Plog’s model of allocentricity and psychocentricity: Made easy

Disclaimer: Some posts on Tourism Teacher may contain affiliate links. If you appreciate this content, you can show your support by making a purchase through these links or by buying me a coffee . Thank you for your support!

Plog’s model of allocentricity and psychocentricity is one of the best-known theoretical models in the travel and tourism industry. Since Plog’s seminal work on the rise and fall of tourism destinations, back in 1974, a vast amount of subsequent research has been based on or derived from this concept- so it is pretty important! But what is Plog’s model of allocentricity and psychocentricity?

In this article I will explain, in simple language, what this fundamental tourism model is and how it works. I will also show you why it is so important to understand Plog’s work, whether you are a student or whether you are working in the tourism industry.

Are you ready to learn more? Read on…

What is Plog’s model of allocentricity and psychocentricity?

How did plog’s model of allocentricity and psychocentricity come about, why destination areas rise and fall in popularity, allocentric tourists, psychocentric tourists, mid-centric tourists, positive aspects of plog’s model of allocentricity and psychocentricity, negative aspects of plog’s model of allocentricity and psychocentricity, key takeaways about plog’s model of allocentricity and psychocentricity, plog’s model of allocentricity and psychocentricity: faqs, to conclude: plog’s model of allocentricity and psychocentricity.

Stanley Plog’s model of allocentricity and psychocentricity has been widely taught and cited for almost 50 years- wow! And I would hazard a guess that you are studying this too? Why else would you be reading this blog post? Well, worry not- I am confident in the knowledge that by the time you get to the end of this article you will be a Plog expert!

Right, so lets get to the point…. what is Plog’s model of allocentricity and psychocentricity?

Plog’s model is largely regarded as a cornerstone of tourism theory. It’s pretty important. This model has provided the foundations for many other studies throughout the past four decades and has helped tourism industry stakeholders to better comprehend and manage their tourism provision.

Plog’s work was the precursor to Butler’s Tourism Area Lifecycle . Plog wanted to examine the way in which tourism destinations develop. How do they grow? How and why do they decline? How can we make (relatively) accurate predictions to help us to better manage the tourism provision at hand?

Plog’s research found that there were (are) distinct correlations between the appeal of a destination to different types of tourists and the rise and fall in popularity of a destination.

Plog essentially delineated these types of tourists according to their personalities. He then plotted these along a continuum in a bell-shaped, normally distributed curve. This curve identified the rise and fall of destinations.

‘You said this would be a simple explanation ! I still don’t understand?!’

OK, OK- I have my academic jargon fix over with. Lets make this easy…

To put it simply, Plog’s theory demonstrates that the popularity of a destination will rise and fall over time depending on which types of tourists find the destination appealing.

‘OK, I get it. Can I read something else now?’.

Well, actually- no.

If you are going to really understand how Plog’s model works and how you can put it into practice, you need a little bit more detail.

But don’t worry, I’ll keep it light… keep reading…

So lets start with a little bit of history. Why did Plog do this research in the first place?

Plog’s research began back in 1967, when he worked for market-research company, Behavior Science Corporations (also known as BASICO). Plog was working on a consulting project, whereby he was sponsored by sixteen domestic and foreign airlines, airframe manufacturers, and various magazines. The intention was to examine and understand the psychology of certain segments of travellers.

During this time, the commercial aviation industry was only just developing . Airlines wanted to better understand their potential customers. They wanted to turn non-flyers into flyers, and they wanted Plog to help. This saw the birth of Plog’s research into tourism motivation, that later spanned into decades of research into the subject.

Plog’s model of allocentricity and psychocentricity demonstrated that destinations rise and fall in popularity in accordance with the types of tourists who find the destination appealing.

Essentially, Plog suggested that as a destination grows and develops (and also declines), it attracts different types of people.

Example: Tortuguero versus Kusadasi

Lets take, for example, Tortuguero. Toruguero is a destination in Costa Rica that is pretty difficult to reach. I travelled here with my husband and baby to see the turtles lay their eggs, it was pretty incredible. If the area was more developed, the turtles probably wouldn’t choose this area as their breeding ground anymore.

To reach Tortuguero, we had many hours in the car on unmade roads . We then had to take a boat , which only left a couple of times a day. This was a small local boat with a small motor. There were only a handful of hotels to choose from.

The only people who were here wanted to be here. The journey would put most tourists off.

In contrast, I was shocked at the overtourism that I experienced when I visited Kusadasi, in Turkey. The beaches here were some of the busiest I have ever seen. The restaurants were brimming with people.

Here you could find all of the home comforts you wanted. There was a 5D cinema, every fast food chain I have ever known, fun fair rides, water parks, water sports and much more. The area was highly developed for tourism.

Plog pointed out that as a destination reaches a point in which it is widely popular with a well-established image, the types of tourist will be different from those who will have visited before the destination became widely developed. In other words, the mass tourism market attracts very different people from the niche and non-mass tourism fields.

Plog also pointed out that as the area eventually loses positioning in the tourism market, the total tourist arrivals decrease gradually over the years, and the types of tourists who are attraction to the destination will once again change.

Plog’s tourist typology

OK, so you get the gist of it, right? Now lets get down to the nitty gritty details…

Plog developed a typology. A typology is basically a way to group people, or classify them, based on certain characteristics. In this case, Plog classifies tourists based on their motivations.

Note: Plog has suggested the updated terms ‘dependables’ and ‘venturers’ to replace pscychocentric and allocentric, but these have not been generally adopted in the literature

Plog examined traveller motivations and came up with his classifications of tourists. He came up with two classifications (allocentric and psychocentric), which were then put at the extremes of a scale.

As you can see in the diagram above, psychocentric tourists are placed on the far left of the scale and allocentric tourists are placed at the far right. The idea is then that a tourist can be situated at any place along the scale.

‘OK, so I understand the scale. But what do these terms actually mean?’

Don’t worry, I am getting there! Below, I have outlined what is meant by the terms allocentric and psychocentric.

In Plog’s model of allocentricity and psychocentricity, the allocentric tourist is most likely associated with destinations that are un(der)developed. These tourists might be the first tourists to visit an area. They may be the first intrepid explorers, the ones brave enough to travel to the ‘unknown’. The types of people who might travel to Torguero- the example I gave previously.

Allocentric tourists like adventure. They are not afraid of the unknown. They like to explore.

No familiar food? ‘Lets give it a try!’

Nobody speaks English? ‘I’ll get my with hand gestures and my translation app.’

No Western toilets? ‘My thighs are as strong as steel!’

Allocentric tourists are often found travelling alone. They are not phased that the destination they are visiting doesn’t have a chapter in their guidebook. In fact, they are excited by the prospect of travelling to a place that most people have never heard of!

Allocentric tourists enjoy cultural tourism , they are ethical travellers and they love to learn.

Research has suggested that only 4% of the population is predicted to be purely allocentric. Whilst many people do have allocentric tendencies, they are more likely to sit further along Plog’s scale and be classified as near or centric allocentics.

OK, so lets summarise some of the common characteristics associated with allocentric travellers in a neat bullet point list (I told you I would make this easy!)

Allocentric tourists commonly:

- Independent travellers

- Excited by adventure

- Eager to learn

- Likes to experience the unfamiliar

- Is put off by group tours, packages and mass tourism

- Enjoys cultural tourism

- Are ethical tourists

- Enjoy a challenge

- Are advocates of sustainable tourism

- Enjoys embracing slow tourism

Psychocentric tourists are located at the opposite end of the spectrum to allocentric tourists.

In Plog’s model of allocentricity and psychocentricity, psychocentric tourists are most commonly associated with areas that are well-developed or over-developed for tourism . Many people will have visited the area before them- it has been tried and tested. These tourists feel secure knowing that their holiday choice will provide them with the comforts and familiarities that they know and love.

What is there to do on holiday? ‘I’ll find out from the rep at the welcome meeting’

Want the best spot by the pool? ‘I’ll get up early and put my towel on the sun lounger!’

Thirsty? ‘Get me to the all-inclusive bar!’

Psychocentric tourists travel in organised groups. Their holidays are typically organised for them by their travel agent . These travellers seek the familiar. They are happy in the knowledge that their holiday resort will provide them with their home comforts.

The standard activity level of psychocentric tourists is low. These tourists enjoy holiday resorts and all inclusive packages . They are components of enclave tourism , meaning that they are likely to stay put in their hotel for the majority of the duration of their holiday. These are often repeat tourists, who choose to visit the same destination year-on-year.

So, here is my summary of the main characteristics associated with psychocentric tourists.

Psychocentric tourists commonly:

- Enjoy familiarity

- Like to have their home comforts whilst on holiday

- Give preference to known brands

- Travel in organised groups

- Enjoys organised tours, package holidays and all-inclusive tourism

- Like to stay within their holiday resort

- Do not experience much of the local culture

- Do not learn much about the area that they are visiting or people that live there

- Pay one flat fee to cover the majority of holiday costs

- Are regular visitors to the same area/resort

The reality is, not many tourists neatly fit into either the allocentric or psychocentric categories. And this is why Plog developed a scale, whereby tourists can be placed anywhere along the spectrum.

As you can see in the diagram above, the largest category of tourists fall somewhere within the mid-centric category on the spectrum. Tourists can learn towards allocentric, or pyschocentric, but ultimately, they sit somewhere in the middle.

Mid-centric tourists like some adventure, but also some of their home comforts. Perhaps they book their holiday themselves through dynamic packaging, but then spend the majority of their time in their holiday resort. Or maybe they book an organised package, but then choose to break away from the crowd and explore the local area.

Most tourists can be classified as mid-centric.

Plog’s model of allocentricity and psychocentricity has been widely cited throughout the academic literature for many years. It is a cornerstone theory in travel and tourism research that has formed the basis for further research and analysis in a range of contexts.

Plog’s theory preceded that of Butler, which is subsequently intertwined with Plog’s model, as demonstrated in the image below. As you can see, Butler was able to develop his Tourism Area Lifecycle based in the premise of the rise and fall of destinations as prescribed by Plog.

Plog’s theory has encouraged critical thinking throughout the tourism community for several decades and it is difficult to find a textbook that doesn’t pay reference to his work.

Whilst Plog’s model of allocentricity and psychocentricity is widely cited, it is not without its critique. In fact, many academics have questioned it’s ‘real-world’ validity over the years. Some common criticisms include:

- The research is based on the US population , which may not be applicable for other nations

- The concepts of personality, appeal and motivation are subjective terms that may be viewed different by different people. This is exemplified when put onto the global stage, with differing cultural contexts.

- Not all destinations will move through the curved continuum prescribed by Plog, in other words- not all destinations will strictly follow this path

- It is difficult to categorise people into groups- behaviours and preferences change overtime and between different times of the year and days of the week. People may also change depending on who they are with.

So, what are the key takeaways about Plog’s model of allocentricity and psychocentricity? Lets take a look…

- Psychocentrics are the majority of travelers who prefer familiar destinations, mainstream attractions, and predictable experiences. They tend to seek comfort, security, and convenience in their travels and are less likely to take risks or seek out new experiences.

- Allocentrics, on the other hand, are a minority of travelers who seek out unique and exotic destinations, adventure, and novelty. They are more willing to take risks and venture into unfamiliar territories in pursuit of new experiences.

- Plog’s model suggests that people’s travel preferences are determined by their personality traits, values, and life experiences.

- The model also proposes that travelers may move along a continuum from psychocentric to allocentric as they gain more experience and exposure to travel.

- Plog’s model has been criticized for oversimplifying travel motivations and not accounting for the diversity of motivations and preferences within each category.

- Despite its limitations, Plog’s model remains a useful tool for understanding tourist behavior and designing marketing strategies that target specific types of travelers.

Finally, lets finish up this article about Plog’s model of allocentricity and psychocentricity by addressing some of the most commonly asked questions.

Do you understand Plog’s model of allocentricity and psychocentricity now? I certainly hope so!

Plog’s model of allocentricity and psychocentricity is important theory in tourism is a core part of most tourism management curriculums and has helped tourism professionals understand, assess and manage their tourism provision for decades, and will continue to do so for decades to come, I’m sure.

If you found this article about Plog’s model of allocentricity and psychocentricity then please do take a look around the website, because I am sure there will be plenty of other useful content!

Liked this article? Click to share!

What Is Psychocentric in Tourism?

By Alice Nichols

Have you ever heard the term ‘Psychocentric’ in tourism? If not, then you are in the right place. In this article, we will discuss what psychocentric means in tourism and its importance.

What Is Psychocentric?

Psychocentric is a term used to describe a type of tourist who prefers to stay within their comfort zone when traveling. They tend to avoid taking risks and prefer familiar experiences rather than trying new things. Psychocentric tourists are often concerned with safety and security and tend to travel in groups or with family members.

Importance of Psychocentric Tourists

While psychocentric tourists may seem less adventurous, they play a crucial role in the tourism industry. They prefer established and popular destinations that have a good reputation for safety and quality services. This means they contribute significantly to the local economy by spending money on hotels, restaurants, transportation, and other activities.

Characteristics of Psychocentric Tourists

Psychocentric tourists have some common characteristics that set them apart from other types of travelers. These include:

- Prefer organized tours or packages

- Choose familiar destinations over new ones

- Avoid physical risk-taking activities

- Prefer to travel with family or friends

- Tend to plan their trips well in advance

- Value safety and security over adventure

Examples of Psychocentric Tourism Destinations

Some examples of popular psychocentric tourism destinations include:

- The Walt Disney World Resort in Florida, USA.

- The Gold Coast in Australia.

- The Maldives Islands.

- Rome, Italy.

- Paris, France.

10 Related Question Answers Found

What does psychocentric mean in tourism, what is poorism tourism, why is enclave a negative impact of tourism, what is economic leakage tourism, how tourism is bad, how does waste affect tourism, what does economic leakage in tourism mean, what is morbid tourism, what are the psychology of tourism, why is tourism bad, backpacking - budget travel - business travel - cruise ship - vacation - tourism - resort - cruise - road trip - destination wedding - tourist destination - best places, london - madrid - paris - prague - dubai - barcelona - rome.

© 2024 LuxuryTraveldiva

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

Tourists’ apprehension toward choosing the next destination: A study based on the learning zone model

Associated data.

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The current research is based on Senninger’s Learning Zone Model applied to the tourists’ comfort zone. This model was created in 2000 and it proved to be useful in many applied areas: Psychology, Sociology, Marketing and Management. This modes is a behavioral one and shows how a person can justify his action based on previous tested experiences (comfort zone) or dares to step beyond in fear, learn or growth zone. Our research is extending the existent area of expertise to tourism. We aimed at exploring whether the tourists’ apprehension toward choosing their next destination from a comfort zone perspective or rather from the other zones’ perspectives such as fear, learning or growth. To meet this purpose we conducted a mixed method: firstly a qualitative one, an in-depth interview based on Delphi method with 10 tourism specialists and secondly an online survey on 208 Generation Z tourists. The interviews were meant to help developing a 20 items scale (5 items for each level of the model) to measure from which of the 4 zones are the respondents making the choice of the future travel destination. Our conclusions show that Gen Z tourists display behaviors that can be associated with learning or growth zones rather than the comfort zone. This is relevant when choosing the next travel destination, because our findings could bring about a new approach to promoting tourist destinations as part of various products. As a result, a large range of managerial tools can better adapt the promotion messages to the target market from a new psychological perspective.

Introduction

The comfort zone could be associated with a warm and familiar hug, nevertheless, psychologists consider it beneficial and restrictive at the same time ( McWha et al., 2018 ). This field of research has been popular with a variety of specialists such as mental health practitioners, behavior therapists, and other psychologists ( Gilligan and Dilts, 2009 ). The paradox noticed by many is that while finding oneself in the comfort zone provides calm and quietness ( Passafaro et al., 2021 ), at the same time it might prevent growth ( Santoro and Major, 2012 ; Woodward and Kliestik, 2021 ). The solution researchers seem to agree upon is to balance those two divergent forces (the one that keeps us wanting to remain still and the one that makes us wanting to grow) to improve our lives ( Berno and Ward, 2005 ).

Bardwick (1995) coined the term “comfort zone” in the management context, in order to help assess more efficiently the motivation behind certain employees’ behaviors. Inside of the comfort zone, the stimulus for performance growth seems scarce. While the routine generally averts risks it can also limit human resources development. That is why Karwowski (2018) considered that this concept also applies to the field of behavioral psychology.

Our comfort zone is considered to be a psychological, emotional, and behavioral construct ( Lichy and Favre, 2018 ; Nica et al., 2022a ) that defines our daily routine and involves familiarity, safety, and security. Although we often hear professors, coaches, or motivational speakers encouraging us to reach beyond our limits and explore activities outside our regular boundaries, this ignores a fundamental reality, namely the existence of personal differences among individuals. Someone’s comfort zone might be completely different from another’s.

Each person has his/her comfort zone modeled by herself, a healthy adaptation to achieve an emotional balance free from anxiety. It is a place where a person feels calm, comfortable, and relaxed. However, experimenting with a reasonable amount of stress or anxiety from time to time can prove beneficial. Miller (2019) refers to the comfort zone as an illusion, a self-imposed mental limitation that is not easy to overcome. The difficulty of overcoming this limitation is mostly linked to the fear of missing the warmth and calm of our imaginary cocoon ( Nica et al., 2022b ).

Page (2020) summarized the most relevant 4 benefits of moving beyond this comfort zone: (i) self-fulfillment, a term retrieved from the classical hierarchy of needs formulated by Maslow (1943) and (ii) growth mindset, a term defined by Dweck (2000) as relying on flexibility, trial and error and unlimited potential as opposed to a fixed mindset where people believe there is a personal threshold for everyone beyond which advance become problematic. (iii) antifragility which regard volatility, hazard, chaos, and stress as push factors for self-development and prosperity ( Taleb, 2014 ), and (iv) self-efficacy explained by Bandura (1997) as the sum of actions to be executed to reach a certain objective.

An interesting approach developed by Senninger (2000) is the Learning Zone Model. According to this model, the fear which settles in once the comfort zone is left behind does not necessarily indicate reaching the panic zone. It is more of a natural emotion accompanying moving into the learning and growth zones.

Once all these obvious advantages of stepping out of the comfort zone are taken into account, the essential question is to find out from which one of the four zones (comfort/fear/learning or growth) is the Gen Z consumer reacting when choosing the next tourist destination?

We want in this paper to investigate, starting from Senninger’s model, Generation Z travelers, aged 18–27, in order to discover which one/ones out of the four zones (comfort/fear/learning or growth) is the most important for them when it comes to choose the next travel destination. For that reason we conducted a mixed method research. Firstly, with the help of tourism and travel specialists (Delphi method), we created a 20 items questionnaire (5 for each zone) and secondly we applied it in an online survey on 208 Gen Z individuals. We set as a research objective the identification of certain behavioral patterns of Gen Z consumers who are currently in their comfort zone.

Section 2 of this paper presents the details of our research design and the following parts describe the findings, discussions and conclusions. This would serve future research on solutions and actions for taking them to the superior level of this model, namely the growth zone, overcoming feelings of fear and anxiety which prevents this progress.

Literature review

The learning zone model.

This model was developed initially by Vygotsky (1978) , later on, the definitive version belonged to Senninger (2000) . The underlying idea is that in order to learn and progress we need to be challenged and stimulated ( Kliestik et al., 2022 ). It is all about the balance of forces. If we are not pushed enough, the probability that we move beyond the comfort zone is rather low, while if we are pushed too hard, the risk is to panic and feel overwhelmed. Both situations lack a proper balance and entail limited learning ( Senninger, 2000 ).

The model has two variations: a limited one with only three zones and an expanded one with four zones. We based our research on the latter. The comfort zone provides a familiar and safe feeling and entitles the subjects of it to feel in control. It is a risk-free area that is also not very eventful ( Karwowski, 2018 ; Kovacova et al., 2022 ). A state of reaching a plateau besides monotony and boredom settles in Kovacova et al. (2022) . Often, people tend to conform to it and even put the effort into maintaining it ( Kliestik et al., 2022 ). However, as life moves on, a series of internal and external factors trigger changes ( Dweck, 2005 ; Kliestik et al., 2022 ). We might get sick, change our job or our family might expand and all these push us outside of our comfort zone.

As soon as we move out of our comfort zone we find ourselves in the fear zone. There, a process of self-inquiry about our choices might occur. It is possible that we face a low self-confidence situation and doubt settles in Miller (2019) . Sometimes we internalize critical voices which have a paralyzing effect on ourselves ( Senninger, 2017 ). Often, we can be scared to the point when we regret moving out of our comfort zone and rush back inside of it ( Andronie et al., 2021 ). Meanwhile, we might start complaining more and focus on obstacles and issues to justify this embarrassing return ( Wallace and Lãzãroiu, 2021 ).

Once we get close enough to the learning zone we score the first victory: we passed the fear zone and we suppressed the internal and external critical voices ( Page, 2020 ). In the learning zone we face new challenges, but we tend to prioritize solutions over problems ( Lyons, 2022 ). In other words, we move from a pessimistic to an optimistic perspective and this allows us to grow ( Pearce and Packer, 2013 ).

The growth zone might be equated with the terminus point for this psychological pursuit. Here, the old fears are slowly receding even if new ones might settle in. The advantage is that we became more resilient during this phase and we learned to set more ambitious goals for ourselves ( Lǎzãroiu and Harrison, 2021 ). As long as our personal development continues our lives gather more sense. Progressively, we define superior objectives, and we create a long-term-based personal view ( Pongelli et al., 2021 ).

This model, besides its significant contribution to human psychology development, remains a resource with robust applied configuration ( Dweck, 2005 ; Kliestik et al., 2022 ). Our work intends to explore how this model could be applied to understanding tourists’ behaviors.

Intentionally leaving the comfort zone can be possible only by developing a growth mindset. While a rigid mindset keeps us in the prison of the fear of failure, a growth mindset expands opportunities and possibilities. It inspires us to overcome fear, to take healthy risks, to learn new lessons and the outcomes are blooming in all life dimensions ( Perruci and Warty Hall, 2018 ).

When it comes to learning, Elbæk et al. (2022) are presenting the effects of Yerkes-Dodson law that stipulates that there is an empirical relationship between stress and performance. In other words, that there is an optimal level of stress that corresponds to an optimal level of performance. Based on Yerkes-Dodson law, learning is possible not only beyond comfort zone, but also beyond fear. Is not defined by stress. Quite the opposite! It is a space for opportunities, where, in order to optimize the performance, people must reach a certain level of stress, higher than normal. So we obtain what they call to be an optimal anxiety.

Comfort zone proves to be nothing but a cozy place to live in, and its only reason is to prepare you for all the challenges in life ( Anichiti et al., 2021 ). Anxiety, fear and stress improve performance until a certain level—called optimum stimulation level. Beyond this point, performance drops while stress is increasing ( Avornyo et al., 2019 ).

What we can see is that comfort, fear and learning are strongly related ( Perruci and Warty Hall, 2018 ). Learning zone model developed by Senninger can be justified by seeking balance ( Freeth and Caniglia, 2020 ). We must exit our comfort zone long enough to reach optimal anxiety, but not too much, for not letting anxiety to take control.

Moreover, all our decisions are facing these mirrors: the comfort mirror—showing the future self that keeps our status quo ; the fear-mirror—presenting the possible panic we have to face in near future; the learning-mirror—with all the lessons we have the assimilate and the growth-mirror—that is indicating the future self we want to become. And, by analyzing all these projections, our mind is developing a cost-benefit analysis ( Zheng et al., 2021 ). As long as we stay in our comfort zone, the benefits are small but guaranteed. We feel good, safe and we are not in danger. However, if we don’t change a thing, we cannot expect something spectacular to happen. If we remain there for a long time, we can limit ourselves, sinking into boredom and monotony.

Plog (1974) , examined the motivations of travelers and arrived at the classification of tourists starting from two approaches: allocentric and psychocentric. Allocentric tourists, or often called ‘wanderers‘, are brave enough to travel to the unknown. They like adventure and would not mind if they were the first to explore a certain area. Allocentric tourists will often travel alone, without the need for a guide. They enjoy cultural tourism, are ethical travelers and love to learn. Stainton (2022) suggested that only 4% of the population is expected to be purely allocentric, most are on Plog’s scale in the category of close or centric cluster. Allocentric tourists have some common features: they are independent travelers, they like adventure; they are eager to learn and like to experience unfamiliar things; they are not followers of mass tourism, tourist packages and group excursions; they are fans of cultural tourism, being ethical tourists; love challenges; prefers sustainable tourism and slow tourism (as opposed to mass tourism). All this being said, making an analogy with the characterization of the four areas of Senninger (2000) , Learning Model allocentric tourists are rather those who are in the growth zone or in transition from the learning zone to the growth zone.

At the opposite side are psychocentric or ‘repeating‘ tourists. They are most often associated with well-developed or overdeveloped areas for tourism. They will choose holiday destinations that have already been “tested,” where they can feel comfortable and familiar. The portrait of a psychocentric tourist ( Stainton, 2022 ), looks like this: he/she enjoys familiarity and likes the chosen destination to offer him/her the comfort of home; prefers well-known brands; often travels in organized groups; is a supporter of holiday packages and all-inclusive holidays; spends a lot of time in the holiday resort and doesn’t know much about the local culture; he/she is not open to learning new things about the area he visits or about the people who live there; pays a single flat fee to cover most of the holiday costs and is a regular visitor to the same resort/destination. This typology, without a doubt, can be associated with the comfort zone, being mentioning key words such as: “comfortable,” “familiar,” “known,” “regular,” “organized” etc.

The reality is that not many tourists fit perfectly into the two typologies at the extremes ( Stainton, 2022 ), respectively, allocentric and psychocentric. And this is why Plog has developed a scale, through which tourists can be placed anywhere along the spectrum. So, the largest category of tourists falls somewhere in the mid-centered category of the spectrum. Mid-center tourists like to have a little adventure, but also something from the comfort of home. Maybe they book their vacation by means of an interesting announcement, but then they spend most of their time in the holiday resort. Or maybe they choose an organized trip, but then they choose to break away from the crowd and explore the local area ( Stainton, 2022 ). These tourists are best suited to the fear zone, where there is a battle between staying in the comfort zone and progressing further toward the learning zone.

Plog (1974) created a fundamental model in travel and tourism research. His theory has encouraged critical thinking throughout the tourism community for several decades. Our paper goes beyond Plog’s model, being enriched by Senninger (2000) explanations of consumer psychology in the face of a purchasing decision. We aim to explore these types of tourists from the perspective of the learning area from which they chose to make the travel decision.

Methodological approach

Research context.

The current research explores the psychographic and behavioral factors determining the choice of a certain tourist destination. It was targeted at the Generation Z adult population within the age range 18–27. The research is based on the Learning Zone Model formulated by Senninger (2000) which features four zones: comfort, fear, learning, and growth. The research results, conclusions, and suggestions will constitute a reference point for formulating various marketing strategies. Those marketing strategies include promoting a tourist destination once the profile of Gen Z tourist is defined according to the 4 above-mentioned zones. Therefore, personalized marketing messages can emerge aiming at for example diminishing the fears and uncertainty of those in the comfort or fear zones or attracting those in the learning or growth zone through new experiences, adventure, and other challenges. Each destination has one or more target markets and a tourist typology-based learning zones model might be a relevant variable when segmenting the market for Gen Z tourists.

Research design

The purchase decisions of Gen Z tourists are largely emotional and can be attributed to certain zones of the learning zone model developed by Senninger (2000) . The consumer acts from within a certain zone such as comfort, fear, learning, or growth. This can lead to certain behavioral patterns when choosing a tourist destination. We devised the following research question:

From which one of the four zones (comfort/fear/learning or growth) is the Gen Z consumer reacting when choosing the next tourist destination?

The research had 2 main phases

Phase 1 involved qualitative research aimed at identifying the keywords corresponding to each of the 4 zones part of the model (comfort, fear, learning, and growth). We planned to do this by exploring tourism specialists’ views. The resulting keywords were subsequently integrated into the quantitative research instrument. The objectives set for phase 1 were:

- O1.1: Generating keywords for describing the behavior of tourists who are in the comfort zone as per the Learning zone model ( Senninger, 2000 ).

- O1.2: Generating keywords for describing the behavior of tourists who are in the fear zone as per Learning zone model ( Senninger, 2000 ).

- O1.3: Generating key words for describing the behavior of tourists who are in the learning zone as per Learning zone model ( Senninger, 2000 ).

- O1.4: Generating key words for describing the behavior of tourists who are in the growth zone as per Learning zone model ( Senninger, 2000 ).

Phase 2 consisted of quantitative research directed toward analyzing the Gen Z tourists’ perspectives from Iasi, Romania. Their perspective was scrutinized corresponding to the Learning Zone Model (comfort, fear, learning, and growth zones) in terms of choice of their future travel destination. More precisely we focused on learning from which of the 4 zones are they making this choice. The objectives set for phase 2 were

- O2.1: Identifying the Gen Z tourist profile (among those living in Iasi). Profiling is based on tourism services purchase frequency, distance traveled, domestic/outbound destinations preference, type of holiday, travel motivation, and travel budget.

- O2.2: Identifying specific behavior related to their comfort zone for Gen Z tourists from Iasi as far as their next holiday choice is concerned.

- O2.3: Identifying specific behavior related to their fear zone for Gen Z tourists from Iasi as far as their next holiday choice is concerned.

- O2.4: Identifying specific behavior related to their learning zone for Gen Z tourists from Iasi as far as their next holiday choice is concerned.

- O2.5: Identifying specific behavior related to their growth zone for Gen Z tourists from Iasi as far as their next holiday choice is concerned.

Research hypotheses

For phase 2 of the research (online survey), we formulated the four hypotheses.

As Stainton (2022) stated, based on Plog (1974) model, there are psychocentric or ‘repeating‘ tourists. Our sample of experts have characterized them with words like: comfort seekers, valuing control and security, having a strong aversion against risk and willing to repeat positive experiences. So, after Plog (1974) ; Stainton (2022) and justified by the choices made by our group of experts, we can formulate the first hypothesis:

H1: There is a connection among the attributes of the comfort zone as per The Learning Model Zone ( Senninger, 2000 ) corresponding to choosing of a tourist destination.

Elbæk et al. (2022) argued that there is a relationship between stress and performance. They said that it is necessary to step into fear in order to thrive. Fear and stress can be challenging, but only until a certain point, beyond what performance is not possible. When it comes to analyze tourists behavior facing fear, our group of specialists selected words like: being suggestible, overcoming fear of unknown and challenges, willing to experience and being courageous. Based on that we formulated the second hypothesis:

H2: There is a connection among the attributes of the fear zone as per The Learning Model Zone ( Senninger, 2000 ) corresponding to choosing of a tourist destination.

Comfort, fear and learning are strongly related ( Perruci and Warty Hall, 2018 ). We must exit our comfort zone long enough to reach optimal anxiety, but not too much, for not letting anxiety to take control ( Freeth and Caniglia, 2020 ). Only those who are willing to learn and keep an open mind are thriving ( Anichiti et al., 2021 ). That is why our group of specialists selected the following words to describe a person that makes a decision justified by his/hers learning zone: is open to novelty, curious, interested in learning new things, loves challenges and risk taking, being explorer and adventurous. As a consequence, the third hypothesis is:

H3: There is a connection among the attributes of the learning zone as per The Learning Model Zone ( Senninger, 2000 ) corresponding to choosing of a tourist destination.

Leaving the comfort zone can be possible only by developing a growth mindset ( Perruci and Warty Hall, 2018 ). Our mind is developing a cost-benefit analysis ( Zheng et al., 2021 ) and puts into balance the cost of leaving the comfort zone with the benefit of reaching the growth zone. Those who see mainly the benefits are, according to our group of specialists: decisive, emotionally developed, willing to fulfill ideals and objectives, committed to their personal growth and seeing traveling as a lifestyle. These conclusions helped us formulate the fourth hypothesis:

H4: There is a connection among the attributes of the growth zone as per The Learning Model Zone ( Senninger, 2000 ) corresponding to choosing of a tourist destination.

Research methods

Phase 1: Semi-Structured interview applied to tourism specialists using the Delphi method. There were 10 experts in tourism (tourism agents, bloggers, and tourism master graduates).

Phase 2: Quantitative research based on an online survey having 208 respondents among travel enthusiastic from Iasi. The gender split was 87 and 121 female respondents, aged 18–27, corresponding to Gen Z.

The research instruments

Phase 1: We used a selection questionnaire for selecting the participants. The interviews required answers regarding the profiling of a tourist who makes the purchase decision from his comfort, fear, learning, or growth zone.

Phase 2: Based on the specialists’ answers, the questionnaire items were realized. The instrument had 3 sections:

- Section 1 was built around determining the profile of Gen Z tourists and consisted of 8 questions. The questions asked the participants to associate the travel with a random word, to assess their travel frequency, preference for either domestic or international destinations, the maximum distance they were eager to travel, holiday type and motivation, and their weekly travel budget.

- Section 2 consisted of 4 sets of 5 statements each using keywords defining tourists from each of the 4 zones (comfort, fear, learning, growth). The statements were based on the specialists’ answers collected through the semi-structured interview described earlier. Respondents were asked to grade the statements on a scale from 1 to 10 where 1 meant full disagreement and 10 full agreement. Each construct contains a so-called key-statement which is formulated based on the most representative key-word.

- I want to feel in control.

- I choose on safety criteria (personal safety, transport, destination, etc.).

- I try to reduce the risk of unforeseen events, which could take me out of my comfort zone.*

- I prefer to repeat positive experiences I have had in the past.

- I avoid any complications that may occur.

- I always want to gather new experiences.

- I try to overcome my fear of the unknown.*

- I let myself be influenced by the opinions of those around me.

- I leave room for the unexpected.

- I accept new challenges, giving up excessive planning.

- I am open to all experiences.

- I allow myself to always be curious.

- I leave room for adventure.

- I am willing to learn new things.*

- I love challenges.

- I am always determined on what I want.

- I consider any experience that contributes to my personal growth.*

- I am getting closer to fulfilling my dreams as a tourist.

- I am looking for experiences that will enrich my soul.

- I consider traveling as a lifestyle.

Section 3 consisted of social and demographic questions for identifying the respondents.

Research results

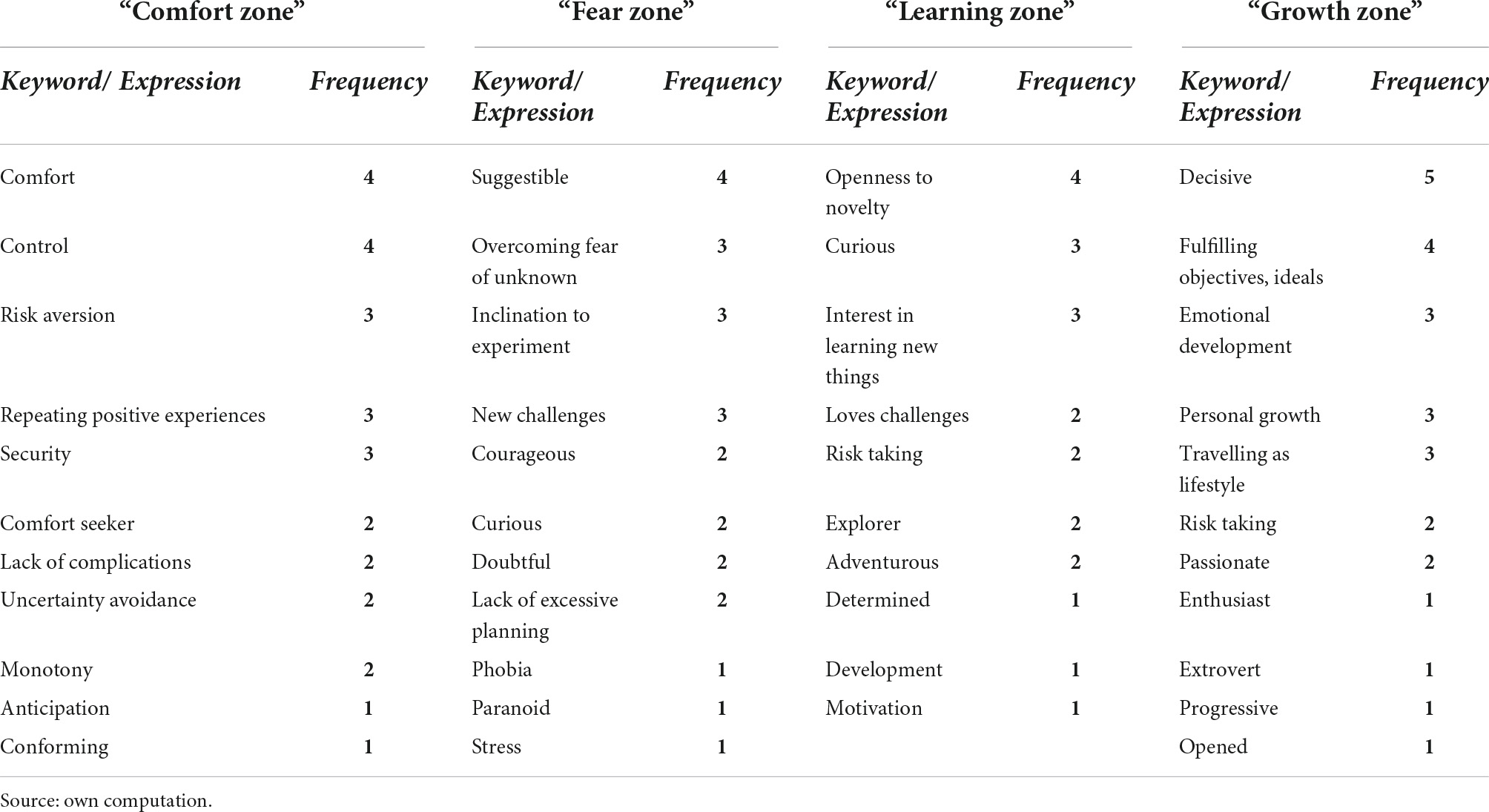

For this initial phase of our research, namely the semi-structured interview using the Delphi method, we inquired a group of 10 tourism experts from Iasi. The objective was to identify keywords in defining the tourists choosing travel destinations from one of the 4 zones of The Learning Zones Model of Senninger (2000) . Table 1 shows the prevalence of the most frequently mentioned keywords.

The prevalence of the most frequently used keywords or expressions describing a tourist according to Senninger’s model.

Source: own computation.

The keywords and expressions provided by the 10 tourism specialists were centralized as per Table 1 . We, therefore, achieved all 4 objectives and ranked the keywords and expressions according to their prevalence. For the comfort zone, the following keywords or expressions were selected: comfort, security, risk aversion, repeating positive experiences, and control. For the fear zone, the following keywords or expressions were selected: suggestible, inclination to experiment, overcoming fear of the unknown, new challenges, and lack of excessive planning. For the learning zone, the following keywords or expressions were selected: openness to novelty, curious, Interest in learning new things, loves challenges and adventurous. For the growth zone, the following keywords or expressions were selected: decisive, fulfilling objectives and ideas, personal growth and emotional development.

We analyzed the results of the survey for each stated objective.

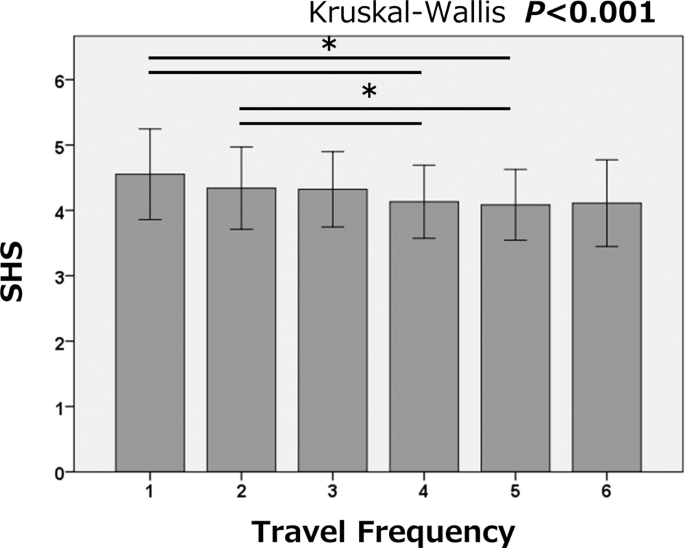

We exported the data from the SPSS software using the “Descriptive Statistics” function in order to obtain the prevalence. According to the Dimensional Analysis, we created the profile of a Gen Z tourist from Iasi. S/he associates travel mostly with relaxation, freedom feelings, adventure, and experience. S/he travels on average 6 times a year and prefers equally domestic and international destinations. We noted an inclination to travel to a maximum distance of 2,300 kilometers from home and he enjoys mostly 2 types of holidays: resort holidays and city breaks. Whenever s/he chooses a holiday destination a number of attributes are sought: relaxation, having fun, exploring nature, understanding local history, and culture, and adventure. The Gen Z tourist from Iasi allocates on average a weekly travel budget of approximately 2,400 RON (500 euros).

- O2: Identifying specific behavior related to their comfort zone for Gen Z tourists from Iasi as far as their next holiday choice is concerned.

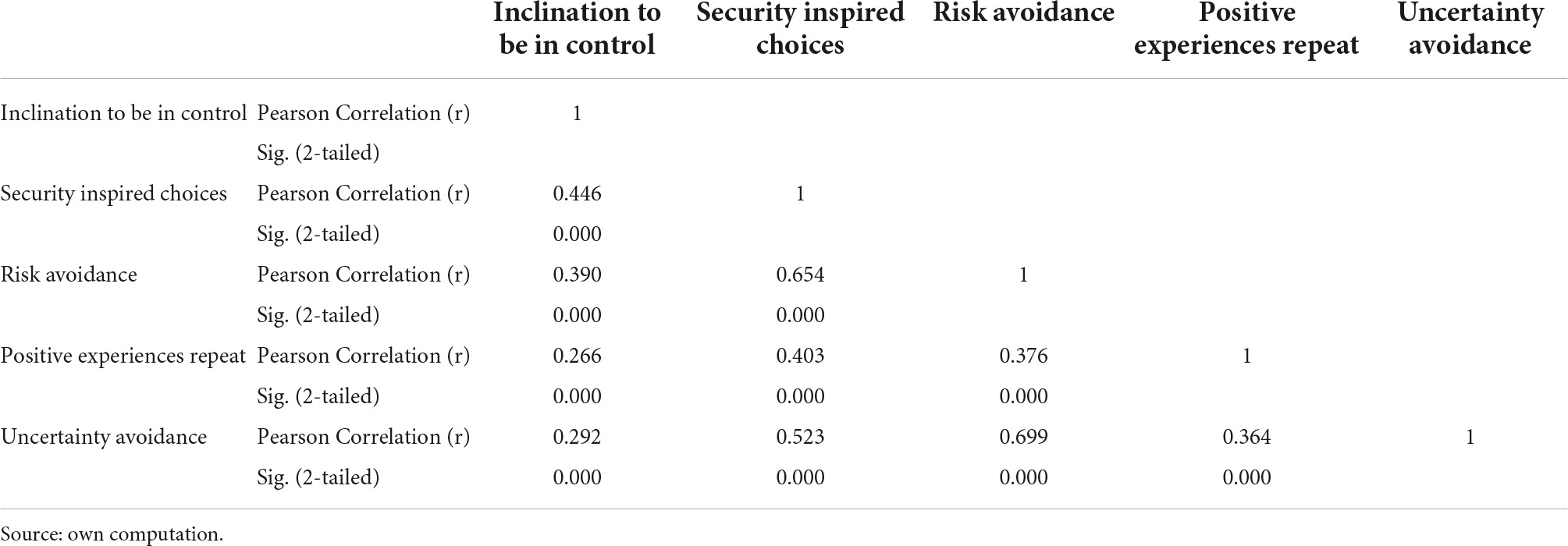

For verifying this hypothesis we performed a correlation test for the variable attributes of the comfort zone based on r Pearson correlation. We used SPSS software for this end.

According to Table 2 , each correlation significant because Sig is 0.000 (< 0.05) and it consists of a direct correlation ( r > 0). The differences are based on the strength of the correlation between 2 variables. The strongest correlation within the comfort zone is between the risk and uncertainty avoidance, the r-value being 0.699 which indicated a strong correlation. Another strong correlation was found between “security inspired choices” and “risk avoidance” with an r-value of 0.654 although this correlation does not involve causality. Among “security inspired choices” and “uncertainty avoidance” we found an average to good correlation, Pearson r-correlation being 0.523.

Pearson correlation for the comfort zone variables.

We used Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of reliability to identify the measure of internal consistency among the items defining the comfort zone, calculated by SPSS software. The aim was to check whether the items contribute to the comfort zone significance or not. The value of Cronbach’s Alpha was 0.779 which indicated a good consistency ( Tavakol and Dennick, 2011 ). A side note would be that once the item “inclination to be in control” is removed the consistency improves. As a conclusion of this test, we can state that the comfort zone items do have an acceptable consistency which means there is consistency among the answers given by respondents for this dimension. This will lead to identifying the specific behaviors of tourists choosing a certain destination from their comfort zone.

- O3: Identifying specific behavior related to their fear zone for Gen Z tourists from Iasi as far as their next holiday choice is concerned.

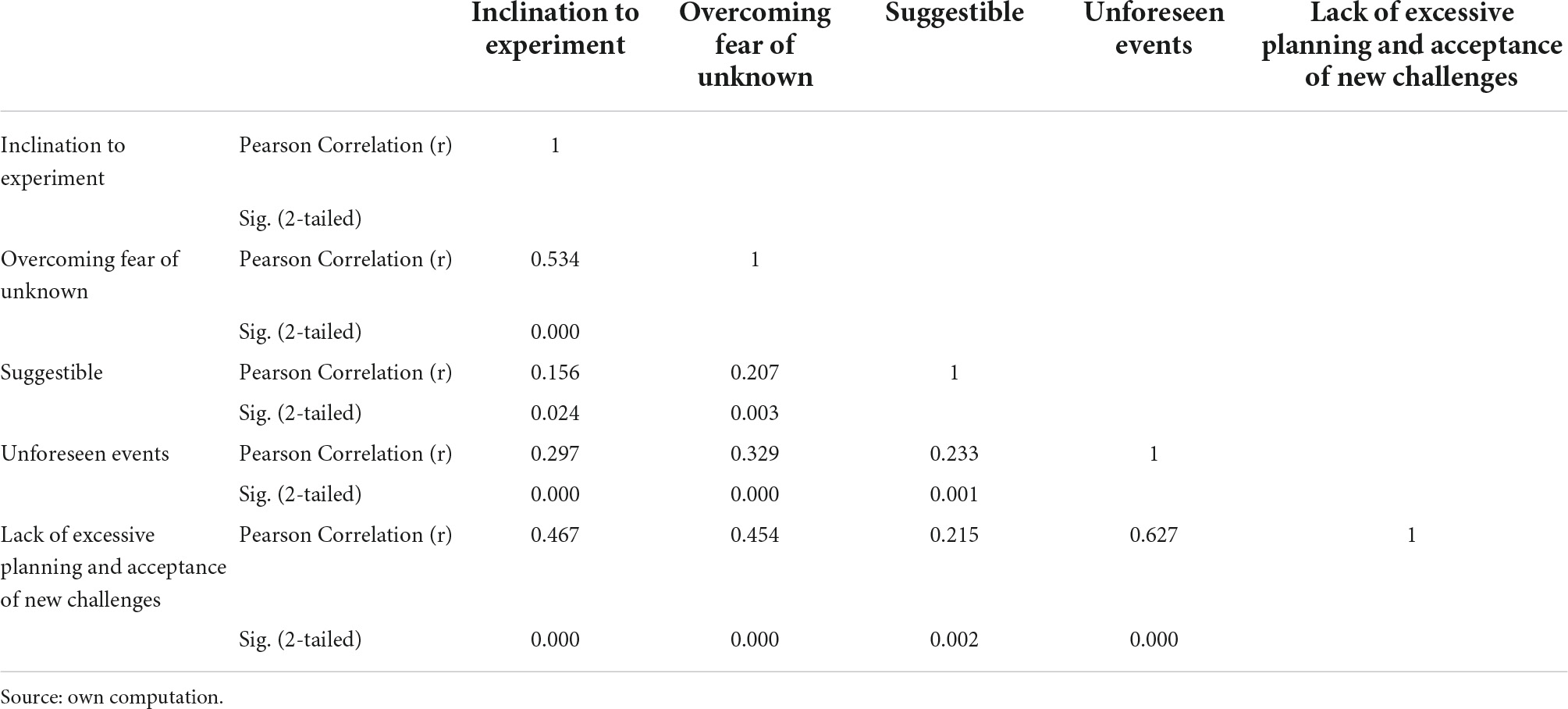

We performed a Pearson correlation test to verify this hypothesis. We aimed at measuring the correlation among the variables defining the fear zone. This test was performed through SPSS software and the results are summarized in Table 3 .

Pearson correlation for the fear zone variables.

As per Table 3 , all correlations are positive for the fear zone, Pearson r correlation displaying beside the positive values significant correlation (Sig < 0.05). The strongest correlation within the fear zone is between “Lack of excessive planning and acceptance of new challenges” and “unforeseen events” with an r correlation value of 0.627 indicates an average to good correlation. A second moderate correlation can be noticed between “Inclination to experiment” and “overcoming fear of the unknown: ( r = 0.534).

We used Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of reliability to identify the measure of internal consistency among the items defining the comfort zone, calculated by SPSS software. The aim was to check whether the items contribute to the comfort zone significance or not. The value of Cronbach’s Alpha was 0.772 which indicated a good consistency ( Tavakol and Dennick, 2011 ). This consistency could be improved if the item “suggestible” was eliminated.

As a conclusion of this test, we can state that the fear zone items do have an acceptable consistency which means there is consistency among the answers given by respondents for this dimension. This will lead to identifying the specific behaviors of tourists choosing a certain destination from the fear zone.

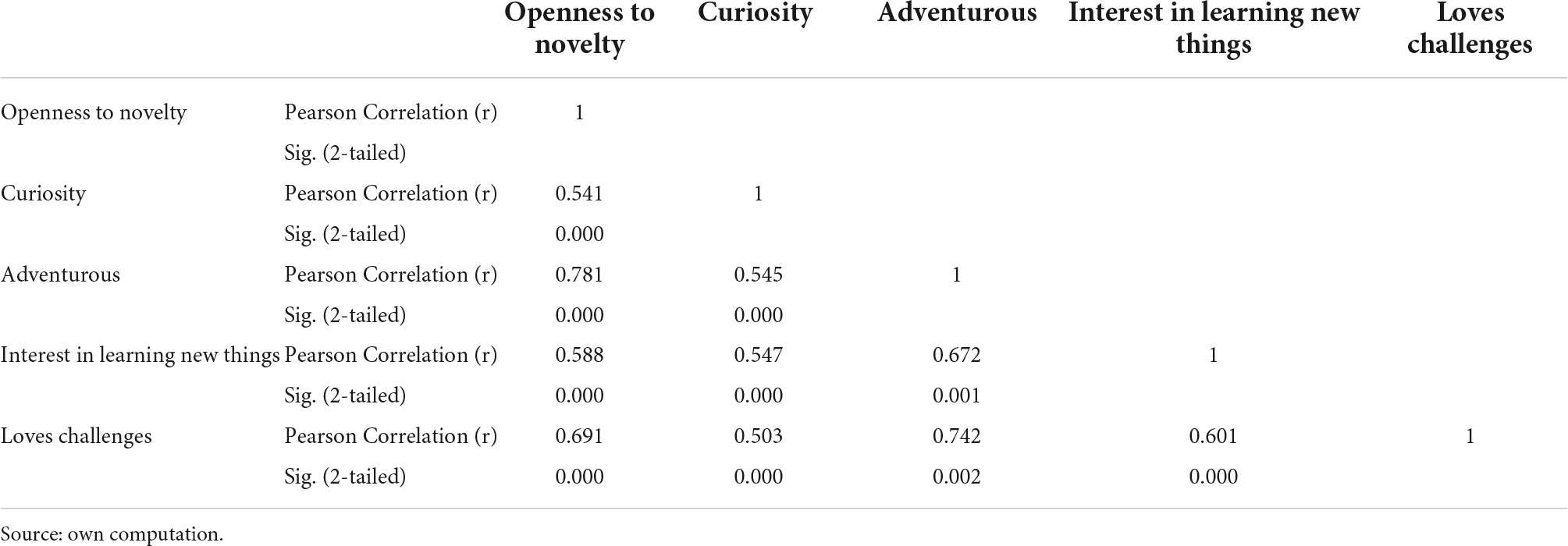

- O4: Identifying specific behavior related to their learning zone for Gen Z tourists from Iasi as far as their next holiday choice is concerned.

H3: There is a connection among the attributes of the learning zone as per The Learning Model Zone ( Senninger, 2000 ) corresponding to choosing a tourist destination.

We performed a Pearson correlation test to verify this hypothesis. We aimed at measuring the correlation among the variables defining the fear zone. This test was performed through SPSS software and the results are summarized in Table 4 .

Pearson correlation for the learning zone variables.

All correlations presented in Table 4 are significant (Sig = 0.000 < 0.05) and we see positive correlation (r correlation > 0). In terms of their strength, we see within this dimension reasonable, good, or strong correlations.

We used Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of reliability to identify the measure of internal consistency among the items defining the learning zone, calculated by SPSS software. The aim was to check whether the items contribute to the comfort zone significance or not. The value of Cronbach’s Alpha was 0.890 which indicated a good to strong consistency ( Tavakol and Dennick, 2011 ). This consistency could be slightly improved if the item “curiosity” was eliminated.

As a conclusion of this test, we can state that the learning zone items do have an acceptable consistency which means there is consistency among the answers given by respondents for this dimension. This will lead to identifying the specific behaviors of tourists choosing a certain destination from the learning zone.

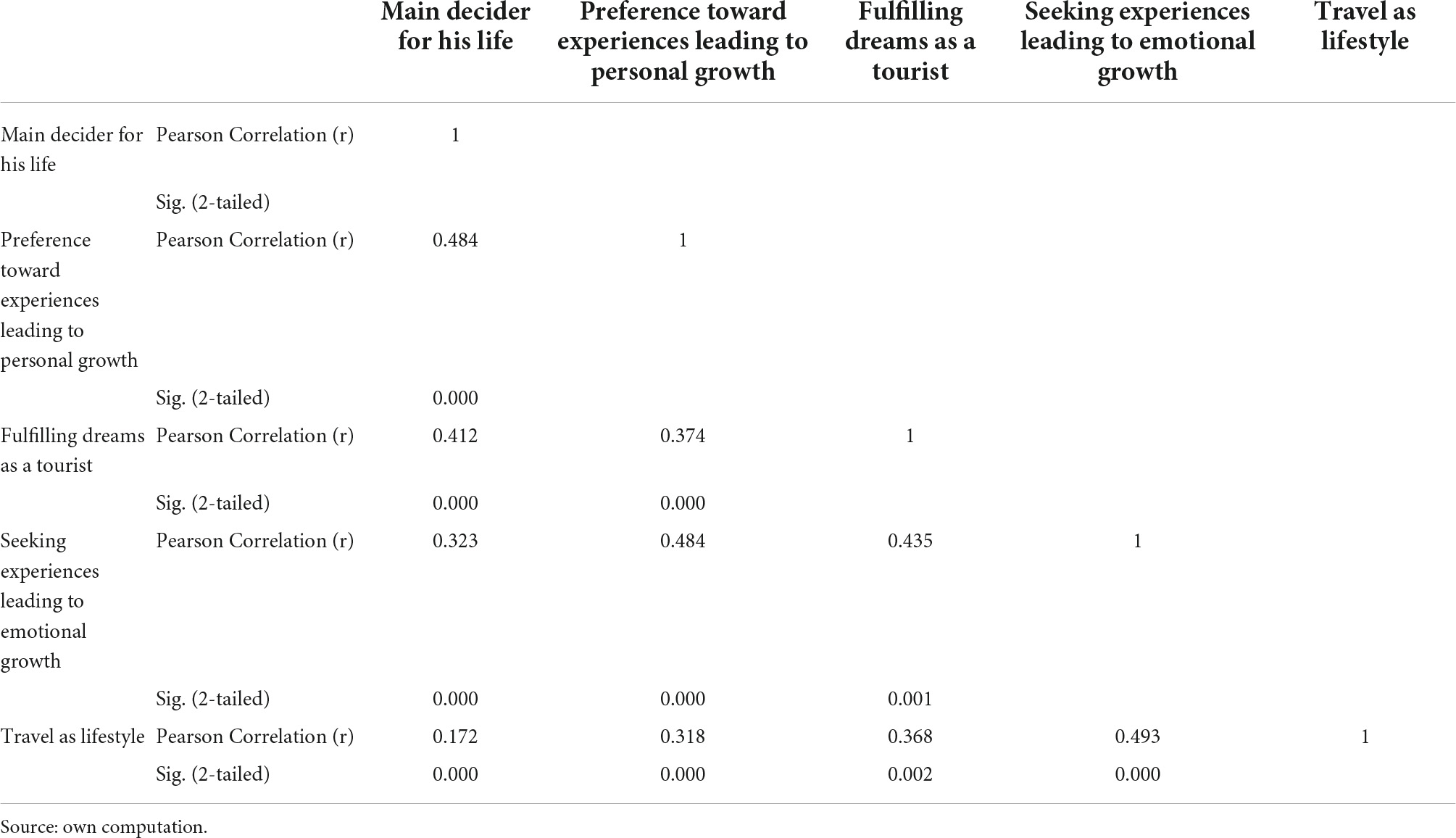

- O5: Identifying specific behavior related to their growth zone for Gen Z tourists from Iasi as far as their next holiday choice is concerned.

We performed a Pearson correlation test to verify this hypothesis. We aimed at measuring the correlation among the variables defining the fear zone. This test was performed through SPSS software and the results are summarized in Table 5 :

Pearson correlation for the growth zone variables.

Although all correlations among variable attributes of the growth zone are significant (Sig = 0.000 < 0.05) and positive (r correlation > 0), we noticed no strong or very strong correlations. Most of the correlations are weak, where the r-correlation is situated between 0.2 and 0.4. We found several moderate correlations ( r = 0.4–0.6) which could be further discussed:

The correlation between “Travel as lifestyle” and “Seeking experiences leading to emotional growth,” r = 0.493.

The correlation between “Preference toward experiences leading to personal growth: and “Main decider for his life,” r = 0.484.

The correlation between “Preference toward experiences leading to personal growth” and “Seeking experiences leading to emotional growth,” r = 0.484.

The correlation between “Main decider for his life” and “Fulfilling dreams as a tourist,” r = 0.412.

The correlation between “Fulfilling dreams as a tourist” and “Seeking experiences leading to emotional growth,” r = 0.435.

We used the Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of reliability to identify the measure of internal consistency among the items defining the growth zone, calculated by SPSS software. The aim was to check whether the items contribute to the comfort zone significance or not. The value of Cronbach’s Alpha was 0.748 which indicated an acceptable consistency ( Tavakol and Dennick, 2011 ). This consistency could not be improved through the removal of any item.

As a conclusion of this test, we can state that the growth zone items do have an acceptable consistency which means there is consistency among the answers given by respondents for this dimension. This will lead to identifying the specific behaviors of tourists choosing a certain destination from the growth zone.

Senninger’s Learning Model is an evergreen one and, moreover, is proving to be a transversal one. It explains the foundations of decision making process. All the time the human mind tries to arbitrate between staying safe and daring for more, between remaining in the comfort zone and overcoming fear of leaving it. The comfort zone is, no matter what, the reference system of all the other levels, even if you decide to buy bread or an electric car ( Wallace and Lãzãroiu, 2021 ; Popescu et al., 2022 ), to choose between staying home or discover a new destination ( Andronie et al., 2021 ; Nica, 2021 ; Pop et al., 2022 ; Robinson, 2022 ).

In tourism and travel, various companies or even cities understood that a traveling decision is facing two alternatives: (1) not to change a thing and repeat a previous choice (like staying home or choosing all over again the same tested destination) and (2) pointing out new destinations, new experiences, new adventures ( Pop et al., 2022 ). So a question is rising: the tourist offer must include arguments for both types of travelers or must be a focused one? Spontaneously we might think dichotomicly: you must be either unique or you do not count. But the reality shows that we can have smart cities, with a smart infrastructure and integrating IoT, but offering also traditional well conserved historical areas ( Andronie et al., 2021 ; Nica, 2021 ; Robinson, 2022 ). Some will come for tasting new experiences and some will be attracted by nostalgic reasons.

In the end everything is a segmentation issue. For different targets you must have different arguments. That is why our research can be a basis for including a new criterion to the segmentation strategy for tourist products and services. By knowing what particular learning zone is the most important in making a travel decision for a certain segment of clients a company can adapt the offer. The case of Gen Z consumers is particularly interesting, because they are the future most important travelers. They are highly educated, social and environmental activists, digital natives and, extremely important, the most significant buyers all over the globe. They know to find without any help the most reliable information online ( Popescu Ljungholm, 2022 ), they are present on various social media and are the most probably to leave a review. In the light of our research model we can ask ourselves: should we treat Gen Z equally, like we used to do with all the other generations before (decision made from our comfort zone)? Should we fear them and decide that they are beyond our marketing possibilities (decision made from our fear zone)? Should we try to understand them (decision made from our learning zone)? Or should we decide to grow with them ( Popescu Ljungholm, 2022 ), to thrive together (decision made from our growth zone)?

Our research offers a glimpse into a very actual and important question: is the buying decision impacted by one of these four learning zones? We added a new perspective to the well-known Senninger’s model, one referring to choosing the next travel destination. We have experienced the Covid-19 pandemic situation and tourism and travel sector was one of the most affected ones. We hesitated to travel because of fear. We chosed to stay safe and we remained home for years. Now, in 2022, we are facing the same old decision related to travel destinations. What we have noticed is that Gen Z dare to exit their comfort zone and to go beyond fear, driven by learning and growth reasons. We still do not know how responded other generations or if Gen Z have the same response for every decisions, no matter the domain.

The main contribution is that we can offer a measuring scale for the 4 zones of the Learning Zone Model. The particularity lies in applying this model to tourism. It opens new possibilities for the model to be applied to other fields as well alongside new possibilities for statistical determinants through inferential statistics. Moreover, understanding the zone where a decision is made, choosing a destination or other products or services allows us to profile better the consumer from a psychological perspective.

The present research explored the Gen Z tourist’s decision for their next holiday. As a theoretical implication, we started by creating a scale based on the 4 zones corresponding to Senninger’s model. Our scale had 20 items (5 statements for each zone/level of the model) regarding choosing the next travel destination and it is measured from 1 to 10 according to the extent to which a respondent agrees, where 1 is full disagreement and 10 is full agreement (Likert scale). Each section involved one key statement which contains the name of the interest zone (e.g., comfort zone).

As a future research perspective, our intention for this statements is to be used in further inferential statistics as part of future research. This key statement had scored consistently the best evaluation as per Cronbach’s Alpha test.

The managerial implications can be helped by our findings. We consider that the Senninger’s Learning Model can provide segmentation criteria (comfort seekers/fear dominants/learners and thrivers) for a new variable: learning type.

To support that, we say that all the statements were based on collected data from tourism specialists. They describe the tourists choosing a travel destination from within their comfort zone as being focused on control and security, being persons who try to mitigate any risks. Therefore they choose their travel destinations depending on security and lack of unforeseen situations criteria. They also rely on repeating positive experiences. Our quantitative research shows for the comfort zone the strongest correlation is between the willingness to mitigate risks and uncertainty avoidance which could take this type of tourist out of his comfort zone. A second strong correlation found was between security-inspired choices and uncertainty avoidance.

According to the specialists choosing a certain travel destination from within the fear zone can be mostly explained through a high degree of being suggestible but also curious and making efforts to overcome the fear of the unknown, lack of excessive planning and welcoming of new challenges. We used those descriptors in realizing our survey and we found out the strongest correlation among the variables of the fear zone was in fact a moderate one. It was the correlation between lack of excessive planning and accepting new challenges. A second reasonable correlation was between new experiences and overcoming the fear of the unknown. All the other correlations within the fear zone were weak toward moderate.

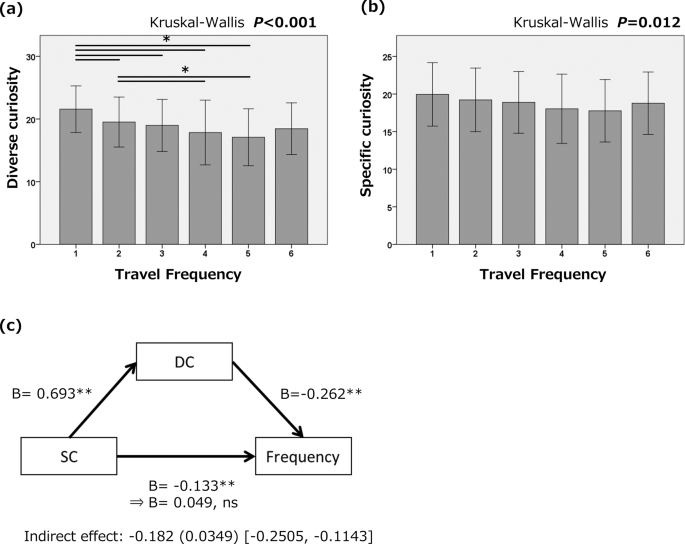

Travelers choosing their destination from within the learning zone were depicted by the specialists as being open to novelty, curious, eager to learn, adventurous, and accepting challenges as well as risks. Our survey results indicated that the Learning zone is the most relevant for Gen Z tourists from Iasi when choosing a travel destination. We recorded the strongest correlations here such as between being adventurous and opened to new experiences; being adventurous and accepting new challenges; being opened to new experiences and a preference for challenges; being adventurous and learning new things and embracing new challenges and the readiness to learn new things. The other correlations were moderate toward good.

For the travelers in the growth zone, the destination choice involves fulfilling certain ideals and objectives from a touristic point of view. Experiences that involve emotional development, passion, decisiveness, personal growth, accepting risks, and perceiving travel as a lifestyle are the most important for them. While most of the correlations are weak, we found, however, a few reasonable correlations: (i) between travel as a lifestyle and seeking experiences leading to emotional growth, (ii) between inclination toward experiences leading to personal development and decisiveness, (iii) between seeking experiences leading to emotional growth and inclination toward experiences leading to personal development, (iv) between decisiveness and fulfilling dreams as a tourist, and (v) between seeking experiences.

To sum up, we can state that the Gen Z tourist from Iasi displays behaviors that can be associated with learning or growth zones rather than the comfort zone. This is relevant when choosing the next travel destination.

As limitations, we can mention that the sample was limited to 209 individuals, a number relatively small to be statistically representative for the Gen Z population of Iasi. The sample’s structure is heterogenic, having more female respondents. We operated with a convenience non-probability sample.

At the theoretical level the model used as the fundament of this research is the Learning Zone Model ( Senninger, 2000 ) which consists of the 4 zones (comfort, fear, learning, and growth) do not offer a clear differentiation of those zones. We cannot assign a precise zone to each tourist since the model was conceived as more of a progressive path.

The research method, an online survey, might reflect the main reason for the lack of representativity of the sample. Since the survey was distributed online using various social media platforms, there was a lack of control over the respondents. Moreover, the collection of data was carried out during the last phase of COVID-19 pandemic restrictions which involved a relevant transition from online to offline.

Data availability statement

Ethics statement.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Faculty of Economics and Business Administration, at University Alexandru Ioan Cuza of Iasi. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- Andronie M., Lãzãroiu G., ?tefãnescu R., Ionescu L., Coco?atu M. (2021). Neuromanagement decision-making and cognitive algorithmic processes in the technological adoption of mobile commerce apps. Oeconom Copernicana 12 863–888. 10.24136/oc.2021.028 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Anichiti A., Dragolea L. L., Tacu Hârşan G. D., Haller A. P., Butnaru G. I. (2021). Aspects regarding safety and security in hotels: Romanian experience. Information 12 :44. 10.3390/info12010044 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Avornyo P., Fang J., Antwi C. O., Aboagye M. O., Boadi E. A. (2019). Are customers still with us? The influence of optimum stimulation level and IT-specific traits on mobile banking discontinuous usage intentions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 47 348–360. 10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.01.001 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bandura A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY: Worth Publishers. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bardwick J. M. (1995). Danger in the comfort zone: From boardroom to mailroom – how to break the entitlement habit that’s killing American business , 2nd Edn. San Diego, CA: Amacom. [ Google Scholar ]

- Berno T., Ward C. (2005). Innocence abroad: A pocket guide to psychological research on tourism. Am. Psychol. 60 593–600. 10.1037/0003-066X.60.6.593 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dweck C. S. (2000). Self-theories: Their role in motivation, personality, and development. Oxforshire: Taylor and Francis. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dweck C. S. (2005). Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York, NY: Ballantine Books. [ Google Scholar ]

- Elbæk C. T., Lystbæk M. N., Mitkidis P. (2022). On the psychology of bonuses: The effects of loss aversion and Yerkes-Dodson law on performance in cognitively and mechanically demanding tasks. J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 98 :101870. 10.1016/j.socec.2022.101870 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Freeth R., Caniglia G. (2020). Learning to collaborate while collaborating: Advancing interdisciplinary sustainability research. Sustain. Sci. 15 247–261. 10.1007/s11625-019-00701-z [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gilligan S., Dilts R. (2009). The hero’s journey: A voyage of self discovery. Carmarthen: Crown House Publishing. [ Google Scholar ]

- Karwowski M. (2018). The flow of learning. Eur. J. Psychol. 14 :291. 10.5964/ejop.v14i2.1660 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kliestik T., Zvarikova K., Lãzãroiu G. (2022). Data-driven machine learning and neural network algorithms in the retailing environment: Consumer engagement, experience, and purchase behaviors. Econ. Manag. Financ. Mark. 17 57–69. 10.22381/emfm17120224 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kovacova M., Machova V., Bennett D. (2022). Immersive extended reality technologies, data visualization tools, and customer behavior analytics in the metaverse commerce. J. Self Govern. Manag. Econ. 10 7–21. 10.22381/jsme10220221 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lǎzǎroiu G., Harrison A. (2021). Internet of things sensing infrastructures and data-driven planning technologies in smart sustainable city governance and management. Geopolit. Hist. Int. Relat. 13 23–36. 10.22381/GHIR13220212 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lichy J., Favre B. (2018). “ Leaving the comfort zone: Building an international dimension in higher education ” in International Enterprise Education eds Mulholland G., Turner J. J. (London:Routledge; ), 234–259. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lyons N. (2022). Talent acquisition and management, immersive work environments, and machine vision algorithms in the virtual economy of the metaverse. Psychosociol. Issues Hum. Resour. Manag. 10 121–134. 10.22381/pihrm10120229 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Maslow A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychol. Rev. 50 370–396. 10.1037/h0054346 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McWha M., Frost W., Laing J. (2018). Travel writers and the nature of self: Essentialism, transformation and (online) construction. Ann. Tour. Res. 70 14–24. 10.1016/j.annals.2018.02.007 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Miller A. L. (2019). The illusion of choice: Parallels between the home cinema industry of the 1980s and modern streaming services, international journal of media. J. Mass Commun. 5 1–8. 10.20431/2454-9479.0504001 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nica E. (2021). Urban big data analytics and sustainable governance networks in integrated smart city planning and management. Geopolit. Hist. Int. Relat. 13 93–106. 10.22381/GHIR13220217 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nica E., Kliestik T., Valaskova K., Sabie O.-M. (2022a). The economics of the metaverse: Immersive virtual technologies, consumer digital engagement, and augmented reality shopping experience. Smart Govern. 1 21–34. 10.22381/sg1120222 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nica E., Sabie O.-M., Mascu S., Luţan A. G. (2022b). Artificial intelligence decision-making in shopping patterns: Consumer values, cognition, and attitudes. Econ. Manag. Finan. Mark. 17 31–43. 10.22381/emfm17120222 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Page O. (2020). How to leave your comfort zone and enter your ‘growth zone’. Available online at: https://positivepsychology.com/comfort-zone/ (accessed May 12, 2022). [ Google Scholar ]

- Passafaro P., Chiarolanza C., Amato C., Barbieri B., Bocci E., Sarrica M. (2021). Outside the comfort zone: What can psychology learn from tourism (and vice versa). Front. Psychol. 12 :650741. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.650741 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pearce P. L., Packer J. (2013). Minds on the move: New links from psychology to tourism. Ann. Tourism Res. 40 386–411. 10.1016/j.annals.2012.10.002 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Perruci G., Warty Hall S. (2018). “ The learning environment ,” in Teaching leadership. Bridging theory and practice , eds Perruci G., Warty Hall S. (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar; ), 1–8. 10.4337/9781786432773 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Plog S. C. (1974). Why destination areas rise and fall in popularity. Cornell Hotel Restaur. Adm. Q. 14 55–58. 10.1177/001088047401400409 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pongelli C., Calabrò A., Quarato F., Minichilli A., Corbetta G. (2021). Out of the comfort zone! Family leaders’ subsidiary ownership choices and the role of vulnerabilities. Fam. Bus. Rev. 34 404–424. 10.1177/08944865211050858 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pop R. A., Sãplãcan Z., Dabija D. C., Alt M. A. (2022). The impact of social media influencers on travel decisions: The role of trust in consumer decision journey. Curr. Issues Tour. 25 823–843. 10.1080/13683500.2021.1895729 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Popescu Ljungholm D. (2022). Metaverse-based 3D visual modeling, virtual reality training experiences, and wearable biological measuring devices in immersive workplaces. Psychosociol. Issues Hum. Resour. Manag. 10 64–77. 10.22381/pihrm10120225 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Popescu G. H., Valaskova K., Horak J. (2022). Augmented reality shopping experiences, retail business analytics, and machine vision algorithms in the virtual economy of the metaverse. J. Self Govern. Manag. Econ. 10 67–81. 10.22381/jsme10220225 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Robinson R. (2022). Digital twin modeling in virtual enterprises and autonomous manufacturing systems: Deep learning and neural network algorithms, immersive visualization tools, and cognitive data fusion techniques. Econ. Manag. Finan. Mark. 17 52–66. 10.22381/emfm17220223 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Santoro N., Major J. (2012). Learning to be a culturally responsive teacher through international study trips: Transformation or tourism? Teach. Educ. 23 309–322. 10.1080/10476210.2012.685068 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Senninger T. (2000). Abenteuer leiten in abenteuern lernen. Aachen: OEkotopia. [ Google Scholar ]

- Senninger T. (2017). Abenteuer leiten in abenteuern lernen: Methodenset zur planung und leitung kooperativer lerngemeinschaften fuer training und teamentwicklung in schule, jugendarbeit und betrieb , 7th Edn. Aachen: OEkotopia. [ Google Scholar ]

- Stainton H. (2022). Plog’s model of allocentricity and psychocentricity: Made easy. Available online at: https://tourismteacher.com/plogs-model-of-allocentricity-and-psychocentricity/ (accessed May 12, 2022). [ Google Scholar ]

- Taleb N. N. (2014). Antifragile: Things that gain from disorder. New York, NY: Random House. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tavakol M., Dennick R. (2011). Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2 :53. 10.5116/ijme.4dfb.8dfd [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Vygotsky L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wallace S., Lãzãroiu G. (2021). Predictive control algorithms, real-world connected vehicle data, and smart mobility technologies in intelligent transportation planning and engineering. Contemp. Read. Law Soc. Just. 13 79–92. 10.22381/CRLSJ13220216 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Woodward B., Kliestik T. (2021). Intelligent transportation applications, autonomous vehicle perception sensor data, and decision-making self-driving car control algorithms in smart sustainable urban mobility systems. Contemp. Read. Law Soc. Just. 13 51–64. 10.22381/CRLSJ13220214 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zheng D., Ritchie B. W., Benckendorff P. J. (2021). Beyond cost–benefit analysis: Resident emotions, appraisals and support toward tourism performing arts developments. Curr. Issues Tour. 24 668–684. 10.1080/13683500.2020.1732881 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Plog’s and Butler’s Models: a critical review of Psychographic Tourist Typology and the Tourist Area Life Cycle

2018, Turizam

This paper attempts to examine the two popular cited theories in tourism studies, Psycho-graphic Tourist Typology by Stanley Plog and the Tourism Area Life Cycles (TALC) by Richard Butler, which have been widely accepted and applied by scholars worldwide and have retained their relevance more than three decades as the pioneer concepts in Tourism. By capturing and reviewing scholarly articles, this paper identifies some key absent issues that should be concerned when use theories in future tourism research.

Related Papers

Sport i Turystyka. Środkowoeuropejskie Czasopismo Naukowe

Karolina Korbiel

In theoretical studies on the typology of tourists, various criteria for their identification can be found. A drawback of this approach is the lack of one common concept of tourist division, which would allow for comparing research results at various academic and marketing centers. There is a definition problem of tourism and the tourist themselves, the concepts often differing from each other, thus, there is no common ground on which the theories of the separation and division of tourists can be built. In the presented publication, a review of selected, varying tourist types have been conducted. Typologies of tourists are based on various criteria, ranging from sociological and psychological to demographic, geographic, economic, marketing and others often having an interdisciplinary basis. First of all, attempts were made to show the diversity of typological concepts presented in the world. They are used in scientific research but only refer to a small group of respondents and it i...

Elvina Daujotaite

girish prayag

Holly Donohoe

Claudia Poletto

Alan A Lew , C. Michael Hall

As comprehensive and far-reaching as this volume has been, in many ways it only scratches the surface of the geographic approach to understanding tourism. It is not a comprehensive state-of-the-art review of tourism geography, let alone tourism studies. It was also not an attempt to delineate the complex evolution of tourism studies, nor to define an agenda for research. Finally, it was not an attempt to provide a rationale for the way tourism is, or should be, structured for academic study.

Antonio Miguel Nogués-Pedregal

Several authors have noted that tourism has always been quite an undisciplined endeavour, and as such, a transdisciplinary topic of scientific research (Xiao, Jafari, Cloke, & Tribe, 2013). In one way or another, this perspective upon tourism has led to comprehensive discussions on epistemological issues. Rather than engage in endogamic self-reflection on the nature and structure of tourism studies and consequently the type of knowledge produced by these academic networks, we should prioritize ontology (Tribe, 2010).

Annals of Tourism Research

Stephen Lea

Jess Ponting

Ute Jamrozy

RELATED PAPERS

jenaro vera guarinos

Lucas Ignacio Hespanhol

International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics

Anatoly Dritschilo

Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses

Richard Njouom

Linguistics

Nikolaos Lavidas

Suzanne Wilson

Gavo Handika

Tarcísio Vanderlinde

Transportation Research Part B: Methodological

R. Jayakrishnan

10° Ecoinovar

Computación y Sistemas

Daniel Reséndiz Gutiérrez

Journal of General Internal Medicine

Terrence Conway

Revista Brasileira de Planejamento e Desenvolvimento

Nuno Patricio

Balkan Region Conference on Engineering and Business Education

Norbert Gruenwald

JORGE HERNAN MUNERA RESTREPO