Antarctica Exploration Timeline

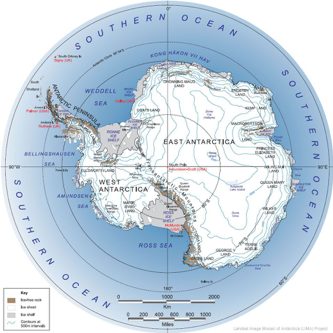

Lt. Charles Wilkes led the U.S. Exploring Expedition to Antarctica in five ships. He charted Wilkes Land south of Australia and was first to recognize Antarctica as a continent.

An American sealer, Nathanial Palmer, discovered mountain peaks in Graham Land on the Antarctic Peninsula.

1837 – 1840

Dumont d’Urville discovered Adelie Land south of Australia and claimed it for France.

1839 – 1843

The British naval officer James Clark Ross circumnavigated Antarctica and entered the Ross Sea where he discovered Ross Island. He named two mountains on the island after his ships the H.M.S. Erebus and H.M.S. Terror .

1898 – 1900

The Norwegian Carsten Borchgrevink lead an expedition from Britain which explored the coast of Victoria Land south of New Zealand. Borchgrevink and 10 men wintered over at Cape Adare. These were the first men to intentionally spend the winter in Antarctica.

1901 – 04

Commander Robert Falcon Scott commanded the British National Antarctic Expedition. Discovery Hut was built on Ross Island in McMurdo Sound as winter over-lodging. Scott, Edward Wilson, and Ernest Shackleton attempted to reach the South Pole in late 1902 but were forced to turn back 530 miles short of their goal due to a shortage of supplies.1901-1904

1907 – 09

Ernest Shackleton led the British Antarctic Expedition to Antarctica and established a winter-over hut at Cape Royds on Ross Island. Shackleton and three companions attempted to reach the South Pole but were forced to turn back 97 miles short of their goal due to a shortage of food and low temperatures.

The Norwegian Roald Amundsen established his Framheim base camp on the Ross Ice Shelf at the Bay of Whales. Amundsen and four companions used skis and sled dogs to be the first to reach the geographic South Pole on December 14, 1911. The 1,600 mile round trip to the South Pole and back took 99 days.

1910 – 1912

Captain Scott returned to Ross Island on his ship the Terra Nova with the stated objective of being first to reach the South Pole. Scott and four companions reached 90 degrees South on January 17, 1912, over a month after Amundsen. Bitterly disappointed, the party turned back towards Ross Island only to perish during the journey weakened by starvation, scurvy, and deteriorating weather conditions.

1911 – 1914

Douglas Mawson landed at Cape Denison on Commonwealth Bay and established a base camp. Mawson and two companions used sled dogs to explore the icecap in the vicinity of the South Magnetic Pole. One man fell in a crevasse, another died of starvation, and Mawson was forced to return to Cape Denison alone only to find his ship the Aurora had left without him. He was forced to spend a second winter over with six companions.

1914 – 16

With the prize of the South Pole claimed by Amundsen, Shackleton returned to Antarctica to attempt the first ever crossing of the continent. His ship the Endurance was crushed by sea ice in the Weddell Sea so Shackleton and his crew were forced to sail to Elephant Island in three small open boats. Incredibly Shackleton and five companions then sailed over 700 miles in 15 days in a small boat to South Georgia Island where, after crossing glacier clad mountains, they reached a whaling station. From there a rescue boat finally reached Elephant Island on the fourth attempt and rescued all hand safely.

1928 – 29

Sir Hubert Wilkins took two Lockheed Vega airplanes to Deception Island off the Antarctic Peninsula. From Deception Wilkins flew the first ever airplane flights over Antarctica.

1928 – 30

1933 – 35

Admiral Byrd returned to Antarctica and spent the first ever winter over in the interior of Antarctica, alone, at Advance Base 120 miles south of Little America. Byrd made daily weather observations but became very ill when carbon monoxide leaked from a faulty stove. Three men: Tom Poulter, Amory Waite, and Pete Demas traversed 120 miles to Advance Base in the dark of winter and in temperatures as low as -70 to nurse Byrd back to health and fly him back to Little America

Lincoln Ellsworth flew his Lockheed Gamma monoplane the Polar Star from Dundee Island at the tip of the Palmer Peninsula across the Antarctic continent to the Ross Ice Shelf. The plane ran out of fuel and landed near Byrd’s Little America camp. Due to a faulty radio Ellsworth and his pilot could not communicate their predicament to the outside world so they were declared missing. They were stranded at Little America for two months before being discovered and rescued.

1939 – 41

In 1939 Hitler sent the Third German Antarctic Expedition to chart the coast of Queen Maude Land. Nazi flags and symbols were distributed along the coast. In response President Roosevelt directed Admiral Byrd to lead the U.S. Antarctic Service, the first of Byrd’s expeditions to receive federal funding. Bases were established on the Palmer Peninsula and Ross Ice Shelf and extensive mapping and scientific research were carried out. American flags and benchmarks were left throughout the territory.

1946 – 47

After WWII Admiral Byrd led Operation Highjump to Antarctica. This was a huge expedition of 4,700 men, 13 ships (including an aircraft carrier), 19 airplanes, and a large contingent of scientists. Vast stretches of unexplored land from the Antarctic Peninsula to the Ross Ice Shelf to Wilkes Land south of Australia were mapped and the expedition returned with a large quantity of meteorological and scientific data.

1956 – 57

The United States launched Operation Deep Freeze I to Antarctica in preparation for the upcoming International Geophysical Year. Under the overall command of Admiral Byrd scientific bases were established at McMurdo Sound on Ross Island, the geographic South Pole, and Byrd Station in western Antarctica.

1957 – 58

12 nations cooperated in the International Geophysical Year (IGY) to establish 55 scientific stations in Antarctica. Extensive scientific research was carried out and this proved to be the genesis for the upcoming Antarctic Treaty ratified in 1961.

Under the leadership of Dr. Vivian Fuchs the British Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition completed the first overland traverse of Antarctica. The expedition departed from the Ronne Ice Shelf in West Antarctica, reached the South Pole, and continued on to Scott base in McMurdo Sound. Sir Edmond Hillary scouted a route from Scott Base to the South Pole and laid supply depots so the Fuchs contingent could continue on from the Pole back to Scott Base.

The Antarctic Treaty, signed by the 12 nations participating in the IGY, went into force in 1961. The Treaty preserves Antarctica for peaceful scientific study, sets aside all territorial claims, bars nuclear materials (weapons, power stations etc.), and prohibits military activity except in the support of science (ships, planes etc.). Since its inception a total of 53 nations have signed the treaty.

Sir Ranulpf Fiennes and his Trans Global Expedition team reached the South Pole on December 15, 1980. His expedition was the first to accomplish a circumnavigation of Earth from Pole to Pole.

1989 – 90

Will Steger led the first non-mechanized crossing of Antarctica using sled dogs. The 220 day journey covered 3,741 miles from the Antarctic Peninsula to the South Pole to the Russian Mirnyy station.

Exploring Antarctica - a timeline

From first sighting to reaching the South Pole, discover the history of exploring Antarctica

Follow the timeline of discovering Antarctica and the 'race' to the South Pole, from first sighting through to Scott, Amundsen, Shackleton and more.

To find out more about the past, present and future of polar exploration, visit the Polar Worlds and Poles Apart galleries for free at the National Maritime Museum .

- Early sightings

- The 'Heroic Age'

- Scott and Amundsen

- Shackleton and Endurance

- Later expeditions

7th century: Polynesian narratives of voyaging suggest that Māori people may have been the first to reach Antarctic waters. A 2021 paper published in the Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand researched oral traditions and other records, which suggest that Māori navigators 'were likely the first humans to set eyes on Antarctic waters and perhaps the continent.'

January 1773: Captain James Cook becomes the first recorded European navigator to cross the Antarctic Circle.

January 1820: Antarctica is 'first sighted' by European explorers. The first person to actually see the Antarctic mainland has been debated: in the last week of January, Thaddeus von Bellingshausen reported seeing 'an ice shore of extreme height' during a Russian expedition to the Antarctic.

Around the same time, Royal Navy officer Edward Bransfield reported seeing 'high mountains, covered with snow' during a British mapping expedition. Captain Cook's expedition 50 years previously never sighted land.

20 February 1823: Captain James Weddell sets a new record for the furthest south ever travelled by an Antarctic explorer. The Weddell Sea is named after him, as is the Weddell seal – the most southerly breeding land mammal in the world.

1831-32 Captain John Biscoe becomes the third person after Cook and Bellingshausen to circumnavigate Antarctica. During his expedition, he sights new areas of the continent including Enderby Land and Graham Land.

1839-41 James Clark Ross commands Erebus and Terror (the ships later to be lost during Franklin’s search for the North-West Passage ) to the Antarctic. During the expedition, Ross discovers the Ross Sea and Ross Ice Shelf: this region would later serve as the starting point for both Amundsen and Scott’s expeditions to the South Pole in 1911.

1898-99 The Belgian ship Belgica led by Adrien de Gerlache becomes the first vessel to spend a winter in the Antarctic after becoming trapped in ice for a year. Among the crew on the ship is Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen, later to become the first person to reach the South Pole.

1899 Norwegian Carsten Borchgrevink leads the first British expedition in what would come to be known as the ‘Heroic Age' of Antarctic exploration. Borchgrevink's expedition is the first to spend a winter on the Antarctic mainland, and the first to use dogs and sledges on the continent.

1901-1904 Captain Robert Falcon Scott leads his first expedition to the Antarctic in the specially built ship Discovery.

During the National Antarctic Expedition, Scott, Ernest Shackleton and EA Wilson travel to within 410 miles of the South Pole before they are forced to turn back on 30 December 1902. When they return to their base at the Discovery , the three men are described as ‘almost unrecognisable’, with ‘long beards, hair dirty, swollen lips & peeled complexions & blood-shot eyes’.

1907-1909 Ernest Shackleton leads the second British Antarctic Expedition on the Nimrod . On 9 January 1909, Shackleton, Frank Wild, Eric Marshall and Jameson Adams come within 97 miles of the South Pole, but the return trip almost costs them their lives. On 3 March, all four men finally arrive back at the Nimrod , after having initially been given up for dead by the men stationed on the ship.

1910 Robert Falcon Scott and Roald Amundsen both depart for Antarctica on their separate expeditions to reach the South Pole. Scott and his crew leave Cardiff on the Terra Nova on 15 June; Amundsen departs Kristiansand on 9 August on the Fram.

Amundsen had originally planned to make a bid for the North Pole, but changed his objective after two American explorers each claimed to have reached the goal. He only revealed his South Pole ambitions to his crew after he had set sail.

Scott discovered that he was in a ‘race’ on 13 October after landing in Melbourne, Australia. Amundsen’s brother Leon had sent Scott a telegram, simply saying: ‘Beg leave to inform you Fram proceeding Antarctica. Amundsen.'

15 October 1911 Amundsen sets out to reach the South Pole with five men, four sledges and 52 dogs, travelling to pre-prepared depots and killing dogs for food as they go. Seventeen of the original 52 dogs would make it to the Pole, and 12 made it back.

1 November 1911 Scott’s main party sets out. The initial plan included the use of ponies, dogs and tractors to carry supplies, with only the final push to the Pole using manpower alone.

However, setbacks and equipment failure meant that Scott would have to man-haul far further and on fewer provisions than he had originally planned.

15 December 1911 At 3pm Roald Amundsen becomes the first person to reach the South Pole. The five men – Amundsen, Helmer Hanssen, Olav Bjaaland, Sverre Hassel and Oscar Wisting – make careful observations of the site for the next two days, and leave behind messages and spare equipment for Scott’s party. The whole team arrive safely back at base camp on 26 January, having travelled more than 1,600 miles in 99 days.

18 January 1912 Scott and his final team – Captain Oates, Lieutenant Bowers, Petty Officer Evans and Dr Wilson – reach the South Pole. They find Amundsen’s tent and realise they have been beaten. ‘Great God!’ wrote Scott, ‘this is an awful place and terrible enough for us to have laboured to it without the reward of priority. Well, it is something to have got here, and the wind may be our friend tomorrow. Now for the run home and a desperate struggle. I wonder if we can do it.’ The party leave the next day.

17 February 1912 Petty Officer Edgar Evans dies in his tent after collapsing during the trip back.

16-17 March 1912 Scott’s diary records Captain Lawrence Oates’s death. According to Scott, Oates walked out of his tent with the words, ‘I am just going outside and may be some time’. His body was never found.

29 March 1912 The remaining three explorers are around 11 miles from their final depot at One Ton when Scott writes his final diary entry:

Had we lived, I should have had a tale to tell of the hardihood, endurance and courage of my companions which would have stirred the heart of every Englishman. These rough notes and our dead bodies must tell the tale. We shall stick it out to the end, but we are getting weaker, of course, and the end cannot be far. It seems a pity but I do not think I can write more. For God’s sake look after our people.

The bodies are discovered seven months later.

26 February 1914 Australian explorer Douglas Mawson returns to Australia after a two-year Antarctic expedition. During a sledging journey, Mawson was forced to trek over 100 miles alone following the death of his two companions, Belgrave Ninnis and Xavier Mertz. Mawson finally returned to base on 8 February 1912, only to discover that his ship had left just hours before. Mawson, along with six others, remained in the Antarctic for another 12 months before help returned.

1 August 1914 Ernest Shackleton departs on the Endurance on his Trans-Antarctic Expedition, aiming to become the first to cross Antarctica from sea to sea via the South Pole.

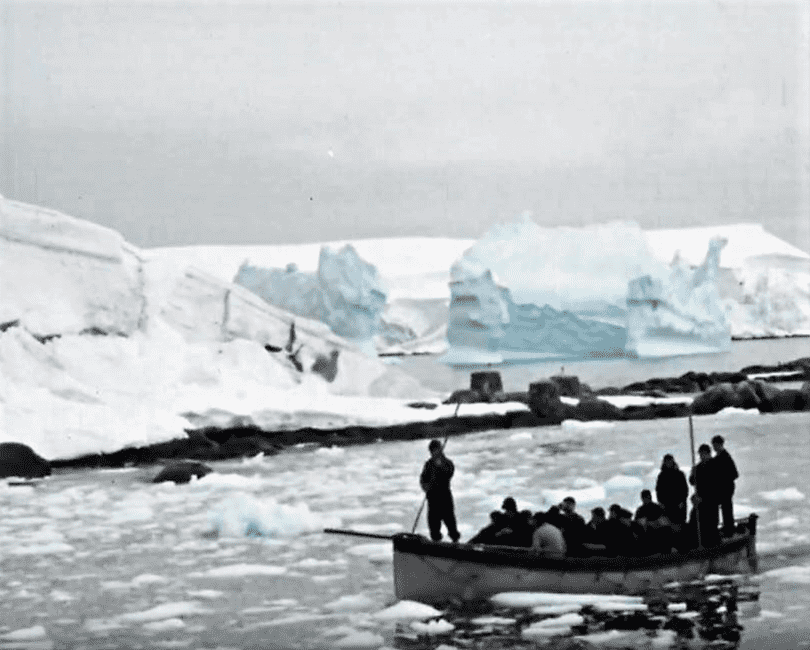

19 January 1915 Endurance becomes stuck in the pack ice of the Weddell Sea. Shackleton hopes to spend the winter on board and wait for the ice to free them, but over the course of the next nine months the ship is gradually crushed. The crew finally abandon the ship on 27 October, and all 28 men are left stranded on the frozen sea.

9 April 1916 Unable to remain on the sea ice any longer, the party abandon their ‘Ocean Camp’ in three lifeboats: the James Caird, the Dudley Docker and the Stancomb-Willis. The closest solid land, the uninhabited Elephant Island, is over 100 miles away, but all three boats reach their destination on 17 April.

24 April 1916 Six men including Shackleton leave on the James Caird in search of rescue, planning to sail 800 miles to the whaling stations of South Georgia. The rest of the group remain on Elephant Island, using the upturned boats as shelter.

Shackleton and the rescue party finally reach South Georgia 17 days later, but are forced to land on the uninhabited side of the island. The party treks without sleep across the unmapped island, finally reaching the Norwegian whaling station at Stromness on 20 May. It would take until 30 August before Shackleton could reach the rest of his men left on Elephant Island. All 28 men survived.

1914-17 While Shackleton and his men struggled to survive the loss of Endurance , the second half of the Trans-Antarctic Expedition faced their own challenges. The Ross Sea Party had been tasked with laying supply depots along the Antarctic route from the opposite side of the continent, which Shackleton planned to use during the final part of his expedition. However, their ship broke free and the men left behind were not rescued until January 1917. While the depots were never used, the group managed to cover 1,356 miles across the ice laying supplies. Three men died during the expedition.

5 January 1922 Ernest Shackleton dies of a heart attack during an expedition to the Antarctic on board the Quest.

29 November 1929 Expedition leader Richard Byrd, pilot Bernt Balchen, co-pilot Harold June and radio operator Ashley McKinley become the first people to fly over the South Pole.

20 February 1935 Danish Norwegian explorer Caroline Mikkelsen becomes the first woman to set foot on Antarctica.

14 December 1943 Britain launches the secret wartime mission Operation Tabarin, establishing permanent bases in the Antarctic for the first time. The resulting bases were later given over to scientific research, and became the foundation for the British Antarctic Survey in 1962.

2 March 1958 The Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition led by Vivian Fuchs becomes the first to successfully cross the continent, travelling 2,158 miles in 99 days. Mount Everest climber Edmund Hillary leads part of the mission, laying supplies for the crossing party as far as the South Pole. In the process he leads just the third group to reach the South Pole, and the first to do so in vehicles.

23 June 1961 The Antarctic Treaty comes into force, an international agreement establishing how the continent should be protected and governed. Twelve countries – Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Chile, France, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, South Africa, the Soviet Union, the UK and the USA – first signed the international treaty in 1959, declaring that Antarctica should be ‘a natural reserve, devoted to peace and science’.

1992-1993 Ranulph Fiennes and Dr Mike Stroud become the first people to cross the Antarctic continent unsupported, without assistance or extra supplies.

Discover more

Explore the past, present and future of polar exploration with the National Maritime Museum

Visit the National Maritime Museum

NOTIFICATIONS

Antarctica: early discoveries – timeline.

- + Create new collection

It’s less than 200 years since people first stepped foot onto Antarctica. Explore this timeline to see some key dates in the early discoveries of this icy continent.

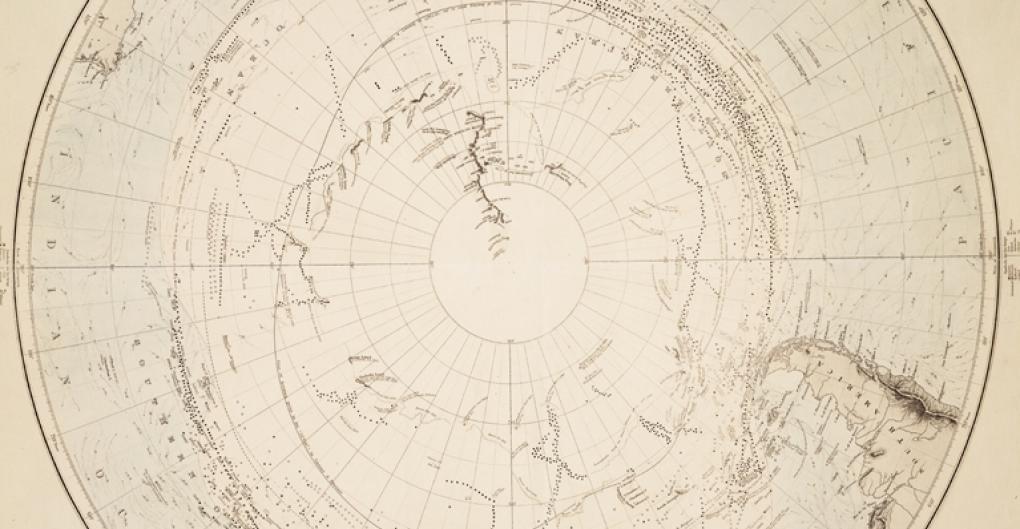

Until 1780 – Terra Australis

The early period consisted mainly of explorations and voyages penetrating to far southern regions. A consequence of this is the reduction of the hypothetical 'Terra Australis'. Charts of the Antarctic progressively showed less land as speculations were steadily disproved.

1772 – Captain Cook’s southern voyages

Captain Cook’s order was to find the ‘southern land’, study rocks, plants and animals and make friends with native people. He never found Antarctica.

1820 – Edward Bransfield’s icy glimpse

On the 30 January 1820 Bransfield sighted Trinity Peninsula , the northernmost point of the Antarctic mainland.

1821 – First landings

Sealers were the first to land and overwinter in Antarctica sometimes involuntarily, as the result of shipwrecks e.g. in 1821 and 1877. During this period there were approximately 1,175 sealing voyages but only 25 scientific expeditions recorded.

1831 – The magnetic North Pole

James Clark Ross located the North Magnetic pole in 1831 and came close to also finding the South Magnetic pole on his epic expedition of 1839-1843.

1837 – A Frenchman in Antarctica

Dumont d’Urville chartered part of the Antarctic peninsula in the ships Astrolabe and Zelée. He returned in 1840 to the opposite side of the continent where he named Terre Adélie (Adelie Land).

1839 – James Clark Ross' southern expedition (1839-1842)

Ross conducted geomagnetic surveys in Erebus and Terror. Penetrating the pack ice in sailing ships they found polynia (open water) of the Ross Sea, and determined the southern Magnetic Pole could not be attained by sea.

1882 – First International Polar Year (1882-83)

A joint effort of 12 countries to operate 14 stations surrounding the North Pole. Forty observatories across the world studied meteorology, geomagnetism, auroral phenomena, ocean currents and tides, structure and motion of ice and atmospheric electricity.

1892 – Icebergs ahoy

Icebergs were exceptionally frequent during several years, with major occurrences in 1892-94, 1903-04 and 1907-09 when almost every ship sailing between Europe and Australasia reported encounters with vast fields of ice.

1893 – The heroic age

The period between 1893-1918 includes many Antarctic explorations, together with the beginnings of the modern whaling industry. During this period, interest in Antarctica was strong, and in 1895, the Antarctic resolution was adopted by the 5th International Geographical Congress.

1898 – Bernacchi's Southern Cross expedition

The Australian physicist, trained in astronomy and terrestrial magnetism, endured the first winter on the Antarctic continent and collected a complete set of magnetic data over an annual cycle from observations at Cape Adare.

1902 – Balloons over Antarctica

Twice in 1902 aircraft (balloons) were used for aerial reconnaissance.

1903 – The first meteorological station

The region's first permanent meteorological station was established on the South Orkney Islands.

1907 – The famous Ernest Shackleton

Shackleton and his men were the first to bring motorised land vehicles to the Antarctic. With their base at Cape Royds in McMurdo Sound, they made the first ascent of Mount Erebus, discovered the Beardmore Glacier, reached a new farthest south of 88° 23' on the polar ice cap and were the first to approach the south magnetic pole located high in the Victoria Land interior.

1911 – Reaching the South Pole

The South Pole was reached twice (by Amundsen and Scott) in the 1911-12 summer (33 days separated these events).

1944 – Permanent stations in Antarctica

From the Second World War, regular annual expeditions from an increasing number of countries were the principal activity, and permanent occupation of Antarctica began in 1944 at Port Lockroy (Wiencke Island) and Hope Bay (Antarctic Peninsula).

1957 – International Geophysical Year

This event was a huge development of science throughout the world. It included a co-operative concentrated research programme by the countries with existing stations in Antarctic regions and by others that established observatories for the purpose. Many of these subsequently remained open.

1958 – Sir Edmund Hillary on ice

Edmund Hillary reached the South Pole on 4 January 1958 and landed later in 1985, together with Neil Armstrong, in a small plane at the North Pole. He became the first man to stand at both poles as well as the summit of Everest.

1959 – The Antarctic Treaty

One of the consequences of the International Geophysical Year was a general appreciation of the efficiency of international scientific co-operation in Antarctica. This promoted discussions that culminated in negotiation of the Antarctic Treaty by the 12 states then active in the Antarctic. It came into force in 1961 and has subsequently been a major influence on Antarctic affairs.

1982 – Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) established

CCAMLR 's objective is to conserve Antarctic marine life. This was in response to increasing commercial interest in Antarctic krill resources, a keystone component of the Antarctic ecosystem and a history of over-exploitation of several other marine resources in the Southern Ocean.

1983 – Pax Antarctica

From 1983, the United Nations organisation began to consider the Antarctica being the continent for science. Pax Antarctica continues to prevail over the Treaty region.

1988 – New codes of practice

In acknowledgement of the sensitivity of the Antarctic biota, various national laws have been enacted that bind virtually all human activity in the far south that affects the fragility of the Antarctic Treaty system (expulsion of sledge dogs is one example).

1991 –Tourism increase

In 1997 the International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators (IAATO) was established to to advocate and promote the practice of safe and environmentally responsible private-sector travel to the Antarctic.

2007–2008 – International Polar Year (IPY)

This was a global scientific programme designed to better understand the land and sea environments of the Arctic and Antarctic and the effects climate change has on them. It was run over two years and included an 8-week voyage to the Ross Sea .

2007 – Looking into the future

What does the future hold?

- Will the peri-Antarctic islands become more commercially significant?

- Could number of scientific stations continue to be replaced by tourist lodges?

- Discovery and exploitation of mineral resources may expand, which could form the basis of conflicts, but perhaps the Pax Antarctica will endure with its beneficial aspects demonstrated for over 40 years.

- Tourism is continuing to increase leading to growing concerns about the impact this could have on the Antarctic environment.

- There is ongoing research to improve our understanding of Antarctica’s climate history and processes and it's influence on the global climate system and links to climate change.

Related content

Find out more about this special continent with our wide range of resources on Antarctica, start with this introductory article . Browse the content under our Antarctica topic .

See our newsletters here .

Would you like to take a short survey?

This survey will open in a new tab and you can fill it out after your visit to the site.

The most comprehensive and authoritative history site on the Internet.

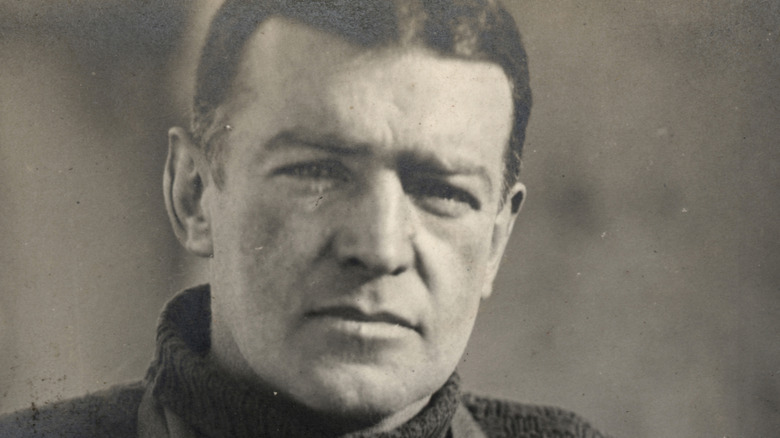

Ernest Shackleton’s Polar Dreams, Polar Disappointments

The following account describes Sir Ernest Shackleton’s expedition to the Antarctic in 1907-09, which followed Captain Robert F. Scott’s earlier (1902-03) attempt to reach the geographic Pole. This year marks the 90th anniversary of the Shackleton expedition.

Just as the race to explore space captured people’s imaginations in the latter part of this century, the quest to conquer the frozen and mysterious lands of the Arctic and Antarctic consumed explorers during the first part. Those who ventured into the vastness of the Polar regions were the popular heroes of the day. Like today’s astronauts—or athletes—they commanded awe and respect. The Antarctic was Earth’s final frontier. Certainly the race for the South Pole was as dramatic and competitive as any race has been.

Ernest Shackleton wanted to be part of something that would bring honour to the British Empire. His interest in the South Pole began at age 16 when he left school to ship out to sea, much to his father’s annoyance. By 24, he was certified to command a ship anywhere on the seven seas. The romance of the sea and the adventure led him to volunteer for Scott’s 1902 National Antarctic Expedition, during which he served as Third Mate.

On that first voyage to the Antarctic, a rift between the Royal Navy officers, including Captain Scott, and Merchant Navy volunteers, such as Shackleton, led to dissension over the chain of command and over the mission’s goals. Shackleton, in particular, disliked formality. Whether whaling seamen or Royal Navy captains, all were men of the sea to him. Stripes—or the lack of them—made no difference.

Despite the personality and rank differences, Scott selected Shackleton to take part in the trek towards the Pole. Shackleton would always be grateful to him for that, considering the men from whom he had to choose. The third member of the team was Dr. Edward A. Wilson, who became Shackleton’s great friend.

The team members encountered numerous problems on that expedition with dogs, transport, diet, and weather. None of them knew how to use dogs and sledges. Physically, all of them had problems, which Wilson diagnosed as scurvy. They did not have the proper type of food to prevent this scourge, and, in the end, they did not bring enough to go around. Blizzards and whiteouts hampered their movement, and eventually they had to abandon their goal of reaching the Pole.

At the same time, this foray yielded many positive results. They all reached 82 degrees, 15 minutes South. Scott and Wilson went on one mile further on 30th December, reaching the “furthest South,” while Shackleton stayed behind, as he was too ill to proceed.

Ultimately, Wilson and Shackleton pressured Scott into abandoning the trek to the Pole. He seemed bent on carrying on, but the Pole was still far off, the three men had already eaten most of their food, and fatigue had taken a heavy toll on their strength. In addition, Shackleton developed scurvy. Had Shackleton not become ill, Scott might not have agreed to return as he did. As it was, they rushed from depot to depot. As ill as Shackleton apparently was, he still assisted with the sledging, although at one point he had to be carried briefly on the sledge. Afterwards, he claimed that he was never as ill as Scott made it appear in his account, The Voyage of the “Discovery.” On 3rd February, 1903, they returned to the ship, just over three months and 960 miles after they began the journey.

Scott then sent Shackleton home, ostensibly to recover from his illness, but Scott may simply have wanted to rid himself of a rival. Shackleton arrived in London on 12th June, 1903. After stints as a journalist, secretary to the Royal Scottish Geographical Society, and an unsuccessful bid for a seat in Parliament, he announced plans for another Antarctic expedition in the March 1907 Geographical Journal. His objectives included geographical exploration and an attempt on the Pole, as well as collecting meteorological, geological, and biological data. But this second voyage also grew out of a personal need to prove to himself–and to sceptics–that he was capable of leading and completing an expedition.

He tackled the time-consuming and difficult tasks of acquiring financing, selecting a crew and ship, and arranging for stores. Thanks to the generosity of many who believed in his work, he soon felt ready to better Scott’s record, and he next set his thoughts to selecting the companions who would accompany him on the shore party.

Shackleton’s first choice, his chum from the Discovery, “Billy” Wilson, declined Shackleton’s invitation. Wilson later perished along with Scott while returning from the famous Terra Nova Antarctic expedition of 1912. Nevertheless, Shackleton assembled a first-rate shore party for the “British Antarctic Expedition, 1907”: Lieutenant James A. Boyd, R.N.R.; Sir Philip Lee Brocklehurst, assistant geologist; Bernard Day, motor mechanic; Ernest Joyce, in charge of the dogs; Alistair Forbes Mackay, second surgeon; Eric Marshall, chief surgeon, photographer, and cartographer; George Marston, artist; James Murray, biologist; Raymond Priestley, geologist and photographer; William Roberts, cook; and Frank Wild, in charge of provisions.

More on shackleton

- Shackleton’s Storied ‘Endurance’ Found After 107 Years

- ‘South: The Endurance Expedition’: A Battle Between Man and the Elements

The ship Shackleton had originally set his sights on proved financially out of the question; he had to settle for an older vessel, the Nimrod. He considered his vessel’s name, taken from a mighty hunter described in the biblical book of Genesis, to be a good omen. Once again, though, he had to make do with second best after his first choice for captain of the Nimrod did not accept his offer. If he had been superstitious, he might have heeded these signs. But, as Shackleton had already contracted for a dozen Manchurian ponies, dogs, sledges, and a pre-fabricated hut, and a benefactor had arranged a specially-built motor car, an Arroll-Johnston—he determined to proceed.

With the benefit of hindsight, many people today look back with amazement on the team’s dependence on the motor car and Manchurian ponies. In fact, Shackleton spent time in Norway before the expedition, consulting two of the most illustrious Polar explorers, Fridtjof Nansen and Otto Sverdrup, who advised Shackleton against using these modes of transportation. In the end, however, he rejected this expert advice. The car, he reasoned, had been specially prepared for Antarctic conditions. And the ponies, Shackleton believed, could haul far more sledge weight than dogs. At the very least, he knew that his team could man-haul the sledges if necessary.

If Shackleton lacked good judgement in his choice of transportation, he made better decisions when it came to shelter. The expedition’s hut, prepared by a firm in Knightsbridge, was prefabricated for ease of assembly, rather than transported whole, as Scott’s had been. Scott’s cumbersome hut had taken up precious cargo space on Discovery. Constructed of fir, Shackleton’s hut was insulated with felt and shredded cork. This habitat of 33 x 19 feet would have to house 15 men in close proximity for many months.

With great anticipation, Shackleton and his men set sail from London for Torquay in the south-west of England on 7th August, 1907. On their way, they received a command to meet King Edward VII, Queen Alexandra, and other members of the Royal Family at Cowes. His Majesty conferred the Commander of the Victorian Order on Shackleton, as he had on Scott some five years earlier. Her Majesty handed Shackleton a Union Jack to place at the Pole. Later at Torquay, he bade farewell to his wife, Emily, his children, and his brother, Frank, a ne’er-do-well, who had recently been linked to the theft of the Irish crown jewels.

Shackleton took care of other business, rejoining Nimrod in Lyttleton, New Zealand. Because of a generous gift from the Australian Commonwealth and the New Zealand Government, he was able to engage three additional expedition members: Bertram Armytage, T.W. Edgeworth David, and Douglas Mawson. They set sail again on New Year’s Day, 1908.

The ship Koonya towed them south to the Ice Barrier, allowing them to save coal they would badly need during their tenure in the Antarctic. They headed south through rough seas for some two weeks, dodging icebergs before passing through the Ross Sea ice into open water.

Shackleton’s original plan had been to establish a base camp in King Edward VII Land, but due to the sea ice conditions, the team couldn’t reach it. Also, the topography at the Bay of Whales had changed, so he decided not to chance a landing. Nimrod had only a short while before it would become frozen in the ice, and Captain England was nervous that his ship would become stuck fast before Shackleton found a place to land his stores, animals, motor car, and shore party.

After wrestling with his conscience, Shackleton made a controversial decision to revoke an agreement he had made with Scott in order to keep his men alive. Prior to Shackleton’s departure, Captain Scott wrote and strongly suggested that Shackleton not use his 1902 Hut Point base or venture into McMurdo Sound, which Scott deemed “his territory.” At the time Shackleton received this “suggestion,” he had no thought of landing there, so he agreed to Scott’s request.

[In an interview last year Shackleton’s granddaughter, The Honourable Alexandra Shackleton, asserted, “Scott should never have asked Grandfather to make such a commitment; and Grandfather should never have given it. Scott considered it a personal betrayal and never forgave Grandfather. The absolutes were different then; it was life or death. The Establishment considered it a most dishonourable action, but it should have been understood that he had no choice.”]

Shackleton’s team finally offloaded near Cape Royds, about 20 miles north of Hut Point. It took them about 15 days to turn their hut into cramped but liveable quarters. In order to make the best use of their small living space, they arranged the dining table so it could be pulled up to the ceiling. The men settled into a routine, trying not to get on each other’s nerves.

Paired off, they moved into their 6 x 7-foot cubicles, which had names reflecting the occupants: “Rogues’ Retreat” was Joyce and Wild’s; “The Pawn Shop” reflected David and Mawson’s untidy habits; Adams and Marshall’s quarters were dubbed “No. 1 Park Lane.”

Wild and Joyce, having had a crash course in printing in London, set about printing the first book published in the Antarctic, Aurora Australis [the Southern Lights], with etchings by Marston. They had to keep a candle burning under the inking plate to prevent it from freezing.

A number of the expedition members captured historic moments on film. Shackleton later used these to prove how much they had accomplished, despite the fact that they did not reach the South Pole. Many of the photographs were reproduced in his book on the expedition, The Heart of the Antarctic.

They hoped to achieve several things that spring. First, the quartet of Adams, Marshall, Wild, and Shackleton would attempt to reach the South Geographic Pole, a 1,708-mile journey, with ponies pulling sledges. David, Mawson, and Mackay would trek to the South Magnetic Pole, a journey of some 1,200 miles. David’s party used the motorcar to relay supplies to two depots, but it became mired in the soft snow of McMurdo Sound and soon was of no use.

Prior to the trek to the Poles, Shackleton assigned Adams, Brocklehurst, David, Mackay, Mawson, and Marshall to undertake the ascent of the volcano, Mount Erebus. All, except Brocklehurst, reached the summit on 10th March, 1908. Getting there had been a tremendous physical struggle. Having no mountaineering gear, as there had been no plan to attempt the climb, they man-hauled all their provisions to the 13,000-foot peak and were the first to ever look into the jaws of the volcano. Through extraordinary resourcefulness, courage, and dedication, the team achieved a triumph.

To the south pole

The team of Shackleton, Jameson Boyd Adams, Eric Marshall, and Frank Wild struck out for the Pole on 29th October, 1908. Even while travelling through the harshest environment on earth, they maintained a semblance of civilization, taking along reading material (including Shakespeare and Dickens), jam and cocoa, and especially tobacco.

The Polar party experienced difficulties with their ponies and the weather right from the outset. The explorers had planned to use the ponies to haul supplies, as well as for meat, but the animals had difficulty walking in deep snow, often sinking up to their bellies. In a strange role reversal, the explorers found themselves having to carry their own provisions as well as fodder for the ponies. As if that were not enough, the ponies became snow blind. The death of all but four of them from eating volcanic sand, while distressing to Shackleton, may have been a blessing in disguise.

The white landscape affected the explorers as well as the ponies. At times they couldn’t distinguish the horizon; the sky and the ice melded into one. The temperature dropped to 52 degrees Fahrenheit. But despite the harsh conditions and unexpected setbacks, the party surpassed Scott’s “Furthest South” almost a month after setting out.

By 1st December, 1908, only one pony, Socks, remained. Then a week later, he disappeared down a crevasse, almost taking Wild with him. The unexpected loss deprived the expedition of a source of meat but freed up the supply of pony fodder, which became part of the team’s daily ration.

The four explorers plodded on, hauling 1,000 pounds through forbidding terrain on below-minimum rations. To lessen the danger of falling through crevasses, they roped themselves together. By 9th December, they were measuring their progress not in miles but yards.

It was gruelling, arduous labour. Because they could not transport all their supplies at once, the party had to constantly backtrack to retrieve what had been left behind, so that every advance of six miles required 18 miles of walking. In his journal, Shackleton described each passing day as “the most difficult we had endured.”

While Shackleton’s team headed for the South Geographic Pole, another party set out for the Magnetic Pole. On 16th January, 1909, this second team reached their goal. They recorded their achievement by taking a photograph of themselves standing by the Union Jack they brought with them. The same day they trudged 24 miles back to their supply depot to rest and then began their journey back to meet their ship, Nimrod.

Midsummer’s Day, 21st December, found Shackleton’s team frost-bitten and hungry. Condensation from their breath froze on their beards, then melted and seeped under their shirts, only to freeze again inside their clothes.

After an 11-hour march on Christmas Day, they rewarded themselves with a splendid Christmas dinner. According to Shackleton’s notes, they feasted on Oxo and pemmican (dried meat pounded into paste with fat and made into patties) boiled with some of the pony food, and plum pudding with a splash of liqueur. The meal ended with a much-welcomed cigar.

As the year’s end approached, wind and snow, less-than-adequate provisions, and the effects of altitude were taking their toll on the explorers. Their body temperatures had dropped to about 94 degrees–not a good indication of their physical state. Although Shackleton resisted the temptation to admit defeat, after 1st January, 1909, he began to realize that he might not achieve his objective. Their food simply would not last long enough.

The expedition leader decided that 6th January would be their last day out. Despite soft snow and biting cold, they advanced another 13 miles. Then, for the next two days a raging blizzard kept them in their tents.

When the storm broke on 9th January, Shackleton reversed his earlier decision and dashed south once more, reaching 88 degrees, 23 minutes south longitude, 162 degrees east latitude. They had gone farther south than anyone ever had, stopping just 97 nautical miles from the Pole. There the party planted the Union Jack and the Queen’s flag, and Marshall photographed the scene. Then, reluctantly, they headed home, a decision Shackleton called the most difficult he ever made. “Whatever regrets may be, we have done our best,” he wrote in his diary.

Even after turning back toward Cape Royds, the Polar party faced great danger. They had eaten most of their food and exhausted much of their energy, and time and the season were running out. However, the wind blew at their backs, helping the team to make runs of 15 to 20 miles for several days.

Food remained their greatest worry. Shackleton continually reduced the daily ration of biscuits, cocoa, and tea. In late January, the party marched for 20 hours with little food and even less rest. With 300 miles to go, they had very nearly reached the limits of their energy. The food ran out on 26th January, and Marshall went on alone to the next depot to bring back pony meat. Shortly thereafter, they all came down with dysentery, which Marshall attributed to bad meat.

Throughout the return trip, the explorers battled difficult terrain, incredible cold, and lack of food. Then the unusually fine weather turned bad and a blizzard struck. By Shackleton’s 35th birthday, on 15th February, they reached another supply depot. To keep up spirits, they imagined the culinary delights awaiting them upon homecoming.

By now, time was running as short as food. Before setting out on his journey, Shackleton had left orders for Nimrod to sail on 1st March, whether the Polar party had returned or not. Now, after trudging and sledging for 126 days and for more than 1,700 miles, it looked as if Shackleton might not be able to meet that deadline.

To quicken his pace, Shackleton left Marshall, who had become very ill, in Adams’ care and set off with Wild and one day’s provisions for the final dash to Hut Point. They arrived to find no ship, just a message indicating that all the other parties had returned safely. Shackleton and Wild spent a sleepless, cold, and anxious night in the hut. Unexpectedly, Nimrod reappeared the next morning, intending to land a rescue party or at least recover the bodies of the missing explorers.

As soon as he had satisfied his hunger, Shackleton set out with a relief party to rescue Marshall and Adams. After marching about 19 hours, he arrived at the camp where he had left his two companions and then led them back to Hut Point.

By about midnight on 4th March, 1909, they were all back on board Nimrod, heading out towards open sea and away from danger.

With the approach of the Antarctic winter, speed was essential, and Shackleton abandoned much of the expedition’s equipment and personal belongings rather than risk being trapped in the ice for another year, as had happened to Captain Robert Scott’s Discovery.

After reaching New Zealand, Shackleton made a brief phonograph record recounting the trek; then he sailed on to Dover. His wife, Emily, met him in mid-June, 1909, and they rode by train to London. The couple arrived at Charing Cross Station to a warm welcome.

A round of parties, lectures, dinners and receptions followed. On 28th June, 1909, Shackleton made a presentation to the Royal Geographical Society Fellows and guests, including Captain Scott. It was the culmination of all he and his companions had achieved. The Prince and Princess of Wales attended and presented the explorer with a medal from the Society. Later that year, he was knighted.

Shackleton died of a heart attack in 1922, just before his 48th birthday, and was buried in South Georgia in the Falkland Islands.

It was left to Roald Amundsen to reach the South Pole on 14th December, 1911. Captain Robert Scott and four companions duplicated the feat a month after Amundsen; but all of them perished on the return trek. Eight months later their bodies were found and remain there still.

Ninety years on, Shackleton would be astonished to learn that management theorists use him as an example of the best of leadership qualities. Such techniques as maintaining a positive outlook, organizational and marketing skills, providing a support system for colleagues, and the importance of loyalty were among Shackleton’s skills. His fame came not so much from what he did–or didn’t–achieve but from his ability to carry on under circumstances that would try abilities of lesser men.

Shackleton’s granddaughter paraphrased the comments of one of her grandfather’s companions when she said, “When all is lost, when there is no hope, pray for Shackleton. He will get you through.”

Related stories

Portfolio: Images of War as Landscape

Whether they produced battlefield images of the dead or daguerreotype portraits of common soldiers, […]

Jerrie Mock: Record-Breaking American Female Pilot

In 1964 an Ohio woman took up the challenge that had led to Amelia Earhart’s disappearance.

What Made Milwaukee Famous? This Blue Ribbon Beer

Frederick Pabst went from boat captain to hops connoisseur.

Gettysburg Had a Lasting Impact on Its Least Known Participants — Its Civilians

Travel along the famous sites of Gettysburg, from the Cashtown Inn to Lee’s headquarters, from the eyes of the locals.

- Science & Environment

- History & Culture

- Opinion & Analysis

Destinations

- Activity Central

- Creature Features

- Earth Heroes

- Survival Guides

- Travel with AG

- Travel Articles

- About the Australian Geographic Society

- AG Society News

- Sponsorship

- Fundraising

- Australian Geographic Society Expeditions

- Sponsorship news

- Our Country Immersive Experience

- AG Nature Photographer of the Year

- Web Stories

- Adventure Instagram

A concise history of Antarctic exploration

Captain James Cook is credited with many discoveries, but Antarctica is not among them. Although Cook, on his 1772–75 voyage, was the first navigator inside the Antarctic Circle and to circumnavigate Terra Australis Incognita, the mythical and unconfirmed great southern land, he never laid eyes on the icy continent.

Cook’s published journal of 1777 predicted Antarctica’s existence based on the extensive sea ice he’d encountered. But he concluded that future explorers would likely never venture further south than he had.

“Thick fogs, snow storms, intense cold and every other thing that can render navigation dangerous must be encountered; and these difficulties are greatly heightened by the inexpressibly horrid aspect of the country,” he wrote. For years, the matter of the frozen southern land was closed.

By 1819 discovery of the southern continent was again deemed necessary. Russian Captain Fabian Gottlieb Thaddeus von Bellingshausen, a great admirer of Cook, was deployed by his emperor, Alexander I, on a mission to proceed as far south as possible.

Armed with a copy of Cook’s records, Bellingshausen helmed an expedition comprising two ships, the 40m-long Vostok and the smaller Mirny. The two ships proceeded south and crossed the Antarctic Circle on 26 January 1820, the first expedition to do so since Cook’s 47 years earlier.

On 27 January, Bellingshausen recorded seeing great ice cliffs and mountains of ice about 32km from what is now Queen Maud Land. In the coming days, their path neared continental land twice more. After horrific storms, the expedition retreated to Sydney, returning to complete its Antarctic circumnavigation the next summer. On 30 January 1820, three days after Bellingshausen’s journal entry, Irish-born navigator Edward Bransfield, on a British expedition, sighted Trinity Land (now the Antarctic Peninsula). Importantly, he knew he’d gazed upon the fabled Terra Australis Incognita.

Throw into the mix American Nathaniel Palmer, who found the Antarctic Peninsula on 18 November 1820, and the battle for who discovered the Antarctic mainland is still contentious today. While it’s likely Bellingshausen was the first to clamp eyes on the continent, he’d not realised his discovery. The journey’s official log was lost, and his story faded into obscurity. It was not until 1902 that Bellingshausen’s personal account was translated from Russian into German, and finally in 1945, to English, prompting many to declare him Antarctica’s unwitting discoverer.

By 1820, when the Antarctic mainland was discovered, fur seals were already being hunted. The death knell had sounded when Cook published records of his journey in 1777, recounting the huge seal resources in the southern oceans.

Sealers came from Britain, Europe and North America, harvesting pelts for fashionable clothing and hats. They arrived on South Georgia in 1788 and by the early 1900s Antarctic fur seals had all but disappeared from the island.

In 1819 British mariner William Smith discovered the Antarctic islands of South Shetland, and the sealers, seeking new colonies, rushed south. Smith himself, along with some 90 other sealing ships, operated in the South Shetlands in the 1820–21 season. When Bellingshausen visited him there in early 1821, Smith boasted his operation had harvested 60,000 skins. By the end of 1821, fur seal populations on the South Shetlands were almost destroyed.

Nathaniel Palmer was searching for new sealing grounds when he found continental Antarctica in November 1820, and in February 1821, English-born American sailor John Davis, also seeking seals, claimed to be the first to set foot on the Antarctic continent. With fur seals dwindling, elephant seals and some species of penguin were targeted for oil, and operations continued intermittently during the 19th century.

Whaling in Antarctic waters began in earnest in 1904 when a whale-oil processing station was established on South Georgia.

As whales stocks dwindled catchers were forced to venture further afield. In the summer of 1929, some 29,000 blue whales were harvested, and, as they too declined, whalers targeted other species. By 1960 1.4 million whales had been removed from Antarctic waters.

Heroic Age of Antarctic exploration

With the presence of Antarctica firmly established, the stage was set for the Heroic Age of Antarctic exploration from the late 19th century to 1917. During this time, some 17 major expeditions were launched. The famous race to the South Pole ended with Norwegian Roald Amundsen being the first on 14 December 1911. He was followed to the pole 34 days later by British explorer Robert Falcon Scott, whose entire party perished on their return journey.

Australian geologist Douglas Mawson eschewed Antarctic races. Despite the tragic loss of team members Belgrave Ninnis and Xavier Mertz, and his own near death, Mawson and his team explored more than 6000km of Antarctic territory during their Australasian Antarctic Expedition (AAE) of 1911–14. They recorded discoveries in the fields of geology, geography, oceanography, meteorology, and magnetism; documented the Aurora Australis; and were first to use radio in the Antarctic.

Ernest Shackleton’s Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914–17 earned him a reputation for unshakeable leadership. Following the destruction of its ship, the Endurance, in sea ice, the expedition made it to inhospitable Elephant Island. Shackleton and a skeleton crew continued some 1300km to South Georgia in a lifeboat, and returned to rescue all the rest of the men.

The birth of the Antarctic Treaty

Following the Heroic Age, scientific exploration continued at a less frenetic rate. Several countries laid claim to land in Antarctica during and after World War II, for strategic military purposes and to investigate potential resources. Following years of minor conflict, 12 countries with scientific interests in the southernmost continent came together in 1959, signing the Antarctic Treaty – the overarching instrument that controls the uses of Antarctica today. A total of 54 nations are now parties to the agreement.

The treaty declares that Antarctica should be used for peaceful purposes and that scientific investigations can be conducted freely and shared. Under the treaty, the status of land claims cannot be advanced or altered. Although any party can call for a review of the treaty, to date none have done so.

In 1991, led by then Australian prime minister Bob Hawke and French prime minister Michel Rocard, the parties adopted the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty (known as the Antarctic-Environmental Protocol, or the Madrid Protocol), which entered into force in 1998. It protects Antarctica as a natural reserve and prohibits all exploitation of mineral resources indefinitely. Hawke later commented that signing the protocol was one of the proudest achievements of his life.

The Madrid Protocol manages environmental impacts in Antarctica, and increasingly this applies to not just scientists and governments, but also tourists as they pursue their own journeys of exploration.

Modern Antarctic tourism

Modern Antarctic tourism began with Swedish-American Lars-Eric Lindblad in 1966, when he chartered an Argentine naval vessel for the first voyage to the Antarctic mainland with fare-paying passengers. In 1969 he launched the purpose-built Lindblad Explorer and a new era of nature-based tourism on the continent began.

Interest in Antarctic tourism has grown and is now controlled by the International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators (IAATO), an organisation with 114 members. While there are no limits on the total number of tourists that can visit Antarctica per season, each of the popular landing sites has its own set of management controls set by IAATO.

At each site, a maximum of 100 tourists may land at one time. Daily limits apply per site for the number of larger ships (with up to 500 passengers) allowed to land, and also the number of smaller ships (with fewer than 200 passengers). Access to landing sites is hotly contested, with companies reserving sites through an online scheduling system in June each year.

Before COVID-19 travel restrictions, IAATO had predicted that 2019-20 would be Antarctica’s busiest tourist season ever. In 2018–19, a record 44,600 people had landed on the continent, and ten thousand more passed through on cruise ships with a capacity greater than 500 passengers, meaning they were not permitted to land. A handful of tourists arrived by air or small yachts, but most arrived on board smaller cruise ships.

I was one of them. Like many others, I was drawn south to see the majestic icebergs, waddling penguins, and tread the icy realm for myself. Melting ice and global warming gave my visit a sense of urgency.

The impact of COVID-19 on the icy continent

My own exploration of Antarctica commenced in late February, straddling the period when the COVID-19 crisis flipped the travel industry on its head. When I embarked in Chile, there had only been one case of the virus recorded in South America, and none in Antarctica.

After a life-changing 18-day Antarctic experience, my symptom-free ship, the Roald Amundsen, owned by Hurtigruten, was turned away from port on the planned day of disembarkation. Eventually, I got off in the Falkland Islands and made it home to Australia. By then the world had shifted and now Antarctic tourism is temporarily uncertain.

The pause of tourism to Antarctica may also have a detrimental impact on scientific research. Many cruise companies provide free passage for scientists, and during my trip the Roald Amundsen hosted three whale researchers.

Lead researcher Professor Ari Friedlaender, from the University of California Santa Cruz and the California Ocean Alliance, explained the benefits of this arrangement. “There’s no question this is a great advantage to the advancement of science,” he said. “Some researchers have used cruises to count penguins for the last 30 to 40 years, and that’s been incredibly successful. As whale research techniques progress, we may see similar benefits.”

I watched Ari’s team in the ship’s tender sampling whale skin through painless biopsies for pollution analysis, and I attended their informal talks. The Roald Amundsen spreads the science message in other ways too. During my expedition, guests attended countless lectures from the Hurtigruten science and history teams and analysed live plankton under microscopes. I participated in a NASA cloud project, a seabird survey and a whale photography identification project.

The loss of tourism may be leaving a temporary gap in research opportunities. However, when the industry bounces back, it is likely to be greener than ever. The Roald Amundsen is the first polar expedition ship to incorporate a hybrid diesel-electric propulsion system, with a battery storage capacity that reduces carbon dioxide emissions by about 20 per cent. Engine heat is recycled to the cabins and water heaters. Kitchen waste and sewage are fed to the ship’s bio-digesters where enzymes reduce waste to sludge.

Hurtigruten carefully controls biosecurity too. To prevent the introduction of plants and diseases, passengers wear rubber boots ashore and walk through a carwash-like scrubbing system after every landing. Hurtigruten has greener intentions still, ultimately planning to run ships on biofuel.

Conservation work in Antarctica

IAATO continually reviews the sustainability of Antarctic visitation. The Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR) facilitates international science in Antarctica and is working together with IAATO to develop a systematic conservation plan for the most heavily visited area: the Antarctic Peninsula. Among other objectives, the project will enable decision-makers to determine where visitor numbers to Antarctic sites could be limited, should that be deemed necessary.

Dr Steven Chown, president of the SCAR and professor of biological sciences at Monash University, gives an example of a series of questions concerning tourist visitation to penguin colonies that might be answered by the study. “What does it mean for their population dynamics? Do they move sites? What does it mean if their populations go down? How do we separate that from the impacts of a rapidly changing climate on the peninsula?”

The COVID-19 crisis is affecting more than just tourism and citizen science in Antarctica, with national science programs also suffering. Steven hopes that, along with protecting the community, governments will continue to fund science.

“In times of crisis, you’re really going to need experts who know what they’re doing,” he says. “Climate change won’t vanish just because we have a pandemic.”

Steven acknowledges that belts will need to be tightened. “But I would say that understanding what happens with Antarctica’s ice sheets is such a pressing question that the world cannot turn away from it.”

In the future, Antarctica may be explored for reasons beyond science and tourism. The Madrid Protocol may one day be revised and resource extraction reconsidered. Countries may seek to establish land claims and commence developments in Antarctica.

Steven notes that interest in upgrading and building new scientific stations is on the rise, for reasons that are not always clear. “Antarctica, like everywhere else, is a geopolitical space,” he says. “As the world fills up, Antarctica is not being overlooked.”

For now, COVID-19 sees Antarctica resting quietly, almost devoid of humans. Seals snooze, penguins caw and whales breach. Perhaps for this blip in time, Antarctica appears as it did to Bellingshausen 200 years ago: a harsh, frozen, and starkly beautiful continent, waiting for its explorers.

Commemorating brothers in arms on Country

<b>Members of Aboriginal communities are warned that this story contains images and names of deceased people.</b>

How to see the ‘devil comet’ from Australia

If you’re a fan of all things space, you’ve doubtless heard about the 'devil comet', which has been captivating keen-eyed observers in the Northern Hemisphere for the past few weeks.

‘Bunyip’ bird returns to restored Tasmanian wetlands

For the first time in more than 40 years, the distinctive booming call of the endangered Australasian bittern once again rings out across the waters of Tasmania’s Lagoon of Islands.

Watch Latest Web Stories

Birds of Stewart Island / Rakiura

Endangered fairy-wrens survive Kimberley floods

Australia’s sleepiest species

Transportation History

Finding the unexpected in the everyday.

The First Flights over Antarctica

February 4, 1902

The first flights over Antarctica took place as part of a British exploration of that region of the world. The British National Antarctic Expedition, which was led by Royal Navy Captain Robert F. Scott, had departed from England in the wooden ship RRS Discovery in August 1901.

The ship crossed the Antarctic Circle that following January, and Scott and his crew eventually found themselves sailing along the enormous platform of ice known at the time as the Great Ice Barrier (since renamed the Ross Ice Shelf in honor of the British explorer who discovered it in 1841). Setting foot on this ice shelf at a small bay there, Scott and others in his party brought with them a deflated balloon that was on board Discovery for use in aerial surveys.

The balloon, which had been named “Eva,” was pumped with hydrogen from cylinders that were likewise part of Discovery’s cargo for the expedition. The balloon’s basket could hold only one person at a time, and Scott — “perhaps somewhat selfishly,” as he later acknowledged — selected himself for the first flight. With the tethered balloon reaching a height of approximately 800 feet (243.8 meters) above the earth, Scott could see a good deal of the massive Great Ice Barrier.

Later that day, another milestone in Antarctica’s aviation history was achieved when Royal Naval Reserve Sub-Lieutenant Ernest Shackleton (who would lead three similarly notable Antarctic expeditions) became the second person to soar above the Great Ice Barrier in the still-tethered balloon. Armed with a camera during his ascent, Shackleton took the first aerial photographs of Antarctica.

The balloon allowed Scott and Shackleton to see more of the interior of a continent that was still mostly unexplored. Their flights were the first of many memorable and significant experiences with airborne transportation in Antarctica.

For more information on aerial explorations of Antarctica, please check out https://www.centennialofflight.net/essay/Explorers_Record_Setters_and_Daredevils/south_pole/EX20.htm#:~:text=On%20February%204%2C%201902%2C%20British,into%20the%20heart%20of%20Antarctica

Share this:

Leave a comment cancel reply.

Create a website or blog at WordPress.com

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

- Today's news

- Reviews and deals

- Climate change

- 2024 election

- Fall allergies

- Health news

- Mental health

- Sexual health

- Family health

- So mini ways

- Unapologetically

- Buying guides

Entertainment

- How to Watch

- My watchlist

- Stock market

- Biden economy

- Personal finance

- Stocks: most active

- Stocks: gainers

- Stocks: losers

- Trending tickers

- World indices

- US Treasury bonds

- Top mutual funds

- Highest open interest

- Highest implied volatility

- Currency converter

- Basic materials

- Communication services

- Consumer cyclical

- Consumer defensive

- Financial services

- Industrials

- Real estate

- Mutual funds

- Credit cards

- Credit card rates

- Balance transfer credit cards

- Business credit cards

- Cash back credit cards

- Rewards credit cards

- Travel credit cards

- Checking accounts

- Online checking accounts

- High-yield savings accounts

- Money market accounts

- Personal loans

- Student loans

- Car insurance

- Home buying

- Options pit

- Investment ideas

- Research reports

- Fantasy football

- Pro Pick 'Em

- College Pick 'Em

- Fantasy baseball

- Fantasy hockey

- Fantasy basketball

- Download the app

- Daily fantasy

- Scores and schedules

- GameChannel

- World Baseball Classic

- Premier League

- CONCACAF League

- Champions League

- Motorsports

- Horse racing

- Newsletters

New on Yahoo

- Privacy Dashboard

In 1898, the first scientific expedition to the Antarctic nearly ended in disaster, here's what it can teach us about the region's plummeting sea ice

On Aug. 16, 1897, the Research Vessel Belgica set sail from Antwerp, Belgium. The ship's destination — via Rio de Janeiro, Montevideo and then Punta Arenas, Chile — was Antarctica, a continent that until that time remained completely unexplored by westerners .

The new land was not kind to its visitors. Shortly after its arrival, the Belgica became stuck in the thick halo of pack ice that surrounded the continent. As the Antarctic's dayless winter set in, the ship's 18 man crew were pushed to their mental and physical limits, consuming penguin and seal meat to survive.

"We are as hopelessly isolated as if we were on the surface of Mars," wrote Frederick Cook, the Belgica's American physician, in 1898. "And we are plunging still deeper and deeper into the white Antarctic silence."

In the days of faint sunlight that came in the following spring, the ship's desperate, disease-ridden crew resorted to dropping sticks of dynamite around the vessel, blasting the thick sea ice that enclosed them to create a narrow path to freedom. All but two of the crew survived the ordeal .

But now, for large parts of the year, the once plentiful sea ice encountered by the ill-fated voyage seems to be disappearing.

To discuss the expedition's history; the importance of Antarctica's sea ice in regulating the global climate; and the planetary implications of its growing absence, Live Science sat down with University of Tasmania oceanographer and climate scientist Edward Doddridge , who uses mathematical models and observations to understand the dynamics of the region. Here's what he had to say:

Ben Turner: What was the voyage of the RV Belgica? And how did it contribute to our understanding of Antarctica?

Edward Doddridge: The RV Belgica's voyage to Antarctica departed in 1897 and was the first of what became known as the "heroic age" of Antarctic exploration. This was the very end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th. Antarctica was a completely unknown place that no one had been to. Then — within just over a decade — people had gone all the way to the South Pole.

Our scientific understanding of the region blossomed as we obtained the first records from the continent. It's still a continent that teaches us so much today, but the RV Belgica's voyage is the start.

Antarctic sea ice decline

Antarctica's sea ice has been declining since 2016. What does that mean for Earth's climate?

— '2023 just blew everything off the charts': Antarctic sea ice hits troubling low for third consecutive year

— Collapse of the West Antarctic ice sheet is 'unavoidable,' study finds

— Antarctic sea ice reached 'record-smashing low' last month

BT: One of the reasons why you've written about the Belgica , and why its voyage is so famous, is because the pack ice there was so thick that the ship became stuck for nearly two winters. What does this tell us about that part of how the Antarctic was like back then? And how has it changed since?

ED: This is why I think that the RV Belgica's voyage is such an interesting one to look at now. The region of the Antarctic coastline they sailed to has been ice-free for the first time since satellite records began — it now doesn't have any ice for months and months of the year. That's pretty surprising in a 45-year record, but when you look back 125 years ago, and you see that they were trapped in ice that was 2 meters [6.6 feet] thick, that's a huge change.

It's a really startling story, because it's a nugget we can use to understand how it's changed over the last century. If you were to go down there this summer in a boat like a Belgica, you could sail all the way to the Antarctic coastline, frolic around on the Antarctic shore and then sail back to Belgium. And you might not have seen any expansive sea ice.

BT: Bringing this closer to the present — in 2023, after several years of record lows, the sea ice over the Antarctic's winter period failed to regrow. By the end of the Antarctic winter in July, the continent was missing a region of ice bigger than Western Europe.

You're a polar researcher, you've studied this for a very long time. What were your thoughts when this happened last year?

ED: Almost disbelief. The measurements that we get for Antarctic sea ice are extremely well-calibrated, we know that the satellite is truthfully telling us how much ice there is. But looking at that graph, it was hard to comprehend that it could be so different from previous years.

As a research community, we've struggled to even describe how unusual the change is. People throw around words like "unprecedented" or "gobsmacked" or "'unbelievable." For a while we were trying to use statistics to say that it was a one in many thousands or millions of years event; then we got into billions and even into tens of billions of years.

At some point along the way, you just have to realize that the statistics aren't useful to understand this anymore. It's so far outside what we've seen in the last 45 years that we just have to say that it's completely different — that's as good as you can do.

BT: Yet even a non-expert in the field, who doesn't know about the different dynamics between the Arctic and Antarctic and is just generally aware of climate change as a thing, might expect this ice to melt at some point. Why did it surprise you so much?

ED: The difference is that the Arctic is an ocean surrounded by continents, whereas the Antarctic is a continent surrounded by ocean. So in the Arctic, the amount of ice that you have in the winter is basically just the amount of ocean that you have, but you're never going to run out of ocean around Antarctica.

So when sea ice forms around Antarctica it can expand a long way, and the limit of this expansion is set by the interaction between the ocean, the atmosphere, and the ice. This means the ocean currents around Antarctica are crucial for how much ice you can have. All of this makes it really difficult to model.

In the past, The [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change] IPCC models suggested that we should be losing ice in the Antarctic, just like we are in the Arctic, but we didn't see that in the satellite data up until 2014.

So last year, when it didn't come back during the winter, it was something that we hadn't predicted. We had the sense that climate change meant we will get less ice at some point in the future. But if you had asked climate scientists in 2020: "What's gonna happen in the winter of 2023?" No one would have predicted what we saw.

BT: So what's going on in the Antarctic to cause it?

ED: Fundamentally, it has to be that the world is getting warmer and we know that a warmer world isn't consistent with lots of sea ice. As the atmosphere and the ocean warm, they're both going to affect the sea ice. But understanding all of the nuances of those interactions is really quite tricky.

There's a layer at the top of the ocean called the mixed layer. It has the same properties at any given location — it doesn't really change in temperature or saltiness. Around Antarctica, that layer is mostly about 100 meters [330 feet] thick during winter. Below that is where warmth comes up from other parts of the ocean and mixes with the top layer where it can inhibit sea ice. We've shown in our research that those subsurface ocean temperatures have been increasing, and the places where they've warmed the most we see the greatest reductions in sea ice.

BT: Playing devil's advocate, how can we rule out for certain that this is some kind of freak event? How do we find the smoking gun of a climate change signal in all of this?

ED: The honest answer at the moment is that we can't — we cannot conclusively rule out that this is just under multi-decadal or centennial variation in the sea ice. What we can do, though, is we can look at the 45 years of data that we have [satellite surveys of the poles began in 1979]. This suggests that, if there is some kind of change or freak event, it doesn't happen in a 45-year timeframe.

The other thing that we can do is we can use models and run them over thousands of years. Again, there's no indication that something like 2023 regularly happens at random in these models.

BT: The Antarctic is one of the most remote regions of the world. Why does a sudden decline in sea ice there matter globally?

ED: So there are a few really crucial things that the sea ice does within the climate system. Firstly, it's really white and bright, so it reflects the sun's rays back out into space. This insulates the ocean underneath it and keeps it cold. If you take that away, you're accelerating the rate of warming in the region and contributing to increased warming globally.

Secondly, tiny microscopic plants called phytoplankton that absorb CO2 in the atmosphere grow on the sea ice, and there are also regions that form around the ice that take CO2 out of the atmosphere and away from the surface — roughly 10% of carbon dioxide that humans have emitted has been absorbed by the Southern Ocean.

Finally, on a human level, so many really iconic species live around Antarctica. Krill feed on the phytoplankton that grow on the ice. So if we take it away, the krill will suffer, and so will the entire Southern Ocean ecosystem.

BT: If the sea ice continues in its current decline, where could it end up? ED: The best tools we have are the models. And if you run them for long enough, then yeah, you reduce the amount of ice around Antarctica substantially. The other way we could guess is by looking at geographic sediment core records for past climate epochs.

From those you can find periods where Antarctica had trees and plants and all sorts of animals living on it, suggesting that it was not a frozen continent. So you can certainly warm the planet up enough that there is no ice left, although I very much hope that we don't get anywhere near that.

RELATED STORIES

— 'Ghost' of ancient river-carved landscape discovered beneath Antarctica

— El Niño kickstarted the melting of Antarctica's 'Doomsday Glacier' 80 years ago, new study reveals

— City-sized holes on Antarctica's ice shelves offer tantalizing 'window' into the frozen continent's underworld

BT: That sounds pretty disastrous for coastal regions, how much would sea levels rise if all that ice melted?

ED: Antarctica contains enough ice to raise global sea levels by 60 meters [200 feet].

BT: The Antarctic's circumpolar current drives the thermohaline circulation and global ocean currents such as Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), which are really important for regulating Atlantic climates. Could this melt affect them?

ED: Changes in the sea ice are definitely going to impact the AMOC. The AMOC has water that forms up in the North Atlantic, it gets cold and salty and it sinks down and then comes back up in Antarctica. And there's another loop to that circulation for the cold dense water that forms around Antarctica.