- Search Menu

- Author Guidelines

- Open Access Options

- Why Publish with JAH?

- About Journal of American History

- About the Organization of American Historians

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- < Previous

Sunshine Paradise: A History of Florida Tourism

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Anthony J. Stanonis, Sunshine Paradise: A History of Florida Tourism, Journal of American History , Volume 98, Issue 4, March 2012, Pages 1220–1221, https://doi.org/10.1093/jahist/jar534

- Permissions Icon Permissions

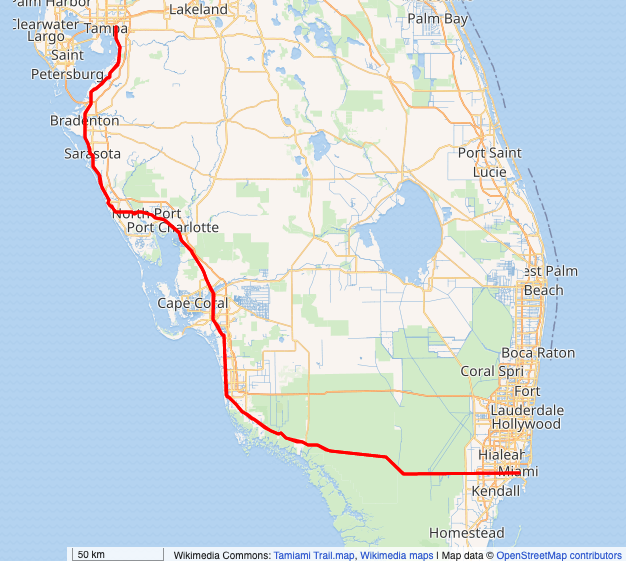

Scholars over the past decade have interrogated tourism and promoters’ manipulation of historical memory. The maturity of this subfield has provided fertile ground for Tracy J. Revels’s much-welcomed, concise survey of Florida tourism from the days of Ponce de León to the present.

Revels provides a highly readable and witty study that focuses on the types of vacationers and promoters who defined eras in the evolution of Florida tourism. For Revels, “Florida is tourism” (p. 1). Beginning in the 1820s, sufferers of respiratory ailments journeyed to Key West, St. Augustine, and Pensacola to enjoy the warmth and fresh air. By the mid-1800s, sportsmen came to hunt and fish. The development of railroads across the American South after the Civil War created a boom in tourism during the 1870s and 1880s. The arrival of the tycoon developers Henry Plant and Henry Flagler made Florida a fashionable winter haven for the wealthy by the turn of the century. Between 1900 and 1945 “Florida gained an international reputation as America’s leisure paradise, and began moving away from its designation as a ‘Southern’ state in terms of culture” (p. 64). Higher wages and more vacation time, along with the advent of the automobile and air travel, made the state increasingly accessible to more people. After World War II, Florida became a “state of imagination” (p. 101). Promoters, most famously Walt Disney, transformed the landscape to appeal to American fantasies of a glorious past, prosperous present, and promising future. By the late twentieth century, however, accommodating the millions of tourists had severely taxed the natural beauty of Florida, as runoff turned once-popular natural springs cloudy, highways scarred the landscape, and condominiums suffocated coastal dunes, all while pollution was also spoiling the air, land, and sea.

Revels convincingly shows how segregation was a “strange curse” in Florida, as catering to tourists undermined the harsh racial regime present elsewhere in the Jim Crow South (p. 73). However, African Americans, denied services, built their own vibrant tourist resorts, as at American Beach. Jews likewise turned into activists in the face of discrimination.

Revels does not show how Florida tourism impacted the United States at large. Mediterranean architecture celebrated by Flagler and Plant, for instance, influenced designs throughout the country. Revels instead strictly uses events in Florida to show trends in American leisure. The study consequently ignores the intense rivalry between Florida and California boosters and also largely overlooks the severe political tension in the twentieth century between tourism interests in southern Florida and agricultural interests in northern Florida. That tension even threatened to divide the peninsula into two states. Given Revels’s aim of providing a brief overview, however, such absences are understandable.

These criticisms should not detract from Revels’s short analysis of Florida tourism. She sets a high standard for future studies, providing an engaging narrative. Tourists’ letters, popular travel guides, and the most recent scholarship inform this statewide study. Academics, students, and general readers interested in tourism and southern history will find this a rigorous, entertaining, and insightful overview.

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Process - a blog for american history

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1945-2314

- Print ISSN 0021-8723

- Copyright © 2024 Organization of American Historians

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

By: History.com Editors

Updated: December 13, 2022 | Original: December 16, 2009

Florida joined the Union as the 27th state in 1845 and is nicknamed the Sunshine State for its balmy climate and natural beauty. Spanish explorer Juan Ponce de Leon, who led the first European expedition to Florida in 1513, named the state in honor of Spain’s Easter celebration known as “Pascua Florida,” or Feast of Flowers. European settlers, mainly from Spain, arrived in the 17th and 18th centuries. The Spanish, French and English battled over Florida until it became a U.S. territory in 1819.

Florida has long been a state of migrants. While European colonists quickly decimated the Indigenous population, Florida became home to a Seminole community of Indigenous and enslaved people who migrated from nearby states in the 18th century. Beginning in the late 19th century, residents of Northern states flocked to Florida to escape harsh winters. Many Cubans also immigrated to Miami throughout the late 19th and 20th centuries, establishing a vibrant Latin American culture.

WATCH: How the States Got Their Shape on HISTORY Vault

Native Americans in Florida

Hunter-gatherers first arrived in the area now known as Florida more than 12,000 years ago. The dominant Native American communities that emerged included the Calusa, Tequesta and Jeaga tribes in southern Florida and the Apalachee and Timucua people in the north. They lived along the coasts as well as near rivers in the interior of Florida. When the Europeans arrived in the 16th century, they started selling Indigenous people and brought disease and warfare that decimated the native population. Nearly all local Indigenous people were gone by the mid-1700s.

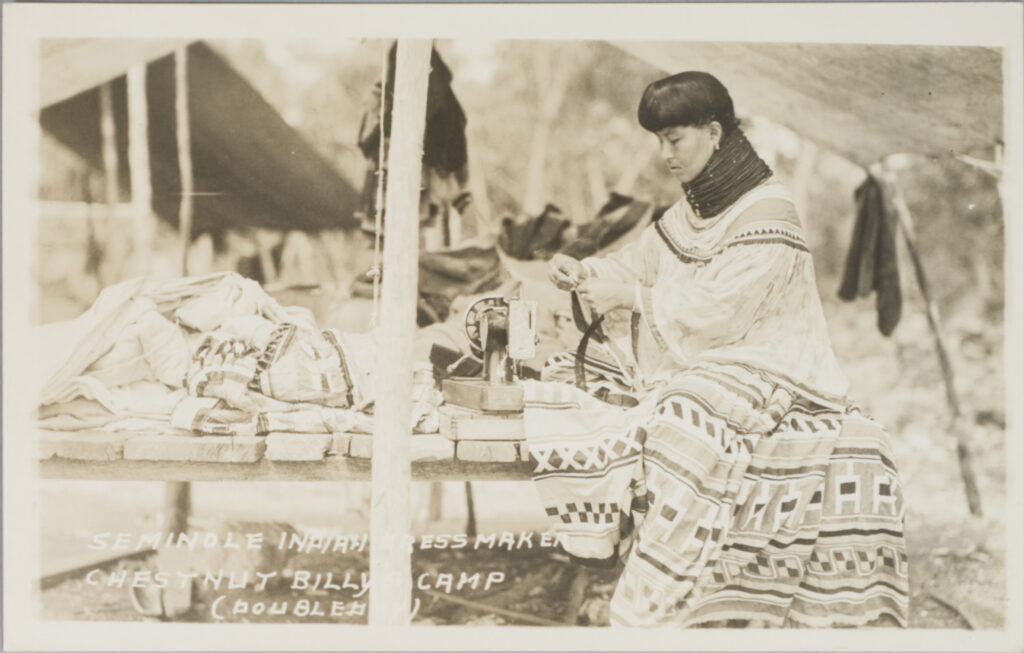

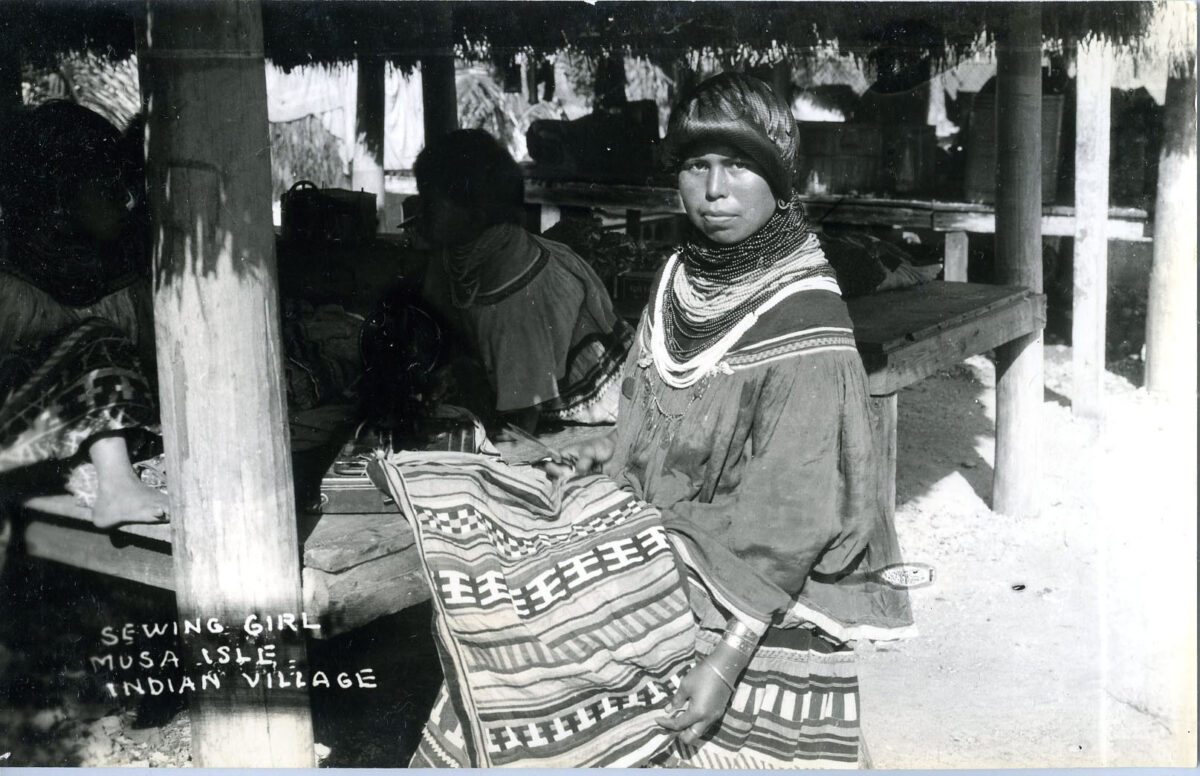

In the mid to late 1700s, Native Americans from Georgia, Alabama and other states, including tribes of the Creek Nation such as the Miccosukee, migrated to Florida to escape European expansion. They were joined by escaped enslaved people, as Spain had announced that anyone who made it to Florida was free. By the end of the century, this diverse community collectively became known as the Seminoles. The name most likely originates from the Spanish word “cimarron,” or “wild runaway.”

Florida's Early Colonial History

Spanish explorer Juan Ponce de León was the first known European to set foot on the area now called Florida when he landed near present-day St. Augustine in 1513. His second expedition in 1521 failed to colonize Florida due to attacks by Indigenous people, although it piqued Spanish interest in the area. Other Spaniards to visit Florida included Hernando de Soto , in 1539, and Tristán de Luna y Arellano, in 1559.

The French also explored Florida, with Jean Ribault landing in 1562 and René Goulaine de Laudonnière establishing Fort Caroline in 1564. However, it was Spanish explorer Pedro Menéndez de Avilés who established the first permanent European settlement in the United States at a place he called St. Augustine in 1565. Menéndez de Avilés expelled the French and captured Fort Caroline , renaming it San Mateo. Although the French fought back over the years, the Spanish military and Catholic missionaries dominated the area and expanded their territory.

During these early years, English colonizers showed limited interest in Florida. But in the 17th and 18th centuries, English colonists began migrating south and set their sights on Spanish holdings in Florida, attacking missions and St. Augustine. At the end of the Seven Years’ War , in 1763, Spain handed Florida to the British in exchange for Cuba, which England had taken from Spain. The British split the land into East Florida and West Florida, both of which remained loyal to England throughout the Revolutionary War . The 1783 Treaty of Paris ended the American Revolution and handed Florida from England to Spain, which acted as an ally to the Americans in exchange for the Bahamas.

The Seminole Wars

As Americans expanded their territory in the 19th century, they coveted Spain’s fertile land in Florida and saw the promise of freedom for escaped slaves there as a threat. The Seminole Wars began when American militias first attacked and seized Spanish and Seminole lands in 1812. In 1817, the U.S. government officially invaded Florida. In 1819, Spain ceded Florida to the United States with the signing of the Florida Purchase Treaty . As part of the agreement, the U.S. paid Spain $5 million for damages incurred.

After the U.S. government failed to displace Indigenous people, including Seminoles in Florida, to modern-day Oklahoma and Arkansas, President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act in 1830. The law forced the Indigenous peoples east of the Mississippi to modern-day Oklahoma on what became known as the Trail of Tears . Many Seminoles in Florida refused to leave. In 1835, the Seminoles attacked American troops, launching seven more years of bloody battles between the two sides. More than 3,000 Seminoles were forcibly moved before the U.S. government withdrew in 1842 without signing a peace treaty.

A third phase of the Seminole War broke out in 1855 when the Seminoles attacked U.S. troops for sending patrols into their territory. The Seminole Wars concluded three years later when a treaty was signed giving land to Seminoles in Oklahoma. Most of the remaining Seminoles in Florida moved to Oklahoma, but about 300 people remained. Today, these “Unconquered People” comprise two federally-recognized tribes: the Seminole Tribe of Florida and the Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida, both of which belong to the Creek Confederacy.

The Civil War

In the 1800s, Florida’s economy was based around crops, cattle and enslaved people—putting it at odds with northern states that opposed slavery. In 1861, Florida became the third state to secede from the Union. The next month, it joined with six other southern states to form the Confederate States of America , which soon incited the Civil War .

While most men in the state fought for the Confederacy, and the state supplied the Confederate troops with food and other important provisions, only two major Civil War battles were fought in Florida. On April 26, 1865, Florida officially surrendered to the Union.

Immigration

While Cubans had already migrated to nearby Florida for many years, immigration accelerated at the end of the 1800s, when many people who no longer wanted to be under Spanish rule left for the U.S. Cuban workers also moved to Florida to work in the sugar, coffee and tobacco industries.

In 1898, the Spanish-American War started and ended within months, when Spain ceded Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippine Islands and Guam to the United States. After the war, Cuba became its own country with increasingly repressive policies, leading more people to leave Cuba for Florida.

From the late 1950s through the 1990s, waves of people emigrated from Cuba to the United States, with most settling in Miami. Along with immigrants from Colombia and Nicaragua, they established a strong Latin American community in the area. Florida has been a destination for Americans moving from neighboring and northern states since the late 1800s for its citrus industry and warm weather.

Thanks to its mild weather, Florida started to develop as a resort vacation destination in the late 1800s. In the 20th century, tourism became one of the state's most important industries, attracting millions of visitors annually. Theme parks started cropping up all over Florida, including Walt Disney World Resort. Opened near Orlando in 1971, Disney World is the world's largest and most visited recreational resort. Spread over some 30,500 acres (about the same size as San Francisco, California), Disney World attracts approximately 46 million annual visitors.

Space Center

Initially a missile testing site in the 1940s, Florida's Cape Canaveral became a hub for the U.S. space program in 1950. On February 20, 1962, John Glenn became the first American to orbit the Earth when he blasted off from Cape Canaveral. Seven years later, Neil Armstrong became the first man to walk on the moon after Apollo 11 launched from the nearby Kennedy Space Center on July 16, 1969. To this day, the Kennedy Space Center remains an active launchpad.

Date of Statehood: March 3, 1845

Capital: Tallahassee

Population: 21,538,187 (2020)

Size: 65,758 square miles

Nickname(s): Sunshine State

Motto: In God We Trust

Tree: Sabal Palm

Flower: Orange Blossom

Bird: Mockingbird

Interesting Facts

- Constructed over a 21-year period from 1845 to 1866, Fort Zachary Taylor in Key West was controlled by Federal forces during the Civil War and used to deter supply ships from provisioning Confederate ports in the Gulf of Mexico. The fort was also used during the Spanish-American War.

- In 1944, airman and pharmacist Benjamin Green from Miami developed the first widely-used sunscreen to protect himself and other soldiers during World War II. He later founded the Coppertone Corporation.

Florida's Earliest Peoples, nps.gov

"Teacher’s Guide to Florida’s Native People," floridamuseum.ufl.edu

The Timucua: North Florida’s Early People, nps.gov

16th Century Settlements, dos.myflorida.com

Seminole History, dos.myflorida.com

History, miccosukee.com

The Long War, semtribe.com

Seminoles, nps.gov

European Exploration and Colonization, dos.myflorida.com

Florida Frontiers “Florida in the American Revolution,” myfloridahistory.org

Florida: As a British Colony, fcit.usf.edu

Acquisition of Florida: Treaty of Adams-Onis (1819) and Transcontinental Treaty (1821), history.state.gov

Florida's Native American Tribes, History & Culture, visitflorida.com

Seminole Indian Wars, seminolecountyfl.gov

Florida Migration History 1850-2018, depts.washington.edu

Spanish-American War for Cuba's Independence, fcit.usf.edu

Crossing the Straits, loc.gov

Cuban Exiles in America, pbs.org

Transforming a City, loc.gov

Florida's Economy Booms, fcit.usf.edu

Tourism in Florida, fcit.usf.edu

Cape Canaveral: Launchpad to the Stars, fcit.usf.edu

Apollo 11 Mission Overview, nasa.gov

Facts About Florida Oranges & Citrus, visitflorida.com

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

History Cooperative

History of Florida: Early History, Exploration, Colonization, Becoming a State, and More!

The history of Florida spans a wide range of periods and influences, from ancient native civilizations and European colonization to its development into a modern center of culture, tourism, and innovation.

Table of Contents

Early History of Florida and Prehistoric Native People

Before European explorers set foot on what is now Florida, it was home to a diverse array of Native American tribes . The earliest inhabitants, dating back to at least 14,000 years ago, were pre- Clovis people who lived in a hunter-gatherer society. Over millennia, these populations evolved into complex societies, such as the Timucua, Apalachee, Calusa, and Tequesta tribes. These communities were sophisticated, with established trade networks, ceremonial complexes, and a deep spiritual connection to the land.

European Exploration and Colonization

The story of European involvement in Florida begins with Juan Ponce de León, who in 1513, while searching for the mythical Fountain of Youth, landed on Florida’s shores. He named the land “La Florida” due to its lush, florid vegetation and because his landing coincided with the Easter season, known as “Pascua Florida” in Spanish. This marked the beginning of European interest in the region, leading to subsequent expeditions and claims by Spain.

READ MORE: New Spain: Spanish Colonization and the Birth of an Empire

16th Century Settlements

The 16th century saw the first European settlements in Florida, notably the French Huguenot settlement at Fort Caroline in 1564, and the Spanish establishment of St. Augustine in 1565, the latter of which is the oldest continuously inhabited European-established settlement in the continental United States. These early settlements were fraught with hardships, conflicts with native populations, and rivalries between European powers.

READ MORE: Who Discovered America: The First People Who Reached the Americas and US History Timeline: The Dates of America’s Journey

First Spanish Period

Florida’s First Spanish Period (1565-1763) was characterized by missions and military forts as Spain sought to convert the indigenous populations to Christianity and protect its territory from other European powers. The Spanish established a network of missions across the peninsula, reaching into Georgia, but their control was often challenged by native resistance and European rivals.

READ MORE: How Did Christianity Spread: Origins, Expansion, and Impact

British Period

The British Period (1763-1783) began when Florida was ceded to Great Britain in exchange for Havana, Cuba, after the Seven Years’ War. During this time, Britain divided Florida into East and West Florida, encouraging settlement and developing the region’s economy. However, British control was short-lived, as Florida was returned to Spain following the American Revolutionary War.

Second Spanish Period

The Second Spanish Period (1783-1821) saw a decline in Spanish influence, as they struggled to attract settlers and maintain control. This period was marked by border disputes and increasing pressure from the United States, leading to Spain selling Florida to the U.S. in the Adams-Onís Treaty of 1819, with transfer formalized in 1821.

Territorial Florida

Following Spain’s cession of Florida to the United States in the Adams-Onís Treaty of 1819, with the transfer being formalized in 1821, the area embarked on a transformative journey. This era heralded the establishment of a territorial government in 1822, with Tallahassee chosen as the capital, underscoring the region’s developmental strides and governance structuring. Amidst this period of growth and settlement, Florida grappled with the challenges of integrating the remaining Native American populations, leading to the seminal Seminole Wars, which were indicative of the broader conflicts and negotiations that characterized the American frontier.

This territorial phase was a crucible of change, laying the groundwork for Florida’s eventual admission to the Union. On March 3, 1845, Florida emerged from its territorial cocoon to join the United States as the 27th state, a milestone that marked the culmination of its complex journey from a contested colonial outpost to a fully integrated state. Before this transition, the region was officially designated as the Florida Territory, reflecting its intermediate status between colonial possession and statehood. This designation, while temporary, was crucial in Florida’s historical arc, serving as a stage for development, conflict resolution, and the establishment of a distinct identity within American history.

Early Statehood and Antebellum Florida

Following its admission as the 27th state, Florida’s economy grew around cotton and sugar plantations, reliant on slave labor. This period, however, was also marked by tensions over issues of state rights and slavery.

READ MORE: Slavery in America: United States’ Black Mark

Civil War and Reconstruction

Florida seceded from the Union in 1861, joining the Confederacy during the American Civil War . Post-war Reconstruction was a challenging time , with efforts to rebuild the state’s economy and integrate freed slaves into society.

Gilded Age and Progressive Era in Florida

The late 19th and early 20th centuries were a time of growth and transformation in Florida, with the development of the railroad by industrialists like Henry Flagler and Henry Plant, promoting tourism and the agricultural industry. This era also saw the implementation of progressive reforms, including women’s suffrage and labor laws.

The Great Depression in Florida

The Great Depression hit Florida hard, with its economy already weakened by the 1926 Miami Hurricane and the real estate collapse. The New Deal programs played a crucial role in Florida’s recovery, funding public works projects and providing employment.

Florida During World War I

While World War I had a relatively limited impact on Florida compared to other regions, it did lead to an increase in military training facilities in the state, laying the groundwork for Florida’s significant military role in the future.

READ MORE: What Caused World War 1? Political, Imperialistic, and Nationalistic Factors

Florida in World War II and Post-War Boom

Florida’s strategic location and climate made it an ideal location for training bases during World War II. The post-war era saw a population boom, driven by returning veterans, the development of the space industry, and the advent of air conditioning, making Florida’s climate more bearable.

READ MORE: WW2 Timeline and Dates

Florida in the Modern Era and Interesting Facts about Florida

In recent decades, Florida has become a leading state in technology, aerospace, and tourism, home to the Kennedy Space Center and major theme parks. Its natural beauty, from the Everglades to its pristine beaches, continues to draw visitors from around the world.

Florida is known as the “Sunshine State,” a nickname officially adopted in 1970 to reflect its sunny climate and to promote tourism. Florida is renowned for its tourism industry, with attractions such as Walt Disney World, the Everglades National Park, its beaches, and as a preferred destination for retirees. It’s also known for its citrus industry, space exploration, and as a cultural melting pot, reflecting a diverse blend of influences.

Sunshine State’s Rich History

The history of Florida is rich and diverse. From the early encounters between Indigenous peoples and European explorers to the waves of settlers and immigrants shaping its landscape, Florida has witnessed dynamic transformations over the centuries.

The state’s strategic importance during the colonial era, its role in the Civil War, and the challenges posed by the harsh climate have all left indelible marks on its history. The quest for land, economic opportunities, and religious freedom attracted various cultures, contributing to the vibrant and diverse society that defines Florida today.

As Florida evolved from a remote outpost to a sought-after destination, the struggles for civil rights and environmental conservation emerged. The state’s proximity to the Caribbean, its thriving tourism industry, and its impact on space exploration have further solidified its significance on the national and global stages.

Therefore, Florida’s history is marked by a rich and varied past, evolving from its ancient roots and colonial struggles to become a contemporary beacon of cultural diversity, tourism, and technological advancement.

How to Cite this Article

There are three different ways you can cite this article.

1. To cite this article in an academic-style article or paper , use:

<a href=" https://historycooperative.org/history-of-florida/ ">History of Florida: Early History, Exploration, Colonization, Becoming a State, and More!</a>

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

- BUCKET LISTS

- TRIP FINDER

- DESTINATIONS

- 48HR GUIDES

- EXPERIENCES

- DESTINATIONS South Carolina 3 Ways to Get Wet and Wild in Myrtle Beach BY REGION South America Central America Caribbean Africa Asia Europe South Pacific Middle East North America Antarctica View All POPULAR Paris Buenos Aires Chile Miami Canada Germany United States Thailand Chicago London New York City Australia

- EXPERIENCES World Wonders 14 Landmarks That Should Be Considered World Wonders BY EXPERIENCE Luxury Travel Couples Retreat Family Vacation Beaches Culinary Travel Cultural Experience Yolo Winter Vacations Mancations Adventures The Great Outdoors Girlfriend Getaways View All POPULAR Cruising Gear / Gadgets Weird & Wacky Scuba Diving Skiing Hiking World Wonders Safari

- TRIP FINDER Peruvian Amazon Cruise BY REGION South America Central America Caribbean Africa Asia Europe South Pacific Middle East North America Antarctica View All POPULAR Colors of Morocco Pure Kenya Costa Rica Adventure Flavors of Colombia Regal London Vibrant India Secluded Zanzibar Gorillas of Rwanda

- Explore Bucket Lists

- View My Bucket Lists

- View Following Bucket Lists

- View Contributing to Lists

Florida — History and Culture

There’s much more to Florida than its stereotype of retirees, ‘snow birds’, celebrities, and people in need of a winter tan. The state was settled by Spaniards looking for gold in the 16th century, but had already had a long Native American heritage stretching back millennia before this point. Today, well over 10 percent of Florida’s population is Hispanic, giving the state a great mix of cultural identity.

More than 100 Native American tribes, such as the Seminoles and Apalachee, lived around Florida when the first Spaniards arrived on its shores in 1513. Famous explorer Juan Ponce de Leon was first on the scene, chasing tales of legendary El Dorado gold and eternal youth. Several competing conquistadors set up forts and towns, some of which remain largely intact today, such as St Augustine.

The British were next to seek control over Florida’s lush lands in the 1700s. They kicked the Spanish out in 1763 and divided the territory into two parts. Florida sided with the British during the American Revolution, but the Spanish returned in 1781 and took back West and East Florida. US President Andrew Jackson invaded Spanish Florida but this only sparked the First Seminole War in 1817, which would pit settler against Indian for the next 50 years.

In 1819, Spain ceded all land to America to settle their debt. During the Civil War, Florida was quick to secede to the Confederacy, but saw little fighting. After being readmitted to the Union, Florida switched its focus to tourism. Entrepreneurs built railroad lines in a bid to lure holiday-makers and in 1888, President Grover even visited. The railroads opened the floodgates to visitors from across the US.

Florida’s first theme parks arrived in the 1930s with Cyprus Gardens, but it wasn’t until 1971, when Walt Disney chose central Florida for his dream, that this state was truly revitalized. Around the same time, the 1960’s Space Race centered itself at Cape Canaveral, adding a different economic boost and prestige. Since then, Florida has been primarily about fantastical theme parks, space launches, beach holidays, and fun in the sun.

Beneath the strip malls, old folks’ homes, and tourist-heavy beach towns, there is a rich spectrum of culture at work in Florida. The allure of Disney, Universal, and the other theme parks in Orlando can’t be dismissed because they contribute a true mark of fantasy to Florida’s culture. The beach towns off the tourist radar are another major facet in Florida’s character. They epitomize the hyper-relaxed atmosphere that pervades over most of the state, with the exception of Miami.

But in Miami, another essential cultural element is at work. The strong Latino and Cuban populations are on full display. Even outside of Little Havana , it’s hard not to notice the ethnic diversity in South Florida. The Hispanic element provides much of the excitement in Florida, in sharp contrast to the state’s geriatric constituency. Simply spend a week in Miami and practice your Spanish because it’s just as prevalent as English. From dizzying nights out in South Beach and Little Havana, to the art and fashion on parade in the Design District, Miami is the pulse of Florida.

- Things To Do

- Attractions

- Food And Restaurants

- Shopping And Leisure

- Transportation

- Travel Tips

- Visas And Vaccinations

- History And Culture

- Festivals And Events

World Wonders

These are the most peaceful countries on the planet, the great outdoors, deserts in bloom: 6 spots for springtime wildflower watching, how to plan a luxury safari to africa, british columbia, yoho national park is the most incredible place you've never heard of.

- Editorial Guidelines

- Submissions

The source for adventure tourism and experiential travel guides.

Click to join floridahistory

CONTACT INFO: [email protected] M. C. BOB LEONARD, DIRECTOR, Florida History Internet Center [email protected]

tampa, florida 33629 please credit fhic for any photographs on content used from this site. .

Mondes du Tourisme

Home Numéros 21 Recherche - Dossier : Imaginaires... Florida: From Tourism to Troubles

Florida: From Tourism to Troubles

Among the fifty states of the American republic, only a very few can project a mystique, a special mythic spirit. From the middle of the nineteenth century, when natural springs and lush foliage attracted some explorers and well-to-do visitors, to the present, when Walt Disney World welcomes many millions of tourists, Florida has offered alluring pleasures. Since the land boom in Miami in the 1920s down to our own day, the state has become home for millions of Northerners and Midwesterners in particular. Very few states have grown faster –too fast, it seems. For the natural basis of harboring so many millions of residents and tourists is buckling under the strain of excessive demands upon resources, and nature is now striking back. The growth upon which Florida has depended for prosperity has become an ecological threat, and the dream of paradise that once drove so many Americans to live in the state is turning sour. Once a source of enormous pride, tourism has become a serious problem for residents and above all for the balance between civilization and nature.

Parmi les cinquante États de la République américaine, peu sont associés à une mystique, à un esprit mythique particulier. Depuis le milieu du xix e siècle, lorsque les sources d’eau naturelles et la nature luxuriante attiraient quelques explorateurs et visiteurs aisés, jusqu’à aujourd’hui, où Walt Disney World accueille plusieurs millions de touristes chaque année, la Floride a toujours proposé des plaisirs séduisants. Depuis le boom foncier de Miami dans les années 1920 jusqu’à nos jours, cet État est devenu le foyer de millions d’habitants, venus du Nord et du Midwest en particulier. Très peu d’États américains ont connu une croissance aussi rapide – trop rapide, semble-t-il. En effet, les conditions naturelles qui permettent d’accueillir ces millions de résidents et de touristes cèdent sous la pression d’une demande excessive de ressources, et la nature contre-attaque. La croissance, dont dépendait la prospérité de la Floride, est devenue une menace écologique et le rêve de paradis, qui poussait autrefois tant d’Américains à venir vivre dans cet État, s’écroule. Auparavant source d’une immense fierté, le tourisme est devenu un sérieux problème pour les résidents, notamment pour l’équilibre entre civilisation et nature.

Index terms

Mots-clés : , keywords: , introduction.

1 The history of Florida is punctuated with a mystique–which none of the states of the union may need, but which a few have nevertheless invoked and transmitted. In this respect Florida differs from, say, New Hampshire, or Missouri, or South Dakota. To be sure, such states have their virtues, but none has the mythic status that Florida projects. It claims to be a kind of hologram of paradise, a place where the most ancient memories of our species are somehow reinvented in the form of modern fantasies (Arsenault, 2019, p. 10). In that sense, no state has been more authentically American. “In the beginning all the world was America,” John Locke philosophized in his Second Treatise of Government (1689); and less than a century later, exultant colonists bent on revolution claimed the power to revitalize human experience itself. The new nation was primed to write a “whole [new] chapter in the history of man,” Thomas Jefferson exulted (Locke, 1980, p. 29; Jefferson, 1975, p. 484). “We have it in our power,” Thomas Paine added in 1776, “to begin the world all over again” (2009, p. 53). Were that power properly deployed, a sequel to Eden might be found in the new United States. No part of it (except California) promoted itself more ardently or successfully as a successor to Eden than Florida. It can be considered “a state of mind” as much as it is a “state of being” (Derr, 1989, p. 13; O’Sullivan and Land, 1991, pp. 11-13).

2 The mystique of Florida has therefore drawn tourists. They have come for the purpose of pleasure; and other travelers have subscribed to an agenda–such as business–that is more varied. The distinction is easily blurred, but tourists should be considered travelers who buy commodified experiences. Tourism often entails predictable and standardized itineraries, and in that sense has been historically less adventurous than travel. The split between travel and tourism emerged in the early nineteenth century, and whether the difference remains tenable is debatable (Revels, 2011, p. 6; Macintosh, 2019, pp. 4-5, 6, 7, 11, 12). What is inarguable, however, is the appeal of Florida. The official tourism marketing corporation called Visit Florida, “a public/private partnership” that Governor Lawton Chiles created in 1996, estimates that 118 million domestic visitors came to the state in 2018, along with 3.5 million Canadians and 10.8 million other foreign visitors. Such statistics, if reliable, are staggering. The mystique with which culture framed nature drew the crowds. But then the crowds made nature less sublime and less viable. Such is the argument of this essay, which synthesizes literary evidence, economic data and press reports to show the role of Florida in the history of tourism as well as the impact of tourism upon a state that once promised proximity to nature. This essay therefore reinforces the tendency of environmental historians to blur at least some of the lines between humanity and its habitat. If civilization and landscape are not “mutually exclusive” (Schama, 1995, p. 14), the history of Florida–especially over the course of the last hundred years or so–shows how entwined they are.

3 Evidence of the idyllic impact that Florida historically registered upon visitors is easy to cite. For instance, the journalist Edward King toured the defeated South in 1873 for Scribner’s Monthly . Spending his first night in Jacksonville, he found the milieu “slumberous, voluptuous... Here beauty peeps from every door-yard. Mere existence is a pleasure... Through orange-groves and grand oaks thickly bordering the broad avenues gleams the wide current of the St. Johns River,” he exulted. Yet King also envisioned prospects of economic development there. He thus already signaled a counter-myth, in which the intrusion of capitalism or an industrial machine disrupts the garden (1972, pp. 380-81; O’Sullivan and Land, 1991, pp. 144-48; Rowe, 1978, pp. xi, xiii-xiv). Although joie de vivre was not something that the Puritans and their descendants extolled, even Harriet Beecher Stowe managed to distance herself from that heritage when she strolled along the St. Johns River. She wrote in 1872 that “life itself is a pleasure when the sun shines warm, and I sit and dream and am happy and never want to go back north.” The rhapsodic reaction of no other visitor shows more effectively the power of Florida, because happiness was hardly the goal that her religious faith fostered (Rowe, 1992, p. 5). The cultural shift therefore needs to be made explicit. The awareness that hedonism might replace moral duty as the purpose of life, that traditional codes of conduct might yield to the definition of a state as a playground, anticipated the state’s winking advertisement of the 1960s: “The rules are different here.” Unobstructed desire, which Christianity was historically designed to stigmatize, gave way to a late-twentieth-century enticement like “Florida. When you want it bad, we got it good” (Mormino, 2005, pp. 120-21).

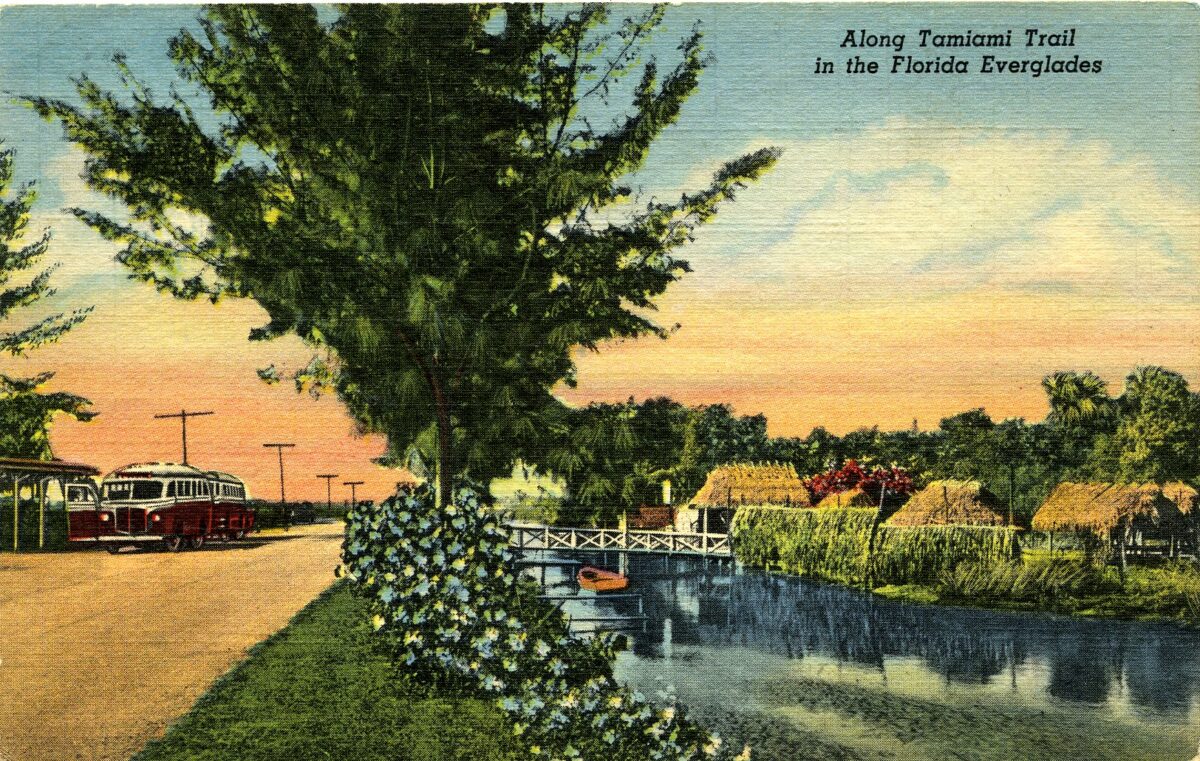

4 With its natural sites and natural springs, postbellum Florida was soon open for business. Bucolic marvels like Sunken Gardens, Cypress Gardens and Weeki Wachee became tourist attractions; and Silver Springs became the state’s most celebrated and promoted natural wonder. There tourists could hop onto a glass-bottom boat, an unusual vessel that enabled passengers to see sixty-feet down into the pure depths of Silver Springs. Among the nineteenth-century Americans who seized this opportunity were Mrs. Stowe, Ulysses S. Grant and Thomas A. Edison. In the era of Jim Crow, black tourists could board glass-bottom boats downriver, at Paradise Park. It was Florida’s only roadside attraction pitched specifically to African-Americans (Mormino, 2005, pp. 86-90; Revels, 2011, pp. 20, 36-37; Vickers and Wilson-Graham, 2015, p. 11). By law and by custom, commitment to white supremacy made Florida recognizably Southern, of course; and only closed societies like Mississippi, for example, permitted the racist record of Florida to escape full scrutiny. Of the eleven states of the former Confederacy, Florida had the lowest percentage of African-Americans, and was also the only one, as the journalist John Gunther awkwardly noted, to have “an Indian problem” (1947, p. 655). In 1940 no Southern state had fewer residents—not even Arkansas. Little more than six decades later, however, Florida jumped ahead of New York as the third most populous state, which suggests an increasing friction with the usual meaning of “the Southern way of life.” It was historically agrarian, and its hamlets were inextricable from its farms and plantations. But no Southern state is currently more urban than Florida, where tourism easily outranks the economic importance of agriculture.

Visitation rites

5 Boosting numerical growth has been the industry that now dominates the state’s economy. Indeed, more tourists visit Florida than any state, other than the nation’s largest, California. How did the allure of Florida get so powerfully emitted?

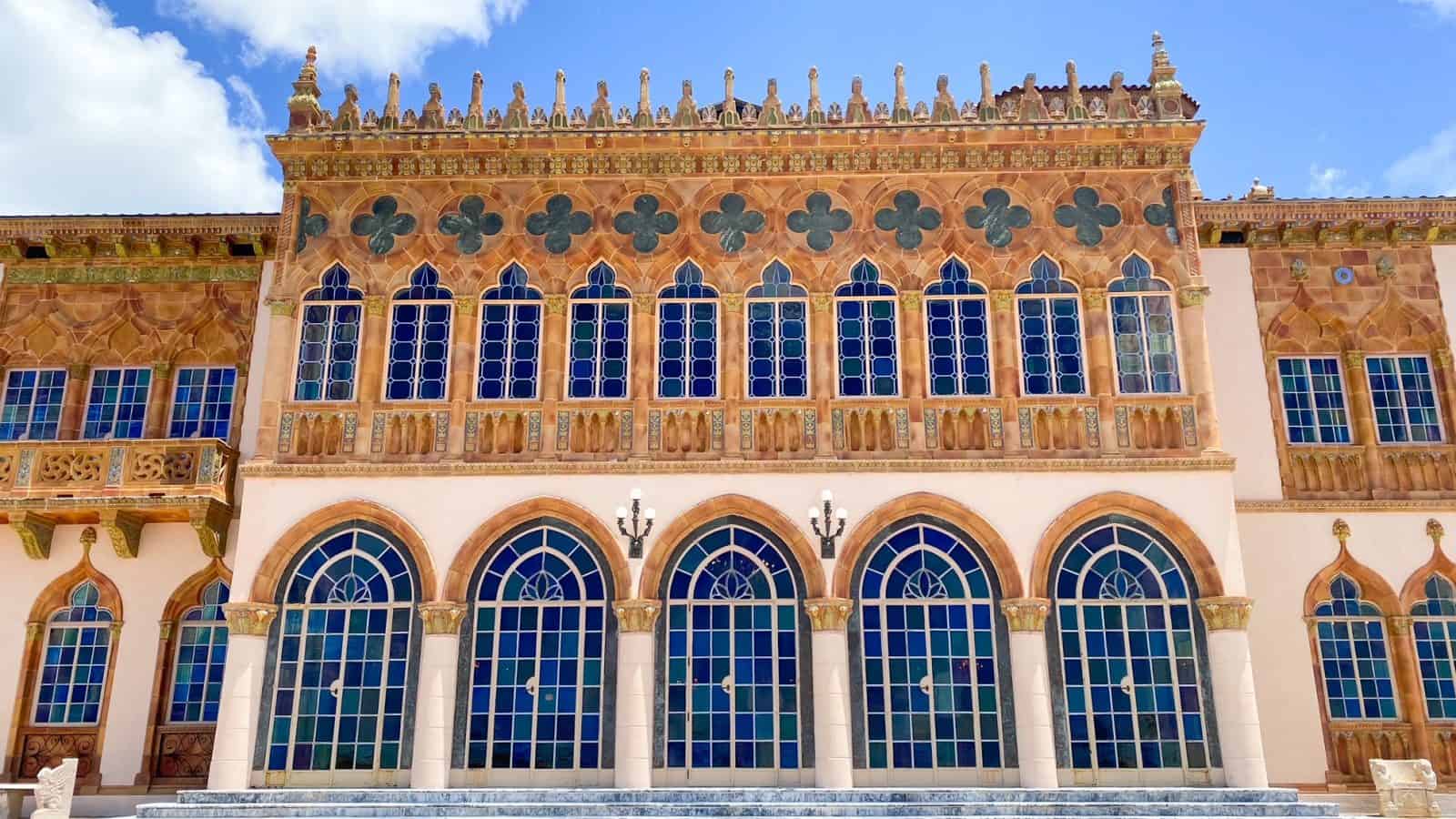

6 Historian Tracy J. Revels, the author of a scholarly study of Florida tourism, has listed four conditions for success: “a population with adequate funds and time for travel, reliable transportation, comfortable and safe destinations, and a body of images and descriptions designed to excite the imagination and lure patrons” (2011, p. 104). The wealthy fit her first category. From the beginning, in the late nineteenth century, they were the only kind of tourists who came to Florida. They hunted, fished and sailed; they played golf; they socialized among themselves during those wish-you-were-here winters. And why not? The state could boast of a tranquil beauty that featured glistening beaches. None of the lower 48 states enjoys a longer seaboard, so that seawater is never more than sixty miles away from any spot on this peninsula (Whitfield, 1993, p. 416). Railroads were constructed to bring the rich to the state, with the tracks going to and going through St. Augustine, Tampa and Miami. Hotels were built to let the leisure class luxuriate in the comfort to which they were accustomed in Newport and on the Riviera. If the characteristic manmade structure of Florida could be identified, the architectural choice would not be a cathedral or a church, not an office building or a mansion, not a tower or a skyscraper, but a hotel (Cox, 2011, pp. 137-38; Rothchild, 1985, p. 57). Catering to Northeastern elites, St. Augustine’s lavish Ponce de Leon Hotel started a trend that included the Vinoy Park Hotel in St. Petersburg.

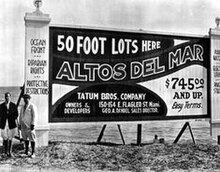

7 But a playground restricted to the privileged could not be permanently assigned to Florida. The ethos of democracy encourages the many to hope to emulate the few, and the Roaring Twenties marked the takeoff for the tourism of the masses. “For a significant proportion of the American populace,” historian Cindy S. Aron concluded, vacations became “an important component of an acceptable standard of living” (Aron, 1999, p. 244). Roads complemented trains; and Henry Ford enabled the common folk—Americans of limited means and plebeian tastes—to go on the move for pleasure. In Florida another populist, three-time Presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan, hawked real estate investment. The masses to whom Ford and Bryan appealed lacked the leisure to “winter” for an entire season in Florida. Their vacations were necessarily brief. Yet the Model T and the land craze (which the Marx Brothers mocked in The Cocoanuts in 1929) sparked the invasion of ordinary or “Tin Can” visitors. By 1925 about 2.5 million of them were arriving annually, and many tourists would decide to stay. Miami ballooned from 5,471 in 1910, to 29,571 in 1920, and to 110,637 in 1930. In the decade of the 1920s, no metropolitan area in the nation grew faster than Miami; Tampa-St. Petersburg came in sixth (Revels, 2011, pp. 2, 68; Cox, 2011, pp. 139, 146-48; Rugh, 2008, p. 3; Tindall, 1965, pp. 76-83, 109-11). Other visitors would soon stampede to Florida in greater hordes.

8 And why not? Contrast its winter season to the Northern and Midwestern cities—not only because of their sometimes bitter cold but also because residents wake up in the dark and return from the day’s work after sundown. St. Petersburg therefore contrived an easy job—a public relations director—and became the first community in the state to make such an attempt to live up to the billing of a “Sunshine City” (Arsenault, 1988, pp. 145, 186, 203, 261-62). St. Petersburg had no manufacturing base, but long attracted honeymooners as well as the very aged. That peculiar demographic pairing led to the jibe that St. Petersburg attracted “the newly wed and the nearly dead” (Revels, 2011, p. 73; Mormino, 2005, p. 79; Rothchild, 1985, p. 52). How poorly some startup marriages eventually fared can be gauged from Ring Lardner’s bleak short story, “The Golden Honeymoon” (1922), set in St. Petersburg. Black tourists took their chances too. By the 1930s, The Negro Motorist Green Book became an indispensable guide in alerting African-Americans to accessible hotels, restaurants and gas stations. Barely three decades later, the interstate highway system would enable black motorists to feel safer. Had they still been forced to wind their way through Florida’s backroads, such strangers would have been dangerously conspicuous. By then the state was becoming less parochial, however. Facing Latin America, Miami welcomed more foreign visitors to its airport than any other besides New York’s Kennedy (formerly Idlewild) (Seiler, 2006, pp. 1110-11; Derr, 1989, p. 338; Gunther, 1947, p. 729). Postwar affluence, advances in travel such as the jet plane and above all the widespread use of air-conditioning became crucial to the allure of Florida.

9 The decades immediately after the Second World War marked what one historian called “the golden era of family vacations.” Typically, these vacations were paid, thanks to the power that the New Deal had bestowed on the labor movement. The maps and atlases of the American Automobile Association and of Rand McNally taught geography to children and made road trips easier. So did the burgeoning numbers of motels that soon became the favored form of roadside lodging. Such vacations provided families with a sense of cohesiveness and of enjoyment that could be shared. Many veterans who had been stationed in Florida during the war loved the state so much that they relocated there with their families (Rugh, 2008, pp. 1, 10-12, 17, 35, 43, 45).

10 To visit Florida became so accessible and so fashionable that the Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist for the New York Times , Russell Baker, made fun of such tourists. In a story datelined Ormond Beach, Baker invoked the satiric tradition of Mark Twain’s The Innocents Abroad (1869) by reporting that “the first thing people do when they plan a Florida vacation is buy a lot of pink and yellow clothing. Everybody then puts on these funny clothes, gets into the car and drives past nine hundred miles of billboards advertising monkeys and beer... It is very hot,” Baker reminded his readers. “The children snarl at each other... Eventually they arrive at... a gigantic shopping center... It is just like home, except that the houses are painted lavender and orange to match the customer’s clothing.” He noticed that “the vacationer feels terrible about being pale. Pale skin marks him as a tourist, and the worst thing about being a tourist is having other tourists recognize you as a tourist. And so, for three or four days, he broils himself mercilessly in the sun... hoping he will become inconspicuous enough to have a wonderful time,” which Baker suspected “isn’t easy.” By the mid-twentieth century, he already suspected trouble in paradise. “There is a lot to be said for fun and comfort,” he wrote in a bittersweet conclusion from Daytona Beach. “But total fun and total comfort wind up being total bores, and in the process, pleasure is lost” (1965, pp. 68-70, 71).

11 Some tourists could afford luxury hotels on Miami Beach like the Fontainebleau and the Eden Roc. Many other visitors ended up staying in seedy motels, of which a fictional example is described in the Miami writer Carl Hiassen’s Tourist Season (1986): “The Flamingo Isles was not a classic Miami Beach motel. There was nothing charming about the color (silt) or the architecture (Early Texaco). At this motel there were not striped canvas awnings, no wizened retirees chirping in the lobby, no lawn chairs lined up on the front porch, no front porch whatsoever. Basically, the Flamingo Isles was a dive for pimps... and hookers. Rooms costs ten dollars an hour, fifteen with porno cassettes” (pp. 30-31). Such settings suggested a devotion to tackiness, if not to downright ugliness, and inspired recourse to derogatory Yiddish terms like shlock and dreck to label the knickknacks commonly for sale in Florida. They have ranged from the shellacked blowfish and plaster flamingoes to the pirate heads carved from coconuts and the pelicans made from seashells (Gopnik, 2013, p. 105; Revels, 2011, p. 118; Rothchild, 1985, pp. 2-5). The democratization of travel and the achievement of prosperity cannot be entirely separated from the widespread evidence of tastelessness.

12 By the second half of the twentieth century, nature was increasingly yielding to culture–and its dominion could easily turn sinister. Here the memoir of journalist Edna Buchanan may be symptomatic. Coming from New Jersey in 1961, Buchanan was stunned when she first saw Miami Beach, “all pink, radiant, and bathed in sunlight.” She was thrilled to discover that “everything is exaggerated” in such scenery, “the clouds, the colors too bright to be real [and] the heat.” She got used to “drifting clouds [that] glow golden at sunset and rosy at dawn” (1987, pp. 31, 43). But Buchanan also realized that local violence was exaggerated too, and she became a crime reporter for the Miami Herald . Her stories showed how terrifyingly far Miami-Dade County would stray from Revels’ definition of “safe destinations” for tourists. The crime wave that hit Miami in 1993-94 brought Buchanan’s shocking reporting to national attention. For example, ten foreign tourists were murdered; and the number of visitors from abroad, especially from Britain and Germany, fell by a fifth. To lessen vulnerability to theft, kidnapping and homicide, rental car companies removed the distinctive license plates that marked the automobiles as rented (Revels, 2011, p. 140). Foreigners were presumably safer when traveling incognito. Not all the local rustics on the west coast of the state adhered to the welcoming messages from the Chamber of Commerce. A columnist for the St. Petersburg Times once spotted a more menacing sign than conventional advisories against trespassing: “My dogs can make it to the fence in three seconds. Can you?” (Klinkenberg, 2008, p. 8; Mormino, 2005, p. 121).

13 Although not every longtime resident was hospitable, the trajectory of the vacationers choosing Florida as their destination is astonishing. Their number increased from 4.5 million in 1950 to over 9 million by the end of the decade. The number doubled again in 1967. In 1971, when the Magic Kingdom at Walt Disney World opened, Florida attracted 23 million tourists (Revels, 2011, pp. 102-3; Arsenault, 1984, pp. 597-628; Mormino, 2005, pp. 95, 96). Their spending habits raised the income of the local inhabitants, but the blessings must be classified as mixed. Take what happened on the day after Thanksgiving, in 1971, when about 56,000 tourists tried to get into the Magic Kingdom. Backing up traffic for ten miles, they made the apocalyptic traffic jam that famously opens Jean-Luc Godard’s Weekend (1967) seem prophetic. Though Disney World is justifiably celebrated for its efficiency in crowd control, the park had to shut down its ticket window early that November afternoon. Yet such harrowing episodes posed no deterrent to Florida’s tourists. Their numbers swelled to more than 70 million in 2000 (Revels, 2011, p. 126; Mormino, 2005, p. 115), and six years later 83.9 million visitors swarmed into Florida–so many that an exasperated Carl Hiassen fantasized confining them solely to “Disney property until their vacation money runs out” (Hiassen, 2001, p. 20; Revels, 2011, pp. 142, 149).

14 Of course, the mass appeal of Florida needs a context. In January 1944, when Franklin D. Roosevelt listed “leisure” along with adequate shelter and the elimination of hunger among his proposed Second Bill of Rights, he could not have foreseen how devoted posterity would be in exercising the option of tourism. Vacationing in the developed world has become the third largest family expense, right after food and housing (Elsworth, 1991, p. F4). No country has been pulling its weight more fully than France–the planet’s most popular destination, according to the United Nations World Tourism Organization. Nor has any museum ever attracted more visitors than the Louvre, which set a record of 10.2 million art lovers in 2018. In that year, throughout the world, visitors who stayed at least one night in a foreign country reached 1.4 billion. In the United States, however, recent fears of a “Trump slump” roiled the international travel industry, which supports 15.7 million jobs and generates $2.5 trillion in economic output. Nearly 80 million foreigners visited the US in 2018. That was a record high. But the American share of the international travel market skidded 13.7 percent from 2015, to the lowest level since 2006. Had the 2015 level remained steady, the US would have welcomed 14 million more international visitors, a magnitude that would have generated enough demand to employ 120,000 more Americans (Nayeri, 2019, p. C1; Mzezewa, 2019, p. TR2). The scale of these missed economic opportunities is poignant.

15 Tsunamis of tourists nevertheless continued to pour into Florida. Over 5 million foreign visitors per year still flock to the theme parks around Orlando, and they have shifted tourism away from south Florida. So dependent is central Florida upon tourism that one in twenty workers in the Metro Orlando area earns a paycheck from Disney World; and the Universal Studios theme park hires as many Florida employees as does Walmart (the largest private employer in the world). Absent significant manufacturing in the state, a whopping four in five jobs there are credited—directly or indirectly—to the service industry. It provides food, lodging and entertainment for tourists and other travelers in a state where most governmental revenue comes from sales and hotel taxes. Florida does not impose an income tax, a policy that encourages many tourists to become residents. Only Nevada tops Florida in the proportion of the population born outside the state. But the boost that Florida gets in the census count does not bring a commensurate increase in state revenue to match social needs. Dependence on tourism also affects the labor market adversely. As liberal economists never tire of declaring, the US has suffered less from a lack of jobs than from a paucity of good jobs; and employment in Florida’s service industry tends to be low-skill and low-status (Revels, 2011, pp. 3, 126, 132-33, 151; Mormino, 2005, pp. 114, 181). The pay is so low that very many employees cannot afford to live near where they work. The infrastructure that keeps Disney World humming so smoothly, for instance, is subterranean. That is where many of its employees toil, deprived of the sunlight that draws Disney World’s “guests” to Florida. Shorn of glamour, such jobs are intended to make the influx of vacationers as frictionless an operation as possible, and to keep these eager out-of-state visitors coming.

16 Yet a glum paradox is embedded in the recent history of Florida. “I spent thirty years of my life trying to get people to move down there,” a former mayor of Orlando, Carl T. Langford, has recalled. “And then they all did” (Painton, 1991, p. 58). He was neither the first nor the last person to learn that in dreams begin responsibilities, and that neither action nor inaction can avoid repercussions. Promises also entail problems. They have included environmental degradation, traffic congestion, gridlock on expressways like the Palmetto and the Sawgrass, as well as the sort of sprawl that can seem almost indigenous to Florida. The structure of services and amenities, as well as the infrastructure, is bound to buckle under the weight of so many people. The underground aquifers are already so depleted that even during the rainy season lawn-watering restrictions have been imposed. This melancholy decline in the quality of life is bound to affect the impressions and experiences of tourists too. The fate of Florida thus exemplifies what economists call “induced demand.” It is defined as an increase in availability (such as more highway lanes and larger parking lots), which instigates an increase in consumption, which worsens traffic congestion. When Langford, the longtime booster, decided to retire, he moved to North Carolina (Grunwald, 2004b, pp. 28-29; Mormino, 2005, pp. 28-29), making the conclusion inescapable: ballyhoo has its downside. Some of its consequences can be tabulated here.

17 The balance between nature and artifice has become disrupted, risking the prospect of dystopia. The Army Corps of Engineers, with its can-do motto of “ Essayons ” (let us try), has indeed been trying very hard to worsen that imbalance, journalist Michael Grunwald charged. The Corps has energetically put on coasts “environmentally damaging seawalls [and] artificial dunes,” and installed “levees and canals and pumps” into the eastern Everglades in particular, so that it “was converted into wall-to-wall sprawl” (Grunwald, 2004b, p. 27; Burleigh, 2020, pp. TR1, 4-5). And now “the financial and environmental bill for a century of runaway growth and exploitation is coming due,” Grunwald added. “The elaborate water-management scheme that made southern Florida habitable has been stretched beyond capacity, yo-yoing between brutal droughts and floods, converting the Everglades into a tinderbox and a sewer, ravaging the beaches, bays, lakes and reefs that made the region so alluring in the first place.” Mercury has contaminated fish, and algal blooms have clouded the bays of south Florida. The depleted marine life, the leaching landfill sites, the “awful traffic,” as well as “red tides that have made it tough for sunbathers to breathe at the beach,” have been among the effects of Florida’s relentless overdevelopment (Grunwald, 2004a, p. 26, and 2008, pp. 28, 29, 30; Davis and Arsenault, 2005, p. 6). Grunwald should know; he lives in Miami-Dade County. Below Tallahassee, the glass-bottom boats at Wakulla Springs barely run, because tannic acid from the state capital polluted waters that were once so pristine that tourists could see straight down for 120 feet. What remains is what Revels calls “a murky brown stew” (2011, p. 150). The new term for this phenomenon, in which too many visitors bear down on an unsustainable infrastructure, is “over-tourism” (Nayeri, 2019, p. C1).

18 The most notorious instance is undoubtedly Venice, a city that in recent years has been subjected to considerable flooding. It is not an entirely natural catastrophe, but is instead due to what the Venetian literary scholar Shaul Bassi has called an “indiscriminate tampering with an ecosystem nurtured by Venice for centuries, the impact of the cruise ships, excavations of the lagoon and the rapacious investment in tourism.” Admittedly profitable for residents, over-tourism has threatened to supersede all other aspects of civic life there. Far too many earthlings have explored the singularity of Venice and have been wearing the T-shirts to prove it (2019, p. A23). But if Venice goes under and becomes uninhabitable, the durability of the fake Piazza San Marco near Orlando will offer little consolation. The ecological peril to a fragile and unique city like Venice, Italy has been widely publicized. The danger posed to Venice, Florida and vicinity is less known but is surely worthy of concern as well.

19 Any student of “over-tourism” need look no further than Walt Disney World. Covering 43 square miles, which is twice the size of Manhattan, this theme park has become the planet’s biggest tourist attraction. The Florida legislature expedited this achievement in bestowing on Disney’s so-called Reedy Creek Improvement District what amounts to its own government. Endowed with extraordinary political and legal authority, Walt Disney World has written its own building codes, formed its own fire department and even granted itself the power to tax. “They could build a nuclear plant out there,” an Orlando City Commissioner grumbled, “and there’d be nothing we could do about it.” Such sovereignty has even provoked comparisons with the Vatican (Mormino, 2005, p. 104; Painton, 1991, p. 54), however slight the danger of either of these tiny states going nuclear. The shadow that the Magic Kingdom and EPCOT (the Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow) casts is nevertheless formidable. Marine craft afloat in Walt Disney World are so numerous that soon after the opening of the theme park, its flotilla constituted the ninth largest navy on the planet. Great Britain, once the greatest naval power in history, must currently reconcile itself to the reduced status of luring fewer tourists than Disney World does (Elsworth, 1991, p. F4).

20 Orlando can be now reached by direct flights from cities as distant as Rio and Frankfurt. Prior to the pandemic, the 2,558-square-mile metropolitan area of Orlando boasted the largest concentration of hotel rooms (76,300) in the nation, as well as the highest occupancy rate (79%). Orlando became second in the nation in the number of conventions that the city hosts, and also in the number of attendees at those conventions (Painton, 1991, p. 52; Mormino, 2005, pp. 116, 117; Whitfield, 1993, p. 431). Because Disney World inspired the installation of other theme parks, such as Sea World and Universal Studios, Metropolitan Orlando became, by the final decade of the twentieth century, the fastest growing region in the US; and Disney World was welcoming approximately thirty million “guests” per year. Unsurprisingly, the hospitality industry had not fully braced itself for such an impact. Take late December 1986, for example. All motel rooms were then reported to be reserved and occupied on I-95 between Richmond and Savannah; and on December 29, an attendance record was set when 148,500 visitors clamored to get inside Disney World. This recreational colossus bypassed and then extinguished the tourist sites that offered to Mrs. Stowe the splendors of natural springs (Revels, 2011, pp. 127, 132-33; Mormino, 2005, pp. 106, 108).

21 Such spectacular success demands an explanation. For most customers, Walt Disney World seems to deliver. Its dream world is predictable and formulaic. Its atmosphere is antiseptic and courteous. It provides wholesome, banal entertainment. Nor should the superb safety record of Walt Disney World be ignored, especially when contrasted with a water park in Vernon, New Jersey, called Action Park. There so many patrons left with chipped teeth, bruised knees and concussions that attorneys nicknamed it Class Action Park. So many patrons ended up with broken bones that physicians in local hospitals nicknamed it Traction Park. Within one two-year period (1984-85), there were 26 head injuries—indeed, so many that Action Park bought the town of Vernon new ambulances. Between 1978, when the park opened, and 1996, when it closed, six deaths were reported–by drowning and by electrocution. A test dummy was sent on a ride that was about to open and came out of the tunnel missing its head. After this decapitation, the son of the owner demonstrated his confidence in the safety of the ride by inaugurating it and managed to come through the tunnel intact. As a precaution he protected himself by wearing hockey equipment. Disney helped put such amusement parks out of business (Barron, 2019, p. A18).

22 Not all of the guests have been satisfied, however. EPCOT Center, which opened in 1982, “has accomplished something I didn’t think possible in today’s world,” the satirist P. J. O’Rourke observed. “They have created a land of make-believe that’s worse than regular life. Unvarnished reality would be preferable,” he wrote in a deliriously dyspeptic book entitled Holidays in Hell . He was evidently taken for a ride. Journalist Mark Derr, based in Miami Beach, has complained that “the attractions” around Orlando “offer little of Florida, and no one seems to care.” To compare Orlando to its famous nearby theme park is to corroborate the claim of the sociologist Jean Baudrillard that “the city and the park are looking more like each other every day” (O’Rourke, 1988, pp. 184-85; Whitfield, 1993, p. 431; Mormino, 2005, p. 104). This common objection to tourism echoed what the historian Daniel J. Boorstin and the critic (and novelist) Umberto Eco formulated too. Such tourist sites risk calling reality itself into question. What Eco called “hyper-reality,” he argued, distorts actuality, and has represented a standard criticism of such theme parks ever since Boorstin’s broader condemnation of the mediated “pseudo-events” that can make modern experience so disorienting. In The Image (1962), he offered nature as a counterpoint to culture, or at least to the sort of culture that permeates so much of the texture of ordinary life through the ubiquity of media (Boorstin, 1962, pp. 4-5, 11; Whitfield, 1995, pp. 211-21). He was only partly right, however, because the relation to nature is also interactive.

23 In 1962, ecological consciousness barely existed; and sensitivity to the devastation of the natural environment was not common. Scientists were not yet warning of the penetration of the ozone layer. The bill now needs to be paid. The American preference for artifice over actuality (as Boorstin argued), as well as the reckless despoliation of the landscape, has now caused nature to retaliate.

24 The destruction of so many mangrove forests has made the west coast of Florida especially subject to flooding. According to one 2015 study, the Tampa-St. Petersburg metropolitan area ranks first in urban America in vulnerability to storm surges. Fort Myers is fifth, and Sarasota ranks seventh (Davis, 2017, p. 521). In Florida hurricanes have long incurred a fear as vivid as it is warranted; they have been lethal. But climate change has expanded the season from June to November. In 2004, one of the four major hurricanes that hit the state shut down the theme parks around Orlando for three days. Such hurricanes are likely to become more frequent, more powerful and more destructive. The southeastern part of the nation annually gets more rain than any other section, and the hurricanes bring more than danger. One resident of central Florida has defined the hurricane season in terms of “the humidity that frizzes your hair. It’s the lizard that crawls inside your coffee mug.” The air is “sticky.” To walk outside may not mean to encounter exquisite beauty but palmetto bugs instead, as well as “hills of fire ants and heaps of molehills.” Central Florida, she added, is where “the sky cracks open and floods the roads” (Davis, 2017, p. 338; Revels, 2011, p. 145-46; Arnett, 2019, pp. C1, C4). Nature has struck back by heightening the dangers of flooding and sinkholes, which is why Craig Pittman, an environmental reporter for the Tampa Bay Times , warned tourists: “Watch where you step.” But “because of the hurricanes,” he added, “always keep an eye on the skies.” They are not entirely friendly. Though some like it hot, the piercing of the ozone layer has made ominous a term like “Sunbelt.” The yearning to become much less pale that once intrigued Russell Baker now looks foolish, an invitation to risk skin cancer rather than signal robust health (Mervosh, 2019, p. A17). Compared to the icy winter of the Northeast, fierce hurricanes and oppressive heat do not automatically favor Florida.

25 The promoters of Florida had presented nature as mostly benign and hospitable. They showed the state to be primarily pastoral and irenic, a revived Garden of Eden. According to Genesis 3:1, only a single serpent could make trouble. But Florida seems less of a paradise than in the untamed nineteenth century. A bull shark got close enough to the shore of the Panhandle to bite off the arm of a swimmer who was training for a triathlon, while another attack near Destin proved lethal for a teenage girl. In central Florida wild hogs can grow to four hundred pounds. At least 72 species of mosquitoes have been found in the state; and in the summer, park rangers in the Everglades must often be outfitted with special clothing, including head nets. Tourists have reason to be apprehensive. They need to be advised that some creatures unmentioned in the Bible have found a home in Florida, thanks mainly to smugglers of exotic animals. Feckless monitoring at the Port of Miami led the Department of Justice to estimate that only the trade in drugs exceed the profits that can be derived from the importation of invasive species. They include Cuban tree frogs that are big enough to have gobbled native-born frogs, as well as the water hyacinth, the Asian walking catfish and the African tree snail (Bilger, 2009, p. 85).

26 Among the least charming of such creatures is the Burmese python, which began to appear in the Everglades in 1995. These reptiles were probably released by a pet shop, or by a breeder or by an owner confronted with the challenge to having to provide a diet of mice, rats and rabbits. Burmese pythons can grow to a length over twenty feet, can weigh two hundred pounds and can live for more than twenty-five years. According to the account in the National Geographic , a group of tourists walking not far from the main entrance to the Everglades in 2003 watched a Burmese python fight a full-grown alligator to the death. That pythons are not venomous is hardly reassuring, because “their upper jaws are fitted with a quadruple row of sharp, inward-curving teeth, their lower jaws with a double row.” Their teeth can hold onto prey until the Burmese pythons “can coil their body around it.” They can swallow leopards and six-foot alligators. Almost as much as tourists, Burmese pythons seem pleased to visit Florida, and have been found as far west as Tallahassee and as far north as Jacksonville. These reptiles are also believed to be growing more numerous. Along a canal, or in a secluded park, children who are smaller than either leopards or gators should be especially careful (Bilger, 2009, pp. 82, 83, 85, 86, 97). No invasive species is more frightening or resilient or ferocious than the Burmese python.

27 A close second, however, is an African lizard called the Nile monitor. It can grow up to seven feet in length. Its powerful legs enable an adult monitor to outrun a human being. This vicious creature has tapered jaws that are like daggers, and it is not picky about what it eats–which is basically whatever can fit inside its mouth. And whatever does not meet that test can be torn apart, from limb to limb. In the wild the Nile monitor can “hunt on land or in the water, climbing trees [and] digging up burrows,” according to science writer Burkhard Bilger. “Monitors often hunt in packs.” A biologist from the University of Tampa added that “they’re very aware, very intelligent.” Their disposition is quite disagreeable; and though they generally leave human beings alone, they attack if cornered. By now Florida may be harboring thousands of them. Because some have been spotted west of Fort Myers, at euphonious Cape Coral, the encounter between humanity and nature may be particularly fraught there. Cape Coral is the largest city between Miami and Tampa. “At the millennium,” historian Jack E. Davis noted, “Cape Coral was the fastest growing US city with a population of 100,000 or more.” The four hundred miles of canals in this planned community were intended to give homeowners some property next to water. Instead, the swamp—and, along with it, the Nile monitor—has come to them (Bilger, 2009, p. 89; Davis, 2017, p. 409), a reckoning that they could hardly have anticipated or sought.

28 The Burmese python and the Nile monitor are among the more than two hundred non-native species of wildlife estimated to be living outside of captivity in south Florida. In 1992 Hurricane Andrew set loose animals that had been confined to the Miami Zoo. They included baboons, orangutans and capybaras, which are rats that grow to the size of hogs. Many fled into the Everglades National Park. Though its 1.5 million acres exhibit less diversity than the Amazon, the mixture of both tropical and temperate species makes this huge section of south Florida unique. Hence southern crocodiles splash around next to northern alligators; and some plants are so weird that they are carnivorous (Goodnough, 2004, pp. 1, 21; Bilger, 2009, p. 82).

29 Most famous is the official state reptile, the native alligator. Somewhere between a million and a half and perhaps two million gators inhabit the state. But drought has reduced their natural habitat, forcing them to move toward places where Floridians have built swimming pools, canals and ponds. The incessant commitment to commercial and residential growth and the extension of agriculture into wetlands have limited the terrain that the gators once considered their own, resulting in a dramatic increase in fatal attacks against household pets and sometimes against humans. Alligators have become so aggressive that over sixteen thousand calls a year are placed at the state’s hot line, reporting nuisances and threats, often in backyards (Lemonick, 2006, pp. 48-49; Grunwald, 2004b, pp. 28-29; Bilger, 2009, p. 88). Consider the iguanas as well. The National Weather Service in Miami advised visitors as well as residents in south Florida to watch the skies again, because at night iguanas climb to treetops to rest. But these lizards, which are not native to the state, cannot maintain their grip when the temperature dips low; and they drop to the ground. Many can recover and slink away when it gets warmer. But tourists have been warned that they might not appreciate having a five-foot lizard land on them (Ortiz and Zraick, 2020, p. A26). Even when compared to the rats in the subways of New York City, the alligators on the lawn and the iguanas in the skies make Florida less enchanting.

30 No wonder then that contemporary Florida fiction is so attuned to ecology. The exploitation of the land has produced a body of work in which “ambition, appetite and absence of memory,” according to one critic’s summation, “lay waste to a once exquisitely delicate environment of wetlands and beaches.” For instance, the protagonists in Hiaasen’s novels “dislike nature. Whether they are predatory developers, corrupt politicians, greedy sugar barons, sleazy corporate lobbyists,” they barely notice the environment, unless they imagine how “to drain it, pave it, dredge it, and otherwise exploit it... They bulldoze mangrove swamps and hardwood hammocks into gated communities and strip malls” (Gopnik, 2013, p. 104; Grunwald, 2004a, p. 33). The urgency of the problem of imbalance did not happen to concern the Nobel laureates in literature who lived in the state—Ernest Hemingway on Key West, Isaac Bashevis Singer on Miami Beach. But if present ecological trends continue unabated, a refuge for retirees like Singer’s Oceanside community will be entirely underwater in three decades. When Groucho Marx was auctioning off Miami real estate in The Cocoanuts , he promised the suckers that “you can have any kind of home you want. You can even get stucco. Oh, can you get stuck-o!” The cynical joke from this 1920s Florida boom stemmed from the phony plots of land that were sold “by the gallon.” But nature will have the last laugh, and it will be grim.

31 Perhaps none of these alarming troubles lack equivalents elsewhere. But such portents seem to loom larger because of the shadow they cast on the mystique, because Florida has exercised such imaginative power over so many human beings. Too many visitors have come to the state; too many have stayed. Yet as historians Jack E. Davis and Raymond Arsenault observed in 2005, with some consternation, “Florida tourism has received very little scholarly attention in general, and the environmental implications of thirty to fifty million annual visitors have all but been ignored.” That is why Florida should be identified as a test-site of whether an erstwhile ideal of paradise can be squared with growth. Florida is where assumptions about economic and demographic growth have defied the fragility of the environment, where the relentless assault of the American way of life may have reached its limits. Has the remorselessness of “progress” therefore become the nemesis of wellbeing? Certainly, the installation of the machine in the garden has constituted one way of thinking about American history in general, but that injection applies especially to a state where prosperity depends so heavily on tourism. When John Muir, a founder of the Sierra Club and the instigator of the conservation movement in the US, arrived in Florida in 1867, he acknowledged the “thorny plants” and the “venomous beasts” that he saw around him. But Muir also revered nature for its powers of rejuvenating humanity, and he objected to the utter subjugation of the environment to social and economic desires (Davis and Arsenault, 2005, p. 19; Davis, 2017, pp. 243-44). The current troubles that Florida faces hint at the timeliness of Muir’s warning. How commerce can be reconciled with conservation, how over-tourism can somehow be accommodated to the natural order is the challenge that the history of Florida presents. It is a disconsolate reminder of the Fall that is integral to the myth of Eden.

Bibliography

Kristen Arnett , “Tough Women Thrive in Florida,” New York Times , 12 October 2019.

Cindy S. Aron , Working at Play: A History of Vacations in the United States , Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1999.

Raymond Arsenault , “Introduction”, in Jennifer Hardin (ed.), Imagining Florida: History and Myth in the Sunshine State , Boca Raton Museum of Art, 2019.

Raymond Arsenault , St. Petersburg and the Florida Dream, 1888-1950 , Brookfield, Donning, 1988.

Raymond Arsenault , “The End of the Long Hot Summer: The Air Conditioner and Southern Culture,” Journal of Southern History , vol. 50, n o 4, 1984.

Russell Baker , All Things Considered , Philadelphia, J. P. Lippincott, 1965.

James Barron , “An Amusement Park That Brought Smiles and Chipped Teeth,” New York Times , 19 October 2019.

Shaul Bassi , “Waters Close Over Venice,” New York Times , 16 November 2019.

Burkhard Bilger , “Swamp Things,” New Yorker , vol. 85, n o 10, 2009.

Daniel J. Boorstin , The Image, or What Happened to the American Dream , Atheneum, 1962.

Edna Buchanan , The Corpse Had a Familiar Face: Covering Miami , America’s Toughest Crime Beat , London, Bodley Head, 1987.

Nina Burleigh , “Shedding Tears for a ‘River of Grass,’” New York Times , 2 February 2020.

Karen L. Cox , Dreaming of Dixie: How the South Was Created in American Popular Culture , Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 2011.

Jack E. Davis , The Gulf: The Making of an American Sea , New York, W. W. Norton, 2017.

Jack E. Davis and Raymond Arsenault (eds), Paradise Lost? The Environmental History of Florida , Gainesville, University Press of Florida, 2005.

Mark Derr , Some Kind of Paradise: A Chronicle of Man and the Land in Florida , New York, Morrow, 1989.

Peter C. T. Elsworth , “Too Many People and Not Enough Places to Go,” New York Times , 26 May 1991.