Fact Animal

Facts About Animals

Wandering Albatross Facts

Wandering albatross profile.

In 1961, Dion and the Del Satins had a song from the perspective of an albatross. It wasn’t accurate on many counts, but it did get one thing right: they get around.

The Diomedea exulans, more commonly known as the wandering albatross is perhaps the most accomplished wanderer of any animal, with routine voyages of hundreds of kilometres per day on record-breaking wings.

They are a large seabird with a circumpolar range in the Southern Ocean, and sometimes known as snowy albatross, white-winged albatross or goonie.

Wandering Albatross Facts Overview

The wandering albatross breeds on islands in the South Atlantic Ocean, such as South Georgia Island, Crozet Islands, Prince Edward Island and others.

They spend most of their life in flight , and land only to breed and feed.

These are phenomenal birds, capable of surviving some of the harshest weather conditions even at the most vulnerable stages of their development.

They are slow to reproduce, spending extra time to develop into one of the biggest and most specialised animals in the air.

Sadly, this is what makes them vulnerable to population declines, and longline fishing vessels are responsible for many adult deaths.

Interesting Wandering Albatross Facts

1. they can travel 120k km (75k) miles in a year.

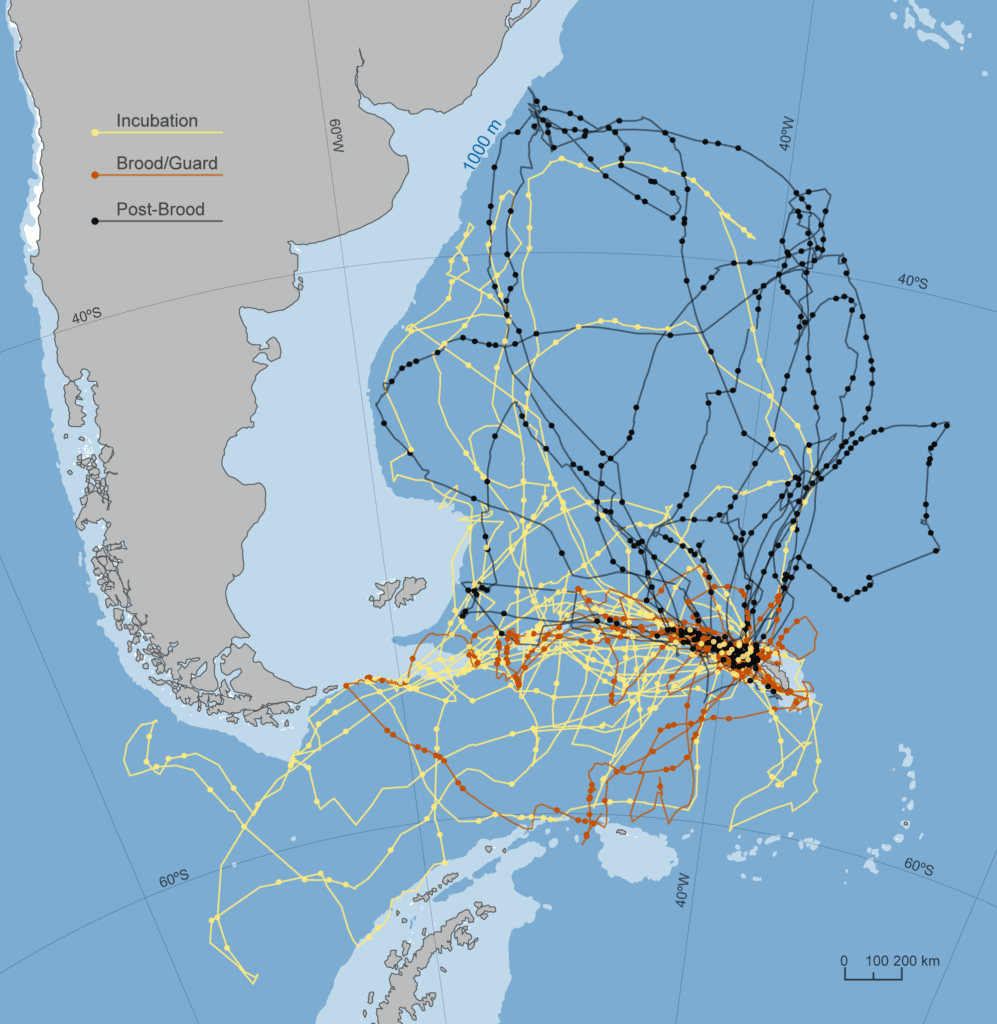

The Wandering albatross might be the most wide-ranging of all foraging sea birds, and maybe of all animals. They’ve been tracked over 15,000 km in a single foraging trip, capable of speeds of up to 80 kmph and distances of over 900 km per day. 1

2. They’re monogamous (mostly)

This goes against the entire theme of the Del Satins song and is probably why it’s no longer used as a learning aid in the zoological curriculum.

Contrary to the promiscuous subject of the ‘60s hit, the Wandering Albatrosses mate for life and are (on average) monogamous.

When breeding, they take on incubation shifts, and it’s during these periods when the wanderer goes out on their epic voyages to return with food for their family.

Still, there’s an element of personal preference when it comes to breeding.

Most females will take a year or two off after the long and arduous task of reproduction. During this time the parents will go their separate ways, only to reunite when the time is right.

In these periods, some females will take on a temporary mate, so they can squeeze out one more chick before reuniting with their permanent nesting partner. 2

3. Wandering albatross are active in moonlight

When on these journeys, the albatross is almost constantly active. During the day they spend the entire time in the air, and while they don’t cover much distance at night, they were still recorded almost constantly moving – never stopping for more than 1.6h in the dark.

They appear to travel more on moonlit nights than on darker ones.

All of this data comes from satellite trackers attached to some birds, which are always going to skew the results.

Flying birds are optimised for weight, and trackers add to this weight, so there’s necessarily a negative effect on the individual’s fitness when lumbering them with a tracker.

Still, these subjects were able to outlast the trackers’ batteries on many occasions, and it’s safe to assume they’re capable of even more than we can realistically measure!

4. They have the largest wingspan of any bird in the world

One advantage that an albatross has over, say, a pigeon, when it comes to carrying a researcher’s hardware, is that it doesn’t need to flap much.

The albatross is the bird with the longest wingspan of any flying animal – growing up to 3.2 m (10.5 ft), and these wings are meticulously adapted for soaring.

The Guiness Book of Records claims the largest wingspan of any living species of bird was a wandering albatross with a wingspan of 3.63m (11 ft 11) caught in 1965 by scientists on the Antarctic research ship USNS Eltanin in the Tasman Sea.

Research has suggested that these wings function best against slight headwinds, and act like the sails of a boat, allowing the bird to cover more ground by “tacking”, like a sailboat: zig-zagging across the angle of the wind to make forward progress into it. 3

5. Fat chicks

As mentioned, these voyages are usually a result of foraging trips for their chicks.

The environment for a growing albatross is one of the least conducive for life. Freezing winter storms and exposed ledges make for a hilly upbringing for the baby birds.

Fed on a healthy diet of regurgitated squid, these albatross chicks grow to enormous sizes. On nesting sites, it’s not uncommon to find a fluffy baby albatross weighing up to 10kg.

These chicks are heavier than their parents, and they need the extra mass to protect them from the Winter season while they grow into fledglings. They’re also such big birds that they take longer than a season to reach maturity.

It takes around ten months of feeding, back and forth from the ocean every few days, for the parents to grow a healthy adult offspring.

6. Being a parent takes practice

When inexperienced parents were compared with those who’d brought up chicks before, it was found that their chicks are a little slower to fatten up, at least in the first few months.

Parents would feed less regularly, but with much larger amounts, and it seems to take a while to get the routine down.

By the end of the breeding season, these differences disappeared and the parents became fully qualified.

7. 25% of chicks die when they leave the colony

The huge chicks have one of the longest rearing periods of any bird, and this is after an 11-month incubation period! And if they survive all this, they still have a long way to go.

There’s a period of 3 to 7 years during which the young chick will leave the colony alone and spend the entire time at sea.

During the first two months of this learning phase, 25% of chicks die. This is a critical time for the young birds, but if they survive, they’ll return to the colony and find a mate. 4

8. They’re good sniffers

These birds feed primarily on smelly things like squid, and they’ve developed a very keen sense of smell to find them from downwind.

Wandering Albatrosses have one of the largest olfactory bulbs of any bird and they’re honed to fishy aromas.

They combine this sense with strong vision to identify productive areas of the ocean for hunting and foraging. 5

9. They are part of a ‘species complex’

When multiple species are so similar in appearance and other features, it makes their boundaries unclear and this group is known as a species complex.

The wandering albatross was long considered the same species as the Tristan albatross and the Antipodean albatross. Along with the Amsterdam albatross, they form a species complex.

Taxonomy of animals in general is tricky, and some researchers still describe them as the same species.

10. The wandering albatross is vulnerable

The ICUN has classified the wandering albatross as vulnerable, and the last study of their population size in 2007 indicated there were an estimated 25,000 birds.

The biggest threat to their survival is fishing, in particular longline fishing. This is where a long mainline is used with baited hooks, and they are prone to accidental catching of birds, as well as dolphins, sharks, turtles and other sea creatures. Pollution, mainly from plastics and fishing hooks is also a problem for birds such as the wandering albatross.

Convervation efforts are underway to reduce bycatch of albatrosses and some breeding islands are now classified as nature reserves.

Wandering Albatross Fact-File Summary

Scientific classification, fact sources & references.

- Jouventin, P., Weimerskirch, H (1990), “ Satellite tracking of Wandering albatrosses “, Nature.

- GrrlScientist (2022), “ Divorce Is More Common In Albatross Couples With Shy Males, Study Finds “, Forbes.

- Richardson, P. L., Wakefield, E. D., & Phillips, R. A. (2018), “ Flight speed and performance of the wandering albatross with respect to wind “, Movement Ecology.

- Weimerskirch, H., Cherel, Y., Delord, K., Jaeger, A., Patrick, S. C., & Riotte-Lambert, L. (2014), “ Lifetime foraging patterns of the wandering albatross: Life on the move! “, Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology.

- Nevitt, G. A., Losekoot, M., & Weimerskirch, H. (2008), “ Evidence for olfactory search in wandering albatross, Diomedea exulans “, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

{{ searchResult.title }}

Wandering Albatross

Diomedea exulans

Known for its majestic wingspan and far-ranging travels, the Wandering Albatross is a captivating presence in the Southern Ocean's expanse. As the bird with the widest wingspan globally, this remarkable creature glides effortlessly across vast oceanic distances, its brilliant white plumage and solitary habits making it a unique symbol of the wild, open sea.

On this page

Appearance and Identification

Vocalization and sounds, behavior and social structure, distribution and habitat, lifespan and life cycle, conservation status, similar birds.

Males and females have similar plumage

Primary Color

Primary color (juvenile), secondary colors.

Black, Grey

Secondary Colors (female)

Secondary colors (juvenile).

White, Grey

Secondary Colors (seasonal)

Wing color (juvenile).

Large, Hooked

Beak Color (juvenile)

Leg color (juvenile), distinctive markings.

Black wings, white tail, large pink beak

Distinctive Markings (juvenile)

Darker than adults, brown beak

Tail Description

White with black edges

Tail Description (juvenile)

Brown with white edges

Size Metrics

107cm to 135cm

250cm to 350cm

6.72kg to 12kg

Click on an image below to see the full-size version

Pair of Wandering Albatrosses

Juvenile Wandering Albatross

Wandering Albatross resting on the sea

Wandering Albatross in-flight over the ocean

Wandering Albatross at nest with downy chick

Primary Calls

Series of grunts and whistles

Call Description

Most vocal on breeding grounds, otherwise silent

Alarm Calls

Loud, harsh squawks

Daily Activities

Active during day, rests on water surface at night

Social Habits

Solitary at sea, social on breeding grounds

Territorial Behavior

Defends nest site during breeding season

Migratory Patterns

Non-migratory but wanders widely at sea

Interaction with Other Species

Occasionally forms loose flocks at sea

Primary Diet

Fish, Squid

Feeding Habits

Surface seizes and scavenges

Feeding Times

Day and night

Prey Capture Method

Plunge-diving, surface-seizing

Diet Variations

May eat carrion

Special Dietary Needs (if any)

Nesting location.

On ground on isolated islands

Nest Construction

Mound of mud and vegetation

Breeding Season

Every other year

Number of clutches (per breeding season)

Once every two years

Egg Appearance

White, oval

Clutch Characteristics

Incubation period.

Around 80 days

Fledgling Period

Approximately 9 months

Parental Care

Both parents incubate and feed chick

Geographic Range

Circumpolar in Southern Ocean

Habitat Description

Open ocean, breeds on remote islands

Elevation Range

Migration patterns, climate zones.

Polar, Temperate

Distribution Map

Please note, this range and distribution map is a high-level overview, and doesn't break down into specific regions and areas of the countries.

Non-breeding

Lifespan range (years)

Average lifespan, maturity age.

7-10 year(s)

Breeding Age

Reproductive behavior.

Monogamous, long-term pair bonds

Age-Related Changes

Younger birds are darker, gain white plumage with age

Current Status

Vulnerable (IUCN Red List)

Major Threats

Longline fishing, plastic ingestion, climate change

Conservation Efforts

Protected under international law, conservation programs on breeding islands

Population Trend

Slow but steady population decrease due to threats

Royal Albatross

Diomedea epomophora

Classification

Other names:

Snowy Albatross, White-winged Albatross

Population size:

Population trend:

Conservation status:

IUCN Red List

Get the best of Birdfact

Brighten up your inbox with our exclusive newsletter , enjoyed by thousands of people from around the world.

Your information will be used in accordance with Birdfact's privacy policy . You may opt out at any time.

© 2024 - Birdfact. All rights reserved. No part of this site may be reproduced without our written permission.

Wandering Albatross

These remarkably efficient gliders, named after the Greek hero Diomedes, have the largest wingspan of any bird on the planet

Region: Antarctica

Destinations: Bouvet Island, Antarctic Peninsula, South Georgia

Name : Wandering Albatross, Snowy Albatross, White-winged Albatross ( Diomedea exulans )

Length: Up to 135 cm.

Weight : 6 to 12kg.

Location : All oceans except in the North Atlantic.

Conservation status : Vulnerable.

Diet : Cephalopods, small fish, crustaceans.

Appearance : White with grey-black wings, hooked bill.

How do Wandering Albatrosses feed?

Wandering Albatrosses make shallow dives when hunting. They’ll also attempt to eat almost anything they come across and will follow ships in the hopes of feeding on its garbage. They can gorge themselves so much that they become unable to fly and just have to float on the water.

How fast do Wandering Albatrosses fly?

Wandering Albatrosses can fly up to 40 km per hour.

What are Wandering Albatross mating rituals like?

Wandering Albatrosses mature sexually around 11 years of age. When courting, the male Wandering Albatross will spread his wings, wave his head around, and rap his bills against that of the female while making a braying noise. The pair will mate for life, breeding every 2 years. Mating season starts in early November with the Albatrosses creating nests of mud and grass on one of the Sub-Antarctic islands. The female will lay 1 egg about 10 cm long, sometime between the middle of December and early January. Incubation takes around 11 weeks, the parents taking turns. Once the chick is born the adults switch off between hunting and staying to care for the chick. The hunting parent returns to regurgitate stomach oil for the chick to feed on. Eventually both parents will start to hunt at the same time, visiting with the chick at widening intervals.

How long do Wandering Albatrosses live?

Wandering Albatrosses can live for over 50 years.

How many Wandering Albatrosses are there today?

There are about 25.200 adult Wandering Albatrosses in the world today.

Do Wandering Albatrosses have any natural predators?

Because they’re so big and spend almost all of their lives in flight, Wandering Albatrosses have almost no natural predators.

7 Wonderful Wandering Albatross Facts

- The Wandering Albatross is the largest member of its genus ( Diomedea ) and is one of the largest birds in the world.

- Wandering Albatrosses are also one of the best known and most studied species of birds.

- Diomedea refers to Diomedes, a hero in Greek mythology; of all the Acheaens he and Ajax were 2 nd only to Achilles in prowess. In mythology all of his companions turned into birds. Exulans is Latin for “exile” or “wanderer.”

- Wandering Albatrosses have the largest wingspan of any bird in the world today, stretching up to 3.5 metres across.

- Wandering Albatrosses are great gliders – they can soar through the sky without flapping their wings for several hours at a time. They’re so efficient at flying that they can actually use up less energy in the air than they would while sitting in a nest.

- Wandering Albatrosses have a special gland above their nasal passage that excretes a high saline solution. This helps keep salt level in their body, combating all the salt water they take in.

- Wandering Albatrosses get whiter the older they get.

Related cruises

Falkland Islands - South Georgia - Antarctica

Meet at least six penguin species!

PLA20-24 A cruise to the Falkland Islands, South Georgia & the Antarctic Peninsula. Visit some of the most beautiful arrays of wildlife on Earth. This journey will introduce you to at least 6 species of penguin and a whole lot of Antarctic fur seals!

m/v Plancius

Cruise date:

18 Oct - 7 Nov, 2024

Berths start from:

Antarctica - Basecamp - free camping, kayaking, snowshoe/hiking, photo workshop, mountaineering

The best activity voyage in Antarctica

HDS21a24 The Antarctic Peninsula Basecamp cruise offers you a myriad of ways to explore and enjoy the Antarctic Region. This expedition allows you to hike, snowshoe, kayak, go mountaineering, and even camp out under the Southern Polar skies.

m/v Hondius

1 Nov - 13 Nov, 2024

Weddell Sea – In search of the Emperor Penguin, incl. helicopters

Searching for the Elusive Emperor Penguins

OTL22-24 A true expedition, our Weddell Sea cruise sets out to explore the range of the Emperor Penguins near Snow Hill Island. We will visit the area via helicopter and see a variety of other birds and penguins including Adélies and Gentoos.

m/v Ortelius

10 Nov - 20 Nov, 2024

OTL23-24 A true expedition, our Weddell Sea cruise sets out to explore the range of the Emperor Penguins near Snow Hill Island. We will visit the area via helicopter and see a variety of other birds and penguins including Adélies and Gentoos.

20 Nov - 30 Nov, 2024

Antarctica - Basecamp - free camping, kayaking, snowshoe/hiking, mountaineering, photo workshop

HDS23-24 The Antarctic Peninsula Basecamp cruise offers you a myriad of ways to explore and enjoy the Antarctic Region. This expedition allows you to hike, snowshoe, kayak, go mountaineering, and even camp out under the Southern Polar skies.

23 Nov - 5 Dec, 2024

We have a total of 62 cruises

Animal encyclopedia

Exploring the magnificent wandering albatross.

September 4, 2023

John Brooks

September 4, 2023 / Reading time: 6 minutes

Sophie Hodgson

We adhere to editorial integrity are independent and thus not for sale. The article may contain references to products of our partners. Here's an explanation of how we make money .

Why you can trust us

Wild Explained was founded in 2021 and has a long track record of helping people make smart decisions. We have built this reputation for many years by helping our readers with everyday questions and decisions. We have helped thousands of readers find answers.

Wild Explained follows an established editorial policy . Therefore, you can assume that your interests are our top priority. Our editorial team is composed of qualified professional editors and our articles are edited by subject matter experts who verify that our publications, are objective, independent and trustworthy.

Our content deals with topics that are particularly relevant to you as a recipient - we are always on the lookout for the best comparisons, tips and advice for you.

Editorial integrity

Wild Explained operates according to an established editorial policy . Therefore, you can be sure that your interests are our top priority. The authors of Wild Explained research independent content to help you with everyday problems and make purchasing decisions easier.

Our principles

Your trust is important to us. That is why we work independently. We want to provide our readers with objective information that keeps them fully informed. Therefore, we have set editorial standards based on our experience to ensure our desired quality. Editorial content is vetted by our journalists and editors to ensure our independence. We draw a clear line between our advertisers and editorial staff. Therefore, our specialist editorial team does not receive any direct remuneration from advertisers on our pages.

Editorial independence

You as a reader are the focus of our editorial work. The best advice for you - that is our greatest goal. We want to help you solve everyday problems and make the right decisions. To ensure that our editorial standards are not influenced by advertisers, we have established clear rules. Our authors do not receive any direct remuneration from the advertisers on our pages. You can therefore rely on the independence of our editorial team.

How we earn money

How can we earn money and stay independent, you ask? We'll show you. Our editors and experts have years of experience in researching and writing reader-oriented content. Our primary goal is to provide you, our reader, with added value and to assist you with your everyday questions and purchasing decisions. You are wondering how we make money and stay independent. We have the answers. Our experts, journalists and editors have been helping our readers with everyday questions and decisions for over many years. We constantly strive to provide our readers and consumers with the expert advice and tools they need to succeed throughout their life journey.

Wild Explained follows a strict editorial policy , so you can trust that our content is honest and independent. Our editors, journalists and reporters create independent and accurate content to help you make the right decisions. The content created by our editorial team is therefore objective, factual and not influenced by our advertisers.

We make it transparent how we can offer you high-quality content, competitive prices and useful tools by explaining how each comparison came about. This gives you the best possible assessment of the criteria used to compile the comparisons and what to look out for when reading them. Our comparisons are created independently of paid advertising.

Wild Explained is an independent, advertising-financed publisher and comparison service. We compare different products with each other based on various independent criteria.

If you click on one of these products and then buy something, for example, we may receive a commission from the respective provider. However, this does not make the product more expensive for you. We also do not receive any personal data from you, as we do not track you at all via cookies. The commission allows us to continue to offer our platform free of charge without having to compromise our independence.

Whether we get money or not has no influence on the order of the products in our comparisons, because we want to offer you the best possible content. Independent and always up to date. Although we strive to provide a wide range of offers, sometimes our products do not contain all information about all products or services available on the market. However, we do our best to improve our content for you every day.

Table of Contents

The Wandering Albatross is a truly remarkable bird that captivates the imagination of wildlife enthusiasts and researchers alike. With its impressive wingspan and majestic flight, this magnificent creature has a unique story to tell. In this article, we will delve into the world of the Wandering Albatross, exploring its characteristics, habitat, life cycle, diet, threats, conservation efforts, and even its role in culture and literature.

Understanding the Wandering Albatross

The Wandering Albatross, a majestic seabird, is a fascinating creature that captures the imagination with its impressive size and unique characteristics . Let’s delve deeper into the defining features and habitat of this remarkable bird.

Defining Characteristics of the Wandering Albatross

With a wingspan of up to 11 feet, the Wandering Albatross boasts the largest wingspan of any bird in the world. This remarkable wingspan allows it to glide effortlessly over the vast open oceans it calls home. As it soars through the air, its wingspan creates a mesmerizing spectacle, showcasing the bird’s incredible adaptability to its environment.

The Wandering Albatross is easily recognizable by its distinctive white feathers , sleek body, and long, slender wings . These defining features not only contribute to its graceful appearance but also serve a purpose in its survival. The white feathers help camouflage the bird against the bright sunlight reflecting off the ocean’s surface, while the sleek body and long wings enable it to navigate the winds with precision.

The Albatross’s Unique Habitat

These graceful birds are found primarily in the southern oceans, particularly around the Antarctic region. The vast expanse of the Southern Ocean provides an ideal environment for the Wandering Albatross to thrive. With its ability to cover immense distances, the bird utilizes the strong winds to its advantage, effortlessly gliding across the ocean in search of food and suitable breeding grounds.

During their long journeys, Wandering Albatrosses traverse various oceanic regions, from the sub-Antarctic to as far as the coast of South America. Their nomadic lifestyle allows them to explore different ecosystems , adapting to the ever-changing conditions of the open ocean.

When on land, the Wandering Albatross prefers remote and isolated islands for nesting. These islands provide the perfect breeding environment, away from human disturbance and terrestrial predators. Here, amidst the rugged cliffs and pristine beaches, the albatrosses establish their colonies, creating a spectacle of life in the midst of the vast ocean.

These incredible birds are known to return to the same nesting sites year after year, demonstrating their strong site fidelity . The remote islands become their sanctuary, where they engage in courtship rituals, build nests, and raise their young. It is a testament to their resilience and adaptability that they have managed to maintain these nesting sites for generations, despite the challenges they face in the ever-changing world.

As we continue to explore and understand the Wandering Albatross, we uncover more about its remarkable adaptations, behaviors, and interactions with its environment. The more we learn, the more we appreciate the intricate web of life that exists in the vast oceans, where these magnificent birds reign supreme.

The Life Cycle of the Wandering Albatross

Breeding and nesting patterns.

The breeding season for the Wandering Albatross begins in the austral summer months, with courtship rituals that involve intricate displays of dance and vocalizations . These courtship displays are not only a way for the albatrosses to attract a mate but also a means of establishing dominance within their colony. The males showcase their impressive wingspan and perform elaborate dances, while the females respond with their own graceful movements.

Once a pair bonds, they establish a nest on the chosen island and begin the process of reproduction. The nests are carefully constructed using a combination of soil, grass, and other materials found on the island. The albatrosses take great care in selecting the perfect location for their nest, ensuring it is protected from the harsh elements and predators.

The female typically lays a single egg, which both parents take turns incubating. Incubation lasts for approximately 60 days, during which the parents rotate shifts to keep the egg warm and protected. This shared responsibility is a testament to the strong bonds formed between Wandering Albatross pairs. The parents take turns leaving the nest to search for food, returning to regurgitate the nutrient-rich meal for their growing chick.

During the incubation period, the albatrosses face numerous challenges. They must withstand strong winds, freezing temperatures, and potential threats from predators . Despite these difficulties, the dedicated parents remain vigilant, ensuring the survival of their offspring.

Growth and Development Stages

After hatching, the chicks are cared for and fed by both parents. The parents regurgitate a nutrient-rich oil that provides essential nourishment for the growing chick. This feeding process continues for several months until the chick becomes independent enough to forage on its own. The oil not only provides the necessary nutrients but also helps to strengthen the chick’s immune system, protecting it from potential diseases.

As the chick grows, it undergoes various developmental stages. Its downy feathers gradually give way to juvenile plumage, which is darker in coloration. The chick’s beak also undergoes changes, becoming stronger and more adapted to catching prey. During this time, the parents continue to provide guidance and protection, teaching the chick essential survival skills.

It takes years for a Wandering Albatross chick to reach maturity. During this time, they undergo a remarkable transformation, gradually developing their characteristic white plumage and mastering their flight skills. The albatrosses spend a significant portion of their juvenile years at sea, honing their flying abilities and exploring vast oceanic territories. It is during this period that they face various challenges, including encounters with other seabirds and potential threats from human activities.

It is this lengthy growth period that contributes to the vulnerability of this species and its slow population recovery. The Wandering Albatross faces numerous threats, including habitat loss, climate change, and accidental capture in fishing gear. Conservation efforts are crucial to ensure the survival of these magnificent birds and their unique life cycle.

The Wandering Albatross’s Diet and Hunting Techniques

Preferred prey and hunting grounds.

The Wandering Albatross is primarily a scavenger, feeding on a variety of marine organisms, including squid, fish, and crustaceans. They use their keen eyesight to spot potential prey items floating on the ocean surface, and once sighted, they plunge-dived from great heights to capture their meal. Additionally, these birds are known to scavenge carrion and exploit fishing vessels for an easy meal.

Adaptations for Hunting in the Open Ocean

Surviving in the harsh oceanic environment requires specialized adaptations, and the Wandering Albatross is well-equipped for the task. Its long wings enable it to glide effortlessly for long periods, conserving energy during hours of flight. The bird’s keen sense of smell allows it to locate food sources, even from great distances. These adaptations make the Wandering Albatross a formidable hunter and a vital component of the oceanic ecosystem.

Threats and Conservation Efforts

Human impact on the wandering albatross.

Despite their grace and beauty, Wandering Albatrosses face numerous threats that have contributed to their decline. One of the main challenges is the destructive impact of longline fishing operations, where the birds mistakenly become hooked or tangled in the fishing gear. Additionally, pollution, habitat degradation, and climate change further jeopardize the survival of these birds.

Current Conservation Strategies and Their Effectiveness

To safeguard the future of the Wandering Albatross, concerted conservation efforts are underway. Several measures have been implemented, including the establishment of protected areas and marine reserves, the development of guidelines for responsible fishing practices, and public awareness campaigns to promote the importance of nurturing this iconic species. While progress has been made, continued efforts are required to ensure the recovery and long-term survival of the Wandering Albatross.

The Role of the Wandering Albatross in Culture and Literature

Symbolism and significance in various cultures.

Throughout history, the Wandering Albatross has held deep cultural significance in many communities. In some cultures, these birds are considered symbols of loyalty, freedom, and endurance. They are often associated with seafaring traditions and are believed to bring good fortune to sailors.

The Albatross in Classic and Contemporary Literature

The haunting imagery of the Wandering Albatross has inspired numerous works of literature. Perhaps the most famous reference is found in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s poem, “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” where an albatross is depicted as a harbinger of both good and ill fortune. Furthermore, many modern authors have woven the essence of the Wandering Albatross into their stories, capturing its mystique and its role as a symbol of the natural world.

In conclusion, the Wandering Albatross is a remarkable bird with a captivating presence. From its unique characteristics to its adaptations for survival in the open ocean , this magnificent creature enthralls all who encounter it. However, its existence is threatened by human activities and environmental changes. Through ongoing conservation efforts and a deeper appreciation of its cultural significance, we can work towards ensuring a future where the Wandering Albatross continues to grace the skies above the vast southern oceans.

Related articles

- Fresh Food for Cats – The 15 best products compared

- The Adorable Zuchon: A Guide to This Cute Hybrid Dog

- Exploring the Unique Characteristics of the Zorse

- Meet the Zonkey: A Unique Hybrid Animal

- Uncovering the Secrets of the Zokor: A Comprehensive Overview

- Understanding the Zebu: An Overview of the Ancient Cattle Breed

- Uncovering the Fascinating World of Zebrafish

- Watch Out! The Zebra Spitting Cobra is Here

- The Fascinating Zebra Tarantula: A Guide to Care and Maintenance

- The Yellow-Bellied Sapsucker: A Closer Look

- Uncovering the Mystery of the Zebra Snake

- The Amazing Zebra Pleco: All You Need to Know

- Discovering the Fascinating Zebra Shark

- Understanding the Impact of Zebra Mussels on Freshwater Ecosystems

- Caring for Your Zebra Finch: A Comprehensive Guide

- The Fascinating World of Zebras

- The Adorable Yorkshire Terrier: A Guide to Owning This Lovable Breed

- The Adorable Yorkie Poo: A Guide to This Popular Dog Breed

- The Adorable Yorkie Bichon: A Perfect Pet for Any Home

- The Adorable Yoranian: A Guide to This Sweet Breed

- Discover the Deliciousness of Yokohama Chicken

- Uncovering the Mystery of the Yeti Crab

- Catching Yellowtail Snapper: A Guide to the Best Fishing Spots

- The Brightly Colored Yellowthroat: A Guide to Identification

- Identifying and Dealing with Yellowjacket Yellow Jackets

- The Yellowish Cuckoo Bumblebee: A Formerly Endangered Species

- The Yellowhammer: A Symbol of Alabama’s Pride

- The Benefits of Eating Yellowfin Tuna

- The Yellow-Faced Bee: An Overview

- The Majestic Yellow-Eyed Penguin

- The Yellow-Bellied Sea Snake: A Fascinating Creature

- The Benefits of Keeping a Yellow Tang in Your Saltwater Aquarium

- The Beautiful Black and Yellow Tanager: A Closer Look at the Yellow Tanager

- The Fascinating Yellow Spotted Lizard

- What You Need to Know About the Yellow Sac Spider

- Catching Yellow Perch: Tips for a Successful Fishing Trip

- The Growing Problem of Yellow Crazy Ants

- The Rare and Beautiful Yellow Cobra

- The Yellow Bullhead Catfish: An Overview

- Caring for a Yellow Belly Ball Python

- The Impact of Yellow Aphids on Agriculture

- Catching Yellow Bass: Tips and Techniques for Success

- The Striking Beauty of the Yellow Anaconda

- Understanding the Yarara: A Guide to This Unique Reptile

- The Yakutian Laika: An Overview of the Ancient Arctic Dog Breed

- The Fascinating World of Yaks: An Introduction

- Everything You Need to Know About Yabbies

- The Xoloitzcuintli: A Unique Breed of Dog

- Uncovering the Mystery of Xiongguanlong: A Newly Discovered Dinosaur Species

- Uncovering the Mysteries of the Xiphactinus Fish

- Camp Kitchen

- Camping Bags

- Camping Coolers

- Camping Tents

- Chair Rockers

- Emergency Sets

- Flashlights & Lanterns

- Grills & Picnic

- Insect Control

- Outdoor Electrical

- Sleeping Bags & Air Beds

- Wagons & Carts

- Beds and furniture

- Bowls and feeders

- Cleaning and repellents

- Collars, harnesses and leashes

- Crates, gates and containment

- Dental care and wellness

- Flea and tick

- Food and treats

- Grooming supplies

- Health and wellness

- Litter and waste disposal

- Toys for cats

- Vitamins and supplements

- Dog apparel

- Dog beds and pads

- Dog collars and leashes

- Dog harnesses

- Dog life jackets

- Dog travel gear

- Small dog gear

- Winter dog gear

© Copyright 2024 | Imprint | Privacy Policy | About us | How we work | Editors | Advertising opportunities

Certain content displayed on this website originates from Amazon. This content is provided "as is" and may be changed or removed at any time. The publisher receives affiliate commissions from Amazon on eligible purchases.

Animal Diversity Web

- About Animal Names

- Educational Resources

- Special Collections

- Browse Animalia

More Information

Additional information.

- Encyclopedia of Life

Diomedea exulans wandering albatross

Geographic Range

Wandering albatrosses are found almost exclusively in the Southern Hemisphere, although occasional sightings just north of the Equator have been reported. ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 )

There is some disagreement over how many subspecies of wandering albatross ( Diomedea exulans ) there are, and whether they should be considered separate species. Most subspecies of Diomedea exulans are difficult to tell apart, especially as juveniles, but DNA analyses have shown that significant differences exist. ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 )

Diomedea exulans exulans breeds on South Georgia, Prince Edward, Marion, Crozet, Kerguelen, and Macquarie islands. Diomedea exulans dabbenena occurs on Gough and Inaccessible islands, ranging over the Atlantic Ocean to western coastal Africa. Diomedea exulans antipodensis is found primarily on the Antipodes of New Zealand, and ranges at sea from Chile to eastern Australia. Diomedea exulans amsterdamensis is found only on Amsterdam Island and the surrounding seas. Other subspecies names that have become obsolete include Diomedea exulans gibsoni , now commonly considered part of D. e. antipodensis , and Diomedea exulans chionoptera , considered part of D. e. exulans . ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 )

- Biogeographic Regions

Wandering albatrosses breed on several subantarctic islands, which are characterized by peat soils, tussock grass, sedges, mosses, and shrubs. Wandering albatrosses nest in sheltered areas on plateaus, ridges, plains, or valleys.

Outside of the breeding season, wandering albatrosses are found only in the open ocean, where food is abundant. ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 )

- Habitat Regions

- terrestrial

- saltwater or marine

- Terrestrial Biomes

- savanna or grassland

- Aquatic Biomes

Physical Description

All subspecies of wandering albatrosses have extremely long wingspans (averaging just over 3 meters), white underwing coverts, and pink bills. Adult body plumage ranges from pure white to dark brown, and the wings range from being entirely blackish to a combination of black with white coverts and scapulars. They are distinguished from the closely related royal albatross by their white eyelids, pink bill color, lack of black on the maxilla, and head and body shape. On average, males have longer bills, tarsi, tails, and wings than females. ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

Juveniles of all subspecies are very much alike; they have chocolate-brown plumage with a white face and black wings. As individuals age, most become progressively whiter with each molt, starting with the back. ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

D. e. exulans averages larger than other recognized subspecies, and is the only taxon that achieves fully white body plumage, and this only in males. Although females do not become pure white, they can still be distinguished from other subspecies by color alone. Adults also have mostly white coverts, with black only on the primaries and secondaries. ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

Adults of D. e. amsterdamensis have dark brown plumage with white faces and black crowns, and are distinguished from juveniles by their white bellies and throats. In addition to their black tails, they also have a black stripe along the cutting edge of the maxilla, a character otherwise found in D. epomophora but not other forms of D. exulans . Males and females are similar in plumage. ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

Adults of D. e. antipodensis display sexual dimorphism in plumage, with older males appearing white with some brown splotching, while adult females have mostly brown underparts and a white face. Both sexes also have a brown breast band. ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

With age, D. e. dabbenena gradually attains white plumage, although it never becomes as white as male D. e. exulans . The wing coverts also appear mostly black, although there may be white patches. Females have more brown splotches than males, and have less white in their wing coverts. ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

- Other Physical Features

- endothermic

- homoiothermic

- bilateral symmetry

- Sexual Dimorphism

- sexes alike

- male larger

- sexes colored or patterned differently

- Average mass 8130 g 286.52 oz AnAge

- Range length 1.1 to 1.35 m 3.61 to 4.43 ft

- Range wingspan 2.5 to 3.5 m 8.20 to 11.48 ft

- Average wingspan 3.1 m 10.17 ft

- Average basal metabolic rate 20.3649 W AnAge

Reproduction

Wandering albatrosses have a biennial breeding cycle, and pairs with chicks from the previous season co-exist in colonies with mating and incubating pairs. Pairs unsuccessful in one year may try to mate again in the same year or the next one, but their chances of successfully rearing young are low. ( Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

After foraging at sea, males arrive first at the same breeding site every year within days of each other. They locate and reuse old nests or sometimes create new ones. Females arrive later, over the course of a few weeks. Wandering albatrosses have a monogamous mating strategy, forming pair bonds for life. Females may bond temporarily with other males if their partner and nest are not readily visible. ( Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

- Mating System

Copulation occurs in the austral summer, usually around December (February for D. e. amsterdamensis ). Rape and extra-pair copulations are frequent, despite their monogamous mating strategy. Pairs nest on slopes or valleys, usually in the cover of grasses or shrubs. Nests are depressions lined with grass, twigs, and soil. A single egg is laid and, if incubation or rearing fails, pairs usually wait until the following year to try again. Both parents incubate eggs, which takes about 78 days on average. Although females take the first shift, males are eager to take over incubation and may forcefully push females off the egg. Untended eggs are in danger of predation by skuas ( Stercorarius ) and sheathbills ( Chionis ). ( Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

After the chick hatches, they are brooded for about 4 to 6 weeks until they can be left alone at the nest. Males and females alternate foraging at sea. Following the brooding period, both parents leave the chick by itself while they forage. The chicks are entirely dependent on their parents for food for 9 to 10 months, and may wait weeks for them to return. Chicks are entirely independent once they fledge. ( Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

Some individuals may reach sexual maturity by age 6. Immature, non-breeding individuals will return to the breeding site. Group displays are common among non-breeding adults, but most breeding adults do not participate. ( Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

- Key Reproductive Features

- iteroparous

- seasonal breeding

- gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate)

- Breeding interval Breeding occurs biennially, possibly annually if the previous season's attempt fails.

- Breeding season Breeding occurs from December through March.

- Average eggs per season 1

- Range time to hatching 74 to 85 days

- Range fledging age 7 to 10 months

- Range time to independence 7 to 10 months

- Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female) 6 to 22 years

- Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female) 10 years

- Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male) 6 to 22 years

- Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male) 10 years

Males choose the nesting territory, and stay at the nest site more than females before incubation. Parents alternate during incubation, and later during brooding and feeding once the chick is old enough to be left alone at the nest. Although there is generally equal parental investment, males will tend to invest more as the chick nears fledging. Occasionally, a single parent may successfully rear its chick. ( Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

- Parental Investment

- provisioning

Lifespan/Longevity

Wandering albatrosses are long-lived. An individual nicknamed "Grandma" was recorded to live over 60 years in New Zealand. Due to the late onset of maturity, with the average age at first breeding about 10 years, such longevity is not unexpected. However, there is fairly high chick mortality, ranging from 30 to 75%. Their slow breeding cycle and late onset of maturity make wandering albatrosses highly susceptible to population declines when adults are caught as bycatch in fishing nets. ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

- Range lifespan Status: wild 60 (high) years

- Average lifespan Status: wild 415 months Bird Banding Laboratory

While foraging at sea, wandering albatrosses travel in small groups. Large feeding frenzies may occur around fishing boats. Individuals may travel thousands of kilometers away from their breeding grounds, even occasionally crossing the equator.

During the breeding season, Wandering albatrosses are gregarious and displays are common (see “Communication and Perception” section, below). Vocalizations and displays occur during mating or territorial defense. ( Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

- Key Behaviors

- territorial

- Average territory size 1 m^2

Wandering albatrosses defend small nesting territories, otherwise the range within which they travel is many thousands of square kilometers. ( Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

Communication and Perception

Displays and vocalizations are common when defending territory or mating. They include croaks, bill-clapping, bill-touching, skypointing, trumpeting, head-shaking, the "ecstatic" gesture, and "the gawky-look". Individuals may also vocalize when fighting over food. ( Shirihai, 2002 )

- Communication Channels

- Perception Channels

Food Habits

Wandering albatrosses primarily eat fish, such as toothfish ( Dissostichus ), squids, other cephalopods, and occasional crustaceans. The primary method of foraging is by surface-seizing, but they have the ability to plunge and dive up to 1 meter. They will sometimes follow fishing boats and feed on catches with other Procellariiformes , which they usually outcompete because of their size. ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 )

- Primary Diet

- molluscivore

- Animal Foods

- aquatic crustaceans

Although humans formerly hunted wandering albatrosses as food, adults currently have no predators. Their large size, sharp bill, and occasionally aggressive behavior make them undesirable opponents. However, some are inadvertently caught during large-scale fishing operations.

Chicks and eggs, on the other hand, are susceptible to predation from skuas and sheathbills, and formerly were harvested by humans as well. Eggs that fall out of nests or are unattended are quickly preyed upon. Nests are frequently sheltered with plant material to make them less conspicuous. Small chicks that are still in the brooding stage are easy targets for large carnivorous seabirds. Introduced predators, including mice, pigs, cats, rats, and goats are also known to eat eggs and chicks. ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; IUCN, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

- skuas ( Stercorariidae )

- sheathbills ( Chionis )

- domestic cats ( Felis silvestris )

- introduced pigs ( Sus scrofa )

- introduced goats ( Capra hircus )

- introduced rats ( Rattus rattus and Rattus norvegicus )

- introduced mice ( Mus musculus )

Ecosystem Roles

Wandering albatrosses are predators, feeding on fish, cephalopods, and crustaceans. They are known for their ability to compete with other seabirds for food, particularly near fishing boats. Although adult birds, their eggs, and their chicks were formerly a source of food to humans, such practices have been stopped. ( IUCN, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 )

Economic Importance for Humans: Positive

Wandering albatrosses have extraordinary morphology, with perhaps the longest wingspan of any bird. Their enormous size also makes them popular in ecotourism excursions, especially for birders. Declining population numbers also mean increased conservation efforts. Their relative tameness towards humans makes them ideal for research and study. ( Shirihai, 2002 )

- Positive Impacts

- research and education

Economic Importance for Humans: Negative

Wandering albatrosses, along with other seabirds, follow fishing boats to take advantage of helpless fish and are reputed to reduce economic output from these fisheries. Albatrosses also become incidental bycatch, hampering conservation efforts. ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; IUCN, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 )

Conservation Status

Diomedea exulans exulans and Diomedea exulans antipodensis are listed by the IUCN Red list and Birdlife International as being vulnerable; Diomedea exulans dabbenena is listed as endangered, and Diomedea exulans amsterdamensis is listed as critically endangered.

All subspecies of Diomedea exulans are highly vulnerable to becoming bycatch of commercial fisheries, and population declines are mostly attributed to this. Introduced predators such as feral cats , pigs , goats , and rats on various islands leads to high mortality rates of chicks and eggs. Diomedea exulans amsterdamensis is listed as critically endangered due to introduced predators, risk of becoming bycatch, small population size, threat of chick mortality by disease, and loss of habitat to cattle farming.

Some conservation measures that have been taken include removal of introduced predators from islands, listing breeding habitats as World Heritage Sites, fishery relocation, and population monitoring. ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; IUCN, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 )

- IUCN Red List Vulnerable More information

- US Migratory Bird Act No special status

- US Federal List No special status

- CITES No special status

Contributors

Tanya Dewey (editor), Animal Diversity Web.

Lauren Scopel (author), Michigan State University, Pamela Rasmussen (editor, instructor), Michigan State University.

the body of water between Africa, Europe, the southern ocean (above 60 degrees south latitude), and the western hemisphere. It is the second largest ocean in the world after the Pacific Ocean.

body of water between the southern ocean (above 60 degrees south latitude), Australia, Asia, and the western hemisphere. This is the world's largest ocean, covering about 28% of the world's surface.

uses sound to communicate

young are born in a relatively underdeveloped state; they are unable to feed or care for themselves or locomote independently for a period of time after birth/hatching. In birds, naked and helpless after hatching.

having body symmetry such that the animal can be divided in one plane into two mirror-image halves. Animals with bilateral symmetry have dorsal and ventral sides, as well as anterior and posterior ends. Synapomorphy of the Bilateria.

an animal that mainly eats meat

uses smells or other chemicals to communicate

the nearshore aquatic habitats near a coast, or shoreline.

used loosely to describe any group of organisms living together or in close proximity to each other - for example nesting shorebirds that live in large colonies. More specifically refers to a group of organisms in which members act as specialized subunits (a continuous, modular society) - as in clonal organisms.

- active during the day, 2. lasting for one day.

humans benefit economically by promoting tourism that focuses on the appreciation of natural areas or animals. Ecotourism implies that there are existing programs that profit from the appreciation of natural areas or animals.

animals that use metabolically generated heat to regulate body temperature independently of ambient temperature. Endothermy is a synapomorphy of the Mammalia, although it may have arisen in a (now extinct) synapsid ancestor; the fossil record does not distinguish these possibilities. Convergent in birds.

offspring are produced in more than one group (litters, clutches, etc.) and across multiple seasons (or other periods hospitable to reproduction). Iteroparous animals must, by definition, survive over multiple seasons (or periodic condition changes).

eats mollusks, members of Phylum Mollusca

Having one mate at a time.

having the capacity to move from one place to another.

the area in which the animal is naturally found, the region in which it is endemic.

generally wanders from place to place, usually within a well-defined range.

islands that are not part of continental shelf areas, they are not, and have never been, connected to a continental land mass, most typically these are volcanic islands.

reproduction in which eggs are released by the female; development of offspring occurs outside the mother's body.

An aquatic biome consisting of the open ocean, far from land, does not include sea bottom (benthic zone).

an animal that mainly eats fish

the regions of the earth that surround the north and south poles, from the north pole to 60 degrees north and from the south pole to 60 degrees south.

mainly lives in oceans, seas, or other bodies of salt water.

breeding is confined to a particular season

reproduction that includes combining the genetic contribution of two individuals, a male and a female

associates with others of its species; forms social groups.

uses touch to communicate

that region of the Earth between 23.5 degrees North and 60 degrees North (between the Tropic of Cancer and the Arctic Circle) and between 23.5 degrees South and 60 degrees South (between the Tropic of Capricorn and the Antarctic Circle).

Living on the ground.

defends an area within the home range, occupied by a single animals or group of animals of the same species and held through overt defense, display, or advertisement

A terrestrial biome. Savannas are grasslands with scattered individual trees that do not form a closed canopy. Extensive savannas are found in parts of subtropical and tropical Africa and South America, and in Australia.

A grassland with scattered trees or scattered clumps of trees, a type of community intermediate between grassland and forest. See also Tropical savanna and grassland biome.

A terrestrial biome found in temperate latitudes (>23.5° N or S latitude). Vegetation is made up mostly of grasses, the height and species diversity of which depend largely on the amount of moisture available. Fire and grazing are important in the long-term maintenance of grasslands.

uses sight to communicate

Birdlife International, 2006. "Species factsheets" (On-line). Accessed November 07, 2006 at http://www.birdlife.org .

IUCN, 2006. "2006 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species" (On-line). Accessed November 06, 2006 at http://www.iucnredlist.org .

Shirihai, H. 2002. The Complete Guide to Antarctic Wildlife . New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Tickell, W. 1968. Biology of Great Albatrosses. Pp. 1-53 in Antarctic Bird Studies . Baltimore: Horn-Schafer.

The Animal Diversity Web team is excited to announce ADW Pocket Guides!

Read more...

Search in feature Taxon Information Contributor Galleries Topics Classification

- Explore Data @ Quaardvark

- Search Guide

Navigation Links

Classification.

- Kingdom Animalia animals Animalia: information (1) Animalia: pictures (22861) Animalia: specimens (7109) Animalia: sounds (722) Animalia: maps (42)

- Phylum Chordata chordates Chordata: information (1) Chordata: pictures (15213) Chordata: specimens (6829) Chordata: sounds (709)

- Subphylum Vertebrata vertebrates Vertebrata: information (1) Vertebrata: pictures (15168) Vertebrata: specimens (6827) Vertebrata: sounds (709)

- Class Aves birds Aves: information (1) Aves: pictures (7311) Aves: specimens (153) Aves: sounds (676)

- Order Procellariiformes tube-nosed seabirds Procellariiformes: pictures (48) Procellariiformes: specimens (15)

- Family Diomedeidae albatrosses Diomedeidae: pictures (27) Diomedeidae: specimens (6)

- Genus Diomedea royal and wandering albatrosses Diomedea: pictures (5) Diomedea: specimens (4)

- Species Diomedea exulans wandering albatross Diomedea exulans: information (1) Diomedea exulans: pictures (3)

To cite this page: Scopel, L. 2007. "Diomedea exulans" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed May 09, 2024 at https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Diomedea_exulans/

Disclaimer: The Animal Diversity Web is an educational resource written largely by and for college students . ADW doesn't cover all species in the world, nor does it include all the latest scientific information about organisms we describe. Though we edit our accounts for accuracy, we cannot guarantee all information in those accounts. While ADW staff and contributors provide references to books and websites that we believe are reputable, we cannot necessarily endorse the contents of references beyond our control.

- U-M Gateway | U-M Museum of Zoology

- U-M Ecology and Evolutionary Biology

- © 2020 Regents of the University of Michigan

- Report Error / Comment

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation Grants DRL 0089283, DRL 0628151, DUE 0633095, DRL 0918590, and DUE 1122742. Additional support has come from the Marisla Foundation, UM College of Literature, Science, and the Arts, Museum of Zoology, and Information and Technology Services.

The ADW Team gratefully acknowledges their support.

Smithsonian Ocean

Wandering albatross.

A wandering albatross has the largest wingspan of any bird, 3.5 meters (11.5 feet) tip to wing tip.

- Make Way for Whales

- Sharks & Rays

- Invertebrates

- Plants & Algae

- Coral Reefs

- Coasts & Shallow Water

- Census of Marine Life

- Tides & Currents

- Waves, Storms & Tsunamis

- The Seafloor

- Temperature & Chemistry

- Ancient Seas

- Extinctions

- The Anthropocene

- Habitat Destruction

- Invasive Species

- Acidification

- Climate Change

- Gulf Oil Spill

- Solutions & Success Stories

- Get Involved

- Books, Film & The Arts

- Exploration

- History & Cultures

- At The Museum

Search Smithsonian Ocean

- Complete List of Animals

- Animals that start with A

- Animals that start with B

- Animals that start with C

- Animals that start with D

- Animals that start with E

- Animals that start with F

- Animals that start with G

- Animals that start with H

- Animals that start with I

- Animals that start with J

- Animals that start with K

- Animals that start with L

- Animals that start with M

- Animals that start with N

- Animals that start with O

- Animals that start with P

- Animals that start with Q

- Animals that start with R

- Animals that start with S

- Animals that start with T

- Animals that start with U

- Animals that start with V

- Animals that start with W

- Animals that start with X

- Animals that start with Y

- Animals that start with Z

- Parks and Zoos

- Diomedeidae

- Diomedea exulans

- Procellariiformes

Wandering Albatross

The Wandering Albatross is a massive bird known by many names. In various regions, people call this bird a Snowy Albatross, Goonie, and White Winged Albatross.

Not only are they the largest of the 22 albatross species, but they also have the longest wingspan of any bird. Their wings commonly measure up to 10 ft. across, and the largest confirmed specimen had a wingspan over 12 ft. across! Read on to learn about the Wandering Albatross .

Description of the Wandering Albatross

This species of albatross has white plumage, or feathers, with darker wings. Their wing feathers are black, and speckled with varying degrees of white. Young birds have brown feathers, which become white as they age.

This bird’s wingspan is quite large, and averages 10 feet across, though some individuals are larger. Finally, their beaks are moderately long, with a hook at the end to help grasp fish.

Interesting Facts About the Wandering Albatross

This species has the longest wingspan of any living bird … Ever! However, that is not the only notable thing about the Wandering Albatross.

- Monogamous Mates – Once a Wandering Albatross has found a suitable mate, it continues to breed with that bird for the rest of its life. They are doting parents, and take great care in rearing their chicks. It sometimes takes up to 10 months for the chick to learn how to fly and become independent of its parents.

- Time Constraints – Obviously when it takes 10 months to raise a single chick, it can be difficult to jump right back into parenthood. For this reason, Wandering Albatrosses breed once every 2 years.

- Slow to Mature – Adult albatrosses don’t even begin reproducing until they are about 10 years old on average. They sometimes join the other birds at the breeding colonies and perform mating displays. However, most of the time they do not find a mate and begin to breed until they are around 10 years old.

- Slow Growth – Unfortunately, because these birds are so slow to mature, and they breed at a very slow rate, their populations do not increase quickly. Because of this, when their populations decline it takes a long time for them to make a comeback. Humans pose threats to these birds in a number of different ways, and the IUCN lists the species as Vulnerable .

Habitat of the Wandering Albatross

These birds spend the vast majority their life flying over, or floating on the surface of, the ocean. They inhabit the open ocean, primarily where the waters are deep, and fish are plentiful. The only time they come to land is for the mating season. During this time, colonies of birds land on plateaus, valleys, and plains.

Distribution of the Wandering Albatross

There are several different subspecies of Wandering Albatross, all of which live in the open oceans of the Southern Hemisphere. Outside of the breeding season, they roam the open oceans in between Antarctica and the southern coasts of Africa, South America, and Australia. Their primary breeding colonies are on various islands across the Southern Hemisphere, including South Georgia, Macquarie, Amsterdam Island, and more.

Diet of the Wandering Albatross

This seabird unsurprisingly feeds primarily on fish and other aquatic organisms. They eat fish, octopus, squid, shrimp, and krill.

They also scavenge on the remains of carcasses, as well as feeding on the scraps from commercial fishing operations and other predators. Though they can dive if they need to, they catch most of their food at the surface of the water.

Wandering Albatross and Human Interaction

Unfortunately, humans are extremely detrimental to these birds. Sailors have killed birds, both at sea and in nesting colonies, for decades. In fact, humans are the only known predator of adult albatrosses.

Nowadays it is illegal to harm these birds, though killing does still occur. Sadly, they frequently, and accidentally, become trapped in fishing nets or on fishing lines. Humans have also introduced many different feral animals to their breeding islands, and these animals eat the eggs and chicks.

Domestication

Humans have not domesticated this species of bird in any way.

Does the Wandering Albatross Make a Good Pet

No, the Wandering Albatross does not make a good pet. Their huge wings carry them across open ocean, which would make them a poor household pet. It most places, it is illegal to harm, harass, capture, or kill these birds.

Wandering Albatross Care

These birds do not often find themselves in zoos. The only time any albatross species lives in a zoo or aquarium is when something has severely injured them in some way.

During those times, zoos attempt to heal and rehabilitate the birds, and release them back into the wild if possible. Albatrosses that live in zoos because they cannot survive in the wild act as ambassadors to the plight of their species.

Behavior of the Wandering Albatross

This species is quite social, even outside of the breeding season. While in the open ocean, small groups of Wandering Albatrosses forage together. These groups frequently converge upon one another when feeding opportunities, like bait balls or fishing vessels, arise.

As the breeding season arrives, huge colonies of birds flock to their breeding grounds together. Birds searching for mates perform elaborate courtship displays, and mated pairs renew their bonds.

Reproduction of the Wandering Albatross

Every 2 years a pair breeds and produces a single egg, usually in December. Both the male and the female help incubate the egg, which hatches after 2.5 months. Once the chick hatches the parents alternate between keeping it warm and fishing for food.

After the chick is a month old, both parents leave it alone to hunt for food. It takes between 9 and 10 months for the chick to learn how to fly and gain independence.

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

![Red Angus Closeup of a beautiful Red Angus cowPhoto by: U.S. Department of Agriculture [pubic domain]https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/](https://animals.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Red-Angus-4-238x178.jpg)

Paint Horse

Expert Recommendations

Best Grain Free Dog Food

Best Dog Car Seat

Best Dog Boots

Best Wireless Dog Fences

Best Dog Food For Allergies

Best Dog Treats

Best Dog Backpack

Best Canned Cat Food

Best Dog Harness

Best Cat Stain Odor Remover

Even more news.

![Red Angus Closeup of a beautiful Red Angus cowPhoto by: U.S. Department of Agriculture [pubic domain]https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/](https://animals.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Red-Angus-4-100x75.jpg)

House Spider

Popular category.

- Chordata 694

- Mammalia 247

- Dog Breeds 184

- Actinopterygii 121

- Reptilia 87

- Carnivora 72

- Privacy Policy

- Terms and Conditions

Albatrosses are threatened with extinction – and climate change could put their nesting sites at risk

Postdoctoral research fellow, Department of Plant and Soil Science, University of Pretoria

Disclosure statement

Mia Momberg does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Pretoria provides funding as a partner of The Conversation AFRICA.

View all partners

The wandering albatross ( Diomedea exulans ) is the world’s largest flying bird , with a wingspan reaching an incredible 3.5 metres. These birds are oceanic nomads: they spend most of their 60 years of life at sea and only come to land to breed approximately every two years once they have reached sexual maturity.

Their playground is the vast Southern Ocean – the region between the latitude of 60 degrees south and the continent of Antarctica – and the scattered islands within this ocean where they make their nests.

Marion Island and Prince Edward Island , about 2,300km south of South Africa, are some of the only land masses for thousands of kilometres in the Southern Ocean.

Together, these two islands support about half of the entire world’s wandering albatross breeding population, estimated at around 20,000 mature individuals . Every year scientists from South African universities survey Marion Island to locate and record each wandering albatross nest.

The species, listed as vulnerable by the International Union for Conservation of Nature , faces huge risks while in the open ocean, in particular due to bycatch from longline fishing trawlers. This makes it important to understand their breeding ecology to ensure that the population remains stable.

I was part of a study during 2021 to investigate which environmental variables affect the birds’ choice of nest site on Marion Island. The birds make their nests – a mound of soil and vegetation – on the ground. We looked at wind characteristics, vegetation and geological characteristics at nest locations from three breeding seasons.

Elevation turned out to be the most important variable – the albatrosses preferred a low (warmer) site and coastal vegetation. But these preferences also point to dangers for the birds from climate change. The greatest risk to the availability of nesting sites will be a much smaller suitable nesting range in future than at present. This could be devastating to the population.

Variables influencing nest site selection

Marion Island is of volcanic origin and has a rough terrain. Some areas are covered in sharp rock and others are boggy, with very wet vegetation. There is rain and strong wind on most days. Conducting research here requires walking long distances in all weathers – but the island is ideal for studying climate change, because the Southern Ocean is experiencing some of the largest global changes in climate and it is relatively undisturbed by humans.

Using GPS coordinate nest data from the entire breeding population on Marion Island, we aimed to determine which factors affected where the birds breed. With more than 1,900 nests, and 10,000 randomly generated points where nests are not present, we extracted:

elevation (which on this island is also a proxy for temperature)

terrain ruggedness

distance to the coast

vegetation type

wind turbulence

underlying geology.

The variables were ranked according to their influence on the statistical model predicting the likelihood of a nest being present under the conditions found at a certain point.

The most important variable was elevation. The majority of the nests were found close to the coast, where the elevation is lower. These areas are warmer, which means that the chicks would be less exposed to very cold temperatures on their open nests.

The probability of nests being present also declined with distance from the coast, probably because there are more suitable habitats closer to the coast.

Vegetation type was strongly determined by elevation and distance from the coast. This was an important factor, as the birds use vegetation to build their nests. In addition, dead vegetation contributes to the soil formation on the island, which is also used in nest construction.

The probability of encountering nests is lower as the terrain ruggedness increases since these birds need a runway of flat space to use for take-off and landing. During incubation, the adults take turns to remain on the nest. Later they will leave the chick on its own for up to 10 days at a time. They continue to feed the chick for up to 300 days.

Areas with intermediate wind speeds were those most likely to have a nest. At least some wind is needed for flight, but too much wind may cause chicks to blow off the nests or become too cold.

Delicate balance

Changing climates may upset this delicate balance. Human-driven changes will have impacts on temperature, rainfall and wind speeds, which in turn affect vegetation and other species distribution patterns .

By 2003, Marion Island’s temperature had increased by 1.2°C compared to 50 years before. Precipitation had decreased by 25% and cloud cover also decreased, leading to an increase in sunshine hours . The permanent snowline which was present in the 1950s no longer exists . These changes have continued in the 20 years since their initial documentation, and are likely to continue.

Strong vegetation shifts were already documented in the sub-Antarctic years ago. Over 40 years, many species have shifted their ranges to higher elevations where the temperatures remain cooler. Wind speeds have also already increased in the Southern Ocean and are predicted to continue doing so, which may have effects on the size of areas suitable for nesting.

If nesting sites move to higher elevations on Marion Island as temperatures warm, and some areas become unsuitable due to changes in vegetation or wind speeds, it is likely that the suitable nesting area on the island will shrink considerably.

Our study adds to what is known about the elements affecting nest-site selection in birds. Notably, we add knowledge of wind, an underexplored element, influencing nest-site selection in a large oceanic bird. The results could also provide insights that apply to other surface-nesting seabirds.

- Climate change

- Southern ocean

- Natural world

Events and Communications Coordinator

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Woods Hole, Mass. — Wandering albatrosses, which are an iconic sight in the Southern Ocean, are highly adapted to long-distance soaring flight. Their wingspan of up to 11 feet is the largest known of any living bird, and yet wandering albatrosses fly while hardly flapping their wings. Instead, they depend on dynamic soaring—which exploits wind shear near the ocean surface to gain energy—in addition to updrafts and turbulence.

Now researchers, including Philip Richardson , a senior scientist emeritus in Physical Oceanography Department at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), are unlocking more clues about exactly how wandering albatrosses are such amazing flyers.

In a new paper analyzing GPS tracks of wandering albatrosses, researchers have found that the birds’ airspeed increases with wind speed up to a maximum airspeed of 20 meters per second (m/s; 45 mph). Researchers developed a model of dynamic soaring, which predicts that the birds could fly much faster than 20 m/s. The paper concludes that the birds limit their airspeed by adjusting the turns in their trajectories to be around 60°, and that in low winds the birds exploit updrafts over waves to supplement dynamic soaring.

“We hypothesize that wandering albatrosses limit their maximum across-wind airspeeds to ~ 20 m/s in higher wind speeds (and greater wind turbulence), probably to keep the aerodynamic force on their wings during dynamic soaring well below the mechanically-tolerable limits of wing strength,” according to the paper, “Observations and Models of Across-wind Flight Speed of the Wandering Albatross,” published in the journal Royal Society Open Science .

The paper adds that, given the complex field of wind waves and swell waves often present in the Southern Ocean, “it is also possible that birds find it increasingly difficult to coordinate dynamic soaring maneuvers at faster speeds.”

Regarding low flight speeds by albatrosses, the paper notes that a theoretical model predicted that the minimum wind speed necessary to support dynamic soaring is greater than 3 m/s. “Despite this, tracked albatrosses were observed in flight at wind speeds as low as 2 m/s. We hypothesize at these very low wind speeds, wandering albatrosses fly by obtaining additional energy from updrafts over water waves,” according to the paper.

“We tried to figure out how these birds are using the winds to go long distances—without overstressing their wings—for foraging for food and returning to feed their chicks. To do that, we modeled dynamic soaring and what different turn angles would do to stress on the birds’ wings and speed over the water,” said journal paper co-author Richardson. A dynamic soaring trajectory is an s-shaped maneuver consisting of a series of connected turns, he noted.

“This research is a step in the direction of understanding how wandering albatrosses are able to do these foraging trips and maintain a fairly large population. These birds figured out an amazing way to use the wind to almost effortlessly soar for thousands of miles over the ocean. We wanted to find out exactly how they did it,” he said.

In addition to learning more about albatrosses, the study could have broader implications for helping researchers better understand how to use dynamic soaring to power potential albatross-type gliders to observe ocean conditions, Richardson added.