative.

Halt All Racist Tours (HART) was organized in New Zealand in 1969 to protest rugby tours to and from South Africa. Their first protest, in 1970, was intended to prevent the All Blacks, New Zealand’s flagship rugby squad, from playing in South Africa, unless the Apartheid regime would accept a mixed-race team. South Africa relented, and an integrated All Black team toured the country.

Two years later, the Springboks arranged a tour of New Zealand. HART held intensive planning meetings, and, after laying out their nonviolent protest strategies to the New Zealand security director, he was forced to recommend to the government that the Springboks not be allowed in the country. Prime Minister Kirk, though he had promised not to interfere with the tour during his election campaign, canceled the Springbok’s visit, citing what he predicted would be the “greatest eruption of violence this country has ever known.”

HART remained active in the anti-apartheid community, continuing to protest the Springboks, and helping to organize a boycott of the 1976 Montreal Olympics. The International Olympic Committee had not banned New Zealand after the All Blacks had toured South Africa, and many African countries saw this failure as a tacit endorsement of Apartheid. In 1980, New Zealand again attempted to bring the Springboks to New Zealand.

The Springboks arrived on July 19, 1981. Though they were officially welcomed by the New Zealand government, there was a sense of dread and anticipation that surrounded their arrival – perhaps, some thought, the 1981 tour should have been cancelled like the tour in 1972 was. The government officials could not anticipate, however, that the country was about to fall into “near-civil war.” In response to HART, pro-rugby groups like Stop Politics in Rugby (SPIR) organized in an effort to help the Springbok’s tour succeed. Both sides tended to be easily identified by armbands that made their affiliation clear. In particular, HART activists wore their armbands for the entire length of the tour, subjecting themselves to constant ridicule and the threat of violence, despite their commitment to nonviolent protest only.

The Springboks played their first game on July 22 in Gisborne. An anti-Springbok rally took place that day, near the rugby pitch. When the campaigners arrived at the arena, they were confronted by pro-rugby demonstrators. Because Gisborne, like most cities in New Zealand, was close-knit, demonstrators on both sides knew each other, and were not afraid to call each other out for supporting the wrong side, whichever they believed that was. The pro-rugby demonstrators did not restrict themselves to words, even throwing stones at the other side. The anti-Springbok protesters could not stop the match that day. Though they were able to break through the perimeter fence, and engage the pro-tour demonstrators face to face, they were prevented from occupying the field. Though both sides reported that they were uneasy with the clashes between fellow New Zealanders, neither side was easily swayed.

Three days later, the Springboks were scheduled to play in Hamilton. Anti-Springbok planners had circulated a strategy that would hopefully allow them to tear down the fence, invade the field, and disrupt the match. Protesters had also secured more than 200 official tickets to the match, to make sure that their presence was felt, even in the event that they could not storm the pitch. Despite the presence of more than 500 police officers and a sizable pro-rugby contingent, the anti-Springbok march would prove unstoppable. 5000 anti-Springbok protesters descended upon the Hamilton pitch, and more than 300 made it onto the field, forcing a match cancellation. Protesters chanted that the whole world was watching. Many of the demonstrators were arrested, and those on the pitch endured a constant bombardment of bottles and other objects from rugby fans in the stands. This entire situation was captured on live TV and shown around the world.

With tensions in New Zealand reaching astronomical proportions, the Springboks were next scheduled to play four days later, on July 29. The anti-Springbok protesters were largely absent from the match, but had instead planned a march on the South African consulate in Wellington, New Zealand. Despite police declaring that a march was not permitted, the protesters marched right up to the police line on Molesworth Street. The police began to stop the marchers with their batons, violently forcing them away from the consulate building. The marchers, stunned and bloodied, turned towards the police station, chanting “Shame, shame, shame.” When they arrived, the accosted marchers pressed assault charges on the police that had attacked them. Though the charges were dismissed, the policing of the tour protests had taken a turn for the worse. From this point on, protesters were careful to carry shields and wear crash helmets in order to protect themselves from attacks.

Protests would continue for the entire length of the Springbok’s stay in New Zealand. Only one more match was cancelled, in Timaru. However, there were a few more notable encounters. In Christchurch, on August 15, protesters failed to occupy the pitch in time for the game to be cancelled. The police cordon around the arena held, and several observers believe that the police saved the lives of many protesters. The attacks of rugby supporters were growing more and more violent, The Christchurch incident was characterized by flying blocks of cement and full beer bottles. Had the anti-Bok protesters succeeded in reaching the field, the attacks would certainly have been even more dangerous.

The final match of the tour was in Auckland on September 12. Not only was the match important as a final chance for protesters to demonstrate their opposition to the Springboks, it was the deciding third meeting between the Springboks and the All Blacks. Doug Rollerson of the 1981 All Blacks recalled that it seemed very important for the All Blacks to win the match, to show that a mixed team was superior to the segregated Springbok side. When the All Blacks won, the sense of victory in New Zealand was similar to the US victory over the Soviet Union in 1980 – the triumph of righteousness over the evil empire. However, for most observers around the world, the off-field events were far more important. Though the protesters were generally non-violent, there were many others that joined in the marches – HART characterized them as opportunists that simply wanted to fight with police. Though eruptions of violence had taken place throughout the campaign, they were largely viewed by the protesters as third-party actions, and HART consistently distanced themselves from violent attacks. More memorably, Max Jones and Grant Cole commandeered a prop plane, and proceeded to drop flares and flour bombs on the pitch during play in an attempt to stop the game. Though the game continued, the actions of the protesters were again the primary news story in New Zealand and throughout the world.

Though the anti-Springbok protests were largely unsuccessful in that the vast majority of the planned contests took place, they were able to raise an incredible amount of awareness for the anti-Apartheid movement. Nelson Mandela recalled that when the game in Hamilton was cancelled, it was “as if the sun had come out.” HART would continue protesting until the fall of the Apartheid regime.

Influenced and influenced by anti-Springbok protests in other countries like Australia, Britain (see "Australians campaign against South African rugby tour in protest of apartheid, 1971" and "British Citizens Protest South African Sports Tours (Stop the Seventy Tour), 1969-1970") (1,2).

This campaign was also influenced by the New Zealand Waterfront Strike (1951) (1).

Additional Notes

Name of researcher, and date dd/mm/yyyy.

- Home Kāinga

- Our Story Ngā Kōrero

- Our Tours Ngā Haerenga

- Wellington Museum Te Waka Huia o Ngā Taonga Tuku Iho

- Space Place Te Ara Whānui ki te Rangi

- Nairn Street Cottage

- Cable Car Museum

- Careers Umanga

- What’s On Ngā Kaupapa Whakatairanga

- Museum Blog

- Our Venues Ngā Wāhi

- Venues at Wellington Museum Ngā Wāhi i Te Waka Huia o Ngā Taonga Tuku Iho

- Venues at Space Place Ngā Wāhi i Te Ara Whānui ki te Rangi

- Birthday Parties Ngā Pāti Rā Whānau

- Recommended Caterers Ētahi Kaitaka Kai

- Education Blog Rangitaki Mātauranga

- Space Place

- Wellington Museum

- Space Place Wāhi Haumaru

- Venues at Space Place Ngā Wāhi i Te Wāhi Haumaru

- Support Us Tautoko

- Museum Blog Te Kāpata Te Curio

Remembering the 81′ Springbok Tour

40 years on, we look back and talk to two Wellington residents who remember those turbulent times.

“All for the sake of a Rugby game. Doesn’t make sense does it?” – Liz Roberts

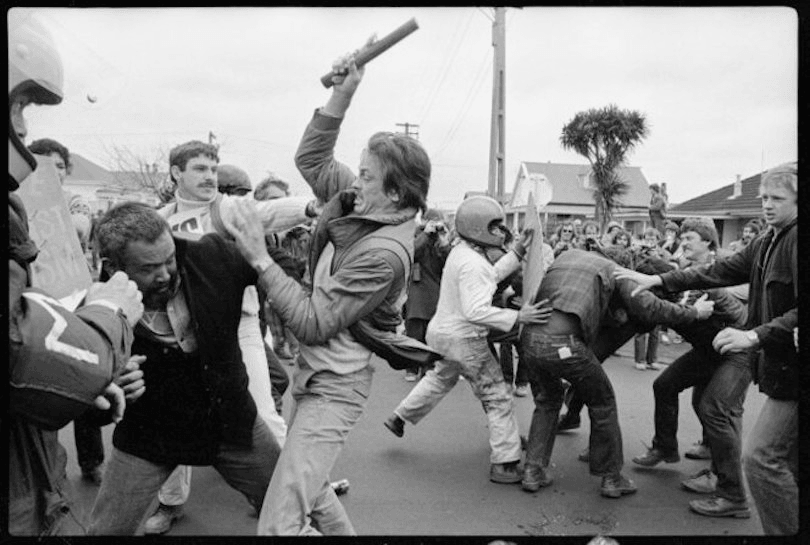

During the winter of 1981, violent clashes between rugby supporters, protesters and the police erupted all over Aotearoa in one of our country’s most tumultuous periods. The Springbok rugby tour brought us to the brink of civil war, as many protested the racial segregation of Apartheid South Africa and made links to racism at home.

On the 29th of July, 1981, protesters opposing the Springbok Tour were met by baton-wielding police trying to stop them marching up Molesworth St to the home of South Africa’s Consul to New Zealand.

This was the first time police had used batons against protestors, and the violence horrified many New Zealanders. Former Prime Minister Norman Kirk’s prediction eight years earlier that a tour would result in the ‘greatest eruption of violence this country has ever known’ seemed to ring true.

Wearing helmets like this one, 7000 protesters gathered in central Wellington and around Athletic Park on 29th of August 1981 to stop pro-tour supporters from gaining access to the second test match. Once again the police intervened, this time using long batons, with many protesters injured as a result. This helmet was worn by Anne Bogle during other anti-tour protests.

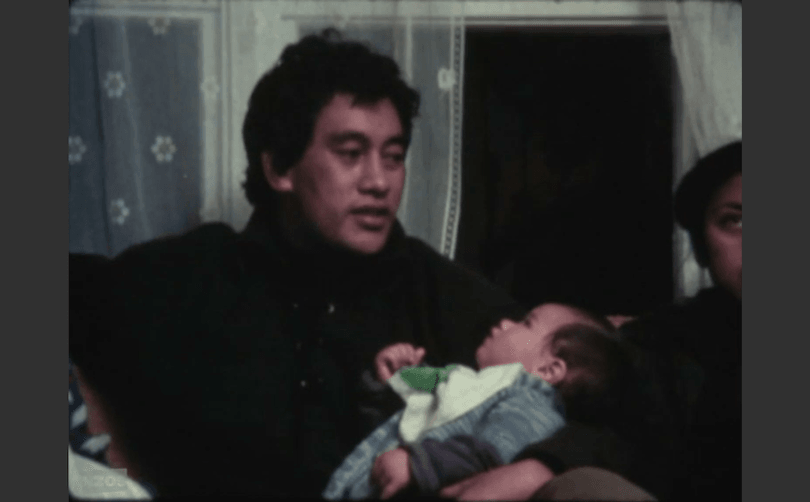

The Merata Mita Estate permitted us to use the Wellington footage from PATU! (1983) – the powerful documentary directed by Merata Mita which shows the harrowing events of the 1981 Springbok Tour.

Ngā Taonga Sound and Vision meticulously restored and preserved the original documentary for the 40th anniversary. With their approval, we were able to use their newly restored and remastered version for these videos.

Liz Roberts lived on Te Wharepōuri Street in Berhampore, close to Athletic Park, and recalls the events of the 2nd Test on August 29th, 1981, where she saw protesters clash with Police on her street.

Anne Bogle was a young Victoria University student studying Law and History in 1981 – and attended a number of Anti-Tour protests in Wellington – she took part in the protest group that blocked the Wellington Motorway on July 25th and the infamous Molesworth Street incident a few days later on July 29th. The protester helmet she used during the anti-tour demonstrations is currently displayed at Wellington Museum.

Thank you to the Merata Mita Estate for their permission to use parts of the film and also to Ngā Taonga Sound and Vision for their great mahi on the preservation and restoration of this important piece of film taonga .

Also thank you to Anne Bogle and Liz Roberts for sharing their stories.

Pin It on Pinterest

- Adding a Story

- Enterprise »

- Your Story »

- Audio Walks »

Springbok Tour in Nelson 1981

In 1981 the South African rugby team, the Springboks, toured New Zealand. The protests against this tour reached a level unparalleled in New Zealand history. This reflected the fact that both the Māori protest movement and anti-apartheid movement had developed significantly ¹. The 1981 tour was the last time the All Blacks and South African rugby teams would play while South Africa was still under an apartheid system. A 1985 tour to South Africa was cancelled after a legal challenge, though a group of rebel players went to South Africa the following year.

Opinion on the Springbok Tour NZ July 1981 From Malcolm McKinnon (ed.), New Zealand historical atlas , David Bateman, Auckland, 1997.

When the Springboks arrived in Nelson on Thursday August 20, 1981 – they were met with strong protest and a city divided over the question of apartheid. There were clashes between pro-tour supporters, anti-tour protestors, and the police. There had already been demonstrations in Christchurch and the Timaru game had been cancelled.

Nelson's mayor Peter Malone's decision to provide an official welcome to the team led to a packed meeting in the Council Chamber - protestors cried “shame” and “racist”, to which the Mayor responded saying "he was “sick and tired” of attempts to link him to apartheid – and that his decision to welcome the team was in a tradition of extending courtesy to visitors. Calls came for Councillors to state where they stood on the Tour - Councillors Craig Potton, Elma Turner and Dorothy Matthews quickly stood up to condemn the tour – others backed the Mayor’s stand.²

Springbok Tour protestors Nelson Church Steps August 1981. Nelson Mail Collection: 6424_FR16 Nelson Provincial Museum

The official welcome at the Rutherford Hotel went off without incident, and was attended by Mayor Malone, Deputy Mayor Pat Tindle, Councillor Malcolm Saunders, and Nelson MP Mel Courtney.

On the morning of the Saturday game roads leading to Trafalgar Park were cleared, barricades were set up and police massed at the Maitai Bridge to control access leading to the park. At the Rutherford Hotel where the Springbok team was staying, about 100 protestors gathered to form a picket line and got into an altercation with police where several were arrested.

The main gathering of protestors ended up at the church steps , where anti-tour banners had appeared over the Nelson Cathedral tower. After that protest they moved down Trafalgar Street as far as Halifax Street where the police diverted the marchers down to Paruparu Road where they continued to chant loudly across the river to Trafalgar Park where supporters of the game were gathered for the match.

The Springboks racked up 83 points during the 80 minutes – with first-five eighth Naas Botha accounting for 31 of them. Nelson Bays coach Mervyn Jaffray was not present to see his team get taken apart, as he elected to stay home on account of his moral opposition to the tour – instead receiving occasional score updates from his wife as he got to work planting in their vegetable garden.

Police said about 30 people were arrested in total throughout the protest, mainly from Christchurch and Wellington.

The anti-apartheid movement in South Africa was buoyed by events in New Zealand. Nelson Mandela recalled that when he was in his prison cell on Robben Island and heard that the game in Hamilton had been cancelled, it was as ‘if the sun had come out’.³

September 2021

- Michelle Bryant

- anti-apartheid

Sources used in this story

- Keane, Basil 'Ngā rōpū tautohetohe – Māori protest movements - Rugby and South Africa', Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand (accessed 7 September 2021) http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/nga-ropu-tautohetohe-maori-protest-movements/page-4

- Newman, T. (2021, August 21) Springbok Tour 'a watershed moment' for Nelsonians on both sides of the divide. Nelson Mail on Stuff : https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/126109153/springbok-tour-a-watershed-moment-for-nelsonians-on-both-sides-of-the-divide

- 'All Blacks versus Springboks' (Ministry for Culture and Heritage), updated 4-Feb-2020 https://nzhistory.govt.nz/culture/1981-springbok-tour/all-blacks-vs-springboks

Want to find out more about the Springbok Tour in Nelson 1981 ? View Further Sources here .

Related Stories

- The history of Nelson rugby

- New Zealand's first Rugby club

- First game of rugby

- Nelson's Church steps

- Trafalgar Park

Do you have a story about this subject? Find out how to add one here.

Comment on this story

Post your comment.

Thank you for writing this article. This brings back a lot of memories. Some sad. From my recollection. In Nelson there were no pitch invasions or other disruption of the match. The protesters got as far as the Trafalgar Street Bridge then split into three groups: the Paruparu road group (described above), another in Millers Acre & the group that roamed the streets in the Wood near the park. At the end of the game the protesters had dispersed when the rugby crowd of about 5,000 made their way home after that drubbing of 83-0. I don't remember the "city being divided over Apartheid" there appeared to me to be a lot of Nelsonians who were neither for or against the tour but sat in the middle - didn't have an opinion either way. The papers said at the time that at the airport when the Springboks arrived that there were a handful of protesters, but they were outnumbered by tour supporters and Nelson people who had just gone out to 'have a look'. What concerned people, especially my mother, was the explosive device found in the bar of the Rutherford Hotel and the other explosive devices found in the foyer of the Post Office. The other thing that I remember was what was called a 'tuna scarer' being used and nail clusters being thrown under the tour bus. It was a frightening time.

Posted by Springbok Tour in Nelson 1981, 19/09/2023 11:35pm (8 months ago)

No one has commented on this page yet.

RSS feed for comments on this page | RSS feed for all comments

Further sources - Springbok Tour in Nelson 1981

- Cameron, D. (1981) Barbed wire Boks. Auckland, NZ. Rugby Press Ltd. https://www.worldcat.org/title/barbed-wire-boks/oclc/13536912

- Chapple, G. (1984) 1981: the tour. Wellington, NZ. A.H. & A.W. Reed. https://www.worldcat.org/title/1981-the-tour/oclc/17222312

- Meurant, R. (1982) The Red Squad story . Auckland, N.Z. : Harlen, 1982 https://tepuna.on.worldcat.org/v2/oclc/13419904

- Newnham, T. (1981) By batons and barbed wire. Auckland, NZ. Real Pictures Ltd https://www.worldcat.org/title/by-batons-and-barbed-wire/oclc/1153492160

- McKinnon, M. (ed.),( 1997) New Zealand historical atlas. Auckland, NZ, David Bateman https://www.worldcat.org/title/bateman-new-zealand-historical-atlas-ko-papatuanuku-e-takoto-nei/oclc/39014539

Shears, R. & Gidley, I. (1981) Storm out of Africa : the 1981 Springbok tour of New Zealand . Auckland, N.Z. : Macmillan https://tepuna.on.worldcat.org/v2/oclc/12664077

- 'Opinion around New Zealand on the 1981 Springbok tour' (Ministry for Culture and Heritage), updated 4-Feb-2020 https://nzhistory.govt.nz/media/photo/opinion-on-the-springbok-tour-around-new-zealand

- 'Police cry wolf claims Hart head' ( 1981, August 25) Nelson Evening Mail, p.2

- 'Poetry read to marchers' (1981, August 24) Nelson Evening Mail, p.10

- 'Blown his cover' (1981, August 21) Nelson Evening Mail, p.1

- 'Angry scenes' (1981, August 21) Nelson Evening Mail, p.1

- It's just a game. Retrieved from Nelson Provincial Museum 7 September 2021: http://www.nelsonmuseum.co.nz/rugby-150/its-just-a-game

Web Resources

- Springbok tour 1981. National Library Services to Schools. Retrieved 7 September 2021: https://natlib.govt.nz/schools/topics/57fd9962fb002c638c0066d7/springbok-tour-1981

Footer Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 New Zealand License

- Accessibility

- Terms of Use

- newzealand.govt.nz

1981 Springbok Tour drove New Zealand to the 'brink of civil war'

Share this article

Reminder, this is a Premium article and requires a subscription to read.

They came to play rugby – but the 1981 Springboks' presence in New Zealand resulted in a torrent of violent protests never previously seen in New Zealand. Neil Reid looks at the Barbed Wire Boks' unhappy place in sporting history

For Errol Tobias, the 1981 Springbok tour to New Zealand should have been a career highlight – a chance to make a global statement for black and coloured South African rugby players.

But just weeks into the tour, the trail-blazing midfielder was ready to pack his bags and fly home.

Then aged 31, Tobias was the only non-white player selected to tour.

Prior to the team's arriving in New Zealand, his selection had been labelled by both New Zealand critics of the South African's racist regime and also by white South Africans who backed the apartheid system as a cynical move from South African rugby officials to try and placate anger from the anti-tour protest movement.

And as he was to find out during the tour which divided our nation so violently, members of the team management - including manager Professor Johan Claassen - several team-mates and also some South African media covering the tour were also of the opinion that his selection wasn't based on his ability.

The issue came to a head when Tobias – who had impressed right from the start of the tour - missed selection for the first test against the All Blacks; being overlooked for midfield rival Willie du Plessis who was struggling with a hamstring injury.

"I seriously considered packing my bags and returning home to [my wife] Sandra who was pregnant with our twins," Tobias reveals in his autobiography, Pure Gold.

"I phoned my wife and poured out my heart about the demonstrators and violence, and our unfeeling, ineffective team management. Sandra immediately said that if I felt unsafe, I should rather ask to come home."

Tobias said in his book – which has never been released in New Zealand in hardcopy form – that he told his wife: "In the current situation no Springbok can feel safe".

After some soul-searching he backtracked on thoughts of quitting the tour from hell.

"I realised it would encourage Professor Claassen in his efforts to keep the Springbok team lily-white," he said in his book.

After the omission he could understand why touring South African reporters gave his strong form "very little coverage".

Tobias – who now serves his church as a lay preacher – also decided to refuse to pray with his team-mates, confiding he "didn't feel up to praying with people who believed only white people were worthy of wearing the green and gold".

Tobias revealed he first felt a "very negative attitude" towards him before the Springboks even arrived in New Zealand.

Claassen didn't make eye contact with him when they met for the first time. He added coach Nelie Smith was also "strangely evasive".

"My sixth sense had never let me down and I immediately had the feeling a very unpleasant time would be ahead of us," he wrote in Pure Gold.

The only person he confided in was friend, team-mate and Springbok great Rob Louw; another player Claassen didn't want on tour and who would also be ostracized by some within the squad while in New Zealand for his friendship with Tobias.

Before boarding their flight to New Zealand, the team received impassioned speeches from South African Rugby Board president Danie 'Doc' Craven and South African Rugby Football Federation president Cuthbert Loriston.

Craven's final words was that the Boks of 1981 would lay the "groundwork" for South Africa to host a Rugby World Cup in 1990. Loriston said he hoped the tour would "pave the way" for the Springboks' readmission to the international rugby fraternity.

Both statements were optimistic – and by the time the Springboks departed New Zealand on September 13, they couldn't have been further from the truth.

No idea of what awaited them

Speaking to the Herald from his home in Stellenbosch, in South Africa's Western Cape province, former Springbok star Theuns Stofberg said when he boarded the plane to New Zealand he was totally unaware of what awaited.

"We were just a group of guys who came to New Zealand to play against the best in the world," he said.

Six years earlier he had made his test debut against the All Blacks on their tour of South Africa. In 1980 he had captained the Boks against the South American Jaguars; an honour he would have again in the first test against the All Blacks at Lancaster Park.

"Playing the All Blacks . . . that is the highlight of any South African, especially on their home field," Stofberg said.

"I got the opportunity in 1976 to play against the All Blacks. Five years later it was my chance to go to New Zealand and it was going to be the highlight of my playing career."

Tobias initially thought the same.

He recalled rugby officials said there was no need "to be concerned" about demonstrators disrupting tour matches.

Among items to be given out by the tourists to members of the rugby community and public during their stay were stickers featuring a Springbok leaping through a silver fern with the wording: "A rugby friend is a friend indeed".

But their unpopularity quickly sunk in during a stop-over in New York on their travels here.

The Boks had to fly via the US after Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser refused to allow their plane to land and refuel in Australia.

Waiting for them were protestors with banners telling them to "Go Home".

And their arrival here proved to be anything but welcoming.

Protestors awaited the Springboks when they finally touched down at Auckland International Airport on July 19, three days out from the tour opener against Poverty Bay.

He described the atmosphere on arrival as "unfriendly".

"Many of the [demonstrators] . . . wanted to know how I could be on the side of such a despicable bunch of racists . . . 'Errol, what are you doing with these racists? They don't belong here'," Tobias wrote in Pure Gold.

"On the one hand, these words hurt me deeply, but on the other hand, it was the best possible motivation to play even better."

More concerning was learning days later of pamphlets from a section of the anti-tour movement offered instructions on how to make firebombs, and also urging them to collect broken glass "by the bucketful" to spread over grounds to host the Springboks.

Tobias was one of the stars of the Boks' first up 24-6 win over Poverty Bay.

But his desire that the "entire New Zealand could experience first-hand that I deserved my position on the team" received a "rude awakening" from management, including Claassen.

"A 'non-white' player wasn't welcome in this Springbok team, not to mention a 'non-white' assistant manager with the tact of Abe Williams," Tobias wrote.

Very early in the tour Williams told media: "As rugby players there's nothing we can do about apartheid because it's the law. Maybe we should rather see this tour as the beginning of a new era for South African rugby. In our team we have Errol Tobias who was selected for the team purely on merit and not because he is coloured.

"This your own scout [an un-named All Black scout] can vouch for, who saw him in action in the second test against Ireland and thought he posed a bigger threat for the All Blacks than Danie Gerber'."

They were the last words Williams spoke at a press conference during the tour.

New Zealand was on the "brink of civil war"

Springbok captain Wynand Claassen fully realised his team were in for a "tough" time after the protests on the day of the Poverty Bay game.

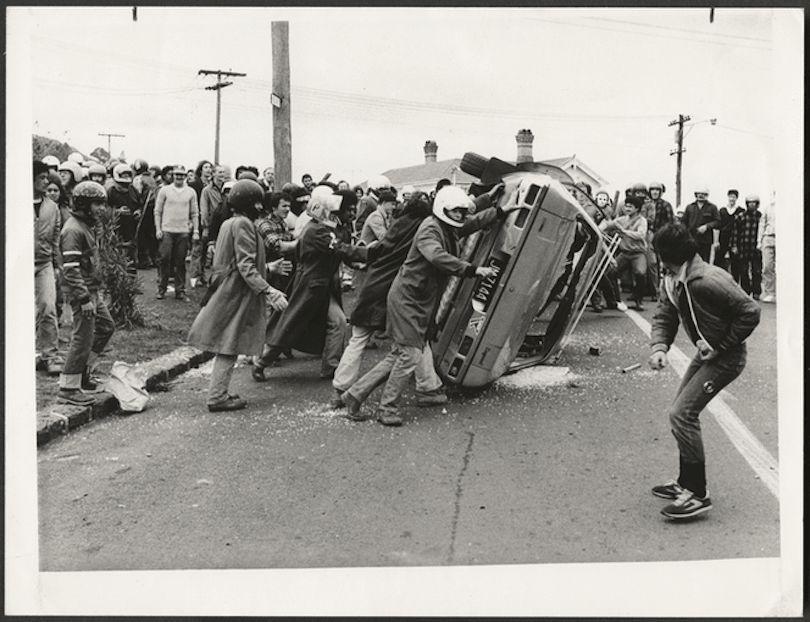

But by the end of what should have been the second match day of the tour – when the scheduled clash against Waikato had been abandoned after a mass pitch invasion and fears a stolen plane would be crashed into Hamilton's Rugby Park – he had upgraded his description the atmosphere the Boks were operating in as "like a war at times".

"Protestors tore down a wire fence and stormed the field. While the police were grappling with those on the field, we rushed back to the change-room where we stood on benches to look out the back window to see what was going on," Claassen recalled in Springbok – The Official Opus.

"I remember seeing a group of protestors overturn one of those big trailers, and then turning and coming towards the change-room."

The charge towards where the Boks had taken sanctuary was halted by police.

Tobias also remembers protestors "bashing" against the windows of his side's dressing room.

The fears by senior police that the stolen light plane was going to crash into the ground if the match wasn't cancelled was also passed onto the Springboks.

"It was now a full-scale war with real blood being shed," Tobias wrote.

"For me, it was equally shocking and tragic to see how the Kiwis were fighting each other, how friendships and families were ripped apart, for example, where one part of the family was waving placards in the streets, while other family members had to protect the Springboks as part of the police force."

While the match was cancelled, the tour continued.

Temporary fortifications were put up around match venues, including heavy shipping containers and thousands of metres of strategically laid barbed wire to keep protesters out; the latter saw the team being dubbed the 'Barbed Wire Boks'.

The police's new anti-riot group - the Red Squad – followed the Springboks everywhere. And the team was not allowed to travel from their hotels in small groups in team gear without the threat of potential violence.

"It was beyond my comprehension how not even the bloodshed in Hamilton could open the eyes of the team management and make them realise that the world was not going to accept a white Springbok team anymore," Tobias said.

"It was one of the largest campaigns of civil disobedience in New Zealand's history and drove the country to the brink of civil war."

Tobias said as the tour progressed it became a "bizarre, never-ending nightmare".

Players had mirrors shone in their eyes from protestors who managed to get into match venues.

Noisy protests were also held outside hotels the team stayed in through the early hours of the morning.

The increasing targeting of hotels saw the Springboks being housed in function rooms at both Athletic Park and Eden Park prior to the second and third tests respectively. The team dubbed those new arrangements as the 'Grandstand Hotel'.

"Don't you have an air force in New Zealand?"

New Zealand witnessed protest scenes with the intensity and violence never seen previously here during the Springboks' 56-day stay here.

None were as shocking as those around Eden Park on September 12, 1981; the day of the third test against the All Blacks.

For several hours, protestors wearing a myriad of protective gear, and some using cricket bats, softball bats and fence palings as weapons, clashed violently with police.

Inside the stadium, crazy scenes were also played out as 50,000 rugby fans watched a pulsating test which went on to be dubbed the 'Flour Bomb Test'.

A light plane piloted by Marx Jones completed numerous low-level passes of Eden Park. Flares, anti-tour pamphlets and flour bombs – one which felled All Black prop Gary Knight – rained down on the playing surface.

After Knight was hit by the flour bomb, Wynand Claassen asked those around him: "Don't you have an air force in New Zealand?'."

"We were under enough pressure as it was and with all this going on around us, it was important – but equally tough – to keep the guys focused," the captain later said.

"I just kept telling them that we should think of the people back home and that we simply must win this test."

Stofberg said the antics of Jones was the extreme end of protests the Springboks never imagined to experience in New Zealand.

By the time they walked onto Eden Park for the final test the team vowed to use the spite directed towards them as a motivating factor.

"When you see the barbed wire [around the field and stadiums] and the plane, it was more of a motivation to play and do the best in the game."

Latest from New Zealand

Ponsonby Rd shooter was son of celebrated filmmaker Don Selwyn

The gunman was Hone Kay-Selwyn. He killed Robert Sidney Horne on Sunday night.

Wrampling, Burr to make season debut for Chiefs

The chief executive of a rugby union who's never played a game in her life

Almost every Kiwi household will benefit from tax relief, Finance Minister promises

Retirement? What retirement?

Libraries and Learning Services

Winter of discontent: 1981 Springbok tour

The South African ‘Springbok’ Rugby Union team toured New Zealand in the winter months of 1981. They played three tests against the All Blacks and 11 games against provincial sides. Two further scheduled games were cancelled due to protests. The 56 days (19 July to 13 September) that the Springbok toured were some of the most turbulent in modern New Zealand history. Families were divided over the tour and opinions were polarised. Tour supporters believed that politics should be left out of sport; tour opponents argued that any sporting contact with South Africa and its racist apartheid regime brought shame on the nation.

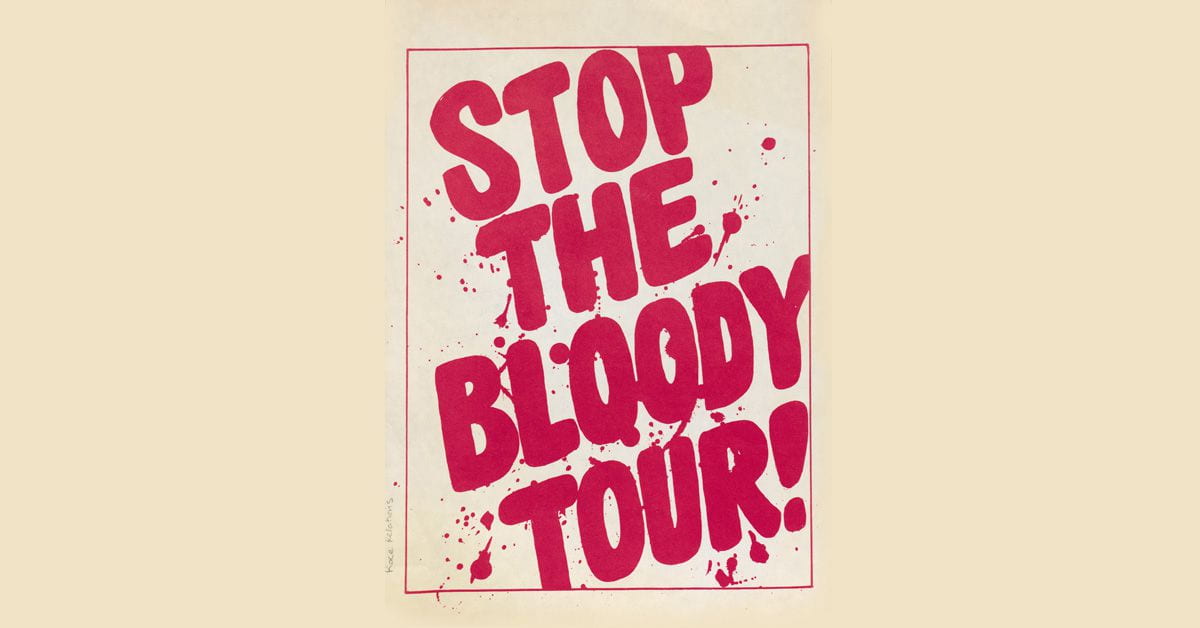

While violent confrontations between anti-tour protesters and police officers dominate popular memories of the winter of 1981, many marches and demonstrations were peaceful, and there were other forms of opposition to the tour such as art works, poems, petitions, and hunger strikes. Special Collections is marking the 40th anniversary of this winter of discontent with a new display capturing the diversity of passions provoked by the Springbok tour.

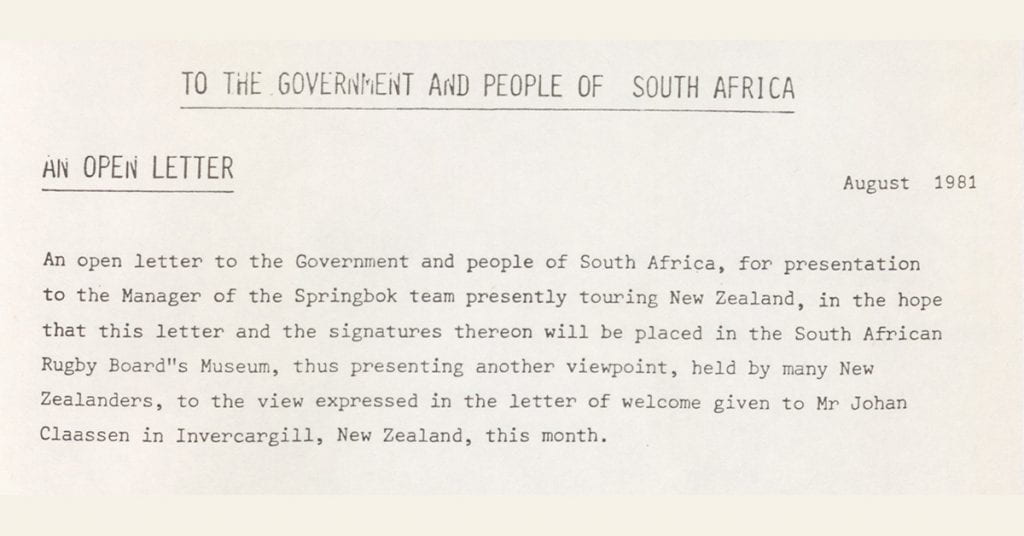

Anti-tour petition mystery

The opening text from the ‘letter of unwelcome’ petition to the South African government and its people, MSS & Archives A-241.

The centrepiece of the display is one of two copies of a hardbound anti-tour petition; Special Collections holds one copy but the whereabouts of the other is unknown. In August 1981, Remuera mother and daughter Jenny and Rebecca Hanify started their ‘letter of unwelcome’ petition to the South Africa government and its people. 1 This was their response to a letter of welcome to the Springbok touring party signed by 1,380 Southland residents and handed over when the team visited Invercargill. Johan Classen, Springbok tour manager, promised to deposit the signed letter of welcome from Southland in the South African Rugby Board’s museum. 2

The anti-tour ‘letter of unwelcome’ petition started by Jenny and Rebecca Hanify was signed by more than 3,500 of Auckland and Dunedin residents, including the respective mayors. One copy of the petition was deposited with the University of Auckland General Library in early 1982. The other copy was mailed to John Ryan, chief assistant editor at the Rand Daily Mail in Johannesburg. He, in turn, passed it on to Dr J. Craven of the South African Rugby Board for depositing in the board’s museum to sit alongside the Southland letter of welcome. However, a letter in our collection from March 1982 indicates that Dr Craven refused to accept the petition from Ryan. The Springbok Experience Rugby Museum in Cape Town closed in 2019; we will probably never know if the other copy of the petition was preserved in post-apartheid South Africa. If the copy sent to South Africa has been lost, our copy is the only one in existence.

- Visit the display until Monday 13 September, Special Collections, Level G, General Library.

- Watch the TVNZ ‘1981: A country at war’ documentary on TV and Radio.

Ian Brailsford, Special Collections

References

1. ‘A letter of unwelcome’, (1981). Auckland Star , 9 September p.3 ; Letters to the people of South Africa from the citizens of Auckland and the citizens of Dunedin to the South African Rugby Board Museum. MSS & Archives A-241.

2. ‘Boks touched as south pens welcome’, (1981). New Zealand Herald , 8 August, p.3.

Did any University of Auckland students write letters in Craccum?

Kia ora Fiona, The answer is yes … and you can search or browse Craccum online in our digital collections.

Kia ora Ian, It is wonderful to see Te Tumu Herenga | Libraries and Learning Services coordinating a display that brings back so many memories for me. I actually liked rugby before the tour and am only slowly coming around again. I was there in 1995 when Nelson Mandela thanked the New Zealanders for highlighting apartheid and racism when he was locked up. Ngā mihi Abigail

Kai ora everyone there were things in my younger days one was looking after the rugby grounds of Eden park, so that no protesters didn’t damaged the grounds and other grounds for that matter, and yes i’ve seen that book, and its should be some were in the general library ,we rebind it and put it into a new cover some years ago.

Kia ora Byron, if you are referring to the petition, the copy is still in the library. You can view the details here: https://archives.library.auckland.ac.nz/repositories/2/resources/152

Comments are closed

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Protests, politics and a bus hijack: the rugby tour that gave Mandela hope

Fifty years ago South Africa were battered on and off the pitch in Britain and Ireland as apartheid felt the fury of the people

T he tour that changed international sport ended 50 years ago. South Africa, No 1 in the world now and vying with New Zealand for supremacy then, returned home after four torrid months in Britain and Ireland when they were dogged by anti-apartheid protests and failed to win any of their four Tests.

It was a rude awakening for the vast majority of the squad who had little experience of the world outside their homeland, their isolation fostered by the lack of television in the country.

Europe was emerging into the world of colour at the end of the 1960s, but black and white in South Africa amounted to a political system that was abhorrent in a world that knew the power of protests.

The Springboks, as Chris Schoeman shows in his book on the tour, Rugby Behind Barbed Wire (Amberley, £20), were innocents abroad. There were exceptions, such as South Africa’s vice-captain Tommy Bedford, who studied at Oxford University and warned at the official reception on the eve of the squad’s departure that what lay ahead would probably be reflected in results.

“If we did not win all our games or even lost Test matches because none of us would have had any idea of how to cope with this additional demonstration phenomenon, the people back home and those in the comfort of the function room should remember this,” he told Schoeman. “That went down like a lead balloon.” A later speaker implied that Bedford was being disloyal.

Fifty years on, Bedford lives in London. He was so changed by the tour – identifying with the aims of the protestors to undermine apartheid through sporting isolation, if not all their methods, one of which involved the commandeering of the squad’s coach when they were on board before a match and crashing it into parked cars – that after his Test career ended in 1971 he committed himself to political change in South Africa.

He was interviewed by the Rugby Paper last November, after Siya Kolisi, the first black captain of the Springboks , had held aloft the World Cup in Yokohama and spoken movingly about his hope that rugby would help unify a divided nation . Those protesting in 1969-70 – the Stop the Seventy Tour was chaired by Peter Hain and one of the organisers in Scotland was Gordon Brown – were written off by the rugby media here as idealists and do-gooders, irritants who did not understand rugby union’s fraternity.

If any of the reporters watched last year’s World Cup, they should by then have come to appreciate not only what the protest was about but that politics and sport were not mutually exclusive, not least because governments such as South Africa’s in the apartheid era used sport for sustenance; and it was South Africa who blocked Basil D’Oliveira after the Worcestershire all-rounder was called up as a replacement for the MCC’s 1968-69 tour, saying it was a politically motivated selection when it seemed that his original omission was exactly that.

“We knew that no other country could afford a tour like this,” said Bedford last year. “That was the catalyst for change in a radical way. When I got back to South Africa from the UK I took time out. I went to a deserted part of the country and I thought about Peter Hain, Bernadette Devlin and all those anti-apartheid people who put us in this laager [camp]. I came to the conclusion that maybe they did have a point.”

Schoeman largely concerns himself with the tour itself, his book ending with a short chapter entitled Aftermath. He interviewed several of the South Africa squad, including Bedford and the captain, Dawie de Villiers, who was to serve on Nelson Mandela’s first cabinet following the fall of the apartheid regime, as well as a player from each of the four home unions: the Springboks lost against England and Scotland before drawing with Ireland and Wales and were beaten by Oxford University, Newport and Gwent in the first two weeks of the trip.

Mandela was on Robben Island when the matches were played. A news blackout for the prisoners was undermined by the warders, who were unable to hide their frustration at both the results and the protests. “It was as if Mandela and his comrades were to blame,” said Peter, now Lord, Hain. “His apartheid jailers were beside themselves with rage and that gave him a glimmer of hope.”

The protestors succeeded in forcing the postponement of one match, Ulster, while the opener against Oxford University, which was played exactly 50 years before South Africa’s victorious 2019 World Cup squad returned home, was switched from Iffley Road to Twickenham on police advice. Protestors who invaded pitches in the early matches were often dealt with by stewards, not always leniently, prompting the government to decree that only the police could take such action.

Personal memories of the tour are disappointment that Cardiff were overwhelmed by players who were far bigger than the usual opponents at the Arms Park. The politics went over the head of a young boy whose questions were to find answers later as rugby, showing its amateur status then, continued to maintain links with South Africa: New Zealand, France, England, South America, Ireland and the Lions all toured there at least once up to 1984. The visit of the Springboks to New Zealand in 1981 sparked protests that rivalled 1969-70 and two matches were called off.

New Zealand were due to visit in 1985 but their tour was called off after a high court ruling that it would contravene the union’s stated purpose of fostering and encouraging the game of rugby. The Cavaliers went there the following year, for money according to reports. It was apartheid’s last, laboured gasp, strangled by the sporting boycott.

- The Breakdown newsletter

- Rugby union

- South Africa rugby team

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

The Spinoff

Ātea December 28, 2021

Three things you didn’t know about the 1981 springboks tour.

- Share Story

Summer read: This year marked the 40th anniversary of the rugby tour that divided a nation. While countless books and articles have been written about that time, some important details have faded with age. Leonie Hayden looks back at three of them.

First published July 22, 2021

Merata Mita’s documentary Patu! opens with a group collecting signatures on the street in Auckland to petition the government to stop the upcoming Springboks’ tour of New Zealand. A young passer-by starts arguing with the organisers, asking how would they feel if a group of “wogs” or “Blacks” came over here. One group member explains that she’s married to a Black South African man. Undeterred, the man continues his tirade about what would happen if “they” were in charge.

It’s 1981 and Mita’s grainy film footage captures one of those most divisive periods in our history since the New Zealand Wars. It was a battle that played out on the rugby field, in the streets, within the halls of parliament and at kitchen tables all over the country. But the fight for New Zealand to take a stand against South Africa’s apartheid regime was far from new.

The New Zealand Rugby Football Union had left rugby legend George Nēpia and other giants of the game at home in 1928 to conform with South Africa’s segregation laws. In 1959, the Citizens’ All Black Tour Association had tried to demand “No Maoris, no tour” when Māori players were excluded from the team’s 1960 visit. They weren’t successful then, but Māori players would go on to tour South Africa as “honorary whites” in 1970 and then in 1976 – the same year as the Soweto uprising that saw hundreds of children and student protestors murdered by police.

While Robert Muldoon campaigned on sports and politics being kept separate, deftly side-stepping the Commonwealth members’ Gleneagles agreement , the world had very much decided the two were connected. Black African nations boycotted the 1976 Montreal Olympics in protest of our ongoing engagement with South Africa. New Zealand was becoming a pariah.

And so when the 1981 tour was announced, anti-apartheid groups such as Halt All Racist Tours (HART), Citizens Association for Racial Equality (CARE) and the Patu Squad (led by Hone Harawira, Donna Awatere, Josie Keelan and Ripeka Evans) began a national campaign to stop it in its tracks.

Ultimately, the demonstrations and petitions to Muldoon’s government – plus a national poll showing only 46% public support for the tour – fell on deaf ears and the South African team were officially welcomed to New Zealand at Te Poho-o-Rawiri marae in Gisborne on July 19, 1981.

Tā Graham Latimer’s wero

It was a pōwhiri with teeth.

The welcome for the Springboks took place at the same time as Māori activists were spreading glass across Gisborne’s Rugby Park ahead of the first game. The speakers that evening comprised Te Poho-o-Rawiri kaumātua, dignitaries of the Tairāwhiti Māori council, and the president of the New Zealand Māori Council, the late Sir Graham Latimer .

To many the welcome would have looked like a sign of a generational divide – conservative assimilationists on the marae versus activists on the field – but Latimer ensured the pōwhiri wasn’t an occasion that ignored or played down what was at stake. In fact, he very politely told Springboks captain Wynand Claassen and his team they wouldn’t be welcome again while apartheid remained in South Africa.

Per tradition, it was Latimer’s role as the New Zealand Māori Council president to extend a greeting to any international group being welcomed onto a marae. The speaker before him, Tom Fox, had emphasised with some pride, and to much applause, that the Tairāwhiti branch was the only Māori council that actively supported the tour.

Latimer, however, was less effusive. “I am fully conscious of the fact that I do not have a complete mandate to make this welcome,” he began. “Seven out of the nine district councils that make up the New Zealand Māori council are opposed to the tour, and one is undecided.” A long pause, silence from the crowd.

“Fifty-four per cent of the general public of New Zealand has expressed opposition to your tour. That’s in a poll. The last time such a tour was mooted, only 16% were against the tour. That you have come has been seen by some as a major victory but it must be recognised that if there were only another 6% against the tour, there would be neither a political party not a rugby union game enough to extend an invitation to you.”

He continued: “There can be no doubt in my mind that we will not be making another such welcome on a Māori marae – I emphasise that point – unless your government can show it is prepared to change its policies on apartheid. We hope we can look forward to a time in the not too distant future when you could be welcomed on any marae. It would be a pity if this could be looked upon as the last international tour by South Africa.”

Latimer finished by giving an especially warm mihi to Errol Tobias, the first player of colour to tour with the Springboks. “I believe he represents hope for 18 million South Africans, for whom there appears to be little hope.”

The genius of Latimer’s challenge was in its statesmanlike delivery. While much of his speech was received with (presumably) shocked silence, he was still rewarded with a huge round of applause at its conclusion, even though he had just told those gathered they would not be welcome in future under the same circumstances. The extraordinary recording of that evening, housed in the Ngā Taonga archive , captures a mild-mannered assassin executing an entire squad with diplomacy.

Naturally we have no way of measuring the effects of that speech on either the Springboks or apartheid. But it may have been the last time the issue was discussed politely.

Police violence was far worse than they’d like you to remember

Nicknamed the Day of Shame, July 22 saw the Springboks’ opener against Poverty Bay. Three hundred protestors marched to Rugby Park in Gisborne via a nearby golf course and attempted to breach a fence. Rugby fans jumped into action and a brawl broke out between the two groups. Police arrived to break up the fighting, and only two men managed to run onto the field. Thirteen were arrested and many were hurt in the resulting brawl, but it was nothing compared to the violence that was to come.

Over the course of the next two months, police, in particular the infamous Red and Blue riot control squads, would become more and more comfortable with using extreme violence against unarmed protestors, causing serious and sometimes permanent injuries. Pro-tour rugby fans were also brutal in their retaliation.

Singer and journalist Moana Maniapoto, then a first-year law student at the University of Auckland, remembers when the fence came down at the second game in Hamilton on July 25. “Everyone’s leaning on it, pushing and pushing it, and then the next minute the fence came down and you just heard this ‘Run!’ You’re just swept along. So then I’m in the middle thinking, ‘what am I doing here? They’re gonna kill us!'”

She recalls looking up at thousands of angry faces in the stands. “They were totally rabid. Screaming, yelling and throwing cans of beer at us.

“The police arrived, just the ordinary cops, not the Red Squad, and I actually thought, ‘oh this is good, surely they’re not gonna let us get murdered’. Then the commissioner came on and said the match has been called off and there was this huge roar from the crowd. At first it was like, ‘yay!’ and then ‘oh my god. How the hell are we gonna get out of here?’”

Maniapoto, along with land protector Eva Rickard and another friend, managed to escape into the surrounding streets. “The cops were sporadically placed so you had to make a run for it to the gate. Then the cops recognised Eva and they were abusing the shit out of her. But we got out, and we were very lucky, my friend’s father heard on the radio that the match had been cancelled and he circled until he found us. A lot of people got attacked.”

Marx Jones and Grant Cole flour bomb Eden Park in a hired Cessna.

She would go on to attend protests in Rotorua and at the third test in Auckland – the latter resulting in a violent clash between police, protestors and rugby fans on the streets of Mount Eden. “Red Squad came out of nowhere and nutted off at everyone. I was with the least militant bunch when they charged. We were just standing there. Couldn’t believe it. I was batoned, kicked by heavy police boots while on the ground. Shock for a young freshie like me. They just smashed into us and left people lying on the ground in their wake.”

For further proof you need only watch the violence through Mita’s lens. The dull thud of police batons hitting flesh and human skull, and the wails of the injured, some of them young teenagers, is the haunting soundtrack for nearly half the film.

Maniapoto scoffs at the selective memory that it was “New Zealand” who took a stand against apartheid. “It’s held out as a landmark, framing New Zealand as a global social justice advocate. It wasn’t New Zealand; it was people power. It was activists, people from across all walks of life, and there were far fewer of us than there were in the stands.”

She talks abut the Nelson Mandela exhibition hosted at Eden Park in 2019 – a strange venue considering the violence that played out on the surrounding streets 38 years earlier. She says at the launch none of the speakers from the New Zealand Rugby Union came close to admitting they’d been wrong, or offering an apology. Instead everybody spoke proudly about the stand taken by the protestors. Says Maniapoto: “They’re starting to rewrite the history!”

The good bishop saves the Patu Squad

It was at the last test at Eden Park on September 12 that a young Hone Harawira, one of the leaders of the predominantly Māori and Pasifika Patu Squad, was finally caught.

Harawira and a handful of others had been arrested at Waitangi earlier in the year, and although they had been denied bail, they were turfed out of the cells for causing a ruckus and told when to attend their court date. They didn’t show up.

The group had outstanding warrants for their arrest before the tour even began.

“It must have got out to the police that we were all going to be involved in the tour, and one by one we were all picked up. One of the brothers, they got him before it started! So he spent the whole of the tour in Mt Eden,” Harawira chuckles.

Harawira says he was caught early on after the test that ended with Marx Jones’ aerial flour bomb attack , so hadn’t been involved in the upturning of a cop car, or the violence that erupted on an unprecedented scale outside Eden Park. Nevertheless, Harawira was charged with the assault of a police officer who’d had both collar bones broken.

“It wasn’t me but they wanted someone to pin it on so they pinned it on me.”

He says he had seven charges against him. “They were serious charges. Three charges of participating in a riot and four charges of assault with intent to cause grievous bodily harm. Which all carried a total of something like 98 years.”

Justice being neither blind nor in a hurry, Harawira wouldn’t stand trial for another two years, alongside many others who he notes were mostly brown, despite the vast majority of protestors being Pākehā. “Most of them were members of the Patu Squad.”

As he had many times before, Harawira planned to defend himself in court. He’d had University of Auckland law lecturers Jane Kelsey and David Williams to rely on for advice, but this time he wasn’t sure it going to be enough.

“The day before my court date, I’m sitting out the back in the cells thinking ‘jeez, what am I gonna do?’ Then the brain wave came to me. Bishop Desmond Tutu had been invited over by the Anglican church to come and do a speaking tour. Interest was still very high in apartheid South Africa. My mum knew George and Jocelyn Armstrong, who were part of the organisation that brought him over.

“So I rang my mum and said look, I want Bishop Tutu as a witness. She said, ‘He wasn’t there!’. I said, ‘that doesn’t matter! I want him for my witness’. So she said ‘OK when is it?’ And I said ‘Tomorrow! I’m gonna need him by about 10.30.’”

The next day Harawira and 10 others prepared to stand trial.

When the time came for him to give his defence, his star witness wasn’t there. “I read my statement. I’d come to the very end and I was dragging it out. I didn’t want to get out of the dock ‘cos I knew it hadn’t been enough to get me off. Then the door burst open, and someone looked at me with a big smile and just nodded and I knew then. So I asked the judge: ‘Can you please call my witness?’”

Harawira still laughs at the memory of the stunned faces of the judge, prosecution and jury as as the now-Archbishop Desmond Tutu, in his signature dark suit and purple cleric’s shirt, walked into the courtroom.

“And then I’m thinking, ‘What the fuck, now what do I do?’

“So he takes the stand and I go, ‘Could you please tell the court your name?’ And then I said, ‘Can you please tell the court your address?’ And he gave an address in Soweto. Instantly, if the room wasn’t already charged, everyone was completely wide-eyed now.

“And then I said, ‘Can you please explain to the court what apartheid is?’. And away he went. He must have spoken for 20 minutes. It was absolutely stunning. You could have heard a pin drop.”

He says that after Tutu had finished, neither he nor the prosecution could think of any more questions.

“As Bishop Tutu stepped out of the dock, all 11 defendants, we all stood up. Then our lawyers stood up, then the public, the screws from Mount Eden, the police stood up, then the jury stood up. Half of them were in tears. If was one of those moments. I knew right then and there we were gonna get off.” He crows in delight at the memory.

The group were acquitted of all charges.

“It’s kind of hard to believe but it’s all true. Meeting Nelson Mandela himself and going to his tangi, that’s another story.”

We are here thanks to you. The Spinoff’s journalism is funded by its members – click here to learn more about how you can support us from as little as $1.

Jump to navigation

- Back issues

Search form

Get connected, remembering the anti-apartheid protests against springbok tour.

The death of Nelson Mandela on December 5 has focused attention once more on the global struggle against South Africa's aparthied regime. The heroic struggle of the Black population inside South Afica and the solidarity shown by ordinary people around the world was essential to winning Mandela's freedom and dismantling apartheid.

Australia was the scene of dramatic protests and repression against South African sporting tours in the 1970s. Hardline conservative Queensland premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen attracted national attention in July 1971 when he declared a "state of emergency" in Queensland to control demonstrations against a South African Springbok rugby union tour.

The Springboks tour resulted in widespread condemnation of South Africa's racial policies around Australia. The last leg of the Springbok rugby tour was to take place in Brisbane in July, 1971.

You need Green Left, and we need you!

Green Left is funded by contributions from readers and supporters. Help us reach our funding target.

Make a One-off Donation or choose from one of our Monthly Donation options.

Become a supporter to get the digital edition for $5 per month or the print edition for $10 per month. One-time payment options are available.

You can also call 1800 634 206 to make a donation or to become a supporter. Thank you.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

How Nelson Mandela Used Rugby as a Symbol of South African Unity

By: Farrell Evans

Updated: October 5, 2023 | Original: July 29, 2021

On June 24, 1995, at Johannesburg's Ellis Park Stadium, South Africa won the Rugby World Cup 15-12 over its arch-rival New Zealand. The match stands as a hugely symbolic moment in South African history. It marked the nation’s first major sporting event since the end of its segregationist apartheid regime in 1991. And in a masterful act of statecraft conducted squarely in the international spotlight, President Nelson Mandela orchestrated a show of unity in one of the world’s most bitterly divided nations, using the slogan “One Team, One Country.”

The reality of the moment proved far more complicated than image-making.

Apartheid's gross human rights violations had long made South Africa an international pariah. In 1973, a UN resolution declared apartheid a "crime against humanity." From 1964 to 1992, the country was banned from the Olympic Games , while its rugby team was kept out of the sport's first two World Cups in '87 and '91. To Black South Africans, the historically white team—along with their green and gold colors and their Springbok mascot—had come to symbolize the nation’s oppressive minority white rule.

President Mandela saw rugby as a way to help lessen divisions between Black and white South Africans and foster a shared national pride. The sport had been a unifying force before, among the nation's competing colonial forces. A 1906 Springbok tour of the British Isles proudly featured players from both sides in the bitter Boer War (1899-1902) between English and Afrikaners, including one player who had been imprisoned in a British concentration camp. To heal the wounds this time, Mandela—who had himself been jailed for 27 years for challenging the white minority-led apartheid system—had to first acknowledge and address the widespread pain and division apartheid had wrought.

The Historic Connection Between Rugby and Apartheid

While racial segregation had been long practiced in South Africa, the official system of apartheid emerged in 1948, after the political ascendance of the Afrikaner National Party. Afrikaners, descendants of Dutch, German and French settlers who saw themselves as a chosen people, worked to shape a government that favored the white minority.

Under apartheid, the Black majority population was moved to segregated townships in conditions of brutal poverty, excluded from any role in national politics and denied jobs beyond those involving unskilled labor. In 1953, the Reservation of Separate Amenities Act passed, officially segregating all public areas in South Africa—including the rugby pitch.

The Afrikaner National Party had deep ties to the rugby team, which had fielded an all-white roster for its first 90 years. The party embraced the team’s success as its own, and players sometimes used the team as a springboard into party positions.

"The National Party envisioned the Springbok symbol [a native antelope] as a representation of the values and characteristics of the Afrikaner people," wrote Simon Pinsky in an essay published in South African History Online . "In their minds, allowing Black players to don the sacred jersey was a step toward the erosion of these values. The Springbok had come to symbolize more than rugby excellence to the hard-line Afrikaner—it had come to symbolize racial superiority."

Truth, Reconciliation and Rugby

In 1995, five years after walking out of prison and one year after being elected the nation’s first Black president, Mandela formed the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to investigate apartheid-related crimes. The hope of the commission was that full disclosure of the truth about the era’s atrocities would lead to healing in the racially divided nation.

Black South Africans wanted to destroy any symbols of the apartheid regime. High on the list: the Springbok, which had been the rugby team’s mascot—and the sport's emblem of apartheid’s National Party—since 1906. After the first free elections in 1994, all South African national teams had adopted a protea, the country’s national flower, as their emblem—except the rugby team. In a country where rugby was the great national pastime, the Springbok emblem with its green and gold colors wasn’t something many white South Africans were willing to give up.

Mandela Pursues a Larger Goal

Understanding this resistance to change, Mandela sought a conciliatory strategy that would allow Afrikaners to keep their treasured emblem as a means to an end: bringing the nation together.

“As far back as the 1960s, Mandela began studying Afrikaans, the language of the white South Africans who created apartheid,” wrote Richard Stengel in Time magazine on Mandela’s 90th birthday in 2008. “His comrades in the ANC [African National Congress] teased him about it, but he wanted to understand the Afrikaner's worldview; he knew that one day he would be fighting them or negotiating with them, and either way, his destiny was tied to theirs.” In his 1994 inaugural speech, he voiced his vision of a “rainbow nation at peace with itself.”

So at the beginning of his first term, he invited Francois Pienaar, the team's captain, to meet with him to discuss how the Springboks could help broker peace between the Black and white populations. Pienaar had grown up in an Afrikaner community, where Mandela's name was associated with "terrorist" and "bad man." To a Black crowd, Mandela said, “I ask you to stand by [these boys] because they are our kind.”

Black Groups Criticize Mandela

Mandela’s conciliatory gestures to a harshly racist apartheid regime didn’t sit well with Black South Africans still dealing with that regime's legacy of oppression and violence. In the 1976 Soweto uprisings alone, police had killed hundreds of Black citizens and injured thousands.

After his 1994 election, Mandela came under fire from militant Black groups who believed his ruling party, the African National Congress, was too conciliatory to the former apartheid regime. One of his most vocal critics was his estranged wife, Winnie Mandela, who believed he focused more on appeasing whites than on ensuring rights for Black South Africans. While Mandela and the ANC listened to these critics, they continued to focus on reassuring the white minority that it wanted to build a strong working relationship. His appeals to Black South Africans were often framed through the lens of what their support could mean for his larger aims for the country.

“We have adopted these young men as our boys, as our own children, as our own stars,” he said during a visit to the Springbok training camp shortly before the start of the World Cup. “The country is fully behind them. I have never been so proud of our boys as I am now and I hope that that pride we all share.”

The 1995 Rugby World Cup Finals

Before the start of the 1995 World Cup Finals against New Zealand, a mostly white audience of 63,000 at Ellis Park sang along as the Springboks led a new national anthem. It combined words from the “Die Stem” (the apartheid-era anthem, which had been subject to earlier protest) and “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika,” an old pan-African liberation hymn from the anti-apartheid movement. When Mandela appeared in the stadium wearing the Springbok green, the mostly Afrikaner crowd shouted, "Nelson, Nelson, Nelson!"

The game showcased Mandela’s work in the weeks leading up to the matches, setting the stage for a historic—and largely symbolic—show of national unity across the races for the whole world to see. In the match, the two teams finished regulation time tied 9-9 in a spirited match of archrivals. With seven minutes left in extra time, the South African team won with a drop goal by Joel Stransky to secure a 15-12 victory.

“The whole of South Africa erupted in celebration, Blacks as joyful as the whites,” wrote Martin Meredith in his biography, Mandela. “Never before had Blacks had cause to show such pride in the efforts of their white countrymen. It was a moment of national fusion that Mandela had done much to inspire.”

A Moment of Symbolic Unity, With a Complicated Legacy

“When the final whistle blew, this country changed forever,” said team captain Pienaar years later, when Mandela died. While this may have been a gross overstatement to most Black South Africans who continued to suffer at the bottom rung of society in the post-apartheid world, it reflected a deft effort by Mandela to use rugby to heal the nation’s wounds.

To many Black South Africans, the Springboks continue to represent a brutal apartheid regime. The team had just one Black player in the 1995 matches and had only six in 2019 when it won the World Cup over England with its first Black captain, Siya Kolisi. “Just as Mandela’s gesture in 1995 was hailed as a metaphor for racial reconciliation in the nation, so rugby’s failure to transform is seen as a metaphor for disillusionment among Black people who gained political but not economic freedom,” wrote journalist David Smith in a 2015 Guardian column.

Still, Mandela’s efforts to use rugby to bring together a new nation struggling to heal its old wounds became one of his signal achievements as president of South Africa—and a sign of what could be done for good through the power of sport. In 2000 at the Laureus World Sports Awards, Mandela said, “Sports has the power to change the world. Sport can create hope, where once there was only despair.”

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Navigation for News Categories

Mandela honoured at protest site.

The life of Nelson Mandela has been commemorated at Waikato Stadium, the scene of a Springbok tour protest in 1981 when protesters swarmed onto the field forcing the cancellation of the match.

The gathering was timed to coincide with the funeral for South Africa's first black president in his home village of Qunu in the Eastern Cape on Sunday.

A ceremony to remember Nelson Mandela was held at Waikato Stadium on Sunday. Photo: RNZ

About 300 people attended the ceremony on the stadium's field to hear speeches and songs.

In 1981, anti-apartheid protest action at the ground, then known as Rugby Park, resulted in the game between the Springboks and Waikato being cancelled.

Veteran protester John Minto told the crowd that the cancellation of the game in 1981 made a difference and was recognised by Nelson Mandela years later as a turning point in the anti-apartheid struggle.

He said the legacy left by Nelson Mandela is enormous and one that will be debated for a long time.

Ross Meurant who was deputy commander of the Police Red Squad, one of two squads set up to stop protestors disrupting the 1981 Springbok tour, was a surprise guest at the service and received a warm welcome.

Mr Meurant said Nelson Mandela is no doubt the most admirable political leader of recent times.

Local anti tour protest leader John Denny said the protestors were as surprised as anyone that the fence around Rugby Park was breached and, as time was to show, the symbolism of that was to reach Mr Mandela himself.

Copyright © 2013 , Radio New Zealand

New Zealand

- Charity behind ‘Win A House’ promotion not yet registered, using raffle money to buy house

- Cost of junior doctors covering workplace shortages doubles in a year

- Man in critical condition after truck rolls down road at Remuera roadworks site

- Passport delays: Man with serious injury stuck overseas, athlete unable to compete

- Cold start to day with main centres not reaching double-digit temperatures

- School lunch revamp: 'The biggest waiting list since 2018'

Get the RNZ app

for ad-free news and current affairs

Top News stories

- 'Darkest before the dawn': Nicola Willis rules out austerity Budget

- 'Completely stupid' - ex-Tuvalu PM on Shane Jones' oil and gas comments

- Battles rage around Rafah after US halts some weapons to Israel

New Zealand RSS

Follow RNZ News

- Preplanned tours

- Daytrips out of Moscow

- Themed tours

- Customized tours

- St. Petersburg

Moscow Metro

The Moscow Metro Tour is included in most guided tours’ itineraries. Opened in 1935, under Stalin’s regime, the metro was not only meant to solve transport problems, but also was hailed as “a people’s palace”. Every station you will see during your Moscow metro tour looks like a palace room. There are bright paintings, mosaics, stained glass, bronze statues… Our Moscow metro tour includes the most impressive stations best architects and designers worked at - Ploshchad Revolutsii, Mayakovskaya, Komsomolskaya, Kievskaya, Novoslobodskaya and some others.

What is the kremlin in russia?

The guide will not only help you navigate the metro, but will also provide you with fascinating background tales for the images you see and a history of each station.

And there some stories to be told during the Moscow metro tour! The deepest station - Park Pobedy - is 84 metres under the ground with the world longest escalator of 140 meters. Parts of the so-called Metro-2, a secret strategic system of underground tunnels, was used for its construction.

During the Second World War the metro itself became a strategic asset: it was turned into the city's biggest bomb-shelter and one of the stations even became a library. 217 children were born here in 1941-1942! The metro is the most effective means of transport in the capital.

There are almost 200 stations 196 at the moment and trains run every 90 seconds! The guide of your Moscow metro tour can explain to you how to buy tickets and find your way if you plan to get around by yourself.

About Karlson Tourism

Karlson Tourism offices :

Moscú de la Revolución

Jueves, 28 de julio de 2016, "oxygen in moscow": el concierto de música más multitudinario de la historia.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario.

Nota: solo los miembros de este blog pueden publicar comentarios.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS