- Mental Health

Want to Give Your Life More Meaning? Think of It As a ‘Hero’s Journey’

Y ou might not think you have much in common with Luke Skywalker, Harry Potter, or Katniss Everdeen. But imagining yourself as the main character of a heroic adventure could help you achieve a more meaningful life.

Research published earlier this year in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology touts the benefits of reframing your life as a Hero’s Journey—a common story structure popularized by the mythologist Joseph Campbell that provides a template for ancient myths and recent blockbusters. In his 1949 book The Hero with a Thousand Faces , Campbell details the structure of the journey, which he describes as a monomyth. In its most elementary form, a hero goes on an adventure, emerges victorious from a defining crisis, and then returns home changed for the better.

“The idea is that there’s a hero of some sort who experiences a change of setting, which could mean being sent off to a magical realm or entering a new thing they’re not used to,” says study author Benjamin A. Rogers, an assistant professor of management and organization at Boston College. “That sets them off on a quest where they encounter friends and mentors, face challenges, and return home to benefit their community with what they’ve learned.”

According to Rogers’ findings, perceiving your life as a Hero’s Journey is associated with psychological benefits such as enhanced well-being, greater life satisfaction, feeling like you’re flourishing, and reduced depression. “The way that people tell their life story shapes how meaningful their lives feel,” he says. “And you don’t have to live a super heroic life or be a person of adventure—virtually anyone can rewrite their story as a Hero’s Journey.”

More From TIME

The human brain is wired for stories, Rogers notes, and we respond to them in powerful ways. Previous research suggests that by the time we’re in our early 20s, most of us have constructed a narrative identity—an internalized and evolving life story—that explains how we became the person we are, and where our life might go in the future. “This is how we've been communicating and understanding ourselves for thousands of years,” he says. Rogers’ research suggests that if people view their own story as following a Hero’s Journey trajectory, it increases meaning regardless of how they initially perceived their lives; even those who thought their lives had little meaning are able to benefit.

While Rogers describes a “re-storying intervention” in his research, some psychologists have used the Hero’s Journey structure as part of their practice for years. Lou Ursa, a licensed psychotherapist in California, attended Pacifica Graduate Institute, which is the only doctoral program in the country focused on mythology. The university even, she notes, houses Campbell’s personal library. As a result, mythology was heavily integrated into her psychology grad program. In addition to reflecting on what the Hero’s Journey means to her personally, she often brings it up with clients. “The way I talk about it is almost like an eagle-eye view versus a snake-eye view of our lives,” she says. “So often we’re just seeing what’s in front of us. I think that connecting with a myth or a story, whether it’s the Hero’s Journey or something else, can help us see the whole picture, especially when we’re feeling lost or stuck.”

As Rogers’ research suggests, changing the way you think about the events of your life can help you move toward a more positive attitude. With that in mind, we asked experts how to start reframing your life story as a Hero’s Journey.

Practice reflective journaling

Campbell described more than a dozen key elements of a Hero’s Journey, seven of which Rogers explored in his research: protagonist, shift, quest, allies, challenge, transformation, and legacy. He says reflecting on these aspects of your story—even if it’s just writing a few sentences down—can be an ideal first step to reframe your circumstances. Rogers offers a handful of prompts that relate back to the seven key elements of a Hero’s Journey. To drill in on “protagonist,” for example, ask yourself: What makes you you ? Spend time reflecting on your identity, personality, and core values. When you turn to “shift,” consider: What change or new experience prompted your journey to become who you are today? Then ponder what challenges stand in your way, and which allies can support or help you in your journey. You can also meditate on the legacy your journey might leave.

Ask yourself who would star in the movie of your life

One way to assess your inner voice is to figure out who would star in a movie about your life, says Nancy Irwin, a clinical psychologist in Los Angeles who employs the Hero’s Journey concept personally and professionally. Doing so can help us “sufficiently dissociate and see ourselves objectively rather than subjectively,” she says. Pay attention to what appeals to you about that person: What traits do they embody that you identify with? You might, for example, admire the person’s passion, resilience, or commitment to excellence. “They inspire us because there’s some quality that we identify with,” Irwin says. “Remember, you chose them because you have that quality yourself.” Keeping that in mind can help you begin to see yourself as the hero of your own story.

Go on more heroic adventures—or just try something new

In classic Hero’s Journey stories, the protagonist starts off afraid and refuses a call to adventure before overcoming his fears and committing to the journey. Think of Odysseus being called to fight the Trojans, but refusing the call because he doesn’t want to leave his family. Or consider Rocky Balboa: When he was given the chance to fight the world’s reigning heavyweight champion, he immediately said no—before ultimately, of course, accepting the challenge. The narrative has proven timeless because it “reflects the values of society,” Rogers says. “We like people who have new experiences and grow from their challenges.”

He suggests asking yourself: “If I want to have a more meaningful life, what are the kinds of things I could do?” One possible avenue is seeking out novelty, whether that’s as simple as driving a new way home from work or as dramatic as finally selling your car entirely and committing to public transportation.

Be open to redirection

The Hero’s Journey typically starts with a mission, which prompts the protagonist to set off on a quest. “But often the road isn’t linear,” says Kristal DeSantis, a licensed marriage and family therapist in Austin. “There are twists, turns, unexpected obstacles, and side quests that get in the way. The lesson is to be open to possibility.”

That perspective can also help you flip the way you see obstacles. Say you’re going through a tough time: You just got laid off, or you were diagnosed with a chronic illness. Instead of dwelling on how unfortunate these hurdles are, consider them opportunities for growth and learning. Think to yourself: What would Harry do? Reframe the challenges you encounter as a chance to develop resilience and perseverance, and to be the hero of your own story.

When you need a boost, map out where you are on your journey

Once you find a narrative hero you can relate to, keep their journey in mind as you face new challenges. “If you feel stuck or lost, you can look to that story and be like, ‘Which part do I feel like I’m in right now?’” Ursa says. Maybe you’re in the midst of a test that feels so awful that you’ve lost perspective on its overall importance—i.e., the fact that it’s only part of your journey. (See: When Katniss was upset about the costume that Snow forced her to wear—before she then had to go fight off a pack of ferocious wolves to save her life.) Referencing a familiar story “can help you have that eagle-eye view of what might be next for you, or what you should be paying attention to,” Ursa says. “Stories become this map that we can always turn to.” Think of them as reassurance that a new chapter almost certainly awaits.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

Environment

The journey of life, ...and the nature of success.

Posted May 24, 2016

Just what is implied nowadays when we say that someone has led a ‘successful life’? I ask the question in general conversation from time to time and, as might be expected, find that nowadays ideas about what constitutes ‘success’ in life tend to be pretty narrow.

For more often than not, ‘success in life’ is generally taken to be (1), attaining a high degree of financial security; (2) having achieved a good social position; or (3), having acquired a fair number of impressive possessions – all opinions and attitudes which I would say reflect a widely held way of looking at contemporary life.

I remember a distinction made on a Royal Air Force Officer’s Record during World War II between two aspects of his overall performance, using a separate column for each: one headed OQ (Officer Qualities) and the other PQ (Personal Qualities). And it was necessary to have positive reports in both columns in order to maintain rank or be promoted.

I mention this ‘two column’ method here because these two ways of assessing overall competence in war are really also applicable to the struggle for success in normal peacetime living. For the OQ column recorded how intelligently and successfully one has responded to all the practical, day-to-day, ‘action-requiring’ decisions confronting one, indicating firmness of resolve in objective and positive action in responding to external situations of the moment… right now. The PQ column represented the extremely personal, psychological integrity of moral character, and insightful level of ‘wisdomly’ intuition , brought to bear more reflectively when taking action in any situation.

I don’t suppose that many contemporary psychologists would have much trouble in agreeing that the mental partnership of the OQ/PQ formula (as prescribed for wartime conditions), also plays a large part in determining the degree of ‘success’ when it comes to peacetime living.

But there is also one other mental activity at work in consciousness that should be recorded in a third column, one absent from official records, the purpose of which is to reveal those aspects of your own essential nature and character that are responsible for the decisions and the actions you take. For it may be in your nature to be constantly critical, even vindictive…. or generally fair and unprejudiced, generally disposed to be generous in the things you say and do. Judgements of this sort constitute a regular and important side of consciousness, and one should be aware of one’s own tendencies to be either hyper-critical or overly optimistic and generous to others as one goes through the day. Always let that well-known aphorism come to mind, ‘There but for the grace of God go I…’

In any event, the third column’s record indicates important personality characteristics: whether it is in one’s nature to be constantly critical, with a tendency to be condemnatory or more generally optimistic and sympathetic with regard to others. It is important to look over this third column from time to time, for it should be seen as a appraisal of one’s own character, speaking to levels of personal integrity and, as such, revealing just how humane you have become. This may help you determine your essential identity in terms of your humanity.

So I would suggest that success in life lies in coming to be aware of the comments secreted in the three-columned record of your life.

From the civilizations of Greece and Rome has come the injunction, ‘Know Thyself….’ in the belief that to know the content of your personal ‘three-columned record’, in and of itself, constitutes success in life.

(You may also attempt to make a ‘character test’ by trying to recognize the ‘face in the mirror’. Recognize Yourself, that is. Try it sometime. See how long you can manage to look into your own eyes. If you can manage two minutes, it is said you are in good humane shape.)

Dr. Carl Gustav Jung (who I regard as the greatest of 20th Century psychologist-psychiatrists), used the word individuation to describe this ‘three-columned’ mental journey as the course we follow to become unique individuals. And he saw the practice of psychiatry – talking to a patient to bring him or her to reach this very point of ‘Knowing Themselves – as the healing job of the psychologist.

But I am not sure if the following statement would carry much weight nowadays:

We moderns are faced with the necessity of rediscovering the life of the spirit; we must experience it anew for ourselves. It is the only way in which we can break the spell that binds us to the cycle of biological events….

C.G.Jung: Psychological Reflections

Graham Collier , the author of What The Hell Are The Neurons Up To? , is an exhibiting landscape and portrait artist in Britain, an artist-philosopher in America, and a frequent Antarctic voyager.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

The customer journey — definition, stages, and benefits

Businesses need to understand their customers to increase engagement, sales, and retention. But building an understanding with your customers isn’t easy.

The customer journey is the road a person takes to convert, but this journey isn’t always obvious to business owners. Understanding every step of that journey is key to business success. After reading this article, you’ll understand the customer journey better and how to use it to improve the customer experience while achieving your business goals.

This post will discuss:

- What a customer journey is

Customer journey stages

Benefits of knowing the customer journey.

- What a customer journey map is

How to create a customer journey map

Use the customer journey map to optimize the customer experience, what is a customer journey.

The customer journey is a series of steps — starting with brand awareness before a person is even a customer — that leads to a purchase and eventual customer loyalty. Businesses use the customer journey to better understand their customers’ experience, with the goal of optimizing that experience at every touchpoint.

Giving customers a positive customer experience is important for getting customers to trust a business, so optimizing the customer journey has never mattered more. By mastering the customer journey, you can design customer experiences that will lead to better customer relationships, loyalty, and long-term retention .

Customer journey vs. the buyer journey

The stages of the customer’s journey are different from the stages of the buyer’s journey. The buyer’s journey follows the customer experience from initial awareness of a brand to buying a product. The customer journey extends beyond the purchase and follows how customers interact with your product and how they share it with others.

Every lead goes through several stages to become a loyal customer. The better this experience is for customers at each stage, the more likely your leads are to stick around.

Ensure that your marketing, sales, and customer service teams optimize for these five stages of the customer journey:

1. Awareness

In the awareness phase, your target audience is just becoming aware of your brand and products. They need information or a solution to a problem, so they search for that information via social media and search engines.

For example, if someone searches on Google for pens for left-handed people, their customer journey begins when they’re first aware of your brand’s left-handed pen.

At this stage, potential customers learn about your business via web content, social media, influencers, and even their friends and family. However, this isn’t the time for hard sells. Customers are simply gathering information at this stage, so you should focus first on answering their questions and building trust.

2. Consideration

In the consideration phase, customers begin to consider your brand as a solution to their problem. They’re comparing your products to other businesses and alternative solutions, so you need to give these shoppers a reason to stick around.

Consideration-stage customers want to see product features that lean heavily toward solving problems and content that doesn’t necessarily push a sale. At this stage, businesses need to position their solution as a better alternative. For example, a nutrition coaching app might create content explaining the differences between using the app and working with an in-person nutritionist — while subtly promoting the benefits of choosing the app.

3. Purchase

The purchase stage is also called the decision stage because at this stage customers are ready to make a buying decision. Keep in mind that their decision might be to go with a competing solution, so purchase-stage buyers won’t always convert to your brand.

As a business, it’s your job to persuade shoppers at this stage to buy from you. Provide information on pricing, share comparison guides to showcase why you’re the superior option, and set up abandoned cart email sequences.

4. Retention

The customer journey doesn’t end once a shopper makes their first purchase. Once you’ve converted a customer, you need to focus on keeping them around and driving repeat business. Sourcing new customers is often more expensive than retaining existing clients, so this strategy can help you cut down on marketing costs and increase profits.

The key to the retention stage is to maintain positive, engaging relationships between your brand and its customers. Try strategies like regular email outreach, coupons and sales, or exclusive communities to encourage customer loyalty.

5. Advocacy

In the advocacy stage, customers are so delighted with your products and services that they spread the word to their friends and family. This goes a step beyond retention because the customer is actively encouraging other people to make purchases.

Customer journeys don’t have a distinct end because brands should always aim to please even their most loyal customers. In the advocacy stage of the customer journey, you can offer referral bonuses, loyalty programs, and special deals for your most active customers to encourage further advocacy.

Being aware of the customer journey helps shed more light on your target audience’s expectations and needs. In fact, 80% of companies compete primarily on customer experience. This means optimizing the customer journey will not only encourage your current customers to remain loyal but will also make you more competitive in acquiring new business.

More specifically, acknowledging the customer journey can help you:

- Understand customer behavior. Classifying every action your customers take will help you figure out why they do what they do. When you understand a shopper’s “why,” you’re better positioned to support their needs.

- Identify touchpoints to reach the customer. Many businesses invest in multichannel marketing, but not all of these touchpoints are valuable. By focusing on the customer journey, you’ll learn which of these channels are the most effective for generating sales. This helps businesses save time and money by focusing on only the most effective channels.

- Analyze the stumbling blocks in products or services. If leads frequently bail before buying, that could be a sign that something is wrong with your product or buying experience. Being conscious of the customer journey can help you fix issues with your products or services before they become a more expensive problem.

- Support your marketing efforts. Marketing requires a deep familiarity with your target audience. Documenting the customer journey makes it easier for your marketing team to meet shoppers’ expectations and solve their pain points.

- Increase customer engagement. Seeing the customer journey helps your business target the most relevant audience for your product or service. Plus, it improves the customer experience and increases engagement. In fact, 29.6% of customers will refuse to embrace branded digital channels if they have a poor experience, so increasing positive customer touchpoints has never been more important.

- Achieve more conversions. Mapping your customers’ journey can help you increase conversions by tailoring and personalizing your approach and messages to give your audience exactly what they want.

- Generate more ROI. You need to see a tangible return on your marketing efforts. Fortunately, investing in the customer journey improves ROI across the board. For example, brands with a good customer experience can increase revenue by 2–7% .

- Improve customer satisfaction and loyalty. Today, 94% of customers say a positive experience motivates them to make future purchases. Optimizing the customer journey helps you meet shopper expectations, which increases satisfaction and loyalty.

What is a customer journey map?

A customer journey map is a visual representation of every step your customer takes from being a lead to eventually becoming an advocate for your brand. The goal of customer journey mapping is to simplify the complex process of how customers interact with your brand at every stage of their journey.

Businesses shouldn’t use a rigid, one-size-fits-all customer journey map. Instead, they should plan flexible, individual types of customer journeys — whether they’re based on a certain demographic or on individual customer personas. To design the most effective customer journey map, your brand needs to understand a customer’s:

- Actions. Learn which actions your customer takes at every stage. Look for common patterns. For example, you might see that consideration-stage shoppers commonly look for reviews.

- Motivations. Customer intent matters. A person’s motivations change at every stage of the customer journey, and your map needs to account for that. Include visual representation of the shopper’s motivations at each stage. At the awareness stage, their motivation might be to gather information to solve their problem. At the purchase stage, it might be to get the lowest price possible.

- Questions. Brands can take customers’ common questions at every stage of the customer journey and reverse-engineer them into useful content. For example, shoppers at the consideration stage might ask, “What’s the difference between a DIY car wash and hiring a professional detailer?” You can offer content that answers their question while subtly promoting your car detailing business.

- Pain points. Everybody has a problem that they’re trying to solve, whether by just gathering intel or by purchasing products. Recognizing your leads’ pain points will help you craft proactive, helpful marketing campaigns that solve their biggest problems.

Customer journey touchpoints

Every stage of the customer journey should also include touchpoints. Customer touchpoints are the series of interactions with your brand — such as an ad on Facebook, an email, or a website chatbot — that occur at the various stages of the customer journey across multiple channels. A customer’s actions, motivations, questions, and pain points will differ at each stage and at each touchpoint.

For example, a customer searching for a fishing rod and reading posts about how they’re made will have very different motivations and questions from when later comparing specs and trying to stay within budget. Likewise, that same customer will have different pain points when calling customer service after buying a particular rod.

It might sound like more work, but mapping the entire customer journey helps businesses create a better customer experience throughout the entire lifecycle of a customer’s interaction with your brand.

Before jumping into the steps of how to create the customer journey map, first be clear that your customer journey map needs to illustrate the following:

- Customer journey stages. Ensure that your customer journey map includes every stage of the customer journey. Don’t just focus on the stages approaching the purchase — focus on the retention and advocacy stages as well.

- Touchpoints. Log the most common touchpoints customers have at every stage. For example, awareness-stage touchpoints might include your blog, social media, or search engines. Consideration-stage touchpoints could include reviews or demo videos on YouTube. You don’t need to list all potential touchpoints. Only list the most common or relevant touchpoints at each stage.

- The full customer experience. Customers’ actions, motivations, questions, and pain points will change at every stage — and every touchpoint — during the customer journey. Ensure your customer journey map touches on the full experience for each touchpoint.

- Your brand’s solutions. Finally, the customer journey map needs to include a branded solution for each stage and touchpoint. This doesn’t necessarily mean paid products. For example, awareness-stage buyers aren’t ready to make a purchase, so your brand’s solution at this stage might be a piece of gated content. With these necessary elements in mind, creating an effective customer journey map is a simple three-step process.

1. Create buyer personas

A buyer persona is a fictitious representation of your target audience. It’s a helpful internal tool that businesses use to better understand their audience’s background, assumptions, pain points, and needs. Each persona differs in terms of actions, motivations, questions, and pain points, which is why businesses need to create buyer personas before they map the customer journey.

To create a buyer persona, you will need to:

- Gather and analyze customer data. Collect information on your customers through analytics, surveys, and market research.

- Segment customers into specific buying groups. Categorize customers into buying groups based on shared characteristics — such as demographics or location. This will give you multiple customer segments to choose from.

- Build the personas. Select the segment you want to target and build a persona for that segment. At a minimum, the buyer persona needs to define the customers’ basic traits, such as their personal background, as well as their motivations and pain points.

For example, ClearVoice created a buyer persona called “John The Marketing Manager.” The in-depth persona details the target customer’s pain points, pet peeves, and potential reactions to help ClearVoice marketers create more customer-focused experiences.

2. List the touchpoints at each customer journey stage

Now that you’ve created your buyer personas, you need to sketch out each of the five stages of the customer journey and then list all of the potential touchpoints each buyer persona has with your brand at every one of these five stages. This includes listing the most common marketing channels where customers can interact with you. Remember, touchpoints differ by stage, so it’s critical to list which touchpoints happen at every stage so you can optimize your approach for every buyer persona.

Every customer’s experience is different, but these touchpoints most commonly line up with each stage of the customer journey:

- Awareness. Advertising, social media, company blog, referrals from friends and family, how-to videos, streaming ads, and brand activation events.

- Consideration. Email, sales calls, SMS, landing pages, and reviews.

- Purchase. Live chat, chatbots, cart abandonment emails, retargeting ads, and product print inserts.

- Retention. Thank you emails, product walkthroughs, sales follow-ups, and online communities.

- Advocacy. Surveys, loyalty programs, and in-person events.

Leave no stone unturned. Logging the most relevant touchpoints at each stage eliminates blind spots and ensures your brand is there for its customers, wherever they choose to connect with you.

3. Map the customer experience at each touchpoint

Now that you’ve defined each touchpoint at every stage of the customer journey, it’s time to detail the exact experience you need to create for each touchpoint. Every touchpoint needs to consider the customer’s:

- Actions. Describe how the customer got to this touchpoint and what they’re going to do now that they’re here.

- Motivations. Specify how the customer feels at this moment. Are they frustrated, confused, curious, or excited? Explain why they feel this way.

- Questions. Every customer has questions. Anticipate the questions someone at this stage and touchpoint would have — and how your brand can answer those questions.

- Pain points. Define the problem the customer has — and how you can solve that problem at this stage. For example, imagine you sell women’s dress shoes. You’re focusing on the buyer persona of a 36-year-old Canadian woman who works in human resources. Her touchpoints might include clicking on your Facebook ad, exploring your online shop, but then abandoning her cart. After receiving a coupon from you, she finally buys. Later, she decides to exchange the shoes for a different color. After the exchange, she leaves a review. Note how she acts at each of these touchpoints and detail her likely pain points, motivations, and questions, for each scenario. Note on the map where you intend to respond to the customer’s motivations and pain points with your brand’s solutions. If you can create custom-tailored solutions for every stage of the funnel, that’s even better.

A positive customer experience is the direct result of offering customers personalized, relevant, or meaningful content and other brand interactions. By mapping your customers’ motivations and pain points with your brand’s solutions, you’ll find opportunities to improve the customer experience. When you truly address their deepest needs, you’ll increase engagement and generate more positive reviews.

Follow these strategies to improve the customer experience with your customer journey map:

- Prioritize objectives. Identify the stages of the customer journey where your brand has the strongest presence and take advantage of those points. For example, if leads at the consideration stage frequently subscribe to your YouTube channel, that gives you more opportunities to connect with loyal followers.

- Use an omnichannel approach to engage customers. Omnichannel marketing allows businesses to gather information and create a more holistic view of the customer journey. This allows you to personalize the customer experience on another level entirely. Use an omnichannel analytics solution that allows you to capture and analyze the true cross-channel experience.

- Personalize interactions at every stage. The goal of mapping the customer journey is to create more personalized, helpful experiences for your audience at every stage and touchpoint. For example, with the right data you can personalize the retail shopping experience and customer’s website experience.

- Cultivate a mutually trusting relationship. When consumer trust is low, brands have to work even harder to earn their customers’ trust. Back up your marketing promises with good customer service, personalized incentives, and loyalty programs.

Getting started with customer journeys

Customer journeys are complicated in an omnichannel environment, but mapping these journeys can help businesses better understand their customers. Customer journey maps help you deliver the exact experience your customers expect from your business while increasing engagement and sales.

When you’re ready to get started, trace the interactions your customers have at each stage of their journey with your brand. Adobe Customer Journey Analytics — a service built on Adobe Experience Platform — can break down, filter, and query years’ worth of data and combine it from every channel into a single interface. Real-time, omnichannel analysis and visualization let companies make better decisions with a holistic view of their business and the context behind every customer action.

Learn more about Customer Journey Analytics by watching the overview video .

https://business.adobe.com/blog/perspectives/introducing-adobes-customer-journey-maturity-model

https://business.adobe.com/blog/how-to/create-customer-journey-maps

https://business.adobe.com/blog/basics/what-is-customer-journey-map

Effective customer journey design: consumers’ conception, measurement, and consequences

- Original Empirical Research

- Published: 07 January 2019

- Volume 47 , pages 551–568, ( 2019 )

Cite this article

- Christina Kuehnl 1 ,

- Danijel Jozic 2 &

- Christian Homburg 3 , 4

26k Accesses

165 Citations

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

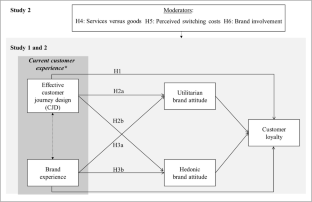

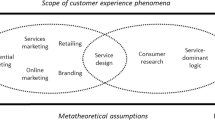

Recently, practitioners have begun appraising an effective customer journey design (CJD) as an important source of customer value in increasingly complex and digitalized consumer markets. Research, however, has neither investigated what constitutes the effectiveness of CJD from a consumer perspective nor empirically tested how it affects important variables of consumer behavior. The authors define an effective CJD as the extent to which consumers perceive multiple brand-owned touchpoints as designed in a thematically cohesive, consistent, and context-sensitive way. Analyzing consumer data from studies in two countries (4814 consumers in total), they provide evidence of the positive influence of an effective CJD on customer loyalty through brand attitude—over and above the effects of brand experience. Importantly, an effective CJD more strongly influences utilitarian brand attitudes, while brand experience more strongly affects hedonic brand attitudes. These underlying mechanisms are also prevalent when testing for the contingency factors services versus goods, perceived switching costs, and brand involvement.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Online influencer marketing

Customer experience: fundamental premises and implications for research

The customer value proposition: evolution, development, and application in marketing.

A multi-group analysis comparing path coefficients across industries indicated that some industries (fast-moving consumer goods, information and communication technology, and restaurant) show a significant, positive effect while other industries show a non-significant effect for H4a in Study 2. These differences might explain the non-significant finding for this effect in Study 2.

Testing for alternative models by removing paths (as proposed in H1 and brand experience ➔ customer loyalty) from the suggested model shows deterioration in model fit, while adding paths (brand experience ➔ CJD, or vice versa, or experience ⇆ CJD) shows no improvement in model fit or explained variance of our dependent variable customer loyalty. We therefore keep the suggested model in the interest of parsimony.

Anderl, E., Becker, I., von Wangenheim, F., & Schumann, J. H. (2016). Mapping the customer journey: Lessons learned from graph-based online attribution modeling. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 33 (3), 457–474.

Article Google Scholar

Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (2012). Specification, evaluation, and interpretation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40 (1), 8–34.

Batra, R., & Keller, K. L. (2016). Integrating marketing communications: New findings, new lessons, and new ideas. Journal of Marketing, 80 (6), 122–145.

Baxendale, S., Macdonald, E. K., & Wilson, H. N. (2015). The impact of different touchpoints on brand consideration. Journal of Retailing, 91 (2), 235–253.

Berry, L. L., Wall, E. A., & Carbone, L. P. (2006). Service clues and customer assessment of the service experience: Lessons from marketing. Academy of Management Perspectives, 20 (2), 43–57.

Blocker, C. P., Flint, D. J., Myers, M. B., & Slater, S. F. (2011). Proactive customer orientation and its role for creating customer value in global markets. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39 (2), 216–233.

Brakus, J. J., Schmitt, B. H., & Zarantonello, L. (2009). Brand experience: What is it? How is it measured? Does it affect loyalty? Journal of Marketing, 73 (3), 52–68.

Burnham, T. A., Frels, J. K., & Mahajan, V. (2003). Consumer switching costs: A typology, antecedents, and consequences. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 31 (2), 109–126.

Calder, B. J., Isaac, M. S., & Malthouse, E. C. (2016). How to capture consumer experiences: A context-specific approach to measuring engagement: Predicting consumer behavior across qualitatively different experiences. Journal of Advertising Research, 56 (1), 39–352.

Castaño, R., Sujan, M., Kacker, M., & Sujan, H. (2008). Managing consumer uncertainty in the adoption of new products: Temporal distance and mental simulation. Journal of Marketing Research, 45 (3), 320–336.

Churchill, G. A., Jr. (1979). A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. Journal of Marketing Research, 16 (1), 64–73.

Dick, A. S., & Basu, K. (1994). Customer loyalty: Toward an integrated conceptual framework. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 22 (2), 99–113.

Duncan, T., & Moriarty, S. (2006). How integrated marketing communication's “touchpoints” can operationalize the service-dominant logic. In R. F. Lusch & S. L. Vargo (Eds.), The service-dominant logic of marketing: Dialog, debate, and directions (pp. 236–249). Armonk: M.E. Sharpe.

Google Scholar

Emrich, O., & Verhoef, P. C. (2015). The impact of a homogenous versus a prototypical web design on online retail patronage for multichannel providers. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 32 (4), 363–374.

Epp, A. M., & Price, L. L. (2011). Designing solutions around customer network identity goals. Journal of Marketing, 75 (2), 36–54.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18 (1), 39–50.

Gerbing, D. W., & Anderson, J. C. (1988). An updated paradigm for scale development incorporating unidimensionality and its assessment. Journal of Marketing Research, 25 (2), 186–192.

Grewal, D., Levy, M., & Kumar, V. (2009). Customer experience management in retailing: An organizing framework. Journal of Retailing, 85 (1), 1–14.

Grohmann, B., Spangenberg, E. R., & Sprott, D. E. (2007). The influence of tactile input on the evaluation of retail product offerings. Journal of Retailing, 83 (2), 237–245.

Gruber, M., De Leon, N., George, G., & Thompson, P. (2015). Managing by design. Academy of Management Journal, 58 (1), 1–7.

Guo, L., Gruen, T. W., & Tang, C. (2017). Seeing relationships through the lens of psychological contracts: The structure of consumer service relationships. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45 (3), 357–376.

Hamilton, R. (2016). Consumer-based strategy: Using multiple methods to generate consumer insights that inform strategy. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 44 (3), 281–285.

Hamilton, R. W., & Thompson, D. V. (2007). Is there a substitute for direct experience? Comparing consumers' preferences after direct and indirect product experiences. Journal of Consumer Research, 34 (4), 546–555.

Homburg, C., Schwemmle, M., & Kuehnl, C. (2015). New product design: Concept, measurement, and consequences. Journal of Marketing, 79 (3), 41–56.

Homburg, C., Jozic, D., & Kuehnl, C. (2017). Customer experience management: Toward implementing an evolving marketing concept. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45 (3), 377–401.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1995). Evaluating model fit. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Structural equation modeling. Concepts, issues, and application (pp. 76–99). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Hulland, J., Baumgartner, H., & Smith, K. M. (2018). Marketing survey research best practices: Evidence and recommendations from a review of JAMS articles. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 46 (1), 92–108.

Jones, M. A., Mothersbaugh, D. L., & Beatty, S. E. (2000). Switching barriers and repurchase intentions in services. Journal of Retailing, 76 (2), 259–274.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow . New York: Farra, Straus, and Giroux.

Keller, K. L. (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. Journal of Marketing, 57 (1), 1–22.

Keller, K. L., & Lehmann, D. R. (2006). Brands and branding: Research findings and future priorities. Marketing Science, 25 (6), 740–759.

Kent, R. J., & Allen, C. T. (1994). Competitive interference effects in consumer memory for advertising: The role of brand familiarity. Journal of Marketing, 58 (3), 97–105.

Lemke, F., Clark, M., & Wilson, H. (2011). Customer experience quality: An exploration in business and consumer contexts using repertory grid technique. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39 (6), 846–869.

Lemon, K. N., & Verhoef, P. C. (2016). Understanding customer experience throughout the customer journey. Journal of Marketing, 80 (6), 69–96.

Li, H. A., & Kannan, P. K. (2014). Attributing conversions in a multichannel online marketing environment: An empirical model and a field experiment. Journal of Marketing Research, 51 (1), 40–56.

Liberman, N., & Trope, Y. (1998). The role of feasibility and desirability considerations in near and distant future decisions: A test of temporal construal theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75 (1), 5–18.

Liberman, N., Trope, Y., & Wakslak, C. (2007). Construal level theory and consumer behavior. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 17 (2), 113–117.

Lindell, M. K., & Whitney, D. J. (2001). Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86 (1), 114–121.

Lovett, M., Peres, R., & Shachar, R. (2014). A data set of brands and their characteristics. Marketing Science, 33 (4), 609–617.

Maechler, N., Neher, K., & Park, R. (2016). From touchpoints to journeys: The competitive edge in seeing the world through the customer’s eyes. McKinsey Insights, 1 (March), 14–23.

Malär, L., Krohmer, H., Hoyer, W. D., & Nyffenegger, B. (2011). Emotional brand attachment and brand personality: The relative importance of the actual and the ideal self. Journal of Marketing, 75 (4), 35–52.

Malär, L., Nyffenegger, B., Krohmer, H., & Hoyer, W. D. (2012). Implementing an intended brand personality: A dyadic perspective. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40 (5), 728–744.

Mano, H., & Oliver, R. L. (1993). Assessing the dimensionality and structure of the consumption experience: Evaluation, feeling, and satisfaction. Journal of Consumer Research, 20 (3), 451–466.

Montoya-Weiss, M. M., Voss, G. B., & Grewal, D. (2003). Determinants of online channel use and overall satisfaction with a relational, multichannel service provider. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 31 (4), 448–458.

Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory . New York: McGraw-Hill.

Oh, L.-B., Teo, H.-H., & Sambamurthy, V. (2012). The effects of retail channel integration through the use of information technologies on firm performance. Journal of Operations Management, 30 (5), 368–381.

Panagopoulos, N. G., Rapp, A. A., & Ogilvie, J. L. (2017). Salesperson solution involvement and sales performance: The contingent role of supplier firm and customer–supplier relationship characteristics. Journal of Marketing, 81 (4), 144–164.

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A., & Berry, L. L. (1985). A conceptual model of service quality and its implications for future research. Journal of Marketing, 49 (4), 41–50.

Park, C. W., Milberg, S., & Lawson, R. (1991). Evaluation of brand extensions: The role of product feature similarity and brand concept consistency. Journal of Consumer Research, 18 (2), 185–193.

Patrício, L., Fisk, R. P., & Falcão e Cunha, J. (2008). Designing multi-interface service experiences: The service experience blueprint. Journal of Service Research, 10 (4), 318–334.

Patrício, L., Fisk, R. P., & Constantine, L. (2011). Multilevel service design: From customer value constellation to service experience blueprinting. Journal of Service Research, 10 (4), 318–334.

Payne, A., & Frow, P. (2005). A strategic framework for customer relationship management. Journal of Marketing, 69 (4), 167–176.

Payne, A., Storbacka, K., & Frow, P. (2008). Managing the co-creation of value. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36 (1), 83–96.

Pine, B. J., & Gilmore, J. H. (1998). Welcome to the experience economy. Harvard Business Review, 76 (4), 97–105.

Pisani, J. (2018) https://eu.usatoday.com/story/tech/news/2018/09/05/amazon-quadruples-order-vans-new-delivery-fleet-now-20-000/1204619002/ . Accessed 1 Nov 2018.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88 (5), 879–903.

Puccinelli, N. M., Goodstein, R. C., Grewal, D., Price, R., Raghubir, P., & Stewart, D. (2009). Customer experience management in retailing: Understanding the buying process. Journal of Retailing, 85 (1), 15–30.

Richardson, A. (2010). Using customer journey maps to improve customer experience. Harvard Business Review, 15 (1), 2–5.

Rossiter, J. R. (2002). The C-OAR-SE procedure for scale development in marketing. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 19 (4), 305–335.

Schmitt, B. (2003). Customer experience management: A revolutionary approach to connecting with your customers . Hoboken: Wiley.

Seiders, K., Voss, G. B., Godfrey, A. L., & Grewal, D. (2007). SERVCON: Development and validation of a multidimensional service convenience scale. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 35 (1), 144–156.

Simoes, C., Dibb, S., & Fisk, R. P. (2005). Managing corporate identity: An internal perspective. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 33 (2), 153–168.

Srinivasan, S., Rutz, O. J., & Pauwels, K. (2016). Paths to and off purchase: Quantifying the impact of traditional marketing and online consumer activity. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 44 (4), 440–453.

Steenkamp, J. B. E., & Baumgartner, H. (1998). Assessing measurement invariance in cross-national consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 25 (1), 78–90.

Tax, S. S., McCutcheon, D., & Wilkinson, I. F. (2013). The service delivery network (SDN): A customer-centric perspective of the customer journey. Journal of Service Research, 16 (4), 454–470.

Teixeira, J., Patrício, L., Nunes, N. J., Nóbrega, L., Fisk, R. P., & Constantine, L. (2012). Customer experience modeling: From customer experience to service design. Journal of Service Management, 23 (3), 362–376.

The Economist (2015). Computing, fast and slow. http://www.economist.com/news/business/21639514-ibm-not-about-go-down-life-cloud-will-be-tough-computing-fast-and-slow . Accessed 2 Aug 2018.

Trope, Y., & Liberman, N. (2003). Temporal construal. Psychological Review, 110 (3), 403–421.

Trope, Y., Liberman, N., & Wakslak, C. (2007). Construal levels and psychological distance: Effects on representation, prediction, evaluation, and behavior. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 17 (2), 83–95.

Verhoef, P. C., Lemon, K. N., Parasuraman, A., Roggeveen, A., Tsiros, M., & Schlesinger, L. A. (2009). Customer experience creation: Determinants, dynamics and management strategies. Journal of Retailing, 85 (1), 31–41.

Vomberg, A., Homburg, C., & Bornemann, T. (2015). Talented people and strong brands: The contribution of human capital and brand equity to firm value. Strategic Management Journal, 36 (13), 2122–2131.

Voss, K. E., Spangenberg, E. R., & Grohmann, B. (2003). Measuring the hedonic and utilitarian dimensions of consumer attitude. Journal of Marketing Research, 40 (4), 310–320.

Wang, G., & Netemeyer, R. G. (2002). The effects of job autonomy, customer demandingness, and trait competitiveness on salesperson learning, self-efficacy, and performance. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 30 (3), 217–228.

Whan Park, C., MacInnis, D. J., Priester, J., Eisingerich, A. B., & Iacobucci, D. (2010). Brand attachment and brand attitude strength: Conceptual and empirical differentiation of two critical brand equity drivers. Journal of Marketing, 74 (6), 1–17.

Wirtz, J., Xiao, P., Chiang, J., & Malhotra, N. (2014). Contrasting the drivers of switching intent and switching behavior in contractual service settings. Journal of Retailing, 90 (4), 463–480.

Yang, X., Mao, H., & Peracchio, L. A. (2012). It's not whether you win or lose, it's how you play the game? The role of process and outcome in experience consumption. Journal of Marketing Research, 49 (6), 954–966.

Zaichkowsky, J. L. (1985). Measuring the involvement construct. Journal of Consumer Research, 12 (3), 341–352.

Zeithaml, V. A. (1981). How consumer evaluation processes differ between goods and services. In J. H. Donnelly & W. R. George (Eds.), Marketing of services (pp. 186–190). Chicago: American Marketing Association.

Zhao, X., Lynch, J. G., Jr., & Chen, Q. (2010). Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 37 (2), 197–206.

Zomerdijk, L. G., & Voss, C. A. (2010). Service design for experience-centric services. Journal of Service Research, 13 (1), 67–82.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Michael Paul, Bernd Schmitt, and Peter Verhoef for their helpful comments on a previous version of the paper. The valuable discussions with Ajay Kohli and the participants of the JAMS Thought Leaders’ Conference and EMAC 2017 are also gratefully acknowledged. Finally, the authors thank the review team for the constructive suggestions.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

ESB Business School, Reutlingen University, 72762, Reutlingen, Germany

Christina Kuehnl

Mainz, Germany

Danijel Jozic

University of Mannheim, 68131, Mannheim, Germany

Christian Homburg

University of Manchester, Manchester, UK

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Christina Kuehnl .

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 22.1 kb)

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Kuehnl, C., Jozic, D. & Homburg, C. Effective customer journey design: consumers’ conception, measurement, and consequences. J. of the Acad. Mark. Sci. 47 , 551–568 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-018-00625-7

Download citation

Received : 13 August 2017

Accepted : 10 December 2018

Published : 07 January 2019

Issue Date : 15 May 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-018-00625-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Effective customer journey design

- Touchpoints

- Customer journey

- Brand experience

- Scale development

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

The Man Behind the Myth: Should We Question the Hero’s Journey?

By sarah e. bond , joel christensen august 12, 2021.

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2021%2F08%2Fodysseus_statue.png)

Campbell passingly cites the stories of Buddhism, Aztec myth, and Ovid's Metamorphoses as examples of virgin birth, then goes on to recount in detail a Tongan folk tale he calls “queer” about a mother giving birth to a clam, which in tum becomes pregnant from eating a coconut husk and gives birth to a human boy. Campbell never specifically explains exactly how the image of virgin birth fits into the heroic cycle as he sets it up.

LARB Contributor s

LARB Staff Recommendations

Undisciplining victorian studies.

"What we ultimately wish to fight for is the freedom of scholars of color to work on any object, topic, and methodology they choose."

Ronjaunee Chatterjee , Alicia Mireles Christoff , Amy R. Wong Jul 10, 2020

Tradition and Its Discontents

Max Norman reviews "Gilgamesh: The Life of a Poem" by Michael Schmidt and "Reading Old Books" by Peter Mack.

Max Norman Dec 19, 2019

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

LIFE IS A JOURNEY

Where will your journey take you.

"Your journey never ends. Life has a way of changing things in incredible ways." --- Alexander Volkov

Life is a journey filled with lessons, hardships, heartaches, joys, celebrations and special moments that will ultimately lead us to our destination, our purpose in life. The road will not always be smooth; in fact, throughout our travels, we will encounter many challenges .

Some of these challenges will test our courage, strengths, weaknesses, and faith. Along the way, we may stumble upon obstacles that will come between the paths that we are destined to take.

In order to follow the right path, we must overcome these obstacles. Sometimes these obstacles are really blessings in disguise, only we don't realize that at the time.

Along our journey we will be confronted with many situations, some will be filled with joy, and some will be filled with heartache. How we react to what we are faced with determines what kind of outcome the rest of our journey through life will be like.

When things don't always go our way, we have two choices in dealing with the situations.

- We can focus on the fact that things didn't go how we had hoped they would and let life pass us by, or

- We can make the best out of the situation and know that these are only temporary setbacks and find the lessons that are to be learned.

"Going by my past journey, I am not certain where life will take me, what turns and twists will happen; nobody knows where they will end up. As life changes direction, I'll flow with it." --- Katrina Kaif

Time stops for no one , and if we allow ourselves to focus on the negative we might miss out on some really amazing things that life has to offer. We can't go back to the past, we can only take the lessons that we have learned and the experiences that we have gained from it and move on. It is because of the heartaches, as well as the hardships, that in the end help to make us a stronger person.

The people that we meet on our journey, are people that we are destined to meet. Everybody comes into our lives for some reason or another and we don't always know their purpose until it is too late. They all play some kind of role. Some may stay for a lifetime; others may only stay for a short while.

It is often the people who stay for only a short time that end up making a lasting impression not only in our lives, but in our hearts as well. Although we may not realize it at the time, they will make a difference and change our lives in a way we never could imagine. To think that one person can have such a profound affect on your life forever is truly a blessing. It is because of these encounters that we learn some of life's best lessons and sometimes we even learn a little bit about ourselves.

People will come and go into our lives quickly, but sometimes we are lucky to meet that one special person that will stay in our hearts forever no matter what. Even though we may not always end up being with that person and they may not always stay in our life for as long as we like, the lessons that we have learned from them and the experiences that we have gained from meeting that person, will stay with us forever.

It's these things that will give us strength to continue on with our journey. We know that we can always look back on those times of our past and know that because of that one individual, we are who we are and we can remember the wonderful moments that we have shared with that person.

"Life is a journey of either Fate or Destiny. Fate is the result of giving in to one's wounds and heartaches. Your Destiny unfolds when you rise above the challenges of your life and use them as Divine opportunities to move forward to unlock your higher potential." --- Caroline Myss

Memories are priceless treasures that we can cherish forever in our hearts. They also enables us to continue on with our journey for whatever life has in store for us. Sometimes all it takes is one special person to help us look inside ourselves and find a whole different person that we never knew existed. Our eyes are suddenly opened to a world we never knew existed- a world where time is so precious and moments never seem to last long enough.

Throughout this adventure, people will give you advice and insights on how to live your life but when it all comes down to it, you must always do what you feel is right .

Always follow your heart, and most importantly never have any regrets. Don't hold anything back. Say what you want to say, and do what you want to do, because sometimes we don't get a second chance to say or do what we should have the first time around.

It is often said that what doesn't kill you will make you stronger. It all depends on how one defines the word "strong." It can have different meanings to different people.

In this sense, "stronger" means looking back at the person you were and comparing it to the person you have become today. It also means looking deep into your soul and realizing that the person you are today couldn't exist if it weren't for the things that have happened in the past or for the people that you have met.

Everything that happens in our life happens for a reason and sometimes that means we must face heartaches in order to experience joy.

Copyright © 2000 Shannon Spaunburg

Stories From January 2001

- Go To Your Previous Page

- Find More Quotes or Stories

- Home - Start Over

More Stories For Life

- How To Turn A Setback Into Triumph

- It Will Be Worth It

- Keep It Moving (Your Life)

- Life Is Like Poker

- Do More Each Day

- It’s Never Too Late (For Your Dreams)

- Face Your Fears

- == Explore Hundreds Of Stories ==

Other Publications

- Thoughts Of The Day

- Motivational Quotes

- Inspiring Quotes

- Success Quotes

- Leadership Quotes

- Quotes For Teachers

- Teen Quotes

- Submit A Positive Quote

- Web Quote Of The Day

- Our Latest Email Quotes

- Archived Email Pictures

- Daily Email – Come Join Us!

- Stories Articles Poems

- Submit Your Story

- Navigation – Site Maps

- Visitor Comments

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

The Metamorphosis of the Hero: Principles, Processes, and Purpose

This article examines the phenomenon of heroic metamorphosis: what it is, how it unfolds, and why it is important. First, we describe six types of transformation of the hero: mental, moral, emotional, spiritual, physical, and motivational. We then argue that these metamorphoses serve five functions: they foster developmental growth, promote healing, cultivate social unity, advance society, and deepen cosmic understanding. Internal and external sources of transformation are discussed, with emphasis on the importance of mentorship in producing metamorphic growth. Next we describe the three arcs of heroic transformation: egocentricity to sociocentricity, dependence to autonomy, and stagnation to growth. We then discuss three activities that promote heroic metamorphosis as well as those that hinder it. Implications for research on human growth and development are discussed.

Introduction

One of the most revered deities in Hinduism is Ganesha, a god symbolizing great wisdom and enlightenment. Ganesha’s most striking attribute is his unusual appearance. In images throughout India and southeast Asia, he is shown to be a man with an ordinary human body and the head of an elephant. According to legend, when Ganesha was a boy, he behaved foolishly in preventing his father Shiva from entering his own home. Shiva realized that his son needed an entirely new way of thinking, a fresh way of seeing the world. To achieve this aim, Shiva cut off Ganesha’s human head and replaced it with that of an elephant, an animal representing unmatched wisdom, intelligence, reflection, and listening. Ganesha was transformed from a naïve boy operating with little conscious awareness into a strong, wise, and fully awakened individual.

This article is about how people undergo dramatic, positive change. We focus on heroic metamorphosis – what it is, how it comes about, and why it’s important. Unlike Ganesha, one need not undergo dramatic physical change to experience heroic transformation. One must engage in any of three types of activities that we describe in this article: (1) training regimens, (2) spiritual practices, and (3) the hero’s journey. Anyone who transforms as a result of these activities emerges a brand-new person, a much-improved version of one’s previous self. Metamorphosis and transformation are both defined as “changing form,” a process that precisely describes the massive alteration undergone by Ganesha. Having undergone the hero’s journey as the pathway to transformation, Ganesha sees the world with greater clarity and insight. The hero’s journey inevitably involves setback, suffering, and a death of some type. What dies is usually the former self, the untransformed version of oneself that sees the world “through a glass darkly” ( Bergman, 1961 ). Ganesha’s decapitation happens to us all metaphorically; the journey marks the death of a narrow, immature way of seeing the world and the birth of a wider, more enlightened way of viewing life.

Overview of Heroic Metamorphosis

Metamorphic change pervades the natural world, from the changing of the seasons to biological growth and decay ( Wade, 1998 ; Allison, 2015 ; Efthimiou, 2015 ). The universe itself is subject to immense transformation on both a microscopic scale as well as a trans -universal scale. Biological cells grow, mutate, and die, and on a much grander scale the galaxies of the universe are in a constant state of flux. Darwinian theory portrays all of life as engaged in an inescapable struggle to survive in response to ever-changing circumstances. Life presents an ultimatum to all organisms: change as all phenomena in the universe must change, or fall.

Heroic transformation appears to be a prized and universal phenomenon that is cherished and encouraged in all human societies ( Allison and Goethals, 2017 ; Efthimiou and Franco, 2017 ; Efthimiou et al., 2018a , b ). Surprisingly, until the past decade there has been almost no scholarship on the topic of heroic transformation. Two early seminal works in psychology offered hints about the processes involved in dramatic change and growth in human beings. In 1902, William James addressed the topic of spiritual conversion in his classic volume, The Varieties of Religious Experience . These conversion experiences bear a striking similarity to descriptions of the hero’s transformation as reported by famed mythologist Campbell (1949) . These experiences included feelings of peace, clarity, union with all of humanity, newness, happiness, generosity, and being part of something bigger than oneself. James emphasized the pragmatic side of religious conversion, noting that the mere belief and trust in a deity could bring about significant positive change independent of whether the deity actually exists. This pragmatic side of spirituality is emphasized today by Thich Nhat Hanh, who observes that transformation as a result of following Buddhist practices can occur in the absence of a belief in a supreme being. Millions of Buddhists have enjoyed the transformative benefits of religion described by James simply by practicing the four noble truths and the noble eightfold path ( Hanh, 1999 , p. 170).

The second early psychological treatment of human transformation was published in 1905 by Sigmund Freud. His Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality described life-altering transformative stages in childhood involving oral, anal, phallic, and latent developmental patterns. None of these changes were particularly “heroic” but they did underscore Freud’s belief in the inevitability of immense psychological change. Although Freud suggested that people tend to resist change in adulthood, several subsequent schools of psychological thought have since proposed mechanisms for transformative change throughout the human lifespan. Humanistic theories, in particular, have embraced the idea that humans are capable of a long-term transformation into self-actualized individuals (e.g., Maslow, 1943 ). Developmental psychologists have also proposed models of transformative growth throughout human life (e.g., Erikson, 1994 ). Recent theories of self-processes portray humans as open to change and growth under some conditions ( Sedikides and Hepper, 2009 ) but resistant under others ( Swann, 2012 ). In the present day, positive psychologists are uncovering key mechanisms underlying healthy transformative growth in humans ( Lopez and Snyder, 2011 ; Seligman, 2011 ).

An important source of transformation resides in tales of heroism told and re-told to countless generations throughout the ages. These mythologies reflect humanity’s longing for transformative growth, and they are packed with wisdom and inspiration ( Allison and Goethals, 2014 ). Just reading, hearing, or observing stories of heroism can stir us and transform us.

According to Campbell (2004 , p. xvi), these hero tales “provide a field in which you can locate yourself” and they “carry the individual through the stages of life” (p. 9). The resultant transformations seen in heroic stories “are infinite in their revelation” ( Campbell, 1988 , p. 183). Rank (1909 , p. 153) observed that “everyone is a hero in birth, where he undergoes a tremendous psychological as well as physical transformation, from the condition of a little water creature living in a realm of amniotic fluid into an air-breathing mammal.” This transformation at birth foreshadows a lifetime of transformative journeys for human beings.

According to Allison and Goethals (2013 , 2017 ), hero stories reveal three different targets of heroic transformation: setting, self , and society . These three loci of transformations parallel Campbell’s (1949) three major stages of the hero’s journey: departure (or separation), initiation, and return. The departure from the hero’s familiar world represents a transformation of one’s normal, safe environment; the initiation stage is awash with challenge, suffering, mentoring, and transformative growth; and the final stage of return represents the hero’s opportunity to use her newfound gifts to transform the world. The sequence of these stages is critical, with each transformation essential for producing the next one.

Without a change in setting, the hero cannot change herself, and without a change in herself, the hero cannot change the world. Our focus here is on the hero’s transformation of the self, but this link in the chain necessarily requires some consideration of the links preceding and following it. The mythic hero must be cast out of her familiar world and into a different world, otherwise there can be no departure from her status quo. Once transformed, the hero must use her newly enriched state to better the world, otherwise the hero’s transformation lacks social significance.

The hero’s transformation plays a pivotal role in her ability to achieve her objectives on the journey. During the quest, “ineffable realizations are experienced” and “things that before had been mysterious are now fully understood” ( Campbell, 1972 , p. 219). The ineffability of these new insights stems from their unconscious origins. Jungian principles of the collective unconscious form the basis of Campbell’s theorizing about hero mythology. Le Grice (2013 , p. 153) notes that “myths are expressions of the imagination, shaped by the archetypal dynamics of the psyche.” As such, the many recurring elements of the mythic hero’s journey have their “inner, psychological correlates” ( Campbell, 1972 , p. 153). The hero’s journey is packed with social symbols and motifs that connect the hero to her deeper self, and these unconscious images must be encountered, and conflicts with them must be resolved, to bring about transformation ( Campbell, 2004 ). Overall, the hero’s outer journey is a representation of an inner, psychological journey that involves “leaving one condition and finding the source of life to bring you forth into a richer or mature condition” ( Campbell, 1988 , p. 152).

Allison and Smith (2015) identified five types of heroic transformation: physical, emotional, spiritual, mental, and moral. A sixth type, motivational transformation, was later proposed by Allison and Goethals (2017) . These six transformation types span two broad categories: physical transformation, which we call transmutation , and psychological transformation, which we call enlightenment . Physical transmutations are endemic to ancient mythologies that featured transforming humans into stars, statues, and animals. Today, transmutation pervades superhero tales of ordinary people succumbing to industrial accidents and spider bites that physically transform them into superheroes and supervillains. These ancient and modern tales of transmutation offer symbolism of the hidden powers residing within each of us, powers that emerge only after dramatic situations coax them out of hibernation. Efthimiou (2015 , 2017 ), Franco et al. (2016) , and Efthimiou and Allison (2017) have written at length about the power and potential of biological transmutation to change the world. The phenomenon of neurogenesis refers to the development of new brain cells in the hippocampus through exercise, diet, meditation, and learning. This transmutative healing and growing can occur even after catastrophic brain trauma. Efthimiou (2017) describes many examples of transmutation occurring as a result of regeneration or restoration processes that refer to an organism’s ability to grow, heal, and re-create itself.

Epigenetic changes in DNA and the science of human limb regeneration are two examples of modern day heroic transmutations ( Efthimiou, 2015 ).

The other five types of heroic transformation – moral, mental, emotional, spiritual, and motivational – comprise the second broad category of transformation that we call enlightenment. Emotional transformations refer to “changes of the heart” ( Allison and Smith, 2015 , p. 23) involving growth in empathic concern for others; we call this transformation compassion .

Spiritual transformations refer to changes in belief systems about the spiritual world and about the workings of life, the world, and the universe; we call this change transcendence . Mental transformations refer to leaps in intellectual growth and significant increases in illuminating insights about oneself and others; we label this wisdom . Moral transformations occur when heroes undergo a dramatic shift from immorality to morality; we call this redemption . Finally, a motivational transformation refers to a complete shift in one’s purpose or perceived direction in life; we label this change a calling (see also Dik et al., 2017 ).

Purpose of the Hero’s Transformation

The purpose of the hero’s journey is to provide a context or blueprint for human metamorphosis. Why do we need such life-changing growth? Allison and Setterberg (2016) argue that people are born “incomplete” psychologically and will remain incomplete until they encounter challenges that produce suffering and require sacrifice to resolve. Transcending life’s challenges enables the hero to “undergo a truly heroic transformation of consciousness,” requiring them “to think a different way” ( Campbell, 1988 , p. 155). This shift offers a new “map or picture of the universe and allows us to see ourselves in relationship to nature” ( Campbell, 1991 , p. 56). Buddhist traditions and twelve-step programs of recovery refer to transformation as an awakening. Using similar language, Campbell (2004 , p. 12) described the function of the journey as a necessary voyage designed to “wake you up.” The long-term survival of the human race may depend on such an awakening, as it becomes increasingly clear that the unawakened, pre-transformed state is unsustainable at the collective level. As individuals, transformation is necessary for our psychological, emotional, social, and spiritual well-being. Collectively, the survival of our planet may depend on broader, enlightened thinking from leaders who must be transformed themselves if they are to make wise decisions about human rights, climate change, peace and war, healthcare, education, and myriad other pressing issues. Nearly 50 years ago, Heschel (1973) opined that “the predicament of contemporary man is grave. We seem to be destined either for a new mutation or for destruction” (p. 176, italics added).

Allison and Goethals (2017) propose five reasons why transformation is such a key element in the hero’s journey, and why it is essential for promoting our own and others’ welfare. First, transformations foster developmental growth. Early human societies understood the usefulness of initiation rituals in promoting the transition from childhood to adulthood ( van Gennep, 1909 ). A number of scholars, including Campbell, have pointed to the failure of our postmodern society to appreciate the psychological value of rites and rituals ( Campbell, 1988 ; Rohr, 2011b ; Le Grice, 2013 ). Stories of young people “coming-of-age” are common in mythic hero tales about children “awakening to the new world that opens at adolescence” ( Campbell, 1988 , p. 167). The hero’s journey “helps us pass through and deal with the various stages of life from birth to death” ( Campbell, 1991 , p. 56).

The second function of heroic transformation is that it promotes healing. Allison and Goethals (2016) argue that sharing stories about hero transformations can offer many of the same benefits as group therapy ( Yalom and Leszcz, 2005 ). These benefits include the promotion of hope; the benefit of knowing that others share one’s emotional experiences; the fostering of self-awareness; the relief of stress; and the development of a sense of meaning about life. A growing number of clinical psychologists invoke hero transformations to help their clients acquire the heroic attributes of strength, resilience, and courage ( Grace, 2016 ). Recent research on post-traumatic growth demonstrates that people can overcome severe trauma and even use it to transform themselves into stronger, healthier persons than they were before the trauma ( Ramos and Leal, 2013 ).

The third function of transformations focuses on their ability to promote social unity.