- Foundations for Being Alive Now

- On Being with Krista Tippett

- Poetry Unbound

- Subscribe to The Pause Newsletter

- What Is The On Being Project?

- Support On Being

Ocean Vuong

A life worthy of our breath.

Last Updated

May 3, 2023

Original Air Date

April 30, 2020

Krista interviewed the wise and wonderful writer Ocean Vuong on March 8, 2020 in a joyful, crowded room full of podcasters in Brooklyn. A state of emergency had just been declared in New York around a new virus. But no one guessed that within a handful of days such an event would become unimaginable. Most stunning is how presciently, exquisitely Ocean speaks to the world we have come to inhabit— its heartbreak and its poetry, its possibilities for loss and for finding new life.

“I want to love more than death can harm. And I want to tell you this often: That despite being so human and so terrified, here, standing on this unfinished staircase to nowhere and everywhere, surrounded by the cold and starless night — we can live. And we will.”

- Books & Music

Reflections

Image by Matt Huynh , © All Rights Reserved.

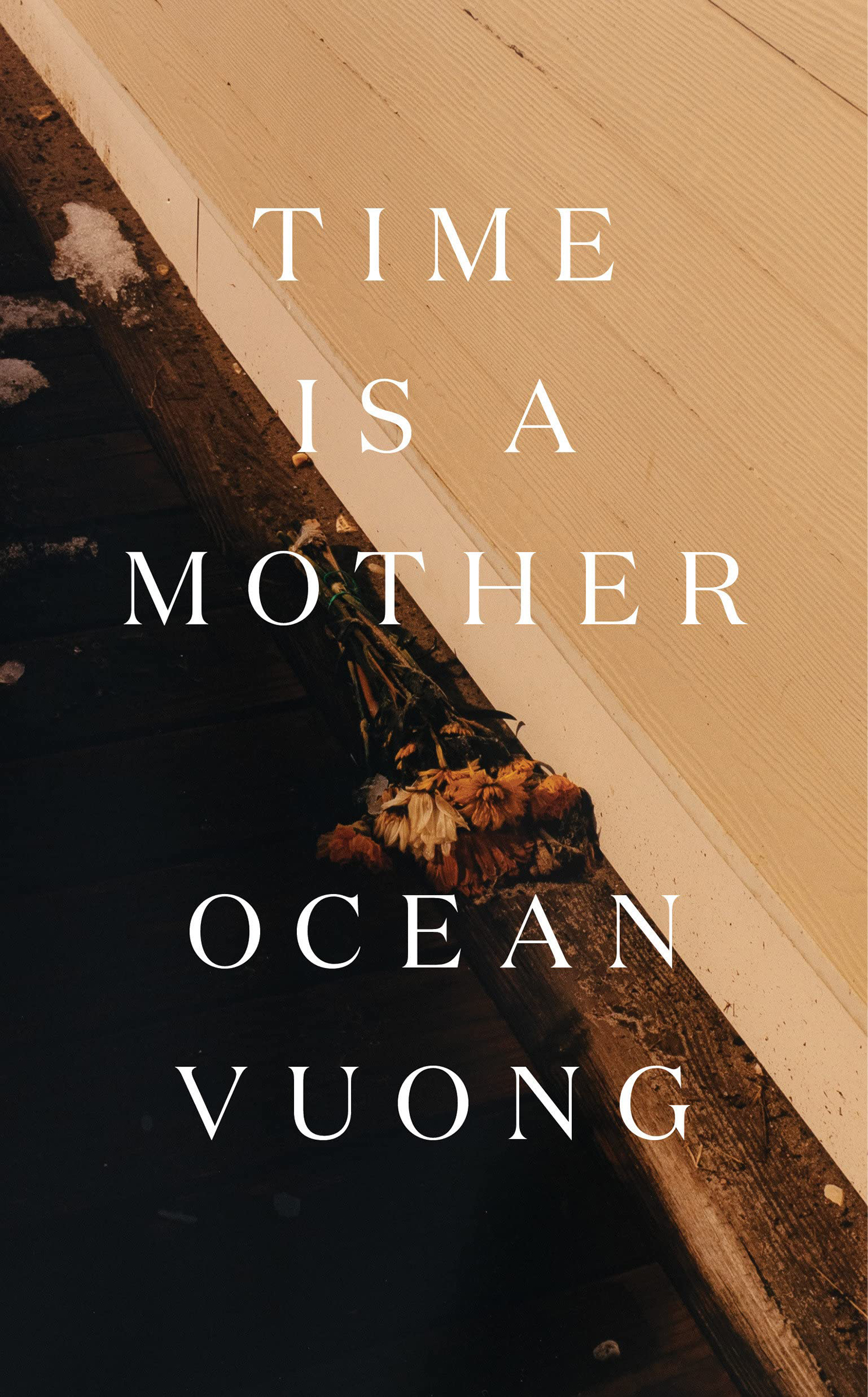

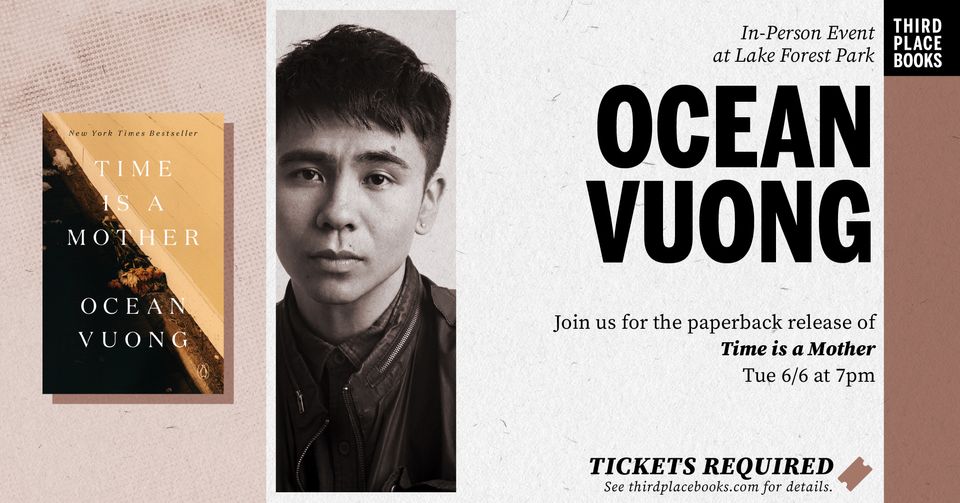

Ocean Vuong is a professor in the MFA Program in Creative Writing at New York University. His new collection of poetry is Time Is a Mother . He is also the author of a novel, On Earth We're Briefly Gorgeous , and the poetry collection Night Sky with Exit Wounds , which won the T.S. Eliot Prize and the Whiting Award. He was a 2019 MacArthur Fellow.

Transcription by Heather Wang

Krista Tippett, host: I interviewed the wise and wonderful writer Ocean Vuong on March 8, 2020, in a joyful, crowded room full of podcasters in Brooklyn. A state of emergency had just been declared in New York around a new virus. But none of us guessed that within a handful of days, such an event would become unimaginable. So, for me, this conversation has become a last memory before the world shifted on its axis. What’s most stunning is how exquisitely this conversation speaks to the world we have since come to inhabit — its heartbreak, its poetry, and its possibilities of both destroying and saving.

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being .

[ music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating ]

Tippett: It’s such an honor to be invited to be part of the On Air Fest and to do a show here. I’m really excited. I love this room, and I love the energy in it that you all are bringing. And what an honor and a delight to be up here with Ocean Vuong …

[ applause ]

… who I want to describe as a writer and wise person who, at a young age, has made a singular contribution to American letters, as a writer of poetry and essays and this novel that you may have heard of. The word “gorgeous” that occurs in the title, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous , is a word that’s also often used to describe your writing and your voice, your literary voice.

And also, Ocean, I want to say I’m aware that when people write about you and introduce you and describe you, they often speak about how your work is shaped by themes of violence and survival, in the context of the immigrant experience, in the context of life and displacement in the aftermath of war, in the context of growing up Asian American and queer in this society. And that is true, and we’re going to talk about violence, but I’d also say that the sweep of your work is about bearing witness to the other side of violence and the possibility of joy, while taking nothing away and continuing to bear witness to the fullness of what has been carried and what has been survived.

So let’s start. Oh, I didn’t mention that you’re a MacArthur genius.

[ laughter ]

Ocean Vuong: I have no proof.

Tippett: You were born in Saigon, and when you were two years old, in 1990, your family came to the U.S. I have this question that I ask at the beginning of most of my conversations: an inquiry about the religious or spiritual background of someone’s childhood, or however they would define that now. I wonder how you — if there are aspects of your childhood to which you would attach that language of “spiritual,” “religious.”

Vuong: My family is traditionally Buddhist, but they were also illiterate, and so the extent of their Buddhism was rooted in rituals and care. And so every day before school, my mother would get me to the altar, and we would start to name this sort of roll call, the people in our family, and try to bless them and think about them and tend to them and to ourselves. And so spirituality began with care, rooted in physical bodies. It didn’t extend beyond the household. There was no mythical presence to it. It was almost like this abracadabra that we did before we stepped out of the house into the rest of the world, and thereby, the rest of America. And I think, for me, whatever my mother presented to me those early mornings in front of the altar is still true.

And I think I embrace that in everything I do — writing, sitting with you now — how do I do it with care. And even in the temples — in many Asian American households, when you enter the house, you take off your shoes. Now, we’re not obsessed with cleanliness any more than anyone else, but the act is an act of respect. I’m going to take off my shoes to enter something important. I’m going to give you my best self. And I think, even consciously, when I read or give lectures or when I teach, I lower my voice. I want to make my words deliberate. I want to enter — I want to take off the shoes of my voice so that I can enter a place with care, so that I can do the work that I need to do.

Tippett: In a number of places, you told a story, also, about a Baptist church in your neighborhood that you would visit on Sundays, partly because they had ice cream …

… but also that you became really taken with the story of Noah’s Ark, in a way that is really — that says a lot about how you approach your art and your life.

Vuong: I think that myth — I would sleep over at a friend’s house, and I grew up in Hartford, a predominantly Black and Brown neighborhood. And the next morning, my friends would give me their clothes, their church clothes, and we would just go. So I would end up attending, throughout my childhood, hundreds of church services in the Baptist church. And the preacher kept talking about Noah’s Ark. And I was so infatuated. I think it embedded into my psyche in really everything that I do, even to this day. What an incredible mythos to work and live by, which is that when the apocalypse comes, what will you put into the vessel for the future?

Tippett: It’s also such an image of — it’s preparing for the apocalypse and getting beyond it, which is also an experience that many people have, even in our world right now. It’s an immigrant experience — a migrant experience, as we’ve started to call it.

Getting ready to interview you made me ponder, also, the particular strangeness and singularity of what it is to be Vietnamese American. Your family — and in your case, your family was not just fleeing a war, and in the aftermath of war, and surviving that, but it was our war. You are Vietnamese American, and both sides of that equation were at war. And you were literally born because of that war. Your mother was the daughter of a …

Vuong: An American soldier.

Tippett: … an American soldier who fell in love with a Vietnamese girl, and then the whole family was blasted apart, just as the country was blasted apart.

Vuong: It’s a strange epic.

Tippett: You wrote somewhere, “No bombs = no family = no me. Yikes.”

Vuong: Yikes, indeed.

[ laughs ] What do we do? But I think it’s also a question integral to our species. And this Michigan farm boy, my grandfather, went to Vietnam to play the trumpet. He was trying to escape his domineering father, who didn’t allow him to go to music school. So a 19-year-old kid, thinking, as teenagers do, Well, I’ll go to war and play the trumpet.

[ laughs ] And so he met my grandmother and they married, and he was going to stay there. He was going to stay in Vietnam and have a new life. And then Saigon fell. So I’m a product of war.

But I think so much of American life is a product of war. You know, we’re standing on stolen ground.

Tippett: It’s just very literal in your story. It’s really concentrated.

Vuong: Well, I’m a first generation. I think this is why the work of Toni Morrison’s Beloved was so important to me, because I saw in Beloved a first-generation testimony, in the character, Sethe, leaving the South and creating Beloved, her daughter, to save her daughter. And never before have I seen a parallel close enough to the story of my own mother, who comes out of her own epicenter, and I’m, being her son, also my own Beloved. To see American literature hold the testimony of the first generation’s survival — to live on both sides of death and life in one short period of time, half of one’s life — felt so powerful to me, and I learned so much from that book.

Tippett: I want to talk about the power of words and language, which, given the beginnings of your life — as you’ve said, your family was illiterate; your mother never spoke English and really only, I think you’ve said, could read and write Vietnamese at about a fifth-grade level. There’s a lot of dyslexia in your family; you also struggled with that. And how old were you when you actually learned to read?

Vuong: A lot of the magazines say 11. I mean, you don’t wake up at 11 —

Tippett: Let’s set the story straight here.

Vuong: [ laughs ] You don’t wake up one morning and start reading books. It’s a slow, arduous task. So I started — I went to ESL; I went through the American education system, for better or for worse. And I was able to read, but my fluid, chapter-book reading, where I could just sit down and read a book, didn’t happen till I was 11. But I was able to pick out words, here and there. It was much delayed.

Tippett: Was there a moment where you can look back and where you started to feel in your body the power of words, which you now work with?

Vuong: Right away. I mean, I was surrounded by storytellers, by survivors and storytellers. And so my grandmother and my mother and my aunt would tell stories to recalibrate their past, to make sense of their past. And my root in the narrative and literary techniques and embodiment begins way before I entered a classroom.

And when you think about how people tell stories, stories are carried in the body, and it’s edited each time the person tells it. And so what you have, by the time someone tells a story, is a masterclass of form, technique, concision, imagery — even how to pause, which you don’t really get on the page. Arguably you do in poetry, with the line break. And this is what these women were giving me. I didn’t know how valuable that gift was.

[ music: “Baleen Morning” by Balmorhea ]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being , today revisiting the extraordinary, prescient conversation I had with the writer Ocean Vuong at On Air Fest in Brooklyn, on the cusp of the pandemic.

It’s also very moving and interesting to me, the way you — and you’ve started talking about this. You write about how Vietnamese culture that you were immersed in, how language is so embodied. Someplace you said, “a lot of love is communicated in Vietnamese culture through service”: “We cook, we massage, we scratch each other’s back.” There’s not a lot of saying “I love you,” but it’s communicated in those ways.

Vuong: The body is the ultimate witness to love. And I learned that right away. We don’t say, “I love you.” If we do, we say it in English, as a sort of goodbye.

Tippett: Really? That’s so interesting.

Vuong: Yeah, it’s almost like a cultural thing, just — we almost say it in lieu of goodbye. We don’t know how to say goodbye, either. It’s just …

… we say, “Bye-bye.”

And I think — because what happens is that through the body and through service, you articulate it through paying attention. Nothing can say “I love you” more than feeling it from somebody. And I think this relationship is how I started to see words. I looked at them as if they were things I could move and care for.

Tippett: The language of energy — and you use a lot of energy metaphors and imagery, for how you work with words and how words work in us.

Vuong: As a species, as life on Earth, we’ve been dying for millennia, but I don’t think energy dies. It’s transformed. And when you’re using language, you can create it, use it to divide people and build walls, or you can turn it into something where we can see each other more clearly, as a bridge. And that notion that you are a participant in the future of language is something I think our American education failed us.

Tippett: Say some more about that, “you are a participant in the future of language.”

Vuong: Well, we’re taught, particularly in elementary school, to learn a standardized language. And when you ask, Why is it this way?, Why is this the standard?, you arrive at a very arbitrary answer, and an answer which actually excludes, often, people of color: Your English is wrong. This English is right.

But in fact, language is always changing. And I think it’s the poets, the writers, and even the youth — they’re using language to cast new meaning, in the same way Chaucer just winged English spelling. There was no standardized spelling.

Tippett: [ laughs ] Right; right.

Vuong: He was like, “Spring? S-p-r-y-u-g? Sure.”

[ laughs ] “Let’s try it out.”

And I think the way language exists is similar to when I was in Hartford, we were surrounded by these abandoned buildings, these old factories. The Colt gun factory was in Hartford, and it sold weapons to both sides during the Civil War. And we would go into these abandoned warehouses just to play and explore, and I remember seeing these old, warped windows, the glass just melting, and looking through at my city, the city I thought I knew so well, through this glass. It was so surreal. Everything changed. Everything was warped.

And to me, that’s what language is: the glass. You think it’s fixed. You think it’s clear pane of glass. But in fact, through years, it starts to drip and melt and change.

Tippett: Right. Even that notion that language is clear, even this presumption that we walk around making — that what we mean when we use any word transmits perfectly to another — it’s always imperfect, which is also what makes art so exciting and creative.

Vuong: Right. We often tell our students, The future’s in your hands. But I think the future is actually in your mouth.

You have to articulate the world you want to live in, first. We pride ourselves as a country that’s very technologically advanced. We have strong, good sciences, good schools; very advanced weaponry, for sure. But I think we’re still very primitive in the way we use language and speak, particularly in how we celebrate ourselves — “You’re killing it.”

Tippett: You’re so acute about the violence of the American lexicon.

Vuong: We have to ask — I’m not saying it’s wrong, per se. I use it too, being a product of this country. But one has to wonder, what is it about a culture that can only value itself through the lexicon of death? I grew up in New England, and I heard boys talk about pleasure as conquest. “I bagged her. She’s in the bag. I owned it. I owned that place. I knocked it out of the park. I went in there, guns blazing. Go knock ‘em dead. Drop dead gorgeous. Slay — I slayed them. I slew them.” What happens to our imagination, when we can only celebrate ourselves through our very vanishing?

Tippett: I mean, even you as a poet have said people say to you, “You’re killing it.”

Vuong: What does it do to the brain? We know language matters.

Tippett: What is it doing to us?

Vuong: We know language matters. They did a control where they were trying to get these lab mice to move through a maze. And they labeled one mouse the smart, intelligent mouse. And the other mouse was the control, just a normal mouse. The reality was that they were both normal mice. There was nothing special about them. But the one labeled the superior mouse always went through the maze faster. And that phenomenon is actually something that’s still studied, but one theory is that it was the human beings who attended them. The ones that had the “good” label, the “promising” label, were tended to with more care — “special.”

Tippett: And I suppose a lot of that was subconscious. But it’s in a way in which even the words we are thinking is shaping the way we’re interacting.

Vuong: Absolutely, at the subconscious level. And so I think, what happens if we alter our language? Where would our future be? Where will we grow towards, if we start to think differently about how the world is? “This is a battleground state.”

Tippett: [ laughs ] Oh, it goes on and on.

Vuong: I thought the Civil War was over.

But we’re in “battleground states.” “Target audience.”

Tippett: Something I started to notice after 9/11 was this language of “hunting down” — “hunting down” terrorists. But that’s language you use for animals. And that coarsens us.

Vuong: I grew up right in the shadow of 9/11. It created something very interesting, because we were essentially the last generation to play outside thoroughly. Things like tag and manhunt, those things were gone overnight. I saw it with my own eyes. Our nation became a nation that dictated fear through colors: today is red; tomorrow is orange; “yellow alert.”

Tippett: So you mentioned the Buddhist practice that was part of your childhood, that you then rediscover and make your own, as an adult. It feels to me like this space you inhabit, what you see so clearly, and insisting on holding the complexity of that — it seems to me that you do have ways — and I think, also, the implications of what you’re saying, because what you’re saying is that these are — this is a rigor of how we use our words and how we understand the power we have to move through time and through ordinary experiences of our day; that we all have it in ourselves to claim right now. But you have ways of making that more possible in yourself. I read — is it true? Do you still live across from a cemetery? Is that right?

Vuong: Yes, I do.

Tippett: And that you perform this Zen Buddhist death meditation?

Vuong: I go out, and I walk around the cemetery, and even without it, I sit down and I do a death meditation. And it sounds very morbid, but the practice is actually supposed to bring yourself into the inevitable. The conditions of our lives will be vanquished through death. And then all the pettiness — the little angers that you have with those you love, with those you don’t love, and your neighbor, the little things — falls away. It’s so small, when the ultimate, lasting reality is death.

And I think it goes back to Noah’s Ark, too. Noah was also doing death meditation.

Tippett: He was a Zen Buddhist without knowing it.

Vuong: [ laughs ] I think so.

Tippett: He didn’t know he was Jewish, so … [ laughs ]

Vuong: I think so. But I think all religions have this — outside of all of the orthodoxy and the rigor of ceremonies, at the center of it is trying to remind us that we will die, and how do we live a life worthwhile of our breath? And I think thinking about death and thinking about what we do towards it, around it, helps me center myself in such a chaotic space. And I do think it’s part of my own nurturing of my own mental health.

[ music: “Paramour” by Pilote ]

Tippett: After a short break, more with Ocean Vuong.

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being . Today, a conversation with the wonderful writer Ocean Vuong that happened right before the world changed in 2020 but that speaks so vividly and helpfully to the realities we have since come to inhabit.

Tippett: There’s so much I wanted to talk to you about, and it’s beautiful, actually, what’s emerging here. And it feels like — you’ve described how your method of creating is that you walk a lot, right? Again, it’s embodied practice. And you walk and you walk, and things build up in you. And there’s a way in which I feel like words and meaning flow out of you, which is also an experience one has in reading your work. And as we’re hearing, it’s consonant with the way you understand reality and help other people understand reality.

Vuong: I mean, it’s not always that smooth. [ laughs ]

Tippett: No; I’m sure.

I’m sure it’s not. [ laughs ]

Vuong: It’s kind of like — a lot of things flow, but not all of them are good, so …

… sometimes, I gotta rein it back. [ laughs ]

Tippett: OK. I didn’t want to suggest that …

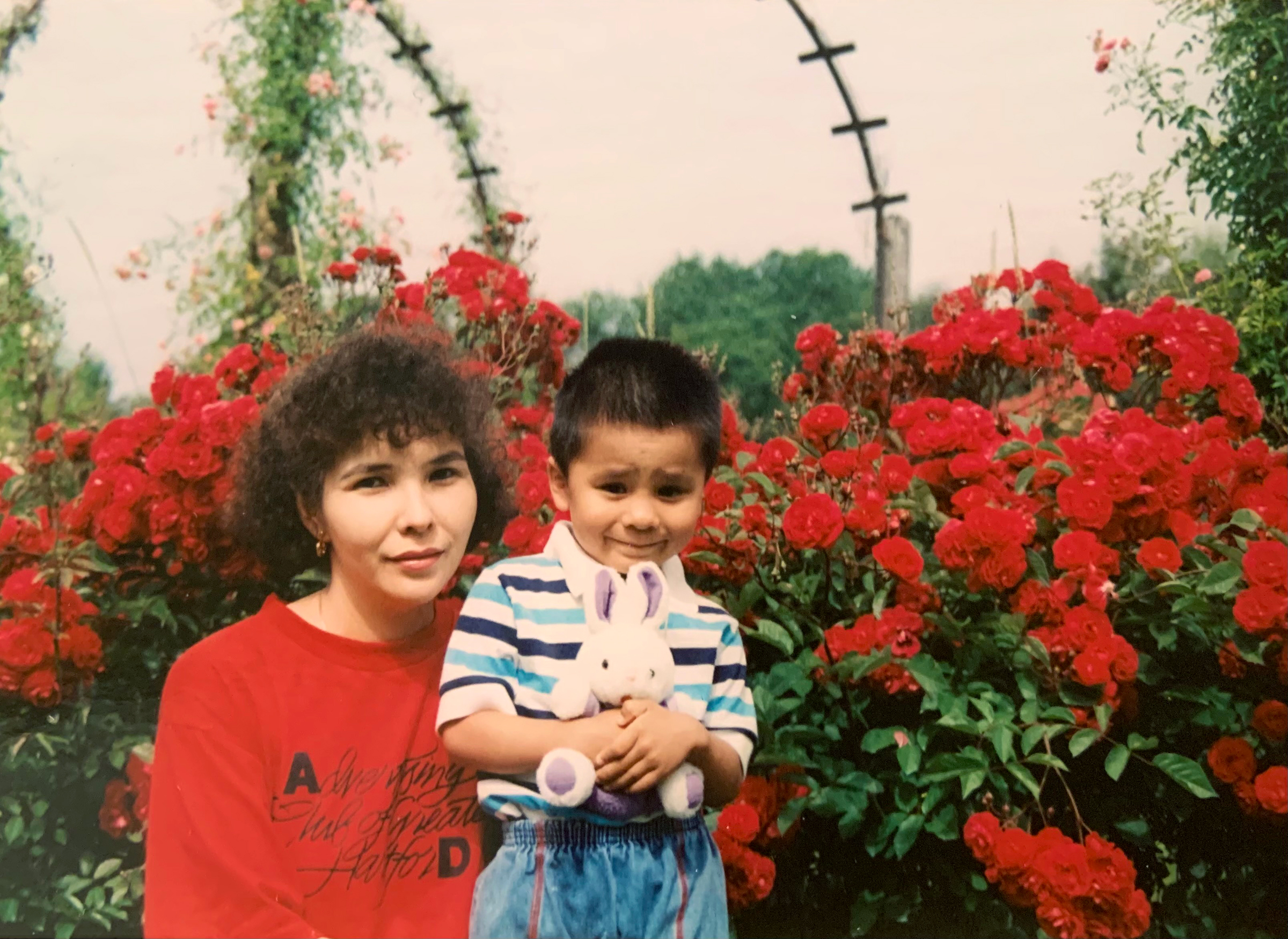

I just wanted to note this: the picture on the cover of Night Sky with Exit Wounds , it looks like such a happy picture of a little boy and two women who love them; you imagine one of them is his mother. And in fact, you guys were in a refugee camp in the Philippines, and you had to — someone took that picture, and you paid them for that picture.

Vuong: Three cups of rice for that photo. We were in a refugee camp, and we got rations. And each day, each family got three cups of rice. And there was a photographer who went around — even in a refugee camp, it’s a microcosm of the world. Somebody’s going to try to make a business.

Tippett: [ laughs ] Of course.

Vuong: And I was thinking about the cover for my first book — that was my first book. And we had several ideas. But I think part of my education with the history of Vietnam and America’s involvement in it became something very different from what was given to me in the textbooks. The textbook says, “Well, first of all, here’s five chapters on George Washington … ”

“ … what he ate, what kind of teeth he had … ”

“ … what kind of tree he chopped down.”

And by the way, if somebody chops down a fruit tree, that’s a red flag, for me.

Tippett: That’s true. [ laughs ]

Vuong: [ laughs ] It’s like, nobody asks why he chopped down a fruit tree.

But the myth — I realized the myth of America was so strong. And it’s very interesting, because when we got to the Vietnam War, it was like two pages. There’s a photo of Kennedy, then there’s a photo of Nixon.

Tippett: [ laughs ] Right.

Vuong: Right? “Something bad happened over there; anyway, it’s over; then we went on to the Gulf War, when we were heroes again.” Right?

So I thought — by the time I was in college, I was like, I gotta figure this out. So I started to do my own research, and I realized right away that one’s research with the Vietnam War — something I was not prepared for was to see upwards of — hundreds of dead bodies. Asian bodies. Bodies that look like me. So when you are most recognizable in your research as a corpse, it does something to you. Sometimes the bodies were so mangled, you didn’t know where one began and ended. And so I wanted for my first book to have Vietnamese bodies on the cover that were living.

And so that photo was a moment of salvaging and preserving bodies in transit. What was it about these women, I thought, that would surrender their very sustenance, in order to preserve their image?

Tippett: Right. And even when you came here — somewhere I think you said that you had to pay for that picture, you had to pay to be seen. And even what you’re saying about how even in that moment — and I was a child, but the fact of being able to see those bodies is actually what ended the war. And then, after that, we never saw bodies come home from war again.

Vuong: They learned. They learned.

Tippett: But even when you came here — and this is about the immigrant experience, but it’s also about being Vietnamese — your mother would say to you, “Remember, child — don’t get noticed. You’re already Vietnamese.”

Vuong: It’s interesting that wisdom often arrives as a warning. I think it’s often something that those in the center, those in power, never know; that before you leave the house, in order to achieve yourself — one sends one’s children to school in order to fulfill their dreams. And in order to do that, you have to be warned that “there is a strike against you, by the way, so sink in. Fade away.”

And I think that’s the great crisis of the first and second generation. The first generation made it here, and to live at all is such a privilege that they’re happy, and even encourage you to put your head down, work, fade away, get your meals, and live a quiet life. And I think the second generation, the great conundrum there, the great paradox, is that they want to be seen. They want to make something. And what a better way to make something and fill yourself with agency than to be an artist? So: so many of us immigrant children end up betraying our parents in order to subversively achieve our parents’ dreams.

Tippett: Right. Right.

Your mother worked in a nail salon all of your life and her life, and you worked there, and members of your family worked there. And I love it that you were eventually able to buy her a house — and she always wanted a garden — because you are now seen. She watched you.

I love the story — I wonder if you would tell it — about the experience she had when she first came to hear you read. And of course, she couldn’t understand the English, but her reaction to you.

Vuong: The first time, I was reading at the Mark Twain House, of all places, in Hartford. And it was nearby, so I asked her to come, and it was the first time she saw me read. And of course, she doesn’t understand the English, but she was so proud to just see her son up there in the spotlight, a small spotlight. And I went back to her — I read, people clapped, and they stood, and it was lovely. And I went back to her, and she was sobbing. And being the dutiful son, I said, “What did I do? What happened? Are you OK?” And she said, “No, I just never thought I’d live to see all these old White people clapping for my son.” [ laughs ]

And I thought it was interesting, because, I said, I’ll try to understand what that means; what it means; what kind of validation is that. It’s not necessarily one that I share myself. So I almost had this arrogant gaze to it. I said, “That doesn’t seem like victory to me, just because a bunch of White folks clapped. Victory is something else, to me, something more.”

Until, the next day, I was at the salon again with her. Her makeup’s off, and she put her nice dress away that she wore at the reading. She took her earrings off. And right out the gate, in the early morning, I saw her and watched her kneel at the pedicure chair before one old, White woman after another. It was so humbling, because I thought, Finally. She was below their eye level for so many years. And for one brief moment, in Mark Twain’s house, [ laughs ] they saw her, face-to-face, as an equal. And that’s when I understood, that is victory.

[ music: “Pearls” by Helios ]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being , today with the writer Ocean Vuong, recorded at On Air Fest in Brooklyn, in March 2020. We also took some questions from the last live audience any of us would be in for some time.

Audience Member: I have to say that probably I’ve been listening to Krista for as long as I can remember, and this has to be one of the most moving, tender, beyond words conversations I’ve heard. And I’m so glad that I got to see the embodiment of your language. So along those lines, I was interested to know about some of the body practices that you do. I completely hear what you’re saying about the potential for language and the care that each word uttered. There also is some preparatory practices that come with that responsibility, and I was wondering if you could share any thoughts on that.

Vuong: I do think it does begin and end in the body. Language is something we carry. I always bring this back to my students, as well. I said, You’re working on a poem or a story, when you’re hitting a dead end, when it’s not going, take it with you. Get away from the desk. Now you have to work with your body. Maybe there’s questions you’re not asking. Maybe you have to recite this poem and walk with it. This is what we’ve always been doing. we’ve been telling stories as we walked; we’ve been telling stories as we work, side-by-side. This idea that language is a private, isolated act is so new that I think we still haven’t figured out if it’s useful or not.

And so I think it’s valuable to open up that debate again and not to say that it has to be like this or like that, for anybody, but to say, if it’s not working, we can do something different, an alternative route. And in this sense, having the words in the air — I feel like the voice in the air is like a second page, the way you can articulate — the pauses, the cadences. I learned this, mostly, from watching Whitney Houston. If you listen to Whitney Houston’s songs, they start like a whisper. And then how do we get to the pinnacles, the bright-lit room of her peaks? But the power and the mastery in her performance is the oscillation, and the respect of how a word, which is static on the page, can be lifted and amplified through using the whole range of human emotion in the voice. So I’m an apprentice of that.

Tippett: I would not have traded the experience of being with you, physically, but I really love — most of my interviews are remote, and I’m in a studio; somebody is coming in through my headphones, basically. But there’s often an assumption, in people who don’t work in this medium, that that makes it less intimate. But to have the human voice to work with, and to get everything that the human voice carries — it is the body — is really magical, to really be able to completely focus on that.

Speaking of the body and walking and movement, I want to close — you wrote this beautiful essay in The Rumpus, in 2014, called “ The Weight of Our Living: On Hope, Fire Escapes, and Visible Desperation .” Part of the context of that piece was your uncle’s death by suicide. He was three years older than you, and you’d grown up together. And that wove into you reflecting, on these walks you do through New York City, on fire escapes. I’m going to read a little bit, and then I want you just to say more.

“All that richness and drama sealed away in a fortress whose walls echoed with communication of elemental and exquisite language” — you’re looking at all the buildings — “and yet only the fire escape, a clinging extremity, inanimate and often rusting, spoke — in its hardened, exiled silence with the most visible human honesty: We are capable of disaster. And we are scared.”

Vuong: It was such a blow. Anyone who has lost anybody to suicide — I lost my uncle; I lost a few friends. The great mystery and the great violence of taking oneself out of the picture — I’ve been grappling with that for so long. And I think one of the things that lead us to that is that you start to feel that you are always out of the picture — this loneliness that language does not allow us to access. The way we say hello to each other — Hi, how are you? Oh, good, good, good, good, good. So the “how are you” is now defunct. It doesn’t access. It fills. It’s fluff.

And so what happens to our language, this great, advanced technology that we’ve had, when it starts to fail at its function, and it starts to obscure, rather than open? And I think the crisis that my uncle went through, and a lot of my friends, was a crisis of communication — that they couldn’t say, “I’m hurt.”

And looking at — I remember when I heard of his suicide, I was a student at Brooklyn College in New York. I went for the longest walk. And I kept seeing these fire escapes. And I said, what happens if we had that? What is the linguistic existence of a fire escape, that we can give ourselves permission to say, Are you really OK? I know we’re talking, but you want to step out on the fire escape, and you can tell me the truth?

And I think we’ve built shame into vulnerability, and we’ve sealed it off in our culture — Not at the table, not at the dinner table, don’t say this here, don’t say that there, don’t talk about this, this is not cocktail conversation, what have you. We police access to ourselves. And the great loss is that we can move through our whole lives, picking up phones and talking to our most beloveds, and yet still not know who they are. Our “how are you” has failed us. And we have to find something else.

And I thought about that. What if literature, my participation in it — that’s my field, if you will — what if the poem, the story, the novel, at its best can serve as a fire escape? Because on the page, you don’t have the awkward reality of a body bumping into someone in the supermarket. You don’t have to say, How ‘bout them Patriots? You don’t have to talk about the weather. You can go right in, deep. And I really have been — it changed the way I thought about writing and literature, in that if we have the fire escape as a reality in our buildings, what does it look like in the reality of our communication, in our language? What does that look like?

And I’m still figuring that out. I’m still — every book, every poem, I think, is my attempt at articulating a fire escape. But I think it was a great reckoning for me, because here I am, supposedly a writer, and then my uncle dies, and I’ve lost so much. We talk all the time, we say all these things, and yet I never knew what was happening. And if that’s the case, language, this field that I chose, this thing that I feel so much hope for, failed me. And it was a reckoning, I think, existentially, with myself as an artist.

Tippett: I wonder if, to close this incredible time together, if you would read — I just copied out a paragraph from the end of this essay from 2014, “The Weight of Our Living.”

Vuong: “The poem, like the fire escape, as feeble and thin as it is, has become my most concentrated architecture of resistance. A place where I can be as honest as I need to — because the fire has already begun in my home, swallowing my most valuable possessions — and even my loved ones. My uncle is gone. I will never know exactly why. But I still have my body and with it these words, hammered into a structure just wide enough to hold the weight of my living. I want to use it to talk about my obsessions and fears, my odd and idiosyncratic joys. I want to leave the party through the window and find my uncle standing on a piece of iron shaped into visible desperation, which must also be (how can it not?) the beginning of visible hope. I want to stay there until the building burns down. I want to love more than death can harm. And I want to tell you this often: That despite being so human and so terrified, here, standing on this unfinished staircase to nowhere and everywhere, surrounded by the cold and starless night — we can live. And we will.”

Tippett: Ocean Vuong, thank you so much.

Vuong: Thank you.

Tippett: Ocean Vuong’s new collection of poetry is Time Is a Mother . His other, celebrated books are On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous and Night Sky with Exit Wounds .

Special thanks this week to Jemma Brown, Scott Newman, Sam Bair, and all of the wonderful staff at On Air Fest, the great gathering of podcast and audio makers.

The On Being Project is: Chris Heagle, Laurén Drommerhausen, Erin Colasacco, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Suzette Burley, Zack Rose, Colleen Scheck, Julie Siple, Gretchen Honnold, Jhaleh Akhavan, Pádraig Ó Tuama, Gautam Srikishan, April Adamson, Ashley Her, Matt Martinez, Amy Chatelaine, Cameron Mussar, and Kayla Edwards.

The On Being Project is located on Dakota land. Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. And the last voice that you hear singing at the end of our show is Cameron Kinghorn.

On Being is an independent, nonprofit production of The On Being Project. It is distributed to public radio stations by WNYC Studios. I created this show at American Public Media.

Our funding partners include:

The Fetzer Institute, helping to build the spiritual foundation for a loving world. Find them at fetzer.org;

Kalliopeia Foundation, dedicated to reconnecting ecology, culture, and spirituality, supporting organizations and initiatives that uphold a sacred relationship with life on Earth. Learn more at kalliopeia.org;

The George Family Foundation, in support of the Civil Conversations Project;

The Osprey Foundation, a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives;

And the Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation, dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education.

Books & Music

Recommended reading.

Time Is a Mother

Author: Ocean Vuong

On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous: A Novel

Night Sky with Exit Wounds

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Music Played

Rivers Arms

Artist: Balmorhea

The Slowdown

Artist: Pilote

Artist: Helios

Seven League Boots

Artist: Zoë Keating

May 1, 2020

Written and read by Ocean Vuong

Aubade with Burning City

This piece is a part of:.

Starting Point

- New to On Being? Start Here

- Words Make Worlds

- Civil Conversations & Social Healing

- Poets & Poetry

- Body, Loss, Trauma, Vitality, Healing

You may also like

January 10, 2019

Claudia Rankine

How can i say this so we can stay in this car together.

The poet, essayist, and playwright Claudia Rankine says every conversation about race doesn’t need to be about racism. But she says all of us — and especially white people — need to find a way to talk about it, even when it gets uncomfortable. Her bestselling book, Citizen: An American Lyric , catalogued the painful daily experiences of lived racism for people of color. Claudia models how it’s possible to bring that reality into the open — not to fight, but to draw closer. And she shows how we can do this with everyone, from our intimate friends to strangers on airplanes.

Search results for “ ”

- Standard View

- Becoming Wise

- Creating Our Own Lives

- This Movie Changed Me

- Wisdom Practice

On Being Studios

- Live Events

- Poetry Films

Lab for the Art of Living

- Poetry at On Being

- Cogenerational Social Healing

- Wisdom Practices and Digital Retreats

- Starting Points & Care Packages

- Better Conversations Guide

- Grounding Virtues

Gatherings & Quiet Conversations

- Social Healing Fellowship

- Krista Tippett

- Lucas Johnson

- Work with Us

- On Dakota Land

Follow On Being

- The On Being Project is located on Dakota land.

- Art at On Being

- Our 501(c)(3)

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Entertainment

Grieving His Mother’s Death, Ocean Vuong Learned to Write for Himself

I n March 2019, three months before the publication of Ocean Vuong’s novel On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous , he called his agent from the hallway of a Hartford, Conn., hospital. “There’s no way I can go on tour,” he said. “My mother has cancer. It’s over.”

The first time his mother, Hong, had gone to the emergency room with terrible back pain, he wasn’t with her. The hospital sent her home with an adhesive heat patch. Vuong, who lives in Northampton, Mass., with his partner Peter, went to see her and took her back to the ER; this time, doctors ran tests and returned with a diagnosis: Stage IV breast cancer. It was in her spine, the marrow of her bones.

“When she went herself, she got a heat pad. When I came, with English, she went to the oncology ward,” Vuong, 33, tells me. In his voice I hear pain, but no shock: he and his mother experienced many similar moments after arriving in the U.S. as refugees in 1990. “I thought, Here we are again: I have to speak for you. I have to speak for your pain. I have to verbalize your humanity. Because it’s not a given. Which is the central problem with how we value Asian American women.”

Even as a celebrated poet and author, Vuong knows he can rely on the privilege of being seen and heard only in certain settings. When he went to get his university ID at UMass Amherst, where he teaches, a white woman asked if he spoke English. “She could have looked in my file and seen that I’m an English professor,” he says, sounding almost amused. “But I’m not legible until my career makes me legible. When I walk into an event, I am Ocean Vuong doing a reading—I bypass some of the coded veils that Asian Americans are made invisible by, but only in that context. It’s an insulated privilege that doesn’t extend to other Asian Americans … to people like my mother, working in a nail salon.”

After his mother’s diagnosis, he says, “it all just fell away”: the tour, the publicity, what the novel would mean for his career. “Who’s Ocean Vuong? I don’t know. Nobody knows, in the hospital ward. None of the powerful sentences do anything when your mother is dying a few feet away from you.”

That June, with his mother’s cancer temporarily held at bay by hormone therapy, Vuong was able to tour after all. On Earth was an instant New York Times best seller. The writer Rebecca Solnit recalls a rapt crowd at an event they did together. “Afterward, a young Asian American woman said to me, ‘Until Ocean, no one was telling our story.’ He knew what the audience needed.”

Read More: The 100 Must-Read Books of 2021

When Vuong was interviewed by Seth Meyers, his mother watched from home, calling him in tears afterward because he’d spoken in Vietnamese at the end. But by September, her cancer had spread, and she was having trouble breathing. She died on Nov. 2.

… stop writing

about your mother they said

but I can never take out

the rose it blooms back as my own

pink mouth …

Vuong worked on his new poetry collection Time Is a Mother while mourning, in a world consumed by the advancing pandemic—“I was grieving, the world was grieving, and the only thing I really had was to go back to poems.” The collection bears witness to love, loss, and trauma in a way that may feel especially resonant to readers right now; it reads as a search for meaning and truth in a life remade by grief. He tells me that it is the only book he’s written that he is proud of, because he compromised nothing. He thinks that has something to do with losing his mother.

“All the things I’d written, it was all to try to take care of her. I went to school for her, I worked for her—she was the source,” he says. “When that was taken away, I didn’t have anything else to answer to. And so I finally wrote for myself.”

Vuong was 2 when his family fled Vietnam; some of his earliest memories are from their back apartment in a townhouse on Franklin Avenue in Hartford. He can recall everything about those rooms, the sounds and the bodies that filled them, the bedroom he shared with six others. “We had so little,” he says, “but I felt safe back then, because I was always surrounded by Vietnamese voices.”

He began learning English when he went to kindergarten. In fourth grade, he wrote his first poem, which he was accused of plagiarizing—his teacher didn’t believe he could have written it. But after that, he noticed, the teacher began to pay attention to him, occasionally helping him type his assignments on the school computer. “I learned that putting the DNA of my mind on paper had garnered this white man’s respect,” he recalls. “I felt incredibly dangerous and powerful.”

… reader I’ve

plagiarized my life

to give you the best

of me …

Vuong tells me he became a writer because he is “full of limitations.” He proceeds to list them: he panics easily; he is dyslexic; he finds paperwork and “the minutiae of life” challenging; he struggled with drug addiction. He believes some of these are responses to trauma, lived and inherited. Another “limitation”? “I can’t fake it,” he laughs. That’s why he left the international marketing program at Pace University in New York City, where he had enrolled in the hope of earning money to help his mother—“a position so many immigrant children are in—we defer our dreams to do the practical thing.” He dropped out once he realized that he was learning “how to lie for corporations.” “If my heart isn’t in something, I can’t do it, you know? Maybe that’s why I don’t have many drafts—by the time I get to the blank page, my heart is already there. That’s a limitation, in a way, but that’s also how I got here.”

Ashamed to return home empty-handed, Vuong worked in a café, slept on friends’ couches, spent his free hours at the New York Public Library, and enrolled at Brooklyn College to study literature. Poems presented at open-mic nights found their way into early chapbooks. He landed prestigious fellowships and earned an MFA at New York University; published a critically acclaimed poetry collection, Night Sky With Exit Wounds; won a Whiting Award and a MacArthur “genius” grant. Vuong calls his career “serendipitous at every turn,” but it’s also clear that there were many points when he could have given up on his writing and didn’t.

His work could sometimes be “a touchy subject” with his family, who couldn’t fully grasp his life as a poet. He suspects that his mother, who was illiterate, didn’t try to read because the struggle might make the distance between herself and her son more explicit. But when he would visit her and read—not his own poems, just a magazine he’d brought with him—she would tell everyone to hush: “Ocean’s reading.”

“It felt like sorcery, a portal to another world—to success, power—that she didn’t understand,” he says. “She didn’t ask me about it, but she was like, OK, good: Do this, read your books, forever. As long as you’re sustaining yourself. You’re the first to be able to do this.”

Read More: The 21 Most Anticipated Books of 2022

When she attended his readings, she would never look at him; she would position her chair so that she could watch the audience watching her son. “She read them while I was reading my work, and then she would say, ‘I understand now. I don’t know what you’re saying, but I can see how their faces change when you speak. I can feel how it’s landing in the world.’” His voice takes on a hint of the wonder his mother must have felt. “I realized this is something she taught me. As a woman of color, an Asian woman, in the world, she taught me how to be vigilant. How people’s faces, posture, tone, could be read. She taught me how to make everything legible when language was not.”

Vuong began writing the poem he calls “the spine” of Time Is a Mother, “Dear Rose,” after finishing the third draft of his novel, partly because it felt important to him to return to poetry. “I thought: What would happen if I tried to rewrite the novel as a poem? I’ve never believed that you write a book and then you’re done. I’ve always felt that our themes are inexhaustible, and our work is to keep building architectures for these obsessions. Who’s to say that one novel, or 35 poems in Night Sky, could exhaust these big questions about love, trauma, migration, American identity, American grief, American history?”

A version of “Dear Rose”—his mother’s name means pink or rose—appeared in Harper’s in 2017, two years before her death. In Time Is a Mother, it lives again, with different opening lines:

Let me begin again now

that you’re gone Ma

if you’re reading this then you survived

your life into this one …

At one point, I share that I also recently lost my mother to cancer , and I know it cannot be easy for him to talk with me about this. He immediately offers his sympathy, noting that we are both “immigrants in this new land of grief.” To his mind, death is “the closest thing we have to a universal,” and so our love for those we’ve lost is also a form of common ground.

He isn’t new to grief—before his mother died, he lost friends to the opioid epidemic; he lost his uncle to suicide; he lost his grandmother. Writing about “the private deaths,” as he calls them, is an extension of the work he’s always done: considering the aftermath of trauma, war, displacement, mass death. “As an Asian American coming out of diasporas, you know this: when you look at Vietnamese conflicts, Korean conflicts, you see a lot of corpses that look like yourself,” he tells me. “The negotiation with death as self-knowledge is something a lot of Asian writers and writers of color encounter. And so grief might actually be the mode in which I write—not all my poems are mournful, but they’re haunted by the inevitability of death, and so the urgency and even the joys that come out of them are through the knowledge of our own end. On good days, that’s also how I live,” he adds with a small smile, “though sometimes I forget that.”

“He’s willing to write about difficult things with vulnerability, and with attention to not only expressing what a thing is—whether it’s grief or loss or addiction or displacement—but how it feels, and also what a way forward can look like,” says author Bryan Washington . “As a queer author of color, I can speak to how difficult that is to do, and how in many ways there is incentive not to do that.”

The author Tommy Orange is likewise an admirer. “The beauty of what Ocean does with language is what gets me first,” he says, “the marriage of his use of language with the reckoning of an American identity … the wisdom and compassion in his work matches his craft, and I think that’s rare.”

Vuong tells me that he is proud of this book because he wrote it freely, expansively, honoring all his curiosities and ambitions. “There’s more humor, more witticism. There are more registers,” he says. “This book is all of me—I’m fully here. That feels kind of like a death in itself, as well as a celebration … Have I stopped growing? Is this my plateau?”

But soon we’re talking about his teaching, his writing practice, new things he wants to try. He’s showing me his favorite Japanese notebook and explaining why he writes by hand: “If you want to write a sentence, you’ll arrive much faster with a computer. With the hand, by the time you get to the end of a sentence, or maybe somewhere in the middle, you find yourself hovering—and now there are detours; other ideas come to you. Where else can you go? There’s much more you can discover.” I suggest that his growth probably hasn’t plateaued if he’s still pushing, pursuing new discoveries in every sentence, and he nods: “That’s the hope.”

After he won the Whiting, he thought: I’m going to buy my mother a house. Though he can no longer make a physical home for her, he’s always thinking about family, chosen and otherwise, and what it means to build a life around them. He tells me that he and Peter just bought a house in Massachusetts, with room for a crowd: “My brother can move in. When he has kids, they can live there. When my aunt gets old, she can live there. Our friends—most of whom are artists, queer folks of color—can come and just recover.” It strikes me as a kind of callback to the community that let him couch-surf when he was a broke young poet, but it’s clear he’s thinking back further than that, to his early childhood surrounded by family, including his mother, speaking in his mother tongue. “I think I still hope for that in some way,” he says. “What do I want my family to look like? What do I want to build in my life with the resources I have? I’d like to build places where people I love can be comfortable and OK. This is what my life has taught me.”

Chung is the author of memoir All You Can Ever Know

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

Ocean Vuong

We may earn commission from links on this page, but we only recommend products we back.

Who is Ocean Vuong?

Vuong has also released two poetry collections: Night Sky with Exit Wounds (2016), which won the T.S. Eliot Prize, and Time is a Mother (2022), in which he wrestles with the emotions following his mom’s 2019 death from breast cancer.

Early Life and Relationship with Mom

Vuong moved from Vietnam with his parents at the age of two. They settled in Glastonbury, Connecticut , just outside of Hartford, and none of the family members spoke English. His mother soon kicked out his father for beating her. Vuong knows very little about his dad except that he ended up going to jail for criminal behavior. His mother could not read and supported the family by working at a nail salon, where she spent 25 years of her life.

When he was in the third grade, he read Patricia Polacco’s Thunder Cake , which he called the “first book that I loved” in a personal essay for The New Yorker in 2017. Also in the piece, formatted as a letter to his mother, he wrote candidly about the first time his mother hit him when he was four—and the times she threw a remote control, Legos and a gallon of milk at him.

Despite this, Vuong says his mother was his world. “Everything I have done, I've done for her,” Vuong told NPR . “I went to school for her. She gave me no pressure… There's a stereotype of the Asian tiger mom. My mother was never such a mother.”

Instead, she encouraged him to be happy, adding that if worse came to worst, there was always a desk at the nail salon next to her where he could also work. “I had ultimate freedom to explore,” he continued. “And I think for me, you know, that freedom really was all to serve her.”

Education and Finding Writing

The complicated multi-layered relationship with his mother may have been the result of her post-traumatic stress disorder from living in the wake of the Vietnam War and then uprooting her life to a new country. Vuong vowed to make his life better than what she had gone through, so after attending Manchester Community College and transferring to Pace University to study international marketing, he decided to go to business school. Vuong only lasted eight weeks there, describing the education as “learning to lie,” as he told The Guardian .

Vuong dropped out of business school and went on to study 19th-century American literature at Brooklyn College . At night, he found solace in writing poetry. “You get the last word of the day,” he told the paper. “The editor in your head—the nagging, insecure, worrisome social editor—starts to retire. When that editor falls asleep, I get to do what I want. The cat’s out to play.” He later went on to get his MFA degree in poetry at New York University.

‘Night Sky With Exit Wounds’

Vuong’s late-night free writes were compiled in the 2016 poetry anthology Night Sky With Exit Wounds , which was published by Copper Canyon Press through an open submission contest . The fanfare came quickly, with The New York Times lauding its “powerful emotional undertow” from Vuong’s “sincerity and candor,” opening up about identity and experiences as both an immigrant and gay man. It also noted the “photographic clarity and a sense of the evanescence of all earthly things.”

The subjects ranged from the fall of Saigon (“Aubade with Burning City”) to the murder of a gay Dallas couple (“Seventh Circle of Earth”). Among the most powerful lines is a passage from the poem “ Someday I’ll Love Ocean Vuong ,” which reads, “The most beautiful part of your body / is where it’s headed. & remember, / loneliness is still time spent with the world,” and these from “ A Little Closer to the Edge ”: “Let every river envy / our mouths. Let every kiss hit the body / like a season.”

The collection was showered with awards, including the T.S. Eliot Prize, Whiting Award, Thom Gunn Award and Felix Dennis Prize for Best First Collection from the Forward Arts Foundation.

Writing poems wasn’t always lucrative for Vuong. He told the Times he was making $8 an hour working at Panera Bread before he sold his first novel.

‘On Earth We're Briefly Gorgeous,’ a ‘Genius’ Grant—and Ultimate Heartbreak

The year 2019 was filled with ups and downs for Vuong. He learned his mother had Stage 4 breast cancer not long before his debut novel On Earth We're Briefly Gorgeous came out that June. The book expands on his essay in The New Yorker , a letter from a son to his illiterate mother, and is a project he started writing as an experiment. As a fictionalized account of his own upbringing, his character is represented by Little Dog.

The novel, released on June 4, 2019, became a New York Times bestseller and received numerous award nominations: The book was longlisted for the National Book Award, the Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence and the PEN/Hemingway Award for Debut Novel. It won the American Book Award and Mark Twain American Voice in Literature Award.

A few months later, Vuong was awarded one of the prestigious MacArthur Foundation's so-called “Genius” grants .

Later that year, Vuong’s mother died from breast cancer.

On an episode of A24's podcast in December 2020, the film studio announced it is working on a big-screen adaptation of On Earth We're Briefly Gorgeous .

Queer Love and Sexuality

Much of On Earth We're Briefly Gorgeous centers around Little Dog exploring his sexuality and starting a romantic relationship with another local boy. Their lives become entwined in small-town drama, bigotry and drugs, leading to some high and very low points. The book, based on Vuong’s personal experiences growing up in Hartford, Connecticut, highlights the struggles of being gay in a family and community that has historically shunned homosexual relationships.

Despite this, Vuong said his mother was accepting when he came out to her.

"When I told her, she said, 'Well, you're still you,' and she said, 'You're all I have,'" Vuong said. "It was really important for me, because it was not like the stereotypical response that you often hear about. It was just so accepting."

His writing has become a beacon for many people of color, especially those of Asian descent, in similar circumstances.

"I don't sit down at the desk saying, well, I'm an LGBTQ writer. I just assume that [what] I write will come out of that filter," Vuong told TMRW magazine in an interview.

Vuong's Mother’s Death

Despite her illiteracy, Vuong’s mother Rose was his biggest supporter. He wrote in that first New Yorker piece: “The first time you came to my poetry reading. After, while the room stood and clapped, I walked back to my seat beside you. You clutched my hand, your eyes red and wet, and said, ‘I never thought I’d live to see so many old white people clapping for my son.’” The weight of that statement really sunk in when he visited her at the nail salon and watched her washing the feet of “one old white woman after another.”

So her death hit hard. “When I lost my mother, I thought, there's no point,” he told NPR. But it also marked an epiphany for him about his writing. “I realized that I was writing with various insecurities or fears, you know, even with all of my books,” he said. “Every writer would tell you that they're writing what they want. But…only when their mother passes away do they realize, oh, wait a minute. There's another level of freedom that I don't know.”

That led him to turn back to writing. “You lose your mother, and you lose your North Star, at least for me. And I became such a child,” he said. “And like any child, I look at the blank page and I said, ‘How do I play? Where do I locate pleasure?’ And the only place I could look to was the poems, because it was the only place I found linguistic pleasure.”

‘Time is a Mother’

That seminal time in Vuong’s life sent him on a creative exploration that has been compiled in his second poetry collection, Time is a Mother , which came out April 5, 2022. In it, he dives into the complicated emotions tied to the loss of his mother and how the hole in his life shifted his entire perspective.

In one piece, “Beautiful Short Loser,” he writes, “How come the past tense is always longer? Is the memory of a song the shadow of a sound, or is that too much? Sometimes when I can sleep, I imagine [artist Vincent] van Gogh singing Leonard Cohen's ‘Hallelujah’ into his cut ear and feeling peace.”

The experience of writing the book itself was a transformative one for Vuong. “I see all of my humor, you know, my mischievousness, my tongue-in-cheek expression, even amongst the great loss,” he tells NPR . “I said, there he is. He's finally here.”

Personal Life

Vuong is a University of Massachusetts, Amherst associate professor in the MFA program for poets and writers and lives in Northampton, Massachusetts.

QUICK FACTS

- Birth Year: 1988

- Birth date: October 14, 1988

- Birth City: Saigon

- Birth Country: Vietnam

- Best Known For: Ocean Vuong is an Asian American writer, best known for his 2019 debut novel, 'On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous.'

- Writing and Publishing

- Education and Academia

- Astrological Sign: Libra

- University of Massachusetts (Amherst)

- Nacionalities

- Vietnamese (Vietnam)

- Interesting Facts

- Winner of T.S. Eliot Prize, American Book Award, MacArthur Foundation Grant

- Occupations

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Ocean Vuong Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/authors-writers/ocean-vuong

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: April 14, 2022

- Original Published Date: April 14, 2022

- Grief is perhaps the last and final translation of love.

William Shakespeare

How Did Shakespeare Die?

Christine de Pisan

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz

14 Hispanic Women Who Have Made History

10 Famous Langston Hughes Poems

5 Crowning Achievements of Maya Angelou

Amanda Gorman

Langston Hughes

7 Facts About Literary Icon Langston Hughes

Maya Angelou

Find anything you save across the site in your account

All products are independently selected by our editors. If you buy something, we may earn an affiliate commission.

Ocean Vuong Is Still Learning

Ocean Vuong was two when he immigrated with his family to the United States from Vietnam. They settled in Hartford, Connecticut, with seven relatives sharing a one-bedroom apartment. At the time, their lives were defined by survival. His father left one day and never came back. His mother worked long hours at a nail salon. Vuong was the first member of the family to learn to read and write proficiently. He was eleven.

As a teen-ager, witness to the opioid abuse and casual hopelessness common in post-industrial New England, Vuong realized that he needed to leave Connecticut. He attended Pace University, in Manhattan, where he planned to study business. But he quickly discovered that this was not for him. He enrolled at Brooklyn College. “I just thought if I could get a degree, I could tell my mother it was bioscience or whatever,” he says. “I just wanted to get the cap and gown.” At Brooklyn College, he studied literature and began taking writing courses. “Once in a while, you get a student who’s not testing to be a writer, but who is already one,” the novelist and poet Ben Lerner, who taught Vuong at Brooklyn College, has said.

Before receiving his M.F.A. at N.Y.U., Vuong published his first collection, “ Night Sky with Exit Wounds ,” a soaring, sober consideration of his family’s absorption into the American fold, in 2016. Three years later, he published a beautifully meditative novel, “ On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous ,” which borrowed from his own life growing up queer and surrounded by despair and addiction. That same year, he received a MacArthur “genius” grant. Two months after news of the MacArthur Fellowship was made official, his mother, who had inspired so much of his work, died from cancer.

Vuong has spent most of the past few years in Northampton, Massachusetts, and he taught nearby at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. He lives with his partner and with his half-brother, whom he took in following their mother’s death. His latest collection of poetry is “ Time Is a Mother ,” which is full of concentrated, kaleidoscopic riffs on the feelings and sounds, the delirious highs and darkest lows, that make up contemporary life. He has also finished a screenplay for a film adaptation of “On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous.” The process required him to learn an entirely new genre of writing. “I’m most myself when I’m learning,” he said. “In martial arts, it’s called the white-belt mentality. So even if you have a black belt, the black belt starts to corrode and dissolve if you don’t approach the art as a white belt.”

Vuong spoke from his apartment in Manhattan, where he is currently a Distinguished Writer in Residence at N.Y.U. He will join the faculty of N.Y.U.’s Creative Writing M.F.A. Program.

I know that you’re enthusiastic about teaching. I’ve always wondered how you balance writing with teaching. Can you do both simultaneously?

I learned that I can’t write and teach. I can only go a hundred and ten per cent. That’s my only register. And so I give all to the students, and then I have nothing left for my work. It’s important to keep them separated.

Do you feel the need to give students written feedback that is as measured and thoughtful as your creative work?

I think my approach with my work and my teaching is just a disposition of mine, and it works really well in those avenues. It doesn’t work well, you know, at home. [ Laughs .] My mode is thoroughness at all costs. Whether it’s my fiction or my poetry, I just go over it again and again, I make sure I did everything I could, I play devil’s advocate with myself. Same with my students. I tend to over-teach . . . not that I’m giving them more knowledge than they need, but I teach beyond the point of what’s relevant. It may have something to do with growing up bilingual and seeing your elders, who are so powerful to you, not being heard. I think I internalized a lot of that, where I just think, Am I being heard?

As a teacher, it’s really good because I just stop for like fifteen minutes and go on a huge digression, I give them all the sources they can read up on to help this one point. And they love it. It exhausts me, but I don’t know any other way. I just have to do it that way, but I’m starting to think it might be because I worry about not being understood, because I’ve seen my family have that verbal invisibility throughout their lives.

That’s really interesting. I find myself sometimes stressing out about writing student feedback in a way that I don’t feel stress when writing professionally. And I think maybe it does come out of some insecurity about my authority. And I’ve sometimes wondered if everyone carries that with them, or whether it does have to do with lineage or not having those models of “visibility” you’re describing.

I don’t think of it as correcting their work as they hand it in but as offering them tools to create the next version. It’s, like, what you’ve done is what you’ve done. It’s there, it’s “finished,” and you have it. We’re gonna build the blueprint for the next draft. And so I just go all in. It doesn’t really undo what they’ve done. You have what you have. Here’s the future—if you want it. Another way to go about it. I just dump everything onto that stage. And then you hand it to them, and you can only wish them well in what they wanna do with that.

You grew up in the Northeast and you’ve lived in western Massachusetts for the past few years. You went to college in Brooklyn, you lived in Queens, and this semester you’re in Manhattan. Do you find your writing is different based on where you find yourself?

You would think so, but I couldn’t pinpoint it. I thought about this a lot, because I’ve been so transient in my career so far—I haven’t been able to find a place and hunker down. Even while I was in New York, we kept moving neighborhoods. I can work literally anywhere. It’s actually my only skill. I have this ability to have an O.C.D. approach to reading and writing. I have this uncanny ability to just dive in, to go into la-la land. And maybe it’s because I grew up queer and poor in a very rough environment. It was the power to escape. The imagination was a portal. It was my time machine. It was my everything. By now I’m just so good at it that I could literally write anywhere other than maybe a techno club or something.

What is the weirdest place you’ve written something that you’ve ended up using?

There was a Popeyes around Fourteenth Street that I would always go to. They had a corner seat and it was always open. Because it’s a franchise, it was almost like you don’t have to think about your surroundings. I wrote a lot in a Popeyes in Manhattan.

I’m surprised more people don’t do that. Most people write in cafés, but I always find the preponderance of other people writing to be off-putting. You look over, someone’s working on a screenplay, someone else has track changes open. But if you’re at a McDonald’s or a Popeyes, it can be a pretty tranquil environment by comparison.

Yeah. Because no one cares. And also, if you’re reading, it’s almost like kryptonite in that space. It’s, like, no one wants to go to a Popeyes to have anything to do with work. They go there to get Popeyes and go on their way. It’s very transient. When you are static in that space, you realize that you almost become invisible. The location absorbs you, which is a wonderful way to work. I used to do that also in the food court in the New World Mall, in Flushing.

Your writing has always shown a lot of awareness to the world around it. I’m not a student of poetry, so maybe I’m drawn to these very obvious, basic things about your work. I don’t have the technical language for it. But I love how you borrow so much from the language of our time—in “Time Is a Mother,” there is a reference to the singer Ashanti, a poem that is essentially an Amazon shopping list, another that captures the rhythm of an AOL chat. What do you want us to recognize about everyday speech?

This is my proudest book. Usually, at this point in publication, I regret everything. If I could get another shot at it, delay the book for two years, I’d take it. Happened with the novel, happened with the poems. But this time I feel really happy in that, as an artist . . . I don’t know if it’s good or “successful,” but I feel like I didn’t compromise anything. And I got to do what I’ve always wanted to do, which is to embrace all linguistic registers that are contemporaneous to me.

I played with that a little more in the novel, but I certainly did not have the courage or the chutzpah to do it in “Night Sky.” “Night Sky” dealt with a lot of family inheritance of stories. It was material that I was inheriting, and I couldn’t make it too affecting. I didn’t want to use too much linguistic altering . . . it had to be austere. That was my decision. I didn’t want to laugh at it, at the risk of a white audience laughing with me, and thereby laughing at something I never experienced, the trauma of my elders. It was a fine line, and I couldn’t risk that. It was a very sombre book, but it didn’t feel like what I was capable of. It’s a very classic début book, in that I showed all the tools that I learned to get a seat at the table. The sharp imagery, the metaphor, the restraint. I showed the long poem, I showed the short lyric poem.

Were you conscious at that time that you were following this formula for a “début book?”

I think so. ’Cause I’m such a student, I love being a student of the form. I put the references in and I kind of just followed the models of my elders. But it was a very insecure book. It was kind of, like, Do I belong here? Do I really have this?

In the new book, one of the voices that you take in is that of your cousin Sara, in the poem “ Dear Sara ,” when she questions the point of writing at all. She asks, “What’s the point of writing if you’re just gonna force a bunch of ants to cross a white desert?”

She’s a genius. She’s gonna be, like, a senator one day. She’s twelve. And when she said that she was just seven, and I was trying to show her how to write. She was actually trying to get out of it. The rhetoric is that this doesn’t matter. At the time, I was stumped. [ Laughs .] You know, I was just, like, “Oh, my god, O.K. All right. Well . . . let’s go get ice cream!”

But it haunted me. I was, like, Oh, my god, here I am doing this thing, and . . . I’m a tyrant! She gave me this perspective . . . I’m a tyrant of insects. And [the poem] was this long rebuttal and it was an embrace at the same time. The rhetoric of the poem is that “you’re right, what are we doing?” And I think there was ultimate sympathy with the desire of a child that wants to live and stay in childhood. Who cares, at the end, about language? Just go out there and play. As we grow older, we just cherish that. I don’t remember moments of reading as much as I remember moments of embodying the world and space. In a way, she really helped me think of that. And the poem negotiates, and earns, her position. I wanted to earn a shared experience with her, earn my agreement with her rather than just say, you know, you’re right or wrong.

In this case, you were clearly mulling over Sara’s provocation. In other cases, where do you begin writing a poem? Is it a word, an image, an idea?

Every poet could probably tell you something different, but for me there’s two general modes. One is the poem of the premise, and the other is the poem of the line. The line is similar to a jazz riff. You have a good line and then you try to build on that. It’s much more playful, it’s much more exploratory. The poem “Almost Human” is like that. I started with this line: “I come from a people of sculptors whose masterpiece was rubble.” And I was, like, “Wow, how do I use that line?”

A premise poem is like the “Sara” poem. I’m gonna retort and explore this statement. And I knew that I wanted to find common ground with her. That was my goal, similar to an essay or even a chapter in a novel. It’s, like, where are we gonna end up at the end of this chapter? Is there gonna be a divorce? How do we engineer that? There’s “American Legend,” which is another premise poem. Two Asian Americans are gonna do this quintessentially American thing. A father and son driving a Ford to put down their dog. It’s so suburban. I was very interested in putting Asian American bodies in mundane American acts, almost to the point of boredom.

There’s another poem, “Old Glory,” where you recount all these everyday phrases (“Knock ’em dead,” “I’d smash it/ good,” “You truly/ murdered”) that remind us how much of our speech is casually inflected with violence.

That poem was very uncomfortable to write and even to read. It’s a found poem: you take these pieces and put them together. I wanted to do something that only the poem could do. Only the poem could show us that. We hear these phrases all the time, we might even say some of these phrases, but they’re diluted in the larger context, and they come at us sporadically through the day, through the media, different voices say them. We don’t notice them. But then, when we take out all the other context and just stack them together, it becomes brutal in its truths.

I was trying to explain this to my aunt, this lexicon of American violence, and she was utterly horrified. She’s, like, “Why would they use those words?” ’Cause in the Vietnamese context—and it might be similar to Chinese—words are like spells. If you talk about death, death visits you, so you don’t talk about death at the dinner table. There’s a lot of taboo around speech and how it brings forth the darkness. And so, for my aunt, it was totally foreign to her, you know? That’s what I wanted to create. I wanted to create a foreign experience of something very familiar.

Right. In Chinese, there are homophonic puns, so that in Mandarin the word for “four” sounds like the word for “death,” and the number is tainted by association. So even the word for a number conjures something taboo.

Chinese and Vietnamese culture is so much older than America. And I think, in this sense, America is still immature. I would argue that the way it renders and handles language is still quite primitive for a nation and a culture that has so much technological prowess. It’s actually quite archaic in how it imagines the capacity of language, and, and in this sense, Chinese and Vietnamese culture are way ahead, both in the time line, but also culturally, in their wisdom. On good days, I believe that America might end up with that wisdom eventually. We often see these foreign countries as “behind,” but we only measure that in G.D.P. and technology. But when it comes to the spiritual wisdom of how to handle something like language, Vietnam is way ahead, and I hope America catches up one day.

You mentioned that, in your first book, “Night Sky,” you weren’t yet ready to bring in these different registers. Were you already thinking about how to do this, and you just weren’t publishing those works, or were you not yet at a level of artistic maturity where you felt like you could do it?

I just didn’t have the courage. Writing a book of poems is a wonderful education for a young writer because it forces you to keep finding new registers. It also forces you to find more premises. A book of poems . . . thirty, thirty-five poems, right? That’s thirty, thirty-five ideas. A novel, maybe one or two ideas expanded through plot and time and character. But when it comes to poems, you can’t really repeat [the premise] over and over. You gotta find completely different angles. And then you gotta find different registers, tones, styles, modes, forms. I was happy enough, but it was only about sixty per cent of what I really wanted to do at the time.