- About the ATTA

- Sustainability

- Our Initiatives

- Adventure Travel Conservation Fund

- Leadership & Team

- Internship Program

- Business Development

- Global Travel News

- Industry Spotlight

- Industry Voices

- Member News

- Regional News

- B2B Marketing

- Signature Events

- Market Activation

- Climate Action

- Storytelling

- B2C Marketing

- Event Calendar

- AdventureELEVATE Latin America 2024

- AdventureELEVATE Europe 2024

- AdventureELEVATE North America 2024

- AdventureWeek Finland 2024

- Climate Action Summit 2024

- AdventureWeek Okinawa 2024

- AdventureNEXT Fiji 2024

- AdventureConnect

- ATTA on the Road / Virtual

- Expert Nomination & Topic Suggestions

- Events Sustainability

- Sustainability Resource Center

- On-Demand / Webinars

- Inspiration

- Guide Standard

- Global Payment Resource

- Free Community Membership

- Become a Member

- ATTA Ambassadors

- Active Members

- Adventure Champions

- Community Books

- Case Studies

Shopping Cart

Shopping cart items, understanding the supply chain of travel.

Even for industry veterans, it can be a confusing process to fully understand the supply chain of travel due to the many layers and different terminologies used. This can lead to confusion and a lack of understanding around the complexities within the industry, the cost of doing business, as well as the advantages and disadvantages of the various supplier layers. In addition, innovation, technology, and modernization are changing the travel supply chain model on a regular basis.

This article will explore the businesses involved in the supply chain, the different terminology used, and also how those terms vary based on where you do business around the globe. For simplicity's sake, here is a classic traditional model that is used often and starts with the traveling consumer.

In this example, the consumer works with a travel advisor, the travel advisor works with an outbound tour operator, the tour operator works with a Destination Management Company (DMC), and the DMC works with local suppliers (operators, accommodations, and transportation). Let’s explore those different layers and the terminologies and meanings of each.

The consumer travels to the destination and experiences the travel product. When a consumer books a trip “direct” with a local supplier or operator, they can skip through many of these intermediaries, which is also referred to as disintermediation. For example, the chain could look like one of these examples:

While booking direct is a growing trend in the travel industry, in adventure travel the consumer is often looking to experience more remote destinations and combine various locations and activities. As a result, there is still a greater need for an intermediary than in other tourism sectors. Post-pandemic, having a trusted partner to provide reassurance and protection is more important and valuable than ever before. Let's take a closer look at those intermediaries, and understand the value and benefit of each.

Travel Advisors

(Also known as Travel Agents or Travel Consultants)

The travel advisor is a curator of a personalized experience for a consumer. The travel advisor’s unique role is to understand the needs of their clients and to know the depths of the travel market so they can craft a travel solution that delivers on those needs. Consumers who value not having to spend hours looking for the perfect accommodation, consider how to get from point A to B to C, decide what destinations have the best option for their current activity requests, or research which options are more sustainable, gain great value and benefits from working with a travel advisor.

A travel advisor often charges a small fee to the consumer for their expertise, and they often receive commissions from businesses. For a tour operator, an advantage of working with travel advisors is that a curated traveler is brought to them; if the traveler has a good experience, the advisor or agent is likely to return with future clients. Often, travel advisors remain involved and handle client questions and support.

One of the greatest values of a travel advisor to a consumer is that in addition to hotels and transportation options, they are knowledgeable about and sell a wide variety of packaged trips from different tour operators, and therefore can provide a diverse range of options. International travel, in particular, can involve more unknowns and uncertainty, making travel advisors' expertise and experience particularly valuable.

Outbound Tour Operator

The outbound tour operator will craft ideal itineraries and sell those itineraries to individuals or groups as a packaged product. The tour operator's value is in knowing current market demand and travel trends and matching those with destinations to keep innovating new products. These are often multi-day itineraries–from three days to three weeks, depending on the destination and experience.

Tour operators are often specialized and cater to a niche market with specific needs, so travelers who book with them tend to be more loyal. This is especially true in adventure travel, where many operators specialize in activities such as trekking or cycling. Tour operators usually work with DMCs in a destination who help them identify the best local suppliers for their tour needs. A consumer who wants to go on a tour through an operator will sometimes also use a travel advisor because the travel advisor can identify the right tour operator for their needs and also add additional experiences before or after the tour.

It is also important to note that tour operators usually hold a legal responsibility or bond to safeguard the consumer, depending on the country in which they operate. This adds an extra layer of protection by requiring transparency, information sharing, cancellation rights, and assistance to travelers.

Destination Management Company (DMC)

(Also known as Wholesalers, Ground Handlers, Inbound Tour Operators)

A DMC is a company that sells and packages solutions within their destination. They have deep knowledge of and connections with accommodations, local transportation, and local suppliers who offer logistics and activity options. DMCs get rates from their suppliers for products which they then package and sell to operators, advisors, or even directly to the consumer. In each case, DMCs can be thought of as wholesalers or ground handlers in their destination.

DMCs work with outbound tour operators or cruise companies (specifically expedition cruise companies within adventure travel) to provide options that meet the tour needs. Travel advisors can also work directly with DMCs to provide a menu of activity options and on-the-ground support for clients if issues arise. However, it is important to note that not all travel advisors can work with DMCs due to variations in laws and business practices across different countries.

Local Suppliers

In the growing and ever-changing world of travel there are many businesses that offer services on the ground for travel experiences. These include varying levels and styles of accommodation, transportation, and activities such as kayaking, climbing, food tours, cultural experiences, and more. Local communities are an important part of the travel experience and DMCs’ relationships with and connections to these communities is important. Understanding the sustainability efforts of local suppliers is key as market trends show that 90% of consumers are asking for sustainable travel options.

Online Travel Agencies (OTAs) / Web-Based Marketplace

OTAs are best known for selling flights, hotels, and cars. However, many also sell packages, such as outbound tour itineraries or packaged tours from DMCs.

OTAs curate products from the DMC and directly connect the DMC with the consumer. The DMC is the one crafting the product and selling it to the consumer, while the OTA takes a commission for bringing the consumer to them. In this case the DMC must be able to sell directly to the consumer to be featured in the OTA’s platform. This is particularly true of tailor-made holidays which require a strong local expertise. The resulting supply chain in this example looks like this:

To further complicate matters, OTA can also stand for Online Tours & Activities (such as Viator, Get your Guide, Klook). These are web-based marketplaces that directly curate activities or experiences from the local activity providers and sell them to individual travelers.

Adventure Travel Terminology

At the Adventure Travel Trade Association (ATTA), we often use the term “supplier” when referring to DMCs and local suppliers and the term “buyer” for outbound tour operators and travel advisors.

“Buyers” are the ones directly connected with the consumer and who influence travelers’ destination and activity decisions. They 'buy' or source products and services from local DMCs in the destination.

“Suppliers” or DMCs in general are 'supplying' services from the ground and destination to the outbound market. Online Travel Agencies (OTA) and online wholesalers are also important players in the market.

Example of Global Differences and a Changing Marketplace

The global travel supply chain is a complex puzzle which is constantly changing in a disruptive world and varies depending in which country the company is based. For instance, in the United Kingdom, there is a clearly defined line between tour operators and travel agencies. Outbound tour operators contract directly with local DMCs, while travel agencies sell products from tour operators or UK-based businesses with a UK tourism license. In contrast, in France, travel agencies work directly with local DMCs as well as with outbound tour operators.

In Asia, travel advisors and outbound tour operators are often one and the same business, calling themselves a travel agent, but taking the role of packaging the trip themselves.

Increasingly more popular in the travel industry is the role of the marketing representative or ‘Sales Rep’ who is in charge of promoting and connecting DMCs with outbound tour operators (and possibly travel advisors). They are based in the targeted market destination and very well-connected. They can work on commission or retainer fees, depending on a country’s practices and agreement between the two parties.

An additional disruption in the market are media influencers who sell their own curated tours to their followers where they often lead the group. Since they have already built trust with their audience, their loyal followers are interested in traveling with them to destinations and experiencing travel through their lens and brand.

Special interest groups are another growing niche market, for example avid cyclists might organize an annual trip overseas for their group, where they might work directly with an outbound tour operator, DMC, or even the local suppliers themselves.

Building Relationships

Developing relationships across the complicated global travel supply chain is more important than ever, especially as destinations and businesses recover from the pandemic . New entrants to the market should ask clear questions when establishing their business relationships to ensure both parties understand their individual roles and expectations and maintain open communication throughout their partnership.

Tourism sustainability during COVID-19: developing value chain resilience

- Published: 27 April 2022

- Volume 16 , pages 391–407, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Zerin Tasnim 1 ,

- Mahmud Akhter Shareef 2 ,

- Yogesh K. Dwivedi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5547-9990 3 , 4 ,

- Uma Kumar 5 ,

- Vinod Kumar 5 ,

- F. Tegwen Malik 6 &

- Ramakrishnan Raman 7

6624 Accesses

12 Citations

Explore all metrics

The aim of this study is to evaluate the perceptions of prospective tourists through parameters by which the tourism and hospitality service sector can withstand the widespread implications to the sector as a result of the current pandemic. In turn this will lead to weighing up the means for recovery. The identified parameters are then classified, categorized and linked up with supply chain drivers to obtain a holistic picture that can feed into strategic planning from which the tourism and hospitality service sector could utilize to establish a resilient supply chain. This data can provide deep insight for both theorists and practitioners to utilize. It was found that reforming six supply chain drivers, whilst at the same time developing core competencies, is the central essence of a resilient supply chain within the tourism and hospitality business sector (who are at present working hard to counterbalance the many threats and consequent risks posed due to the pandemic).

Similar content being viewed by others

Knowledge Dynamics in Rural Tourism Supply Chains: Challenges, Innovations, and Cross-Sector Applications

Designing a Sustainable Tourism Supply Chain: A Case Study from Asia

The Perfect Storm: Navigating and Surviving the COVID-19 Crisis

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

People all over the world are suffering from severe physical and mental distress due to the prolonged effect of the COVID-19 pandemic (Chatterjee et al. 2021 ) which has been having an unparalleled impact on work life (Carrol and Conboy 2020 ; Chamakiotis et al. 2021 ; Islam et al. 2022 ; Shirish et al. 2021 ; Trkman et al. 2021 ; Venkatesh 2020 ). People’s daily individual, social, professional, organizational and financial activities have been experiencing extreme involuntary as well as forceful changes due to the unexpected assault of COVID-19 (Dubey et al. 2021b ; Kock et al. 2020 ; Wachyuni and Kusumaningrum 2020 ) such as lockdowns and temporary postponements of physical operations (Dwivedi et al. 2020 ; Papadopoulos et al. 2020 ).

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted global supply chains and exposed weak links in the chains far beyond what most people have witnessed in their living memory. The scale of disruption affects every nation and industry, and the sudden and dramatic changes in demand and supply that have occurred during the pandemic crisis clearly differentiates in its impact from other crises. All of this has disrupted the habitual behavior of customers, causing a shifting of the general customer base, with businesses and organizations struggling to survive such multidimensional challenges (Kausha and Srivastava 2020 ; Kumar 2020 ; Lew et al. 2020 ). As such, global supply chain management of various industries has been hit hard by the pandemic resulting in enormous losses for many with weak connections in the supply chain network being exposed (Dubey et al. 2021a ).

Creating resilient supply chains has gained much attention lately in academia and among practitioners (Dubey et al. 2021c ) wtih policy makers being required to focus on creating a resilient framework that can help to overcome some of the challenges of Covid-19 as well as help to grow overall performance (Chowdhury et al. 2020 ; Das et al. 2021 ). Many industries have been impacted by this pandemic but it is fair to say that the tourism and hospitality sector has faced unprecedented challenges due to the substantial restrictions that have been enforced in many countries around the world on people, travel agencies and flights for leisure holidays (Chakraborty and Kar 2021 ; Kausha and Srivastava 2020 ; Lew et al. 2020 ). As a direct result of the COVID-19 pandemic, around 100 million jobs have been put at risk because of international travel restrictions and low confidence in traveling. International travel declined around 82% in the Asia pacific from January to October 2020 that is much higher when compared to other regions in the world (UNWTO 2020 ). According to experts’ opinion, it may take 2.5 to 4 years for this industry to rebound back to pre-pandemic levels (Goh 2021 ). However, it is not just external restrictions and protections that are impacting the sector, but also people’s perception of risk due to the virus, unavailability of medical assistance (if someone were to travel), financial hardships faced as a result of the pandemic, and the psychological trauma and panic felt that is all adding to a paralytic mindset making people reluctant to take such travel for leisure (Ćosić et al. 2020 ; Matias et al. 2020 ). According to Chin et al. ( 2020 ), as a consequence of restrictions due to COVId-19, change is occurring in human–environment interactions with limited movement of people. All these circumstances are creating anxiety within the tourism and hospitality sector with some speculating that it may continue, even after the end of this devastating pandemic (Kar et al. 2021 ; Obembe et al. 2021 ; Ćosić et al. 2020 ; Karim et al. 2020 ; Li et al. 2020 ).

It is for all these reasons that it is critical to assess the tourism and hospitality sector’s supply chain resilience by detecting loopholes and flaws in the affected areas of the value chain to shed light on which areas or activities are creating value and which are not. Whilst determination of a resilient value chain for this sector is still in the premature stage when it comes to the existing literature (Brouder et al. 2020 ; Gössling et al. 2021 ; Kausha and Srivastava 2020 ; Kumar 2020 ), all of the scholarly articles on supply chain of tourism and hospitality discuss this issue from three distinct viewpoints. The first group of researchers focuses on the current situation faced by the sector and simply attempts to assess the untold losses and damages incurred by this sector due to the ongoing global crisis (Brouder et al. 2020 ; Kumar 2020 ; Lew et al. 2020 ). The second category of researchers (Ćosić et al. 2020 ; Kock et al. 2020 ; Li et al. 2020 ; Matias et al. 2020 ; Wachyuni and Kusumaningrum 2020 ) address and explore the psychological intention and human behavioral perspective of a tourist/traveler faced with such uncertainty and travel conditions. These researchers streamline and unveil human behavior during crisis moments. The third category of studies (Gössling et al. 2021 ; Karim et al. 2020 ; Kausha and Srivastava 2020 ) investigates and speculates on the future of the tourism and hospitality business sector with distinct recommendations based on present trends and human mindsets. However, these three viewpoints should not be considered in isolation, instead the development of a resilient value chain of the tourism and hospitality sector and its sustainability are best addressed, investigated, and theorized analyzing all the three areas discussed above comprehensively and holistically.

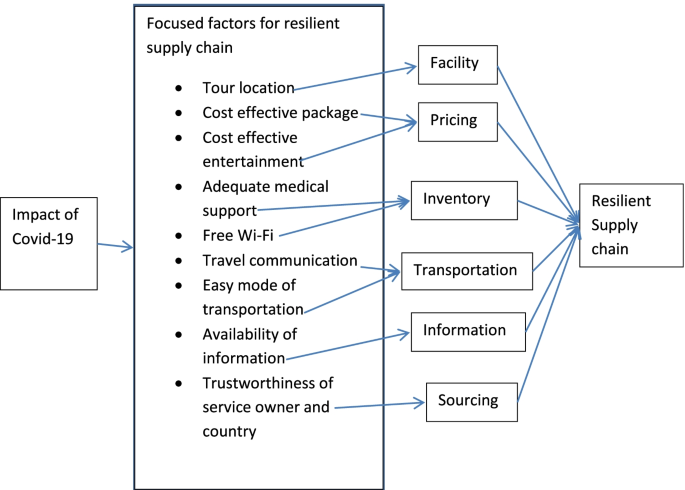

According to the Tourism 2020-OECD library, effective tourism policy development needs to focus on some essential factors such as, long term tourism planning, government support, cooperation among all members, human resource development, helping the tourism organizations to run globally, accessibility to destinations, promoting economic development, promoting local cultures and attributes and finally, measuring the performance. This study will assess these factors under five key areas, namely facility (physical location or site), pricing, inventory, information and finally sourcing.

With this in mind, this empirical research-based study has chosen to answer the following two research questions:

What are the parameters required for the sustainability of tourism and hospitality businesses in the post-COVID-19 era in light of prospective tourist’s perception?

How are the identified parameters related to the primary strategic drivers (i.e. the parameters of supply chain performance) of supply chain network, namely facilities, inventory, transportation, information, sourcing and pricing?

This paper thus starts with a review of the literature that covers this pandemic and its effect on tourism and the hospitality service and the development of resilient supply chains. This leads into the next section which explains the research methodology for this study before discussing the findings and interpretations for a resilient supply chain. All of this is then given context in terms of the theoretical and managerial implications of these research findings, followed by conclusions drawn for the benefit of the sector in question whilst considering any limitations and future research directions.

2 Literature review

Tourism is one of the largest and fastest-growing industries worldwide (Ranasinghe and Pradeepamali 2020 ). The tourism supply chain (TSC) consists of a network of different kinds of tourism organizations that deal with tourism-related products or services both in the public and private sectors. To maintain competitiveness in the entire supply chain network of the tourism sector, it is necessary to manage effective coordination in upstream and downstream organizations. Coordination between the vertically related ones such as the hotels and tour operators are very important. With coordination among the horizontally related or same level firms being important as well to nurture the sustainable TSCs. It is therefore pertinent to understand the current situation faced by the tourism and hospitality sector as a result of this pandemic and to consider its impact on the whole supply chain network and the condition in the post-COVID-19 era. Hence, moving forward, it is critical to consider the relevant supply chain drivers which truly impact this sector along with maintaining cooperation among all TSC sectors. This in turn could help to improve brand value, reputation, reduce costs and enhance system efficiency. Furthermore, it could help to respond to any future risks and challenges promptly (González-Torres et al. 2021 ).

In 2015, all United Nations Member States agreed to adopt 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs) regardless of if they were considered a developed or developing country which aimed to reduce the global poverty level, use environmentally friendly systems (by tackling climate change and sustaining forests and oceans), engage with relevant stakeholders of tourism sectors and provide guidelines and policy around sustainability (Birendra et al. 2021 ). According to Scheyvens and Hughes ( 2019 ), SDGs can be applied globally to achieve sustainability in the tourism sector by 2030. In fact, tourism-related SMEs can contribute to social and economic development as well as to the conservation of natural tourism destinations. Hence it is good news that many small and medium enterprises (SMEs) are growing in this sector, which indicates positive consequences including social, economic and environmental outcomes (Rasoolimanesh et al. 2020 ; Birendra et al. 2019 ).

The tourism and hospitality industry is responsible for one-tenth of the global GDP and can significantly contribute to economic and social development. If it is managed properly, then it can expedite the attainment of sustainability (Birendra et al. 2021 ). Sustainable tourism can also have a significant contribution to poverty reduction, attain gender equity and protect the environment (Rasoolimanesh et al. 2020 ; Scheyvens and Hughes 2019 ). In fact, whilst Trupp and Dolezal ( 2020 ) mentioned the importance of tourism for economic development and poverty mitigation in Southeast Asia, it is also necessary to point out that tourism is linked with gender equality (which is imbedded within the SDGs), as such, tourism policy should be redesigned to promote gender equality. Another important point to focus on in sustainable tourism is to maintain good connections among stakeholders. Good communication and collaboration among all stakeholders can help to attain sustainability and overcome the challenges (Movono and Hughes 2020 ; Trupp and Dolezal 2020 ). With the tourism industry, now more than ever, being uncertain in nature (Robinson et al. 2019 ), collaboration of this kind will only benefit the industry.

Analyzing the economic, social and environmental development issues are crucial for building up a sustainable tourism and hospitality sector globally. For example, Sigala ( 2020 ) highlighted that sustainable tourism is based on the ecological, social and cultural capacities of the local community for the acceptance of a tourism territory (that can be considered as public goods/grounds). Sustainability can be affected negatively by global economic instability, natural disasters, climate change, the loss of biodiversity and regional and international security. As a consequence, tourism can be considered a very sensitive and vulnerable sector. Any shock from one agent rapidly spreads to others and spreads out into the whole tourism supply chain (González-Torres et al. 2021 ).

Recently, the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly impacted the hospitality and tourism industry worldwide (Rivera 2020 ) with most tourist sites not yet open for visitors and travelers having to quarantine along with maintaining social distancing to reduce the transmission of coronavirus (Kılıç et al. 2020 ). It is fair to say that the tourism and hospitality industry facing all these challenges and regulations is one of the sectors most affected by this current pandemic. This has adversely impacted the livelihood of millions of industry stakeholders that span around the world (such as hotels, airlines, etc.). Due to COVID-19, many flights have been canceled and tour guides have also been forced to stop their operations. This is highlighted by the fact that due to COVID-19, the number of passengers traveling by air has declined from 44 to 80 percent, around 100 to 120 million tourism jobs have been lost and, direct aviation jobs at airlines and airports have fallen by 4.8 million (that is 43 percent less compared to the pre-COVID-19 situation) (UNWTO 2020 ). Considering that 58 percent of tourists arrive at their destination by air, that is a big loss to the industry as a result of lockdowns and border closure that has hindered air travel. Coupling this with a drop of 850 million in the number of international tourists to 1.1 billion, the revenue from tourism has fallen by $910 billion to $1.2 trillion (Jata 2021 ). Hence the impact of COVID-19 needs to be investigated to sort out the areas of the supply chain which should be focused on to attain sustainability in tourism (Birendra et al. 2021 ) so that the industry can recover from the crippling effects of this pandemic.

For low income countries, poor internal infrastructure and amenities can be one of the main reasons behind low tourism demand (Khan et al. 2020 ). With present travelers being very aware of the local situation in this regard due to online access to tourist spot information. Before visiting any place, tourists are able to collect all sorts of online information about their favorite or probable holiday destinations with the recent COVID-19 pandemic only strengthening the importance of e-tourism. It is for these reasons that online tourist information or e-tourism is expected to become an important driver for future growth of tourism (Goh 2021 ), informing and reassuring a tourist before they choose their location of travel.

The other major reasons for the decline in tourism includes health concerns, a decline in disposable incomes, and reduction in the number of flights worldwide and restructuring of airlines (Sheller 2021 ). Zenker and Kock ( 2020 ) also discusses a few other reasons for the decline in tourism that we are witnessing, such as a change in destination images, a change in tourist behavior, a change in resident behavior, changes in the tourism industry, among others. Since the outbreak of coronavirus, tourists are more mindful of the rate of infection in tourist locations thus leading tourists to prefer local destinations rather than foreign ones (minimizing the risk posed of catching Covid-19 during travel along with potential delays and disruptions) and to avoid overcrowded places. This is why more remote destinations are becoming more popular over the once populat mass tourism destinations.

Collaboration with health care systems or with other emergency systems are required in the post pandemic era for betterment of the tourism sector along with the improvement in overall customer service experience to benefit the sector (as is being seen in the Indian tourism industry). The predominant factors for overall customer service experiences are price, cleanliness, hospitality (Zenker and Kock 2020 ).

People are becoming ever more aware of the need for sustainability in all sectors, tourism included. Part of this would also be what footprint is being left behind by the visiting tourists and how can this be minimized to ensure the conservation of natural and cultural resources. This was highlighted at a popular tourist location in Wales, the summit of Snowdon (Wales’ tallest mountain), where an influx of local tourists visited during the pandemic and left behind all sorts of litter at the beauty site. Hospitality and maintenance (including cleanliness) of tourist spots can motivate tourists to spread positive word of mouth that enhance publicity of particular such tourist locations. In addition, security, safety and amenities of a location is crucial to attract potential tourists. The arrangements of toilets, restaurants, accommodation, and transport facilities are all important to a tourist choosing where to visit (Kar et al. 2021 ). It is thus imperative to keep in mind a typical tourism value chain which is composed of suppliers, tour operators, competitors, partners, governments and other firms carrying out complementary activities (González-Torres et al. 2021 ).

3 Areas of tourism supply chain need to be focused for sustainability in post COVID-19 Era

From the literature review, it is clear that numerous factors are needed to be considered for effective tourism. This study will assess these factors under five key areas, namely facility (physical location or site), pricing, inventory, information and finally sourcing.

3.1 Facility

A tourist’s travel decision is influenced by perceiving the travel risks and external information they obtain from different sources. These decisions are also impacted by tourist destinations and traveler types. Experienced travelers typically perceive less risk while choosing travel destinations compared to an inexperienced traveler who is more concerned about security and safety issues (Lew et al. 2020 ). A traveler’s culture and nationality play a vital role in travel decisions. Tourists from risk-oriented cultures (e.g. western tourists) are more likely to travel anywhere they plan compared to travelers from risk-intolerant cultures (e.g. Asian tourists). In fact, tourists from risk intolerant cultures are more likely to cancel travel plans if they perceive any risk in traveling (Villac and Fuentes-moraleda 2021 ).

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the tourism sector has changed considerably with the typical tourist now selecting tourism destinations after considering only local and nearby destinations with the sense of protection being considered an important factor here (Prayag 2020 ; Duro et al. 2021 ). It is for these reasons that during this current pandemic (and moving into the endemic stage of COVID-19 for some countries), most travelers are coming from nearby localities (Haywood 2021 ). Many countries and regions have restricted travel movements and imposed strict policies on traveling requiring Covid tests, vaccination passports and quarantine (or isolation) restrictions for travelers arriving at their destination. All of this is having a huge impact on the global tourism industry and will be overcome only when borders reopen, and international flights are permitted to fly without any obstacles (Sharma et al. 2021 ). Some studies have highlighted that in the post-Covid era, choosing a local destination for a traveling plan will act as a favorable alternative for many travelers (Baum and Hai 2020 ; Higgins-desbiolles 2020 ). The industry also had to contend with limiting the number of tourists at a tourist site to reduce the chance of spread of this disease and at the same time avoiding mass gatherings of people for the same reason. However, this will at least enable the industry to remain open whilst ensuring the leisure and comfort of tourists are framed in an environment of less risk.

Several diseases that spread in the last two decades have profoundly damaged the image of several countries as safe tourist destinations; although it is evident from analyzing the past histories after any epidemic or pandemic, like Ebola or severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), the tourism industry does not take long to recover the losses (Günay et al. 2020 ). As international tourist spots are mostly closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, domestic tourism will get the opportunity to flourish as tourists find local options that they feel are safe and reliable in terms of travel to these nearby locations (that come with a feeling of belongingness that enhance their experience) whilst at the same time mitigating the hassle of quarantine/isolation (Brouder et al. 2020 ). It is interesting to note that in different tourist locations advanced technologies like robots, automation technologies, and artificial intelligence can reduce cost, enhance flexibility and help to maintain social distance (Sharma et al. 2021 ). Thus, technology can handle pandemic-specific problems such as screening travelers, discovering COVID-19 cases and tracking contacts (Hall et al. 2020 ).

3.2 Pricing

Like all other industries, the tourism industry is mostly contingent upon government aids that support it to operate its supply chain network efficiently. A number of multinational tourism organizations access government aid and support which helps them reduce their operational costs and improve their global productivity (Higgins-desbiolles 2020 ; Sharma et al. 2021 ). Government plays a vital role to help stakeholders of the tourism industry survive and for the sector to run efficiently, this is especially so due to the impact that the COVID-19 crisis has had on the tourism industry. In the post-COVID-19 era, it has been suggested to reopen everything on a limited scale but to run the whole industry profitably, government subsidies and support is going to be essential (Hall et al. 2020 ; Tsionas 2020 ). Such governmental support will reduce the risk faced by the tourism industry and will help create a sustainable one, thus government measures are a must. To achieve this, governments could look to provide interest-free loans, flexible mortgages and financing options to support tourism-related SMEs. Governments could also promote tourism destinations to attract international and local tourists (Assaf and Scuderi 2020 ) with tourist travel decisions being influenced by such local government initiatives that also manage the safety and security of tourists during and post COVD-19 era. If governments fail to deliver and communicate adequate and appropriate messages to tourists, then it may affect their travel plans negatively (Villac and Fuentes-moraleda 2021 ). With government assistance and support towards recovering losses due to the pandemic, coupled with public–private relationship, the tourism industry can get a new outlook in the post-COVID-19 era (Mccartney 2020 ).

There are different types of partnerships and alliances among competitors within the industry that could help those in the sector to gain competitive advantages and create sustainability within the tourism industry. For example, companies could share skills and resources with each other that would help to fill up the weaknesses of each other. Screening companies for creating such partnerships will be important during which taking into consideration their common interests, trustworthiness and identifying if there are any conflicts. Collaboration is not a new thing with large firms generally collaborating with other firms to address environmental threats related to the maturity phase of the industry. For an established market, firms should focus on development activities that can improve their position in the market. Hence using tried and tested methods of working together will maintain a competitive environment among similar tourism firms whilst helping them to grow. Thus, companies could also provide cost-effective services and offer several cost-effective travel packages for tourists.

To overcome the challenges due to the COVID-19 pandemic, all firms in the tourism sector are trying to reduce their costs. At the same time, they need to focus on attracting tourists, reduce dependence on tour operators and achieve an effective partnership with other firms to maintain the competitiveness of individual firms and the whole supply chain. The relationship between the upstream and downstream firms is a key factor in this regard (González-Torres et al. 2021 ). By effective partnership both firms will benefit in terms of cost and offer efficient cost-effective services and entertainment facilities to their potential tourist clients.

3.3 Inventory

As the frequency of disastrous events has accelerated over the past few years, technologies have been rapidly changing to handle these adverse situations with technology being a major force in creating flexibility in the tourism industry (Hall et al. 2020 ). During COVID-19, the necessity of technological advancement in every industrial sector has been evident. The supply chain management processes of almost all industries have faced huge disruption that had a lack of adequate technological support. During COVID-19 people have been mainly depending on technologies like automation, digitization and artificial intelligence which have been helping to reduce costs and enhance flexibility by maintaining social distance (Assaf and Scuderi 2020 ; Sharma et al. 2021 ). Looking forward to the post-COVID-19 era, technology will be the most essential element to run various tourism activities without any physical contact such as screening travelers, screening COVID-19 affected passengers, tracing and tracking contacts, etc. (Hall et al. 2020 ). With all this technology, there is also a positive side and that is that COVID-19 has created an opportunity for e-Tourism. Moving forward, Gretzel et al. ( 2020 ) have proposed six pillars for e-Tourism, namely historicity, reflexivity, transparency, equity, plurality, and creativity.

King ( 1995 ) claims that the hospitality and tourism industry is concerned with security, psychological and physical comfort. This could be achieved if, as discussed by Signh et al. ( 2021 ), tourists traveling locally can more easily follow the protocols of COVID-19 whilst visiting local tourist spots. Such protocols would include travelers carrying and wearing face masks, utilization of hand sanitizers whilst maintaining social distancing. Furthermore, the number of visitors needs to be limited at a tourist site to reduce the chance of infection. Adopting all these measures will help to maintain the leisure industry whilst maintaining safety and hygiene alongside providing comfort to tourists by ensuring an environment that is of less risk. Thus, the tourism industry needs to take time to consider the most appropriate health and safety protocols in a post-COVID-19 era (for example all tourist sites will need more medical support, adequate health insurance and sufficiently trained staff to provide proper safety).

3.4 Information

The level of risks while choosing local or international travel destinations will mostly depend on whether a potential tourist makes use of online information sources. International travelers largely depend on friends, family, tour guides and travel magazines for choosing travel destinations. Correct and clear information is thus very important to attract and retain potential tourists and to give them confidence in the sector. Sometimes negative information from social media can adversely impact travel decisions (Villac and Fuentes-moraleda 2021 ). If a place is suddenly deemed too risky to travel to, then tourists will ultimately cancel their travel plans to those sites (Neuburger and Egger 2021 ). Hence proper information is needed to regain the confidence of travelers to travel again and help the industry to bounce back fast in the post-Covid era. To regain the trust of travelers, information from government officials and health professionals is very important (Husnayain et al. 2020 ) with factual information being provided during outbreaks that helps tourists to assess the risks for themselves. Communication is the key here with any unnecessary information being minimized as this can induce public restlessness or panic (Husnayain et al. 2020 ).

3.5 Sourcing

Many hotels, resorts, and tourist destinations are largely dependent on tour operators for their promotion by word of mouth, visibility and services. Frequent conflict arises between tour operators and hotel management because of the detrimental focus of hotel management on maintaining a standard number of customers and average room rate. Nevertheless, tour operators’ efficiency depends on price reduction and profit margins paid to hotel management (Tapper and Font 2004 ). In fact, tour operators are often related to other tourism activities such as controlling carriers and retailers along with controlling various important activities in the tourism and hospitality industry, including contracts related to payments, guarantees and release conditions. Hence whilst the relationship between tour operators and hotel management plays a vital role in the tourism industry, the impact of disastrous events like terrorist attacks and most recently the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak, many tourism and hospitality companies are choosing to depend on their own websites to directly deal with potential tourists. As a consequence, this is reducing the dependence of tourism/hospitality companies on tour operators (González-Torres et al. 2021 ). That said, even with this happening, Calveras and Orfila-Sintes ( 2019 ) found that despite depending on information technologies to maintain the value chain efficiently, there has been no significant decrease in the presence of intermediaries of tour operators in the industry.

4 Research methodology

This research was intended to capture actual tourists’ perceptions in the light of developing a resilient supply chain within the tourism and hospitality service. In this context, the researchers conducted a detailed empirical study among prospective tourists to understand their individual opinion about how this vulnerable sector can gain new life again after the devastating effect of COVID-19. The experienced tourists were requested to provide their opinion in a structured questionnaire based on their past experience and future expectations.

4.1 Proposed factors to boost up tourism and hospitality service and develop resilient supply chain

Several factors that were revealed in the aforementioned literature review, which could help in turning the tide on the stagnant tourism and hospitality services, were considered and the key factors elicited. The following twenty factors were considered to boost up the tourism and hospitality service and develop a resilient supply chain within this sector (Shown in Table 1 ).

4.2 Empirical study and data collection

The twenty factors listed in Table 1 were sent to prospective tourists to rate the factors as per their opinions which were then utilized to assess how to use this information to assist the sector in overcoming the stagnant nature tourism and hospitality services are currently finding themselves in. These factors were adopted from previous studies and thus ensure the validity and reliability of the factors. The study participants were asked to put the factors in sequential order as per their importance, with the most important at the top and ending with the least important at the bottom. Participants were asked to assign a score of twenty to the most important factor, then nineteen for the second most important, and so on and so forth until reaching one for the least important factor. Participants were requested to consider the factor that they labeled twenty to be the most essential in helping to boost the stagnant tourism and hospitality services (after the devastating impact of the prolonged pandemic) and the factor they labelled as one to be the least critical in this regard. Respondents were asked to provide their opinions based on their present perceptions, past experiences, and future expectations. They were also requested to provide some demographic information listed in Table 2 .

4.3 Sample selection

As the basic aim of this study was to capture tourists’ perceptions about how to boost travel and leisure tours in the post-COVID-19 era, the selection of the survey sample had to ensure the variability and representation of the population. Thus, the survey-based empirical study was conducted among experienced and prospective tourists in Bangladesh. The survey was carried out from a random sample of the population living in eight of the big cities in Bangladesh. These cities are Dhaka, Sylhet, Chattogram, Khulna, Cumilla, Barishal, Noakhali, and Rajshahi. To ensure that the study targeted potential tourists, the researchers liaised with the three leading organizations in this sector namely, Association of Travel Agents of Bangladesh (ATAB), Tour Operators Association of Bangladesh (TOAB) and Bangladesh International Hotel Association (BIHA). Potential participants were then sourced from the client contact list of these three organizations (i.e. people who utilized their tourism services at least twice in the past three years). Once study participants were identified, a demographic analysis was performed to evaluate the sample characteristics (shown in Table 2 ). This enabled the study to ensure that prospective tourists that were part of this study had variations in their demographic factors (particularly in age and education) as a whole.

5 Findings and interpretation of the study data and supply chain drivers that make for a resilient supply chain within the sector

The following factors (shown in Table 3 ) were identified and listed as the strategic initiatives to establish a future resilient supply chain of tourism and hospitality service that will aid recovery from the severe negative impact of the current pandemic.

Stevens ( 1996 ) and Kline ( 2010 ) suggested for exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis that if any scale item has a loading value lower than 50 percent under the respective latent variable, it can be excluded on the assumption that its contribution in the respective latent variable is negligible. Following the same argument, this study has also set its cut-off value to be 50 percent and thus accepted only those factors as the reasons for boosting up tourism and hospitality service.

Based on the above listed factors for boosting up the tourism and hospitality service, a conceptual model has been conceived from this research (see Fig. 1 ) to illustrate the areas the industry needs to focus on for building a resilient post-pandemic tourism supply chain.

Proposed conceptual model illustrating the key areas that require focused attention when building a resilient tourism supply chain due to the impacts of Covid-19

5.1 Resilient supply chain and supply chain drivers

This section will now take each of the supply chain drivers in turn and extrapolate the key findings from this study under each.

5.1.1 Facility

Researchers working on resilient supply chains (Abdelsalam and Elbelehy 2020 ; Christopher and Peck 2004 ; Dubey et al. 2014 ; Ivanov et al. 2017 ; Shareef et al. 2020a , b ) have prioritized the development of supply chain drivers with the structured and organized facility. Shedding light on the conceptual definition of the resilient supply chain, it is strongly recommended that due to the devastating and prolonged impact of COVID-19 on tourism and hospitality sector, a resilient supply chain is a mandatory requirement to establish improvised drivers of the supply chain (Abdelsalam and Elbelehy 2020 ). The capacity and capability of the supply chain in the tourism and hospitality sector should be extended, enhanced and strengthened so that it can independently protect and resist the long-lasting and widespread effect of quarantine, social distancing and lockdown pandemic measures and expedite its motivational effort to recover from the negative phenomena and situations that have arisen as a result.

Shedding light on ontological paradigms of the resilient supply chain (Dubey et al. 2017 ; Dwivedi et al. 2018 ; Kamalahmadi and Parast 2016 ; Purvis et al. 2016 ; Scholten and Schilder 2015 ; Scholten et al. 2020 ; Sheffi 2001 ; Stevenson and Busby 2015 ; Tukamuhabwa et al. 2017 ; Shareef et al. 2019 ), this study has highlighted that a self-protective, adaptive and improvised supply chain of the tourism and hospitality sector can mitigate all negative aspects such as the disruptions witnessed globally by the sector. Unprecedented threats caused by the current pandemic through reforming an organizations capacity can ensure the development and establishment of a resilient supply chain, but it should be pointed out that this path may not be easy tactically, procedurally or when it comes to organizations structures. Thus, substantial improvement of supply chain drivers is the essential precondition in this context (Christopher and Peck 2004 ; Shareef et al. 2020a , b ).

Analyzing the present impact of COVID-19 and its enduring aggressiveness, researchers are striving and searching for effective alternatives (de Sá et al. 2020 ). In this regard, scholarly articles (Dubey et al. 2014 ; Sifolo et al. 2019 ; Shareef et al. 2019 ) have heuristically focused on capacity development by restructuring the six drivers of supply chain namely, facility, inventory, transportation, information, sourcing and pricing in the hope to ensure a resilient supply chain in future. To facilitate the drivers of supply chain with new scopes and opportunities aligning with the changed situation of tourism and hospitality service, distinct and phase-wise processes are recommended to reduce the disruptions in developing resilient supply chains (Dubey et al. 2014 ; Ivanov et al. 2017 ; Scholten et al. 2020 ; Shareef et al. 2020a , b ). Mittal and Sinha ( 2021 ) discuss how assurance of a resilient supply chain mitigating disruptions without potential shrinkage in performance is substantially dependent on the restructuring of the supply chain driver: facility.

When it comes to the tourism and hospitality service, this driver can be viewed as the physical location or site as well as accommodation with surrounding areas where tourists will visit and stay, i.e. their primary destination of the planned tour (Mittal and Sinha 2021 ; Ngoc Su et al. 2021 ; Sifolo et al. 2019 ). Respondents of this survey are keenly aware of this driver in energizing potential future tours and in overcoming all the negative consequences of the current pandemic. This study found that a well-designed facility equipped with new features to protect and withstand contamination threats, such as that of COVID-19, is an essential and almost mandatory desire of prospective tourists. Study participants expressed their immense eagerness to have a physical location or site as well as accommodation as a tourist place that has certain new features which can support the new equilibrium of the world in the post-pandemic era. Among several desires, they pointed out that in the future they would like to be able to once again select any venue or facility as their tour location which is a well-known place, both familiar and common. However, they felt that the location should not be too crowded as this would make it difficult to avoid physical interaction and contamination. Thus, having the ability to maintain physical safety is the prime criterion for prospective tourists to plan their future tours after this pandemic ends.

Therefore, withstanding and recovering from the current threats of the pandemic and establishing a resilient supply chain for the tourism and hospitality service is fundamentally rooted in the design of an innovative facility as the supply chain driver. This finding is well supported by many scholars (Hall et al. 2020 ; Lengnick-Hall et al. 2011 ; Nilakant et al. 2014 ; Shareef et al. 2021a ) working on the destructive impact of the current pandemic on tourism and hospitality service and the successive recovery procedures. Some researchers (Mittal and Sinha 2021 ; Ngoc Su et al. 2021 ) have suggested that to design a well-equipped facility that can provide satisfactory and adaptable features meeting the new expectations of tourists to fight against all the negative consequences of the pandemic based on their experience, is not only crucial but also could be a vulnerable issue and the most challenging task faced by tourism and hospitality companies. Selecting a new, uncommon, and challenging venue for the tour was a common and traditional behavior of tourists prior to the tribulations experienced from COVID-19 (Mittal and Sinha 2021 ; Ngoc Su et al. 2021 ; Shareef et al. 2021b ). Whilst present tourists would like to start vacation tours again there are certain new adjustments that now have to be taken into account along with, for instance, tourists wishing to travel to a neighborhood place that is familiar, reliable and trustworthy in location and free from mass gathering so that social distancing can be maintained (Mittal and Sinha 2021 ; Ngoc Su et al. 2021 ). This leads to the first proposition of this study:

Proposition 1

More structured and organized facility provides greater opportunity to create resilience within tourism supply chain management.

5.1.2 Pricing

Supply chain driver “ Pricing ” is one of the most important issues to design an effective and sustainable supply chain for tourism and hospitality service especially nowadays having faced a prolonged and continuous lockdown that has created stagnant business issues for this sector. This driver has potential contribution in designing, organizing and planning a resilient supply chain for tourism and hospitality services counter balancing scarcity of income and restraint on the scope of luxury. For the tourism and hospitality services supply chain, this driver can be deemed to be how much expenditure is required as the package cost for any tour so that the supply chain can properly adjust costs to take into account tourists' present financial distress due to COVID-19 (Sifolo et al. 2019 ).

It is fair to say that researches unanimously agree that one of the major thrusts and experiences of this current pandemic is that general tourists have suffered as a consequence of the severe financial uncertainty and hardship (Abdelsalam and Elbelehy 2020 ; Christopher and Peck 2004 ; Mittal and Sinha 2021 ; Ngoc Su et al. 2021 ; Sifolo et al. 2019 ). Among the many reasons for this financial suffering has been prominent incidents like losing one’s job, reduced opportunity to secure a new job, the decreased earning potential, financial uncertainty, reduced salary or income, stagnant business all of which have been contributing to the alarming growth of unemployment, etc. (Manhas and Nair 2020 ; de Sá et al. 2020 ). These insecurities have provoked general people to shrink their transaction money and accentuate precautionary money (Shareef et al. 2021b ). At the same time, extreme financial hardship and unusual, prolonged and unprecedented uncertainty has resulted in mental health difficulties for some along resulting in all sorts of distress such as nervousness and fidgetiness among people curtailing any kind of voluntary expenditure (Manhas and Nair 2020 ; de Sá et al. 2020 ).

The survey result from this study indicated that tourists believe that future vacation trips should be planned as a trade-off between necessity and capability. Participants felt that such trips should be considered and organized as recreation with several restrictions and limitations in place. After all, for physical change and mental relief of stress, vacation tours are essential for prospective tourists (Shareef et al. 2021b ); however, in this case, the potential consideration by study participants is the amount of expenditure required to conduct that trip. They look for cost-effective tours, accommodation, food and transportation along with entertainment with limited prices during vacation. Therefore, one of the primary drivers of the supply chain is pricing with measured consideration needed to be given to this driver when designing any package tour, hotel, and food and vacation expenditure. It is thus one of the key deciding factors in the recovery from the current stagnant situation the tourism and hospitality service finds itself in along with this driver being critical in establishing a resilient supply chain that can withstand all present day threats. This leads to the second proposition of this study:

Proposition 2

More cost-effective tour planning will lead to the creation of more resilience in tourism supply chain management.

5.1.3 Inventory

Inventory management as a supply chain driver is crucial for any traditional commodity-based service flow (Dwivedi et al. 2018 ). For a service type business like tourism and hospitality, its characteristics and significance are quite different; nevertheless, as a supplementary tool, inventory control and management of this service needs careful planning to reflect the current situation and demand due to the COVID-19 health crisis. This driver can be viewed as the service components, any supplementary facilities, and amenities provided to the tourists by the service providers (primarily by the owner of the facility) during the period of the tour (Mittal and Sinha 2021 ). To cope with the current unexpected situation and adapt to the unprecedented threats imposed by the spread of this infectious disease, tourists are conscious of multidimensional threats related to health, finance, stress, isolation, mental agony and unfortunately death (Shareef et al. 2021b ). Thus, they propose new facilities, alternative arrangements, and constructive support from service providers within the tourism and hospitality sector during this crisis.

Respondents of this survey were found to be cautious about at least two urgent and mandatory support service components which, in the past, were not in that much demand for past vacation tours. Irrespective of country of residence, this is a global pandemic and as such, people have experienced unprecedented suffering having to contend with multiple threats as a result of the devastating spread of this infectious disease. The impact of this pandemic was not even imagined before it hit, and consequently people somehow assumed and obtained the impression that some supplementary services would almost be mandatory for a healthy existence during any travels and leisure tours (Li et al. 2020 ; Ngoc Su et al. 2021 ). Health crisis and continuous threat of sickness forced the potential tourist to consider and evaluate the merit and quality of a tour based on definite availability of and accessibility to medical support by the service provider of tourism and hospitality, transportation, and accommodation during the vacation. This leads to the second proposition of this study:

Proposition 3

Effective inventory management planning will create more resilience in tourism supply chain management.

5.1.4 Transportation

Transportation and logistics management is a strong driver for a sustainable supply chain (Dwivedi et al. 2018 ; Shareef et al. 2019 ). Convenient transportation scope which is both easy and cost-cutting is the fundamental issue to fight and withstand this pandemic and to recover from the losses on many levels by promoting the tourism and hospitality business (Kock et al. 2020 ; Li et al. 2020 ; Wachyuni and Kusumaningrum 2020 ). This driver can be defined for tourism and hospitality service as the entire movement of tourists from the origin to the destination through different intermediary points (if any) (Dwivedi et al. 2018 ; Shareef et al. 2019 ). This pandemic has a crippled many business sectors; however, among the most severely affected sectors, the transportation business including airlines, buses, train services is the leading one (Brouder et al. 2020 ; Ćosić et al. 2020 ; Gössling et al. 2021 ; Karim et al. 2020 ). This sector has incurred severe losses, laid–off many employees, and almost collapsed. Now to turn around this sector that has been brought to its knees requires a recovery strategy, with the first and foremost initiative being to design a cost-effective tour plan for vacation lovers (Mittal and Sinha 2021 ; Ngoc Su et al. 2021 ; Sifolo et al. 2019 ).

This present survey acknowledged the same findings revealed by many scholarly studies, and that is, while the widespread effect and threat of the pandemic is gradually diminishing, tourists have started cognition and deliberation over different types of vacation and leisure tours; however, in this context, mode and cost of transportation are two vital issues for them. This pandemic has raised many issues of risk including sickness and other medical problems, mass contamination and gathering, financial hardship, social isolation, etc. (Brouder et al. 2020 ; Gössling et al. 2021 ), thus the tourist feels they need a cost-effective mode of transportation from their place of origin to the travel destination. With regards transportation, the potential tourists’ essential requirements include an easy mode of transportation, free from risk of contamination, and a trustworthy and reliable servicer. Considering the aforementioned requirements, it can be postulated that designing a resilient supply chain for tourism and hospitality services substantially depends on the desired features and characteristics of the supply chain driver, transportation. This leads on to the fourth proposition of this study:

Proposition 4

Convenient and cost-effective transportation will create more resilience in tourism supply chain management.

5.1.5 Information and sourcing

Sociologists and behavioral psychologists revealed that uncertainty in life and society may inflict nervousness and panic among people (Brouder et al. 2020 ; Gössling et al. 2021 ; Ćosić et al. 2020 ; Kock et al. 2020 ; Li et al. 2020 ; Matias et al. 2020 ; Wachyuni and Kusumaningrum 2020 ). Heuristically, this symptom creates a deep urge for transparency, accountability, and accessibility (Shareef et al. 2021b ). During a similar situation, for instance, this current pandemic, people start searching for explicit and detailed information about the problems, incidents, and recovery procedures (Mittal and Sinha 2021 ). Information is a strong driver for developing a resilient supply chain, and its urge is growing rapidly and urgently from the tourists. Shedding light on tourism and hospitality service, information as a driver of the supply chain can be explained as the accessibility and availability of detailed data about resources, protocols, procedures, reputation, and reliability for all other five drivers of the supply chain (Dwivedi et al. 2018 ; Shareef et al. 2021b ).

Psychologists affirm that uncertainty in life necessitates the presence of belongingness, empathy and mental support (Brouder et al. 2020 ; Ćosić et al. 2020 ; Gössling et al. 2021 ). Due to panic and mental agony, people during the pandemic have been striving to maintain connectivity with family members and friends (around the world and locally), and thus, technological support like wi-fi is an essential tool and requirement for the prospective tourist to evaluate the venue of the tour, travel and accommodation while planning for leisure tours. Pragmatically, any crisis moment instigates a search for clear information about the phenomenon multiple times (Matias et al. 2020 ). Therefore, during the present pandemic period when crisis, mental distress agony, social unrest and a heightened awareness of the severity of a wave of infection (which are increasingly common and currently regular trends), tourists aggressively look for detailed information about the entire tour while designing the tour plan to give them peace of mind (Brouder et al. 2020 ; Gössling et al. 2021 ; Ćosić et al. 2020 ).

Respondents of this study’s survey, who were considered as prospective tourists, have, like us all, suffered enormously due to this pandemic. The respondents as a consequence had strongly recommended the need for a clear and big picture of their entire tour before they embarked on the tours practically. Study participants felt that it should include information from each and every sector associated with their tours including rules and regulations. Due to uncertainty everywhere, tourists are nervous and panicky (Kock et al. 2020 ; Li et al. 2020 ; Matias et al. 2020 ; Wachyuni and Kusumaningrum 2020 ) with feelings of stress, tension and unrest. It is for these reasons that our respondents felt that they essentially needed to collect detailed information about the entire torus and its associated areas without any possible loopholes so that they could satisfy their inquisitive (and anxious) mind.

Under the aforementioned rationales, people also eagerly look for reliability, accountability, and authenticity of the collected information (Matias et al. 2020 ). As such, the social reputation and trustworthiness of the information provided is extremely important, particularly in the crisis moment, suggested by the sociologists (Shareef et al. 2021b ). For the first couple of months of the pandemic, social, national and individual life was very much unsettled, unpredictable, fuzzy and indistinguishable. Information about current situations, country status, the future trends of the corona is so unclear that people enthusiastically search for the reliability of the source (something they had time to do when in lockdown or under local restrictions). Consequently, the importance of the source of the information is gradually climbing up (Shareef et al. 2021b ). This driver can be restructured and defined for tourism and hospitality service as the person, company and country that is designated to serve and perform any activities of the entire tour package (Abdelsalam and Elbelehy 2020 ; Mittal and Sinha 2021 ). This is required so that image and reputation of the service provider of the supply chain can be undisputedly verified and evaluated. Respondents of this study also echoed such requirements from this driver of the supply chain.

There are lots of concerning issues now surfacing in tourists minds about the tour package which include, the infection rate of the place of the tour, accessibility of medical support at the location, availability of health facilities, provision of health insurance, hygiene protocol of the accommodator, cultural motive and behavior of the people at the tour location and surroundings along with reliability of and confidence in the country of destination. Potential tourists overall are looking for trustworthiness, reliability, reputation and transparency along with assessing the image of the people, society, and country related with the tour. Tourists, according to the findings of this survey, believe that a resilient supply chain of tourism and hospitality service is connected with the image of the stakeholders of the tours: this is the supply chain driver sourcing. Thus, leading on to the fifth proposition of this study:

Proposition 5

Information and sourcing is crucial for convenient and cost-effective transportation and will lead to the creation of more resilience in tourism supply chain management.

6 Theoretical and managerial implications

Developing and establishing a resilient supply chain for tourism and hospitality services as they endure or emerge from this pandemic, is something this study can provide deep insight into for both theorists and practitioners. People associated with this tourism and hospitality sector are striving to find some definite ways to resist the ongoing threats imposed by this widespread infectious disease, such as withstanding the resulting global economic downturn, design effective exit plans to recover their losses (if businesses have been fortunate not to have to close) and at the bare minimum survive the current economic climate incurred, and formulate strategic action to boost their future growth.

Academics are deeply aware and keenly interested in exploring this turbulent situation the business sector finds itself in, particularly for the tourism and hospitality services. They are keen to identify the plausible problems of disruptions in the supply chain of this service sector, and recommend some specific guidelines in light of the theoretical (and observed) aspects of tourists’ behavior and supply chain management (Abdelsalam and Elbelehy 2020 ; Christopher and Peck 2004 ; Mittal and Sinha 2021 ). Under these circumstances, developing a resilient supply chain for this vulnerable and cross-functional business is extremely important to turn around the sector's current woes through adaptation and learning that embrace positive change. Since the finding of this study is completely dependent on the perception, experience and recommendations of actual prospective tourists, it has potential merit for academics, sector managers and governments alike.

Counterbalancing all disruptions during disaster and uncertainty and developing a resilient supply chain is a potential issue for those analyzing and informing this sector. The ongoing uncertainty of this current pandemic (including the emergence of new variants) is a serious challenge for researchers of resilient supply chains trying to formulate and assess theoretical solutions to disruptions for any vulnerable sector (Dubey et al. 2014 ; Ivanov et al. 2017 ). To this end, evaluating and reflecting on consumers’ behavior can be effective when seeking remedial supply chain data (within the tourism and hospitality sector) that ultimately provides deep insight for the researcher. In that sense, this study has opened many doors for potential researchers in this area wishing to understand major stakeholders on the service receiver side. Using this study’s findings, researchers could apply prospective tourists’ perceptions and recommendations in the theoretical development of a resilient supply chain for the tourism and hospitality service sector.

Evidently, this study could help both researchers and practitioners obtain interesting characteristics and information about possible exit strategies that the tourism and hospitality service supply chain could use. For example, from the expectations of actual tourists, based on their perceptions of the industry, this study has clearly revealed that a resilient supply chain should meet the essential characteristics of both an efficient and responsive supply chain. For all the six drivers of the supply chain, respondents almost unanimously expressed their mandatory desire that they would choose to return to normal tourist behavior and initiate leisure tours if, in all sectors, all components of service (and in all phases) are designed in a cost-effective manner. That means cross-functional cost-cutting is a fundamental requirement. Pragmatically, this demand necessitates service providers of the tourism and hospitality sector to design an efficient supply chain. Study participants also expressed their immense desire (actually compulsory) that tour packages should be furnished with some additional features and unique quality assurance, for instance, the availability of free and seamless wi-fi, accessibility and availability of adequate and personalized medical support, innovative entertainment, space that is free from mass gatherings, transparency in information, proper maintenance of hygiene, etc. Consequently, the design of a responsive supply chain is a predetermined mandate of service providers when assessing their responses in this investigation. Therefore, the design of a resilient supply chain for the service sector essentially needs a well-balanced trade-off between an efficient and responsive supply chain. This really is a new and interesting proposal for researchers and practitioners to think about and deliberate over.

From the practitioner’s perspective, this study provides insight into this sector to assist their understanding and decision making. For tourism and hospitality service providers to be able to turn around with new hope from the relentless uncertainty they have had to endure, they have to consider reforming their service patterns. During and after the pandemic, tourists’ behavior and attitude, and expectations have changed drastically; hence the need to adjust to such changing phenomena for the future to be bright, with the critical need in establishing a resilient supply chain. Transparency, accountability, reliability, and reputation of the tour venues are of utmost importance in the new equilibrium of the post-pandemic era. Information regarding hygiene, medical support and health insurance is a prime consideration. Now tourists prefer more common, well known and neighborhood local places to take leisure trips instead of challenging and adventurous sites. However, moving forward for any kind of tour package, cost-effectiveness is a mandatory requirement for the tourists.

7 Conclusions

Understanding the true situation and performance of the tourism and hospitality business during this current pandemic, it is critical to take into account the perceptions, thoughts, and responses of prospective tourists due to extreme stress and negative impacts resulting from multiple areas. For instance, the financial, social, cultural, family bonding, health, sickness (and sadly death), job, and finally recreation, all depend on analyzing and synthesizing several areas of the tourism and hospitality service through these multiple lenses. The heuristics, impacts and probable future in the light of the capability of firms working in this sector needs to thus consider an array of issues a tourist faces under extreme personal stress and uncertainty that arises from these multiple areas. Keeping this in mind, the drivers of the supply chain should be focused to resolve the catastrophic situation by developing a resilient supply chain and for sustainability of tourism and hospitality business.

This study was designed to achieve two interconnected objectives. Initially, the research focused on exploring the recommendations as parameters (elicited from the study data) by which the tourism and hospitality service sector can use in the future to withstand the widespread attack of not only the current pandemic but future pandemics (including concerning mutations of the current pandemic as we have seen with the likes of Delta and now Omicron variants) and for the industry to utilize this intelligence strategically to turn around the sector and as a tourist ecosystem and into recovery mode. Finally, this study classified, categorized and related identified parameters with supply chain drivers to gain a holistic picture of a strategic plan to establish a resilient supply chain for this tourism and hospitality service sector through data collection using a detailed survey from the actual and prospective tourists in Bangladesh. Results indicated that reforming the six drivers of the supply chain and at the same time developing core competencies was deemed to be the central essence of a resilient supply chain of tourism and hospitality business which is at present trying to counter balance all the negative threats and their successive consequences of the pandemic.

It was found that whilst selecting any venue for vacation and tour, tourists’ mentality is shifting due to the physical, financial and mental risks of the pandemic. Tourists are no longer that adventurous about the tour site, accommodation and surrounding arrangements. While planning for a trip, tourists now consider a range of factors, not just the non-monetary value of a trip in terms of enjoyment and hedonic appeal; they now give more priority to the monetary expenditure required to conduct that trip (due to the personal financial stresses they are currently under). This identification explicitly indicates that pricing as a driver of the supply chain should be restructured with new features to establish a resilient supply chain that must be efficient. In the light of the findings on inventory management for a service sector, at present, tourists have become aware of and as such demand certain services and products which were not so important in the past. Knowing this, the inventory of the service providers in every phase of an entire tour, requires an urgent need for several supplementary commodities related to health risk, social isolation, and uncertainty to withstand and move against the strike of current or future bio-threats such as pandemics/epidemics. Among many new features, future tour packages should be furnished with seamless wi-fi, innovative technology and hygiene-related materials. Supply chain resilience is substantially dependent on the availability of this inventory management.

Designing a resilient supply chain is also deeply connected with reforming another significant driver of the supply chain, that of transportation. Findings clearly suggested that reforming this driver should focus on designing an efficient supply chain with a cost-effective multi-faceted transportation system. Experts on innovation and information and communication technology (ICT) acknowledge that usage of technology exponentially expedites access and collect information so that people can acquire a clear and comprehensive picture of the crisis. Information can be thought of as a constructive driver of the supply chain which has felt exponential power during this crisis moment. Lastly, the image of sourcing as a supply chain driver is now keenly verified by tourists for reliability and trustworthiness before planning any future leisure tour. Therefore, sourcing as a driver of the supply chain has received special attention and unexpected momentum nowadays by prospective tourists to consider the entire tour including the mode of transportation, final destination, supplementary amenities, accommodation, food and everything else related to the tour in question.

8 Limitations and future research direction